Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Searchable Attribute-Based Encryption with Multi-Keyword Fuzzy Matching for Cloud-Based IoT

School of Computer Science and Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110819, China

* Corresponding Author: Shi Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069628

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 15 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Internet of Things (IoT) interconnects devices via network protocols to enable intelligent sensing and control. Resource-constrained IoT devices rely on cloud servers for data storage and processing. However, this cloud-assisted architecture faces two critical challenges: the untrusted cloud services and the separation of data ownership from control. Although Attribute-based Searchable Encryption (ABSE) provides fine-grained access control and keyword search over encrypted data, existing schemes lack of error tolerance in exact multi-keyword matching. In this paper, we proposed an attribute-based multi-keyword fuzzy searchable encryption with forward ciphertext search (FCS-ABMSE) scheme that avoids computationally expensive bilinear pairing operations on the IoT device side. The scheme supports multi-keyword fuzzy search without requiring explicit keyword fields, thereby significantly enhancing error tolerance in search operations. It further incorporates forward-secure ciphertext search to mitigate trapdoor abuse, as well as offline encryption and verifiable outsourced decryption to minimize user-side computational costs. Formal security analysis proved that the FCS-ABMSE scheme meets both indistinguishability of ciphertext under the chosen keyword attacks (IND-CKA) and the indistinguishability of ciphertext under the chosen plaintext attacks (IND-CPA). In addition, we constructed an enhanced variant based on type-3 pairings. Results demonstrated that the proposed scheme outperforms existing ABSE approaches in terms of functionalities, computational cost, and communication cost.Keywords

With the rapid development of Internet of Things (IoT), pervasive IoT devices (IoTDs) have become capable of sensing their environments and processing data, thereby bridging the physical and digital worlds. IoT has been widely applied in industrial production, agriculture, public safety monitoring, smart cities, mobile healthcare, and so on. For instance, IoT-enabled medical systems utilize embedded and wearable equipments to collect health-related data for clinical diagnosis [1]. It was predicted that the growth of wearable IoTDs will reach 265.4 USD billion in 2026 [2].

To address the computational and storage limitations of IoTDs, cloud computing has emerged as a cost-effective and scalable solution. In cloud-assisted IoT systems, IoTDs like sensors transmit data to cloud servers via wireless networks. The cloud infrastructure offers abundant storage and computational resources, enabling efficient data processing and reducing the burden on IoTDs. However, outsourcing sensitive IoT data to third-party cloud servers introduces serious privacy leakage and security concerns.

Encrypting IoT data before outsourcing is a simple solution to protecting privacy. However, once data is encrypted and stored, users cannot directly retrieve specific data. Instead, they are forced to download all ciphertexts, which significantly degrades system efficiency. Searchable encryption (SE) scheme [3] was introduced to address this issue. By leveraging keyword matching, users can search encrypted data to retrieve specific information without decrypting the entire dataset. SE schemes typically bind search capabilities to a specific user’s key, limiting their effectiveness in multi-user environments. To achieve fine-grained access control of data, attribute-based encryption (ABE) mechanisms [4] have been introduced. ABE can identify users based on their attribute sets, grant each user unique identity characteristics, and provide flexible representation of access control policies at the expense of increased computational and communication costs compared to traditional encryption techniques. Attribute-based keyword-searchable encryption (ABSE) scheme [5] can address the fine-grained access control and search issue by combining ABE and SE. In ABSE schemes, data users can only retrieve and recover the plaintext if their own attribute set matches the access control policy specified by the data owner. However, most existing ABSE schemes support only exact keyword matching, which may fail to reflect a user’s actual search intent and limits the expressiveness of search strategies.

In 2000, Song et al. [3] introduced searchable encryption, enabling data users to perform keyword searches on encrypted cloud data without decryption. They implemented a symmetric searchable encryption (SSE) scheme based on symmetric cryptography. However, this scheme requires a centralized key management authority to distribute keys to users, leading to complex key distribution and management challenges. After that, although many improved SSE schemes have been introduced and formally proven secure, they are unsuitable for multi-user data-sharing cases. To address this, Boneh et al. [6] in 2004 suggested a public key encryption with keyword search (PEKS) scheme based on identity-based encryption [7] for ciphertext retrieval in public key cryptosystems. PEKS allows a sender to create searchable ciphertext using a keyword and the public key of the receiver. The receiver generates a trapdoor using its private key and sends it to cloud servers. The server returns matching ciphertexts to the user if and only if the keyword in the trapdoor matches the one in the ciphertext. Chen et al. [8] improved multi-keyword PEKS by reducing computational cost and trapdoor sizes. However, their scheme strictly enforces exact-match queries. Any input errors or formatting inconsistencies in user queries will prevent the system from returning valid results, thus severely compromising practical usability. For error-tolerant scenarios, Li et al. [9] first suggested fuzzy search PEKS using wildcards and edit distance. Servers can return results similar to the queried keywords at the expense of significantly increased storage and computational overhead. Dong et al. [10] designed a homomorphic encryption based fuzzy keyword search scheme which is more efficient than [9]. Zhang et al. [11] introduced a scalable fuzzy keyword ranked search scheme over encrypted data to achieve fuzzy keyword search for any similarity threshold with a constant storage size and accurate search results. Jiang et al. [12] proposed a fuzzy keyword searchable encryption scheme based on blockchain. Their scheme leverages blockchain to ensure equitable service payment transactions between users and cloud servers.

Most existing SE schemes exhibit expressive search policies and support only single-keyword or conjunctive keyword queries. To address expressiveness challenges in SE, Lai et al. [5] proposed an expressive PEKS (EPEKS) scheme on composite-order groups with high computational costs. Cash et al. [13] designed a searchable symmetric encryption, which supports boolean queries. Xu et al. [14] developed an efficient multi-keyword search mechanism that operates without predefined keyword fields, utilizing an anti-collusion box to enable boolean search functionality. Li et al. [15] further advanced this domain by proposing a verifiable boolean search protocol over encrypted data within an SSE framework, which guarantees forward privacy and weak backward privacy. Tong et al. [16] proposed a privacy-preserving boolean range query with temporal access control. Their scheme achieves privacy-preserving boolean range query and forward/backward derivation functions. Liu et al. [17] developed a verifiable dynamic encryption with ranked search (VDERS) scheme to secure top-K searches and verifiable results on dynamic document collections.

In terms of search privacy, Li et al. [18] introduced forward search privacy, enabling secure searches on newly added documents without leaking historical query information. Gan et al. [19] introduced a forward private SSE scheme for multiple clients. Their scheme involves no bilinear pairing computation, which has better efficiency on search. Guo et al. [20] designed a verifiable and forward-privacy SSE scheme that achieves sublinear search time and efficient file updates with guaranteed security. Cui et al. [21] proposed a dynamic and verifiable fuzzy keyword search with forward security scheme that adopts uni-gram and locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) to achieve efficient search.

1.1.2 Attributed-Based Encryption

Sahai and Waters [22] first proposed fuzzy identity-based encryption in 2005, laying the foundation for ABE as a means of achieving fine-grained access control. Building on this, Goyal et al. [4] formally defined two principal variants of ABE schemes: key-policy attribute-based encryption (KP-ABE) and ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE). In KP-ABE, secret keys are related to access control policies and ciphertexts are associated with attribute sets. CP-ABE inversely links ciphertexts to access control policies while binding secret keys to attribute sets. Bethencourt et al. [23] subsequently proposed the first concrete construction of CP-ABE. However, their implementation employed access trees as policy representation structures, resulting in limited expressive power for complex access control requirements. To improve security, efficiency, and expressiveness, Waters [24] later enhanced CP-ABE by implementing arbitrary monotonic access policies with linear secret sharing scheme (LSSS) matrices. Despite these improvements, these schemes lacked support for attribute negation. Ostrovsky et al. [25] utilized the broadcast revocation mechanism to achieve KP-ABE with negation operations, doubling the size of the ciphertext, keys, and computational costs. Lewko et al. [26] later optimized [25] by reducing public key size with longer ciphertexts.

Extensive ABE works have focused on enhancing ABE schemes. Meng et al. [27] introduced a dual-policy ABME scheme with forward security. However, their scheme requires updating the ciphertext, which is impractical in end-to-end data sharing scenarios. Luo et al. in [28] suggested a hidden policy scheme that relies on the user revocation mechanism on fog nodes, making it vulnerable if those nodes are compromised. Miao et al. [29] introduced a verifiable outsourced ABME scheme, but its lack of cryptographic agility and limited access delegation models restrict its adaptability and flexibility. Duan et al. [30] introduced a muti-authority ABME scheme. This scheme’s security depends on trusted third parties (central/attribute authorities), creating a single point of failure if these entities are compromised. Ruan et al. [31] introduced an ABME scheme that supports attribute and user revocation. However, this scheme lacks public traceability, limiting its ability to identify and trace malicious users.

1.1.3 Attributed-Based Searchable Encryption

To enable searchable encryption as well as multi-user access control, Lai et al. [5] designed a key-policy ABSE scheme combining KP-ABE with PEKS. In 2014, Zheng et al. [32] presented a verifiable attribute-based keyword search (VABKS) scheme that outsources complex search operations to cloud servers. Their design uses Bloom filters and digital signatures to ensure that only authorized users can retrieve cloud data, while enabling verification of the cloud server’s search integrity. Han et al. [33] introduced the concept of weak anonymous ABE and established a generic transformation between ABE and key-policy ABSE schemes. They also proposed a multi-user ABSE scheme for flexible collaborative searches on remotely encrypted data. However, this scheme’s reliance on composite-order groups resulted in low efficiency. Zhang et al. [34] suggested a blockchain-based anonymous ABSE scheme for data sharing. In their scheme, attributes of the access policy are hidden, ensuring the confidentiality of those attributes. In 2021, Ge et al. [35] proposed an ABSE scheme that supports both attribute-based keyword search and data sharing. Notably, this scheme enables keyword updates during the sharing phase without requiring interaction with the private key generator. Ali et al. [36] introduced a verifiable online/offline multi-keyword search (VMKS) scheme that implements outsourced encryption and decryption. In their scheme, the outsourcing part of the encryption and decryption computations significantly reduces the computational cost. Moreover, their scheme supports threshold-based search, where a match succeeds only when the intersection between the keywords in the trapdoor and those in the ciphertext exceeds the specified threshold. Miao et al. [37] designed an optimized verifiable fine-grained keyword search scheme in the static multi-owner setting (VFKSM) to significantly reduce both the ciphertext length and communication overhead. Their scheme achieves ciphertext length linear in the number of keywords, and employs a threshold signature mechanism to convert multiple signatures into a single threshold signature. Huang et al. [38] suggested an expressive multi-keyword ABSE scheme with ranked search results. While their solution supports AND/OR logical search predicates, it incurs substantial communication and computational overhead. To support attribute tracking and multi-keyword search, Huang et al. [39] proposed an ABSE scheme, which employs a new security model in its proof. However, this scheme suffers from a critical design flaw where portions of user private keys are exposed as trapdoors. Chen et al. [40] introduced a fair-and-exculpable-attribute-based searchable encryption with revocation and verifiable outsourced decryption (FE-ABSE-RV) scheme. Their scheme prevents malicious accusations from the client side against the cloud for returning incorrect results, thereby realizing fair exculpability for both ends. Tian et al. [41] designed an attribute-based heterogeneous data privacy sharing (AB-HDPS) scheme. Their scheme leverages the immutability of blockchain to achieve traceability and auditing of user access behaviors, while also implementing attribute revocation by subset-cover trees.

The above ABSE schemes have limited search capabilities, supporting only single-keyword or simple conjunctive keyword searches. Issues on existing ABSE schemes are summarized as follows.

• Only support exact match. In most existing ABSE schemes, the data owner specifies a set of keywords for their data. The cloud server will return the search ciphertext when keywords in the ciphertext and keywords in the trapdoor match exactly (i.e., both keyword sets are identical or the keyword set in the trapdoor is a subset of the keyword set in the ciphertext). This exact match search method exhibits very poor fault tolerance, as even a single erroneous keyword input (such as a typographical error) will result in failed searches.

• No forward security. Existing ABSE schemes require data users to create a trapdoor for querying encrypted data stored on cloud servers. However, third-party cloud servers are often untrusted. After completing the search, the cloud server can store these trapdoors and perform unauthorized future searches. The cloud server can verify whether newly added encrypted data matches previous search queries, which may result in the frequency attack issue [42] and expose keyword privacy.

• High computational and communication costs. In most existing verifiable ABSE schemes, data users needs download the partially decrypted ciphertext to verify the validity of outsourced decryption. This means that even if the cloud server performs search and partial decryption operations, users still need to download the whole ciphertext. This increases the user’s bandwidth and communication overhead, which is not suitable for resource-constrained IoT applications.

To address these challenges, we introduced an attribute-based multi-keyword fuzzy searchable encryption with forward ciphertext search (FCS-ABMSE) scheme. FCS-ABMSE supports multi-keyword fuzzy search based on the number of elements of the intersection keyword sets, forward security, and outsourced decryption and verification. The main functions are listed below.

• Multi-keyword fuzzy matching: Our scheme allows ciphertext and query keywords to have a certain degree of lexical deviation rather than being restricted to exact matching for search fault tolerance in real-world scenarios.

• Forward security: Even if query a trapdoor is leaked, the scheme can ensure that attackers cannot access historical encrypted data.

• Outsourced decryption and verification: Outsourced encryption and verification can reduce the computational cost of data uses, and mitigate the risk of the cloud server tampering with query results or altering data.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines cryptographic preliminaries. Section 3 presents the system model. Section 4 explains the proposed FCS-ABMSE scheme with formal security analysis, followed by performance evaluations in Section 5. Section 6 presents an enhanced scheme while Section 7 concludes this paper with future work.

This section describes essential cryptographic preliminaries employed in our scheme.

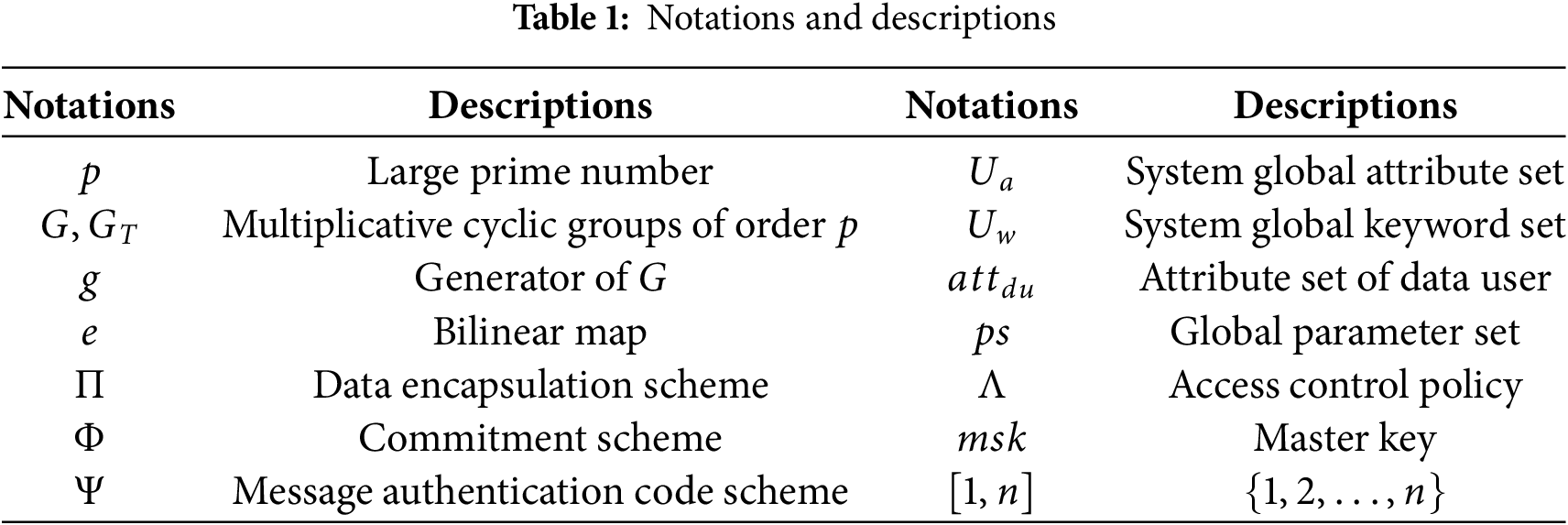

Notations used throughout the paper are defined in Table 1.

Definition 1. Let

• For any

•

• For any

A bilinear map

The security of the proposed scheme relies on two difficult problems.

Definition 2. Let

Definition 3. Let

2.4 Linear Secret Sharing Scheme

Definition 4. A linear secret sharing scheme (LSSS) for a set of participants

• Each participant receives a share represented as a vector with components in

• There exists a matrix

Definition 5. A key derivation function (KDF) accepts a secret

Definition 6. A KDF is said to be secure if the advantage

2.6 Data Encapsulation Mechanism

Definition 7. A data encapsulation mechanism (DEM) is a symmetric encryption scheme consisting of two algorithms:

•

•

Definition 8. A DEM

where

Definition 9. A commitment scheme is a cryptographic protocol that is specified by the two following algorithms:

•

•

Definition 10. A commitment scheme

where

2.8 Message Authentication Code

Definition 11. A message authentication code (MAC) is a cryptographic scheme that is specified by the two following algorithms:

•

•

Definition 12. A MAC scheme

In the proposed scheme, we compare two time points

• 0-encoding: Given a

• 1-encoding: Given a

According to [43], for any two integer values

3 System Model, Synax, and Security Definition

This section gives the system model, synax, and security definitions of the FCS-ABMSE scheme in turn.

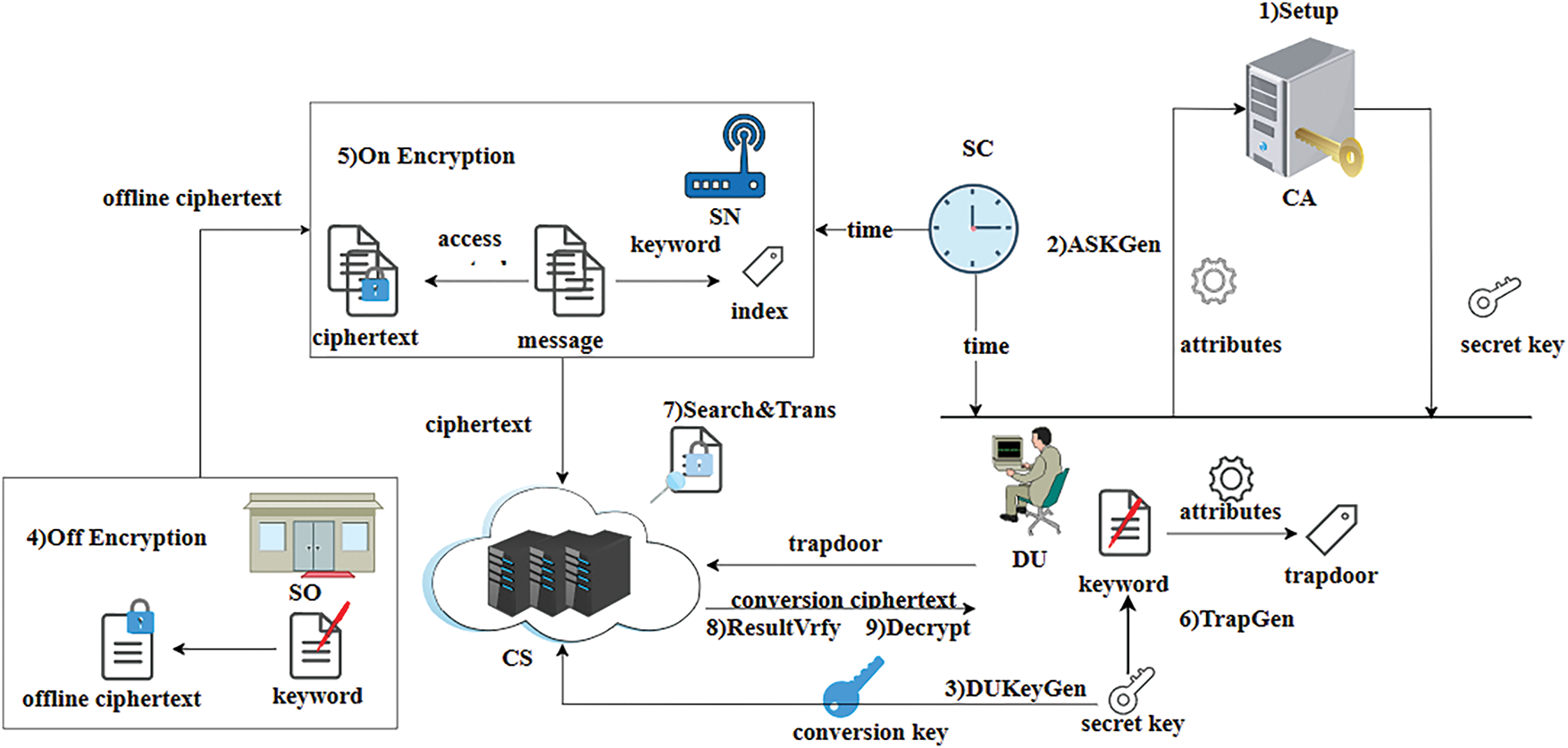

As shown in Fig. 1, the proposed FCS-ABMSE scheme involves the following six different entities:

• Central Authority (CA): The CA generates the system’s global parameters and master key, and issues attribute keys to users.

• Sensor’s Owner (SO): The SO encrypts keywords offline and stores offline ciphertexts of keywords onto sensors.

• Sensors (SN): The SN is responsible for collecting user data, creating searchable ciphertexts, and then sending them to the CS.

• Data User (DU): The DU retrieves matching ciphertext from the cloud server using a trapdoor, downloads them, and then decrypts the data using their decryption key.

• Cloud Server (CS): The CS provides ciphertexts storage and retrieval services, while assisting DUs with partial decryption of ciphertexts.

• System Clock (SC): The SC provides the current system timestamp in ciphertext and trapdoor generation.

Figure 1: System model of FCS-ABMSE

The interaction among the entities proceeds as follows: First, the CA distributes the system’s global parameters to other entities and transmits the attribute keys to the DU. Second, the SC transmits the current system timestamp to the SN and the DU. Third, the SO transmits the offline ciphertext to the SN. Then, the SN transmits the online ciphertext to the CS. After that, the DU transmits the trapdoor to the CS. Last, the CS stores the ciphertexts received from the SN, performs search operations upon receiving trapdoors from the DU, and returns pre-decrypted results to the DU.

The FCS-ABMSE scheme is defined by the following nine algorithms:

(1) Setup(

(2) ASKGen(

(3) DUKeyGen(

(4) offEncrypt(

(5) onEncrypt (

(6) TrapGen(

(7) Search(

(8) ResultVrfy(

(9) Decrypt (

Definition 13. An FCS-ABMSE scheme is correct if for a message

3.3 Security Definitions of FCS-ABMSE

An FCS-ABMSE scheme must satisfy the two following security notions: indistinguishability of ciphertext under the chosen keyword attack (IND-CKA) and indistinguishability of ciphertext under the chosen plaintext attack (IND-CPA).

IND-CKA. The security is defined by a game between an adversary

Initialization.

Setup.

Phase 1.

•

•

•

•

Challenge.

Phase 2. This phase is identical to Phase 1.

Guess.

Definition 14. An FCS-ABMSE scheme is IND-CKA secure if

IND-CPA. The security is defined by a game between an adversary

Initialization. Identical to the initialization process in the IND-CKA security game.

Setup. Identical to the setup process in the IND-CKA security game.

Phase 1. Identical to Phase 1 in IND-CKA security game, except that

Challenge.

Phase 2. Same as the IND-CKA security game, except that

Guess.

Definition 15. An FCS-ABMSE scheme is IND-CPA secure if

4 The Proposed FCS-ABMSE Scheme

This section presents the concrete construction of the FCS-ABMSE scheme, along with its correctness analysis and security proof.

The proposed FCS-ABMSE scheme is described as follows. (1) Setup(

• Generate two prime

• Randomly choose

• For each attribute in

• Choose an IND-DEM-CCA secure data encapsulation scheme

• Output

(2)

• Randomly select

• For each

• Output

(3)

• Randomly select

• For each

• Output

(4)

• For each

• Output

(5)

• Randomly select

• Run

• Randomly select

• Compute

• Randomly select

• For each

• Set

• Run the 0-encoding algorithm to transform

• For each

• For each

• Set

• Set

(6)

• Run 1-encoding algorithm to transform

• Randomly select

• Compute

• For each

• Set

(7)

• If

• Check whether

• If not, output

• Output

(8)

• Before downloading the decryption ciphertext

• If

(9)

• Compute

• If

According to the scheme description, we can deduce that

Clearly, if

Therefore, keyword search works correctly. In addition, we can deduce that

We demonstrate that our FCS-ABMSE scheme meets the IND-CKA and the IND-CPA security.

Theorem 1. If a polynomial-time adversary

Proof. Given a random instance of the DBDH problem

Initialization.

Setup.

X, Y,

Phase 1.

•

•

•

•

Challenge.

• For each

•

•

•

Phase 2. This phase is identical to Phase 1.

Guess.

If

Theorem 2. Assuming that the q-parallel-BDHE problem is difficult, the FCS-ABMSE meets the IND-CPA security. If a polynomial-time adversary

Proof. Given a random instance of the decisional q-parallel-BDHE problem

Initialization.

Setup.

Phase 1. In order to answer the queries in this phase,

•

•

•

Challenge.

Phase 2. Identical to Phase 1. The queried

Guess.

If

This section compares the proposed scheme with four benchmark approaches [36,37,40], and [41] for IoT environments in terms of functionalities, computational cost, and communication cost.

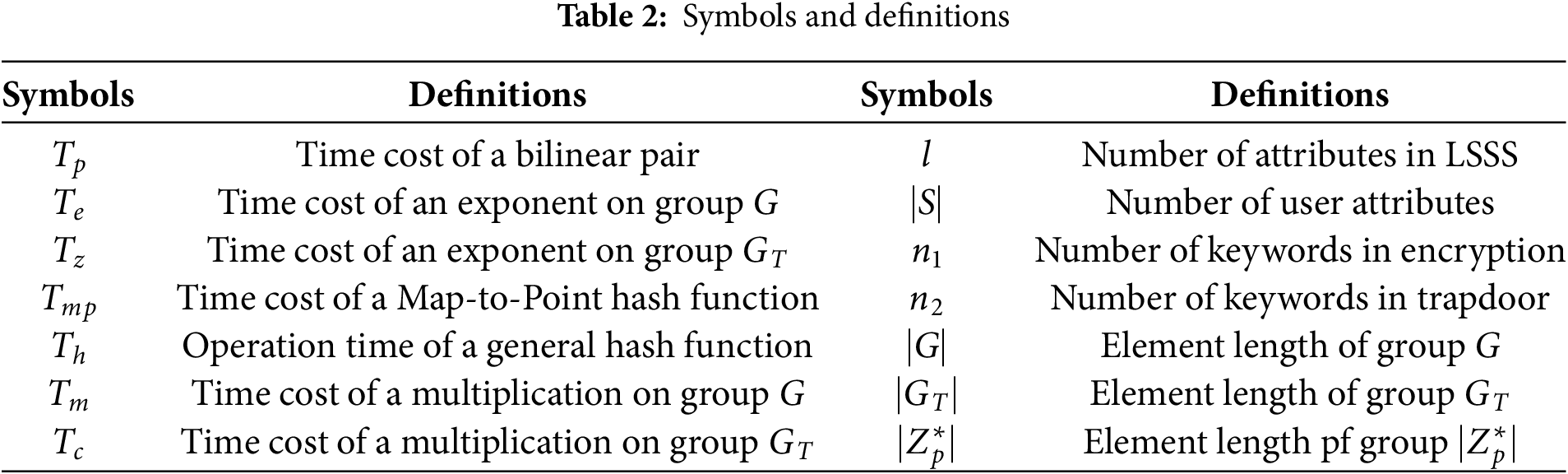

The Java Pairing-Based Cryptography Library (JPBC) was adopted [44] for simulations. The experiment was conducted using the JPBC-2.0.0 library on a system equipped with a Core i5-13500HX processor at 2.50 GHz and 16 GB of RAM. The bilinear map follows a type-1 pairings structure, with the curve equation

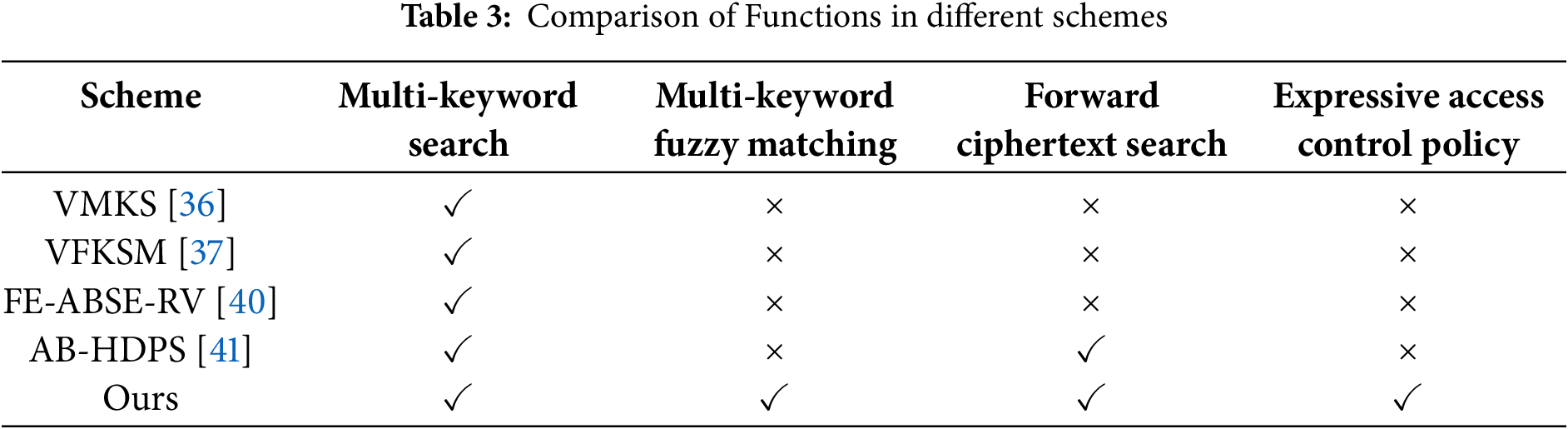

Table 3 compares this scheme with VMKS [36], VFKSM [37], FE-ABSE-RV [40], AB-HDPS [41]. VMKS, VFKSM, FE-ABSE-RV can only support multi-keyword search while AB-HDPS can support multi-keyword search and forward ciphertext search. Only the proposed scheme can support two additional functions including multi-keyword fuzzy matching, enabling tolerance to minor input errors, and expressive access control policies, which allow for fine-grained and flexible authorization beyond the capabilities of prior schemes.

Current fuzzy keyword search schemes mainly adopt two architectural approaches: (1) edit distance; (2) LSH. The former approach primarily utilizes edit distance to construct a collection of fuzzy keywords approximating original keywords. The latter employs the LSH algorithm to generate a bloom filter for keyword sets, subsequently encrypting the filter into index structures. Both approaches operate by building indexes and resembling original keywords to enable fuzzy search. In contrast, our scheme’s core innovation lies in threshold-based intersection search, which achieves multi-keyword fuzzy search by comparing intersections between distinct keyword sets.

Traditional fuzzy keyword search is designed to tolerate typos and spelling mistakes in user queries. It typically performs single-keyword search, determining whether a potentially incorrect search term belongs to a predefined set of fuzzy variants of the specific keyword. In contrast, our scheme is designed to evaluate whether a ciphertext contains a partial or complete match to a set of keywords being searched for. It supports multi-keyword fuzzy matching by assessing the similarity between two distinct keyword sets—one encrypted within the ciphertext and the other encoded in the trapdoor based on the size of their intersection. As we know, the search efficiency of single-keyword search is significantly lower than that of multi-keyword search. To conduct a fair comparison, we only include the ABSE schemes that support multi-keyword search in the performance comparison.

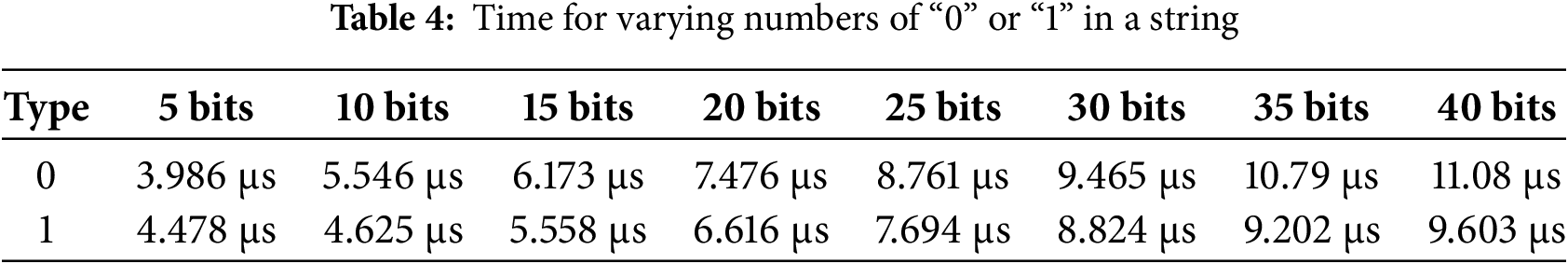

The experiment obtains the system time generated timestamp with a fixed length of 40 bits. For 0-1 encoding, its computational efficiency is related to the numbers of 0 and 1 characters in the bit string. We randomly generated eight bit strings with a total length of 40 bits. Different numbers of 0/1 bits are used to test the computational efficiency of 0 encoding and 1 encoding. As shown in Table 4, it can be seen that 0-1 encoding is highly efficient. When the number of “0” or “1” is 40, the time for all 0 bit strings and all 1 bit strings is

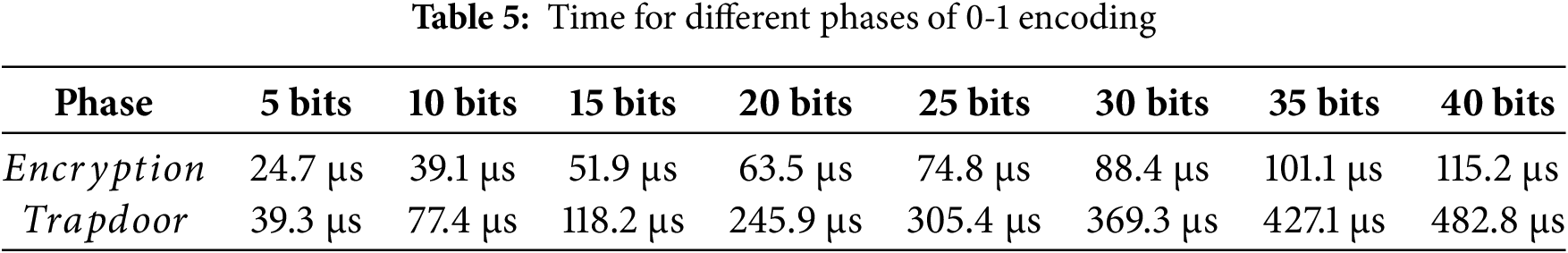

The impact of time sets in ciphertext generation and trapdoor generation on computation efficiency was investigated. Due to the use of 0-1 encoding in this scheme to generate a time set, elements in the set are then subjected to exponential operation on group G. Therefore, as the number of elements in the time set grows, the corresponding ciphertext and trapdoor time costs also increase. Table 5 shows the time required to generate ciphertext using 0-encoding and the time required to generate trapdoors using 1-encoding technology. Similarly, in order to demonstrate the authenticity of the experiment, the total length of the string is 40. From Table 5, it can be observed that the time consumed by all 0 and 1 bit strings is 115.2 and 482.8

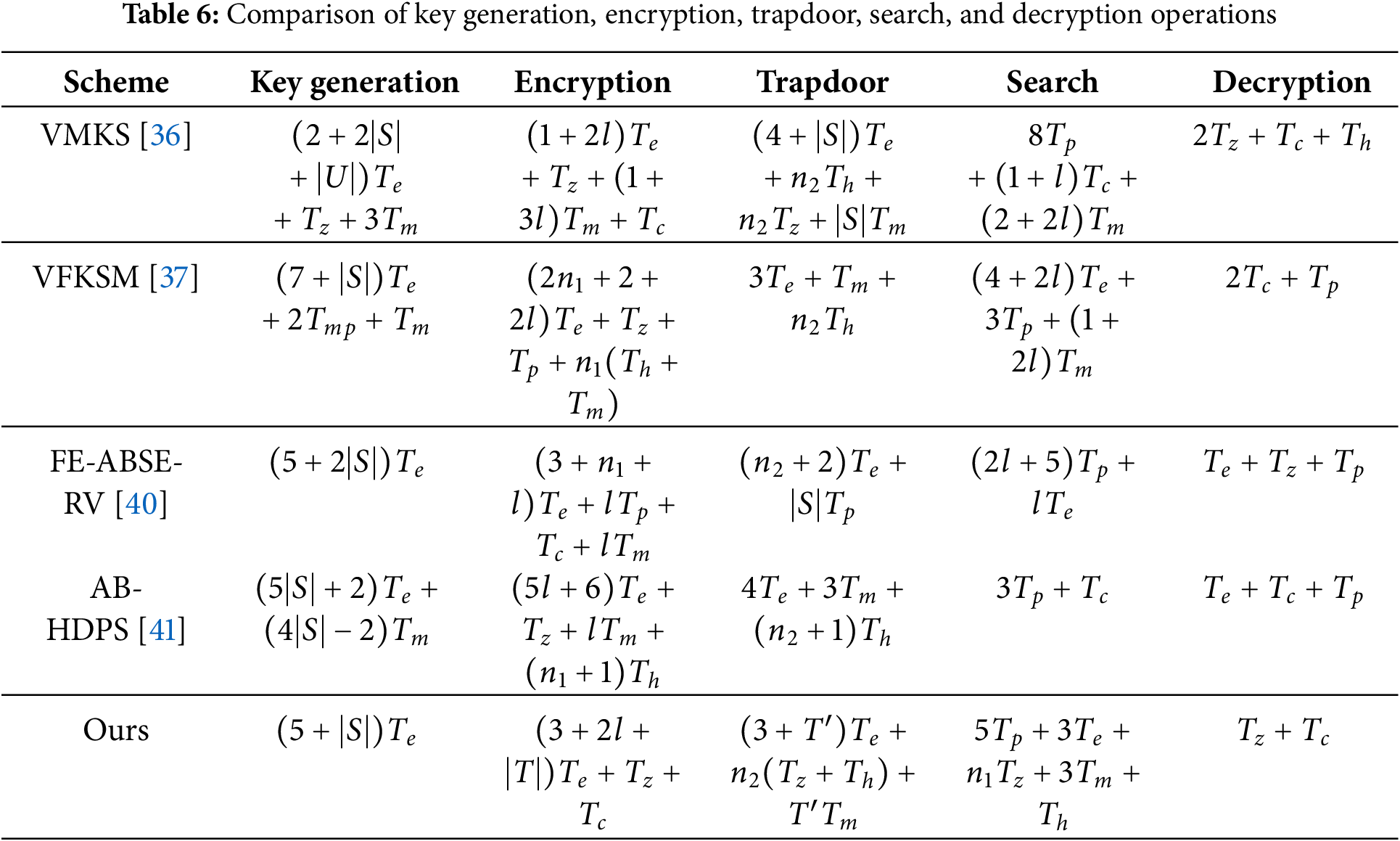

Table 6 summarizes computational costs associated with key generation, encryption, trapdoor generation, search, and decryption operations. The computational cost of an algorithm is calculated as the sum of the time costs of all related operations. As the symmetric encryption, commitment methods, mac functions, and other mature methods in the encryption process require very small time, they are omitted from the analysis. In addition, these schemes only require an exponential operation of Group G and decryption calculation in the symmetric encryption algorithm during the user decryption process. Therefore, we will not elaborate on them here. Finally, although the owner performs offline encryption, this operation only needs to be calculated once in this scheme, [36], and [40]. Hence, the computational cost of this operation is not discussed.

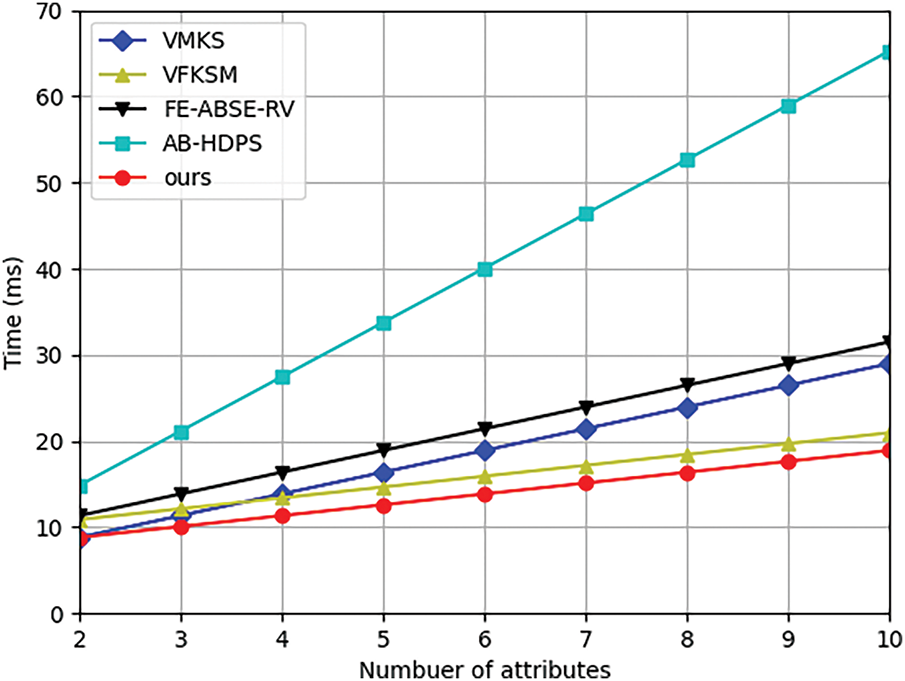

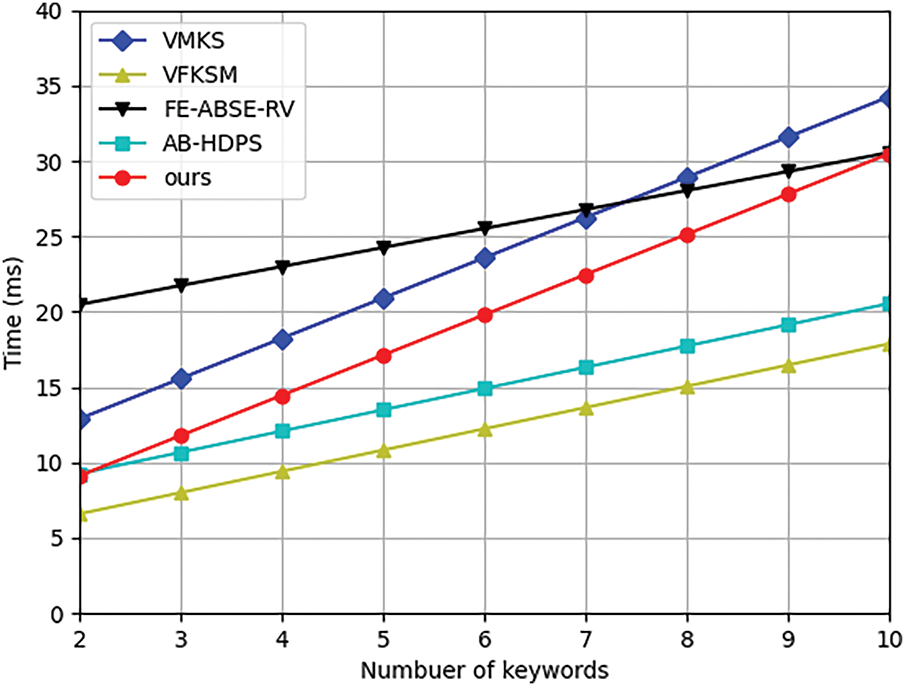

Fig. 2 illustrates the computational cost in key generation for each scheme. The computation time of our scheme in key generation is the lowest. Taking the computational cost of a set of 6 attributes as an example, the key generation algorithm in our scheme takes about 13.86 ms, while that in schemes [36,37,40,41] is about 18.9, 15.918, 21.42, and 40.45 ms, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, the computational cost of our scheme in trapdoor is higher than that of [37] and [41] due to its support for multi-keyword fuzzy search functions. Compared to [36] and [40], our computational cost is lower. For a search with a set of 6 keywords, the trapdoor algorithm in our scheme takes about 19.81 ms, while that in schemes [36,37,40,41] is about 23.58, 12.24, 25.52, and 14.91 ms, respectively.

Figure 2: Computational cost of key generation

Figure 3: Computational cost of trapdoor

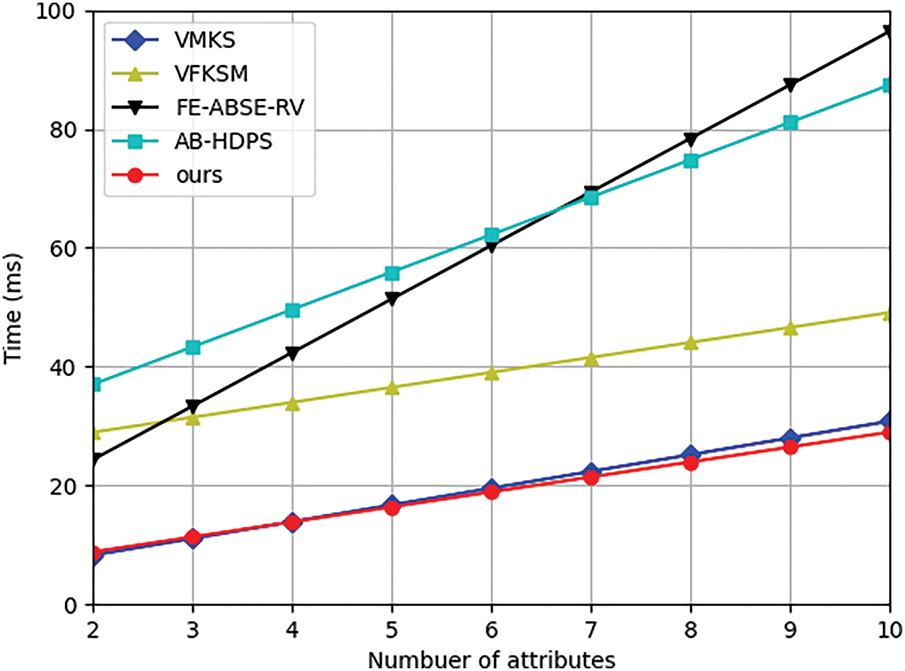

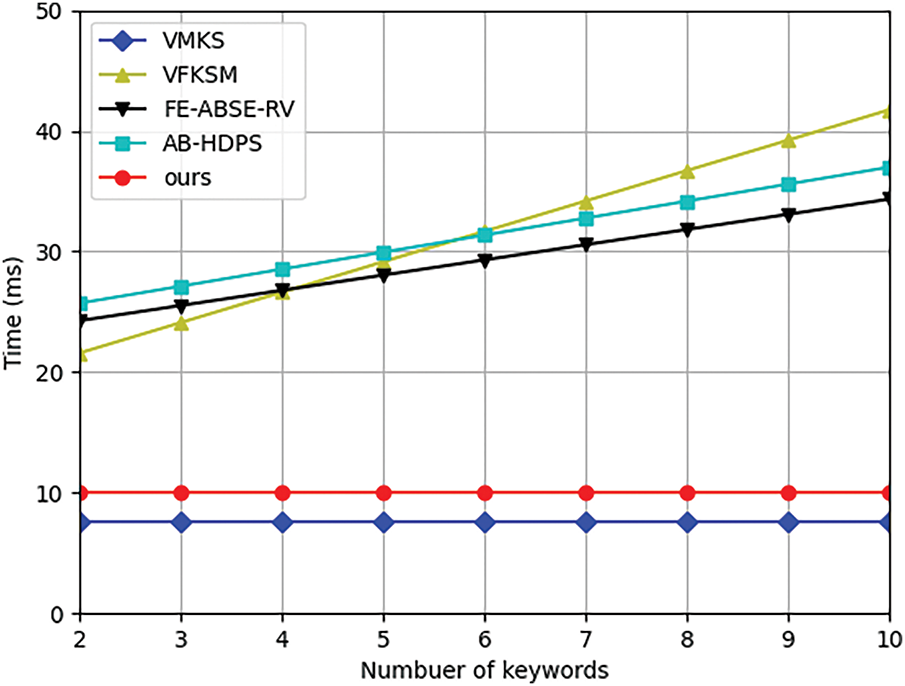

The computational cost of the encryption algorithm is affected by both the number of attributes and the number of keywords. Fig. 4 illustrates the relationship between computational cost and the number of attributes on encryption time. The number of keywords is set to two. The encryption time increases with the number of attributes. For a set of six attributes, the encryption algorithm in our scheme takes about 18.82 ms, while that in schemes [36,37,40,41] is about 19.54, 39.02, 60.36, and 62.19 ms, respectively. When the number of attributes is large enough, the encryption time in [40] becomes the longest. Fig. 5 illustrates the relationship between computational cost and the number of keywords on encryption time. The number of attributes is two. As our scheme and [36] can achieve outsourced assisted keyword encryption, the computational cost is independent of the number of keywords. Due to the implementation of multi-keyword fuzzy search, the cost of our scheme is higher than that of [36]. For six attributes, the encryption time in our scheme is about 10.08 ms, while that in [36,37,40,41] is about 7.56, 31.66, 29.3, and 31.35 ms, respectively. As our scheme and [36] implement outsourced keyword encryption, both schemes can achieve computational cost invariance regardless of the number of keywords.

Figure 4: Computational cost of encryption vs. number of attributes

Figure 5: Computational cost of encryption vs. number of keywords

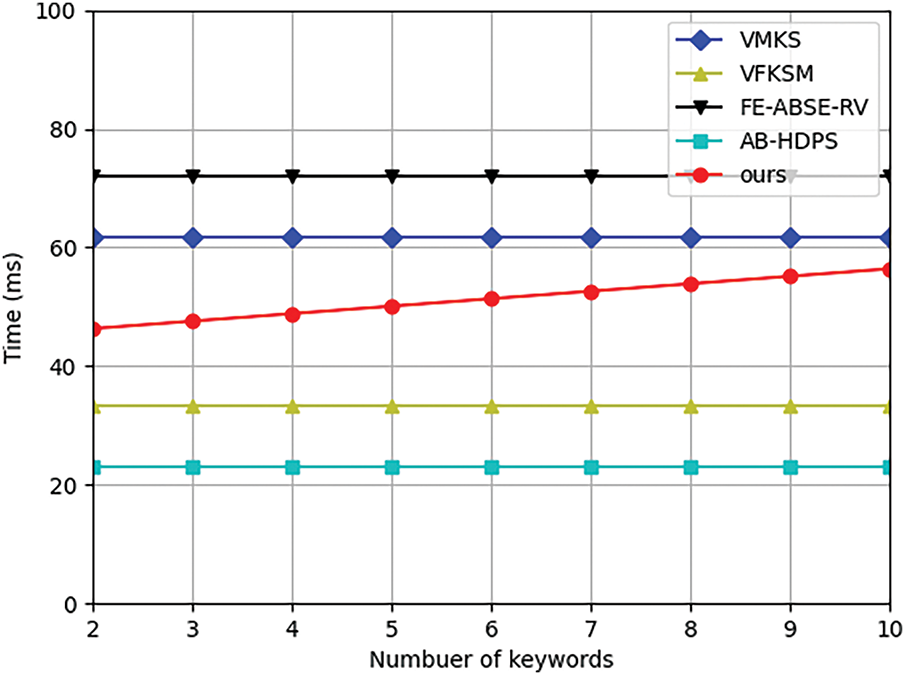

Fig. 6 presents the computational cost of the search operation. Besides our scheme, the computational cost of other schemes is independent of the number of keywords. Due to the support of multi-keyword fuzzy search, the cost of our scheme is higher than that in [37] and [41]. However, this workload is computed by cloud servers, and this additional computational cost is acceptable in practical deployment scenarios. For six keywords, the search algorithm in our scheme takes about 51.37 ms, while that in schemes [36,37,40,41] is about 61.76, 133.24, 72, and 23.16 ms.

Figure 6: Computational cost of search

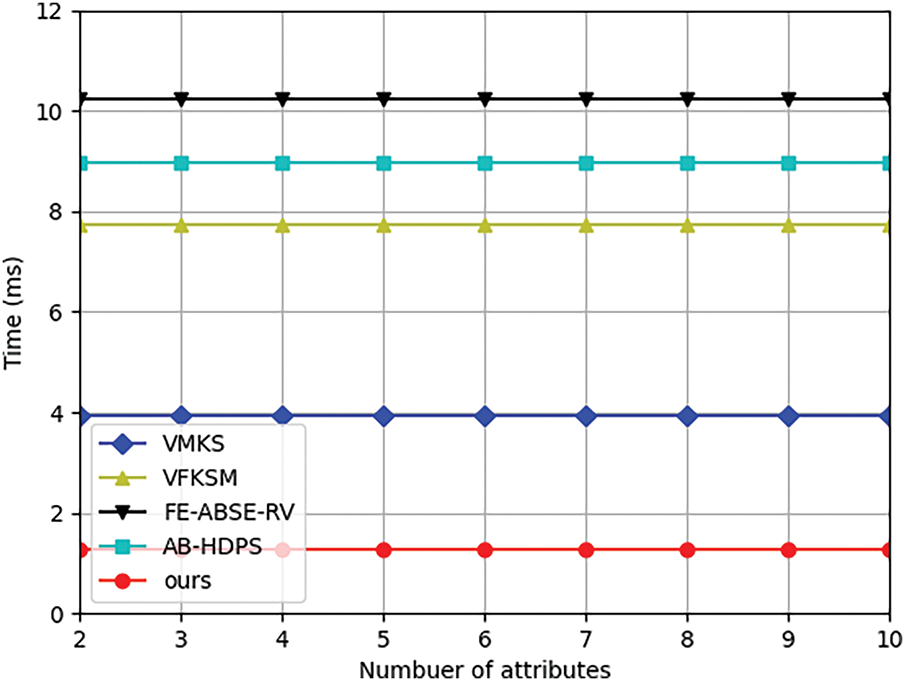

Fig. 7 compares the computational cost of decryption of each scheme. All schemes implement outsourced decryption and our scheme performs best. The decryption algorithm in our scheme takes about 1.26 ms, while that in schemes [36,37,40,41] is about 3.93, 7.72, 10.24, and 8.98 ms, respectively.

Figure 7: Computational cost of decryption

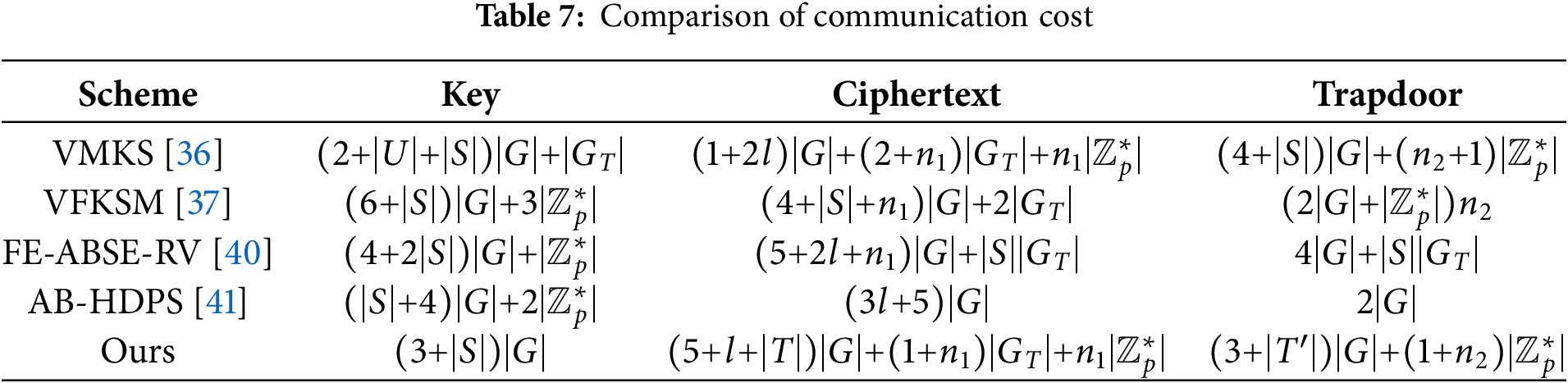

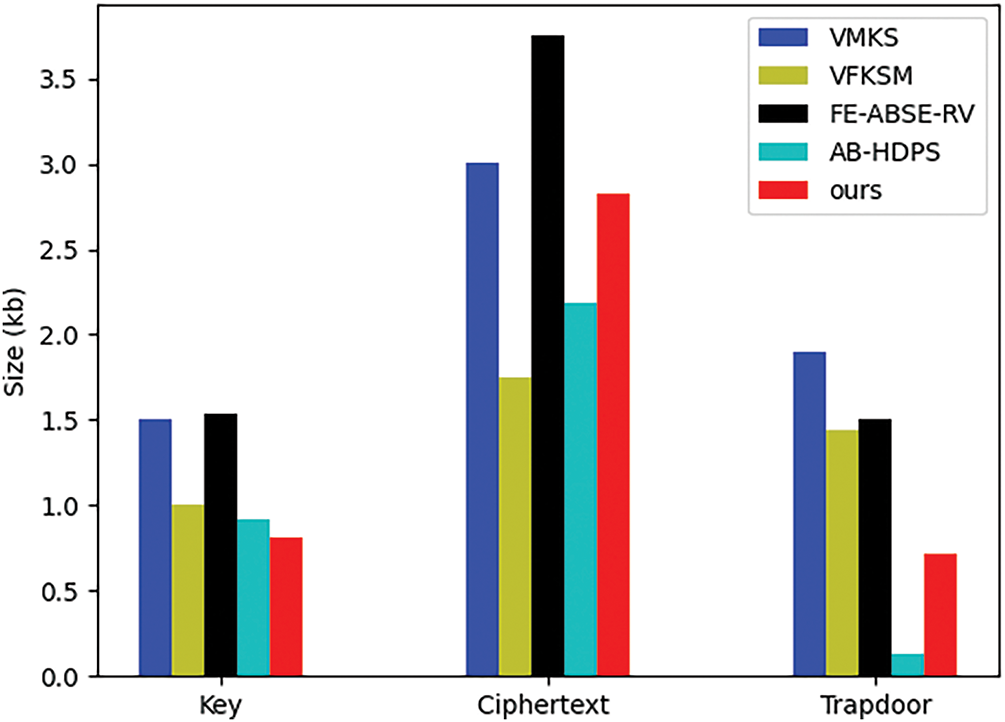

Due to the incorporation of a forward security function in our scheme, the communication cost of ciphertexts and trapdoors is affected by the number of elements in the time set. The validity period of the trapdoor is related to the value of parameter T. The larger the value of T, the longer the validity period. In the experiment, T is set to be 5. The proposed scheme demonstrates superior overall communication efficiency compared to existing alternatives. As we can see from Table 7, our scheme achieves lower key management communication cost compared to the others, while incurring higher ciphertext cost. The trapdoor communication cost of our scheme is slightly higher than that of [41].

To better compare the communication cost among different schemes, Fig. 8 compares the communication costs between each scheme in the key, ciphertext, and trapdoor. We set the number of attributes and keywords to be ten and remove the communication costs generated by the forward security function of this scheme. Our scheme achieves the lowest communication cost during key generation, with trapdoor transmission costs only higher than [41]. Although the ciphertext storage cost is relatively higher, this overhead is deemed acceptable given that ciphertexts are stored on cloud servers with substantial storage capacity.

Figure 8: Comparison of communication cost

6 Enhancement of the FCS-ABMSE Scheme with Type-3 Pairings

This section illustrates the enhanced scheme based on type-3 pairings. Type-3 elliptic curves offer superior computational performance and security. It can be used to enhance the FCS-ABMSE scheme by adjusting certain parameters. It is worth noting that the core contribution of multi-keyword fuzzy search and forward ciphertext search remains unaffected by this algorithmic-level adjustment.

(1) Setup(

• Generate three prime

• Randomly choose

• For each attribute in

• Choose an IND-DEM-CCA secure data encapsulation scheme

• Output

(2)

• Randomly select

• For each

• Output

(3)

• Randomly select

• For each

• Output

(4)

(5)

• Randomly select

• Run

• Randomly select

• Compute

• Randomly select

• For each

• Set

• Run the 0-encoding algorithm to transform

• For each

• For each

• Set

• Set

(6)

• Run 1-encoding algorithm to transform

• Randomly select

• Compute

• For each

• Set

(7)

• If

• Check whether

• If not, output

• Output

(8)

(9)

In this paper, we proposed an FCS-ABMSE scheme and an improved construction based on type-3 elliptic curves. The scheme supports multi-keyword fuzzy search without relying on predefined keyword fields, thereby overcoming the lack of error tolerance in exact matching. It also incorporates forward ciphertext search to mitigate trapdoor reuse vulnerabilities in IoT environments. Furthermore, the scheme enables verifiable outsourced decryption, which eliminates bilinear pairing operations on the client side and reduces computational overhead. This deign achieves millisecond-level decryption of search results on user devices while allowing verification of outsourced decryption correctness. However, the incorporation of multi-keyword fuzzy search and forward ciphertext search introduces a slight efficiency loss in encryption and trapdoor generation, and search verification incurs substantial bilinear pairing costs. Rigorous security analysis proved that the FCS-ABMSE scheme meets both IND-CKA and IND-CPA. Additionally, the workload of the cloud server remains high and access policies lack flexibility. Future works will focus on designing more efficient and flexible ABMSE schemes with expressive access policy and reduced server-side burden.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, He Duan and Shi Zhang; methodology, He Duan; validation, He Duan and Shi Zhang; formal analysis, He Duan; simulations, He Duan; resources, He Duan and Dayu Li; writing—original draft preparation, He Duan, Shi Zhang, and Dayu Li; writing—review and editing, He Duan; visualization, He Duan; supervision, Shi Zhang and Dayu Li; project administration, He Duan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shwetha D, Swetha. IoT’s impact on personal devices and health: wearable technology. In: 2024 International Conference on Advances in Modern Age Technologies for Health and Engineering Science (AMATHE); 2024 May 16–17; Shivamogga, India. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

2. Bisht RS, Jain S, Tewari N. Study of wearable IoT devices in 2021: analysis & future prospects. In: 2021 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM); 2021 Apr 28–30; London, UK. p. 577–81. [Google Scholar]

3. Song DX, Wagner D, Perrig A. Practical techniques for searches on encrypted data. In: Proceeding 2000 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P '00); 2000 May 15–18; Oakland, CA, USA. p. 44–55. [Google Scholar]

4. Goyal V, Pandey O, Sahai A, Waters B. Attribute-based encryption for fine-grained access control of encrypted data. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS '06). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2006. p. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

5. Lai J, Zhou X, Deng RH, Li Y, Chen K. Expressive search on encrypted data. In: Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGSAC Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security (ASIA CCS '13). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2013. p. 243–52. [Google Scholar]

6. Boneh D, Di Crescenzo G, Ostrovsky R, Persiano G. Public key encryption with keyword search. In: Cachin C, Camenisch JL, editors. Advances in cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2004. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. p. 506–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-24676-3_30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Boneh D, Franklin M. Identity-based encryption from the weil pairing. In: Kilian J, editor. Advances in cryptology—CRYPTO 2001. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2001. p. 213–29. doi:10.1007/3-540-44647-8_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen Z, Wu C, Wang D, Li S. Conjunctive keywords searchable encryption with efficient pairing, constant ciphertext and short trapdoor. In: Chau M, Wang GA, Yue WT, Chen H, editors. Intelligence and security informatics. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 176–89. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30428-6_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li J, Wang Q, Wang C, Cao N, Ren K, Lou W. Fuzzy keyword search over encrypted data in cloud computing. In: 2010 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM; 2010 Mar 14–19; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

10. Dong Q, Guan Z, Wu L, Chen Z. Fuzzy keyword search over encrypted data in the public key setting. In: Wang J, Xiong H, Ishikawa Y, Xu J, Zhou J, editors. Web-age information management. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013. p. 729–40. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38562-9_74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang H, Zhao S, Guo Z, Wen Q, Li W, Gao F. Scalable fuzzy keyword ranked search over encrypted data on hybrid clouds. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(1):308–23. doi:10.1109/tcc.2021.3092358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jiang Y, Lu J, Feng T. Fuzzy keyword searchable encryption scheme based on blockchain. Information. 2022;13(11):517. doi:10.3390/info13110517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cash D, Jarecki S, Jutla C, Krawczyk H, Roşu MC, Steiner M. Highly-scalable searchable symmetric encryption with support for boolean queries. In: Canetti R, Garay JA, editors. Advances in cryptology—CRYPTO 2013. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013. p. 353–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40041-4_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xu P, Tang S, Xu P, Wu Q, Hu H, Susilo W. Practical multi-keyword and boolean search over encrypted e-mail in cloud server. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2021;14(6):1877–89. doi:10.1109/tsc.2019.2903502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li F, Ma J, Miao Y, Liu Z, Choo KKR, Liu X, et al. Towards efficient verifiable boolean search over encrypted cloud data. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(1):839–53. doi:10.1109/tcc.2021.3118692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tong Q, Li X, Miao Y, Liu X, Weng J, Deng RH. Privacy-preserving boolean range query with temporal access control in mobile computing. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(5):5159–72. doi:10.1109/tkde.2022.3152168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu Q, Tian Y, Wu J, Peng T, Wang G. Enabling verifiable and dynamic ranked search over outsourced data. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;15(1):69–82. doi:10.1109/tsc.2019.2922177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li J, Huang Y, Wei Y, Lv S, Liu Z, Dong C, et al. Searchable symmetric encryption with forward search privacy. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;18(1):460–74. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2019.2894411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gan Q, Wang X, Huang D, Li J, Zhou D, Wang C. Towards multi-client forward private searchable symmetric encryption in cloud computing. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;15(6):3566–76. doi:10.1109/tsc.2021.3087155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Guo Y, Zhang C, Wang C, Jia X. Towards public verifiable and forward-privacy encrypted search by using blockchain. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2023;20(3):2111–26. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3173291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cui N, Wang Z, Pei L, Wang M, Wang D, Cui J, et al. Dynamic and verifiable fuzzy keyword search with forward security in cloud environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(9):11482–94. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3517165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sahai A, Waters B. Fuzzy identity-based encryption. In: Cramer R, editor. Advances in cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2005. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2005. p. 457–73. doi:10.1007/11426639_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP ’07); 2007 May 20–23; Berkeley, CA, USA. p. 321–34. [Google Scholar]

24. Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption: an expressive, efficient, and provably secure realization. In: Catalano D, Fazio N, Gennaro R, Nicolosi A, editors. Public key cryptography—PKC 2011. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 53–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-19379-8_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ostrovsky R, Sahai A, Waters B. Attribute-based encryption with non-monotonic access structures. In: CCS ’07. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2007. p. 195–203. doi:10.1145/1315245.1315270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lewko A, Sahai A, Waters B. Revocation systems with very small private keys. In: 2010 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy; 2010 May 16–19; Oakland, CA, USA. p. 273–85. [Google Scholar]

27. Meng L, Xu H, Tang R, Zhou X, Han Z. Dual Hybrid CP-ABE: how to provide forward security without a trusted authority in vehicular opportunistic computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(5):8800–14. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3321563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Luo W, Lv Z, Yang L, Han G, Zhang X. FOC-PH-CP-ABE: an efficient CP-ABE scheme with fully outsourced computation and policy hidden in the industrial internet of things. IEEE Sensors J. 2024;24(18):28971–81. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3432276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Miao Y, Li F, Li X, Ning J, Li H, Choo KKR, et al. Verifiable outsourced attribute-based encryption scheme for cloud-assisted mobile e-health system. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2024;21(4):1845–62. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2023.3292129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Duan P, Ma Z, Gao H, Tian T, Zhang Y. Multi-authority attribute-based encryption scheme with access delegation for cross blockchain data sharing. IEEE Trans Information Forensics Secur. 2025;20(2327):323–37. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3515812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ruan C, Hu C, Li X, Deng S, Liu Z, Yu J. A revocable and fair outsourcing attribute-based access control scheme in metaverse. IEEE Trans Consumer Electron. 2024;70(1):3781–91. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3377107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zheng Q, Xu S, Ateniese G. VABKS: Verifiable attribute-based keyword search over outsourced encrypted data. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2014—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2014 Apr 27–May 2; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 522–30. [Google Scholar]

33. Han F, Qin J, Zhao H, Hu J. A general transformation from KP-ABE to searchable encryption. Fut Gener Comput Syst. 2014;30(2–3):107–15. doi:10.1016/j.future.2013.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang K, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu X, Lu L. A blockchain-based anonymous attribute-based searchable encryption scheme for data sharing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(1):1685–97. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3290975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ge C, Susilo W, Liu Z, Xia J, Szalachowski P, Fang L. Secure keyword search and data sharing mechanism for cloud computing. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;18(6):2787–800. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2020.2963978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ali M, Sadeghi MR, Liu X, Miao Y, Vasilakos AV. Verifiable online/offline multi-keyword search for cloud-assisted Industrial Internet of Things. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;65(3):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Miao Y, Deng RH, Choo KKR, Liu X, Ning J, Li H. Optimized verifiable fine-grained keyword search in dynamic multi-owner settings. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;18(4):1804–20. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2019.2940573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Huang Q, Yan G, Wei Q. Attribute-based expressive and ranked keyword search over encrypted documents in cloud computing. IEEE Trans Services Comput. 2023;16(2):957–68. doi:10.1109/tsc.2022.3149761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Huang Q, Yan G, Yang Y. Privacy-preserving traceable attribute-based keyword search in multi-authority medical cloud. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(1):678–91. doi:10.1109/tcc.2021.3109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen L, Xu S, Zhang H, Weng J. Fair-and-exculpable-attribute-based searchable encryption with revocation and verifiable outsourced decryption using smart contract. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(4):4302–17. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3484227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tian T, Shen Y, Gao H, Ma Z, Guo Z, Duan P. Attribute-based heterogeneous data privacy sharing in blockchain-assisted Industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(8):10404–19. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3510872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Li J, Qin C, Lee PPC, Zhang X. Information leakage in encrypted deduplication via frequency analysis. In: 2017 47th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN); 2017 Jun 26–29; Denver, CO, USA. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

43. Lin HY, Tzeng WG. An efficient solution to the millionaires’ problem based on homomorphic encryption. In: Ioannidis J, Keromytis A, Yung M, editors. Applied cryptography and network security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germnay: Springer; 2005. p. 456–66. doi:10.1007/11496137_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. De Caro A, Iovino V. JPBC: java pairing based cryptography. In: Proceedings of the 16th IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications, ISCC 2011; 2011 Jun 28–Jul 1; Corfu, Greece. p. 850–5. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools