Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Unveiling Zero-Click Attacks: Mapping MITRE ATT&CK Framework for Enhanced Cybersecurity

1 School of Computing, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460, USA

2 Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Dartmouth, MA 02747, USA

3 Department of Software Engineering, Daffodil International University, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh

4 School of Computing Sciences and Computer Engineering, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA

5 Department of Computer Science, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78249, USA

6 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, National Institute of Textile Engineering and Research, Dhaka, 1350, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Authors: Md Shohel Rana. Email: ; Anichur Rahman. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069212

Received 17 June 2025; Accepted 18 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Zero-click attacks represent an advanced cybersecurity threat, capable of compromising devices without user interaction. High-profile examples such as Pegasus, Simjacker, Bluebugging, and Bluesnarfing exploit hidden vulnerabilities in software and communication protocols to silently gain access, exfiltrate data, and enable long-term surveillance. Their stealth and ability to evade traditional defenses make detection and mitigation highly challenging. This paper addresses these threats by systematically mapping the tactics and techniques of zero-click attacks using the MITRE ATT&CK framework, a widely adopted standard for modeling adversarial behavior. Through this mapping, we categorize real-world attack vectors and better understand how such attacks operate across the cyber-kill chain. To support threat detection efforts, we propose an Active Learning-based method to efficiently label the Pegasus spyware dataset in alignment with the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This approach reduces the effort of manually annotating data while improving the quality of the labeled data, which is essential to train robust cybersecurity models. In addition, our analysis highlights the structured execution paths of zero-click attacks and reveals gaps in current defense strategies. The findings emphasize the importance of forward-looking strategies such as continuous surveillance, dynamic threat profiling, and security education. By bridging zero-click attack analysis with the MITRE ATT&CK framework and leveraging machine learning for dataset annotation, this work provides a foundation for more accurate threat detection and the development of more resilient and structured cybersecurity frameworks.Keywords

Cyberattacks have become a persistent and evolving threat in the digital age, presenting complex challenges to individuals, organizations, and national security. These malicious operations are conducted by a diverse range of adversaries, including cybercriminals, state-sponsored entities, and hacktivists, each driven by motivations such as financial exploitation, political agendas, or ideological disruption. The arsenal of cyberattack methodologies continues to expand, with common tactics including malware, ransomware, phishing, and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks [1]. Malware infiltrates systems to compromise data or cause damage, ransomware encrypts critical files and demands payment for restoration, phishing scams deceive users into divulging sensitive information, and DDoS attacks overwhelm network resources, disrupting normal operations. The consequences of these attacks can be severe, resulting in financial losses, reputational damage, and threats to national security.

With rapid technological progress, cyberattacks have become more sophisticated; zero-click threats are a prime example. These attacks do not require user interaction, allowing adversaries to execute exploits silently and remain undetected. They typically exploit hidden vulnerabilities in software or hardware. A single message or data packet can trigger the exploit; no clicks or downloads are necessary. This passive vector is favored by advanced adversaries, including state sponsored actors. It bypasses conventional defenses and evades user awareness mechanisms with remarkable efficiency. The consequences can be serious. Zero-click attacks have led to the theft of personal data and the disruption of critical infrastructure. Many such attacks rely on zero-day vulnerabilities, flaws unknown to software vendors. These unpatched weaknesses make even security-aware users vulnerable to exploitation. As adversarial tactics evolve, zero-click threats continue to push the limits of modern cybersecurity. Their stealth and complexity demand adaptive behavior-based defense strategies that exceed traditional methods.

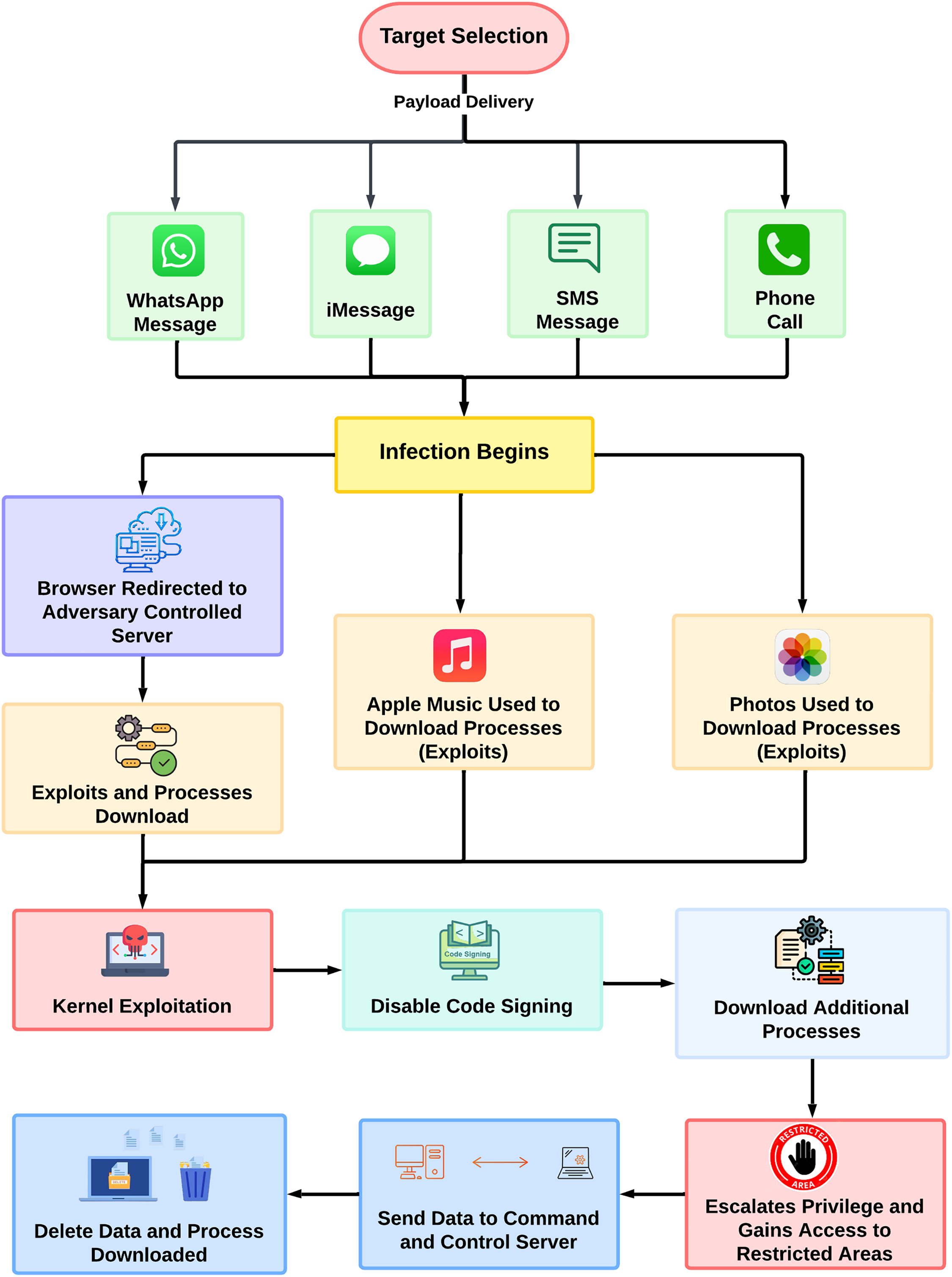

One of the most prominent examples of zero-click attacks is Pegasus, a sophisticated spyware developed by the Israeli cyber-intelligence firm NSO Group. Pegasus is engineered for remote and covert installation on iOS and Android devices by exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities to gain unauthorized access without user interaction [2] (see Fig. 1). The first in-depth technical analysis was published in August 2016 by Citizen Lab and Lookout Security after an unsuccessful attempt to infiltrate the iPhone of a human rights activist [3,4]. Since then, Pegasus has drawn widespread media and academic attention, particularly through investigations by Amnesty International and Citizen Lab. One of the most notable efforts, the Pegasus Project, revealed in July 2021, analyzed a leaked dataset containing over 50,000 phone numbers allegedly selected for surveillance [5].

Figure 1: Overview of pegasus spyware infection chain; Outlines how Pegasus initiates infection via zero-click vectors, downloads exploits, disables protections, exfiltrates data, and escalates privileges for full device control

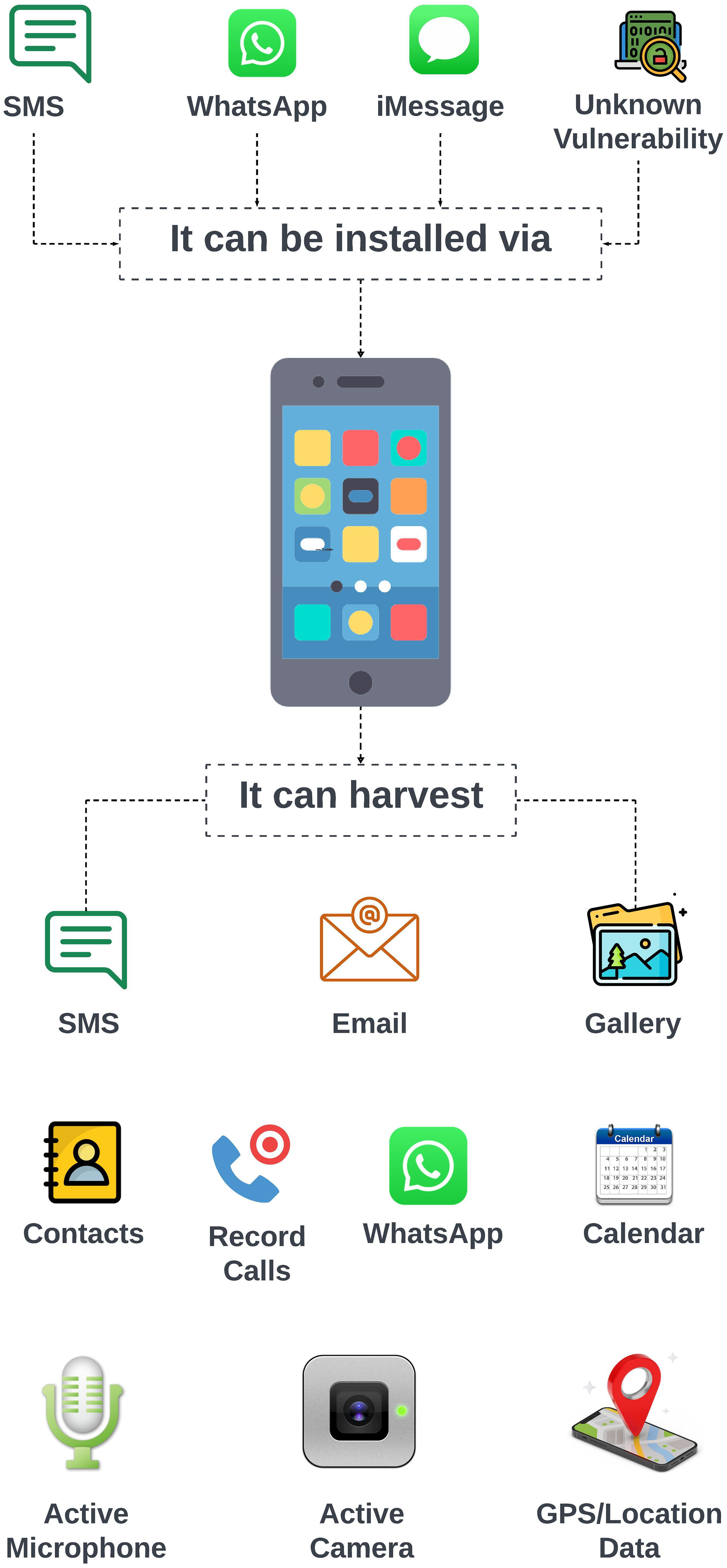

As illustrated in Fig. 2, Pegasus can infiltrate devices through vectors such as SMS, WhatsApp, iMessage, or unknown vulnerabilities. Once deployed, it operates stealthily to exfiltrate sensitive data including SMS, emails, media files, contacts, and app data such as WhatsApp and calendar entries. It can also activate the microphone, camera, and GPS, enabling continuous real-time surveillance and location tracking of the target [6,7].

Figure 2: Pegasus spyware infection and surveillance capabilities; It can silently infect devices via SMS, messaging apps, or unknown exploits, and harvests data including messages, media, calls, and location, while activating the microphone and camera for live surveillance [6]

Zero-click attacks pose a significant challenge to cybersecurity due to their covert execution and lack of user engagement [8]. Unlike traditional cyber threats that rely on tactics such as phishing or social engineering [9], zero-click attacks exploit vulnerabilities within messaging protocols [10], application frameworks [11], and device firmware [12], making them exceptionally difficult to detect and mitigate. Conventional defense mechanisms-such as behavioral detection, intrusion prevention systems (IPS), and user-awareness training-offer limited protection against such attacks [13], necessitating a structured and systematic approach to their analysis, classification, and mitigation.

To address this challenge, this study leverages the MITRE ATT&CK framework [14], a globally recognized knowledge base of adversarial tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP) derived from real-world cyber threat observations. The MITRE ATT&CK framework provides a standardized model to map attack behaviors and enables cybersecurity professionals to systematically assess, classify, and respond to cyber threats. Historically, mapping cyberattacks to the MITRE ATT&CK framework has been instrumental in improving cybersecurity readiness, offering the following capabilities:

• Threat Attribution: Identifying and categorizing attack behaviors to distinguish adversarial tactics used in zero-click exploits.

• Improved Detection Mechanisms: Enhancing existing cybersecurity defenses through structured threat modeling and behavior-based anomaly detection.

• Proactive Mitigation Strategies: Developing tailored defense mechanisms based on known attack vectors, significantly reducing susceptibility to zero-click attacks.

We apply the MITRE ATT&CK framework to systematically map zero-click attack tactics and techniques. This approach will provide deeper insights into attacker methodologies and facilitate the development of robust defense mechanisms against such advanced exploitations. To demonstrate the effectiveness of our mapping strategy, we introduce a structured evaluation using a synthetic dataset—the Pegasus Spyware dataset [15]—as a case study. This dataset consists of structured threat intelligence reports, Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), and forensic traces from documented incidents of zero-click attacks. We apply an Active Learning-based approach to automate data categorization and annotation based on our mapping of zero-click attack behaviors within the MITRE ATT&CK framework. By integrating automated data labeling techniques, we aim to improve the accuracy and efficiency of zero-click attack classification, ultimately strengthening cybersecurity defenses. Through this study, we provide a comprehensive framework for understanding zero-click attacks, mapping their operational mechanics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework, and demonstrating how structured data-driven approaches improve the ability to detect and respond to such advanced cyber threats.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. Mapping zero-click attacks to the MITRE ATT&CK framework: A comprehensive mapping of zero-click attack behaviors is provided, offering a structured approach to understanding these threats.

2. Identification and collection of evidence-based Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) data: This study gathers and analyzes real-world data on zero-click attacks, including Pegasus, Simjacker, Bluebugging, and Bluesnarfing.

3. Active Learning-based dataset labeling: We introduce an automated labeling method for the zero-click dataset, improving annotation accuracy and aligning dataset classification with the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

4. Proactive defense strategies: Actionable security measures-including real-time monitoring, device-level security enhancements, and user education-are proposed to mitigate the risks associated with zero-click attacks.

The structure of this reminder of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews key literature on zero-click mobile attacks, highlighting gaps in behavioral attribution. Section 3 details our proposed mapping framework, which links observed features to ATT&CK techniques. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and discusses performance metrics and insights. In Section 5, we apply Active Learning to label the Pegasus spyware dataset using the MITRE ATT&CK taxonomy. Section 6 introduces targeted defense strategies informed by the mapped behaviors. Section 7 outlines key limitations and methodological boundaries. Finally, Section 8 summarizes our contributions and proposes avenues for future research in stealth threat detection.

A comprehensive review of zero-click attacks and MITRE ATT&CK mapping methodologies reveals significant research gaps. While previous studies have repurposed existing MITRE ATT&CK information, many lack original behavioral analysis and structured insights. In contrast, this work incorporates real behavioral observations, executed malware analysis, and data-driven insights to offer a more comprehensive understanding of zero-click attacks. The prior research falls into two key categories: (i) studies on zero-click attacks and (ii) MITRE ATT&CK mapping approaches, given the extensive use of the MITRE ATT&CK framework in cybersecurity research.

Zero-click attacks represent a significant cybersecurity concern due to their ability to exploit vulnerabilities without requiring user interaction. Younis et al. [16] attempted to map zero-click attacks to the MITRE ATT&CK framework; however, their study lacked detailed explanations for each mapping. Similarly, Shaker et al. [17] examined the severity of zero-click attacks and proposed general prevention measures, but their analysis remained superficial. Kareem [18] investigated the root causes of Pegasus spyware, proposing broad countermeasures, while Nisha and Kulkarni [19] assessed the theoretical implications of zero-click attacks within the banking sector, suggesting security strategies without practical validation.

Shafqat et al. [20] explored the isolation of mobile devices by installing vulnerable software on a dedicated server to mitigate infection risks. However, their approach had significant flaws, as acknowledged in [21]. Wen et al. [22] examined SMS-based vulnerabilities but did not address more advanced threats such as Simjacker. Daid [23] provided a detailed analysis of Simjacker, outlining its exploitation mechanisms and inherent system vulnerabilities, whereas Kumar et al. [24] applied deep learning techniques to detect SMS-based attacks, though their model lacked real-world applicability.

Bluetooth-related threats such as Bluebugging and Bluesnarfing have also been extensively studied. Ali et al. [25] conducted a systematic review of Bluetooth security vulnerabilities, while Indumathi et al. [26] surveyed Bluetooth security concerns and recommended best practices. Other studies [27,28] identified security flaws in Bluetooth-enabled devices, highlighting the necessity for enhanced protection measures.

2.2 MITRE ATT&CK Mapping Approach

The MITRE ATT&CK framework has been widely adopted as a foundational tool for understanding adversarial tactics and techniques. Sun et al. [29] employed graph neural networks and knowledge graph classification to map malware behaviors within the MITRE ATT&CK framework, enhancing malware classification accuracy. Kwon et al. [30] integrated the MITRE ATT&CK framework with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework to develop a comprehensive policy structure for cyberattack prevention and response.

Octavian et al. [31] automated the association between Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) and MITRE ATT&CK techniques using machine learning and BERT-based models, improving threat intelligence operations. Xiong et al. [32] introduced a threat modeling language based on the MITRE Enterprise ATT&CK Matrix, offering a structured approach to threat modeling. Rajesh et al. [33] explored threat detection methodologies, utilizing the MITRE ATT&CK framework to improve cyber threat detection and response strategies.

While prior studies aimed to align zero-click attacks with the MITRE ATT&CK framework, most relied on generalized threat descriptions without capturing the behavioral nuance or validating mappings against real-world attack traces. Our methodology addresses these gaps through four key innovations:

• Behavior-First Mapping: Unlike previous works that repurposed existing MITRE techniques through static analysis, we executed malware samples in controlled sandbox environments to extract forensic artifacts and observe run-time behaviors directly. This approach yielded high-fidelity behavioral evidence, forming a solid foundation for mapping.

• Granular Technique Attribution: Each observed attack phase was meticulously matched to MITRE tactics, techniques, and sub-techniques (TTPs), providing greater precision than prior studies. We identified Event-Triggered Execution (T1546) and Hijack Execution Flow (T1574) in Pegasus spyware highlighting privilege escalation paths previously undocumented in ATT&CK-based mappings.

• Empirical Coverage Evaluation: To substantiate mapping completeness, we conducted a quantitative coverage analysis across the Mobile Matrix. Our findings demonstrate alignment with 90.9% of MITRE Tactics and over 50% of Techniques, visualized via structured matrices. This metric-based validation advances mapping transparency and reproducibility.

• Iterative Mapping Refinement: Moving beyond assumption-based labeling, we applied Active Learning and artifact-centric analysis to iteratively refine the mapping logic. This methodology reduces false-positive correlations and enhances contextual fidelity—ensuring that observed behaviors anchor the mapping rather than inferred intent.

These enhancements position our work as the first to combine controlled execution environments, trace-level behavioral evidence, and quantitative validation to produce a fine-grained, empirically grounded mapping of zero-click attacks to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This behavior-first mapping not only deepens threat characterization but also establishes a robust foundation for downstream evaluation of classifier performance and threat detection efficacy, as explored in the next sections.

3 Methodology and Behavioral Analysis of Zero-Click Attacks

Zero-click attacks, due to their stealthy nature, present significant challenges in gathering comprehensive data for analysis. To address these challenges, we adopted a structured and systematic methodology that integrates primary research, data-driven analysis, and mapping to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This approach ensures the integrity and relevance of our findings while providing actionable insights for cybersecurity professionals.

3.1 Primary Research: Behavioral Analysis in Controlled Environments

To gain a deeper understanding of zero-click attacks, we conducted primary research by executing malware in controlled environments, including sandboxes and virtual machines. This controlled execution allowed us to observe and document zero-click attack behaviors in real time, providing novel insights that are often absent in existing literature.

• Controlled Environment Setup: We established isolated environments using VMware and sandboxing tools to execute malware samples associated with zero-click attacks, including Pegasus [34], Simjacker [4], Bluebugging [35], and Bluesnarfing [36]. These environments were configured to replicate the conditions of the real world mobile device, covering both the iOS and Android operating systems [37,38].

• Behavioral Observation: During execution, we monitored the malware’s activities, focusing on several key attack phases:

– Initial Access: Examination of how malware exploits vulnerabilities in messaging applications, web browsers, or wireless protocols to gain unauthorized entry [4,39].

– Execution: Identification of techniques used to deploy and execute malicious code without user interaction [35,36].

– Persistence: Analysis of strategies employed to ensure malware remains active after system reboots or software updates [39–41].

– Defense Evasion: Investigation of methods used to conceal the presence of malware and circumvent security detection mechanisms [37,42–45].

– Data Exfiltration: Study of data extraction techniques leveraged by adversaries to access and transmit sensitive information from compromised devices [46–50].

• Data Collection: We systematically recorded detailed logs of system activities, including process execution traces, memory usage fluctuations, network interactions, and unauthorized API calls. This data was instrumental in identifying the specific tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) employed in zero-click attacks [51–54].

To support our analysis, we used the Pegasus Spyware Dataset, which contains structured threat intelligence reports, Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), and forensic traces from real-world incidents. This dataset provides valuable information on the operating behaviors of Pegasus spyware, enabling a systematic analysis of zero-click attack methodologies.

• Dataset Size: The dataset consists of 1400 documented Pegasus infections in 20 countries, covering incidents involving journalists, human rights activists, and political dissidents [55,56].

• Data Characteristics: The dataset includes the following components:

– Device Information: Details on operating system versions, device models, and installed applications affected by Pegasus spyware [4,39].

– Attack Vectors: Methods used for malware delivery, including SMS-based payloads, iMessage exploits, and WhatsApp vulnerabilities [39,57].

– Behavioral Patterns: Documented activities associated with Pegasus infections, such as unauthorized data exfiltration, privilege escalation, and sophisticated defense evasion techniques [46–48].

– Forensic Traces: Logs and artifacts generated by Pegasus spyware, including altered system files, network activity records, and evidence of persistent surveillance mechanisms [39,58].

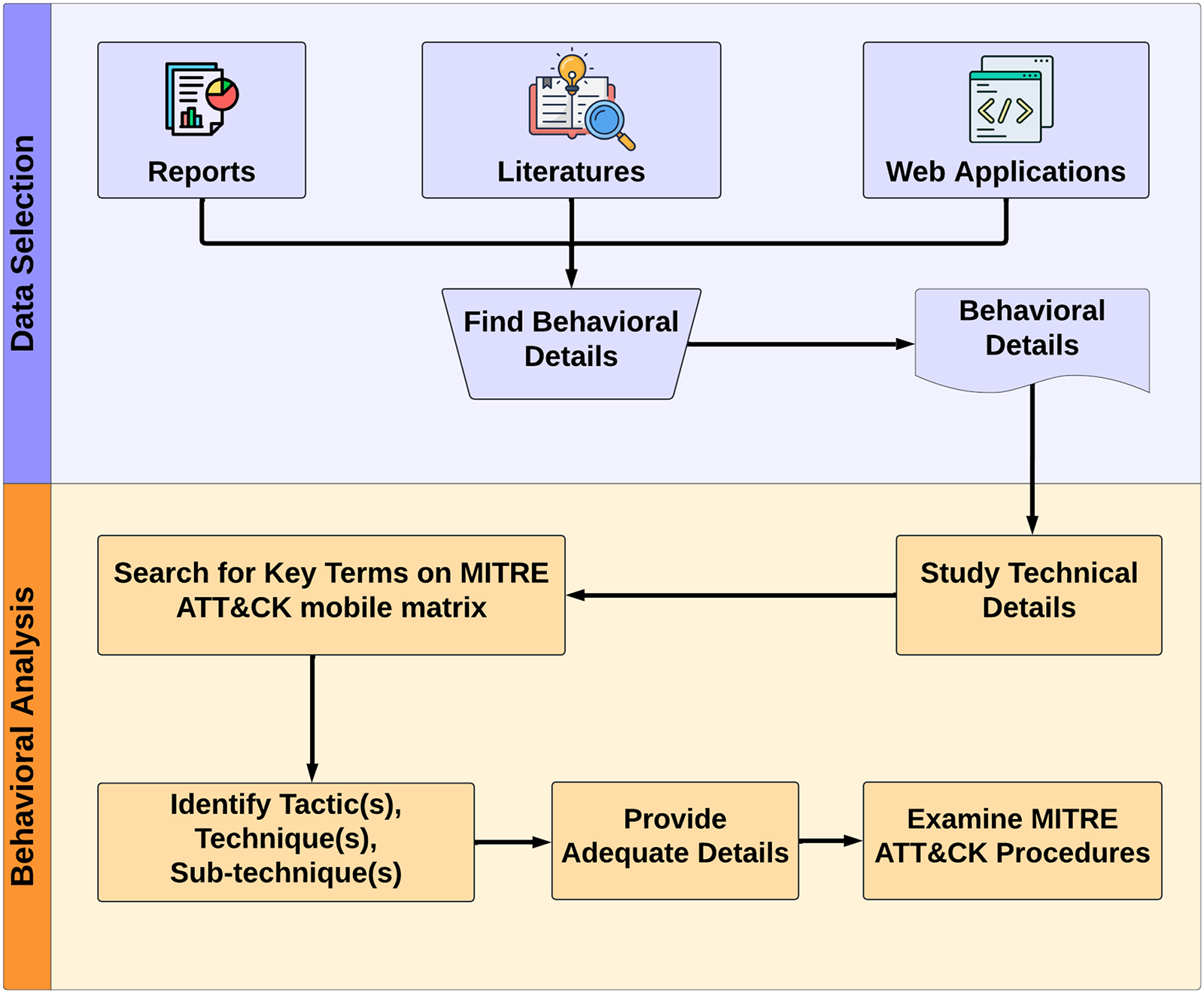

3.1.2 Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted a comprehensive exploration of various sources to gather relevant data for our investigation on Zero-click attacks, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Our systematic search spanned multiple avenues, including technical reports, academic literature, and web applications. Key sources considered in this process include:

• Citizen Lab: Detailed reports on Pegasus infections and zero-click attack techniques, providing insights into the exploitation of vulnerabilities in messaging apps and wireless protocols [59–61].

• Amnesty International: Forensic analysis of compromised devices, offering critical data on malware persistence, defense evasion, and data exfiltration techniques [39].

• Lookout Security: Technical analysis of Pegasus spyware and its variants, highlighting the use of zero-day vulnerabilities and advanced evasion tactics [58].

Figure 3: Workflow for behavioral data collection and analysis from controlled malware execution environments

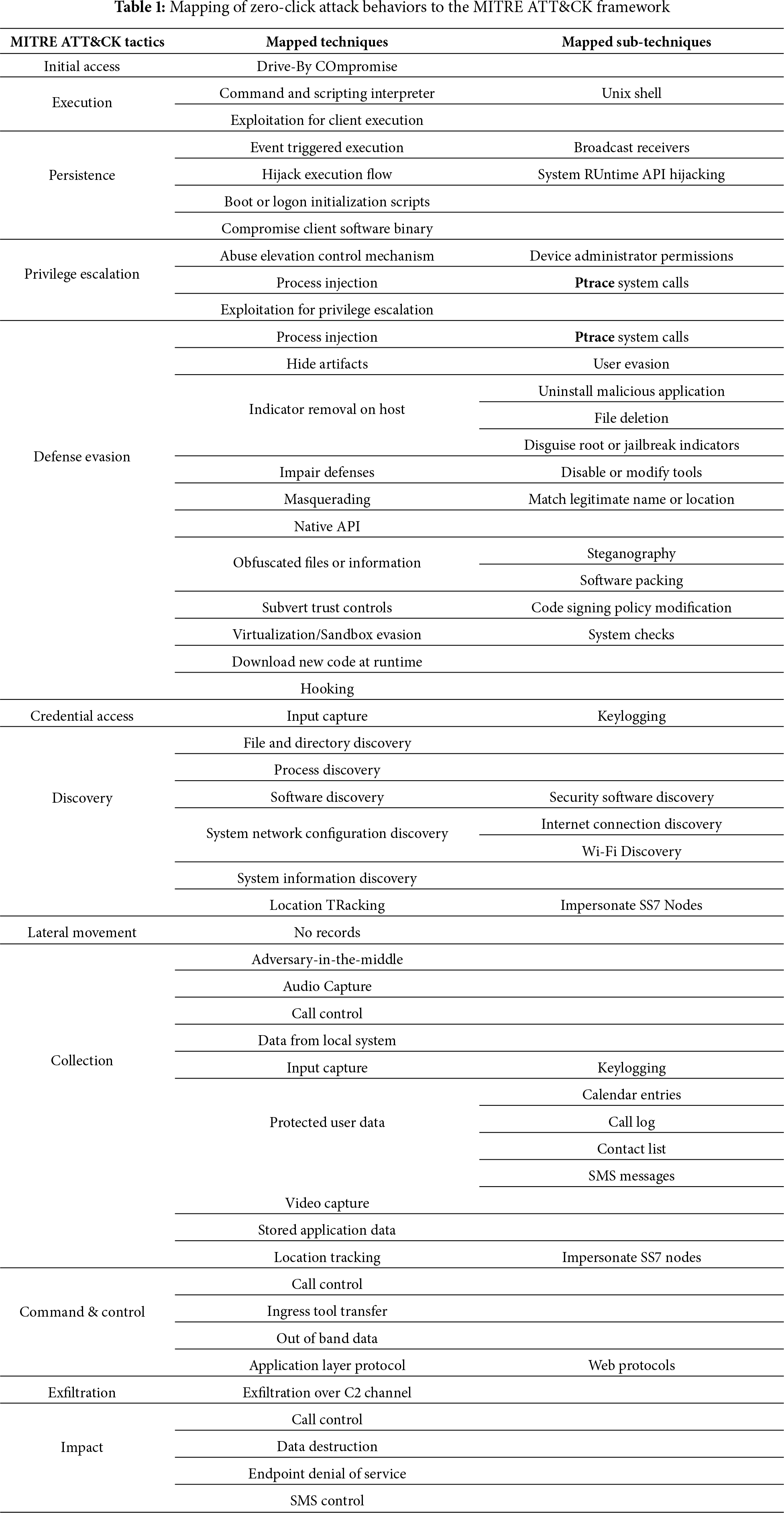

We collected data with careful deliberation, as shown in Table 1. Detailed explanations for each selection are provided in the table below. This comprehensive approach ensures a robust and accurate mapping of zero-click attack behaviors to the MITRE ATT&CK framework, aiding in the understanding and mitigation of these sophisticated cyber threats.

3.2 Data Validation and Mapping

To systematically analyze Zero-click attacks, we mapped their behaviors to the MITRE ATT&CK framework, a globally recognized knowledge base of adversarial tactics and techniques. The mapping process involved the following steps.

3.2.1 Identify Relevant Tactics and Techniques

We analyzed the MITRE ATT&CK framework to identify tactics relevant to zero-click attacks. For each tactic, we mapped specific techniques and sub-techniques used in these attacks, such as:

i. Initial Access: Zero-click attacks typically begin by exploiting vulnerabilities in messaging apps, browsers, or wireless communication protocols to infiltrate a target system [14].

ii. Execution: Once access is gained, the adversary executes malicious code on the victim’s device using various sub-techniques [4,39].

iii. Persistence: To maintain access, attackers employ techniques that ensure malware remains active even after reboots or software updates [39,40].

iv. Privilege Escalation: This enables attackers to escalate privileges, granting them unrestricted control over the compromised device, closely mirroring the procedural methods used in Zero-click attacks [4,39].

v. Defense Evasion: To remain undetected and bypass security controls, adversaries employ various Defense Evasion techniques, for example, system logs, security tools, and forensic traces [37,42,43].

vi. Credential Access: This enables adversaries to steal sensitive authentication data. Input Capture (Keylogging) allows attackers to log keystrokes to intercept credentials. Pegasus used this method to record login information and other sensitive user data, storing it for later exfiltration [44,45,62,63].

vii. Discovery: The Discovery phase in zero-click attacks allows adversaries to gather information about the compromised device and network to refine their attack strategy. After gaining access, attackers analyze the system’s properties to determine vulnerabilities, identify security mechanisms, and decide how to proceed [51,58].

viii. Collection: phase is vital for adversaries to identify, extract, and exfiltrate sensitive data from compromised devices [46–48].

ix. Command and Control (C2): The method enables adversaries to maintain control over compromised devices by establishing covert communication channels. These allow botnet management, DDoS execution, and other malicious activities. In zero-click attacks, C2 servers coordinate operations and evade detection [40,64].

x. Exfiltration: This refers to adversaries’ methods of secretly transferring data from a compromised mobile device to an external location. Mobile devices frequently connect to unsecured networks, allowing attackers to exploit non-IP methods like SMS to evade detection [36,45,62].

xi. Impact: Through this method, adversaries seek to control, disrupt, or destroy compromised devices and their data. This phase includes techniques such as toll fraud, data destruction, and access denial, many of which align with zero-click attack strategies [39,58].

3.2.2 Match Observed Behaviors to MITRE ATT&CK

We matched observed behaviors to the corresponding MITRE ATT&CK tactics, techniques, and subtechniques, using data collected from our primary research. Below are examples of this mapping:

i. Initial Access:

• Drive-By Compromise (T1189): Pegasus exploits browser vulnerabilities to automatically download and execute malware when a victim visits a malicious website [4].

• Exploitation for Client Execution (T1203): Pegasus leverages vulnerabilities in iMessage and WhatsApp to deliver malware without user interaction [4,34].

ii. Execution:

• Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059): Pegasus uses JavaScript execution to take over infected devices [35–38].

• Exploitation for Client Execution (T1203): Malware is triggered upon receiving a crafted message, executing without user interaction [4].

iii. Persistence:

• Event Triggered Execution (T1546): Pegasus uses BOOT_COMPLETED broadcasts to ensure persistence (S0316) after device reboots [39–41].

• Hijack Execution Flow (T1574): Pegasus hijacks the iOS JavaScript Core framework (S0420, S0408, S0494) to execute malicious code [65–67].

• Boot or Logon Initialization Scripts: Malware is placed in startup scripts to run automatically during device boot-up. Pegasus leveraged this to execute unsigned code (S1079, S0285) [62,68].

• Compromise Client Software Binary: Attackers alter core system files or application binaries to embed malware, making removal difficult. Pegasus modified device partitions for persistence (S0316, S0289, S0293, S0294) [4,40,69].

iv. Privilege Escalation:

• Abuse Elevation Control Mechanism (T1546): Attackers exploit permission management features such as Device Administrator Permissions to gain system control. Malware such as Asacub has used this method to manipulate security settings and prevent removal (S1061, S0540, S1077) [36,42,70].

• Process Injection (T1055): Attackers inject malicious code into legitimate processes to execute arbitrary commands stealthily, as observed in Pegasus spyware (S1061, S1056) [39,71].

• Exploitation for Privilege Escalation (T1068): Adversaries exploit system vulnerabilities to escalate privileges and bypass security restrictions. Pegasus successfully leveraged this technique by exploiting iOS kernel vulnerabilities, allowing it to gain root access without user interaction(S0316, S0289, S0440, S0463) [4,40,72,73].

v. Defense Evasion:

• Hide Artifacts (T1564): Pegasus remains invisible in system logs and disables security notifications (S0655, S1077) [37,42].

• Indicator Removal on Host (T1070): Malware deletes forensic traces, including logs and security software artifacts, making detection harder (S0480, S1062, S1055) [43–45]:

– Uninstall Malicious Application: Malware deletes itself or removes indicators of infection.

– File Deletion: Pegasus actively removed forensic traces after execution (S0407, S0399, S0558).

– Disguise Root/Jailbreak Indicators: Attackers modify security indicators to make it appear as if the device is clean.

• Impair Defenses (T1562): Pegasus disabled Play Protect on Android devices (S0422, S1054, S1067) [4].

• Masquerading (T1036): Pegasus renamed system utilities to evade security monitoring, such as renaming /sbin/mount_nfs.temp to /sbin/mount_nfs [4].

• Native API (T1106): Pegasus exploited the Native Development Kit (NDK) and Java Native Interface (JNI) in Android to execute malicious code at a lower level [70]. Reports indicate that threats like Asacub (S0540), CarbonSteal (S0529), and CHEMISTGAMES (S0555) have leveraged native code for stealthy execution, decryption, and system control, demonstrating it’s role in Zero-click attacks.

• Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027): Pegasus used Steganography and software packing to conceal malicious payloads [46]:

– Steganography (T1027.003): Malicious data is embedded within SMS, iMessage, or WhatsApp messages.

– Software Packing (T1027.002): Malware is compressed or encrypted to alter its signature. Pegasus and other Zero-click exploits have used this technique to hide jailbreak files and malicious payloads within packed executables (S1062) [43,58].

• Subvert Trust Controls: Attackers modify security policies to allow execution of unsigned or malicious code (S1056, S0490) [35,74].

• Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion (T1497): Pegasus used kernel-level variables to bypass sandbox restrictions (S1083, S0427) [58].

• Download New Code at Runtime (T1105): Pegasus dynamically fetched additional files based on system checks. The attack manipulated native code, kernel functions, and memory structures to achieve full device compromise while evading detection (S0550, S0325, S0295, S0327, S0324, S0545) [51–54].

• Hooking (T1176): Pegasus manipulated system API behavior to execute malicious instructions at the kernel level when certain system calls were triggered (S0507, S0405, S0535, S0485) [75,76].

vi. Credential Access: Pegasus used this method to record login information and other sensitive user data, storing it for later exfiltration (S1079, S0480, S0407, S1062):

• Input Capture (Keylogging) (T1056): Pegasus records keystrokes to intercept login credentials [44,62,63].

• Credentials from Password Stores (T1555): Pegasus extracts credentials from password storage locations, such as the iOS Keychain [44,62,63].

vii. Discovery

• File and Directory Discovery (T1083): Pegasus scans directories to locate sensitive information or determine where to inject malicious code (S0577, S0551, C0016) [51,58].

• Process Discovery (T1057): Pegasus identifies active processes to understand running applications, replace system processes, and ensure malware execution (S0577, S0551, C0016) [53,77,78].

• Software Discovery (T1518): Pegasus inventories installed applications to detect security tools. It also analyzes security software to evade detection (S0505, S0478, S0509, S0423, S0489, S0418, S1069) [79–81].

• In System Network Configuration Discovery (T1016): Pegasus collects IP addresses, MAC addresses, Wi-Fi settings, and network activity to identify exploitable entry points (S0310, S0432, S0315, S1093, S0326) [40,82,83].

(a) Internet Connection Discovery (T1016.001): Pegasus checks whether the device is online to establish a C2 link (S0425, S0506, S0326) [40,84].

(b) Wi-Fi Discovery (T1016.002): Pegasus gathers information about network names (SSIDs) passwords, and signal strength to facilitate persistent access (S1056, S0407, S0425, S1079) [44,62].

• System Information Discovery (T1082): Pegasus collects device hardware [9] and OS details [12] (S0406, S0485, S0289, S0403, S0411, S0313, S0427) to tailor exploits [21,23] for specific target environments [39,58].

• Location Tracking (T1537): Pegasus exploits GPS [85], Wi-Fi [86], or SS7 vulnerabilities [87,88] to monitor victims’ movements. The NSOlinked firm Circles has reportedly used this method [89,90], making it likely Pegasus employed the same [91] (S0309, S1083, S0408, S0577, S0544, S0291, S0305, S0314, G0112, S1128).

viii. Collection

• Adversary-in-the-Middle (T1537): Pegasus intercepts network traffic to manipulate transmitted data [16,23,39,58].

• Audio Capture (T1123): Pegasus exploits OS APIs to record conversations and eavesdrop on calls [92–95].

• Call Control (T1499): Pegasus places, forwards, or blocks calls for surveillance or C2 operations [96–98].

• Data from Local System (T1005): Pegasus accesses Wi-Fi passwords [46], authentication tokens [47,48], photos [49], and keyboard cache [50] from compromised devices [21,64,25].

• Input Capture and Keylogging: Discussed in previous section.

• Protected User Data (T1537): Pegasus exploits OS APIs to access sensitive user data like contacts, call logs, calendars, and SMS messages. Key sub-techniques include:

(a) Calendar Entries (T1537.001): Pegasus extracts calendar data [42,44] using Android’s Content Provider [75,48] or iOS EventKit [25,38].

(b) Call Log (T1537.002): Pegasus retrieves call history for intelligence gathering [16,21,29,34,40].

(c) Contact List (T1537.003): Pegasus maps social connections and tracks relationships [40,47,99–101].

(d) SSMS Messages (T1537.004): Pegasus enables credential theft and surveillance [11,22,25,27,102].

• Video Capture (T1125): Pegasus turns devices into surveillance tools [54,76] for visual data collection [103,93] using camera access capabilities [16,20,64,40]. MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs: S0301, S0320, S0535, S0324, S0558, S0489.

• Stored Application Data (T1537): Pegasus extracts data from popular apps like Gmail [42], WeChat [52], and Facebook [53]. Pegasus spyware retrieves private messages [75,83] and directory listings from multiple applications [20,21,64,40]. MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs: S0405, S1093, S0295, S0327, S1082, S0329.

• Location Tracking: Discussed in the previous section.

ix. Command & Control

• Call Control (T1499): Pegasus manipulates phone calls for C2 communication, surveillance, or disruption [16,17,20].

• Ingress Tool Transfer (T1105): Pegasus downloads files post-exploitation to expand its capabilities [36,45,58].

• Out of Band Data (T1499): Pegasus uses alternative channels (Bluetooth, NFC, SMS) to evade detection and maintain device access [40,54,62].

• Application Layer Protocols (T1071): Pegasus leverages encrypted web protocols for undetected communication [40,64].

x. Exfiltration Over C2 Channel (T1041): Pegasus blends exfiltration with normal C2 traffic to evade detection [36,45,62].

xi. Impact

• Call Control (T1499): Manipulate calls to intercept or block communications. Pegasus exploits this for surveillance.

• Data Destruction (T1485): Delete files to prevent access and cover tracks. Pegasus erases databases to evade detection [39,58].

• Endpoint Denial of Service (DoS) (T1499): Crash devices or overwhelm resources. Simjacker renders devices unusable [11,12].

• SMS Control (T1499): Send, modify, or delete messages covertly. Simjacker sends fraudulent messages [12,25].

While not part of the primary mapping pipeline, Table 2 offers an important contextual layer highlighting ATT&CK techniques and sub-techniques that may be employed in zero-click mobile attacks. These stealth exploits function without user interaction, making attribution difficult and forensic visibility limited. The listed entries reflect behaviors that are rarely observable in isolation, yet repeatedly emerge across threat disclosures, forensic artifacts, and operational patterns.

Techniques such as Suppress Application Icon, Access Notifications, and Remote Device Management Services illustrate adversarial strategies for maintaining invisibility, harvesting data, and executing remote control often without alerting the victim or triggering traditional detection mechanisms. Though definitive attribution is challenging given the covert nature of zero-click campaigns, these entries provide domain-informed scaffolding to guide annotation, shape threat understanding, and preempt analytic blind spots.

We present this table not as exhaustive or directly validated, but as an adversarially motivated reference. It complements our active learning and labeling strategy by anchoring it in plausible behavioral tactics enhancing both forensic fidelity and threat relevance.

3.3.1 Consideration 1: Defense Evasion

Adversaries employ techniques such as Hide Artifacts (T1564), specifically Suppress Application Icon, to conceal malicious applications from the device launcher, enabling stealthy persistence. Zero-click attacks, including Pegasus and Simjacker, exploit this method to evade detection [104–107]. Corresponding MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs include S0525, S0550, S0419, S0302, S0311.

3.3.2 Consideration 2: Credential Access

Key credential theft techniques utilized in zero-click attacks include:

• Access Notifications (T1412): Intercepting notifications containing sensitive authentication data such as one-time codes [108]. MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs: S0432, S0489.

• Clipboard Data (T1113): Exploiting clipboard APIs to extract stored credentials [44]. MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs: S1079, S0421.

• Credentials from Password Store (T1555): Targeting password storage repositories, such as iOS Keychain, to harvest authentication credentials [109]. MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs: S0432, S0489, S1092.

3.3.3 Consideration 3: Discovery

Zero-click malware often engages in reconnaissance to collect device and network intelligence:

• Location Tracking (T1537): Leveraging GPS data and cellular networks to monitor device location. Sub-technique: Remote Device Management Services [109,110].

• Network Service Scanning (T1046): Identifying exploitable network vulnerabilities to escalate attacks [108,111].

3.3.4 Consideration 4: Collection

Zero-click attacks facilitate extensive intelligence gathering through automated data extraction techniques:

• MediaProjectionManager: Capturing screenshots and video recordings of foreground applications [112–114].

• Accessibility Services: Exploiting system accessibility permissions to enable hidden screen recording functionality [44].

• Screencap and Screenrecord Commands: Using privileged system commands (through root or ADB access) for covert screen capture operations [115].

Although no direct forensic evidence explicitly confirms the use of these methods in zero-click attacks, their intelligence gathering capabilities make them plausible attack vectors. Screen capture techniques, for example, are commonly used by adversaries in cyber espionage and surveillance-based operations [78,96,103,116,117]. Relevant MITRE ATT&CK procedure IDs—including S0479, S0558, S1069, S0485, S0421, S0551, S0423, S0408, S1079, S0422—highlight the role of such methodologies in cyber intelligence and unauthorized surveillance.

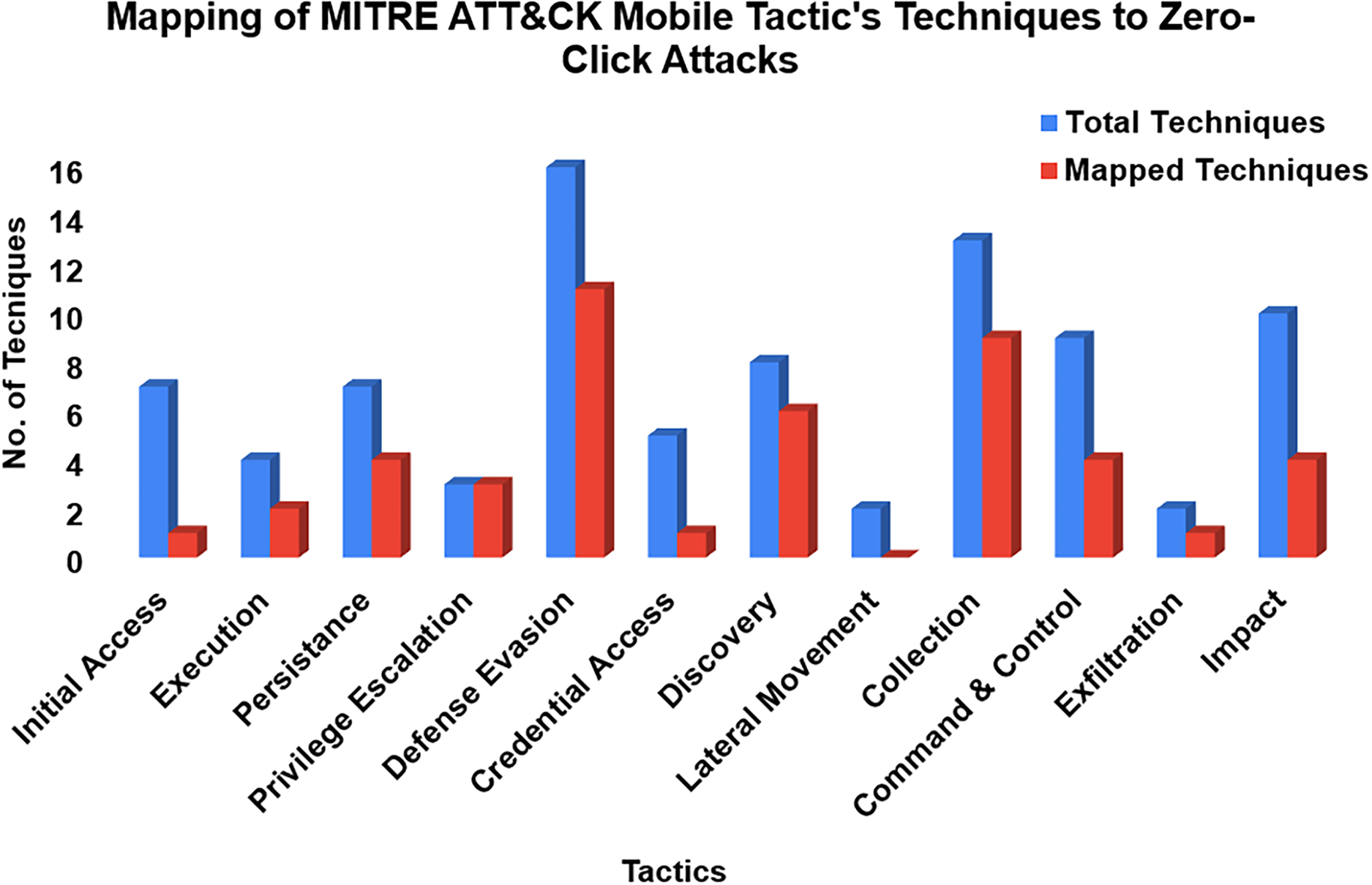

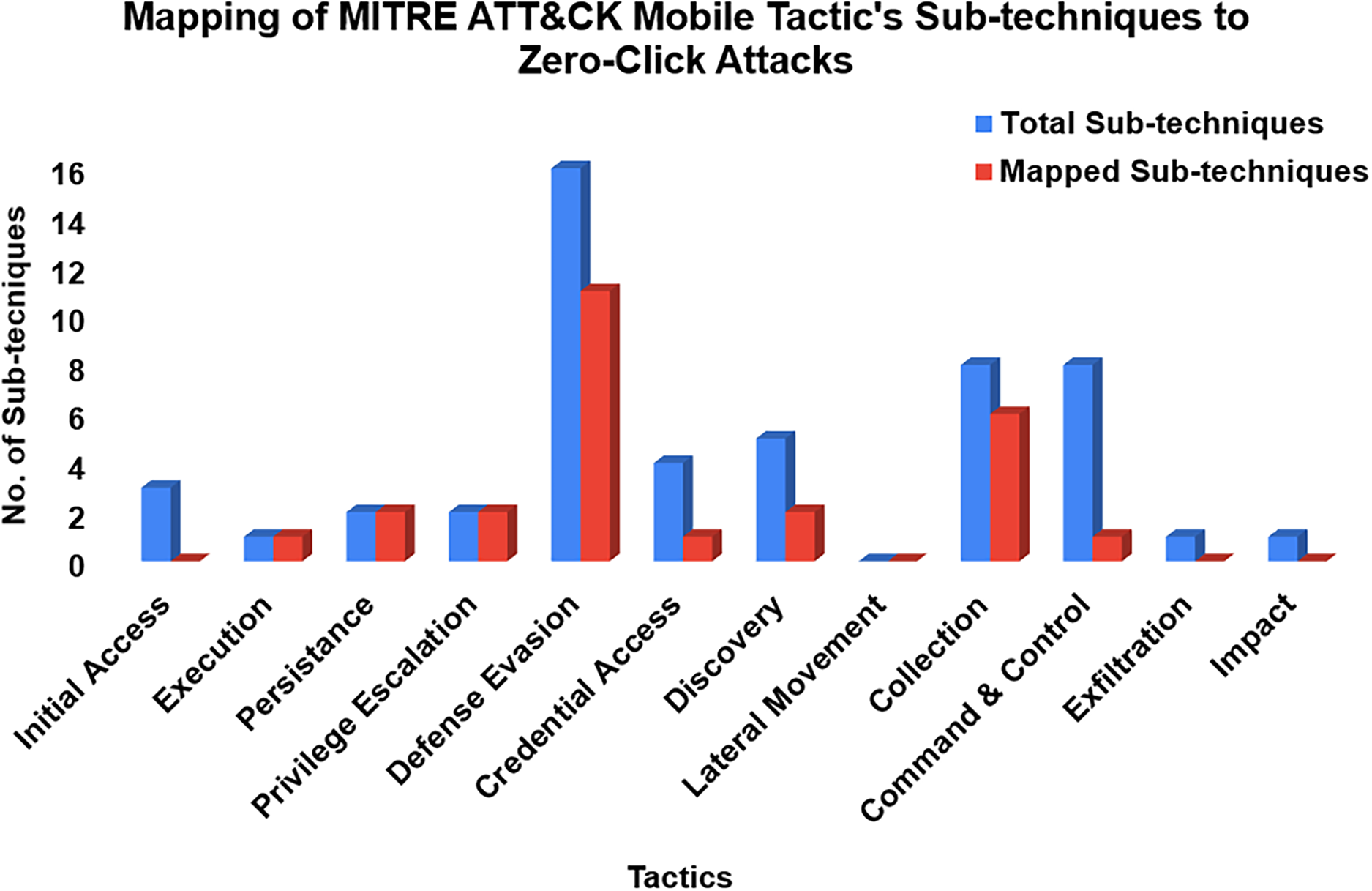

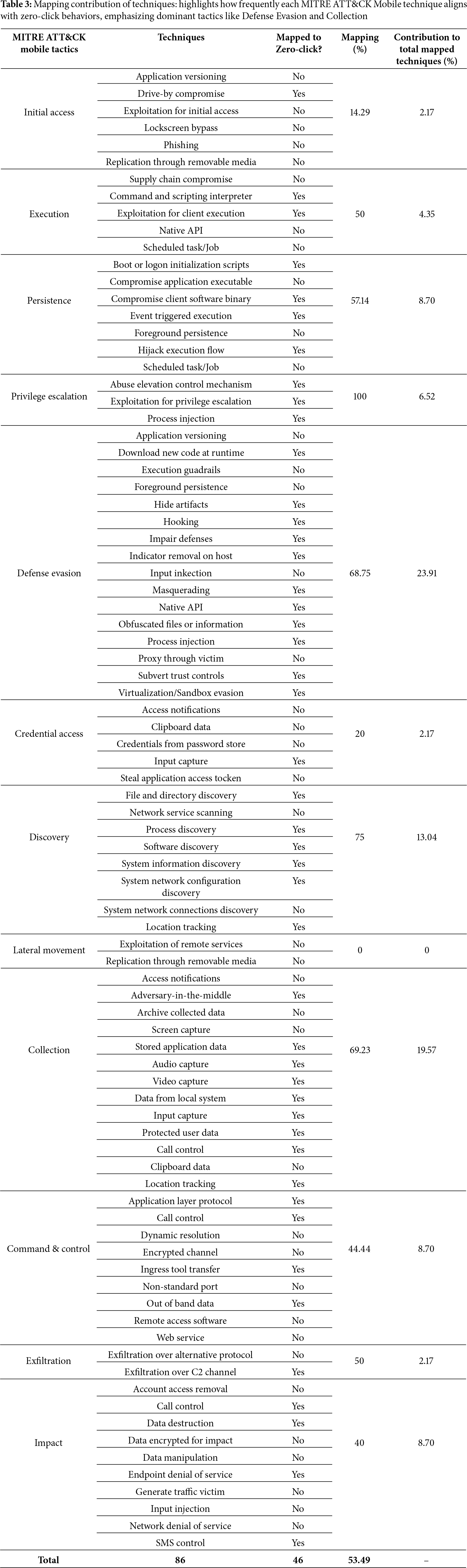

In the preceding sections, we systematically examined and mapped zero-click attack behaviors against the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This evaluation provides a quantitative analysis, illustrating how these attacks align with established adversarial tactics, techniques, and sub-techniques. The MITRE ATT&CK Mobile Matrix defines 12 tactics, of which 11 (90.90%) correspond with observed zero-click attack behaviors, highlighting their ability to infiltrate multiple security layers. Within these tactics, 86 techniques are documented, with 46 (53.49%) directly relevant to zero-click attacks. Additionally, among 51 sub-techniques, 26 (50.98%) correspond to exploitation methods leveraged by these attacks.

Figs. 4 and 5 illustrate key patterns in adversarial behaviors within the MITRE ATT&CK Mobile Matrix. Fig. 4 reveals how certain tactics, such as Defense Evasion and Collection are disproportionately targeted in zero-click campaigns, providing insight into commonly exploited attack surfaces. Fig. 5 extends this analysis by charting the distribution of sub-techniques: some, like keylogging and sandbox evasion, appear frequently across case studies, while others remain uncited, highlighting gaps in current mappings or areas of emerging interest.

Figure 4: Mapped MITRE ATT&CK techniques relevant to zero-click attacks. The X-axis represents MITRE Tactics, and the Y-axis shows the Number of Techniques

Figure 5: Distribution of sub-techniques from the MITRE Mobile Matrix observed in zero-click attack behaviors. The X-axis represents MITRE Tactics, and the Y-axis shows the Number of Sub-techniques

4.1 Breakdown of Mapped Techniques and Sub-Techniques

Table 3 reveals the distribution of mapped techniques across various attack phases:

• Defense Evasion (23.91%) dominates the mapped techniques, reinforcing its role in stealth persistence via sandbox evasion, process injection, and masquerading.

• Collection (19.57%) emphasizes adversaries’ focus on harvesting sensitive data, including audio, video, and stored credentials.

• Discovery (13.04%) highlights reconnaissance strategies such as system information scanning to prepare for exploitation.

• Execution and Impact (8.70% each) play essential roles in executing malicious payloads and disrupting device functionality.

• Privilege Escalation (6.52%) enables attackers to gain higher system access through vulnerabilities.

• Command & Control (8.70%) facilitates persistent communication between attackers and infected devices.

• Initial Access, Exfiltration, and Credential Access exhibit minimal contributions due to the nature of zero-click attacks requiring no direct user interaction.

Similarly, sub-technique analysis in Table 4 reveals:

• Defense Evasion Sub-Techniques (39.29%) are the most prevalent, reinforcing attackers’ ability to evade detection.

• Collection Sub-Techniques (21.43%) confirm reliance on intelligence gathering, including screen capture and input logging.

• Discovery Sub-Techniques (14.29%) demonstrate the importance of system reconnaissance.

• Privilege Escalation and Execution Sub-Techniques (7.14% each) highlight elevated access and malicious execution strategies.

• Command & Control and Credential Access Sub-Techniques (3.57%) are lower in contribution but remain critical for maintaining device compromise.

• Initial Access, Lateral Movement, Exfiltration, and Impact Sub-Techniques were not mapped, as they require user interaction, contradicting the zero-click attack methodology.

4.1.1 Implications for Cybersecurity Defense

Mapping zero-click attack vectors within MITRE ATT&CK reinforces the need for:

• Behavior-Based Detection Models: Traditional signature-based intrusion detection systems are ineffective against stealthy threats. Implementing anomaly detection enhances the identification of subtle attack behaviors.

• Real-Time Threat Intelligence: Continuous monitoring and data-driven analysis are critical for anticipating zero-click attack variations.

• Proactive Mitigation Strategies: Enhancing endpoint security measures, including sandboxing, runtime code integrity enforcement, and automated patching, can significantly reduce exposure to these threats.

4.1.2 Significance of Mapping Zero-Click Attacks to MITRE ATT&CK

This structured evaluation highlights a meaningful alignment between zero-click attack patterns and the MITRE ATT&CK framework. By mapping observed behavioral indicators, such as silent execution triggers, anomalous background processes, or C2 communications to established tactics and techniques, we provide a standardized way to interpret attacker behavior. Such mapping enables cybersecurity practitioners to better understand the lifecycle of zero-click attacks, including stages like initial access, persistence, and command-and-control. It facilitates the development of more effective detection models and threat-hunting strategies grounded in a well-recognized adversarial taxonomy. This alignment improves situational awareness, enhances response efforts, and emphasizes the importance of proactive defense strategies to mitigate the evolving threat landscape posed by stealthy zero-click exploits.

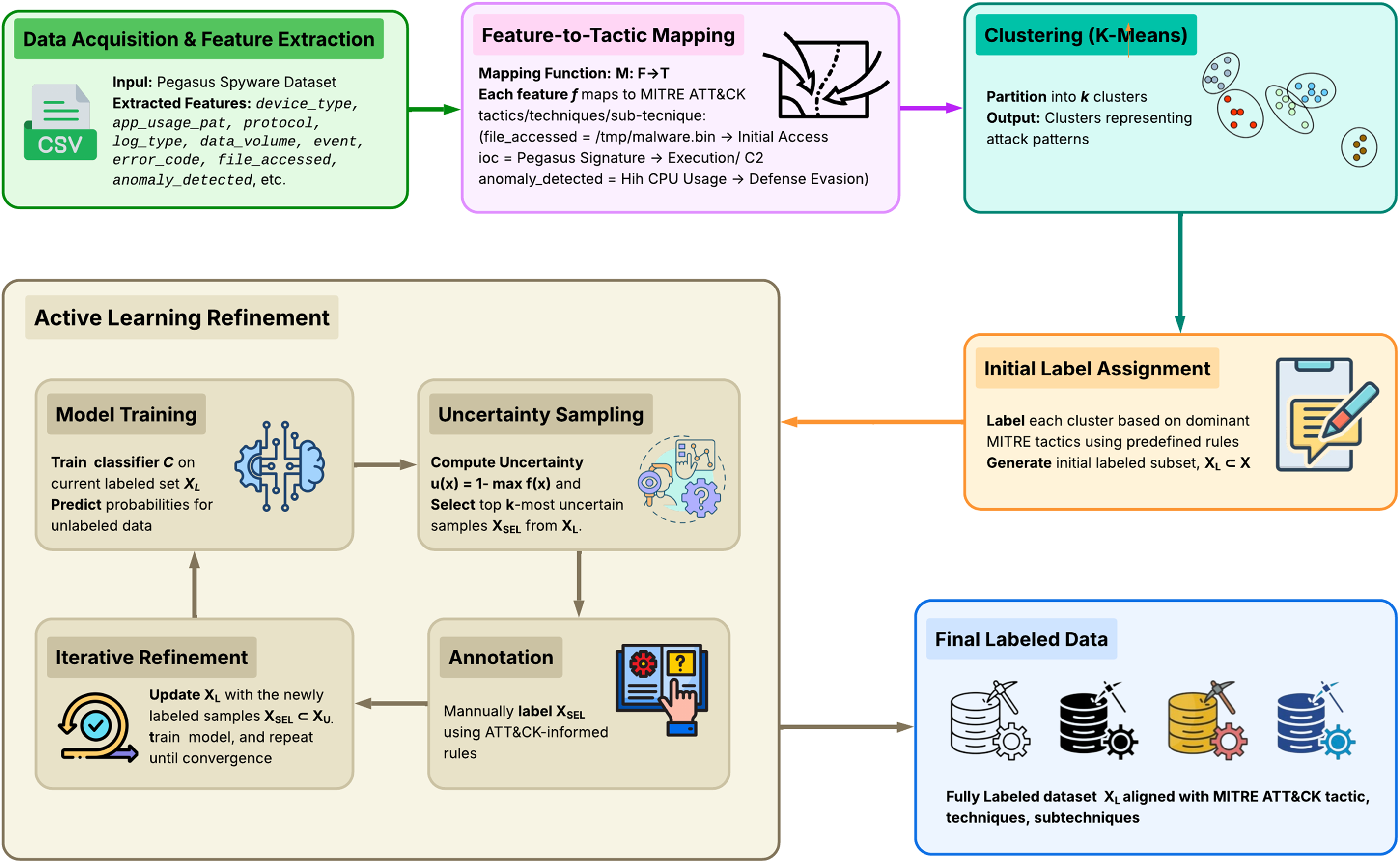

5 Labeling Pegasus Spyware Dataset via Active Learning and MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

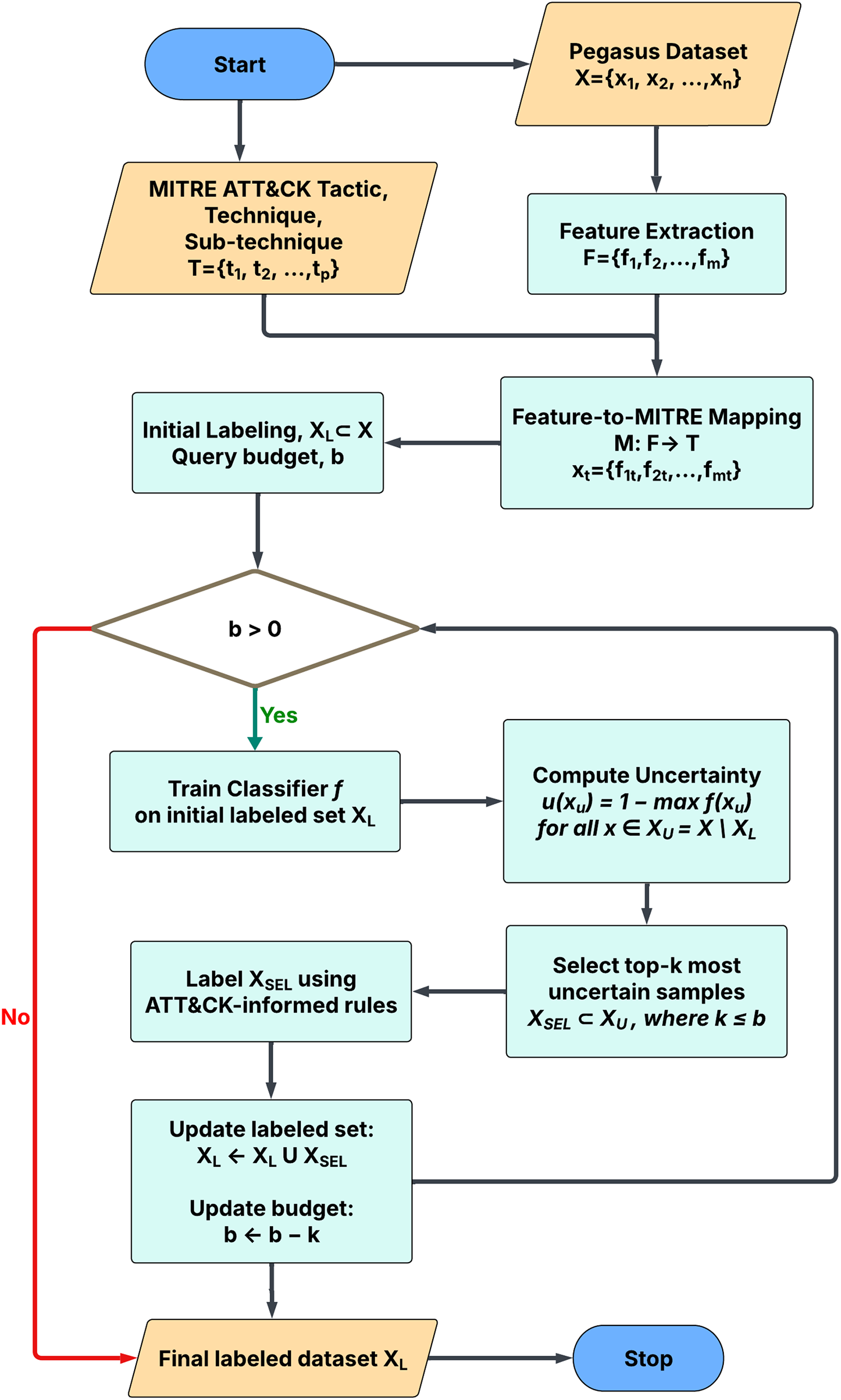

As cyber threats continue to evolve in sophistication, datasets like those associated with Pegasus spyware have become increasingly large and complex, rendering manual labeling both time-consuming and error-prone. Fig. 6 illustrates the ALUDAL framework, which addresses this challenge by combining Active Learning with MITRE ATT&CK tactic mapping [118]. This integrated pipeline enables scalable, automated labeling aligned with established cybersecurity frameworks, thereby supporting more accurate and actionable threat intelligence.

Figure 6: Technical overview of the active learning-based unsupervised data labeling (ALUDAL); Integrates feature extraction, tactic mapping, clustering, and iterative Active Learning to generate a high-quality labeled Pegasus spyware dataset aligned with the MITRE ATT&CK framework

5.1 Active Learning-Based Unsupervised Data Labeling

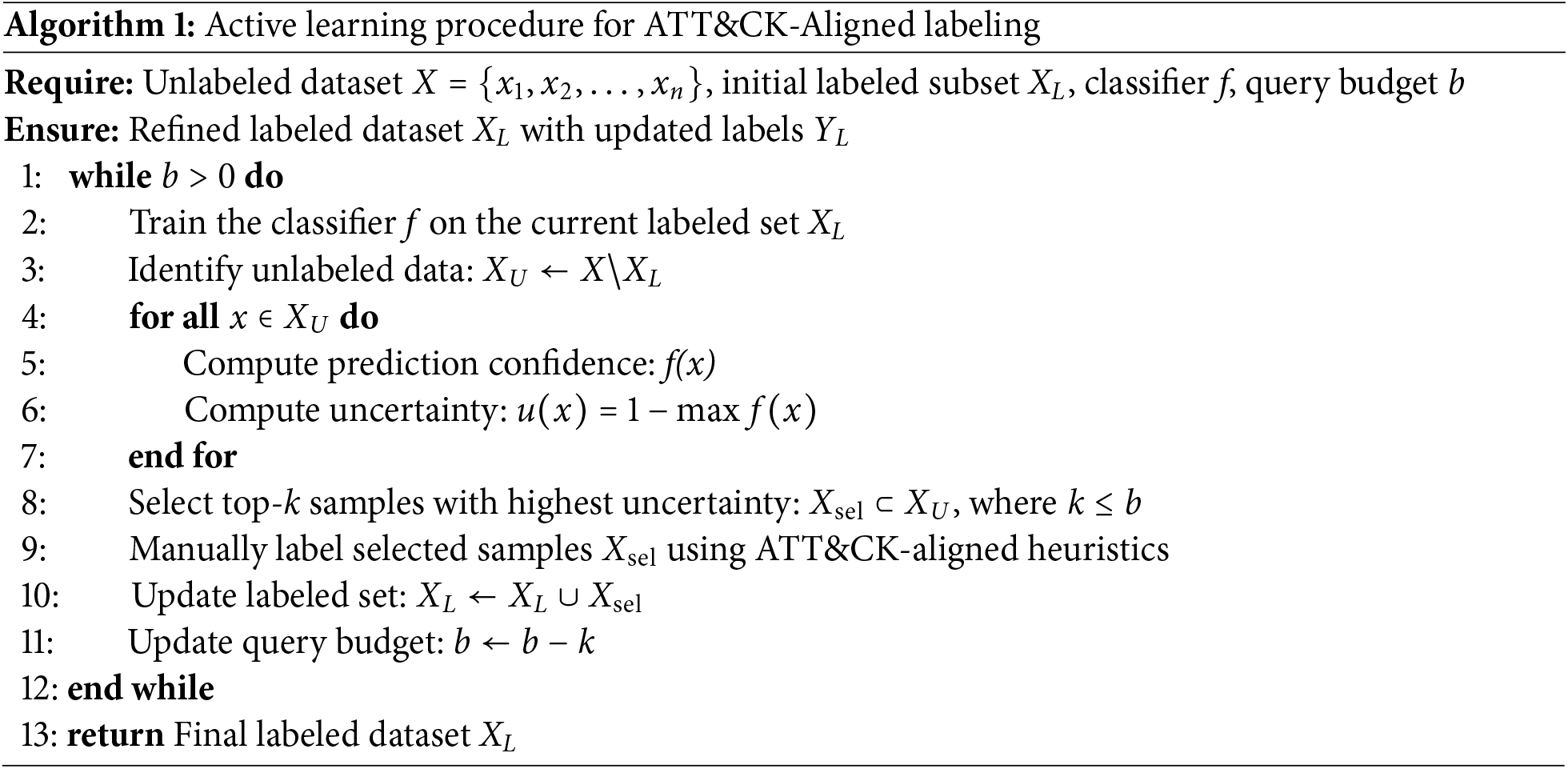

This section presents the Active Learning-based Unsupervised Data Labeling (ALUDAL) approach, an iterative framework specifically developed to classify the Pegasus spyware dataset [15] by aligning extracted behavioral features with the MITRE ATT&CK mobile matrix. As illustrated in Fig. 7 and formally described in Algorithm 1, ALUDAL combines feature-to-tactic mapping, clustering, and active learning to progressively refine labels with minimal manual intervention.

Figure 7: ALUDAL’s Pipeline for data labeling, outlining a stepwise process for mapping Pegasus spyware features to MITRE ATT&CK tactics using active learning, combining initial expert labeling with iterative model refinement

The Pegasus dataset comprises structured threat intelligence reports gathered from various cybersecurity platforms, enriched with real-world attack logs, Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), and forensic traces tied to zero-click attacks. Unlike prior studies that primarily relied on secondary sources, our experimental setup executed malware in a controlled, secure environment to capture authentic behaviors. These include execution traces, memory footprint changes, abnormal network traffic, and unauthorized API activity.

ALUDAL begins by extracting relevant features from the Pegasus dataset and mapping them to MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques. It then applies clustering to uncover latent attack patterns and leverages Active Learning to iteratively refine labels based on model uncertainty and expert-informed feedback. This process produces a high-quality, labeled dataset aligned with adversarial tactics and techniques, forming a strong foundation for training effective cybersecurity models and conducting subsequent threat analysis.

5.2 Why Active Learning Was Chosen?

Active Learning was selected because it allows the model to focus on labeling the most informative and uncertain samples, significantly reducing the effort required for manual annotation. Unlike fully supervised approaches that require extensive labeled datasets upfront or purely rule-based techniques that lack adaptability, Active Learning iteratively improves the labeling process based on feedback. This is particularly beneficial in cybersecurity, where threat behavior evolves over time and datasets often lack reliable ground truth.

The ALUDAL method leverages an initial clustering phase to structure the dataset and then uses uncertainty sampling to refine labels in successive iterations. This approach bridges the gap between unsupervised clustering and fully supervised classification, enabling the efficient and context-aware annotation of security data in alignment with MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques.

Given a dataset

where M is the mapping function from features to tactics/techniques, F is the set of features, and T is the set of MITRE ATT&CK tactics/techniques.

5.4.1 Dataset Preparation: Feature Extraction and Mapping to MITRE ATT&CK

Initially, we extract key features from the dataset X. For the Pegasus spyware dataset, critical attributes include device_type, app_usage_pattern, protocol, log_type, data_volume, event, error_code, file_accessed, anomaly_detected, process, and ioc. These features are mapped to corresponding MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques. Let

where

We define a mapping function M such that

where

5.4.2 Initial Clustering Using KMeans

To provide structural organization to the dataset, we use KMeans clustering, an unsupervised learning algorithm that partitions data points based on the similarity of features. Each cluster is expected to correspond to a distinct attack pattern. To ensure uniform contribution from all features, we standardize the dataset

where

KMeans clustering is then applied to the standardized data

where

5.4.3 Cluster Labeling and Active Learning Refinement

Once clustering is complete, each cluster

Active Learning is then employed to iteratively refine labels. This process includes:

i. Initial Labeling: Select an initial subset

ii. Model Training: Train a classifier

iii. Uncertainty Sampling: Evaluate the prediction confidence for unlabeled samples

where

iv. Iterative Refinement: Update

5.5 Performance Evaluation of ALUDAL

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed ALUDAL methodology, we performed a detailed analysis of the cluster behavior generated via KMeans and mapped the associated labels to relevant MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques. Each feature vector was constructed from behavioral indicators such as process, file_accessed, anomaly_detected, and ioc, which served as contextual signals for inferring likely attack stages. For instance:

• Entries with process = malware.exe and file_accessed = /tmp/malware.bin indicate unauthorized file deployment.

• Rows containing ioc = “Pegasus Signature” or ioc = “Known Malicious IP” are treated as high-confidence threat indicators.

• Anomalies such as “High CPU Usage” or “Unknown Process Execution” are typically associated with execution and evasion phases observed in real-world malware behavior.

This structured use of domain-aware features allowed the Active Learning loop to iteratively refine the labels, improving their semantic alignment with MITRE ATT&CK sub-techniques over successive sampling rounds. The overall Active Learning workflow used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 6.

To evaluate the robustness of the clustering and the quality of the resulting annotations, we performed a simulated validation using synthetically generated ground truth labels. The following domain-informed rules were applied to produce pseudo-labels, enabling us to benchmark ALUDAL’s annotation accuracy and assess the effectiveness of its prioritization strategy:

• If ioc = “Pegasus Signature”

• If anomaly_detected = “High CPU Usage” or “Unknown Process Execution”

• If process = “malware.exe” or file_accessed = /tmp/malware.bin

• If ioc = “Known Malicious IP”

These rules were used to construct a pseudo-labeled subset, which served as a reference to evaluate the alignment between clusters and MITRE ATT&CK tactics. After applying KMeans clustering with

• Precision (ALUDAL labeling): 98.5%

• Recall: 95.3%

• F1-Score: 96.9%

This controlled validation provides a reliable approximation of labeling performance, demonstrating use of ALUDAL for security data annotation aligned with MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques. To further assess cluster quality, we computed two widely accepted unsupervised metrics:

• Silhouette Score: 0.62, indicating moderately well-separated clusters with consistent intra-cluster cohesion.

• Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI): 0.41, suggesting compact and distinct cluster structures; lower values imply stronger separation.

The final ALUDAL-labeled dataset, enriched with MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques, offers a structured foundation for downstream analysis, threat modeling, and robust cybersecurity model development. Our experiments revealed that the dataset was effectively organized into four core MITRE ATT&CK tactics/techniques: (i) Execution, (ii) Initial Access, (iii) Persistence, and (iv) Privilege Escalation. Additionally, an alternative classification scheme uncovered four dominant techniques across these tactics: (i) Hijack Execution Flow, (ii) Masquerading, (iii) System Information Discovery, and (iv) Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion.

These findings reinforce the technical validity of the ALUDAL methodology and demonstrate its practical applicability for high-fidelity annotation of cybersecurity datasets in alignment with adversarial threat frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK.

6 Proactive Defense Strategies

As zero-click attacks continue to pose significant risks to organizations, the adoption of proactive defense strategies is essential in mitigating these advanced threats. One of the most effective approaches is the deployment of real-time threat intelligence and monitoring systems. These systems leverage AI-driven algorithms to continuously analyze network traffic, software processes, and user activity for any anomalous behavior. By integrating advanced anomaly detection techniques, such systems can identify deviations from normal operational patterns that may indicate the presence of a zero-click attack, allowing security teams to intervene before an attack escalates. Additionally, real-time monitoring tools integrate with threat intelligence feeds that provide continuous updates on known and emerging attack vectors, enabling organizations to stay informed and enhance their defense posture.

6.1 Device-Level Security Enhancements

A critical aspect of mitigating zero-click attacks involves strengthening device-level security to protect vulnerable endpoints. This can be achieved through:

• Application Sandboxing: Sandboxing isolates applications from the operating system and critical system components, restricting malicious processes from propagating across the system.

• Runtime Code Integrity Enforcement: Ensures that software running on devices has not been altered or tampered with by adversaries. This mechanism includes code signing, which restricts execution to verified code, preventing unauthorized modifications that exploit system vulnerabilities.

• Execution Control of Unverified Files: Restricting the execution of unverified messages, files, or scripts mitigates social engineering attacks that trigger malicious payloads upon opening attachments or clicking links.

6.2 Behavior-Based Intrusion Detection

To improve attack detection-

• Organizations should integrate advanced Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS)

• Behavior-based anomaly detection should be prioritized over traditional signature-based methods.

• Signature-based IDS are effective for identifying known threats but struggle with:

– Zero-click attacks, which exploit previously unknown vulnerabilities.

• Behavior-based IDS detect abnormal system behaviors by analyzing:

– Network traffic

– File modifications

– Process executions

• These systems focus on Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) to:

– Detect emerging threats

– Enable real-time mitigation of zero-click and other advanced attacks

6.3 Automated Patching and Zero-Day Mitigation

Regular patching of firmware and software plays a crucial role in minimizing exposure to zero-day vulnerabilities. Since zero-click attacks often exploit undisclosed software flaws, organizations must implement an automated patch management system to ensure timely security updates across devices and networks. This approach should encompass:

• Operating system and application patches.

• Embedded firmware updates, as vulnerabilities in hardware components can also be exploited.

• Continuous vulnerability scanning to detect security flaws and prioritize remediation.

Maintaining a consistent and rapid patch deployment process mitigates the risk of attackers exploiting known vulnerabilities before corrective measures are implemented.

6.4 Cyber Forensics and Incident Response

In the event of an attack, a robust cyber forensics and incident response framework is essential for identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impact of zero-click attacks. Effective incident response strategies include:

• Malware Behavior Profiling: Documenting the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used in zero-click attacks enables security teams to recognize patterns and proactively respond to future threats.

• Forensic Analysis Tools: Tracing the attack’s origin, assessing its impact on affected systems, and collecting evidence for further analysis or legal proceedings.

• Coordinated Incident Handling: A structured response plan ensures that organizations effectively contain, mitigate, and prevent the recurrence of zero-click attacks.

6.5 User Awareness and Education

While zero-click attacks do not require user interaction, user behavior remains a critical factor in overall security effectiveness. Organizations must emphasize cybersecurity awareness by:

• Educating users on secure communication practices, including avoiding suspicious links and using encrypted messaging services.

• Training personnel to recognize attack vectors, such as phishing emails and malicious websites, which attackers may use to gain an initial foothold in a network.

• Encouraging strong authentication measures, such as multi-factor authentication (MFA) and password hygiene, to reduce susceptibility to unauthorized access.

6.6 Comprehensive Security Framework

By incorporating AI, machine learning, and real-time monitoring into cybersecurity defense mechanisms, organizations can significantly enhance their security posture against zero-click attacks.

• These proactive strategies create a robust security framework that:

– Strengthens detection and response capabilities

– Minimizes the likelihood of successful attacks

• Continuous improvements in security methodologies help organizations stay resilient against increasingly sophisticated adversarial techniques.

Our behavior-centric malware analysis framework advances the forensic fidelity and interpretability of ATT&CK-based threat mapping. Yet, as with any system grounded in simulation, design choices come with trade-offs that shape the boundaries of generalizability, ecological realism, and classifier robustness.

7.1 Controlled Environments vs. Operational Complexity

Running malware in sandbox environments gives us clarity and repeatability but it also means we miss the messy, unpredictable dynamics of everyday mobile device use. In real settings, behaviors emerge from interactions with countless variables: app ecosystems, personalized device configurations, network quirks, and human habits. For example, malware may activate in response to subtle user actions like delayed tapping, biometric authentication, or co-app chaining that our simulated environments can not fully recreate. We varied permission stacks, latency profiles, and interaction triggers to introduce execution noise. Yet these strategies only partially bridge the gap between simulation and field realism.

7.2 Synthetic Dataset Constraints

Some of the malware samples in our dataset were synthetically generated to reflect adversarial behaviors like delayed activation, privilege escalation, and code obfuscation. These synthetic examples help us stress test classifiers and replicate emerging attack strategies, but they come with caveats. By design, they may over represent certain threat types while missing the subtle or incomplete patterns typical of real world attacks. To broaden our dataset’s realism, we incorporated obfuscated and adversarially altered samples from open source repositories, and finetuned our classifiers to improve generalization across varied behaviors. More importantly, our mapping framework does not depend on preassigned labels or static threat descriptions instead, it focuses on runtime signals observed during execution. This shift toward behavioral evidence helps reduce bias and improve interpretability across both synthetic and natural attack sources.

7.3 Limited ATT&CK Technique Scope

Our approach prioritizes behavioral precision over exhaustive techniques. Instead of trying to capture every possible ATT&CK tactic, we focus on reliably modeling those we can observe and validate especially through runtime behavior. As a result, techniques that depend on specialized hardware emulation like firmware tampering or sensor spoofing fall outside our current scope. Similarly, socially engineered attack pathways, which rely heavily on user psychology and deception, are excluded due to their indirect runtime signatures. We center our efforts on the mobile specific subset of MITRE ATT&CK, tailoring detection to behaviors prevalent in handheld and embedded systems. However, given the growing prevalence of cross platform threats, future iterations may require hybrid modeling approaches that span mobile, desktop, and cloud environments to preserve both interpretability and relevance.

7.4 Interpretability vs. Detection Performance

We prioritized interpretability throughout our classifier design, selecting lightweight models and attribution methods that align with runtime behavioral signals. By focusing on execution-based features rather than static representations, we ensured that decision logic remains traceable and reproducible critical for forensic auditing and threat communication. This emphasis on transparency does impose limits: more complex approaches, such as deep ensembles or transformer-based architectures, may offer higher predictive accuracy but would compromise our ability to clearly explain model decisions. We view this trade-off as an intentional design choice, aligning with our broader goals of accountable, explainable, and operationally viable AI in security settings.

7.5 Benchmarking with Known Samples

Our current evaluation benchmarks classifier performance against labeled samples with consistent behavioral traits, which helps validate accuracy but also introduces a risk of bias. Specifically, the results may lean toward known attack patterns, potentially overlooking emergent or ambiguous threats that fall outside typical behavioral profiles. To counteract this, we diversified our test set by including obfuscated variants and adversarially altered samples designed to challenge the classifier’s adaptability and reduce overfitting to predictable signals. Looking ahead, we plan to expand this framework using out-of-distribution testing and anomaly-based scoring, ensuring the system can detect and respond to threats that defy conventional classification.

Zero-click attacks, exemplified by Pegasus, Simjacker, Bluebugging, and emerging Bluetooth/IoT threats, present a sophisticated and stealth cybersecurity challenge. This study mapped the behavioral traits of such attacks to 46 techniques in 11 MITRE ATT&CK tactics, revealing their extensive reach and operational patterns. By introducing the ALUDAL method, we offer a practical, Active Learning-based solution for automated dataset labeling that supports threat detection with high precision. Labeled data sets and mappings can be directly integrated into SIEM systems and behavior-based intrusion detection models, enabling organizations to detect malicious activity even in the absence of user interaction or recognizable signature patterns. These contributions help security teams develop SOC playbooks tailored to stealth attacks and prioritize defense against high-impact techniques like defense evasion and command-and-control operations.

Beyond Pegasus, our framework is applicable to a wider range of zero-click vectors that affect mobile, IoT and embedded devices. Organizations can implement our findings by building runtime monitors, improving app sandboxing, and refining patch management using our mapped behaviors. The systematic alignment with MITRE ATT&CK also facilitates the exchange of standardized threat intelligence across sectors. As these threats evolve, future research will focus on extending this behavior-first approach to multiplatform environments, desktop, IoT, and cloud environments, and integrating adaptive AI models like transformers for deeper, real-time threat profiling. This continued innovation is essential to stay ahead of adversaries in a rapidly changing cybersecurity landscape. In addition, future work will focus on expanding this mapping methodology to cross-platform attacks, integrating real-time SIEM feeds, and improving generalizability across IoT and edge computing environments..

Acknowledgement: We thank the School of Computing, Georgia Southern University, for supporting this research work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the article as follows: Conceptualization, Md Shohel Rana, and Tonmoy Ghosh; methodology, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, and Mohammad Nur Nobi; software, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, and Anichur Rahman; validation, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, and Andrew H. Sung; formal analysis, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, Mohammad Nur Nobi, Anichur Rahman, and Andrew H. Sung; investigation, Md Shohel Rana, Anichur Rahman, and Andrew H. Sung; resources, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, and Mohammad Nur Nobi; data curation, Md Shohel Rana; writing-original draft preparation, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, and Mohammad Nur Nobi; writing-review and editing, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, Mohammad Nur Nobi, Anichur Rahman, and Andrew H. Sung; visualization, Md Shohel Rana, Tonmoy Ghosh, and Anichur Rahman; supervision, Md Shohel Rana and Andrew H. Sung; project administration, Md Shohel Rana, Mohammad Nur Nobi, Anichur Rahman, and Andrew H. Sung; funding acquisition, Md Shohel Rana and Andrew H. Sung. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shaha P, Khan MSI, Rahman A, Hossain MM, Mammun GM, Nasir MK. A prevalent model-based on machine learning for identifying DRDoS attacks through features optimization technique. Statist Optimizat Inform Comput. 2025;13(1):409–33. doi:10.19139/soic-2310-5070-2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Timberg C, Albergotti R, Guéguen E. Despite the hype, iPhone security no match for NSO spyware, The Washington Post [Internet]. 2021 July 19 [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/07/19/apple-iphone-nso/. [Google Scholar]

3. Marczak B, Railton JS. The million dollar dissident: NSO Group’s iPhone zero-days used against a UAE human rights defender, RESEARCH REPORT #78 [Internet]. 2016 Aug 24 [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://citizenlab.ca/2016/08/million-dollar-dissident-iphone-zero-day-nso-group-uae/. [Google Scholar]

4. Technical analysis of pegasus spyware, lookout [Internet]. 2016 Dec 12 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://info.lookout.com/rs/051-ESQ-475/images/lookout-pegasus-technical-analysis.pdf. [Google Scholar]

5. Pegasus project: Apple iPhones compromised by NSO spyware [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/07/pegasus-project-apple-iphones-compromised-by-nso-spyware/. [Google Scholar]

6. Pegasus: who are the alleged victims of spyware targeting? BBC [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-57891506. [Google Scholar]

7. Rahman A, Islam MJ, Band SS, Muhammad G, Hasan K, Tiwari P. Towards a blockchain-SDN-based secure architecture for cloud computing in smart industrial IoT. Digit Commun Netw. 2023;9(2):411–21. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2022.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Simjacker: A New Level of Threat Complexity. Simjacker Technical Report, 10OCT19-v1.01 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://info.enea.com/Simjacker-Technical-Paper. [Google Scholar]

9. McDaid C. Simjacker-next generation spying via SIM card vulnerability, ENEA [Internet]. 2019 Sep 11 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.enea.com/insights/simjacker-next-generation-spying-over-mobile/. [Google Scholar]

10. Harel O. Simjacker: how to protect devices from an emerging threat, Telit Cinterion [Internet]. 2020 May 15 [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.telit.com/blog/simjacker-attacks-cellular-iot-devices/. [Google Scholar]

11. First steps for mitigating Simjacker-related risks right now [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.gsma.com/get-involved/gsma-membership/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PT-AG_Simjacker_PP_A4.ENG_.0003.03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

12. Paganini P. Simjacker attack allows hacking any phone with just an SMS, Security Affairs [Internet]. 2019 Sep 12 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://securityaffairs.com/91176/hacking/simjacker-flaw.html. [Google Scholar]

13. Muraleedhara P, Christo MS, Jaya J, Yuvasini D. Any bluetooth device can be hacked. Know how? Cyber Secur Applicat. 2024;2:100041. doi:10.1016/j.csa.2024.100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. MITRE ATT&CK Framework [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://attack.mitre.org/matrices/mobile/. [Google Scholar]

15. Pegasus Spyware Attack (Synthetic Dataset). kaggle [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/krishna1502/pegasus-spyware-attacksynthetic-dataset. [Google Scholar]

16. Younis A, Daher Z, Martin B, Morgan C. Mapping zero-click attack behavior into MITRE ATT&CK mobile: a systematic process. In: 2022 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI); 2022 Dec 14–16; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 890–6. [Google Scholar]

17. Shaker AMNF, Mohamed AM. Zero click attack. Int Undergrad Res Conf. 2021;5(5):46–9. doi:10.21608/IUGRC.2021.245413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kareem KM. A Comprehensive analysis of pegasus spyware and its implications for digital privacy and security. Int J Intell Syst Appl Eng. 2024;12(3):1360–73. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.11092140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nisha TN, Kulkarni MS. Zero click attacks-a new cyber threat for the e-banking sector. J Financ Crime. 2023;30(5):1150–61. doi:10.1108/JFC-06-2022-0140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shafqat M, Topcuoglu C, Kirda E, Ranganathan A. Experience report on the challenges and opportunities in securing smartphones against zero-click attacks. arXiv:2211.03015. 2022. [Google Scholar]

21. Yasmeen K, Adnan M. Zero-day and zero-click attacks on digital banking: a comprehensive review of double trouble. Risk Manag. 2023;25(4):25. doi:10.1057/s41283-023-00130-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wen H, Porras PA, Yegneswaran V, Lin Z. Thwarting smartphone SMS attacks at the Radio Interface Layer. In: Proceeding of the ISOC Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS); 2023 Feb 27–Mar 3; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. Daid CM. STK, A-OK? Mobile messaging attacks on vulnerable SIMs. In: The 31st Annual Virus Bulletin International Conference (VB2021 Localhost); 2021 Oct 7–8; Online. [Google Scholar]

24. Kumar A, Sharma I, Sharma A. Understanding the behaviour of android SMS malware attacks with real smartphones dataset. In: 2023 International Conference on Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application (ICIDCA); 2023 Mar 14–16; Uttarakhand, India. p. 655–60. [Google Scholar]

25. Ali T, Baloch R, Azeem M, Farhan M, Naseem S, Mohsin B. A systematic review of bluetooth security threats, attacks & analysis. Int J Comput Trends Technol. 2021;69(7):1–18. doi:10.14445/22312803/IJCTT-V69I7P101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Indumathi J, Gitanjali J. Bluetooth: state of the art, taxonomy, and open issues for managing security services in heterogeneous networks. In: Managing security services in heterogenous networks. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Taylor & Francis Group; 2020. p. 137–181. [Google Scholar]

27. Rana A, Kumar K. Security issues in bluetooth network. In: Tripathi AK, Shrivastava V, editors. Advancements in communication and systems. Hanover, MD, USA: SCRS; 2024. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

28. Githami SA, Solangi ZA, Rahim MSBM. Investigation of bluetooth security issues. In: 2023 IEEE 8th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS); 2023 Oct 25–27; Bahrain. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

29. Sun H, Shu H, Kang F, Zhao Y, Huang Y. Malware2ATT&CK: a sophisticated model for mapping malware to ATT&CK techniques. Comput Secur. 2024;140(12):103772. [Google Scholar]

30. Kwon R, Ashley T, Castleberry J, Mckenzie P, Gupta Gourisetti SN. Cyber threat dictionary using MITRE ATT&CK matrix and NIST cybersecurity framework mapping. In: 2020 Resilience Week (RWS); 2020 Oct 19–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 106–12. doi:10.1109/RWS50334.2020.9241271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Octavian G, Nica A, Dascalu M, Rughinis R. CVE2ATT&CK: bERT-based mapping of CVEs to MITRE ATT&CK techniques. Algorithms. 2022;15(9):314. doi:10.3390/a15090314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xiong W, Legrand E, Aberg O, Lagerström R. Cyber security threat modeling based on the MITRE Enterprise ATT&CK Matrix. Softw Syst Model. 2022;21:157–77. [Google Scholar]

33. Rajesh P, Alam M, Tahernezhadi M, Monika A, Chanakya G. Analysis of cyber threat detection and emulation using MITRE attack framework. In: 2022 International Conference on Intelligent Data Science Technologies and Applications (IDSTA); 2022 Sep 5–7; San Antonio, TX, USA. p. 4–12. [Google Scholar]

34. Dong Z, Yarochkin F, Du S. StrongPity APT group deploys android malware for the first time, TREND Micro. 2021 Jul 21 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/21/g/strongpity-apt-group-deploys-android-malware-for-the-first-time.html. [Google Scholar]

35. TianySpy malware uses smishing disguised as message from telco, Trend MICRO, TREND Micro [Internet]. 2022 Jan 25 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/22/a/tianyspy-malware-uses-smishing-disguised-as-message-from-telco.html. [Google Scholar]

36. Shunk P, Balaam K. Rooting malware makes a comeback: lookout discovers global campaign, Lookout [Internet]. 2021 Oct 28 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.lookout.com/threat-intelligence/article/lookout-discovers-global-rooting-malware-campaign. [Google Scholar]

37. Firsh A. BusyGasper–the unfriendly spy, SecureList by Kaspersky [Internet]. 2018 Aug 29 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://securelist.com/busygasper-the-unfriendly-spy/87627/. [Google Scholar]

38. Hinchliffe A, Harbison M, Osborn JM, Lancaster T. HenBox: the chickens come home to roost, UNIT 42 [Internet]. 2018 Mar 13 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/unit42-henbox-chickens-come-home-roost/. [Google Scholar]

39. Forensic Methodology Report: How to Catch NSO Group’s Pegasus. Amnesty International [Internet]. 2021 Jul 18 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2021/07/forensic-methodology-report-how-to-catch-nso-groups-pegasus/. [Google Scholar]

40. Murray M. Pegasus for Android: the other side of the story emerges. Lookout [Internet]. 2017 Apr 3 [cited 2025 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.lookout.com/threat-intelligence/article/pegasus-android. [Google Scholar]

41. Sophisticated new Android malware marks the latest evolution of mobile ransomware, Microsoft Threat Intelligence [Internet]. 2020 Oct 8 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://shrturl.app/FwWr3M. [Google Scholar]

42. Kumar A, Rosso KD. Novel confucius APT android spyware linked to India-Pakistan conflict [Internet]. 2021 Feb 10 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://surl.li/kyvfbq. [Google Scholar]

43. S.O.V.A.-A new Android Banking trojan with fowl intentions, ThreatFabric [Internet]. 2021 Sep 9 [cited 2025 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.threatfabric.com/blogs/sova-new-trojan-with-fowl-intentions. [Google Scholar]

44. Bauer A, Kumar A, Hebeisen C, Murray M, Flossman M. Monokle: the mobile surveillance tooling of the special technology center, Lookout. Security Research Report [Internet]. 2019 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.lookout.com/documents/threat-reports/lookout-discovers-monokle-threat-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

45. SharkBot: a new generation android banking trojan being distributed on google play store [Internet]. 2022 Mar 2 [cited 2025 Apr 20]. Available from: https://surl.li/nfhlcr. [Google Scholar]

46. Ferrante AJ. Project CATO [Internet]. 2019 Nov [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6668313-FTI-Report-into-Jeff-Bezos-Phone-Hack/. [Google Scholar]

47. Flossman M. ViperRat-Mobile APT targeting Israeli defense force, Lookout [Internet]. 2017 Feb 16 [cited 2025 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.lookout.com/threat-intelligence/article/viperrat-mobile-apt. [Google Scholar]

48. Desai S. SpyNote RAT posing as Netflix app, Zscaler Blog [Internet]. 2017 Jan 23 [cited 2025 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.zscaler.com/blogs/security-research/spynote-rat-posing-netflix-app. [Google Scholar]

49. Use of fancy bear android malware in tracking of ukrainian field artillery units, CrowdStrike Global Intelligence Team [Internet]. 2017 Mar 23 [cited 2025 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.crowdstrike.com/wp-content/brochures/FancyBearTracksUkrainianArtillery.pdf. [Google Scholar]

50. Ventura V. GPlayed Trojan -.Net playing with google market, CISCO TALOS [Internet]. 2018 Oct 11 [cited 2025 Apr 21]. Available from: https://blog.talosintelligence.com/gplayedtrojan/. [Google Scholar]

51. Kumar A, Rosso KD, Albrecht J, Hebeisen C. Mobile APT surveillance campaigns targeting Uyghurs-A collection of long-running Android tooling connected to a Chinese mAPT actor, Lookout. Security Research Report [Internet]. 2020 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.lookout.com/documents/threat-reports/us/lookout-uyghur-malware-tr-us.pdf. [Google Scholar]