Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Learning Time Embedding for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion

1 College of Management and Economics, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300072, China

2 The State Key Laboratory of Multimodal Artificial Intelligence Systems, Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100190, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenhao Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069331

Received 20 June 2025; Accepted 18 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Temporal knowledge graph completion (TKGC), which merges temporal information into traditional static knowledge graph completion (SKGC), has garnered increasing attention recently. Among numerous emerging approaches, translation-based embedding models constitute a prominent approach in TKGC research. However, existing translation-based methods typically incorporate timestamps into entities or relations, rather than utilizing them independently. This practice fails to fully exploit the rich semantics inherent in temporal information, thereby weakening the expressive capability of models. To address this limitation, we propose embedding timestamps, like entities and relations, in one or more dedicated semantic spaces. After projecting all embeddings into a shared space, we use the relation-timestamp pair instead of the conventional relation embedding as the translation vector between head and tail entities. Our method elevates timestamps to the same representational significance as entities and relations. Based on this strategy, we introduce two novel translation-based embedding models: TE-TransR and TE-TransT. With the independent representation of timestamps, our method not only enhances capabilities in link prediction but also facilitates a relatively underexplored task, namely time prediction. To further bolster the precision and reliability of time prediction, we introduce a granular, time unit-based timestamp setting and a relation-specific evaluation protocol. Extensive experiments demonstrate that our models achieve strong performance on link prediction benchmarks, with TE-TransR outperforming existing baselines in the time prediction task.Keywords

Knowledge Graphs (KGs) are large multilateral relationship networks where nodes depict entities and edges capture the relations among them. In KGs, knowledge is organized into triples (head entity, relation, tail entity) which can be expressed as

It should be noted that KG facts are not static and permanently true, but are typically valid within specific temporal bounds. For example, (Ban Ki-moon, secretaryGeneralOf, the United Nations) was true between 2007 and 2016, and (Obama, presidentCandidateOf, USA) was true in 2008 and 2012. Since temporal characteristics are crucial for tracing the evolution of real-world events, the temporal knowledge graph (TKG) has been put forward and has attracted lots of interest. ICEWS [16], Wikidata [17], GDELT [18], and YAGO [5] are typical TKGs that incorporate a large amount of temporal facts in quadruple format

Given the incompleteness of most TKGs, the capability to infer absent information is essential for the utilization of TKGs. KG embedding is among the most effective methods for completing KGs, aiming to map KGs into continuous vector spaces while retaining their main characteristics [19]. Traditional static knowledge graph (SKG) embedding models are proven to be useful in inferring new facts for SKGs [20–24], but they do not consider the time dimension. In order to handle time-sensitive facts, TKG embedding models integrate temporal information and achieve better performance [25–29]. Among these methods, translation-based methods are a typical and important field, which attempts to minimize the distance between the translated head entity and the tail entity in the embedding space [20–22,26,29].

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of translation-based methods for TKGC, several challenges remain: (1) Existing methods normally embed timestamps into entities or relations and utilize only the relation as the translation vector, which neglects the important value of temporal information and limits the model’s expressive capability. (2) Many methods assume that entities, relations, and timestamps reside in the same semantic space and build the translation without any transformations, leading to the loss of semantics of different elements and the lack of information interaction between them. (3) Previous methods often fail to learn independent time embeddings to fully exploit the semantics inherent in temporal information, thus constraining the model’s ability to perform time prediction. While some methods may address certain aspects, a unified solution has yet to emerge.

In this work, to address the above problems comprehensively, we embed timestamps in one or more dedicated embedding spaces to adequately leverage the rich semantics of temporal information. Additionally, we model the relation-timestamp pair as the translation vector instead of modeling only the relation, thus enhancing the flexibility and expressive capability of the model. We propose two novel translation-based models for TKGC, referred to as TE-TransR and TE-TransT. In both models, we learn the embeddings of entities, relations, and timestamps in distinct semantic spaces, respectively. Various embedding vectors can be mapped into a unified space through either relation-specific or time-specific matrices, in which translations are built. Concretely, in TE-TransR, we model an entity space, a time space, and multiple relation spaces. Entity embeddings and time embeddings are mapped into the corresponding relation space through relation-specific matrices. In TE-TransT, we model multiple time spaces, into which entity embeddings and relation embeddings are projected through time-specific matrices. These transformation matrices facilitate information interaction between different embedding spaces, thereby reducing semantic loss. Furthermore, our method can learn independent time embeddings within distinct spaces, which enhances the ability to make precise time predictions.

We also observe that existing methods do not segment timestamps based on fundamental time units, but instead divide time into intervals of varying lengths, based on a threshold number of facts [26]. For simplicity, these time intervals are still denoted as

We conduct a wide range of experiments on several real-world datasets, including link prediction, time prediction, and other analytical experiments. The outcomes of our experiments validate the effectiveness of our method. Our key contributions are summarized below:

• We propose two novel translation-based models to learn embedding vectors for TKGC. In these models, we (1) independently learn entity, relation, and time embeddings in distinct semantic spaces, (2) utilize relation-specific or time-specific matrices for transformations between spaces, and (3) model the combination of relation and timestamp as the translation vector.

• We introduce a novel time prediction scheme, which includes a time unit-based timestamp setting and a relation-specific evaluation protocol, enabling more precise and reliable time prediction for TKGC. Our evaluation protocol provides an evaluation metric that rewards accurate time point predictions that align with the duration of the involved relation.

• We conduct extensive experiments, including comprehensive comparisons with existing models and detailed qualitative analysis, to demonstrate the effectiveness of our method.

This section reviews the related work on SKG and TKG embedding models.

The task of SKGC focuses on inferring missing links within a KG that does not change over time. A diverse range of SKG embedding models has been proposed for SKGC, evolving from classic translation mechanisms to sophisticated neural architectures.

The earliest translation-based model, TransE [20], pioneered the idea of modeling the relation as the translation vector between entities in the embedding space. However, TransE is limited to handling 1-on-1 relations. To address this, several extensions of TransE were proposed [19,22,30]. For instance, TransH [19] allows entity embeddings to vary across relation-specific hyperplanes, while TransR [22] separates entity and relation spaces through projection matrices. RotatE [31] further represents relations as rotations in the complex space to capture a wider variety of relation patterns. Later, BoxE [32] proposes a bounded region representation for relations, enhancing the expressiveness for logical reasoning.

In parallel, semantic matching models gained traction by focusing on scoring functions to evaluate the plausibility of a triple. DistMult [21] applies bilinear scoring to assess triple plausibility, while ComplEx [23] generalizes this formulation to the complex space. Models like SimplE [24] and TuckER [33] further refine these ideas by leveraging tensor decompositions. CapsE [34], built upon capsule networks, captures dimension-wise interactions within entity and relation embeddings. Additionally, methods such as McRL [35] and MLI [36] explore multi-level semantics or conceptual abstraction to improve representation fidelity.

Neural network-based approaches have also been integrated into SKGC. ConvE [37] utilizes 2D convolutions to model entity-relation interactions in a spatial context. R-GCN [38] introduces message-passing mechanisms based on relational graph convolutional networks (GCN). Innovative designs such as M-DCN [39] and TDN [40] further explore adaptive message distribution and dynamic neighborhood encoding to improve representation learning in SKGs.

Even though the models listed above can obtain promising results on link prediction of SKGs, they fail to capture the temporal information of TKGs. To address this time-sensitive challenge, various TKG embedding models are proposed for TKGC. Existing approaches are commonly categorized according to their differing strategies in incorporating temporal information.

The first category primarily evolves from SKGC methodologies, directly incorporating the temporal dimension within established embedding frameworks. The translation-based method t-TransE [41] extends classical TransE [20] by learning the temporal order of relations. TTransE [25] expands TransE by embedding relation-timestamp pairs as translation vectors between entity embeddings, while simply assuming that timestamps share the common space with entities and relations. RTS [29] is also an extension of TransE, transforming relation embeddings from the relation space into the entity space through timestamp-specific matrices. Extending complex-space representations, TeRo [42] encodes timestamps as rotations affecting entities within the complex embedding space, capturing dynamic entity changes. Similarly, ChronoR [43], based upon the RotatE [31] framework, represents the interaction of relations and timestamps as rotations connecting head and tail entity embeddings. TComplEx [44] and TuckERTNT [45] expand traditional third-order embeddings into fourth-order tensor formats to encapsulate temporal interactions on the basis of ComplEx [23] and TuckER [33], respectively, while TNTComplEx [44] innovatively differentiates between temporally evolving facts and those that remain stable across timestamps, providing a nuanced representation of temporal dynamics.

The second category, differently, employs a modular design where temporal information is independently processed via deep learning or explicitly crafted temporal modeling techniques, subsequently applying conventional SKGC methods for completion. Methods such as TA-TransE and TA-DistMult [27] utilize recurrent neural networks (RNN) to encode temporal evolution dynamically into entity representations. HyTE [26] maps entity and relation embeddings onto distinct hyperplanes determined by timestamps, thus allowing translation-based operations within a temporally specific embedding space. DE-SimplE [46] introduces diachronic embeddings by modeling entity states distinctly at discrete timestamps, subsequently using the SimplE [24] decoder for effective prediction. The ATiSE [47] model further refines temporal representations by decomposing timestamps into additive components—trend, seasonal, and irregular—capturing intricate evolutionary behaviors and uncertainties via multidimensional Gaussian distributions. TeLM [48] employs multivector embeddings combined with temporal regularizers to enhance generalization and expressivity. BoxTE [49] expands upon BoxE [32] by explicitly embedding temporal information within flexible box-shaped embeddings, and TPBoxE [50] achieves better results by incorporating time probability box embeddings. BDME [51] introduces a fine-grained multigranularity embedding framework. QDN [52] extends the triplet distributor in TDN [40] into a quadruplet distributor and applies fourth-order tensor decomposition to facilitate comprehensive interactions. Zhang et al. [53] propose a joint framework that enhances tensor decomposition by integrating temporal and static modules. TeAST [54] aligns each relation with an Archimedean spiral timeline, introducing a temporal spiral regularizer to maintain temporal order while allowing entity embeddings to remain time-invariant. Several methods, including DyERNIE [55], IME [56], and MADE [57], embed TKGs into multi-curvature spaces to better capture complex structures. SANe [58] introduces the space adaptation network to effectively handle temporal variability. ConvTKG [59] and JointDE [60] employ advanced CNN-based frameworks to capture the complex interactions within TKGs. LGRe [61] and EHPR [62] improve the model’s expressive ability by learning granularity representations and evolutionary hierarchy perception representations, respectively.

2.3 Differences with Existing Work

The methods most related to our work are translation-based TKG embedding models, including TTransE [25], HyTE [26], and RTS [29]. Similar to our approach, TTransE learns time embeddings for timestamps and employs relation-timestamp pairs as translation vectors. However, a key distinction lies in its simple assumption that entities, relations, and timestamps all reside within the same semantic space, without modeling explicit transformations between them. In contrast, our model learns embeddings for entities, relations, and timestamps in separate vector spaces, and introduces time-specific or relation-specific projection matrices to bridge these spaces. While prior works such as HyTE and RTS also apply temporally specific hyperplanes or matrices to map entities and relations, they neither learn independent time representations nor incorporate time embeddings as components of translation vectors. These distinctions highlight the fundamental differences between our approach and previous methods.

In this section, we introduce two innovative translation-based models for TKGC: TE-TransR and TE-TransT. To detail our approach accurately, we first provide the definition of the problem and related terminologies.

Given a TKG

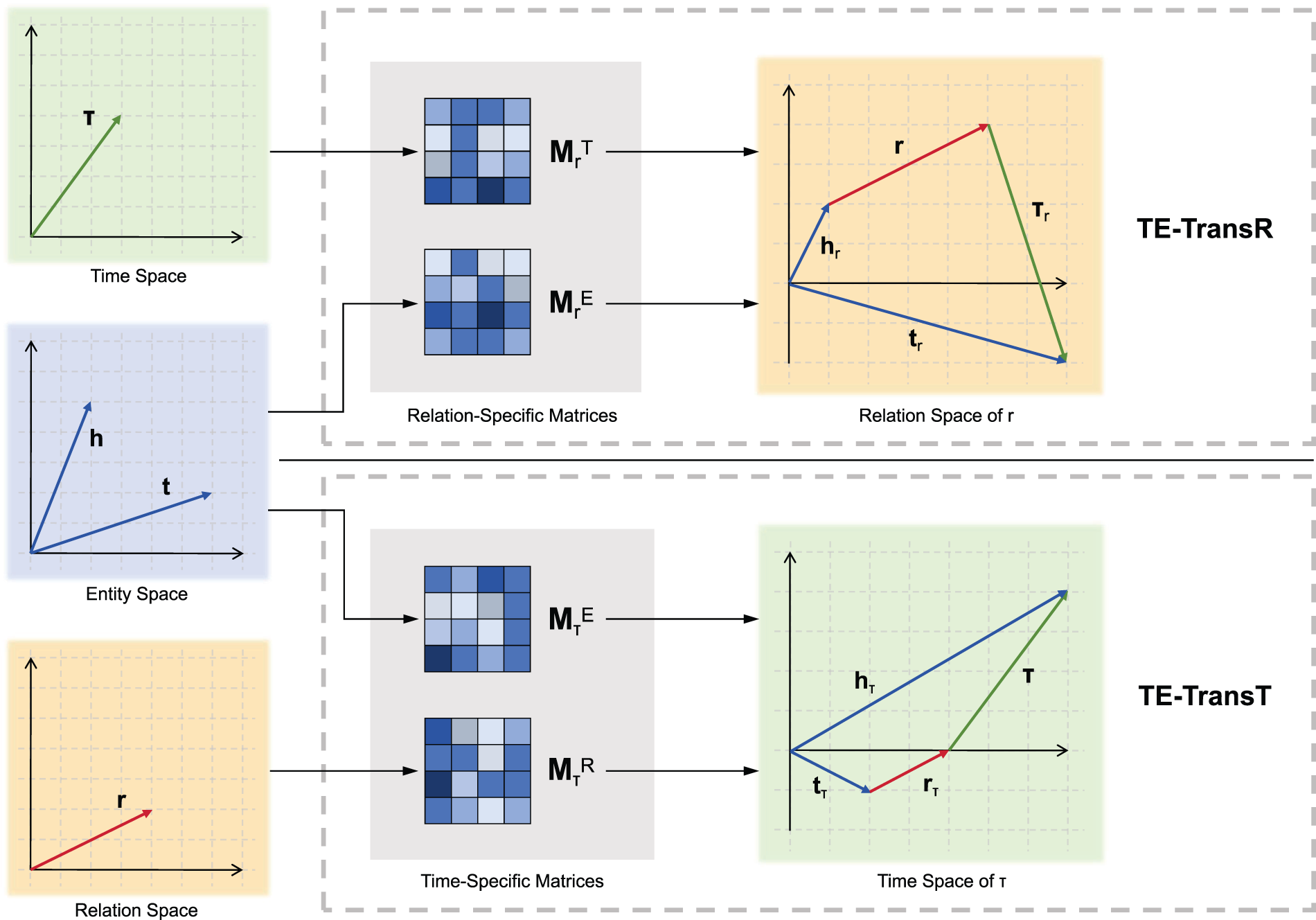

To fully capture the rich semantics inherent in temporal data, we propose TE-TransR and TE-TransT. As illustrated in Fig. 1, our models learn the embeddings of entities, relations, and timestamps in distinct semantic spaces. Different embedding vectors can be mapped into a unified space through either relation-specific or time-specific matrices. Furthermore, our method models the relation-timestamp pair as the translation, instead of modeling only the relation, highlighting the significance of temporal information.

Figure 1: Illustration of TE-TransR and TE-TransT. In both models, we embed entities, relations, and timestamps in distinct semantic spaces. As shown on the top, TE-TransR utilizes relation-specific matrices to project entity and time embeddings to the corresponding relation space. The down panel shows that TE-TransT, differently, maps entity and relation embeddings to the time space with time-specific matrices. The relation-timestamp pair is then employed to build the translation between entities in the unified space

We first introduce TE-TransR, an extension of TransR [22]—a model that represents entities and relations in separate spaces and projects entity embeddings into relation-specific spaces before translation. While effective for SKGs, TransR lacks the capacity to model temporal dynamics. TE-TransR addresses this by introducing a time dimension and modeling timestamps in a dedicated semantic space. It further projects both entity and time embeddings into the relation space via relation-specific matrices to enable temporally-aware translation. The underlying assumption of TE-TransR is that both entities and time are relation-sensitive. TransR has demonstrated a strong correlation between entities and relations, and recent TKGC approaches have also identified a close link between time and relations [26,29,41]. TE-TransR integrates the strengths of these methods, inheriting the effectiveness of TransR in handling 1-on-N, N-on-1, and N-on-N relations while introducing a time dimension to leverage the interplay between timestamps and relations.

In TE-TransR, given a quadruple

For relation-specific matrices, given a relation

The corresponding score function is represented as

where

TE-TransT also embeds entities, relations, and timestamps in separate semantic spaces, but explores performing translations in time spaces. It utilizes time-specific matrices to map entity embeddings and relation embeddings into the corresponding time space. Different from TE-TransR, TE-TransT assumes that both entities and relations are time-sensitive. Intuitively, the time-specific projection matrices function as temporal adaptation mechanisms, enabling the model to adjust the semantic representations of entities and relations according to the specific timestamp. This design captures the dynamic nature of real-world knowledge, where the meanings and semantics of entities and relations may vary significantly over time. Previous works have attempted to utilize temporal information through time-specific hyperplanes [26] or matrices [29], mapping entities and relations into corresponding hyperplanes or embedding spaces, followed by applying TransE’s score function

For each timestamp

The corresponding score function becomes

Both the projected relation embedding

We minimize the following margin-based ranking loss to optimize the model’s performance on the link prediction task:

where

As in previous works, we utilize two different negative sampling methods for link prediction and time prediction. Here we first introduce the time-agnostic method for the link prediction task, which selects negative samples from the entirety of triples that are absent from the existing KG, without considering timestamps [26]. Specifically, for a given timestamp, we obtain negative samples from

Many TKG embedding models [27,43,63–65] treat temporal information only as a supplementary instrument for link prediction and give relatively insufficient attention to time prediction, which is also an important task for TKGC. We identify several limitations with the existing time prediction scheme. To tackle these limitations, here, we introduce a novel time prediction scheme, composed of a time unit-based timestamp setting and a relation-specific evaluation protocol. We also present our time-dependent negative sampling method for the time prediction task.

A widely adopted timestamp setting is a frequency-based method [26], which handles time in an unintuitive manner. Specifically, it divides time into timestamps, not based on the duration of time, but rather on the occurrence frequency of facts. Each timestamp must contain a number of facts exceeding a certain threshold. As a result, the timestamps are essentially intervals where facts tend to be evenly distributed, but the actual lengths of timestamps vary. This implies that, with such a frequency-based timestamp setting, the predicted timestamp

We introduce a timestamp setting for time prediction to address the previous vague representation of time, by assigning each timestamp to a precise time unit (e.g., in our experiments, each timestamp

We observe a significant correlation between the duration of a fact and its relation type. To improve the validity of time prediction evaluation, we propose linking the evaluation metrics to specific relations. As far as we are aware, it has not been used by previous methods.

4.2.1 Relation-Specific Evaluation Protocol

The process of our relation-specific evaluation protocol is as follows: (1) For each time-missing quadruple

where

Previous works, relying on frequency-based timestamps, are limited to predicting a vague time interval for a fact, without specific handling of its duration. By leveraging time unit-based timestamps, our new evaluation protocol takes into account the feature of a specific relation type to determine the required number of time points for evaluation and is capable of predicting discrete time points, improving the flexibility and reliability of the evaluation process.

4.2.2 Metric Suitability across Dataset Types

It is important to note that the MOC metric is more suitable for evaluation on interval-based datasets, such as YAGO11k and Wikidata12k, where facts are typically valid over a time interval rather than a single time point. This is because the computation of MOC relies on a relation-specific strategy, selecting top-ranking candidate timestamps based on the average time interval length of a given relation type. In this scenario, MOC effectively captures the extent to which the predicted timestamps match the ground-truth interval. However, in certain datasets such as the event-driven ICEWS14, all facts are only valid at a single timestamp. In this case, both the real set

4.3 Model Training for Time Prediction

For the time prediction task, we propose a time-dependent negative sampling method, which maintains the

Our proposed time unit-based timestamp setting provides a larger number of timestamps with finer granularity, which can compatibly support the time-dependent negative sampling. With this negative sampling method, the margin-based ranking loss for time prediction is modified to

TE-TransR and TE-TransT are both trained for the time prediction task using the training strategy above.

In this part, we assess the performance of TE-TransR and TE-TransT through various experiments, including link prediction, time prediction, ablation studies, and qualitative analysis. Extensive comparisons and analysis showcase the effectiveness of our method for TKGC.

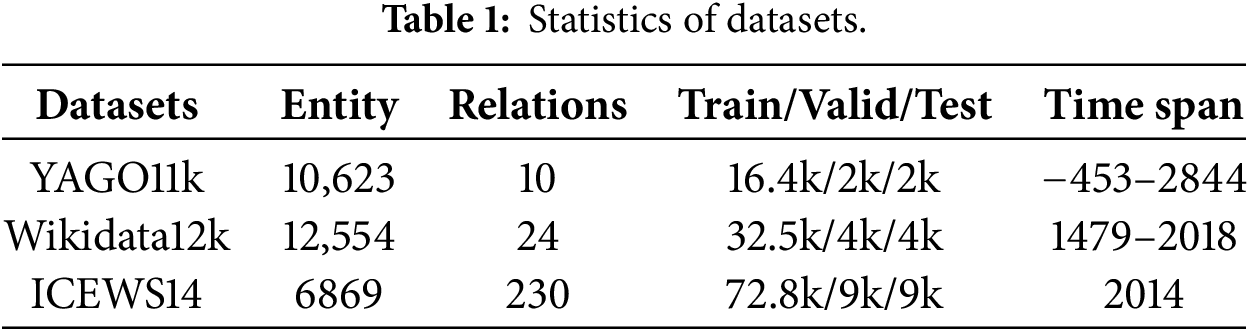

We use three commonly employed benchmark datasets: YAGO11k, Wikidata12k, and ICEWS14 to evaluate our proposed models. The details of these datasets are reported in Table 1. Consistent with prior work, we preserve the original train/valid/test splits for all datasets.

YAGO11k and Wikidata12k are TKG datasets constructed by HyTE [26]. YAGO11k, derived from YAGO3 [66], adheres to the following extraction criteria: (1) inclusion of temporally annotated facts that specify both start and end time points, (2) selection of the ten most frequent temporally rich relations, and (3) exclusion of edges associated with entities mentioned only once within the subgraph. This process yields a temporal graph comprising 20.5k triples and 10.6k entities. Wikidata12k, sourced from Wikidata [67], follows analogous criteria to those of YAGO11k but expands the selection to the 24 most frequent relations. This results in a temporal graph with 40k triples and 12.5k entities. Both YAGO11k and Wikidata12k feature a temporal granularity of one year. Section 5.4.4 provides a discussion of our strategy for handling missing timestamps.

ICEWS14 [27] is derived from the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) repository [16], which records structured political and social events. The ICEWS14 subset specifically contains event-based facts occurring within the year 2014. Different from YAGO11k and Wikidata12k, its temporal granularity is one day.

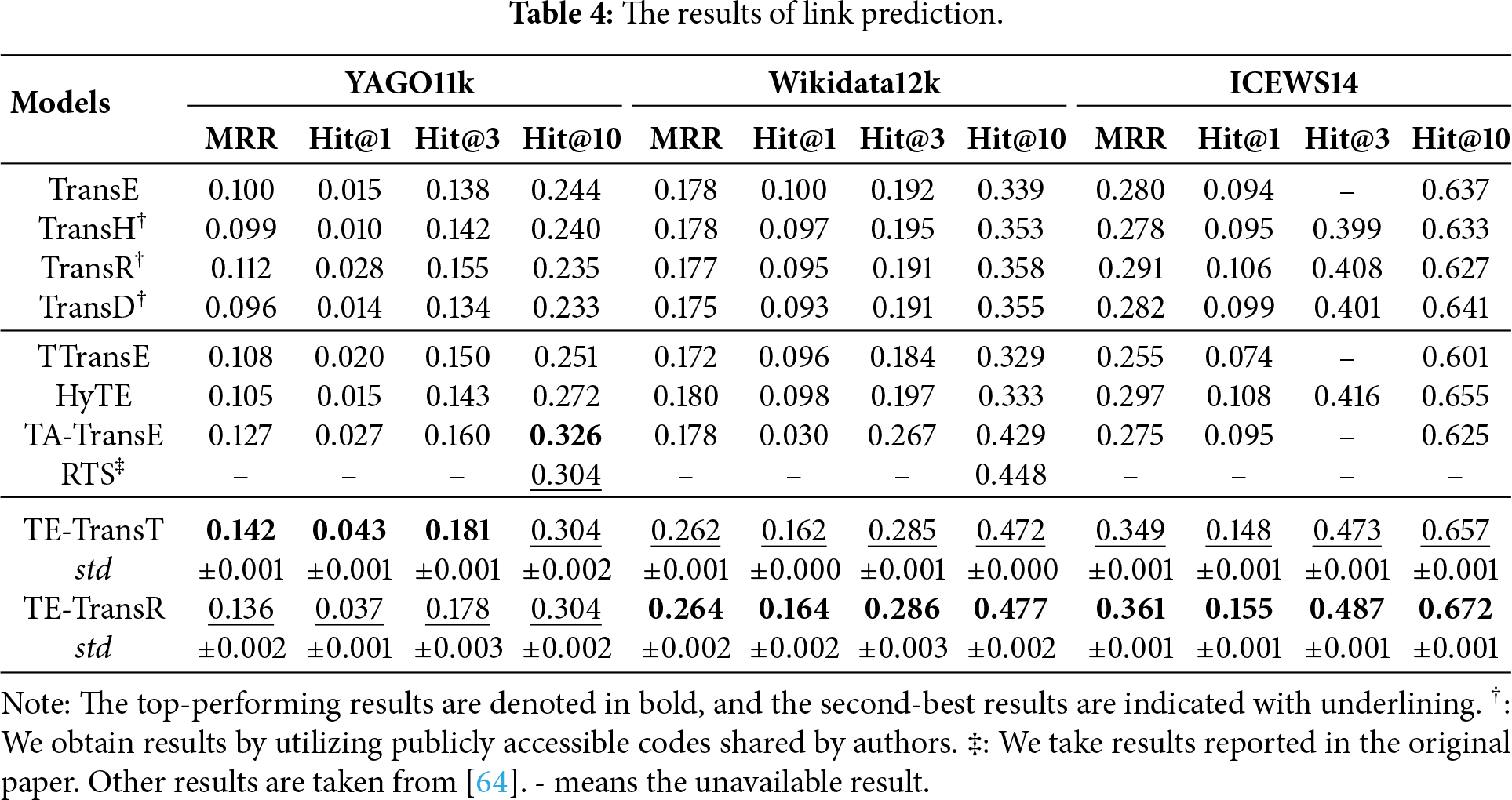

To examine the capability of our models, we compare them with translation-based baselines, including SKG embedding models and TKG embedding models.

SKG embedding models: We use four conventional baseline models including TransE [20], TranH [19], TransR [22], and TransD [30]. In these models, TKG quadruples

TKG embedding models: We also compare our models against recent TKG embedding models. We include TTransE [25], HyTE [26], TA-TransE [27], and RTS [29] in this realm.

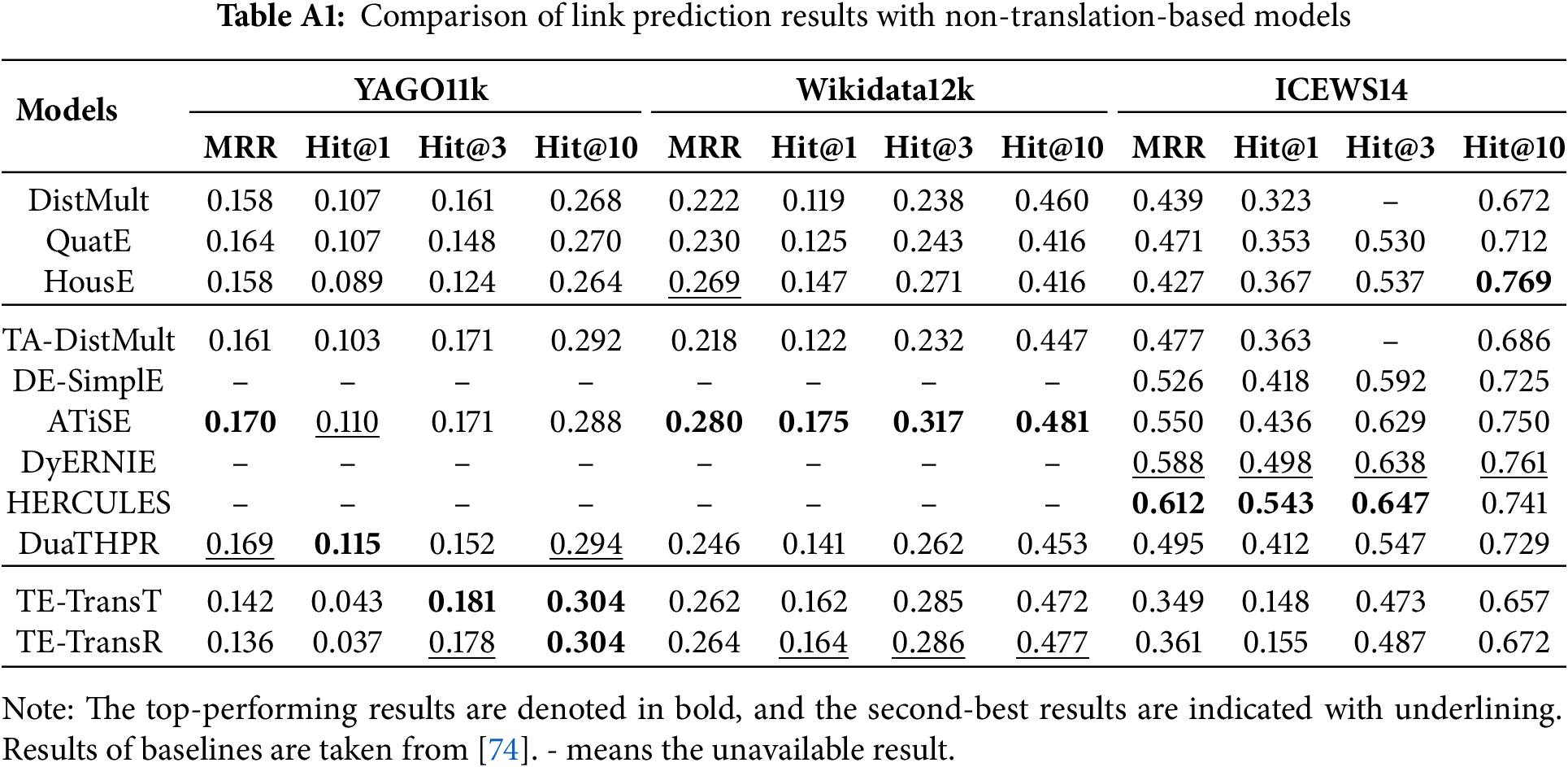

To more precisely situate our proposed models within the spectrum of TKGC approaches, we have also conducted extensive comparisons with a range of non-translation-based baselines. A brief description of these baselines and the corresponding experimental results can be found in the Appendix A.

5.1.3 Implementation Details and Complexity Analysis

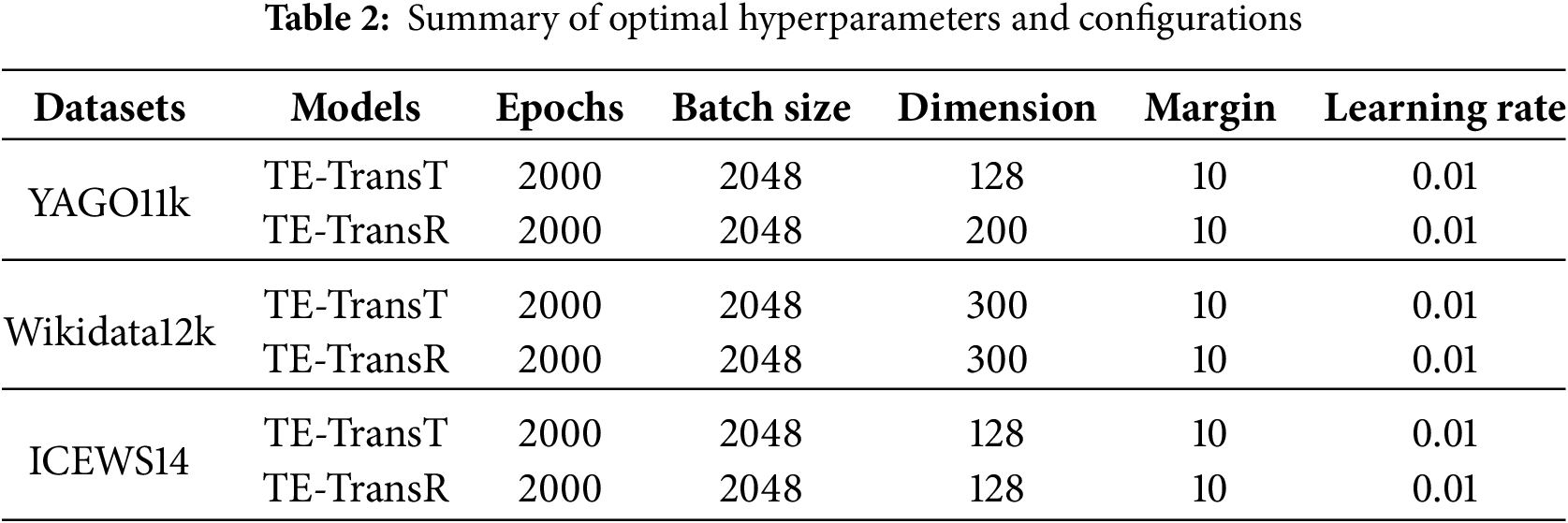

We implement our models using the PyTorch framework and run the models on four NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs. We train our models utilizing stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and pick up the optimal hyper-parameters using Optuna [68], referring to the MRR performance on the validation set. We set the number of training epochs N to 2000 and keep the embedding dimensions of entities, relations, and timestamps the same. The embedding dimension

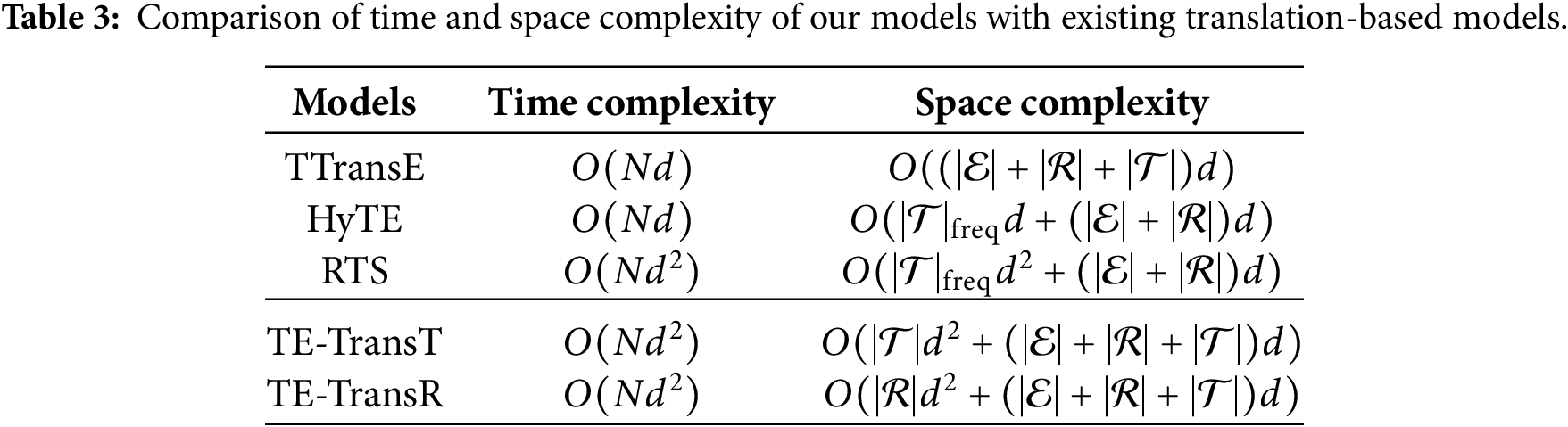

Time and space complexity are key indicators for evaluating the practicality and scalability of TKGC models. As shown in Table 3, we compare our proposed models with several representative translation-based methods in terms of these two aspects.

In terms of time complexity, TTransE does not involve any transformation operations and only performs the score function computation, i.e., building the translation, which is an

As for space complexity, we present a more detailed comparison. TTransE only stores embeddings, resulting in a complexity of

Overall, compared to existing projection-matrix-based models, the asymptotic complexity of our methods remains unchanged, with differences only in constant factors. Nonetheless, it should be noted that our time-unit-based timestamp setting can introduce additional computational cost, and the actual memory usage of time-specific and relation-specific matrices may vary depending on dataset characteristics, which should be taken into account in practical applications. In our experiments, TE-TransT occupies approximately 10 GB of memory and converges in 4.4 h/1.9 h/0.3 h on YAGO11k, Wikidata12k, and ICEWS14, respectively. In contrast, TE-TransR uses about 8 GB of memory and converges in 3.8 h/1.2 h/0.2 h on these datasets. This difference may be attributed to the fact that, in these datasets, the number of relations is significantly smaller than the number of timestamps, implying a smaller constant factor in the

Link prediction aims to identify the missing head or tail entity in a given fact. Link prediction has been widely explored since being proposed in [69] and has become a critical measurement for KG completion techniques.

In this task, we utilize the method of Eq. (6) to generate negative samples for training. For every test quadruple

We employ two standard evaluation metrics to measure the prediction results: MRR (mean reciprocal rank) and Hit@

As reported in Table 4, TE-TransT and TE-TransR outperform baseline models across all metrics on the Wikidata12k dataset and ICEWS14 dataset. Although our models fail to beat all baselines in terms of the Hit@10 metric on the YAGO11k dataset, they tie with the second best-performing model, RTS, and surpass all baselines in terms of other metrics. The results suggest that our approach is capable of effectively embedding temporal information and utilizing it for link prediction. In comparisons within our models, TE-TransT slightly outperforms TE-TransR on the YAGO11k dataset, while TE-TransR slightly edges out TE-TransT on the Wikidata12k dataset and ICEWS14 dataset.

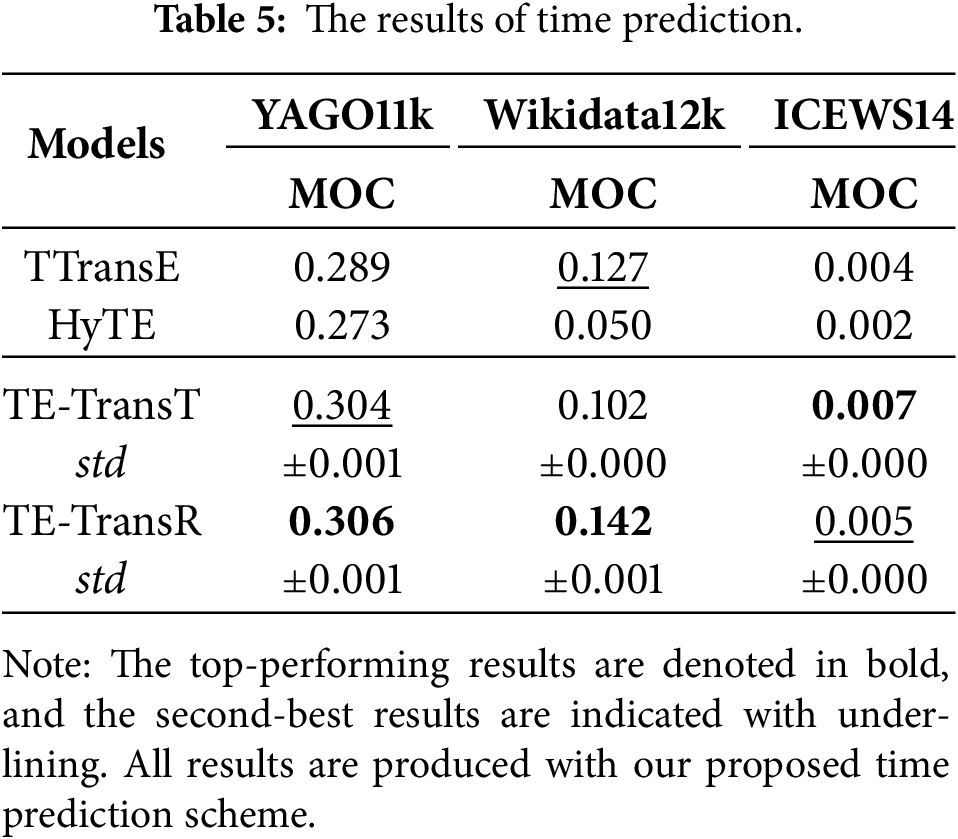

Time prediction involves predicting the missing time point or time interval of a fact, which is also an important task for TKGC. In the time prediction task, the incorporation of time embeddings in our method allows for an explicit and direct replacement of the time dimension during negative sampling as in Eq. (8). The remainder of the training process aligns with the procedures of the link prediction task. We utilize the identical training set and the same best parameters that are employed in link prediction for model training. Following the evaluation protocol introduced in Section 4, we apply relation-specific evaluation to all time-missing triples

TTransE [25] and HyTE [26] serve as baselines for the time prediction task. Since static KG embedding methods do not consider the time dimension and other TKG embedding methods are not tailored for time prediction, they are not suitable for this task. TTransE incorporates timestamps within the same embedding space as entities and relations, thus allowing direct compatibility with our setup for the time prediction task. Regarding HyTE, to ensure fairness, we adapt its original timestamp setting based on the frequency of facts to our time unit-based setting and then produce the results.

Evaluation results of time prediction are shown in Table 5. The models exhibit close performance on the YAGO11k dataset, with TE-TransT and TE-TransR marginally outperforming TTransE and HyTE. On the Wikidata12k dataset, HyTE performs significantly worse than other models, highlighting the critical flaw of not learning an independent representation for timestamps. TE-TransT’s performance falls below both TTransE and TE-TransR, indicating that representing each timestamp in a different embedding space could be detrimental to the time prediction task in certain settings. This might be due to the sparsity of training data for individual timestamps. TE-TransR outperforms TTransE, suggesting that building translation in the relation space effectively facilitates information interaction among different embeddings. As for the ICEWS14 dataset, all methods yield relatively low MOC scores. This is because MOC is better suited for datasets like YAGO11k and Wikidata12k, where facts are valid over a time interval. In such cases, MOC effectively measures the overlap between the predicted timestamps and the ground-truth interval. However, in datasets like ICEWS14, where each fact is only valid at a single timestamp, correct predictions of the exact timestamp are required to achieve a high MOC score, which is much more difficult. Despite the overall low values, our models still outperform TTransE and HyTE, further demonstrating the generalizability of our approach across different types of TKGs.

5.4.1 Temporal Sensitivity of Relations

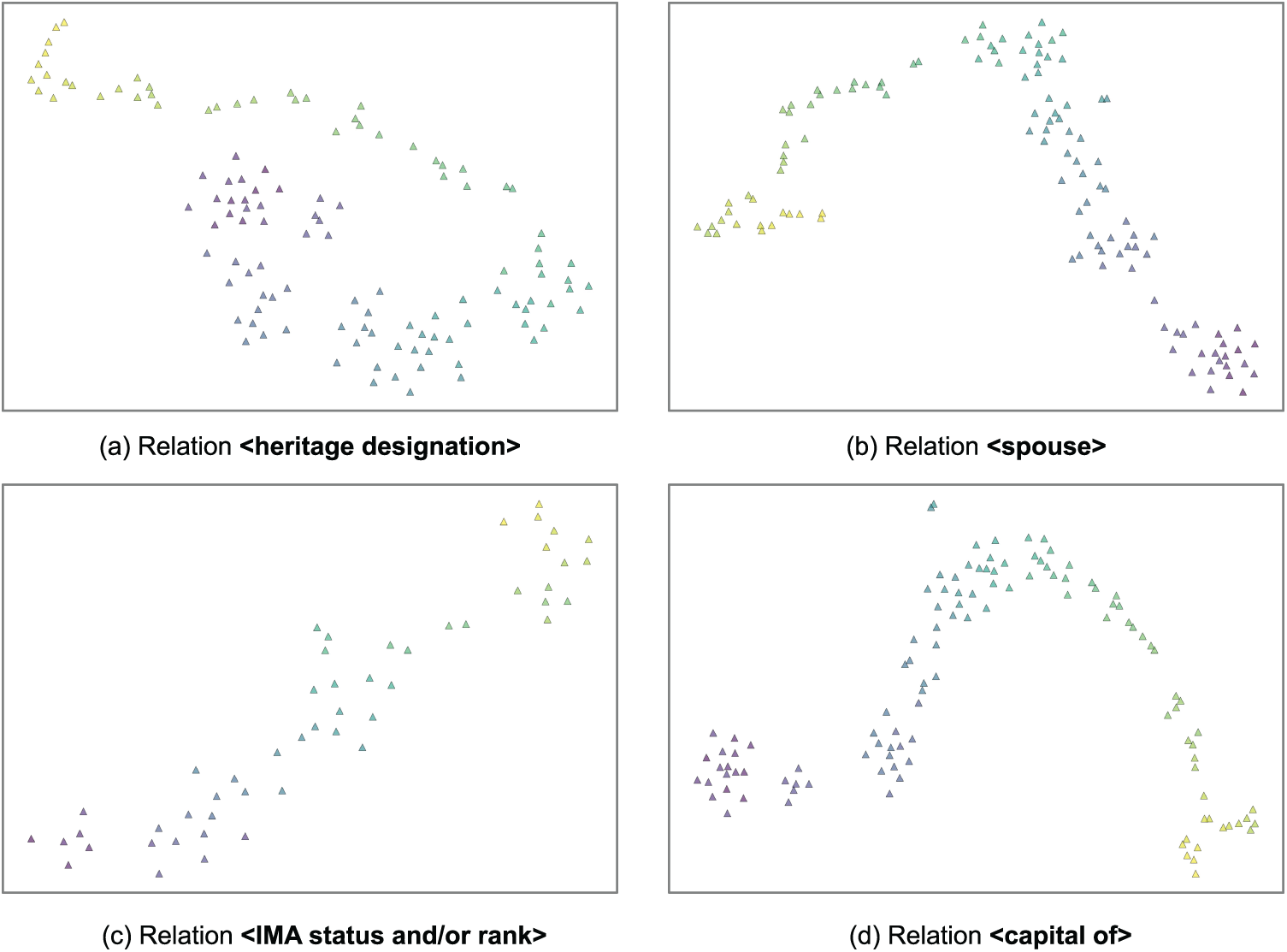

Previous works have made significant progress in demonstrating that relations are often time-sensitive. To verify that our model has captured the close correlation between relations and timestamps, we use TE-TransT as an example and present t-SNE visualizations in Fig. 2, showing the relation embeddings of some randomly selected relations projected into different time spaces. As observed, the embeddings of the same relation exhibit a clear and continuous ordering over time, indicating that the model has learned the temporal sensitivity of relations. Additionally, it is evident that the influence of time varies across different relations.

Figure 2: t-SNE visualization of relation embeddings. Scatter points in each subplot represent the embeddings of the same relation with different timestamps. Warmer and brighter colors indicate later times. Other relations exhibit similar results

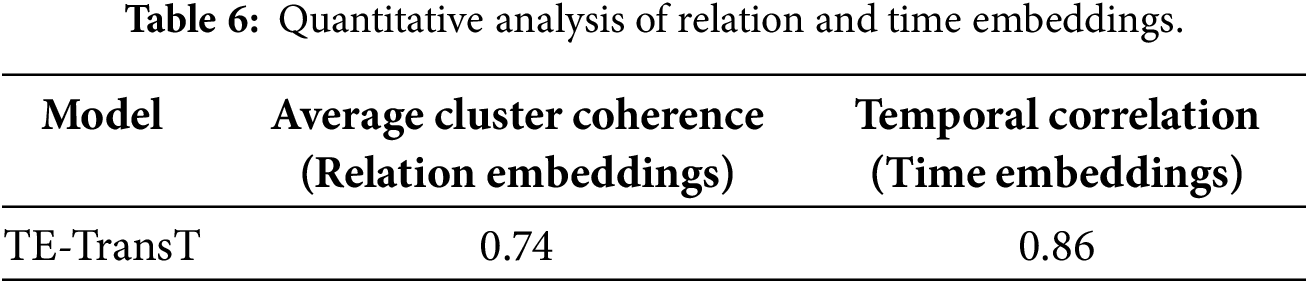

To move beyond qualitative plots, we quantify how well time-specific transformations preserve relation identity while allowing timestamp-specific variation. For each relation

For any cluster C, we define its coherence as the average pairwise cosine similarity among its members:

where

Based on the value reported in Table 6, the relatively high Average Cluster Coherence indicates that, after time-specific transformations, embeddings of the same relation remain tightly grouped while avoiding collapse to a single point—consistent with the t-SNE trajectories—since embeddings within each cluster still carry timestamp-specific characteristics.

5.4.2 Evolution of Time Embeddings

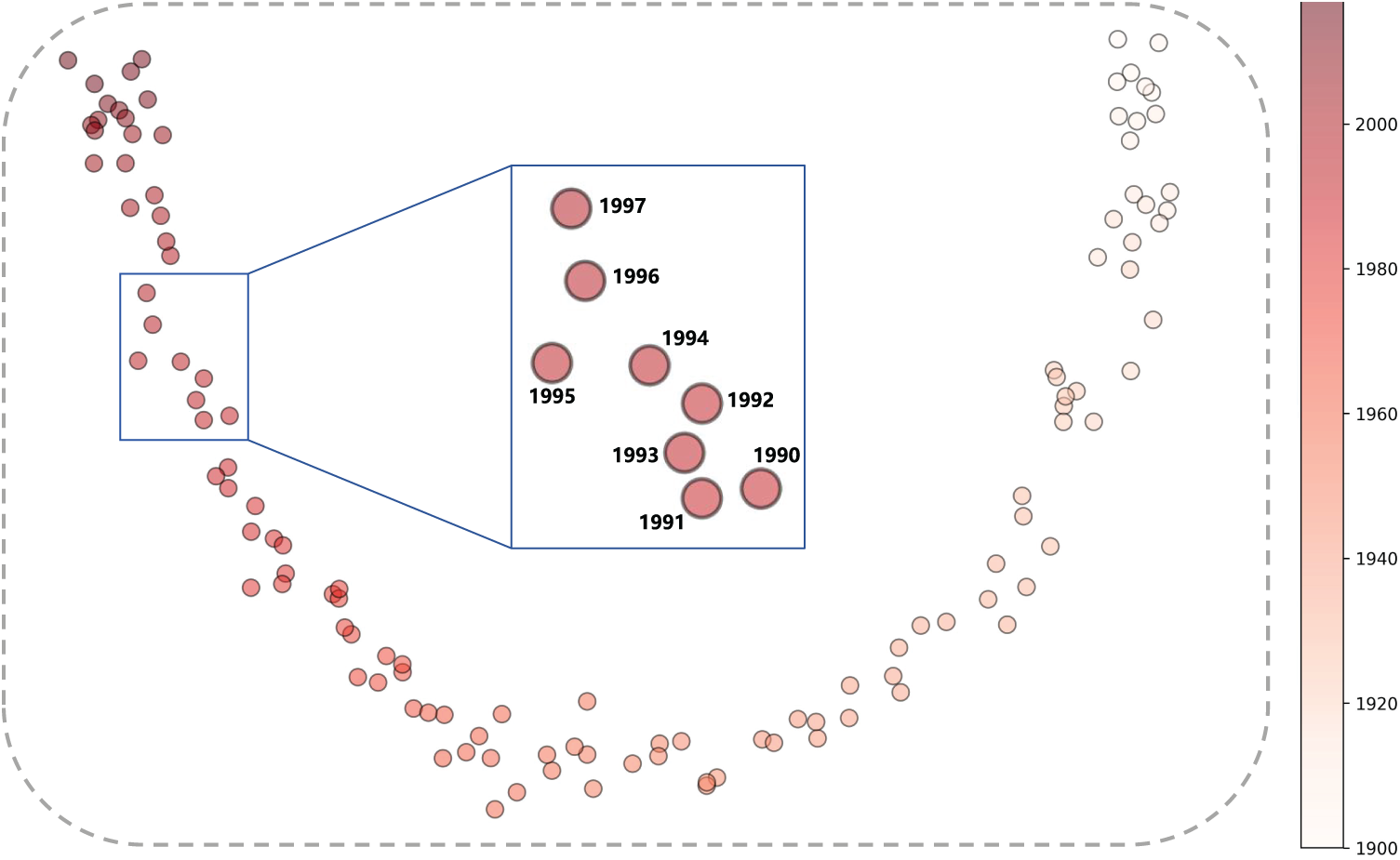

Figure 3 illustrates the 2D PCA projection of the 128-dimensional time embeddings from the TE-TransT model, trained for the time prediction. We can observe that, even without the addition of any time-related constraints, the time embeddings naturally exhibit discernible patterns. Similar time points form clusters, and an ordering is observed as time progresses, indicating that our independent representation for timestamps successfully captures the rich semantics of temporal information through time-dependent negative sampling.

Figure 3: 2D PCA visualization of time embeddings. Colors become darker as time progresses. A zoomed-in region is marked by a blue box, providing a closer look at the clustering pattern in greater detail. Only timestamps later than 1900 are retained for better visual presentation

To complement the qualitative observations from Fig. 3, we further introduce a Temporal Correlation metric to quantitatively assess whether the learned time embeddings preserve the chronological ordering of timestamps. Let

where

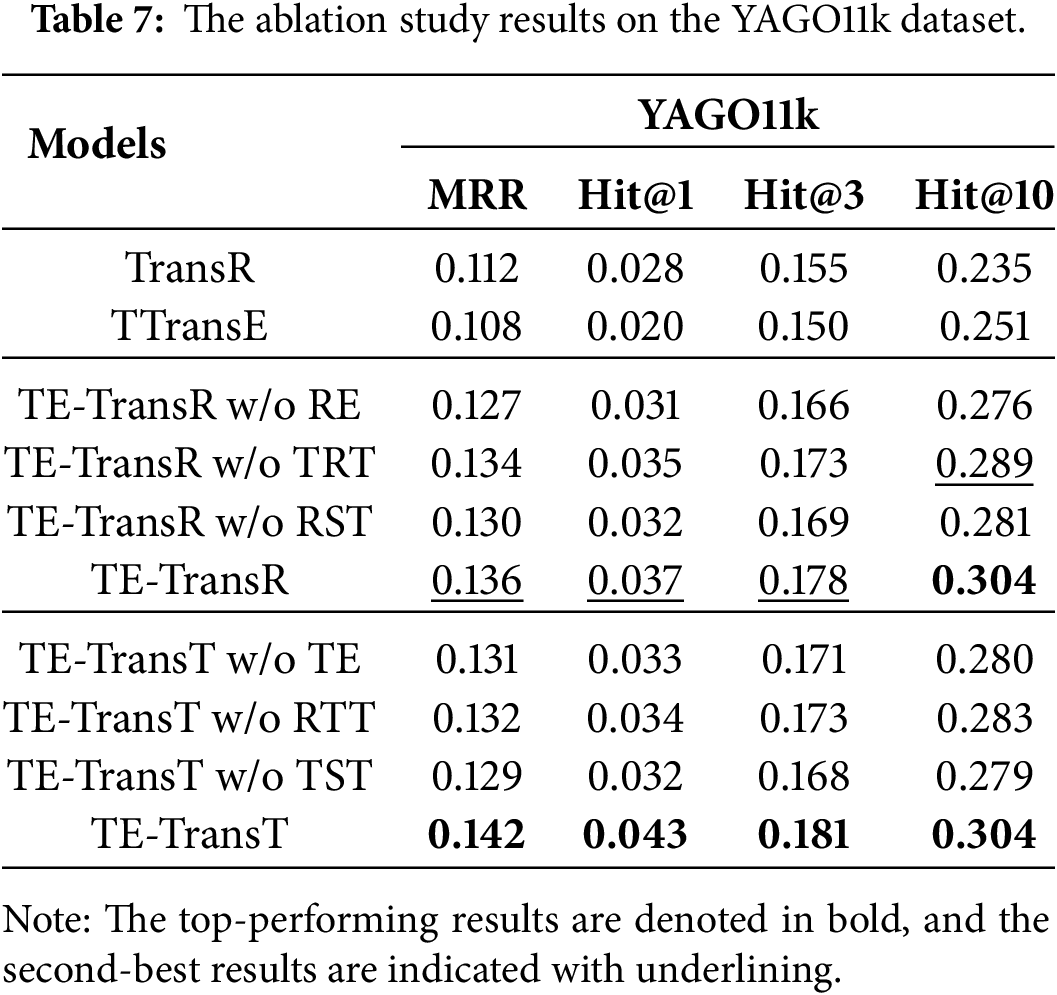

To investigate the individual contributions of each component of our proposed method to the final outcomes, we conduct a series of ablation studies. Link prediction results on the YAGO11k dataset for the ablation study are reported in Table 7. As demonstrated in Table 7, two existing methods, TransR [22] and TTransE [25], are included for comparisons. TTransE can be seen as our models stripped of all embedding transformations between different spaces, while TransR represents TE-TransR without considering the time dimension. Additionally, as the ablation methods of TE-TransR, “TE-TransR w/o RE” denotes TE-TransR with the relation embedding removed from the score function, “TE-TransR w/o TRT” indicates TE-TransR without the transformation from time space to relation space, and “TE-TransR w/o RST” represents TE-TransR without relation-specific transformations, meaning that the projection operations are performed using shared matrices across all relations. Similarly, ablation methods of TE-TransT include “TE-TransT w/o TE”, which denotes TE-TransT with the time embedding removed from the score function, “TE-TransT w/o RTT”, which represents TE-TransT without the transformation from relation space to time space, and “TE-TransT w/o TST”, which indicates TE-TransT without time-specific transformations by using shared projection matrices for all timestamps.

Firstly, the proposed models outperform the baseline models, TransR and TTransE. This is because TransR lacks the leverage of temporal information, while TTransE crudely represents entities, relations, and timestamps all within a common space, thereby limiting the model’s expressive capability. Secondly, our models perform better than “TE-TransR w/o RE” and “TE-TransT w/o TE”. These two ablation methods share a commonality: the removal of either relation embedding or time embedding from the score function, which means keeping only one of them as the translation vector. This simplification leads to diminished model performance, thus demonstrating the effectiveness of modeling the relation-timestamp pair as the translation. Thirdly, TE-TransR and TE-TransT also surpass “TE-TransR w/o TRT” and “TE-TransT w/o RTT”, both of which eliminate the transformation between time space and relation space. The results indicate that this alteration leads to poorer outcomes, suggesting that representing timestamps and relations in the same space leads to the loss of semantics. This further substantiates the notion that relations evolve over time. Finally, our models outperform both “TE-TransR w/o RST” and “TE-TransT w/o TST”, highlighting the importance of relation-specific and time-specific transformations. These results demonstrate that such tailored transformations could significantly enhance the expressiveness of the models.

5.4.4 Impact of Timestamp Settings

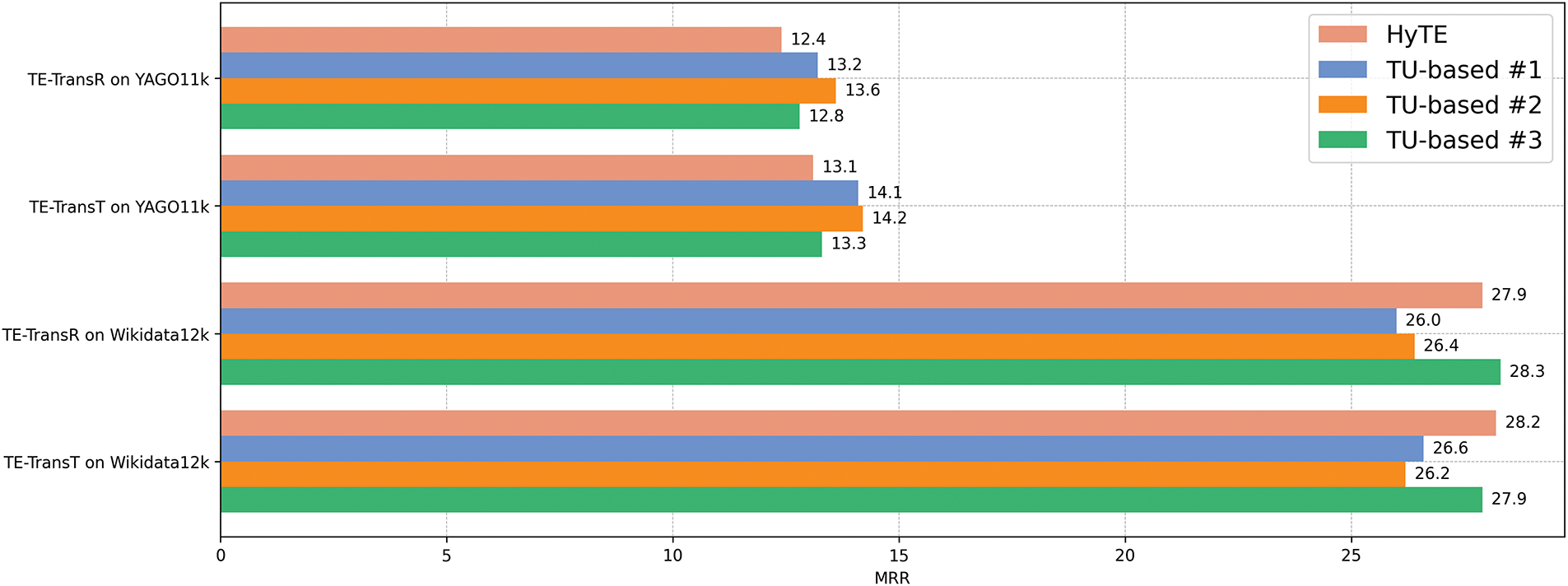

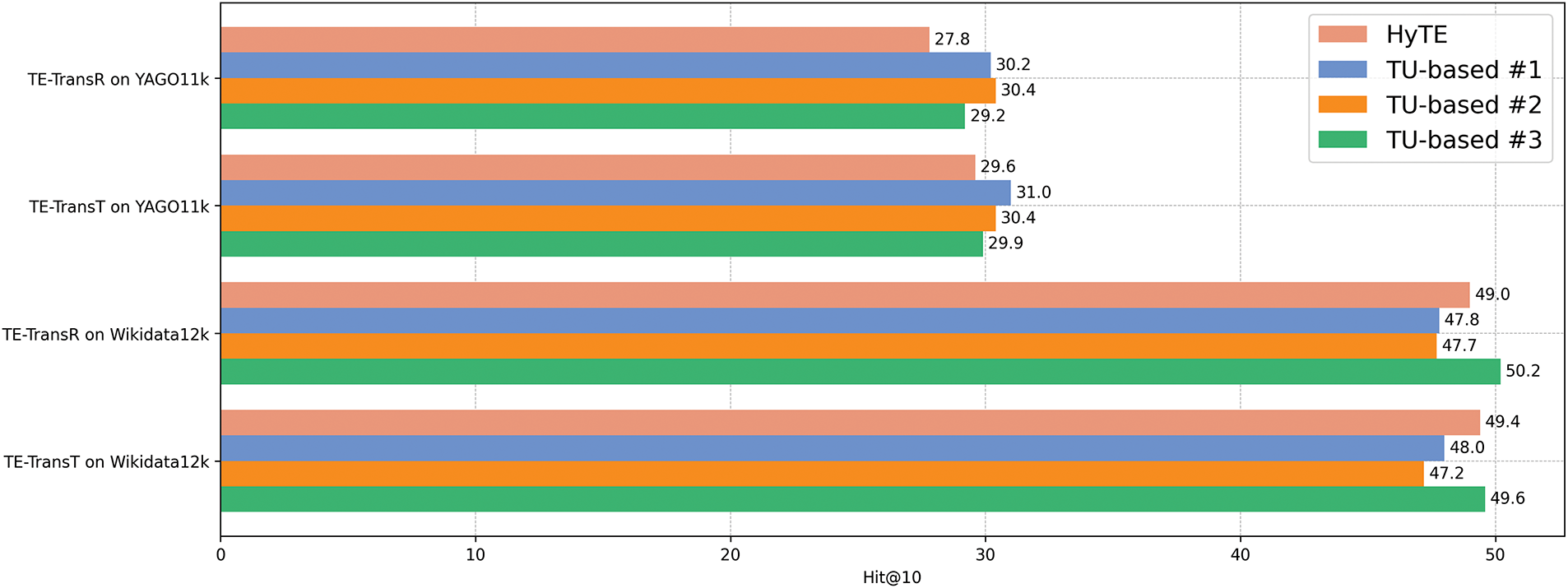

We also design experiments to explore the impact of different timestamp settings on the link prediction task. The corresponding results are summarized in Figs. 4 and 5.

Figure 4: Impact of different timestamp settings on MRR

Figure 5: Impact of different timestamp settings on Hit@10. The results of Hit@1 and Hit@3 show similar patterns

1. “HyTE” utilizes the frequency-based timestamp setting of HyTE [26], where timestamps are essentially variable-length time intervals. Missing values are replaced with the earliest or latest time across the entire dataset.

2. “TU-based #1” adopts the time unit-based timestamp setting proposed in this paper, where timestamps correspond to the dataset’s inherent time units. Missing values are also replaced with the earliest or latest time across the dataset.

3. “TU-based #2” employs the proposed time unit-based timestamp setting but uses a different strategy for replacing missing values, substituting them with the earliest or latest time associated with the specific relation.

4. “TU-based #3” also uses the proposed time unit-based timestamp setting, where missing values are replaced with the fact’s start or end time that exists. If both start and end times are missing, that fact is discarded.

We can observe that different timestamp settings have a discernible influence on the evaluation results, with a consistent effect on both MRR and Hit@10. The results obtained from “TU-based #1” and “TU-based #2” are relatively higher on the YAGO11k dataset, while lower on the Wikidata12k dataset. In contrast, “HyTE” and “TU-based #3” show the opposite trend. The results of link prediction and time prediction presented in this paper are all based on “TU-based #2”. These observations suggest that while the proposed time unit-based timestamp setting enables more fine-grained predictions in the time prediction task, it is not necessarily optimal for link prediction. Due to the inherent differences in dataset distributions, the time unit-based setting may suffer from data sparsity in certain cases. This is likely a contributing factor to the superior performance of the frequency-based setting on the Wikidata12k dataset.

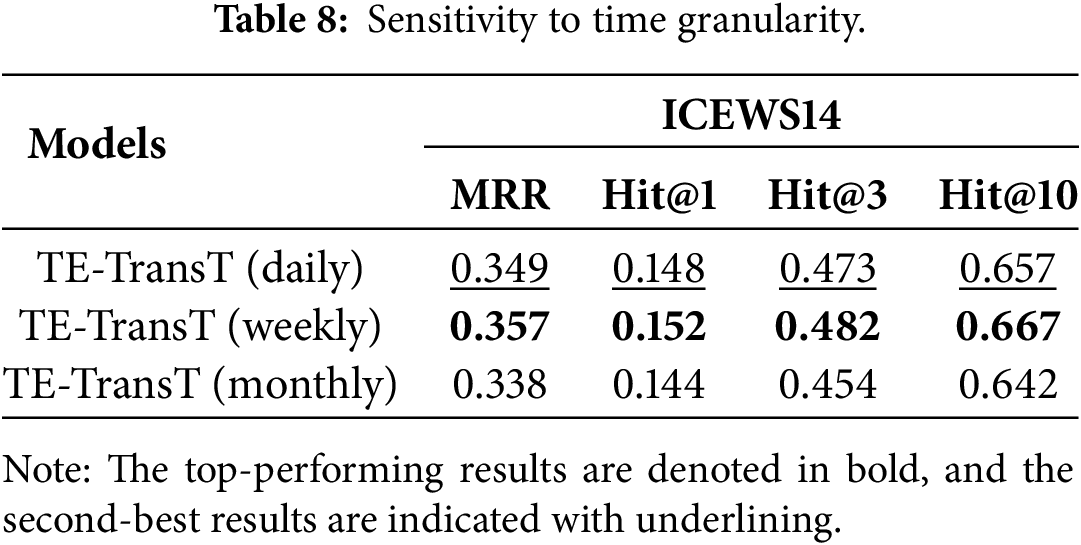

Time granularity has a significant impact on the data sparsity of TKGs. Coarser granularity can help alleviate data sparsity issues; however, it may also limit the model’s ability to capture fine-grained temporal patterns, thereby reducing its expressiveness. In Table 8, we report the sensitivity of TE-TransT to different levels of time granularity, including daily, weekly, and monthly settings, on the ICEWS14 dataset. We observe that increasing the granularity from one day to one week leads to improvements across all metrics. However, when the granularity is further increased to one month, the performance drops sharply and falls below that of the daily setting. These results indicate a trade-off between mitigating data sparsity and preserving temporal expressiveness, which should be carefully considered based on the characteristics of each dataset.

5.4.5 Discussion of Dataset-Induced Variations

Due to the varying data distributions and temporal characteristics across datasets, the performance improvements of our method are not entirely consistent. In the link prediction task, our proposed models generally achieve solid gains over existing translation-based models across nearly all datasets and metrics. However, the imbalance in performance becomes more pronounced in the time prediction task. For example, TE-TransR achieves a relatively modest improvement of 5.9% over the strongest baseline on YAGO11k, whereas the improvement rises to 11.8% on Wikidata12k. TE-TransT exhibits even greater fluctuations: while its performance on YAGO11k and Wikidata12k falls short of TE-TransR—and on Wikidata12k it even underperforms a baseline model—it achieves the best result on ICEWS14. We attribute this discrepancy to the influence of data distribution and sparsity. In our approach, TE-TransR and TE-TransT employ relation-specific and time-specific transformations, whose projection matrices depend heavily on whether sufficient data are available for the corresponding relation or timestamp. In YAGO11k and Wikidata12k, the temporal span is wide but the distribution is uneven, with facts concentrated toward later timestamps. As a result, the time-specific matrices for certain timestamps may not be adequately trained, leading to unstable predictions. By contrast, ICEWS14 covers only a single year, where data are relatively evenly distributed across days, enabling TE-TransT to learn more effectively. Regarding sparsity, we have already discussed in Section 5.4.4 the importance of selecting an appropriate time granularity to avoid poor training for underrepresented timestamps. In principle, TE-TransR may also suffer from similar issues, since different relation types are not equally represented, though the effect is less pronounced than in TE-TransT. Because our method does not explicitly address data imbalance, the performance can inevitably be affected by the inherent distribution of the datasets.

Our proposed method enhances model expressiveness by embedding temporal information into dedicated semantic spaces and employing time-specific and relation-specific projection matrices to facilitate transformations across different spaces. While such fine-grained modeling improves temporal reasoning, it introduces additional runtime and memory costs, which may affect the scalability of our models. We leave the exploration of more cost-efficient alternatives for future work. For the time prediction task, we introduce the MOC metric, which is particularly suitable for datasets where facts remain valid over a time interval, as it effectively captures the overlap between predicted timestamps and ground-truth intervals. However, for datasets where each fact is only valid at a single timestamp, MOC has certain limitations. Future work may involve designing more unified and robust evaluation metrics that are applicable across different temporal settings. Moreover, when learning time embeddings and time-specific matrices for the link prediction task, our method requires careful calibration of time granularity to balance the trade-off between mitigating data sparsity and preserving temporal expressiveness. Adopting the finest possible granularity may not always yield optimal results, and choosing an appropriate granularity should depend on the characteristics of the dataset.

While translation-based models offer the advantages of structural simplicity, fewer parameters, and high inference efficiency, neural-based approaches—such as those built on GNNs, RNNs, or Transformers—are typically more expressive due to their ability to model complex temporal interactions, capture long-term dependencies, and attend to critical contextual signals. In future work, we aim to explore hybrid architectures that combine the strengths of translation-based modeling with attention mechanisms.

Currently, our work is confined to incorporating independent time embeddings for TKGC tasks. Moving forward, we intend to extend this method to additional challenges, including event graph prediction.

We have presented two novel translation-based TKG embedding models: TE-TransR and TE-TransT. As the key to our method, we have explored learning embeddings of timestamps in different spaces from entities and relations, and modeling the relation-timestamp pair as the translation. Concretely, we embed entities, relations, and timestamps in multiple distinct embedding spaces, respectively. Different types of embeddings are projected into a common space through either relation-specific or time-specific matrices. We utilize the relation-timestamp pair as translation vectors, improving the flexibility and expressive capability of models. Furthermore, we propose a novel time prediction scheme, comprising a time unit-based timestamp setting and a relation-specific evaluation protocol, allowing for more precise and reliable time prediction. Extensive quantitative and qualitative evaluations show that our models, particularly TE-TransR, surpass previous translation-based approaches, offering a more accurate method for TKGC.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 72293575.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jinglu Chen and Daniel Dajun Zeng; methodology, Jinglu Chen, Mengpan Chen and Wenhao Zhang; software, Mengpan Chen and Huihui Ren; validation, Mengpan Chen, Wenhao Zhang and Huihui Ren; formal analysis, Jinglu Chen and Wenhao Zhang; investigation, Jinglu Chen, Mengpan Chen and Wenhao Zhang; resources, Jinglu Chen and Daniel Dajun Zeng; data curation, Mengpan Chen and Huihui Ren; writing—original draft preparation, Jinglu Chen, Mengpan Chen and Wenhao Zhang; writing—review and editing, Jinglu Chen, Wenhao Zhang and Daniel Dajun Zeng; visualization, Wenhao Zhang; supervision, Jinglu Chen and Daniel Dajun Zeng; project administration, Jinglu Chen and Daniel Dajun Zeng; funding acquisition, Daniel Dajun Zeng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on the website: https://github.com/cmp11/tkgc_trans (accessed on 17 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Comparison of Link Prediction Results with Non-Translation-Based Methods

Appendix A1 Baselines

To better position our proposed models within the broader TKGC landscape, we also conduct comparisons with non-translation-based baselines. These baselines include both SKG embedding models and TKG embedding models.

SKG embedding models: Our SKG embedding baselines include DistMult [21], QuatE [71], and HousE [72], encompassing bilinear, quaternion-based, and reflection-based modeling paradigms.

TKG embedding models: For TKG embedding baselines, we consider TA-DistMult [27], DE-SimplE [46], ATiSE [47], DyERNIE [55], HERCULES [73], and DuaTHPR [74], covering a diverse range of temporal modeling strategies from RNN-based models to Transformer-based architectures.

Appendix A2 Evaluation Results

The experimental results reported in Table A1 reveal mixed outcomes. For YAGO11k, our models achieve superior performance over all non-translation-based baselines on Hit@3 and Hit@10, but fall behind neural-based models ATiSE and DuaTHPR on MRR and Hit@1. On Wikidata12k, our models consistently perform slightly below ATiSE yet slightly above DuaTHPR across all metrics. However, on ICEWS14, the baselines generally achieve better performance than our models. This discrepancy may be related to the substantially higher relation diversity in ICEWS14, which contains 230 relation types—23 times more than YAGO11k and 9.6 times more than Wikidata12k—thereby making temporal modeling more challenging. These findings align with our discussion in Section 6, where we acknowledge that neural-based models, through their ability to capture complex temporal interactions, tend to achieve advantageous performance in such highly heterogeneous environments.

References

1. Miller GA. WordNet: a lexical database for English. Commun ACM. 1995;38(11):39–41. [Google Scholar]

2. Bollacker K, Evans C, Paritosh P, Sturge T, Taylor J. Freebase: a collaboratively created graph database for structuring human knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data; 2008 Jun 10–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1247–50. [Google Scholar]

3. Auer S, Bizer C, Kobilarov G, Lehmann J, Cyganiak R, Ives Z. DBpedia: a nucleus for a web of open data. In: International Semantic Web Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2007. p. 722–35. [Google Scholar]

4. Carlson A, Betteridge J, Kisiel B, Settles B, Hruschka E, Mitchell T. Toward an architecture for never-ending language learning. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2010 Jul 11–15; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 1306–13. [Google Scholar]

5. Suchanek FM, Kasneci G, Weikum G. YAGO: a core of semantic knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2007 May 8–12; Banff, AB, Canada. p. 697–706. [Google Scholar]

6. Yates A, Banko M, Broadhead M, Cafarella MJ, Etzioni O, Soderland S. TextRunner: open information extraction on the web. In: Proceedings of Human Language Technologies: The Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL-HLT). Rochester, NY, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2007. p. 25–6. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhang Z, Han X, Liu Z, Jiang X, Sun M, Liu Q. ERNIE: enhanced language representation with informative entities. arXiv:1905.07129. 2019. [Google Scholar]

8. Wang H, Zhang F, Wang J, Zhao M, Li W, Xie X, et al. RippleNet: propagating user preferences on the knowledge graph for recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2018 Oct 22–26; Turin, Italy. p. 417–26. [Google Scholar]

9. Gao M, Li JY, Chen CH, Li Y, Zhang J, Zhan ZH. Enhanced multi-task learning and knowledge graph-based recommender system. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(10):10281–94. doi:10.1109/tkde.2023.3251897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bao J, Duan N, Yan Z, Zhou M, Zhao T. Constraint-based question answering with knowledge graph. In: Proceedings of COLING 2016, the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers. Osaka, Japan: The COLING 2016 Organizing Committee; 2016. p. 2503–14. [Google Scholar]

11. Huang X, Zhang J, Li D, Li P. Knowledge graph embedding based question answering. In: Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2019 Feb 11–15; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 105–13. [Google Scholar]

12. Whan Kim Y, Kim JH. A model of knowledge based information retrieval with hierarchical concept graph. J Doc. 1990;46(2):113–36. doi:10.1108/eb026857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bounhas I, Soudani N, Slimani Y. Building a morpho-semantic knowledge graph for Arabic information retrieval. Inf Process Manag. 2020;57(6):102124. [Google Scholar]

14. Liu Y, Wan Y, He L, Peng H, Philip SY. KG-BART: knowledge graph-augmented BART for generative commonsense reasoning. In: Proceedings of the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2021 Feb 2–9; Online. p. 6418–25. [Google Scholar]

15. Wan G, Pan S, Gong C, Zhou C, Haffari G. Reasoning like human: hierarchical reinforcement learning for knowledge graph reasoning. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-20); 2021 Jan 7–15; Online. [Google Scholar]

16. Boschee E, Lautenschlager J, O’Brien S, Shellman S, Starz J, Ward M. ICEWS coded event data. Harv Dataverse. 2015:V37. [Google Scholar]

17. Vrandečić D, Krötzsch M. Wikidata: a free collaborative knowledgebase. Commun ACM. 2014;57(10):78–85. [Google Scholar]

18. Leetaru K, Schrodt PA. GDELT: global data on events, location, and tone, 1979–2012. In: ISA annual convention. Vol. 2. Easton, PA, USA: Citeseer; 2013. p. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

19. Wang Z, Zhang J, Feng J, Chen Z. Knowledge graph embedding by translating on hyperplanes. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2014 Jul 27–31; Québec City, QC, Canada. Vol. 28. p. 1112–9. [Google Scholar]

20. Bordes A, Usunier N, Garcia-Duran A, Weston J, Yakhnenko O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2013;26:2787–95. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang B, Wt Yih, He X, Gao J, Deng L. Embedding entities and relations for learning and inference in knowledge bases. arXiv:1412.6575. 2014. [Google Scholar]

22. Lin Y, Liu Z, Sun M, Liu Y, Zhu X. Learning entity and relation embeddings for knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2015 Jan 25–30; Austin, TX, USA. Vol. 29. p. 2181–7. [Google Scholar]

23. Trouillon T, Welbl J, Riedel S, Gaussier É, Bouchard G. Complex embeddings for simple link prediction. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2016. p. 2071–80. [Google Scholar]

24. Kazemi SM, Poole D. Simple embedding for link prediction in knowledge graphs. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2018;31:4289–4300. [Google Scholar]

25. Leblay J, Chekol MW. Deriving validity time in knowledge graph. In: WWW ’18: Companion Proceedings of the the Web Conference 2018; 2018 Apr 23–27; Lyon, France. p. 1771–6. [Google Scholar]

26. Dasgupta SS, Ray SN, Talukdar P. HYTE: hyperplane-based temporally aware knowledge graph embedding. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium. p. 2001–11. [Google Scholar]

27. García-Durán A, Dumančić S, Niepert M. Learning sequence encoders for temporal knowledge graph completion. arXiv:1809.03202. 2018. [Google Scholar]

28. Wu J, Cao M, Cheung JCK, Hamilton WL. Temp: temporal message passing for temporal knowledge graph completion. arXiv:2010.03526. 2020. [Google Scholar]

29. Wang Z, Li L, Zeng DD. Time-aware representation learning of knowledge graphs. In: 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2021 Jul 18–22; Shenzhen, China. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

30. Ji G, He S, Xu L, Liu K, Zhao J. Knowledge graph embedding via dynamic mapping matrix. In: Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. Vol. 1: Long Papers. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2015. p. 687–96. [Google Scholar]

31. Sun Z, Deng ZH, Nie JY, Tang J. Rotate: knowledge graph embedding by relational rotation in complex space. arXiv:1902.10197. 2019. [Google Scholar]

32. Abboud R, Ceylan I, Lukasiewicz T, Salvatori T. Boxe: a box embedding model for knowledge base completion. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2020;33:9649–61. [Google Scholar]

33. Balažević I, Allen C, Hospedales TM. Tucker: tensor factorization for knowledge graph completion. arXiv:1901.09590. 2019. [Google Scholar]

34. Nguyen DQ, Vu T, Nguyen TD, Nguyen DQ, Phung D. A capsule network-based embedding model for knowledge graph completion and search personalization. arXiv:1808.04122. 2018. [Google Scholar]

35. Wang J, Wang B, Gao J, Hu Y, Yin B. Multi-concept representation learning for knowledge graph completion. ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data. 2023;17(1):1–19. doi:10.1145/3533017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang J, Wang B, Gao J, Hu S, Hu Y, Yin B. Multi-level interaction based knowledge graph completion. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2023;32:386–96. doi:10.1109/taslp.2023.3331121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Dettmers T, Minervini P, Stenetorp P, Riedel S. Convolutional 2D knowledge graph embeddings. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Feb 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. Vol. 32. p. 1811–8. [Google Scholar]

38. Schlichtkrull M, Kipf TN, Bloem P, Van Den Berg R, Titov I, Welling M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In: The Semantic Web: 15th International Conference, ESWC 2018; 2018 Jun 3–7; Crete, Greece. 2018. p. 593–607. [Google Scholar]

39. Zhang Z, Li Z, Liu H, Xiong NN. Multi-scale dynamic convolutional network for knowledge graph embedding. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2020;34(5):2335–47. doi:10.1109/tkde.2020.3005952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang J, Wang B, Gao J, Li X, Hu Y, Yin B. TDN: triplet distributor network for knowledge graph completion. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(12):13002–14. doi:10.1109/tkde.2023.3272568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Jiang T, Liu T, Ge T, Sha L, Li S, Chang B, et al. Encoding temporal information for time-aware link prediction. In: Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2016. p. 2350–4. [Google Scholar]

42. Xu C, Nayyeri M, Alkhoury F, Yazdi HS, Lehmann J. TeRo: a time-aware knowledge graph embedding via temporal rotation. arXiv:2010.01029. 2020. [Google Scholar]

43. Sadeghian A, Armandpour M, Colas A, Wang DZ. ChronoR: rotation based temporal knowledge graph embedding. In: Proceedings of the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2021 Feb 2–9; Online. Vol. 35. p. 6471–9. [Google Scholar]

44. Lacroix T, Obozinski G, Usunier N. Tensor decompositions for temporal knowledge base completion. arXiv:2004.04926. 2020. [Google Scholar]

45. Shao P, Zhang D, Yang G, Tao J, Che F, Liu T. Tucker decomposition-based temporal knowledge graph completion. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;238:107841. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Goel R, Kazemi SM, Brubaker M, Poupart P. Diachronic embedding for temporal knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 34th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020 Feb 7–1; New York, NY, USA. Vol. 35. p. 3988–95. [Google Scholar]

47. Xu C, Nayyeri M, Alkhoury F, Yazdi H, Lehmann J. Temporal knowledge graph completion based on time series Gaussian embedding. In: The Semantic Web–ISWC 2020: 19th International Semantic Web Conference; 2020 Nov 2–6; Athens, Greece. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 654–71. [Google Scholar]

48. Xu C, Chen YY, Nayyeri M, Lehmann J. Temporal knowledge graph completion using a linear temporal regularizer and multivector embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 2569–78. [Google Scholar]

49. Messner J, Abboud R, Ceylan II. Temporal knowledge graph completion using box embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 36th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022 Feb 22–Mar 1; Online. Vol. 36. p. 7779–87. [Google Scholar]

50. Li S, Wang Q, Li Z, Zhang L. TPBoxE: temporal knowledge graph completion based on time probability box embedding. Comput Sci Inf Syst. 2025;22(1):153–80. [Google Scholar]

51. Yue L, Ren Y, Zeng Y, Zhang J, Zeng K, Wan J. Block decomposition with multi-granularity embedding for temporal knowledge graph completion. In: International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 706–15. [Google Scholar]

52. Wang J, Wang B, Gao J, Li X, Hu Y, Yin B. QDN: a quadruplet distributor network for temporal knowledge graph completion. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(10):14018–30. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2023.3274230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Zhang F, Chen H, Shi Y, Cheng J, Lin J. Joint framework for tensor decomposition-based temporal knowledge graph completion. Inf Sci. 2024;654(2):119853. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Li J, Su X, Gao G. TeAST: temporal knowledge graph embedding via Archimedean spiral timeline. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. Vol. 1: Long Papers. p. 15460–74. [Google Scholar]

55. Han Z, Ma Y, Chen P, Tresp V. DyERNIE: dynamic evolution of Riemannian manifold embeddings for temporal knowledge graph completion. arXiv:2011.03984. 2020. [Google Scholar]

56. Wang J, Cui Z, Wang B, Pan S, Gao J, Yin B, et al. Integrating multi-curvature shared and specific embedding for temporal knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2024; 2024 May 13–17; Singapore. p. 1954–62. [Google Scholar]

57. Wang J, Wang B, Gao J, Pan S, Liu T, Yin B, et al. MADE: multicurvature adaptive embedding for temporal knowledge graph completion. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2024;54(10):5818–31. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2024.3392957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Li Y, Zhang X, Zhang B, Huang F, Chen X, Lu M, et al. SANe: space adaptation network for temporal knowledge graph completion. Inf Sci. 2024;667:120430. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. He M, Zhu L, Bai L. ConvTKG: a query-aware convolutional neural network-based embedding model for temporal knowledge graph completion. Neurocomputing. 2024;588(5):127680. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.127680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. He M, Zhu L, Bai L. Jointly leveraging 1D and 2D convolution on diachronic entity embedding for temporal knowledge graph completion. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;176(2):113144. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Zhang J, Wan T, Mu C, Lu G, Tian L. Learning granularity representation for temporal knowledge graph completion. In: International Conference on Neural Information Processing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

62. Guo J, Zhao M, Yu J, Yu R, Song J, Wang Q, et al. EHPR: learning evolutionary hierarchy perception representation based on quaternion for temporal knowledge graph completion. Inf Sci. 2025;688:121409. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Li Z, Jin X, Li W, Guan S, Guo J, Shen H, et al. Temporal knowledge graph reasoning based on evolutional representation learning. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2021 Jul 11–15; Online. p. 408–17. [Google Scholar]

64. Xie Z, Zhu R, Liu J, Zhou G, Huang JX. TARGAT: a time-aware relational graph attention model for temporal knowledge graph embedding. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing. 2023;31:2246–58. doi:10.1109/taslp.2023.3282101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Yang F, Bai J, Li L, Zeng D. A continual learning framework for event prediction with temporal knowledge graphs. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI); 2023 Oct 2–3; Charlotte, NC, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

66. Mahdisoltani F, Biega J, Suchanek FM. YAGO3: a knowledge base from multilingual Wikipedias. In: 7th Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research (CIDR 2015); 2015 Jan 4–7; Asilomar, CA, USA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

67. Erxleben F, Günther M, Krötzsch M, Mendez J, Vrandečić D. Introducing Wikidata to the linked data web. In: The Semantic Web–ISWC 2014: 13th International Semantic Web Conference; 2014 Oct 19–23, Riva del Garda, Italy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. p. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

68. Akiba T, Sano S, Yanase T, Ohta T, Koyama M. Optuna: a next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2019 Aug 4–8; Anchorage, AK, USA. p. 2623–31. [Google Scholar]

69. Bordes A, Weston J, Collobert R, Bengio Y. Learning structured embeddings of knowledge bases. In: Proceedings of the 25th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2011 Aug 7–11; San Francisco, CA, USA. Vol. 25. p. 301–6. [Google Scholar]

70. Jain P, Rathi S, Mausam, Chakrabarti S. Temporal knowledge base completion: new algorithms and evaluation protocols. arXiv:2005.05035. 2020. [Google Scholar]

71. Zhang S, Tay Y, Yao L, Liu Q. Quaternion knowledge graph embeddings. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2019;32:2735–45. [Google Scholar]

72. Li R, Zhao J, Li C, He D, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. House: knowledge graph embedding with householder parameterization. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 13209–24. [Google Scholar]

73. Montella S, Barahona LMR, Heinecke J. Hyperbolic temporal knowledge graph embeddings with relational and time curvatures. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 3296–308. [Google Scholar]

74. Chen Y, Li X, Liu Y, Hu T. Integrating transformer architecture and householder transformations for enhanced temporal knowledge graph embedding in DuaTHP. Symmetry. 2025;17(2):173. doi:10.3390/sym17020173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools