Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Improving Online Restore Performance of Backup Storage via Historical File Access Pattern

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering (School of Cyber Security), University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

2 Zhejiang Institute of Marine Economic Development, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhoushan, 316022, China

* Corresponding Author: Ting Chen. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 65 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068878

Received 09 June 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The performance of data restore is one of the key indicators of user experience for backup storage systems. Compared to the traditional offline restore process, online restore reduces downtime during backup restoration, allowing users to operate on already restored files while other files are still being restored. This approach improves availability during restoration tasks but suffers from a critical limitation: inconsistencies between the access sequence and the restore sequence. In many cases, the file a user needs to access at a given moment may not yet be restored, resulting in significant delays and poor user experience. To this end, we present Histore, which builds on the user’s historical access sequence to schedule the restore sequence, in order to reduce users’ access delayed time. Histore includes three restore approaches: (i) the frequency-based approach, which restores files based on historical file access frequencies and prioritizes ensuring the availability of frequently accessed files; (ii) the graph-based approach, which preferentially restores the frequently accessed files as well as their correlated files based on historical access patterns, and (iii) the trie-based approach, which restores particular files based on both users’ real-time and historical access patterns to deduce and restore the files to be accessed in the near future. We implement a prototype of Histore and evaluate its performance from multiple perspectives. Trace-driven experiments on two datasets show that Histore significantly reduces users’ delay time by 4-700Keywords

Backups are widely used to increase the reliability of users’ data against disasters [1–4]. However, it brings problems such as time-consuming restoration and increasing user delay time to access files. Take offline backup restore as an example, users need to wait until the entire backup is restored before they can access each file, usually taking several hours [5–8]. Online backup restore [9,10] allows users to recover backup in the background while performing operations such as reading and writing in the foreground. The user can operate on the restored files without waiting for the entire backup to be restored, thereby effectively reducing the user’s delay time. To this end, we aim to further optimize online recovery performance, building on our preliminary work [11].

However, even with the online restore, there is a challenge in scheduling the restore sequence to match users’ access sequence as closely as possible. Take a user’s backup as an example. It contains file identifiers (denoted as

This paper presents Histore, a backup storage system with improved users’ experience in online restoration. The overall idea is to build on the user’s historical access sequence to schedule the restore sequence, thereby reducing users’ access delay time. Specifically, in the previous works, users’ historical access information is widely used to predict the possible future user access to improve the availability of the file to be accessed [12–15]. The core design of Histore is three approaches that improve the online restore experience.

First, informed by the observation that the user’s file access pattern is highly skewed [16], we propose a frequency-based approach, which prioritizes the restoration of the frequently accessed files. This ensures that most of the user’s operations during the restoration process can be satisfied by already restored files. Also, inspired by the correlation of accessed files [14], we propose a graph-based approach, which establishes a correlation graph based on historical access patterns and generates the restore sequence (of files) via a greedy algorithm. Furthermore, we propose a trie-based approach, which combines users’ historical and real-time access patterns to deduce (and restore) the files to be accessed in the near future.

To summarize, this paper makes the following contributions:

• We show via a case study that a baseline approach that restores files in alphabetical order incurs extremely high delay time, and hence significantly affects users’ experience on foreground operations.

• We propose three restoration approaches to schedule the restore sequence of files based on historical access patterns.

• We design and implement Histore, a backup system that equips the three approaches to improve users’ experience in online backup restore.

• We conduct extensive trace-driven experiments to evaluate Histore using two datasets. We show that all three proposed approaches can reduce users’ delay by 4

2 Background, Problem and Access Patterns

Background. We focus on backup workloads [17,18]. Specifically, we consider a backup as a complete copy of the primary data snapshotted from users’ home directories or application states. Users periodically generate backups and store them in a storage system in order to protect their data against disasters, accidents, or malicious actions. Specifically, old backups can be restored either online or offline. That is, operate after complete restoration or operate while restoring. This paper focuses on online backup restore, which is widely deployed in existing cloud backup services [19]. It allows users to recover backups in the background while performing file operations in the foreground. Considering that backup restore often takes a long time [6], online restore significantly reduces the downtime since users can operate on the already restored files of the backup even if the whole backup is still under recovery.

One critical requirement for online restoration is to minimize user-perceived performance degradation of the foreground operations. Specifically, online restore recovers backups gradually in the background and needs to ensure that the operating files in the foreground have already been restored, in order to hide the performance degradation from the users.

However, to our knowledge, existing approaches (Section 6) focus on improving the overall restore speed, yet none of them are aware of minimizing user-perceived performance degradation. We establish a theoretical restore model (in contrast, we evaluate the practical online restore performance based on real-world access patterns in Section 5) to characterize the availability of users’ foreground operations in the online restore procedure, and justify the problem based on the real-world file access trace collected by ourselves.

Theoretical restore model. We consider a set of unique files in a backup and define

We consider a generic scenario in which the metadata of all unique files, as well as the contents of

We characterize two metrics to measure the performance of the foreground operations. The first metric is the availability rate, which is the number of successfully accessed files (i.e., these files have been restored when they are accessed) divided by the total number of accessed files. In addition, for the file that is unavailable for access, we consider its delayed time, which is the number of time slots when the file is available after it is accessed.

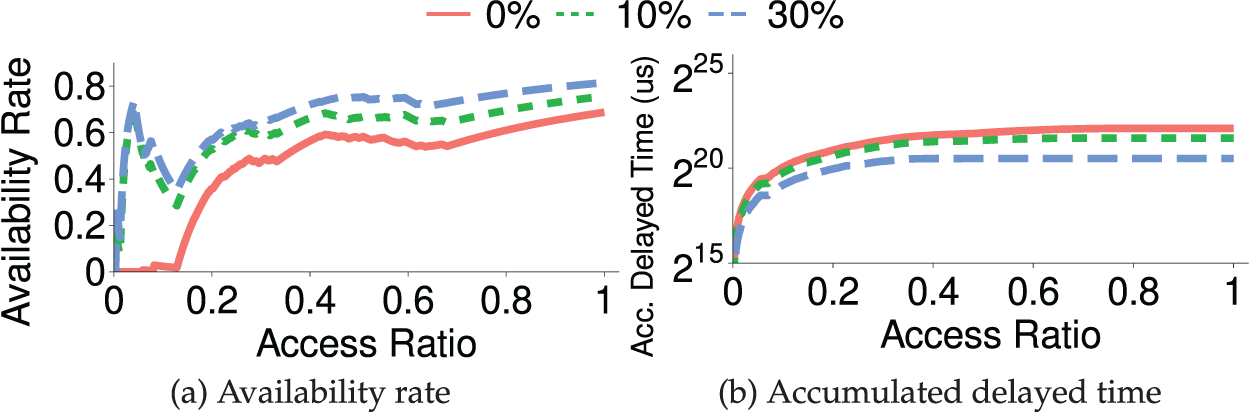

Simulation results. We study the availability of the foreground operations based on the real-world access log of a student (see Section 5 for dataset information). We focus on the access sequences of two consecutive days and consider a baseline approach that generates the restore sequence

Fig. 1a presents the results for the availability rate (see theoretical restore model for metric definition), where the access ratio on the x-axis indicates the fraction of the files in

Figure 1: Availability rate and accumulated delayed time with 0%, 10%, 30% files have been restored

In summary, we observe that the baseline approach incurs a low availability rate (especially for the initial file access in

We build on previous file access prediction techniques [14,15], and propose three approaches to improve the online restore performance. Specifically, we assume that the sequence of historical access records

Building on prior work [16], which shows that real-world file access distributions are skewed, we prioritize the restoration of frequently accessed files to ensure that the majority of operations in

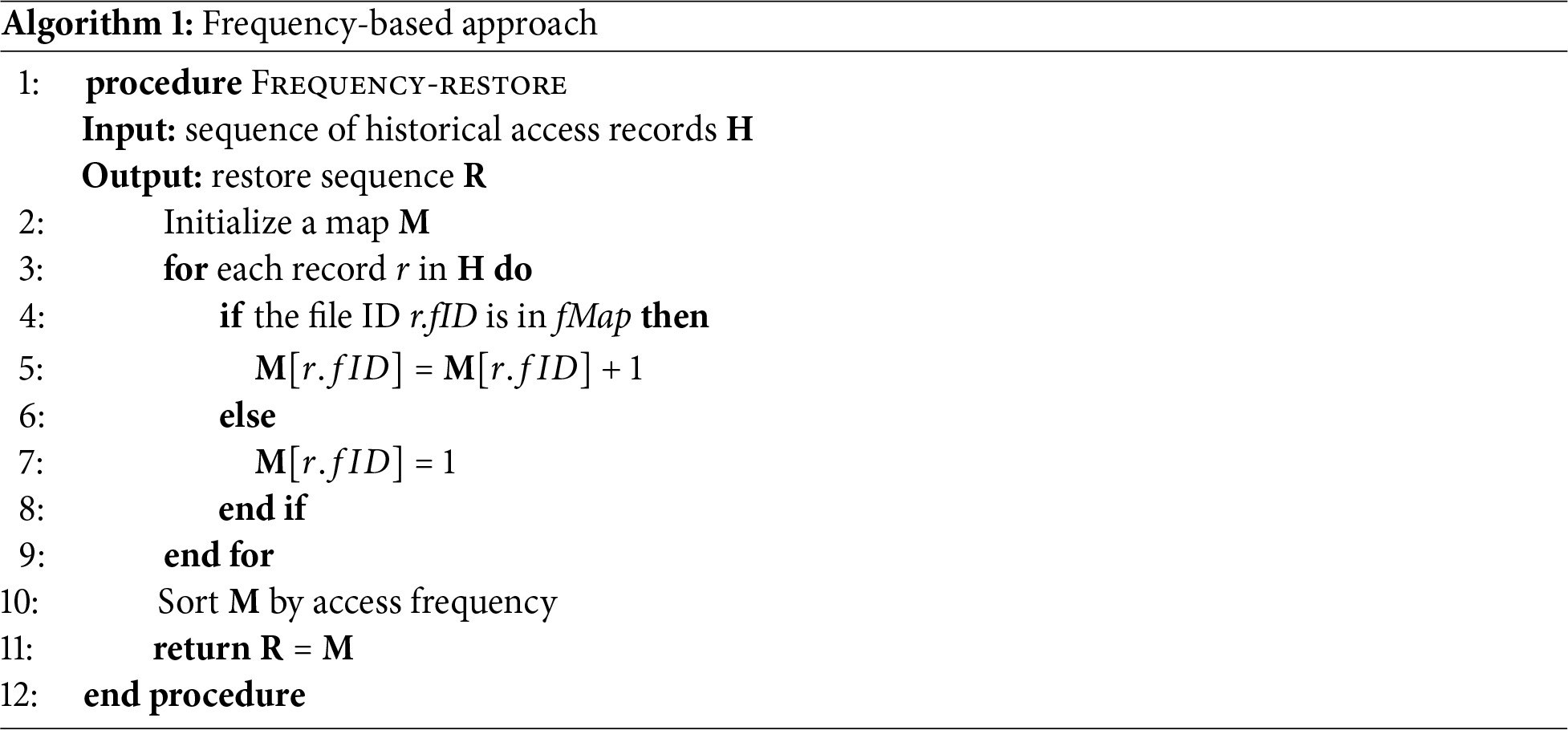

Algorithm 1 presents the details of the frequency-based approach. It takes the sequence of historical access records

The frequency-based approach does not capture the correlation of file access, while in practice, users may access a set of files together (rather than each file, individually). For example, when the user launches an application, the application program is likely to access a set of files in a deterministic order for initialization [21]. Previous work [14] builds on the access correlation among files to predict which file will be accessed in the future. Specifically, it partitions the sequence of historical file access records into many non-overlapped fixed-size windows, such that each window includes a number of file access records. It builds a directed graph to model file access patterns. Each node of the graph corresponds to a unique file, and stores how many times the file has been accessed, while each directed edge stores how many windows, in which the corresponding files are accessed in order. Given a currently accessed file, it predicates the file that is likely to be accessed as the one that connects with the current access file with the highest weight.

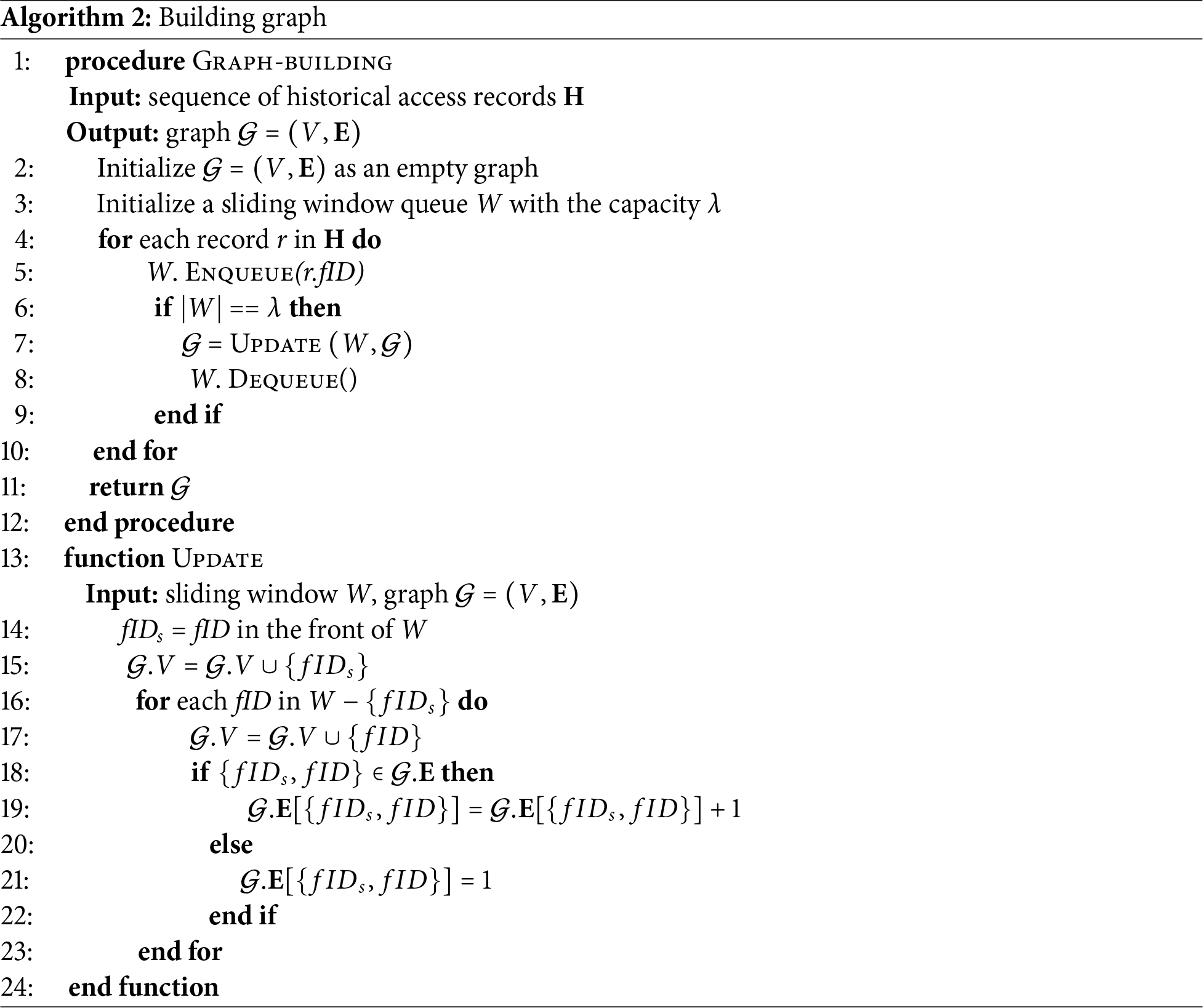

The insight of our graph-based approach is to prioritize the restoration of correlated files that are also frequently accessed in a short time. Specifically, we extend the above graph-based modeling by measuring access correlation based on a sliding window approach. Here, we configure a sliding window with a fixed size of five access records and count how likely a file is to be co-accessed with other files in the same sliding window. Also, we construct an undigraph such that each edge stores the number of times that the corresponding files are co-accessed in identical sliding windows. Based on the graph, we use a greedy algorithm to generate the restore sequence

Algorithm 2 presents the details of the graph construction algorithm, which takes the sequence of historical records as input. It first initializes an empty

The Update algorithm takes a sliding window W and the graph

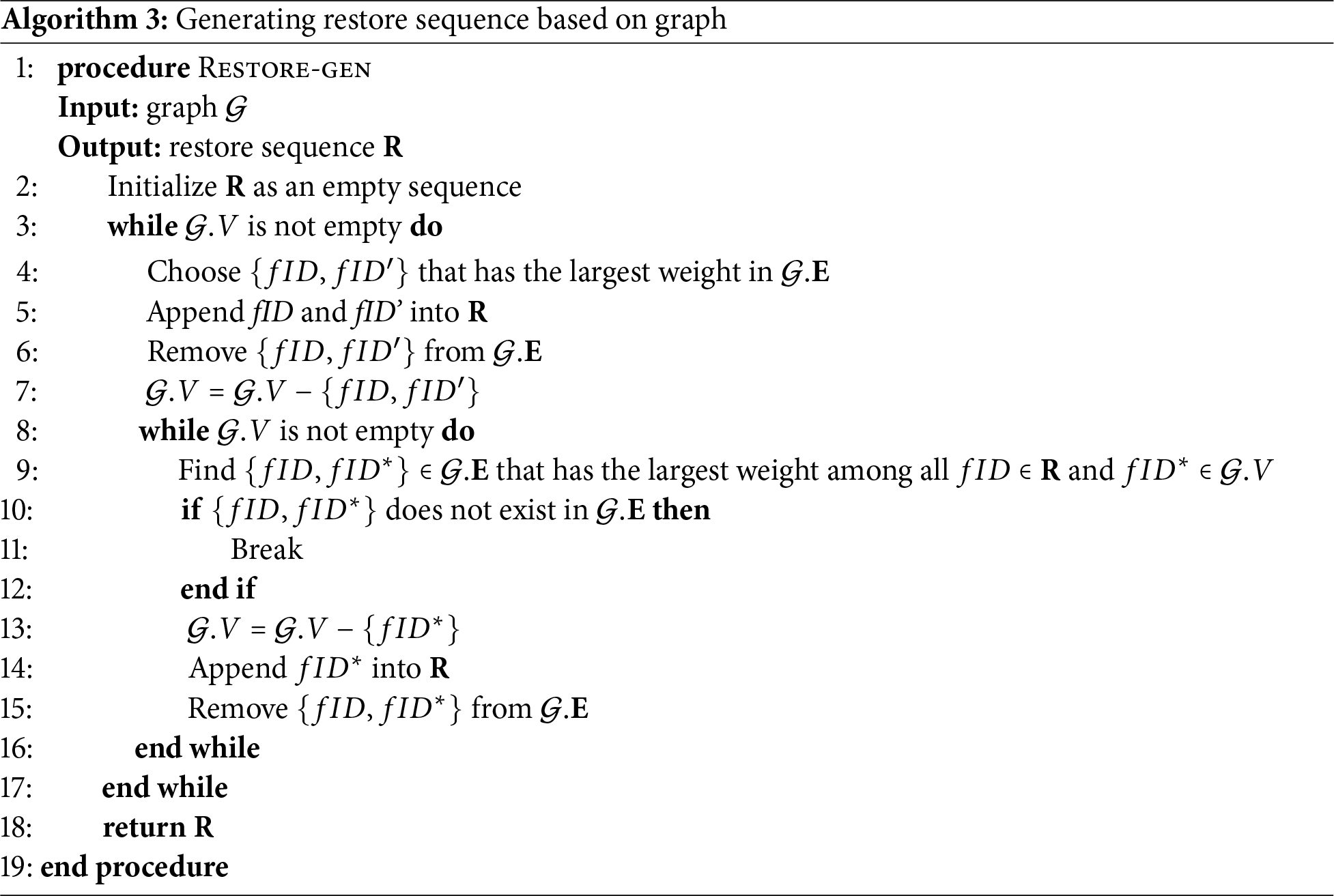

Algorithm 3 shows the greedy-based file restoration algorithm, which builds on the updated graph

Both frequency-based and graph-based approaches generate the restore sequence

The proposed trie-based approach extends the principles of partitioned context modeling (PCM) [15], which predicts the occurrence of a symbol using a trie structure. In PCM, each trie node represents a symbol and stores its occurrence count (referred to as weight) relative to its parent node. An edge in the trie connects two symbols that co-occur, with the parent node representing the first symbol and the child node representing the subsequent symbol. For a given input string (a sequence of symbols), PCM traces a path from the root to a non-leaf node and predicts the next symbol based on the most probable continuation along the path.

We adapt PCM to predict file access patterns based on real-time user behavior. Our trie-based method operates in two stages. In the first stage, the trie is constructed using the historical sequence

In the second stage, the constructed trie is used to predict the next file to be accessed. If the predicted file is not yet restored, it is pre-emptively restored. Otherwise, the file with the highest access frequency in

In the prediction process, the trie uses a sequence of recently accessed file IDs, derived from users’ real-time access patterns, to match a path in the trie. It selects the child node (i.e., the file ID) connected to the path with the largest weight. If no matching path exists, no subsequent node is found after the path, or the predicted file has already been restored, the sequence of recently accessed file IDs is updated to retain only the most recent items, reducing the sliding window size. The process then attempts prediction again. The rationale here corresponds to the case of decreasing the sliding window size after finding a new path in the trie-building process. In essence, the approach ensures that a shorter matched path is considered. If the shorter path also fails, the process falls back to the basic case of using only the most recently accessed file ID for prediction.

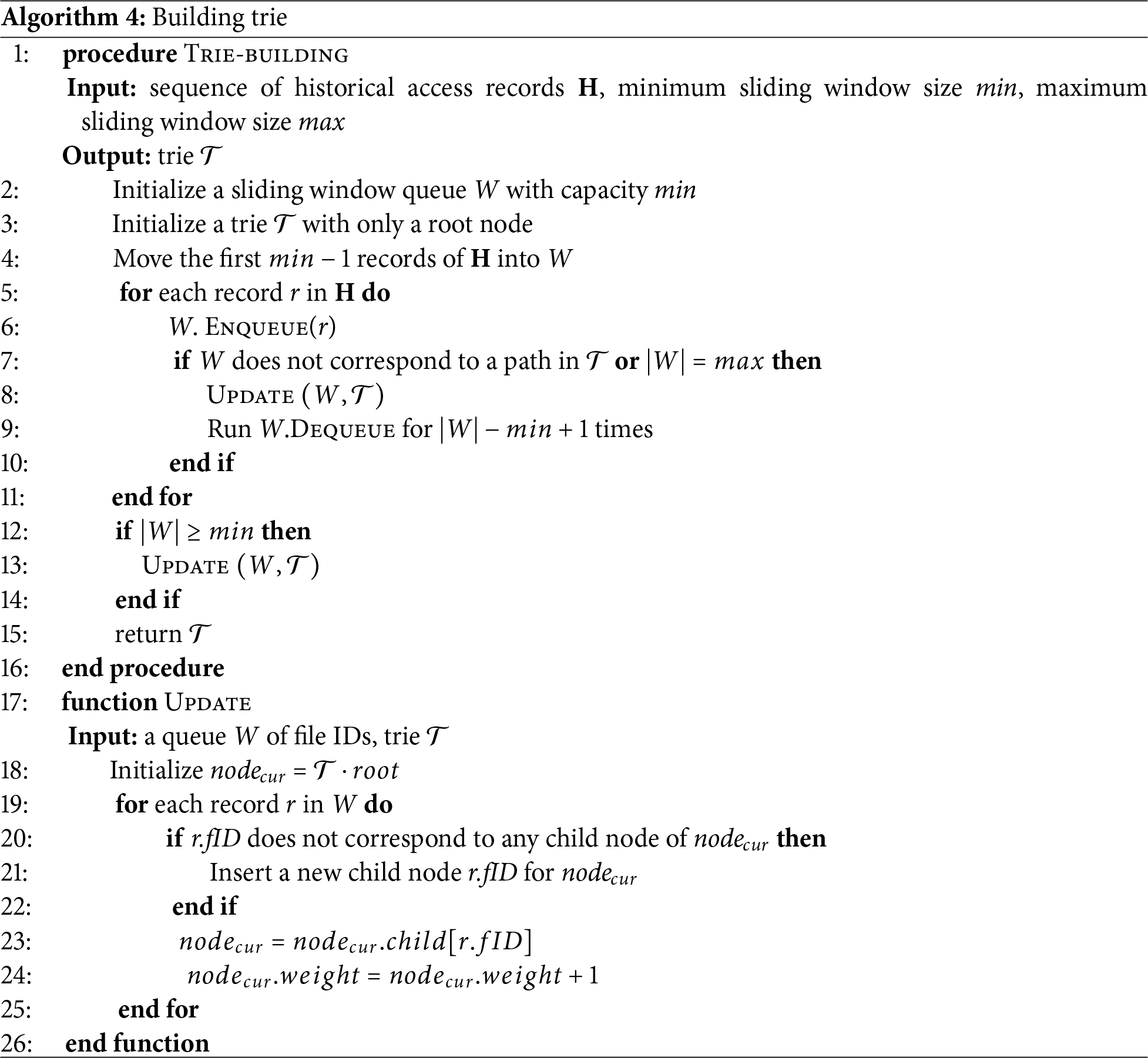

Algorithm 4 presents the pseudocode of the trie construction algorithm. It takes the sequence

In the main loop, it adds the record

The Update algorithm takes the sliding window W and the trie

Algorithm 5 presents the trie prediction algorithm to predict file access sequence. It takes the trie

Note that

The Predict function takes the recent access file queue

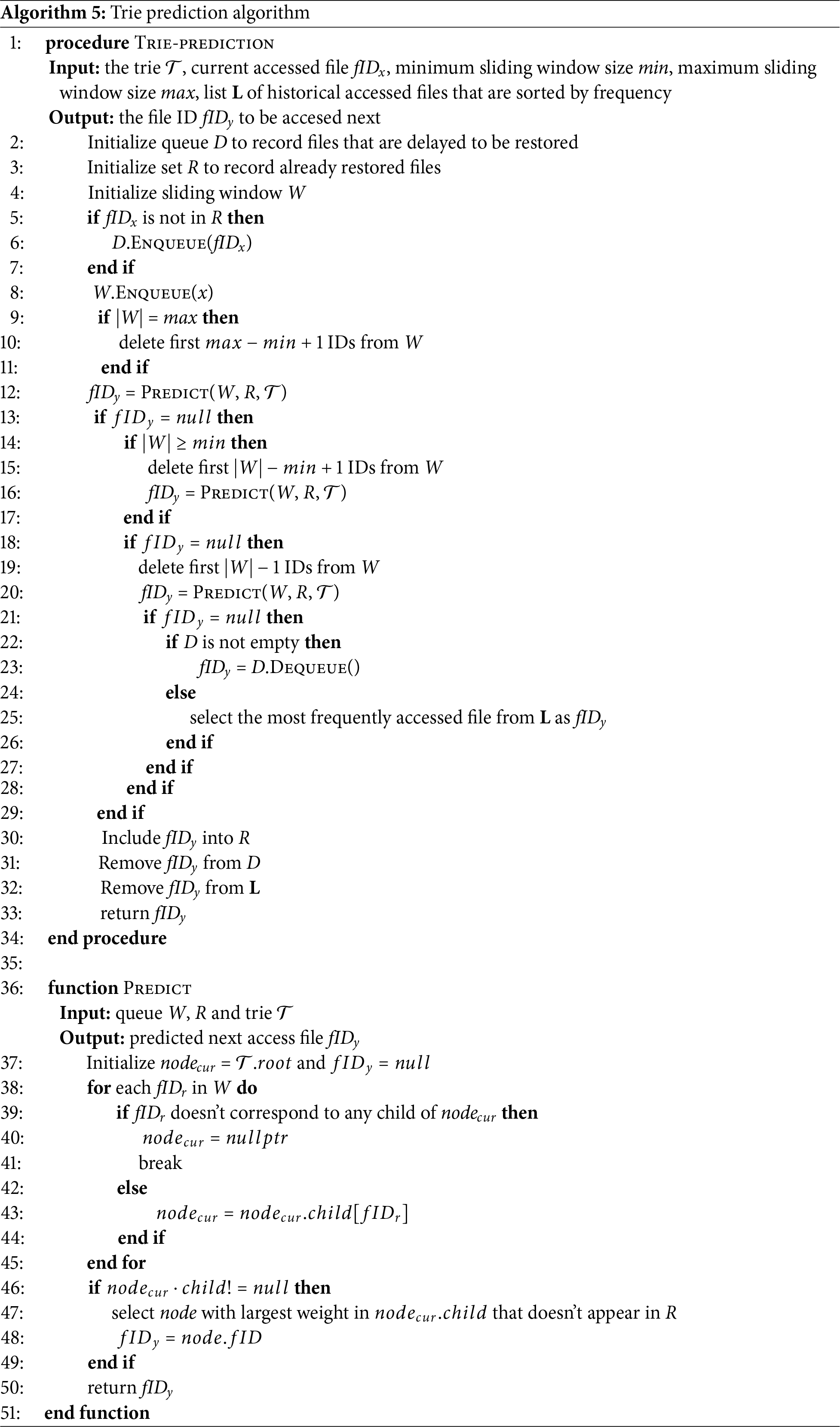

Example. We present an example to illustrate the trie-based approach. Let the minimum and maximum window sizes be 3 and 5, respectively, and consider a historical sequence of accessed files

For instance, after scanning the first seven file IDs, sliding windows such as

Figure 2: Example of constructing trie with minimum sliding window size of 3 and max size of 5 for the historical sequence

Next, assume the ground truth of the user’s access sequence is

When the user accesses B again, the sliding window

The final restore sequence generated by the prediction algorithm is

We present Histore for outsourced backup management. Histore provides a client, which realizes an interface to outsource (restore) backups to (from) a remote cloud server. The client implements online restore approaches (Section 3) that can improve users’ online restore experience based on historical access patterns. Specifically, to capture historical access patterns, we assume that the cloud maintains access logs about users. We argue that the assumption is practical since many service providers track users’ access statistics to improve the quality of service [22–25]. Our current Histore prototype includes 5.3 K lines of code (LoC) of C++ code.

To store a backup, a client first collects the file metadata (e.g., name and size), as well as the ownership information (e.g., the identifier of the user that processes the backup). and then transmit both file data and metadata to the cloud.

The cloud maintains two key-value stores (both of which are implemented via LevelDB [26]) to manage the metadata information. Specifically, the file index maps each backup’s file pathnames to the corresponding files’ metadata, such as size. The user index maps each user identifier to the latest backup version number of the user.

To manage stored backups, Histore maintains a home directory for each available client. When a client stores a backup, the cloud creates a version directory to store the backup’s files. Here, in the version directory, we preserve the original filename of each file in a backup. In addition to backup contents, the cloud manages a log file access.log in the version directory to record the historical access pattern of the corresponding backup. In our current implementation of Histore, the cloud only keeps the most recent K backups. If the client stores the

Histore implements three restoration approaches (Section 3), allowing clients to select their preferred method. Specifically, upon receiving a restore request from a client, the cloud decides which files in the corresponding backup need to be restored first. The cloud generates a stored file list for the backup, where items are sorted by historical access frequency. The frequency-based approach directly restores each file based on the list.

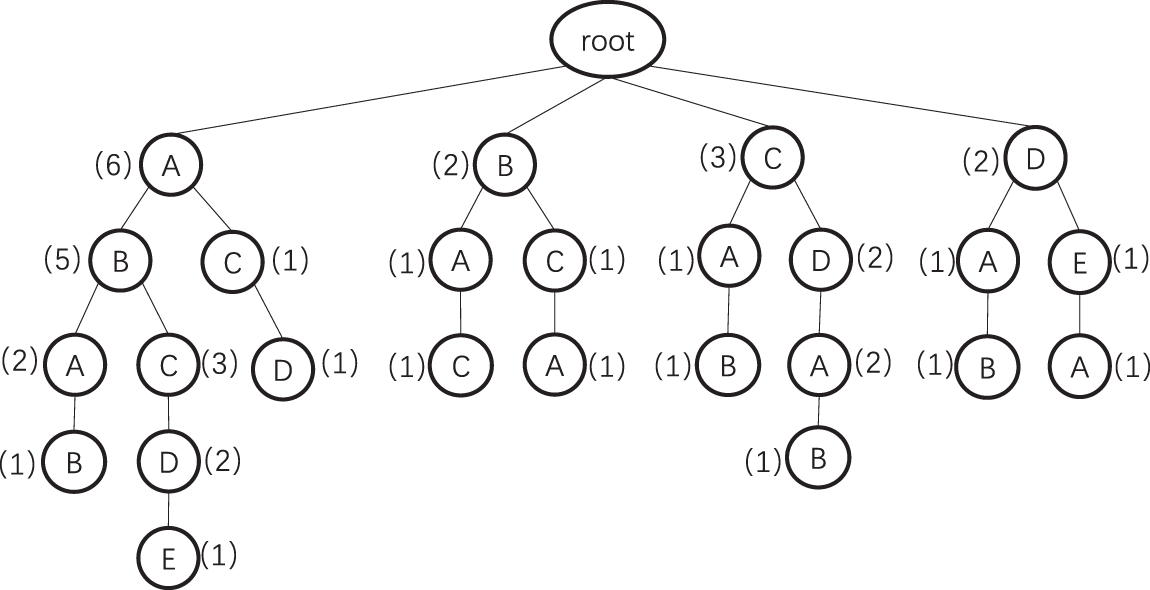

In the graph-based approach, Histore implements the graph via an adjacency list shown as Fig. 3a, as well as stores the edge weights in a hash table shown as Fig. 3b. The hashtable is mainly used to speed up the process of graph building.

Figure 3: Key data structures used in the graph-based approach

The index of the hashtable is computed as the hash of an edge, derived from the hashes of the two file pathnames. The corresponding value in the hashtable is a Binary Sort Tree [27], which resolves hash collisions. This structure enables efficient edge lookup during insertion to determine whether the edge already exists. If the edge does not exist, a new node is appended to the binary tree; otherwise, the weight of the existing node is updated.

The adjacency list is employed to accelerate graph splitting. The head nodes of the adjacency list store all vertices of the graph (represented by the hashes of file pathnames), while the adjacent vertices of each node are stored as entries following the corresponding head node. During graph splitting, the greedy algorithm iteratively retrieves a vertex’s adjacent vertices and removes edges from the graph. With the adjacency list, locating a vertex’s neighbors only requires traversing its head node, and edge deletion involves simply removing the corresponding entries.

In the trie-based approach, the trie is implemented as a multi-fork tree, where each node maintains the filename, its weight, and a child map. The child map stores mappings between filenames and pointers to their respective child nodes.

To restore a backup, the client sends a restore request to the cloud. The cloud first retrieves the user’s latest backup version using the user index. If the frequency-based or graph-based method is selected, the cloud invokes the corresponding module to generate the restore sequence R using access.log, sending file pathnames, sizes, and content to the client in the order specified by R. If the trie-based method is used, the cloud initializes the trie structure from access.log. Concurrently, the client periodically transmits the most recent access sequence (five items at a time) to the cloud, which uses this sequence to predict subsequent restore targets. Once the entire backup is transmitted, the cloud signals completion by sending a flag to the client before closing the connection.

We adapt the commonly used multi-threading optimization techniques to parallelize the communication, processing, and storage I/O of the cloud in the pipeline. Also, we are multi-threading the service for different clients.

Histore currently focuses on scenarios where a single cloud server processes unencrypted plaintext backups. In this section, we address the potential limitations under such a scenario.

Distributed cloud storage. At present, Histore only supports backup restoration using a single cloud server. To enhance scalability and support distributed storage, Histore can partition backups and store them across multiple storage backends. During restoration, these backends can operate in parallel, significantly improving the throughput of Histore. However, this approach reduces system reliability, as the failure of any storage backend may render part or all of the backup unrecoverable, leading to restoration failure. To mitigate this issue, redundant storage [28] or erasure coding technique [29] can be employed to improve system stability and ensure data recovery in the presence of backend failures.

Data security. Currently, Histore handles plaintext backup content in the cloud. Given that the cloud and client often belong to different organizations and third-party cloud providers operate in potentially vulnerable network environments [30,31], users may distrust cloud memory and persistent storage devices [32]. To ensure data confidentiality, backups can be encrypted on a per-file basis at the client side prior to upload and decrypted during restoration. However, as the proposed methods (Section 3) rely on access patterns and metadata, these inevitably become exposed to the cloud, introducing the risk of side-channel attacks. While existing techniques, such as Oblivious RAM [33,34], can fully obscure access patterns and metadata, they conflict with the design goals of Histore. Addressing this limitation remains an open problem for future work.

Datasets. We use two mixed datasets to drive our evaluation. The first dataset is mix-1. We use the process monitor [35] to collect the file system, registry, and process/thread activities of a student’s machine (that runs Windows 10) in our research group in the period of June 19 to June 25, 2021. We exclude the system directories Windows, ProgramData, Intel, AMD, and Drivers (if the latter three exist), and focus on the readFile and writeFile operations that are applied on the remaining files. We merge multiple consecutive reads (writes) on an identical file into one read (write) to the file.

However, since our collected logs do not contain file metadata, we associate each unique file record in the access log with a file in the FSL snapshots, which represent daily backups of students’ home directories from a shared network file system [36]. Each FSL snapshot consists of a sequence of file names and their corresponding sizes. We choose two FSL snapshots with as many files as access logs and write random values repeatedly to each file (in these snapshots) with the specified size. We then map each file record of the access log to a replayed file in the FSL snapshots based on the principle that small files are likely to be accessed frequently. The mix-1 dataset contains the file access data of the same user for 2 consecutive days, and the dataset finally includes 59 GiB of file data.

The second dataset is mix-2, which maps on access records in the Microsoft Research Cambridge (MSRC) dataset [37] to files in the MS dataset [38]. Specifically, the MSRC dataset includes the block-level access records collected from multiple servers, and we focus on the directory hm_1. Note that we assume that each independent access block corresponds to a distinct file. Since the MS dataset only contains a list of file metadata, which is similar to that in FSL, we randomly choose three MS snapshots and generate synthetic files with random content based on the metadata and map the files to the access sequence in hm_1 based on the principle that small files are accessed more frequently. The resulting mix-2 dataset contains 333 GiB of file data.

Testbeds. We configure a LAN cluster for the cloud and multiple clients. We have two types of machines: host and cloud. Our host machines are equipped with an 8-core 2.9 GHz Intel Core i7-10700 CPU, 32 GB RAM, and a 512 GB Non-Volatile Memory Express (NVMe) SSD alongside a 4 TB 7200 rpm SATA HDD. While our cloud machine has a 16-core 2.1 GHz Intel Xeon E5-2683 v4 CPU, 64 GB RAM, and a RAID 5 disk array based on four 4 TB 7200 rpm SATA HDD. All machines are running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS and connected with a 10 Gigabit Switch.

To illustrate the effectiveness of the three restoration approaches, we followed the simulation (see Section 2 for details) to compare the availability ratio and delayed time of the three approaches to the baseline approach. We split the two datasets mix-1 and mix-2 to generate historical access sequences

Here, we run the cloud program on our cloud machine and the client’s program on the host machine, while setting the network bandwidth as 100 MiB/s to get each file’s restored time. We evaluate the availability rate, which is the number of successfully accessed files divided by the total number of current accessed files. In addition, we consider delayed time rate as the current cumulative delayed time of the target approach divided by the baseline approach’s cumulative delayed time.

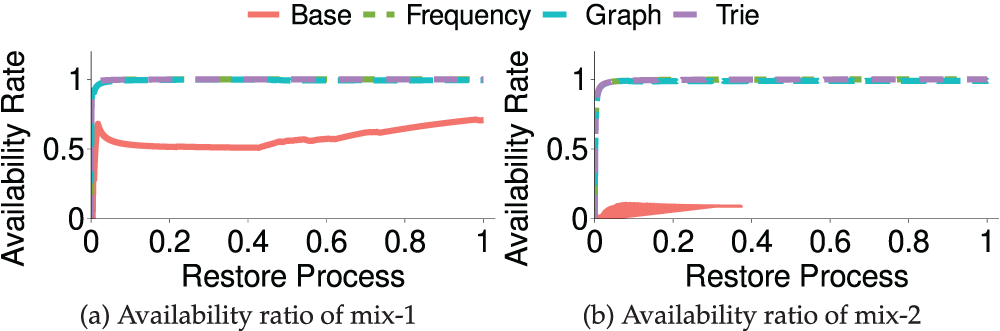

Fig. 4a,b shows the theory availability ratio of four restoration approaches changes with the restoration process. For both mix-1 and mix-2 datasets, with the Frequency, Graph and Trie restore sequence, the system can achieve more than 99% availability ratio after restoring about 7% of the files, while with the baseline (alphabetical) restore sequence, it can only reach 50%–70% and 12% for the mix-1 and mix-2 datasets, respectively. We noticed that the availability ratio of the baseline approach differs significantly in the two datasets. This is because the name of the frequently accessed file in

Figure 4: Availability ratio of two datasets on different restoration approaches. The x-axis presents the whole restore process

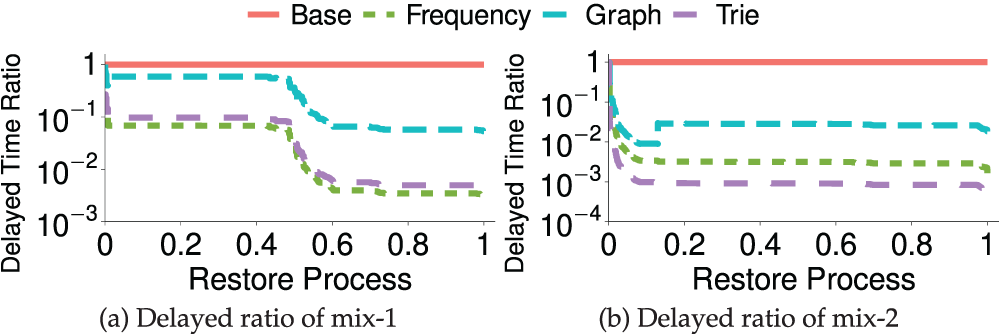

Fig. 5a,b shows the delayed time ratio of four restoration approaches when processing the two datasets. Since the cumulative delayed time of the baseline is the denominator for calculating the delayed time rate, its delayed time ratio is always kept as 1 (the red line), and the lower the delayed time rate, the lower the access delayed time than the baseline. For both mix-1 and mix-2 datasets, the three approaches can effectively reduce the delayed time in the whole process. For the mix-1 dataset, the frequency-based approach is the best that could reduce the delayed time by up to 99.7%. While the graph-based approach is the worst, which could only reduce the delayed time by 94%. In addition, for the mix-2 dataset, the graph approach first reduces the delayed time, then increases the delayed time by a part. This is mainly because the graph approach utilizes the principle of the local optimal solution used, which is not globally optimal on the mix-2 dataset.

Figure 5: Delayed ratio of two datasets on different restoration approaches. The x-axis presents the whole restore process

In the performance evaluation, we focus on the impact of different storage media, network bandwidth, and the number of users on the three restore approaches compared with the baseline alphabetical approach. Our key findings are as follows:

1) Our three approaches have performed well on different storage media for different datasets. They can reduce the client’s delay time by 4

2) Increasing the bandwidth of the network can effectively reduce the delay time of users. When the network bandwidth is increased by 10

3) Our system’s store throughput can reach 829.0 MiB/s, and restore throughput can reach 1083.5 MiB/s with multiple clients.

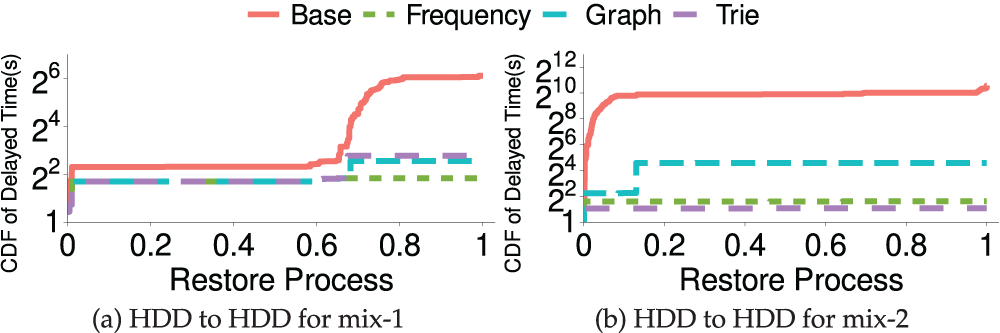

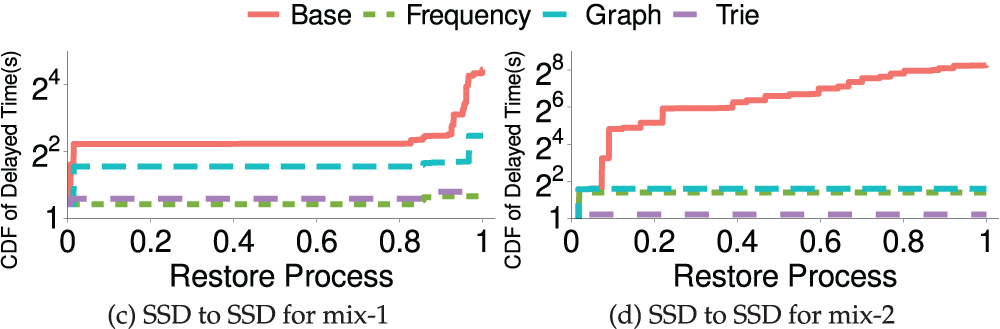

Exp#1 (Delayed time of restoration approaches). We evaluate the actual cumulated delay time based on two types of storage media during restoration. Here, unlike in the theoretical analysis, we deploy both cloud and client programs on the host machine to evaluate the cumulated read delay when restoring files from cloud-side HDD to client-side HDD and from cloud-side SSD to client-side SSD.

Figs. 6 and 7 show the results of accumulated delayed time on the client side with the restore process. Obviously, under the condition of SSD storage media, the overall restore time is significantly lower than that of HDD storage media due to higher I/O bandwidth. And under each storage media, the baseline approach (alphabetical order) has the worst performance. In addition, the current access sequence

Figure 6: (Exp#1) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) of delayed time of two datasets on different storage media. HDD to HDD means restoring files from the cloud-side HDD to the client-side HDD. The x-axis presents the whole restore process

Figure 7: (Exp#1) CDF of delayed time of two datasets on different storage media. SSD to SSD means restoring files from the cloud-side SSD to the client-side SSD. The x-axis presents the whole restore process

For the mix-1 dataset, the frequency-based approach outperforms all approaches with both SSD and HDD storage media. The reason is that the frequency-based approach has a very low computation overhead for generating a restore sequence and has no communication overhead during the restoration process. Under SSD storage media, trie-based and frequency-based approaches have a better performance than HDD. In addition to the reason for the faster read and write speed of SSD, it also shows that trie-based and frequency-based approaches have better performance when the frequently accessed files are small files.

For the mix-2 dataset, the trie-based approach performs better than the others. The reason it outperforms the other approaches in the mix-2 dataset but not in the mix-1 dataset is that the mix-2’s access sequence during restoration has higher locality than mix-1 and the trie-based approach restores files with priority in terms of locality. The graph approach has the longest delay time due to high computation overhead. However, the three approaches have significantly reduced the delay time compared to the baseline approach. Although the graph-based approach has the worst performance, it can still reduce 4

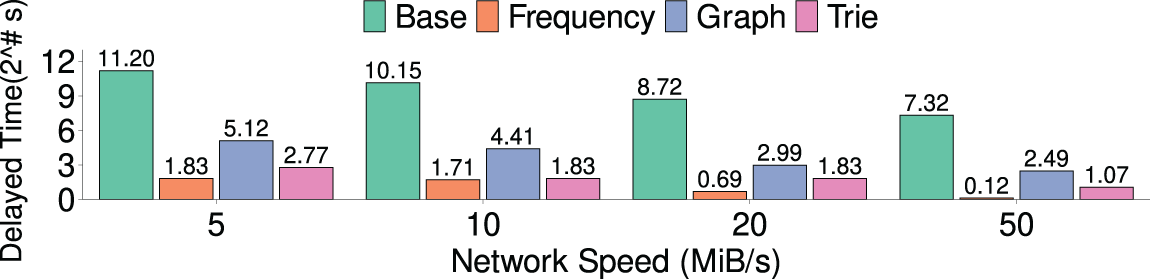

Exp#2 (Network speed’s influence on delay time). To study the impact of network bandwidth on cumulative delayed time, we set up the cloud program on our cloud machine and the client programs on the host machines. In addition, we controlled the network bandwidth at 5, 10, 20, and 50 MiB/s via trickle [39].

Fig. 8 shows the results of four approaches to the cumulative delayed time when finishing the restore for the mix-1 dataset under different network bandwidths. When the network bandwidth is 50 MiB/s, the frequency-based approach could reduce the total delayed time to the lowest 1.08 s. In contrast, when the network bandwidth is reduced to 5 MiB/s, the total delayed time of the frequency-based approach reaches 3.6 s, which is 3.3

Figure 8: (Exp#2) The cumulative delayed time of the four restore approaches under different network bandwidth (For clarity, the y-axis uses a base-2 logarithmic axis)

Exp#3 (Multi-client stores and restores). We evaluate the performance when one or more clients issue Store/Restore concurrently. We extend Exp#2 from two aspects. First, we deploy the clients and the cloud’s storage backend in ramdisk. Also, we set each client to store 3.97 GiB files data sampled from mix-1 dataset to the cloud, and then restore files of the same size from the cloud, and evaluate the aggregate store (restore) speed as the ratio of the total stored (restored) data size to the total time all clients finish the stores (restores).

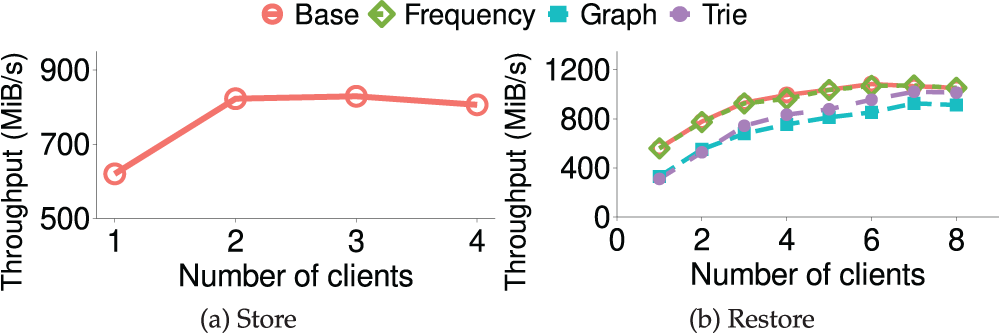

Fig. 9a shows the accumulated store throughput, which is the same for all four approaches due to the files being stored in the order of appearance. The overall store throughput of the system increases with the number of clients first (620.1 MiB/s for one client) and reaches the maximum throughput of 829.0 MiB/s at two clients due to resource contention, then decreases with the increase of the number of clients.

Figure 9: (Exp#3) Multi-client throughput. The store throughput is the same for all four schemes as all files are stored in the order in which they appeared

Fig. 9b shows the accumulated restore throughput vs. the number of clients. The aggregate restores throughput of four approaches increases with the number of clients and finally plateaus when reaching the maximum throughput of 1083.5 MiB/s at 6 clients for the baseline approach and 1072.2, 926.4, and 1021.2 MiB/s at 7 clients for frequency-based, graph-based and trie-based approaches, respectively.

Compared with the baseline approach, the frequency-based approach introduced merely 1.0% performance overhead since it only needs to process the historical sequence once, which has only minimal computing overhead. The graph-based approach has the lowest throughput of the four approaches and introduced 14.5% overhead compared with the baseline approach. The reason is that obtaining the correlation between files for each client requires a fixed computational overhead, which would not change with the number of clients. Since the trie-based approach needs to constantly predict the restore file through the current access file’s information, it leads to enormous computational overhead. It has the slowest restore throughput when the client number is small. However, it outperforms the graph-based approach when the number of clients increases since the restore manager uses the file in the default frequency sequence as the target restore file to take the place of the target file that cannot be calculated in time.

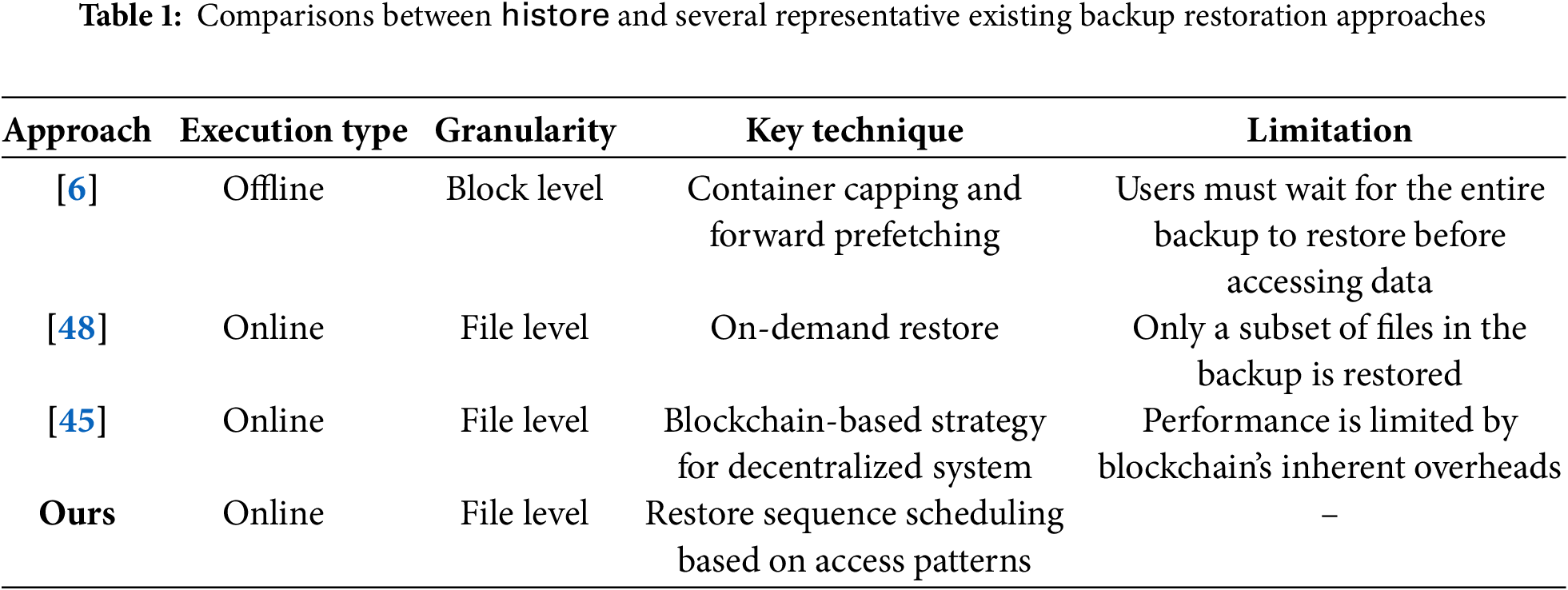

Backup restore. Previous works focus on accelerating restore speed. Cumulus [5] applies segment cleaning to reduce the amount of backup data to be downloaded in the restore procedure. Data deduplication [40,41] introduces chunk fragmentation [6] and degrades restore performance. A large body of works [6–8,42] address chunk fragmentation to improve restore speed. This paper focuses on online restoration and preserves the performance of users’ foreground operations. In addition, the rapid evolution of blockchain technology [43,44] has significantly advanced data storage infrastructure in recent years. Sokolov et al. [45] proposed improvements to backup restoration leveraging blockchain, while Singh and Batra [46] examined its applications across multiple cloud service providers. Nevertheless, the performance of blockchain-based backup restoration remains constrained by the overhead introduced by consensus mechanisms and communication requirements [47].

Nemoto et al. [48] propose on-demand restore, which recovers directories and files based on users’ requests prior to less important ones. This work differs from on-demand restore [48] for automatically scheduling the restore sequence of files.

Table 1 compares Histore with several representative backup restoration approaches. In summary, Histore is the first online backup restoration system to leverage access patterns, achieving superior restoration performance compared to existing approaches.

Modeling access patterns. This paper is related to previous works that model historical access patterns from the block level (e.g., [12,49,50]) and the file level [14,15,51–53], in order to predict future access. We focus on modeling the file-level access pattern. The last successor predicts that access to each file will be followed by the same file that followed the last access to the file. Amer and Long [51] extend the last successor model by tracking access locality (i.e., some files are more likely to be successively accessed, followed by each file), and makes predictions only for the files with strong access locality. Amer et al. [52] augment Noah with the tunability of the prediction accuracy and the number of predictions made.

In addition to the last successor model, Kroeger et al. [14,53] propose two context-aware models to make predictions. The first model builds a graph to track the frequency counts of file accesses within a sliding window, and predicts future access based on the file that is most likely to be accessed after the current file. The second model builds a trie to track file access events via the multi-order context modeling, and predicts future access based on the probability that the child’s access occurs. EPCM [15] extends the trie-based approach [14,53] to predict the sequence of upcoming file access. Nexus [54] extends the graph-based approach [14] to aggressively prefetch metadata. We highlight that our schemes are focused on generating predicted sequences of restore files rather than individual files.

Additional works (e.g., FARMER [55], SmartStore [56], SANE [57], and SMeta [13]) build semantic-aware models on metadata, in order to accelerate metadata queries or improve prefetching accuracy in distributed file systems. However, the semantic-aware models incur high storage overhead for storing the attributes of metadata objects, as well as high computational overhead for counting the similarity degrees of different objects.

We present Histore, which exploits correlation among backup files through the user’s file historical access information to adapt the backup file restore sequence. Our main concern is to improve the user’s access success rate during the restoration period while reducing the user’s delayed time under the online restore scenario. We propose three different approaches for generating restore sequences, namely frequency-based, graph-based, and trie-based approaches, and implement a system to evaluate our idea. We discuss the limitations of our current system in terms of scalability and security. We extensively evaluate our system from the theoretical and practical aspects. We show that Histore effectively reduces users’ delayed time by 4–700

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the funding program that supported this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4501200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62332018), Science and Technology Program (2024NSFTD0031, 2024YFHZ0339 and 2025ZNSFSC0497).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ruidong Chen, Guopeng Wang and Ting Chen; methodology, Ruidong Chen, Guopeng Wang, Jingyuan Yang and Xingpeng Tang; software, Jingyuan Yang, Ziyu Wang, Fang Zou and Jia Sun; validation, Ruidong Chen, Guopeng Wang and Ting Chen; resources, Jingyuan Yang, Ziyu Wang, Fang Zou and Jia Sun; data curation, Ziyu Wang, Fang Zou and Jia Sun; writing—original draft preparation, Ruidong Chen, Guopeng Wang, Jingyuan Yang and Ting Chen; writing—review and editing, Jingyuan Yang and Ting Chen; supervision, Ting Chen; funding acquisition, Ting Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations/Acronyms

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| LoC | Lines of Code |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| AMD | Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. |

| NVMe | Non-Volatile Memory Express |

| LAN | Local Area Network |

| HDD | Hard Disk Drive |

| SSD | Solid State Drive |

| NVMe | Non-Volatile Memory Express |

| MSRC | Microsoft Research Cambridge |

References

1. Google Cloud [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://cloud.google.com/storage. [Google Scholar]

2. Amazon Cloud Storage. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://aws.amazon.com. [Google Scholar]

3. Xue K, Chen W, Li W, Hong J, Hong P. Combining data owner-side and cloud-side access control for encrypted cloud storage. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2018;13(8):2062–74. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2018.2809679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gao Y, Li Q, Tang L, Xi Y, Zhang P, Peng W, et al. When Cloud Storage Meets RDMA. In: 18th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 21). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2021. p. 519–33. [Google Scholar]

5. Vrable M, Savage S, Voelker GM. Cumulus: filesystem backup to the cloud. ACM Trans Storage. 2009;5(4):1–28. doi:10.1145/1629080.1629084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lillibridge M, Eshghi K, Bhagwat D. Improving restore speed for backup systems that use inline chunk-based deduplication. In: 11th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST ’13). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2013. p. 183–97. [Google Scholar]

7. Fu M, Feng D, Hua Y, He X, Chen Z, Xia W, et al. Accelerating restore and garbage collection in deduplication-based backup systems via exploiting historical information. In: 2014 USENIX Annual Technical Conference. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2014. p. 181–92. [Google Scholar]

8. Cao Z, Wen H, Wu F, Du DHC. ALACC: accelerating restore performance of data deduplication systems using adaptive look-ahead window assisted chunk caching. In: 16th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 18). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 309–24. [Google Scholar]

9. Chaudhary J, Vyas V, Saxena M. Backup and restore strategies for medical image database using NoSQL. In: Communication, software and networks. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 161–71. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-4990-6_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bogatyrev VA, Bogatyrev SV, Bogatyrev AV. Recovery of real-time clusters with the division of computing resources into the execution of functional queries and the restoration of data generated since the last backup. In: Distributed computer and communication networks: control, computation, communications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 236–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-50482-2_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tang X, Li J. Improving online restore performance of backup storage via historical file access pattern. In: Frontiers in cyber security. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 365–76. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-8445-7_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liao J, Trahay F, Gerofi B, Ishikawa Y. Prefetching on storage servers through mining access patterns on blocks. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2016;27(9):2698–710. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2015.2496595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen Y, Li C, Lv M, Shao X, Li Y, Xu Y. Explicit data correlations-directed metadata prefetching method in distributed file systems. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2019;30(12):2692–705. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2019.2921760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kroeger TM, Long DDE. The case for efficient file access pattern modeling. In: Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems; 1999 Mar 30–30; Rio Rico, AZ, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2002. p. 14–9. doi:10.1109/HOTOS.1999.798371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kroeger TM, Long DD. Design and implementation of a predictive file prefetching algorithm. In: 2001 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 01); 2001 Jun 25–30; Boston, MA, USA; 2001. p. 105–18. [Google Scholar]

16. Li J, Nelson J, Michael E, Jin X, Ports DR. Pegasus: tolerating skewed workloads in distributed storage with in-network coherence directories. In: 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2020. p. 387–406. [Google Scholar]

17. Zou X, Xia W, Shilane P, Zhang H, Wang X. Building a high-performance fine-grained deduplication framework for backup storage with high deduplication ratio. In: Proceeding of 2022 USENIX Annual Technical Conference. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2022. p. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

18. Yang J, Wu J, Wu R, Li J, Lee PP, Li X, et al. ShieldReduce: fine-grained shielded data reduction. In: USENIX ATC '25: Proceedings of the 2025 USENIX Conference on Usenix Annual Technical Conference; 2025 Jul 7–9; Boston, MA, USA. p. 1281–96. [Google Scholar]

19. Restore your iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch from a Backup [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT204184. [Google Scholar]

20. Douceur JR, Bolosky WJ. A large-scale study of file-system contents. SIGMETRICS Perform Eval Rev. 1999;27(1):59–70. doi:10.1145/301464.301480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tang Y, Li D, Li Z, Zhang M, Jee K, Xiao X, et al. NodeMerge: template based efficient data reduction for big-data causality analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2018. p. 1324–37. doi:10.1145/3243734.3243763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cheng X, Dale C, Liu J. Statistics and social network of YouTube videos. In: 2008 16th Interntional Workshop on Quality of Service; 2008 Jun 2–4; Enschede, The Netherlands; 2008. p. 229–38. doi:10.1109/IWQOS.2008.32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lyu F, Ren J, Cheng N, Yang P, Li M, Zhang Y, et al. LeaD: large-scale edge cache deployment based on spatio-temporal WiFi traffic statistics. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2021;20(8):2607–23. doi:10.1109/TMC.2020.2984261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shvachko K, Kuang H, Radia S, Chansler R. The hadoop distributed file system. In: 2010 IEEE 26th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST); 2010 May 3–7; Incline Village, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2010. p. 1–10. doi:10.1109/msst.2010.5496972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ousterhout JK, Da Costa H, Harrison D, Kunze JA, Kupfer M, Thompson JG. A trace-driven analysis of the UNIX 4.2 BSD file system. In: Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 1985. p. 15–24. doi:10.1145/323647.323631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. LevelDB [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://github.com/google/leveldb. [Google Scholar]

27. Binary search tree [Internet]. 1960 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_search_tree. [Google Scholar]

28. Luo R, He Q, Xu M, Chen F, Wu S, Yang J, et al. Edge data deduplication under uncertainties: a robust optimization approach. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2025;36(1):84–95. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2024.3493959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ren Y, Ren Y, Li X, Hu Y, Li J, Lee PP. ELECT: enabling erasure coding tiering for LSM-tree-based storage. In: 22nd USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 24); 2024 Feb 26–29; Santa Clara, CA, USA. p. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

30. Li J, Yang Z, Ren Y, Lee PPC, Zhang X. Balancing storage efficiency and data confidentiality with tunable encrypted deduplication. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth European Conference on Computer Systems. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2020. p. 1–15. doi:10.1145/3342195.3387531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang W, Gong X, Chen Y, Wang Q, Dong J. SwiftTheft: a time-efficient model extraction attack framework against cloud-based deep neural networks. Chin J Electron. 2024;33(1):90–100. doi:10.23919/cje.2022.00.377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li J, Ren Y, Lee PPC, Wang Y, Chen T, Zhang X. FeatureSpy: detecting learning-content attacks via feature inspection in secure deduplicated storage. In: IEEE INFOCOM, 2023-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2023 May 17–20; New York City, NY, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–10. doi:10.1109/INFOCOM53939.2023.10228971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Stefanov E, Dijk MV, Shi E, Chan TH, Fletcher C, Ren L, et al. Path ORAM: an extremely simple oblivious RAM protocol. J ACM. 2018;65(4):1–26. doi:10.1145/3177872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li X, Luo Y, Gao M. Bulkor: enabling bulk loading for path ORAM. In: 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2024 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 4258–76. doi:10.1109/sp54263.2024.00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Process Monitor [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/downloads/procmon. [Google Scholar]

36. FSL Traces and Snapshots Public Archive [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: http://tracer.filesystems.org/. [Google Scholar]

37. SNIA. Microsoft research cambridge target block traces. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: http://iotta.snia.org/traces/block-io/388. [Google Scholar]

38. Microsoft UBC-Dedup Traces [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: http://iotta.snia.org/traces/static/3382. [Google Scholar]

39. Eriksen MA. Trickle: a userland bandwidth shaper for UNIX-like systems. In: FREENIX Track: 2005 USENIX Annual Technical Conference. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2005. p. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

40. Yang Z, Li J, Lee PP. Secure and lightweight deduplicated storage via shielded deduplication-before-encryption. In: 2022 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 22). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2022. p. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

41. Zhao J, Yang Z, Li J, Lee PPC. Encrypted data reduction: removing redundancy from encrypted data in outsourced storage. ACM Trans Storage. 2024;20(4):1–30. doi:10.1145/3685278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Cao Z, Liu S, Wu F, Wang G, Li B, Du DH. Sliding look-back window assisted data chunk rewriting for improving deduplication restore performance. In: 17th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 129–42. [Google Scholar]

43. Yang K. Zero-cerd: a self-blindable anonymous authentication system based on blockchain. Chin J Electron. 2023;32(3):587–96. doi:10.23919/cje.2022.00.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Su J. A hybrid entropy and blockchain approach for network security defense in SDN-based IIoT. Chin J Electron. 2023;32(3):531–41. doi:10.23919/cje.2022.00.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sokolov S, Vlaev S, Iliev TB. Technique for improvement of backup and restore strategy based on blockchain. In: 2022 International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES); 2022 Nov 24–26; Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CIEES55704.2022.9990781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Amanpreet S, Jyoti B. Strategies for data backup and recovery in the cloud. Int J Perform Eng. 2023;19(11):728. doi:10.23940/ijpe.23.11.p3.728735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Shi D. RESS: a reliable and effcient storage scheme for Bitcoin blockchain based on Raptor code. Chin J Electron. 2023;32(3):577–86. doi:10.23919/cje.2022.00.343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Nemoto J, Sutoh A, Iwasaki M. File system backup to object storage for on-demand restore. In: 2016 5th IIAI International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI); 2016 Jul 10–14; Kumamoto, Japan. p. 946–52. doi:10.1109/iiai-aai.2016.116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Li Z, Chen Z, Srinivasan SM, Zhou Y, et al. C-Miner: mining block correlations in storage systems. In: 3rd USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 04). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

50. Soundararajan G, Mihailescu M, Amza C. Context-aware prefetching at the storage server. In: ATC'08: USENIX, 2008 Annual Technical Conference; 2008 Jun 22–27; Boston, MA, USA. p. 377–90. [Google Scholar]

51. Amer A, Long DD. Noah: low-cost file access prediction through pairs. In: Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Performance, Computing, and Communications Conference; 2001 Apr 4–6; Phoenix, AZ, USA. p. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

52. Amer A, Long DDE, Paris JF, Burns RC. File access prediction with adjustable accuracy. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Performance, Computing, and Communications Conference; 2002 Apr 3–5; Phoenix, AZ, USA. p. 131–40. [Google Scholar]

53. Kroeger TM, Long DDE. Predicting file system actions from prior events. In: USENIX 1996 Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 96). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

54. Gu P, Zhu Y, Jiang H, Wang J. Nexus: a novel weighted-graph-based prefetching algorithm for metadata servers in petabyte-scale storage systems. In: Sixth IEEE International Symposium on Cluster Computing and the Grid (CCGRID'06); 2006 May 16–19; Singapore. doi:10.1109/CCGRID.2006.73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Xia P, Feng D, Jiang H, Tian L, Wang F. FARMER: a novel approach to file access correlation mining and evaluation reference model for optimizing peta-scale file system performance. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on High Performance Distributed Computing. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2008. p. 185–96. doi:10.1145/1383422.1383445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hua Y, Jiang H, Zhu Y, Feng D, Tian L. SmartStore: a new metadata organization paradigm with semantic-awareness for next-generation file systems. In: Proceedings of the Conference on High Performance Computing Networking, Storage and Analysis; 2009 Nov 14–20; Portland, OR, USA. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

57. Hua Y, Jiang H, Zhu Y, Feng D, Xu L. SANE: semantic-aware namespacein ultra-large-scale file systems. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2014;25(5):1328–38. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2013.140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools