Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An IoT-Based Predictive Maintenance Framework Using a Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Smart Industrial Systems

1 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Madinah, 42353, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Artificial Intelligence and Data Science, College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Madinah, 42353, Saudi Arabia

3 Computer Science and Computer Information Technology Department, College of Business, Technology & Professional Studies, Methodist University, Fayetteville, NC 28311, USA

* Corresponding Author: Talal H. Noor. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 93 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070741

Received 23 July 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Modern industrial environments require uninterrupted machinery operation to maintain productivity standards while ensuring safety and minimizing costs. Conventional maintenance methods, such as reactive maintenance (i.e., run to failure) or time-based preventive maintenance (i.e., scheduled servicing), prove ineffective for complex systems with many Internet of Things (IoT) devices and sensors because they fall short in detecting faults at early stages when it is most crucial. This paper presents a predictive maintenance framework based on a hybrid deep learning model that integrates the capabilities of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The framework integrates spatial feature extraction and temporal sequence modeling to accurately classify the health state of industrial equipment into three categories, includingKeywords

In modern industrial environments, ensuring the continuous operation of critical equipment is essential to maintaining productivity, reducing downtime, and minimizing financial loss. Traditional maintenance strategies such as reactive repair and time-based preventive actions are no longer sufficient in complex data-driven systems [1,2]. As machinery becomes increasingly embedded with IoT sensors and connected to intelligent monitoring systems, the need for predictive maintenance (i.e., capable of identifying faults before they escalate) has become more pressing than ever [3–5]. However, designing accurate and generalized models for such systems remains a significant challenge due to the noisy, high-dimensional, and time-dependent nature of industrial sensor data [6–8].

With the growing emphasis on the concept of the Internet of Things (IoT), modern industrial systems are moving towards real-time monitoring of assets in an on-site environment with the help of a distributed, often dense network of embedded sensors [9–12]. These sensors capture multivariate time series data on operational variables (e.g., temperature, pressure, vibration, etc.), which is then used for equipment fault diagnosis. In most industrial applications, however, sensor data often contains missing values, noise, and inconsistencies caused by harsh production conditions, making it challenging for classical analytical tools to provide robust and valuable insights from the data [3,13].

In the context of predictive maintenance, recent research has also been motivated by the critical need for prediction models to reliably forecast future equipment failure, in order to prevent unexpected downtime [14]. While many conventional techniques exist that help model the data in question to some extent, their practical utility has been shown to be limited by the inability to model real-world spatio-temporal properties present in industrial data. As such, many recent attempts have been made to apply Deep Learning (DL) techniques in order to help automatically extract non-linear representations from such noisy, high-dimensional sensor data in an unsupervised manner, without requiring feature engineering [3,15].

Recent research in the field has also shown that hybrid approaches that take into account both the spatial and temporal aspects of the data help to provide a more robust solution to fault diagnosis in industrial sensor data [16,17]. Motivated by this, we propose a hybrid LSTM-CNN model in this work, designed to address industrial predictive maintenance tasks by capturing both local and sequential features of the input data for more reliable predictions. Compared to existing LSTM-CNN predictive maintenance architectures which are commonly restricted to binary classification or have been trained on synthetically balanced datasets, we propose: (i) a three-class predictive maintenance structure (i.e., Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed) which captures more nuanced and realistic stages for maintenance decision-making; (ii) a threshold-based scheme for three-class labeling that can naturally reflect degradation sequences without synthetically oversampling; and (iii) a modular and deployment-oriented pipeline which can be easily packaged into a Computerized Maintenance Management System (CMMS). These key contributions reflect our emphasis on interpretability and real-world applicability. In a nutshell, the silent features of our work are as follows:

• We present the design of a modular and scalable predictive maintenance framework for predicting equipment failures before they cause unplanned downtime. The framework integrates spatial feature extraction and temporal sequence modeling within a complete pipeline that encompasses data collection, preprocessing, hybrid classification, and actionable decision-making, making it suitable for real-world industrial deployment.

• We propose a hybrid model that leverages Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to extract local spatial features from raw sensor signals. At the same time, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units capture temporal dependencies across sequences. This model enables the joint learning of spatio-temporal representations, improving the model’s ability to detect subtle degradation patterns and anticipate complex fault conditions more accurately than standalone architectures.

• Unlike binary classification approaches, our model accurately predicts three health states (i.e., Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed), enabling more informed and proactive maintenance decisions.

• We benchmark our hybrid model against alternative architectures, including Long Short-Term Memory and Support Vector Machine (LSTM-SVM), and LSTM and Recurrent Neural Network (LSTM-RNN), that demonstrate superior performance across multiple metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, particularly in detecting critical fault conditions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the recent literature on deep learning-based predictive maintenance approaches. Section 3 describes the architecture and processing pipeline of the proposed predictive maintenance framework. Section 4 presents the hybrid model that leverages CNN and LSTM. Section 5 details the implementation and experimental setup, dataset preparation, and training methodology. Section 6 discusses the performance results and comparative evaluation. Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

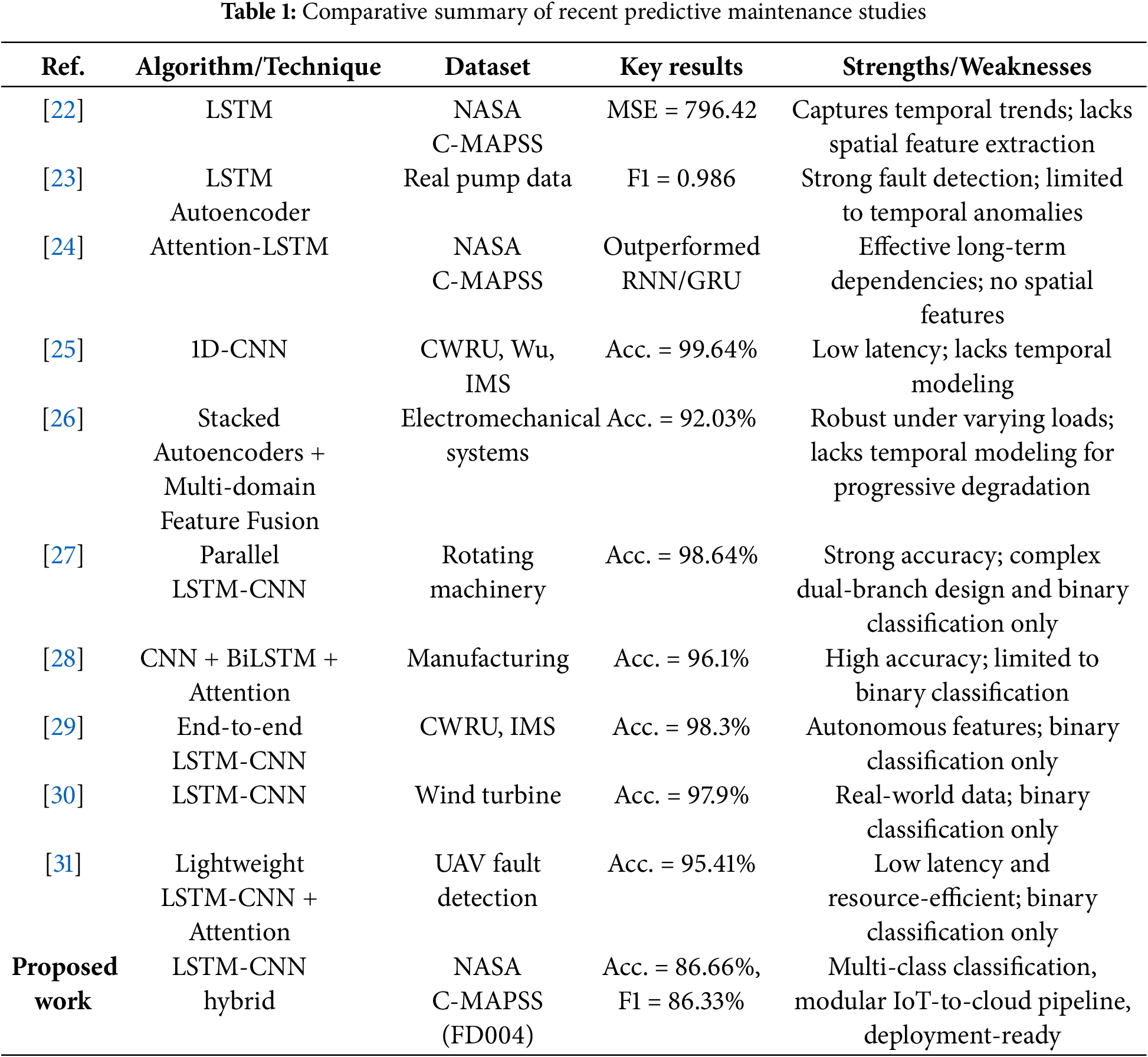

Recent research in predictive maintenance has increasingly adopted deep learning approaches to handle the complex and noisy nature of industrial sensor data [18–21]. Among the most prominent architectures are LSTM networks, CNNs, and hybrid combinations of the two. Several studies have utilized LSTM networks exclusively to exploit their strength in modeling temporal dependencies. Peringal et al. [22] applied an LSTM-based model to the NASA C-MAPSS dataset, focusing on predicting the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of aircraft engines. The model was trained using 20-timestep sequential inputs, and it achieved a strong performance on the testing set (i.e., Mean Squared Error (MSE) scoring 796.42). The LSTM was able to effectively model long-term temporal degradation trends in the data, which outperformed the baseline Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model. The paper did not make use of any methods to explicitly account for spatial dependencies between the multivariate sensor data, which could limit its robustness to noisy or redundant features in some applications. In a similar work, Dallapiccola [23] constructed a model that combines an LSTM Autoencoder model for predictive maintenance on centrifugal pumps with real-world sensor data. The model was capable of capturing temporal anomalies effectively through time-series forecasting. Still, it did not include any explicit spatial feature extraction mechanisms that could be useful for applications with multivariate sensor data and more complex spatial relationships. Boujamza and Elhaq [24] presented an LSTM model with an attention mechanism for Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation of aircraft engines with the C-MAPSS dataset. The results of their study indicated that the attention mechanism helped the model learn long-term dependencies, outperforming Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) baseline models. These LSTMs have all shown good performance at capturing sequential degradation patterns over time. However, there are no explicit methods for extracting spatial features from different sensor inputs, which can improve the robustness and interpretability of predictions. Our proposed hybrid LSTM-CNN model overcomes these issues by incorporating convolutional layers for spatial feature extraction before performing sequential memory modeling.

CNN-only models have also been utilized to learn localized features for various sensors in numerous studies. For example, Chuya-Sumba et al. [25] proposed a 1D-CNN model for rotating machinery fault detection with vibration signals. Their network achieved up to 99.64% accuracy on three benchmark datasets (i.e., CWRU, Wu, and IMS), while having low processing latency for real-time deployment. In another paper, Arellano-Espitia et al. [26] introduced a DL-based approach for fault diagnosis in electromechanical equipment using a stacked autoencoder with time, frequency, and time-frequency domain feature fusion. Their approach achieved high performance in classifying different abrupt faults in the data. Still, it did not explicitly model temporal information, which limits its ability to generalize to more progressive degradation trends. Our proposed hybrid LSTM-CNN model can account for both spatial and temporal feature extraction, enabling it to achieve better accuracy in predicting such data over time.

Hybrid LSTM-CNN models have also been introduced to leverage the benefits of each model type. In one paper, Zhou and Tang [27] proposed a parallel LSTM-CNN model for rotating machinery fault classification. Their model integrated both raw time-series signals and Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT)-based representations into both the LSTM and CNN branches. The dual-branch architecture allowed spatial and temporal features to be fused effectively, enabling robust classification even under varying operational conditions. Zhao et al. [28] introduced a multi-scale deep learning model combining CNN, BiLSTM, and attention mechanisms for binary fault detection in manufacturing. However, their classification task was limited to binary outcomes (i.e., fault/no-fault), lacking nuance in reflecting varying levels of degradation. Similarly, Khorram et al. [29] implemented an end-to-end CNN-LSTM architecture trained on benchmark datasets (i.e., CWRU and IMS), reaching a diagnostic accuracy of 98.3%. Although their model autonomously learned feature representations, the use of controlled laboratory data limited its generalization. While these models contributed significantly to the field, many suffer from limitations such as excessive architectural complexity, reliance on clean datasets, binary classification scopes, or lack of generalization under real-world variability. On the other hand, our proposed model is relatively lightweight in terms of architecture, and it also offers a three-level maintenance state classification scheme (i.e., Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed) with threshold-based labeling, providing a more immediately useful tool for industrial operators in the context of maintenance planning and failure prevention support.

Some studies have emphasized efficiency and deployment readiness over the complexity of systems. Stow [30] developed an LSTM-CNN model trained on real-world wind turbine gearbox data, achieving 97.9% accuracy using the AI4I Predictive Maintenance dataset. Although highly accurate, the model was limited to binary fault classification. Wang et al. [31], in contrast, proposed a lightweight LSTM-CNN model with attention modules for fault detection in fixed-wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Their architecture prioritized low latency and resource efficiency, achieving 95.41% accuracy but only supporting binary classification. Compared to these models, our proposed LSTM-CNN framework supports robust multi-class health classification without dynamic tuning or sacrificing performance, positioning it for real-time deployment in diverse industrial scenarios.

In summary, while previous models have contributed significantly to the field, many suffer from limitations such as excessive architectural complexity, reliance on synthetic or clean datasets, narrow classification scopes, or lack of generalization under real-world variability. Our proposed hybrid model overcomes these issues by supporting multi-class classification (i.e., Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed) and training exclusively on realistic, multivariate datasets. In particular, the hybrid model exploits CNN and LSTM in a streamlined architecture trained on the FD004 subset of the C-MAPSS dataset. It avoids data augmentation or artificial balancing, relying instead on carefully selected RUL thresholds to define interpretable and realistic health states. By addressing both spatial and temporal challenges, our model offers a reliable, efficient, and deployable solution for predictive maintenance in modern industrial environments. Table 1 provides an overview of recent predictive maintenance research work in terms of algorithm or technique used, dataset used, reported key performance metrics, and their strengths and weaknesses, highlighting the research gap that is addressed by the proposed LSTM-CNN framework.

3 Predictive Maintenance Framework

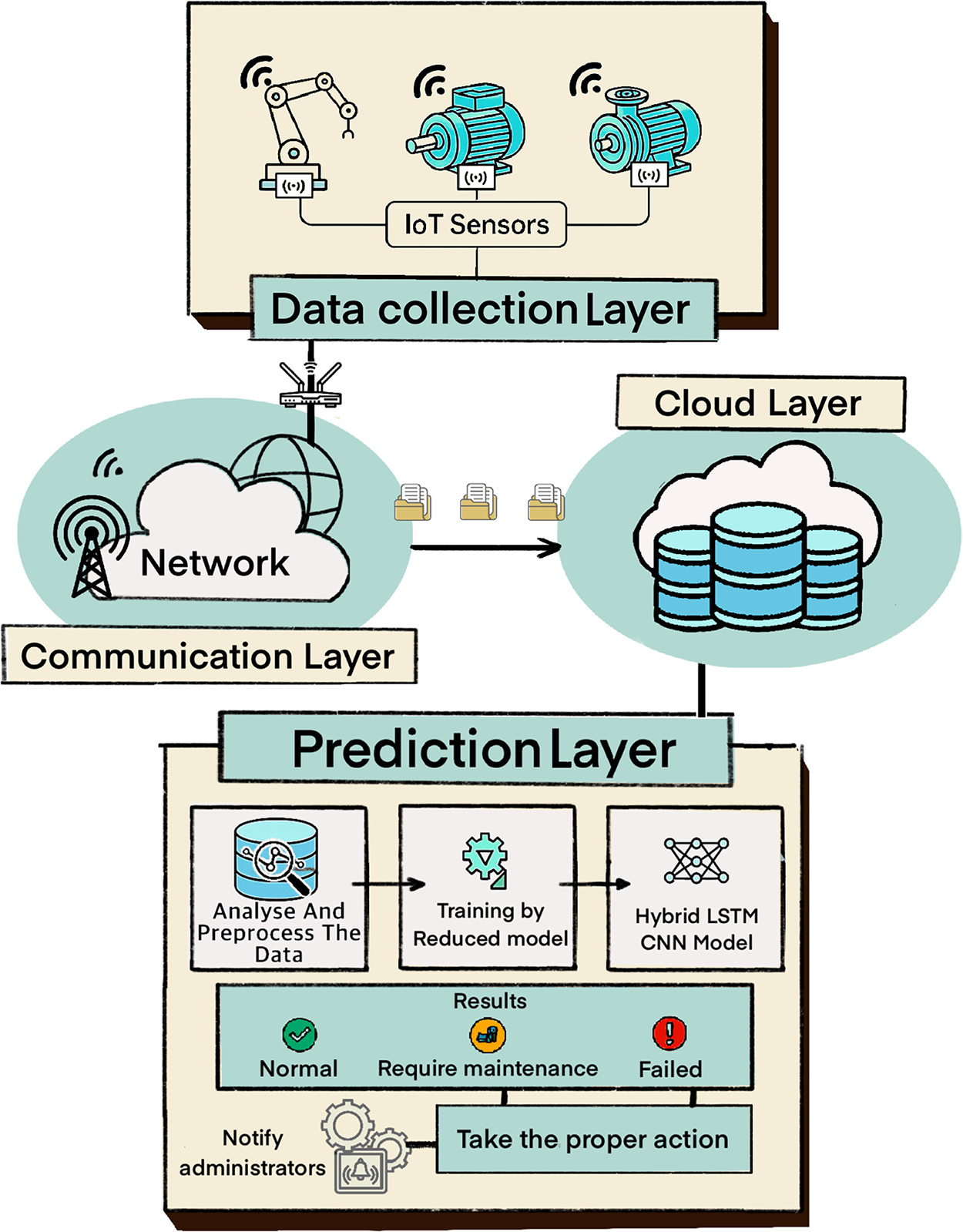

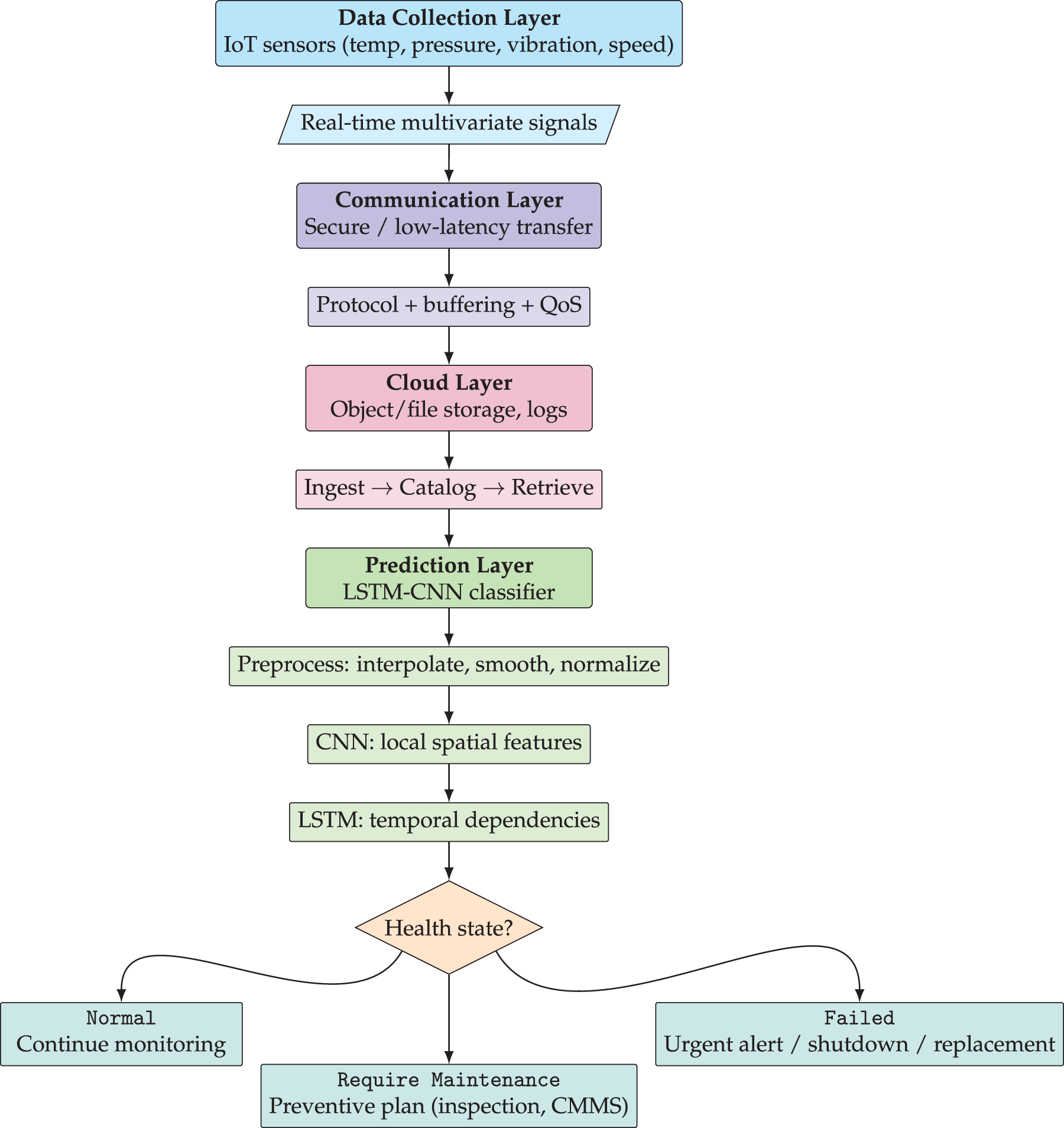

The proposed predictive maintenance framework is designed to deliver accurate, real-time diagnostics of industrial machinery health by leveraging IoT technologies, cloud infrastructure, and a hybrid deep learning model combining LSTM and CNNs networks. The system contains four main layers: the Data Collection Layer, the Communication Layer, the Cloud Layer, and the Prediction Layer. Each layer performs a distinct function, with a clearly defined data flow from sensor acquisition to intelligent decision-making. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall system architecture.

Figure 1: Architecture of the proposed predictive maintenance framework

The Data Collection Layer is responsible for acquiring real-time data from IoT-enabled sensors deployed across critical industrial equipment such as motors, bearings, turbines, and actuators. These sensors continuously monitor vital parameters, including temperature, vibration, pressure, and rotational speed. The collected data form multivariate time-series streams that capture both transient faults and long-term degradation behavior. All data are collected with high temporal granularity to ensure accurate tracking of subtle changes in machine behavior. Sensor calibration, synchronization, and integrity checks are assumed to be handled at the hardware level to preserve data quality. Once gathered, the raw sensor data is forwarded to the Communication Layer for further transmission.

The Communication Layer is the communication network of the system, designed for high-speed, reliable, and secure transfer of sensor data from the field to the cloud platform. Networks, access points, and satellite links can be part of this layer based on the specific deployment scenario. The Communication Layer also handles the real-time aspects of data delivery to the Cloud with minimal packet loss and latency, using industrial communication protocols. The Communication Layer interfaces with physical sensors on one side and cloud-based services on the other, ensuring uninterrupted data transmission even in distributed or complex manufacturing settings. The Communication Layer is designed modularly and can scale to span multiple facilities while remaining compatible with various network infrastructures.

Sensor data received through the Communication Layer is structured and persisted in the cloud. The Cloud Layer is made of file-based and object-based storage services with support for high-throughput ingestion and fast data retrieval. Cloud services like Amazon Web Services (AWS-S3), Google Cloud Storage, or Azure Blob Storage can be used to store historical logs of equipment behavior in CSV, Parquet, or binary schemas, to create a persistent and structured log of equipment behavior over time. This layer is performance-optimized to ensure data durability and scalability, allowing for the long-term persistence of time-series data from various assets. This decoupling of data acquisition from prediction also provides for the reuse of persisted data for retraining or other purposes.

The Prediction Layer is the analytical component of the system. It interfaces directly with the Cloud, fetching historical and live sensor data for processing. The input data is then pre-processed, including imputation of missing values, noise filtering (i.e., smoothing filters), normalization, and feature selection. The pre-processed data is then used to calculate the RUL for each machine cycle. Based on predefined thresholds, engine cycles are categorized into three health states, including Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed. This three-class labeling structure enables the system to move beyond simple binary classification and provide nuanced maintenance insights. The preprocessed dataset is fed into a reduced training model, optimized for efficiency through dimensionality reduction techniques. This model is built on a hybrid architecture that includes CNN layers, which extract spatial patterns from sensor readings, and LSTM layers, which track how these patterns evolve over time. The final classification output identifies the machine’s current health state, empowering operators with timely and actionable intelligence.

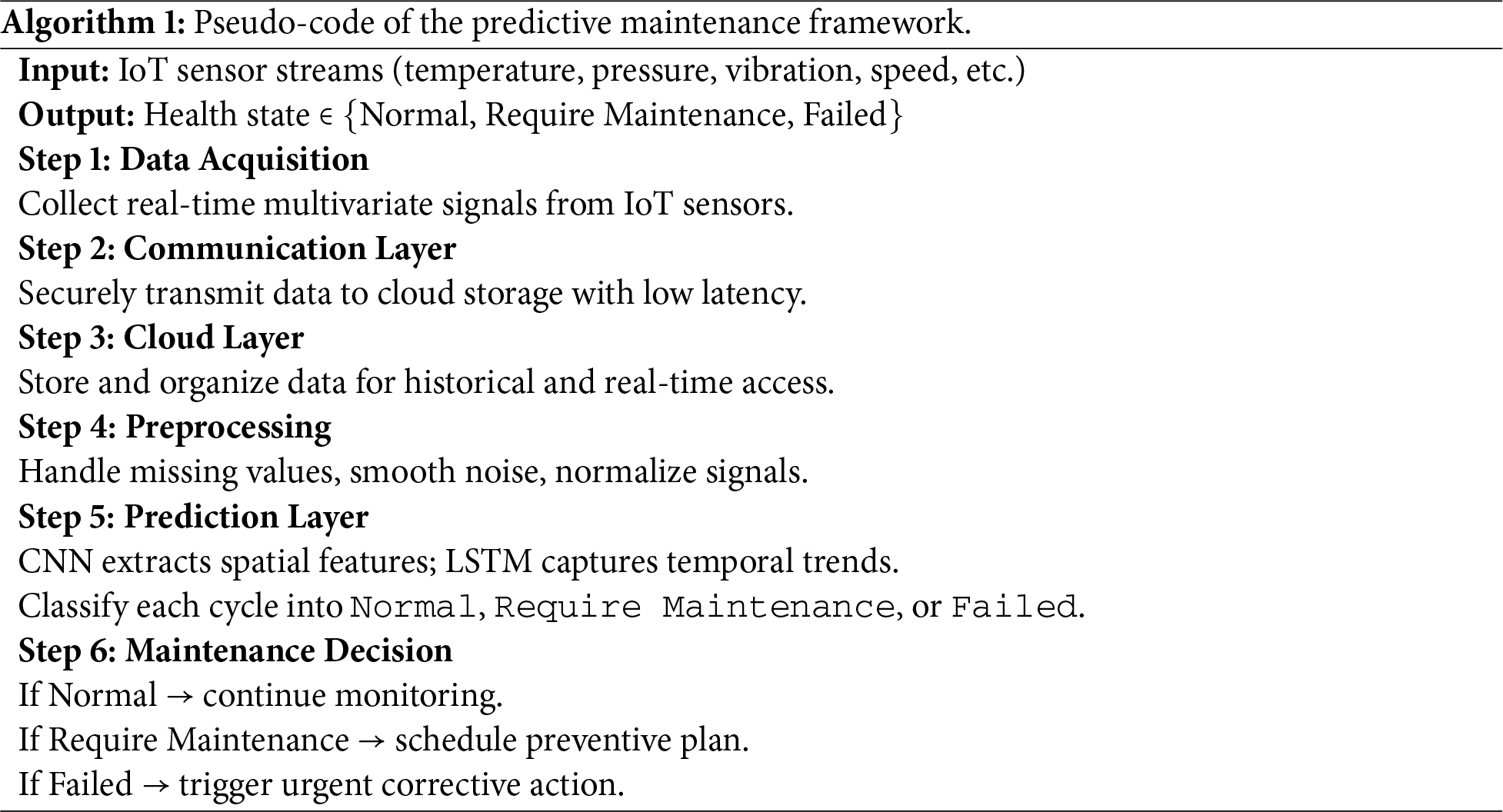

Once the health state is classified, the system triggers the appropriate maintenance response. Assets classified as Normal remain under routine monitoring. If the classification indicates Require Maintenance, a preventive plan is scheduled, such as inspection, lubrication, or component adjustment to prevent future failure. For assets predicted to be in the Failed state, immediate alerts are sent to the maintenance team, prompting urgent interventions such as complete part replacement or system shutdown to prevent safety hazards. These decision outputs are designed to integrate with Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS), allowing automatic work order generation, resource scheduling, and real-time alerts. This facilitates a proactive maintenance environment that reduces costs, minimizes disruptions, and extends equipment lifespan. Algorithm 1 displays the pseudo-code that is a structured, step-by-step, textual representation of the predictive maintenance framework. The general workflow is also represented in the data flow diagram in Fig. 2, showing the data pipeline and decision points.

Figure 2: Data flow diagram of the proposed predictive maintenance framework, showing modular layers, preprocessing, LSTM-CNN prediction, and decision points leading to CMMS actions

The hybrid DL architecture integrates LSTM and CNN models to effectively capture both spatial and temporal dependencies present in the input data. The motivation behind the chosen LSTM and CNN models is justified based on their complementary capabilities to address different aspects of the predictive maintenance task. CNN models are well-suited to extract spatial features and patterns from raw sensor data, allowing the network to learn relevant features automatically without extensive manual feature engineering. This can be particularly beneficial for detecting localized anomalies, such as sudden temperature spikes or localized vibrations. On the other hand, LSTM, being a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) architecture, is capable of modeling long-term temporal dependencies. It can capture temporal patterns and gradual degradation trends over multiple engine cycles, which is essential for accurately predicting the remaining useful life. The proposed hybrid LSTM-CNN model leverages the strengths of both architectures to extract both spatial and temporal features, leading to a more comprehensive and robust spatio-temporal representation of the input data. This enriched representation is expected to enhance fault detection capabilities and improve the accuracy of RUL estimation. While other models, such as Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs), and Transformer-based architectures, have been explored in recent literature, the selection of LSTM-CNN is a compromise between predictive performance, interpretability, and practical considerations for industrial deployment, including computational efficiency and established robustness.

CNNs serve as the first stage in the architecture, responsible for extracting local features from raw sensor data. CNNs are widely known for their ability to learn spatial hierarchies by applying convolutional filters across the input, detecting low-level and high-level patterns without manual feature engineering. In our model, we use two convolutional layers, each with 64 filters of kernel size 3, followed by ReLU activation and max pooling to reduce spatial dimensionality while retaining essential features. CNNs are particularly effective for identifying localized signals that may correspond to early fault symptoms. Moreover, their ability to generalize through shared weights and local connectivity reduces the number of parameters, improving efficiency and convergence speed [28,32,33].

Once spatial features are extracted, they are flattened and passed into the LSTM layer. LSTM networks are a specialized type of recurrent neural network designed to capture long-range dependencies in sequential data. Our LSTM layer comprises 100 hidden units and processes the temporal evolution of extracted features across engine cycles. With internal memory cells and gating mechanisms including input, forget, and output gates, LSTMs regulate the flow of information, enabling the network to preserve relevant history over time [28,34]. This design makes them particularly suited for capturing gradual degradation trends in equipment monitoring applications.

The final output from the LSTM is passed to a fully connected dense layer with a Softmax activation, generating probabilities over the three health states, including Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed. This multi-class classification allows the model to support proactive and nuanced maintenance scheduling.

In the convolutional layers, the primary operation involves applying a set of learnable filters over the input sequence to detect local spatial patterns. This operation is mathematically represented in Eq. (1):

where

where

After spatial feature extraction, the flattened outputs are passed into the LSTM layer, which captures temporal dependencies across cycles. LSTM units consist of several internal gates designed to regulate information flow over time. The forget gate is computed as in Eq. (3):

This gate (

The input modulation gate

The memory cell is then updated by combining the retained and added information:

The output gate determines what information from the memory cell should be sent to the next step’s hidden state, as shown in Eq. (7):

Finally, the hidden state output is computed as Eq. (8):

This mathematical model is designed to capture the hierarchical structure of the hybrid model. It first learns the robust spatial patterns using CNN. It then takes in those patterns as input to model how they change and evolve using LSTM, which is critical for predictive maintenance tasks that require both signal behavior and its evolution across operational cycles [35–37].

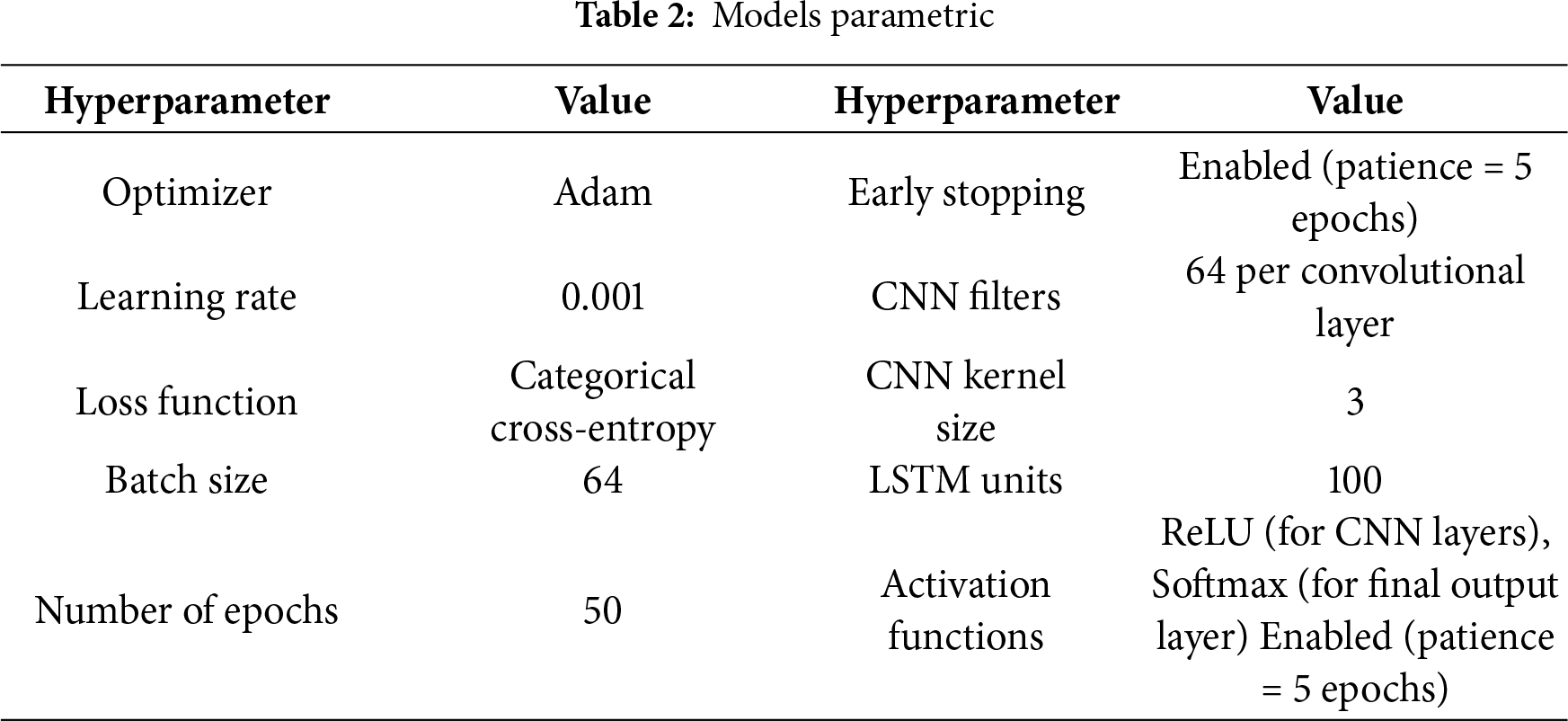

To train and evaluate the proposed hybrid LSTM-CNN model, several hyperparameters were carefully selected as listed in Table 2 after an iterative process of experimentation and tuning. The aim was to choose hyperparameters that would ensure optimal learning performance while avoiding overfitting and minimizing computational cost. The selected parameters reflect a balance between model depth, complexity, and generalization capability, allowing the network to effectively extract spatial and temporal features from the multivariate time-series data. The table below summarizes the final parameter values used for implementation.

These hyperparameters were chosen as a result of some initial trial-and-error to ensure convergence without overfitting. The selected settings enabled the construction of a robust and computationally efficient model that performed with a high level of accuracy in predictive maintenance classification. In addition, a dropout layer (i.e., rate = 0.3) was included after the LSTM layer to prevent overfitting. The LSTM-CNN architecture is therefore composed of two 1D convolutional layers (i.e., 64 filters, kernel size = 3, ReLU activation, max pooling size = 2), one LSTM layer with 100 hidden units and dropout 0.3, and one fully connected dense layer with Softmax activation for the three-class output.

5 Implementation and Experimental Setup

5.1 Implementation, Hardware, and Software Configuration

The implementation was conducted on Google Colab, which is a free cloud-based tool that provides a GPU for code execution. Python 3.9 is used as the core programming language. Libraries used in the implementation are Tensorflow 2.9, Keras (i.e., for deep learning model development), and Scikit-learn (i.e., for pre-processing, evaluation, and some other analytical aspects of the project). Google Drive was used for storing datasets, as Google Colab offers the ability to mount Google Drive for dataset access. This approach not only provides flexibility in loading data dynamically (i.e., during training or testing the model) but also facilitates efficient experimentation, as compared to the hassle of manual data management on local devices. On the same lines, Google Colab’s GPU acceleration plays a crucial role in reducing training time for both CNN and LSTM layers, particularly for operations such as convolution and sequence modeling. In addition, early stopping and model checkpointing strategies were applied to monitor validation loss and prevent overfitting. In particular, we used a variety of regularization techniques, including early stopping (i.e., patience = 5 epochs), a dropout layer (i.e., rate = 0.3) following the LSTM, and L2 weight decay (i.e., 1e-4) on the final dense layer. These techniques ensured that the most optimal model weights (i.e., based on validation performance) were retained for final evaluation and stabilized the validation loss. In other words, hyperparameters were adjusted iteratively, where the final hyperparameters used include Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001), batch size = 64, and up to 50 epochs. Model checkpointing was used to save the best weights.

The experimental setup evaluated the predictive performance and robustness of the proposed CNN-LSTM framework in real-time industrial environments, using cloud-based resources for scalability and accessibility. The primary goal of the experiment was to classify the condition of aircraft engines into one of three discrete health states: Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed. This classification was derived from the RUL of each engine unit. To generate these labels, the RUL for each engine cycle was computed by subtracting the current cycle index from the engine’s final cycle (i.e., the point of failure). Regarding RUL thresholds, various configurations were explored to examine different boundary options that can provide a proper, realistic degradation representation while maintaining a reasonable balance in sample distribution. No particular balancing technique (e.g., Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), artificial data generation, etc.) was performed, as the options were selected based on realistic representations in degradation while maintaining the real-life nature of the data.

The hybrid LSTM-CNN model was evaluated against two other LSTM-based architectures, including LSTM combined with Support Vector Machine (LSTM-SVM) and Recurrent Neural Network (LSTM-RNN). Training and test conditions were equal for all the models, and accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were used as the performance evaluation metrics.

For our work, we utilized the FD004 subset of the NASA Commercial Modular Aero-Propulsion System Simulation dataset (C-MAPSS) [38], a standard industry benchmark for verifying predictive maintenance solutions. The FD004 includes synthetic, realistic degradation data of aircraft engines under several fault modes and operating environments. It is more complex than the rest of the FD sets as it includes non-trivial engine behaviors (e.g., high-pressure compressor degradation and turbine degradation). The dataset was generated by simulating the engines for several cycles under operational conditions, from the initial healthy cycle to the end of the mission (i.e., failure). For each cycle, three operating conditions are known, including altitude, throttle resolver angle, and Mach number, as well as 21 engine sensor readings. Sensors measure essential parameters like fan speed, exhaust gas temperature, and other temperature and pressure ratios. These measurements are recorded at different points during the engine’s life cycle, providing a comprehensive view of its operational history.

The resulting dataset with more than 61,000 records was then labeled using a pre-processing pipeline and criteria and divided into three health states Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed using RUL thresholds. The final counts for each health category for this dataset are 21,668, 19,675, and 19,906 for Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed, respectively. As the class distribution for this dataset is approximately balanced, it will allow for fair and accurate evaluation and training. In particular, degradation patterns of the engines in the data going from healthy to failure stages are very close to the real case of industrial plants. They thus are suitable for developing robust predictive maintenance models.

It was necessary to preserve temporal information in the data when splitting the dataset into subsets; therefore, we applied a chronological data splitting method. We divided the dataset into training 70%, validation 15%, and testing 15% datasets. We kept the time order of cycles during the split to prevent any data leakage due to information from later time points being present in the data before the engine unit has experienced it. We also partitioned the dataset at engine unit granularity to prevent temporal leakage. Whole engine trajectories have been assigned to the training, validation, or testing set, and we have avoided splitting the same engine in different sets (i.e., no partial cycles per engine). This way, we could make sure that we present a model with unseen engines for testing, and at the same time, keep all temporal information within a trajectory group. This method of data preparation is crucial for evaluating the predictive maintenance models in a way that reflects how they would be deployed in real-world settings. By partitioning the dataset in a way that is both realistic and challenging, we can ensure that the resulting model is truly applicable to smart industrial environments.

5.4 Data Pre-Processing and Labeling

Pre-processing steps were applied to the FD004 subset of the NASA C-MAPSS dataset before model training. The time-series sensor data was cleaned, normalized, and labeled appropriately for deep learning. Linear interpolation was used to fill in gaps in missing sensor readings. This maintains continuity of the signals across operational cycles without introducing artificial spikes or anomalies. A moving average filter was applied to smooth out short-term noise and highlight long-term trends in the sensor signals. The filter smoothed out transient fluctuations while preserving underlying degradation patterns. Feature selection was done based on the variance and correlation of sensor signals. Sensors with consistently low variance or redundant information were removed to reduce dimensionality and improve model generalization. After selecting the most informative features, Min-Max scaling was applied to normalize all values between 0 and 1, ensuring uniform input across the network and accelerating model convergence.

For labeling, the RUL of each engine cycle was computed by subtracting the current cycle index from the engine’s final failure cycle, as shown in Eq. (9):

where

where

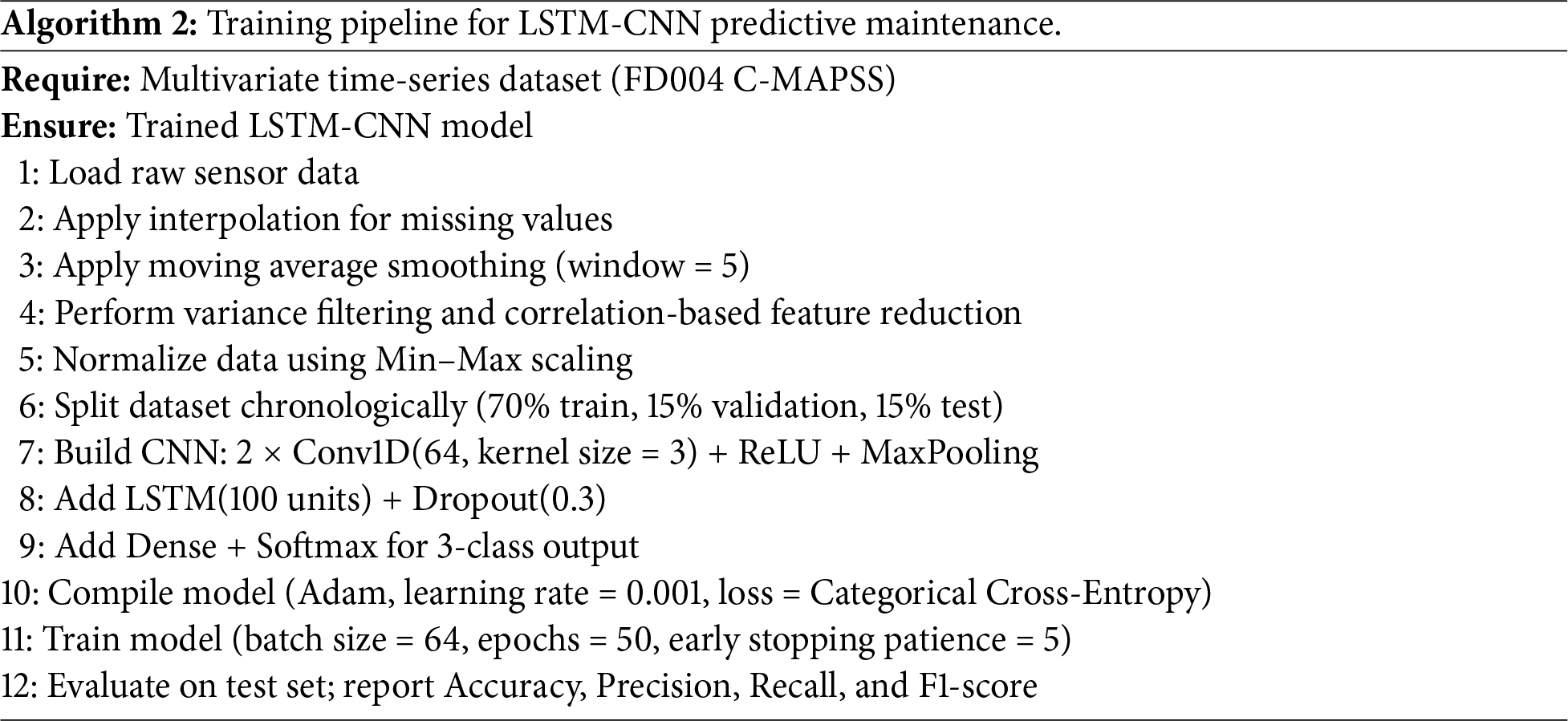

This pre-processing pipeline ensured that the dataset accurately represented real-world machinery behavior and supported the model’s ability to generalize across diverse degradation patterns. Algorithm 2 summarizes the end-to-end training process. The complete implementation, including preprocessing scripts and trained models:

6.1 Analysis of the LSTM–CNN Hybrid Model

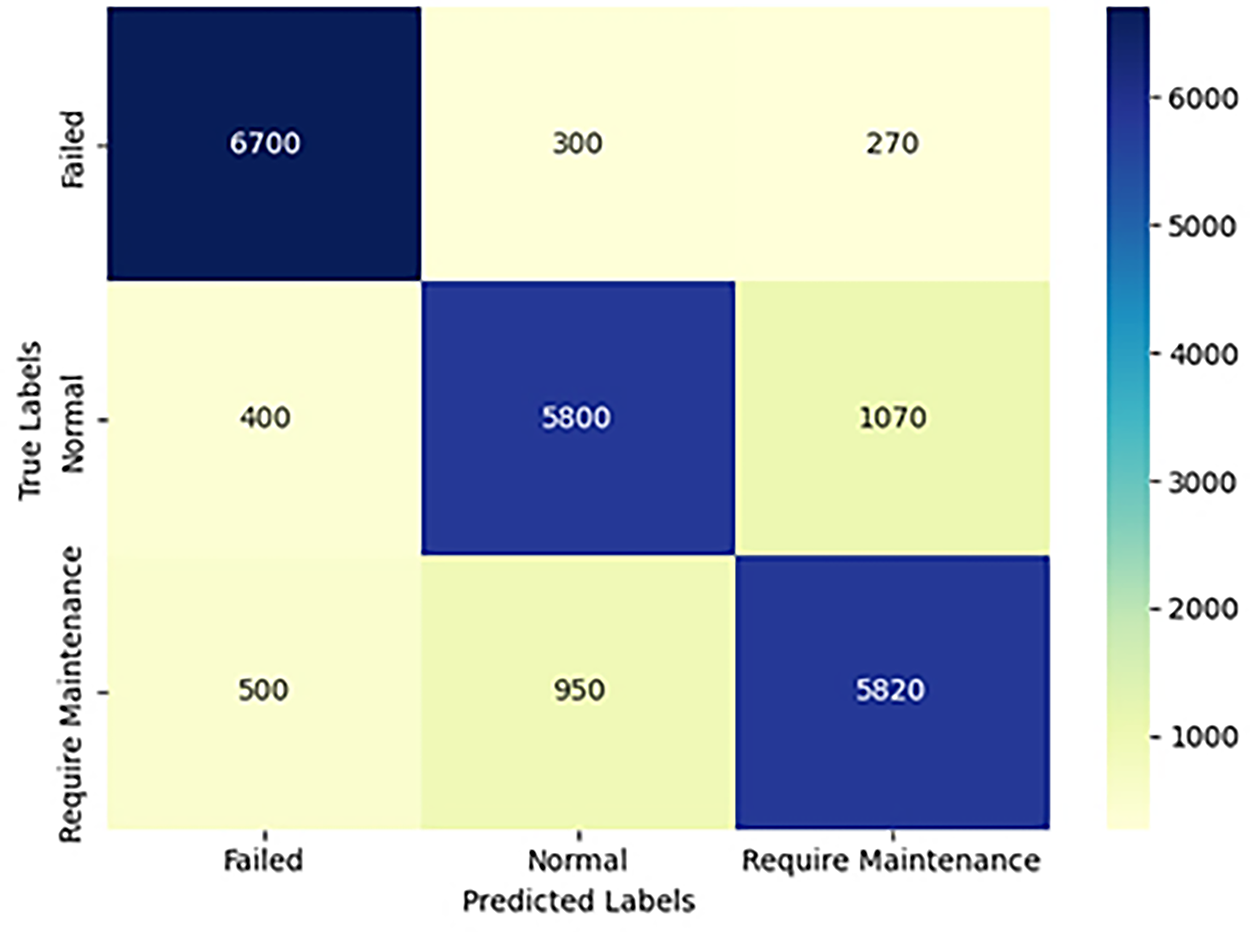

We first evaluate the hybrid LSTM–CNN model for predicting equipment health states. The classification performance of the proposed hybrid was assessed using confusion matrix analysis as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Confusion matrix of the LSTM–CNN model

The results highlight the classification performance of the LSTM–CNN model across three health states (i.e., Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed). The model shows high accuracy when identifying failed cases by correctly classifying 6700 instances while mistakenly labeling 300 as Normal and 270 as Require Maintenance. The model exhibited strong performance in identifying Normal states with 5800 correct classifications, but still misclassified some as Require Maintenance 1070 and Failed 400 states. The Require Maintenance category causes the most confusion because, although 5820 samples were correctly identified, 950 samples were wrongly classified as Normal, and 500 samples were mislabeled as Failed. Real-world scenarios frequently have unclear boundaries between Normal and degrading conditions, which leads to this overlap. The performance matrix indicates that the hybrid model demonstrates robust capabilities, especially in identifying critical system failures and maintaining acceptable sensitivity levels for distinguishing between normal operations and maintenance-needed conditions.

6.2 Performance Evaluation by Metric

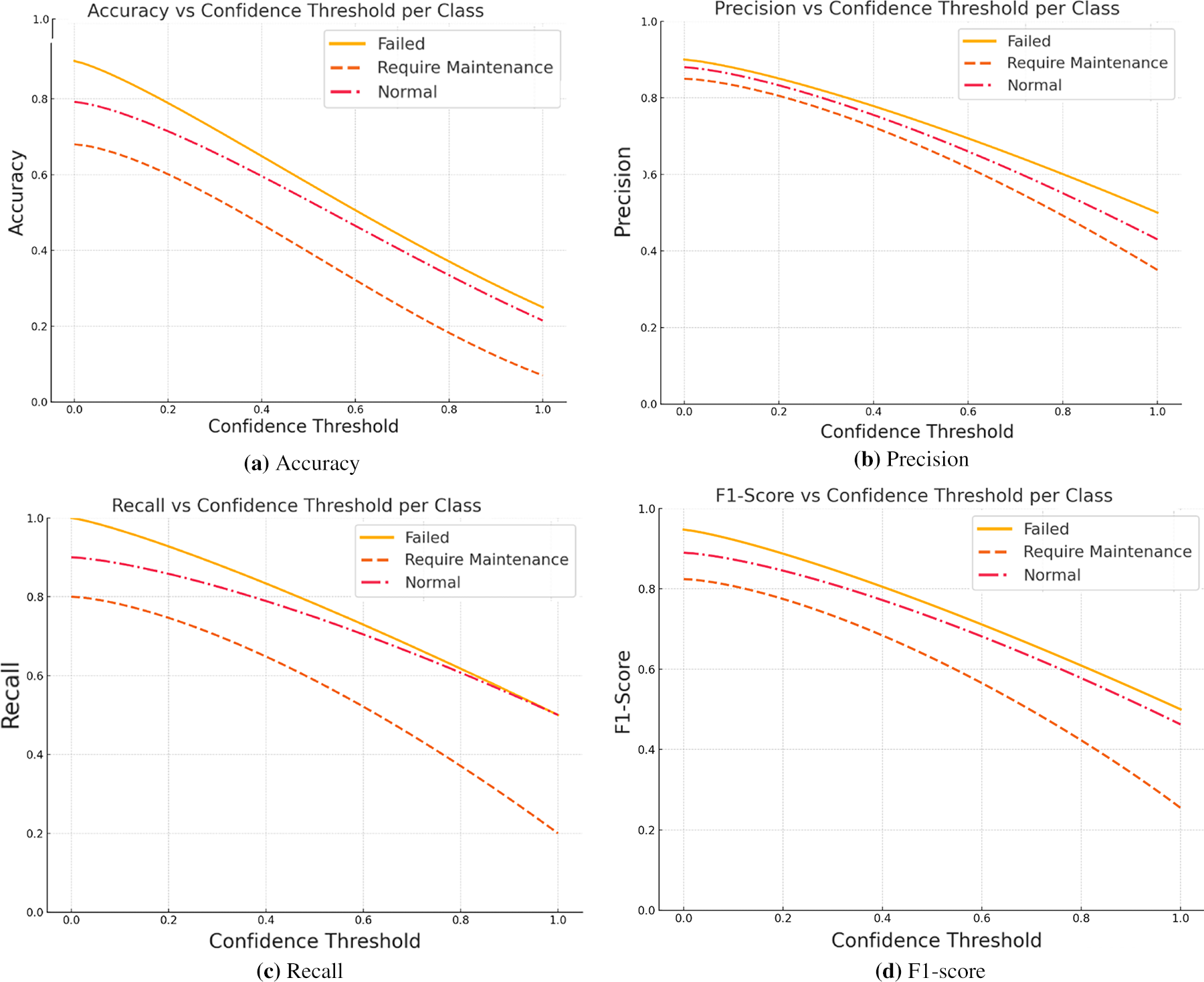

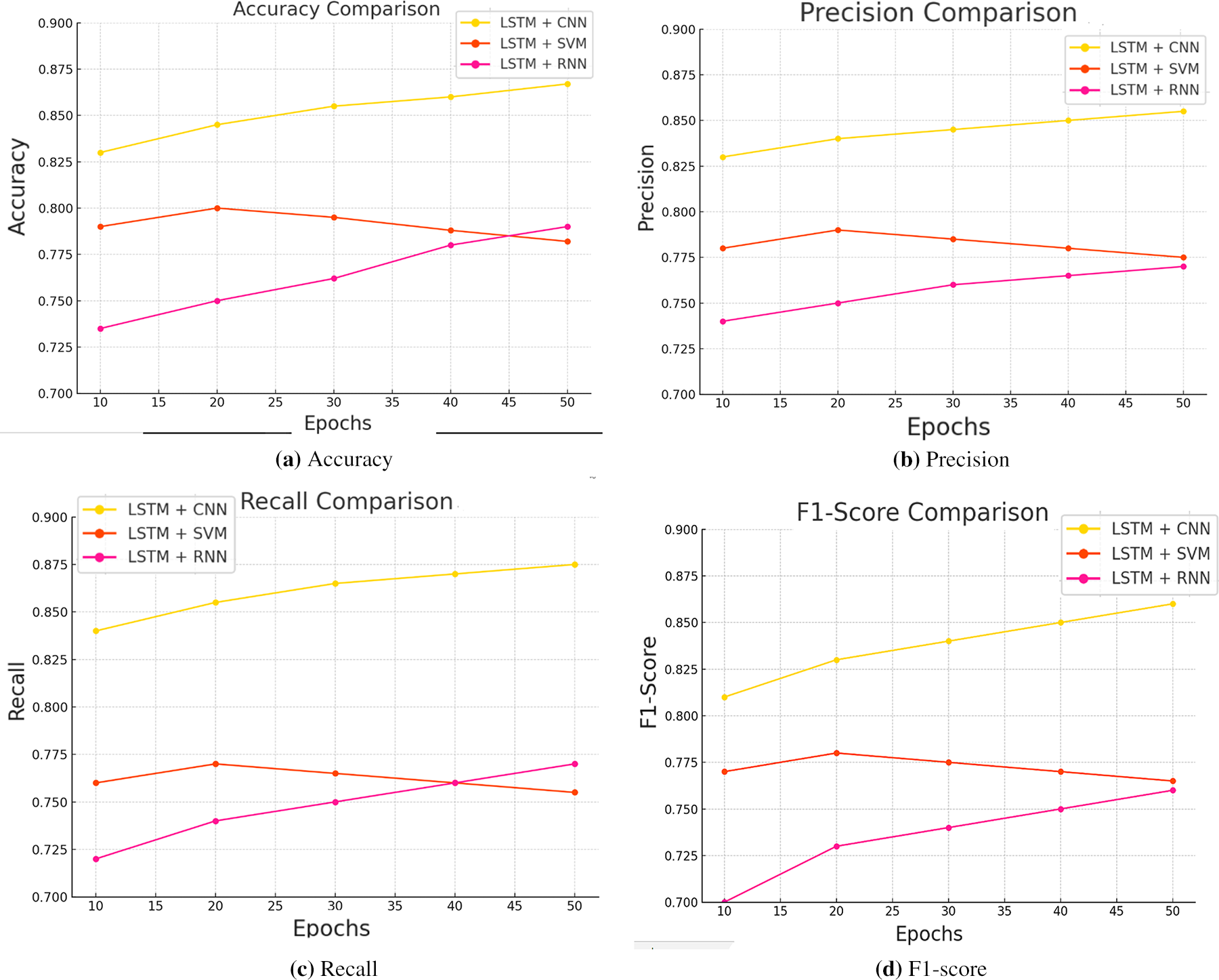

To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed hybrid model (LSTM-CNN), four key performance metrics were analyzed, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics were assessed for each of the three health states (i.e., Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed) based on the confusion matrix and validation performance. The results are summarized and visualized in Fig. 4a–d.

Figure 4: Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score of hybrid model

In Fig. 4a, the accuracy of the model is represented, which achieved an overall classification accuracy of 85.00% within the first 30 epochs. It demonstrated particularly robust performance in identifying the Failed class, with a class-specific accuracy of 93.00%, which is crucial for minimizing unexpected breakdowns. The Normal and Require Maintenance classes were also well recognized, with accuracy of 85.00% and 82.00%, respectively. In Fig. 4b, precision measures the proportion of true positives among all predicted positives. The model achieved 91.00% precision in predicting Failed states, 89.00% for Normal, and 78.00% for Require Maintenance. These values suggest the model maintains a low false-positive rate, even for less critical classes. Recall scores indicate the model’s ability to capture all actual positives. The Failed class achieved the highest recall at 92.00%, followed by Normal at 87.00% and Require Maintenance at 80.00%. These results confirm the model’s robustness in identifying both immediate and early-stage faults, as shown in Fig. 4c. The last one, which is the F1-score as shown in Fig. 4d, that is a measure of precision and recall balance, was best for the Failed class at 92.00%, which also means that it is reliable and consistently detects critical failures. The obtained F1-scores for the other two classes, Normal and Require Maintenance, are 87.00% and 80.00%, respectively, which demonstrates that the model is still able to balance across all three classes.

6.3 Comparative Analysis and Discussion

In order to validate the proposed hybrid LSTM–CNN architecture, we conducted comparative experiments with two alternative architectures, LSTM-SVM and LSTM-RNN. We also computed the overall performance of the models in terms of their predictive accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, as well as their capabilities in identifying each equipment health state.

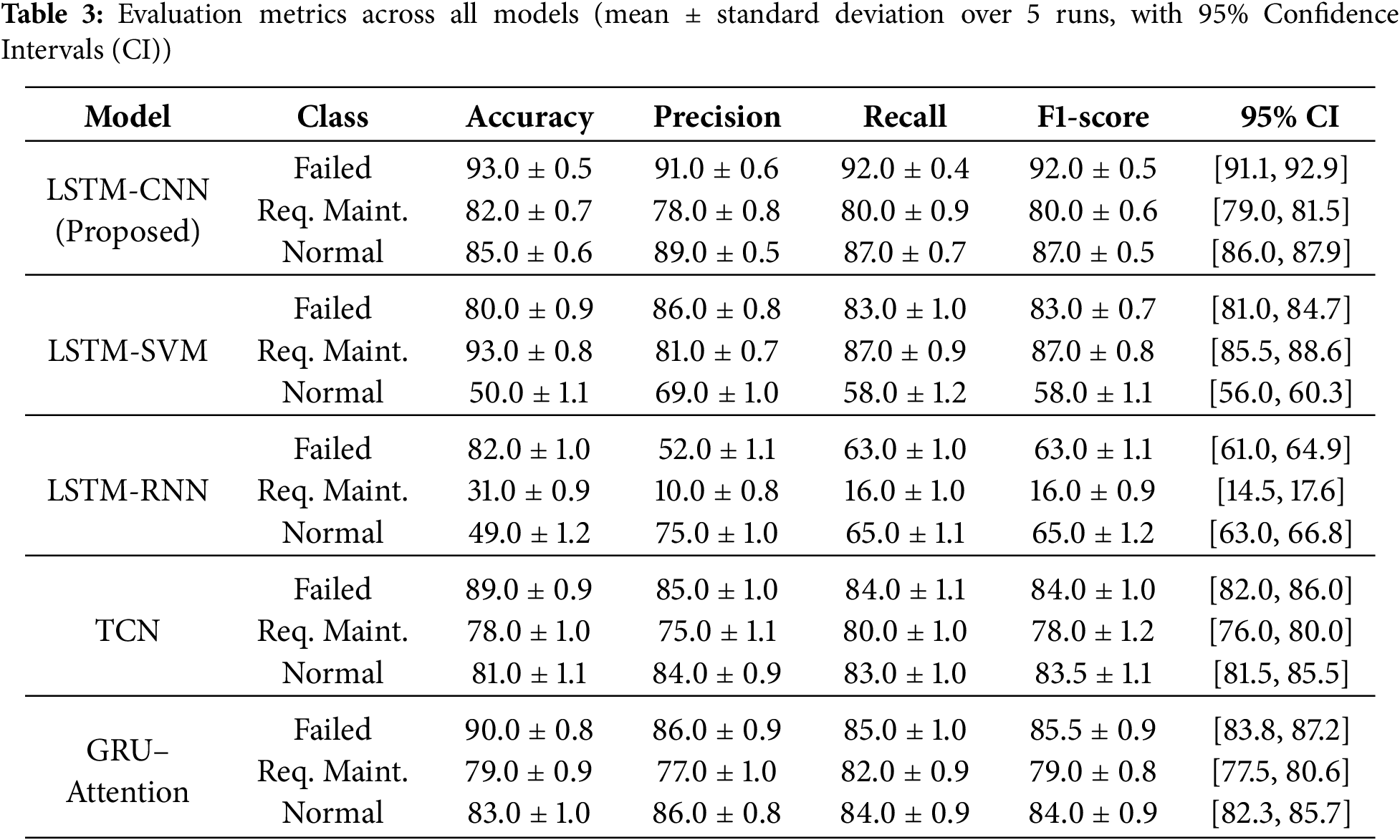

The proposed LSTM–CNN model demonstrated superior predictive performance, achieving 85% classification accuracy overall. It was able to accurately capture both spatial and temporal degradation patterns, resulting in high F1-scores across all three classes. The model obtained an F1-score of 92% for the Failed class and 87% for the Normal class. This suggests that the model is capable of detecting both catastrophic failures and healthy operating states with high reliability. Furthermore, its performance on the Require Maintenance class was also strong, with an F1-score of 80%. This suggests that the model is able to capture intermediate degradation patterns reasonably well.

In contrast, the LSTM-SVM model achieved a lower accuracy of 79%. While the LSTM-SVM model performs well in detecting the Require Maintenance state with an F1-score of 87%, its performance in the Normal class drops to 58% F1-score, revealing the model’s limitations in differentiating between stable operating conditions. This suggests that while traditional classifiers, such as SVM, may provide more robust decision boundaries, they may struggle with more nuanced sensor signal variations in real-time data.

The LSTM-RNN model had the lowest accuracy at 65%, and struggled significantly with the Require Maintenance class, achieving a mere 16% F1-score. This underscores the challenges of relying solely on sequential modeling without effective spatial feature extraction. While it performed moderately well on the Normal class, scoring 65% in F1-score, it lacked the discriminative capability to separate intermediate and failing states, which are critical in predictive maintenance applications.

The summary of the comparative result in Fig. 5a–d compares model performance over epochs across four key metrics. Fig. 5a shows that LSTM–CNN consistently maintained the highest accuracy, approaching 87% at the final epoch, while LSTM-RNN gradually improved and surpassed LSTM-SVM near the end. Fig. 5b highlights precision, with LSTM–CNN maintaining a steady lead, and LSTM-RNN showing improvement but still trailing. In Fig. 5c, the recall metric indicates strong performance for LSTM–CNN, particularly in capturing true positive cases, while LSTM-SVM deteriorates slightly across epochs. Fig. 5d illustrates F1-score progression, where LSTM–CNN again dominates, while LSTM-RNN slowly outpaced LSTM-SVM beyond epoch 40.

Figure 5: Comparison accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across all models

The comparative validation confirms the advantage of integrating CNN layers for local feature extraction with LSTM layers for temporal modeling. The hybrid approach allows the system to capture complex spatio-temporal patterns inherent in multivariate sensor data, a capability essential for accurate prediction in real industrial environments. Moreover, the confidence-based performance evaluation showed that the LSTM–CNN model maintained high recall and F1-score values even at moderate confidence thresholds. The recall remained above 85% up to a threshold of 0.7, while the F1-score remained stable above 80% up to a threshold of 0.65 (i.e., as shown in Fig. 4). This demonstrates that the model is robust under uncertain conditions and suitable for real-time deployment where the cost of false negatives can be high. It is worth mentioning that no synthetic resampling techniques (e.g., SMOTE or data augmentation) were applied to alter class balance. This decision was made to preserve the natural degradation behavior captured in the dataset. Artificially changing the sequences was found to distort the realistic progression of faults, potentially leading to misleading training signals. Instead, carefully chosen RUL thresholds were used to ensure natural yet balanced class distributions without compromising data authenticity.

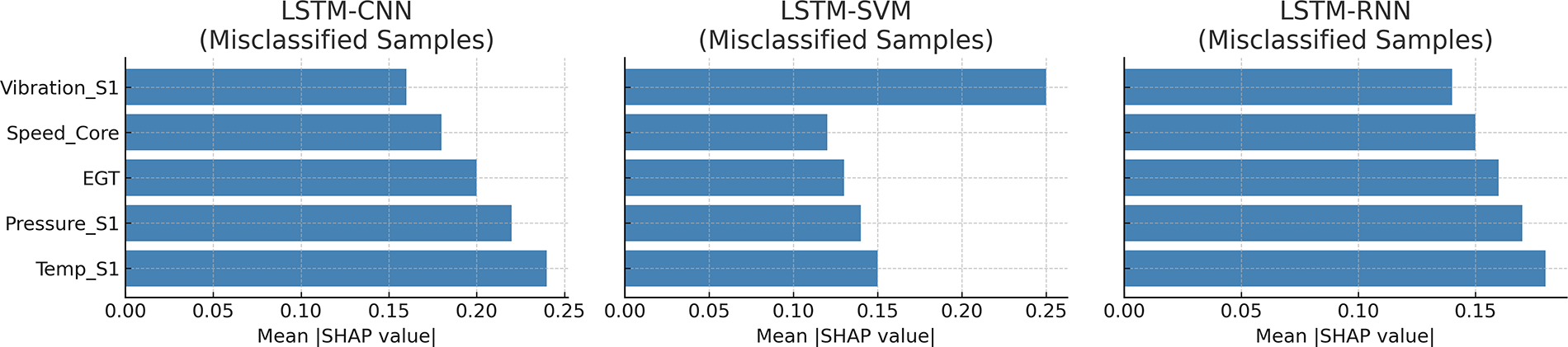

To better understand and increase interpretability, we also performed SHAP-based analysis on misclassified samples from the three baseline models (i.e., LSTM-CNN, LSTM-SVM, and LSTM-RNN). Fig. 6 visualizes the average feature importance (i.e., mean |SHAP| values) that drives the incorrect predictions. In the LSTM-CNN model, temperature and pressure signals drive the most misclassifications. This suggests that the marginal cases of Normal and Require Maintenance are more challenging to distinguish, which is consistent with the gradual process nature of early degradation. In the LSTM-SVM model, vibration features are overly favored, leading to its overreaction in stable operating conditions and failure in correctly classifying the Normal state. By contrast, there is no clear feature that dominates in the LSTM-RNN model, consistent with the above analysis of the overall poorer performance in capturing complex spatio-temporal patterns. To sum up, LSTM-CNN is the most robust and interpretable, but can be further improved with attention-based model mechanisms to highlight degradation-critical signals better. Meanwhile, feature attribution analysis is a complementary evaluation to metrics such as accuracy, as it provides further insights into where different architectures may lead to systematic errors in real-world predictive maintenance.

Figure 6: SHAP summary for misclassified samples across different models

Table 3 summarizes the complete comparison across all models and classes, consolidating the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score values. For a more comprehensive comparison, we also considered two recent architectures, Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) with attention mechanism (GRU–Attention), which were also proposed as competitive baselines for time-series classification in the predictive maintenance context. While both baselines could obtain comparable results to our LSTM-CNN, our model outperforms them in terms of both overall accuracy and macro F1-score, with the LSTM-CNN reaching an average F1-score of

Finally, despite its robust performance, the hybrid model exhibited some confusion between the Normal and Require Maintenance classes. This is expected due to the gradual and overlapping nature of early degradation stages in industrial equipment. Future improvements may include attention mechanisms or Transformer-based enhancements to focus on degradation-critical signals and improve distinction in borderline cases. In conclusion, the LSTM–CNN hybrid framework demonstrated a reliable and balanced performance across all key metrics, validating its suitability for predictive maintenance tasks that demand early, accurate, and interpretable fault classification under real-world conditions.

This paper introduced a predictive maintenance framework that depends on a proposed hybrid model that exploits Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to enhance predictive maintenance in smart industrial systems. By leveraging real-world sensor data from the NASA C-MAPSS FD004 dataset, the proposed model effectively classified machinery health into three categories, including Normal, Require Maintenance, and Failed. The integration of spatial pattern extraction through CNNs and temporal sequence modeling via LSTMs enabled the model to detect both early-stage degradation and imminent failures with high reliability. Among the evaluated configurations, the LSTM-CNN model achieved the highest overall accuracy of 86.66% and demonstrated superior F1-scores across all health classes, affirming its robustness and practical applicability for real-time industrial deployment. The novelty of this research work can be attributed to the LSTM-CNN hybrid model and three methodological contributions, including i) a three-class maintenance model that corresponds to the stages in the decision-making during operation, ii) a threshold-based labeling scheme that does not sacrifice the quality of the data, and iii) a modular design for the system with an emphasis on the deployment readiness.

While the proposed framework demonstrates promising results and robustness, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the model occasionally misclassifies ambiguous or borderline health states, such as Normal and Require Maintenance, which may stem from the inherent imprecision of early degradation stages. Secondly, the assessment was predominantly performed on a subset of the NASA C-MAPSS dataset, known as FD004, which is a well-established and widely used dataset; however, it may not accurately represent other industrial domains or sensor modalities. Thirdly, the hybrid LSTM-CNN architecture, while achieving accurate predictions, can be computationally demanding to train compared to lightweight alternatives, which may hinder its applicability in highly resource-constrained scenarios.

Looking ahead, future work will focus on enhancing the model by incorporating attention mechanisms, such as Transformer-based components, to improve its ability to prioritize critical signals within the multivariate time-series data. Further improvements may also involve extending the framework to include additional sensor modalities such as thermal imaging or acoustic data to enrich diagnostic accuracy. Finally, developing lightweight versions of the model for edge computing devices will support real-time inference at the equipment level, reducing latency and reliance on cloud infrastructure while enabling more responsive and scalable predictive maintenance solutions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Ayman Noor and Reyadh Alluhaibi; methodology, Atheer Aleran and Ayman Noor; software, Atheer Aleran and Hanan Almukhalfi; validation, Atheer Aleran and Hanan Almukhalfi; formal analysis, Atheer Aleran and Hanan Almukhalfi; investigation, Hanan Almukhalfi, Ayman Noor and Reyadh Alluhaibi; resources, Reyadh Alluhaibi and Talal H. Noor; data curation, Atheer Aleran and Hanan Almukhalfi; writing—original draft preparation, Atheer Aleran and Ayman Noor; writing—review and editing, Abdulrahman Hafez and Talal H. Noor; visualization, Atheer Aleran, Abdulrahman Hafez and Hanan Almukhalfi; supervision, Ayman Noor and Abdulrahman Hafez; project administration, Talal H. Noor; funding acquisition, Ayman Noor, Reyadh Alluhaibi, Abdulrahman Hafez and Talal H. Noor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study are publicly available from the FD004 subset of the NASA Commercial Modular Aero-Propulsion System Simulation (C-MAPSS) dataset at https://data.nasa.gov/dataset/c-mapss-aircraft-engine-simulator-data (accessed on 01 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Susto GA, Schirru A, Pampuri S, McLoone S, Beghi A. Machine learning for predictive maintenance: a multiple classifier approach. IEEE Trans Indus Inform. 2014;11(3):812–20. doi:10.1109/tii.2014.2349359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yazdi M. Maintenance strategies and optimization techniques. In: Advances in computational mathematics for industrial system reliability and maintainability. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 43–58 doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-53514-7_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Emilyn J, Kumar V, Azariya DS, Prakash M, Thamburaj SA. Deep learning-based predictive maintenance for industrial IoT applications. In: 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1197–202. [Google Scholar]

4. Alqattan D, Ojha V, Habib F, Noor A, Morgan G, Ranjan R. Modular neural network for edge-based detection of early-stage iot botnet. High-Confid Comput. 2025;5(1):100230. doi:10.1016/j.hcc.2024.100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Scott MJ, Verhagen WJ, Bieber MT, Marzocca P. A systematic literature review of predictive maintenance for defence fixed-wing aircraft sustainment and operations. Sensors. 2022;22(18):7070. doi:10.3390/s22187070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang P, Liu Y, Liu Z. A fault diagnosis method for rotating machinery in nuclear power plants based on long short-term memory and temporal convolutional networks. Ann Nucl Energy. 2025;213(1):111092. doi:10.1016/j.anucene.2024.111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bousdekis A, Papageorgiou N, Magoutas B, Apostolou D, Mentzas G. Sensor-driven learning of time-dependent parameters for prescriptive analytics. IEEE Access. 2020;8:92383–92. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2994933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Noor TH. Human action recognition-based IoT services for emergency response management. Mach Learn Knowl Extrac. 2023;5(1):330–45. doi:10.3390/make5010020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pech M, Vrchota J, Bednář J. Predictive maintenance and intelligent sensors in smart factory. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1470. doi:10.3390/s21041470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ayvaz S, Alpay K. Predictive maintenance system for production lines in manufacturing: a machine learning approach using IoT data in real-time. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;173(6):114598. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alabadi M, Habbal A, Guizani M. An innovative decentralized and distributed deep learning framework for predictive maintenance in the industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2024;11(11):20271–86. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3372375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Altunay HC, Albayrak Z. A hybrid CNN+LSTM-based intrusion detection system for industrial IoT networks. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2023;38:101322. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2022.101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhu J, Ge Z, Song Z, Gao F. Review and big data perspectives on robust data mining approaches for industrial process modeling with outliers and missing data. Annu Rev Control. 2018;46(12):107–33. doi:10.1016/j.arcontrol.2018.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lee J, Ni J, Singh J, Jiang B, Azamfar M, Feng J. Intelligent maintenance systems and predictive manufacturing. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2020;142(11):110805. doi:10.1115/1.4047856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen K, Zhang D, Yao L, Guo B, Yu Z, Liu Y. Deep learning for sensor-based human activity recognition: overview, challenges, and opportunities. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2021;54(4):1–40. doi:10.1145/3447744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang H, Guo H, Shang J, Peng K. SpatioTemporal generative adversarial network for industrial fault diagnosis with imbalanced data. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:3524811. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3551442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Noor TH, Noor A, Alharbi AF, Faisal A, Alrashidi R, Alsaedi AS, et al. Real-time arabic sign language recognition using a hybrid deep learning model. Sensors. 2024;24(11):3683. doi:10.3390/s24113683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang H, Zhang W, Yang D, Xiang Y. Deep-learning-enabled predictive maintenance in industrial internet of things: methods, applications, and challenges. IEEE Syst J. 2022;17(2):2602–15. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2022.3193200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Serradilla O, Zugasti E, Rodriguez J, Zurutuza U. Deep learning models for predictive maintenance: a survey, comparison, challenges and prospects. Appl Intell. 2022;52(10):10934–64. doi:10.1007/s10489-021-03004-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Achouch M, Dimitrova M, Ziane K, Sattarpanah Karganroudi S, Dhouib R, Ibrahim H, et al. On predictive maintenance in industry 4.0: overview, models, and challenges. Appl Sci. 2022;12(16):8081. doi:10.3390/app12168081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Azari MS, Flammini F, Santini S, Caporuscio M. A systematic literature review on transfer learning for predictive maintenance in industry 4.0. IEEE Access. 2023;11:12887–910. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3239784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Peringal A, Mohiuddin MB, Hassan A. Remaining useful life prediction for aircraft engines using lstm. arXiv: 2401.07590. 2024. [Google Scholar]

23. Dallapiccola D. Predictive maintenance of centrifugal pumps: a neural network approach [master’s thesis]. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid; 2020. [Google Scholar]

24. Boujamza A, Elhaq SL. Attention-based LSTM for remaining useful life estimation of aircraft engines. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2022;55(12):450–5. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.07.353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chuya-Sumba J, Alonso-Valerdi LM, Ibarra-Zarate DI. Deep-learning method based on 1D convolutional neural network for intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machines. Appl Sci. 2022;12(4):2158. doi:10.3390/app12042158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Arellano-Espitia F, Delgado-Prieto M, Martinez-Viol V, Saucedo-Dorantes JJ, Osornio-Rios RA. Deep-learning-based methodology for fault diagnosis in electromechanical systems. Sensors. 2020;20(14):3949. doi:10.3390/s20143949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou Q, Tang J. An interpretable parallel spatial CNN-LSTM architecture for fault diagnosis in rotating machinery. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2024;11(19):31730–44. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3422969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhao D, Tian C, Fu Z, Zhong Y, Hou J, He W. Multi scale convolutional neural network combining BiLSTM and attention mechanism for bearing fault diagnosis under multiple working conditions. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):13035. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96137-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Khorram A, Khalooei M, Rezghi M. End-to-end CNN + LSTM deep learning approach for bearing fault diagnosis. Appl Intell. 2021;51(2):736–51. doi:10.1007/s10489-020-01859-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Stow MT. Hybrid deep learning approach for predictive maintenance of industrial machinery using convolutional LSTM networks. Int J Comput Sci Eng. 2024;12(4):1–11. [Google Scholar]

31. Kumar A, Wang S, Shaikh AM, Bilal H, Lu B, Song S. Building on prior lightweight CNN model combined with LSTM-AM framework to guide fault detection in fixed-wing UAVs. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2024;15(9):4175–91. doi:10.1007/s13042-024-02141-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Taye MM. Theoretical understanding of convolutional neural network: concepts, architectures, applications, future directions. Computation. 2023;11(3):52. doi:10.3390/computation11030052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Park J, Samarakoon S, Elgabli A, Kim J, Bennis M, Kim SL, et al. Communication-efficient and distributed learning over wireless networks: principles and applications. Proc IEEE. 2021;109(5):796–819. doi:10.1109/jproc.2021.3055679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mienye ID, Swart TG, Obaido G. Recurrent neural networks: a comprehensive review of architectures, variants, and applications. Information. 2024;15(9):517. doi:10.3390/info15090517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cacciari I, Ranfagni A. Hands-on fundamentals of 1D convolutional neural networks—a tutorial for beginner users. Appl Sci. 2024;14(18):8500. doi:10.3390/app14188500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Boulila W, Ghandorh H, Khan MA, Ahmed F, Ahmad J. A novel CNN-LSTM-based approach to predict urban expansion. Ecol Inform. 2021;64(5):101325. doi:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Gupta S, Kumar A, Maiti J. A critical review on system architecture, techniques, trends and challenges in intelligent predictive maintenance. Saf Sci. 2024;177(17):106590. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Aeronautics N. (NASA) SA. C-MAPSS aircraft engine simulator data; 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://data.nasa.gov/dataset/c-mapss-aircraft-engine-simulator-data. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools