Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Blockchain-Based Efficient Verification Scheme for Context Semantic-Aware Ciphertext Retrieval

1 The School of Information Science and Technology, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

2 The Key Laboratory of Educational Information for Nationalities, Ministry of Education, Kunming, 650500, China

* Corresponding Author: Lingyun Yuan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069240

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

In the age of big data, ensuring data privacy while enabling efficient encrypted data retrieval has become a critical challenge. Traditional searchable encryption schemes face difficulties in handling complex semantic queries. Additionally, they typically rely on honest but curious cloud servers, which introduces the risk of repudiation. Furthermore, the combined operations of search and verification increase system load, thereby reducing performance. Traditional verification mechanisms, which rely on complex hash constructions, suffer from low verification efficiency. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a blockchain-based contextual semantic-aware ciphertext retrieval scheme with efficient verification. Building on existing single and multi-keyword search methods, the scheme uses vector models to semantically train the dataset, enabling it to retain semantic information and achieve context-aware encrypted retrieval, significantly improving search accuracy. Additionally, a blockchain-based updatable master-slave chain storage model is designed, where the master chain stores encrypted keyword indexes and the slave chain stores verification information generated by zero-knowledge proofs, thus balancing system load while improving search and verification efficiency. Finally, an improved non-interactive zero-knowledge proof mechanism is introduced, reducing the computational complexity of verification and ensuring efficient validation of search results. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed scheme offers stronger security, balanced overhead, and higher search verification efficiency.Keywords

With the proliferation of cloud computing, data storage and management have become increasingly convenient and efficient. Cloud storage provides users with easy storage and access services, but it also raises data privacy and security concerns. The devices directly used to store data are often untrusted third-party cloud servers, prompting users to encrypt their data before uploading it to the server. While this approach mitigates the risks of malicious attacks from the server, it also introduces new challenges for data retrieval. Efficient and rapid retrieval from encrypted data remains a significant issue worthy of further research. To address this, Searchable Encryption (SE) [1] technology has emerged, allowing users to perform keyword searches over encrypted data without revealing the original data content, thereby achieving secure data retrieval.

Traditional SE schemes generally support only exact matching for single or multiple keywords, which makes them inadequate for complex semantic queries involving contextual relationships [2–4]. For example, in a computer science context, when using keywords related to “nerve,” the retrieval engine often performs simple keyword matching based on a predefined lexicon, resulting in search results that may include content from various fields, such as neurological diseases in medicine, neural networks in computer science, and nerve cells in biology. However, what we actually wish to retrieve are data related to computer neural networks. Such results clearly do not meet expectations, as traditional SE techniques cannot accurately perform searches based on the semantic context of the keywords, leading to decreased efficiency and precision in retrieval.

Since SE schemes rely on honest-but-curious cloud servers, there is a high risk of data leakage and dispute between transacting parties. Therefore, researchers have begun to explore the integration of blockchain technology with SE to address these security concerns [5,6]. However, existing schemes typically adopt a single-chain architecture to store indices and perform both search and verification operations, resulting in high on-chain load and difficulties in handling large-scale data storage and dynamic updates [7,8]. Thus, there is an urgent need for a concise and efficient architecture that can support large-scale index storage and updating while ensuring balanced system load and enabling efficient search and verification [9–11]. A promising approach is to allocate system workloads and decouple the architecture design of different functional modules to address the performance bottlenecks of previous single-chain solutions.

In SE systems, data users not only expect correctness and completeness of the search results but also require consistency, meaning that the data have not been tampered with. However, existing verification mechanisms, such as homomorphic MACs [9], Merkle hash trees [12], and trusted third-party entities [4,13], can theoretically ensure data integrity but often rely on frequent interactions between the cloud server and the user in practice. These multi-round interactive verifications significantly increase time and computational costs, making them unsuitable for real-time requirements in large-scale data retrieval. Hence, there is an urgent need for a solution that can reduce interaction frequency while ensuring the accuracy of search results and maintaining verification efficiency. Zero-knowledge succint non-interactive arguments of knowledge (zk-SNARK) [14], as an advanced zero-knowledge proof technology, provides a potential solution by enabling efficient verification of the correctness of search results without disclosing any sensitive information. However, the polynomial commitment schemes offered by existing zk-SNARK technology are not applicable to searchable encryption.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a blockchain-based efficient verification scheme for context semantic-aware ciphertext retrieval (BC-VSCR). This scheme employs a word2vec model to retain semantic information in encrypted data, and uses blockchain technology for storing and verifying encrypted indices to prevent unfair transactions among data-sharing participants. It also introduces a fair trade contract to address unfaithful execution by the cloud server. Moreover, a verification scheme supporting dynamic updates is constructed based on zk-SNARK. Due to its lightweight and non-interactive nature, it is highly suitable for verification on the slave chain without generating significant communication or computational overhead, ensuring the correctness and integrity of the search results. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a context semantic-aware ciphertext retrieval scheme. The word vector model is applied during the index construction process for encrypted datasets to capture semantic relationships between words, generating encrypted word vector indices and thus improving retrieval accuracy.

• An updatable blockchain-based master-slave chain storage model for searchable encryption is designed. The master chain stores encrypted keyword indices, while the slave chain stores verification information generated by zero-knowledge proofs. By separating the search and verification processes, this approach not only balances the system load and avoids the bottleneck of a single-chain design but also significantly enhances both search and verification efficiencies, while ensuring fair data transactions.

• We propose an improved verification mechanism that combines blockchain with an enhanced non-interactive zero-knowledge proof protocol, simplifying the snark proof generation process and effectively reducing the computational complexity of search result verification, achieving efficient and secure verification of search results.

Searchable encryption (SE) was first introduced by Song et al. [1] in 2000, employing a single keyword search method without index structures for encrypted data retrieval. However, due to the lack of support from an index structure, the search overhead was significant. As research progressed, various SE schemes were proposed to meet different needs. Goh [15] constructed a secure index model, defined security patterns, used pseudorandom numbers to generate secure indices, and stored document keywords in Bloom filters to enable efficient ciphertext search. In 2006, Curtmola et al. [16] introduced the leakage model and demonstrated that, apart from leakage functions, searchable symmetric encryption (SSE) does not reveal other information through Real and Ideal games. During this period, many researchers [17–19] proposed optimizations to improve the performance of SSE. However, these works largely focused on single-keyword ciphertext search, which could not meet the demand for multi-keyword searches. As a result, numerous multi-keyword SE schemes were introduced [4,10,20,21], supporting multi-keyword search requests. However, these schemes mainly relied on keyword frequency statistics, neglecting the importance of contextual semantics.

In recent years, with the evolution of machine learning and related technologies, significant advances have been made in SE focused on contextual semantics, resulting in many innovative solutions. Cao et al. [22] first proposed a scheme to solve the multi-keyword ranked search problem over encrypted cloud data (MRSE), employing inner product similarity and coordinate matching to evaluate the relevance scores between keywords and files. Fu et al. [23] further utilized conceptual graphs (CG) as knowledge representation tools to convert CG into linear forms for quantitative analysis. However, this scheme remained at the level of fuzzy search and did not achieve true semantic search over ciphertext. Consequently, their team later attempted to use machine learning tools such as BERT [24] to enhance understanding of text semantics, proposing secure and semantic retrieval schemes based on BERT (SSRB), achieving promising retrieval results. Subsequently, more machine learning methods were applied to context semantic-aware search. Dai et al. [25] extracted features from document collections using the Doc2Vec model and performed semantic search based on these features, significantly improving search accuracy and efficiency while supporting dynamic updates to document collections. Zhou et al. [26] proposed two schemes, AF-SRSE and EF-SRSE, for enhancing privacy-preserving semantic-aware search in cloud environments. The former prioritized search accuracy using the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model and bisecting k-means clustering, suitable for high-precision search scenarios, while the latter optimized the search structure, sacrificing some accuracy to improve efficiency. Ge et al. [27] introduced lookup tables and a two-stage query strategy, enabling not only the verification of whether the returned files correctly contained the query phrases but also ensuring that all files containing the phrase were returned. Chen et al. [28] proposed a context-aware semantically extensible searchable symmetric encryption scheme based on the Word2vec model, using the original dataset to train the Word2vec model and achieve semantic expansion of query keywords, thus significantly improving search accuracy and efficiency. The scheme also employed a two-tier index structure to improve search efficiency and provided security guarantees under known ciphertext and background models. However, this scheme required re-indexing during dynamic updates, potentially introducing additional computational overhead in frequently updated scenarios. Liu et al. [29] proposed an LDA topic model-based scheme, incorporating an

The aforementioned search operations are executed by the cloud server, and dishonest cloud servers may produce fraudulent search results or results aligned with specific business objectives. Therefore, verifying search results and addressing dishonest behavior by both parties are equally crucial. While the schemes in [26,31] included verification mechanisms, they were limited to multi-keyword search. Li et al. [31] designed basic and enhanced verification mechanisms based on semantic understanding using the LDA topic model to ensure the correctness and completeness of search results. However, these schemes still could not resolve fairness issues in transactions.

The emergence of blockchain offers a new perspective for addressing these challenges. Utilizing the traceable and tamper-proof features of blockchain, fairness between transacting parties can be ensured. In situations such as a user refusing to pay or the cloud server being dishonest, smart contracts on the blockchain can provide immediate feedback and post-event handling. As a result, several researchers have explored blockchain-based searchable encryption. Yang et al. [32] proposed a secure heuristic semantic search scheme verified by blockchain. The primary advantage of this scheme lies in combining privacy-preserving non-linear word matching with blockchain consensus mechanisms, ensuring high accuracy in search results even in untrusted environments, while enabling a fair payment mechanism through blockchain technology. Huang et al. [5] effectively reduced the risk of data leakage by combining blockchain with multi-cloud storage technology and adopted a tree structure index for efficient ciphertext retrieval. Additionally, the use of smart contracts ensured fairness in data transactions. Although the introduction of blockchain technology in the above scheme enhances the trustworthiness and verifiability of data, it also introduces additional storage and computational overhead, which becomes more significant, especially when dealing with large-scale transactions or complex smart contracts. Moreover, these schemes still fail to effectively verify the correctness of search results. Thus, existing SE schemes often suffer from incomplete semantic search, difficulty in verification, and lack of fairness. In response, this paper proposes a blockchain-based efficient verification scheme for context semantic-aware ciphertext retrieva scheme.

When handling text data, the Word2vec model embeds words into a high-dimensional vector space, capturing the semantic relationships between words [33]. There are two main training methods for Word2vec: Skip-gram and Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW). In the Skip-gram model, the goal is to predict surrounding words based on a given word. For each word

3.2 Adaptive Hash Indexing and Incremental Index Updatel

The adaptive hash indexing mechanism works as follows: if a word

Incremental index updating refers to updating only the changed part of the data rather than regenerating the entire index each time the data changes. Let

Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge (zk-SNARK) is a zero-knowledge proof technology characterized by its succinctness, non-interactivity, and efficiency. It allows one to prove the truth of a statement without revealing any data content. Typically, zk-SNARK transforms the computation to be proven into a circuit C, consisting of logic gates that describe all operations during the computation process. Then, a generator algorithm G is used to generate public parameters

KZG [34] (based on elliptic curves) and hash function-based protocols [35] are the most common polynomial commitment schemes today. KZG polynomial commitments feature low verification costs and constant-sized evaluation proofs for univariate polynomial verification. However, their generation process depends on a trusted setup, and the computation for the prover is intensive, requiring extensive Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and Multi-Scalar Multiplication (MSM) calculations. Elliptic curve-based polynomial commitments (such as Bulletproofs) offer homomorphic properties, support efficient batch processing, and significantly reduce verification time, though they produce larger proof sizes. Hash function-based polynomial commitments (such as FRI) [36] do not require MSM operations, support recursive computation, balance proof and verification costs, and have quantum security. However, they lack homomorphic hiding, which limits their application in specific scenarios. For text data, directly applying FRI polynomial commitments may face challenges. However, in the BC-VSCR scheme, by processing text data to generate word vectors, polynomial commitments can be applied effectively, making the process simpler and more efficient. Due to zk-SNARK’s advantages of succinct proofs, efficient verification, and non-interactivity, it is suitable for scenarios like blockchain where efficient verification is required. If the server behaves maliciously, the client can detect it by verifying the succinct proof.

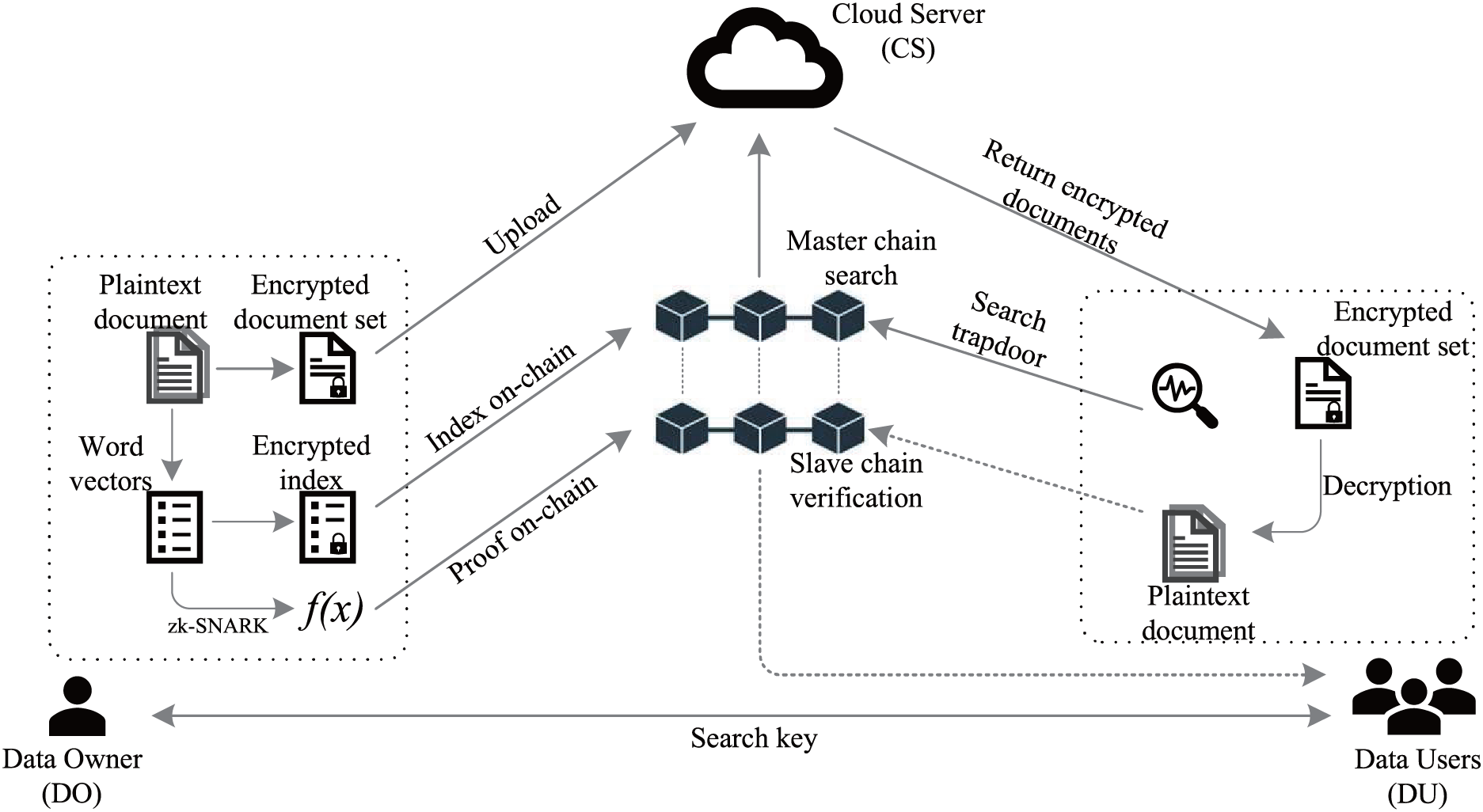

To achieve secure and efficient encrypted data retrieval, we constructed a context semantic-aware ciphertext retrieval system model based on blockchain technology. The model includes several modules and roles: Data Owner (DO), Data User (DU), Blockchain (BC), and Cloud Server (CS). The following describes the workflow and interactions among these roles in detail. In the system model, the DO first processes the plaintext dataset D to generate the encrypted dataset C and the encrypted index I. The encrypted index is then stored on the BC, while the encrypted data are uploaded to the CS. When the DU needs to perform a query, a query request Q is generated and sent to the DO. The DO then generates a trapdoor T based on Q and returns it to the DU. The DU sends the trapdoor T to the cloud server, which searches the encrypted dataset C based on T and returns the search result R to the DU. The DU then decrypts the result and verifies its integrity and correctness. The system model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: System model

To describe the key steps and corresponding algorithm processes of the proposed scheme, this section provides formal definitions for each module.

Fig. 2 illustrates the workflow of the algorithms in the proposed scheme.

Figure 2: Time series diagram

4.3 Contextual Semantic Similarity Calculation Method

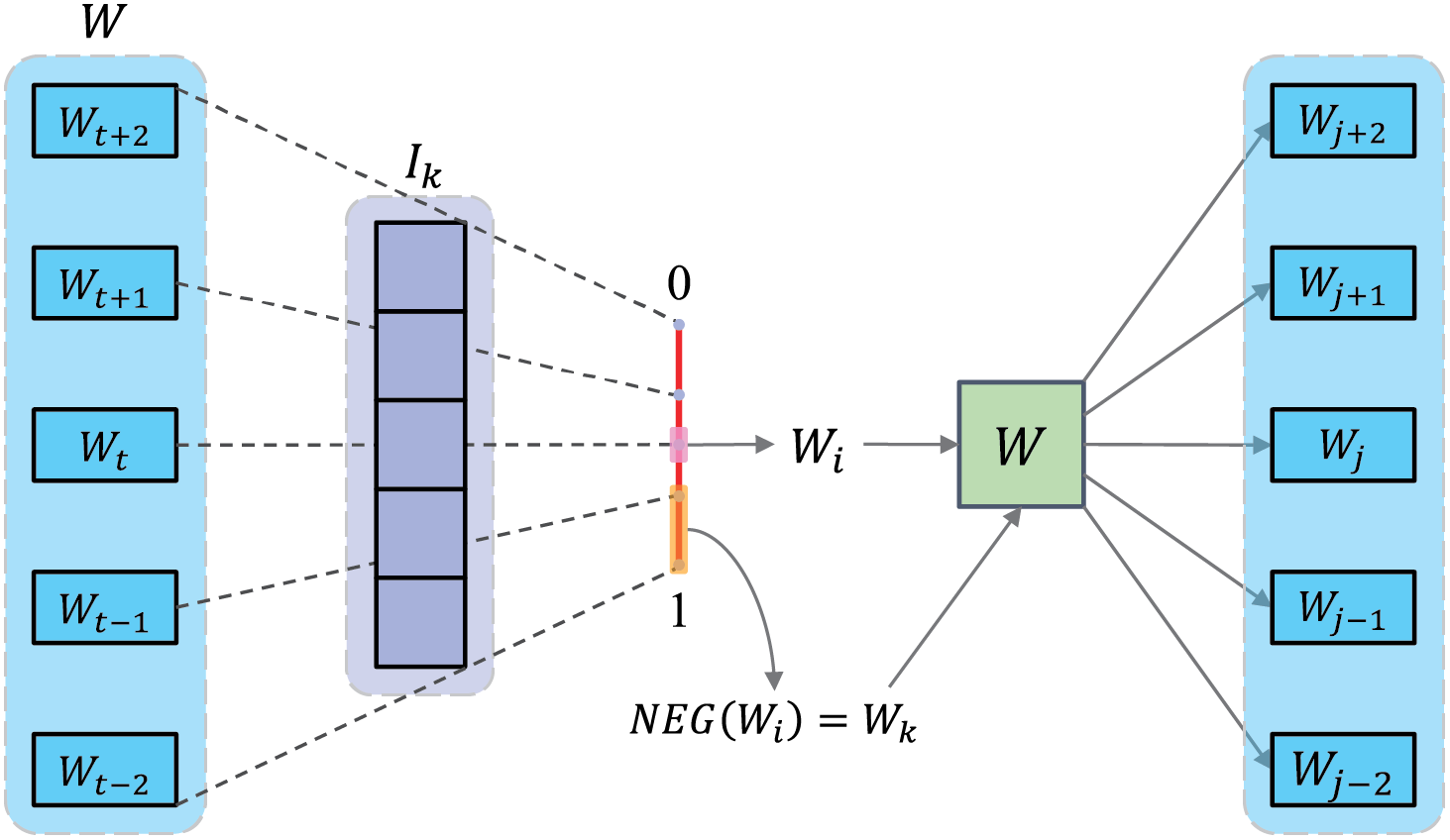

4.3.1 Word Vector Model Construction Based on Negative Sampling

In the word vector model of BC-VSCR, we employ the word2vec approach based on negative sampling for word vector training. The target word is treated as a positive sample, while other words are treated as negative samples. Due to the large number of negative samples, we use a negative sampling algorithm to simplify the computation process. The core idea of negative sampling is to optimize the model by selecting only a small subset of negative samples to reduce computational complexity, rather than traversing all possible words. Before sampling, we divide a line segment of length 1 into M equal parts. Next, each word w in the vocabulary W is mapped to the [0, 1] interval according to its occurrence frequency. Each of the M segments will fall on the line segment corresponding to a word. The word corresponding to the segment of the sampled position is our negative sample

Subsequently, we map each word in the vocabulary to a segment on the interval [0, 1], with the length of the segment being proportional to the frequency of the word’s occurrence. Words with higher frequencies occupy larger portions of the interval space. During the mapping process, we assume the initial node to be

These negative samples are subsequently used to optimize the model parameters, allowing the model to better distinguish the target word from randomly chosen negative words during training. In the CBOW model, the target word is predicted based on its surrounding context. Given the context, the model learns the word vectors through training, optimizing parameters to predict the target word’s vector effectively. This model consists of an input layer, a projection layer, and an output layer, and it uses backpropagation to adjust its parameters. Conversely, the Skip-Gram model aims to predict the context given the target word, adjusting the word vector representation by maximizing the co-occurrence probability between the target word and the context words. Similar to CBOW, the Skip-Gram model includes an input layer, a projection layer, and an output layer, and utilizes stochastic gradient ascent for parameter updates. By leveraging the Word2Vec model, we can effectively capture the semantic relationships among words, thereby enhancing the accuracy of encrypted data retrieval. The process of constructing the word vector model is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Construction of word vector model

4.3.2 Topic Vector and Index Tree Construction

After obtaining word vectors, we utilize the k-means clustering algorithm to assign each word to its nearest cluster center. The assignment minimizes the Euclidean distance between the word vector

The cluster centers are iteratively recalculated by averaging all word vectors within each cluster, and the algorithm converges when the positions of all cluster centers no longer change. At this point, word vectors are partitioned into several clusters, each representing a distinct topic. The quality of clustering is typically evaluated using the silhouette coefficient, which ranges from −1 to 1. A higher silhouette coefficient, closer to 1, indicates better clustering quality, as it suggests that the word vectors are well-matched to their own cluster and poorly matched to neighboring clusters.

The clustering results of each word vector are mapped to their corresponding topic words. Using each topic word

4.3.3 Semantic Similarity Calculation

During the retrieval process, to evaluate the relevance between the query keywords and the documents, we use a similarity scoring method. The similarity score is calculated by taking the inner product between the query vector T and the document index vector I, as follows:

The result of the inner product,

This solution adopts a dual-chain architecture, with the platform being the consortium blockchain Hyperledger Fabric 2.5.4. In this architecture, we typically establish Shim as an intermediary between the node and the chaincode. When the chaincode needs to perform read/write operations on the ledger, it sends the corresponding contract information to the node via the shim layer. This approach combines the main chain and the slave chain to implement the query and verification mechanisms for encrypted data.

Users initiate a query request via the DU-side SDK (Data User-side Software Development Kit), submitting a proposal containing the query keywords, query ID, and payment information, which is then sent to the endorsement nodes in Fabric for validation. The endorsement nodes verify the request’s permissions, and once validated, the query request is recorded on the main chain. The endorsement nodes validate the transaction proposal, simulate the query execution, and interact with the chaincode Docker to ensure the legality of the query data. Once verified, the endorsement conclusions are returned to the DU.

After the query request is validated, it is submitted to both the main chain and the slave chain. The main chain stores the encrypted data index to ensure data integrity, while the slave chain records the verification information generated by the zero-knowledge proof to ensure the correctness of the query results. The query results are then returned to the user, and based on the payment conditions, the transaction status is updated. Payment and query transaction records are written to the blockchain.

Upon completion of the query, the smart contract updates the index data on both the main chain and the slave chain, ensuring the coordinated operation of the dual-chain architecture. Finally, all data is written to the blockchain via the slave chain’s verification information. The detailed process is shown in Fig. 4. Through the collaboration of the dual-chain architecture, efficient data querying, verification, and payment processes are achieved, ensuring high system performance and data immutability.

Figure 4: Smart contract workflowl

We construct a succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge scheme with zero-knowledge properties by organically combining the Polynomial Commitment Scheme (PCS) with the FRI protocol and transforming the interactive proof into a non-interactive one using the Fiat-Shamir heuristic.

The PCS is utilized to generate a compact commitment for any polynomial

where the size of the commitment

Let N = |H| be the size of a multiplicative subgroup,

Thus,

In the zk-SNARK scheme design, inspired by the folding concept in the FRI protocol, we introduce the folding operation to progressively reduce the degree of the polynomial while retaining its structural properties, thus enabling more efficient proof generation.

The core idea of folding is to recursively reduce the degree of a high-degree polynomial. Let

Although a single folding operation effectively reduces the degree of the polynomial, to better control the randomness of the polynomial and ensure the security of the proof, we typically employ a recursive folding method, as illustrated in Fig. 5. In the first iteration of folding, random coefficients

Figure 5: The zk-Snark construction

To formalize this folding process, we define the polynomial construction in the operation as a triplet of algorithms

• Completeness: For every public parameter

• Soundness: For any probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) prover

• Zero-Knowledge: There exists a PPT simulator S such that for any PPT verifier

4.5.3 Blockchain-Based Zero-Knowledge Verifiable Polynomial Commitment (zkBC)

Although the verification scheme described above is capable of validating results, to further ensure data privacy and computational correctness, this section introduces a Blockchain-based Zero-Knowledge Verifiable Polynomial Commitment (zkBC) scheme. This scheme combines polynomial commitments with blockchain technology, utilizing decentralized verification to achieve an efficient and secure polynomial verification process.

In the blockchain environment, the generation of polynomial commitments and their storage on the blockchain are crucial steps to ensuring transparency and immutability of the entire system. The verifier selects a point

•

•

In the slave chain, the verification process can be executed via a smart contract on the blockchain, ensuring decentralized and independent validation. The verifier V selects a verification point

• Completeness: In the blockchain environment, completeness ensures that any honest prover P can submit a proof and commitment to the blockchain, enabling the verifier V to successfully verify the correctness of the polynomial

• Soundness: To ensure that a malicious prover cannot deceive the verifier into accepting an incorrect polynomial evaluation, for any probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary A, the probability that A forges a commitment

• Zero-Knowledge: Zero-knowledge ensures that the verifier only learns the polynomial evaluation

In the Adaptive Chosen Keyword Attack (ACK) model [16], the security definition of the BC-VSCR scheme is similar to the non-adaptive model, with the key difference being that the adversary can adaptively choose queries based on the query history. Specifically, in the adaptive model, the adversary first submits the document set D, then receives the encrypted index

In this scenario, the adversary in the adaptive model is capable of performing more complex attacks than in the non-adaptive model because they can dynamically adjust their strategy based on the feedback from previous queries. The adversary can not only infer information from the index but also gain insights by observing the relationships between query trapdoors.

We define the adaptive semantic security by introducing a polynomial-time simulator S, ensuring that the adversary’s output is indistinguishable between the real world and the simulation world. The definition is as follows:

Let

• Real Experiment

The system generates the secret key

For each subsequent query

Finally, the system outputs

• Simulation Experiment

The adversary

For each subsequent query

Finally, the simulator outputs

If for any polynomial-time adversary A, there exists a polynomial-time simulator S such that for any polynomial-time distinguisher D, the following difference is negligible:

then it follows that even when the adversary can dynamically adjust its strategy based on query history and trapdoor information, the system’s encrypted documents, indices, and query results remain statistically indistinguishable to the adversary. This ensures that the BC-VSCR scheme is semantically secure under adaptive chosen keyword attacks.

The key generation algorithm is used for system initialization. It takes the security parameter

5.2

The index construction algorithm works as follows. During the preprocessing phase, we conduct semantic training on the dataset D to generate the word vector set

For each word vector

The resulting two sub-vectors, I′ and I″, are then linearly transformed to obtain the encrypted index vector I. The vector is further processed using an adaptive hash function H, and subsequently stored on the blockchain.

1. Master Chain: The master chain index

2. Slave Chain: The index on the slave chain is used for verification purposes. Using the polynomial commitment of BC-VSCR, a low-degree polynomial commitment is generated as

The specific algorithm is illustrated in Algorithm 1:

The encryption algorithm is used by the DO to encrypt each plaintext document

The trapdoor generation algorithm is executed by the DO, taking the query keyword set

Initially, we set the sliding window size

The search algorithm begins when the CS receives the query trapdoor

The cloud server searches for matching hash value nodes in the master chain index

The verification algorithm is executed by the DU to validate the query results R and the slave chain index

1. Generate Public Parameters: First, the public parameters

2. Polynomial Commitment Generation: The prover P generates a commitment to the polynomial

3. Generate Verification Values and Polynomial: The prover P first calculates the value of the polynomial

4. Introduce Randomized Polynomial: To ensure the zero-knowledge property of the verification, the prover P randomly samples a polynomial

5. Polynomial Combination and Low Degree Test: The verifier V randomly selects an

The prover and verifier jointly perform a low-degree test to verify the correctness of the polynomial

5.7

In our scheme, when the DO initiates an update operation, the system handles the changes in the new data and index through incremental updates. At the same time, the synchronization of the master chain and slave chain updates is ensured by adaptive hash indexing. The specific steps are as follows:

1. Incremental Data and Index Update: For the data documents that need to be added to the index tree, suppose a node

2. Adaptive Hash Index Update: During the index update process, the hash index must be adjusted according to changes in the data. Suppose the original hash function is

3. zk-SNARK Dynamic Verification Update: For the newly updated data documents

In the

Here,

Based on the semantic security definition in Section 4.5, the proposed BC-VSCR scheme satisfies the CKA [16]. By constructing a simulator, we prove that in both the real and simulated worlds, the adversary cannot distinguish between real encrypted documents and simulated encrypted documents, thus proving the adaptive semantic security of the system.

During the simulated ciphertext generation phase, the adversary

his ensures that the ciphertext generated by

The adversary may attempt to leak information through the search pattern by obtaining the search token

In this case, even if the adversary observes multiple trapdoors from repeated queries, due to the randomness in the trapdoor generation function, the adversary cannot distinguish whether these trapdoors correspond to the same keyword Q or different keywords. Therefore, as long as

This demonstrates that even if the adversary can dynamically adjust its strategy based on query history and trapdoor information, the system’s encrypted documents, indices, and query results remain statistically indistinguishable to the adversary. Thus, the BC-VSCR scheme ensures semantic security under adaptive chosen keyword attacks.

To further validate that our solution can resist attacks such as replay attacks and man-in-the-middle attacks, we used the ProVerif verification tool to conduct experimental tests, and the results are shown in the Fig. 6.

Figure 6: ProVerif testing

In the ProVerif verification analysis, we first verified whether the key-sharing process could be successfully executed. The query results showed that the event reachK (lambda) is guaranteed to occur, indicating that the key-sharing mechanism in the protocol is effective. Next, the private key (AttestationPrivatekey) was found to be adequately protected, and the attacker could not steal the private key (attsk[]), ensuring the confidentiality of the key. Finally, the public key (AttestationPublicKey) was also effectively protected, and the attacker could not steal the public key (attpp[]), even though public keys are usually exposed. This is because additional protection was applied to the public key in the model.

In conclusion, both the private and public keys in the protocol are effectively protected, ensuring the security of the key-sharing process.

If a user attempts to tamper with the search request or results after each transaction to gain unfair advantage, the smart contract will prevent such actions. When the DU initiates a search request, they must send both the search token and the verification token to the slave chain, and deposit a sufficient search fee in the smart contract on the master chain as collateral. The smart contract will verify the DU’s authorization and fee deposit. If the verification fails, the search request will not be broadcast, thereby blocking any fraudulent requests. Additionally, the master chain’s smart contract records all transaction information, ensuring that the DU cannot alter this data.

If the CS attempts to return incorrect search results or forged verification proofs, the smart contract will automatically validate whether these proofs are correct. When the CS returns search results and verification proofs from the slave chain, they must submit these results to the master chain’s smart contract for validation. The smart contract uses the pre-stored verification key to perform the validation. If the validation fails, the CS will not receive the service fee and will forfeit the previously paid deposit, with the search fee being refunded to the DU.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed scheme, a comprehensive performance assessment and comparison analysis is conducted with relevant studies from the literature. This analysis covers key metrics including keyword search, contextual semantics support, fairness, search time, verification time, and storage overhead. A detailed comparison is presented in the Table 1:

Through theoretical comparative analysis, it is evident that our scheme outperforms existing approaches in several key areas, including keyword search, contextual semantics support, fairness, search and verification time, and storage overhead. Compared to works in [2,22], we introduce contextual semantics-aware technology, which further enhances the accuracy of multi-keyword queries. The time complexity of our search operation is

In terms of contextual semantics support, the scheme in [24] uses the BERT model for semantic search, which has limitations in handling semantic associations. In contrast, our word vector model effectively captures complex contextual semantics, especially in dealing with polysemy and dynamic data, leading to search results that more accurately align with user intent.

Furthermore, our scheme ensures fairness in search transactions through the blockchain master-slave chain architecture, addressing the issues of denial of transaction responsibility seen in [2–4,22,24]. Regarding search and verification efficiency, we improve the zk-SNARK verification mechanism, achieving a verification time complexity of

Additionally, by separating the encrypted index and verification information, we distribute the storage load effectively across the master and slave chains. Our scheme reduces storage overhead, making it more suitable for large-scale, dynamic data environments, with a lower storage requirement compared to the approaches in [7] and others.

To more comprehensively evaluate the performance of our solution, we conducted experimental comparisons and analysis with the following schemes: MRSE [22], FWSR [2], HLZ [3], SSRB [24], and VSRD [4]. The experimental data were sourced from a real-world dataset: Semantic Textual Similarity. The dataset underwent standard preprocessing steps, including stopword removal, stemming, and other common text processing techniques. The RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) digital signature used a public exponent of 65,537 and a key length of 2048 bits. The experimental results were obtained by averaging 100 local executions. The experimental setup is detailed in Table 2.

7.3.1 Model Training Time and Index Construction Overhead

Fig. 7 illustrates the model training time for preprocessing the DO data using word2vec. From the figure, it is evident that as the number of documents increases, the training time exhibits a linear growth trend. This process only requires training once, and the trained model can be reused multiple times without affecting the efficiency of subsequent index construction or trapdoor generation. During subsequent updates, only a small number of randomly selected negative samples undergo gradient updates, rather than performing a full update on all vocabulary.

Figure 7: Training time

After the completion of word vector training, the system proceeds to the index generation and blockchain uploading phase. To conduct a comparative analysis of the performance of different schemes, we evaluated the index construction time from two dimensions. As shown in Fig. 8a, with a fixed document count of 100, we assessed the impact of varying keyword counts on the index construction time overhead. In [2,3], the use of a counting Bloom filter for pre-mapping keywords leads to relatively higher computational overhead during the index generation process. Scheme [4] constructs the index using vector range decisions, whereas our approach significantly reduces index generation time by employing clustered topic word vectors as parent nodes. Overall, the index construction overhead of our scheme is similar to that of scheme [4], but it is notably lower than the overhead in [2,3].

Figure 8: Index construction overhead. (a) Impact of different keyword counts on index construction time, (b) Impact of different document counts on index construction time

Fig. 8b illustrates the impact of varying document counts on the index construction overhead, with the keyword count fixed at 100. As the document count increases, the index construction time for all schemes shows an upward trend. Schemes [22,24] generate the index directly from the document dictionary, while our scheme introduces a clustering algorithm to reduce the index construction time. Compared to scheme [22], our approach reduces the index construction time by approximately 54%, and by about 24% compared to scheme [24]. Overall, our scheme outperforms the other comparative schemes in terms of index construction efficiency.

7.3.2 Trapdoor Generation Time

Fig. 9 shows the overhead of trapdoor generation time. Similar to the index construction scheme, the time overhead of trapdoor generation increases as the number of query keywords grows. Compared to the trapdoor generation scheme in [4], where the three steps—generation, sharing, and distribution—are processed separately, our scheme incurs slightly higher overhead due to the need to first locate the corresponding topic word vectors during trapdoor generation. However, this overhead remains within an acceptable range. In [22], trapdoor randomization is achieved by adding fake keywords, and in [3], a counting Bloom filter is used for trapdoor processing, both of which result in relatively high overhead. Additionally, in [24], the dimensionality of the vectors increases with the number of query keywords, leading to higher trapdoor generation costs. When the number of query keywords reaches 1000, our scheme effectively leverages contextual semantic information, controlling the trapdoor generation time to 2.927 s, significantly outperforming the schemes in [3,22,24].

Figure 9: Trapdoor generation time

To provide a more intuitive comparison with existing literature, we evaluated the search overhead of our scheme from two dimensions. The part a of Fig. 10 illustrates the impact of varying keyword counts on query time overhead with a fixed document count of 100. Schemes in [2,3] implement search by combining traditional LSH (Locality Sensitive Hashing) with Bloom filters. However, when the number of keywords increases to 1000, these schemes fail to fully capture the semantic intent of the DU, and the search time overhead exceeds 3 s, making it difficult to handle complex semantic queries. The search time overhead of our scheme is similar to that of [4], but since our similarity scoring mechanism directly matches with the on-chain index, it better understands and reflects the user’s semantic information. As a result, it performs better than the range decision search approach in [4] when handling complex semantic queries.

Figure 10: Search overhead. (a) Impact of varying keyword counts on query time overhead, (b) Impact of varying document counts on query time overhead

Part b of Fig. 10 shows the impact of varying document counts on query overhead with the number of keywords fixed at 100. Scheme [22] requires not only the computation of index and trapdoor inner products but also TF-IDF-based similarity score calculations for result ranking, leading to relatively higher overhead. In contrast, our scheme performs both search and ranking with only inner product calculations, resulting in lower overhead. Compared to the semantic search scheme based on the BERT model in [24], our scheme significantly reduces time overhead while maintaining search accuracy, achieving higher efficiency.

Search accuracy is one of the core metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of a scheme. In this experiment, we use Precision to measure the retrieval performance of BC-VSCR. Precision is defined as the proportion of relevant documents among all retrieved documents, calculated as follows:

As shown in the Fig. 11, the search accuracy of BC-VSCR demonstrates a noticeable improvement as the number of documents increases. The specific data are shown in the figure. The average precision of BC-VSCR is 96.64%. Scheme [2], which uses Bloom filters, is limited by its false positive rate, resulting in a decline in query accuracy. In contrast, Scheme [24], which is also based on machine learning, achieves a precision of 85.11% under the same conditions. Scheme [4], due to its use of vector range decisions, performs slightly better than our scheme on small-scale datasets with precise keywords. However, as the document count increases, Scheme [4] shows a decline, which is attributed to the limitations of its vector range decision approach. Our machine learning-based scheme, on the other hand, is capable of extracting more contextual semantic features, which Scheme [4] does not, leading to a steady increase in accuracy as the document count grows. Overall, our scheme demonstrates superior search accuracy.

Figure 11: Accuracy

In terms of verification overhead, schemes [2,3,24] do not provide a verification mechanism for search results, which undoubtedly increases the risk of server malfeasance. Compared to scheme [4], the verification time overhead of our scheme is

Figure 12: Verification time

In terms of smart contract storage, the vector inner product result is a 4-dimensional row vector, with each element being a double-precision floating point (8 bytes), totaling 32 bytes. The index operation is based on the algorithm described in Section 4.3.2 for index construction, generating a 256-bit hash that occupies 32 bytes of space. The verification identifier generates a 128-bit ciphertext (16 bytes). When

To comprehensively assess the performance of blockchain smart contracts in BC-VSCR under high concurrency, we used Hyperledger Fabric’s performance testing tool, Tape, to evaluate several dimensions of concurrent transactions, including throughput, transaction duration, latency, and success rate. In the experiment, we simulated between 100 and 1000 concurrent query requests, focusing on evaluating the execution efficiency of the main chain and slave chain smart contracts in Search and Verify operations.

The experimental results show that as the number of concurrent transactions increases, the transaction duration grows linearly. With 1000 concurrent transactions, the transaction duration for search and verification operations was 21.6 and 22.8 s, respectively. Throughout the entire test, throughput remained relatively stable, with the average throughput for both search and verification consistently around 45 TPS (transactions per second), as shown in Fig. 13. Even under high concurrency, the system’s throughput remained at a high level, significantly outperforming similar solutions.

Figure 13: TPS

We also measured latency (the average time from sending the request to receiving the response) and success rate. When the number of concurrent requests reached 1000, the latency for search and verification operations was 32 and 37 ms, respectively, demonstrating good response times. Additionally, all operations achieved a 99.8

In the experiment, the search smart contract on the main chain was primarily responsible for the lookup and matching of the encrypted index, while the verification smart contract on the slave chain was used to validate the correctness of the search results. As shown in Fig. 14, as the number of concurrent requests increased, the average computation time for the search operation on the main chain was 2.92 s, with a slight increase but still within an acceptable range. On the other hand, the average computation time for the verification operation on the slave chain was 2.45 s, demonstrating higher processing efficiency. Even when handling up to 1000 concurrent query requests, the system maintained low latency, high throughput, and extremely high transaction success rates. The main chain handles fast lookups of the encrypted index, while the slave chain focuses on the verification operation. Together, they complement each other, effectively reducing computational pressure and improving the overall efficiency of the system.

Figure 14: Computation time

This paper addresses the challenges faced by traditional SE schemes in ciphertext retrieval, including the inability to handle complex semantic queries, frequent data leakage and repudiation issues, and the high overhead of existing verification mechanisms. We propose a blockchain-based, efficient verification contextual semantic-aware ciphertext retrieval scheme.The proposed scheme introduces the word2vec word vector model to construct a semantically-aware encrypted index, enabling ciphertext retrieval that is no longer limited to simple keyword matching. This significantly improves retrieval accuracy in the context of complex queries. To further reduce system load and ensure fairness in data exchange, the scheme designs an updatable master-slave chain blockchain structure. The master chain stores encrypted keyword indices, while the slave chain stores verification information generated by zero-knowledge proofs, thereby ensuring load balancing and effectively improving the system’s search and verification efficiency. In terms of the verification mechanism, we integrate zk-SNARK zero-knowledge proofs with blockchain technology, simplifying the proof generation process and storing the proof on-chain, enabling fast, non-interactive verification of search results. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed scheme outperforms existing approaches in terms of keyword search accuracy, response time, verification efficiency, and dynamic data processing capability, offering superior performance, more comprehensive functionality, broader application adaptability, and higher practicality.

Future research will continue to optimize the verification process to reduce computational costs and explore more potential applications of deep learning models combined with blockchain technology.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62262073; in part by the Yunnan Provincial Ten Thousand People Program for Young Top Talents under Grant YNWR-QNBJ-2019-237; and in part by the Yunnan Provincial Major Science and Technology Special Program under Grant 202402AD080002.

Author Contributions: Haochen Bao conceptualized the research, designed the methodology, and wrote the main manuscript text. Lingyun Yuan supervised the project, acquired funding, and contributed to the writing—review & editing and validation. Tianyu Xie contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, visualization, and formal analysis. Han Chen contributed to the visualization, validation, and formal analysis. Hui Dai contributed to the visualization, validation, and formal analysis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sets used in this study can be in the following website for: https://paperswithcode.com/dataset/sts-benchmark (accessed on 29 July 2025). Experimental data will be shared upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Song DX, Wagner D, Perrig A. Practical techniques for searches on encrypted data. In: Proceeding 2000 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, S&P 2000; 2000 May 14–17; Berkeley, CA, USA. p. 44–55. [Google Scholar]

2. Fu Z, Wu X, Guan C, Sun X, Ren K. Toward efficient multi-keyword fuzzy search over encrypted outsourced data with accuracy improvement. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2016;11(12):2706–16. doi:10.1109/tifs.2016.2596138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. He H, Liu C, Zhou X, Feng K. FMSM: a fuzzy multi-keyword search scheme for encrypted cloud data based on multi-chain network. In: 50th International Conference on Parallel Processing Workshop; 2021 Aug 9–12; Lemont, IL, USA. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

4. Han J, Qi L, Zhuang J. Vector sum range decision for verifiable multiuser fuzzy keyword search in cloud-assisted IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(1):931–43. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3288276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Huang W, Chen Y, Jing D, Feng J, Han G, Zhang W. A multi-cloud collaborative data security sharing scheme with blockchain indexing in industrial Internet environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(16):27532–44. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3398774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu P, He Q, Zhao B, Guo B, Zhai Z. Efficient multi-authority attribute-based searchable encryption scheme with blockchain assistance for cloud-edge coordination. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;76(3):3325–43. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.041167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xu C, Yu L, Zhu L, Zhang C. A blockchain-based dynamic searchable symmetric encryption scheme under multiple clouds. Peer-Peer Netw Appl. 2021;14(6):3647–59. doi:10.1007/s12083-021-01202-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. He K, Chen J, Zhou Q, Du R, Xiang Y. Secure dynamic searchable symmetric encryption with constant client storage cost. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2020;16:1538–49. doi:10.1109/tifs.2020.3033412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li X, Tong Q, Zhao J, Miao Y, Ma S, Weng J, et al. VRFMS: verifiable ranked fuzzy multi-keyword search over encrypted data. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;16(1):698–710. doi:10.1109/tsc.2021.3140092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sun W, Wang B, Cao N, Li M, Lou W, Hou YT, et al. Verifiable privacy-preserving multi-keyword text search in the cloud supporting similarity-based ranking. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2013;25(11):3025–35. doi:10.1109/tpds.2013.282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu X, Yang X, Luo Y, Zhang Q. Verifiable multikeyword search encryption scheme with anonymous key generation for medical Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(22):22315–26. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3056116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tong Q, Miao Y, Weng J, Liu X, Choo KKR, Deng RH. Verifiable fuzzy multi-keyword search over encrypted data with adaptive security. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2022;35(5):5386–99. doi:10.1109/tkde.2022.3152033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Y, Zhu T, Guo R, Xu S, Cui H, Cao J. Multi-keyword searchable and verifiable attribute-based encryption over cloud data. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2021;11(1):971–83. doi:10.1109/tcc.2023.3312918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Parno B, Howell J, Gentry C, Raykova M. Pinocchio: nearly practical verifiable computation. Commun ACM. 2016;59(2):103–12. [Google Scholar]

15. Goh EJ. Building secure indexes for searching efficiently on encrypted compressed data. Cryptology ePrint Archive: 2003/216. 2003. [Google Scholar]

16. Curtmola R, Garay J, Kamara S, Ostrovsky R. Searchable symmetric encryption: improved definitions and efficient constructions. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2006 Oct 30–Nov 3; Alexandria, VA, USA. p. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

17. Chang YC, Mitzenmacher M. Privacy preserving keyword searches on remote encrypted data. In: International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Gearmany: Springer; 2005. p. 442–55. [Google Scholar]

18. Kamara S, Papamanthou C, Roeder T. Dynamic searchable symmetric encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2012 Oct 16–18; Raleigh, NC, USA. p. 965–76. [Google Scholar]

19. Kurosawa K, Ohtaki Y. UC-secure searchable symmetric encryption. In: Financial Cryptography and Data Securit. Berlin/Heidelberg, Gearmany: Springer; 2012. p. 285–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32946-3_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu Q, Peng Y, Pei S, Wu J, Peng T, Wang G. Prime inner product encoding for effective wildcard-based multi-keyword fuzzy search. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2020;15(4):1799–812. doi:10.1109/tsc.2020.3020688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhong H, Li Z, Cui J, Sun Y, Liu L. Efficient dynamic multi-keyword fuzzy search over encrypted cloud data. J Netw Comput Appl. 2020;149(1):102469. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2019.102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cao N, Wang C, Li M, Ren K, Lou W. Privacy-preserving multi-keyword ranked search over encrypted cloud data. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2013;25(1):222–33. doi:10.1109/tpds.2013.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fu Z, Huang F, Ren K, Weng J, Wang C. Privacy-preserving smart semantic search based on conceptual graphs over encrypted outsourced data. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2017;12(8):1874–84. doi:10.1109/tifs.2017.2692728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fu Z, Wang Y, Sun X, Zhang X. Semantic and secure search over encrypted outsourcing cloud based on BERT. Front Comput Sci. 2022;16(2):162802. doi:10.1007/s11704-021-0277-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dai X, Dai H, Yang G, Yi X, Huang H. An efficient and dynamic semantic-aware multikeyword ranked search scheme over encrypted cloud data. IEEE Access. 2019;7:142855–65. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2944476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou Q, Dai H, Hu Z, Liu Y, Yang G. Accuracy-first and efficiency-first privacy-preserving semantic-aware ranked searches in the cloud. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(11):9213–44. doi:10.1002/int.22989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ge X, Yu J, Chen F, Kong F, Wang H. Toward verifiable phrase search over encrypted cloud-based IoT data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(16):12902–18. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3063855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chen L, Xue Y, Mu Y, Zeng L, Rezaeibagha F, Deng RH. Case-SSE: context-aware semantically extensible searchable symmetric encryption for encrypted cloud data. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;16(2):1011–22. doi:10.1109/tsc.2022.3162266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu Y, Dai H, Zhou Q, Li P, Yi X, Yang G. EPSMR: an efficient privacy-preserving semantic-aware multi-keyword ranked search scheme in cloud. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;159(1):1–14. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.04.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hou Y, Yao W, Li X, Xia Y, Wang M. Lattice-based semantic-aware searchable encryption for Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(17):28370–84. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3400816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li J, Ma J, Miao Y, Chen L, Wang Y, Liu X, et al. Verifiable semantic-aware ranked keyword search in cloud-assisted edge computing. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2021;15(6):3591–605. doi:10.1109/tsc.2021.3098864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang W, Sun B, Zhu Y, Wu D. A secure heuristic semantic searching scheme with blockchain-based verification. Inf Process Manag. 2021;58(4):102548. [Google Scholar]

33. Mikolov T. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv:1301.3781. 2013. [Google Scholar]

34. Kate A, Zaverucha GM, Goldberg I. Constant-size commitments to polynomials and their applications. In: Advances in cryptology-ASIACRYPT 2010. Berlin/Heidelberg, Gearmany: Springer; 2010. p. 177–94. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-17373-8_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bünz B, Bootle J, Boneh D, Poelstra A, Wuille P, Maxwell G. Bulletproofs: short proofs for confidential transactions and more. In: 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 315–34. [Google Scholar]

36. Chen B, Bünz B, Boneh D, Zhang Z. Hyperplonk: plonk with linear-time prover and high-degree custom gates. In: Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 499–530. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools