Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Real-Time Cheating Behaviour Detection in Online Exams Using Video Captured Analysis

1 School of Computer Science, Duy Tan University, Danang, 550000, Vietnam

2 Faculty of Information Technology, Haiphong University, Haiphong, 180000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Dac-Nhuong Le. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 48 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070948

Received 28 July 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Online examinations have become a dominant assessment mode, increasing concerns over academic integrity. To address the critical challenge of detecting cheating behaviours, this study proposes a hybrid deep learning approach that combines visual detection and temporal behaviour classification. The methodology utilises object detection models—You Only Look Once (YOLOv12), Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (RCNN), and Single Shot Detector (SSD) MobileNet—integrated with classification models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU), and CNN-LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory). Two distinct datasets were used: the Online Exam Proctoring (EOP) dataset from Michigan State University and the School of Computer Science, Duy Tan Unievrsity (SCS-DTU) dataset collected in a controlled classroom setting. A diverse set of cheating behaviours, including book usage, unauthorised interaction, internet access, and mobile phone use, was categorised. Comprehensive experiments evaluated the models based on accuracy, precision, recall, training time, inference speed, and memory usage. We evaluate nine detector–classifier pairings under a unified budget and score them via a calibrated harmonic mean of detection and classification accuracies, enabling deployment-oriented selection under latency and memory constraints. Macro-Precision/Recall/F1 and Receiver Operating Characteristic-Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) are reported for the top configurations, revealing consistent advantages of object-centric pipelines for fine-grained cheating cues. The highest overall score is achieved by YOLOv12 + CNN (97.15% accuracy), while SSD-MobileNet + CNN provides the best speed–efficiency trade-off for edge devices. This research provides valuable insights into selecting and deploying appropriate deep learning models for maintaining exam integrity under varying resource constraints.Keywords

Recent advancements in e-learning technologies have significantly reshaped educational methodologies, leading to the widespread adoption of online examinations. While this digital transformation has enabled accessibility and convenience in educational practices, it has concurrently introduced challenges related to academic integrity, primarily the increasing incidence of student cheating during online assessments. Cheating activities during online examinations can generally be categorized into pre-exam and exam-time behaviors. Consequently, strategies designed to mitigate these activities often segment their approaches into phases corresponding to the timing of cheating occurrences: before, during, and after exams. Despite numerous initiatives, existing methodologies predominantly address isolated aspects of cheating detection rather than providing a comprehensive, systematic solution. Such fragmented approaches have demonstrated limited effectiveness in curbing cheating behaviors [1–3].

In response to these limitations, this study proposes a unified approach employing advanced deep learning techniques for video-based analysis aimed at comprehensive cheating detection in online examinations. Our proposed methodology integrates multiple deep learning models, specifically leveraging object detection and classification algorithms to precisely identify and classify various cheating behaviors. We particularly focus on detecting activities such as interactions with unauthorized individuals (e.g., another face detected), the illicit use of mobile phones, and unauthorized use of books or notes. This study rigorously evaluates and compares state-of-the-art object detection models including Faster-RCNN, SSD MobileNet, and YOLOv12, alongside classification models such as Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), and CNN-LSTM. Empirical results demonstrate that the combination of YOLOv12 and CNN models yields the highest accuracy, reinforcing their suitability for real-time cheating detection.

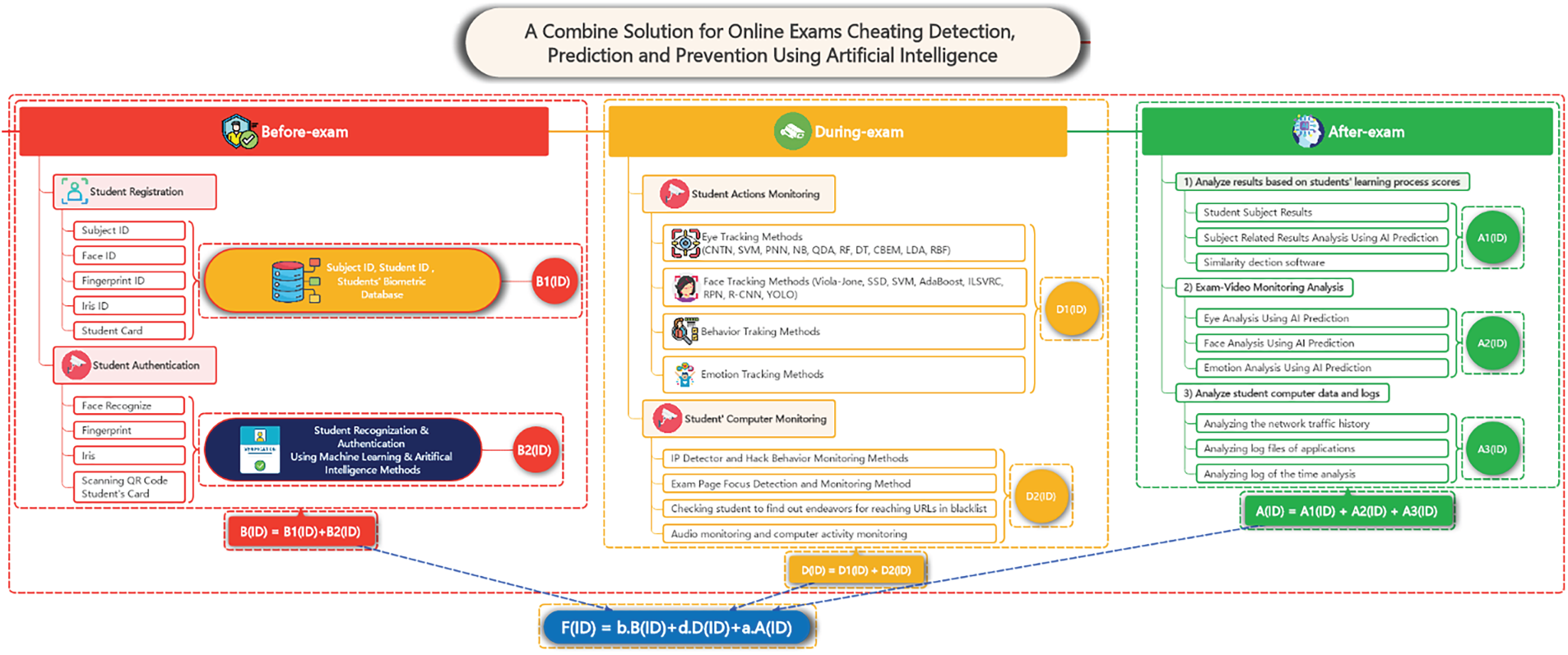

The system includes three modules to monitor identification, detect and prevent fraud before, during, and after the exam, as shown in Fig. 1 [1–3].

Figure 1: The solution proposed for exame cheating detection, prediction and prevention using artificial intelligence

The rest of this paper is divided into five sections. Section 2 presents the literature survey. Section 3 describes the proposed methodology. Section 4 covers the experimental setup and comparison of several algorithms. Finally, the conclusion is presented in the last section.

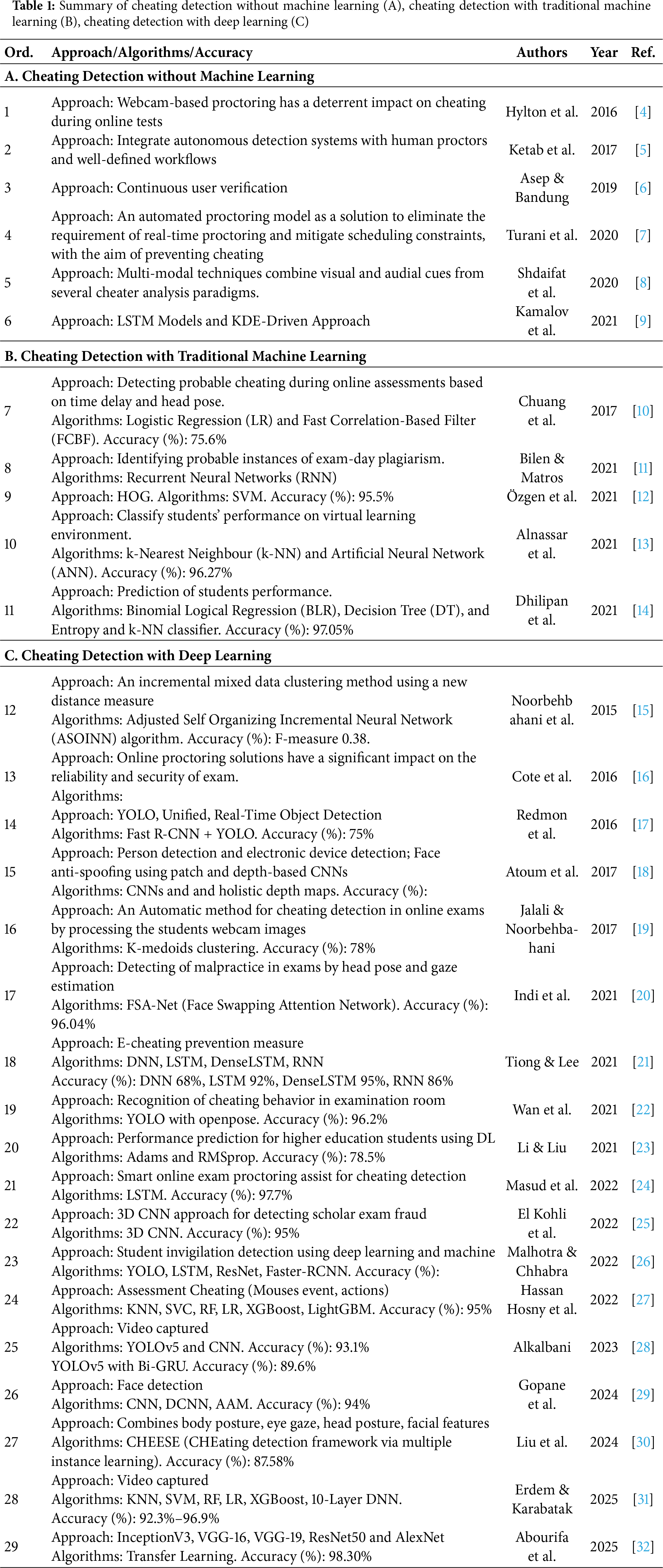

Existing literature on cheating detection in online examinations can be broadly classified into three categories: methods without machine learning, traditional machine learning-based methods, and deep learning-based methods. Cheating detection differs from broader in-class analytics in its need for small-object detection and explicit attribution of policy-violating items, which aligns with recent trends toward attention-centric detectors and object-aware temporal modeling. We further discuss how this contrasts with general engagement recognition and refer to recent surveys and application papers (including the reviewer-suggested reference) to position our contributions. We can summary of cheating detection approaches shown in Table 1.

Traditional approaches not involving machine learning primarily rely on webcam-based proctoring systems and human surveillance. For instance, Hylton et al. [4] discussed webcam-based proctoring systems as effective deterrents against cheating. Similarly, Ketab et al. [5] integrated autonomous detection mechanisms with human proctors, whereas Turani et al. [7] utilized automated proctoring models leveraging visual and audial cues to monitor students. However, these approaches require substantial human oversight, reducing scalability and efficiency.

Machine learning-based methods address scalability concerns by automating the detection process. Chuang et al. [10] employed logistic regression (LR) and Fast Correlation-Based Filter (FCBF) methods to detect cheating through head pose analysis. Similarly, Alnassar et al. [13] used Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) algorithms for performance classification with high accuracy rates. Despite these advancements, traditional machine learning models are often constrained by the necessity for extensive feature extraction and limited capability to generalize across diverse cheating scenarios.

Deep learning-based methods have emerged as highly effective due to their ability to automatically learn discriminative features from raw data. Notably, Atoum et al. [18] developed a model combining CNN-based face anti-spoofing techniques for automated online exam proctoring. Indi et al. [20] proposed the FSA-Net model for malpractice detection through head pose and gaze estimation, achieving significant accuracy. Further, YOLO-based models have become popular due to their speed and accuracy; Wan et al. [22] utilized YOLO with OpenPose achieving 96.2% accuracy, and recent studies by Erdem & Karabatak [31] demonstrated impressive accuracy with YOLOv5 combined with deep neural network (DNN) classifiers. These approaches illustrate the robustness and real-time applicability of deep learning methods in identifying complex cheating behaviors.

This paper builds upon these foundations by proposing a sophisticated integration of YOLOv12 and CNN models, aiming to enhance both detection precision and practical applicability in online exam environments.

3 Our Model Combination Proposed

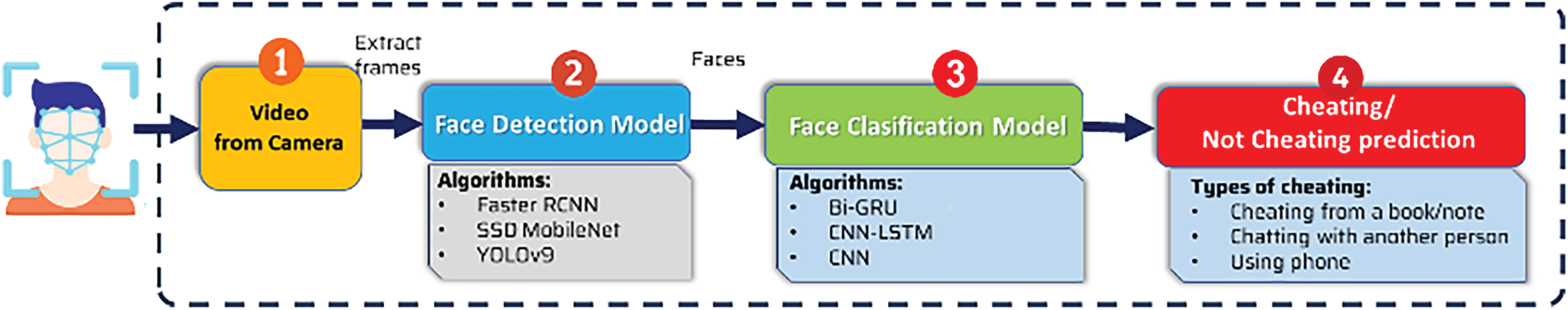

To address the previously outlined challenges in detecting cheating behaviors during online examinations, this study introduces a robust methodology combining advanced object detection and classification models using deep learning algorithms. The central objective is to accurately identify instances of cheating from video feeds captured during examinations and classify these events effectively to distinguish cheating from normal exam behaviors.

The proposed system comprises two integrated modules: (i) a face detection module responsible for identifying faces and related suspicious objects within video frames, and (ii) a face classification module that classifies detected faces as engaging or not engaging in cheating behaviors. Fig. 2 presents the comprehensive structure of our proposed solution.

Figure 2: Our effective two-models combination proposed for cheating detection problem

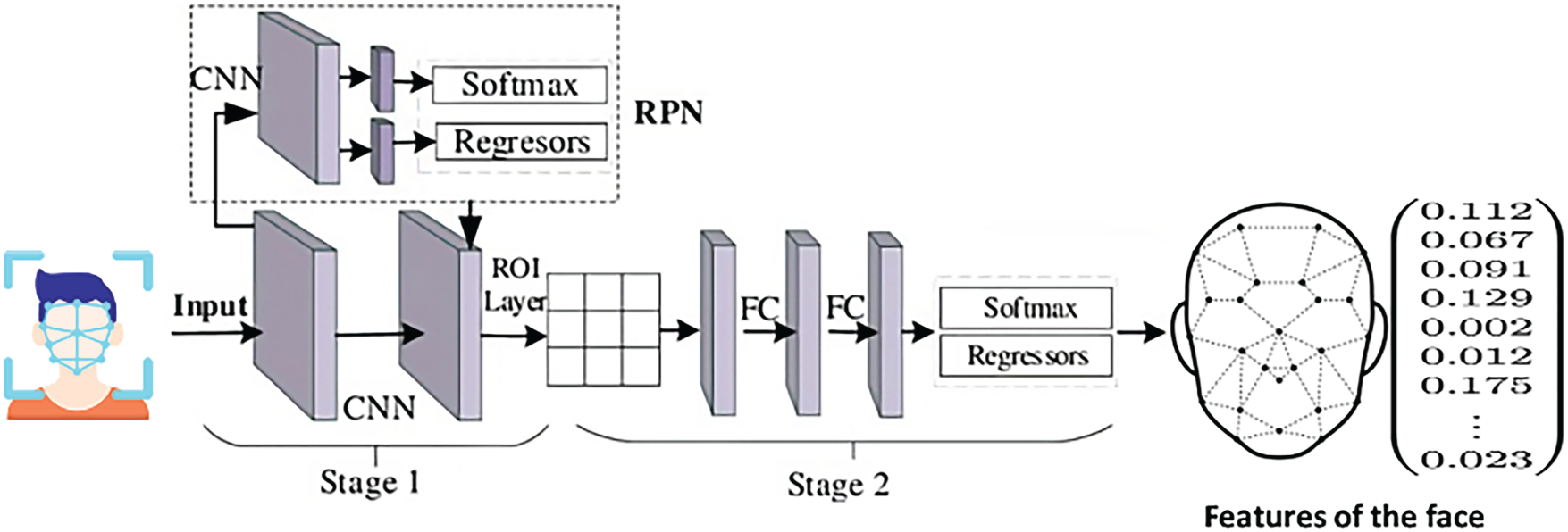

Faster RCNN [33] is a widely-used deep learning model that comprises two key modules: a Region Proposal Network (RPN) for generating candidate regions likely containing objects, and a Fast RCNN detector to refine these proposals into precise object detections. Due to its high accuracy, Faster RCNN is particularly suited to complex tasks like detecting faces and suspicious objects in exam environments. The Faster RCNN model comprises two main modules: a RPN and a detection network shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The faster RCNN model for face detection

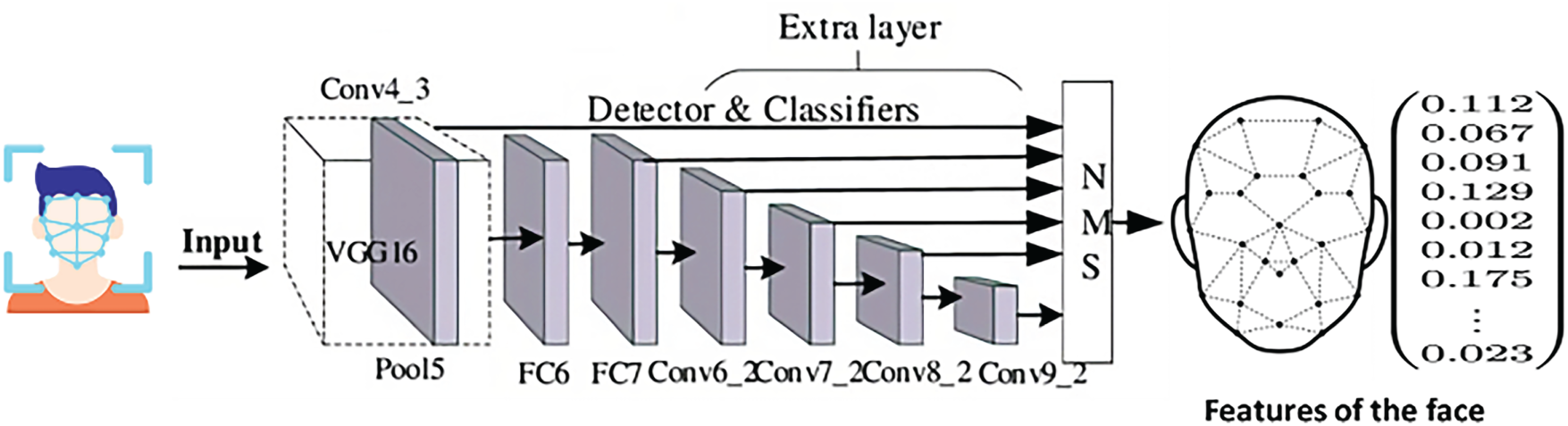

3.1.2 Single Shot Detector and MobileNet Model (SSDN MobiNet)

SSD MobileNet [34] integrates the MobileNet architecture, known for its efficiency and speed, with a Single Shot Detector (SSD), which performs object detection in a single forward pass through the neural network. This combination enables real-time face detection capabilities, particularly useful in resource-constrained environments like online exam proctoring systems. The SSD MobileNet model, shown in Fig. 4, consists of a base MobileNet network followed by a set of convolutional feature maps at different scales. These feature maps are then fed into a set of detection heads, which predict the locations and classes of objects in the input image.

Figure 4: The SSD MobileNet model for face detection

3.1.3 You Only Look Once (YOLOv12)

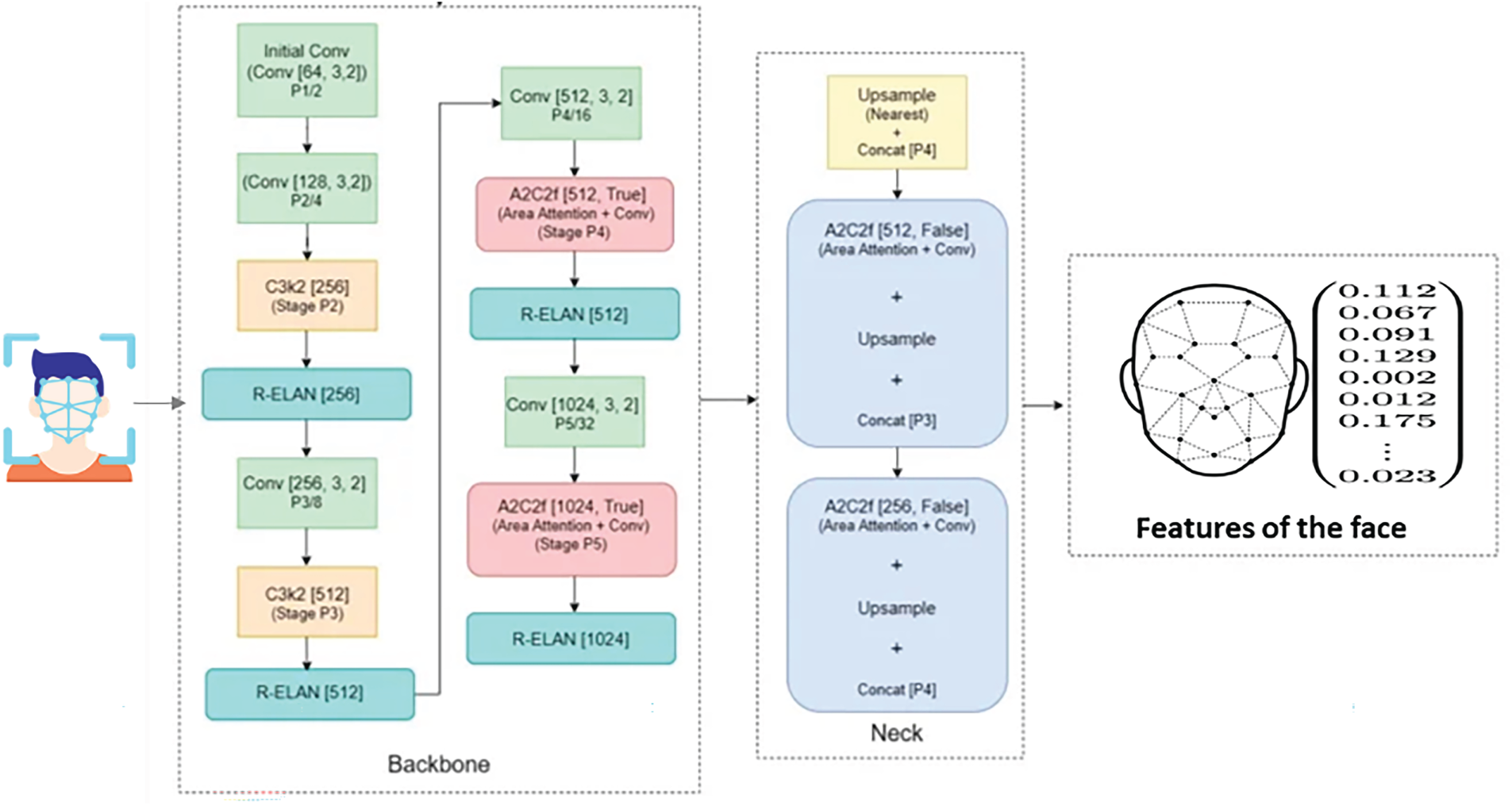

YOLOv12 [35] is an advanced one-stage object detection model that directly predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities. Leveraging the Swin Transformer v2 as its backbone architecture and RepOptimizer for optimization, YOLOv12 excels in accuracy and inference speed, making it particularly effective for real-time face and object detection during online examinations (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5: The YOLOv12 model for face detection

In this study, “YOLOv12” denotes an attention-centric one-stage detector as described in recent preprint literature. We implemented the model with a Swin-v2-style backbone and standard training heuristics (mosaic/copy-paste, EMA). To reduce dependency on a single architecture, we verified that substituting YOLOv8-s yields the same relative ranking across classifier heads (slightly lower absolute scores). We adopt a modern one-stage, anchor-free detector with a decoupled classification–regression head and a PAN-style multi-scale feature fusion neck. The backbone follows a Swin-v2–style hierarchical transformer; training uses 640 × 640 inputs with SGD (lr 0.01, momentum 0.9, weight decay 5 × 10−4) and depth/channel multipliers (0.33/0.25) to meet latency–memory budgets in Table 2. Empirically in our data, this detector gives higher recall on small handheld objects (e.g., phones) and multi-face scenes, which are frequent cheating cues in our setting (Section 4.4).

3.2 Face Classification Models

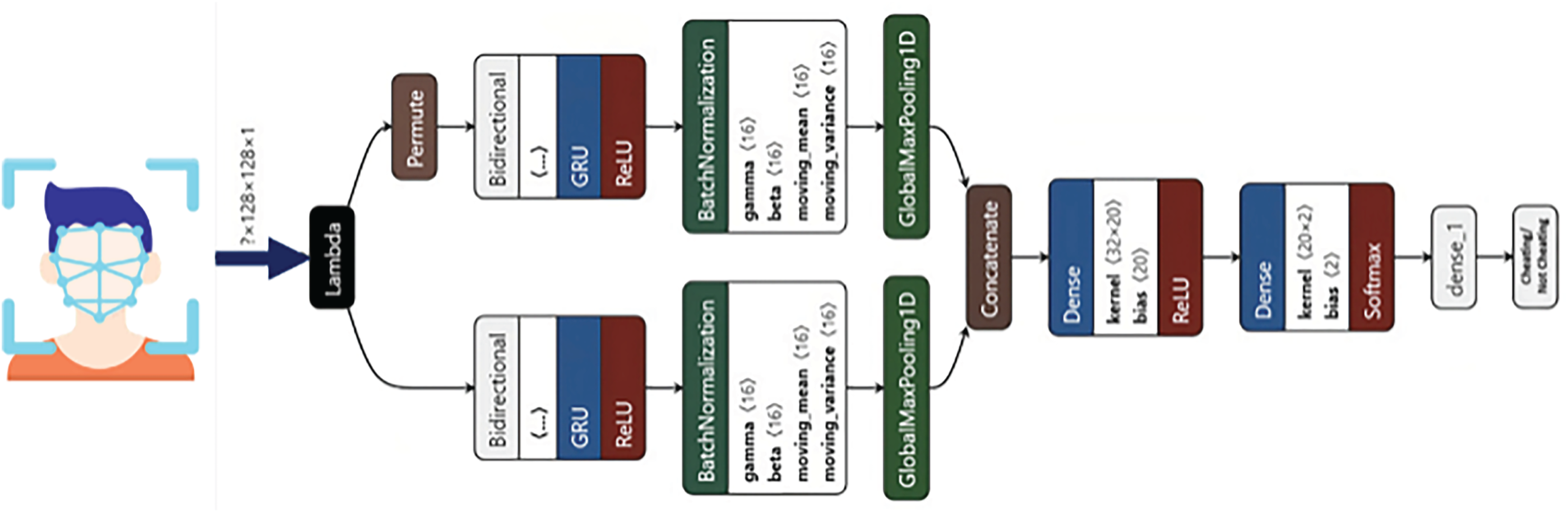

3.2.1 Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU)

Bi-GRU [36] is an advanced recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to process sequential data efficiently. By using gated mechanisms to selectively retain relevant information and discard irrelevant details, Bi-GRU effectively captures long-term dependencies within sequences. This capability is especially advantageous in recognizing subtle, sequential cheating behaviors, such as prolonged gaze shifts or repeated actions indicative of cheating. Fig. 6 shows the input of the face portion, and the output is the classification of cheating/not cheating. The bidirectional aspect of the model allows it to learn from both past and future context, which makes it more effective in capturing long-term dependencies in sequences of data.

Figure 6: The BiGRU model for cheating/not cheating face classification

3.2.2 Convolutional Neural Network and Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-LSTM)

CNN-LSTM [37] combines the spatial feature extraction strengths of CNNs with the temporal dependency modelling capabilities of LSTM networks. This hybrid approach allows for comprehensive analysis of both static image features and dynamic temporal sequences, beneficial in accurately classifying complex cheating behaviours.

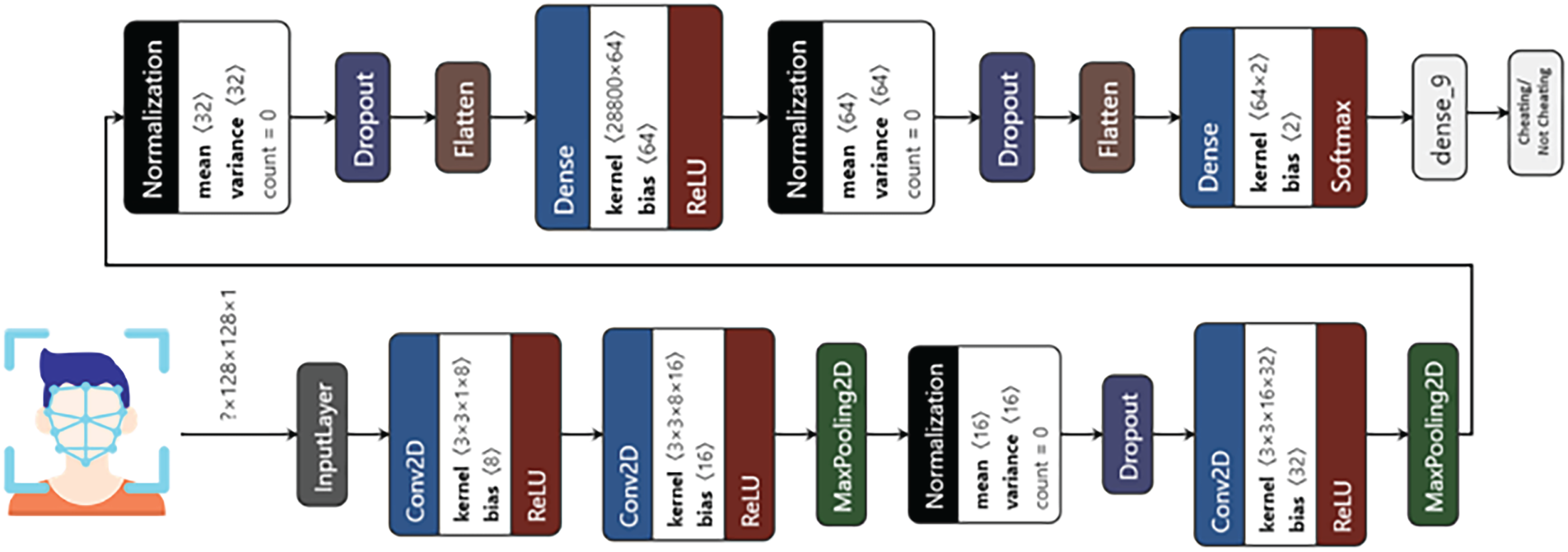

The CNN [38] architecture employed in this study adopts a standard deep image-classification pipeline composed of successive convolutional and pooling layers followed by fully connected layers. The convolutional layers apply learnable filters to each input frame, enabling hierarchical extraction of salient spatial patterns and discriminative features, while the pooling layers reduce spatial resolution and enhance invariance to local transformations. The final fully connected layers map the learned feature representations to a binary decision space, classifying each frame as cheating or non-cheating. As illustrated in Fig. 7, this architecture is particularly well suited to capturing subtle visual cues in individual exam frames, thereby allowing the system to effectively distinguish cheating behaviors from normal examination activities.

Figure 7: The CNN model for cheating/not cheating face classification

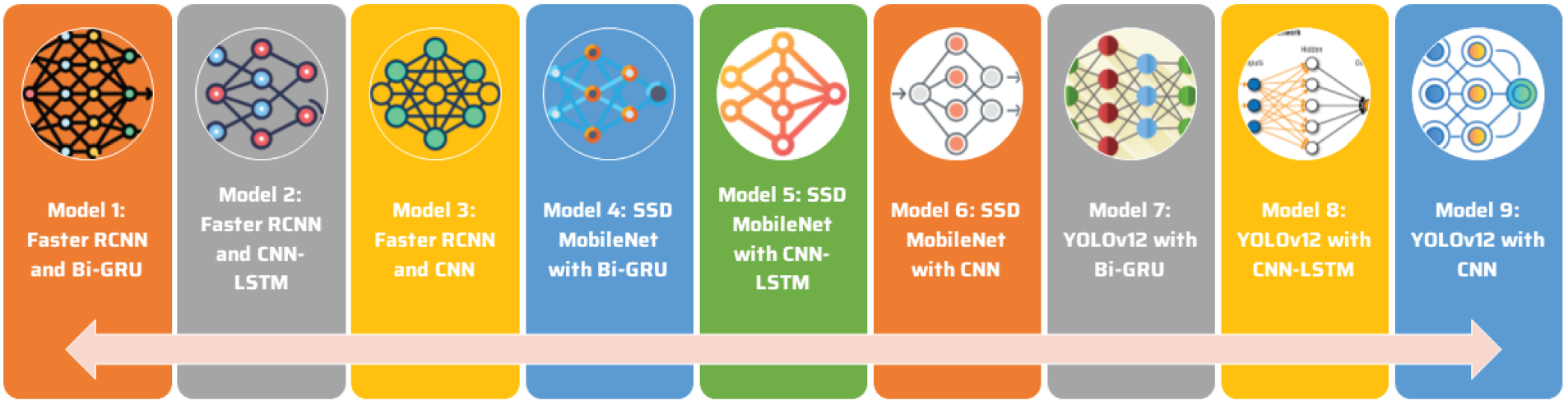

The effectiveness of the proposed methodology arises from strategically integrating face detection and classification models. In our approach, the detection model initially identifies faces and suspicious objects within each video frame. Subsequently, the classification model processes these detections to determine whether the identified behavior constitutes cheating. To rigorously evaluate the proposed approach, we conducted nine experimental combinations, leveraging various detection and classification models. Through comprehensive experiments on a custom dataset specifically designed for this research, we identified YOLOv12 coupled with CNN as the most effective combination, delivering the highest accuracy in identifying and classifying cheating behaviors in video-recorded online examinations (see Fig. 8).

Figure 8: The combined models proposed for cheating/not cheating face classification

4 Experimental Data and Results

This section describes the experimental setup, datasets employed, evaluation criteria, results analysis, and comparative insights regarding the performance of the proposed deep learning models in detecting cheating behaviors during online examinations.

Prior to the commencement of the examination, explicit rules were provided to participants, including prohibitions on the use of books, notes, mobile phones, laptops, and internet access, as well as a clear instruction to complete the exam independently. To simulate realistic cheating scenarios and diversify the dataset, experiments involved two distinct participant groups: actors instructed to simulate cheating without specific guidance on methods, and actual students unaware of testing conditions but subtly prompted by the proctor through interactions such as offering books, initiating conversation, or handing them unauthorized devices. The dataset captures five main categories of cheating behaviors: (1) Unauthorized use of books or notes; (2) Interaction or communication with another individual present in the examination room; (3) Unauthorized internet usage; (4) Communication via mobile phone calls; (5) Unauthorized usage of mobile phones for various activities. The deliberate inclusion of both simulated and realistic scenarios enriches the dataset, enabling robust analysis and ensuring that the proposed detection models generalize effectively across various cheating behaviors and circumstances.

Two datasets were utilized for this study:

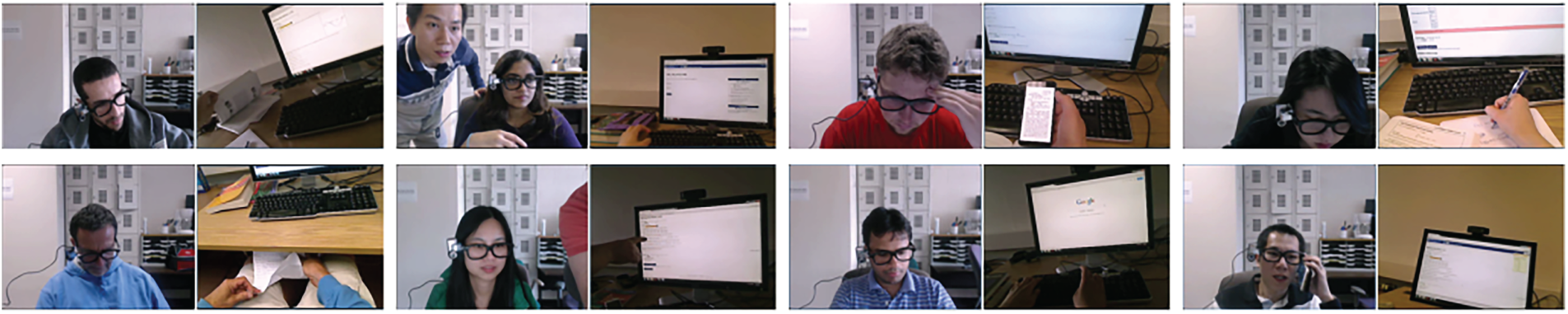

i) EOP dataset [28,39] comprises video recordings of 24 Michigan State University students completing online mathematics examinations, encompassing both normal test-taking behavior and explicitly annotated cheating events. Each recording has an average duration of approximately 17 min, and is accompanied by detailed offline annotations produced by human raters who jointly inspect the video and audio streams. For every cheating instance, the annotators specify the start time, end time, and cheating category, thereby providing temporally precise and semantically rich labels. Overall, roughly 20% of the recorded material corresponds to cheating behavior, while the remaining 80% reflects typical examination conduct (see Fig. 9).

ii) SCS-DTU Dataset: All DTU recordings were collected exclusively from volunteer students and staff in a controlled classroom simulation with prior written informed consent. No covert prompting was used; instead, cheating behaviors were scripted (e.g., placing a phone, opening a book, brief peer interaction) to ensure transparency and ethical compliance. Videos average 20 min with dual-camera views (face webcam + room view). We annotated five behavior classes with start/end timestamps (see Fig. 10).

Figure 9: The sample of OEP videos

Figure 10: The sample of SCS-DTU videos. (a) Zoom QT 502, (b) Zoom QT 507, (c) Zoom QT 508, (d) Zoom E401, (e) Zoom E403, (f) Zoom E404

Dataset statistics: SCS-DTU subset: n = 48 videos (mean 20.4 ± 3.2 min), 178 annotated cheating segments: book/notes (42), phone-in-hand (39), phone-call (21), peer interaction (31), web navigation (45). EOP subset: n = 24 videos (mean 17 ± 2.5 min), with public annotations.

Annotation protocol: Two annotators independently labeled segments from synchronized audio-video, followed by adjudication.

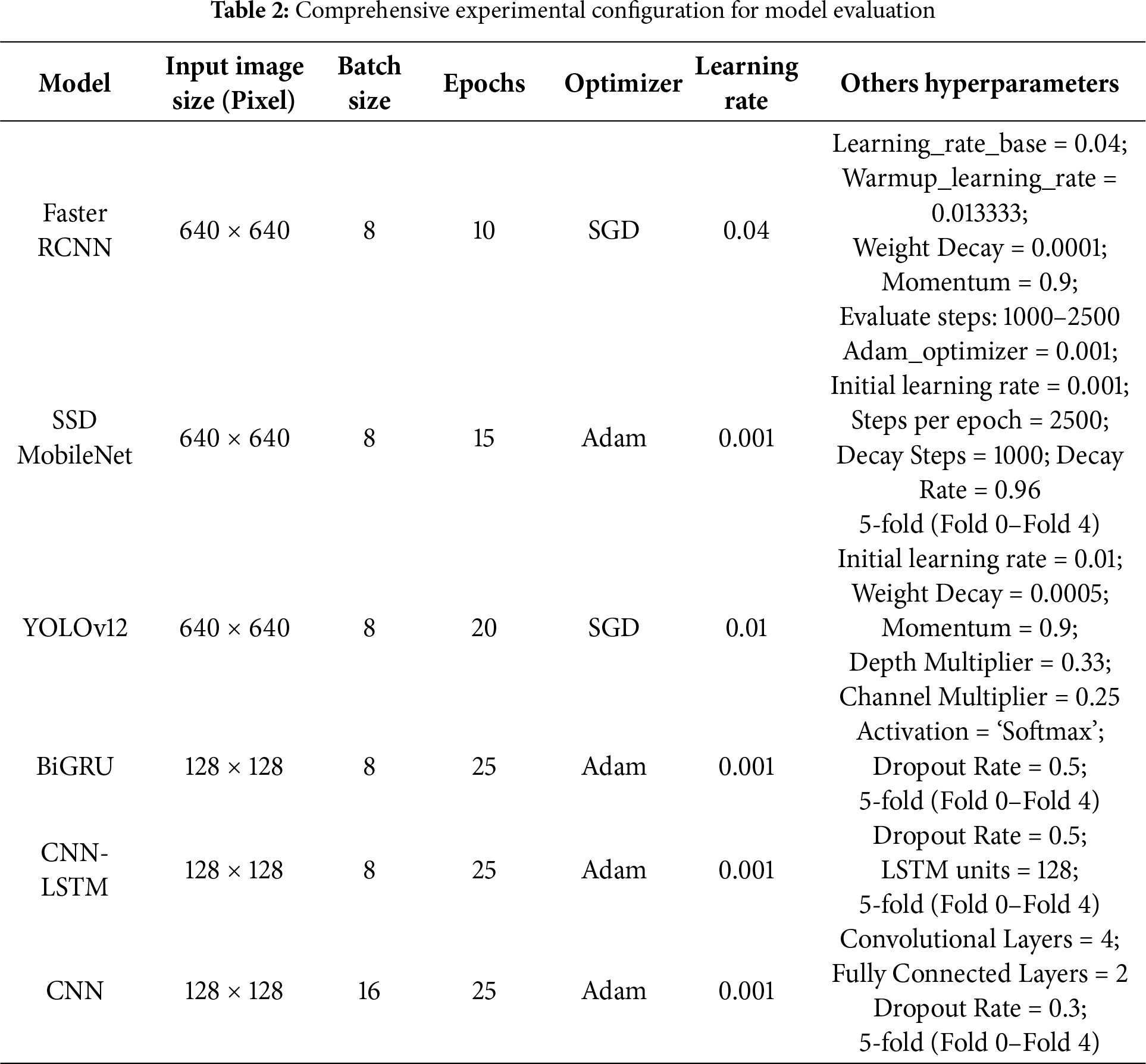

4.2 Setup and Hyper-Parameters

The experiments were conducted using Python 3.12 with TensorFlow 2.16.1, PyTorch 2.6, and CUDA 11.8 for GPU support. Datasets were partitioned into training and validation subsets to accurately evaluate model performance.

The models’ hyperparameters, such as image resolution, batch size, epochs, and optimizers, were fine-tuned individually for each model to achieve optimal performance. Detailed configurations for each model are presented in Table 2.

We standardize input sizes (detectors: 6402; classifiers: 1282), batch sizes, and epochs across combinations to ensure a fair budget. Cross-camera splits are used for DTU to test view-generalization.

Model performance was rigorously assessed using metrics such as precision, recall, accuracy, and ROC-AUC scores [28]. These metrics provided comprehensive insights into the models’ effectiveness in correctly detecting and classifying cheating behaviors. The following performance metrics can be evaluated:

The ROC-AUC as area under ROC, to combine detection and classification model we use harmonic mean to calculate the overall score (H), the harmonic mean of detector and classifier accuracies, encouraging balanced improvements. We use this equation:

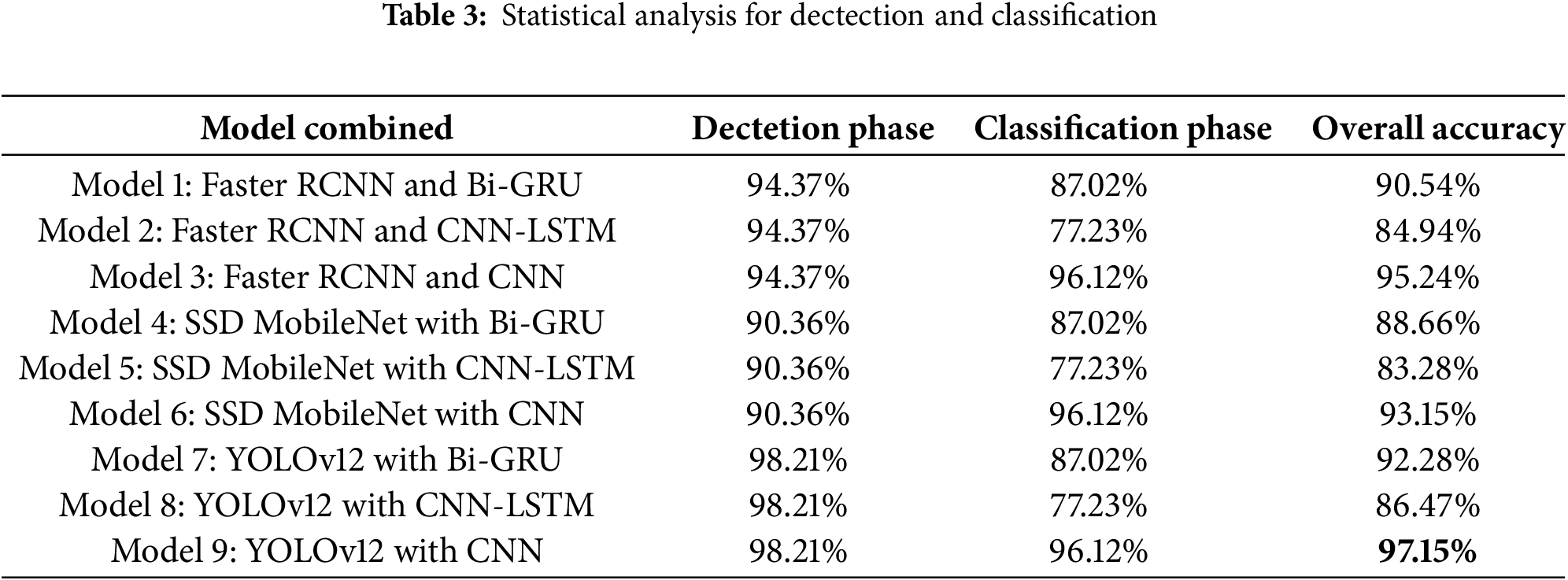

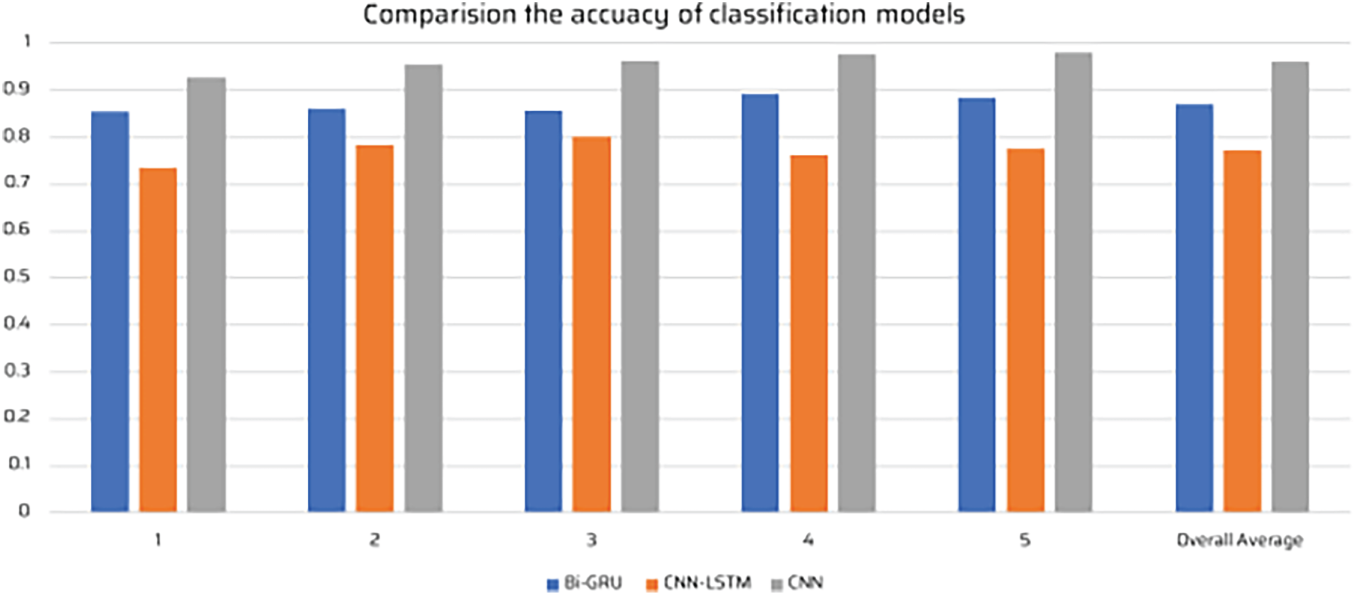

The experimental results indicate that the combination of object detection and classification models significantly improves the accuracy of online examination cheating detection. Table 3 presents the accuracy of different model combinations. Across nine detector–classifier pairings under a unified budget, two patterns emerge. First, object-centric detection with frame-wise classification consistently outperforms sequence models on our short, fast-changing clips: YOLOv12 + CNN gives the best balance of accuracy and practical latency, while SSD-MobileNet + CNN offers the best speed–efficiency trade-off for edge devices. Second, sequence models (Bi-GRU/CNN-LSTM) do not translate their theoretical advantages here: cheating cues are often small objects with brief visibility, so temporal aggregation can dilute strong per-frame evidence—explaining the gap to CNN.

Why CNN-LSTM underperforms in our setting. Our clips predominantly contain short-lived, object-centric cues (phones, books, a brief peer glance). Discriminative evidence is often confined to a few frames; when an LSTM aggregates over many benign frames, the signal can be diluted relative to a frame-wise CNN. Further, LSTM adds latency/parameters without offsetting accuracy gains on short sequences. Finally, dominant errors are tied to small objects and partial occlusions—phenomena better addressed by higher detector recall and high-quality per-frame features than by long-range temporal modeling.

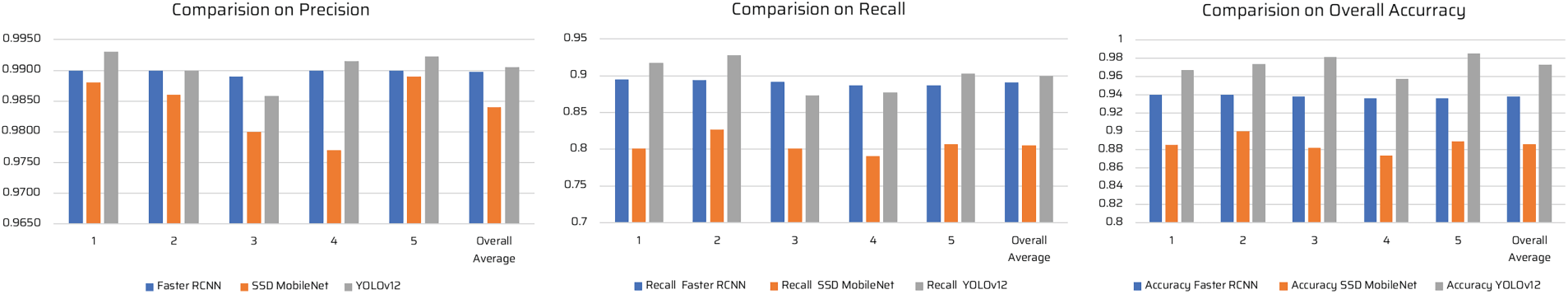

Figs. 11 and 12 illustrate the comparison of precision, recall, and accuracy across different detection methods from Fold 1 to Fold 5. It is evident that YOLOv12-based models consistently outperform other methods, particularly when paired with CNN. Faster-RCNN and SSD MobileNet also yield competitive results, but their overall performance is lower than YOLOv12. From the precision-recall curves, it is observed that YOLOv12 has a higher true positive rate compared to Faster-RCNN and SSD MobileNet, demonstrating its robustness in detecting cheating activities in online examinations. Furthermore, the CNN model’s classification capability outperforms Bi-GRU and CNN-LSTM in terms of distinguishing cheating behaviors from normal actions, particularly in scenarios involving subtle movements such as using a mobile phone or hidden notes.

Figure 11: Comparision on precision, recall and accuracy of the dectection methods with Fold 1 to Fold 5

Figure 12: Comparison of precision, recall, and accuracy across folds for detector backbones

Beyond headline accuracy, YOLO-based detectors exhibit higher recall on small handheld objects (phones) and multi-face scenes. CNN classifiers are less prone to temporal dilution on short clips, explaining the gap to CNN-LSTM. Error analysis shows most false positives arise from glare artifacts and hand-held non-phone objects; false negatives cluster in occluded books under low light. We include qualitative successes/failures with per-panel labels: (a) book/notes, (b) phone-in-hand, (c) phone-call, (d) peer interaction, (e) web navigation; green = detections, label = class, score. The sample of cheating detection results from SCS-DTU videos show in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: Qualitative results on DTU/EOP

In this section, we determine the best accuracy for each model by training with different hyperparameter configurations for both the object detection and classification tasks. In particular, we vary the batch size used during training for each model, as this parameter directly influences the gradient update dynamics and can therefore affect convergence and generalization performance. Batch size specifies the number of samples processed before each model update. Our initial plan was to conduct a more exhaustive hyperparameter search (e.g., exploring additional learning rates and other training settings) to further investigate potential accuracy gains. However, due to time constraints, we restricted our experiments to batch-size variations. Even with this limitation, the models trained with the selected batch sizes achieved noticeably improved accuracy compared to the original baseline results.

Table 3 presents accuracy metrics for different combinations of face detection and classification models. The logical evaluation of the data from this table reveals the following:

– The YOLOv12 + CNN model achieved the highest overall accuracy (97.15%), suggesting that YOLOv12 excels in real-time detection capabilities, and CNN is highly effective at feature recognition and classification tasks. The pairing leverages YOLO’s real-time detection efficiency and CNN’s classification accuracy.

– Faster RCNN-based models:

+ Faster RCNN + CNN (95.24%): Performed notably well, highlighting Faster RCNN’s strength in accurate detection, paired effectively with CNN’s classification capability.

+ Faster RCNN + Bi-GRU (90.54%): Also performed strongly, suggesting that Bi-GRU effectively captures temporal sequences but slightly less efficiently than CNN.

+ Faster RCNN + CNN-LSTM (84.94%): Demonstrated weaker classification results, indicating that CNN-LSTM struggled to capture necessary temporal-spatial features effectively for this specific task.

– SSD MobileNet-based models:

+ SSD MobileNet + CNN (93.15%): Achieved respectable performance, balancing efficiency and accuracy effectively.

+ SSD MobileNet + Bi-GRU (88.66%): Moderately effective, suggesting Bi-GRU may struggle with capturing finer spatial details when combined with lightweight models like SSD MobileNet.

+ SSD MobileNet + CNN-LSTM (83.28%): Lowest among SSD models, again indicating that CNN-LSTM may not be optimal for this particular classification task.

– YOLOv12 + Bi-GRU (92.28%) and YOLOv12 + CNN-LSTM (86.47%): These combinations showed substantial accuracy drops compared to YOLOv12 + CNN, suggesting limitations of Bi-GRU and CNN-LSTM in efficiently handling the complexity and immediacy of cheating behavior classification.

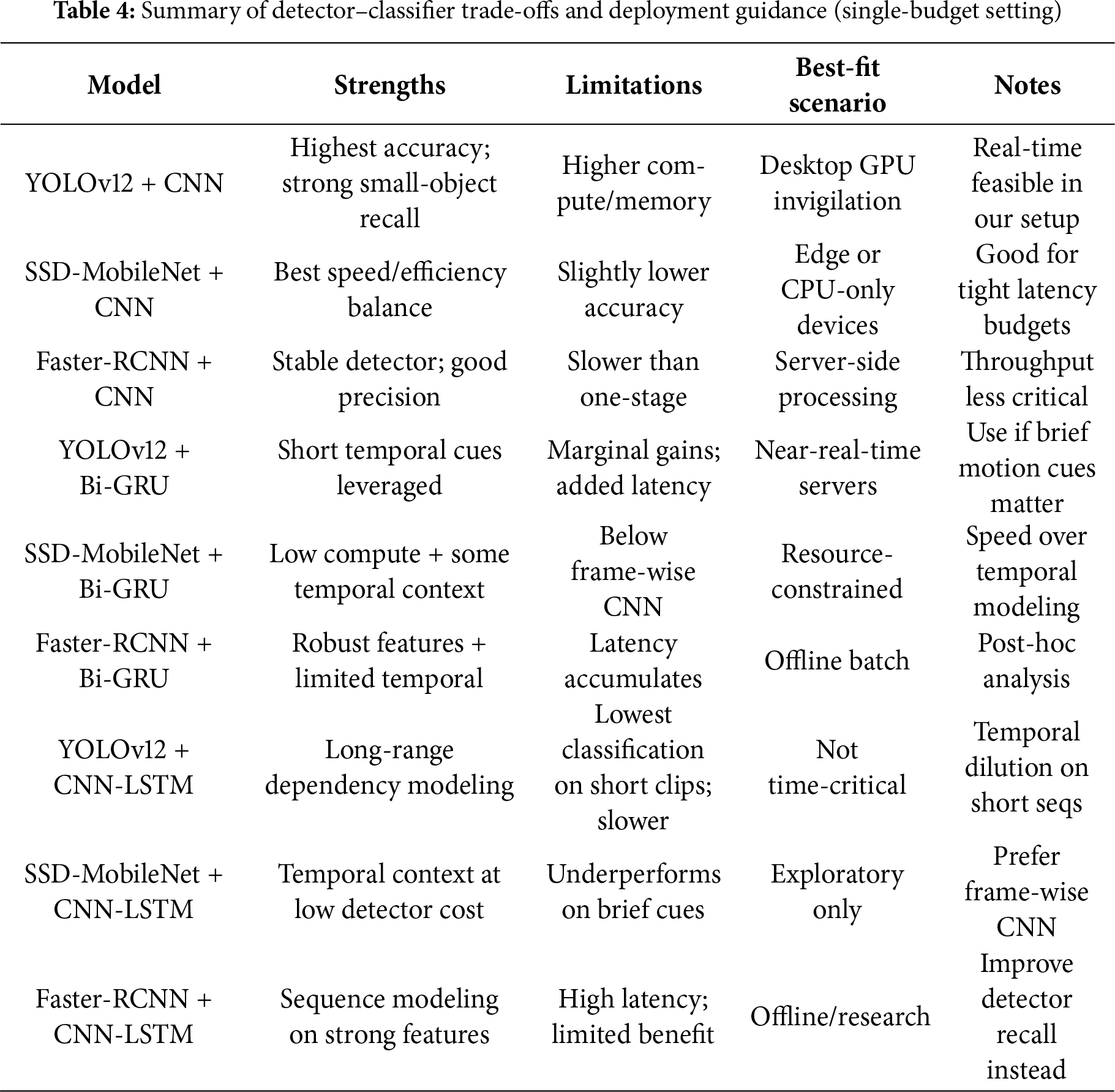

To further understand the strengths and weaknesses of each model combination in Table 3, we analyze their advantages and disadvantages based on accuracy, speed, computational efficiency, and robustness in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that:

‐ Best performance: YOLOv12 + CNN achieved the highest overall accuracy (97.15%) and fastest detection time, making it the most suitable for real-time cheating detection.

‐ Best for sequential behaviors: Bi-GRU models (Models 1, 4, 7) performed well in detecting gradual cheating behaviors (e.g., whispering, looking at notes over time).

‐ Best for speed-efficiency trade-off: SSD MobileNet + CNN (Model 6) offers a good balance between accuracy and speed, making it useful for low-power devices.

‐ Worst performance: CNN-LSTM models (Models 2, 5, 8) struggled in classification, showing that CNN-LSTM is not suitable for real-time cheating detection.

‐ Best for complex scenes: Faster RCNN-based models (Models 1, 2, 3) performed well in structured settings but were slower than YOLOv12.

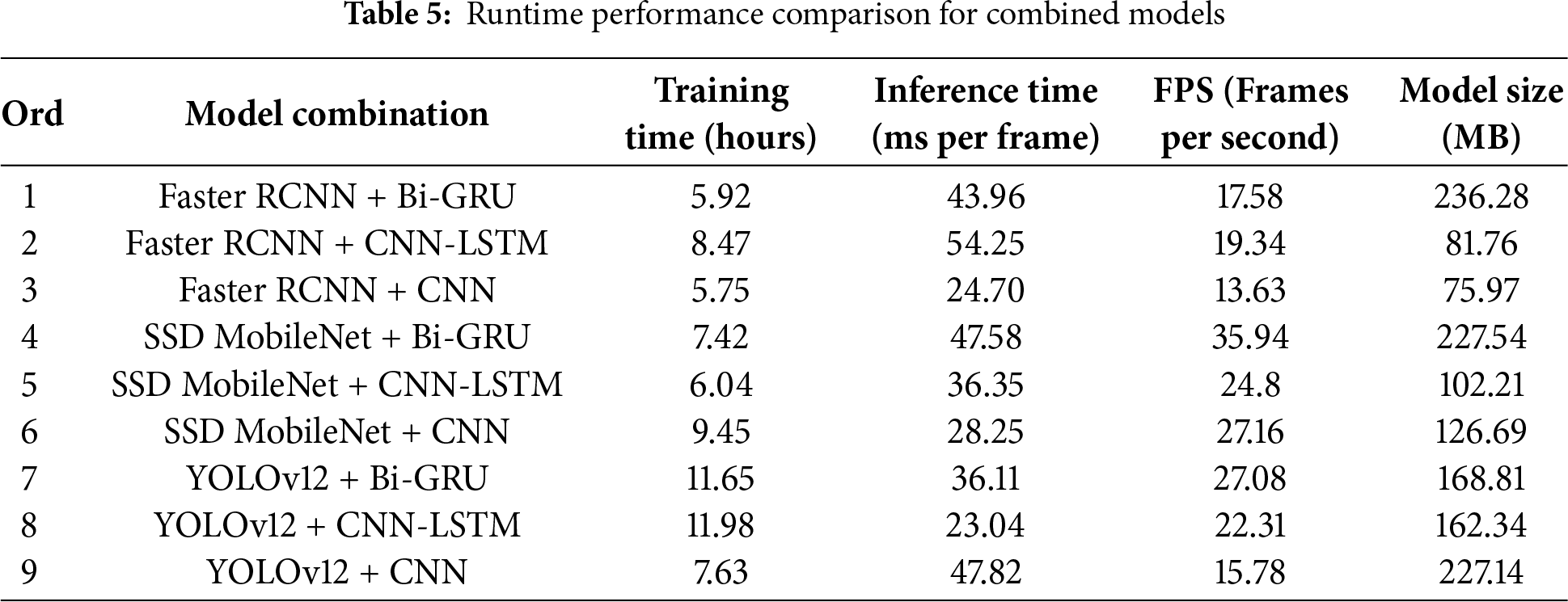

Table 5 compares the runtime performance of various combined models across four criteria: training time, inference time per frame, frames per second (FPS), and model size. YOLOv12 combined with CNN-LSTM had the longest training time (11.98 h), followed closely by YOLOv12 with Bi-GRU (11.65 h), reflecting the complexity of temporal-spatial models. In contrast, Faster RCNN combined with CNN and Bi-GRU demonstrated the shortest training times (5.75 and 5.92 h, respectively), indicating faster convergence during model training. In terms of inference efficiency, YOLOv12 + CNN-LSTM (23.04 ms/frame) and Faster RCNN + CNN (24.70 ms/frame) were the fastest, enabling near real-time evaluation. However, Faster RCNN + CNN-LSTM was the slowest (54.25 ms/frame), suggesting high overhead from temporal modeling. When evaluating FPS, SSD MobileNet combinations were the most efficient, with SSD MobileNet + Bi-GRU reaching the highest frame rate of 35.94 FPS, and SSD MobileNet + CNN achieving 27.16 FPS—making them ideal for low-latency applications. On the other hand, combinations like YOLOv12 + CNN and Faster RCNN + CNN achieved lower FPS (15.78 and 13.63, respectively), trading speed for higher accuracy. Regarding model size, the largest models were Faster RCNN + Bi-GRU (236.28 MB) and YOLOv12 + CNN (227.14 MB), implying higher memory and storage needs. The smallest configuration was Faster RCNN + CNN (75.97 MB), offering efficiency for constrained deployment environments. Overall, the results show a clear trade-off between detection/classification accuracy and runtime performance. For applications requiring both real-time processing and high accuracy, YOLOv12 + CNN offers the best balance, albeit with high computational demands. In contrast, SSD MobileNet + CNN provides lightweight and fast alternatives with slightly reduced accuracy, making it suitable for real-time deployment on edge devices. CNN-LSTM combinations, while conceptually robust, demonstrated inferior performance in both speed and accuracy, and are not recommended for deployment in time-sensitive or high-accuracy environments. Table 5 links each pairing to training time, per-frame latency, FPS, and model size, motivating: (i) edge (SSD-MobileNet + CNN), (ii) desktop GPU (YOLOv12 + CNN), (iii) hybrid human-in-the-loop for borderline cases.

This work demonstrates that a detector-first pipeline coupled with frame-wise classification is the most dependable strategy for real-time cheating detection in short, fast-changing exam clips. In our setting, object-centric detectors paired with CNN classifiers consistently outperform sequence models, because the salient cues are brief and often tied to small objects (e.g., phones, books), where temporal aggregation can dilute frame-level evidence. Among the evaluated pairings, the YOLOv12 + CNN configuration emerges as the most accurate choice for high-end deployments, while SSD-MobileNet + CNN offers a strong speed–efficiency profile for edge devices.

For practice, we recommend two deployment profiles. (i) Desktop/GPU: prefer YOLOv12 + CNN to maximize detection of small, transient cues while maintaining acceptable latency for live alerting. (ii) Edge/CPU-constrained: prefer SSD-MobileNet + CNN to meet tight per-frame latency and memory budgets with minimal accuracy loss. These choices should be embedded in an engineering envelope that standardizes input resolutions and training budgets across components, and that validates generalization across camera viewpoints and environments. Operators should also track end-to-end KPIs (per-frame latency, missed-cue rate on small objects, false-alert rate under glare/occlusion) and adopt human-in-the-loop escalation for borderline cases, acknowledging the accuracy–throughput–memory trade-offs surfaced by our runtime study.

This study has limitations. First, it targets short, object-centric behaviors rather than long, structured interaction sequences; as a result, temporal models such as CNN-LSTM underperform here and may be more competitive in settings with extended actions or richer context. Second, although we controlled for budgets and used cross-camera splits, external validity beyond our DTU and EOP subsets still requires broader multi-institutional validation. Third, like any video-based proctoring system, deployment must remain aligned with ethics, privacy, and transparency expectations; our recordings relied on consented simulations and de-identification, and operational systems should continue to enforce strict minimization, encryption, and retention controls.

Future work will focus on four directions: (1) Detector recall and robustness—data augmentation targeted at small handheld objects and low-light occlusions; self-training or test-time adaptation to new cameras; and uncertainty-aware thresholds for safer alerting. (2) Temporal modeling without dilution—per-frame evidence pooling with attention or gated temporal filters that preserve rare, high-value frames, rather than long recurrent rollouts. (3) Multi-modal signals—optional fusion of keystroke/mouse metadata or network events where policy allows, to boost precision on borderline visual cases. (4) Responsible deployment—auditable pipelines, liveness prompts, spoofing/camouflage checks, and calibrated human review policies to reduce harm from false positives while preserving exam integrity.

In sum, the findings support a pragmatic blueprint: use a high-recall, small-object-aware detector with a lightweight frame-wise classifier, select the backbone according to resource constraints (GPU vs. edge), and harden the system with principled evaluation, privacy safeguards, and human oversight. This balances technical performance with trustworthy operation in real online exam environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dao Phuc Minh Huy and Gia Nhu Nguyen; methodology, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; software, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; validation, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; formal analysis, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; investigation, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; resources, Dao Phuc Minh Huy and Gia Nhu Nguyen; data curation, Dao Phuc Minh Huy and Gia Nhu Nguyen; writing—original draft preparation, Dao Phuc Minh Huy and Gia Nhu Nguyen; writing—review and editing, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; visualization, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; supervision, Dao Phuc Minh Huy, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le; project administration, Gia Nhu Nguyen and Dac-Nhuong Le. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: We apply data minimization, encryption in transit/at rest, and strict retention policies; any shared artifacts blur identities unless explicit permission is granted.

Ethics Approval: The DTU data collection procedures (simulated online exam sessions with students) were reviewed by the Duy Tan University Research Ethics Committee and classified as minimal-risk/exempt research involving consented participants. All participants provided informed consent before recording. Video data were anonymised and stored on secure, access-controlled servers, and only de-identified frames are presented in the figures of this article.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Huy DPM, Thom HTH, Nhu NG, Le DN. Student monitoring system combining facial recognition and identification methods. In: Satapathy SC, Bhateja V, editors. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Information System Design and Intelligent Applications; 2024 Jan 6–7; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 241–9. [Google Scholar]

2. Huy DPM, Nhu NG, Le DN. A combine solution for online exams cheating detection, prediction, and prevention using artificial intelligence. In: Ghosh A, Nayak J, editors. Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Analytics & Management; 2015 Jun 13–15; London, UK. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 665–76. [Google Scholar]

3. Huy DPM, Nhu NG, Le DN. CNN-FSPM-based fingerprint indexing and matching for detecting, predicting, and preventing cheating in online examinations. Int J Knowl Syst Sci. 2024;15(1):1–20. doi:10.4018/ijkss.364843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hylton K, Levy Y, Dringus LP. Utilizing webcam-based proctoring to deter misconduct in online exams. Comput Educ. 2016;92:53–63. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ketab SS, Clarke NL, Dowland PS. A robust e-invigilation system employing multimodal biometric authentication. Int J Inf Educ Technol. 2017;7(11):796–802. doi:10.18178/ijiet.2017.7.11.975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Asep HSG, Bandung Y. A design of continuous user verification for online exam proctoring on M-learning. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI); 2019 Jul 9–10; Bandung, Indonesia. p. 284–9. [Google Scholar]

7. Turani AA, Alkhateeb JH, Alsewari AA. Students online exam proctoring: a case study using 360 degree security cameras. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Emerging Technology in Computing, Communication and Electronics (ETCCE); 2020 Dec 21–22; Dhaka, Bangladesh. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

8. Shdaifat AM, Obeidallah RA, Ghazal G, Abu Sarhan A, Abu Spetan NR. A proposed iris recognition model for authentication in mobile exams. Int J Emerg Technol Learn. 2020;15(12):205. doi:10.3991/ijet.v15i12.13741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kamalov F, Sulieman H, Santandreu Calonge D. Machine learning based approach to exam cheating detection. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0254340. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Chuang CY, Craig SD, Femiani J. Detecting probable cheating during online assessments based on time delay and head pose. High Educ Res Dev. 2017;36(6):1123–37. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1303456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bilen E, Matros A. Online cheating amid COVID-19. J Econ Behav Organ. 2021;182:196–211. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2020.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Özgen AC, Öztürk MU, Bayraktar U. Cheating detection pipeline for online interviews and exams. arXiv:2106.14483. 2021. [Google Scholar]

13. Alnassar F, Blackwell T, Homayounvala E, Yee-king M. How well a student performed? A machine learning approach to classify students’ performance on virtual learning environment. In: Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM); 2021 Apr 28–30; London, UK. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

14. Dhilipan J, Vijayalakshmi N, Suriya S, Christopher A. Prediction of students performance using machine learning. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1055(1):012122. [Google Scholar]

15. Noorbehbahani F, Fanian A, Mousavi R, Hasannejad H. An incremental intrusion detection system using a new semi-supervised stream classification method. Int J Commun Syst. 2017;30(4):e3002. doi:10.1002/dac.3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cote M, Jean F, Albu AB, Capson D. Video summarization for remote invigilation of online exams. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2016 Mar 7–10; Lake Placid, NY, USA. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

17. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. [Google Scholar]

18. Atoum Y, Chen L, Liu AX, Hsu SDH, Liu X. Automated online exam proctoring. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2017;19(7):1609–24. doi:10.1109/tmm.2017.2656064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jalali K, Noorbehbahani F. An automatic method for cheating detection in online exams by processing the students Webcam images. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering Technology (E-Tech 2017); 2017 May 12; Tehran, Iran. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

20. Indi CS, Pritham V, Acharya V, Prakasha K. Detection of malpractice in E-exams by head pose and gaze estimation. Int J Emerg Technol Learn. 2021;16(8):47. doi:10.3991/ijet.v16i08.15995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tiong LCO, Lee HJ. E-cheating prevention measures: detection of cheating at online examinations using deep learning approach—a case study. arXiv:2101.09841. 2021. [Google Scholar]

22. Wan Z, Li X, Xia B, Luo Z. Recognition of cheating behavior in examination room based on deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA); 2021 Jun 25–27; Kunming, China. p. 204–8. [Google Scholar]

23. Li S, Liu T. Performance prediction for higher education students using deep learning. Complexity. 2021;2021:9958203. doi:10.1155/2021/9958203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Masud MM, Hayawi K, Mathew SS, Michael T, El Barachi M. Smart online exam proctoring assist for cheating detection. In: Advanced data mining and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 118–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95405-5_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. El Kohli S, Jannaj Y, Maanan M, Rhinane H. Deep learning: new approach for detecting scholar exams fraud. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spat Inf Sci. 2022;46:103–7. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-xlvi-4-w3-2021-103-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Malhotra M, Chhabra I. Student invigilation detection using deep learning and machine after COVID-19: a review on taxonomy and future challenges. In: Rocha Á, Peter MKA, editors. Future of organizations and work after the 4th industrial revolution. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 311–26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-99000-8_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hassan Hosny HA, Ibrahim AA, Elmesalawy MM, Abd El-Haleem AM. An intelligent approach for fair assessment of online laboratory examinations in laboratory learning systems based on student’s mouse interaction behavior. Appl Sci. 2022;12(22):11416. doi:10.3390/app122211416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alkalbani AS. Cheating detection in online exams based on captured video using deep learning [master’s thesis]. Al Ain, United Arab Emirates: United Arab Emirates University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

29. Gopane S, Kotecha R, Obhan J, Pandey RK. Cheat detection in online examinations using artificial intelligence. ASEAN Eng J. 2024;14(1):121–8. doi:10.11113/aej.v14.20188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu Y, Ren J, Xu J, Bai X, Kaur R, Xia F. Multiple instance learning for cheating detection and localization in online examinations. IEEE Trans Cogn Dev Syst. 2024;16(4):1315–26. doi:10.1109/tcds.2024.3349705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Erdem B, Karabatak M. Cheating detection in online exams using deep learning and machine learning. Appl Sci. 2025;15(1):400. doi:10.3390/app15010400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Abourifa H, Qarbal I, Ouahabi S, Sael N, Elfilali S, El Guemmat K. Cheating detection in online exams using transfer learning. In: Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET); 2025 May 15–16; Fez, Morocco. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

33. He Z, He Y. AS-faster-RCNN: an improved object detection algorithm for airport scene based on faster R-CNN. IEEE Access. 2025;13:36050–64. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3539930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sugiharto A, Kusumaningrum R. Enhanced automatic license plate detection and recognition using CLAHE and YOLOv11 for seat belt compliance detection. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2025;15(1):20271–8. doi:10.48084/etasr.9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. [Google Scholar]

36. Manoharan J, Sivagnanam Y. A novel human action recognition model by grad-CAM visualization with multi-level feature extraction using global average pooling with sequence modeling by bidirectional gated recurrent units. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2025;18(1):118. doi:10.1007/s44196-025-00848-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Asadi M, Heidari A, Jafari Navimipour N. A new flow-based approach for enhancing botnet detection efficiency using convolutional neural networks and long short-term memory. Knowl Inf Syst. 2025;67(7):6139–70. doi:10.1007/s10115-025-02410-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tsirtsakis P, Zacharis G, Maraslidis GS, Fragulis GF. Deep learning for object recognition: a comprehensive review of models and algorithms. Int J Cogn Comput Eng. 2025;6:298–312. doi:10.1016/j.ijcce.2025.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Malhotra M, Chhabra I, Bharany S, Ur Rehman A, Hussen S. Examining the landscape of proctoring in upholding academic integrity: a bibliometric review of online examination practices. Discov Educ. 2025;4(1):227. doi:10.1007/s44217-025-00661-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools