Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Federated Dynamic Aggregation Selection Strategy-Based Multi-Receptive Field Fusion Classification Framework for Point Cloud Classification

1 Shanxi Key Laboratory of Cryptography and Data Security, Shanxi Normal University, Taiyuan, 030031, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data, Guizhou University, Guizhou, 550025, China

3 College of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Shanxi Normal University, Taiyuan, 030031, China

4 College of Artificial Intelligence, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, 116026, China

* Corresponding Author: Zijian Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069789

Received 30 June 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Recently, large-scale deep learning models have been increasingly adopted for point cloud classification. However, these methods typically require collecting extensive datasets from multiple clients, which may lead to privacy leaks. Federated learning provides an effective solution to data leakage by eliminating the need for data transmission, relying instead on the exchange of model parameters. However, the uneven distribution of client data can still affect the model’s ability to generalize effectively. To address these challenges, we propose a new framework for point cloud classification called Federated Dynamic Aggregation Selection Strategy-based Multi-Receptive Field Fusion Classification Framework (FDASS-MRFCF). Specifically, we tackle these challenges with two key innovations: (1) During the client local training phase, we propose a Multi-Receptive Field Fusion Classification Model (MRFCM), which captures local and global structures in point cloud data through dynamic convolution and multi-scale feature fusion, enhancing the robustness of point cloud classification. (2) In the server aggregation phase, we introduce a Federated Dynamic Aggregation Selection Strategy (FDASS), which employs a hybrid strategy to average client model parameters, skip aggregation, or reallocate local models to different clients, thereby balancing global consistency and local diversity. We evaluate our framework using the ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness. The proposed method is expected to significantly advance the field of point cloud classification in a secure environment.Keywords

Point cloud classification aims to categorize large sets of discrete points into different categories based on their distinctive attributes, such as location, color, and normal direction [1]. It aids in understanding and analyzing complex three-dimensional (3D) environments and provides essential spatial information and data foundations for various downstream applications, such as object detection [2], 3D scene reconstruction [3], autonomous driving [4], robot navigation [5], and medical image processing [6].

With the popularization of devices such as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) [7] and LiDAR cameras [8], point cloud data is becoming more accessible. Meanwhile, advancements in computational power have enabled the application of deep learning techniques to point cloud classification. In general, point cloud classification methods can be categorized into traditional methods and deep-learning-based methods. Among them, traditional methods mainly rely0020on hand-crafted means of feature extraction, such as geometric features [9,10], topological structures [11,12], and statistical methods [13–15]. These methods often suffer from limited feature expressiveness, sensitivity to noise and point cloud sparsity, and difficulty in handling complex shapes. Therefore, many deep-learning-based methods have been proposed to overcome these limitations [16]. These methods can process large amounts of data, automatically extract features, and convert geometric information into semantic representation [17,18]. Compared to traditional methods, deep learning offers stronger robustness and adaptability, achieving superior performance in point cloud classification tasks [19,20].

However, existing methods require collecting data from multiple participants to train models centrally, which may expose sensitive data [21,22]. Federated learning offers a promising solution by allowing multiple participants to collaboratively train models without compromising data privacy [23]. Specifically, the federated learning process consists of four key steps: 1) the central server distributes initial models; 2) clients train updated models on their private data; 3) clients upload their locally updated models; 4) the central server aggregates these models to improve overall performance.

Nevertheless, variations in data from various clients can lead to suboptimal performance of local models, which in turn hampers the global model’s recognition accuracy [24–26]. As a result, effectively coordinating local model updates to ensure quick and accurate convergence of the global model remains a significant challenge.

To address these challenges, we propose a Federated Dynamic Aggregation Selection Strategy-based Multi-Receptive Field Fusion Classification Framework (FDASS-MRFCF). The central server sends the global model to the clients, who then update the lightweight and efficient Multi-Receptive Field Fusion Classification Model (MRFCM). The clients subsequently upload their model parameters. Finally, the central server implements a Federated Dynamic Aggregation Selection Strategy (FDASS), which intentionally disrupts parameter synchronization across client models to address the uneven distribution of client data. This promotes robust model generalization across diverse client datasets. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

• We design a MRFCM, which significantly improves point cloud classification accuracy by dynamically updating neighborhood information to effectively capture local geometric features while extracting multi-level global features.

• We propose a FDASS, which introduces variability in the training process through alternate perturbation and average aggregation to mitigate parameter homogeneity among client models. This greatly enhances the diversity of the models and thus better adapts to different data distributions.

• We demonstrate the effectiveness of our method on the ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart datasets, and the results indicate that the performance of FDASS-MRFCF is comparable to that of centralized training.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work; Section 3 introduces FDASS-MRFCF in detail; Section 4 presents the experimental setup and results analysis; Section 5 concludes the paper.

Federated learning, introduced by Google in 2016, is a secure distributed learning paradigm that enables collaborative training of global models across multiple clients without direct raw data exchange, enhancing data privacy and security [27]. The first federated learning methodology is Google’s FedAvg, which is a foundational and widely adopted optimization technique [28]. It iteratively trains the global model through multiple rounds of localized client data training, followed by the transmission of updated model parameters to a centralized server for aggregation. FL is particularly relevant to cloud computing as it allows for collaborative model training without requiring data centralization. In cloud environments, FL enhances data privacy and security by keeping sensitive data on local devices while sharing only model parameters with a central server, thereby avoiding direct data transfer to the cloud and ensuring privacy. As discussed in [29], FL can be deployed in cloud-based infrastructures, where edge devices (clients) interact with cloud servers for model aggregation and coordination. This architecture not only addresses privacy concerns but also facilitates efficient resource utilization in distributed cloud systems. Moreover, FL has been widely adopted across various industrial applications, ranging from healthcare to Internet of Things (IoT) and edge computing. Notably, recent studies have demonstrated its capability to preserving data privacy while enabling collaborative model training in distributed environments. For instance, [30,31] explore FL in healthcare, while [32] highlights its use in industrial IoT systems. These studies provide valuable context for understanding the practical relevance and generalizability of our proposed FDASS framework. Nonetheless, FedAvg falls short of fully addressing the heterogeneity of data across diverse clients, which may limit the overall effectiveness of the global model [33]. To overcome this limitation, researchers have developed various optimization strategies, which are broadly classified into three primary categories: dynamic aggregation strategies [34], joint optimization methods [35], and personalized model approaches [36].

Dynamic aggregation strategies are designed to address client update heterogeneity by dynamically adjusting the aggregation weights [34]. For example, Adaptive Aggregation For Federated Learning (FedAvg-ADA) [37] adjusts the aggregation method based on factors such as the training status and data characteristics of the client, thereby reducing the impact of heterogeneity on the global model. Similarly, FedNova [38] reduces the impact of system heterogeneity by normalizing update weights for each client. Although these dynamic strategies provide flexibility, they often necessitate more complex algorithmic designs and communication protocols, potentially increasing system computational costs.

Joint optimization methods enhance the robustness and convergence of the global model by incorporating supplementary optimization steps [35]. FedOpt [39] combines multiple optimization strategies and regularization techniques to better accommodate model heterogeneity among clients. A Federated Learning Framework for Diverse Computer Vision Tasks (FedCV) [40] employs control variate techniques to mitigate the effects of randomness and noise in client model updates, thereby enhancing model performance. While these methods effectively improve model performance, they may decelerate algorithm convergence and demand meticulous tuning of numerous parameters and hyperparameters.

Conversely, personalized model approaches focus on meeting the needs of individual clients by allowing each client to maintain a private local model in conjunction with the global model [36]. Federated Learning with Personalization Layers (FedPer) [41] retains client-specific data distribution information, while Federated Multi-Task Learning (FMTL) [42] conceptualizes federated learning as a multi-task learning problem, developing tailored task models for each client. Despite improving the personalization of client models, these strategies increase model storage and computational overhead. Furthermore, they pose the challenge of effectively balancing the coordination between the global model and the private models.

In conclusion, existing strategies for solving client-side data heterogeneity still face the problems of slow aggregation, high computational effort, and high storage requirements. Therefore, we propose the FDASS approach, which aims to effectively address these issues. FDASS alternates between perturbation and averaging techniques to significantly reduce the computational effort while optimizing the storage requirements and accelerating the aggregation process. FDASS not only enhances the model diversity but also effectively mitigates the data heterogeneity among clients by alternating between perturbation and averaging techniques in the aggregation, thus improving the adaptability and robustness of the global model.

2.2 Point Cloud Classification

Point cloud classification involves labeling each point or segmented-group with a specific class and assigning semantic meaning to it. Therefore, point cloud classification is also called point cloud semantic segmentation or point labeling [43]. Generally, the pipeline of point cloud classification is primarily divided into two steps: first, the extraction of representative features from both local and global perspectives, and then these representative features are used to classify each point into a predefined semantic category. Different approaches to feature extraction and classification can vary depending on how the point cloud data is represented and processed [44].

According to the representation and processing of point clouds, deep-learning-based point cloud classification algorithms can be broadly categorized into projection-based and raw point cloud-based methods [45]. Notable examples of projection-based methods include VoxNet [46] and 3DShapeNet [47]. VoxNet first converts point cloud data into a 3D voxel grid, then uses a 3D convolutional neural network (CNN) for feature extraction and classification. This approach effectively captures spatial relationships through 3D convolution and provides a rich 3D shape representation. 3DShapeNet transforms point cloud data into voxel grids and employs a Convolutional Deep Belief Network to learn 3D shape representations, specifically encoding 3D object features through unsupervised learning, making it effective for processing unlabeled data. Projection-based methods benefit from the ability to apply standard neural network architectures such as 3D convolution, facilitating the capture of spatial relationships and 3D shapes, while allowing for the transfer of 2D image processing techniques to 3D data. However, voxelization incurs significant computational overhead in high-resolution scenarios. Furthermore, voxelization can result in a loss of detail [48], particularly in object boundaries and sparse point clouds, making it challenging to preserve fine structures.

As the point cloud research community evolves, there is substantial academic interest in methods that directly classify point cloud data. These approaches aim to directly learn and perceive representations from raw point cloud data, thereby effectively overcoming the resolution limitations and information loss typically associated with voxel-based techniques [49]. The most representative methods that process raw point clouds are PointNet [50] and DGCNN [51]. PointNet is a pioneering deep learning method to directly process raw point cloud data. It applies a shared MLP to each point and uses a symmetric function, such as max pooling, to aggregate global features, thereby achieving point cloud classification. DGCNN further enhances PointNet by introducing graph convolution, allowing it to capture local geometric relationships within the point cloud, thereby improving the ability to detect local structural information. Deep-learning-based methods can process raw point cloud data directly, avoiding the information loss associated with manual feature extraction or projection in traditional methods [52]. While PointNet represents a breakthrough in handling raw point cloud data, its ability to capture local structure is limited, and its performance remains insufficient when classifying point clouds with complex geometries.

In conclusion, existing deep-learning-based point cloud classification methods often struggle to effectively capture local structural representations, which makes the networks vulnerable to noise. To overcome this issue, we propose a novel approach that combines dynamic local representation learning with multi-scale feature fusion, enhancing the model’s ability to capture both local geometric structures and global information, which significantly improves its generalization capabilities.

In this section, we present our methodology for addressing the challenges of point cloud classification while maintaining data privacy. We begin with the problem definition in Section 3.1, highlighting the need for extensive training data and the privacy issues associated with collecting data from multiple clients. We introduce federated learning to mitigate these concerns. In Section 3.2, we provide an overview of our training pipeline, FDASS-MRFCF, detailing the steps of global model distribution, local model training, parameter uploading, and global model updating. Section 3.3 introduces the MRFCM to enhance feature extraction by capturing both local and global features through EdgeConv blocks and Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution layers. We further elaborate on the EdgeConv process, including dynamic graph construction, edge feature calculation, and aggregation. Finally, we describe the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution technique, which uses various kernel sizes to extract comprehensive multi-scale features, enhancing the model’s ability to capture global structures within point cloud data. Section 3.4 introduces FDASS, which handles client-side models by alternating between perturbation and average aggregation. This enhances model diversity to accommodate different data distributions. We further elaborate on specific implementations of perturbation and averaging aggregation, including skip aggregation and random initialization.

In real-world applications, acquiring extensive training data is vital for developing effective point cloud classification models. However, collecting point cloud data from multiple clients raises concerns regarding data privacy and the potential for data leakage. To tackle these issues, we introduce the application of federated learning. This approach facilitates the training of robust point cloud classification models by enabling the exchange of model parameters instead of raw data, thereby reducing the risks associated with data transmission.

In this paper, we address the following problems: Given data

where ∆ is a very small non-negative real number,

To further specify the local training process, we define

where

This formulation ensures that each client performs supervised learning locally while contributing to the global objective in a privacy-preserving manner.

3.2 Overview of Training Pipeline

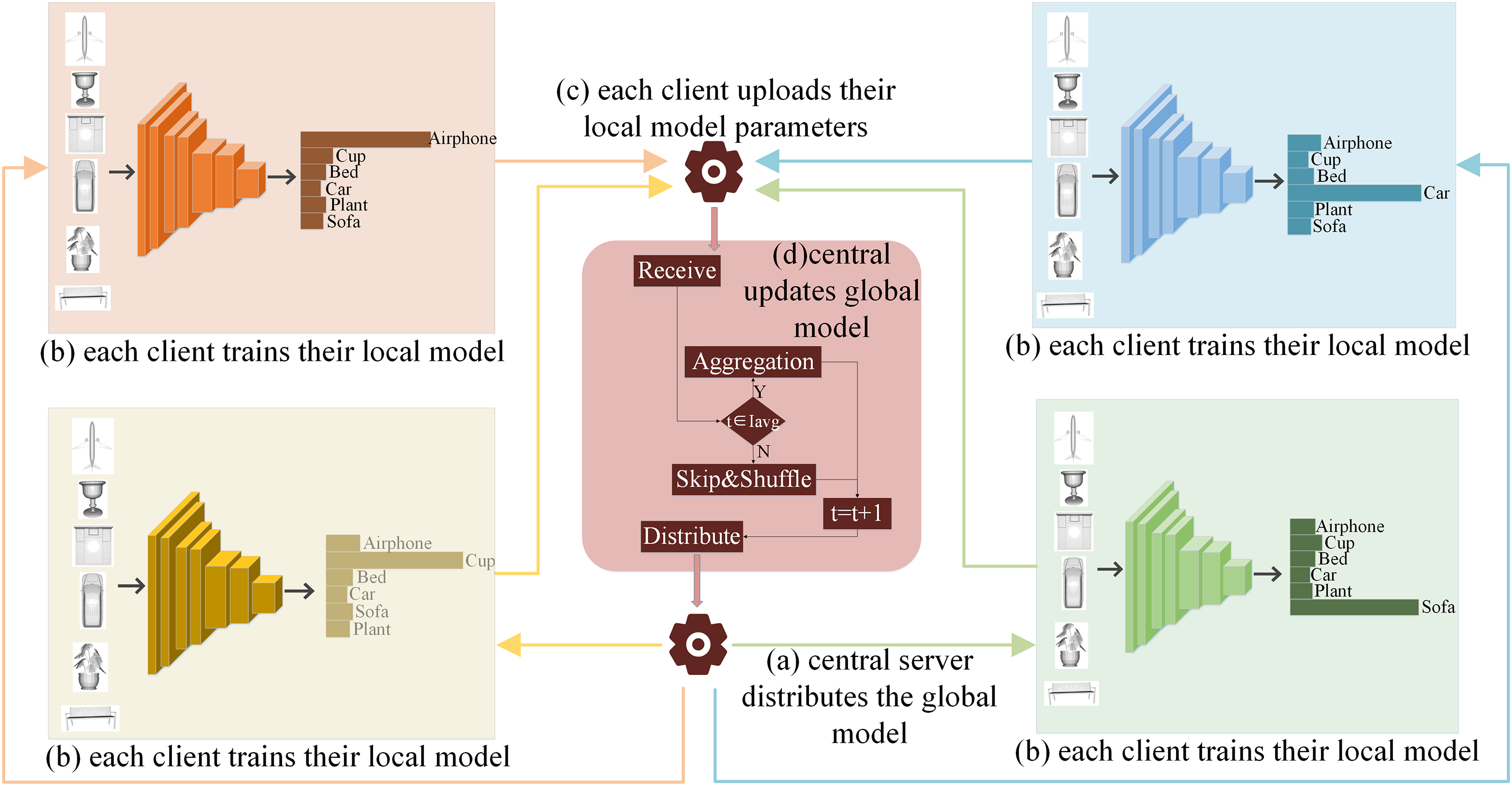

The overall architecture of FDASS-MRFCF, as depicted in Fig. 1, encompasses four key steps. The process of each step is as follows:

1. The central server distributes the global model

2. Each client relies on the local data

as shown in Fig. 1b. It is important to note each client is responsible only for updating its local parameters, and model weights are not shared among clients, ensuring privacy and security.

3. The client uploads the updated model parameters to the central server, as depicted in Fig. 1c. Here, we emphasize that clients upload model parameters instead of raw training data, thus maintaining complete data privacy and security. Gradients are not transmitted, thereby reducing communication overhead and mitigating potential privacy leakage. This design choice reduces communication cost and enhances privacy, since gradients may leak sensitive information through model inversion attacks.

4. The central server decides whether to perform average aggregation or parameter perturbation in the current iteration based on a predefined strategy. If it is an average aggregation iteration, the server averages the model parameters received from different clients. Conversely, if it is a parameter perturbation iteration, the server randomly perturbs and combines the model parameters from various clients, as illustrated in Fig. 1d.

Figure 1: The overall pipeline of the proposed FDASS-MRFCF

To clarify the process, we also provide a detailed algorithm. The pipeline of our proposed FDASS-MRFCF is outlined in Algorithm 1. As illustrated in Algorithm 1, the server coordinates the training process by selecting a subset of clients in each communication round, aggregating their local updates, and broadcasting the global model. In each communication round,

3.3 Multi-Receptive Field Fusion Classification Model

In this section, we delve into the intricacies of our client-side local point cloud classification model MRFCM. Many existing point cloud classification models focus primarily on extracting either local or global features for classification, often overlooking the interaction and fusion of these two types of features. Additionally, the large model parameters can significantly increase the communication cost in federated learning.

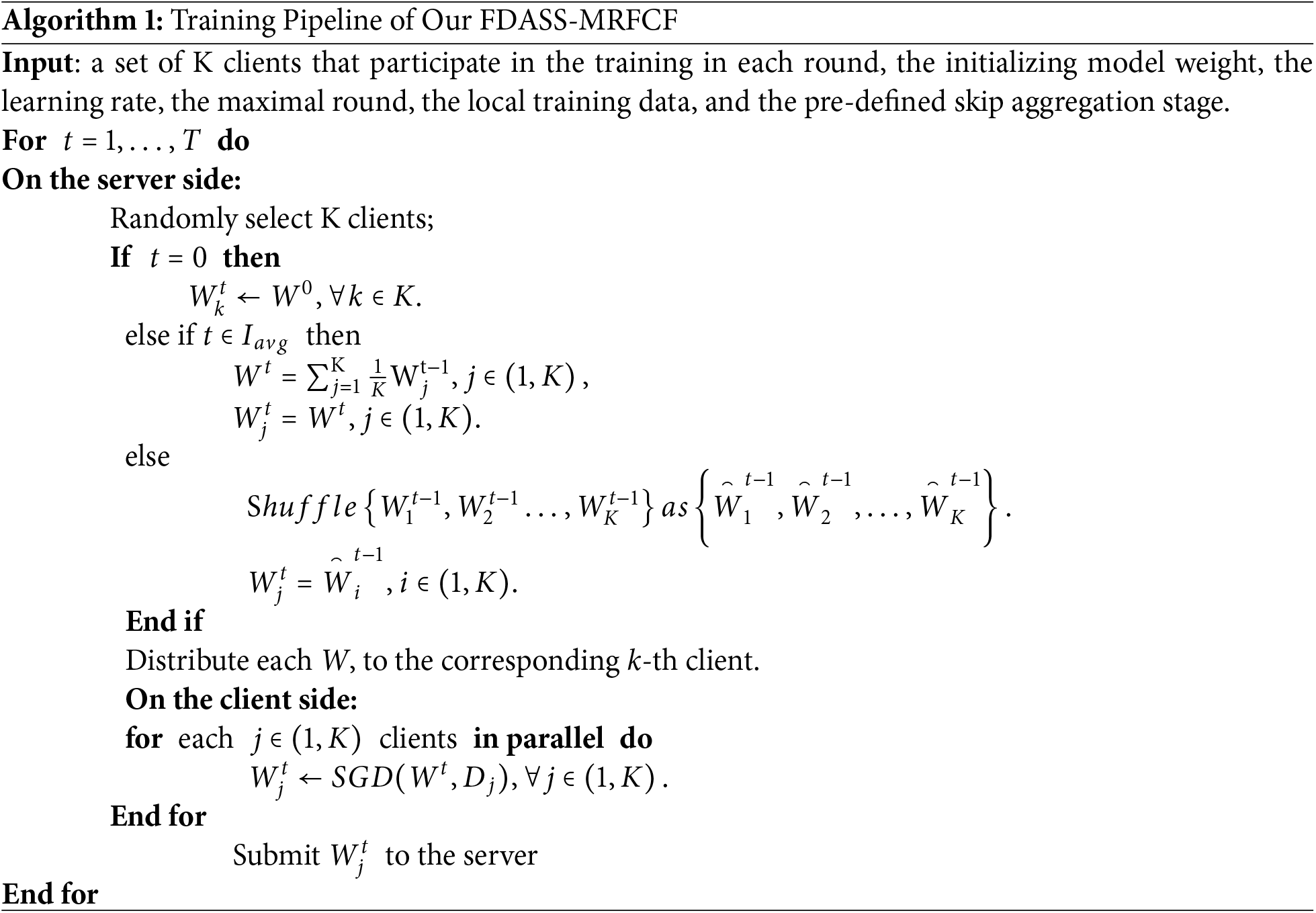

To address these challenges, we introduce the MRFCM, an efficient network designed for point cloud classification that captures both local and global features. As depicted in Fig. 2, the MRFCM comprises EdgeConv blocks and Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution layers. The EdgeConv blocks dynamically refresh neighborhood information to capture local geometric features, while the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution layers extract multi-scale global features, ensuring a holistic feature representation. To alleviate potential redundancy introduced by multiple kernel branches and improve generalization, we apply a dropout layer (dropout rate = 0.3) after the fusion step. Section 3.3.1 will describe the EdgeConv process, detailing dynamic graph construction, edge feature calculation, and feature aggregation. Section 3.3.2 will introduce the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution technique, explaining how various kernel sizes are used to extract comprehensive multi-scale features. The seamless integration of these components within the MRFCM framework not only streamlines feature extraction and fusion but also markedly elevates the accuracy of point cloud classification. Additionally, by curtailing model parameters, the MRFCM diminishes the communication burden in federated learning, rendering it a potent and pragmatic solution suited for real-world deployment.

Figure 2: The illustration of the MRFCM model

Consider the local data

Point cloud classification poses significant challenges, as it requires capture both local and global geometric features while maintaining computational efficiency.

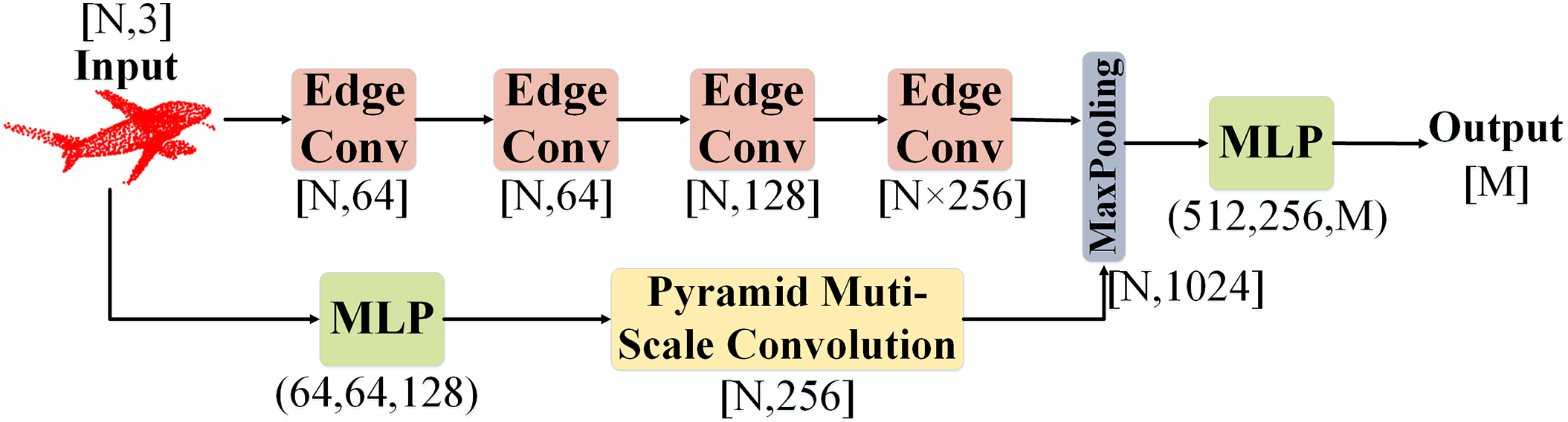

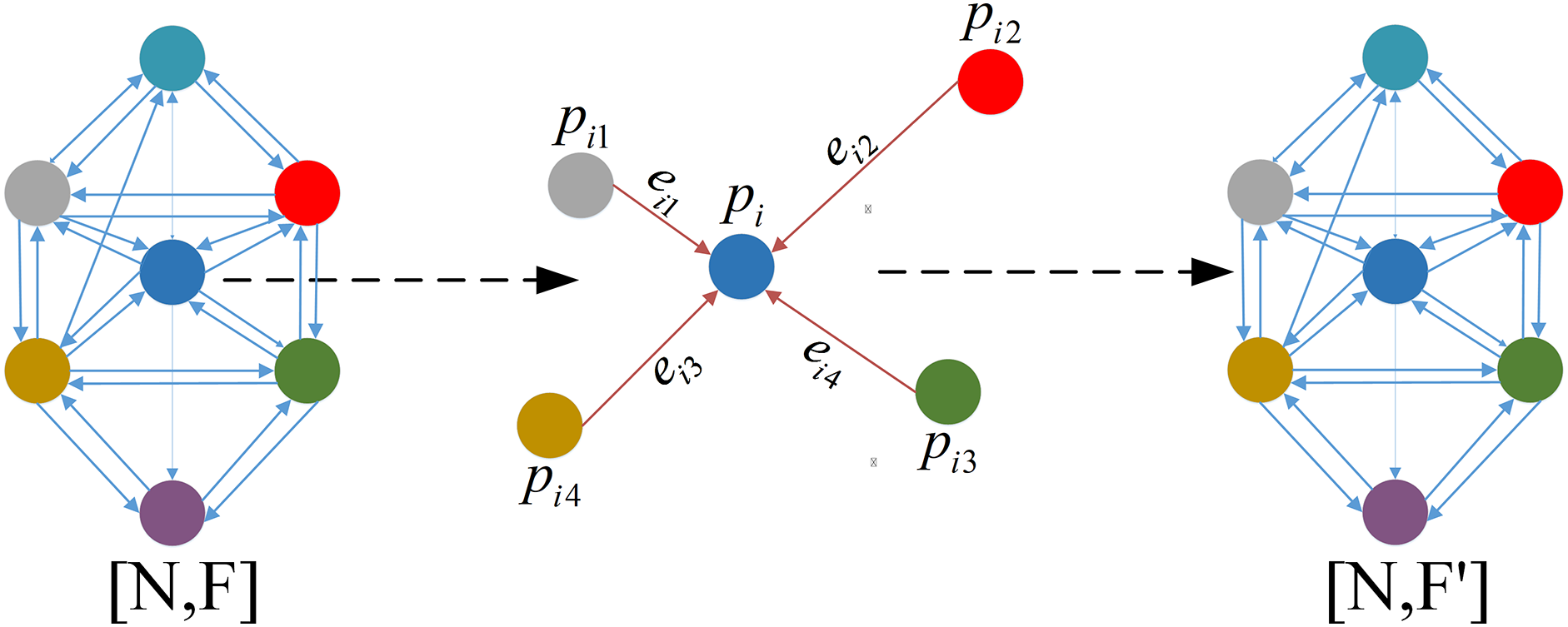

To address these issues, we introduce the EdgeConv method, which captures geometric relationships between points and neighbors by applying MLP on a dynamically constructed neighborhood graph, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Prior to each MLP, the adjacency relations are recalculated based on the current features of the points, allowing for the dynamic construction of the neighborhood graph. The features of each point are updated by aggregating their own features along with those of their neighbors. This adaptive mechanism allows EdgeConv to effectively respond to local structural variations within the point clouds, thereby extracting a wealth of information from the data. In the subsequent sections, we will elaborate on each specific process that constitutes EdgeConv.

Figure 3: The illustration of the EdgeConv

A 3D point cloud is comprised of a discrete collection of points, with each point linked to a subset of neighboring points that together constitute the local structure of the cloud. This characteristic makes Graph Neural Network (GNN) [53] particularly well-suited for processing point clouds, as they treat each point as a node in a graph and construct edges based on the geometric relationships among these points. By emphasizing the connections between nodes, GNNs can effectively learn the inherent dependencies within the point cloud.

To apply GNN to a point cloud, the point cloud must first be transformed into a directed graph, which is defined as follows:

where the graph

Given the substantial time and computational resources required to construct a complete graph, we opt for a K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) [54] method to build a locally directed graph. However, traditional KNN methods assign equal weights to all neighbors, making these methods susceptible to the influence of outliers in the data. To address this, we implement an enhanced kernel-KNN method that assigns weights to neighbors based on their distances, utilizing a kernel function. This method provides a more accurate representation of the local structure, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The illustration of the kernel-KNN

Within this locally directed graph framework, each point acts as a central node. The distance to each neighboring point in the feature space is calculated using the Gaussian kernel, as shown in the following formula:

where

We apply kernel-KNN before each MLP to reconstruct the local graph in the feature space.

In EdgeConv, edge features between nodes on the constructed neighborhood graph are calculated using the formula presented below:

where

After constructing the local graph, EdgeConv applies max pooling to the edge features of each point’s neighbors to obtain new point features. The formula for this operation is expressed as follows:

The updated features mentioned above serve as the input for the subsequent MLP, continuing the construction of the dynamic neighborhood graph and the edge convolution operations. In this manner, the features progressively capture the local structural information of the point cloud data through layer-by-layer propagation and updating.

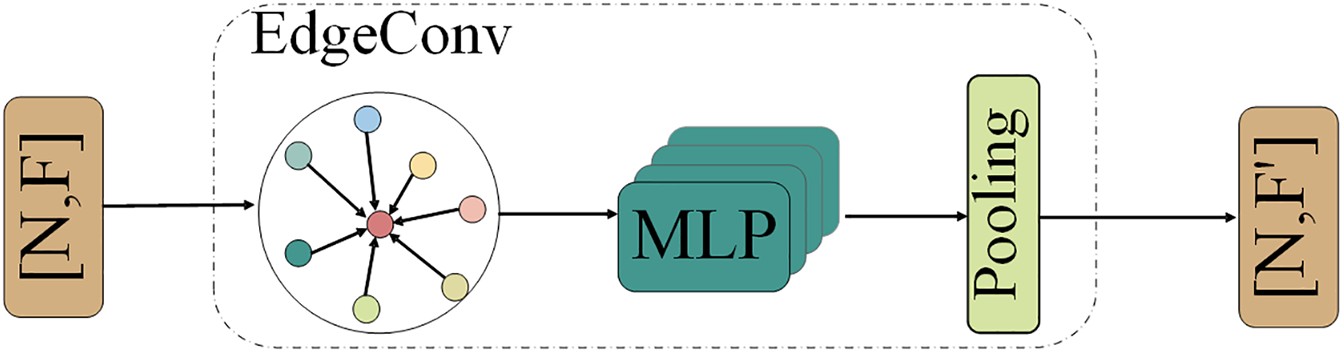

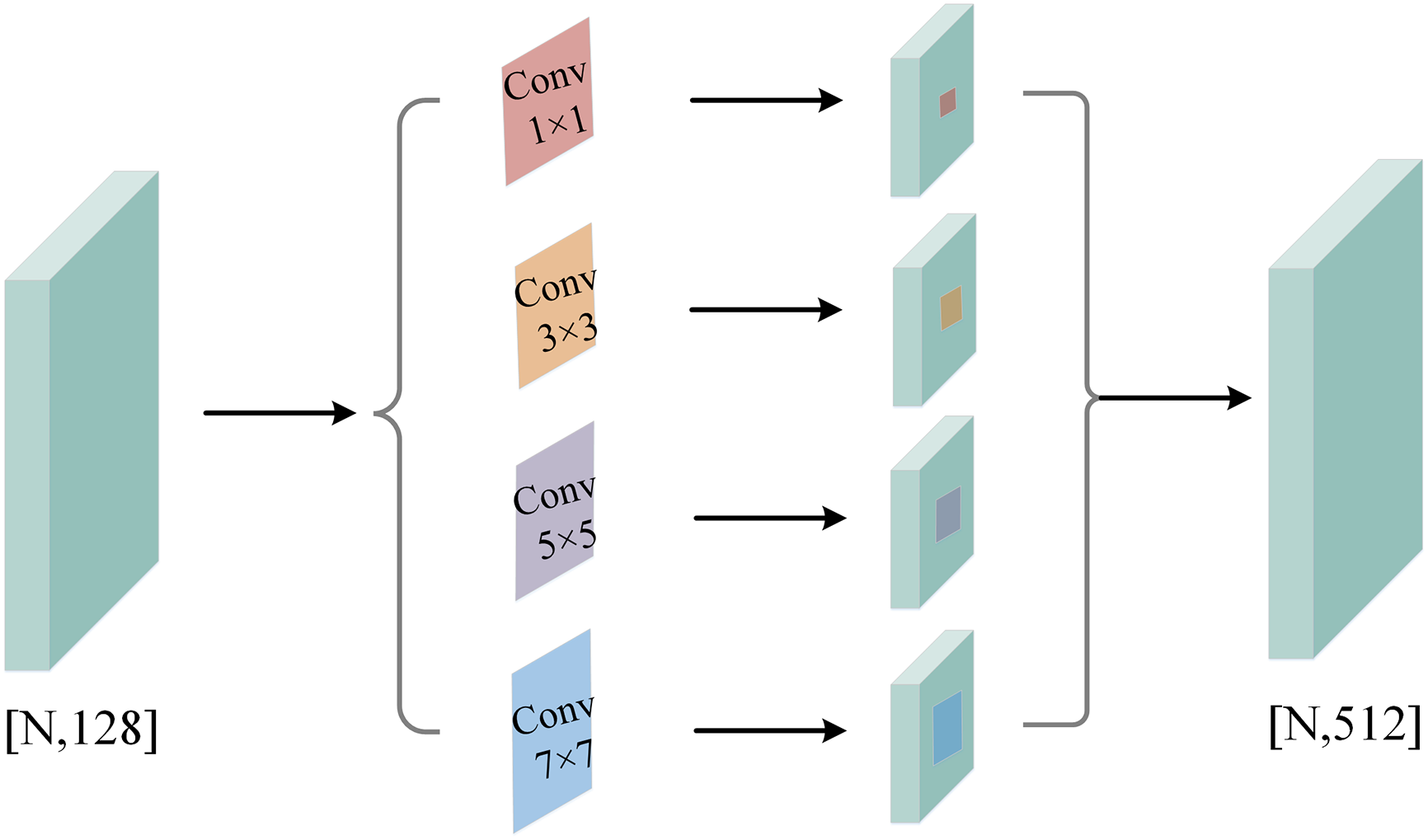

3.3.2 Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution

Considering that the object representation in point cloud data often exhibits multi-scale features, we propose a novel Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution to extract rich multi-scale point cloud features. The Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution extracts features across various scales by applying convolutions with four distinct kernel sizes. It then aggregates these multi-scale features to enhance the global capture capability of point cloud data, resulting in point cloud features that encompass rich multi-scale geometric information.

For input

where

Figure 5: The illustration of the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution

In conventional federated learning, the central server aggregates the model parameters contributed by all clients following each training round, subsequently disseminating these consolidated parameters to each client as the foundation for the next round’s model. However, frequent aggregation can lead to model homogenization, and its performance can be adversely affected by the uneven distribution of data across clients.

To address this issue, FDASS introduces a skip-aggregation phase at the end of each training round. Specifically, at the conclusion of each t round of training, the central server first determines whether the current round is part of the skip aggregation phase

where

Meanwhile, to further mitigate overfitting to a limited set of dominant or potentially poisoned client updates, FDASS employs a perturbation aggregation strategy during non-skipped rounds. Specifically, in each aggregation round, a small random noise is injected into each local model update prior to averaging:

where

While the proposed perturbation aggregation introduces controlled stochasticity to enhance robustness, other robust aggregation methods have also been extensively studied in FL. Notably, strategies such as Krum [55], Trimmed Mean [56] focus on detecting and filtering out anomalous client updates based on statistical properties.

• Krum selects a single client update that lies closest to its nearest neighbors, thereby providing resilience against a limited number of Byzantine attackers. However, it incurs high computational complexity and may discard useful updates under benign conditions.

• Trimmed Mean and Median aggregation compute element-wise statistics across client updates, discarding extreme values to suppress outliers. These methods offer theoretical robustness guarantees under specific assumptions but may result in biased updates, especially when client data distributions are highly non-IID.

Compared with these deterministic and often rigid strategies, our perturbation-based aggregation incorporates lightweight random noise into update averaging without requiring prior knowledge of adversary ratios or data distributions. This flexibility allows FDASS to maintain robustness while preserving adaptability in dynamic and heterogeneous federated environments.

To augment model diversity, FDASS employs a random initialization strategy. During each training round

where

FDASS enhances local models by allowing them to indirectly benefit from data across multiple clients during training, thereby improving performance in heterogeneous environments. The periodic skip aggregation and random shuffling of local models occur on the server side, ensuring data privacy. Each local client remains unaware of the origin of its local model, whether it is an averaged model or one from the skip aggregation phase.

FDASS’s random initialization strategy disrupts the synchronization of client model parameters, introducing variability into the training process. This prevents the homogenization of models that often result from traditional averaging aggregation. By training clients under a variety of initial conditions, FDASS enhances the model’s ability to generalize across clients with different data distributions. Distinct from previous optimization-based methods, FDASS employs a data-driven strategy, offering increased flexibility and robustness in federated learning, particularly in scenarios characterized by uneven data distribution.

Although random initialization can enhance model diversity, it may also pose the risk of model poisoning, where malicious clients submit poisoned models that are propagated to other clients. To prevent this, if malicious clients are present, the random initialization strategy can be modified to the following initialization strategy [2]:

Step 1: Client Model Difference Measurement and Clustering. First, we calculate the difference between each client model and the global model to assess potential deviations. If the client model deviates significantly, it may indicate an issue with the client’s model. Let

Next, we use

Step 2: Anomaly Detection and Model Selection. After clustering the models, anomaly detection is applied to identify and exclude client models that deviate substantially from their respective cluster centers. To achieve this, we calculate the deviation of each client model within its cluster, i.e., the distance between the client model and the cluster center.

Let the center of the

where

If the deviation

Step 3: Model Update and Protection: After filtering, only models identified as ‘normal’ will be retained for initialization. Specifically, only the trusted client models that pass the filtering process will participate in model initialization, while the excluded models have no influence on the training process. The update formula is as follows:

where

By introducing the model filtering mechanism, the robustness of the FDASS framework is substantially improved, mitigating the influence of malicious or poisoned client models on global training. The combination of trust scores and model filtering ensures that only trusted and non-anomalous models are incorporated into the global aggregation process, thus reducing the risk of model poisoning.

3.4.3 Client Selection Strategy

In each communication round

Formally, the client selection set

The probability that any client

This uniform strategy guarantees that no client is disproportionately favored or neglected in the long term, ensuring statistical fairness in participation. To avoid sampling imbalance, each round’s selected clients are chosen independently without consideration of historical participation frequency.

In real-world FL scenarios, client availability may vary due to network latency, device heterogeneity, or resource limitations. In such cases, the client selection process can be extended to incorporate availability-aware or priority-based sampling. For example, let

However, in this study, we assume full client availability in each round to isolate and evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed aggregation and fusion strategies.

To analyze the convergence behavior of our proposed FDASS strategy with skip aggregation and random reinitialization, we consider a standard federated optimization setting. The goal is to minimize the following global objective function:

where

We adopt the following standard assumptions in federated optimization [56]:

A1 (L-smoothness): Each

A2 (Unbiased local gradients): For each local update, the gradient is unbiased:

A3 (Bounded variance): The variance of the local gradients is bounded:

A4 (Bounded gradient norm):

3.5.1 Global Model Update with FDASS

Let

where

3.5.2 Expected Descent per Round

Let us define the expected change in global loss across one round of training (ignoring higher-order terms):

When

When

That is, perturbation increases the expected loss slightly, while average rounds decrease it.

3.5.3 Convergence Bound over T Rounds

Suppose we perform

This shows that FDASS converges at a rate of

Overall, the convergence slows slightly compared to standard FedAvg, proportional to

3.6 Privacy-Preserving Analysis

While FDASS introduces parameter swapping to improve model diversity and robustness, its implications for data privacy must also be considered. Notably, model inversion attacks attempt to reconstruct client data by exploiting shared model updates. To mitigate such risks, FDASS incorporates multiple privacy-preserving mechanisms:

♦ Stochastic Parameter Swapping: The swapped parameters are randomly sampled from trusted clients and periodically refreshed, preventing consistent observation patterns that adversaries could exploit.

♦ Partial Exchange and Filtering: Only a subset of model parameters is exchanged and only after rigorous filtering (e.g., anomaly detection), reducing the exposure of sensitive information.

♦ Aggregation Noise: Perturbation aggregation adds Gaussian noise

♦ Extension with DP: If stronger privacy guarantees are required, FDASS can be combined with client-side differential privacy mechanisms to provide

These design choices ensure that FDASS retains the privacy-preserving characteristics inherent to federated settings, while offering additional resilience to model inversion attacks.

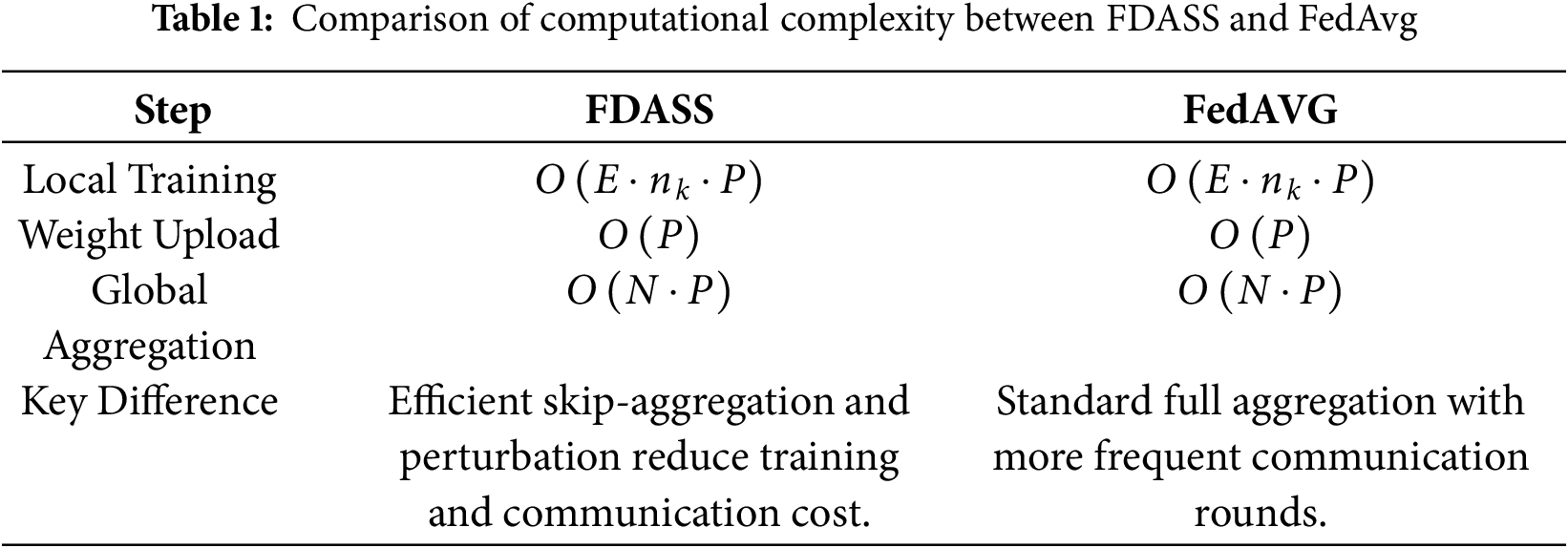

The time complexity analysis of Algorithm 1 directly reflects the computational complexity of the proposed FDASS model. Since Algorithm 1 describes the core steps of FL, including local training, parameter upload, and global aggregation, its complexity analysis offers a clear perspective on the computational cost associated with the entire process, especially in relation to our lightweight design.

(1) Local Training Complexity: In each round, client

(2) Parameter Update and Communication Complexity: After local training, the updated weights

(3) Global Aggregation Complexity: The central server aggregates the weights from all clients. If there are

Overall, considering all the steps—local training, weight uploading, and global aggregation—the overall time complexity for a single communication round is:

In practice, the communication time (i.e., uploading and aggregation) is typically negligible compared to local training time, especially when dealing with large datasets and complex models. Therefore, optimizing the local training process and reducing unnecessary communication rounds can greatly improve the overall system efficiency.

Table 1 compares the computational complexity of FDASS and FedAvg. FDASS achieves reductions in both training and communication cost through techniques such as skip-aggregation and perturbation aggregation, which results in more efficient resource utilization and fewer communication rounds compared to the standard full aggregation paradigm adopted in FedAvg.

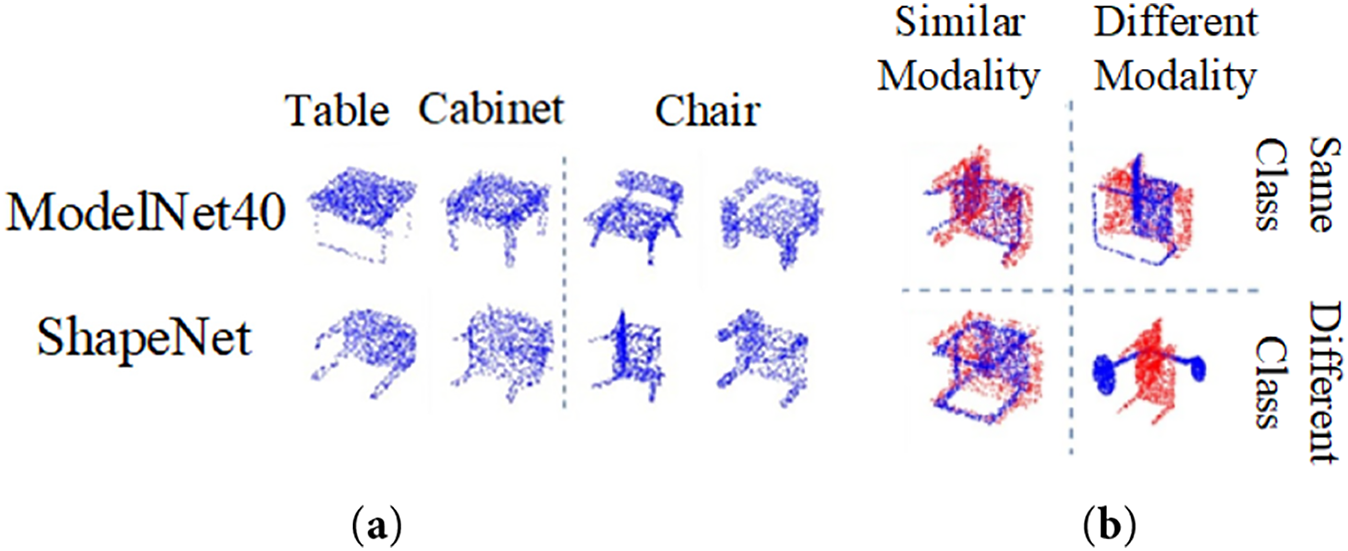

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we use two widely utilized datasets, ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart, in this study.

The ModelNet40 dataset, released by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) in 2013, includes high-quality 3D models of 40 common object categories, such as tables, chairs, beds, sofas, bookshelves, and monitors. The dataset encompasses 9840 training samples and 2468 test samples, offering a wealth of geometric diversity. Fig. 6a illustrates some examples of objects from the ModelNet40 dataset.

Figure 6: Visualization of some samples in the datasets. (a) ModelNet40 datasetl; (b) ShapeNetPart dataset

The ShapeNetPart dataset, jointly developed in 2015 by institutions including Princeton University, Stanford University, and the University of Michigan, comprises 16 categories, encompassing various items from cars and airplanes to furniture and buildings. The ShapeNetPart dataset offers 14,034 training samples and 2847 test samples, providing a broad experimental basis for 3D shape analysis. Examples of some objects are shown in Fig. 6b.

Additionally, Fig. 7 displays various feature diagrams that illustrate the geometric and semantic characteristics in 3D datasets geometric and semantic domain differences. Fig. 7a shows samples of tables, cabinets and chairs from the ModelNet and ShapeNet datasets, highlighting geometric structural differences within the same category across different datasets. Fig. 7b compares geometric similarities within and across classes: the upper left quadrant features comparisons of the same category and modality (e.g., chair vs. chair); the upper right quadrant presents comparisons of the same category with different modalities (e.g., chair in varying contexts); the lower left quadrant contrasts different categories but the same modality (e.g., chair vs. table), while the lower right quadrant compares different categories and modalities (e.g., chair vs. lamp).

Figure 7: Different feature diagrams of data in 3D datasets. (a) Intra and inter-dataset geometric and semantic domain differencesl; (b) Geometric similarity comparisons within and between classes

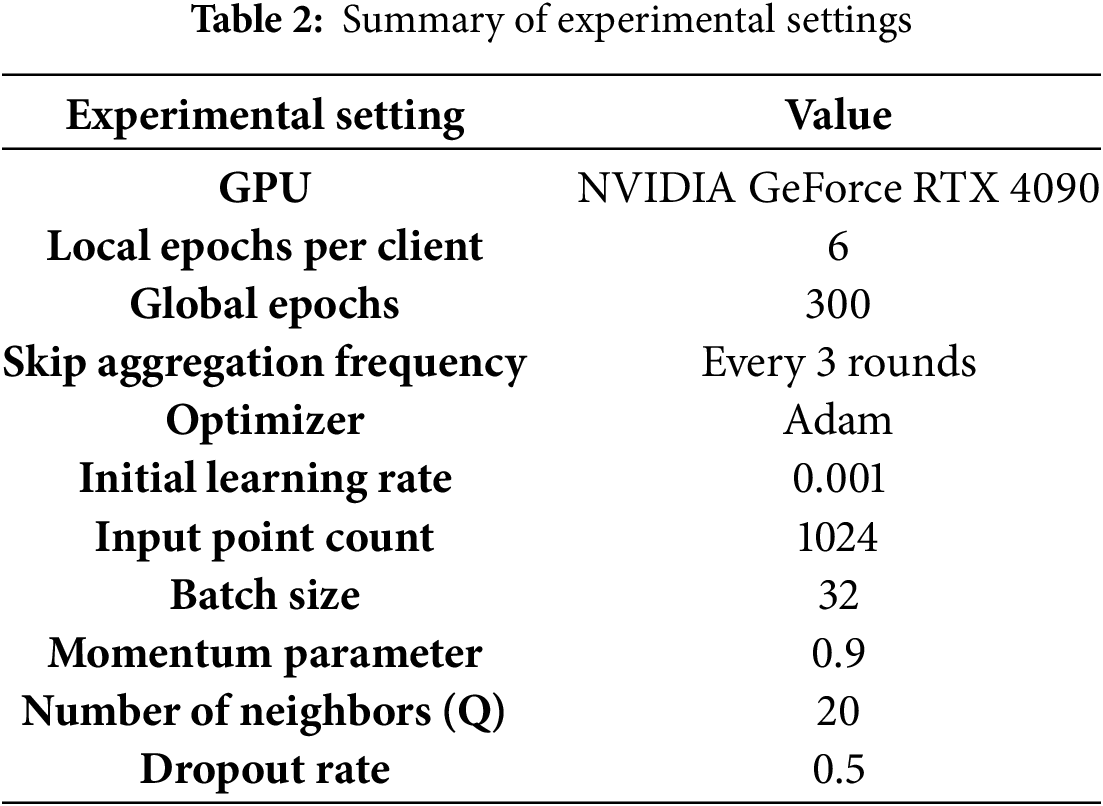

In this study, all experiments are implemented using the PyTorch 1.8.1 deep learning framework with Python, running on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU. The federated learning training process is configured with 6 local epochs per client and 300 global epochs, with averaging aggregation skipped every 3 rounds. For the classification tasks, the Adam optimizer is employed with an initial learning rate of 0.001. The input point count is set to 1024, the batch size is 32, the momentum parameter is 0.9, and the number of neighbors Q is set to 20. The dropout rate across all dropout layers is 0.5. A similar hyperparameter configuration strategy is utilized for other tasks. The training duration for the ModelNet40 dataset was approximately 2.5 days, while for the ShapeNetPart dataset, it was around 2 days. Table 2 summarizes the experimental settings used in this study, including the configuration of local and global epochs, optimizer settings, and other relevant hyperparameters.

To evaluate the classification performance, we utilize two widely recognized metrics: mean accuracy (mAcc) and overall accuracy (OA). mAcc represents the average accuracy across all categories, while OA reflects the model’s performance across all test samples, offering a comprehensive measure of its effectiveness. The formulas for calculating OA and mAcc are as follows:

where True Positives (TP) is the number of samples correctly predicted as the positive class. True Negatives (TN) is the number of samples correctly predicted as the negative class. False Positives (FP) is the number of samples incorrectly predicted as the positive class. False Negatives (FN) is the number of samples incorrectly predicted as the negative class. These metrics provide a comprehensive perspective for evaluating the model’s classification performance both across different categories and overall.

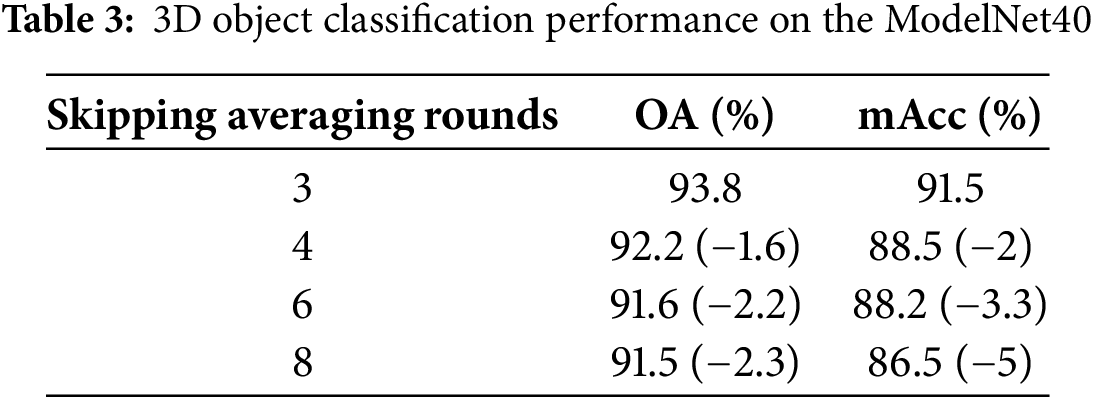

4.4.1 Analysis of the Impact of Skipping Averaging Rounds

In our experiment, we vary the number of rounds for skipping averaging aggregation to 3 (default), 4, 6, and 8 to evaluate its impact on model performance.

Table 3 demonstrates that the frequency of skipping averaging rounds markedly influences the overall performance and category balance of the FDASS-MRFCF model. Setting the skip rounds to 3 yields OA of 93.8% and mAcc of 91.5%, which we identify as the optimal configuration. This setup adeptly harmonizes global information with local updates, ensuring robust classification performance and stability.

However, when the skip rounds increase to 4, the overall accuracy and mean accuracy decrease by 1.6 and 3 percentage points, respectively. This decline suggests that model performance begins to suffer as local model updates fail to promptly reflect global changes. Further increasing the skip rounds to 6 and 8 results in a reduction in overall accuracy by 2.2 and 2.3 percentage points, respectively, while mean accuracy declines more significantly by 3.3 and 5 percentage points, with the drop in mAcc being particularly pronounced.

These results indicate that excessive skipping rounds create a considerable discrepancy between local updates and the global model, significantly undermining the model’s generalization ability and category balance across different datasets. Therefore, setting the number of skip rounds to 3 is optimal, ensuring global consistency while maintaining efficient classification performance and category balance. Setting skip rounds too high may diminish the model’s sensitivity to different categories, consequently degrading classification performance.

As shown in Table 1, increasing the skip frequency results in a gradual degradation in model accuracy. This performance drop is expected, as excessive skipping may reduce parameter synchronization across clients. Although a fixed skip interval

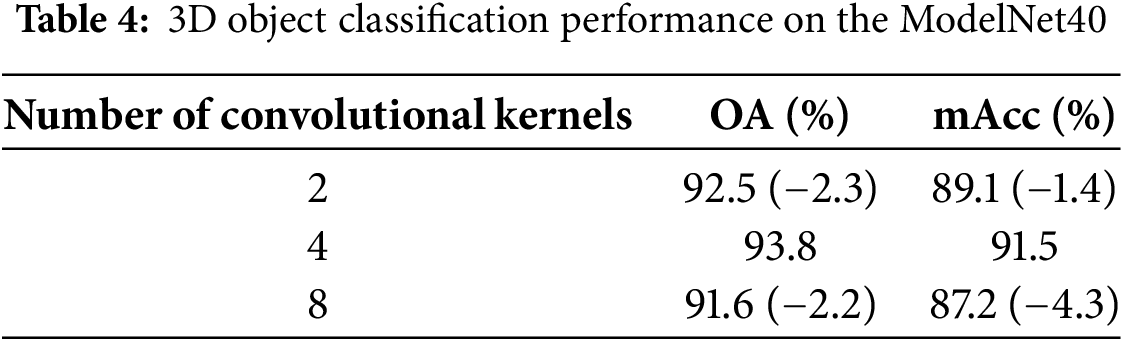

4.4.2 Analysis of the Number of Convolutional Kernels for Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution

This study assesses how the number of convolutional kernels influences model performance within the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution framework. We evaluate three distinct kernel configurations:

• 2 kernels, consisting of 1 × 1 and 3 × 3.

• 4 kernels, comprising 1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7.

• 8 kernels, which include two of each size: 1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7.

This approach enables us to systematically evaluate the impact of kernel quantity on the model’s feature extraction capabilities and its performance in classification tasks.

Table 4 reveals that the convolutional kernel significantly impacts the model’s OA and mAcc. The optimal performance, with OA of 93.8% and mAcc of 91.5%, is achieved using four kernels. This setup enables the model to adeptly capture geometric features of point clouds, ensuring a well-balanced feature extraction process.

When the kernel count is reduced to two, there is a decrease of 2.3 percentage points in OA and 1.4 percentage points in mAcc. This indicates that an insufficient number of kernels impairs the model’s feature extraction, adversely impacting classification accuracy. On the other hand, augmenting the kernel count to eight leads to a more significant decrease in OA by 2.2 percentage points and mAcc by 4.3 percentage points. This reduction is likely due to overfitting and heightened computational demands, which impede the model’s generalization across various datasets.

These findings underscore the importance of selecting an appropriate number of kernels to optimize model performance. By utilizing four kernels, the model sustains high accuracy and circumvents overfitting arising from excessive complexity. Achieving a balance between complexity and generalization is crucial for excelling in 3D object classification tasks.

Consequently, forthcoming comparative, robustness and ablation studies will employ the FDASS-MRFCF model, configured with three skip rounds for averaging and a kernel set of four (1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5, 7 × 7) within the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution.

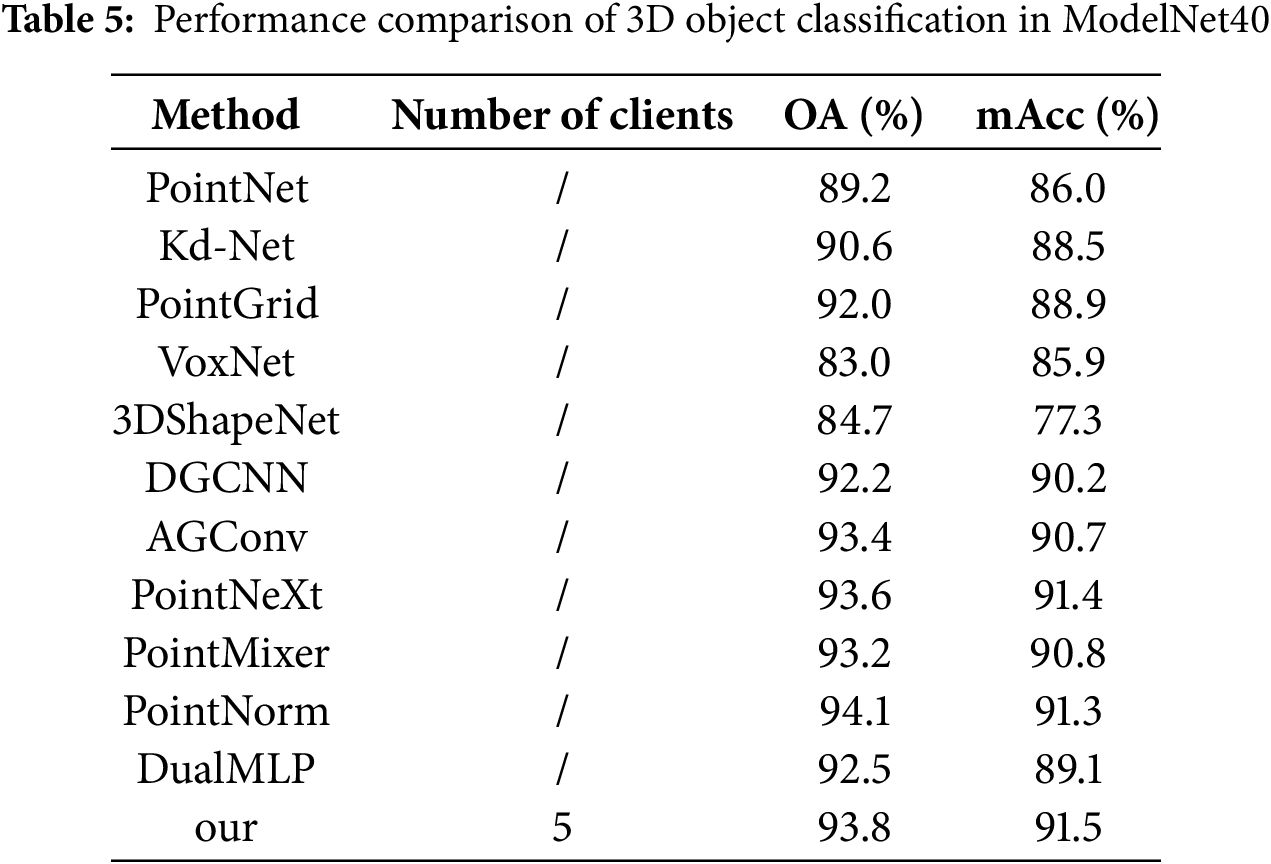

4.5 Comparison with the State-of-the-Art Methods

In practical applications, client data can vary significantly in terms of sample size and category distribution. As the number of clients increases, the original dataset is divided into multiple subsets, complicating federated learning tasks. To reflect these challenges accurately, we design experiments comparing centralized and federated point cloud classification methods. In the centralized approach, we set the number of clients to one for baseline evaluation. Conversely, in the federated learning scenario, our method is tested with five clients to assess its performance in addressing data heterogeneity and multi-client collaboration.

To comprehensively demonstrate the superiority of FDASS-MRFCF, we select two representative and popular categories of point cloud classification methods for comparison: projection-based and raw point cloud-based methods. The projection-based classification methods comprise VoxNet [46], 3DShapeNet [47], KD-Net [57] and PointGrid [58], while the raw point cloud-based classification methods include PointNet [50], DGCNN [51], AGConv [59], PointNeXt [60], PointMixer [61], PointNorm [62] and DualMLP [55].

VoxNet voxelizes point cloud data and employs a 3D CNN for classification, transforming point clouds into voxel grids before feature extraction. 3DShapeNet, an early voxel-based model, effectively handles incomplete and noisy data. KD-Net recursively partitions 3D point clouds and organizes data using a KD-tree structure, and extracts features through the network for classification. PointGrid embeds point clouds into a 3D grid structure, combining point and grid features to capture local geometric information for 3D object classification and segmentation.

Among the raw point cloud-based methods, PointNet was the first deep learning model to process point cloud data directly, it independently processes each point and uses global pooling to aggregate information without voxelization or grid-based preprocessing, thus preserving the original spatial structure. DGCNN utilizes graph neural networks to dynamically construct local neighborhoods and learn point relationships through graph convolution, enhancing local structure representation. AGConv adaptively adjusts the neighborhood structure based on point cloud features, improving classification accuracy. PointNeXt is an enhancement of PointNet, further introducing deeper network architectures and residual connections to improve the model’s representational capacity and classification performance. PointMixer uses a Transformer-like architecture with a self-attention mechanism to capture global and local features, excelling in complex structure handling. PointNorm standardizes point cloud data to reduce distribution variability and improve generalization across different data distributions. DualMLP, a dual-path MLP model, learns from both local and global feature levels, significantly enhancing classification accuracy.

As detailed in Table 5, our method achieves excellent performance on the ModelNet40 dataset, with OA of 93.8% and mAcc of 91.5%. In comparison to other state-of-the-art methods, our approach outperforms PointNeXt by 0.2 percentage points (93.6%), AGConv by 0.4 percentage points (93.4%), and the foundational PointNet by 4.6 percentage points (89.2%) in overall accuracy. Notably, our method significantly surpasses the projection-based VoxNet by 10.8 percentage points, with VoxNet scoring 83.0%.

In terms of mean accuracy, our method leads PointNeXt by 0.1 percentage points (91.4%) and AGConv by 0.8 percentage points (90.7%), showcasing consistent and reliable performance across various categories. While PointNorm slightly edges out our method in overall accuracy with 94.1%, this is likely due to PointNorm’s prowess in capturing intricate local geometric features.

Despite this, our method’s robustness in multi-client environments and its adaptability to diverse data distributions provide substantial benefits for real-world applications. These strengths position FDASS-MRFCF as a formidable contender in the realm of complex point cloud classification, establishing a robust basis for future research and practical implementations.

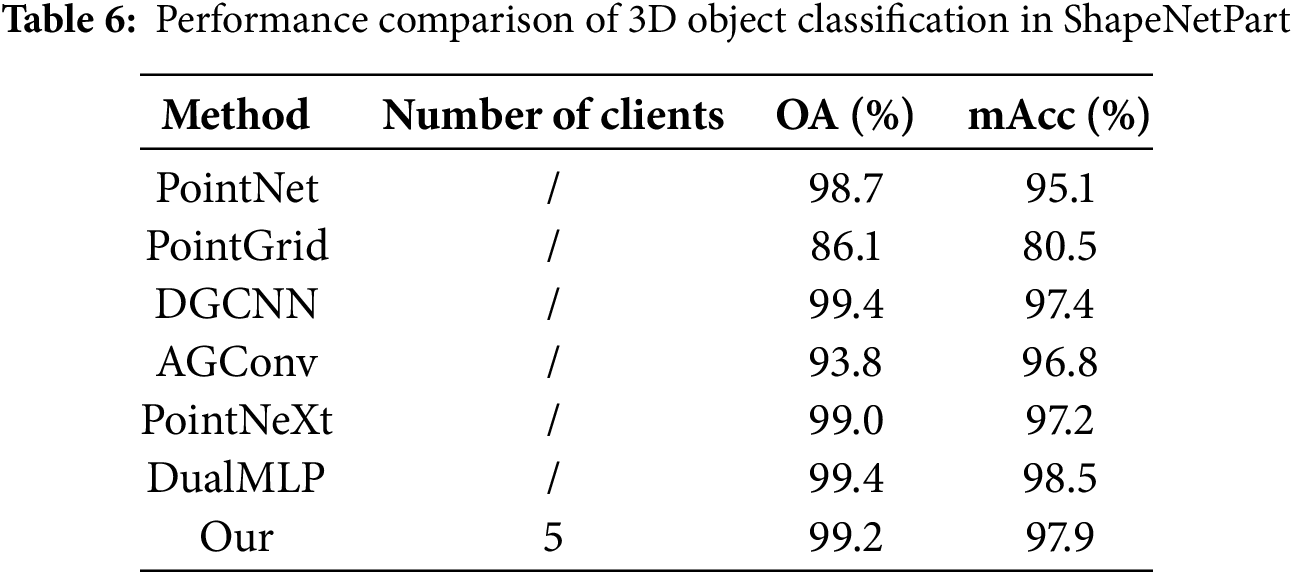

According to Table 6, our method exhibits outstanding performance on the ShapeNetPart dataset. Notably, in terms of mAcc, our method achieves 97.9%, which is only slightly below DualMLP. This performance is 0.6 percentage points higher than DualMLP (98.5%), 0.5 percentage points higher than DGCNN (97.4%), and is far ahead of PointNet by 2.8 percentage points (95.1%).

Regarding OA, our method scores 99.2%, just shy of DGCNN and DualMLP, both at 99.4%. This minor gap may be attributed to DGCNN’s proficiency in learning local feature topologies through dynamic graph construction and DualMLP’s dual-path architecture, which enables feature learning at both local and global scales.

Despite these advantages, our method outperforms other methods, such as PointNeXt (99.0%) and PointNet (98.7%). Overall, our method showcases robust performance across diverse data distributions, a testament to our superior global feature extraction capabilities and dynamic aggregation strategies within multi-client settings. This leads to a notable advantage in mAcc over other methods, underscoring our model’s ability to sustain high overall efficiency while adeptly navigating the intricacies of varied categories.

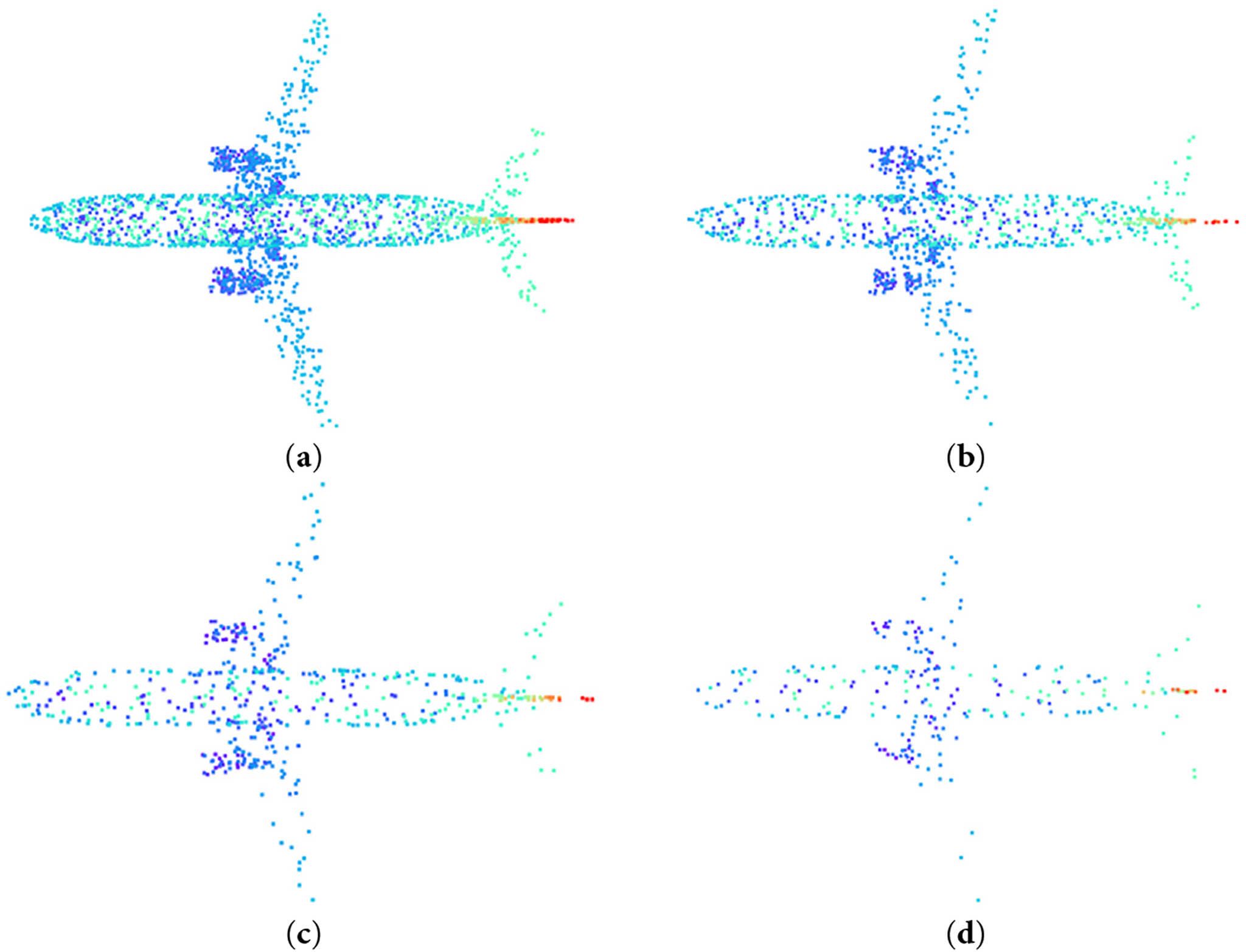

In the field of point cloud data processing, the density of sampling points varies with different input scales. The same object’s geometric features can be represented by point sets of varying densities, ranging from the intricate details of high-density point clouds to the basic outlines in low-density ones. Fig. 8 illustrates the distribution of point clouds at different densities for airplane samples within the ModelNet40 dataset.

Figure 8: Visualization of scatter plots for point clouds at different densities. (a) 2048 sampling points; (b) 1024 sampling points; (c) 512 sampling points; (d) 256 sampling points

The figure indicates that clarity in point cloud samples diminishes as sampling density decreases. With 2048 points, the point cloud retains a highly distinct shape, as depicted in Fig. 8a. At 1024 points, the object’s outline remains discernible, as illustrated in Fig. 8b. Even at a reduced count of 512 points, category-specific features remain identifiable, as shown in Fig. 8c. However, at 256 points, morphological details become markedly blurred, as seen in Fig. 8d, potentially impacting recognition accuracy.

To evaluate the robustness of the FDASS-MRFCF model, we resample the test samples to 2048, 1024, 512, and 256 points for evaluation. This experiment aims to examine the model’s stability and accuracy across different sampling densities.

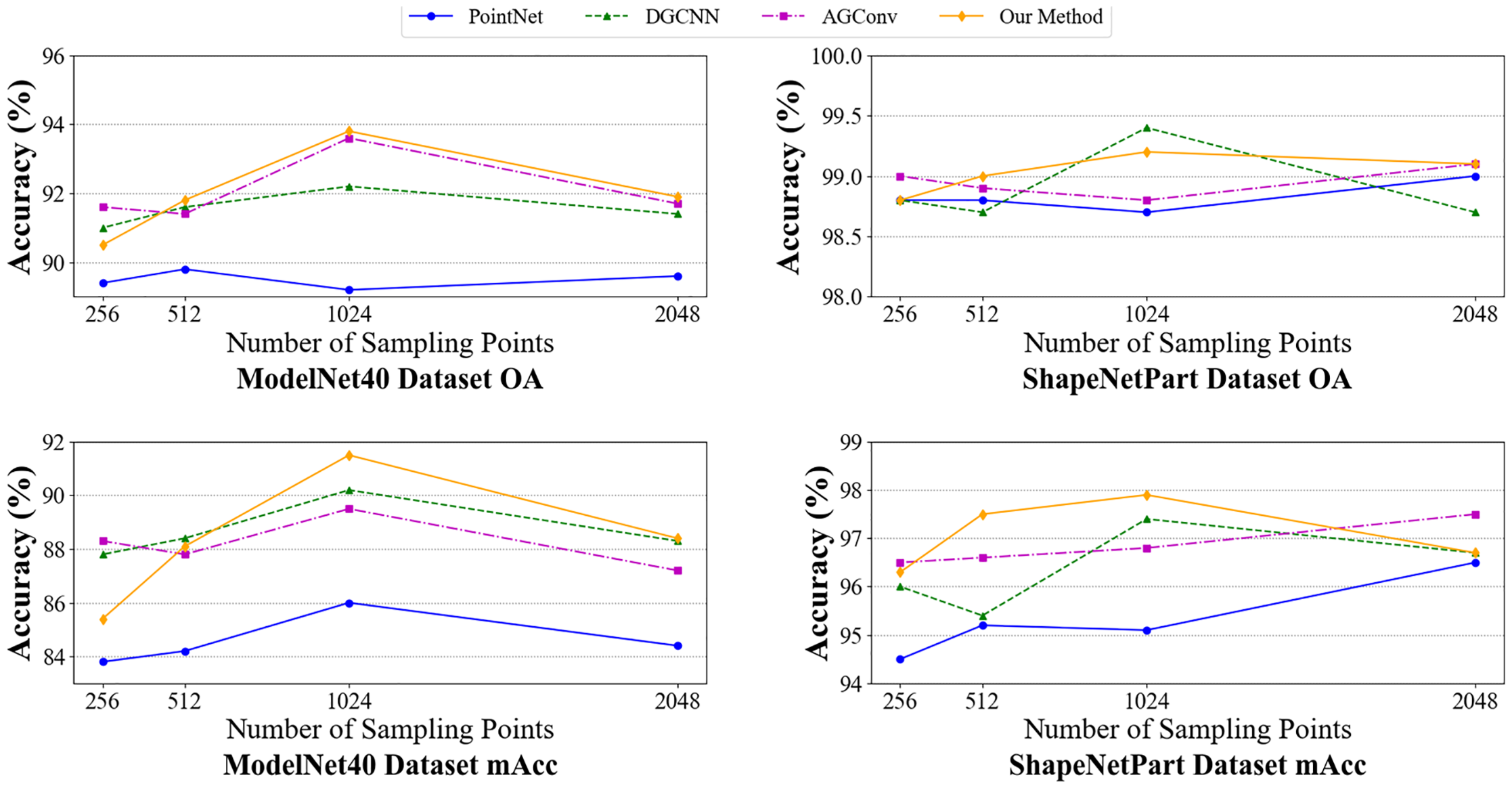

As depicted in Fig. 9, our method outperforms other methods regarding OA and mAcc on both the ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart datasets. On the ModelNet40 dataset, FDASS-MRFCF outperforms the other methods at medium and high density sample points. It performs best at 1024 and 2048 sample points, which shows its strong feature extraction and classification ability on medium and high isodensity point clouds. DGCNN and AGConv perform well at low densities. While PointNet performs poorly at all sampling points, showing its limitation in point cloud classification tasks.

Figure 9: Performance comparison of our method and other methods on different density point clouds

In the ShapeNetPart dataset, FDASS-MRFCF significantly outperforms the other methods at low and medium sampling points, indicating that it still maintains good classification performance under low-resolution point cloud data. As the number of sampling points increases, AGConv and PointNet accuracies are improved, which shows that it can perform better under high-density point clouds.

Overall, our method demonstrates balanced high performance across different sampling densities, effectively managing the trade-off between accuracy and computational complexity at medium sampling points.

To assess the contribution of each component within our federated learning aggregation approach, we conduct two ablation experiments:

First, Averaging Aggregation: In this experiment, we utilize the traditional federated averaging aggregation method. After each training round, the central server averages the model parameters received from all clients and subsequently redistributes the updated model back to the clients without any perturbation. This setup serves as a baseline for evaluating the performance and stability of standard averaging aggregation.

Second, Perturbation Aggregation Only: This experiment examines the sole effect of perturbations. We introduce random perturbations to the model parameters received from clients before redistributing them, omitting the averaging step. This configuration allows us to gauge the influence of perturbations in enhancing model diversity and adaptability.

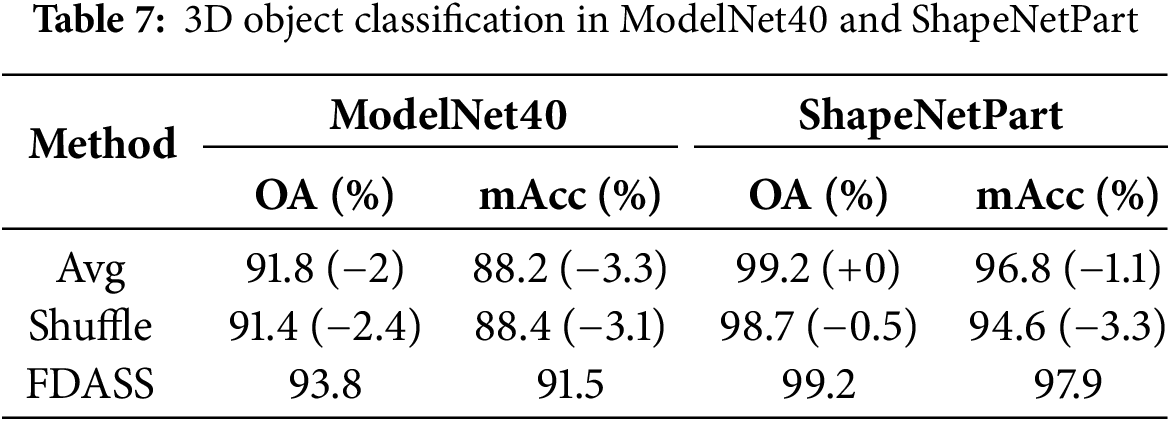

Table 7 illustrates the superior performance of the FDASS method compared to the Avg and Shuffle methods in terms of OA and mAcc across both the ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart datasets. Specifically, on the ModelNet40 dataset, FDASS achieves an OA of 93.8%, exceeding the Avg method by 2.0 percentage points and the Shuffle method by 2.4 percentage points. Additionally, in terms of mAcc, FDASS reaches 91.5%, showing improvements of 3.3 and 3.1 percentage points over Avg (88.2%) and Shuffle (88.4%), respectively.

On the ShapeNetPart dataset, FDASS achieves OA of 99.2%, matching the Avg method but significantly surpassing the Shuffle method’s 98.7% by 0.5 percentage points. For mAcc, FDASS scores 97.9%, which is 1.1 and 3.3 percentage points higher than Avg (96.8%) and Shuffle (94.6%), respectively.

Overall, FDASS enhances overall performance and significantly bolsters the model’s equilibrium across various categories, effectively countering the negative impacts of class imbalance. By employing a dynamic aggregation strategy, FDASS adeptly merges the benefits of perturbation and average aggregation. This approach renders the model more resilient to complex data distributions and diverse samples, underscoring its substantial practical utility in federated learning scenarios.

We conduct an ablation study to evaluate the impact of the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution module within the MRFCM. In this experiment, we deactivate the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution module while retaining other integral components, thereby assessing its contribution to the model’s overall performance. Our analysis of the results aims to elucidate the module’s role in multi-scale feature extraction and its subsequent impact on classification accuracy.

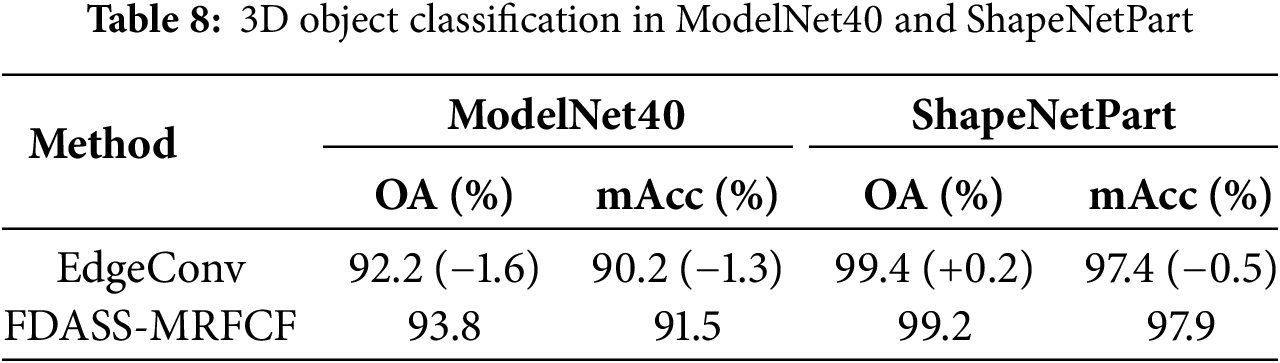

Table 8 indicates that the absence of the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution module results in a 1.6 percentage point reduction in OA on the ModelNet40 dataset, along with a 1.3 percentage point decrease in mACC. On the ShapeNetPart dataset, while OA slightly increased, mACC dipped by 0.5 percentage points. These results highlight the Pyramid Multi-Scale Convolution’s pivotal role in capturing the diverse features of complex geometric structures through multi-scale feature extraction. The module’s proficiency in handling objects with varying details and shapes markedly enhances the model’s ability to discern intricate shapes during the feature extraction phase. This enhancement fosters improved generalization across diverse categories and subtle distinctions, underscoring the module’s essential function within the network architecture.

4.8 Scaling Analysis with Varying Client Numbers

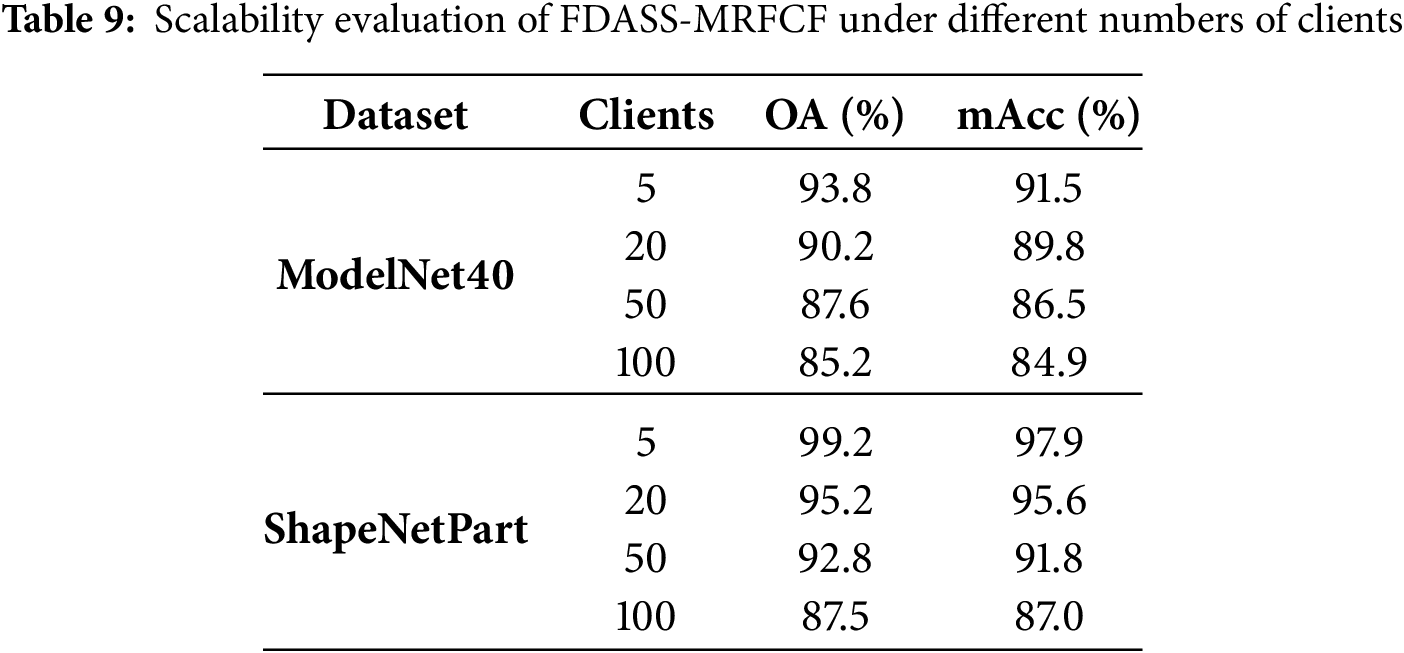

To further evaluate the scalability of the proposed FDASS-MRFCF framework, we conducted experiments under varying numbers of participating clients: 5, 20, 50, and 100 [45]. The same experimental settings described in Section 4.5 were maintained, with clients randomly assigned non-IID data partitions.

As shown in Table 9, the scalability of FDASS-MRFCF was evaluated with 5, 20, 50, and 100 clients on ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart datasets. The results show that the model performs best with 5 clients, where the balance of data volume and efficient aggregation leads to optimal performance. As the number of clients increases, performance gradually declines, particularly after 20 clients. This drop can be attributed to smaller datasets available to each client as the client pool grows, which reduces the model’s ability to learn effectively. Additionally, the increased communication overhead associated with a larger number of clients slows down the synchronization and aggregation process, further hindering performance. These findings highlight the challenges of scaling federated learning in large-scale settings and suggest that future work should focus on developing adaptive aggregation strategies to optimize performance as the number of clients increases.

4.9 Robustness Evaluation against Model Poisoning and Backdoor Attacks

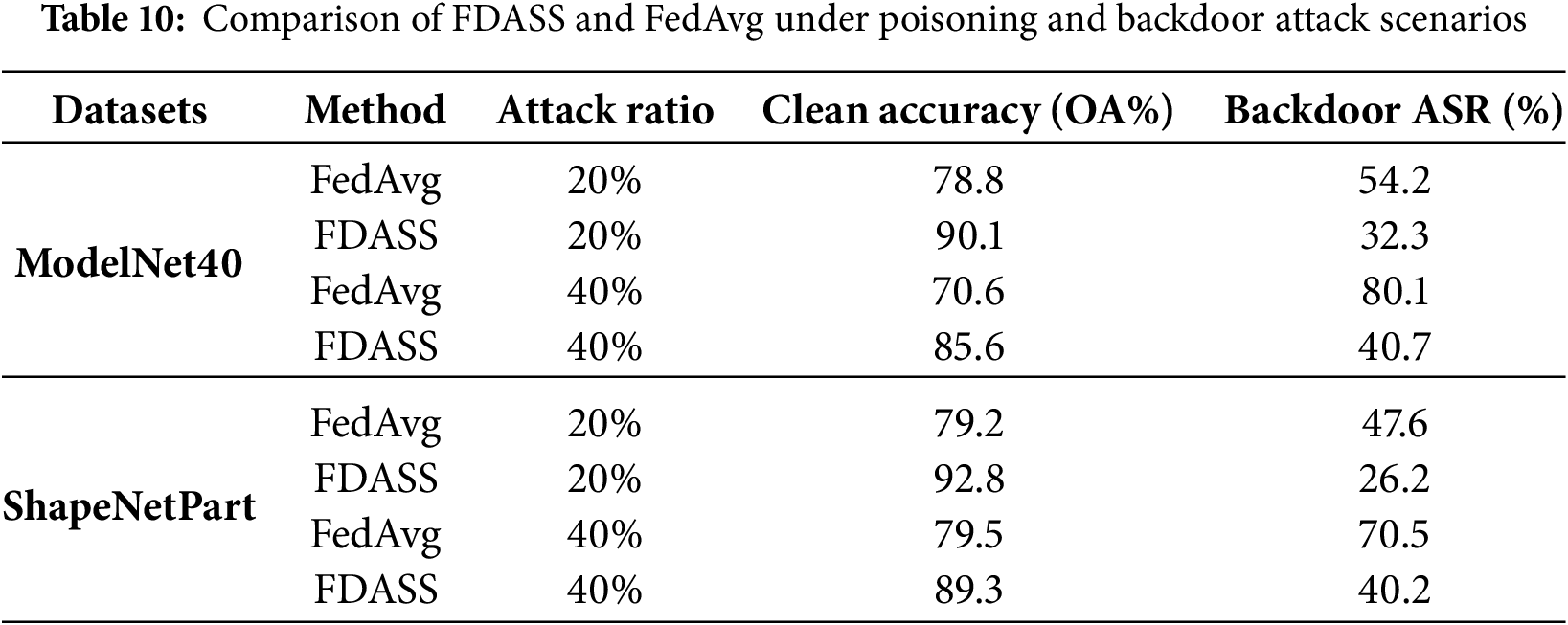

In order to further evaluate the robustness of the proposed FDASS strategy, we conduct additional experiments under adversarial FL settings, including model poisoning and backdoor attacks. Model poisoning is simulated by introducing malicious parameter updates from a subset of clients, while backdoor attacks are implemented by inserting a trigger pattern into training samples of certain clients and modifying the corresponding labels. These experiments aim to assess whether FDASS can maintain stable performance when exposed to adversarial perturbations in client updates. We compare FDASS with the baseline FedAvg under the identical attack settings, considering two proportions of malicious clients: 20% and 40% malicious clients. The target label for the backdoor attack is fixed across all experiments, and the trigger pattern is defined as small fixed patch inserted into the input point clouds. The performance is evaluated in terms of OA and backdoor attack success rate (ASR), with the results summarized in Table 10.

Compared with FedAvg, FDASS consistently achieves higher clean accuracy and significantly reduces the attack success rate (ASR), demonstrating its inherent robustness to poisoning and backdoor attacks. This improvement is attributed to the perturbation mechanism and skip aggregation, which jointly disrupt the influence of malicious updates and limit the propagation of poisoned parameters in the global model. These results confirm that FDASS not only sustains model accuracy in benign environments but also effectively mitigates the impact of malicious updates in adversarial settings. This dual advantage highlights its potential as a robust and secure aggregation strategy for real-world federated learning applications where both performance and security are critical.

In this paper, we introduce an innovative approach to point cloud classification within the federated learning framework, addressing the critical issues of data privacy and heterogeneity. Our method integrates a dynamic aggregation selection strategy, which combines perturbation with average aggregation, significantly improving the model’s adaptability and generalization capabilities. Furthermore, we propose a novel multisensory fusion classification model that enhances the robustness of point cloud classification. This model leverages dynamic neighborhood feature learning and multilevel feature extraction to accurately capture local geometric structures while seamlessly incorporating global information. Extensive experiments on benchmark datasets, including ModelNet40 and ShapeNetPart, demonstrate the superior performance and effectiveness of our approach. The results highlight the method’s robustness and its potential to serve as a powerful solution for complex point cloud classification tasks. The successful application of our method underscores its viability in addressing the diverse and intricate challenges associated with FL environments. In future work, we plan to explore adaptive control of skip-aggregation intervals, enabling a dynamic trade-off between communication efficiency and convergence performance across diverse federated settings. Additionally, we aim to investigate adaptive regularization or kernel pruning techniques to reduce redundancy in multi-receptive field fusion, as observed in Table 4, where employing eight kernels led to performance degradation, indicative of potential overfitting or suboptimal feature utilization. In addition to the point cloud classification task explored in this work, the FDASS-MRFCF framework holds potential for broader applications. Future work could extend FDASS-MRFCF to more tasks such as point cloud segmentation, where the model could be adapted to generate per-point or per-region predictions. Another exciting direction is multi-task learning, where FDASS-MRFCF could be applied to jointly solve related tasks, such as classification and segmentation, in which FDASS-MRFCF could simultaneously tackle related tasks—such as classification and segmentation—within a federated setting while safeguarding data privacy. The flexibility of the FDASS aggregation strategy can help address the challenges of model heterogeneity and improve the performance of FL systems in su0ch settings. Moreover, An interesting direction for future work is the potential extension of FDASS to fully decentralized, peer-to-peer paradigms. In such scenarios, spatially proximate nodes may exchange model parameters during non-aggregation rounds, potentially reducing communication latency and mitigating server synchronization bottlenecks. This approach would improve the scalability and responsiveness of federated learning systems, particularly in environments with high communication overhead or when the server experiences delays due to high computational load. Future investigations will focus on adapting the FDASS aggregation mechanism to peer-to-peer communication protocols and validating its effectiveness in decentralized FL settings.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under (Grant 2021YFB3101100), in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under (Grant 42461057), (Grant 62272123), and (Grant 42371470), in part by the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province under (Grant 202303021212164), in part by the Postgraduate Education Innovation Program of Shanxi Province under (Grant 2024KY474), in part by the Liaoning Natural Science Funds (Grant No. 2025-BS-0212), and in part by the Open Research Project of Key Laboratory of Symbolic Computation and Knowledge Engineering, Ministry of Education (Grant No. 93K172025K17).

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of Chinaunder (Grant 2021YFB3101100), in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of Chinaunder (Grant 42461057), (Grant 62272123), and (Grant 42371470), in part by the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province under (Grant 202303021212164), in part by the Postgraduate Education Innovation Program of Shanxi Province under (Grant 2024KY474).

Author Contributions: Yuchao Hou: Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition. Biaobiao Bai: Writing & editing, Validation, Methodology. Shuai Zhao: Visualization, Data curation. Yue Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation. Jie Wang: Formal analysisSupervis1on. Zijian Li: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be available on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tang Y, Liang Y. Credit card fraud detection based on federated graph learning. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;256(2):124979. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pei J, Liu W, Li J, Wang L, Liu C. A review of federated learning methods in heterogeneous scenarios. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(3):5983–99. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3385440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen J, Yan H, Liu Z, Zhang M, Xiong H, Yu S. When federated learning meets privacy-preserving computation. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(12):1–36. doi:10.1145/3679013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zamanakos G, Tsochatzidis L, Amanatiadis A, Pratikakis I. A comprehensive survey of LIDAR-based 3D object detection methods with deep learning for autonomous driving. Comput Graph. 2021;99:153–81. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.20443107.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mehranfar M, Arefi H, Alidoost F. Knowledge-based 3D reconstruction of bridge structures using UAV-based photogrammetric point cloud. J Appl Remote Sens. 2021;15(4):044503. doi:10.1117/1.jrs.15.044503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Pan Y, Dong Y, Wang D, Chen A, Ye Z. Three-dimensional reconstruction of structural surface model of heritage bridges using UAV-based photogrammetric point clouds. Remote Sens. 2019;11(10):1204. doi:10.3390/rs11101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yazdinejad A, Dehghantanha A, Karimipour H, Srivastava G, Parizi RM. A robust privacy-preserving federated learning model against model poisoning attacks. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:6693–6708. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3420126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xia S, Chen D, Wang R, Li J, Zhang X. Geometric primitives in LiDAR point clouds: a review. IEEE J Select Topics Appl Earth Observatote Sens. 2020;13:685–707. doi:10.1109/jstars.2020.2969119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fan B, Wu F, Hu Z. Rotationally invariant descriptors using intensity order pooling. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2011;34(10):2031–45. doi:10.1109/tpami.2011.277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Liu B, He S, He D, Zhang Y, Guizani M. A spark-based parallel fuzzy c-Means segmentation algorithm for agricultural image Big Data. IEEE Access. 2019;7:42169–80. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2907573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tang Y, Liang Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Ni L, Qi L. Reliable federated learning based on dual-reputation reverse auction mechanism in Internet of Things. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;156:269–84. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lu Z, Pan H, Dai Y, Si X, Zhang Y. Federated learning with non-iid data: a survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(11):19188–209. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3376548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Che E, Olsen MJ. Fast ground filtering for TLS data via Scanline Density Analysis. ISPRS J Photogram Remote Sens. 2017;129:226–40. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2017.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Vo AV, Truong-Hong L, Laefer DF, Bertolotto M. Octree-based region growing for point cloud segmentation. ISPRS J Photogram Remote Sens. 2015;104:88–100. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2015.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ni L, Song C, Zhao H, Tang Y, Ma Y, Zhang J. Personalized medical federated learning based on mutual knowledge distillation in object heterogeneous environment. In: Blockchain and Web3 Technology Innovation and Application Exchange Conference. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 362–74. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhang H, Wang C, Yu L, Tian S, Ning X, Rodrigues J. PointGT: a method for point-cloud classification and segmentation based on local geometric transformation. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2024;26:8052–62. doi:10.1109/tmm.2024.3374580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen J, Zhang Y, Ma F, Tan Z. EB-LG module for 3D point cloud classification and segmentation. IEEE Robot Automat Letters. 2022;8(1):160–7. doi:10.1109/lra.2022.3223558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shi L, Yuan Z, Cheng M, Chen Y, Wang C. DFAN: dual-branch feature alignment network for domain adaptation on point clouds. IEEE Transact Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–12. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2022.3171038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang Y, Zeng D, Luo J, Fu X, Chen G, Xu Z, et al. A survey of trustworthy federated learning: issues, solutions, and challenges. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2024;15(6):1–47. doi:10.1145/3678181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhai Z, Zhang X, Yao L. Multi-scale dynamic graph convolution network for point clouds classification. IEEE Access. 2020;8:65591–98. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2985279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kuze N, Ishikura S, Yagi T, Chiba D, Murata M. Classification of diversified web crawler accesses inspired by biological adaptation. Int J Bio-Insp Computat. 2021;17(3):165–73. doi:10.1504/ijbic.2021.114877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Cui Z, Zhao Y, Cao Y, Cai X, Zhang W, Chen J. Malicious code detection under 5G HetNets based on a multi-objective RBM model. IEEE Network. 2021;35(2):82–7. doi:10.1109/mnet.011.2000331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen T, Tong Y. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Transact Intell Syst Technol. 2019;10(2):1–19. doi:10.1145/3298981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Criado MF, Casado FE, Iglesias R, Regueiro CV, Barro S. Non-iid data and continual learning processes in federated learning: a long road ahead. Information Fusion. 2022;88(3):263–80. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2022.07.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhu H, Xu J, Liu S, Jin Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: a survey. Neurocomputing. 2021;465:371–90. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.07.098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ma X, Zhu J, Lin Z, Chen S, Qin Y. A state-of-the-art survey on solving non-iid data in federated learning. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2022;135:244–58. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shen S, Zhu T, Wu D, Wang W, Zhou W. From distributed machine learning to federated learning: in the view of data privacy and security. Concurr Comput. 2022;34(16):e6002. doi:10.1002/cpe.6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Artificial intelligence and statistics. Brooklyn, MA, USA: PMLR; 2017. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

29. Rezaei H, Taheri R, Jordanov I, Shojafar M. Federated RNN for intrusion detection system in IoT environment under adversarial attack. J Netw Syst Manag. 2025;33(4):82. doi:10.1007/s10922-025-09963-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ahmed ST, Kaladevi AC, Kumar VV, Shankar A, Alqahtani F. Privacy enhanced edge-ai healthcare devices authentication: a federated learning approach. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):5676–82. doi:10.1109/tce.2025.3542955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li X, Lin Q, Khan F, Kumari S, Alenazi MJF, Yang J. Enhancing cancer detection capabilities in medical consumer electronics through split federated learning and deep learning optimization. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):6673–85. doi:10.1109/tce.2025.3545963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tang Y, Ni L, Li J, Zhang J, Liang Y. Federated learning based on dynamic hierarchical game incentives in Industrial Internet of Things. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;65:103214. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2025.103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liu J, Huang J, Zhou Y, Li X, Ji S, Xiong H, et al. From distributed machine learning to federated learning: a survey. Knowl Inform Syst. 2022;64(4):885–917. doi:10.1007/s10115-022-01664-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen S, Shen C, Zhang L, Tang Y. Dynamic aggregation for heterogeneous quantization in federated learning. IEEE Transact Wireless Communicat. 2021;20(10):6804–19. doi:10.1109/twc.2021.3076613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kang J, Xiong Z, Niyato D, Xie S, Zhang J. Incentive mechanism for reliable federated learning: a joint optimization approach to combining reputation and contract theory. IEEE Inter Things J. 2019;6(6):10700–14. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2940820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. He C, Shah A, Tang Z, Sivashunmugam D, Bhogaraju K, Shimpi M, et al. Fedcv: a federated learning framework for diverse computer vision tasks. arXiv 2111.11066. 2021. [Google Scholar]

37. Jayaram KR, Muthusamy V, Thomas G, Verma A, Purcell M. Adaptive aggregation for federated learning. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 180–5. [Google Scholar]

38. Wang J, Liu Q, Liang H, Joshi G, Poor HV. Tackling the objective inconsistency problem in heterogeneous federated optimization. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2020;33:7611–23. [Google Scholar]

39. Reddi S, Charles Z, Zaheer M, Garrett Z, Rush K, Konečný J, et al. Adaptive federated optimization. arXiv:2003.00295. 2020. [Google Scholar]

40. Tan A, Yu H, Cui L, Yang Q. Towards personalized federated learning. IEEE Transact Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;34(12):9587–603. [Google Scholar]

41. Arivazhagan M, Aggarwal V, Singh AK, Choudhary S. Federated learning with personalization layers. arXiv:1912.00818. 2019. [Google Scholar]

42. Smith V, Chiang C-K, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar AS. Federated multi-task learning. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017:30. [Google Scholar]

43. Yang S, Hou M, Li S. Three-dimensional point cloud semantic segmentation for cultural heritage: a comprehensive review. Remote Sens. 2023;15(3):548. doi:10.3390/rs15030548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Huang W, Ye M, Shi Z, Wan G, Li H, Du B, Yang Q. Federated learning for generalization, robustness, fairness: a survey and benchmark. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(12):9387–9406. doi:10.1109/tpami.2024.3418862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Guo Y, Wang H, Hu Q, Liu H, Liu L, Bennamoun M, et al. Deep learning for 3D point clouds: a survey. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;43(12):4338–64. doi:10.1109/tpami.2020.3005434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Maturana D, Scherer S. Voxnet: a 3D convolutional neural network for real-time object recognition. In: 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 922–8. [Google Scholar]

47. Wu Z, Song S, Khosla A, Yu F, Zhang L, Tang X, et al. 3D shapenets: a deep representation for volumetric shapes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2015 Jun 11–15; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 1912–20. [Google Scholar]

48. Bello SA, Yu S, Wang C, Adam JM, Li J. Deep learning on 3D point clouds. Remote Sens. 2020;12(11):1729. doi:10.3390/rs12111729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang J, Zhao X, Chen Z, Lu Z. A review of deep learning-based semantic segmentation for point cloud. IEEE Access. 2019;7:179118–33. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2958671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Qi CR, Su H, Mo K, Guibas LJ. Pointnet: deep learning on point sets for 3D classification and segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 652–60. [Google Scholar]

51. Wang Y, Sun Y, Liu Z, Sarma SE, Bronstein MM, Solomon JM. Dynamic graph cnn for learning on point clouds. ACM Transact Graph. 2019;38(5):1–12. doi:10.1145/3326362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang R, Wu Y, Jin W, Meng X. Deep-learning-based point cloud semantic segmentation: a survey. Electronics. 2023;12(17):3642. doi:10.3390/electronics12173642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wu Z, Pan S, Chen F, Long G, Zhang C, Philip SY, et al. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Transact Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2020;32(1):4–24. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2020.2978386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Mucherino A, Papajorgji PJ, Pardalos PM. K-nearest neighbor classification. In: data mining in agriculture. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 83–106. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-88615-2_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Paul S, Patterson Z, Bouguila N. DualMLP: a two-stream fusion model for 3D point cloud classification. Visual Comput. 2024;40(8):5435–49. doi:10.1007/s00371-023-03114-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Stich SU. Local SGD converges fast and communicates little. arXiv:1805.09767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

57. Klokov R, Lempitsky V. Escape from cells: deep kd-networks for the recognition of 3D point cloud models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 863–72. [Google Scholar]

58. Le T, Duan Y. Pointgrid: a deep network for 3D shape understanding. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 9204–14. [Google Scholar]

59. Wei M, Wei Z, Zhou H, Hu F, Si H, Chen Z, et al. AGConv: adaptive graph convolution on 3D point clouds. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(8):9374–92. doi:10.1109/tpami.2023.3238516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Qian G, Li Y, Peng H, Mai J, Hammoud H, Elhoseiny M, et al. Pointnext: revisiting pointnet++ with improved training and scaling strategies. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2022;35:23192–204. [Google Scholar]

61. Choe J, Park C, Rameau F, Park J, Kweon IS. Pointmixer: mlp-mixer for point cloud understanding. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2022. p. 620–40. [Google Scholar]

62. Zheng S, Pan J, Lu C, Gupta G. Pointnorm: dual normalization is all you need for point cloud analysis. In: 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools