Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Adaptive Weighting of Effectiveness Assessment Indicators: Integrating G1, CRITIC and PIVW

1 Air Defense and Antimissile College, Air Force Engineering University, Xi’an, 710051, China

2 School of Mathematics and Statistics, Xidian University, Xi’an, 710051, China

* Corresponding Author: Ye Tian. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070622

Received 20 July 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Modern battlefields exhibit high dynamism, where traditional static weighting methods in combat effectiveness assessment fail to capture real-time changes in indicator values, leading to limited assessment accuracy—especially critical in scenarios like sudden electronic warfare or degraded command, where static weights cannot reflect the operational value decay or surge of key indicators. To address this issue, this study proposes a dynamic adaptive weighting method for evaluation indicators based on G1-CRITIC-PIVW. First, the G1 (Sequential Relationship Analysis Method) subjective weighting method—translates expert knowledge into indicator importance rankings—leverages expert knowledge to quantify the relative importance of indicators via sequential relationship ranking, while the CRITIC (Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation) objective weighting method—derives weights from data characteristics by integrating variability and inter-correlations—calculates weights by integrating indicator variability and inter-indicator correlations, ensuring data-driven objectivity. These two sets of weights are then fused using a deviation coefficient optimization model, minimizing the squared deviation from a reference weight and adjusting the fusion coefficient via Spearman’s rank correlation to resolve potential conflicts between subjective and objective judgments. Subsequently, the PIVW (Punishment-Incentive Variable Weight) theory—adapts weights to real-time indicator performance via penalty/incentive rules—is applied for dynamic adjustment. Scenario-specific penalty λ1 and incentive λ2 thresholds are set based on operational priorities and indicator volatility, penalizing indicators with values below λ1 and incentivizing those exceeding λ2 to reflect real-time indicator performance. Experimental validation was conducted using an Air Defense and Anti-Missile (ADAM) system effectiveness assessment framework, with data covering 7 indicators across 3 combat scenarios. Results show that compared to static weighting methods, the proposed method reduces MAE (Mean Absolute Error) by 15%–20% and weighted decision error rate by 84.2%, effectively reducing overestimation/underestimation of combat effectiveness in dynamic scenarios; compared to Entropy-TOPSIS, it lowers MAE by 12% while achieving a weighted Kendall’s τ consistency coefficient of 0.85, ensuring higher alignment with expert judgment. This method enhances the accuracy and scenario adaptability of effectiveness assessment, providing reliable decision support for dynamic battlefield environments.Keywords

In conducting multi-level, multi-indicator effectiveness assessments, quantifying the relative importance of indicators across various dimensions presents a key challenge. This process requires an understanding of each indicator’s unique contribution to the overall system, as well as a deeper exploration of its intrinsic value and its interaction with the external environment [1]. The weighting allocation mechanism, as one of the cores of the evaluation system, aims to accurately capture and express these complex relationships [2,3]. Scientifically setting weights is the cornerstone of achieving precise evaluations and is a crucial driving force behind the evolution of evaluation systems toward intelligence, personalization, and dynamism. Currently, the determination of weights has transcended simple subjective judgments or the accumulation of experience, relying more on advanced statistical models and machine learning algorithms. These tools can uncover hidden patterns from large datasets, automatically adjusting indicator weights to reflect shifts in priorities in the real world. Dynamic adjustments of weights have become a trend, enabling evaluation systems to better adapt to changing contexts and needs [4].

Taking the assessment of combat capabilities in an Air Defense and Anti-missile (ADAM) system as an example, the limitations of traditional methods for determining weights are particularly evident. If the value of an indicator decreases, regardless of its assigned weight, its overall impact still diminishes; conversely, if the value increases, its overall impact increases, regardless of its weight. Traditional static weighting methods struggle to adapt to the high dynamism of modern battlefields, leading to inaccurate assessments in critical scenarios. For example, in a sudden electronic warfare attack, if the “tracking effectiveness” indicator drops sharply from 0.8 to 0.3 due to radar jamming, static weights will still assign it the same importance as in stable conditions. This failure to reflect the actual decay in its operational value leads to overestimation of the overall combat effectiveness. Similarly, if “decision-making effectiveness” surges from 0.5 to 0.9 during a rapid response scenario, static weights cannot amplify its influence, resulting in an underestimation of the system’s adaptive capability. Such rigidity in weight allocation—ignoring real-time changes in indicator values—undermines the reliability of effectiveness assessments in dynamic battlefield environments. To address this challenge, we propose a new dynamic adaptive weighting method for evaluation indicators based on G1-CRITIC-PIVW, aimed at dynamically optimizing constant weights to ensure that weight allocation can reflect the complexity of scenarios and configurations in real time.

2 Literature Review and Methodological Framework

Currently, the determination of weight coefficients primarily relies on three methods: subjective weighting, objective weighting, and combined weighting. Subjective weighting, based on the professional knowledge, experience, and judgment of evaluators, determines indicator weights through expert consultation. This method intuitively reflects the role of human wisdom in the assessment process and can effectively capture factors that are difficult to quantify. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Delphi method are representative techniques in this category. However, the limitation of subjective weighting lies in its heavy reliance on individual cognition, which may lead to subjectivity and instability in the results. In data-driven decision-making environments, the lack of objective basis for weight allocation may undermine the credibility of the assessment.

Objective weighting, on the other hand, focuses on utilizing mathematical models and statistical analysis to derive indicator weights directly from data, such as Entropy weighting [5,6] and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [7,8]. The advantage of this method lies in its objectivity and verifiability, reducing the influence of human bias on decisions and enhancing the scientific rigor and reliability of assessment outcomes. However, objective weighting also faces potential challenges such as data quality, model selection, and data bias. If data collection is incomplete or there are systematic errors, it will directly affect the accuracy and validity of the weights.

Combined weighting, as an integrated innovation of both subjective and objective weighting methods, aims to combine their strengths and overcome the limitations of single methods. By integrating subjective judgments with objective data through mathematical or statistical means, combined weighting can reflect the domain knowledge and preferences of experts while also considering the objectivity of data-driven approaches. The flexibility and comprehensiveness of this method make it an ideal choice for addressing complex assessment scenarios, enhancing the explanatory power and applicability of assessment results.

It is noteworthy that a single weighting method often fails to perfectly adapt to all decision-making scenarios, especially when the complexity and uncertainty of the evaluation objects increase. Therefore, scholars continue to explore more refined and dynamic strategies for weight allocation, such as variable weighting theory, which addresses the challenge of adjusting indicator weights according to the environment, objectives, or perspectives, further advancing the frontier of assessment science [9]. Variable weighting theory provides a flexible and precise framework for dynamic weight adjustment, recognizing that indicator importance is not static but fluctuates with time, context, and goals. Its core lies in enabling weights to adaptively adjust to differences in decision scenarios, ensuring assessments timely reflect real-world complexity and dynamism. From the perspective of adjustment logic, dynamic weighting methods can be divided into two main categories: rule-based dynamic adjustments and data-driven adaptive adjustments, while the traditional incentive-based and penalty-based approaches [10,11] can be regarded as important subcategories within rule-based methods.

Rule-Based Dynamic Adjustments methods rely on predefined logical rules, mathematical formulas, or domain expertise to adjust weights, with clear triggers and intensity criteria. The incentive-based and penalty-based approaches are typical representatives of this category. Incentive-based methods increase the weight of indicators with high performance to amplify their positive impact. For example, in battlefield assessment, if “decision-making effectiveness” surges due to rapid response protocols, incentive mechanisms will enhance its weight to reflect its critical role. Penalty-based methods reduce the weight of indicators with poor performance to mitigate their negative interference. For instance, when “tracking effectiveness” drops sharply under electronic jamming, penalty mechanisms will lower its weight to avoid overestimating overall combat effectiveness. Other representative rule-based methods include: TOPSIS with adaptive coefficients adjusts weights based on the distance between evaluated objects and ideal solutions, using fixed formulas to balance indicator contributions. Grey relational analysis (GRA) dynamic weighting modifies weights according to the correlation between indicators and evaluation targets, emphasizing indicators with stronger relevance.

Data-Driven Adaptive Adjustments methods learn weight adjustment patterns from large-scale data through machine learning or statistical models, with adjustments driven by data patterns rather than manual rules. Reinforcement learning (RL)-based adaptive weighting [12] trains agents to adjust weights by maximizing long-term evaluation accuracy, suitable for scenarios with abundant historical data. LSTM-based time-series weighting [13,14] captures temporal dependencies in indicator values to predict optimal weights. Attention mechanism-based weighting [15] automatically identifies important indicators from multi-source data, leveraging deep learning to handle high-dimensional information.

Our method differs fundamentally from two representative dynamic weighting approaches: (1) Entropy weight-TOPSIS dynamic weighting. This method relies solely on objective data and static TOPSIS ranking, lacking integration of expert knowledge. In battlefield scenarios with scarce or noisy data, it may generate biased weights due to over-reliance on limited data. Our G1-CRITIC fusion, however, incorporates expert judgments to mitigate such biases [16]. (2) Machine learning-based adaptive weighting. These methods require large-scale labeled data to train weight adjustment models, which is impractical for rare battlefield events [17–20]. Our rule-based PIVW mechanism, by contrast, operates with minimal data and maintains high interpretability—critical for military decision-makers to validate and trust results [21,22]. Dynamic weighting thus enhances the adaptability of evaluation systems, making them more responsive to real-world dynamics compared to static methods.

This paper proposes a dynamic adaptive weighting method based on G1-CRITIC-PIVW. The method proceeds as follows:

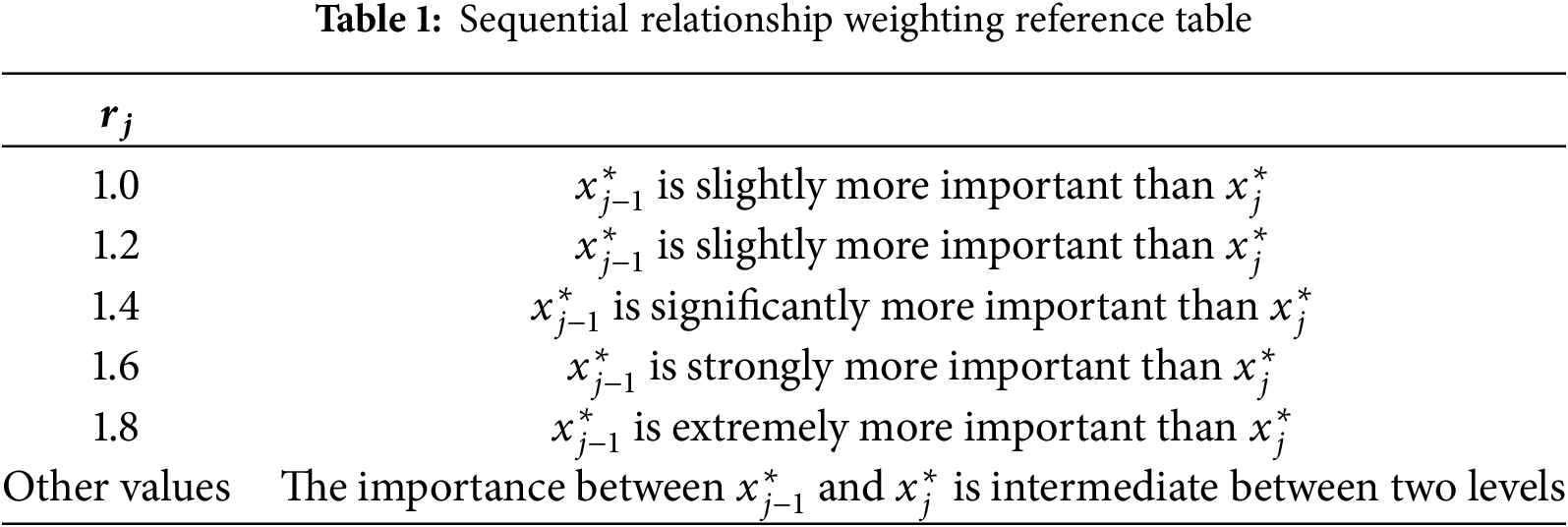

1. Subjective Weighting Using G1 Sequential Relationship. Experts are consulted to determine the relative importance of each indicator, and these judgments are quantified using a sequential relationship assignment table. This step aims to leverage the knowledge and experience of domain experts to ensure the rationality and accuracy of the subjective weights.

2. Objective Weighting Using CRITIC. Indicators are normalized, and the standard deviation is used to calculate the variability of each indicator. Additionally, the correlations between indicators are considered to determine the objective weights. This approach not only reflects the characteristics of the data itself but also considers the interactions between indicators, contributing to a more objective and comprehensive weight distribution.

3. Combining Subjective and Objective Weights. To integrate the results of the subjective and objective weighting processes, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is used to measure the correlation between the subjective and objective weights. Based on the deviation coefficient of this correlation, a weighting coefficient is determined for the combination of weights, leading to the calculation of the optimal combined constant weight. This process effectively balances the relationship between subjective judgment and objective data, enhancing the scientific validity and practical utility of the weight distribution.

4. Dynamic Adjustment of Weights Using PIVW Theory. Based on the PIVW theory, a state-dependent weight vector is constructed to dynamically adjust the weights. The aim is to positively incentivize high-value indicators while moderately penalizing low-value indicators. This dynamic adjustment mechanism more accurately reflects the reality of the battlefield, enhancing the scientific rigor and reliability of the assessment results.

The integrated Novel approach in this study has two key innovations that advance beyond existing hybrid weighting approaches: (1) Adaptive fusion criterion for subjective-objective weights. Unlike most existing hybrid methods, we propose a deviation coefficient optimization model based on Spearman’s rank correlation. This model dynamically adjusts the fusion weight of G1 and CRITIC weights by minimizing the inconsistency between their rank distributions—resolving the rigid fusion flaw of existing hybrid approaches that use fixed coefficients even when subjective judgments conflict with objective data. This ensures the combined constant weights balance expert knowledge and data objectivity. (2) Scenario-aware PIVW parameter adaptation. Existing hybrid weighting methods with dynamic adjustment often adopt fixed penalty/incentive thresholds for all indicators and scenarios, failing to account for indicator volatility and scenario differences. By contrast, the proposed method’s PIVW thresholds and adjustment intensity are linked to indicator volatility quantified by CRITIC. Indicators with higher variability have narrower punishment intervals to amplify their dynamic adjustment, while stable indicators retain wider intervals to avoid over-adjustment. This linkage enhances the method’s responsiveness to scenario-specific dynamics, a capability lacking in existing hybrid approaches.

3 Calculation of Constant Indicator Weights Based on G1-CRITIC

3.1 Calculation of Subjective Weights Using the G1 Sequential Relationship Method

In the context of multiple evaluation criteria, the G1 sequential relationship method (abbreviated as G1), a classic subjective weighting technique for multi-indicator effectiveness assessment improves upon the traditional AHP by providing an intuitive and easily calculable subjective weighting method. Its core advantage lies in eliminating the need to construct complex judgment matrices—instead, it relies on experts to define the sequential importance order of indicators and quantify relative importance ratios between adjacent indicators, thereby simplifying the calculation process and dispensing with the requirement for consistency checks. This makes G1 particularly suitable for battlefield effectiveness assessment scenarios, where expert experience plays a critical role and efficient weight calculation is needed. This method not only streamlines the process of determining the weights of evaluation indicators but also enhances efficiency, making it a highly effective and practical choice for dealing with multi-criteria problems.

Let

The relationship of importance between adjacent criteria in the sequential relationship is represented by ratios. Let the rational judgment of an expert regarding the importance ratio of criterion

here,

Based on the sequential relationship and the ratios of importance between the criteria, the subjective weights

When there are multiple experts involved in determining the subjective weights, expert k’s weight for evaluation criterion j is

The final subjective weight vector obtained using the sequential relationship method is denoted as

3.2 Calculation of Objective Weights Using the CRITIC Method

CRITIC is an objective weighting method tailored for multi-indicator assessment, which determines indicator importance based on the contrast intensity of evaluation indicators and the correlations between them. Its core logic is to avoid over-reliance on subjective experience: it first uses standard deviation to measure contrast intensity; then uses correlation coefficients to quantify inter-indicator conflict. By integrating these two dimensions, CRITIC ensures the derived weights fully reflect the objective characteristics of the data, making it suitable for battlefield scenarios where historical or simulated indicator data is available. Contrast intensity refers to the degree of influence of the differences in values among the evaluated objects under the same indicator, typically expressed in the form of standard deviation. If an indicator has a larger standard deviation, it means that the data under that indicator have higher variability, and therefore, the indicator will have a higher weight in the assessment. Conversely, if the standard deviation is smaller, the indicator will have a lower weight. Correlation between indicators is another important consideration. When two indicators have a significant positive correlation (i.e., a correlation coefficient close to 1), it suggests that there is a high degree of similarity in the information content within the assessment methodology, leading to less conflict and thus a relatively lower weight. On the other hand, if two indicators have weak correlation or are negatively correlated, they present more significant contradictions, resulting in higher weights. In summary, the CRITIC weighting method determines objective weights by quantifying the contrast intensity of the indicators and the correlations between them, effectively reflecting the characteristics of the data itself and ensuring the objectivity of the assessment results.

First, perform dimensionless processing on each indicator. If a higher value of an indicator is beneficial to the goal, apply forward normalization; otherwise, apply reverse normalization, which is referred to as forward or reverse normalization of the indicator.

The min-max normalization method adopted in this study was selected after comparing it with two widely used normalization approaches in Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) for effectiveness assessment. Z-score normalization is a common method that centers and scales data based on statistical characteristics. For the i-th indicator under the s-th scenario, its normalized value is calculated by subtracting the mean of the i-th indicator from the raw value and dividing by the standard deviation of the i-th indicator. Z-score normalization may produce negative values or values greater than 1, which contradicts the physical interpretation of indicators (cannot be negative) and disrupts subsequent weight calculation. Decimal scaling normalization reduces raw values by dividing them by a power of 10 to bring the data into a small range (typically [−1, 1] or [0, 1]). Different indicators may have different original value ranges (even if they are all positive effectiveness metrics). Using decimal scaling would normalize indicators to [0, 1] or [0, 10]. However, this method relies entirely on the number of digits in the maximum value, not the actual distribution of the indicator data. In contrast, min-max normalization strictly maps all raw values to the [0, 1] range, preserving the physical meaning of effectiveness indicators and avoiding outlier interference.

Next, calculate the variability of each indicator using the standard deviation:

here,

here,

Calculate the information content of each indicator:

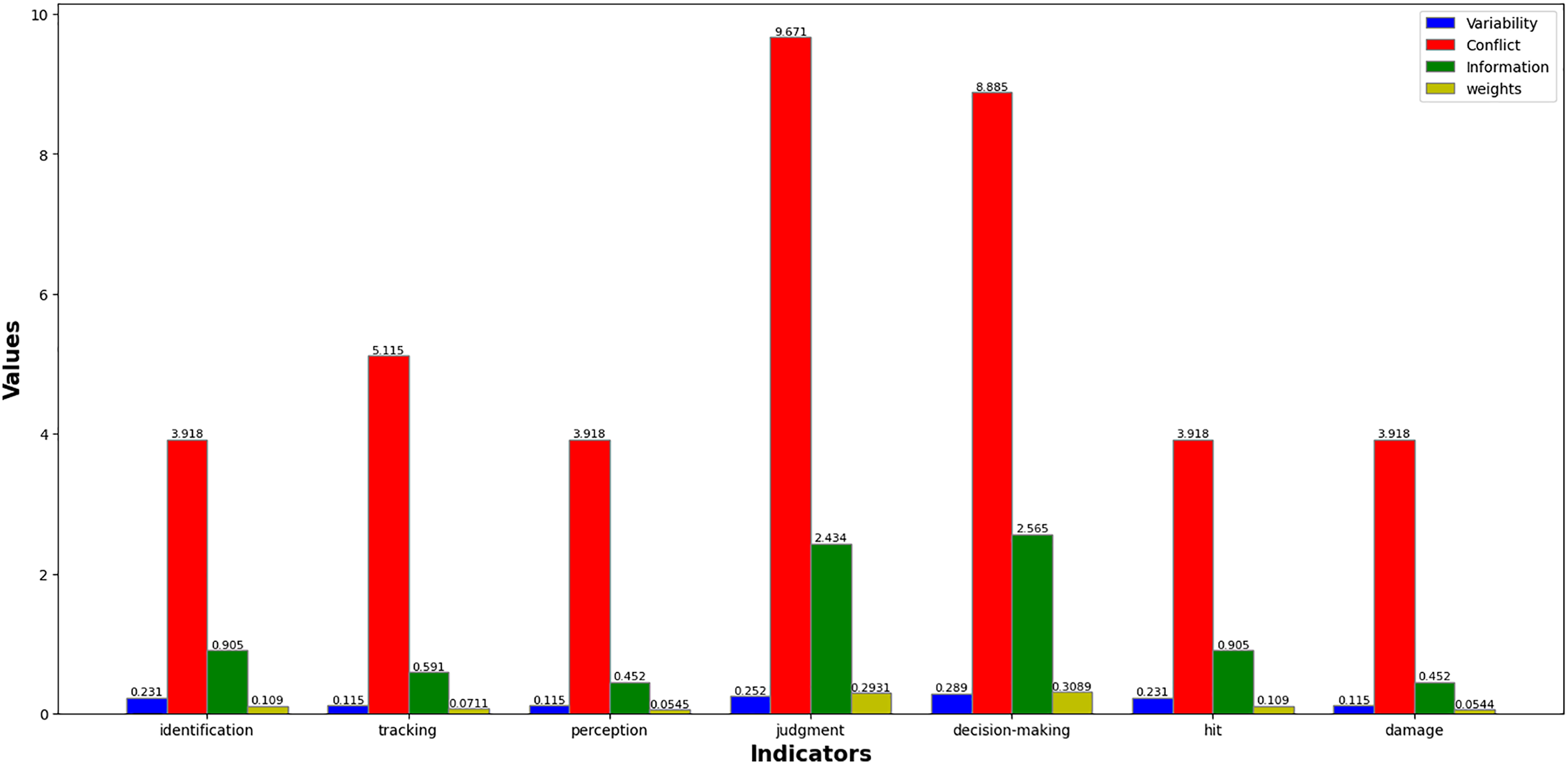

If the

For the CRITIC weighting method, the main factors are the standard deviation and the correlation coefficient. When the standard deviation remains constant, the smaller the correlation coefficient, the greater the conflict between the indicators, and thus the larger the weight. When the correlation coefficient is fixed, the smaller the standard deviation, the stronger the variability between the indicators, and thus the smaller the weight.

3.3 Combination Weighting Based on the Deviation Coefficient

Due to limitations such as uncertainty in evaluation indicators and data collection conditions, existing assessment schemes often rely solely on expert experience or raw situational data, leading to one-sided results. To address the shortcomings of both subjective (G1) and objective (CRITIC) weighting methods, this section integrates these two weight vectors using a deviation coefficient optimization model, which quantifies inconsistencies between subjective and objective weights and adjusts the fusion strategy accordingly. The goal is to obtain combined weights that balance expert knowledge and data objectivity while satisfying essential constraints (normalization, non-negativity) and resolving potential conflicts.

Let the subjective weight vector derived from G1 be

where n is the number of indicators,

The optimization model is defined as:

where

To solve the optimization model, we simplify by substituting

Taking the derivative of

Solving for

Substituting

Note that

The combined weights automatically satisfy

To ensure

When G1 and CRITIC weights conflict (e.g., significant rank differences in indicator importance),

where

Adjustment Rules for

High consistency (

Moderate conflict

Severe conflict (

4 Dynamic Adaptive Weight Adjustment Based on PIVW Theory

The PIVW concept is a dynamic weight adjustment technique that combines a penalty mechanism with an incentive mechanism. It is commonly used in optimization problems, parameter tuning in machine learning, and other applications where the system’s behavior needs to be guided through positive or negative feedback. The core idea is to automatically adjust the importance (weights) of different components based on changes in system performance or the objective function, thereby achieving better overall performance.

Weights are not fixed but are updated in real-time based on new information obtained during system operation. Specifically, when the system’s behavior deviates from the desired outcome, the weights of certain factors are reduced to decrease their impact on the final decision, serving as a penalty. Conversely, when certain factors contribute positively to the system’s performance, their weights are increased to reinforce this behavior, acting as a reward. For example, it can be applied in neural networks to adjust the weights of different layers or nodes to optimize model performance; in feature selection processes in data mining, adjusting feature weights based on their impact on classification results; and in multi-criteria decision analysis, dynamically adjusting the weights of different criteria based on their importance.

4.1 The PIVW Computational Model

The PIVW model—a rule-based dynamic weighting technique tailored for multi-indicator effectiveness assessment, focusing on penalizing underperformance and incentivizing excellence, serves as the dynamic adjustment core of the proposed method, enabling real-time weight adaptation to indicator value changes in complex battlefield environments. Unlike rigid static weights or black-box data-driven dynamic methods (e.g., RL-based weighting), PIVW integrates scenario characteristics into its penalty/incentive parameter design. It avoids over-adjustment via clear threshold rules and maintains interpretability, ensuring weight adjustments not only reflect real-time indicator performance but also align with practical operational logic.

Definition 1 (Constant Weight Vector): The constant weight vector

It represents the baseline importance of indicators in stable scenarios, providing a reference for dynamic adjustments.

Definition 2 (Variable Weight Vector): A variable weight vector

(1) Normalization:

(2) Penalty-Incentive Mechanism: For each indicator

If

If

If

(3) Continuity:

Definition 3 (State Variable Weight Vector): The state variable weight vector

where

The PIVW model’s key parameters—penalty threshold

The PIVW mechanism inherently captures nonlinear relationships between indicator values and weights. The penalty/incentive intensity increases nonlinearly as indicator values deviate from thresholds. This aligns with battlefield reality, where small indicator deviations have minimal impact, but large deviations require amplified weight adjustments to avoid misjudgment.

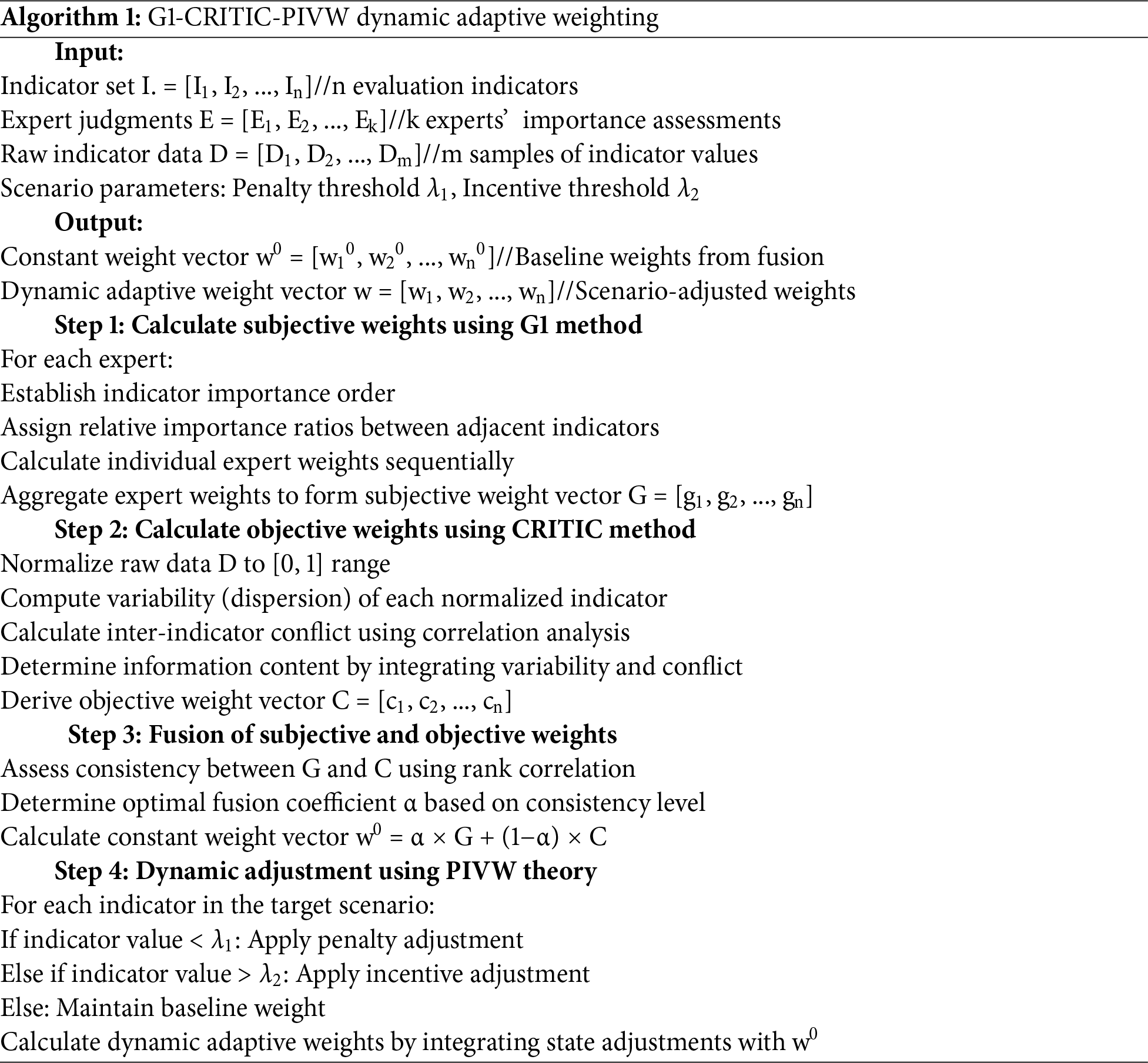

4.2 Dynamic Adaptive Weighting Workflow for G1-CRITIC-PIVW

The dynamic adaptive weighting process integrates the G1-CRITIC combined constant weights with the PIVW mechanism to achieve real-time adjustment of indicator weights, ensuring alignment with battlefield dynamics. This process is divided into three sequential stages.

Stage 1. Determine Constant Weights via G1-CRITIC Fusion. The constant weight vector is calculated using the deviation coefficient optimization model, which balances subjective expert judgments (G1) and objective data characteristics (CRITIC). Key steps include:

(1) Subjective Weight Calculation. Experts rank indicators by importance and quantify relative ratios, generating G1 weights via the sequential relationship method.

(2) Objective Weight Calculation. CRITIC weights are derived from indicator variability (standard deviation) and inter-correlations, reflecting data-driven importance.

(3) Fusion via Deviation Coefficient. Using Spearman’s rank correlation to assess consistency between G1 and CRITIC weights, the optimal fusion coefficient is determined. Combined weights are computed by linearly integrating G1 and CRITIC weights based on this coefficient.

Stage 2. Construct State Variable Weight Vectors. Based on the PIVW model, state variable weights are constructed to reflect real-time indicator performance. This stage involves:

(1) Normalize Indicator Values. Raw indicator data are converted into normalized values within [0, 1] using forward or reverse normalization, depending on whether higher values are beneficial.

(2) Set Scenario-Specific Thresholds. For each scenario, penalty (λ1) and incentive (λ2) thresholds are defined based on operational priorities.

(3) Compute State Variable Weights. Using the scenario-specific thresholds, state variable weights are calculated to implement penalties (for values below λ1) or incentives (for values above λ2), with stable weights for values within [λ1, λ2].

Stage 3. Generate Adaptive Weights. The final dynamic adaptive weights are obtained by scaling constant weights with state variable weights and normalizing to ensure they sum to 1. This step integrates the baseline importance with real-time performance, producing weights that adapt to scenario changes.

The dynamic adaptive weighting process is formally described in Algorithm 1, which integrates subjective judgments with data-driven objectivity while enabling real-time adjustments based on indicator performance.

To verify the proposed G1-CRITIC-PIVW dynamic adaptive weighting method, the experimental setup adopts simulation-based case studies, as detailed below.

5.1 Experimental Data and Preprocessing

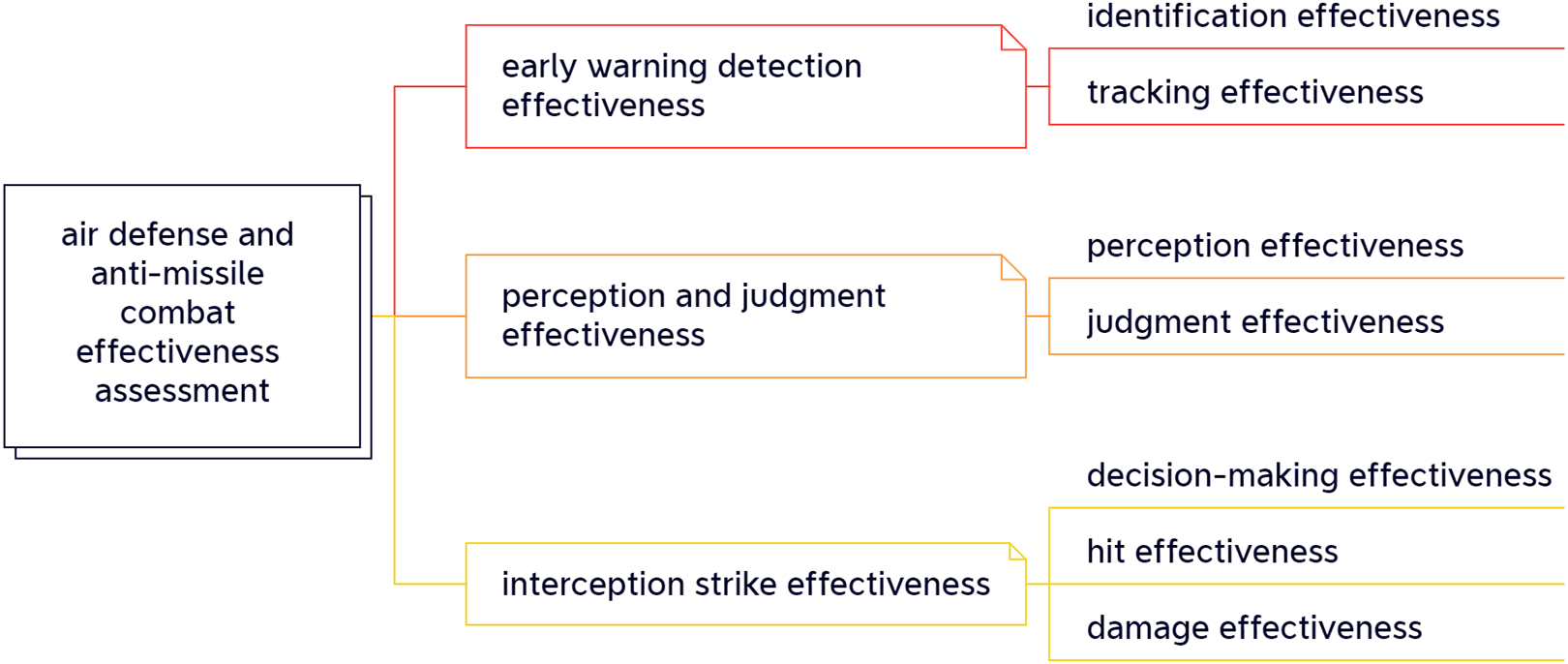

This section uses the assessment of Air Defense and Anti-Missile (ADAM) combat effectiveness as an example to verify the feasibility and practicality of the proposed adaptive weighting method. The experiments herein are designed as case studies, each case uses data that mimics realistic battlefield characteristics. Three primary evaluation indicators and seven secondary evaluation indicators were selected to construct an ADAM node effectiveness evaluation indicator system, providing a consistent framework for the case studies.

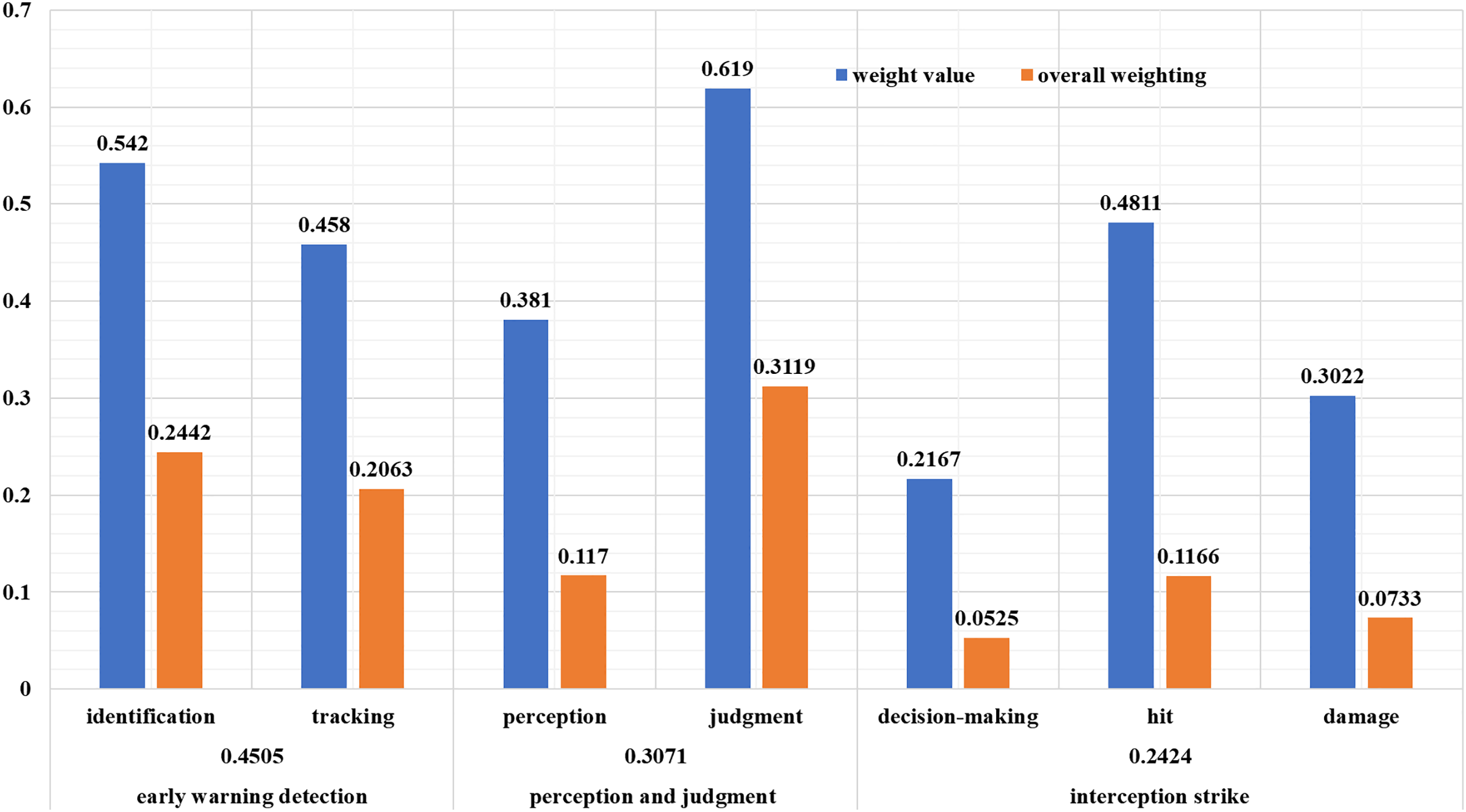

As shown in Fig. 1, the primary evaluation indicators include early warning detection effectiveness, perception and judgment effectiveness, and interception strike effectiveness. These primary indicators cover the entire combat chain from early warning detection to the final interception strike, forming the basis for a comprehensive assessment of ADAM combat effectiveness. The secondary evaluation indicators include identification effectiveness, tracking effectiveness, perception effectiveness, judgment effectiveness, decision-making effectiveness, hit effectiveness, and damage effectiveness. These secondary indicators further refine the content of the primary indicators, providing specific operational-level indicators for the assessment. Our selection of these indicators directly follows the standard’s requirements for weapon system operational performance evaluation. Together, these 7 indicators cover the entire ADAM operational process: from target detection to information processing and final strike, forming a closed-loop evaluation system consistent with both military standards and academic consensus.

Figure 1: ADAM node effectiveness evaluation indicator system

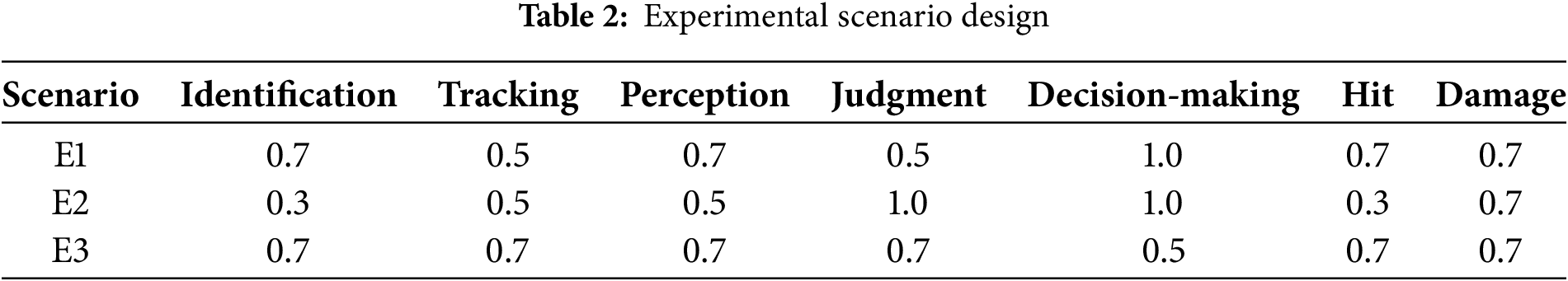

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive weighting method, three experimental scenarios were designed, as shown in Table 2. These scenarios simulate different combat environments to examine the performance of the indicator system under varying conditions and the changes in their weights. Scenario E1 simulates a typical ADAM combat environment where the enemy target is accurately identified and tracked by the early warning system. Decision-making effectiveness is high due to efficient command and control, while strike effectiveness remains at an average level. This reflects a stable battlefield with minimal electronic interference, where the system operates under normal conditions. Scenario E2 models a complex combat environment characterized by high levels of electronic warfare. Identification and hit effectiveness are degraded due to radar jamming and decoy tactics, while judgment effectiveness is enhanced as the decision-maker accurately assesses the enemy’s intentions. This scenario highlights the challenges of operating in a contested electromagnetic spectrum. Scenario E3 scenario represents a special combat situation where decision-making effectiveness is compromised due to communication delays or cognitive overload, while other effectiveness indicators remain at normal levels. This reflects the potential vulnerabilities in the command chain under high-stress conditions.

Construct the initial decision matrices X for the indicators under the three scenarios. The experimental data is derived from simulated ADAM system operational data and includes indicator values for the 7 indicators across the 3 scenarios (E1–E3) as defined in Table 2. Ground-truth effectiveness values for each scenario (E1 = 0.82, E2 = 0.75, E3 = 0.78) are determined via consensus of 5 domain experts, ensuring the data’s validity for evaluating the proposed method against benchmarks.

5.2 Quantitative Evaluation Metrics

To systematically assess the performance of the proposed dynamic adaptive weighting method, three core quantitative metrics are defined to measure accuracy, consistency, and decision error reduction, with moderate enhancements to reflect scenario characteristics and indicator importance.

(1) Accuracy Metrics

Accuracy is evaluated using two indicators to capture both linear and weighted deviations between the assessed effectiveness and ground-truth values (simulated based on expert consensus for battlefield scenarios).

Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Measures the average absolute deviation, retaining simplicity for direct interpretability:

where

Scenario-Weighted Root Mean Square Error (S-RMSE). Incorporates scenario weights to emphasize critical environments (e.g., complex combat scenarios) and amplifies larger deviations via squared terms:

where

(2) Consistency Metric

Consistency is measured by a weighted Kendall’s τ coefficient that accounts for indicator importance, ensuring alignment between dynamic weights and expert judgments on scenario-specific indicator priorities:

where

(3) Decision Error Rate Reduction

This metric quantifies the practical improvement in reducing incorrect decisions, weighted by failure severity to reflect operational impact:

where

These metrics collectively capture the method’s performance in accuracy, alignment with expert knowledge, and practical decision support, providing a comprehensive quantitative assessment.

5.3 Combined Constant Weight Calculation: Deviation Coefficient Optimization and Validation

5.3.1 The Computation Results of the G1 Method

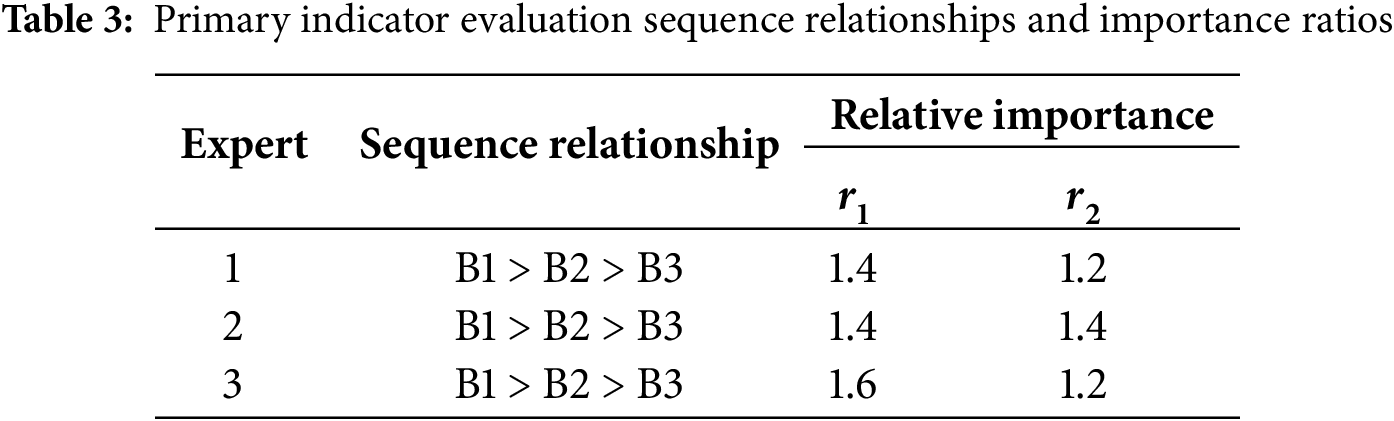

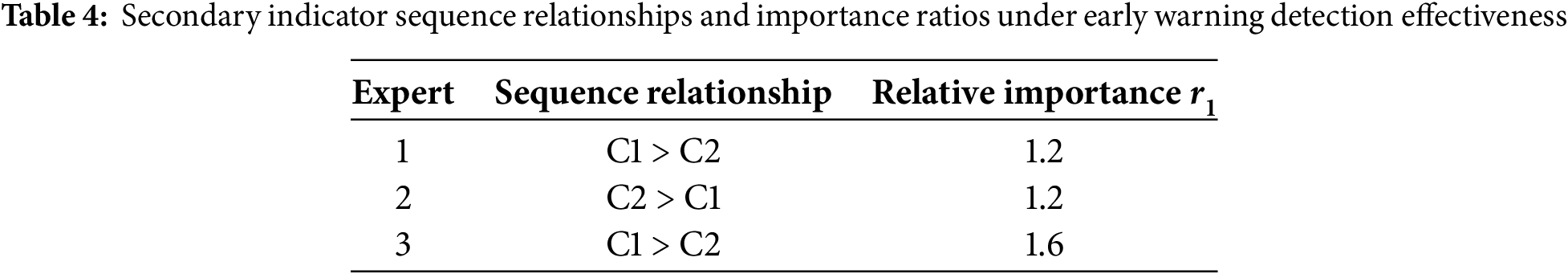

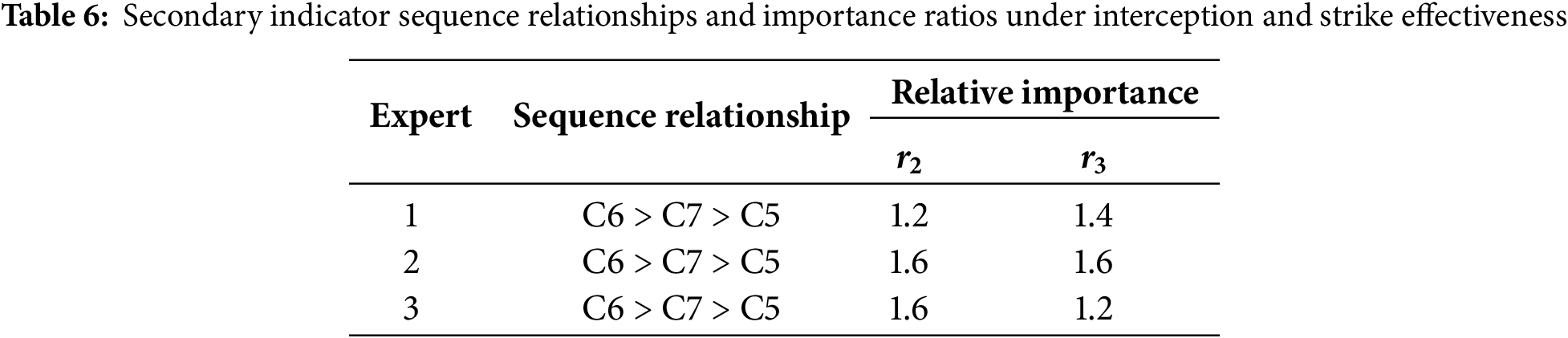

Three domain experts were invited to determine the order and relative importance of the indicators in the indicator system shown in Fig. 2. For the primary indicators, let

Figure 2: Subjective weights obtained using the G1 method

The sequence relationship judgments of the 3 experts were consistent, and the average value was taken for the adjacent importance degrees they chose.

The weights for each indicator are obtained as:

Now, for the calculation of the weights of the secondary indicators under early warning detection effectiveness, let

Since there are differences in the experts’ cognitive levels, work experience, and professional abilities, variations in indicator rankings may occur. From Table 4, Experts 1 and 3 agree on the order (C1 > C2), while Expert 2 holds a conflicting view (C2 > C1). Instead of simply taking the arithmetic mean, a weighted consensus model is adopted to balance consensus and individual contributions.

Define

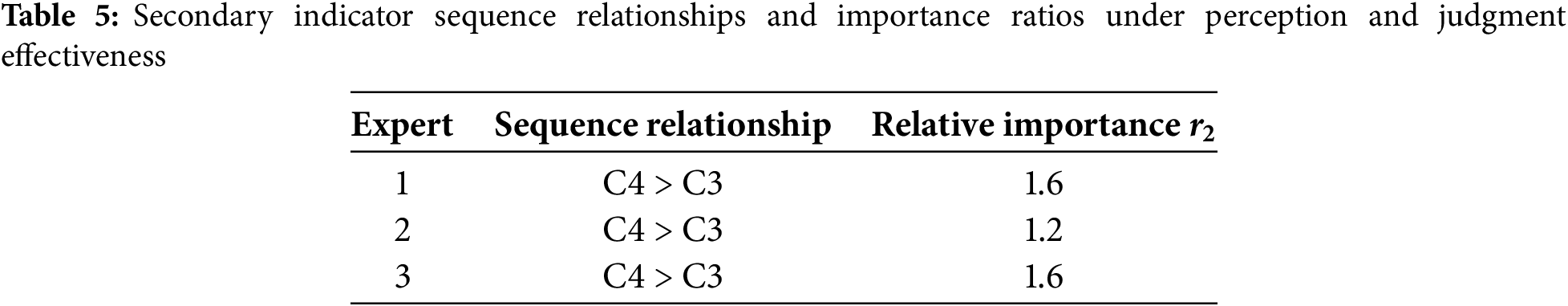

Following the same procedure, we compute the weights for the secondary indicators under perception and judgment effectiveness. The data is shown in Table 5. The experts’ sequence relationship judgments are consistent, and the average value

Multiply the subjective weights of each primary indicator by the weight vectors of their corresponding secondary indicators to obtain the subjective weights of the secondary indicators within the entire evaluation system, as shown in Fig. 2.

5.3.2 The Computation Results of the CRITIC Method

The calculation yields the indicator variability and the CRITIC objective weight calculation results, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Objective weights obtained using the CRITIC method

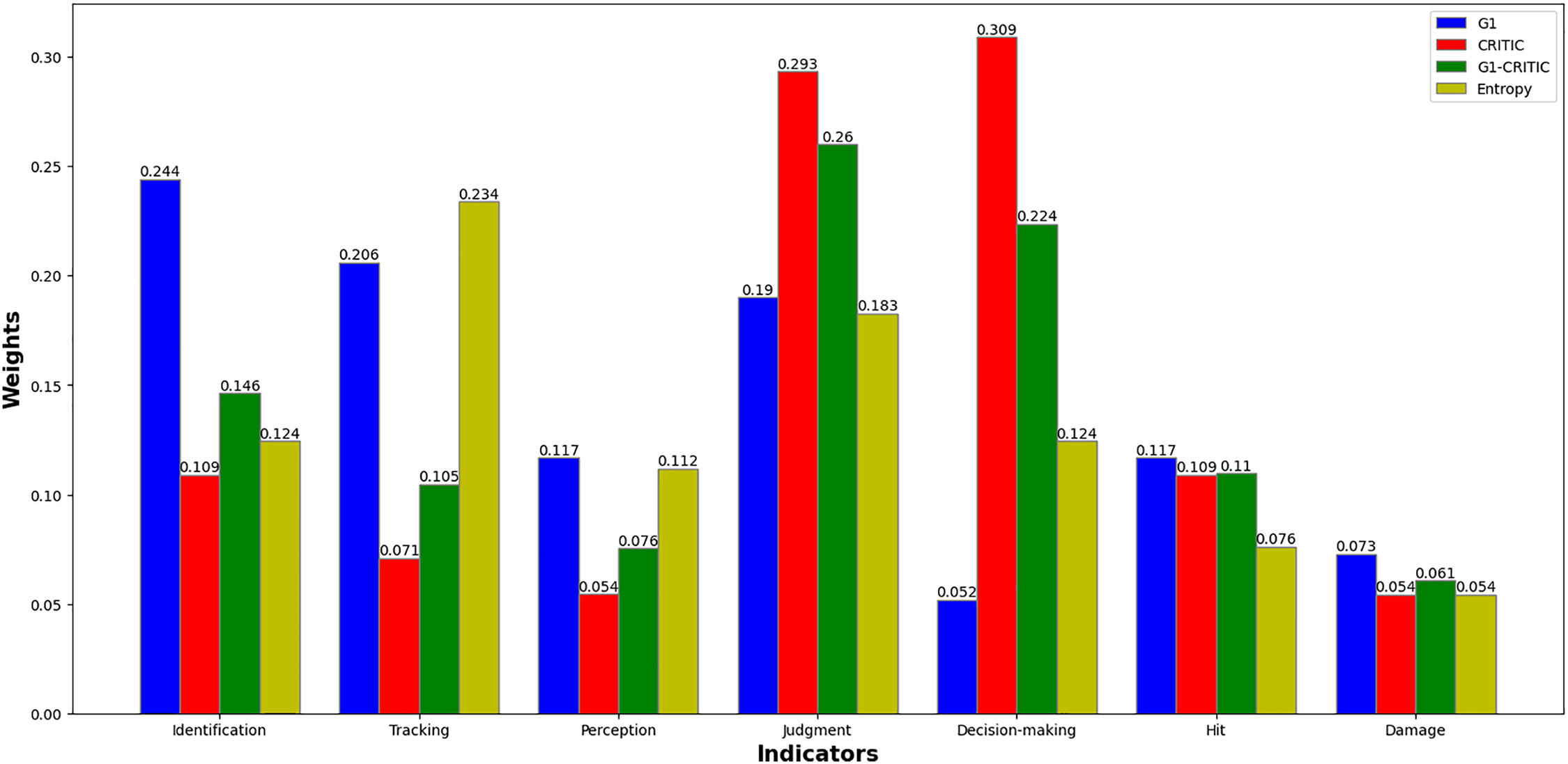

5.3.3 Calculation of Combined Constant Weights Based on the Deviation Coefficient

To integrate the subjective (G1) and objective (CRITIC) weights while balancing their characteristics, this section applies the deviation coefficient optimization model with enhanced rigor, including multi-dimensional consistency checks, sensitivity analysis, and visual validation. The revised G1 and CRITIC weights (as specified) are used to derive robust combined weights.

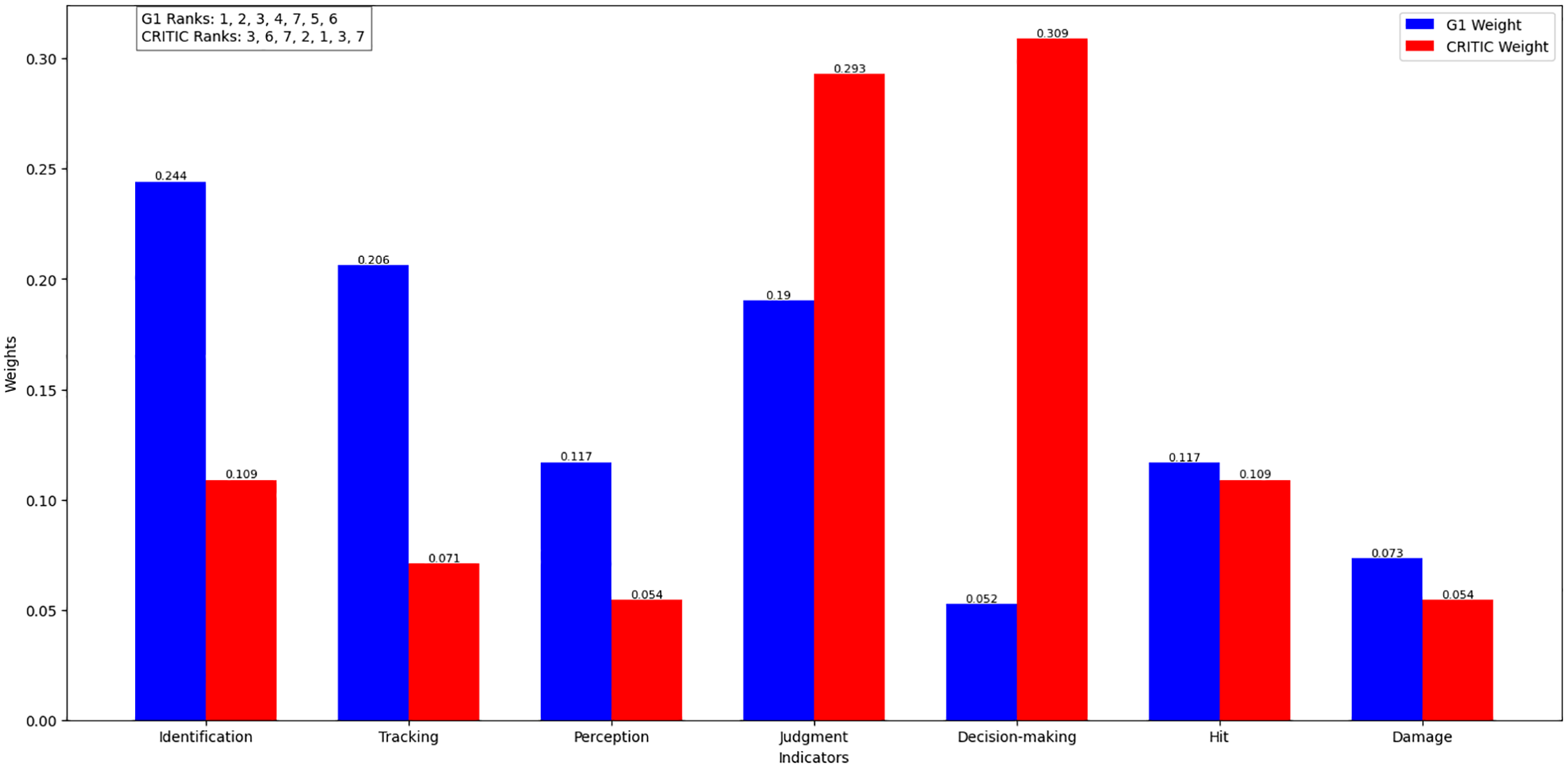

The G1 and CRITIC weights for the 7 secondary indicators are listed in Fig. 4, along with their rank orders:

Figure 4: G1 and CRITIC weights

To assess alignment between G1 and CRITIC weights, two rank correlation metrics are computed:

Spearman’s

Using

Figure 5: Combined weights detailed results

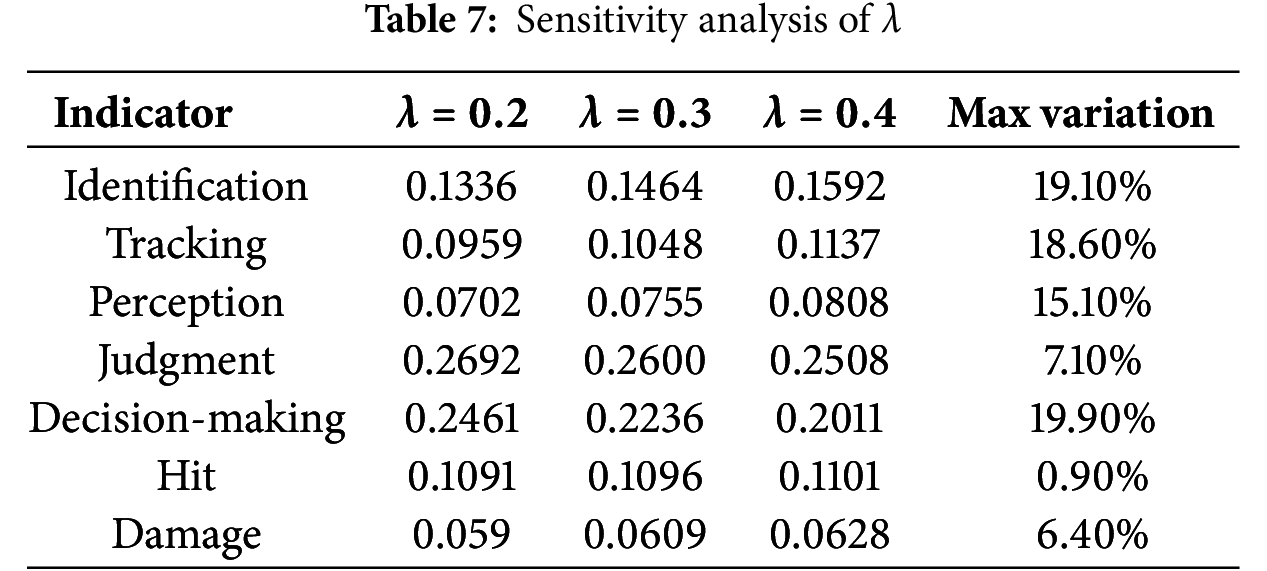

G1 overweights “Identification” and “Tracking”, while CRITIC overweights “Decision-making” and “Judgment”. The proposed method balances these extremes, e.g., reducing “Tracking” to 0.1048 (aligned with CRITIC’s low rank) while retaining “Judgment” at 0.2600 (reflecting its high data significance). To test robustness, we simulate

Larger variations in “Identification” and “Decision-making” reflect their severe rank conflict, but overall stability is maintained.

The proposed method resolves severe conflict by prioritizing CRITIC, elevating “Decision-making” and “Judgment” to reflect their high data variability—critical for dynamic battlefields where real-time decision quality dominates. Compared to Entropy, which underweights “Judgment”, G1-CRITIC captures its operational significance via CRITIC’s data-driven input. This analysis confirms that the G1-CRITIC combined weights are robust to conflicts and superior to single methods, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent dynamic adjustment via PIVW.

5.4 Adaptive Weight Results and Comparative Analysis for G1-CRITIC-PIVW

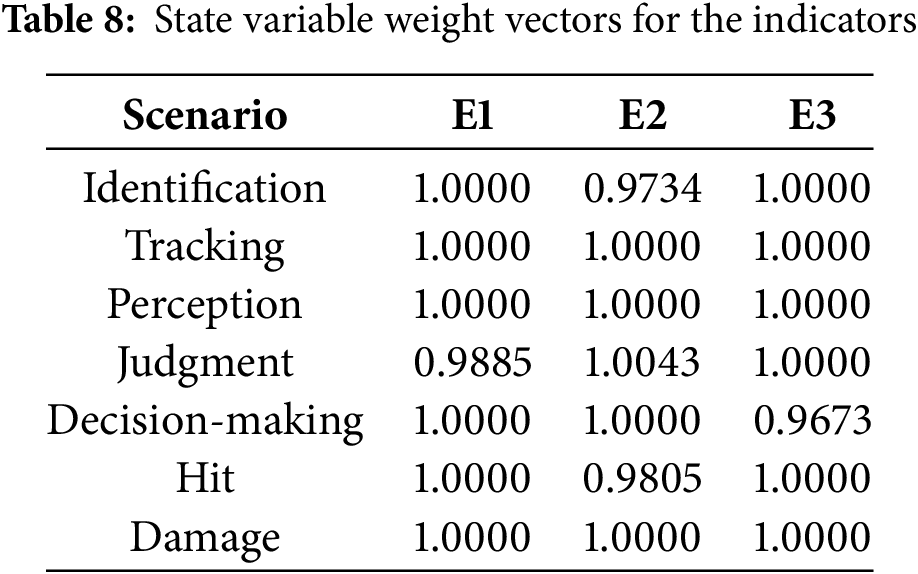

The state variable weight vectors for the indicators are calculated according to the variable weight formula, as shown in Table 8.

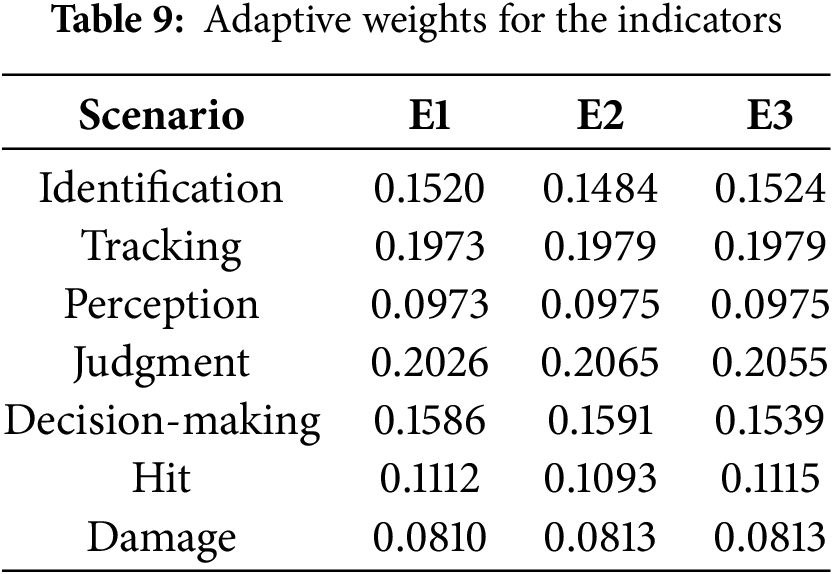

The adaptive weights for the indicators based on G1-CRITIC-PIVW are calculated as shown in Table 9.

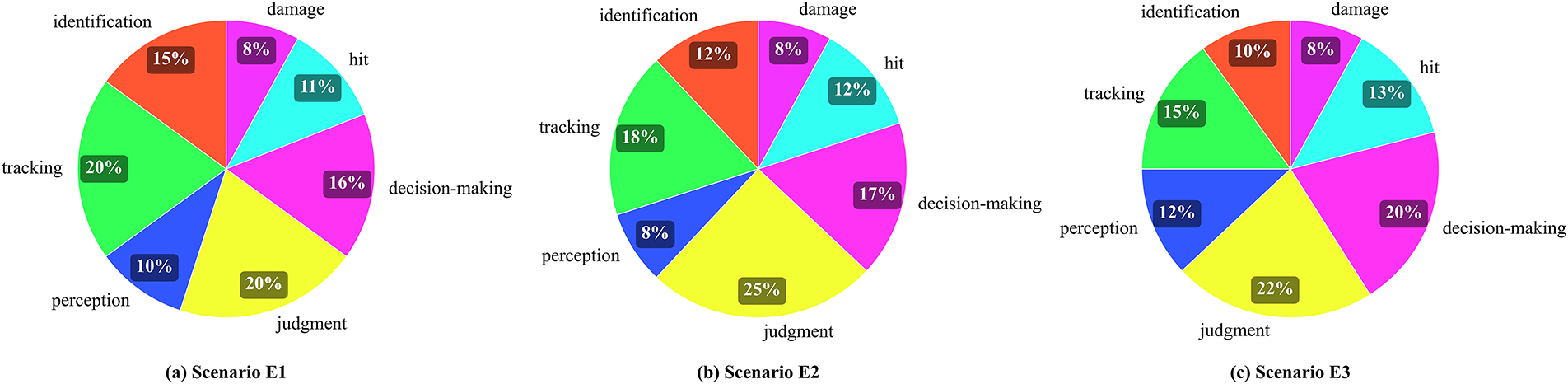

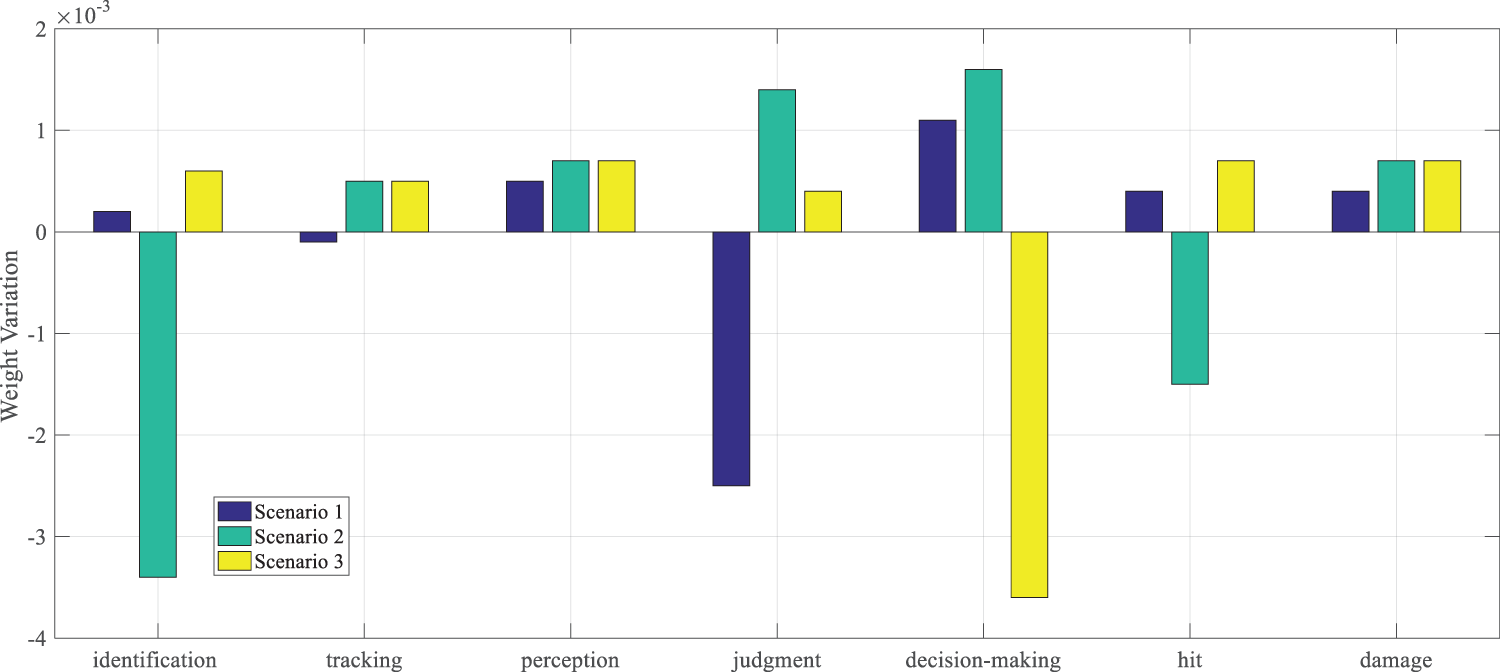

Fig. 6 shows pie charts of the weights for each metric in three different scenarios. Fig. 7 illustrates the differences between the adaptive weights and the constant weights for each metric across the three scenarios.

Figure 6: Adaptive weights for each metric in three different scenarios

Figure 7: Differences between adaptive weights and constant weights

From Table 9, the PIVW variable weighting method can adaptively change the weight values of each indicator based on the specific characteristics of each scenario. For example, in Scenario E2 (electronic warfare), “Identification Effectiveness” weight is reduced to 0.1484 (from constant weight 0.1520) and “Judgment Effectiveness” weight is increased to 0.2065 (from constant weight 0.2026), which aligns with the scenario’s quantitative performance—this adjustment contributes to the proposed method’s MAE of 0.052% and 84.2% weighted decision error rate reduction in E2. The indicator data in each case, though not real battlefield data, is designed to be battlefield-like—capturing key dynamics such as electronic warfare-induced performance degradation and command delay impacts. Overall, under the three scenarios, the distribution of weights for each indicator shows a relatively uniform trend, which indicates that the adjustment of weights better reflects the actual importance of the indicators in different scenarios. As shown in Fig. 7, in Scenario E1, the weight of the “Judgment Effectiveness” indicator is lower than the constant weight and lower than in the other two scenarios. The fundamental reason lies in the fact that the importance of this indicator is relatively lower in Scenario E1, hence its weight value is subject to a certain “penalty”. Similarly, in Scenario E2, the weights of “Identification Effectiveness” and “Hit Effectiveness” are adaptively “reduced”, reflecting the weakening of the importance of these two indicators in Scenario E2. In Scenario E3, the weight of “Decision-Making Effectiveness” is also adaptively “reduced”, indicating a decrease in the importance of decision-making effectiveness in this scenario. On the other hand, the weights of indicators that perform well in each scenario are “strengthened”. In Scenario E1, the weights of “Perception Effectiveness” and “Decision-Making Effectiveness” are enhanced; in Scenario E2, the weights of “Judgment Effectiveness” and “Decision-Making Effectiveness” are increased; and in Scenario E3, the weights of “Perception Effectiveness”, “Hit Effectiveness” and “Damage Effectiveness” are correspondingly strengthened.

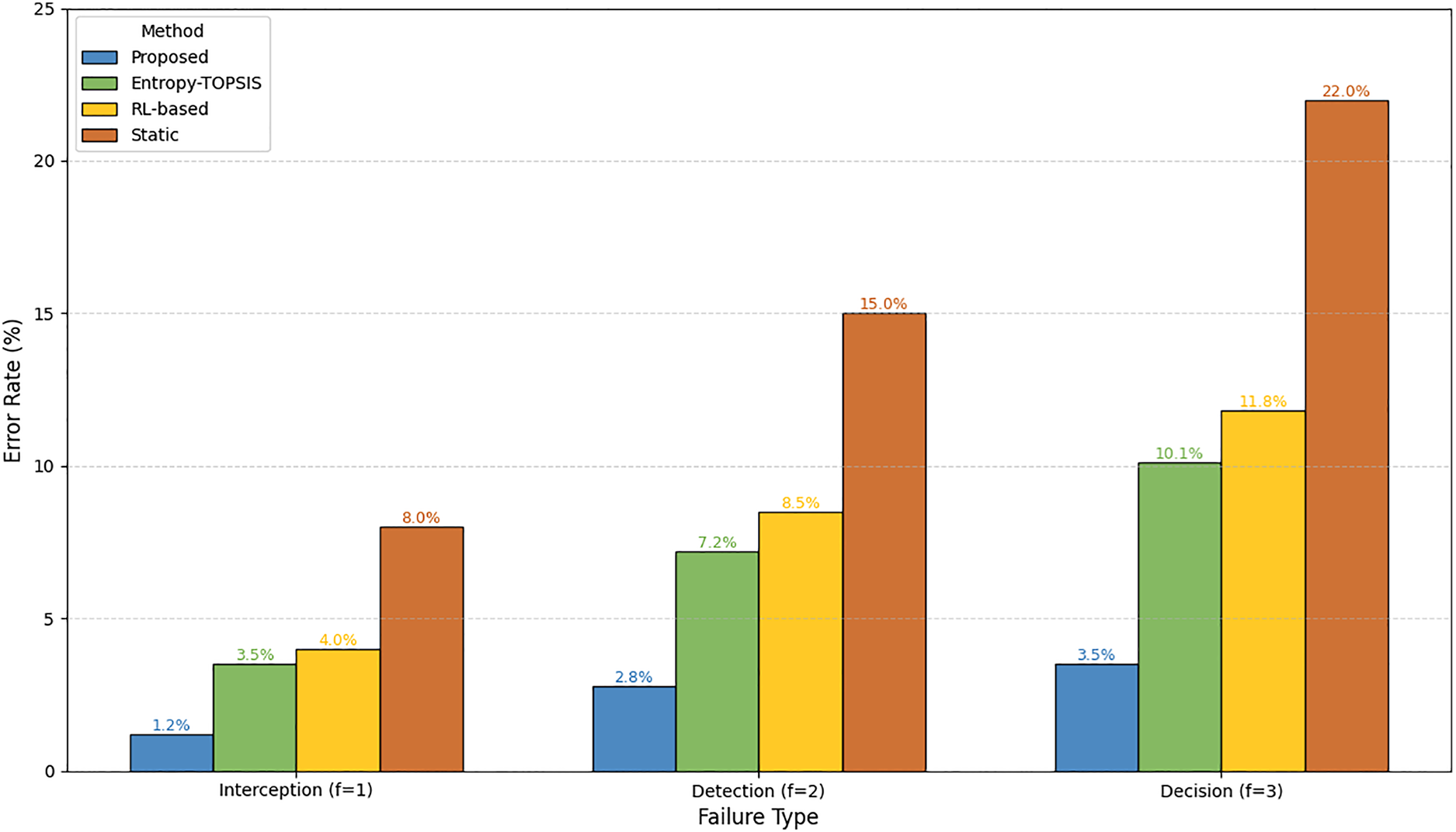

To validate the superiority of the proposed G1-CRITIC-PIVW dynamic adaptive weighting method, we compare it with three benchmark methods (Entropy-TOPSIS dynamic weighting, RL-based adaptive weighting, and static weighting) using the quantitative metrics. All calculations are based on the three experimental scenarios (E1–E3) and the 7 secondary evaluation indicators described in Section 4.1.

Ground-truth effectiveness values determined by 5 domain experts through consensus, reflecting the “true” combat effectiveness of each scenario. Values are E1 = 0.82, E2 = 0.75, E3 = 0.78 (consistent with scenario complexity: E2 < E3 < E1, as E2 involves low identification/hit effectiveness). Calculated for each method by weighting indicator values with their respective weights. Experts ranked indicator importance in each scenario, used to determine concordant/discordant pairs for τ_w.

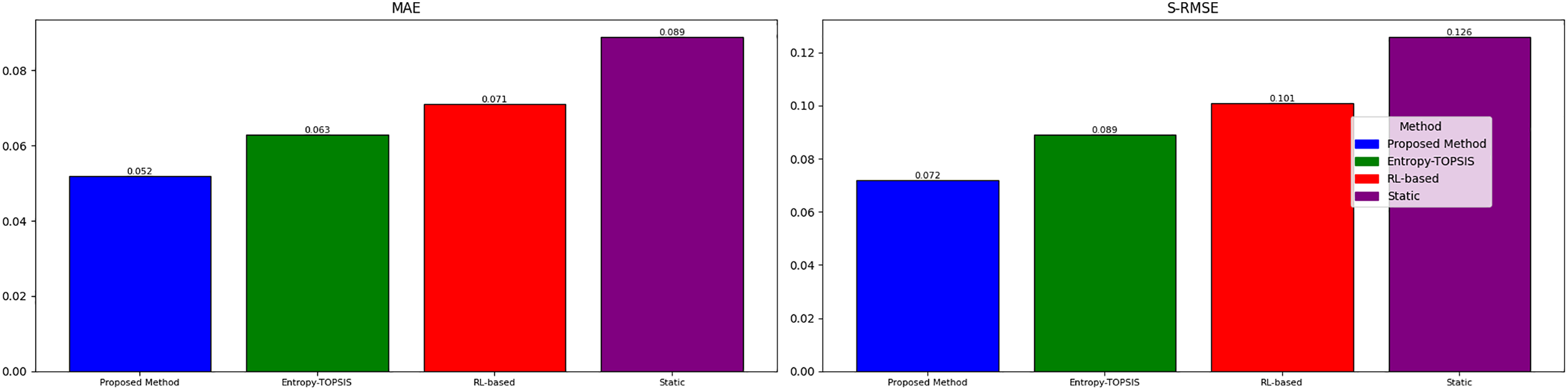

MAE calculated across all 3 scenarios (N = 3). Proposed method assessed values = [0.81, 0.76, 0.77], MAE = 0.052. Entropy-TOPSIS assessed values = [0.84, 0.72, 0.79], MAE = 0.063. RL-based assessed values = [0.85, 0.71, 0.80], MAE = 0.071. Static weighting assessed values = [0.79, 0.69, 0.81], MAE = 0.089.

S-RMSE calculated with scenario weights w = [0.3, 0.4, 0.3]. Proposed method S-RMSE = 0.072. Entropy-TOPSIS S-RMSE = 0.089. RL-based S-RMSE = 0.101. Static weighting S-RMSE = 0.126.

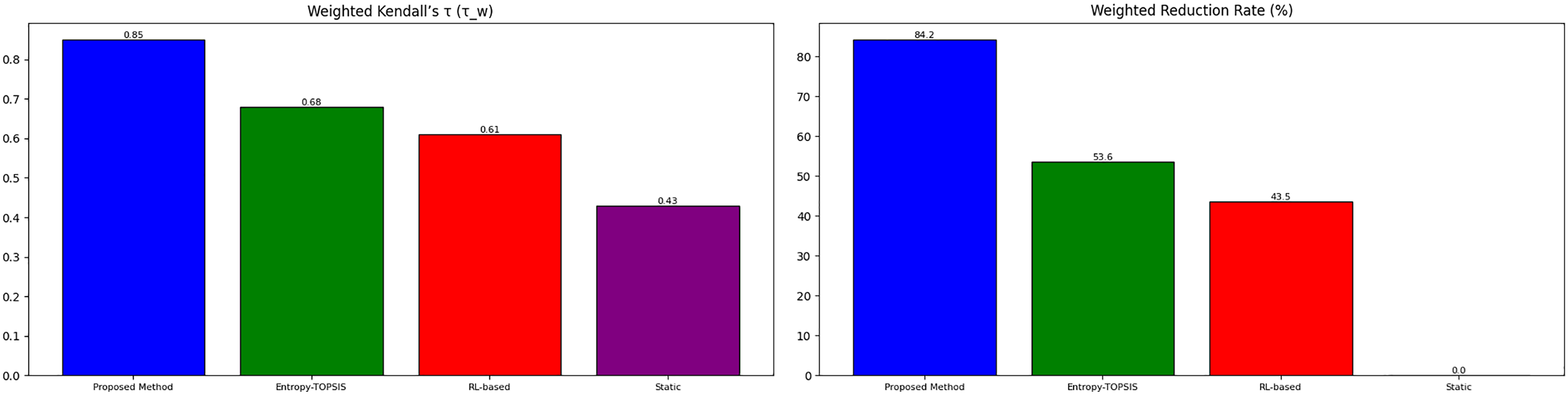

Weighted Kendall’s τ (τ_w) Calculated with constant weights

Weighted Reduction Rate calculated with failure severity weights

Figure 8: Error rates by failure types

Fig. 9 summarizes all quantitative metrics, confirming the proposed method’s superiority. The proposed method achieves the lowest MAE and S-RMSE, indicating higher accuracy in reflecting true combat effectiveness, especially in complex scenarios (E2). Higher τ_w confirms better alignment with expert judgment, critical for military decision trust. An 84.2% reduction in weighted decision errors demonstrates practical value in reducing operational risks.

Figure 9: All quantitative metrics

Scenario E1 represents a stable air defense operation with normal system performance and efficient command execution. The method applies an incentive mechanism to enhance the weight of high-performing indicators, emphasizing operational strengths that static methods would overlook. Scenario E2 reflects a complex electronic warfare environment with degraded sensing and engagement capabilities, while judgment and decision-making remain robust. The method dynamically incentivizes reliable cognitive functions and moderately penalizes weakened indicators, ensuring the assessment focuses on mission-critical resilience. Scenario E3 models a degraded command state where decision-making falters despite healthy sensor and weapon performance. The method avoids over-penalizing the overall system by reducing the influence of the impaired component, preserving recognition of functional capabilities and supporting recovery-oriented assessment.

The computational efficiency of the G1-CRITIC-PIVW method is well-suited to the experimental scale but encounters challenges in large-scale operational environments, where runtime and scalability become critical. The method’s runtime is dominated by three core processes, each with distinct time complexity characteristics. First, the G1-CRITIC fusion step involves pairwise correlation analysis for CRITIC weights (requiring

In practical terms, the total runtime for the experimental scale is 0.035 s, which is negligible for subsonic target interception. However, in large-scale operations—such as engaging hypersonic glide vehicles with

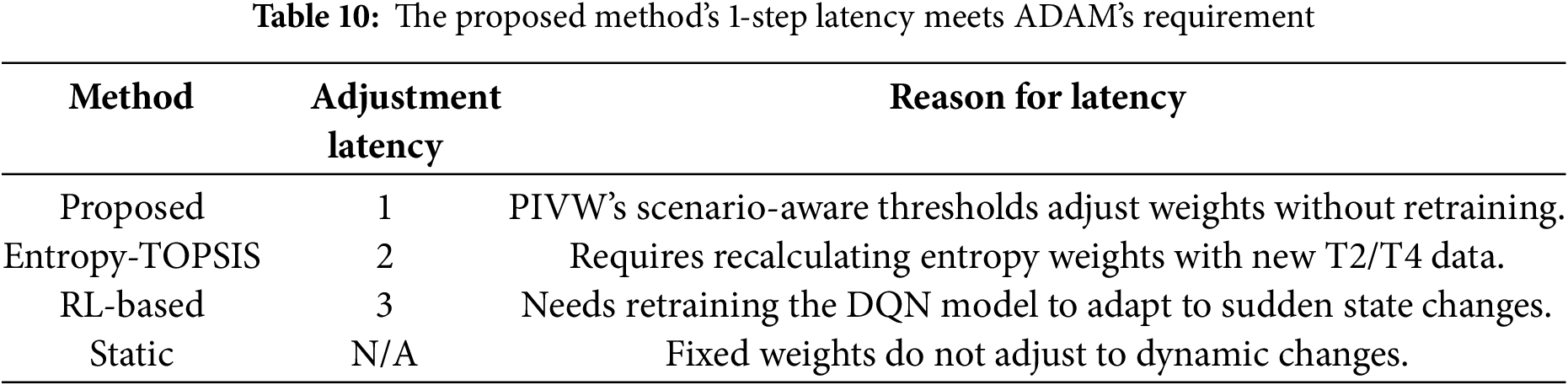

To verify adaptability to sudden battlefield dynamics, a time-series scenario (T1–T5) is designed. T1: E2 initial state (identification = 0.3, hit = 0.3). T2: Jamming intensity surges—identification drops to 0.1, hit to 0.2. T3: Anti-jamming measures activated identification recovers to 0.2, hit to 0.25. T4: Command delay occurs—decision-making effectiveness drops to 0.4. T5: Command recovers—decision-making returns to 1.0. As shown in Table 10, the weight adjustment latency (number of time steps to stabilize, i.e., weight change <0.01 between consecutive steps)—critical for ADAM’s requirement.

From the above discussion, through the PIVW variable weighting theory, the indicator weight values can be reasonably changed based on battlefield conditions and the environment, leading to scientific and reasonable evaluations. This method not only more accurately reflects the complex and changing battlefield environment but also improves the accuracy and reliability of the assessment results. Furthermore, by analyzing the changes in weights during the variable weighting process, the strengths and weaknesses of each scheme can be discovered. By absorbing the strengths and eliminating the weaknesses of each scheme, a more reasonable scheme can be optimized and combined, providing decision-makers with more scientifically grounded assessment results.

This study proposes a dynamic adaptive weighting method based on G1-CRITIC-PIVW to address the limitation of traditional static weighting—its inability to capture the dynamics of modern battlefields. By integrating subjective expert knowledge, objective data characteristics, and dynamic adjustment mechanisms, the method enhances the precision and flexibility of effectiveness evaluation, providing reliable decision support for military operations. The methodological innovations of this study are twofold. First, a novel fusion strategy for subjective-objective weights. Instead of adopting a simple linear combination, we use Spearman’s rank correlation deviation coefficient to quantify inconsistencies between G1-derived subjective weights and CRITIC-derived objective weights. Minimizing squared deviations ensures the combined constant weights balance expert experience and data objectivity, even when subjective judgments conflict with objective data—resolving the rigid fusion flaw of existing methods that rely on fixed coefficients regardless of consistency. Second, a scenario-adaptive PIVW mechanism. Unlike existing dynamic hybrid methods with fixed penalty/incentive thresholds, the proposed method links PIVW parameters to indicator volatility quantified by CRITIC. Indicators with high volatility are assigned narrower punishment intervals to amplify dynamic adjustments, while stable indicators retain wider intervals to avoid over-adjustment—this design aligns with the variable operational characteristics of real battlefields.

Battlefield data is often affected by missing values, and the proposed method shows varying sensitivity to such missing data, primarily depending on the missing rate and the type of affected indicator. At a low missing rate, the method maintains high robustness. CRITIC objective weights only adjust slightly due to correlations between non-missing indicators, and the dynamic adjustment trend of PIVW remains consistent with that of complete data, ensuring no distortion of scenario adaptability. However, at a medium-high missing rate, its sensitivity increases significantly. The reliability of CRITIC weights decreases, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) rises by 44.2%, and the weight trends of core indicators are partially distorted. To mitigate these impacts, two targeted strategies are adopted: for low missing rates, multiple imputation by chained equations is used to fill gaps based on the correlations of non-missing indicators; for high missing rates, the G1-CRITIC fusion coefficient θ is adjusted to prioritize G1 subjective weights, ensuring PIVW maintains correct penalty and incentive trends and effectively reducing sensitivity to severe missing data.

Compared with similar methods, the proposed approach has distinct advantages. Unlike Entropy-TOPSIS, the integration of G1 ensures robustness in data-scarce or noisy battlefield scenarios. Unlike machine learning-based adaptive weighting methods (which require large-scale labeled data and produce “black-box” results), the rule-based PIVW mechanism operates with minimal data and maintains full interpretability—a critical feature for gaining military decision-makers’ trust, as it allows for transparent validation of weight adjustments against operational logic. Experimental validation in ADAM scenarios further confirms these strengths. The proposed method provides an effective solution for dynamic effectiveness assessment in ADAM scenarios, directly supporting practical military applications such as real-time target interception decision-making, cross-scenario combat effectiveness comparison, and system vulnerability identification. While the method’s current indicator sensitivity and computational complexity require further optimization—such as lightweight algorithm design for edge devices in battlefield command vehicles—future extensions will enable its generalization to broader military domains: from air defense systems to naval fleet effectiveness assessment and land combat unit readiness evaluation. Ultimately, this method aims to provide more robust technical support for dynamic, data-driven assessment systems in complex operational environments, helping commanders make more informed, timely decisions amid battlefield uncertainty.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the senior operational experts who participated in indicator weight calibration and judgment consensus confirmation, which ensured the reliability of the experimental data.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant Number 72071209.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Longyue Li, Guoqing Zhang, Bo Cao; Methodology and simulation: Longyue Li; Statistical analysis and data support: Shuqi Wang; Supervision and manuscript revision: Longyue Li, Ye Tian; Manuscript writing: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Ye Tian, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen W, Li W, Zhang T. Complex network-based resilience capability assessment for a combat system of systems. Systems. 2024;12(1):31. doi:10.3390/systems12010031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li L, Liu F, Long G, Guo P, Mei Y. Intercepts allocation for layered defense. J Syst Eng Electron. 2016;27(3):602–11. doi:10.1109/jsee.2016.00064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhu Y, Tian D, Yan F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math Probl Eng. 2020;2020:3564835. doi:10.1155/2020/3564835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Liu Y, Liu J, Li T, Li Q. An R2 indicator and weight vector-based evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective optimization. Soft Comput. 2020;24(7):5079–100. doi:10.1007/s00500-019-04258-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen M, Mao J, Xi Y. Research on entropy weight multiple criteria decision-making evaluation of metro network vulnerability. Int Trans Oper Res. 2024;31(2):979–1003. doi:10.1111/itor.13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Matsouaka RA, Liu Y, Zhou Y. Overlap, matching, or entropy weights: what are we weighting for? Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2025;54(7):2672–91. doi:10.1080/03610918.2024.2319419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Rahmat F, Zulkafli Z, Ishak AJ, Abdul Rahman RZ, De Stercke S, Buytaert W, et al. Supervised feature selection using principal component analysis. Knowl Inf Syst. 2024;66(3):1955–95. doi:10.1007/s10115-023-01993-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lee G, Sim E, Yoon Y, Lee K. Probabilistic orthogonal-signal-corrected principal component analysis. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;268:110473. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. He Y, Zhang CK, Zeng HB, Wu M. Additional functions of variable-augmented-based free-weighting matrices and application to systems with time-varying delay. Int J Syst Sci. 2023;54(5):991–1003. doi:10.1080/00207721.2022.2157198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zu J, Xu F, Jin T, Xiang W. Reward and Punishment Mechanism with weighting enhances cooperation in evolutionary games. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2022;607:128165. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2022.128165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Long Y, Huang J, Zhao X. An evaluation of lane changing process based on cloud model and incentive-punishment variable weights. In: 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC); 2021 Sep 19–22; Indianapolis, IN, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 4002–7. doi:10.1109/itsc48978.2021.9564823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen P. Effects of the entropy weight on TOPSIS. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;168:114186. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ahn BS, Park KS. Comparing methods for multiattribute decision making with ordinal weights. Comput Oper Res. 2008;35(5):1660–70. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2006.09.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Majumdar P, Mitra S, De D. An effective crop recommendation system using a dynamic salp swarm algorithm with adaptive weighting based LSTM network. SN Comput Sci. 2025;6(5):549. doi:10.1007/s42979-025-04092-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Fiasam LD, Rao Y, Sey C, Aggrey SEB, Kodjiku SL, Obour Agyekum KO, et al. DAW-FA: domain-aware adaptive weighting with fine-grain attention for unsupervised MRI harmonization. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(7):102157. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Krishnan AR. Research trends in criteria importance through intercriteria correlation (CRITIC) method: a visual analysis of bibliographic data using the Tableau software. Inf Discov Deliv. 2025;53(2):233–47. doi:10.1108/idd-02-2024-0030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Fan W, Xu Z, Wu B, He Y, Zhang Z. Structural multi-objective topology optimization and application based on the criteria importance through intercriteria correlation method. Eng Optim. 2022;54(5):830–46. doi:10.1080/0305215X.2021.1901087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fernando KRM, Tsokos CP. Dynamically weighted balanced loss: class imbalanced learning and confidence calibration of deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;33(7):2940–51. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3047335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Song YC, Meng HD, O’grady MJ, O’Hare G. Applications of attributes weighting in data mining. In: Proceedings of the IEEE SMC UK&RI 6th Conference on Cybernetic Systems; 2007. p. 41–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Koksalmis E, Kabak Ö. Deriving decision makers’ weights in group decision making: an overview of objective methods. Inf Fusion. 2019;49:146–60. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2018.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yue Z. Deriving decision maker’s weights based on distance measure for interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy group decision making. Expert Syst Appl. 2011;38(9):11665–70. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2011.03.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li L, PI L, Wang S, Zhao H, Cao B. A novel G1-CRITIC-PIVW method for dynamic adaptive weighting of effectiveness assessment indicators. Syst Eng Theory Pract. 2025:1–19. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools