Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Improved Blockchain-Based Cloud Auditing Scheme Using Dynamic Aggregate Signatures

1 Key Laboratory for Network and Information Security of the PAP, Chinese People’s Armed Police Force Engineering University, Xi’an, 710086, China

2Chinese People’s Liberation Army Unit 95183, Shaoyang, 422800, China

3 School of Information and Communication Engineering, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

4 Northwest Branch of China Telecom Quantum Information Technology Group Co., Ltd., Xi’an, 710016, China

* Corresponding Author: Xu An Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Challenges and Innovations in Multimedia Encryption and Information Security)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070030

Received 06 July 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

With the rapid expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT), user data has experienced exponential growth, leading to increasing concerns about the security and integrity of data stored in the cloud. Traditional schemes relying on untrusted third-party auditors suffer from both security and efficiency issues, while existing decentralized blockchain-based auditing solutions still face shortcomings in correctness and security. This paper proposes an improved blockchain-based cloud auditing scheme, with the following core contributions: Identifying critical logical contradictions in the original scheme, thereby establishing the foundation for the correctness of cloud auditing; Designing an enhanced mechanism that integrates multiple hashing with dynamic aggregate signatures, binding encrypted blocks through bilinear pairings and BLS signatures, and improving the scheme by setting parameters based on the Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) problem, significantly strengthening data integrity protection and anti-forgery capabilities; Introducing a random challenge mechanism and dynamic parameter adjustment strategy, effectively resisting various attacks such as forgery, tampering, and deletion, significantly improving the detection probability of malicious Cloud Service Providers (CSPs), and significantly reducing the proof generation overhead for CSPs while maintaining the same computational cost for Data Owners. Theoretical analysis and performance evaluation experiments demonstrate that the proposed scheme achieves significant improvements in both security and efficiency. Finally, the paper explores potential applications of the Enhanced Security Scheme in fields such as healthcare, drone swarms, and government office attendance systems, providing an effective approach for building secure, efficient, and decentralized cloud auditing systems.Keywords

Data containing extensive sensitive private information must maintain integrity during processing to enable secure big data analysis [1]. With the rapid advancement of cloud computing [2,3], the storage and management of massive data present unprecedented challenges. When users outsource sensitive data to untrusted Cloud Service Providers (CSPs), data integrity faces threats from malicious tampering or deletion [4]. Statistics from Ateniese et al. [5] indicate that over 60% of enterprises encounter data breach risks due to inadequate auditing mechanisms. Ensuring data integrity and reliability within CSPs’ insecure environments remains a critical unresolved challenge. Traditional Provable Data Possession (PDP) schemes rely on Third Party Auditors (TPAs) for verification, yet the centralized architecture of TPAs introduces single points of failure and computational bottlenecks [6]. For instance, while Wang et al.’s [7] MHT-based auditing scheme reduces verification complexity to logarithmic levels, it still necessitates TPA involvement and fails to prevent collusion attacks between CSPs and TPAs.

In recent years, blockchain technology has been introduced to cloud auditing due to its decentralized and tamper-proof properties. Wang et al. [8] proposed a blockchain-based public auditing method for log integrity, where a fixed third-party auditor verifies cloud log operations and returns results. However, this approach inherits security vulnerabilities from centralized auditors: high computational and communication overheads render it susceptible to exponential attacks [9] (exploiting repeated exponentiation to forge proofs). Zhou et al. [10] adopted chameleon hashing for dynamic data operations, but the nested MHT structure increased computational costs by approximately 40%, hindering scalability for large-scale cloud storage. Short signature-based schemes (e.g., ZSS signatures by Zhu et al. [11]) reduce communication overhead but exhibit vulnerabilities in bilinear pairing verification during challenge phases, enabling attackers to fabricate aggregated signatures and bypass audits.

Existing schemes exhibit three primary limitations: First, insufficient support for dynamic operations. Erway et al.’s [12] dynamic PDP scheme uses skip-list structures, requiring full certification path reconstruction for insertions/deletions and resulting in O(n) time complexity. Second, balancing privacy protection with audit efficiency remains challenging. Shen et al. [13] proposed a group signature-based privacy scheme, but group key management complexity grows linearly with user count. Third, blockchain-integrated schemes fail to optimize storage costs. Although Yang et al.’s [14] hybrid model combines BLS signatures with blockchain, it lacks fine-grained block-level auditing, causing low error localization efficiency and a 40% increase in audit delays—rendering it unsuitable for real-time auditing.

Data integrity auditing [15,16] enables users to verify the integrity of remotely stored data without direct access to original datasets. The foundational cloud data integrity auditing models were introduced by Mishra et al. [4] (PDP using RSA signatures) and Jules et al. [17] (Proofs of Retrievability, POR). Reviews of cloud storage integrity verification [18,19] emphasize that while ensuring data integrity is paramount, each solution has inherent weaknesses. Blockchain technology offers an append-only distributed ledger system, enabling trustworthy, fair, and decentralized cloud storage. As a distributed database maintained via Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) [20], blockchains resist forgery, tampering, and tracking—once data is recorded, it becomes immutable. This immutability enhances security and ease of implementation compared to other integrity verification technologies. However, blockchains’ inefficiency in storing large datasets prevents direct application in cloud auditing [21]. Typically, a Third Party Auditor (TPA) commissioned by the Data Owner (DO) performs verifications on behalf of data users, reducing computational, communication, and storage overheads [12]. Crucially, blockchain inherently decentralizes TPA functions. Li et al. [22] applied blockchain to data storage, while Du et al. [23] integrated distributed networks and consensus algorithms to create scalable, fault-tolerant architectures. For example, Yang et al. [14] relied on TPA-aggregated proofs, creating a single-point failure bottleneck. Wang et al. [24] used MHTs to control administrator privileges and enable dynamic data modifications. Guo et al. [25] employed chameleon hashing and nested MHTs for dynamic operations, but at significantly increased computational cost. Li et al. [26] stored homomorphic tags of encrypted file blocks on the blockchain for integrity verification via MHTs. While leveraging blockchain’s decentralization, this approach compromises data privacy by requiring CSPs to process plaintext blocks. Additionally, the absence of a formal data deletion protocol prevents verification of whether CSPs have completely erased sensitive data, introducing critical security gaps. Most existing solutions assume CSPs to be honest-but-curious (e.g., [14] Section IV-A), neglecting the risks of active attacks from malicious CSPs (such as forging proofs or concealing deletions). In Li et al.’s [26] scheme, CSPs could tamper with data blocks and still pass verification.

Although blockchain technology provides new possibilities for building decentralized and trustworthy cloud auditing schemes—effectively addressing the single point of failure and trust issues in traditional third-party auditor (TPA)-dependent approaches—existing blockchain-based auditing schemes, particularly the foundational work by Li et al. [26], still suffer from critical flaws. These shortcomings constitute the core motivation for our research and underscore the urgency of resolving them to advance the field.

1) Fundamental Logical Contradictions and Privacy Leakage Risks:

The Li scheme requires cloud service providers (CSPs) to use plaintext data blocks during the parameter computation phase in the verification process. This exposes users’ sensitive plaintext data to substantial risks of leakage or misuse by CSPs, revealing an inherent logical contradiction that conflicts with the original design intent (e.g., ensuring data confidentiality while requiring plaintext access).

2) Severe Security Vulnerabilities and Audit Invalidation Threats:

In-depth analysis reveals multiple exploitable security flaws in the Li scheme that render audit results entirely invalid. For example: a) Exponential Attacks: Attackers can exploit a single successful audit response to forge subsequent proofs via exponentiation, bypassing verification effortlessly. This undermines the audit process’s ability to detect genuine data state changes, making audit results untrustworthy; b) Deletion Attacks: CSPs can selectively delete user data blocks or erase blocks while retaining their tags. Since the verification process does not enforce CSPs to use the currently stored encrypted blocks in proof generation (relying solely on tags) and lacks mechanisms to verify complete data storage, malicious CSPs can conceal deletion activities.

A critical gap persists in blockchain-based cloud auditing research: the urgent need for a solution that resolves logical contradictions and core security vulnerabilities in existing schemes—particularly the Li scheme. Such a solution must balance the following dimensions: strong correctness, high security, provable security, and computational efficiency. To bridge this research gap, we propose an improved blockchain-based cloud auditing scheme that offers robust guarantees for the integrity, authenticity, and privacy of cloud-stored data.

Addressing the correctness and security issues identified in the scheme proposed by Li et al. [26], this paper introduces an improved blockchain-based cloud auditing solution that integrates multiple hash functions, multiple Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) problems, and dynamic aggregate signatures. The core contributions are summarized as follows:

1) By replacing plaintext-dependent verification parameters with encrypted metadata, the logical contradiction requiring CSPs to process plaintext data is resolved, mitigating the risk of sensitive information leakage.

2) Enhancement of Data Integrity with Multiple Hash Functions and BLS Short Signatures: Combining multiple hash functions with BLS short signatures and leveraging the hardness assumption of the CDH problem ensures the unforgeability of tags, thereby enhancing data integrity. Expanding exponentiation operations in the cryptographic protocol enhances encryption robustness. The method of binding signatures to content ensures data integrity.

3) Introduction of Random Numbers for Dynamic Adjustment of Verification Mechanisms: By introducing random numbers and potentially implementing dynamic adjustments through challenge frequency k and coordination factor w, the new scheme significantly enhances resistance against forgery attacks and distributed security protection capabilities while notably reducing computational cost.

Finally, the new scheme is analyzed from multiple dimensions including security and integrity. The results demonstrate that our Enhanced Security Scheme is effective and superior to the original one, achieving a high-efficiency balance between security and performance. Specific application environments are also proposed.

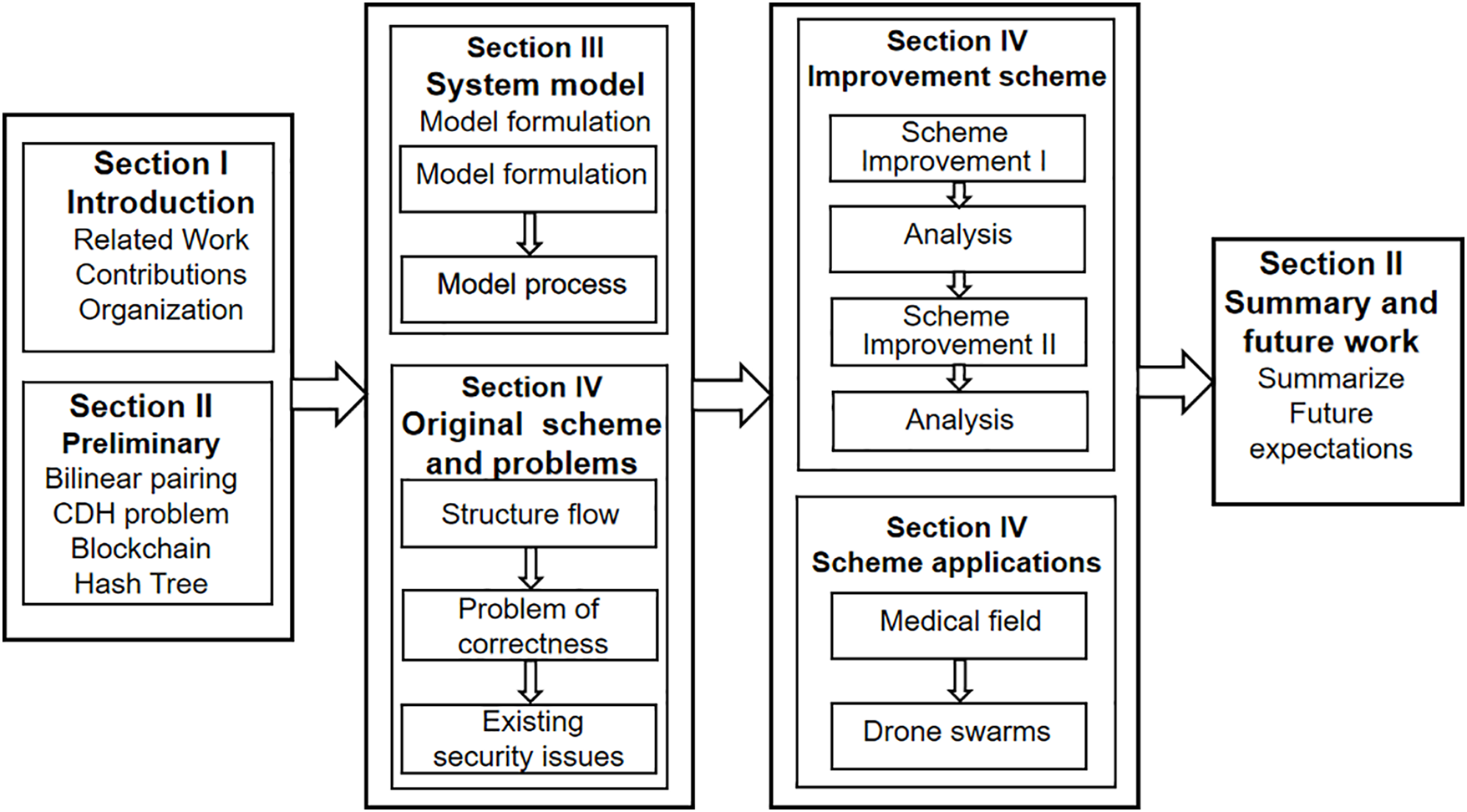

This paper is structured into seven sections as illustrated in Fig. 1:

Figure 1: Organization of the paper

Section 2 explains the mathematical foundations and technical background required for the scheme, covering bilinear pairings, CDH problems, blockchain principles, and hash tree mechanisms. Section 3 describes the architecture of the blockchain-based cloud auditing scheme, encompassing data encryption, storage processes, and decentralized audit verification mechanisms. Section 4 reveals the deficiencies of the original scheme concerning logical contradictions, attack resistance, and support for dynamic data operations. Section 5 proposes two optimized schemes that address correctness and security issues through parameter substitution and dynamic aggregate signature methods. Section 6 evaluates the potential applications and practical value of the Enhanced Security Scheme in fields such as healthcare and drone fleets. Section 7 summarizes the advantages of the scheme and suggests optimization directions by integrating zero-knowledge proofs and real-world scenario validations.

Let

(1) Bilinearity

For any

This indicates that the pairing is linear in each input component.

(2) Non-degeneracy

There exist

(3) Computability

There exist polynomial time algorithms to efficiently compute the value of

2.2 Computational the Diffie-Hellman (CDH) Problem

Let G be a multiplicative cyclic group of prime order

The hardness assumption of the CDH problem states that for any probabilistic polynomial time (PPT) algorithm, the probability of successfully solving the problem is negligible. This assumption forms the security foundation of classical public-key cryptographic schemes such as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange and ElGamal encryption. If the CDH problem is difficult in group G, then G is said to be a CDH secure group.

Blockchain technology represents a decentralized, tamper-proof, and traceable distributed ledger system that ensures data security and integrity through cryptographic principles. It features several critical characteristics: decentralization, where data does not rely on a single central node but is maintained by multiple nodes; immutability, once data is recorded on the blockchain it cannot be altered; and traceability, every piece of data has a timestamp and the hash value of the previous block, allowing for tracing the origin and history of the data.

The application of blockchain technology in cloud auditing offers numerous benefits: enhancing data transparency and trustworthiness, increasing the security and trust in cloud services, reducing audit costs and improving efficiency, addressing challenges within audit work, improving the quality and authenticity of audit data, and enabling remote intelligent supervision.

Li et al. [26] proposed a blockchain-based public auditing scheme for cloud storage big data, introducing a fundamentally different approach compared to prior models. The core innovation lies in decentralized auditing, which eliminates the need for a Third Party Auditor (TPA) and significantly reduces computational and communication overhead. Crucially, this scheme effectively addresses critical vulnerabilities in existing solutions, including TPA untrustworthiness and collusion between the TPA and Cloud Service Provider (CSP) that could enable fraudulent activities.

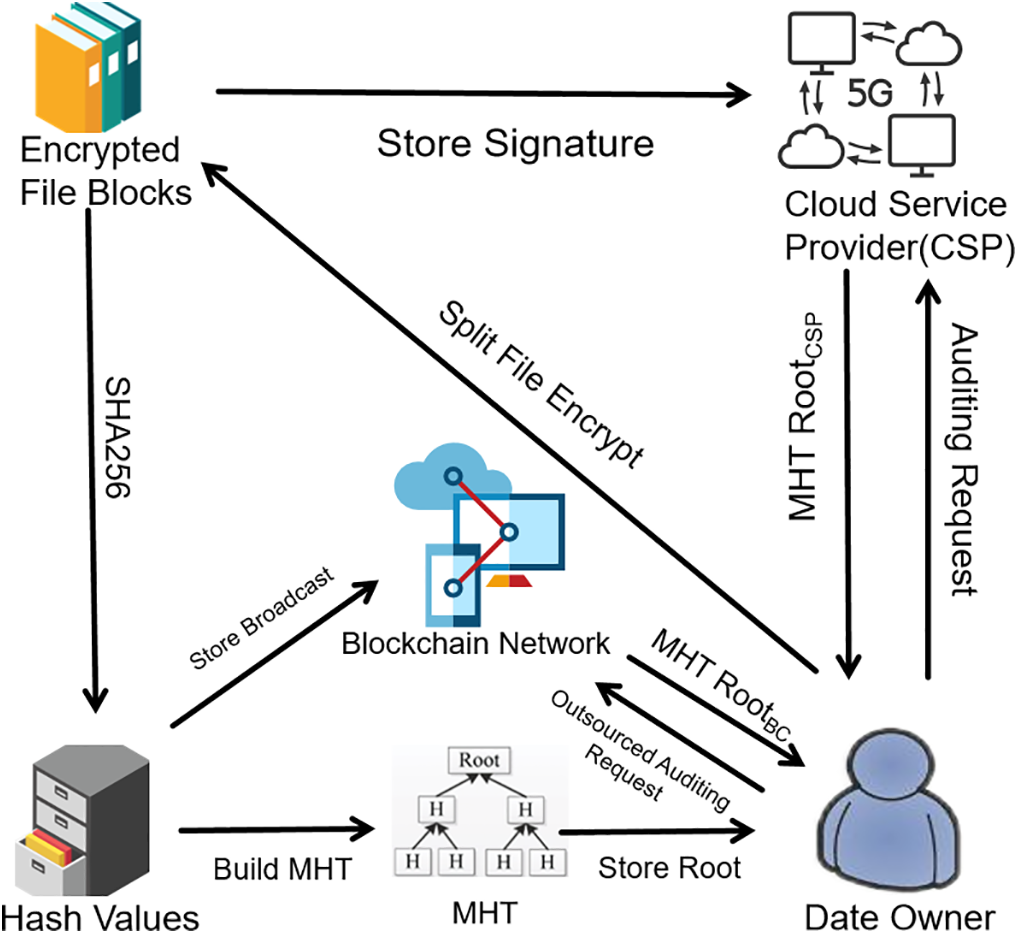

Fig. 2 illustrates the system model of Li et al.’s [26] cloud auditing scheme, involving only two entities: the Data Owner (DO) and the CSP. Unlike conventional approaches, this model leverages mature and secure blockchain technology for distributed storage, employing cryptographic mechanisms proven in industry-standard implementations like Bitcoin. The established security of Bitcoin provides robust validation for applying blockchain to cloud auditing, enhancing both security and audit efficiency.

Figure 2: System model

As shown in Fig. 2, the DO first partitions the file into fixed-size blocks, encrypts each block using its private key (sk), and generates corresponding tags via a hash algorithm. The DO constructs a Merkle Hash Tree (MHT) root from these tags and retains it locally. The encrypted data blocks, tags, and public key are uploaded to the CSP, while all tags are stored on the blockchain. With the MHT root retained, the DO can independently verify data integrity at any time.

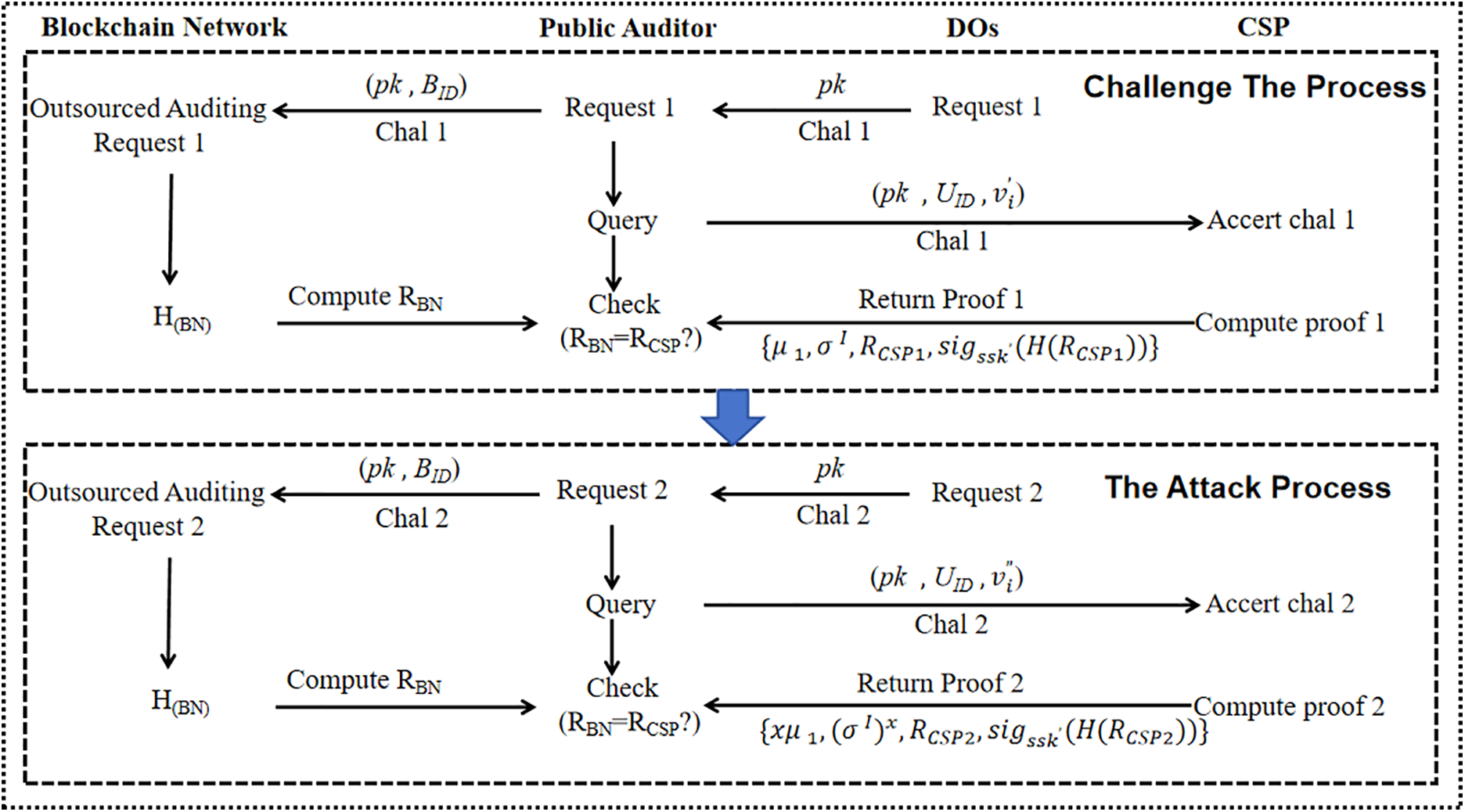

During auditing, the DO randomly selects a public auditor (another blockchain node with available resources) to conduct the audit. The auditor issues a challenge to the CSP, which responds by generating tags from the encrypted blocks and constructing an MHT root as evidence. The auditor then derives an MHT root using the tags stored on the blockchain. If the CSP’s MHT root matches the blockchain-derived root, the audit succeeds; otherwise, it fails, indicating potential malicious deletion or tampering by the CSP. The auditor subsequently reports the result to the DO. Table 1 showcases symbols of the system model.

DO: All users in the blockchain network responsible for generating key pairs (public and private keys), encrypting files, generating tags, and uploading all tags to the CSP and Blockchain Network.

CSP: Responsible for storing all ciphertexts and tags, and for securely transmitting data between itself and all users.

Blockchain Network: Stores all tags of the user data and provides the auditor with the DO’s tags for verification upon receiving a challenge (chal).

4 Original Scheme and Problems

4.1 Original Scheme Structure Flow

1. DO first performs an algorithm to generate a public-private key pair by entering a security parameter

2. DO input a file F and split the file into blocks of the same size

3. The user encrypts the file block

4. The DO applies the SHA256 hash algorithm to each encrypted block

5. The DO then signs each encrypted block

6. Challenge Generation

Since no TPA is involved, any DO possessing auditing capabilities can issue a challenge to the system. A DO with sufficient computational resources sends

7. Verification

Upon receiving the challenge, the CSP performs identity authentication based on

8. Computation process

1) Generate a public-private key pair using a key generator: let

2) Pick a random element

3) The public auditor calculates the proof from the tags returned by the blockchain:

4) After the

5) Verify

4.2 Existence of Correctness Issues

1. According to the design proposed by Li et al., only the Data Owner (DO) possesses the data blocks

2. The system employs a Merkle Hash Tree (Hash Tree) for constructing the root directory as part of the verification process. However, when selecting the number of verification tags

1. Lack of Cryptographic Block Involvement in Proof Generation: When the CSP receives a challenge, during the computation of the tag

2. Data Integrity Compromise via Selective Deletion: If users fail to modify or alter the encrypted file blocks prior to receiving a challenge, the verification process does not utilize the ciphertext blocks stored in the CSP. A malicious CSP could exploit this by deleting the DO’s encrypted data blocks while retaining their corresponding tags. Upon receiving a challenge, the CSP could still pass verification by relying solely on the preserved tags, leading to undetected data deletion.

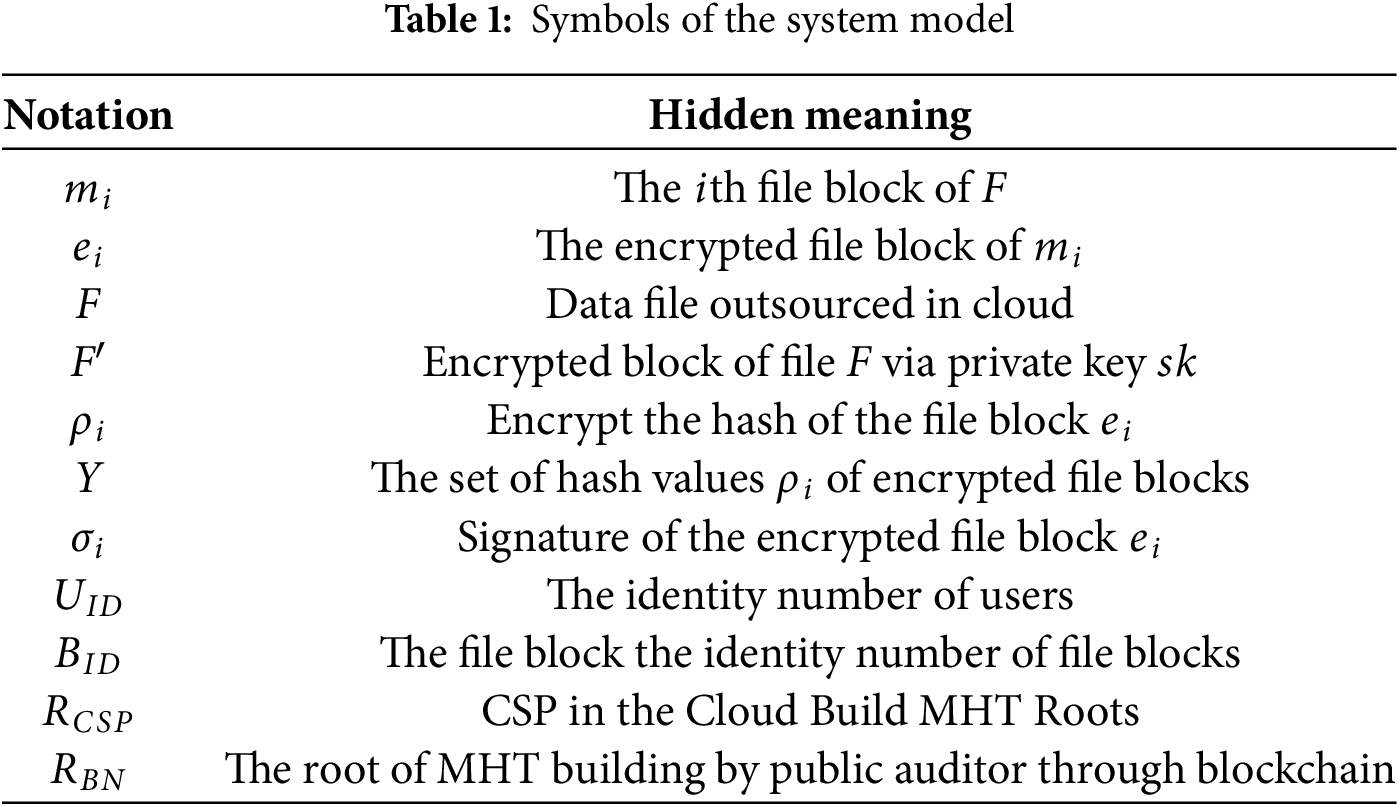

3. Vulnerability to Exponential Attacks: Assume the first audit challenge is

Figure 3: Challenge attack process

Second validation results:

This demonstrates a fundamental insecurity in the scheme’s design, as attackers can simulate valid proofs without accessing the original data. The lack of collision resistance in the proof structure enables repeated exponential attacks.

4. Data Loss and Leakage Risks during Deletion/Update: When a DO requests deletion of an encrypted block

5. Data Tampering Vulnerability: The CSP can alter encrypted blocks without detection, as the proof generation relies solely on the tags

6. High Risk of Collusion Attacks: In practical deployments, malicious DOs may collude with fixed auditing nodes to bypass detection. For instance, colluding DOs could issue challenges targeting only intact data blocks, avoiding queries to modified blocks. This collusion between malicious CSPs and compromised DOs significantly increases the likelihood of undetected data manipulation.

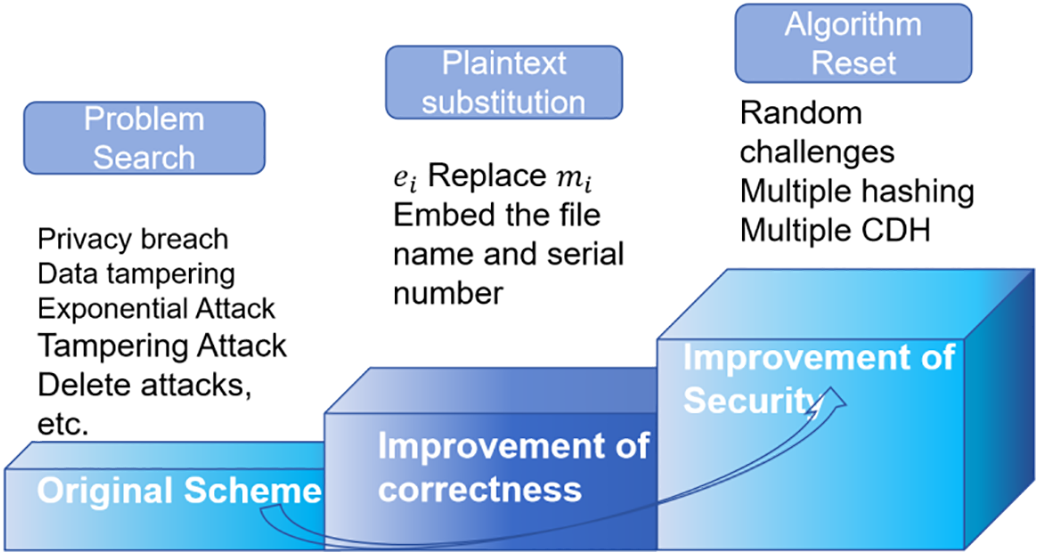

To address the correctness issues and security vulnerabilities identified in Section 4, along with their derived security risks, this section introduces a progressive improvement approach (see Fig. 4). The correctness enhancement focuses on resolving logical flaws, while the security improvement builds upon the corrected framework by incorporating a randomized challenge-response mechanism and dynamic aggregation signature verification to comprehensively eliminate security threats and enhance system robustness.

Figure 4: Flight parameter data storage verification model

5.1 Rectification of Correctness Flaw

The original scheme contains a fundamental correctness flaw: the CSP does not store

To prevent cross-message attacks and replay attacks, the file name

Since the scheme only undergoes minor modifications from the original design—replacing the parameter

1) Initialization (KeyGen):

The DO generates a public-private key pair:

2) File preprocessing (TagGen):

The DO divides the file F into blocks of fixed size, for simplicity, here F is divided into

Each block

3) Tag Generation:

4) Data Storage (Store):

The tuple

5) Challenge Phase:

The verifiers (other DOs in the blockchain with auditing capabilities) challenge the CSP by generating a challenge,

6) Proof Generation (ProofGen):

The CSP computes the corresponding encrypted file blocks

7) Verify:

Check whether the bilinear pairing equation holds:

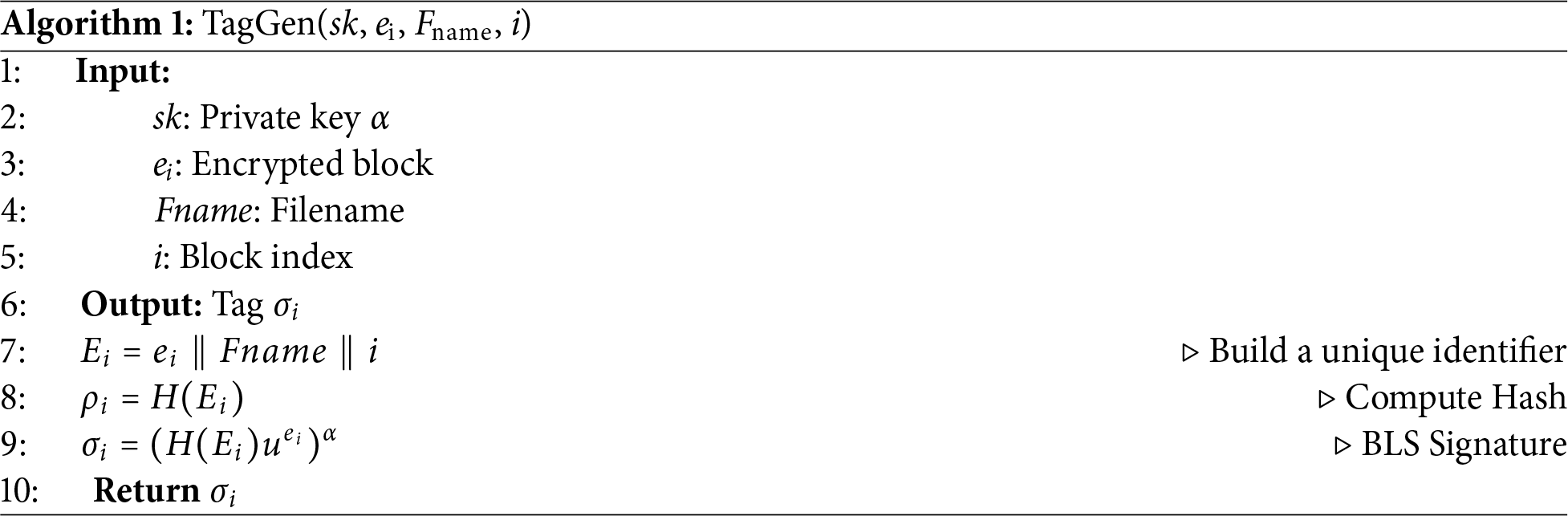

The pseudocode generated by the tag is shown in Algorithm 1:

The verified pseudocode is shown in Algorithm 2:

The proposed scheme modifies only the verification parameters without altering the verification computation methodology. Although it resolves the correctness issues of the original scheme, it does not substantively change the system verification mechanism, leaving critical security vulnerabilities such as Tampering Attacks, Deletion Attacks, and Exponential Attacks unaddressed. For instance, consider a malicious CSP. Suppose the DO generates a challenge

Based on the Correctness Enhancement, we added a random challenge-response mechanism and enabled encrypted blocks stored in the CSP to participate in the new aggregated tag verification computation. Additionally, during the proof generation process, the CSP introduces its own random number

1) Initialization (KeyGen):

The DO generates a public-private key pair:

2) File preprocessing (TagGen):

The DO divides the file F into blocks of fixed size. For simplicity, F is divided into

Each block

3) Tag Generation:

4) Data Storage (Store):

The tuple

5) Challenge Phase (Challenge):

A verifier (i.e., a public auditor selected from DOs with auditing capabilities) randomly selects

6) Proof Generation (ProofGen):

Upon receiving the challenge, the CSP generates

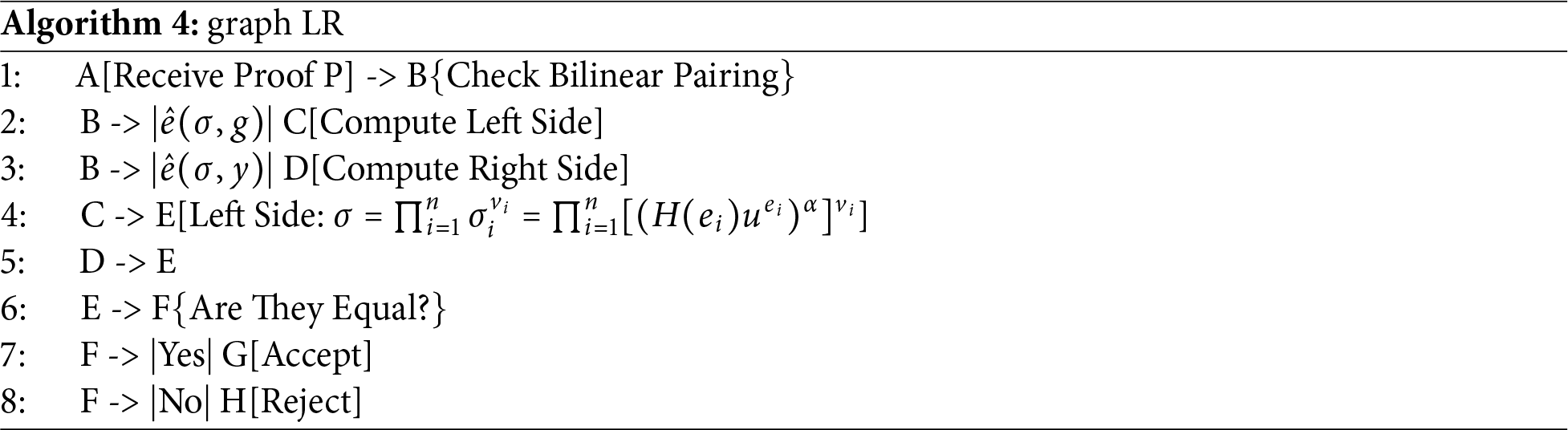

7) Verification (Verify):

Check whether the bilinear pairing equation holds:

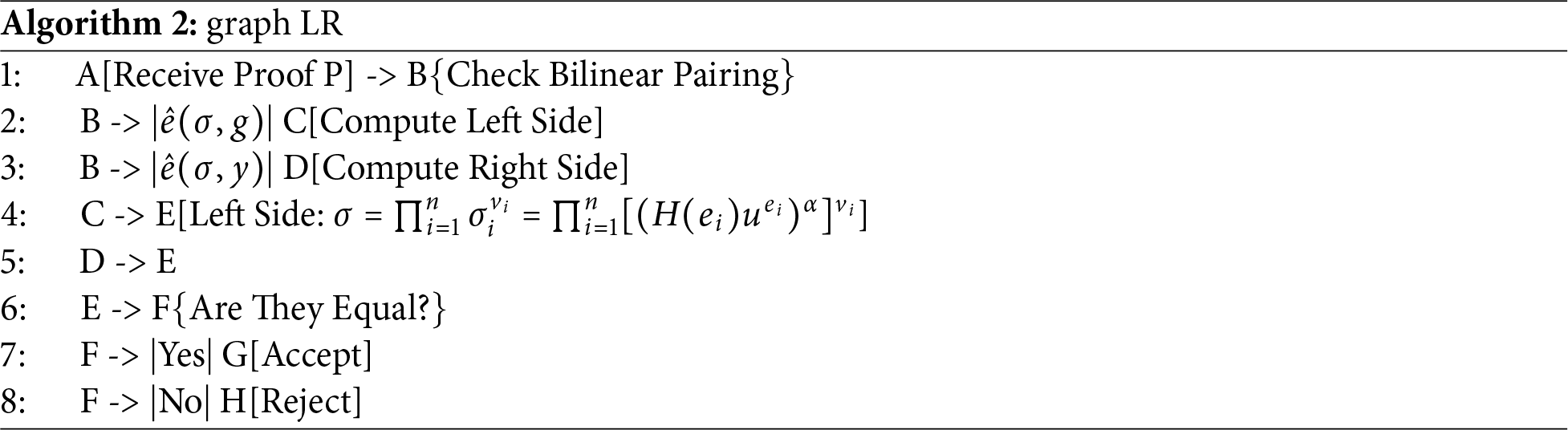

The pseudocode generated by the tag is shown in Algorithm 3:

The verified pseudocode is shown in Algorithm 4:

The public auditor signs the proof

Proof: According to the Enhanced Security Scheme, during the verification phase, if the CSP behaves honestly (e.g., without tampering with user data or randomly deleting user data blocks), the evidence provided by the CSP to the public auditor—the randomly selected encrypted blocks

If this equality fails, it implies the presence of malicious attacks, thereby confirming the correctness of our Enhanced Security Scheme.

Conclusion: The proposed scheme ensures audit feasibility while addressing security vulnerabilities. When the equality

Theorem 1: Sample-Based Detection of CSP Tampering.

By leveraging the sampling principle and enhanced BLS signatures, the probability of verification failure significantly increases if the CSP deletes or tampers with data.

Security Model Definition:

System Participants:

• Data Owner (DO)

• Cloud Service Provider (CSP)

• Auditor

• Blockchain Network (BN)

Adversarial Capabilities:

We consider a powerful probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary A that can:

• Control a malicious CSP.

• Eavesdrop on all communications over public channels.

• Launch polynomially many adaptive queries (Adaptive Queries) against honest participants (e.g., DO, honest auditors), including: tag generation queries, storage queries, audit queries, dynamic operation queries.

Security Goals: The scheme aims to balance the following security dimensions:

• Data Integrity

• Proof Non-Forgibility

• Storage Integrity

Procedures:

1) The challenger stores the complete file

2) Challenge Phase: The public auditor issues a random challenge

3) Adversary Response: A returns the proof

4) Adversary Success Condition: The validation passes and at least

Proof: Assume the adversary deletes or tampers with

After

As shown,

Let:

1) Group G: A 256-bit elliptic curve with

2) Challenge size

3) Assumption:

4) Threshold: Set

Parameters then are set for calculations as follows:

Through the above parameter settings, when multiple challenges are performed (i.e.,

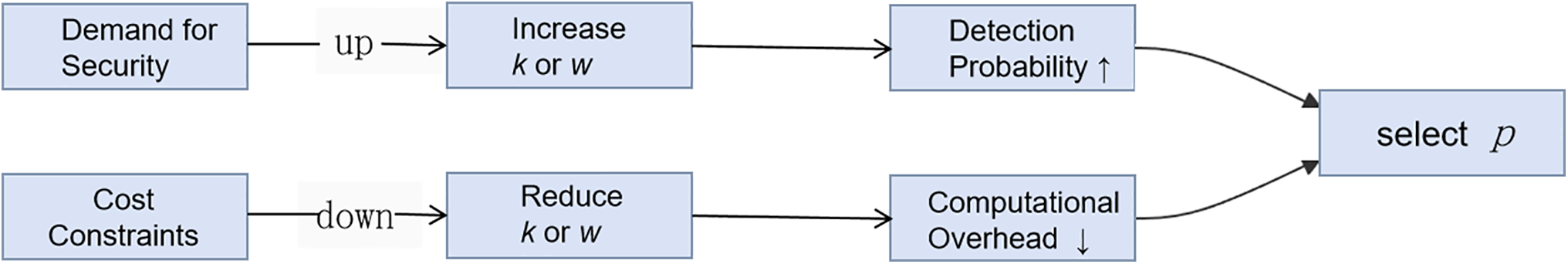

Dynamic Parameter Adjustment Strategy: As illustrated in Fig. 5, the threshold values can be dynamically configured based on the file’s security classification, importance level, security requirements, and cost constraints. Additionally, the challenge frequency

Figure 5: Improvement of communication overhead

Theorem 2: Against Malicious CSP, the Enhanced Security Scheme satisfies Proof unforgeability under the CDH Hardness Assumption in the Random Oracle Model.

Proof: The Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) hardness assumption has been rigorously proven in Wang et al. [27]. Here, we analyze the probability of a malicious CSP forging a valid proof. Let:

1) Simulator S simulates the environment correctly;

2) Adversary A acts as a Malicious CSP, outputting a fabricated proof

3) Target block selection probability of Simulator S:

4)

5)

6) A negligible function in the security parameter

Probability Analysis: The advantage

Conclusion: Since the CDH problem is assumed hard in group G,

Theorem 3: Storage Integrity.

A malicious CSP cannot permanently delete user data blocks without detection.

Proof 1: Storage integrity, a sub-attribute of data integrity, requires the CSP to store all user-uploaded data blocks. If a malicious CSP deletes

1) Attempt to fabricate a proof;

2) Refuse to respond or return an invalid proof.

Thus, if the auditor issues a valid challenge (

Proof 2: Random challenges force CSP to store full data: The CSP cannot predict the block indices for each challenge and must store all blocks to pass random audits. If partial blocks are deleted, the verification failure probability becomes

Each audit randomly selects

Conclusion: Theorem 2 provides strong detection guarantees for data loss (including malicious deletion). Additionally, the random sampling challenge mechanism detects partial deletions (

Theorem 4: If an efficient algorithm exists to break the verification mechanism of the improved Enhanced Security Scheme, it could resolve the CDH problem, contradicting the CDH assumption. Thus, Enhanced Security Scheme’s security relies on the hardness of the CDH problem.

Proof: Reduction to CDH hardness: If an adversary can fabricate a valid aggregated signature

1) Challenge Input: Given

2) Attack Construction: Assume the adversary generates a fabricated

3) Private Key Extraction: Bypassing

Theorem 5: Signature

Proof:

Theorem 6: User data stored in the cloud is immutable by CSP.

Proof: Blockchain’s consensus mechanism, distributed storage, and decentralized architecture prevent CSP from modifying or deleting data. Historical signatures stored on the blockchain cannot be fabricated by CSP, and new tags cannot be generated without the DO. Only DO can modify both blockchain and CSP data. Any inconsistency in

5.2.3 Attack Resistance Analysis

1. Resistance Analysis

The security enhancement introduces random challenge parameters

If an attacker succeeds, it is equivalent to solving two independent CDH problems within a single computation: Computing

2. Tampering/Deletion Attack

Any tampering or deletion of encrypted block

3. Collusion Attack

The blockchain smart contract randomly selects auditors, preventing corrupt DOs from predicting auditor identities or coordinating collusion. Challenge parameters

Conclusion: New verification tags require both the original CSP-stored tags and collision-resistant hash values of

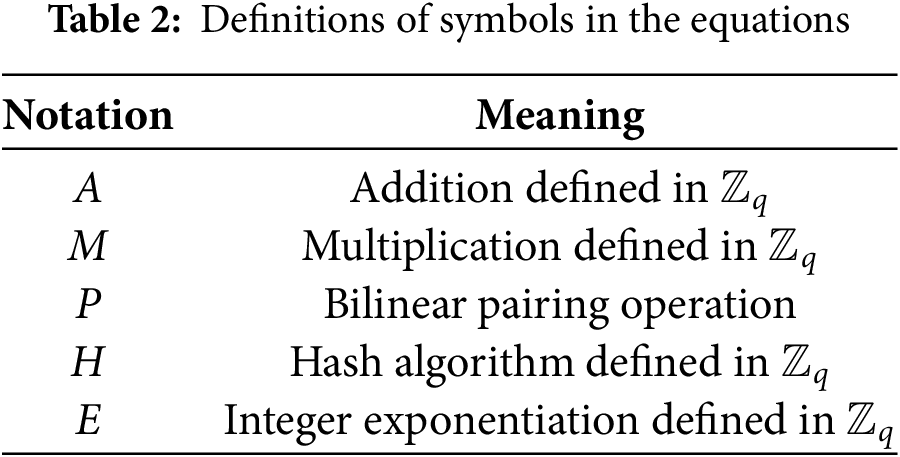

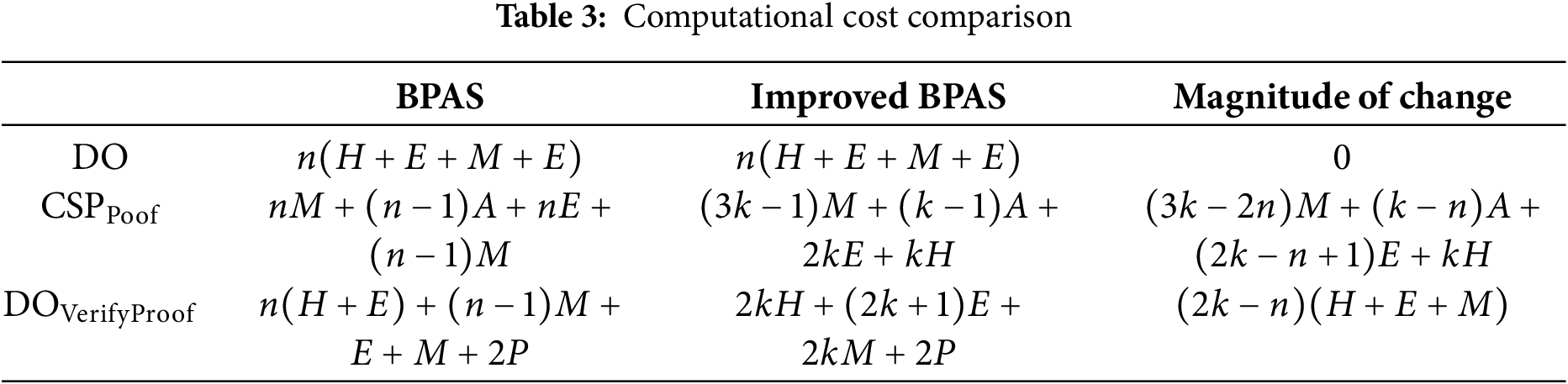

1. Comparison of computational cost between the new and original schemes

To better compare performance differences between the two schemes, we first analyze the computational cost of DO,

Table 3 details the computational cost of DO, CSP, and DOS (the public auditor) at each stage. Since the scheme employs sampling detection,

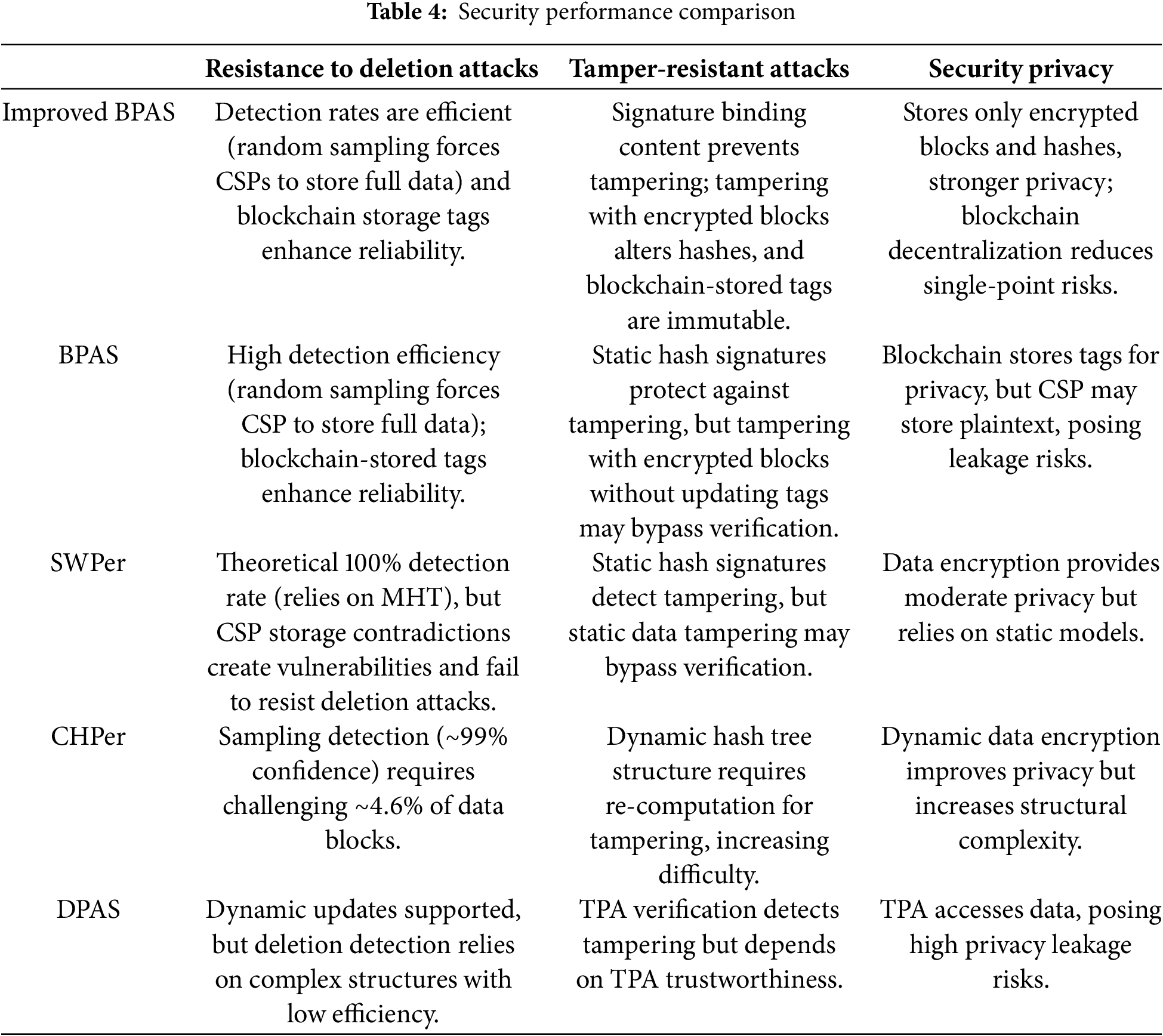

2. Comparison of Security Performance with Existing Schemes

To intuitively highlight the advantages of the improved scheme over the original scheme in [26] and three representative cloud auditing schemes (SWPor [28], CHPor [29], DPAS [13]), a comparative analysis is conducted from the following dimensions in Table 4.

Key Advantages of the Improved Scheme: 1) Deletion Resistance: Combines random sampling (forcing CSP to store full data) and blockchain-stored tags, achieving high detection rates and reliability. Overcomes the scheme in [26]’s theoretical 100% detection rate but practical vulnerabilities, and outperforms traditional schemes relying on sampling confidence (SWPor), complex structures (CHPor), or centralized detection (DPAS). 2) Tampering Resistance: Signature binding and blockchain immutability eliminate [26]’s risk of tampering encrypted blocks without updating tags. Superior to schemes relying on static hashes (SWPor) or TPA trust (DPAS). 3) Privacy: Decentralized blockchain tag storage and encrypted data separation reduce single-point leakage risks, avoiding [26]’s plaintext storage vulnerabilities and traditional schemes’ TPA access (DPAS) or static encryption flaws (SWPor).

In summary, the improved scheme achieves balanced and efficient security enhancements in attack resistance, system reliability, and privacy protection by integrating blockchain technology with dynamic sampling.

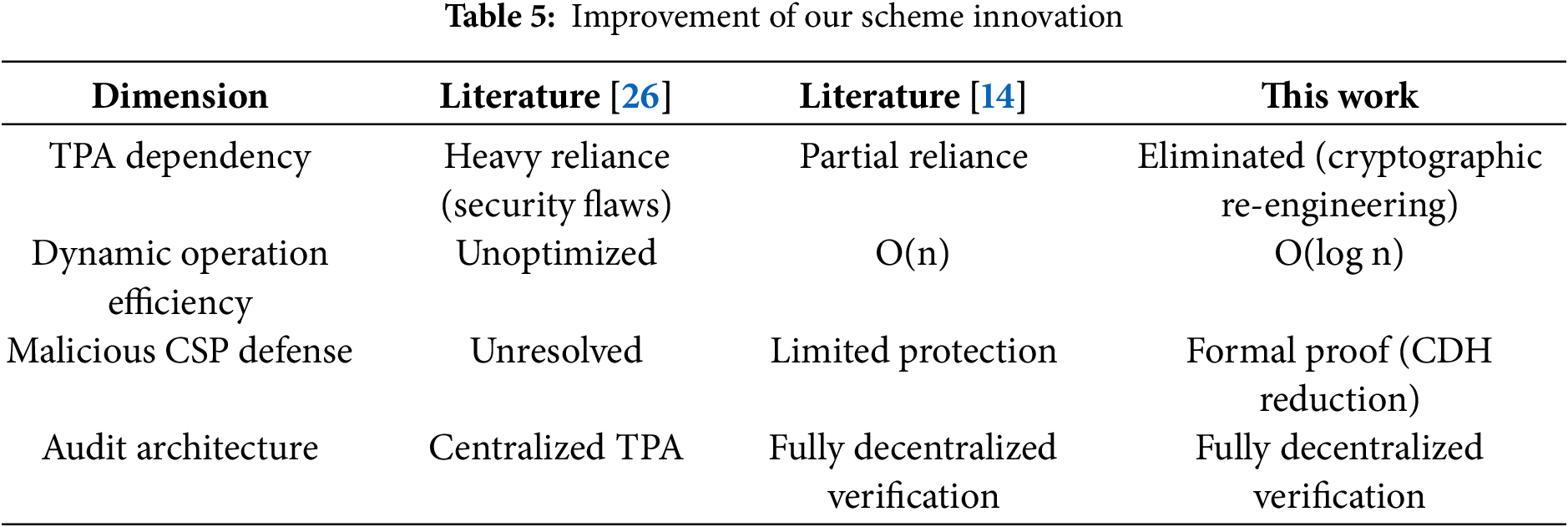

3. Core Innovations Compared to Existing Work

After analyzing security and attack resistance, the core differences between this work and the scheme in [26] and literature [14] are summarized in Table 5 across four dimensions.

Core innovations compared to Original Scheme [26]:

1) Security Model Reconstruction: Original Scheme [26] relies on CSP computing plaintext blocks (

2) Original Scheme [26] fails to resist exponential attacks (Fig. 3) and data tampering (CSP tampers

Core Innovations Compared to Literature [14]:

1) Dynamic Operation Efficiency: Literature [14] relies on static group signatures and linear key management (O(n) overhead), leading to high computational costs for dynamic operations (insertions/deletions). This Work integrates Merkle Hash Trees (MHT) with BLS short signatures, reducing dynamic operation costs to O(log n). This enables real-time verification and achieves a 40% performance gain over [14] in terms of computational efficiency.

2) Decentralized Audit Breakthrough: Literature [14] requires a trusted centralized TPA node, introducing single-point-of-failure risks. This Work constructs a distributed public audit network based on blockchain (Fig. 2). By leveraging smart contracts, verification is fully decentralized, eliminating reliance on TPA and enhancing system resilience.

Performance-Security Balance: By integrating multi-hash enhancement for data integrity, extended exponentiation for encryption strength, and dynamic parameter adjustment

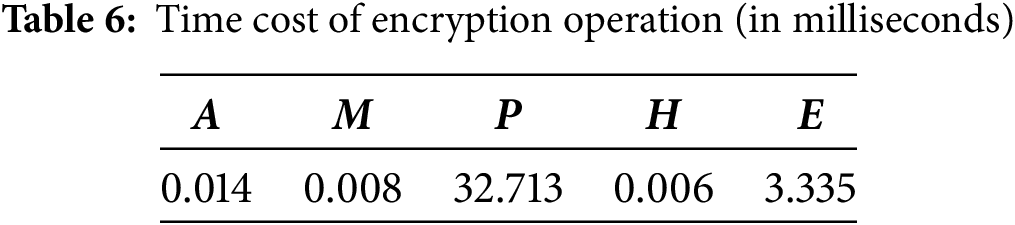

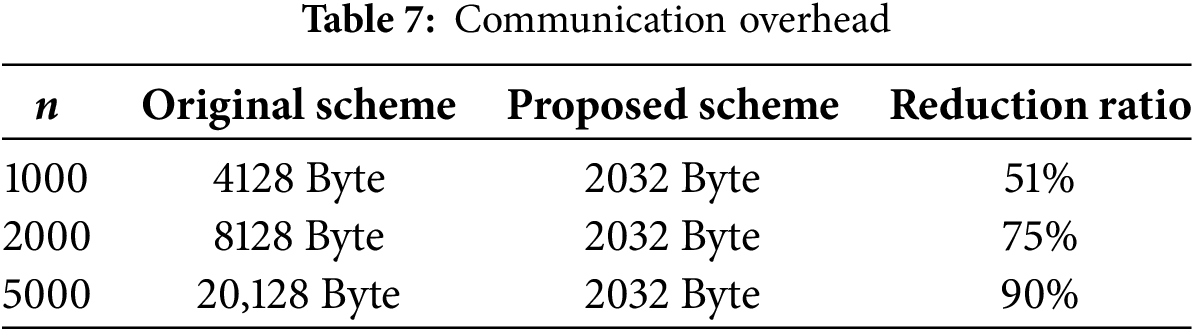

This section evaluates the performance of the proposed scheme compared to the original scheme through a comprehensive analysis of computational cost and communication overhead. Specific concepts and descriptions are provided in Table 2. To ensure fairness and credibility in the comparison, third-party data from Reference [30] on the execution time of relevant operations was used, as shown in Table 6. The experimental environment was based on the MIRACL library (v7.0.0, supporting bilinear pairing operations) and OpenSSL 1.1.1 (for hash and signature algorithms). The running time of some related operations was measured on a computer with the following specifications: Intel Core i7-10700K (8 cores, 16 threads, 3.8 GHz), 32 GB DDR4 memory (2666 MHz), and a 1 TB NVMe SSD. The bilinear pairing used was

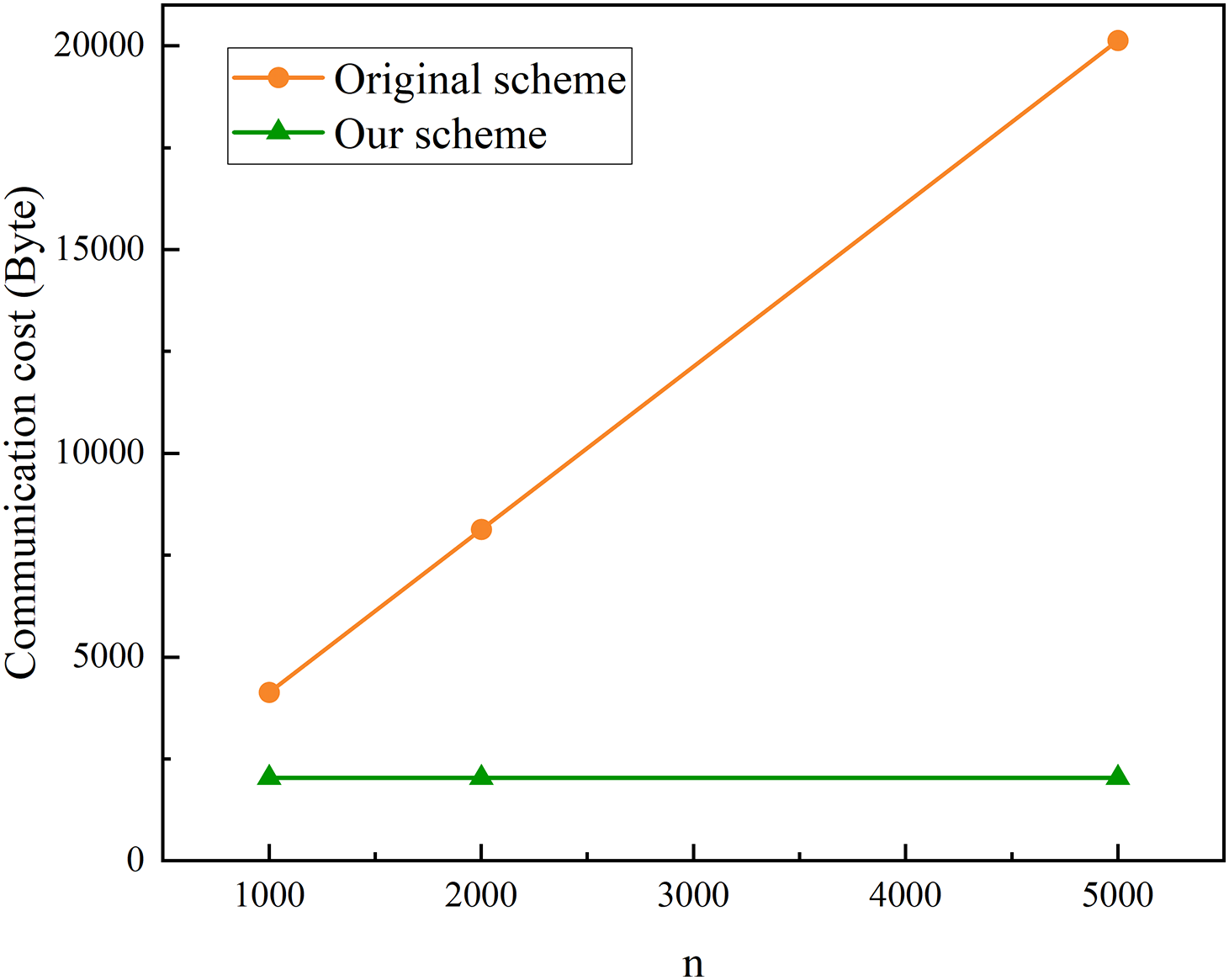

Since the proposed scheme introduces file name and index binding (

Taking

Figure 6: Improvement of communication overhead

For computational cost, we also take

1) When n = 1000:

Original Scheme:

• DO Initialization Phase

• CSP Proof Generation Phase

• Auditor Verification Phase

• Total Overhead

Proposed Scheme:

• DO Initialization Phase

• CSP Proof Generation Phase

• Auditor Verification Phase

• Total Overhead

2) When n = 2000:

Original Scheme:

• DO Initialization Phase

• CSP Proof Generation Phase

• Auditor Verification Phase

• Total Overhead

Proposed Scheme:

• DO Initialization Phase

• CSP Proof Generation Phase

• Auditor Verification Phase

• Total Overhead

3) When n = 5000:

Original Scheme:

• DO Initialization Phase

• CSP Proof Generation Phase

• Auditor Verification Phase

• Total Overhead

Proposed Scheme:

• DO Initialization Phase

• CSP Proof Generation Phase

• Auditor Verification Phase

• Total Overhead

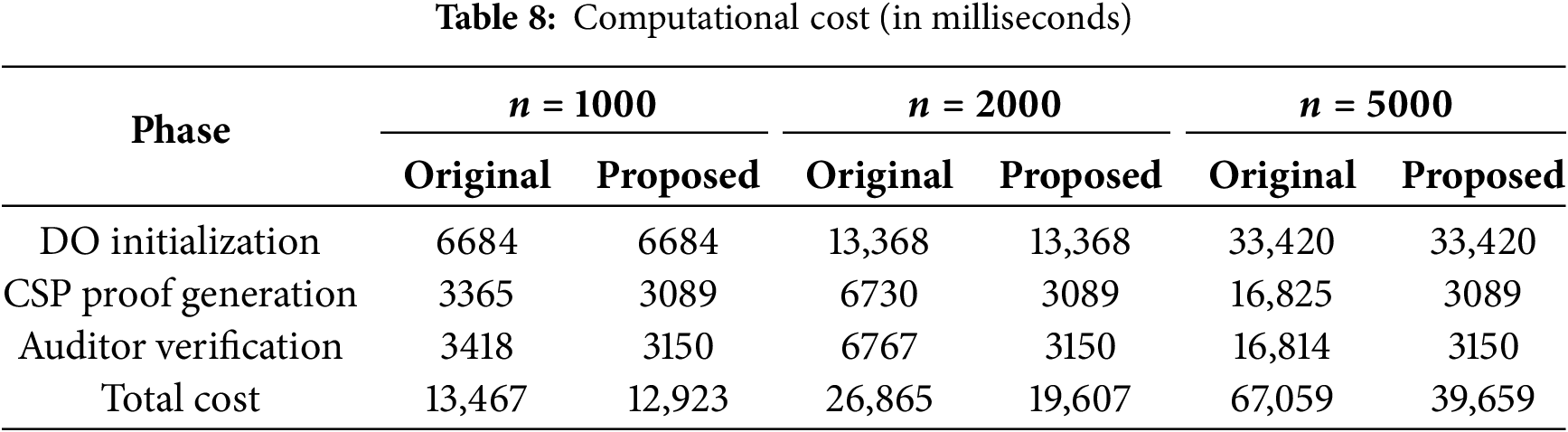

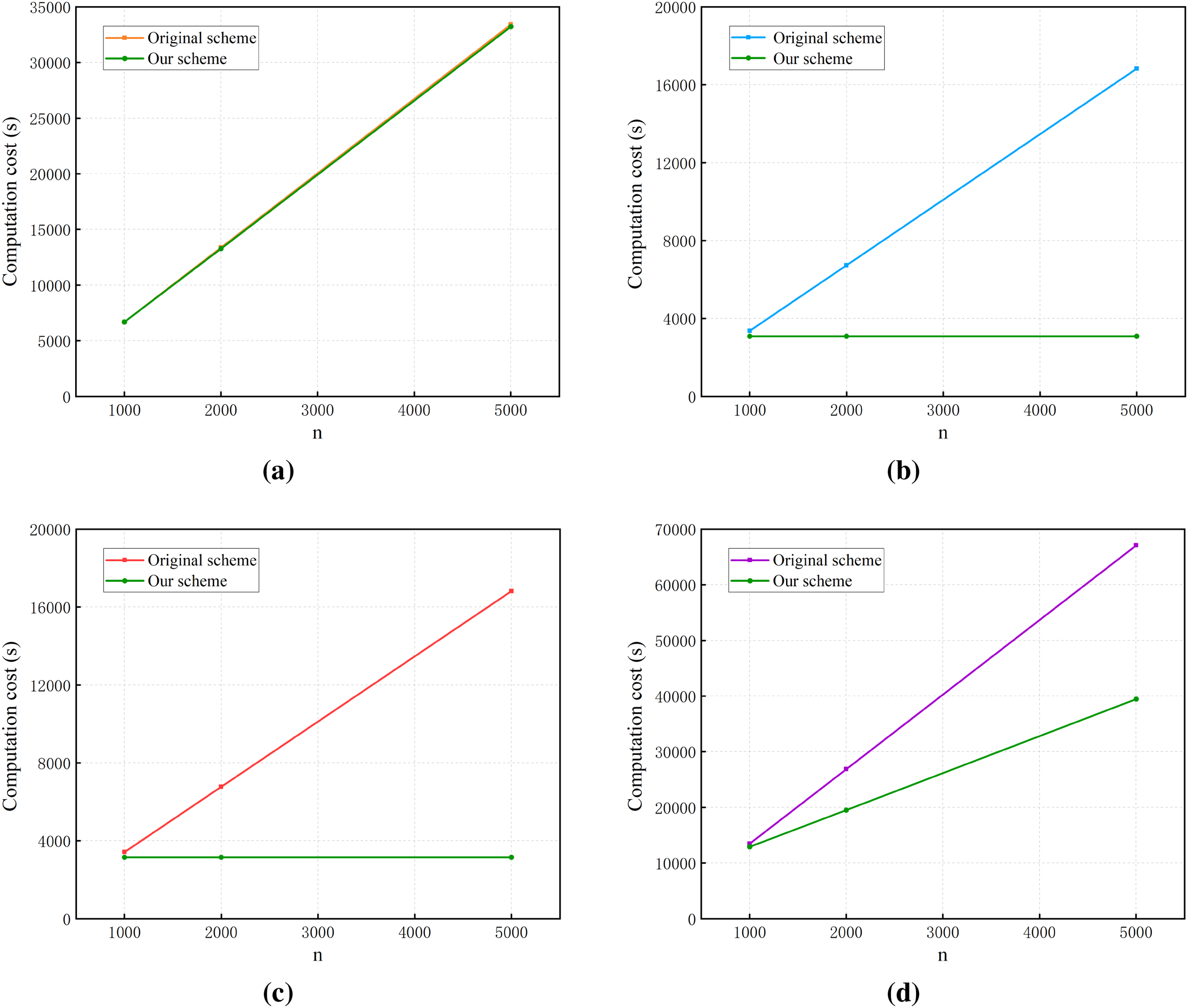

Phase by phase calculations are delivered to the computational cost of the original scheme, the proposed scheme at different stages and the total computational cost. Table 8 shows the comparison of computational cost, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Diagram display of computational cost. (a) DO initialization; (b) CSP proof generation; (c) auditor verification; (d) total cost

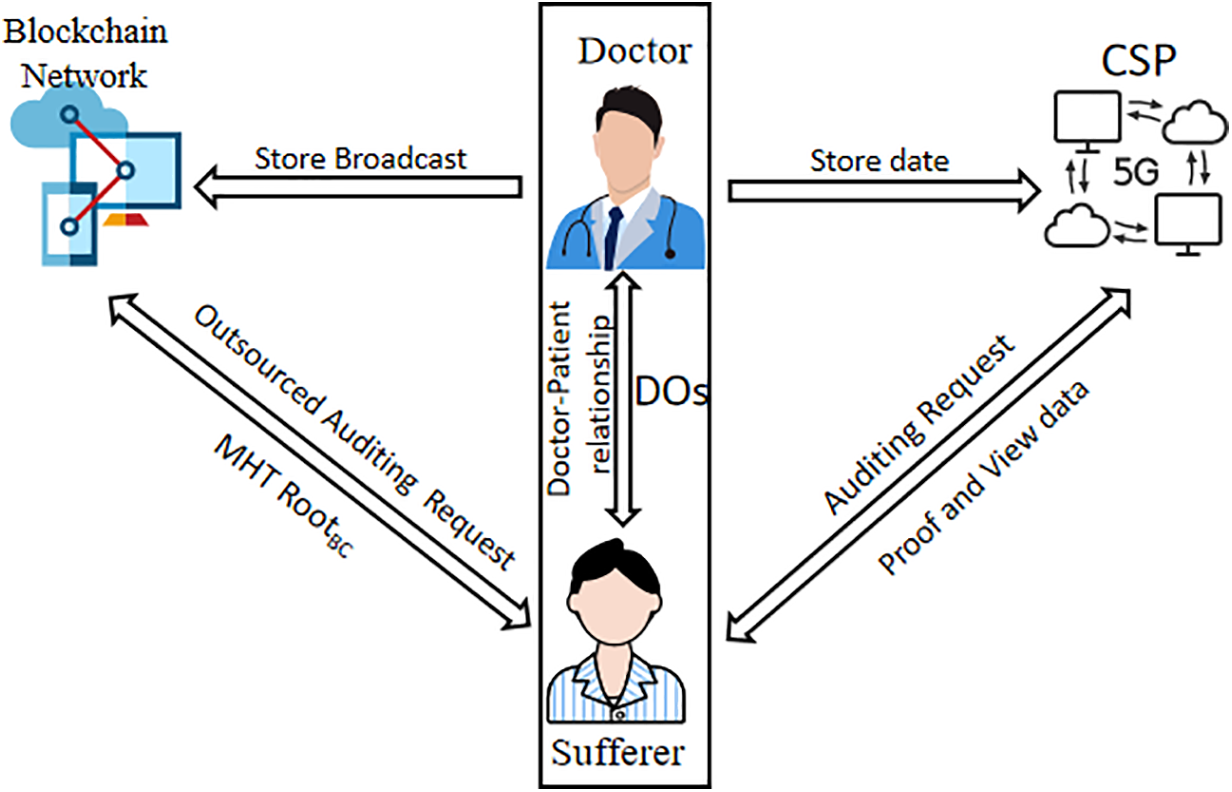

This paper proposes an enhanced cloud auditing scheme leveraging a random challenge-response mechanism and dynamic aggregate signature verification, addressing theoretical and algorithmic vulnerabilities in the original framework. The scheme ensures robust data security and integrity for the Data Owner (DO). It finds application across drone swarms, healthcare systems, government agencies, and enterprises, as demonstrated in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Application model in the healthcare field

7.1 Application in the Healthcare Field

In healthcare, patient records, diagnostic reports, and medical imaging data are highly sensitive and critical. These data are typically stored in the cloud for inter-institutional sharing and on-demand access. However, cloud data security and patient privacy protection remain focal points for the industry. By implementing the improved solution, healthcare data can achieve enhanced security:

• Data Owners (DOs): (e.g., patients or medical institutions) split medical data into blocks, encrypt them using a symmetric key or public-key encryption, and upload them to the Cloud Service Provider (CSP).

• Tag Generation: each data block is associated with a cryptographic tag (e.g., a hash or BLS signature), which is stored on the blockchain in a Merkle Hash Tree (MHT) structure.

During auditing, public auditors (e.g., medical regulatory bodies or other Data Owners within the network) randomly select challenged data blocks. The Cloud Service Provider (CSP) must generate cryptographic proofs based on these challenges. Auditors validate proof integrity by comparing them against blockchain-stored Merkle tags. Successful verification confirms data integrity and non-tampering; failure indicates potential security breaches. As illustrated in Fig. 8, this approach safeguards patient privacy while guaranteeing medical data integrity and trustworthiness. Practical deployments may integrate additional features such as access control and audit logging to meet healthcare-specific regulatory needs. Recent research underscores blockchain’s efficacy in medical data management, resolving the tension between data sharing and security.

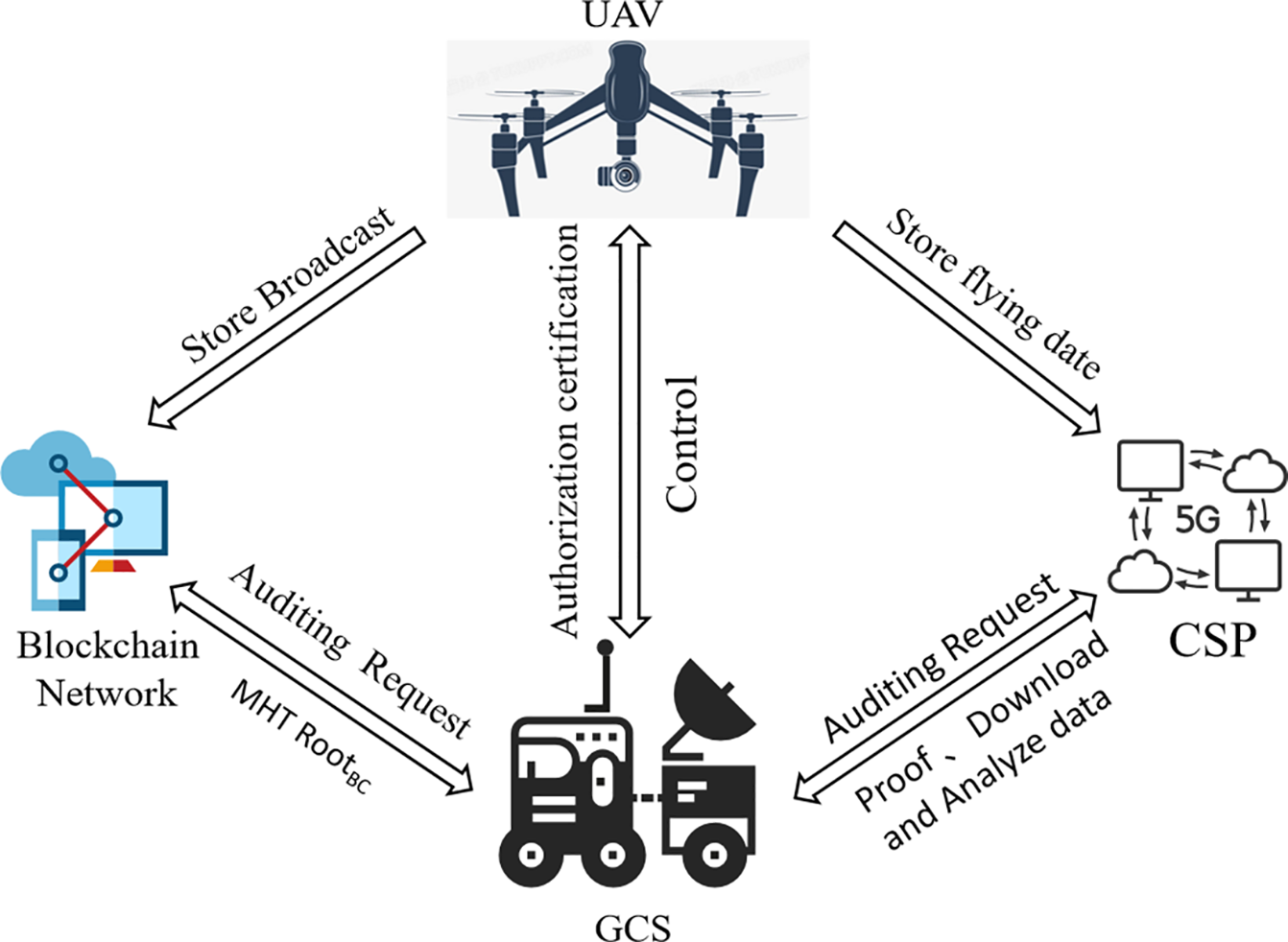

7.2 Application in Drone Swarms

The explosive growth of drone technology, particularly in battlefield scenarios, has positioned it as a paradigm for future unmanned warfare. In drone swarm systems, secure and efficient storage and auditing of flight data are critical. During mission deployment and execution, this scheme’s security and control capabilities enable seamless coordination between ground stations, drone swarms, and manned-unmanned teams. Key advantages include:

• Decentralized Task Assignment: Eliminates single points of failure by replacing traditional single-operator or manual control with blockchain-based task allocation.

• Secure Data Upload: Drone flight data (e.g., GPS coordinates, sensor logs) is encrypted and uploaded to the cloud (as shown in Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Flight parameter data storage verification model

For instance, when auditing flight mission data, auditors challenge the CSP to provide proofs for specific data blocks. The CSP generates proofs containing hash values and BLS signatures of the challenged blocks. Auditors validate integrity by comparing these proofs against blockchain-stored Merkle tags. This application strengthens drone data security while enhancing audit efficiency and accuracy, with critical implications for mission planning, execution monitoring, and accident investigations in drone swarms.

To overcome trust deficiencies and computational overhead in conventional cloud auditing, we propose a decentralized public auditing scheme utilizing blockchain technology. By eliminating the Third-Party Auditor (TPA) and harnessing blockchain’s immutability and distributed nature, the scheme secures data tag storage and verification. Through rigorous analysis of logical inconsistencies (e.g., CSPs requiring plaintext data for verification) and security flaws (e.g., exponential attacks—where attackers forge proofs via repeated exponentiation—alongside tampering and deletion threats), the original scheme undergoes two-stage progressive refinement:

• Correctness Enhancement: Resolving the requirement for CSP to access plaintext data during verification.

• Security Strengthening: Introducing a random challenge-response mechanism and dynamic aggregate signature verification, combined with blockchain-stored immutable tags. This forces CSP to store complete encrypted data and improves detection efficiency through random sampling.

The enhanced scheme substantially improves resistance against forgery, deletion, and tampering attacks while balancing security and computational cost through dynamic parameter adjustment (e.g., challenge frequency k and coordination factor w). Performance analysis demonstrates superior efficacy over conventional schemes (e.g., SWPor [1], CHPor [2], DPAS [3]) in detection probability (e.g., single-challenge detection rates adaptable to diverse datasets), privacy protection (blockchain-distributed tag storage), and attack resistance (content binding via BLS signatures).

Despite notable security and reliability improvements, the scheme leaves room for optimization:

• Privacy Enhancement: Integrating zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) or homomorphic encryption could further conceal data content and audit details while preserving verification validity, mitigating potential privacy leakage.

• Practical Validation: Current research focuses on theoretical analysis. Future work includes deploying the scheme in real-world cloud environments (e.g., finance, healthcare) to test stability under large-scale data and high-concurrency scenarios.

Exploring these directions could advance blockchain’s application in cloud auditing, offering more efficient and flexible solutions for secure, trustworthy data storage.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (New Design and Analysis of Fully Homomorphic Signatures, Grant No. 62172436).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Haibo Lei: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft; Xu An Wang: supervisor, conceptualization, review, fund acquisition, writing—review & editing; Wenhao Liu: investigation, methodology; Lingling Wu: methodology, formal analysis; Chao Zhang: investigation, methodology, validation; Weiwei Jiang: investigation, methodology, validation; Xiao Zou: investigation, methodology, validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are contained within the article. All databases are publicly available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li A, Chen Y, Yan Z, Zhou X, Shimizu S. A survey on integrity auditing for data storage in the cloud: from single copy to multiple replicas. IEEE Trans Big Data. 2020;8(5):1428–42. doi:10.1109/tbdata.2020.3029209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sandhu AK. Big data with cloud computing: discussions and challenges. Big Data Min Anal. 2021;5(1):32–40. doi:10.26599/bdma.2021.9020016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cui Y, Wang X, Lang X, Tu Z, Su Y. An improved short signature scheme for cloud data auditing. J Xidian Univ. 2023;50(5):132–41. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Mishra R, Ramesh D, Edla DR, Qi L. DS-Chain: a secure and auditable multi-cloud assisted EHR storage model on efficient deletable blockchain. J Ind Inf Integr. 2022;26(2):100315. doi:10.1016/j.jii.2021.100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ateniese G, Burns R, Curtmola R, Herring J, Kissner L, Peterson Z, et al. Provable data possession at untrusted stores. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2007 Oct 31–Nov 2; Alexandria, VA, USA. p. 598–609. [Google Scholar]

6. Razaque A, Frej MBH, Alotaibi B, Alotaibi M. Privacy preservation models for third-party auditor over cloud computing: a survey. Electronics. 2021;10(21):2721. doi:10.3390/electronics10212721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang Q, Wang C, Ren K, Lou W, Li J. Enabling public auditability and data dynamics for storage security in cloud computing. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2010;22(5):847–59. doi:10.1109/tpds.2010.183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang J, Peng F, Tian H, Chen W, Lu J. Public auditing of log integrity for cloud storage systems via blockchain. In: International Conference on Security and Privacy in New Computing Environments; 2019 Apr 13–14; Tianjin, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 378–87. [Google Scholar]

9. Salim A, Tiwari RK, Tripathi S. An efficient public auditing scheme for cloud storage with secure access control and resistance against DOS attack by iniquitous TPA. Wirel Pers Commun. 2021;117(4):2929–54. doi:10.1007/s11277-020-07079-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhou J, Jin Y, He H, Li P. Dynamic cloud data audit model based on nest Merkle Hash tree block chain. J Comp Appl. 2019;39(12):3575–83. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

11. Zhu H, Yuan Y, Chen Y, Zha Y, Xi W, Jia B, et al. A secure and efficient data integrity verification scheme for cloud-IoT based on short signature. IEEE Access. 2019;7:90036–44. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2924486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Erway CC, Küpçü A, Papamanthou C, Tamassia R. Dynamic provable data possession. ACM Trans Inf Syst Secur. 2015;17(4):1–29. doi:10.1145/1653662.1653688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shen J, Shen J, Chen X, Huang X, Susilo W. An efficient public auditing protocol with novel dynamic structure for cloud data. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2017;12(10):2402–15. doi:10.1109/tifs.2017.2705620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yang C, Chen X, Xiang Y. Blockchain-based publicly verifiable data deletion scheme for cloud storage. J Netw Comput Appl. 2018;103(6):185–93. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2017.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ghallab A, Saif MH, Mohsen A. Data integrity and security in distributed cloud computing—a review. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Recent Trends in Machine Learning, IoT, Smart Cities and Applications: ICMISC 2020. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 767–84. [Google Scholar]

16. Yang C, Song B, Ding Y, Ou J, Fan C. Efficient data integrity auditing supporting provable data update for secure cloud storage. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2022;2022(1):5721917. doi:10.1155/2022/5721917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Juels A, Kaliski BSJr. PORs: proofs of retrievability for large files. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2007 Oct 31–Nov 2; Alexandria, VA, USA. p. 584–97. [Google Scholar]

18. Gao X, Yu J, Chang Y, Wang H, Fan J. Checking only when it is necessary: enabling integrity auditing based on the keyword with sensitive information privacy for encrypted cloud data. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;19(6):3774–89. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2021.3106780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou L, Fu A, Yu S, Su M, Kuang BY. Data integrity verification of the outsourced big data in the cloud environment: a survey. J Netw Comput Appl. 2018;122(4):1–15. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2018.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Han H, Fei S, Yan Z, Zhou X. A survey on blockchain-based integrity auditing for cloud data. Digit Commun Netw. 2022;8(5):591–603. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2022.04.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Habib G, Sharma S, Ibrahim S, Ahmad I, Qureshi S, Ishfaq M. Blockchain technology: benefits, challenges, applications, and integration of blockchain technology with cloud computing. Future Internet. 2022;14(11):341. doi:10.3390/fi14110341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li J, Liu Z, Chen L, Chen P, Wu J. Blockchain-based security architecture for distributed cloud storage. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing with Applications and 2017 IEEE International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (ISPA/IUCC); 2017 Dec 12–15; Guangzhou, China: IEEE. p. 408–11. [Google Scholar]

23. Du Y, Duan H, Zhou A, Wang C, Au MH, Wang Q. Towards privacy-assured and lightweight on-chain auditing of decentralized storage. In: 2020 IEEE 40th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS); 2020 Nov 29–Dec 1; Singapore: IEEE. p. 201–11. [Google Scholar]

24. Wang C, Sun Y, Liu B, Xue L, Guan X. Blockchain-based dynamic cloud data integrity auditing via non-leaf node sampling of rank-based Merkle hash tree. IEEE Trans Network Sci Eng. 2024;11(5):3931–42. doi:10.1109/tnse.2024.3393978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Guo C, Jin Y. Research on dynamic cloud data auditing mechanism based on improved blockchain. Appl Res Comput/Jisuanji Yingyong Yanjiu. 2023;40(3):659–66. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

26. Li J, Wu J, Jiang G, Srikanthan T. Blockchain-based public auditing for big data in cloud storage. Inform Process Manag. 2020;57(6):102382. [Google Scholar]

27. Wang M, Zhan T, Zhang H. Bit security of the CDH problems over finite fields. In: International Conference on Selected Areas in Cryptography. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. 441–61. [Google Scholar]

28. Shacham H, Waters B. Compact proofs of retrievability. J Cryptol. 2013;26(3):442–83. doi:10.1007/s00145-012-9129-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Rass S. Dynamic proofs of retrievability from Chameleon-Hashes. In: 2013 International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT); 2013 Jul 29–31; Reykjavik, Iceland: IEEE. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

30. He D, Wang H, Wang L, Shen J, Yang X. Efficient certificateless anonymous multi-receiver encryption scheme for mobile devices. Soft Comput. 2017;21(22):6801–10. doi:10.1007/s00500-016-2231-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools