Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

State Space Guided Spatio-Temporal Network for Efficient Long-Term Traffic Prediction

School of Information Science and Technology, School of Artificial Intelligence, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, 100083, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaoyu Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancing Network Intelligence: Communication, Sensing and Computation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072147

Received 20 August 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Long-term traffic flow prediction is a crucial component of intelligent transportation systems within intelligent networks, requiring predictive models that balance accuracy with low-latency and lightweight computation to optimize traffic management and enhance urban mobility and sustainability. However, traditional predictive models struggle to capture long-term temporal dependencies and are computationally intensive, limiting their practicality in real-time. Moreover, many approaches overlook the periodic characteristics inherent in traffic data, further impacting performance. To address these challenges, we introduce ST-MambaGCN, a State-Space-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolution Network. Unlike conventional models, ST-MambaGCN replaces the temporal attention layer with Mamba, a state-space model that efficiently captures long-term dependencies with near-linear computational complexity. The model combines Chebyshev polynomial-based graph convolutional networks (GCN) to explore spatial correlations. Additionally, we incorporate a multi-temporal feature capture mechanism, where the final integrated features are generated through the Hadamard product based on learnable parameters. This mechanism explicitly models short-term, daily, and weekly traffic patterns to enhance the network’s awareness of traffic periodicity. Extensive experiments on the PeMS04 and PeMS08 datasets demonstrate that ST-MambaGCN significantly outperforms existing benchmarks, offering substantial improvements in both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency for long-term traffic flow prediction.Keywords

With rapid urbanization, increasing traffic demand and expanding infrastructure, traffic flow prediction has become a key problem in the Intelligent Transportation of traffic flow plays a vital role in traffic management, route planning, accident prevention, and environmental protection. Among them, the importance of long-term traffic flow prediction is particularly prominent. The traditional short-term traffic flow prediction usually only focuses on traffic conditions within a few minutes or hours. Although it can meet daily traffic scheduling needs, it is difficult to deal with traffic pressure in special circumstances, such as holiday peaks and major events. The long-term traffic flow prediction can identify the trend of traffic flow in advance on a longer time scale and provide scientific basis for the optimization of urban traffic networks. For example, during holidays or large-scale activities, accurate long-term traffic flow prediction can be used to plan the control strategy of traffic signals, the selection of dredging routes and the capacity scheduling of public transport in advance, so as to effectively avoid traffic congestion and improve road traffic efficiency.

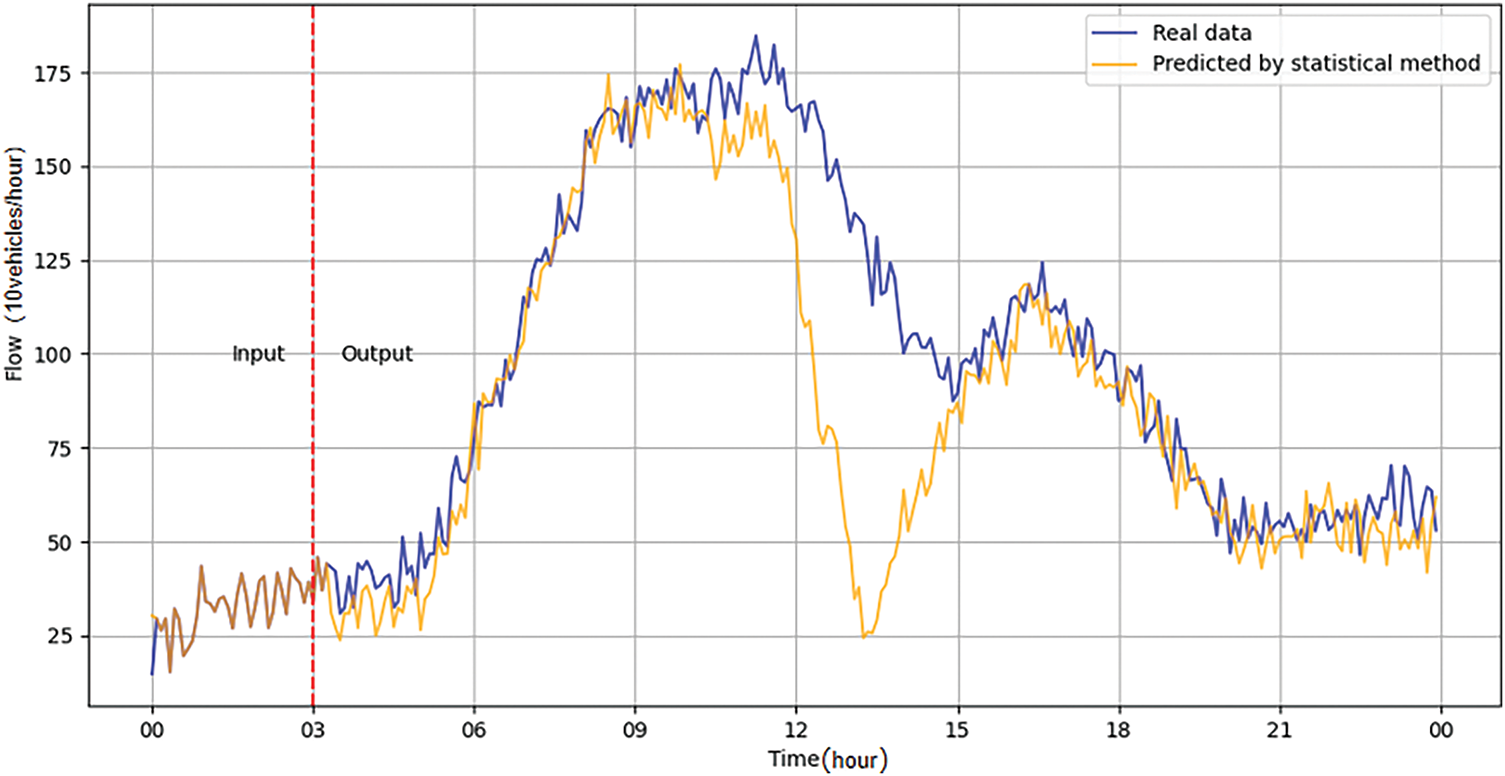

Early research on traffic flow prediction focused mainly on statistical methods, such as the Historical Average Madel (HA) [1,2], the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) [3,4], the Vector Autoregressive Model (VAR) [5], etc. It exposes significant defects in long-term traffic flow prediction: its linear assumption is difficult to capture the dynamic change law of traffic flow, especially the lack of modeling ability for the long-term evolution trend of complex models such as periodic fluctuations and sudden congestion. For example, the average absolute error of ARIMA in forecasting for over 30 min often exceeds 25% of the actual flow rate [6]. The example in Fig. 1 vividly illustrates the disadvantages of traditional traffic flow prediction methods in long-term traffic flow prediction.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of prediction by statistical methods: In long-term traffic flow prediction, there will be large errors in some periods

To break through the limitations of statistical methods, machine learning methods such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) [7] and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) [8] were introduced. Although these methods can partially deal with nonlinear relationships, they still face two challenges in long-term traffic flow prediction. First, only using sensor data is difficult to retain long-term dependent information of time-series, resulting in exponential accumulation of prediction errors with time step; second, strict requirements on data stationarity (such as KNN’s strong time homogeneity hypothesis) make it less stable in long-term prediction across time periods and seasons. Experiments show that when the prediction span of SVR exceeds 1 h, the value of R2 will drop to less than 0.5 [6].

In recent years, deep learning has made remarkable achievements in fields such as computer vision and natural language processing, which has inspired researchers to apply it to the field of traffic prediction, hoping to improve the prediction effect. Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [9,10] have been used in the field of transportation widely because of their unique advantages in dealing with non-Euclidean structures. At the same time, in order to better model the spatial and temporal features, the attention mechanism such as that in Transformer [11], is also integrated into it. Since the key to traffic flow prediction is to accurately model the complex nonlinear spatio-temporal dependence of dynamic traffic flow at different traffic nodes, GCN and Transformer have become two core components widely used in many representative traffic flow prediction models.

Although this spatio–temporal modeling method has achieved good results in traffic flow prediction, the current method still has the following limitations in long-term traffic flow prediction:

1) Although a Transformer-based model can capture long-term dependencies through the self-attention mechanism, when the input sequence (such as the time-series of traffic flow data) becomes longer, its computational complexity grows quadratically with the input length. The data in [12] illustrates the high cost issues of the Transformer model in terms of memory and training time as the input length increases and the dataset size expands. This makes the model inefficient when dealing with very time-series and difficult to cope with the actual needs of long-term traffic flow prediction.

2) Traffic flow data show obvious periodic characteristics. For instance, during the morning and evening rush hours on weekdays, there are regular large fluctuations in traffic flow. There are also significant differences in weekend and weekday traffic. These periodic patterns are a key basis for long-term traffic flow prediction, helping the model to more accurately capture long-term trends in traffic flow. However, the current long-term traffic flow prediction model has obvious shortcomings in utilizing these periodic rules, and can not fully tap its potential value, thus limiting the performance of the model in the long-term traffic flow forecasting task.

To solve these problems, we propose a novel deep learning model: State-Space-Based Spatio–Temporal Graph Convolution Network (ST-MambaGCN). Specifically, Mamba [13] is used to replace the traditional temporal attention layer. Mamba is a State-Space Model (SSM) that can effectively capture long-term dependencies in multivariate time-series data. The computational complexity of Mamba increases nearly linearly, which greatly reduces the computational cost compared with the traditional attention mechanism. In addition, the Mamba layer is better able to capture periodic and long-term correlations of traffic flow data through multi-scale context cues and channel hybrid/independent processing mechanisms. In structural design, the graph convolution block of our model is responsible for analyzing the spatial dependence. Inspired by ASTGCN [14], the model introduces a multi-temporal feature capture mechanism. Three independent components are used to model the near-term, daily cycle and weekly cycle dependence of traffic flow respectively, and conduct a comprehensive analysis of historical data from multiple time scales, so as to more accurately grasp the change law of traffic flow over time. With the above characteristics, ST-MambaGCN model performs well in the analysis of spatial and temporal elements of traffic prediction, can accurately grasp the cyclical characteristics, and shows stronger adaptability and superiority in dealing with long-term traffic prediction tasks.

In summary, the contribution of this paper can be summarized as follows:

• A new deep learning framework, ST-MambaGCN, is proposed. In the time dimension, the state space model Mamba is used to capture the long-term dependency of multivariate time series with near-linear computational complexity, which solves the problem that the computational cost of the transformer increases quadratically with the length of the input sequence. In the spatial dimension, with the help of Chebyshev convolutional analysis of the local spatial correlation of road network nodes, the traffic flow correlation of adjacent regions can be mined more efficiently than the traditional GCN, and the collaborative optimization modeling of spatio-temporal features is realized.

• A multi-component fusion structure is constructed, and a multi-temporal feature capture mechanism containing three independent components is introduced. These components are used to model the recent, diurnal, and weekly dependencies of traffic flow, respectively. By comprehensively analyzing historical data from multiple time scales and learning the influence weights of each component on each node, the model can better capture the periodic characteristics of traffic flow.

• The dataset uses PEMS series highway data from California, USA, and metro data from Beijing, China. The performance of the proposed method is better than the existing benchmark methods, and the optimal prediction results are obtained, which verifies its effectiveness and superiority in practical application.in practical application.

2.1 Spatio-Temporal Prediction

As the core task of intelligent transportation systems, spatio-temporal prediction of traffic conditions has emerged in a variety of innovative models in recent years: STGCN [15] captures the spatial correlation of nodes by combining the predefined adjacency matrix with GCN. MSTDFGRN [16] captures the spatial correlation of nodes by combining multi-scale spatio-temporal dynamic features with Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN). PSTCGCN [17] utilizes a multi-task learning framework and GCN to simultaneously predict multiple related traffic indicators, dynamically modeling the spatio-temporal characteristics of traffic flow. SDSINet [18] further introduces an attention-based adaptive graph embedding to generate dynamic spatial correlation structures, enhancing the model’s adaptability to various traffic conditions. GMAN [19] achieves multi-dimensional feature fusion through a triple attention mechanism. MPGCN [20] identifies bus station travel modes through cluster analysis and builds a GCN2Flow prediction block. The improved version of MGNNFormer [21] designed the STIGNNFormer structure to integrate the advantages of GCN and Transformer.

In recent years, emerging approaches integrating diffusion models, graph attention mechanisms, adaptive graph learning, and physics-informed models have injected new vitality into the field of traffic prediction. In the realm of diffusion models, some studies have leveraged their powerful probabilistic generative capabilities for traffic flow prediction, demonstrating unique advantages in handling multimodal prediction problems under complex traffic scenarios [22]. The development of graph attention mechanisms has further optimized spatial correlation modeling [23]. Adaptive graph learning techniques have become a key direction for breaking through the limitations of static graph structures. Existing studies dynamically learn the topological structure of graphs from traffic data, replacing traditionally manually defined fixed adjacency matrices, thereby enabling models to adapt in real time to dynamic changes in traffic networks [24]. Meanwhile, physics-informed models incorporate physical principles such as traffic flow theory into the model design, avoiding unrealistic predictions that may arise from purely data-driven models [25].

The Mamba model can make up for the deficiencies of the GCN to a certain extent. It has better dynamic adaptability, can effectively handle dynamic graph data that changes over time, and can capture the dynamic change information of nodes and edges in the graph. For example, in traffic flow prediction, Mamba can quickly adjust its predictions according to new data, while the GCN requires complex mechanisms to adapt to such dynamic changes. In terms of long-range sequence dependency modeling, Mamba is proficient in handling long-range dependency relationships, can effectively capture the dependencies between distant nodes, and makes up for the limitations of the GCN, such as its limited receptive field and the difficulty in obtaining global information.

2.2 Long-Term Traffic Flow Prediction

In recent years, numerous scholars have come to realize the latent capabilities of Graph Neural Networks [26] in the field of traffic prediction. As an important branch of Graph Neural Networks, the Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [27,28] has been widely applied to traffic prediction tasks due to its excellent spatial feature extraction capabilities. Meanwhile, Transformers have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in handling long-term time series tasks [29,30], which is attributed to their outstanding advantages in capturing and processing long-term dependencies. Recently, there have been some research achievements in the field of the spatio-temporal graph Transformer framework. For example, Graphormer [31]. This model innovatively applies the Transformer architecture to graph-structured data and shows unique advantages when dealing with non-Euclidean structures such as traffic networks, providing new ideas for subsequent research. There is also STFormer [32], whose Transformer module specifically designed for spatio-temporal data effectively captures spatio-temporal dependencies and has achieved good results in the task of traffic flow prediction.

However, there are obvious shortcomings in the current research. As the prediction step length increases, the accuracy of most existing spatio-temporal prediction models drops sharply, resulting in unsatisfactory performance in long-term time series prediction. Although the self-attention mechanism of Transformers can capture long-term dependencies, its

Considering the drawbacks of current deep learning techniques, selective state-space models, commonly known as Mamba, distinguish themselves. They are capable of delivering high-precision traffic flow predictions over extensive distances with reduced computational requirements. This efficiency is of great significance in long-term traffic management.

The Mamba can be regarded as a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) [33] of fixed length, and its computational complexity does not increase with the growth of the length of the input. Compared with Transformer architecture, Mamba has significant advantages in inference speed and computational efficiency [34]. The performance of Mamba is comparable to that of Transformer in time-series analysis [35–37], computer vision [38,39], natural language processing [40,41], and multimodal and multimedia analysis [42].

However, traffic flow prediction inherently requires mining spatio-temporal features simultaneously. Although existing methods focus on time series modeling, they lack in explicitly modeling spatial dependencies. For example, Ahamed and Cheng [36] capture the multi-scale temporal features of traffic data mainly through the channel mixing mechanism and four-branch Mamba structure, without integrating graph modules such as GCN, and lack explicit modeling of spatial dependencies in transportation networks; Wang et al. [43] enhance the ability to model correlations between variables in time series data through the bidirectional design of the Mamba layer, but like the former study, they do not integrate GCN, rely only on temporal modeling, and fail to handle the spatial relationships between traffic nodes.

Notably, the integration of state space models with emerging fusion technologies has recently become a research hotspot. STG-Mamba [37] attempts to combine Mamba with adaptive graph learning, while other studies explore incorporating physics-informed constraints into the Mamba framework to align the state transition process of state space models more closely with the physical principles of traffic flow [44]. These explorations provide new directions for enhancing long-term traffic flow prediction performance and underscore the innovativeness and necessity of the ST-MambaGCN model proposed in this paper, which integrates the advantages of classical models to address the challenges of long-term traffic flow prediction.

In traffic research, the road network is typically conceptualized as a spatial configuration consisting of a specific set of traffic nodes and the connections between them. Mathematically, it is formalized as a weighted undirected graph denoted as

In the road network

We utilize the data matrix

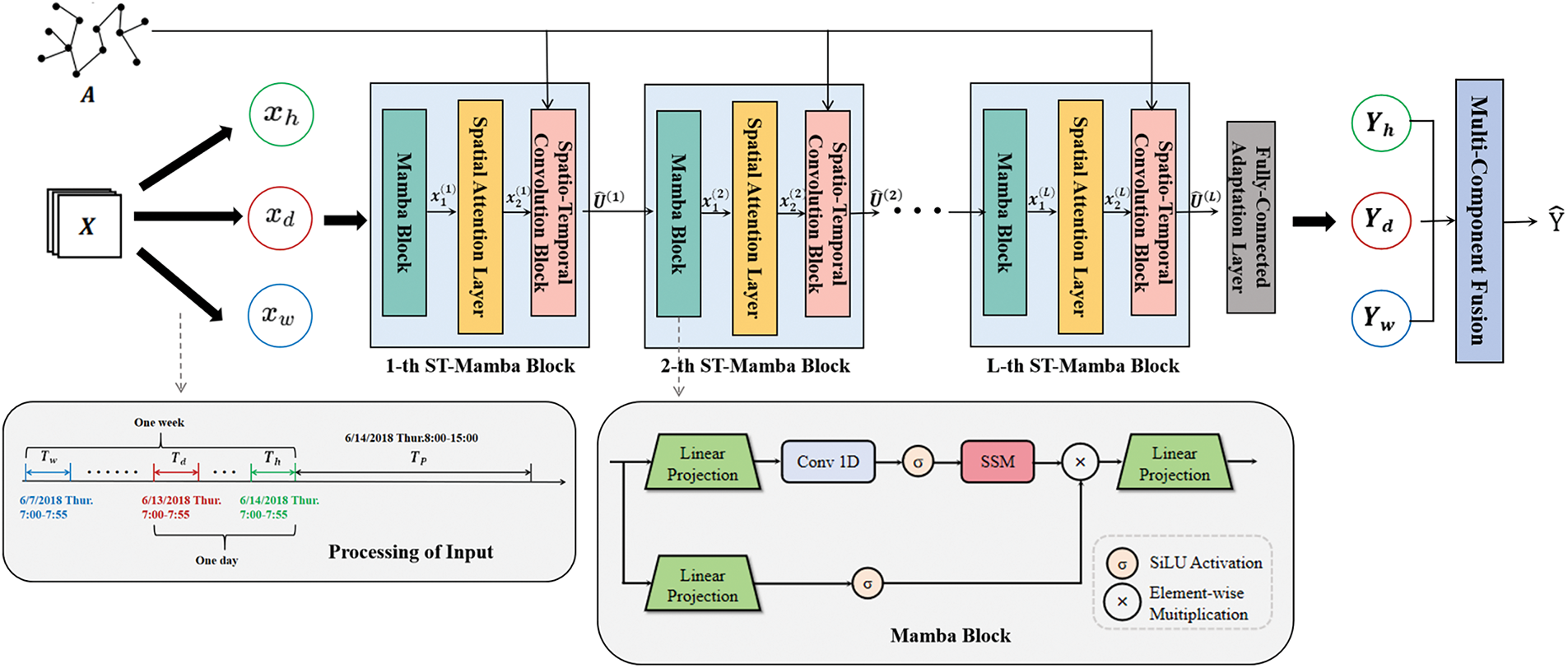

To predict long-term traffic flow more accurately, we propose a novel State-Space-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolution Network (ST-MambaGCN) for traffic flow prediction. The basic structure of ST-MambaGCN is shown in Fig. 2. First, the temporal correlation is extracted using the Mamba block. After applying a layer of spatial attention, a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) is employed to extract spatial correlations and periodic patterns.

Figure 2: The framework of ST-MambaGCN

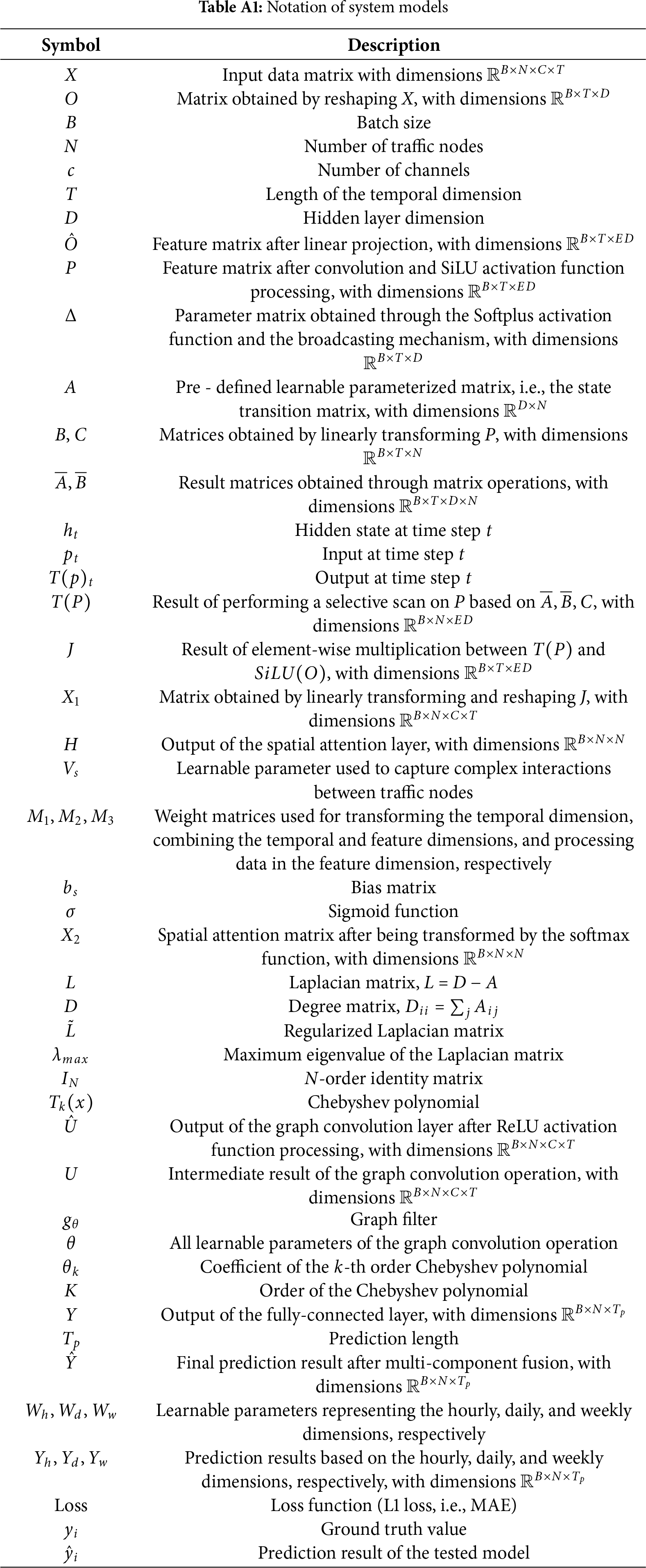

The letters defined in the Methodology are organized in Table A1. A for the convenience of readers’ understanding and reading.

Mamba significantly boosts computational efficiency through its integration of hardware-parallel algorithms and implementation of data-dependent selection mechanisms within its iterative process. This innovative design enables Mamba to capture temporal dependencies in long sequences effectively. Moreover, as a sequence model with near-linear complexity, Mamba demonstrates superior efficiency and performance compared to the Transformer, especially in tasks involving long sequences.

The input

Initially, the hidden dimension is increased to

Use the Softplus activation function and the broadcasting mechanism to obtain the parameter matrix

The discretized

The result of applying the matrix exponential function

where

Based on the discretized matrixes and

Inspired by the continuous system, the mapping from the input

The derivation from continuous to discrete is obtained by approximating the continuous-time model at discrete time points. Assuming that the input

Perform element-wise multiplication between

Finally, the output

Combining Transformer and GCN, see Section 4.3, to extract spatial dependence is effective. This combination balances focusing on local context, preserving memory, and capturing long-term dependencies for more comprehensive and efficient information processing in neural networks. Spatial attention layer is shown as,

After obtaining the attention matrix

4.3 Spatio-Temporal Convolution Block

Graph Convolutional Networks excel at modeling non-Euclidean spatial data, making them suitable for complex traffic networks. To understand traffic network topology and node relationships, we use graph convolution based on spectral graph theory. It processes time-step signals and explores traffic information’s spatial correlations. Spectral graph theory uses algebraic transformations with Laplacian matrices [46] for graph analysis. Eigenvalue decomposition of the Laplacian enables graph convolution but is resource-intensive for large graphs. So, in this paper, we apply the Chebyshev polynomial approximation method. The Laplacian matrix is defined as follows:

Among them,

To safeguard the stability of the graph convolution operation, regularization is applied to the Laplacian matrix. This regularization confines the numerical range of the Laplacian matrix to

The recursive definition of the Chebyshev polynomials is shown in Eq. (16).

Among them,

The final activation function employed in the graph convolution layer is ReLU.

Finally, a fully-connected layer is added to ensure that the output of each component has the same dimension and shape as the prediction target. The fully-connected layer uses ReLU as the activation function and the output of the fully-connected layer is denoted as

4.4 Multi-Component Fusion and Loss Function

Based on historical data, the model learns the influence weights of each component on each node, enabling the final prediction results to better align with the actual situation. The three components of the multi-cycle modeling module have the same structure and operate independently. Each component processes historical data over different time spans. Specifically, the input of short-term components is a historical time series segment directly adjacent to the forecast period. The daily cycle component takes the data of the same time period in the past day as input. Meanwhile, the weekly cycle component uses the data of the past week with the same weekly attributes and time intervals. This independent processing method enables each module to focus on extracting the relevant temporal features without being disturbed by other modules. Although these components operate independently, the final prediction results are obtained through collaborative work. The outputs of these three components will be weighted and fused based on a parameter matrix. During this fusion process, the influence weights of different components on each node are different. These weights are learned from historical data and are designed to accurately reflect the degree of influence of each component on the prediction target.

Among them,

During the model training stage, the optimization algorithm Adam is adopted to continuously adjust the weight of each component to minimize the loss function. If the output of a certain component makes a significant contribution to the reduction of the loss function, the optimization algorithm will increase the corresponding weight of that component. Conversely, if the output of a certain component contributes very little to the reduction of loss, its weight will be reduced. This dynamic adjustment mechanism ensures that the model can adaptively assign appropriate importance to each multi-cycle modeling module, ultimately improving the accuracy of the prediction results.

The loss function used is the L1 loss (MAE). The advantage of MAE is that it is insensitive to outliers and does not cause the model to be over-adjusted due to these occasionally occurring abnormal traffic data. By using MAE as the loss function, the model can pay more attention to the overall distribution and general trends of the data, thereby maintaining stable performance in traffic data with noise and outliers.

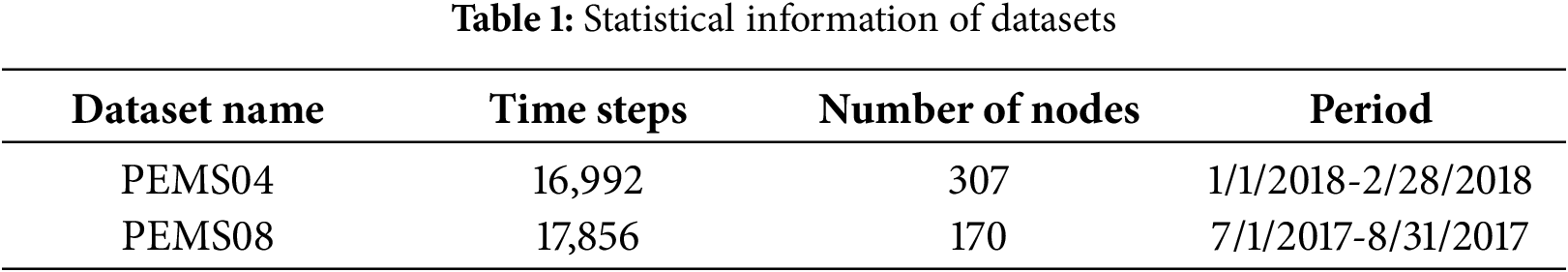

We evaluated the proposed model using the PEMS04 and PEMS08 datasets from the California highway traffic system. These datasets are sourced from the Caltrans Performance Measurement System (PeMS) [47], which collects data at 30-s intervals. They contain both traffic flow and sensor-based geographical data. By consolidating the traffic flow data every 5 min, each detector logs 12 entries per hour. Detailed statistics of these datasets are provided in Table 1.

we divide the data into a training set, a validation set, and a test set in chronological order at a ratio of 6:2:2. All experiments are conducted on a Linux server (CPU: 12 vCPUs Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8352V CPU @ 2.10GHz; GPU: 1 x RTX 4090 (24 GB x 1)). We configure the following hyperparameters: for graph convolution and residual convolution, 64 convolution kernels are utilized. The number of terms in the Chebyshev polynomial is set to

• HA [1]: A time series prediction model that forecasts subsequent values by calculating the average of data from the previous 12 time slices.

• ARIMA [3]: A classic model for time series prediction based on the analysis of autoregressive, differencing, and moving average patterns.

• VAR [5]: A multivariate time series model capable of capturing complex correlations among multiple variables.

• LSTM [30]: A variant model within Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) used for processing long sequences and overcoming the long-term dependency limitations of traditional RNNs.

• GRU [48]: A recurrent neural network model that simplifies the structure of traditional RNNs and is used for sequential data modeling.

• STGCN [15]: A spatio-temporal model that combines graph convolution with one-dimensional convolutional neural networks to process spatial and temporal data.

• ASTGCN [14]: A spatio-temporal graph convolutional network model that applies the attention mechanism in spatio-temporal convolution for analysis.

• InFormer [49]: An efficient Transformer-based model for long sequence time-series forecasting that improves computational efficiency through probabilistic attention mechanisms.

• AutoFormer [50]: An automatic Transformer architecture search framework that adaptively discovers optimal structures for time series forecasting tasks.

• FEDFormer [51]: A frequency-enhanced decomposed Transformer model that combines seasonal-trend decomposition with Fourier transform for improved time series prediction.

• STG-Mamba [37]: A spatio-temporal model integrating Mamba architecture, efficiently capturing spatial correlations and long-term temporal dependencies with computational efficiency.

The evaluation metrics used are: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). Lower values indicate better performance.

Here,

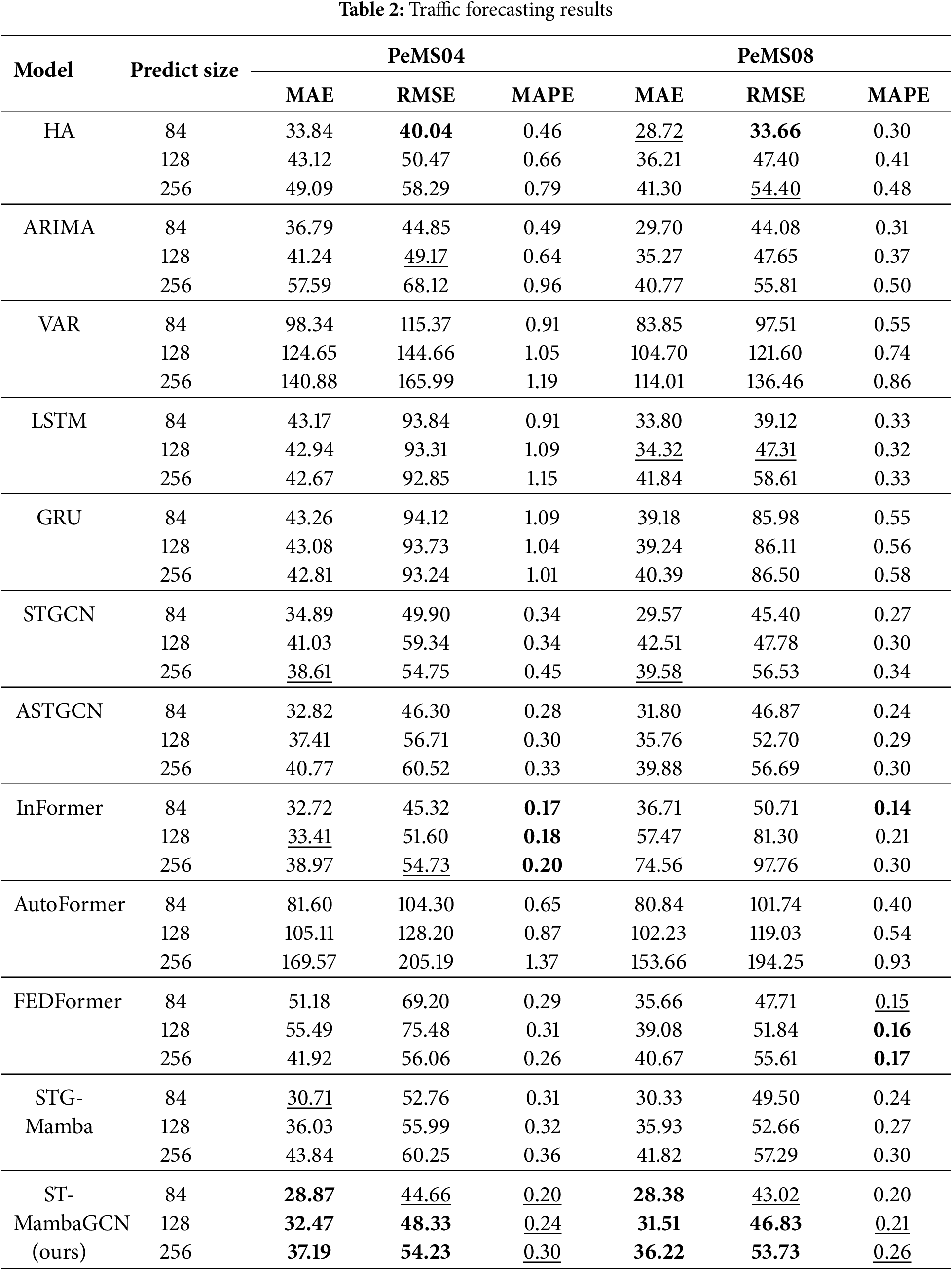

5.5 Analysis of Performance Indicators

As shown in Table 2, the optimal results are highlighted in bold, and the suboptimal results are underlined. Because some models have an early stopping mechanism, the training time is the average time spent on each epoch, while the inference time is the total inference time. Traditional statistical models have obvious shortcomings in long-term traffic flow prediction. In PEMS08, when the prediction length of VAR is 256, the MAE reaches 114.01 and the RMSE reaches 136.46. The decreased accuracy of the experimental results indicates that statistical models lack the ability to model complex patterns such as periodic fluctuations and sudden congestion. Machine learning methods such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) can handle some nonlinear relationships, but experimental data show that they also have limitations in long-term traffic flow prediction. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) can achieve suboptimal results in some experiments. In the STGCN model, when the prediction length is 256 time steps, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) is 54.75 on the PEMS04 dataset and 56.53 on the PEMS08 dataset, which indicates the effectiveness of GCNs in feature extraction. Some experiments on Transformer-based models have also achieved good results. For example, when the prediction length is short, InFormer has a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 32.72 (with an input size of 84) on the PEMS04 dataset and 36.71 on the PEMS08 dataset. However, the efficiency of these models decreases when processing long input sequences, making it difficult to meet the practical needs of long-term traffic flow prediction, which will be analyzed in detail in Section 5.6. On both datasets, the ST-MambaGCN model consistently achieves the lowest or near-lowest MAE, RMSE, and MAPE values. It ensures computational efficiency while achieving high-precision long-term traffic flow prediction.

Notably, despite the relatively high missing rate (3.182%) of the PeMS04 dataset, the ST-MambaGCN model maintained a highly competitive performance on MAE vs. RMSE indicators. Although the overall value is slightly higher than that of PEMS08, the fluctuation is not significant. Compared to traditional machine learning methods and some transformer models such as FEDFormer, its performance fluctuates more gently and shows excellent stability. This robust performance fully proves that the model is robust in the face of incomplete data. In real-world application scenarios, data integrity is often difficult to guarantee, so this feature is particularly important.

The model demonstrates excellent stability. On the PEMS08 dataset (with 170 nodes), even when the prediction length is extended to 256, it can still achieve excellent results, with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 36.22 and a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 0.26. On the PEMS04 dataset with 307 nodes, when the prediction length is increased to 256, it not only maintains stable performance but also outperforms many other models in terms of accuracy, highlighting its remarkable ability to make accurate predictions over a relatively long period.

By contrast, the performance of some models declines significantly as the prediction range expands, especially Autoformer. STG-Mamba, which incorporates Mamba, is also quite stable. Mamba ensures that it can make stable and accurate predictions across different time horizons.

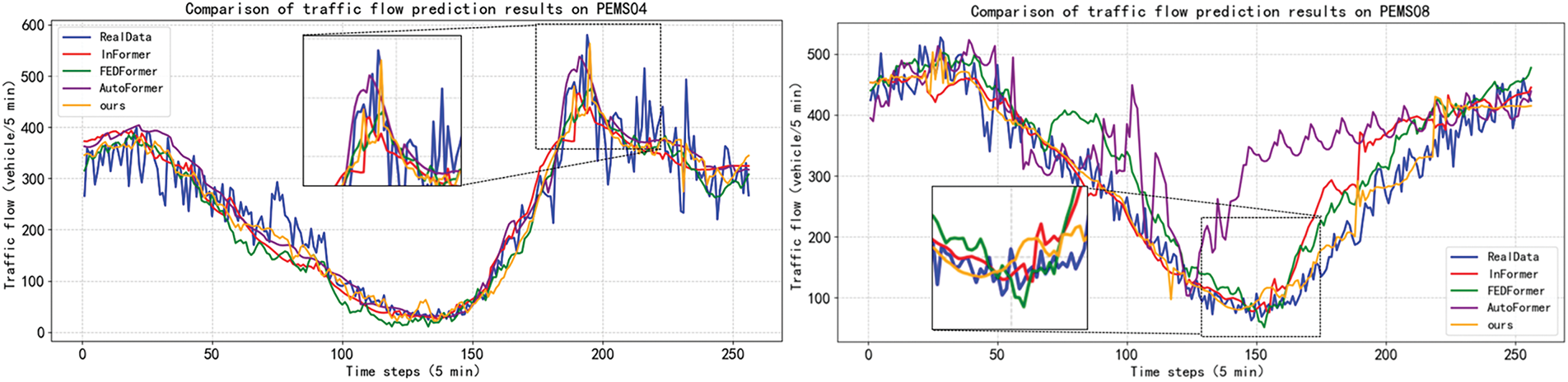

In addition, in order to more intuitively evaluate the predictive power of ST-MambaGCN, we visualized the prediction results of ST-MambaGCN with the prediction results of the main baseline. Specifically, we randomly selected nodes from the dataset and plotted curves for actual and forecasted traffic data over 256 time steps (21 h). As shown in Fig. 3, ST-MambaGCN captures the changing trend faster than the other two models when the traffic flow fluctuates suddenly. The general trend of traffic changes was successfully captured, thus proving its effectiveness.

Figure 3: Comparison of traffic flow prediction results

5.6 Analysis of Computational Costs

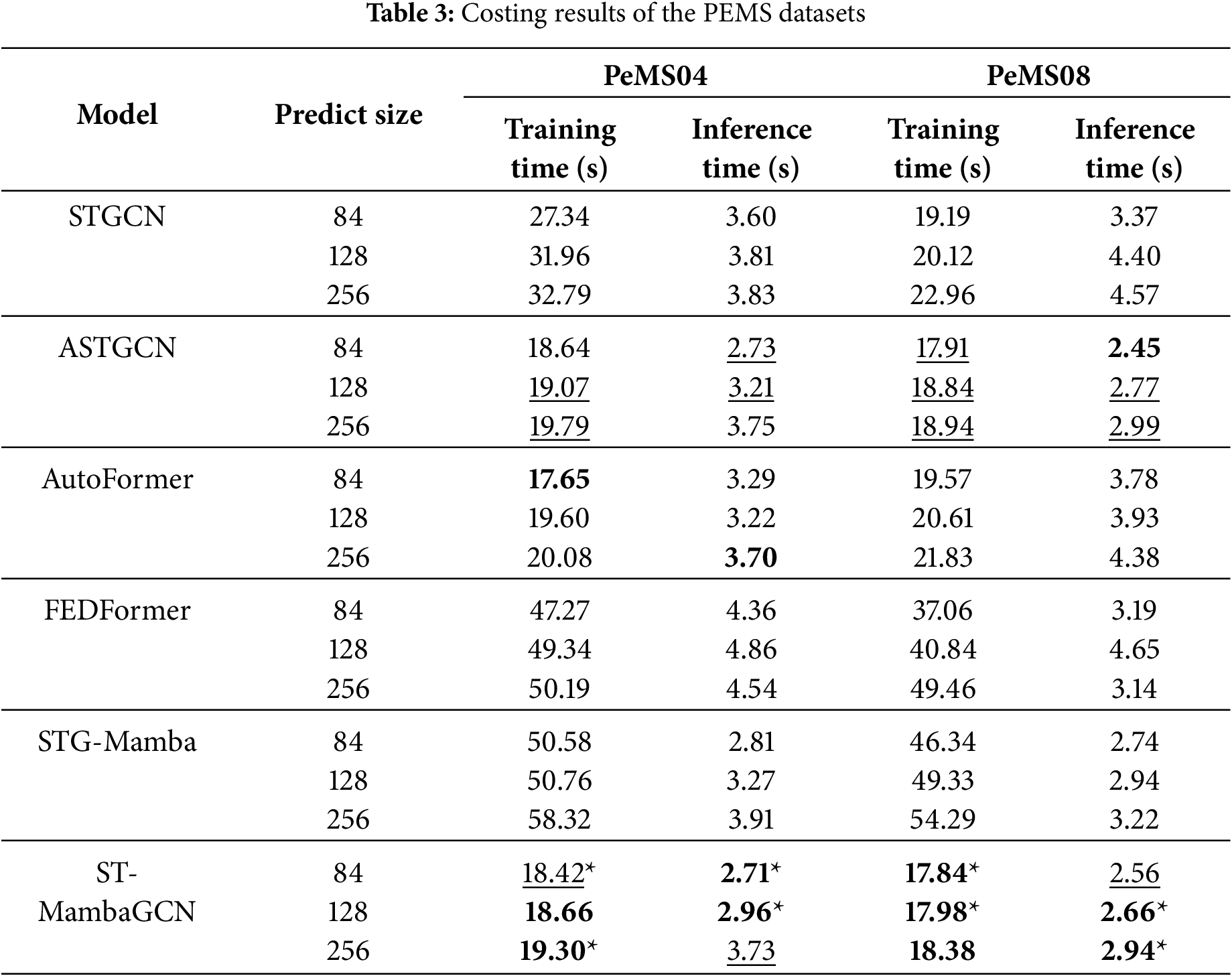

As shown in Table 3, the optimal results are highlighted in bold, and the suboptimal results are underlined. * indicates that through the paired

Although FEDFormer performs well in terms of performance, its relatively slow processing speed pose challenges in deployment. ASTGCN adopts a new graph attention mechanism to optimize modeling, when the prediction length is short, the training time is comparable to that of ST-MambaGCN. However, on datasets with a large number of nodes, the

It is worth noting that the inference time of the STG-Mamba model is superior to that of other Transformer models, which demonstrates the advantages of Mamba. However, the training process of STG-Mamba is relatively time-consuming, making it more suitable for deployment after completion of training. During actual deployment and application (i.e., the inference phase), it is faster and more lightweight than other Transformer-based models, and thus more suitable for use in resource-constrained environments.

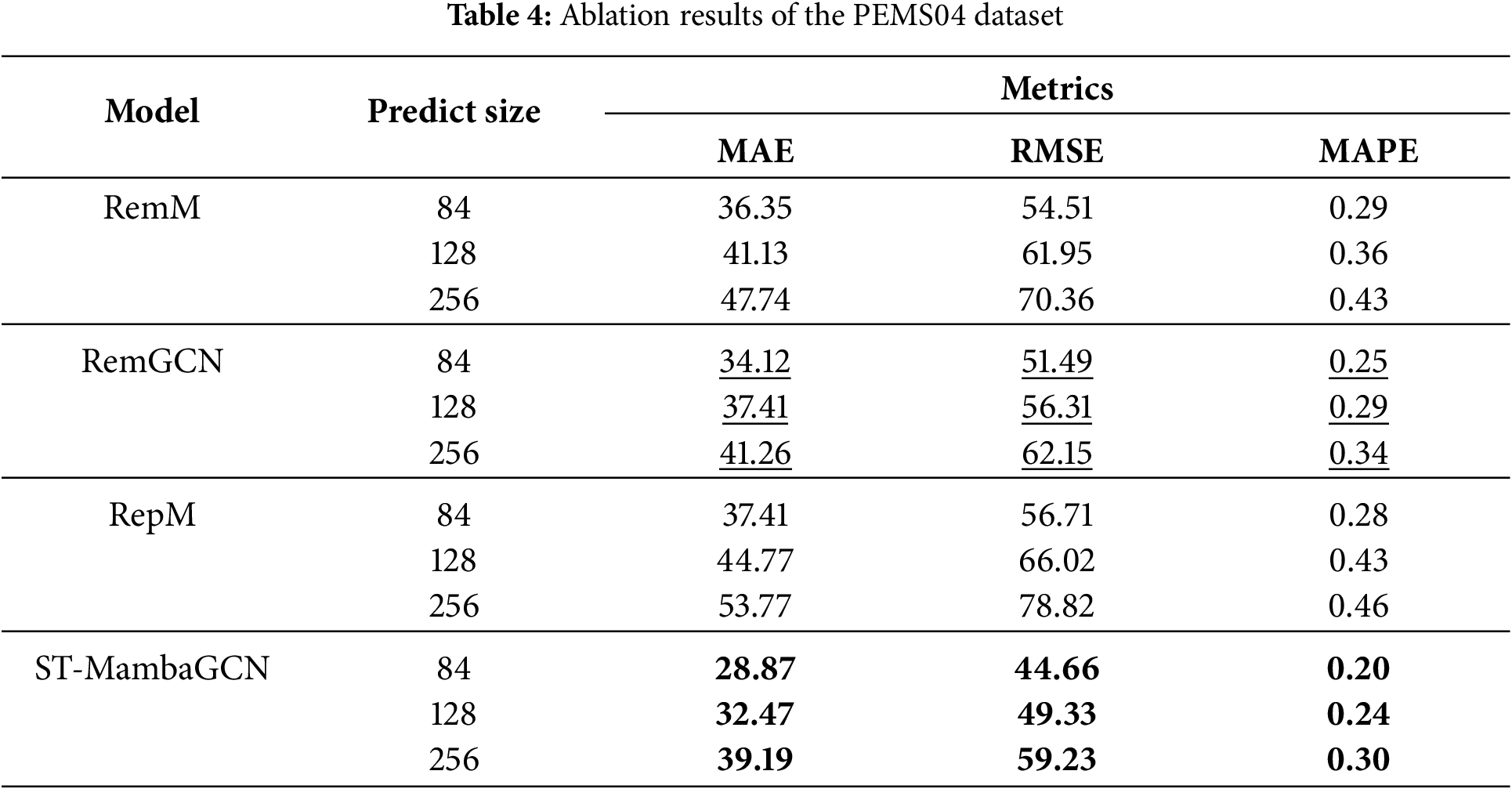

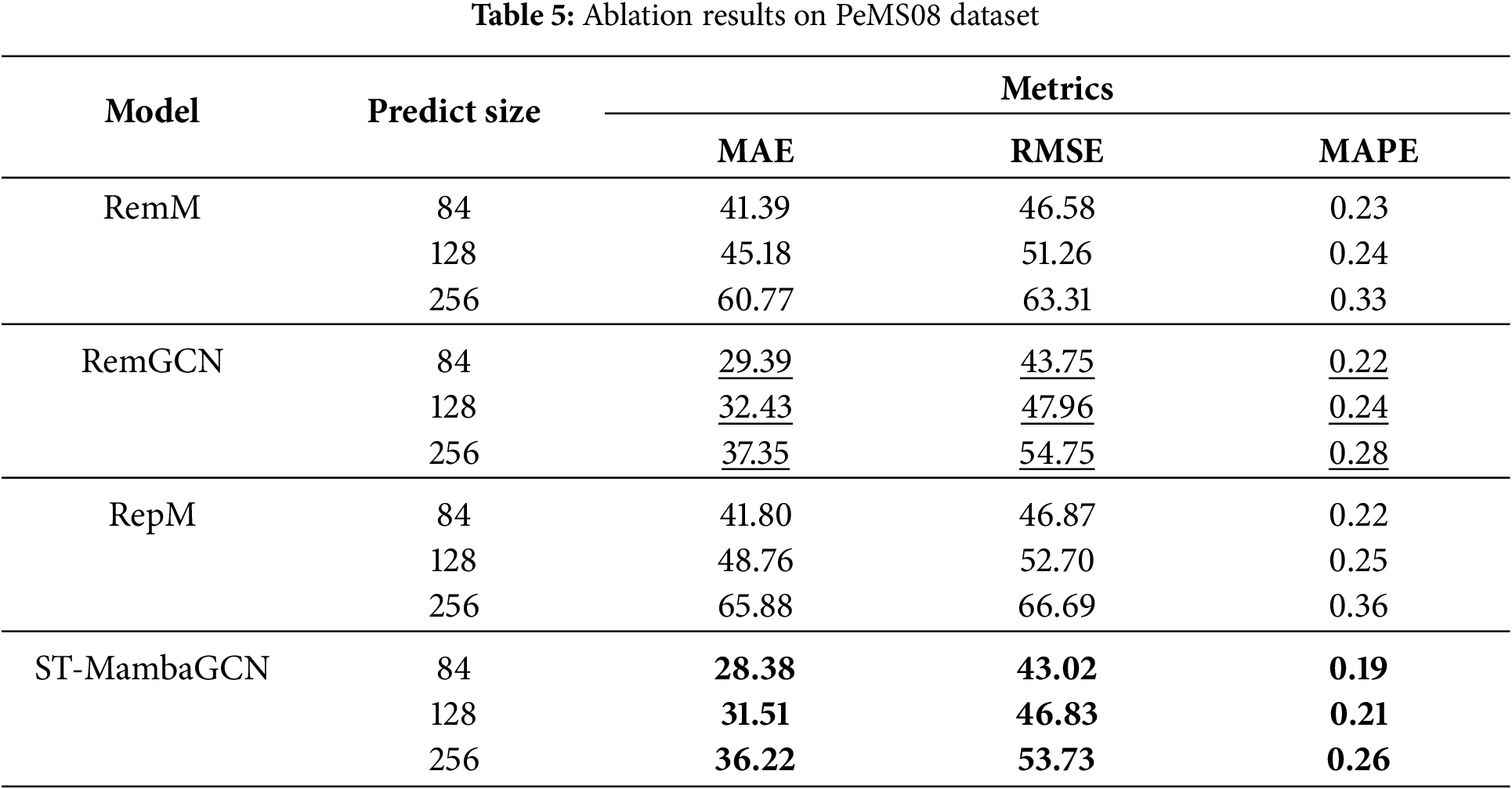

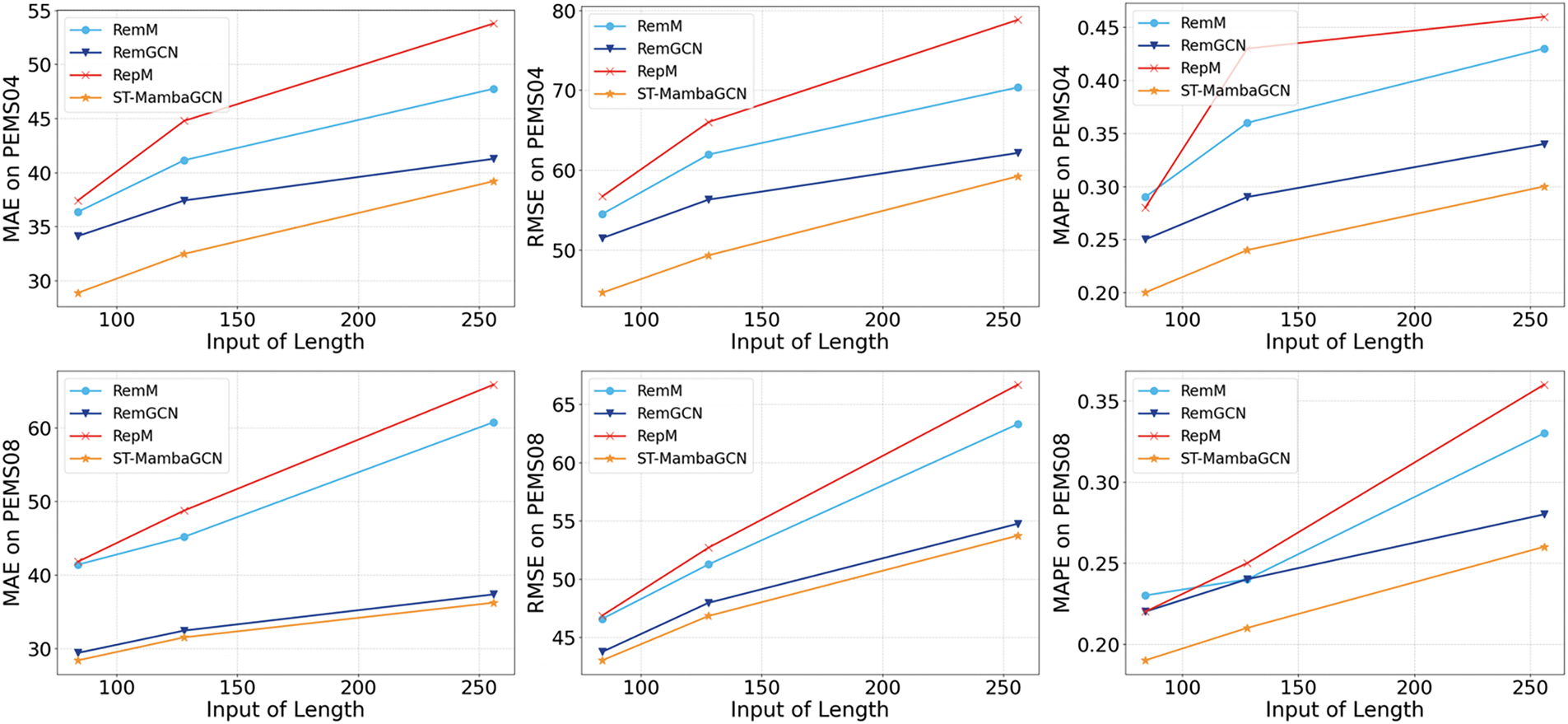

To assess the efficacy of each component within the proposed ST-MambaGCN model, we implemented the following alterations: RemM: In this variant, the Mamba block was entirely removed. RemGCN: Here, the spatial-temporal convolution block was eliminated. RepM: The Mamba block was substituted with a Transformer.

Our experiments on the PEMS datasets are detailed in Tables 4 and 5, Fig. 4. The optimal results are highlighted in bold, and the suboptimal results are underlined. On the PEMS04 dataset, RemM’s accuracy lagged behind ST-MambaGCN, highlighting the Mamba block’s pivotal role in enhancing prediction precision. In contrast, RepM showed reduced accuracy when compared with ST-MambaGCN, signaling Mamba’s superior performance over Transformers in traffic forecasting. Furthermore, ST-MambaGCN’s outperformance over RemGCN indicates that incorporating spatial relationships can significantly improve predictive accuracy.

Figure 4: Ablation result on the PEMS dataset

Consistent with PEMS04, PEMS08 results also favored ST-MambaGCN. RemM and RepM’s accuracies were significantly lower, reaffirming Mamba’s edge in traffic flow predictions. When predicting 256 time steps on the PeMS08 dataset, ST-MambaGCN achieves an MAE of 36.22, while RemM (with the Mamba block removed) yields an MAE of 60.77, and the simplified model with the GCN module removed results in an MAE of 37.35. Both modules contribute significantly to the model’s performance, further reducing prediction errors in long-term forecasting. Collectively, these results substantiate ST-MambaGCN’s superior performance over its counterparts, validating the efficacy of each component within our proposed framework.

Meanwhile, we can observe that RemGCN generally performs second-best. This is because even though the graph convolution block is removed, the model still retains the Mamba block, which can effectively capture temporal dependencies. Temporal information plays a vital role in traffic flow data, as traffic patterns often show certain periodicity and continuity over time. Even without explicitly considering spatial relationships, the Mamba block can learn the sequential characteristics of traffic data in different time steps. Additionally, the basic structure of the model may still have some inherent capabilities to process data in a way that captures part of the relevant information, allowing the RemGCN to achieve relatively good results compared to RemM and RepM.

Notably, RemM demonstrates better performance than RepM. One possible reason is that without the Mamba block, RemM simplifies the model structure, reducing the complexity that might lead to overfitting. In contrast, although RepM replaces the Mamba block with a Transformer, the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism, while powerful in handling long-range dependencies in some scenarios, may not be as well-suited to the specific characteristics of traffic flow data. Traffic data often has local temporal correlations that are more effectively captured by the relatively simpler structure of RemM. Moreover, the computational cost of RemM is relatively lower, enabling it to converge faster during training and potentially leading to more stable predictions.

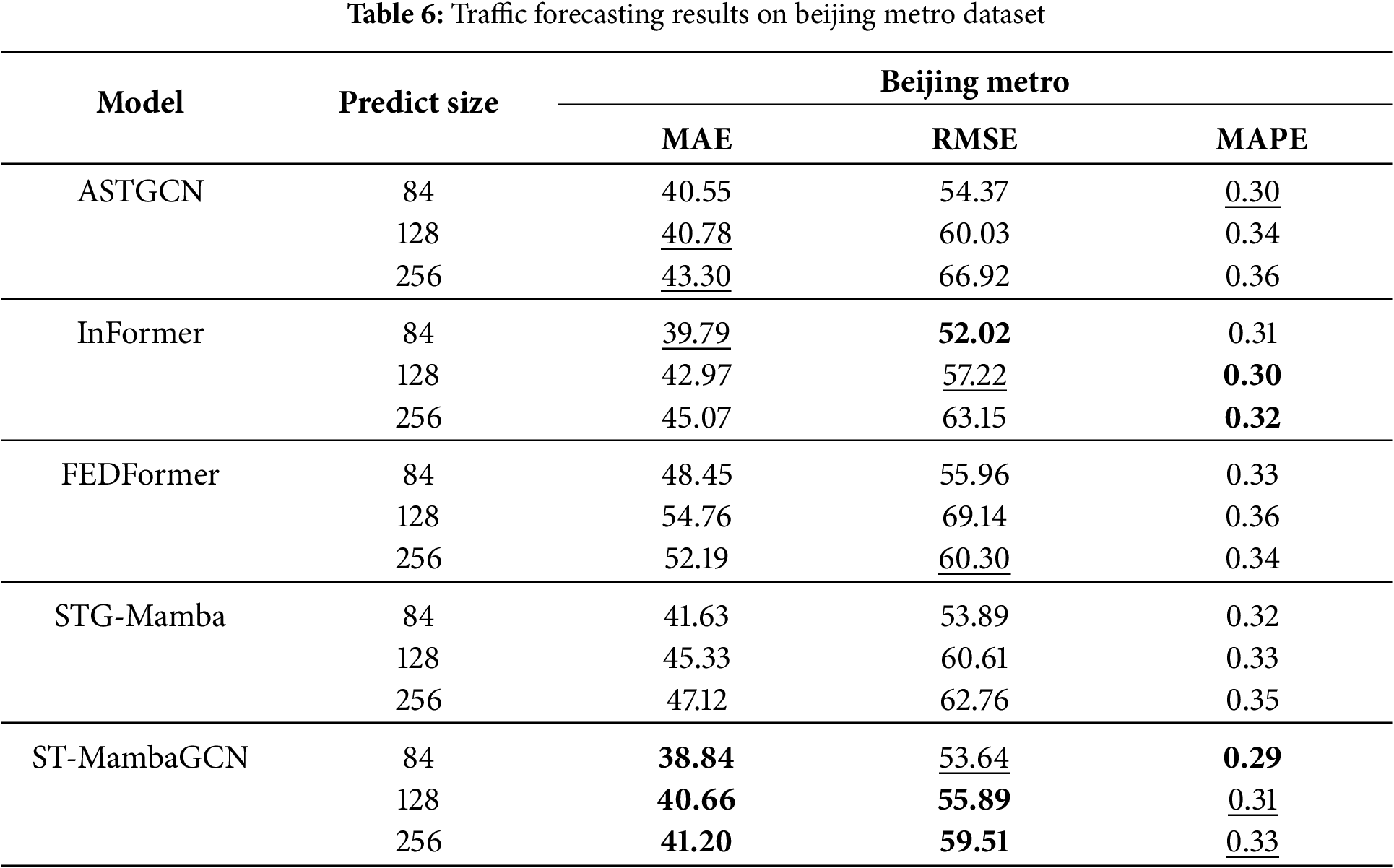

5.8 Exploration of Universality

To explore the universality of the model, we used a set of data of different types and from different regions—Beijing Metro traffic data in China [52]. It is a larger scale dataset with more nodes. As shown in Table 6, the optimal results are highlighted in bold, and the suboptimal results are underlined. The ST-MambaGCN model maintains the same excellent performance as with PEMS data, demonstrating its applicability to a wide range of scenarios.

In this study, we present a novel deep-learning framework, ST-MambaGCN, tailored for traffic prediction. The motivation behind this framework is to address the limitations of current spatio-temporal models in long-term traffic flow forecasting. To achieve this, in the spatial domain, the ST-MambaGCN model capitalizes on Chebyshev convolution to capture the intricate spatial relationships between nodes in the road network. This convolution method allows the model to understand how different parts of the network interact with each other. In the temporal domain, the Mamba block plays a crucial role. It delves into historical traffic data to extract meaningful temporal dependencies, enabling the model to recognize patterns over time.

By integrating the merits of GCN and Mamba, the developed ST-MambaGCN model can handle complex data dependencies with low computational complexity and notably enhance prediction accuracy. When benchmarked against several state-of-the-art baseline methods on public datasets, it demonstrates superior traffic prediction performance, marking a substantial advancement in traffic prediction capabilities.

However, our research is not without limitations. Real-world traffic is highly dynamic, influenced by factors such as traffic accidents, traffic control measures, and special events. These factors cause spatial dependencies in the road network to change over time. Currently, the ability of GCN to capture spatial relationships is based on a static graph, which falls short in dealing with these dynamic changes.

Based on the existing research conclusions of the ST-MambaGCN model and the dynamic adaptive graph, future work could further advance dynamic spatial dependency modeling and enhance practical applicability. On one hand, addressing the limitations of static graph modeling in GCN highlighted in the document, real-time traffic incidents (e.g., accidents, temporary controls), meteorological data (such as rainfall, ice, and snow), and vehicle trajectory data could be integrated into the construction of dynamically adaptive graphs. By designing a multi-dimensional “flow-event-environment” driven adjacency matrix update mechanism, the graph topology can adapt dynamically to real-time scenarios, thereby resolving the documented issue of static graphs’ inability to cope with dynamic changes in road networks. Furthermore, practical deployment scenarios such as real-time traffic signal control and emergency evacuation route planning could be explored. Through lightweight adaptations to ensure compatibility with edge computing devices, the core objective of “enhancing urban traffic management and sustainability” can be further advanced.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank everyone who helped during the research and preparation of the article.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 62402046; and the Beijing Forestry University Science and Technology Innovation Project under Grant No. BLX202358.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Guangyu Huo; methodology, Chang Su, Guangyu Huo; software, Chang Su; validation, Chang Su; formal analysis, Xiaoyu Zhang; data curation, Chang Su; writing—original draft preparation, Chang Su, Guangyu Huo; writing—review and editing, Guangyu Huo, Chang Su, Lizhong Zhang; visualization, Chang Su; supervision, Guangyu Huo, Xiaoyu Zhang, Xiaohui Cui; funding acquisition, Guangyu Huo, Xiaohui Cui. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets are publicly available. The PEMS dataset from https://paperswithcode.com/task/traffic-prediction (accessed on 10 August 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A: These are the notation of system models and their descriptions mentioned in the method section for the convenience of readers’ reading.

References

1. Pan B, Demiryurek U, Shahabi C. Utilizing real-world transportation data for accurate traffic prediction. In: 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Data Mining; 2012 Dec 10–13; Brussels, Belgium. p. 595–604. [Google Scholar]

2. Sun Y, Zhang G, Yin H. Passenger flow prediction of subway transfer stations based on nonparametric regression model. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc. 2014;2014:397154. doi:10.1155/2014/397154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Williams BM. Multivariate vehicular traffic flow prediction: evaluation of ARIMAX modeling. Transport Res Record. 2001;1776(1):194–200. doi:10.3141/1776-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Williams BM, Durvasula PK, Brown DE. Urban freeway traffic flow prediction: application of seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average and exponential smoothing models. Transport Res Record. 1998;1644(1):132–41. doi:10.3141/1644-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zivot E, Wang J. Vector autoregressive models for multivariate time series. In: Modeling financial time series with S-Plus®. Vol. 1. New York, NY, USA: Springer New York; 2003. p. 369–413. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21763-5_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang L, Chen J, Wang W, Song R, Zhang Z, Yang G. Review of time series traffic forecasting methods. In: 2022 4th International Conference on Control and Robotics (ICCR); 2022 Dec 2–4; Guangzhou, China. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

7. Awad M, Khanna R. Support vector regression. In: Efficient learning machines. Berkeley, CA, USA: Apress; 2015. p. 67–80. doi:10.1007/978-1-4302-5990-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lint JV, Hinsbergen CV. Short-term traffic and travel time prediction models. Artifi Intell Appl Critic Transport Issues. 2012;222(1):22–41. [Google Scholar]

9. Bai J, Zhu J, Song Y, Zhao L, Hou Z, Du R, et al. A3T-GCN: attention temporal graph convolutional network for traffic forecasting. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. 2021;10(7):485. doi:10.3390/ijgi10070485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen L, Zheng L, Yang J, Xia D, Liu W. Short-term traffic flow prediction: from the perspective of traffic flow decomposition. Neurocomputing. 2020;413(1):444–56. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang Z, Li M, Lin X, Wang Y, He F. Multistep speed prediction on traffic networks: a deep learning approach considering spatio-temporal dependencies. Transport Rese Part C Emerg Technol. 2019;105(1):297–322. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2019.05.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hoffmann J, Borgeaud S, Mensch A, Buchatskaya E, Cai T, Rutherford E, et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv:2203.15556. 2022. [Google Scholar]

13. Gu A, Dao T. Mamba: linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv:2312.00752. 2023. [Google Scholar]

14. Guo S, Lin Y, Feng N, Song C, Wan H. Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow forecasting. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2019;33(1):922–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.3301922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Song C, Lin Y, Guo S, Wan H. Spatial-temporal synchronous graph convolutional networks: a New framework for spatial-temporal network data forecasting. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(1):914–21. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang S, Wu Q, Wang Y, Zhou Z. MSTDFGRN: a multi-view spatio-temporal dynamic fusion graph recurrent network for traffic flow prediction. Comput Elect Engi. 2025;123(2):110046. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.110046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yang S, Wu Q, Li Z, Wang K. PSTCGCN: principal spatio-temporal causal graph convolutional network for traffic flow prediction. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(20):14751–64. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10591-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang S, Wu Q. SDSINet: a spatiotemporal dual-scale interaction network for traffic prediction. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;173(11):112892. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.112892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zheng C, Fan X, Wang C, Qi J. GMAN: a graph multi-attention network for traffic prediction. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(1):1234–41. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kong X, Wang K, Hou M, Xia F, Karmakar G, Li J. Exploring human mobility for multi-pattern passenger prediction: a graph learning framework. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2022;23(9):16148–60. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3148116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kong X, Shen Z, Wang K, Shen G, Fu Y. Exploring bus stop mobility pattern: a multi-pattern deep learning prediction framework. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2024;25(7):6604–16. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3345872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhou Z, Ding J, Liu Y, Jin D, Li Y. Towards generative modeling of urban flow through knowledge-enhanced denoising diffusion. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. SIGSPATIAL ’23; 2023 Nov 13–16; Hamburg, Germany. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

23. Li C, Lai PY, Zhou YX, Wang CD. Temporal hierarchical graph attention network for traffic prediction with prompt learning. In: 2024 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC); 2024 May 27–31; Ayia Napa, Cyprus. p. 1460–5. doi:10.1109/iwcmc61514.2024.10592462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang D, Wang P, Ding L, Wang X, He J. Spatio-temporal contrastive learning-based adaptive graph augmentation for traffic flow prediction. IEEE Trans Intell Trans Syst. 2025;26(1):1304–18. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3487982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li Z, Wang T, Zou G, Wang R, Li Y. Physics-informed deep operator network for traffic state estimation. arXiv:2508.12593. 2025. [Google Scholar]

26. Rahmani S, Baghbani A, Bouguila N, Patterson Z. Graph neural networks for intelligent transportation systems: a survey. IEEE Trans Intell Trans Syst. 2023;24(8):8846–85. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3257759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Feng T, Rasouli S, Wong M. ST-DAGCN: a spatiotemporal dual adaptive graph convolutional network model for traffic prediction. Neurocomputing. 2024;550(1):494–505. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu Y, Feng T, Rasouli S, Wong M. Linear attention based spatiotemporal multi-graph GCN for traffic flow prediction. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12345. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93179-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ma J, Zhao J, Hou Y. Spatial—temporal transformer networks for traffic flow forecasting using a pre-trained language model. Sensors. 2024;24(17):5502. doi:10.3390/s24175502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:654. [Google Scholar]

31. Ying C, Cai T, Luo S, Zheng S, Ke G, He D, et al. Do transformers really perform bad for graph representation? arXiv:2106.05234. 2021. [Google Scholar]

32. Li H, Wang W, Wang M, Tan H, Lan L, Luo Z, et al. STFormer: spatial-temporal-aware transformer for video instance segmentation. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(7):12910–24. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2024.3455551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Schuster M, Paliwal KK. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans Sig Process. 1997;45(11):2673–81. doi:10.1109/78.650093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Patro BN, Agneeswaran VS. Mamba-360: survey of state space models as Transformer alternative for long sequence modeling: methods, applications, and challenges. arXiv:2404.16112. 2024. [Google Scholar]

35. Xu X, Liang Y, Huang B, Lan Z, Shu K. Integrating mamba and transformer for long-short range time series forecasting. arXiv:2404.14757. 2024. [Google Scholar]

36. Ahamed MA, Cheng Q. TimeMachine: a time series is worth 4 mambas for long-term forecasting. In: ECAI 2024: 27th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Including 13th Conference on Prestigious Applications of Intelligent Systems. Santiago de Compostela, Spain: IOS Press; 2024. Vol. 392(1). p. 168–95. [Google Scholar]

37. Li L, Wang H, Zhang W, Coster A. STG-mamba: spatial-temporal graph learning via selective state space model. arXiv:2403.12418. 2024. [Google Scholar]

38. Zhu L, Liao B, Zhang Q, Wang X, Liu W, Wang X. Vision Mamba: efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. In: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML’24); 2024 Jul 21–27; Vienna, Austria. Vol. 235. p. 62429–42. [Google Scholar]

39. Yan JN, Gu J, Rush AM. Diffusion models without attention. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 8239–49. [Google Scholar]

40. Xu Z. RankMamba, benchmarking mamba’s document ranking performance in the era of transformers. arXiv:2403.18276. 2024. [Google Scholar]

41. Pióro M, Ciebera K, Król K, Ludziejewski J, Jaszczur S. Moe mamba: efficient selective state space models with mixture of experts. arXiv:2401.04081. 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Grazzi R, Siems J, Schrodi S, Brox T, Hutter F. Is mamba capable of in-context learning? arXiv:2402.03170. 2024. [Google Scholar]

43. Wang Z, Kong F, Feng S, Wang M, Yang X, Zhao H, et al. Is Mamba effective for time series forecasting? Neurocomputing. 2025;619(1):129178. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Meng G, Cai Z, Tu J, Wang Y, Li C, Huang Y, et al. PCMamba: physics-informed cross-modal state space model for dual-camera compressive hyperspectral imaging. arXiv:2505.16373. 2025. [Google Scholar]

45. Elfwing S, Uchibe E, Doya K. Sigmoid-weighted linear units for neural network function approximation in reinforcement learning. Neural Netw. 2018;107(1):3–11. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2017.12.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Shuman DI, Narang SK, Frossard P, Ortega A, Vandergheynst P. The emerging field of signal processing on graphs: extending high-dimensional data analysis to networks and other irregular domains. IEEE Signal Process Magaz. 2013;30(3):83–98. doi:10.1109/msp.2012.2235192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Chen C, Petty K, Skabardonis A, Varaiya P, Jia Z. Freeway performance measurement system: mining loop detector data. Transp Res Rec. 2001;1748(1):96–102. doi:10.3141/1748-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Dauphin YN, Fan A, Auli M, Grangier D. Language modeling with gated convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2024 Aug 6–11; Sydney, Australia. Vol. 70. p.933–941. [Google Scholar]

49. Zhou H, Zhang S, Peng J, Zhang S, Li J, Xiong H, et al. Informer: beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(12):11106–15. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i12.17325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wu H, Xu J, Wang J, Long M. Autoformer: decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. In: Ranzato M, Beygelzimer A, Dauphin Y, Liang PS, Vaughan JW, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 34. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2021. p. 22419–30. [Google Scholar]

51. Zhou T, Ma Z, Wen Q, Wang X, Sun L, Jin R. FEDformer: frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. 1 p. [Google Scholar]

52. Huo G, Zhang Y, Wang B, Gao J, Hu Y, Yin B. Hierarchical spatio–temporal graph convolutional networks and transformer network for traffic flow forecasting. IEEE Tran Intell Trans Syst. 2023;24(4):3855–67. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3234512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools