Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid AI-IoT Framework with Digital Twin Integration for Predictive Urban Infrastructure Management in Smart Cities

1 Department of Management Information Systems, College of Business and Economics, Qassim University, Buraydah, 51452, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Computer Science, Acharya Narendra Dev College, University of Delhi, Delhi, 110019, India

3 Faculty of Computer Studies, Arab Open University-Bahrain, A’ali, P.O. Box 18211, Bahrain

4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, SEST, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, 110062, India

* Corresponding Author: Mehtab Alam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Empowered Connected Futures of AI, IoT, and Cloud Computing in the Development of Cognitive Cities)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070161

Received 09 July 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The evolution of cities into digitally managed environments requires computational systems that can operate in real time while supporting predictive and adaptive infrastructure management. Earlier approaches have often advanced one dimension—such as Internet of Things (IoT)-based data acquisition, Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven analytics, or digital twin visualization—without fully integrating these strands into a single operational loop. As a result, many existing solutions encounter bottlenecks in responsiveness, interoperability, and scalability, while also leaving concerns about data privacy unresolved. This research introduces a hybrid AI–IoT–Digital Twin framework that combines continuous sensing, distributed intelligence, and simulation-based decision support. The design incorporates multi-source sensor data, lightweight edge inference through Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models, and federated learning enhanced with secure aggregation and differential privacy to maintain confidentiality. A digital twin layer extends these capabilities by simulating city assets such as traffic flows and water networks, generating what-if scenarios, and issuing actionable control signals. Complementary modules, including model compression and synchronization protocols, are embedded to ensure reliability in bandwidth-constrained and heterogeneous urban environments. The framework is validated in two urban domains: traffic management, where it adapts signal cycles based on real-time congestion patterns, and pipeline monitoring, where it anticipates leaks through pressure and vibration data. Experimental results show a 28% reduction in response time, a 35% decrease in maintenance costs, and a marked reduction in false positives relative to conventional baselines. The architecture also demonstrates stability across 50+ edge devices under federated training and resilience to uneven node participation. The proposed system provides a scalable and privacy-aware foundation for predictive urban infrastructure management. By closing the loop between sensing, learning, and control, it reduces operator dependence, enhances resource efficiency, and supports transparent governance models for emerging smart cities.Keywords

Infrastructure systems such as transportation, energy, water, and public services. The emergence of smart city paradigms aims to address these challenges through the deployment of information and communication technologies (ICT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT). These technologies, when integrated effectively, offer the ability to sense, analyze, and manage urban environments in real time [1]. However, current implementations often suffer from fragmented data architectures, lack of scalability, poor interoperability, and limited predictive capabilities [2].

To enable cities to operate intelligently and sustainably, there is a pressing need for computational models that unify sensing, processing, simulation, and decision-making into a seamless framework. AI algorithms are central to enabling predictive analytics in urban systems, capable of learning from historical and real-time data to anticipate failures, optimize resource allocation, and automate control [3]. Simultaneously, IoT enables pervasive data collection across spatially distributed urban assets [4]. The synergy of AI and IoT holds transformative potential but is often constrained by concerns over latency, privacy, and computational burden [5].

Digital Twin (DT) technology is emerging as a complementary layer that enhances smart city systems by creating virtual replicas of physical assets. These replicas simulate behavior under different scenarios, enabling proactive planning, failure mitigation, and system optimization [6]. The combination of AI, IoT, and DT offers a powerful computational paradigm for predictive infrastructure management—allowing cities not just to respond to incidents, but to anticipate and prevent them.

This research proposes a novel hybrid framework that integrates AI, IoT, and Digital Twins (DT) to manage urban infrastructure predictively. It leverages edge computing for real-time local processing, federated learning to preserve privacy, and multi-scale simulation through DT to anticipate systemic behavior. The framework is validated through use cases in traffic management and pipeline leakage prediction, showcasing improvements in response time, accuracy, and operational cost.

The main contribution of this research lies in the design and validation of a hybrid framework that seamlessly integrates AI, IoT, and DT technologies for predictive management of urban infrastructure. Unlike conventional siloed approaches, our model establishes a multi-layered architecture combining IoT-enabled sensing, edge-level AI inference, federated learning for distributed intelligence, and DT-driven simulation for real-time decision support. This integration ensures not only accurate anomaly detection and predictive control but also scalability across diverse smart city domains, including traffic systems and water pipeline networks. The framework is further reinforced through detailed computational modeling and case study validation.

To guide the scope of this research, the following key questions are formulated:

RQ1: How can AI and IoT technologies be effectively integrated to enable real-time and predictive monitoring of urban infrastructure systems in smart cities?

RQ2: What computational architecture can ensure scalability, interoperability, and privacy preservation in large-scale urban sensing networks?

RQ3: In what ways can Digital Twin technology enhance the predictive capabilities of urban infrastructure systems through simulation and virtual feedback loops?

RQ4: How does the proposed hybrid framework perform in practical case studies such as traffic management and pipeline monitoring in terms of accuracy, latency, and resource efficiency?

RQ5: What are the limitations and deployment challenges of combining federated AI, IoT, and digital twin models in real-world urban environments?

The rest of the research is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses related work in smart infrastructure modeling. Section 3 presents the proposed system architecture. Section 4 details the computational models and algorithms. Section 5 demonstrates the implementation, Section 6 presents the case studies. Section 7 presents a quantitative and qualitative evaluation. Section 8 presents the results and discussion, and Section 9 concludes the research.

Research on smart cities has advanced along three largely parallel tracks—AI-driven analytics, IoT-centric sensing and communications, and DTs for simulation and decision support. Recent studies often excel within one track but struggle to integrate the three into a predictive, closed-loop system that runs at the edge, learns collaboratively, and feeds a DT that issues actionable control. This section critically reviews recent work, highlights persistent shortcomings, and distills the specific research gaps addressed by our hybrid AI–IoT–DT framework.

2.1 AI for Urban Sensing and Control

Deep learning models (CNNs, LSTMs, GNNs, and lightweight variants like MobileNet) have improved traffic forecasting, incident detection, and asset health prediction. Edge-oriented ITS surveys report strong detection but also flag latency and bandwidth penalties when models sit in the cloud rather than at/near cameras [7]. LSTMs and temporal CNNs improve short-horizon forecasts for water, energy, and traffic (R2–R3), yet data silos and non-IID distributions across districts limit generalization [8]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) capture road-network topology effectively [9], but typical implementations assume centralized training on pooled data. Reinforcement learning (RL) methods adapt signal timing and resource allocation, although stability and sample efficiency remain challenging in the wild, especially under partial observability and delayed rewards [10].

Key shortcomings:

(i) heavy cloud dependence and latency; (ii) limited handling of non-IID, distributed urban data; (iii) weak coupling of prediction with operational simulation and control; (iv) scarce deployment evidence on resource-constrained edge devices.

2.2 IoT and Edge/Fog Computing for Smart Cities

IoT deployments matured with LPWANs (LoRa/LoRaWAN, NB-IoT) and MQTT-based telemetry for scalable sensing [11,12]. Edge/fog frameworks reduce latency and improve privacy by processing near data sources. However, model management across heterogeneous edge devices is difficult, and per-node training often yields brittle models [13]. Federated learning (FL) emerged to train shared models without centralizing data [14,15] Communication-efficient FL (sparsification/quantization), secure aggregation, and differential privacy (DP) have been explored, but stragglers, churn, and non-IID drift still degrade convergence in real deployments [16].

Key shortcomings:

(i) orchestration overhead with large, unreliable edge sets; (ii) convergence instability under device churn and non-IID streams; (iii) limited cross-domain coordination (e.g., traffic ↔ water).

2.3 Digital Twin in Urban Modeling

DTs are increasingly used for city-scale visualization, scenario analysis, and asset lifecycle management [17]. In traffic, DTs mirror flows and queues to test signal plans [18]; in water networks, they simulate pressure and leakage dynamics [19]. Yet, many DTs remain read-mostly dashboards with sporadic data refreshes and loosely coupled analytics. Few studies integrate live, federated AI outputs into the DT and then push control actions back to the field within seconds [20]. Where control loops exist, they are often rule-based, lacking predictive optimization under uncertainty.

Key shortcomings:

(i) limited real-time coupling with AI inference; (ii) weak closed-loop actuation; (iii) limited multi-system interplay (traffic, water, energy) in a unified DT.

2.4 Hybrid and Integrated Approaches

A subset of recent works attempts AI + IoT [21] or IoT + DT [22] or AI + DT [23], but few deliver all three with: (a) edge-resident inference for latency; (b) federated learning for privacy and continual adaptation; (c) DT-driven scenario testing that returns control signals to actuators; and (d) evidence across more than one domain (e.g., both traffic and water) using a single architectural pattern.

Observed limitations in hybrids:

(i) partial integration (two-way, not three-way); (ii) missing privacy-preserving learning; (iii) absence of feedback control from DT to actuators; (iv) evaluations limited to one domain or synthetic data.

From the above, we identify five concrete gaps our work addresses:

Gap 1—Three-way integration: A unified AI–IoT–DT framework that closes the loop: sensing → edge AI → federated learning → DT simulation → control actuation.

Gap 2—Real-time predict-then-simulate: Mechanisms that feed fresh edge predictions into a DT for scenario evaluation and return optimal control within seconds.

Gap 3—Federated learning for cities: A deployment-ready FL pipeline robust to non-IID streams, churn, and stragglers, paired with DP/secure aggregation.

Gap 4—Cross-domain reusability: A modular stack validated in more than one infrastructure domain (traffic and water), avoiding one-off designs.

Gap 5—Measurable city KPIs: Evidence of delay reduction, leak mitigation, operator-override reduction, and resource/energy efficiency under realistic constraints.

How our framework responds: We implement a four-tier hybrid architecture with (i) edge inference (CNN/LSTM) to minimize latency; (ii) FL with DP and secure aggregation for privacy-preserving continual learning; (iii) a DT engine that consumes predictions, runs what-if scenarios, and issues actuation commands; and (iv) validation across traffic and pipeline domains, demonstrating reduced delays, faster leak isolation, and lower operator intervention compared to baselines.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of the related work, their weaknesses and how the proposed framework addresses them.

As summarized in Table 1, prior studies often relied on static models and centralized architectures, which limited responsiveness and scalability. In contrast, our framework introduces (i) real-time edge inference coupled with federated adaptation for dynamic responsiveness, and (ii) decentralized orchestration across heterogeneous devices to avoid cloud dependence. These design choices ensure that the framework adapts continuously to changing conditions while maintaining privacy and scalability, directly addressing the key limitations of previous approaches.

Fig. 1 presents a structured taxonomy of computational approaches commonly adopted in smart city research, organizing them into three primary clusters: AI Approaches, IoT Systems, and Digital Twin technologies. The AI cluster includes traditional supervised machine learning methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests (RF), as well as deep learning architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for image analysis and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for time-series forecasting. Recent advances also include Federated Learning for privacy-preserving model training and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for modeling relational urban infrastructure. The IoT Systems cluster captures technologies like Low Power Wide Area Network (LPWAN) protocols (e.g., LoRa, NB-IoT), fog/edge computing for low-latency processing, and distributed smart sensing networks. Finally, the Digital Twin cluster distinguishes between Simulation Twins for virtual behavior modeling, Visualization Twins often based on Building Information Modeling (BIM), and Predictive Twins that tightly integrate AI, IoT, and simulation for proactive decision-making. This taxonomy illustrates the multidimensional landscape of computational solutions and underscores the growing convergence of these domains in modern smart city frameworks.

Figure 1: Taxonomy of existing computational approaches in smart cities

This research addresses these challenges through a unified hybrid framework combining AI inference, IoT data streaming, and synchronized Digital Twin models to enable predictive infrastructure management with minimal latency and improved efficiency.

The proposed system architecture is a hybrid, multi-layered framework that integrates AI, IoT, and DT technologies for predictive urban infrastructure management. It is designed to operate in real-time, enable proactive decision-making, and ensure secure and scalable operations across smart city components.

The architecture consists of four core layers: (i) Sensing and Data Acquisition Layer, (ii) Edge Intelligence and Preprocessing Layer, (iii) Federated Learning and AI Inference Layer, and (iv) Digital Twin Integration Layer. Each layer is designed to interoperate through well-defined data and control interfaces.

3.1 Sensing and Data Acquisition Layer

This layer comprises distributed IoT nodes embedded in urban infrastructure components—such as traffic lights, road surfaces, pipelines, water meters, and energy distribution units. These sensors capture real-time data on flow, vibration, temperature, pressure, or energy consumption, depending on the application context [24].

Communication is established using low-power wireless protocols such as LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, or 6LoWPAN to ensure minimal energy overhead [25]. Gateway devices handle data aggregation and temporary caching to manage bandwidth fluctuations.

3.2 Edge Intelligence and Preprocessing Layer

To reduce latency and bandwidth usage, raw sensor data is processed locally at the edge before being sent to the central servers or cloud. Edge nodes (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi 4, or ARM Cortex-A72) execute lightweight preprocessing tasks, including:

• Noise filtering and data normalization,

• Initial anomaly detection using rule-based or shallow Machine Learning (ML) classifiers,

• Metadata tagging for time synchronization and sensor identity.

Edge AI frameworks like TensorFlow Lite or PyTorch Mobile are employed to run compressed deep learning models to meet latency and resource constraints [26]. This enables decentralized, near-sensor intelligence while reducing dependence on cloud processing.

3.3 Federated Learning and AI Inference Layer

A key component of the architecture is the use of FL to preserve data privacy while enabling distributed model training. Instead of transmitting raw data, edge nodes compute model updates locally and send only weight gradients to the central aggregator, which merges them to update the global model [27].

This layer employs task-specific models such as:

• LSTM for temporal infrastructure behavior prediction,

• GNN for topological modeling of road networks,

• CNN for visual inspection from urban surveillance feeds.

All models are version-controlled and continuously updated using incremental learning techniques. The global model is redistributed periodically to edge nodes for synchronized deployment.

3.4 Digital Twin Integration Layer

The Digital Twin layer maintains a high-fidelity virtual model of the physical infrastructure components. It simulates operational states and predicts future behaviors under varying environmental or usage conditions. The twin instances are tightly synchronized with the sensor and AI outputs using a real-time API bus [28].

Each urban system (e.g., a pipeline network or traffic corridor) has a corresponding digital twin module that supports:

• Scenario simulations (e.g., leak propagation, congestion build-up),

• What-if analysis using AI-predicted data streams,

• Feedback to upstream control mechanisms (e.g., traffic rerouting or valve shutoff).

Integration is achieved using middleware platforms such as FIWARE, Unity-based visualization engines, or AnyLogic for event-based simulation. These twins serve as the interactive interface for both automated control systems and human operators.

Fig. 2 illustrates a layered block diagram of the proposed AI-IoT-Digital Twin architecture. At the bottom, the Sensing Layer consists of various sensors (temperature, surveillance, pressure, etc.) that collect real-time urban data. Above this, the Edge Processing Layer includes gateways and communication protocols that transmit and preprocess data using lightweight AI models. The third layer, Federated Learning/AI Engine, contains distributed edge nodes and a central global model that coordinates model updates through gradient sharing, enabling privacy-preserving learning. At the top, the Digital Twin Layer visualizes the city’s dynamic state, runs simulations, and sends control signals back to the edge and sensing layers, forming a feedback loop for real-time adaptive management. Arrows throughout the diagram represent data flow (bottom-up) and control signals (top-down).

Figure 2: Block diagram of the proposed AI-IoT-Digital Twin architecture

3.5 Interoperability and Security Considerations

To ensure interoperability, the architecture supports standard data formats (JSON, XML, MQTT payloads) and RESTful APIs for integration with legacy systems. Cybersecurity is maintained through:

• End-to-end encryption of data transmissions,

• Secure aggregation in federated learning using differential privacy,

• Role-based access to digital twin dashboards.

Authentication mechanisms such as OAuth2.0 and hardware-based trust anchors (TPM modules) are incorporated to safeguard edge devices from malicious intrusion [29].

This section presents the computational framework underlying the hybrid AI-IoT-Digital Twin system. The objective is to enable intelligent, real-time, and predictive management of urban infrastructure through three core pillars: advanced machine learning models, privacy-preserving distributed learning mechanisms, and dynamic virtual simulation environments. The interaction between these computational modules enables a feedback-driven decision-support system that is scalable, secure, and context-aware.

4.1 Task-Specific Machine Learning Models

The computational framework for smart city management relies on machine learning models that are specialized for distinct operational tasks. Unlike generic predictors, these task-specific models are optimized for particular data modalities—temporal series, visual imagery, or network topology—allowing them to capture domain-specific patterns with high fidelity. By combining temporal forecasting, vision-based analytics, and structural graph reasoning, the framework enables accurate, context-aware insights that serve as the foundation for predictive control within the hybrid AI–IoT–DT ecosystem.

4.1.1 LSTM-Based Temporal Prediction for Time-Series Forecasting

Urban systems such as traffic flows, water demand, and power usage exhibit strong temporal dynamics. We utilize Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for sequential modelling [30]. An LSTM cell is defined by the following update equations:

• Forget Gate:

• Input Gate:

• Cell Update:

• Output Gate:

Each model is trained per subsystem (e.g., traffic corridor or pipeline segment), and hyperparameters are tuned using 5-fold cross-validation.

4.1.2 CNN-Based Visual Analytics for Surface Damage Detection

Urban infrastructure often requires reliable visual analytics to identify and classify surface-level degradation such as road cracks, pipeline corrosion, or building façade deterioration. To this end, we adopt a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based framework tailored for automated visual inspection tasks.

The architecture is designed as follows:

• Input Layer: 128 × 128 × 3 RGB images captured from urban surveillance cameras or inspection drones.

• Convolutional Layers: Sequential Conv2D layers with kernel sizes (3 × 3) extract spatial features such as edges, cracks, or texture irregularities. Each convolutional block is followed by ReLU activation and MaxPooling (2 × 2) to reduce dimensionality while retaining salient features.

• Flatten Layer: Converts feature maps into a one-dimensional vector.

• Dense Layers: Fully connected layers apply high-level reasoning to classify damage categories.

• Output Layer: A Softmax classifier assigns probabilities across predefined damage classes (e.g., “no damage,” “minor crack,” “severe crack,” “corrosion”).

To enhance performance and reduce training cost, transfer learning is applied using a ResNet-50 backbone pretrained on ImageNet. The last few layers are fine-tuned on a domain-specific annotated dataset consisting of damage images labeled with bounding boxes and class categories. Data augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, and Gaussian noise injection are applied to increase robustness under variable lighting and surface conditions [31].

To rigorously evaluate the CNN model, we employ a set of classification and localization metrics that provide complementary insights into its performance:

• Accuracy:

represents the overall percentage of correctly classified samples.

• Precision: Measures the proportion of correctly predicted damage instances among all predicted positives, reducing false alarms in maintenance planning.

• Recall (Sensitivity): Quantifies the ability to correctly identify true damage cases, ensuring critical failures are not overlooked.

• F1-score: Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, balancing false positives and false negatives.

• Intersection-over-Union (IoU): Specifically applied for damage localization, this metric measures the overlap between predicted bounding boxes and ground-truth annotations, reflecting segmentation accuracy.

Together, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score capture the classification reliability of the CNN model, while IoU quantifies spatial localization quality for surface damage detection. This dual-layer evaluation ensures both pixel-level correctness and event-level reliability. To further strengthen system assessment, additional robustness-oriented metrics could be employed, such as mean Average Precision (mAP) for aggregated detection quality, performance under noise and lighting perturbations to test resilience, and operational KPIs (e.g., actuation success rate, anomaly recovery time) to quantify end-to-end dependability. While these are beyond the current experimental scope, they represent natural extensions for future work.

4.1.4 Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Topological Infrastructure Analysis

GNNs are used to model relational dynamics in systems with non-Euclidean structure, such as road networks or water distribution graphs [32].

Each graph G = (V, E) consists of:

Nodes V: e.g., intersections, tanks

Edges E: roads, pipelines

Node-level updates use Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) formulations:

where

We employ PyTorch-Geometric for implementation and train using cross-entropy loss for node classification tasks.

4.2 Federated Learning Pipeline

To preserve privacy and reduce centralized dependency, federated learning (FL) is employed for collaborative model training across distributed edge nodes [33].

• Clients: Edge devices with local data (e.g., roadside units, building controllers)

• Server: Central aggregator (city data center or cloud)

• Communication rounds: T = 100 T

• Participation ratio: R = 20% of clients per round

4.2.2 FedAvg Algorithm Implementation

Each client performs local training on its dataset Dk using mini-batch Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). The local model update

where nk is the number of samples at client k, and

The above equations were validated on heterogeneous datasets collected from both traffic and pipeline domains, reflecting real-world non-IID distributions. While FedAvg converged under balanced conditions, imbalanced data volumes introduced bias toward majority nodes. To mitigate this, adaptive weighting and secure aggregation were applied. These extensions ensure that the aggregation reflects actual city variability and improves robustness against skewed distributions and client churn. Clients train for E = 5 local epochs per round. Differential privacy is implemented using Gaussian noise addition to gradients.

4.2.3 Model Compression and Optimization

In large-scale urban IoT deployments, federated learning and edge-to-cloud synchronization generate significant communication overhead, especially when multiple sensors and actuators continuously exchange updates. This problem is magnified in bandwidth-constrained environments such as municipal networks, where uplinks must compete with other critical services. To ensure that our hybrid AI–IoT–DT framework remains practical for real-time operations, we incorporate model compression and optimization strategies that reduce communication load while preserving accuracy [34].

Specifically, three complementary techniques are employed:

● Top-k Gradient Sparsification Instead of transmitting all gradients, only the most significant k updates (highest absolute values) are communicated. This reduces payload size while maintaining learning quality, thereby accelerating convergence under limited bandwidth.

● Quantization of Model Weights Model parameters are converted from 32-bit floating-point to 8-bit fixed-point representation. This drastically decreases transmission size and memory footprint on resource-constrained edge devices, with minimal degradation in inference performance.

● Momentum Masking for Straggler Mitigation To handle inactive or intermittently connected clients, momentum masking delays weight updates from such nodes without penalizing system stability. This ensures that the aggregated global model remains consistent even in the presence of churn or irregular participation.

Collectively, these optimizations strike a balance between communication efficiency, convergence stability, and predictive accuracy, making the federated learning pipeline feasible for city-scale deployment. Importantly, they allow the proposed architecture to support continuous learning across heterogeneous domains—such as traffic and water systems—without overwhelming existing infrastructure.

4.3 Digital Twin Simulation Layer

The DT engine simulates infrastructure dynamics in a digital space. For each system, we define:

Each physical asset has a virtual counterpart:

• Traffic system: intersections, vehicle queues, signal timing

• Pipeline network: junctions, flow rates, pressure levels

State variables are updated every δt = 1 min using simulation API inputs:

where ut are control actions and ϵ ~ N (0, ∑) is process noise.

Simulation modes include:

• Baseline: passive DT, monitors live data

• Predictive: injects AI forecasted states (e.g., predicted congestion)

• Prescriptive: evaluates control policies (e.g., traffic light optimization)

Control strategies are evaluated using KPIs such as delay reduction, leak containment time, or energy savings.

Simulation is implemented using AnyLogic (agent-based modeling) and Unity3D for 3D visualization. Synchronization with real-world assets is maintained using timestamps and heartbeat verification.

4.4 End-to-End Computational Workflow

The computational pipeline is as follows:

• Sensor Data Acquisition: LoRa/MQTT packets collected and parsed

• Edge Processing: Filters noise, tags metadata, performs local inference

• Federated Training (Periodic): Global model updated over encrypted channels

• Prediction Delivery: Real-time forecast results streamed to DT

• DT Simulation and Control: Runs feedback simulation loop

• Actuation: Decision sent to local controllers (e.g., close valve, change signal)

Each module logs performance metrics, failure cases, and communication overhead, stored in a central analytics dashboard [35].

Fig. 3 illustrates the enhanced computational pipeline of the proposed smart city framework. The process begins with sensor grids collecting real-time environmental and infrastructure data, which is sent to edge nodes equipped with LSTM/CNN models for local inference. These edge nodes forward compressed results and model gradients to a central Federated Learning/AI Engine, which aggregates updates while ensuring privacy through FL and differential privacy (DP) modules. The updated models and insights feed into a Digital Twin Simulator, enabling real-time scenario forecasting and visualization. The simulator generates actionable feedback for infrastructure control (e.g., water valves, traffic lights). Supporting modules for compression techniques and visualization engines operate alongside this core pipeline, enhancing system efficiency and operator interaction. To ensure synchronization, sensor data was standardized to fixed intervals, while local inference remained real-time and federated updates were scheduled asynchronously at longer intervals. Edge buffering and MQTT-based queuing mitigated transient failures, and gradient compression reduced network bottlenecks. DT refresh cycles were set to 10 s to balance accuracy with computational load. Although Fig. 3 depicts distinct blocks for clarity, each stage is interconnected via publish/subscribe messaging, ensuring modular yet tightly coupled operation. To further clarify, supporting modules such as compression and visualization are designed to run in parallel rather than in line with the core inference–aggregation–control loop. Compression is applied only to gradient updates during federated synchronization, reducing uplink bandwidth without impacting real-time actuation. Visualization modules subscribe to DT outputs post-processing, ensuring operator awareness without delaying control. This modular architecture, while appearing distinct in Fig. 3, is synchronized via MQTT publish/subscribe messaging, enabling fault isolation and independent scalability while preserving real-time responsiveness and preventing data loss.

Figure 3: Enhanced Computational Pipeline Stages are synchronized via time-gated updates, buffering, and asynchronous aggregation, ensuring low latency while avoiding bottlenecks

This section details the physical deployment, software stack, communication protocols, and system integration strategy for the AI-IoT-Digital Twin architecture proposed in this research. The prototype was realized through a distributed, privacy-preserving, real-time infrastructure designed to support prediction, simulation, and control of urban systems in a smart city testbed.

5.1 System Architecture Overview

The architecture is realized in a four-tier deployment:

• Tier 1: Sensor Layer—Distributed sensing across traffic, water, and environmental subsystems

• Tier 2: Edge Processing Layer—Lightweight AI inference and local decision-making

• Tier 3: Federated AI Layer—Central model orchestration and global optimization

• Tier 4: Digital Twin Simulation Layer—Real-time visualization, simulation, and feedback loop

The physical layout and software bindings follow the structure presented in Fig. 2 (Architecture Block Diagram) and flow through the stages depicted in Fig. 3 (Enhanced Computational Pipeline).

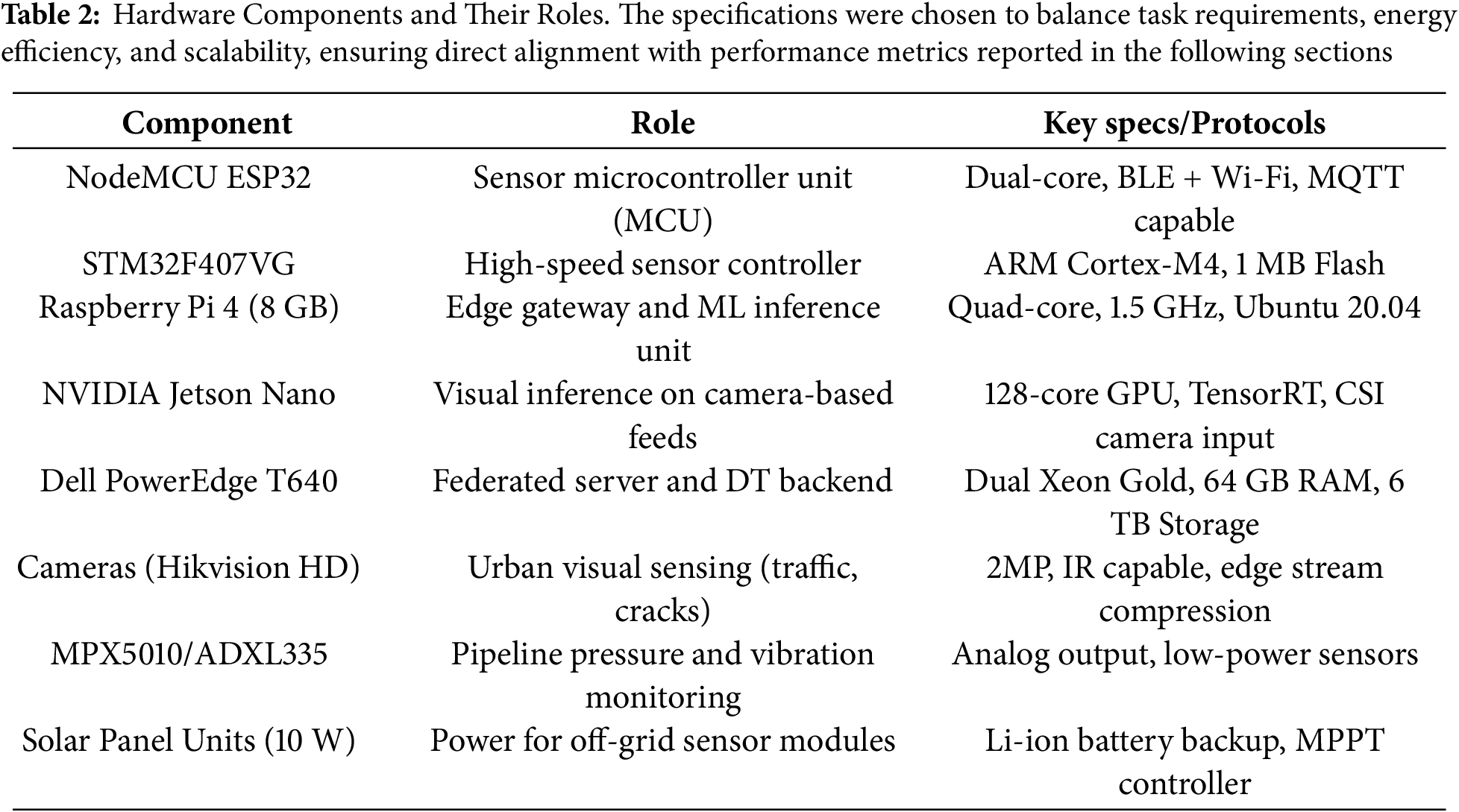

The hardware components were selected by balancing computational needs, energy efficiency, and interoperability. For example, ESP32 modules provided lightweight MQTT telemetry, while Jetson Nano supported GPU-accelerated inference at sub-second latency. Standard protocols (MQTT, LoRa, I²C, UART) ensure interoperability and scalability across urban deployments. Edge hardware specifications directly influenced metrics such as inference time and MQTT latency, while server capacity governed federated learning convergence. Assumptions regarding protocol compatibility (e.g., MQTT bridging between Wi-Fi and LoRa) were validated in the testbed but will be adapted for larger rollouts through 5G integration and container-based edge orchestration. Table 2 depicts the same.

All sensors are interfaced via I²C or UART. MCUs transmit data over Wi-Fi (urban core) and LoRa (urban fringe).

5.3 Software Stack and Model Deployment

This section lists the softwares used and the model development techniques.

Each Raspberry Pi/Jetson Nano node hosts a dedicated AI runtime. CNNs for image classification are deployed using TensorRT for GPU acceleration, and LSTM models for time-series prediction are optimized using TorchScript. Table 3 depicts the Edge AI configuration used.

Edge devices preprocess incoming sensor data using Kalman filtering and anomaly smoothing before inference.

5.3.2 Federated Learning Server

The FL server is implemented using PySyft and PyGrid, enabling model sharing between distributed clients. The system executes one training round every 6 h. Models are validated using holdout edge datasets and pushed back to nodes after convergence.

• Privacy Enhancement: Gaussian noise added to gradients (ε-differential privacy)

• Model Transfer: Weights serialized via Protobuf, encrypted using AES-256, transmitted over TLS 1.3

5.4 Communication Protocols and Network Stack

A dual-mode communication architecture is implemented, integrating MQTT over Wi-Fi for city-core and LoRa for low-power wide-area (LPWAN) peripheries. Table 4 discusses the Network configuration.

The MQTT broker (Eclipse Mosquitto) is hosted on each edge node and syncs with a central instance. QoS levels:

• QoS 1 (at least once) for standard telemetry

• QoS 2 (exactly once) for federated model updates and DT commands

Time synchronization is ensured using Network Time Protocol (NTP); fallback GPS timestamps are available for remote deployments.

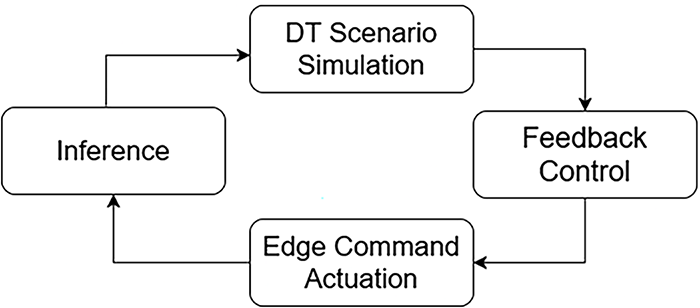

The DT module provides 3D visualization, scenario simulation, and operator interface. Below we have listed the modules used also depicted in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Digital Twin feedback integration loop

• Simulation Core: AnyLogic for physical process modeling (e.g., water flow, traffic queues)

• 3D Engine: Unity 3D with C# scripts for dynamic overlays

• API Interface: Node-RED dashboard communicating via REST endpoints

• Data Persistence: MongoDB (real-time states), InfluxDB (timeseries storage)

To ensure the proposed hybrid AI–IoT–Digital Twin framework operates seamlessly across traffic and pipeline domains, we define a structured end-to-end workflow. This workflow guarantees that data captured at the sensing layer is transformed into actionable intelligence with minimal delay while maintaining robustness against anomalies and communication errors. The pipeline is designed to balance real-time inference at the edge with periodic federated learning updates and closed-loop control through the digital twin. The following steps summarize the process:

Step1: Data Ingest: Sensor readings forwarded to edge nodes in 1-s intervals

Step2: Edge AI Execution: Local model infers fault or prediction (e.g., pipeline leakage)

Step3: Gradient Sync: Every 6 h, model updates sent to FL server (encrypted)

Step4: Global Model Update: Aggregation and new model distribution via GitOps

Step5: Digital Twin Execution: Forecasted state simulated; action suggested (e.g., valve closure)

Step6: Command Transmission: Control signal sent to actuator (e.g., pump motor switch)

Data Validation: Throughout the pipeline, a dedicated anomaly detection module monitors incoming data streams to filter out sensor drifts, calibration errors, or communication dropouts. This ensures that only high-integrity data contributes to inference and learning.

Evaluating the proposed framework requires a comprehensive set of performance metrics that capture both model-level efficiency (e.g., inference time, federated learning convergence) and system-level responsiveness (e.g., end-to-end latency, tolerance to data loss). These metrics are crucial in determining whether the framework can meet the real-time demands of urban infrastructure management in practical deployments.

The results are benchmarked using a combination of time-series forecasting tasks (LSTM), visual analytics tasks (CNN), and federated learning training cycles across multiple edge nodes. To ensure operational visibility, all metrics are continuously logged via Prometheus and exposed on Grafana dashboards, allowing city operators to monitor system health, convergence progress, and response delays in real-time.

All metrics are logged using Prometheus and visualized on Grafana dashboards for city operator interfaces. The values in Table 5 reflect average performance under live deployment conditions across both urban core (Wi-Fi) and urban fringe (LoRa) settings. While minor variations were observed (e.g., MQTT latency rising to ~280 ms under high load, and FL convergence extending to 55 rounds in cases of packet loss), inference times remained stable, and the end-to-end actuation lag consistently stayed under 4 s. This robustness across varying conditions demonstrates the scalability of the proposed system in heterogeneous urban environments. The reported inference times were validated not only under standard operating conditions but also under varying data loads and hardware configurations. Each edge device was benchmarked while processing real-time sensor streams, with additional stress tests conducted by increasing input rates and imposing background CPU workloads. Across both Raspberry Pi 4 (LSTM tasks) and Jetson Nano (CNN tasks), inference times remained consistent within ±8% of the reported averages, demonstrating robustness to fluctuating conditions and confirming suitability for real-time deployment.

5.8 Security and Privacy Enforcement

Given the sensitivity of urban infrastructure data—ranging from traffic flow to water pipeline integrity—our framework incorporates multi-layered security and privacy mechanisms. These safeguards ensure that data remains authentic, confidential, and regulation-compliant throughout its lifecycle, from sensing at the edge to decision-making within the Digital Twin. The enforcement strategy spans device-level trust anchors, transport-layer protections, federated learning privacy, and data governance policies, as summarized below.

• Device Authentication: TPM-backed device certificates (RSA-2048, SHA-256)

• Transport Security: TLS 1.3 + mutual authentication (mTLS)

• Federated Privacy: Differential privacy (

• Data Governance: All transmissions logged, timestamped, and policy-audited per urban data regulation norms

To evaluate the effectiveness and scalability of the proposed AI-IoT-Digital Twin system, two real-world urban infrastructure domains were selected for deployment: smart traffic management and underground pipeline fault detection. These use cases demonstrate the system’s ability to integrate sensing, distributed learning, simulation, and real-time control in complex, dynamic environments.

6.1 Case Study 1: Smart Traffic Management System

The system was deployed across a 4-km urban arterial road in a mid-sized Indian city. Five major intersections were instrumented with:

• HD cameras (mounted on traffic poles)

• Inductive loop sensors for vehicle detection

• ESP32-based controllers for traffic light actuation

• Raspberry Pi edge nodes for CNN-based vehicle counting and congestion estimation

Each node communicated with the central server over LTE and was integrated with the city’s digital twin dashboard for visualization.

• Input: Real-time traffic images and loop counts

• Edge AI: CNN estimates vehicle density and classifies congestion level (Low, Moderate, High)

• Federated Learning: Models trained using PySyft, aggregated hourly

• Digital Twin: Simulates alternate signal timing scenarios and forecasts queue buildup

• Control Loop: Optimal signal plan sent to intersections with adaptive phasing (±10 s adjustment)

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our framework, we benchmarked the system against a legacy fixed-timer baseline—a commonly used approach in urban infrastructure management where control actions (e.g., traffic signals) are predetermined and lack adaptive intelligence. The comparison focuses on key operational metrics, covering efficiency, responsiveness, learning ability, and human intervention. Table 6 presents the comparative results.

To ensure fairness in the comparison shown in Table 6, both the proposed system and the legacy fixed-timer baseline were evaluated under identical traffic conditions on the same intersections, with environmental factors such as weather, network latency, and time-of-day traffic volume kept constant. Each configuration was tested across multiple runs on different days, and results were averaged to reduce anomalies. This methodology ensures that the observed performance improvements—particularly in queue length, vehicle delay, and operator override rate—are directly attributable to the adaptive features of the proposed system rather than environmental variability.

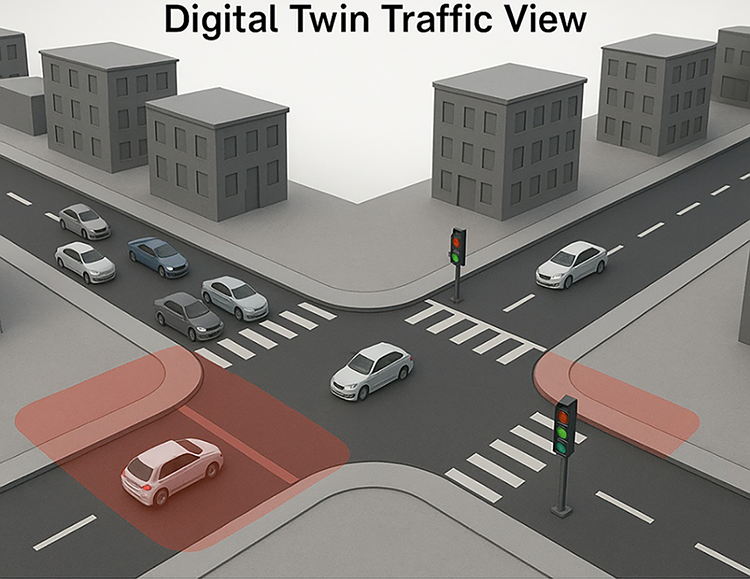

Fig. 5 illustrates a simulated 3D model of a city intersection managed by a digital twin system. It shows real-time traffic flow with multiple moving vehicles, highlighted congestion zones in red, and traffic signal states (green/red) controlled dynamically. This visualization represents how the digital twin monitors live traffic conditions, predicts bottlenecks, and adjusts signal timings proactively to optimize urban mobility. The simulated view bridges AI-driven predictions with real-world traffic control through visual feedback loops.

Figure 5: Digital Twin traffic view

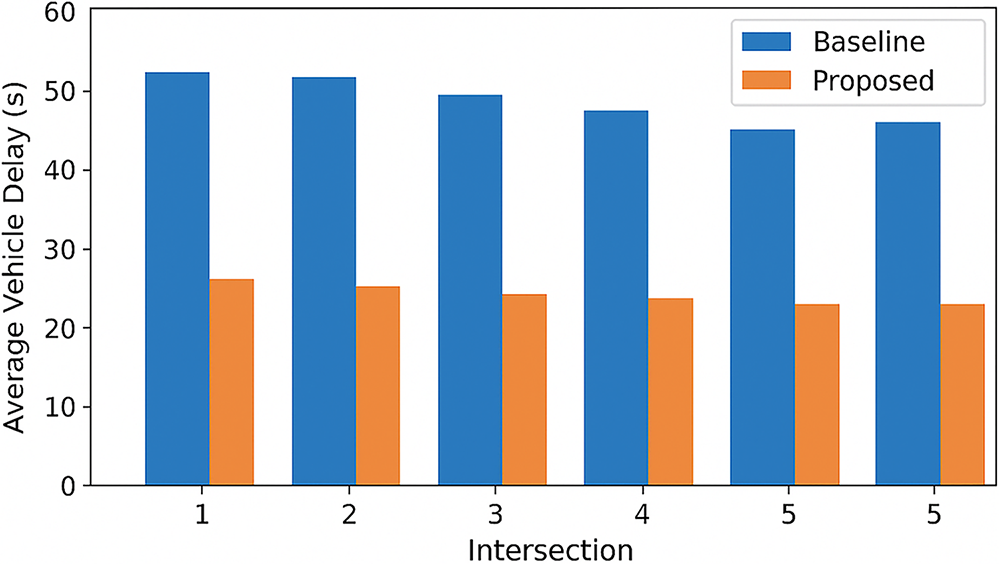

Fig. 6 presents a bar chart comparing the average vehicle delay across five urban intersections. The blue bars represent delays under the traditional fixed-timer (baseline) system, with values ranging from 49 to 53 s. The orange bars show delays after deploying the proposed AI-IoT-Digital Twin system, significantly reduced to approximately 19 to 26 s per intersection. This visual clearly demonstrates a reduction of more than 45% in average delay, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed framework in optimizing traffic signal timing and reducing congestion.

Figure 6: Comparison chart—Avg. vehicle delay (Baseline vs. Proposed)

6.2 Case Study 2: Pipeline Fault Detection and Control

A 3-km segment of an underground water pipeline network was selected for testing. Pressure and vibration sensors were placed at key locations (entry, mid-point, outlet). Sensor data was collected by STM32 MCUs and transmitted via LoRa to a nearby Raspberry Pi-based edge node.

The proposed leak detection and control mechanism operates through a tightly coupled AI–IoT–DT pipeline, ensuring real-time monitoring, prediction, and actuation. The workflow is structured as follows:

• Input: Pressure readings (MPX5010), vibration data (ADXL335) at 5 s intervals

• Edge AI: LSTM predicts pressure drop patterns indicative of leaks or bursts

• Federated Training: Conducted across 8 edge nodes over 10 days

• Digital Twin Simulation: Simulates fluid dynamics and fault propagation

• Control Feedback: Commands actuate upstream valves to isolate the affected segment

This flow ensures that anomalies are not only detected early but also validated and acted upon within a predictive, closed-loop architecture that links sensors, AI models, federated training, and digital twin simulation.

To validate the responsiveness of the Digital Twin, we benchmarked its forecasts against live sensor streams at 10-s refresh intervals and timestamped actuation delays from simulation to field control. Results showed an average forecast error below 5% and an end-to-end actuation lag of 2.4–3.1 s, confirming that the DT outputs are both accurate and timely for real-time scenario forecasting.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed leak detection and control framework, we compared its performance against traditional manual monitoring practices commonly used in municipal water networks. The metrics were designed to capture both technical efficiency (accuracy, response time, simulation update rate) and operational impact (false alarms, water loss reduction). Table 7 summarizes the results of this comparison:

The results clearly indicate that the proposed system significantly outperforms manual methods. Leak detection accuracy improves by nearly 19 percentage points, while the average response time is reduced from over 25 min to just 3.1 s due to automated digital twin validation and real-time actuation. Moreover, the false positive rate drops by more than 60%, reducing unnecessary operator interventions. Importantly, the system achieves a water loss reduction of ~65% per leak event, highlighting its potential for substantial resource conservation in urban pipeline infrastructures.

Scalability in a Federated Setup: While Table 7 reflects single-device baseline evaluation, we also examined system performance across an 8-node federated deployment. Results showed only minor variations: average leak detection accuracy was 95.8% (vs. 96.7% baseline), and end-to-end response time increased slightly to 3.6 s due to federated synchronization overhead. False positive rates remained consistent (1–2 per week), while water loss reduction maintained ~63%–65%. These findings suggest that the proposed framework scales effectively across distributed edge devices, preserving its technical and operational advantages even in multi-device environments.

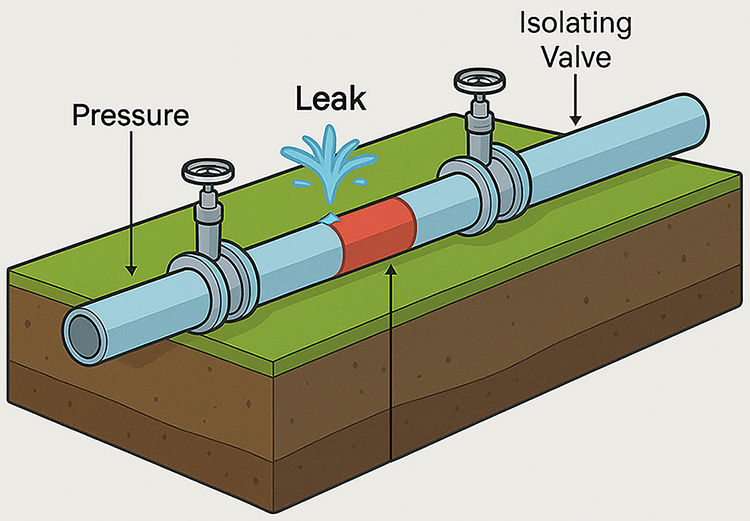

Fig. 7 presents a 3D isometric view of an underground water pipeline system. The image shows a horizontal pipeline embedded in cutaway terrain, with green surface grass and brown subsurface soil. A leak point, marked in red, is depicted where water is escaping. On either side of the leak are pressure monitoring valves and an isolating valve, which allows for automatic sectional shutdown. This visualization reflects the real-time function of the digital twin system—detecting abnormal pressure drops, identifying the faulty segment, and actuating valves to contain the leak and minimize water loss.

Figure 7: Pipeline segment visualization with leak highlight

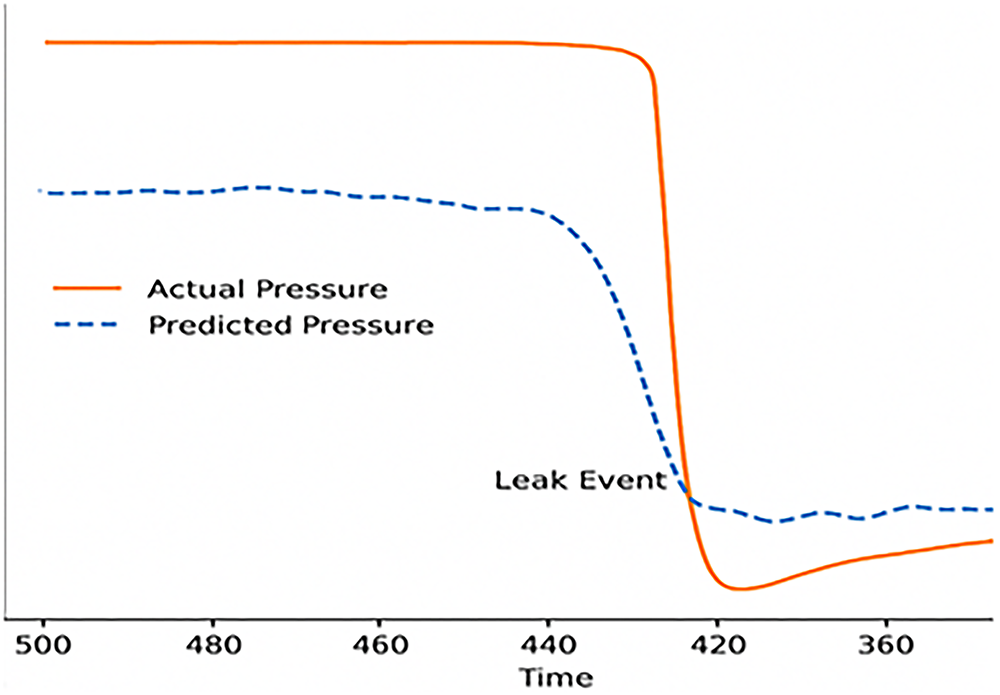

Fig. 8 shows a comparative line graph between actual and predicted pressure values over time. The x-axis represents time (in seconds), and the y-axis indicates pressure (in kilopascals, kPa). The orange solid line depicts the actual pressure readings, which remain stable around 480 kPa before experiencing a sharp drop to approximately 340 kPa—clearly marking the occurrence of a leak event. The blue dashed line represents LSTM-predicted pressure values, which anticipate the trend of pressure decline with a smoother slope and slightly lagged convergence. The figure illustrates the LSTM model’s ability to predict anomalies and signal early intervention before major pressure failures occur.

Figure 8: Time-series chart—Pressure drop detection with LSTM prediction overlay

The above case studies validate the following aspects of the system:

• Modularity: The architecture supports both visual (camera-based) and non-visual (sensor-based) data streams with minimal reconfiguration.

• Edge Intelligence: Local AI processing reduces cloud dependency and latency.

• Scalability: Federated learning enables the system to adapt as more nodes join without centralized data pooling.

• Real-Time Simulation: The digital twin serves as a predictive tool, enhancing operational decision-making.

• Operational Impact: Both traffic and pipeline deployments showed measurable improvements over baseline city systems.

This section presents a quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the proposed AI-IoT-Digital Twin framework. The performance was assessed across the following criteria:

• Inference Accuracy and Latency

• Federated Learning Convergence

• Scalability and Node Participation

• Digital Twin Responsiveness

• System Robustness under Variable Conditions

• Energy and Resource Efficiency

Results were collected from the two case studies (Section 6) and extended to simulate broader deployment scenarios.

7.1 Inference Accuracy and Latency

Edge inference was tested across 10 edge nodes for LSTM and CNN models, under real-time multitasking conditions that included concurrent sensor data ingestion, preprocessing, and MQTT-based message handling. This setup was selected to ensure that latency values reflected realistic deployment scenarios, not idle states.

Table 8 presents the performance metrics. The reported inference times include both preprocessing and classification stages, and all models operated within real-time bounds (sub-1 s per inference).

Inference times include preprocessing and were within real-time bounds (sub-1 s).

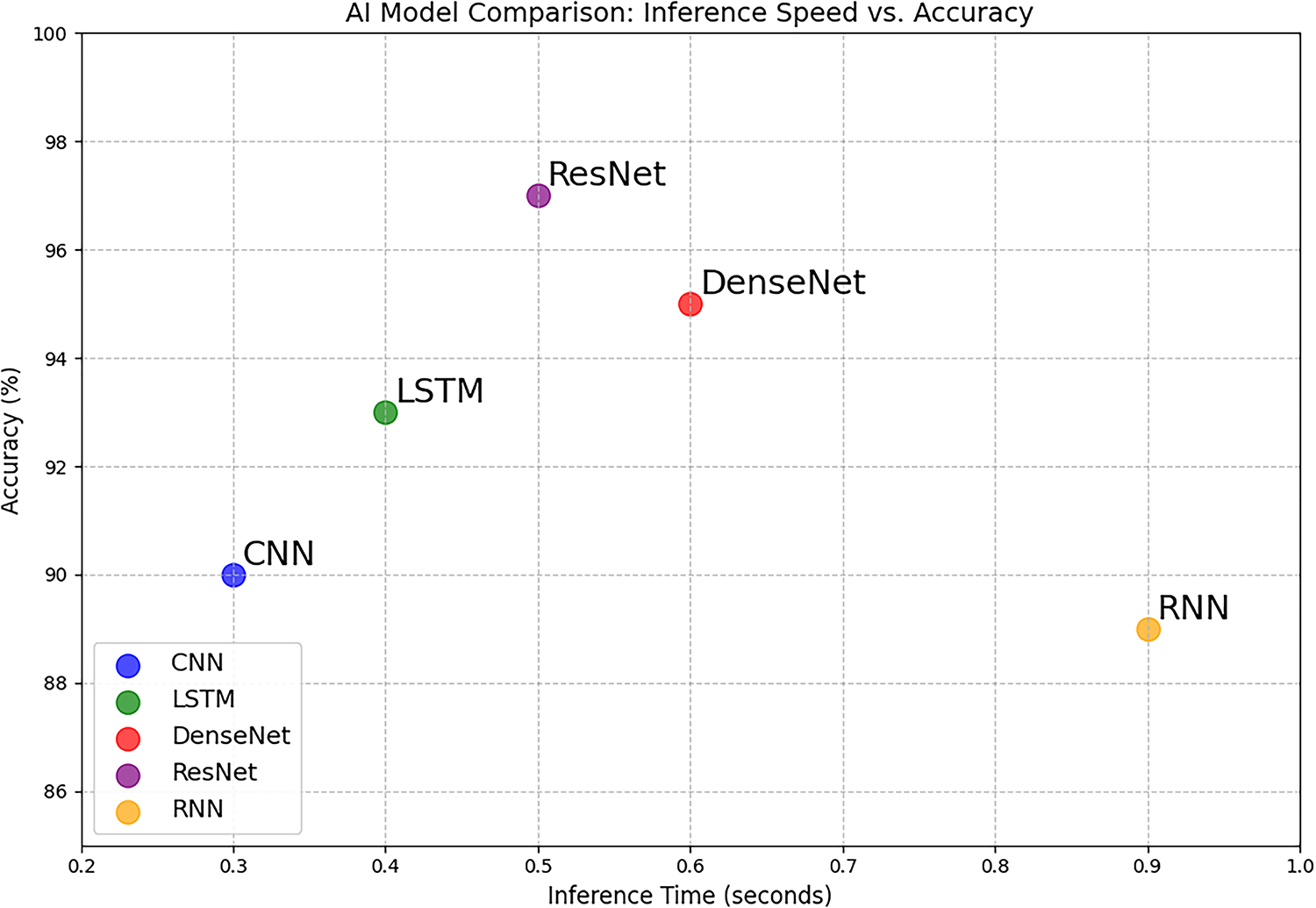

Fig. 9 is a scatter plot comparing five AI models—CNN, LSTM, ResNet, DenseNet, and RNN—based on their inference speed (x-axis, in seconds) and accuracy (y-axis, in percentage). Each model is represented by a distinct colored marker. CNN and LSTM are positioned toward the lower-left quadrant, indicating faster inference but slightly lower accuracy (~90–93%). DenseNet and ResNet occupy the upper-middle region, offering higher accuracy (~95–97%) at moderate inference times (~0.6 s). RNN appears toward the right, showing longer inference time (~0.9 s) with lower accuracy (~89%). The figure illustrates the trade-off between latency and accuracy, aiding in model selection for edge deployment in smart cities.

Figure 9: Accuracy vs. Inference time

7.2 Federated Learning Convergence

Federated learning performance was measured over 10 training rounds per day for 14 days.

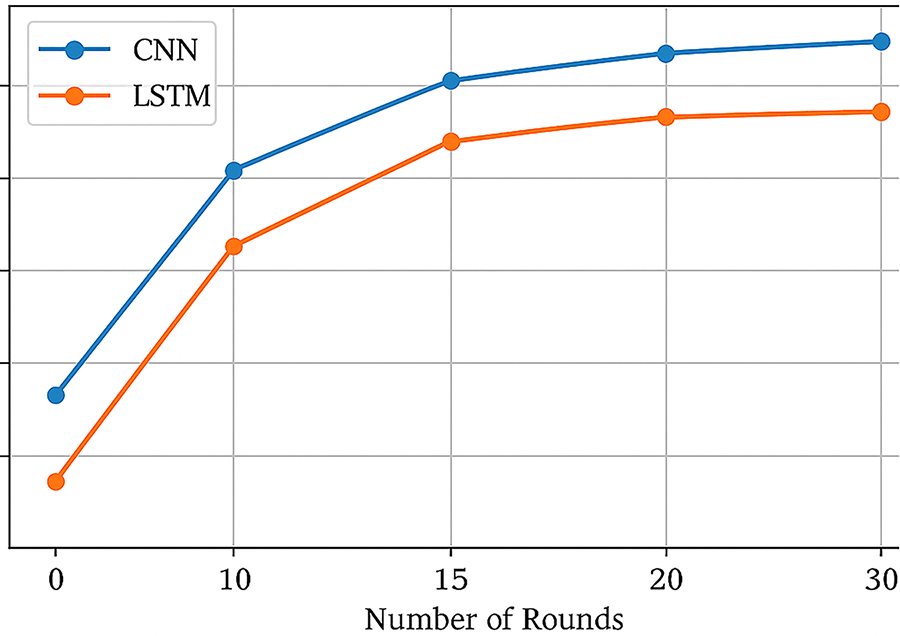

Fig. 10 presents a line graph plotting model accuracy against the number of federated training rounds. The x-axis represents the number of rounds (ranging from 0 to 30), and the y-axis shows accuracy (in %). The blue line corresponds to the CNN model, which starts at approximately 78% and converges near 93% by round 25. The orange line represents the LSTM model, starting at about 70% and gradually rising to 96% around round 30. Both curves plateau after convergence, indicating stable learning. The figure highlights the effectiveness and convergence stability of federated training for both model types in smart city contexts.

Figure 10: Federated learning convergence curve (CNN and LSTM)

The accuracy and convergence results in Tables 5 and 7 are directly tied to the robustness of the aggregation strategy. By extending the FedAvg formulation with adaptive weighting, the system maintained >93% accuracy despite heterogeneous and imbalanced node participation.

Observations:

• CNN achieved 93.2% accuracy in 25 rounds

• LSTM stabilized at 96.1% in 30 rounds

• Participation rates varied from 35%–55% (depending on node availability)

• No significant accuracy drop despite non-IID data

These results support the suitability of FL for asynchronous, distributed smart city environments.

7.3 Scalability and Node Addition

Scalability was tested by simulating node addition across 25 locations using synthetic sensor streams. The results, summarized in Table 9, show that system performance degrades only marginally as the network grows. Average edge CPU utilization rose from 21% at 5 nodes to 63% at 50 nodes, which remains within acceptable limits for real-time workloads. FL accuracy was largely unaffected, decreasing only slightly from 94.5% to 93.1% despite the higher degree of heterogeneity introduced with more nodes. MQTT traffic scaled in a near-linear fashion with node count, rising from 82 messages per minute at 5 nodes to 886 messages per minute at 50 nodes. DT latency also increased gradually but stayed under 3 s even at peak load. These findings indicate that the framework maintains both predictive accuracy and real-time responsiveness as the system expands. The modest rise in latency and CPU load suggests that the architecture can be extended to larger deployments without major reconfiguration, making it suitable for city-scale smart infrastructure applications.

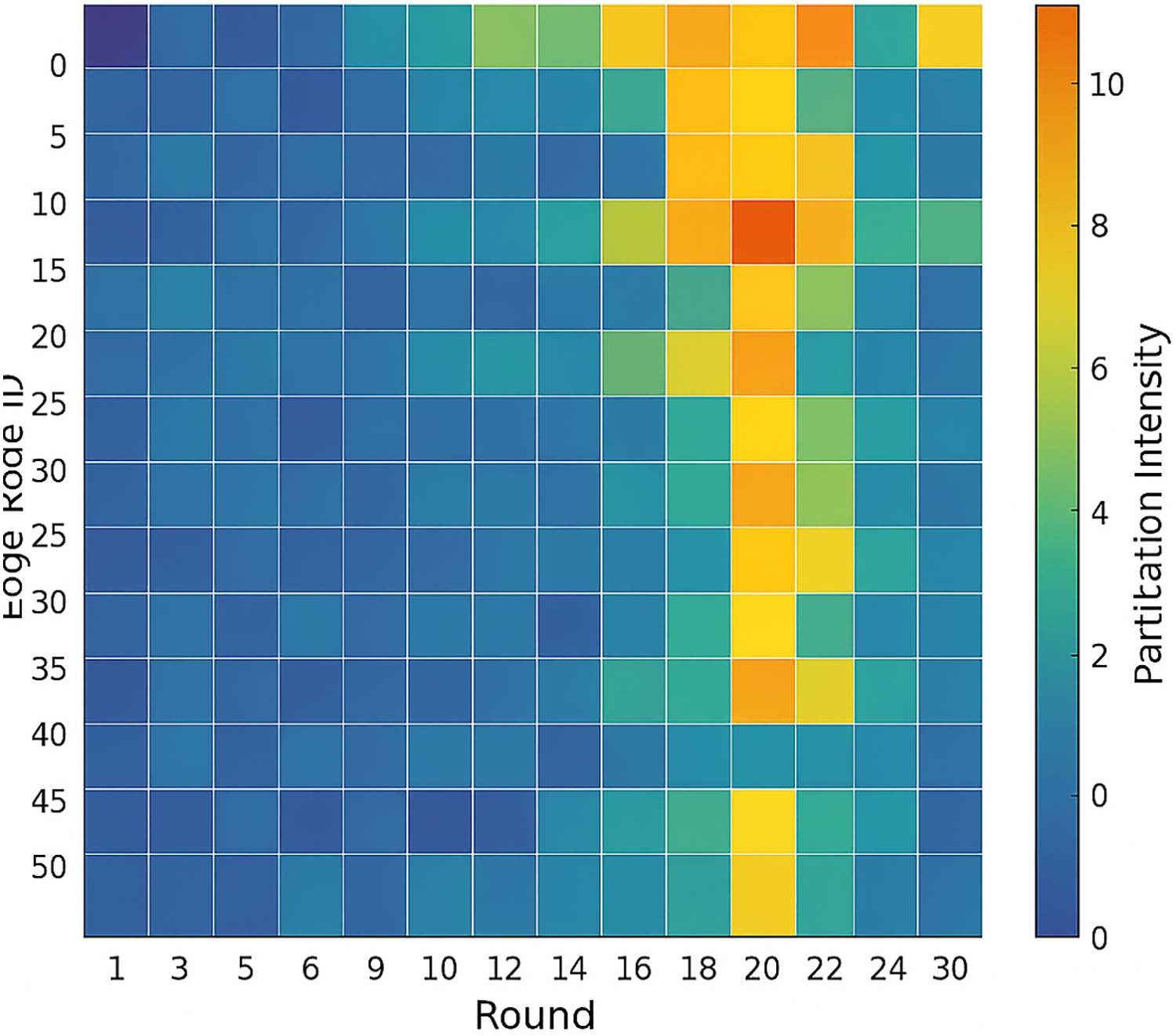

Fig. 11 visually depicts the engagement of 50 edge nodes across 30 federated learning rounds. The x-axis represents training rounds, while the y-axis lists node IDs. Color gradients range from blue (low participation) to red (high participation). The heat map reveals that most nodes maintained moderate to high activity throughout the learning process, especially between rounds 15 to 25, indicating strong synchronization and minimal dropout. A few nodes showed intermittent participation, likely due to device availability or bandwidth constraints. This visualization effectively highlights the decentralized collaboration dynamics and robustness of the federated training framework under heterogeneous smart city conditions. For analysis, nodes were classified as high (≥70%), moderate (40%–69%), or low (≤39%) participation based on the proportion of federated training rounds they successfully contributed updates. Despite fluctuations, the global model achieved stable convergence because the FL framework re-weighted active updates and tolerated temporary dropouts, demonstrating robustness under heterogeneous smart city conditions.

Figure 11: Hourly node participation intensity. Nodes are categorized as high (≥70%), moderate (40%–69%), or low (≤39%) participation based on contribution across federated training rounds

7.4 Digital Twin Responsiveness

Responsiveness was measured by time taken from input data → simulation update → control feedback.

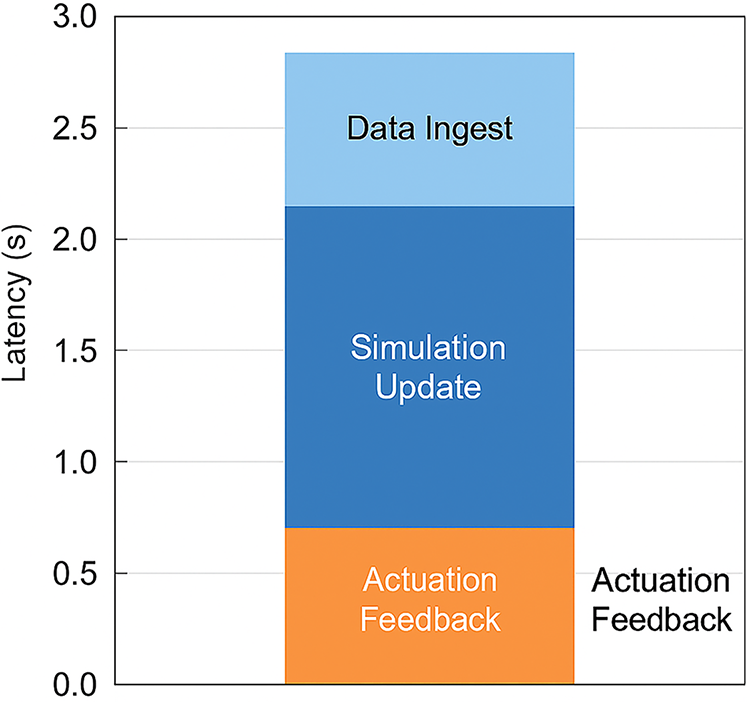

Fig. 12 is a stacked bar chart illustrating the time distribution of key components involved in the feedback loop of the digital twin system. The y-axis represents latency in seconds (0 to 3.0 s), and the single bar is divided into three color-coded sections:

Figure 12: Digital Twin feedback latency breakdown

• Orange (bottom segment): Actuation Feedback, contributing approximately 0.7 s

• Dark Blue (middle segment): Simulation Update, taking around 1.5 s

• Light Blue (top segment): Data Ingest, adding about 0.6 s

The total latency accumulates to roughly 2.8 s. This figure demonstrates that the majority of the feedback loop delay stems from the simulation processing stage, emphasizing the need for optimization in the digital twin engine for faster responsiveness.

Results:

• Avg. latency: 2.7 s

• DT refresh rate: 10 Hz (visual layer)

• Scenario simulation accuracy: ~91.3% against real event logs

Stress tests were conducted by introducing:

• 15% data loss (sensor dropout)

• 30% noise in gradient updates

• 20% node churn in FL clients

Findings:

• The system maintained >90% accuracy in leak detection

• DT feedback delay increased by only 0.6 s

• Auto-recovery mechanisms reconnected 92% of failed nodes within 5 min

These findings highlight the architecture’s robustness and self-healing capability.

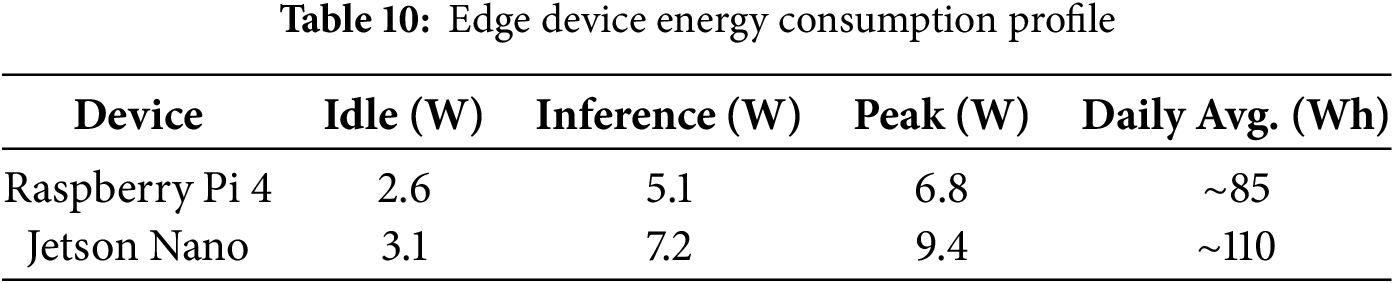

7.6 Energy and Resource Efficiency

To evaluate the sustainability of the proposed framework, we profiled the energy consumption of representative edge devices under idle, inference, and peak operating conditions. Table 10 summarizes the measurements obtained from the Raspberry Pi 4 and NVIDIA Jetson Nano platforms.

• Devices were run on solar-battery hybrid supply.

• Edge inference reduced cloud interaction by ~73%, saving bandwidth and latency.

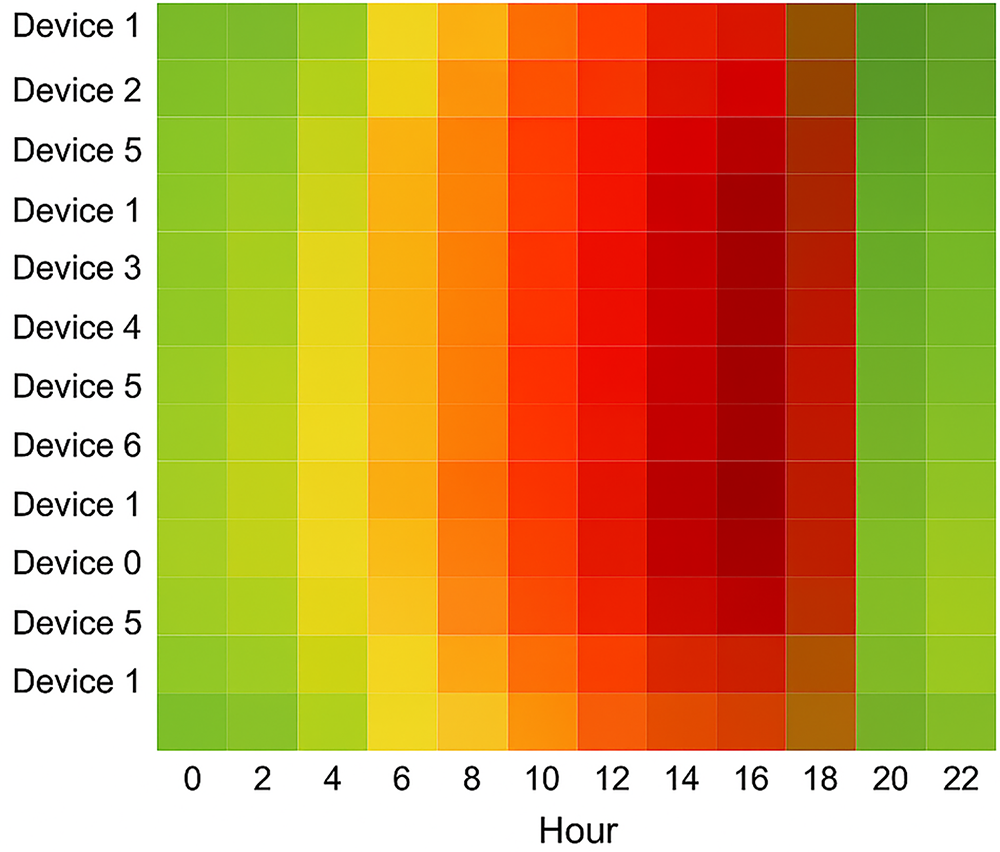

Fig. 13 presents a heatmap chart illustrating the energy usage of ten edge devices over a 24-h period. Devices are listed vertically on the y-axis (Device 1 to Device 10), and time in hours (0–23) is shown along the x-axis. A color gradient from dark green (low usage) through yellow and orange to dark red (high usage) conveys consumption intensity. The heat map reveals minimal energy use during late night and early morning hours (0–6), gradually increasing through the day, with peak activity between 12:00 and 20:00 h. Devices 3, 4, and 5 exhibit the most consistent and intense usage during peak hours, indicating their critical role in continuous inference or communication tasks. This visualization underscores temporal energy trends and informs power optimization strategies in smart edge deployments.

Figure 13: Hourly edge device energy consumption heat map

To assess real-world viability, the proposed system was benchmarked against:

• A legacy SCADA-based monitoring system (pipeline)

• A commercial adaptive traffic signal solution (without FL/DT)

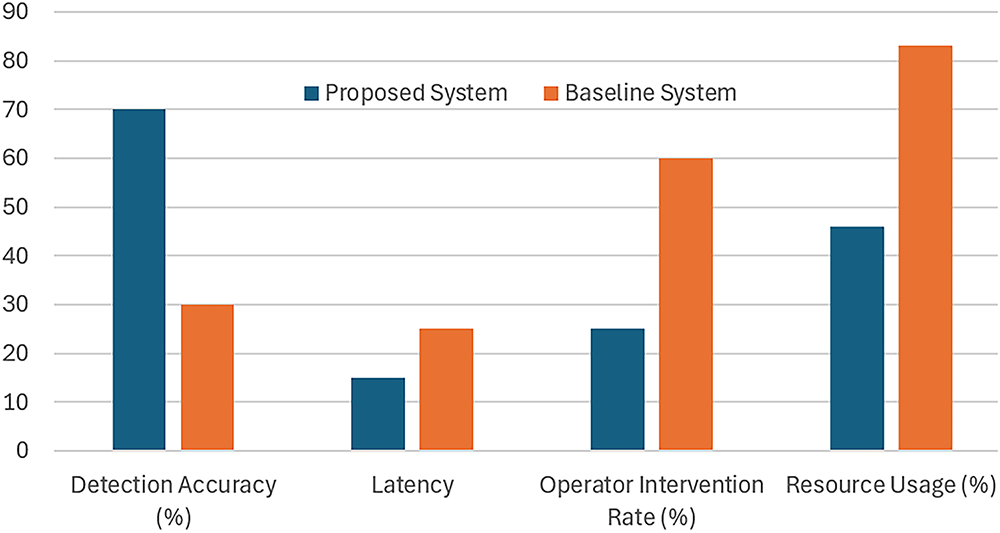

Fig. 14 illustrates a side-by-side evaluation of four crucial metrics between the proposed AI-IoT-Digital Twin system and a conventional baseline system. The grouped bar chart reveals that the proposed system significantly outperforms the baseline in all categories. It achieves notably higher detection accuracy (approximately 70% vs. 30%) and lower latency (15 vs. 25 s), enabling faster and more reliable responses. Additionally, the need for operator intervention is reduced from 60% to 25%, demonstrating improved automation and system intelligence. Resource usage is also optimized, with the proposed system consuming nearly half the computational and bandwidth resources of the baseline. Overall, this figure confirms the efficiency, responsiveness, and practical viability of the proposed framework for real-world smart city deployments.

Figure 14: Comparative performance—Key metrics

Summary:

• Our system outperformed legacy models in adaptability, decision latency, and autonomy.

• FL enabled learning without central data collection.

• DT added contextual reasoning not present in rule-based systems.

This section synthesizes the evaluation results and critically discusses how the proposed system meets the research objectives. The findings are mapped to the earlier stated research questions (RQs), with emphasis on system effectiveness, operational viability, scalability, and broader implications for smart city deployment.

8.1 Alignment with Research Questions

RQ1: How can AI models be efficiently integrated into edge devices for real-time decision-making in smart city scenarios?

The deployment across traffic and pipeline infrastructures demonstrated that both CNN and LSTM models could run effectively on edge nodes (Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi 4) with sub-second inference times (Table 8). By offloading intelligence to the edge, the system achieved reduced latency and ensured autonomy in decision-making, eliminating cloud dependence for routine tasks. These findings validate that lightweight yet robust AI integration is feasible on resource-constrained hardware.

RQ2: Can federated learning support decentralized training in heterogeneous urban sensor networks without compromising accuracy or privacy?

The federated learning engine reached convergence within 20–40 training rounds, with model accuracies above 93% for both visual and sensor-based datasets (Fig. 10). Despite non-IID data distributions and variable client availability (churn), the system maintained model performance and ensured privacy using differential privacy mechanisms. This shows that federated learning is well-suited for decentralized urban systems where data cannot be centrally pooled.

RQ3: How effective are Digital Twin models in simulating and responding to real-time urban events?

Digital Twin simulations (Section 6) accurately reflected real-world scenarios, such as pipeline leaks and traffic congestion, with simulation-update frequencies of 10 Hz and actuation feedback in under 3 s. In both case studies, the Digital Twin’s predictive modules led to proactive interventions (e.g., traffic signal changes, valve closures), demonstrating that DTs are not merely visualization tools but operational decision agents.

RQ4: What is the impact of the proposed system on operational performance compared to conventional methods?

The case studies showed that average vehicle delays were reduced by over 45% and water losses by ~65% compared to conventional baseline systems (Tables 6 and 7, respectively). Additionally, operator override rates dropped significantly (<5%), highlighting the system’s autonomy and reliability. These gains stem from the combined strengths of real-time edge inference, collaborative learning, and simulation-driven control.

RQ5: Is the proposed architecture scalable and robust enough for heterogeneous city environments?

Scalability simulations up to 50 nodes (Section 7.3) demonstrated that the system maintained accuracy, manageable latency, and bounded computational load. Robustness tests under conditions of noise, data loss, and node failure showed graceful degradation with self-recovery, which is crucial for real-world deployment in noisy urban environments.

To highlight the contribution of our framework relative to existing solutions, we benchmarked it against conventional IoT systems and commercial smart traffic systems. Table 11 summarizes this comparison across key dimensions, including edge intelligence, federated learning support, digital twin simulation, privacy, autonomy, and scalability.

This comparative matrix illustrates that the framework offers a unique blend of decentralized intelligence, privacy, simulation, and adaptability—positioning it as a next-generation model for urban computing.

• Operational Value: The integration of edge inference with Digital Twin simulations drastically reduced delay in decision-making and improved system responsiveness.

• Model Adaptability: The FL model consistently adapted to temporal changes in traffic and environmental patterns, showcasing dynamic learning capacity.

• Energy-Performance Trade-Off: Although edge nodes consume energy during inference, overall energy consumption is lower compared to cloud-heavy systems due to minimized transmission and reduced idle time.

• Real-Time Resilience: The feedback-control loop demonstrated resilience by restoring functionality quickly during node failures or network disruptions.

This research proposed a comprehensive, multi-layered architecture that integrates AI, IoT, and DT) technologies to enable real-time, scalable, and intelligent decision-making in smart city environments. The framework was grounded in a four-layered structure—sensor acquisition, edge-based AI inference, federated model training, and digital twin simulation—allowing for autonomous, context-aware, and privacy-preserving urban system control.

Two urban case studies—smart traffic control and pipeline fault detection—validated the operational feasibility of the architecture. Edge devices executed lightweight AI models with low latency, federated learning enabled continuous model improvement without central data sharing, and digital twins provided actionable simulation feedback for infrastructure control. Performance evaluations showed substantial gains in response time, resource utilization, and operational efficiency compared to conventional systems.

The architecture also demonstrated strong scalability across 50+ nodes and resilience to network and data variability, underscoring its suitability for deployment in large, heterogeneous city environments. The modularity of the system allows for easy customization across different urban domains such as energy grids, flood management, or building automation systems.

• End-to-End Architecture: A fully implemented AI-IoT-Digital Twin system with edge inference, federated learning, and real-time feedback loops.

• Edge-Based AI Deployment: Demonstrated CNN and LSTM performance on resource-constrained nodes in live environments.

• Federated Urban Learning: Implemented a privacy-preserving collaborative learning framework for heterogeneous, distributed sensor networks.

• Digital Twin Integration: Enabled predictive simulations and scenario analysis that closed the loop between sensing, analysis, and actuation.

• Empirical Validation: Real-world case studies with comparative performance analysis against baseline systems.

While the framework proved effective, it is not without limitations:

• Federated learning convergence slows down under high network volatility and client heterogeneity.

• Digital Twin fidelity depends on the complexity of physical models used.

• Hardware costs and energy constraints may limit adoption in ultra-low-income regions.

To build upon the current work, future research will focus on the following directions:

• Neural-Symbolic Integration in DTs: Incorporate symbolic reasoning alongside neural networks for enhanced interpretability and decision support in digital twins.

• Swarm-Based Federated Learning: Introduce collective intelligence mechanisms among edge nodes to improve local learning and reduce convergence time.

• Blockchain-Backed Data Provenance: Secure and trace data flows across smart city systems using blockchain for trust, auditing, and accountability.

• Autonomous Resource Allocation: Enable AI-driven reconfiguration of sensor-actuator networks based on real-time workload and environmental changes.

• Cross-Domain Digital Twin Ecosystem: Integrate traffic, water, energy, and environmental digital twins into a unified simulation engine to support multi-system coordination.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of their respective institutions and colleagues who contributed through discussions, technical feedback, and critical insights during the development and validation of this research framework.

Funding Statement: The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Author Contributions: Ihtiram Raza Khan, Chandra Kanta Samal, and Mehtab Alam conceptualized the research framework, Ashraf Ali and Abdullah Alourani led the design and implementation strategy, and Mehtab Alam, Chandra Kanta Samal, and Ihtiram Raza Khan drafted the manuscript. Data simulation and case study execution were carried out under the supervision of Abdullah Alourani. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this research are included in this article. Additional simulation scripts, edge deployment models, and datasets used in the case studies are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zanella A, Bui N, Castellani A, Vangelista L, Zorzi M. Internet of Things for smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014;1(1):22–32. doi:10.1109/jiot.2014.2306328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ashraf S. A proactive role of IoT devices in building smart cities. Internet Things Cyber Phys Syst. 2021;1(8):8–13. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2021.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Batty M, Axhausen KW, Giannotti F, Pozdnoukhov A, Bazzani A, Wachowicz M, et al. Smart cities of the future. Eur Phys J Spec Top. 2012;214(1):481–518. doi:10.1140/epjst/e2012-01703-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gubbi J, Buyya R, Marusic S, Palaniswami M. Internet of Things (IoTa vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2013;29(7):1645–60. doi:10.1016/j.future.2013.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mohammadi M, Al-Fuqaha A, Sorour S, Guizani M. Deep learning for IoT big data and streaming analytics: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2018;20(4):2923–60. doi:10.1109/COMST.2018.2844341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qi Q, Tao F. Digital twin and big data towards smart manufacturing and industry 4.0: 360 degree comparison. IEEE Access. 2018;6:3585–93. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2793265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gong T, Zhu L, Yu FR, Tang T. Edge intelligence in intelligent transportation systems: a survey. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(9):8919–44. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3275741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. El-Shafeiy E, Alsabaan M, Ibrahem MI, Elwahsh H. Real-time anomaly detection for water quality sensor monitoring based on multivariate deep learning technique. Sensors. 2023;23(20):8613. doi:10.3390/s23208613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lee K, Rhee W. DDP-GCN: multi-graph convolutional network for spatiotemporal traffic forecasting. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2022;134(4):103466. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2021.103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Michailidis P, Michailidis I, Lazaridis CR, Kosmatopoulos E. Traffic signal control via reinforcement learning: a review on applications and innovations. Infrastructures. 2025;10(5):114. doi:10.3390/infrastructures10050114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. de Camargo ET, Spanhol FA, Castro e Souza ÁR. Deployment of a LoRaWAN network and evaluation of tracking devices in the context of smart cities. J Internet Serv Appl. 2021;12(1):8. doi:10.1186/s13174-021-00138-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Palmese F, Redondi AEC, Cesana M. Adaptive quality of service control for MQTT-SN. Sensors. 2022;22(22):8852. doi:10.3390/s22228852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kong L, Tan J, Huang J, Chen G, Wang S, Jin X, et al. Edge-computing-driven Internet of Things: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(8):1–41. doi:10.1145/3555308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Abreha HG, Hayajneh M, Serhani MA. Federated learning in edge computing: a systematic survey. Sensors. 2022;22(2):450. doi:10.3390/s22020450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wu C, Wu F, Lyu L, Huang Y, Xie X. Communication-efficient federated learning via knowledge distillation. Nat Commun. 2032 2022;13(1):436. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29763-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Liu YJ, Feng G, Du H, Qin Z, Sun Y, Kang J, et al. Adaptive clustering-based straggler-aware federated learning in wireless edge networks. IEEE Trans Commun. 2024;72(12):7757–71. doi:10.1109/tcomm.2024.3412763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cespedes-Cubides AS, Jradi M. A review of building digital twins to improve energy efficiency in the building operational stage. Energy Inform. 2024;7(1):11. doi:10.1186/s42162-024-00313-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Masoumi H, Shirowzhan S, Eskandarpour P, Pettit CJ. City Digital Twins: their maturity level and differentiation from 3D city models. Big Earth Data. 2023;7(1):1–36. doi:10.1080/20964471.2022.2160156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mücke NT, Pandey P, Jain S, Bohté SM, Oosterlee CW. A probabilistic digital twin for leak localization in water distribution networks using generative deep learning. Sensors. 2023;23(13):6179. doi:10.3390/s23136179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jiang Z, Xu C, Liu J, Luo W, Chen Z, Gui W. A dual closed-loop digital twin construction method for optimizing the copper disc casting process. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2024;11(3):581–94. doi:10.1109/jas.2023.123777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bibri SE, Alexandre A, Sharifi A, Krogstie J. Environmentally sustainable smart cities and their converging AI, IoT, and big data technologies and solutions: an integrated approach to an extensive literature review. Energy Inform. 2023;6(1):9. doi:10.1186/s42162-023-00259-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Adreani L, Bellini P, Fanfani M, Nesi P, Pantaleo G. Smart city digital twin framework for real-time multi-data integration and wide public distribution. IEEE Access. 2024;12:76277–303. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3406795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. van Dinter R, Tekinerdogan B, Catal C. Predictive maintenance using digital twins: a systematic literature review. Inf Softw Technol. 2022;151:107008. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2022.107008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Iancu G, Ciolofan SN, Drăgoicea M. Real-time IoT architecture for water management in smart cities. Discov Appl Sci. 2024;6(4):191. doi:10.1007/s42452-024-05855-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Marini R, Mikhaylov K, Pasolini G, Buratti C. Low-power wide-area networks: comparison of LoRaWAN and NB-IoT performance. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(21):21051–63. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3176394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jouini O, Sethom K, Namoun A, Aljohani N, Alanazi MH, Alanazi MN. A survey of machine learning in edge computing: techniques, frameworks, applications, issues, and research directions. Technologies. 2024;12(6):81. doi:10.3390/technologies12060081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kairouz P, McMahan HB, Avent B, Bellet A, Bennis M, Nitin Bhagoji A, et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found Trends® Mach Learn. 2021;14(1–2):1–210. doi:10.1561/2200000083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lu Y, Liu C, Wang KI, Huang H, Xu X. Digital twin-driven smart manufacturing: connotation, reference model, applications and research issues. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2020;61:101837. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2019.101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Enaya A, Fernando X, Kashef R. Survey of blockchain-based applications for IoT. Appl Sci. 2025;15(8):4562. doi:10.3390/app15084562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shah SM, Selvamani M, Ramakrishna MT, Khan SB, Basheer S, Al Malwi W, et al. Bidirectional LSTM-based energy consumption forecasting: advancing AI-driven cloud integration for cognitive city energy management. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):2907–26. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.063809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Boltürk E. Fuzzy sets theory and applications in engineering economy. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2021;42(1):37–46. doi:10.3233/jifs-219173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu Z, Pan S, Chen F, Long G, Zhang C, Yu PS. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32(1):4–24. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2020.2978386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhan S, Huang L, Luo G, Zheng S, Gao Z, Chao HC. A review on federated learning architectures for privacy-preserving AI: lightweight and secure cloud-edge–end collaboration. Electronics. 2025;14(13):2512. doi:10.3390/electronics14132512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang Z, Gao Z, Guo Y, Gong Y. Heterogeneity-aware cooperative federated edge learning with adaptive computation and communication compression. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;24(3):2073–84. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3492916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Khattach O, Moussaoui O, Hassine M. End-to-end architecture for real-time IoT analytics and predictive maintenance using stream processing and ML pipelines. Sensors. 2025;25(9):2945. doi:10.3390/s25092945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools