Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Review of Metaheuristic Optimization Techniques for Enhancing E-Health Applications

1 Chongqing Intelligence Perception and Block Chain Technology Key Laboratory, The Department of Artificial Intelligent, National Research Base of Intelligent Manufacturing Service, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, 400067, China

2 Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, 999078, China

* Corresponding Authors: Huafeng Qin. Email: ; Simon Fong. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-49. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070918

Received 28 July 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Metaheuristic algorithms, renowned for strong global search capabilities, are effective tools for solving complex optimization problems and show substantial potential in e-Health applications. This review provides a systematic overview of recent advancements in metaheuristic algorithms and highlights their applications in e-Health. We selected representative algorithms published between 2019 and 2024, and quantified their influence using an entropy-weighted method based on journal impact factors and citation counts. CThe Harris Hawks Optimizer (HHO) demonstrated the highest early citation impact. The study also examined applications in disease prediction models, clinical decision support, and intelligent health monitoring. Notably, the Chaotic Salp Swarm Algorithm (CSSA) achieved 99.69% accuracy in detecting Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. Future research should progress in three directions: improving theoretical reliability and performance predictability in medical contexts; designing more adaptive and deployable mechanisms for real-world systems; and integrating ethical, privacy, and technological considerations to enable precision medicine, digital twins, and intelligent medical devices.Keywords

Complex optimization problems, prevalent across numerous scientific and industrial domains, often prove challenging for traditional optimization methods. Metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as effective tools to address these complexities. They employ strategies that combine randomization with local search to explore large solution spaces and identify near-optimal solutions. These algorithms fall into two main categories: population-based approaches, which evolve multiple solutions simultaneously, and single-solution-based approaches, which refine one candidate solution iteratively. A classic example of the latter is simulated annealing, which iteratively explores neighboring solutions based on a probabilistic acceptance criterion analogous to thermodynamic annealing [1].

The inspiration for many early metaheuristic algorithms came from observing natural phenomena. For instance, genetic algorithms emulate biological evolution and inheritance [2]. Ant colony optimization and particle swarm optimization instead draw upon collective intelligence in insect colonies and animal swarms [3,4]. As the field matured, research expanded beyond direct natural mimicry. It advanced toward hybrid algorithms that combine multiple methods and theoretical studies on convergence and complexity. This progression has been driven by the need to tackle increasingly intricate real-world challenges, leading to notable successes in areas such as cancer data classification and green pharmaceutical supply chain optimization [5,6].

In parallel, the landscape of healthcare delivery has been significantly transformed by e-Health, which leverages information and communication technologies (ICT) to enhance health services and systems [7]. E-Health encompasses a wide range of applications, including remote disease diagnosis, digital health management tools, and electronic medical records. These aim to improve the quality, accessibility, and convenience of care [7]. The rise of online medical services has notably increased the timeliness and efficiency of healthcare delivery, addressing demands for cross-regional medical consultations and alleviating the strain on traditional offline facilities [8]. Platforms like internet hospitals have proven crucial during public health emergencies. They facilitate remote consultations, reduce cross-infection risks, and provide the public with self-protection information [9]. Despite these advancements, e-Health systems face significant operational challenges, particularly in allocating and utilizing critical medical resources during health crises. Moreover, complex predictive tasks within e-Health, such as forecasting infant health outcomes using machine learning techniques [10], represent areas where advanced optimization could provide substantial benefits.

Recognizing the complex optimization and prediction challenges inherent in modern healthcare systems, metaheuristic algorithms offer considerable potential within the e-Health domain. They have already achieved significant success in enhancing diagnostic and prognostic model accuracy for conditions such as heart disease, Alzheimer’s, brain disorders, and diabetes. This is often accomplished by optimizing feature selection or model parameters [11]. Beyond predictive modeling, these algorithms have also been applied to improve operational efficiencies, such as Vahit Tongur’s work achieving an approximate 58% improvement in a large university hospital’s layout optimization [12]. In future applications, metaheuristics hold promise for critical areas such as emergency medical supply distribution logistics and advanced medical forecasting. Despite the development of numerous metaheuristic algorithms in recent years, no prior review has systematically summarized their applications and outcomes in e-Health. To address this gap, the present review provides a comprehensive analysis of state-of-the-art contributions of metaheuristic algorithms to e-Health. It synthesizes achievements, evaluates current limitations, and outlines pathways for future research and development.

2 Metaheuristic Metaheuristic: Development and Key Approaches

2.1 Algorithm Selection Method

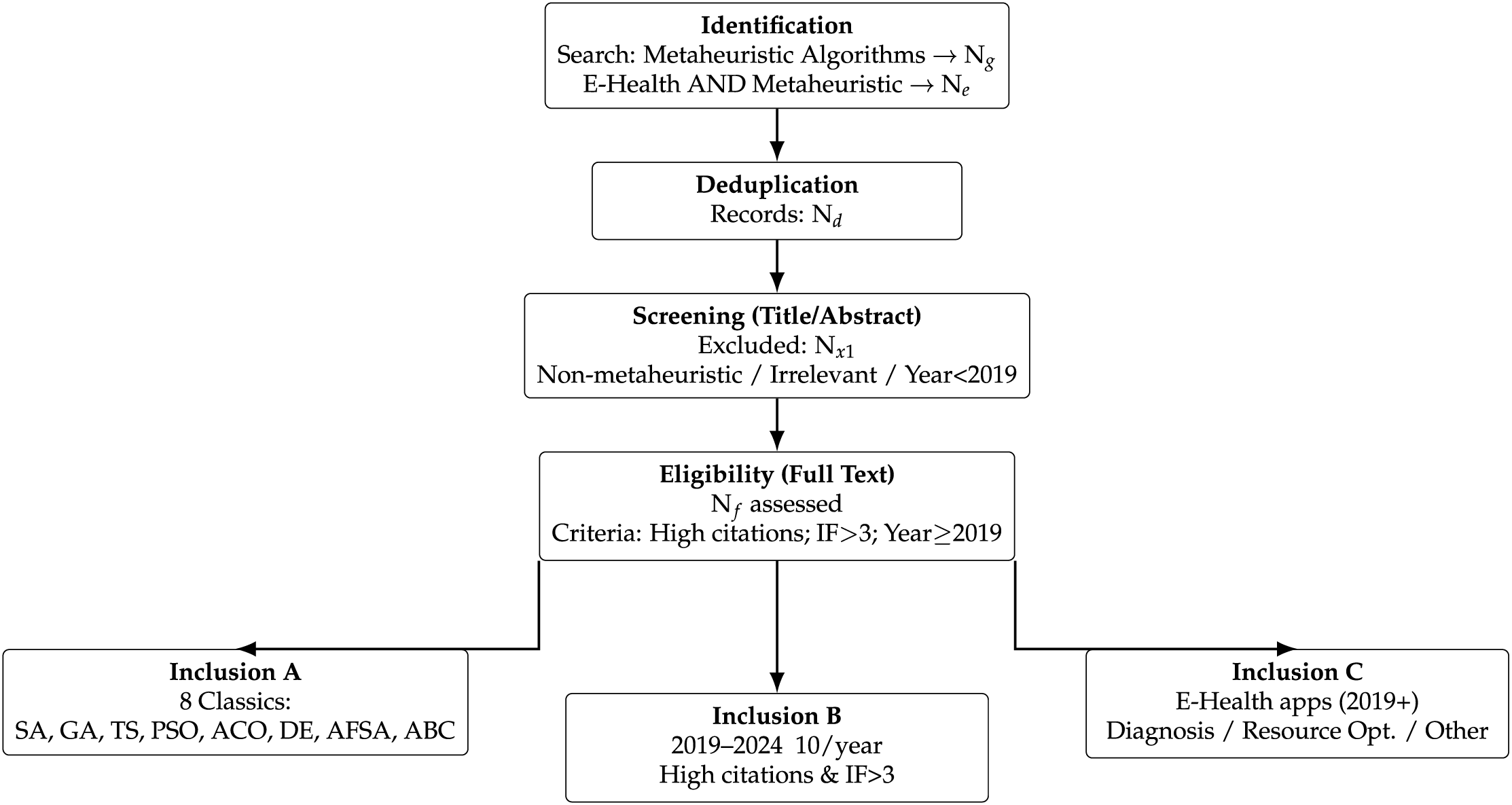

Fig. 1 presents a compact PRISMA-like selection process adapted for algorithms. The process begins with identification, where records are gathered from general searches on metaheuristic algorithms (

Figure 1: PRISMA-like algorithm selection flowchart

2.2 Historical Development and Foundational Algorithms

The quest to solve complex optimization problems has driven the evolution of computational techniques. Traditional deterministic methods, such as the gradient method [13], Newton’s method [14], and the conjugate gradient method [15], are effective for certain problems. However, they often face limitations in efficiency and convergence when applied to large-scale, high-dimensional, or highly nonlinear optimization landscapes. A significant challenge is their tendency to become trapped in local optima, failing to identify the globally best solution.

To overcome these limitations, heuristic algorithms emerged as pragmatic alternatives. These methods employ experience-based rules or intuitive judgments to guide the search process. They explore broad solution spaces to find near-optimal solutions efficiently, often at lower computational cost. Early examples include greedy algorithms, conceptualized for graph traversal and shortest path problems, with Huffman coding [16] representing a notable application. The Nelder-Mead simplex method, introduced in 1965, offered a more sophisticated approach for unconstrained optimization. It adapts a simplex shape to the function’s local topology, effectively extending hill climbing [17]. However, heuristic algorithms typically do not guarantee the absolute optimal solution, and they rarely indicate how close a solution is to the true optimum.

Building upon the foundation of heuristics, metaheuristic algorithms represent a significant advancement. They offer higher-level strategies or frameworks that orchestrate heuristic procedures to achieve robust global search performance. A defining feature of many metaheuristics is their inspiration drawn from natural processes, including genetics, biological evolution, collective animal behavior (swarm intelligence), or physical phenomena like annealing. Their conceptual simplicity, intuitive nature, and relative ease of implementation have contributed to their widespread applicability across a diverse range of complex optimization problems. Conceptual groundwork for some approaches, such as simulation-based evolutionary algorithms, dates back to the 1950s, leveraging insights from biological mechanisms to tackle optimization tasks.

The development of specific, widely recognized metaheuristic algorithms gained substantial momentum in the subsequent decades. Key foundational algorithms include:

• Simulated Annealing (SA): Originating from the Metropolis algorithm used in statistical physics (1953), SA was adapted by Kirkpatrick et al. in 1983 for combinatorial optimization [18]. It mimics the physical annealing process of materials, allowing probabilistic escapes from local optima to explore the solution space more broadly and converge towards a global optimum. Its versatility has led to wide application.

• Genetic Algorithms (GA): Introduced by John Holland in 1975 [19], GAs simulate the principles of Darwinian evolution, employing operators like selection, crossover, and mutation on a population of candidate solutions. Their inherent parallelism and strong global search capabilities make them particularly effective for multi-objective optimization, combinatorial problems (such as the Traveling Salesman Problem), and machine learning tasks.

• Tabu Search (TS): Proposed by Fred Glover in 1986 [20], TS is characterized by its use of adaptive memory structures. By maintaining a “tabu list” of recently explored solutions or moves, it prevents cycling and guides the search away from previously visited regions, enabling a more focused exploration of the solution space. It has had a notable impact, particularly in the field of integer programming.

• Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): Developed by James Kennedy and Russell Eberhart in 1995 [4], PSO draws inspiration from the social dynamics of bird flocks or fish schools. A population of “particles” navigates the search space, adjusting their trajectories based on their own best-discovered positions and the best position found by the entire swarm. PSO is recognized for its simplicity and effectiveness, especially in continuous nonlinear optimization problems.

• Ant Colony Optimization (ACO): Introduced by Marco Dorigo and colleagues in 1996 [21], ACO mimics the foraging behavior of ants, particularly their use of pheromone trails to communicate paths to food sources. This stigmergic communication, combined with distributed computation and constructive greedy heuristics, makes ACO well-suited for complex combinatorial optimization problems, such as routing and scheduling.

• Differential Evolution (DE): Proposed by Rainer Storn and Kenneth Price in 1997 [22], DE is a powerful and relatively simple population-based algorithm designed primarily for continuous optimization. It utilizes vector differences between population members to create mutant solutions, followed by crossover and selection steps. DE is often noted for its strong performance in numerical optimization and its use in tuning machine learning models.

• Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA): Developed by Li et al. in 2002 [23], AFSA models the collective behaviors observed in fish schools, such as random movement, foraging, swarming (aggregating), and following behaviors, to guide the search towards optimal regions in nonlinear optimization landscapes.

• Artificial Bee Colony (ABC): Proposed by Karaboga in 2005 [24], the ABC algorithm simulates the intelligent foraging behavior of honeybee swarms. It divides the bee population into different roles (employed bees exploring known food sources, onlooker bees choosing sources based on information shared, and scout bees searching for new sources) to balance exploration and exploitation in the search for optimal solutions.

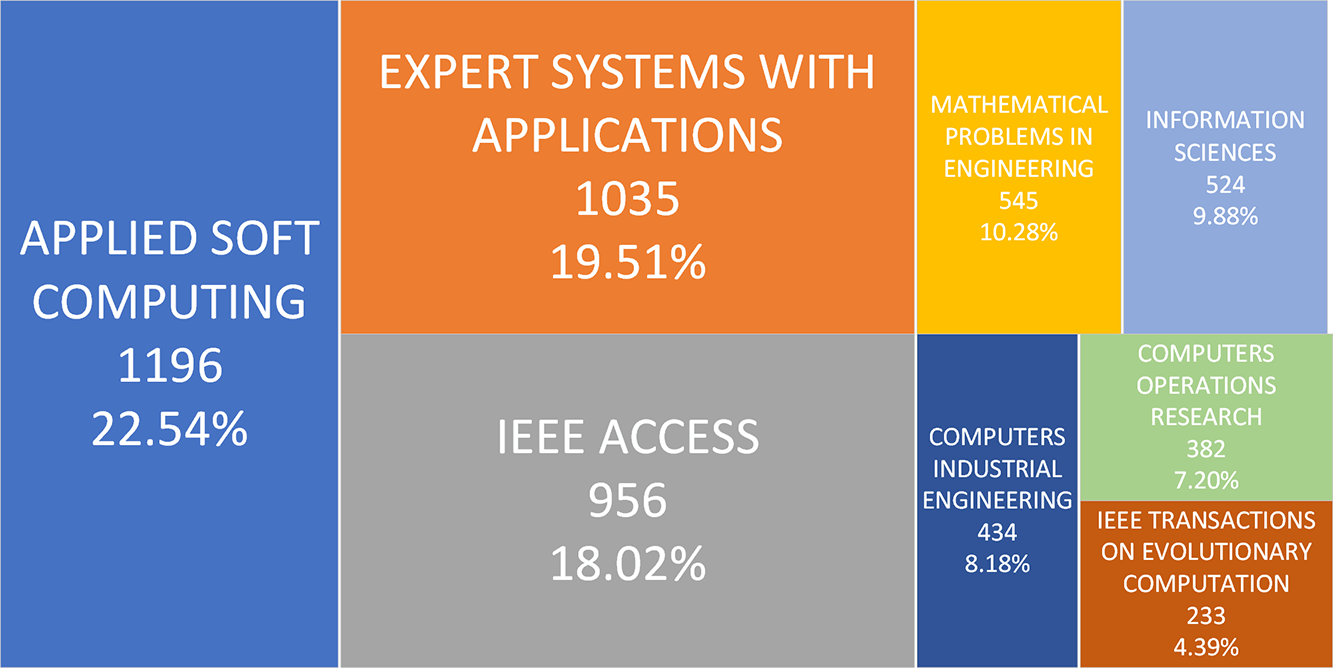

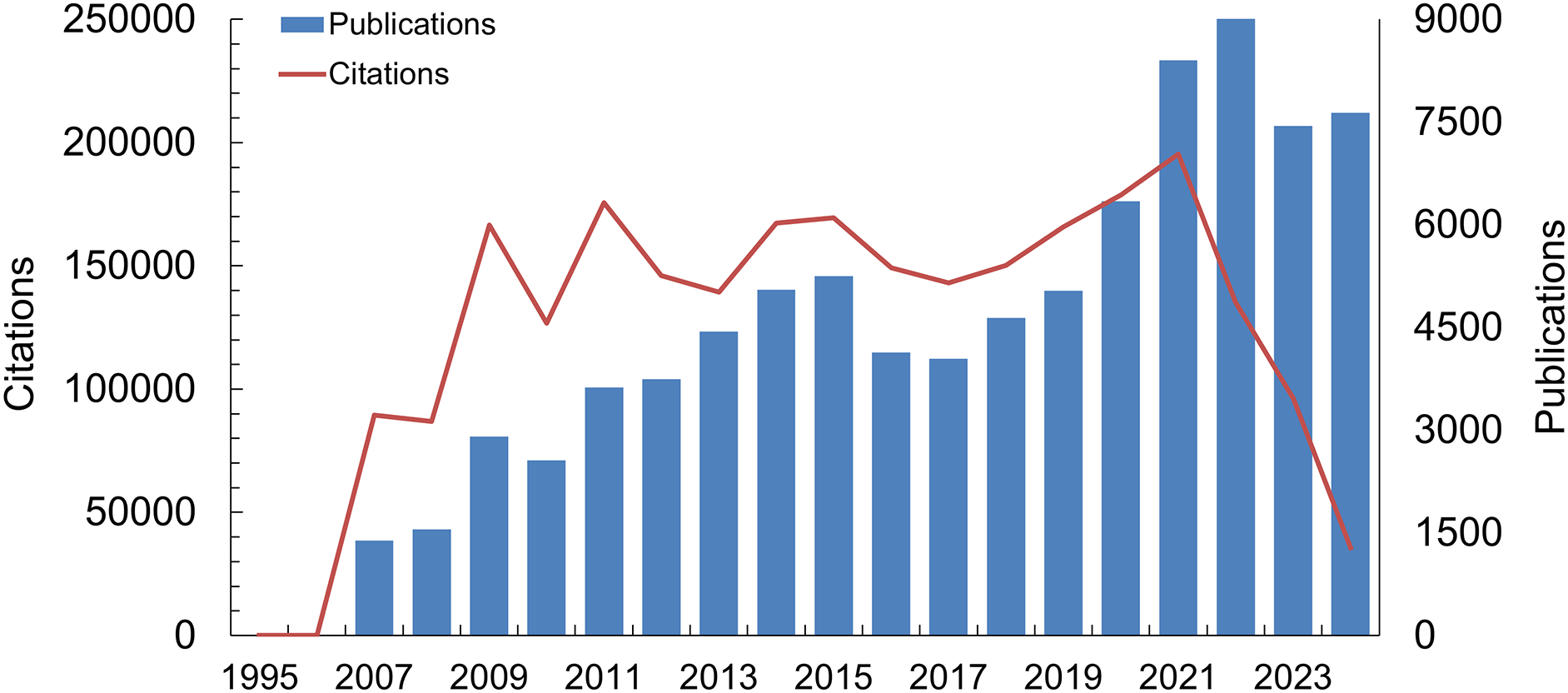

These foundational metaheuristic algorithms, most of which were established prior to the mid-2000s, have gained substantial recognition and widespread application across diverse scientific and engineering domains. To illustrate their influence, a survey of seven leading journals—including Applied Soft Computing—identified 5305 related publications (Fig. 2). Furthermore, by restricting the search to ten representative traditional algorithm keywords within the Web of Science (WOS) Core Collection, and excluding non-journal formats such as conference proceedings and books, we conducted an analysis of publication and citation records from 1994 to 2024. The results reveal a clear and sustained upward trend in both publications and citations for these classic algorithms (Fig. 3). This growth became especially pronounced after 2008, reflecting intensified research activity and the enduring academic influence of these methods. This persistent interest suggests that studies applying these fundamental metaheuristic approaches are likely to remain a vibrant research focus in the foreseeable future.

Figure 2: Distribution of classic metaheuristic algorithms in various situations

Figure 3: Publication and citation count of classic metaheuristic algorithms

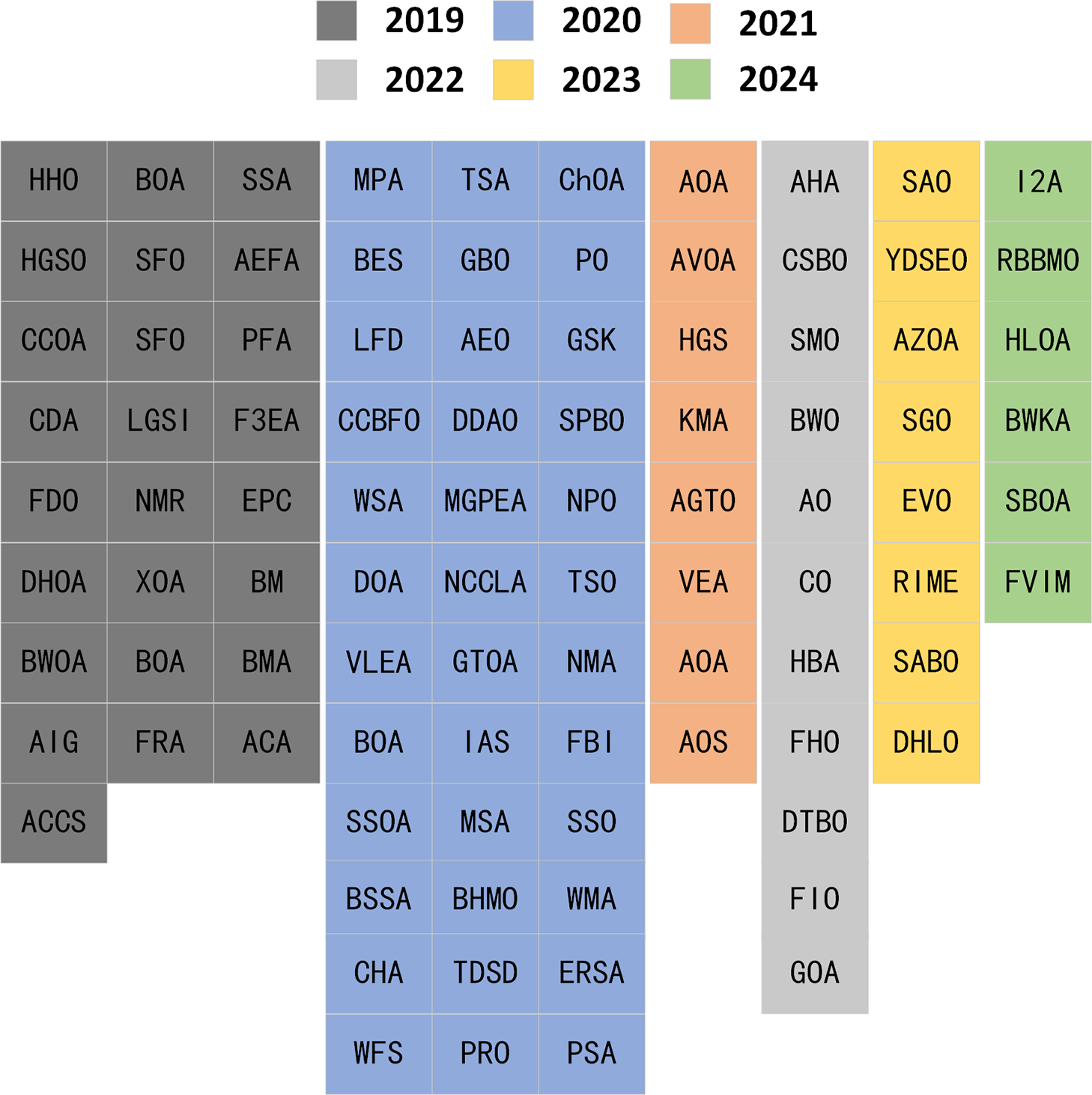

The foundational metaheuristics previously discussed highlight the effectiveness of drawing inspiration from a wide array of natural and scientific phenomena. The field continues to benefit from diverse sources of inspiration. These include biological evolution, collective behavior of social organisms, principles from physics and chemistry, and human social dynamics. This variety fuels ongoing innovation, producing novel algorithms that refine established methods or introduce new search strategies. Recognizing this dynamic progress, the subsequent sections are dedicated to surveying the landscape of recently developed metaheuristic algorithms, focusing specifically on those proposed within the six-year timeframe from 2019 to 2024, as illustrated in Fig. 4. To facilitate a structured overview, these algorithms will be presented chronologically and grouped within two-year intervals.

Figure 4: Optimization algorithms classification

2.3 Newly Introduced Algorithms (2019–2020)

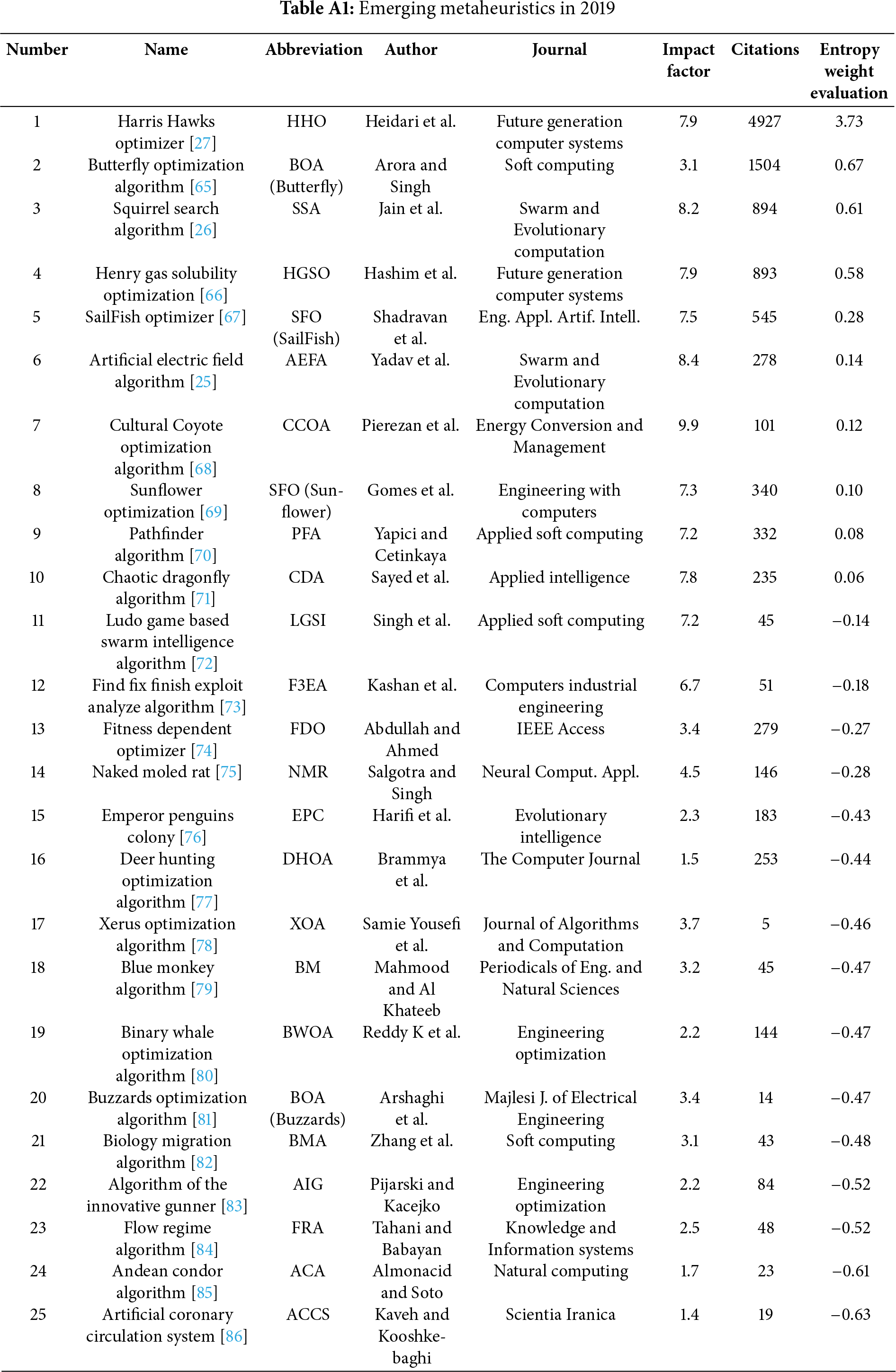

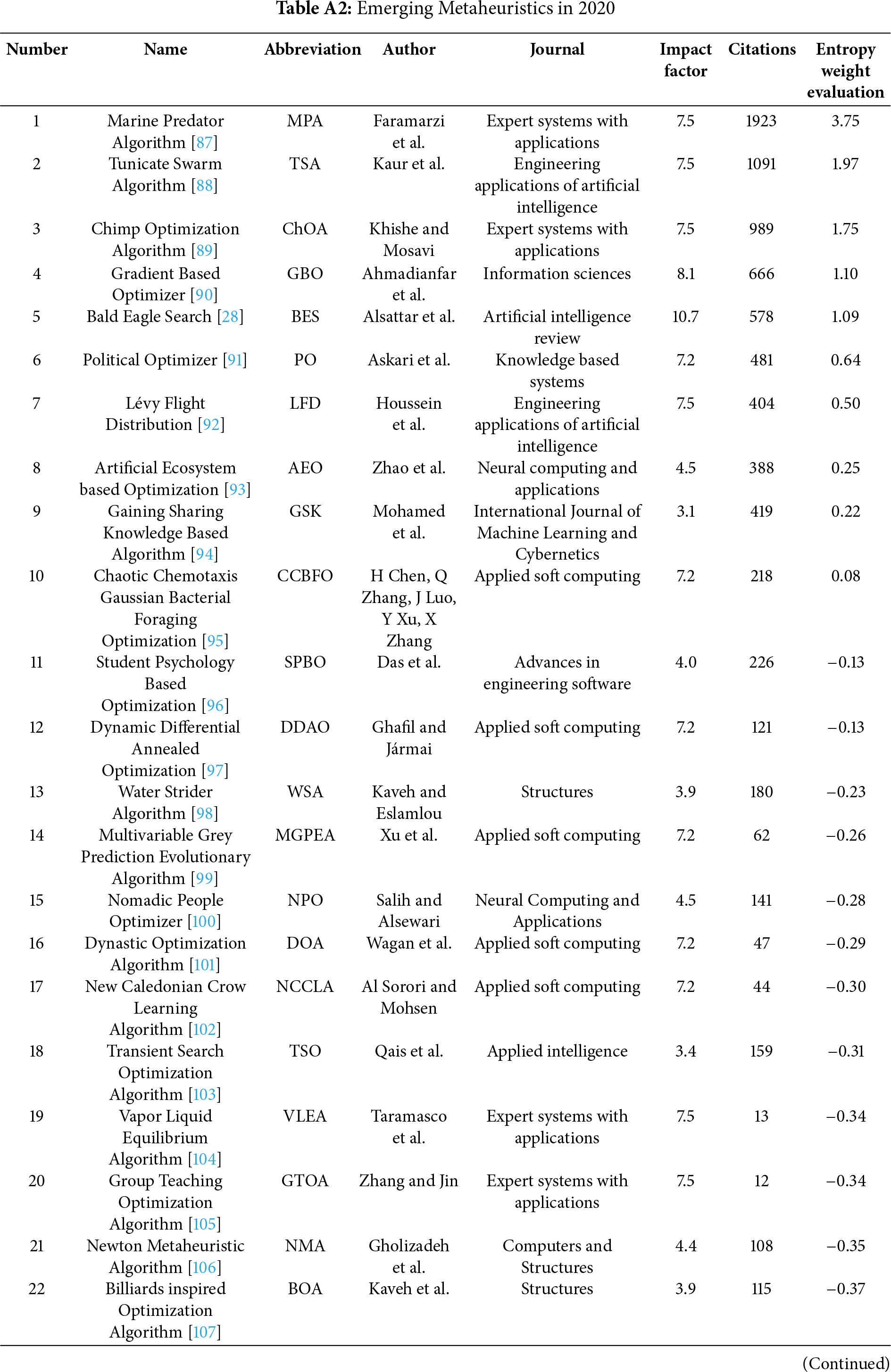

To identify novel metaheuristic algorithms proposed during the 2019–2020 period, comprehensive searches were conducted within the Web of Science Core Collection and Google Scholar databases. After filtering to include only peer-reviewed journal articles, a significant number of new algorithms were identified: 28 distinct algorithms originating from 2019 and 39 from 2020. Given this high volume, a systematic approach was required to select a representative subset for detailed discussion in this review. Therefore, a quantitative selection strategy was employed. It focused on early academic impact, measured by journal Impact Factor (IF) and article citation count. This methodology provides an objective basis for highlighting algorithms that quickly gained visibility and demonstrated influence within the research community. Applying these criteria, four particularly prominent algorithms from this timeframe were selected for an in-depth overview:

• Artificial Electric Field Algorithm (AEFA) [25], published in “Swarm and Evolutionary Computation” (2019), accumulating 278 citations.

• Squirrel Search Algorithm (SSA) [26], also published in “Swarm and Evolutionary Computation” (2019), accumulating 894 citations.

• Harris Hawks Optimizer (HHO) [27], published in “Future Generation Computer Systems” (2019), accumulating 4927 citations.

• Bald Eagle Search (BES) [28], published in “Artificial Intelligence Review” (2020), accumulating 573 citations.

(Note: Citation counts reflect the data available during the collection period for this review). For a comprehensive catalog of all algorithms identified from 2019 and 2020, please refer to Tables A1 and A2, respectively.

2.3.1 Quantitative Evaluation Methodology

To enable an objective comparison and ranking of the identified algorithms based on their initial impact, a quantitative evaluation methodology was implemented. This scheme integrates journal Impact Factor (IF) and citation counts, providing a composite measure of influence. The rationale for using this methodology, especially the entropy weight method, is that it objectively determines the relative importance of each indicator (IF and citations). Unlike subjective weighting, the entropy method derives weights from the data’s statistical properties, specifically the variance or information content of each indicator across the algorithms. The evaluation procedure, applied independently to the algorithms grouped by their publication year (2019 or 2020), consists of the following steps:

(a) Data Standardization (Z-score): To ensure comparability between indicators with different scales and units (IF and citation counts), the raw data (

where

-

This method avoids dependency on extreme values (minimum and maximum) and better reflects the relative deviation of each algorithm’s impact within its group.

(b) Data Normalization: To ensure comparability between indicators with different scales and units (IF and citation counts), the raw data (

Here,

This adjustment ensures numerical stability with negligible impact on the relative normalized values (

(c) Calculate Indicator Entropy: The entropy

where

(d) Calculate Information Redundancy (Diversity): The information redundancy, or diversity,

A higher

(e) Calculate Objective Indicator Weights: The objective weight

These weights reflect the objective importance of each indicator based on the observed data distribution, satisfying

(f) Calculate Comprehensive Impact Score: Finally, a comprehensive score

This score

2.3.2 The Artificial Electric Field Algorithm

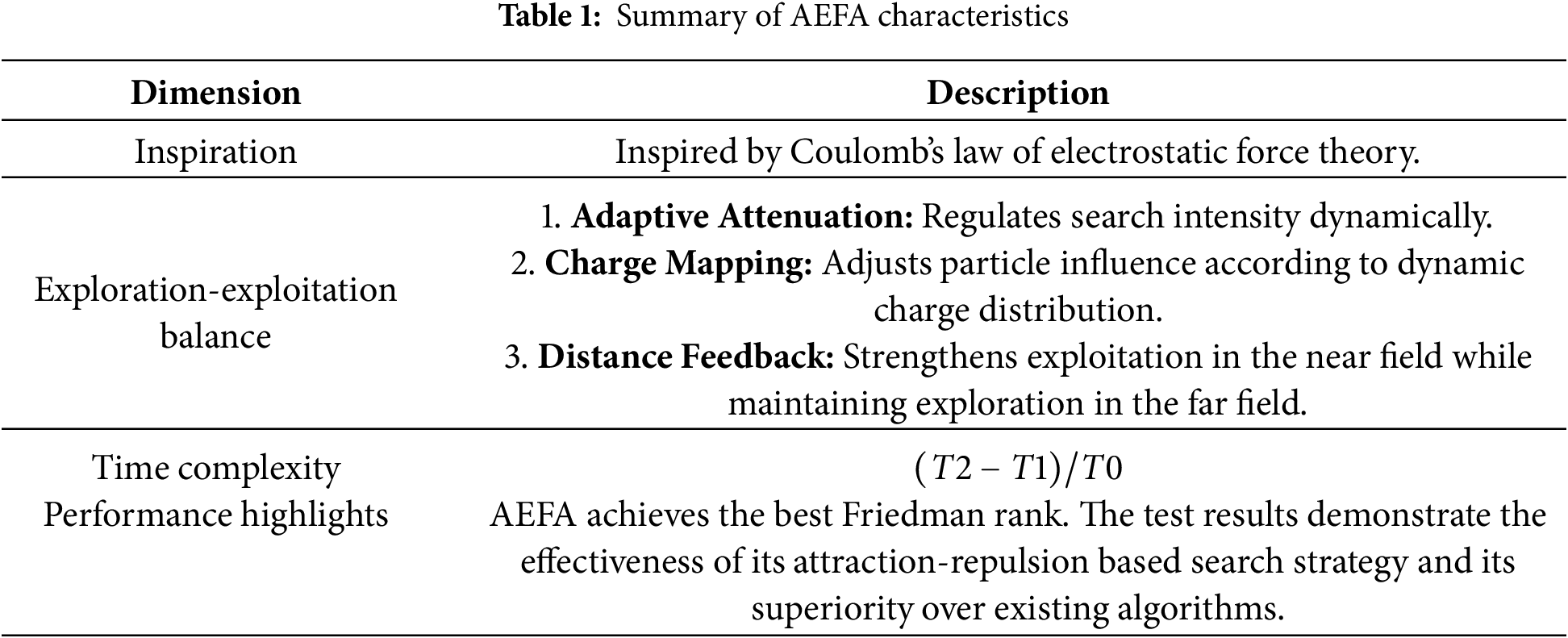

The Artificial Electric Field Algorithm (AEFA) [25] is a physics-inspired metaheuristic that models candidate solutions as charged particles in the search space. Each particle’s fitness is directly mapped to an electrical charge (

Particles interact through simulated electrostatic forces, and their positions are iteratively updated according to these forces. To enhance search efficiency, AEFA incorporates stochasticity and an adaptive Coulomb constant, which gradually decreases to balance exploration in early iterations and exploitation in later ones.

For clarity and completeness, the detailed formulas for particle interactions, force computation, velocity, and position updates are provided in Appendix B.1. This separation keeps the main text concise while allowing readers to refer to full algorithmic details if needed. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is presented in Table 1, highlighting the key mechanisms such as charge mapping, force computation, and adaptive control.

2.3.3 The Squirrel Search Algorithm

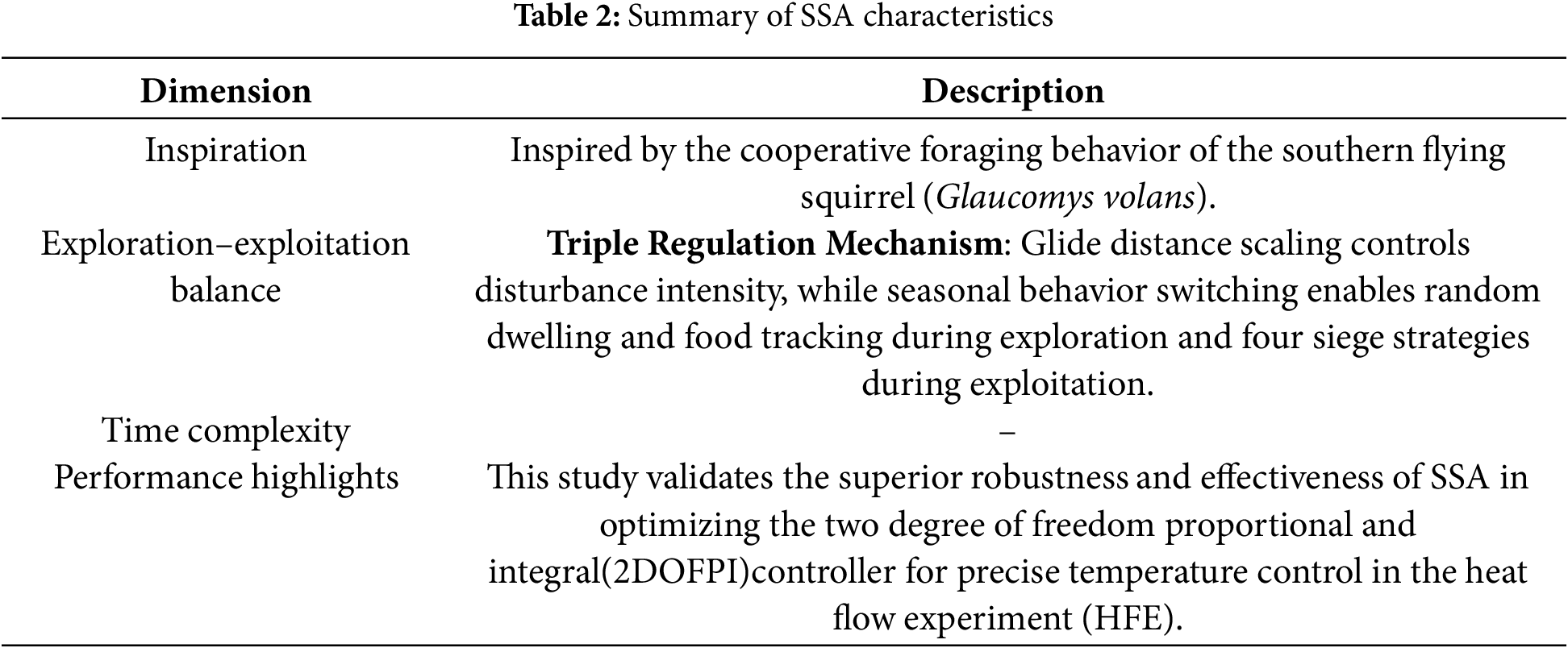

The Squirrel Search Algorithm (SSA) [26] is a population-based metaheuristic designed for global optimization. Its novelty lies in the spherical boundary search mechanism, where candidate solutions are generated on the surfaces of (D-1)-dimensional spheres within the D-dimensional search space. The algorithm adaptively balances exploration and exploitation through step-size control and a dual search direction strategy.

The core trial solution generation can be summarized as:

where

SSA employs a dual search direction approach: fitter solutions explore using a “towards-rand” strategy, while less fit solutions exploit using a “towards-best” strategy. The detailed calculation of these search directions is provided in Appendix B.2.

Overall, SSA’s innovation stems from its geometric projection mechanism combined with the population-segregated search directions, enabling a structured yet diverse exploration of the solution space. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 2.

2.3.4 The Harris Hawks Optimizer

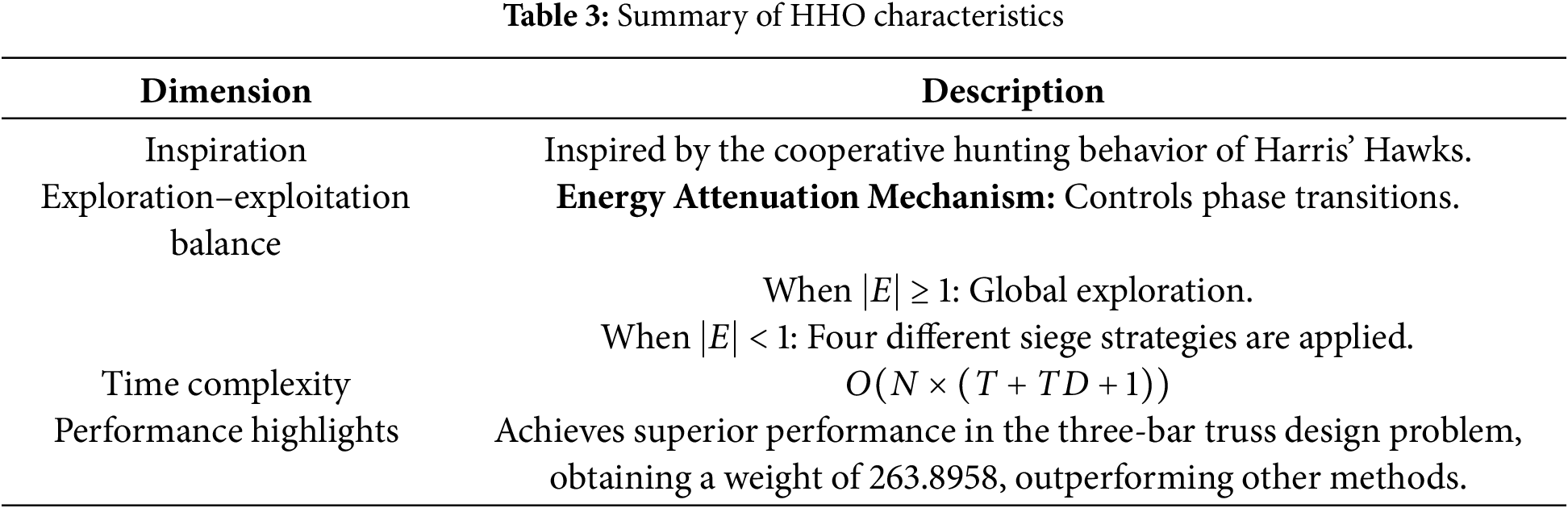

The Harris Hawks Optimizer (HHO) [27] is a population-based, gradient-free metaheuristic inspired by the cooperative hunting behavior of Harris hawks. Candidate solutions (“hawks”) adaptively switch between exploration and exploitation phases based on the prey’s escape energy (E), which decreases over iterations and simulates the prey’s exhaustion.

During exploration, hawks search the solution space using two strategies, probabilistically chosen via

The prey’s escape energy E governs the adaptive transition to exploitation:

In the exploitation phase, hawks employ four distinct siege strategies, including “soft” and “hard” sieges. Some strategies incorporate Levy flight to simulate rapid, irregular dives, enhancing local search around the prey. The detailed exploitation update equations, including Levy flight components and position refinements, are provided in Appendix B.3.

Overall, HHO’s novelty stems from its intelligent energy-based adaptive mechanism, dynamic attack strategies, and stochastic enhancements that collectively enable efficient exploration and exploitation of the solution space. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 3.

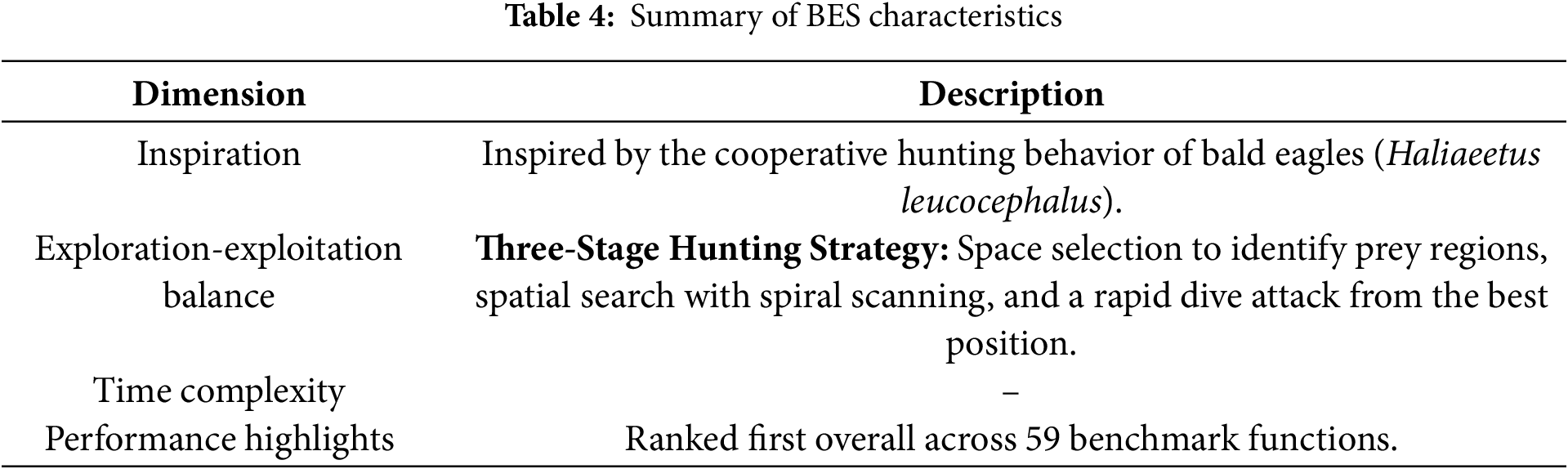

The Bald Eagle Search (BES) [28] algorithm is a metaheuristic inspired by the hunting strategy of bald eagles. It divides the optimization process into three phases: select, search, and swoop, mimicking how eagles locate, approach, and capture prey. This phased strategy balances global exploration and local exploitation.

In the select phase, eagles move towards promising regions guided by the current best solution (

where

During the search phase, eagles explore locally using a spiral trajectory to refine promising regions. The swoop phase models a rapid dive toward the prey, converging agents toward

Overall, BES’s novelty lies in its structured three-phase hunting strategy, combining attraction, spiral exploration, and hyperbolic dive movements to effectively balance exploration and exploitation. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 4.

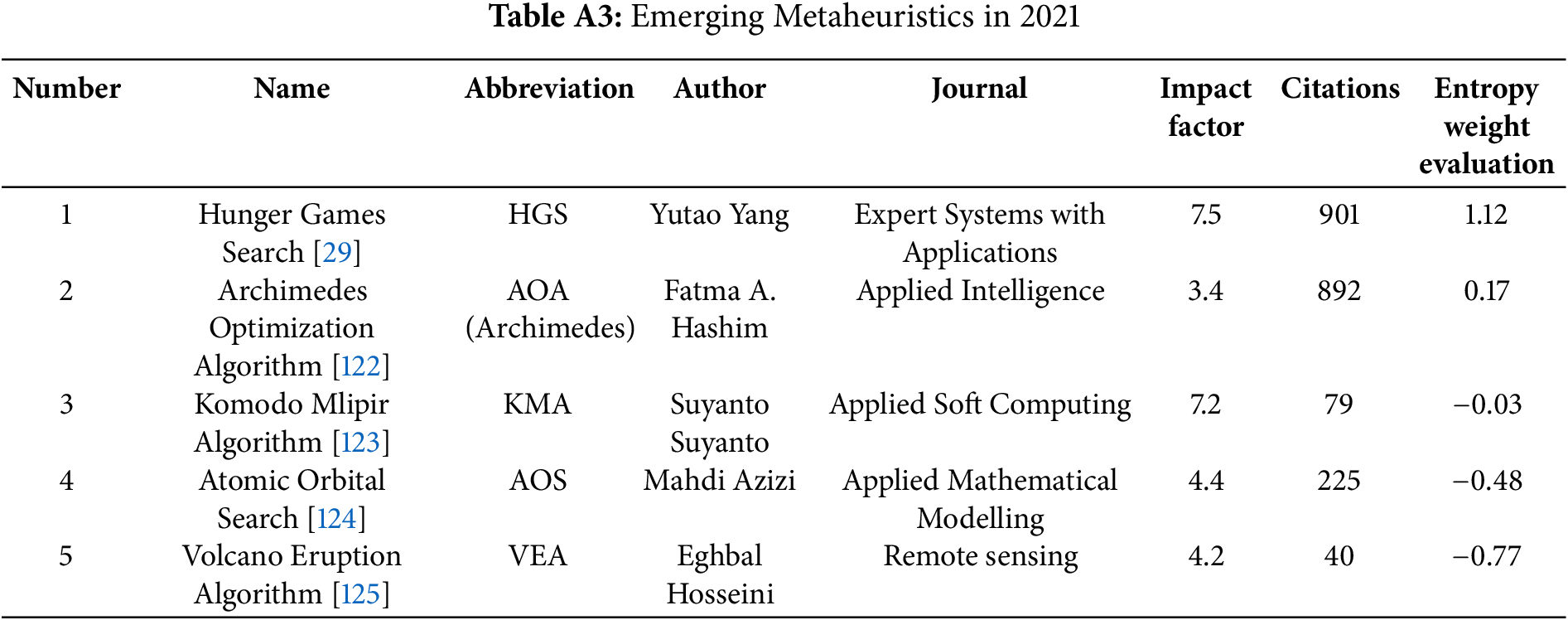

2.4 Newly Introduced Algorithms (2021–2022)

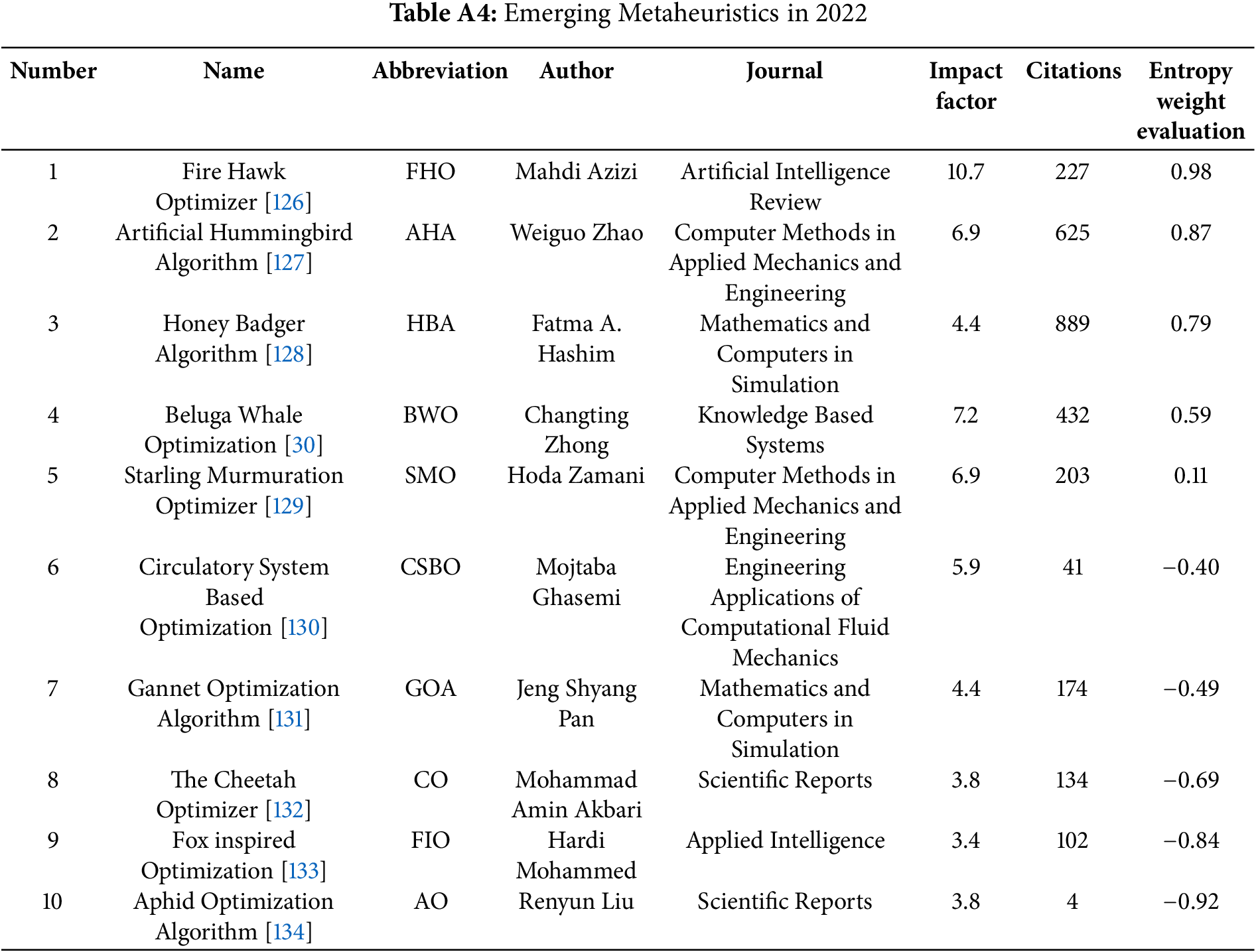

The period between 2021 and 2022 witnessed a continued proliferation of innovative metaheuristic algorithms, predominantly drawing inspiration from diverse natural systems and phenomena, as detailed in Tables A3 and A4. These algorithms translate observed biological or physical behaviors into optimization strategies that navigate complex, high-dimensional search spaces. A central theme in their design remains the dynamic balancing of exploration and exploitation phases, crucial for enhancing the probability of locating global optima while mitigating the risk of premature convergence to local solutions. The diversity of inspiration during this timeframe is well illustrated by several notable examples: the Hunger Games Search (HGS) algorithm models the adaptive foraging behaviors driven by hunger, emphasizing environmental interaction and resource prioritization [29]; and the Beluga Whale Optimization Algorithm (BWOA) emulates the coordinated social hunting tactics, including pair swimming and dive foraging, characteristic of beluga whales [30]. These examples collectively underscore the ongoing trend of exploring increasingly nuanced natural behaviors and physical principles to engineer powerful new optimization tools for challenging problems.

The Hunger Games Search (HGS) algorithm [29] simulates animal foraging driven by hunger. Candidate agents update their positions adaptively using dynamic hunger weights, which balance exploration and exploitation based on an individual’s fitness relative to the population.

The core position update in HGS can be summarized as:

The detailed formulas for attraction, repulsion, and adaptive hunger weight updates are provided in Appendix B.5. These mechanisms enable poorer solutions to explore more aggressively, while fitter solutions exploit promising regions, reflecting the biological concept that hunger drives foraging intensity.

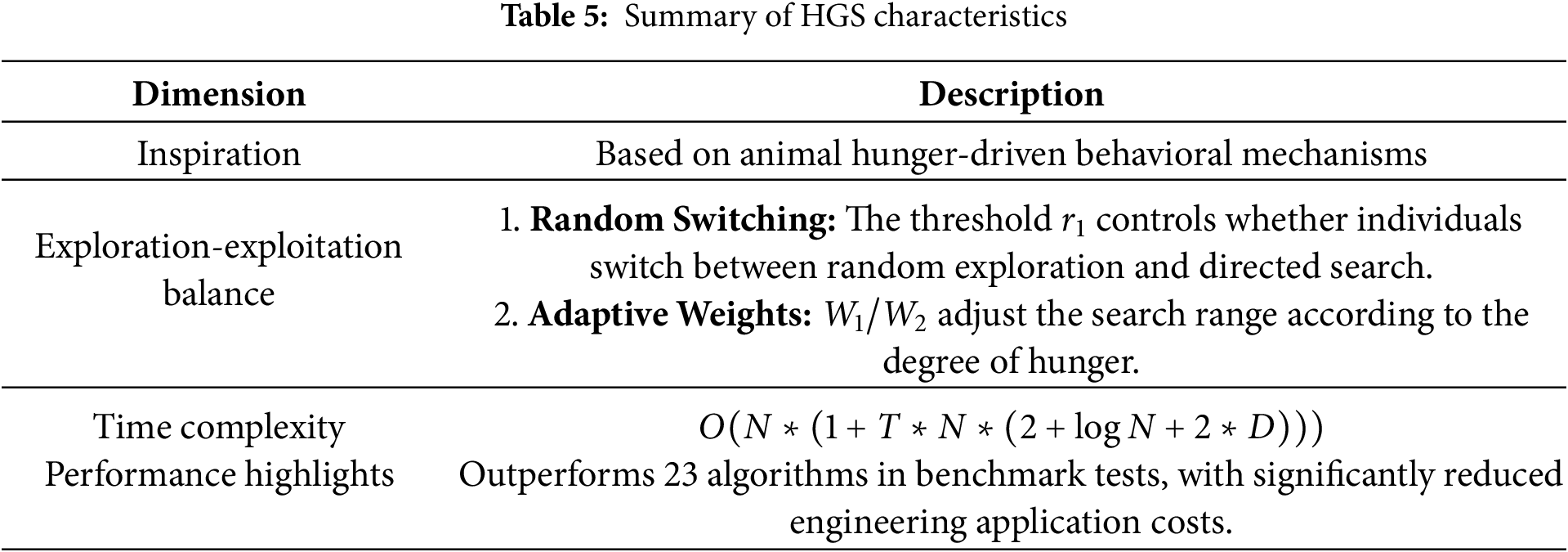

Overall, HGS’s novelty lies in its adaptive hunger-based search mechanism, which dynamically modulates exploration and exploitation. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 5.

2.4.2 Beluga Whale Optimization Algorithm

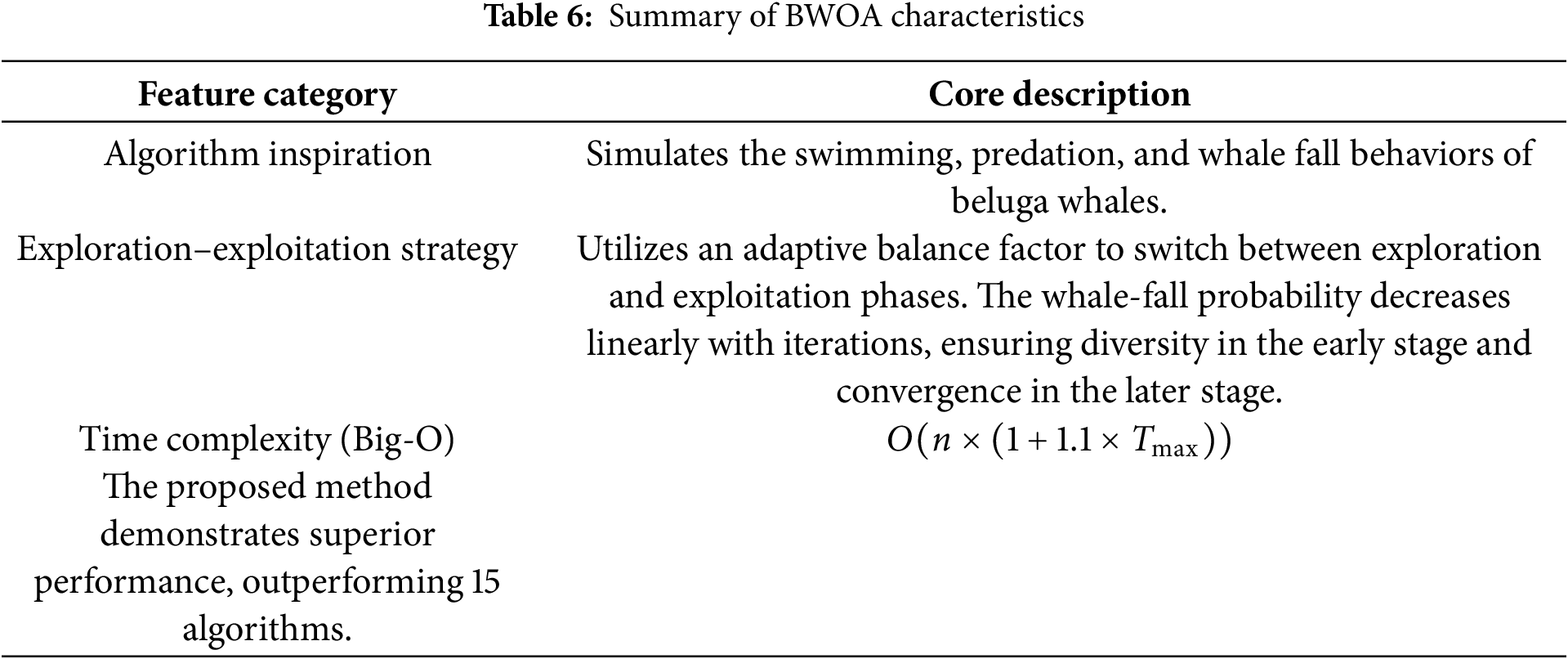

Beluga Whale Optimization Algorithm (BWOA) [30] is inspired by beluga whale behaviors, including swimming, cooperative predation, and the ‘whale fall’ phenomenon. The algorithm organizes the search into three main phases: exploration, exploitation, and whale fall.

A balance factor

Exploration phase (

Exploitation phase (

Whale fall phase: Introduces probabilistic diversification where a small fraction of whales update positions based on random perturbations to enrich local areas. Detailed formulas are in Appendix B.6.

BWOA’s novelty lies in its three-phase biologically inspired mechanism, effectively balancing global exploration and local exploitation, with additional diversification from the whale fall phase. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 6.

2.5 Newly Introduced Algorithms (2023–2024)

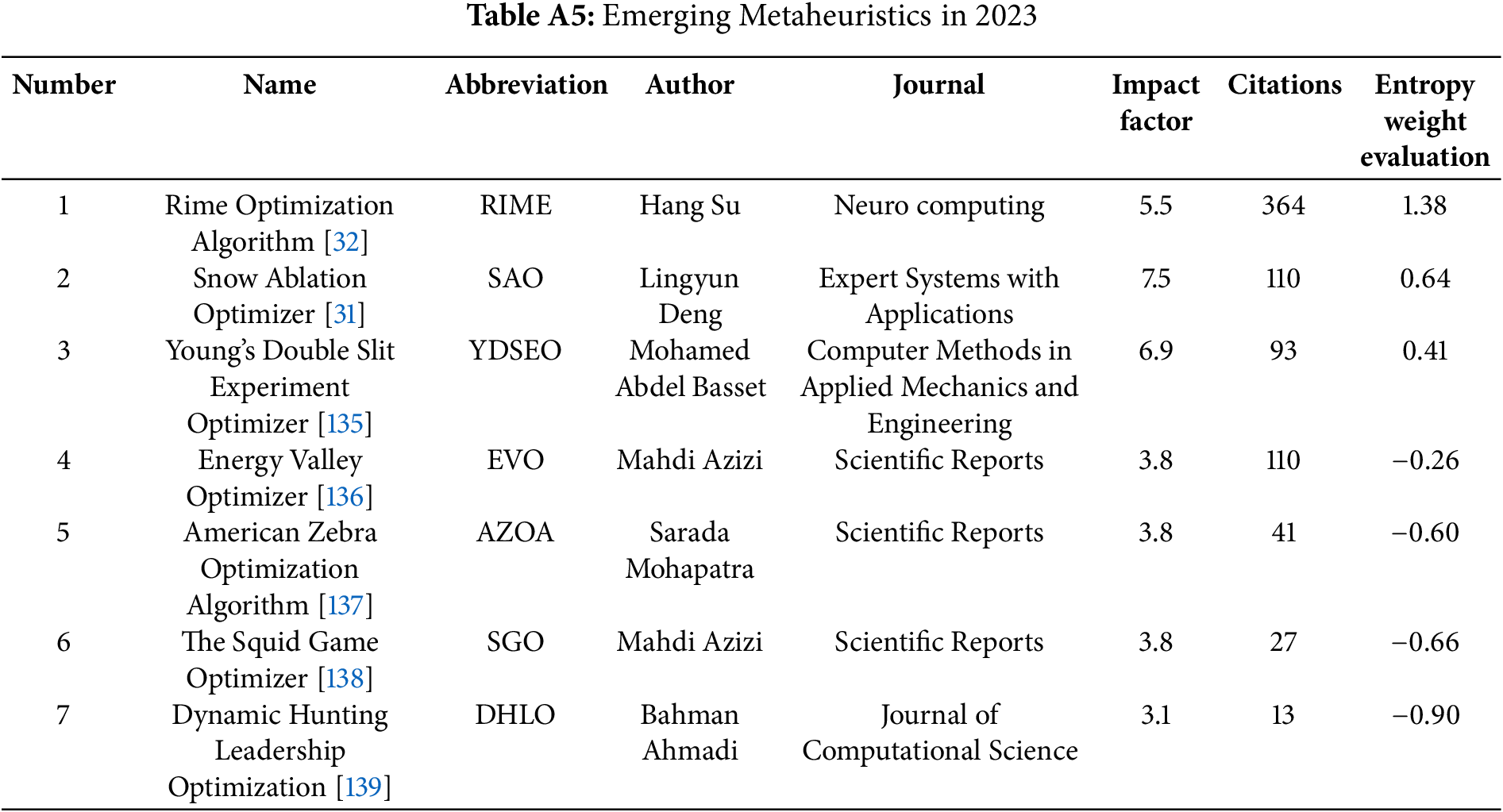

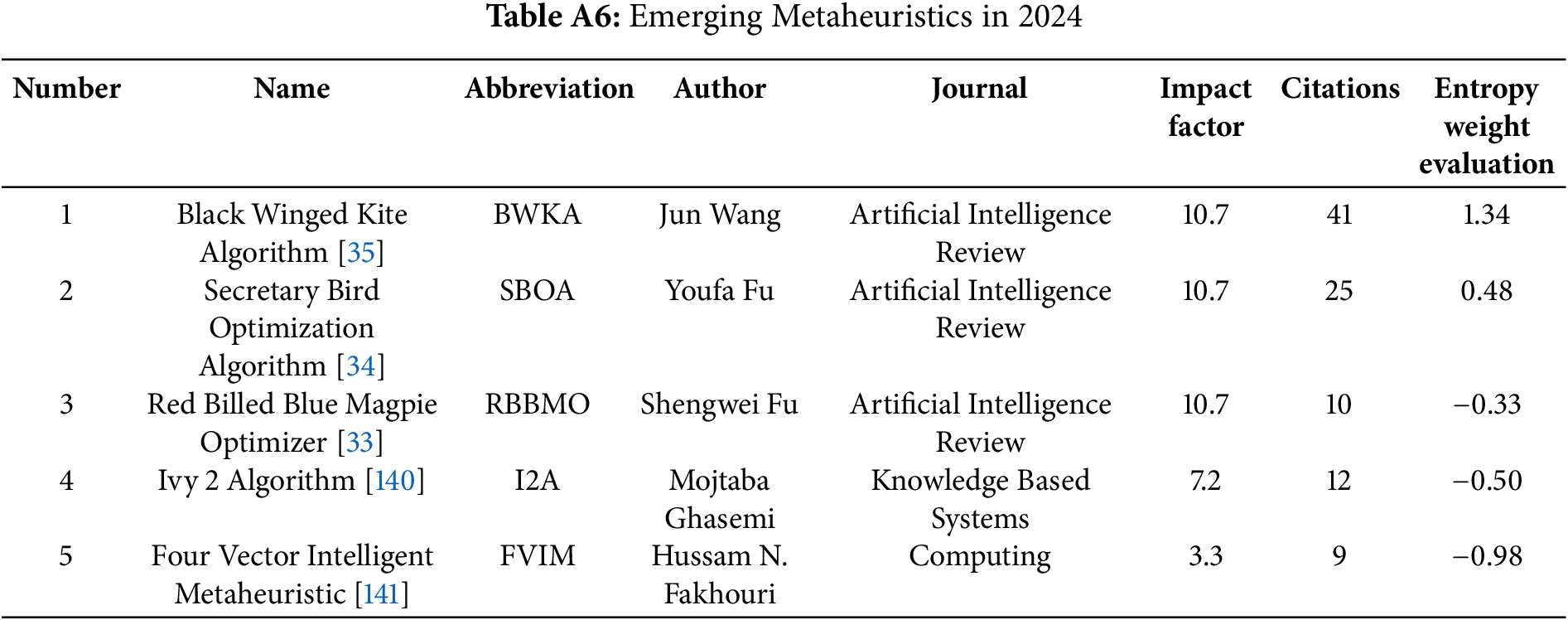

The period 2023–2024 witnessed further innovations in metaheuristic algorithm design, continuing the rapid evolution observed in previous years, as detailed in Tables A5 and A6. Researchers expanded their sources of inspiration, drawing from diverse natural, physical, and social phenomena to devise novel optimization approaches.

Illustrating the trend of modeling complex environmental processes, algorithms emerged based on thermodynamic and crystallization behaviors. For instance, the Snow Ablation Optimizer (SAO) [31] simulates snow sublimation and melting dynamics under varying environmental conditions, translating phase transition processes into adaptive search mechanisms. Complementing this, the Rime Optimization Algorithm (RIME) [32] draws inspiration from natural rime ice formation, modeling ice crystal accretion as a strategy for solution refinement.

Shifting focus to biological phenomena, particularly sophisticated animal behaviors, several algorithms were introduced based on avian hunting strategies. The Red-billed Blue Magpie Optimizer (RBMO) [33] models the cooperative hunting tactics of these birds, emphasizing coordinated search efforts among multiple agents. Similarly, the Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA) [34] simulates terrestrial hunting behaviors, translating prey-striking actions into distinct operators. Furthermore, the Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) [35] derives logic from specialized hunting patterns of raptors, modeling behaviors such as hovering, diving strikes, or predator-prey dynamics to guide the search.

These 2023–2024 examples underscore a persistent theme: the ongoing quest to mathematically capture increasingly complex natural processes. By abstracting mechanisms like phase transitions, crystal growth, or specialized predation, researchers develop unique optimization strategies that enrich the metaheuristic toolkit for complex computational problems.

2.5.1 The Snow Ablation Optimizer

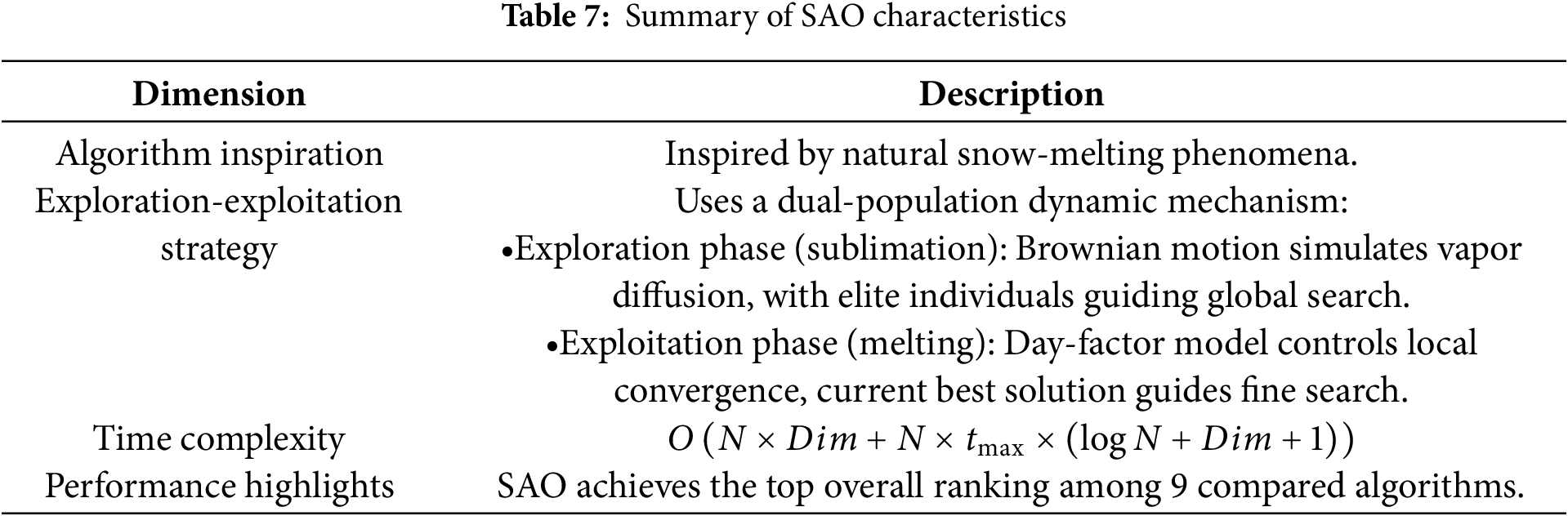

The Snow Ablation Optimizer (SAO) [31] is inspired by snow melting and sublimation processes. It employs a dual-population structure: ‘Leaders’ (top 50%, focused on exploitation) and ‘Followers’ (remaining 50%, focused on exploration).

Exploration phase (Followers): Simulates dispersion due to sublimation. Particle positions are updated towards elite individuals and population centroids. Key update formula:

Exploitation phase (Leaders): Models snow melting, with updates guided towards the best solution

Additional detailed update rules, including Brownian motion generation and parameter adaptations, are provided in Appendix B.7.

SAO’s novelty lies in its physics-inspired dual-population framework, explicitly balancing exploration and exploitation while incorporating stochastic perturbations and a melting rate for guided local refinement. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 7.

2.5.2 The Rime Optimization Algorithm

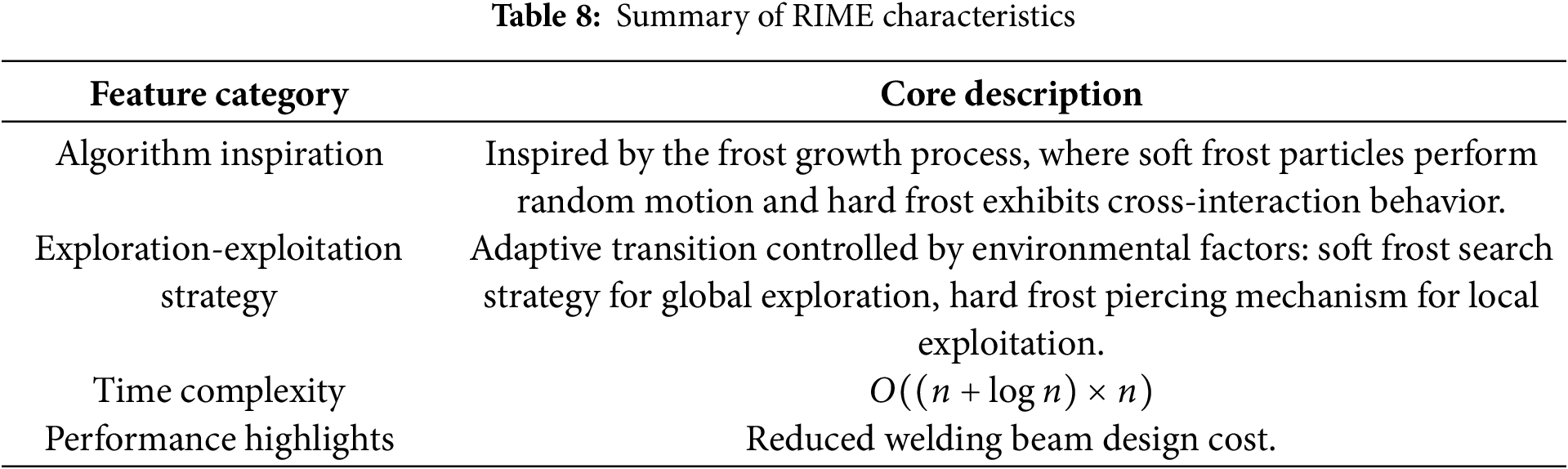

The Rime Optimization Algorithm (RIME) [32] is inspired by rime ice formation, distinguishing between soft rime (low wind, exploration) and hard rime (high wind, exploitation).

Soft-rime phase (Exploration): Simulates stochastic movement and adhesion. Key update formula:

Hard-rime phase (Exploitation): Models directional growth, driving convergence towards the best solution:

Additional stochastic updates, condensation coefficient adaptation, and conditional rules are detailed in Appendix B.8.

RIME’s novelty lies in translating the distinct physics of soft and hard rime formation into separate mechanisms that manage exploration and exploitation. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 8.

2.5.3 The Red-Billed Blue Magpie Optimizer

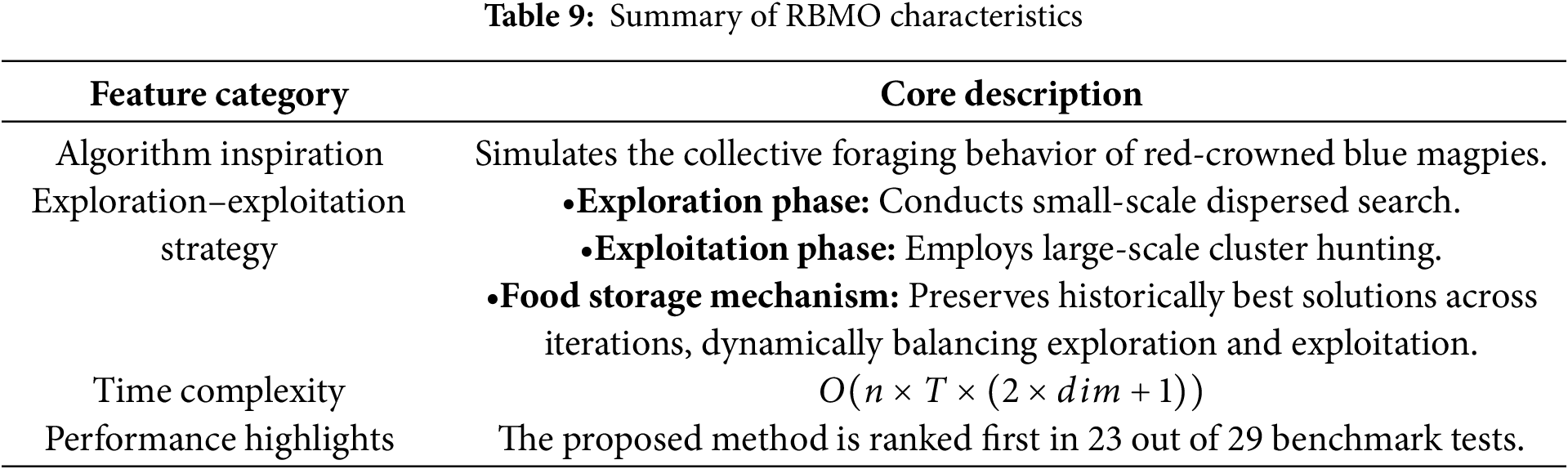

The Red-billed Blue Magpie Optimizer (RBMO) [33] is inspired by the cooperative hunting and social behaviors of red-billed blue magpies. It models two main phases: group-based food searching and coordinated prey attacking.

Food search phase: Agents collaboratively explore in groups. Key update formula:

Prey attack phase: Agents move towards the food location

- **Adaptive coefficient CF:**

Additional stochastic rules, variable group sizes (

RBMO’s novelty lies in mimicking cooperative social dynamics and adaptively balancing exploration and exploitation via group-based interactions and the CF factor. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 9.

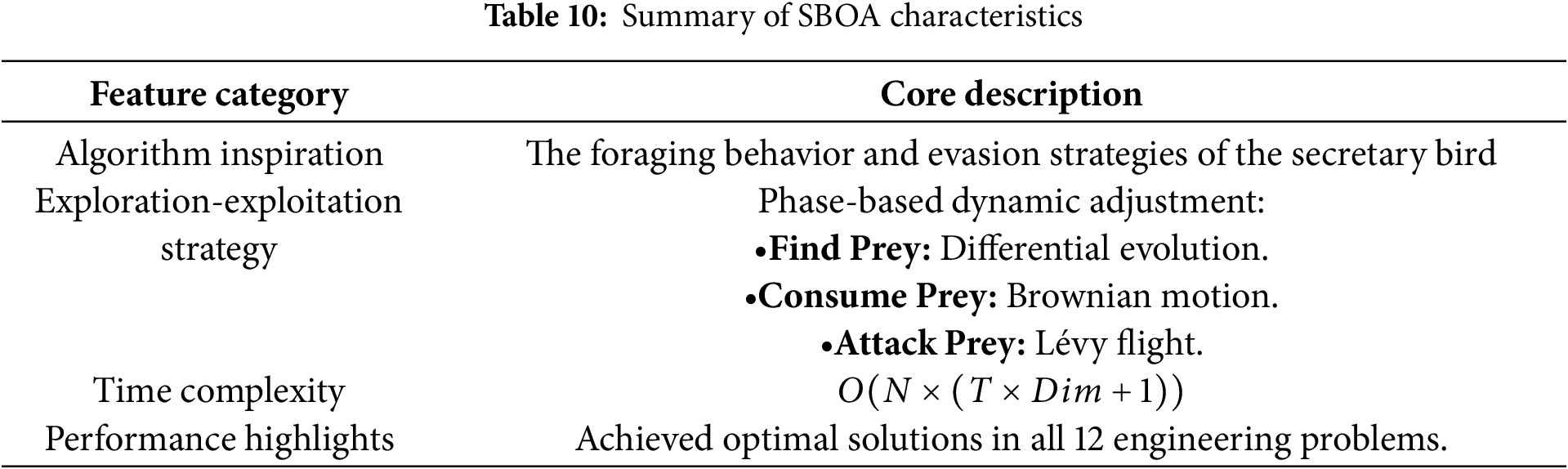

2.5.4 The Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm

The Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA) [34] models the hunting and evasion behaviors of secretary birds. It employs sequential hunting stages (exploration

Hunting stages: The position of agent

where

Escape mechanism: Diversification updates are applied probabilistically:

Detailed forms of

SBOA’s main contribution lies in its sequential hunting phases combined with a dual-mode escape strategy, effectively balancing exploration and exploitation while enhancing search robustness. A summary of algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 10.

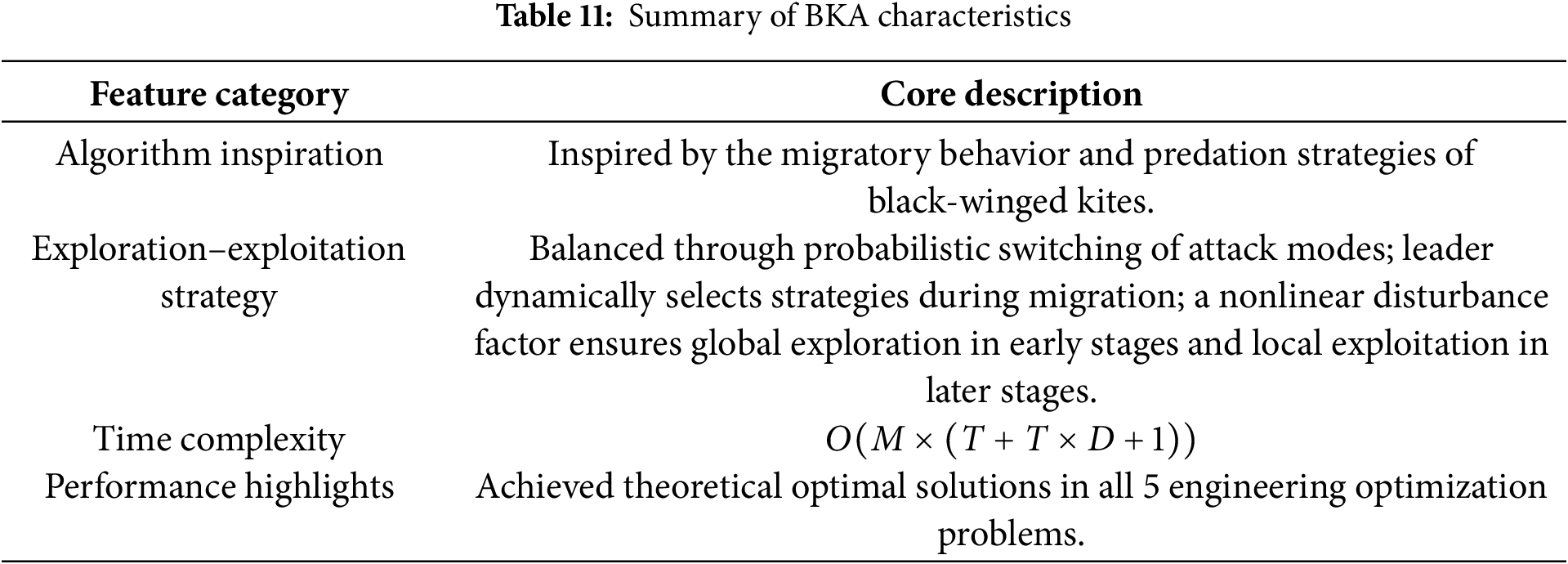

2.5.5 The Black-Winged Kite Algorithm

The Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) [35] is inspired by the hunting and migration behaviors of black-winged kites. It consists of two main phases: attack (local search/perturbation) and migration (leader-guided exploitation).

Attack phase: Agents perform decaying local perturbations. Key update formula:

where

Migration phase: Agents move under leader guidance with fitness-adaptive updates:

where

Detailed expressions for

BKA’s novelty lies in combining decaying perturbation-based local search with fitness-guided leader migration, effectively balancing exploration and exploitation. A summary of the algorithmic characteristics is provided in Table 11.

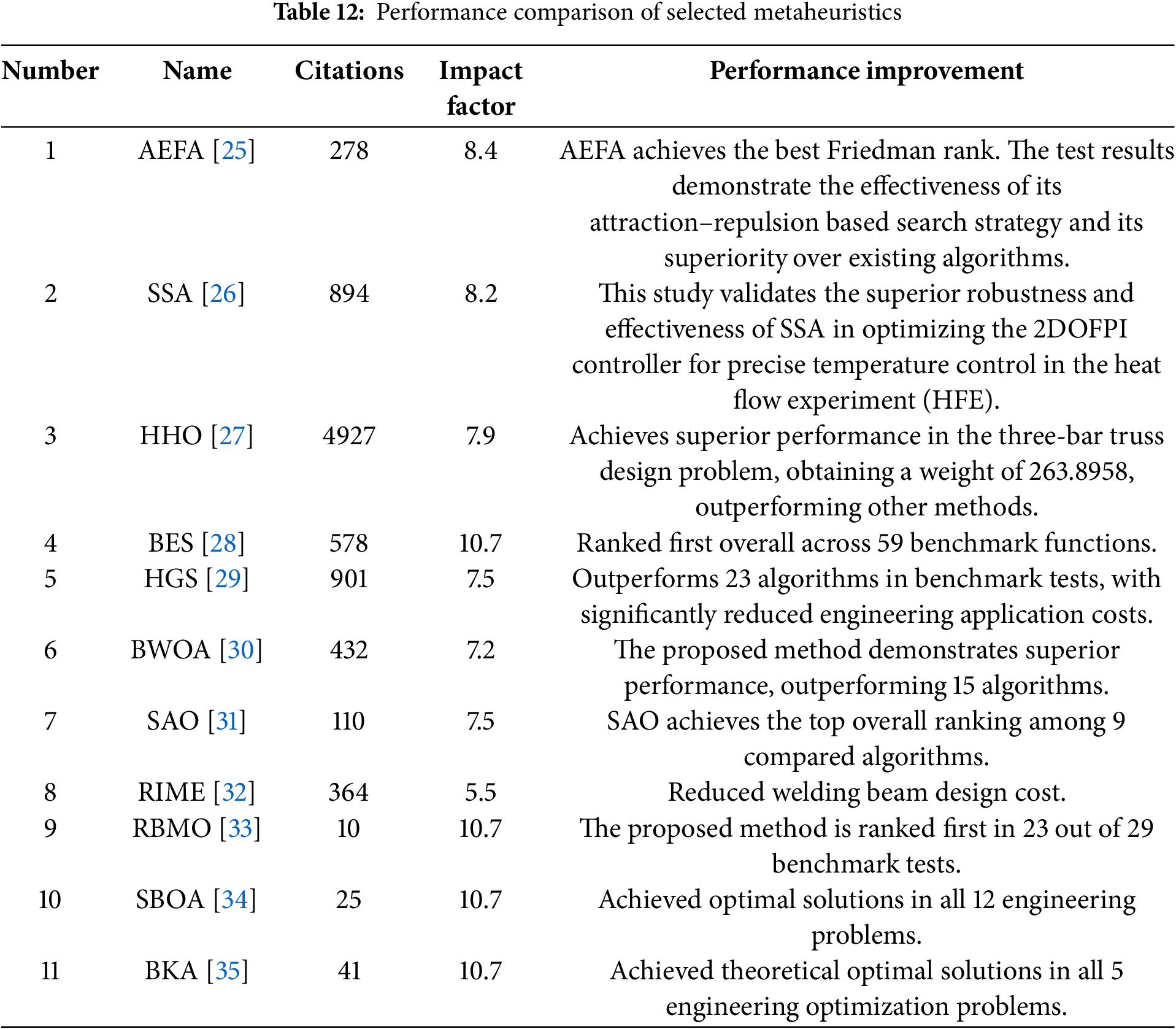

2.6 Metaheuristics: Extensions to e-Health Applications

Table 12 summarizes the performance of selected single metaheuristic algorithms in benchmark and engineering optimization problems, highlighting their effectiveness and practical impact. Beyond these individual algorithms, hybrid metaheuristics have also demonstrated considerable potential in addressing complex optimization problems. For instance, the hybrid Genetic Algorithm-Particle Swarm Optimization (GA-PSO) [36] outperforms Simulated Annealing (SA) and standalone Genetic Algorithm (GA) in solving the Reliability Redundancy Allocation Problem (RRAP), particularly in the optimization of series systems, series-parallel systems, and complex bridge systems. In the medical domain, some studies have attempted to apply metaheuristics in practice; for example, a Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) [37]-based ensemble learning framework achieved high accuracy in COVID-19 prediction, while an improved Hunger Games Search (mHGS) [38] algorithm enhanced feature selection for high-dimensional medical data. Nevertheless, such explorations remain limited. By contrast, metaheuristic algorithms have achieved more mature outcomes in tasks such as prediction and scheduling: the Modified Bald Eagle Search (MBES) [39] has been employed to optimize Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) hyperparameters, significantly improving short-term wind power forecasting accuracy, and the Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA) [40] has been successfully applied to unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) path planning, addressing challenges in navigation, obstacle avoidance, and route optimization. Therefore, future research is expected to further advance the application of metaheuristic algorithms in e-health, particularly in prediction and scheduling tasks, to provide more effective solutions to real-world problems.

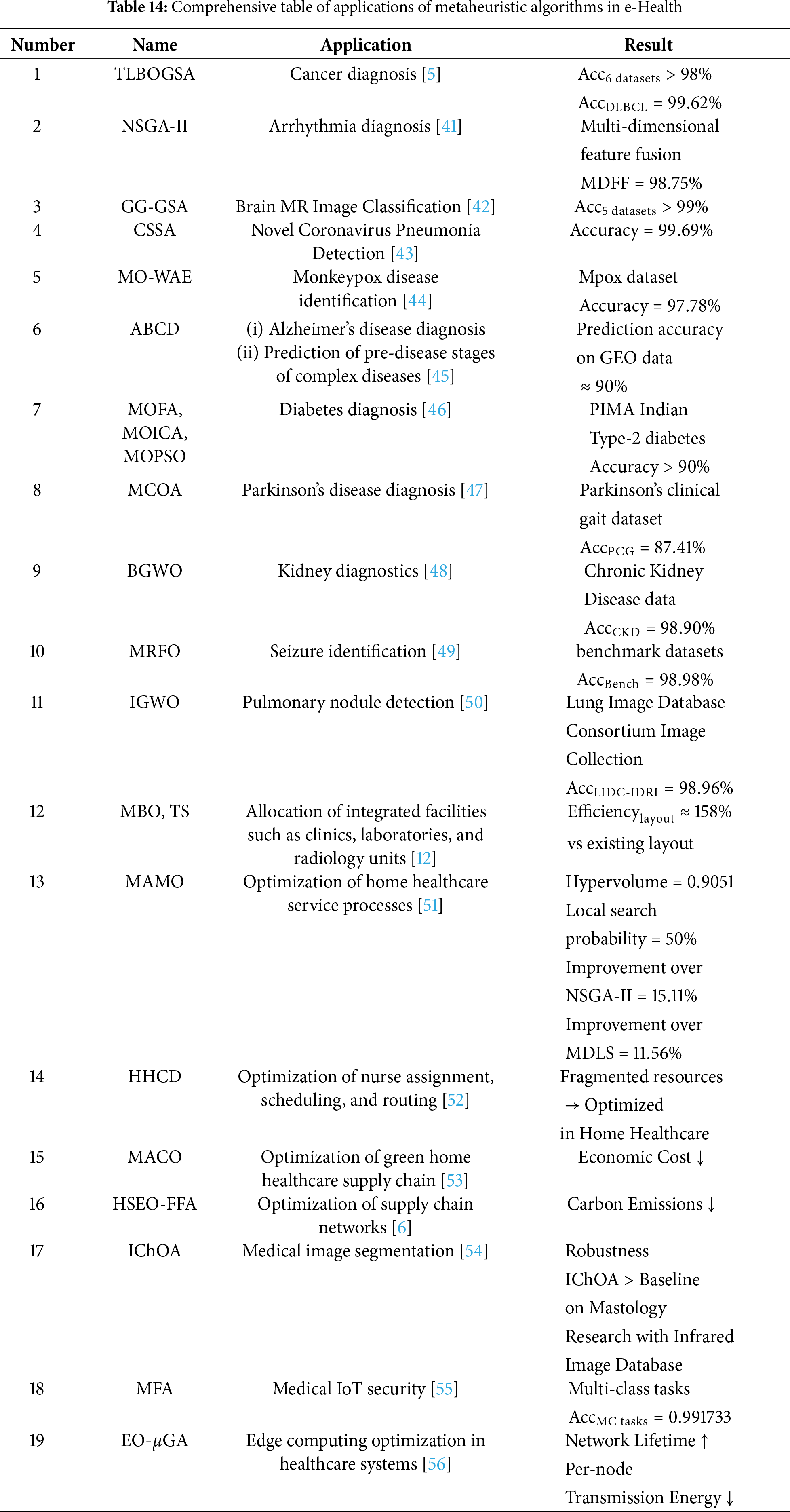

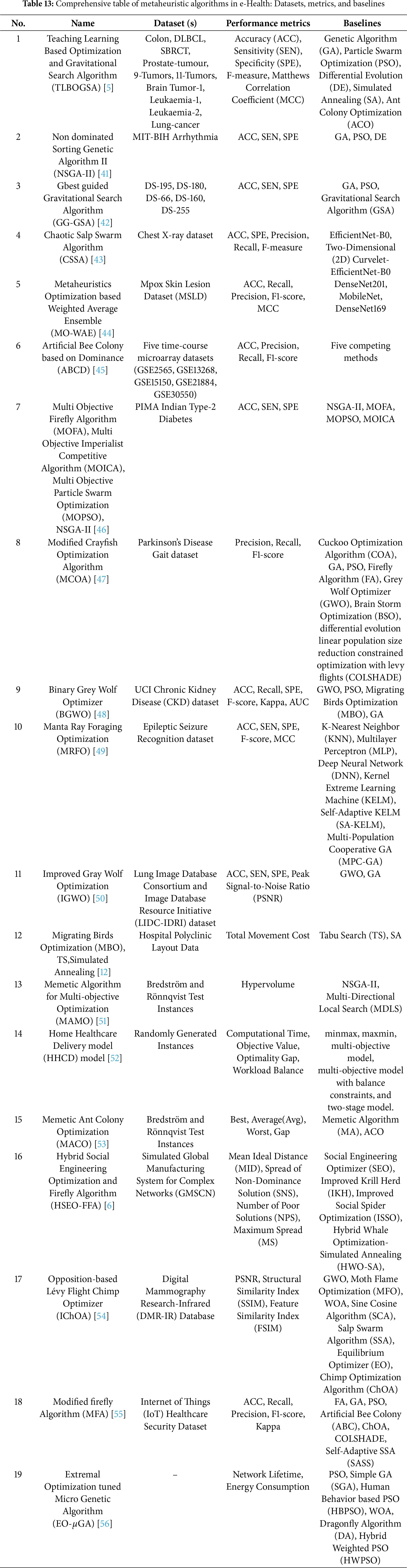

3 Application of Metaheuristic Algorithms in the Field of e-Health

Having surveyed the considerable advancements and diversification in metaheuristic algorithm design, especially the emergence of numerous nature-inspired and physics-based techniques, the focus now shifts to their practical deployment and impact. These optimization tools are increasingly used across scientific and engineering domains, with e-Health emerging as one of the most promising areas. To provide a structured overview of their applications in e-Health, Table 13 summarizes representative studies, including datasets, performance metrics, baseline methods, and reported outcomes. The subsequent subsections build on this overview, offering more detailed insights into specific optimization challenges and metaheuristic solutions.

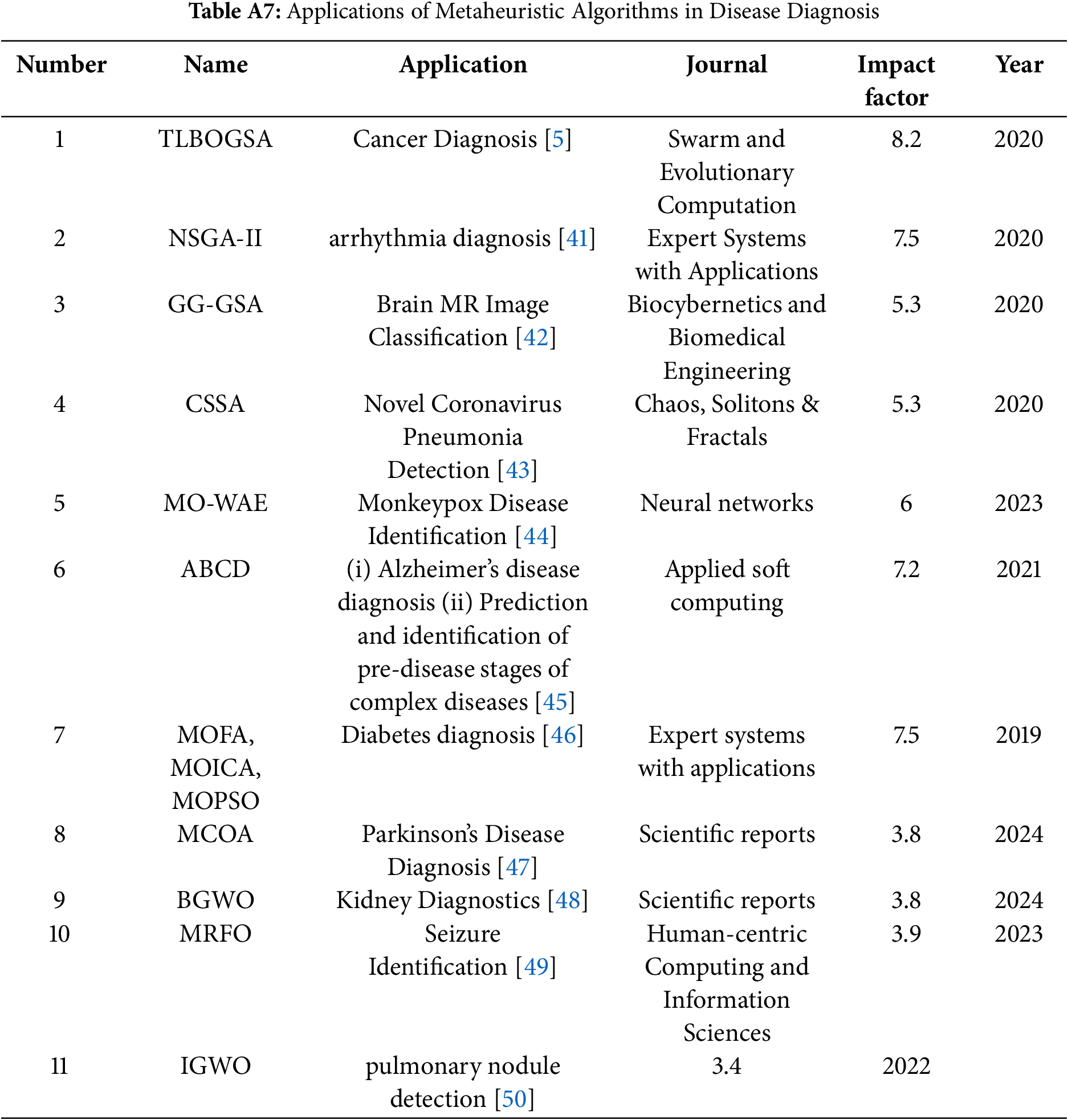

Metaheuristic algorithms have become pivotal tools for enhancing disease diagnosis in e-Health, demonstrating strong potential in addressing complexities inherent in medical data analysis. By effectively translating diagnostic challenges into solvable optimization problems, these algorithms improve accuracy, efficiency, and extraction of clinically relevant insights from diverse data sources. Their versatility is evidenced by successful applications across a wide spectrum of medical conditions, including cancer diagnosis [5], arrhythmia detection [41], brain MR image classification [42], COVID-19 detection [43], monkeypox identification [44], Alzheimer’s assessment [45], diabetes diagnosis [46], kidney disease assessment [48], epilepsy identification [49], and pulmonary nodule detection [50]. Table A7 provides a detailed overview of representative studies in this area.

Fundamentally, metaheuristics succeed in disease diagnosis because they address three core computational tasks: feature selection, model parameter optimization, and multiobjective optimization. In feature selection, algorithms identify the most salient diagnostic markers from high-dimensional datasets, reducing model complexity and potentially improving generalization. For model parameter optimization, metaheuristics fine-tune hyperparameters of diagnostic models to achieve better performance than manual or grid-search methods. Multiobjective optimization frameworks simultaneously consider competing diagnostic goals, such as maximizing sensitivity and specificity or balancing accuracy with computational efficiency, yielding clinically relevant solutions.

A crucial element enabling metaheuristics to address these tasks effectively is the design of an appropriate fitness function. This function mathematically encodes the diagnostic goal, allowing the algorithm to quantitatively evaluate candidate solutions (e.g., feature subsets, parameter sets). The following examples illustrate how different fitness functions capture diverse diagnostic objectives, tailored for optimization by specific metaheuristic algorithms.

• Balancing Feature Differentiation and Classifier Confidence (TLBOGSA [5]):

Used in gene expression analysis for cancer, this function uses

• Minimizing Image Segmentation Error (GG-GSA [42]):

Minimizing the Mean Squared Error between true (

• Optimizing Accuracy vs. Feature Usage (CSSA [43]):

Maximizes a weighted sum of classification accuracy (Acc) and feature sparsity (

• Minimizing Classification Error Rate (Modified COA [47]):

A direct optimization objective focused on minimizing misclassifications, applied here for Parkinson’s disease diagnosis using selected features.

• Balancing Feature Relevance and Dimensionality (Binary GWO [48]):

Selects feature subsets (S) for kidney disease diagnosis by balancing correlation with disease state (

• Directly Minimizing Misclassification Percentage (MRFO [49]):

Optimizes classification performance by directly minimizing the error percentage, shown effective for EEG-based epilepsy identification.

• Dual-Objective: Detection Rate vs. False Positives (Improved GWO [50]):

Addresse the trade-off in detection tasks (e.g., pulmonary nodules) by simultaneously optimizing detection rate (P) and false positive suppression (

Through the application of such tailored optimization strategies, metaheuristic algorithms are significantly advancing the accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of automated disease diagnosis systems, thereby offering valuable support for clinical practice and decision-making.

3.1.1 Optimizing Feature Extraction for Enhanced Diagnosis

High-dimensional data, common in medical applications like genomics, imaging, and signal processing, presents a significant challenge known as the ’curse of dimensionality’. Metaheuristic algorithms are crucial for addressing this challenge, facilitating effective feature extraction and selection [57]. By identifying the most diagnostically relevant features and discarding redundant or noisy ones, these algorithms can significantly improve the performance, efficiency, and interpretability of diagnostic models.

Several studies exemplify this capability across different medical domains. In cancer genomics, predicting discriminative genes from thousands of expression profiles is particularly challenging due to high dimensionality and inefficiency of existing hybrid approaches. To address this, Shukla et al. proposed a hybrid Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization and Gravitational Search Algorithm (TLBOGSA) [5]. Their method was evaluated on multiple datasets, including Colon, DLBCL, SBRCT, Prostate-tumour, and Leukaemia, consistently outperforming traditional methods such as GA, PSO, DE, SA, and ACO in accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F-measure.

Similarly, in cardiology, automatically classifying arrhythmias from complex Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals remains challenging due to high dimensionality and redundancy. Mazaheri and Khodadadi applied a multi-objective metaheuristic algorithm, non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II), for feature selection on the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia dataset [41]. Compared with GA, PSO, DE, and NSGA, this approach significantly improved accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, reaching 98.75% classification accuracy, thereby enhancing both diagnostic efficiency and feature selection effectiveness.

Furthermore, in medical imaging, conventional brain MR image analysis is time-consuming and less effective. To address these challenges, Shanker et al. employed a Gbest-guided Gravitational Search Algorithm (GG-GSA) within a CAD system for brain MR image classification [42]. GG-GSA optimized texture feature selection across multiple benchmark datasets (DS-195, DS-180, DS-66, DS-160, and DS-255), achieving accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity exceeding 99%. Compared with GA, PSO, and standard GSA, GG-GSA consistently outperformed baseline methods while reducing the need for manual intervention.

These examples illustrate the power of metaheuristics in distilling high-dimensional medical data into informative feature subsets essential for accurate disease diagnosis.

3.1.2 Fine-Tuning Diagnostic Models via Parameter Optimization

Beyond selecting salient features, metaheuristic algorithms also excel at optimizing the internal parameters and hyperparameters of diagnostic models, a crucial step for maximizing predictive performance [58]. Traditional methods, such as grid search or manual tuning, can be inefficient in high-dimensional parameter spaces. Metaheuristics offer a more effective approach, enhancing model accuracy, generalization, and stability while mitigating risks like overfitting.

Addressing the urgent need for rapid COVID-19 detection, RT-PCR tests are limited, time-consuming, and carry infection risks. Altan et al. proposed a hybrid model combining 2D Curvelet transformation, deep learning, and the Chaos Salp Swarm Algorithm (CSSA) [43]. CSSA optimized the hyperparameters of the deep learning architecture trained on chest X-ray datasets. This enhanced performance metrics including accuracy, specificity, precision, recall, and F-measure. Compared with EfficientNet-B0 and 2D Curvelet-EfficientNet-B0, the CSSA-optimized model achieved 99.69% accuracy, demonstrating suitability for rapid clinical screening.

Monkeypox detection remains challenging, as most existing methods rely solely on CNN architectures without metaheuristic-based ensemble optimization. To improve prediction accuracy, Asif et al. proposed a metaheuristic-optimized weighted average ensemble (MO-WAE) model combining multiple CNNs [44]. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) optimized the ensemble weights. Evaluated on the Mpox Skin Lesion Dataset (MSLD), the MO-WAE model achieved 97.78% accuracy, outperforming DenseNet201, MobileNet, and DenseNet169, demonstrating its effectiveness for robust disease identification.

These studies underscore the value of metaheuristics in fine-tuning diverse diagnostic models, ranging from traditional machine learning to deep learning and ensemble systems, thereby enhancing clinical utility.

3.1.3 Addressing Complex Trade-Offs with Multi-Objective Optimization

While optimizing individual aspects like feature selection or model parameters is valuable, many real-world diagnostic scenarios involve inherent trade-offs between multiple, often conflicting objectives. For example, maximizing diagnostic sensitivity might increase false positives, reducing specificity, or achieving highest accuracy might require computationally expensive models or large feature sets impractical for clinical use. Multi-objective optimization (MOO) techniques, particularly metaheuristic-driven ones, are designed to address such complex situations [59]. Rather than finding a single optimal solution, MOO identifies a set of non-dominated solutions, each representing a different balance among competing objectives, providing decision-makers with viable options tailored to clinical needs or resource constraints.

The application of metaheuristic-based MOO offers significant advantages for disease diagnosis, particularly early detection. Early-stage detection often requires identifying subtle dynamic changes, as traditional static molecular biomarkers are insufficient. Coleto-Alcudia and Vega-Rodríguez framed the identification of Dynamic Network Biomarkers (DNBs) as a multi-objective problem [45]. Using a multi-objective Artificial Bee Colony algorithm (ABCD), they simultaneously optimized network simplicity, the strength of early warning signals, and the association between gene networks and disease phenotypes. The method was validated on multiple GEO datasets (GSE2565, GSE13268, GSE15150, GSE21884, GSE30550), evaluating accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Compared with five competing methods, ABCD consistently achieved approximately 90% prediction accuracy, highlighting its potential for identifying pre-disease stages often overlooked by single-objective approaches.

Similarly, diabetes diagnosis involves analyzing high-dimensional patient data with outliers and redundant features, making classification challenging. Alirezaei et al. combined k-means clustering for outlier removal with multi-objective metaheuristics—including MOFA, MOICA, NSGA-II, and MOPSO—to select key features and optimize SVM classification [46]. Experiments on the PIMA Indian Type-2 Diabetes dataset evaluated accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. All algorithms achieved over 90% accuracy and provided a diverse Pareto front, enabling clinicians to balance predictive performance with interpretability and practical considerations.

By explicitly managing these trade-offs, multi-objective metaheuristic optimization provides more nuanced, flexible, and clinically practical solutions than single-objective approaches, marking a significant advancement in e-health tool development.

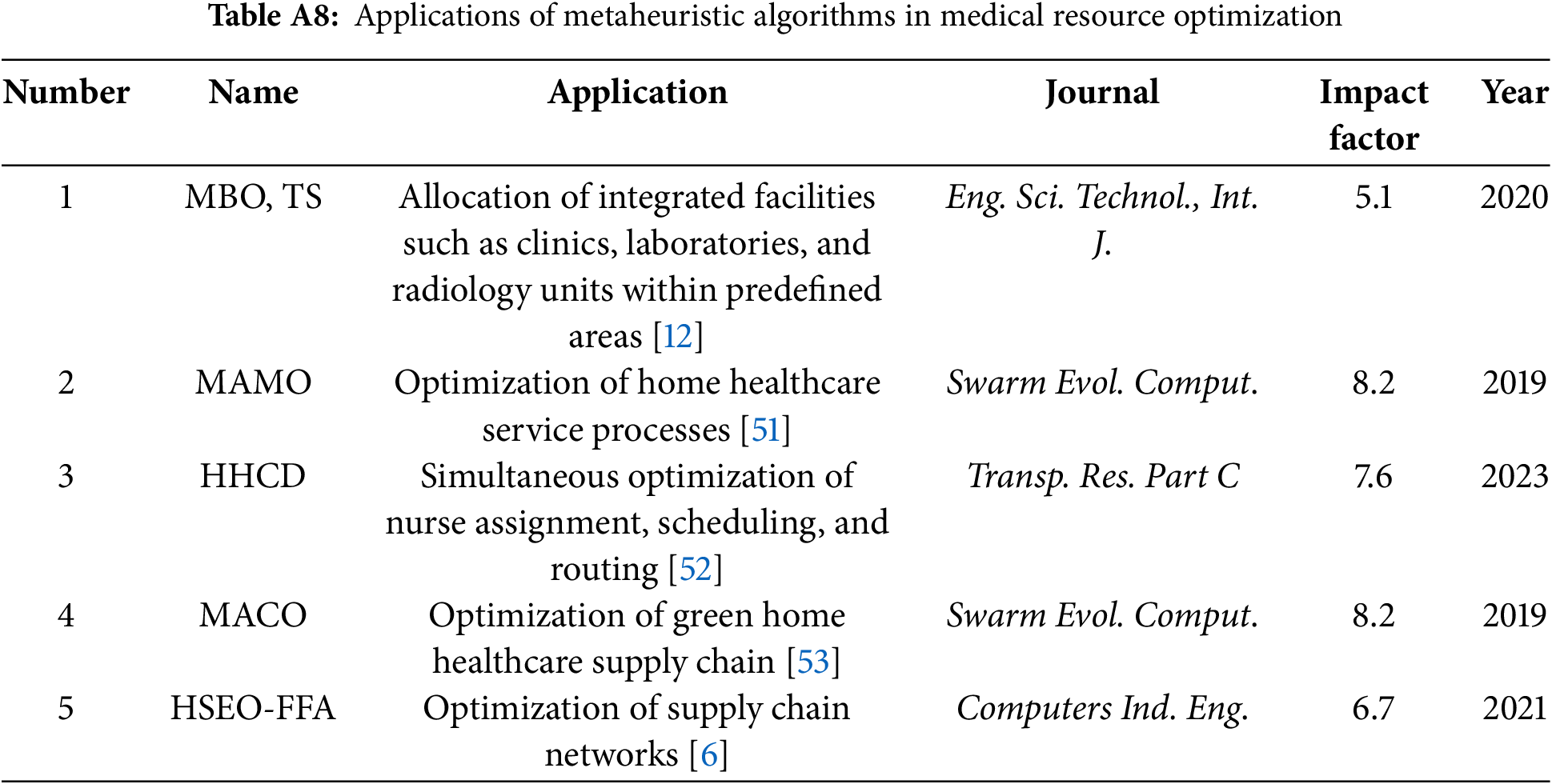

3.2 Medical Resource Optimization

Effective resource optimization is essential for improving healthcare system performance, covering infrastructure, workforce, and service delivery [60–62]. Given the growing complexity of multi-objective and multi-modal problems in healthcare, metaheuristic algorithms have been widely applied to provide efficient and high-quality solutions. Representative studies include the Migrating Birds Optimization and Tabu Search for facility allocation [12], Memetic Multi-objective Optimization (MAMO) for home healthcare services [51], the HHCD model for nurse scheduling and routing [52], Memetic Ant Colony Optimization (MACO) for green supply chains [53], and the Hybrid Socio-engineering Firefly Algorithm (HSEO-FFA) for supply chain network design [6]. The details are summarized in Table A8. Overall, metaheuristic algorithms have become crucial tools in this domain, offering robust capabilities to navigate complex optimization challenges and improve medical resource utilization [60].

3.2.1 Optimization of Healthcare Infrastructure

The physical and organizational infrastructure of healthcare, including hospitals, clinics, and laboratories, dictates service accessibility and operational efficiency [63]. These facilities form complex systems where layout and location significantly impact costs and quality of care. Metaheuristics are increasingly applied to address inherent optimization problems in infrastructure design.

Efficient hospital facility layout is crucial for minimizing patient and staff movement, particularly in large hospitals with multiple specialized departments. This is a complex optimization challenge due to numerous interacting units and constraints. To address this, Tongur et al. [12] applied metaheuristic algorithms—including Migrating Birds Optimization (MBO), Tabu Search (TS), and Simulated Annealing (SA)—to optimize the placement of polyclinics, laboratories, and radiology units. Experiments on real hospital layout data evaluated performance using the Total Movement Cost. Results showed that MBO and TS consistently produced superior layouts, with MBO achieving approximately 58% improvement in internal movement efficiency compared to SA. The study also highlighted the sensitivity of algorithm performance to parameter tuning, emphasizing the importance of adaptive strategies in practical hospital planning.

3.2.2 Optimization of Healthcare Human Resources

The healthcare workforce is a cornerstone of any health system, and its effective management—addressing size, composition, distribution, training, and particularly scheduling—is essential for quality care and operational performance [64]. Metaheuristics provide powerful solutions for the complex combinatorial optimization problems common in human resource management, which are particularly challenging in distributed e-Health contexts such as home healthcare (HHC).

Home health care (HHC) scheduling involves complex planning, as caregivers’ assignments must minimize total work time, ensure high-quality service, and maintain fair workload distribution. Decerle et al. [51] proposed a multi-objective memetic algorithm (MAMO) for HHC route planning and scheduling. The algorithm was validated on Bredström and Rönnqvist benchmark test instances, with performance assessed using the Hypervolume metric. Applying a 50% local search probability, MAMO achieved a hypervolume of 0.9051, improving 15.11% over NSGA-II and 11.56% over MDLS. These results demonstrate that the memetic approach effectively balances multiple objectives, offering an efficient and practical solution for caregiver scheduling.

Similarly, HHC planning requires simultaneously assigning nurses, scheduling their workdays, and routing them between patients while balancing objectives such as minimizing service costs and ensuring fair workload distribution. Alkaabneh and Diabat [52] proposed a multi-objective Home Health Care Delivery (HHCD) model using a two-stage metaheuristic approach. The method was evaluated on randomly generated test instances, with performance metrics including computational time, objective value, optimality gap, and workload balance. Compared with baseline methods such as MinMax and MaxMin, the HHCD framework achieved superior results in cost reduction and nurse–patient workload balancing, highlighting its effectiveness and practical applicability in real-world HHC operations.

These studies exemplify how metaheuristics can navigate the multi-objective trade-offs inherent in optimizing healthcare personnel deployment and scheduling, providing effective solutions for complex real-world scenarios.

3.2.3 Optimization of Healthcare Service Logistics and Supply Chains

Beyond personnel, optimizing the logistics involved in delivering healthcare services and managing essential supplies, such as pharmaceuticals, is critical for overall system efficiency and responsiveness. Metaheuristics are instrumental in addressing complex routing, scheduling, and supply chain network design problems.

Home health care (HHC) routing and supply chain planning must satisfy multiple constraints, including caregiver skills, time windows, synchronization requirements, and workload balancing, while maintaining operational efficiency. Decerle et al. [53] proposed a hybrid Memetic-Ant Colony Optimization algorithm (MACO) for green HHC supply chains. The method was evaluated on Bredström and Rönnqvist benchmark instances, with performance compared against classical Memetic Algorithm (MA) and standard Ant Colony Optimization (ACO). MACO consistently reduced economic costs, demonstrating its effectiveness in achieving fair and efficient planning while integrating sustainability considerations.

Designing a green pharmaceutical supply chain requires addressing complex, uncertain, and multi-objective decisions across production, distribution, and routing, while minimizing environmental impacts. Goodarzian et al. [6] proposed a hybrid Social Engineering Optimizer-Firefly Algorithm (HSEO-FFA) to optimize the supply chain network. The approach was tested on simulated green medicine supply chain instances, with performance evaluated using Pareto-based metrics such as Mean Ideal Distance (MID) and Spread of Non-dominated Solutions (SNS). Compared with baseline methods including SEO, IKH, ISSO, HWO-SA, and HFFA-SA, HSEO-FFA effectively reduced logistics costs and greenhouse gas emissions, demonstrating its efficiency in solving multi-objective MILP models under uncertainty.

These case studies illustrate how metaheuristics can integrate naturally into healthcare logistics and supply chains, improving operational performance while addressing both practical and environmental considerations.

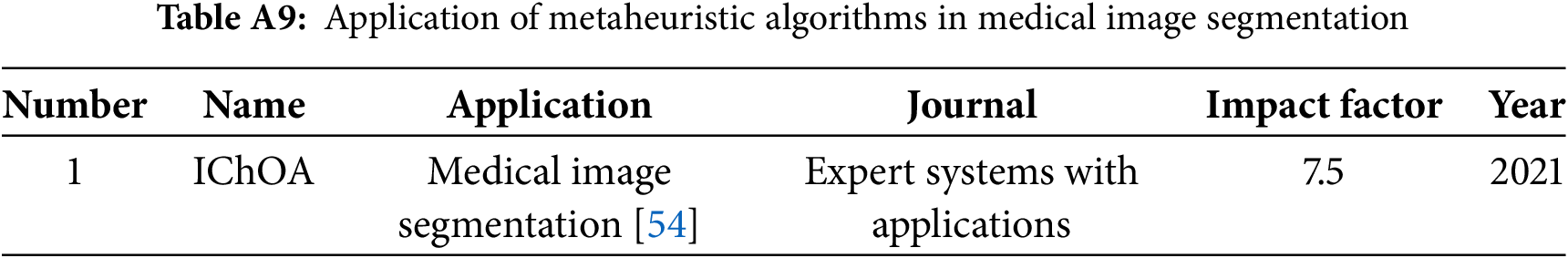

3.3 Medical Image Segmentation

Metaheuristic algorithms are effectively applied to medical image analysis, particularly in segmentation tasks crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning (see Table A9). Houssein et al. [54] demonstrated that these algorithms can improve segmentation efficiency and precision, supporting reliable e-Health applications.

Accurate delineation of anatomical structures in breast cancer thermography images is critical for early diagnosis and treatment planning. Conventional segmentation methods often face challenges such as premature convergence to local optima. To address this, Houssein et al. [54] proposed an improved Chimpanzee Optimization Algorithm (IChOA) that incorporates adversarial learning and a Lévy flight strategy to enhance exploration and convergence. The approach was evaluated on a breast cancer thermal image dataset using segmentation accuracy, precision, and image quality indices. Compared with the original ChOA and seven other metaheuristic algorithms, IChOA achieved superior segmentation performance, highlighting its effectiveness in supporting early breast cancer detection.

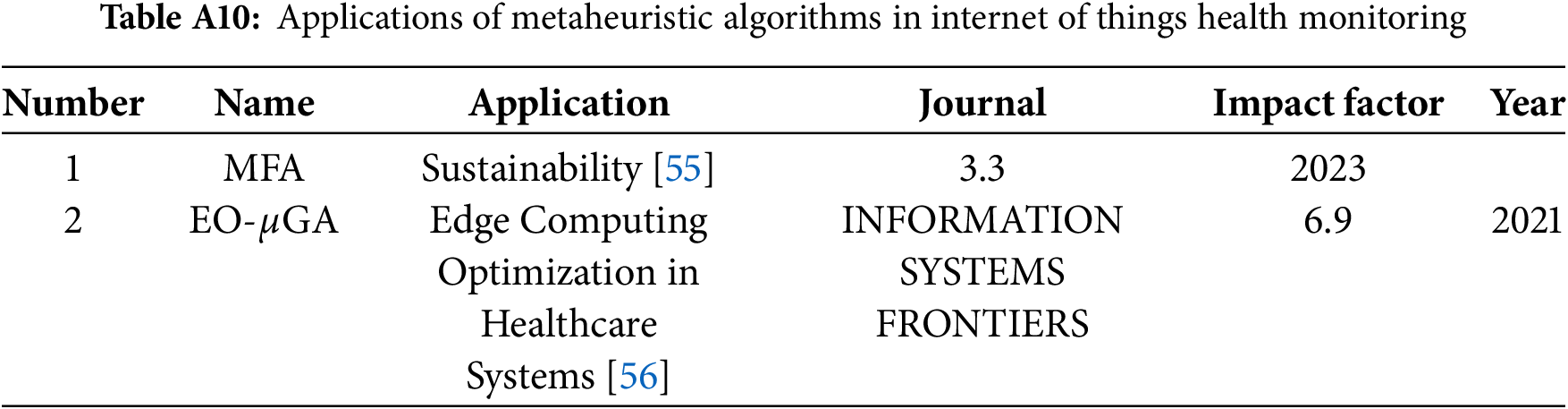

3.4 Internet of Things Health Monitoring

Metaheuristic algorithms play a vital role in securing and optimizing IoT infrastructures in healthcare. Applications include intrusion detection and energy-efficient resource management in IoT-enabled health systems [55,56]. These approaches enhance the safety, performance, and sustainability of IoT-based medical services, highlighting the diverse impact of metaheuristics in e-Health (see Table A10).

Ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of data transmitted by connected health devices is a critical challenge. Addressing this, Savanovic et al. [55] optimized machine learning models for intrusion detection in medical IoT environments using a modified Firefly Algorithm to fine-tune parameters. SHAP analysis identified key factors indicative of security threats. The approach was evaluated on a benchmark intrusion detection dataset using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Compared with standard ML classifiers without metaheuristic optimization, the Firefly-optimized models achieved superior detection performance, reinforcing IoT-based Healthcare 4.0 system security and reliability.

Beyond security, energy-efficient and reliable infrastructure is critical for responsive e-Health services. Majumdar et al. [56] optimized cluster communication and energy usage in healthcare-oriented edge computing networks. They proposed a clustering approach based on an extremal optimization–tuned micro-genetic algorithm (EO-

In conclusion, these examples, systematically summarized in Table 14, highlight the expanding and multi-faceted role of metaheuristic algorithms in advancing e-Health. Their applications extend beyond general optimization to address task-specific challenges:

In disease diagnosis, metaheuristics contribute to robust feature selection, effective model parameter tuning, and multi-objective trade-off handling, thereby improving predictive accuracy and clinical interpretability across diverse medical conditions.

In healthcare resource management, they enable efficient facility layout planning, equitable workforce scheduling, and sustainable logistics and supply chain optimization, balancing cost, efficiency, and fairness under real-world constraints.

In specialized domains, such as medical image segmentation, IoT healthcare security, and edge computing optimization, metaheuristics provide tailored solutions that enhance diagnostic precision, fortify data integrity, and extend system sustainability.

Collectively, these capabilities demonstrate that metaheuristics are not merely generic optimization tools but domain-adaptive frameworks capable of capturing the complexities of e-Health tasks. By systematically leveraging appropriate datasets, performance metrics, and baselines, they enable measurable and reproducible improvements in diagnostic accuracy, operational efficiency, security, and infrastructure resilience. Thus, metaheuristic-driven optimization represents a pivotal enabler for building robust, secure, efficient, and clinically effective e-Health systems. Table 14 provides a comprehensive summary of these applications, consolidating their datasets, evaluation criteria, and comparative baselines

4 Critical Analysis and Limitations

Despite these advancements, several challenges and limitations persist. A critical comparison of different metaheuristic algorithms reveals that their performance often varies significantly depending on the problem domain, with some algorithms converging faster but being more prone to local optima, while others offer better global exploration at the cost of computational efficiency. Many metaheuristic algorithms exhibit sensitivity to parameter settings, requiring careful tuning for optimal performance. The risk of premature convergence to local optima remains a concern for some algorithms, necessitating strategies to enhance global exploration capabilities.

Furthermore, the inherent complexity and often stochastic nature of metaheuristics can lead to “black-box” models, posing challenges for interpretability and trust, which are crucial in high-stakes medical applications; integrating explainability techniques is therefore becoming increasingly important. In medical contexts, the lack of intrinsic interpretability can hinder clinical decision-making, as physicians require transparent reasoning to validate algorithmic recommendations. The theoretical foundations of many metaheuristic algorithms remain underdeveloped, with limited convergence guarantees or performance bounds, a critical concern in medical contexts where decisions impact patient outcomes.

Scalability to handle massive datasets and the computational demands of real-time e-Health applications present ongoing hurdles. Particularly in IoT-enabled health monitoring, real-time constraints impose strict limits on algorithm complexity, requiring lightweight and efficient optimization methods. Bridging the gap between theoretical algorithm development and robust, validated clinical implementation requires significant effort, as most research remains at theoretical or simulation stages rather than proceeding to rigorous clinical validation. Reproducibility is also a challenge due to stochastic behavior and inconsistent parameter reporting, which limits validation across diverse datasets and clinical settings.

Finally, addressing data quality issues and ethical considerations, such as algorithmic bias in resource allocation or diagnostic recommendations, is paramount for responsible innovation in this domain. In addition, healthcare-specific constraints such as heterogeneous data sources, patient privacy, and compliance with regulations necessitate privacy-preserving optimization strategies and secure data handling mechanisms.

5 Conclusion and Future Directions

This review has provided a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of metaheuristic optimization algorithms and their significant contributions to the burgeoning field of e-Health. We traced the development from foundational algorithms like Genetic Algorithms and Particle Swarm Optimization to a plethora of recently proposed nature-inspired and physics-based techniques, highlighting the continuous innovation driven by the need to solve complex real-world problems. The application-focused sections demonstrated the tangible impact of these algorithms across critical e-Health domains, including enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of disease diagnosis through optimized feature selection, model parameter tuning, and multi-objective considerations, optimizing the allocation and management of vital medical resources such as infrastructure, personnel, and supply chains, and addressing specialized challenges in medical image analysis, IoT security, and edge computing.

The synergy between metaheuristic optimization and e-Health is evident in the improved performance of diagnostic systems, more efficient utilization of healthcare resources, and enhanced robustness and security of health informatics infrastructure. Metaheuristics have proven adept at navigating the high-dimensional, multi-modal, and often multi-objective optimization landscapes inherent in healthcare data and operations, offering powerful tools to support clinical decision-making and streamline healthcare delivery. These algorithms demonstrate unique capabilities in handling the complexity and uncertainty characteristic of medical environments, with their adaptability and flexibility proving particularly valuable in dynamic healthcare settings. Multi-objective optimization techniques, in particular, enable a more nuanced approach to balancing conflicting goals, such as diagnostic sensitivity vs. specificity or cost vs. quality of care, providing practical solutions for complex real-world scenarios where single-objective approaches would be insufficient. The original contribution of this study lies in systematically synthesizing both algorithmic advances and their concrete applications in e-Health, bridging the gap between theoretical development and clinical practice, and highlighting emerging opportunities where metaheuristics can address unmet healthcare needs.

Going forward, future research in metaheuristic optimization for e-Health may advance along three key directions. First, improving the theoretical reliability and performance predictability of algorithms in medical contexts remains crucial, including developing frameworks that provide convergence guarantees and performance bounds even in noisy and uncertain medical environments, designing robust multi-objective optimization strategies capable of handling increasing complexity, competing demands, and dynamic changes in critical care, emergency settings, and large-scale IoT or edge computing systems, and implementing adaptive parameter mechanisms that reduce dependence on manual tuning. Despite these advances, there is still a lack of concrete, actionable research gaps directly linking algorithmic innovation with specific clinical needs, such as optimizing individualized treatment plans, integrating heterogeneous medical data, or tailoring algorithms for low-resource healthcare systems. Second, developing more adaptive, deployable, and interpretable algorithmic mechanisms suitable for real-world e-Health systems is essential, including novel hybrid algorithms that combine the strengths of different metaheuristics or integrate them with machine learning, particularly deep learning paradigms, embedding explainable AI (XAI) methods to achieve intrinsic transparency rather than relying solely on post-hoc explanations, and exploring dynamic, real-time optimization techniques that can adapt to rapidly changing healthcare environments. Implementation research for resource-limited settings, seamless integration into clinical workflows, and development of practical deployment strategies will further ensure that theoretical advances translate into meaningful clinical impact. Third, incorporating ethical, privacy, and emerging technology considerations into optimization frameworks is increasingly important, including fairness-constrained optimization, privacy-preserving approaches such as federated learning combined with metaheuristics, and exploration of emerging trends such as AI–metaheuristic hybrid systems, federated optimization, and quantum metaheuristics, which offer potential applications in precision medicine, digital twin healthcare systems, brain-computer interfaces, medical robotics, and intelligent medical devices. By emphasizing both technical and healthcare-specific challenges, this review not only maps the current state of the field but also outlines a pathway for future advances that could significantly improve patient outcomes, healthcare system efficiency, and health equity.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all colleagues and collaborators who contributed to discussions and data collection for this study.

Funding Statement: Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62506054), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (Grant Nos. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX1571, CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX1118), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant Nos. KJQN202400841, KJZD-M202500804), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61976030), Chongqing Technology and Business University High-level Talent Research Initiation Project (Grant No. 2256004).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Simon Fong, Huafeng Qin; data collection: Chao Gao, Han Wu, Zhiheng Rao; draft manuscript preparation: Qun Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new data were generated or analyzed in this study. All data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding references cited in this paper.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Supplementary Tables

Appendix A.1 Emerging Metaheuristics in 2019

Appendix A.2 Emerging Metaheuristics in 2020

Appendix A.3 Emerging Metaheuristics in 2021

Appendix A.4 Emerging Metaheuristics in 2022

Appendix A.5 Emerging Metaheuristics in 2023

Appendix A.6 Emerging Metaheuristics in 2024

Appendix A.7 Applications of Metaheuristic Algorithms in Disease Diagnosis

The following table summarizes recent applications of metaheuristic algorithms in disease diagnosis, including datasets, journals, impact factors, and publication years.

Appendix A.8 Applications of Metaheuristic Algorithms in Medical Resource Optimization

Appendix A.9 Application of Metaheuristic Algorithms in Medical Image Segmentation

Appendix A.10 Applications of Metaheuristic Algorithms in Internet of Things Health Monitoring

Appendix B Supplementary Materials

Appendix B.1 Artificial Electric Field Algorithm Formulas

The detailed AEFA equations include the relative charge calculation:

Force between particles:

Adaptive Coulomb constant:

Total force, velocity, and position updates:

Appendix B.2 Squirrel Search Algorithm Formulas

Detailed SSA equations include:

Trial solution generation:

Towards-rand search direction:

Towards-best search direction:

Additional details include randomized step-size ranges, projection operations using orthogonal matrices, and selection procedures based on fitness comparison.

Appendix B.3 Harris Hawks Optimizer Formulas

Detailed HHO equations include:

Additional exploitation updates may involve the average population position

Appendix B.4 Bald Eagle Search Formulas

Detailed BES equations include:

Select phase:

Search phase (spiral exploration):

Swoop phase (dive toward prey):

The coefficients

Appendix B.5 Hunger Games Search Formulas

Detailed HGS equations include:

Position update:

Energy calculation:

Adaptive hunger weight:

These dynamic weight mechanisms ensure that individuals with poorer fitness increase their search activity, thereby promoting exploration and guiding the optimization process adaptively.

Appendix B.6 Beluga Whale Optimization Algorithm Formulas

Exploration phase update:

Exploitation phase update:

Whale fall phase update:

These formulas allow BWOA to dynamically switch between exploration, exploitation, and diversification while maintaining the balance necessary for effective global optimization.

Appendix B.7 Snow Ablation Optimizer Formulas:

Follower (Exploration) detailed updates:

Additional stochastic updates, centroid computations, and Brownian motion generation formulas are included here.

Leader (Exploitation) detailed updates:

Additional guidance rules and dynamic adaptation of melting rate M are included here.

Appendix B.8 Rime Optimization Algorithm Formulas

Soft-rime (Exploration) detailed updates:

Additional rules: iteration-dependent evolution of

Hard-rime (Exploitation) detailed updates:

Additional updates: probabilistic adoption of best solution, normalized fitness scaling, and greedy selection steps.

Appendix B.9 Red-Billed Blue Magpie Optimizer Formulas

Food search phase (detailed):

Additional details: random group selection (

Prey attack phase (detailed):

Additional rules: group size modulation, random perturbation

Adaptive coefficient:

Appendix B.10 Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm Formulass

Hunting stage detailed updates:

Escape mechanism detailed updates:

Appendix B.11 Black-Winged Kite Algorithm Formulas

Attack phase (detailed):

Migration phase (detailed):

References

1. Bertsimas D, Tsitsiklis J. Simulated annealing. Stat Sci. 1993;8(1):10–5. doi:10.1214/ss/1177011077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Holland JH. Genetic algorithms. Sci Am. 1992;267(1):66–73. [Google Scholar]

3. Dorigo M, Birattari M, Stutzle T. Ant colony optimization. IEEE Comput Intell Mag. 2006;1(4):28–39. doi:10.1109/mci.2006.329691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kennedy J, Eberhart R. Particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks. Vol. 4. New York. NY, USA: IEEE; 1995. p. 1942–8. [Google Scholar]

5. Shukla AK, Singh P, Vardhan M. Gene selection for cancer types classification using novel hybrid metaheuristics approach. Swarm Evol Comput. 2020;54:100661. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2020.100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Goodarzian F, Wamba SF, Mathiyazhagan K, Taghipour A. A new bi-objective green medicine supply chain network design under fuzzy environment: hybrid metaheuristic algorithms. Comput Ind Eng. 2021;160:107535. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2021.107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. WhatEysenbach G. What is e-health? J Med Internet Res. 2001;3(2):e833. [Google Scholar]

8. Jiang X, Xie H, Tang R, Du Y, Li T, Gao J, et al. Characteristics of online health care services from China’s largest online medical platform: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e25817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Gong K, Xu Z, Cai Z, Chen Y, Wang Z. Internet hospitals help prevent and control the epidemic of COVID-19 in China: multicenter user profiling study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e18908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Harahap TH, Mansouri S, Abdullah OS, Uinarni H, Askar S, Jabbar TL, et al. An artificial intelligence approach to predict infants’ health status at birth. Int J Med Inform. 2024;183:105338. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kaur S, Kumar Y, Koul A, Kumar Kamboj S. A systematic review on metaheuristic optimization techniques for feature selections in disease diagnosis: open issues and challenges. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2023;30(3):1863–95. doi:10.1007/s11831-022-09853-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Tongur V, Hacibeyoglu M, Ulker E. Solving a big-scaled hospital facility layout problem with meta-heuristics algorithms. Eng Sci Technol, Int J. 2020;23(4):951–9. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2019.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cauchy A. Méthode générale pour la résolution des systemes d’équations simultanées. Comp Rend Sci Paris. 1847;25(1847):536–8. (In French). [Google Scholar]

14. Ypma TJ. Historical development of the newton-raphson method. SIAM Rev. 1995;37(4):531–51. doi:10.1137/1037125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hestenes MR, Stiefel E. Methods of conjugate gradients for solving linear systems. J Res Natl Bur Stand. 1952;49(6):409–36. [Google Scholar]

16. Huffman DA. A method for the construction of minimum-redundancy codes. Proc IRE. 1952;40(9):1098–101. doi:10.1109/jrproc.1952.273898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nelder JA, Mead R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput J. 1965;7(4):308–13. doi:10.1093/comjnl/7.4.308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD, Vecchi MP. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science. 1983;220(4598):671–80. doi:10.1126/science.220.4598.671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Holland JH. Adaptation in natural and artificial systems: an introductory analysis with applications to biology, control, and artificial intelligence. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

20. Glover F. Future paths for integer programming and links to artificial intelligence. Comput Oper Res. 1986;13(5):533–49. [Google Scholar]

21. Dorigo M, Maniezzo V, Colorni A. Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part B. 1996;26(1):29–41. doi:10.1109/3477.484436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Storn R, Price K. Differential evolution-a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J Global Optimiz. 1997;11:341–59. doi:10.1023/a:1008202821328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li XL, Shao ZJ, Qian JX. An optimizing method based on autonomous animats: fish-swarm algorithm. Syst Eng-Theory Pract. 2002;22(11):32–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

24. Karaboga D. An idea based on honey bee swarm for numerical optimization. Kayseri, Türkiye: Technical Report-tr06, Erciyes University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

25. Anita, Yadav A. AEFA: artificial electric field algorithm for global optimization. Swarm Evol Comput. 2019;48:93–108. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2019.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jain M, Singh V, Rani A. A novel nature-inspired algorithm for optimization: squirrel search algorithm. Swarm Evol Comput. 2019;44:148–75. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2018.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Heidari AA, Mirjalili S, Faris H, Aljarah I, Mafarja M, Chen H. Harris hawks optimization: algorithm and applications. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;97:849–72. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.02.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alsattar HA, Zaidan A, Zaidan B. Novel meta-heuristic bald eagle search optimisation algorithm. Artif Intell Rev. 2020;53:2237–64. doi:10.1007/s10462-019-09732-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yang Y, Chen H, Heidari AA, Gandomi AH. Hunger games search: visions, conception, implementation, deep analysis, perspectives, and towards performance shifts. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;177:114864. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhong C, Li G, Meng Z. Beluga whale optimization: a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;251:109215. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Deng L, Liu S. Snow ablation optimizer: a novel metaheuristic technique for numerical optimization and engineering design. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;225:120069. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Su H, Zhao D, Heidari AA, Liu L, Zhang X, Mafarja M, et al. RIME: a physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing. 2023;532:183–214. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fu S, Li K, Huang H, Ma C, Fan Q, Zhu Y. Red-billed blue magpie optimizer: a novel metaheuristic algorithm for 2D/3D UAV path planning and engineering design problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(6):1–89. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10716-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fu Y, Liu D, Chen J, He L. Secretary bird optimization algorithm: a new metaheuristic for solving global optimization problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(5):1–102. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10729-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang J, Wang Wc, Hu Xx, Qiu L, Zang Hf. Black-winged kite algorithm: a nature-inspired meta-heuristic for solving benchmark functions and engineering problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(4):98. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10723-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sheikhalishahi M, Ebrahimipour V, Shiri H, Zaman H, Jeihoonian M. A hybrid GA-PSO approach for reliability optimization in redundancy allocation problem. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2013;68(1):317–38. doi:10.1007/s00170-013-4730-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Debjit K, Islam MS, Rahman MA, Pinki FT, Nath RD, Al-Ahmadi S, et al. An improved machine-learning approach for COVID-19 prediction using Harris Hawks optimization and feature analysis using SHAP. Diagnostics. 2022;12(5):1023. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12051023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Houssein EH, Hosney ME, Mohamed WM, Ali AA, Younis EM. Fuzzy-based hunger games search algorithm for global optimization and feature selection using medical data. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(7):5251–75. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07916-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Tuerxun W, Xu C, Guo H, Guo L, Zeng N, Gao Y. A wind power forecasting model using LSTM optimized by the modified bald eagle search algorithm. Energies. 2022;15(6):2031. doi:10.3390/en15062031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lyu L, Kong G, Yang F, Li L, He J. Augmented gold rush optimizer is used for engineering optimization design problems and UAV path planning. IEEE Access. 2024;12:134304–39. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3445269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mazaheri V, Khodadadi H. Heart arrhythmia diagnosis based on the combination of morphological, frequency and nonlinear features of ECG signals and metaheuristic feature selection algorithm. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;161:113697. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Shanker R, Bhattacharya M. An automated computer-aided diagnosis system for classification of MR images using texture features and gbest-guided gravitational search algorithm. Biocybern Biomed Eng. 2020;40(2):815–35. doi:10.1016/j.bbe.2020.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Altan A, Karasu S. Recognition of COVID-19 disease from X-ray images by hybrid model consisting of 2D curvelet transform, chaotic salp swarm algorithm and deep learning technique. Chaos Solit Fract. 2020;140:110071. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Asif S, Zhao M, Tang F, Zhu Y, Zhao B. Metaheuristics optimization-based ensemble of deep neural networks for Mpox disease detection. Neural Netw. 2023;167:342–59. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.08.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Coleto-Alcudia V, Vega-Rodríguez MA. A metaheuristic multi-objective optimization method for dynamical network biomarker identification as pre-disease stage signal. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;109:107544. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Alirezaei M, Niaki STA, Niaki SAA. A bi-objective hybrid optimization algorithm to reduce noise and data dimension in diabetes diagnosis using support vector machines. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;127:47–57. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.02.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Cuk A, Bezdan T, Jovanovic L, Antonijevic M, Stankovic M, Simic V, et al. Tuning attention based long-short term memory neural networks for Parkinson’s disease detection using modified metaheuristics. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):4309. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54680-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]