Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Secure and Efficient Distributed Authentication Scheme for IoV with Reputation-Driven Consensus and SM9

1 School of Digital and Intelligence Industry, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, 014010, China

2 School of Information Engineering, Ordos Vocational College, Ordos, 017010, China

3 School of Information Science and Technology, Baotou Teachers College, Baotou, 014010, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhanfei Ma. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069236

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 07 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) operates in highly dynamic and open network environments and faces serious challenges in secure and real-time authentication and consensus mechanisms. Existing methods often suffer from complex certificate management, inefficient consensus protocols, and poor resilience in high-frequency communication, resulting in high latency, poor scalability, and unstable network performance. To address these issues, this paper proposes a secure and efficient distributed authentication scheme for IoV with reputation-driven consensus and SM9. First, this paper proposes a decentralized authentication architecture that utilizes the certificate-free feature of SM9, enabling lightweight authentication and key negotiation, thereby reducing the complexity of key management. To ensure the traceability and global consistency of authentication data, this scheme also integrates blockchain technology, applying its inherent invariance. Then, this paper introduces a reputation-driven dynamic node grouping mechanism that transparently evaluates and groups’ node behavior using smart contracts to enhance network stability. Furthermore, a new RBSFT (Reputation-Based SM9 Friendly-Tolerant) consensus mechanism is proposed for the first time to enhance consensus efficiency by optimizing the PBFT algorithm. RBSFT aims to write authentication information into the blockchain ledger to achieve multi-level optimization of trust management and decision-making efficiency, thereby significantly improving the responsiveness and robustness in high-frequency IoV scenarios. Experimental results show that it excels in authentication, communication efficiency, and computational cost control, making it a feasible solution for achieving IoV security and real-time performance.Keywords

With the rapid development of intelligent transportation technology and the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), high-frequency data exchange between vehicles and between vehicles and infrastructure is becoming a key method to improve real-world traffic safety and efficiency [1]. However, the highly dynamic, open, and heterogeneous network environment of the IoV poses severe information security challenges [2], particularly in terms of identity authentication [3] and consensus mechanisms. Existing authentication approaches often depend on centralized management and complex certificate mechanisms, which are challenging to meet the requirements of low-latency, high-reliability, and lightweight computing in the IoV environment. Besides, although mainstream consensus mechanisms such as PBFT (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) and Raft have their advantages, they still face problems, including high computational and communication overhead, complex node management, and insufficient fault tolerance, particularly when dealing with high-frequency communication and large-scale node collaboration.

In recent years, researchers have attempted to combine cryptography and blockchain technology with the security mechanism of IoV [4–6]. Among them, Identity-Based Cryptography (IBC) has received widespread attention due to its advantages of simplifying key management and reducing certificate dependencies. In particular, the SM9 algorithm, as a certificate-free identity-based cryptography [7,8], has the characteristics of lightweight, security, and scalability, making it exceedingly suitable for key negotiation and authentication in resource-constrained and highly dynamic scenarios. Meanwhile, blockchain technology naturally supports building a trusted authentication and consensus environment, thanks to its decentralized, tamper-proof and traceable characteristics.

However, existing research still faces many challenges when combining blockchain with IoV. For example, some blockchain-based anonymous authentication schemes have implemented identity privacy protection, but they have not fully considered the use of key distribution and tamper-proof devices [9], and the delay in ticket processing becomes a significant issue when facing a large number of vehicles. Consequently, specific consensus mechanisms in the IoV environment suffer from high communication complexity and poor scalability, which makes it challenging to meet the demands of real-time and high efficiency.

Regarding the above questions, this paper proposes an optimized distributed authentication scheme that integrates the SM9 algorithm and improved blockchain technology. It has built a multi-level consensus mechanism that is more scalable, stable, and secure.

On balance, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a secure and efficient distributed authentication scheme for IoV with reputation-driven consensus and SM9 to achieve secure and efficient identity verification and key management in IoV environments.

• To achieve transparent evaluation and trusted grouping of node behaviors, and enhance network trust management and system resilience, we introduce a reputation-driven dynamic node grouping mechanism that combines blockchain smart contracts.

• We also integrate the advantages of PBFT and Raft mechanisms, propose a new RBSFT consensus algorithm, and introduce SM9 aggregate signature and reputation scoring mechanisms. This design significantly enhances the efficiency and robustness in high-frequency communication scenarios while ensuring the security of the consensus process.

• The performance advantages of this scheme in typical IoV scenarios have been verified through many experiments, which include multiple dimensions such as authentication delay, communication overhead, and consensus efficiency. A feasible path is offered for building the next-generation vehicle networking security system.

The remaining content is as follows: Section 2 summaries the relevant works and analyses their shortcomings; Section 3 introduces the preliminary work and system model; Then, Section 4 states the proposed plan in detail; And Section 5 conducts security analysis; Section 6 describes performance comparison and simulation experiments; Finally, Section 7 provides a summary of the entire text and outlines future directions for work.

The latest developments in the IoV have driven extensive research on secure authentication and consensus mechanisms to address their dynamic, open, and resource-constrained environment issues. Blockchain technology has been widely explored in IoV authentication and data management due to its decentralized and tamper-proof characteristics. For instance, Zheng et al. [10] proposed a VANET authentication scheme based on a traceable blockchain, which enables anonymous Vehicle-RSU communication, but its dependence on frequent Trusted Authority (TA) interactions increases latency and limits scalability. Similarly, Noh et al. [11] introduced a blockchain-based message authentication scheme that achieved decentralization, but incurred high computational overhead due to its complex cryptographic operations. Yao et al. [12] developed a lightweight blockchain-assisted authentication (BLA) mechanism using the PBFT protocol, which reduces duplicate authentication. However, its dependence on traditional Public-Key Infrastructure (PKI) introduced complexity in the management of certificates. Although Shen et al. [13] proposed a mutual authentication scheme for edge computing based on ECC, its certificate overhead places a burden on resource-constrained OBUs. Besides, Bojjagani et al. [14] integrated blockchain and edge computing together for security key management, yet their anonymity is weak, and they are vulnerable to traceability attacks.

Regarding consensus mechanisms, existing research (e.g., PoW and PoS) is computationally intensive, while Wang et al. [15] analyzed the PBFT, which provides reliability, but there is a secondary communication complexity (O(N2)) in large-scale IoV networks. Although the R-PBFT proposed by Kumar et al. [16] is a reputation-based variant of PBFT, it ignores node mobility and reduces efficiency in dynamic scenarios. Then, Xu et al. [17] introduced SG-PBFT, which reduces communication overhead but lacks robust defenses against malicious nodes. Liu et al. [18] combined the blockchain with edge computing to implement low-latency access control, but their simplified PBFT sacrifices Byzantine fault tolerance. Although El-Zawawy et al. [19] used ECC and blockchain for drone-assisted IoV, their scalability is limited by the computational intensity of ECC. Additional studies, such as Karim et al. [20], proposed blockchain-based data exchange solutions, but their high communication costs consistently hinder real-time performance. Chen et al. [21] provided a summary of the blockchain security technology in IoV and highlighted the scalability challenges in high-frequency scenarios. Furthermore, Sharma et al. [22] developed an energy-efficient blockchain transaction model, but it lacks consensus on optimizing the dynamic structure of IoV. Mu et al. [23] explored the secure signature of SM9, which emphasizes its advantages of being certificate-free, but they did not address the consensus optimization problem. Meanwhile, Xu et al. [24] proposed GPU-accelerated SM9 processing, which improves efficiency, but it was not tailored for the distributed consensus needs of IoV. Dong et al. [25] designed an improved PBFT consensus mechanism (IPBFT) that uses group signatures for voting-based sorting and clustering, thereby enhancing privacy, but lacking efficient smart contract triggering and dynamic node management. A dual-blockchain layered PBFT (DBPBFT) for IoT, introduced by Wu et al. [26], is suitable for static scenarios but is limited by complex certificate management and a lack of a fast re-authentication mechanism. The MGRS-PBFT proposed by Zheng et al. [27] combines credit scoring of node behavior, but lacks robust ledger auditing and fast re-authentication mechanisms. Although Zheng et al. [28] developed TRBFT, an efficient blockchain consensus for edge computing IoT, it does not completely solve the high mobility or integrated aggregation signature problem of the IoV. Deshmukh et al. [29] presented a scalable Byzantine fault-tolerant consensus for vehicular networks, but its fixed leader election limits its adaptability in dynamic IoV environments. In addition, a shard-based consensus protocol introduced by Lu et al. [30] advances scalability but lacks reputation-driven trust management and SM9 integration.

Our proposed scheme addresses the shortcomings of existing IoT systems in terms of security, efficiency, and scalability through multiple innovations. Firstly, unlike [10,12,13,26], introducing the identity-based uncertified cryptographic system SM9 simplifies key management and reduces the computational burden on VU and RSU. Then, the RBSFT consensus mechanism integrates the fault tolerance of PBFT, the log synchronization of Raft, and the SM9 aggregate signature, reducing communication complexity from O(N2) to O(N), which is superior to PBFT, SG-PBFT [17], IPBFT [25], and others. Unlike R-PBFT [16] and IPBFT [25], we employ a reputation-driven dynamic grouping mechanism to eliminate node location dependence, which is more suitable for the dynamic structure of the IoV and superior to the fixed grouping or voting methods in [29,30]. Besides, building a reputation evaluation mechanism through smart contracts, prioritizing the participation of high-reputation nodes in consensus, and enhancing anti-attack capabilities, is superior to [17,18,25,27]. SM9 aggregate signature optimization in the Prepare and Commit stages reduces verification overhead and solves the issues of high communication costs in [20] and insufficient privacy protection in [11,14]. Finally, the lightweight re-authentication mechanism we designed combines blockchain certificates with SM9 signatures to avoid duplicate calculations and reduce authentication latency, which is superior to the authentication redundancy issues in [12,26,27].

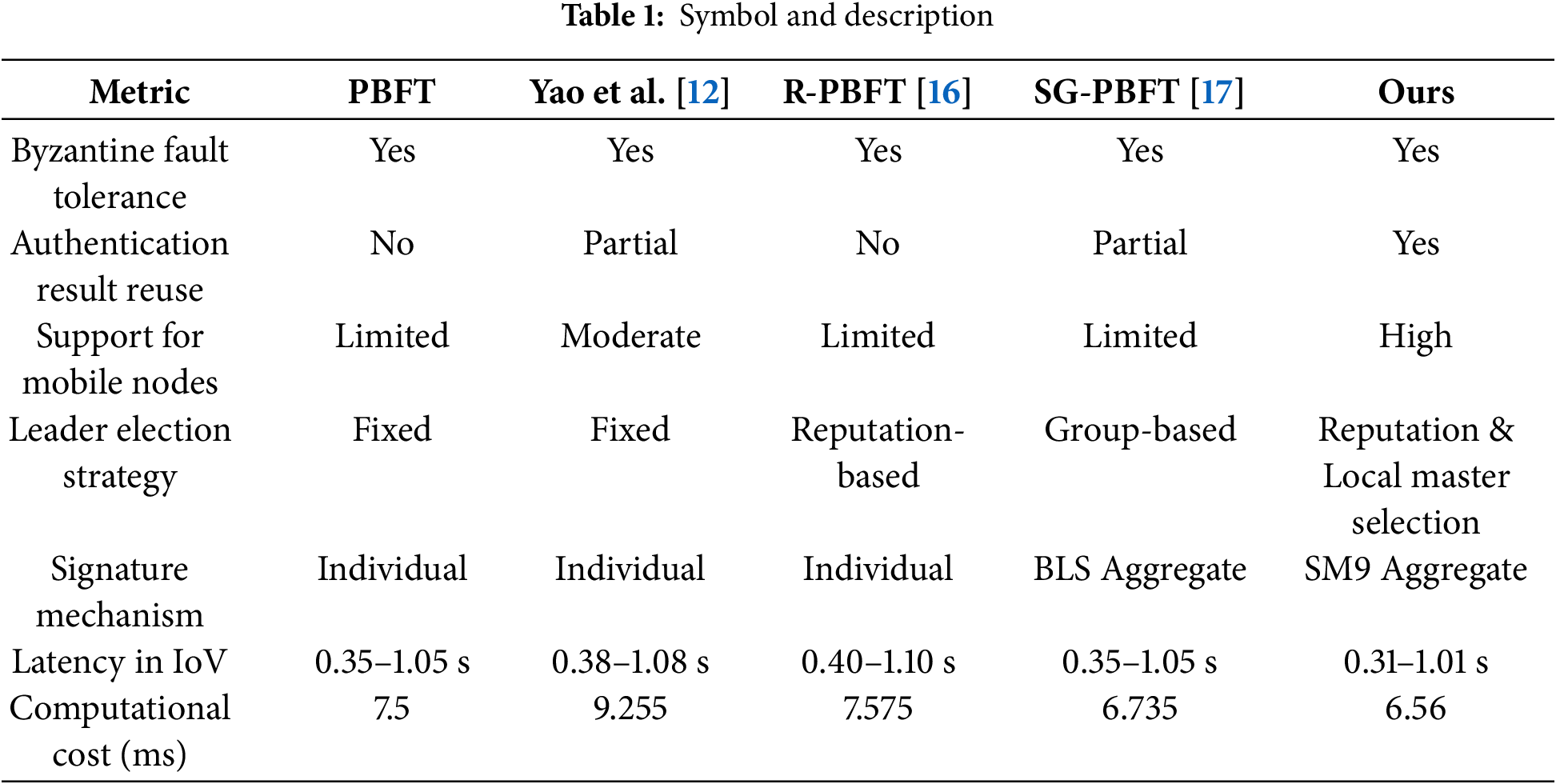

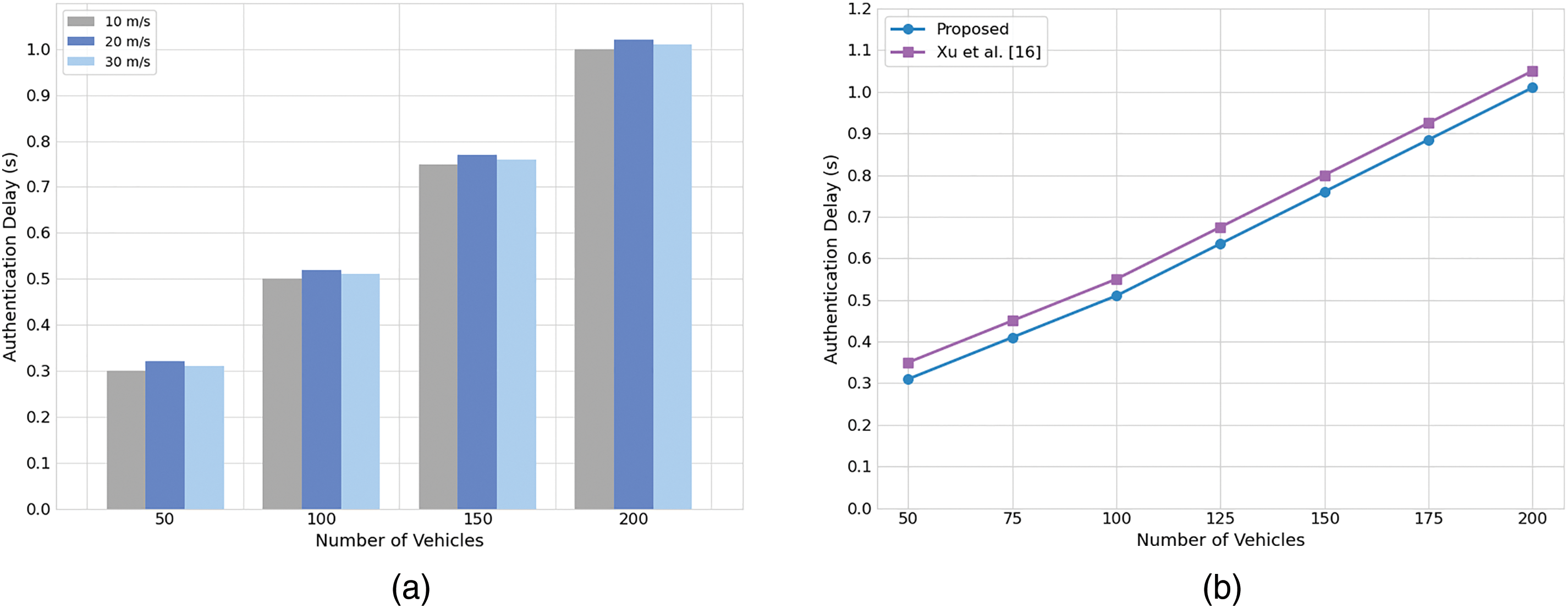

To clearly demonstrate these advantages, we create Table 1 and compare RBSFT with PBFT, Yao et al. [12], R-PBFT [16], and SG-PBFT [17] using key IoV metrics. All schemes maintain Byzantine Fault Tolerance to ensure robustness against malicious nodes. However, our scheme supports the reuse of authentication results, which differs from the partial reuse in [12,17] or none in [16], thereby reducing redundant computations. Due to its reputation-driven grouping, RBSFT offers high support for mobile nodes, surpassing the limited support in [16,17] and the moderate support in [12]. The leader election strategy in RBSFT combines reputation-based selection with local master selection, providing more dynamic and trustworthy leadership than the fixed strategies in [12] or group-based in [17]. Compared with the single signatures in [12,16] and BLS aggregation in [17], the SM9 aggregate signature reduces verification overhead. The latency of IoV (0.31–1.01 s) is lower than that of competitors (0.35–1.10 s), reflecting the efficiency of RBSFT. Finally, due to the lightweight operations and optimized consensus of SM9, the computational cost (6.56 ms) is the lowest, outperforming [12] (9.255 ms), [16] (7.575 ms), and [17] (6.735 ms).

3 Preliminaries and System Model

This section first introduces the theoretical foundations of blockchain technology, the SM9 signature mechanism, and smart contracts. Subsequently, the system model proposed in this paper is systematically elaborated, laying a theoretical foundation and offering architectural support for subsequent scheme design.

Blockchain is a decentralized distributed ledger technology that stores transaction records by a chained data structure to ensure data immutability and transparent traceability [31]. All nodes in the system maintain the same ledger copy to record transactions and status updates, thereby eliminating reliance on centralized institutions and providing a solid foundation for establishing decentralized trust mechanisms and secure collaboration. In the IoV scenario, blockchain can not only store authentication results and node reputation scores, but also realize automatic policy execution through smart contracts, ensuring the efficiency and credibility of authentication and consensus processes.

A smart contract [32] is an automated program deployed on the blockchain that autonomously executes through pre-defined rules and logic. Compared to traditional contracts, smart contracts have the following significant advantages: Firstly, their blockchain-based non-tampering characteristics ensure the transparency and immutability of the contract terms; Then, the automatic execution mechanism eliminates dependence on intermediaries, which significantly improves execution efficiency, and reduces trust costs; Finally, their flexible programmability can support the implementation of complex business logic. In this paper, a smart contract is deployed on the Road Side Units (RSUs), mainly responsible for triggering authentication logic, verifying timestamps, and querying authentication credentials in the blockchain ledger, thereby providing efficient support for distributed authentication and consensus processes.

3.1.2 PBFT Consensus Mechanism

The Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerant (PBFT) algorithm was proposed by Castro et al. in 1999 [33], which solves the Byzantine problem in distributed systems by ensuring consistency in the presence of malicious nodes. The algorithm consists of four phases: Pre-Prepare, Prepare, Commit and Reply. In a system with a total number of N nodes, PBFT can tolerate a maximum of f = (N − 1)/3 faulty or malicious nodes. This paper applies the improved PBFT algorithm to the IoV scenario because it can effectively defend against tampering attacks against the centralized database while satisfying the requirements of high security and low latency. However, the communication complexity of traditional PBFT is O(N2), which can lead to significant performance bottlenecks when the number of nodes is large, limiting its applicability in highly dynamic IoV environments.

3.1.3 Raft Consensus Mechanism

Raft is a distributed consensus algorithm proposed by Ongaro et al. [34]. It is mainly used to ensure consistency in log replication, and its design focuses on simplicity and efficiency. The Raft algorithm consists of two core mechanisms: Leader Election and Log Replication.

Leader Election: Raft divides nodes into Leader, Follower, and Candidate roles. There is usually only one leader in the system, responsible for coordinating log replication and client requests. If the leader fails, the followers will become candidates after a timeout and become the new leader by initiating an election and obtaining the votes of the majority of nodes. This mechanism reduces election conflicts through a randomized timeout strategy, ensures quick recovery, and maintains a single leader in the event of failure, thereby avoiding brain-disruption problems.

Log Replication: The leader receives client requests, packages the operations in the form of log entries to generate blocks, and sends the logs to all follower nodes through the heartbeat mechanism. After confirming the log, the followers append the block to the local ledger.

The communication complexity of the Raft algorithm is O(N). The consensus is efficient and easy to realize, but it lacks Byzantine fault-tolerance to deal with malicious nodes or Byzantine failures. Therefore, the RBSFT consensus mechanism proposed in this paper combines the efficient log replication characteristics of Raft and the Byzantine fault-tolerance capability of PBFT, making it quite suitable for the IoV environments.

SM9 was proposed by the Chinese government in 2016 [35] as an Identity-Based Cryptography (IBC) standard, and was later included in the ISO 2021 international standard. This standard is widely used in secure authentication and key negotiation in certificate-free scenarios. SM9 is built on bilinear pairing and elliptic curve cryptography, and its significant advantage lies in eliminating certificate management in traditional public key infrastructure (PKI), allowing users to directly use identity information as the public key, thereby significantly simplifying the process of key distribution and storage. The SM9 signature mechanism has the characteristics of high generation and verification efficiency, and is quite suitable for resource-constrained IoV scenarios. Additionally, SM9 supports signature aggregation functionality, which can compress the signatures of multiple nodes into a fixed-length unified signature, thereby effectively reducing network traffic and verification burden. Therefore, this article introduces this feature for the first time into the identity authentication system of the Internet of Vehicles, filling a gap in existing research in this field. In the RBSFT consensus mechanism, the SM9 aggregate signature is used to optimize the Prepare and Commit stages. The master node can aggregate the signatures by no less than 2f + 1 nodes into a single signature, thereby reducing the communication complexity from O(N2) to O(N). Thanks to the certificate-free nature of SM9 and its high efficiency in signature verification, this solution not only helps to build a distributed system that supports high concurrency and low latency, but also further enhances the overall system’s performance in terms of security and anti-counterfeiting capabilities.

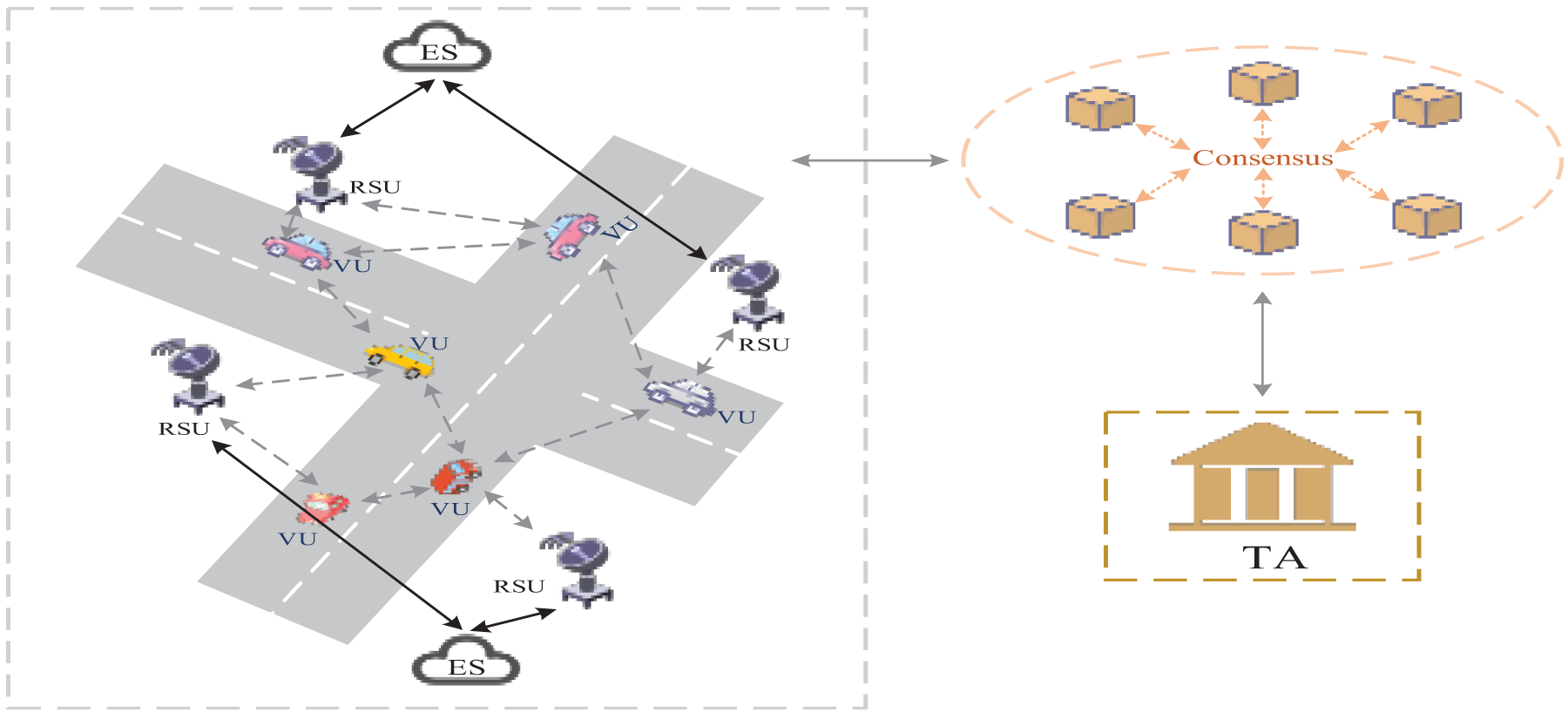

As shown in Fig. 1, this paper proposes a system model comprising two modules: the blockchain network and the IoT, to create a secure and efficient communication architecture for the IoV. The blockchain module adopts a federation chain consisting of RSUs and ESs, with TAs acting as fully trusted organizations to ensure system security and data reliability. RSUs and ESs are exposed to threats as semi-trusted nodes deployed in open environments, and are thus equipped with SM9 signatures and smart contracts to enhance security. The Telematics module consists of VUs that form a dynamic network through wireless communication for real-time interaction between vehicles and infrastructure. To enhance authentication efficiency, RSU deploys smart contracts that supports SM9 signatures, enabling automatic authentication and access control to provide trusted smart services. The architecture integrates the decentralized trust mechanism of blockchain with the real-time communication advantages of IoT to build a secure, low-latency and scalable solution. A detailed description of each component function will follow.

Figure 1: Proposed system model

As a fully trusted entity, the Trusted Authority (TA) is responsible for the initialization and registration of vehicles, and serves as the Key Generation Center (KGC). TA has powerful computing and storage capabilities to ensure the efficiency and security of data processing.

ES is equipped with powerful computing and storage resources, deployed near RSUs, and is responsible for supervising operations in its respective regions. The main responsibilities include: unified management of RSUs within the area, collaborative identity verification, participation in blockchain consensus, and maintenance of a shared ledger that records vehicle access and verification results. As a consensus node in the consortium chain, ES has block generation and on-chain permissions to ensure data consistency and security. ES handles consensus computing with high resource consumption, while RSU focuses on local identity authentication, with a clear division of labor to optimize system efficiency, security, and scalability.

Road Side Units (RSUs) are deployed along the road, managed by ES, and wirelessly interact with VUs using the Dedicated Short-Range Communication (DSRC) protocol. RSU is equipped with a data exchange module and a smart contract module, supporting SM9 signature verification to perform efficient identity authentication and data processing. Without participating in blockchain consensus or block generation, RSU focuses on low-latency local identity verification through smart contracts and forwards the results to ES for recording in the blockchain ledger. This division of labor ensures that RSUs focus on local tasks, while ES handles computation-intensive operations.

Vehicle Unit (VU) is mounted on the vehicle and realizes efficient communication between the vehicle and external entities based on wireless communication technology through two-way authentication with the RSU. The VU supports the provision of road accident information, traffic condition updates, driving safety tips, as well as communication, computation, and data storage functions, thus providing comprehensive assistive services to drivers and passengers.

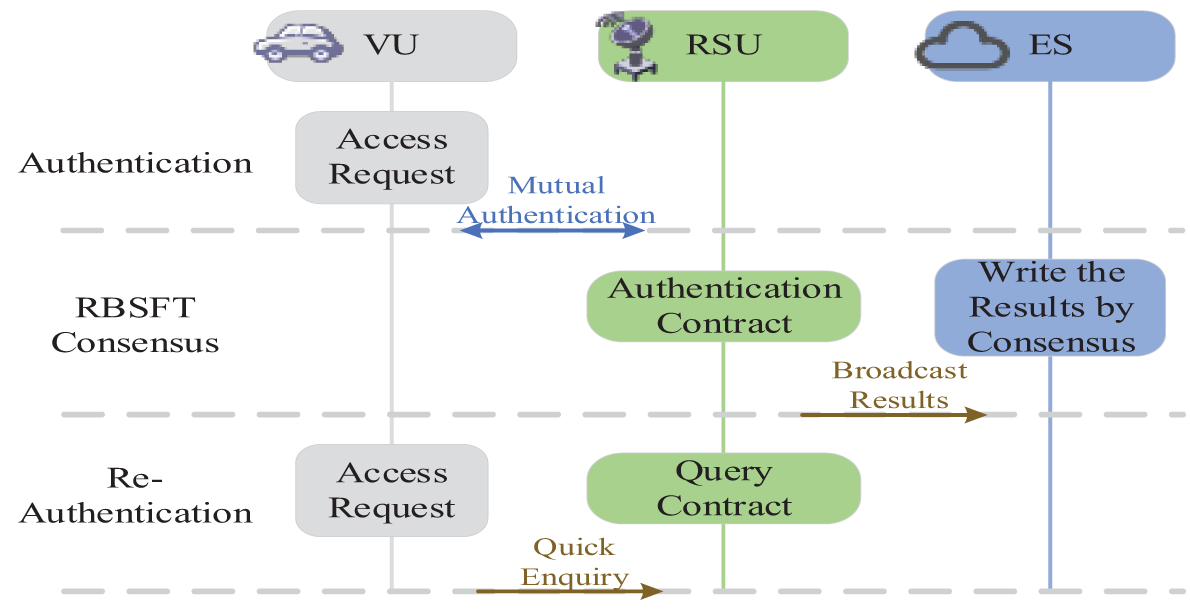

In this section, the authentication mechanism and overall process of the proposed scheme are systematically described, covering five key phases: Initialization, Registration, Authentication, Consensus and Re-Authentication. As shown in Fig. 2, it mainly illustrates the last three stages, the initialization and registration phases are executed only once. The related symbols and their meanings are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the proposed scheme

In this phase, the TA is responsible for completing the initialization operation of the system. As the Key Generation Center (KGC), the TA selects a 256-bit Barreto-Naehrig (BN) elliptic curve E of order a large prime number N according to the SM9 standard. Meanwhile, TA defines the bilinear pairing function e:

The public keys of RSUs and ESs directly use identifiers (e.g., IP address, device ID) and do not need to be generated independently. TA generates the respective SM9-based private key

In this phase, the VU completes registration with the TA, generates the SM9 private key and stores the signature record on the blockchain. The specific process is as follows.

1. First, the VU hashes its MAC address to obtain a unique identity

2. Then, VU generates a timestamp

3. When TA receives the message, it first verifies

4. After the TA check is passed, the initial identity credential

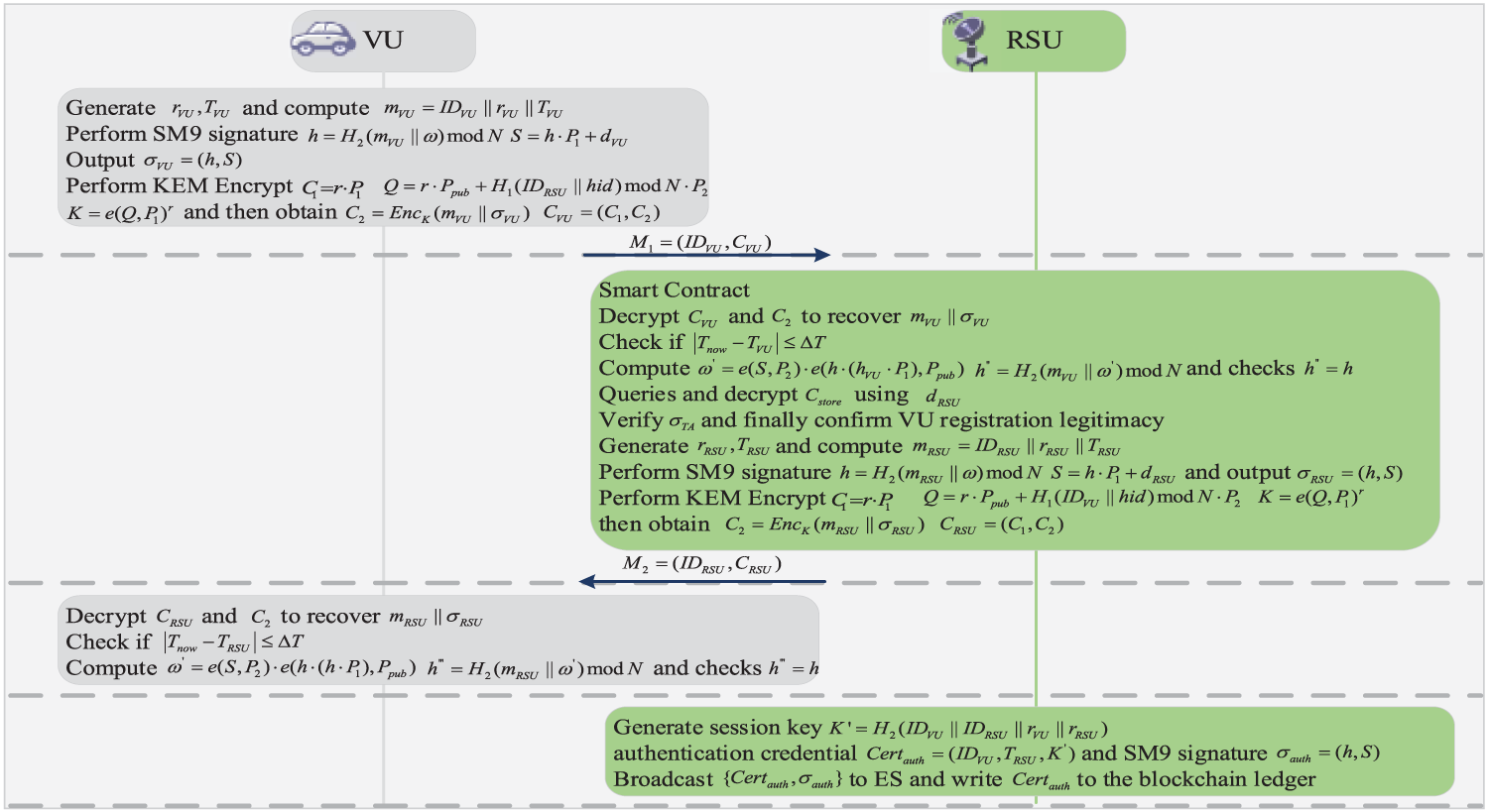

After the registration is completed, VU and nearby RSUs authenticate each other, and RSUs broadcast the authentication results to ES. ES then uses an improved consensus mechanism to write the results into the blockchain ledger. When VU initiates access again, the specific process is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Mutual authentication mechanism diagram

Step 1: VU generates a random number

Step 2: RSU receives

Step 3: RSU generates a random number

Step 4: VU receives

Step 5: Upon successful mutual authentication, VU and RSU derive a session key

After receiving the broadcast authentication result from RSU, ES first verifies its legitimacy and securely writes the result into the blockchain ledger by consensus algorithm. To address the disadvantages of PBFT and Raft mechanisms in terms of performance and security, this paper proposes an improved consensus mechanism RBSFT, which combines the advantages of both and the SM9 algorithm. This mechanism inherits the Byzantine fault-tolerant features of PBFT, while drawing on Raft’s efficient log synchronization design, and introducing a reputation-driven node grouping strategy, a dynamic leader election mechanism, and an improved SM9 signature aggregation algorithm. It improves the scalability and response speed of the system structurally, constructs a more elastic and adaptive consensus system, and significantly advances the security and privacy protection capabilities of the consensus process.

RBSFT supports aggregating multiple node signatures into a single verification object, which effectively reduces computational and communication overhead and improves system performance in high-frequency interaction scenarios. Meanwhile, the SM9 algorithm supports the encryption processing of log data, further improving the confidentiality and tamper resistance of on-chain data, and building a dual defense line of consensus layer and privacy protection layer.

The system divides nodes into High Reputation Group (HRG) and Regular Group (RG) based on their historical behavior and dynamic reputation rating. HRG nodes have higher priority in consensus due to their stable participation and complete records. Before each round of consensus, the system automatically selects the node with the highest reputation in HRG as the leader, and the rest as followers to jointly complete the consensus task. The system regularly updates the reputation score, removes nodes below the threshold, and adopts an adaptive management strategy based on reputation to ensure the dynamic effectiveness of the mechanism.

Besides, SM9 aggregate signatures play a crucial role in node elections and role adjustments. By aggregating signatures of election messages and identity authentication information, the authenticity and non-repudiation of node identities are ensured, effectively preventing attacks such as man-in-the-middle forgery and replay, and consolidating the trust foundation of the consensus process. The specific steps are as follows.

1. Pre-prepare phase: After receiving the client request, the master node constructs a message

2. Prepare phase: The replica node verifies the signature: calculates

3. Commit phase: The master node collects at least 2f + 1 SM9 signatures and aggregates them into a single SM9 signature

4. Consensus phase within the group: The master node signs the Log using SM9 and then broadcasts it to the HRG through a secure channel. All replica nodes in the HRG receive the message, verify the signature, and after they all pass, the replica node appends the Log to the local log storage and sends an acknowledgement message to the master node to ensure that the master node is aware of the Log replication status. If there are more than 2k/3 (k is the number of HRG nodes, which ensures Byzantine fault tolerance) valid confirmations, the Log is considered to have been successfully replicated. The master node submits the log to the blockchain, triggering the smart contract to update the global state.

5. Reply phase: The master node sends a confirmation message to the client, while the replica node updates its reputation score based on the consensus results of this round. If the node’s judgment is consistent with the final consensus result, its reputation score will increase; On the contrary, it will decrease. The system dynamically adjusts the membership composition of HRG and the RG based on the updated reputation scores.

Given the high mobility of vehicles, when VU initiates another authentication request, the system simplifies the authentication process to a query operation on the blockchain ledger to avoid duplicate authentication. Thus, it reduces communication overhead and computational costs and realizes lightweight re-authentication. The authentication credential

1. The VU generates the current timestamp

2. The RSU decrypts it using

This section first elaborates on the threat model of the proposed scheme and then comprehensively evaluates its security using various approaches, including security analysis based on the Real-Or-Random (ROR) model, formal verification using the AVISPA tool, and informal security discussions.

The threat model presented in this paper describes the potential security risks and the capabilities of attackers in the IoV network environment. We assume that TAs are usually operated by government departments or highly trusted entities that are fully credible and immune to attacks, ensuring that all data they generate or store remains secure. In contrast, ESs, RSUs, and VUs are considered semi-trusted entities because they operate in open and dynamic environments, making them vulnerable to multiple attacks. Based on the information security CIA triad model, they can be compromised in several ways. An attacker can compromise the confidentiality of the system and eavesdrop on authentication messages to extract sensitive information. Besides, an attacker can destroy the integrity of the system by forging or tampering with authentication messages, signatures, or blockchain ledger records (The attacks that adversaries can perform are detailed in the following ROR analysis).

5.2 Formal Security Analysis Using ROR Model

In authentication protocols for the IoV, we prove the security of the proposed scheme using the ROR model, a widely used tool for proving the security of authentication protocols, whose effectiveness is recognized by the academic community. By simulating various passive and active attacks, we verified the resistance of session keys to attacks and designed multiple game experiments in an instantiated network to distinguish between random numbers and session keys by testing queries.

For this purpose, we define an adversary

1. Message Interception Query:

2. Message Sending Query:

3. Identity Disguise Query:

4. Key Attack Query:

5. Security Test Query:

Definition 1: SM9 Bilinear Pairing Problem (SBPP): Given a bilinear pair e in the SM9 algorithm,

Theorem 1: Assume that

Proof: We construct three games

Initial game

Since

Hash Query Attack

Due to the strong collision resistance of the hash function,

SBPP and Reputation Scoring Attack

The reputation scoring mechanism ensures that low-reputation nodes are removed from the HRG, limiting the success of

After

Substitute the probability boundaries of

Finally, multiply both sides by 2 to obtain:

This formula indicates that the probability of

5.3 Security Analysis of AVISPA Tool

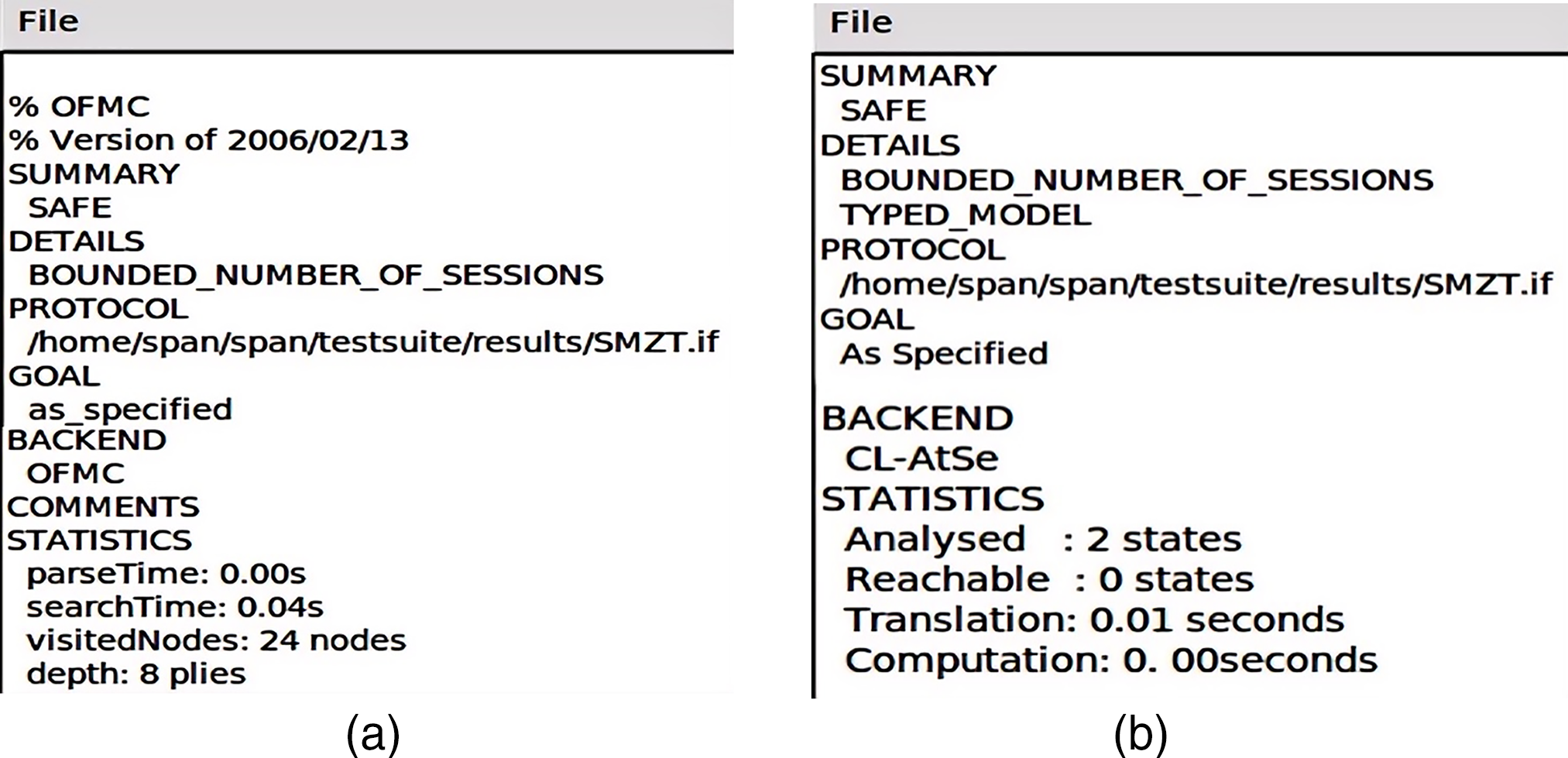

To further verify the security of the proposed scheme, we employed formal security validation using the Automated Validation of Internet Security Protocols and Applications (AVISPA). AVISPA is a powerful and widely used open-source security protocol analysis toolkit [37], which supports protocol modelling, automatic verification, and result visualization, and is particularly suitable for complex distributed system scenarios such as IoV. Its back-end analysis engines include OFMC (On-the-Fly Model Checker), CL-AtSe (Constraint-Logic-based Attack Searcher), SATMC, and TA4SP, among which OFMC and CL-AtSe are the most commonly used and stable modules.

During the formal modelling process, the core entity roles including VU, RSU, ES and TA, are defined, and the corresponding session logic and communication environment are established. The protocol model covers the Registration, Authentication, Consensus and Re-Authentication phases, focusing on verifying the security of SM9 signatures, the Key Encapsulation Mechanism (KEM), and the RBSFT consensus. We verify the protocol through OFMC and CL-AtSe back-end engines separately to detect the presence of potential vulnerabilities.

As shown in Fig. 4a,b, the protocol is determined to be “SAFE” in both OFMC and CL-AtSe environments, and no feasible attack paths are found. This indicates that the proposed scheme can effectively resist common active and passive attacks, including message tampering, signature forgery, and malicious node jamming. The formal validation results of AVISPA further confirm the security and robustness of the protocols in highly dynamic IoV environments.

Figure 4: The simulation results of the proposed method in the AVISPA environment: (a) Under OFMC circumstance; (b) Under CL-AtSe circumstance

5.4 Informal Security Analysis

This section discusses the proposed scheme’s defense against common attacks, which contains Sybil attacks, Masking attacks, Man-in-the-Middle attacks, Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks, Replay attacks, and Forgery attacks and so on, by an informal analysis.

In Sybil attack, an attacker tries to control the network or disrupt normal operations by forging multiple false identities (Sybil nodes). In the proposed scheme, the identification

Masking attack is when an attacker impersonates a legitimate entity (e.g., VU or RSU) to gain unauthorized access. In the proposed scheme, all entities must register with the TA to obtain SM9-based private keys (e.g.,

5.4.3 Man-in-the-Middle Attack

In a Man-in-the-Middle attack, the attacker intercepts and may tamper with communication messages between VU and RSU. In the proposed scheme, after passing through the SM9 KEM mechanism, the authentication message

5.4.4 Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks

DDoS attacks paralyze the system through a large number of invalid requests or forged signatures. To cope with this threat, the smart contract verifies the message timestamp during authentication, promptly discards invalid or malicious requests, and reduces the computational burden on RSUs. The RBSFT consensus mechanism identifies and isolates malicious nodes by reputation grouping (HRG and RG), reduces the reputation score of nodes that send false signatures or disrupt the consensus, and excludes HRGs from participating in the subsequent consensus. The distributed nature of the blockchain avoids a single point of failure, and the authentication results are stored in the distributed ledger in real-time, which enhances the DDoS resistance of the system.

Replay attacks involve attackers repeatedly sending expired legitimate messages to deceive the system. In the proposed scheme, each authentication message contains a dynamic timestamp

Forgery attacks involve an attacker forging authentication messages or signatures to spoof the system. In the proposed scheme, the authentication message is encrypted by SM9 KEM using the public key of the RSU and can be decrypted only by the private key of the RSU. The signature is generated based on the SM9 algorithm, which depends on a random number r, a hash value h and a private key

5.4.7 Smart Contract Vulnerability Attack

Attackers may exploit logic vulnerabilities (e.g., reentry attacks or overflow errors) in the smart contract code to corrupt the authentication process. The smart contract of the proposed scheme is deployed in the RSU with clear responsibilities, which is only responsible for triggering the authentication logic, verifying the timestamp and querying the

5.4.8 Resistance to ESL, Desynchronization, and Side-Channel Attacks

The proposed scheme resists ESL attacks in which temporary secrets (e.g., r,

The asynchronous attack disrupts the synchronization between VU and RSU by delaying or discarding messages. The scheme adopts internally validated timestamps (

Side-channel attacks exploit physical features such as time and power consumption. The scheme uses optimized SM9 operation (based on GMSSL/MIRACLE) and constant-time algorithm to defend against time and power consumption analysis. The RSU smart contract code is concise and reduces side-channel vulnerabilities. The RBSFT consensus mechanism mitigates the risk of side-channel attacks in consensus by restricting the participation of malicious nodes through reputation management.

5.4.9 Unlinkability, Indistinguishability, and Forward/Backward Secrecy

The scheme ensures unlinkability and prevents an attacker from linking multiple authentication sessions to the same VU. Each session uses a fresh

For an attacker without a private key, the authentication message is indistinguishable from random data. SM9 KEM encryption offers semantic security, as

This scheme implements forward and backward confidentiality to ensure that leaked session keys do not affect historical or subsequent sessions. Generate new keys

This section comprehensively evaluates the performance of the proposed SM9-based distributed identity authentication and RBSFT consensus scheme in the IoV environment, focusing on three key aspects: the efficiency of the RBSFT consensus algorithm, the computational and communication overhead in the authentication process, and the authentication delay under different network conditions.

The RBSFT consensus algorithm combines the advantages of PBFT, Raft, and SM9 aggregated signatures to achieve efficient and secure consensus in IoV. To evaluate the performance, RBSFT is compared to traditional PBFT and SG-PBFT [17]. Assuming that the network has N ESs, RBSFT and SG-PBFT use N/2 consensus nodes, and PBFT uses all N nodes. The communication cost is measured by the number of messages exchanged in each phase of consensus (Pre-prepare, Prepare, Commit, Reply).

For traditional PBFT, the communication cost is (2N(N − 1)), because all nodes broadcast messages in the Prepare and Commit phases. SG-PBFT reduces it to (N/2 − 1) (N/2 + 1) by restricting consensus to half of the nodes. In our RBSFT scheme, the use of SM9 aggregate signatures converts the Prepare phase into a unicast message to the leader node, and the Commit phase broadcasts a single aggregated signature. Besides, the reputation-based grouping mechanism ensures that only HRG participate, further reducing the overhead. The total communication cost of RBSFT is (3(N/2 − 1)). The exact expression is shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 2, the communication complexity of PBFT and SG-PBFT is quadratic

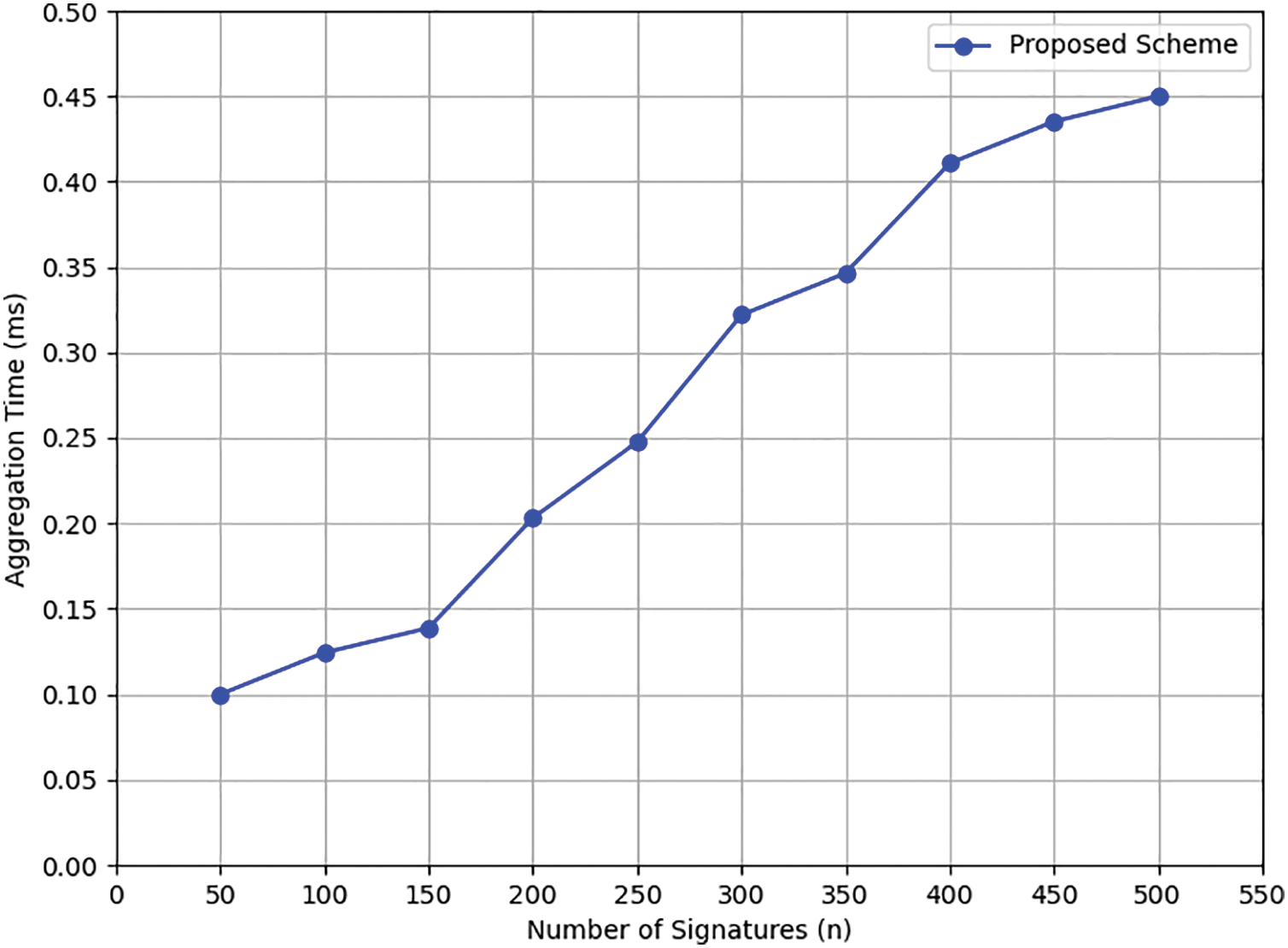

Figure 5: Time consumed for aggregating (N) signatures

The computational cost of the proposed scheme is evaluated based on the execution time of cryptographic primitives in the registration, authentication, and re-authentication phases. We use the Multi-precision Integer and Rational Arithmetic Library (MIRACL) [38] to measure the runtime of key operations: one-way hash function

In the registration phase, the VU performs one hash operation

We compare our scheme with schemes [12,16,17,41–43], as shown in Table 5. Although ECC point multiplication (0.675 ms) is quicker, our scheme’s certificate-free SM9 operations simplify key management, offsetting the slightly higher computational cost.

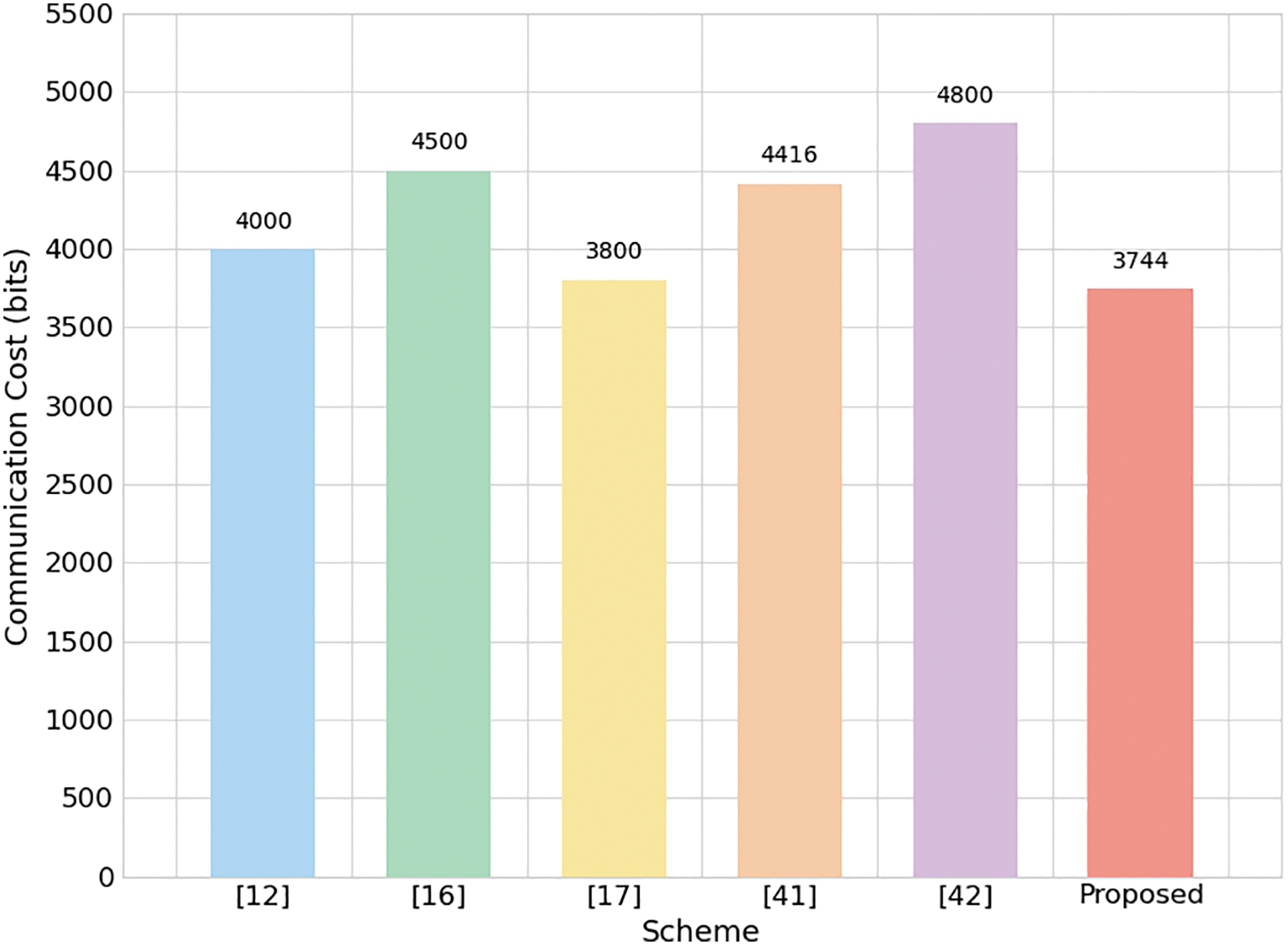

The communication cost is measured as the total number of bits exchanged during the registration, authentication, and re-authentication phases. We assume the following bit lengths: identity (160 bits), random number (160 bits), timestamp (32 bits), elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) (160 bits), SM9 signature (256 bits), SM9 KEM ciphertext (320 bits), and hash function (256 bits).

We compare the proposed scheme with [12,16,17,41,42] as shown in Fig. 6. In the scheme proposed by Eddine et al. [41], the number of exchanged messages is six, consisting of two message exchanges during the registration phase (1280 bits), three message exchanges during the authentication phase (2688 bits), and one message exchange during the re-authentication phase (448 bits). Therefore, the total communication cost is 4416 bits. In contrast, Zhang et al. [42] scheme requires six message interactions with a communication overhead of 4800 bits; The scheme proposed by Yao et al. [12] is implemented through four message interactions, with a communication overhead of 4000 bits; Kumar et al. [16] conducted a total of five message interactions with a communication overhead of 4500 bits; The scheme proposed by Xu et al. [17] also involves four message exchanges, with relatively low communication overhead of 3800 bits.

Figure 6: Comparison of communication cost

The communication costs of this scheme mainly come from the registration, authentication, and re-authentication stages. In the registration phase, the VU sends a message

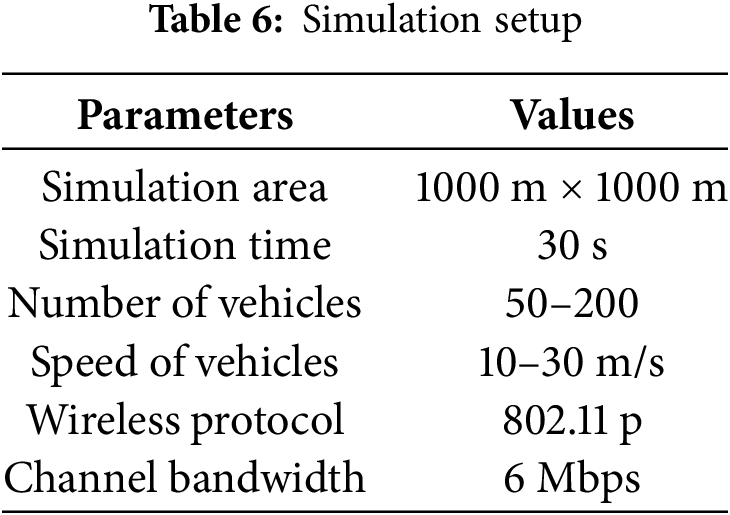

This section focuses on the performance evaluation of identity verification delay. The experiment uses the urban transportation simulation tool SUMO, and the relevant parameters are detailed in Table 6. SUMO is an open-source traffic simulation software developed in C++, widely used to measure the average authentication delay in the IoV. Identity verification delay is defined as the total time spent on the entire process of registration, authentication, and re-authentication. Fig. 7a shows the test results at vehicle speeds of 10 m/s, 20 m/s, and 30 m/s. The results show that as the vehicle speed increases, the overall authentication delay shows a slight upward trend, but the difference in delay at different speeds is small, indicating that this scheme still has good stability and robustness in the dynamic environment of vehicle speed changes.

Figure 7: (a) Comparison of authentication delay for different speeds; (b) Average authentication delay

To further validate the performance, we compare the average authentication delay of the proposed scheme with Xu et al. [17], which employs the SG-PBFT consensus algorithm and has a computational cost (6.735 ms) and communication cost (3800 bits) comparable to our scheme (6.56 ms, 3744 bits). Fig. 7b shows a comparison of the average authentication delay for vehicle counts ranging from 50 to 200, with data points for every 25 vehicles. The proposed scheme’s delay ranges from 0.31 to 1.01 s, consistently lower than Xu et al.’s 0.35 to 1.05 s. This advantage is attributed to the proposed scheme’s optimized RBSFT consensus algorithm, which leverages SM9 aggregate signatures and reputation-based node grouping, and its lower communication overhead (3744 bits vs. 3800 bits).

This paper proposes an efficient and secure distributed authentication scheme for the IoT based on SM9 and a reputation-driven consensus mechanism, aiming to solve the security and performance challenges in highly dynamic and open network environments. Existing solutions are limited by complex certificate management and inefficient consensus protocols, which make it challenging to meet the low latency and high robustness requirements of IoV. Therefore, this paper introduces a dynamic node grouping strategy driven by smart contracts and reputation to enhance network stability and flexibility in trust management. The innovative RBSFT algorithm overcomes the limitations of traditional protocols, enhancing PBFT fault tolerance and Raft election efficiency by integrating SM9 lightweight signatures, while also reducing the computational burden. Compared with previous studies, RBSFT significantly optimizes communication complexity, improves consensus efficiency and system resilience, while ensuring security and meeting the real-time and scalability requirements of IoV.

Future research should focus on building small-scale prototypes or simulation systems to empirically verify end-to-end latency, throughput, and consensus success rates. Meanwhile, SM9 signature is efficient in typical applications, but its computational and storage overhead may still limit its application in large-scale networks. Combining federated learning technology is expected to improve the performance and system scalability of SM9, with significant research prospects.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank all the authors for their efforts.

Funding Statement: This study is fully supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61762071, Grant No. 61163025).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma; methodology, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma; validation, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma; formal analysis, Hui Wei, Jing Jiang and Bisheng Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma; writing—review and editing, Hui Wei, Jing Jiang, Bisheng Wang and Zhong Di; visualization, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma; supervision, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma; project administration, Hui Wei, Zhanfei Ma, Jing Jiang, Bisheng Wang and Zhong Di; funding acquisition, Hui Wei and Zhanfei Ma. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: No applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Aldhanhani T, Abraham A, Hamidouche W, Shaaban M. Future trends in smart green IoV: vehicle-to-everything in the era of electric vehicles. IEEE Open J Veh Technol. 2024;5(10):278–97. doi:10.1109/ojvt.2024.3358893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ji B, Chen Z, Mumtaz S, Han C, Li C, Wen H, et al. A vision of IoV in 5G HetNets: architecture, key technologies, applications, challenges, and trends. IEEE Netw. 2022;36(2):153–61. doi:10.1109/mnet.012.2000527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khezri E, Hassanzadeh H, Yahya RO, Mir M. Security challenges in internet of vehicles (IoV) for ITS: a survey. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2025;30(4):1700–23. doi:10.26599/tst.2024.9010083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jatoth C, Doriya R. IoV block secure: blockchain based secure data collection and validation framework for internet of vehicles network. Peer Netw Appl. 2024;17(6):3964–90. doi:10.1007/s12083-024-01802-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shah K, Chadotra S, Tanwar S, Gupta R, Kumar N. Blockchain for IoV in 6G environment: review solutions and challenges. Clust Comput. 2022;25(3):1927–55. doi:10.1007/s10586-021-03492-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tu S, Yu H, Badshah A, Waqas M, Halim Z, Ahmad I. Secure Internet of Vehicles (IoV) with decentralized consensus blockchain mechanism. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;72(9):11227–36. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3268135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ji H, Zhang H, Shao L, He D, Luo M. An efficient attribute-based encryption scheme based on SM9 encryption algorithm for dispatching and control cloud. Connect Sci. 2021;33(4):1094–115. doi:10.1080/09540091.2020.1858757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang B, Li B, Zhang J, Wei Y, Yan Y, Han H, et al. An efficient SM9 aggregate signature scheme for IoV based on FPGA. Sensors. 2024;24(18):6011. doi:10.3390/s24186011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Laghari AA, Khan AA, Alkanhel R, Elmannai H, Bourouis S. Lightweight-bIoV: blockchain distributed ledger technology (BDLT) for internet of vehicles (IoVs). Electronics. 2023;12(3):677. doi:10.3390/electronics12030677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zheng D, Jing C, Guo R, Gao S, Wang L. A traceable blockchain-based access authentication system with privacy preservation in VANETs. IEEE Access. 2019;7:117716–26. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2936575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Noh J, Jeon S, Cho S. Distributed blockchain-based message authentication scheme for connected vehicles. Electronics. 2020;9(1):74. doi:10.3390/electronics9010074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yao Y, Chang X, Mišić J, Mišić VB, Li L. BLA: blockchain-assisted lightweight anonymous authentication for distributed vehicular fog services. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(2):3775–84. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2892009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shen M, Duan J, Zhu L, Zhang J, Du X, Guizani M. Blockchain-based incentives for secure and collaborative data sharing in multiple clouds. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2020;38(6):1229–41. doi:10.1109/jsac.2020.2986619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bojjagani S, Reddy YP, Anuradha T, Rao PV, Reddy BR, Khan MK. Secure authentication and key management protocol for deployment of Internet of Vehicles (IoV) concerning intelligent transport systems. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(12):24698–713. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3207593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang X, Zhu H, Ning Z, Guo L, Zhang Y. Blockchain intelligence for internet of vehicles: challenges and solutions. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2023;25(4):2325–55. [Google Scholar]

16. Kumar A, Vishwakarma L, Das D. R-PBFT: a secure and intelligent consensus algorithm for Internet of vehicles. Veh Commun. 2023;41(7):100609. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2023.100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu G, Bai H, Xing J, Luo T, Xiong NN, Cheng X, et al. SG-PBFT: a secure and highly efficient distributed blockchain PBFT consensus algorithm for intelligent Internet of vehicles. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2022;164:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2022.01.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Y, Xiao M, Chen S, Bai F, Pan J, Zhang D. An intelligent edge-chain-enabled access control mechanism for IoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(15):12231–41. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3061467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. El-Zawawy MA, Brighente A, Conti M. Authenticating drone-assisted Internet of Vehicles using elliptic curve cryptography and blockchain. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2022;20(2):1775–89. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3217320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Karim SM, Habbal A, Chaudhry SA, Irshad A. BSDCE-IoV: blockchain-based secure data collection and exchange scheme for IoV in 5G environment. IEEE Access. 2023;11:36158–75. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3265959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen C, Quan S. A summary of security techniques-based Blockchain in IoV. Secur Commun Netw. 2022;2022(1):8689651. doi:10.1155/2022/8689651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sharma V. An energy-efficient transaction model for the blockchain-enabled internet of vehicles (IoV). IEEE Commun Lett. 2018;23(2):246–9. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2018.2883629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mu Y, Xu H, Li P, Ma T. Secure two-party SM9 signing. Sci China Inf Sci. 2020;63(8):189101. doi:10.1007/s11432-018-9589-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xu W, Ma H, Zhang R. GAPS: GPU-accelerated processing service for SM9. Cybersecurity. 2024;7(1):29. doi:10.1186/s42400-024-00217-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dong S, Su H, Hou R, Shankar A. Improved PBFT consensus mechanism based on voting sort clustering partition with group signature for IoT. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;26(2):2239–51. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3495991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu X, Wang Z, Li X, Chen L. DBPBFT: a hierarchical PBFT consensus algorithm with dual blockchain for IoT. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2025;162(5):107429. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zheng J, Li J. MGRS-PBFT: an optimized consensus algorithm based on multi-group ring signatures for blockchain privacy protection. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2025;1. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2025.3580403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zheng J, Zhang Y. TRBFT: an efficient blockchain consensus for edge computing-enabled IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(11):15853–68. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3529723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Deshmukh A, Baiju D, Atish A, Alladi T, Yu FR. An efficient and scalable byzantine fault tolerant consensus for vehicular networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2025;1–12. doi:10.1109/tvt.2025.3561360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lu L, Sun L, Zou Y. An efficient sharding consensus protocol for improving blockchain scalability. Comput Commun. 2025;231(4):108032. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2024.108032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Nakamoto S, Bitcoin A. A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Bitcoin [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

32. Gabashvili N, Gabashvili T, Kiknadze M. From paper contracts to smart contracts. Sci Eur. 2022;2022(107):124–7. [Google Scholar]

33. Castro M, Liskov B. Practical byzantine fault tolerance. OsDI. 1999;99:173–86. [Google Scholar]

34. Ongaro D, Ousterhout J. The raft consensus algorithm. Lect Notes CS. 2015;190:2022. [Google Scholar]

35. Yuan F, Cheng Z. Overview on SM9 identity-based cryptographic algorithm. J Inf Secur Res. 2016;2(11):1008–27. [Google Scholar]

36. Suzuki K, Tonien D, Kurosawa K, Toyota K. Birthday paradox for multi-collisions. In: Proceedings of the Information Security and Cryptology–ICISC 2006: 9th International Conference; 2006 Nov 30–Dec 1; Busan, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

37. Vigano L. Automated security protocol analysis with the AVISPA tool. Electron Notes Theor Comput Sci. 2006;155:61–86. doi:10.1016/j.entcs.2005.11.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sdk MC. MIRACL Cryptographic SDK: multiprecision integer and rational arithmetic cryptographic library [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://github.com/miracl/MIRACL. [Google Scholar]

39. Roy S, Nandi S, Maheshwari R, Shetty S, Das AK, Lorenz P. Blockchain-based efficient access control with handover policy in IoV-enabled intelligent transportation system. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;73(3):3009–24. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3322637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Saha S, Bera B, Das AK, Kumar N, Islam SH, Park Y. Private blockchain envisioned access control system for securing industrial IoT-based pervasive edge computing. IEEE Access. 2023;11(2):130206–29. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3333441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Eddine MS, Ferrag MA, Friha O, Maglaras L. EASBF: an efficient authentication scheme over blockchain for fog computing-enabled internet of vehicles. J Inf Secur Appl. 2021;59(3):102802. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang H, Lai Y, Chen Y. Authentication methods for internet of vehicles based on trusted connection architecture. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2023;122:102681. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2022.102681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Dwivedi SK, Amin R, Vollala S, Khan MK. B-HAS: blockchain-assisted efficient handover authentication and secure communication protocol in VANETs. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2023;10(6):3491–504. doi:10.1109/tnse.2023.3264829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools