Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Blockchain-Assisted Improved Cryptographic Privacy-Preserving FL Model with Consensus Algorithm for ORAN

1 Department of Network Technology, T-Mobile USA Inc., Bellevue, WA 98006, USA

2 Department of Professional Services, Axyom.Core, North Andover, MA 01810, USA

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Saveetha School of Engineering, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai, 602105, India

* Corresponding Author: Surendran Rajendran. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069835

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The next-generation RAN, known as Open Radio Access Network (ORAN), allows for several advantages, including cost-effectiveness, network flexibility, and interoperability. Now ORAN applications, utilising machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, have become standard practice. The need for Federated Learning (FL) for ML model training in ORAN environments is heightened by the modularised structure of the ORAN architecture and the shortcomings of conventional ML techniques. However, the traditional plaintext model update sharing of FL in multi-BS contexts is susceptible to privacy violations such as deep-leakage gradient assaults and inference. Therefore, this research presents a novel blockchain-assisted improved cryptographic privacy-preserving federated learning (BICPPFL) model, with the help of ORAN, to safely carry out federated learning and protect privacy. This model improves on the conventional masking technique for sharing model parameters by adding new characteristics. These features include the choice of distributed aggregators, validation for final model aggregation, and individual validation for BSs. To manage the security and privacy of FL processes, a combined homomorphic proxy-re-encryption (HPReE) and lattice-cryptographic method (HPReEL) has been used. The upgraded delegated proof of stake (Up-DPoS) consensus protocol, which will provide quick validation of model exchanges and protect against malicious attacks, is employed for effective consensus across blockchain nodes. Without sacrificing performance metrics, the BICPPFL model strengthens privacy and adds security layers while facilitating the transfer of sensitive data across several BSs. The framework is deployed on top of a Hyperledger Fabric blockchain to evaluate its effectiveness. The experimental findings prove the reliability and privacy-preserving capability of the BICPPFL model.Keywords

The extensive use of mobile devices, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and innovations like 5G have led to an exponential increase in demand for wireless communication services, necessitating radical changes in Radio Access Network (RAN) technologies. An evolutionary step that adds new features to the traditional RAN configuration is Open RAN (ORAN) [1]. It offers several benefits, including network optimisation, scalability, security, resilience, interoperability, and vendor diversity. Intending to promote a more open, interoperable, and economical network infrastructure, this strategy represents a significant change in the design and deployment of RANs. The Service Management and Orchestration Framework (SMO), ORAN Distributed Unit (O-DU), ORAN Central Unit (OCU), RAN Intelligent Controller (RIC), O-Cloud, and ORAN Radio Unit (O-RU) are the six main parts of the ORAN architecture, which has been thoroughly described by the ORAN Alliance [2]. Improved interference control, resource allocation, spectrum management, predictive maintenance, security, and anomaly detection are just a few of the many benefits that machine learning (ML) brings to ORAN systems [3]. The quantity and diversity of data help to improve the performance of ML models. Using data from various base stations (BSs) in ORAN contexts greatly improves ML model training because these BSs experience a range of user behaviours and network characteristics [4]. However, centralising data collection for ML model training maximises exposure to possible attacks, and sharing data inside BS cell zones creates privacy problems. It is not feasible to centrally aggregate data from BS cell locations due to the significant resources required [5].

Federated Learning (FL) [6] is an innovative ML technique that permits cooperative model training in local settings while protecting the privacy of training data. FL tackles the drawbacks of conventional ML techniques [7]. FL can be implemented in RAN contexts more successfully in the ORAN alliance’s modular architecture than conventional systems. Thus, in beyond 5G (B5G)/6G networks, FL and ORAN can be used to create optimised RAN settings [8]. Even if FL provides some partial answers to the problems listed above, some restrictions might still exist. Even when the model parameters are shared rather than the raw training data, adversaries may still be able to perform inference attacks to extract private information about the model parameters and training data. Furthermore, the centralised server is a single point of failure in FL. For essential or localised applications, this reliance on a centralised server might not be appropriate. Moreover, the centralised organisation is frequently taken for granted. However, there is a chance that the received local models will be incorrectly aggregated if this aggregator turns out to be malevolent or unreliable, which would prevent ML models from performing as expected [9]. This research presents a novel approach for implementing a safe and privacy-preserving machine learning framework for ORAN contexts by combining blockchain, FL, and Improved Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC). With assistance from ORAN SMO and the mobile core network, the first stage entails distributing ML models among BSs. To avoid unwanted access to sensitive data contained in locally trained models, it is essential that BSs securely share these models.

Blockchain technology is used to solve possible problems resulting from an unreliable centralised entity by establishing trust inside the system [10]. The proposed system conceals real model updates from local models using a proven masking technique that was chosen for its user-friendliness. Nevertheless, we have effectively addressed the drawbacks of the masking technique in our suggested mechanism, including aggregator validation and individual operator validation. A series of experiments and the implementation of a sample prototype have demonstrated the usefulness of the suggested framework. The major contribution of the proposed method is provided below as follows:

• To propose a novel blockchain-assisted improved cryptographic privacy-preserving federated learning (BICPPFL) model that incorporates blockchain technologies and enhanced cryptographic techniques toward privacy, security, and trust in the FL method within the ORAN architecture.

• To utilise a hybrid cryptographic scheme called Homomorphic Proxy-ReEncryption and Lattice Cryptographic Algorithm (HPReEL), which aids in secure model aggregation through homomorphic operations, resists quantum attacks, and reduces computation overhead.

• The Hyperledger Fabric blockchain will be incorporated to enable a secure, decentralised, and transparent recording of model updates, validation results, and participant contributions, thereby reducing the risks associated with single-point failures.

• To introduce an upgraded delegated proof of stake (Up-DPoS) consensus protocol for achieving faster transaction finality, secure validation of model exchanges and safeguarding against malicious attacks within the blockchain network.

For effective jamming attack detection in O-RAN, Abou El Houda et al. [11] offered a unique architecture that blends deep reinforcement learning (DRL) and FL. Using their data sources, FL enabled decentralised agents to train local models. These models were then combined into a global model at a Non-real-time RAN Intelligent Controller (RIC) to inform decision-making. Distributed intelligence was made possible by the FL process, and robust and adaptive jamming attack detection was guaranteed by DRL. This system used adaptive DRL and collaborative FL to enhance security, privacy, and resilience in ORAN. However, its superiority in scalability, resource efficiency, and detection accuracy was low. A novel FL framework with dropout-resilient and highly secure aggregation (HSADR) was suggested by Wu et al. [12] using edge computing systems for radio access networks. Here, the dropout-resilient and highly secure aggregation FL technique that used differential privacy and consortium blockchain was applied mainly to preserve the security environment. Second, the aggregation process had achieved the first strategy to accomplish the IND-CCA2 security level. Finally, tests demonstrated that HSADR was resistant to typical test elements. However, the obtained outcomes were not satisfactory due to security issues. Singh and Nguyen [13] introduced communication-effective compressed and accelerated FL in ORAN Intelligent Controllers. Here, MCORANFed, a second-order gradient descent-based FL training approach, was used to converge faster than state-of-the-art FL variations while minimising communication costs through the use of compression techniques. To reduce the total cost of resources and learning time, a joint optimisation problem was formulated and solved using the decomposition approach. The experimental results demonstrated that MCORANFed outperforms other FL approaches in terms of costs and convergence rate, and that it was communication efficient concerning the ORAN system. However, the accuracy of this model was poor.

A Zero-Trust architecture specifically designed for ORAN (ZTORAN) was suggested by Moudoud et al. [14]. The two primary components of ZTORAN were (1) a decentralised trust management system based on blockchain technology for safe xApp authentication, verification, and dynamic access control, and (2) a threat detection module that employs Federated Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (FMARL) to continuously monitor network activity and identify irregularities in the ORAN ecosystem. This method illustrated ZTORAN’s efficacy in offering a robust and secure architecture for next-generation wireless networks with thorough simulations and assessments. However, an efficient cryptographic algorithm was required to improve privacy performance. To maintain heterogeneous FL execution in optimised ORAN and intelligent core network architectures, Tam and Kim [15] intended to design autonomous FL management using integrated graph neural networks (GNN) and DRL, specifically AutoFedGDRL. Additionally, it would provide automated policy-driven orchestration by an intelligent agent controller. To enable numerous services with elastic containerised resource scaling and aid in model computation, edge cloud virtualised O-RAN was integrated. By representing the participants and aggregators as a graph and then analysing the results to forecast the nodes’ reliability and accessibility, bandwidth capacity, and virtual connection relationships, FL systems become more feasible. Even though performance improved, security was considered a major concern. Table 1 provides the contributions and limitations of the existing methods.

Problem statement: The existing literature discusses several challenges that underscore the need for the proposed BICPPFL. Although the existing methods incorporated FL with some security measures (including differential privacy, blockchain validation, and cryptographic protocols), there were limitations in terms of accuracy, computational costs, and resistance to attacks. Even if the FL approaches for DRL and dropout resilient aggregation provide some improvement in the area of security, these are compromised or inefficient due to a high resource cost with limited scalability to multi-intentions or network ORAN. Furthermore, in the complex and dynamic environment of ORAN, especially in multi-base station (multi-BS) environments, the existing models lack thorough validation and a balance between security, privacy, and system efficiency.

This section provides a detailed explanation of the proposed model. The proposed model begins with choosing a random aggregator through a hash-based strategy, guaranteeing unpredictability. The proposed method encompasses each base station (BS) with locally trained models, then encrypting and masking updates by utilising homomorphic proxy-re-encryption (HPReE) and lattice-cryptographic algorithm (HPReEL) for improved privacy and security. These masked models are recorded on the blockchain, where the upgraded delegated proof of stake (Up-DPoS) consensus algorithm validates contributions securely and efficiently. The blockchain nodes verify model integrity and provide secure aggregation without revealing raw data. Then, the encrypted aggregation model is decrypted securely for deployment to BSs. This process ensures robustness, privacy and trustworthiness in the FL environment.

