Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MFF-YOLO: A Target Detection Algorithm for UAV Aerial Photography

1 CI Xbot School, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

2 School of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

3 School of Safety Science and Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongyuan Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072494

Received 28 August 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

To address the challenges of small target detection and significant scale variations in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) aerial imagery, which often lead to missed and false detections, we propose Multi-scale Feature Fusion YOLO (MFF-YOLO), an enhanced algorithm based on YOLOv8s. Our approach introduces a Multi-scale Feature Fusion Strategy (MFFS), comprising the Multiple Features C2f (MFC) module and the Scale Sequence Feature Fusion (SSFF) module, to improve feature integration across different network levels. This enables more effective capture of fine-grained details and sequential multi-scale features. Furthermore, we incorporate Inner-CIoU, an improved loss function that uses auxiliary bounding boxes to enhance the regression quality of small object boxes. To ensure practicality for UAV deployment, we apply the Layer-adaptive Magnitude-based pruning (LAMP) method to significantly reduce model size and computational cost. Experiments on the VisDrone2019 dataset show that MFF-YOLO achieves a 5.7% increase in mean average precision (mAP) over the baseline, while reducing parameters by 8.5 million and computation by 17.5%. The results demonstrate that our method effectively improves detection performance in UAV aerial scenarios.Keywords

With the continuous development of object detection technology, it has been widely used in various industrial fields, and the object detection of UAV aerial images is one of them. The success of UAV object detection in industrial fields lies in its low cost, convenience, and efficiency [1]. However, there are still many challenges in UAV object detection. For instance, UAVs typically operate at high altitudes with instability in flight height, resulting in most captured objects being small and experiencing significant variations in scale, which can lead to reduced detection accuracy [2]. Furthermore, the UAV is a small mobile device, and the algorithm model should be lightweight if it is applied to the UAV.

Currently, object detection methods are mainly categorized into two major types based on their operational procedures: two-stage object detection and single-stage object detection [3]. The workflow of two-stage object detection involves selecting several candidate regions and further classifying and identifying these regions. It has high detection accuracy but is computationally complex and slow, making it unsuitable for drone object detection. Representative algorithms of the two-stage approach include R-CNN [4], Faster R-CNN [5], and Mask R-CNN [6]. Single-stage object detection algorithms can directly predict object bounding boxes from images and complete classification. Compared to two-stage algorithms, single-stage detection is faster but slightly less accurate. Representative algorithms include the YOLO [7] series, SSD [8], and CenterNet [9]. YOLOv8, the most mature version of the YOLO model proposed by Ultralytics, excels at both detection accuracy and speed. YOLOv8’s anchor-free detection design speeds up post-processing for non-maximum suppression, greatly improving the speed of object identification and location. Its network structure mainly consists of three parts: Backbone, Neck, and Head. The Backbone part is primarily responsible for feature extraction. The Neck part of YOLOv8 uses the PANet structure, integrating features of different scales through top-down and bottom-up paths. The Head part includes a detection head and a classification head, mainly responsible for the final object detection and classification tasks. Additionally, YOLOv8 is divided into five different sizes, n, s, m, l, and x, based on network depth and width. This study comprehensively considers model accuracy and computational resources, selecting YOLOv8s as the baseline model for improvement and optimization, and proposing an algorithm model more suitable for drone object detection.

The aforementioned object detection methods have achieved groundbreaking results and provided numerous ideas and approaches; however, these models still have shortcomings in the field of drone aerial photography object detection, which remains full of challenges. For instance, the proportion of small targets in images captured by drones is very high, with small targets occupying a limited number of pixels, and some even only a few pixels. As the depth of the network increases, feature maps are very prone to losing the features of small objects after multiple convolutional and pooling operations. This makes the localization and classification of small targets extremely difficult. Additionally, the bounding boxes of small targets are usually very small, and under the same offset value, the offset degree of small targets relative to large targets is much greater. This makes the IoU value of small targets very sensitive; even a slight offset between the target box and the true box can cause a significant change in the IoU value, leading to poor regression quality of small target boxes and reduced detection accuracy. The scale of targets may vary greatly under unstable flight heights of drones and complex terrains, which undoubtedly greatly increases the difficulty of precise target recognition and accurate localization. The issue of scale variation poses a significant challenge to the network model’s ability to extract multi-scale features. Moreover, drones are edge devices with limited computational power, which presents another challenge for model lightweight. It is necessary to maintain a low model parameter volume and computational volume while ensuring detection accuracy. In response to these issues, this study proposes a new detection algorithm, MFF-YOLO (Multi-scale Feature Fusion YOLO), based on the YOLOv8s model, aiming to further improve detection accuracy to meet the needs of actual production.

To tackle these challenges, we propose MFF-YOLO, an enhanced version of YOLOv8s specifically designed for UAV aerial imagery. The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose the MFFS that incorporates two novel modules: the MFC module, which aggregates features from large, medium, and small scales to preserve fine-grained details of small objects, and the SSFF module, which employs 3D convolution to extract cross-scale sequential features. An additional detection head is introduced to further enhance small object detection capability.

We introduce the Inner-CIoU loss function, an extension of CIoU that incorporates auxiliary bounding boxes to reduce the sensitivity of IoU to minute localization errors. This significantly improves bounding box regression quality, especially for small objects.

To facilitate real-world deployment on UAV platforms, we apply the LAMP algorithm to substantially reduce model parameters and computational overhead while maintaining competitive accuracy.

Extensive experiments on the VisDrone2019 dataset demonstrate that MFF-YOLO achieves mAP of 45.2%, outperforming the baseline YOLOv8s by 5.7%, while also reducing parameters by 8.5 million and computational cost by 17.5%. The results validate the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed method in addressing critical challenges in UAV-based object detection.

2.1 UAV Small Target Detection

In recent years, drone-based object detection has been widely applied and valued, with the continuous emergence of target detection algorithms designed for drones. However, most of these algorithms struggle to balance precision and model complexity, each with its own set of issues. Zhu et al. [10] proposed a network model called TPH-YOLOv5, which achieves decent detection accuracy by integrating a Transformer detection head and CBAM attention mechanism, but the model’s ability to classify similar targets is poor. Quan et al. [11] introduced the CFP module, which combines the Inception module and dilated convolution modules, significantly reducing the model’s parameter count and size. The CFPNet, designed based on the CFP module, boasts advanced real-time detection performance but lacks competitive accuracy. Sun et al. [12] proposed a real-time object detection algorithm for drones called RSOD, which employs an adaptive weighted fusion strategy to improve the FPN and uses the SE attention mechanism to enhance the network’s ability to capture dependencies between channels. RSOD can effectively detect high-density small targets but lacks a lightweight design. Wang et al. [13] addressed the issue of small target bounding boxes being highly sensitive to IoU values due to their size of only a few pixels, proposing a new loss function called NWDLoss, which significantly improves the regression quality of small target boxes but struggles with multi-scale issues. Cao et al. [14] proposed a novel two-stage detection algorithm called D2det, which introduces dense local regression for more precise target localization. Additionally, D2det incorporates a discriminative RoI merging scheme to improve classification accuracy. However, the complexity of this model is too high to be applied to mobile devices. Zuo et al. [15] proposed a UAV small target detection model (UAV-STD), which incorporates an attention mechanism-based small target detection module (AMSTD) to effectively extract and preserve the feature information of small targets. Meanwhile, the model also introduces a spatial- and scale-aware prediction head (SSP Head), which applies distinct attentional weights across spatial and scale dimensions, thereby enhancing the model’s perceptual capabilities regarding both the scale and spatial location of small targets. Jiao et al. [16] proposed an object detection model based on the Transformer architecture. This model incorporates a two-dimensional Gaussian probability density function as an auxiliary attention mechanism to accelerate the localization of small objects in images and improve detection accuracy. Additionally, a denoising training strategy was introduced during the training process, which expedited model convergence.

In object detection tasks, the scale variation of targets is a challenging issue, with objects of different shapes and sizes posing significant difficulties for target localization and recognition. Multi-scale feature fusion can mitigate the impact of scale variation; shallower feature maps contain more positional and detailed information conducive to localization, while deeper feature maps are richer in semantic information, which is beneficial for classification. Integrating multi-scale features from different layers allows the network to better capture global information, thereby improving model performance.

For the past few years, scholars proposed numerous innovative approaches to the field of multi-scale feature fusion. Lin et al. [17] presented the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), which integrates feature maps from different stages, capturing both high-level semantic information and low-level positional details. Liu et al. [18] proposed PANet, which, building on the top-down fusion of FPN, added a bottom-up pathway to further merge information and enhance detection performance. Tan et al. [19] introduced EfficientDet, which employs a novel feature fusion method called BiFPN. This method constructs a feature fusion module, the BiFPN layer, with self-learning weights and reuses it, making feature fusion simpler and more efficient. Xu et al. [20] proposed RepGFPN, which uses a varying number of channels in features of different scales, allowing for flexible control over the feature representation capabilities at different levels while maintaining a lightweight design. Tong amd Wu [21] designed a Deep Feature Learning and Feature Fusion Network (DFLFFN) for small object detection. By introducing a Feature Fusion Block (FFB), the network effectively integrates shallow features, which are rich in detailed information, with deep features generated by a single-layer Deep Feature Learning Module (DFLM). This architecture enables the detection of objects across diverse scenes by activating multi-scale receptive fields over a broader range.

3.1 Multi-Scale Feature Fusion YOLO

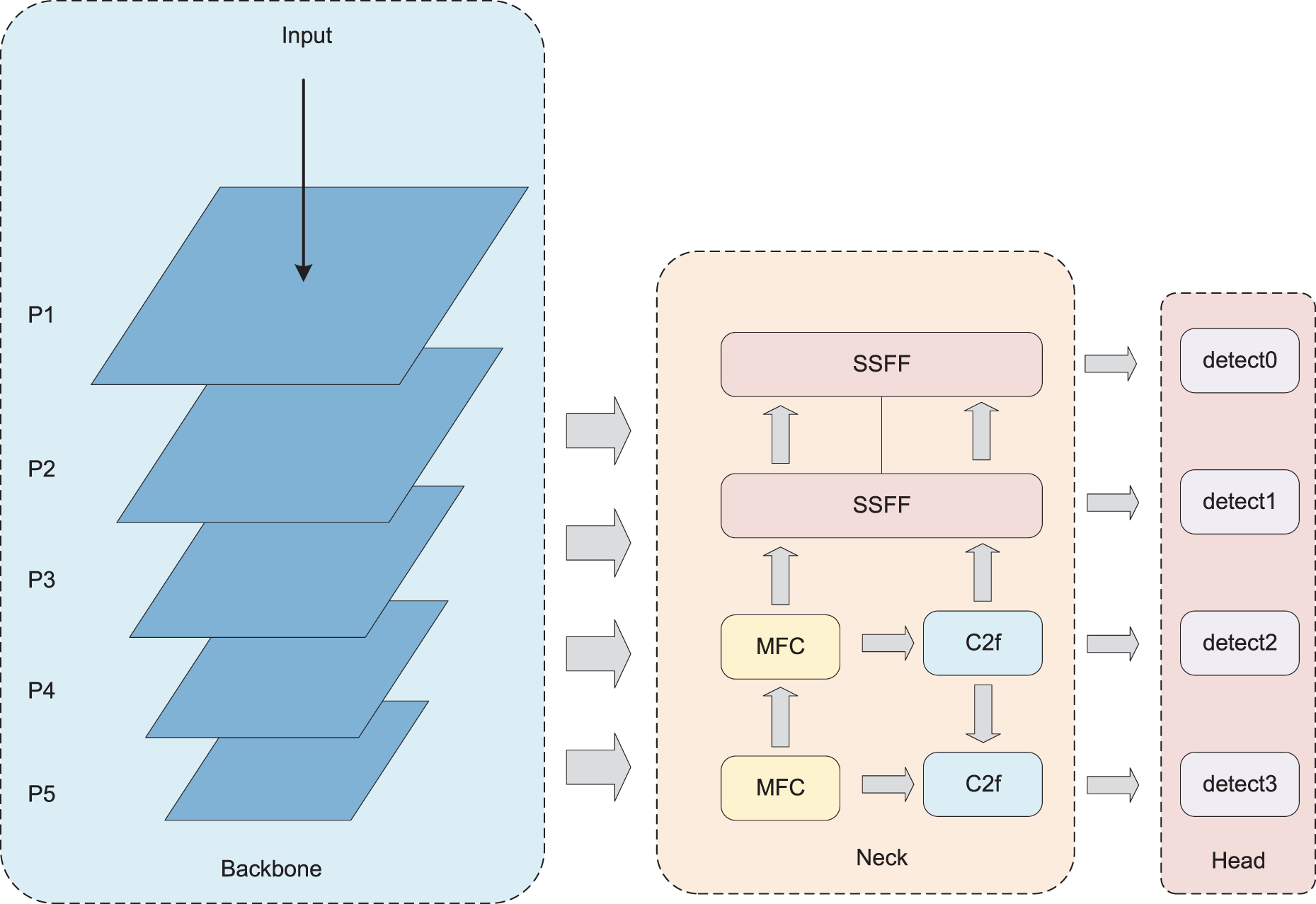

The designed network of MFF-YOLO in this paper is shown in Fig. 1. The input image first undergoes multi-level feature extraction through the Backbone. Then, extracted-features are sent to the Neck part for feature fusion, and finally, the targets are detected and classified through the Head. To address the scale variation and small target issues in drone aerial imagery, this paper designs a multi-scale feature fusion strategy, MFFS, to improve the Neck part. By integrating large, medium, and small three-level feature maps through the MFC module, the information richness of the fused features is enhanced, retaining more positional information of small targets. MFFS also introduces the SSFF module, which aims to combine deep and shallow features, extract scale sequence features by 3D convolution. Additionally, to make the most of the small target information in the shallow, large-sized feature maps, this study introduces an extra small target detection layer from the P2 layer. To improve the regression quality of small target boxes and enhance model performance, this study introduces Inner-IoU, which combines with YOLOv8’s original loss function to form Inner-CIoU. Inner-IoU improves the regression quality of small target boxes by introducing auxiliary bounding boxes. Finally, to better adapt the model to the drone platform, this study used the LAMP pruning method to trim a large number of useless branches, greatly reduce the number of parameters and computational operations.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the overall MFF-YOLO architecture

3.2 Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Strategy

The traditional PANet structure merely upscales smaller-sized feature maps and then either fuses or distributes them to other layers, neglecting the rich fine-grained information contained within the larger-sized feature maps. This results in the features fused by the traditional PANet being insufficiently informative and weak in detecting small targets. This study proposes MFFS to address these issues. This strategy initially integrates multi-level features extracted by the backbone through the MFC module to capture more detailed information about small targets. Subsequently, the SSFF module is introduced to effectively fuse P3, P4, and P5 feature maps, preserving target information across different spatial scales. Finally, the detailed feature information output by the MFC and SSFF modules is integrated into each feature branch of the PANet for detection. Moreover, an extra small target detection layer is incorporated into this model to improve the detection performance of the model for small targets.

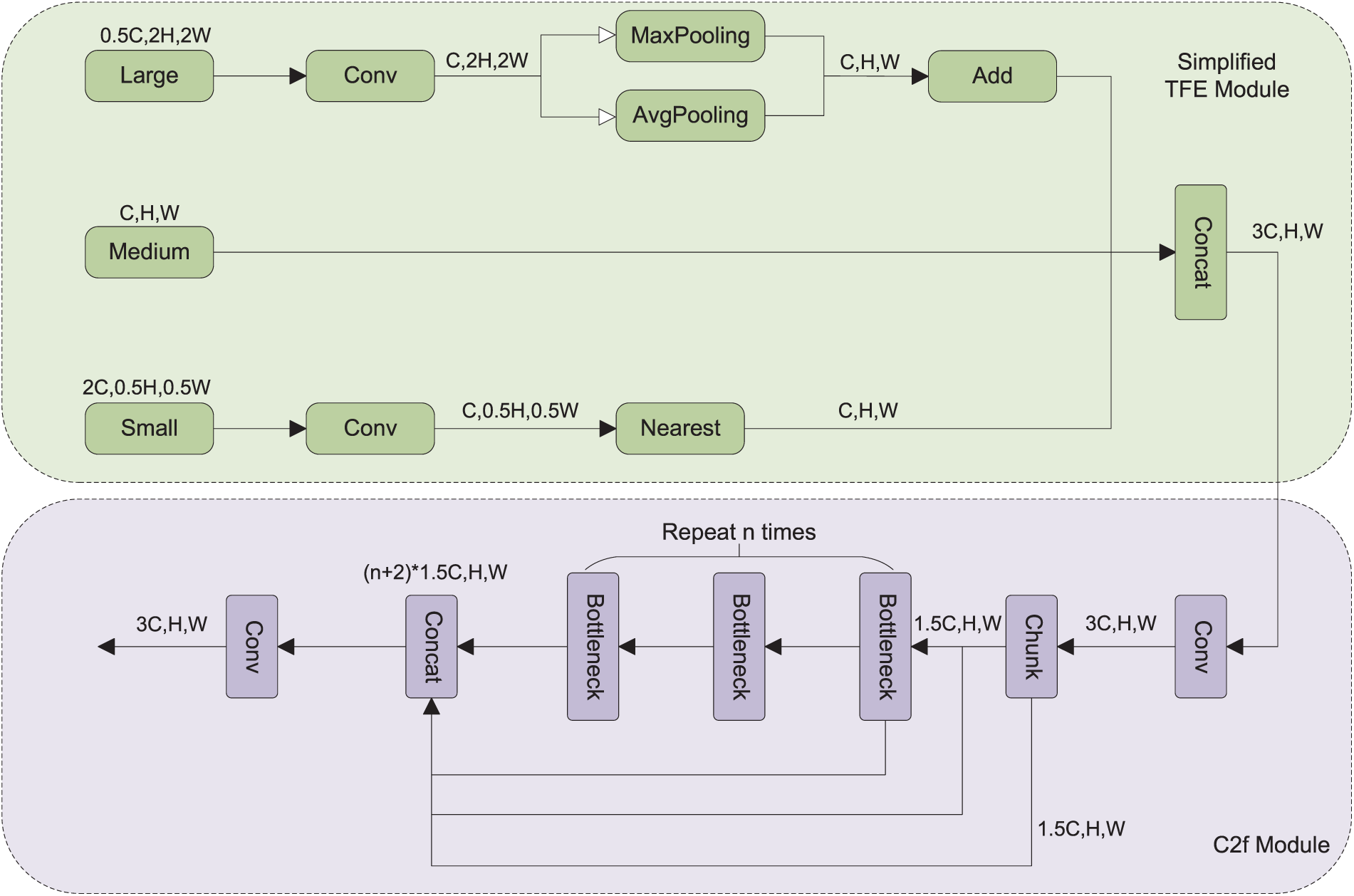

3.3 Multiple Features C2f Module

This study introduces and simplifies the TFE module [22], combining it with the C2f module to propose the MFC module. The TFE module not only fuses features from two levels but also splits and merges features from three levels—large, medium, and small—to enhance the capture of small target information. The C2f employs a CSP architecture, first transforming features through two convolutional layers, and then dividing the input into two branches. One branch is directly passed to the output, while the other undergoes multiple Bottleneck modules before being concatenated on the channel dimension to complete feature fusion. The structure of the MFC module is shown in Fig. 2. The MFC module first adjusts the channel numbers of the large and small feature maps, aims to match the middle size using 1

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the MFC module structure

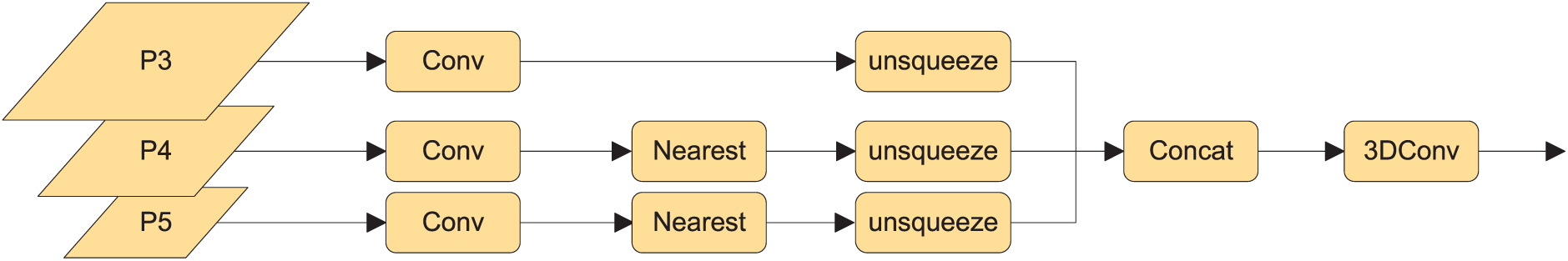

3.4 Scale Sequence Feature Fusion Module

For the multi-scale challenges of targets in drone aerial imagery, traditional feature pyramid structures merely use summation or concatenation for feature fusion, which does not effectively utilize the correlations between feature maps at different levels. The SSFF module introduced in this paper employs a novel scale sequence feature fusion approach. Feature maps at different sizes can be regarded as a scale space, and effective feature maps of various resolutions can be resized to the same resolution for concatenation. Although the size of the image changes during downsampling, the scale of the target remains constant, and the feature information remains unchanged. The structure of the SSFF module is shown in Fig. 3. It first uses 1

Figure 3: SSFF module structure diagram

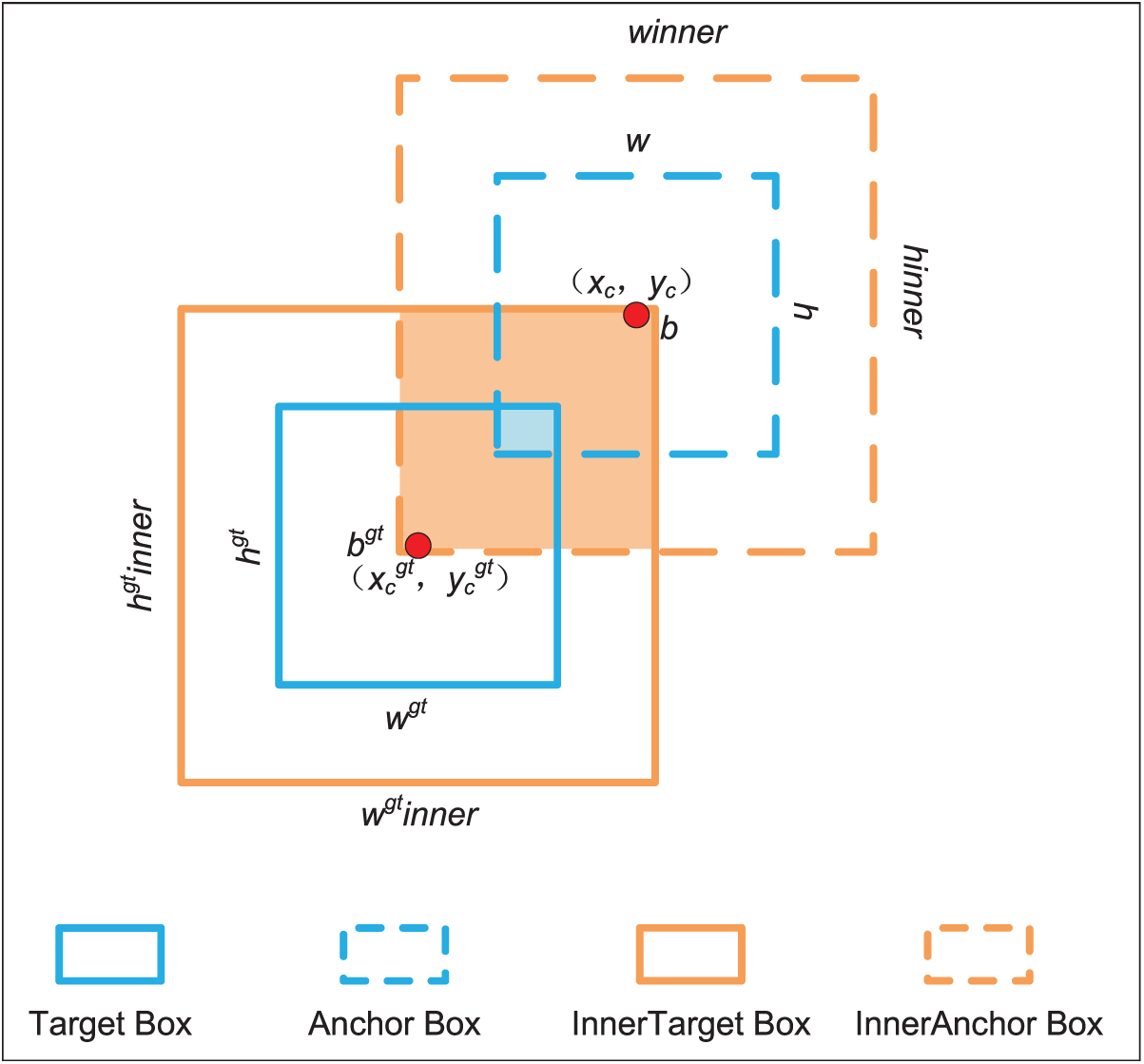

3.5 The Inner-CIoU Loss Function

The Intersection over Union (IoU) loss function is widely applied in object detection. The IoU value represents the ratio between the predicted box and the ground truth box, and its calculation method is shown in Eq. (1), where A and B represent the two boxes, respectively. YOLOv8 employs a variant of the IoU loss called CIoU [23], which takes into account the three most important factors in box regression tasks: overlapping area, aspect ratio, and center point distance. Compared to the IoU loss, the CIoU loss significantly improves convergence speed and detection accuracy. The CIoU loss is calculated using Eqs. (2)–(4), where the predicted box and the ground truth box are denoted as

Current IoU-based loss functions are enhancing performance by embedding extra loss terms, but they overlook the inherent issues with IoU itself. Although IoU loss can effectively describe the state of bounding box regression, it fails to self-adjust according to different task scenarios and lacks strong generalization capabilities. Small targets in images occupy a tiny proportion. They may only be a few pixels in size, making their IoU values highly sensitive to even slight displacements, which can result in significant changes in IoU values with minor shifts. The Inner-IoU [24] mitigates this sensitivity by introducing the auxiliary bounding box for loss calculation. As shown in Fig. 4, the blue box represents the actual bounding box, and the orange box represents the auxiliary bounding box. The dashed and solid lines represent the predicted and actual bounding boxes, denoted as

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of the Inner-IoU auxiliary bounding box

The value of

After adding detection layers, the improved model inevitably increases computational load and parameter count. To make the model more lightweight and adaptable to mobile platforms such as drones, this study employed the LAMP [25] model pruning algorithm. Model pruning can eliminate a large number of unimportant connections within the network, reducing the model’s computational load and parameter count, and mitigating overfitting issues.

LAMP is a global pruning algorithm based on the computation of weight scores. It first assumes that each weight tensor is unfolded into a one-dimensional vector and that the weights are sorted in ascending order according to a given index map, such that for every unfolded tensor, whenever

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

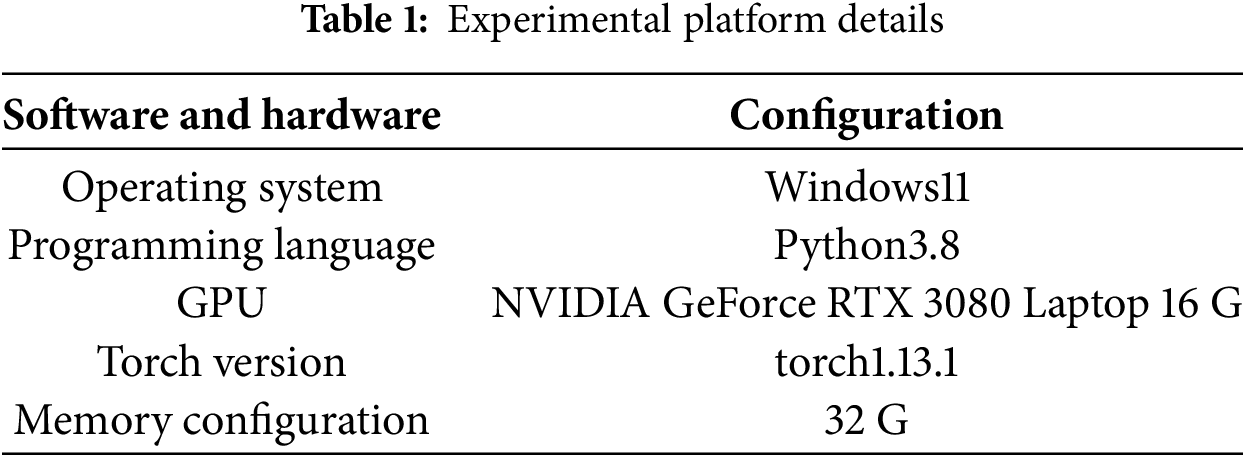

The platform details for experiment is listed in Table 1. The learning rate was set to 0.01, a value determined through grid search over the interval [0.001, 0.1]. This learning rate achieves an optimal balance between convergence speed and detection stability. To ensure a fair comparison with baseline and other models, the input resolution was set to 640

The VisDrone2019 dataset [26] was selected for experimentation in this study. This dataset, created by the Machine Learning and Data Mining Laboratory of Tianjin University, comprises 10,209 drone aerial images from various environments across different cities in China, along with over 2.6 million annotated bounding boxes. The dataset encompasses ten categories: pedestrians, people, cars, vans, buses, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, rickshaws, and tricycles. The experiment utilized 6471 images for training set, and 548 images for validation set.

Meanwhile, another dataset was also used. The SeaDronesSee dataset, which is a large-scale visual dataset specifically designed for maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) scenarios, aiming to facilitate research and development of UAV-based maritime search and rescue systems. The dataset comprises 5630 images for training, 859 for validation, and 1796 for testing. It consists of imagery collected from real maritime environments, featuring a significant number of small objects, along with diverse and complex weather and lighting conditions—such as open waters, islands, and vessels under various meteorological settings. These characteristics endow the dataset with high authenticity and diversity.

To thoroughly assess model performance, the experiment employs Average Precision (AP) and mAP to measure model accuracy comparatively. AP is the average precision for a given category, while mAP is the mean of average precision for all categories. This experiment also evaluates model complexity in terms of the number of model parameters and computational load (FLOPs). The parameter count refers to the number of trainable parameters in the model, which is directly proportional to memory usage. FLOPs stands for the number of floating-point operations performed by the model.

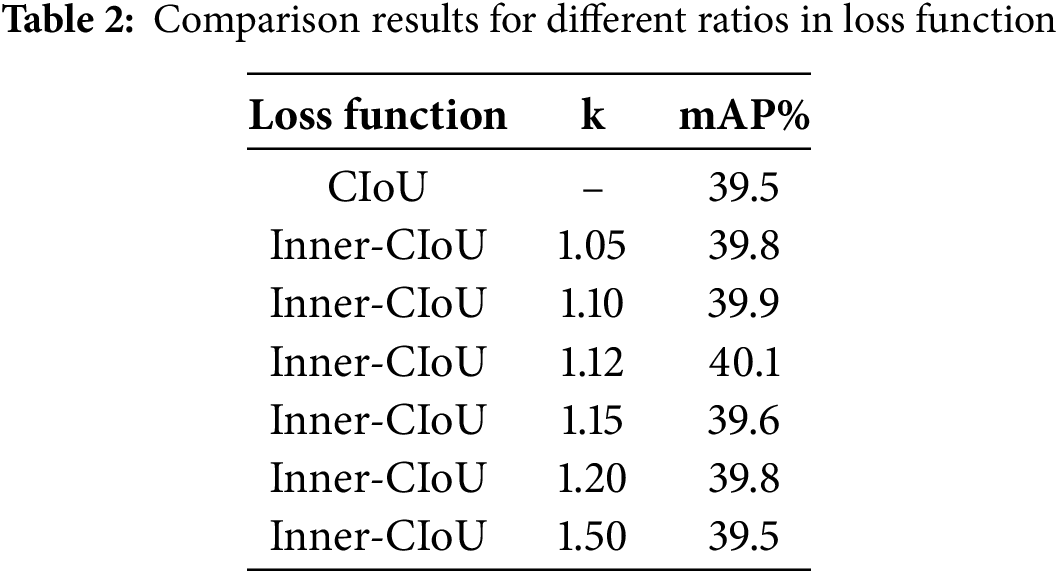

4.4.1 Comparison of Results with Different Ratios in Loss Function

The Inner-IoU requires an appropriate ratio to control the auxiliary-bounding-box’s size. A larger auxiliary box is typically necessary for small targets, meaning the ratio k should be over than 1. This experiment set up four different ratios for comparative testing to find the most suitable value, with the results shown in Table 2. The results in the table indicate that the best performance was achieved when the ratio k was set to 1.12, with a precision of 40.1%, which is 0.6 percentage points better than the baseline.

4.4.2 Comparison of Different Pruning Rates

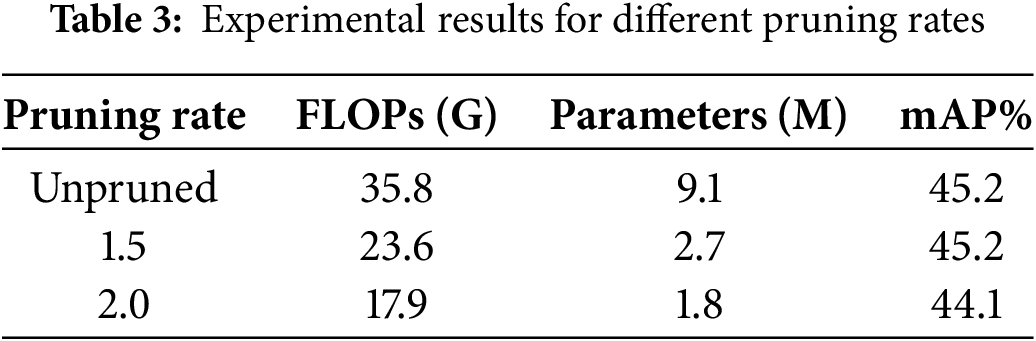

Model pruning algorithms can eliminate a large number of unimportant branches, but they also likely reduce model accuracy. This experiment set different pruning rates for comparison to find the balance between model lightweight and accuracy. The results are shown in Table 3.

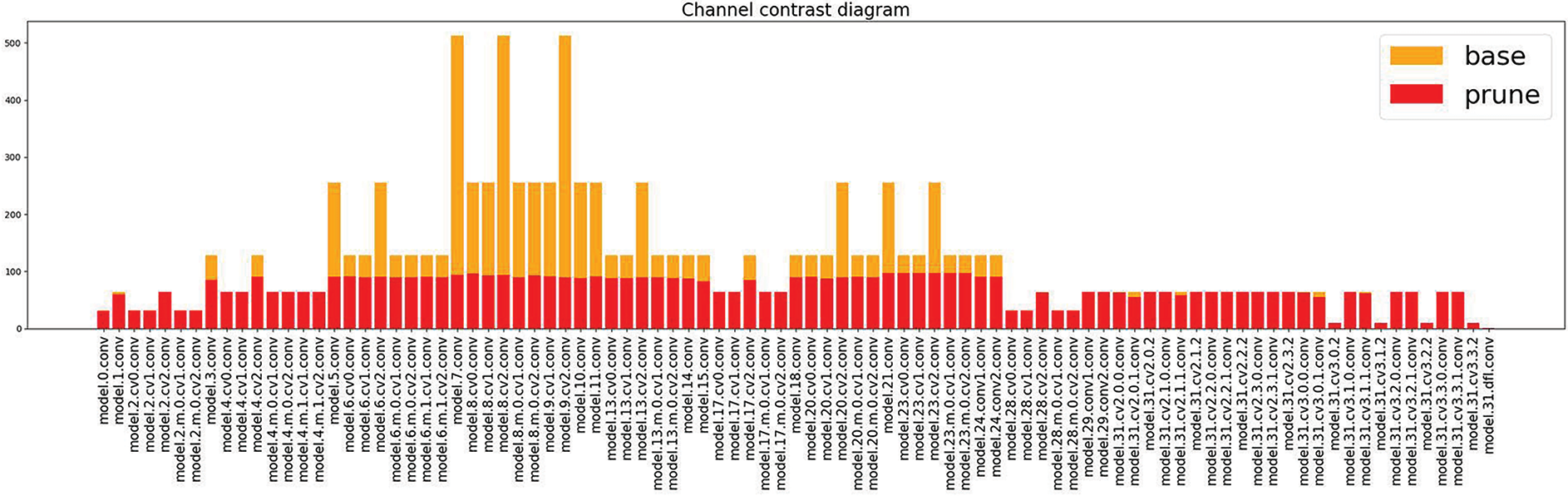

The pruning rate directly correlates with the model’s compression ratio. The upper table shows that a compression rate of 1.5 yields the best overall performance; the computational load of the model is 65.9% of its original, and also, the parameter count is significantly reduced by 6.4 M while maintaining the original accuracy after fine-tuning. Fig. 5 compares the channel count in each layer between the pruned and unaltered model, with orange representing before pruning and red after pruning. When the pruning rate is 2.0, the computational load is reduced by 50%, and parameter count is reduced by 7.3 M, but the accuracy also decreases by 1.1%. After comprehensive consideration, this study adopted a pruning rate of 1.5 that does not compromise accuracy.

Figure 5: Comparison of channel numbers in each layer

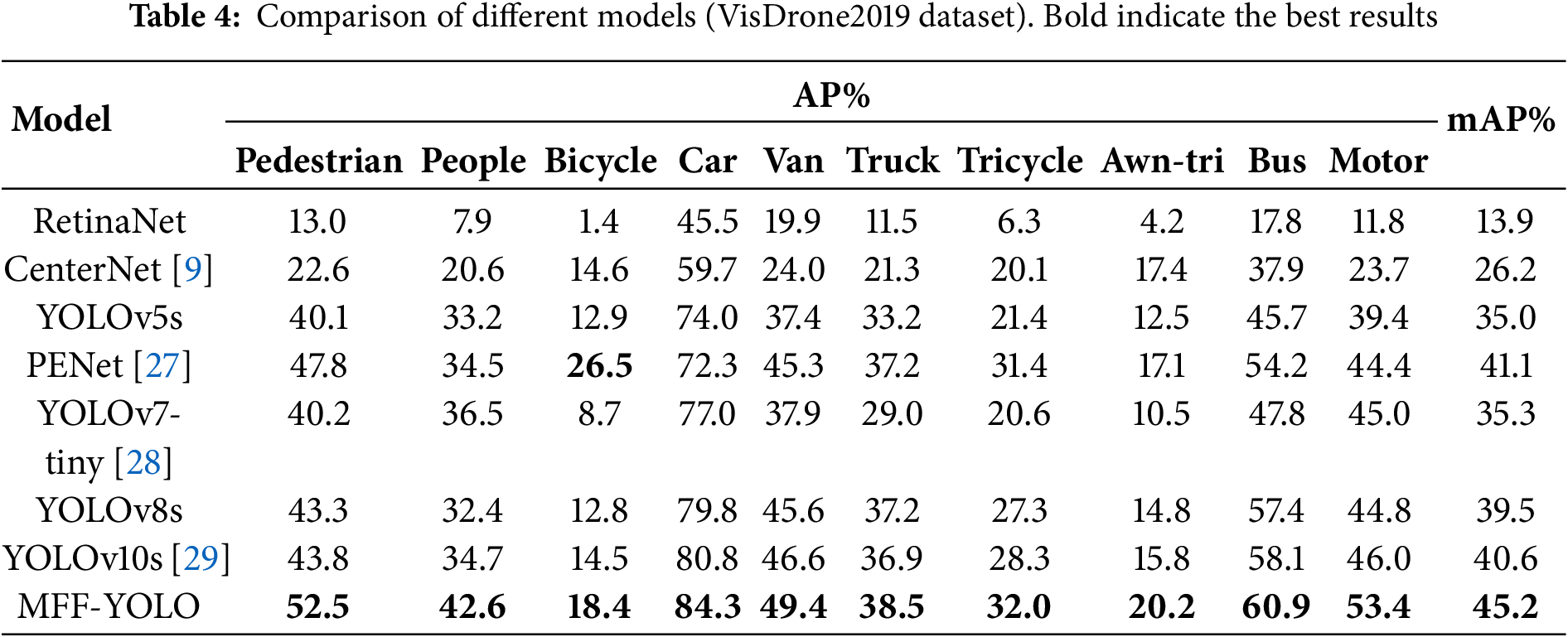

4.4.3 Performance Comparison of Different Models

To validate the advancement of the improved algorithm MFF-YOLO in this study, this experiment compared it with recent algorithmic models on the VisDrone2019 dataset. The specific results of the experiment are shown in Table 4.

In the table, it shows that the improved MFF-YOLO algorithm exhibits superior performance in terms of mAP compared to other algorithms. The mAP of MFF-YOLO is 5.7% higher than the baseline YOLOv8s, and it outperforms the state-of-the-art (SOTA) models YOLOv10s, YOLOv7-tiny, and PENet by 4.6%, 9.9%, and 4.1%, respectively. Additionally, it significantly surpasses the classic models RetinaNet, CenterNet, and YOLOv5s.

MFF-YOLO demonstrates significant performance improvements in detecting small objects such as pedestrians, persons, bicycles, and motorcycles. Compared to the baseline model, it achieves an increase in AP of 9.2% for pedestrians, 10.2% for persons, and 8.6% for motorcycles. This enhancement is attributed to the MFFS and the newly incorporated P2 detection layer, which collectively improve the capability to capture fine-grained spatial information. For more challenging categories like tricycles and covered tricycles, which are hindered by extreme scale imbalance and frequent occlusion, the proposed method still delivers performance gains. For instance, the AP for tricycles improved from 27.3% to 32.0%. This indicates MFF-YOLO’s stronger capability in handling complex spatial structures.

Furthermore, when compared to other efficient architectures such as YOLOv7-tiny and YOLOv10s, MFF-YOLO not only achieves higher accuracy in nearly all categories but also maintains an optimized parameter count and computational overhead. This confirms its suitability for practical deployment in UAV-based applications.

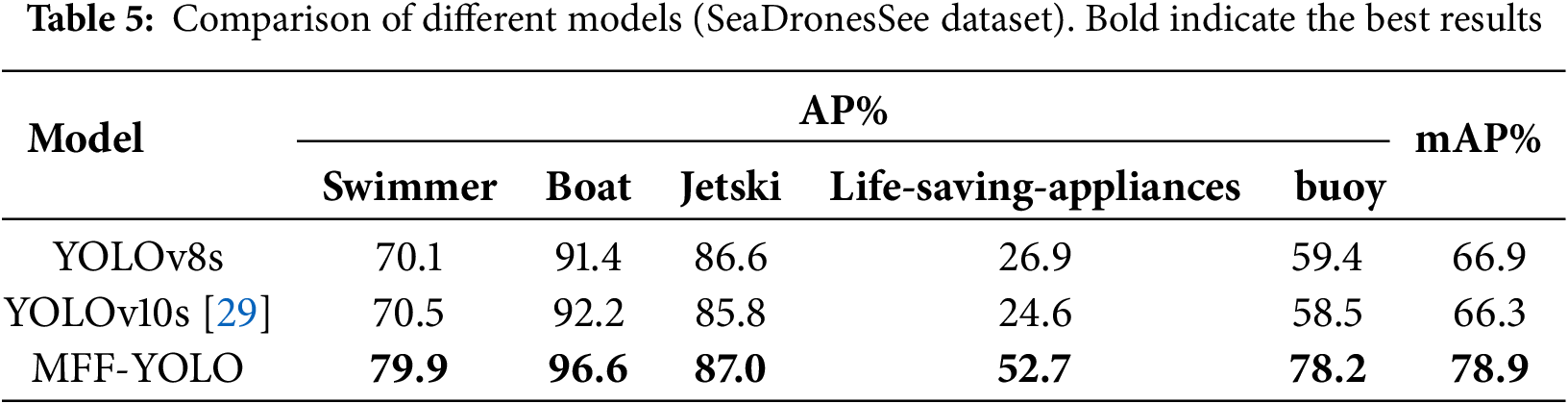

To evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed MFF-YOLO model across diverse scenarios, we did comparative experiments on the SeaDronesSee dataset against the baseline model YOLOv8s and the state-of-the-art detector YOLOv10s, the results are summarized in Table 5.

The experimental results demonstrate that MFF-YOLO achieves the highest detection accuracy across all object categories, attaining a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 78.9%, which exceeds YOLOv8s and YOLOv10s by 12.0% and 12.6%, respectively. For distinct categories such as swimmer, boat, and jetski, MFF-YOLO maintains a considerable performance advantage, with the AP for swimmer detection improved by nearly 10%. More notably, the model shows remarkable detection capability for challenging small object categories like life-saving-appliances and buoy, achieving AP scores of 52.7% and 78.2%, an increase of 25.8% and 18.8% compared to YOLOv8s. These results indicate a significant mitigation of missed detections for small objects, which commonly plague conventional detection models.

The findings fully demonstrate that the proposed multi-scale feature fusion strategy and optimized loss function collectively enhance the model’s perception and localization ability for objects of various scales, proving particularly advantageous in complex scenarios and small target detection.

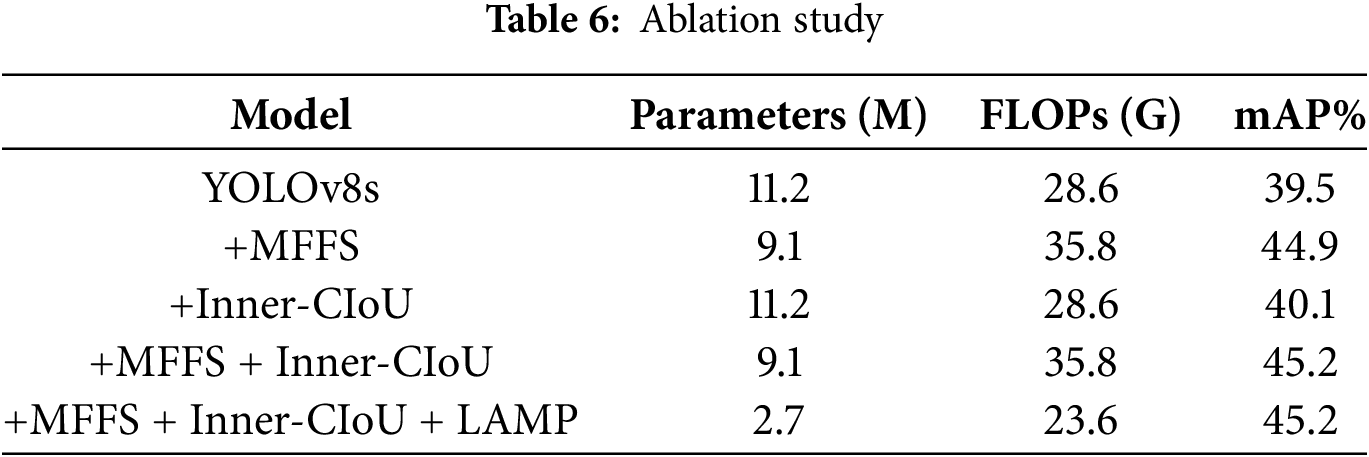

To validate the effectiveness of the improvements presented in this paper, an ablation study was conducted on the VisDrone2019 dataset under the same experimental conditions, with the results shown in Table 6. The table indicates that after enhancing the multi-scale feature fusion strategy, the parameter count was reduced by 2.1 M, the computational load increased by 25%, and the accuracy improved by 5.4%. This demonstrates that the MFFS is highly effective in enhancing the detection capability for small targets and strengthening the model’s ability to handle multi-scale targets. The introduction of Inner-CIoU resulted in a 0.6% increase in mAP, indicating that Inner-CIoU improves the regression quality of small target boxes and enhances model performance. After integrating MFFS and Inner-CIoU, the accuracy reached 45.2%, which is a 5.7% improvement over the baseline model. Building on the model with these two improvements, the use of LAMP pruning reduced the parameter count by 6.4 M and the computational load to 65.9% of its original, while maintaining the model’s accuracy. Ultimately, MFF-YOLO achieved a parameter reduction of 8.5 M, a 17.5% decrease in computational load, and a 5.7% increase in accuracy compared to the baseline. The experimental results show that the improved model is more suitable for UAV target detection.

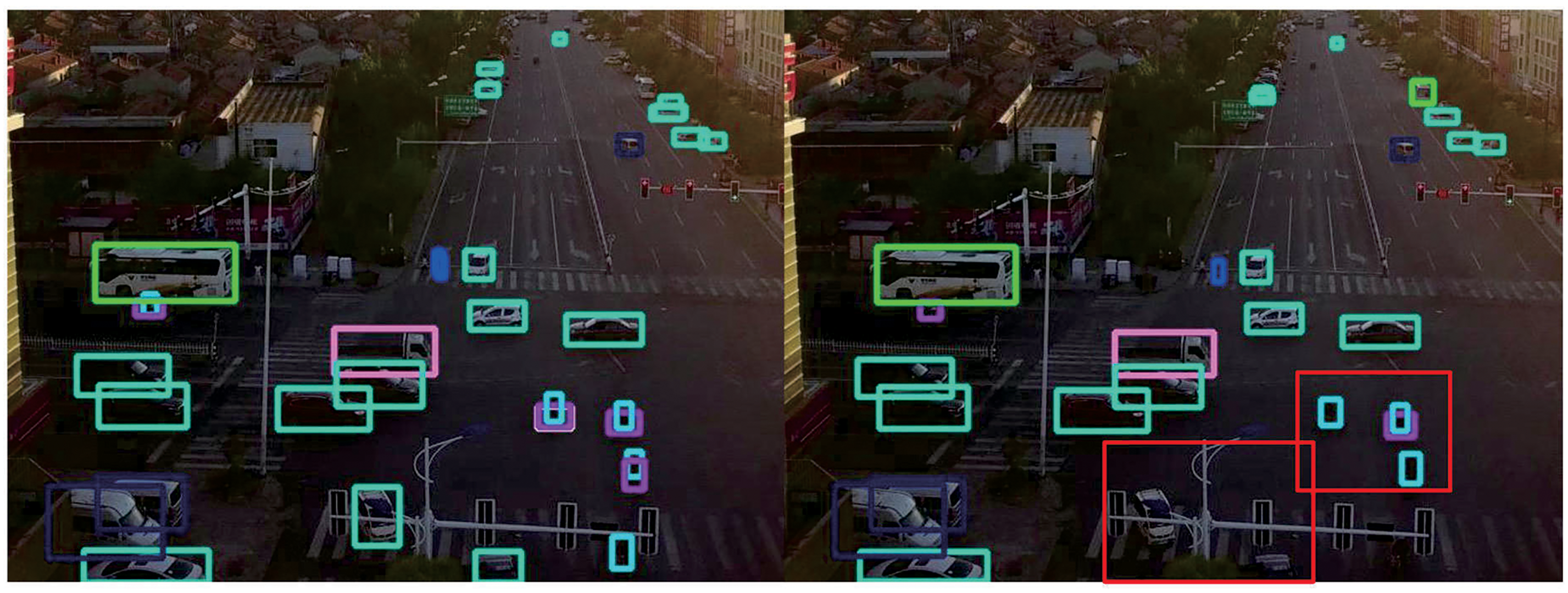

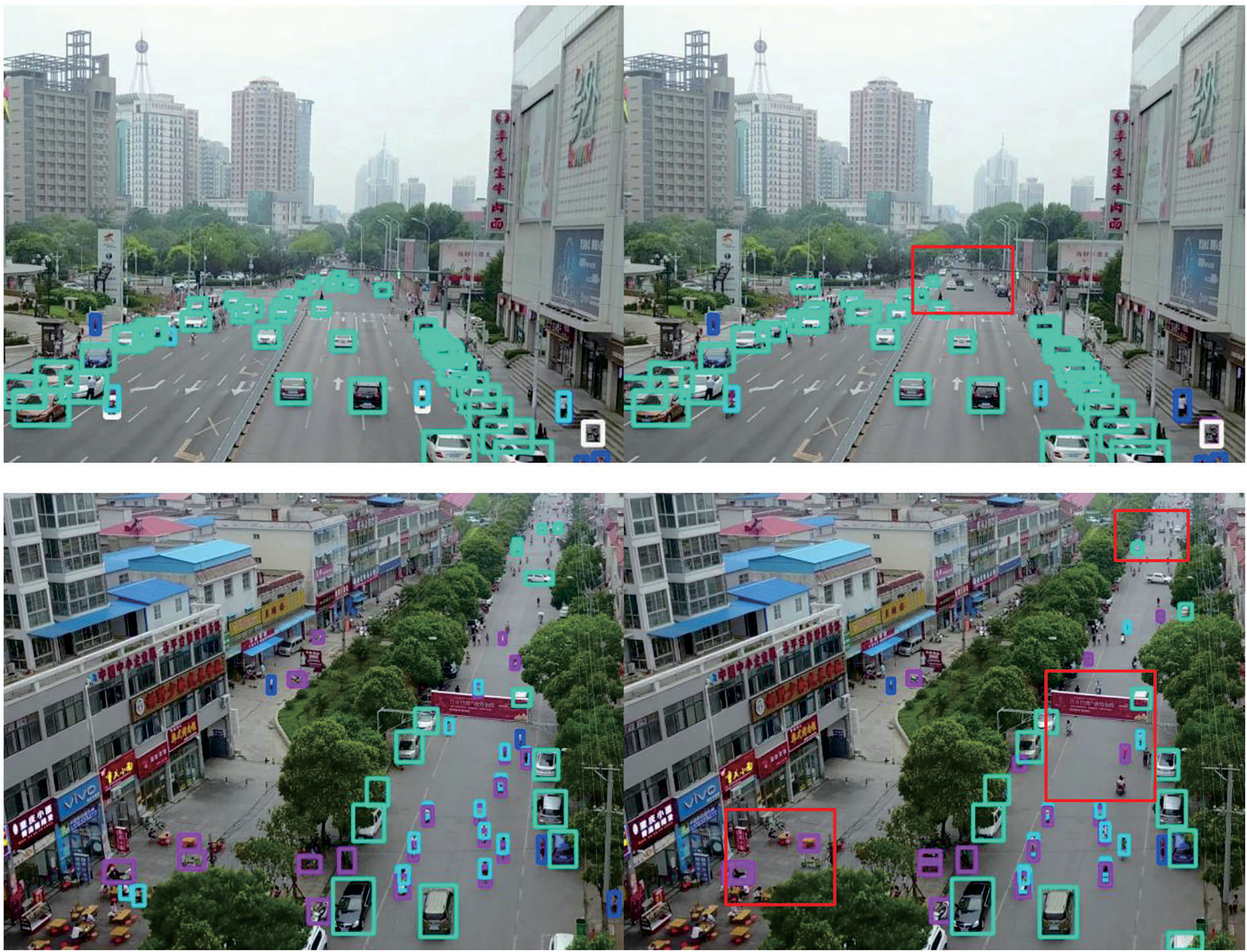

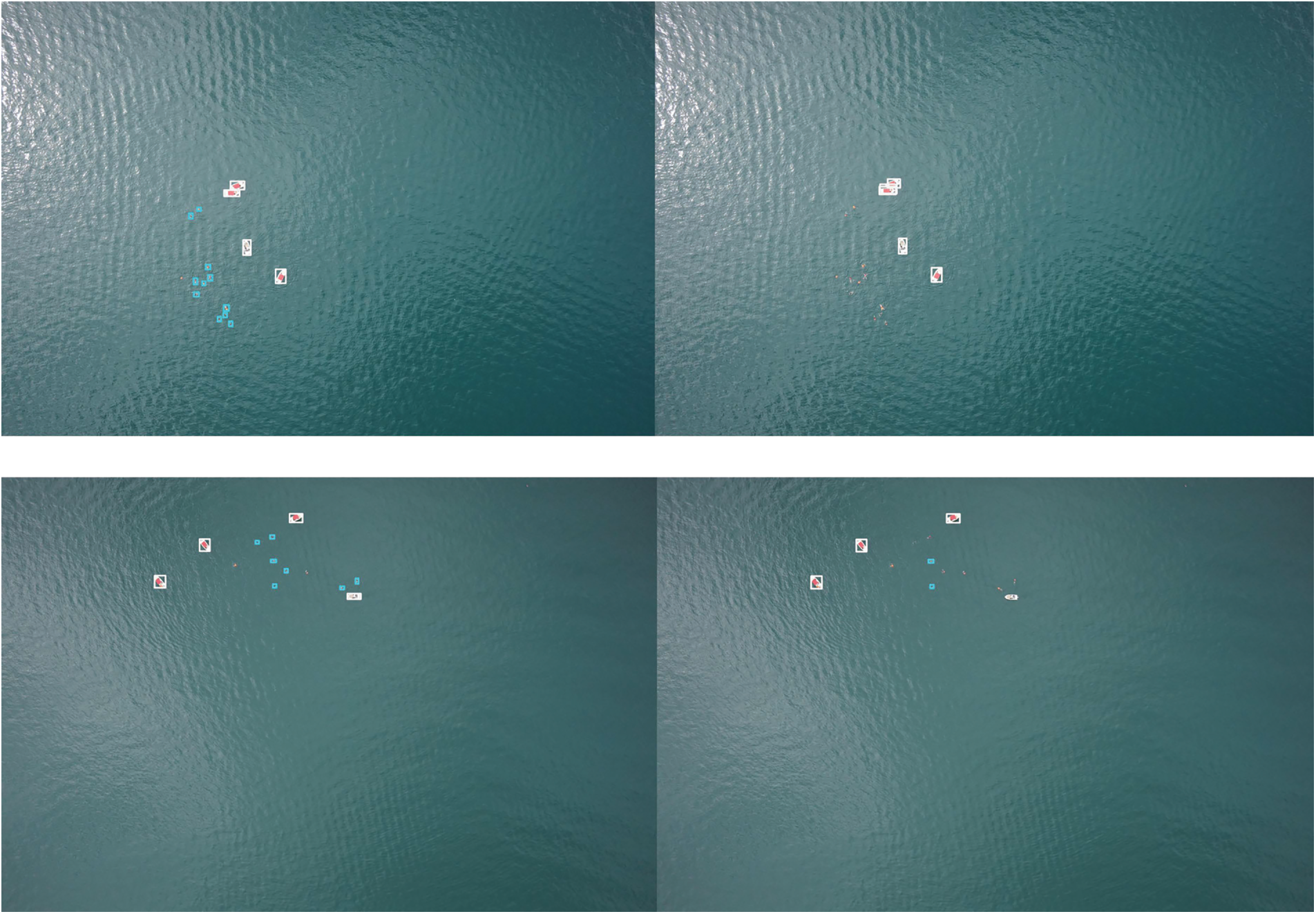

Visual Analysis of Detection Results

To more intuitively compare the improvement of the algorithm proposed in this paper, Figs. 6 and 7 show the comparison of the detection effects of the YOLOv8s model and the MFF-YOLO by using VisDrone2019 and SeaDronesSee dataset. The left side is result of MFF-YOLO and the right side is of YOLOv8s. In Fig. 6, the pictures in the first row were taken when the light was relatively dark. It can be seen that the YOLOv8s model has missed detection at this time, and the algorithm proposed in this paper is better. The pictures in the second row are all cars with obvious scale changes. It can be seen that MFF-YOLO can better cope with this situation and detect more targets. There are many extremely small targets in the pictures in the third row. It can also be seen that the algorithm improved in this study has a better detection effect. In Fig. 7, the results shown in the figure can well confirm that the MFF-YOLO has a significant advantage in the detection of small targets. In conclusion, compared with YOLOv8s, MFF-YOLO has improved detection ability in the UAV aerial photography scene.

Figure 6: Comparison of detection results between YOLOv8s and MFF-YOLO (VisDrone2019 dataset)

Figure 7: Comparison of detection results between YOLOv8s and MFF-YOLO (SeaDronesSee dataset)

In this paper, we propose MFF-YOLO, an enhanced object detection framework designed to address the critical challenges of small target detection and significant scale variations in UAV aerial imagery. The key developments and contributions of our work are summarized as follows: First, we introduced MFFS, which consists of the MFC module and the SSFF module. The MFC module effectively integrates multi-level features to retain fine-grained spatial information, while the SSFF module employs 3D convolution to capture structured cross-scale dependencies. Together, these components significantly enhance the model’s ability to detect small objects and handle targets with large scale variations. Second, to improve localization accuracy for small objects, we incorporated the Inner-CIoU loss function. By introducing auxiliary bounding boxes during IoU computation, Inner-CIoU reduces the sensitivity of small object regression to minor offset errors, thereby increasing both detection precision and robustness. Third, to ensure practical deployment on computationally constrained UAV platforms, we applied the LAMP structured pruning algorithm. This resulted in a substantially lighter model with reduced parameter count and FLOPs, while maintaining competitive accuracy.

Comprehensive experiments conducted on the VisDrone2019 dataset validate the effectiveness of the proposed method. MFF-YOLO achieves a mAP of 45.2%, outperforming the baseline YOLOv8s by 5.7%, and also excels in comparison to state-of-the-art models including YOLOv10s and YOLOv7-tiny. Notably, the model achieves these results with 8.5 million fewer parameters and 17.5% lower computational cost than the baseline, demonstrating its suitability for real-time UAV applications.

In future work, we plan to explore end-to-end optimization strategies to jointly optimize feature extraction, multi-scale fusion, and model compression within a unified framework. Additionally, we aim to extend the current image-based detection model to video sequences by incorporating temporal modeling and motion-aware mechanisms, which would significantly enhance detection continuity and accuracy in dynamic aerial environments. These improvements are expected to boost the robustness and real-time performance of UAV-based detection systems under complex scenarios such as high-speed movement, occlusions, and changing viewpoints.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge Changzhou University, the relevant colleges, and all laboratory colleagues.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61976028).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dike Chen and Zhiyong Qin; methodology, Dike Chen; software, Zhiyong Qin; formal analysis, Dike Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Dike Chen and Zhiyong Qin; writing—review and editing, Dike Chen and Ji Zhang; supervision and funding acquisition, Hongyuan Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dai J, Wu L, Wang P. Overview of UAV target detection algorithms based on deep learning. In: 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA); 2021 Dec 17–19; Chongqing, China. p. 736–45. [Google Scholar]

2. Al-lQubaydhi N, Alenezi A, Alanazi T, Senyor A, Alanezi N, Alotaibi B, et al. Deep learning for unmanned aerial vehicles detection: a review. Comput Sci Rev. 2024;51(1):100614. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2023.100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu Y, Sun P, Wergeles N, Shang Y. A survey and performance evaluation of deep learning methods for small object detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;172(4):114602. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. p. 580–7. [Google Scholar]

5. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2016;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask r-cnn. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2961–9. [Google Scholar]

7. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. [Google Scholar]

8. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. Ssd: single shot multibox detector. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer; 2016. p. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhou X, Wang D, Krähenbühl P. Objects as points. arXiv:1904.07850. 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhu X, Lyu S, Wang X, Zhao Q. TPH-YOLOv5: improved YOLOv5 based on transformer prediction head for object detection on drone-captured scenarios. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 2778–88. [Google Scholar]

11. Quan Y, Zhang D, Zhang L, Tang J. Centralized feature pyramid for object detection. IEEE Trans Image Proc. 2023;32(6):4341–54. doi:10.1109/tip.2023.3297408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sun W, Dai L, Zhang X, Chang P, He X. RSOD: real-time small object detection algorithm in UAV-based traffic monitoring. Appl Intell. 2022;52(8):8448–63. doi:10.1007/s10489-021-02893-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang J, Xu C, Yang W, Yu L. A normalized Gaussian Wasserstein distance for tiny object detection. arXiv:2110.13389. 2021. [Google Scholar]

14. Cao J, Cholakkal H, Anwer RM, Khan FS, Pang Y, Shao L. D2det: Towards high quality object detection and instance segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19. Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11485–94. [Google Scholar]

15. Zuo G, Zhou K, Wang Q. UAV-to-UAV small target detection method based on deep learning in complex scenes. IEEE Sens J. 2025;25(2):3806–20. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3505551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jiao Z, Wang M, Qiao S, Zhang Y, Huang Z. Transformer-based object detection in low-altitude maritime UAV remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63(12):4210413. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2025.3594085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2117–25. [Google Scholar]

18. Liu S, Qi L, Qin H, Shi J, Jia J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 8759–68. [Google Scholar]

19. Tan M, Pang R, Le QV. Efficientdet: scalable and efficient object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 10781–90. [Google Scholar]

20. Xu X, Jiang Y, Chen W, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Sun X. Damo-yolo: a report on real-time object detection design. arXiv:2211.15444. 2022. [Google Scholar]

21. Tong K, Wu Y. Small object detection using deep feature learning and feature fusion network. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;132(7):107931. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.107931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kang M, Ting CM, Ting FF, Phan RCW. ASF-YOLO: a novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image Vis Comput. 2024;147(4):105057. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zheng Z, Wang P, Liu W, Li J, Ye R, Ren D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI; 2020. Vol. 34. p. 12993–3000. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhang H, Xu C, Zhang S. Inner-iou: more effective intersection over union loss with auxiliary bounding box. arXiv:2311.02877. 2023. [Google Scholar]

25. Lee J, Park S, Mo S, Ahn S, Shin J. Layer-adaptive sparsity for the magnitude-based pruning. arXiv:2010.07611. 2020. [Google Scholar]

26. Du D, Zhu P, Wen L, Bian X, Lin H, Hu Q, et al. VisDrone-DET2019: the vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2019 Oct 27–28; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 213–26. [Google Scholar]

27. Tang Z, Liu X, Shen G, Yang B. Penet: object detection using points estimation in aerial images. arXiv:2001.08247. 2020. [Google Scholar]

28. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. [Google Scholar]

29. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. Yolov10: real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv Neural Inf Proc Syst. 2024;37:107984–8011. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools