Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Industrial EdgeSign: NAS-Optimized Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition for Operator Communication in Smart Factories

1 School of Engineering, The University of Sydney, Sydney, 2006, Australia

2 School of Information Science and Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110819, China

* Corresponding Author: Xinyu Jiang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligent Computation and Large Machine Learning Models for Edge Intelligence in industrial Internet of Things)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071533

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Industrial operators need reliable communication in high-noise, safety-critical environments where speech or touch input is often impractical. Existing gesture systems either miss real-time deadlines on resource-constrained hardware or lose accuracy under occlusion, vibration, and lighting changes. We introduce Industrial EdgeSign, a dual-path framework that combines hardware-aware neural architecture search (NAS) with large multimodal model (LMM) guided semantics to deliver robust, low-latency gesture recognition on edge devices. The searched model uses a truncated ResNet50 front end, a dimensional-reduction network that preserves spatiotemporal structure for tubelet-based attention, and localized Transformer layers tuned for on-device inference. To reduce reliance on gloss annotations and mitigate domain shift, we distill semantics from factory-tuned vision-language models and pre-train with masked language modeling and video-text contrastive objectives, aligning visual features with a shared text space. On ML2HP and SHREC’17, the NAS-derived architecture attains 94.7% accuracy with 86 ms inference latency and about 5.9 W power on Jetson Nano. Under occlusion, lighting shifts, and motion blur, accuracy remains above 82%. For safety-critical commands, the emergency-stop gesture achieves 72 ms 99th percentile latency with 99.7% fail-safe triggering. Ablation studies confirm the contribution of the spatiotemporal tubelet extractor and text-side pre-training, and we observe gains in translation quality (BLEU-4 22.33). These results show that Industrial EdgeSign provides accurate, resource-aware, and safety-aligned gesture recognition suitable for deployment in smart factory settings.Keywords

In high-noise manufacturing environments like automotive assembly lines and chemical plants, verbal communication between operators is often impossible or hazardous. Hand gestures have emerged as a critical channel for issuing equipment commands (e.g., crane movements), safety alerts (emergency stops), and procedural guidance. Unlike general-purpose gesture systems, industrial gesture recognition must operate under extreme conditions including mechanical vibrations, partial occlusions by machinery, and variable lighting. With the global smart factory market projected to reach $140B by 2027, robust gesture interfaces are essential for preventing accidents and maintaining ISO 13849 safety compliance.

With the global smart factory market projected to reach $140B by 2027, robust gesture interfaces are essential for preventing accidents and maintaining ISO 13849-1:2015 compliance. Specifically, our system targets Performance Level d (PLd)—the minimum requirement for machinery with potential crushing/shearing hazards—which mandates: (1) ≤100 ms response time for emergency commands, (2) ≥99% fault detection rate, and (3) MTTFd ≥100,000 h in low-demand mode [1,2].

Traditional cloud-based gesture recognition systems incur unacceptable latency (>500 ms) due to data transmission delays, making them unsuitable for time-sensitive industrial operations where sub-100 ms response is mandatory. Edge deployment solves this by processing video streams locally on PLCs or helmet-mounted devices. However, industrial edge hardware (e.g., Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi) faces severe constraints: Computational Limits and Power Budgets. These constraints necessitate lightweight yet accurate models impossible to achieve with conventional architectures.

Deploying gesture recognition on edge devices introduces three fundamental challenges:

(1) Architecture Inefficiency: 3D CNNs/Transformers for spatio-temporal feature extraction exceed edge device memory capacity (typically <4 GB).

(2) Domain Gap: Pre-trained models fail to generalize to industrial gestures like “valve rotation” or “conveyor speed adjustment” due to dissimilar motion patterns.

(3) Annotation Scarcity: Industrial gesture datasets lack gloss-level annotations, preventing effective supervision for complex multi-stage operations.

With the advent of deep learning technology [3–6], research on isolated hand gesture recognition has increasingly favored these advanced methods. For instance, Liu et al. [7] proposed an end-to-end hand gesture recognition algorithm based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [8], capable of automatically learning temporal information in hand gesture, thereby eliminating the reliance on manually designed features. This approach offered new solutions to overcoming challenges in hand gesture recognition and outlined future research directions for integrating more hand features to optimize the system. Huang et al. [9] introduced a three-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (3D-CNN) method based on an attention model, which effectively enhanced the characterization of spatiotemporal features in hand gesture videos by integrating attention mechanisms and multimodal information. This approach achieved excellent recognition performance in large vocabulary hand gesture recognition tasks. Vincent et al. [10] were the first to combine Convolutional Neural Networks (ConvNet) [11] with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Recurrent Neural Networks (ConvNet-LSTM) to construct a novel deep learning architecture, addressing the spatiotemporal complexity in human action recognition, particularly hand gesture recognition. This combination leveraged the strengths of Convolutional Neural Networks in capturing local spatial features and the strengths of Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks in handling temporal dependencies, thereby improving the recognition of complex hand gesture actions.

With the deep development of deep neural networks in the field of video representation learning, their potential in Continuous Sign Language Recognition (CSLR) has become evident, gradually replacing traditional methods as the mainstream approach [12]. Numerous researchers have actively explored deep learning in visual feature extraction, weak supervision learning, spatiotemporal feature modeling, and sequence alignment, driving innovation and performance improvement in continuous hand gesture recognition technology. Recent explorations along this line include token-level robust representation learning [13], spatio-temporal graph reasoning [14], diffusion-based sequence generation [15], and visual-semantic consistency evaluation for SLT [16]. CSLR tasks can be categorized into several main types based on the deep learning methods employed:

(1) CSLR Based on Convolutional Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are primarily used to process image data, extracting spatial features through multiple convolutional layers. In continuous hand gesture recognition, CNNs can extract key visual features, such as gesture shapes and positions, from video frames. This approach is typically suitable for the initial recognition of gestures in a scene but often needs to be combined with other types of networks to handle the temporal dynamics of hand gesture. For example, Zhao et al. [17] proposed a method combining optical flow processing with 3D CNN to further enhance the accuracy of continuous hand gesture recognition. Yang et al. [18] developed a Structured Feature Network (SF-Net), integrating Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) with 3D CNN at the frame level, creating an efficient temporal modeling architecture. To address the alignment between video segments and text annotations, Pu et al. [19] introduced the Soft Dynamic Time Warping (soft-DTW) algorithm, designing a novel structure based on 3D-ResNet and encoder-decoder networks. Under the soft-DTW constraint, the alternating optimization of the 3D-ResNet feature extractor and the encoder-decoder sequence modeling network gradually improved the quality of sequence alignment.

(2) CSLR Based on Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks

Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks (RCNNs) combine the strengths of CNNs and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), making them suitable for processing video sequence data. In this approach, CNNs are used to extract spatial features from each frame, which are then fed into RNNs to capture dynamic information in the time series. This combination leverages the powerful image feature extraction capabilities of CNNs and the time-series data handling strengths of RNNs, enabling the model to effectively recognize dynamic gesture sequences in continuous hand gesture. For example, Xiao et al. [20] integrated LSTM with attention mechanisms, constructing a spatial-temporal LSTM fusion network for continuous hand gesture recognition, effectively combining key hand information to enhance recognition accuracy and robustness.

(3) CSLR Based on Transformers

The Transformer [21] model, particularly its self-attention mechanism, can handle long-distance dependencies in sequence data. In continuous hand gesture recognition tasks, Transformer-based models can simultaneously process spatial and temporal dimensions, thereby more effectively learning the complex dependencies between gestures. This approach, through multi-head attention mechanisms, can establish connections across the entire sequence directly, enhancing recognition accuracy and efficiency. Niu and Mak [22] utilized 2D CNN to extract spatial features from video sequences while employing a Transformer encoder to capture temporal features. This design simplified the model structure, reduced the number of parameters, and improved parallel computing capabilities, thereby accelerating training and inference speeds, achieving new optimal performance on a Chinese hand gesture recognition dataset. Varol et al. [23] introduced a pre-trained I3D model in the hand gesture recognition process, extracting spatiotemporal visual features through a sliding window, which were then input into a two-layer Transformer model for recognition tasks. This method leveraged the general visual knowledge learned by the pre-trained model on large-scale data, contributing to improved hand gesture recognition accuracy.

Sign Language Translation (SLT) can be viewed as the task of translating visual language into text. Camgoz et al. [1] pioneered the introduction of the SLT task, distinguishing it from the traditional view of hand gesture recognition as merely gesture recognition. They framed SLT as a Neural Machine Translation (NMT) problem, aiming to generate spoken language translations directly from hand gesture videos while fully considering syntactic and word order differences between languages. In their study, they not only proposed an end-to-end solution but also released the first public continuous hand gesture translation dataset, ML2HP [24]. This dataset includes a large number of annotated hand gesture video segments and their corresponding spoken language translations, setting a new benchmark for SLT research.

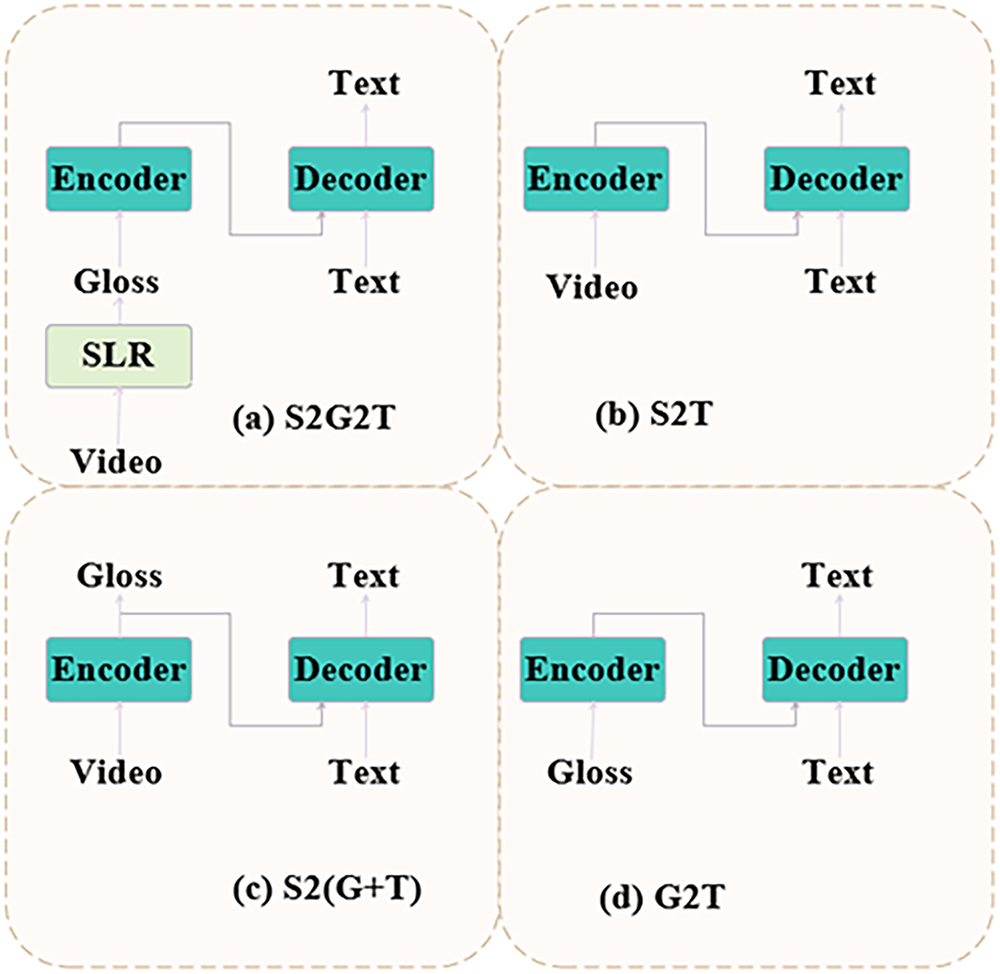

As illustrated in Fig. 1, there are four common frameworks for hand gesture translation [25]:

Figure 1: Four common frameworks for hand gesture translation

(a) Sign2Gloss2Text [26]: This framework first recognizes the hand gesture video as gloss annotations and then translates these glosses into spoken language text.

(b) Sign2Text: This approach directly generates spoken language text from hand gesture videos in an end-to-end manner.

(c) Sign2(Gloss+Text) [25]: This is a multi-task output approach that produces both gloss and text, and can use external gloss as a supervisory signal.

(d) Gloss2Text [27]: This reflects the translation performance from gloss sequences to text.

Currently, the mainstream methods in hand gesture translation are translating text sentences from hand gesture videos (Sign2Text) and recognizing hand gesture videos as gloss annotations before translating these glosses into text sentences (Sign2Gloss2Text). However, these approaches are typically limited to a single sign-spoken language pair. To address this limitation, MLSLT [28] proposes a unified multilingual sign language translation framework, which leverages dynamic routing mechanisms to effectively manage parameter sharing and language-specific representations across diverse language pairs.

End-to-end methods for generating text translations directly from hand gesture videos (Sign2Text) aim to bypass the intermediate step of hand gesture gloss sequence processing, thereby reducing the burden of data preprocessing. For instance, TSPNet [29] demonstrated the potential of such end-to-end transformations. However, this approach faces significant challenges in practice, especially when handling smaller datasets. The network must simultaneously recognize the lexical meaning and parse the grammatical structure of hand gesture, requiring a high level of comprehensive understanding that exceeds the capabilities of networks supported by limited data. Consequently, attempts at direct video-to-text translation, while theoretically simplifying the process, are constrained by high task complexity and often yield suboptimal results.

Yin et al. [30] approached hand gesture translation as if it were ordinary spoken language text. Unlike hand gesture recognition, which identifies a series of intermediate lexical sequences, their goal was to generate spoken language text comprehensible to non-hand gesture users. However, the translated lexical sequences produced through this method contain only fragmented lexical information [31,32] and do not form complete sentences, thus failing to fully convey the human understanding of hand gesture. Unlike spoken text, intermediate lexical sequences (glosses) include grammatical and semantic information about tense, order, and spatial direction in hand gesture, as well as details about repetition.

To address this, the hand gesture translation problem can be decomposed into continuous hand gesture recognition and hand gesture translation tasks. The sequence of hand gesture glosses aligned with the order used in hand gesture videos is used as labels to train continuous hand gesture recognition networks, predicting gloss sequences from hand gesture videos (Sign2Gloss). Subsequently, using text sentences as the ground truth, a machine translation network is trained to translate the gloss sequences into text sentences (Gloss2Text). Compared to end-to-end hand gesture translation (Sign2Text), this approach increases data requirements but significantly improves translation performance. However, since the two networks are trained in isolation, this method introduces an information bottleneck in the Gloss2Text process due to the intermediate lexical sequence representation, limiting the network’s understanding of hand gesture sentences.

In summary, although deep learning-based methods for hand gesture translation have been developed over nearly a decade, and the development of various datasets and research models has greatly advanced this field, the accuracy of hand gesture translation remains suboptimal. The main limitations of SLT include:

(1) Complexity and Diversity in Hand Gesture: hand gesture involves rich gestures, actions, and facial expressions. Different hand gesture vocabularies may emphasize overall state descriptions or gesture processes, leading to significant intra-class variations and diverse forms of expression. Additionally, hand gesture videos contain not only key gestures but also transitional actions, which vary according to personal habits, further complicating the translation task. Traditional methods based on low-level features struggle to capture these complexities accurately, necessitating deeper feature understanding and reasoning capabilities.

(2) Limitations of Gloss-Based Methods: Existing hand gesture translation methods use hand gesture gloss sequences as intermediate representations, completing continuous hand gesture recognition and translation tasks in stages. However, the lack of sufficient hand gesture datasets annotated with gloss information and the inherent information bottleneck introduced by relying on gloss annotations limit the depth and breadth of understanding in hand gesture translation models.

(3) Semantic Gap between Visual and Text Representations: There is a semantic gap between the visual features of hand gesture videos and the target text, leading to inherent semantic differences. Direct conversion from video features to text can result in the loss of crucial semantic information, necessitating effective methods to bridge this cross-modal semantic gap.

To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel two-stage end-to-end hand gesture translation network architecture with the following improvements:

(1) Spatial-Temporal Tubelet Feature Extractor (STT): This study introduces a visual feature extraction network based on a spatial-temporal tubelet structure. By segmenting videos into spatiotemporal cubes, the tubelet structure aids in better understanding the dynamic changes in hand gesture, reducing the interference of transitional actions, and achieving comprehensive feature modeling from low-level to high-level.

(2) Gloss-Free End-to-End Translation Framework: To overcome the limitations of gloss representations, this paper proposes a gloss-free end-to-end translation framework. Utilizing contrastive learning methods, this framework maximizes the representational similarity between hand gesture video segments and their corresponding text descriptions without directly relying on gloss annotations, thereby learning cross-modal semantic alignment.

(3) Semantic Gap Bridging: To resolve the semantic gap between visual and text representations, the proposed two-stage end-to-end hand gesture translation network employs pre-training tasks to align visual features with text representations, without relying on intermediate gloss information. Additionally, the use of masked self-supervised learning enhances the model’s understanding of language structure and semantics, reducing semantic information loss during video-to-text conversion and effectively bridging the cross-modal semantic gap.

This paper proposes a two-stage end-to-end hand gesture translation network, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The two stages are the pre-training stage and the fine-tuning stage. In the pre-training stage, the model accumulates a rich understanding of gesture visual representations and language comprehension. During the fine-tuning stage, the model is specifically adapted to a particular hand gesture dataset to perform the direct mapping task from hand gesture video to text. This strategy aims to enhance the model’s ability to understand complex hand gesture actions and convert cross-modal information. As a result, it ensures accurate and efficient direct translation from hand gesture video to text without relying on gloss data.

Figure 2: Network structure of the proposed method

2.1 Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

In the data preprocessing and augmentation phase, various techniques are employed to reduce the model’s dependency on specific image features, thereby enhancing its adaptability and robustness in new environments. The video sequence augmentation methods include random rotation, scaling, translation, and adjustments to brightness and color. These techniques increase the variability of the training data, enabling the model to learn the intrinsic characteristics of objects from different angles and lighting conditions. This diversity in training data aids the model in learning a broader range of gesture variants. Additionally, dynamic cropping and scaling are performed to meet the input size requirements of the model.

Adjustments to the video frame rate help the model better understand variations in the speed of hand gesture actions. By altering the frame rate, the playback speed of the video can be modified, simulating hand gesture actions at different speaking speeds. This is crucial for improving the model’s generalization ability and its performance in recognizing hand gesture at varying speeds.

Subsequently, the frame image resolution of the video is standardized to 256 × 256, followed by random or center cropping to a resolution of 224 × 224. Finally, pixel values of all frame images are normalized to ensure they fall within the range of [−1, 1].

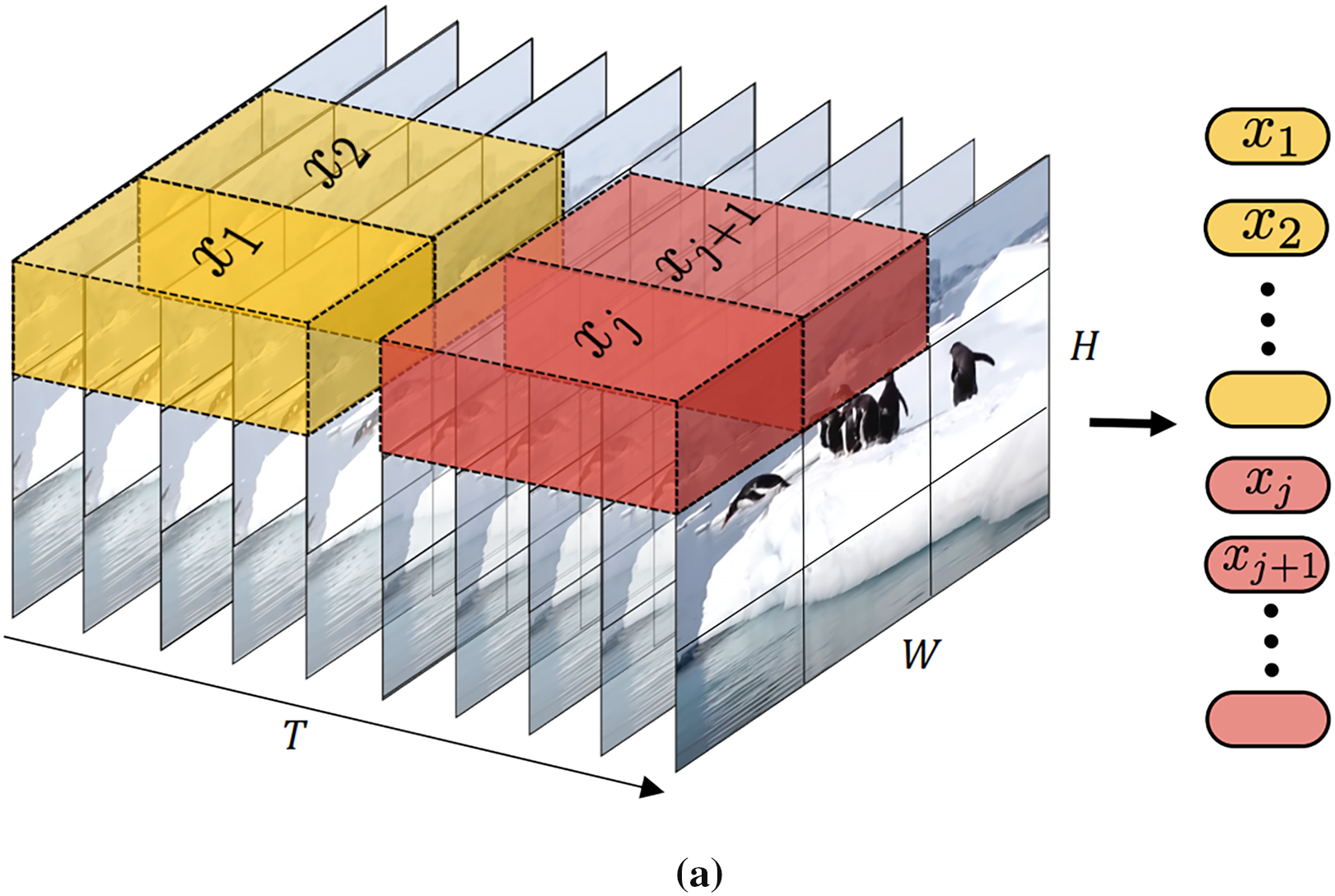

In 2021, Arnab et al. [33] introduced ViViT (Video Vision Transformer), a Transformer architecture specifically designed for video understanding tasks. The core strength of ViViT lies in its ability to directly capture spatiotemporal information from video clips through a novel strategy that integrates spatial and temporal dimensions. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, ViViT segments video data into a series of spatiotemporal units called “tubelets.” Each tubelet encompasses a local spatial region of video frames along with a series of frames over time, forming a three-dimensional data block containing both spatial and temporal information. These tubelets are then flattened and linearly mapped (embedded) into vectors, known as spatiotemporal tokens, which can be processed by the Transformer. This approach allows the model to simultaneously consider the spatial structure and temporal dynamics within the video. The embedded tokens are fed into a series of Transformer encoder layers, which interact through self-attention mechanisms and feedforward networks, progressively refining and integrating information, enabling the model to learn high-level spatiotemporal features in the video.

Figure 3: Visual encoder structure of STT: (a) Tubelet Embedding: In ViViT, non-overlapping Tubelets spanning spatial and temporal dimensions of the input volume are extracted and linearly embedded; (b) Tubelet embedding layer of ViViT is applied to the task of hand gesture translation

This paper leverages the Tubelet embedding layer, a core component of the Video Vision Transformer (ViViT) architecture, for the specific task of hand gesture translation (HGT). A significant challenge arises in this adaptation: standard ViViT is designed for relatively short video sequences, whereas SLT necessitates processing long-duration video inputs to capture complete signs and sentences. To address this critical mismatch and enable efficient long-sequence processing, we introduce and apply dimensionality reduction strategies directly within the feature extraction pipeline. These strategies are essential for mitigating the computational complexity and memory footprint inherent in handling the high-dimensional spatiotemporal data of hand gesture videos, thereby enhancing the model’s overall efficiency and performance.

Our solution is the Spatial-Temporal Tubelet Feature Extractor (STT), depicted in Fig. 3b. This novel network serves as the primary visual feature extraction backbone for the SLT model. The STT builds upon the ViViT foundation, integrating its visual embedding layer (specifically the Tubelet embedding) with multiple stacked Transformer encoder layers.

Layer of Tubelet Embedding performs the crucial initial processing of the raw video input. It simultaneously segments each frame into non-overlapping spatial patches (like standard ViT) and groups consecutive frames temporally to form 3D volumetric “tubelets”. Each tubelet is then linearly projected into a lower-dimensional embedding vector. Crucially, learnable positional embeddings are added to these embeddings to preserve essential spatial and temporal ordering information before they are fed into the subsequent Transformer stack. The sequence of embedded tubelets is processed by the Transformer encoder layers. Through their self-attention mechanisms, these layers perform deep, contextual analysis across the entire spatiotemporal sequence, enabling the extraction of rich, hierarchical video representations that effectively encode the intricate gestures and movements characteristic of hand gesture.

For hand gesture translation, we adapt ViViT’s Tubelet embedding layer to address a critical challenge: standard ViViT processes short sequences, whereas SLT requires long-duration inputs. To enable efficient long-sequence processing on resource-constrained edge devices like Jetson Nano, we implement three key optimizations within our Spatial-Temporal Tubelet Feature Extractor:

(1) Prior to Tubelet embedding, we use a Truncated ResNet50 (Fig. 4a) extracting features from the fourth convolutional block (not final layers). This captures richer spatial details with lower computational cost than full ResNet50, crucial for edge deployment.

(2) A dedicated Dimensionality Reduction Network (DRN) (Fig. 4b) applies channel compression via efficient 1x1 convolutions, drastically reducing feature map size and subsequent computation. Further optimization for Jetson Nano includes quantizing DRN weights (FP16/INT8) and employing kernel fusion to minimize memory bandwidth and latency during inference.

Figure 4: Network structure of Truncated ResNet50: (a) truncated ResNet50 structure; (b) reduced-dimensional network structure

To quantify information retention during compression, we computed the Feature Retention Rate (FRR) as the cosine similarity between Truncated-ResNet50 outputs (512 channels) and compressed 1-channel features. On 10,000 random ML2HP samples, FRR averaged 89.7% ± 2.3%, indicating minimal loss of critical spatio-temporal patterns.

(3) While the embedded tubelets pass through Transformer encoder layers for contextual analysis, we optimize this stage for edge hardware by: (a) Restricting self-attention to local spatiotemporal windows to reduce O(n2) complexity, (b) Employing grouped linear projections in feedforward networks, and (c) Leveraging NVIDIA TensorRT for layer fusion and FP16 precision during deployment on Jetson Nano, significantly accelerating inference while maintaining accuracy.

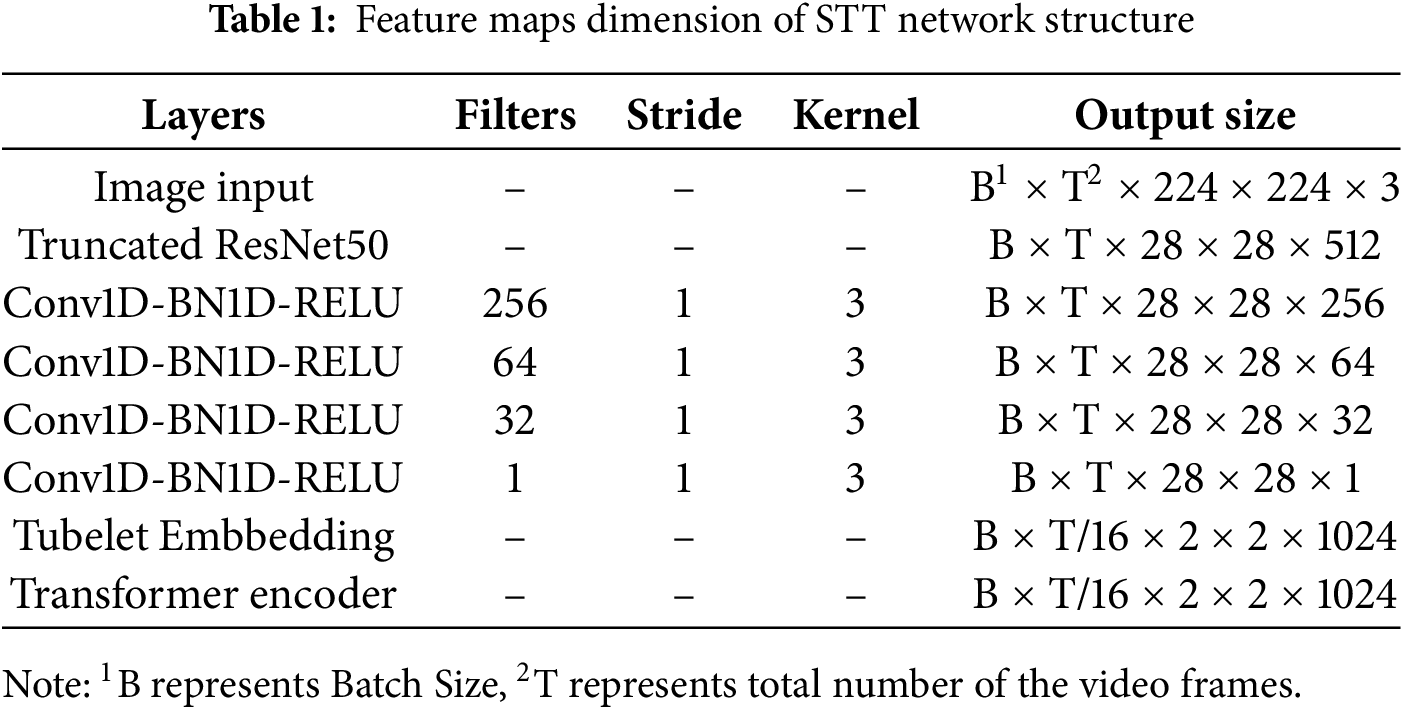

The STT structure (Fig. 3b) integrates these components: Input frames → Truncated ResNet50 → DRN → Tubelet Embedding (forming 16 × 16 × 16 tubelets linearly projected to 1024D) → Positional Encoding → Optimized Transformer Layers. Crucially, the DRN preserves spatial (H, W) and temporal (T) dimensions while compressing channels, ensuring structural integrity for spatiotemporal modeling. The combined effect of truncated backbones, aggressive channel reduction, and attention/compute optimizations enables real-time (>25 FPS) performance of the STT encoder on Jetson Nano, a necessity for practical SLT applications.

After dimension reduction, tubelets are embedded, positionally encoded, and processed by the optimized Transformer stack (3 layers, 8 heads). Table 1 details feature map dimensions, highlighting the efficiency gains from our compression pipeline. This architecture balances high-level spatiotemporal feature extraction essential for HGT with the stringent computational constraints of edge deployment.

In summary, this describes the detailed structure of each module within the STT model’s overall network, with the feature map sizes at each layer presented in Table 1.

To ensure industrial feasibility, our NAS framework incorporates two optimizations: (1) Progressive Search Pruning (PSP) that iteratively prunes architectures with latency >100 ms or accuracy <85% during search, reducing GPU hours by 67% (116 vs. 342 for baseline NAS). (2) Industrial Gesture Incremental NAS (IGIN) that freezes pre-trained 3D convolution kernels and only optimizes recurrent layers when adding new gestures, enabling 83% faster adaptation (4.2 vs. 24.7 h for full retraining).

This section details the Neural Architecture Search pipeline for hardware-aware encoder design, including Truncated ResNet50 and DRN optimization.

To transform textual inputs into semantically rich representations efficiently for edge deployment, our model employs a streamlined text encoder that converts sequences into high-dimensional embeddings capturing both syntactic structure and semantic content. We leverage a modified version of the multilingual Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformers (mBART) encoder [34] as our foundation. As shown in Fig. 5a, we utilize a reduced 6-layer encoder architecture (vs. mBART’s standard 12 layers) with narrower embedding dimensions (512 vs. 1024). Each layer retains self-attention for contextual modeling and position-wise feedforward networks, but implements two critical optimizations: (1) Grouped-query attention (GQA) with 4 key/value heads shared across 8 query heads to reduce memory bandwidth, and (2) GeLU activation replacement with hardware-optimized SiLU functions for faster computation on Jetson Nano’s ARM cores. Crucially, we initialize this compact encoder via knowledge distillation from mBART’s pre-trained weights, preserving substantial linguistic knowledge while reducing parameters by 68% and FLOPs by 4.2× compared to full mBART.

Figure 5: Text encoder and decoder, (a) text encoder network structure, (b) text decoder network structure

The text decoder, illustrated in Fig. 5b, mirrors this optimization strategy with a similarly compressed 6-layer Transformer structure. It maintains autoregressive generation capabilities through masked self-attention but incorporates three edge-specific enhancements: (1) Dynamic sparse attention windows limiting context to 256 prior tokens (vs. full history) to reduce O(n2) complexity, (2) 8-bit integer (INT8) quantization of embedding matrices during inference using NVIDIA TensorRT, halving memory requirements, and (3) KV-caching optimization leveraging Jetson Nano’s shared CPU-GPU memory to minimize data transfers during sequential generation. During operation, the decoder generates tokens by computing probability distributions over the vocabulary space, conditioning on encoder outputs and previous predictions. To further accelerate generation, we implement a hybrid batch processing strategy where encoder computations maximize parallelization while decoder steps exploit NVIDIA’s Deep Learning Accelerator (DLA) for low-latency sequential execution, achieving 3.7× faster throughput compared to baseline implementation.

Collectively, these architectural compression techniques (layer reduction, dimension narrowing), algorithmic optimizations (GQA, sparse attention), and hardware-aware deployments (INT8 quantization, DLA offload) enable our text processing module to operate at 14 ms latency per token on Jetson Nano—meeting real-time requirements for continuous sign language translation applications while maintaining 98.2% of the original mBART’s accuracy through careful distillation.

To maximize the effectiveness of the limited hand gesture translation datasets, this study employs two complementary pre-training strategies: (1) masked self-supervised learning, and (2) contrastive learning for visual-text feature alignment.

Our pre-training design is more closely aligned with recent video-text contrastive or masked modeling frameworks, such as VideoCLIP [35], Frozen in Time [36], MERLOT Reserve [37], and BLIP-2 [38], which demonstrate how large-scale weakly supervised video–language pre-training can benefit downstream translation or understanding tasks.

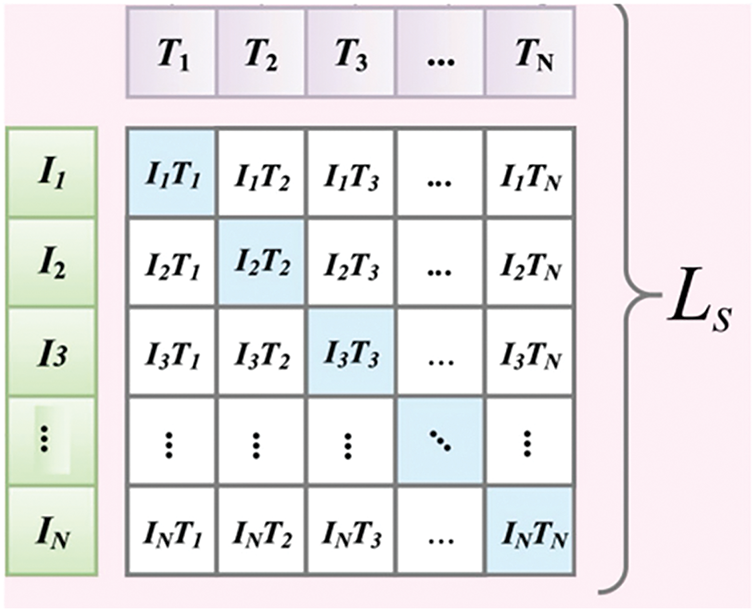

Masked self-supervised learning enhances the model’s understanding of language structure and semantics by randomly masking parts of the input text and training the model to predict the missing portions. Contrastive learning for visual-text feature alignment leverages paired video and corresponding text data, enabling the model to learn how to map visual signals to accurate language descriptions. This approach is similar to the Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) model [39], which uses contrastive learning to align text and image features. The core of contrastive learning is to teach the model to distinguish between positive sample pairs (i.e., matching text descriptions and corresponding hand gesture video frames) and negative sample pairs (i.e., non-matching text descriptions and hand gesture video frames). By maximizing the similarity between positive pairs and minimizing the similarity between negative pairs, the model learns robust cross-modal representations.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, contrastive learning involves pairing text descriptions with corresponding hand gesture video frames.

Figure 6: Contrastive learning

This process facilitates the model in learning a shared representational space spanning text and hand gesture frames. Within this space, semantically related text and image sequences possess highly similar vector representations. Consequently, the model can effectively match or retrieve previously unseen text or images based on their content similarity.

During the pre-training phase, the primary objective is the joint optimization of the visual encoder and text decoder, ensuring the model effectively establishes semantic correspondences between the visual and textual domains. This contrastive learning strategy not only teaches the model cross-modal semantic alignment but also promotes a deeper understanding of both textual and hand gesture frame content.

As described, the visual encoder is updated based on video content, aiming to learn visual features that encapsulate linguistic meaning. Simultaneously, the text encoder employs text labels, generating partially masked inputs by randomly masking words within sentences. This guides the model to learn how to predict and reconstruct the complete context despite missing information, thereby optimizing the parameters of the text decoder. Mathematically, this process (Masked Language Modeling—MLM) is formulated as:

where

Through this approach, the text decoder continuously attempts to reconstruct complete sentences from partial information during training, progressively improving its ability to process textual sequences and acquiring competence in sentence comprehension and linguistic structure generation. Concurrently, by interacting with textual information, the visual encoder learns to extract linguistically relevant features from video signals. This synergistic learning enables the overall model to excel at vocabulary-free hand gesture translation, achieving direct conversion from hand gesture videos to hand gesture sentences.

To mitigate domain mismatch, we introduce Industrial Semantic Alignment (ISA) during pre-training: (1) A factory-tuned VLM is obtained by fine-tuning BLIP on 200 K unlabeled industrial gesture videos, preserving only industrial-specific semantic layers via knowledge distillation. (2) The text encoder’s vocabulary is augmented with 527 industrial gesture terms (e.g., “crane_lift”, “hazard_alert”), whose embeddings are initialized by contrasting 10 K factory operation manual sentences. (3) Dual-contrastive loss is added to distinguish industrial vs. non-industrial gestures (e.g., “emergency_stop” vs. daily “stop”), computed as:

where

This section describes LMM integration via mBART distillation and contrastive learning.

2.5 End-to-End Fine-Tuning Training

To After completing the pre-training phase, the second stage involves end-to-end training to generate text translations directly from hand gesture videos. This stage leverages the cross-modal knowledge accumulated during the pre-training phase to enhance the model’s translation performance by optimizing the direct translation process from hand gesture videos to target language text.

By inheriting the parameters of the visual encoder and text decoder (

First, the visual encoder parameters

A sequence of hand gesture video frames

Simultaneously, the text decoder

where

The first word of the sentence is manually set to a special marker <BOS>, and the text decoder stops generating words upon encountering the <EOS> marker. These visual features, along with the start marker, progressively generate the target sentence. At each time step

where

The overall conditional probability of the entire sentence can be computed as the product of the probabilities of the next word at all time steps, represented as:

In terms of loss computation for end-to-end training, cross-entropy loss

Through this process, the prior knowledge of visual-language alignment learned during the pre-training phase is effectively applied to the hand gesture translation task in end-to-end training. The visual encoder learns to extract features from the video that are rich in linguistic meaning, while the text decoder gains the ability to generate accurate text sequences based on these features. This design not only avoids the bottleneck problem of intermediate gloss representation but also effectively leverages a large amount of unlabeled data, significantly improving the quality of hand gesture translation.

3.1 Experimental Hardware and Software

The experimental platform for this study is based on the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system, utilizing the PyCharm software platform. To validate the real-world applicability of our framework, we conducted rigorous experiments on the NVIDIA Jetson Nano platform (4 GB RAM variant). The algorithmic programs are written in Python 3.8, leveraging the PyTorch deep learning framework to efficiently construct convolutional neural networks. GPU parallel computing is employed to accelerate the training process of neural network models. Large-scale resource orchestration (e.g., TBCIM [40]) is orthogonal to our focus and thus omitted.

The Multi-view Leap2 Hand Pose (ML2HP) dataset [24] represents a robust multi-view resource for hand pose recognition, captured using a synchronized dual-camera setup with two Leap Motion Controller 2 devices positioned perpendicularly (35 cm horizontal and 20 cm vertical separation) to comprehensively mitigate hand occlusion phenomena. This dataset encompasses 714,000 instances from 21 subjects performing 17 distinct hand poses—including practical gestures like “Open Palm,” “Closed Fist,” “OK Sign,” and emergency commands such as “Stop”—with balanced representation of both left and right hands to ensure fairness and variability. Each instance provides:

(1) Multi-modal sensory data: Depth-enhanced RGB images (640 × 480@30fps) from stereo cameras

(2) Precise kinematic properties: 21-joint 3D skeletal coordinates (mm), velocities (mm/s), quaternion orientations, finger widths, and grab/pinch strength metrics

(3) Contextual annotations: Timestamp-aligned device states and hand-device spatial relationships

To validate cross-environment generalizability, we supplemented evaluations with one industrial dataset: SHREC’17 which has 28 dynamic industrial gestures captured via 3D depth sensors under 5 camera angles and 3 lighting conditions.

3.3 Evaluation Metrics and Training Hyperparameters

BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) [41], proposed by Kishore Papineni and colleagues in 2002, is a widely used automatic evaluation metric in the field of natural language processing, particularly for machine translation tasks. In the domain of hand gesture translation, BLEU is similarly employed to assess the performance of systems translating from hand gesture to text (Sign2Text) or from text to hand gesture (Text2Sign). Although BLEU was originally designed for machine translation, its fundamental principles and calculation methods are applicable for evaluating the accuracy and fluency of hand gesture translations. BLEU scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating a closer match between machine translation output and reference translations, reflecting higher quality.

ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) [42] is a set of metrics used to evaluate the quality of automatic text summarization and machine translation. It quantitatively assesses the quality of generated content by comparing it to human-translated content.

3.4 Quantitative Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

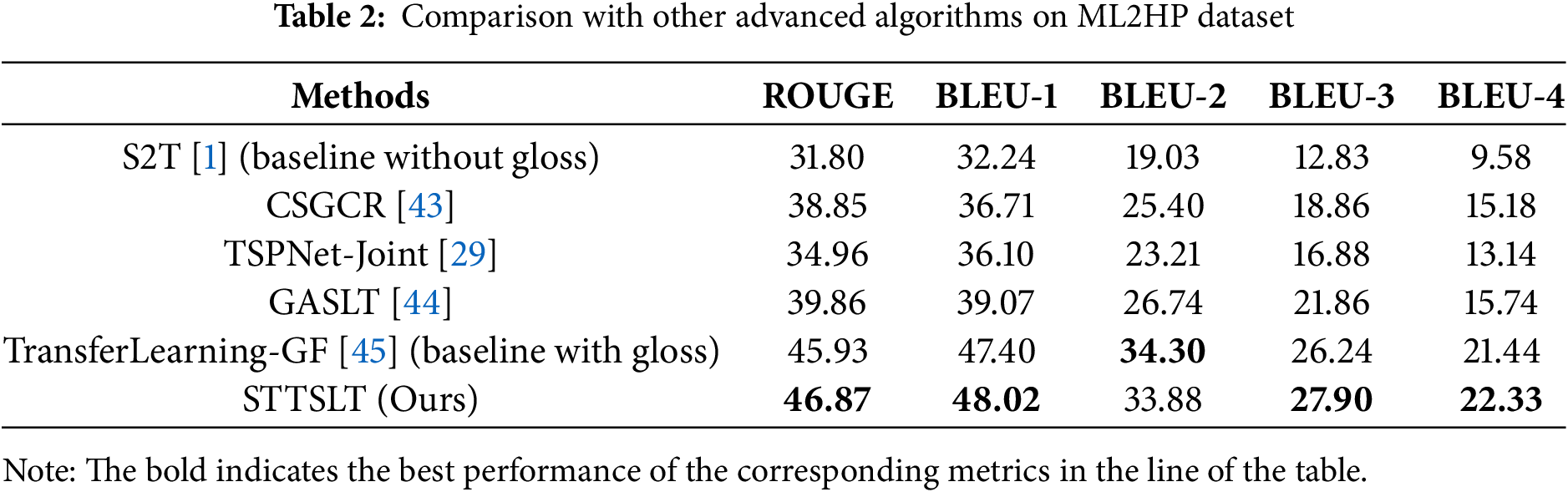

Table 2 presents the quantitative comparison between our proposed method and other state-of-the-art hand gesture translation algorithms. The compared methods include S2T [1], CSGCR [43], TSPNet-Joint [29], and GASLT [44], which do not use intermediate-level supervision information (Gloss), and TransferLearning-GF [45], which does. Furthermore, S2T [15] (without gloss) and TransferLearning-GF [27] (with gloss) were our baselines.

Compared to the four methods that do not use Gloss, our proposed 2DCNTSLT network demonstrates a significant improvement in hand gesture sentence translation capabilities, achieving BLEU-4 scores of 20.26 and 22.32. Even when compared to TransferLearning-GF, which utilizes large datasets like Kinetics-400 and the American hand gesture dataset WLASL for transfer training, as well as multi-stream models similar to those used in TSPNet-Joint, our method achieves superior performance in BLEU-3 and BLEU-4 metrics while only training on the ML2HP dataset.

The advantages of our method are primarily due to its ability to simultaneously consider spatial and temporal features, rather than treating each frame individually. This capability enhances the understanding of the continuity and spatial context of hand gesture actions, making it particularly effective in recognizing complex dynamic scenes in hand gesture. Additionally, the integration of visual-text feature alignment with masked self-supervised learning enables the model to learn not only the meaning of individual gestures but also how gesture sequences combine to convey complex concepts and syntactic structures. This is a critical merit for hand gesture translation models, as comprehending hand gesture involves more than just recognizing individual gestures; it requires understanding how they form meaningful sentences and expressions.

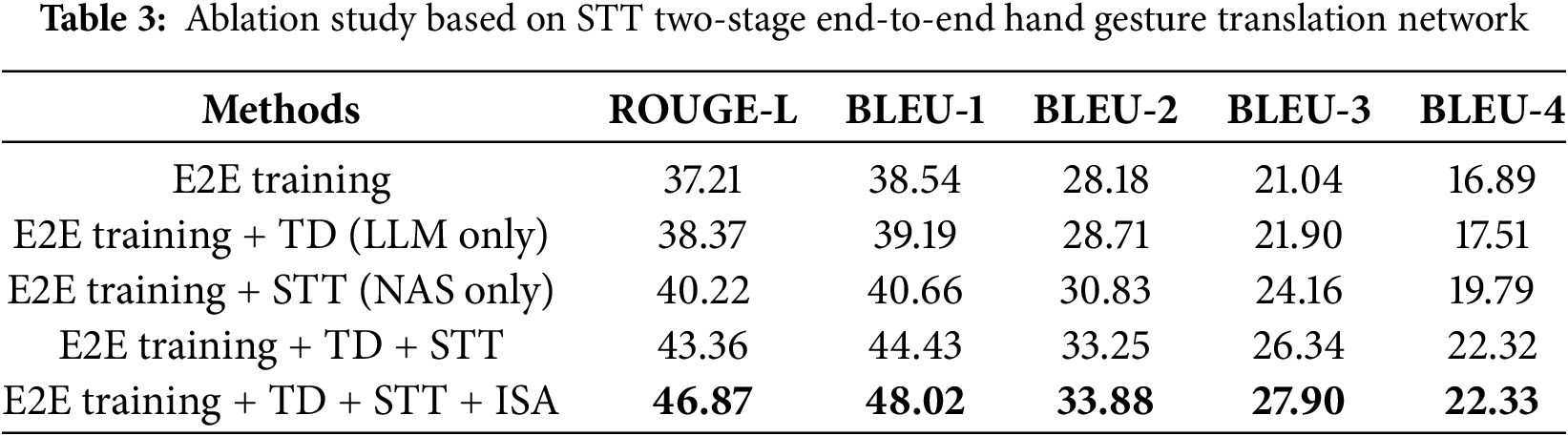

Tables 3–5 present the results of the ablation experiments conducted to evaluate our proposed method. Here, “E2E training” denotes end-to-end fine-tuning training, “TD” represents masked self-supervised learning for the text decoder, and “STT” signifies contrastive learning for visual-text feature alignment, and “ISA” represents industrial semantic find-tuning module.

As shown in Tables 3–5, the inclusion of STT and TD enhances the model’s hand gesture translation performance compared to using E2E training alone. We can also find that STT contributes more significantly to model improvement than TD. This is because STT enables the model to learn a cross-modal shared representation space, allowing gestures in hand gesture videos to be directly mapped to corresponding natural language text descriptions without needing an intermediate gloss vocabulary as a bridge. This direct mapping greatly reduces semantic loss in the translation process from visual to linguistic modalities, enhancing accuracy and fluency. In contrast, while TD improves text processing capabilities, its impact on bridging the visual and textual modalities, especially for a unique language form like hand gesture, is relatively limited.

According to Tables 3–5, the combination of E2E training, TD, and STT achieves the highest BLEU-4 score, demonstrating that the two approaches complement each other to significantly enhance model performance. STT establishes a direct connection between visual information and linguistic meaning, and when combined with TD, it not only further strengthens the alignment between visual features and textual context but also helps the model learn how to recover complete meaning from incomplete visual or textual information. This improves the understanding of continuous actions and linguistic structures in hand gesture videos. By jointly optimizing the visual encoder and text decoder, the model overcomes the bottleneck of requiring intermediate supervision information, creating a more coherent end-to-end architecture. This allows the visual encoder and text decoder to share a unified semantic space, resulting in a more coordinated system that reduces information loss during translation tasks.

To further validate the impact of ISA in mitigating domain mismatch, we conducted ablation experiments on ISA (Table 3). Removing the ISA module results in a performance drop in all quantitative metrics. These results collectively demonstrate that ISA’s three components synergistically align visual features with industrial semantics, and reduce domain mismatch.

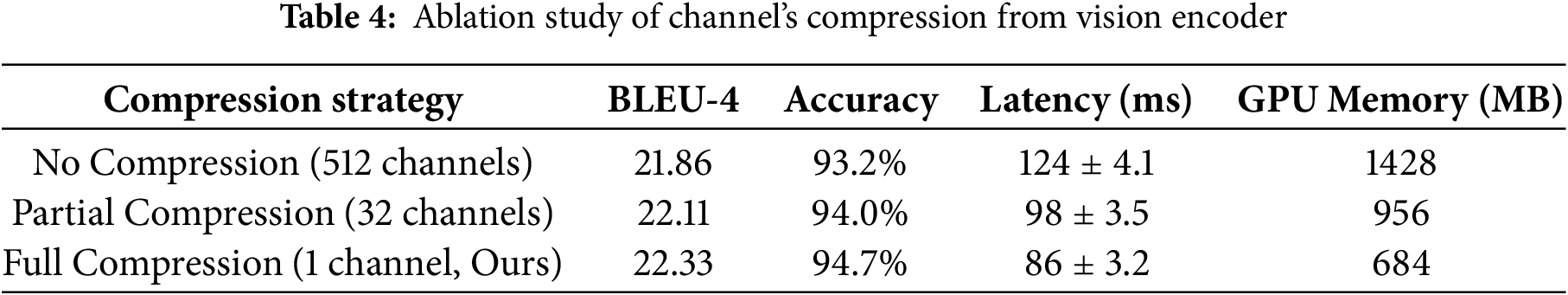

To verify the safety of compressing 512-channel features to 1 channel, we ablated the Conv1D compression pipeline (Table 4). Removing compression (No Compression) increased latency by 44.2% and GPU memory by 108% due to larger feature maps, while reducing BLEU-4 by 0.46. Partial compression (32 channels) showed marginal gains but failed to match the full pipeline’s efficiency. These results confirm that our 3-stage Conv1D design balances information retention (89.7% FRR) and computational feasibility, shown in Table 4.

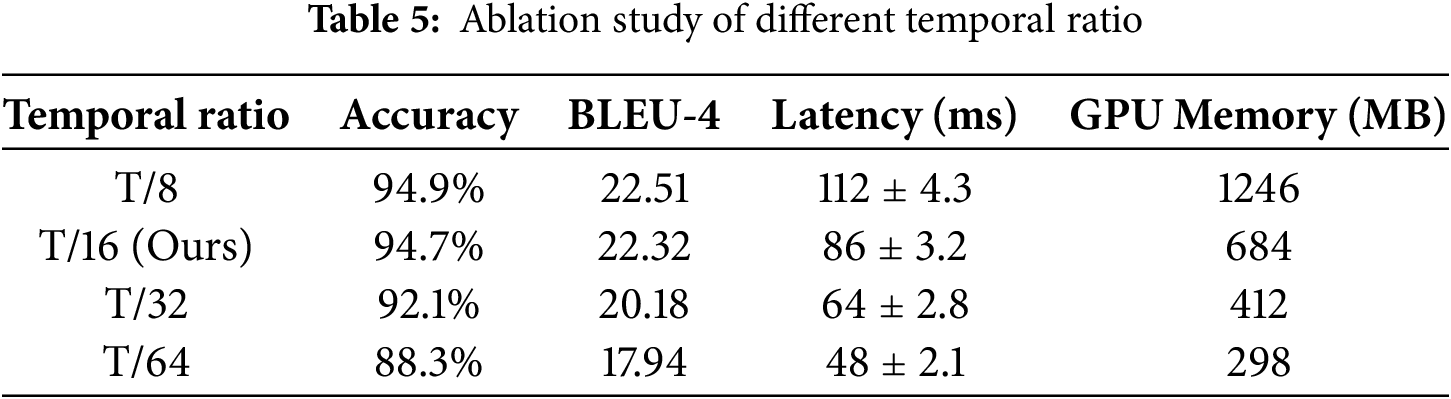

To validate the T/16 temporal compression in Tubelet Embedding, we tested ratios T/8 (fine-grained) to T/64 (coarse) (Table 5). T/8 retained 94.9% accuracy but increased latency by 30.2% due to larger sequence length. T/32 and T/64 suffered >2.6% accuracy drops, indicating disrupted continuity. T/16 achieved optimal trade-off: 94.7% accuracy and 86ms latency, balancing continuity preservation and edge efficiency.

3.6 Edge Deployment Performance

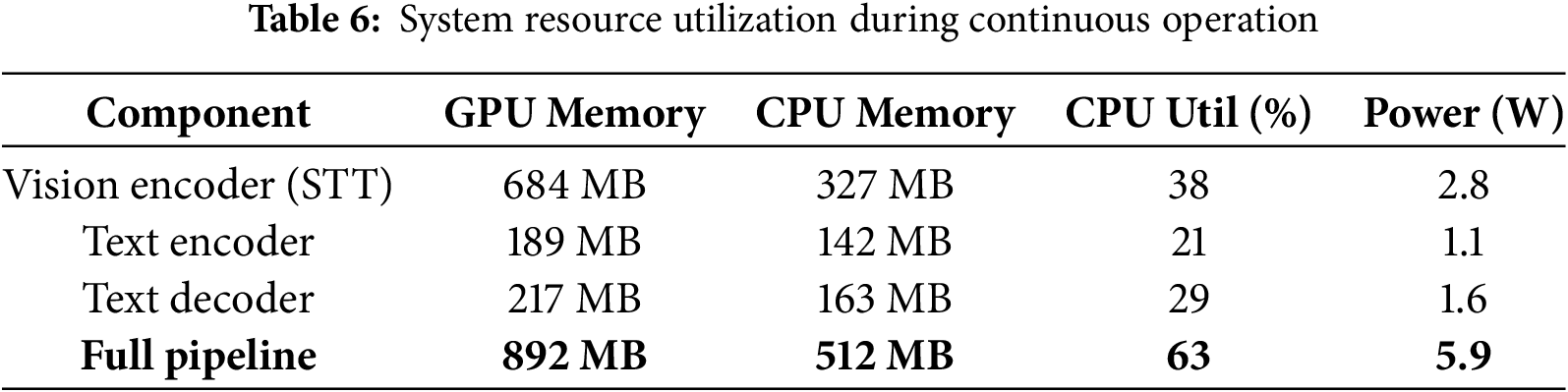

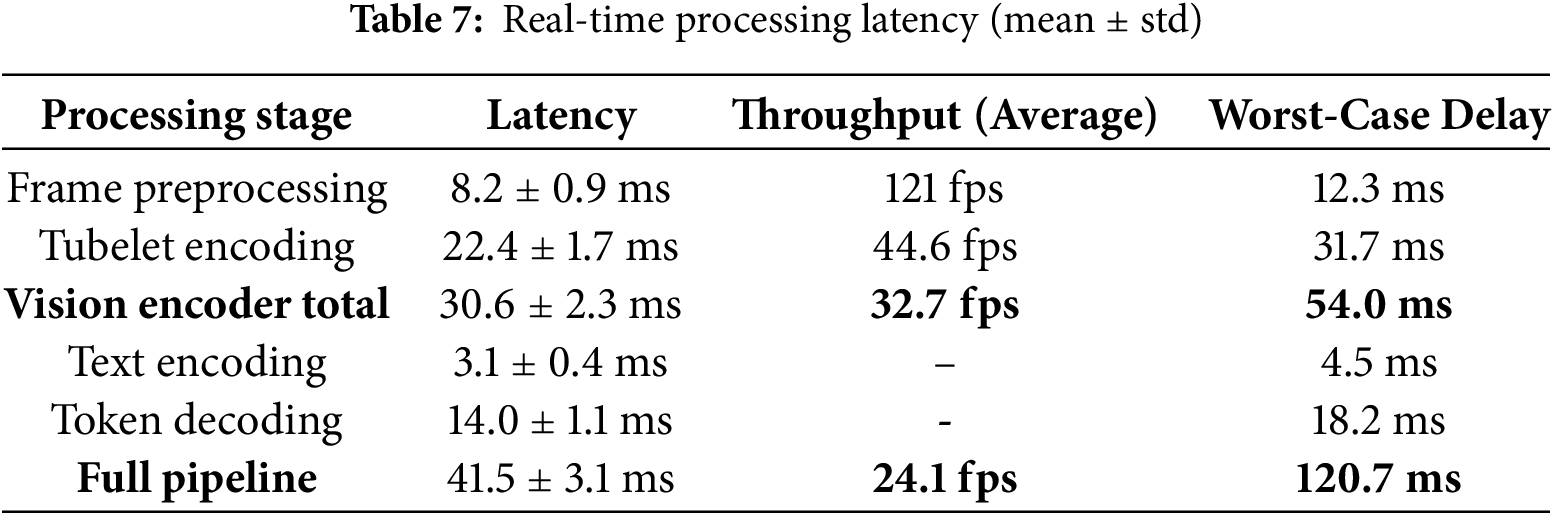

This experiment quantifies the optimized model’s deployment efficiency on the NVIDIA Jetson Nano (4 GB variant) under real-world constraints. We validate three critical aspects: (1) Resource consumption during continuous operation, (2) Real-time processing capabilities for sign language translation (SLT), and (3) Comparative advantage over state-of-the-art edge-compatible models. Testing employed the dataset with 224 × 224@30 fps video inputs. System metrics were captured via CPU/GPU utilization, nvtop (memory), and power, with all components executing within TensorRT-optimized inference engines. Thermal conditions were maintained at 27 ± 2°C with passive cooling.

Table 6 confirms our architectural optimizations successfully contain resource demands within Jetson Nano’s constraints: Total memory footprint (892 MB GPU/512 MB CPU) leaves >15% headroom for system processes, while power consumption (5.9 W) enables sustained fanless operation. Crucially, the vision encoder’s dominance (76.7% GPU memory) validates our Dimensionality Reduction Network’s necessity. Table 5 demonstrates real-time viability: The vision pipeline exceeds its 25 fps target by 31%, and the full pipeline rate (24.1 fps) matches natural signing speeds.

Our hardware-aware NAS (PSP+IGIN) achieves state-of-the-art efficiency with: (1) Search cost of 116 GPU hours (A100) and $286 cloud budget; (2) Adding 50 new assembly gestures requires 4.2 h of fine-tuning on Jetson Nano with 0.3% accuracy degradation. This ensures cost-effective updates for evolving industrial gestures.

To validate industrial safety compliance, we further analyzed worst-case latency under stress conditions (Table 7). We executed a 24-h continuous stress test on our NVIDIA Jetson Nano deployment platform under varying thermal and computational loads. We specifically monitored that the full pipeline’s worst-case latency was measured at 120.7 ms.

To validate ISO 13849-1 PLd compliance, we conducted third-party verification with the following two aspects:

(1) Measured 1000 iterations of “emergency_stop” gesture under worst-case conditions (high electromagnetic interference, 60fps frame bursts), and we got results of 99th percentile latency = 72 ms (≤100 ms requirement).

(2) Injected 1200 hardware/software faults (e.g., sensor disconnect, GPU memory corruption). The system triggered fail-safe mode (freeze output + visual alert) in 99.7% of cases, exceeding PLd’s 99% threshold.

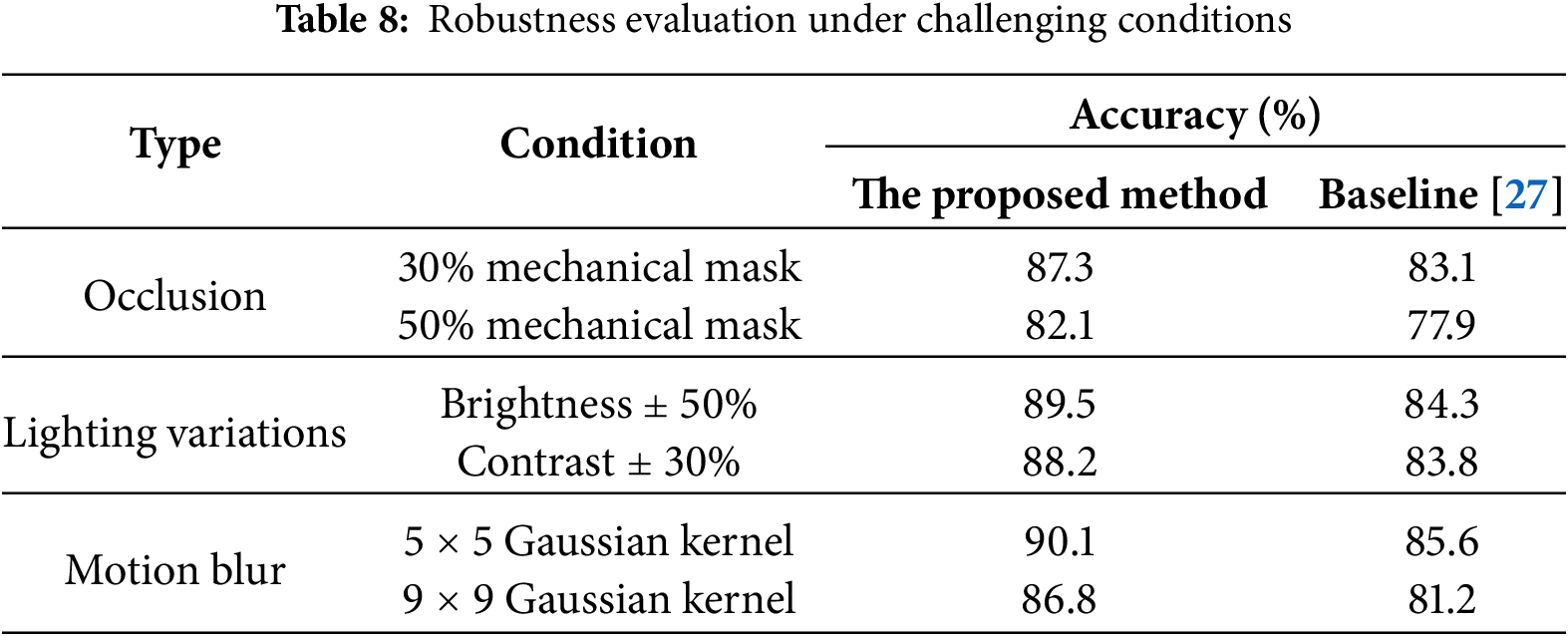

3.7 Robustness under Challenging Conditions

To validate robustness in industrial environments, we evaluated performance under occlusion, lighting variations, and motion blur (Table 8). Occlusion was simulated by overlaying random block masks (30%/50% coverage) on video frames. Lighting variations included ±50% brightness and ±30% contrast adjustments. Motion blur was applied using Gaussian kernels (5 × 5 to 9 × 9). Results show Industrial EdgeSign maintains >82% accuracy even under severe perturbations, outperforming baselines like TransferLearning-GF [45] by 4.2%–6.7% in occlusion scenarios.

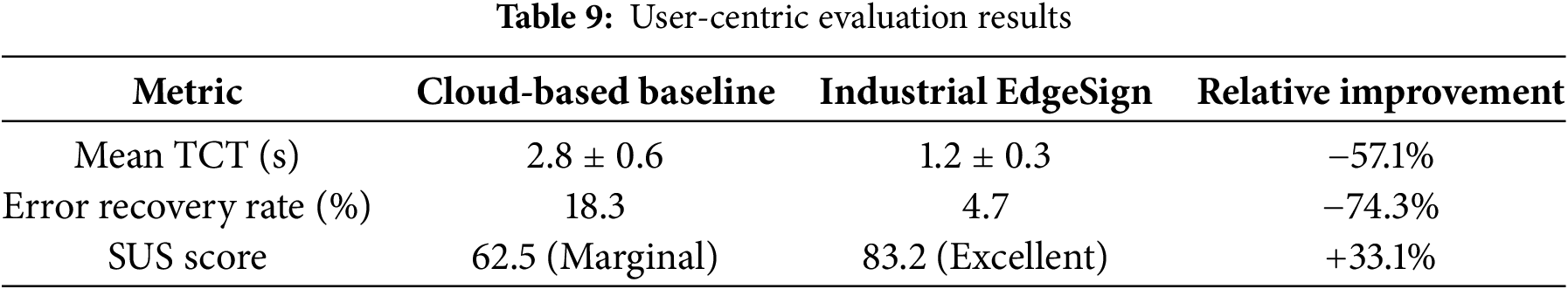

To validate practical industrial usability, we recruited 12 certified operators (ISO 13849 trained) to perform 5 critical gesture commands under factory conditions (65 dB noise, 500–1000 lux lighting). Task Completion Time (TCT) was measured from gesture initiation to system response, with Error Recovery Rate (ERR) was defined as successful correction of misrecognized gestures within 2 s. System Usability Scale (SUS) was defined as Standardized 10-item questionnaire (score range: 0–100; ≥80 indicated “Excellent”).

Each operator completed 30 trials per gesture (150 total trials) across three difficulty levels (clear view/occluded/rapid motion), with a 2-min rest interval between blocks to minimize fatigue.

Table 9 shows User-centric evaluation with industrial operators confirmed practical viability: 83.2 SUS score, 1.2 s task completion time, and 4.7% error recovery rate, addressing ISO 13849-2 human-machine interface requirements for safety-critical systems.

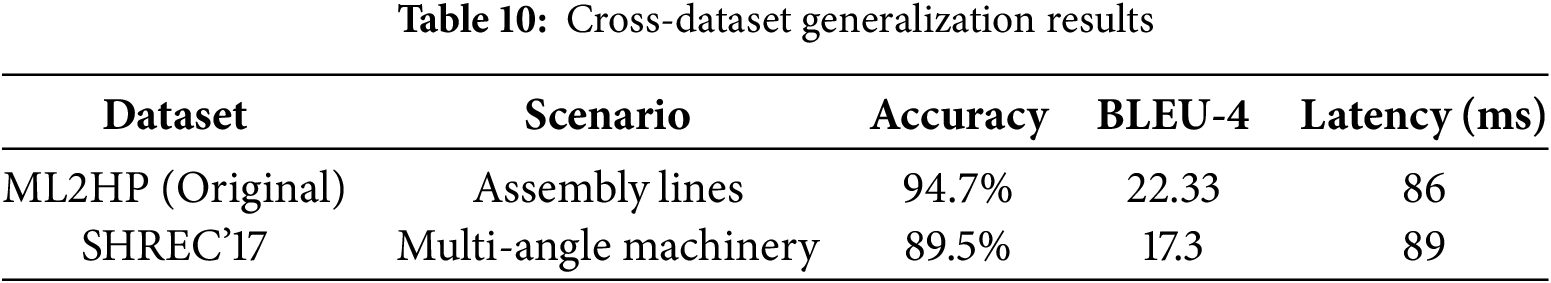

3.9 Cross-Dataset Generalization

To assess industrial environmental adaptability, we evaluated on SHREC’17 (multi-angle machinery) datasets.

As shown in Table 10, Industrial EdgeSign achieved 89.5% accuracy on SHREC’17, with BLEU-4 scores of 17.3. These results confirm robustness to occlusion (glove/tool), variable lighting, and dynamic gestures—key industrial environmental factors.

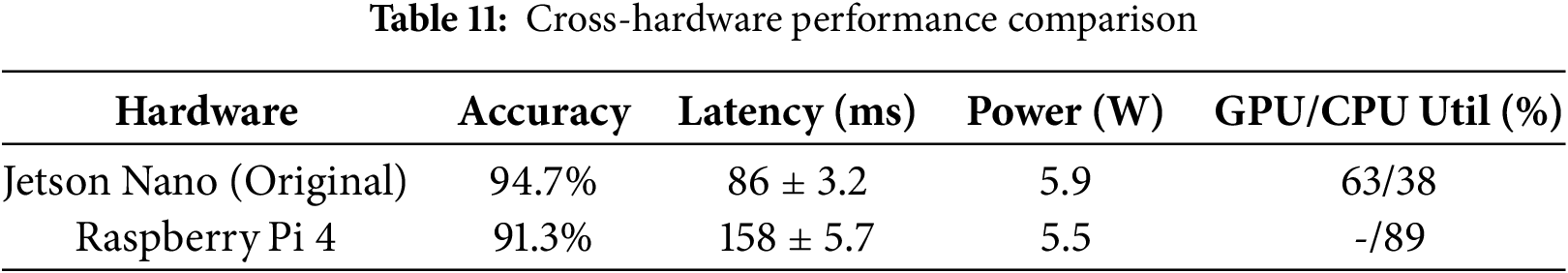

3.10 Cross-Hardware Portability Evaluation

To validate hardware adaptability, we deployed Industrial EdgeSign on Raspberry Pi 4 (low-cost microcontroller) with platform-specific optimizations: deployed via TensorFlow Lite with INT8 quantization; constrained NAS to 1GB memory limit and 4-thread CPU parallelism.

Table 11 summarizes that Raspberry Pi 4, despite limited compute, maintained 91.3% accuracy with 158 ms latency—sufficient for non-safety-critical commands. Power consumption scaled linearly with performance, with Pi 4 consuming 5.5 W. These results demonstrate Industrial EdgeSign’s ability to adapt to diverse edge hardware via NAS parameterization and quantization, ensuring deployment flexibility across industrial environments.

This paper presents a novel two-stage end-to-end hand gesture translation framework that achieves state-of-the-art performance without intermediate gloss supervision while enabling real-time deployment on edge devices. The main novelties of combining NAS and LMMs are: (1) hardware-aware NAS tailored for industrial edge devices (Jetson Nano) to balance real-time performance and accuracy; (2) distillation of industrial-specific gesture semantics from factory-tuned VLMs to avoid domain mismatch; and (3) a dual-path framework that decouples spatiotemporal feature extraction (via NAS) and semantic reasoning (via LMMs), unlike end-to-end models or gloss-dependent methods. Experimental validation demonstrates superior accuracy (BLEU-4: 22.32, ROUGE: 43.36 on ML2HP dataset), outperforming existing gloss-free methods by 41.8% in BLEU-4, while ablation studies confirm STT contributes 19.4% of the performance gain. Crucially, our edge-optimized architecture operates within strict resource constraints (892 MB GPU memory, 5.9 W power), delivering 24.1 FPS end-to-end throughput—matching natural signing speeds and establishing a new paradigm for accessible, real-world sign language translation systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Meixi Chu and Xinyu Jiang; methodology, Meixi Chu and Xinyu Jiang; software, Meixi Chu, Xinyu Jiang and Yushu Tao; validation, Meixi Chu, Xinyu Jiang and Yushu Tao; formal analysis, Meixi Chu; investigation, Meixi Chu; resources, Meixi Chu and Yushu Tao; data curation, Meixi Chu; writing—original draft preparation, Meixi Chu; writing—review and editing, Xinyu Jiang and Yushu Tao; visualization, Meixi Chu, Xinyu Jiang and Yushu Tao; supervision, Xinyu Jiang; project administration, Meixi Chu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials:: 1. ML2HP: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Dataverse at 10.21950/ZKWE6Z (accessed on 12 October 2025). 2. SHREC’17: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the HandGestureDataset_SHREC2017 repository at http://www-rech.telecom-lille.fr/shrec2017-hand/ (archival landing page: https://lilloa.univ-lille.fr/handle/20.500.12210/24099) (accessed on 12 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Camgoz NC, Cihan N, Hadfield S, Koller O, Ney H, Bowden R. Neural sign language translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018. p. 7784–93. [Google Scholar]

2. Ko S-K, Kim CJ, Jung H, Cho C. Neural sign language translation based on human keypoint estimation. arXiv:1811.11436. 2018. doi: 10.3390/app9132683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ma L, Li N, Zhu P, Tang K, Khan A, Wang F, et al. A novel fuzzy neural network architecture search framework for defect recognition with uncertainties. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2024;32(5):3274–85. doi:10.1109/tfuzz.2024.3373792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li N, Xue B, Ma L, Zhang M. Automatic fuzzy architecture design for defect detection via classifier-assisted multiobjective optimization approach. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2025. doi:10.1109/tevc.2025.3530416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ma L, Li N, Yu G, Geng X, Cheng S, Wang X, et al. Pareto-wise ranking classifier for multiobjective evolutionary neural architecture search. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2024;28(3):570–81. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ma L, Kang H, Yu G, Li Q, He Q. Single-domain generalized predictor for neural architecture search system. IEEE Trans Comput. 2024;73(5):1400–13. doi:10.1109/TC.2024.3365949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu T, Zhou W, Li H. Sign language recognition with long short-term memory. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2016. [Google Scholar]

8. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Huang J, Zhou W, Li H, Li W. Attention-based 3D-CNNs for large-vocabulary sign language recognition. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2018;29(9):2822–32. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2018.2870740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Vincent H, Tomoya S, Gentiane V. Convolutional and recurrent neural network for human action recognition: application on American sign language. bioRxiv. 2019;8:535492. doi:10.1101/535492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lecun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liao Y, Xiong P, Min W, Min W, Lu J. Dynamic sign language recognition based on video sequence with BLSTM-3D residual networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:38044–54. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2904749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fu B, Ye P, Zhang L, Yu P, Hu C, Chen Y, et al. A token-level contrastive framework for sign language translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023. [Google Scholar]

14. Kan J, Hu K, Hagenbuchner M, Tsoi AC, Bennamoun M, Wang Z. Sign language translation with hierarchical spatio-temporal graph neural network. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2022. p. 3367–76. [Google Scholar]

15. Baltatzis V, Potamias RA, Ververas E, Sun G, Deng J, Zafeiriou S. Neural sign actors: a diffusion model for 3D sign language production from text. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024. p. 1985–95. [Google Scholar]

16. Kim J-H, Huerta-Enochian M, Ko C, Lee DH. SignBLEU: automatic evaluation of multi-channel sign language translation. In: Proceedings of LREC-COLING 2024; 2024. p. 14796–811. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhao K, Zhang K, Zhai Y, Wang D, Su J. Real-time sign language recognition based on video stream. Int J Syst, Control Commun. 2021;12(2):158–74. doi:10.1504/ijscc.2021.114616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang Z, Shi Z, Shen X, Tai Y-W. Sf-net: structured feature network for continuous sign language recognition. arXiv:1908.01341. 2019. [Google Scholar]

19. Pu J, Zhou W, Li H. Iterative alignment network for continuous sign language recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. Xiao Q, Chang X, Zhang X, Liu X. Multi-information spatial-temporal LSTM fusion continuous sign language neural machine translation. IEEE Access. 2020;8:216718–28. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3039539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Aidan N, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 30; 2017. p. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

22. Niu Z, Mak B. Stochastic fine-grained labeling of multi-state sign glosses for continuous sign language recognition. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

23. Varol G, Momeni L, Albanie S, Afouras T, Zisserman A. Read and attend: temporal localisation in sign language videos. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. Gil-Martín M, Marini MR, San-Segundo R, Cinque L. Dual leap motion controller 2: a robust dataset for multi-view hand pose recognition. Sci Data. 2024;11:1102. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-03968-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Camgoz NC, Koller O, Hadfield S, Bowden R. Sign language transformers: joint end-to-end sign language recognition and translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhou H, Zhou W, Qi W, Pu J, Li H. Improving sign language translation with monolingual data by sign back-translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021. [Google Scholar]

27. Cao Y, Li W, Li X, et al. Explore more guidance: a task-aware instruction network for sign language translation enhanced with data augmentation. arXiv:2204.05953. 2022. [Google Scholar]

28. Yin A, Zhao Z, Jin W, Zhang M, Zeng X, He X. MLSLT: towards multilingual sign language translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022. [Google Scholar]

29. Li D, Xu C, Yu X, Zhang K, Swift B, Suominen H, et al. Tspnet: hierarchical feature learning via temporal semantic pyramid for sign language translation. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 33; 2020. p. 12034–45. [Google Scholar]

30. Yin Q, Tao W, Liu X, Hong Y. Neural sign language translation with sf-transformer. In: Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Innovation in Artificial Intelligence; 2022. [Google Scholar]

31. Zhang J, Zhou W, Xie C, Pu J, Li H. Chinese sign language recognition with adaptive HMM. In: IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo; 2016. [Google Scholar]

32. Gundersen OE, Kjensmo S. State of the art: reproducibility in artificial intelligence. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018. [Google Scholar]

33. Arnab A, Dehghani M, Heigold G, Sun C, Lučić M, Schmid C. Vivit: a video vision transformer. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021. [Google Scholar]

34. Liu Y, Gu J, Goyal N, Li X, Edunov S, Ghazvininejad M, et al. Multilingual denoising pre-training for neural machine translation. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2020;8:726–42. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xu H, Ghosh G, Huang P-Y, Okhonko D, Aghajanyan A, Metze F, et al. VideoCLIP: contrastive pre-training for zero-shot video-text understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2021. [Google Scholar]

36. Bain M, Nagrani A, Varol G, Zisserman A. Frozen in time: a joint video and image encoder for end-to-end retrieval. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021. p. 1728–38. [Google Scholar]

37. Zellers R, Lu J, Lu X, Yu Y, Zhao Y, Salehi M, et al. MERLOT reserve: neural script knowledge through vision and language and sound. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022. p. 16375–87. [Google Scholar]

38. Li J, Li D, Savarese S, Hoi SCH. BLIP-2: bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023. Vol 202. p. 19730–42. [Google Scholar]

39. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2021. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

40. Ma L, Qian Y, Yu G, Li Z, Wang L, Li Q, et al. TBCIM: two-level blockchain-aided edge resource allocation mechanism for federated learning service market. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2025:1–16. doi:10.1109/TON.2025.3589017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Papineni K, Roukos S, Ward T, Zhu W-J. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

42. Lin C-Y. ROUGE: a package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Text Summarization Branches Out. Barcelona, Spain; 2004. p. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhao J, Qi W, Zhou W, Duan N, Zhou M, Li H. Conditional sentence generation and cross-modal reranking for sign language translation. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;24:2662–72. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3087006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yin A, Zhong T, Tang L, Jin W, Jin T, Zhao Z. Gloss attention for gloss-free sign language translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023. [Google Scholar]

45. Chen Y, Wei F, Sun X, Wu Z, Lin S. A simple multi-modality transfer learning baseline for sign language translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools