Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Artificial Intelligence Design of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys: A Review

1 Shanghai Key Lab of Advanced High-Temperature Materials and Precision Forming, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 200240, China

2 Inner Mongolia Research Institute, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Hohhot, 010010, China

* Corresponding Author: Chao Yang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070735

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Sustainable aluminum alloys, renowned for their lower energy consumption and carbon emissions, present a critical path towards a circular materials economy. However, their design is fraught with challenges, including complex performance variability due to impurity elements and the time-consuming, cost-prohibitive nature of traditional trial-and-error methods. The high-dimensional parameter space in processing optimization and the reliance on human expertise for quality control further complicate their development. This paper provides a comprehensive review of Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques applied to sustainable aluminum alloy design, analyzing their methodologies and identifying key challenges and optimization strategies. We review how AI methods such as knowledge graphs, evolutionary algorithms, and machine learning transform conventional processes into efficient, data-driven workflows, thereby enhancing development speed and precision. The review explicitly highlights existing bottlenecks, including insufficient data quality and standardization, the complexity of cross-scale modeling, and the need for industrial coordination. We conclude that AI holds immense potential to drive the recycled aluminum industry toward a more sustainable and intelligent future. Future research is poised to leverage generative AI, autonomous experimental platforms, and blockchain for improved life-cycle management, while also focusing on developing physics-informed models and establishing standardized data ecosystems.Keywords

1.1 Definition and Application Range of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys

Aluminum ranks as the second most produced and consumed metallic material of the world, surpassed only by steel, and finds extensive application across the global transportation and construction sectors [1]. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, both primary aluminum and its downstream processing industries have experienced rapid expansion, ushering in a new era of technological advancement [2]. In 2023, global primary (electrolytic) aluminum output reached 70.593 million tons, representing a year-on-year increase of 2.25%. Meanwhile, the primary aluminum production incurred enormous energy and carbon costs: approximately 95.254 billion kWh of electricity was consumed, yielding some 1.154 billion t of CO2 emissions [3]. According to forecasts by the International Aluminum Institute, global aluminum demand will rise to 160 million tons per annum by 2040 [4]. If this entire requirement were met by primary aluminum production, total electricity consumption would surge to roughly 215.894 billion kWh and CO2 emissions to about 2.616 billion tons—outcomes clearly at odds with international energy-saving and emission-reduction targets [5]. Against the backdrop of escalating aluminum demand, the resource and energy burdens, as well as greenhouse-gas outputs, tied to primary production have become unsustainable [6]. Thus, a fundamental solution necessitates a substantial reduction in both the production and consumption of primary aluminum.

Sustainable aluminum alloys are produced from scrap aluminum—including both new and post-consumer scrap—or aluminum-bearing waste, which, after pretreatment, smelting, and refining, is re-alloyed into high-quality materials [7]. The recycling of aluminum constitutes the necessary viable pathway for the global aluminum industry to achieve low-carbon, green, and sustainable development, making the sustainable aluminum sector an indispensable component of the broader aluminum-industry ecosystem [8]. Compared with primary aluminum production, the manufacture of one ton of sustainable aluminum reduces electricity consumption by approximately 95%, saves 3.4 t of standard coal, conserves 14 m3 of water, decreases solid-waste generation by 20 t, and cuts CO2 emissions by 15.91 t as well as sulfur-oxide emissions by 90% [6]. Moreover, it eliminates the need to handle 1.9 t of slag and wastewater, avoids stripping 0.6 t of topsoil, and circumvents the excavation of 6.1 t of overburden. Sustainable aluminum alloys span two principal categories: casting alloys and wrought alloys [9]. Casting grades are predominantly employed in the fabrication of automotive, motorcycle, machinery, and telecommunications cast components—such as engine blocks, wheels, and transmission housings—whereas wrought grades serve the construction, packaging, and electronics industries [10]. In addition, sustainable aluminum alloys have found extensive application in new-energy vehicles, including body structures, engine parts, and wheel rims, thereby contributing to vehicle light weighting and energy-efficiency improvements [11]. By 2050, it is projected that some 550 million tons of recycled aluminum will enter the global circular-economy chain, representing nearly 60% of total aluminum supply [12]. Consequently, scaling up the sustainable aluminum industry and enhancing alloy quality are paramount strategies for diminishing dependence on primary aluminum consumption and for constructing a truly green aluminum ecosystem [7]. Beyond their established roles in traditional sectors, sustainable aluminum alloys also exhibit promising growth potential in emerging fields such as renewable-energy infrastructure, aerospace, and electronic communications [13].

1.2 Difficulties in High Quality Utilization of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys

The greatest technical obstacle to the large-scale use of sustainable aluminum in wrought-alloy profiles lies in the scrap-recovery process itself, which not only induces significant fluctuations in the concentrations of primary alloying elements (Al, Zn, Mg, Cu), but also promotes the accumulation of impurity elements such as Fe, Si, Mn, and Ti [14]. To meet strict compositional requirements, large quantities of primary aluminum must be added during scrap melting. Even so, the overall higher impurity content of sustainable aluminum—relative to primary aluminum—leads to the precipitation of various intermetallic compounds during solidification, which detrimentally affect microstructural integrity, formability, and mechanical performance [15].

High-quality datasets are the cornerstone of AI-driven design for recycled aluminum alloys. Such datasets must possess standardization and completeness, ensuring consistent data collection that includes all critical information, from composition to microstructure. They must also be accurate and reliable, validated through rigorous experimentation to eliminate noise. Furthermore, they need to be representative, encompassing the full range of compositional variability inherent in recycled materials. These requirements collectively ensure that AI models can learn the true, complex processing-structure-property relationships, thereby avoiding the “garbage in, garbage out” dilemma [16].

Addressing data fragmentation is another significant challenge for effective AI implementation. The conventional practice of isolated data silos severely limits a model’s generalizability. To overcome this, the industry needs to establish a unified ontological framework that serves as a shared data language, integrating disparate data from various sources into a coherent knowledge graph. Additionally, through the creation of collaborative data platforms or the use of techniques like federated learning, data can be securely shared across manufacturers, pooling vast amounts of information to train more powerful and accurate predictive models while protecting proprietary information. These strategies collectively pave the way for the deep application of AI in the field of recycled aluminum alloys [17].

1.3 The Dilemma of Traditional Design Methods for Aluminum Alloys

Traditional sustainable-aluminum-alloy design remains hindered by three interrelated bottlenecks. Firstly, the process is profoundly empirical: researchers must amass years of experience to identify critical impurity thresholds—such as the need to add manganese to neutralize brittle iron-rich phases once Fe content exceeds 0.5 wt.%—yet when dealing with compositional variability of ±0.3 wt.% inherent to mixed scrap sources, the conventional trial-and-error approach becomes prohibitively inefficient, requiring five to seven melting trials per formulation, each consuming two to three weeks and costing over ¥50,000. Secondly, existing computational tools are inadequate to capture the realities of industrial solidification. Although CALPHAD-based thermodynamic models can reliably predict equilibrium phase assemblages, they face significant limitations in accurately accounting for rapid, non-equilibrium cooling rates, which are characteristic of industrial processes like die casting (~100°C/s). This deficiency can lead to errors in predicted elemental solubility reaching up to 18%, as demonstrated in recent studies. Such discrepancies result in considerable errors in mechanical-property predictions, particularly in tensile strength and ductility, which can reach 20% under typical casting conditions [18]. Such uncertainties compel engineers to adopt overly conservative “over-alloying” strategies that result in a considerable waste of scarce alloying additions (e.g., Sc, Zr), a well-documented challenge in transitioning to a circular economy for aluminum alloys [19]. Thirdly, the traditional orthogonal-array methodology exhibits weak multi-objective optimization capability: to meet simultaneous targets of tensile strength (>300 MPa), ductility (>10%), and electrical conductivity (>50% IACS), manufacturers must evaluate over 200 parameter combinations, yet such approaches cannot quantify the nonlinear influence of processing variations—such as ±10°C in homogenization temperature—on microstructural outcomes (e.g., recrystallized grain-size fluctuations of ±5 µm), and this persistent knowledge gap has constrained production yields to a plateau of only 82%–85% [20].

1.4 Advantages of AI-Driven Design of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys and the Challenges Currently Faced

Artificial intelligence has engendered a revolutionary paradigm shift in the design of sustainable aluminum alloys, delivering transformative benefits across three key dimensions. First, machine-learning algorithms—such as random forests and deep neural networks—can mine vast repositories of historical experimental data and high-throughput computational results to elucidate the nonlinear relationships between scrap-derived impurity elements (e.g., Fe, Si) and alloy performance [21]. For instance, a Transformer model incorporating attention mechanisms has been shown to detect the synergistic embrittlement effect of Fe/Mn atomic ratios in the 0.8–1.2 range at grain boundaries, achieving prediction accuracies more than 40% higher than those of conventional empirical formulas [22]. Second, the integration of generative adversarial networks (GANs) with reinforcement-learning frameworks enables autonomous optimization of alloy compositions [23]. In a 2023 collaborative project between Northwestern University and Arconic, an AI-driven system iteratively developed a novel Al–Mg–Si–Cu recycled alloy for automotive lightweighting in just three weeks—one-fifth the time required by traditional methodologies—yielding a tensile strength of 380 MPa and electrical conductivity exceeding 48% IACS. Third, digital-twin platforms that couple multiphysics simulations (e.g., melt-flow, heat-transfer, and phase-change models) allow real-time optimization of casting parameters, reducing the energy consumption of scrap-aluminum remelting by 12%–15% [24].

Despite these advances, AI-driven design of sustainable aluminum alloys still confronts several formidable challenges. First, severe data fragmentation persists: variations in melting-furnace parameters and quality-control standards among different manufacturers have produced isolated “data islands”, necessitating the establishment of ASTM- or ISO-level protocols for data cleaning and normalization. Second, the compatibility of “black-box” models with fundamental materials-science principles remains problematic—for example, deep-learning predictions of grain-size distributions can violate thermodynamic constraints—highlighting the need to develop physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) that embed metallurgical knowledge directly into model architectures. Third, few-shot learning capabilities are limited by the scarcity of high-value alloy failure data (e.g., for aerospace-grade Al–Li systems), causing transfer-learning models to exhibit error increases of over 30% when generalized across different alloy families [25,26]. Moreover, industrial deployment faces hardware–software integration hurdles: synchronizing industrial-IoT data-acquisition rates (>10 Hz) with AI-model inference latencies (<50 ms) demands dedicated edge-computing infrastructures. Overcoming these bottlenecks will require deep collaboration among academia, industry, and national laboratories to build an intelligent R&D ecosystem that unites a comprehensive materials–genome database, multiscale simulation platforms, and autonomous experimental robotics [27].

This review systematically surveys recent advances in the design of sustainable aluminum alloys enabled by artificial intelligence, encompassing knowledge-graph frameworks, evolutionary algorithms, computer-vision diagnostics, natural-language-processing of technical literature, and a variety of machine-learning methodologies. It further delineates the principal challenges—data-quality deficiencies, the complexity of multiscale modeling, and the lack of integrated industry-chain collaboration—and proposes corresponding optimization strategies, such as the development of standardized data-cleansing protocols, physics-informed hybrid modeling, and the creation of unified digital-twin platforms. Our analysis demonstrates that AI has instigated a paradigm shift from empirical to data-driven alloy development, substantially accelerating R&D cycles and enhancing control over performance. Nonetheless, overcoming persistent barriers in data integrity, cross-scale model fidelity, and ecosystem interoperability will be essential [28]. By driving technological innovation and fostering a cohesive research-industry-infrastructure ecosystem, AI promises to propel the sustainable aluminum sector toward efficient, low-carbon, and intelligent manufacturing, thereby underpinning global green-manufacturing objectives [29].

2 Artificial Intelligence Techniques Applied in the Design of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys

In the design of sustainable aluminum alloys, artificial intelligence spans several critical technological domains [30]. Knowledge-graph frameworks integrate scrap-aluminum sources, impurity-threshold data, and process parameters into a computable network of empirical rules. Evolutionary algorithms such as NSGA-III efficiently address multi-objective optimization, rapidly converging on performance–cost Pareto fronts [31,32]. Computer-vision techniques employing YOLO models automate the recognition of microstructural features, enabling precise quantification of precipitate phases, while natural-language-processing methods mine patent literature to uncover latent composition–performance correlations [33,34]. Machine learning functions as the central data-intelligence hub, reshaping R&D paradigms through high-dimensional feature extraction and nonlinear modeling. Reinforcement learning further refines melting strategies within virtual environments to minimize energy use and metal loss, and federated learning dismantles data silos by uniting multi-source datasets to enhance predictive accuracy [35,36]. Moreover, digital-twin platforms that couple multi-physics simulations facilitate real-time control of casting parameters, markedly improving production yields. The synergistic application of these AI techniques has transformed the sustainable aluminum-alloy development paradigm, propelling materials design toward a more intelligent, systematic, and integrated future.

Over decades of development, the field of materials science has accumulated a vast body of domain knowledge. However, this knowledge is predominantly embedded in unstructured textual formats—dispersed across experimental reports, research articles, and process manuals—resulting in two fundamental bottlenecks. First, the lack of a unified ontological framework and structured relational schema for heterogeneous knowledge prevents its direct integration into machine-learning workflows. Second, implicit correlations between discrete knowledge fragments remain unmodeled, severely limiting the efficiency of knowledge reuse in multiscale materials design. Addressing the challenge of systematically extracting, structurally reorganizing, and intelligently managing domain knowledge has thus become a pressing issue in the advancement of materials informatics [36,37].

Knowledge graph (KG) technology offers an innovative solution to this bottleneck. A KG functions as a semantic network composed of ‘entities’ (e.g., specific alloys, process parameters) and ‘relations’ (e.g., ‘forms, influences’). By transforming scattered knowledge into structured network data, KGs enable computers to understand and process information in a human-like manner. Furthermore, by applying graph-based algorithms and AI techniques, such as graph neural networks, KGs can perform reasoning on this complex network, uncovering hidden correlations to accelerate the design and development of new materials, particularly for the compositionally and process-variable systems like sustainable aluminum alloys [38].

By constructing semantic networks based on “entity–relation–attribute” triples, it enables the systematic integration of multimodal materials knowledge—such as melting-parameter thresholds and phase-transformation kinetics—and, through the application of reasoning algorithms like graph neural networks (GNNs), facilitates the discovery of hidden relational rules [36,37].

The knowledge graph is a set of triples, which can be expressed as

The introduction of knowledge graphs into materials science has the potential to significantly enhance capabilities across three key dimensions:

1. Ontology-based knowledge representation systems: address issues of terminological ambiguity and missing conceptual hierarchies in materials science—for example, enabling dynamic mappings between impurity Fe content and the formation of β-Al5FeSi phases.

2. Graph embedding-based knowledge representation learning: supports cross-scale predictive modeling of composition–process–performance relationships, allowing for more comprehensive understanding and inference across material design variables.

3. Path reasoning-based decision optimization: enables intelligent generation and validation of materials design schemes under multiple constraints, facilitating automated exploration of viable solutions [40,41].

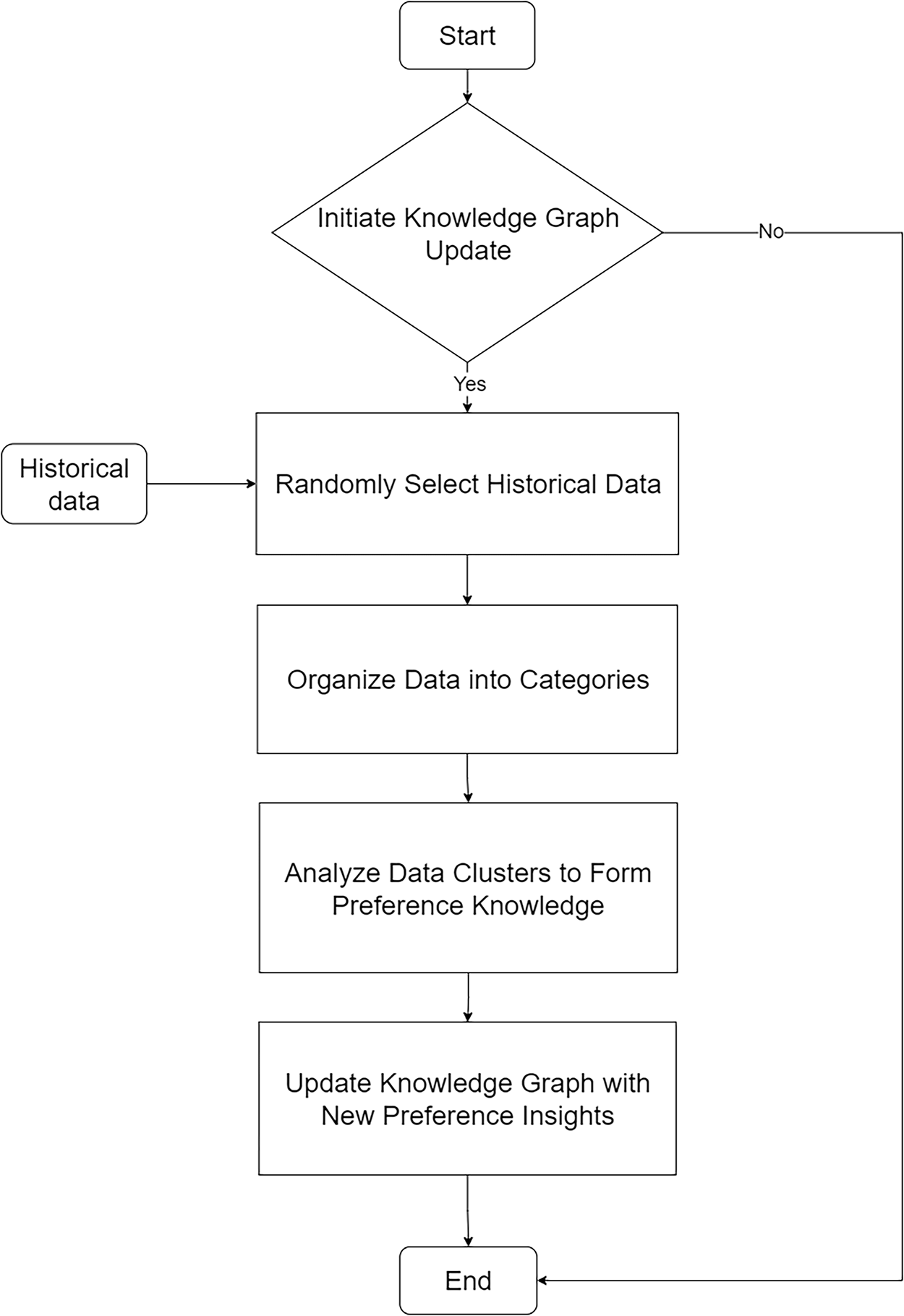

Together, these capabilities provide a methodological foundation for overcoming key challenges in materials machine learning, including data scarcity, poor model interpretability, and limited transferability—thus advancing the development of a knowledge-driven paradigm in materials innovation. Fig. 1 below illustrates the overall workflow of updating the Knowledge Graph with operation preferences extracted from historical data.

Figure 1: The workflow of updating the Knowledge Graph with operation preference extracted from historical data

2.1.1 An Example of Knowledge Graph Construction

To overcome the limitations of existing sparse knowledge graph inference algorithms, Jian Liu and Quan Qian from Shanghai University proposed a reinforcement learning–based reasoning algorithm for knowledge graphs. This approach employs multi-agent collaboration to reduce the exploration space and introduces a novel reward shaping mechanism to effectively address the challenges posed by sparsity in the graph [36].

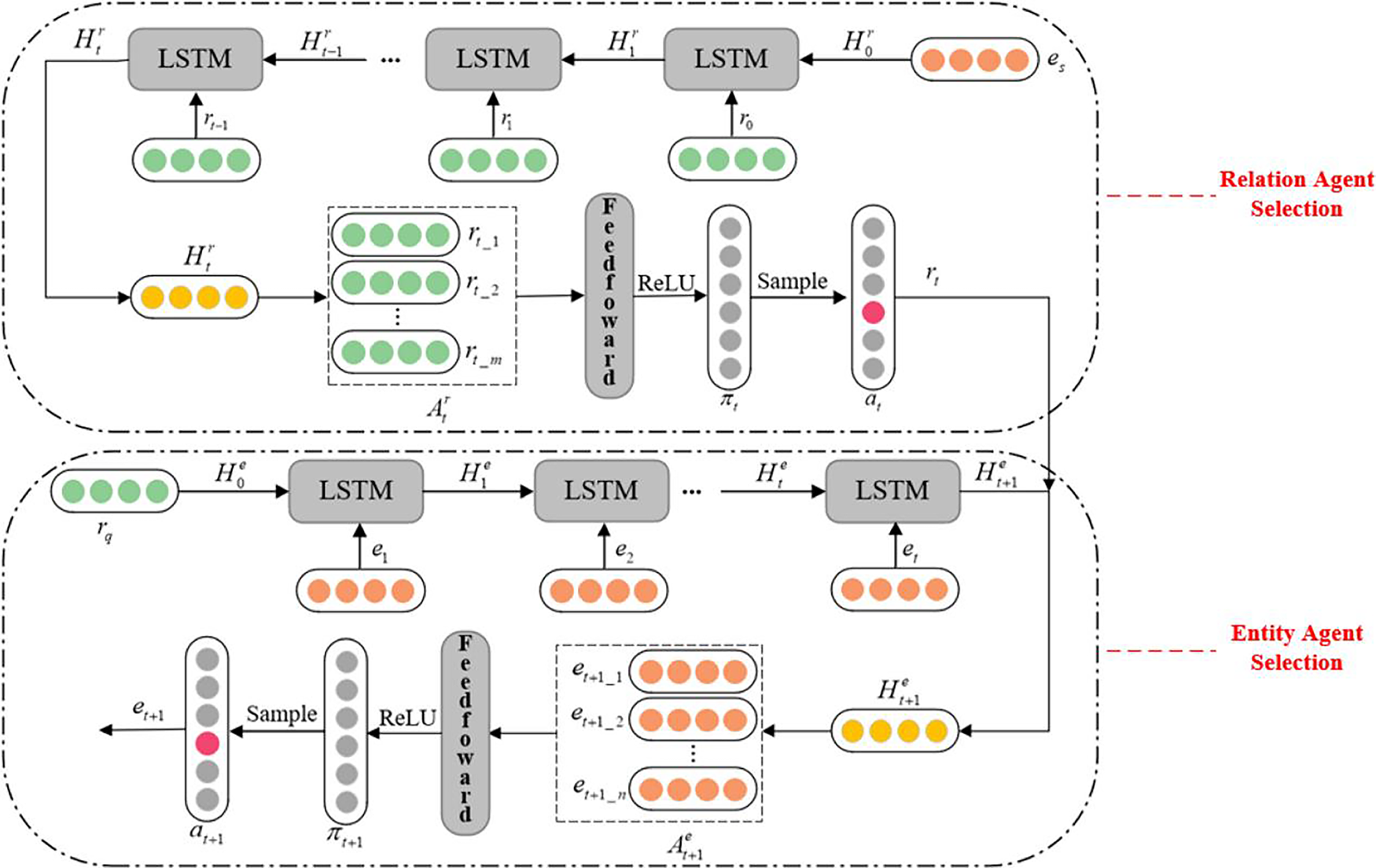

Fig. 2 illustrates the reinforcement learning–based knowledge graph reasoning framework. A knowledge graph is composed of multiple triples in the form of (head entity, relation, tail entity). First, we input the constructed aluminum alloy domain knowledge graph and then map the high dimensional semantic information to low dimensional vectors/matrices through embedding, which will participate in the interaction between agents as the environment in the reinforcement learning system. After the interaction, the proposed RL algorithm will give the optimal action policy, according to which we can get the most likely answer of the query [36].

Figure 2: Process of knowledge graph reasoning algorithm based on reinforcement learning. Reprinted with permission from [36]. Copyright 2023, Computational Materials Science

The general framework of reinforcement learning is illustrated in Fig. 3, which primarily consists of two core components: the environment and the agent. Reinforcement learning focuses on the dynamic interaction between these two elements. In reinforcement learning, the agent must complete a series of interactions with the environment: (1) at every moment, the environment will be in a state. (2) the agent will try to obtain observations on the current state of the environment. (3) the agent then takes action based on the observations and its historical behavior (termed the ‘‘policy’’). (4) this action will affect the state of the environment and cause certain changes to it, the agent will then take new actions based on new observations [36]. During the interaction process, the agent selects its next action based on its current state. Upon executing the action, the agent transitions to a new state and receives a reward signal from the environment corresponding to the outcome of that state transition. More specifically, the goal of reinforcement learning is to learn the mapping between states and actions from the interaction experience, thereby guiding the agent to make optimal decisions based on its current state. This ultimately aims to maximize the cumulative reward, enabling effective learning and policy optimization over time.

Figure 3: Reinforcement learning framework. Reprinted with permission from [36]. Copyright 2023, Computational Materials Science

The primary function of the policy network is to construct a model that, by observing the state of the environment, directly predicts the strategy that maximizes expected return. It comprises two main components: (1) a long short-term memory (LSTM) network, which encodes the historical trajectory traversed by the agent, and (2) a feedforward neural network, which selects the next action from the set of all possible actions.

Fig. 4 depicts the policy-generation details for both the relation agent and the entity agent, corresponding to Step 2 in Fig. 1. Here, a policy is defined as the sequence of actions leading from the initial entity to the target entity. The training of the policy network is organized into two hierarchical layers—the relation-agent layer and the entity-agent layer—each consisting of an LSTM for encoding the agent’s path history and a feedforward neural network for sampling the next agent action based on the learned action distribution.

Figure 4: Training process of the policy network. Reprinted with permission from [36]. Copyright 2023, Computational Materials Science

This study leverages multi-agent reinforcement learning and a tailored reward-shaping mechanism to markedly enhance inference efficiency on sparse knowledge graphs, and it establishes a domain-specific knowledge-graph system for aluminum alloys (including recycled variants). The proposed methodology is directly transferable to sustainable aluminum-alloy design, enabling dynamic composition balancing, process-parameter optimization, and multi-objective decision-making—thereby furnishing critical technical support for AI-driven green materials development.

2.1.2 Other Typical Application Scenarios and Cases

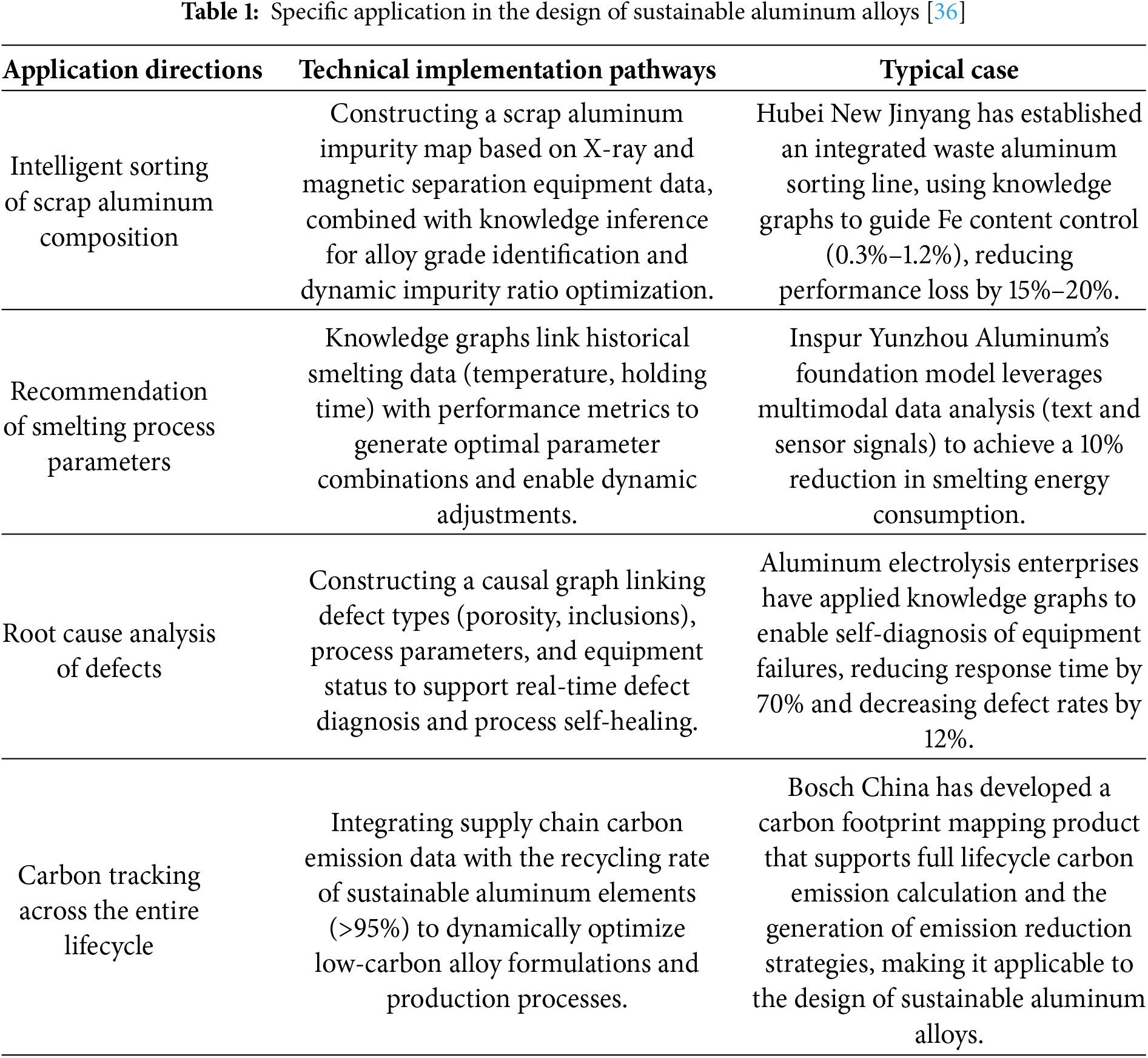

In practical applications, knowledge graphs can assist researchers and engineers in rapidly retrieving and analyzing massive amounts of data, uncovering complex relationships among different design variables, accelerating the formulation design and performance optimization processes of sustainable aluminum alloys, and promoting more efficient and precise customized applications in fields such as aerospace and automotive manufacturing. This enhances their market competitiveness, broadens their application scope, and supports the upgrading of the sustainable aluminum industry. Table 1 provides specific application examples to further illustrate the key roles and practical effectiveness of knowledge graphs in the design of sustainable aluminum alloys [36].

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) are a class of global optimization methods inspired by biological evolution principles such as natural selection, inheritance, and mutation. they primarily include [42,43]:

A. Genetic Algorithm (GA): iteratively optimizes candidate solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations.

B. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): simulates bird flock foraging behavior, adjusting the search direction based on individual and collective experience.

C. Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA): such as NSGA-II, designed to optimize multiple conflicting objectives simultaneously (e.g., strength and cost).

Using evolutionary algorithms in sustainable aluminum alloy design offers significant advantages over traditional empirical methods. The complex nature of these alloys, characterized by compositional variability from mixed scrap sources and the presence of detrimental impurities like Fe, necessitates a robust optimization approach. Evolutionary algorithms, such as NSGA-II, excel at handling multiple conflicting objectives simultaneously—for instance, maximizing strength and ductility while minimizing impurity content. They can efficiently explore a vast, high-dimensional design space to identify a set of Pareto-optimal solutions, providing engineers with a range of optimal trade-offs. This capability is crucial for balancing desired mechanical properties with cost-effectiveness and impurity tolerance. By systematically navigating this intricate landscape, these algorithms help mitigate the inefficiencies of trial-and-error, reduce reliance on costly “over-alloying,” and accelerate the development of high-performance, sustainable aluminum alloys, thereby contributing to a more efficient and circular materials economy [18]. The application of evolutionary algorithm in sustainable aluminum alloy design can be roughly divided into the following aspects:

1. Composition Optimization and Impurity Control:

Evolutionary algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II) excel in multi-objective optimization scenarios, especially in recycled aluminum alloy design where mechanical performance (e.g., tensile strength >300 MPa), electrical conductivity (≥50% IACS), and impurity thresholds (e.g., Fe content fluctuating between 0.3% and 1.2%) must be balanced [44].

(1) Coordinated optimization of Al-Si-Mg alloy composition: By using the NSGA-II algorithm to globally search the Mg/Si ratio, it is possible to suppress the precipitation of the brittle β-Al5FeSi phase while maximizing both conductivity and strength.

(2) Accurately predicting the phase stability of recycled aluminum alloys during solidification is achievable. Furthermore, by coupling evolutionary algorithms, such as genetic algorithms, with the CALPHAD thermodynamic model, the proportions of added chromium and manganese can be dynamically optimized. This process suppresses the formation of the detrimental β-AlFeSi phase, thereby enhancing the alloy’s mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [18].

2. Process Parameter Optimization:

Intelligent control of smelting processes: The particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm can dynamically adjust smelting temperature (650°C–750°C) and holding time, reducing energy consumption by 10%–15% and decreasing porosity defect rates by 12% [45].

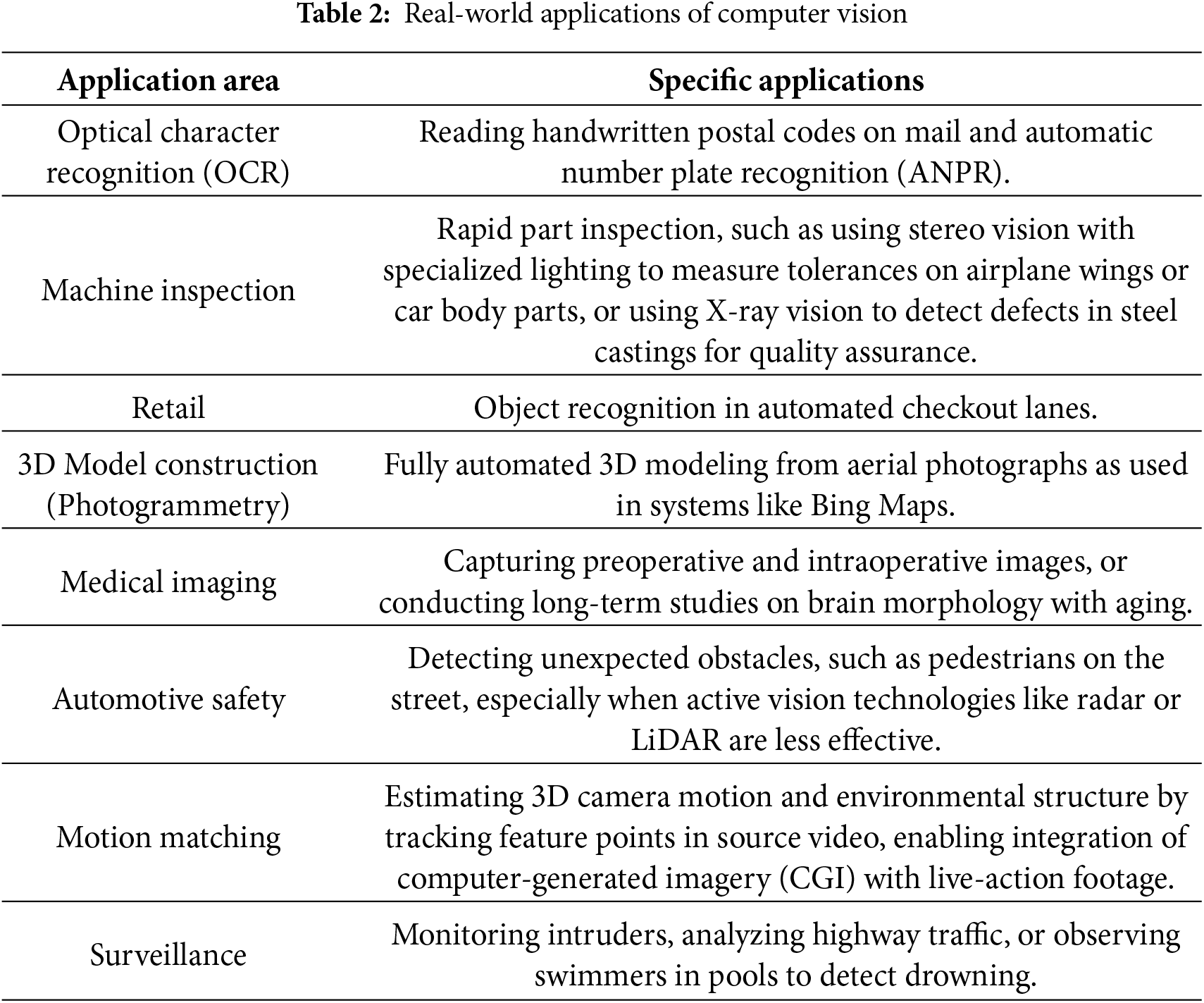

Computer vision technology is a branch of artificial intelligence that enables computers to automatically extract, analyze, and interpret information from digital images or videos using algorithms. This technology captures visual data through imaging devices (such as industrial cameras), then processes it through steps including preprocessing, feature extraction, and object recognition, ultimately converting pixel data into actionable semantic information [46]. It supports industrial intelligent applications such as quality inspection, positioning guidance, and process monitoring. At its core lies a full-chain intelligent system comprising “optical perception–feature analysis–decision control.” Typical applications can achieve micron-level precision and processing speeds exceeding 200 frames per second, making it a key enabling technology for intelligent manufacturing [47].

Computer vision is widely applied in real-world scenarios, including those listed in Table 2. This table highlights some key areas where computer vision is making significant contributions, such as in 3D model construction, medical imaging, automotive safety and so on.

2.3.1 Principles of Computer Vision Technology

1. Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

A. Image Acquisition: Visual data (such as surface images of scrap aluminum and thermal images of molten pools) are captured using industrial cameras, infrared sensors, laser scanners, and other devices [48].

B. Preprocessing: Includes denoising (e.g., Gaussian filtering), contrast enhancement (e.g., histogram equalization), and geometric correction (e.g., eliminating perspective distortion) to improve data quality [48].

2. Feature Extraction and Representation

A. Traditional Methods: Manually designed features (such as edge detection with the Canny operator and texture analysis with the LBP algorithm) are used in structured scenarios [49].

B. Deep Learning Methods: Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), such as VGG and ResNet, automatically learn multi-level features to address complex texture and shape recognition problems (e.g., scrap aluminum classification) [50].

3. Model Training and Inference

A. Supervised Learning: Models are trained on labeled data (e.g., defect images labeled as “crack” or “pore”) by optimizing loss functions such as cross-entropy.

B. Transfer Learning: Pretrained models (e.g., weights from ImageNet) are reused to address small-sample problems, such as the scarcity of defect data in recycled aluminum [51].

4. Postprocessing and Decision-Making

A. Object Localization: Object detection models (e.g., YOLO, Faster R-CNN) output bounding boxes and class labels [52].

B. Semantic Segmentation: Models like U-Net and Mask R-CNN segment microstructures within images (e.g., Al3(Mg, Sc) nanoprecipitates) [53].

C. Decision Output: Results are mapped into control commands (e.g., robotic arm actions for sorting, adjustments to melting parameters).

2.3.2 Application of Computer Vision Technology in the Design of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys

1. Scrap Aluminum Sorting and Classification

A. Primary challenge in recycled aluminum alloy design is the complexity of raw scrap and the diversity of impurities (e.g., Fe content fluctuations between 0.3% and 1.2%). Computer vision enables efficient sorting of aluminum from various sources (e.g., cast vs. wrought aluminum) through image classification and object detection, enhancing raw material purity before melting [54].

B. Deep Learning-Based Sorting Systems: Real-time sorting systems based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), such as Dense Convolutional Network (DenseNet), integrate RGB (Red, Green, Blue) and depth images to distinguish cast and wrought aluminum with up to 98% accuracy. For instance, cast parts (e.g., engine blocks) and wrought parts (e.g., body panels) from automotive scrap can be automatically classified based on surface texture and geometry, reducing manual labor costs.

C. 3D Point Cloud Analysis: Using stereo vision (e.g., Intel D435i cameras), 3D reconstruction and volume measurement of scrap piles can be conducted to optimize logistics and reduce storage costs.

2. Process Monitoring and Defect Detection

The melting and processing of recycled aluminum alloys involve multi-parameter control. Computer vision enables real-time monitoring and defect detection, improving process stability.

A. Melting Process Monitoring: Through the acquisition of image and video data via high-speed cameras, CV (Computer Vision) systems can leverage deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to perform real-time analysis of melt pool morphology, molten metal flow, and temperature distribution. This capability enables precise control over the production process, thereby predicting and preventing the occurrence of defects like porosity and inclusions. Furthermore, CV offers an efficient solution for post-processing product evaluation. By analyzing high-resolution images or integrating with X-ray imaging, CV models can automatically identify and classify surface defects such as cracks and scratches, as well as internal defects like pores and lack of fusion [55].

B. Automated Defect Detection: Deep learning-based systems (e.g., You Only Look Once (YOLO), Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN)) can detect surface cracks, pores, and other casting defects with over 95% accuracy, reducing missed detections in manual inspection. International Business Machines (IBM)’s Maximo Visual Inspection platform has been successfully deployed in industrial production lines for real-time aluminum sheet defect detection and automated repair triggering.

3. Microstructure Analysis and Performance Prediction

The properties of recycled aluminum alloys are strongly influenced by microstructures (e.g., second-phase particle distribution). Computer vision, combined with high-resolution imaging, enables quantitative microstructure analysis to guide alloy design [56].

(1) 3D Atom Probe and Image Processing: The team at Xi’an Jiaotong University used 3D atom probe tomography (APT) to characterize the distribution of Al3(Mg,Sc) nanoparticles. Image segmentation algorithms (e.g., U-Net(a convolutional neural network architecture for image segmentation)) extracted particle size and density data to optimize the microstructure for hydrogen embrittlement resistance.

(2) Cross-Scale Manufacturing Monitoring: Westlake University developed aluminum-based cross-scale 3D printing techniques. By integrating nanoimprint lithography with visual detection, precise multi-scale structuring was achieved, improving the functional performance of anodized aluminum (e.g., photoelectric conversion efficiency).

4. Intelligent Logistics and Lifecycle Management

Computer vision supports intelligent logistics and carbon footprint tracking across the supply chain and recycling stages of recycled aluminum alloys [57].

(1) Inventory and Traceability Management: Quick Response (QR) codes or Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags, combined with vision-based localization (e.g., PnP algorithm), are used to track batch information and processing history of recycled aluminum materials, ensuring compositional traceability.

(2) Carbon Emission Monitoring: Visual sensors integrated with IoT platforms monitor real-time energy consumption during melting, optimizing emission factors (e.g., 4 t CO2-equivalent savings per ton of recycled aluminum) to promote green manufacturing goals.

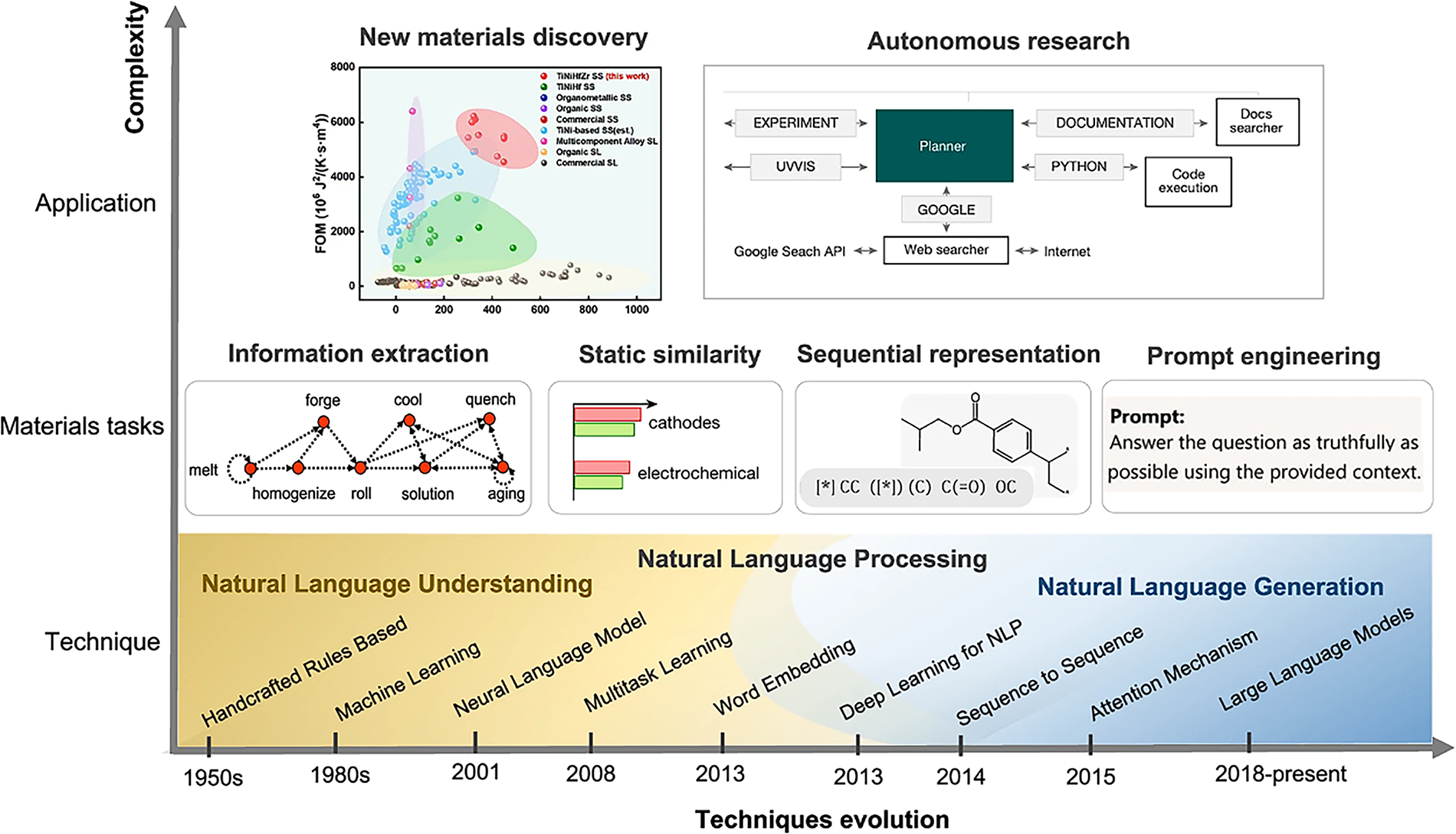

2.4 Natural Language Processing, NLP

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a core technology in the field of artificial intelligence. It establishes nonlinear mappings between linguistic symbols and semantic spaces through deep neural networks and leverages self-supervised learning to extract language patterns from massive amounts of text. Ultimately, it enables semantic understanding and knowledge reasoning in specific domains [58]. In simple terms, NLP can transform unstructured text into computable knowledge, thereby simplifying human-computer interaction and improving the efficiency of data-driven research and development [59]. The design of recycled aluminum alloys involves a vast amount of interdisciplinary knowledge—such as materials science, thermodynamics, and process parameter optimization—which is typically presented in unstructured formats across academic papers, patents, and experimental reports. Integrating this information using traditional methods would require extensive manual effort. In contrast, NLP allows for the efficient transformation and integration of unstructured text, effectively decoding the implicit process-performance relationships embedded in literature and accelerating the digitization of experiential knowledge. Fig. 5 shows how natural language processing technology can extract the phase-property relationship of aluminum alloys from literature [34].

Figure 5: Application of natural language processing in extraction of aluminum alloy properties from literature. Reprinted with permission from Reference [34]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature

2.4.1 Applications of NLP in Alloy Design and the Impact of Large Language Models (LLMs)

Natural language processing (NLP) has emerged as a powerful tool for extracting, structuring, and utilizing knowledge from the vast body of scientific literature and patents in materials science. In the context of alloy design, NLP-based pipelines such as ChemDataExtractor have been successfully applied to automatically identify alloy compositions, processing conditions, and property–performance relationships from unstructured text, enabling the construction of structured knowledge bases that support data-driven design [60]. Early studies have demonstrated the feasibility of applying text mining to aluminum and superalloy systems, despite challenges posed by the relatively small size and complex annotation requirements of alloy-related corpora [61]. Beyond information extraction, word embedding models have been shown to capture latent semantic relationships among alloying elements, processing strategies, and target properties, offering a pathway to identify candidate compositions and performance trends [62]. Fig. 6 summarizes the development and application of NLP in this field.

Figure 6: The development and application of NLP [60]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [60]. Copyright 2025, npj Computer Materials

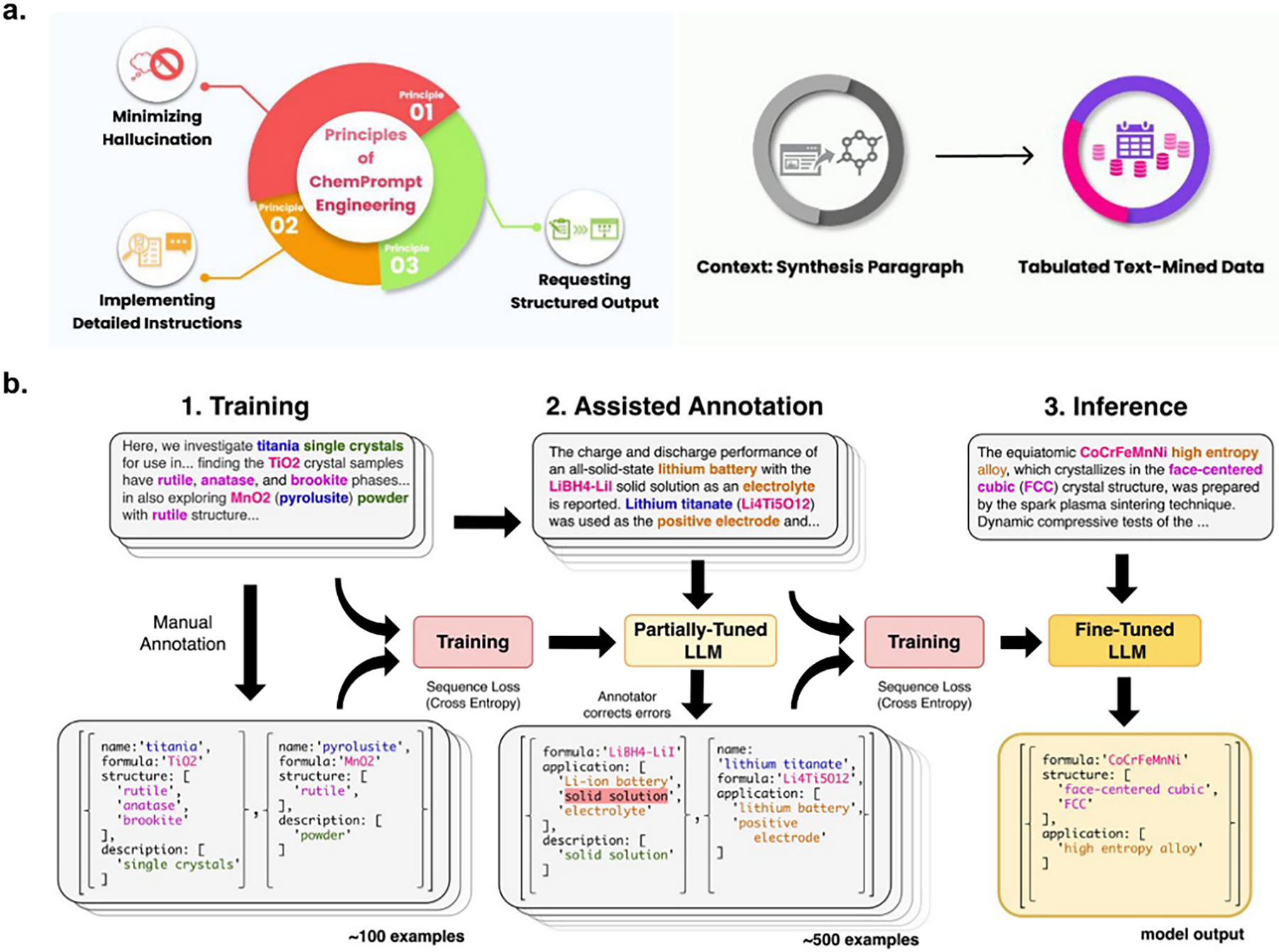

The recent introduction of large language models (LLMs) has significantly expanded the scope of NLP in alloy research. Through prompt engineering and domain-specific fine-tuning, LLMs can achieve high precision and recall in extracting synthesis parameters, property values, and experimental outcomes from heterogeneous sources. Moreover, specialized models such as MatSciBERT and SteelBERT illustrate how pretraining on domain-specific corpora enhances predictive accuracy for alloy properties under small data regimes. The integration of LLMs into multi-agent frameworks further enables autonomous workflows that combine literature retrieval, knowledge extraction, numerical simulation, and even robotic experimentation. While current limitations remain—particularly in numerical reasoning, quantitative prediction, and ensuring reproducibility—LLMs are expected to accelerate the discovery of sustainable alloy systems, including recycled aluminum alloys, by bridging unstructured text with data-driven and physics-based design strategies. Fig. 7 as shown below illustrates the procedure how information can be extracted by LLMs.

Figure 7: Information extraction by LLMs [60]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [60]. Copyright 2025, npj Computer Materials

2.4.2 Four Algorithms Based on Natural Language Processing and Their Comparison

Akshansh Mishra focused on the field of friction stir welding of aluminum alloys and applied natural language processing (NLP) algorithms to achieve automatic information extraction from scientific literature abstracts. By constructing a test corpus annotated by domain experts, the system integrated four classical summarization algorithms: Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), Luhn heuristic algorithm, LexRank (Lexical PageRank graph-based algorithm), and Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence optimization algorithm. In the evaluation phase, the ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) automatic evaluation framework was introduced, with quantitative assessments conducted from three dimensions: n-gram overlap rate (ROUGE-N), longest common subsequence (ROUGE-L), and skip-bigram with unigram (ROUGE-SU). Experimental results showed that the Luhn algorithm significantly outperformed others with an F1-score of 0.413, particularly achieving 0.512 and 0.467 in ROUGE-1 and ROUGE-L, respectively. This performance is closely related to its characteristics of frequency-based term weighting and positional heuristics. These results indicate that in technical domains such as welding processes, where terminology repetition is high, traditional heuristic approaches remain practically valuable, though they simultaneously reveal limitations in semantic understanding [63]. The four algorithms and their performance evaluations are as follows:

1. LexRank Algorithm

LexRank algorithm is an unsupervised graph-based method grounded in eigenvector centrality, primarily used for automatic text summarization. The algorithm represents and processes text through the following steps: First, it constructs a similarity matrix based on cosine similarity, which serves as the adjacency matrix of a graph structure, modeling the input sentences as nodes within this graph. At its core, the algorithm iteratively computes and identifies the central sentence, which holds the highest semantic representativeness within the entire text. Using this as the reference point, it then calculates the ranking weights of all sentences based on their similarity to the central sentence. During the similarity computation phase, the algorithm employs the Bag of Words (BoW) model for text vectorization, representing each sentence as a point in an N-dimensional vector space, where N denotes the dimensionality of a predefined vocabulary.

2. Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) Algorithm

Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), also known as Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI), is a semantic modeling method based on linear algebraic decomposition. The algorithm constructs a semantic space through the following process: it first converts raw text into a term-document matrix, and then applies Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to reduce the dimensionality of this high-dimensional matrix, thereby forming a latent semantic space. Within this space, the algorithm statistically analyzes word co-occurrence patterns, effectively capturing latent semantic associations among terms in the document. Additionally, through low-rank approximation via dimensionality reduction, LSA mitigates the interference caused by synonymy and polysemy in natural language expressions. Specifically, LSA mathematically optimizes vector representations of both terms and documents in the latent semantic space, such that semantically similar text units exhibit higher cosine similarity in the resulting geometric space.

3. Luhn Algorithm

The Luhn algorithm, as a pioneering method in the field of automatic text summarization, adopts a heuristic strategy based on word frequency statistics to filter document content. It implements key sentence extraction through a two-stage weighting mechanism: first, it constructs a word frequency distribution histogram and selects high-frequency keywords from the document based on a predefined statistical threshold. second, it introduces a positional weighting factor, assigning additional weight to words appearing in the opening segments of the text, thereby simulating the human cognitive preference for introductory information during reading. This quantitative evaluation approach, which fuses statistical and positional features, effectively identifies core thematic terms within the document. Subsequently, it extracts sentences containing these key terms to generate the summary content. It is worth noting that although the Luhn algorithm was innovative when proposed in the 1950s, its reliance solely on surface-level statistical features limits its capacity to handle complex semantic relationships.

4. KL-Algorithm

The Kullback-Leibler (KL) summarization algorithm is based on the Kullback-Leibler divergence (KL divergence) in information theory and operates within a greedy strategy framework. This algorithm generates summaries through an iterative optimization mechanism: starting with an empty summary set, it gradually selects sentences that minimize the divergence between the current summary and the original document’s probability distribution. Specifically, the algorithm dynamically evaluates the relative entropy (Kullback-Leibler divergence) between the word distributions of the candidate summary S and the original document D, denoted as D\_KL(P\_D||P\_S). The optimal summary combination is determined by solving the optimization problem S = argmin D\_KL(P\_D||P\_S), where L is the predefined summary length constraint parameter.

In terms of technical implementation, the word probability distribution model of document D is first constructed by converting the frequency of each word into a discrete probability estimate. Then, a greedy selection strategy is employed, where in each iteration, the sentence that leads to the greatest reduction in D\_KL is added to the summary set until the predefined summary length threshold L is reached. It is worth noting that while this algorithm has a solid theoretical basis in information theory, it may lead to summaries that lack logical coherence since it only considers word frequency distributions without accounting for semantic coherence. Table 3 presents the performance evaluation of four natural language processing algorithms, highlighting their effectiveness in the context of alloy design.

In the development of automatic text summarization systems, machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) technologies play a crucial role. The aforementioned study validated the application value of NLP technologies through algorithm comparison experiments: in the task of summarizing research literature on friction stir welding aluminum alloy joints, a successful system integration of four classical algorithms, including LexRank, Luhn, LSA, and others, was achieved. Experimental results show that the heuristic-based Luhn algorithm, with an F1 score of 0.413, significantly outperforms other graph model-based and latent semantic analysis-based algorithms. This could be attributed to the high term repetition rate and structured expression characteristics of the welding domain literature.

From a technological development perspective, the NLP field still faces challenges in terms of insufficient depth of semantic understanding. However, by continuously optimizing the fusion of language models and knowledge graphs, there is potential to construct intelligent summarization systems with contextual awareness in the future. This study further confirms that by utilizing text mining technologies for automated processing of vast research data, researchers can be liberated from information overload, effectively shortening the experimental design cycle by approximately 30%–45%. It is worth noting that while statistical methods perform well in handling structured texts, deep learning frameworks are still necessary when dealing with complex tasks such as cross-document concept associations.

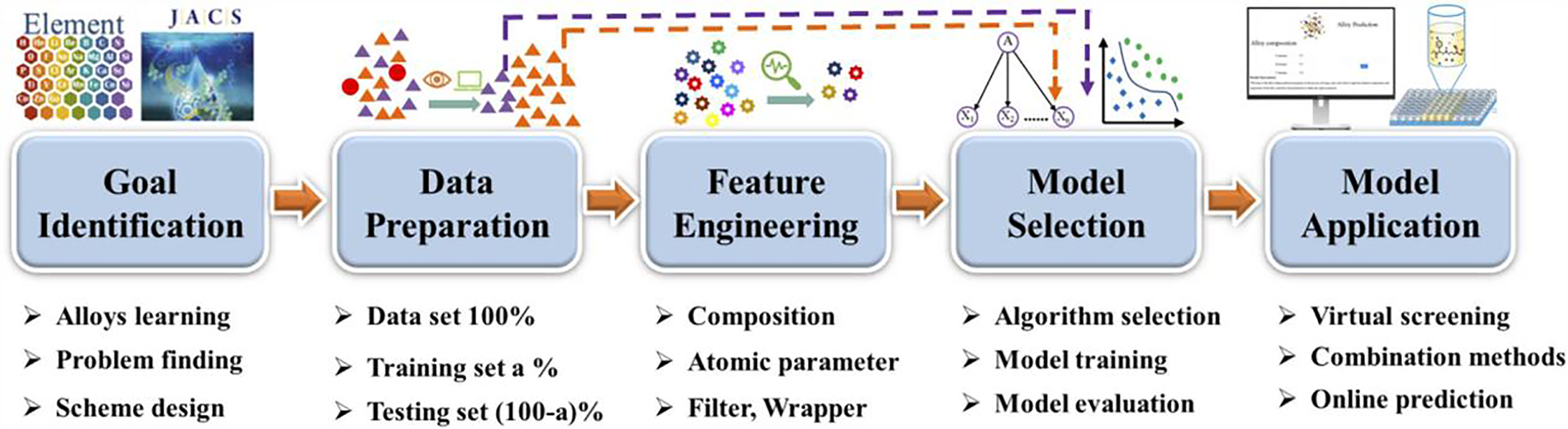

2.5.1 Machine Learning Process in Alloy Design

An effective method for designing high-performance alloys is highly sought after. Using first-principles calculations to predict alloy performance requires substantial time and effort. Machine learning (ML) can leverage given data to build models. The main objective of an ML model is to predict the target performance of candidate alloys that can be synthesized by experimentalists. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning in quantitatively predicting key properties of aluminum alloys. For instance, Jack et al. (2021) employed a gradient boosting tree (GBT) model trained on 1592 data points of Al–Cu–Mg alloys, achieving a coefficient of determination (R²) above 0.9 and MSE as 7.27 for hardness prediction [64]. Similarly, Li et al. (2025) used a random forest (RF) model to successfully predict the mechanical properties of recycled Al–Mg–Si alloys with varying rare earth (RE) additions (0–0.2 wt%). Their model identified the optimal addition as 0.10 wt% Sc, which was then experimentally validated. X-ray CT quantification of Fe-rich phases and microporosity confirmed a 4.37% improvement in tensile strength, validating the model’s prediction [65]. These results collectively highlight that AI-driven approaches are not only theoretically promising but also practically validated across diverse property domains.

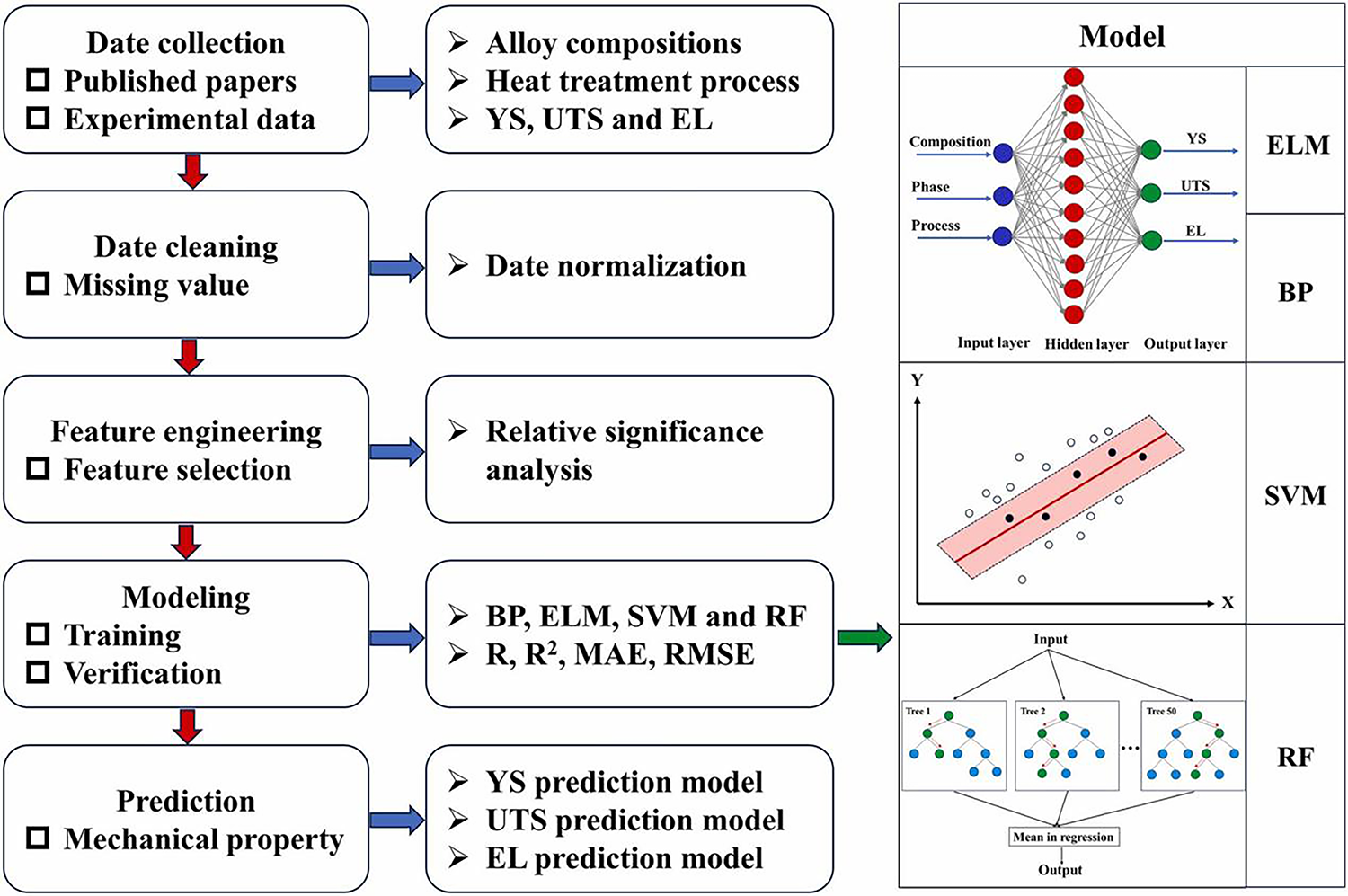

The ML workflow in alloy design is shown in Fig. 8, which includes goal identification, data preparation, feature engineering, model selection, and model application [66].

Figure 8: Machine learning workflow in alloys design. Reprinted with permission from Reference [66]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier

1. Goal Identification

The primary step of machine learning in materials development is to clearly define the target performance indicators (e.g., strength, corrosion resistance, etc.), which requires combining domain expert knowledge with practical application needs. Key requirements include: ① The target parameters should be learnable, capable of extracting meaningful features from existing experimental/simulation data; ② The parameter definitions must be clearly quantified (e.g., yield strength ≥ 800 MPa). Correctly setting the goals will directly impact the subsequent algorithm selection and model performance. For example, predicting the grain boundary diffusion coefficient requires time series modeling rather than conventional regression methods.

2. Data Preparation

Data construction in materials research using machine learning requires systematic integration of multi-source information and specialized processing methods. The research data mainly come from public databases (such as NIMS, Materials Project), academic literature, and proprietary experiments. These include input features such as alloy element composition, crystal structure parameters, and heat treatment processes, as well as target performance indicators like hardness and corrosion resistance. The quality of the data directly impacts the reliability of the model, and the data scale must be matched to the algorithm’s characteristics: deep neural networks typically require samples on the order of 104, while support vector machines (SVM) can build predictive models with a few hundred samples. It is also necessary to quantify the range of experimental errors (e.g., ±5% strain accuracy) and truncation energy thresholds for computational parameters.

To ensure data validity, raw information must undergo a standardized preprocessing procedure. This includes removing outliers beyond three standard deviations, converting unstructured literature data into Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) crystallography format, and performing z-score normalization on multi-dimensional parameters. Especially for data integrated across different databases, missing values should be repaired using the Monte Carlo imputation method, and the uniformity of test methods should be verified in accordance with standards such as American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). After this processing, the material dataset can reliably support multi-level machine learning modeling, from composition optimization to performance prediction.

3. Feature Engineering

The key to building high-performance material machine learning models lies in the optimization of feature engineering. Effective alloy features must meet three major criteria: specificity (e.g., accurately characterizing the local atomic environment), sensitivity (significantly correlated with target performance), and accessibility (easily obtainable through computation or experiments). Feature selection involves selecting the optimal subset of features through supervised and unsupervised methods. For instance, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression can automatically eliminate redundant parameters, while principal component analysis (PCA) can reduce dimensionality while retaining key information. Studies have shown that reasonable feature selection can reduce model complexity by 40%–60% and improve prediction accuracy by over 15%. In titanium alloy fatigue life prediction, the use of recursive feature elimination reduced the 128-dimensional features to 18 dimensions, which not only lowered the mean squared error of the random forest model by 22%, but also reduced training time by 73%, significantly improving model efficiency and interpretability.

4. Model Selection

When constructing machine learning models, the key lies in balancing model complexity to avoid overfitting and underfitting issues. Overfitting occurs when a model excessively adapts to the details of the training data (e.g., noise or outliers), leading to a decline in its ability to predict new data. On the other hand, underfitting arises when a model is too simple to capture the underlying patterns in the data. For example, in alloy performance prediction, when dealing with small-scale datasets (sample size <500), support vector machines (SVM) typically show better generalization ability through kernel function mapping and structural risk minimization strategies. Experiments have shown that when predicting the creep strength of nickel-based superalloys, the mean squared error of SVM is 40% lower than that of neural networks, especially when the feature dimension exceeds 50, where the advantage is more pronounced.

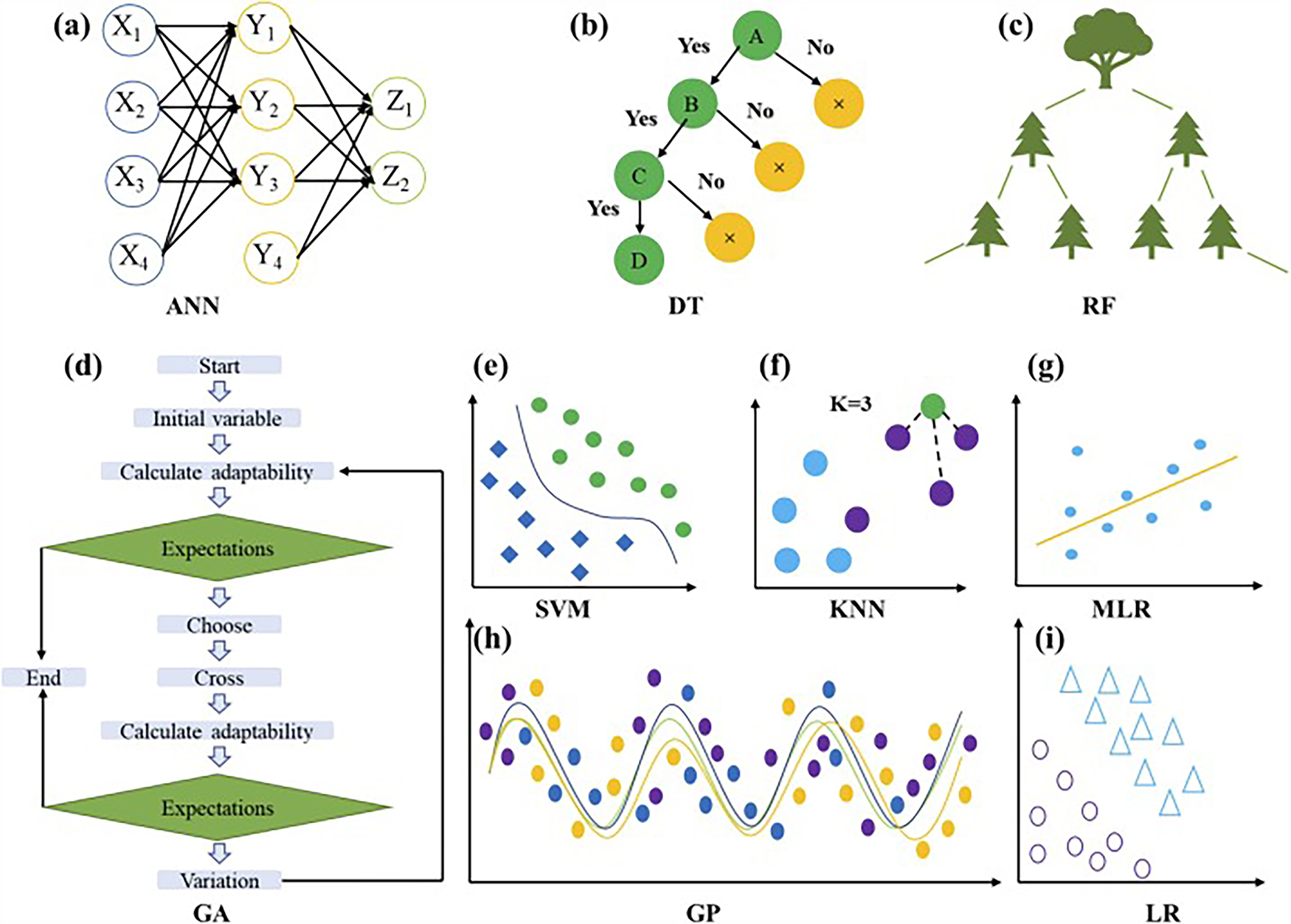

Algorithm selection must closely align with data characteristics: supervised learning (e.g., random forests) is suitable for scenarios with complete labels (such as alloy composition datasets with known yield strength) and builds predictive relationships through feature-label mapping; unsupervised methods (e.g., t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) clustering) can reveal latent structural patterns in unlabeled data (such as alloy phase composition pattern recognition); semi-supervised learning effectively utilizes a small amount of labeled data with a large number of unlabeled samples (typically in a 1:9 ratio). In the fatigue life prediction task for titanium alloys, this method can improve model accuracy by 25%. Common machine learning algorithms are shown in Fig. 9. Neural networks exhibit strong representational capability when handling massive datasets (sample size >104), while gradient boosting trees (e.g., Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)) often achieve optimal performance in medium-sized datasets (on the order of 103). It is noteworthy that ensemble learning methods, by combining multiple base models (e.g., Stacking strategy), improve prediction stability by about 30% compared to single models in complex alloy system multi-objective optimization problems.

Figure 9: Schematic diagrams of the common machine learning algorithms in designing alloys. ANN: Artificial neural networks. DT: Decision tree. RF: Random forests. GA: Genetic algorithm. SVM: Support vector machine. KNN: K-nearest neighbor regression. MLR: Multiple logistic regression. GP: Gaussian process regression. LR: Linear regression. Reprinted with permission from Reference [66]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier

5. Model Application

Model application refers to how to fully utilize the model to discover candidate alloys and provide theoretical guidance to experimenters. One method of applying machine learning models is high-throughput screening. First, potential virtual samples are designed within the original sample space. Then, machine learning models are used to predict the properties of these virtual samples. Finally, the selected samples are further used for experimental synthesis and characterization to discover new alloys with exceptional performance. In addition, machine learning models can be shared on network servers, facilitating more convenient model application through online predictions.

2.5.2 Application of Machine Learning in Aluminum Alloy Design

The machine learning research on aluminum alloys has penetrated into the entire material lifecycle management.

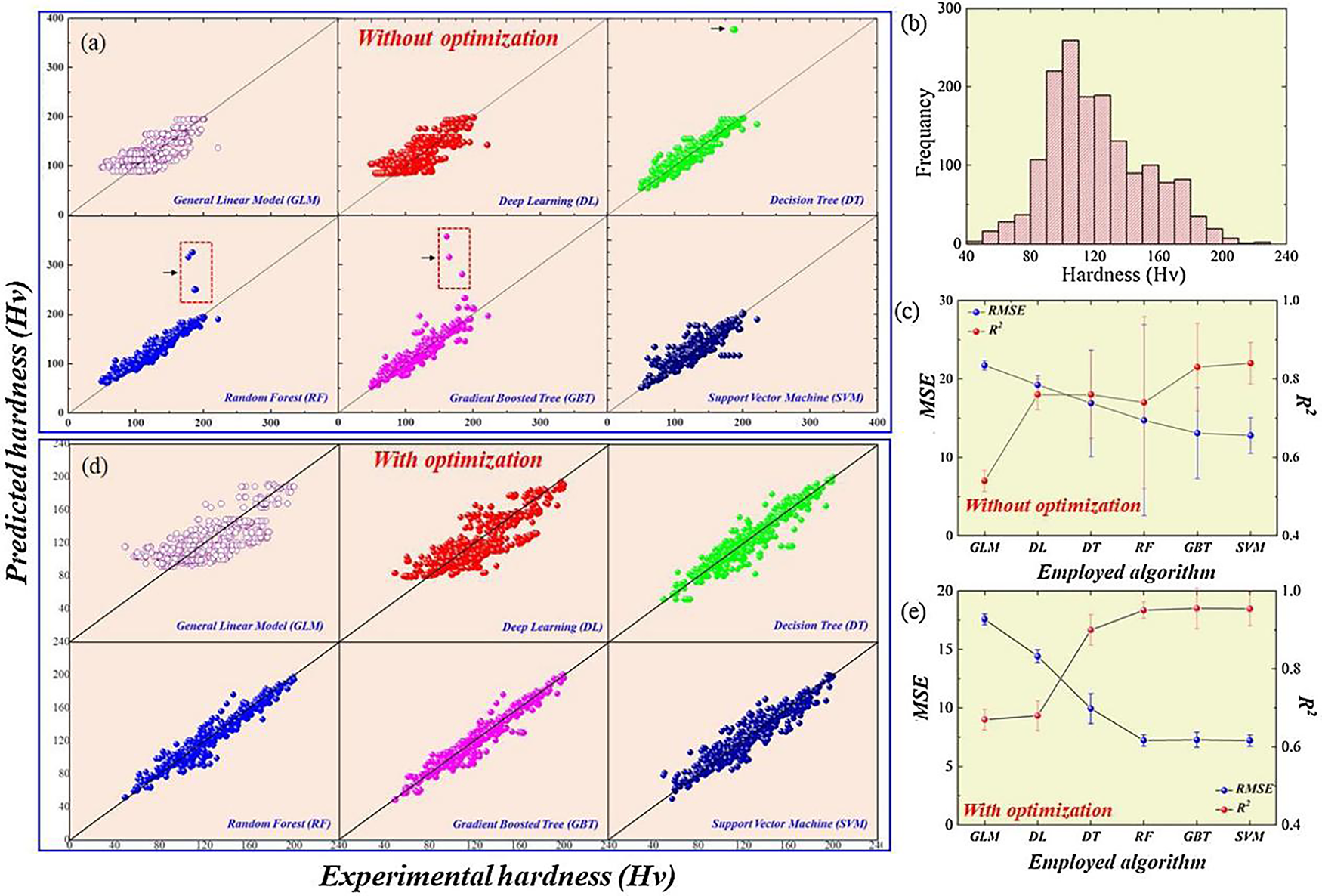

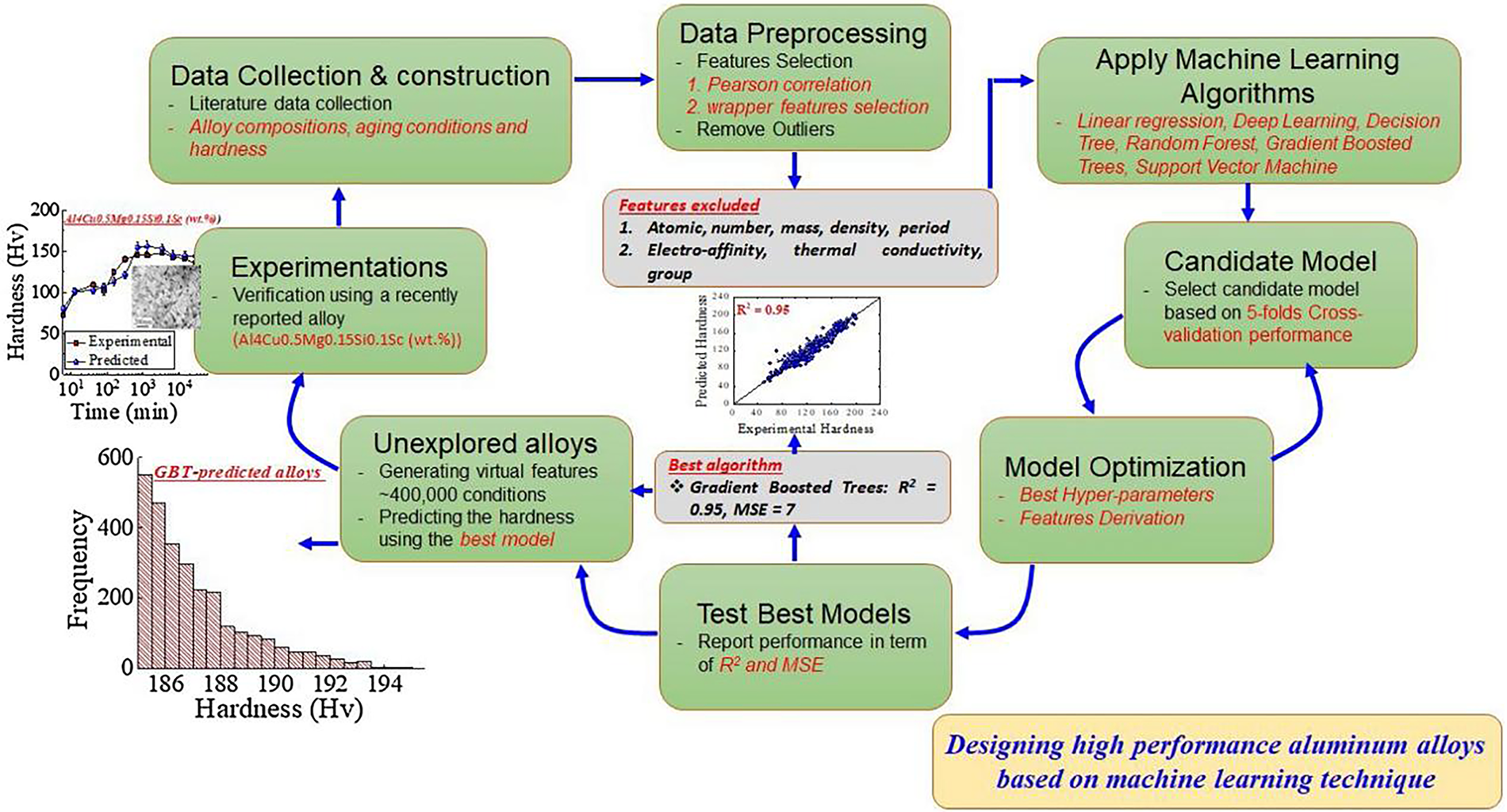

A research team in South Korea developed a hardness prediction model for aluminum alloys using the Gradient Boosting Tree (GBT) algorithm, enabling intelligent co-optimization of alloy composition and aging processes. The study integrated 1592 historical datasets encompassing 15 key features, including multi-component Al–Cu–Mg alloy compositions, aging temperatures and durations. Notably, the model innovatively incorporated physicochemical parameters of elements—such as electronegativity and atomic radius—as weighted input features. By quantitatively mapping the complex relationships among composition, processing, and performance, the model effectively circumvented the high-cost trial-and-error approach of conventional methods, significantly reducing the development cycle for new materials. Fig. 10 shows the comparison between experimental hardness and predicted hardness of each model in the test data set and the comparison before and after optimization [35]. Fig. 11 shows the high performance aluminum copper magnesium alloy design process based on machine learning technology [35].

Figure 10: (a,c) and (d,e) Experimental vs. predicted hardness of various models of the testing data set and the related R2 and MSE recorded for the employed algorithms without optimization and with optimization, respectively, (b) Hardness distribution profile for the input dataset. Reprinted with permission from Reference [35]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier

Figure 11: The loop used for designing high performance Al-Cu-Mg alloys based on the machine learning technique. Reprinted with permission from Reference [35]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier

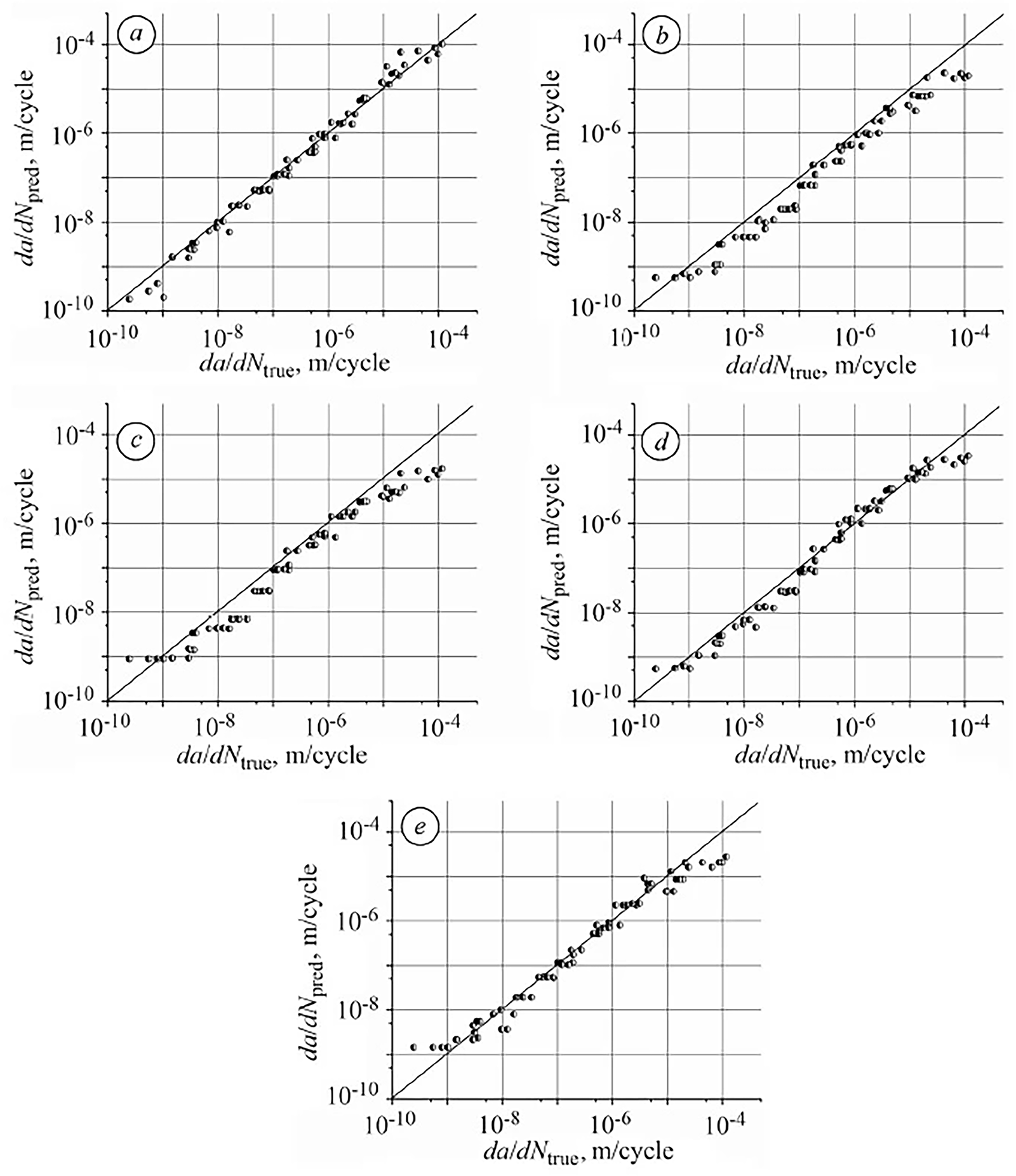

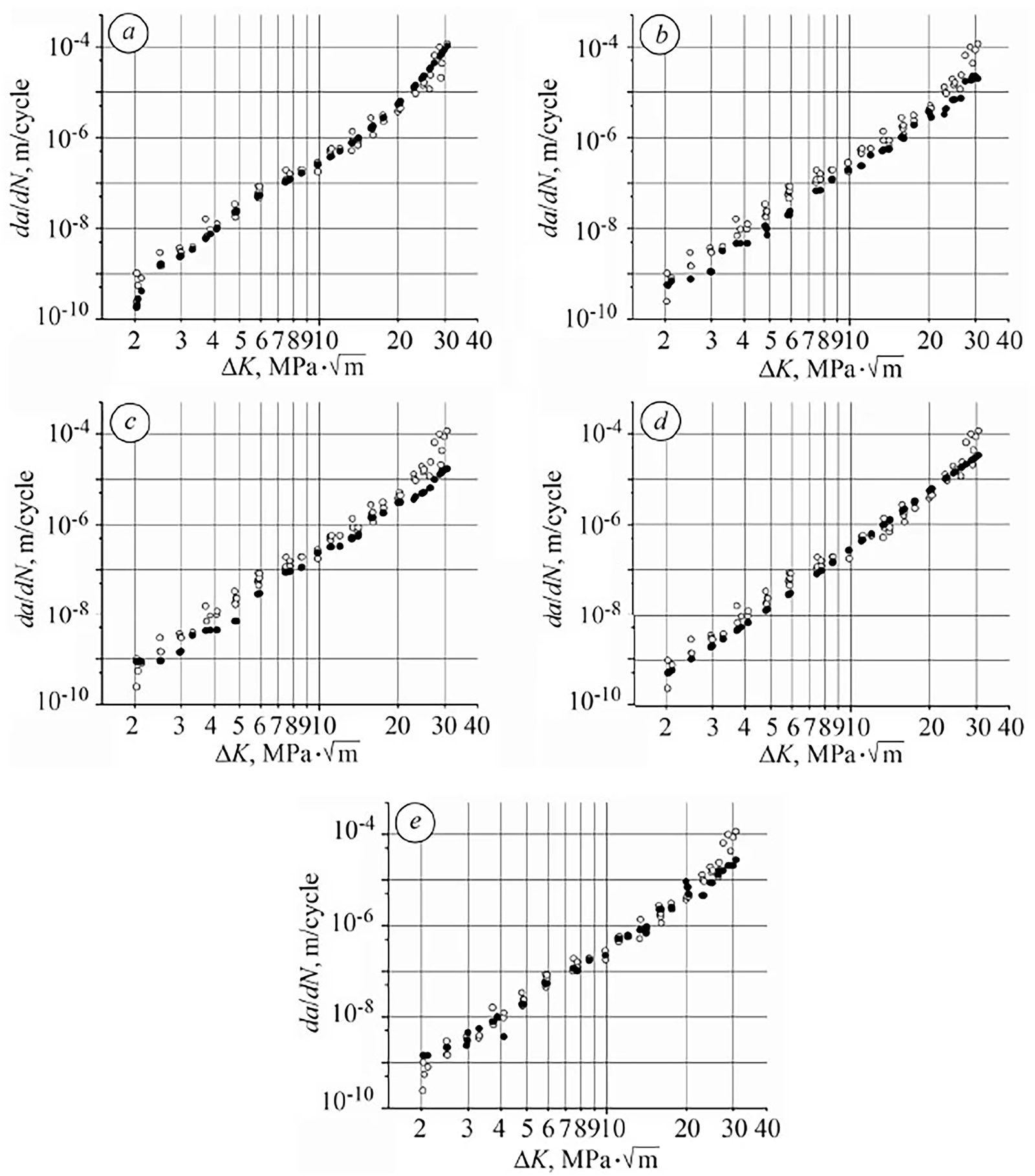

For mechanical property prediction, Yasnii successfully developed a fatigue crack propagation model using deep learning, achieving a test set error of 2.5%. This model effectively captured the nonlinear effect of load ratio on the crack propagation rate of 2024-T3 aluminum alloy. Figs. 12 and 13 compare the predictions and experimental results obtained from various methods: (a) neural networks, (b) boosted trees, (c) random forests, (d) support vector machines, and (e) k-nearest neighbors [67].

Figure 12: Predicted (da/dNpred) and experimental FCG rates (da/dNtrue) obtained for R = 0.4 by the methods of neural networks (a), boosted trees (b), random forests (c), support-vector machines (d), and k-nearest neighbors (e). Reprinted with permission from Reference [67]. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature

Figure 13: Predicted (·) and experimental (ο) dependences of the FCG rate on the SIF for R = 0.4 obtained by the methods of neural networks (a), boosted trees (b), random forests (c), support-vector machines (d), and k-nearest neighbors (e). Reprinted with permission from Reference [67]. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature

These advances indicate that machine learning is driving a paradigm shift in aluminum alloy research toward digitalization: from elucidating corrosion inhibition mechanisms at the molecular scale to multi-objective optimization of macroscopic properties, forming intelligent solutions that span the entire material development chain. With the improvement of cross-institutional data platforms and the integration of physics-informed models, machine learning is expected to achieve greater breakthroughs in the design of complex alloy systems.

2.5.3 The Application of Machine Learning in Impurity Control and Performance Optimization of Recycled Aluminum Alloys

Moreover, as a powerful data-driven approach, machine learning has demonstrated significant potential in addressing the challenges posed by high and unstable impurity levels (e.g., Fe, Si) in recycled aluminum alloys, aiming to minimize the formation of detrimental phases (such as β-Al5FeSi) while simultaneously optimizing mechanical properties. For instance, in a recent study by Li et al., multiple machine learning models were employed to provide concrete strategies for mitigating common iron (Fe) impurities in recycled aluminum alloys [65].

In this study, alloy composition, secondary phase fraction, and heat treatment parameters were selected as input features for the machine learning models to predict the strength and elongation of recycled aluminum alloys. By comparing the performance of four models—backpropagation neural network (BPNN), extreme learning machine (ELM), support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF)—the results revealed that the RF model achieved the highest accuracy in predicting both strength and elongation. The successful establishment of the model demonstrates that machine learning can effectively capture the complex nonlinear relationships among alloy composition, microstructure, and macroscopic properties. Some schematics of machine learning models are listed below in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: Schematics of machine learning models. Reprinted with permission from Reference [65]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier

This study successfully demonstrates the use of machine learning, specifically a Random Forest (RF) model, to guide the design of recycled aluminum alloys. By predicting the effects of various elements and phases, the model identified that adding 0.1 wt% Scandium (Sc) is the optimal solution to mitigate detrimental iron (Fe)-rich intermetallics. This data-driven approach led to a significant improvement in mechanical properties: a 4.37% increase in ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and a 27.12% improvement in elongation, showcasing the power of AI in materials design.

Furthermore, a team led by Lei Jiang has proposed an interpretable machine learning-based design strategy. By utilizing the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) algorithm, they revealed explicit relationships influencing the properties of aluminum alloys, leading to the identification of Ti, Cr, and Zr as micro-alloying elements capable of simultaneously enhancing ultimate tensile strength (UTS), fracture toughness (KIC), and stress corrosion resistance (ISSRT). Based on the optimization results, a new aluminum alloy with the composition Al-10.50Zn-2.31Mg-1.56Cu-0.09Ti-0.15Cr-0.10Zr was designed and fabricated. Experimental results show that, after RRA treatment, the alloy exhibited a UST of 760 ± 4 MPa, a KIC of 34.9 ± 0.3 MPa·m1/2, and an ISSRT of 13.3% ± 1.7%. Compared to the commercial AA7136 alloy, this new alloy demonstrated a 17%–27% increase in tensile strength, a 30%–45% improvement in fracture toughness, and over a 33% reduction in stress corrosion sensitivity. This achievement powerfully demonstrates the significant role of machine learning algorithms in the design of aluminum alloys and the optimization of multiple performance objectives [68].

2.5.4 Data Requirements for Reliable AI Predictions

AI-based predictions in alloy design rely heavily on the availability of high-quality datasets. While there is no universal threshold for dataset size, empirical evidence suggests that models trained on only a few hundred data points often fail to generalize, particularly for complex tasks such as predicting mechanical strength or electrical conductivity of multicomponent alloys. In contrast, datasets on the order of several thousand to tens of thousands of entries tend to provide more reliable and stable predictions. For example, machine learning studies on steels and Al–Mg–Si alloys report improved accuracy once the dataset exceeds ~1000–2000 labeled samples, with further gains as the data size approaches ~10,000 entries [69].

However, in practice, especially for recycled aluminum alloys, such large and clean datasets are rarely available. To overcome this limitation, several strategies can be adopted:

A. Transfer learning and domain-specific pretraining: models pretrained on large materials databases (e.g., MatWeb, Materials Project) can be fine-tuned on smaller alloy-specific datasets.

B. Physics-informed machine learning: embedding thermodynamic or process-based constraints (e.g., CALPHAD calculations, phase diagrams) into the learning framework reduces the risk of non-physical predictions.

C. Data augmentation and weak supervision: leveraging text mining (via NLP) to extract composition–property pairs from literature and patents can expand the dataset without expensive new experiments.

4. Active learning and Bayesian optimization: iterative model-guided data acquisition focuses experimental efforts on the most informative regions of the design space, thereby maximizing predictive accuracy with limited data.

These approaches indicate that reliable AI-assisted alloy predictions do not depend solely on the absolute dataset size, but also on how effectively prior knowledge, transfer learning, and active sampling are incorporated into the modeling process.

2.6 Summary of the Application of Artificial Intelligence Technology in the Design of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys

To better illustrate the contributions of these algorithms to recycled aluminum alloy desisgn, we have provided the Table 4, which systematically outlines their key features, advantages, and limitations across various application scenarios. This table is intended to serve as a quick guide for readers, offering a comparative analysis of different AI algorithms’ capabilities in areas such as composition optimization, property prediction, process control, and defect detection. This overview can assist researchers and engineers in making informed decisions when selecting the most effective computational tools to address the complex challenges inherent in recycled aluminum alloy design.

3 Potential Challenges in AI-Driven Design of Sustainable Aluminum Alloys and Corresponding Optimization Strategies

In the field of AI-driven recycled aluminum alloy design, several critical bottlenecks remain to be overcome. Foremost among these are dual challenges at the data level. On one hand, the production process of recycled aluminum generates heterogeneous data streams (e.g., melting parameters, microstructures, mechanical properties), which are highly fragmented. For example, analysis of an enterprise database revealed that approximately 60% of process parameters lacked time-stamp associations, resulting in temporal modeling errors as high as 32% [70]. On the other hand, the development of new alloys faces a small-sample dilemma—typical Al-Mg-Si recycled alloy datasets contain fewer than 300 valid process–property pairs, severely limiting the generalization ability of machine learning models [71]. To address this, researchers have proposed a multimodal data fusion framework. By employing transfer learning, models are pre-trained on aerospace aluminum datasets (e.g., AA7075), and paired with active learning strategies that prioritize high-value data points with information entropy greater than 2.5, annotation costs can be reduced by over 50% [72]. Simultaneously, the integration of physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) helps bridge the gap between data and underlying mechanisms. By embedding nine physics constraints (e.g., dislocation density evolution equations) into the loss function, prediction error under small-sample conditions was reduced from ±18% to ±7.5% [73].

At the algorithm design level, challenges in coupling multi-objective optimization with cross-scale modeling are particularly prominent. Traditional Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III (NSGA-III) algorithms, when applied to optimize trade-offs among strength, conductivity, and cost, yield approximately 17% of solutions that violate thermodynamic phase rules and are thus infeasible [74]. To resolve this, a mechanism-constrained optimization framework was developed. It incorporates physical boundaries (e.g., Fe/Si ratio of 1.2–1.8, eutectic temperature range of 582°C–615°C) as hard constraints, and uses a regret-based screening mechanism to eliminate low-feasibility solutions (satisfaction rate < 85%), increasing the proportion of engineering-feasible solutions to 93%. For cross-scale modeling, the long-standing error in linking microstructural features (e.g., β-AlFeSi phase distribution) to macroscopic mechanical properties has been significantly reduced by employing graph neural networks (GNNs). These models map grain boundary topology to macroscopic responses using end-to-end learning. The use of non-local attention mechanisms to capture long-range dislocation interactions further reduced grain size prediction error to ±3.1 μm—a 68% improvement over traditional methods.

At the engineering deployment stage, a lack of interpretability in black-box models and delays in real-time control remain major barriers. Industry surveys indicate that 86% of process prediction results are difficult to act upon due to the absence of physical explanations [75]. To address this, a SHAP-gradient joint interpretability framework has been proposed, capable of quantifying the marginal effect of laser power on porosity (e.g., ΔP = 100 W → porosity reduction of 0.7%). Additionally, a knowledge graph is used to decode hidden features into actionable rules (e.g., melt flow rate > 1.2 m/s suppresses pore formation). Regarding real-time performance, current online quality prediction systems exhibit latency of ~300 ms, insufficient for high-speed continuous casting lines (>2 m/min). By using a TensorRT-optimized MobileNetV3 model within an edge computing architecture, inference speed has been raised to 67 FPS. Coupled with a cascaded prediction mechanism (coarse-grained model trigger + fine-grained model refinement), this setup reduces response latency to just 40 ms while maintaining 95% detection accuracy [76].

Future breakthroughs are expected to focus on multidisciplinary innovation. Digital twin systems—driven by hybrid mechanistic–data models—enable pre-optimization of virtual smelting, reducing process iteration by 70%. Low-carbon-aware learning frameworks embed lifecycle assessment indicators into the loss function, successfully reducing the carbon footprint of recycled aluminum to 1.6 kg CO2/kg Al. Meanwhile, federated learning with differential privacy (ε = 0.8) enables secure cross-company data pooling, improving model performance by 41% after deployment. Empirical studies demonstrate that an intelligently optimized design system can shorten new alloy development cycles to one-fifth of traditional approaches, increase material utilization by 28%, and mark the formal entry of recycled aluminum alloy design into a new era of intelligent innovation.

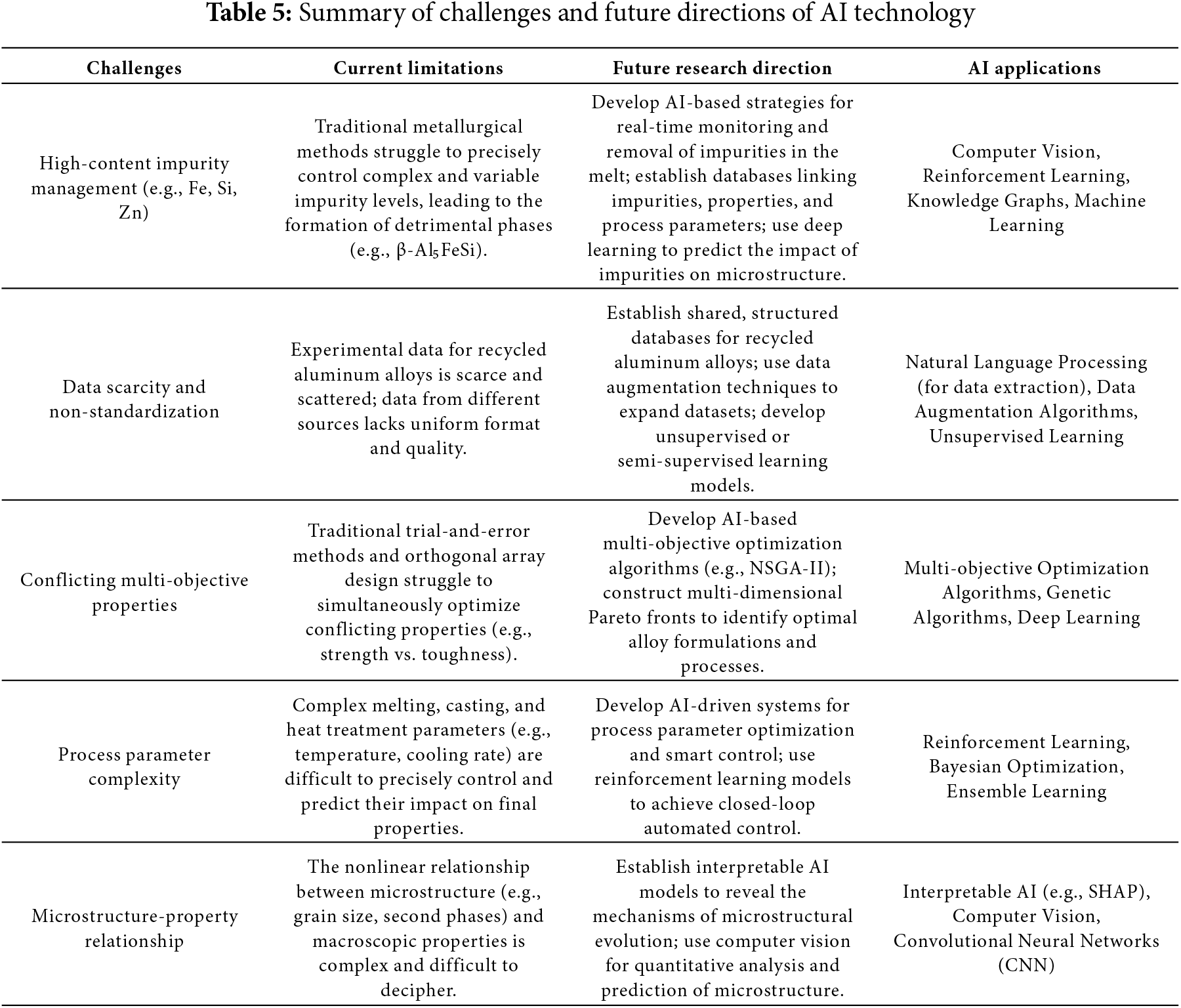

Table 5 summarizes the challenges and future directions of AI technology, highlighting key obstacles and potential solutions for advancing its application in material design.

From the perspective of technological integration and innovation, breakthroughs in multimodal learning will lead to the construction of a cross-domain knowledge transfer framework. By pretraining vision-language joint models (such as Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLP) variants), a semantic alignment between metallographic image features and process documentation can be achieved (cosine similarity >0.75), enabling the system to automatically identify latent associations like “feather-like β phase → Mn/Si ratio imbalance.” Digital twin technologies will deeply couple mechanistic models with data-driven methods; for instance, by embedding Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) networks into melt flow simulations and introducing the Navier–Stokes equations as physical constraints, the dynamic prediction error of the virtual melt pool can be reduced from 12% to 4%. Advanced applications of federated learning will form industry-level collaborative design platforms, employing differential privacy (ε = 0.6) and homomorphic encryption to securely share data across enterprises. After heterogeneous model aggregation, the development cycle of new materials can be shortened to 45 days.

In addition, next-generation algorithms will overcome the limitations of single-objective optimization and evolve into multi-criteria decision-making systems under carbon-neutral constraints. A dynamic optimization framework based on deep reinforcement learning can adjust smelting parameters in real time to respond to electricity price fluctuations, reducing the unit energy consumption of recycled aluminum production by 18%. The topological learning capabilities of graph neural networks (GNNs) will be enhanced to establish a three-dimensional hypergraph structure linking grain boundary networks, process parameters, and performance indicators, achieving cross-scale modeling of microstructural evolution (accuracy ±1.5 μm). In terms of interpretable AI, causal inference-based process attribution models will be developed. Counterfactual analysis can quantify the impact weight of impurity elements (e.g., a 0.1 wt.% increase in Fe content leads to a 9% reduction in fatigue life), providing operable quantitative guidance for process optimization [36].

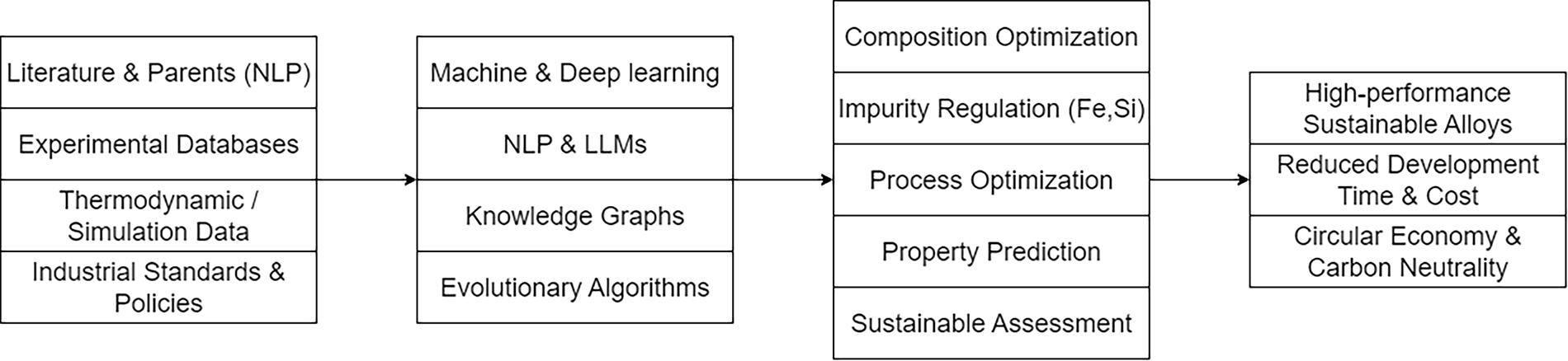

Artificial intelligence will become a core driver for the low-carbon transformation of recycled aluminum. Through reinforcement learning constrained by life cycle assessment (LCA), the alloy compositional space that minimizes CO2 emissions can be explored, reducing emissions from 2.1 kg CO2/kg Al (in traditional processes) to 1.4 kg. Intelligent optimization of emerging processes such as microwave smelting will significantly improve energy efficiency, with AI-driven electromagnetic field control increasing energy utilization to 92% (compared to the current 78%). The establishment of an urban mine big data platform will enable dynamic global scheduling of scrap aluminum resources. Spatiotemporal prediction models can optimize the layout of regional smelting centers, reducing transport-related carbon emissions by 34% [37,38]. Fig. 15 shows the framework for AI applications in sustainable aluminum alloy design.

Figure 15: Framework for AI applications in sustainable aluminum alloy design

Artificial intelligence has fundamentally transformed sustainable aluminum alloy design, shifting the paradigm from experience-driven to data-driven approaches and enabling more efficient and precise materials development.

Main Advantages: AI significantly enhances the efficiency of alloy design and the accuracy of performance prediction by leveraging large datasets and advanced learning algorithms. Techniques such as machine learning and predictive modeling allow rapid screening of compositions and optimization of processing parameters, thereby reducing experimental costs and accelerating the development cycle.

Current Challenges: Despite these advancements, several obstacles remain. Data quality and availability are often insufficient, cross-scale modeling—from atomistic simulations to macroscopic performance—is highly complex, and coordination across the industrial chain is still limited. These factors hinder the full exploitation of AI’s potential in recycled aluminum alloy design.

Future Goals: Looking ahead, the integration of generative AI with autonomous experimental platforms is expected to accelerate the discovery of novel alloy compositions. Multimodal data fusion and blockchain technologies can improve transparency in full life-cycle management. Technically, embedding physical models into AI frameworks and deploying edge intelligence applications are critical directions. At the industrial level, establishing standardized data ecosystems and fostering collaboration among academia, industry, and research institutions will be essential. Together, these efforts will drive the recycled aluminum industry toward high-efficiency, low-carbon, and intelligent sustainable development, contributing to global green manufacturing objectives.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (25ZR1401430), and Science and Technology Cooperation Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region-Action Plan of Shanghai Jiao Tong University for “Revitalizing Inner Mongolia through Science and Technology” (2023XYJG0001-01-01).

Author Contributions: The corresponding author conceived and supervised the study. The first author Zhijie Lin performed the data collection, analysis, interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. The corresponding author Chao Yang provided guidance, manuscript revision, and project management including funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: There are no new data or materials for this review.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Das S, Yin W. Trends in the global aluminum fabrication industry. JOM. 2007;59(2):83–7. doi:10.1007/s11837-007-0027-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ashkenazi D. How aluminum changed the world: a metallurgical revolution through technological and cultural perspectives. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2019;143:101–13. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gautam M, Pandey B, Agrawal M. Carbon footprint of aluminum production. In: Environmental carbon footprints. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2018. p. 197–228. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-812849-7.00008-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Eheliyagoda D, Li J, Geng Y, Zeng X. The role of China’s aluminum recycling on sustainable resource and emission pathways. Resour Policy. 2022;76:102552. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Menzie W, Barry J, Bleiwas D, Bray E, Goonan T, Matos G. The global flow of aluminum from 2006 through 2025. Reston, VA, USA: US Geological Survey; 2010. [Google Scholar]

6. Green JA. Aluminum recycling and processing for energy conservation and sustainability. Materials Park, OH, USA: ASM International; 2007. [Google Scholar]