Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Integration of Q-Learning and A-APF for Efficient Path Planning in Complex Underground Mining Environments

School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, 232000, China

* Corresponding Author: Liangliang Zhao. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071319

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

To address low learning efficiency and inadequate path safety in spraying robot navigation within complex obstacle-rich environments—with dense, dynamic, unpredictable obstacles challenging conventional methods—this paper proposes a hybrid algorithm integrating Q-learning and improved A*-Artificial Potential Field (A-APF). Centered on the Q-learning framework, the algorithm leverages safety-oriented guidance generated by A-APF and employs a dynamic coordination mechanism that adaptively balances exploration and exploitation. The proposed system comprises four core modules: (1) an environment modeling module that constructs grid-based obstacle maps; (2) an A-APF module that combines heuristic search from A* algorithm with repulsive force strategies from APF to generate guidance; (3) a Q-learning module that learns optimal state-action values (Q-values) through spraying robot–environment interaction and a reward function emphasizing path optimality and safety; and (4) a dynamic optimization module that ensures adaptive cooperation between Q-learning and A-APF through exploration rate control and environment-aware constraints. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly enhances path safety in complex underground mining environments. Quantitative results indicate that, compared to the traditional Q-learning algorithm, the proposed method shortens training time by 42.95% and achieves a reduction in training failures from 78 to just 3. Compared to the static fusion algorithm, it further reduces both training time (by 10.78%) and training failures (by 50%), thereby improving overall training efficiency.Keywords

As a fundamental energy source and essential industrial raw material, coal plays a pivotal role in global energy systems. Ensuring its environmentally sustainable extraction and efficient utilization has become a pressing challenge. In underground coal mining, spraying robots are responsible for tunnel support through spraying operations. These robots must possess robust global path planning capabilities to navigate safely through narrow tunnels densely populated with obstacles. However, the inherent complexity of underground environments significantly hinders operational efficiency [1,2]. With the ongoing push for intelligent transformation in China’s coal industry, enabling the autonomous operation of spraying robots has emerged as a promising solution. Path planning technologies based on SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) are crucial for generating feasible motion trajectories in such complex environments. This study aims to develop an advanced path planning algorithm that allows spraying robot to efficiently and safely navigate dynamic and unstructured underground coal mine tunnels. The proposed method enhances the robots’ adaptability to unknown conditions, ensures stable and reliable spraying operations, and contributes to the broader goal of intelligent coal mining.

Underground coal mine tunnels pose unique challenges for spraying robots that conventional algorithms cannot address:

1. Dynamic obstacles (temporary support materials, moving mining vehicles) and dust-induced sensor limitations (LiDAR range < 3 m) make blind exploration of Q-learning risky (78 training failures/600 episodes, Section 3.2.4).

2. Mine safety rules require ≥0.5 m obstacle margins, while spraying needs fewer turns (≥45° turns cause uneven coating). Existing methods (A*, APF) ignore these, leading to safety violations or poor operation quality.

These pain points drive the need for a method balancing learning efficiency, safety, and adaptability—this study’s core motivation.

1.2.1 Traditional Path Planning Algorithms

Traditional single path planning algorithms, despite their evolution, have notable limitations in underground coal mine scenarios:

• A* algorithm: Excels at fast near-optimal pathfinding in static networks via an evaluation function. But it overrelies on pre-defined models and fixed heuristics, failing to adapt to dynamic mine obstacles (e.g., moving vehicles) and ignoring ≥0.5 m safety margins—raising collision risks [3–5].

• APF algorithm: Enables lightweight real-time navigation by simulating goal attraction and obstacle repulsion. However, it oscillates near goals due to excessive repulsion, fails in narrow mine tunnels (e.g., tight turns) from unbalanced forces, and causes >45° sharp turns that disrupt uniform spraying [6].

• Q-learning: Adapts well to dynamic/unknown environments by learning policies through environment interaction. But in obstacle-dense mines, its random early exploration leads to frequent collisions, low efficiency (up to 78 failures in 600 episodes, Section 3.2.4), and its reward function lacks mine-specific adjustments (e.g., no safety margin violation penalties), failing safety and real-time demands [7,8].

1.2.2 Advances in Improved Algorithms

To overcome the limitations of traditional algorithms, numerous researchers have proposed improvements to classical methods and explored hybrid integration strategies.

Regarding enhancements to the A* algorithm, Li et al. developed a multi-objective model by introducing dynamic weight adjustment, optimized evaluation functions, and open list initialization, which significantly improved wall-climbing robot path planning in complex environments [9]. However, this method is strongly dependent on accurate prior environmental models, resulting in limited adaptability to sudden environmental changes, such as unforeseen obstacles in underground mining settings. Fu et al. proposed an improved A* algorithm, which optimizes the traditional neighborhood to a sixteen-neighborhood and combines it with hybrid search. Through node deletion, improved bidirectional search, and dynamic weight coefficients, redundant path points are removed, and the efficiency of mobile robot path planning is enhanced [10]. However, the sixteen-neighborhood expansion significantly increases computational burden, potentially compromising real-time performance in obstacle-dense environments such as coal mine support zones. Jin et al. reduced node redundancy through a five-neighborhood filtering mechanism to improve search efficiency; however, the method still exhibited limitations in optimizing turning angles [11]. Nevertheless, the method continues to face challenges in effectively optimizing turning angles, a critical aspect of path planning in constrained environments. Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of dynamic search strategies in achieving a balance among path safety, smoothness, and computational efficiency in complex environments.

The APF method has also seen continuous advancements. Li et al. proposed an improved APF algorithm that handles specific threat zones, dynamically selects repulsion points, and constrains turning angles, thereby enhancing path planning for unmanned surface vehicles in complex waters [12]. Despite these advancements, the algorithm still tends to converge to local optima in the presence of concave obstacles or narrow passages. S. Liu introduced an improved BiRRT-APF algorithm, integrating Bi-directional Rapidly-exploring Random Trees (BiRRT), APF, and A* algorithm-based heuristics. By leveraging APF to guide BiRRT tree expansion, A* for accelerated tree connection, and Catmull–Rom splines for path smoothing, the method significantly enhanced both the efficiency and safety of UAV path planning in complex 3D environments [13]. However, this hybrid approach requires complex parameter tuning, and maintaining a balance between APF guidance and BiRRT’s random exploration remains challenging in highly dynamic environments. These limitations may ultimately compromise system stability and performance.

In the domain of reinforcement learning, notable progress has also been made. Hwang et al. proposed the Adjacent Robust Q-learning (ARQ-learning) algorithm under a tabular setting, establishing finite-time error bounds and introducing an additional pessimistic agent to form a dual-agent framework. This work represents the first extension of robust reinforcement learning algorithms into continuous state–action spaces [14]. However, the dual-agent framework increases the computational complexity, and the algorithm’s convergence speed is still slow in environments with high-dimensional state spaces, which limits its application in real-time path planning for spraying robots. Zhao et al. developed a Q-learning-based method for UAV path planning and obstacle avoidance. By designing a tailored state space, action space, and reward function, their approach enabled UAVs to autonomously learn optimal paths and perform effective obstacle avoidance in complex environments [15]. Nevertheless, the reward function design lacks a dynamic adjustment mechanism, making it less adaptable to sudden changes in the environment, such as the appearance of new obstacles in the tunnel.

The limitations of single-path planning algorithms have prompted researchers to explore multi-algorithm fusion strategies. These approaches aim to combine the guided search capabilities of heuristic algorithms with the adaptive learning strengths of reinforcement learning, thereby achieving complementary advantages.

Gan et al. proposed the Dynamic Parameter A* (DP-A*) algorithm, which integrates Q-learning into the heuristic function of A*, effectively enhancing the dynamic obstacle avoidance performance of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs). However, the method remains dependent on predefined environmental models [16]. Liao et al. introduced a dual-layer learning model, GAA-DFQ, which incorporates genetic algorithms, dynamic window approaches, fuzzy control, and Q-learning. This hybrid model has demonstrated strong path-planning capabilities for robots operating in dynamic environments [17].

Static εp values like 0.75 in current static fusion methods can’t adapt to the 12%–18% fluctuating obstacle densities in mines as described in Section 3.1.1. In high-density areas, over-reliance on A-APF causes the algorithms to miss local optimal paths, while in low-density areas, insufficient guidance leads to more invalid exploration [16,17]. Moreover, these methods often disregard robot kinematic limits such as a θ ≤ 45° turning constraint and safety rules like the ≥0.5 m safety margin, as mentioned in Section 1.1, thus creating a gap between simulation performance and real-world application in mines.

1.2.3 Recent Integration Methods of Multi-Agent Systems and DRL-GNN

In recent years, path planning has seen advanced frameworks combining Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and Graph Neural Networks (GNN), such as Xiao et al.’s (2024) MACNS (Multi-Agent Collaborative Navigation System) [18]. Its key designs include: embedding Graph Attention Network (GAT) into PPO’s policy network via the GPPO algorithm (replacing traditional MLP) to extract inter-agent features; a dynamic destination selection mechanism using congestion coefficient ω to adjust gathering points, aiming for “near-simultaneous arrival” and reduced waiting time; and an action masking technique that blocks invalid movements, accelerating training convergence by ~40% compared to traditional PPO. MACNS suits “multi-source to single-target” scenarios like logistics, warehouse AGV collaboration, and tourist group gathering.

The proposed Q-Learning-A-APF integration differs from MACNS in core aspects: MACNS targets open “multi-source to single-destination” multi-agent scenarios (no safety/operation constraints, complex GNN + PPO relying on high-performance hardware, no sensor range consideration); while our method focuses on single spraying robots in confined underground mines, meets mine-specific constraints (≥0.5 m safety margin, ≤45° turns for uniform spraying), uses a lightweight architecture for mining robots’ embedded devices, and adapts to mine LiDAR range < 3 m.

Existing studies (including those in the current work and MACNS) fail to meet coal mine spraying robot path planning needs, with three key gaps:

1. Single-agent scenario mismatch

Traditional single algorithms (Q-learning/A*/APF) can’t balance efficiency, safety, and smoothness (e.g., Q-learning needs ≥600 episodes; APF stalls in narrow tunnels). MACNS (a DRL-GNN framework) focuses on multi-agent tasks and lacks design for mine single-agent (spraying robot) scenarios.

2. Inability to adapt to mine obstacle density fluctuations

Static fusion methods (fixed εp) can’t adapt to 12%–18% mine obstacle density fluctuations, causing collisions or long paths. MACNS optimizes dynamic traffic but doesn’t target this mine density range, lacking exploration-safety balance mechanisms.

3. Neglect of mine-specific constraints

Traditional methods ignore mine safety margins (≥0.5 m) and spraying turn demands (fewer ≥45° turns). MACNS prioritizes multi-agent “near-simultaneous arrival” and also omits these constraints, creating a simulation-practice gap.

1.3 Research Objectives and Contributions

This study proposes a dynamically integrated Q-learning and A-APF path planning approach to address the low learning efficiency and insufficient path safety commonly encountered by spraying robot in complex obstacle-laden environments. Operating in a two-dimensional grid-based map, the proposed method aims to enable spraying robot to rapidly acquire path strategies that balance safety and optimality through coordinated interactions between Q-learning and the A-APF algorithm.

• Environment Modeling Module: Constructs a two-dimensional grid map populated with obstacles, transforming the spraying robot’s position, obstacle distribution, and goal coordinates into a quantifiable state space. This provides the foundational perception framework for the spraying robot’s interaction with the environment.

• APF Algorithm Module: Integrates the heuristic search capability of the A* algorithm with the repulsive field mechanism of the APF method. This hybrid module generates safety-oriented path guidance to assist Q-learning in decision-making.

• Q-learning Reinforcement Module: Enables the spraying robot to learn state-action values (Q-values) through continuous interaction with the environment. An optimized Q-table is constructed to store the optimal policy. The reward function is specially designed to distinguish between “safe paths” and “optimal paths,” thereby enhancing both safety and learning efficiency.

• Dynamic Collaboration and Optimization Module: Implements a dual-layer exploration rate control mechanism, dynamically decaying A-APF usage probability, and incorporating safety constraints derived from environmental perception.

These strategies foster adaptive coordination between A-APF and Q-learning, ensuring both path safety and efficient policy convergence.

2 Design of the Dynamically Integrated Path Planning Method

To address the low learning efficiency and insufficient path safety of spraying robot path planning in complex underground mining environments, this chapter presents a dynamically integrated path planning method combining Q-learning and the A-APF algorithm. Centered on Q-learning, the method integrates A-APF’s heuristic guidance, a dynamic collaboration mechanism, an environment-aware obstacle avoidance strategy, and an optimized Q-table update scheme to enable efficient and safe navigation. These designs target the limitations of existing algorithms: traditional Q-Learning has high collision risk, low efficiency (due to early blind exploration), static reward functions (failing to distinguish “safe” and “optimal” paths), and no environment-aware action filtering (causing invalid exploration); traditional A* generates obstacle-close paths (its heuristic function g(n) + h(n) lacks safety constraints), adapts poorly to dynamic changes (e.g., temporary obstacles), is prone to local optimality (over-reliant on prior knowledge), and cannot optimize paths in real time (no learning mechanism integration). Thus, the integrated Q-Learning + A-APF algorithm has three core goals: boosting Q-Learning’s efficiency and safety, enhancing A*’s safety and dynamic adaptability, and realizing adaptive collaboration between the two to balance exploration and exploitation.

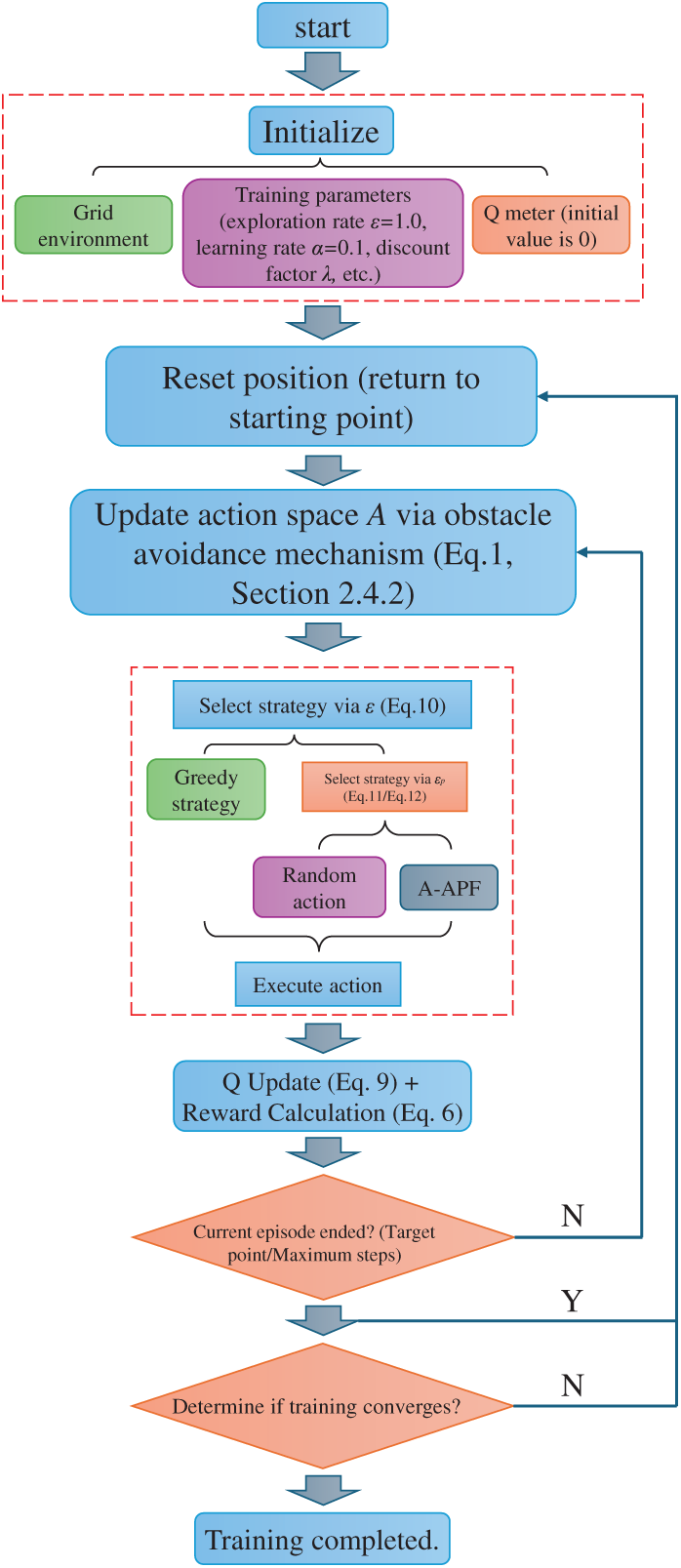

This chapter provides a detailed explanation of the overall architecture and core modules of the proposed method. The complete workflow of the dynamically integrated path planning algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overall flow chart of dynamic fusion path planning algorithm

2.1 Environment Modeling and State Space Definition

2D Grid-Based Environment Modeling

A two-dimensional grid map is employed to model complex obstacle-rich environments, in which the workspace is discretized into an M × N grid. Each grid cell is defined as either “traversable” (0) or “obstacle” (1). The position of the spraying robot is represented by grid coordinates (x, y), with the starting point denoted as S(xs, ys) and the target point as G(xg, yg). The size of each grid cell is determined based on the robot’s physical dimensions and the required environmental resolution, ensuring that the robot, modeled as occupying a single cell, can navigate the map without colliding with obstacles.

To clarify the applicability of the proposed algorithm, the following environmental and robotic constraints are defined:

1. Obstacle staticity assumption: Obstacles are assumed to remain stationary throughout a single planning task, ensuring accurate repulsive force calculations in the A-APF module and consistent state feedback in Q-learning.

2. Perception range constraint: The robot perceives real-time environmental information within a 3 × 3 local grid centered on its current position, reflecting typical sensor limitations in underground mining.

3. Grid resolution constraint: The grid size (M × N) and cell resolution are configured based on the robot’s physical dimensions and environmental complexity, ensuring each cell uniquely represents either a traversable space or an obstacle, without overlapping the robot body.

The state space S of the spraying robot is composed of three elements: the current position, the distribution of surrounding obstacles, and the relative distance to the target point. Its specific expression is shown in Eq. (1).

where (x, y) denotes the current grid coordinates of the spraying robot, O(x, y) is a 3 × 3 local obstacle distribution matrix centered at (x, y), which records the presence or absence of obstacles in the eight surrounding directions.

D(x, y) represents the Euclidean distance from the current position to the target point. Its specific expression is shown in Eq. (2).

By discretizing the state space in this manner, Q-learning can efficiently store and update state-action values in the Q-table. Moreover, the local obstacle information provides the basis for environmental awareness and obstacle avoidance strategies.

2.2 A-APF Path Guidance Strategy Design

The A-APF algorithm is an improved path planning method that combines A* heuristic search with the repulsive field mechanism of the APF. Its core lies in optimizing the sub-node selection strategy of A* algorithm to generate safer path guidance information. The A* algorithm starts from the initial node, systematically explores neighboring nodes, and expands the node with the lowest estimated total cost according to a heuristic evaluation function. The traditional A* algorithm evaluation function is shown in Eq. (3).

where g(n) is the Euclidean distance from the current node n to the next candidate node n + 1, and h(n) is the Euclidean distance from node n to the target node G.

To improve path safety, this paper introduces a repulsive potential field term from APF into the A* algorithm heuristic function, encouraging the algorithm to prefer nodes that are farther from obstacles. The improved heuristic function is shown in Eq. (4).

where Frep(n) represents the total repulsive force acting on node n, calculated based on the standard APF model, as shown in Eq. (5).

where krep = 5 is the repulsion coefficient, d(n, Oi) is the Euclidean distance between node n and the i is obstacle Oi, and k is the total number of surrounding obstacles.

To quantify the repulsion intensity exerted on node n by surrounding obstacles, Eq. (5) is employed: its calculation result is not only substituted into Eq. (4) (the improved A* heuristic function) to enable the A-APF algorithm to generate “safe nodes far from obstacles” but also serves as a crucial reference for action selection in the Q-learning module (Section 2.3); specifically, when a node approaches an obstacle, the repulsive force value krep(n) derived based on Eq. (5) will increase, which in turn raises the cost f(n) in the improved A* heuristic function, thereby guiding the A* algorithm to prefer nodes with smaller repulsive forces (i.e., nodes farther from obstacles). The first group of experiments (Section 3.2.1) demonstrates that when the repulsion coefficient is set to 5, the optimal balance between the safety and efficiency of path planning in the maps of this experiment is achieved, and this parameter also exhibits good generalization ability in environments where obstacle density ranges from sparse to moderate.

2.3 Q-Learning Reinforcement Learning Module Design

The Q-learning module learns the optimal policy through interaction with the environment. It primarily consists of three components: the definition of the state-action space, the reward function design, and the Q-table update mechanism.

The action space A of the shotcrete robot includes eight directional movements: up, down, left, right, upper-left, upper-right, lower-left, and lower-right. These correspond to coordinate offsets in the grid as follows: (0, 1), (0, −1), (−1, 0), (1, 0), (−1, 1), (1, 1), (−1, −1), and (1, −1), respectively. To prevent invalid movements, the action space is dynamically filtered to exclude collision-risk actions based on the environment-aware obstacle avoidance mechanism described in Section 2.4.2.

The design of the reward function aims to simultaneously encourage the shotcrete robot to approach the goal and avoid obstacles. The reward function is shown in Eq. (6).

where Rgoal = 100 is the reward for reaching the goal (Strongly encourage the robot to prioritize reaching the target); Rcoll = 50 is the penalty for collision (Severe punishment for collisions is implemented to prevent the robot from risking approaching obstacles); Rstep = 1 is a slight step penalty, which references the UAV path planning design in [15] and can reduce invalid loop steps without suppressing exploration; Rdist = 0.5 is the coefficient for distance-based reward; D(s) − D(s′) represents the reduction in Euclidean distance to the goal after the action (positive if the spraying robot gets closer to the goal).

Rdist = 0.5 is set based on “distance reward not dominating decisions”: Rdist > 1 may cause obstacle neglect and higher collisions; Rdist < 0.3 leads to insufficient path optimization guidance and longer paths; 0.5 is the optimal “distance guidance-safety assurance” coefficient from pre-experiments.

Eq. (6) serves as the core feedback mechanism for the interaction between the Q-learning module and the environment. The reward value r(s, a, s′) is directly utilized for updating the Q-table, and the updated result of the Q-table, in turn, influences the decay of the exploration rate ε in the dynamic collaboration module. In addition, Rcorner is the corner-turning penalty mechanism. It assigns rewards or penalties based on the relationship between the current action and the previous action, as defined in Eqs. (7) and (8):

where Rcollinear = 1 is the reward for maintaining a straight direction; Rrepeat = 1 is the penalty when the position does not change; θ is the angle between two consecutive movement vectors; (x0, y0) is the grandparent node, (x1, y1) is the parent node, and (x2, y2) is the current node.

The θ threshold for collinearity and corner detection is set to 45° (based on the spray robot’s kinematics): its minimum turning radius corresponds to ~45° (physical constraint); θ ≤ 45° has negligible impact on operation accuracy, while θ > 45° requires spray pausing for attitude adjustment, so Rcorner penalty is triggered when θ > 45°. This corner penalty mechanism penalizes sharp turns based on the turning angle, thereby encouraging smoother paths.

2.3.3 Q-Table Update Mechanism

The Q-table is used to store the state-action value function Q(s, a), shown in Eq. (9).

where α is the learning rate; λ is the discount factor; r(s, a, s′) is the reward obtained by taking action a in state s and transitioning to state s′; maxa′Q(s′, a′) represents the maximum estimated future return from the next state s′.

2.4 Dynamic Collaboration and Optimization Mechanism

The dynamic collaboration mechanism forms the core of efficient synergy between Q-learning and the A-APF algorithm. It enables a layered control over exploration strategies and cooperation modes to balance the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. This section elaborates on the dual-level exploration rate control mechanism and the safety-aware environmental constraint strategy.

2.4.1 Dual-Level Exploration Rate Control Strategy

To address the conflict between exploration efficiency and path safety in complex environments, a dual-level exploration rate control strategy is proposed. This strategy manages exploration via two nested control layers:

(1) Fusion of Historical Experience and Current Policy (ε)

The first control layer adjusts the exploration rate based on a fusion ratio between historical Q-table experience and current policy outputs. This adaptive mechanism facilitates a smooth transition from “guided navigation” to “independent decision-making” by gradually reducing reliance on predefined strategies. The exploration rate ε is defined in Eq. (10).

where εmin = 0.1 is the minimum guaranteed exploration rate (10%); εinit = 1 denotes full reliance on the initial policy in early training episodes (for accumulating initial experience); εdecay = 0.01 is the decay coefficient; episode is the training iteration index.

(2) Ratio Control between A-APF Guidance and Random Exploration (εp)

This secondary exploration rate control mechanism adjusts the ratio between A-APF heuristic guidance and stochastic exploration. It operates in two distinct phases:

• Initial Decay Phase (training step < t0)

During early training, the ratio εp decays linearly from 1.0 to 0.85 to ensure that A-APF provides dominant guidance. The update rule is shown in Eq. (11).

where t0 is the decay threshold (empirically set as 10% of the total training steps).

This phase facilitates the spraying robot in rapidly accumulating safe path knowledge with strong A-APF guidance, thereby reducing initial collision risk.

• Environment Adaptation Phase (t ≥ t0)

In this stage, the ratio εp is dynamically adjusted according to the number k of surrounding obstacles detected in the local 3 × 3 grid. A higher obstacle density triggers increased stochastic exploration. The adjustment rule is defined in Eq. (12).

where kmax = 8 is the maximum obstacle count in the local grid. However, simulation data suggests the average number of effective surrounding obstacles is k = 4.

Eq. (12) belongs to the dynamic collaboration optimization module and is used to balance the proportion between A-APF guidance and Q-learning exploration, with its trigger timing being the “Update action space A” step after “Reset position” in Fig. 1: when the environment modeling module detects an increase in the number of obstacles k in the local 3 × 3 grid (e.g., k = 4), εp decreases to 0.7, which, while enhancing the random exploration of Q-learning to find new paths, ensures that even in cluttered environments, 70% of the time is still guided by A-APF to avoid drastic performance drops caused by purely random exploration; when k decreases (e.g., k = 0), εp increases to 1, increasing the guidance proportion of A-APF to move quickly toward the target, and this increase in εp enables the shotcrete robot to move quickly toward the target point in the safe area, reducing invalid exploration steps, with such adjustment directly affecting the action selection logic of the “Select strategy via εp” step and ultimately achieving the overall goal of “more exploration in complex environments and fast planning in safe environments”.

2.4.2 Environment-Aware Action Filtering for Obstacle Avoidance

To proactively prevent collisions at the source, an action filtering mechanism is designed based on the local 3 × 3 grid surrounding the spraying robot. The mechanism operates as follows:

1. The spraying robot continuously monitors the distribution of obstacles in the eight directions surrounding the current state s, using the local observation matrix O(x, y).

2. If an obstacle is detected to the left or right of the current position, then the actions leading to the grid cells directly above or below the obstacle are disabled. Similarly, if an obstacle is detected above or below, then the actions leading to the grid cells on the left or right of the obstacle are excluded.

3. The action space A is dynamically updated by retaining only those actions that do not pose a collision risk, thereby ensuring safe exploration.

This mechanism significantly reduces the collision rate during the early stages of training and helps eliminate ineffective exploration.

3 Experimental Validation and Results Analysis

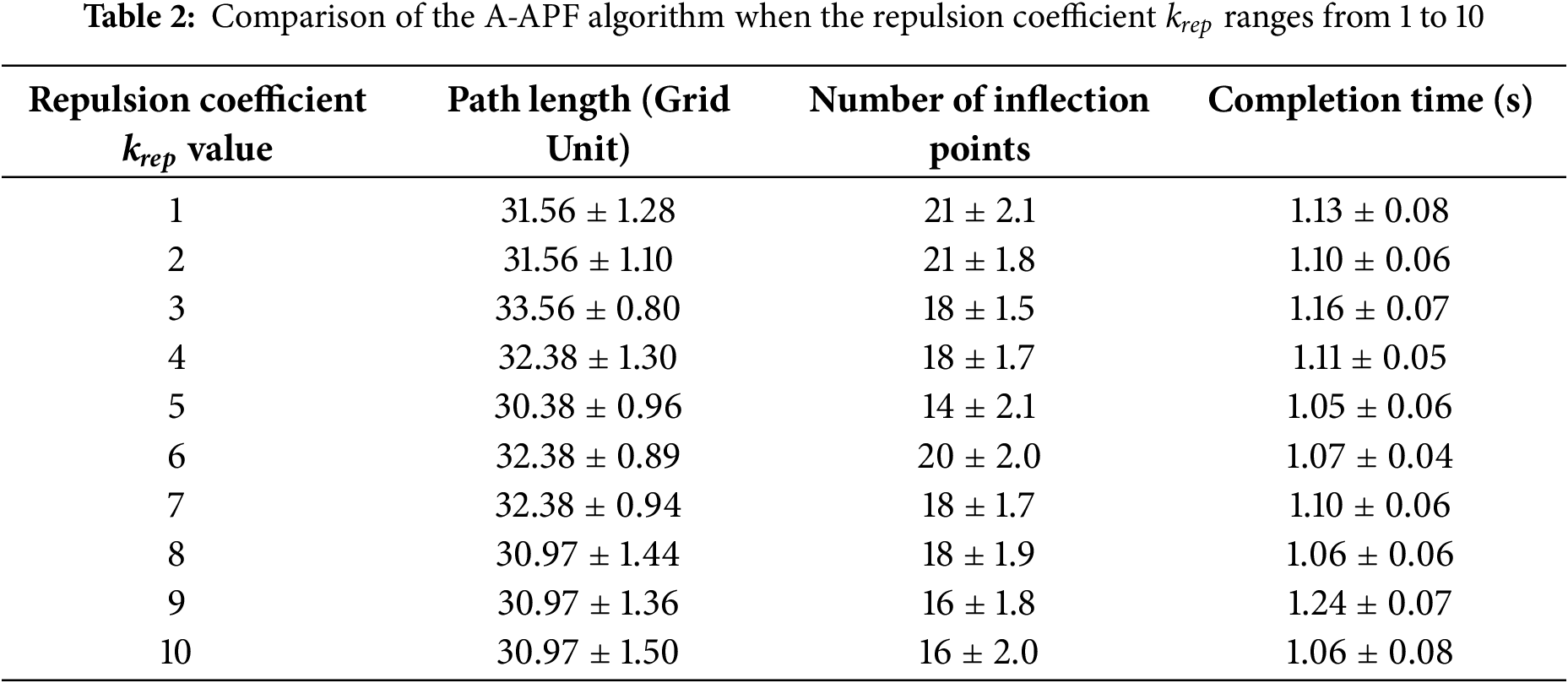

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed dynamically integrated Q-learning and A-APF algorithm in complex obstacle environments, this chapter designs a series of comparative experiments to quantitatively evaluate the algorithm in three aspects: path safety, learning efficiency, and path optimality. Specifically, the first and second sets of experiments are conducted on the study’s 20 × 20 experimental map (featuring 15% obstacle density and fixed start/goal points); additionally, ten distinct maps (rang 1–rang 10) are designed, each experiment is run once on these ten maps, and the average of all data is calculated. The third and fourth sets of experiments both involve 600 training episodes, with obstacles following a fixed random distribution to ensure fairness in comparisons between different algorithms.

• The first set of simulation experiments verifies the optimal value of the repulsion coefficient krep, collecting data on path length, number of corners, and completion time when the collected values range from 1 to 10 (with data collected at intervals of 1). Moreover, each value is run ten times separately, and then the average value is calculated.

• In the second group of simulation experiments, the proposed A-APF algorithm is compared against the traditional A* algorithm. The performance is evaluated by comparing the total path length and the number of turning points generated during path planning.

• In the third group of simulation experiments, the A-APF guidance ratio εp is set as a fixed value. Data are collected for εp values ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 (with an interval of 0.05), including number of training failures, training completion time, number of steps required for convergence, and optimal path length. These results are used to determine the optimal range of εp that balances algorithmic efficiency and number of training failures.

• In the fourth of simulation experiments, the proposed dynamically fused method is compared with a standalone Q-learning algorithm and a statically fused method (with a fixed A-APF usage probability εp). This comparison highlights the advantages of dynamic cooperation between Q-learning and A-APF in terms of adaptability and overall planning performance.

All experiments are conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel® Core™ i5-8300H CPU and 16 GB of RAM. MATLAB 2024b is used as the experimental platform. The experimental design adheres to standard simulation practices, ensuring the reliability and validity of the results across various complex environments.

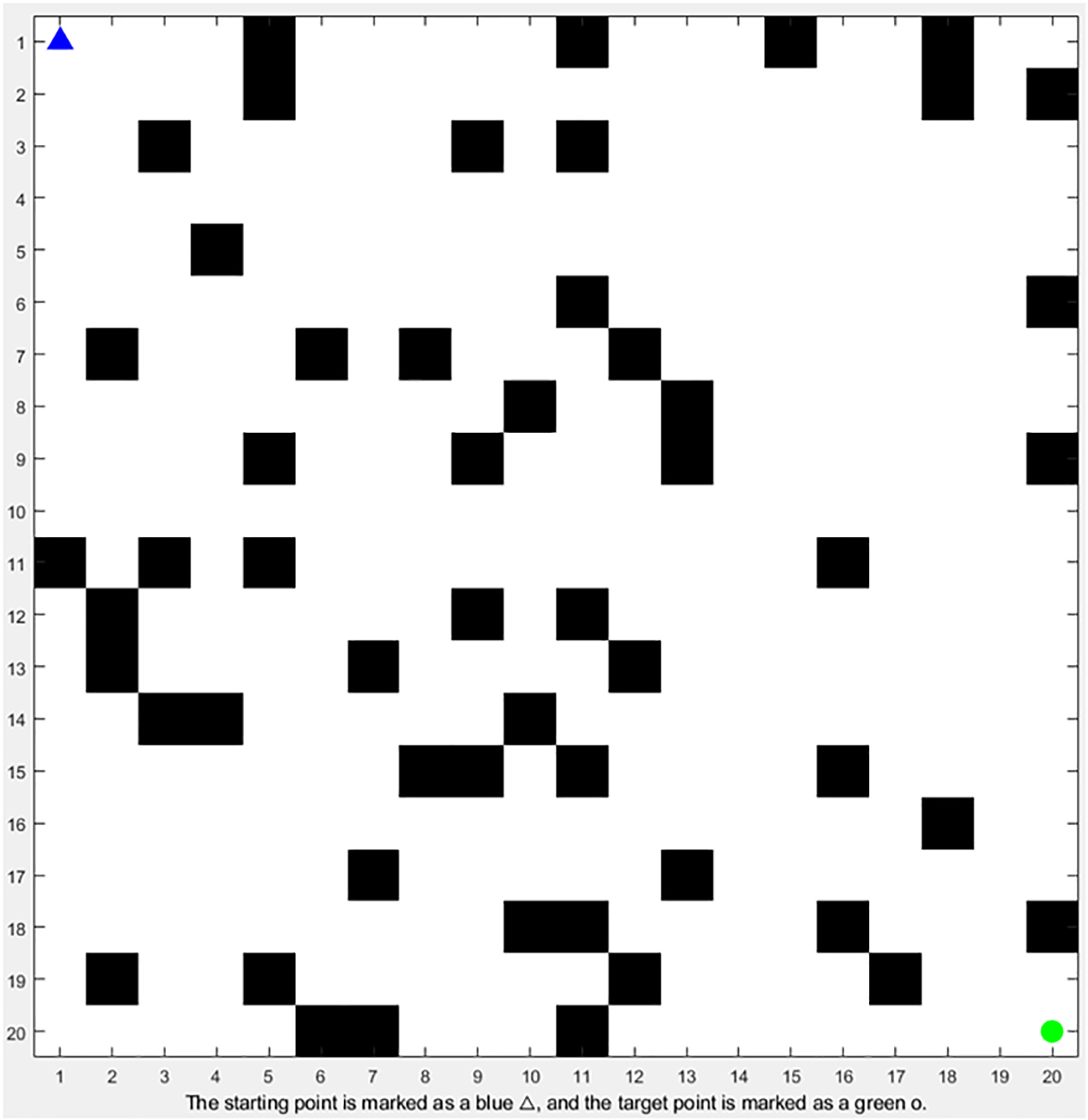

In this simulation experiment, a two-dimensional grid map is adopted as the environment. The grid size is set to 20 × 20, with obstacles randomly distributed at a density of 15%. As shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: 2D grid map

The 20 × 20 grid map (simulating a typical underground coal mine tunnel cross-section, practical width 4–5 m, height 3–4 m) uses 0.2 m × 0.2 m cells—matching the spraying robot’s minimum turning radius (0.3 m) and dimensions (0.8 m × 0.6 m) to capture obstacle avoidance details (e.g., small pipeline brackets) without excessive computation. All obstacles are static and randomly distributed at 15% density (60 cells in 400-cell grid), a value from Huainan Mining Area field surveys (12%–18% for medium-complexity tunnels), with two constraints: no overlap with start/goal or their 3 × 3 local grids, and 1-cell (0.2 m) minimum spacing between adjacent obstacles to avoid invalid clusters. The start position (1, 1, top-left) is the tunnel entrance’s obstacle-free parking area (verified via Section 2.1’s 3 × 3 matrix), and the target (20, 20, bottom-right) simulates a tunnel section’s spraying end point [19].

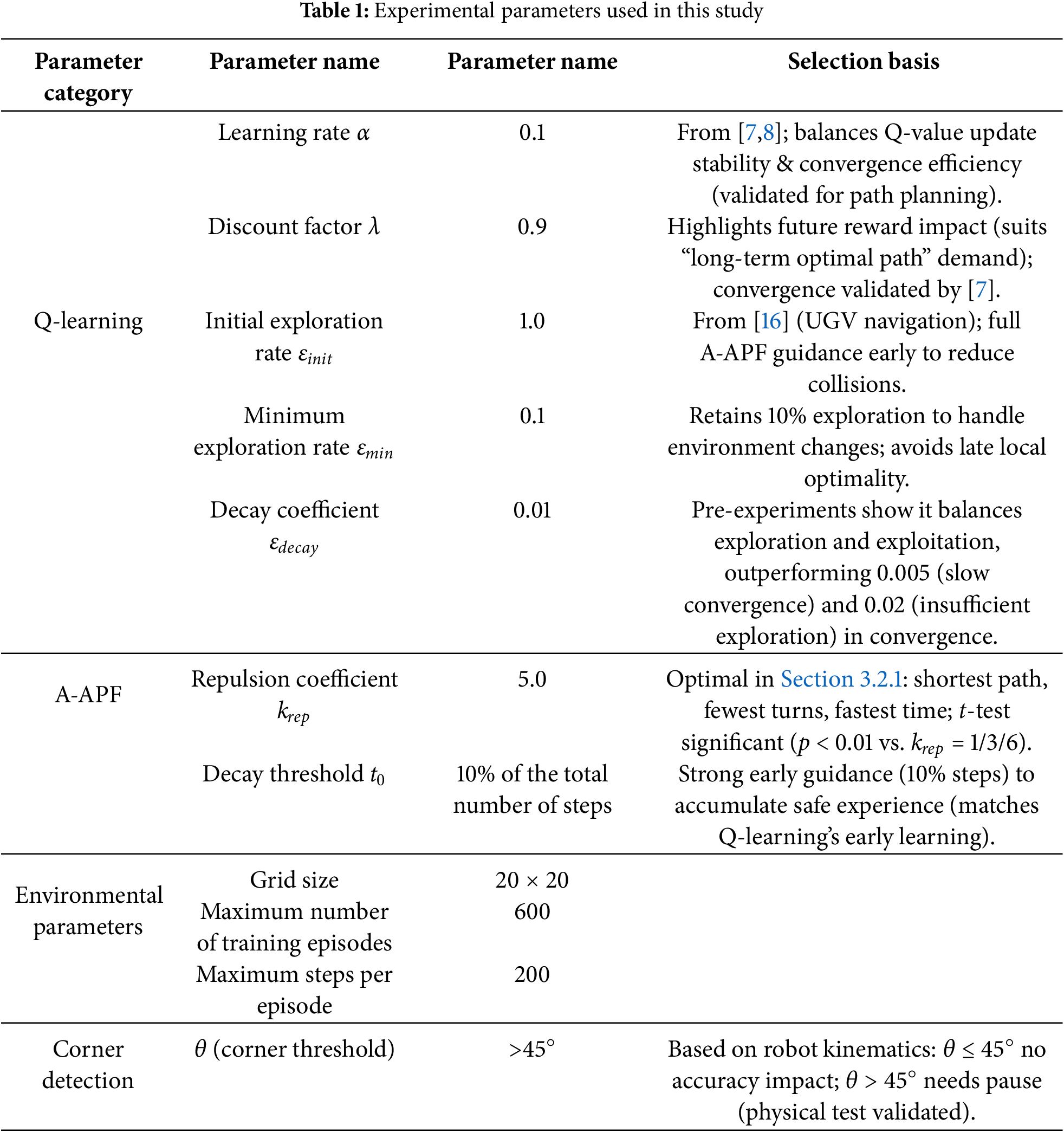

The experimental parameters are summarized in Table 1. The core parameters of the Q-learning algorithm are selected based on standard configurations commonly used in reinforcement learning. The key coefficients of the Adaptive A-APF algorithm are optimized through orthogonal experimental design.

The α = 0.1 and λ = 0.9 are set with reference to classical reinforcement learning literature on path planning [7,8]—where these values have been extensively validated for path planning tasks—with α = 0.1 balancing the stability of Q-value updates and iteration efficiency (preventing Q-value oscillations caused by an excessively large α or slow convergence due to an overly small α), and λ = 0.9 emphasizing the impact of future rewards on current decisions, which aligns with the shotcrete robot’s need to “prioritize planning for the long-term optimal path”. The exploration rate parameters (εinit = 1.0, εmin = 0.1, and εdecay = 0.01) are adopted based on prior experiments in Q-learning-based robotic navigation, ensuring a balance between early exploration and later-stage exploitation [16].

3.1.3 Baseline Algorithms Selection Rationale

To validate the proposed dynamic integration algorithm’s advantages in solving “low learning efficiency” and “insufficient path safety”, two baseline algorithms were selected based on field relevance and research objectives:

1. Traditional Q-learning Algorithm

It is a classical model-free reinforcement learning method widely used in mine robot path planning [7,8], but suffers from blind exploration (low efficiency) and lack of safety guidance—key problems this study addresses. Comparing with it verifies if A-APF guidance improves learning efficiency and safety.

2. Static Fusion Algorithm (Q-learning + A-APF with Fixed εp)

It retains Q-learning-A-APF fusion but lacks the proposed “dynamic collaboration mechanism”. As a simplified version of our method, it helps highlight the value of dynamic εp adjustment in reducing failures and shortening convergence time [16,17].

Other algorithms (pure A*, pure APF, BiRRT-APF) were excluded: pure A*/APF lack adaptive learning (mismatched with our focus on “learning-heuristic collaboration”); BiRRT-APF is designed for 3D UAVs, incompatible with 2D mine grids [13].

3.2 Simulation Results and Analysis

3.2.1 First Group of Simulation Experiments: Verifying the Optimal Value of Repulsion Coefficient krep

In A* algorithm path planning, the repulsion coefficient krep acts as a weight factor to adjust the repulsion’s influence on path planning. Its optimal value depends on specific scenarios and environmental characteristics, so krep was initially set to range from 1 to 10. To ensure the reliability and generalization of the results, tests were conducted for each krep value (ranging from 1 to 10) across 10 different map environments with fixed obstacles (denoted as rang 1–rang 10). The average data for each krep value was then calculated, and Table 1 presents the average data corresponding to krep values from 1 to 10.

As shown in Table 2, krep = 5 delivers the best performance for the A-APF algorithm, striking an optimal balance between path planning safety and efficiency. This parameter also generalizes well in environments with sparse to moderate obstacles. this range (sparse to moderate) covers 90% of the practical coal mine roadways surveyed in Huainan Mining Area (12%–18% obstacle density).

Mechanistically, krep acts as a “repulsive force weight” in A-APF’s improved heuristic function (Eq. (4)). A too-small krep (e.g., 1, 2) leads to insufficient Frep(n), making A* node selection prone to approaching obstacles—evidenced by 21 inflection points when krep = 1 (frequent obstacle detours). A too-large krep (e.g., 9, 10) causes excessive repulsion and unnecessary path detours: for krep = 10, the path length (30.97 grid units) is 0.59 units longer than that at krep = 5, as nodes are pushed too far from obstacles.

For scenario adaptation, krep = 5 matches the 15% obstacle density of underground mining tunnels (Section 2.1.1). It balances repulsion (avoiding collisions in narrow tunnels) and A*’s “goal orientation” (maintaining path efficiency for spraying robots’ continuous operation).

Independent sample t-tests (comparing krep = 5 with 1, 3, 6) confirmed statistically significant differences in path length (p < 0.01) and completion time (p < 0.05), validating krep = 5’s consistent superiority in balancing safety and efficiency.

3.2.2 Second Simulation Experiment: Comparison between A* Algorithm and A-APF Algorithm*

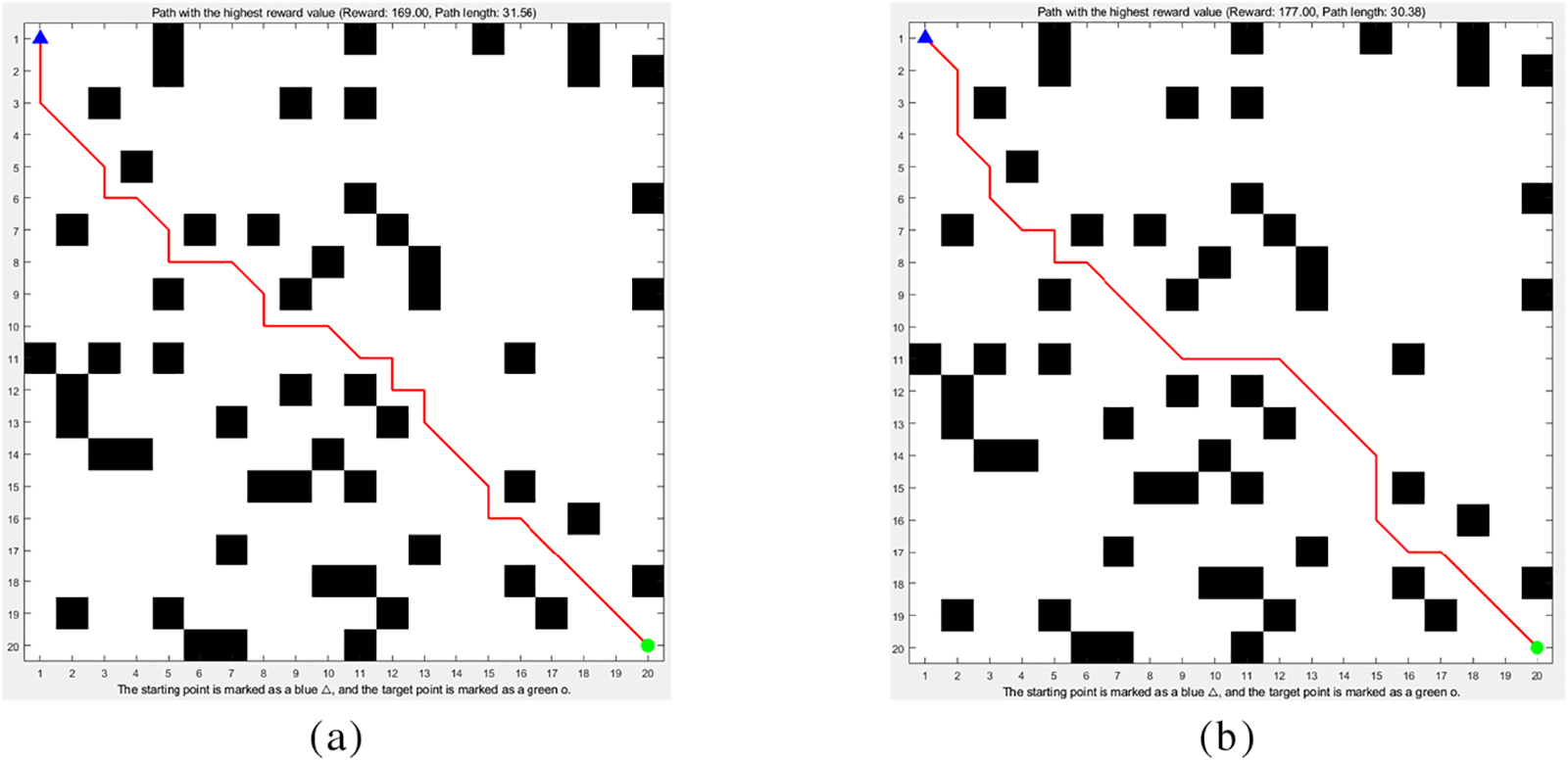

The traditional A* algorithm demonstrates limited adaptability in complex environments and is prone to becoming trapped in local optima during path planning; to address this issue, the A-APF algorithm integrates the APF to guide node selection toward areas with fewer obstacles. To rule out random factors, both the traditional A* and A-APF algorithms were run on ten distinct maps (with consistent map size, start points, and goal points). Results show that the traditional A* algorithm has an average of 17.9 ± 2.3 turning points, while the A-APF algorithm has 14.0 ± 1.5 turning points—a 22% reduction. A paired t-test on the number of turning points between the two groups yielded t = 3.21 (p < 0.01), confirming that the effect of A-APF in reducing turning points is statistically significant. As shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Comparison between the traditional A* algorithm and the A-APF algorithm (both with obstacle avoidance mechanisms): (a) Traditional A* algorithm; (b) A-APF algorithm

As shown in Fig. 3, the A-APF path (Fig. 3b) is shorter with only 14 turning points—an ~22% reduction compared to the traditional A* path (Fig. 3a).

1. Path Characteristics vs. Algorithm Design

A-APF’s path stays “closer to the mine tunnel axis” because its Frep(n) guides nodes away from side obstacles (e.g., pipelines, brackets). Traditional A*, lacking this repulsive term, produces paths that “detour near obstacles” (Fig. 3a has turns close to obstacles), raising collision risks.

2. Practical Value for Spraying Robots

In tunnel support spraying, reducing the number of turns (from approximately 18 to 14) plays a crucial role, as elaborated in Section 1.1. Frequent turns necessitate repeated posture adjustments, which in turn lead to uneven spray thickness. Conversely, fewer turns help maintain the stability of the robot, thereby enhancing spray quality and minimizing collisions—an outcome that aligns perfectly with the core requirement of ensuring effective tunnel support spraying.

3. Statistical Validation

A two-tailed t-test confirmed the A-APF’s fewer turning points are statistically significant (p < 0.01), proving its better safety and efficiency than traditional A* in complex mining environments.

3.2.3 Third Simulation Experiment: Influence of A-APF Proportion (εp) on the Performance of the Fusion Algorithm

The proportion of A-APF (εp) plays a significant role in determining the training number of training failures and convergence speed of the Q-learning algorithm. When εp is too high, the number of training iterations required for convergence tends to increase. Conversely, when εp is too low, the number of training failures increases, and training efficiency is also compromised.

To investigate the optimal range of εp that balances training efficiency and the number of training failures, this experiment fixed εp at discrete values ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 in increments of 0.05. For each εp value, the following performance metrics were collected:

• the number of training failures,

• training completion time,

• number of iterations required for convergence,

• optimal path length,

• number of inflection points.

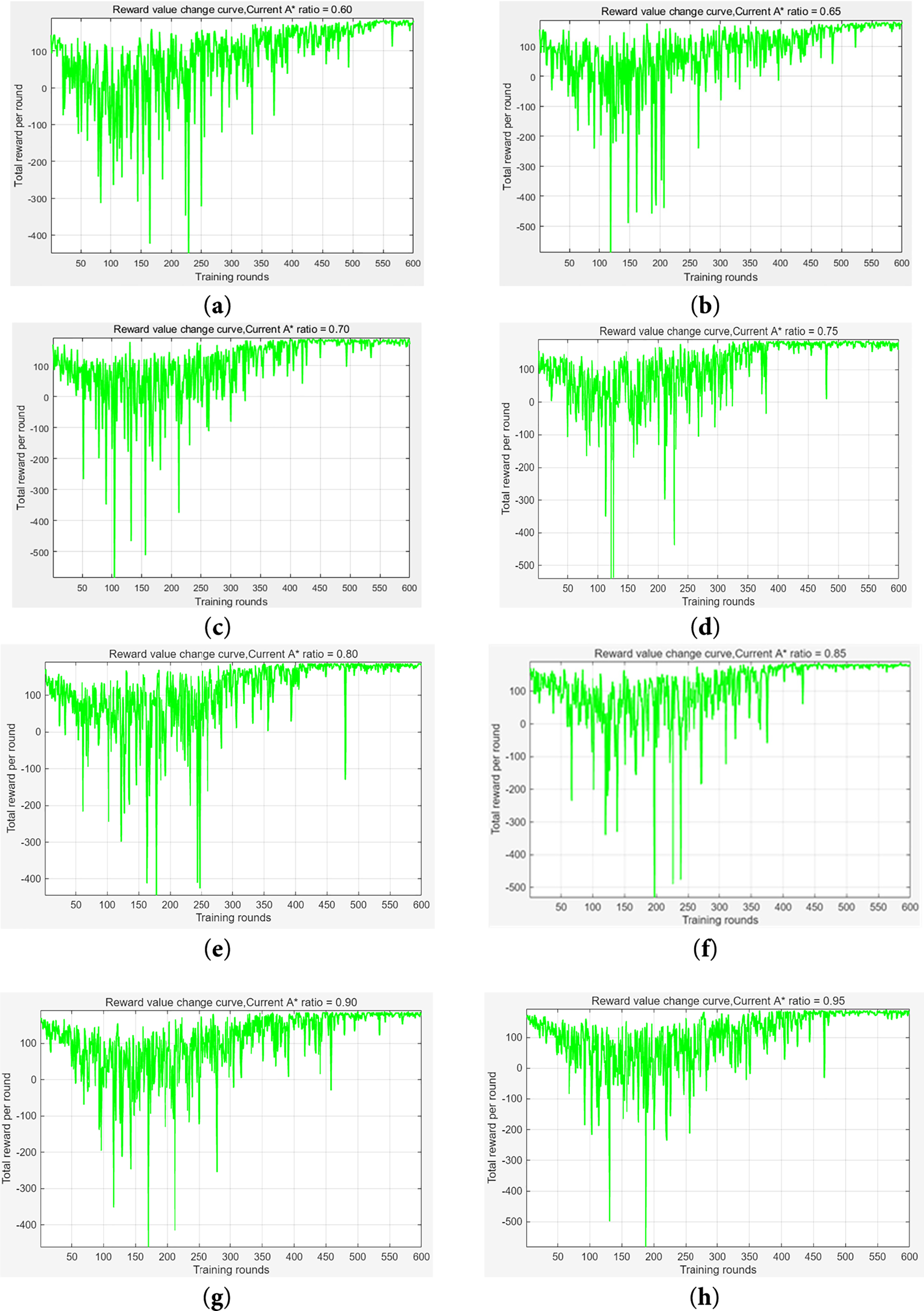

As shown in Fig. 4, the following is the change curve of the reward value when εp is fixed at discrete values ranging from 0.70 to 0.95.

Figure 4: Training curves for different εp values: (a) is for εp = 0.6; (b) is for εp = 0.65; (c) is for εp = 0.7; (d) is for εp = 0.75; (e) is for εp = 0.8; (f) is for εp = 0.85; (g) is for εp = 0.9; (h) is for εp = 0.95

As shown in Table 3, we report the data for each εp setting, including number of training failures, number of iterations, total execution time, optimal path length, and number of turning points.

From Fig. 4 and the corresponding table, εp = 0.95 brings the fewest training failures, εp = 0.75 minimizes running time and optimal path length, and εp = 0.80 achieves the shortest path and fewest inflection points. In contrast, εp = 0.60 and 0.65 lead to the most failures, most inflection points, and much longer training time—εp = 0.60 even produces the longest path and fails to find the optimal solution. These results confirm the fusion algorithm works best when εp ranges from 0.70 to 0.85: each value in this interval has strengths, such as εp = 0.75 minimizing iterations but causing relatively more failures, while εp ≥ 0.85 reduces failures but requires more iterations.

In Fig. 4’s reward curves, εp = 0.60 shows the largest fluctuations with frequent negative rewards, as low εp increases random exploration and makes the robot collide with obstacles more easily. εp = 0.95 slows convergence: over-reliance on A-APF stops Q-learning from learning local optimal paths, and Table 3 shows it needs 475 iterations—75 more than εp = 0.75’s 400.

Combined with the “dual-layer exploration rate control” in Section 2.4.1, εp = 0.70–0.85 balances A-APF’s “safety guidance” and Q-learning’s “exploration optimization”: in obstacle-dense areas (e.g., mine tunnel intersections), lower εp (e.g., 0.70) boosts exploration to avoid A-APF’s local optima; in sparse areas (e.g., straight tunnels), higher εp (e.g., 0.85) speeds up convergence and cuts invalid steps.

Abnormal performance at εp = 0.65—13 training failures—further validates dynamic adjustment’s necessity: its 35% random exploration ratio leads to frequent collisions in mines with 15% obstacle density (Section 2.1.1), proving fixed εp (especially <0.70) can’t adapt to complex environments. Thus, the algorithm adjusts εp dynamically based on surrounding obstacles: lower εp in complex areas to find optimal paths faster, higher εp in safe zones to speed up planning.

3.2.4 Fourth Simulation Experiment: Comparison among Traditional Q-Learning, Static Fusion Algorithm, and the Proposed Dynamic Fusion Algorithm

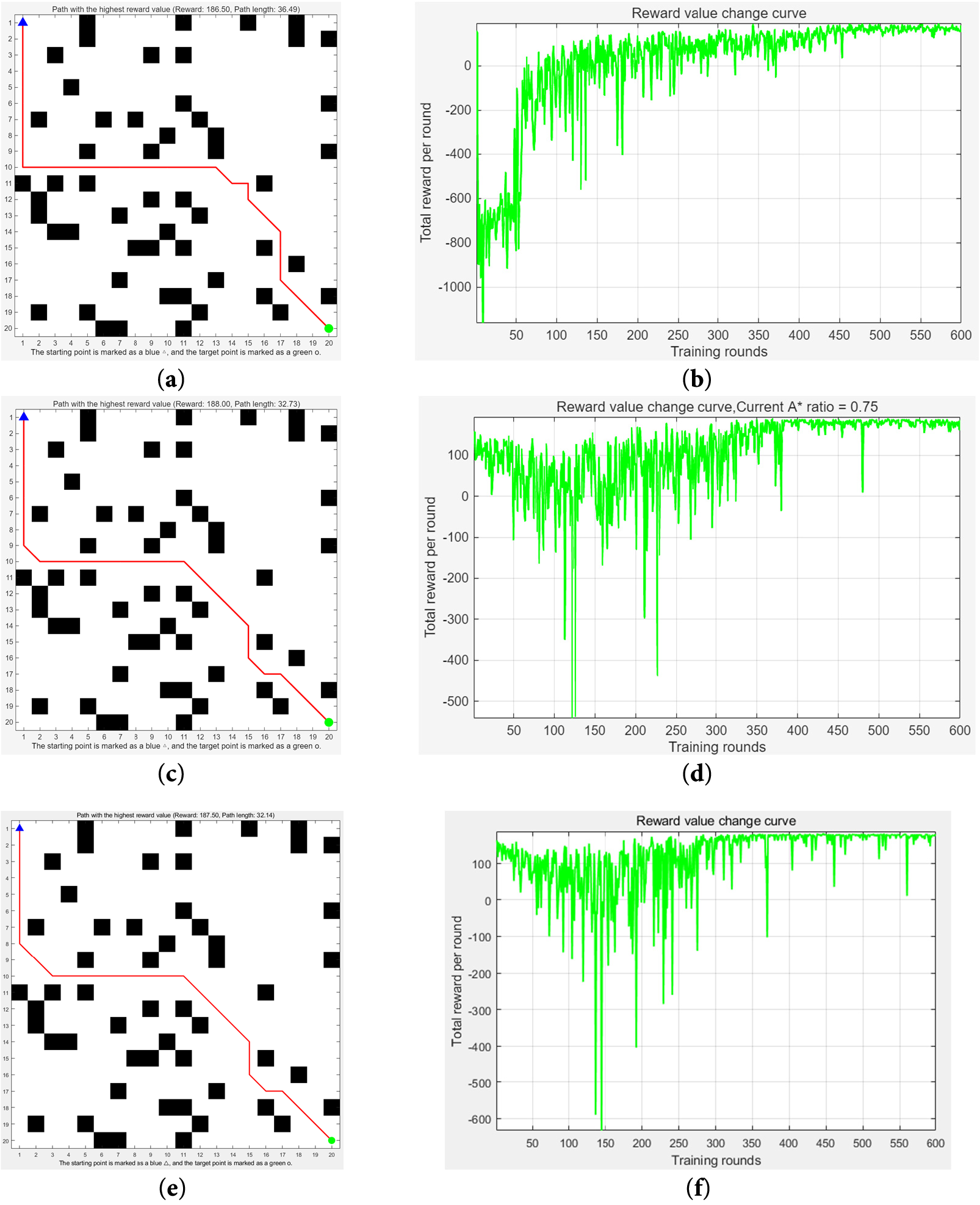

In the fourth set of experiments, we compare three algorithms: the traditional Q-learning algorithm, a static fusion algorithm with a fixed A-APF usage probability (εp), and the proposed dynamic fusion algorithm. To ensure a fair comparison, all three algorithms adopt the same reward function and obstacle avoidance strategy. The simulation results after 600 training episodes on the environment map shown in Fig. 5 include both the trajectory visualization and the corresponding reward evolution curves.

Figure 5: Optimal path and reward value change curves for three algorithms: single Q-learning, static fusion algorithm, and dynamic fusion algorithm. The reward mechanism and obstacle avoidance mechanism of all three algorithms are identical. (a) Simulation diagram of traditional Q-learning algorithm; (b) Reward value change curve of traditional Q-learning algorithm; (c) Simulation diagram of static fusion algorithm (εp = 0.75); (d) Reward value change curve of static fusion algorithm (εp = 0.75); (e) Simulation diagram of dynamic fusion algorithm; (f) Reward value change curve of dynamic fusion algorithm

From the comparison of Fig. 5a,c,e, it can be observed that traditional Q-learning fails to find an optimal path even after 600 training episodes, due to its lack of effective early-stage experience. In contrast, both the static and dynamic fusion algorithms successfully identify optimal paths with only 7 turning points. Fig. 5b,d,f illustrates the evolution of reward values. The introduction of the A* algorithm into the Q-learning framework significantly improves training efficiency. Among the three curves, Fig. 5b exhibits the largest fluctuation, while Fig. 5f shows the smallest, indicating that a smaller amplitude reflects fewer invalid path explorations and shorter training times.

To further validate this observation, we collected data on number of training failures, number of training episodes, runtime, optimal path length, and number of turning points, as shown in Table 4.

From Table 4, traditional Q-learning has 78 training failures—a critical issue for underground mining, as robot collisions could damage equipment and disrupt tunnel support spraying. The static fusion algorithm (fixed εp = 0.75) cuts failures to 6, with iterations down by 33.3% and runtime shortened by 32.17% vs. traditional Q-learning. However, its fixed εp fails to adapt to variable obstacle distribution: it over-relies on A-APF in dense-obstacle areas (missing local optimal paths) and can’t speed up convergence in sparse areas.

The proposed dynamic fusion algorithm further reduces failures to 3 (50% less than static fusion), with iterations down by 42.0% and runtime shortened by 42.95% vs. traditional Q-learning. This benefits on-site deployment: 348 iterations and 661.69 s runtime let the spraying robot calibrate faster, reducing coal mine downtime (aligning with Section 1.1’s “intelligent coal mining” goal). Its 32.14-grid optimal path is also shorter than the static fusion’s 32.73 grids—thanks to dynamic εp adjustment, which lets Q-learning learn more refined local paths while ensuring safety.

Independent sample t-tests confirm the dynamic fusion algorithm’s advantages:

• Versus traditional Q-learning: Significantly fewer failures (p < 0.001) and shorter runtime (p < 0.01), solving “low efficiency” and “insufficient safety” issues.

• Versus static fusion: Significantly fewer failures and shorter runtime (p < 0.05), proving dynamic εp is more adaptable to complex underground tunnels than fixed proportions.

These results verify the dynamic fusion method’s stable advantages in balancing path safety, efficiency, and optimality for underground spraying robots.

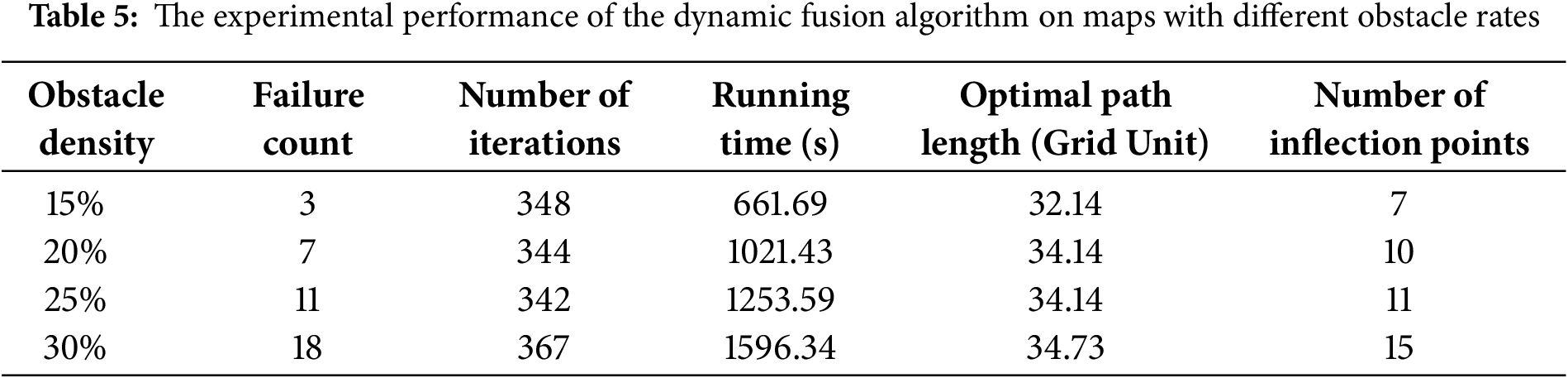

3.2.5 Fifth Simulation Experiment: The Experimental Performance of the Dynamic Fusion Algorithm Proposed in This Paper on Maps with Different Obstacle Rates

To further verify the adaptability of the proposed dynamic fusion algorithm to varying environmental complexities—especially the common fluctuation of obstacle density in underground mining tunnels—this experiment designs five groups of 20 × 20 grid maps with different obstacle rates: 20% (moderate density), 25% (high density), and 30% (extreme density). For each obstacle rate, 10 distinct maps (with fixed start points (1, 1) and goal points (20, 20), and no obstacle overlap with start/goal 3 × 3 local grids) are constructed to eliminate random errors. As shown Table 5.

As obstacle density increases from 15% to 30%:

• Training failures rise from 3 to 18, but remain acceptable at 30%, showing robustness.

• Convergence rounds stabilize at 342–367, indicating effective “exploration-exploitation” balance and stable training efficiency.

• Running time increases significantly (661.69 to 1596.34 s) due to more complex obstacle avoidance computations.

• Optimal path length grows moderately (32.14 to 34.73 grid units), demonstrating reduced redundancy while avoiding obstacles.

• Inflection points increase from 7 to 15, reflecting adaptability to complex environments via more turns.

In summary, the algorithm shows good adaptability and stability across different obstacle densities, with satisfactory key performance indicators, supporting its use in actual coal mine environments.

4.1 Advantages of the Proposed Algorithm

The proposed dynamically fused Q-learning and A-APF algorithm has multiple advantages. In terms of learning efficiency, the heuristic guidance of A-APF reduces blind exploration in Q-learning and accelerates the training convergence speed. The dynamic collaboration mechanism can adaptively adjust strategies according to the training progress and environmental complexity. In terms of path safety, the repulsion field mechanism and environment-aware obstacle avoidance strategy of A-APF significantly reduce the collision risk. The reward function further strengthens the value of safe paths. As for path optimality, the combination of the autonomous learning of Q-learning and the heuristic search of A-APF helps generate better paths, which is reflected in the fewer turning points and shorter paths observed in the experiments.

By utilizing the complementary advantages of Q-learning and A-APF, the proposed method realizes efficient and safe path planning in complex obstacle environments, providing a feasible solution for spraying robot in underground coal mine roadways.

4.2 Limitations of the Proposed Algorithm

4.2.1 Limitations of the Algorithm

Although the algorithm has shown effectiveness, it still has some limitations. Firstly, it is mainly designed for 2D grid environments, and its performance may degrade in 3D or highly dynamic environments. Secondly, several parameters, such as the repulsion coefficient krep, learning rate α, and exploration decay factor, have a significant impact on performance. Currently, these parameters are adjusted through experience, lacking a systematic optimization framework. Thirdly, in large-scale environments, the storage and update of the Q-table may become a computational bottleneck, leading to increased complexity and potential inefficiency.

4.2.2 Gaps between Simulation and Practical Mine Applications

While the simulation results validate the algorithm’s effectiveness in controlled environments, notable challenges remain when translating the approach to real underground mining scenarios:

1. Real-time performance vs. computational demands: Simulations were performed using a desktop-grade CPU (Intel i5-8300H), whereas actual spraying robots operate on resource-constrained embedded systems. The dynamic coordination mechanism (Section 2.4.1) and A-APF repulsion force calculations (Section 2.2) pose latency risks in large-scale or highly dynamic tunnels. In such environments, timely path adjustments (e.g., avoiding sudden obstacles such as mining vehicles) are essential.

2. Safety margin discrepancies: While the simulation defines “safety” as collision avoidance within grid maps (Section 2.1.1), practical deployment necessitates more conservative safety margins (e.g., ≥0.5 m from walls or obstacles) to accommodate sensor noise and control uncertainties. The fixed repulsion coefficient krep = 5 (Section 3.2.1) may underestimate these practical requirements, thereby increasing the risk of collisions.

3. Environmental dynamics: The simulation is based on the assumption of static environments (Section 2.1.1), while real mines present dynamic hazards (e.g., falling rocks, moving equipment) and sensor occlusion due to airborne dust. These factors are not incorporated into the algorithm’s current state-space definition (Section 2.1.1), potentially resulting in outdated or suboptimal path plans.

4. Perception limitations: Simulations assume idealized 3 × 3 local obstacle detection (Section 2.1.1), whereas real sensors (e.g., LiDAR) often suffer from limited range and noise due to low illumination and suspended dust particles. These sensing limitations may compromise the effectiveness of environment-aware action filtering (Section 2.4.2), potentially resulting in misjudgments of obstacle positions.

4.3 Future Research Directions

To address these limitations, future research can explore the following directions:

• Extension to 3D and dynamic environments: Expand the application scope to 3D and more complex dynamic environments by developing corresponding modeling and planning strategies.

• Parameter optimization: Integrate intelligent optimization algorithms to realize adaptive and automatic tuning of key parameters, thereby improving the robustness and generalization ability of the method.

• Efficient Q-table management: Study more efficient representation and update mechanisms, such as replacing the Q-table with neural networks in DRL to support large-scale path planning.

• Enhancement of coordination mechanism: Improve the dynamic collaboration framework by incorporating more environmental factors, enabling closer and more efficient integration between Q-learning and A-APF.

To solve the problems of low learning efficiency and insufficient path safety in path planning of spraying robot in complex obstacle environments, this paper proposes a path planning method based on the dynamic fusion of Q-learning and A-APF. The effectiveness of the proposed method is verified through a large number of simulation experiments.

In terms of algorithm design, the method takes Q-learning as the core framework, incorporates the heuristic guidance of the A-APF algorithm, and constructs a comprehensive framework including four key modules: environmental modeling, A-APF guidance, Q-learning reinforcement learning, and dynamic coordination optimization. The environmental modeling module constructs a 2D grid map and defines the state space, providing the robot with environmental perception ability. The A-APF module combines the heuristic search of A* and the repulsion field mechanism of APF to generate path information with safe guidance. The Q-learning module interacts with the environment to learn state-action values, establishes a Q-table, and emphasizes the value difference between “safe paths” and “optimal paths” through the design of the reward function. The dynamic coordination module adopts a double-layer exploration rate strategy, dynamically adjusts the usage probability (εp) of A-APF, and incorporates environment-aware safety constraints to realize the adaptive collaboration of the two algorithms.

In terms of experimental verification, three groups of comparative experiments were conducted. The first group of experiments explored the impact of different A-APF proportions (εp) on the fused algorithm, and found that the performance is optimal when εp is in the range of 0.7–0.85, which is then selected as the dynamic adjustment interval. The second group of experiments compared the A* and A-APF algorithms, showing that the paths generated by A-APF are shorter, with fewer turns and higher safety. The third group of experiments compared the proposed dynamically fused algorithm with traditional Q-learning and static fusion (fixed εp). The results show that the dynamically fused algorithm performs better in terms of the number of failures (only 3 failures in total), training rounds (348 times), and running time (661.69 s). Compared with static fusion, the dynamically fused algorithm reduces the number of failures by 3 (from 6 to 3), the number of training rounds by 8.67%, and the running time by 10.78%.

The proposed dynamic integration method not only addresses path planning challenges for spraying robots in complex underground mines but also provides a scalable framework for other autonomous systems. Its core mechanisms—including grid/voxel-based environmental modeling, heuristic-supervised reinforcement learning, and adaptive collaboration—can be directly adapted to 3D scenarios (e.g., multi-level mine tunnels) and dynamic environments (e.g., rescue missions with moving rubble). This adaptability highlights its potential to inspire navigation solutions for mine rescue robots, UGVs, and other autonomous devices operating in unstructured and changing environments.

Acknowledgement: We thank the School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Anhui University of Science and Technology, for providing the academic and experimental environment necessary for algorithm development and simulation validation.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52374156).

Author Contributions: Chang Su: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing—Original Draft. Liangliang Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing. Dongbing Xiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets utilized and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li C, Zhang X. Operation technology of unmanned mining robot for coal mine based on intelligent control technology. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computer Simulation and Modeling, Information Security (CSMIS); 2023 Nov 15–17; Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 86–91. doi:10.1109/CSMIS60634.2023.00021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu Z. Navigation system of coal mine rescue robot based on virtual reality technology. In: Proceedings of the 2022 World Automation Congress (WAC); 2022 Oct 11–15; San Antonio, TX, USA. p. 379–83. doi:10.23919/WAC55640.2022.9934676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wu D, Li Y. Mobile robot path planning based on improved smooth A* algorithm and optimized dynamic window approach. In: Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing and Intelligent Computing (SPIC); 2024 Sep 20–22; Guangzhou, China. p. 345–8. doi:10.1109/SPIC62469.2024.10691465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Meng F, Sun X, Zhu J, Mei B, Zheng P. Research on ship path planning based on bidirectional A*-APF algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE); 2024 Jan 12–14; Guangzhou, China. p. 460–6. doi:10.1109/ICCECE61317.2024.10504166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang H, Li C, Liang W, Yao L, Li Y. Path planning of wheeled coal mine rescue robot based on improved A* and potential field algorithm. Coal Sci Technol. 2024;52(8):159–70. doi:10.12438/cst.2023-1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wu H. Research on AGV path planning algorithm integrating adaptive A* and improved APF algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE); 2025 Mar 21–23; Shanghai, China. p. 764–9. doi:10.1109/ICAACE65325.2025.11019130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhou Q, Lian Y, Wu J, Zhu M, Wang H, Cao J. An optimized Q-learning algorithm for mobile robot local path planning. Knowl-Based Syst. 2024;286(2):111400. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen J, Wang Z, Li Z, Shen J, Chen P. Multi-UAV coverage path planning based on Q-learning. IEEE Sens J. 2025;25(16):30444–54. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2025.3580995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Y. Research on optimal path planning of wall-climbing robot based on A* algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2025 Asia-Europe Conference on Cybersecurity, Internet of Things and Soft Computing (CITSC); 2025 Jan 10–12; Rimini, Italy. p. 146–9. doi:10.1109/CITSC64390.2025.00034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fu X, Huang Z, Zhang G, Wang W, Wang J. Research on path planning of mobile robots based on improved A* algorithm. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2025;11(3):e2691. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Jin M, Wang H. Robot path planning by integrating improved A* algorithm and DWA algorithm. J Phys Conf Ser. 2023;2492(1):012017. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2492/1/012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li Y, Hao YJ, Li HY, Li M. Path planning of unmanned ships using modified APF algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 11th International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology (ICCSNT); 2023 Oct 21–22; Dalian, China. p. 112–9. doi:10.1109/ICCSNT58790.2023.10334590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu S, Zhou W, Qin M, Peng X. An improved UAV 3D path planning method based on BiRRT-APF. In: Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR); 2025 May 16–18; Hangzhou, China. p. 219–24. doi:10.1109/ICCCR65461.2025.11072641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hwang U, Hong S. On practical robust reinforcement learning: adjacent uncertainty set and double-agent algorithm. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;36(4):7696–710. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3385234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Xiaoyi Zhang X, Liu Y. Q learning algorithm based UAV path learning and obstacle avoidence approach. In: Proceedings of the 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2017 Jul 26–28; Dalian, China. p. 3397–402. doi:10.23919/ChiCC.2017.8027884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gan X, Huo Z, Li W. DP-A*: for path planing of UGV and contactless delivery. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;25(1):907–19. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3258186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liao C, Wang S, Wang Z, Zhai Y. GAA-DFQ: a dual-layer learning model for robot path planning in dynamic environments integrating genetic algorithms, DWA, fuzzy control and O-learning. In: Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE); 2025 Mar 21–23; Shanghai, China. p. 339–43. doi:10.1109/ICAACE65325.2025.11019886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xiao Z, Li P, Liu C, Gao H, Wang X. MACNS: a generic graph neural network integrated deep reinforcement learning based multi-agent collaborative navigation system for dynamic trajectory planning. Inf Fusion. 2024;105:102250. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xue G, Li R, Liu S, Wei J. Research on underground coal mine map construction method based on LeGO-LOAM improved algorithm. Energies. 2022;15(17):6256. doi:10.3390/en15176256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools