Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Dynamic Masking-Based Multi-Learning Framework for Sparse Classification

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, 16419, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Woo Hyun Park. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 57 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069949

Received 04 July 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the recent increase in data volume and diversity, traditional text representation techniques are struggling to capture context, particularly in environments with sparse data. To address these challenges, this study proposes a new model, the Masked Joint Representation Model (MJRM). MJRM approximates the original hypothesis by leveraging multiple elements in a limited context. It dynamically adapts to changes in characteristics based on data distribution through three main components. First, masking-based representation learning, termed selective dynamic masking, integrates topic modeling and sentiment clustering to generate and train multiple instances across different data subsets, whose predictions are then aggregated with optimized weights. This design alleviates sparsity, suppresses noise, and preserves contextual structures. Second, regularization-based improvements are applied. Third, techniques for addressing sparse data are used to perform final inference. As a result, MJRM improves performance by up to 4% compared to existing AI techniques. In our experiments, we analyzed the contribution of each factor, demonstrating that masking, dynamic learning, and aggregating multiple instances complement each other to improve performance. This demonstrates that a masking-based multi-learning strategy is effective for context-aware sparse text classification, and can be useful even in challenging situations such as data shortage or data distribution variations. We expect that the approach can be extended to diverse fields such as sentiment analysis, spam filtering, and domain-specific document classification.Keywords

As the complexity of data processing and analysis increases, effectively representing and classifying text data in natural language processing (NLP) has gained significant prominence. However, existing embedding techniques still face several limitations [1]. For instance, existing word embedding methods quantify relationships between words within a sentence but struggle with contextual information. Data sparsity also presents limitations in addressing this issue. For example, the same word can have different meanings depending on the contextual structure of the sentence it relates to. Even with the same dictionary set, meanings can vary depending on the context, making simple embedding techniques insufficient for accurate adaptation. Therefore, learning methods are needed to minimize and preserve contextual information loss, which impacts prediction accuracy [2,3]. To overcome these limitations, approaches that learn relationships between different data sources are on the rise. They enable the representation of complex, multi-relational connections between various types of data, making them more robust than existing single-relational approaches. In healthcare data networks, to derive more meaningful information, models consider not only direct connections between reports but also various association paths, such as report-patient-annotation. However, existing models fail to fully utilize these diverse relational paths. In this study, we propose a novel embedding classification model that overcomes the dependency structure that causes structural information loss and simultaneously mitigates data sparsity and contextual information loss [4]. Specifically, by integrating heterogeneous information, we capture contextual features and accurately analyze the diverse semantic structures of text data. This can be seen in a movie recommendation system, where the accuracy of recommendations can be significantly improved by considering direct interactions between users and movies while simultaneously integrating diverse relational paths. This study has utilized this multi-relational approach to apply it not only to recommendation systems but also to other applications such as sentiment analysis and spam detection [5,6]. The goal of this research is to propose a more effective context-based text analysis methodology within diverse data sets and to complement the limitations of existing embedding techniques. This study defines three key contributions:

• We aim to collect rich relational path information in multi-relational structures without significant information loss by employing dynamic weight learning to reflect the relative importance of each connection, rather than treating all information uniformly.

• We strengthen representational power by differentially capturing the relative importance of each connected element.

• We design a learning framework that preserves information even in data-scarce situations by incorporating masking and a dynamic learning structure to compensate for data sparsity and incompleteness.

2 Background and Related Research

Within the latest trends in information representation technology, research on information selection and sentiment classification is ongoing. Previous studies have trained models on various datasets, including COVID-19-related documents. Specifically, dynamic learning methods demonstrated superior performance in terms of representation depth when using bagging methods with parameters set to a range of 2 to 4 [7]. The model proposed in this study demonstrated competitive performance, approximately 4% higher than baseline models in key metrics such as accuracy and AUC, and particularly excelled in handling imbalanced and small datasets. Various algorithms have been used for sentiment classification tasks, including Glove, information gain, wrapper-based methods, and evolutionary algorithms. For example, a study utilizing speeches on COVID-19 from the World Health Organization (WHO) and SST data yielded meaningful results using these approaches. Specifically, a logistic regression model achieved an SST score of 0.845, an improvement of approximately 0.08 over existing models, but still leaves room for improvement [8]. This study improves this performance by introducing advanced deep learning techniques and a novel selective window mechanism. Starting with information selection, sentiment classification becomes a key research area in this study.

In education, AI-based sentiment classification has been actively applied to enhance student-teacher interaction. For example, high performance has been achieved in classification tasks using datasets from Coursera and MOOC platforms, with random forest models achieving up to 99.43% accuracy [9]. However, machine learning models for sentiment classification require extensive parameter tuning and have limited generalizability. To address these issues, this study proposes a novel ensemble learning component for sentiment classification models. In the field of author verification, existing approaches have used the POSNoise technique, which utilizes topic masking to mitigate bias issues [10]. While this method has shown improvement over existing author verification techniques, it still faces challenges related to linguistic features and temporal factors. Therefore, we sought to establish a more general feature extraction approach by applying advanced machine learning techniques. For example, in the domain of Greek legal texts, high precision, recall, and F1 scores were achieved by combining heuristic rules, regular expression patterns, and deep learning techniques [11]. However, while these approaches have shown excellent performance, they are often limited to specific languages and domains.

IMO [12] introduced a masking technique in a single-source domain to remove false correlations at each layer and learn domain-invariant features. While this approach performed well in various OOD scenarios, it has limitations, requiring a large data source size of over 10,000 items. Furthermore, learning the mask layer results in a static inference process, making it difficult to adapt to new distributional changes. Therefore, this method is primarily limited to text classification and cannot properly handle dynamic integration of multiple instances. In contrast, our MJRM improves adaptability through selective dynamic masking and a multi-module architecture.

DCASAM in [13] proposed a combination of BERT, DBiLSTM, and DGCN for dependency analysis and sentiment analysis. However, DCASAM’s specialization in polarity recognition limits its adaptability to domain distributional changes. Our MJRM actively addresses review-level analysis and various distributional changes through sparsity-based representation learning and selective dynamic masking. Research [14] discussed the use of static machine learning models and semi-supervised learning (SSL) to address issues related to data distribution changes. For example, it has been utilized in cybersecurity fields such as attack detection. This study proposes a novel model called sparsity-based representation learning with selective dynamic masking, which can adapt to various domains. This model addresses performance degradation in sparse data environments and dynamic distribution changes in sentiment analysis.

Recent research [15] demonstrates that the super-class neural network language model LLM can outperform Naive Bayes and LightGBM methods, such as naive, for preserving the energy of its original members. For example, the Spam-T5 model, which leverages Flan-T5 to cluster data sparsity, improves performance regardless of the shared context. This study draws on the concept of a generator in generative adversarial networks (GANs), which aims to address the transformation of the underlying approach. While the basic GAN generates fake data to directly generate training datasets, the core principle of the generator, which generates new factor sets, is utilized to design a model that generates learning sets based on a limited set of representational and topical information. This approach enhances the data sets and allocates the data sparsity inherent in the underlying single-embedding population. Furthermore, the proposed model demonstrates applicability to various text analysis, as well as to feature provision, through learning modules that combine the same features as the underlying topical information. While structural associations maintain data dependency, the proposed model implements a generative learning approach.

Recent advances in neural network-based language models are remarkable. However, they often result in poor performance on sparse and domain-specific datasets, especially in data-constrained environments. For example, the internal workings of LLMs are not easily interpretable, limiting their applicability in applications such as public health text analysis and security. This requires techniques that dynamically adapt to changing distributions in resource-constrained environments and sparse and specialized datasets. For example, clinical text analysis faces the challenge of small and imbalanced datasets, while security and spam detection tasks require effective handling of biased distributions. To address these challenges, this study proposes the Masked Joint Representation Model (MJRM). The proposed model features a multi-learning architecture that integrates selective dynamic masking, attention, and regularization techniques. This model directly combines emotional and topical elements to enhance representation learning in sparse data environments. Furthermore, it dynamically scales by retraining multiple instances in parallel and aggregating results based on weights as the data distribution changes.

This study proposes an extended theoretical framework that integrates sparsity-inducing approaches. At its core, the proposed model features a dynamic learning capability that automatically adapts to changes in the multi-modal distribution of input data within sentence vectors. To achieve this, masking and attention mechanisms are interlinked, enabling the model to detect evolving data patterns and generate a more accurate origin distribution. The learning process is structured into three stages: Learning A, Learning B, and Learning C, each serving a distinct role in improving the model’s performance. Learning A handles the initial masking and representation learning of the input data. Learning B refines the learned representations through regularization. Learning C optimizes the parameters for final classification. Additionally, the model trains multiple instances of the Masked Joint Representation Model (MJRM) in parallel on different subsets of the data and ensembles their prediction outputs dynamically. The weights

4.1 Masked Joint Representation Model (MJRM)

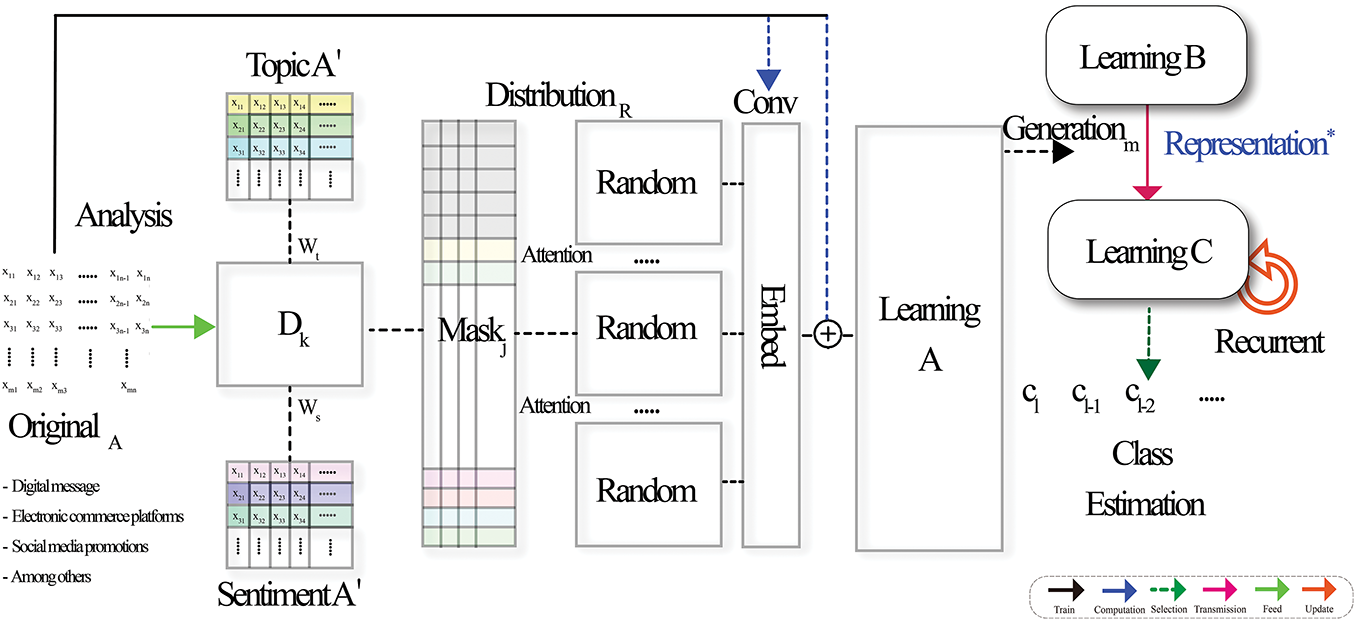

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the workflow of MJRM consists of three sequential stages: Learning A, Learning B, and Learning C, which respectively handle masked representation learning, refinement with regularization, and final classification. This part discusses an overview of the structure, key components, and operational principles of the proposed Masked Joint Representation Model (MJRM). In addition, it discusses the foundational models and methodologies that underpin this approach, the datasets used for validation, and the characteristics of the employed learning algorithms.

Figure 1: The process begins with topic and sentiment analysis, continues through masking and embedding in Learning A, representation refinement in Learning B, and concludes with class estimation in Learning C

First, the initial matrix O, representing the original data, serves as the input to the proposed MJRM algorithm. Through the masking mechanism, portions of the data are selectively blocked, enabling the model to autonomously identify and learn the most relevant information. The module responsible for handling the mask operates selectively based on the outcomes obtained during the optimization learning phase, thereby capturing the varying significance of emotional and topical patterns across sentences and documents. This process is reinforced through recursive learning, iteratively optimizing the model. The workflow is broadly organized into three stages: Learning A, Learning B, and Learning C. To address the limitations of conventional adversarial learning techniques—which often fail to capture the complex and dynamic context of natural language—this study integrates a selective window mechanism with random distribution, further combining topical and emotional information within the learning structure.

In particular, the proposed MJRM adopts a multi-instance structure, where the same input data is partitioned into multiple subsets, and each subset is trained independently. The predictions learned from these instances are then aggregated into a final output using a weighted average.

This structure reflects diverse perspectives within the data, mitigates overfitting by adapting to distributional changes, and strengthens generalization performance. Furthermore, the model is designed to adjust weights dynamically during training by integrating a dynamic feedback loop and convolution operations, which respond to the error rates encountered during the learning process.

The operational flow of the model is detailed in the accompanying figures and experimental results, which confirm that the proposed MJRM achieves strong performance across various text datasets.

In summary, the MJRM presented in this study contributes a novel text analysis framework that dynamically reconstructs distributions based on emotional and topical information, thereby alleviating data sparsity issues and minimizing contextual information loss. The key hyperparameters of our model are as follows. The learning rate was fixed at 0.01 with a batch size of 64, and training proceeded for approximately 100 iterations. Regularization was controlled by λ, α, and β to balance reconstruction, convolutional stability, and overfitting prevention. The mask ratio was set between 0.2 and 0.3 depending on the dataset, ensuring that informative features were retained. The number of topics (nT) was set to 20 for large datasets and 10 for small datasets, while the threshold (k) controlled the sparsity level in the selector function.

4.2 Information Transformation and Masking

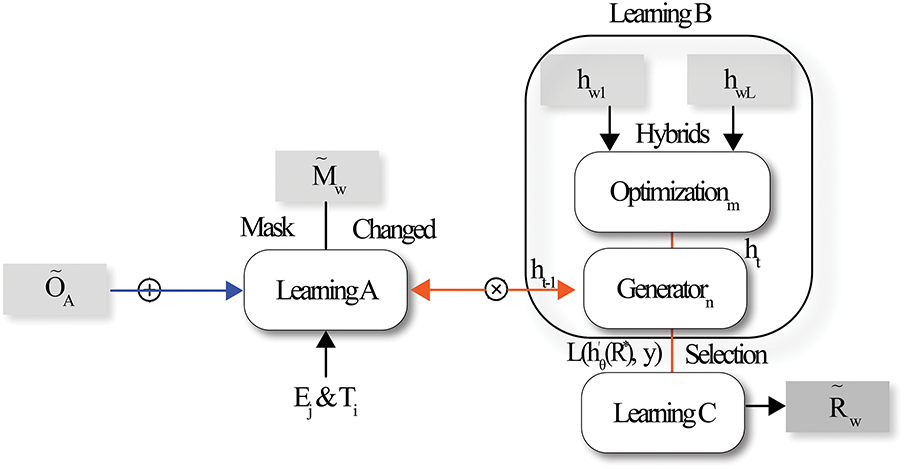

Fig. 2 provides the structural framework of the proposed MJRM, showing how the masking, optimization, and classification modules are integrated. It also presents the flow of information between components and the role of the Generator for handling sparsity. The model proposed in this study demonstrates several unique features that distinguish it from conventional neural network structures. While traditional relation-based models are often limited to homogeneous information, our approach extends the concept of dynamic representation generation to incorporate diverse types of neighboring matrices, thereby minimizing information loss. In particular, the model integrates a GAN-like Generator structure, enabling it to flexibly adapt to missing data and new patterns. This design allows for richer vector representations even in environments with data sparsity and partially missing information. A key feature is the masking technique, which intentionally conceals portions of the input data to encourage the model to infer missing information and learn critical features autonomously. This mechanism compensates for data incompleteness and contributes to improved generalization performance.

Figure 2: Overall architecture of the proposed masked joint representation model (MJRM)

The first stage of the learning process, Learning A, focuses on data transformation and masking. The original data matrix A undergoes a random masking process, introducing uncertainty by hiding certain data points. This encourages the model to learn essential features on its own. This process is mathematically presented as follows:

The expected loss LA controls both the reconstruction quality and the effect of masking.

R(m, n) is the learned representation at step (m, n), h~(EF) the reconstruction from masked input EF, and λ (lambda) the regularization weight. The first term minimizes reconstruction error to preserve semantic consistency, while the second prevents excessive masking.

Minimizing LA thus ensures that the learned representation converges toward the data manifold while maintaining robustness to incomplete inputs. It guarantees that, as the number of iterations increases, the masked representation gradually aligns with the underlying data distribution. This ensures that the optimization process converges appropriately to the dataset.

The mask and learner selection function is formulated as:

This selector function maps the masked random distribution to a binary vector, enabling dynamic feature selection during training. It is computed based on the masked topic matrix (TA), data matrix (DA), and sentiment matrix (SA). This operation also induces sparsity by retaining only informative features and addressing data sparsity.

Through Selectorm, only the most informative features from TA′, D′, and SA′ are propagated to subsequent stages. This removes noisy components, allowing the learned representation to converge to a sparse but semantically rich subspace.

In the second stage, Learning B, the outputs from Learning A are further transformed through a series of convolutional layers and fully connected layers. L1 and L2 regularization techniques are applied in this stage to prevent overfitting.

Here, RB represents the output of the Learning B stage. α and β are learnable parameters. Conv(O) denotes the convolution operation applied to the output O from Learning A. L1 and L2 are the regularization terms. Additionally, batch normalization is introduced at each layer to mitigate internal covariate shift and stabilize training, and accelerate convergence.

The next proceeds the loss function

E denotes the original embedding vector before being fed into the network, which combines sentiment (SA), topic (TA), and other features (Dx). EF refers to the vectorized version of the masked random distribution that is loaded during the operational phase, while EA represents the transition from O.

As a result of Learning A, the representations generated by the nth Generator and those passed through the Selector during optimization learning are computed. These are calculated using Mean Square Error (MSE) and Alternating Least Squares (ALS) and are then passed to the convolution operation for subsequent stages of learning.

The final stage, Learning C, aims to optimize the parameters hθ for the representations R and class labels Yc using an inference mechanism. Once the optimal feature representation is obtained, the estimator

In this stage, representation learning is performed as close as possible to the original data O, approximating the extracted probability distribution to a normal distribution and dynamically adjusting to match various target data distributions. Inspired by the Generator structure of GANs by [16], our model approximates the target distribution P(x)* through the following estimation:

This objective ensures that partially masked inputs are mapped to a stable and learnable distribution, allowing the Generator to capture missing semantic contexts and adapt to incomplete inputs. This objective function minimizes the divergence between the derived distribution G(z; θ) and the true target distribution P*(x). By doing so, the model aligns generated features with the original data manifold, enabling the model to better handle distributional variations and address difficulties under sparse and incomplete inputs. Moreover, this masking-driven mechanism explicitly transitions from a partially masked random distribution to a learnable target distribution through the Generator structure.

In this stage, classes are then classified through iterative training using the mean square error loss function. During the convolution operations, matrices within the set A actively participate in training through randomly initialized distributions. During the convolution stage, the model integrates masked embeddings with generator outputs and original matrices to enrich representation learning:

4.3 Dynamic Learning with Masking Techniques

The MJRM incorporates a multi-learning procedure combining topic and emotion clustering on the original dataset. This research examines the applicability of topic modeling across various domains and confirms that LDA-based topic modeling has been widely used for information retrieval, social media analysis, and more. When the raw data is fed into the model, major topics are extracted using the following method [17].

This represents the generative process for topic extraction, forming the basis for the subsequent masking mechanism. This approach helps to understand reactions and conversations in online communities through social media analytics, extracting meaningful patterns and valuable insights from user interactions. For example, in the case of malicious spam documents, supervised learning is employed to maintain semantic consistency across the dataset. The data analysis module k performs basic statistical analyses, while the Sentiment A module carries out emotion clustering in conjunction with the original data, forming unsupervised learning clusters defined as

These clusters capture diverse emotional patterns and characteristics within the data, grouping sentiment-influencing terms into similar classes and vectorizing them accordingly.

This study empirically demonstrates that the interaction between topic modeling and emotion analysis can help mitigate data missingness and sparsity issues, leading to performance improvements in various classification tasks.

The proposed methodology employs a partial masking technique on the analyzed topic, data, and sentiment matrices. During this process, two types of learning selectors are utilized. The first selector, Mj(h, L(w)), dynamically determines the scope and method of masking application, referencing the hyperparameter (h) and weight information L(w) to minimize the impact of outliers in the data distribution.

This selector is integrated into the Learning A stage and the optimization module, supporting the appropriate application of masking. For vectorization, random distributions are generated for both the original and masked Topic A, Sentiment A, and Data A matrices. During training, loss values are calculated, and the final generative model (Generator1) is derived through n iterations. After Learning A and optimization, the mask is strategically combined with selector information and reflected in the training loss and mask embedding positions.

This optimizes representations by employing a mapping

During the optimization phase, the model flexibly utilizes algorithms such as stochastic gradient descent, alternating squares, and mean square error, depending on the task’s requirements and data conditions. When handling high-dimensional but sparse datasets, dimensional decomposition is used to reduce the dimensionality of the input matrix O, improving computational efficiency and reducing the risk of information.

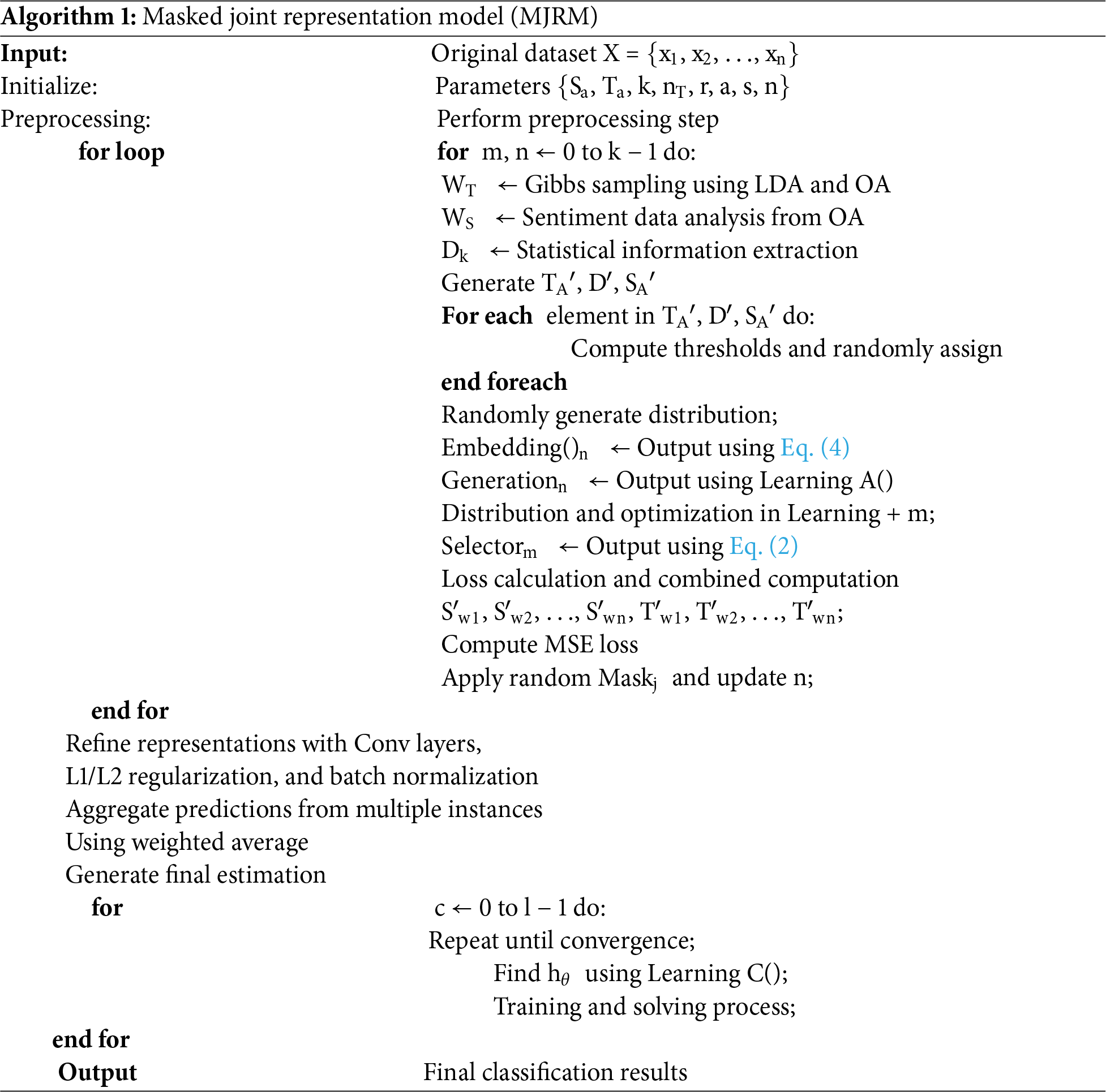

Conversely, when the focus is on deeply understanding the statistical properties of the transformed features, distribution learning is applied to achieve more accurate regression results. The model typically undergoes about 100 iterations, computing and optimizing the class representation. The default learning rate is set at 0.01. During this phase, the representations are learned to remain as close as possible to the original data matrix O, approximating the probability distribution to a normal probability distribution. The transformed features are then used for the final classification task in the Learning C stage. The overall procedure of the proposed MJRM is summarized in Algorithm 1.

This method is designed to increase how clearly the model’s reasoning is explained. Better results are obtained when compared to ML models such as logistic regression and k-nearest neighbors, as will be demonstrated with quantitative metrics in the experimental section. The algorithm covers a comprehensive workflow, from data preprocessing to final output, and consists of the following key phases:

In the initial stage, the algorithm iterates from m, n = 0 to k − 1, using Latent Dirichlet Allocation to generate WT and performing sentiment data analysis from OA to produce WS. Statistical information is then extracted into Dk. Next, thresholds for each element in TA′, D′, and SA′ are calculated and assigned randomly. During the embedding and distribution phases, the algorithm uses the learning function A(), selectors, and various equations to produce and optimize outputs. Finally, mean square error (MSE) is used to calculate the loss, followed by the application of a mask for the random distribution and subsequent updates.

We conducted experiments on three datasets: D1-popcorn, D2-spam, and D3-pubmed article datasets. The D1-popcorn dataset consists of 50,000 IMDB movie reviews with equally distributed positive and negative sentiment classes. It has also been widely explored in previous studies, serving as the basis for baseline experiments, inspiration for model design [18], and comparative analyses with other review datasets [19–22]. This is mainly used for natural language processing and sentiment analysis tasks. The D2-spam dataset is obtained from the UCI Repository and includes approximately 5000 email messages. Spam detection has been extensively studied with a variety of datasets, including those reported in [23–26]. This dataset is often skewed, containing more non-spam emails than spam emails. The D3-pubmed article dataset in database, studied in [19], contains a total of 331 articles, with two classes: ‘linked’ (272 articles) and ‘separated’ (60 articles). The ‘separated’ class represents articles not related to respiratory diseases, serving as a distinction. Articles falling into this class make up approximately 22% of the total dataset.

Before supporting the data into the model, several preprocessing ways were made. For text data, we applied standard text normalization techniques such as lowercasing, removal of special characters, and stemming. Additionally, feature selection and extraction was made using term frequency-inverse document frequency for all datasets.

The models were implemented using Python with TensorFlow and Keras. For classification, we employed algorithms based on established methods for text classification such as a distribution learning for base 1, a decomposition learning for base 2, and emotional nonlinear system for base 3. These algorithms have been shown to be effective in similar tasks, as evidenced by their performance in recent studies. We performed approximately 100 training iterations with a constant learning rate of 0.01. The learning rate was set based on variables Sa, Ta, k, and nT, which represent emotions, topics, threshold values, and the number of topics, respectively.

5.2 Comparison with Existing Work

We performed comparative evaluations against four baseline architectures inspired by prior studies [23–25]. Specifically, T-Base_O1, as proposed in them, adapted the subject model and performed a decomposition-learning task and T-base_O2, which was based on the model proposed in [26], focused on approximating the subject distribution task. Finally, E-base_O3, drawn from [19,27], employed weighted decomposition learning for emotion clustering.

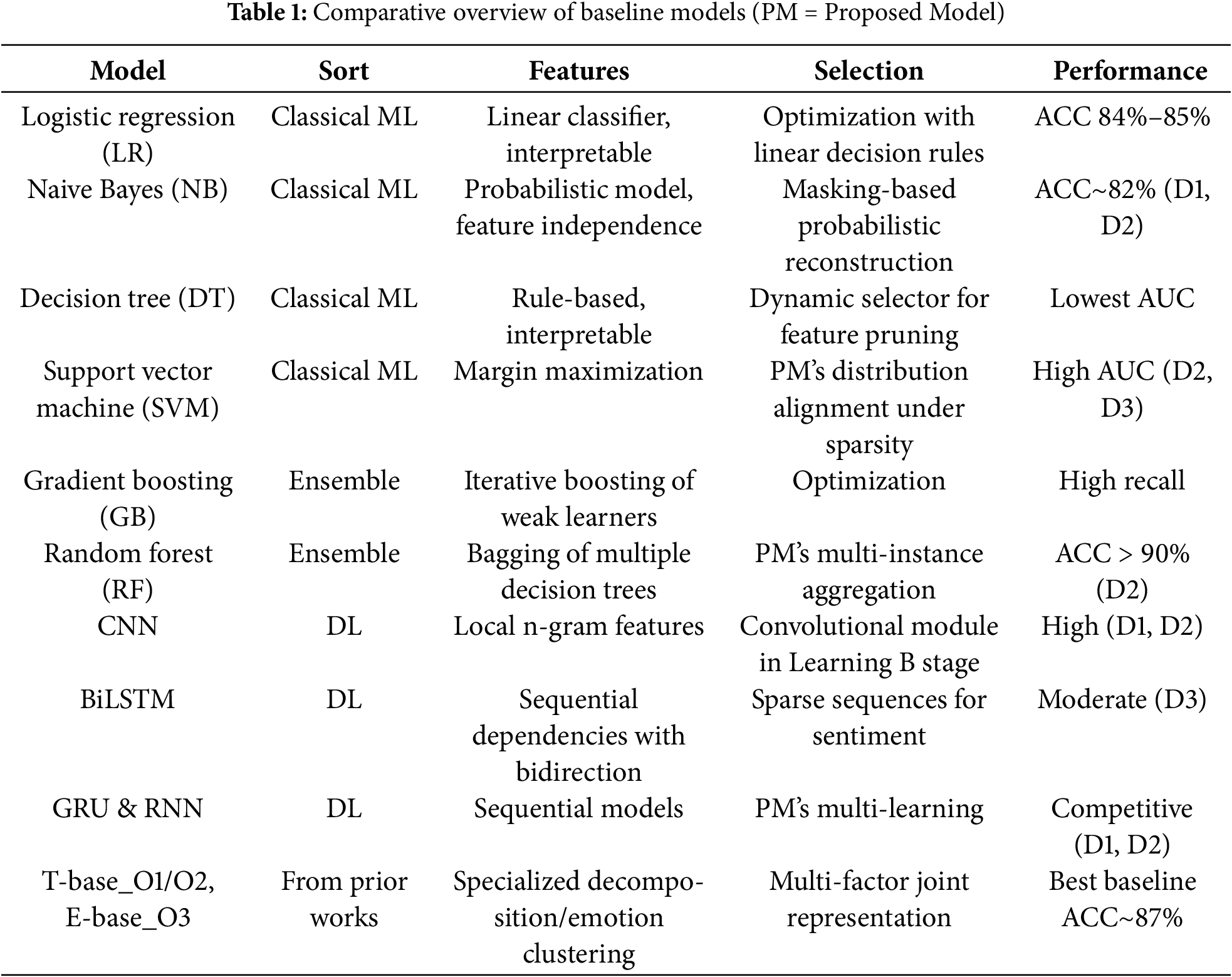

Table 1 summarizes the baseline models, their key features, reasons for selection, and the performance in the experiments. MJRM is explicitly compared with baseline models in both architecture and performance.

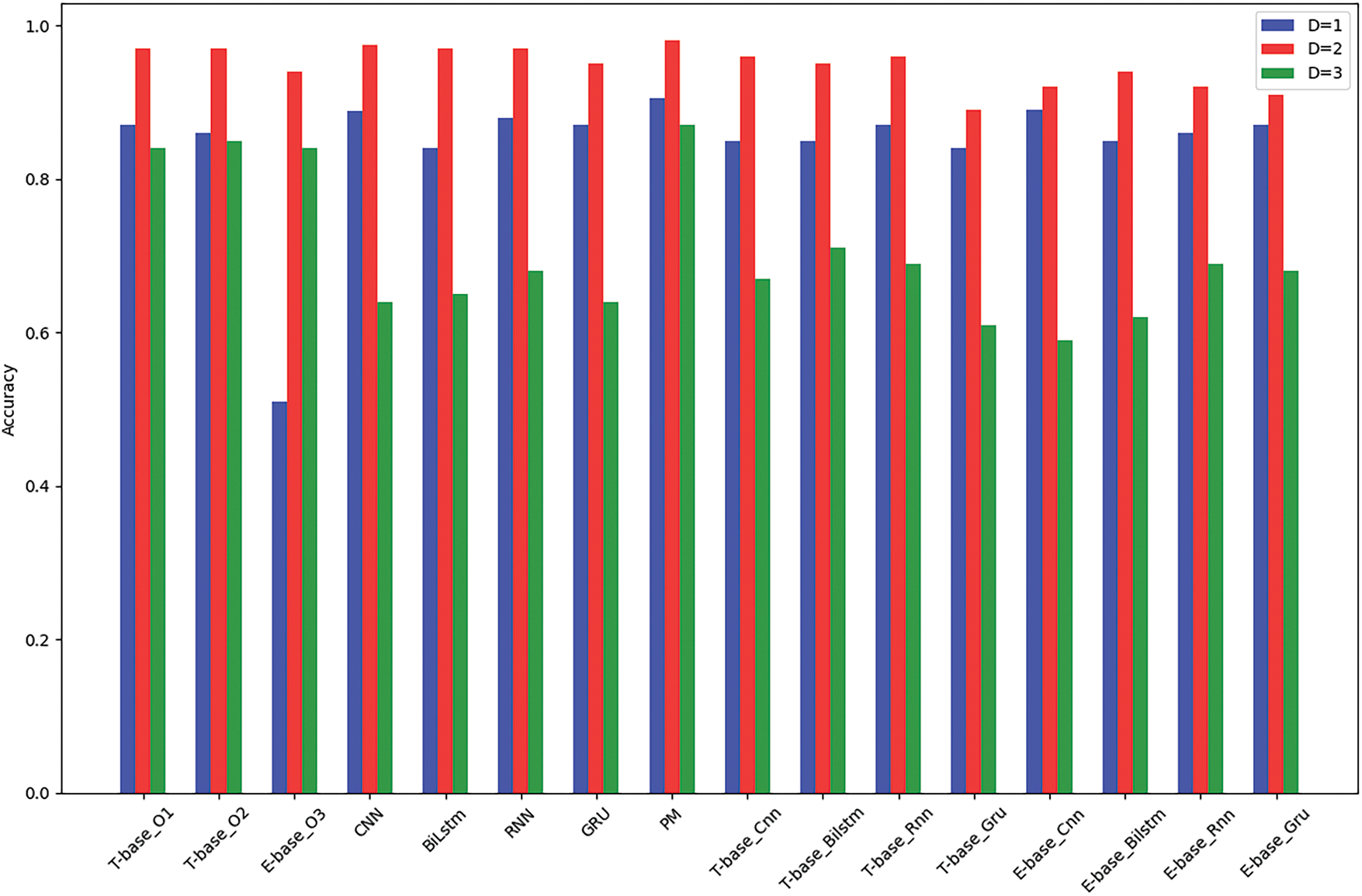

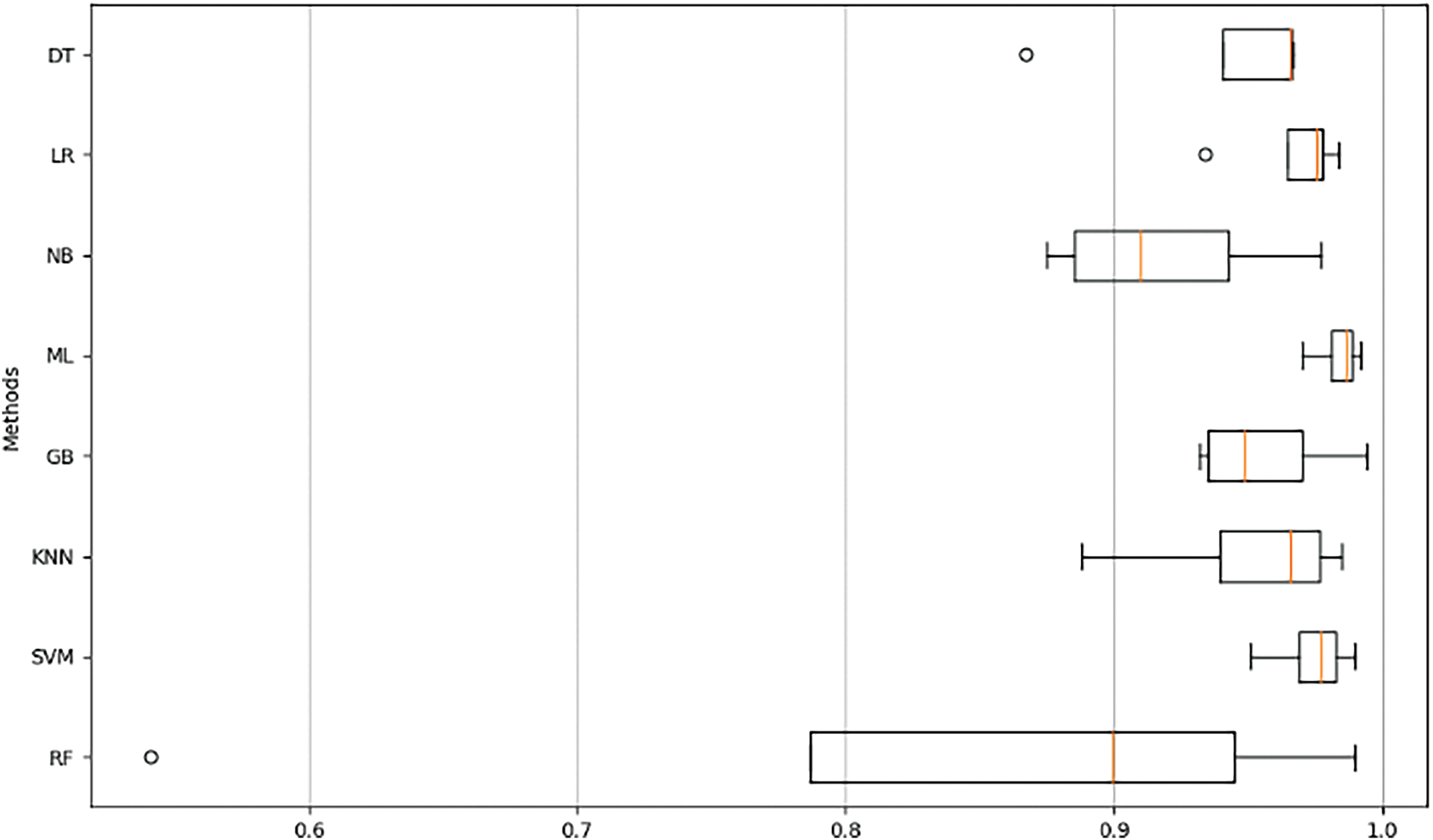

While classical ML models such as LR, NB, and SVM rely on shallow decision rules, and deep learning baselines like CNN and BiLSTM emphasize local and sequential features, MJRM uniquely integrates masking, multi-instance learning, and generator-based representation alignment. This allows MJRM to recover missing semantics under sparsity and achieve higher robustness than the baselines. The effectiveness of the proposed model, when compared with these baselines, is presented in the following Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Comparative accuracy of the proposed model (PM) and established models

Figure 4: Comparison of metrics for different methods, including DT, LR, NB, ML, KNN, GB, SVM, and RF

Our empirical analysis provides a comprehensive performance assessment of various models, including the proposed model, across different datasets (D1, D2, D3). In addition to accuracy and the area under the curve (AUC), we also calculated other metrics which are particularly important for evaluating models on imbalanced datasets. In dataset D1, among the existing models, Base 1 achieved the best measurement with an accuracy of 87.6%, followed by Base 2 with 87.3%. Base 3 lagged significantly, registering only a 50.5% accuracy rate.

Our proposed model, PM, surpassed all baseline models, achieving an average accuracy of 90.4% and an AUC of 0.95. In dataset D2, for this dataset, the accuracy rates were 97.8%, 98%, and 94.4% for Base 1, Base 2, and Base 3, respectively. The proposed PM model demonstrated comparable performance to the best-performing existing models, recording an average accuracy of approximately 98%. The AUC for this model was also the highest at 0.992. In dataset D3, despite the small dataset size, our PM model achieved an accuracy of 87.3%, outperforming existing models. This effectiveness is attributed to our unique approach of optimizing representation and estimators through multi-learning. Previous models were ranked in the order of Base 2, Base 3, and Base 1, with improvements achieved through error function learning and multi-analysis.

In Fig. 4, using meticulously collected data, we comprehensively analyzed various machine learning models and evaluated their performance based on AUC, precision, recall, F1 score, and the complex relationships between each model and these performance metrics. In the AUC domain, the SVM model shows the highest AUC value, followed by the ML model. SVMs may have higher AUC values than other models due to higher linear and non-linear separability in some datasets. Additionally, SVM classifies data by maximizing margins. The DT model has the lowest AUC value. In terms of precision, the ML model achieved the best precision, followed by the SVM model.

In terms of recall, the GB model achieved the highest recall, and then the ML model. The KNN model has the lowest recall. In terms of F1 score, the ML model has the highest F1 score, with the SVM model coming next. The DT model has the lowest F1 score. The F1 score is useful, especially when the percentage of positive classes (spam) is low, such as spam detection. In conclusion, ML models are useful.

5.3 Dynamic Parameter Analysis

Fig. 3 presents accuracy trends under different dynamic parameters, including decomposition order, and topic parameters. The model’s accuracy increased until it plateaued at approximately 98.2%, beyond which no further improvement was observed. Overall performance indicates the PM consistently performs well across all datasets, achieving the highest accuracy in D = 2 and D = 3, and competitive results in D = 1. Regarding baseline models (B = 1, B = 2, B = 3), B = 1 and B = 2 perform well in D = 1 and D = 2 but fall short in D = 3. B = 3 shows significantly lower performance across all datasets, especially in D = 1. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) performs exceptionally well in D = 1 and D = 2 but struggles in D = 3. Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory (BiLSTM) shows moderate performance across all datasets, with its weakest performance in D = 3. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) performs well in D = 1 and D = 2 but has room for improvement in D = 3. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) shows similar patterns, with competitive performance in D = 1 and D = 2 but lesser performance in D = 3.

The proposed model is robust across different types of datasets, indicating its generalizability. For model selection, if the task primarily focuses on D = 3, the proposed model is recommended. For D = 1 and D = 2, both PM and CNN could be considered depending on the specific requirements. The noticeable decline in performance observed for certain models when applied to dataset D3 implies that this particular dataset may present unique challenges, which appear to be effectively mitigated by the proposed model.

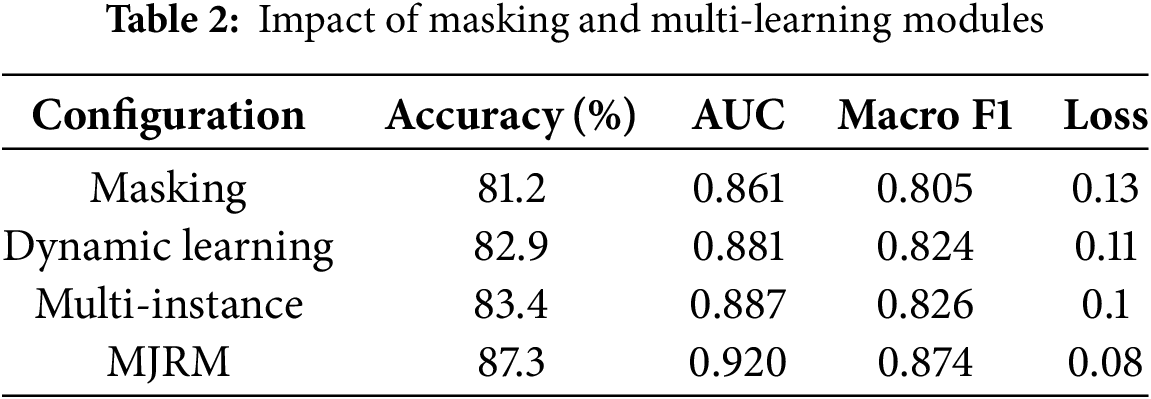

As shown in Table 2, removing any single component leads to a noticeable drop in performance. Without masking, the model’s ability to generalize degrades significantly, as evidenced by the lowest accuracy 81.2% and highest loss 0.13. Disabling dynamic learning slightly improves performance compared to masking alone but remains suboptimal. The multi-instance component contributes to robust ensemble effects; removing it reduces performance moderately. In contrast, the full MJRM configuration consistently achieves the highest scores across all metrics, confirming the complementary contributions of each module. The final ablation scores are adjusted using a weighted average, prioritizing the PubMed dataset to better reflect real-world performance in sparse and domain-specific contexts such as medical text analysis. This mitigates the bias that would otherwise arise from the larger and more balanced spam dataset.

On the D = 2 dataset, most models achieve an accuracy of 0.95 or better. The models of T-base_O1 and T-base_O2 show high accuracy at D = 1 and D = 2, but the accuracy decreases at D = 3. The E-base_O3 model shows low accuracy at D = 1, but increases at D = 2 and D = 3. CNN, BiLstm, RNN, and GRU generally show stable performance and record high accuracy at D = 2. MJRM maintains high accuracy on all datasets (D = 1, D = 2, D = 3). T-base_Cnn, T-base_Bilstm, T-base_Rnn, T-base_Gru: T-base models generally show stable performance and record relatively high accuracy at D = 2. The models of E-base_Cnn, E-base_Bilstm, E-base_Rnn, E-base_Gru show high accuracy at D = 1, but decrease at D = 2 and D = 3. Overall, the performance of the models exceeds the inherent challenges of the dataset. Depending on (D), certain models perform better on specific datasets.

MJRM shows stable performance in the most dynamic environments. The high accuracy and AUC achieved by our model, particularly in datasets D1 and D2, demonstrate its robustness in text classification tasks. The use of additional metrics like precision and recall corroborate its effectiveness. The proposed model effectively transforms data and outperforms the baseline approach due to its multi-masking strategy.

This model has potential applications in diverse scenarios, such as automated sentiment analysis of customer reviews, spam detection in email filters, and electronic text classification in the medical field.

Depending on the characteristics of the dataset, D1 is large and balanced, allowing distribution-and decomposition-based baselines (Bases 1 and 2) to effectively detect general sentiment patterns. D3 is small and domain-specific, resulting in sparse and imbalanced data. Despite this, MJRM demonstrates a clear advantage by recovering missing meaning through masking and generative learning and adapting to limited samples. For D2, which has highly biased features, MJRM achieves similar accuracy to the best baseline and is more robust in AUC and F1.

In this study, we introduced a novel framework, the MJRM, which effectively integrates dynamically multiple learning paradigms. Initially, we highlighted the model’s unique approach to text representation by incorporating emotion and topic distributions. Following this, we discussed how this multi-learning strategy addresses challenges related to data scarcity, offering a systematic mechanism for classifying and embedding sparse textual information. This advantage manifests through the dynamic tuning of multiple parameters, enhancing the model’s efficacy. Importantly, our empirical evaluation confirmed the model’s robust performance across both large and small datasets. As a result, the MJRM model outperformed traditional models by an approximate margin of 4% in classification tasks. Looking forward, the multi-task capabilities of MJRM promise broad applicability in various computational challenges, a prospect we aim to explore in future research. Overall, our work signifies a step forward in the field of text data representation and classification.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the SungKyunKwan University and the BK21 FOUR (Graduate School Innovation) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE, Korea) and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Funding Statement: The authors received no external funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, formal analysis, and manuscript preparation: Woo Hyun Park; conceptualization and supervision: Dong Ryeol Shin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sharma R, Sungheetha A. An efficient dimension reduction based fusion of CNN and SVM model for detection of abnormal incident in video surveillance. J Soft Comput Paradig. 2021;3(2):55–69. doi:10.36548/jscp.2021.2.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pham P, Nguyen LT, Pedrycz W, Vo B. Deep learning, graph-based text representation and classification: a survey, perspectives and challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(6):4893–927. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10265-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li Q, Peng H, Li J, Xia C, Yang R, Sun L, et al. A survey on text classification: from traditional to deep learning. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2022;13(2):1–41. doi:10.1145/3495162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jiang Z, Zheng Y, Tan H, Tang B, Zhou H. Variational deep embedding: an unsupervised and generative approach to clustering. arXiv:1611.05148. 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. Duarte JM, Berton L. A review of semi-supervised learning for text classification. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(9):9401–69. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10393-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gao C, Zheng Y, Li N, Li Y, Qin Y, Piao J, et al. A survey of graph neural networks for recommender systems: challenges, methods, and directions. ACM Trans Recomm Syst. 2023;1(1):1–51. doi:10.1145/3568022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Rakotoson L, Letaillieur C, Massip S, Laleye F. BagBERT: BERT-based bagging-stacking for multi-topic classification. arXiv:2111.05808. 2021. [Google Scholar]

8. Deniz A, Angin M, Angin P. Evolutionary multiobjective feature selection for sentiment analysis. IEEE Access. 2021;9:142982–96. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3118961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Edalati M, Imran AS, Kastrati Z, Daudpota SM. The potential of machine learning algorithms for sentiment classification of students’ feedback on MOOC. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys); 2021 Sep 2–3; Virtual. p. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

10. Halvani O, Graner L. Posnoise: an effective countermeasure against topic biases in authorship analysis. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security; 2021 Aug 17–20; Vienna, Austria. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

11. Papaloukas C, Chalkidis I, Athinaios K, Pantazi DA, Koubarakis M. Multi-granular legal topic classification on Greek legislation. arXiv:2109.15298. 2021. [Google Scholar]

12. Feng T, Qu L, Li Z, Zhan H, Hua Y, Haffari G. IMO: greedy layer-wise sparse representation learning for out-of-distribution text classification with pre-trained models. arXiv:2404.13504. 2024. [Google Scholar]

13. Jiang X, Ren B, Wu Q, Wang W, Li H. DCASAM: advancing aspect-based sentiment analysis through a deep context-aware sentiment analysis model. Complex Intell Syst. 2024;10(6):7907–26. doi:10.1007/s40747-024-01570-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mvula PK, Branco P, Jourdan GV, Viktor HL. A survey on the applications of semi-supervised learning to cyber-security. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(10):1–41. doi:10.1145/3657647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Labonne M, Moran S. SPAM-T5: benchmarking large language models for few-shot email spam detection. arXiv:2304.01238. 2023. [Google Scholar]

16. Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2014;27(11):1–9. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jelodar H, Wang Y, Yuan C, Feng X, Jiang X, Li Y, et al. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: models, applications, a survey. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(11):15169–211. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6894-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sadeghian A, Sharafat AR. Bag of words meets bags of popcorn. CS224N Proj. 2015;4–9. [Google Scholar]

19. Park WH, Siddiqui IF, Shin DR, Qureshi NMF. NLP-based subject with emotions joint analytics for epidemic articles. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;73(2):2985–3001. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.028241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dahir UM, Alkindy FK. Utilizing machine learning for sentiment analysis of IMDB movie review data. Int J Eng Trends Technol. 2023;71(5):18–26. [Google Scholar]

21. Domadula PSSV, Sayyaparaju SS. Sentiment analysis of IMDB movie reviews: a comparative study of lexicon based approach and BERT neural network model [master’s thesis]. Karlskrona, Sweden: Blekinge Institute of Technology; 2023. [Google Scholar]

22. Yang G, Xu Y, Tu L. An intelligent box office predictor based on aspect-level sentiment analysis of movie review. Wirel Netw. 2023;29(7):3039–49. doi:10.1007/s11276-023-03378-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gomez Hidalgo JM, Almeida TA, Yamakami A, Wani MA, Khoshgoftaar T, Zhu X, et al. On the validity of a new SMS spam collection. In: Proceedings of the 2012 11th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA 2012); 2012 Dec 12–15; Boca Raton, FL, USA. 6 p. [Google Scholar]

24. Sousa G, Pedronette DCG, Papa JP, Guilherme IR. SMS spam detection through skip-gram embeddings and shallow networks. In: Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; 2021 Aug 1–6; Online. p. 4193–201. [Google Scholar]

25. Nandhini S, KS JM. Performance evaluation of machine learning algorithms for email spam detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Information Technology and Engineering (IC-ETITE); 2020 Feb 24–25; Vellore, India. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

26. Park W, Faseeh Qureshi NM, Shin DR. Pseudo NLP joint spam classification technique for big data cluster. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;71(1):517–35. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.021421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Park WH, Shin DR, Qureshi NMF. Effective emotion recognition technique in NLP task over nonlinear big data cluster. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2021;2021(1):5840759. doi:10.1155/2021/5840759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools