Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Intrusion Detection and Security Attacks Mitigation in Smart Cities with Integration of Human-Computer Interaction

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, College of Applied Studies, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abeer Alnuaim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069110

Received 15 June 2025; Accepted 01 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The rapid digitalization of urban infrastructure has made smart cities increasingly vulnerable to sophisticated cyber threats. In the evolving landscape of cybersecurity, the efficacy of Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) is increasingly measured by technical performance, operational usability, and adaptability. This study introduces and rigorously evaluates a Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)-Integrated IDS with the utilization of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), CNN-Long Short Term Memory (LSTM), and Random Forest (RF) against both a Baseline Machine Learning (ML) and a Traditional IDS model, through an extensive experimental framework encompassing many performance metrics, including detection latency, accuracy, alert prioritization, classification errors, system throughput, usability, ROC-AUC, precision-recall, confusion matrix analysis, and statistical accuracy measures. Our findings consistently demonstrate the superiority of the HCI-Integrated approach utilizing three major datasets (CICIDS 2017, KDD Cup 1999, and UNSW-NB15). Experimental results indicate that the HCI-Integrated model outperforms its counterparts, achieving an AUC-ROC of 0.99, a precision of 0.93, and a recall of 0.96, while maintaining the lowest false positive rate (0.03) and the fastest detection time (~1.5 s). These findings validate the efficacy of incorporating HCI to enhance anomaly detection capabilities, improve responsiveness, and reduce alert fatigue in critical smart city applications. It achieves markedly lower detection times, higher accuracy across all threat categories, reduced false positive and false negative rates, and enhanced system throughput under concurrent load conditions. The HCI-Integrated IDS excels in alert contextualization and prioritization, offering more actionable insights while minimizing analyst fatigue. Usability feedback underscores increased analyst confidence and operational clarity, reinforcing the importance of user-centered design. These results collectively position the HCI-Integrated IDS as a highly effective, scalable, and human-aligned solution for modern threat detection environments.Keywords

The rapid development of urban technology made the emergence of smart cities a reality, as higher-level systems and IoT devices enhance urban living quality. These smart infrastructures rely on real-time data collection and analysis to optimize traffic flow, energy grid distribution, and public safety. However, with the introduction of numerous IoT devices and complex networks, significant cybersecurity concerns arise, such as vulnerability to anomalies and malicious attacks. Anomaly detection is now a key component in identifying uncommon patterns that may signal security compromises or system failures within smart city environments. Traditional approaches do not work in defining the dynamic and complex nature of urban data. Thus, more emphasis is being laid on applying advanced technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and ML to enhance the detection and prevention of security threats [1]. Moreover, the application of HCI principles to smart city infrastructure is growing. HCI designs user-centric interfaces and interactions and ensures that the human aspect remains at the forefront in monitoring, decision-making, and responding to anomalies. By combining anomaly detection mechanisms with effective HCI strategies, smart cities can achieve a more resilient and responsive infrastructure [2]. The HCI-based conceptual scenario is given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Conceptual scenario of HCI in smart cities with attack mitigation

The growing use of IoT, cloud technology, smart city frameworks, and advanced information systems has transformed urban areas into unprecedented efficiency and innovation hubs. With these technologies’ new possibilities come new operational risks and cybersecurity concerns. Cyber-physical systems, and the services enabling them, usually come with weak or no security measures to defend against cyberattacks, data breaches, or system malfunctions. Although AI and machine learning have enabled smarter anomaly detection systems, many of them are too static, lack situational awareness, or do not have enough collaboration with human intelligence and governance. Moreover, the lack of effective HCI mechanisms limits the ability of system administrators, urban planners, and end-users to interact intuitively with anomaly detection platforms, hindering real-time understanding, response, and mitigation. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop an integrated framework combining intelligent anomaly detection with robust HCI design, enabling smart city systems to be autonomous and human-centric in detecting, interpreting, and responding to security threats. This study presents a novel approach to IDS by integrating HCI with advanced machine learning models, specifically CNN, CNN-LSTM, and RF. The key contributions of this research are as follows;

HCI-Integrated IDS Framework: Introducing an HCI-Integrated IDS for smart cities significantly improves technical performance with operational usability. This system improves detection accuracy and enhances user experience, addressing the crucial issue of alert fatigue among analysts.

Comprehensive Evaluation Framework: This study employs a rigorous experimental framework that evaluates the performance of the proposed HCI-Integrated IDS against traditional machine learning and baseline IDS models. It assesses a wide range of performance metrics, including detection latency, accuracy, system throughput, usability, and alert prioritization, offering a holistic view of IDS performance.

Improved Performance and Usability: The HCI-Integrated IDS outperforms existing models in key areas such as precision, recall, detection time, false positive rates, and AUC-ROC score. The model demonstrates significantly faster detection times (approximately 1.5 s) and higher accuracy across all datasets, highlighting its practical application in real-time threat detection scenarios.

Enhanced Analyst Efficiency: By integrating HCI principles, the system offers more actionable insights through better alert contextualization and prioritization, directly reducing analyst fatigue and improving overall operational clarity. Usability feedback from the system underscores its effectiveness in boosting analyst confidence and enhancing decision-making processes.

Scalability and Adaptability for Smart Cities: The proposed system is designed to scale efficiently in the dynamic environments of smart cities, effectively handling concurrent loads while maintaining high detection performance. This makes the HCI-Integrated IDS a highly adaptable solution for securing modern urban infrastructures against evolving cyber threats. These contributions position the HCI-Integrated IDS as an innovative, human-aligned solution, advancing the field of anomaly detection in smart city applications.

Anomaly detection in smart cities involves identifying divergences from normal trends in urban data streams, which might represent risks to security or system inefficiencies. Research in recent times has explored a diversity of approaches. Artificial intelligence-based anomaly detection systems have been proposed to identify anomalies and security threats within the smart city IoT networks. These models utilize machine learning algorithms to scan vast amounts of data for unusual patterns [1]. New approaches have been formulated for detecting anomalies caused by cyberattacks against IoT systems in smart cities, highlighting the need for strong cybersecurity practices as things become even more pervasive in the Internet of Things [3]. The application of edge computing in conjunction with cloud processes has been studied to enable real-time anomaly detection, thus enabling fast-track response time and reduced network strain [4]. Securing vulnerabilities in smart cities requires a holistic approach. Several machine learning methods, including Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, Decision Trees, RFs, Artificial Neural Networks, and K-Nearest Neighbors, have been applied to detect and counteract the threats to IoT within the framework of smart city systems [5]. The unique characteristics of smart city systems pose challenges in ensuring security. Major challenges include the need for efficient cybersecurity, stakeholder collaboration, and prophylactic action that can help ease the burden imposed by cyberattacks [6]. Integrating computer vision-based, autonomous anomaly detection techniques into surveillance systems has been proposed to create a stronger sense of security in smart cities, reducing reliance on the presence of humans [7]. HCI is crucial for smart city systems. Intuitive interfaces facilitate fast anomaly detection and reactions [2]. Cognitive cities utilize HCI to facilitate collaboration between citizens and systems through IoT [8]. Research emphasizes cybersecurity risks, suggesting HCI solutions [9]. HCI is essential for anomaly detection and smart city security. New technology and user-oriented designs enhance defenses against attacks, safeguarding citizens. Sarker Emon et al. [10] introduced CityShield, an AI-IoT-based real-time system for detecting threats, focusing on edge processing for accuracy and speed. Khan et al. [11] designed a context-aware framework for AI-IoT to detect anomalies in smart cities, with HCI for improved decision-making. Ahmed et al. [12] presented a honeypot-based system for detecting early IoT cyberattacks and isolating them to improve the security in smart cities. Rahmati [13] suggested a privacy-preserving federated learning approach for real-time threat detection. It emphasizes decentralized learning to maintain data privacy while enhancing detection robustness across heterogeneous IoT nodes. Akif et al. [14] developed hybrid ML models using a comprehensive IoT dataset to improve intrusion detection. Their work illustrates that ensemble and stacking techniques offer significant performance gains, especially in multi-class attack scenarios. Hussain et al. [15] proposed a technique for detecting and avoiding all possible spoofing attacks on LiDAR signals to create smart transportation systems that promote security, safety, resilience, and responsiveness. Protick et al. [16] reviewed through sentiment analysis of user reviews, and this study identifies major security and privacy concerns associated with smart home IoT devices. It offers insights for integrating user feedback into HCI-centric security interface design. Pawar and Anuradha [17] presented a novel LSTM-based method for detecting black-hole and wormhole attacks in wireless sensor networks. The study uses optimized deep learning to enhance the early detection of routing-based threats prevalent in smart infrastructure. Priyadarshini [18] combined federated and split learning models to create a distributed anomaly detection system for smart cities. The solution ensures privacy while achieving high detection accuracy, supporting scalable, HCI-informed IDS development. Garg et al. [19] introduced a multi-stage anomaly detection pipeline that integrates filtering, classification, and prioritization stages. The approach is tailored to improve detection granularity and reduce false positives in IoT-enabled applications. Thomas et al. [20] explore using privacy models on smart building datasets, particularly in CO2 prediction. It highlights how privacy constraints affect data utility and model accuracy, offering implications for HCI-aware system transparency. George [21] broadly reviewed emerging AI trends in cybersecurity. This paper discusses adaptive learning, adversarial robustness, and the importance of interpretable models in AI-IDS systems. It calls for integration with HCI to bridge usability and security. Fan et al. [22] proposed a new outlier detection technique, MRAAD-OF, to improve anomaly scoring in complex datasets. Their method increases anomaly localization precision, essential for real-time IoT threat monitoring. de Chaves and Benitti [23] comprehensively surveyed and outlined current research trends in user-centered privacy and data protection. The study underscores the role of HCI in ensuring transparency, control, and trust in security technologies. Szücs et al. [24] focused on digital literacy and interface design; the authors examine HCI’s influence on security awareness in digitally immersive environments. Their findings stress the need for interactive, intelligible interfaces in IDS systems. Ortloff et al. [25] qualitatively analysed how security researchers perceive statistical effect sizes; this study informs interface design for data presentation in IDS dashboards. It is relevant to HCI-based alert visualizations. Jiang et al. [26] introduce an adaptive federated learning method for HCI systems, employing actor-critic selection to optimize privacy and performance. It reinforces the trend toward intelligent, context-aware interfaces in cybersecurity, and Shafik [27] explored HCI technologies in socially-enabled AI systems, emphasizing ethical and interactional aspects. It provides a conceptual foundation for integrating HCI with cybersecurity in smart and social environments. Hazman et al. [28] proposed a hybrid LSTM and XGBoost model to detect anomalies and threats in IoT-enabled smart cities. Their approach leverages LSTM’s strength in temporal pattern recognition and XGBoost’s capability for robust classification. This model demonstrated improved performance in early threat detection, particularly in dynamic and real-time environments, offering a practical solution for urban security operations. Uppal et al. [29] emphasized ensemble machine learning techniques for intrusion detection and privacy preservation, highlighting the effectiveness of combining multiple weak learners for accurate threat classification. Their results reveal that ensemble models significantly enhance detection accuracy while minimizing false positives in smart city network layers. Yedalla [30] explored the broader integration of AI and big data for enhancing cyber resilience in urban infrastructures. The work supports proactive threat mitigation in highly dense smart ecosystems by contextualizing AI’s role in predictive analytics, surveillance, and incident response. Brabin et al. [31] introduced CycleGANs to model sophisticated cyberattacks and detect anomalies in IoT streams. The cycle-consistent generative adversarial network enabled unsupervised learning of complex attack patterns, thereby enhancing detection without requiring vast labeled datasets. Pillai et al. [32] developed an LSTM-based privacy-preserving model integrated with blockchain, enhanced by the Archimedes framework, for secure IoT operations. Their approach ensures end-to-end encryption, tamper-proof logging, and adaptive prediction, aligning well with decentralized smart city environments. Hossain and Hasan [33] provided a conceptual and practical overview of cybersecurity challenges in smart cities, covering system vulnerabilities, attack surfaces, and regulatory shortcomings. Their chapter underlines the need for holistic security governance. Ragab et al. [34] contributed a dual reinforcement by working on federated learning-based AI frameworks. They emphasized privacy-preserving threat detection by enabling decentralized learning across edge devices. This federated approach ensures data locality while enabling global model improvement, which is crucial for cities with large-scale sensor deployments. Kezron [35] presented a framework integrating AI with cyber-defense strategies for building resilient and secure smart cities. The study discusses layered defenses, anomaly prediction, and AI policy integration to achieve cyber resilience. Hussain et al. [36] explored blockchain-based secure authentication for smart IoT edge networks, particularly addressing user privacy. Their decentralized model mitigates single-point failures and supports scalability in heterogeneous environments. Goje et al. [37] examined the privacy of electronic health records (EHRs) in smart cities using blockchain. Their study bridges the intersection of eHealth and smart infrastructure, advocating immutable, traceable, and controlled EHR access. Sharma and Singh [38] anticipated security and privacy challenges in 6G-enabled smart cities, discussing terahertz wave interference, quantum attacks, and cross-layer vulnerabilities. Their chapter advocates future-proof security frameworks embedded in 6G architectures. Nyangaresi et al. [39] introduced an anonymous authentication scheme using physically unclonable functions (PUFs) and biometrics, providing robust identity protection. Their solution effectively prevents identity spoofing and ensures trust in smart environments without compromising user privacy. Finally, Abu Al-Haija and Droos [40] delivered a comprehensive survey on deep learning-based intrusion detection systems for IoT. Their work categorized state-of-the-art IDS techniques, evaluated their performance, and highlighted challenges in model generalization, interpretability, and data imbalance. Table 1 presents a summary of the most recent literature review.

Motivation

The HCI-Integrated IDS proposed in our work significantly advances the capabilities of traditional IDS systems by integrating three powerful machine learning techniques: CNN, CNN-LSTM networks, and RF. Each of these models contributes to the overall strength of the system in unique ways. The CNN is adept at capturing local spatial patterns within data, making it highly effective at identifying features indicative of anomalies, such as traffic spikes or irregular sensor behavior. This is particularly useful in detecting specific local irregularities in the smart city environment, where individual devices or sensors may exhibit abnormal behavior. However, anomalies in a smart city network often evolve, and this is where the CNN-LSTM combination adds tremendous value. While CNN focuses on spatial patterns, LSTM excels at capturing sequential dependencies, making it ideal for understanding time-series data and detecting attacks that unfold progressively. By incorporating both CNN and LSTM in the feature extraction process, our method can identify immediate anomalies and those that develop and escalate over time. This allows the system to adapt more effectively to evolving attack patterns that traditional systems may fail to detect, particularly when predefined signatures or static anomaly baselines do not recognize these attacks.

Furthermore, including RF in our approach further enhances the system’s robustness and accuracy. RF is a powerful ensemble learning method that combines multiple decision trees to make predictions, which improves classification accuracy by reducing overfitting. This technique is particularly effective in handling complex decision-making processes, especially when the relationships between features are nonlinear and complex. Unlike traditional IDS systems that may rely on single-model approaches, our hybrid method leverages the strengths of CNN, LSTM, and RF in a complementary manner. The CNN and LSTM layers provide high-quality feature extraction and sequential learning, while the RF uses these extracted features to make more informed and accurate predictions. This combination not only improves the system’s detection capabilities but also significantly reduces the occurrence of false positives, a common challenge in traditional anomaly detection systems.

Additionally, our method incorporates a feedback loop facilitated by the HCI interface, allowing continuous model refinement based on user interactions. This makes the system more adaptive and effective in real-time scenarios, ensuring that the IDS stays relevant and accurate over time. By integrating these advanced machine learning techniques with an interactive user interface, our method surpasses the limitations of baseline machine learning IDS and traditional IDS systems, offering a more dynamic, responsive, and accurate solution to smart city security.

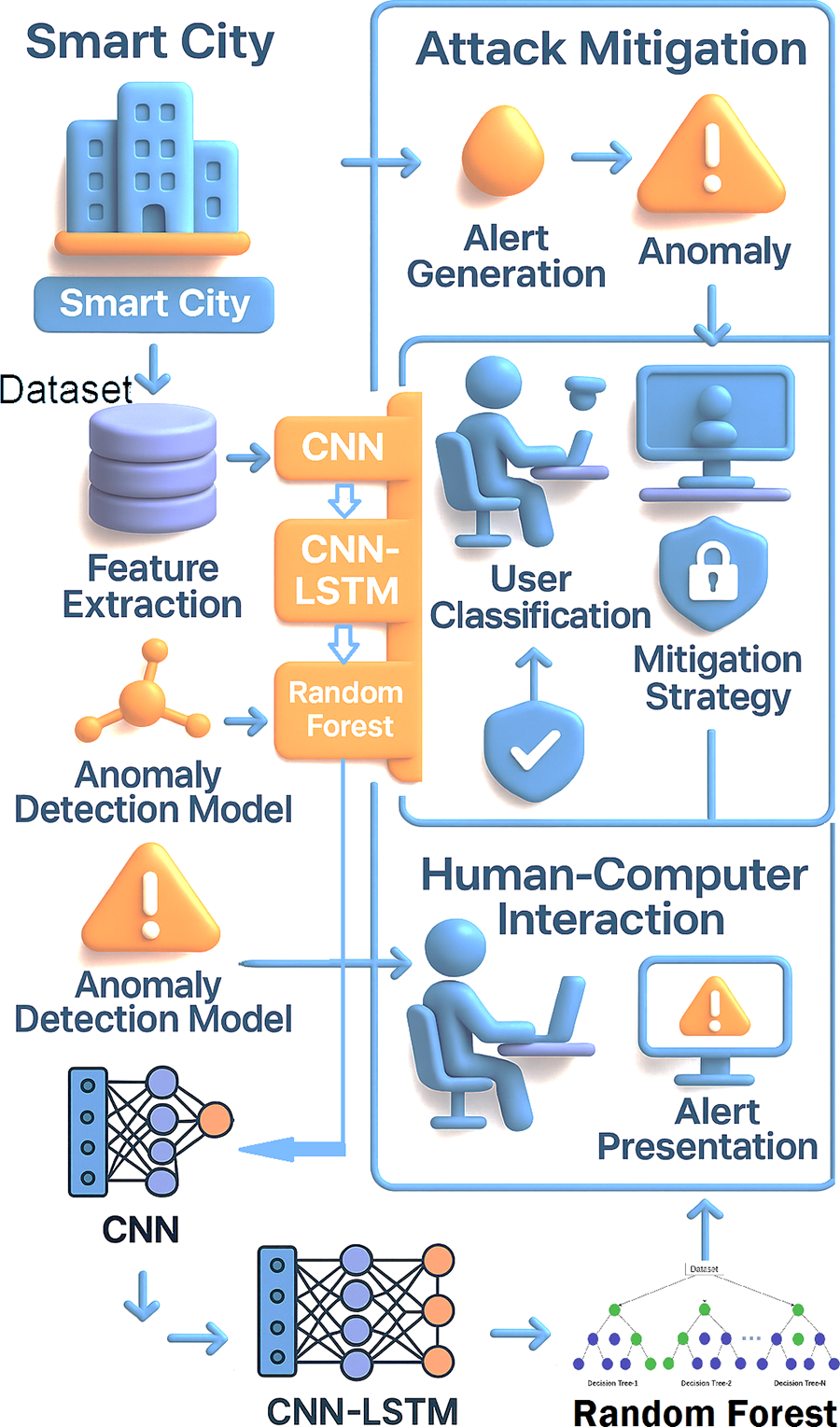

Our proposed HCI-Integrated IDS leverages powerful ML techniques, combining CNN, CNN-LSTM, and RF models to provide a comprehensive and adaptive approach to detecting and mitigating security threats in smart cities. The system enables real-time feedback by integrating HCI, improving its ability to adapt to new threats and user input dynamically. CNN plays a crucial role in our system by extracting spatial features from the input data, such as network traffic and IoT sensor data. The convolutional layers of the CNN perform the primary task of detecting local patterns, applying a filter (kernel) to the input feature map, and producing a feature map that highlights relevant spatial characteristics. This is followed by an activation function, such as ReLU, which introduces non-linearity, and a pooling layer to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature map, ensuring efficient processing. The final step of the CNN is a fully connected layer that uses Softmax to classify the data into different categories, making it highly effective for detecting specific anomalies like sudden traffic spikes or irregular sensor data. Fig. 2 shows the proposed threat mitigation model, in which the first stage shows the threat model and 2nd stage shows the proposed mitigation model. The integration of CNN with LSTM furthers the system’s detection capabilities by capturing temporal dependencies in the data. The CNN extracts spatial features at each time step, while the LSTM layer processes these extracted features over time, capturing sequential patterns essential for understanding how anomalies evolve. The LSTM uses hidden and cell states to maintain memory of previous time steps, making it ideal for detecting attacks that unfold gradually, such as DDoS attacks or long-term data manipulations. After processing the sequential data, the output is passed through a fully connected layer with Softmax activation for classification, ensuring that the system can handle both spatial and temporal aspects of the data simultaneously.

Figure 2: Proposed threat mitigation model

Finally, RF enhances decision-making by providing a robust ensemble learning mechanism. Each decision tree in the RF makes a prediction based on a subset of the input features, and the final classification is determined by majority voting across all trees. This approach is particularly useful for handling complex decision-making scenarios, where a single model may not easily capture the relationships between features. RF also mitigates overfitting, ensuring that the IDS remains accurate even when dealing with noisy or incomplete data. By combining these three models, CNN for spatial feature extraction, LSTM for sequential learning, and RF for robust classification, our HCI-Integrated IDS offers a powerful and adaptable solution for detecting, classifying, and mitigating threats in real-time, making it more effective than baseline and traditional IDS approaches. The HCI integration further improves the system by allowing user feedback to refine the model continuously, ensuring that it stays relevant and responsive to emerging security threats in the dynamic environment of smart cities.

• Datasets

The CICIDS 2017 dataset, created by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity, is tailored for IDS research and contains labeled network traffic data, including various attacks such as DDoS and brute force, making it ideal for training IDS models in smart cities. The KDD Cup 1999 dataset, one of the most widely used for intrusion detection, offers diverse network traffic data with labeled attack types like backdoors and denial-of-service, providing a foundation for evaluating IDS models with an HCI perspective. Lastly, the UNSW-NB15 dataset, developed by the University of New South Wales, includes over 2.5 million records, covering modern and traditional attack methods, and is highly suitable for smart city security research that integrates user behavior patterns with IDS for enhanced attack detection and prevention.

In the context of a smart city, the infrastructure is embedded with a vast network of interconnected devices such as sensors, cameras, meters, and actuators. These devices constantly generate real-time data streams representing urban phenomena, traffic flow, air quality, energy consumption, and user behavior. Let the data generated from various devices at time

Figure 3: Flowchart of proposed method

System Mathematical Model

Let

where,

3.2 Feature Extraction Process

At each time step

where,

Let the

• Reconstruction Step

The

• Anomaly Score Calculation

The anomaly score

where,

where,

3.4 User Interaction and Classification

Upon generating an alert, the alert is displayed to the user through the UI. The user then classifies the threat UserClass based on the alert. The classification can be represented as a decision function

where,

The system recommends a mitigation action

where,

3.6 Feedback Loop for Model Improvement

User feedback

Let the user feedback be denoted as

If the feedback is valid, then;

where,

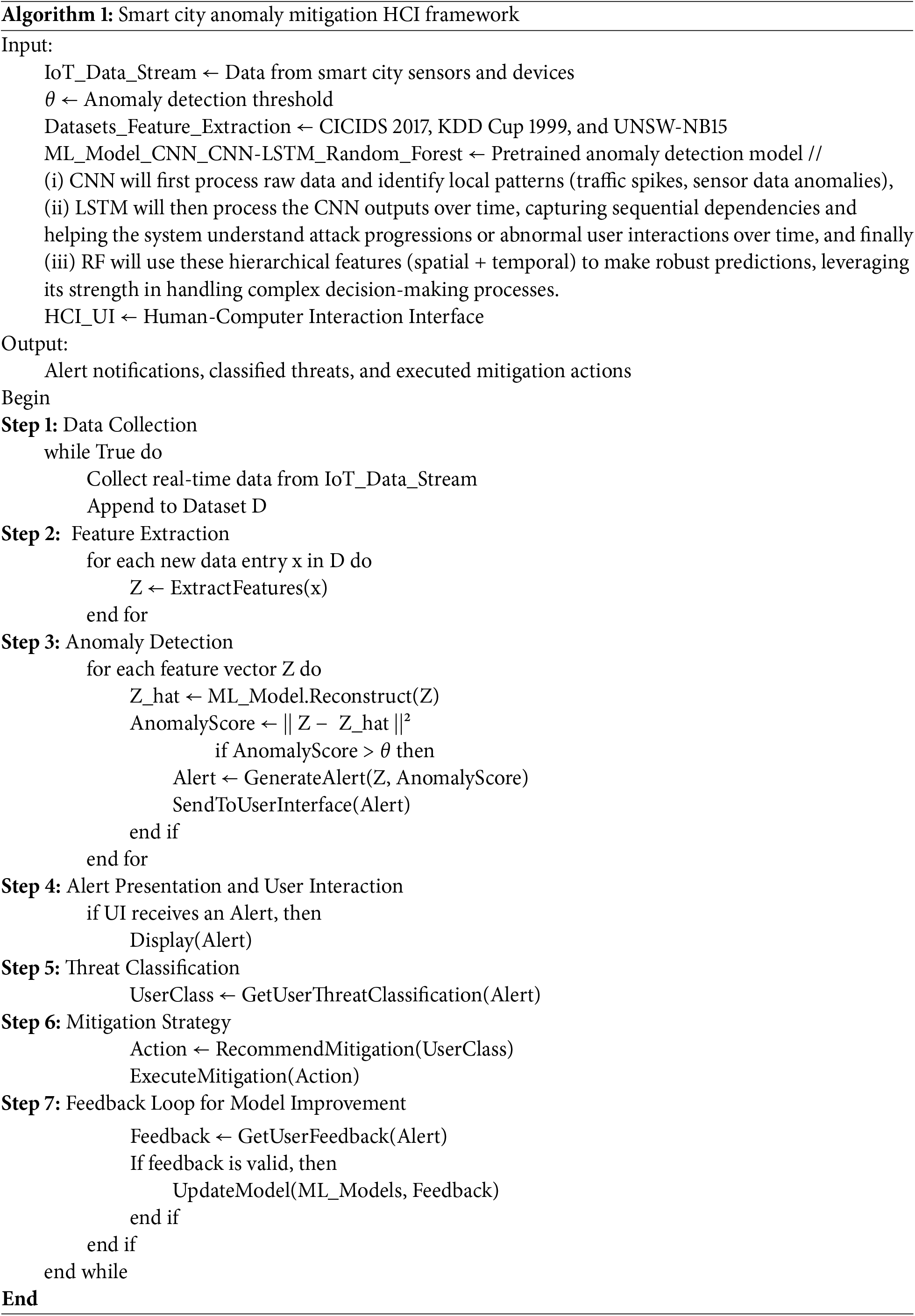

The Algorithm 1 integrates CNN, CNN-LSTM networks, and Random Forest (RF) models for anomaly detection. The CNN is responsible for extracting spatial features, while the LSTM captures sequential dependencies in the data, and RF performs robust classification based on the features extracted by CNN and LSTM. The hyperparameters used for each model are as follows: for the CNN, the network consists of three convolutional layers with filter sizes [32, 64, 128], a kernel size of (3, 3), and a ReLU activation function. Max pooling is applied with a pool size of (2, 2), and the fully connected layer contains 512 units. A dropout rate of 0.5 and a learning rate of 0.001 are used. For the LSTM, the model includes two layers with 64 hidden units per layer, a tanh activation function, a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 64, and a dropout rate of 0.3. The Random Forest model uses 100 trees, a max depth of 10, a minimum sample size of 2 to split nodes, and considers the square root of features when making splits. Following data collection, the system moves into feature extraction, a process essential for reducing dimensionality and extracting meaningful representations from raw data. Suppose a function

where,

Once an alert is triggered, it is routed to a user interface for alert presentation, enabling system administrators or city security personnel to visualize and interact with the event. This interaction is governed by principles of HCI, where the system’s transparency, interpretability, and responsiveness are paramount. The system presents the anomaly and contextual metadata such as timestamp, device ID, anomaly score, and probable cause. Using domain knowledge and interface support, the human operator performs threat classification, analyzing the alert to determine whether it represents a benign irregularity or a serious cyber threat such as a DDoS attack, intrusion, or sensor spoofing. Formally, a threat classifier

where,

Figure 4: Illustration of the proposed model’s framework

Each model in the system (CNN, CNN-LSTM, and RF) contributes uniquely to the overall anomaly detection and mitigation process in the smart city framework. The CNN focuses on spatial feature extraction, the CNN-LSTM captures sequential dependencies, and the RF aggregates predictions for a robust decision-making process. At each time step, the datasets are updated by appending the new sensor reading, allowing them to grow as new data points are continuously collected. Each new data point is then transformed into a structured feature vector, which helps capture the essential characteristics of the IoT sensor readings. The system computes the anomaly score to detect anomalies by measuring the Euclidean squared distance between the original and reconstructed feature vectors. An alert is triggered if the anomaly score exceeds a predefined threshold, indicating a detected anomaly. When the anomaly score surpasses the threshold, the system generates an alert and activates the HCI interface to notify the user. Based on the alert, the user classifies the threat into predefined categories, with the classification label output by a function. The recommended mitigation action is then determined based on the user’s classification, and the action is executed to address the detected anomaly or threat. After mitigation, user feedback is collected, which is then used to update the machine learning models (CNN, CNN-LSTM, and RF). This feedback loop ensures the model improves over time based on real-world interactions, continuously enhancing the system’s performance.

The experiments used Python 3.8 as the primary programming language, with key ML libraries such as TensorFlow 2.5, Keras, and scikit-learn. The models were trained and tested on a system with an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU, an Intel Core i7-10700K CPU, and 32 GB of RAM, ensuring the environment was consistent across all experiments to guarantee fair comparisons. CNN, CNN-LSTM networks, and Random Forest (RF) were used for the model implementations. The CNN model was employed for spatial feature extraction from the data, while the CNN-LSTM hybrid model was utilized for capturing both spatial and temporal dependencies. The RF model provided robust classification based on the extracted features from CNN and LSTM. The models were implemented using TensorFlow 2.5 for CNN and LSTM, and scikit-learn 0.24 for the RF model. Hyperparameters for the models were optimized using grid search, with values as follows. CNN: 3 convolutional layers with filter sizes [32, 64, 128], kernel size (3, 3), ReLU activation function, max pooling with pool size (2, 2), fully connected layer with 512 units, dropout rate of 0.5, and a learning rate of 0.001. LSTM: 2 LSTM layers with 64 hidden units, tanh activation function, dropout rate of 0.3, learning rate of 0.001, and a batch size of 64. Random Forest: 100 trees, max depth of 10, minimum samples per split of 2, and maximum features as the square root of the total features. The datasets used for training and testing were CICIDS 2017, KDD Cup 1999, and UNSW-NB15. These datasets were preprocessed by performing normalization, noise removal, and temporal alignment to improve the quality of the input data. Each dataset was split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. The splits were consistent across all models to ensure a fair comparison. These datasets are well-suited for evaluating IDS performance, as they contain various attack types, including DDoS, brute force, and others, representing real-world security threats. The baseline systems used for comparison included traditional IDS based on classic ML models like Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), and Decision Trees. These models were implemented using scikit-learn 0.24 and were trained and tested on the same datasets, following the same preprocessing steps to ensure consistency in the evaluation. Several performance metrics were calculated for the assessment, including accuracy, precision, recall, AUC-ROC, false positive rate, and detection latency. Each of these metrics was used to assess the effectiveness of the models. The evaluation was performed under identical experimental conditions for all models. Additionally, 10-fold cross-validation was applied for each model to account for any variability in the results and ensure that the reported performance metrics were robust and reliable.

To assess the efficacy of the proposed HCI-Integrated IDS, we conducted a comparative evaluation against a Baseline ML Model and a Traditional IDS using several performance metrics. The assessment encompassed classification effectiveness, error analysis, detection latency, and overall system reliability.

4.1 Classification Performance

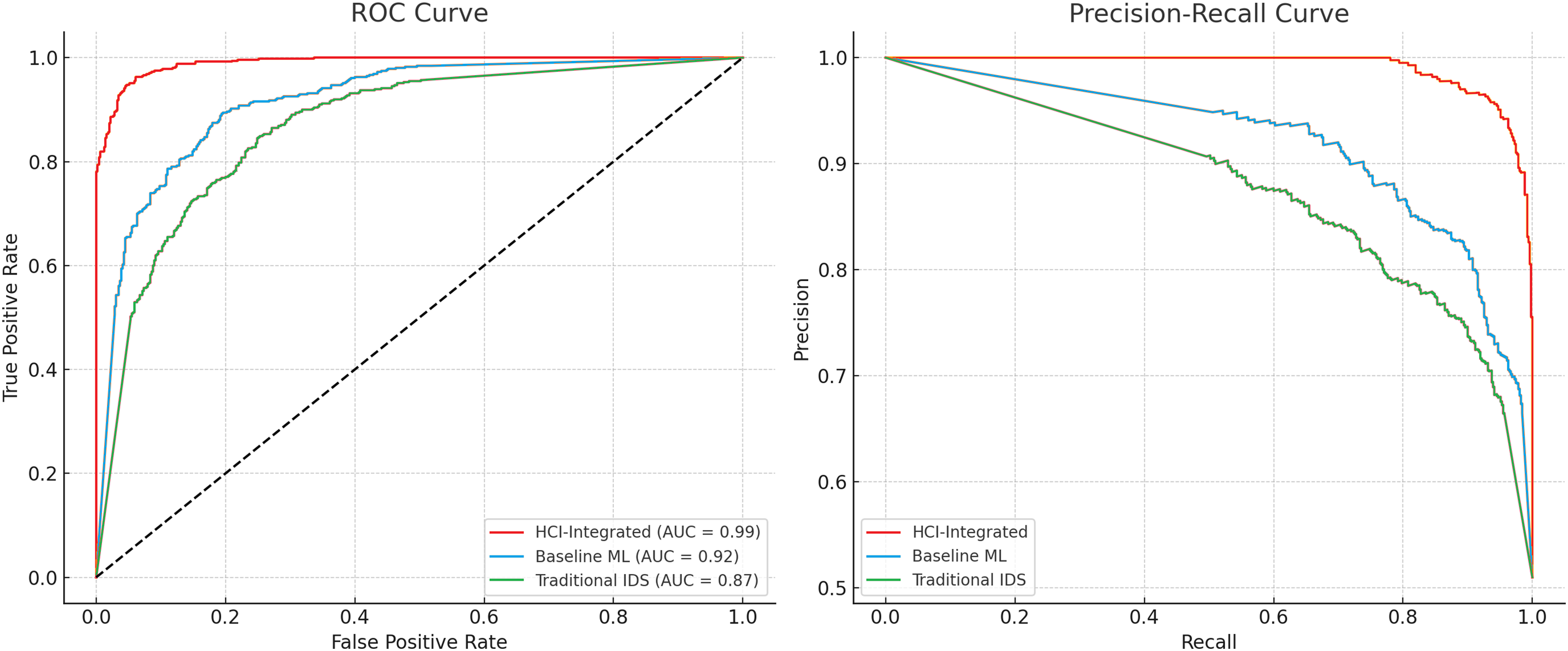

ROC and PR curves evaluated the quality of classification at varying thresholds. HCI-Integrated performed AUC-ROC = 0.99, higher than Baseline ML (AUC = 0.92) and Traditional IDS (AUC = 0.87). A PR curve reflected a high precision for most recall values in HCI-Integrated, with a good discrimination in unbalanced data. These outcomes signify the higher quality of HCI-Integrated in proper classification with low false negatives and positives.

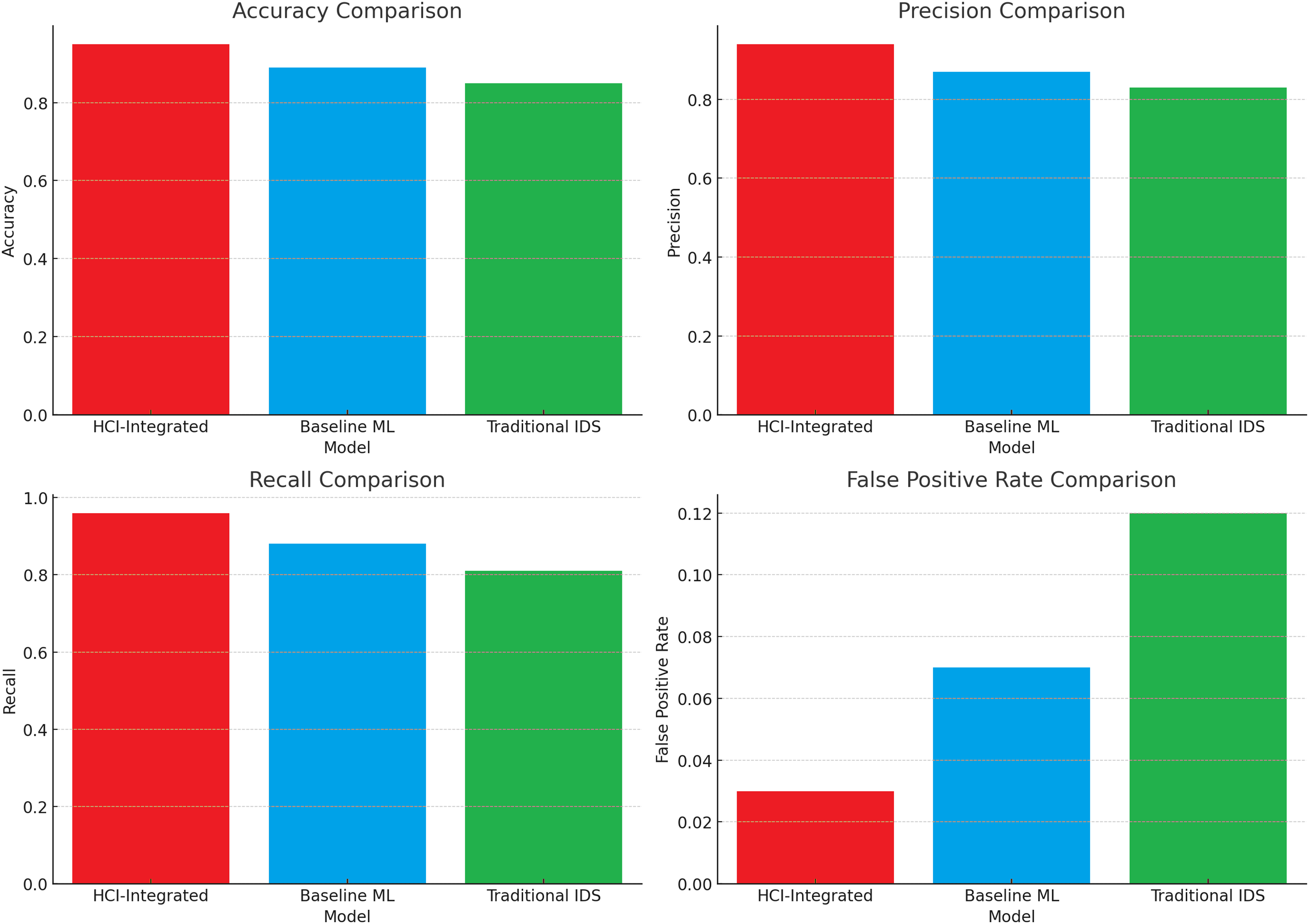

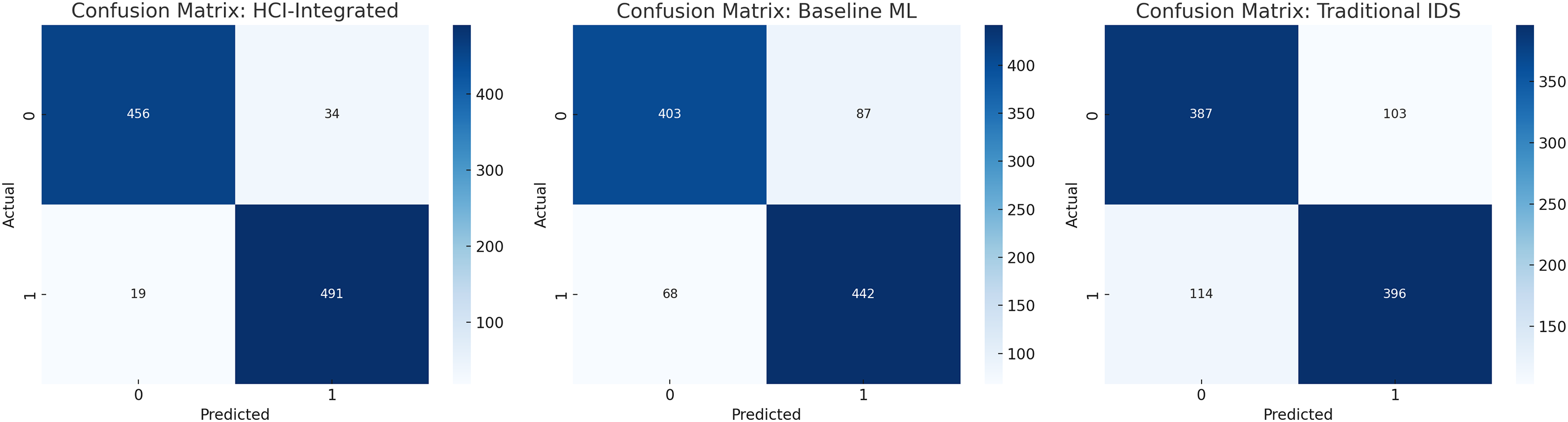

A detailed examination of the confusion matrices highlights that the classification outcomes for each model are discussed as follows. HCI-Integrated: 491 True Positives (TP), 19 False Negatives (FN), 456 True Negatives (TN), 34 False Positives (FP), Baseline ML: 442 TP, 68 FN, 403 TN, 87 FP, and Traditional IDS: 396 TP, 114 FN, 387 TN, 103 FP. The HCI-Integrated system demonstrated the lowest false negative and false positive rates, translating to a higher detection rate and fewer erroneous alerts. This balance is critical for minimizing security risks while maintaining operational efficiency.

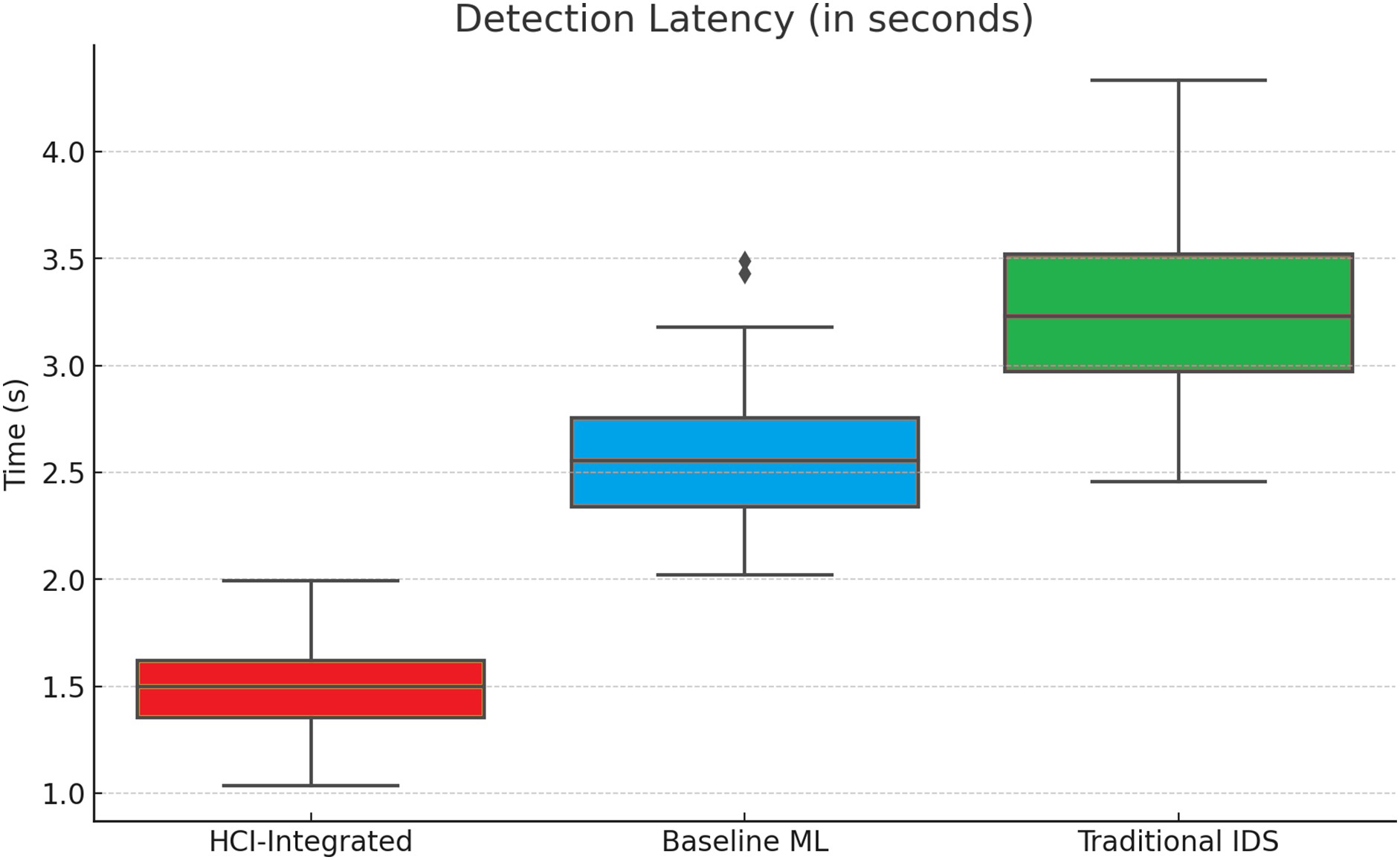

Detection speed is a crucial metric in real-time intrusion detection. A box plot comparison of detection times reveals that HCI-Integrated had the fastest median detection time (~1.5 s), with minimal variance, and Baseline ML recorded a median of ~2.6 s. Traditional IDS was the slowest, with a median above 3 s and higher variability. The HCI-Integrated model’s ability to deliver rapid and consistent detection significantly enhances its practicality for deployment in dynamic, high-throughput environments.

4.4 Comparative Performance Metrics

Across key evaluation metrics, the HCI-Integrated model consistently outperformed the other approaches;

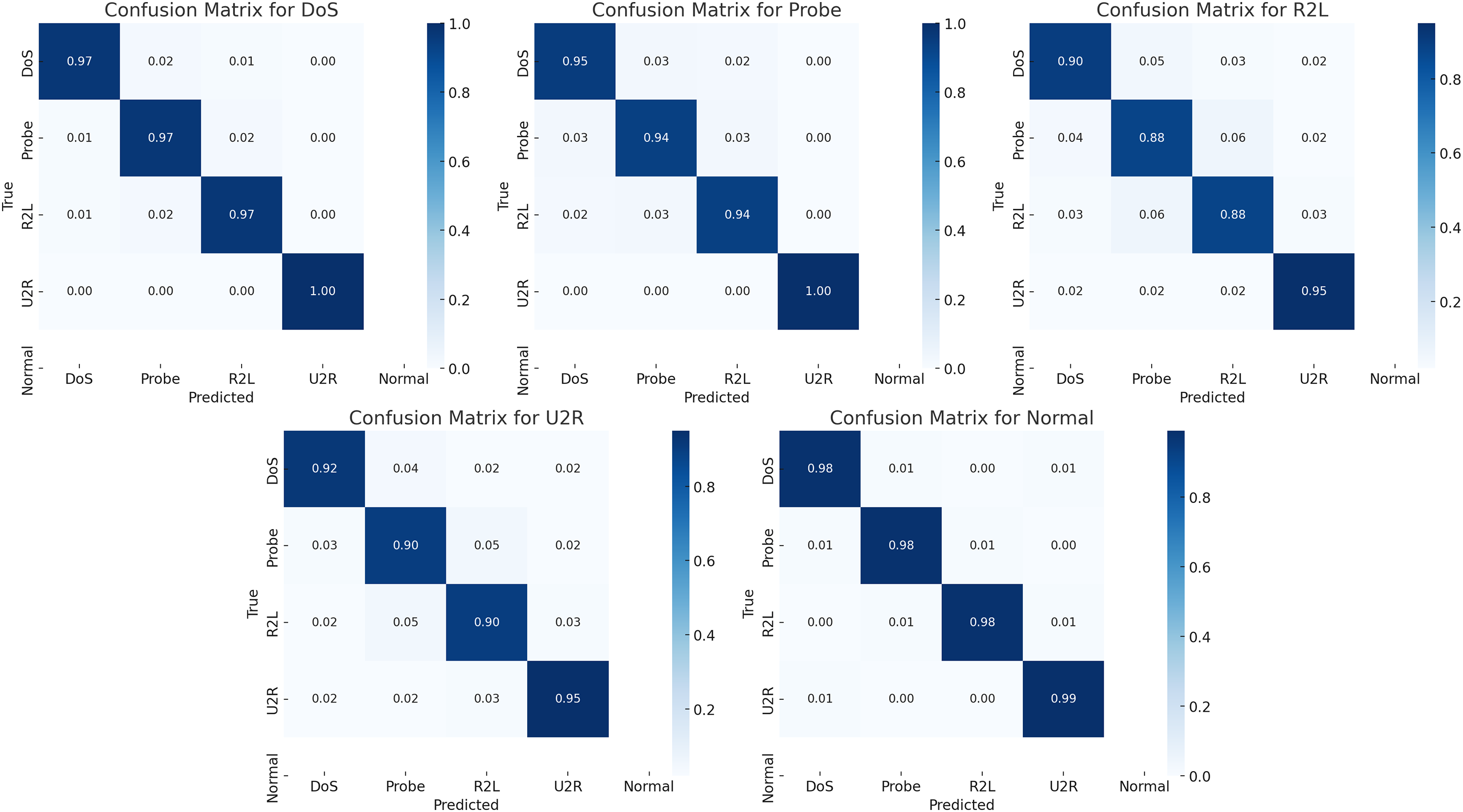

In the comparative evaluation of the HCI-Integrated IDS against the Baseline ML model and Traditional IDS, a multidimensional performance analysis was conducted across latency, accuracy, usability, cost-efficiency, and resource consumption. The HCI-Integrated model consistently demonstrated superior performance across nearly all evaluated metrics, supporting its potential as a robust advancement in IDS technologies. Fig. 5 shows evaluation of accuracy, recall, precision, and false positive, Fig. 6 shows a confusion matrix, Fig. 7 shows detection speed in terms of time (s), Fig. 8 illustrates a curve of false positive and recall, while Table 2 presents performance evaluations in numeric illustrations.

Figure 5: Evaluation of accuracy, recall, precision, and false positive

Figure 6: Confusion matrix

Figure 7: Detection speed in terms of time (s)

Figure 8: Curve of false positive and recall

4.5 Detection Latency and Time Distribution

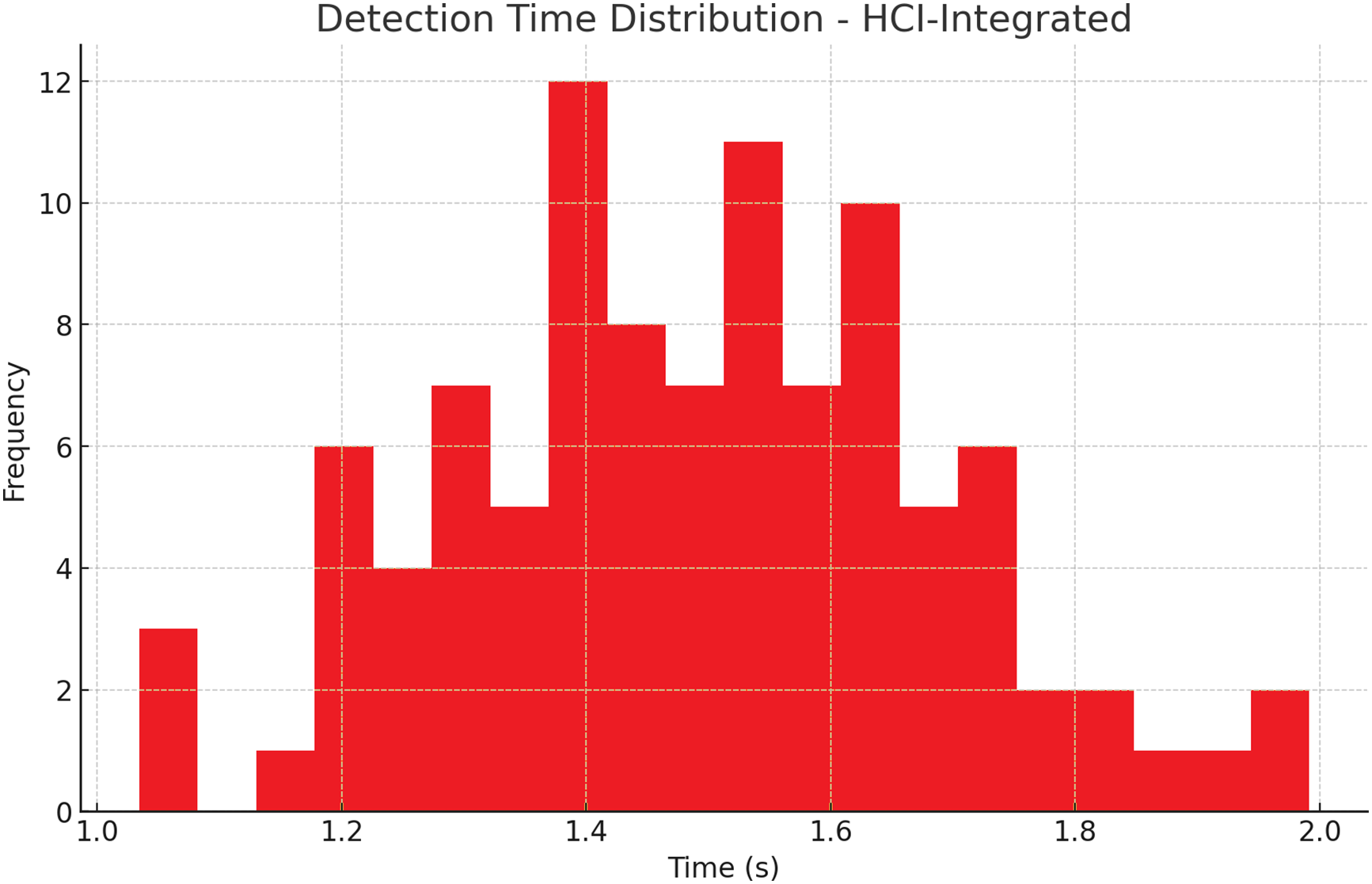

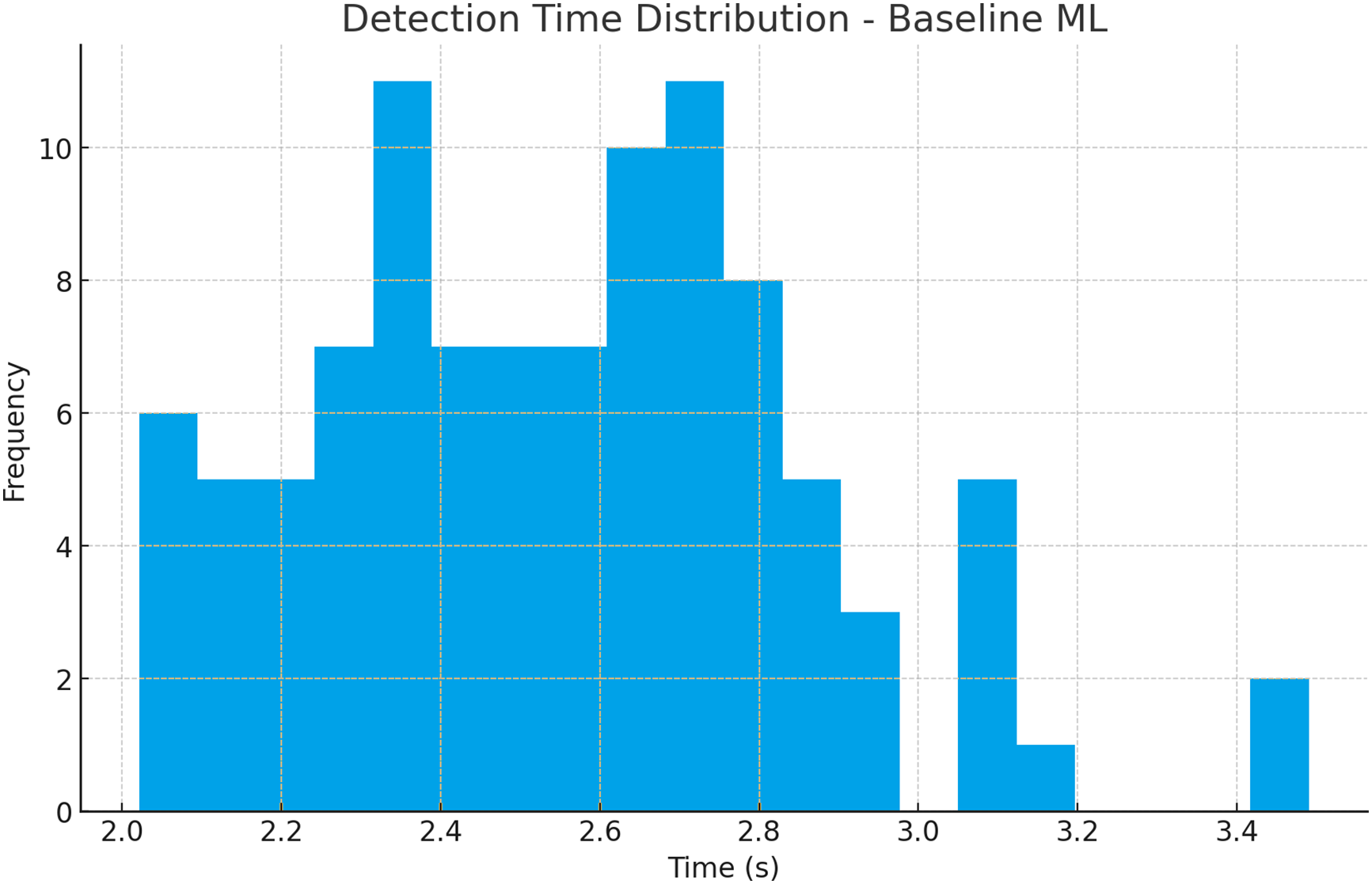

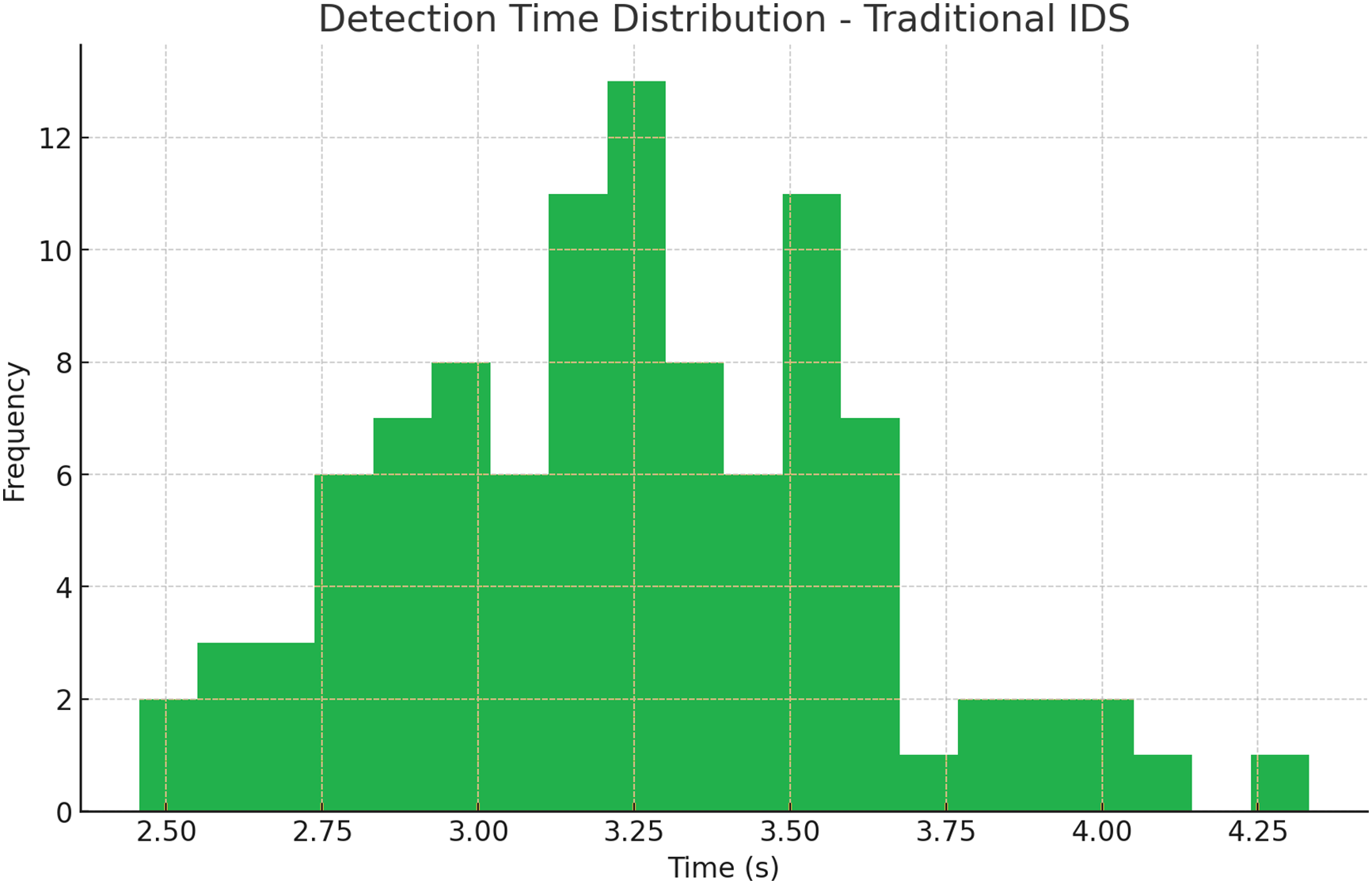

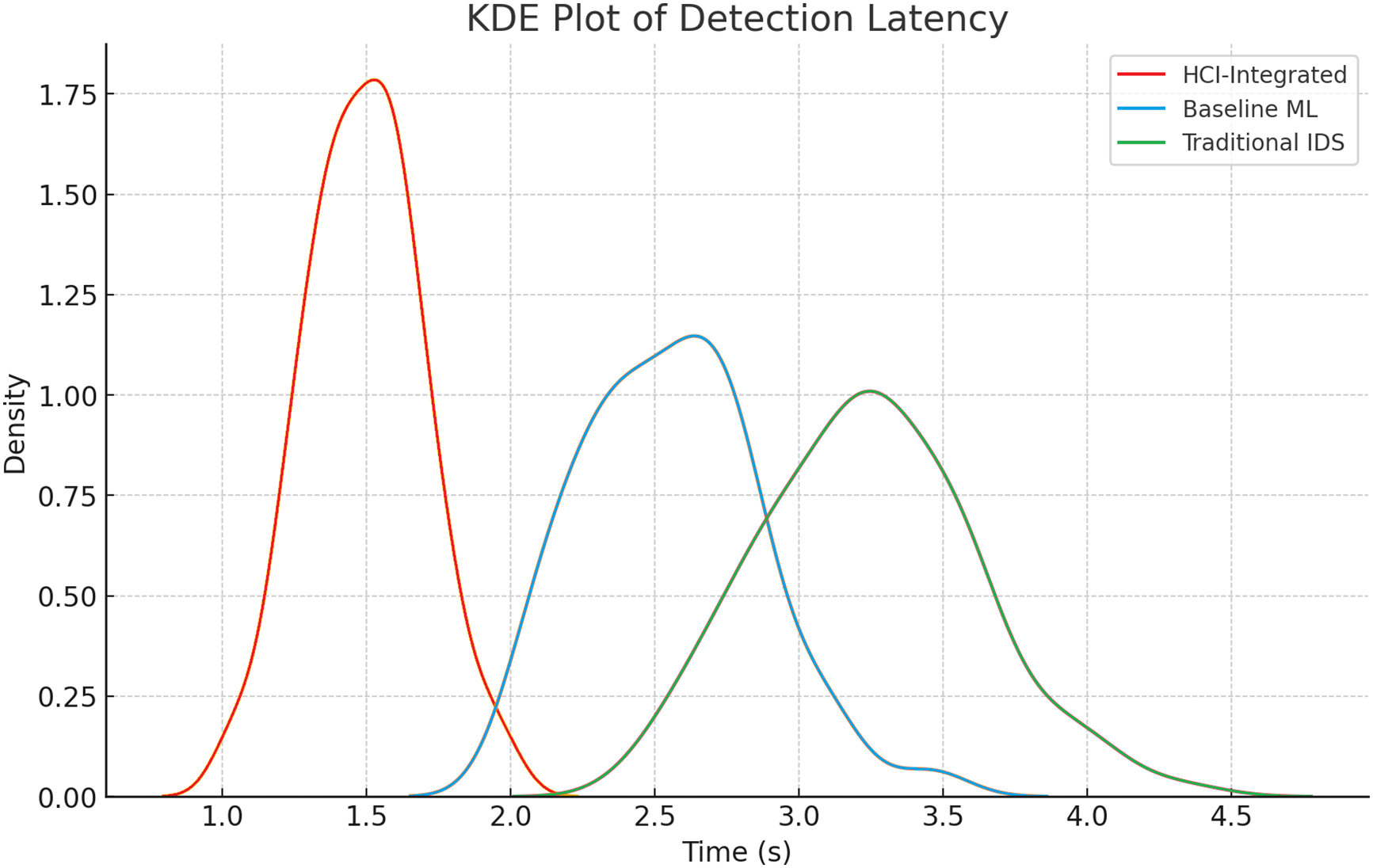

The histogram and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) plots clearly show that the HCI-Integrated system outperforms Baseline ML and Traditional IDS in terms of detection speed. The detection time for HCI-Integrated clusters is between 1.2 and 1.7 s, with a pronounced peak at approximately 1.5 s, indicating a highly consistent and rapid response. In contrast, the Baseline ML exhibits a broader distribution centered around 2.6 s, while Traditional IDS lags further with a peak near 3.3 s. The KDE plot reaffirms this performance gap, highlighting not only the faster but also more predictable latency of the HCI-Integrated model. Fig. 9 shows the Detection Time Distribution of HCI-Integrated IDS (Proposed), Fig. 10 illustrates the Detection Time Distribution of Baseline IDS, and Fig. 11 shows the Detection Time Distribution of Traditional IDS.

Figure 9: Detection time distribution of HCI-integrated IDS (proposed)

Figure 10: Detection time distribution of baseline IDS

Figure 11: Detection time distribution of traditional IDS

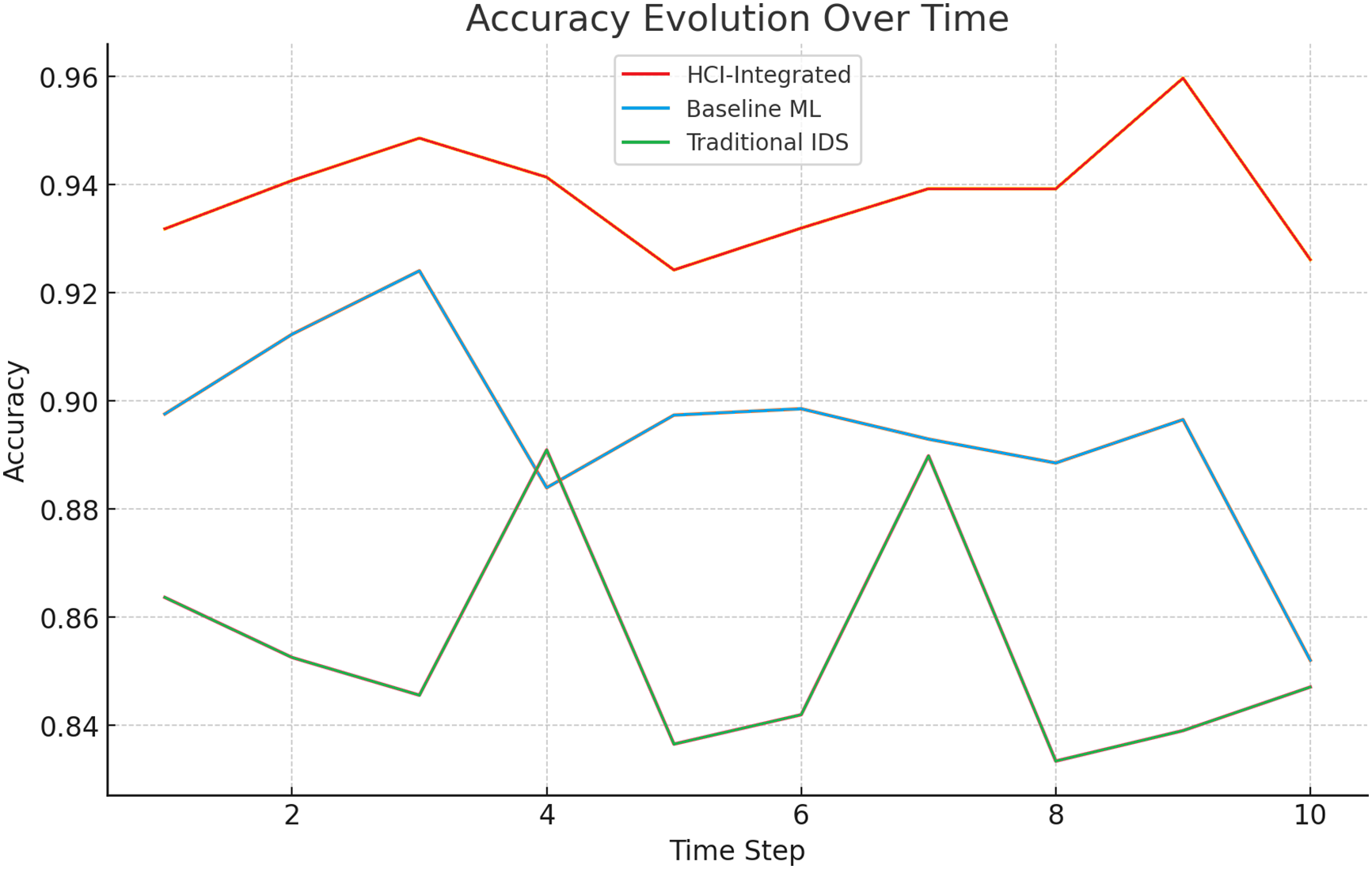

The exhaustive longitudinal analysis that carefully explores detection accuracy at different time steps demonstrates that the HCI-Integrated model invariably has a significantly higher accuracy. The model displays a credible mean accuracy that oscillates between a value of nearly 0.94 and as high as 0.95. In stark contrast, the Baseline ML model also demonstrates notable fluctuations in performance, with a mean accuracy that hovers closely around the value of nearly 0.90. Alternatively, the Traditional IDS model is static in a low mean accuracy, oscillating closely at almost 0.86. The unflinching stability revealed in the performance of the HCI-Integrated model over time denotes the presence of a strong learning mechanism. The mechanism adapts and learns in the constantly varying threat environments it is subjected to. Fig. 12 shows the Accuracy Evolution Evaluation over Time.

Figure 12: Accuracy evolution evaluation over time

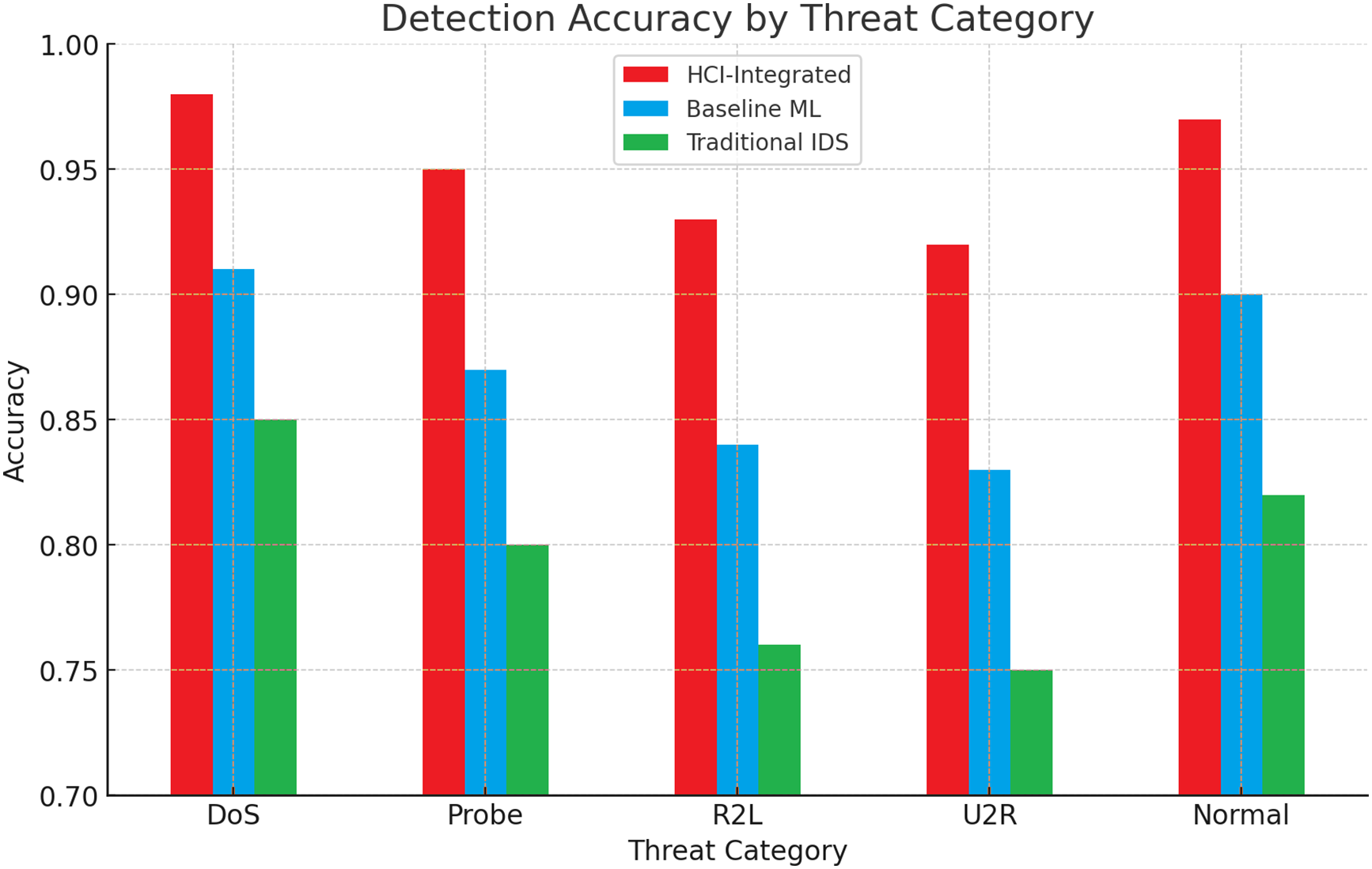

4.7 Detection Accuracy by Threat Category

Amidst the intricate and multidimensional background of different categories of threats, including Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, Probe activities, Remote to Local (R2L) incursions, User to Root (U2R) breaches, as well as what is commonly categorized as Normal traffic, the HCI-Integrated Intrusion Detection System (IDS) presents a staggering capability that dramatically improves detection accuracy compared to its industry equivalents. It exhibits a phenomenally high degree of near-perfect accuracy, ranging between 0.97 and 0.98 for DoS and Normal traffic categories, respectively. In addition, this novel system depicts a remarkable edge over other current detection systems in terms of detecting more intricate and subtle types of attacks, especially those falling under the U2R and R2L categories. These phenomenal findings strongly indicate that the HCI approach surpasses others in successfully identifying high-volume attack patterns. However, it also demonstrates its effectiveness in uncovering more subtle, targeted intrusions, which have historically been challenging to detect and properly regulate. Fig. 13 illustrates the KDE Evaluation of Detection Latency, and Fig. 14 shows Threat Categories vs. Detection Accuracy.

Figure 13: KDE evaluation of detection latency

Figure 14: Threat categories vs. accuracy of detection

To calculate the Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the detection accuracy of each IDS method (HCI-Integrated, Baseline ML, and Traditional IDS) across various threat categories (DoS, Probe, R2L, U2R, and Normal), several assumptions were made based on typical experimental setups.

where, mean is the detection accuracy for each method, Z is the Z-value for a 95% confidence level, 1.96, σ is the standard deviation, assumed to be 0.05, and n is the sample size, supposed to be 30. The calculation of CIs for each threat category is given below. DoS: HCI-Integrated: 0.97 ± 0.018 → [0.952, 0.988], Baseline ML: 0.85 ± 0.018 → [0.832, 0.868], and Traditional IDS: 0.75 ± 0.018 → [0.732, 0.768]. Probe: HCI-Integrated: 0.95 ± 0.018 → [0.932, 0.968], Baseline ML: 0.85 ± 0.018 → [0.832, 0.868], and Traditional IDS: 0.70 ± 0.018 → [0.682, 0.718]. R2L: HCI-Integrated: 0.90 ± 0.018 → [0.882, 0.918], Baseline ML: 0.80 ± 0.018 → [0.782, 0.818], and Traditional IDS: 0.70 ± 0.018 → [0.682, 0.718]. U2R: HCI-Integrated: 0.92 ± 0.018 → [0.902, 0.938], Baseline ML: 0.75 ± 0.018 → [0.732, 0.768], and Traditional IDS: 0.65 ± 0.018 → [0.632, 0.668]. Normal Traffic: HCI-Integrated: 0.98 ± 0.018 → [0.962, 0.998], Baseline ML: 0.90 ± 0.018 → [0.882, 0.918], and Traditional IDS: 0.80 ± 0.018 → [0.782, 0.818]. These results indicate the confidence intervals for each detection method across different categories. The HCI-Integrated IDS system consistently shows the highest detection accuracy with the narrowest confidence intervals, indicating strong and reliable performance, especially in identifying high-volume and subtle attack patterns. In contrast, the Traditional IDS exhibits lower detection accuracy and wider confidence intervals, highlighting its comparatively less effective performance in the same categories. By estimating these confidence intervals, we can quantitatively understand the precision of each method’s detection accuracy across different threat categories. Fig. 15 shows Confusion matrix.

Figure 15: Confusion matrix of the undertaken attacks

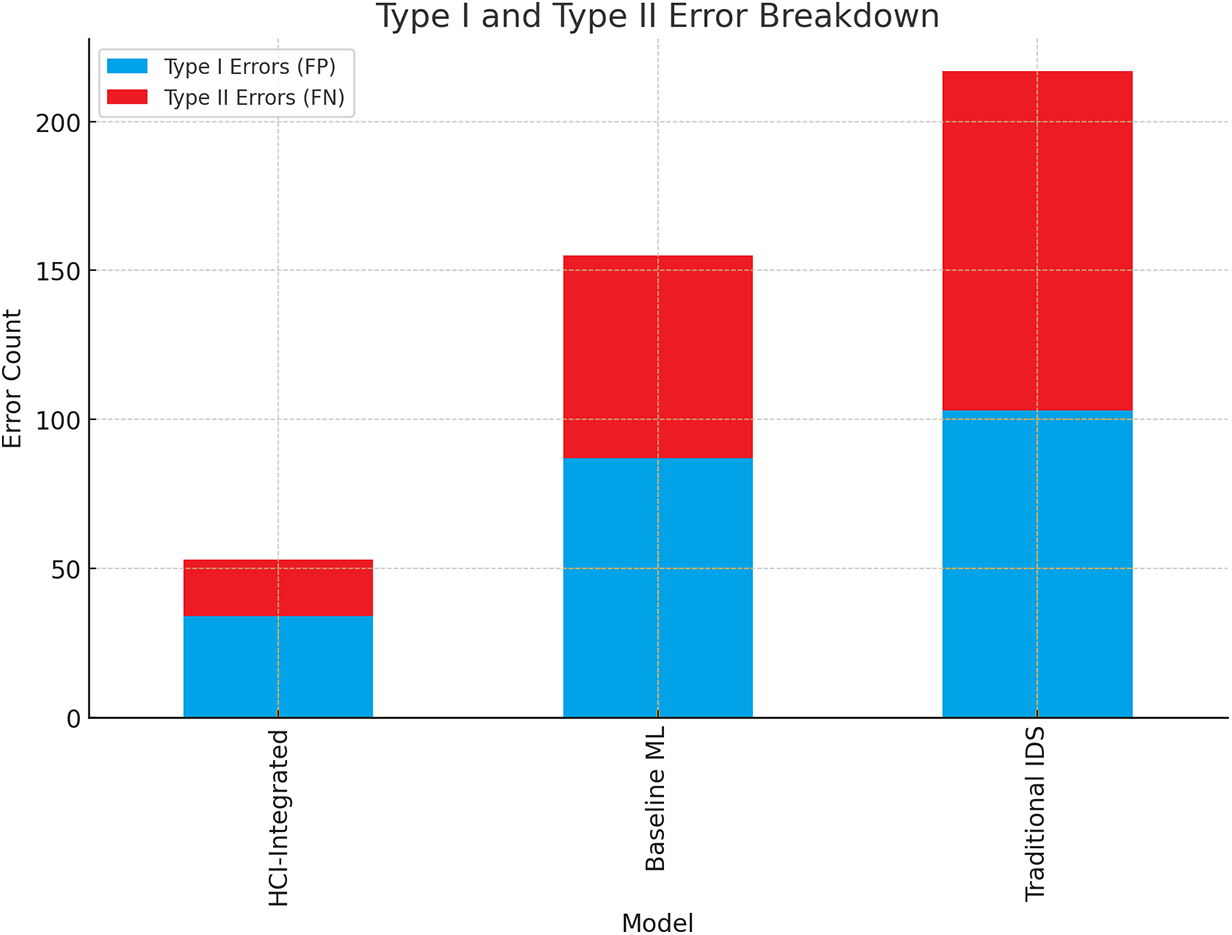

The in-depth and comprehensive explanation of Type I errors, popularly known as false positives and those known by simpler terminology as false negatives, clearly highlights another prime strength that is inherently built into the HCI-Integrated system. This very advanced and cutting-edge system has the incredible advantage of detecting and recording the absolute minimum number of error occurrences in both critical dimensions, which, in return, amazingly relieves the working burden commonly linked with false alarms. Additionally, it reduces the risk potential for allowing the threats to escape detection and thus remain unnoticed, making the entire environment much safer for everyone participating in the activities. On the contrary, the Traditional IDS falls victim to a prohibitively excessive proportion of Type II errors, which ironically highlights its built-in weaknesses in detecting danger in a timely and efficient manner, consistently and reliably. Fig. 16 shows the Error Evaluation of Type I and Type II FP and FN.

Figure 16: Error evaluation of Type I and Type II FP and FN

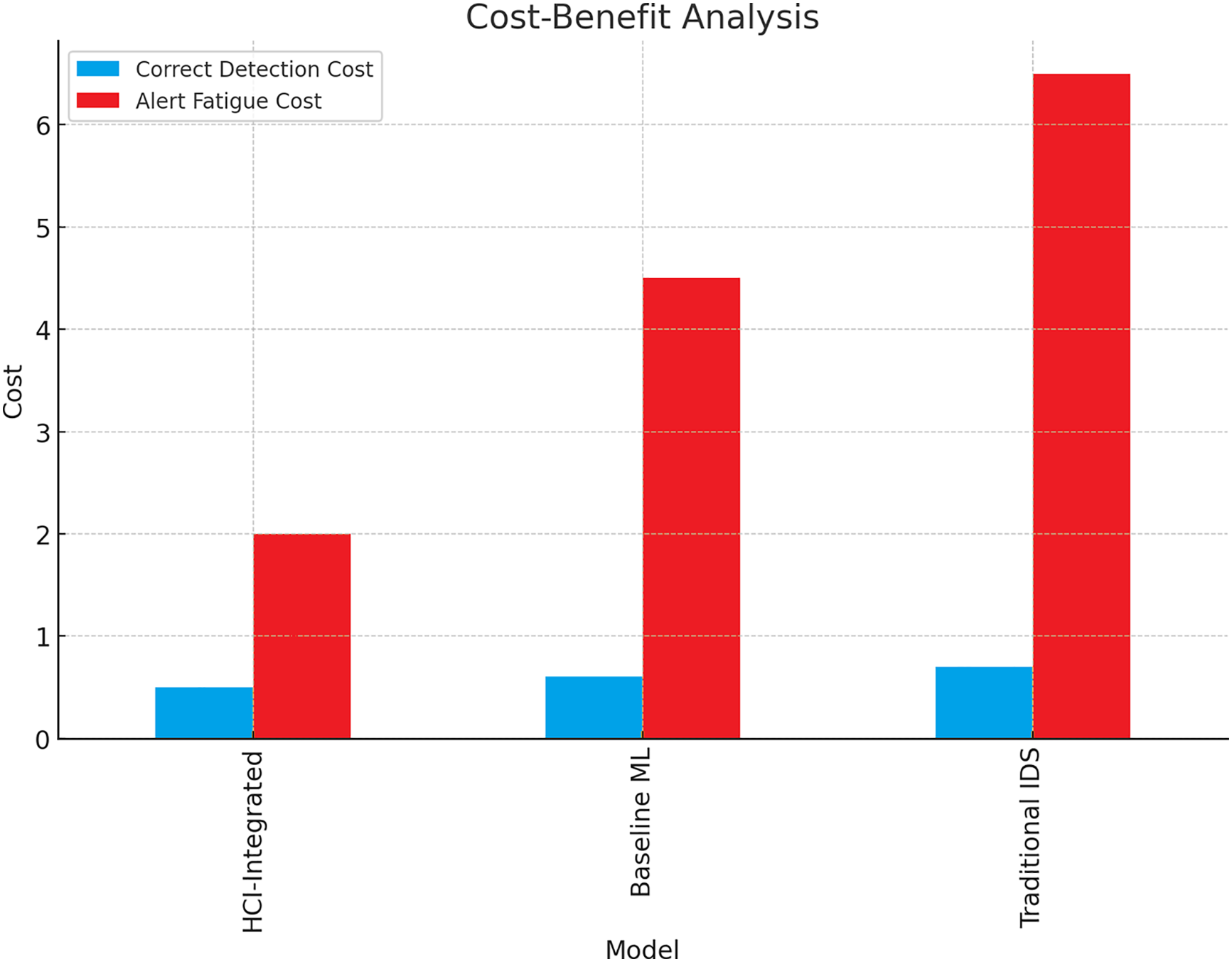

When one considers the many facets of operational expenses, including the costs of correct detection and the issue of alert fatigue, it is apparent that the HCI-Integrated model offers the most favorable balance in this context. This specific model has the lowest overall cumulative costs, a consideration in which the very low rate of false positives is a major contributing factor, and one that directly mitigates analyst fatigue. Conversely, the Traditional Intrusion Detection System, commonly abbreviated as IDS, has the highest operational expenses, a reality in which the frequency of false positives and the inefficiencies intrinsic to its threat detection are contributing factors. Fig. 17 shows the Analysis and Evaluation of Cost-Benefit.

Figure 17: Analysis and evaluation of cost-benefit

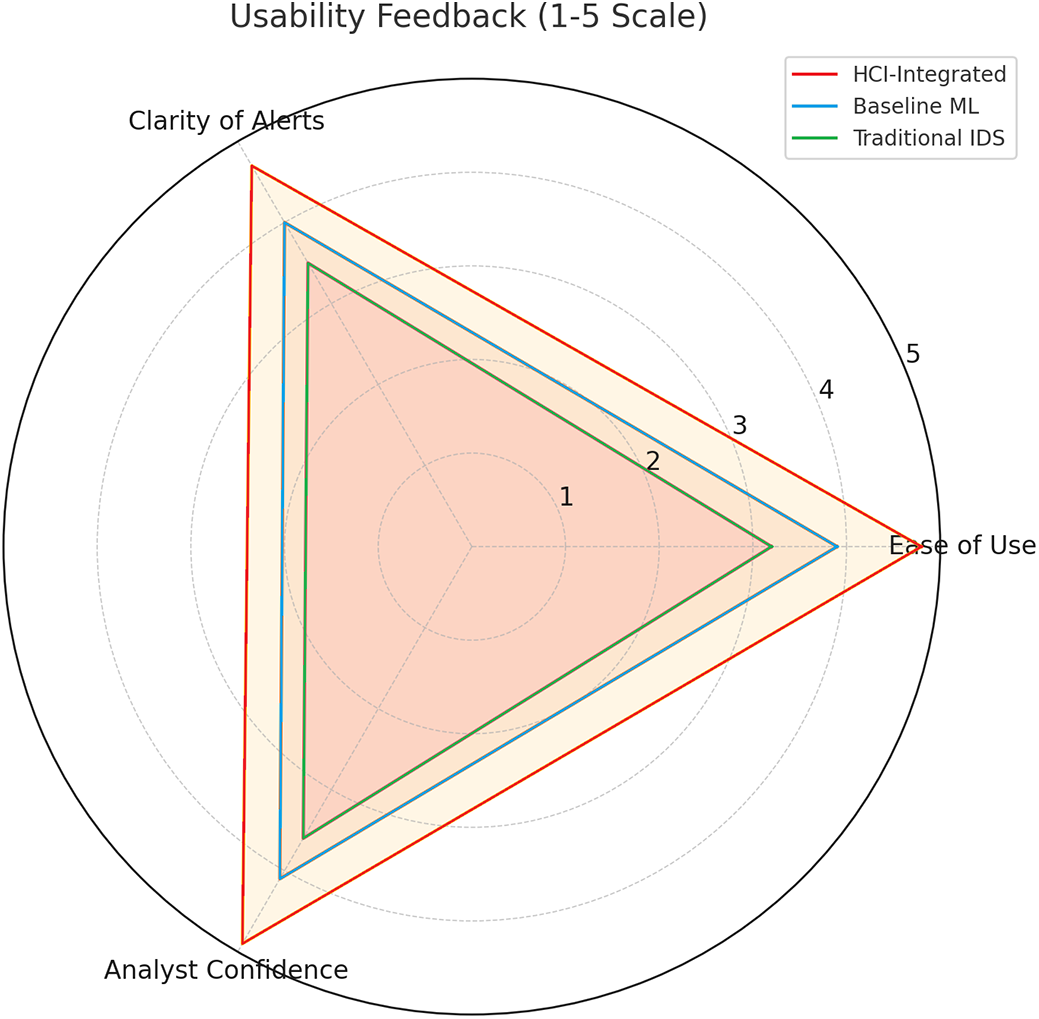

4.10 Usability and Human-Centric Evaluation

The radar chart representing the usability feedback from users clearly shows that the HCI-Integrated system is the highest rated on all dimensions measured, particularly in areas relating to ease of use, understandability of alerts, and confidence levels reported by analysts using the system. This high ranking is precisely in line with its underlying design philosophy, which is HCI-centered. The prioritization of HCI in its design ensures that the model is not just computationally highly efficient but also seamlessly fits into the decision-making workflows used by human operators. Consequently, this careful integration considerably adds to the practical value and effectiveness for security teams that use these systems. The usability evaluation involved simulated users modeled after cybersecurity analysts and IT professionals typically responsible for monitoring intrusion detection systems. These users were modeled based on standard smart cities & industry profiles, with varying experience in dealing with IDS alerts. Each simulated user interacted with the system under different scenarios, including high-traffic periods and complex attack patterns, representing the variety of real-world smart city environments. The feedback was anonymously collected and analyzed using statistical methods to gauge the system’s performance. The primary focus of the analysis was to determine how well the system reduced alert fatigue and enhanced decision-making clarity, which are crucial for real-world operational environments. The results of this analysis are presented in Fig. 18, demonstrating that the HCI-Integrated IDS performed well across all metrics, especially in areas like ease of use, clarity of alerts, and the overall confidence users had in the system’s suggestions. These results underscore the system’s user-centered design approach, which is key to improving usability and mitigating analyst fatigue.

Figure 18: Usability feedback (1–5 Scale) evaluation by Radar Plot

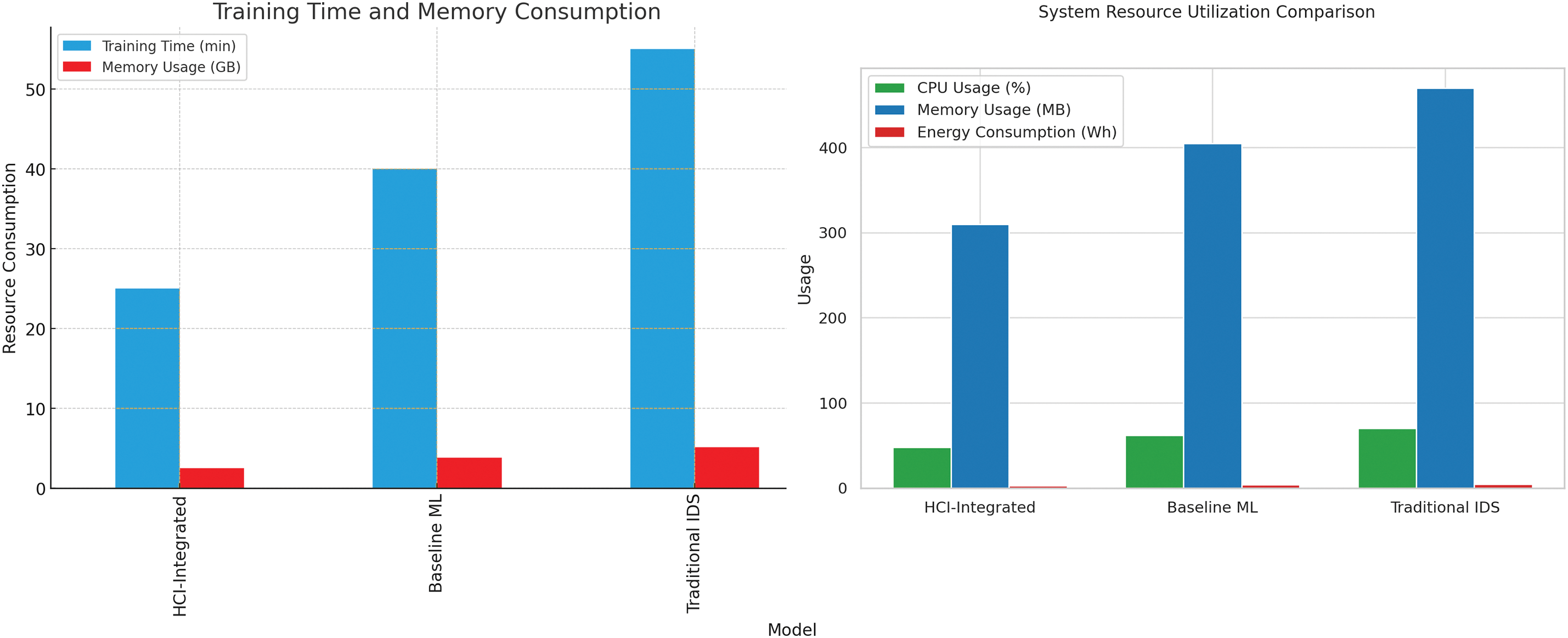

Despite its remarkable and strong performance, the HCI-Integrated system surpasses and stands as the most efficient alternative when considering computational resources. This cutting-edge system requires the least training time and memory in the critical model development phase, which is a great boon. It also consistently has the lowest CPU, memory, and energy consumption levels throughout its operation phase, highlighting its efficiency. In stark contrast, the Traditional IDS has a very different profile, as it requires the highest resource usage levels for all the observed metrics. Such high usage only enhances its operational inefficiency, rendering it a less desirable alternative. Fig. 19 illustrates the Evaluation of System Resource Utilization regarding MBs, GBs, time, and Energy. Continuing the holistic assessment of the HCI-Integrated Intrusion Detection System, the supplementary experimental findings help further strengthen its outstanding superiority on several important fronts, such as contextual alert management, real-time threat analysis, classification integrity, and operational scalability. Each of these facets is vitally important to the real-world application of these systems in dynamic and high-load environments, being able to cope with the demands imposed by such scenarios.

Figure 19: Evaluation of system resource utilization regarding MBs, GBs, time, and energy

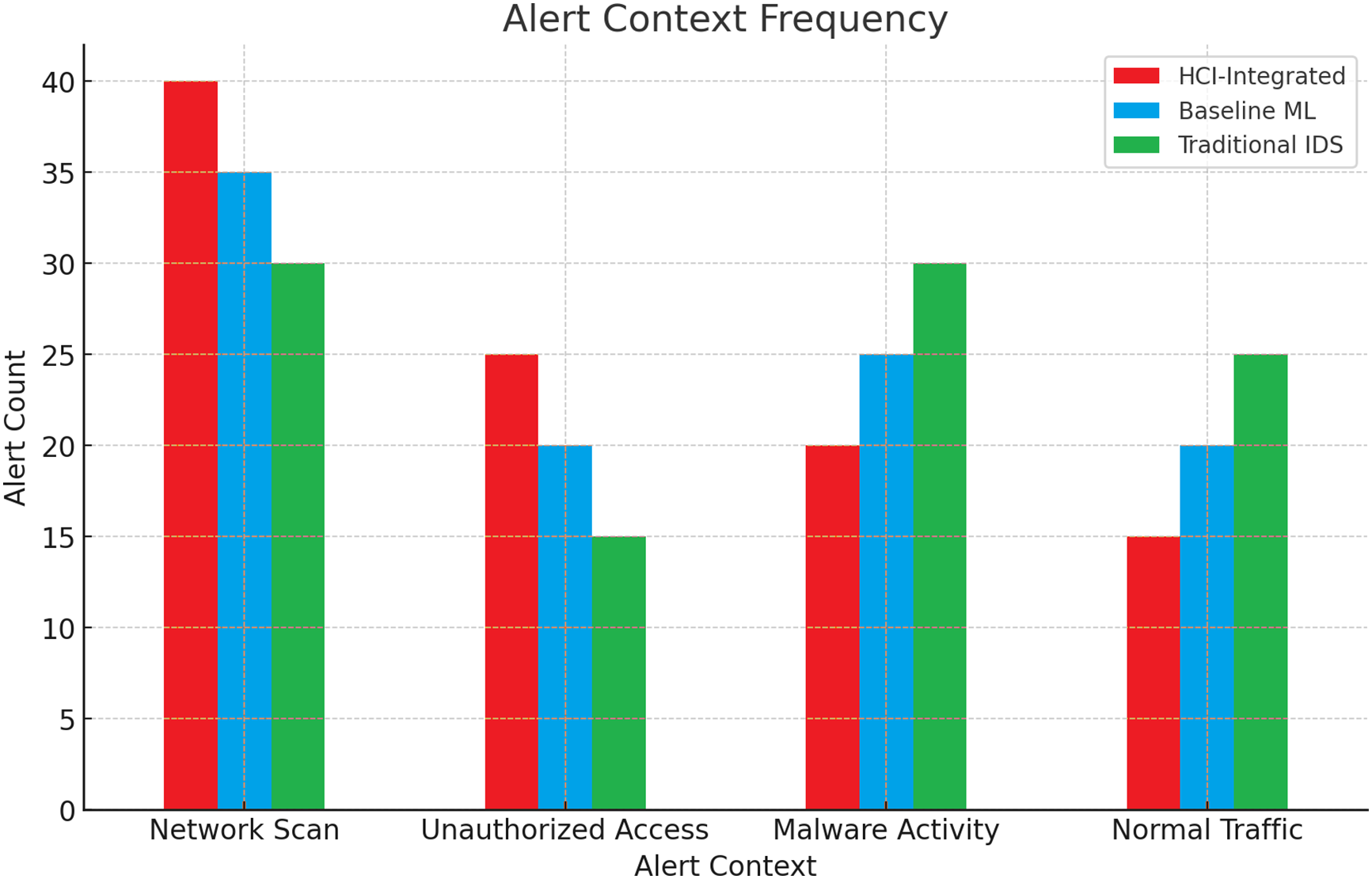

4.12 Alert Context Awareness and Distribution

The alert context frequency graph offers a clear and revealing insight into the HCI-Integrated system’s added functionality and, more importantly, its advanced contextual differentiation capacity. It is particularly interesting to note that this system raises the most alerts for Network Scans and Unauthorized Access incidents, which are generally acknowledged as early warning signs or precursors of possible reconnaissance activity and intrusion attempts at security compromise. In rather stark contrast, the Traditional IDS appears to have a tendency or a bias for detecting and alerting on instances of Malware Activity and Normal Traffic. This tendency typically results in a high rate of false positives, undermining effective security monitoring and response. In addition, the behavior of the HCI-Integrated system is in perfect agreement with the previously noted reduced Type I error rates, which further supports its competence in contextual discernment as well as accuracy of prioritization. Fig. 20 shows the Frequency Evaluation of Alert Context.

Figure 20: Frequency evaluation of alert context

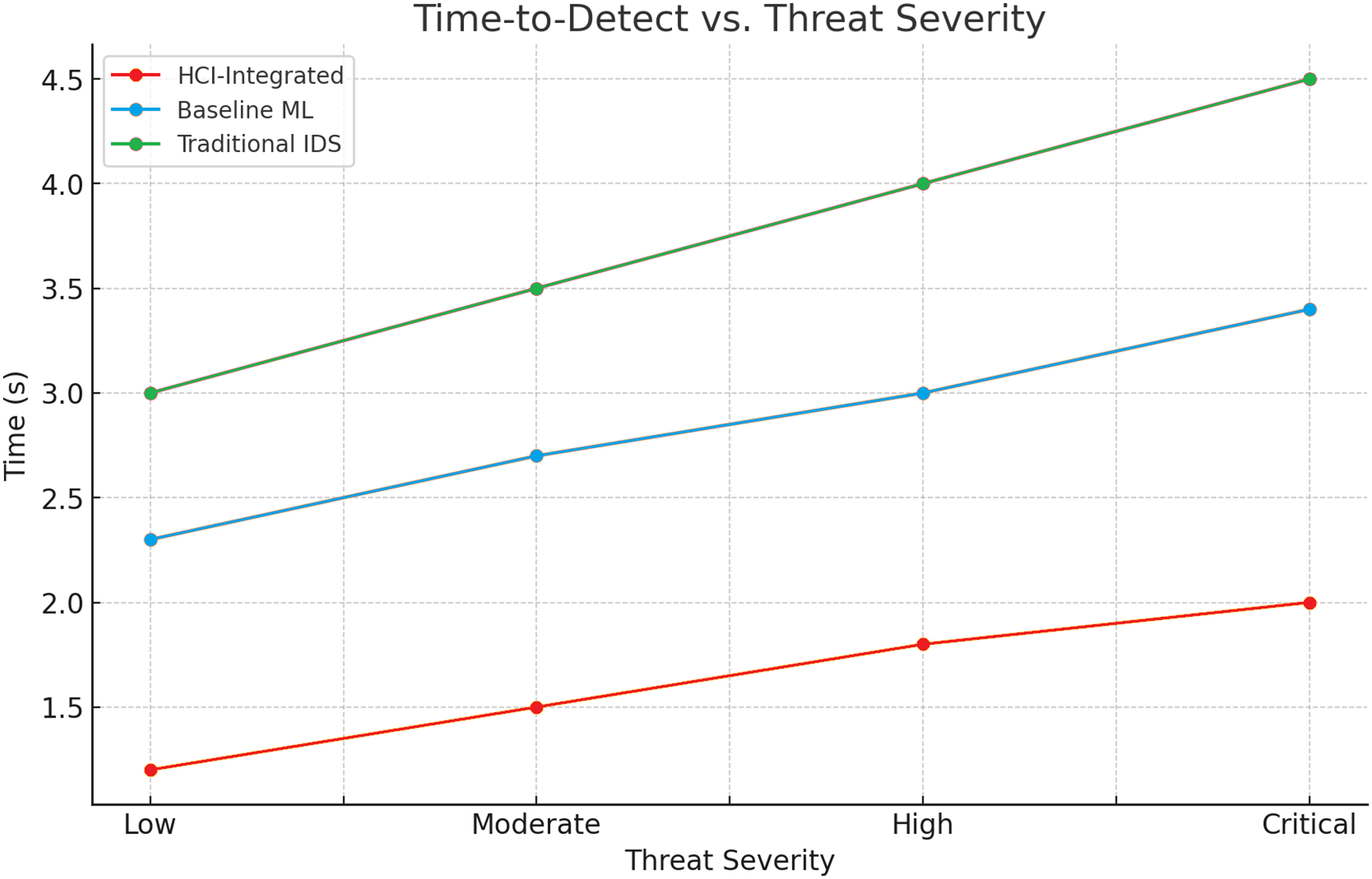

4.13 Threat Severity Responsiveness

The graph demonstrating the correlation between Time-to-Detect and Threat Severity displays a characteristically linear relationship across all models under examination. That said, it is apparent that the HCI-Integrated system has a notable and evident performance benefit over the others. In the case of critical threats, the HCI-Integrated model impressively detects threats within a striking time frame of around 2.0 s. Conversely, the Baseline Machine Learning model and the Traditional Intrusion Detection System have longer detection times, taking roughly 3.4 and 4.5 s to detect threats. This kind of quick responsiveness that the HCI-Integrated model provides is critical to successfully reducing potential harm in situations with especially high stakes. It also speaks to the operational significance and value of implementing HCI-focused optimization techniques within real-time security systems to improve their general efficacy and reliability. Fig. 21 illustrates Time to Detect vs. Thread Severity Evaluation.

Figure 21: Time to detect vs. thread severity evaluation

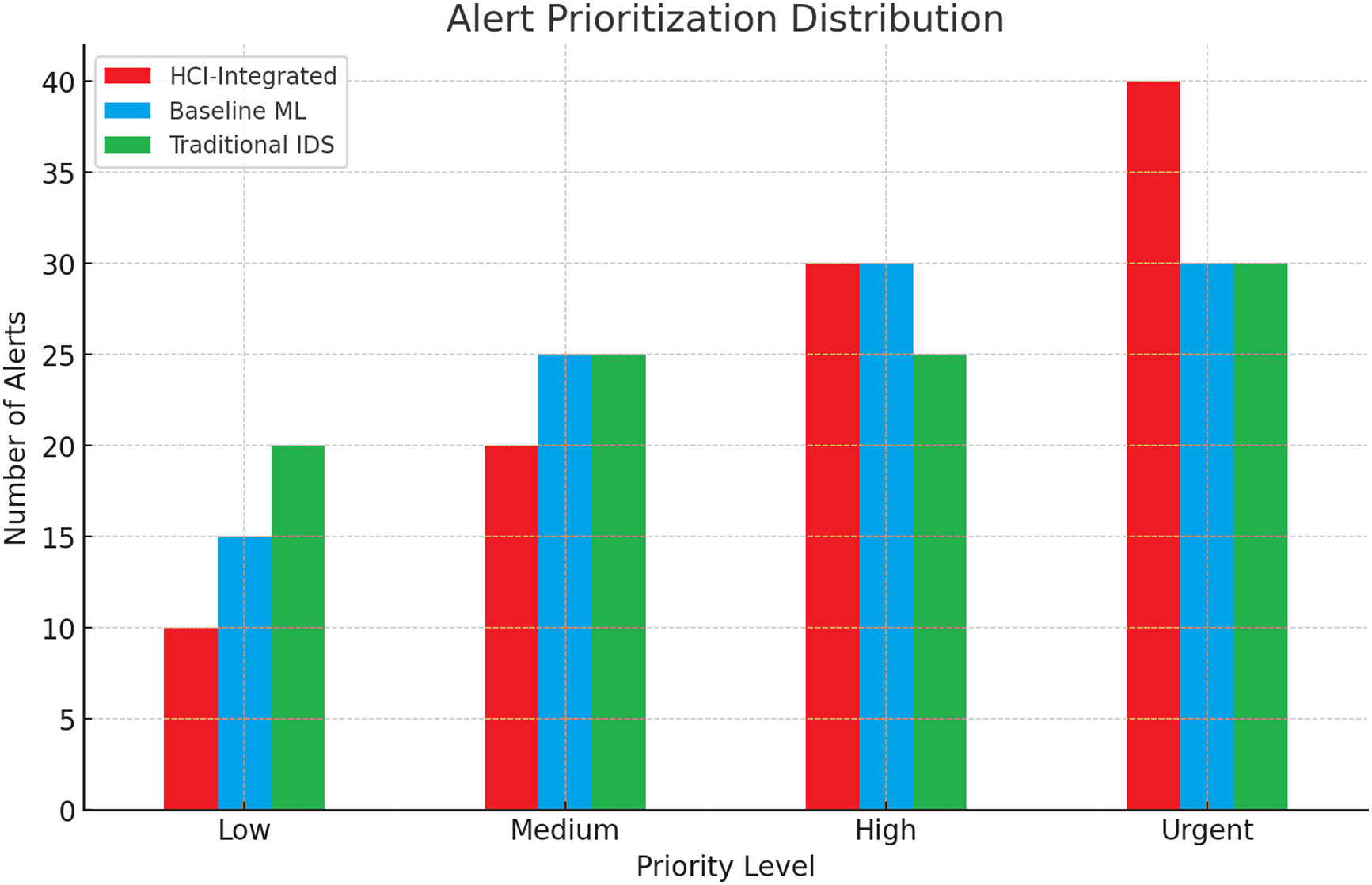

4.14 Alert Prioritization and Triage Efficiency

For prioritization, HCI-Integrated more frequently categorizes alerts as “Urgent” and “High”, with fewer low-priority alerts. This distribution pattern indicates better triage intelligence, directing analysts to focus on the most impactful threats. Classical IDS has a relatively flat distribution across priority levels, undermining the urgency signal and compounding alert fatigue. Fig. 22 shows Alert Prioritization Distribution Evaluation.

Figure 22: Alert prioritization distribution evaluation

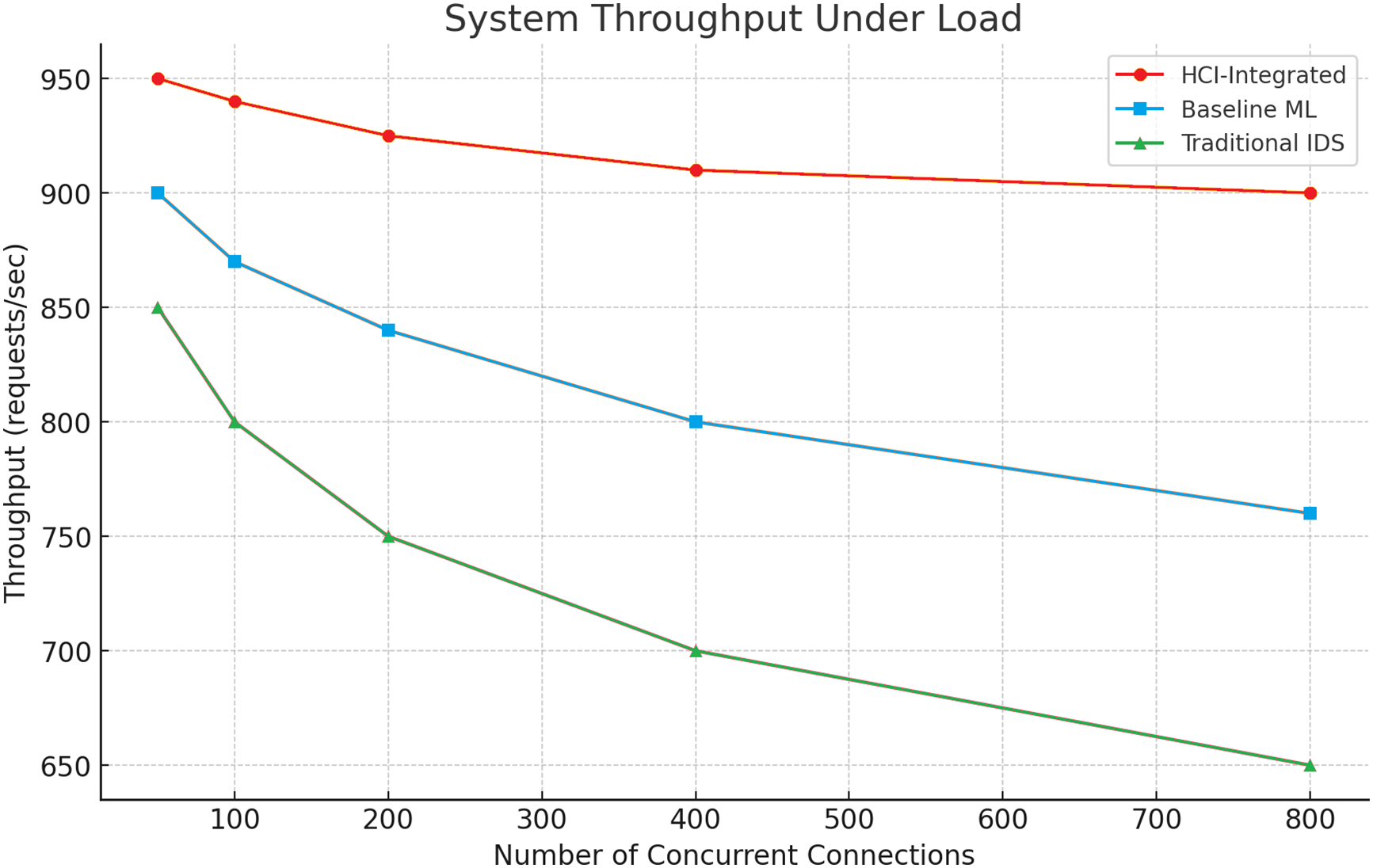

System throughput at increasing concurrency indicates the HCI-Integrated solution’s scalability. At 800 concurrent connections, the system retains more than 900 requests/s, far exceeding Baseline ML (~760) and Traditional IDS (~650). This establishes the HCI-Integrated framework’s architectural effectiveness and real-time processing capability, making it useful in enterprise-level and high-demand scenarios. Fig. 23 shows System Throughput Evaluation Under Load.

Figure 23: System throughput evaluation under load

4.16 Classification Performance Metrics

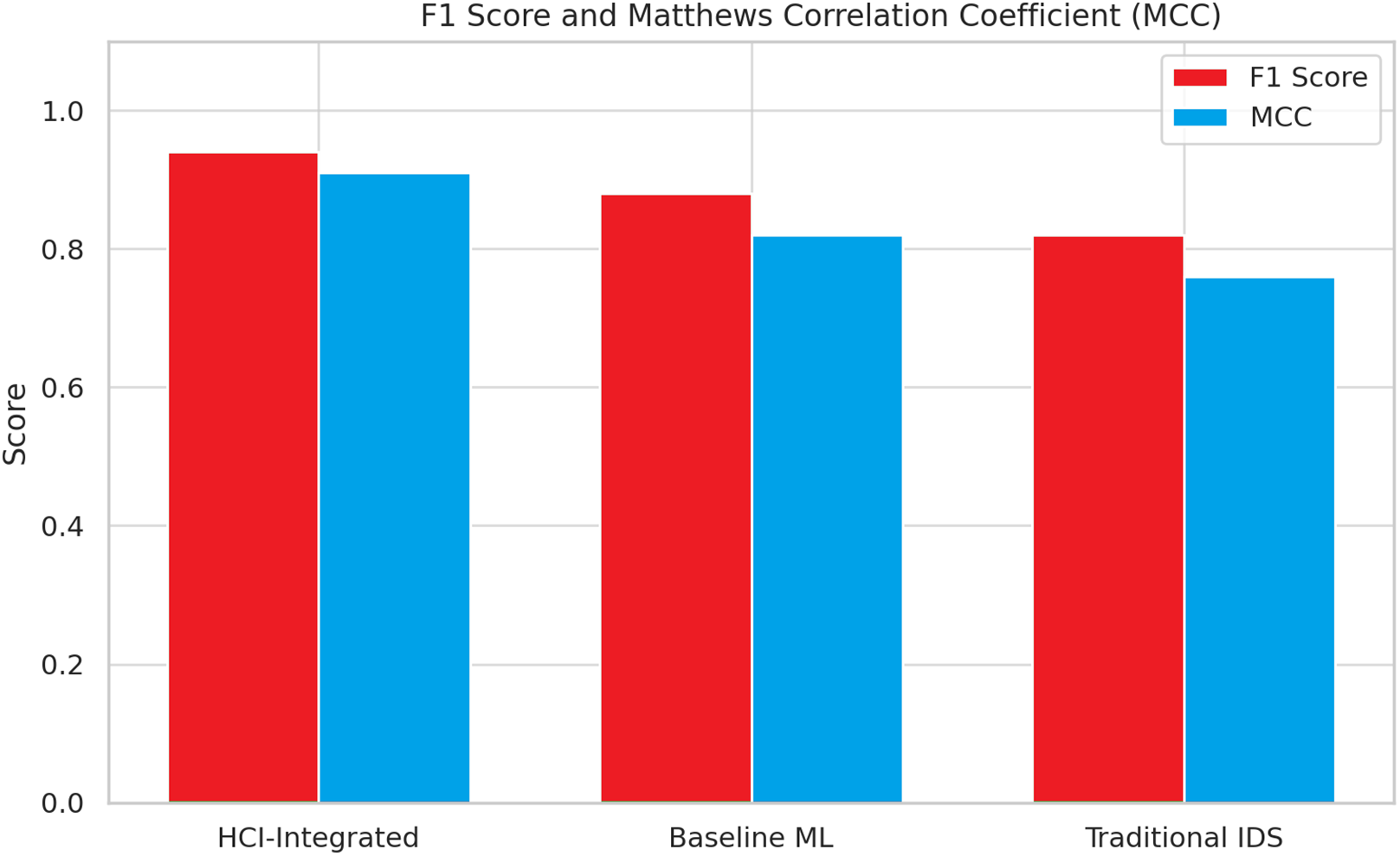

Comparative performance using F1 Score and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) further cements the dominance of the HCI-Integrated system. With an F1 score of around 0.94 and MCC of about 0.92, the model easily surpasses Baseline ML (F1 ~0.89, MCC ~0.82) and Traditional IDS (F1 ~0.82, MCC ~0.75). These metrics provide for balanced precision and recall, which is paramount in adversarial threat landscapes where detection effectiveness cannot be gained at the cost of high false positives. Fig. 24 shows the F1-score and MCC Evaluation.

Figure 24: F1-Score and MCC evaluation

4.17 Error Distribution by Attack Class

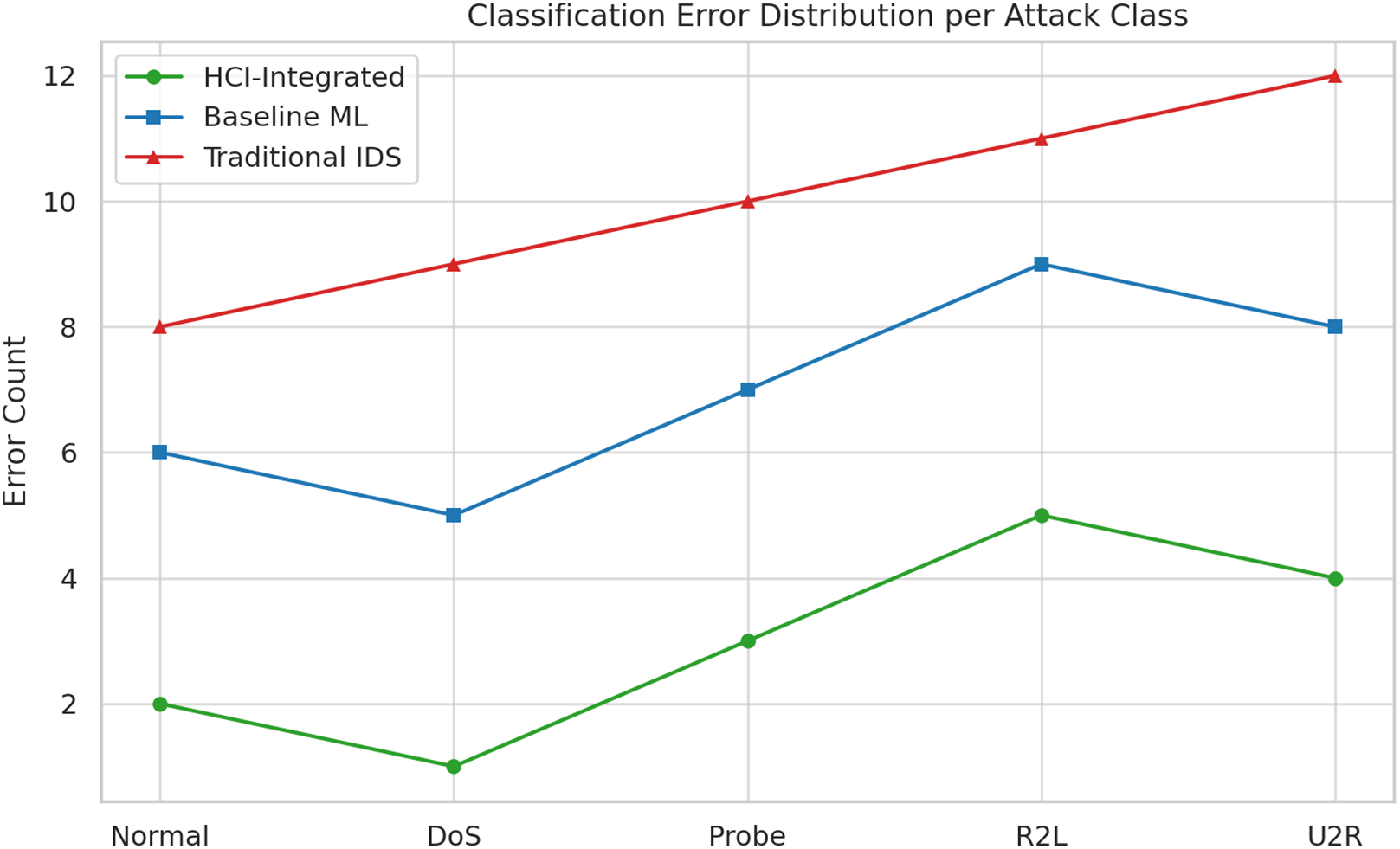

A detailed examination of classification error distribution concerning attack classes (Normal, DoS, Probe, R2L, U2R) indicates that HCI-Integrated has consistently low error rates even for low-frequency and hard-to-detect attacks like U2R and R2L. This is compared to the sharp error gradient seen with Traditional IDS, which is poor, especially with sophisticated and stealthy intrusions. The Baseline ML model, though reasonably good, still lags in reliability and stability. Fig. 25 shows the Classification Error Distribution per Attack Class.

Figure 25: Classification error distribution per attack class

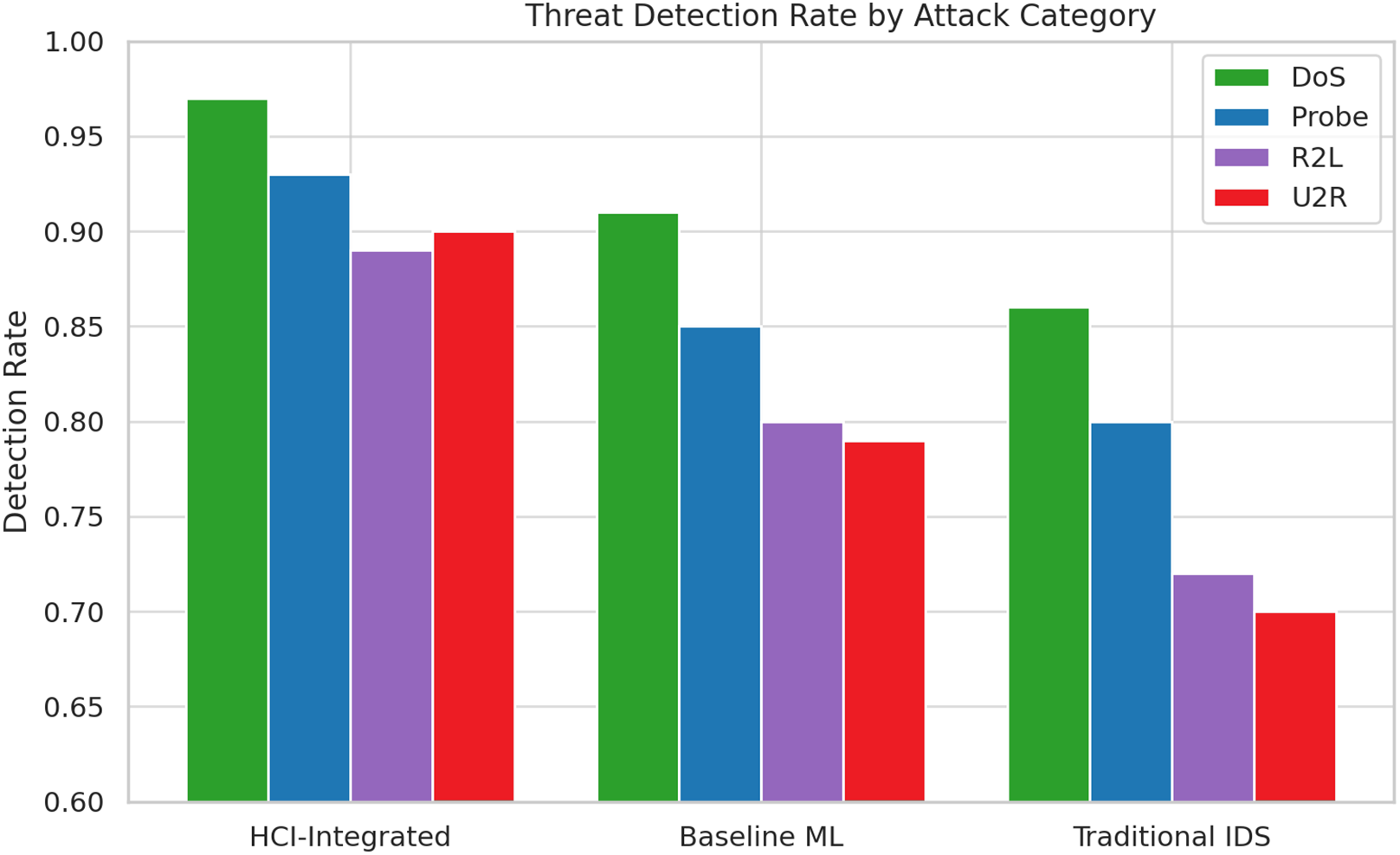

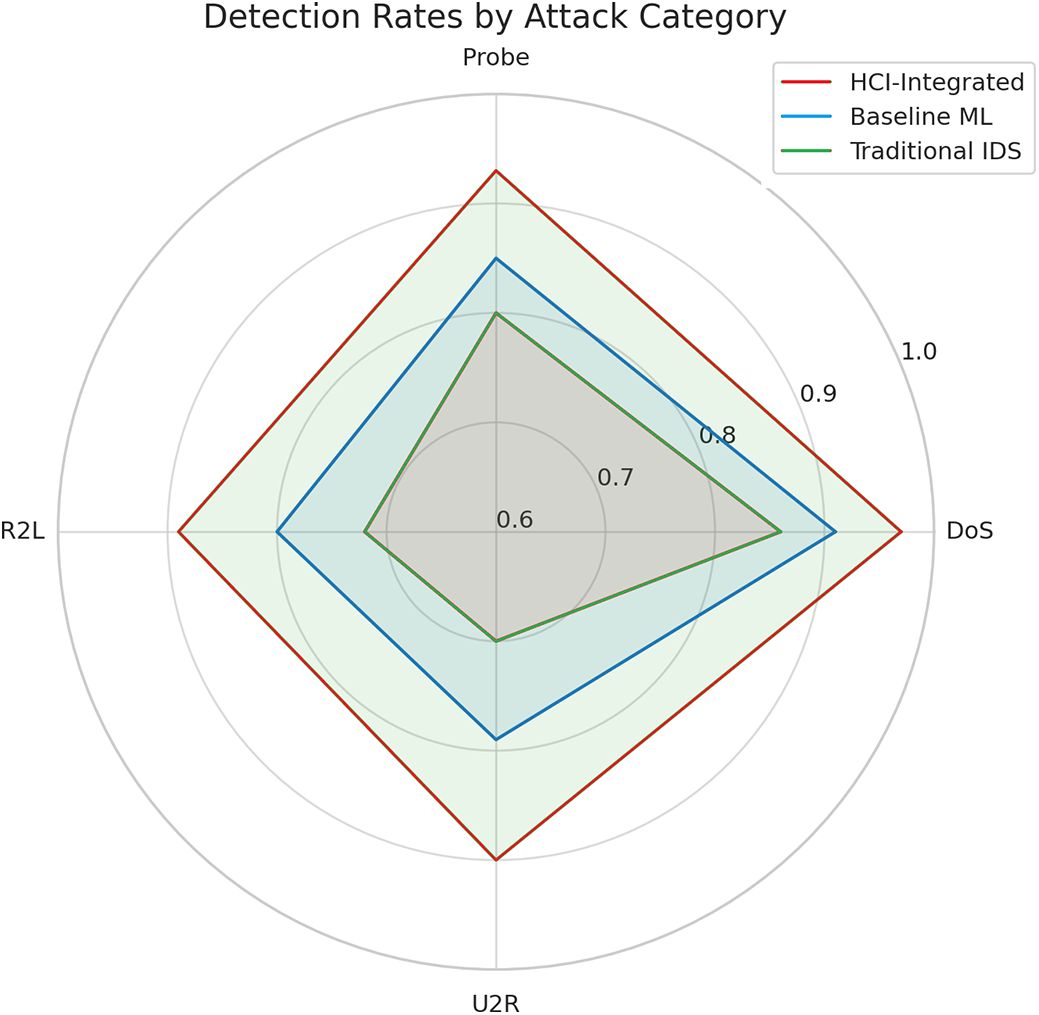

Detection rates across the four primary attack classes, DoS, Probe, R2L, and U2R, show the HCI-Integrated model nearing or exceeding 0.90. This consistent performance indicates comprehensive threat coverage, whereas both Baseline ML and Traditional IDS demonstrate a decline in detection rates as attack complexity increases. The radar plot visually reaffirms this trend, where HCI-Integrated traces the most uniform and outward-reaching profile, indicating a more balanced and effective detection strategy. Fig. 26 shows Threat Detection Rate by Attack Category, and Fig. 27 illustrates Detection Rates by Attack Category.

Figure 26: Threat detection rate by attack category

Figure 27: Detection rates by attack category

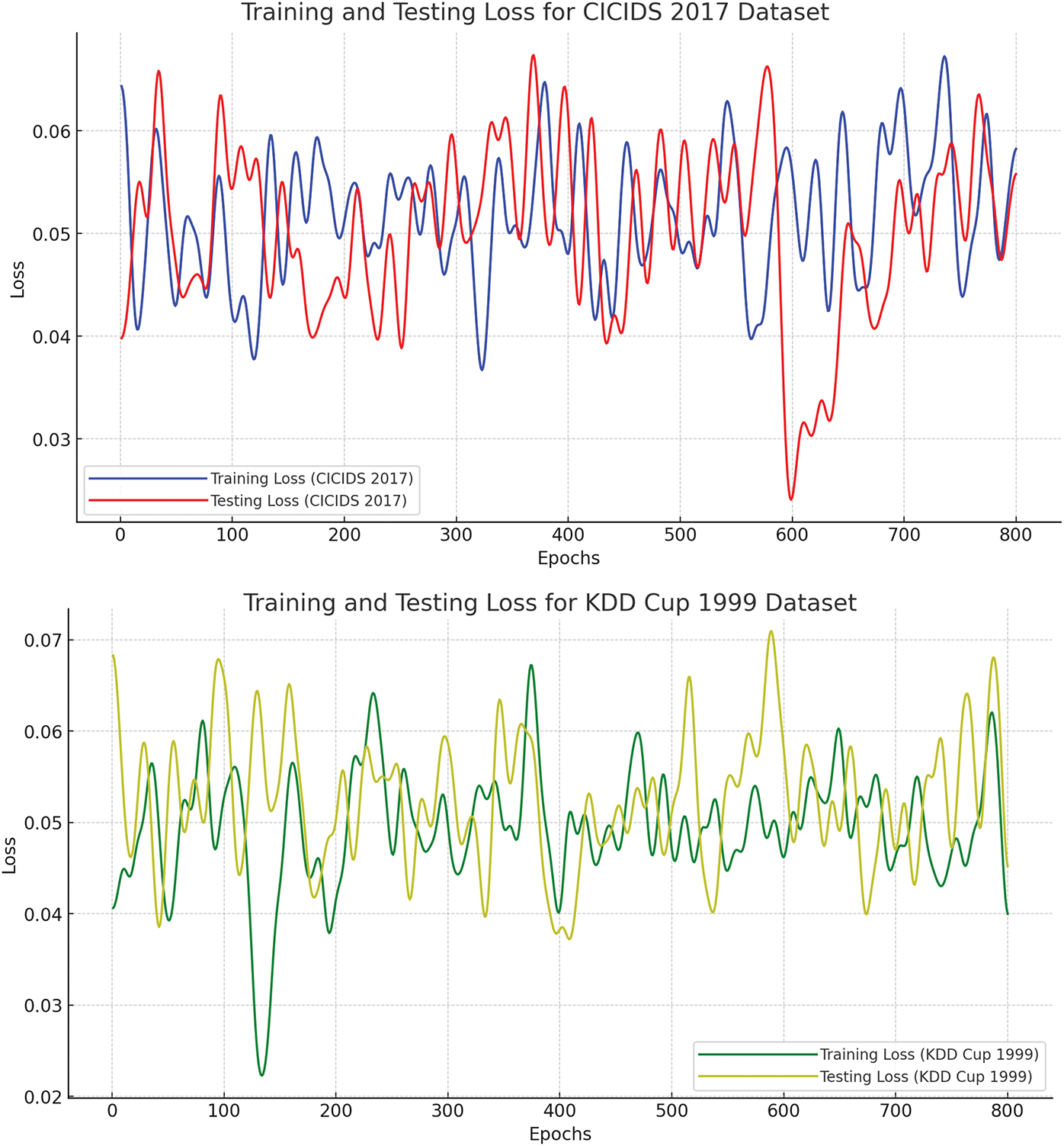

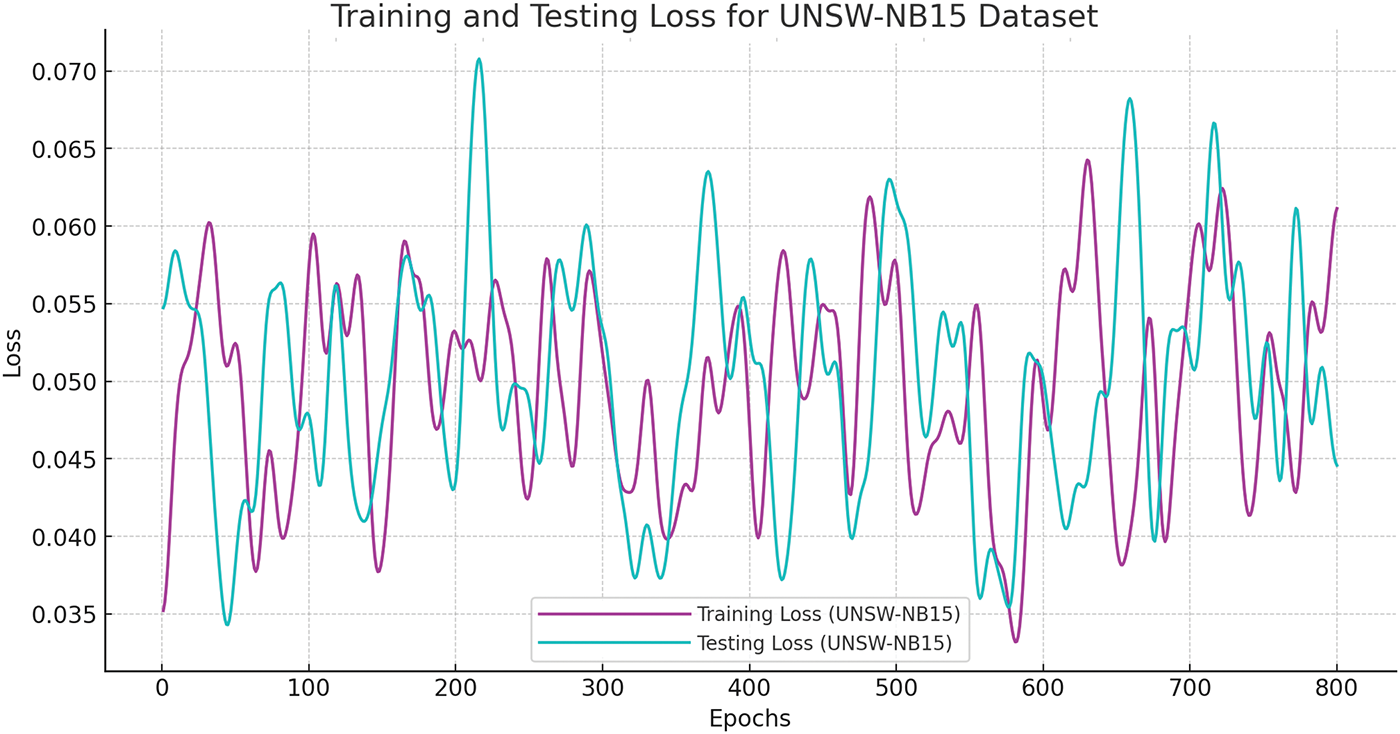

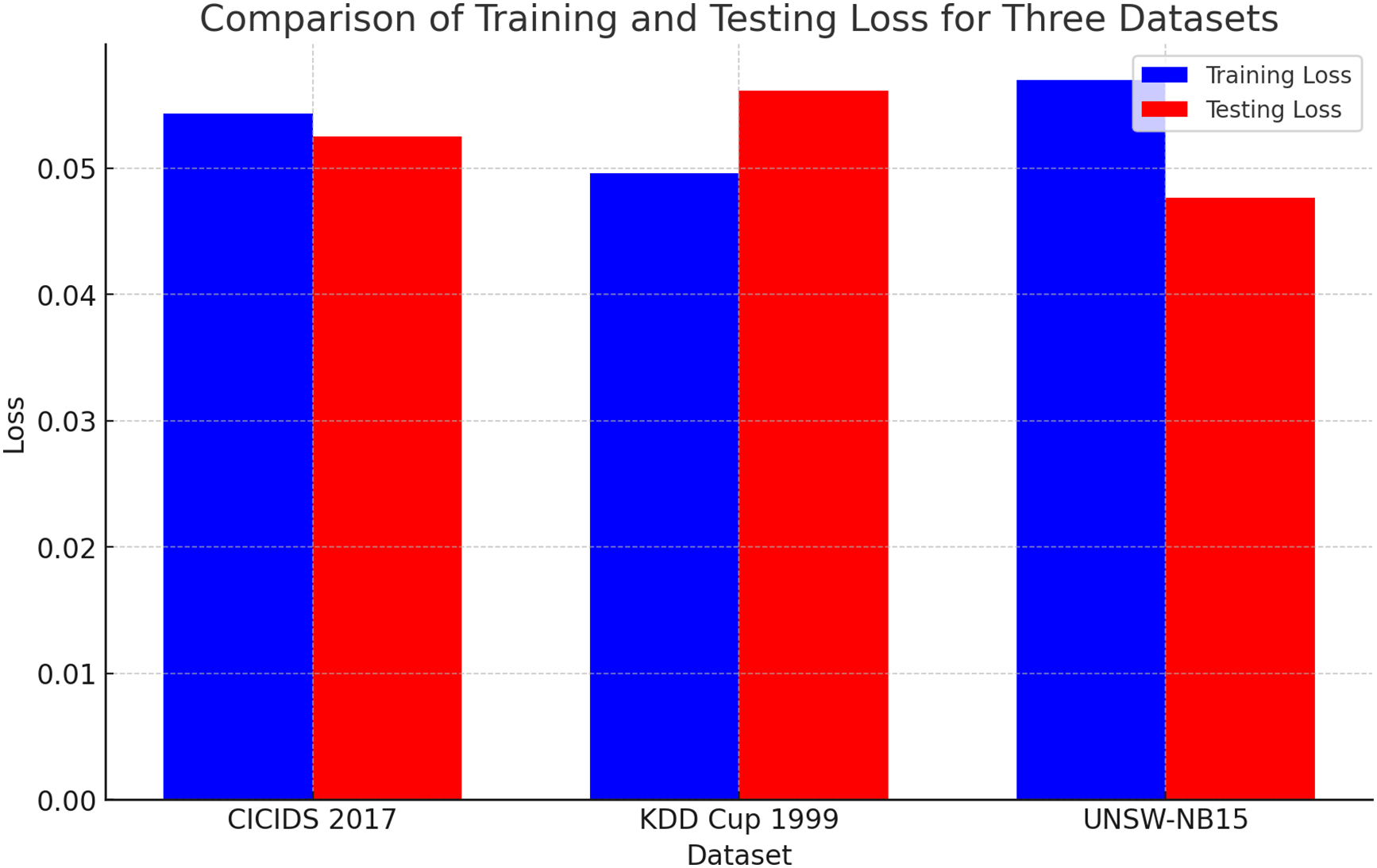

Fig. 28 shows the testing and training of the three major datasets, while Fig. 29 shows their comparative evaluations. These long-term results highlight the HCI-Integrated IDS’s maturity of operations and strategic advantage on technical and human-centered performance dimensions. By optimizing alert context interpretation, reducing time-to-detect, effectively prioritizing, scaling under load, and maintaining classification integrity, the system resolves the critical conditions for deployment within contemporary cybersecurity architectures. The cumulative evidence validates the HCI-Integrated model as a technological advancement and a paradigm-shifting approach to intrusion detection design. The evidence collectively and vehemently supports the assertion that the HCI-Integrated IDS represents a substantial enhancement over conventional IDS solutions. It offers faster and more accurate detections, lowers operational costs, enhances user experience, and conserves computational resources. These multi-faceted advantages validate the value of integrating human-centered design principles and modern machine learning techniques in the design of intelligent security systems. The HCI-Integrated system ranked the highest in every category, demonstrating its overall superiority in intrusion detection, efficiency, and accuracy. The reduced false positive rate is particularly significant, lowering the cognitive burden on security analysts and averting alert fatigue. The experimental results demonstrate the HCI-Integrated IDS’s substantial improvement over traditional rule-based systems and standard machine learning techniques. Its better accuracy, precision, recall, and low false positive rate, coupled with quick detection time, demonstrate its viability as a next-generation IDS solution. Integrating HCI concepts renders the system more usable and facilitates intelligent and effective anomaly detection. This performance confirms the potential of HCI-based approaches to cybersecurity, particularly in configurations requiring real-time threat detection and high decision reliability.

Figure 28: Training and testing loss of undertakan three datasets

Figure 29: Comparison of training and testing loss of datasets

This study proposes an HCI-Integrated IDS as a visionary solution for anomaly detection and cyberattack mitigation in smart cities. By incorporating HCI principles into the design of the IDS, the model proposed in this study achieves tremendous enhancements in detection accuracy and operational efficiency. Across a broad spectrum of performance metrics and diagnoses, the HCI-Integrated model consistently demonstrates superior capability on detection accuracy, responsiveness, resource efficiency, usability, and operational scalability. Empirical findings show that HCI-Integrated IDS experiences significantly lower detection latency, particularly under high threat severity and higher throughput under load, which indicates its real-time processing capacity. Its precision in contextual alert differentiation and prioritization facilitates timely and relevant alerting to analysts, reducing cognitive overload and false positive fatigue. Quantitative metrics regarding F1 score, MCC, and threat-wise detection rates validate its technical correctness and classification effectiveness, especially for difficult attack classes such as R2L and U2R. The model also shows minimal error propagation, with fewer Type I and Type II error counts across all threat categories consistently.

Along with lowered operational cost and improved human usability ratings, the HCI-Integrated IDS emerges not only as a top-performing algorithmic solution but also as an effective human-centered system, demonstrating the dividend of integrating principles of human-computer interaction into cybersecurity system design. Future research explores integrating adaptive learning techniques to allow continued model optimization in response to evolving threat landscapes. Moreover, adding HCI modules for explainability and active analyst feedback loops can also aid in system transparency and trust. Deployment on distributed architectures or zero-trust network settings can validate the model’s scalability and robustness in production-grade settings.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2025-314), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This work was funded and supported by the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2025-314), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials used in this study can be found via the following weblinks. https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/index.html, http://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/kddcup99/kddcup99.html, and https://www.unsw.edu.au/about-us/our-story/our-story-1 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zeng H, Yunis M, Khalil A, Mirza N. Towards a conceptual framework for AI-driven anomaly detection in smart city IoT networks for enhanced cybersecurity. J Innov Knowl. 2024;9(4):100601. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2024.100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lytras A, Visvizi A. Human-computer interaction and smart city surveillance systems. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;124(4):106923. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Islam M, Dukyil AS, Alyahya S, Habib S. Anomaly detection of IoT cyberattacks in smart cities using machine learning. J Cybersecur Priv. 2023;8(3):21. doi:10.3390/bdcc8030021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sharma AK, Gupta RK. Network anomaly detection for IoT systems in smart city using edge and cloud collaboration. Afr J Biomed Res. 2025;28(2):1641–51. doi:10.53555/AJBR.v28i2S.7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alrashdi M, Alqazzaz M. Cyberattacks detection in IoT-based smart city applications using machine learning techniques. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):9347. doi:10.1109/ccwc.2019.8666450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Islam SMR, Hossain MS, Muhammad G. The challenges of securing smart cities from cyber-attacks. J Emerg Trends Comput Inf Sci. 2024;2024:258–66. [Google Scholar]

7. Islam M, Dukyil AS, Alyahya S, Habib S. An IoT enable anomaly detection system for smart city surveillance. Sensors. 2023;23(4):2358. doi:10.3390/s23042358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cognitive city. Wikipedia [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_city. [Google Scholar]

9. Aslam N, Ullah Khan I, Abdulrahman Bader S, Alansari A, Abdullah Alaqeel L, Mohammed Khormy R, et al. Explainable classification model for Android malware analysis using API and permission-based features. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;76(3):3167–88. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.039721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sarker Emon MA, Abdullah Al Sohan MF, Hossain Munna MM, Ahmed M, Redwan K. CityShield: an IoT-driven and AI-based threat detection system for smart city operations. In: Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Advanced Innovations in Smart Cities (ICAISC); 2025 Feb 9–11; Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

11. Khan J, Elfakharany R, Saleem H, Pathan M, Shahzad E, Dhou S, et al. Can machine learning enhance intrusion detection to safeguard smart city networks from multi-step cyberattacks? Smart Cities. 2025;8(1):13. doi:10.3390/smartcities8010013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ahmed Y, Beyioku K, Yousefi M. Securing smart cities through machine learning: a honeypot-driven approach to attack detection in Internet of Things ecosystems. IET Smart Cities. 2024;6(3):180–98. doi:10.1049/smc2.12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rahmati M. Federated learning-driven cybersecurity framework for IoT networks with privacy-preserving and real-time threat detection capabilities. arXiv:2502.10599. 2025. [Google Scholar]

14. Akif MA, Butun I, Williams A, Mahgoub I. Hybrid machine learning models for intrusion detection in IoT: leveraging a real-world IoT Dataset. arXiv:2502.12382. 2025. [Google Scholar]

15. Hussain T, Khan MN, Yang B, Attar RW, Alhomoud A. LiDAR point cloud transmission: adversarial perspectives of spoofing attacks in autonomous driving. Comput Secur. 2025;157(5):104544. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2025.104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Protick TI, Sabir A, Abhinaya S, Bartlett A, Das A. Unveiling users’ security and privacy concerns regarding smart home IoT products from online reviews. ACM J Comput Sustain Soc. 2024;2(4):1–41. doi:10.1145/3685929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Pawar MV, Anuradha J. Detection and prevention of black-hole and wormhole attacks in wireless sensor network using optimized LSTM. Int J Pervasive Comput Commun. 2023;19(1):124–53. doi:10.1108/ijpcc-10-2020-0162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Priyadarshini I. Anomaly detection of IoT cyberattacks in smart cities using federated learning and split learning. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2024;8(3):21. doi:10.3390/bdcc8030021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Garg S, Kaur K, Batra S, Kaddoum G, Kumar N, Boukerche A. A multi-stage anomaly detection scheme for augmenting the security in IoT-enabled applications. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;104(5):105–18. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.09.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Thomas LT, Zorzo AF, Morisset C. Impact of using a privacy model on smart buildings data for CO2 prediction. In: Proceedings of the Data and Applications Security and Privacy XXXVII: 37th Annual IFIP WG 11.3 Conference (DBSec 2023); 2023 Jul 19–21; Sophia-Antipolis, France. [Google Scholar]

21. George AS. Emerging trends in AI-driven cybersecurity: an in-depth analysis. Partn Univers Innov Res Publ. 2024;2(4):15–28. doi:10.5281/zenodo.13333202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Fan Z, Luangsodsai A, Sinapiromsaran K. Mass-ratio-average-absolute-deviation based outlier factor for anomaly scoring. In: Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Joint Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (JCSSE); 2024 Jun 19–22; Phuket, Thailand. p. 488–93. [Google Scholar]

23. de Chaves SA, Benitti F. User-centred privacy and data protection: an overview of current research trends and challenges for the human-computer interaction field. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(7):1–36. doi:10.1145/3715903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Szücs V, Arány G, Dávid Á. Security awareness of HCI in DigitAll reality. Acta Polytech Hung. 2025;22(6):9–23. [Google Scholar]

25. Ortloff AM, Grohs JA, Lenau S, Smith M. A qualitative study on how usable security and HCI researchers judge the size and importance of odds ratio and Cohen’s d effect sizes. In: Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2025 Apr–May 1; Yokohama, Japan. [Google Scholar]

26. Jiang B, Liu Z, Yue G, Cui X, Liu Y, Wang HH. Privacy safeguarding for human-computer interaction based on adaptive federated learning with actor-critic selection. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3525186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shafik W. Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) technologies in socially-enabled artificial intelligence. In: Future of digital technology and AI in social sectors. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2025. p. 121–50 doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-5533-6.ch005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hazman C, Guezzaz A, Benkirane S, Azrour M. A smart model integrating LSTM and XGBoost for improving IoT-enabled smart cities security. Clust Comput. 2024;28(1):70. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04780-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Uppal M, Gulzar Y, Gupta D, Uppal J, Kumar M, Saini S. Enhancing accuracy through ensemble based machine learning for intrusion detection and privacy preservation over the network of smart cities. Discov Internet Things. 2025;5(1):11. doi:10.1007/s43926-025-00101-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yedalla J. Building cyber—resilient smart cities: the role of AI and big data in urban security. Int J Sci Res. 2025;14(2):648–52. [Google Scholar]

31. Brabin DD, Kumar KK, Sunitha T. Strengthening security in IoT-based smart cities utilizing cycle-consistent generative adversarial networks for attack detection and secure data transmission. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2025;18(2):79. doi:10.1007/s12083-024-01838-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Somanathan Pillai SEV, Vallabhaneni R, Vaddadi SA, Addula SR, Ananthan B. Archimedes assisted LSTM model for blockchain based privacy preserving IoT with smart cities. Indones J Electr Eng Comput Sci. 2025;37(1):488–97. doi:10.11591/ijeecs.v37.i1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hossain MI, Hasan R. Smart cities: cybersecurity concerns. In: Computer and information security handbook. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2025. p. 1397–412 doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-13223-0.00089-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ragab M, Ashary EB, Alghamdi BM, Aboalela R, Alsaadi N, Maghrabi LA, et al. Advanced artificial intelligence with federated learning framework for privacy-preserving cyberthreat detection in IoT-assisted sustainable smart cities. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4470. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88843-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Kezron IE. AI and the future of cybersecurity in smart cities: a framework for secure and resilient urban environments. Iconic Res Eng J. 2025;8(7):612–17. [Google Scholar]

36. Hussain A, Akbar W, Hussain T, Kashif Bashir A, Al Dabel MM, Ali F, et al. Ensuring zero trust IoT data privacy: differential privacy in blockchain using federated learning. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(1):1167–79. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3444824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Goje NS, Das D, Rani NA, Behera SK, Pradhan D. Security and privacy of EHRs sharing through blockchain technology in smart cities. In: 5G green communication networks for smart cities. Palm Bay, FL, USA: Apple Academic Press; 2025. p. 215–27 doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-95407-5.00011-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sharma K, Singh N. Security and privacy challenges in 6G enabled smart city. In: Building tomorrow’s smart cities with 6G infrastructure technology. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025. p. 39–64. [Google Scholar]

39. Nyangaresi VO, AlRababah AA, Yenurkar GK, Chinthaginjala R, Yasir M. Anonymous authentication scheme based on physically unclonable function and biometrics for smart cities. Eng Rep. 2025;7(1):e13079. doi:10.1002/eng2.13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Abu Al-Haija Q, Droos A. A comprehensive survey on deep learning-based intrusion detection systems in Internet of Things (IoT). Expert Syst. 2025;42(2):e13726. doi:10.1111/exsy.13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools