Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Retraining Approach for Category-Specific 3D Reconstruction Models from a Single 2D Image

1 LAMIS Laboratory, University of Larbi Tebessi, Tebessa, 12002, Algeria

2 College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Medina, 41477, Saudi Arabia

3 Energy, Industry, and Advanced Technologies Research Center, Taibah University, Madinah, 41477, Saudi Arabia

4 Lire Laboratory, University of Constantine 2 Abdelhamid Mehri, Constantine, 25000, Algeria

5 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Computers and Artificial Intelligence, Cairo University, Giza, 12613, Egypt

6 Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, 23890, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Akram Bennour. Email: ; Mohammed Al-Sarem. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 41 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070337

Received 14 July 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The generation of high-quality 3D models from single 2D images remains challenging in terms of accuracy and completeness. Deep learning has emerged as a promising solution, offering new avenues for improvements. However, building models from scratch is computationally expensive and requires large datasets. This paper presents a transfer-learning-based approach for category-specific 3D reconstruction from a single 2D image. The core idea is to fine-tune a pre-trained model on specific object categories using new, unseen data, resulting in specialized versions of the model that are better adapted to reconstruct particular objects. The proposed approach utilizes a three-phase pipeline comprising image acquisition, 3D reconstruction, and refinement. After ensuring the quality of the input image, a ResNet50 model is used for object recognition, directing the image to the corresponding category-specific model to generate a voxel-based representation. The voxel-based 3D model is then refined by transforming it into a detailed triangular mesh representation using the Marching Cubes algorithm and Laplacian smoothing. An experimental study, using the Pix2Vox model and the Pascal3D dataset, has been conducted to evaluate and validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Results demonstrate that category-specific fine-tuning of Pix2Vox significantly outperforms both the original model and the general model fine-tuned for all object categories, with substantial gains in Intersection over Union (IoU) scores. Visual assessments confirm improvements in geometric detail and surface realism. These findings indicate that combining transfer learning with category-specific fine tuning and refinement strategy of our approach leads to better-quality 3D model generation.Keywords

3D reconstruction is a key area in computer vision, focused on generating accurate 3D models from one or multiple 2D images. By extracting depth and spatial information, this process enables the representation of objects and environments in three dimensions, supporting applications across various domains.

In medical imaging, accurate 3D models of internal organs and structures are essential for precise diagnosis and surgical planning. These models enable healthcare professionals to visualize complex anatomical structures, identify abnormalities, and simulate surgical procedures [1,2]. In robotics, 3D reconstruction plays a pivotal role in enabling robots to perceive and interact with the physical world. By generating accurate 3D models of environments and objects; robots can perform tasks such as autonomous navigation, object manipulation, and human-robot interaction [3]. In virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) applications, 3D reconstruction is used to create immersive digital environments for gaming, training simulations, and educational experiences [4,5]. In the field of 3D printing, the accuracy of 3D models is crucial for translating digital designs into physical objects. By precisely capturing the geometry and topology of objects, 3D printing technology enables the creation of complex and customized products [6,7].

However, the generation of high-quality 3D reconstruction from 2D images poses several challenges. One of the primary concerns is achieving a high rate of accuracy in the reconstructed models; especially in fields like medical imaging and robotics where the 3D models must closely align with the real-world objects they represent. Additionally, completeness is vital to capture all relevant details and ensure the fidelity of the reconstructed models, particularly in applications like 3D printing and VR, where even minor discrepancies can have substantial implications. Furthermore, real-time 3D model generation is crucial for applications such as AR and gaming where responsiveness and interactivity are essential for enhancing user interaction.

In response to these challenges, researchers have explored various approaches. One significant approach involves refining the existing traditional 3D reconstruction techniques founded on the principles of multi-view geometry (MVG) [8,9], through advanced mathematical techniques and optimization methods. Traditional methods encompass approaches such as Structure from Motion (SfM) [10–12], Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) [13,14], Shape from Shading (SfS) [15], Shape from Polarization (SfP) [16–18], and Multi-View Stereo (MVS) [19,20]. SfM reconstructs 3D structures by estimating camera poses and matching features across multiple images, while SLAM integrates mapping and localization for real-time applications. SfS infers object shapes from shading variations, assuming ideal lighting and surface conditions, and SfP derives surface normals by analyzing polarized light reflection angles, extending its application from dielectric to metallic objects. MVS, in turn, reconstructs detailed 3D models by leveraging image correspondences from various viewpoints. Additionally, gathering more data from multiple sources, such as cameras and sensors, has shown potential for enhancing the accuracy and completeness of 3D models.

While effective, traditional methods face several drawbacks: They rely heavily on precise camera calibration and complex feature mapping, which restricts their flexibility and makes the reconstruction process sensitive to errors caused by changes in camera settings and environmental conditions. Additionally, these methods struggle with reconstructing occluded or self-occluded regions of objects, often requiring multiple viewpoints and longer processing times to achieve satisfactory results.

Deep learning (DL) techniques have emerged as a promising alternative for 3D reconstruction. Convolutional neural networks (CNN) can automatically extract high-level features from images, enabling the generation of more accurate and robust 3D models. Yet, developing a DL model from scratch requires significant time and computational resources. Transfer learning offers an efficient solution by utilizing pre-trained models, which can be fine-tuned on specific datasets. This approach enhances model performance and adapts it to task-specific requirements, optimizing both resource utilization and development time.

However, a major limitation remains: general-purpose models trained on diverse object categories often struggle to capture the fine-grained geometry of specific classes, resulting in blurred or incomplete reconstructions. Recent research has shown that incorporating category-specific knowledge can alleviate this issue by guiding the model toward the structural and textural regularities of each class. For instance, Refs. [21,22] demonstrated that learning class-specific pipelines achieve higher accuracy and consistency in 3D reconstruction, highlighting the importance of specialization. These findings motivate the development of approaches that combine the efficiency of general-purpose models with the precision of category-specific adaptation.

Based on this motivation, our study is guided by the following research questions:

1. Is transfer learning an effective strategy for adapting general models to specific object classes?

2. Can category-specific retraining improve the accuracy of 3D reconstruction from a single 2D image?

3. Does the combination of transfer learning and category-specific retraining yields better geometric fidelity and surface realism compared to general models?

In this paper, we present a transfer learning-based approach for 3D reconstruction from a single 2D image. The core of our approach involves fine-tuning a pre-trained 3D reconstruction model using a new, unseen dataset. The innovation lies in specializing the general model to a specific class of objects by retraining and fine-tuning it with data exclusively related to that class. The goal of this idea is to enhance the accuracy and quality of the resulting 3D models by creating specialized versions of the original model for each class of objects.

In addition to the reconstruction operation, our approach incorporates two critical phases: image acquisition and 3D model refinement. The image acquisition phase ensures high-quality input images, which serve as a foundation for generating precise 3D models. The refinement phase applies optimization techniques to improve the geometric and visual quality of the reconstructed 3D models. Together, these three phases form a pipeline that takes an image as input and produces a good quality 3D model.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related works in the field of 3D reconstruction. Section 3 introduces our proposed deep retraining approach. Section 4 details the evaluation and validation process. Section 5 discusses the experimental results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper, summarizing the main findings, implications, and future research directions.

The evolution of 3D modeling has been significantly influenced by technological advancements, transitioning from traditional techniques to sophisticated DL-based approaches. To overcome the limitations of traditional methods, DL techniques have emerged as a powerful alternative, offering precise and efficient 3D reconstructions. These methods have demonstrated remarkable capabilities across computer vision tasks including classification [23], segmentation [24–26], detection and localization [27], recognition [28] and scene understanding [29]. Early DL approaches focused on single-view depth prediction using CNN [30]. Subsequent advancements led to the development of more sophisticated multi-view reconstruction models, such as 3D Recurrent Reconstruction Neural Network (3D-R2N2). The integration of generative adversarial networks (GAN) [31] and variational autoencoders (VAEs) [32], exemplified by (3D-VAE-GAN) [33], further expanded the capabilities of DL-based 3D reconstruction.

DL has further expanded its influence to encompass diverse 3D representations, including: voxels, point clouds, and meshes.

Voxel-based methods represent 3D shapes as structured grids of volumetric pixels (voxels), enabling the use of 3D convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for geometric understanding and reconstruction. One foundational work in this area is 3D-R2N2, which introduced a recurrent neural network that learns to predict voxel grids from single or multiple images, allowing progressive refinement of 3D reconstructions. In [34], Authors extended this idea by incorporating 2.5D sketches—such as depth and normal maps—as intermediate representations to improve reconstruction accuracy from single images. Further developments include SLICENet [35], which reconstructs 3D shapes slice-by-slice, enabling more detailed volumetric outputs with reduced memory usage. Im2Avatar [36] focused on enhancing the color and texture quality of voxel-based reconstructions, generating visually rich 3D models from single RGB inputs. Additionally, 3D ShapeNets laid the groundwork for learning deep generative models over voxel grids, using probabilistic 3D shape representations for recognition and reconstruction tasks. These works highlight the strengths of voxel-based frameworks in providing regular, grid-like structures for leveraging 3D CNNs, although often at the cost of memory efficiency and resolution.

Despite their simplicity and capability to encode 3D shape and viewpoint information, voxel representation may not be efficient because it represents both occupied and non-occupied parts of the scene, leading to high memory consumption and limiting their use in high-resolution reconstruction. To alleviate this, the Octree Generating Networks (OGN) [37] leverage octree structure to efficiently represent high-resolution 3D volumes within memory constraints. Octrees are particularly effective in representing fine-grained details of 3D objects with fewer computations, as they can share the same value for large regions of space. However, both voxels and octree representations fail to maintain the intrinsic properties and surface smoothness of 3D objects.

To overcome the limitations of voxel-based representations, many works have explored point cloud-based 3D reconstruction. In [38], Authors initiated this direction by proposing a DL framework that directly predicts point clouds from single RGB images using a Chamfer distance loss. Building upon this, Authors in [39] introduced the PointNet, an architecture that processes point sets through symmetric functions, enabling effective 3D classification and segmentation. Subsequent works extended these ideas: Guo and Li [40] designed an encoder-decoder model for reconstructing 3D shapes from 2D images [6], Authors proposed a fusion-based approach integrating virtual and real-world data using machine learning techniques. Collectively, these approaches demonstrate the growing effectiveness and versatility of point cloud-based representations in 3D vision tasks.

While Point cloud methods excel at capturing local geometric features, they can be affected by point density variations and may not fully capture the overall structure leading to ambiguity in surface representation. Consequently, researchers began exploring alternative methods of 3D representation, such as using mesh structures. These approaches focus on directly predicting 3D vertex coordinates to construct detailed surface meshes. For instance, Pixel2Mesh [41] generates 3D mesh models from a single RGB image by progressively deforming a template mesh using graph-based convolutions. Similarly, Mesh R-CNN [42] extends Mask R-CNN by incorporating a mesh prediction branch that reconstructs object meshes from multi-view or single-view images within a unified detection framework.

However, the task of learning 3D meshes is highly challenging for two key reasons. First, seamless extension of deep learning methods to irregular representations remains elusive, which poses a major obstacle to achieving accurate reconstructions. Additionally, the complexity of 3D data presents a multitude of challenges, including noise, missing data, and accuracy issues. This is why many studies have focused on 3D shape completion and inpainting techniques. In [43], Authors proposed a high-resolution shape completion method that uses DNN to infer both global structures and fine-grained local geometry, effectively reconstructing detailed 3D meshes from partial inputs. In a complementary direction, Authors in [44] introduced a framework combining 3D generative adversarial networks (GANs) with recurrent convolutional networks to perform shape inpainting. Their model learns to fill in missing regions of 3D shapes, enhancing both the realism and structural coherence of the output. These works have significantly advanced the field by enabling more accurate and complete 3D reconstructions from partial data.

Despite this significant progress, a central challenge remains: balancing generalization and specialization. General-purpose models trained on diverse object categories with a single architecture often fail to capture delicate, category-specific details. In contrast, specialized models trained for individual categories consistently demonstrate superior reconstruction accuracy, by focusing on the unique geometric and structural properties of each object type. Recent studies confirm this trend: Authors in [21] proposed a Category-Specific Mesh Reconstruction framework that learns deformable 3D mesh models from single images, enabling accurate shape and texture recovery by capturing object-category priors without requiring ground-truth 3D data. Extending this idea, Ref. [45] introduces a bird-specific reconstruction pipeline that leverages bird-specific datasets and multi-view optimization to reconstruct intricate avian geometries, demonstrating the effectiveness of specialization in handling complex biological shapes. These findings establish that specialization offers a clear advantage over generalization when the goal is to capture delicate, category-unique details. However, their main drawback lies in computational cost, requiring complex model design and full training from scratch.

This trade-off has motivated the integration of transfer learning to enhance the model performance and reduce training time. By leveraging knowledge from pre-trained models trained on large-scale datasets, TL enables the adaptation of deep learning techniques to tasks with limited data.

Prior studies have shown its effectiveness on 3D reconstruction tasks by repurposing models originally trained for related vision problems, such as facial mesh recovery and pose estimation. For instance, architectures and models developed for large-pose facial 3D reconstruction have been successfully fine-tuned to generalize across different object categories with minimal supervision, thus accelerating convergence and enhancing reconstruction accuracy [46]. By adapting pre-trained weights through task-specific fine-tuning, researchers can leverage prior knowledge to reduce reliance on large annotated 3D datasets, which are often difficult and costly to acquire.

Our proposed approach builds directly on these insights, by refining pre-trained general-purpose models with category-specific retraining instead of training from scratch. This strategy combines the efficiency and scalability of general-purpose models with the precision of specialization, enabling detailed 3D reconstructions at a lower computational cost.

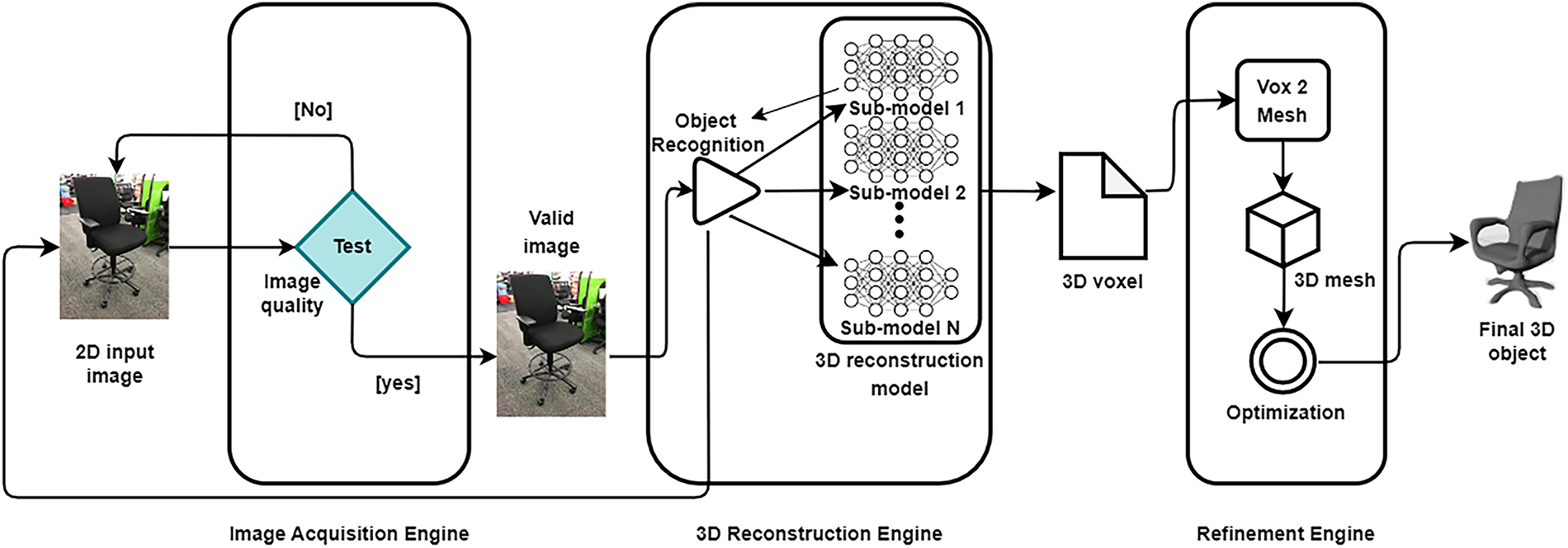

The proposed approach leverages transfer learning, specifically fine-tuning, to enhance 3D reconstruction from a single 2D image. In our previous work [47], we applied transfer learning by fine-tuning an existing 3D reconstruction model (Pix2Vox) [48] on a new dataset, giving promising results. This demonstrated the effectiveness of fine-tuning in improving reconstruction accuracy while reducing the need for extensive training from scratch. Building on these findings, our current approach aims to further refine this strategy by specializing the pre-trained model for specific classes of objects. By fine-tuning the model on category-specific datasets, we generate multiple specialized versions, each optimized for a distinct category of objects, thereby improving reconstruction precision and consistency. Around fine-tuning, we propose a 3D reconstruction pipeline comprising three key phases: (a) Image acquisition, (b) 3D Reconstruction, and (c) Refinement. The image acquisition phase ensures high-quality input image, which is critical for accurate reconstructions. The 3D reconstruction phase utilizes the adequate fine-tuned model to generate an initial 3D model, while the refinement phase further optimizes the reconstructed model to enhance its geometric and visual quality. This structured pipeline, as illustrated in Fig. 1, aims to produce high-fidelity 3D models with improved precision and robustness.

Figure 1: The proposed 3D reconstruction pipeline

The image acquisition phase is critical for ensuring the suitability of the input image for 3D reconstruction, guided by predefined criteria such as image size, blur level, and lighting conditions to ensure optimal outcomes. First, the image size is standardized to 600 pixels in height and width using a Python function with the Python Imaging Library (PIL) [49]. This standardization ensures consistency and facilitates the following processing steps. Additionally, to maintain image clarity and minimize blurriness, a Laplacian operator from the Open-Source Computer Vision library (OpenCV) [50] is applied, quantifying the degree of motion distortion in the input image by computing the Laplacian of the grayscale image. This allows accurate measurement of the image’s blur level. Furthermore, lighting conditions are evaluated by calculating the average pixel intensity. Images with moderate lighting levels are considered optimal for 3D reconstruction. To achieve this, a Python script computes the average pixel intensity, ensuring that each image fulfills the required lighting standards for optimal outcomes.

The image acquisition phase is critical for ensuring the suitability of the input image for 3D reconstruction, guided by predefined criteria such as image size, blur level, and lighting conditions to ensure optimal outcomes. This standardization ensures consistency and facilitates the following processing steps. Additionally, to maintain image clarity and minimize blurriness, a Laplacian operator from the OpenCV is applied, quantifying the degree of motion distortion in the input image by computing the Laplacian of the grayscale image. This allows accurate measurement of the image’s blur level. Furthermore, lighting conditions are evaluated by calculating the average pixel intensity. Images with moderate lighting levels are considered optimal for 3D reconstruction. To achieve this, a Python script computes the average pixel intensity, ensuring that each image fulfills the required lighting standards for optimal outcomes.

The 3D reconstruction phase involves two steps for transforming a validated image into a 3D model: (a) object recognition and (b) 3D object reconstruction. First, the input image undergoes an object recognition to identify the object class. Then, the image is processed by a specialized model, fine-tuned for that specific class of objects, to generate the corresponding 3D model.

The initial step in the reconstruction phase involves identifying the object depicted in the input image. This is accomplished through precise recognition using a pre-trained ResNet50 model, which has been extensively trained on the ImageNet dataset [51]. Once the object class is identified, the image is forwarded to the corresponding 3D reconstruction model.

This step focuses on reconstructing a voxel-based 3D model of the object from the input image using the corresponding class-specific model. Voxel-based representation is used to capture the 3D structure of the object [51]. By dividing the 3D space into a regular grid of voxels, this representation effectively encodes both surface and interior details, allowing for the creation of a more complete representation. Moreover, the regular grid structure of voxels aligns well with the architecture of CNNs, enabling efficient parallel processing across the entire voxel grid, which significantly enhances the model’s computational efficiency and effectiveness.

As explained earlier, the 3D representation of the object from the input image is generated by the corresponding model, fine-tuned specifically for this class of objects. To achieve this, we selected Pix2Vox as the base model for our study and the Pascal3D [52] dataset for fine-tune. Further details on the Pix2Vox model, Pascal3D dataset, and the fine-tuning process are provided in Section 4.

Following the generation of the 3D voxel representation, a refinement phase is applied to enhance the quality of the 3D model. This phase involves converting the voxel-based representation into a triangular mesh using the Marching Cubes algorithm [53], a well-established technique for surface reconstruction.

The Marching Cubes algorithm divides 3D space into small cubes and checks the values at the corners of each cube to determine where the surface of an object passes through. By analyzing the configurations of adjacent cubes using a set of predefined patterns, the algorithm generates a triangular mesh that approximates the 3D object and ensures its smooth and continuous surface.

To further improve the quality of the mesh, the Laplacian Smoothing algorithm [54] is applied. This technique iteratively adjusts the position of each vertex based on the average position of its neighboring vertices, effectively smoothing the surface and reducing noise and artifacts. This result in a more visually appealing and geometrically accurate 3D model.

Despite the potential variability in mesh quality and inconsistent topology [55], using voxels as an intermediate stage ensures accurate conversion into a mesh representation, effectively resolving issues like mesh noise, holes, and irregular vertex connectivity. Consequently, our approach merges the strengths of both voxel and mesh representations, harnessing the effectiveness of CNNs while producing detailed and accurate mesh representations of object surface geometry.

In this section, we present an experimental study conducted to evaluate and validate our proposed approach for 3D reconstruction. We begin with an overview of the selected base model, Pix2Vox, and the Pascal3D dataset used for fine-tuning. Next, we detail the fine-tuning process employed to adapt the model to specific object categories and analyze the results obtained. Finally, we discuss the performance of our approach, highlighting its strengths and advantages.

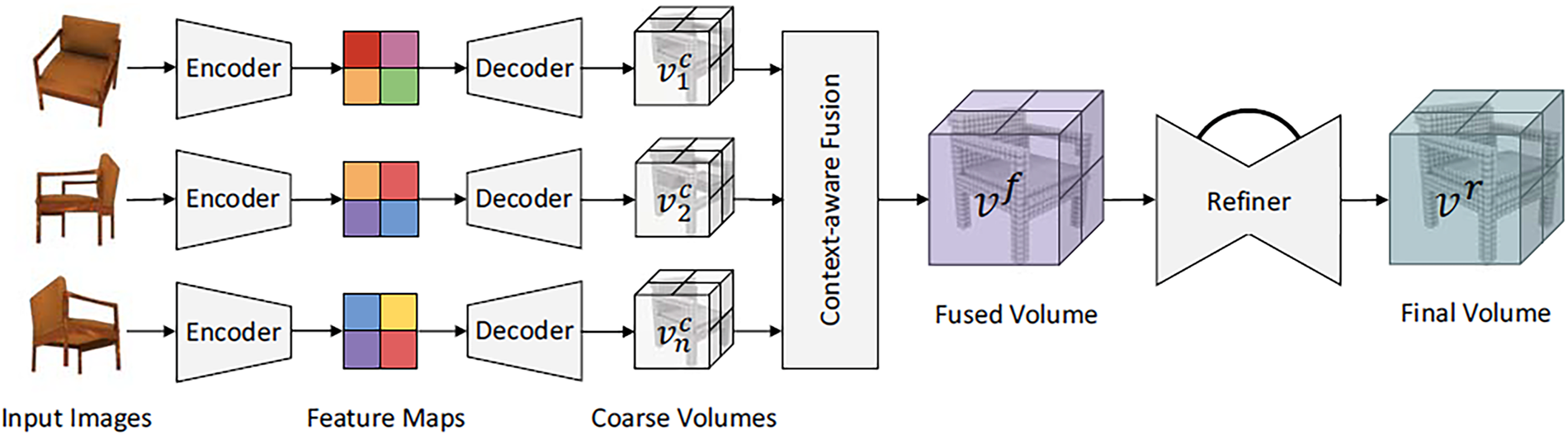

Pix2Vox is a well-established model known for its simplicity and efficiency in generating 3D voxel representations. It offers a robust framework for both single and multi-view 3D reconstruction. As illustrated in Fig. 2, The Pix2Vox architecture consists of four key components: Encoder, Decoder, Context-Aware Fusion, and Refiner.

Figure 2: Pix2Vox architecture [52]

The encoder is based on a pre-trained VGG16 network, utilizing its first nine convolutional layers, trained on ImageNet, to extract essential image features. These features are further refined using three additional 3D convolutional layers, producing a feature tensor that effectively represents the object from the input image. The decoder transforms this feature tensor into a 3D voxel grid through a series of five 3D transposed convolutional layers, progressively reconstructing the object in a coarse 3D form.

To enhance reconstruction quality, the context-aware fusion module integrates multi-view coarse voxel representations. It assigns quality-based score maps to each volume and merges them using a weighted sum, producing a more refined and coherent 3D model.

Finally, the refiner applies 3D convolutional layers to correct errors and enhance details in the reconstructed volume, resulting in a more precise and good-quality final 3D representation.

To fine-tune the selected base model, we selected Pascal3D dataset. This dataset offers a comprehensive and well-structured collection of 3D object models and corresponding 2D images, making it suitable for training and evaluating our 3D reconstruction model. Pascal3D dataset extends the Pascal VOC dataset with detailed 3D annotations for 12 object classes, including airplanes, bicycles, boats, bottles, buses, cars, chairs, tables, motorcycles, sofas, trains and televisions. It features over 3000 objects per class, providing valuable information about 3D shapes, poses and scales.

Pascal3D was selected due to its diverse collection of both synthetic and real images. By fine-tuning and evaluating the model on synthetic images (generated with known ground truth) and real images (captured across various real-world scenarios), we are able to evaluate the effectiveness and the generalization capabilities of our approach.

Our case study focused on five object classes from two categories within Pascal3D: chairs and sofas from the furniture category, and bicycles, motor-bikes, and aero-planes from the vehicle category. The Pascal3D dataset stores 3D models, which is incompatible with our approach requiring “.binvox” format for 3D voxel data. To ensure compatibility with the Pix2Vox model, a preprocessing step was performed to convert the “.off” files into 3D voxel grids. This transformation was carried out using the Binvox voxelization software [56], which rasterizes 3D model files in the “.off “ format into binary 3D voxel grids, producing the necessary “.binvox” files.

To evaluate the performance and accuracy of our approach, we used the IoU metric [57], which is widely adopted for voxel-level evaluation in 3D reconstruction tasks. IoU quantifies the overlap between the predicted voxel model and the ground truth, and is defined as the ratio of the volume of their intersection to the volume of their union. Mathematically, it is expressed according to Eq. (1).

where Vpred and Vgt represent the predicted and ground truth voxel sets, respectively.

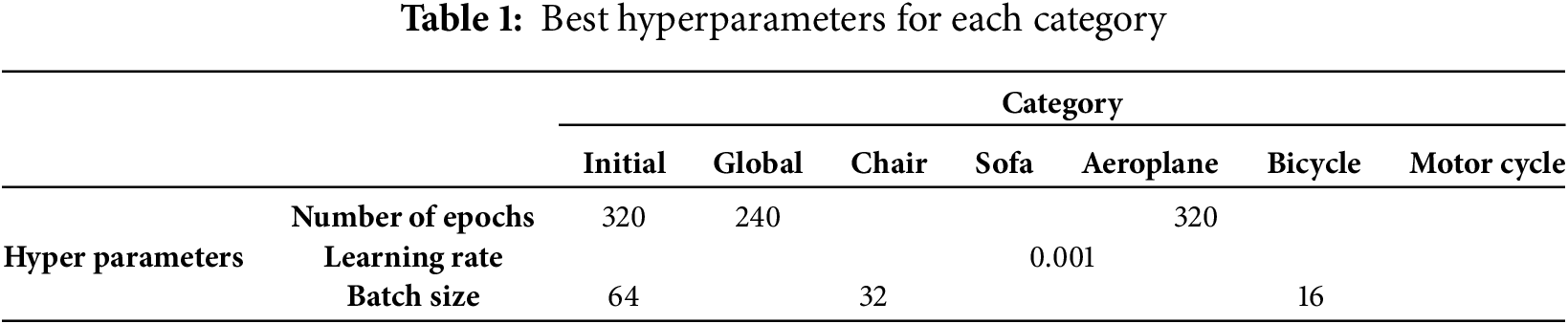

To adapt the Pix2Vox model to a specific object category, we retrained it on subsets of the Pascal3D dataset. For each category, and based on empirical evaluations, we fine-tuned the model using an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 32, training for 240 epochs. By optimizing these hyperparameters, we achieved a balance between convergence, training stability, and computational efficiency. Table 1 summarizes the optimal hyperparameters used during the Pix2Vox fine-tuning process.

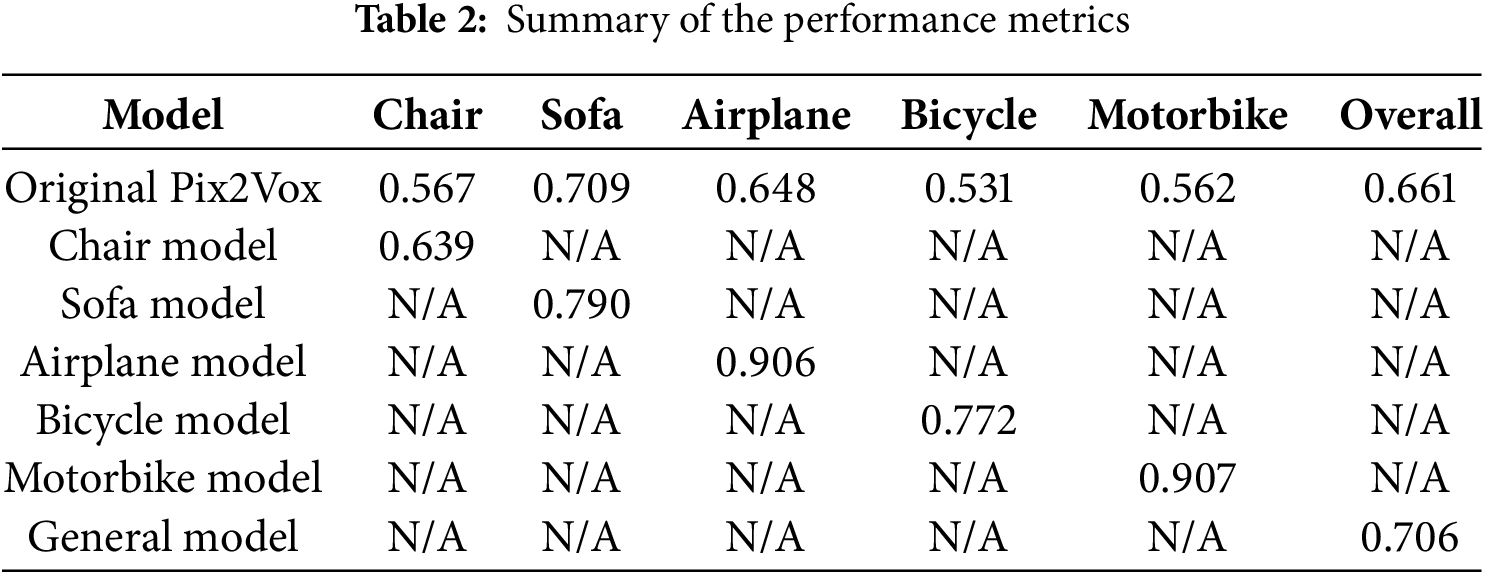

This section presents the results obtained from retraining the Pix2Vox model using the Pascal3D dataset, with the goal of evaluating the effectiveness of our category-specific fine-tuning approach. The evaluation includes both quantitative analyses using the IoU metric and qualitative comparison through visual inspection of the reconstructed 3D models. In the quantitative evaluation, we compare the performance of three model types: the original Pix2Vox model, the Pix2Vox model fine-tuned using the entire Pascal3D dataset, and multiple versions of Pix2Vox model fine-tuned on subsets of Pascal3D dataset corresponding to individual object categories. Importantly, although Pix2Vox was fine-tuned using the entire Pascal3D dataset for the general model and category-specific subsets for the specialized versions, all models, including the original Pix2Vox, were evaluated on the same test data, ensuring a fair comparison and directly highlighting the advantage of specialization over generalization. For the qualitative evaluation, we compare 3D models generated by five configurations: the original Pix2Vox model, the general model, category-specific models before and after refinement, and the Mesh R-CNN model as an external baseline. This comparison highlights the impact of category-specific fine-tuning and the refinement phase in enhancing the quality, accuracy, and visual detail of the reconstructed 3D models.

5.1 IoU Based Evaluation and Models Comparison

Table 1 presents the IoU scores obtained from evaluating the original Pix2Vox model, a general model, and multiple category-specific models of five object categories from the Pascal3D dataset: Chair, Sofa, Airplane, Bicycle, and Motorbike.

The original Pix2Vox model achieved an overall IoU of 0.661, with per-category performances ranging from 0.531 (Bicycle) to 0.709 (Sofa), indicating a solid baseline but with noticeable variation across object types.

The general fine-tuned model, trained on the whole Pascal3D dataset without category specialization, improved the overall IoU to 0.706, representing a moderate performance gain of 0.045 over the original model. This result suggests that fine-tuning on a broader dataset enhances general reconstruction ability, though not uniformly across all object classes. In contrast, the category-specific models demonstrated significantly higher IoU scores in their respective categories:

• The Chair model achieved an improvement of approximately 12.7% over the original model.

• The Sofa model showed an improvement of about 11.4%.

• The Airplane model exhibited a substantial increase of approximately 39.8%.

• The Bicycle model improved by around 45.4%.

• The Motorbike model also achieved an improvement of approximately 61.2%.

These results highlight the effectiveness of category-specific fine-tuning, which consistently outperformed both the original Pix2Vox model and the general fine-tuned model. The improvements were particularly significant in the Airplane and Motorbike categories, each achieving an IoU greater than 0.9, corresponding to a significant increase over the original model.

The variation in performance across category-specific models can be attributed to two main factors: First, the number of training examples available for each object category and the quality of the images in the dataset. Categories with more abundant and higher-quality training data tend to yield better reconstruction results after fine-tuning. Second, the intrinsic complexity of object geometry also affects reconstruction accuracy. For instance, objects with relatively simple and regular shapes, such as airplanes, are easier for the model to learn and reconstruct, which explains the high IoU scores achieved in this category. In contrast, objects with more complex and irregular structures, such as chairs, present greater challenges, leading to lower reconstruction accuracy.

In summary, while general fine-tuning improves overall model performance, specializing the model for individual object categories yields the most significant accuracy gains, validating the core premise of our approach (Table 2).

Beyond IoU scores, category-specific retraining enables the model to learn and preserve distinctive geometric features more effectively, resulting in more precise and reliable reconstructions. For example, in the Airplane category, our approach reconstructed delicate structures like wings and tails with much better precision, whereas the general model frequently produced blurred or misaligned shapes. Similarly, in the Motorbike category, our approach successfully preserved the circular geometry of the wheels and the alignment of the frame, details that were often lost in the baseline model.

Scalability is another advantage of our approach. New categories can be incorporated by fine-tuning the existing base model instead of training a new model from scratch, which substantially reduces both training time and computational resources. This demonstrates both the efficiency and practicality of our approach for real-world applications, where systems often need to handle a wide variety of object categories quickly and with limited computational resources.

Despite the overall improvements, some limitations remain. For example, in the Chair category, the model occasionally generates a chair that differs from the input image in structure or style. This indicates that, although the model captures general geometric features of chairs, it can struggle to reproduce unique or complex designs accurately. One contributing factor is that, in the dataset, some images of different objects are associated with the same ground truth 3D object, which can confuse the model during training.

5.2 Visual Evaluation & Comparison

This section presents a qualitative analysis of 3D reconstruction results obtained through our proposed fine-tuning approach. The analysis includes visual comparisons of reconstructed 3D models generated from single-view images sourced from the ObjectNet3D datasets.

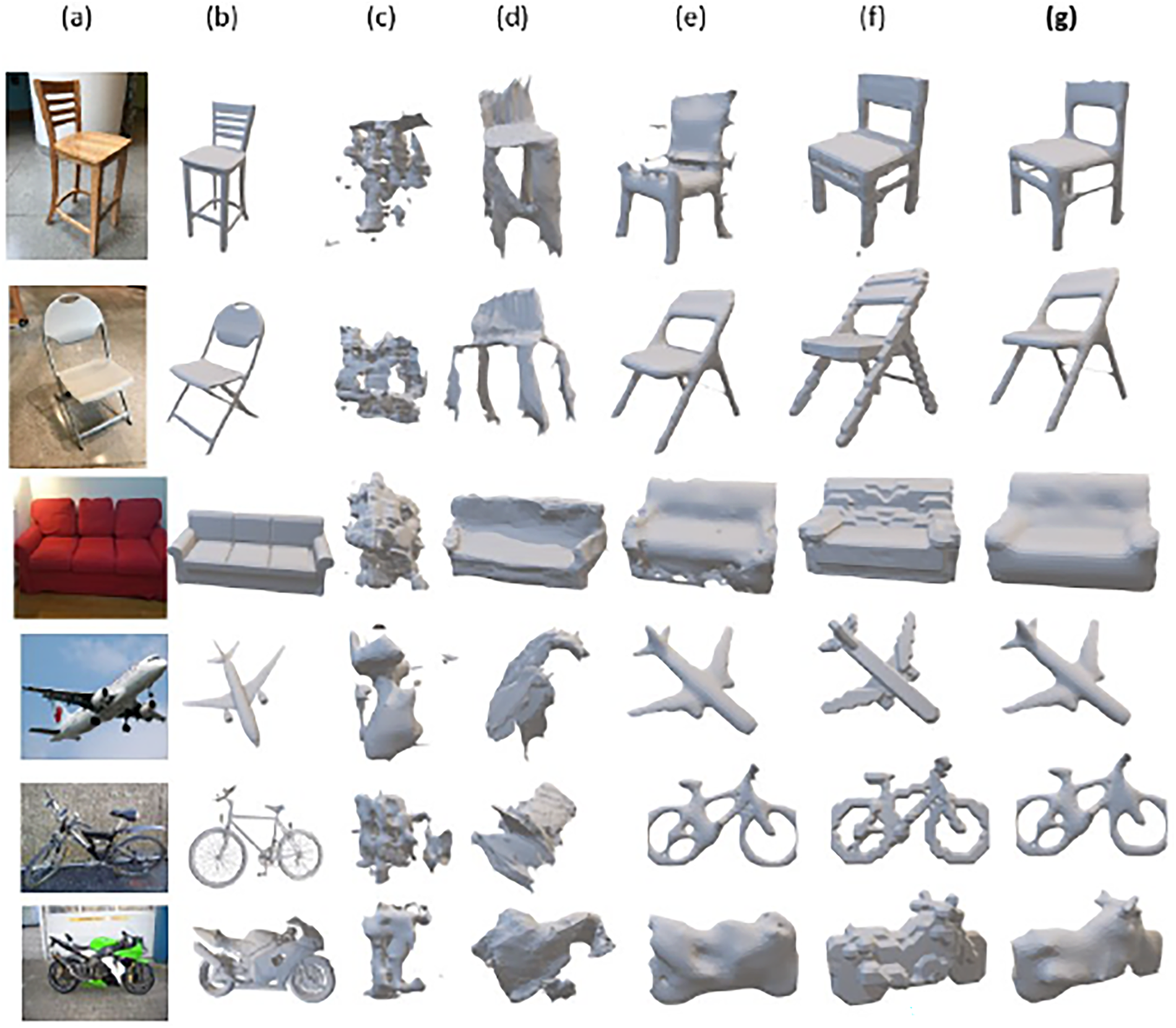

To evaluate our approach, we compared the results of our category-specific models with the 3D models generated by baseline models, specifically using publicly available checkpoints for the original Pix2Vox model and Mesh R-CNN. As shown in Fig. 3, the visual results clearly illustrate the superior performance of our category-specific models, fine-tuned individually for each object category. These specialized models capture geometric features more accurately compared to the baseline models, including Pix2Vox, Mesh R-CNN, and the general model fine-tuned on the entire dataset.

Figure 3: Results of our proposed approach using different images from specific categories. (a) Input image, (b) GT, (c) Initial Pix2Vox model, (d) Mesh R-CNN model, (e) General Model, (f) Proposed Approach before Refinement, (g) Proposed Approach after Refinement

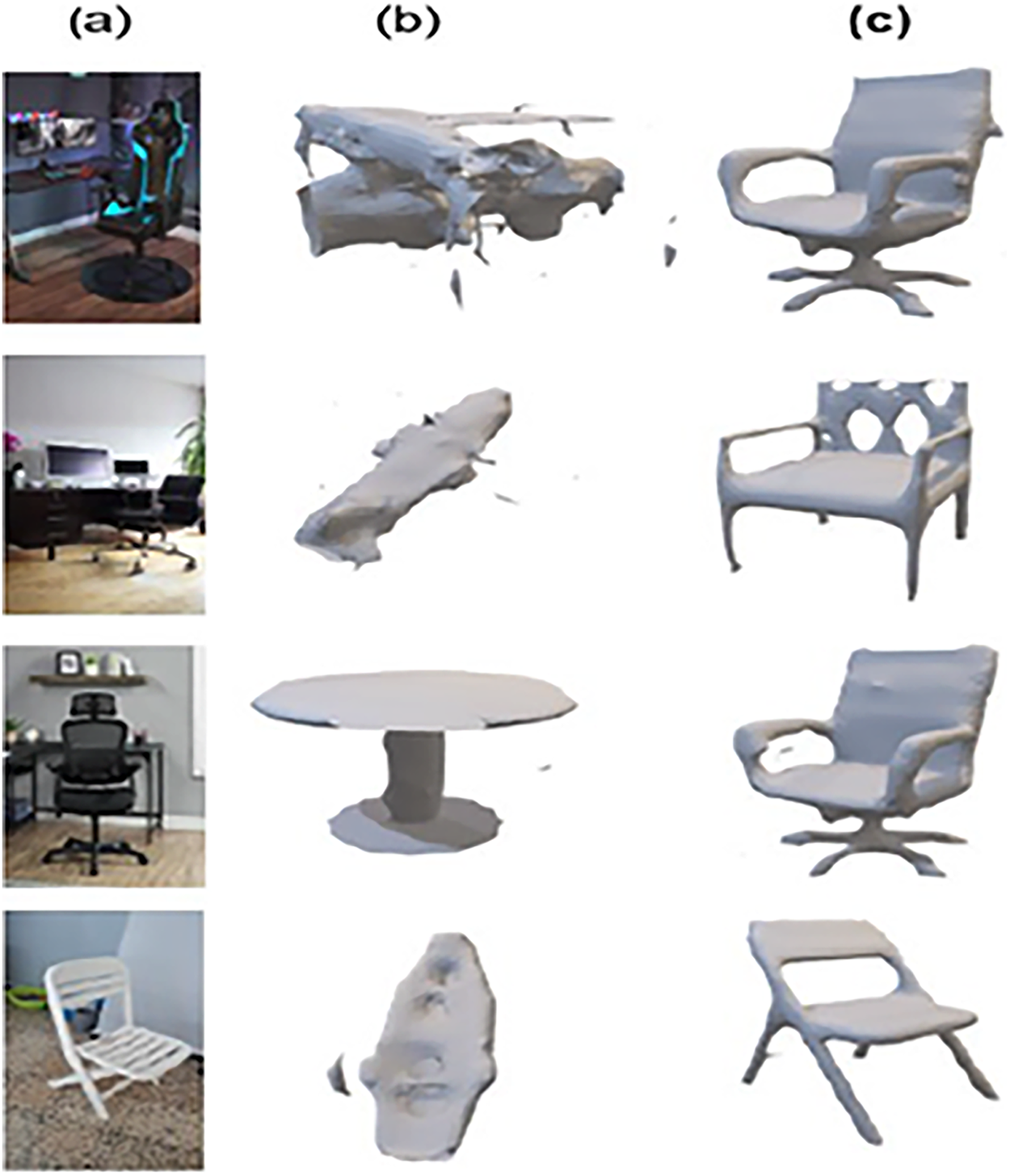

Additionally, Fig. 4 presents real-world examples, comparing 3D reconstructions from the general model and the proposed approach using real world images sourced from the internet. The general model tends to produce noticeable errors and inaccuracies, whereas our approach demonstrates significantly improved geometric accuracy and visual consistency. This comparison further underscores the practical effectiveness and robustness of our proposed fine-tuning approach.

Figure 4: Results of real-world images from the Internet. (a) Input image, (b) General Model, (c) Category-specific Models after Refinement

Overall, this visual comparison validates the advantages of our category-specific fine-tuning and subsequent refinement, confirming the substantial improvements in detail, accuracy, and realism achieved by our proposed method.

5.3 Advantageous of Refinement Step

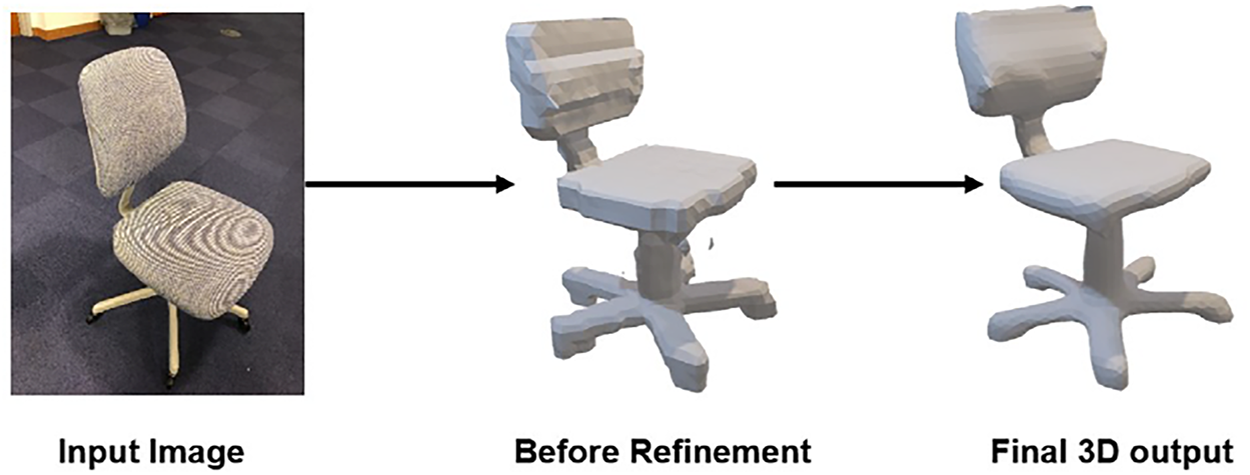

The refinement phase is critical for enhancing the visual quality and accuracy of the reconstructed 3D models. This step significantly reduces noise, corrects surface imperfections, and emphasizes fine-grained geometric details, resulting in noticeably improved realism. In addition to the improvements achieved through category-specific fine-tuning, the refinement phase further enhances the quality of the generated models compared to baseline methods such as the original Pix2Vox and Mesh R-CNN. The effectiveness of this step is clearly illustrated in Fig. 5, which provides a direct comparison of a reconstructed chair model before and after refinement. Additionally, as previously shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the refinement phase consistently contributes to higher fidelity and precision across various object categories, highlighting its essential role within our proposed pipeline.

Figure 5: Impact of the refinement phase on the quality of the 3D model

In this paper, we introduced a deep retraining approach for category-specific 3D reconstruction from a single 2D image, using transfer learning to improve model accuracy, completeness, and visual quality. The proposed approach integrates three key phases: image acquisition, where input quality is ensured through standardized resolution, blur detection, and lighting checks; 3D reconstruction, where a pre-trained model is individually fine-tuned on specific categories of objects to generate voxel-based representations; and refinement, which converts voxels into smooth and detailed triangular meshes using marching cubes and Laplacian smoothing algorithms.

The experimental study, conducted using the Pix2Vox model and the Pascal3D dataset, demonstrated that category-specific fine-tuning significantly improves reconstruction accuracy over general or baseline models. The proposed approach achieved higher IoU scores across all tested object categories, particularly in complex shapes. Visual comparisons further validated the effectiveness of our approach, showing that the combination of high-quality input image, tailored fine-tuning and mesh refinement produces more realistic and geometrically accurate 3D models, both for synthetic and real-world images.

Our results emphasize the advantage of using transfer learning and category-specific retraining. Transfer learning accelerates model training and reduces the dependence on large datasets, while specialized models increase reconstruction fidelity by capturing object-specific features. Additionally, the structured pipeline, beginning with image acquisition and concluding with mesh refinement, ensures that each step contributes to improving the model quality, addressing challenges like noise, incomplete geometry, and low resolution.

This study serves as a proof of concept, as experiments were limited to a subset of categories and benchmark data. Building on this foundation, future work will explore a wider range of objects, including deformable and articulated objects, and extend the framework beyond single-image reconstruction to multi-view or video-based inputs for greater completeness.

Evaluation will also be strengthened by incorporating surface-based metrics, alongside with perceptual quality measures. To better understand the contribution of each component, ablation studies will be conducted to isolate the impact of each step in the proposed pipeline. Furthermore, validation on larger datasets, as well as under real-world conditions involving noise, occlusion, and lighting variation, will provide a more rigorous assessment of robustness.

Looking further ahead, we envision extending the pipeline into a hybrid framework that combines DL with classical geometry-based methods, leveraging the strengths of both paradigms. Beyond industrial scenarios such as AR/VR, robotics, and manufacturing, this work was also motivated by potential applications in medical imaging, particularly in the dental field. In such contexts, category-specific retraining could be highly valuable: for example, fine-tuning the model on a specific type of tooth (e.g., molars or incisors) may enable sharper and more clinically precise reconstructions than generalized models. While this study was limited to benchmark datasets (furniture, vehicles) as a proof of concept due to the lack of publicly available dental data, future work will focus on extending the pipeline to medical scenarios where high-fidelity reconstructions are of critical importance.

Acknowledgement: This scientific paper is derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—with grant number (12979-iau-2023-TAU-R-3-1-EI-).

Funding Statement: This paper was funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—under supervision Energy, Industry, and Advanced Technologies Research Center, Taibah University, Madinah, Saudi Arabia with grant number (12979-iau-2023-TAU-R-3-1-EI-).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conception and design: Nour El Houda Kaiber, Tahar Mekhaznia, Zakaria Lakhdara; Data collection: Akram Bennour, Mohammed Al-Sarem; Models implementation, training and evaluation: Nour El Houda Kaiber, Zakaria Lakhdara; Analysis and interpretation of results: Nour El Houda Kaiber, Tahar Mekhaznia, Zakaria Lakhdara; Manuscript writing: Akram Bennour, Mohammed Al-Sarem; Reviewing and editing: Fahad Ghaban, Mohammad Nassef; Overall supervision and critical guidance: Tahar Mekhaznia, Zakaria Lakhdara. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang K, Ho CC, Zhang C, Wang B. A review on the 3D printing of functional structures for medical phantoms and regenerated tissue and organ applications. Engineering. 2017;3(5):653–62. doi:10.1016/j.eng.2017.05.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jin Z, Li Y, Yu K, Liu L, Fu J, Yao X, et al. 3D printing of physical organ models: recent developments and challenges. Adv Sci. 2021;8(17):2101394. doi:10.1002/advs.202101394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Li B, An Y, Cappelleri D, Xu J, Zhang S. High-speed 3D structured light imaging techniques and potential applications to intelligent robotics. Int J Intell Robot Appl. 2017;1(1):86–103. doi:10.1007/s41315-016-0001-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Johnson J, Ravi N, Reizenstein J, Novotny D, Tulsiani S, Lassner C, et al. Accelerating 3D deep learning with PyTorch3D. In: SA’20: SIGGRAPH Asia 2020 Courses; 2020 Dec 4–13. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020. doi:10.1145/3415263.3419160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pena-Tapia E, Hachiuma R, Pasquali A, Saito H. LCR-SMPL: toward real-time human detection and 3D reconstruction from a single RGB image. In: 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct); 2020 Nov 9–13; Recife, Brazil. doi:10.1109/ismar-adjunct51615.2020.00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhu W, Zhou S. 3D reconstruction method of virtual and real fusion based on machine learning. Math Probl Eng. 2022;2022:7158504. doi:10.1155/2022/7158504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hatamikia S, Gulyas I, Birkfellner W, Kronreif G, Unger A, Oberoi G, et al. Realistic 3D printed CT imaging tumor phantoms for validation of image processing algorithms. Phys Med. 2023;105:102512. doi:10.1016/j.ejmp.2022.102512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Aliakbarpour H, Surya Prasath VB, Palaniappan K, Seetharaman G, Dias J. Heterogeneous multi-view information fusion: review of 3-D reconstruction methods and a new registration with uncertainty modeling. IEEE Access. 2016;4:8264–85. doi:10.1109/access.2016.2629987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hartley R, Zisserman A. Multiple view geometry in computer vision. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511811685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gao L, Zhao Y, Han J, Liu H. Research on multi-view 3D reconstruction technology based on SFM. Sensors. 2022;22(12):4366. doi:10.3390/s22124366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Schonberger JL, Frahm JM. Structure-from-motion revisited. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2016.445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen Y, Li Q, Gong S, Liu J, Guan W. UV3D: underwater video stream 3D reconstruction based on efficient global SFM. Appl Sci. 2022;12(12):5918. doi:10.3390/app12125918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xi Y. Application of SLAM in endoscopic imaging. Appl Comput Eng. 2023;12(1):28–33. doi:10.54254/2755-2721/12/20230290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cadena C, Carlone L, Carrillo H, Latif Y, Scaramuzza D, Neira J, et al. Past, present, and future of simultaneous localization and mapping: toward the robust-perception age. IEEE Trans Robot. 2016;32(6):1309–32. doi:10.1109/tro.2016.2624754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Horn BKP, Brooks MJ. The variational approach to shape from shading. Comput Vis Graph Image Process. 1986;33(2):174–208. doi:10.1016/0734-189x(86)90114-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ba Y, Gilbert A, Wang F, Yang J, Chen R, Wang Y, et al. Deep shape from polarization. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58586-0_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Huang T, Li H, He K, Sui C, Li B, Liu YH. Learning accurate 3D shape based on stereo polarimetric imaging. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.1109/cvpr52729.2023.01658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Atkinson GA, Hancock ER. Recovery of surface orientation from diffuse polarization. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2006;15(6):1653–64. doi:10.1109/tip.2006.871114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wang X, Wang C, Liu B, Zhou X, Zhang L, Zheng J, et al. Multi-view stereo in the deep learning era: a comprehensive review. Displays. 2021;70:102102. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2021.102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Y, Li Z. A multi-view stereo algorithm based on homogeneous direct spatial expansion with improved reconstruction accuracy and completeness. Appl Sci. 2017;7(5):446. doi:10.3390/app7050446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kanazawa A, Tulsiani S, Efros AA, Malik J. Learning category-specific mesh reconstruction from image collections. In: Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01267-0_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Badger M, Wang Y, Modh A, Perkes A, Kolotouros N, Pfrommer BG, et al. 3D bird reconstruction: a dataset, model, and shape recovery from a single view. In: Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58523-5_1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Guo MH, Xu TX, Liu JJ, Liu ZN, Jiang PT, Mu TJ, et al. Attention mechanisms in computer vision: a survey. Comp Visual Med. 2022;8(3):331–68. doi:10.1007/s41095-022-0271-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Minaee S, Boykov YY, Porikli F, Plaza AJ, Kehtarnavaz N, Terzopoulos D. Image segmentation using deep learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(7):3523–42. doi:10.1109/tpami.2021.3059968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Noh H, Hong S, Han B. Learning deconvolution network for semantic segmentation. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. doi:10.1109/iccv.2015.178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Manakitsa N, Maraslidis GS, Moysis L, Fragulis GF. A review of machine learning and deep learning for object detection, semantic segmentation, and human action recognition in machine and robotic vision. Technologies. 2024;12(2):15. doi:10.3390/technologies12020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Singh SP, Wang L, Gupta S, Goli H, Padmanabhan P, Gulyás B. 3D deep learning on medical images: a review. Sensors. 2020;20(18):5097. doi:10.3390/s20185097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Cui H, Hu L, Chi L. Advances in computer-aided medical image processing. Appl Sci. 2023;13(12):7079. doi:10.3390/app13127079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Farabet C, Couprie C, Najman L, LeCun Y. Learning hierarchical features for scene labeling. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2013;35(8):1915–29. doi:10.1109/tpami.2012.231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Rajapaksha U, Sohel F, Laga H, Diepeveen D, Bennamoun M. Deep learning-based depth estimation methods from monocular image and videos: a comprehensive survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(12):1–51. doi:10.1145/3677327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Labaca-Castro R, Generative adversarial nets. In: Machine learning under malware attack. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Vieweg; 2013. p. 73–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-40442-0_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. In: 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014—Conference Track Proceedings; 2014 Apr 14–16; Banff, AB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

33. Wu J, Zhang C, Xue T, Freeman WT, Tenenbaum JB. Learning a Probabilistic Latent Space of Object Shapes via 3D Generative-Adversarial Modeling, Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1610.07584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wu Z, Song S, Khosla A, Yu F, Zhang L, Tang X, et al. 3D ShapeNets: a deep representation for volumetric shapes. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2015.7298801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wu Y, Sun Z, Song Y, Sun Y, Shi J. Slicenet: slice-wise 3D shapes reconstruction from single image. In: ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. doi:10.1109/icassp40776.2020.9054674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sun Y, Liu Z, Wang Y, Sarma SE. Im2Avatar: colorful 3D reconstruction from a single image. arXiv:1804.06375. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1804.06375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tatarchenko M, Dosovitskiy A, Brox T. Octree generating networks: efficient convolutional architectures for high-resolution 3D outputs. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. doi:10.1109/iccv.2017.230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Charles RQ, Hao S, Mo K, Guibas LJ. PointNet: deep learning on point sets for 3D classification and segmentation. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fan H, Su H, Guibas L. A point set generation network for 3D object reconstruction from a single image. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Guo Q, Li J. A learning based 3D reconstruction method for point cloud. In: 2020 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech); 2020 Aug 17–22; Calgary, AB, Canada. doi:10.1109/dasc-picom-cbdcom-cyberscitech49142.2020.00055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang N, Zhang Y, Li Z, Fu Y, Liu W, Jiang YG. Pixel2Mesh: generating 3D mesh models from single RGB images. In: Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01252-6_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Gkioxari G, Johnson J, Malik J. Mesh R-CNN. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Cosmo L, Rodola E, Bronstein MM, Torsello A, Cremers D, Sahillioǧlu Y. SHREC’16: partial matching of deformable shapes. In: Proceedings of the Eurographics 2016 Workshop on 3D Object Retrieval; 2016 May 8; Lisbon, Portugal. doi:10.2312/3dor.20161089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wang W, Huang Q, You S, Yang C, Neumann U. Shape inpainting using 3D generative adversarial network and recurrent convolutional networks. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29. Venice, Italy. doi:10.1109/iccv.2017.252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Frolov V, Faizov B, Shakhuro V, Sanzharov V, Konushin A, Galaktionov V, et al. Image synthesis pipeline for CNN-based sensing systems. Sensors. 2022;22(6):2080. doi:10.3390/s22062080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Nguyen DP, Nguyen TN, Dakpé S, Ho Ba Tho MC, Dao TT. Fast 3D face reconstruction from a single image using different deep learning approaches for facial palsy patients. Bioengineering. 2022;9(11):619. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9110619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. El Houda Kaiber N, Mekhaznia T, Lakhdara Z. Transfer learning-based approach for 3D reconstruction from a single 2D image. In: 2024 6th International Conference on Pattern Analysis and Intelligent Systems (PAIS); 2024 Apr 24–25; El Oued, Algeria. doi:10.1109/pais62114.2024.10541132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Xie H, Yao H, Sun X, Zhou S, Zhang S. Pix2Vox: context-aware 3D reconstruction from single and multi-view images. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Jeffrey A. Clark and contributors. Pillow 11.2.1. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://pillow.readthedocs.io/en/stable/. [Google Scholar]

50. Bradski G. The OpenCV library. San Francisco, CA, USA: Dr. Dobb’s Journal; 2000. [Google Scholar]

51. Ahishakiye E, Van Gijzen MB, Tumwiine J, Wario R, Obungoloch J. A survey on deep learning in medical image reconstruction. Intell Med. 2021;1(3):118–27. doi:10.1016/j.imed.2021.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Xiang Y, Mottaghi R, Savarese S. Beyond PASCAL: a benchmark for 3D object detection in the wild. In: IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2014 Mar 24–26; Steamboat Springs, CO, USA. doi:10.1109/wacv.2014.6836101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Lorensen WE, Johnson C, Kasik D, Whitton MC. History of the marching cubes algorithm. IEEE Comput Graph Appl. 2020;40(2):8–15. doi:10.1109/MCG.2020.2971284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Vollmer J, Mencl R, Müller H. Improved Laplacian smoothing of noisy surface meshes. Comput Graph Forum. 1999;18(3):131–8. doi:10.1111/1467-8659.00334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Charton J, Baek S, Kim Y. Mesh repairing using topology graphs. J Comput Des Eng. 2021;8(1):251–67. doi:10.1093/jcde/qwaa076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Arjan Westerdiep. Binox visualization software. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://drububu.com/miscellaneous/voxelizer/?out=obj. [Google Scholar]

57. Alberto R, Simon E, Azzini A, Anastasia K, Vignesh K, Chris W. IoU metric. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.v7labs.com/about-v7. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools