Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Structural and Helix Reversal Defects of Carbon Nanosprings: A Molecular Dynamics Study

1 Semenov Institute of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119991, Russia

2 Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Moscow, 117997, Russia

3 Laboratory of Metals and Alloys under Extreme Impacts, Ufa University of Science and Technology, Ufa, 450076, Russia

4 Polytechnic Institute (Branch) in Mirny, North-Eastern Federal University, Mirny, 678170, Sakha Republic (Yakutia), Russia

5 Department of Equipment and Technologies for Welding and Control, Ufa State Petroleum Technological University, Ufa, 450064, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Sergey V. Dmitriev. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072786

Received 03 September 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Due to their chiral structure, carbon nanosprings possess unique properties that are promising for nanotechnology applications. The structural transformations of carbon nanosprings in the form of spiral macromolecules derived from planar coronene and kekulene molecules (graphene helicoids and spiral nanoribbons) are analyzed using molecular dynamics simulations. The interatomic interactions are described by a force field including valence bonds, bond angles, torsional and dihedral angles, as well as van der Waals interactions. While the tension/compression of such nanosprings has been analyzed in the literature, this study investigates other modes of deformation, including bending and twisting. Depending on the geometric characteristics of the carbon nanosprings, the formation of structural and helix reversal topological defects is described. During these structural transformations of the nanosprings, only van der Waals bonds break and recover, but breaking or recovery of covalent bonds does not take place. It is found that nanosprings demonstrate a significantly higher coefficient of axial thermal expansion than many metals and alloys. Under axial compression, Euler instability leads to lateral bending with continuous deformation of the nanospring axis at relatively low compression, while at high compression, bending kinks form. Various types of topological defects form on the instantly released nanospring during its relaxation from a highly stretched configuration. These results are useful for the development of nanosensors operating over a wide temperature range.Keywords

Carbon, an element in the fourth group of the periodic table, can form a wide variety of

The helical graphene displays fascinating electronic properties [22–25], which are primarily determined by the interactions between layers [26,27]. The twisted nanoribbons can be used as nanocoils of inductance [28,29]. Coiled carbon nanotubes have potential in applications as nanoelectromechanical devices [30]. A change in the pitch of the helical graphene results in the metal-semiconductor transition [31]. The double-layer spiral graphene is metallic in an equilibrium state [32]. It has been determined that the electronic properties of helical graphene with armchair and zigzag edges differ significantly [33]. It has been shown experimentally and theoretically that DNA molecular springs modulate protein-protein interactions [34]. Various techniques are used for fabrication of nanospring: vapor phase synthesis, post-treatment techniques, templating methods, and molecular engineering [35]. The elastic properties of carbon and silicon based core-shell nanosprings have been found to be better than those of pure C and Si [36].

Helical carbon nanosprings are a unique material that combines the properties of single-layer nanoribbons and multilayer graphene. Due to their distinctive properties, they are of significant interest for nanotechnology. Not only electronic but also magnetic properties of helical graphene depend on the structure and elastic stretching [37]. Compression and stretching of helical graphene nanoribbons have been shown to cause a significant change in their thermal conductivity [38–41]. Tightly-wound helical carbon nanotubes exhibit giant elastic deformation under cyclic stretching and unloading and return to their original shape after more than doubling their length [42].

The mechanical properties of helical graphene nanoribbons have been analyzed in numerous studies. The nanosprings exhibit exceptional elasticity, with a maximum reversible tensile strain of hundreds percent [43,44]. The nanosprings, under tension, demonstrate a deviation from Hooke’s law due to the breaking of the van der Waals bonds between coils, which leads to non-homogeneous stretching [45]. Graphene nanoribbon nanosprings exhibit a distinctive force-strain relationship under tension, characterized by a constant force plateau across a broad range of tensile strain [9,46–48]. This phenomenon was explained in [9] by non-convex dependence of the potential energy of a structural unit of the nanospring as the function of tensile strain. A similar phenomenon has been observed for DNA [49–51] and for intermetallic NiAl and FeAl nanofilms [52–54].

Elastic and mechanical properties, the microscopic tensile deformation and fracture mechanisms of nanoentwined carbon nanocoils have been reported in the work [55]. Alternative terms are used for chiral extended metamaterials, including coiled and helical structures, whereas in the review [13] the term “spiral” has been chosen.

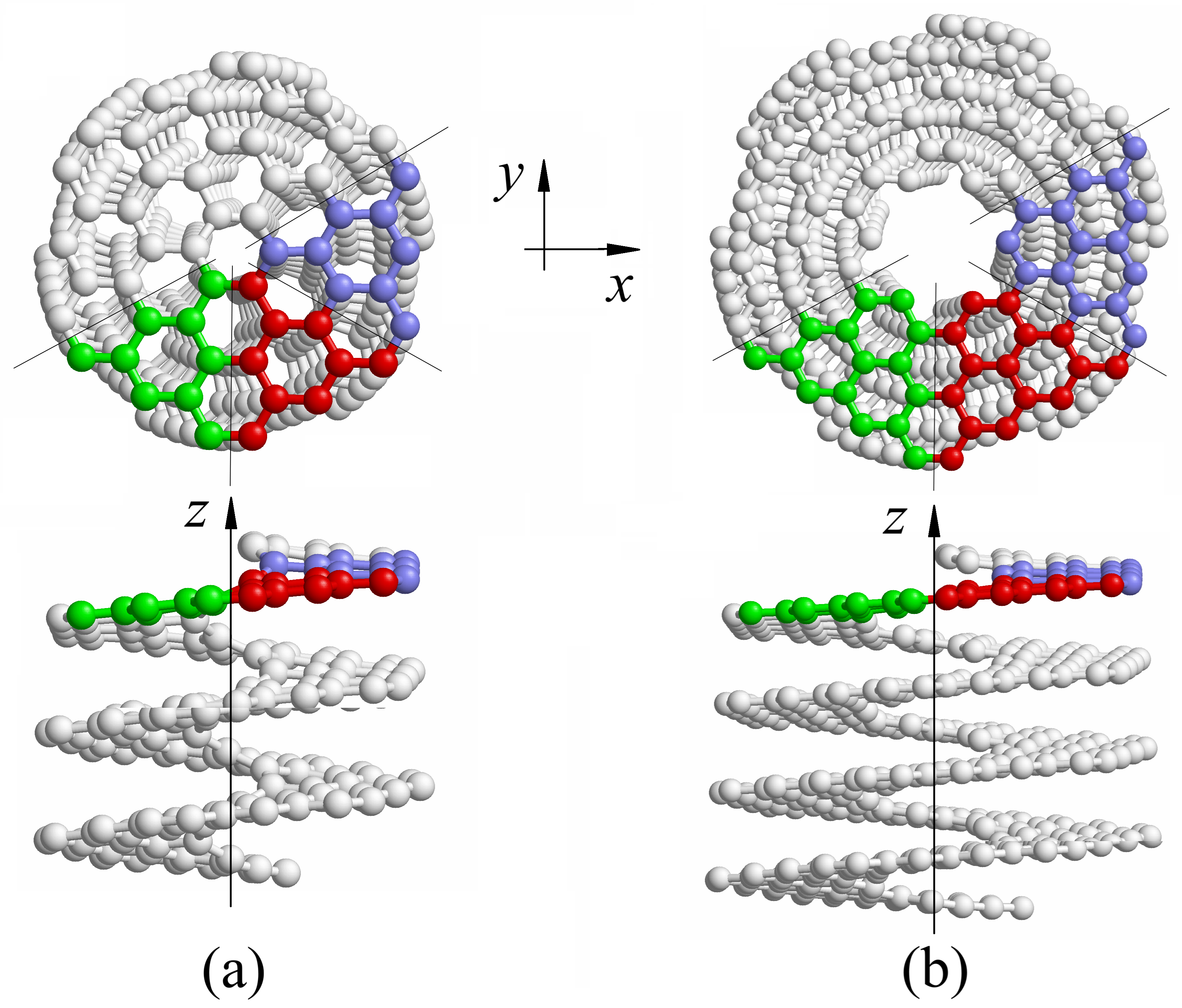

A comprehensive analysis of the mechanical and thermal properties of carbon nanosprings has been conducted, with a focus on tension and compression deformation [9,41,45,56–58]. Other modes of loading have not been addressed by the researchers, and here axial compression, bending, and twisting of the carbon nanosprings is analyzed using molecular dynamics simulations. The structures under consideration in this work can be divided into two categories: helicoids, Fig. 1a, and helical graphene nanoribbons, Fig. 1b. The chiral structures of the second type possess an inner channel, while the structures of the first type are devoid of such a feature.

Figure 1: Atomic tructure of (a) helix

In this work, we show that helical carbon nanosprings, in addition to their high tensile ability, have other unique mechanical properties. Thus, their compression can lead to the formation of stable folded structures with fractures, and their twisting can lead to the formation of structures with localized helix reversal defects separating parts of the nanospring with opposite chirality.

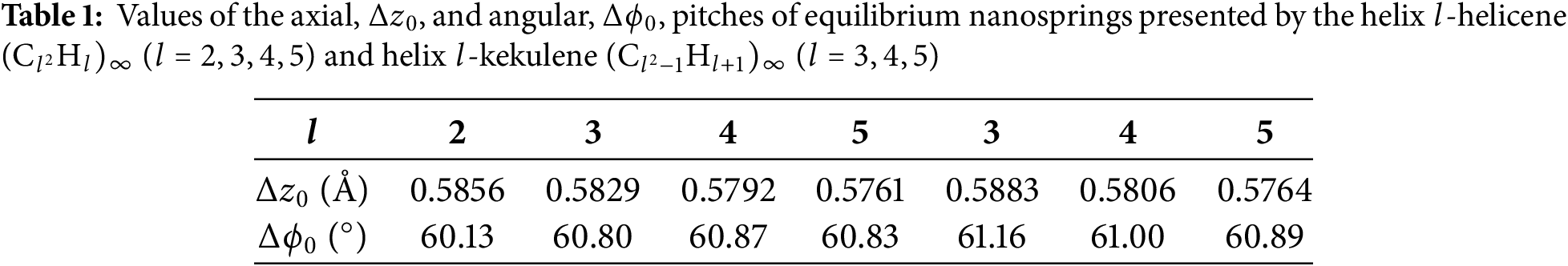

Consider helical molecular structures derived from planar molecules

Figure 2: Spiral

To simplify the modeling, valence-bonded CH groups of atoms at the edges of spiral structures are considered as a single carbon atom of mass

The coordinates of the carbon atoms of the

where the vector

A helical nanospring built from

The deformation of nanosprings is modeled using the force field described in Ref. [9]. This force field accounts for the deformation of valence bonds and angles, as well as torsional and dihedral angles, and van der Waals interactions between atoms [59–64]. The Hamiltonian of a finite-length nanospring is given by

where

The van der Waals interactions are described by the Lennard-Jones potentials

where the distance between the

and the parameters are

More complex reactive potentials have been developed to model the formation and breaking of covalent bonds between carbon atoms under thermomechanical loading, such as the Tersoff [66], ReaxFF [67], REBO [68] and AIREBO [69,70] potentials. These potentials describe the mechanical and elastic properties of carbon nanomaterials quite accurately [71–73]. However, they are more complex for numerical modeling and less accurately reproduce the phonon spectrum of graphene [66,74]. Therefore, their use is justified only when modeling processes involving changes in the topology of the valence bond network. It should be noted that the structural transformations of the nanosprings modeled in this work do not lead to the breaking or recovery of covalent bonds. Consequently, reactive force fields will lead to qualitatively the same results as the simple potential used in this work, since the interparticle distances change only slightly, and the reactive component of the potential is ineffective.

To find the ground state of the nanospring, the following potential energy minimization problem is numerically solved using the conjugate gradient method [75,76]:

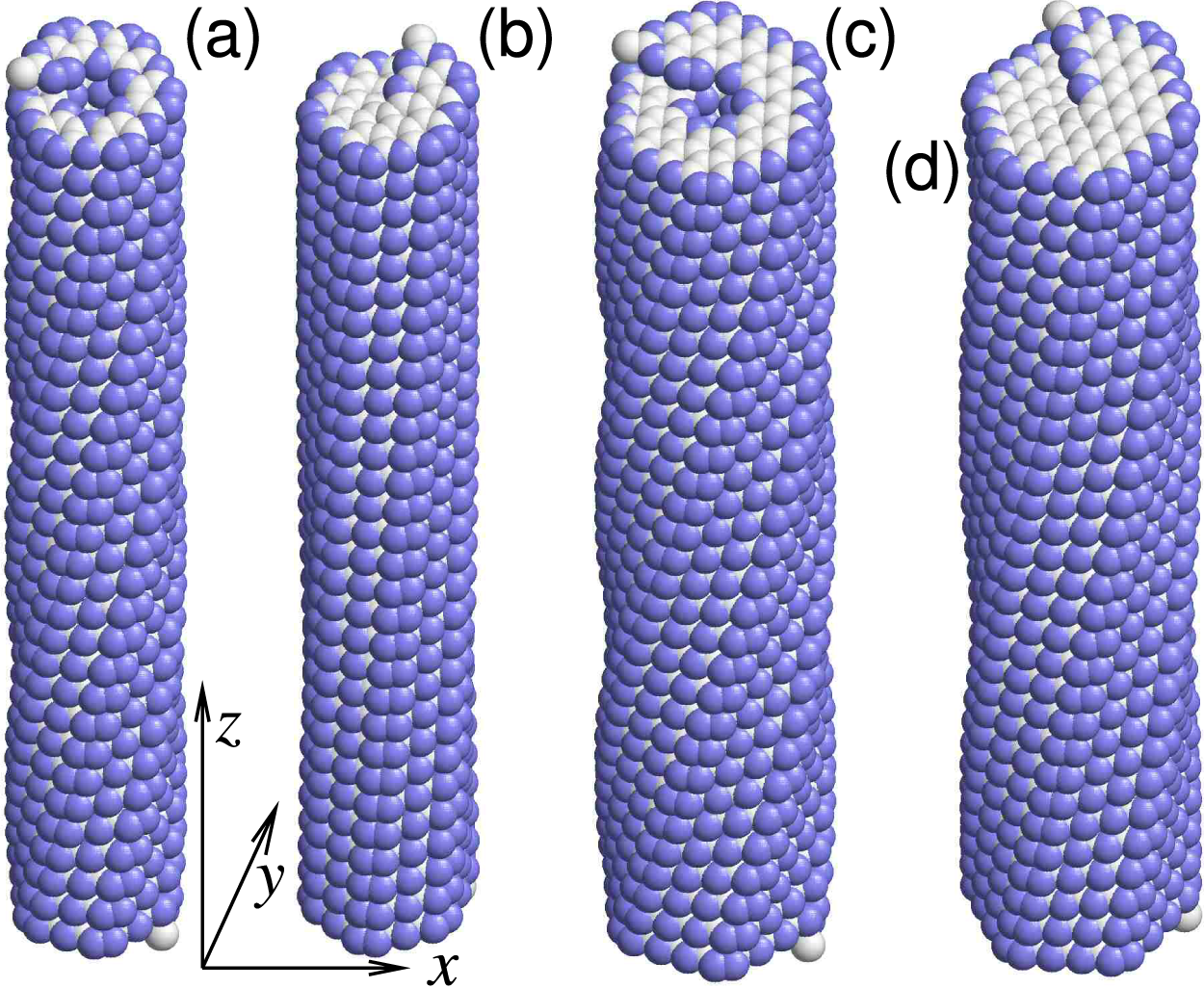

The ground states of the nanosprings of

The following system of Langevin equations is integrated numerically to model the thermal oscillations of the nanosprings:

with the initial conditions corresponding to the ground state

where

with

The equations of motion Eq. (6) are solved numerically using the velocity Verlet method [77]. A time step of 1 fs is used in the simulations, since further reduction of the time step has no appreciable effect on the results.

Once equilibrium is reached between the molecular system and the thermostat, the mean energy

Numerical modeling of nanosprings consisting of

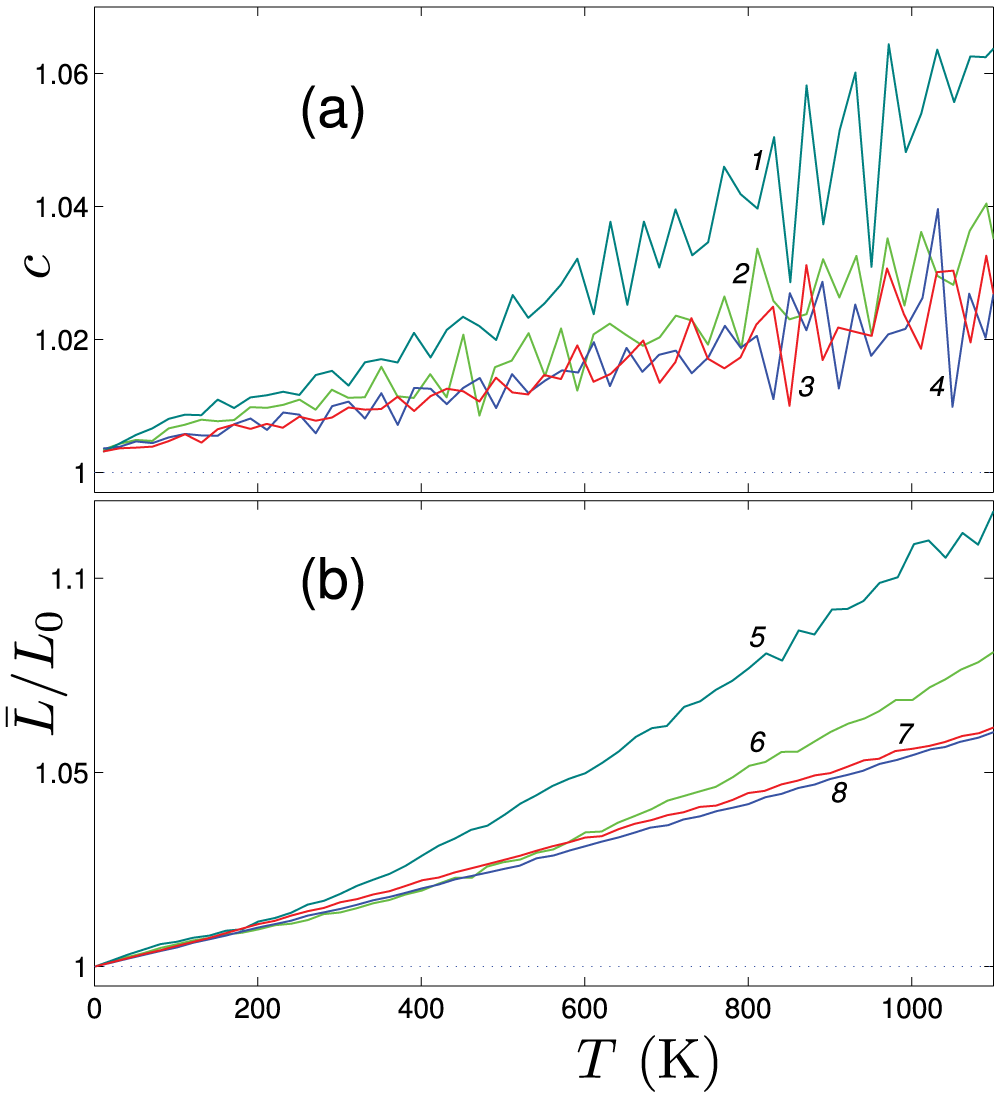

Figure 3: The temperature dependencies of (a) the dimensionless heat capacity

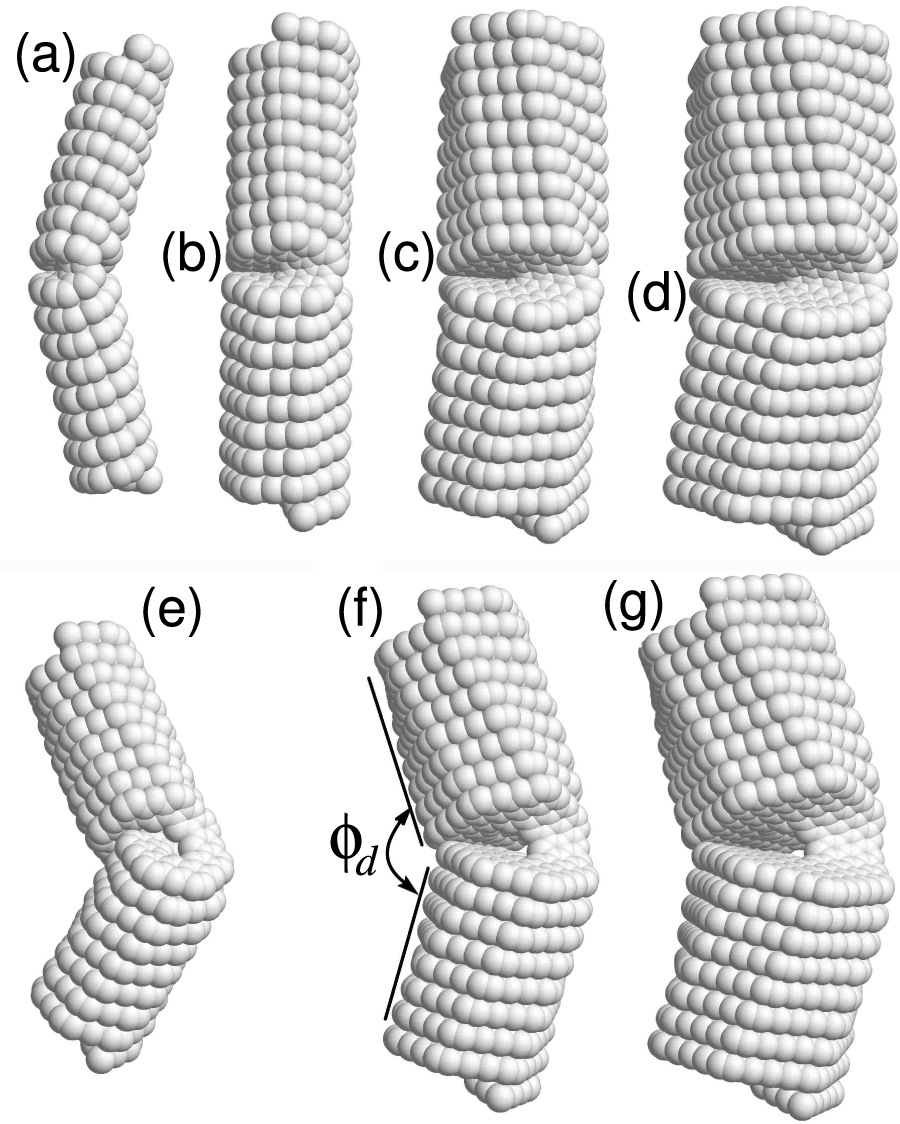

3 Axial Compression of Nanosprings

The longitudinal compression of a nanosprings consisting of

and initial conditions Eq. (7). The rate of compression is

After reaching the desired value of longitudinal dimensionless compression

and the initial conditions

After the system reaches the equilibrium with the thermostat, the mean value of its total energy

The energy

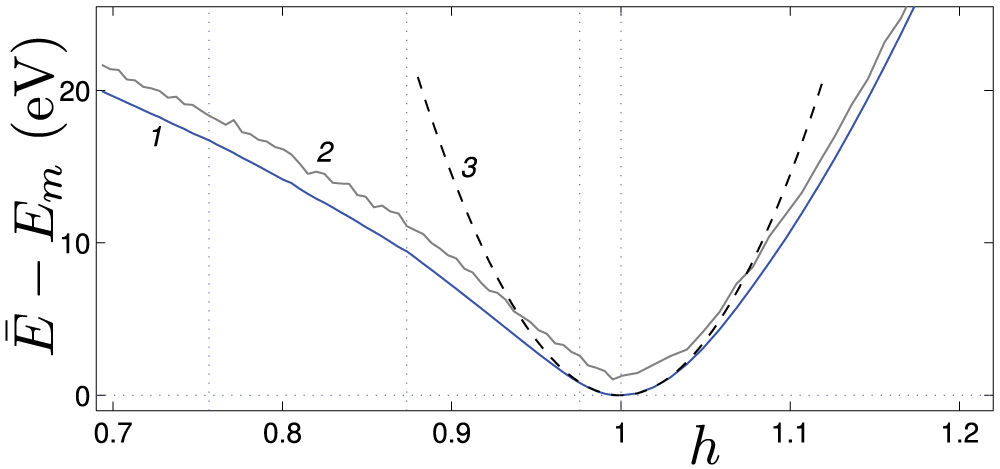

Figure 4: The dependence of the energy

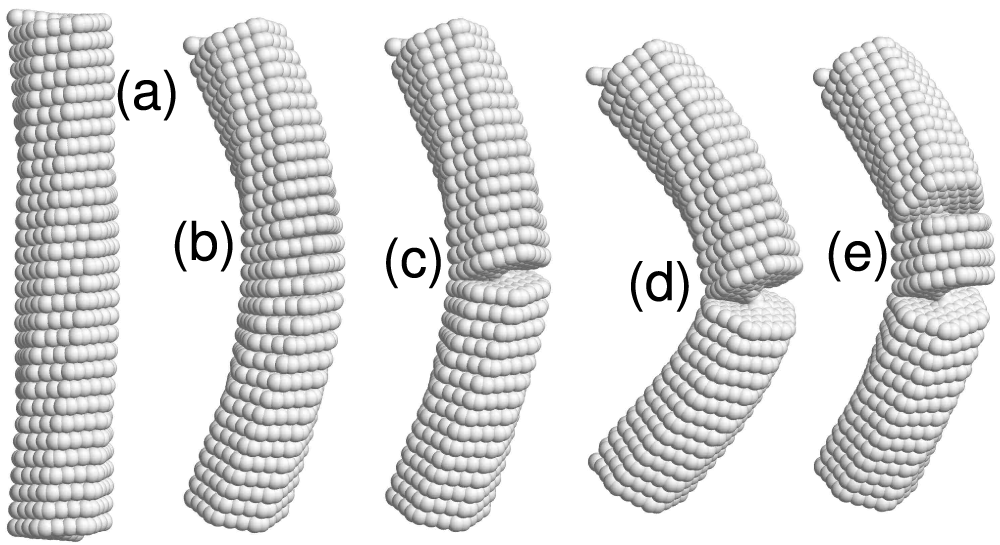

Figure 5: The

At weak relative compression,

The energy

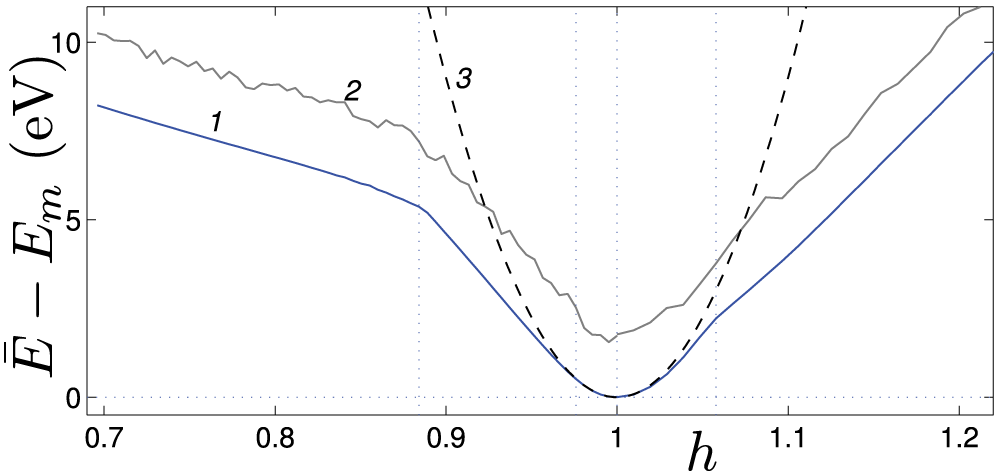

Figure 6: The dependence of the energy

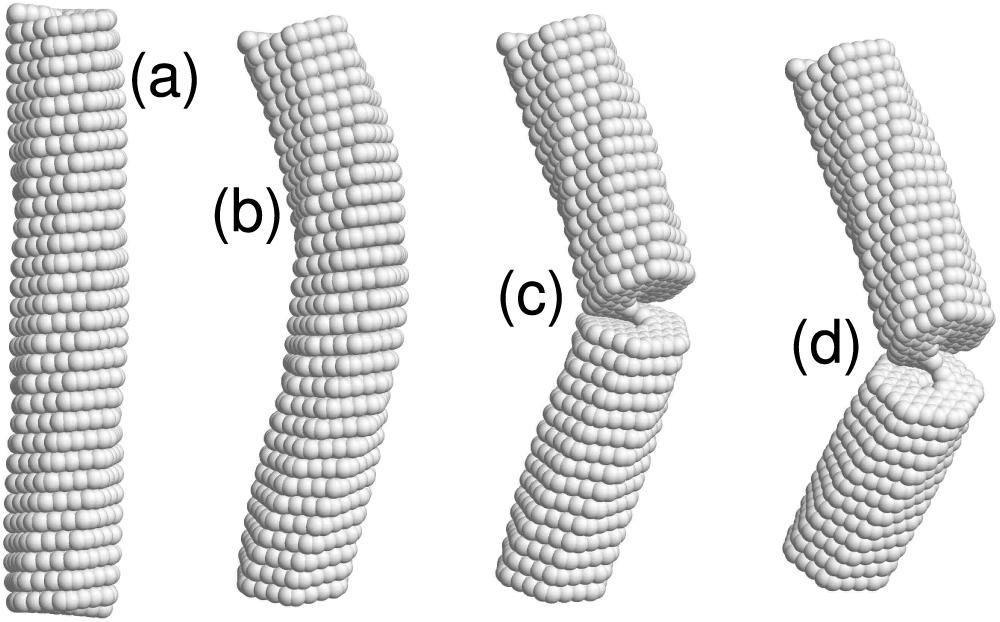

Figure 7: The

Note that, unlike the 4-coronene nanospring, compressing the 4-kekulene nanospring does not result in the formation of a second crack. Several cracks appear in the 4-coronene nanospring due to the presence of a rigid core that limits crack opening, making the formation of new cracks energetically preferable.

4 Bending and Fracture of Nanosprings

In order to bend the nanosprings, lateral forces must be applied in opposite directions to their ends and middle. This can be achieved by numerically integrating the following system of equations of motion

where the index

Integrating the system of equations of motion Eq. (11) with the initial conditions Eq. (7) shows that there is a critical force,

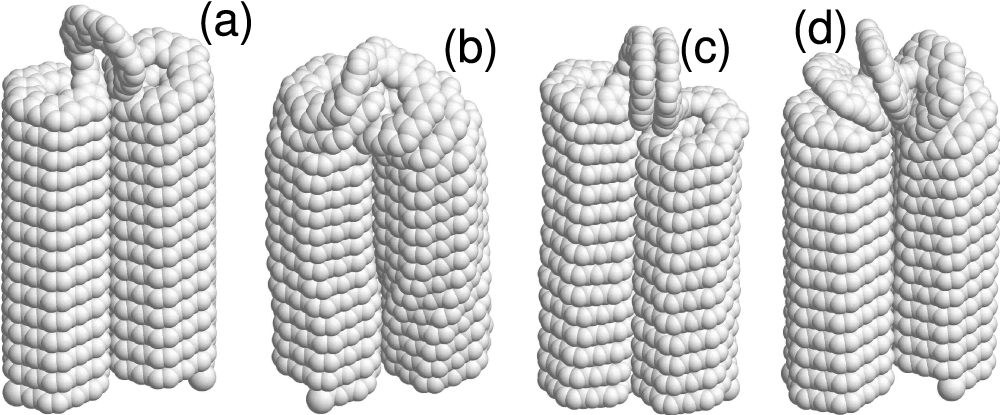

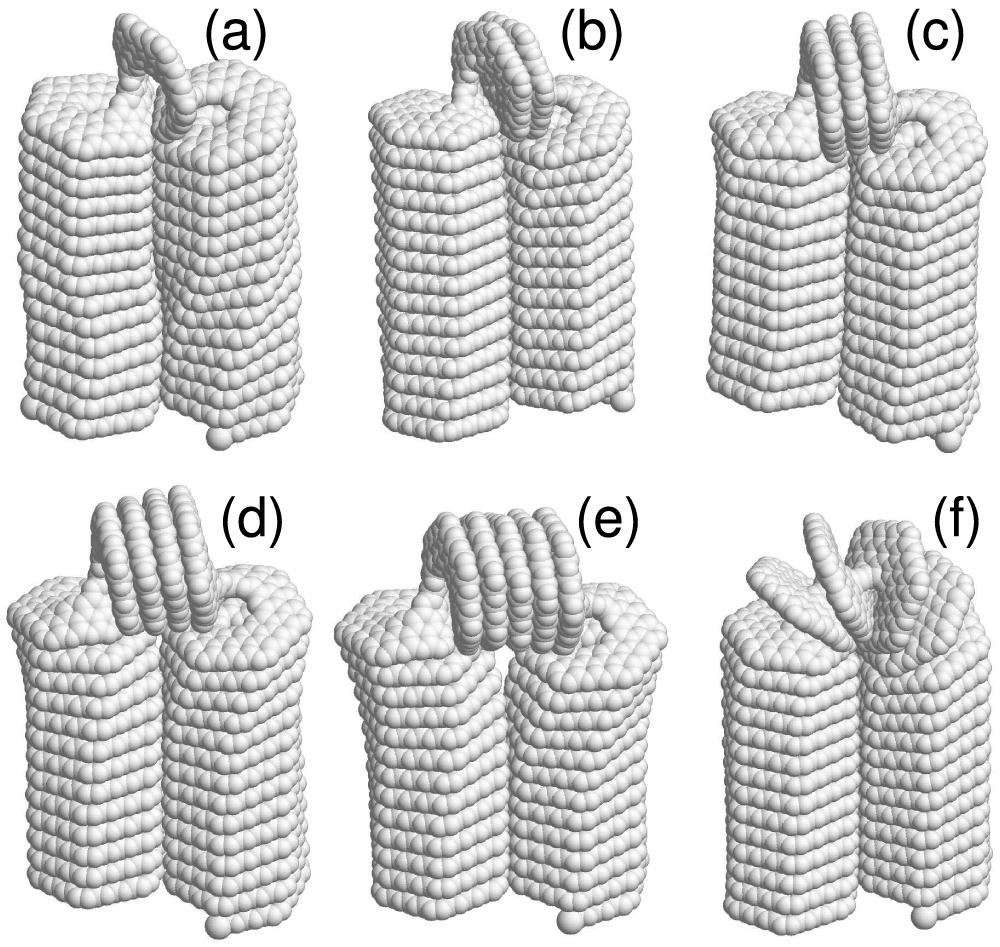

Figure 8: The equilibrium folded 3-kekulene nanosprings (

Figure 9: The equilibrium folded

Figure 10: Stationary states of

For the 3-coronene nanospring (

For the 3-kekulene nanospring (

As mentioned above, the folded nanosprings shown in Figs. 8 and 9 are stabilized by van der Waals interactions between the adjacent halves. The energy of these interactions increases proportionally to the length of the nanospring, L. Therefore, very short nanosprings cannot remain in the folded state after unloading because the van der Waals energy is less than the elastic energy of bending. Conversely, for sufficiently long nanosprings, the folded structure is more favorable energetically than the straight configuration. Sufficiently long nanosprings will fold and form a bundle of adjacent parallel fragments of the same length, as often happens with

5 Helix Reversal Defects in Nanosprings

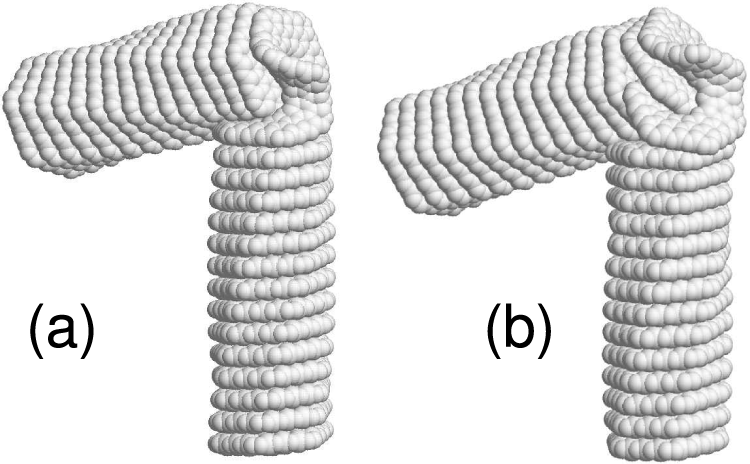

Nanosprings in the form of helical macromolecules can exist in two equivalent ground states: a right-twisted helix or a left-twisted helix. A helix reversal defect occurs when one part of the macromolecule is a left-twisted helix and the other part is a right-twisted helix. This defect occurs at the boundary between these two regions, see Fig. 11. This structural defect describes a local change in the direction of rotation of the helix. Such defects are characteristic of helical polymer molecules. Helix reversal defects are present in polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) crystals, where they cause helical inversion [80], and in other helical polymers [15,81,82].

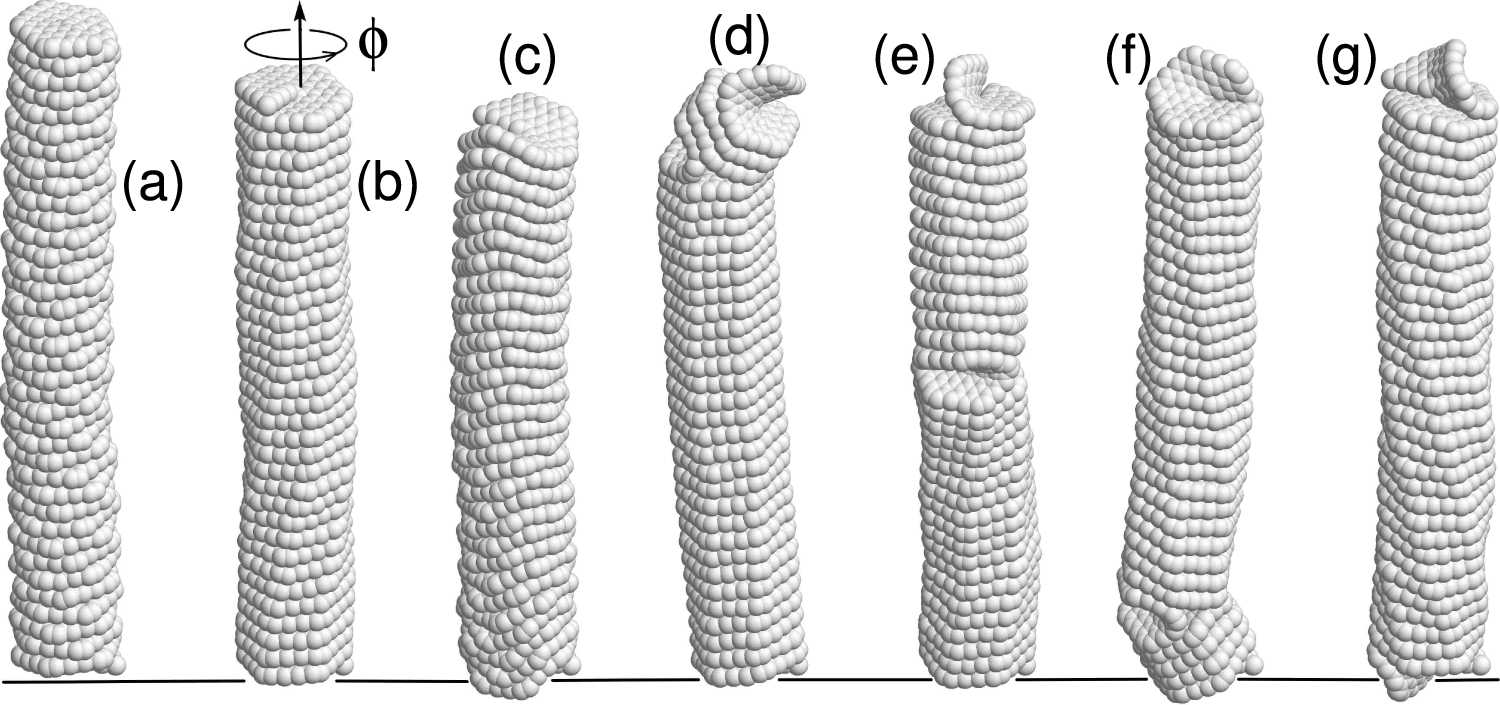

Figure 11: The helix reversal defects in

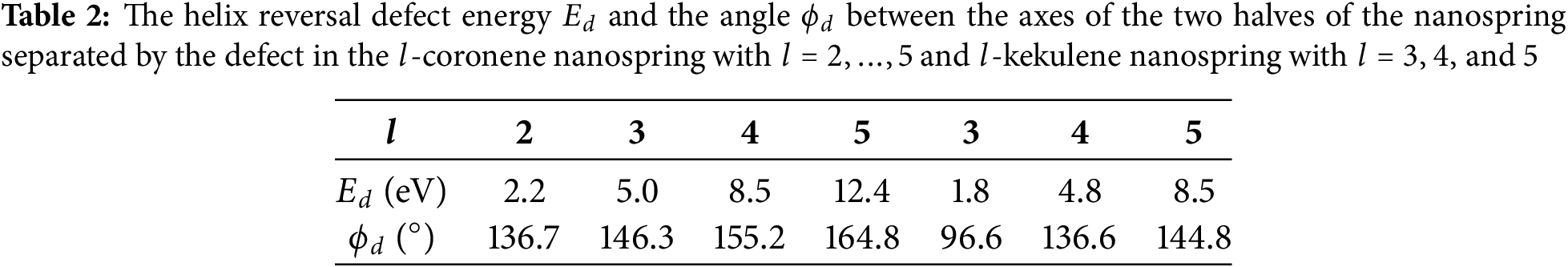

Solving the minimum potential energy problem Eq. (5) shows that the helix reversal defect is localized on two coils of the nanospring. The defect is characterized by the energy

6 Relaxation of a Highly Stretched Nanospring

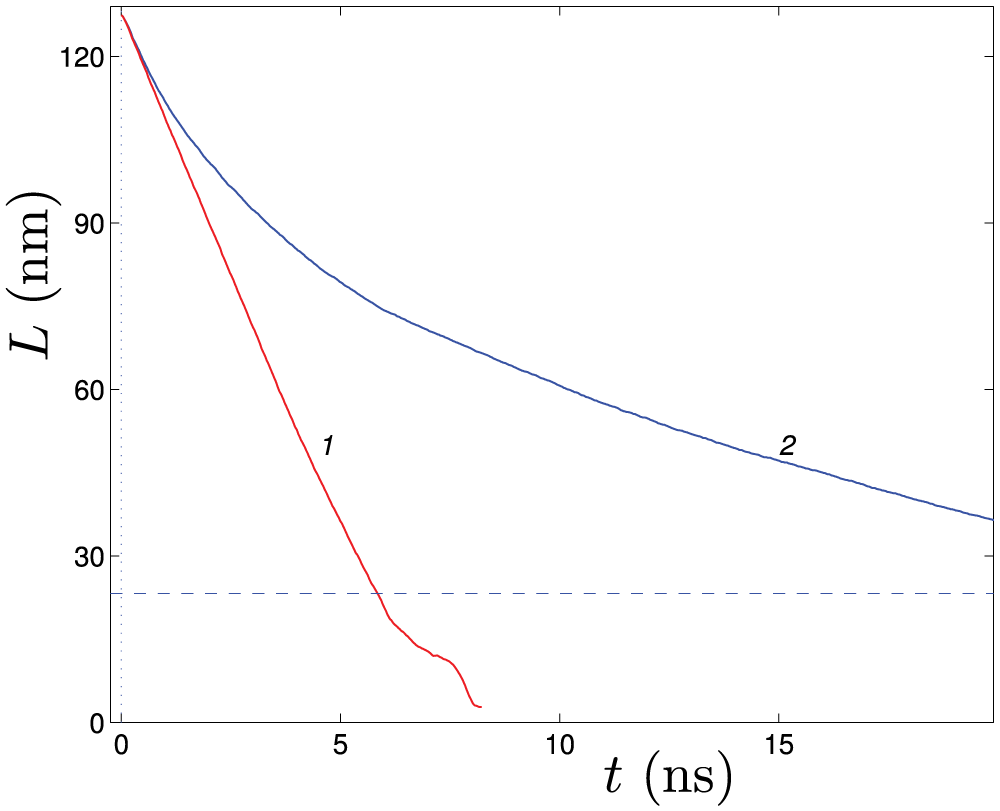

The structural and helix reversal defects discussed above can form when nanosprings are rapidly relaxed after being stretched. To demonstrate this, the dynamics of a 4-kekulene nanospring (

To model the relaxation, the dynamics of a nanospring with free ends is considered. For this purpose the system of equations of motion (6) with the initial conditions

is numerically integrated, where the vector

It is found that in the absence of interaction with the thermostat (at friction coefficient

Figure 12: Relaxation of the 4-kekulene nanospring (

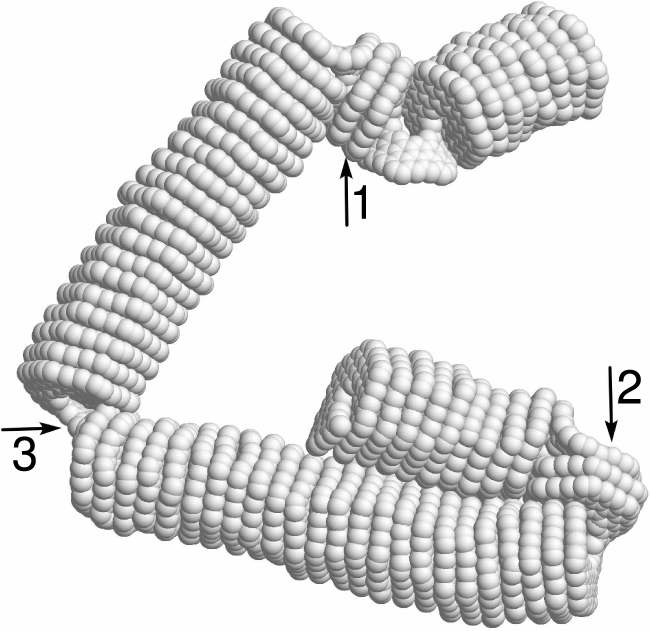

Figure 13: The structure of the initially stretched 4-kekulene nanospring (

If the relaxation of the stretched nanospring takes place in a viscous medium, i.e., taking into account its interaction with the thermostat, viscosity leads to slowing down of the convergence of the ends, see curve 2 in Fig. 12. In this case, the convergence time is sufficient to remove the negative twist arising in the center of the nanospring due to the rotation of the ends. Therefore, the helix relaxes directly to its ground state and no defects are formed. Note that the friction coefficient value

The helix reversal defect in a nanospring can also be obtained by twisting, which will be simulated for a nanospring of

where

The twisting of the nanospring starts at

where

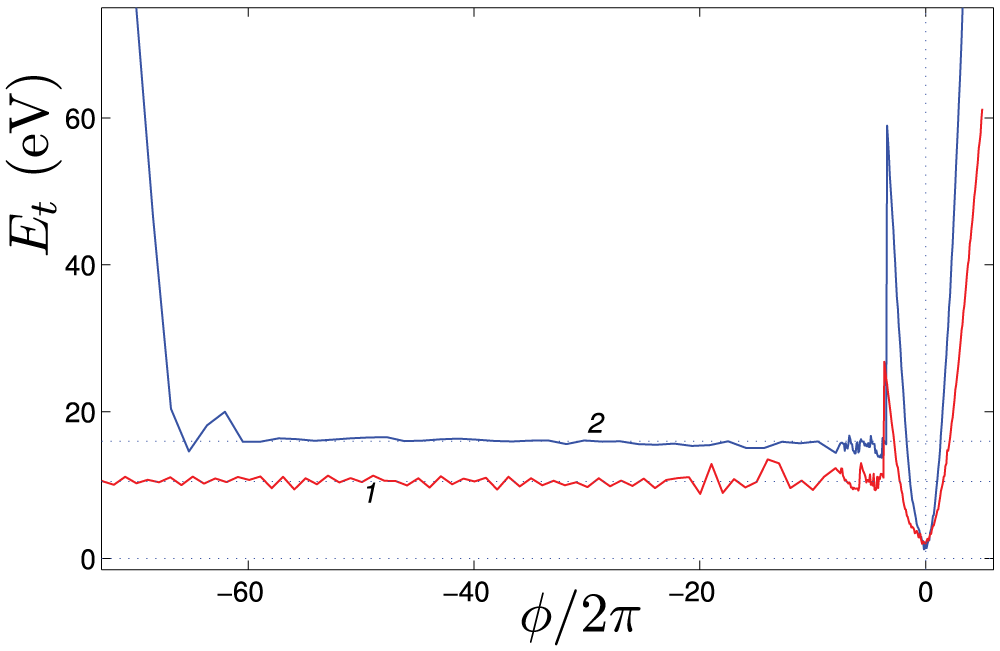

The twist energy

Figure 14: The energy

Figure 15: The structure of 4-coronene nanospring (

When

A study was conducted to analyze the mechanical behavior of carbon nanosprings in the form of spiral macromolecules formed from

The primary distinction between

The primary findings of the present study can be outlined as follows.

• The dimensionless heat capacity and the coefficient of axial thermal expansion were calculated in a wide range of temperatures, as shown in Fig. 3. The heat capacity increases with temperature linearly due to the soft anharmonicity of the van der Waals interactions between coils of the nanosprings. The coefficient of axial thermal expansion is as large as

• Nanosprings under axial compression have been shown to behave similarly to hinged elastic rods (see Fig. 5 for 4-coronene and Fig. 7 for 4-kekulene). They maintain a straight shape below the critical value of the compressive force, see panels (a), and demonstrate lateral buckling in the post-critical regime, see panels (b). It is evident from panels (c) that an even higher compressive force causes fracture of the nanosprings. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, 4-coronene nanosprings lacking an inner channel may exhibit multiple cracks. In contrast, Fig. 7d shows that for 4-kekulene, with an inner channel and consequently reduced bending stiffness, only a single crack is formed.

• The bending of nanosprings initiates with their arching, which is elastic deformation, and ceases once the bending forces are eliminated. At a certain level of bending force, nanosprings undergo irreversible changes in shape. In Figs. 8 and 9, the folded equilibrium structures of the 3-kekulene and 4-kekulene nanosprings are shown. These structures are stabilized by the van der Waals interactions between the halves of the folded nanosprings. The folded structures exhibit even smaller potential energy than the straight nanosprings. In Fig. 10, another stable configuration of 4-kekulene nanospring is shown. This configuration is stabilized by the presence of a topological defect in the corner. This structure exhibits a higher potential energy than the straight nanospring.

• Carbon nanosprings may exhibit helix reversal defects, separating the left-handed part from the right-handed part, as illustrated in Fig. 11. The energies of the equilibrium helix reversal defects and the angle between the axis of the adjacent halves of the nanosprings are given for

• Twisting of nanosprings increasing its twist, leads to quadratic growth of potential energy with twist angle. Twisting in the opposite direction is more interesting. The potential energy increases quadratically at first, but after reaching a specific twist angle, the energy of the nanospring drops sharply. At this stage, a helix reversal defect is formed, and a part of the nanospring acquires the opposite chirality. A subsequent twist leads to the movement of the helix reversal defect along the nanospring, ultimately resulting in a transformation of the entire structure to the opposite chirality. The structural transformation of the nanospring under twisting is illustrated in Fig. 15.

The results of this study show the unique behavior of carbon nanosprings when they are subjected to different types of deformation, such as compression, bending, and twisting. These deformation modes were not thoroughly explored in previous research. These results are particularly useful for the design of nanosensors that operate over a wide range of temperatures.

Acknowledgement: Sergey V. Dmitriev thanks the PRIORITY 2030 program of the Ufa State Petroleum Technological University (writing—review and editing, data curation).

Funding Statement: For Alexander V. Savin, the research work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), grant No. 25-73-20038 (conceptualization, methodology, manuscript writing).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Alexander V. Savin; methodology, Alexander V. Savin; software, Elena A. Korznikova; investigation, Sergey V. Dmitriev; data curation, Sergey V. Dmitriev; writing—original draft preparation, Alexander V. Savin; writing—review and editing, Sergey V. Dmitriev. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang S, Chen X, Motojima S. Morphology of the growth tip of carbon microcoils/nanocoils. Diam Relat Mater. 2004;13(11–12):2152–5. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2004.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Qian Y, Jiang S, Li Y, Yi Z, Zhou J, Tian J, et al. Water-induced growth of a highly oriented mesoporous graphitic carbon nanospring for fast potassium-ion adsorption/intercalation storage. Angew Chem. 2019;58(50):18108–15. doi:10.1002/anie.201912287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ghaderi SH, Hajiesmaili E. Molecular structural mechanics applied to coiled carbon nanotubes. Comput Mater Sci. 2012;55:344–9. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2011.11.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Poggi MA, Boyles JS, Bottomley LA, McFarland AW, Colton JS, Nguyen CV, et al. Measuring the compression of a carbon nanospring. Nano Lett. 2004;4(6):1009–16. doi:10.1021/nl0497023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu J, Lu YL, Tian M, Li F, Shen J, Gao Y, et al. The interesting influence of nanosprings on the viscoelasticity of elastomeric polymer materials: simulation and experiment. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23(9):1156–63. doi:10.1002/adfm.201201438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tang S, Ding G, Xie X, Chen J, Wang C, Ding X, et al. Nucleation and growth of single crystal graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Carbon. 2012;50(1):329–31. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2011.07.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nakakuki Y, Hirose T, Sotome H, Miyasaka H, Matsuda K. Hexa-peri-hexabenzo[7]helicene: homogeneously π-extended helicene as a primary substructure of helically twisted chiral graphenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(12):4317–26. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b13412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Nakakuki Y, Hirose T, Matsuda K. Synthesis of a helical analogue of kekulene: a Flexible π-expanded helicene with large helical diameter acting as a soft molecular spring. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(45):15461–9. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Savin AV, Dmitriev SV. Inhomogeneous elastic stretching of carbon nanosprings. Comput Mater Sci. 2024;244(14):113254. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.113254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhao Y, Zhang C, Kohler DD, Scheeler JM, Wright JC, Voyles PM, et al. Supertwisted spirals of layered materials enabled by growth on non-Euclidean surfaces. Science. 2020;370(6515):442–5. doi:10.1126/science.abc4284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bie Z, Liu X, Tao J, Zhu J, Yang D, He X. Investigation of carbon nanosprings with the tunable mechanical properties controlled by the defect distribution. Carbon. 2021;179:240–55. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2021.04.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bie Z, Deng Y, Liu X, Zhu J, Tao J, Shi X, et al. The controllable mechanical properties of coiled carbon nanotubes with Stone-Wales and vacancy defects. Nanomater. 2023;13(19):2656. doi:10.3390/nano13192656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Sharifian A, Fareghi P, Baghani M, Odegard GM, van Duin ACT, Rajabpour A, et al. Unveiling novel structural complexity of spiral carbon nanomaterials: review on mechanical, thermal, and interfacial behaviors via molecular dynamics. J Mol Struct. 2025;1321:139837. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.139837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nakano T, Okamoto Y. Synthetic helical polymers: conformation and function. Chem Rev. 2001;101(12):4013–38. doi:10.1021/cr0000978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Yashima E, Maeda K, Iida H, Furusho Y, Nagai K. Helical Polymers: synthesis, structures, and functions. Chem Rev. 2009;109(11):6102–211. doi:10.1021/cr900162q. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ikai T, Miyoshi S, Oki K, Saha R, Hijikata Y, Yashima E. Defect-Free synthesis of a fully π-conjugated helical ladder polymer and resolution into a pair of enantiomeric helical ladders. J Mol Biol. 2023;62(20):e202301962. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-hqk71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qiu Y, Wei X, Lam JWY, Qiu Z, Tang BZ. Chiral nanostructures from artificial helical polymers: recent advances in synthesis, regulation, and functions. ACS Nano. 2025;19(1):229–80. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c14797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lei X, Koyane J, Lu T, Matsuzaki K, Yan Y, Shi J, et al. Mechanical and geometric properties of nanosprings based on carbon nanotubes with dislocation dipoles. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2025;8(18):9192–200. doi:10.1021/acsanm.5c00619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Feng H, Cai K, Shi J, Zhang Y. A high-frequency nanoscale positioner driven by an external electric field: a molecular dynamics study. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2025;27(14):7326–35. doi:10.1039/d4cp04379k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wan J, Cai K, Kang Y, Luo Y, Qin Q. Adjustable gas adsorption and desorption via a self-shrinking nanoscroll. Appl Phys Lett. 2023;123(23):233501. doi:10.1063/5.0175953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xu X, Xiao H, Ouyang T, Zhong J. Improving the thermoelectric properties of carbon nanotubes through introducing graphene nanosprings. Curr Appl Phys. 2020;20(1):150–4. doi:10.1016/j.cap.2019.10.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Avdoshenko S, Koskinen P, Sevincli H, Popov AA, Rocha CG. Topological signatures in the electronic structure of graphene spirals. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):1632. doi:10.1038/srep01632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Tan J, Zhang X, Liu W, He X, Zhao M. Strain-induced tunable negative differential resistance in triangle graphene spirals. Nanotechnology. 2018;29(20):205202. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/aab1d9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, Zhao M. Strain-induced phase transition and electron spin-polarization in graphene spirals. Sci Rep. 2014;4(1):5699. doi:10.1038/srep05699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Atanasov V, Saxena A. Helicoidal graphene nanoribbons: chiraltronics. Phys Rev B. 2015;92(3):035440. doi:10.1103/physrevb.92.035440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xu X, Liu B, Zhao W, Jiang Y, Liu L, Li W, et al. Mechanism of mechanically induced optoelectronic and spintronic phase transitions in 1D graphene spirals: insight into the role of interlayer coupling. Nanoscale. 2017;9(27):9693–700. doi:10.1039/c7nr03432f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Korhonen T, Koskinen P. Electromechanics of graphene spirals. AIP Adv. 2014;4(12):127125. doi:10.1063/1.4904219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Porsev V, Evarestov R. Riemann surfaces of carbon as graphene nanosolenoids magnetic properties of zig-zag-edged hexagonal nanohelicenes: a quantum chemical study. Nanomater. 2023;13(3):415. doi:10.3390/nano13030415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Xu F, Yu H, Sadrzadeh A, Yakobson BI. Riemann surfaces of carbon as graphene nanosolenoids. Nano Lett. 2016;16(1):34–9. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lin Y, Shi Q, Hao Y, Song Z, Zhou Z, Fu Y, et al. The effect of non-uniform pitch length and spiraling pathway on the mechanical properties of coiled carbon nanotubes. Int J Mech Sci. 2023;257:108532. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2023.108532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu ZP, Guo YD, Yan XH, Zeng HL, Mou XY, Wang ZR, et al. A metal-semiconductor transition in helical graphene nanoribbon. J Appl Phys. 2019;126:144303. [Google Scholar]

32. Thakur R, Ahluwalia PK, Kumar A, Sharma R. Stability and electronic properties of bilayer graphene spirals. Physica E. 2021;129:114638. doi:10.1016/j.physe.2021.114638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhou Z, Yan L, Wang XM, Zhang D, Yan JY. The sensitive energy band structure and the spiral current in helical graphenes. Results Phys. 2022;35(5696):105351. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2022.105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang K, Duan J, Li C, Song C, Chen Z. How do DNA molecular springs modulate protein-protein interactions: experimental and theoretical results. Biochemistry. 2024;63(24):3369–80. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.4c00280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yang D, Huang R, Zou B, Wang R, Wang Y, Ang EH, et al. Unraveling nanosprings: morphology control and mechanical characterization. Mater Horiz. 2024;11(15):3500–27. doi:10.1039/d4mh00503a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Karabacak AY, Oguz HZ, Kart SO, Kart HHU. Mechanical properties of carbon and silicon core-shell nanosprings: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Physica B Condens Matter. 2025;716(3):417673. doi:10.1016/j.physb.2025.417673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Porsev VV, Bandura AV, Lukyanov SI, Evarestov RA. Expanded hexagonal nanohelicenes of zigzag morphology under elastic strain: a quantum chemical study. Carbon. 2019;152(3):755–65. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2019.06.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhan H, Zhang G, Yang C, Gu YT. Graphene helicoid: the distinct properties promote application of graphene related materials in thermal management. Phys Chem C. 2018;122(14):7605–12. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b00868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Norouzi S, Fakhrabadi MMS. Anisotropic nature of thermal conductivity in graphene spirals revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem Solids. 2020;137(11):109228. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2019.109228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sharifian A, Karbaschi T, Rajabpour A, Baghani M, Wu J, Baniassadi M. Insights into thermal characteristics of spiral carbon-based nanomaterials: from heat transport mechanisms to tunable thermal diode behavior. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2022;189(6):122719. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.122719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li H, Hassanzadeh afrouzi H, Zahra MMA, Bashar BS, Fathdal F, Hadrawi SK, et al. A comprehensive investigation of thermal conductivity in of monolayer graphene, helical graphene with different percentages of hydrogen atom: a molecular dynamics approach. Colloid Surface A. 2023;656(A):130324. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wu J, He J, Odegard GM, Nagao S, Zheng Q, Zhang Z. Giant stretchability and reversibility of tightly wound helical carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(37):13775–13785. doi:10.1021/ja404330q. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sestak P, Wu J, He J, J P, Zhang Z. Extraordinary deformation capacity of smallest carbohelicene springs. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17(28):18684–18690. doi:10.1039/c5cp02043c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zhan H, Zhang Y, Yang C, Zhang G, Gu Y. Graphene helicoid as novel nanospring. Carbon. 2017;120(5496):18684–264. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2017.05.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhan H, Zhang G, Yang C, Gu Y. Breakdown of Hooke’s law at nanoscale-2D materials-based nanospring. Nanoscale. 2018;10(40):18961–8. doi:10.1039/c8nr04882g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Norouzi S, Fakhrabadi MMS. Nanomechanical properties of single- and double-layer graphene spirals: a molecular dynamics simulation. Appl Phys A. 2019;125(5):321. doi:10.1007/s00339-019-2623-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhu C, Ji J, Zhang Z, Dong S, Wei N, Zhao J. Huge stretchability and reversibility of helical graphenes using molecular dynamics simulations and simplified theoretical models. Mech Mater. 2021;153:103683. doi:10.1016/j.mechmat.2020.103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sharifian A, Moshfegh A, Javadzadegan A, Afrouzi HH, Baghani M, Baniassadi M. Hydrogenation-controlled mechanical properties in graphene helicoids: exceptional distribution-dependent behavior. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2019;21(23):12423–33. doi:10.1039/c9cp01361j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Savin AV, Kikot IP, Mazo MA, Onufriev AV. Two-phase stretching of molecular chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(8):2816–21. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218677110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Afanasyev AY, Onufriev AV. Stretching of long double-stranded DNA and RNA described by the same approach. J Chem Theory Comput. 2022;18(6):3911–20. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.1c01221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. Overstretching B-DNA: the elastic response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science. 1996;271(5250):795–9. doi:10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Babicheva RI, Bukreeva KA, Dmitriev SV, Zhou K. Discontinuous elastic strain observed during stretching of NiAl single crystal nanofilms. Comp Mater Sci. 2013;79(2):52–5. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2013.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Babicheva RI, B KA, Dmitriev SV, Mulyukov RR, Zhou K. Strengthening of NiAl nanofilms by introducing internal stresses. Intermetallics. 2013;43:171–6. doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2013.07.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Bukreeva KA, Babicheva RI, Dmitriev SV, Zhou K, Mulyukov RR. Negative stiffness of the FeAl intermetallic nanofilm. Phys Solid State. 2013;55(9):1963–7. doi:10.1134/s1063783413090072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wu J, Shi Q, Zhang Z, Wu H, Wang C, Ning F, et al. Nature-inspired entwined coiled carbon mechanical metamaterials: molecular dynamics simulations. Nanoscale. 2018;10(33):15641–15653. doi:10.1039/c8nr04507k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Dmitriev SV, Baimova JA, Savin AV, Kivshar YS. Ultimate strength, ripples, sound velocities, and density of phonon states of strained graphene. Comput Mater Sci. 2012;53(1):194–203. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2011.08.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Liu R, Zhao J, Wang L, Wei N. Nonlinear vibrations of helical graphene resonators in the dynamic nano-indentation testing. Nanotechnology. 2020;31(2):025709. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/ab4760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Mokhalingam A, Gupta SS. Helical single-walled carbon nanotubes under mechanical and electrostatic loading. Carbon Trends. 2022;9(4):100204. doi:10.1016/j.cartre.2022.100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Cornell WD, Cieplak WP, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117(19):5179–5197. doi:10.1021/ja00124a002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Savin AV, Kivshar YS, Hu B. Suppression of thermal conductivity in graphene nanoribbons with rough edges. Phys Rev B. 2010;82(19):195422. doi:10.1103/physrevb.82.195422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Lisovenko DS, Baimova JA, Rysaeva LK, Gorodtsov VA, Rudskoy AI, Dmitriev SV. Equilibrium diamond-like carbon nanostructures with cubic anisotropy: elastic properties. Phys Status Solidi (B) Basic Res. 2016;253(7):1295–1302. doi:10.1002/pssb.201600049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Pavlov IS, Galiakhmetova LK, Kudreyko AA, Dmitriev SV. Mobility of dislocations in carbon nanotube bundles. Mater Today Commun. 2024;40(6348):110094. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.110094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Ilgamov MA, Aitbaeva AA, Pavlov IS, Dmitriev SV. Carbon nanotube under pulsed pressure. Facta Univ Ser Mech Eng. 2024;22(2):275–92. doi:10.22190/fume230820049i. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Andrukhova OV, Ovcharov AA, Andrukhova T, Morkina AY. Evolution of the single-wall carbon nanotubes bundle structure under compressive deformation. Mech Solids. 2025;60(2):872–82. doi:10.1134/s002565442460569x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Setton R. Carbon nanotubes-II. Cohesion and formation energy of cylindrical nanotubes. Carbon. 1996;34(1):69–75. doi:10.1016/0008-6223(95)00136-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Lindsay LR, Broido DA. Optimized Tersoff and Brenner empirical potential parameters for lattice dynamics and phonon thermal transport in carbon nanotubes and graphene. Phys Rev B. 2010;81(20):205441. doi:10.1103/physrevb.82.209903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Goverapet Srinivasan S, van Duin ACT, Ganesh P. Development of a ReaxFF potential for carbon condensed phases and its application to the thermal fragmentation of a large fullerene. J Phys Chem A. 2015;119(4):571–80. doi:10.1021/jp510274e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Brenner DW, Shenderova OA, Harrison JA, Stuart SJ, Ni B, Sinnott SB. A second-generation reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential energy expression for hydrocarbons. J Phys Condens Matter. 2002;14(4):783–802. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/4/312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Nikitin A, Ogasawara H, Mann DA, Denecke R, Zhang Z, Dai H, et al. Hydrogenation of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95(22):225507. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.95.225507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Stuart SJ, Tutein AB, Harrison JA. A reactive potential for hydrocarbons with intermolecular interactions. J Chem Phys. 2000;112(14):6472–86. doi:10.1063/1.481208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Polyakova PV, Murzaev RT, Baimova JA. Mechanical properties of diamane: orientation dependence of strength and fracture strain. Appl Surf Sci. 2025;681(3):161441. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2024.161441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Polyakova PV, Murzaev RT, Lisovenko DS, Baimova JA. Elastic constants of graphane, graphyne, and graphdiyne. Comput Mater Sci. 2024;244(3):113171. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Polyakova PV, Murzaev RT, Baimova JA. Determination of graphyne elasticity constants by the molecular dynamics method. J Appl Mech Tech Phys. 2023;64(6):1097–9. doi:10.1134/s0021894423060202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Bourque AJ, Rutledge GC. Empirical potential for molecular simulation of graphene nanoplatelets. J Chem Phys. 2018;148(14):144709. doi:10.1063/1.5023117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Fletcher R, Reeves C. Function minimization by conjugate gradients. Comput J. 1964;7(2):149–54. [Google Scholar]

76. Shanno DF, Phua KH. Algorithm 500: minimization of unconstrained multivariate functions [E4]. ACM Trans Math Software. 1976;2(1):87–94. doi:10.1145/355666.355673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Verlet L. Computer “Experiments” on classical fluids. I. Thermodynamical properties of Lennard-Jones molecules. Phys Rev. 1967;159(1):98–103. doi:10.1103/physrev.159.98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Schafmeister CE, LaPorte SL, Miercke LJ, Stroud RM. A designed four helix bundle protein with native-like structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 1997;4:1039–46. [Google Scholar]

79. Liu J, Deng Y, Zheng Q, Cheng CS, Kallenbach NR, Lu M. A parallel coiled-coil tetramer with offset helices. Biochemistry. 2006;45(51):15224–31. doi:10.1021/bi061914m. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Holt DB, Farmer BL. Modeling of helix reversal defects in polytetrafluoroethylene II. Molecular dynamics simulations. Polymer. 1999;40(16):4673–84. doi:10.1016/s0032-3861(99)00076-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Rey-Tarrio F, Rodriguez R, Quinoa E, Freire F. Screw sense excess and reversals of helical polymers in solution. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1742. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37405-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Jeon Y, Goh B, Choi J. Nanomechanical investigation of deformation behavior of π–π stacked helical polymers. Int J Mech Sci. 2025;290:110100. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2025.110100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools