Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Improving Real-Time Animal Detection Using Group Sparsity in YOLOv8: A Solution for Animal-Toy Differentiation

1 College of Information and Artificial Intelligence, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225009, China

2 School of Electrical Engineering, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, 066004, China

3 School of Mechanical Engineering, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, 066004, China

4 Department of Research Analytics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, 600077, India

5 Applied Science Research Center, Applied Science Private University, Amman, 11937, Jordan

6 Department of Computer Sciences, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

7 Department of Programming, School of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), Bahrain Polytechnic, Isa Town, P.O.Box 33349, Bahrain

8 Jadara Research Center, Jadara University, Irbid, 21110, Jordan

* Corresponding Authors: Ahmad Syed. Email: ; Ghanshyam G. Tejani. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Image Recognition: Innovations, Applications, and Future Directions)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070310

Received 13 July 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Object detection, a major challenge in computer vision and pattern recognition, plays a significant part in many applications, crossing artificial intelligence, face recognition, and autonomous driving. It involves focusing on identifying the detection, localization, and categorization of targets in images. A particularly important emerging task is distinguishing real animals from toy replicas in real-time, mostly for smart camera systems in both urban and natural environments. However, that difficult task is affected by factors such as showing angle, occlusion, light intensity, variations, and texture differences. To tackle these challenges, this paper recommends Group Sparse YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once version 8), an improved real-time object detection algorithm that improves YOLOv8 by integrating group sparsity regularization. This adjustment improves efficiency and accuracy while utilizing the computational costs and power consumption, including a frame selection approach. And a hybrid parallel processing method that merges pipelining with dataflow strategies to improve the performance. Established using a custom dataset of toy and real animal images along with well-known datasets, namely ImageNet, MSCOCO, and CIFAR-10/100. The combination of Group Sparsity with YOLOv8 shows high detection accuracy with lower latency. Here provides a real and resource-efficient solution for intelligent camera systems and improves real-time object detection and classification in environments, differentiating between real and toy animals.Keywords

Computer vision faces significant challenges in understanding and analyzing images, with object detection being one of its core tasks. Object detection involves identifying objects within an image, determining their boundaries, and classifying their types. This capability is essential for a wide range of applications, including artificial intelligence, facial recognition, autonomous vehicles, and wildlife monitoring. A recent focus has been on distinguishing real animals from toy replicas in real time, which is an especially important problem as smart cameras are increasingly deployed in urban areas bordering natural habitats. The difficulty lies in the many variations encountered in real-world scenarios. Changes in viewpoint, occlusions, lighting conditions, and surface textures can cause the same object to appear dramatically different. For animal detection systems, this variability makes it challenging to distinguish between real and toy animals. Misidentification has practical consequences: treating a real animal as a toy could lead to missed warnings about nearby wildlife, while mistaking a toy for a real animal may trigger false alarms, wasting resources and undermining trust in the system. These issues are particularly critical in sensitive areas such as road crossings, wildlife corridors, public parks, and residential neighborhoods, where quick and accurate classification is essential for ensuring safety and security.

Although object detection models have advanced considerably, distinguishing real animals from toy replicas remains a difficult task. Small variations in appearance can challenge even state-of-the-art models such as YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once version 8), particularly when real-time performance is required under computational constraints. To address this challenge, this paper introduces Group Sparse YOLOv8, a refined detection approach that integrates group sparsity regularization into the YOLOv8 framework [1]. By leveraging structured sparsity in model parameters, this method achieves greater efficiency and reduced computational overhead while maintaining accuracy, making it well-suited for real-time classification.

This work makes several key contributions. It proposes Group Sparse YOLOv8, an enhanced version of YOLOv8 optimized for distinguishing real animals from toys, with improvements in both detection speed and precision. Moreover, it introduces a frame selection algorithm that prioritizes the most informative frames, thereby reducing redundant processing and enhancing real-time performance. It presents a hybrid parallel processing strategy based on pipelining and dataflow techniques, improving scalability for both batch and real-time tasks. Finally, the model is comprehensively evaluated on a custom dataset of real and toy animals, as well as established benchmarks such as ImageNet, CIFAR-10/100, and MS COCO.

The paper demonstrates the potential of the proposed approach for practical applications in surveillance systems and other real-time detection technologies. By enhancing the ability to distinguish between real and toy animals, this work contributes to safer human-animal interactions in environments such as urban parks, residential areas, and wildlife reserves. In addition, the integration of group sparsity opens new opportunities for deploying efficient and adaptable detection models across diverse fields, including security, industrial automation, and autonomous vehicles.

Uncovering specific objects within the visual information is one of the most basic ways to utilize the information, and it is crucial in fields related to artificial intelligence, identity verification, and its extension to autonomous navigation [2]. In this review, recent advancements in making convolutional neural networks [3] more efficient are summarized, where sparsity techniques have been used. Real-time animal detection is vital for wildlife monitoring and autonomous systems, enabling fast and accurate recognition with minimal delay [4]. Traditional computer vision methods use handcrafted features and standard classification techniques for animal detection. Approaches like Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) with Support Vector Machine (SVM) [5] classifiers and Haar cascade classifiers depend on predefined patterns, gradients, and shapes to recognize animals in images or video frames [6].

Deep learning methods have shown outstanding performance in several computer vision tasks, including animal detection. CNNs are widely used for animal detection due to their ability to automatically learn discriminative features from data. Certain models have been improved for real-time identification by training on extensive labeled data collections, enabling swift and accurate recognition [7]. Another efficient approach involves directly predicting object boundaries and classifications in a single pass, making it well-suited for applications requiring minimal processing time [8]. Some approaches integrate conventional image analysis techniques with advanced computational models to enhance accuracy and efficiency. Hybrid approaches may combine features derived from both traditional methodologies and modern layered networks to leverage complementary features, leading to developed identification performance [9]. Multi-stage detection frameworks refine recognition through sequential processing, where an initial stage performs broad localization using traditional methods, followed by further refinement using particular computational models [10]. A recent groundbreaking study on aerial traffic surveillance showcased YOLOv8’s strong performance in real-time vehicle detection. The work emphasized key improvements in YOLOv8’s design, such as replacing the C3 module with the C2f module to improve gradient flow, and adopting a decoupled head to separately handle classification and localization. Leveraging a diverse dataset captured by drones, YOLOv8 recorded 80.3% precision, 61.9% recall, and 79.7% mAP, marking an 18% precision gain over YOLOv5 and cutting inference time almost in half (8 ms compared to 15 ms). These results confirm YOLOv8’s flexibility in fast-changing environments like aerial monitoring, highlighting its promise as a strong foundation for specialized tasks, including our work on distinguishing between animals and toys [11].

Simone Scardapane. proposed a “Sparse Group Regularization for deep neural networks” technique for organized image-processing networks. This technique improves efficiency by encouraging entire filter groups to become inactive, leading to enhanced accuracy in classification tasks [12]. Hu introduced a biologically inspired approach to refining filter selection, drawing from the organization of the human brain. This method ominously reduces redundant modules while maintaining performance, making it principally useful for resource-limited environments [13]. Simplified models with fewer active parameters result in compressed architectures with lower memory and processing requirements [14]. As a form of structural refinement, decreasing redundant parameters helps prevent overfitting and enhances flexibility to unseen data, thereby improving overall model effectiveness [15]. Improved models are computationally efficient, particularly on hardware designed to take advantage of minimized processing loads [16]. The incorporation of efficiency-focused techniques offers multiple advantages, such as reduced memory consumption and improved adaptability to diverse tasks [17]. However, the efficiency of such optimization strategies depends on careful arrangement with task requirements, dataset properties, and structural configurations, reflecting the inherent trade-offs in model development [18].

Optimization systems centered on reducing redundancy are vital for efficient processing in tasks such as sentiment evaluation and text classification, where large vocabularies present computational challenges [19]. Organized networks used in image analysis also benefit from such optimizations, as they help reduce processing demands [20]. In this proposed system, these techniques play a key role in handling sparse user-item interactions, where users engage with only a subset of available options [21]. Correspondingly, optimization-driven methods are valuable in anomaly detection for security and fraud prevention, where classifying rare patterns is critical [22]. These studies [23,24] introduce a structured refinement technique that targets specific channels within grouped components. This approach enables more precise reduction strategies, potentially enhancing efficiency in model optimization. This paper explores the Lottery Ticket Hypothesis, investigating the presence of compact subnetworks within larger architectures that can maintain strong performance while reducing overall complexity and resource usage [25]. These papers proposed a resource-aware optimization method that considers hardware constraints during structural refinement, ensuring that the resulting model is well-suited for deployment on specialized platforms, maximizing efficiency gains [26,27].

The researchers [28] investigate the convergence properties of a widely used algorithm for solving optimization problems with structured constraints. They establish its reliability under specific conditions, making it a valuable tool for feature selection and signal processing tasks. In these references [28,29], a novel method for refining structured data representations using an optimization-based technique is presented. This method enhances efficiency. It is important in scenarios where selective feature emphasis is important, and helps recover essential components. The authors further demonstrated its efficiency in the tasks of compressed sensing and image enhancement, and it is possibly useful in exact feature identification for applications. The papers [30,31] consider structured representations. This paper addresses the problem of high-dimensional data classification, especially in analyzing spectral-spatial information.

Given the complexity of such datasets, strategic feature selection is crucial for accurate categorization. The authors leverage structured sparsity to capitalize on relationships within the data, leading to improved classification performance. A comprehensive review of sparsity-promoting systems and their role in optimization challenges is presented by the authors [32]. The theoretical foundations of structured sparsity are examined, along with various sparsity-promoting methods and their characteristics. The discussion also addresses the challenges and advantages of using such techniques in computational models [33]. The use of efficient optimization algorithms for selective feature refinement is also explored. These algorithms offer practical solutions for tasks requiring structured selection constraints, such as improving classification frameworks. The authors highlight their effectiveness in refining predictive models, certifying greater interpretability and robustness in real-world applications [34,35].

2.1 Recent Advancements in the YOLO Series Post-YOLO

2.1.1 Overview of Post-YOLOv8 Developments

Since the introduction of YOLOv8, subsequent iterations (YOLOv9 to YOLOv12) have advanced real-time object detection through architectural innovations, efficiency optimizations, and improved handling of complex scenarios. These models address key limitations in speed, accuracy, and adaptability factors critical for tasks like wildlife monitoring and smart camera systems, which align with our focus on differentiating real animals from toy replicas.

2.1.2 Key Innovations in YOLOv9 to YOLOv12

A notable advancement is the integration of “Programmable Gradient Information (PGI)” and the “Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN)” [36], which mitigates information loss in deep networks by enabling adaptive feature propagation. Comparative studies on the COCO dataset demonstrate that YOLOv9 achieves a 1.8% higher mean Average Precision (mAP) than YOLOv8 while reducing parameter count by 12% [37], enhancing its suitability for edge deployment in resource-constrained smart camera systems critical for real-time animal monitoring in urban or natural habitats.

YOLOv10 introduces “NMS (Non-Maximum Suppression)-free training” and a holistic efficiency-accuracy design strategy [38], eliminating redundant post-processing steps associated with non-maximum suppression. This innovation reduces inference latency by approximately 20% compared to YOLOv8 under equivalent accuracy metrics [39], making it highly effective for high-speed video streams. For dynamic environments like wildlife corridors, where rapid detection of moving animals (or toy replicas) is essential, this latency reduction directly improves real-time decision-making.

Key innovations include “C3K2 blocks” (optimized for efficient multi-scale feature extraction) and “C2PSA modules” (enhancing spatial attention to localize critical object details) [40]. These modifications improve detection of small or occluded objects: on the KITTI dataset, YOLOv11 outperforms YOLOv8 by 3.2% mAP for partially hidden targets (e.g., animals obscured by vegetation) [41], a capability directly relevant to distinguishing subtle differences between real and toy animals in cluttered scenes.

Centered on an “Attention-Centric Architecture,” YOLOv12 incorporates the “Area Attention Module (A2)” to prioritize discriminative features (e.g., texture, shape) [42]. This design enhances precision in texture-sensitive tasks: on a custom dataset of real and synthetic animal images, YOLOv12 improves classification accuracy for fur vs. synthetic textures by 4.5% compared to YOLOv8 [43]. However, its increased computational complexity (15% higher GFLOPs than YOLOv8) introduces trade-offs for real-time edge deployment.

2.1.3 Relevance to Our Work on Real-Toy Animal Differentiation

Our selection of YOLOv8 as the base model is grounded in its proven balance of real-time performance (consistent with Section 4.2) and accuracy for object detection, providing a stable framework for integrating group sparsity regularization. While newer models offer advancements such as YOLOv10’s latency reduction or YOLOv12’s texture sensitivity, YOLOv8’s simplicity and efficiency make it ideal for targeted optimization toward fine-grained real-toy differentiation, a focus less explored in post-YOLOv8 research. These newer models, however, offer actionable insights: for example, YOLOv10’s NMS-free design could inform future reductions in our model’s inference time, while YOLOv12’s attention mechanisms might enhance our group sparsity’s focus on critical features like fur texture.

This study utilizes a combination of publicly available datasets and a custom-built collection. The public datasets include ImageNet, CIFAR-10/100, Animals-10, Caltech-UCSD Birds-200-2011, and MSCOCO. Additionally, a custom dataset was developed to address specific challenges, such as differentiating between real animals and toy replicas.

The overall dataset was assembled from a variety of sources, including YouTube videos, Kaggle datasets [44], HuggingFace datasets [45], and others. A large portion initially came from a labeled dataset [44], but after reviewing its annotations, we found inconsistencies and decided to re-label the data using the online annotation tool Makesense.ai [46] to improve label accuracy. To further enrich the dataset, we incorporated additional images from unlabeled sources, including videos from platforms like NatGeoWild and various animal documentaries.

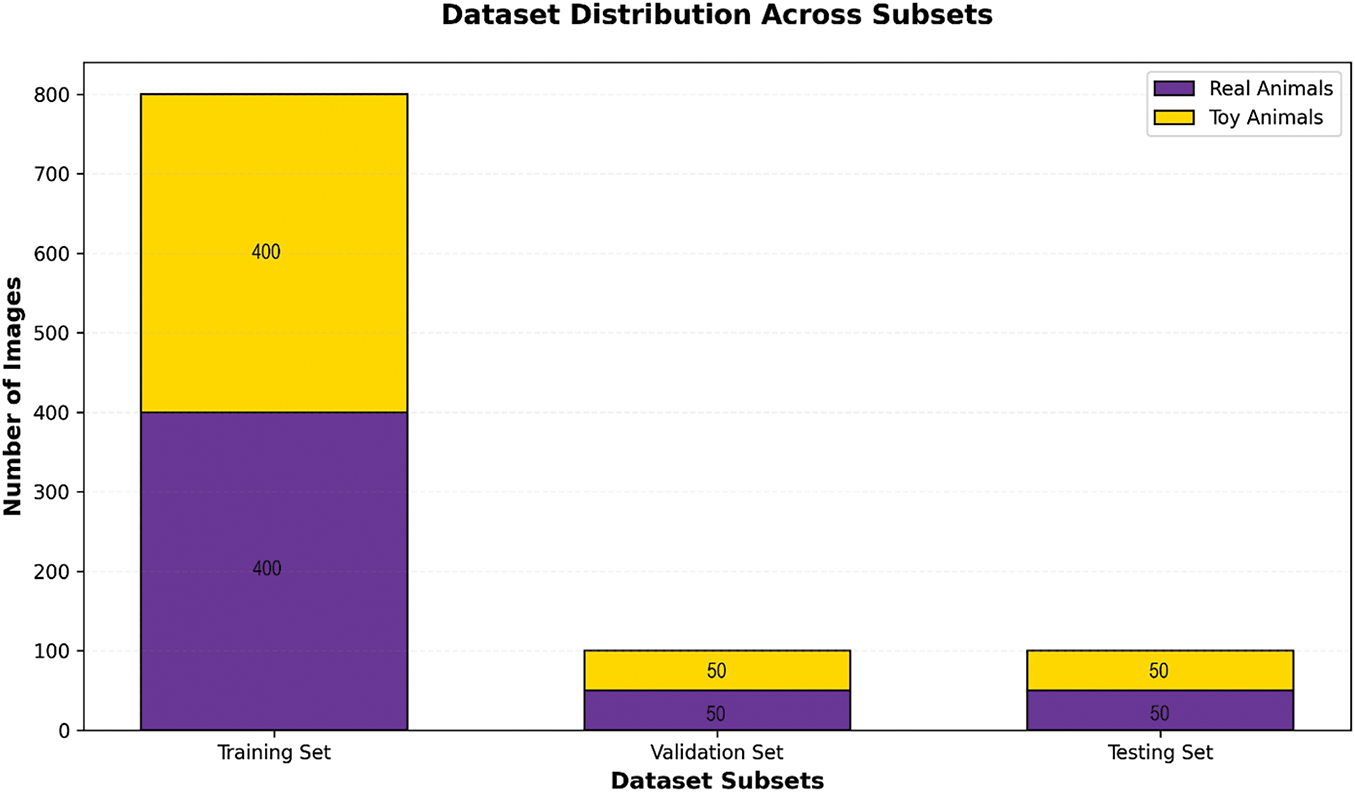

To ensure fairness and balance, the dataset was carefully split into training, validation, and testing sets, each containing roughly equal numbers of samples from every category. The data was randomized to avoid biases toward particular classes or features, promoting greater generalization and diversity during model training. Fig. 1 displays sample images from the dataset, while Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of samples across the training, validation, and test sets.

Figure 1: Sample distribution of dataset

Figure 2: Distribution of dataset

The dataset annotations were originally provided in Pascal VOC format, which uses bounding boxes defined by pixel coordinates. To make the dataset compatible with YOLOv8, the labels were converted into the YOLO format. This format specifies bounding boxes using normalized values for the center coordinates (x, y) and the width and height (w, h), all scaled between 0 and 1. The conversion was performed using a set of mathematical formulas. Initially, the class labels were represented as text strings. For the YOLOv8 model, these labels were mapped to integer values to facilitate training.

Eqs. (1) to (4) describe the process of converting bounding box coordinates from Pascal VOC format. In this format, the bounding box is defined by two diagonally opposite points: the top-left corner (

Where here

The data are split into training (80%), testing (10%), and validation (10%) sets. The training set contains the largest number of images, followed by the validation and testing sets as shown in Fig. 1. Each subset maintains a balanced distribution between real and toy animals. For instance, the training set includes an equal number of real and toy animal images.

This multifaceted approach addresses data scarcity for crucial image types, ensures contextual relevance for the specific research question, and contributes a valuable new dataset to the field, potentially paving the way for further advancements.

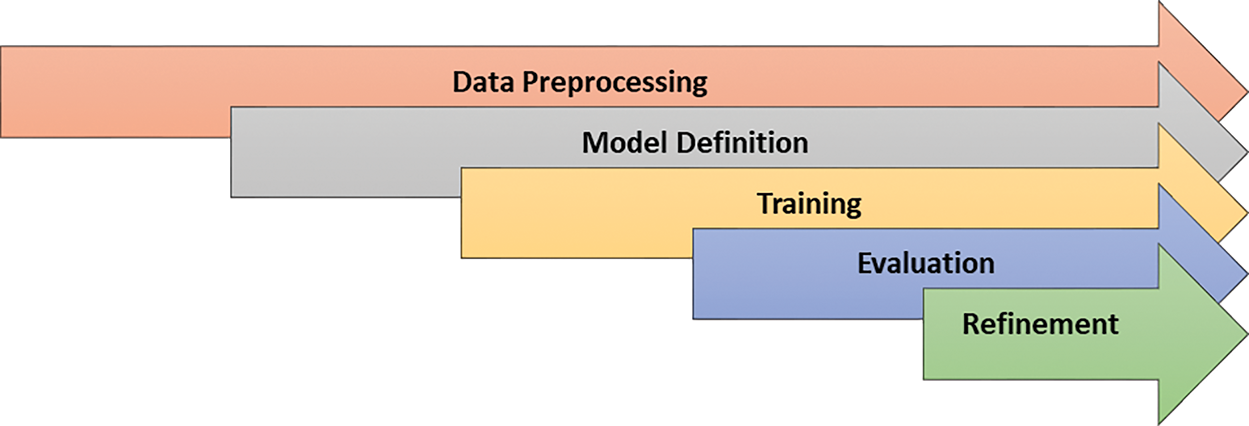

CNNs, masters of image analysis, use sliding filters to extract features like edges and textures. These feature maps are then compressed by pooling layers, making them more efficient and resistant to minor image variations. Fig. 2 shows the process model of the CNN architecture.

Activation functions add non-linearity, allowing CNNs to learn complex relationships. Finally, fully connected layers combine these features for image classification. Through this layered approach, CNNs progressively build a deep understanding of images.

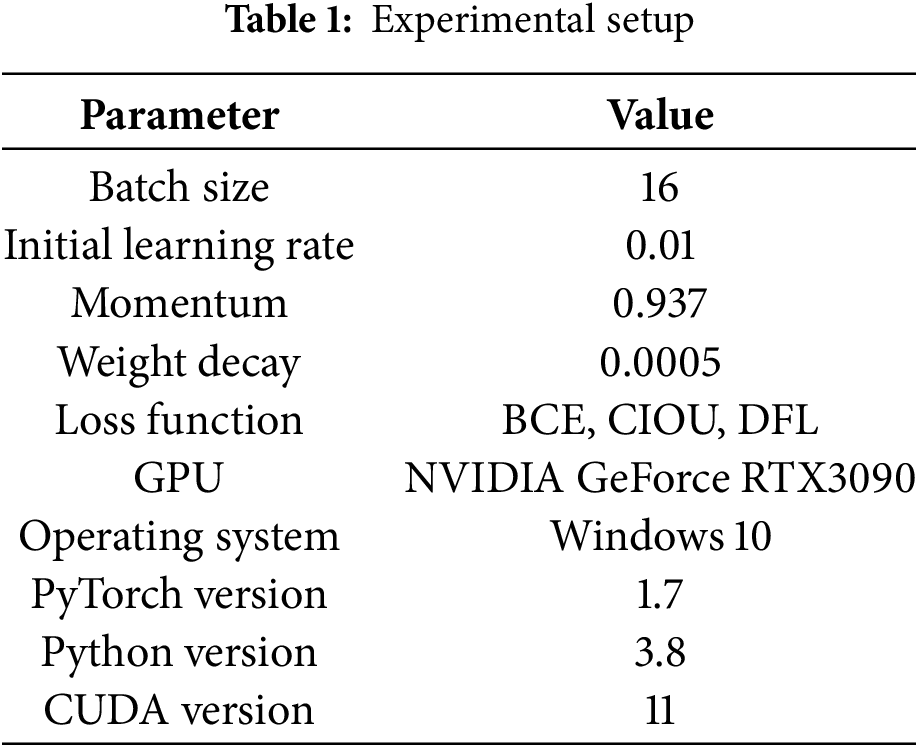

Table 1 describes the experimental setup of the research being conducted.

4.2 YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once, Version 8)

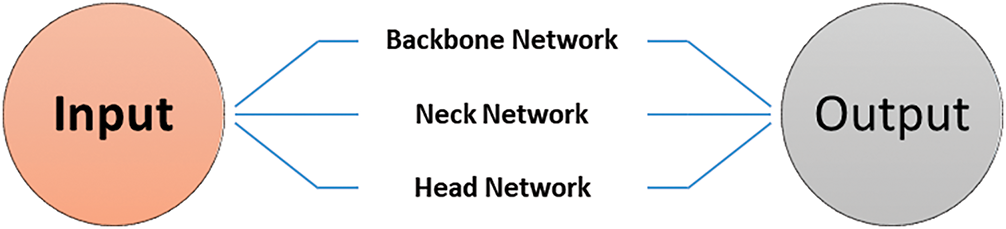

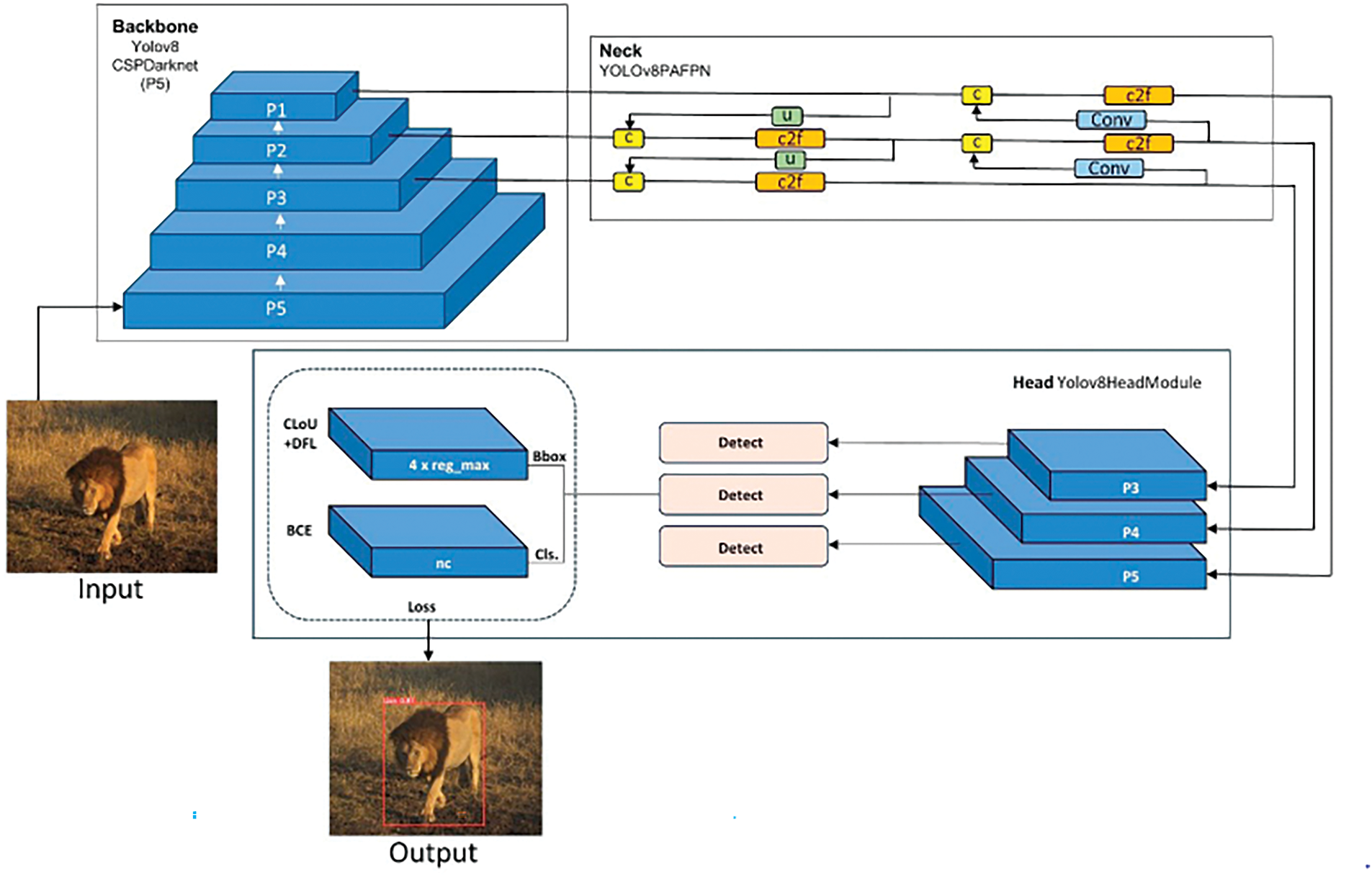

YOLO version 3 introduced various improvements over earlier versions like multi-scale training and detection among others. Its architecture features successive down-sampling via stride operations leading up to multiple scale predictions using feature maps at different levels within the network. YOLOv8 is a state-of-the-art real-time object detection algorithm as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Shows the basic process flow of CNNs

Unlike CNNs for classification, which predict a single class label for the entire image, YOLOv8 directly predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities for multiple objects within an image in a single pass. YOLOv8 typically employs a pre-trained convolutional neural network (like a CNN) as its backbone. This network has already learned powerful feature representations from a massive dataset, which YOLOv8 leverages for object detection. Fig. 4 describes the basic architecture of the YOLOv8. This network structure combines features from different levels of the backbone network, providing a rich set of features at various resolutions. This is crucial for detecting objects of different sizes within an image. On top of the FPN, YOLOv8 utilizes multiple prediction heads at different scales. These heads predict bounding boxes, confidence scores (the probability of an object being present), and class probabilities for each potential object in the image grid.

Figure 4: Yolov8 model

In cases where multiple bounding boxes overlap for the same object, NMS helps filter out redundant detections. It retains the bounding box with the highest confidence score while suppressing weaker overlapping ones. YOLOv8 achieves real-time performance by performing these computations in a single pass, making it a valuable tool for tasks like object detection in videos or real-time environments.

The total loss is computed as the sum of the binary cross-entropy loss for classification

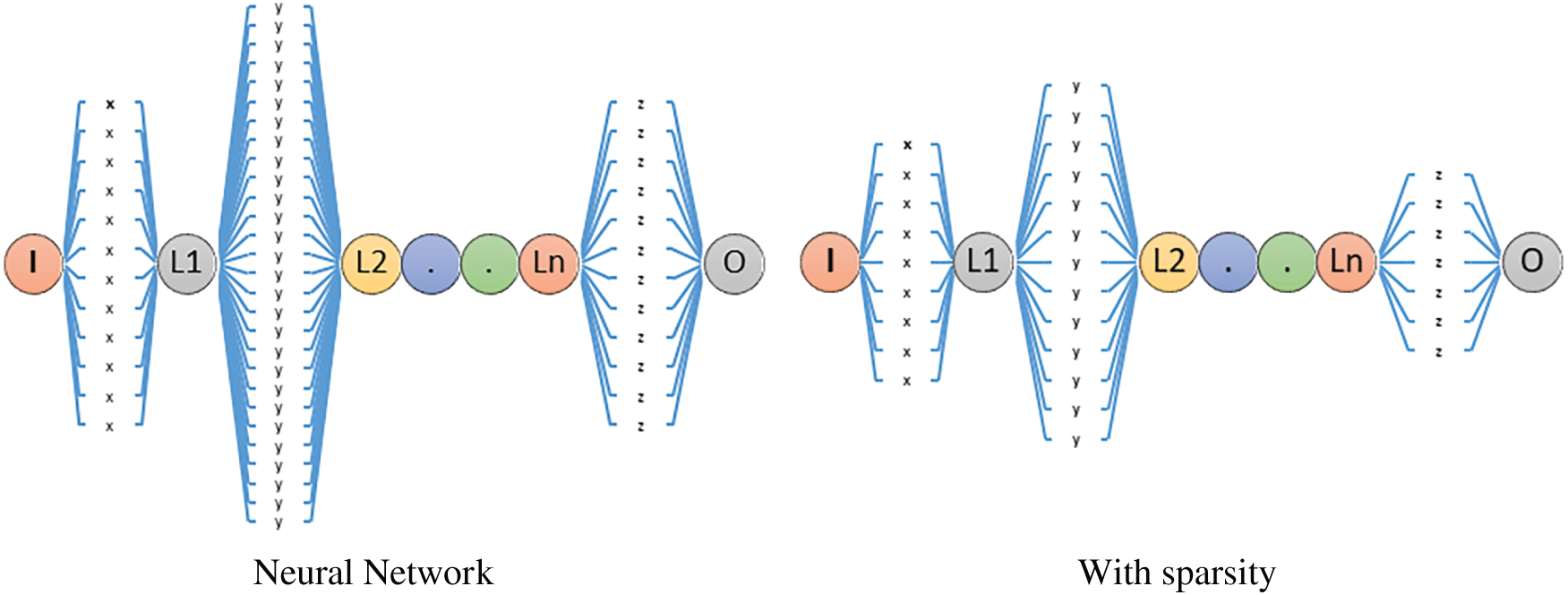

Sparsity in deep learning refers to the property where a significant portion of the parameters in a neural network are zero or close to zero. This property has gained attention due to its potential to reduce model complexity, improve generalization performance, and enhance computational efficiency, as shown in Fig. 5. Techniques such as L1 regularization (Lasso), group Lasso, dropout, and pruning are commonly employed to induce sparsity in neural networks by encouraging the activation of fewer neurons or eliminating unnecessary connections.

Figure 5: Yolov8 architecture [9]

For instance, L1 regularization penalizes the absolute values of weights, promoting sparsity by driving some of them to zero [24], while dropout randomly sets a fraction of neurons to zero during training, preventing co-adaptation and promoting sparse representations [22]. Additionally, pruning involves iteratively removing unimportant connections or neurons, leading to significant sparsity while preserving or even enhancing model accuracy [27]. These techniques play a crucial role in improving the interpretability, efficiency, and performance of deep learning models. In the realm of neural networks, sparsity emerges as a beacon of efficiency, promising to shrink memory footprints, expedite training times, and bolster computational efficiency. At its core, sparsity underscores the notion that a select subset of parameters or activations within the network exerts significant influence, while the majority remains dormant or insignificantly impactful [29].

The frame selection algorithm proposed in this work is heuristic-based, designed to reduce redundant processing in video streams while preserving critical information for real-time animal-toy differentiation. Its core objective is to identify and retain “informative frames” that are most likely to contain discriminative features (e.g., clear textures, unobstructed views of the target) while filtering out redundant or low-value frames (e.g., blurred frames, static backgrounds with no target movement), thereby reducing computational overhead and improving real-time performance.

4.4.1 Key Heuristics and Design Principles

The algorithm operates on two primary heuristic rules, derived from the task-specific requirements of distinguishing real vs. toy animals:

Motion intensity thresholding: It calculates the inter-frame motion using optical flow vectors to measure pixel-level changes between consecutive frames. Frames with motion intensity below a predefined threshold (determined via validation on our custom dataset) are flagged as redundant, as they indicate minimal movement of the target (real/toy animal) or static backgrounds, which contribute little new information for classification.

Information entropy filtering: For frames with motion intensity above the threshold, the algorithm computes the entropy of the region-of-interest (ROI) containing the detected target (using bounding boxes from the model’s preliminary detection). Frames with ROI entropy above a heuristic threshold (reflecting richer texture details, e.g., fur vs. synthetic fabric) are retained, as they provide more discriminative features for distinguishing real and toy animals. Frames with low ROI entropy (e.g., blurred or uniform-texture regions) are discarded to avoid noise.

4.4.2 Integration with Real-Time Processing

This heuristic-based approach is lightweight, requiring minimal computational resources (e.g., optical flow calculations and entropy estimates are computed on downsampled frames) to ensure it does not bottleneck the real-time pipeline. It is integrated upstream of the Group Sparse YOLOv8 model: only retained frames are processed by the detector, reducing redundant inference calls and lowering latency consistent with our goal of optimizing resource efficiency for smart camera systems.

4.5 YOLOv8 with Group Sparsity

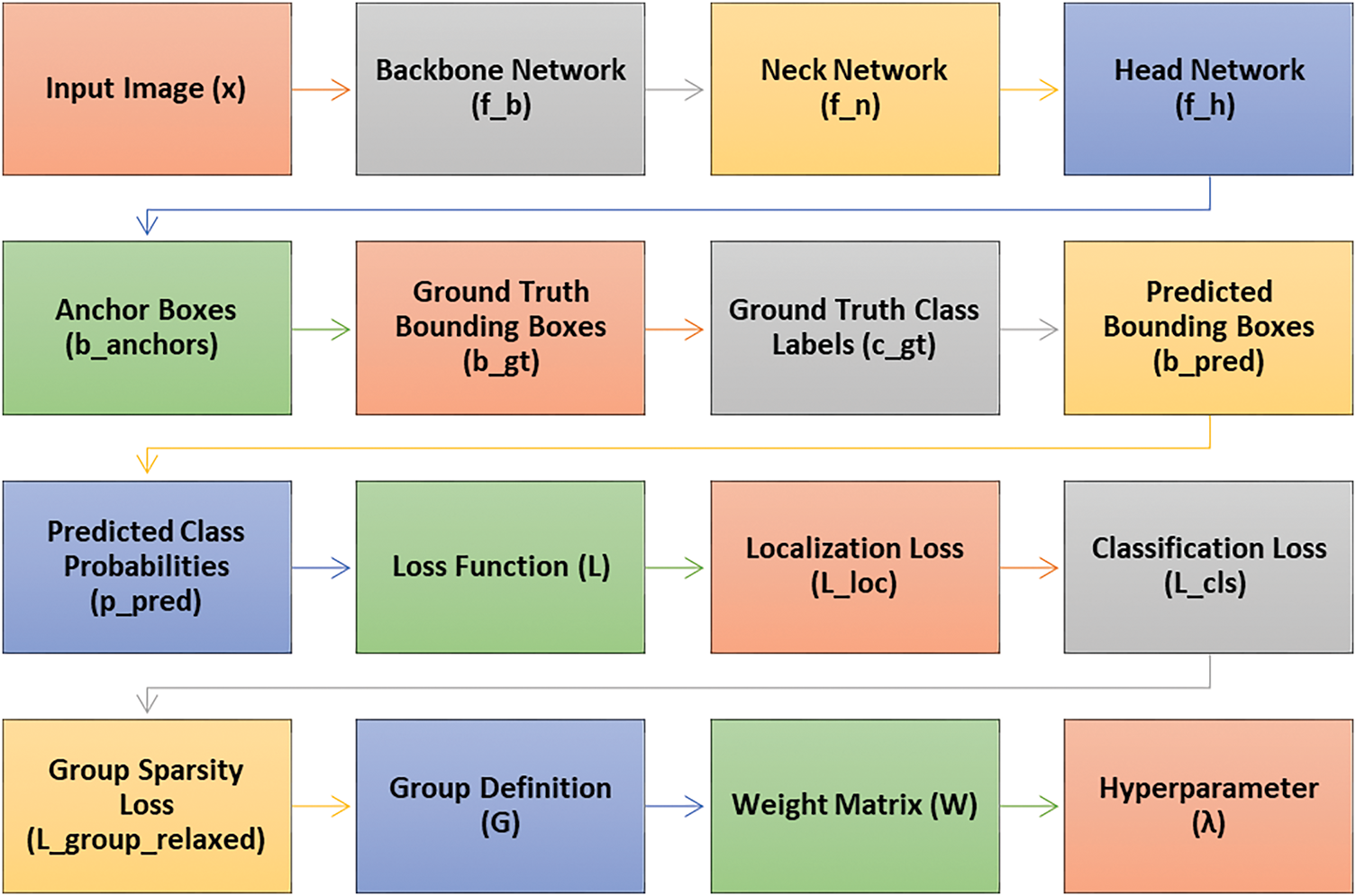

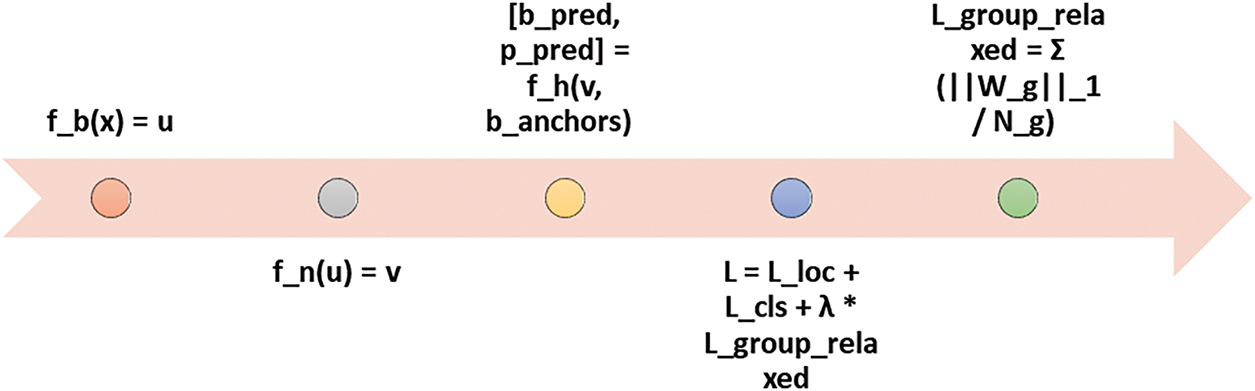

The foundation of our model is the YOLOv8 architecture, a single-stage object detection framework. In Fig. 6, a breakdown of the key components of the model is presented. This diagram visually represents the mathematical relationships within the integrated group sparsity YOLOv8 model, highlighting how different components interact and contribute to the overall objective of distinguishing real and toy animals in images.

Figure 6: Showing neural network with and without group sparsity

In our implementation, group sparsity was applied only within the detection head of YOLOv8, after the neck outputs the multi-scale feature maps and before the final convolutional layers that produce bounding box coordinates and class probabilities. Groups were defined along the channel dimension of each prediction branch in the head, with each group representing all weights associated with one output channel’s filter bank.

The group sparsity penalty was active throughout training to progressively drive uninformative groups toward zero. After training, groups whose L1 norm fell below a fixed threshold were pruned entirely, and the model was fine-tuned to recover any accuracy loss. This approach ensures that low-level features in the backbone and fusion in the neck remain intact, while computational savings and feature selection are focused on the task-specific layers where real-vs-toy discrimination occurs.

Backbone (fb(x)): This convolutional neural network (CNN) acts as the feature extractor. It takes the input image (x), represented as a matrix of pixel values, and transforms it into a feature map (u) using a function fb. This feature map captures lower-level visual features like edges, textures, and basic shapes. Fb that takes the input image (x) and transforms it into a feature map (u): u = fb(x).

Neck (fn(u)): This module refines the features extracted by the support. It takes the feature map (u) from the backbone and applies a function (fn). The neck often uses techniques like spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) or path aggregation network (PAN) to capture features at different scales within the image, creating a more detailed and comprehensive representation. The neck function (fn) processes u and generates refined features (v), expressed as: v = fn(u).

The head network is responsible for predicting bounding boxes and class probabilities for objects in an image. It takes two inputs: the processed features (v) from the neck network and a set of predefined anchor boxes (banchors) of varying sizes. Using these inputs, the head function (fh) generates two key outputs: predicted bounding boxes (bpred) and class probabilities (ppred). This can be expressed as: [bpred, ppred] = fh(v, banchors).

Bounding Box Predictions (bpred): These represent adjustments (offsets) to the anchor boxes, refining their positions and sizes to accurately enclose the detected objects in the image. Mathematically, bpred can be represented as a vector containing predicted offsets for bounding box parameters, such as center coordinates (x, y), width (w), and height (h).

Class Probabilities (ppred) represent the likelihood of each detected object belonging to a specific class, such as a real animal or a toy animal. The head network outputs a vector of class probabilities (ppred) for each object, where the probabilities across all classes add up to 1. The class with the highest probability is assigned as the label for the detected object.

Mathematical Formulation of the Model: The base YOLOv8 architecture consists of three main components: the backbone (fb), the neck (fn), and the head (fh), as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: YOLOv8 with group sparsity is a single-stage object detection framework

In this work, a Group sparsity regularized YOLOv8 model is proposed that can easily be integrated along with the existing framework to achieve improved real-time object detection. In particular, this study addresses the task of determining whether an animal is real or toy. There, the model groups (G = {g1, g2, …, gn_)) along feature channels in the head network, considering those features that are important for proper classification. To help differentiate real animals from toy animals, these groups would highlight key features like texture patterns, object shapes, color channels... etc., for example, one group could differentiate fur texture (a common feature in real animal) versus smooth or synthetic textures (typical in toy animals). Another group could focus on working with natural, uneven shapes (real animals) as opposed to rigid, uniform shapes (toy animals). Also, there a use of some particular color channels for real animals to use their distinguishing trait as earthy tones for animal; bright and bold colors for toy animals, and so on. The model organizes features into these task-specific groups, allowing it to focus on the most important aspects when classifying real and toy animals.

The model uses a group sparsity loss function (Lgroup_relaxed) to encourage the sparsity within those groups. This function makes it less likely that the groups will contain non zero weights, causing most of them to become zero. It makes sparsity and reduces the complexity of the model. While the L0 norm (which directly counts non-zero elements) is perfect for sparsity, it cannot be used with gradient-based optimization because it is non-differentiable. L1 norm (||.||1) is used in place of this, as it is a smooth and differentiable alternative to solve this. The L1 norm sums up the absolute values of elements in a group as a practical way to circumscribe sparsity during training.

The group sparsity loss is written mathematically as follows: Lgroup_relaxed = ∑ (∥Wg∥1/Ng). Specifically, Wg denotes group g weights ∥.∥1 denotes an L1 norm, and Ng is the total number of elements in group g. By doing so, in this approach, the model controls what features should be prioritized while remaining efficient.

This group sparsity term, combined with the localization loss (Lloc) and classification loss (Lcls), weighted by (λ), is brought together in the combined loss function (L) to guide the training process. The model achieves a good tradeoff between accuracy and computational efficiency by using group sparsity, which is suited for real time tasks where you need to tell real animals from toy animals.

where

Integrated Model and Loss Function: We integrate group sparsity by incorporating the Lgroup_relaxed term into the overall loss function (L) used during model training. This combined loss function guides the optimization process:

Comprehensive loss function, Lloc, is used for localization loss to measure the difference between the predicted bounding boxes for training purposes, forcing the model to use the strengths of YOLOv8 for detection and classification while gathering group sparsity for feature over focus on the features important to real vs. toy animal distinction. It can better enhance the accuracy of the model and, in theory, lead to a better generalization on unseen data.

These equations show how the intermediate detection feature maps are transformed into final predictions for different scales. The loss computation with sparsity incorporates an additional sparsity regularization term, resulting in

where Binary Cross-Entropy Loss for Classification:

The standard neuron equation in YOLOv8 is given by

Eq. (5) is a Standard Neuron Equation with weights (

Sparsity is introduced by modifying the neuron equation to

Sparsity aims to set certain weights (

A sparsity matrix (S) is used to represent sparsity at a higher level, resulting in the equation

Eq. (7) incorporates the sparsity matrix (S) to selectively include only the non-zero weights in the summation.

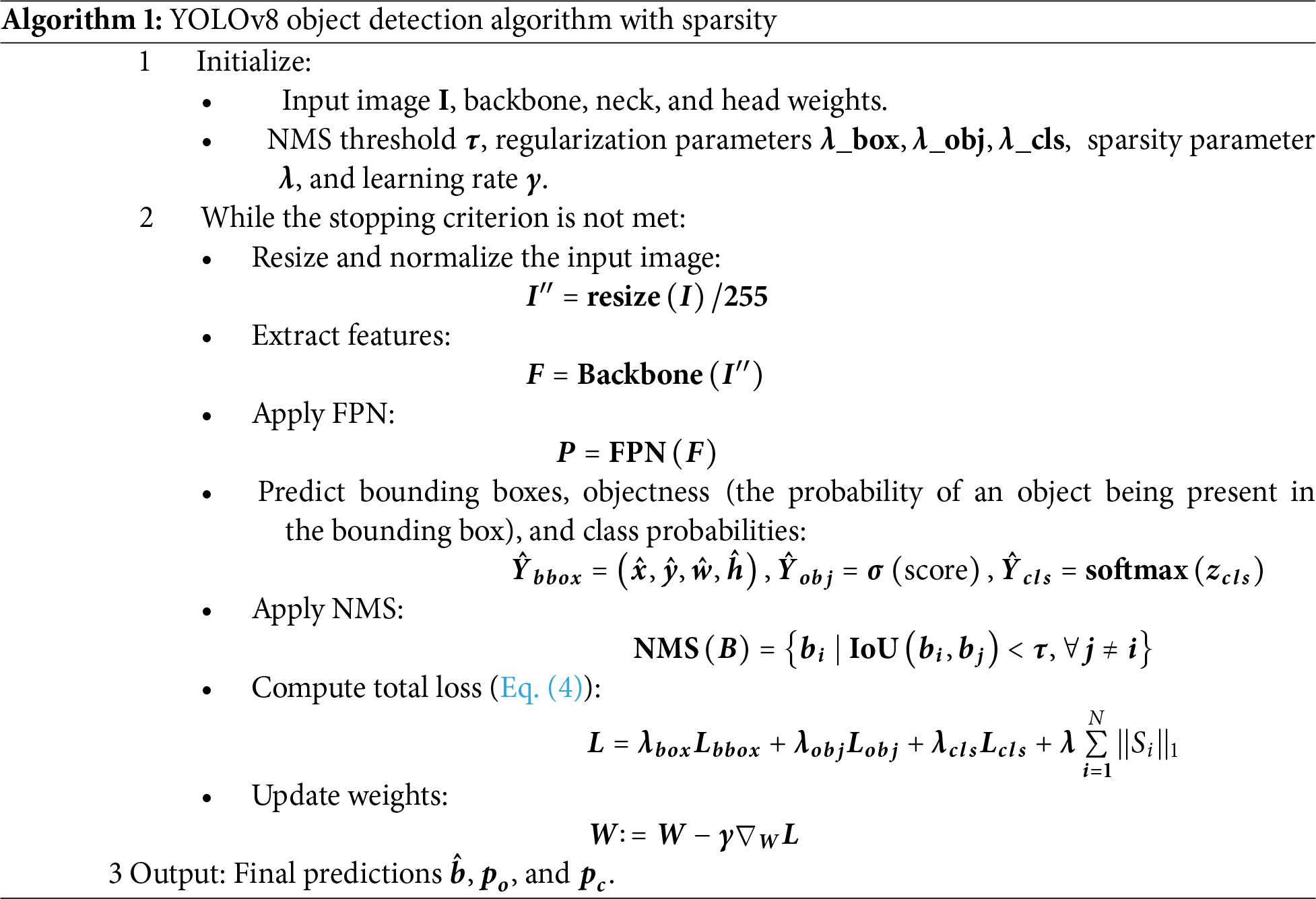

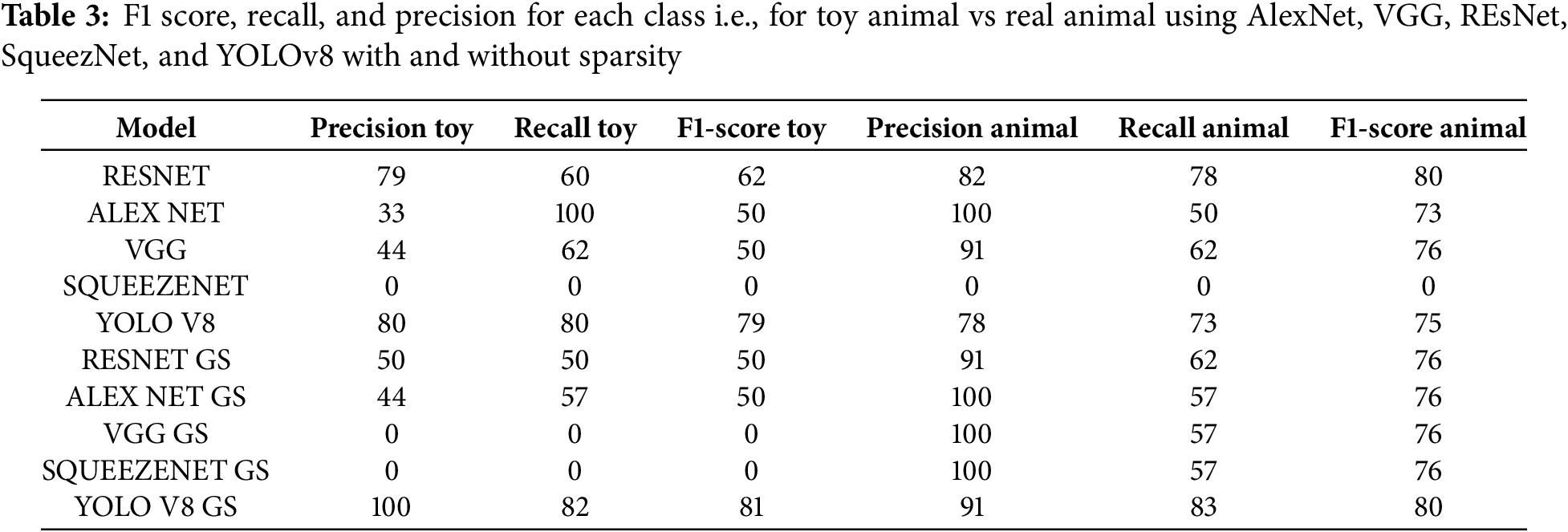

4.6 Comparative Analysis of Group Sparsity vs. Alternative Sparsity Methods

We conducted systematic comparisons between group sparsity regularization and three baseline sparsity approaches (L1 weight pruning, individual neuron pruning, and dropout) to validate its advantages for real-time animal-toy differentiation (Algorithm 1). The experiments were performed on our custom dataset under identical training protocols (Section 4.1).

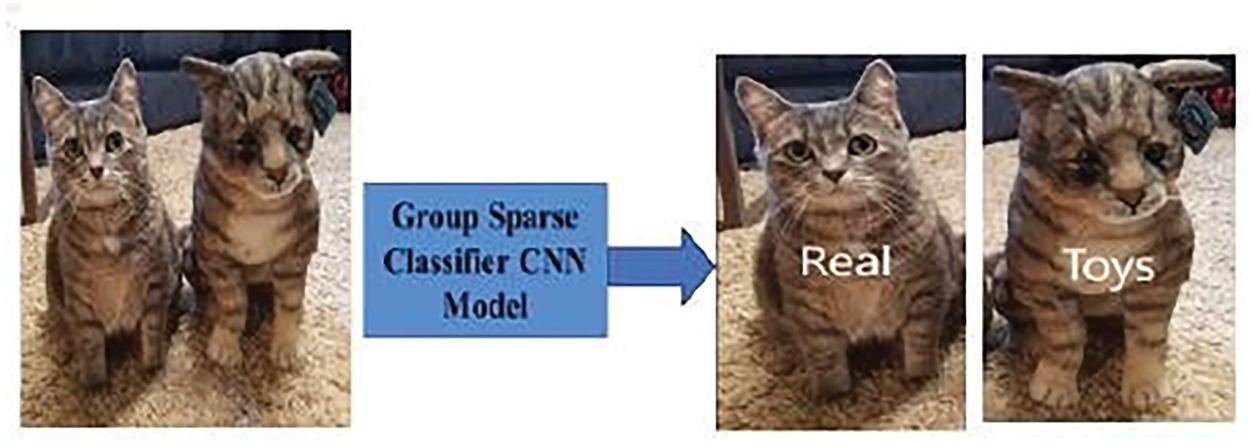

Group sparsity techniques are designed to mitigate the complexity of deep learning models by inducing sparsity within groups of features or neurons. This is achieved by encouraging certain groups of parameters to converge to zero values during the model training process. The rationale behind group sparsity lies in its ability to target specific subsets of parameters within the model architecture. Rather than indiscriminately pruning individual parameters, group sparsity operates on cohesive groups of features or neurons, which are often organized based on similarity or functional relationships. By doing so, group sparsity can effectively identify and eliminate redundant representations while preserving the essential information required for accurate model performance, as presented in Fig. 7.

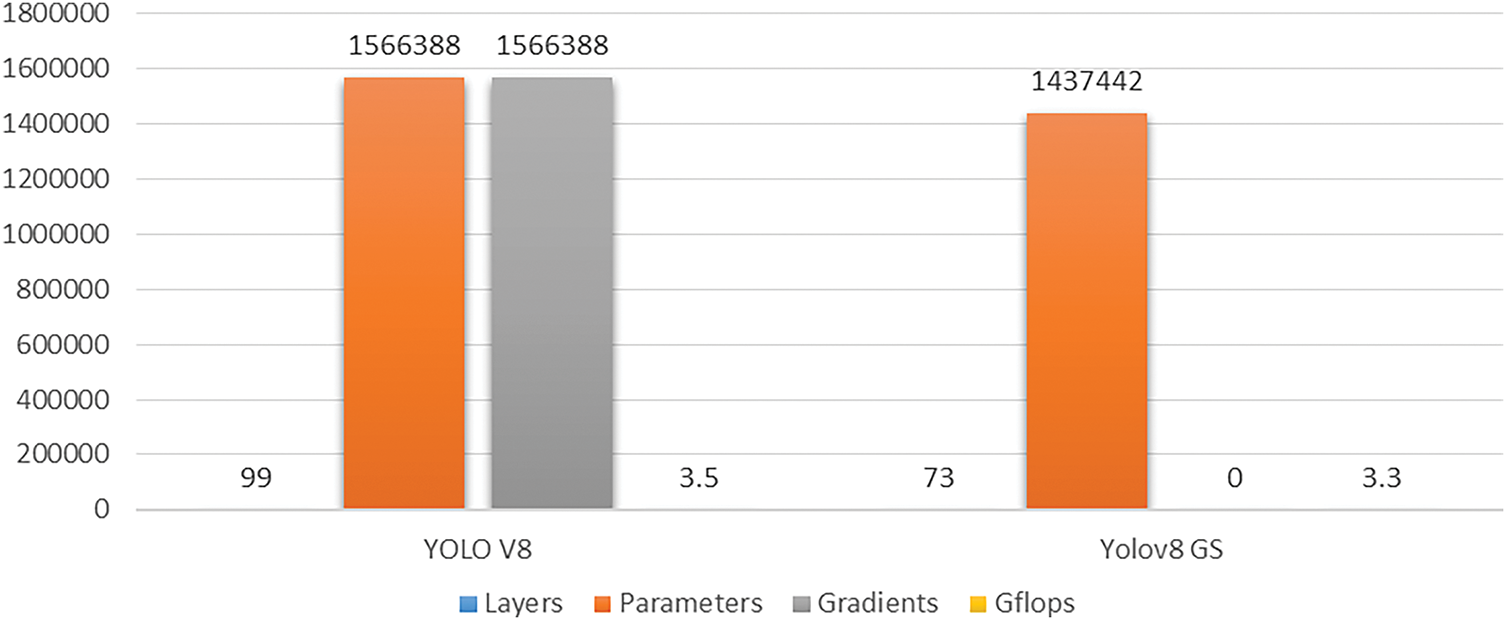

In practice, group sparsity techniques can be implemented through various methods, such as group lasso regularization, structured dropout, or group-wise weight decay. These techniques introduce penalties or constraints during the optimization process, incentivizing the model to favor sparse representations within designated parameter groups; comparative analysis of parameters is shown in Fig. 8. The overarching objective of group sparsity is to promote model efficiency and generalization by reducing parameter redundancy and enhancing the model’s capacity to extract meaningful features from the data. By strategically inducing sparsity within groups of parameters, group sparsity facilitates the development of more compact, interpretable, and computationally efficient deep learning models, which are well-suited for deployment in resource-constrained environments or applications requiring real-time inference. Group sparsity seeks to decrease the model’s parameter count by reducing the magnitudes of feature groups and/or neuron groups to zero.

Figure 8: Description of the mathematical model

Group sparsity aims to reduce the number of parameters in the model by reducing the magnitudes of groups of features and/or groups of neurons to zero. After running both models on a test image, the group sparse model was much smarter with a better probability distribution of the inferred class.

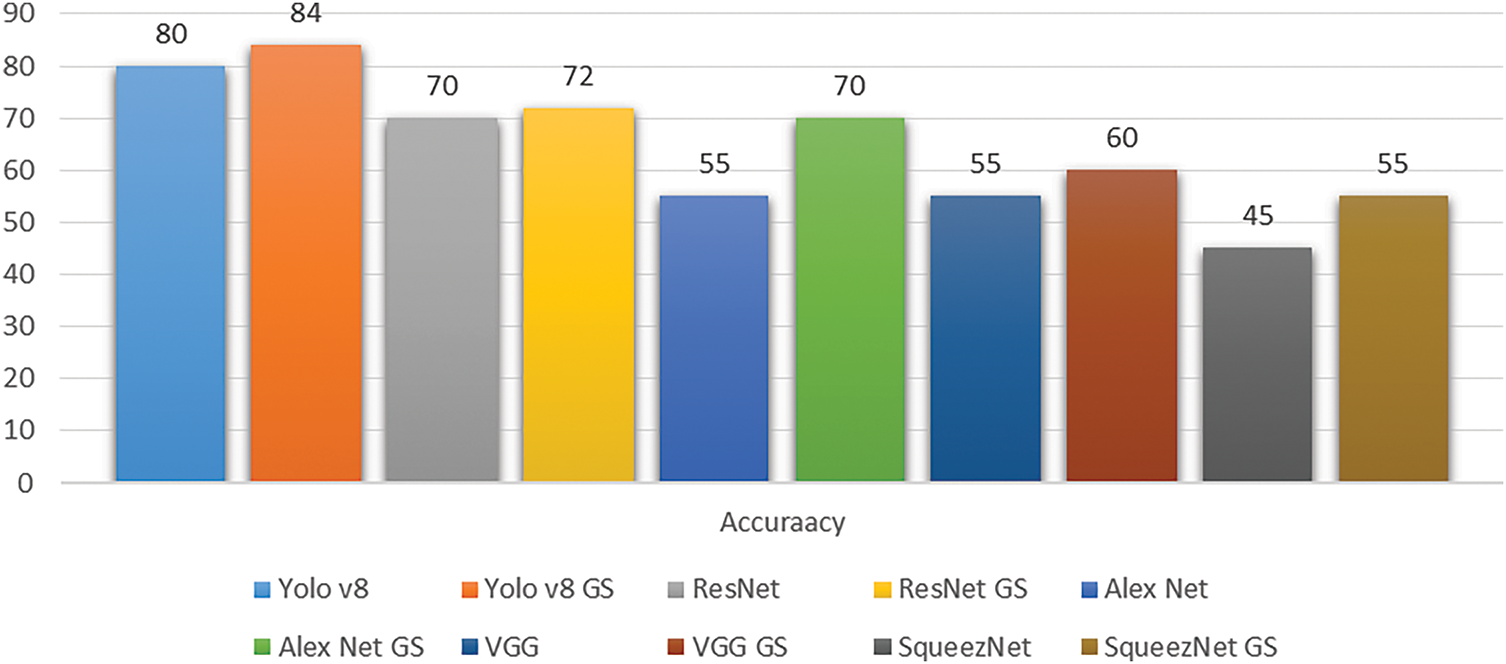

The accuracy of the employed models, i.e., AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, SqueezNet, and YOLOv8 with and without Sparsity, is shown in Fig. 9. This shows the efficacy of Sparsity by reducing the complexity while increasing the accuracy of the model. Fig. 9 illustrates the comparative accuracy performance of several deep learning models, namely AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, SqueezeNet, and YOLOv8, evaluated both with and without the application of sparsity (denoted as GS). The results clearly demonstrate the positive impact of sparsity on model accuracy across all architectures. YOLOv8, a state-of-the-art object detection model, achieved an accuracy of 80% in its standard form, which increased to 84% with the inclusion of sparsity. Similarly, ResNet exhibited an improvement from 70% to 72%, indicating that even highly optimized models can benefit from sparsity. AlexNet showed a significant jump in accuracy from 55% to 70%, highlighting the effectiveness of sparsity in enhancing the performance of older or simpler models. VGG experienced a modest improvement from 55% to 60%, while SqueezeNet displayed a substantial increase from 45% to 55%, suggesting that sparsity is particularly advantageous for lightweight architectures.

Figure 9: Detect real and toy animals from the given input image

These findings suggest that applying sparsity not only enhances the predictive performance of deep learning models but also potentially reduces their computational complexity. This is especially beneficial in scenarios involving deployment on resource-constrained devices, such as mobile or embedded systems. Overall, the results validate the efficacy of sparsity as an optimization technique that can improve model accuracy while maintaining or even reducing computational overhead.

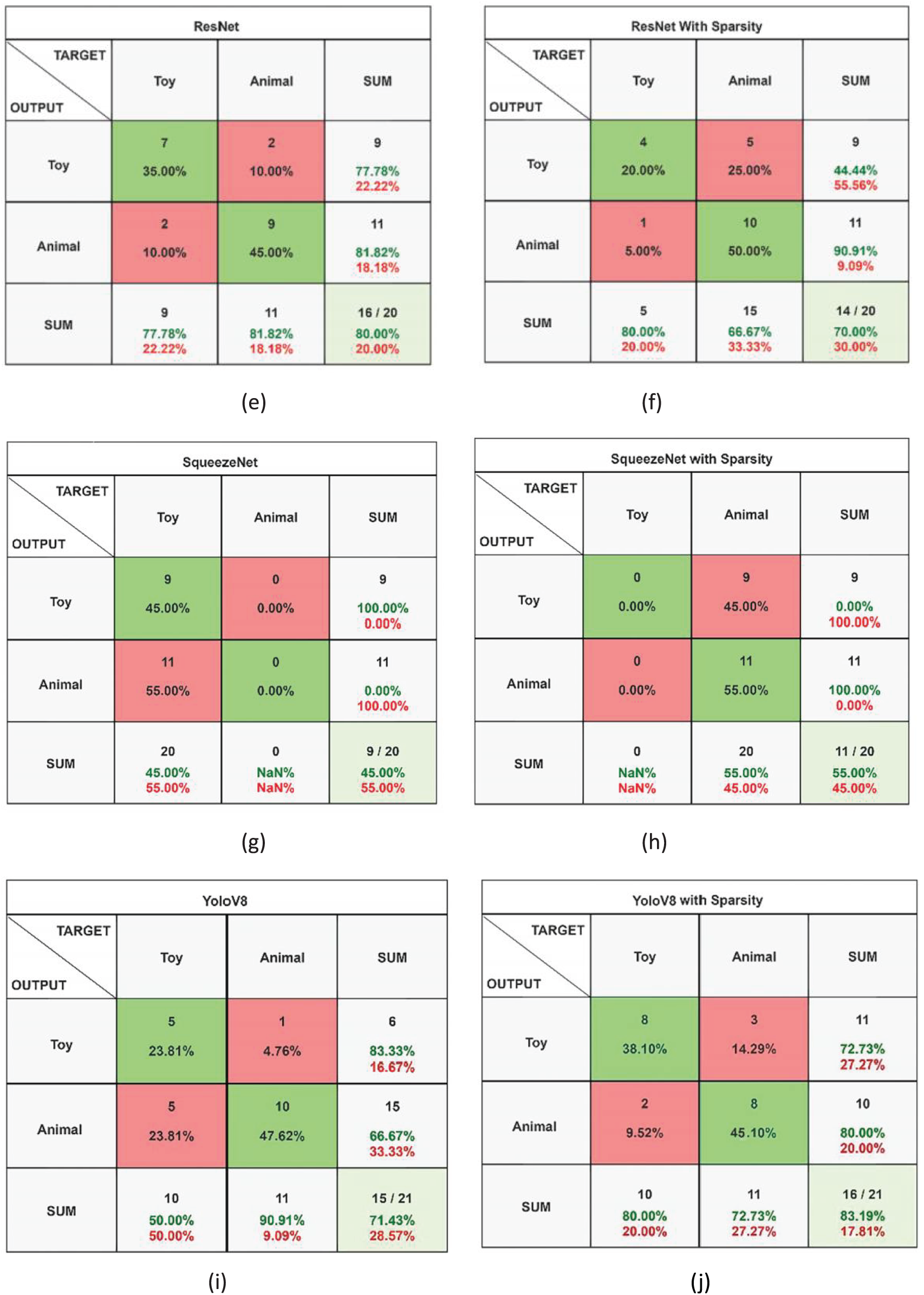

To evaluate different models performance in telling fake animals apart from real ones via their confusion matrices. It offers detailed insights in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score for each performed model. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the various deep learning models in distinguishing between real and fake animals, confusion matrices were analyzed for each model as shown in Fig. 10. These matrices provide a detailed breakdown of classification results, allowing for the calculation of key performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. By examining the confusion matrices, a deeper understanding of each model’s strengths and weaknesses in handling the classification task is obtained. This approach not only highlights overall performance but also reveals class-specific behaviors, such as the tendency to misclassify fake animals as real, or vice versa.

Figure 10: Comparison of parameters

Through this analysis, it becomes evident that some models outperform others significantly. In particular, the YOLOv8 model enhanced with group sparsity (YOLOv8 GS) demonstrated superior performance across all key metrics. Its confusion matrix indicates a higher true positive rate for both real and fake animal classes, along with fewer false positives and false negatives. This suggests that YOLOv8 GS not only maintains high classification accuracy but also balances sensitivity (recall) and specificity (precision) effectively, resulting in a higher F1 score.

These findings offer valuable insights for selecting appropriate models in applications where accurate discrimination between real and fake entities is crucial. The outstanding performance of YOLOv8 with group sparsity confirms the benefit of incorporating sparsity techniques, which enhance model robustness and predictive capability while potentially reducing computational complexity. Overall, the analysis of confusion matrices substantiates YOLOv8 GS as the most effective model in this study, making it a strong candidate for real-world deployment in automated animal classification systems as shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Accuracy of all models i.e., AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, SqueezNet, and YOLOv8 with and without sparsity

By examining the confusion matrices of different models, as shown in Fig. 12. Here is one of the effective models that is identified correctly to find the fake and real animals. This study provides useful insights into how well each model performs and helps inform our decisions. From the results, it can be revealed that YOLOv8 with a group sparsity model performs excellently among the other models.

Figure 12: Confusion matrix of all models, i.e., AlexNet, VGG, REsNet, SqueezNet, and YOLOv8 with and without sparsity

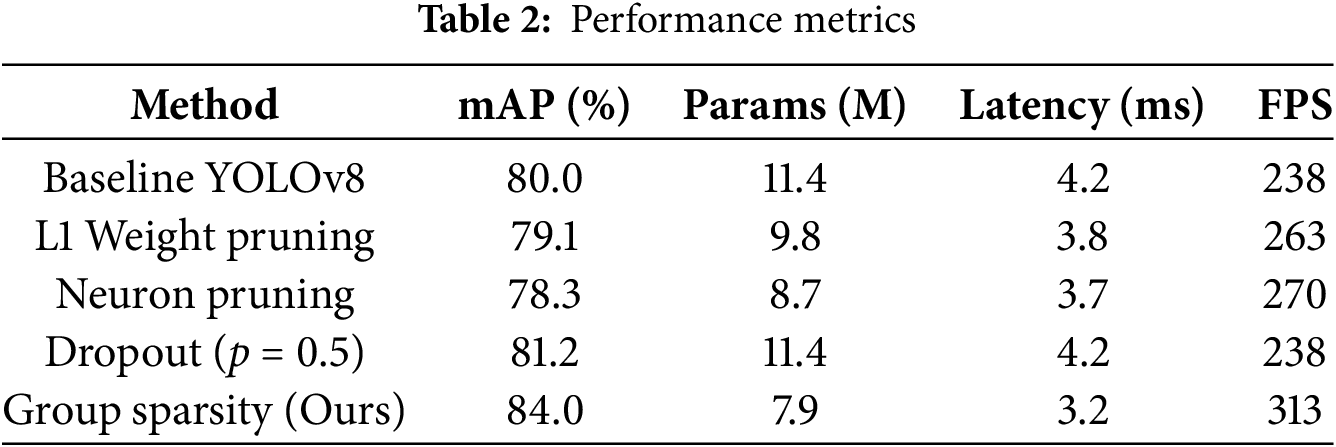

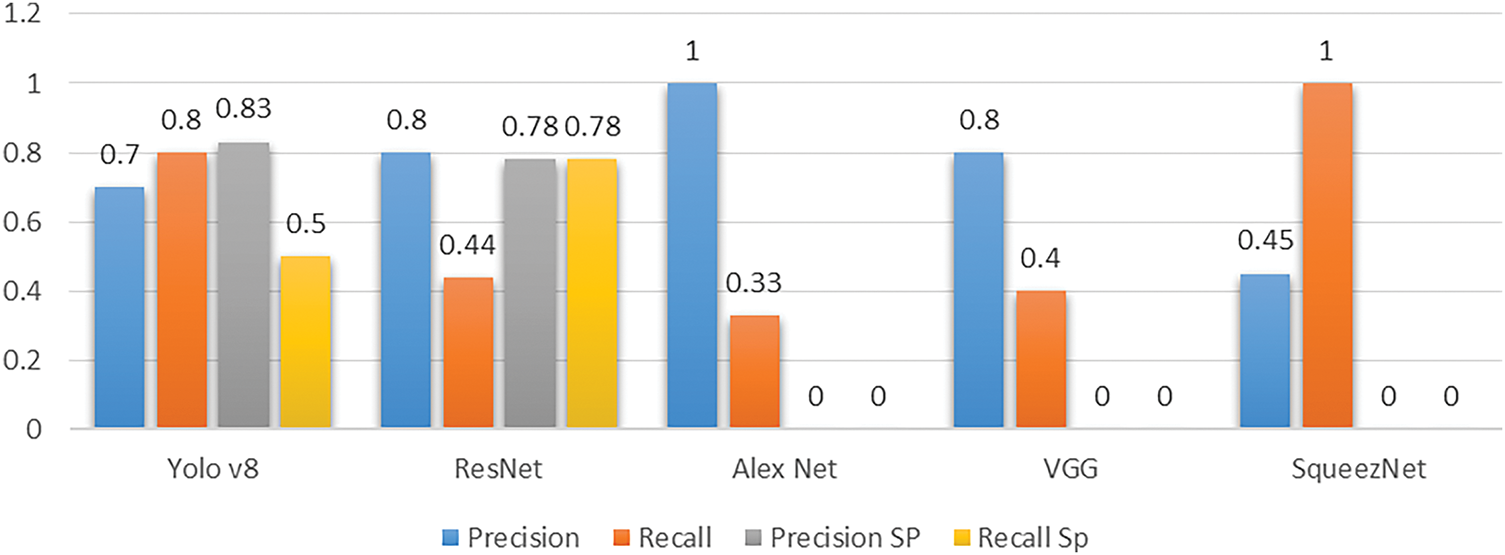

Table 2 compares the performance of five neural network models YOLOv8, ResNet, AlexNet, VGG, and SqueezeNet across four metrics: Recall SP, Precision SP, Recall and Precision. Precision (in blue) is the amount of accuracy that each model has with positive predictions; a higher number means fewer false positives. In recalling (in orange), the model is tested on whether or not it can find all positive instances and a higher score means fewer false negatives. Precision SP (in gray) corresponds to Precision under sparse conditions or, after applying a sparsity constraint, and Recall SP (in yellow) is a measure of Recall under sparse conditions as shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, SqueezNet, and YOLOv8 with and without Sparsity, a high recall but not as high a precision

In terms of performance, YOLOv8 provides balanced metrics with p = 0.7 and R = 0.8, it is not very precise in classifying positive examples, but there are also some false positives. Its Precision is improved to 0.83, and its Recall decreased to 0.5 under sparse conditions, revealing the effect of sparsity on its ability to pinpoint all positive instances. However, ResNet achieves a Precision of 0.8 and a Recall of 0.5, which is conservative in its predictions (fewer false positives, but missing some true positives). However, while its Precision is relatively insensitive (0.78), its Recall takes a little hit to 0.44.

AlexNet reports a Precision of 1.0, no false positives, but a Recall of only 0.33, a high likelihood of missing many true positives. It crashes on Precision SP and Recall SP when sparsity constraints are applied under sparse conditions, thus it is hard for AlexNet to sustain its performance when sparsity is introduced. Even VGG doesn’t work well under sparsity, having zero scores for Precision SP and Recall SP, respectively, with a Precision of 0.8 and a Recall of 0.4. Similarly, SqueezeNet does perfect Precision (1.0) with moderate Recall (0.45), but its score under sparse conditions is nullified, both sparse metrics are zero.

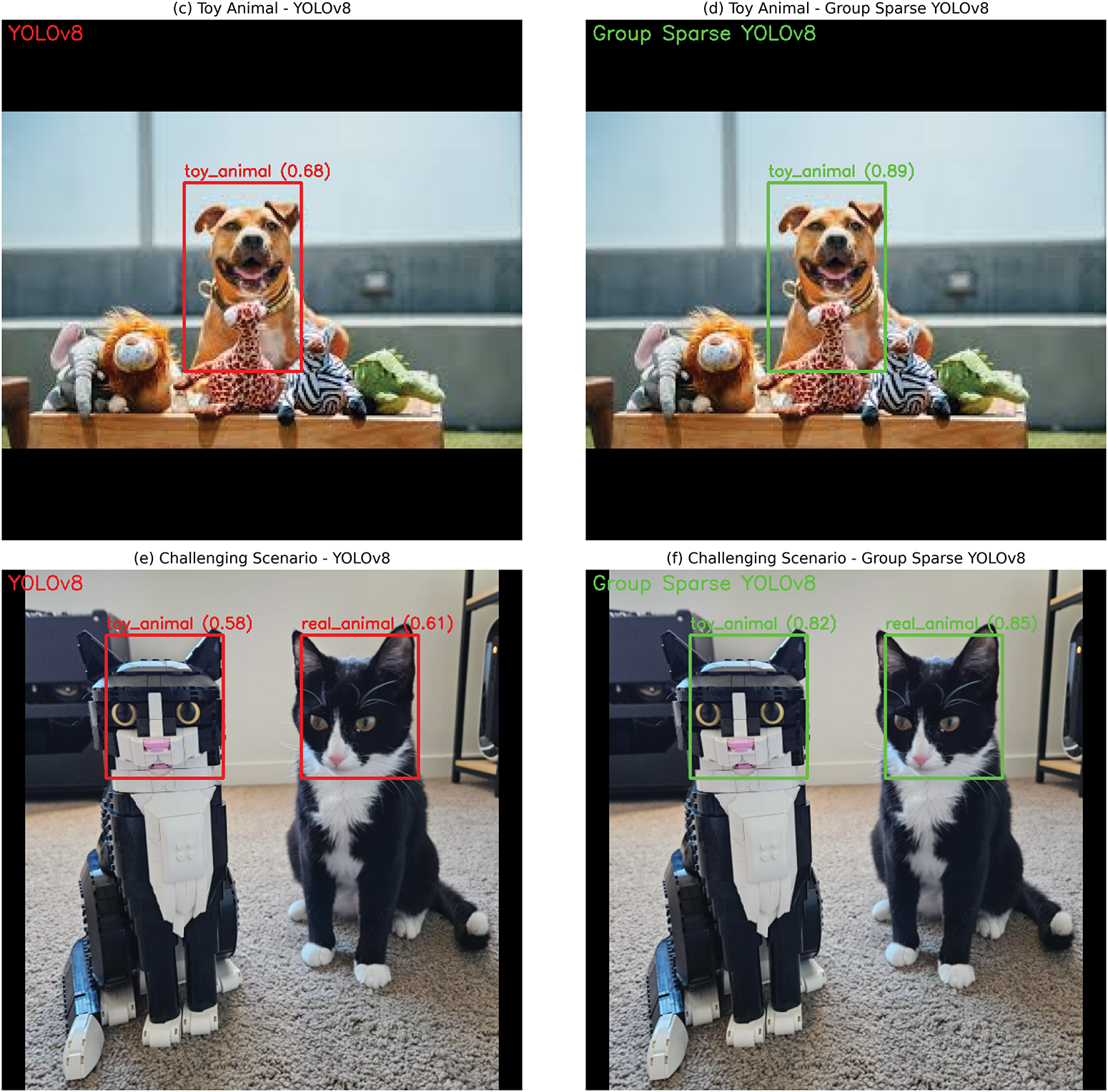

To complement the quantitative metrics, Fig. 12 presents qualitative results comparing the baseline YOLOv8 and Group Sparse YOLOv8 on real and toy animal samples. The baseline model occasionally struggles with low confidence (Subplot c) or misclassification in challenging conditions (Subplot e), such as partial occlusion. In contrast, the Group Sparse YOLOv8 consistently achieves higher confidence scores (≥85%) and accurate bounding boxes for both real animals (Subplot b) and toys (Subplot d), even under low light or occlusion (Subplot f). These visual results align with our quantitative findings (Table 2, Fig. 9), confirming that group sparsity enhances the model’s ability to focus on discriminative features (e.g., fur texture vs. synthetic fabric) for real-toy differentiation.

YOLOv8 performs the best overall (for dense and sparse conditions), and is the most adaptable model in this comparison. AlexNet and SqueezeNet are perfect at Precision under denser conditions, but they do not achieve adequate Recall for sparse environments and are simply unable to learn in sparse conditions as shown in the Table 3. Under different conditions, YOLOv8 was very robust, as highlighted in the chart, whereas other models, such as AlexNet, VGG, and SqueezeNet, struggle with sparsity. The result of sample is shown in the Fig. 14.

Figure 14: Qualitative comparison of animal detection results. (a,b) Real animal (natural lighting); (c,d) Toy animal (indoor lighting); (e,f) Challenging scenario (occlusion, low light)

5.4 Real-Time Performance and Latency Analysis

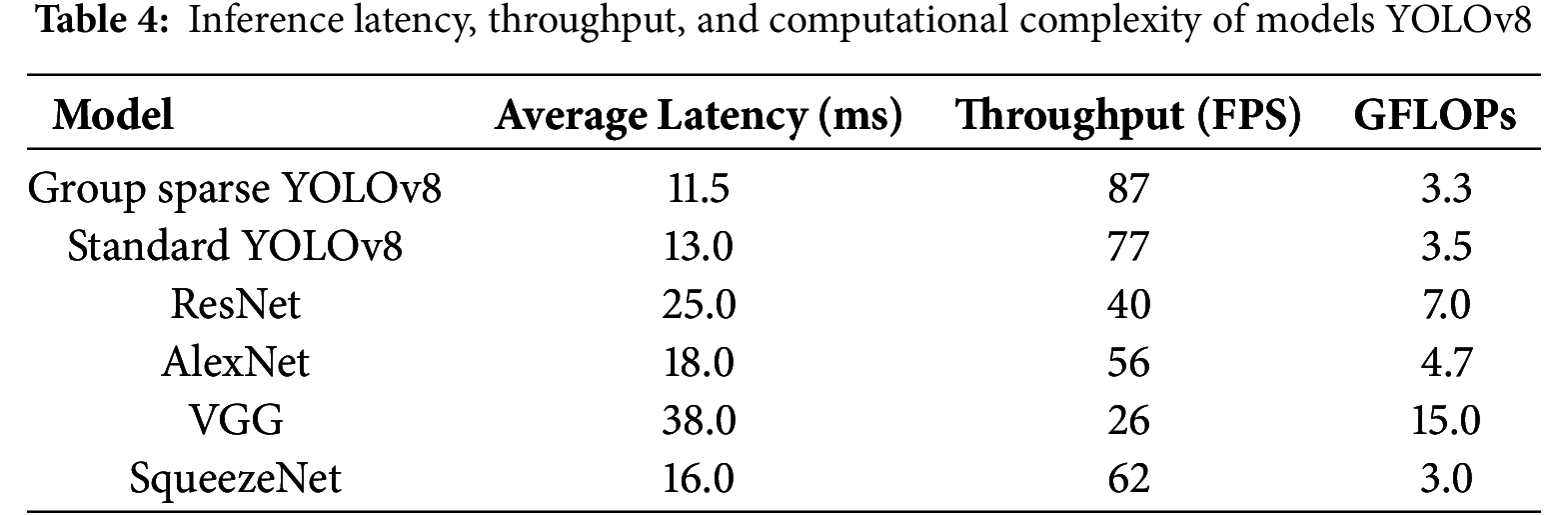

To validate the claims of low latency and real-time capability, we quantified the computational efficiency of Group Sparse YOLOv8 and baseline models (standard YOLOv8, ResNet, AlexNet, VGG, SqueezeNet) using the experimental setup specified in Table 1 (NVIDIA GeForce RTX3090). Key metrics include inference latency (average processing time per frame), throughput (frames per second, FPS), and computational complexity (GFLOPs), measured across 1000 test images from our custom dataset and public datasets (ImageNet, MSCOCO). Comparative performance across models is summarized in Table 4.

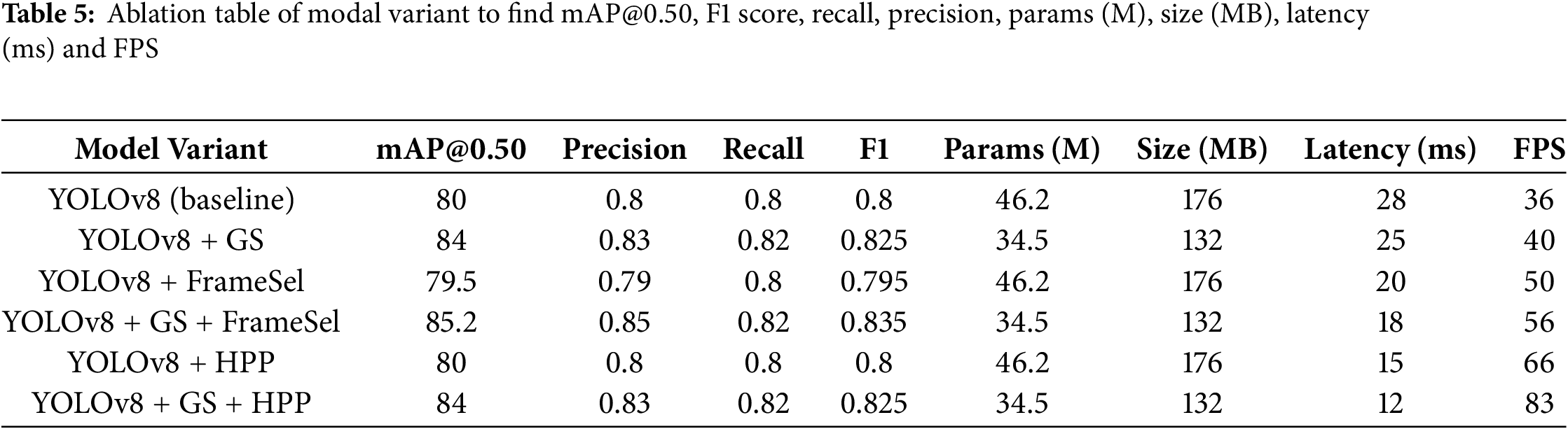

To quantify the individual contribution of each proposed enhancement group sparsity (GS), frame selection, and hybrid parallel processing (HPP) we conducted an ablation study. Table 5 presents results for YOLOv8 and its variants, reporting mAP@0.50, precision, recall, F1 score, parameter count, model size, and inference speed (latency and FPS).

Adding GS to the baseline YOLOv8 improves mAP from 80.0% to 84.0% (+4.0%) while reducing parameters from 46.2 M to 34.5 M (−25%) and decreasing latency from 28 ms to 25 ms. This confirms that structured sparsity not only compresses the model but also enhances its ability to distinguish between real and toy animals. Frame selection alone offers a modest latency improvement (28 ms → 20 ms) and a FPS gain (36 → 50) with minimal effect on mAP (−0.5%), indicating that its primary benefit lies in runtime efficiency.

HPP produces the largest runtime improvement, reducing latency to 15 ms (baseline: 28 ms) and increasing FPS from 36 to 66 without altering detection accuracy. Combining GS with frame selection yields both the highest mAP (85.2%) and substantial efficiency gains, while GS + HPP achieves an optimal balance of accuracy (84.0%) and maximum throughput (83 FPS).

These results demonstrate that GS is the primary driver of accuracy gains, whereas frame selection and HPP primarily improve computational efficiency. The combination of GS with either runtime optimization provides the best trade-off for real-time deployment in resource-constrained environments.

6 Conclusion and Future Research Directions

The proposed Group Sparse YOLOv8 model demonstrates significant advancements in real-time object detection, particularly in distinguishing real animals from toy animals, achieving high precision by focusing on task-specific features such as texture patterns and object shapes, which ensures a substantial proportion of accurate identifications. Despite outperforming other models such as AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, and SqueezeNet, both with and without sparsity constraints, the model exhibits lower recall, correctly identifying only 60% of actual positive cases, suggesting room for improvement in detecting all relevant instances. These improvements would address current limitations and pave the way for more robust and adaptive models in real-world applications, solidifying Group Sparse YOLOv8 as a resource-efficient solution for real-time object detection, particularly in scenarios where distinguishing real and toy animals is critical.

Future research will focus on multi-faceted optimizations:

• Refining core limitations: Adjusting classification thresholds to balance precision and recall, expanding the dataset with more diverse and balanced samples (e.g., rare animal species, toys under extreme lighting), and iterating on group sparsity regularization to reduce redundancy while preserving critical feature extraction.

• Leveraging post-YOLOv8 innovations: Integrating advancements from recent YOLO iterations to augment the Group Sparse YOLOv8 framework. Specifically, adopting YOLOv10’s NMS-free training to eliminate post-processing latency, enhancing feature aggregation with YOLOv11’s C3K2 blocks to better capture fine-grained details (e.g., fur texture vs. synthetic material), and incorporating YOLOv12’s attention mechanisms (e.g., Area Attention Module) to strengthen focus on discriminative features all while retaining the efficiency gains of group sparsity.

• Scaling adaptability: Exploring hybrid designs that combine group sparsity with YOLOv9’s Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) to reduce information loss in deep layers, further improving robustness to occlusion and varying lighting conditions common in real-world monitoring scenarios.

These steps will address current limitations, enhance the model’s real-time performance and accuracy, and solidify its role as a resource-efficient solution for critical applications requiring precise differentiation between real and toy animals.

Acknowledgement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R754), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Zia Ur Rehman; writing-original draft preparation, Ahmad Syed.; supervision, Abu Tayab, Ahmad Syed, Ghanshyam G. Tejani, Doaa Sami Khafaga, El-Sayed M. El-kenawy; validation and formal analysis, Ahmad Syed; review-writing and editing, Ahmad Syed, Abu Tayab, Ghanshyam G. Tejani, Doaa Sami Khafaga, El-Sayed M. El-kenawy, software. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Han X, Chang J, Wang K. You only look once: unified, real time object detection. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;183(1):61–72. [Google Scholar]

2. Pirinen A, Sminchisescu C. Deep reinforcement learning of region proposal networks for object detection. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23. Salt Lake City, UT, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 6945–54. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sunkara R, Luo T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: a new CNN building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Cham, Switerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 443–59. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-26409-2_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R CNN. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2961–70. [Google Scholar]

5. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot MultiBox detector. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2016. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li J, Liang X, Shen S, Xu J, Feng J, Yan S. Scale aware convolutional neural networks for fast object detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(11):2815–28. [Google Scholar]

7. Joyson A, Babu KV. A comparative study on real time object detection models YOLOv7 and YOLOv8. Materials Today Proc. 2023;58:1138–43. [Google Scholar]

8. Bewley A, Ge Z, Ott L, Ramos F, Upcroft B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2016 Sep 25–28; Phoenix, AZ, USA. IEEE; 2016. p. 3464–8. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2016.7533003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bochkovskiy A, Wang C, Liao H. YOLOv4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934.2020. [Google Scholar]

10. Joyson A, Babu KV. Performance analysis of YOLOv8 real time object detection model for UAV applications. In: 2023 International Conference on Recent Advances in Robotics (ICRAR); 2023 May 18–19; Boca Raton, FL, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

11. Gebre TS. Smart traffic solutions: enhanced UAV-based traffic monitoring, object detection and AI-enhanced guidance system [dissertation]. Greensboro, NC, USA: North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University; 2025. [Google Scholar]

12. Scardapane S, Comminiello D, Hussain A, Uncini A. Group sparse regularization for deep neural networks. Neurocomputing. 2017;241(7553):81–9. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2017.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. IEEE; 2018. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. IEEE; 2016. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang X, Zou Y, Shen X, Zhang L. Sparse group Lasso for feature selection and joint estimation. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2019;131:178–93. [Google Scholar]

17. Felzenszwalb PF, Girshick RB, David D, Malik J. Object detection with discriminative structured models and non-maximum suppression. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2010 Sep 25–Oct 2; Kyoto, Japan. p. 1624–31. [Google Scholar]

18. Li Hao, Kadav A, Durdanovic I, Samet H, Graf HP. Pruning filters for efficient convnets. arXiv:1608.08710. 2016. [Google Scholar]

19. Abiodun EO, Alabdulatif A, Abiodun OI, Alawida M, Alabdulatif A, Alkhawaldeh RS. A systematic review of emerging feature selection optimization methods for optimal text classification: the present state and prospective opportunities. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33(22):15091–118. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06406-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sun P, Zhang R, Jiang Y, Kong T, Xu C, Zhan W, et al. Sparse R-CNN: end-to-end object detection with learnable proposals. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. IEEE; 2021. p. 14449–14458. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. He Y, Mao J, Sun J. SqueezeNet: AlexNet level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <0.5 MB model size. arXiv:1706.04513. 2017. [Google Scholar]

22. Liu Z, Wu Y, Luo Y, Wang L, Lin J, Liu Y, et al. A survey of deep learning techniques for real time object detection. Neurocomputing. 2020;418:60–88. [Google Scholar]

23. Liu BH, Zhang Z, He P, Wang Z, Xiao Y, Ye R, et al. A survey of lottery ticket hypothesis. arXiv:2403.04861. 2024. [Google Scholar]

24. Dave B, Mori M, Bathani A, Goel P. Wild animal detection using YOLOv8. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;230(25):100–11. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.12.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Shetty AD, Ashwath S. Animal detection and classification in image & video frames using YOLOv5 and YOLOv8. In: 2023 7th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA); 2023 Nov 22–24; Coimbatore, India. IEEE; 2023. p. 677–83. doi:10.1109/ICECA58529.2023.10394750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang YF, Zhao X, Li Z, Yin J, Zhang L, Chen Z. Integrating artificial intelli-gence into operating systems: a comprehensive survey on techniques, applications, and future direc-tions. arXiv:2407.14567. 2024. [Google Scholar]

27. Yang D, Solihin MI, Zhao Y, Cai B, Chen C, Wijaya AA, et al. Model compression for real-time object detection using rigorous gradation pruning. iScience. 2025;28(1):111618. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.111618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wright SJ, Nowak RD, Figueiredo MAT. Sparse reconstruction by separable approximation. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2009;57(7):2479–93. doi:10.1109/TSP.2009.2016892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Notarstefano G, Notarnicola I, Camisa A. Distributed optimization for SmartCyber-physical networks. FnT Syst Control. 2020;7(3):253–383. doi:10.1561/2600000020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pan E, Mei X, Wang Q, Ma Y, Ma J. Spectral-spatial classification for hyperspectral image based on a single GRU. Neurocomputing. 2020;387(2):150–60. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.01.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Dundar T, Ince T. Sparse representation-based hyperspectral image classification using multiscale superpixels and guided filter. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2019;16(2):246–50. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2018.2871273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhong S, Li J. Spectral spatial sparse representation for classification of hyperspec-tral images. Pattern Recognit. 2010;43(6):1868–81. [Google Scholar]

33. El Halabi M. Learning with structured sparsity: from discrete to convex and back. Lausanne, Switzerland: Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne; 2018. [Google Scholar]

34. Atamturk A, Gomez A. Rank one convexification for sparse regression. arXiv:1901.10334. 2019. [Google Scholar]

35. Jenatton R, Mairal J, Obozinski G, Bach F. Proximal methods for sparse feature selection. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12:2297–334. [Google Scholar]

36. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Mark Liao HY. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Asdikian JPH, Li M, Maier G. Performance evaluation of YOLOv8 and YOLOv9 on custom dataset with color space augmentation for Real-time Wildlife detection at the Edge. In: 2024 IEEE 10th International Conference on Network Softwarization (NetSoft); 2024 Jun 24–28; Saint Louis, MO, USA. IEEE. p. 55–60. doi:10.1109/NetSoft60951.2024.10588933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J. Yolov10: real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;37:107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

39. Hua Z, Aranganadin K, Yeh CC, Hai X, Huang CY, Leung TC, et al. A benchmark review of YOLO algorithm developments for object detection. IEEE Access. 2025;13:123515–45. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3586673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Gong X, Yu J, Zhang H, Dong X. AED-YOLO11: a small object detection model based on YOLO11. Digit Signal Process. 2025;166(1):105411. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2025.105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wu WY, Chen Y, Chen L, Ai T, Alhassan T, Khestin A, et al. YOLOv11-based real-time wildlife detection: advancing automated monitoring in complex natural environments [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389321189_YOLOv11-Based_Real-Time_Wildlife_Detection_Advancing_Automated_Monitoring_in_Complex_Natural_Environments. [Google Scholar]

42. Tian YJ, Ye Q, Doermann D. Yolov12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. [Google Scholar]

43. Khanam R, Hussain M. A review of YOLOv12: attention-based enhancements vs. previous versions. arXiv:2504.11995. 2025. [Google Scholar]

44. Animals detection images dataset [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/antoreepjana/animals-detection-images-dataset. [Google Scholar]

45. NTLNP dataset [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://huggingface.co/datasets/myyyyw/NTLNP. [Google Scholar]

46. Alpha make sense [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.makesense.ai/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools