Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on Integrating Deep Learning-Based Vehicle Brand and Model Recognition into a Police Intelligence Analysis Platform

Graduate Institute of Vehicle Engineering, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 50007, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Shih-Lin Lin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligent Vehicles and Emerging Automotive Technologies: Integrating AI, IoT, and Computing in Next-Generation in Electric Vehicles)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071915

Received 15 August 2025; Accepted 17 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

This study focuses on developing a deep learning model capable of recognizing vehicle brands and models, integrated with a law enforcement intelligence platform to overcome the limitations of existing license plate recognition techniques—particularly in handling counterfeit, obscured, or absent plates. The research first entailed collecting, annotating, and classifying images of various vehicle models, leveraging image processing and feature extraction methodologies to train the model on Microsoft Custom Vision. Experimental results indicate that, for most brands and models, the system achieves stable and relatively high performance in Precision, Recall, and Average Precision (AP). Furthermore, simulated tests involving illicit vehicles reveal that, even in cases of reassigned, concealed, or missing license plates, the model can rely on exterior body features to effectively identify vehicles, reducing dependence on plate-specific data. In practical law enforcement scenarios, these findings can accelerate investigations of stolen or forged plates and enhance overall accuracy. In conclusion, continued collection of vehicle images across broader model types, production years, and modification levels—along with refined annotation processes and parameter adjustment strategies—will further strengthen the method’s applicability within law enforcement intelligence platforms, facilitating more precise and comprehensive vehicle recognition and control in real-world operations.Keywords

1.1 Research Objectives and Contributions

This study aims to translate deep learning–based vehicle understanding into actionable policing workflows. We aim to (i) develop an appearance-driven brand–model recognizer that remains reliable when license-plate cues are absent, occluded, swapped, or counterfeit; and (ii) integrate this recognizer—together with license plate recognition (LPR) and spatiotemporal analytics—into a modular architecture that supports event correlation, cross-camera reidentification, stolen-vehicle tracing, and counterfeit-plate auditing across heterogeneous sensors and jurisdictions.

We present an appearance-based brand–model recognizer that maintains high confidence when plates are missing, occluded, swapped, or counterfeit, and cross-verifies LPR at the event level. Contributions include a diversified dataset (incl. modified cars), vehicle identification number (VIN)-location catalog, interpretable processing pipeline, deployment architecture, calibrated post-processing, and fine-grained analyses with documented limitations.

Alwateer et al. [1] enhance license-plate detection with explainable deep learning (DL), prioritizing transparency over raw throughput, whereas Bae and Hong [2] emphasize environmental robustness for frontline crime-prevention deployments. Bharti et al. [3] couple plate recognition with vehicle-type identification for controlled-access settings, trading granularity for speed. Gholamhosseinian and Seitz [4] map the software/method spectrum, clarifying where lightweight pipelines suffice and where heavier models are justified. Gopichand et al. [5] broaden the scope to Artificial Intelligence (AI)-assisted on-road crime detection, but their threat taxonomy outpaces validated benchmarks. Guo [6] targets counterfeit-plate signals directly, complementing but not replacing appearance cues. Hoang et al. [7] incorporate dense 3D reconstruction and pose, which improves cross-view persistence at a higher computational cost. Hu et al. [8] learn discriminative brand patterns for near-real-time use, offering stronger fine-grained cues than [3]. Lu and Huang [9] proposed a hierarchical approach for accurate vehicle make and model recognition. Li et al. [10] integrate end-to-end LPR, reducing input/output latency relative to multi-stage stacks. Manzoor et al. [11] developed a real-time system for vehicle make and model recognition. Mustafa and Karabatak [12] deliver real-time brand/plate detection, but with constrained generalization to modified vehicles. Nam and Nam [13] fuse visible/thermal streams to stabilize classification under illumination shifts, an advantage over single-modal baselines. Pan et al. [14] detect fake plates in surveillance videos, while Sajol et al. [15] operationalize low-cost closed-circuit television (CCTV) object detection; both privilege deployment efficiency over fine-grained model identity. Xiang et al. [16] introduced a global topology constraint network for fine-grained vehicle recognition. Algorithmic and theoretical foundations span classical statistics and modern deep architectures, shaping what is feasible at the edge. Abdi and Williams [17] formalize Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction and multi-modal fusion, useful when bandwidth caps preclude high-dimensional features. Babaud et al. [18] establish the Gaussian kernel’s uniqueness for scale-space filtering, underpinning stable multi-scale preprocessing. Gu et al. [19] synthesize Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) advances for hierarchical features, crucial for sub-model cues that plate-only systems miss. He et al. [20] unify detection and instance segmentation via Mask Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN), enabling pixel-aware vehicle parsing that improves part-level evidence. Hearst et al. [21] position support vector machines (SVMs) as margin-based baselines when labeled data are scarce, clarifying trade-offs with data-hungry CNNs. Kanopoulos et al. [22] detail Sobel operators, providing gradient primitives that remain competitive for plate/contour extraction when latency budgets are tight. Jamil et al. [23] introduced a “bag of expressions” representation, showing competitive vehicle make–model recognition without heavy networks. Hassan et al. [24] systematically compared deep architectures, highlighting performance–complexity trade-offs and strong CNN baselines. Ali et al. [25] released a curated vehicle image dataset, enabling reproducible benchmarking across viewpoints and lighting. Building on data scale and efficiency, Lyu et al. [26] proposed a large-scale dataset and an efficient two-branch, two-stage framework, advancing accuracy with balanced feature sharing and specialization. Prabakaran and Mitra [27] surveyed machine learning (ML) pipelines for detection/forecasting, highlighting evaluation pitfalls that our study addresses through average precision (AP)/recall analyses. Amirkhani and Barshooi [28] presented DeepCar 5.0. Lu et al. [29] optimized part-level features. Anwar and Zakir [30] used mixed-sample augmentation. Zhang et al. [31] employed Faster R-CNN; Wang et al. [32] adopted active learning. Gayen et al. [33] surveyed VMMR. Ünal et al. [34] evaluated You Only Look Once version 8 (YOLOv8). Bularz et al. [35] leveraged rear-lamp cues. Zhang et al. [36] introduced magnetic fingerprints. Liu et al. [37] enabled view-independent models. Kerdvibulvech [38] explored zero-shot. Puisamlee and Chawuthai [39] minimized CNNs. Zhao et al. [40] proposed the YOLOv8-MAH. Extending sensing breadth, Bakirci [41] couples Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) collection with YOLOv8 to boost intelligent transportation system vehicle detection, while the companion study [42] applies YOLOv8 to traffic monitoring, highlighting accuracy gains and operational feasibility that complement fixed-camera deployments.

Despite the widespread deployment of LPR in monitoring, enforcement, and parking, reliance on plates as the sole identifier leaves systems vulnerable when plates are concealed, forged, tampered with, or absent. Field practice suffers from a lack of brand/model expertise among officers, hindering rapid verification. This study addresses these gaps by integrating deep learning–based brand and model recognition with plate analysis: (i) improving identification completeness and accuracy beyond plate-only cues; (ii) targeting forged and unlicensed vehicles via training on obscured or modified specimens; (iii) operationalizing dual recognition within police platforms to reduce misidentification and wrongful accusations; and (iv) enabling benefits across parking, traffic monitoring, tolling, and stolen-vehicle recovery, thereby lowering social and economic costs.

2 Theoretical Foundations of Vehicle Brand and Model Recognition

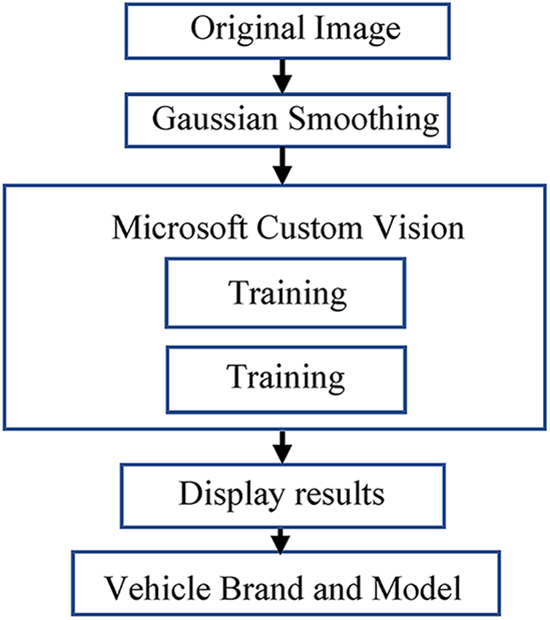

Fig. 1 illustrates the functional block diagram of the vehicle brand and model recognition framework, showing the workflow from image input and preprocessing to training, result display, and final recognition.

Figure 1: Functional block diagram of the vehicle brand and model recognition framework

An essential first step in recognizing vehicle brands and models involves image preprocessing, which aims to reduce noise while amplifying salient features. A common initial procedure is grayscale conversion, where each pixel’s red, green, and blue intensity values

This transformation Eq. (1) lowers computational overhead and focuses subsequent methods on brightness gradients rather than color disparities.

To further mitigate noise, a Gaussian filter is often applied. Its kernel is defined by Babaud et al. [18]:

where

Finally, edge detection techniques the Sobel operator—highlight object boundaries in the preprocessed image. The Sobel method computes horizontal

where ∗ denotes 2D convolution. The gradient magnitude at each pixel is then:

which indicates how strongly intensity values change in the local neighborhood. Larger magnitudes typically correspond to potential edges, the boundaries between a vehicle’s body and its background—thus creating a cleaner, feature-rich foundation for subsequent stages of vehicle recognition.

2.2 Microsoft Custom Vision for Vehicle Recognition

Due to the wide variations in real-world vehicle images—ranging from different lighting conditions and occlusions to partial modifications—this study utilizes Microsoft Custom Vision to facilitate the development of deep learning models. Custom Vision implements a transfer learning paradigm, wherein convolutional neural network (CNN) weights trained on large-scale datasets (e.g., ImageNet) are fine-tuned on domain-specific images of car brands and models (Gu et al. [19]). In practice, the platform’s graphical interface allows researchers to upload and label images according to brand (e.g., Audi, BMW, Subaru) and specific model (e.g., A4, 3 Series, WRX). Once the initial dataset is labeled, Custom Vision runs a cloud-based training procedure that iteratively adjusts hyperparameters—such as the learning rate or the number of epochs—and measures progress through metrics like Precision, Recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP). If certain samples prove to be consistently misclassified, the researcher can relabel them or provide additional training instances that depict varied angles, lighting conditions, or partial occlusions. This process—often referred to as Retraining—cycles continually until the model demonstrates stable performance.

A key benefit of Custom Vision is that it offloads computational demands to cloud infrastructure. Even with large datasets, training remains efficient, enabling the model to adapt quickly when new vehicle types or modifications emerge. This characteristic is especially valuable in law enforcement scenarios, where rapid iteration is critical in responding to trends such as counterfeit license plates or newly introduced car models. Lastly, Custom Vision’s versioned model deployment and automated tuning streamline integration into existing police systems, ensuring minimal downtime and consistent updates as new data is acquired.

Following basic image preprocessing (e.g., grayscale conversion, noise filtering, and edge detection), effective feature extraction forms the backbone of vehicle brand and model recognition. This section revisits the original theoretical formulations—encompassing PCA, SVM, CNN, and 3D Reconstruction—and explains their connection to the current research [7,17,19–21].

2.3.1 Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

In many machine learning tasks, PCA helps reduce high-dimensional data to a smaller subspace, capturing the largest variance. Suppose we have an

where rows of

2.3.2 Support Vector Machines (SVM)

Once key features are extracted—whether through PCA or other descriptors—this study employs a Support Vector Machine to distinguish vehicles by brand or model. The original SVM optimization problem is summarized as [21]:

where

2.3.3 Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

Unlike approaches that require manually crafted features, CNNs (Gu et al. 2018) learn representational hierarchies from images directly. The core operation involves a convolution, wherein a kernel

where the summation indices

2.4 Object Detection and Segmentation: Mask R-CNN

In more advanced image analysis tasks, Mask R-CNN [20] combines object detection with semantic segmentation, enabling the model to localize objects (e.g., vehicle outlines) and assign per-pixel masks simultaneously. Its loss function jointly considers classification

This integrated approach allows the model to precisely locate objects and parse their shapes at the pixel level. In vehicle brand and model recognition, such detailed segmentation can enhance the discrimination of exterior designs or modified components, thus improving overall accuracy.

2.5 3D Reconstruction and Pose Estimation

The study further acknowledges 3D Reconstruction and Pose Estimation [7] for scenarios demanding spatial analysis. Suppose

where

This section has presented a comprehensive overview of the underlying theories and methods essential for vehicle brand and model recognition. These include preliminary image processing (grayscale conversion, Gaussian filtering, Sobel edge detection), feature extraction (PCA), and classification models (SVM and CNN). For more complex detection needs, Mask R-CNN provides both object detection and segmentation, whereas 3D reconstruction and pose estimation provide deeper spatial insights. Notably, this study utilizes Microsoft Custom Vision as its primary training and deployment framework. By leveraging cloud-based resources and automated iterative processes, Custom Vision significantly reduces development time and adapts rapidly to new vehicle types or modifications. The subsequent chapters will focus on data collection and experimental design, further validating the applicability and effectiveness of the aforementioned theoretical constructs in real-world vehicle recognition scenarios.

3 Description of Research Data

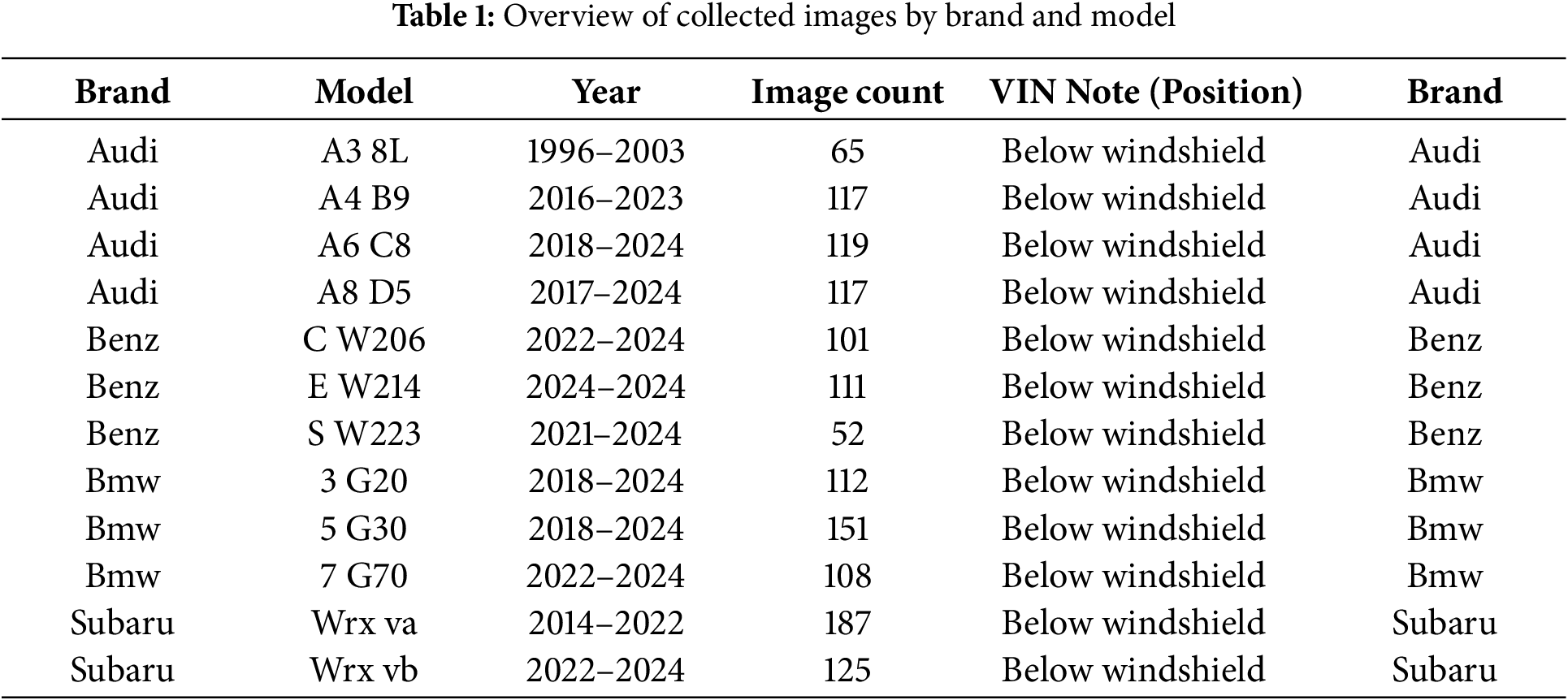

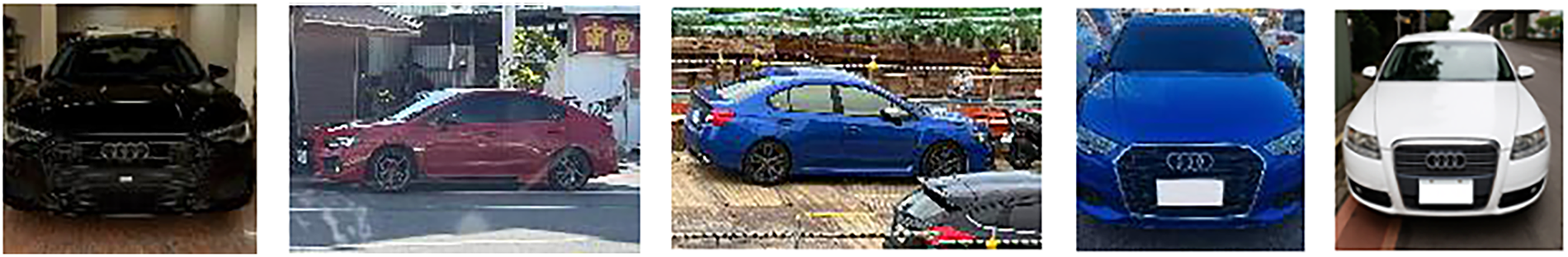

In the section on researching vehicle brand and model recognition, data collection and organization play a pivotal role in constructing high-quality deep learning models. In this study, real-world photographs of targeted vehicle models were gathered, categorized, and archived based on attributes such as “production year”, “Brand”, and “model generation”. Additionally, the VIN position of each vehicle was annotated to facilitate subsequent comparisons and validation. Once annotations were complete, the images were uploaded to the Custom Vision platform for model training and evaluation. The following sections detail the considerations and planning involved in data collection, culminating in an overview of the total number of images in Table 1. Fig. 2 shows representative training images from the database. Fig. 3 shows representative test images from the database.

Figure 2: Examples of training images in the database

Figure 3: Examples of testing images in the database

1. Image Sources and Shooting Conditions

∘ Multi-Environment Shooting: To enhance the model’s adaptability to various lighting conditions, backgrounds, and environmental changes, photographs were taken in diverse settings such as outdoor sunlight, indoor parking garages, and rainy weather.

∘ Different Angles and Distances: Beyond the primary front, rear, and side views, images were captured from varying distances and heights, ensuring the model could learn a broad range of vehicle features.

∘ Image Quality Control: To guarantee that key body characteristics remain identifiable, each photo needed to meet minimum resolution and clarity standards, thereby avoiding excessive noise or blur.

2. Image Classification and Labeling Strategies

∘ Vehicle Model Year and Generation: Since model designs may vary across different years or generations (facelifts or generations), images were grouped by production year or generation. This approach helps the deep learning model recognize design evolutions over time.

∘ Brand and Model: Given that a single Brand may offer multiple models, separate folders—for instance, “Audi A3 8L” and “Audi A4 B9”—were assigned. This practice yields more precise labeling.

∘ VIN Annotation: As shown in Table 1, each vehicle’s standard VIN location (often beneath the windshield) was recorded, allowing future identification to cross-reference actual vehicle information and reinforce detection reliability.

3. Quantitative Comparison and Completeness Evaluation

∘ Image Distribution: Table 1 summarizes the number of images collected for each Brand and model. Efforts were made to avoid single models with scant samples or covering only certain production years, thus maintaining representative data coverage.

∘ Data Diversity: Particular emphasis was placed on variations in vehicle modifications, shooting environments, and camera angles, strengthening the model’s adaptability to real-world scenarios.

∘ Data Quality: Photos deemed too dark, overexposed, or excessively blurry were filtered out to ensure that the final training set could effectively support feature learning.

4. Subsequent Applications and Significance

∘ Extended Use Cases: Beyond detecting vehicle brands, models, and VIN positions, the collected images also serve as foundational data for research on modified or unregistered vehicles, addressing practical issues such as illegal modifications, concealed license plates, and forged plates.

∘ Integration into Law Enforcement Platforms: Once the model acquires a wide range of vehicle appearance features, law enforcement intelligence platforms can prioritize more precise model comparisons and identity verifications, substantially enhancing policing efficiency.

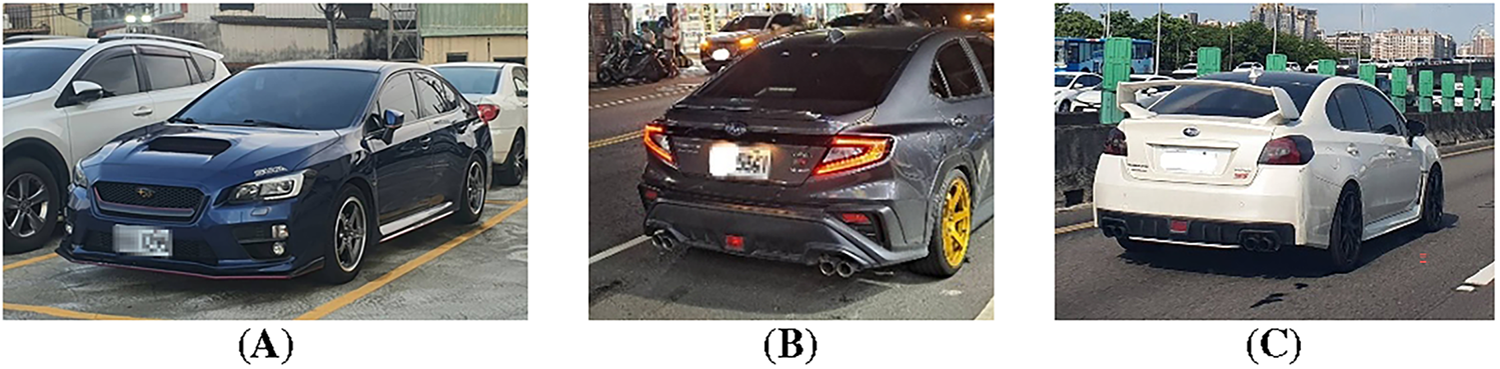

5. Modified Vehicles

∘ Inclusion of commonly modified cars—aftermarket aero kits, rear wings, diffusers, non-OEM bumpers/lights, wheels, and ride height—to test robustness under non-stock appearances. Fig. 4 shows examples of modified vehicles.

∘ Labeled as “Modified” with coarse severity (mild/moderate/heavy) to enable per-subset metrics, hard-example mining, and targeted augmentation.

Figure 4: Examples of modified vehicles. (A) Front-quarter view with aftermarket aero components and wheels; (B) rear view with diffuser, quad-exhaust, and bumper kit; (C) rear-quarter view with large rear wing and non-OEM lighting/tint

This study subdivided image data according to specific Brands, model generations, and varied considerations of environments, angles, and modifications in order to build a diverse and representative training set. Table 1 presents an overview of the principal Brands and models sampled, laying a solid groundwork for future model training. Such a multi-tiered data collection strategy lends greater robustness, accuracy, and scalability to the vehicle brand and model recognition model developed in this research.

4.1 Model Performance Metrics and Evaluation Methods

Using the Custom Vision platform, we train and evaluate models with an emphasis on accuracy and stability. Three metrics guide assessment. Precision quantifies the correctness of positive predictions, prioritized to minimize false positives and reduce erroneous vehicle identifications in deployment. Recall measures detection completeness, indicating the proportion of actual positives captured; higher recall helps surface most suspicious vehicles and mitigate false negatives. Average Precision (AP) summarizes performance across confidence thresholds by integrating precision–recall behavior, revealing robustness and class-or context-specific weaknesses. Insights from these metrics inform iterative tuning of datasets, thresholds, and architectures to achieve reliable, field-ready recognition performance overall.

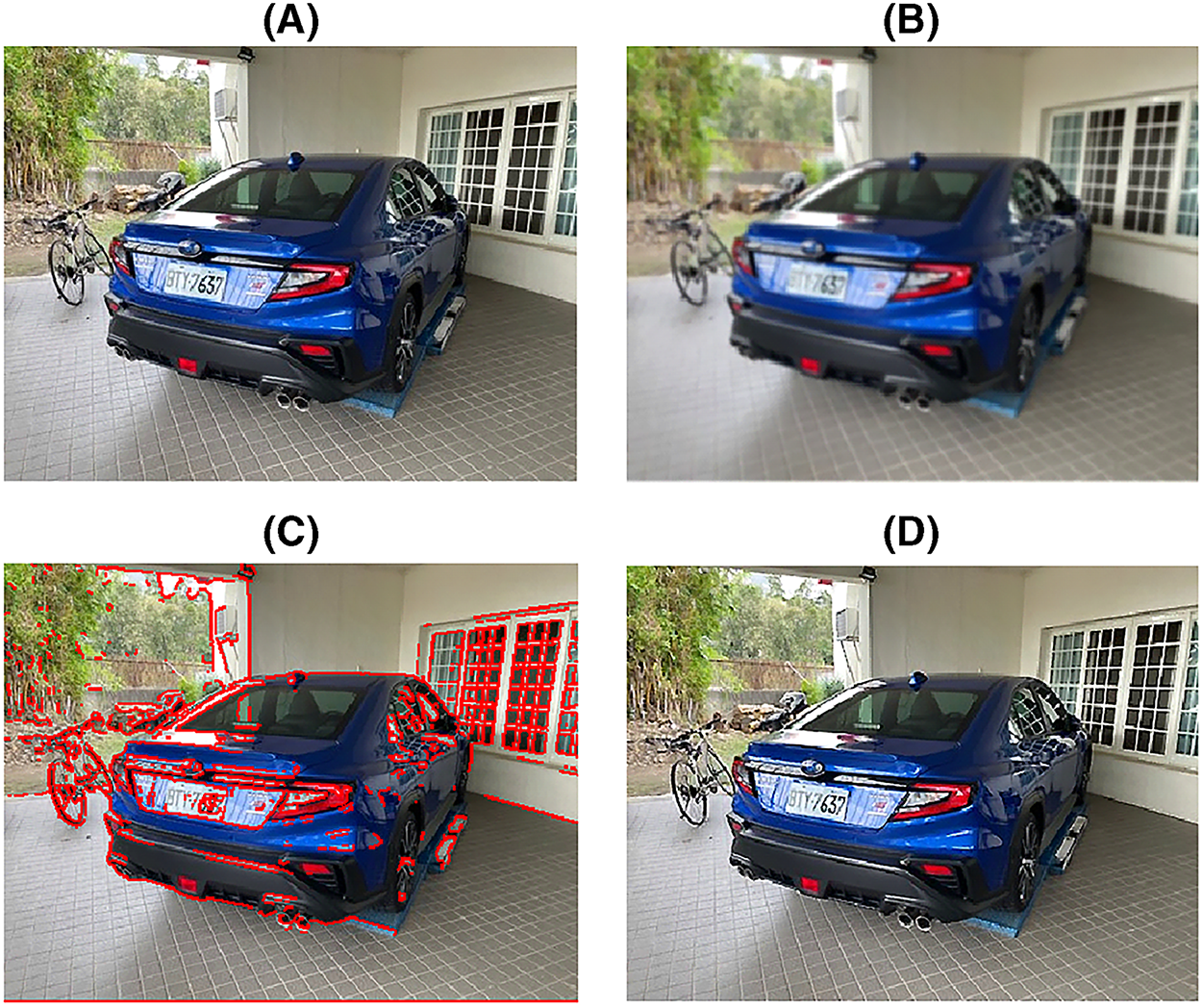

Fig. 5 presents the enhancement pipeline: (A) Original RGB image; (B) Gaussian smoothing; (C) Sobel edge overlay after denoising; (D) Edge-guided unsharp sharpening. (A) provides the unprocessed baseline retaining native color, texture, and sensor noise. (B) applies an isotropic Gaussian (σ ≈ 1.2, 5 × 5) to suppress high-frequency noise and micro-textures, stabilizing gradients while preserving global structure. (C) computes Sobel edges on the smoothed grayscale using an automatically estimated threshold scaled by a conservative factor (~0.7), then lightly dilates to connect fragmented contours; the binary edges are overlaid in red on the original to visualize salient boundaries without altering underlying chroma. (D) forms a detail layer as original minus smoothed and injects it back only where the edge mask is active, scaling by α ≈ 1.6 and clipping to valid ranges. This selective sharpening increases acutance and micro-contrast at genuine structures while minimizing noise amplification and halos in flat regions, yielding crisper, more natural results. Relative to Fig. 5A, Fig. 5D exhibits higher acutance and edge coherence, with crisper boundaries and improved micro-contrast around fine structures while preserving color fidelity. Compared with naïve global unsharp masking, the edge-guided approach minimizes noise amplification and halo artifacts in smooth regions, yielding sharper yet natural-looking results.

Figure 5: Image processing technology. (A) Original RGB Image. (B) Gaussian Smoothing. (C) Sobel Edge Overlay after Denoising. (D) Edge-Guided Unsharp Sharpening

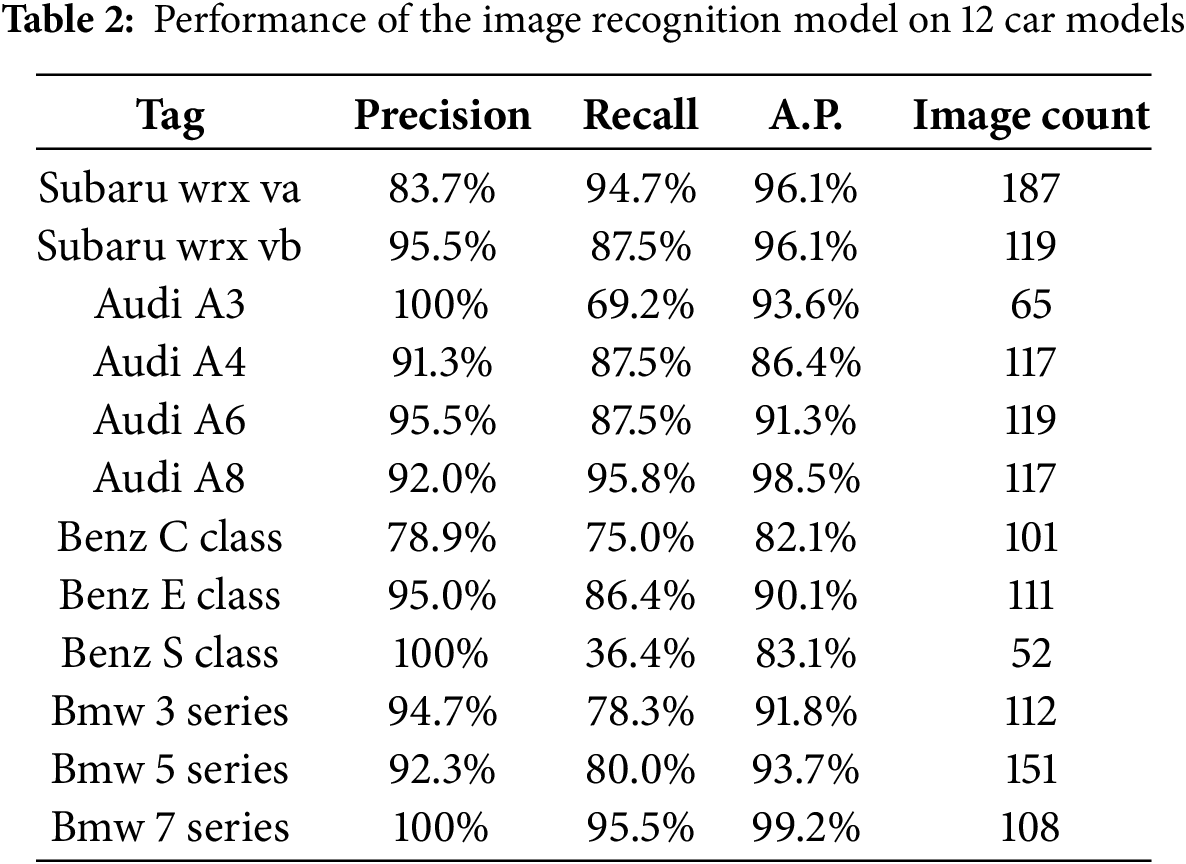

Analysis of the proposed approach for Subaru WRX VA and WRX VB indicates that each vehicle model exhibits distinct advantages. WRX VB achieves a higher Precision of 95.5%, reflecting a lower false-positive rate, whereas WRX VA attains a superior Recall of 94.7%, signifying stronger detection capability. Both models maintain an Average Precision (AP) of 96.1%, demonstrating stable classification performance across different thresholds. Because WRX VA has 187 images (more than WRX VB’s 119), its larger data volume likely contributes to higher recall but may slightly reduce precision. In practical applications where minimizing false positives is paramount, WRX VB is preferable; in contrast, WRX VA is more suitable when maximizing sample detection is the priority. Future efforts could expand WRX VB’s dataset to improve recall and refine the annotation quality for WRX VA to further enhance precision.

Regarding the Audi A3, despite achieving 100% precision, its recall stands at only 69.2%, indicating insufficient detection coverage. The AP is 93.6%, slightly lower than that of the Subaru WRX models, likely influenced by the relatively small dataset (65 images). Substantial increases in data volume, broader angles and environments, and data augmentation (e.g., rotation, cropping) are recommended to boost the model’s ability to capture critical features.

Audi A4 presents a precision of 91.3%, indicating a stable (though not outstanding) false-positive rate. Its recall is 87.5%, trailing slightly behind Audi A8 (95.8%). With an AP of 86.4%, which falls short of Audi A6 (91.3%) and Audi A8 (98.5%), the A4 model calls for more diverse data and improved labeling to enhance classification stability and recall. Considering that the total of 117 images is comparable to other Audi models, strategic data enrichment and annotation optimization seem essential.

Audi A6 performs well in both precision (95.5%) and AP (91.3%), surpassing Audi A4 and nearing Audi A8. However, its recall of 87.5% remains slightly lower than A8’s 95.8%, implying that some samples remain undetected. With 119 images—comparable to A4 and A8—a focus on data diversity and labeling precision may further strengthen recall and classification stability.

Among the Audi models, the Audi A8 achieves the highest recall (95.8%) and AP (98.5%), demonstrating strong consistency and accuracy at various thresholds. Its precision is 92.0%, slightly below A6 (95.5%) yet still high overall. With 117 images, on par with other Audi models, these exceptional results likely stem from clear features and high-quality annotations. Continuing to add varied images and data augmentation techniques could further enhance model performance.

Benz C-Class shows relatively low precision (78.9%) and recall (75.0%), with an AP of 82.1% reflecting limited classification stability across thresholds—both false-positive and false-negative rates are higher. Although 101 images were gathered, performance may be constrained by feature ambiguity and background interference. Greater data volume, refined labeling, and data augmentation strategies are advised to boost both precision and recall.

For the Benz E-Class, the precision (95.0%) and recall (86.4%) are both moderately high, while the AP of 90.1% is slightly below Audi A8 (98.5%) and BMW 7 Series (99.2%), yet still indicative of stable performance. With 111 images, there is sufficient support for learning, but further diversity in samples and the use of data augmentation or parameter tuning could raise its recall and overall classification effectiveness.

Benz S-Class achieves a precision of 100% but only a 36.4% recall, indicating a significant under-detection problem (a 63.6% miss rate). Its AP stands at 83.1%, falling short of stronger performers such as Audi A8 or the BMW 7 Series. The available images (52) are the fewest among all models, constraining training. Substantially increasing the dataset, adjusting classification thresholds, and employing data enhancement methods are strongly recommended to improve detection in practical applications.

BMW 3 Series attains a comparatively high precision (94.7%), yet its recall (78.3%) suggests a 21.7% miss rate. The AP remains decent at 91.8%, though behind top performers like the BMW 7 Series. With 112 images, the dataset is adequate for stable learning, but additional data augmentation and model refinements could help reduce missed detections.

Both precision (92.3%) and recall (80.0%) for BMW 5 Series remain at mid-to-high levels, and its AP is 93.7%, slightly outpacing BMW 3 Series (91.8%) but trailing BMW 7 Series (99.2%). Although it holds the highest image count among all models (151), constraints in feature complexity and diversity may limit further gains. Continuous data enrichment and augmentation could achieve a more balanced performance profile.

Finally, the BMW 7 Series exhibits exceptional classification and detection efficacy across precision (100%), recall (95.5%), and AP (99.2%), ranking it among the top performers. While its image count (108) is lower than BMW 5 Series (151), the apparent clarity of features and annotation quality seem to drive superior results. Expanding the dataset and employing advanced feature augmentation may further bolster its robustness and accuracy under broader usage scenarios.

4.4 Comprehensive Analysis and Discussion

Based on Table 2, the overall recognition results yield several key observations:

1. Balance between Precision and Recall

∘ High Precision Models: Certain models, such as Audi A3 (100%), Benz S Class (100%), and BMW 7 Series (100%), exhibit extremely low false positive rates. However, some of these (e.g., Audi A3 and Benz S Class) show relatively low recall, implying that while precision is high, the model may miss a substantial number of actual positive samples in practice.

∘ High Recall Models: Subaru WRX VA (94.7%) and Audi A8 (95.8%) demonstrate stronger coverage of positive samples, suitable for high-sensitivity scenarios. Yet certain high-recall models (e.g., WRX VA) exhibit marginally lower precision, calling for trade-off considerations depending on application requirements.

2. Overall Trends in Average Precision (AP)

∘ Highest AP: BMW 7 Series (99.2%) and Audi A8 (98.5%) stand out, indicating exceptional stability and minimal error across various thresholds.

∘ Relatively Lower AP: Benz C Class (82.1%) and Audi A4 (86.4%) appear less stable under changing thresholds (e.g., lighting, angle, or confidence adjustments), suggesting a heightened risk of misclassification or incomplete detection in more varied conditions.

3. Impact of Image Count on Model Performance

∘ Sufficient and Balanced Sample Sizes: Subaru WRX VA (187 images) supports a notably high recall, although precision experiences some trade-off; BMW 5 Series (151 images) maintains balanced mid-to-high precision and recall.

∘ Insufficient Sample Sizes: Models like Audi A3 (65 images) or Benz S Class (52 images) achieve high precision in certain metrics yet clearly fall short on recall or AP, likely due to a limited dataset that constrains adaptability to diverse conditions, risking overfitting to specific features.

4. Distinctiveness of Features and Model Similarity

∘ Marked Exterior Differences Lead to Higher Precision: More recognizable high-end designs, such as BMW 7 Series and Benz S Class, facilitate easier detection of salient features.

∘ Highly Similar Exteriors May Affect Recall: Subaru WRX VA and VB, for instance, exhibit near-identical designs, demanding more comprehensive data and refined annotation to maintain both high precision and recall. Thus, data volume and labeling quality become essential.

5. Practical Application Contexts and Future Directions

∘ High-Precision Scenarios: Where false positive costs are high (e.g., to avoid misclassification), models with 100% precision like Audi A3, Benz S Class, or BMW 7 Series may be preferable—though users should remain aware of potential under-detection.

∘ High-Recall Scenarios: For law enforcement or investigative settings requiring thorough coverage of suspicious samples, emphasis on high-recall models (e.g., WRX VA, Audi A8) is recommended, while mitigating excessive drops in precision.

∘ Enhancing Model Quality: For models with suboptimal metrics (e.g., Benz C Class, Audi A4), strategies include increasing the image pool, diversifying angles and lighting, and refining annotation to continuously balance precision and recall.

∘ Customized Thresholds and Post-Processing: Adjusting confidence thresholds, deploying post-processing (e.g., Non-Maximum Suppression or background detection), and tailoring classification priorities for specific applications can further improve real-world effectiveness.

The 12 car models exhibit varying strengths and weaknesses across Precision, Recall, and AP, primarily influenced by dataset size, distinctiveness of physical features, labeling accuracy, and model parameter settings.

4.5 Simulation and Analysis of Three Illicit Vehicle Scenarios

This section presents simulations evaluating the model’s recognition performance under three different illicit vehicle conditions: altered plates, concealed plates, and no plates. Illustrated in Figs. 6–10, the scenarios involve both the 2018 Subaru WRX VA and the 2023 Subaru WRX VB, examining the ability to detect the correct brand-model despite mismatched or missing plate information. In Fig. 6, the 2018 WRX VA is shown with a plate belonging to the 2023 WRX VB, yet the model predominantly labels it as WRX VA (95%), underscoring its reliance on intrinsic vehicle features rather than plate data. Fig. 7 depicts a 2018 WRX VA lacking a license plate entirely, which yields a 99.1% confidence for WRX VA and 0.8% for WRX VB, implying that plate absence does not significantly impede identification. Conversely, Fig. 8 reverses the altered plate situation, wherein a WRX VB uses a WRX VA plate. Here, the model assigns 98.8% to WRX VA and 1.1% to WRX VB, again highlighting the primacy of body-based attributes. In Fig. 9, the 2023 WRX VB without a plate is recognized at 88.4%, with 11.5% attributed to WRX VA. Although still highly accurate, the greater confusion compared to Fig. 7 emphasizes the need for extensive training samples to mitigate the challenge of nearly identical sub-models. Lastly, Fig. 10 reveals a WRX VB with its plate obscured, which the system detects at 97.8% confidence. Minor misclassification (1.5% for WRX VA and 0.3% for Audi A4 B9) further demonstrates that exterior design traits drive the model’s robust performance despite intentional plate concealment. Fig. 11 shows the simulation of a 2022 Subaru WRX VB modified car without a license plate, equipped with an aerodynamic kit, where the system recognizes it as WRX VB with 85.3% confidence and WRX VA with 14.7% confidence. Fig. 12 shows the simulation of a 2020 Subaru WRX VA modified car with a fake license plate, where the system recognizes it as WRX VA with 84.6% confidence and WRX VB with 15.4% confidence. Overall, these results confirm that the trained system effectively differentiates vehicle brands and models under varying plate conditions, although closely related vehicle versions (e.g., WRX VA vs. VB) benefit from additional data augmentation and refined annotation to reduce residual errors.

Figure 6: Simulation of an illicit vehicle scenario in which a 2018 Subaru WRX VA is equipped with a 2023 WRX VB license plate, yielding recognition outcomes of 95% for WRX VA and 5% for WRX VB

Figure 7: Simulation of a 2018 Subaru WRX VA lacking a license plate. The model’s predictions identify WRX VA with 99.1% confidence and WRX VB with 0.9%

Figure 8: Simulation of an illicit vehicle scenario in which a 2023 WRX VB mounts a WRX VA license plate, producing recognition results of 98.8% for WRX VA and 1.2% for WRX VB

Figure 9: Simulation of a 2023 Subaru WRX VB with no license plate. The system recognizes WRX VB at 88.4% and WRX VA at 11.6%

Figure 10: Simulation of a 2023 Subaru WRX VB with a concealed license plate, resulting in detection probabilities of 97.8% for WRX VB, 1.5% for WRX VA, 0.4% for Audi A6, and 0.3% for Audi A4

Figure 11: Simulation of a 2022 Subaru WRX VB modified car without a license plate, featuring an aerodynamic kit. The system recognizes WRX VB at 85.3% and WRX VA at 14.7%

Figure 12: Simulation of a 2020 Subaru WRX VA modified car with a fake license plate. The system recognizes WRX VA at 84.6% and WRX VB at 15.4%

4.6 Complementary Benefits of This Study’s Model to Existing License Plate Recognition Systems

In practical law enforcement settings, current license plate recognition systems face numerous illegal or non-compliant scenarios—such as vehicles with no license plates, plates that are obscured or defaced, and plates belonging to another vehicle. Under such conditions, timely identification and investigation can be challenging. The vehicle brand–model recognition method proposed in this study offers an additional layer of verification by focusing on the vehicle’s intrinsic characteristics. This allows officers to more accurately ascertain the vehicle’s true identity, even in cases where plate data may be misleading or unreadable. The table below summarizes the differences and complementary aspects of plate recognition and model-based recognition across various types of violations:

• No License Plate

∘ License Plate Recognition System: Unable to identify the vehicle due to missing plate data.

∘ This Study’s Model (Brand–Model Recognition): Assesses the vehicle’s brand and model, then traces ownership records accordingly.

• Plate Obscured or Defaced

∘ License Plate Recognition System: Cannot recognize or read the complete license number.

∘ This Study’s Model: Identifies key exterior features to infer the vehicle’s brand and model, thus facilitating backtracking of ownership details.

• Using Another Vehicle’s Plate (Registered Owner Exists)

∘ License Plate Recognition System: Reads the plate as recorded and issues a notice to that plate’s legitimate owner, inadvertently causing inconvenience to innocent parties.

∘ This Study’s Model: Verifies whether the recognized brand–model aligns with the displayed plate details, enabling prompt detection of inconsistencies.

• Using Another Vehicle’s Plate (No Registration Records)

∘ License Plate Recognition System: If no registration exists for the displayed plate, further investigation must rely on external cues such as vehicle features.

∘ This Study’s Model: Directly identifies the brand and model, facilitating a targeted ownership search and cross-referencing.

• Using a Forged or Altered License Plate (Originally Valid Plate)

∘ License Plate Recognition System: May detect the plate and summon the original plate owner, misdirecting investigative resources if the plate is fake.

∘ This Study’s Model: Confirms whether the recognized brand–model matches the plate records, expediting the process of isolating the true vehicle and its owner.

Overall, brand–model recognition proves invaluable when dealing with unregistered or unreadable plates, serving as an independent verification path. In instances where the plate data is intact yet suspicious, comparing the recognized brand–model to the stored plate information further increases the likelihood of detecting forged or altered plates. By integrating conventional plate recognition with the proposed brand–model approach, law enforcement can operate more efficiently and accurately in a wide range of non-compliant or illegal vehicle scenarios.

4.7 System Integration and Ethical Governance

The proposed brand–model recognition module is positioned as a complementary mechanism to existing license plate recognition (LPR). Under adverse conditions—such as missing plates, occluded plates, plate swapping, or forgery—the module provides an independent, body–appearance–based source of evidence that can be cross-validated against plate outputs. At the event level, the system conducts a “plate result × body result” consistency check; whenever inconsistencies are detected (e.g., a mismatch between the plate record and the inferred vehicle model), it triggers an alert and routes the case to human review, thereby reducing misidentification risk and enforcement costs. To reflect common field scenarios, we design three simulation experiments (plate swapping, no plate, and plate occlusion). Results show that, even when plate cues are insufficient, the model can still identify vehicles from exterior features, while also revealing confusion factors for closely related sub-models (e.g., WRX VA/VB) and corresponding avenues for improvement. Furthermore, the module is integrated with a police intelligence analysis platform that combines the existing LPR pipeline with downstream data flows, supporting real-time video, historical retrieval, cross-checks between plate and body results, and trajectory estimation. The platform unifies plate querying, historical comparison, path reconstruction, and real-time alerting, enabling rapid aggregation of multi-sensor detections to reconstruct the movement of suspect vehicles. This cross-module integration not only improves investigative accuracy and timeliness but also mitigates risks arising from reliance on a single information source. From a governance perspective, the module serves as decision support rather than a sole basis for action, emphasizing human-in-the-loop operation and auditability. We institute second-stage human verification, audit trails, and clear lines of responsibility, alongside use-limitation and privacy safeguards, to uphold proportionality and system transparency.

4.8 Limitations and Future Work

Data and external validity: Although the dataset spans multiple brands, model years, and imaging conditions, several classes (e.g., Audi A3, Benz S-Class) remain under-represented, yielding unstable recall or AP and raising concerns about overfitting and long-tail class imbalance. In addition, because most data were collected in the Taiwan market, cross-regional transfer may be affected by differences in trims, exterior details, and modification practices. Future work will expand the corpus across markets and time periods (covering year, trim level, and modification degree), adopt stratified sampling and hard-example mining, and strengthen annotation consistency and QA procedures to improve robustness to fine-grained appearance differences and scene variability.

Model baselines and performance analysis: This study employed Microsoft Custom Vision to enable rapid iteration and deployment, but it did not yet conduct a systematic, same-data comparison against other lightweight backbones. We will benchmark, on the identical dataset, YOLOv8, Faster R-CNN, and ResNet/MobileNet variants, reporting mAP, precision/recall, latency, and FLOPs, together with error-set characterization and uncertainty calibration (e.g., confidence calibration). These analyses will establish a complete and reproducible performance-benchmarking framework.

Adverse-condition and stress testing: We evaluated three adverse scenarios—plate swapping, missing plates, and occluded plates—to verify the complementarity of body features when plate information is degraded. Subsequent tests will cover broader conditions (nighttime, backlighting, rain/fog, motion blur, and varying occlusion ratios), forming a contextualized, reproducible stress-testing protocol. We will also assess how threshold settings, NMS, and background filtering affect the precision–recall trade-off to support operational needs across high-recall vs. high-precision modes.

Platform integration and procedural governance: On the systems side, we will formalize event-level consistency checks with LPR and the alerting pipeline, expand anomaly taxonomies (mismatched plates, no plate, occluded/damaged/temporary plates), and define cross-module consensus/divergence rules and human-review SLAs, with auditable tracking for operationalization. On the ethics/compliance side, we will implement bias monitoring (by brand/model year/color/modification type), define use limitations, and design an appeals mechanism to mitigate potential harms from systematic bias or misidentification.

Data engineering and continual learning: To shorten the model–data feedback loop, we plan to incorporate active and continual learning: difficult samples identified via human review and field feedback will be fed back into the dataset and labeling guidelines. Along with data augmentation and rigorous versioning, this will progressively improve separability for highly similar sub-models (e.g., WRX VA/VB) and enhance deployment stability.

This study leverages deep learning technologies to develop a model capable of recognizing vehicle brands and models. Integrated with a law enforcement–oriented analytics platform, the approach addresses shortcomings in existing license plate recognition systems when handling counterfeit, obscured, or absent plates. The results indicate that, for most vehicle models, the proposed method maintains high precision and stability. However, data distribution and the distinctiveness of certain vehicles’ exterior features substantially influence precision and recall, especially in cases where a limited sample size or near-identical body designs introduce a trade-off between these metrics. More extensive image collection and diversified annotation practices are, therefore, necessary. Overall, simulations involving illicit vehicles demonstrate that the model successfully detects and classifies cars by relying on body characteristics, thereby reducing overdependence on plate-based data. This finding offers substantial benefits for practical enforcement, particularly in investigating and tracking suspect vehicles, as it significantly accelerates detection processes and enhances accuracy. By continually expanding the dataset with a broader range of vehicles, applying data augmentation techniques, and improving labeling quality, this study’s approach could further bolster recognition of rare or modified models and strengthen the effectiveness and reliability of law enforcement analytics in real-world conditions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author would like to thank the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, for financially supporting this research (grant No. NSTC 114-2221-E-018-003) and the Ministry of Education’s Teaching Practice Research Program, Taiwan (PSK1142780).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Shih-Lin Lin and Cheng-Wei Li; Formal analysis, Cheng-Wei Li; Funding acquisition, Shih-Lin Lin; Investigation, Shih-Lin Lin; Methodology, Shih-Lin Lin and Cheng-Wei Li; Project administration, Shih-Lin Lin; Resources, Shih-Lin Lin; Software, Cheng-Wei Li; Supervision, Shih-Lin Lin; Validation, Cheng-Wei Li; Visualization, Cheng-Wei Li and Shih-Lin Lin; Writing—original draft, Shih-Lin Lin and Cheng-Wei Li; Writing—review & editing, Shih-Lin Lin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alwateer M, Aljuhani KO, Shaqrah A, ElAgamy R, Elmarhomy G, Atlam ES. XAI-SALPAD: explainable deep learning techniques for Saudi Arabia license plate automatic detection. Alex Eng J. 2024;109:578–90. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.09.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bae SH, Hong JE. A vehicle detection system robust to environmental changes for preventing crime. J Korea Multimed Soc. 2010;13(7):983–90. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

3. Bharti N, Kumar M, Manikandan VM. A hybrid system with number plate recognition and vehicle type identification for vehicle authentication at the restricted premises. In: Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Emerging Frontiers in Electrical and Electronic Technologies (ICEFEET); 2022 Jun 24–25; Patna, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICEFEET51821.2022.9847975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gholamhosseinian A, Seitz J. Vehicle classification in intelligent transport systems: an overview, methods and software perspective. IEEE Open J Intell Transp Syst. 2021;2:173–94. doi:10.1109/OJITS.2021.3096756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gopichand G, Vijayakumar, Pasupuleti NS. On-road crime detection using artificial intelligence. In: Innovations in electrical and electronic engineering. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 423–32. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-4692-1_32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Guo D. A method of recognition for fake plate vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Network, Communication, Computer Engineering (NCCE 2018); 2018 May 26–27; Chongqing, China. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2018. p. 692–9. doi:10.2991/ncce-18.2018.114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hoang DC, Lilienthal AJ, Stoyanov T. Object-RPE: dense 3D reconstruction and pose estimation with convolutional neural networks. Robot Auton Syst. 2020;133:103632. doi:10.1016/j.robot.2020.103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hu C, Bai X, Qi L, Wang X, Xue G, Mei L. Learning discriminative pattern for real-time car brand recognition. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2015;16(6):3170–81. doi:10.1109/tits.2015.2441051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lu L, Huang H. A hierarchical scheme for vehicle make and model recognition from frontal images of vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2019;20(5):1774–86. doi:10.1109/TITS.2018.2835471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li H, Wang P, Shen C. Toward end-to-end car license plate detection and recognition with deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2019;20(3):1126–36. doi:10.1109/TITS.2018.2847291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Manzoor MA, Morgan Y, Bais A. Real-time vehicle make and model recognition system. Mach Learn Knowl Extr. 2019;1(2):611–29. doi:10.3390/make1020036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mustafa T, Karabatak M. Real time car model and plate detection system by using deep learning architectures. IEEE Access. 2024;12:107616–30. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3430857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nam Y, Nam YC. Vehicle classification based on images from visible light and thermal cameras. EURASIP J Image Video Process. 2018;2018(1):5. doi:10.1186/s13640-018-0245-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pan W, Zhou X, Zhou T, Chen Y. Fake license plate recognition in surveillance videos. Signal Image Video Process. 2023;17(4):937–45. doi:10.1007/s11760-022-02264-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sajol HC, Santos JC, Agustin LM, Zafra JJ, Teogangco M. OCULAR: object detecting CCTV using a low-cost artificial intelligence system with real-time analysis. AIP Conf Proc. 2022;2502(1):050007. doi:10.1063/5.0109030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xiang Y, Fu Y, Huang H. Global topology constraint network for fine-grained vehicle recognition. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2020;21(7):2918–29. doi:10.1109/TITS.2019.2921732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abdi H, Williams LJ. Principal component analysis. Wires Comput Stat. 2010;2(4):433–59. doi:10.1002/wics.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Babaud J, Witkin AP, Baudin M, Duda RO. Uniqueness of the Gaussian kernel for scale-space filtering. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1986;PAMI-8(1):26–33. doi:10.1109/tpami.1986.4767749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Gu J, Wang Z, Kuen J, Ma L, Shahroudy A, Shuai B, et al. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 2018;77:354–77. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2017.10.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollar P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 2980–8. doi:10.1109/iccv.2017.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hearst MA, Dumais ST, Osuna E, Platt J, Scholkopf B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intell Syst Their Appl. 1998;13(4):18–28. doi:10.1109/5254.708428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kanopoulos N, Vasanthavada N, Baker RL. Design of an image edge detection filter using the Sobel operator. IEEE J Solid State Circ. 1988;23(2):358–67. doi:10.1109/4.996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jamil AA, Hussain F, Yousaf MH, Butt AM, Velastin SA. Vehicle make and model recognition using bag of expressions. Sensors. 2020;20(4):1033. doi:10.3390/s20041033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hassan A, Ali M, Durrani NM, Tahir MA. An empirical analysis of deep learning architectures for vehicle make and model recognition. IEEE Access. 2021;9:91487–99. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3090766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ali M, Tahir MA, Durrani MN. Vehicle images dataset for make and model recognition. Data Brief. 2022;42:108107. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2022.108107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lyu Y, Schiopu I, Cornelis B, Munteanu A. Framework for vehicle make and model recognition-a new large-scale dataset and an efficient two-branch-two-stage deep learning architecture. Sensors. 2022;22(21):8439. doi:10.3390/s22218439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Prabakaran S, Mitra S. Survey of analysis of crime detection techniques using data mining and machine learning. J Phys Conf Ser. 2018;1000:012046. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1000/1/012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Amirkhani A, Barshooi AH. DeepCar 5.0: vehicle make and model recognition under challenging conditions. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(1):541–53. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3212921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lu L, Cai Y, Huang H, Wang P. An efficient fine-grained vehicle recognition method based on part-level feature optimization. Neurocomputing. 2023;536:40–9. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.03.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Anwar T, Zakir S. Vehicle make and model recognition using mixed sample data augmentation techniques. IAES Int J Artif Intell. 2023;12(1):137. doi:10.11591/ijai.v12.i1.pp137-145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang H, Li X, Yuan H, Liang H, Wang Y, Song S. A multi-angle appearance-based approach for vehicle type and brand recognition utilizing faster regional convolution neural networks. Sensors. 2023;23(23):9569. doi:10.3390/s23239569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang X, Yang S, Xiao Y, Zheng X, Gao S, Zhou J. A vehicle classification model based on deep active learning. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2023;171:84–91. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2023.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gayen S, Maity S, Singh PK, Geem ZW, Sarkar R. Two decades of vehicle make and model recognition—survey challenges and future directions. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(1):101885. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ünal Y, Bolat M, Dudak MN. Examining the performance of a deep learning model utilizing Yolov8 for vehicle make and model classification. J Eng Technol Appl Sci. 2024;9(2):131–43. doi:10.30931/jetas.1432261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bularz M, Przystalski K, Ogorzałek M. Car make and model recognition system using rear-lamp features and convolutional neural networks. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(2):4151–65. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15081-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang H, Zhou W, Liu G, Wang Z, Qian Z. Fine-grained vehicle make and model recognition framework based on magnetic fingerprint. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(8):8460–72. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3374888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu C, Pu Z, Li Y, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Du Y. Enabling edge computing ability in view-independent vehicle model recognition. Int J Transp Sci Technol. 2024;14:73–86. doi:10.1016/j.ijtst.2023.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kerdvibulvech C. Multimodal AI model for zero-shot vehicle brand identification. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(27):33125–44. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-20559-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Puisamlee W, Chawuthai R. Minimizing model size of CNN-based vehicle make recognition for frontal vehicle images. IEEE Access. 2025;13:97409–20. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3574187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao Y, Zhao H, Shi J. YOLOv8-MAH: multi-attribute recognition model for vehicles. Pattern Recognit. 2025;167:111849. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bakirci M. Enhancing vehicle detection in intelligent transportation systems via autonomous UAV platform and YOLOv8 integration. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164:112015. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Bakirci M. Utilizing YOLOv8 for enhanced traffic monitoring in intelligent transportation systems (ITS) applications. Digit Signal Process. 2024;152:104594. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2024.104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools