Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Overcoming Dynamic Connectivity in Internet of Vehicles: A DAG Lattice Blockchain with Reputation-Based Incentive

1 Inner Mongolia Key Laboratory of Beijiang Cyberspace Security, College of Intelligent Science and Technology, Inner Mongolia University of Technology, Hohhot, 010051, China

2 School of Computer and Control Engineering, Yantai University, Yantai, 264000, China

3 College of Computer Science, Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot, 010021, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenhan Hou. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072384

Received 26 August 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Blockchain offers a promising solution to the security challenges faced by the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). However, due to the dynamic connectivity of IoV, blockchain based on a single-chain structure or Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) structure often suffer from performance limitations. The DAG lattice structure is a novel blockchain model in which each node maintains its own account chain, and only the node itself is allowed to update it. This feature makes the DAG lattice structure particularly suitable for addressing the challenges in dynamically connected IoV environment. In this paper, we propose a blockchain architecture based on the DAG lattice structure, specifically designed for dynamically connected IoV. In the proposed system, nodes must obtain authorization from a trusted authority before joining, forming a permissioned blockchain. Each node is assigned an individual account chain, allowing vehicles with limited storage capacity to participate in the blockchain by storing transactions only from nearby vehicles’ account chains. Every transmitted message is treated as a transaction and added to the blockchain, enabling more efficient data transmission in a dynamic network environment. A reputation-based incentive mechanism is introduced to encourage nodes to behave normally. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed architecture achieves better performance compared with traditional single-chain and DAG-based approaches in terms of average transmission delay and storage cost.Keywords

The blockchain is a distributed technology that can effectively address issues such as the vulnerability of centralized architecture, privacy information leakage, and lack of trust between entities in the traditional Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment. At present, there have been many studies on blockchain in the IoV, mainly including authentication mechanism [1,2], privacy protection [3,4], trust management [5,6], certificate management [7,8], data sharing [9,10], etc.

In the IoV, the mobility of vehicles leads to high dynamicity, which causes network splits and merging [11]. After network splits, multiple disconnected subnets are formed. When network merging, these disconnected subnets will again form a connected network. Therefore, the connectivity of the network continuously changes in the IoV, and there are no stable routes between nodes. These characteristics of IoV lead to dynamic connectivity issues, which significantly affects the performance of blockchain systems in the IoV. However, blockchain is a decentralized technology that requires consistency in storage among all participating nodes. Currently, the blockchain storage structures used in the IoV mainly include the single-chain structure and the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) structure. These two kinds of storage structures need the ledger of nodes to be consistent all the time, which is difficult to achieve this consistency in a dynamically connected IoV.

The IoV applications mainly rely on interactions between nodes and surrounding nodes. For each node, the focus is more on the transactions generated by nearby vehicles, while transactions generated by nodes outside the communication range do not need to be acquired in real-time. This characteristic allows the consideration of a new blockchain structure to meet the demands.

The DAG lattice structure [12,13] is developed from the DAG structure. In the DAG lattice structure, each node has its own account chain, and only the node itself can update its account chain. Transactions from different accounts can reach a consensus parallelly. When two nodes interact, the transaction is added to their respective account chains, without affecting the account chains of other nodes. In the DAG lattice structure, even if transactions are not synchronized in real-time to all nodes in the blockchain network, they will not impact other nodes’ processing of transactions. This characteristic perfectly aligns with the local clustering feature in dynamically connected IoV. Moreover, the DAG lattice structure also performs well in terms of transactions per second (TPS). Dong et al. conducted performance evaluations on three popular DAG implementations (IOTA [14], Byteball [15], and Nano) through experiments. The results showed that the Nano system, based on the DAG lattice structure, consistently achieved higher TPS than the other two implementations under varying transaction generation rates [16].

Therefore, this paper adopts a DAG lattice structure to address the issues caused by dynamic connectivity in the IoV, and proposes a security architecture based on DAG lattice blockchain, referred to as DAGL-IoV. In this architecture, all the ledger information is stored in the roadside units (RSUs), while the moving vehicles only need to store transaction information from nearby vehicles. This approach avoids the issue of being unable to synchronize transactions due to network splits, while also better aligning with the characteristics of the IoV. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• This paper proposes a security architecture for the IoV based on the DAG lattice blockchain. In this architecture, an account chain is created for each node, and each transmitted message is added as a transaction to the blockchain, ensuring better performance in the dynamic IoV.

• A reputation-based incentive mechanism is introduced, drawing from the slow-start and congestion-avoidance ideas in Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) congestion control, to update the reputation scores of nodes and incentivize nodes to behave normally in the blockchain.

• Experimental results demonstrate that DAGL-IoV outperforms solutions based on single-chain and DAG structures in terms of average transmission delay and storage cost.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the related works; Section 3 provides a detailed design of the DAG lattice-based secure IoV architecture; Section 4 describes the proposed incentive mechanism. Section 5 describes potential malicious attack scenarios within the architecture and analyzes how to counter these attacks; Section 6 validates the performance of the architecture; and Section 7 concludes the paper.

Many studies have applied blockchain technology in the IoV. In these studies, the blockchain storage structures include both the single-chain structure and the DAG structure.

The single-chain structure is the earliest structure used in the Bitcoin system proposed by Nakamoto [17], where transactions within each block are organized through a Merkle tree. Islam et al. [18] proposed a lightweight blockchain architecture for knowledge sharing, deploying smart contracts within the blockchain to enable automated knowledge sharing, thereby enhancing trustworthiness, verifiability, and non-repudiation in communication processes. Cui et al. [19] used consortium blockchain to provide a trusted environment for secure and efficient data sharing between vehicles. They deployed the blockchain on moving vehicles, enabling data sharing without the participation of RSU. Xu et al. [20] introduced a new framework for secure intelligent vehicle data sharing, where each vehicle can connect to a blockchain platform based on biometric recognition. Kulathunge and Dayarathna [21] proposed a blockchain-based communication framework that stores data in a Hyperledger blockchain. To improve performance and reduce computational costs in message processing within IoV, Zang et al. [22] proposed an efficient vehicle safety communication authentication scheme based on blockchain, introducing smart contracts to restrict malicious vehicles from entering the network.

To improve the TPS of blockchain in IoV environments, many researchers have considered using the DAG structure to store blockchain data. Chai et al. [23] proposed a framework for intelligent vehicle knowledge sharing based on adaptive asynchronous distributed learning and blockchain. In this framework, a lightweight Tip selection algorithm was designed for the DAG. Li et al. [24] proposed a decentralized solution based on the DAG structure to address the peer disclosure issue in social IoV. In this solution, a mutual supervision algorithm was designed to deal with untrusted vehicles. Fu et al. [25] designed a blockchain-based architecture for IoV transactions, which integrates the DAG blockchain to record data and bandwidth transactions between vehicles and RSUs, with vehicles and RSUs jointly maintaining the blockchain ledger. Jiang et al. [26] proposed a privacy-preserving computing scheme based on homomorphic encryption and blockchain, where the DAG data structure replaced the chain structure to allow parallel processing and reduce transmission confirmation delay. Liu et al. [27] proposed a reputation management system based on hierarchical blockchain, where vehicles and RSUs jointly maintain and generate local DAG ledgers, utilizing the DAG blockchain structure to design reputation value evaluation.

When a single-chain structure is applied in the IoV, network splits can prevent blocks that reach consensus in separate subnets from being synchronized in real-time across other connected subnets. This can result in new blocks being generated simultaneously in different subnets, causing frequent forks and reducing TPS, which clearly fails to meet the real-time requirements of the IoV. The DAG structure allows the blockchain to fork, enabling parallel consensus. However, when the DAG structure is applied in the IoV, there remains the issue that nodes cannot maintain a unified DAG ledger. When the network splits, the local DAG ledger maintained in a connected subnet cannot be synchronized to other connected subnets in real-time. When the network merges again, conflicts may arise in the DAG structure, making it impossible to merge each local DAG ledger into a global unified DAG ledger. Therefore, maintaining a consistent blockchain ledger between moving nodes is not feasible.

In current research, there is limited exploration of the impact of mobility on blockchain performance, whether in single-chain or DAG-based blockchain systems.

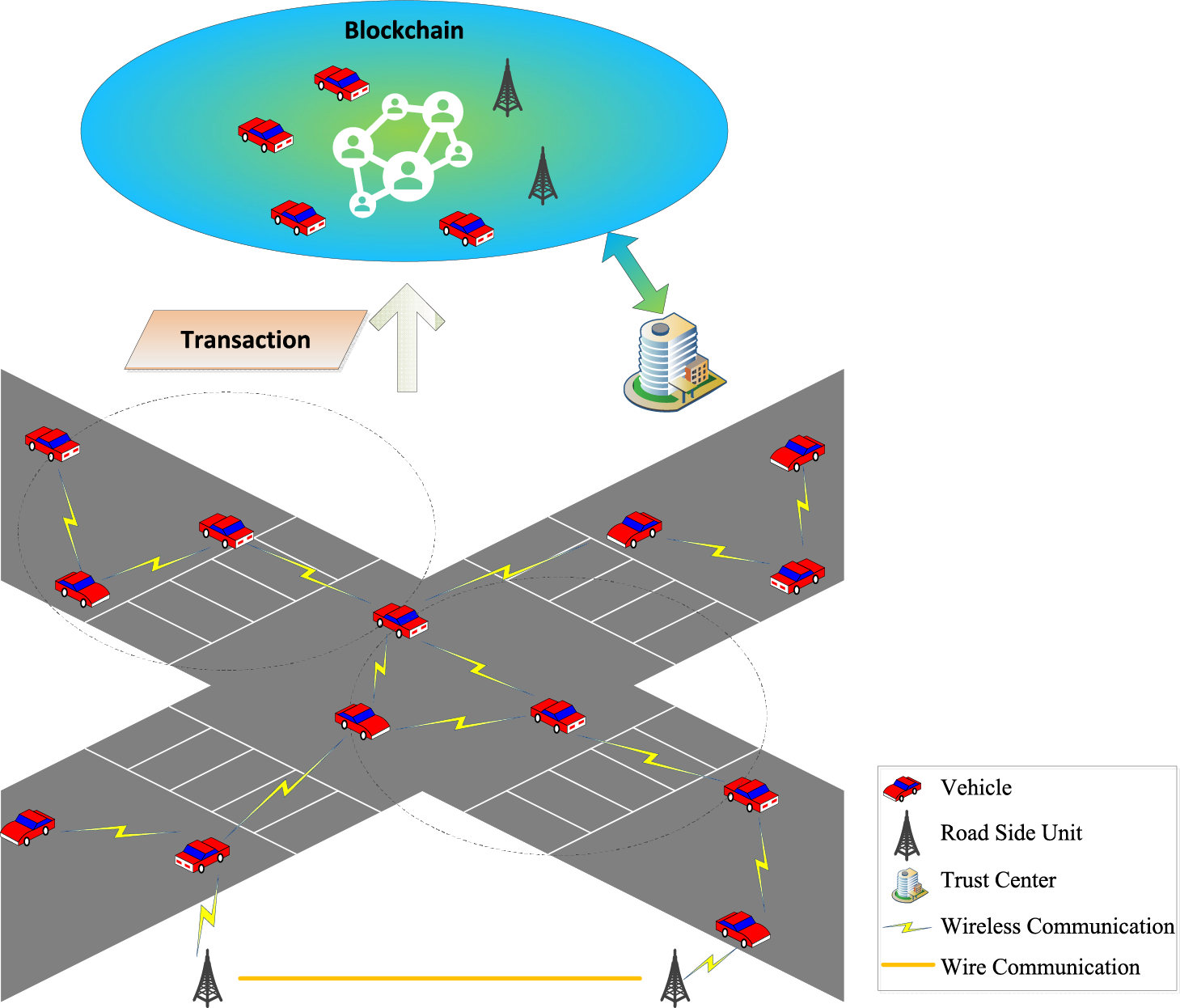

In the proposed system, both vehicles and RSUs jointly constitute the blockchain network. This architecture not only capitalizes on the stable connectivity and rapid data dissemination capabilities of RSUs but also extends network coverage to areas with limited RSU deployment through vehicular participation. Wireless communication between vehicles, as well as between vehicles and RSUs, is realized using technologies such as Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC) and Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything (C-V2X). In contrast, communication among RSUs is conducted via wired links, wherein the Gossip protocol is employed to ensure the consistency and synchronization of the distributed ledger. The overall system model is depicted in Fig. 1, where the main entities include the Trust Center (TC), vehicles, and RSUs.

• TC: Serving as a fully trusted authority, the TC is responsible for generating public-private key pairs for both vehicles and RSUs. It further assists RSUs in the verification of account information and credentials generated by blockchain nodes, thereby ensuring the integrity and authenticity of network identities.

• Vehicles: As lightweight nodes with limited storage, vehicles maintain a pruned version of the blockchain to reduce computational and storage overhead. Depending on their storage capacity, the system considers three storage methods: 1) For nodes with larger storage, they store all transactions generated by surrounding nodes; 2) When storage space is insufficient, they send a pruning request to save the pruned transactions; 3) To enable vehicles to validate transactions and participate in consensus, they store only the minimum number of transactions necessary for blockchain operation, including the latest transaction information for the vehicle itself and other nearby vehicles. To enhance blockchain security, vehicles are encouraged to store more transactions and only prune locally stored transactions when storage space is insufficient.

• RSUs: As full nodes with substantial storage capacity and computing power, RSUs are capable of performing all blockchain-related functions, including data storage, transaction validation, and block generation. To prevent data loss, RSUs must store the entire blockchain data to ensure data integrity. Newly added nodes can retrieve the entire blockchain data from RSUs, eliminating issues related to guiding new nodes. Transactions that reach consensus on vehicles must be quickly synchronized with the RSUs. To encourage nodes to maintain normal behavior, a reputation-based incentive mechanism is introduced, where each node’s reputation score is maintained by the RSUs.

Figure 1: The system model

Due to the high dynamics of the IoV, a fully decentralized public blockchain is not suitable for large-scale IoV applications [28]. Moreover, many applications in IoV are related to road traffic safety, and allowing any node to freely join the blockchain network would inevitably increase the risk of IoV attacks. The permissioned blockchain [29] requires institutional authorization to join the blockchain and can control the addition of unrelated or malicious entities, making it highly effective in privacy or security-sensitive scenarios. Therefore, this architecture constructs a permissioned blockchain on both vehicles and RSUs.

This section defines the basic components of DAGL-IoV from four aspects: nodes, accounts, transactions, and ledger.

Each node can perform full or partial blockchain operations, including transaction generation, verification, consensus, and storage. In DAGL-IoV, both vehicles and RSUs act as blockchain nodes, collaboratively maintaining the distributed ledger. Vehicle nodes are denoted as

An account represents the unique identity of a blockchain node in the system. For management efficiency, each node is assigned a single account consisting of a public-private key pair

In the DAG lattice blockchain structure, each account maintains its own account chain. To minimize coupling among account chains and enable parallel transaction processing, a traditional blockchain transaction is divided into sending and receiving transactions, which are stored separately in the corresponding account chains. Each transaction is treated as an independent block and appended individually to the blockchain. The system defines four types of transactions: account creation (

For each account, the transactions on its account chain include both message-related and reputation-related records. To enhance processing efficiency, facilitate transaction queries, and enable parallel execution, the account chain is divided into a message chain and a reputation chain for separate storage. The ledger adopts a DAG lattice structure, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The genesis block is generated during system initialization and serves as the parent block for all account creation transactions. Each account creation transaction acts as the genesis transaction of its respective account chain, to which the message and reputation chains are linked through

Figure 2: DAG lattice structure

In practical IoV applications, nodes typically interact with surrounding nodes and are more focused on the messages from nearby nodes, without the need to access messages generated by nodes in other connected subnets in real-time. Additionally, in different connected subnets, nodes can implement related applications in parallel. Using the DAG lattice structure shown in Fig. 2, transactions between different accounts can be processed in parallel. Within the same account, transactions in the message chain and reputation chain can also be processed in parallel. Each node can independently operate its own account chain, needing only to synchronize with the account chains of nearby nodes to complete the blockchain functionality. This approach aligns well with the characteristics of the IoV application scenario.

To enable nodes to access the account chains of other nodes or participate in consensus for transactions, they need to synchronize the account chain data from neighboring nodes. In the DAGL-IoV, transaction synchronization primarily occurs in two scenarios: when a new node joins the blockchain or when a node moves into the communication range of another node.

3.3.1 New Node Joining the Blockchain

When a new node joins, it synchronizes the blockchain ledger from the RSUs. Considering the limited storage resources of vehicles, new vehicles can synchronize only partial blockchain data, such as the transactions needed to verify transactions and participate in consensus, as well as transactions of interest generated by other nodes.

When a new node synchronizes transactions, it first synchronizes the genesis block to its local ledger, then determines which nodes to synchronize transaction information from, and synchronizes the account creation transactions of these nodes. Lastly, depending on its local storage capacity, it synchronizes transactions from the node account chain. To ensure that the newly joined node can verify transactions and participate in consensus, it must synchronize the latest message-related and reputation-related transactions from the node account chain.

3.3.2 Node Moving into the Communication Range of Another Node

As vehicles on the road are in moving, each vehicle’s account chain moves along with the vehicle. The nodes near vehicle A always store the latest transactions of that vehicle, whereas nodes farther away may not need to or cannot store its most recent transactions. During the vehicle’s movement, when it enters the communication range of A, its local ledger may not have stored the latest transactions of A, preventing it from verifying or participating in consensus for transactions generated by A. In such cases, synchronization of the A’s latest transactions is necessary.

The process begins by determining whether A is a newly joined node to the blockchain. If so, the account creation transaction of A must first be synchronized, followed by the synchronization of the latest message-related and reputation-related transactions from its account chain.

In the DAGL-IoV framework, the types of transactions that can be generated include account creation transactions, message sending transactions, reputation score sending transactions, and receive transactions.

3.4.1 Account Creation Transaction

To create an account, a blockchain node initiates an account creation transaction defined as

3.4.2 Message Sending Transactions

When a node sends a message, it generates a message sending transaction defined as

3.4.3 Reputation Sending Transaction

When an RSU updates a node’s reputation score, it issues a reputation sending transaction defined as

When a node receives either a message sending or a reputation sending transaction, it generates a receive transaction defined as

When a node in the blockchain network receives a transaction T generated by node

(1) Nonce value

The correctness of the nonce value determines whether node K has successfully completed the corresponding PoW. Only nodes that have completed PoW are permitted to broadcast transactions to the blockchain network; thus, nonce validation is essential. The verification process checks whether hash(type, difficulty, timestamp, nonce) meets the specified PoW difficulty. If the nonce satisfies the difficulty condition, node K is deemed to have completed the required PoW; otherwise, the transaction is discarded.

(2) Timestamp

The purpose of timestamp validation is to ensure that node K transmits the transaction immediately after its creation, thereby preventing malicious nodes from performing pre-computation PoW attacks (as discussed in Section 5). The timestamp is validated by checking whether the time interval

(3) Signature of transaction

Validating a transaction’s signature ensures that it is generated by the legitimate creator rather than a malicious node. The verification process computes the hash of the transaction (excluding the

It is noteworthy that for reputation sending transactions, if the transaction is generated by an RSU, only the signature requires verification. However, if it is generated by the node whose reputation score is being updated, both the signature and

(4) Associated transactions

For account creation and message sending transactions, no associated transactions require verification. However, reputation sending transactions must be linked to the corresponding transaction that triggers the reputation change, and receive transactions must verify their associated message sending or reputation sending transactions. Upon receiving a reputation sending or receive transaction, the system checks whether the related transactions already exist on the blockchain. If they do, validation succeeds; otherwise, the transaction is discarded.

Transactions that pass the above validation steps are subsequently finalized through the consensus process and appended to the blockchain.

Due to the high dynamic nature of the network, nodes in a blockchain are typically unfamiliar with each other, making it difficult to establish trust. Therefore, it is essential to implement an incentive mechanism to encourage nodes to join the blockchain and maintain normal behavior. The DAGL-IoV framework adopts a reputation-based incentive mechanism, assigning a reputation score to each node. By dynamically updating reputation scores, the system incentivizes well-behaved nodes while penalizing malicious ones. Nodes with higher reputation scores have more opportunities to generate transactions, and their transactions are prioritized for processing. This incentive mechanism helps to encourage nodes to maintain high reputation scores, allowing trust to be established even when communicating with unfamiliar nodes.

Before sending a transaction, a node must first complete a PoW process (it should be noted that, unlike Bitcoin’s PoW, the PoW in the DAGL-IoV is solely used for spam prevention). The node calculates a random number that meets a specific difficulty, filling in the difficulty and nonce fields. Only after completing the PoW can the transaction be sent. Other nodes, upon receiving the transaction, will first verify whether the nonce value is correct. Since PoW consumes computational resources, it prevents malicious nodes from flooding the network with spam messages, thus avoiding Denial of Service (DoS) attacks. The lower the PoW difficulty, the fewer computational resources are required, and the faster the transaction can be generated. Conversely, the higher the PoW difficulty, the more computational resources are needed, which slows down the transaction generation speed.

In this architecture, the PoW difficulty is dynamically adjusted according to the node’s reputation score. Nodes with higher reputation scores are assigned lower PoW difficulty, while those with lower scores face higher difficulty. This mechanism incentivizes nodes to maintain a high reputation to increase their chances of generating transactions. Since the node’s reputation score is dynamic, the difficulty is also dynamic. The specific calculation methods are given by the equations Eqs. (6) and (7).

Here,

Once the difficulty is determined, the node attempts to find a nonce that satisfies the PoW. This is done by repeatedly trying different nonce values until one is found that meets the difficulty requirement, that is,

In traditional reputation score updating methods, nodes are rewarded with a fixed score for sending truthful messages and penalized with a fixed deduction for sending false messages [30,31]. However, this method only updates a node’s reputation score based on current behavior and does not consider the influence of the node’s historical actions. For instance, a malicious node may send false messages to lower its score, but then send truthful messages to recover its score, engaging in On-Off attacks [32] by periodically alternating between false and true messages. Traditional reputation score updating methods do not account for historical behavior and thus cannot prevent On-Off attacks.

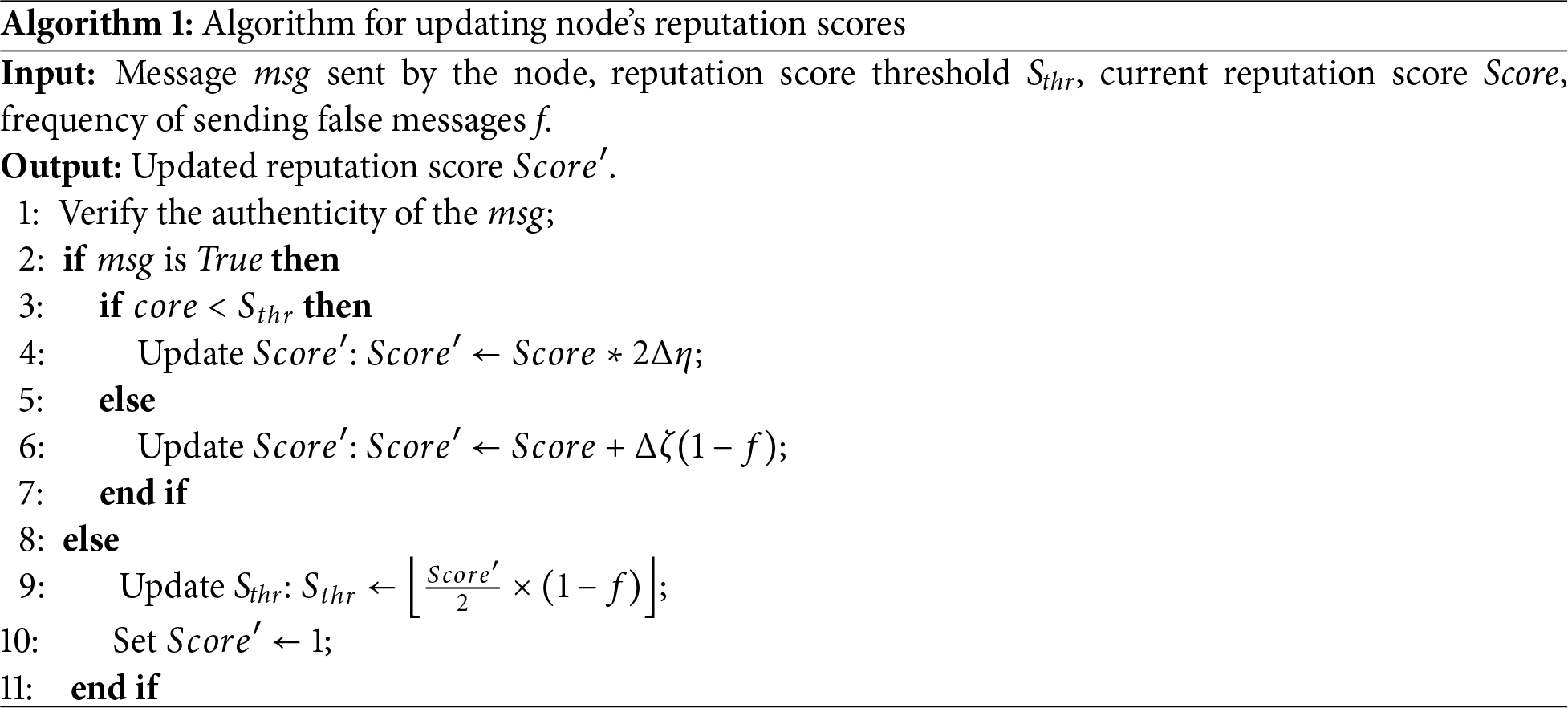

Therefore, this framework draws inspiration from the ideas of “slow start” and “congestion avoidance” from TCP congestion control to update nodes’ reputation scores, introducing a reputation score threshold

In this algorithm, the first step is to verify the authenticity of the message sent by the node. The authenticity of messages can be determined by combining salient object detection methods, which is not the focus of this paper. For specific information, please refer to references [33,34]. If the message is truthful, the reputation score is increased. The method of increasing the reputation score is determined by the reputation score threshold

where

As illustrated in Algorithm 1, the calculation and updating of a node’s reputation score are influenced by its historical behavior. Specifically, a higher frequency of sending false messages in the past results in a longer time required for the node to achieve a high reputation score. Additionally, the reputation score is directly linked to the PoW difficulty for the node’s transactions: a higher reputation score corresponds to a lower PoW difficulty. To ensure that a node’s transactions are prioritized for inclusion on the blockchain, it must consistently maintain a high reputation score over time. In this way, this system effectively incentivizes nodes to behave honestly.

This section describes the potential security issues that may arise in the proposed DAGL-IoV and analyzes how to address these problems. Malicious or attacked nodes in the blockchain may initiate the following types of network attacks.

Malicious nodes may create multiple accounts to launch a Sybil attack. In the DAGL-IoV, both the public and private keys of vehicles and RSUs are issued by a trusted center. Additionally, when creating accounts, RSUs are validated through the trusted center, ensuring that each node creates a genuine, valid, and unique account. Therefore, under this architecture, malicious nodes cannot create numerous accounts to launch a Sybil attack.

5.2 Transaction Flooding Attack

Malicious nodes may send a large number of valid but meaningless transactions to the blockchain, consuming substantial network bandwidth and wasting node resources in the transaction validation and consensus process. In the DAGL-IoV, before sending a transaction, a node must complete a PoW process, making it impossible for nodes to generate large numbers of transactions simultaneously. Moreover, PoW difficulty is related to the node’s reputation score. If transaction flooding attacks are detected, the node’s reputation score will be reduced, making it harder to generate transactions. When the computational resources consumed by PoW exceed the benefits obtained from launching the attack, the node will proactively abandon the attack.

Malicious nodes may initiate an On-Off attack by alternating between sending false and truthful messages. During the reputation score update process, the rate of increase in a node’s reputation score is much lower than the rate of decrease. Therefore, after a malicious node performs an attack, it takes a long time to recover its reputation score before it can launch another attack. Furthermore, for nodes that frequently send malicious messages, the reputation score threshold controls the speed of their reputation score recovery, making it even more difficult for such nodes to carry out On-Off attacks.

5.4 Integrity of the Blockchain

An attacker could target vehicles or RSUs within the blockchain to tamper with the data stored on the blockchain, thereby compromising the integrity of the ledger. In the DAGL-IoV, vehicles, due to their limited storage capacity, only store recent transactions, while RSUs store the full blockchain ledger. For recent transactions, both vehicles and RSUs store them, and an attacker would need to control 51% of the nodes in the network to alter the transactions, which is very difficult to achieve. For older transactions, they are only stored on RSUs. As time passes, older transactions become more difficult to tamper with. Additionally, RSUs are typically deployed and maintained by government agencies, making them less likely to be attacked. Therefore, while vehicles only store recent transaction information, it remains very difficult for attackers to compromise the integrity of the blockchain ledger.

A malicious node may attempt to conduct a double-spending attack by simultaneously issuing two transactions. Within a connected network, such attacks can be prevented through transaction validation and consensus mechanisms. However, due to the dynamic connectivity of the IoV, partitions may occur, allowing the malicious node to disseminate the two transactions to different connected regions, thereby launching a double-spending attack. In DAGL-IoV, nodes serve as the carriers of their ledgers, and the surrounding nodes remain synchronized with them in real time. Consequently, even if a malicious node sends transactions to different regions, a double-spending attack cannot be successfully executed.

This section focuses on experimentally simulating the proposed DAGL-IoV for IoV. The goal is to validate the performance of the architecture in terms of average transmission delay and storage cost, as well as assess the feasibility of the incentive mechanism.

6.1.1 Experimental Environment

The experimental simulations were implemented using the traffic flow simulation tool VanetMobiSim (version 1.1) and the network simulation platform OPNET (version 14.5) to model vehicular mobility and network communication behaviors, respectively. The DAG lattice-based blockchain is implemented using OPNET, where the related operations of the DAG lattice structure and blockchain are executed on vehicles and RSUs. Initially, the traffic scenario is modeled using VanetMobiSim. A simulation area of 4500 m was created, and node trajectories were generated within this area and imported into the OPNET environment to simulate node mobility. Nodes communicated with neighbors using a log-normal connection model, with a communication range of 450 m, consistent with C-V2X technology [35].

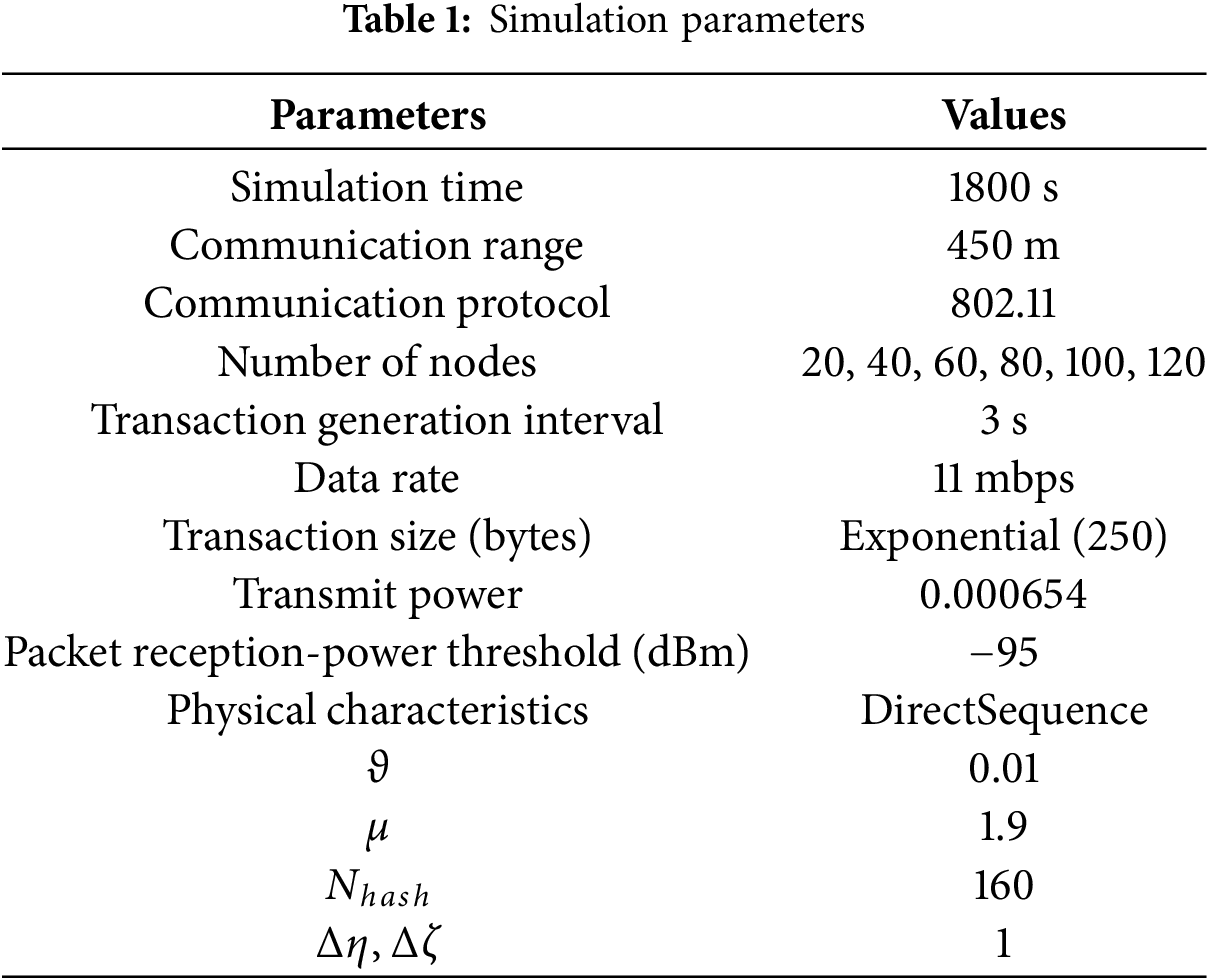

The simulation parameters used in the experiment are shown in Table 1.

(1) Average Propagation Delay (

The average propagation delay refers to the average time taken for a block, after consensus completion, to propagate to other nodes in the network. This metric reflects the time required to synchronize the block to other nodes once consensus is completed. The calculation method for

where

(2) Storage Cost

Storage cost refers to the storage space required by a node to store the blockchain ledger. This metric reflects the lightweight nature of the architecture. For a blockchain system, the more ledger data a node stores, the more secure the system becomes. However, for nodes with limited storage resources, the goal is to store as little ledger data as possible without affecting the blockchain.

This section analyzes the performance of the architecture proposed in this paper and the feasibility of the incentive mechanism. When evaluating the performance of the architecture, comparisons are made with blockchain systems using a single-chain structure and a DAG structure in the IoV. In the figure, the single-chain structure is labeled as “Single Chain”, the DAG structure is labeled as “DAG”, and the DAG lattice structure is labeled as “DAG lattice”.

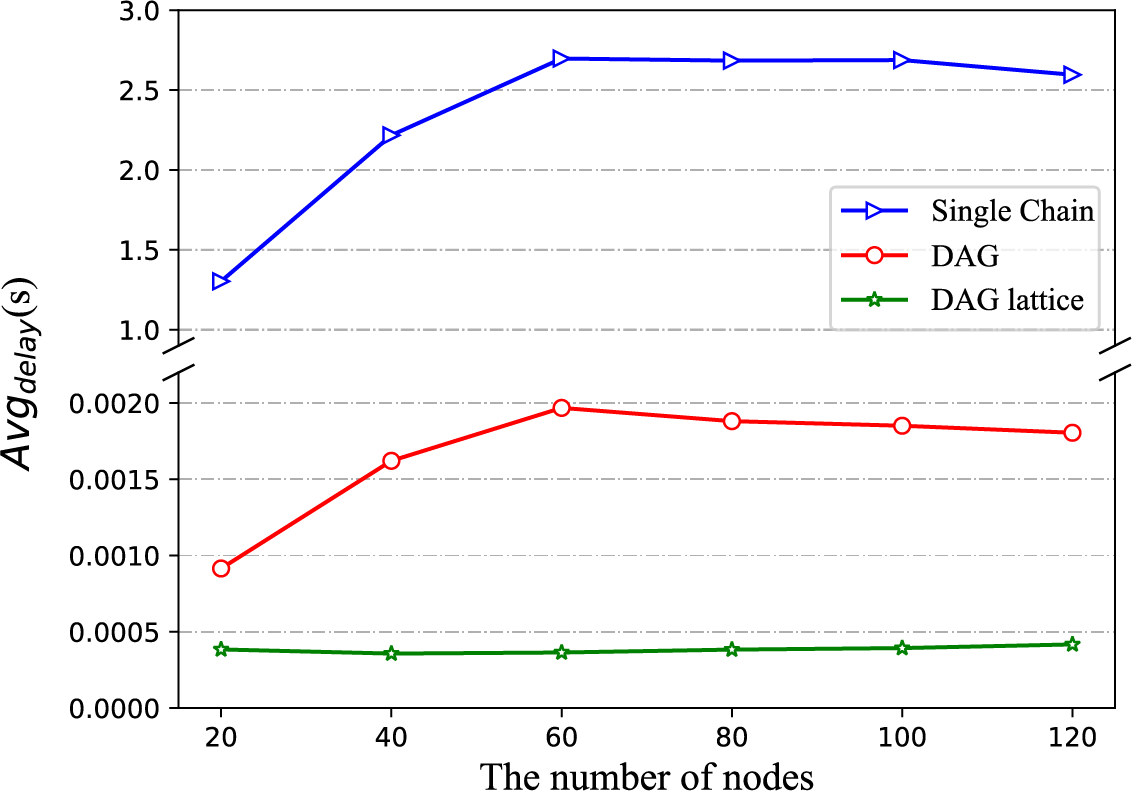

(1) Average transmission delay under different numbers of nodes

Fig. 3 presents a comparison of the average transmission delay under different numbers of nodes. The x-coordinate represents the number of nodes (20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120), while the y-coordinate shows the average transmission delay under different structures. As can be seen from Fig. 3, regardless of the number of nodes, the average transmission delay using the DAG lattice structure blockchain is the lowest, while the single-chain structure exhibits the highest average transmission delay. This is because, under the single-chain structure, multiple transactions need to be packaged into blocks, resulting in larger block sizes and higher transmission delays. Both the DAG and DAG lattice structures achieve consensus on a per-transaction basis, leading to lower transmission delays. However, the average transmission delay in the DAG lattice structure is lower than in the DAG structure, as the former only requires consensus among neighboring nodes, while the latter necessitates the transmission of transactions to all nodes in the network.

Figure 3: The comparison of

(2) Storage cost of nodes

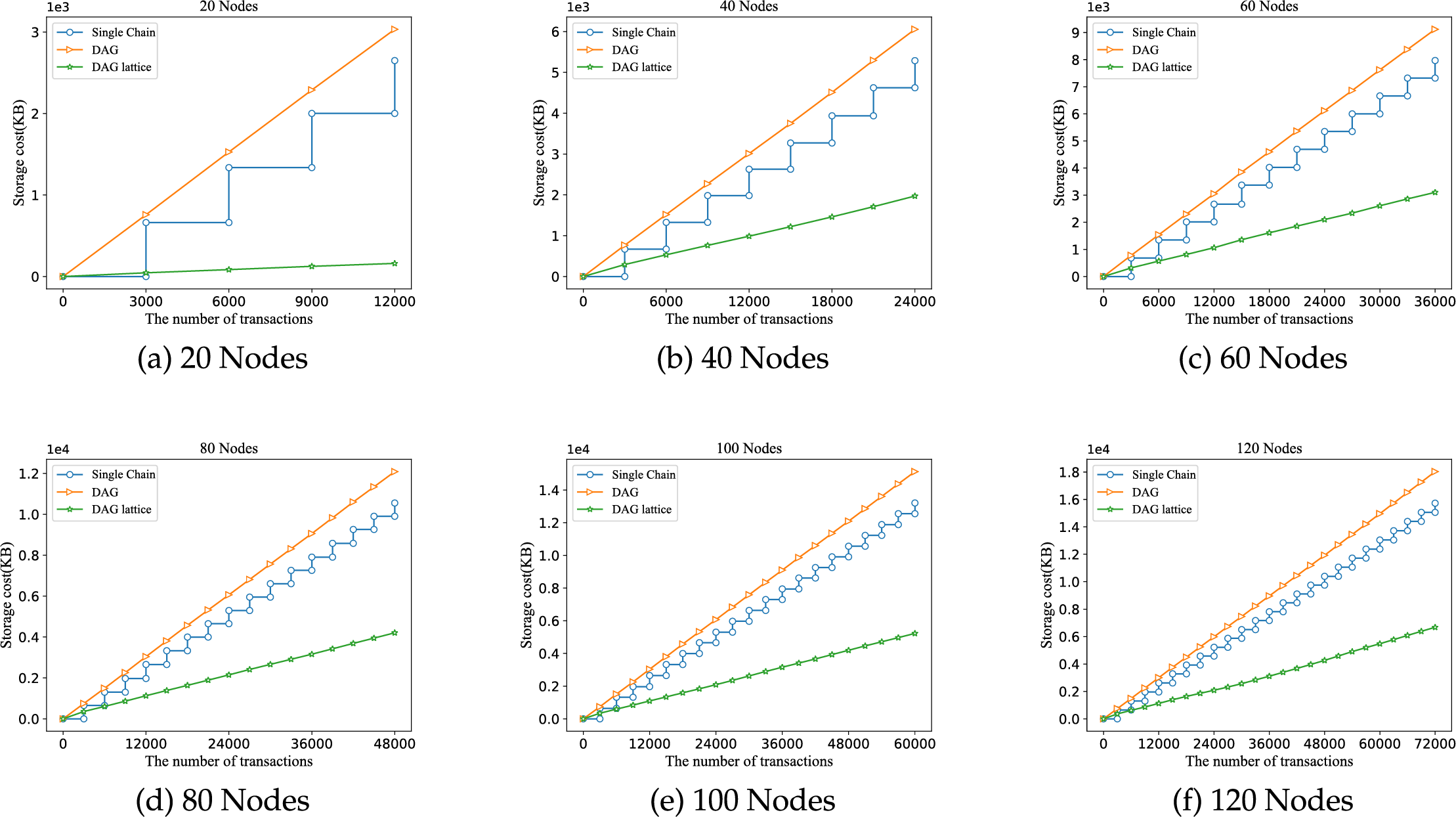

1) Storage cost of nodes under different structures

Fig. 4 presents a comparison of the storage cost of nodes under different structures as the number of system transactions increases. The x-coordinate represents the number of transactions generated by the system, while the y-coordinate shows the storage cost of the nodes. Fig. 4a–f respectively describes the storage costs in scenarios with 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 nodes. In both the DAG and DAG lattice structures, the storage is updated with each new transaction, while in the single-chain structure, the storage is updated with each new block. As can be seen from Fig. 4, regardless of the scenario, the storage cost of nodes in the DAG lattice structure is always lower than that of the other two structures. This is because, in the DAG lattice structure, nodes only store the account chain data of neighboring nodes. In the DAG structure, each transaction includes information about its parent node, whereas in the single-chain structure, each block (with 3000 transactions per block in this experiment) only contains the block header. Therefore, the storage cost in the single-chain structure is lower than in the DAG structure.

Figure 4: The comparison of storage cost under different structures

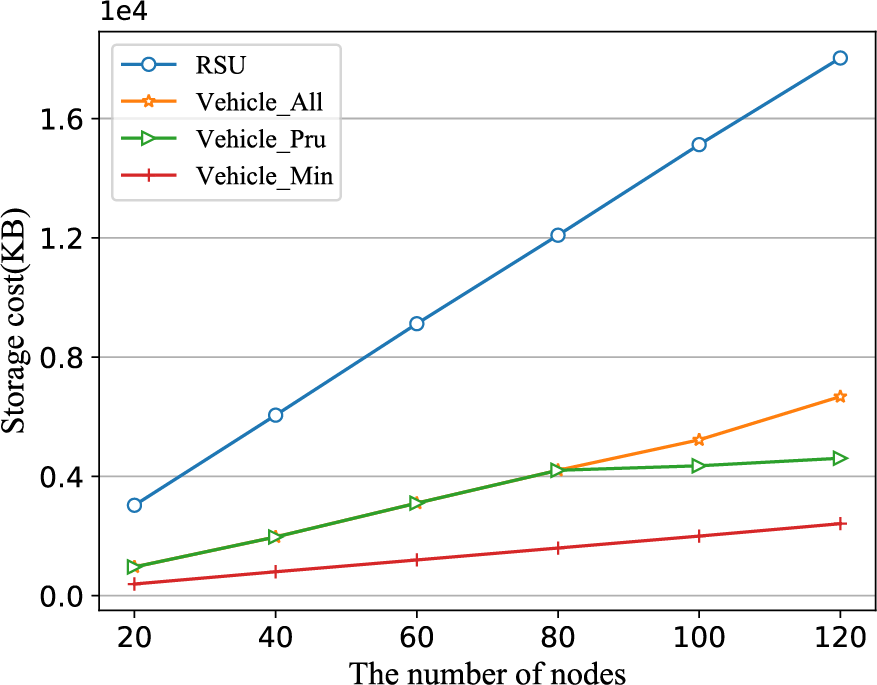

2) Storage cost of RSU and vehicles under different numbers of nodes

Fig. 5 presents a comparison of the storage costs of different types of nodes in the DAGL-IoV system as the number of nodes increases. The x-coordinate represents the number of nodes (20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120), while the y-coordinate shows the storage costs for different types of nodes. In this experiment, the storage costs of RSU nodes (labeled as “RSU”) and vehicle nodes are compared. For the vehicle nodes, three different storage methods are considered based on their storage capacity, namely: (1) storing all transactions generated by surrounding nodes (labeled as “Vehicle_All”), (2) storing pruned transactions (labeled as “Vehicle_Pru”), and (3) storing only the minimal number of transactions that do not affect blockchain operation (labeled as “Vehicle_Min”).

Figure 5: The storage cost of RSU and vehicle under different number of nodes

As shown in Fig. 5, as the number of nodes increases, the storage costs for different types of nodes also increase. The RSU, which stores the entire blockchain ledger, incurs the highest storage cost. The storage cost for vehicles is lower than that for RSU, with the “Vehicle_Min” storage method having the lowest cost. When the number of nodes is small (20, 40, 60, 80), fewer transactions are generated, so there is no need to prune transactions. However, when the number of nodes is large (100, 120), more transactions are generated. Due to insufficient storage space, vehicles prune partial transactions, thus the storage cost of the “Vehicle_All” method is higher than that of “Vehicle_Pru”.

Discussion: As the blockchain operates, the storage space required for maintaining the DAG lattice ledger grows continuously, which imposes heavy storage burden and maintenance costs on RSUs. To address this, a layered ledger design can be adopted, where RSUs only maintain chain data related to their geographic regions, while cross-regional queries are handled through communication among different RSUs. However, this goes beyond the scope of this paper, and we will focus on addressing this issue in our future work.

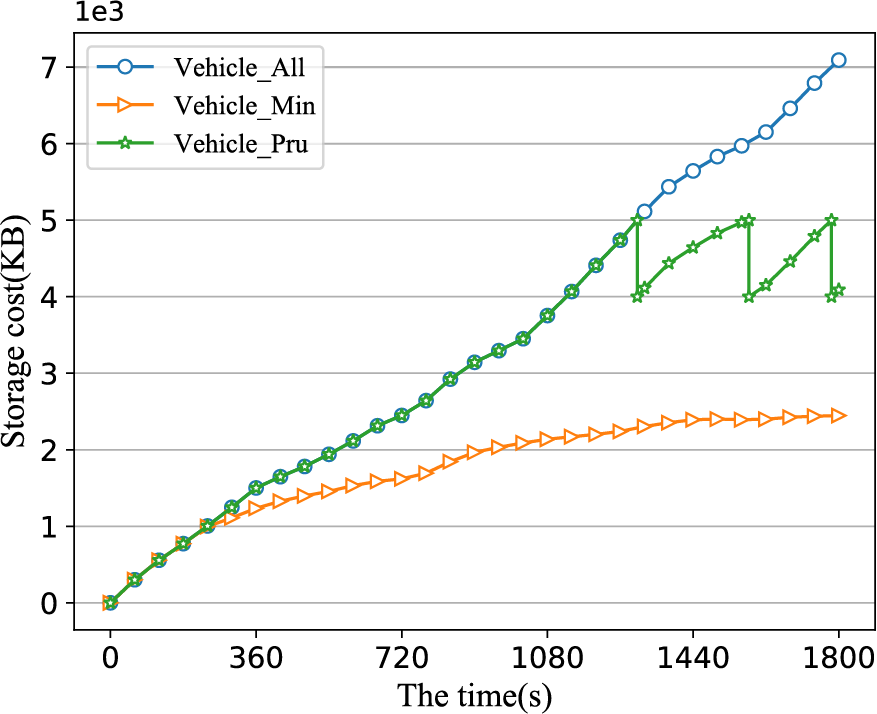

3) Storage cost of a single vehicle node under different storage methods

Fig. 6 shows the variation in the storage cost of a single vehicle node in the DAGL-IoV system under different storage methods. The data in the figure are from randomly selected nodes in a scenario with 120 nodes. The x-coordinate represents the system runtime, while the y-coordinate shows the storage costs for the vehicle node under three different storage methods. These three methods are: (1) storing all transactions generated by surrounding nodes (labeled as “Vehicle_All”), (2) storing pruned transactions (labeled as “Vehicle_Pru”), and (3) storing only the minimal number of transactions that do not affect blockchain operation (labeled as “Vehicle_Min”).

Figure 6: The storage cost of a single vehicle node under different storage methods

As shown in Fig. 6, the storage cost is lowest when using the “Vehicle_Min” method. As the system runs, when the storage cost of the vehicle exceeds a certain threshold, the “Vehicle_Pru” method will prune transactions locally, keeping the storage cost consistently below that threshold.

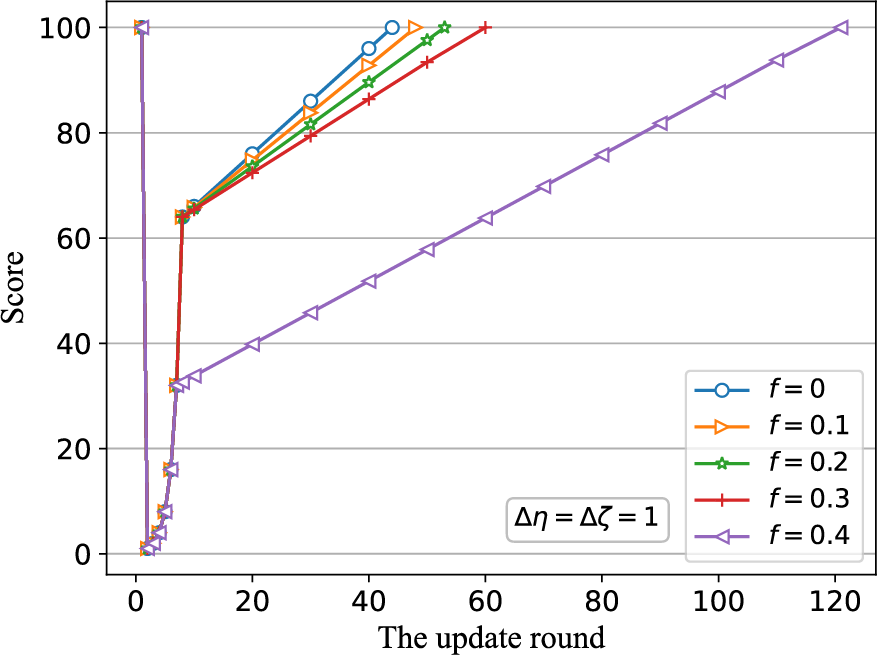

(3) The impact of different false message sending frequencies

Fig. 7 illustrates the impact of different false message sending frequency

Figure 7: The impact of

This paper adopts a DAG lattice structure to address the issues caused by dynamic connectivity in the IoV, and proposes a security architecture based on DAG lattice blockchain. This architecture avoids the issue of being unable to synchronize transactions due to network splits, while also better aligning with the characteristics of the IoV. The experimental results show that the blockchain based on the DAG lattice structure performs better in terms of average propagation delay compared to the singlechain structure and DAG structure. At the same time, while ensuring the normal operation of the blockchain, the storage space required by the DAG lattice structure is smaller than that of the single-chain structure and DAG structure. In future work, we plan to design a layered ledger to reduce the storage burden and maintenance costs of RSUs and deploy the proposed scheme in a real-world setting to verify its effectiveness.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded in part by the Supported by Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China under Grants 2024QN06022 and 2023QN06008, in part by the First-Class Discipline Research Special Project under Grant YLXKZX-NGD-015, in part by the Inner Mongolia University of Technology Scientific Research Start-Up Project under Grant BS2024067.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Methodology and validation, Xiaodong Zhang; conceptualization, Wenhan Hou; data curation and visualization, Juanjuan Wang; formal analysis, Leixiao Li; writing—original draft preparation, Pengfei Yue. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No datasets were used or generated during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the present study.

Key Abbreviations

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| DAG lattice | Directed Acyclic Graph lattice |

| RSU | Roadside Units |

| TPS | Transactions Per Second |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| DSRC | Dedicated Short Range Communication |

| C-V2X | Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything |

| TC | Trust Center |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

References

1. Yang Y, Wei L, Wu J, Long C, Li B. A blockchain-based multidomain authentication scheme for conditional privacy preserving in vehicular Ad-Hoc network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(11):8078– 8090. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sang G, Chen J, Liu Y, Wu H, Zhou Y, Jiang S. PACM: privacy-preserving authentication scheme with on-chain certificate management for VANETs. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2023;20(1):216– 228. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3201551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Luo S, Zhong J. A conditional privacy protection scheme for IoV based on blockchain. In: 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Electronic Materials, Computers and Software Engineering (AEMCSE); 2025 May 9–11; Nanjing, China. p. 284–7. [Google Scholar]

4. Su H, Dong S, Zhang T. A hybrid blockchain-based privacy-preserving authentication scheme for vehicular Ad Hoc networks. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2024;73(11):17059– 72. doi:10.1109/tvt.2024.3424786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen C, Wang L, Shi Q. Blockchain-enabled trust management in internet of vehicles: a joint pre-reward-penalty and consensus approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(6):6961– 78. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3491852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhao J, Huang F, Liao L, Zhang Q. Blockchain-based trust management model for vehicular Ad Hoc networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(5):8118– 32. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3318597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lin C, He D, Huang X, Kumar N, Choo K-KR. BCPPA: a blockchain-based conditional privacy-preserving authentication protocol for vehicular Ad Hoc networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;22(12):7408–20. doi:10.1109/tits.2020.3002096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhu Q, Jing A, Gan C, Guan X, Qin Y. HCSC: a hierarchical certificate service chain based on reputation for VANETs. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(6):6123– 45. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3250279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang Y, Chen Y, Liu Z, Tan H, Luo Y. Verifiable and redactable blockchain for internet of vehicles data sharing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(4):4249– 61. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3483809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Guo Z, Wang G, Li Y, Ni J, Zhang G. Attribute-based data sharing scheme using blockchain for 6G-enabled VANETs. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(4):3343–60. doi:10.1109/tmc.2023.3273222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cordova D, Laube A, Nguyen T-M-T, Pujolle G. Blockgraph: a blockchain for mobile ad hoc networks. In: 2020 4th Cyber Security in Networking Conference (CSNet); 2020 Oct 21–23; Lausanne, Switzerland. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

12. LeMahieu C. Nano: a feeless distributed cryptocurrency network [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 11]. Available from: http://media.abnnewswire.net/media/cs/whitepaper/rpt/91948-whitepaper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

13. JURA: an ultrafast, feeless self-regulated decentralized network [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 11]. Available from: https://docsend.com/view/p9f87gp. [Google Scholar]

14. An Open. Feeless data and value transfer protocol [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.iota.org/. [Google Scholar]

15. Churyumov A. Byteball: a decentralized system for storage and transfer of value [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 11]. Available from: https://obyte.org/Byteball.pdf. [Google Scholar]

16. Dong Z, Zheng E, Choon Y, Zomaya AY. DAGBENCH: a performance evaluation framework for DAG distributed ledgers. In: 2019 IEEE 12th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD); 2019 Jul 8–13; Milan, Italy. p. 264–71. [Google Scholar]

17. Nakamoto S. Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 2]. Available from: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

18. Islam S, Badsha S, Sengupta S. A light-weight blockchain architecture for V2V knowledge sharing at vehicular edges. In: 2020 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2); 2020 Sep 28–Oct 1; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

19. Cui J, Ouyang F, Ying Z, Wei L, Zhong H. Secure and efficient data sharing among vehicles based on consortium blockchain. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(7):8857–67. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3086976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu B, Agbele T, Jiang R. Biometric blockchain: a secure solution for intelligent vehicle data sharing. In: Deep biometrics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 245–56. [Google Scholar]

21. Kulathunge AS, Dayarathna HROE. Communication framework for vehicular ad-hoc networks using blockchain: case study of metro manila electric shuttle automation project. In: 2019 International Research Conference on Smart Computing and Systems Engineering (SCSE); 2019 Mar 28; Colombo, Sri Lanka. p. 85–90. [Google Scholar]

22. Zang M, Zhu Y, Lan R, Liu Y, Luo X. BAVC: efficient blockchain-based authentication scheme for vehicular secure communication. In: 2021 13th International Conference on Advanced Computational Intelligence (ICACI); 2021 May 14–16; Wanzhou, China. p. 346–50. [Google Scholar]

23. Chai H, Leng S, Wu F, He J. Secure and efficient blockchain based knowledge sharing for intelligent connected vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(9):14620– 31. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3131240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li Y, Tao X, Zhang X, Xu J, Wang Y, Xia W. A DAG-based reputation mechanism for preventing peer disclosure in SIoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(23):24095–106. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3189108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Fu Y, Wang S, Zhang Q, Zhang D. Game model of optimal quality experience strategy for internet of vehicles bandwidth service based on DAG blockchain. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2023;72(7):8898–913. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3246221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jiang W, Tao J, Guan Z. A trusted data privacy computing method for vehicular Ad Hoc networks based on homomorphic encryption and DAG blockchain. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(6):6621–32. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3492031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu D, Jin R, Wei S. A distributed vehicle networking node reputation management system based on consortium chain. Comput Eng. 2024. (In Chinese). Doi: 10.19678/j.issn.1000-3428.0069457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chai H, Leng S, Zhang K, Mao S. Proof-of-reputation based-consortium blockchain for trust resource sharing in internet of vehicles. IEEE Access. 2019;7:175744–57. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2956955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zeng S, Huo R, Huang T, Liu J, Wang S, Feng W. Survey of blockchain: principle, progress and application. J Commun. 2020;41:134–51. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

30. Lu Z, Liu W, Wang Q, Qu G, Liu Z. A privacy-preserving trust model based on blockchain for VANETs. IEEE Access. 2018;6:45655–64. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2864189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu H, Han D, Li D. Behavior analysis and blockchain based trust management in VANETs. J Parallel Distr Comput. 2021;151(2):61–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2021.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cao Y, Lyu C, Sun Y, Zhang Y. Review of research on misbehavior detection in VANET. Netinfo Secur. 2023;23(4):10–9. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

33. Khan H, Usman MT, Koo J. Bilateral feature fusion with hexagonal attention for robust saliency detection under uncertain environments. Inf Fusion. 2025;121(7):103165. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Usman MT, Khan H, Rida I, Koo J. Lightweight transformer-driven multi-scale trapezoidal attention network for saliency detection. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;155:110917. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li Y, Cao Y, Chen S, Du Z, Qiu H, Gao L, et al. 5G and internet of vehicles: internet of vehicles technology and intelligent connected vehicles based on mobile communication. Vol. 6. Beijing, China: Publishing House of Electronics Industry; 2019. p. 91–4. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools