Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Beyond Accuracy: Evaluating and Explaining the Capability Boundaries of Large Language Models in Syntax-Preserving Code Translation

1 School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

2 Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Yan Guang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Powered Software Engineering)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070511

Received 17 July 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly applied in the field of code translation. However, existing evaluation methodologies suffer from two major limitations: (1) the high overlap between test data and pretraining corpora, which introduces significant bias in performance evaluation; and (2) mainstream metrics focus primarily on surface-level accuracy, failing to uncover the underlying factors that constrain model capabilities. To address these issues, this paper presents TCode (Translation-Oriented Code Evaluation benchmark)—a complexity-controllable, contamination-free benchmark dataset for code translation—alongside a dedicated static feature sensitivity evaluation framework. The dataset is carefully designed to control complexity along multiple dimensions—including syntactic nesting and expression intricacy—enabling both broad coverage and fine-grained differentiation of sample difficulty. This design supports precise evaluation of model capabilities across a wide spectrum of translation challenges. The proposed evaluation framework introduces a correlation-driven analysis mechanism based on static program features, enabling predictive modeling of translation success from two perspectives: Code Form Complexity (e.g., code length and character density) and Semantic Modeling Complexity (e.g., syntactic depth, control-flow nesting, and type system complexity). Empirical evaluations across representative LLMs—including Qwen2.5-72B and Llama3.3-70B—demonstrate that even state-of-the-art models achieve over 80% compilation success on simple samples, but their accuracy drops sharply below 40% on complex cases. Further correlation analysis indicates that Semantic Modeling Complexity alone is correlated with up to 60% of the variance in translation success, with static program features exhibiting nonlinear threshold effects that highlight clear capability boundaries. This study departs from the traditional accuracy-centric evaluation paradigm and, for the first time, systematically characterizes the capabilities of large language models in translation tasks through the lens of program static features. The findings provide actionable insights for model refinement and training strategy development.Keywords

Code translation refers to the automatic transformation of a program written in a source language into a semantically equivalent implementation in a target language. It is a core capability that underpins legacy system migration, cross-platform deployment, and multi-language software support [1,2]. This task inherently requires models to not only master the syntactic rules of both source and target languages but also understand program semantics and control logic, so as to generate executable and structurally complete target code while preserving semantic consistency. Early approaches primarily relied on manually crafted syntax mapping rules or template matching. While such methods achieved some success for specific language pairs (e.g., Java

Recent advances in large-scale pretrained language models (LLMs) have extended their success in natural language processing to code understanding and generation. Transformer-based models such as Codex [3], StarCoder [4], CodeGen [5], CodeLlama [6], and GPT-4 [7] demonstrate strong cross-lingual semantic capabilities by learning from massive code corpora, enabling accurate code translation without handcrafted rules. These models are increasingly adopted in real-world tasks such as automated code migration, API transformation, and bilingual development. Despite these advances, the systematic evaluation of LLMs’ true capabilities in code translation remains underexplored. Existing approaches suffer from two key limitations: (1) Data contamination: Widely used benchmarks such as TransCoder [8] and CodeXGLUE [9] are built from public repositories (e.g., GitHub), which are likely included in pretraining corpora. This results in inflated performance due to “seen” data, undermining evaluation fairness. (2) Lack of feature-level interpretability: Existing evaluation metrics such as BLEU, Exact Match, and CodeBLEU mainly focus on surface-level correctness (i.e., “whether it is correct”), but fail to address “what factors make it incorrect.” These metrics cannot reveal the model’s capability gaps in handling complex syntax, control flow structures, or expression composition.

To address these issues, we propose a systematic solution from two dimensions:

(1) A contamination-free benchmark dataset with controllable complexity. We present TCode, a benchmark constructed using Csmith to generate structurally diverse, syntactically complete C programs, while ensuring zero overlap with the pretraining corpora of large language models. Unlike many existing datasets that mix syntactic transformation with semantic-level API behavior, TCode focuses exclusively on pure syntax-level C-to-X translation, intentionally avoiding cross-language semantic mappings involving APIs or library functions. To regulate task complexity, we introduce a five-factor scoring scheme based on: maximum syntactic nesting depth (Depth), number of statements (Stmt), expression complexity (Expr), number of function definitions (Func), and maximum pointer indirection level (Ptr). All features are normalized to eliminate scale bias, enabling fine-grained control over sample complexity. Together, these design choices make TCode an ideal platform for probing the performance boundaries of large language models in code translation tasks.

(2) A static-feature-based correlation analysis framework: Going beyond traditional accuracy-based evaluations, we introduce a structural modeling approach to examine correlations between static code features and translation success rates. By extracting nine core static features (e.g., code length, syntactic depth, pointer usage, type system complexity), we build a random forest model to highlight influential factors and their association with translation outcomes. This enables a shift in the evaluation paradigm—from merely detecting failure to analyzing contributing factors.

In summary, this work fills the gap in LLM code translation research, where existing evaluations lack interpretability and rely solely on accuracy. We advance the evaluation paradigm from result-driven metrics to correlation-driven analysis. Moreover, our benchmark dataset offers controllability, reproducibility, and theoretical grounding, providing a unified foundation for future research in LLM architecture design, performance optimization, and interpretability in code translation tasks.

In recent years, numerous high-quality datasets have been proposed for code translation and generation tasks, driving continuous improvements in model performance and evaluation standards. Lu et al. [9] introduced CodeXGLUE, which includes 14 subsets and 10 code intelligence tasks, notably featuring CodeTrans, a dataset for Java-to-C# function-level translation. Puri et al. [10] released CodeNet, comprising approximately 14 million code samples in 55 programming languages, widely used in multilingual code research. Zhu et al. proposed the CoST dataset, offering parallel code snippets across 7 languages, and later extended it to XLCoST [11], which covers 42 language pairs and supports both snippet- and program-level translation. Ahmad et al. [12] constructed the AVATAR and AVATAR-TC datasets for Java-Python program translation, emphasizing executability and test case verification. Zheng et al. [13] introduced HumanEval-X, featuring 820 high-quality programming problems and multilingual test cases to assess the cross-lingual capabilities of code generation models. Yan et al. [14] proposed CodeTransOcean, supporting diverse translation tasks among mainstream and underrepresented languages, further enriching multilingual code translation benchmarks.

Unlike traditional benchmarks, TCode introduces several key innovations: it employs automated generation to ensure diversity and contamination-free data, enables controllable adjustment of sample complexity, and focuses exclusively on pure syntax-level translation tasks. In addition, program complexity metrics are incorporated into the dataset to support subsequent feature correlation analysis, thereby enabling a systematic revelation of the capability boundaries of LLMs in code translation.

Current evaluation methodologies adopt multi-dimensional metrics to systematically assess the quality of code translation. Calculation Accuracy measures the functional consistency of generated code, Exact Match Accuracy evaluates token-level correctness, while Compilation Accuracy captures syntactic validity. The BLEU metric, proposed by Papineni et al. [15], though widely used in NLP, fails to account for code-specific structural and semantic properties. To address this, Ren et al. [16] proposed CodeBLEU, which combines n-gram matching, weighted BLEU, abstract syntax tree matching, and data flow matching to comprehensively evaluate code generation quality. Additionally, Kulal et al. [17] introduced the pass@k metric to evaluate a model’s ability to generate test-passing code, which has become a vital complement in the assessment of code generation models.

Unlike traditional metrics that only measure accuracy or token overlap, our evaluation framework introduces a static-feature-based sensitivity analysis. This structural modeling approach examines correlations between static code features and translation success rates. By extracting nine core static features (e.g., code length, syntactic depth, pointer usage, and type system complexity), we build a random forest model to identify which factors most strongly influence performance. This shifts the evaluation paradigm from simply reporting success or failure toward analyzing the underlying factors that contribute to failures. Compared with BLEU, CodeBLEU, or pass@k, our framework provides greater diagnostic and explanatory power, offering deeper insights into the capability boundaries of code translation models.

2.3 Code Translation Approaches

Existing code translation approaches fall into two categories: traditional static tools based on program analysis, and learning-based models. The former includes source-to-source compilers such as C2Rust [18], CxGo [19], Sharpen [20], and Java2CSharp [21], which enable cross-language translation through syntax-preserving rewrites. The latter ranges from early statistical machine translation and syntax-tree-based neural networks to the current mainstream LLM-driven models, which significantly improve translation quality and generalization.

LLMs have achieved breakthroughs in code generation and translation tasks. StarCoder [4], trained on 1TB of code spanning 80+ languages, excels in industrial translation scenarios. CodeGen [5], through multi-stage training, enhances language migration ability and performs strongly across benchmarks. CodeT5 [22] adopts a unified architecture supporting multi-task learning such as generation, translation, and summarization, with fine-grained syntactic modeling capabilities. CodeX [3] leverages test-case-driven learning to enhance code executability. CodeGeeX [23] emphasizes migration in Chinese development scenarios. GPT-4 [7], with strong contextual reasoning, demonstrates exceptional performance in code translation tasks. Llama 3 [24] provides robust multilingual and open-source ecosystem support, and serves as the foundation of projects like CodeLlama. DeepSeek-Coder [25] focuses on structural and semantic preservation, making it particularly suitable for semantically sensitive translation tasks.

These contributions collectively advance code translation research toward higher quality and greater generalization capacity.

3 Construction of TCode with Controllable Complexity and Annotated Features

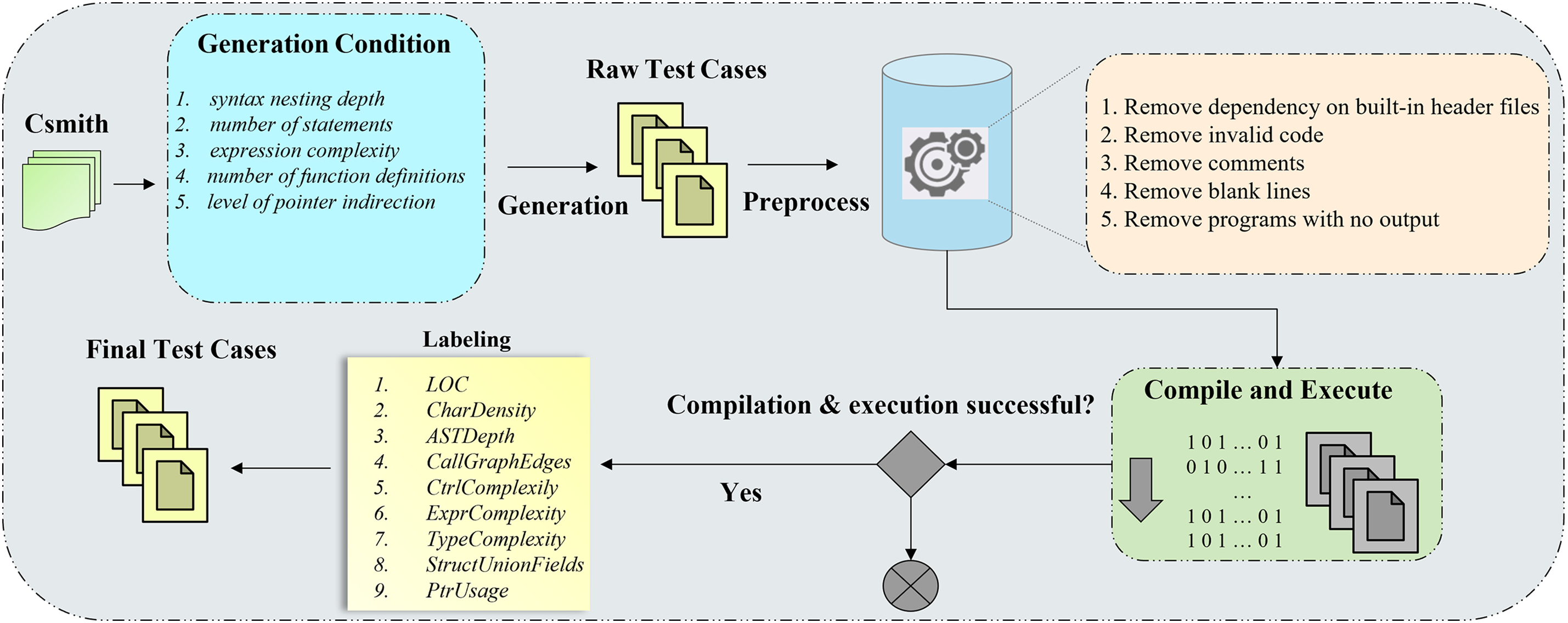

To comprehensively evaluate the code translation capabilities of large language models (LLMs), we construct a structurally diverse, complexity-controllable, and semantically complete C language test set, named TCode. This dataset is built upon the Csmith [26] random program generator, which offers efficient program synthesis and rich syntactic diversity, and is widely used in compiler validation research. Csmith [26] supports generating C programs with diverse syntactic features, including function and variable definitions, control flow statements (e.g., if/else, for, goto, return), arithmetic and logical expressions, multi-level pointers, array operations, and structs and unions (including nesting and bitfields), ensuring diversity and representativeness in language structures of the generated samples. Based on this, we design an automated pipeline for program generation, cleaning, and filtering, ensuring that all samples are compilable, executable, and semantically correct. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall dataset construction process. To categorize the generated samples by complexity, we propose a scoring mechanism composed of five core structural features: syntax nesting depth (Depth), number of statements (Stmt), expression complexity (Expr), number of function definitions (Func), and level of pointer indirection (Ptr) (these features are selected because Csmith supports explicit control over these parameters). To eliminate the influence of differing scales among features, we first normalize each metric as follows:

Figure 1: Dataset construction pipeline for TCode

Based on our preliminary regression analysis conducted on models such as Qwen2.5-7B and Llama3.3-8B, we observed that expression complexity (Expr) and nesting depth (Depth) have the most significant impact on model performance. Therefore, these two features are assigned higher weights in the complexity scoring function. The overall complexity score is defined as follows:

The weight parameters are set as

To enhance the informational richness and evaluative interpretability of the test set, we introduce a set of static complexity metrics on the constructed TCode dataset. These metrics are categorized into two classes: Code Form Complexity and Semantic Modeling Complexity. They aim to comprehensively characterize program features from both surface representation and structural depth, supporting downstream correlation analysis.

Code Form Complexity measures the size and encoding density of program inputs at the character-level, reflecting the perceptual burden on the model when processing raw code. It includes the following metrics:

(1) Number of Code Lines: Indicates the total lines of the program, serving as a direct quantification of input context length and determining the token sequence length to be processed by the model.

(2) Character Density: Defined as the average number of characters per line, representing the information density per line and the cognitive load required to read and understand the code.

In contrast, Semantic Modeling Complexity focuses on the depth of syntax structures, control logic, and type systems within the program. These metrics reflect the modeling challenges involved in parsing structure, mapping types across languages, and preserving control flow. It includes the following seven metrics:

(1) Maximum AST Depth: Refers to the maximum nesting level in the program’s Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), which serves as a core indicator of syntactic structural complexity.

(2) Number of Edges in the Call Graph: Represents the number of invocation relationships among functions within the program, reflecting the degree of module coupling and call depth.

(3) Control Complexity E: Measures the nesting level of control structures, defined as:

Specifically,

(4) Average Expression Complexity: Computes the average nesting level of all expressions in the program, capturing the complexity of statement-level logical structures, including logical operations and nested function calls.

(5) Type System Complexity: Measures the total number of distinct data types used in the program, including primitive types, structs, unions, enums, arrays, and function pointers, reflecting the difficulty of cross-language type mapping.

(6) Struct and Union Field Complexity: Indicates the average number of fields in struct and union types, which characterizes the internal organization density of compound data structures. A higher number of fields suggests more complex information representation, thus imposing a heavier burden on semantic modeling.

(7) Pointer Usage Count: Counts all occurrences of pointer declarations, address-of operations (&), and dereferencing operations (*), representing the structural challenges in modeling low-level memory semantics and address manipulation.

In summary, this section introduces the construction of TCode, a C-language test set that is semantically complete, complexity-controllable, and free from pretraining contamination. We select five structural complexity features—syntax depth, statement count, expression complexity, function count, and pointer level—based on the fact that they are directly controllable in Csmith. Using a weighted normalization strategy, samples are categorized into three difficulty levels. Additionally, we annotate each sample with nine static features (e.g., lines of code, AST depth, control complexity). These annotations provide a rich foundation for downstream analysis of contributing factors.

4 An Evaluation Framework Based on Correlation Analysis of Static Program Complexity

To address the limitations of existing evaluation methods in structural sensitivity and interpretability, we propose a framework that integrates correlation analysis of static program complexity. The framework consists of two core modules:

• Semantic Verification: By executing the translated code and comparing outputs with the original program, this module evaluates whether semantic equivalence is achieved—addressing the limitations of BLEU [15] and CodeBLEU [16] in assessing functional correctness.

• Static Program Complexity Correlation Analysis: This module extracts syntactic, control-flow, and type-level static features, and examines their correlations with translation outcomes. It identifies structural factors associated with failures and delineates performance boundaries.

Using the TCode dataset, we extract static features across multiple dimensions, including code length, AST depth, expression complexity, type system diversity, and pointer usage, providing a rich basis for correlation analysis. To quantitatively associate static features with translation performance, we employ a supervised learning model based on Random Forest [27], using static features as input and translation success or failure as the output label. This model captures predictive associations between program features and translation outcomes, offering correlation-based insights into feature influence. To mitigate data imbalance, ASN-SMOTE [28] (Adaptive qualified Synthesizer-selected SMOTE) is applied to oversample failure samples during training, enhancing the model’s sensitivity to minority cases. Five-fold cross-validation is used to ensure stability and generalization, and the modeling process is summarized in Table 3.

Based on the proposed correlation evaluation framework and the TCode dataset, this section aims to systematically investigate the performance and capability boundaries of large language models (LLMs) on syntax-preserving code translation tasks. Specifically, we address the following four key research questions:

• RQ1: How well do mainstream LLMs perform on syntax-preserving code translation tasks?

• RQ2: What types of syntactic or semantic errors frequently occur during the translation process?

• RQ3: Which static features are most strongly associated with translation outcomes, indicating higher model sensitivity or reliance?

• RQ4: In what ways do static complexity features correlate with translation performance, and are there critical inflection points or identifiable performance bottlenecks?

• RQ5: What are the possible explanations for the performance patterns observed in LLMs on syntax-preserving code translation?

To comprehensively evaluate the performance and capability boundaries of LLMs on syntax-preserving code translation tasks, we construct a unified evaluation pipeline based on the TCode dataset and select a diverse set of representative LLMs for testing and correlation analysis. This section presents the setup in terms of model selection, task configuration, evaluation metrics, and environment setup.

To cover various parameter scales, optimization targets, and model types, we evaluate six mainstream LLMs:

• DeepSeek-Coder-V2-Lite-Instruct-16B [29]: A lightweight code model with 16B total parameters and 2.4B active parameters, supporting 338 programming languages and approaching GPT-4 Turbo [7] in code generation and mathematical reasoning.

• Gemma3-27B [30]: An open-weight large language model with 27B parameters, supporting multimodal inputs (text and images), extended context length up to 128K tokens, and function calling, achieving state-of-the-art performance among open models.

• Qwen2.5-Coder-32B [31]: A high-performance code model based on the Qwen2.5 architecture, trained on over 5.5 trillion tokens, with strong performance in code completion and repair tasks.

• CodeLlama-34B [6]: Meta’s open-source code-specific model with 34B parameters, excelling in Python code generation and semantic modeling.

• Llama3.3-70B [24]: Meta’s general-purpose model with 70B parameters and a 128k context window, combining reasoning capabilities and multilingual generation.

• DeepSeek-R1-70B [25]: A general-purpose LLM with multimodal capabilities and strong performance on complex tasks, approaching GPT-4 levels.

• Qwen2.5-72B [32]: Alibaba DAMO Academy’s flagship model with 72.7B parameters, supporting up to 131k context tokens, designed for long-text understanding, structured information processing, and complex code generation.

These models span a wide range of architectures and training paradigms, offering a solid basis for comparative evaluation under syntax-preserving translation settings.

All experiments are conducted on the TCode dataset constructed in this study. The dataset consists of 3000 valid C programs with semantic completeness, controllable complexity, and zero overlap with pretraining data.

The translation task is standardized as C

As an expert code converter, translate the following C code into Python. Return only the translated Python code, with no additional explanations or comments. [C code]

We adopted a unified Ollama inference configuration across all experiments: temperature = 0.8, top-k = 40, top-p = 0.9, with automatic termination at the end-of-sequence token. The maximum output length was not manually constrained and was limited only by the model’s context window. When truncation was required, we applied a tail-truncation strategy, discarding tokens at the end of the input to ensure the prompt fit within the context window.

5.1.3 Evaluation Pipeline and Metrics

To evaluate the performance of large language models in syntax-preserving code translation, we adopt the framework introduced earlier, which integrates semantic verification and static feature correlation analysis. An automated evaluation pipeline was implemented, with the evaluation metrics defined as follows:

• Compilation Success Rate. A translated program is counted as a success if it can be parsed and executed without syntax errors in a controlled environment.

• Computational Accuracy Rate (Semantic Verification). Since all C programs in our dataset are self-contained and have no external inputs, each translated Python program is executed once and its standard output is captured. A program is considered correct if and only if its output exactly matches the reference output produced by the original C program.

Execution Environment and Limits. All executions are carried out in isolated Python sandboxes with restricted file system and network access. A maximum runtime of 10 s per program is enforced to terminate non-terminating processes.

5.1.4 Experimental Environment

All experiments are conducted on a unified hardware/software platform to ensure reproducibility and fair comparisons.

Hardware:

• 7

• AMD EPYC 7T83 CPU, 64 cores

• 512 GB DDR4 RAM

• 4 TB NVMe SSD storage

Software:

• Ubuntu 24.04.2: LTS operating system

• OLlama 0.3.14: Local LLM inference for open-source models

• CSmith 2.4.0: Automatic generation of structurally complex C programs

• GCC 9.4.0: C code compilation and semantic output validation

• Python 3.10: Verification script execution and auxiliary processing

5.2.1 Model Performance on the TCode Dataset

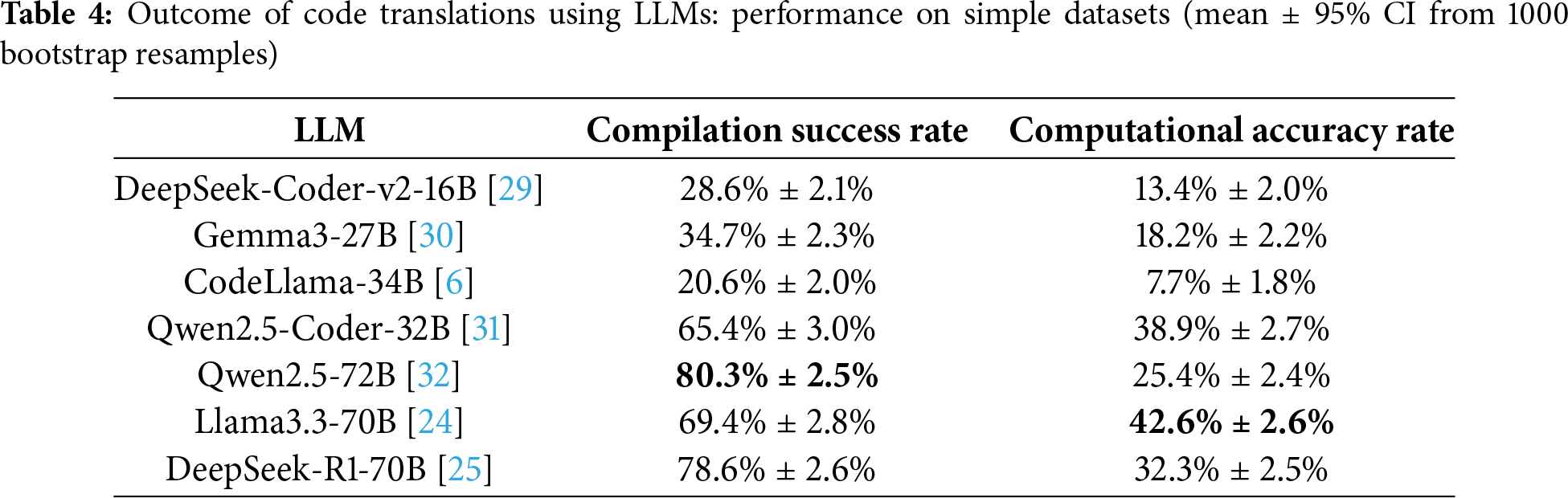

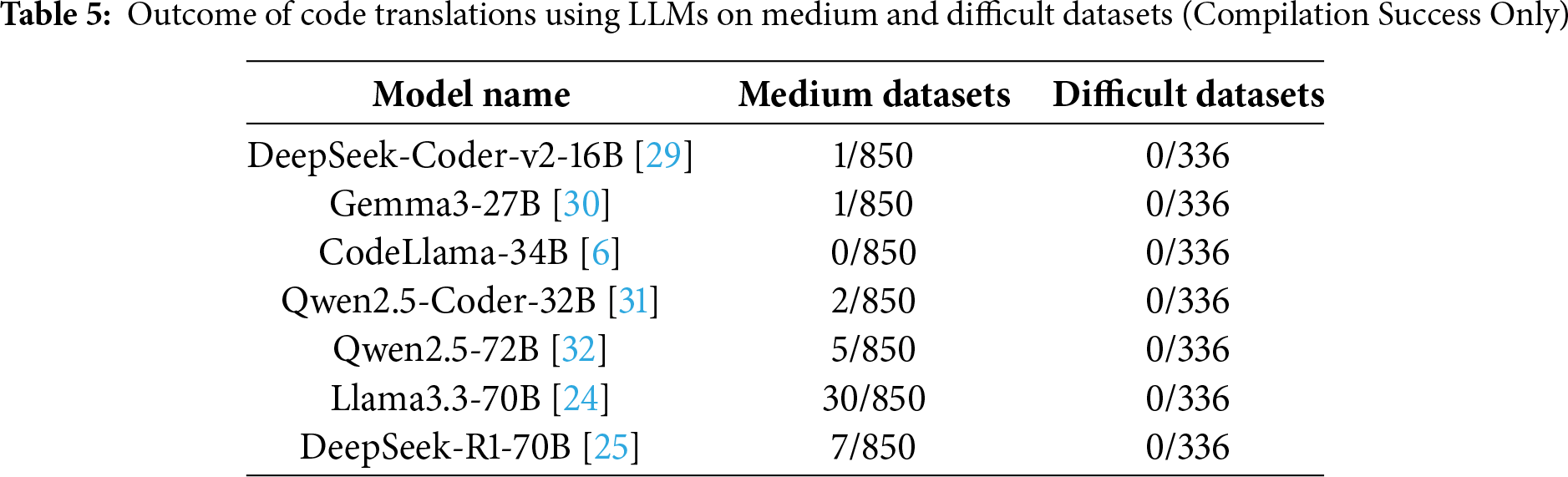

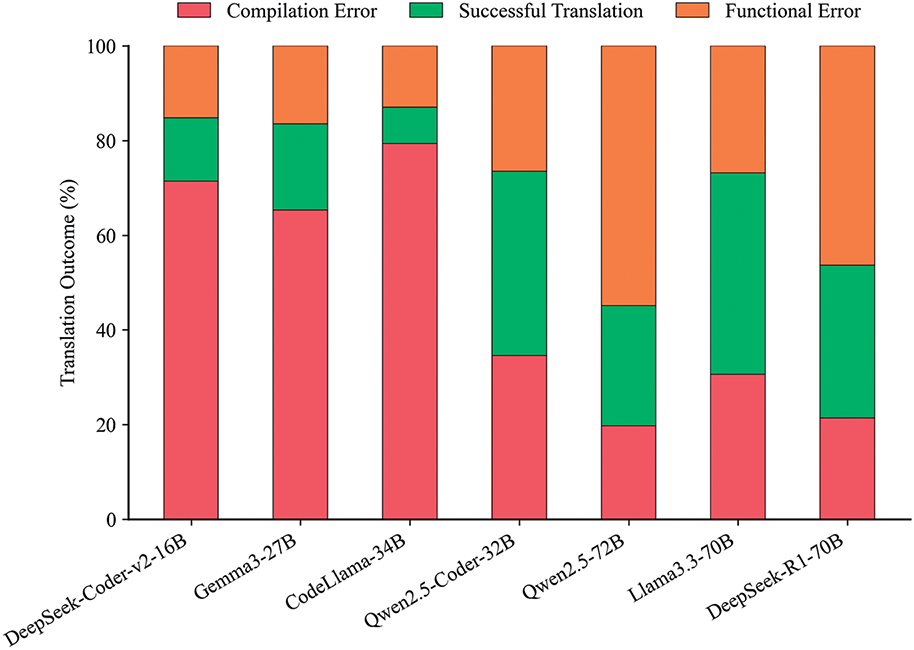

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of large language models (LLMs) on the syntax-preserving code translation task, we assess six representative models across three complexity levels (Simple, Medium, Hard) in the TCode dataset. Specifically, we report both the compilation pass rate and computation accuracy. The detailed results are summarized in Tables 4 and 5, and visualized in Figs. 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Outcome of code translations using LLMs: performance on simple datasets

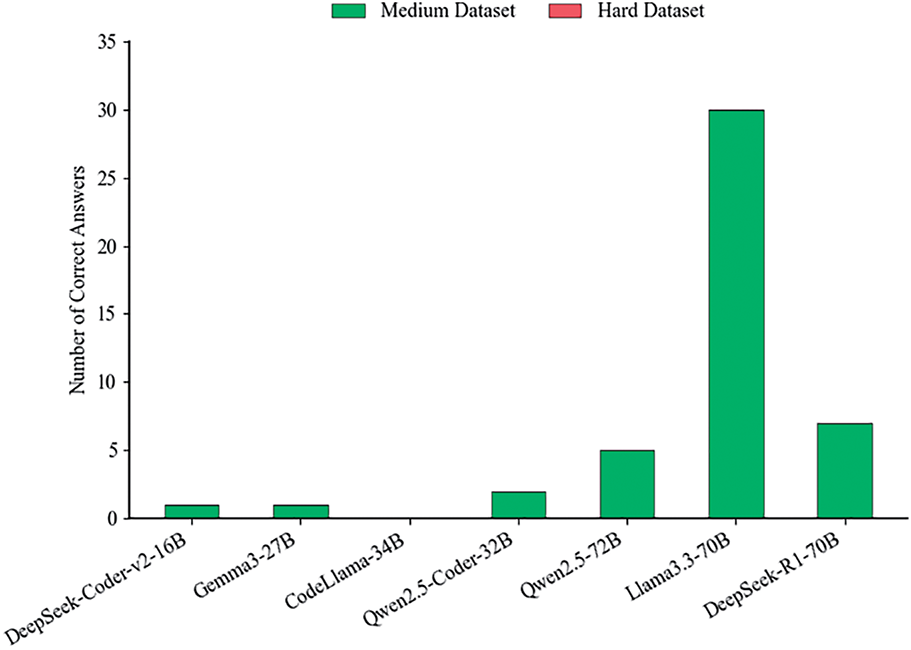

Figure 3: Outcome of code translations using LLMs: performance on medium and difficult datasets (Compilation success only; outputs do not match expected functionality)

(1) Performance on Simple Datasets. As shown in Table 4, the translation results of various LLMs on the simple dataset (1814 samples) reveal substantial performance differences. In terms of compilation success rate, Qwen2.5-72B [32] achieves the highest score at 80.3%, followed by DeepSeek-R1-70B [25] at 78.6% and Llama3.3-70B [24] at 69.4%. In contrast, CodeLlama-34B [6] and DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16B [29] show significantly lower pass rates at only 20.6% and 28.6%, respectively. These discrepancies suggest that model size and architectural optimization play a crucial role in generating syntactically correct translations. High-parameter models exhibit stronger robustness in maintaining both syntactic and semantic consistency.

Regarding computational accuracy, Llama3.3-70B [24] performs the best with a score of 42.6%, indicating its advantage in preserving semantic correctness and logical functionality. Qwen2.5-Coder-32B [31] and DeepSeek-R1-70B [25] follow closely with 38.9% and 32.3%, respectively, demonstrating solid semantic modeling capabilities.

It is noteworthy that although Qwen2.5-72B [32] achieves the highest compilation success rate, its computational accuracy remains only 25.4%, suggesting that the generated code, while syntactically valid, may fall short in semantic fidelity or logical correctness. This limitation may stem from the absence of task-specific instruction tuning. In contrast, Qwen2.5-Coder-32B [31], despite having fewer parameters, demonstrates stronger semantic performance—likely due to targeted optimization for code-related tasks. Similarly, although Gemma3-27B [30] has a comparable parameter scale to Qwen2.5-Coder-32B, its performance lags substantially behind, reflecting its general-purpose design and the lack of specialized tuning. Meanwhile, another code-specialized model, CodeLlama-34B [6], also performs poorly, further indicating that neither larger model size nor domain specialization alone is sufficient to ensure high computational accuracy. Overall, the key determinant lies in the effectiveness of task-specific optimization.

(2) Performance on Medium and Difficult Datasets

Model performance declines sharply with increasing complexity. On the medium-complexity set (850 samples), Llama3.3-70B [24] achieves the highest score with 30 syntactically correct translations, followed by DeepSeek-R1-70B [25] with 7 and Qwen2.5-72B [32] with 5. Qwen2.5-Coder-32B [31] manages 2 correct outputs, while both Gemma3-27B [30] and DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16B [29] succeed only once. CodeLlama-34B [6] fails completely. On the difficult set (336 samples), none of the models produce a single syntactically correct translation. These results highlight a critical bottleneck: current LLMs, even those exceeding 70B parameters, struggle to handle deeply nested syntax and complex control flows, indicating significant limitations in structural abstraction and semantic reasoning.

5.2.2 Syntax-Level Attribution of Translation Failures

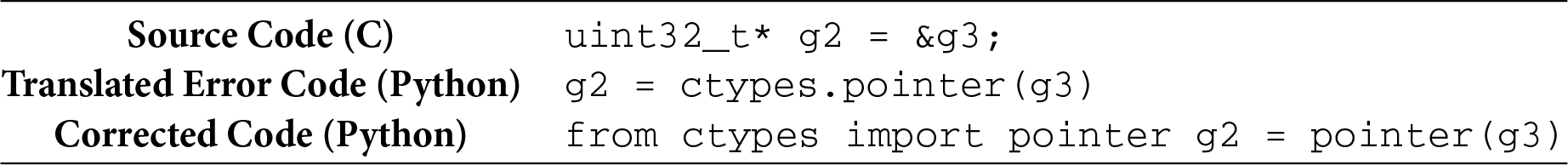

To gain deeper insight into the behavior of large language models (LLMs) when translations fail, we conducted a detailed analysis of the failure cases. Fig. 4 presents the taxonomy of error types commonly observed during code translation. Fig. 5 further illustrates the distribution of these error categories across all failed samples, offering a quantitative perspective on how frequently each type of error occurs in practice. Below, we introduce each type of error along with specific examples, and in the Appendix A, we provide successful translation examples for complex samples.

Figure 4: Categories of errors introduced by large models during code translation

Figure 5: Distribution of translation error categories in LLM-generated code

(1) Syntactic and Semantic Differences between Languages

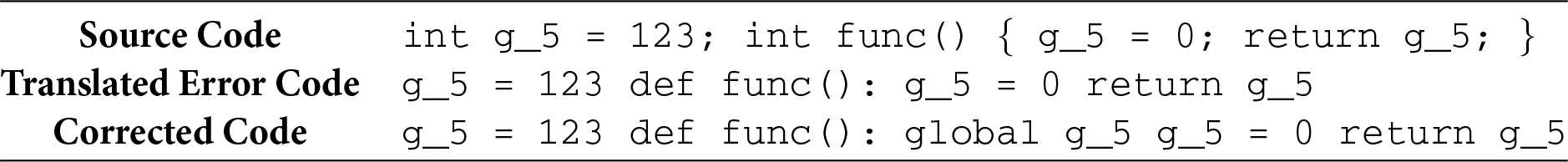

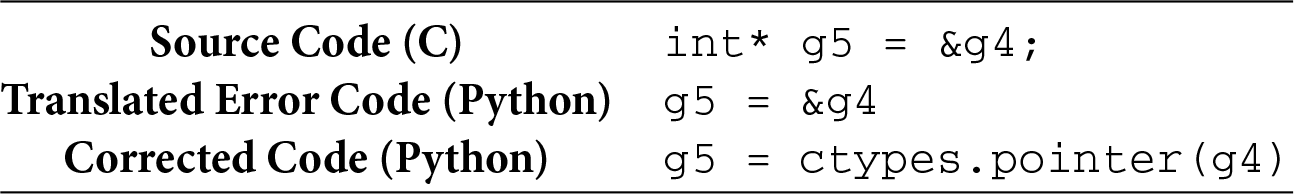

On average, errors caused by syntactic and semantic differences between languages account for 40.16% of all translation failures. A typical manifestation of such issues lies in the direct syntactic mapping from source to target language, often violating the target language’s conventions. This “mechanical translation” phenomenon indicates a limited ability of current models to migrate between distinct syntactic systems and coding styles, particularly in terms of rule comprehension and contextual adaptation. The main types of errors include:

• A1: Target Language Rule Violation. LLMs often fail to adapt to strict syntactic or semantic rules of the target language. For example, modifying global variables in Python requires an explicit global declaration—unlike C. Such omissions can cause semantic errors and reflect inadequate rule migration capabilities.

• A2: Source Syntax Copy. Large language models often copy syntactic constructs from the source language directly into the target language, even when those constructs are not supported. This mechanical replication can easily result in syntactic errors. For example, in C, long integer constants are often annotated with suffixes like L or UL (e.g., 0xFFBEL) to indicate their data type. However, such suffixes are not allowed in Python, where integer constants follow different syntactic rules.

• A3: Lack of Understanding of Target Language API Behavior. During code translation, large language models often need to simulate source-language semantics using library functions in the target language, especially when direct language-level equivalents are unavailable. However, due to insufficient understanding of the design and usage conventions of target-language APIs, models frequently make errors in API invocation, resulting in semantic inaccuracies or runtime exceptions in the generated code.

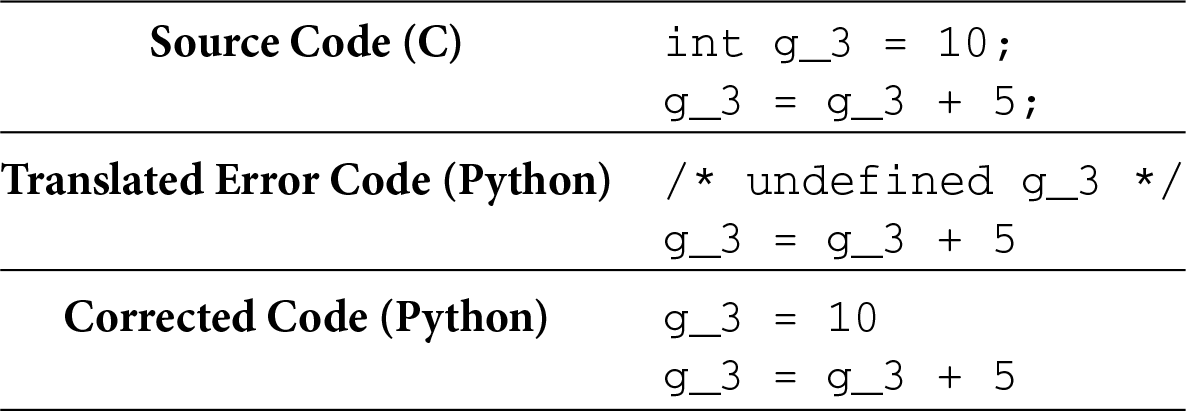

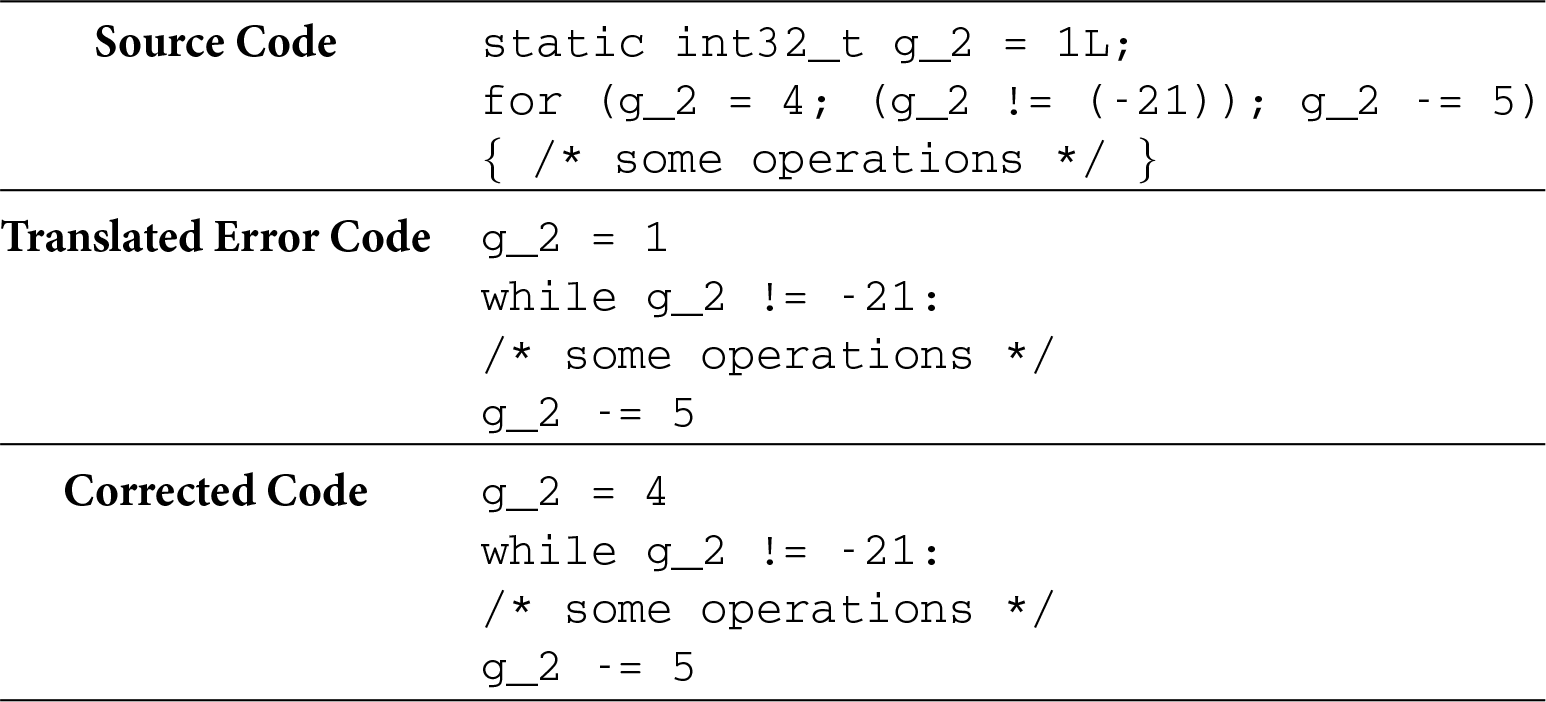

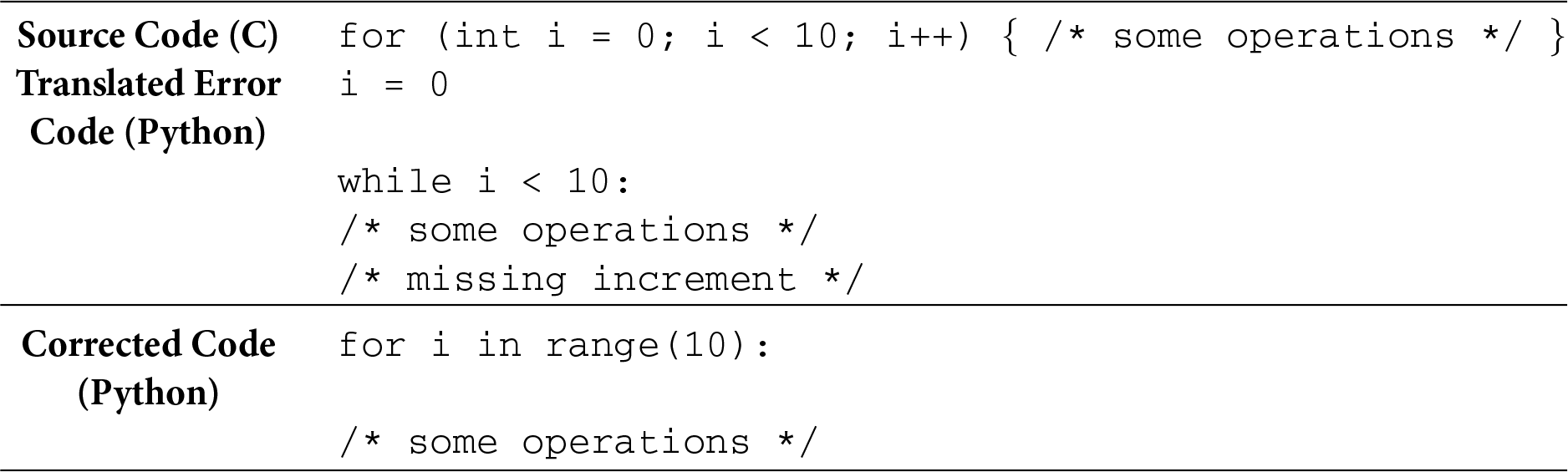

(2) Dependency & Logic Bugs

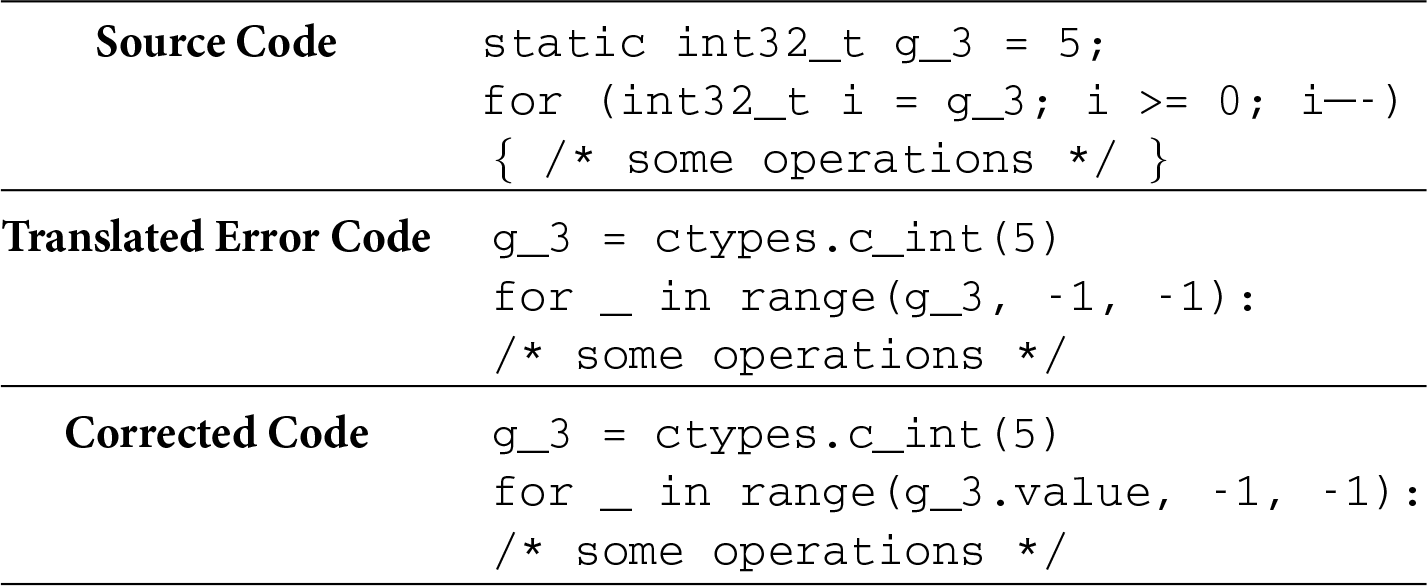

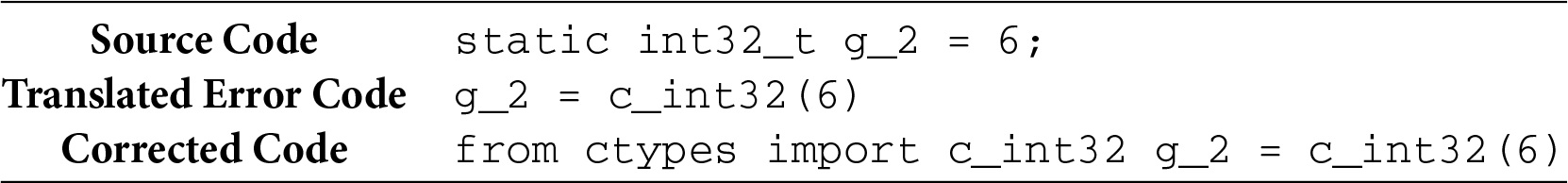

Dependency and logic structure errors account for an average of 24.37%, mainly involving missing essential definitions, translation errors in loops or conditional logic, and omitted library imports. These issues often lead to execution failures or incorrect logic behavior, indicating insufficient capabilities of current models in semantic preservation, context modeling, and dependency management. They can be categorized as follows:

• B1: Missing Library Imports. Models often omit necessary imports for standard or third-party libraries, or incorrectly include unrelated modules, leading to runtime errors or incomplete functionality.

• B2: Missing Definitions. Key components such as variables, functions, or data structures are sometimes absent in generated code, causing structural gaps and semantic inconsistencies.

• B3: Loop and Conditional Translation Errors. Loop and branch logic is frequently misinterpreted—e.g., incorrect bounds, reversed conditions—resulting in execution semantics deviating from the source.

For example, in the case below, when translating a loop structure from C to Python, the model incorrectly retains the initialization of the loop variable and ignores the semantics of reassignment in the loop header, leading to logical distortion.

(3) Data-Related Bugs

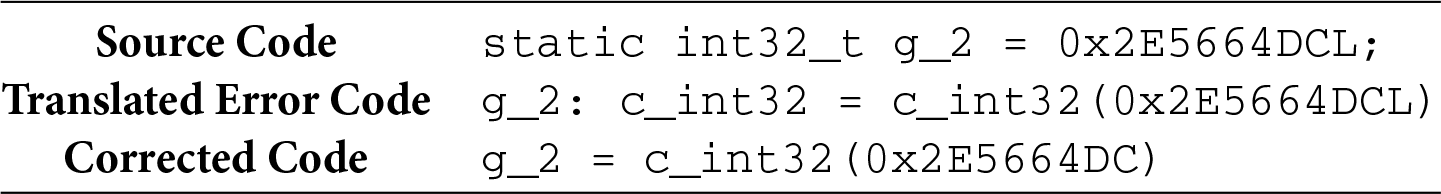

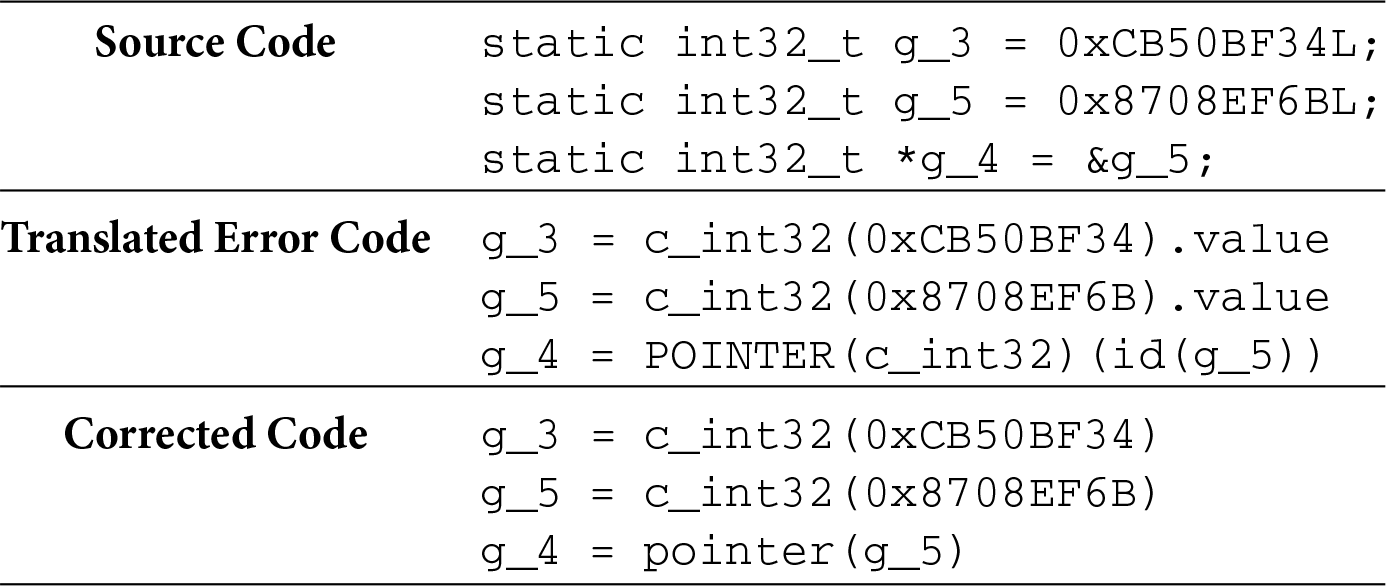

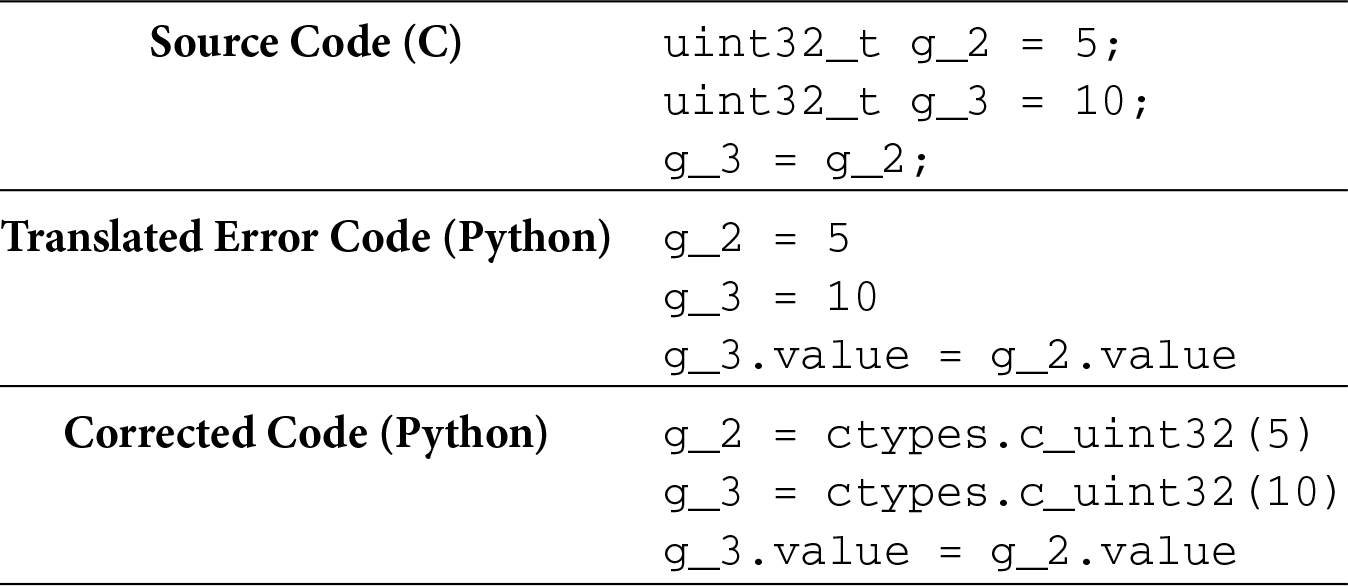

Data-related errors account for an average of 32.30% of all translation failures, with primitive type issues being the most prominent, followed by composite type errors. This indicates that large language models still face significant bottlenecks in cross-language data type mapping and memory layout transformation. The major error types include:

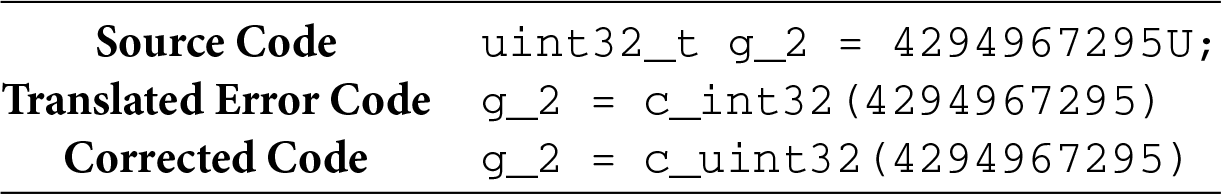

• C1: Primitive Data Type Translation Errors. During translation, models frequently map variables to target types that are semantically inconsistent with those in the source language. This leads to type mismatches, precision loss, or misinterpretation of signed/unsigned semantics, which can cause serious runtime errors. Since different programming languages vary significantly in terms of data type ranges, default behaviors, and boundary handling, a failure to capture such distinctions often results in improper type usage, semantic deviations, or functional anomalies.

• C2: Composite Data Type Translation Errors. When translating structures such as struct or union from the source language, models often fail to preserve their intended memory layouts and access semantics. For instance, translating a union in C to a Structure in Python (e.g., using ctypes.Structure) causes its fields to no longer share memory, thus breaking value reuse mechanisms and semantic consistency inherent in the original C implementation.

(4) Model-Related Bugs

Although model-related output errors are the least frequent—averaging only 3.17%—their potential impact on code usability and reliability should not be overlooked. These errors typically manifest as natural language prompts, incomplete code fragments, or invalid pseudocode. Such outputs severely compromise the executability and practical utility of the translated code and highlight the lack of a robust output strategy when the model encounters uncertain or ambiguous inputs.

• D1: Model Output Errors. These issues arise due to inherent limitations in the model’s capability to generate correct translations. Instead of producing valid target-language code, the model may output unrelated explanatory or instructional content. For example:

Here’s an example of how you might rewrite the code using loops and assuming a structure definition like this:

Fig. 5 illustrates clear differences in error type distributions across different models:

• DeepSeek-Coder-V2-Lite-Inst-16B exhibited the highest proportion of errors caused by syntactic and semantic differences between languages (51.9%), with A3: Incorrect API Use (21.7%) being the most prominent. This suggests the model struggles with syntax transfer and API adaptation. However, it had the lowest rates in B1: Missing Import (0.7%) and C2: Composite Type Errors (7.5%), indicating strong robustness in managing external dependencies and composite structures.

• Gemma3-27B exhibited 36.7% of data-related errors, with C2: Composite Type Errors (20.1%) as the dominant category, reflecting its difficulty in handling complex data structures. Across all error categories, it did not achieve the lowest rate among the compared models, indicating a relatively middling overall performance.

• Qwen2.5-Coder-32B showed 36.9% of data-related errors, with C2: Composite Type Errors (20.5%) as its main issue, indicating challenges in modeling complex variables. In contrast, it achieved the lowest rate in B2: Missing Definition (8.8%), reflecting relatively good handling of identifier declarations and symbol management.

• CodeLlama-34B had 38.4% of errors caused by syntactic and semantic differences between languages, with C1: Primitive Data Type Errors (21.5%) as the major source. However, it recorded the lowest rate of A2: Source Syntax Copy (4%), suggesting it better adapts to target language conventions and avoids mechanical copying.

• Llama3.3-70B had the largest proportion of data-related issues (48.4%), particularly C1: Primitive Type Errors (33.3%), revealing weaknesses in type conversion. Nevertheless, it achieved the lowest rates in D1: Non-Translational Output (0.1%), B3: Loop/Condition Errors (1.6%), and A1: Target Language Rule Violation (10.1%), suggesting strong reliability in maintaining syntactic correctness and stable control-flow translation.

• DeepSeek-R1-70B also had a high share of of errors caused by syntactic and semantic differences between languages (48%), dominated by A3: Incorrect API Use (19.1%). However, it had the lowest share of C1: Primitive Type Errors (5.6%), implying strength in low-level data handling and conversions.

• Qwen2.5-72B had the highest proportion of data-related errors (35.7%), with C1: Primitive Type Errors (17.9%) as the main cause. Interestingly, it had the lowest proportion of A3: Incorrect API Use (12.8%), highlighting better reliability in using target-language APIs and handling function calls appropriately.

5.2.3 Translation Error Association from Code Complexity Perspective

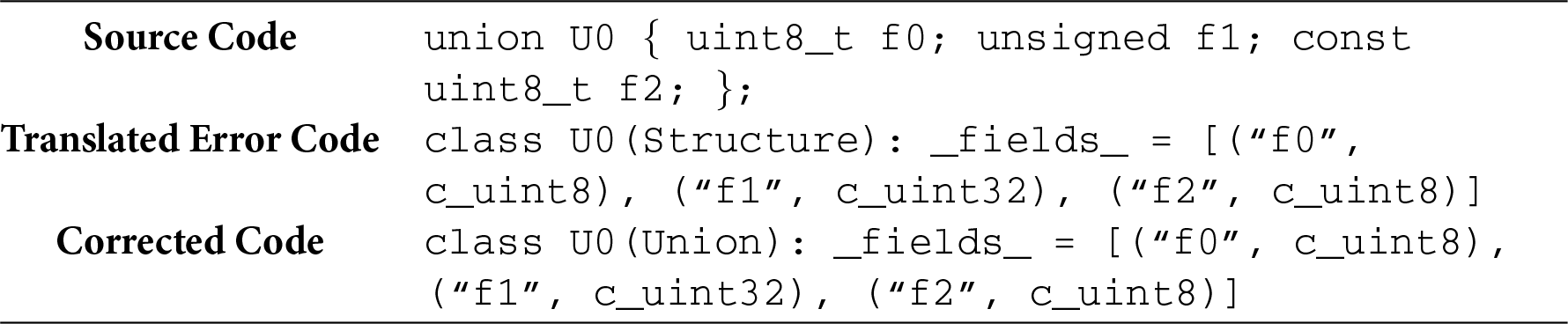

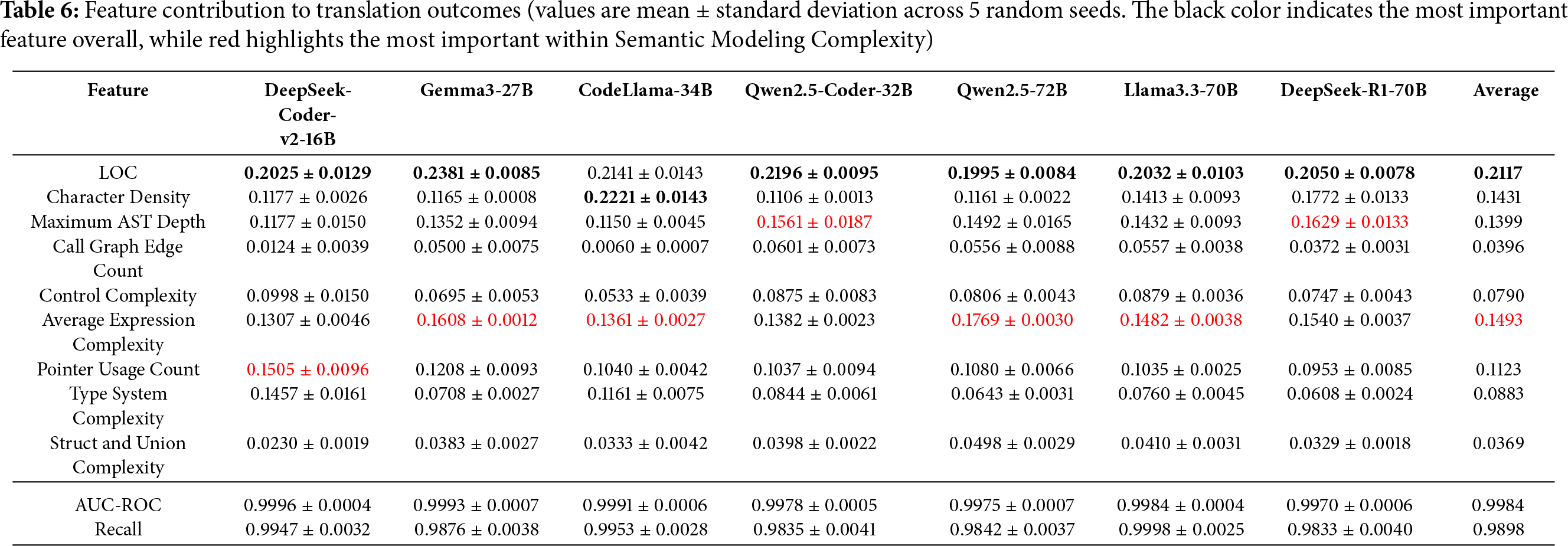

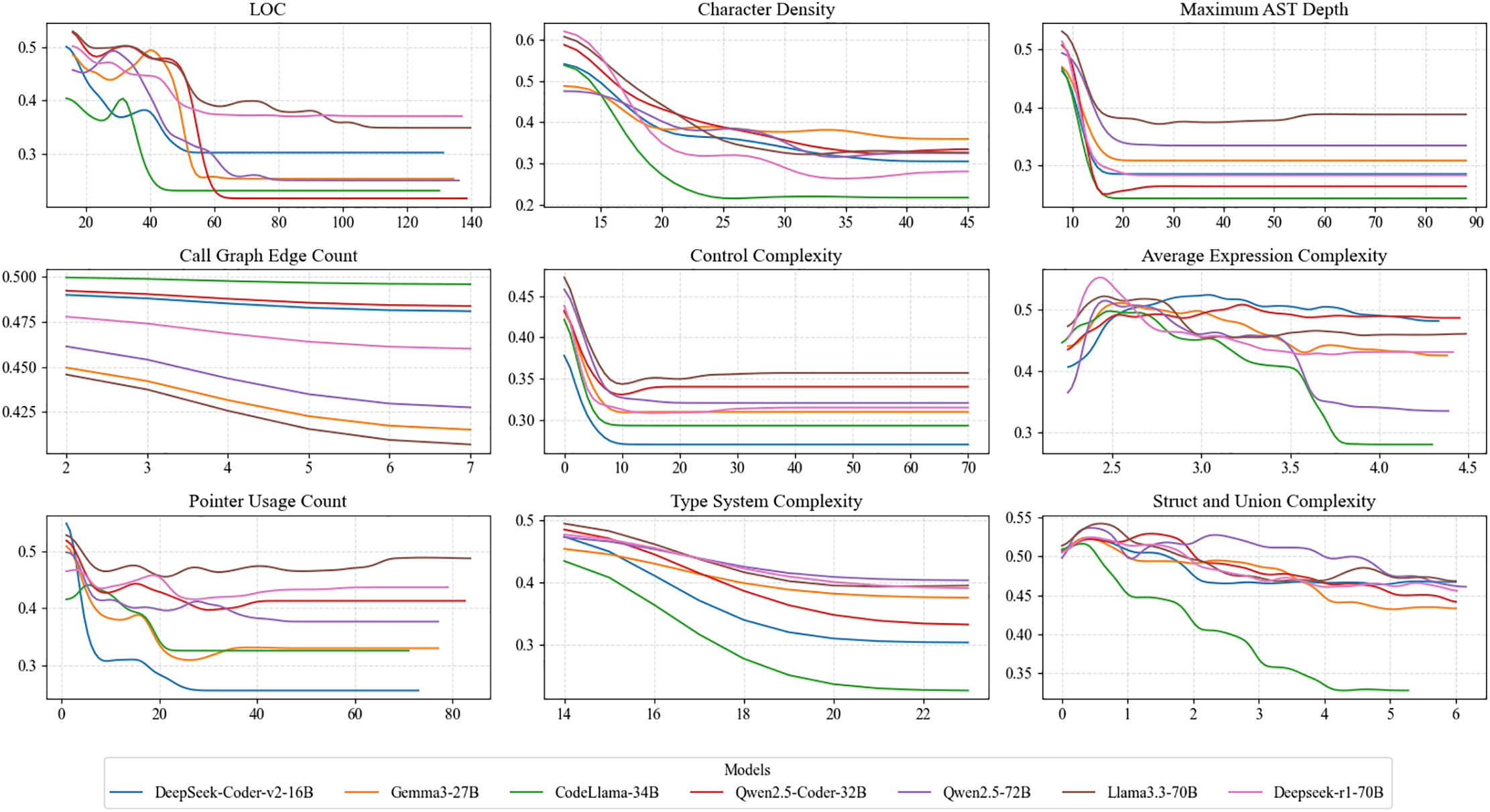

To further analyze the relationship between static code features and the translation capabilities of large language models, we conducted a predictive modeling experiment using the Random Forest algorithm [27]. Specifically, we built a classifier designed to predict translation success based on various code complexity features. This classifier utilizes static code characteristics such as code length, abstract syntax tree depth, and control flow complexity to estimate the likelihood of a successful translation. By training this classifier, we were able to evaluate the relative importance of different features and identify those most strongly associated with translation outcomes, providing valuable insights into the structural patterns that correlate with the translation performance of large language models. The experimental results are presented in Table 6 and visualized in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Partial dependence plots: analyzing the influence of static features on code translation performance

The results indicate consistently high performance across all settings, with Area Under the Curve - Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUC-ROC) values exceeding 0.99 and recall scores above 0.98. These findings demonstrate both the effectiveness of our feature selection strategy and the robustness of the fitted model in capturing structural associations linked to translation outcomes.

Based on the experimental results, we summarize the following key findings:

Finding 1: Syntax-dominant complexity is strongly correlated with model performance.

Static feature correlation analysis shows that Semantic Modeling Complexity accounts for approximately 60% of the observed performance variance, while Code Form Complexity accounts for about 40%. This suggests that large language models (LLMs) exhibit higher sensitivity to syntactic hierarchy in code translation tasks, making syntactic complexity a major factor correlated with generalization limits and upper-bound performance. In comparison, input size and character density show weaker correlations.

Finding 2: Different LLMs display varying associations with semantic-related features such as AST depth, expression complexity, type system complexity, and pointer usage.

DeepSeek-R1-70B shows the strongest association with AST depth, with performance degrading as nesting increases, whereas CodeLlama-34B is relatively more robust. For expression complexity, Qwen2.5-72B is the most sensitive, while DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16B exhibits greater stability. In terms of type system complexity, DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16B shows the highest association, whereas DeepSeek-R1-70B remains more stable. For pointer-intensive code, DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16B is more sensitive, whereas DeepSeek-R1-70B remains relatively stable.

Finding 3: Call graph edge count, control complexity, and struct/union complexity exhibit weak correlations with model performance.

The average importance weights of these features are 0.0396, 0.0883, and 0.0369, respectively—considerably lower than other metrics. For instance, the call graph edge count has weights below 0.0601 across all models, with the lowest being 0.0060 for CodeLlama-34B. Struct and union complexity also remain below 0.0498 across all models. These findings suggest that LLM translation performance remains relatively stable regardless of function call structure complexity or extensive use of structs/unions. Although control complexity might theoretically impact control flow analysis, its correlation with performance is low (maximum 0.0998 for DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16B), indicating that current LLMs demonstrate robustness in managing branching and looping constructs.

Finding 4: Complexity-related performance degradation follows nonlinear trends with identifiable threshold zones.

Features such as code length, AST depth, and control complexity display clear nonlinear degradation patterns: performance remains relatively stable at low complexity, but drops sharply after crossing a certain threshold, eventually staying in a low-efficiency region.

Finding 5: Model scaling shows diminishing association with performance gains on high-complexity inputs.

Cross-model comparison reveals that although increasing model size improves overall performance, all models converge to similar limits when exposed to high-complexity inputs (e.g., AST depth of 20, control complexity of 10). This suggests that merely enlarging parameter count is insufficient to overcome capability bottlenecks.

Finding 6: An optimal complexity window exists; performance does not always improve as complexity decreases.

Analysis of performance trends across different complexity levels shows that peak translation accuracy is often reached in a specific mid-to-low complexity window (e.g., expression complexity of 2.5–3.0). Slight performance drops are observed in lower-complexity regions, likely reflecting imbalanced training data distributions and the non-uniform generalization capacity of models across the complexity space.

This study systematically evaluates the performance of several mainstream large language models (LLMs) on pure syntax-level code translation tasks across datasets of varying difficulty. Furthermore, we investigate model behavior and performance boundaries from two perspectives: error type and static code complexity. Based on the experimental results, we discuss the following research questions:

RQ1: How well do mainstream LLMs perform on syntax-preserving code translation tasks?

Current mainstream large language models perform well in syntax-preserving code translation tasks only on structurally simple code. However, when faced with high-complexity programs featuring deep nesting and complex control structures, their translation success rates drop sharply, revealing clear limitations in syntax modeling, semantic preservation, and structural generalization.

RQ2: What types of syntactic or semantic errors frequently occur during the translation process?

We observe several representative error patterns. These include violations of target language rules, omission of essential components (e.g., missing library imports or variable definitions, incorrect translation of loops and conditions), mismanagement of data types (e.g., primitive type mismatches and structural semantics distortion), and irrelevant explanatory outputs. These errors indicate that models lack sufficient understanding of cross-language syntactic and semantic mappings and often produce generalized suggestions under uncertainty. Such errors reveal key limitations in current LLM capabilities and highlight concrete directions for future improvements.

RQ3: Which static features are most strongly associated with translation outcomes, indicating higher model sensitivity or reliance?

Modeling the correlations between static code features and translation outcomes reveals that Semantic Modeling Complexity is correlated with approximately 60% of the overall performance variance, while Code Form Complexity is correlated with about 40%. This highlights the strong relevance of syntactic hierarchy and organization. Among these features, code length and average expression complexity show the strongest correlations with translation difficulty, reflecting the challenges large language models face in handling long-range dependencies and complex expressions.

RQ4: In what ways do static complexity features correlate with translation performance, and are there critical inflection points or identifiable performance bottlenecks?

Translation success degrades nonlinearly as code complexity increases, with performance dropping sharply past certain thresholds. While larger models improve results on simpler inputs, they show diminishing returns under high complexity. Interestingly, performance peaks within a mid-complexity range on certain metrics, suggesting that both overly simple and overly complex inputs can undermine translation reliability.

RQ5: What are the possible explanations for the performance patterns observed in LLMs on syntax-preserving code translation?

Since the detailed training processes of these models are not publicly available, we cannot make definitive causal claims. However, our observations suggest several plausible explanations for the performance patterns we observed.

First, the discrepancy between high compilation success and low semantic correctness in some models suggests that they may be better at capturing surface-level syntactic plausibility than at preserving program semantics. This could reflect training objectives that prioritize syntactic validity, while lacking execution-based supervision to guarantee semantic fidelity.

Second, models frequently make errors on specific syntactic elements. A possible reason is that these elements, such as pointer operations or loop conditions, are inherently more difficult to translate and may not have been particularly emphasized during training.

Third, models show strong sensitivity to specific complexity features. Our analysis of feature weights indicates that code length (LOC), character density, average expression complexity, and AST depth are the most influential factors. A plausible explanation is that these features directly stress the model’s capacity for attention and representation. Longer sequences and denser tokens require more stable global context management, while complex expressions and deeper AST hierarchies challenge the model’s ability to handle multi-step reasoning and long-range dependencies. Consequently, performance fluctuates more sharply with changes in these features compared to others.

Fourth, the nonlinear performance trends across complexity levels may reflect both architectural limitations and data distribution effects. On the one hand, the quadratic scaling of attention and its limited ability to propagate hierarchical information across many layers mean that once the effective receptive field is exceeded, performance collapses abruptly rather than degrading smoothly. On the other hand, performance peaks observed in mid-range complexity zones may be explained by the training data distribution: such zones are often overrepresented in large corpora, making models disproportionately robust there. In contrast, very low- and very high-complexity samples are relatively underrepresented, which likely contributes to weaker generalization at the two extremes.

Conclusion. This study focuses on evaluating the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) in syntax-preserving code translation tasks and proposes a systematic evaluation framework incorporating complexity analysis. Experimental results demonstrate that while large models exhibit strong transfer capabilities when handling simple syntactic structures, their translation accuracy significantly declines on medium- and high-complexity samples.

The analysis of translation errors reveals that failures primarily fall into four categories: (1) violations of target language rules, (2) omission of essential components such as imports, variable definitions, or loop/condition structures, (3) mismanagement of data types, including both primitive and composite types, and (4) irrelevant or non-translational outputs. To further account for performance differences, we adopt static feature modeling from the perspective of program complexity.

Machine learning analysis shows that syntactic features (with a weight of approximately 60%) are more strongly associated with translation outcomes than surface-level textual features (around 40%). Among these, code length and average expression complexity are identified as major performance bottlenecks. Moreover, LLMs exhibit nonlinear sensitivity to complexity: once input complexity exceeds a certain threshold, translation performance drops sharply. This trend persists even in models with large parameter scales, indicating diminishing marginal returns. Interestingly, translation success peaks within specific ranges of complexity, suggesting that the distribution of training data across complexity levels may play a critical role in shaping the model’s generalization capability.

In summary, this study constructs a high-quality evaluation framework and syntax-level test set to systematically reveal the capability boundaries and performance correlation mechanisms of LLMs in code translation.

Future Work. Future work can be divided into two complementary directions:

• Framework refinement. Although our experiments are limited to the C

• Large model optimization. Building on our findings, several optimization directions can be pursued:

1. Optimize input through structural preprocessing. A promising strategy to alleviate the modeling burden of LLMs is to introduce preprocessing techniques that simplify the syntactic form of the input before translation. For example, long code segments can be automatically decomposed into modular subunits (e.g., function-level or block-level granularity), which reduces sequence length and enhances locality of dependencies. Similarly, code with deeply nested control structures can be normalized by restructuring loops or flattening conditionals, thereby lowering the effective syntactic depth without altering program semantics. These preprocessing steps not only reduce long-range dependency challenges but also provide the model with inputs that are structurally more uniform, leading to improved stability and higher success rates in syntax-preserving translation.

2. Enhance training on error-prone syntactic categories. Based on the taxonomy of translation errors established in this study, we find that LLMs exhibit systematic weaknesses in certain syntax transformations. A promising direction for future work is to place greater emphasis on these error-prone categories during both pre-training and fine-tuning. By augmenting the training corpus with targeted examples and weighting them more heavily in the learning process, models may progressively overcome such weaknesses and achieve greater reliability in syntax-preserving code translation.

3. Adjust the complexity distribution of training corpora. Current LLM training heavily relies on internet-collected code, whose complexity distribution is shaped by natural data availability rather than deliberate design. Such distributions may over-represent certain ranges while under-representing others, leading to a mismatch with the balanced coverage required for systematic capability development. A promising direction for future work is to statistically profile training corpora with complexity metrics and intentionally rebalance the dataset across different difficulty levels. This adjustment would not imply that current data is deficient, but rather ensure that models are exposed to a controlled and representative spectrum of code complexity, thereby improving robustness in boundary cases.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yaxin Zhao, Yan Guang, Qi Han, Hui Shu; data collection: Yaxin Zhao, Hui Shu; analysis and interpretation of results: Yaxin Zhao, Qi Han; draft manuscript preparation: Yaxin Zhao, Qi Han. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Yan Guang) upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Successful Examples of Complex Code Translation

The complete successful examples of complex code translation (C and Python) are available at https://github.com/whcadbq/Successful-Examples-of-Complex-Code-Translation (accessed on 25 September 2025).

References

1. Macedo M, Tian Y, Nie P, Cogo FR, Adams B. InterTrans: leveraging transitive intermediate translations to enhance LLM-based code translation. arXiv:2411.01063. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2411.01063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang H, David C, Wang M, Paulsen B, Kroening D. Scalable, validated code translation of entire projects using large language models. arXiv:2412.08035. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2412.08035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen M, Tworek J, Jun H, Yuan Q, de O Pinto HP, Kaplan J, et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv:2107.03374. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li R, Ben Allal L, Zi Y, Muennighoff N, Kocetkov D, Mou C, et al. StarCoder: may the source be with you! arXiv:2305.06161. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2305.06161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nijkamp E, Pang B, Hayashi H, Tu L, Wang H, Zhou Y, et al. CodeGen: an open large language model for code with multi-turn program synthesis. arXiv:2203.13474. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2203.13474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sadkowska AK, Muennighoff A, Cosentino R, Bechtel R, Bouslama R, Dettmers T, et al. CodeLlama: open foundation models for code. arXiv:2308.12950. 2023. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2308.12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. OpenAI, Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Ahmad L, Akkaya I, et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv:2303.08774. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rozière M, Barrault L, Lample G. Unsupervised translation of programming languages. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2020;33:20601–11. [Google Scholar]

9. Lu Z, Liu D, Guo J, Ren A, Tang S, Huang Y, et al. CodeXGLUE: a benchmark dataset and open challenge for code intelligence. arXiv:2102.04664. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2102.04664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Puri R, Kung D, Janssen G, Zhang W, Domeniconi G, Zolotov V, et al. Project CodeNet: a large scale AI for code dataset for learning a diversity of coding tasks. arXiv:2105.12655. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2105.12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu M, Jain A, Suresh K, Ravindran R, Tipirneni S, Reddy CK. XLCoST: a benchmark dataset for cross-lingual code intelligence. arXiv:2206.08474. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2206.08474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ahmad WU, Tushar GRM, Chakraborty S, Chang KW. AVATAR: a parallel corpus for Java-Python program translation. arXiv:2108.11590. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2108.11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zheng Y, Yuan H, Li C, Dong G, Lu K, Tan C, et al. HumanEval-X: evaluating the generalization of code generation in multiple programming languages. arXiv:2307.14430. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2307.14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yan W, Tian Y, Li Y, Chen Q, Wang W. CodeTransOcean: a comprehensive multilingual benchmark for code translation. arXiv:2310.04951. 2023. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2310.04951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Papineni K, Roukos S, Ward T, Zhu W. BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics; 2002 Jul 7–12; Stroudsburg, PA, USA. p. 311–8. [Google Scholar]

16. Ren S, Tu D, Lin S, Zhang D, Zhou L. CodeBLEU: a method for evaluating code generation. arXiv:2009.10297. 2020. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2009.10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kulal A, Jain A, Zheng M, Chen M, Sutton C, Srebro N. SPoC: search-based pseudocode to code. arXiv:2005.08824. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2005.08824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. C2Rust Transpiler; 2023. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://github.com/immunant/c2rust. [Google Scholar]

19. C to Go Translator; 2023. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://github.com/gotranspile/cxgo. [Google Scholar]

20. Mono Project. Sharpen–Automated Java to C# Conversion; 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Java 2 CSharp Translator for Eclipse; 2023. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://sourceforge.net/projects/j2cstranslator/. [Google Scholar]

22. Wang Y, Wang W, Joty S, Hoi SCH. CodeT5: identifier aware unified pre trained encoder decoder models for code understanding and generation. arXiv:2109.00859. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2109.00859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zheng Y, Liu Z, Li S, Chen Y, Xu Y, Ren X, et al. CodeGeeX: a pre-trained model for code generation with multilingual and cross-platform support. arXiv:230617107. 2023 Jun. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2306.17107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Meta AI. Introducing Meta Llama 3: the most capable openly available LLM to date. Meta AI Blog; 2024. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://ai.meta.com/blog/meta-Llama-3/. [Google Scholar]

25. DeepSeek AI, Guo D, Yang D, Zhang H, Song J, Zhang R, et al. DeepSeek R1: incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv:2501.12948. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2501.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yang X, Chen Y, Eide E, Regehr J. Finding and understanding bugs in C compilers. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation (PLDI); 2011 Jun 4–8; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 283–94. [Google Scholar]

27. Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

28. Yi X, Xu Y, Hu Q, Krishnamoorthy S, Li W, Tang Z. ASN-SMOTE: a synthetic minority oversampling method with adaptive qualified synthesizer selection. Comp Intell Syst. 2022;8(3):2247–72. doi:10.1007/s40747-021-00638-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. DeepSeek-AI, Zhu Q, Guo D, Shao Z, Yang D, Wang P, et al. DeepSeek-Coder-V2: breaking the barrier of closed-source models in code intelligence. arXiv:2406.11931. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2406.11931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Team G. Gemma 3. Kaggle; 2025 Mar. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://goo.gle/Gemma3Report. [Google Scholar]

31. Hui B, Yang J, Cui Z, Yang J, Liu D, Zhang L, et al. Qwen2.5 coder technical report. arXiv:2409.12186. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2409.12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Qwen Team. Qwen2.5 technical report. arXiv:2412.15115. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2412.15115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools