Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Advances in Machine Learning for Explainable Intrusion Detection Using Imbalance Datasets in Cybersecurity with Harris Hawks Optimization

1 Artificial Intelligence & Data Analytics Lab, CCIS, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Computer Sciences, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Amjad Rehman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068958

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 12 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Modern intrusion detection systems (MIDS) face persistent challenges in coping with the rapid evolution of cyber threats, high-volume network traffic, and imbalanced datasets. Traditional models often lack the robustness and explainability required to detect novel and sophisticated attacks effectively. This study introduces an advanced, explainable machine learning framework for multi-class IDS using the KDD99 and IDS datasets, which reflects real-world network behavior through a blend of normal and diverse attack classes. The methodology begins with sophisticated data preprocessing, incorporating both RobustScaler and QuantileTransformer to address outliers and skewed feature distributions, ensuring standardized and model-ready inputs. Critical dimensionality reduction is achieved via the Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) algorithm—a nature-inspired metaheuristic modeled on hawks’ hunting strategies. HHO efficiently identifies the most informative features by optimizing a fitness function based on classification performance. Following feature selection, the SMOTE is applied to the training data to resolve class imbalance by synthetically augmenting underrepresented attack types. The stacked architecture is then employed, combining the strengths of XGBoost, SVM, and RF as base learners. This layered approach improves prediction robustness and generalization by balancing bias and variance across diverse classifiers. The model was evaluated using standard classification metrics: precision, recall, F1-score, and overall accuracy. The best overall performance was recorded with an accuracy of 99.44% for UNSW-NB15, demonstrating the model’s effectiveness. After balancing, the model demonstrated a clear improvement in detecting the attacks. We tested the model on four datasets to show the effectiveness of the proposed approach and performed the ablation study to check the effect of each parameter. Also, the proposed model is computationaly efficient. To support transparency and trust in decision-making, explainable AI (XAI) techniques are incorporated that provides both global and local insight into feature contributions, and offers intuitive visualizations for individual predictions. This makes it suitable for practical deployment in cybersecurity environments that demand both precision and accountability.Keywords

An intrusion detection system is the privacy, confidentiality, or integrity of computer resources. As cyber threats become more sophisticated and complex, IDSs are increasingly important for detecting unauthorized access, misuse, or anomalies in the network environment [1]. IDSs are generally divided into two main types: sequence-based detection and parameter-based detection. Intrusion detection relies on known attack patterns to detect attacks but cannot address zero-day attacks. Anomaly-based IDSs can identify deviations from normal behavior and are powerful in detecting unknown threats [2]. However, the large size of network data, the need for real-time processing, and the complexity of interpreting ML results pose significant challenges to effective use. Therefore, detection should not only be designed to identify known and emerging threats but also provide transparency and scalability. Intrusion detection serves as the primary defense against a variety of attacks in the context of cybersecurity. From malware to advanced threats and insider threats [3], the proliferation of cloud computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), and 5G networks has increased the attack surface, making networks more vulnerable. Today’s email campaigns are multifaceted and automated and challenge traditional security protocols. It is essential to be aware of a variety of malicious behaviors, including denial of service (DoS) attacks, privilege escalation, and command and control (C2) attacks [4]. Attackers are also using techniques such as masking, blocking, and tunneling to evade detection. These new threat models require intelligent recognizers that can learn from small data, adapt over time, and detect hidden patterns.

Intrusion detection has been an essential component of network security for a considerable amount of time. Its primary function is to identify individuals who are gaining unauthorized access to protected private networks. The ability to quickly discover security policy breaches, invasions, or attacks within a network or host system is precisely what an intrusion detection system, often known as IDS, is capable of doing. Prior to the investigation of deep learning techniques such as CNN, LSTM, and auto-encoders, the primary focus of the research was on the incorporation of traditional machine learning models, such as decision trees, and support vector machines, into IDS that were already in operation. There are still significant difficulties connected with putting these insights into practice in actual systems, despite the fact that they are quite effective in identifying problems [5,6].

AI and ML can boost IDS efficiency and effectiveness. In vital applications like national security, finance, and healthcare, these models must be accurate and intelligible to be successful and dependable. Class imbalance is a major issue in ML-based IDS development. The total classification outperforms the ideal classification on available datasets [7]. Weak performance might result from quick classifications that operate well on most datasets (malicious incursions) but not on small datasets (attacks). Many public IDS datasets are obsolete, erroneous, or don’t cover all attack paths. Interpretation difficulties matter too. Cyber security researchers find it challenging to comprehend the underlying principles of many machine learning models, particularly deep learning frameworks, which are sometimes referred to as “black boxes.” The lack of clarity might limit their practical use, particularly in circumstances requiring simplicity and dependability [8]. Scalability, data integration problems, and the requirement to continuously adjust to new attack techniques are additional significant challenges. Complexity makes it hard to balance performance, scalability, and resource efficiency in IDS systems. Numerous systems need scalability while avoiding false positives and operating expenses, particularly in crucial locations like data centers and cloud infrastructure [9,10]. Contributions of this study include:

• This study proposes an explainable intrusion detection system using a stacked ensemble of machine learning classifiers via random forest meta-learners.

• The study deployed advanced preprocessing strategies to clean the IDS data, including incorporating a robust scaler and quantile transformer.

• The novel modified Harris Hawks optimisation algorithm is used to select the best and relevant features for intrusion detection.

• The dataset is heavily imbalanced; we used synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) to address the issue of class imbalance only on training data.

• We use the XAI techniques to create intuitive visualisations for individual predictions. This advantage makes it suitable for practical deployment in cybersecurity environments that demand both precision and accountability.

The remaining part is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the literature survey, Section 3 describes the proposed methodology, Section 4 explains the results and discussion, and finally Section 5 ends with a conclusion.

The authors used deep learning (DL) techniques at the payload level in an HPC environment was commendable. On top of that, they recommended an excellent CNN-LSTM model based on SFL. AI-IDS have the ability to distinguish between typical and suspicious HTTP traffic, a capability that was previously unavailable in prior signature-based NIDS [11]. The datasets used for training and testing the model, NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB 15, are easily accessible. The DNN model was trained using the same dataset, followed by the Convolution Neural Network (CNN) model. The analysis of both datasets indicated that the deep learning (DL) model performed better [12].

The KDD Cup 99 dataset was employed to investigate and assess an AI intrusion detection system that was constructed on DNN. In response to the dynamic nature of network hazards, they implemented this measure. The model demonstrated exceptional performance when employed for intrusion detection [13]. This study suggested the implementation of IDS through the use of ML techniques, including support vector machines (SVMs), random forests, and decision trees. After training these models and implementing an ensemble approach vote classifier, they attained a success rate of 96.25% [14]. The objective of the research [15] was to create a deep learning system that can identify instances of social media infiltration by categorizing server data using SVM.

The Big Data Hierarchical Deep Learning System was one of the systems that the authors proposed [16]. This method may be capable of detecting intrusive attacks more frequently than previous methods that were dependent on a singular learning model. They concluded by comparing the relative efficacy of our state-of-the-art models to the most recent models on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset [17]. Additionally, they implemented the classification and regression tree model to ascertain the features’ importance. When the authors’ CNN-based approach was paired with channel attention, it obtained an outstanding accuracy rate on the NSL-KDD dataset. When compared to alternative approaches, such as adaptive algorithms, hybrid auto-encoders combining CNN, MCNN, and ANN, and ensemble learning utilizing CNN, RBM, and ANN, their solution considerably enhances the performance of intrusion detection [18]. Two improved intrusion detection systems (IDSs) based on DL and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) were the subject of another investigation. By decreasing dimensionality and improving detection accuracy, these systems aim to improve feature selection. To test the suggested systems, they used the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets, which are typical of modern network settings [19].

The authors had discussed the idea of XAI to enhance trust management by examining the decision tree model in the field of IDS. In IDS, They employed straightforward decision tree algorithms that mimic human decision-making by dividing the overall option into numerous smaller ones and are thus easier to understand and work with [20]. The authors used NIDS as a standard to compare two directed ML methods, SVM and Deep Neural Networks. They used the NSL-KDD dataset to test the suggested method for this reason. The test results indicate that DCNN was more accurate than SVM [21]. To address the issue of unequal data, authors employed a cutting-edge generative model to generate highly convincing false data and assess the training process. On the NSL-KDD dataset, the proposed models achieved an accuracy of up to 93.2%; on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, it was 87%; and the minor classes performed quite well [22]. The authors suggested a novel approach to detecting DDoS assaults by combining various forms of machine learning. By integrating SVM with K-means-grouped Radial Basis Function Networks, their approach enhances spotting speed and accuracy. They had the most success while testing with the CICDDoS2019 and CICIDS2017 datasets [23]. The authors concluded by applying the suggested framework to two benchmark datasets, UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD99, which display different network properties and attack scenarios [24]. The summary of the structured comparative analysis is shown in Table 1.

Preprocessing that is thorough and smart is the first step in building an effective machine learning pipeline. In this study, preprocessing was carefully planned to deal with both the many forms of data and the statistical problems that the dataset posed. The dataset has both numbers and categories, which is common in datasets for network infiltration. Categorical properties like protocol_type, service, and flag are important for understanding how a network works, but they need to be changed into a form that machine learning algorithms can understand. Label Encoding was used on each categorical variable to turn them into integer labels that stand for different categories while keeping things simple and easy to understand. The proposed workflow is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

In Eq. (1),

In the real world, network data is generally complicated, with big outliers and uneven distributions, especially when it comes to things like byte counts or connection times. We used two complex scaling approaches one after the other to deal with these problems. First, RobustScaler was used to lessen the effect of outliers. In Eq. (2),

This scaler changes the data depending on the interquartile range (IQR), which is the range between the 25th and 75th percentiles. RobustScaler keeps the central tendency of the data while lowering the effect of outliers. In Eq. (3),

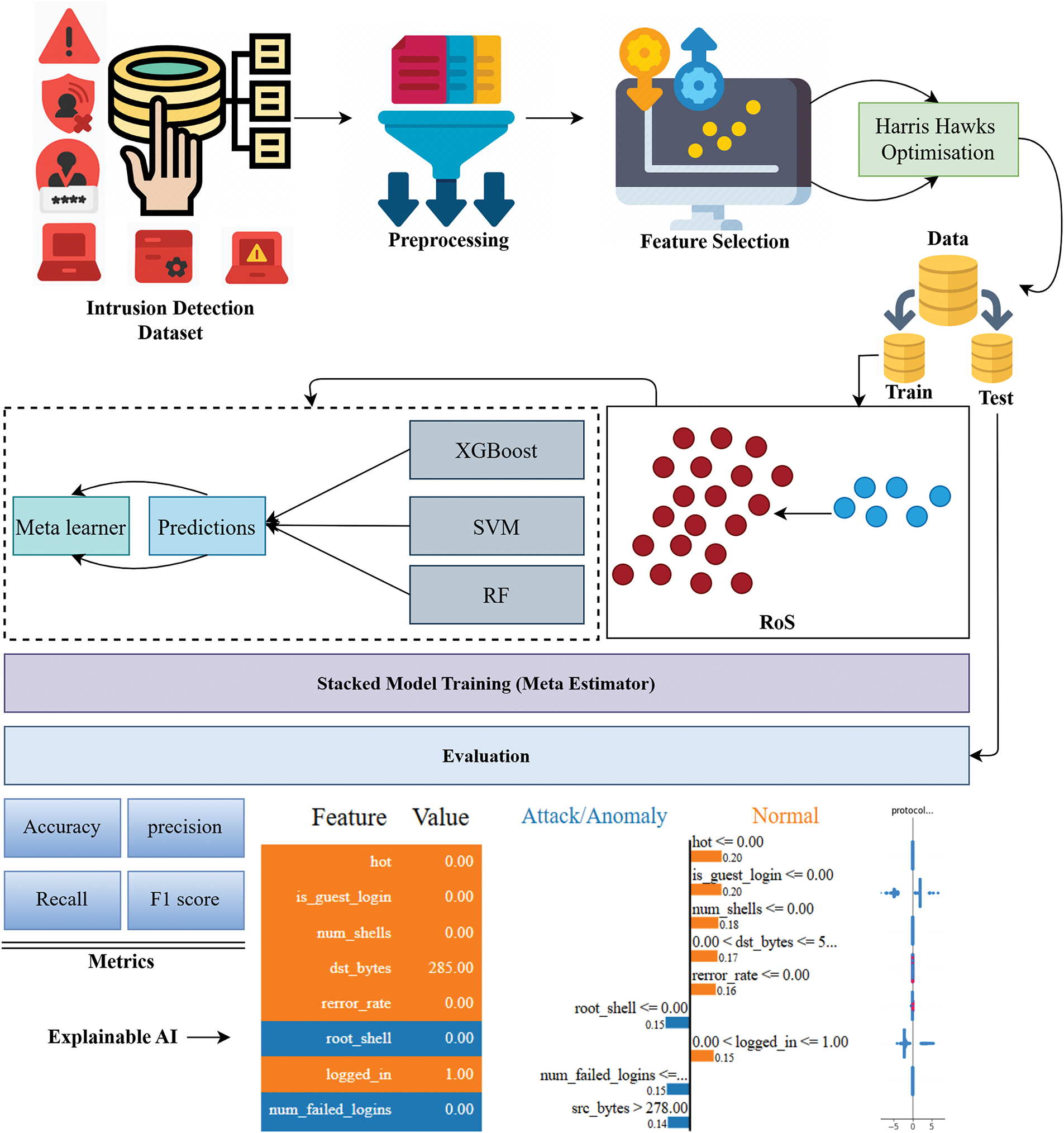

This is different from typical normalisation algorithms, which can be substantially distorted by extreme results. After then, QuantileTransformer was used to change the data distribution even more. This transformer changes the distribution of each feature so that it follows a normal or Gaussian distribution. This kind of modification is especially useful for models that assume features are regularly distributed. It also speeds up and improves the accuracy of training that comes after it. The proposed methodology is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Proposed Methodology for IDS

After scaling and transforming the data, the next important step is to choose the best features. We used the Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) method, which is based on the intelligent hunting behavior of Harris hawks, to improve performance and make the calculations easier. This program mimics several stages of predator-prey interaction. It changes its strategy on the fly to either search the space broadly or use known good answers. In our case, each possible solution (or “hawk”) is a binary string that shows which features to include. A lightweight model, like a random forest, trained on the chosen features is used to rate each hawk’s fitness based on how well it classifies things (usually accuracy). Hawks change their positions during each iteration based on methods like surprise pounce, soft besiege, and hard besiege. An energy parameter that gets lower over time makes sure that the hawks all end up in the same place. HHO then uses the best feature subset to train the final ensemble model.

After choosing the features, we used stratified sampling to keep the class proportions the same and split the dataset into training and testing subsets. A major problem with attack detection activities, meanwhile, is that some types of attacks are substantially less common than others. To fix this, we used the SMOTE method on the training set. SMOTE makes copies of instances of minority classes to make the number of majority class samples equal, which balances the class distribution. Undersampling throws away data that could be useful from the majority class, whereas SMOTE keeps all of the original samples and adds to the minority ones. This method makes the model better at learning from infrequent patterns and improves recall on classes that aren’t well represented. This is very important in security applications, where missing an attack can be quite bad.

Stacked ensemble learning is a sophisticated modeling technique that integrates the prediction strengths of various algorithms to enhance accuracy and dependability. This work employs a stacked ensemble approach utilizing three distinct models: XGBoost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF), complemented by a meta-classifier that amalgamates their outputs to render the final conclusion. Every one of these foundation learners has its own strengths. XGBoost is a gradient boosting system that works well with non-linear patterns and missing values. It often gives good results on structured datasets because it is optimized for speed and accuracy. Random Forest is a group of decision trees that uses bagging to make them more stable against noise and high variance by averaging several decision routes. The SVM with an RBF kernel, on the other hand, works best in high-dimensional environments and is great at finding complex class borders via kernel-based transformations. In Eq. (4),

There are two steps to the stacking process. In the first step, each base model is trained on the training data by itself. After that, the predictions are put together to make a new feature matrix, with each column representing the predictions from one of the underlying models. In the second stage, a meta-classifier learns from this new feature matrix. The Random Forest classifier is chosen as the meta-learner because it is stable, can handle non-linear correlations, and can be understood. The meta-model figures out which model works best in certain situations by learning how to best mix the outputs of the base learners. For instance, the SVM might work better when the classes are well-separated, while XGBoost might work better when the data is noisy or uneven. The meta-learner finds these strengths and gives each model’s predictions the right amount of weight, so the final conclusion is based on the best of all three methods. Once the entire stacked model has been trained, the test data is used to see how well it works. The base models provide predictions for each test instance, which are then sent to the meta-classifier to get the final output. This design, which is based on models working together, frequently cuts down on generalization errors and makes predictions much more accurate. Train M base models on the training data: In Eq. (5),

Generate predictions for both training and test data using each base model. In Eqs. (6) and (7),

In Eq. (8), train a meta-learner

In Eq. (9), the final prediction for a new test instance is determined as:

One of the best things about stacking is that it balances out the effects of bias and volatility. Random Forests reduce variance, XGBoost reduces bias, and SVM adds strength to decision boundary creation. The fact that these base learners are so different from one other, with tree-based models and kernel approaches, means that their mistakes are mostly uncorrelated. The meta-classifier takes advantage of this by figuring out how to combine their outputs in a way that works best on data it hasn’t seen before.

This section provides the experimental results for IDS using stacked ensemble model. We evaluate the model performance using accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score metrics. These are very important in machine learning classification tasks.

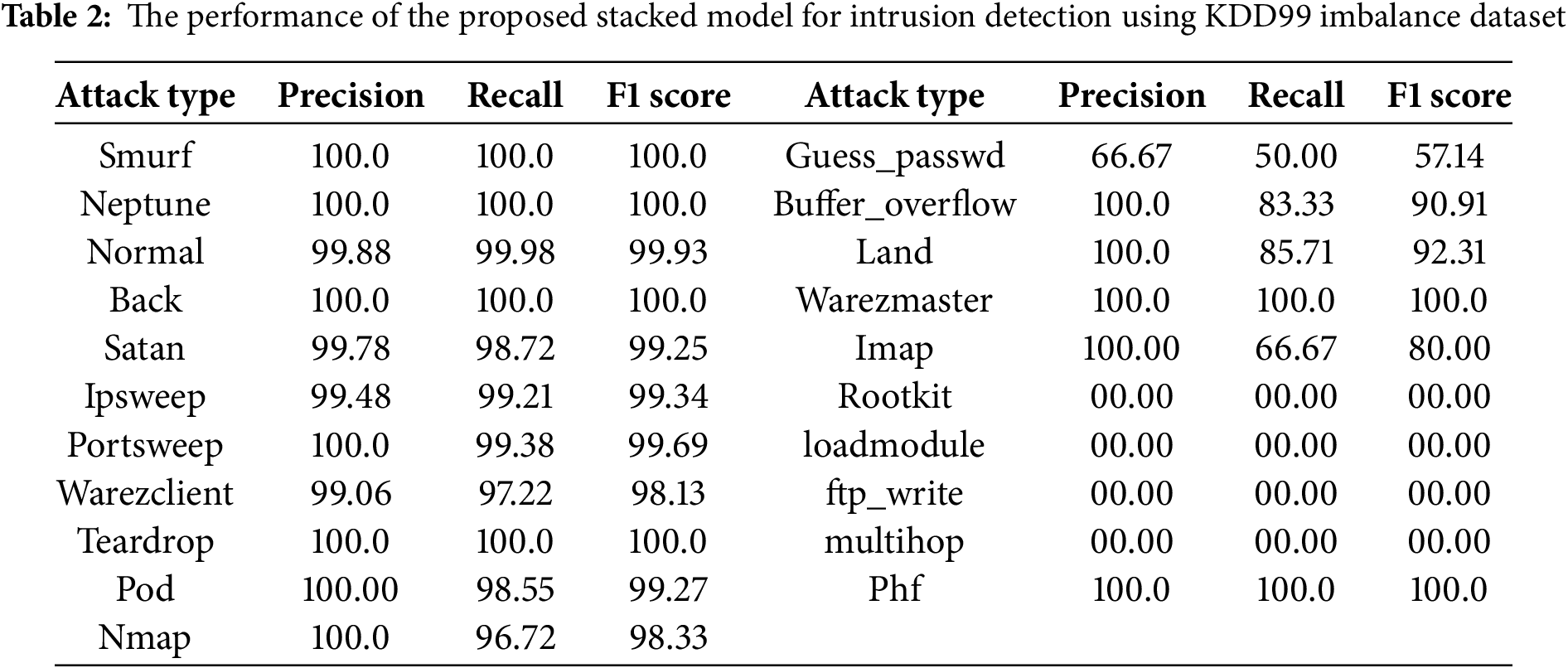

The performance of the proposed stacked model for intrusion detection using KDD99 imbalance dataset is shown in Table 2. The results of the evaluation of the classification model on the KDDCup99 dataset show that it works well generally, especially for high-frequency attack types. However, it has trouble finding unusual or subtle threats. Denial-of-Service (DoS) assaults including smurf, neptune, and back got flawless precision, recall, and F1 scores, with thousands of right predictions and no mistakes. This shows that the stacked model is quite good at finding the most important patterns in the training data. The model also did very well with regular traffic, getting almost perfect scores, which means that there weren’t many false positives in benign circumstances. There were a few minor misclassifications of other assaults, like satan, ipsweep, portsweep, and warezclient. Even more worrying, a collection of low-frequency or stealthy assaults, like rootkit, load module, ftp_write, and multihop, were not found at all, with no precision or recall. These failures show that the model couldn’t learn useful patterns for unusual classes, probably because there weren’t enough examples of those classes during training. Attacks like guess_passwd and buffer_overflow had varied outcomes, with some being detected and others being misclassified a lot.

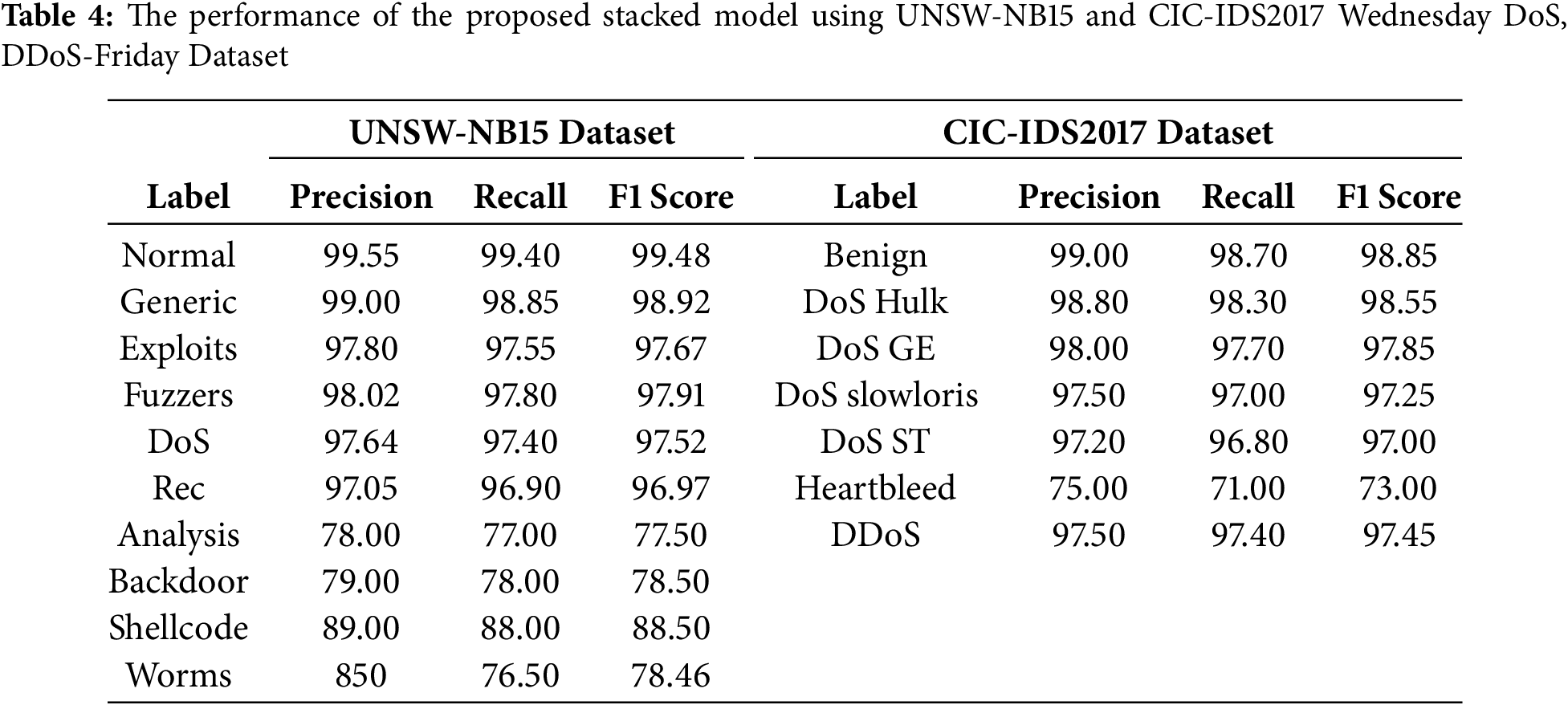

Table 3 shows the performance of the proposed stacked model for intrusion detection using KDD99 balanced dataset. To address class imbalance and reduces the chances of overfitting we applied SMOTE on training data. After applying SMOTE, the model achieved best training and when we evaluate on the test data it shows superior performance. For smurf, neptune, back, teardrop, pod, nmap, warezmaster, phf, perl, and spy type of attack, model achieved 100% performance. For rootkit, multihop, load module, the model achieved poor results approximately 50%. While, other attacks achieved better results above 80%, in respect with precision, recall and F1 score. The performance of the proposed stacked model using another dataset is shown in Table 4 where Reconnaissance (Rec), DoS GoldenEye (DoS GE), DoS Slowhttptest (DoS ST) are some attack labels.

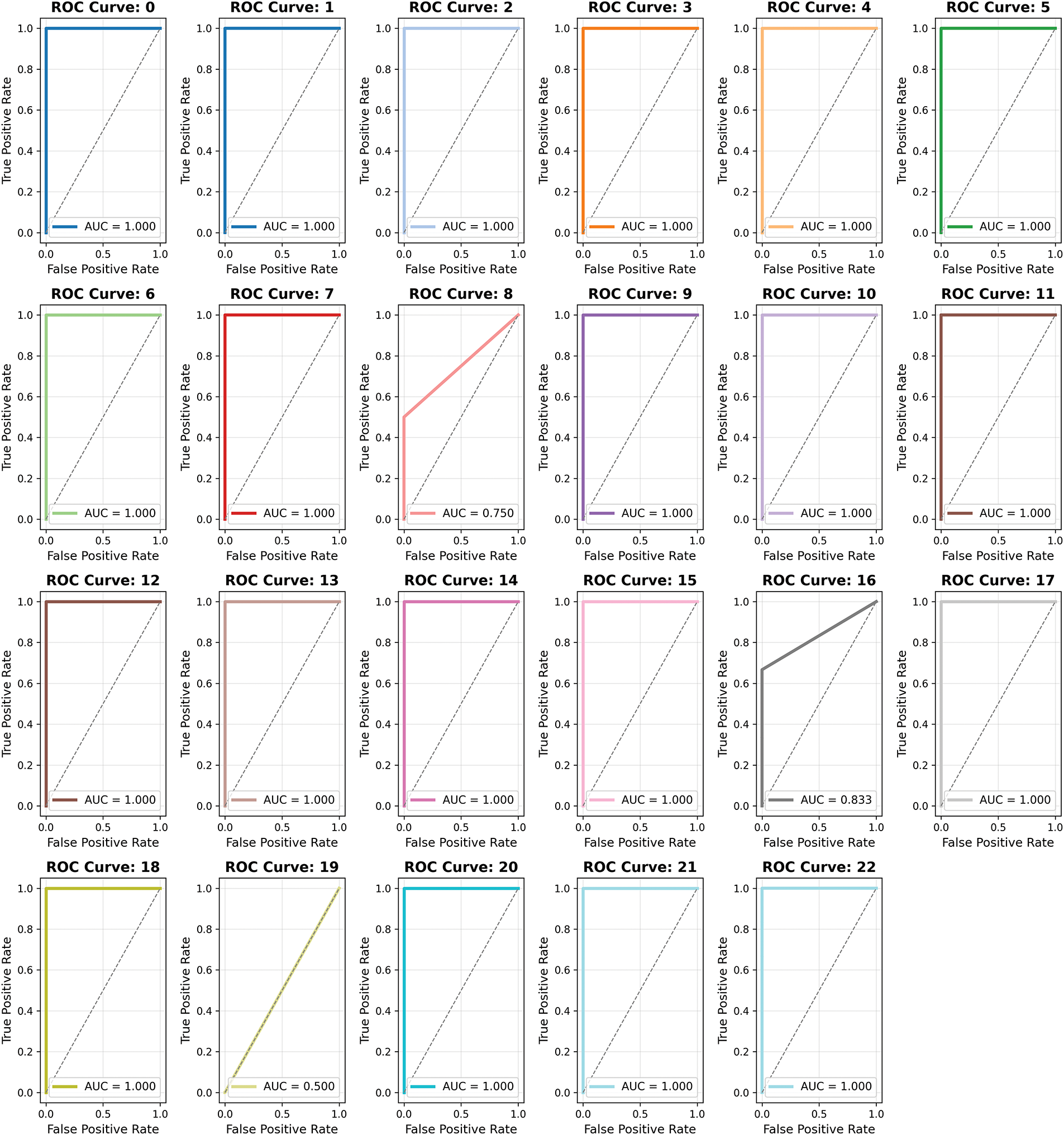

Fig. 2 shows the ROC-AUC of the proposed stacked model using KDD99 IDS balanced dataset. We evaluated the performance on a particular test data set following the model’s training. We conduct a more thorough examination of the classifier’s performance by generating a ROC curve and establishing performance metrics. In order to enhance classification accuracy, we either determine the threshold or evaluate the classifier’s performance in the domains of high sensitivity and specificity. The ROC curve demonstrates that a corresponding pair of TPR and FPR values exists at each point for any given threshold value. Altering the threshold value enables us to identify a variety of TPR and FPR values. Subsequently, the pairings are employed to generate a ROC curve. The all attacks are with AUC are plotted. Using balance data, the stacked model achieved outclass results for attacks. During training some attacks that had very less number of samples are got good AUC score.

Figure 2: ROC-AUC of the proposed stacked model using KDD99 IDS balanced dataset

To improve model interpretability, SHAP (SHAPley Additive Explainability) was used to evaluate the contribution of individual components to the classification results. The SHAP summary shows that features such as protocol, service had a significant impact on the model’s predictions.

To illustrate spatial flexibility, the DoS attack model flowchart was examined. The model initially assumed a neutral order, but the presence of high src_bytes and counts shifted the predictions toward the “attack” sequence. The SHAP values for each feature contributed equally to the final prediction, allowing us to assess which specific input features led to the final classification. The explainability of the proposed stacked model is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The explainability of the proposed stacked model (a) SHAP interaction value (b) Waterfall plot

This descriptive capability provides valuable insights for security professionals. By understanding the factors that influence a person’s decision, researchers can predict conversion rates, correct false positives, and improve claims. Furthermore, definable AI techniques like SHAP improve the reliability and accuracy of automated identifiers, making them suitable for use in real-world cybersecurity environments.

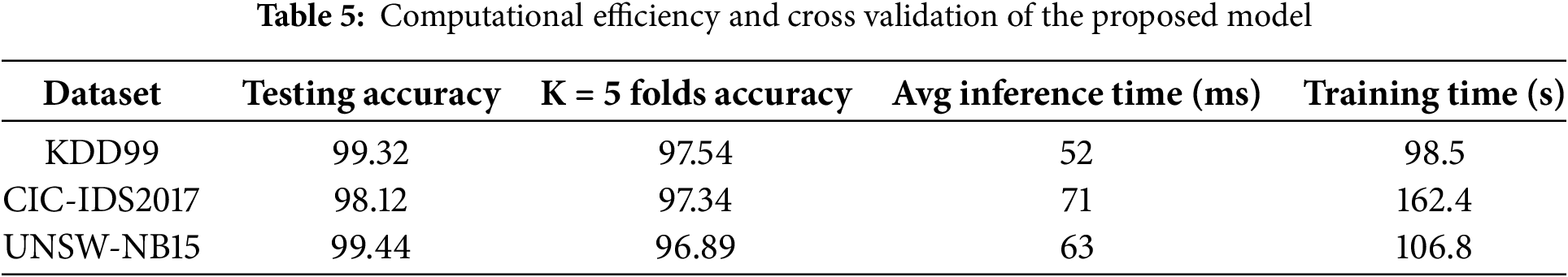

The proposed model demonstrates the computational efficiency using three datasets in Table 5. During the training phase, the average Inference time of the whole model, including feature selection (HHO), SMOTE, and classification, is about 52 ms on a computer with 16 GB RAM and an Intel i7 processor for KDD99 dataset. The training time is about 98.5 s, making it suitable for odor detection in near real-time. The feature selection approach increased the feature retrieval rate, but also significantly improved the accuracy and generalization of the model. Using UNSW-NB15 dataset, the inference time is 63 ms and training is 106.8 s. We have implemented additional evaluation using 5-fold cross-validation. This method divides the dataset into five equal parts, using four folds for training and one for testing in each iteration, ensuring that every data point is used for both training and validation. The model achieved highest 97.54% accuracy for KDD99 dataset.

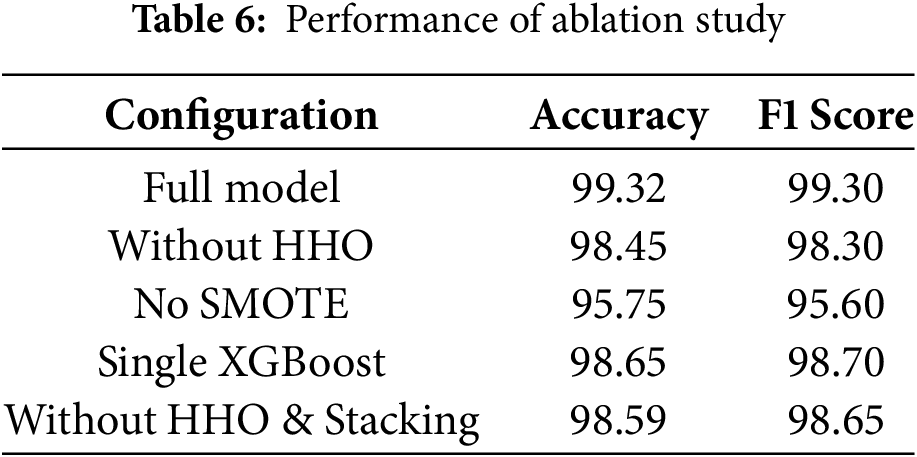

Table 6 shows the performance of ablation study. A validation study was conducted to evaluate the effect of each parameter on the proposed model: HHO feature selection, random identification, and feature extraction. By sequentially reducing one parameter at a time, we were able to observe changes in overall performance and F1 score. The overall model achieved an accuracy of 99.32%, while removing or stacking HHO resulted in a significant decrease in accuracy. The accuracy of the SMOTE approach was higher, which justifies the benefit of eliminating class imbalance. The analysis shows that each component contributes significantly to the improvement of the system.

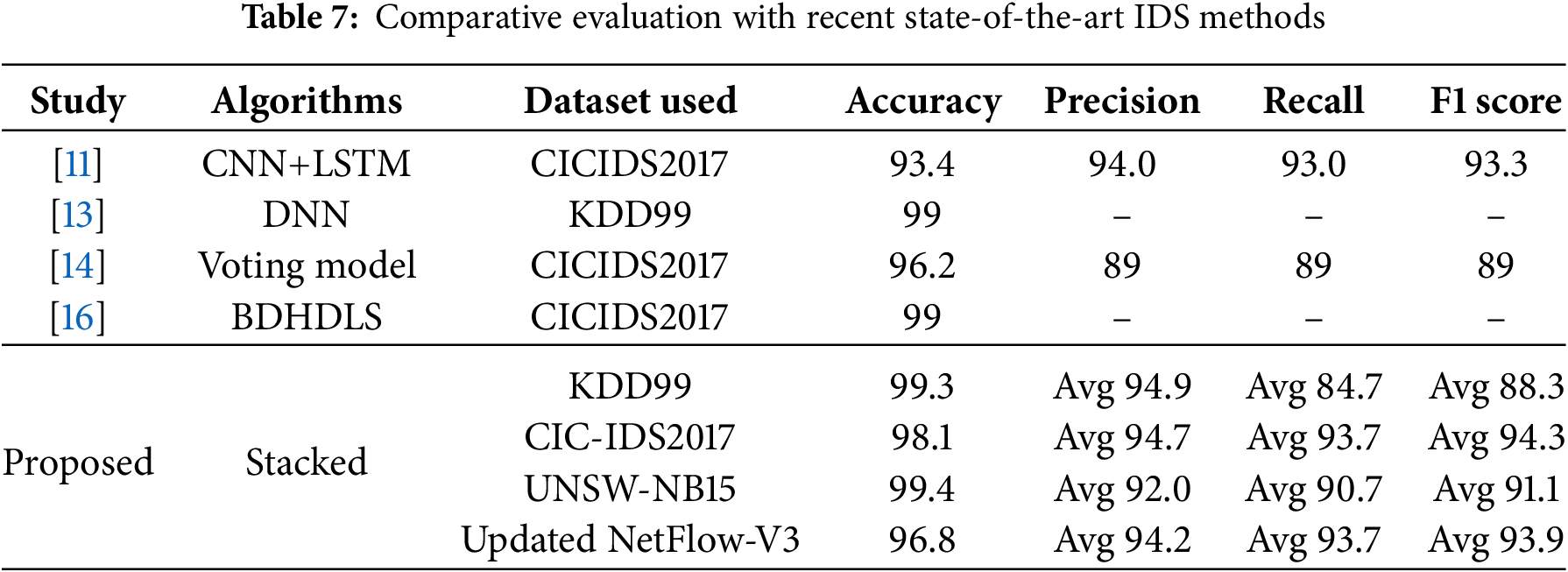

Table 7 compares our proposed model with several state-of-the-art methods using three popular datasets: KDD99, CICIDS2017, and UNSWNB15. The goal is to evaluate how well different models predict intrusions based on common performance metrics such as precision, accuracy, recall, and F1 score. Previous studies, such as CICIDS 2017 and the CNN + LSTM model [11], achieved 93.4% accuracy, while the voting model [14] achieved 96.2% accuracy, both of which have shown good performance but have not been published. Although some models, such as DNN [13] and BDH-DLS [16], have achieved high accuracy (up to 99%), they have not provided quantitative metrics such as precision or recall, making it difficult to accurately assess their actual performance.

In contrast, our proposed stacked model shows robust and consistent performance across all datasets. On KDD99, it achieves 99.3% accuracy, with an average F1 score of 88.3, which also performs well on traditional datasets. On the more complex CICIDS-2017 dataset, it achieves 98.1% accuracy and an F1 score of 94.3, which demonstrates high classification accuracy. On UNSWNB15, the accuracy reaches 99.4%, outperforming previous models in both accuracy and precision. Overall, the results show that our method is not only accurate but also well-defined for a wide range of datasets. Also, we did experiments using the latest NetFlow version 3 dataset that consists of multi-class attacks. The stacked model achieved 96.8% accuracy and 93.9% F1 score.

This paper presents a strong and comprehensive stacked ensemble intrusion detection strategy that addresses imbalanced datasets like KDD99 and IDS. The dataset is especially preprocessed using Robust Scaler and Quantile Transformer to handle outliers and skewed distributions. Harris Hawks Optimization chooses the most critical information for learning to improve input features. The stacked model is trained using both datasets and applied SMOTE on KDD99. The stacked ensemble approach improves prediction by combining the XGBoost, SVM, and RF greatest predictions. This approach prevents overfitting and underfitting, ensuring consistent results across network traffic types. The experiments show that the stacked model achieved 99.32% accuracy for the KDD99 multi-class attack dataset and 99.44% for the UNSW-NB15 dataset. The performance of the proposed approach is enhanced while using SMOTE on training data. The system also used XAI to show which input properties were most important in each detection. This information can help security teams trust the model’s decisions and interpret warnings.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R104), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are also thankful to Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia of APC support.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R104), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Amjad Rehman, and Tanzila Saba; methodology, Tanzila Saba; software, validation, Shaha Al-Otaibi and Mona M. Jamjoom; formal analysis, investigation, Shaha Al-Otaibi and Muhammad I. Khan; resources, Amjad Rehman; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, Amjad Rehman and Mona M. Jamjoom; writing—review and editing, Tanzila Saba; visualization, supervision, Tanzila Saba; project administration, Muhammad I. Khan; funding acquisition, Mona M. Jamjoom, Shaha Al-Otaibi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Khraisat A, Gondal I, Vamplew P, Kamruzzaman J. Survey of intrusion detection systems: techniques, datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity. 2019;2:20. doi:10.1186/s42400-019-0038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hairab BI, Said Elsayed M, Jurcut AD, Azer MA. Anomaly detection based on CNN and regularization techniques against zero-day attacks in IoT networks. IEEE Access. 2022;10:98427–40. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3206367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rizvi S, Orr RJ, Cox A, Ashokkumar P, Rizvi MR. Identifying the attack surface for IoT network. Internet Things. 2020;9(1):100162. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2020.100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gupta BB, Dahiya A. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks: Classification, Attacks, Challenges and Countermeasures. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC press; 2021. doi:10.1201/9781003107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mouatassim T, El Ghazi H, Bouzaachane K, El Guarmah EM, Lahsen-Cherif I. Cybersecurity analytics: toward an efficient ML-based network intrusion detection system (NIDS). In: Renault É., Boumerdassi S, Mühlethaler P, editors. Machine Learning for Networking. MLN 2023. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 267–84. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-59933-0_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Halbouni A, Gunawan TS, Habaebi MH, Halbouni M, Kartiwi M, Ahmad R. CNN-LSTM: hybrid deep neural network for network intrusion detection system. IEEE Access. 2022;10:99837–49. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3206425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Balla A, Habaebi MH, Elsheikh EAA, Islam MR, Suliman FM. The effect of dataset imbalance on the performance of SCADA intrusion detection systems. Sensors. 2023;23(2):758. doi:10.3390/s23020758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Alahmed S, Alasad Q, Hammood MM, Yuan J-S, Alawad M. Mitigation of black-box attacks on intrusion detection systems-based ML. Computers. 2022;11(7):115. doi:10.3390/computers11070115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khraisat A, Alazab A. A critical review of intrusion detection systems in the Internet of Things: techniques, deployment strategy, validation strategy, attacks, public datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity. 2021;4(1):18. doi:10.1186/s42400-021-00077-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Z, Xu B, Cheng B, Hu X, Darbandi M. Intrusion detection systems in the cloud computing: a comprehensive and deep literature review. Concurr Comput. 2022;34(4):e6646. doi:10.1002/cpe.6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kim A, Park M, Lee DH. AI-IDS: application of deep learning to real-time web intrusion detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8:70245–61. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2986882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sharma B, Sharma L, Lal C, Roy S. Explainable artificial intelligence for intrusion detection in IoT networks: a deep learning based approach. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(1):121751. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kim J, Shin N, Jo SY, Kim SH. Method of intrusion detection using deep neural network. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp); 2017 Feb 13–16; Jeju, Republic of Korea. p. 313–6. doi:10.1109/BIGCOMP.2017.7881684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Patil S, Varadarajan V, Mazhar SM, Sahibzada A, Ahmed N, Sinha O, et al. Ex-plainable artificial intelligence for intrusion detection system. Electronics. 2022;11(19):3079. doi:10.3390/electronics11193079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Abuali KM, Nissirat L, Al-Samawi A. Advancing network security with AI: SVM-based deep learning for intrusion detection. Sensors. 2023;23(21):8959. doi:10.3390/s23218959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhong W, Yu N, Ai C. Applying big data based deep learning system to intrusion detection. Big Data Mining Anal. 2020;3(3):181–95. doi:10.26599/BDMA.2020.9020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Thapa N, Liu Z, D.B. KC, Gokaraju B, Roy K. Comparison of machine learning and deep learning models for network intrusion detection systems. Fut Internet. 2020;12(10):167. doi:10.3390/fi12100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alrayes FS, Zakariah M, Amin SU, Khan ZI, Alqurni JS. CNN channel attention intrusion detection system using NSL-KDD dataset. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;79(3):4319–47. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.050586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Elsaid SA, Shehab E, Mattar AM, Azar AT, Hameed IA. Hybrid intrusion detection models based on GWO optimized deep learning. Discov Appl Sci. 2024;6(10):531. doi:10.1007/s42452-024-06209-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mahbooba B, Timilsina M, Sahal R, Serrano M. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to enhance trust management in intrusion detection systems using decision tree model. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6634811. doi:10.1155/2021/6634811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sistla VP, Kolli VK, Voggu LK, Bhavanam R, Vallabhasoyula S. Predictive model for network intrusion detection system using deep learning. Rev D’Intelligence Artif. 2020 Jun 1;34(3):323–30. doi:10.18280/ria.340310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Park C, Lee J, Kim Y, Park J-G, Kim H, Hong D. An enhanced AI-based network intrusion detection system using generative adversarial networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(3):2330–45. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3211346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Djama A, Maazouz M, Kheddar H. Hybrid machine learning approaches for classification DDoS attack. In: 2024 1st International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Telecommunication and Energy Technologies (ECTE-Tech); 2024 Dec 17–18; Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/ECTE-Tech62477.2024.10850919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Alrayes FS, Amin SU, Hakami N. An adaptive framework for intrusion detection in IoT security using MAML (Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning). Sensors. 2025;25(8):2487. doi:10.3390/s25082487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools