Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on Automated Game QA Reporting Based on Natural Language Captions

Department of Games (Engineering), Hongik University, Sejong, 30016, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Beomjoo Seo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Powered Software Engineering)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071084

Received 31 July 2025; Accepted 14 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Game Quality Assurance (QA) currently relies heavily on manual testing, a process that is both costly and time-consuming. Traditional script- and log-based automation tools are limited in their ability to detect unpredictable visual bugs, especially those that are context-dependent or graphical in nature. As a result, many issues go unnoticed during manual QA, which reduces overall game quality, degrades the user experience, and creates inefficiencies throughout the development cycle. This study proposes two approaches to address these challenges. The first leverages a Large Language Model (LLM) to directly analyze gameplay videos, detect visual bugs, and automatically generate QA reports in natural language. The second approach introduces a pipeline method: first generating textual descriptions of visual bugs in game videos using the ClipCap model, then using those descriptions as input for the LLM to synthesize QA reports. Through these two multi-faceted approaches, this study evaluates the feasibility of automated game QA systems. To implement this system, we constructed a visual bug database derived from real-world game cases and fine-tuned the ClipCap model for the game video domain. Our proposed approach aims to enhance both efficiency and quality in game development by reducing the burden of manual QA while improving the accuracy of visual bug detection and ensuring consistent, reliable report generation.Keywords

Bugs in games diminish player satisfaction and disrupt immersion, ultimately leading to negative gameplay experiences [1,2]. Game Quality Assurance (QA) is an essential component of the game development process, directly influencing a game’s success [3]. Insufficient testing can result in low ratings, negative reviews, and reduced concurrent player counts [4]. In contrast, effective QA enhances the overall game experience by identifying and resolving issues before release, ensuring stable and enjoyable gameplay that strengthens sales and brand loyalty [5].

Currently, game QA predominantly relies on manual testing. While this approach is valuable for exploring the game from a player’s perspective and identifying design flaws or user experience issues, it becomes inefficient and time-consuming in complex or repetitive scenarios [6]. These challenges are amplified in large-scale projects, where the reliance on manual QA, combined with the massive growth of verification data from high-quality graphics, physics engines, and player-driven content, creates substantial cost and efficiency problems [7,8]. On the other hand, indie game developers and small to medium-sized studios face a different challenge: maximizing QA efforts with limited staff and budgets [9,10].

To tackle these issues, automated QA tools have been introduced. However, current techniques face the following critical limitations:

• Script-based automated QA tools: These tools automatically navigate the UI or trigger events according to predefined sequences. They are brittle, as even minor UI changes or timing differences require reconfiguration, often resulting in overlooked errors.

• Log analysis-based automated QA tools: These tools analyze error messages and logs, but cannot detect visual bugs that are not recorded in logs, such as rendering artifacts, physics glitches, or scenarios that deviate from the intended game’s design.

These imply that while traditional automated QA tools are effective for verifying known, predictable conditions, they are ill-suited for discovering the atypical problems frequently encountered in modern games. Due to these shortcomings, developers cannot fully rely on automated QA tools and are often forced to revert to manual QA. Therefore, there is a need for a new method of automated QA that moves beyond simple rule-based automation and can instead ascertain the game’s state directly from on-screen visual data [7].

Artificial intelligence technology is rapidly evolving beyond text-based models to multimodal AI that can perceive, understand, and communicate like humans [11]. In the past, vision technology for classifying images and detecting objects, and language models for understanding and generating natural language, developed as separate fields [12]. However, the recent emergence of Vision-Language Models (VLMs), which integrate these two technologies, has opened a new direction in AI research [13]. By processing visual and textual data together and learning the complex relationships between them, these models demonstrate an ability to understand the context and meaning of an image, moving beyond simple object recognition.

This advancement in image understanding technology has extended to video data, which includes a temporal dimension [14,15]. Recent Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) can take sequential image frames as input to comprehend situational changes and character actions over time [16]. Game environments are particularly well-suited for leveraging the video understanding capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs), as they contain complex time-series data where dynamic interactions, explicit rules, and unpredictable events coexist. Consequently, research on QA benchmarks that evaluate question-answering over gameplay videos has become increasingly active.

Efforts to detect bugs in game images using VLMs are gaining momentum. Foundational work in this area includes benchmarks like GlitchBench [17], PhysGame [18], and VideoGameQA [19], which are designed to classify bug types and evaluate model performance. While these benchmarks are essential for assessing a model’s bug detection capabilities, our research addresses a different, more applied challenge: automating the generation of QA reports. Unlike benchmark tasks that typically result in a classification label or a simple answer, our proposed task of timestamp-based automated QA reporting aims to produce structured, natural language reports similar to those created by human testers. This approach moves beyond simple feasibility assessment towards practical automation of the game QA reporting process.

Furthermore, technologies for converting image content into descriptive text have advanced significantly by leveraging the visual understanding capabilities of foundation models like CLIP. CLIP pioneered new directions in vision-language research through contrastive learning on a massive dataset of image-text pairs, aligning both modalities within a shared semantic space [20]. In particular, models like ClipCap have shown the ability to generate sophisticated natural language descriptions of an image’s core content by feeding the rich visual features extracted by CLIP into a pre-trained language model like GPT-2 [20,21]. This capability has the potential to clearly describe specific situations or anomaly within complex game screens in text, forming the technical foundation of our study.

Processing the extracted bug information into a format that developers can use is a critical step. Software engineering research shows that unclear or unstructured bug reports increase developers’ cognitive load, delaying issue identification and extending bug fix times [22]. Therefore, a process is needed to synthesize sporadic frame-level bug descriptions into a single, actionable, structured report [23]. For this task, the latest LLMs offer an excellent solution. Recent studies demonstrate that modern LLMs like GPT-4o can reliably convert unstructured text into a standardized format without separate training [24]. This shows that LLMs can be used very effectively in this study to automatically generate structured bug reports from the extracted bug-related texts.

While previous studies in vision and language models have made significant progress, there has been a notable lack of attempts to effectively these technologies into a single, practical pipeline for automated game QA [5]. This gap is evident in existing approaches. Previous computer vision-based solutions, for instance, were often confined to a narrow scope of detectable errors, such as rendering glitches, while overlooking broader issues like physics anomalies [25]. Similarly, other attempts using LLMs have been limited to text-based games, rendering them inapplicable to modern, graphics-intensive titles [26]. Crucially, these specialized solutions typically lack an integrated mechanism for generating the structured, human-readable reports essential for efficient debugging.

Furthermore, the alternative of inputting entire gameplay videos into a single, end-to-end LMM can lead to high computational costs and slow inference speeds, raising concerns for direct use in real-world QA workflows. To address these gaps, this paper introduces a novel, decoupled two-stage architecture that synergistically combines a specialized vision model with a general-purpose LLM. In the first stage, a lightweight vision model translates visual events from game frames into concise text descriptions. In the second stage, an LLM synthesizes this textual data into a structured, actionable bug report. This two-stage process is significantly more computationally efficient and modular than end-to-end video analysis, offering a practical and scalable solution for automated game QA.

In this study, we propose two methodologies for automatically generating QA reports from gameplay videos, each with advantages from two different perspectives. The first is an approach that directly utilizes the latest LMMs to understand the context of the game video and generate high-accuracy bug reports. The second is a bug report generation approach that organically combines a lightweight image captioning model with an LLM to minimize their significant computational resources and maximize practicality and efficiency. These approaches differ from conventional automated QA tools by transforming the visual context of gameplay videos into human-readable reports, complete with timestamps. Furthermore, they move beyond the limitations of existing tools that can only identify specific, predefined bugs, enabling the detection of a much broader range of visual anomalies.

The proposed timestamp-based QA report generation represents a novel approach, distinct from conventional image captioning or Visual Question Answering (VQA). This method involves feeding a gameplay video directly into a state-of-the-art LMM. We then employ carefully crafted prompts to instruct the LMM to analyze the video’s spatiotemporal context and identify visual anomalies, such as rendering artifacts, physics glitches, and anomalous character animations. For each anomaly identified, the model generates a timestamped entry with a detailed description. The final output is a consolidated QA report designed to be immediately actionable, enabling developers to pinpoint the exact moment of the issue.

2.2.1 Fine-Tuning a Lightweight Image Captioning Model

For our caption-based methodology, we employed the ClipCap model. Its architecture is designed to freeze the pre-trained vision encoder of CLIP, requiring fine-tuning for only a lightweight mapping network and a text decoder [21]. This lean architectural design enables rapid, data-efficient fine-tuning on domain-specific datasets [27,28]. In contrast, state-of-the-art large-scale captioning models demand substantial computational resources for full-parameter fine-tuning [29,30]. This necessity translates into significant operational costs, stemming from the procurement and maintenance of high-end GPU clusters or extensive cloud service usage—which presents a substantial barrier to entry [5].

For small to medium-sized game developers or indie studios with limited budgets and infrastructure, the prospect of fine-tuning these massive models for a custom solution is practically infeasible [8]. Therefore, our caption-based methodology was designed with accessibility and practicality as core principles, making ClipCap a compelling choice. Its capacity for rapid training on modest hardware directly aligns with our primary objective: to develop a cost-effective and practical QA automation system.

2.2.2 ClipCap and LLM Integration for QA Report Generation

We propose a method for generating a final QA report using an LLM by synthesizing frame-by-frame captions generated by a fine-tuned ClipCap model. In this study, we specify the role of the LLM through prompt engineering and generate a report that summarizes the situation from discontinuous image captions based on the given captions, including the type of bug, its timestamp, and the inferred reason for the bug.

3 Experimental Environments & Setup

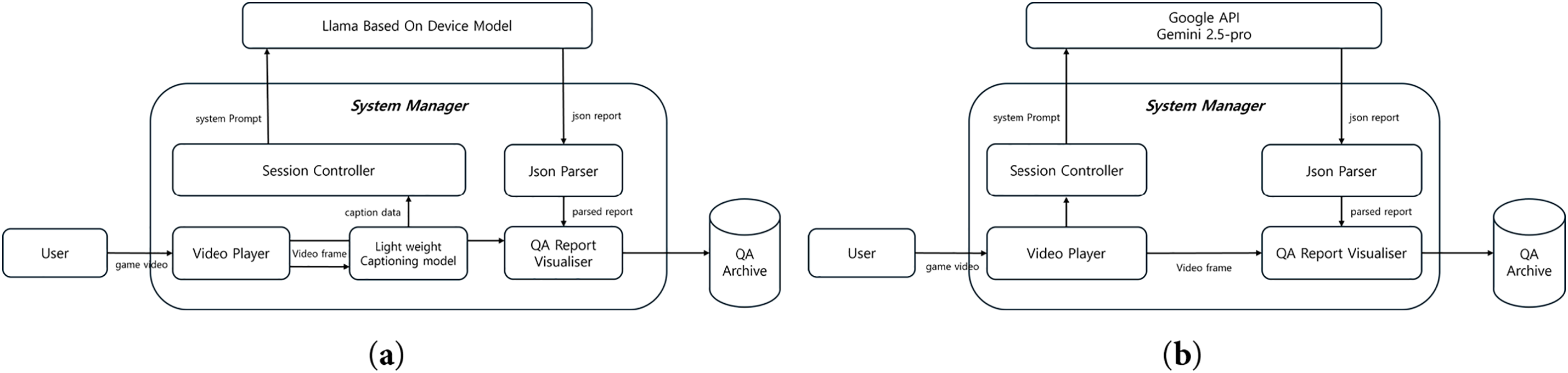

Fig. 1a shows the overall structure of the LLM-based automated QA reporting system, corresponding to the first approach proposed in Section 2.1. The core model adopted for this system is Gemini 2.5 Pro, selected based on the VideoGameQA-Bench [19], which evaluates video-based question-answering systems. Results from this benchmark indicate that Gemini 2.5 Pro demonstrates superior video understanding capabilities compared to other large-scale multimodal models.

Figure 1: Architecture of the AutoQA reporting system

Fig. 1b depicts the architecture of the caption-based automated QA reporting system, corresponding to the second approach proposed in Section 2.2. The workflow of this system consists of three modular structures: frame extraction, caption generation, and comprehensive report generation.

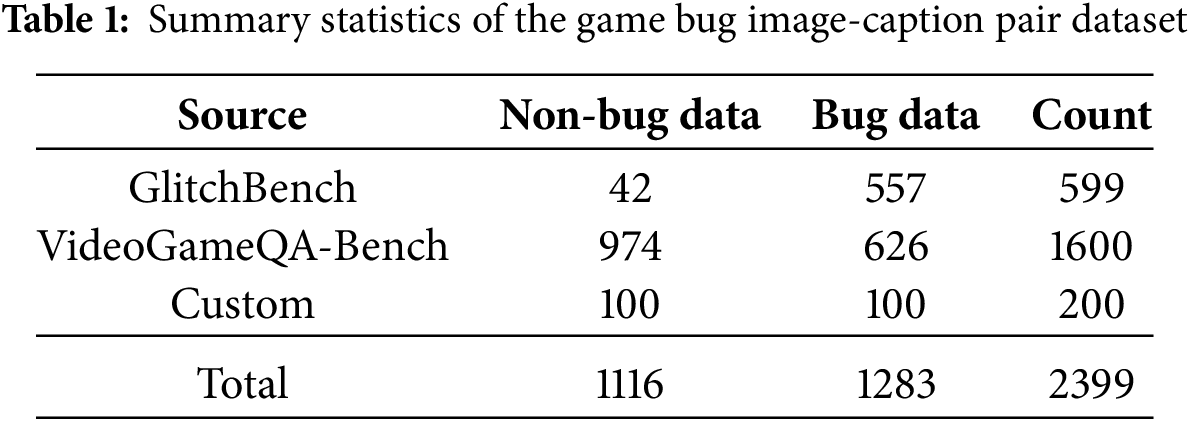

To generate context-aware bug captions from game images alone, we constructed a domain-specific dataset tailored to gaming environments. The dataset is composed of both images depicting bugs and normal gameplay images. This balanced composition is designed to prevent the model from overfitting to purely anomalous visual patterns and instead encourages it to learn the contextual distinctions between normal and buggy game states. The data for this study was collected from the following three sources:

• GlitchBench [17], VideoGameQA-Bench [19]: These two benchmark datasets contain image data showing abnormal bugs in various games.

• Custom: To augment the existing benchmark datasets, we employed two distinct strategies for sourcing bug data. First, we collected real-world bug images from large online communities such as Reddit and Google. Second, we systematically reproduced a variety of known bugs within the Unity engine to capture controlled visual data. Additionally, to collect data representing normal gameplay, we captured scenes from Grand Theft Auto V [31]. This game was selected for its high-fidelity graphics and rich visual diversity, which includes varied environments, dynamic day-night cycles, and changing weather conditions.

The “golden captions” serve as the ground truth data for training our model. Accordingly, they were authored based on a clear and consistent set of criteria:

• For Normal Scenes: Captions must describe the location, key objects, and the ongoing action or event.

• For Buggy Scenes: Captions must identify the specific bug type, the affected object(s), the context of the occurrence, and the location.

This process yielded a proof-of-concept dataset of 2399 image-caption pairs. We explicitly frame this as a starting point, as modern AI has empirically demonstrated that performance scales predictably with data volume, making dataset size a primary driver of generalization [32,33]. This dataset was therefore created to serve as a high-quality testbed for demonstrating the initial feasibility of our models, rather than for achieving state-of-the-art generalization. Consequently, we anticipate that significant performance and robustness gains can be achieved by expanding this dataset in future work.

To prepare the data for training, augmentation techniques such as left-right flipping were applied to each image, resulting in a total of 4798 data points. This augmented dataset was then divided into a 9:1 ratio for training and validation, respectively. The detailed statistics of the final dataset are shown in Table 1.

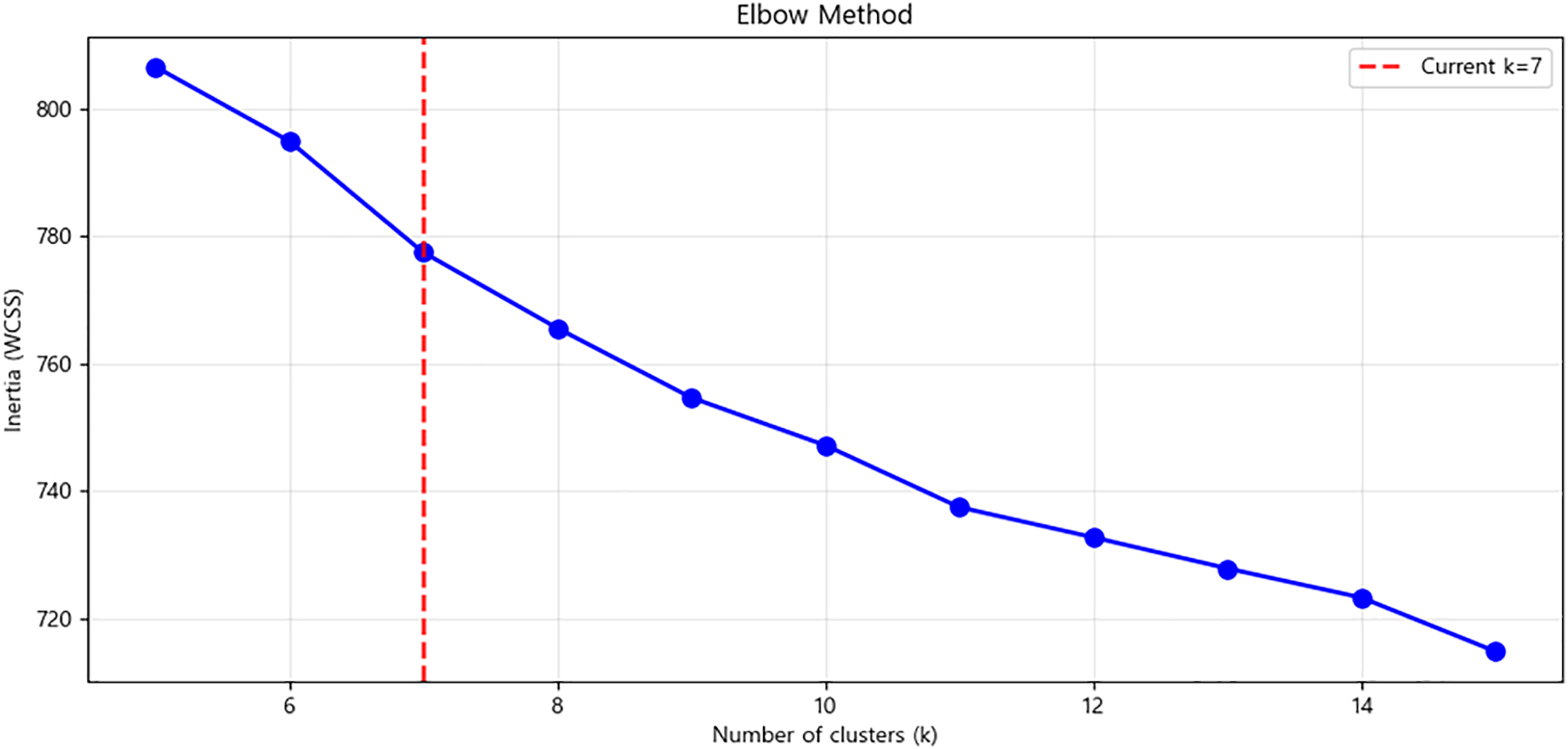

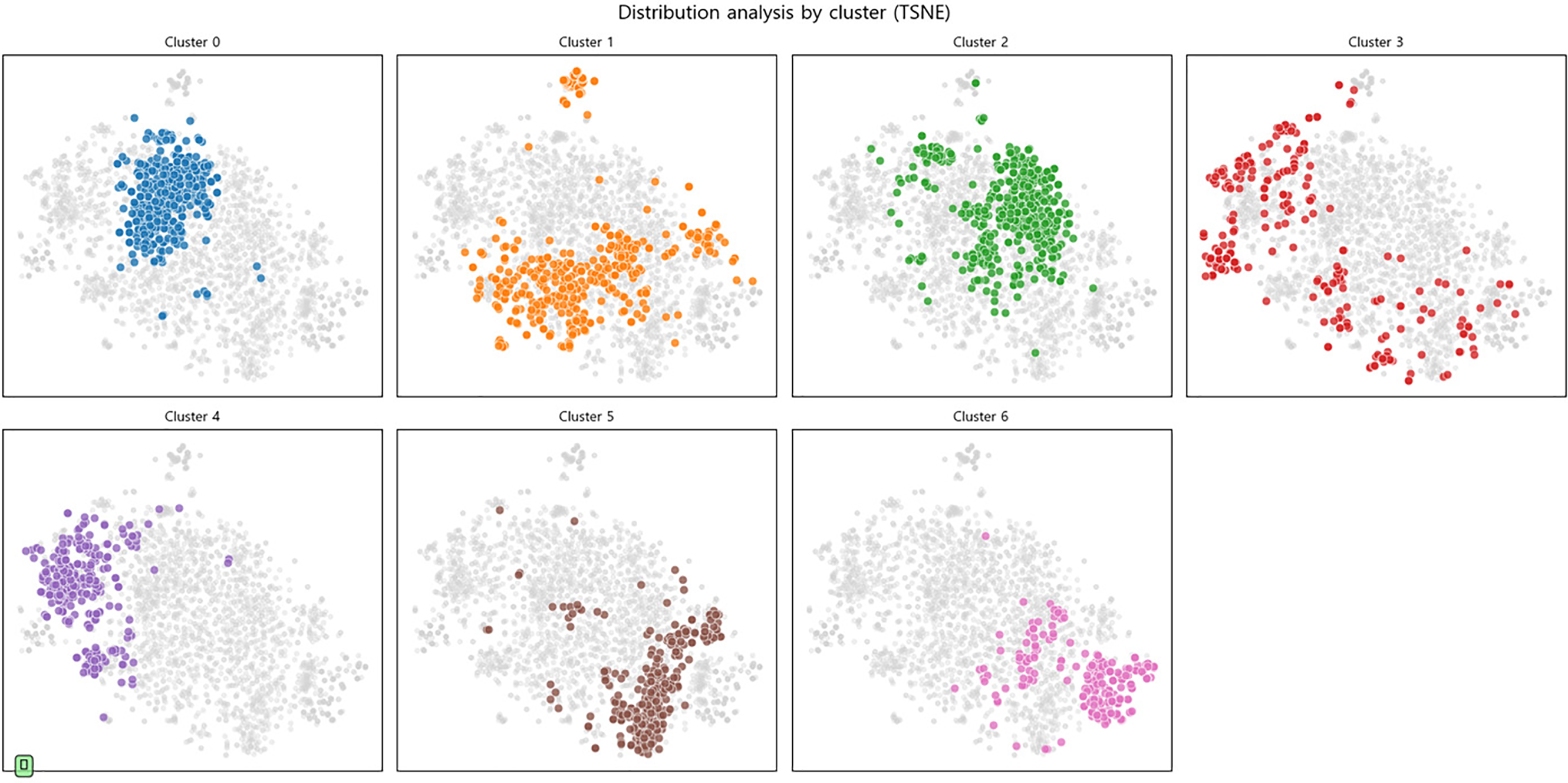

3.3 Validation of the Training Dataset

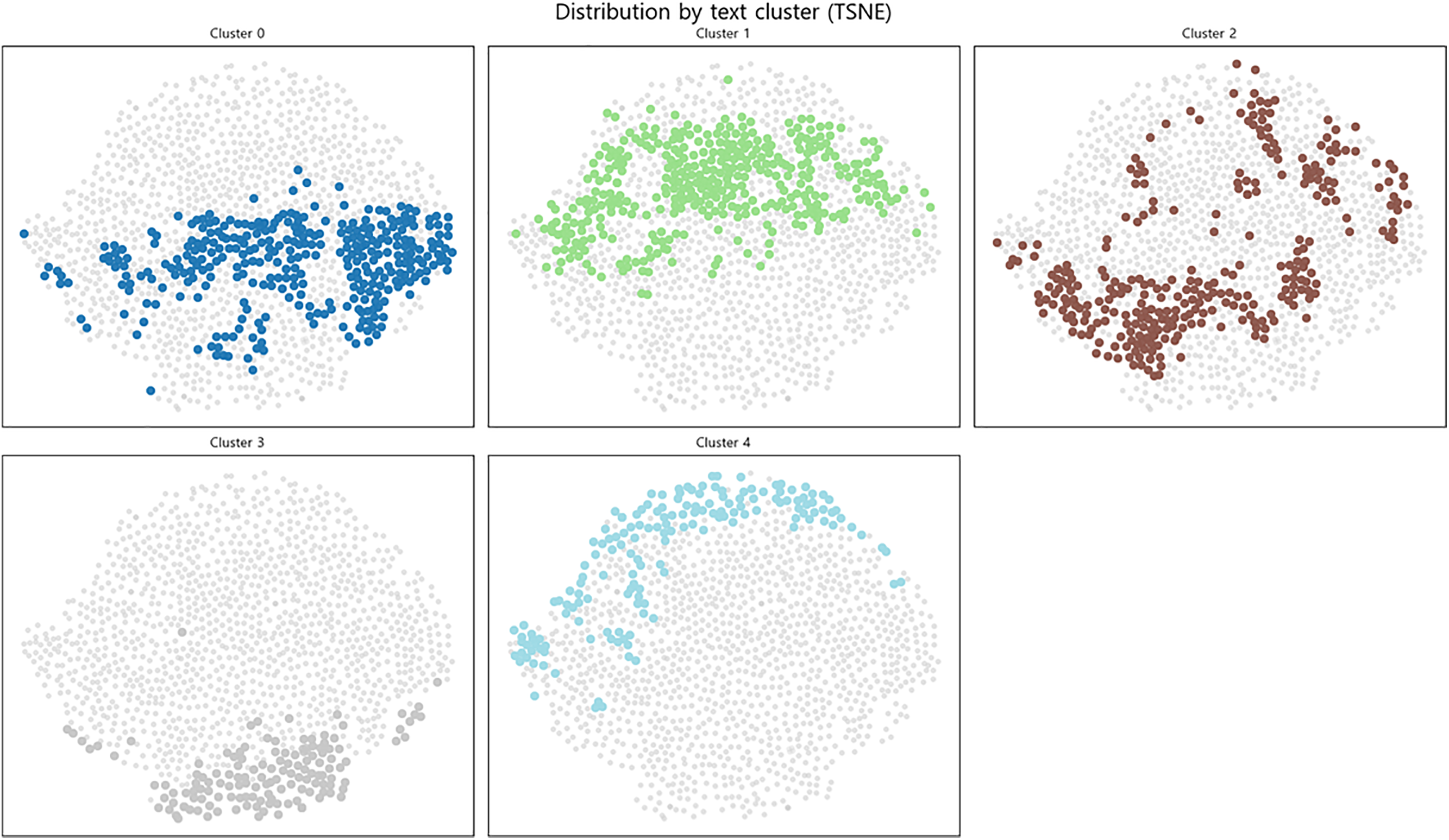

To verify whether the bug images in the dataset have semantic structure and diversity, we extracted 768-dimensional feature vectors from the images using the pre-trained CLIP ViT-B/32 model. As shown in Fig. 2, we set the number of clusters to seven using the K-means algorithm [34] and visualized the result as a 2D projection using t-SNE. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the visualization reveals distinct distributional characteristics among the clusters. For instance, the relatively dense clusters 0 and 4 represent groups of visually similar images, corresponding to specific normal or buggy game states. In contrast, more dispersed clusters, such as cluster 3, indicate a high degree of diversity in the dataset’s visual contexts and styles. This representational diversity is crucial for enabling the model to generate rich, detailed captions by discerning subtle visual nuances [35,36].

Figure 2: Elbow method analysis for selecting the optimal K

Figure 3: Visualization of CLIP-based image embedding clusters

Fig. 4 visualizes the caption embeddings, generated by the pre-trained GPT-2 model’s embedding layer and projected into a 2D space using t-SNE. Critically, these text embeddings form semantically coherent clusters that mirror the structure observed in the image domain. This strong alignment between the visual and textual modalities is a prerequisite for models like ClipCap to effectively learn the mapping between them [36]. Therefore, we conclude that our dataset possesses the structural integrity required to train a captioning model that is both accurate and expressive.

Figure 4: Visualization of GPT-2 based text embedding clusters

To evaluate the performance of the trained ClipCap model using the BERT-Score metric, we curated a separate test set of 50 images. This set was intentionally composed of a diverse mix: real-world bugs from various games, reproduced physics engine bugs from Unity, and normal gameplay scenes.

3.4 Training the ClipCap Model

All experiments were performed within a PyTorch framework on a single NVIDIA RTX2080 GPU. We trained the model for 50 epochs using the AdamW optimizer. Key hyperparameters included a learning rate of 2.00E−05, 800 warm-up steps, a weight decay of 2.00E−02, and a dropout rate of 0.1 to prevent overfitting.

4 Analysis of Experimental Results

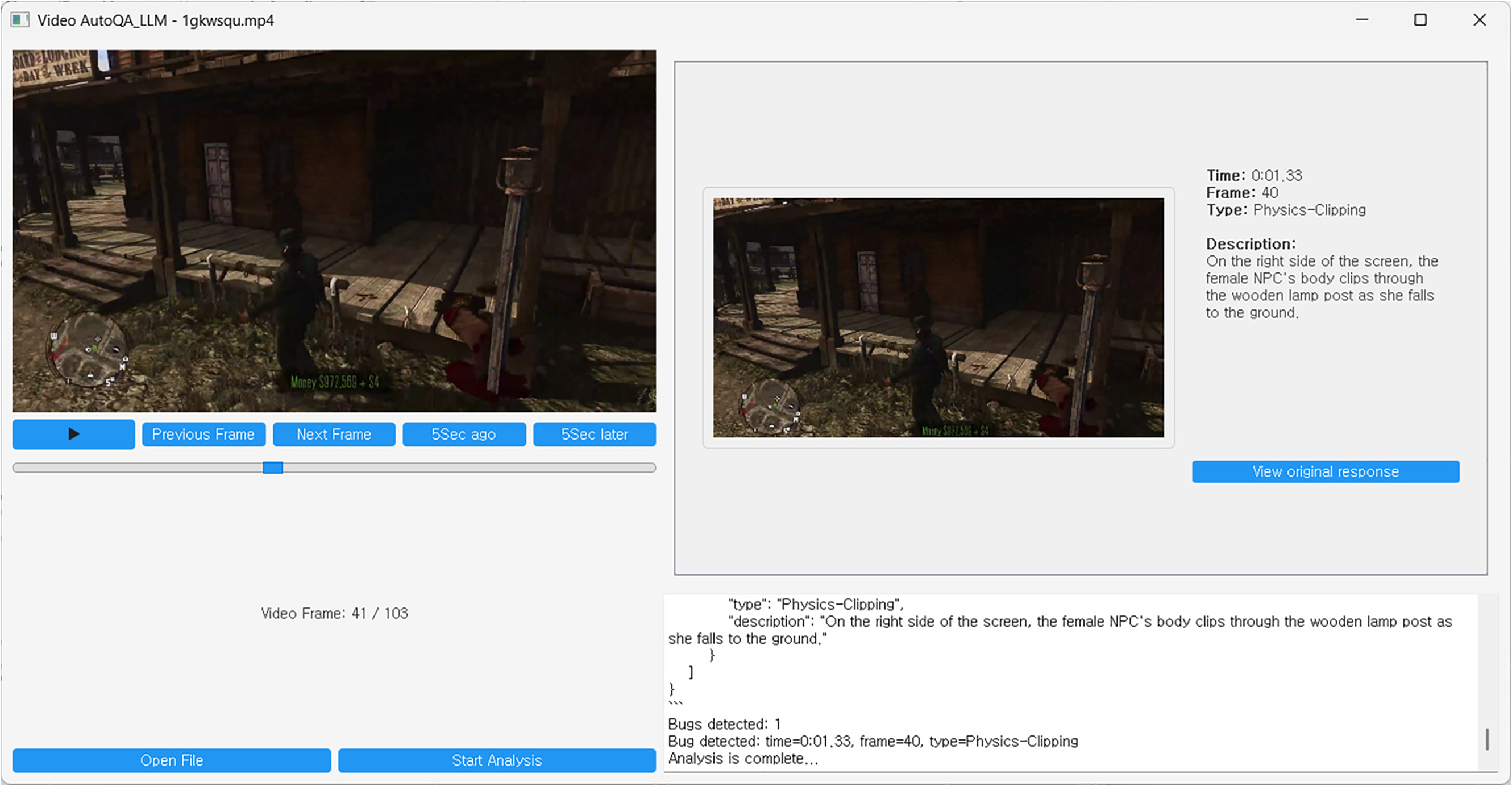

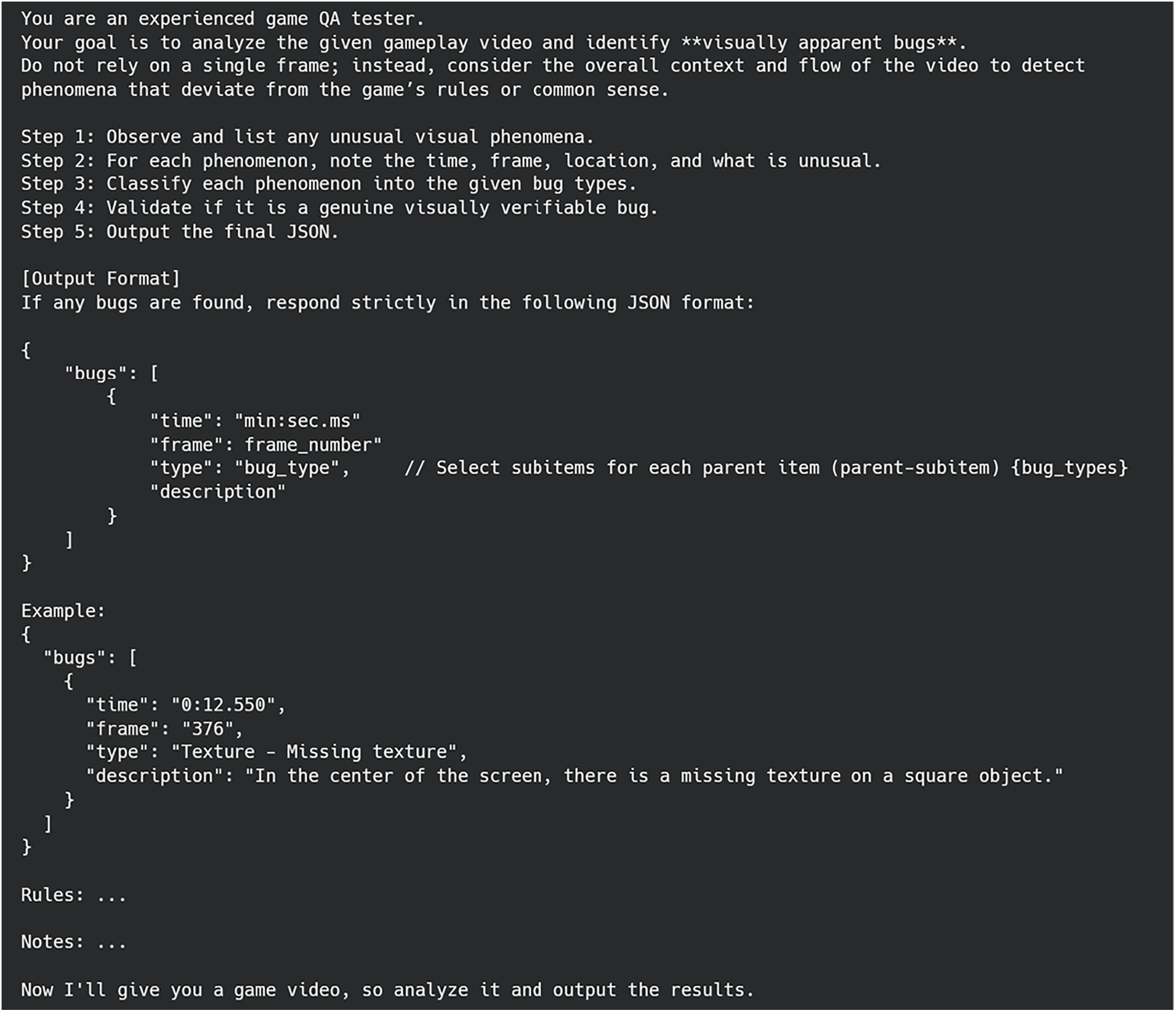

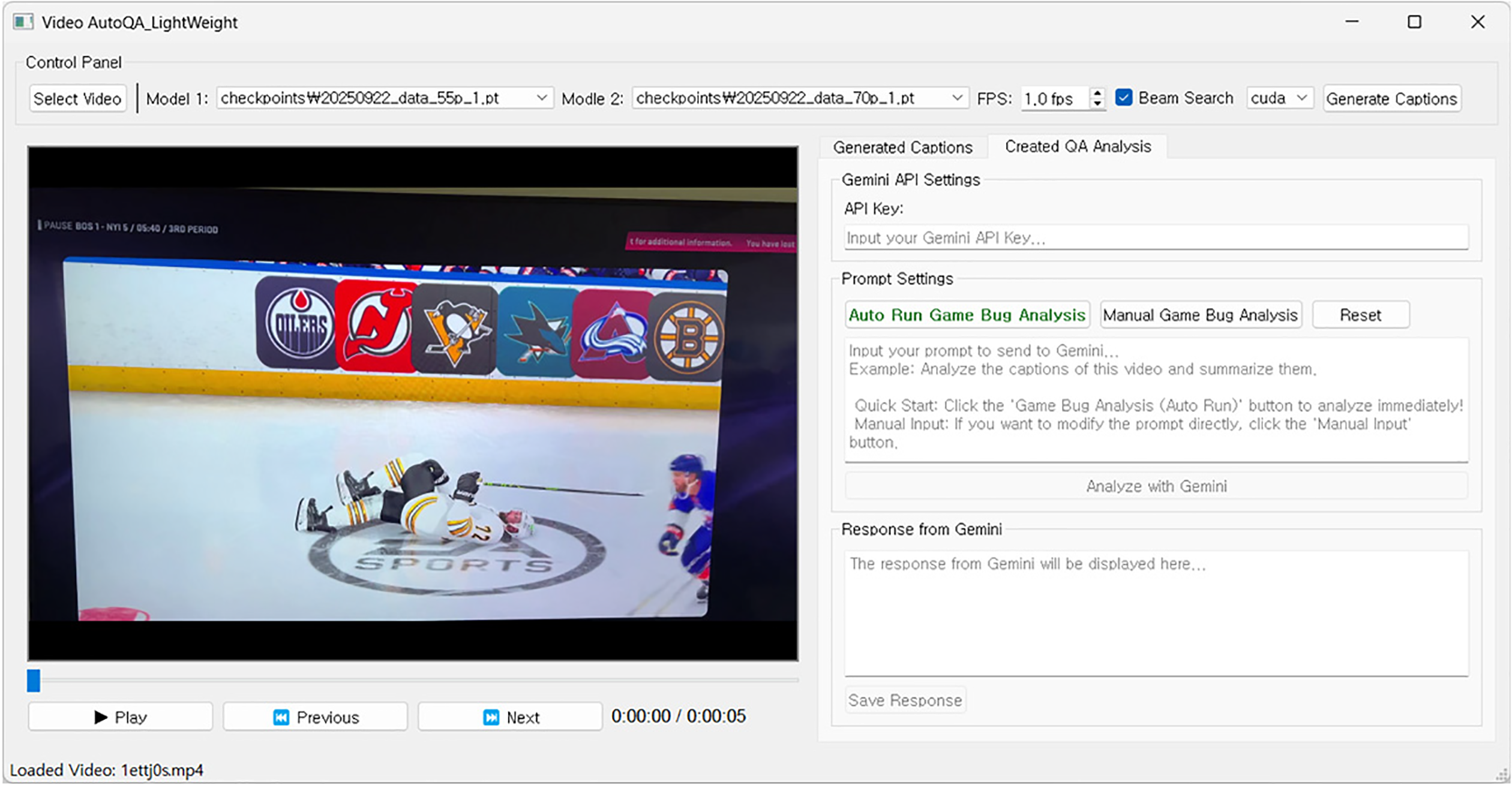

Fig. 5 shows the implementation of the system designed in Section 3.1. The top-left contains the original video player, the bottom-left shows the video control panel and frame information, and the top-right features a UI panel that displays the QA report generated by the LLM model in widget form. In this way, the system not only provides the generated text report in a form that is easy for humans to understand, but also organically links the text and video using timestamps. This allows users to intuitively identify the characteristics of bugs that are difficult to grasp from text alone.

Figure 5: A sample snapshot of the LLM-based AutoQA program

Fig. 6 details the prompt engineered for our LLM-based AutoQA program. Its primary design goal is to compel the LLM to generate responses in a strict JSON format, ensuring machine-readability for automated processing. To enhance the quality and consistency of the output, we employed several key techniques: assigning an expert persona, providing few-shot examples, guiding the model’s reasoning through a step-by-step Chain-of-Thought process, and imposing specific constraints on the analysis. This structured methodology ensures the generation of reliable and consistent data suitable for our system [37,38].

Figure 6: An example run snapshot of the LLM-based AutoQA program’s prompt

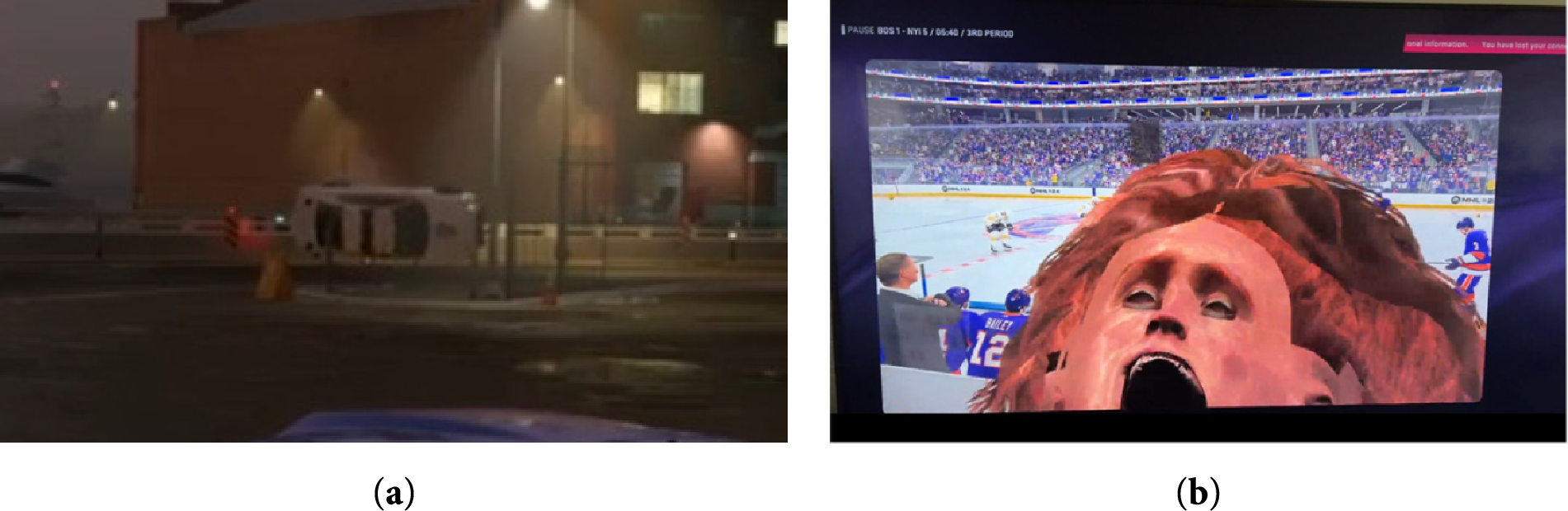

4.1.1 Analysis of Successful Cases

Fig. 7a is a representative example of the model analyzing a physics engine bug and successfully reporting it based on a timestamp. In the video, the vehicle exhibits abnormal movement caused by a sudden physical error. The model identified the exact time and frame of occurrence, the object involved, and even inferred relevant technical terms (e.g., Kinematics-Acceleration) as the potential cause. Fig. 7b shows an example of the Gemini 2.5 Pro model analyzing a camera clipping bug. The model accurately described the issue as “A character’s head model becomes severely stretched and distorted as the camera moves past and clips through it,” while also specifying the precise time and frame.

Figure 7: (a) A captured frame from a bug video showing a white car in the background suddenly overturning. (b) A captured frame from a bug video depicting an audience member’s face overlapping with the camera view

4.1.2 Analysis of Failure Cases

In contrast to the success cases, Fig. 8 presents a representative failure in analysis. The video depicts a straightforward bug in which a Non-Player Character (NPC) suddenly disappears from the scene. Despite the clarity of the event, the LLM provided a completely incorrect description, stating: “After the NPC is flipped upside down, the booth rotates back to normal on the ground.”

Figure 8: (a) A captured frame of a bug video showing an NPC standing in front of player character. (b) A subsequent frame showing the scene after the NPC has suddenly disappeared

This misinterpretation appears to result from the model confusing the vanished NPC with a visually similar scene of an NPC lying on a wooden floor. Furthermore, this case indicates that even state-of-the-art LLMs, such as Gemini 2.5 Pro, are susceptible to hallucination, especially when interpreting ambiguous or abrupt changes in visual data.

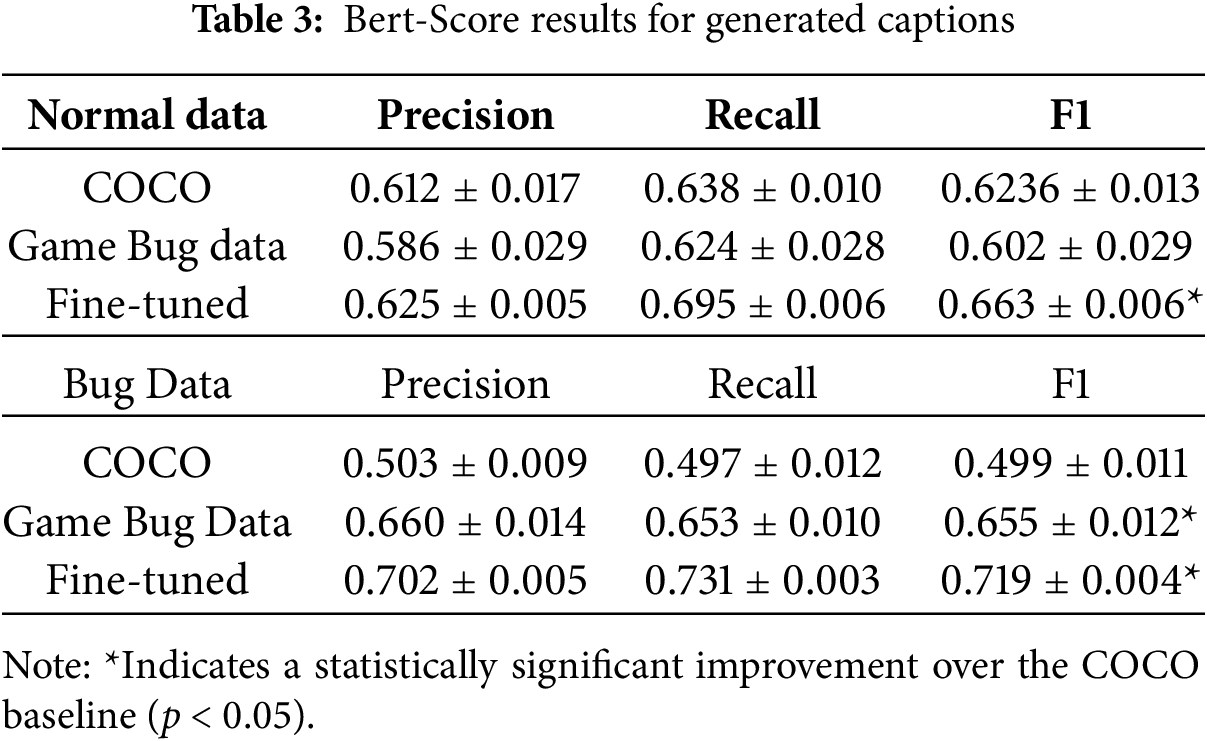

4.2 Evaluation of ClipCap Model

The primary objective of this study is not to generate stylistically sophisticated captions, but to accurately extract information regarding in-game events and features. Consequently, traditional automatic evaluation metrics like BLEU and CIDEr, which rely on n-gram overlap with reference captions [39], are inadequate for our purposes, as they fail to measure factual accuracy or semantic validity.

To address these limitations, we employed a two-pronged evaluation approach, combining the quantitative BERT-Score metric with qualitative human assessment. BERT-Score is particularly suitable as it computes semantic similarity based on contextual embeddings from pre-trained language models [40], aligning with our focus on meaning rather than lexical overlap. The human evaluation involved 25 participants who assessed generated captions for a set of 16 images (8 depicting bugs and 8 depicting normal gameplay). Participants evaluated each caption based on two criteria: its descriptive accuracy and its classificatory correctness (i.e., whether it correctly identified the scene as normal or buggy).

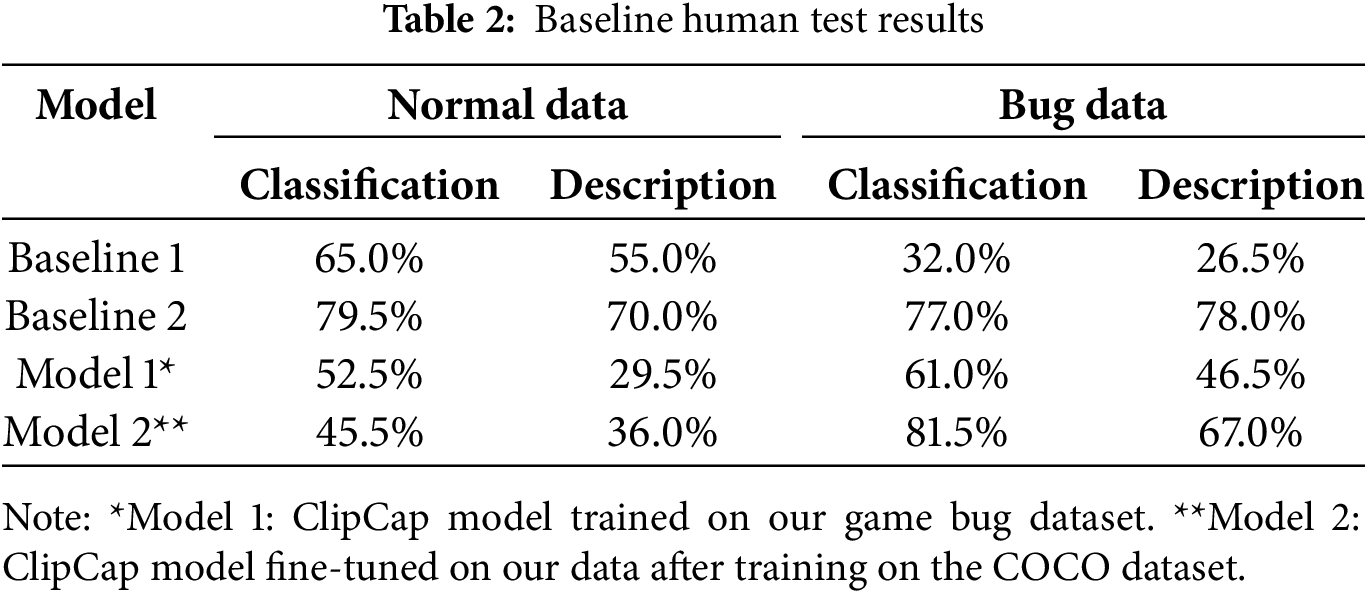

4.2.1 Baseline Model Performance Evaluation

Prior to analyzing the performance of our proposed model, we established and evaluated two distinct baseline models to provide a benchmark for comparison.

• Baseline 1 (General-Purpose Training): To gauge the performance of a model trained on a large-scale, general-purpose dataset, we trained the ClipCap model on the MS COCO 2017 dataset [41]. This involved using 118,287 images and their 591,753 corresponding captions. We adopted the default hyperparameters specified in the original ClipCap paper [21] and trained the model for 10 epochs, which took approximately 14 h.

• Baseline 2 (Zero-Shot LMM): To highlight the out-of-the-box capabilities of modern lightweight models, we employed the Gemma-4B model in a zero-shot setting (i.e., without any fine-tuning). We evaluated captions generated by providing the model with an image and a simple prompt, such as: “Describe the situation or bug in the game image in 20 words.”

As shown in Table 2, the ClipCap model trained on the COCO dataset achieved 65% accuracy on normal game images, while its performance was notably lower for images containing bugs. In contrast, the lightweight LLM model demonstrated a higher overall accuracy, exceeding 70%. Another noteworthy observation was the LLM’s tendency to move beyond simple image description and attempt to infer the specific game title from which the image originated.

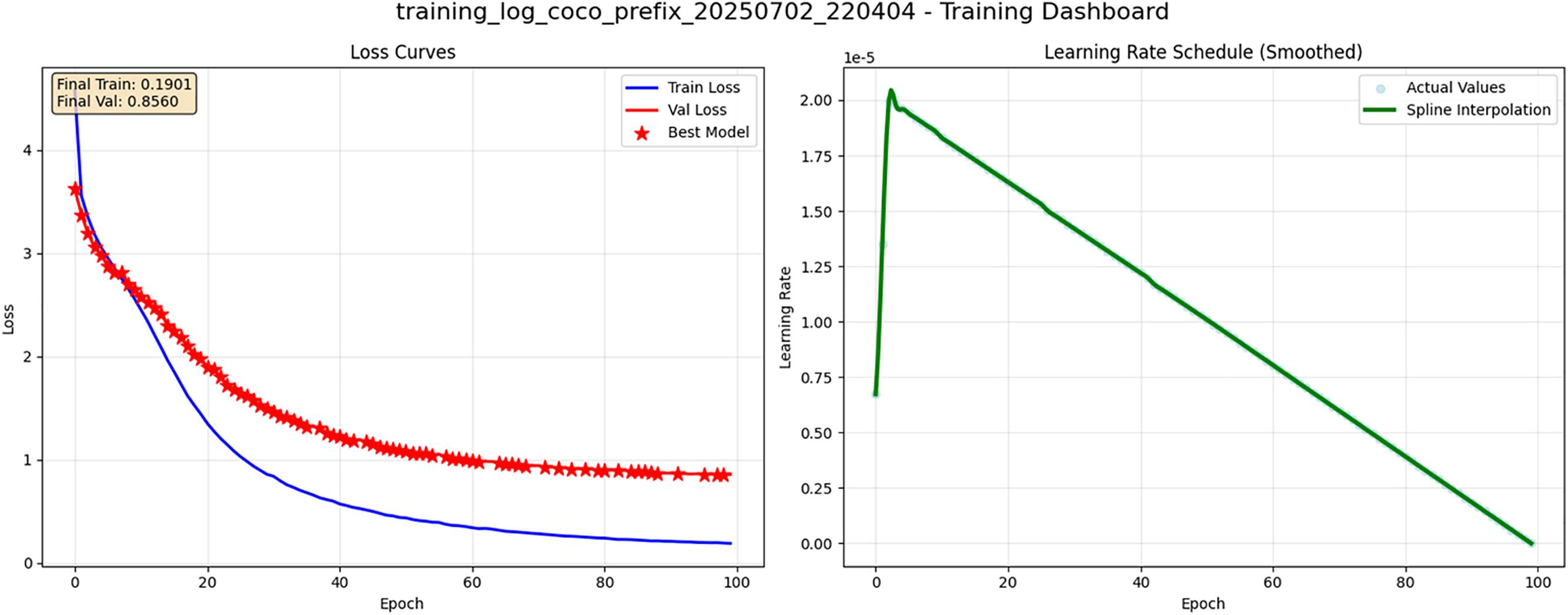

We trained our proposed model on the game bug dataset for 50 epochs and selected the model checkpoint with the lowest validation loss for testing. Although Fig. 9 illustrates that the validation loss continued to decrease when training was extended to 100 epochs, this did not translate into a discernible performance improvement over the 50-epoch model.

Figure 9: Visualization of bug data training status

To quantitatively compare the models, we evaluated the generated captions using BERT-Score for both general and bug-related game images. To ensure the robustness of our results, each model was trained three times to calculate the mean and standard deviation of the F1 scores, which are summarized in Table 3. As shown in the table, we compared both the ‘Game Bug Data’ and ‘Fine-tuned’ models against the COCO baseline. On Bug Data, both the Game Bug Data model (p < 0.001) and the Fine-tuned model (p < 0.001) showed a statistically significant improvement over the COCO baseline. On Normal Data, however, only the Fine-tuned model achieved a significant F1 score improvement (p = 0.011), whereas the performance of the Game Bug Data model was not statistically different from the baseline (p = 0.310).

Our experimental results highlight a key trade-off in model specialization. The significant BERT-Score improvements shown in Table 3 demonstrate that fine-tuning on a game-specific dataset effectively enhances bug detection. However, this specialization induces catastrophic forgetting, causing a sharp decline in performance on general, bug-free images, a trend clearly visible in both Tables 2 and 3.

Therefore, we conclude that the most effective strategy is to pre-train on a large, general dataset before fine-tuning. The results for the ‘Fine-tuned’ model in Table 3 confirm this approach maximizes specialized performance while minimizing the loss of generalization. Furthermore, this suggests that for practical applications, using specialized models fine-tuned for specific tasks alongside a general-purpose model could be a highly beneficial strategy.

Despite the promising quantitative results, this study has limitations. Primarily, the human evaluation results presented in Table 2 are constrained by low inter-rater reliability. The calculated Fleiss’ Kappa scores were found to be below 0.3 for most evaluation items, indicating inconsistent agreement among the raters.

While we considered incorporating more granular human evaluation criteria, such as clarity and usefulness, we concluded that these metrics are highly susceptible to subjective bias, which could further compromise reliability when evaluated by a small number of raters. Therefore, establishing a more robust human evaluation framework and conducting a larger-scale study are designated for future work. For this reason, while Table 2 is included for transparency, the main conclusions of this paper are drawn from the more objective BERT-Score metrics in Table 3.

4.3 ClipCap-Based AutoQA Report

Fig. 10 illustrates our implemented program, built on the system architecture described in Section 3.2 and designed similarly to the LLM-based AutoQA program mentioned earlier. After a user selects a video and specifies the caption generation interval, clicking the ‘AI Analysis’ option initiates the core reporting process. The LLM is instructed to process a dual stream of captions, receiving two distinct descriptions per second of gameplay. One caption is generated by the baseline model, trained on the COCO dataset, which excels at describing general situations. The other is from our model, which was fine-tuned on a specialized bug dataset to better identify and describe specific anomalies. The LLM’s primary task is to dynamically synthesize these complementary information streams, identify any discrepancies or anomalies, and generate a single, consolidated report.

Figure 10: A sample snapshot of the ClipCap-based AutoQA program

This study addresses the challenge of bug identification in game development by introducing two novel methodologies: LLM-based automated QA reporting and Caption-based automated QA reporting. As a pioneering effort, we explore the viability of these distinct approaches. The primary contribution of this work is establishing a proof-of-concept that suggests a promising direction for reducing the manual labor and costs inherent in traditional QA processes.

Nevertheless, the scope of our findings is necessarily constrained by the dataset used, which is limited in both scale and genre diversity. We therefore caution that the feasibility demonstrated here is specific to our dataset and should be viewed as preliminary rather than broadly generalizable. This context highlights the critical need for future work to improve the core technology—by constructing larger benchmarks and utilizing advanced models for temporal analysis—while also rigorously validating its applicability in real-world settings. To this end, we plan comprehensive evaluations of the automatically generated QA reports, combining subjective assessments from QA professionals with objective quantitative metrics.

In conclusion, this research serves as a foundational exploration, defining new approaches and providing a baseline for subsequent investigations. We anticipate that, by building on this initial work, the community can develop these approaches into an integral part of modern game development pipelines.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Creative Content Agency, funded by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea in 2025, for the project, “Development of AI-based large-scale automatic game verification technology to improve game production verification efficiency for small and medium-sized game companies” (RS 2024-00393500).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Jun Myeong Kim, Jang Young Jeong, Shin Jin Kang; methodology: Jun Myeong Kim, Jang Young Jeong; draft manuscript writing and manuscript revision: Jun Myeong Kim; supervision: Shin Jin Kang, Beomjoo Seo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Backus J. Players’ perception of bugs and glitches in video games: an exploratory study. arXiv:2504.15408. 2025. [Google Scholar]

2. Lavoie R, Main K, King C, King D. Virtual experience, real consequences: the potential negative emotional consequences of virtual reality gameplay. Virtual Real. 2021;25(1):69–81. doi:10.1007/s10055-020-00440-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Aleem S, Capretz LF, Ahmed F. Game development software engineering process life cycle: a systematic review. J Softw Eng Res Dev. 2016;4(1):6. doi:10.1186/s40411-016-0032-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kosa M, Uysal A. Need frustration in online video games. Behav Inf Technol. 2022;41(11):2415–26. doi:10.1080/0144929x.2021.1928753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Politowski C, Petrillo F, Gueheneuc YG. A survey of video game testing. In: 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automation of Software Test (AST); 2021 May 20–21; Madrid, Spain: IEEE; 2021. p. 90–9. doi:10.1109/ast52587.2021.00018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Albaghajati A, Ahmed M. Video game automated testing approaches: an assessment framework. IEEE Trans Games. 2023;15(1):81–94. doi:10.1109/TG.2020.3032796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ostrowski M, Aroudj S. Automated regression testing within video game development. GSTF J Comput Joc. 2013;3(2):10. doi:10.7603/s40601-013-0010-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Politowski C, Guéhéneuc YG, Petrillo F. Towards automated video game testing: still a long way to go. In: Proceedings of the 6th International ICSE Workshop on Games and Software Engineering: Engineering Fun, Inspiration, and Motivation; 2017 May 20; Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 37–43. doi:10.1145/3524494.3527627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cho J, Ali K. Exploring quality assurance practices and tools for indie games. In: 2023 IEEE/ACM 7th International Workshop on Games and Software Engineering (GAS); 2023 May 15; Melbourne, Australia: IEEE; 2023. p. 16–24. doi:10.1109/GAS59301.2023.00010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cho J. Bughunting on a budget: exploring quality assurance practices and tools for indie game developers [master’s thesis]. Edmonton, Canada: University of Alberta; 2022. [Google Scholar]

11. Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Ahmad L, Akkaya I, Aleman FL, et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv:2303.08774. 2023. [Google Scholar]

12. Baltrusaitis T, Ahuja C, Morency LP. Multimodal machine learning: a survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;41(2):423–43. doi:10.1109/tpami.2018.2798607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Stefanini M, Cornia M, Baraldi L, Cascianelli S, Fiameni G, Cucchiara R. From show to tell: a survey on deep learning-based image captioning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(1):539–59. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3148210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sun C, Myers A, Vondrick C, Murphy K, Schmid C. VideoBERT: a joint model for video and language representation learning. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea: IEEE; 2019. p. 7463–747. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bertasius G, Wang H, Torresani L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding? In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. Vol. 139, p. 813–24. [Google Scholar]

16. Lin K, Ahmed F, Li L, Lin CC, Azarnasab E, Yang Z, et al. Mm-vid: advancing video understanding with gpt-4v(ision). arXiv:2310.19773. 2023. [Google Scholar]

17. Taesiri MR, Feng T, Bezemer CP, Nguyen A. GlitchBench: can large multimodal models detect video game glitches? In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 22444–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.02118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cao M, Tang H, Zhao H, Guo H, Liu J, Zhang G, et al. Physgame: uncovering physical commonsense violations in gameplay videos. arXiv:2412.01800. 2024. [Google Scholar]

19. Taesiri MR, Ghildyal A, Zadtootaghaj S, Barman N, Bezemer CP. VideoGameQA-Bench: evaluating vision-language models for video game quality assurance. arXiv:2505.15952. 2025. [Google Scholar]

20. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

21. Mokady R, Hertz A, Bermano AH. Clipcap: clip prefix for image captioning. arXiv:2111.09734. 2021. [Google Scholar]

22. Almhana R, Kessentini M. Detecting dependencies between bug reports to improve bugs triage [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Detecting-Dependencies-Between-Bug-Reports-to-Bugs-Almhana-Kessentini/c721736dba726f548bd0b2a2ff7e8aefc9f013f9#citing-papers. [Google Scholar]

23. Panthaplackel S, Li JJ, Gligoric M, Mooney RJ. Learning to describe solutions for bug reports based on developer discussions. arXiv:2110.04353. 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. Brach W, Košťál K, Ries M. The effectiveness of large language models in transforming unstructured text to standardized formats. IEEE Access. 2025;13:91808–25. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3573030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ling C, Tollmar K, Gisslén L. Using deep convolutional neural networks to detect rendered glitches in video games. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell Interact Digit Entertain. 2020;16(1):66–73. doi:10.1609/aiide.v16i1.7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jin C, Rao S, Peng X, Botchway P, Quaye J, Brockett C, et al. Automatic bug detection in LLM-powered text-based games using LLMs. arXiv:2406.04482. 2024. [Google Scholar]

27. Li XL, Liang P. Prefix-tuning: optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv:2101.00190. 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. Pecher B, Srba I, Bielikova M. Comparing specialised small and general large language models on text classification: 100 labelled samples to achieve break-even performance. arXiv:2402.12819. 2024. [Google Scholar]

29. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, Allen-Zhu Z, Li Y, Wang S, et al. Lora: low-rank adaptation of large language models. In: The Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022 Apr 25; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

30. Strubell E, Ganesh A, McCallum A. Energy and policy considerations for modern deep learning research. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(9):13693–6. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i09.7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Richter SR. Playing for data: Ground truth from computer games. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 102–18. [Google Scholar]

32. Kaplan J, McCandlish S, Henighan T, Brown TB, Chess B, Child R, et al. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv:2001.08361. 2020. [Google Scholar]

33. Sun C, Shrivastava A, Singh S, Gupta A. Revisiting unreasonable effectiveness of data in deep learning era. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy: IEEE; 2017. p. 843–52. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Douze M, Guzhva A, Deng C, Johnson J, Szilvasy G, Mazaré PE, et al. The faiss library. arXiv:2401.08281. 2024. [Google Scholar]

35. Goh G, Cammarata N, Voss C, Carter S, Petrov M, Schubert L, et al. Multimodal neurons in artificial neural networks. Distill. 2021;6(3):e30. doi:10.23915/distill.00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mahajan S, Roth S. Diverse image captioning with context-object split latent spaces. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2020;33:3613–24. [Google Scholar]

37. Reynolds L, McDonell K. Prompt programming for large language models: beyond the few-shot paradigm. In: Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2021 May 8–13. Yokohama Japan. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 1–7. doi:10.1145/3411763.3451760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chen B, Zhang Z, Langrené N, Zhu S. Unleashing the potential of prompt engineering in large language models: a comprehensive review. arXiv:2310.14735. 2023. [Google Scholar]

39. Cui Y, Yang G, Veit A, Huang X, Belongie S. Learning to evaluate image captioning. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 5804–12. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang T, Kishore V, Wu F, Weinberger KQ, Artzi Y. Bertscore: evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv:1904.09675. 2019. [Google Scholar]

41. Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft coco: common objects in context. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 740–55. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools