Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

First-Principles Study on the Mechanical and Thermodynamic Properties of (NbZrHfTi)C High-Entropy Ceramics

1 College of Mechanical and Vehicle Engineering, Changsha University of Science and Technology, Changsha, 410114, China

2 National Institute of Defense Technology Innovation, Academy of Military Sciences PLA China, Beijing, 100091, China

3 National Engineering Research Center for Mechanical Products Remanufacturing, Army Academy of Armored Forces, Beijing, 100072, China

4 Hunan Key Laboratory of Super Microstructure and Ultrafast Process, School of Physics and Electronics, Central South University, Changsha, 410083, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yonggang Tong. Email: ; Xiubing Liang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computational Analysis of Micro-Nano Material Mechanics and Manufacturing)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071890

Received 14 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

(NbZrHfTi)C high-entropy ceramics, as an emerging class of ultra-high-temperature materials, have garnered significant interest due to their unique multi-principal-element crystal structure and exceptional high-temperature properties. This study systematically investigates the mechanical properties of (NbZrHfTi)C high-entropy ceramics by employing first-principles density functional theory, combined with the Debye-Grüneisen model, to explore the variations in their thermophysical properties with temperature (0–2000 K) and pressure (0–30 GPa). Thermodynamically, the calculated mixing enthalpy and Gibbs free energy confirm the feasibility of forming a stable single-phase solid solution in (NbZrHfTi)C. The calculated results of the elastic stiffness constant indicate that the material meets the mechanical stability criteria of the cubic crystal system, further confirming the structural stability. Through evaluation of key mechanical parameters—bulk modulus, shear modulus, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio—we provide comprehensive insight into the macro-mechanical behaviour of the material and its correlation with the underlying microstructure. Notably, compared to traditional binary carbides and their average properties, (NbZrHfTi)C exhibits higher Vickers hardness (Approximately 28.5 GPa) and fracture toughness (Approximately 3.4 MPa·m¹/²), which can be primarily attributed to the lattice distortion and solid-solution strengthening mechanism. The study also utilizes the quasi-harmonic approximation method to predict the material’s thermophysical properties, including Debye temperature (initial value around 563 K), thermal expansion coefficient (approximately 8.9 × 10−6 K−¹ at 2000 K), and other key parameters such as heat capacity at constant volume. The results show that within the studied pressure and temperature ranges, (NbZrHfTi)C consistently maintains a stable phase structure and good thermomechanical properties. The thermal expansion coefficient increasing with temperature, while heat capacity approaches the Dulong-Petit limit at elevated temperatures. These findings underscore the potential of (NbZrHfTi)C applications in ultra-high temperature thermal protection systems, cutting tool coatings, and nuclear structural materials.Keywords

High-entropy alloys (HEAs), a relatively novel class of multi-component materials, exhibit certain distinctions from conventional alloys typically based on one or two primary elements [1]. They typically consist of five or more principal elements, each with a molar content of between 5 and 35 atomic percent [2]. The mixed entropy increases with the rise of the main elements (>1.61R), and high-entropy alloys tend to form simple single-phase face-centred cubic (FCC) or body-centred cubic (BCC) solid solution structures, rather than intermetallic compound phases [3]. HEAs exhibit many excellent properties, such as outstanding strength, high hardness, superior wear resistance, and good oxidation resistance, which are mainly due to four core effects: the high entropy effect, severe lattice distortion effect, slow diffusion effect, and the cocktail effect [4]. The concept of high-entropy alloys has been extended to the field of ceramics, thereby giving rise to the development of high-entropy ceramics (HECs). Single-phase compounds composed of cations or anions of not less than four elements with equimolar or nearly equimolar ratios are defined as high-entropy ceramics (HECs) [5].

As one of the HECs, carbide-based HECs exhibit [6,7] high hardness, superior oxidation resistance, and excellent wear resistance, granting them broad wide application prospects in aerospace, mechanical, and metallurgical fields. Early research on carbide HECs mainly focused on HECs based on the five-component transition metal carbide systems. For example, Sarker et al. [8] pioneered the prediction of HEC stability using the energy distribution spectrum (defined as the entropy stability parameter EFA), calculated from the randomization of the structure. However, the EFA parameter only considered five-component equimolar ratio HECs, which could not be extended to predict the four-component HECs. Consequently, studies on four-component HECs have primarily relied on experimental approaches [9,10]. Although various microstructures and mechanical properties of four-component HECs have been reported, traditional experimental methods are suffered from with limitations such as high cost, low efficiency, and long development time.

Theoretical approaches based on first-principles calculations provide an effective solution to these limitations [11]. Furthermore, as first-principles calculations are rooted in quantum mechanics, they require no empirical parameters in their derivation, making them a powerful tool for predicting and optimizing the properties of HECs [12,13]. Herein, we established the special quasi-random structure (SQS) [14] model of (NbZrHfTi)C HECs to analyze its structural, mechanical, and electronic properties by applying first-principles calculations. The thermodynamic properties, including the thermal expansion coefficient and constant-volume heat capacity under varying pressure and temperature conditions, were also examined using a combined approach incorporating the Debye–Grüneisen model [15].

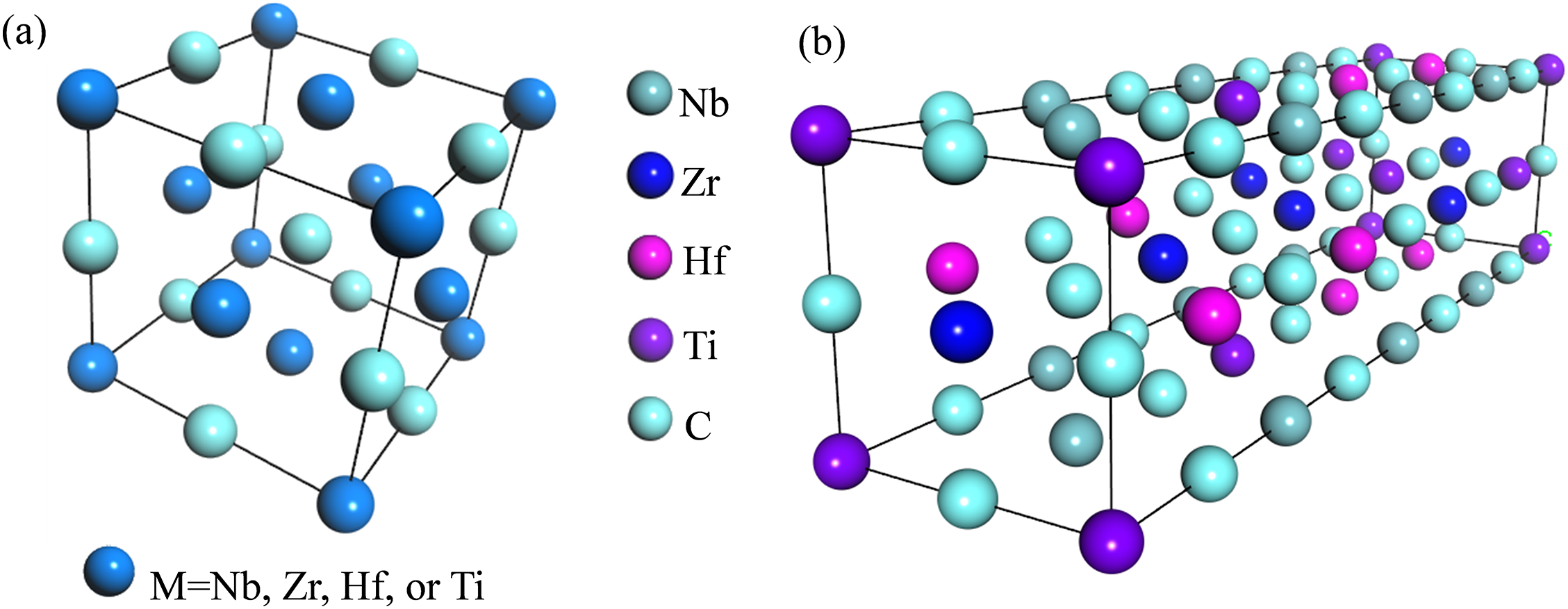

In this work, first-principles calculations were performed by the CASTEP (Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package) module in Materials Studio 2017, which is based on density functional theory [16]. The plane-wave pseudopotential method was used to treat all calculations [17]. In general, single binary metal carbides, including NbC, ZrC, HfC, and TiC, consist of two face-centered cubic sublattices [18,19]. One of the FCC sublattices is occupied by metal atoms, and the other is occupied by carbon atoms, as shown in Fig. 1a. To model the compositional disorder in the solid solution, a 4 × 1 × 1 special quasi-random structure (SQS) supercell containing 32 atoms was constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

Figure 1: Crystal structure model (a) and 4 × 1 × 1 supercell model (b) of (NbZrHfTi)C

In the calculation, the exchange-correlation interactions were treated using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) [20]. The electron-ionic interaction was calculated in reciprocal space using norm conserving pseudopotential. The k-points in the Brillouin zone were generated by the Monkhorst-Pack method [21], with a k-point mesh of 6 × 2 × 2. The geometry optimization adopted the Broyden Fletcher Goldfarb Shanno (BFGS) algorithm, and the convergence criteria were as follows: the electron energy was less than 1 × 10−5 eV/atom, the Hellmann-Feynman force was less than 0.03 eV/Å, the maximum stress deviation was lower than 0.05 GPa and the maximum ion displacement deviation was less than 0.001 Å. The plane wave cut-off energy was set to 1550 eV to ensure computational accuracy.

At present, the quasi-harmonic Debye model has been extensively employed to investigate the thermal properties of high-entropy systems owing to its computational efficiency and simplicity, and it demonstrates strong agreement with experimental results [13]. Accordingly, the quasi-harmonic Debye model was adopted in the present study to compute all thermodynamic quantities using the GIBBS software package [22]. The Gibbs free energy for a non-equilibrium state is given by [23]:

where E (V) represents the static energy of the crystal as a function of cell volume, PV corresponds to the constant hydrostatic pressure condition,

where

where M represents the mass of the cell, Bs approximates the adiabatic bulk modulus, and σ is the Poisson’s ratio.

The non-equilibrium Gibbs function G (V;P,T) for volume minimization is simplified to a function of V [23]:

By solving Eq.(5), constant volume heat capacity CV, isothermal elastic modulus BT and the coefficient of thermal expansion α can be obtained:

where

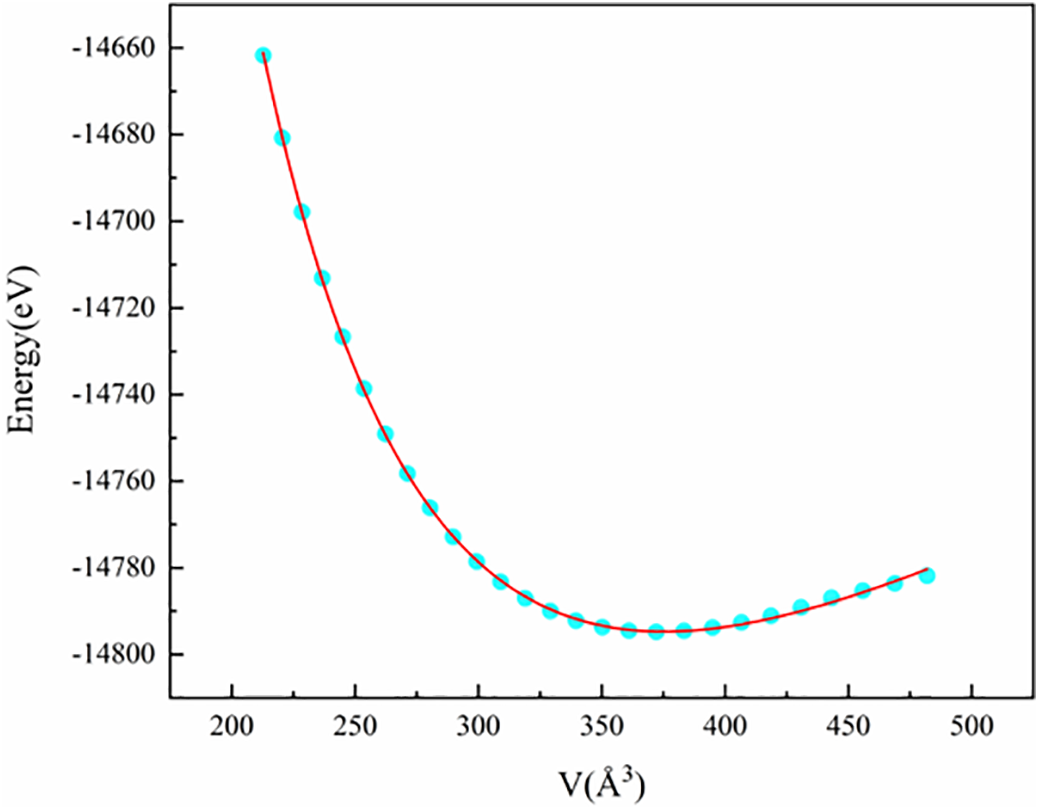

To determine the lattice constants, equilibrium bulk modulus, and some relevant parameters of (NbZrHfTi)C after relaxation, the lattice structure of the (NbZrHfTi)C supercell was optimized and its equilibrium energy at different volumes was obtained. Fitting the energy-volume data to the third-order Birch-Murnaghan equation of state [24]:

where V and E (V) are the calculated volume and corresponding energy, respectively. V0 and E0 are respectively lattice volume and energy at equilibrium, and B0 and

Figure 2: Calculated E-V curve for (NbZrHfTi)C

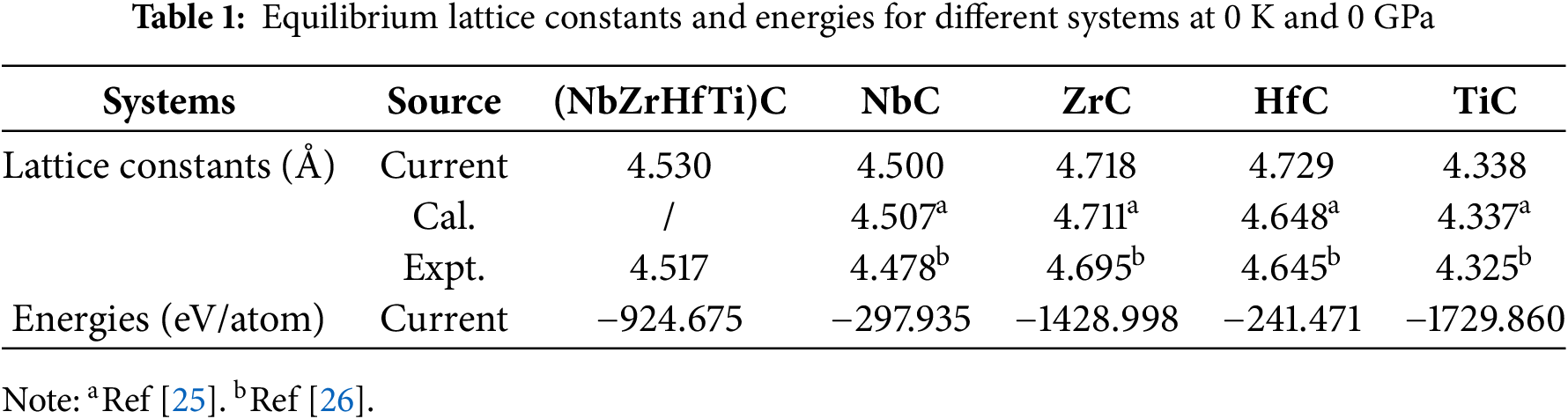

The data presented in Table 1 are the equilibrium lattice parameters of (NbZrHfTi)C and binary carbides calculated by MS at 0 K and 0 GPa. It is observed that the lattice constant a = 4.53. Å of (NbZrHfTi)C is similar to the fitting results, and is approximately equal to the average lattice constant 4.53 Å of the four-component binary carbides. Consistent with the behavior of most high-entropy alloys (HEAs), the lattice parameters of high-entropy carbides (HECs) approximately adhere to the mixing rule, suggesting a nearly random distribution of the constituent elements. Furthermore, the calculated lattice constants of (NbZrHfTi)C align closely with previously reported experimental and theoretical values for both the multicomponent carbide and its constituent binary carbides, thereby corroborating the reliability of our computational results.

To further analyze the structural stability of (NbZrHfTi)C, we calculated the energies of (NbZrHfTi)C and binary carbides after relaxation at 0 K and 0 GPa, as listed in Table 1, and calculated the Gibbs free energy of (NbZrHfTi)C by the following equation:

where

where E is the energy of (NbZrHfTi)C or individual metal carbides at 0 K and 0 GPa equilibrium. According to the energy obtained by the first-principle calculation, the

where R is the ideal gas constant (R ≈ 8.314 J·mol−1K−1), and h and k represent the carbon sublattice and metal sublattice, respectively. N represents the species of elements in the h or k sublattice,

The mixing enthalpy of (NbZrHfTi)C is 0.693 R by Eq. (14). Then, the Gibbs free energy of (NbZrHfTi)C (298 K) is calculated by Eq. (11) to be −12.21 kJ/mol.

where n is the binary metal carbide species in the solid solution of the high entropy carbides,

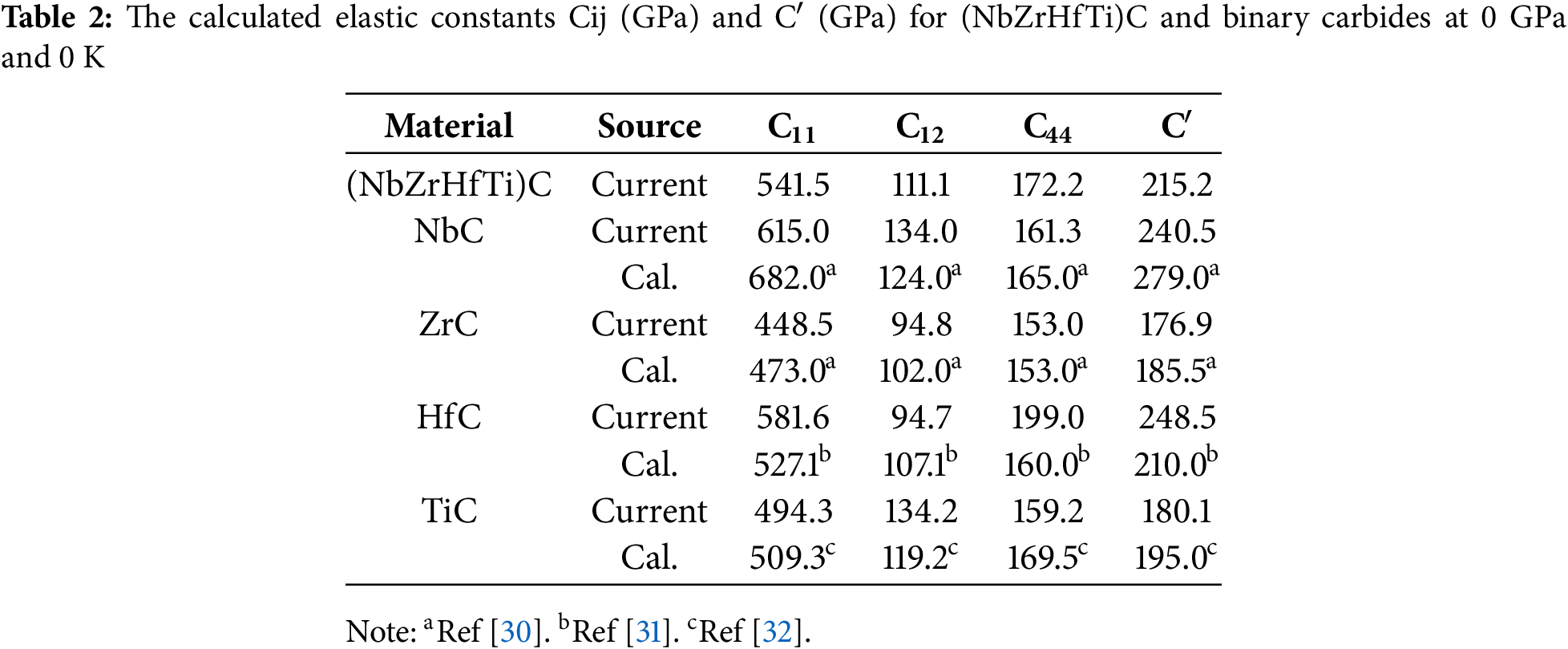

The single-crystal elastic stiffness constants (Cij) serve as fundamental parameters for characterizing crystalline materials, providing direct insight into key mechanical properties such as intrinsic strength and mechanical stability. Therefore, the three independent single-crystal elastic stiffness constants C11, C12, and C44 for FCC (NbZrHfTi)C at 0 GPa and 0 K, and the tetragonal shear modulus C′ (C′ = (C11 − C12)/2) were calculated by using the stress-strain method based on density functional theory as shown in Table 2.

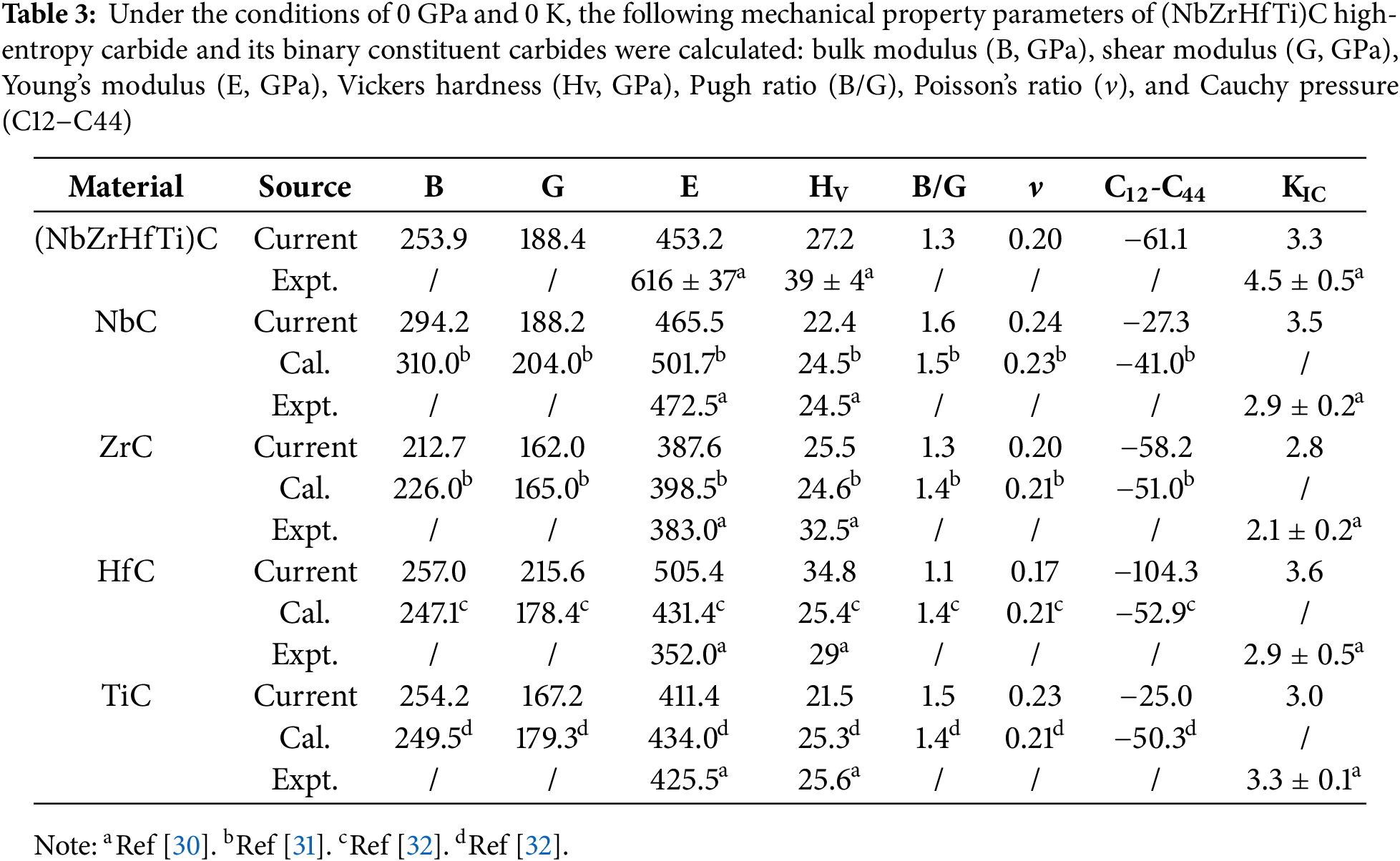

Consistent with observations in metallic high-entropy alloys, the elastic constants of (NbZrHfTi)C fall between those of the constituent binary carbides, approximately obeying the rule of mixtures. Moreover, through these elastic stiffness constants and tetragonal shear modulus, it is observed that (NbZrHfTi)C satisfies the following mechanical stability criteria: C11 > 0, C44 > 0, C11 + 2C12 > 0, C11 – C12 > 0, and the tetragonal shear modulus C′ > 0. Therefore, (NbZrHfTi)C is mechanically stable. The elastic modulus represents a fundamental mechanical property of engineering materials. In this study, the elastic moduli of the carbide systems were determined using the Voigt-Reuss-Hill (VRH) approximation, based on the previously derived elastic constants. The results are listed in Table 3 and the formula is as follows [33,34]:

where B is bulk modulus,

From Table 3, it is seen that the bulk modulus B, shear modulus G, and Young’s modulus E of (NbZrHfTi)C approximately obey the mixing rule, and the calculated results are similar to those of Refs [30–32]. These results confirm the reliability of the computational approach. The bulk modulus (B) serves as a fundamental indicator of a material’s resistance to uniform external compression within the elastic regime. It quantitatively characterizes the volumetric stiffness and compressibility of the solid under hydrostatic stress. Since the bulk modulus B of (NbZrHfTi)C does not show a significant increase, it has not contributed to an effective enhancement of its incompressibility. The shear modulus G characterizes the material’s resistance to shear deformation, similarly, no significant enhancement is observed in the shear deformation resistance of (NbZrHfTi)C. Equations underpins the macroscopic mechanical properties 6 to 10 show that the elastic moduli are closely related to the elastic constants, and they together reflect no significant change in the fracture resistance and shear deformation resistance of (NbZrHfTi)C compared to binary carbides. However, Table 3 shows that the hardness of (NbZrHfTi)C is higher than the average value for the binary carbides, suggesting that there may be a solid solution strengthening effect for (NbZrHfTi)C HECs. Notably, as presented in Table 3, the Young’s modulus, Vickers hardness of (NbZrHfTi)C surpass the averaged properties of the constituent binary carbides in both calculated and experimental results. Although the experimental values are significantly higher, the theoretically calculated data have the same trend as the experimental, which indicates that there is a significant solid solution strengthening effect of (NbZrHfTi)C. In addition, compared to the pure metal HEAs Ti0.2Zr0.2Hf0.2Nb0.2, there is a significant improvement in elastic moduli and hardness [35,36]. This implies that (NbZrHfTi)C retains the characteristic properties of high-entropy carbides, such as high strength and hardness.

Poisson’s ratio (ν) is not only an elastic constant but also an important indicator for assessing the toughness or brittleness behaviour of polycrystalline materials. In general, Poisson’s ratio for elastic deformation varies between 0.2 and 0.3. If ν is approximately 0.1, the material is strongly covalent, if ν is greater than 0.25, the material is ductile. For metallic materials, the ν value is approximately 0.33 [37,38]. The Poisson’s ratio for (NbZrHfTi)C is 0.2, implying that (NbZrHfTi)C is a brittle material in which ionic and covalent bonds are present. Pugh ratio B/G can also be used to predict the brittleness and ductility of materials. If B/G > 1.75, the material is described as ductile, otherwise, it is brittle. According to the Pugh criterion, a higher B/G ratio generally indicates better ductility in materials. The calculated B/G value for (NbZrHfTi)C is 1.3, which falls below the ductility threshold of 1.75, confirming its brittle nature. Furthermore, the Cauchy pressure (C12–C44) serves as an additional indicator for evaluating ductile vs. brittle behavior in alloys [39], it can predict the bondability of the material. A negative value of Cauchy pressure implies the material is brittle and otherwise behaves as ductile. The calculated C12 − C44 = −61.1 at 0 GPa and 0 K for (NbZrHfTi)C is higher than the value for its component binary carbides, which indicates (NbZrHfTi)C has a fracture toughness than the component binary carbides, corresponding to its higher theoretical hardness. Overall, Poisson’s ratio, Pugh’s ratio, and Cauchy pressure are consistent in determining the brittleness of (NbZrHfTi)C.

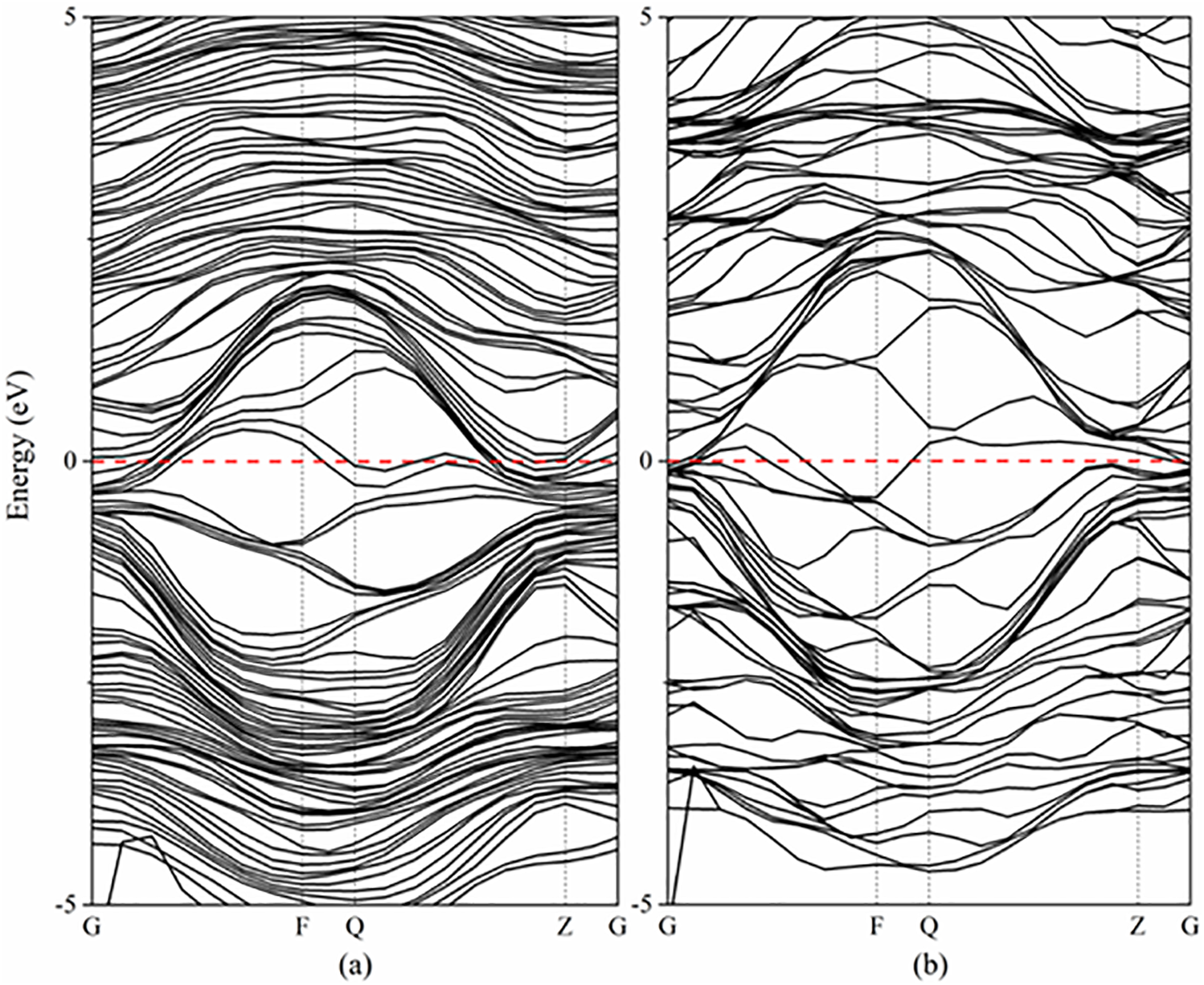

The electronic structure and atomic interaction of materials explain the macroscopic mechanical properties at the microscopic scale. Therefore, the energy band structure (Fig. 3) and density of states (Fig. 4) of (NbZrHfTi)C and its component TiC were calculated for comparison. Fig. 3 shows the energy band structure being calculated along the high symmetry direction G-F-Q-Z-G within the Brillouin zone [40]. The Fermi energy level (EF) is set to 0 eV and indicated by the red dashed line. Evidently, the Fermi level intersects multiple energy bands in both (NbZrHfTi)C and TiC, with a greater number of bands crossing the Fermi level in (NbZrHfTi)C. This indicates that both TiC and (NbZrHfTi)C have metallic properties and that (NbZrHfTi)C is more metallic. On the other hand, the energy band of (NbZrHfTi)C is more compact compared to TiC, indicating more intense orbital electronic hybridization and stronger interaction between the atoms.

Figure 3: Energy band structure of (NbZrHfTi)C (a) and TiC (b)

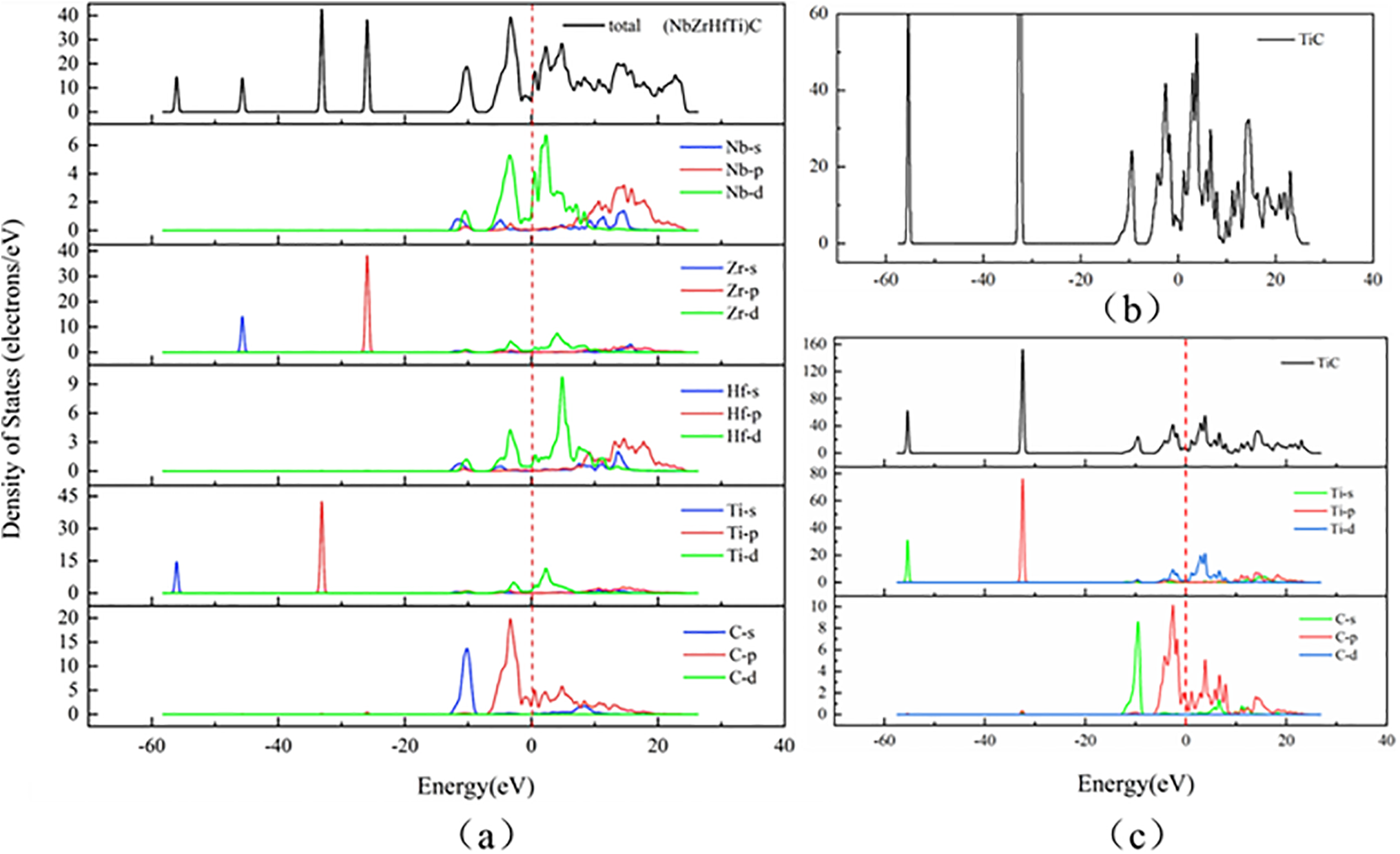

Figure 4: (a) Total and partial electronic DOS of (NbZrHfTi)C. (b) Enlargement of total DOS of TiC. (c) Total and partial electronic DOS of TiC

To elucidate the electronic energy states within the system, we calculated the density of states (DOS) for both (NbZrHfTi)C and TiC. As shown in Fig. 4, it is observed that the total density of states waveforms of both vary slightly, and the DOS at the Fermi energy level is not zero, demonstrating that (NbZrHfTi)C has similar structural stability to TiC and has metallic properties. The reduced amplitude of peaks in the total density of states (DOS) of (NbZrHfTi)C, along with the denser distribution of states in the high-energy region and diminished fluctuation in conduction behavior, collectively suggest enhanced electronic interaction and orbital hybridization among the constituent elements. This corresponds to the more dense energy band of (NbZrHfTi)C. The electronic state density near the Fermi level of (NbZrHfTi)C is primarily contributed by the hybridisation of d electronic states from the transition metals (Nb, Zr, Hf, Ti) and p electronic states from C. This electronic structure suggests strong covalent bonding between carbon and metal atoms. The strong peak energies on either side of the Fermi energy level of (NbZrHfTi)C are −3.28 and 2.29 eV, while TiC is −1.76 and 2.95 eV, suggesting pseudo-energy gaps of 5.57 and 4.71 eV for (NbZrHfTi)C and TiC, respectively. The pseudogap reflects the strength of the bonding covalency of the system, the wider it is, the stronger the covalency is. (NbZrHfTi)C has a wider pseudo-energy gap, demonstrating stronger covalency.

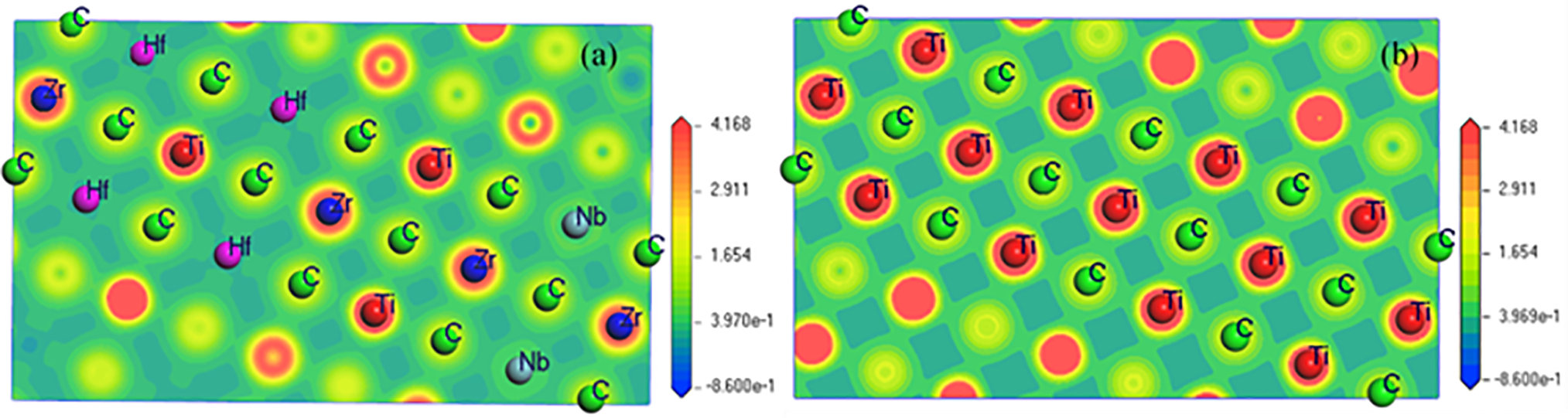

To clearly describe the spatial distribution of charge around the atoms, the charge densities of (NbZrHfTi)C and TiC along the crystal plane (100) were calculated (Fig. 5). There is the overlap of electron cloud around each atom, and the electron cloud around the Hf atom of (NbZrHfTi)C has clear directionality, this verifies the formation of covalent bonds. As shown in Fig. 5. that the Zr atoms are the brightest around, and have the highest overlap of electron cloud with the C atoms; The charge density around Hf atoms is the lowest, and the overlap with the electron cloud around C atoms is the lowest. Therefore, the binding of Zr atoms to C atoms is the strongest, and that of Hf atoms to C atoms is the weakest.

Figure 5: Charge density distribution on the (100) plane of (NbZrHfTi)C and TiC

The thermodynamic properties are important theoretical guides to the engineering applications of materials. It mainly refers to the evolution of physical quantities such as volume, heat capacity, thermal expansion coefficient, and Debye temperature with temperature and pressure when the material is under a certain temperature and pressure. Therefore, the Debye-Grüneisen model combined with first-principles calculations was utilized to investigate these thermophysical properties.

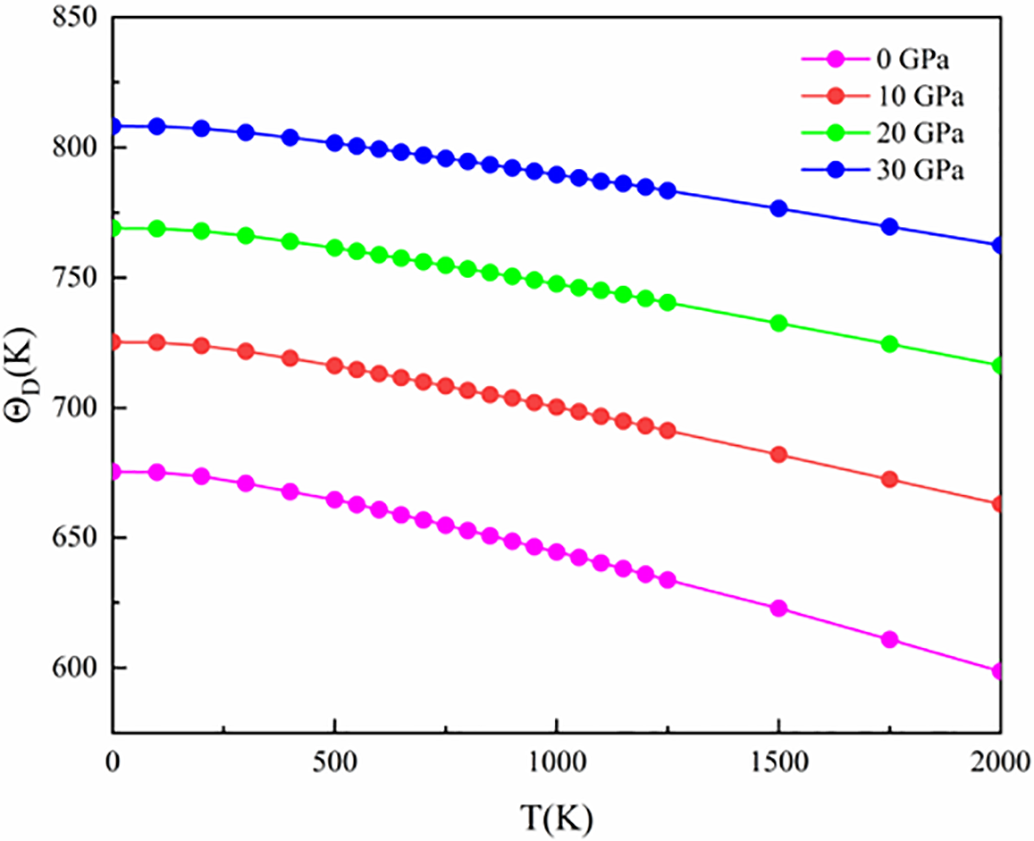

The Debye temperature is a key physical parameter of solid materials, closely related to several properties such as specific heat capacity, melting point, elastic constants, and thermal conductivity. As shown in Fig. 6, the Debye temperature of (NbZrHfTi)C changes with temperature and pressure. Under constant pressure, this Debye temperature approximately decreases linearly as temperature increases. This change reflects the weakening of atomic interactions in the material with rising temperature. Since the Debye temperature is directly associated with the strength of covalent bonds—the higher the value, the greater the bond strength—the phenomenon described indicates that the strength of covalent bonds in (NbZrHfTi)C gradually decreases with increasing temperature. However, from 0 to 2000 K, the curve exhibits a relatively stable decreasing trend, implying that (NbZrHfTi)C has somewhat resistance to high temperature. Under isothermal conditions, the Debye temperature of (NbZrHfTi)C is positively correlated with pressure, which is attributed to the reduction in interatomic distances and enhanced bonding effects caused by high pressure, thereby increasing the macroscopic strength of the material.

Figure 6: Temperature and pressure dependence of Debye temperature of (NbZrHfTi)C Ceramic

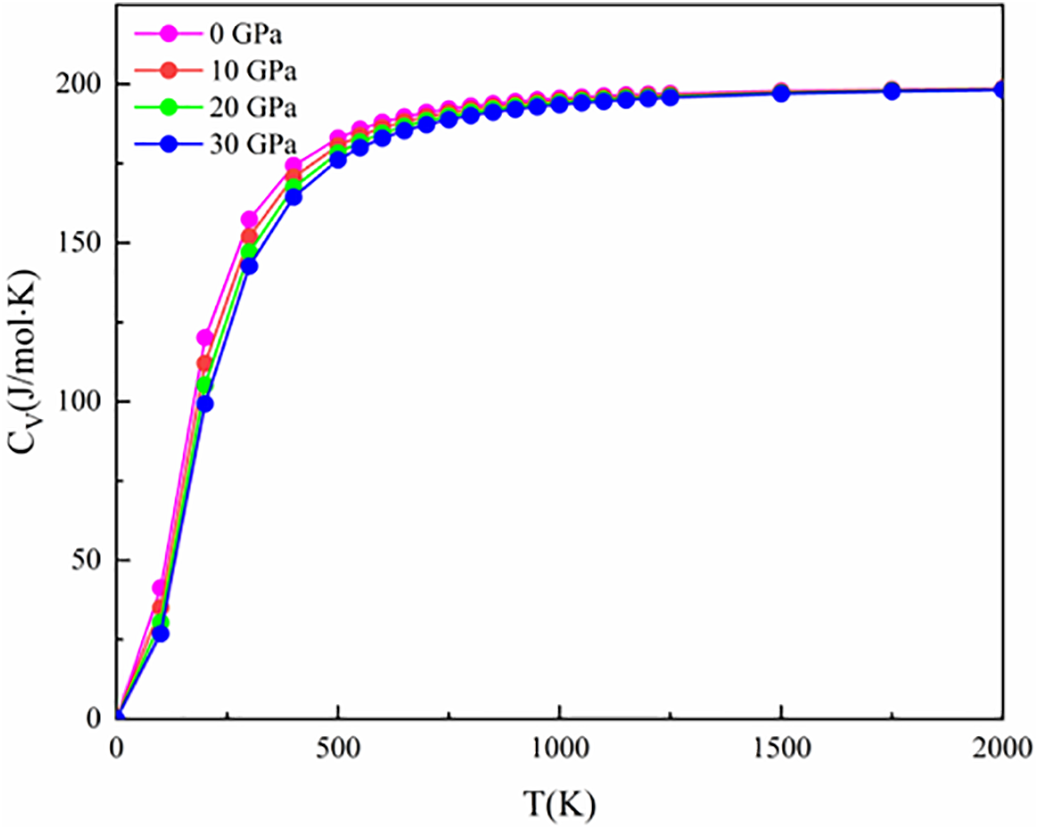

We calculated the variation of the heat capacity CV of (NbZrHfTi)C with temperature and pressure using the quasi-harmonic Debye model (Fig. 7). It is worth noting that the variation of CV with temperature is essentially the same for different pressures, indicating that the heat capacity of (NbZrHfTi)C is not greatly affected by the pressure. CV increases rapidly with temperature β and T <500 K. As the temperature continues rising, the heat capacity increases flatly and gradually converges to the Dulong-Petit limit, indicating that the CV is strongly influenced by lattice vibration at low temperatures.

Figure 7: Temperature and pressure dependence of heat capacity of (NbZrHfTi)C Ceramic

The thermal expansion coefficient is one of the key parameters characterising the temperature properties of materials and can be used to evaluate their thermal stability. Fig. 8 shows the relationship of the thermal expansion coefficient α of (NbZrHfTi)C with changes in temperature and pressure. It is observed that, under normal pressure conditions, the α value rapidly increases with temperature in the low-temperature range, while it exhibits an approximately linear growth in the high-temperature range. As pressure increasing, the trend of the thermal expansion coefficient with increasing temperature becomes significantly weaker, and this suppression effect is more pronounced in high-temperature environments. The above phenomena indicate that (NbZrHfTi)C is more sensitive to thermal disturbances under low temperature and low pressure conditions, while it exhibits superior thermal stability in high temperature and high pressure environments.

Figure 8: Temperature and pressure dependence of thermal expansion coefficient of (NbZrHfTi)C Ceramic

In summary, the mechanical and thermodynamic properties of (NbZrHfTi)C high-entropy ceramics were systematically investigated using first-principles calculations combined with Debye-Grüneisen model. The calculated

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 92166105 and 52005053), High-Tech Industry Science and Technology Innovation Leading Program of Hunan Province (No.2020GK2085), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (No. 2021RC3096).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yonggang Tong, Yongle Hu, Pengfei Li; data collection: Kai Yang, Pengfei Li, Xiubing Liang; analysis and interpretation of results: Jian Liu, Yejun Li, Kai Yang; draft manuscript preparation: Jingzhong Fang, Kai Yang, Yejun Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are contained within the article. All databases are publicly available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Balaji V, Anthony XM. Development of high entropy alloys (HEAscurrent trends. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e26464. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Miracle DB, Senkov ON. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017;122:448–511. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2016.08.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu J, Wang X, Singh A, Xu H, Kong F, Yang F. The evolution of intermetallic compounds in high-entropy alloys: from the secondary phase to the main phase. Metals. 2021;11(12):2054. doi:10.3390/met11122054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hsu WL, Tsai CW, Yeh AC, Yeh JW. Clarifying the four core effects of high-entropy materials. Nat Rev Chem. 2024;8(6):471–85. doi:10.1038/s41570-024-00602-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Huang S, Zhang J, Fu H, Xiong Y, Ma S, Xiang X, et al. Irradiation performance of high entropy ceramics: a comprehensive comparison with conventional ceramics and high entropy alloys. Prog Mater Sci. 2024;143:101250. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tian D, Denny SR, Li K, Wang H, Kattel S, Chen JG. Density functional theory studies of transition metal carbides and nitrides as electrocatalysts. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(22):12338–76. doi:10.1039/d1cs00590a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li Y, Xu X, Fang X, Li F. Ion transport mechanism in the sub-nano channels of edge-capping modified transition metal carbides/nitride membranes. Separations. 2025;12(4):78. doi:10.3390/separations12040078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sarker P, Harrington T, Toher C, Oses C, Samiee M, Maria JP, et al. High-entropy high-hardness metal carbides discovered by entropy descriptors. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4980. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07160-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Castle E, Csanádi T, Grasso S, Dusza J, Reece M. Processing and properties of high-entropy ultra-high temperature carbides. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8609. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-26827-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ye B, Wen T, Nguyen MC, Hao L, Wang CZ, Chu Y. First-principles study, fabrication and characterization of (Zr0.25Nb0.25Ti0.25V0.25)C high-entropy ceramics. Acta Mater. 2019;170:15–23. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2019.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu B, Zhao J, Liu Y, Xi J, Li Q, Xiang H, et al. Application of high-throughput first-principles calculations in ceramic innovation. J Mater Sci Technol. 2021;88:143–57. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2021.01.071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang Q, Zhang J, Li N, Chen W. Understanding the electronic structure, mechanical properties, and thermodynamic stability of (TiZrHfNbTa)C combined experiments and first-principles simulation. J Appl Phys. 2019;126(2):025101. doi:10.1063/1.5094580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Huang Z. Prediction of mechanical and thermo-physicalproperties of (Nb-Ti-V-Zr)C high entropy ceramics: a first principles study. J Phys Chem Solids. 2020;151:109859. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kim J, Kwon H, Kwon CW. Temperature dependent phase stability of Ti(C1-N) solid solutions using first-principles calculations. Ceram Int. 2017;43(1):650–7. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.09.209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang Y, Liu H, Hao X, Yang C, Liu Y, Chen L, et al. First-principles calculations to investigate phase stability, elastic and thermodynamic properties of TiMoNbX (X=Cr, Ta, Cr and Ta) refractory high entropy alloys. J Phys Condens Matter. 2024;36(48). doi:10.1088/1361-648X/ad7437.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Almahmoud A, Alkhalidi H, Obeidat A. Comprehensive DFT analysis of structural, mechanical, electronic, optical, and hydrogen storage properties of novel perovskite-type hydrides Y2CoH6 (Y=Ca, Ba, Mg, Sr). J Energy Storage. 2025;117(9):116146. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.116146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu Z, Luo J, Yang A, Xie Z, He L, Tan M. First-principles study of the electronic structure and optical properties of Eu2+ and Mn2+-doped NaLi3SiO4 phosphor. Eur Phys J B. 2024;97(12):209. doi:10.1140/epjb/s10051-024-00839-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yan ZH. Oxidation resistance of equimolar multicomponent transition metal carbide solid solution. Adv Ceram. 2024;45(6):541–57. [Google Scholar]

19. Sahafi MH, Cholaki E, Bashir AI. First-principles calculations to investigate phonon dispersion, mechanical, elastic anisotropy and thermodynamic properties of an actinide-pnictide ceramic at high pressures/temperatures. Results Phys. 2024;58:107495. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2024.107495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kumar S. Ab-initio investigations of novel potential all-d metal Heusler alloys Co2MnNb. arXiv:2406.05527. 2024. [Google Scholar]

21. Mal I, Samajdar DP. Investigation of optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties of InAsBi for LWIR applications: a first principles and k dot p study. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2022;137:106178. doi:10.1016/j.mssp.2021.106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Blanco MA, Francisco E, Luaña V. GIBBS: isothermal-isobaric thermodynamics of solids from energy curves using a quasi-harmonic Debye model. Comput Phys Commun. 2004;158(1):57–72. doi:10.1016/j.comphy.2003.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Otero-de-la-Roza A, Luaña V. Gibbs2: a new version of the quasi-harmonic model code. I. Robust treatment of the static data. Comput Phys Commun. 2011;182(8):1708–20. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2011.04.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang K, Xu J, Zhang S, Zhong Q, Zhao W, Fan D. Equation of state of FeTiO3 and MgTiO3 by in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction at high pressures. Phys Chem Miner. 2025;52(3):23. doi:10.1007/s00269-025-01324-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jiang S, Shao L, Fan TW, Duan JM, Chen XT, Tang BY. Elastic and thermodynamic properties of high entropy carbide (HfTaZrTi)C and (HfTaZrNb)C from ab initio investigation. Ceram Int. 2020;46(10):15104–12. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.03.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Buyakova SP, Dedova ES, Wang D, Mirovoy YA, Burlachenko AG, Buyakov AS. Phase evolution during entropic stabilization of ZrC, NbC, HfC, and TiC. Ceram Int. 2022;48(8):11747–55. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.01.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shulumba N, Hellman O, Raza Z, Alling B, Barrirero J, Mücklich F, et al. Lattice vibrations change the solid solubility of an alloy at high temperatures. Phys Rev Lett. 2016;117(20):205502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.205502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Rogal L, Bobrowski P, Körmann F, Divinski S, Stein F, Grabowski B. Computationally-driven engineering of sublattice ordering in a hexagonal AlHfScTiZr high entropy alloy. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2209. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02385-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wen T, Ning S, Liu D, Ye B, Liu H, Chu Y. Synthesis and characterization of the ternary metal diboride solid-solution nanopowders. J Am Ceram Soc. 2019;102(8):4956–62. doi:10.1111/jace.16373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bhattacharya C. Effect of shock on transition metal carbides and nitrides{MC/N (M=Zr, Nb, Ta, Ti)}. Comput Mater Sci. 2017;127(C8):85–95. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2016.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li H, Zhang L, Zeng Q, Guan K, Li K, Ren H, et al. Structural, elastic and electronic properties of transition metal carbides TMC (TM=Ti, Zr, Hf and Ta) from first-principles calculations. Solid State Commun. 2011;151(8):602–6. doi:10.1016/j.ssc.2011.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen L, Wang Q, Xiong L, Gong H. Mechanical properties and point defects of MC (M=Ti, Zr) from first-principles calculation. J Alloys Compd. 2018;747:972–7. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.03.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chung DH, Buessem WR. The Voigt-Reuss-Hill approximation and elastic moduli of polycrystalline MgO, CaF2, β-ZnS, ZnSe, and CdTe. J Appl Phys. 1967;38(6):2535–40. doi:10.1063/1.1709944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Niu H, Niu S, Oganov AR. Simple and accurate model of fracture toughness of solids. J Appl Phys. 2019;125(6):065105. doi:10.1063/1.5066311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Dai JH, Li W, Song Y, Vitos L. Theoretical investigation of the phase stability and elastic properties of TiZrHfNb-based high entropy alloys. Mater Des. 2019;182:108033. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ye YX, Liu CZ, Wang H, Nieh TG. Friction and wear behavior of a single-phase equiatomic TiZrHfNb high-entropy alloy studied using a nanoscratch technique. Acta Mater. 2018;147:78–89. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2018.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jiang M, Zheng JW, Xiao HY, Liu ZJ, Zu XT. A comparative study of the mechanical and thermal properties of defective ZrC, TiC and SiC. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9344. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09562-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Yao T, Wang Y, Li H, Lian J, Zhang J, Gou H. A universal trend of structural, mechanical and electronic properties in transition metal (M=V, Nb, and Ta) borides: first-principle calculations. Comput Mater Sci. 2012;65:302–8. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.07.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Parvin F, Naqib SH. Elastic, thermodynamic, electronic, and optical properties of recently discovered superconducting transition metal boride NbRuB: anab-initioinvestigation. Chin Phys B. 2017;26(10):106201. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/26/10/106201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, Xie M, Wang Z, Song X, Mu R, Du L, et al. Design and thermal conduction mechanisms of rare-earth zirconate high-entropy ceramics with low photon thermal conductivity. J Alloys Compd. 2025;1036:181946. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2025.181946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools