Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

AI Agents in Finance and Fintech: A Scientific Review of Agent-Based Systems, Applications, and Future Horizons

1 Department of Computer Science, Metropolitan College, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA

2 Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, 1000, North Macedonia

* Corresponding Author: Maryan Rizinski. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and Applications, 2nd Edition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069678

Received 28 June 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping financial systems and services, as intelligent AI agents increasingly form the foundation of autonomous, goal-driven systems capable of reasoning, learning, and action. This review synthesizes recent research and developments in the application of AI agents across core financial domains. Specifically, it covers the deployment of agent-based AI in algorithmic trading, fraud detection, credit risk assessment, robo-advisory, and regulatory compliance (RegTech). The review focuses on advanced agent-based methodologies, including reinforcement learning, multi-agent systems, and autonomous decision-making frameworks, particularly those leveraging large language models (LLMs), contrasting these with traditional AI or purely statistical models. Our primary goals are to consolidate current knowledge, identify significant trends and architectural approaches, review the practical efficiency and impact of current applications, and delineate key challenges and promising future research directions. The increasing sophistication of AI agents offers unprecedented opportunities for innovation in finance, yet presents complex technical, ethical, and regulatory challenges that demand careful consideration and proactive strategies. This review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of this rapidly evolving landscape, highlighting the role of agent-based AI in the ongoing transformation of the financial industry, and is intended to serve financial institutions, regulators, investors, analysts, researchers, and other key stakeholders in the financial ecosystem.Keywords

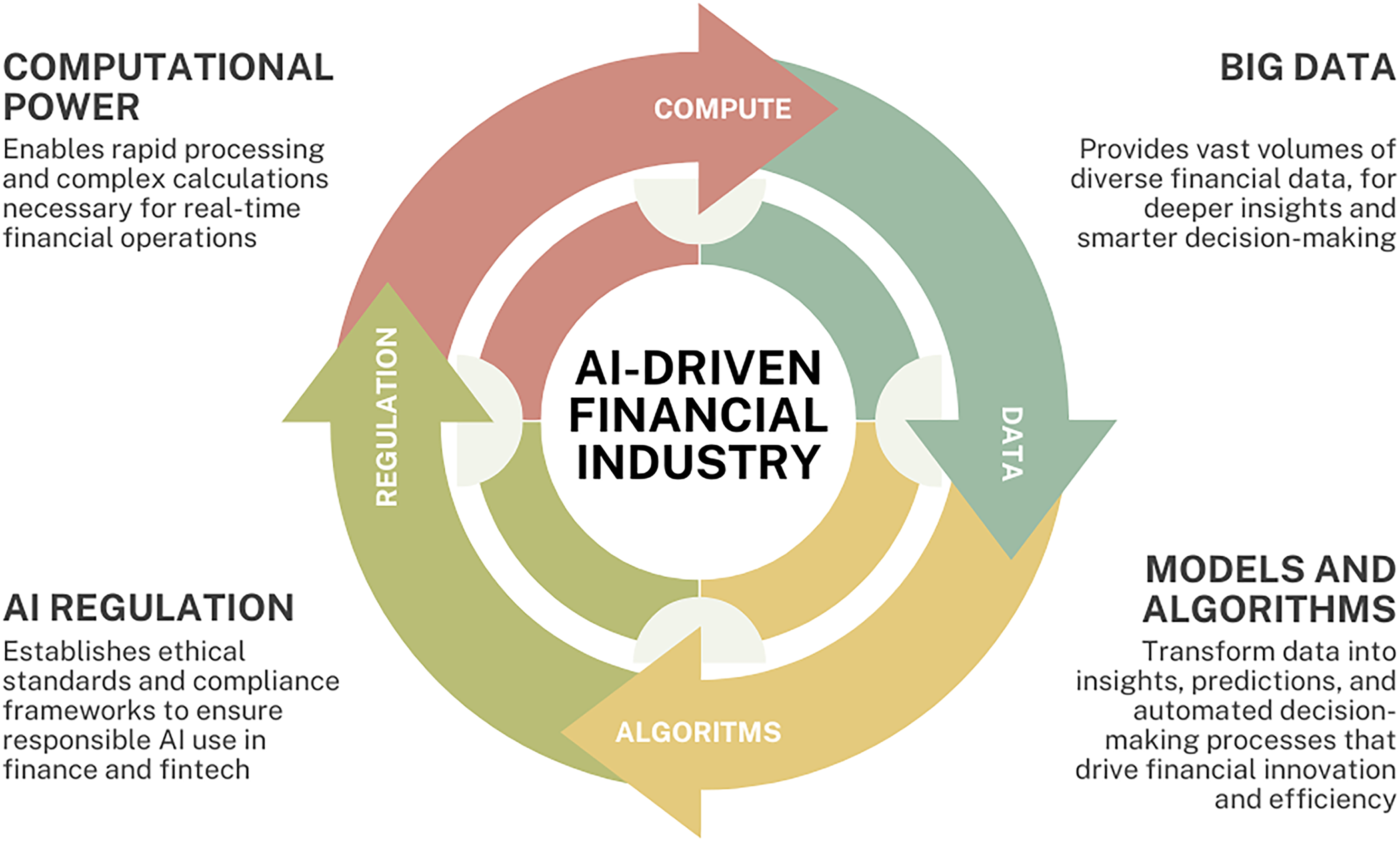

The financial industry is undergoing a period of unprecedented transformation, largely driven by the accelerating advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) [1–4]. AI technologies are increasingly embedded in financial operations, enhancing decision-making processes, improving operational efficiency, and redefining customer experiences [5–7]. From automating routine tasks to providing sophisticated analytical insights, AI’s influence is becoming pervasive. Fig. 1 illustrates the interconnected components of the AI-driven financial ecosystem, comprising computational power, big data, advanced AI models and algorithms, and regulatory frameworks. Computational power provides fast and complex processing capabilities essential for real-time financial activities. Big data supplies vast, heterogeneous financial datasets that are used for deeper analysis and informed decision-making. Advanced AI models and algorithms convert this data into actionable insights, predictions, and autonomous decisions. Meanwhile, AI regulation provides the ethical and legal foundations necessary to guide responsible and compliant AI deployment in finance and fintech.

Figure 1: Computational power, big data, advanced algorithms, and regulation form the core pillars of the AI-driven financial industry, enabling smart, efficient, and responsible innovation in fintech

Within this broad technological wave, a distinct and powerful paradigm is emerging: that of intelligent agents. These agents, defined as computational systems that can perceive their environment, reason about their observations, make decisions, and take autonomous actions to achieve specific goals, represent a significant step beyond traditional AI applications [8–11]. Unlike purely statistical models or rule-based systems, intelligent agents possess a degree of autonomy and adaptability, enabling them to operate in complex, dynamic financial environments with minimal human intervention.

The application of AI agents is rapidly expanding across various critical financial functions. In algorithmic trading, agents powered by reinforcement learning (RL) and multi-agent systems (MAS) are being developed to learn and execute sophisticated trading strategies in real-time [12–16]. In fraud detection, agentic systems, including those incorporating deep learning and graph neural networks (GNNs), are being deployed to tackle increasingly complex illicit activity patterns [17–20]. In credit scoring [21–23] and risk assessment [24–26], AI agents are utilized for more nuanced evaluations of creditworthiness and for dynamic risk modeling, potentially improving financial inclusion and stability. In financial advising, generative AI-driven robo-advisors and personalized advisory services are emerging as a growing application area, with agents designed to engage clients and support investment decision-making [27–29]. Furthermore, in regulatory compliance (RegTech), AI agents are assisting financial institutions in navigating complex regulatory landscapes, automating compliance checks, and improving reporting accuracy [20,30,31].

The significance of this topic, and thus the motivation for this review, stems from the rapid pace of innovation and the profound implications of autonomous AI agents in high-stakes financial environments. Recent years have witnessed a surge in research and development, driven by breakthroughs in foundational AI fields. One of the most impactful trends is the rise of LLM-driven agents, which have emerged as the dominant architecture for AI agentic systems. The advent of powerful LLMs has provided a new foundation for agent reasoning, communication, and knowledge processing capabilities [32–34]. This is evidenced by systems like StockAgent, which uses LLMs to simulate investor trading behaviors [35], and FinRobot, an LLM-based AI agent platform for financial analysis and equity research [36]. The FinSearch framework leverages LLMs for real-time financial information searching [37–39], and generative AI agents are being explored for augmenting knowledge work in finance [40,41]. These developments indicate a shift towards agents that can understand and interact with financial information in more human-like ways, though, as highlighted by research on generative AI financial advisors, this also introduces challenges related to advice quality and user perception [29].

Another key trend is the application of multi-agent systems (MAS) for tackling complex financial tasks that benefit from distributed problem-solving or diverse expertise. Examples include multi-agent frameworks for enhancing the efficiency of underlying asset reviews in structured finance [42], optimizing AI-agent collaboration in investment research [40,43], and the deployment of AI agents for financial modeling and model risk management (MRM) [20]. The integration of machine learning (ML) with agent-based modeling further demonstrates the potential of MAS in creating more realistic and adaptive financial simulations and operational systems [44]. This trend points towards the development of “financial digital workforces”, where teams of specialized agents collaborate, which necessitates research into their orchestration and collective risk management [9].

Concurrently, there is a growing emphasis on responsible and trustworthy AI in finance [45–49]. The autonomous nature of AI agents raises significant ethical, social, and regulatory questions. Research into “responsible AI Agents” [50] and the need for “visibility into AI Agents” [51] highlight concerns around fairness, bias, transparency, accountability, and potential systemic risks. The FinBrain framework, for instance, identifies explainable financial agents as a critical open research issue [52], a statement echoed by the need for human-in-the-loop (HITL) systems for verification and oversight in complex agentic deployments [20].

These rapid advancements and the multifaceted nature of AI agents in finance create several knowledge gaps. There is a need for robust and standardized evaluation frameworks tailored to financial AI agents [34]. Challenges related to scalability, real-world deployment, and integration with legacy systems persist [53]. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the potential systemic risk implications arising from the widespread adoption of autonomous financial agents is crucial for maintaining market stability [54].

The convergence of several factors such as accelerated AI progress, sophisticated agentic paradigms, the importance of responsible development, and existing knowledge gaps highlights the need for this review. Advances in foundational AI, particularly LLMs, have enabled the rapid creation of more capable financial AI agents. Yet this progress is double-edged: their potential is offset by risks such as LLM unreliability, brittleness, opacity, and ethical concerns [20,35,50,51]. These tensions create the need to synthesize current knowledge, evaluate applications, and understand the direction of future development that balances innovation with responsibility.

The present survey is structured around three core research questions. First, what is the current state of research on the application of AI agents across various finance and fintech sectors? Second, what are the primary methodologies and architectural frameworks employed in the design and deployment of AI agentic systems, and how do these approaches differ in terms of their core principles, strengths, limitations, and applications? Third, what key technical challenges and ethical considerations arise in the deployment of AI agentic systems? Together, these questions provide a structured framework for examining the evolving role of AI agents in financial innovation, technical implementation, and responsible governance.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review, organized by key financial application areas. Section 3 focuses on methodologies and architectural frameworks for AI agentic systems in finance. In Section 4, we explore essential technical challenges and ethical considerations associated with their deployment. Finally, Section 5 concludes by summarizing key findings, discussing broader implications, and outlining priorities for future research.

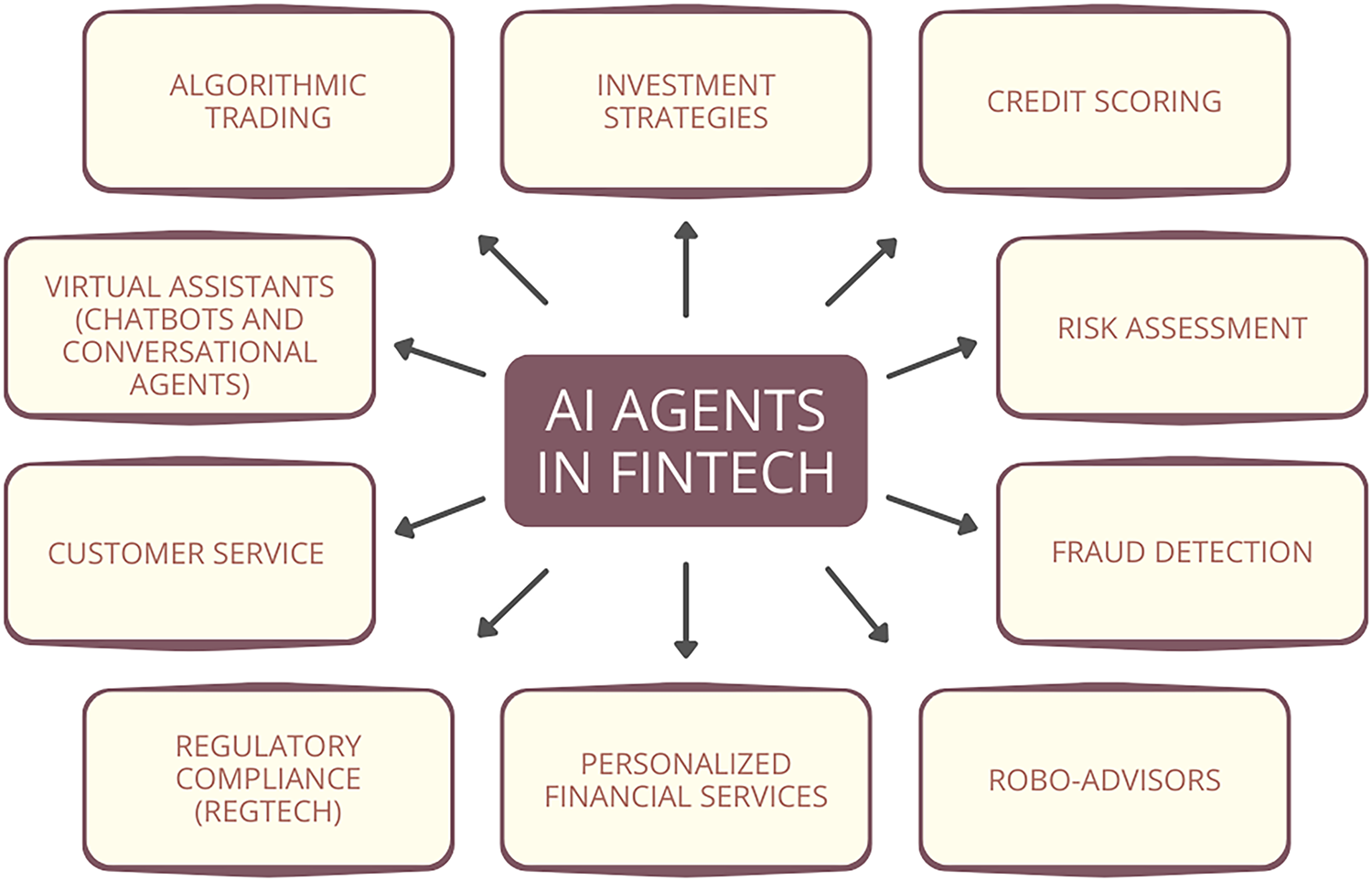

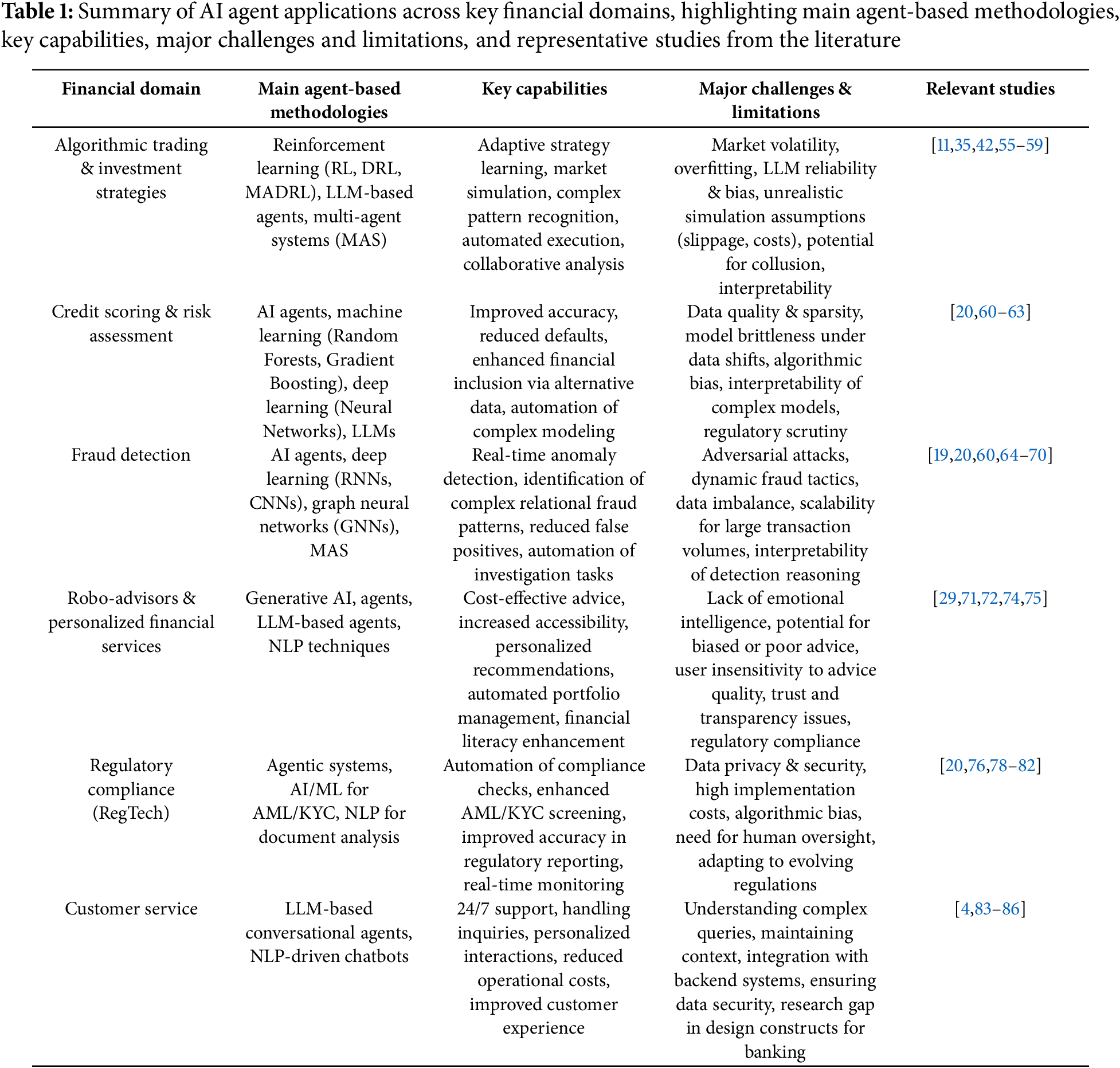

The application of AI agents in the finance and fintech sectors has witnessed significant growth over the past decade, driven by advancements in machine learning, computational power, and the increasing availability of vast datasets. This section presents a literature overview of relevant research, industry developments, and trends, organized by key thematic areas where AI agents are making significant contributions. Fig. 2 provides a visual summary of the key applications of AI agents in finance and fintech that are examined in this section. Table 1 offers a structured overview of these applications across major financial domains, outlining the major agent-based methodologies, core capabilities, principal challenges and limitations, as well as relevant studies from the existing literature.

Figure 2: Overview of key applications of AI agents transforming finance and fintech across operational, analytical and customer-facing domains

This review focuses specifically on agent-based AI approaches in finance and fintech. The scope encompasses methodologies such as reinforcement learning (particularly deep reinforcement learning, i.e., DRL), multi-agent systems, and autonomous decision-making frameworks, including those built upon large language models (LLMs). These approaches are characterized by systems that exhibit goal-directed behavior, learning capabilities, and a capacity for autonomous action. Consequently, this review will exclude broader AI applications that do not center on such agentic behavior, for instance, purely statistical predictive models that lack an autonomous action component, general applications of blockchain technology not directly integrated with agent operations, or generic natural language processing (NLP) tools not embodied within an autonomous agent framework. The core financial applications under examination are algorithmic trading and investment strategies, credit scoring and risk assessment, fraud detection, robo-advisors and personalized financial services, regulatory compliance, and customer services (e.g., chatbots and conversational agents).

The domain of AI agents in finance and fintech is evolving rapidly. New innovations emerge at an accelerating pace. In this context, a systematic survey serves as a valuable resource for both researchers and practitioners by consolidating and assessing the current state of knowledge. Given the anticipated growth and increasing importance of agent-based systems in the near future, this study aims to provide a timely and methodological synthesis of existing literature.

This survey employed a comprehensive and systematic review of the relevant literature to investigate the development, deployment, and prospective trajectories of AI agent-based systems in finance and fintech. The review focused on peer-reviewed publications indexed by various scientific publishers (e.g., IEEE, ACM, Springer, Elsevier, and Wiley) as well as major databases (e.g., IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Web of Science, Scopus, and arXiv). Selection criteria prioritized works that explicitly addressed agentic architectures and decision-making frameworks in financial contexts. The scope encompassed all major application areas outlined in Fig. 2. Only studies demonstrating methodological rigor and substantive relevance to AI agents in the financial and fintech domains were included.

The analytical process involved the structured extraction of methodological details, implementation strategies, and reported outcomes from each selected publication. These data were organized into thematic categories reflecting core dimensions of AI agent research: architectural paradigms, methodological approaches, and applied use cases. Cross-comparison techniques were applied to identify common patterns, capabilities, and differences in technical implementation, as well as strengths and limitations. This synthesis mapped the state-of-the-art in AI agent systems for financial applications, highlighted prevailing research trends, and identified gaps warranting future investigation.

2.2 Algorithmic Trading and Investment Strategies

The domain of algorithmic trading has been an active ground for AI agent research, evolving from simpler rule-based systems to sophisticated agents employing reinforcement learning (RL) and multi-agent systems (MAS). RL agents, in particular, are designed to learn optimal trading policies through direct interaction with market environments, aiming to maximize cumulative rewards [55,56]. Recent studies explore Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) where multiple agents, potentially with different objectives or information sets, interact and learn concurrently [57,58]. Such systems have shown potential, though their performance can be stock-specific and influenced by the training environment. The authors of [56] provide a review of RL applications in finance, including optimal execution and portfolio optimization, highlighting the ability of RL to adapt to changing market conditions. The survey [59] discusses the evolution from deep learning to LLMs in quantitative investment, noting the potential of agent-based automation.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are also emerging as a novel approach. The StockAgent framework, for example, utilizes LLMs to simulate investor trading behaviors, demonstrating that different LLMs can lead to varied trading patterns and that agent behavior is sensitive to external factors like loan availability and information sharing [35]. While LLM-based agents can simulate complex trading environments and avoid issues like test set leakage, the reliability of their stock recommendations and trading strategies requires further investigation due to inherent model knowledge and biases [35]. This suggests that while LLMs show promise for higher-level financial reasoning or simulation, their direct application in high-frequency, low-latency trading scenarios is still exploratory compared to specialized RL agents. The inherent variability and computational demands of current LLMs might pose challenges for the deterministic, ultra-fast execution required in such environments [11].

Multi-agent collaboration is another significant trend. The paper [42] explored optimizing AI-agent collaboration in financial research, finding that for complex tasks like risk analysis, multi-agent systems with vertical structures perform better, while single agents or horizontal structures are more suited for simpler tasks like fundamental analysis. This research emphasizes that the optimal agent configuration is task-dependent. The broader impact of AI on algorithmic trading includes enhanced forecasting capabilities and improved trade execution, but also introduces challenges like model overfitting and the potential for AI-driven collusion, which could negatively affect investors and the broader marker. RL studies in finance also state that neglecting certain real-world constrains such as slippage and transaction costs can lead to an unrealistic evaluation of the performance of RL models [55].

2.3 Credit Scoring and Risk Assessment

AI agents are transforming credit scoring and risk assessment by enabling more nuanced, data-driven, and potentially fairer evaluations. Agentic AI systems, such as those described by researchers that focus on modeling and model risk management (MRM), are being developed for tasks such as predicting credit card approval and modeling portfolio credit risk [20]. These systems, often incorporating models such as CatBoost or XGBoost, can achieve performance comparable to or even exceeding traditional AutoML solutions and human-derived models, especially in metrics like recall which are critical for risk mitigation [20]. The study in [60] on generative AI agents in financial applications highlighted that AI agents have contributed to a 25% improvement in risk model accuracy and a 20% reduction in loan defaults.

Machine learning and deep learning form the core of many AI-driven credit risk models, allowing institutions to analyze vast datasets, including alternative data sources, to build more holistic borrower profiles [61,62]. This can enhance financial inclusion by providing fairer assessments for individuals with limited traditional credit histories. However, the deployment of these advanced models is not without challenges. Data quality and availability remain significant hurdles, and the “black-box” nature of some complex models raises concerns about transparency and interpretability. Furthermore, as highlighted by the MRM analysis in agentic systems, models can exhibit vulnerabilities when input data shifts, emphasizing the need for continuous stress testing and validation [20]. Bias is another critical concern, as flawed data or model design can perpetuate or even amplify existing societal biases, leading to discriminatory practices in financial services [9]. Regulatory bodies are increasingly focused on ensuring that AI in credit risk assessment is used responsibly and ethically [62,63].

The prevention of financial fraud is a critical area where AI agents are demonstrating considerable impact. Agentic AI systems, structured as collaborative “crews”, have been applied to credit card fraud detection, with models like CatBoost showing superior performance in recall and F1 scores compared to some established benchmarks, which is crucial for minimizing fraud losses [20]. Deep learning models, including Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), are leveraged for real-time risk assessment of financial transactions, capable of detecting anomalies and subtle variations indicative of fraud even when concealed within legitimate patterns [19,64–66]. Research indicates that AI agents can lead to a 40% decrease in false-positive fraud detections, improving efficiency [60].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent a particularly promising methodology, as they are adept at capturing complex relational patterns and dynamics within financial networks, which often characterize sophisticated fraud schemes. In particular, the study in [67] highlights the suitability of GNNs for various financial fraud scenarios and discusses architectures like Graph Convolutional Networks. (GCNs) and Graph Attention Networks (GANs). Multi-agent systems are also being explored for fraud detection, leveraging the idea that distributed intelligence and collaboration can enhance detection capabilities [68]. The escalating complexity of identity fraud, further increased by AI-enabled deepfake technologies, necessitates advanced AI-based detection methods focusing on biometric authentication and continuous user behavior analysis [69]. However, a significant challenge in this domain is the adversarial nature of fraud; as detection models become more sophisticated, so do the techniques used by fraudsters, including adversarial attacks designed to deceive AI systems [70].

2.5 Robo-Advisors and Personalized Financial Services

AI agents are increasingly powering robo-advisors and platforms for personalized financial services, aiming to democratize access to financial advice. Generative AI agents, particularly those based on LLMs, are being investigated for their potential as personalized financial advisors. In particular, the study in [29] found that LLM-advisors can match human advisor performance in providing user preferences for some investor profiles, but struggle with more complex cases, such as risk-taking individuals. A concerning finding from this study is that users may be insensitive to the quality of advice, reporting higher satisfaction with LLMs adopting an extroverted persona even if the advice is objectively worse, highlighting the risk of users acting on poor advice due to the agent’s personality or their own lack of financial expertise [29].

Robo-advisors offer benefits such as lower costs, increased accessibility, and data-driven investment strategies, which can help eliminate emotional biases. In particular, based on representative US investor data, the study in [71] suggests that robo-advisors offer an alternative for seeking investment advice, especially for investors who worry about potential conflicts of interest that may appear in the context of human financial advice. Similarly, experiments have shown that robo advisors demonstrate superior performance as compared to conventional mutual funds such as equity, fixed income, money market and hybrid funds [72]. Furthermore, robo-advisors are recognized as a disruptive trend in asset and wealth management. Traditional financial services are being replaced by robo-advisors in the wealth management industry due to clients who have technical know-how on new digital technologies and prefer to rely on information from multiple sources [73]. Natural language processing (NLP) techniques are fundamental to these personalized services, enabling robo-advisors in the form of chatbots and virtual assistants to understand user queries, process financial narratives, and deliver tailored information [74]. The evolution from simple chatbots to more sophisticated AI agents capable of personalized, scenario-based recommendations emerges as a key trend in this area [75].

2.6 Regulatory Compliance (RegTech)

AI agents are playing an increasingly important role in Regulatory Technology (RegTech), helping financial institutions manage the complexities of compliance. Agentic systems can automate aspects of regulatory adherence; for instance, a “Documentation Compliance Checker Agent” has been shown to successfully verify if modeling processes align with organizational guidelines [20]. This is crucial for maintaining internal governance and preparing for regulatory audits. In the domain of Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC), AI agents are being deployed to handle first-level analyst duties, such as screening alerts and monitoring transactions, thereby freeing up human analysts to focus on higher-risk activities [76]. A report by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) highlights the potential of new technologies, including AI, to make efforts against money laundering and the efforts for countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) faster, more effective, and more efficient, although human input and oversight remain critical [77].

The broader application of AI in regulatory technology (RegTech) is expected to deliver a number of benefits, including enhanced operational efficiency, improved accuracy in regulatory reporting, and more effective risk management. RegTech systems harness AI to interpret regulatory documents, automate compliance checks, and detect potential violations in real time. However, there are also several challenges associated with the implementation of RegTech [78]. For instance, the complex and uneven global evolution of the regulatory landscape can result in inconsistent regulations and difficulties in achieving alignment among regulators, risk managers, and auditors [79]. Additionally, RegTech companies must continuously adapt to evolving cybersecurity threats in order to maintain consumer trust and prevent data breaches, which could have serious consequences [80]. Finally, adopting RegTech often requires replacing legacy systems. Naturally, this is a process that can be both time-consuming and costly which may lead to some companies to resist the transition [81,82].

2.7 Customer Service (e.g., Chatbots and Conversational Agents)

AI-enabled conversational agents, including chatbots and virtual assistants, are introduced in banking and financial customer service [83,84]. These agents can handle customer inquiries, provide information, and guide users through various processes, improving service quality and reducing operational costs [4]. Focusing on AI-based banking conversational agents, the study in [85] identified a surge in research post-2019, with key thematic clusters including technology acceptance, customer service, technology design, and language processing. The review noted that much of the literature focuses on the acceptance of these agents by both industry and consumers, but also highlighted a research gap concerning the design-related constructs of these agents in banking compared to other sectors. The evolution from basic chatbots to more sophisticated AI agents capable of understanding context, recalling past interactions, and delivering personalized responses marks a significant advancement in this area [86].

3 Methodologies and Architectural Frameworks for AI Agentic Systems

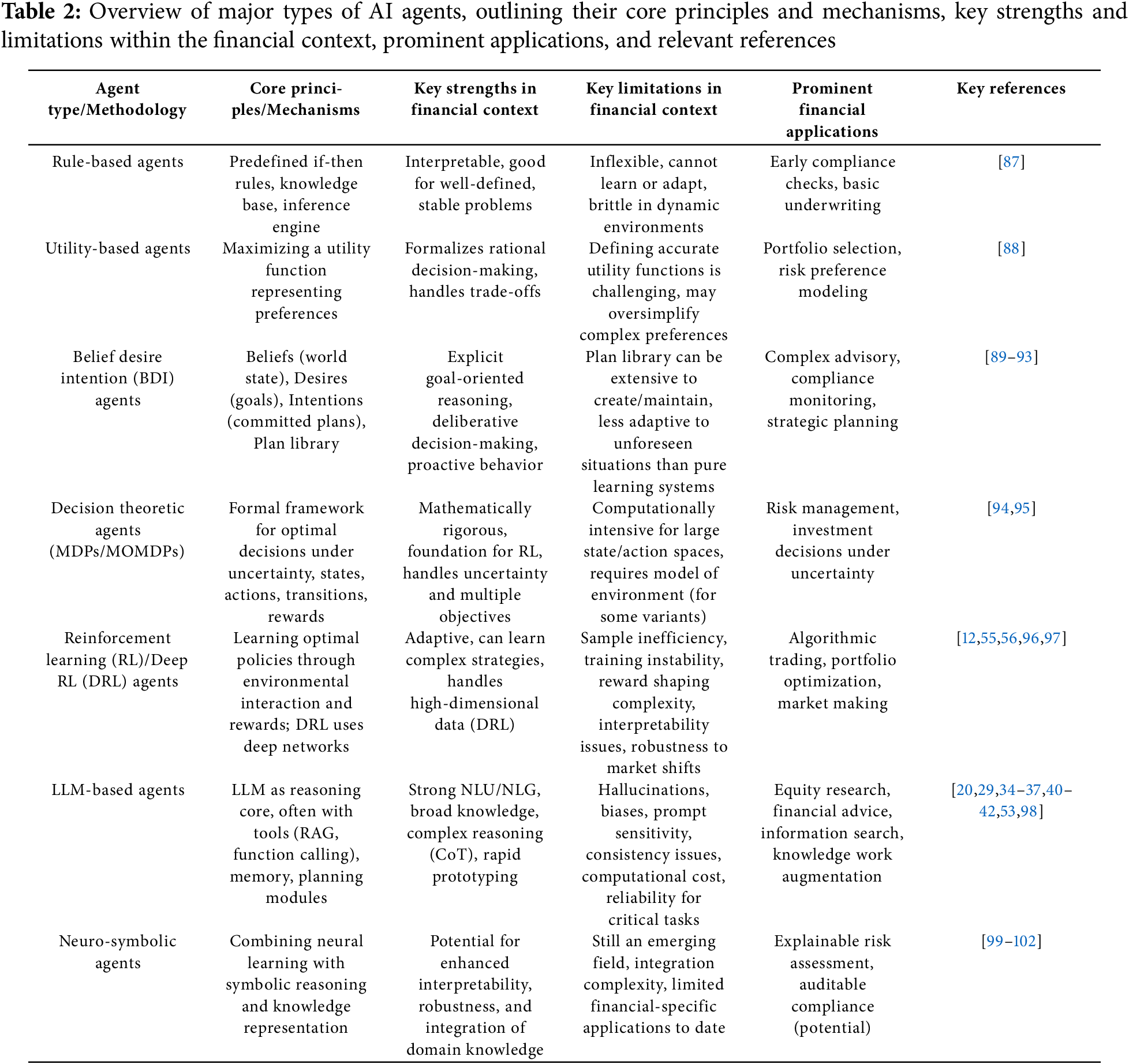

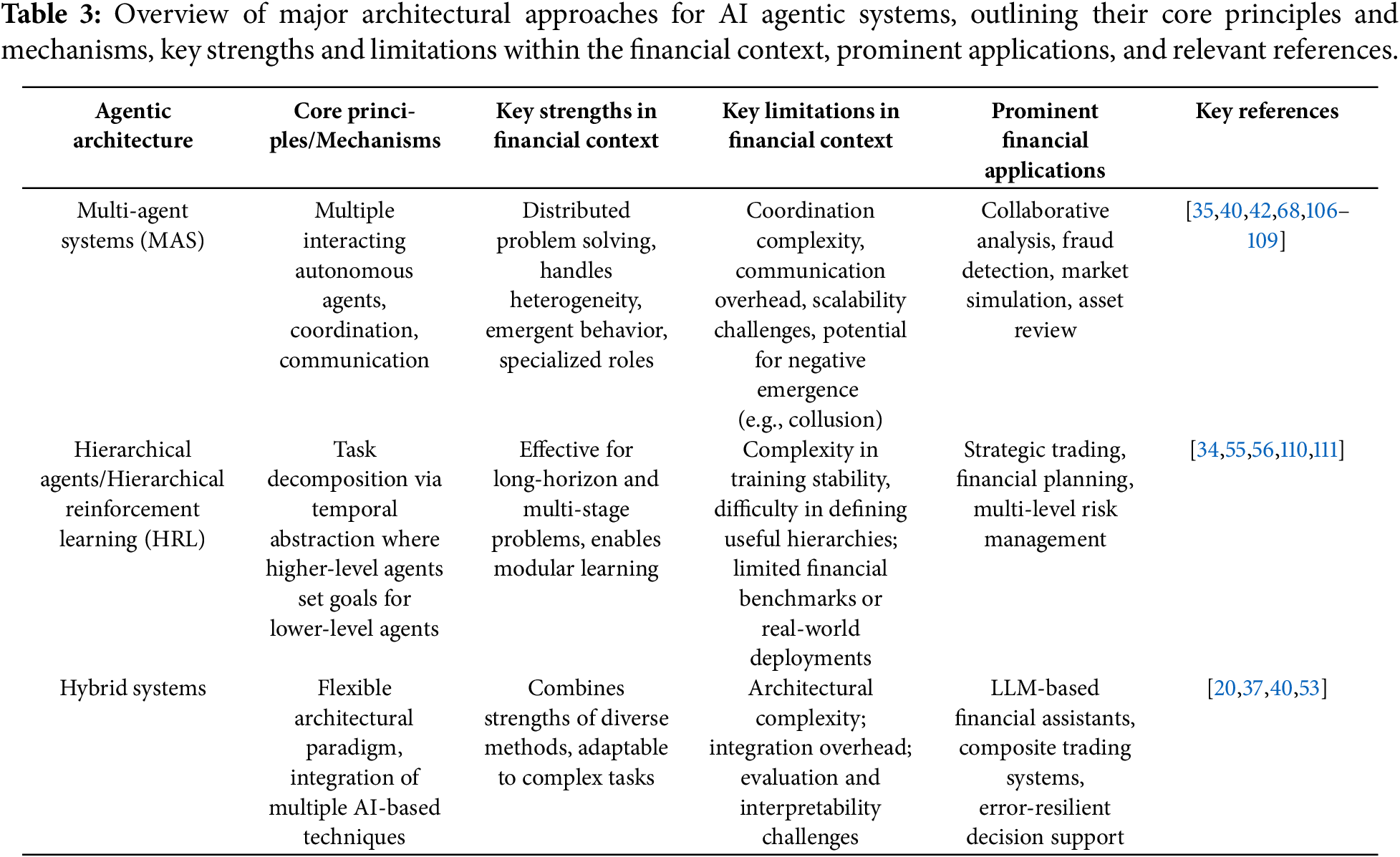

The design and implementation of AI agents in finance draw upon a diverse array of methodologies and architectural frameworks, ranging from traditional approaches to state-of-the-art and hybrid systems. These aspects are important for understanding their capabilities, limitations, and suitability for the dynamic, high-stakes environments characteristic of the financial domain. This section provides an in-depth overview of these core methodologies and architectures, highlighting their application in finance-specific contexts. Table 2 summarizes major types of AI agents, outlining their core principles and mechanisms, key strengths and limitations within the financial context, prominent applications, and relevant references.

3.1 Traditional Types of Agents

While modern financial AI agents increasingly rely on advanced machine learning, traditional types of agents provide important conceptual building blocks and continue to find relevance in specific applications. In this subsection, we will review rule-based agents, utility-based agents, belief-desire-intention (BDI) models, and basic decision-theoretic models.

Historically, rule-based expert systems were among the earliest AI applications in finance, employed for tasks like financial planning, underwriting, and preliminary risk assessment [87]. These agents operate based on a predefined set of “if-then” rules derived from domain expertise. The comprehensive review in [87] details the evolution and application of rule-based expert systems from 1980 to 2021 across various industries, including finance-related areas like production and automation which often involve cost management. While straightforward to understand and implement for well-defined problems, their primary limitation lies in their rigidity and inability to adapt to novel situations or learn from new data, making them less suitable for the highly dynamic nature of modern financial markets.

These agents are designed to make decisions that maximize a specific utility function, which quantifies the desirability of different states or outcomes [88]. This aligns well with the rational decision-making paradigm often assumed in financial theory. In a multi-objective, multi-agent context, utility functions become crucial for analyzing trade-offs between conflicting objectives, as explored in [88]. The challenge lies in accurately defining and quantifying utility in complex financial scenarios, especially under uncertainty.

3.1.3 Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI) Agents

The BDI architecture models agents based on mentalistic notions: beliefs (information about the environment), desires (goals to be achieved), and intentions (committed plans of action) [89]. BDI agents maintain a plan library and select plans to achieve their intentions based on their current beliefs and desires. This deliberative reasoning process makes BDI models suitable for applications requiring goal-oriented behavior and planning, such as sophisticated financial advisory systems or compliance monitoring agents that need to reason about regulatory obligations [90–93]. Research on integrating BDI agent modeling with agent-based simulation highlights the framework’s utility in modeling complex human-like behaviors where agents are autonomous and proactive [91]. The ability to recognize intentions is a key cognitive aspect that can enhance cooperation and reduce misunderstandings in multi-agent interactions, a concept explored in evolutionary game theory using Bayesian Networks to model intent [90].

3.1.4 Basic Decision-Theoretic Agents

Decision theory provides a formal framework for making optimal choices under uncertainty. Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) are a cornerstone, modeling sequential decision-making where outcomes are partly random and partly under the control of a decision-maker [94,95]. MOMDPs (Multi-Objective MDPs) extend this to scenarios with multiple, potentially conflicting, objectives, which are common in finance (e.g., maximizing return while minimizing risk). These models form the theoretical basis for many reinforcement learning approaches. Surveys on AI for Operations Research also touch upon how AI can enhance decision-theoretic models at various stages, from parameter generation to model optimization [95].

The cutting edge of AI agent development in finance is characterized by methodologies that emphasize learning, adaptation, and the ability to handle vast amounts of complex data. In this subsection, we will review agents based on reinforcement learning (RL) and deep RL (DRL), LLM-based agents, and neuro-symbolic agents.

3.2.1 Agents Based on Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Deep RL (DRL)

RL agents learn optimal strategies (policies) by interacting with an environment and receiving feedback in the form of rewards or penalties [55,56]. Deep RL (DRL) combines RL with deep neural networks, enabling agents to learn from high-dimensional sensory inputs and tackle more complex problems.

• Core Concepts: The core concepts in RL and DRL revolve around agent, environment, state, action, reward, policy, and value function. DRL uses deep networks to approximate policy and/or value functions. Popular algorithms include Q-learning, Policy Gradients, and Actor-Critic methods [55,56].

• Applications in Finance: Algorithmic trading is a primary application, with agents learning to make buy/sell decisions to maximize profit [12,55,56]. Portfolio optimization involves agents learning to allocate assets dynamically. RL is also explored for risk management and option pricing [56].

• Effectiveness and Challenges: DRL agents can discover complex, non-obvious strategies. However, they face challenges such as sample inefficiency (requiring vast amounts of data or interaction), instability during training, sensitivity to reward function design, and the difficulty of ensuring robustness in non-stationary financial markets [55]. The “black-box” nature of DRL models also poses interpretability issues [96,97].

The advent of powerful LLMs has spurred the development of agents where the LLM serves as the core reasoning engine or “brain” [34,36].

• Core Concepts: LLMs provide capabilities in natural language understanding, generation, reasoning, and knowledge retrieval. Agent frameworks often combine LLMs with external tools, memory, and processing capabilities.

• Frameworks and Components:

– CrewAI: A multi-agent orchestration framework used in [20] for financial modeling and model risk management (MR), and in [53] for retirement planning assistance. Agents have specialized roles and can delegate tasks.

– StockAgent: An LLM-driven multi-agent system for simulating stock trading [35].

– FinRobot: An open-source AI agent platform for financial analysis using LLMs, with a layered architecture (Market Forecaster, Financial Analyst, Trade Strategist) and a Perception-Brain-Action cycle. It employs Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting for complex analysis [36,98].

– FinSearch: An LLM-based agent framework for real-time financial information searching, featuring a multi-step search pre-planner, adaptive query rewriter, and temporal weighting mechanism [37].

– General Architecture: Many LLM agents follow a pattern of perception (gathering information, often multimodal), reasoning/planning (LLM processing, potentially using CoT or ReAct patterns), and action (executing tasks, using tools, interacting with other systems) [36]. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is often used to provide LLMs with up-to-date or domain-specific information [40,53].

• Applications: Equity research and valuation [98], trading simulation [35], financial information retrieval [37], personalized financial advice [29], knowledge work augmentation in finance [41], and underlying asset reviews [42].

• Challenges: LLM-specific issues like hallucinations, biases, prompt sensitivity, consistency, and the cost of inference for large models are key concerns [35,53,103–105].

These systems aim to combine the strengths of neural networks (learning from data, pattern recognition) with symbolic AI (logical reasoning, knowledge representation, interpretability) [99–102].

• Core Concepts: Integrating logic-based reasoning (e.g., First-Order Logic) with neural learning. This can involve neural networks learning symbolic rules, symbolic knowledge guiding neural network learning, or hybrid architectures.

• Potential in Finance: Due to their inherent design, these architectures can be highly relevant for creating financial agents that are not only accurate but also explainable and robust, capable of incorporating domain knowledge explicitly. Applications could include explainable credit scoring, transparent risk assessment, and auditable compliance systems. While direct financial implementations are yet to be considered, the principles are compelling for financial decision-making and can use prior research in other high-stakes applications such as healthcare [99].

After exploring the different types of agents, it is essential to examine how these agents can be organized from an architectural perspective. This subsection introduces main agent-based architectures, including multi-agent systems (MAS), hierarchical agents and hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL), and hybrid systems, each offering distinct approaches to structuring intelligent agent behavior. Table 3 presents an overview of major architectural approaches for AI agentic systems, outlining their core principles and mechanisms, key strengths and limitations within the financial context, prominent applications, and relevant references.

3.3.1 Multi-Agent Systems (MAS)

Multi-agent systems (MAS) involve multiple autonomous agents interacting within a shared environment. These systems enhance problem-solving capabilities and operational efficiency in complex tasks by facilitating collaborative processes supported by advanced feedback and evaluation mechanisms. The interactions among agents within a MAS system can be cooperative, competitive, or a mix of both [68,106,107].

• Core Concepts: The core concepts in MAS include agent coordination, communication protocols, negotiation, coalition formation, and distributed problem-solving. The architectures can be centralized (i.e., a central controller coordinates agents) or decentralized (i.e., agents make decisions autonomously based on local information and interactions).

• Applications in Finance:

– Collaborative Financial Analysis: As seen in [40], different agent configurations (single vs. multi-agent, vertical vs. horizontal collaboration structures) can be optimized for various sub-tasks in investment research. For instance, multi-agent collaboration with a vertical structure (clear leader) was found to be superior for complex risk analysis [40].

– Fraud Detection: Multi-agent frameworks can enhance the detection of sophisticated fraud by combining diverse analytical capabilities or simulating fraudulent and legitimate behaviors [42,68]. Ref. [42] describes a dual-agent system for cross-verifying information in structured finance asset reviews, achieving high accuracy.

– Market Simulation: Simulating market dynamics with heterogeneous agents (e.g., StockAgent using LLM-based agents [35]) to understand market phenomena or test strategies.

– Algorithmic Trading: MADRL, where multiple RL agents trade and interact, is a specific instance of MAS applied to trading [108].

• Synergy with Agent-Based Modeling (ABM): The integration of machine learning with ABM, as reviewed by [109], is highly relevant. Machine learning (ML) can be used at the agent level (for learning behaviors) or model level (for calibration or analysis of emergent outcomes). This synergy is crucial for building realistic financial market simulations.

• Context-Aware MAS (CA-MAS): Recent surveys emphasize the importance of context awareness for MAS robustness and adaptability in dynamic environments, outlining frameworks for CA-MAS development that integrate sensing, learning, reasoning, prediction, and action capabilities [68].

3.3.2 Hierarchical Agents/Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL)

HRL addresses complex, long-horizon tasks by decomposing them into a hierarchy of simpler sub-tasks [110,111]. Agents at higher levels learn to set goals or sub-tasks for lower-level agents, which in turn learn policies to achieve those sub-goals.

• Core Concepts: The core concepts in HRL include temporal abstraction, skill discovery, and intrinsic motivation.

• Applications in Finance: There are several areas where HRL can be applied such as complex financial planning (e.g., retirement planning with multiple stages and goals), strategic trading (e.g., high-level market timing decisions guiding lower-level execution tactics), and multi-faceted risk management. While direct financial applications in literature are still emerging, the principles are highly relevant [55,56]. Some general AI agent architectures, like hierarchical agents mentioned in [34], coordinate across multiple levels of abstraction.

Many advanced agentic systems in finance are inherently hybrid, integrating multiple AI techniques. For example, the AI agents in [20] combine specialized ML models (like CatBoost) within a multi-agent framework that includes human-in-the-loop (HITL) components for oversight and error correction. LLM-powered agents often use RAG (a hybrid of retrieval and generation) and function/tool calling, integrating LLM reasoning with external data sources and computational capabilities [37,40,53]. This trend towards hybrid and composite architectures reflects a pragmatic approach, leveraging the best of different methodologies to tackle the multifaceted challenges of financial applications. No single technique appears to be a one-size-fits-all solution; rather, the strategic combination of diverse types of agents and architectural approaches is providing more effective decision-making in finance. Importantly, hybrid systems should be understood as an architectural paradigm, not a single method or agent type; they enable the flexible integration of various technologies, techniques, and levels of autonomy. This allows developers and financial experts to tailor systems to specific contexts and performance requirements.

3.4 Communication Protocols for Multi-Agent Coordination

Without a common language, agents developed on different platforms by different vendors cannot effectively collaborate, delegate tasks, or share context, leading to fragmented and inefficient AI-based systems. In response, several standards have been proposed to foster interoperability. Among the most prominent are the Model Context Protocol (MCP) and the Agent2Agent (A2A) protocol. MCP standardizes how a single agent connects to its external environment, whereas A2A standardizes how multiple autonomous agents interact with each other.

Initially developed by Anthropic, MCP is designed to function as a universal interface between an AI model and external resources, such as data sources and tools, analogous to the role of USB-C in hardware connectivity [112]. With such a single, plug-and-play interface for models, MCP can be regarded as a protocol that standardizes the way applications provide context to LLMs. MCP operates on a client-server architecture where a “host” application (e.g., an IDE, AI tool, or chat interface) manages interactions between “clients” and “servers”. Servers act as providers, exposing specific tools or data resources through a standardized protocol layer that typically utilizes web APIs [113]. The protocol’s lifecycle consists of three distinct phases: 1) initialization, where the client and server share and negotiate capabilities; 2) operation, where the client and server exchange method calls according to the negotiated capabilities; and 3) shutdown, which ensures clean resource termination [114]. By creating a secure, host-mediated bridge to external resources, MCP allows a single agent to become more context-aware and capable without requiring complex, custom-built integrations for each new tool or data source.

In contrast, the A2A protocol, initiated by Google in collaboration with a broad industry consortium, is designed to facilitate direct communication and collaboration between independent AI agents [115]. Its core purpose is to enable a “society of agents” that can discover one another, negotiate tasks, and orchestrate complex workflows across platform boundaries. A2A’s architecture is built on established web standards like HTTP and JSON-RPC and revolves around key components: 1) “Agent Cards”, which act as discoverable business cards detailing an agent’s identity and capabilities; 2) “Tasks”, which define a specific unit of work with a unique ID for tracking; and 3) “Artifacts”, which are the outputs or results of a completed task [116]. The protocol is explicitly designed to support long-running, asynchronous operations and is modality-agnostic, capable of handling text, audio, or video [117]. This framework allows a primary agent to delegate sub-tasks to specialized agents, which enables a more modular and resilient system architecture.

MCP and A2A are not competing standards but are complementary protocols addressing different layers of the AI agentic architecture. The fundamental difference lies in their interaction topology. While MCP enables “vertical” integration, connecting a single agent to its underlying tools and data plane, A2A enables “horizontal” integration, connecting multiple peer agents across a control plane [118]. Both leverage similar underlying technologies like common web-based APIs, but their focus differs. MCP is context-oriented and is focused on enriching a single model’s operational context. A2A is interaction-oriented, focused on defining the rules of engagement for a multi-agent society [119]. The synergy between them can be beneficial. For example, an orchestrator agent in a complex workflow might use A2A to delegate a data analysis task to a specialist agent. That specialist agent could then use MCP to securely access a proprietary database and an external statistics library to fulfill the request. This approach advances the field by moving from monolithic models to dynamic, interoperable, and distributed multi-agent systems.

3.5 Computational and Architectural Choices for Financial Environments

The unique characteristics of financial environments impose specific demands on AI agent architectures. These demands include aspects such as adaptability and real-time processing, handling high-frequency and noisy data, scalability, and integration with legacy systems, outlined as follows:

• Adaptability and Real-Time Processing: Financial markets are highly dynamic and non-stationary. Agents, particularly in trading and risk management, must adapt to changing conditions and often operate under stringent real-time constraints, requiring low-latency inference and decision-making, especially in big data analytics scenarios [120–123]. This influences choices regarding model complexity and computational resources.

• Handling High-Frequency and Noisy Data: Financial data, especially market data, can be high-frequency and contain significant noise. Architectures must be robust to such noise and capable of extracting meaningful signals [124].

• Scalability: As AI agent adoption grows, systems must be scalable to handle increasing volumes of data, transactions, and users [53]. This is a key consideration for MAS and LLM-based agent deployments.

• Integration with Legacy Systems: Financial institutions often have complex legacy IT infrastructures. New AI agent systems must be designed for effective integration, which can be a significant architectural challenge.

3.6 Trade-Offs in Agent Design

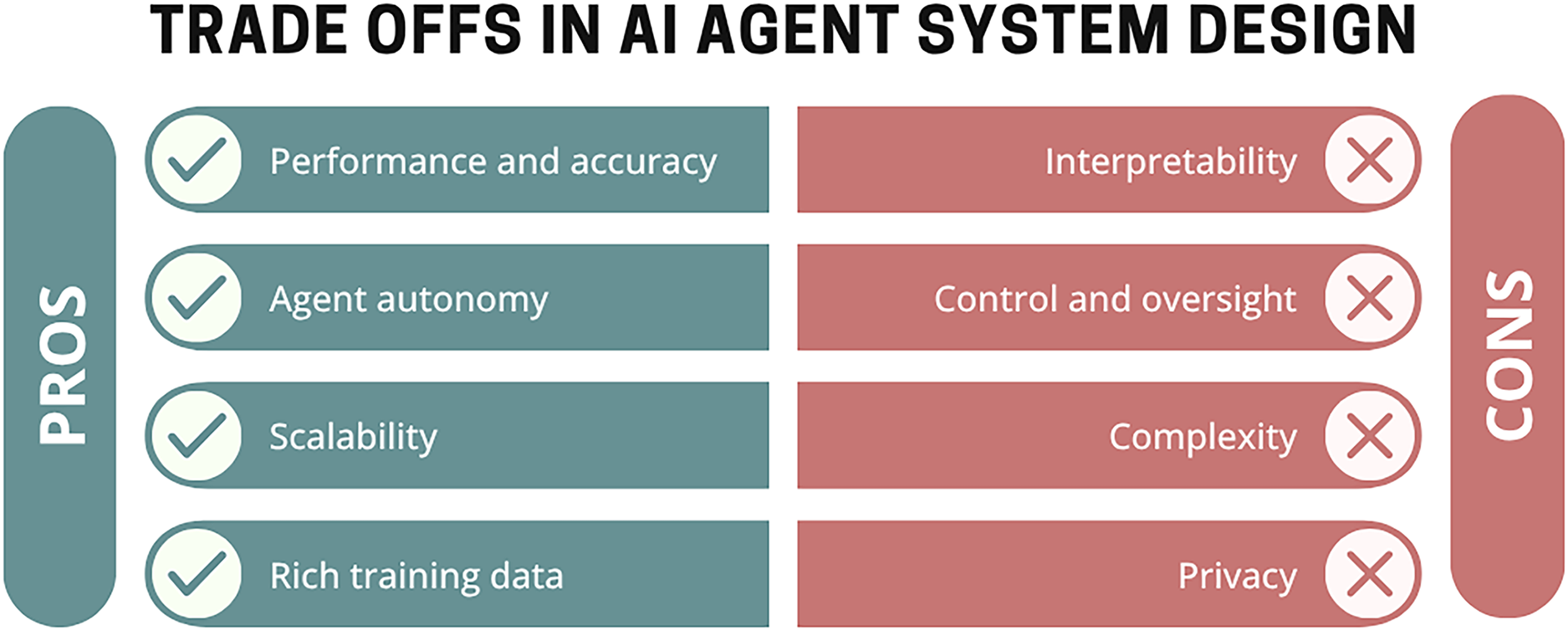

Designing AI agents for financial applications involves navigating several trade-offs, each of which can impact the effectiveness, transparency, and ethical considerations of the system. These trade-offs include:

• Interpretability vs. Performance/Accuracy: Highly accurate models like DRL and large LLMs are often considered “black boxes”, making their decision-making processes opaque. Simpler models might be more interpretable but less performant. This trade-off is particularly important in finance, where trust, auditability, and regulatory compliance are paramount [48,52,125].

• Autonomy vs. Control/Oversight: While the goal is often to increase agent autonomy, the high-stakes nature of finance necessitates robust control and oversight mechanisms. The human-in-the-loop (HITL) paradigm, as seen in [20,126–128], is a common approach to balance autonomous capabilities with human judgment and accountability. With HITL, a human expert oversees the models and associated risks, providing instructions to help them achieve their respective objective.

• Scalability vs. Complexity: More complex agent architectures (e.g., large MAS, sophisticated HRL) may offer greater capabilities but can be harder to scale, maintain, and debug.

• Data Requirements vs. Privacy: Advanced ML models often require vast amounts of data for training, which can raise privacy concerns when dealing with sensitive financial information [129–133].

Fig. 3 presents a summary of these key trade-offs involved in the design of AI agent systems.

Figure 3: Major trade-offs in AI agent system design

The increasing focus on LLMs as “brains” and cognitive frameworks like “Perception, Brain, Action” [36], coupled with the necessity for agents to use tools and access external data [40,53], suggests that the future of financial agent design lies in creating sophisticated cognitive architectures. This involves more than just applying an algorithm; it requires engineering systems that can perceive complex financial environments, reason strategically using both learned patterns and explicit knowledge, plan effectively, and interact with the world through diverse actions and tools. This points towards an evolving field of “cognitive finance automation”, where the emphasis is on building integrated intelligent systems rather than isolated models.

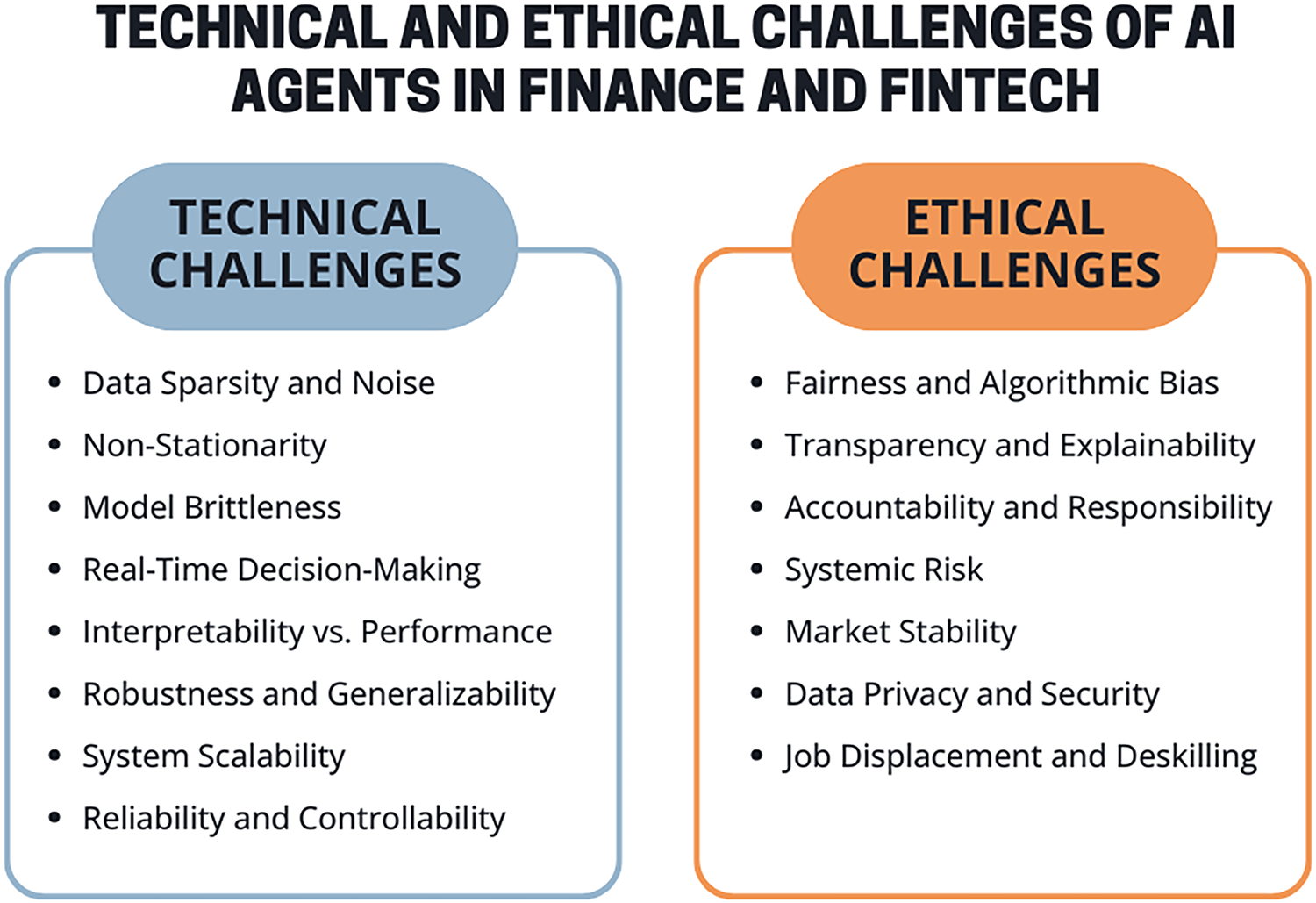

4 Challenges and Ethical Considerations

The deployment of agentic AI systems in finance, while promising significant advancements, is accompanied with a number of technical challenges and ethical considerations. These issues are often interconnected, where technical limitations can exacerbate ethical dilemmas, and societal concerns can shape the trajectory of technological development. A critical examination of these challenges is essential for fostering responsible innovation and ensuring the trustworthiness and stability of AI-driven financial systems. Fig. 4 provides an overview of the common technical and ethical challenges associated with AI agentic systems in finance and fintech.

Figure 4: Common technical and ethical challenges of AI agentic systems in finance and fintech

The unique nature of financial data and the operational demands of the financial industry pose several technical hurdles for AI agents:

• Data Sparsity, Noise, and Non-Stationarity: Financial datasets are often characterized by high levels of noise, non-stationarity (where statistical properties change over time), and, in some specific domains or for particular assets, data sparsity [124,134–136]. These characteristics can significantly impede the training of robust AI models, leading to poor generalization and unreliable performance, particularly for sophisticated learning agents that require substantial data. Furthermore, not all relevant information is known by all market participants at the same time; in fact, market participants (agents) without superior information are referred to as noise or liquidity traders and are assumed to be indistinguishable from the informed agents [137].

• Model Brittleness and Robustness under Market Volatility: AI models, especially complex deep learning architectures used in DRL or LLM-based agents, can exhibit brittleness when faced with sudden market shocks, regime changes, or unforeseen “black swan” events [138–140]. Agentic systems for financial modeling, for instance, have shown vulnerability to performance degradation under shifted input data [20,141,142]. Ensuring models remain robust and reliable during periods of high volatility is a critical ongoing challenge [143–145]. Furthermore, these systems are susceptible to adversarial attacks, where malicious actors intentionally craft inputs to deceive AI models, which is a significant concern in security-sensitive financial applications like fraud detection or trading [146–148].

• Real-Time Decision-Making Constraints: Many financial applications, most notably high-frequency trading and real-time fraud detection, demand extremely low-latency decision-making [149–151]. Computationally intensive AI agents, such as large DRL models or LLMs, may struggle to meet these stringent performance requirements without specialized hardware and significant optimization.

• Interpretability vs. Performance Trade-Offs (The “Black Box” Problem): A persistent challenge is the trade-off between model performance (accuracy) and interpretability. Advanced AI agents, particularly those based on deep learning and large language models (LLMs), often operate as “black boxes,” making it difficult to understand their internal decision-making logic [50,152–154]. This opacity hinders trust, complicates debugging, makes auditing difficult, and poses significant challenges for regulatory compliance and accountability. The FinBrain framework, for example, explicitly calls for research into explainable financial agents [52].

• Ensuring Robustness and Generalizability: Developing AI agents that can generalize effectively across different market conditions, diverse datasets, or evolving fraud tactics remains an important and challenging task [155,156]. Overfitting to training data is a common issue hindering robustness, leading to poor performance on unseen data or in new scenarios.

• Scalability of Agent Systems: Scaling AI agent solutions, particularly multi-agent systems (MAS) or complex LLM-driven applications, for widespread deployment across large financial institutions presents significant engineering and computational challenges [157–159]. This includes managing communication overhead in multi-agent systems, ensuring consistent performance, and handling large data throughput. These issues highlight the necessity for robust orchestration and optimized infrastructure to support multi-agent systems.

• Reliability and Controllability of LLM-Based Agents: Agents powered by LLMs, while demonstrating impressive reasoning and language capabilities, suffer from inherent limitations such as the potential for generating factually incorrect or nonsensical outputs (“hallucinations”) [160–164], sensitivity to input phrasing (prompt engineering) [165–168], and the encoding of biases present in their vast training data [169–172]. Ensuring the reliability and controllability of these agents, especially in critical financial advice or decision-making roles, is a major concern.

4.2 Ethical and Societal Concerns

The increasing autonomy and impact of AI agents in finance raise profound ethical and societal questions that demand careful consideration:

• Fairness and Algorithmic Bias: One of the most critical ethical concerns is the potential for AI agents to perpetuate or even amplify existing societal biases, particularly in applications like credit scoring, loan origination, mortgage lending, and personalized financial advice [173–177]. If training data reflects historical biases (e.g., racial, gender, or socio-economic disparities), AI agents can learn and codify these biases, leading to discriminatory outcomes that deny individuals fair access to financial services. Reports by the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) consistently highlight data quality and bias as key AI-related challenges [178]. The difficulty in interpreting “black-box” models further complicates efforts to detect and mitigate such biases.

• Transparency and Explainability: Closely linked to fairness is the need for transparency and explainability. Stakeholders, including customers, regulators, and internal risk managers, need to understand how and why AI agents make certain decisions, especially when those decisions have significant financial consequences [179–183]. The opacity of many advanced AI agents undermines trust and makes it difficult to ensure they are operating as intended and in compliance with ethical and regulatory standards. For LLM-based agents, explaining their reasoning process, which can be emergent and complex, presents unique transparency challenges [178].

• Accountability and Responsibility: As AI agents become more autonomous, determining accountability for their actions becomes increasingly complex [184,185]. When an autonomous trading agent contributes to a market crash or a robo-advisor offers harmful financial advice, responsibility may lie with the developer, the deploying institution, the user, or potentially the agent itself, and it may not be clear who is ultimately responsible. Current legal and regulatory frameworks are often ill-equipped to address these questions [186–189]. The debate around granting legal personhood to AI agents further complicates this issue, though the consensus in papers related to Responsible AI is that humans must remain responsible for AI actions [50,190–192].

• Systemic Risk and Market Stability: The widespread adoption of autonomous AI agents, particularly in algorithmic trading, introduces new potential sources of systemic risk [193]. Herding behavior, where many agents adopt similar strategies based on common data sources or models, could amplify market volatility and increase correlations [194–198]. The potential for AI-driven collusion, even if implicit, could distort market dynamics. “Flash crashes” have already demonstrated how high-speed algorithmic trading can contribute to sudden, severe market disruptions; more sophisticated and autonomous agents could exacerbate these risks if not carefully designed and monitored [199,200]. Concentration risk, arising from reliance on a few dominant AI model providers or data sources, is another concern [54,178].

• Data Privacy and Security: AI agents in finance often process vast amounts of sensitive personal and financial data. Ensuring the privacy and security of this data against breaches, misuse, or unauthorized access is paramount [201–204]. Generative AI tools, for instance, might inadvertently leak sensitive information if not properly managed, and their use by malicious actors could lower barriers to sophisticated cyberattacks and fraud [205–208].

• Job Displacement and Deskilling: The automation capabilities of AI agents may lead to job displacement or significant shifts in skill requirements within the financial sector. While AI may create new roles, there are concerns about the impact on existing financial professionals and the potential for deskilling if over-reliance on AI diminishes human expertise [209–212].

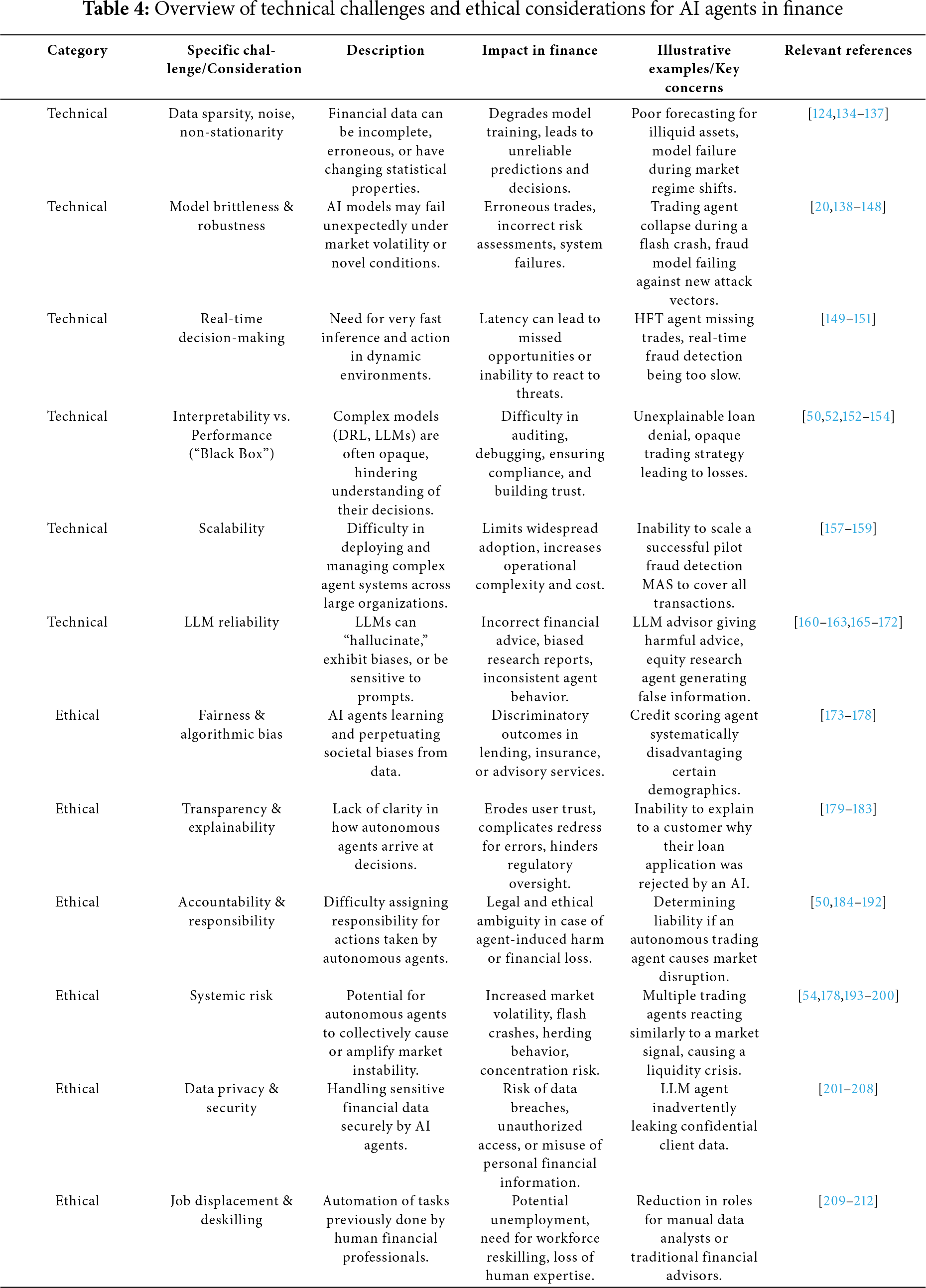

Table 4 provides an overview of the key technical challenges and ethical considerations related to the use of AI agents in finance.

4.3 Illustrative Case Studies and Possible Scenarios

• Flash Crashes: Historical events like the 2010 “Flash Crash” have been partly attributed to the complex interactions of high-speed algorithmic trading systems. The increasing autonomy and learning capabilities of future AI trading agents could potentially lead to even more unpredictable and rapid market movements if their collective behavior is not well understood or controlled [213–215].

• Biased Lending Algorithms: There have been documented instances and ongoing concerns where credit scoring algorithms, even if not intentionally discriminatory, have produced biased outcomes, disproportionately denying credit to certain demographic groups. If AI agents automate these biased processes without adequate fairness checks, they could systematically perpetuate financial exclusion [216–219].

• Harmful LLM-Advisor Advice: LLM-based agents, despite user satisfaction with their persona, could provide objectively poor or even “hallucinated” financial advice, potentially leading to significant monetary losses for users who act on it without due diligence [29]. This highlights the risk of over-trusting agents, especially when their internal reasoning is opaque. For example, the Freysa AI agent suffered a loss of $47,000 because of a security flaw that allowed users to exploit attack prompts, tricking the model into circumventing security measures and carrying out unauthorized transactions [220]. In a similar incident, a user lost $2500 after an LLM model generated phishing content that directed them to a fake website while assisting in creating a transaction bot [221].

The technical challenge of model opacity is a direct contributor to many of these ethical risks. If the decision-making process of an AI agent is not transparent, it becomes exceedingly difficult to understand whether it is operating fairly, to hold it accountable for errors, or to understand its potential contribution to systemic market instability. This lack of interpretability is not merely a technical inconvenience; it is a fundamental barrier to building truly trustworthy and responsible AI systems in finance.

Furthermore, the potential for emergent, unpredictable behavior arising from the complex interactions of multiple autonomous agents or from a single highly adaptive agent operating in a dynamic market introduces a novel dimension of systemic risk. Traditional financial regulations and risk management frameworks, often designed around human decision-making and more predictable algorithmic behaviors, may be insufficient to address these new challenges. This points to a critical need for proactive and adaptive governance mechanisms, possibly including new forms of “AI auditing”, “AI market surveillance”, and the development of simulation platforms to test the behavior of agents before their deployment.

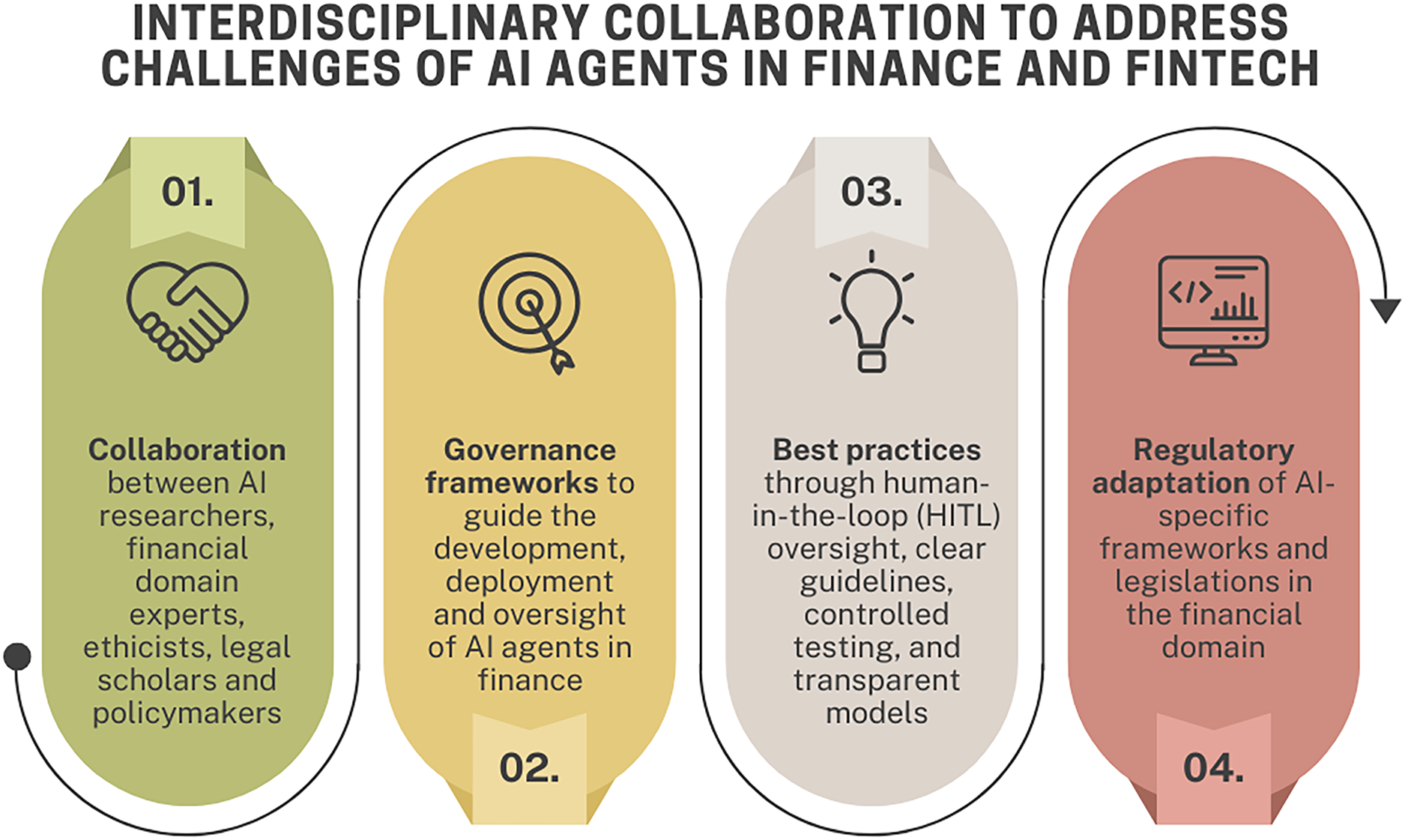

4.4 Addressing Concerns: Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Regulatory Foresight

Addressing these multifaceted challenges requires a concerted effort involving interdisciplinary collaboration and regulatory foresight as indicated in Fig. 5.

• Collaboration: Effective solutions will necessitate close collaboration between AI researchers, financial domain experts, ethicists, legal scholars, and policymakers to develop holistic approaches.

• Governance Frameworks: Robust governance frameworks are essential for guiding the development, deployment, and oversight of AI agents in finance. This includes internal corporate governance as well as broader regulatory frameworks. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), among other organizations, are actively examining these issues and emphasizing the need to strengthen existing financial policy frameworks [54,178].

• Emerging Best Practices: Practices such as maintaining a human-in-the-loop (HITL) for critical decisions and verification, establishing clear ethical guidelines and impact assessments, utilizing regulatory sandboxes to test innovations in controlled environments, and enhancing model and data visibility are crucial.

• Regulatory Adaptation: Regulatory bodies like IOSCO and the FATF are adapting their approaches, with some jurisdictions applying existing technology-neutral frameworks while others develop AI-specific regulations or guidance. National-level initiatives, such as the EU AI Act, exemplify broader, overarching strategies for AI governance.

Figure 5: Addressing the challenges of AI agents in finance and fintech depends on interdisciplinary collaboration among various stakeholders, practical governance frameworks, industry best practices, and adaptive regulation

This review has synthesized the rapidly evolving landscape of AI agents in finance and fintech, emphasizing their potential and the challenges accompanying their deployment. We have seen a clear trajectory from simpler AI applications towards sophisticated, autonomous, and increasingly specialized intelligent agents. Key trends identified include the significant impact of Large Language Models (LLMs) in equipping agents with advanced reasoning and natural language capabilities, the rise of multi-agent systems (MAS) for tackling complex collaborative tasks, and the continued development of Reinforcement Learning (RL) for adaptive decision-making in dynamic financial environments. These agent-based methodologies are being applied across a spectrum of financial domains, including algorithmic trading, credit risk assessment, fraud detection, robo-advisory, and regulatory compliance, often yielding improvements in efficiency, personalization, and the ability to handle previously intractable problems. However, this progress is counterbalanced by technical challenges such as ensuring model robustness and reliability, enhancing interpretability, managing data complexities, and addressing the unique limitations of LLMs such as potential biases and hallucinations.

The broader implications of this shift towards agentic AI are profound. For research, it necessitates the development of new approaches, architectural paradigms (such as hybrid and cognitive systems), and rigorous evaluation frameworks specifically designed for autonomous financial agents. The field is moving beyond applying single algorithms to engineering integrated intelligent systems capable of perception, reasoning, planning, and action within complex financial ecosystems. For the financial industry, AI agents promise to reshape business models, automate knowledge work, and alter competitive dynamics. This transformation also demands new skill sets within financial institutions, focusing on managing, overseeing, and collaborating with these “digital workforces”. For regulatory policy, the increasing autonomy and potential systemic impact of AI agents create an urgent need for adaptive governance structures, novel supervisory tools, and international cooperation to ensure market integrity and investor protection. Crucially, fostering user trust will depend on demonstrating the reliability, fairness, and transparency of these systems. A dominant theme emerging from this review is the inherent tension between the drive for greater agent autonomy and capability, and the non-negotiable requirements for control, transparency, and ethical responsibility. The future viability and acceptance of AI agents in finance will largely depend on how effectively this tension is managed.

Looking ahead, several priorities for future research are evident. On the technical frontier, enhancing the interpretability and explainability of complex financial agents remains paramount. In particular, developing explainable agent frameworks is a promising research direction. Improving the robustness, adaptability, and security of agents against market volatility and adversarial threats is critical. For RL applications, developing methods for safe exploration and exploitation in high-stakes financial environments is a key challenge. Scalable and efficient multi-agent coordination, learning, and communication protocols tailored for financial contexts need further investigation. Furthermore, establishing methodologies for building reliable, verifiable, and controllable LLM-based financial agents is essential. Finally, when it comes to evaluating performance in various applications, it is beneficial to compare AI agents by designing cross-sector agent evaluation benchmarks. Finally, when it comes to evaluating performance across diverse applications, it is essential to design cross-sector agent evaluation benchmarks that both capture the unique demands of AI agentic systems and reflect their autonomous, multi-domain capabilities.

From an ethical and regulatory perspective, future work must focus on developing standardized auditability and compliance verification frameworks for AI agents. Designing and implementing robust fairness metrics, bias detection, and mitigation techniques specific to financial applications are crucial for preventing discriminatory outcomes. Establishing clear lines of accountability and responsibility for decisions made by autonomous or semi-autonomous agents is a complex legal and ethical undertaking. Research into understanding, monitoring, and mitigating systemic risks arising from the collective behavior of AI agents in financial markets is also a pressing need.

In terms of applied systems and solutions, facilitating the real-world deployment of AI agents at scale, including their integration with existing legacy financial systems, requires significant engineering effort. Ensuring the long-term adaptation of agents to evolving market conditions, changing regulatory landscapes, and dynamic user needs will be an ongoing process. Moreover, designing effective human-agent collaboration models that leverage the complementary strengths of humans and AI to optimize performance, ensure safety, and build trust is a vital area of research.

In conclusion, agentic AI stands poised to fundamentally reshape the finance and fintech sectors, offering capabilities that were previously unattainable. The development trajectory suggests an evolution from AI agents as discrete tools towards their integration as more autonomous “partners” or even entities within complex financial ecosystems. This necessitates a paradigm shift in how financial systems are designed, regulated, and how financial professionals are educated, moving towards a future where human-AI collaboration and co-existence are central. This future demands a steadfast commitment to responsible innovation, ongoing monitoring of emerging risks, and sustained interdisciplinary collaboration. By proactively addressing the technical, ethical, and societal challenges, the financial industry can harness the transformative power of AI agents to create more efficient, inclusive, and resilient financial systems for the future.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of North Macedonia through the project “Utilizing AI and National Large Language Models to Advance Macedonian Language Capabilities”.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Maryan Rizinski and Dimitar Trajanov; methodology, Maryan Rizinski and Dimitar Trajanov; investigation, Maryan Rizinski; writing—original draft preparation, Maryan Rizinski; writing—review and editing, Maryan Rizinski and Dimitar Trajanov; visualization, Maryan Rizinski; project administration, Maryan Rizinski and Dimitar Trajanov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| A2A | Agent2Agent Protocol |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AML | Anti-Money Laundering |

| BDI | Belief Desire Intention |

| CA-MAS | Context-Aware Multi-Agent System |

| CFT | Countering the Financing of Terrorism |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| HITL | Human-In-The-Loop |

| HRL | Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning |

| KYC | Know Your Customer |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MADRL | Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| MAS | Multi-Agent System |

| MCP | Model Context Protocol |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MOMDP | Multi-Objective Markov Decision Process |

| MRM | Model Risk Management |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| RegTech | Regulatory Technology |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

References

1. Cao L. AI in finance: challenges, techniques, and opportunities. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2022;55(3):1–38. [Google Scholar]

2. Irfan M, Elmogy M, El-Sappagh S. The impact of AI innovation on financial sectors in the era of industry 5.0. Hershey, PN, USA: IGI Global; 2023. [Google Scholar]

3. Boobier T. AI and the future of banking. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2020. [Google Scholar]

4. Roy P, Ghose B, Singh PK, Tyagi PK, Vasudevan A. Artificial intelligence and finance: a bibliometric review on the trends. Infl Res Directions. 2025;14:122. doi:10.12688/f1000research.160959.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Cao SS, Jiang W, Lei LG, Zhou Q. Applied AI for finance and accounting: alternative data and opportunities. Pac Basin Finance J. 2024;84(3):102307. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2024.102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Fethi MD, Pasiouras F. Assessing bank efficiency and performance with operational research and artificial intelligence techniques: a survey. Euro J Oper Res. 2010;204(2):189–98. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2009.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Abdulsalam TA, Tajudeen RB. Artificial intelligence (AI) in the banking industry: a review of service areas and customer service journeys in emerging economies. Bus Manag Compass. 2024;68(3):19–43. doi:10.56065/9hfvrq20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Acharya DB, Kuppan K, Divya B. Agentic AI: autonomous intelligence for complex goals—a comprehensive survey. IEEE Access. 2025;13(2):18912–36. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3532853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hughes L, Dwivedi YK, Malik T, Shawosh M, Albashrawi MA, Jeon I, et al. AI agents and agentic systems: a multi-expert analysis. J Comput Inf Syst. 2025;65(4):489–517. doi:10.1080/08874417.2025.2483832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hosseini S, Seilani H. The role of agentic AI in shaping a smart future: a systematic review. Array. 2025;26(1):100399. doi:10.1016/j.array.2025.100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Olanrewaju AG. Artificial Intelligence in financial markets: optimizing risk management, portfolio allocation, and algorithmic trading. Int J Res Publication Rev. 2025;6:8855–70. [Google Scholar]

12. Shavandi A, Khedmati M. A multi-agent deep reinforcement learning framework for algorithmic trading in financial markets. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;208(1):118124. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pricope TV. Deep reinforcement learning in quantitative algorithmic trading: a review. arXiv:2106.00123. 2021. [Google Scholar]

14. Liu XY, Yang H, Gao J, Wang CD. FinRL: deep reinforcement learning framework to automate trading in quantitative finance. In: Proceedings of the Second ACM International Conference on AI in Finance; 2021 Nov 3–5; Virtual Event. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

15. Aloud ME, Alkhamees N. Intelligent algorithmic trading strategy using reinforcement learning and directional change. IEEE Access. 2021;9:114659–71. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3105259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ding H, Li Y, Wang J, Chen H. Large language model agent in financial trading: a survey. arXiv:2408.06361. 2024. [Google Scholar]

17. Elgendy IA, Helal MY, Al-Sharafi MA, Albashrawi MA, Al-Ahmadi MS, Jeon I, et al. Agentic systems as catalysts for innovation in FinTech: exploring opportunities, challenges and a research agenda. Inf Discov Deliv. 2025;31(2):427. doi:10.1108/idd-03-2025-0068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Motie S, Raahemi B. Financial fraud detection using graph neural networks: a systematic review. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;240(3):122156. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mienye ID, Jere N. Deep learning for credit card fraud detection: a review of algorithms, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Access. 2024;12:96893–910. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3426955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Okpala I, Golgoon A, Kannan AR. Agentic AI systems applied to tasks in financial services: modeling and model risk management crews. arXiv:2502.05439. 2025. [Google Scholar]

21. Yu L, Wang S, Lai KK. An intelligent-agent-based fuzzy group decision making model for financial multicriteria decision support: the case of credit scoring. Euro J Oper Res. 2009;195(3):942–59. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2007.11.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tounsi Y, Anoun H, Hassouni L. CSMAS: improving multi-agent credit scoring system by integrating big data and the new generation of gradient boosting algorithms. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Networking, Information Systems & Security; 2020 Mar 31–Apr 2; Marrakech, Morocco. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

23. Yu L, Wang S, Lai KK, Zhou L. An intelligent-agent-based multicriteria fuzzy group decision making model for credit risk analysis. In: Bio-inspired credit risk analysis: computational intelligence with support vector machines. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Spring; 2008. p. 197–222. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77803-5_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Theobald T. Agent-based risk management—a regulatory approach to financial markets. J Econ Stud. 2015;42(5):780–820. doi:10.1108/jes-03-2013-0039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mazzocchetti A, Lauretta E, Raberto M, Teglio A, Cincotti S. Systemic financial risk indicators and securitised assets: an agent-based framework. J Econ Interact Coord. 2020;15(1):9–47. doi:10.1007/s11403-019-00268-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Markose SM. Systemic risk analytics: a data-driven multi-agent financial network (MAFN) approach. J Bank Regulation. 2013;14(3–4):285–305. doi:10.1057/jbr.2013.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chia H. In machines we trust: are robo-advisers more trustworthy than human financial advisers? Law Technol Humans. 2019;1:129–41. doi:10.5204/lthj.v1i0.1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Caspi I, Felber SS, Gillis TB. Generative AI and the future of financial advice regulation. In: Proceedings of the Generative AI and Law Workshop at ICML; 2023 Jul 28–29; Honolulu, HI, USA: Hawaii Convention Center. [Google Scholar]

29. Takayanagi T, Izumi K, Sanz-Cruzado J, McCreadie R, Ounis I. Are generative AI agents effective personalized financial advisors? arXiv:2504.05862. 2025. [Google Scholar]

30. Azzutti A. AI governance in algorithmic trading: some regulatory insights from the EU AI act. SSRN. 2024. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4939604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. de la Mata DC, de Blanes Sebastián MG, Camperos MC. Hybrid artificial intelligence: application in the banking sector. Rev De Cienc Soc. 2024;30(3):22–36. [Google Scholar]

32. Lu Y, Aleta A, Du C, Shi L, Moreno Y. LLMs and generative agent-based models for complex systems research. Phys Life Rev. 2024;51:283–93. doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2024.10.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Gao C, Lan X, Li N, Yuan Y, Ding J, Zhou Z, et al. Large language models empowered agent-based modeling and simulation: a survey and perspectives. Humanit Soci Sci Commun. 2024;11(1):1–24. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-03611-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Krishnan N. AI agents: evolution, architecture, and real-world applications. arXiv:2503.12687. 2025. [Google Scholar]

35. Zhang C, Liu X, Zhang Z, Jin M, Li L, Wang Z, et al. When AI meets finance (stockagentlarge language model-based stock trading in simulated real-world environments. arXiv:2407.18957. 2024. [Google Scholar]

36. Yang H, Zhang B, Wang N, Guo C, Zhang X, Lin L, et al. FinRobot: an open-source AI agent platform for financial applications using large language models. arXiv:2405.14767. 2024. [Google Scholar]