3.1 Federated Learning Model for ORAN

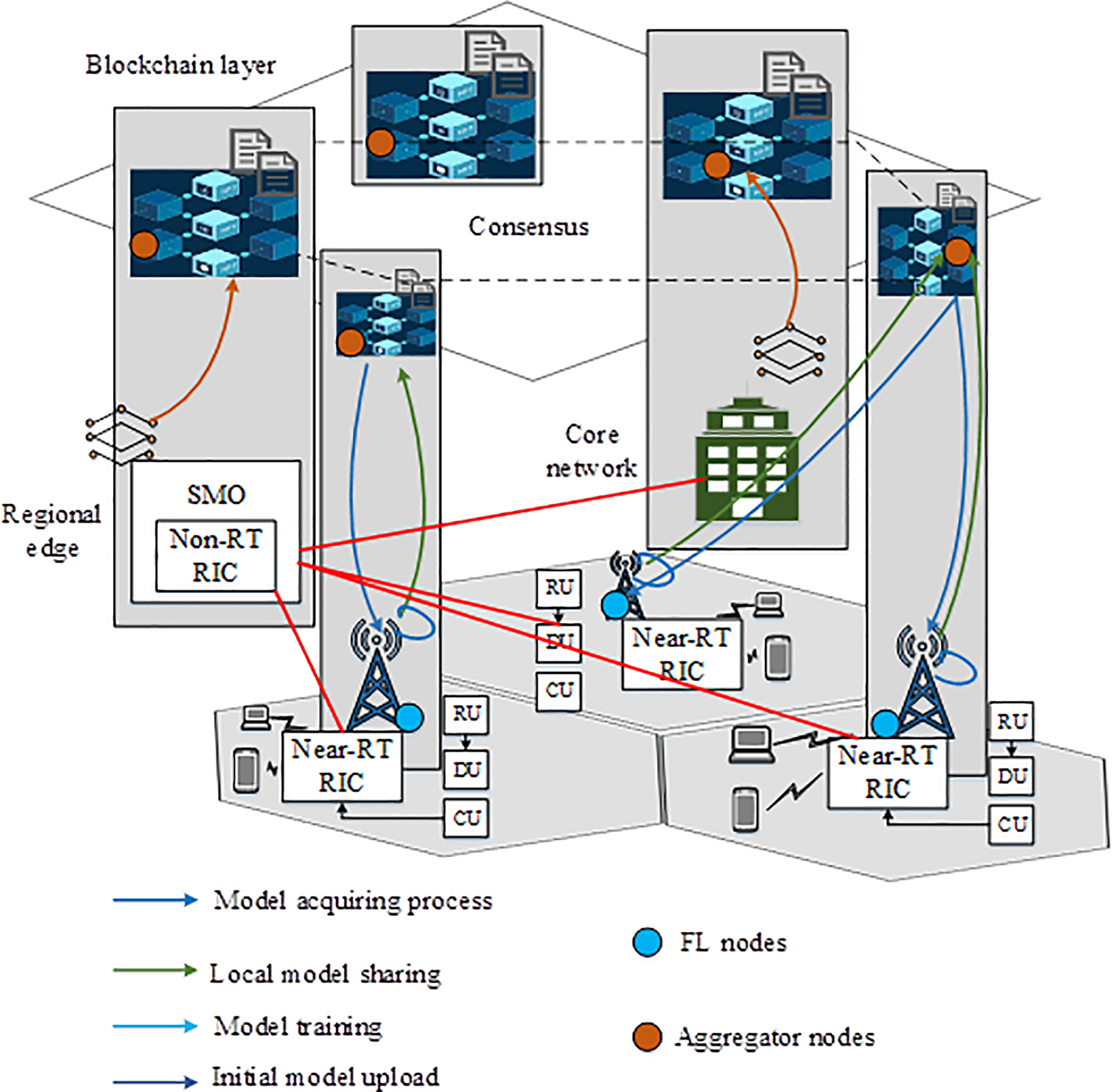

This section introduces the proposed effective consensus-based FL model for ORAN environments. In this model, a consortium blockchain network is regarded since every blockchain node gets the chance to become an aggregator for a specific FL round. Fig. 1 illustrates the architecture of the suggested framework. The figure demonstrates the layered design of the proposed BICPPFL architecture in the ORAN environment. The illustration provides the interactions of the layered blockchain layer and the regional edge components (e.g., SMO, Non-RT RIC, Near-RT RIC, CU, DU, RU), core network and how they can communicate while transferring model acquisition, model sharing, model training, and uploading the initialised model. Also, it depicts the tasks relevant to FL nodes and aggregator nodes.

Figure 1: Architecture of the suggested framework

The domain parameters of the cryptographic algorithm used in the learning process should be shared in the ledger so that all the participating BSs have access to them. Every element that needs to join the blockchain must have a private and public key pair, essential to the FL process. Near-RT RIC accomplishes the FL worker role, and non-RT RIC accomplishes the FL aggregator role (rApps and xApps must be executed to complete the respective FL role). RAN-related data are gathered by the xApps, and the deep learning (DL) models are trained based on the gathered data. After that, the trained local models are distributed to the blockchain ledger.rApps obtain the locally trained models, perform the model aggregation, and send back the aggregated model to the blockchain ledger.rApps obtain the locally trained models, perform the model aggregation, and send back the aggregated model to the blockchain ledger. In the blockchain network, the management role is carried out by the core network and the service management and orchestration framework (SMO). The core network, BSs, and regional clouds with more resources can hold blockchain nodes. The nodes holding the management role will distribute initial DL models to the blockchain network. Next, the xApps can obtain the initial models from the blockchain.

Fig. 2 illustrates the structure of the deployment of the proposed framework in an ORAN environment. This diagram describes the deployment architecture of the proposed BICPPFL framework within an ORAN environment, with emphasis on the interactions between xApps and rApps. It shows how locally trained parameters from Node 1 (xApps) and the aggregate model from Node 2 (rApps) exist in an ORAN environment, including O-eNB, O-NB, O-RU, O-DU, O-CU-UP, and the E2 interface. The figure subsequently illustrates the process flow, including unique rApp selections from multiple nodes, based on hash values and Hamming distance, which is an important aspect of the FL process.

Figure 2: Structure of the deployment of the proposed framework

Procedural Steps Carried out by Different xApps and rApps

Here, the steps that different xApps and rApps must take to complete a single federated round (from this point on, xApp refers to the xApp that is deployed in near-RT RIC in a specific BS, and rApp refers to the rApp that is deployed in non-RT RIC in the regional cloud, which is related to the suggested framework) are discussed. The three phases that make up the suggested process include a series of ten different steps.

Stage 1: In this stage, the initial part of a given FL round is provided. The first action is the randomised selection of the aggregator rApp node from amongst the non-RT nodes across various regional clouds. The process must be fully randomised so it is unpredictable for any party in order to facilitate fair possibilities for all the nodes to function as the aggregator for an individual federated round. The selection of the aggregator node for the current round is calculated based on non-RT RICs node IDs. To trigger this mechanism, the hash value is calculated for the previous FL round aggregated model

Following the selection of the aggregator rApp node, other xApps share their respective first masking value contributions via the blockchain network. The chosen aggregator starts the FL process by selecting a random integer,

Stage 2: The second phase involves sharing masking commitments with the blockchain and computing the total masking values. In the preceding stage, the aggregator and xApps retrieve encrypted masked values from the blockchain ledger. With its contribution, represented

Stage 3: The third stage involves sharing the local model with the aggregator, masking, and training. xApps find other participants in the current FL round after carefully examining the list of participating xApps in the ledger released in the previous phase. Then, calculate the total masking value. Next, using the computed masked values for each model weight value as determined, each xApp individually trains its local models, represented by

The proposed model employs homomorphic proxy-re-encryption (HPReE) and a lattice-cryptographic algorithm (HPReEL) to handle the security and privacy of the FL process within ORAN environments. The HPReEL algorithm is used to enable cryptographic operations like generating secure key pairs, encrypting and obfuscating model updates, and validating participants’ contributions. This helps avoid the risks associated with data leakage, model and inference attacks. Furthermore, the HPReEL achieves quantum-resistant, secure, and privacy-preserving model aggregation and masking, thus strengthening the overall security, trustworthiness, and robustness of the FL system in ORAN environments. The proxy, delegate, and delegator are the three participants involved in a proxy re-encryption (PReE) scheme. The delegator is the entity that initially encrypts and holds the local DL model before sharing for FL. The delegate is the aggregator rApp that receives the re-encrypted ciphertext to access the model or data for further processing, and the proxy is the blockchain network or designated re-encryption node that performs the re-encryption transformation on the ciphertext. A proxy with specific information can be used to transform the ciphertext of a delegator into the ciphertext of a delegate. However, there is no unencrypted information that the proxy can obtain. The PRe-E schemes can be divided into three groups. The transformation times are the first. Specifically, they can be divided into two classes: single-use and multi-use. If the proxy is able to convert the delegator’s ciphertext to the delegate’s, the PReE scheme is unidirectional. If the ciphertext may be encrypted and decrypted more than once, the PReE method is multipurpose. The HPRe-E method combines the characteristics of the PReE and homomorphic encryption (HE) approaches. PRe-E is regarded as a more advanced type of public-key encryption. Additionally, the three primary parties in PRe-E are discussed: the proxy, the delegator, and the delegate. Through the proxy, a delegator’s ciphertext can be changed into a delegatee’s ciphertext. The proxy can also calculate the same user’s actual and re-encrypted ciphertext similarly. The proposed method has employed a novel HPReEL to encrypt the model updates in order to enhance privacy in the ORAN network.

Lattice: Consider as

The concentration of the integer the lattice here indicates that lattice

Definition 1: Let

Notice that, if

Lemma 1: Consider

Definition 2: Consider that the full rank fundamental of a

3.2.1 Homomorphic Proxy Re-Encryption

Four applications for data sharing are often included in the HPRe-E: blockchain network, proxy, individual BS or local model contributor (xApp), and aggregator rApp. All of the applicants have faith in the blockchain network. Through a proxy, all parties are given a degree of trust. The local model contributor has both saved and encrypted the data. Additionally, the upgraded elliptic curve cryptographic (UECC) algorithm has been used to generate the PRe-E key for the users. The following points outline the main steps involved in creating the HPReE strategy.

Stage 1:

here, the upper constraint on the enlarged multiplicative depth

Stage 2:

For

Stage 3:

The users like local model contributor or aggregator xApp outcomes an actual cipher text

Stage 4:

The user

Stage 5:

For

Stage 6:

The proxy results

Stage 7:

Both the data

3.2.2 Anti-Quantum Security of HPReEL

The HPReEL used in the proposed approach provides strong anti-quantum security because it depends on the hardness of lattice-based problems, such as Learning with Errors (LWE) and the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP). These lattice problems are generally accepted in cryptography as being secure against classical and quantum adversaries since there are no known efficient quantum algorithms to solve them in polynomial time. Therefore, the cryptographic operations that were the foundation of HPReEL will held under some prospective increased quantum attacks. This procedure also ensures the privacy of sensitive model updates and data masking of end users within the federated learning approach. The proposed method uses lattice-based cryptography to assure post-quantum security, which occupies a prominent and stable location in providing assurances against future computing attacks toward privacy and security in an ORAN environment. In particular, HPReEL’s security can be argued using a reductionist proof that shows if an adversary exists for breaking the scheme, then it can be used to solve the underlying lattice problem, which is considered computationally infeasible. Typically, the proof involves constructing a simulator that simulates the environment of the cryptographic scheme in the presence of a lattice problem instance, such that any distinguisher can differentiate the ciphertexts or key transformations and random information when given an instance of a lattice problem. Thereby, violating the assumption that the underlying lattice problem can be solved efficiently. In addition, the scheme uses standard lattice-based primitives (error distributions, trapdoor function) that are provably secure when accessible to a quantum algorithm. These mathematical constructs challenge the effectiveness of Shor’s and Grover’s algorithms in various classical cryptosystems. The HPReEL scheme maintains security even when considering quantum computational access methods. Therefore, in combination with these lattice-based hardness assumptions and well-designed cryptographic methods, HPReEL offers a strong security basis to substantiate the scheme’s robustness against a future quantum computational access method.

3.2.3 Security Proof with a Difficult Reduction Based on the LWE Problem

The fundamental security of the proposed BICPPFL is based on the hardness of the LWE problem. More specifically, BICPPFL reduces the protocol’s security guarantee to the indistinguishability of the LWE problem, under which any polynomial-time adversary should have no non-negligible advantage in distinguishing between real and random ciphertexts.

Assumption 1: The LWE problem with parameters

Protocol with context: In BICPPFL, masking values (or encryption of model updates) are generated using lattice-based cryptographic primitives based on LWE assumptions, e.g., homomorphic encryption schemes.

Security Reduction: Let

Formal statement:

Theorem 1: Given LWE assumption

where,

This reduction ensures that, assuming the hardness of the LWE problem, the leakage of the BICPPFL protocol is computationally infeasible as a task for any polynomial-time adversary and maintains the confidentiality and privacy of local models.

3.3 Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain Technology

A collection of open-source blockchain projects, known as “Hyperledger,” was first introduced by the Linux Foundation in December 2015 and is supported by several major industry players. The fabric is the name given to the Hyperledger’s approved blockchain system component. Fabric enables the implementation of smart contracts, sometimes referred to as chain-codes, against the data provided by clients and ledgers. Chain-codes are developed using general-purpose programming languages such as Go or Node.js. Similar to earlier blockchain systems, chain-code must exhibit determinism, meaning that each execution with the same set of inputs should yield a unique set of recorded outcomes. This characteristic enables the validation and execution of chain-code across multiple untrustworthy nodes. A coin has not been connected to the fabric execution technique. Fabric’s infrastructure nodes, such as peers and orderers, are authenticated by a trustworthy membership service provider (MSP). While orderers are responsible for adding new blocks to the chain, peers are responsible for validating and executing chaincodes. Fabric is used to split the tasks. Within this division of tasks, users can utilize pluggable consensus protocols, such as Byzantine fault-tolerant services like BFT-Smart or crash fault-tolerant services like Apache Kafka. To process and carry out transactions for peers who keep an entire ledger copy, the network uses the execute-order-validate (EOV) methodology. Chain codes for initial execution are executed first by the endorsers, who are subsets of peers. After gathering endorsements, the client incorporates them into a trade proposition. Through a consensus process, the orderers receive the proposals, append them to a block, and add them to the blockchain. Every freshly created block is then sent to each peer in their local network for validation. The outcomes of valid transactions correspond with the copies of the local ledger. In contrast to other open blockchains, the EOV technique requires peer participation for consensus and does not require transactions on every peer to build tentative blocks, resulting in an execution process that is essentially sequential.

This section discusses an upgraded DPoS schema known as Up-DPoS, which aims to validate contributions securely and efficiently by reducing transaction costs while increasing transaction efficiency per second for DPoS. Up-DPoS enables the blockchain to construct a Layer 2 network on top of the current DPoS consensus. Furthermore, the idea of Super BP is presented. The user has the option of sending it to L2 or the mainnet for processing. An L2 transaction might be less expensive than a mainnet transaction. When a transaction is routed straight to the mainnet, it is referred to as Up-DPoS. Because it reaches finality more quickly than L2, the customer will pay more. DPoS might be used on the mainnet; however, block producers would have to stake more tokens to verify a transaction. Additionally, compared to the L2 network, the incentives for voting and validating should be greater. Even while the L2 network would still be in charge of DPoS consensus, the transaction could not be verified, and the user would have to pay more to send the transaction straight to L1. It is possible for any L2 transaction to eventually join the mainnet. This would happen each time, or after a 24-h, the mainnet throughput would sharply decline (limits are to be defined). Fig. 3 provides the design and transaction flow of the Up-DPoS transaction. This diagram depicts the design and transaction processing of the Up-DPoS consensus protocol, which is an essential part of the BICPPFL model. It shows how the user transaction flows on either the L2 network (low fee and delayed finality) or the mainnet (faster finality but greater fee). It also highlights BPs, Super BPs, and the movement of transactions between Layer 1 and Layer 2 to illustrate the method of secure and efficient agreement between blockchains.

Figure 3: Design of Up-DPoS transaction

3.4.1 Convergence and Security Analysis of UP-DPoS Consensus Protocol

In the proposed framework, the Up-DPoS consensus protocol achieves both convergence and security through stake-based validator selection, a hierarchical layered design, and cryptographic security. Convergence is quickly achieved through a stake and hourly vote selection of block producers (BPs), and super BPs, while ensuring that honest and accurate validating nodes have succeeded in enough blocks and rounds of confirmation (with a high probability of

3.4.2 Quantification of Consensus Efficiency

The performance characteristics of the Up-DPoS consensus protocol can be valued in three ways: transaction throughput (TPS), fault-tolerant threshold, and time taken for confirmation.

Transaction Throughput (TPS): It is assumed that in each epoch (hour), the Up-DPoS network processes around 20,000 transactions on Layer 2 and therefore, if each block has an average block size of

As Layer 2 transactions are settled with a period of 12 h, the cumulative throughput from the combined network extents around 60,000 TPS in total from mainnet transactions, which is suitable for a fast user data interchange.

Fault tolerance threshold: The consensus indicates guaranteed safety (guarantee correctness) and holds as long as the fraction

This aligns with traditional BFT, where the system is able to reach consensus, preserving safety, and ensuring the system can correctly tolerate up to 33% of malicious nodes without risking divergence.

Latency and finality: Average confirmation latency for Layer 2 transactions ranges from approximately 2–3 s, while Layer 1 mainnet transactions will take at least 24 h with periodic aggregation before reaching finality. These efficiency measurements demonstrate how Up-DPoS can facilitate high-throughput, safe, and scalable federated learning systems in ORAN environments.

To evaluate the performance, a prototype of the proposed model is implemented by utilising the Hyperledger Fabric blockchain network. In order to accomplish model training and associated masking procedures, the Python programming language is used. Then, it sends the masked model updates to a blockchain client application that runs on Java. The masked models are directed to the Java chain code inside the Hyperledger Fabric network’s peer nodes by this client application, which communicates with the blockchain network. For computing the aggregated model, the rApp blockchain node uses Python. It then uses Java chain codes to publish the aggregated model to the network. A server with 20 CPU cores and 128 GB of RAM is used for the experiments. Depending on the number of BSs that participated in a specified experiment, the Fabric network’s scalability has adjusted. The 5G NIDD dataset, which includes information gathered at the 5G BSs, has been used. Additionally, the CIFAR 100 image dataset is utilised to demonstrate the framework’s privacy-preserving features because it is more practical and easier to demonstrate the impact. Table 2 presents the experimental parameter setup of the proposed method. In FL, client failure negatively affects model performance and overall accuracy. Therefore, the dropout of a significant number of clients during training rounds can have a substantial impact. To measure the drop-out performance impact, a consistent experimental set-up has been used. The total clients has been set to 50, each client utilised a batch size of 32, the learning rate is set to 0.01, and training has been conducted over 100 federated rounds. Client failures are modelled as random dropouts at drop rates of 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 50%-simulating increasing levels of dropout unavailability. The results showed that up to a 10%–20% fail rate, performance converged with nearly optimal accuracy (greater than 99%) and only low increases in convergence time. At failure rates greater than 30%, there are increasingly greater performance drops, where accuracy reached as low as 95% with 50% fail rate, with the number of rounds greatly increasing in time needed to achieve target accuracy. These results underscore the need for fault-tolerance in terms of client selection, redundancy, and other mechanisms for minimal impact of dropouts through peer-discovered training.

Table 3 provides the client failure analysis of the proposed work. This assessment signifies that the federated learning framework is quite robust to low/mid client failures, since it gives similar model accuracy and convergence speeds. However, with higher dropout rates, the framework significantly reduces model accuracy and convergence ability, and consequently, practical systems require improved fault-tolerance.

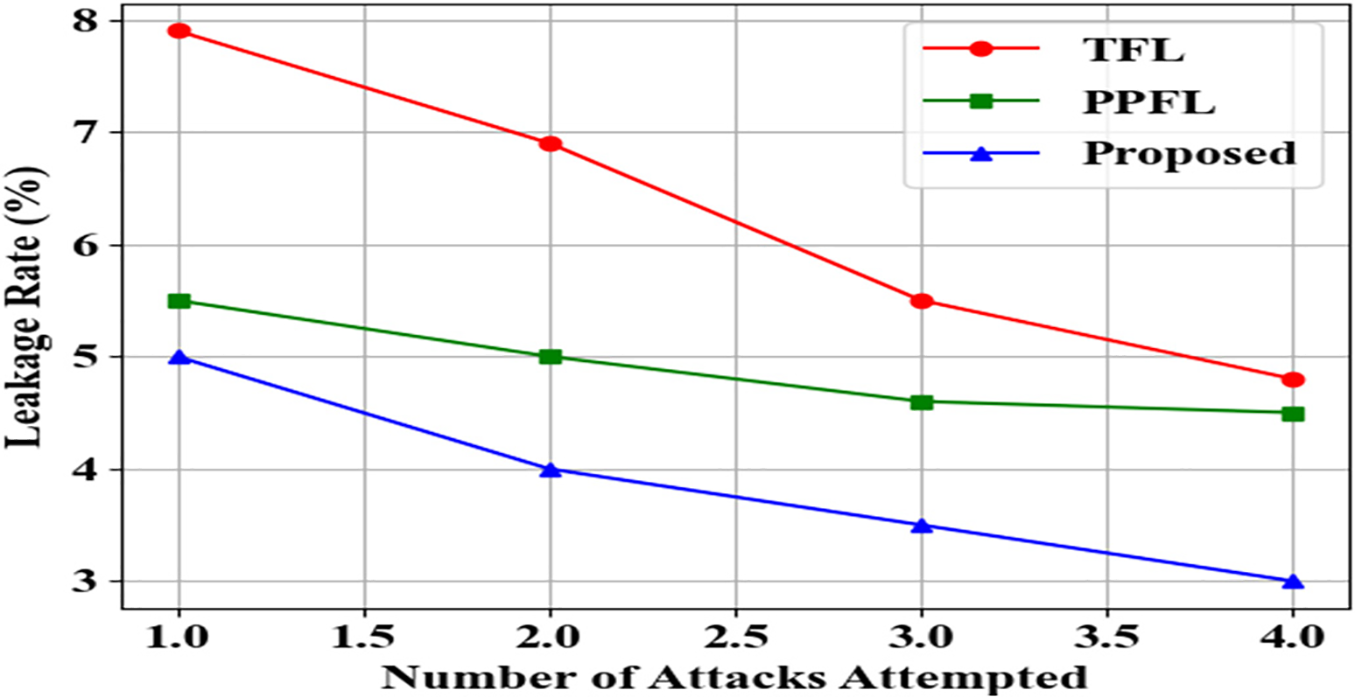

4.1 Defence against Attacks Involving Deep Leaks

Deep leakage attacks specifically involve capturing local model gradients to reconstruct the original training dataset. This experiment investigates how the proposed model can mitigate the impact of deep leakage attacks. The proposed model compares the effects on traditional FL (TFL), which shares unmasked models. Using the CIFAR100 image dataset, the proposed method demonstrates the extraction of private data from shared local models. Both the Deep Leakage from Gradients (DLG) and improved DLG (IDLG) [17] techniques are employed to reconstruct the training data from the shared local models in both approaches.

Fig. 4 shows the effect of retrieving training data from model parameters. Comparing the IDLG method to the DLG method, the trained images can be rebuilt in fewer iterations. This figure clearly shows the experimental results, which indicate the effectiveness of the proposed BICPPFL model against deep leakage attacks, depicting the reconstruction of the original training data (first image) from shared model parameters over iterations by using the classical Deep Leakage from Gradients (DLG) methodology as well as the improved methodology, or improved DLG (IDLG). The illustration illustrates that by masking model gradients, the proposed method restricts the access of trained data to MITM attackers, while TFL was more susceptible.

Figure 4: Effect of retrieving training data from model parameters in deep leakage attacks

4.2 Assessment in Terms of Different Metrics

In this experiment, the proposed model compares the performance of the DL model trained using the TFL approach with DL models trained utilising the suggested security framework. The proposed model compares the two approaches, like TFL and privacy-preserving FL (PPFL), in terms of important metrics such as precision, accuracy, recall, computational overhead, communication cost, scalability and privacy leakage resistance. The 5G NIDD produced from the data gathered at 5G BSs is used in the experiment. For consistent evaluation in this study, this dataset is evenly dispersed across different BSs inside the system.

Table 4 presents the comparison of proposed and existing TFL and PPFL methods in terms of various assessment metrics like accuracy, precision and recall outcomes of the proposed and existing methods. The graph presents accuracy percentages as the number of contributing BSs varies from 2 to 5, indicating that the proposed model has high and stable accuracy, better than other existing approaches, even in the presence of privacy-preserving capabilities. Considering the precision and recall metrics, the proposed method also attains maximum performance of 98.4% and 98.12%, which is better than the existing methods.

Fig. 5 presents the training and validation accuracy analysis of the proposed model. The training and validation accuracy graphs for the proposed method show that when privacy-preserving techniques like HPReEL and blockchain validation are used, there is an impact on the performance of the overall model. As can be seen from the tabular representation, the accuracy metrics for models trained under the proposed method are better compared to those obtained through TFL approaches without privacy enhancements. It suggests that cryptographic operations like masking and model validation processes have added minimal overhead and do not affect learning efficiency. The reason can be found in the efficient execution of all cryptographic processes, protecting model update integrity and confidentiality. Finally, indeed, experiments demonstrate high accuracy sustained by the framework working across diverse BS counts. These are critical traits for any practical deployment of a system. Thus, analysis confirms that security/privacy is not gained at some predictive performance cost. Indeed, it validates the viability of the proposed framework for practical 5G beyond network applications real world. Fig. 6 presents the computation cost, analysis of the proposed BICPPFL and existing methods. The graph of computational cost in which the number of BSs is on the x-axis, and the amount of data exchanged in megabytes (MB), compares how effective the BICPPFL is against several other methods. Results show that irrespective of the federated rounds, the data exchanged stays within manageable limits as BSs increase from 2 to 5. Thus, it demonstrates a scalable property. Also, it shows a slight growth in data exchange due to extra cryptographic operations and blockchain interactions required for privacy, accountability, and model validation assurance. This growth is rather marginal and well-justified by significant security benefits obtained in terms of model leakage mitigation, along with preventing aggregation with malicious intent. On the other hand, existing methods with unprotected models tend to exchange approximately the same or slightly lower quantities of data but at a higher cost in terms of reduced privacy and security guarantees. The justification provided here will prove that overheads are quite reasonable and scale appropriately with network size to support practical feasibility for large-scale deployments under federated models. Thereby, BICPPFL introduces a fine balance between computational efficiency and enhanced privacy/security. Also, the BICPPFL is considered a viable method for secure federated learning within wireless network contexts.

Figure 5: Training and validation accuracy analysis

Figure 6: Computation cost analysis

Fig. 7 provides the computation overhead analysis of the proposed BICPPFL and existing methods. Here, the processing time is measured in milliseconds (ms) for assessing the overhead communication burden. In comparison to the existing approaches, this reflects the efficiency of the proposed BICPPFL. As more BSs are added between 2 and 5, more communication exchanges are generally required for federated model updates. The cryptographic operations, and interactions with the blockchain, hence, increased processing time. The BICPPFL method, involving blockchain and HPReEL, adds secure masking, validation, and consensus protocols as extra steps, thus slightly increasing the processing time in comparison to FL methods that do not incorporate these security measures. However, this increase is well within an acceptable range. In particular, while the BICPPFL approach does process significantly more than the existing ones, such incremental overhead is justified by substantial enhancements in security, namely privacy preservation, attack resistance, and accountability. Despite the added cryptographic and blockchain-based operations, the communication overhead remains scalable and practical for network deployment. The performance numbers show linear or sub-linear growth with the number of BSs, suggesting that the security gains from the framework are not excessively costly in terms of efficiency. Thus, it confirms that the proposed BICPPFL model declares reasonable communication and processing overhead to make it viable in real-world multi-BS network environments. Fig. 8 offers the privacy leakage rate analysis of the proposed BICPPFL and existing methods. The graphical representation demonstrates that the BICPPFL model keeps the privacy leakage rate at a low level and is also quite robust to the increasing number of BSs. The leakage rate increases minimally with the number of BSs, which is an excellent scalability feature of the privacy-preserving mechanisms. They provide solid privacy guarantees with no significant degradation in security. On the contrary, existing approaches show much higher leakage rates and are prone to increase significantly with network size, indicating their inherent vulnerability. This assessment proves that the BICPPFL model gives strong privacy protection, while making the network size increase unlinked to the proportional increase of privacy risk. It also highlights the BICPPFL model’s scalability as well as its efficiency in protecting confidential data from inference attacks within different sizes of systems.

Figure 7: Computation overhead analysis

Figure 8: Privacy leakage rate analysis

Fig. 9 demonstrates the scalability analysis of the proposed BICPPFL and existing methods. The scalability analysis is plotted (2, 3, 4, 5) BSs vs. privacy leakage rate (%), aimed at checking how the BICPPFL and existing methods can guard against information disclosure as the system scales. The BICPPFL model, through hybrid cryptographic masking, consensus-based hyperledger fabric blockchain validation, and decentralised aggregation, shows low and fairly stable privacy leakage rates with increasing numbers of BSs. This stability marks the mechanism as scorable in terms of privacy preservation. It effectively contains any potential information leakage with more participants involved. On the other hand, existing methods typically have much less encryption coverage or validation strategy and thus show much higher leakage rates that also increase quite rapidly with the number of BSs. This clearly shows their weakness in inference attacks when network growth occurs. Accordingly, results show that security strategies are integrated into frameworks robustly scalable in privacy protection without giving up on data confidentiality in a proportional relation to network size expansion. In contrast, the growing leakage seen in other methodologies signifies their non-scalability as well as poential security concerns within bigger and more complicated network environments. For every security system, encryption times become essential performance indicators. The encryption time is evaluated and provided based on the time performance. The encryption time performance of the proposed approach employing the widely used tiny encryption algorithm (TEA), Blowfish, homomorphic encryption (HE), and ECC algorithms is shown in Fig. 10. The proposed method’s minimum encryption time is 12 ms, while the usage of popular TEA, HE, ECC and Blowfish increases processing. The average encryption time for proposed, TEA, HE, ECC and Blowfish is 12, 13, 18, 22 and 14 ms. Consequently, it is evident that the proposed method’s encryption time is significantly less than the current methods. Also, the HPReEL offers enhanced security features, encompassing resistance to quantum attacks as well as support for homomorphic operations vital for improved privacy-preserving FL with less computation cost. The comparison of processing times for different numbers of xApps is assessed to measure the efficiency and scalability of the proposed framework under various network loads. As the number of xApps grows, these various levels of computational and communication costs can also be maximised and affect the system performance. Measuring processing times over a set of distinct xApp configurations can help evaluate the framework on handling real-world scenarios where several xApps can be executed at a time and latency is controlled within acceptable limits. The graphical representation comparison clearly shows that the proposed methodology efficiently manages a larger-scale deployment without losing the scalability or responsiveness. Thus, validating the proposed approach’s applicability in the context of complex ORAN scenarios.

Figure 9: Scalability analysis

Figure 10: Encryption time comparison

The dynamic scene experiment has been extended to determine how node participation variation impacts both aggregation time and model accuracy within a federated learning (FL) system with a combined HPReE and lattice-based component (HPReEL), allowing for an additional layer of security and privacy protections. The system also utilised a modified delegated proof-of-stake (Up-DPoS) consensus protocol, which allowed for fast validation of model exchanges and protection against malicious actors. Table 5 presents the dynamic scene experiment analysis. The experiments varied the number of nodes participating in the network (20–100) and included nodes that joined and left at various training stages to simulate real-world scenarios of network dynamism. The averages indicated that as the number of nodes and dynamism increased, the average aggregation time increased because of the added proliferation of cryptographic operations and consensus validation overhead. However, as indicated, in all scenarios the model accuracy remained stable above 90%, signifying that the addition of cryptographic and consensus methods for assuring privacy and security of the model is designed to maintain model performance. According to the analysis, the combination of HPReE, HPReEL with Up-DPoS provides a compromise between security and privacy with efficient operation in dynamic FL scenarios.

4.4 Comparison with Other Existing Methods

To further validate the proposed BICPPFL framework, a comparative analysis against other existing methods focusing on privacy leakage rate and communication overhead has been conducted. The experiments utilised the same datasets, such as the 5G-NIDD and CIFAR-100. The experiments measured the privacy leakage for DLG attacks and IDLG attacks, and the communication overhead measured the amount of data exchanged in a single round of federated learning. The results showed that the BICPPFL networks has been better privacy protection than the compared methods concerning the overall privacy leakage rate, yielding a privacy leakage rate of around 4.05%, while yielded privacy leakage rates of around 24.4%, 15.9%, and 12.1%, respectively. The existing methods provided more privacy than traditional federated, but, experienced significant leakage under similar attack models. In terms of communication overhead, the proposed solution has an additional exchange of data of around 1.3 MB per round compared to around 0.5, 1.2 and 1.0 MB, respectively [18]. The framework incurred slightly higher communication costs; however, the cost was minor compared to the significant improvements in privacy resistance. The other methods did not seriously consider security mechanisms such as cryptographic masking and blockchains for validations, nor highlighted the impact of their proposed implementations and changes to secure any deployment for multi-BS contexts [19]. Table 6 provides the comparative analysis against other existing methods in terms of privacy leakage rate and communication overhead.

In the proposed work, the BICPPFL model improves FL of O-RAN by introducing blockchain, HPReEL, and an enhanced delegated proof of stake (Up-DPoS) consensus to privacy, security, and accountability. Cryptographic functions help enable the security and privacy of operations in dynamic O-RAN environments, but they also introduce latency and affect real-time performance. The BICPPFL model is designed to lessen the impact of cryptographic overhead, while guaranteeing that appropriate security measures are upheld. As part of the BICPPFL model, which incorporates privacy-preserving mechanisms such as HPReEL and blockchain validation, some performance impact should be noted, primarily in terms of processing time and computational overhead. Although the proposed protocol has additional steps, such as secure masking, validation and consensus protocols, the increased overhead is extremely negligible and not considered to be outside of reasonably acceptable bounds. The BICPPFL experiments demonstrated that computation overhead grows as the number of participating base stations increases. Therefore, if there are many BS, the computation complexity increases as a function. However, the effect of communication overhead is linear or sub-linear, signifying that the increased security is not inconsistent with the impacts on operational efficiency that arise. The data exchanged using the BICPPFL model reflects a slight increase due to the additional cryptographic operations and communications with the blockchain for privacy, accountability and assurance of validity of the model. Despite, the data exchanged remaining within reasonable bounds, even with the increase in the number of BSs from 2 to 5, indicating a significant property of scalability. This shows that the overheads for the procedure are reasonable, scale with network size, and therefore, could be practical for real-world scalability. The overhead associated with cryptographic operations, including masking and modelling validation procedures, is found to be negligible and did not significantly influence learning efficiency. Due to the performance of cryptographic operations, there is increasingly more assurance of the integrity and confidentiality associated with model updates. The overall accuracy of the framework is high and stable across a wide number of BSs, demonstrating that security or privacy are not compromised at the cost of predictive performance. The time required for encryption is an important performance measure for any security system. The encryption time for the proposed method is much shorter than Eisner, TEA, Blowfish, HE and ECC algorithms. The proposed method had a maximum encryption time of 12 ms. The efficiency of the proposed methods’ encryption included more security features, quantum-safe measures and also increased levels of homomorphic support than previous methods.

This study presents a BICPPFL framework in order to improve the ML models in ORAN contexts in a multi-BS setting while boosting security, privacy, and accountability. To overcome the drawbacks of the conventional masking approach, the BICPPFL model offers a number of modifications, such as validation procedures for the aggregator rApp and individual xApp masking operations incorporating HPReEL. The end-to-end FL process is managed using a role-based approach. Furthermore, any rApp node in the hyperledger fabric blockchain network can act as the aggregator due to the randomized system provided for choosing aggregator rApp nodes. For efficient consensus across blockchain nodes, the Up-DPoS consensus protocol is used, which will provide rapid validation of model exchanges and guard against malicious attacks. Further, the proposed BICPPFL model creates a sample prototype on top of the Hyperledger Fabric blockchain network and carries out several tests to show how well the proposed approach performs. The experimental outcomes demonstrated the superiority of the proposed BICPPFL model in contrast to the existing methods. However, implementing BICPPFL in a practical ORAN deployment does present some challenges associated with computational latency, especially concerning resource-constrained base stations like ORUs. To address this issue, the cryptographic operations required (i.e., homomorphic proxy-re-encryption and lattice-cryptography) have been designed in both a homomorphic manner and optimised to support all existing ORAN interfaces, such as E2 and A1) using standard cryptographic primitives that introduce efficient integration. Lightweight cryptographic algorithms, specifically TEA, are used to minimise processing overhead, and hardware acceleration will be used to boost computational efficiency. These adaptations intend to ensure that the cryptographic functions do not significantly obstruct real-time operation. Also, this architecture will be further enhanced to function in heterogeneous data sources, and more complex AI models can broaden its applicability in dynamic ORAN environments. This encompasses developing techniques to deal with various data formats and incorporating hybrid transformer-based deep learning model architectures while maintaining privacy.

Acknowledgement: Sincerely thank T-Mobile USA Inc., Axyom.Core, and the Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, for providing the necessary support, infrastructure, and collaborative environment that enabled the successful completion of this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Surendran Rajendran; methodology, Raghavendra Kulkarni; software, Binu Sudhakaran Pillai; validation, and Venkata Satya Suresh kumar Kondeti; formal analysis, Binu Sudhakaran Pillai; investigation, Venkata Satya Suresh kumar Kondeti; resources, Raghavendra Kulkarni; data curation, Surendran Rajendran; writing—original draft preparation, Surendran Rajendran; writing—review and editing Venkata Satya Suresh kumar Kondeti; visualization, Binu Sudhakaran Pillai; supervision, Raghavendra Kulkarni; project administration, Raghavendra Kulkarni; funding acquisition, Binu Sudhakaran Pillai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This article does not involve any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors; hence, ethics approval is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Soltani S, Amanloo A, Shojafar M, Tafazolli R. Intelligent control in 6G open RAN: security risk or opportunity? IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2025;6(1):840–80. doi:10.1109/ojcoms.2025.3526215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Santos JF, Huff A, Campos D, Cardoso KV, Both CB, DaSilva LA. Managing O-RAN networks: XAPP development from zero to hero. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. Forthcoming 2025. doi:10.1109/COMST.2025.3539687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mungari F, Puligheddu C, Garcia-Saavedra A, Chiasserini CF. O-RAN intelligence orchestration framework for quality-driven xApp deployment and sharing. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(6):4811–28. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3527707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Habibi MA, Yilma GM, Fattore U, Costa-Pérez X, Schotten HD. Unlocking O-RAN potential: how management data analytics enhances SMO capabilities? IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2024;5:4710–30. doi:10.1109/ojcoms.2024.3431286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lakshman A. Challenges of O-RAN integration with existing RAN architecture [master’s thesis]. Espoo, Finland: Aalto University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

6. Tahir HA, Nabi F, Tariq MZ, Khan AF, Mahmud A. Insights into the future: XAI integration in O-RAN and space communication systems. In: 2024 Multimedia University Engineering Conference (MECON); 2024 Jul 23–25; Cyberjaya, Malaysia: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/MECON62796.2024.10776550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khan AA, Ali Laghari A, Baqasah AM, Alroobaea R, Reddy Gadekallu T, Avelino Sampedro G, et al. ORAN-B5G: a next-generation open radio access network architecture with machine learning for beyond 5G in industrial 5.0. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2024;8(3):1026–36. doi:10.1109/TGCN.2024.3396454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Brik B, Chergui H, Zanzi L, Devoti F, Ksentini A, Siddiqui MS, et al. Explainable AI in 6G O-RAN: a tutorial and survey on architecture, use cases, challenges, and future research. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2024;PP(99):1. doi:10.1109/COMST.2024.3510543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Al-Karawi YAA. Analysing the quality of service of quantum oriented open radio access networks in 5G and 6G [dissertation]. Uxbridge, UK: Brunel University of London; 2024. [Google Scholar]

10. Kulkarni R, Suresh kumar Kondeti VS, Pillai BS, Surendran R. ImConv_RNN: improved convolutional recurrent model based channel estimation for 6G networks. In: 2025 4th International Conference on Sentiment Analysis and Deep Learning (ICSADL); 2025 Feb 18–20; Bhimdatta, Nepal: IEEE; 2025. p. 338–45. doi:10.1109/icsadl65848.2025.10933349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abou El Houda Z, Moudoud H, Brik B. Federated deep reinforcement learning for efficient jamming attack mitigation in O-RAN. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(7):9334–43. doi:10.1109/TVT.2024.3359998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wu F, Li X, Li J, Vijayakumar P, Gupta BB, Arya V. HSADR: a new highly secure aggregation and dropout-resilient federated learning scheme for radio access networks with edge computing systems. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2024;8(3):1141–55. doi:10.1109/TGCN.2024.3441532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Singh AK, Nguyen KK. Communication efficient compressed and accelerated federated learning in open RAN intelligent controllers. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(4):3361–75. doi:10.1109/TNET.2024.3384839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Moudoud H, Abou El Houda Z, Brik B. Zero trust security architecture for 6G open radio access networks (ORAN). IEEE Netw Lett. 2024;6(4):272–5. doi:10.1109/LNET.2024.3514357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tam P, Kim S. Graph-based deep reinforcement learning in edge cloud virtualized O-RAN for sharing collaborative learning workloads. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2024;12(1):302–18. doi:10.1109/tnse.2024.3495583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gu X, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Letaief KB. DRL-based federated self-supervised learning for task offloading and resource allocation in ISAC-enabled vehicle edge computing. Digit Commun Netw. Forthcoming 2024. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2024.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kumar M, Samriya JK, KaurWalia G, Verma P, Wu H, Gill SS. Blockchain empowered secure federated learning for consumer IoT applications in cloud-edge collaborative environment. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):3986–96. doi:10.1109/TCE.2025.3532676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kumar AM, Anil K, Kumar NP, Prasad P, Bharath Raju VV. Enhanced proxy re-encryption with blockchain for privacy-preserving IOT data exchange. In: 2025 International Conference on Computational Robotics, Testing and Engineering Evaluation (ICCRTEE); 2025 May 28–30; Virudhunagar, India: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCRTEE64519.2025.11053119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. kumar Kondeti VSS, Kulkarni R, Pillai BS, Rajendran S. Slice-based 6G network with enhanced Manta ray deep reinforcement learning-driven proactive and robust resource management. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(3):4973–95. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.066428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools