Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MFCCT: A Robust Spectral-Temporal Fusion Method with DeepConvLSTM for Human Activity Recognition

1 Department of Computer Science, COMSATS University Islamabad, Vehari Campus, Vehari, 61100, Pakistan

2 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O.Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

3 Riphah School of Computing & Innovation, Riphah International University, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Rashid Jahangir. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071574

Received 07 August 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Human activity recognition (HAR) is a method to predict human activities from sensor signals using machine learning (ML) techniques. HAR systems have several applications in various domains, including medicine, surveillance, behavioral monitoring, and posture analysis. Extraction of suitable information from sensor data is an important part of the HAR process to recognize activities accurately. Several research studies on HAR have utilized Mel frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) because of their effectiveness in capturing the periodic pattern of sensor signals. However, existing MFCC-based approaches often fail to capture sufficient temporal variability, which limits their ability to distinguish between complex or imbalanced activity classes robustly. To address this gap, this study proposes a feature fusion strategy that merges time-based and MFCC features (MFCCT) to enhance activity representation. The merged features were fed to a convolutional neural network (CNN) integrated with long short-term memory (LSTM)—DeepConvLSTM to construct the HAR model. The MFCCT features with DeepConvLSTM achieved better performance as compared to MFCCs and time-based features on PAMAP2, UCI-HAR, and WISDM by obtaining an accuracy of 97%, 98%, and 97%, respectively. In addition, DeepConvLSTM outperformed the deep learning (DL) algorithms that have recently been employed in HAR. These results confirm that the proposed hybrid features are not only practical but also generalizable, making them applicable across diverse HAR datasets for accurate activity classification.Keywords

HAR is a process that detects and categorizes specific human behaviors and motions based on sensor data [1]. Recently, research on HAR using wearable sensors has attracted significant interest from both industry and academia. Advances in semiconductor technology have enabled the integration of compact, lightweight, low-power, and cost-effective sensors into wearable devices [2]. The HAR system has been one of the most popular research topics due to its extensive applications, including smart home environments [3], smart healthcare [4], security [5], robotics [6], and sports [7]. Any physical activity, gesture, or motion that involves energy consumption is classified as ‘human action.’ Typical examples of such actions are drinking, walking, and eating [8]. Generally, human activities are classified into simple and complex types. In the simple category, body movement and posture are used to define a range of actions, such as jogging, running, and walking. Complex human activities are formed when simple activities are combined with functional tasks [9]. For example, consider the action of working on a computer, where a person performs a simple activity like sitting while performing the functional task of typing or data processing. This emerging area of research mainly concentrates on two core aspects: the use of smartphone sensor data and the use of ML techniques for data interpretation [10]. Current smartphones are designed with a variety of advanced sensors, such as those for motion, orientation, location tracking, and network connectivity. In addition, modern smartphones are integrated with sensors that support health and fitness monitoring, enabling users to monitor their physical activities and maintain better control over their personal well-being. For instance, these sensors can be used in healthcare to observe the movements and behaviors of elderly or disabled individuals, enabling timely assistance when needed. In the sports domain, HAR systems help monitor and analyze athletes’ movements to identify areas where performance can be enhanced.

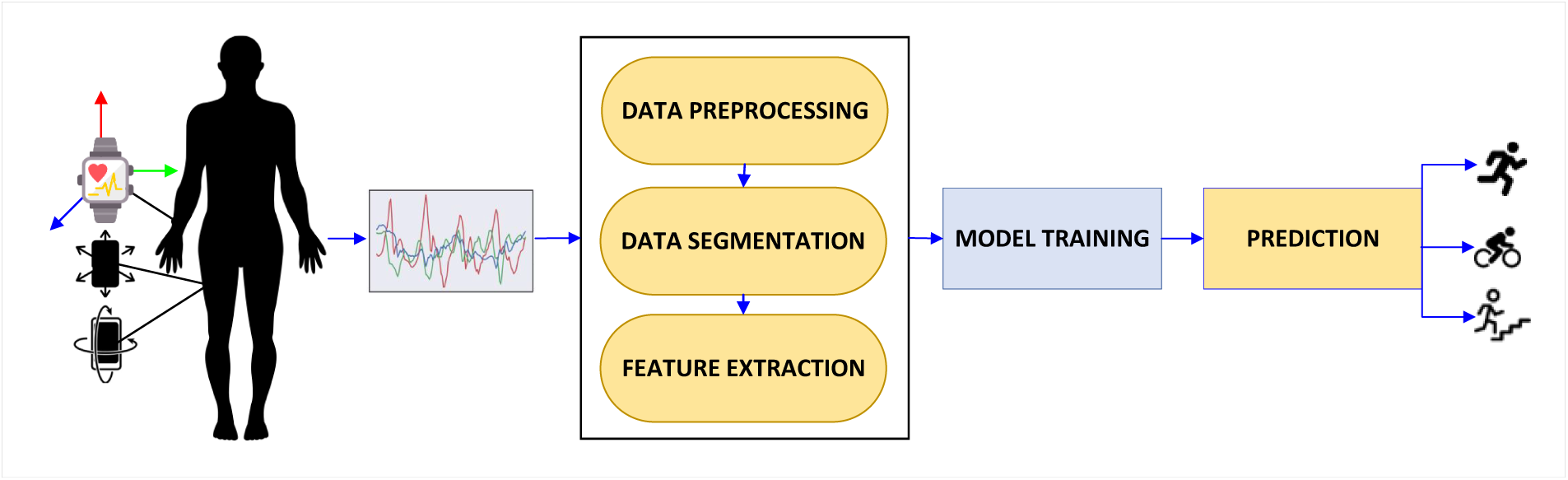

Recently, sensor-based HAR has gained significant attention due to growing concern about privacy and its user-friendly nature [11]. Fig. 1 presents the flow design of the HAR system using wearable devices. Traditionally, the HAR process using wearable sensors consists of three main stages: data acquisition, feature extraction, and activity classification [12]. In the first stage, time-series data and detailed information about specific activities are collected from a variety of wearable devices integrated with sensors such as accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers, electromyography (EMG), and electrocardiography (ECG). The position of these sensors significantly influences the accuracy of the recorded activity data. In the subsequent stage, the sensor’s data is used to extract suitable features, including time-domain, statistical, and frequency-domain characteristics. The final stage involves the application of classification algorithms to map these features into specific activity categories such as walking, running, sitting, and standing.

Figure 1: A framework for HAR based on wearable sensor data

The extraction of relevant and suitable features is crucial to predict different human physical activities accurately. Traditional ML approaches typically depend on handcrafted, heuristic features. In contrast, DL models can automatically learn high-level representations directly from raw time-series data [13]. Recent research on DL approaches for HAR has demonstrated better performance compared to ML methods [14]. Among DL approaches, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are widely utilized to capture both spatial and temporal features. However, while CNN is effective in achieving invariance through pooling and scalar outputs, it cannot maintain equivariance. Likewise, a well-known variant of LSTM called Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [15] is characterized by its simpler architectural complexity, quicker convergence, and lower parameter count. The attention mechanism [16] integrated with the GRU can dynamically prioritize information by assigning different weights to its output elements. This GRU-attention framework has been successfully employed in several fields such as stock trend prediction, health status analysis, and question classification [17].

The primary challenge in the HAR model is to handle the variability (intensity, duration, and context) in human activities [18]. This challenge makes it difficult to develop accurate and robust HAR models. Additionally, the choice and placement of sensors on the body play a crucial role in enhancing the system’s performance. For instance, wearable sensors can provide high-precision data. However, they may intrude on user comfort, while non-wearable sensors offer a more user-friendly experience at the cost of reduced data accuracy. There is a growing interest in designing HAR systems to function in real-world environments, which are typically unstructured and unpredictable. Therefore, this study presents a novel HAR approach that integrates time-domain with MFCC features extracted from sensor data. The proposed methodology comprises four stages: (1) data acquisition, (2) feature extraction, (3) DL model training, and (4) activity prediction. During the feature extraction phase, both traditional MFCCs and time-domain features are computed and subsequently fused through concatenation. For classification, a lightweight DeepConvLSTM model is employed. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, three publicly available datasets were utilized. The proposed framework demonstrated improved recognition accuracy compared to baseline HAR methods.

While CNN-LSTM and related hybrid models have been widely applied in HAR, they primarily depend on the network depth and architectural design to extract multi-scale features. In contrast, the contribution of this study lies in the design of a robust feature representation (MFCCT) that combined frequency-based MFCCs with time-domain descriptors prior to model training. This reduced the burden on the network to learn all discriminative patterns from raw data, thereby enhancing generalization across diverse datasets. Hence, the novelty of our work is not limited to architectural modifications, but also extends to the fusion-based feature engineering pipeline that significantly improves HAR performance. In summary, the main contributions of this work include the development of a robust feature extraction algorithm that combines frequency- and time-domain (MFCCT) information and the implementation of an efficient ConvLSTM model that enhanced HAR performance across diverse datasets.

The rest of this study is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the literature on HAR systems and feature extraction techniques. Section 3 details the proposed methodology, including data preprocessing and model architecture. Section 4 reports experimental results and comparative evaluations. Finally, Section 5 discusses limitations and future directions.

Extensive research has been conducted to identify physical activities using data obtained from smartphone sensors, notably accelerometers and gyroscopes. In these studies, data collection typically involves recording routine human movements such as walking, standing, and sitting while individuals carry smartphones in their personal belongings. HAR based on sensor data has become a prominent area of study, with various approaches utilizing either conventional ML techniques or DL models. One study [19] introduced a method that extracted features from accelerometer and gyroscope data to identify physical activities. This method implemented k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) and support vector machines (SVM) algorithms on data sourced from two publicly available datasets. These methods highlight the importance of sensor features, but they fail to capture complex temporal dependencies. Spectral features such as MFCCs and their fusion with time-domain descriptors have been explored to capture periodic activity patterns. However, these methods often smooth temporal variability, which leads to confusion between activities with similar frequency profiles (e.g., sitting vs. standing). Thus, prior fusion strategies remain limited because they do not explicitly preserve temporal dynamics. This limitation motivates the shift toward DL models that can automatically learn hierarchical representations.

Numerous DL models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and their hybrid forms have been explored in the field of HAR. Specifically, different CNN architectures have shown effectiveness in identifying activities by processing data from inertial sensors. For example, the work in [20] developed a deep CNN that utilized data from gyroscopes and accelerometers integrated into smartphones. This model leveraged the sequential nature of 1D time-series data to extract meaningful features from raw sensor inputs. To enhance parameter selection for CNNs, the study in [21] introduced a 1D CNN optimized through seven distinct metaheuristic algorithms and evaluated using the UCI-HAR dataset. The findings highlighted the potential of metaheuristic strategies to improve CNN performance significantly. Additionally, reference [22] proposed a CNN model to incorporate a hierarchical split (HS) strategy to accommodate diverse receptive fields within the feature extraction layers. The evaluation of the proposed study using standard datasets such as UCI-HAR, PAMAP2, WISDM, and UNIMIB-SHAR indicated that the HS method outperformed traditional models and demonstrated its ability to extract more discriminative features through multiscale receptive fields.

LSTM was applied in [23] to tri-axial accelerometer sensor data for HAR and conducted experiments on the WISDM dataset [24]. Similarly, a semi-supervised learning method that combined deep Q-networks (DQN) and an LSTM model was proposed in [25] to improve the prediction using the weakly labeled sensor databases. In the proposed framework, the DQN performed automatic data classification using distance-based reward signals, while the LSTM network extracted detailed motion features and achieved an ROC curve score of 0.95. The authors in [26] utilized a BiLSTM model with data from smartphone sensors and concluded that “laying down” activity was the easiest to predict, while “sitting” posed the most significant challenge. Hybrid methods integrate different models to extract state-of-the-art features. For instance, reference [27] evaluated SVM, ANN, and HMM-SVM models on data gathered from elderly individuals. The predicted activities were incorporated into a bidirectional activity system to improve connectivity and context detection. In domains such as image and speech processing, CNN-LSTM architectures have shown significant effectiveness. Despite the above-mentioned DL techniques having demonstrated notable performance, the prediction accuracy needs further enhancement in domains like image and speech processing. Consequently, recent research has focused on integrating convolutional layers (CLs) with LSTM layers to develop hybrid DL architectures for HAR. For instance, reference [28] proposed a CNN-LSTM model using smartphone sensor data to demonstrate a superior performance compared to models relying solely on LSTM networks. Within these architectures, CNN layers captured suitable features, while LSTM layers captured temporal dependencies. The experimental results revealed that the combined CNN-LSTM architecture outperformed both LSTM and BiLSTM models. The study [29] proposed a DeepConvLSTM, which incorporated CL and LSTM layers to extract temporal dependencies from multimodal sensor data automatically. Reference [30] explored a DL framework for HAR using data from mobile gyroscopes and accelerometers. The proposed approach combined three DL models: autoencoders, LSTM, and CNN. In this setup, CNN was utilized to extract suitable features, autoencoders were used for dimensionality reduction, and the LSTM network handled the temporal sequence modeling. This hybrid ConvAE-LSTM model was evaluated on different datasets, including UCI-HAR, WISDM, PAMAP2, and OPPORTUNITY. The findings showed improved recognition performance in terms of both computational efficiency and accuracy when compared to baseline methods. Furthermore, research in [31] investigated the use of environmental context to augment sensor data via a CNN-LSTM hybrid approach. This method integrated high-level contextual information with fundamental sensor signals to enhance recognition performance. Two experiments were conducted: the first used only triaxial sensor signals to train the baseline models, while the second incorporated both contextual and sensor data. Results from the study showed that including contextual features significantly boosted accuracy compared to models relying solely on sensor inputs. While CNN, LSTM, BiLSTM, and CNN-LSTM architectures achieve high recognition accuracy, most approaches depend heavily on architectural complexity. This increases computational cost and reduces generalization in real-world noisy environments.

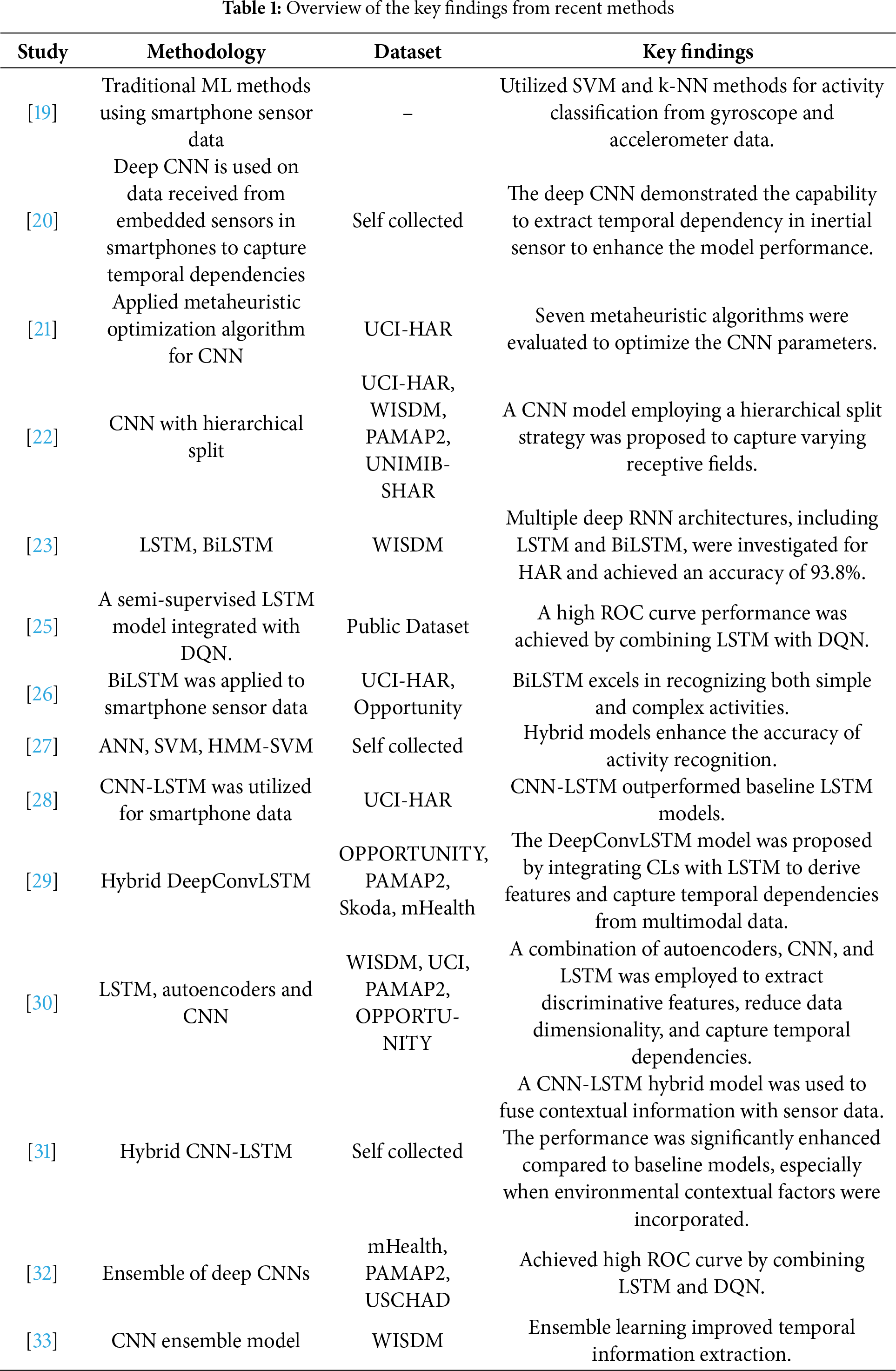

Wearable devices have become increasingly popular due to the rich data collected by their embedded sensors, which is highly beneficial for sensor-based HAR. Each sensor captures distinct complementary information, but also introduces complexities such as temporal variation and data heterogeneity. To address this challenge, reference [32] processed each sensor data independently to learn its unique information and classify the data before integration. The authors utilized an ensemble of deep CNNs to get patterns at various temporal resolutions. This method enabled the model to extract both complex and straightforward behaviors effectively. Similarly, reference [33] introduced an ensemble learning method that incorporated multiple CNNs to recognize human activities. The model focused on extracting useful temporal features directly from raw data to improve HAR performance. Although DL approaches have shown strong performance in HAR, challenges like class imbalance and noisy data make effective feature extraction difficult in this area. Additionally, many existing HAR methods continue to rely on manually engineered features. This study proposes effective time and frequency-based features extracted directly from raw sensor data and a hybrid DeepConvLSTM model. Table 1 presents an overview of the key findings from recent methods in this area, emphasizing the range of techniques used and their corresponding results.

In summary, two key shortcomings persist in prior work: (i) handcrafted features lack robustness and generalization, and (ii) deep CNN-LSTM architectures depend on increased depth and complexity rather than improved feature representations. To address these gaps, this study introduced MFCCT, which explicitly enriches MFCC features with temporal descriptors at the bin level and integrates them with DeepConvLSTM. This approach directly targets the problem of temporal variability and offers superior generalization across benchmark datasets.

This section presents the detailed methodology (Fig. 2) adopted for human activity recognition. Firstly, the datasets were collected to perform the experiments. Secondly, discriminative and suitable features were retrieved from sensor data to create a master feature vector (MFV). This vector was then fed to a CNN to construct the HAR model. Afterwards, the constructed HAR models were assessed using benchmark performance metrics. Finally, the proposed HAR model was compared with existing HAR baseline models. The detail of each phase is presented in subsequent sections.

Figure 2: Proposed research methodology for HAR

The proposed HAR model was evaluated on three datasets: PAMP2, UCI-HAR, and WISDM. These datasets contain sensor data collected through different human activities. WISDM is a dataset constructed to assess the performance of HAR models. The 1098208 acceleration data points are heterogeneously distributed into six human activities. The second UCI-HAR dataset is widely used to evaluate the HAR models. It contains six human activities: lying, sitting, walking upstairs, walking downstairs, standing, and walking. Each data sample in this dataset includes nine channels. The third dataset used in this research is PAMAP2. It includes data received from multiple sensors placed on human ankles, chest, and hands. It integrates samples from gyroscopes, magnetometers, temperature, accelerometers, and other wearable sensors [34]. It includes nine subjects participating in 18 activities, with six of them being optional. The experiments recognized only 12 of these activities. No substantial correlation between other data and gyroscope sources due to the statistical similarities among various columns in the PAMAP2 dataset. Consequently, the data from the gyroscope sensor is omitted from further analysis. In addition, correlations are observed between accelerometer and temperature data, as well as between heart rate and chest magnetometer data.

Fig. 3 presents a comparative overview of activity distributions across three widely used HAR datasets. The UCI HAR dataset (Fig. 3a) includes six balanced activity classes while Fig. 3b exhibits a more diverse range of activities, including not only basic movements like walking and sitting but also complex actions such as rope jumping, vacuum cleaning, and ironing. In contrast, the WISDM dataset (Fig.3c) is dominated by walking and jogging activities, with fewer samples for other actions such as sitting, standing, and climbing stairs. This comparison highlights the differences in class diversity and sample distribution among the datasets.

Figure 3: Distribution of activity classes in three publicly available HAR datasets: (a) UCI HAR, (b) PAMAP2, and (c) WISDM

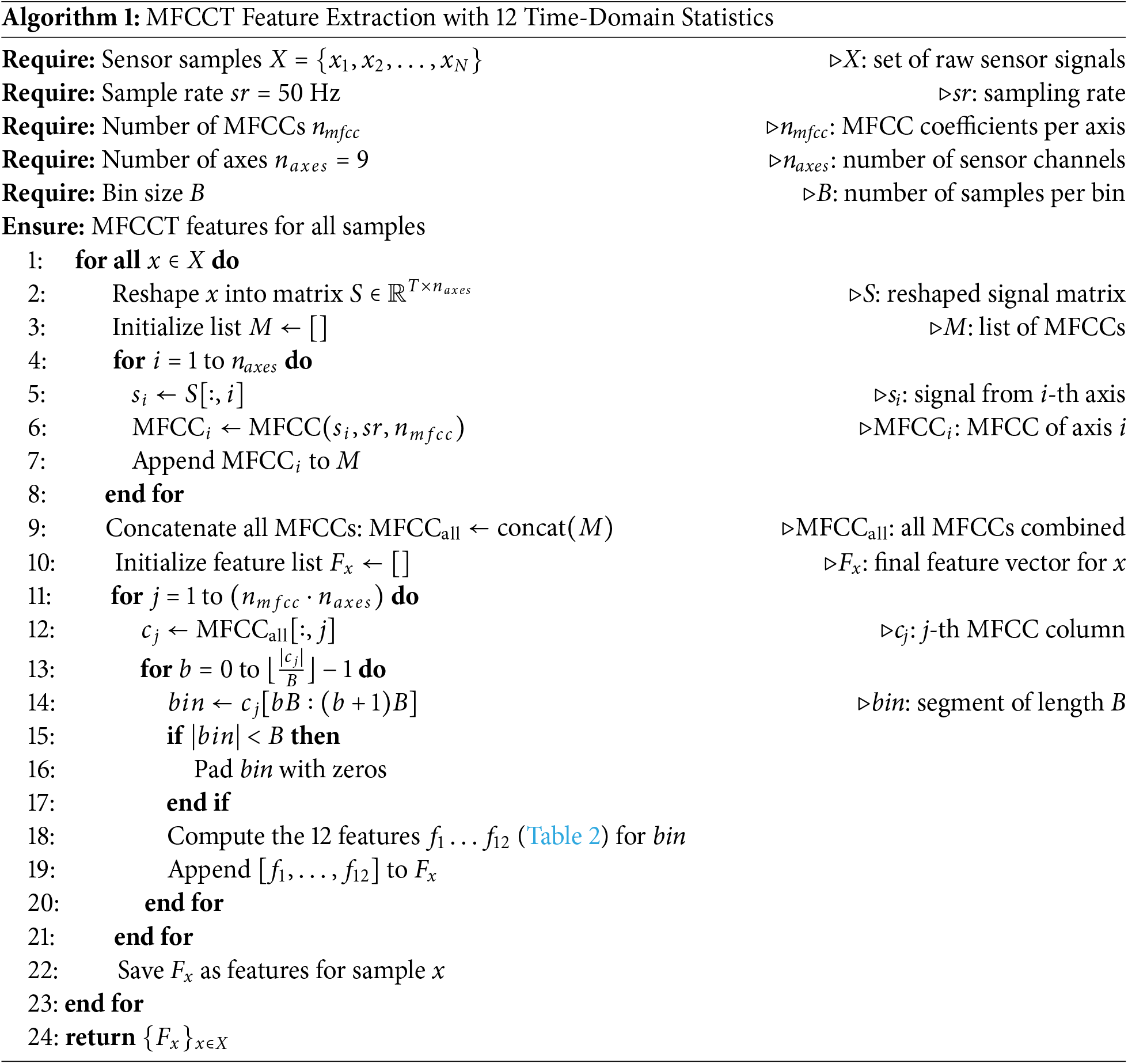

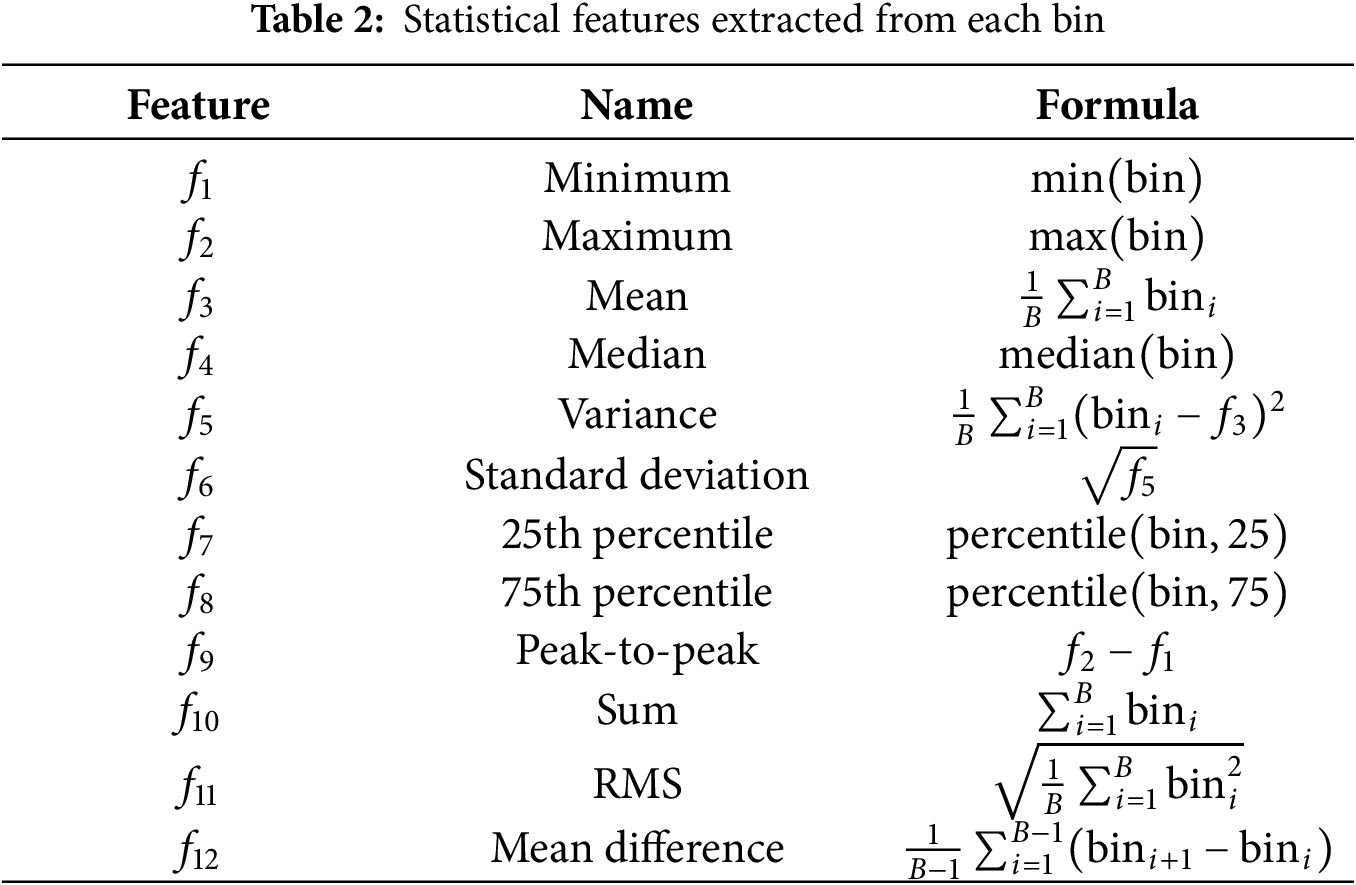

The classification accuracy of the HAR model is mainly dependent on the quality of the features. Thus, irrelevant features may produce poor classification results. In machine learning (ML), a suitable and relevant feature vector plays a crucial role in achieving better classification results. For instance, reference [35] concluded that feature retrieval is an important step in ML classification problems, as the success or failure of the HAR model hugely relies on the variability used in the task. The identification becomes precise if the extracted feature vector is strongly correlated with the relevant activity. In contrast, it becomes inaccurate and difficult if the extracted feature vector is not highly correlated with the activity. Therefore, the extraction of useful feature vectors from sensor data is very crucial to learn the classification rules. In this study, a novel feature retrieval method is implemented to get suitable and practical information, called MFCCT, from the sensor data to construct an accurate HAR model. The details of the extracted MFCCT information are given below.

MFCCT Features

The MFCCT features are retrieved from sensor data into two phases: (1) extraction of MFCC features, and (2) integration of MFCCs and time-domain features. The MFCC features are retrieved to identify the changes in movement rhythm, frequency, and intensity linked to different human activities. MFCCs convert the time-series sensor data into the frequency components that correspond to human activities using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), then map those frequency components using a mel scale. The pipeline of MFCCs feature extraction includes framing, windowing, the fast Fourier transform (FFT), Mel filter scale, and discrete cosine transform (DCT). Each continuous human activity signal is divided into several overlapping frames. The sum of frames is calculated using Eq. (1).

In HAR, this equation ensures that short-term motion patterns are captured in a time-localized manner.

Eq. (2) is used to compute an appropriate frame length to ensure that one frame contains enough information to represent a complete activity.

Once the frames are computed, a Hamming windowing method is applied to each single frame to confirm that the edges of the frame are smoothed using Eq. (3). This ensures that periodic activities like running or cycling are represented more faithfully in the frequency domain.

where N is the number of samples. Afterwards, the spectrum of each frame is given to the Mel filter scale. The Mel is computed as:

where f represents the definite frequency while the Mel(f) represents the perceived frequency.

Finally, the MFCCs were retrieved by applying DCT to the log Mel spectrum of all frames by using Eq. (5).

where C is the number of MFCCs, which represents the energy in different frequency bands evolved. For instance, walking activity has a periodic pattern with a dominant frequency, while sitting or jumping produces different frequency patterns. Moreover, MFCCs reflect the intensity and type of movements in HAR. Instead of directly feeding

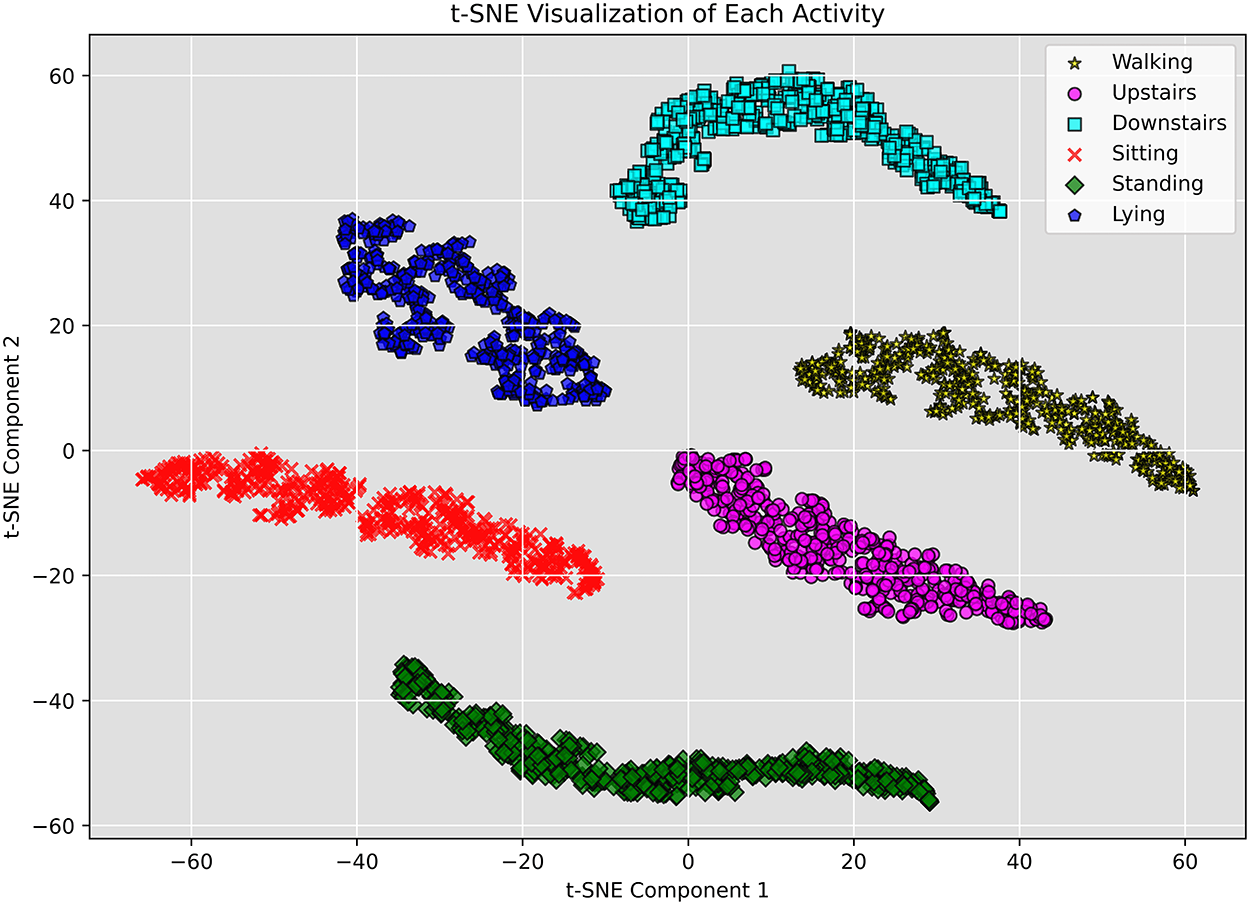

Fig. 4 demonstrates a clear separation between activity classes, indicating that the MFCCT features effectively captured discriminative patterns relevant to the recognition of human activity. The clusters are well-formed with minimal overlap and suggest the suitability of these features for HAR classification tasks.

Figure 4: t-SNE visualization of activities based on MFCCT features

The proposed methodology for HAR constructed a novel CNN integrated with long short-term memory (LSTM)—DeepConvLSTM to recognize human activities, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The proposed DeepConvLSTM model is constructed to effectively capture the hierarchical characteristics from the derived MFCCT data and enhance the accuracy of HAR models. Firstly, an input layer is utilized to process the MFCCT data (X) to derive local features using a 1D convolutional (

The output of each CL is given to a 1D max-pool layer (

Following the flattening layer, an LSTM layer is used to acquire long-term temporal dependencies in the time-series data as given in Eq. (9), where

A dense layer is used with an optimum number of neurons to make the HAR model computationally robust and efficient, as given in Eq. (9). Lastly, the output layer with an activation function called softmax is employed to compute the probability of each human activity. The proposed HAR model, as shown in Fig. 2, is compiled utilizing an Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss function to improve the accuracy of each activity class.

For imbalanced datasets like WISDM, when a classification algorithm predicts each instance as belonging to a particular activity and evaluates the model’s performance using average accuracy, the results may appear impressive. Average accuracy is measured by the proportion of correctly classified activity instances to the total number of activity instances, as given by the following equation:

where N denotes the total instances of activity. However, the average accuracy metric can lead to misleading results. The F1 score is a widely used evaluation metric in the field of machine learning. It considers both false positives and false negatives. It is calculated using two key metrics, namely precision and recall. Precision is used to compute the ratio of correctly predicted positive activity instances to the total number of instances predicted as positive, as shown in the following equation: Eq. (19).

Recall is calculated as the ratio of correctly classified positive activity instances to the total number of actual positive instances, which includes both correctly identified positives and incorrectly classified negatives, as shown in the following equation:

As a result, the F1 score often provides a more reliable assessment of model performance than average accuracy, particularly in cases of class imbalance. It is the weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall, as shown in the following equation.

This study utilized three publicly and widely available datasets, namely UCI-HAR, WISDM, and PAMAP2, to evaluate the performance and generalized capabilities of the proposed method. These datasets have been consistently collected, and a common technique is to use a fixed-length sliding window to segment the input signals. Each sliding window has a 128-sample size with a 64-step size. The dataset was divided into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing subsets. This protocol was primarily used for hyperparameter tuning and performance evaluation. The fixed split provides a fair comparison of precision, recall, and F1-scores across different activity classes. This section discusses the experimental conclusions, including the comprehensive comparison of the proposed method and state-of-the-art methods.

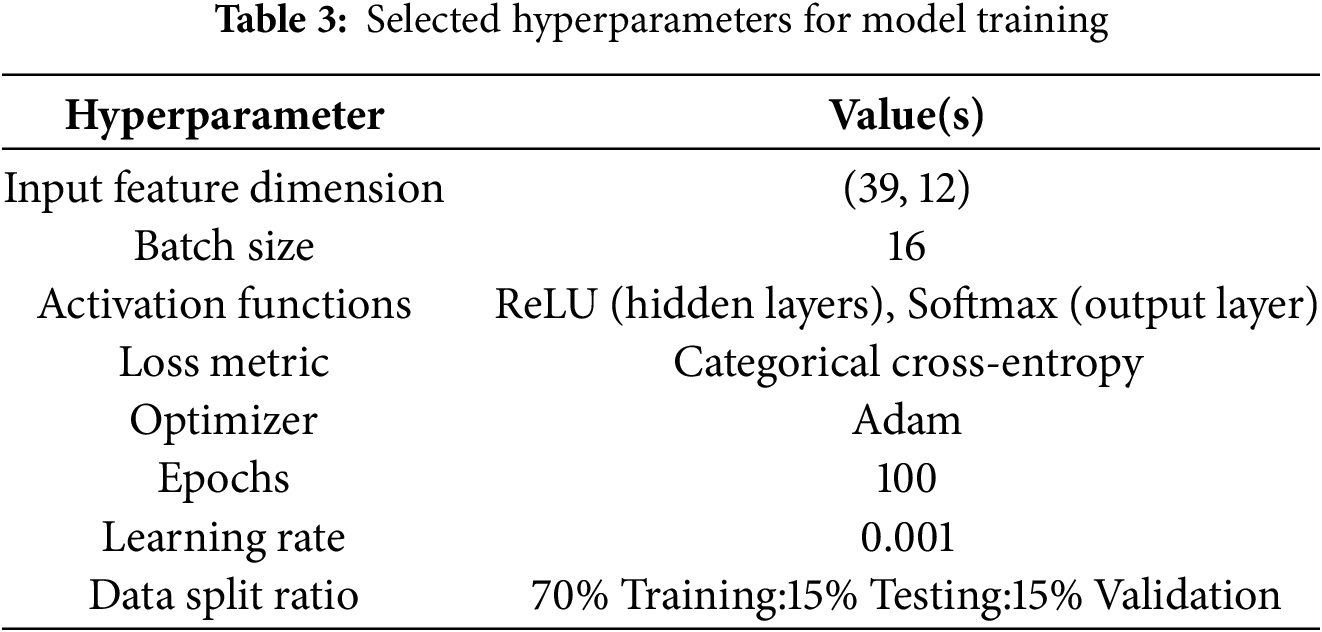

The proposed DeepConvLSTM model was implemented through Keras, a high-level deep neural network API in Python. Cross-entropy loss was employed to measure the difference between predicted and actual values. It provides a quantitative assessment of how much the estimated probabilities deviate from the actual distribution. The model optimization was performed using Adam [36], a stochastic gradient-based optimization algorithm. During training, a batch size of 16 was adjusted on each dataset: Hyperparameters were selected through a grid-based tuning process on the validation set of each dataset. This study evaluated batch sizes (8, 16, 32, 64), learning rates (0.01, 0.001, 0.0001), and dropout rates (0.1, 0.2, 0.3). The configuration of batch size = 16, learning rate = 0.001, and dropout = 0.2 consistently provided the best accuracy and stability, and was therefore adopted for all experiments. A detailed summary of the hyperparameters used is provided in Table 3.

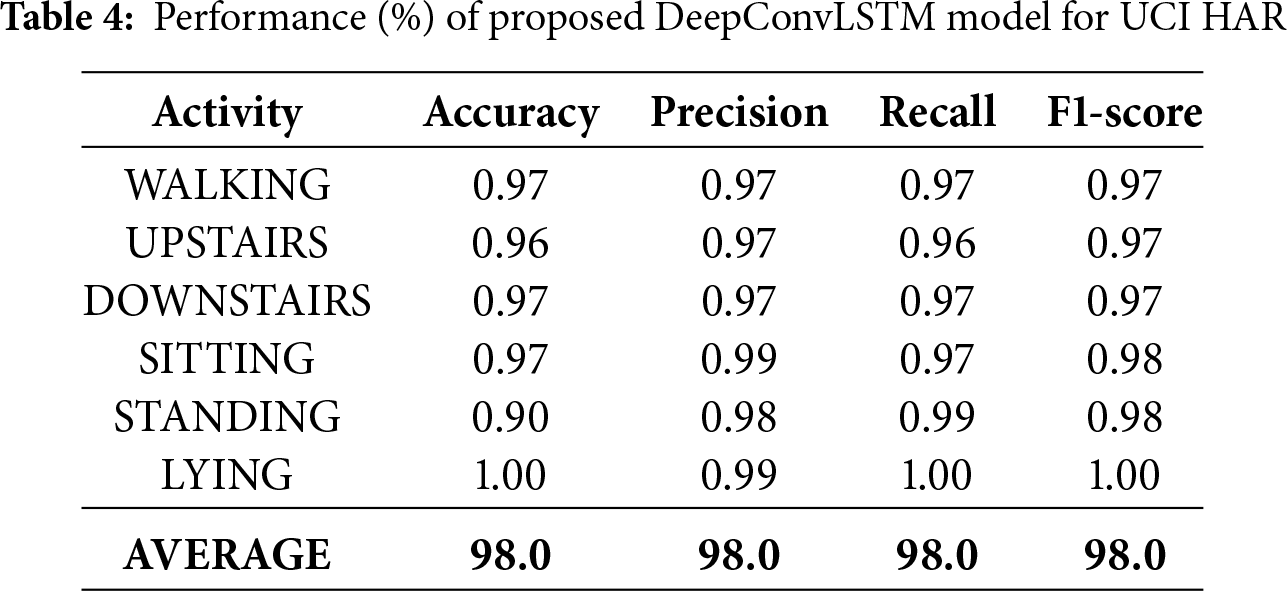

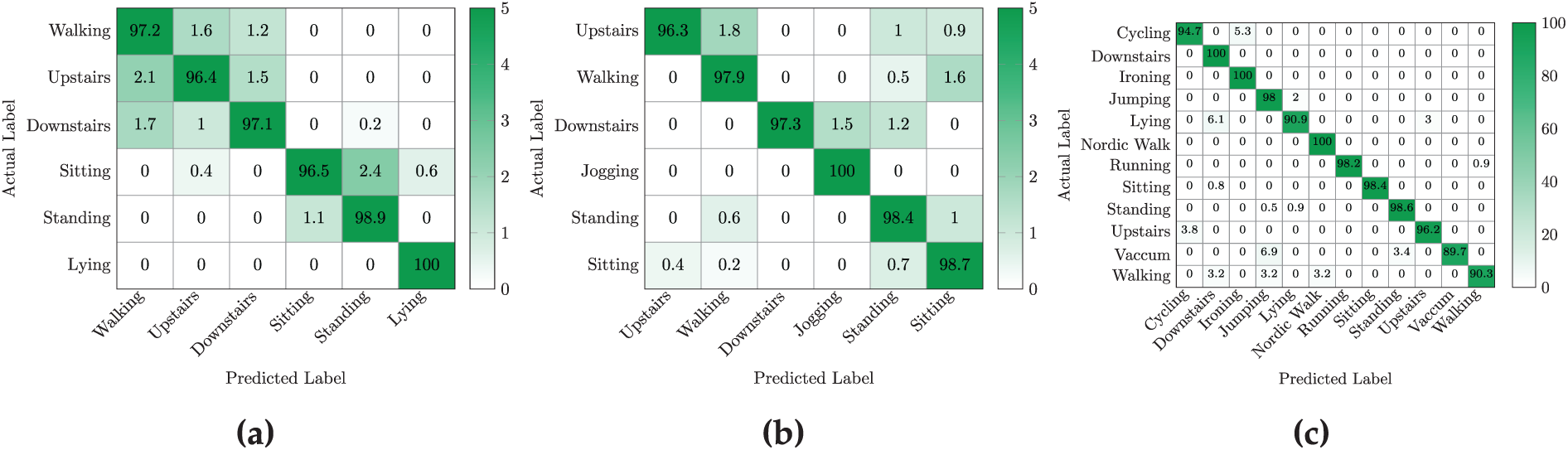

The DeepConvLSTM model using MFCCT features demonstrated high accuracy and robustness across all human activity classes. The proposed model achieved an average accuracy of 98% with an average F1 score of 0.98 as given in Table 4. This performance indicates a balanced performance across different activities. The confusion matrix shown in Fig. 5a further confirms that the majority of the predictions fall on the diagonal, particularly the perfect classification (100%) for ‘lying’ activity. Minor misclassifications occurred mainly between closely related activities. For example, eight samples of walking were predicted as walking upstairs and six as walking downstairs. Similarly, some samples of sitting were misclassified as lying or standing. Overall, these results demonstrate the ability of models to correctly predict human activities with minimal confusion, particularly for static activities such as standing and lying. During training, the proposed DeepConvLSTM model coupled with the features of MFCCT showed stable and efficient convergence, as shown in Fig. 6a. The training accuracy steadily increased around 99%, while the validation accuracy closely followed the training curve without overfitting. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 6b, the training and validation loss consistently decreased and reached a minimal value, which confirms the model’s generalization ability to unseen data. The narrow gap between the training and validation curves confirms that the model did not suffer from high variance or underfitting.

Figure 5: Confusion matrix for the (a) UCI HAR (b) WISDM (c) PAMAP2. The y-axis indicates the true activity class, while the x-axis shows the predicted activity class

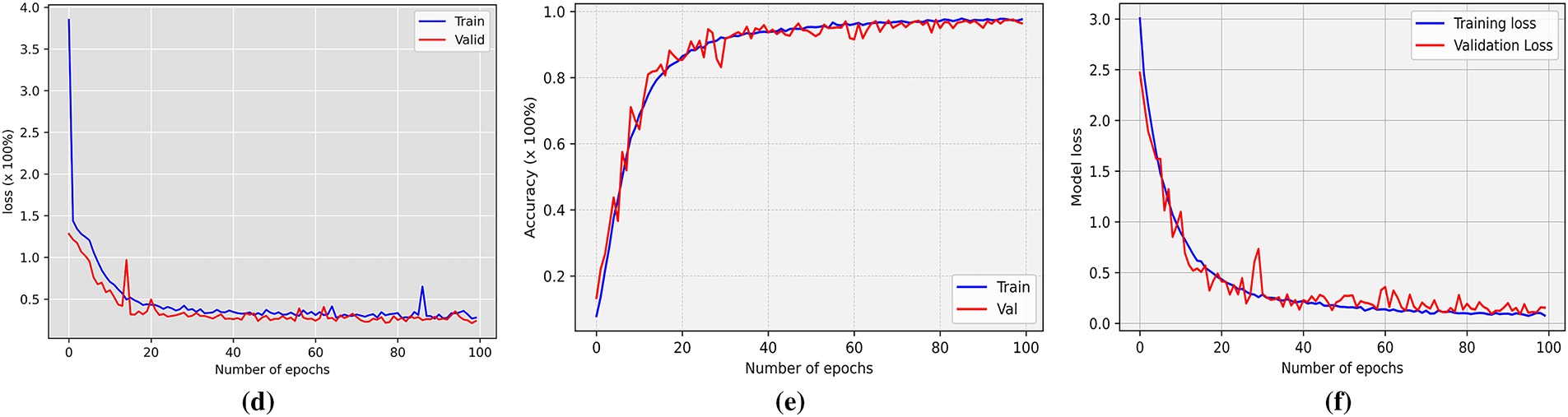

Figure 6: The performance of DeepConvLSTM model (a) training and validation accuracy using UCI HAR (b) training and validation loss using UCI HAR (c) training and validation accuracy using WISDM (d) training and validation loss using WISDM (e) training and validation accuracy using PAMAP2 (f) training and validation loss using PAMAP2

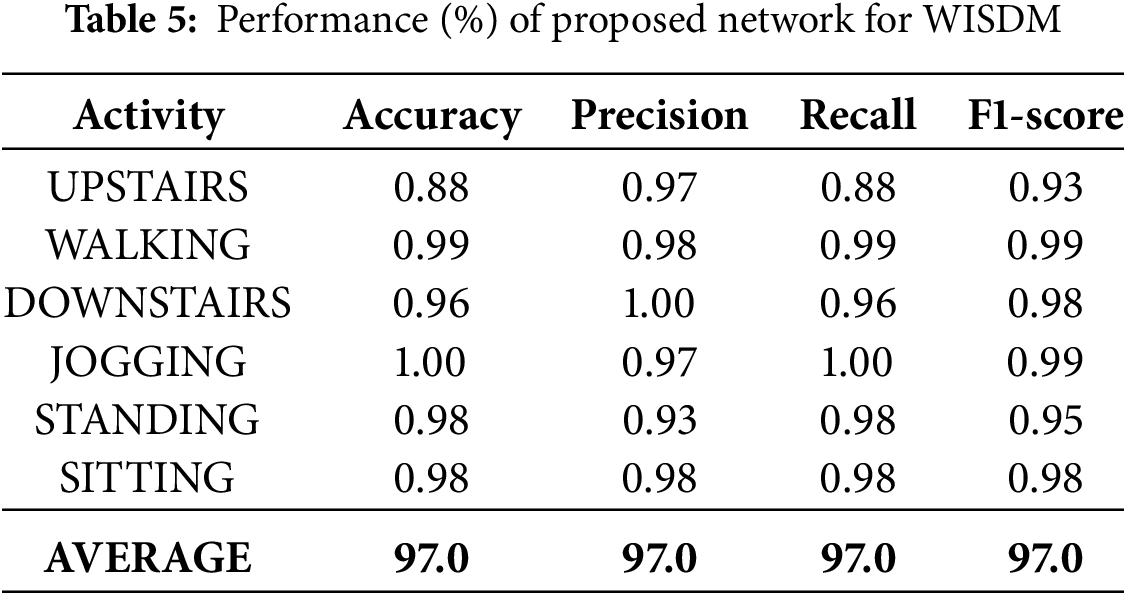

On the WISDM dataset, the proposed model delivered strong performance across all activity classes. The model attained an overall accuracy of 97% and a macro F1-score of 0.97, as presented in Table 5. These metrics reflect a consistent ability to predict a wide range of activities with high precision. The confusion matrix in Fig. 5b shows that the predicted activity classes aligned correctly with actual activity classes. The model classified ‘jogging’ with 100% accuracy, and achieved high performance for ‘walking’ (98.9%) and ‘sitting’ (98.2%) as well. Slight misclassifications were observed in the ‘upstairs’ category, where some samples were wrongly identified as ‘sitting’ or ‘standing’. The learning curves illustrated in Fig. 6c shows that both training and validation accuracy improved rapidly during the early epochs and continued to increase gradually and stabilized around 97%–98%. The corresponding loss curves also showed (Fig. 6d) a consistent decline and eventually converged, which indicates that the model is efficient and optimized. The close alignment between training and validation metrics suggests the model generalized well and avoided overfitting, which makes it suitable for real-world activity recognition tasks.

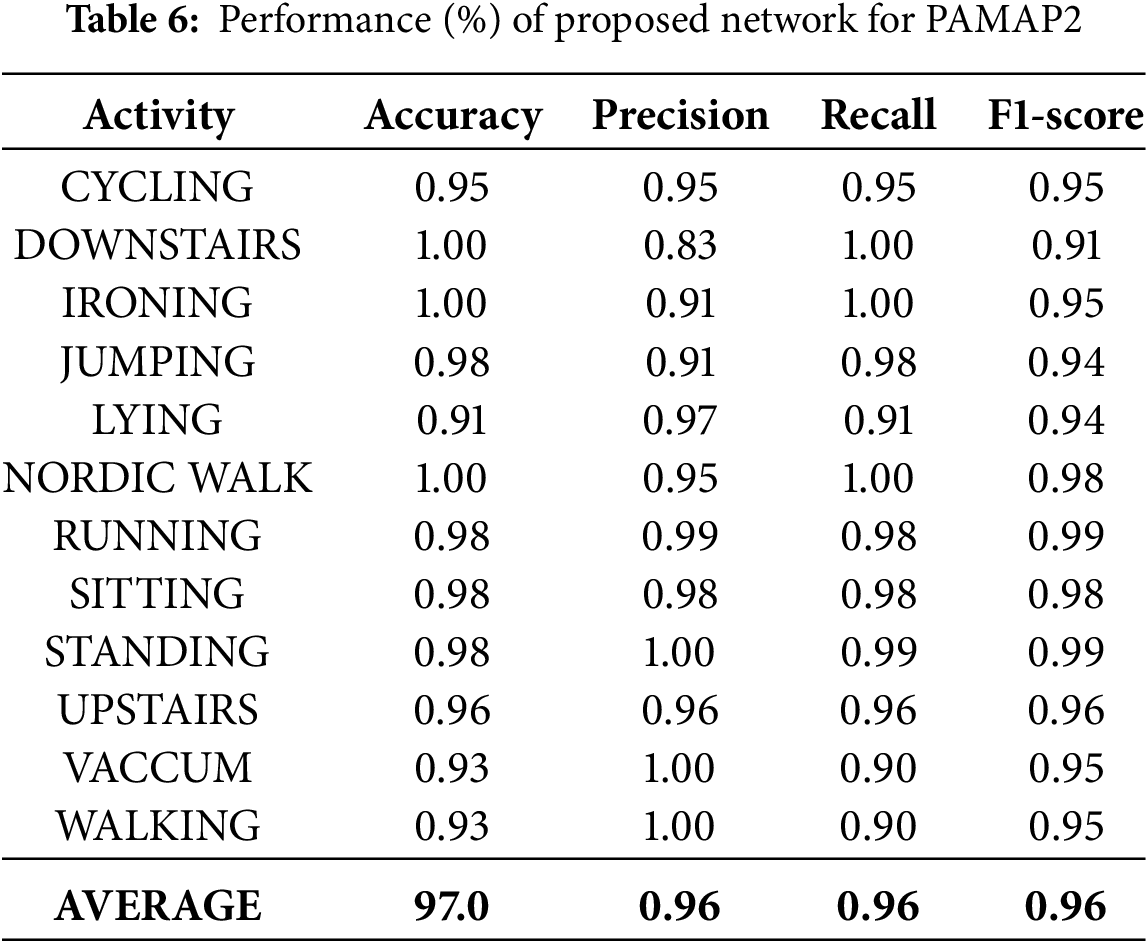

The results on the PAMAP2 dataset demonstrate outstanding model performance across all activity classes. Table 6 shows an overall accuracy of 97% with a macro average F1-score of 0.96 and a weighted average F1-score of 0.97. These results indicate that the model maintained high predictive quality across both frequent and infrequent activity classes. Most activities, including Running, Standing, Sitting, and Nordic Walking, achieved near-perfect precision and recall. Minor confusion was observed in activities like Cycling, Walking, and Vacuuming, which occasionally overlapped with similar movements such as Jumping or Lying. The confusion matrix shown in Fig. 5c reinforce these observations and highlight a strong prediction diagonal pattern with very low off-diagonal misclassifications. Additionally, the learning curves (Fig. 6e) show stable and consistent training behavior. The accuracy plot indicates that both training and validation accuracy rapidly improve during early epochs and converge to nearly 100%. Similarly, the loss curves (Fig. 6f) exhibit a smooth and sharp decrease for both training and validation losses, with no significant gap between them. Overall, the model effectively distinguished between various human activities and generalized well to unseen data.

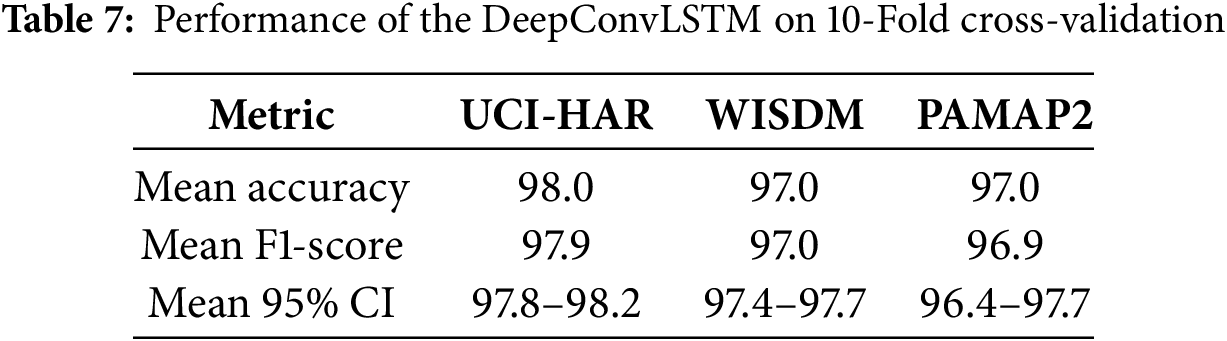

To further validate the robustness of the model, this study also applied 10-fold cross-validation. In these experiments, each dataset is split into ten equal subsets. In each iteration, one subset is used for validation while the remaining nine are used for training. The mean accuracy, F1-score, and 95% confidence intervals of the results are presented in Table 7. Notably, both the fixed-split and cross-validation were conducted in a subject-independent manner; windows generated from the same participant never appear simultaneously in training, validation, or test sets. This ensures that the reported performance reflects true generalization across subjects.

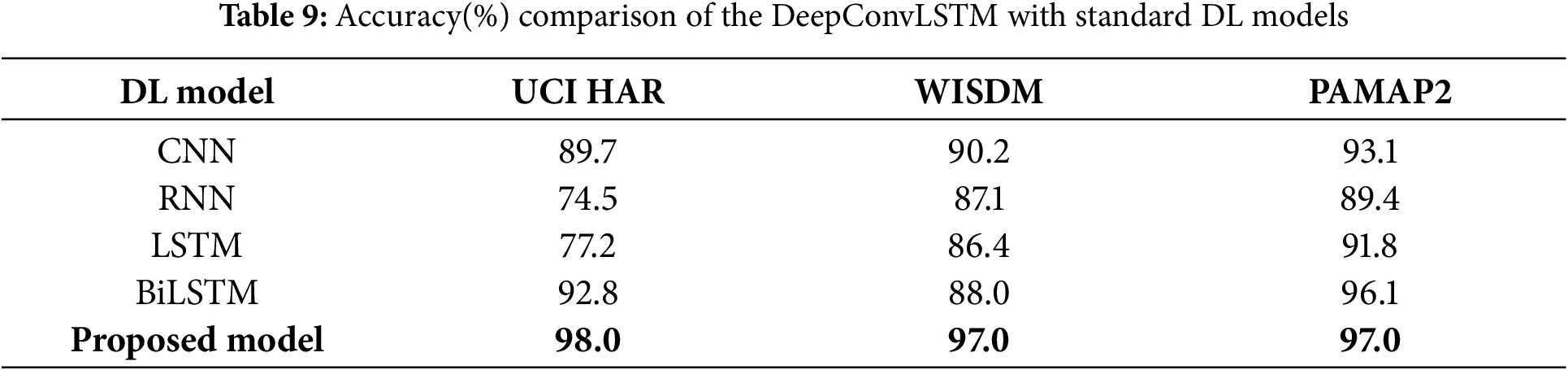

To assess the capability of the proposed DeepConvLSTM model enhanced with MFCCT features, a detailed comparison was performed against several established methods across standard HAR datasets. Table 8 summarizes a detailed comparison of the performance of the DeepConvLSTM with baseline methods on UCI-HAR, WISDM, and PAMAP2 datasets. The proposed approach achieved accuracies of 98.0% on UCI-HAR, 97.0% on WISDM, and 97.0% on PAMAP2. These results outperformed those reported by existing DL models such as CNN-LSTM [37], Residual-BiLSTM [38], and U-Net [39]. This consistent performance across multiple datasets indicates that the DeepConvLSTM model, when combined with MFCCT-based feature extraction, is highly effective for activity recognition tasks. Although the DeepConvLSTM model demonstrated strong overall accuracy, it is important to note that for certain individual activities, other models may perform slightly better. For instance, in the UCI-HAR dataset, a previous study [37] achieved 98% accuracy for the “upstairs” activity, whereas the proposed method yielded 96% for the same class. Despite such variations at the class level, the overall classification results reflect the reliability and robustness of the DeepConvLSTM model. In conclusion, the experimental findings confirm that the proposed MFCCT + DeepConvLSTM framework offers competitive performance compared to existing methods and is well-suited for practical HAR applications.

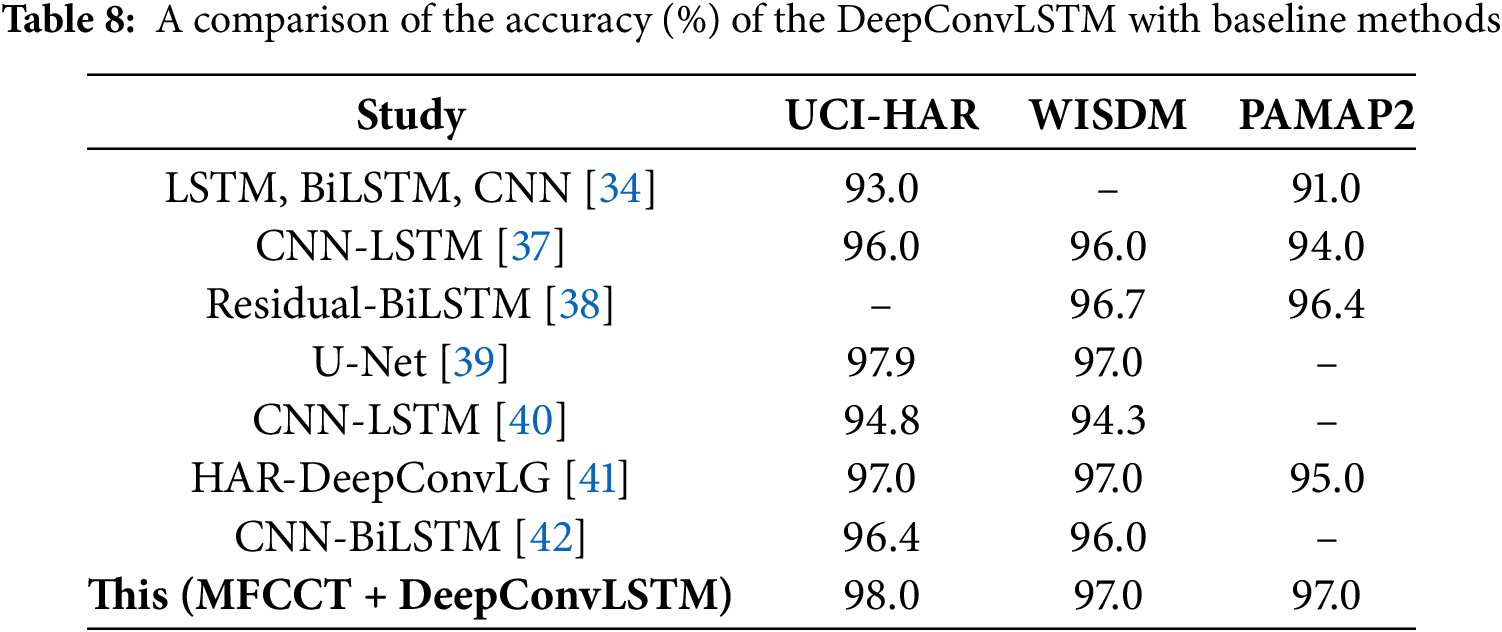

To evaluate the proposed model for HAR, the derived MFCCT features were input into four widely adopted benchmark DL architectures, including CNN, RNN, LSTM, and BiLSTM. A total of 12 experiments (four DL models

The challenge in HAR lies in extracting discriminative and robust features that effectively represent the complexity of human physical movements. In this study, a comprehensive and diverse set of features is extracted to represent both the structural and temporal characteristics of sensor data. These features are then utilized as input to the DeepConvLSTM architecture for activity classification. The DeepConvLSTM combined the strengths of convolutional layers for spatial feature extraction and LSTM layers for capturing temporal dependencies in activity sequences. To enhance robustness and predictive performance, the model was trained and evaluated on three widely used benchmark datasets: UCI HAR, WISDM, and PAMAP2. The proposed model achieved accuracy rates of 98.0%, 97.0%, and 97.0% on these datasets, respectively, and outperformed conventional models such as CNN, RNN, LSTM, and BiLSTM. These results demonstrate the model’s superior generalization and ability to distinguish between complex and overlapping activity patterns effectively. Additionally, the model’s performance was assessed using mean accuracy and F1-score through k-fold cross-validation, which further confirms its reliability. The DeepConvLSTM architecture also shows notable advantages in capturing multi-scale temporal dynamics compared to individual DL models. Future work will focus on extending the framework to recognize more complex and composite activities that involve multiple motion patterns. Additionally, the domain adaptation and transfer learning can be applied to improve generalization across unseen datasets and diverse sensor placements. To reduce dependence on labeled data, self-supervised strategies could be explored for feature learning. Finally, integration of the attention mechanism with MFCCT features may further enhance the ability to capture long-range temporal dynamics in human activity sequences.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia through the Researchers Supporting Project PNURSP2025R333.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation, Rashid Jahangir; visualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition: Nazik Alturki; data curation, resources, software, Muhammad Asif Nauman; conceptualization, visualization, Faiqa Hanif. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Saidani O, Alsafyani M, Alroobaea R, Alturki N, Jahangir R, Jamel L. An efficient human activity recognition using hybrid features and transformer model. IEEE Access. 2023;11:101373–86. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3314492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Aggarwal P, Syed Z, Niu X, El-Sheimy N. A standard testing and calibration procedure for low cost MEMS inertial sensors and units. J Navig. 2008;61(2):323–36. doi:10.1017/s0373463307004560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bianchi V, Bassoli M, Lombardo G, Fornacciari P, Mordonini M, De Munari I. IoT wearable sensor and deep learning: an integrated approach for personalized human activity recognition in a smart home environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(5):8553–62. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2920283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Subasi A, Khateeb K, Brahimi T, Sarirete A. Human activity recognition using machine learning methods in a smart healthcare environment. In: Innovation in health informatics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

5. Sunil A, Sheth MH, Shreyas E, Mohana SE. Usual and unusual human activity recognition in video using deep learning and artificial intelligence for security applications. In: 2021 Fourth International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Technologies (ICECCT); 2021 Sep 15–17; Coimbatore, India. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

6. Tammvee M, Anbarjafari G. Human activity recognition-based path planning for autonomous vehicles. Signal Image Video Process. 2021;15(4):809–16. doi:10.1007/s11760-020-01800-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khatun MA, Yousuf MA, Ahmed S, Uddin MZ, Alyami SA, Al-Ashhab S, et al. Deep CNN-LSTM with self-attention model for human activity recognition using wearable sensor. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2022;10:1–16. doi:10.1109/jtehm.2022.3177710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Gupta S. Deep learning based human activity recognition (HAR) using wearable sensor data. Int J Inf Manag Data Insights. 2021;1(2):100046. doi:10.1016/j.jjimei.2021.100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Vrigkas M, Nikou C, Kakadiaris IA. A review of human activity recognition methods. Front Rob AI. 2015;2:28. [Google Scholar]

10. Ghafoor HY, Jahangir R, Jaffar A, Alroobaea R, Saidani O, Alhayan F. Sensors-based human activity recognition using hybrid features and deep capsule network. IEEE Sensors J. 2024;24(14):23129–39. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3402314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang S, Zhou G. A review on radio based activity recognition. Digit Commun Netw. 2015;1(1):20–9. [Google Scholar]

12. Zhang B, Xu H, Xiong H, Sun X, Shi L, Fan S, et al. A spatiotemporal multi-feature extraction framework with space and channel based squeeze-and-excitation blocks for human activity recognition. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2021;12(7):7983–95. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02526-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang J, Nguyen MN, San PP, Li X, Krishnaswamy S. Deep convolutional neural networks on multichannel time series for human activity recognition. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2015); 2015 Jul 25–31; Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 3995–4001. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang J, Chen Y, Hao S, Peng X, Hu L. Deep learning for sensor-based activity recognition: a survey. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2019;119(4):3–11. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2018.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang Z, Kang K. Adaptive temporal attention mechanism and hybrid deep CNN model for wearable sensor-based human activity recognition. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):33389. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-18444-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Xu K, Ba J, Kiros R, Cho K, Courville A, Salakhudinov R, et al. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2015. p. 2048–57. [Google Scholar]

17. Lalapura VS, Bhimavarapu VR, Amudha J, Satheesh HS. A systematic evaluation of recurrent neural network models for edge intelligence and human activity recognition applications. Algorithms. 2024;17(3):104. doi:10.3390/a17030104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jegham I, Khalifa AB, Alouani I, Mahjoub MA. Vision-based human action recognition: an overview and real world challenges. Forensic Sci Int Digit Investig. 2020;32(3):200901. doi:10.1016/j.fsidi.2019.200901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jain A, Kanhangad V. Human activity classification in smartphones using accelerometer and gyroscope sensors. IEEE Sens J. 2017;18(3):1169–77. doi:10.1109/jsen.2017.2782492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ronao CA, Cho SB. Human activity recognition with smartphone sensors using deep learning neural networks. Expert Syst Appl. 2016;59(6):235–44. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2016.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Raziani S, Azimbagirad M. Deep CNN hyperparameter optimization algorithms for sensor-based human activity recognition. Neurosci Informatics. 2022;2(3):100078. doi:10.1016/j.neuri.2022.100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tang Y, Zhang L, Min F, He J. Multiscale deep feature learning for human activity recognition using wearable sensors. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2022;70(2):2106–16. doi:10.1109/tie.2022.3161812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chen Y, Zhong K, Zhang J, Sun Q, Zhao X. LSTM networks for mobile human activity recognition. In: 2016 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence: Technologies and Applications. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2016. p. 50–3. [Google Scholar]

24. Kwapisz JR, Weiss GM, Moore SA. Activity recognition using cell phone accelerometers. ACM SIigDD Explor Newsletter. 2011;12(2):74–82. doi:10.1145/1964897.1964918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou X, Liang W, Kevin I, Wang K, Wang H, Yang LT, et al. Deep-learning-enhanced human activity recognition for internet of healthcare things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(7):6429–38. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.2985082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hernández F, Suárez LF, Villamizar J, Altuve M. Human activity recognition on smartphones using a bidirectional LSTM network. In: 2019 XXII Symposium on Image, Signal Processing and Artificial Vision (STSIVA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

27. Davis K, Owusu E, Bastani V, Marcenaro L, Hu J, Regazzoni C, et al. Activity recognition based on inertial sensors for ambient assisted living. In: 2016 19th International Conference on Information Fusion (fusion). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 371–8. [Google Scholar]

28. Deep S, Zheng X. Hybrid model featuring CNN and LSTM architecture for human activity recognition on smartphone sensor data. In: 2019 20th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing, Applications and Technologies (PDCAT). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 259–64. [Google Scholar]

29. Ordóñez FJ, Roggen D. Deep convolutional and LSTM recurrent neural networks for multimodal wearable activity recognition. Sensors. 2016;16(1):115. doi:10.3390/s16010115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Thakur D, Biswas S, Ho ES, Chattopadhyay S. ConvAE-LSTM: convolutional autoencoder long short-term memory network for smartphone-based human activity recognition. IEEE Access. 2022;10(4):4137–56. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3140373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Omolaja A, Otebolaku A, Alfoudi A. Context-aware complex human activity recognition using hybrid deep learning models. Appl Sci. 2022;12(18):9305. doi:10.3390/app12189305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sena J, Barreto J, Caetano C, Cramer G, Schwartz WR. Human activity recognition based on smartphone and wearable sensors using multiscale DCNN ensemble. Neurocomputing. 2021;444(3):226–43. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.04.151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zehra N, Azeem SH, Farhan M. Human activity recognition through ensemble learning of multiple convolutional neural networks. In: 2021 55th Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

34. Wan S, Qi L, Xu X, Tong C, Gu Z. Deep learning models for real-time human activity recognition with smartphones. Mob Netw Appl. 2020;25(2):743–55. doi:10.1007/s11036-019-01445-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Saha A, Rajak S, Saha J, Chowdhury C. A survey of machine learning and meta-heuristics approaches for sensor-based human activity recognition systems. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2024;15(1):29–56. doi:10.1007/s12652-022-03870-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2014. [Google Scholar]

37. Xia K, Huang J, Wang H. LSTM-CNN architecture for human activity recognition. IEEE Access. 2020;8:56855–66. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2982225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li Y, Wang L. Human activity recognition based on residual network and BiLSTM. Sensors. 2022;22(2):635. doi:10.3390/s22020635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Bao J, Song Y. Human activity recognition based on time series analysis using U-Net. arXiv:1809.08113. 2018. [Google Scholar]

40. Mutegeki R, Han DS. A CNN-LSTM approach to human activity recognition. In: 2020 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 362–6. [Google Scholar]

41. Ding W, Abdel-Basset M, Mohamed R. HAR-DeepConvLG: hybrid deep learning-based model for human activity recognition in IoT applications. Inf Sci. 2023;646(4):119394. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Challa SK, Kumar A, Semwal VB. A multibranch CNN-BiLSTM model for human activity recognition using wearable sensor data. Vis Comput. 2022;38(12):4095–109. doi:10.1007/s00371-021-02283-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools