Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CASBA: Capability-Adaptive Shadow Backdoor Attack against Federated Learning

School of Computer Science and Technology, Harbin University of Science and Technology, Harbin, 150080, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongwei Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 46 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071008

Received 29 July 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Federated Learning (FL) protects data privacy through a distributed training mechanism, yet its decentralized nature also introduces new security vulnerabilities. Backdoor attacks inject malicious triggers into the global model through compromised updates, posing significant threats to model integrity and becoming a key focus in FL security. Existing backdoor attack methods typically embed triggers directly into original images and consider only data heterogeneity, resulting in limited stealth and adaptability. To address the heterogeneity of malicious client devices, this paper proposes a novel backdoor attack method named Capability-Adaptive Shadow Backdoor Attack (CASBA). By incorporating measurements of clients’ computational and communication capabilities, CASBA employs a dynamic hierarchical attack strategy that adaptively aligns attack intensity with available resources. Furthermore, an improved deep convolutional generative adversarial network (DCGAN) is integrated into the attack pipeline to embed triggers without modifying original data, significantly enhancing stealthiness. Comparative experiments with Shadow Backdoor Attack (SBA) across multiple scenarios demonstrate that CASBA dynamically adjusts resource consumption based on device capabilities, reducing average memory usage per iteration by 5.8%. CASBA improves resource efficiency while keeping the drop in attack success rate within 3%. Additionally, the effectiveness of CASBA against three robust FL algorithms is also validated.Keywords

In the digital era, data has become a core asset, and its increasing value and sensitivity have made data privacy protection a critical global challenge. Federated Learning (FL), as an emerging distributed machine learning paradigm, allows multiple privacy-sensitive clients to collaboratively train a model under the coordination of a central server. This framework effectively addresses the issue of data silos while preserving user privacy [1]. By aggregating knowledge from decentralized local training processes, FL enhances data utilization efficiency and produces a global model that outperforms any individual local model.

However, the distributed nature of FL inevitably introduces heterogeneity, including disparities in data distribution and variations in client computing capabilities. In practice, the central server in FL can only access the locally trained models submitted by participants, not their raw data. As a result, it cannot ensure that all participants are benign, which brings new security risks [2]. Including backdoor attacks that tamper with model behavior by embedding triggers, data reconstruction attacks that recover sensitive information from shared updates [3], and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks that disrupt the training process [4].

Backdoor attacks refer to a type of attack in classification tasks where adversaries implant specific malicious patterns into the training process so that the resulting model maintains high performance on clean inputs but produces attacker-controlled outputs on poisoned inputs. These attacks are highly stealthy, especially when the integrity of the data source cannot be guaranteed. In real-world scenarios, backdoor attacks have been used to deceive facial recognition systems [5], mislead word prediction models [6], and target various other AI-based applications.

The earliest study of backdoor attacks in FL was presented in [2], which introduced the model replacement attack. In this method, attackers inject the same backdoor trigger into their local training data and rely on the global aggregation process to propagate it into the global model. This method was later referred to as the Centralized Backdoor Attack (CBA). A further enhancement, the Distributed Backdoor Attack (DBA), was proposed in [7], which splits the global trigger into multiple local triggers. These are injected by different attackers and implicitly recombined during aggregation on the central server, thereby enhancing stealthiness and success rate.

Building upon DBA, Ren et al. introduced the concept of attacker strength and proposed the Shadow Backdoor Attack (SBA) [8]. In SBA, a primary attacker uses the full global trigger, while shadow attackers use partial fragments of the trigger (i.e., shadow triggers). Through the collaboration of attackers with varying strengths, the global model is guided to reliably learn the backdoor behavior. This design significantly improves both the attack’s success rate and persistence, making it effective against anomaly-based defenses and adaptable to the complex non-Independent and Identically Distributed (non-IID) data distributions common in federated environments.

Nevertheless, existing backdoor attack methods fail to fully consider the internal heterogeneity of malicious clients, such as differences in computational power and communication capabilities, which limits the effectiveness of the attack. Moreover, most of these methods embed triggers by modifying the original data, which increases the risk of detection during data inspection or auditing.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel method called Capability-Adaptive Shadow Backdoor Attack (CASBA). CASBA dynamically adapts the malicious training process based on in-depth analysis of the behavioral characteristics of malicious clients, enabling it to better align with heterogeneous client environments.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. Enhancement and Optimization of DCGAN: By optimizing the architectures of the generator and discriminator networks, the detail quality of generated images is significantly improved. Meanwhile, adversarial loss is combined with perceptual loss and hinge loss, and their weights are dynamically adjusted according to the training phase. This ensures stable model training while further improving the quality of generated images.

2. CASBA: To address differences in the computational and communication capabilities of malicious clients, different attack intensities are flexibly assigned and the local training process is optimized to enhance attack adaptability. Using a DCGAN jointly trained by malicious clients, high-quality forged images are generated, into which triggers are then embedded, achieving backdoor injection without modifying the original data.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the background of federated learning, backdoor attacks, and generative adversarial networks; Section 3 details the DCGAN model enhancement and optimization methods; Section 4 presents the CASBA approach; Section 5 describes the experimental setup and results analysis; finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

In addition, to promote research reproducibility, we have made the experimental code and related resources publicly available, which can be accessed via the provided link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/16auhGhwn7lx0naJHYeQ3s-EpdbXxbnk- (accessed on 21 September 2025). During manuscript preparation, a large language model (GPT-4o, OpenAI) was employed to assist with English translation and language refinement; all scientific content and conclusions were determined by the authors.

2.1 Federated Learning and Backdoor Attacks

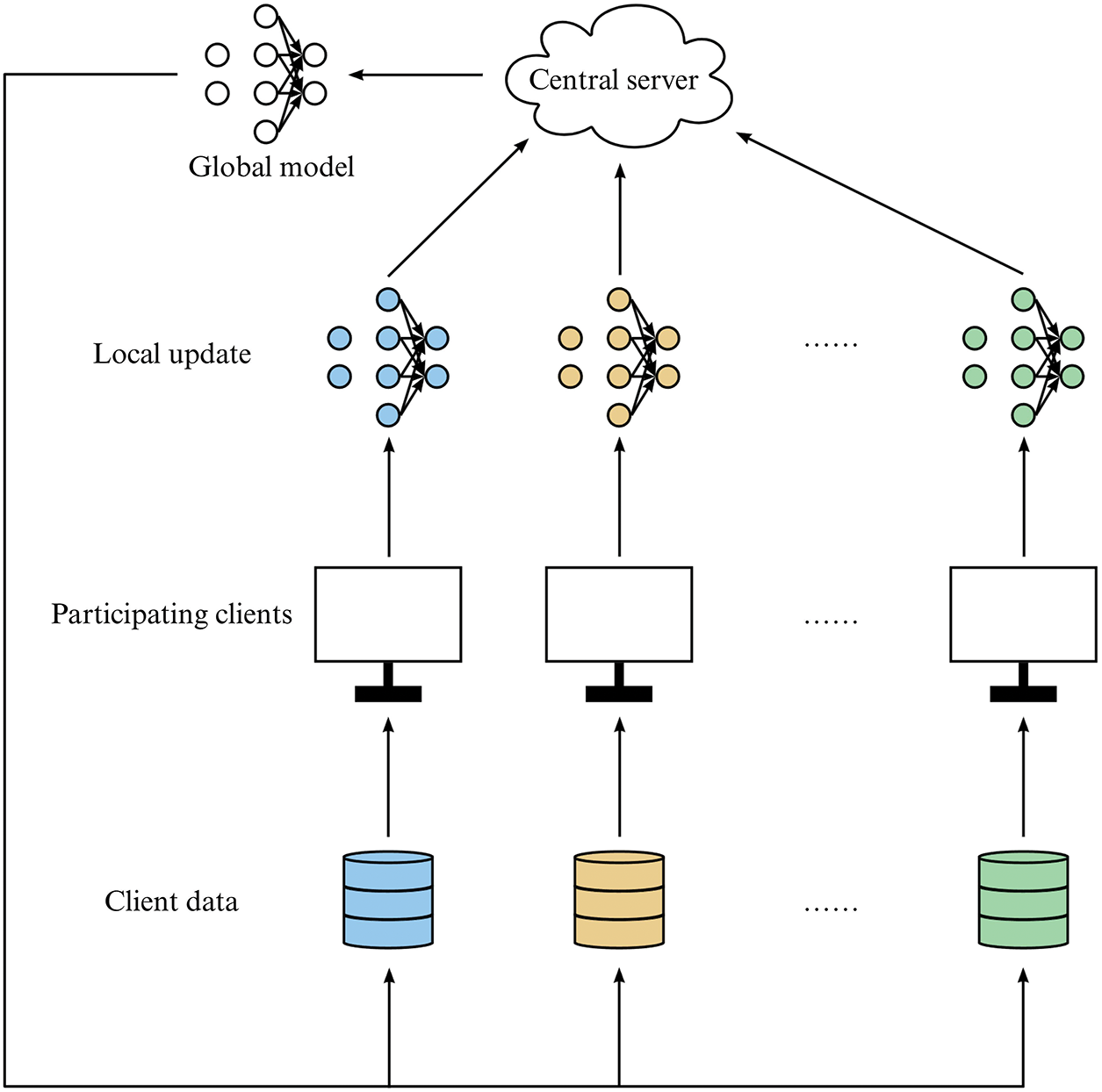

FL is a distributed paradigm that supports privacy-preserving collaborative model training, following the principle that data remains local while only models are shared (see Fig. 1). FL can be categorized into three primary modes—horizontal, vertical, and federated transfer learning—each corresponding to a distinct data distribution scenario.

Figure 1: The process of federated learning

Among various aggregation methods, the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm is the most widely adopted for updating global model parameters [1]. The server first initializes the global model and distributes it to selected clients. Each client then performs several local training iterations on its private data. The locally updated model parameters are subsequently uploaded to the server, which aggregates them using a weighted average, as defined by the FedAvg algorithm.

The aggregation step is mathematically defined in Eq. (1):

where

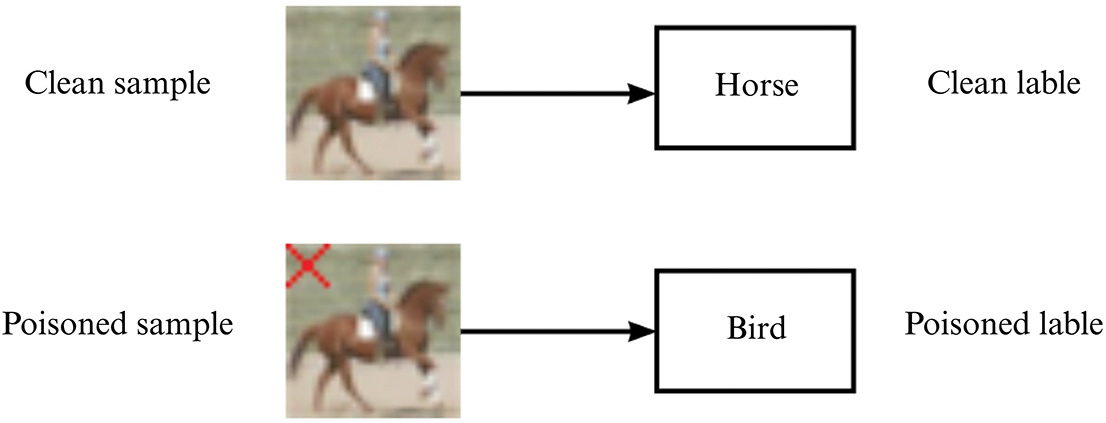

However, while this decentralized nature ensures privacy protection, it also exposes security risks in model updates. Attackers can manipulate the local training process to embed covert backdoor behaviors into the global model. The effectiveness of such backdoor attacks is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Illustration of the effects of backdoor attacks

Early backdoor attacks are exemplified by CBA [2], which inject backdoors by scaling model parameters. However, since all attackers employ the same trigger, CBA is vulnerable to gradient-based defenses such as norm clipping and robust aggregation. Its stealth and adaptability are also limited in distributed federated learning environments. To address these issues, backdoor attacks have gradually evolved toward distributed and collaborative paradigms: DBA [7] decomposes the global trigger into multiple local triggers, each injected by different attackers, thereby improving stealth and persistence; SBA [8] further introduces a collaboration mechanism among attackers with varying intensities and combine global and shadow triggers, enabling better adaptation to non-IID data distributions and enhancing both persistence and concealment.

Researchers have also focused on trigger stealth. Hidden trigger backdoor attacks [9] minimize the feature-space distance between poisoned and benign samples, making poisoned images visually similar to benign ones while establishing latent associations that guide the model to learn the backdoor. Trojaning Generative Adversarial Networks (TroGAN) [10] introduces an auxiliary discriminator into a GAN to generate high-quality poisoned samples, achieving effective attacks even with few poisoned examples. Frequency-domain injection attacks [11] embed low-frequency triggers into clean images via Fourier transforms, making them nearly imperceptible in the spatial domain while preserving attack effectiveness, and combine this with projected gradient descent to evade defenses.

Moreover, some methods further enhance attack dynamics and adaptability. A Backdoor Attack to Federated Learning with Refined Evasion (FLARE) [12] dynamically generates and selects concealed triggers, applies them at low poisoning rates, and amplifies their effect during testing, achieving high stealth and success rates. Neurotoxin [13] identifies frequently updated coordinates in benign gradients and projects attack updates onto less commonly modified parameter subspaces, reducing the risk of backdoor overwriting and enhancing both stealth and robustness.

In summary, backdoor attacks in federated learning have evolved from centralized to distributed settings, from explicit to feature-space manipulation, and from static to dynamically optimized strategies, thereby requiring defense mechanisms that integrate gradient analysis [14], frequency-domain inspection, neuron output discrepancy detection [15], and dynamic aggregation. Such discrepancy-based defenses detect anomalous activations at the neuron level, which are complementary to CASBA’s generative attack paradigm.

Nevertheless, existing generative and clean-label backdoor attacks, while enhancing stealthiness and attack performance, often neglect device heterogeneity. For example, FLARE [12] employs a three-phase trigger strategy and achieves high stealthiness under low poisoning rates, but fails to adapt to clients with varying computational capacities. Similarly, FL Arbitrary-Target Attack (FLAT) [16] can generate multi-target triggers, yet overlooks resource constraints of heterogeneous devices. By contrast, CASBA improves the DCGAN model with a hybrid loss function and dynamic weight mechanism to generate trigger-embedded data, while a hierarchical strategy enables adaptive alignment with clients of different capabilities. This design enhances both adaptability and efficiency, effectively addressing the limitations of existing approaches.

2.2 Generative Adversarial Networks

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) model data through adversarial training between a generator and a discriminator. Deep Convolutional GANs (DCGANs) [17] enhance training stability by employing strided convolutions, batch normalization, and the removal of fully connected layers, demonstrating the effectiveness of convolutional architectures in image generation. Conditional GANs (CGANs) [18] incorporate class labels to enable controllable generation, while Auxiliary Classifier GANs (AC-GANs) [19] integrate an auxiliary classification branch into the discriminator, improving semantic consistency between the generated content and target labels.

To address mode collapse and suboptimal generation quality, Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) [20] replace the traditional adversarial loss with the Wasserstein distance, enhancing training stability. WGANs with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) [21] further enforce the Lipschitz constraint via gradient norm penalties, mitigating mode collapse. Self-Attention GANs (SAGANs) [22] combine spectral normalization with attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in complex images. More recently, StyleGAN [23] introduces disentangled latent representations and multi-level style control, enabling fine-grained attribute manipulation and significantly improving both image fidelity and diversity. Rebooted Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (ReACGAN) [24], built upon AC-GAN, integrates normalization techniques and a data-to-data cross-entropy (D2D-CE) loss, further improving training stability and the diversity of generated samples.

The application scope of GANs has expanded considerably. In large-scale image generation, BigGAN [25] scales model architectures to enhance image quality and diversity. In network security, VagueGAN [26] can generate poisoned data for federated learning attacks, while lightweight DCGANs [27] enable intrusion detection in resource-constrained wireless sensor networks. In contrast, this study employs DCGANs offensively to synthesize forged data for backdoor injection in federated learning, highlighting the dual-use versatility of GANs across diverse domains.

3 DCGAN Model Enhancement and Optimization

This section details the optimizations undertaken to address the original DCGAN model’s shortcomings in terms of image generation quality and training stability. The improvements encompass enhancements to the generator and discriminator network architectures, the design of a hybrid loss function, dynamic weight adjustment mechanisms during training, and other auxiliary optimization techniques.

3.1 Optimized Design of the Generator Network Architecture

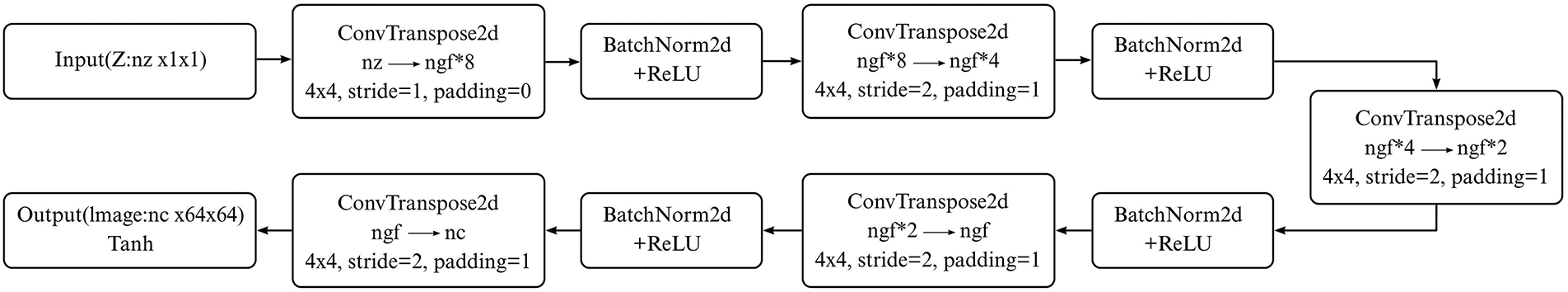

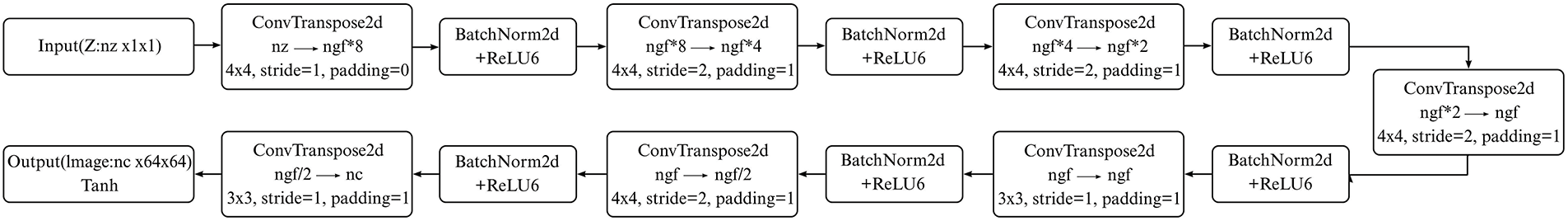

To improve the generator’s performance in image generation tasks, several architectural enhancements were applied, including adjustments to convolution kernel sizes, refinement of transposed convolution parameters, and redistribution of feature channel widths. These modifications aim to strengthen the generator’s ability to capture image details, improve training stability, and enhance the quality of generated images. Figs. 3 and 4 illustrate the generator network architectures before and after these optimizations, respectively.

Figure 3: Network architecture of the generator before optimization

Figure 4: Network architecture of the generator after optimization

First, to enhance the generator’s capability in modeling local image details, certain convolution layers had their kernel sizes reduced from

Second, during the upsampling stage, the stride and padding parameters of certain transposed convolutional layers were optimized. In particular, the stride was reduced from 2 to 1 in some layers to reduce artifacts introduced during upsampling, thereby ensuring smoother and more consistent resolution enhancement. Moreover, to balance local detail modeling and global structure representation, the number of feature channels was gradually decreased following the sequence

3.2 Design of the Hybrid Loss Function for the Generator

Conventional generator loss functions often rely solely on adversarial objectives, such as the Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss, which can effectively guide the global data distribution of generated images. However, such losses are typically insufficient for optimizing local detail fidelity and perceptual quality. To address this limitation, a hybrid loss function is proposed in this work, combining the BCE loss with a perceptual loss. This design aims to jointly enhance both the global distribution and local visual details of the generated images.

The perceptual loss is computed based on high-level features extracted from the first eight layers of a pretrained Visual Geometry Group (VGG) network. It measures the mean squared error (MSE) between the generated image and the real image in the feature space. Given the relatively low resolution

where

The total generator loss is defined as a combination of the BCE loss and the perceptual loss, as described in Eq. (3):

where

To further improve image quality and detail consistency, a dynamic weight adjustment strategy is introduced. In this mechanism, the weight of the perceptual loss

where

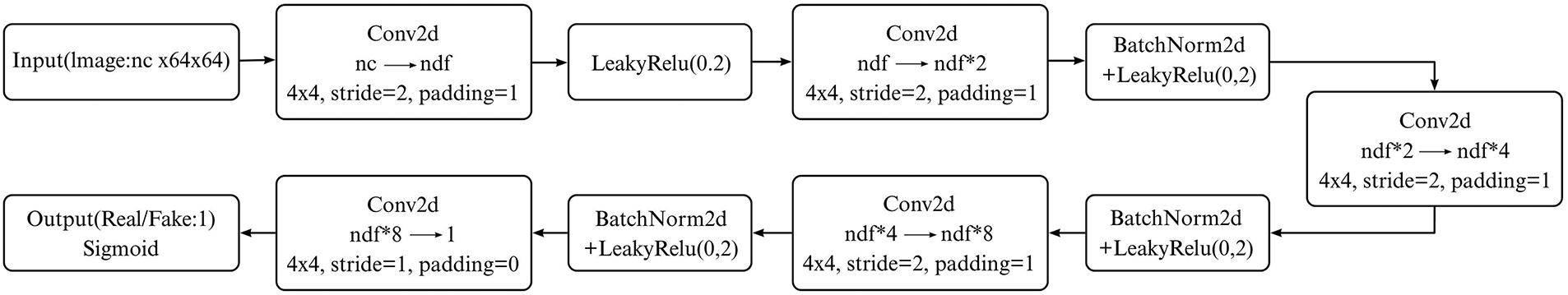

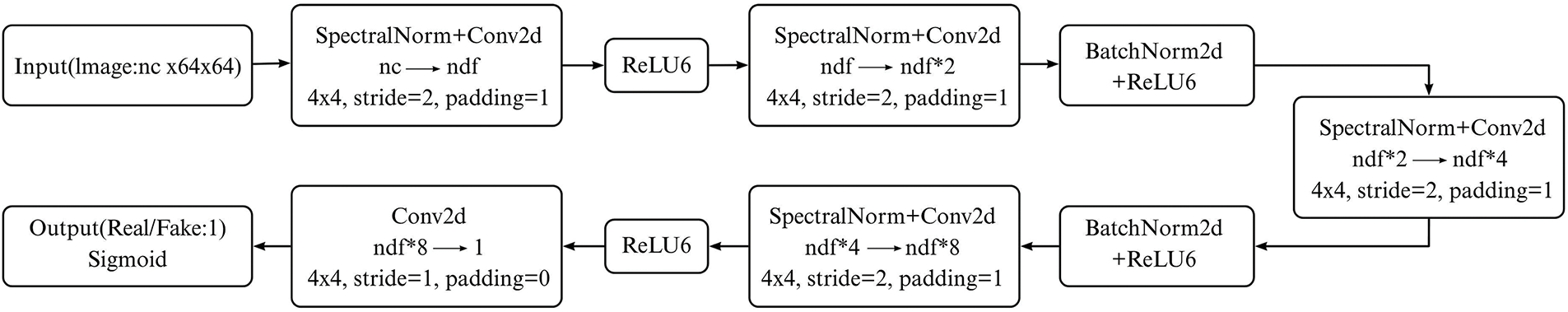

3.3 Optimized Design of the Discriminator Network Architecture

To enhance the training stability and adversarial performance of the discriminator, this study introduces several architectural optimizations, primarily focusing on activation function improvements and the incorporation of weight normalization techniques. These enhancements aim to strengthen the discriminator’s capability to distinguish image authenticity and provide higher-quality gradient feedback to the generator. Figs. 5 and 6 illustrate the discriminator network architectures before and after the optimizations, respectively.

Figure 5: The network architecture of the discriminator before optimization

Figure 6: The network architecture of the discriminator after optimization

Regarding the activation function, the original discriminator utilized LeakyReLU with a negative slope of 0.2. Although LeakyReLU partially mitigates the “dying neuron” problem, its fixed negative slope limits flexibility in regulating neuron activations. Therefore, it is replaced with ReLU6 in this work. ReLU6 effectively prevents gradient explosion and significantly enhances gradient stability in deep networks. Additionally, ReLU6 involves only simple comparison and clipping operations, making it computationally lightweight and reducing hardware overhead.

Furthermore, spectral normalization is applied to the convolutional layers of the discriminator for further refinement. By normalizing the largest singular value of the convolutional weights, spectral normalization effectively controls the Lipschitz constant of the discriminator, thereby constraining weight updates. This method suppresses abnormal gradient behaviors and enables the discriminator to provide smoother and more reliable gradient feedback during training, ultimately improving the stability of adversarial learning.

3.4 Design of the Hybrid Loss Function for the Discriminator

Conventional discriminator loss functions typically rely on BCE loss, which can improve the discriminator’s capability to some extent. However, during training, BCE often suffers from gradient vanishing or exploding problems and lacks sensitivity to local details. To address these issues, this study proposes a hybrid loss function that combines BCE loss with Hinge loss.

Hinge loss enhances the discriminator’s sensitivity and discriminative power for fine-grained features by optimizing the decision boundary region. The loss function is defined in Eq. (5):

where

The total loss function for the discriminator is formulated as:

where

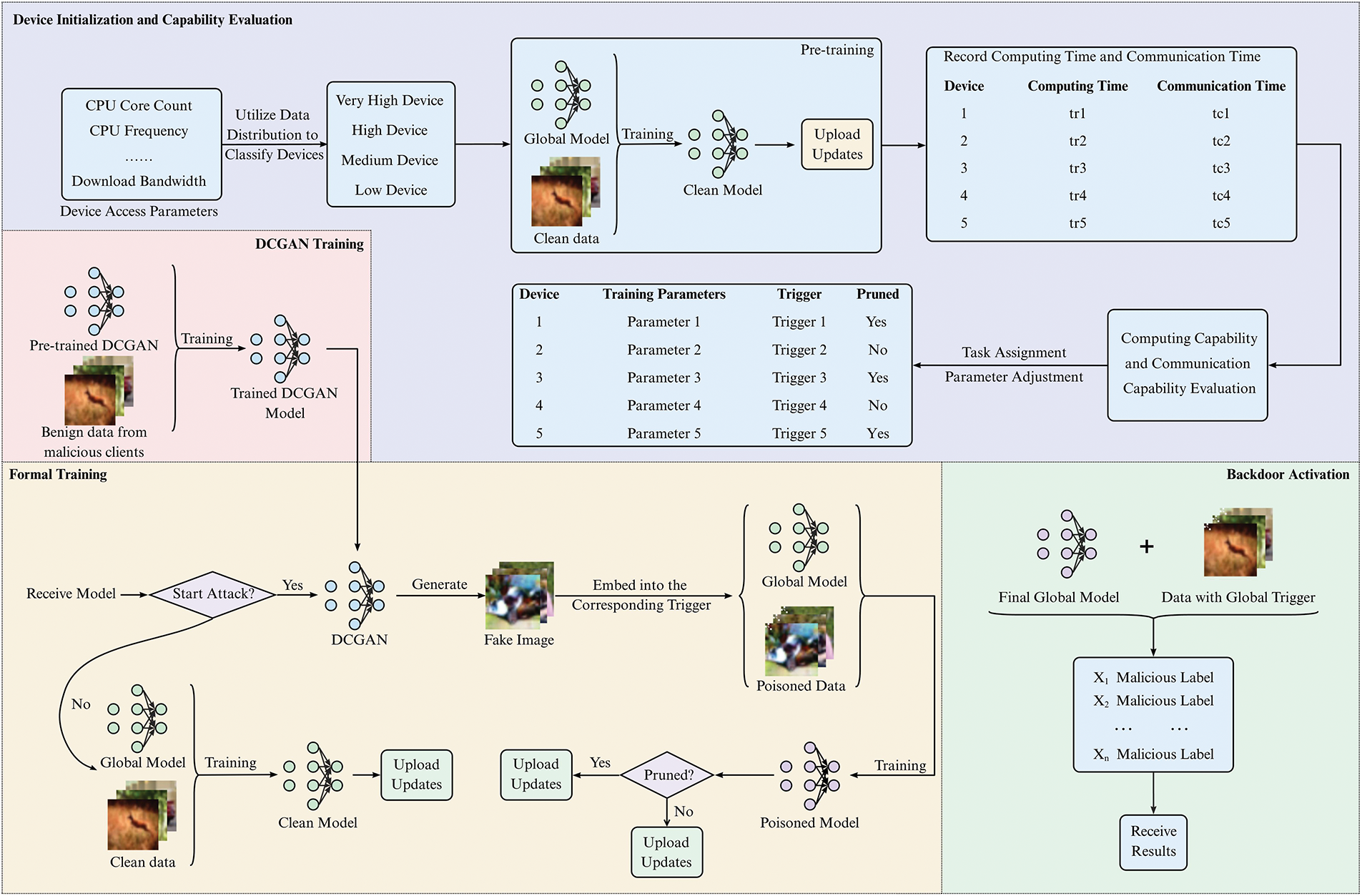

This section presents the CASBA, a method that dynamically adjusts attack intensity and local training parameters based on the characteristics of malicious clients. By incorporating a hierarchical adaptation strategy and employing a GAN to synthesize poisoned samples, the proposed approach enables more efficient and stealthy backdoor attacks.

This study assumes that attackers can modify local data and hyperparameters, upload backdoor updates via multiple malicious clients, and tamper with training weights, but cannot access the server or benign clients. The server strictly follows the federated learning protocol, without backdoor detection or robust aggregation mechanisms, and benign clients fully trust the server. CASBA improves conventional SBA by introducing a dynamic adjustment mechanism tailored to each client’s resources and employs a lightweight DCGAN to generate synthetic samples resembling the original dataset, into which backdoor triggers are embedded. The DCGAN is pretrained for 30 epochs and further fine-tuned collaboratively by malicious clients, enabling efficient deployment across heterogeneous clients. The workflow (Fig. 7) comprises device initialization, GAN training, formal training, and backdoor activation.

Figure 7: The attack workflow of CASBA

During the device initialization phase, malicious clients assess their computational and communication capabilities to dynamically adjust attack intensity and training strategies. In the DCGAN training phase, clients collaboratively train a DCGAN to generate synthetic samples resembling the original dataset. During the formal training phase, backdoor triggers are embedded into the synthetic samples, and the resulting updates are aggregated into the global model. Finally, in the backdoor activation phase, the compromised model responds to inputs containing the predefined trigger, executing the attacker-specified behavior. This workflow highlights CASBA’s dynamic and adaptive optimization of attack feasibility, effectiveness, and stealth.

The primary objective of CASBA is to maximize the effectiveness of the backdoor attack while preserving the performance of the main task (i.e., benign classification). To achieve this, a two-phase pretraining process is performed to evaluate each malicious client’s computational and communication capabilities. Based on this profiling, the attack strength and training strategy are dynamically adjusted to mitigate the impact of system heterogeneity on the attack performance. During the formal training phase, the adversary employs the improved DCGAN to generate high-quality synthetic data, embedding predefined triggers into these samples and assigning them target labels. These poisoned samples are then mixed into the training set without modifying the original data, allowing the global model to be stealthily implanted with a backdoor. This approach effectively balances attack intensity with client resource constraints, enhances the overall effectiveness of the attack, minimizes the risk of detection, and exerts negligible influence on the primary task. The formal definition of the attack objective is given in Eq. (7):

where

For training the backdoor task, the attacker first generates synthetic images using the DCGAN model. These generated images are then embedded with predefined triggers, thereby transforming arbitrary clean samples into poisoned backdoor data. The attacker aims to optimize the model parameters through dual-task training such that the updated global model

1) predict the target label

2) correctly predict the ground-truth label

4.3 Malicious Client Initialization and Device Modeling

Device heterogeneity in FL significantly impacts the effectiveness of attacks launched by malicious clients. To address this issue, this study presents a detailed device model based on three key dimensions: computational capability, communication performance, and device type classification.

4.3.1 Computational Capability Modeling

To accurately simulate computational capability, various hardware characteristics are taken into account, including the number of CPU cores, CPU frequency, memory size, and storage speed. A weighted formula is designed to quantify the overall capability, as follows:

where C denotes the device’s computational capability;

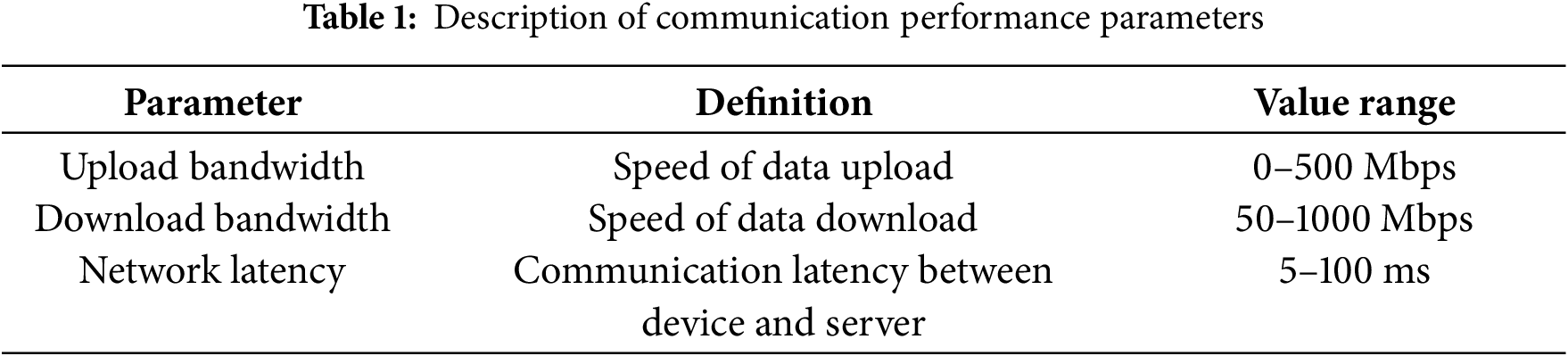

4.3.2 Communication Performance Modeling

To simulate data transmission between devices and the server, several communication parameters are defined, including upload bandwidth, download bandwidth, and network latency. The definitions and ranges are shown in Table 1:

These parameter values are carefully designed to effectively emulate the communication capabilities of heterogeneous devices in a FL setting. This fine-grained modeling provides a solid foundation for evaluating the stealth and adaptability of the attack in subsequent experiments.

4.3.3 Device Type Classification

These parameter ranges are designed to realistically capture the communication characteristics of heterogeneous devices in FL settings.

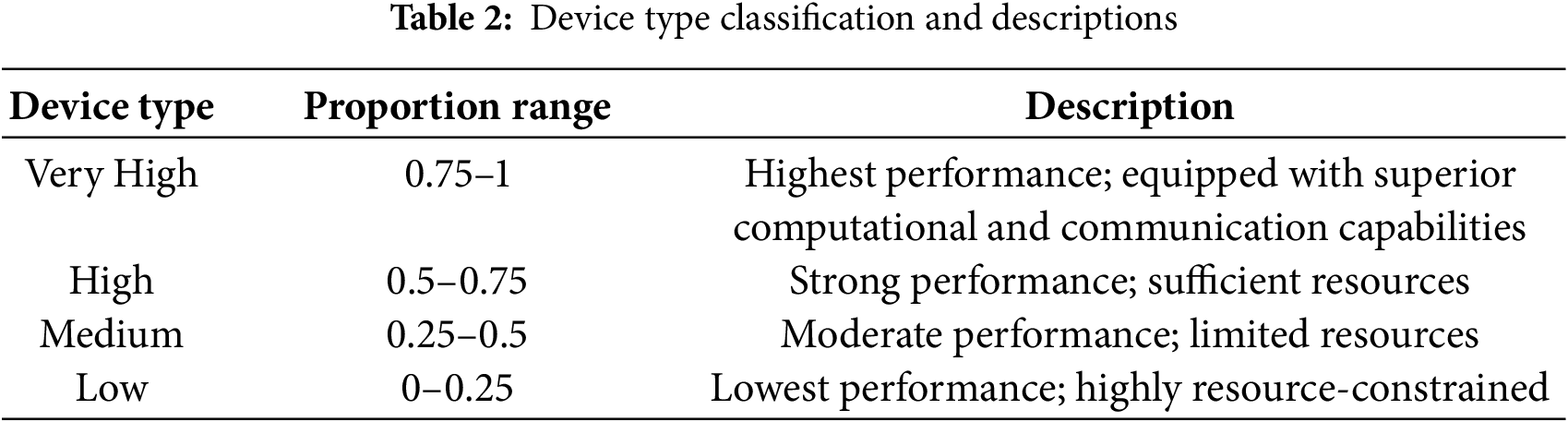

To realistically simulate device heterogeneity, this study generates normalized proportion values based on a Gaussian distribution and classifies devices according to a predefined mapping scheme. The classification rules are summarized in Table 2:

The proportion values are generated according to a normal distribution with a mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 0.2. Most of the values naturally fall within the [0, 1] range, while a small number that exceed this range are truncated. This method not only reflects the natural distribution of device performance but also provides a theoretical basis for simulating device diversity in the experiments.

To ensure the attack effectiveness of malicious clients in the experiments, a special configuration is applied to the final malicious client: it is forcibly designated as a Very High device. This assignment bypasses the standard proportion generation and mapping rules, directly setting the client to the highest performance level. This design highlights the performance contrast between the malicious client and other devices and serves as a consistent baseline for performance evaluation.

By modeling the multidimensional characteristics of computational and communication capabilities and adopting a fine-grained classification of device types, the experimental environment realistically reproduces device heterogeneity. Although real-world parameters such as bandwidth, latency, and computational resources vary over time, prior studies [28–30] show that static parameterization effectively captures their macro-level impact. Accordingly, this work employs static modeling, providing a practical approximation while acknowledging that dynamic fluctuations and complex interactions are not captured. Future work may incorporate dynamic network simulation or cross-platform hardware emulation for more realistic evaluations.

Remark (Static vs. Dynamic Modeling). Static modeling can be regarded as an averaged approximation of dynamic modeling, effectively reflecting long-term performance differences across heterogeneous devices. It is suitable for macroscopic evaluation and efficient large-scale experiments, whereas dynamic modeling is preferable when short-term fluctuations or temporal interactions play a critical role.

4.4 Dynamic Tiered Attack Strategy

To address the impact of device heterogeneity on attack efficiency, this study proposes a dynamic tiered strategy. This strategy dynamically adjusts training parameters and attack intensity based on the hardware performance and communication capabilities of malicious clients, thereby optimizing resource utilization.

Prior to formal training, all malicious clients undergo two rounds of pretraining to evaluate their computational and communication capacities. Based on a normalization scoring mechanism (Eq. (9)), device capabilities are quantified into scores:

where

Attack tasks are dynamically allocated based on the scores: clients with higher scores undertake more complex attack tasks (tasks involving higher attack intensity), while clients with lower scores perform lighter tasks. This mechanism effectively improves resource utilization and prevents low-performance devices from becoming bottlenecks.

Moreover, for attackers constrained by limited communication capabilities, a pruning optimization strategy is adopted. Only parameter updates with norms exceeding a predefined threshold are transmitted, thereby reducing communication overhead while maintaining attack effectiveness. The pruning process is defined in Eq. (10):

where D is the original set of parameter updates; D′ is the filtered set after pruning;

Regarding trigger embedding, this study leverages an improved DCGAN to generate synthetic images embedded with backdoor triggers, avoiding direct modification of original data to enhance stealthiness. To ensure the quality and reliability of generated images in single-shot attack (Attack A-S) scenarios—where each malicious client has only one opportunity to launch the attack—the Mahalanobis distance [31] is introduced as an image filtering criterion. Compared to Euclidean distance, the Mahalanobis distance accounts for both mean and covariance information of the data distribution, making it more suitable for high-dimensional data filtering. The Mahalanobis distance is computed as follows Eq. (11):

where

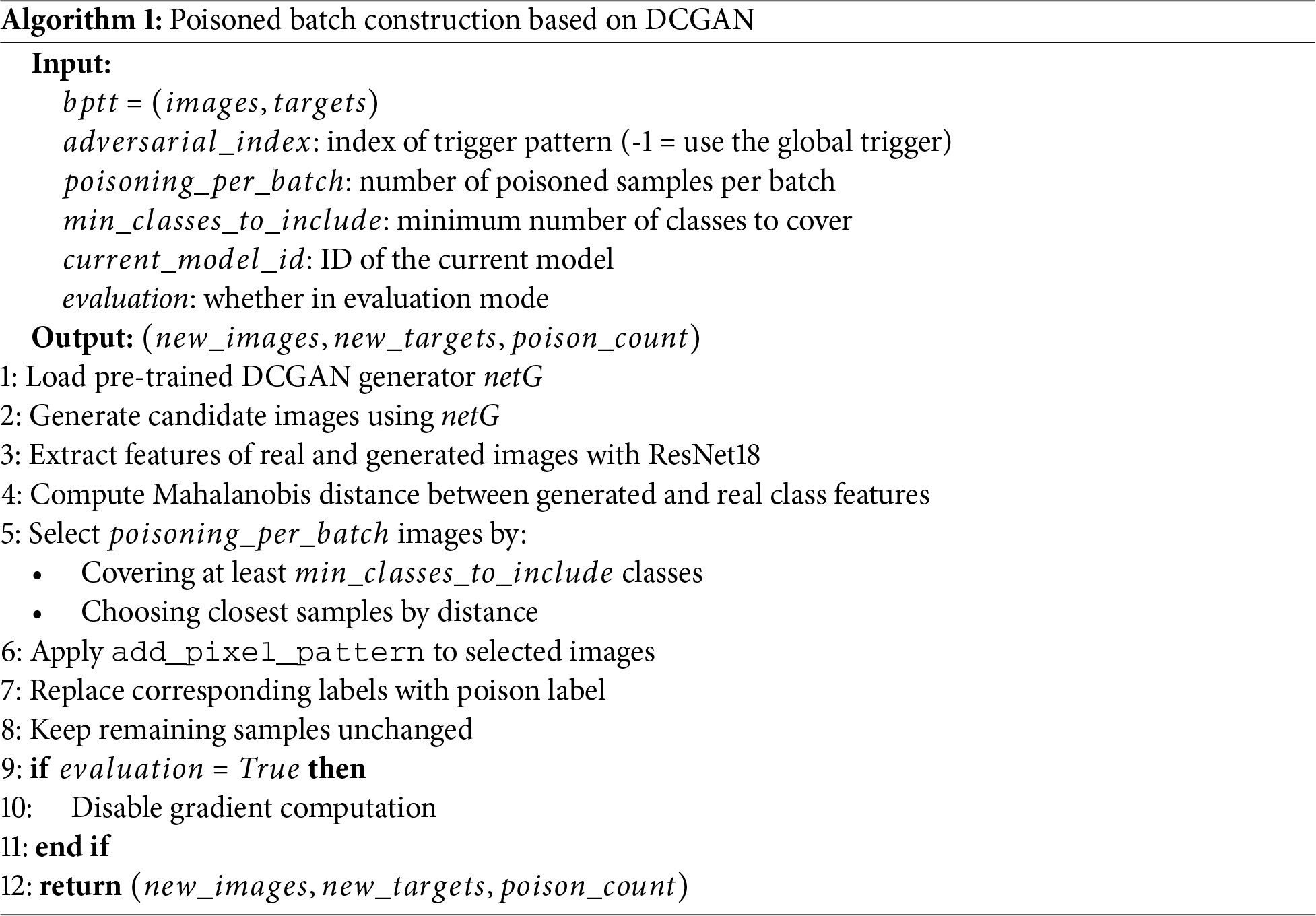

Based on the above generation and screening strategies, the final construction process of poisoned batches is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 presents the construction of poisoned batches based on DCGAN generation and Mahalanobis distance-based selection. Specifically, an initial set of synthetic samples is first generated, and the Mahalanobis distance between each sample and the target distribution is computed to discard samples that do not meet the threshold criteria. Finally, backdoor triggers are superimposed onto the remaining DCGAN-generated samples (Algorithm 1, Step 6) with their labels reassigned to the attacker-specified target class, forming the poisoned batch while leaving the original client data untouched.

In summary, this study proposes an efficient and covert attack method by integrating capability scoring, dynamic task allocation, pruning optimization, DCGAN-based synthetic image generation, and Mahalanobis distance filtering. The multi-stage optimization strategy designed for heterogeneous hardware and communication conditions of malicious clients significantly enhances the adaptability and stealthiness of the attack.

5.1 Experimental Data and Environment Setup

This study evaluates attack performance using the CIFAR-10 [32] and MNIST [33] datasets. CIFAR-10 consists of multi-class color images, simulating complex scenarios in FL tasks, while MNIST contains handwritten digit images, suitable for validating the model’s fundamental performance on simpler tasks. To simulate a FL environment, 100 clients are configured, among which 5 clients are malicious (accounting for 5%). A highly non-IID data distribution is generated using a Dirichlet distribution [34] with a concentration parameter of 0.5 to assess the model’s robustness and applicability under data heterogeneity conditions.

This study was conducted in an experimental environment supported by a high-performance computing platform, equipped with a 10-core CPU, a single NVIDIA A40 GPU (46 GB of memory), and 20 TB of storage. All experiments were implemented using the Python-based deep learning framework PyTorch.

5.2 Experimental Evaluation of the Improved DCGAN

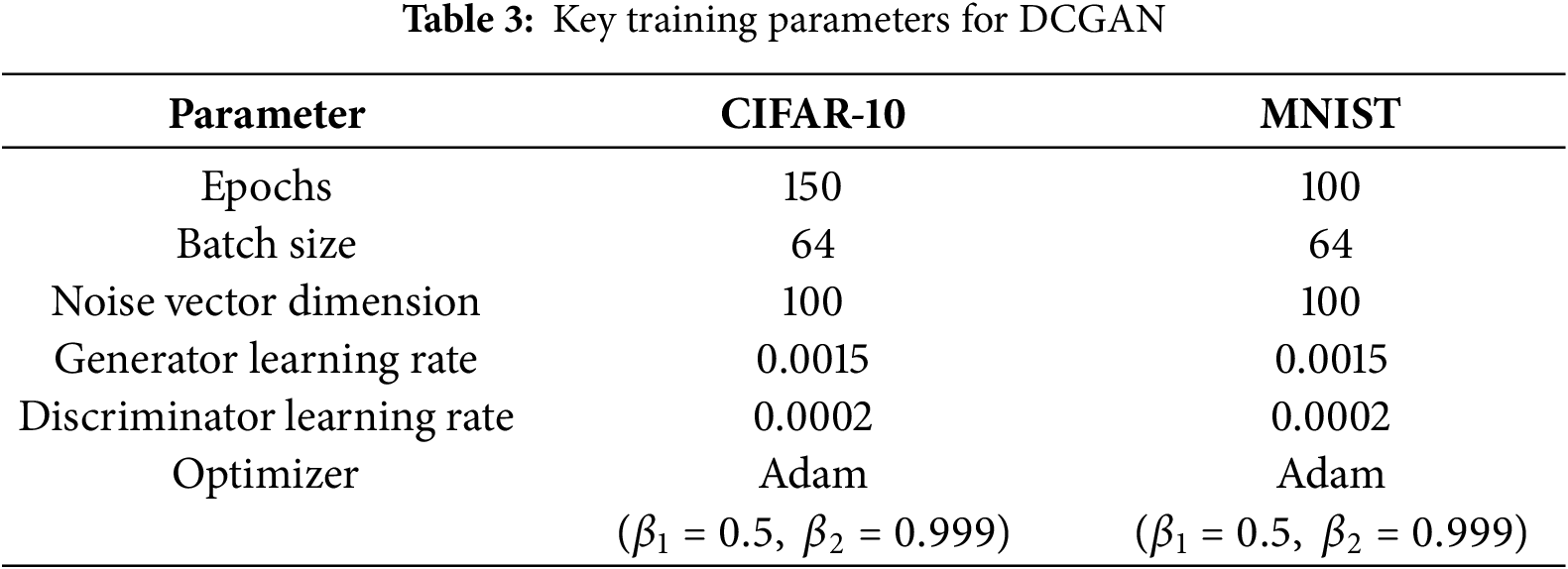

To quantitatively assess the performance of the improved DCGAN model, This study first lists the key training parameters of DCGAN (see Table 3). These parameters were fine-tuned to ensure stable training and the generation of high-quality images.

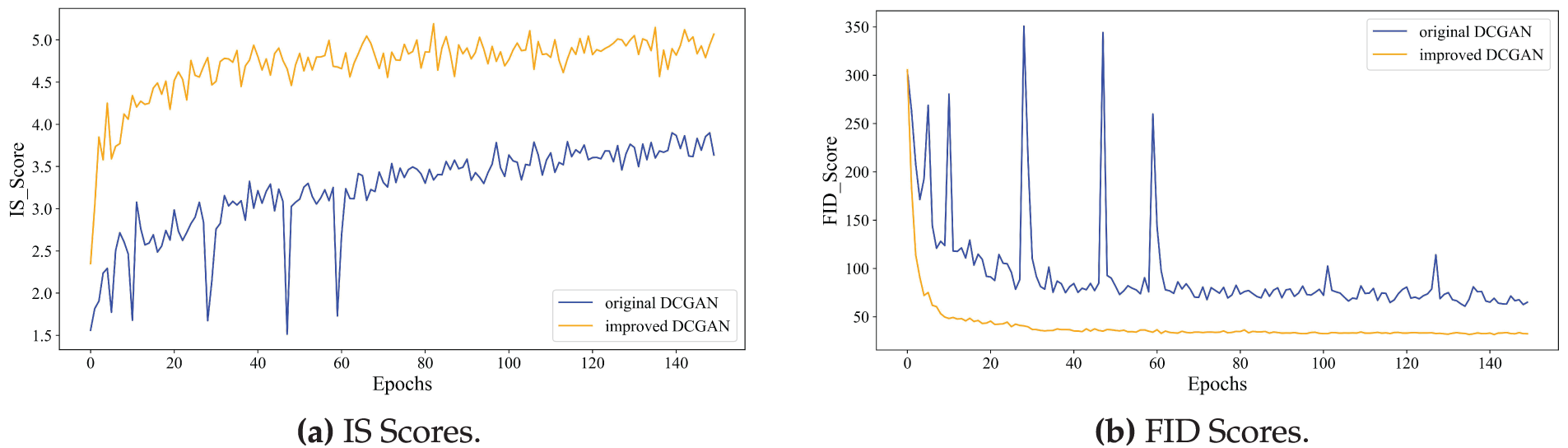

This study utilizes the Inception Score (IS) and Frechet Inception Distance (FID) as evaluation metrics. The IS measures the quality and diversity of generated images by extracting the classification probability distributions using a pre-trained Inception network, evaluating both class distinctiveness and coverage. Higher IS values indicate better image quality and diversity. The FID assesses the similarity between the distributions of generated images and real images, calculated based on their means and covariances in the feature space. Lower FID scores signify that the distribution of generated images is closer to that of real data, reflecting higher quality.

In the experiments, the IS is computed using 1000 images generated per epoch to evaluate image quality and diversity, while the FID is calculated from 5000 generated images per epoch to ensure the stability and reliability of the evaluation results.

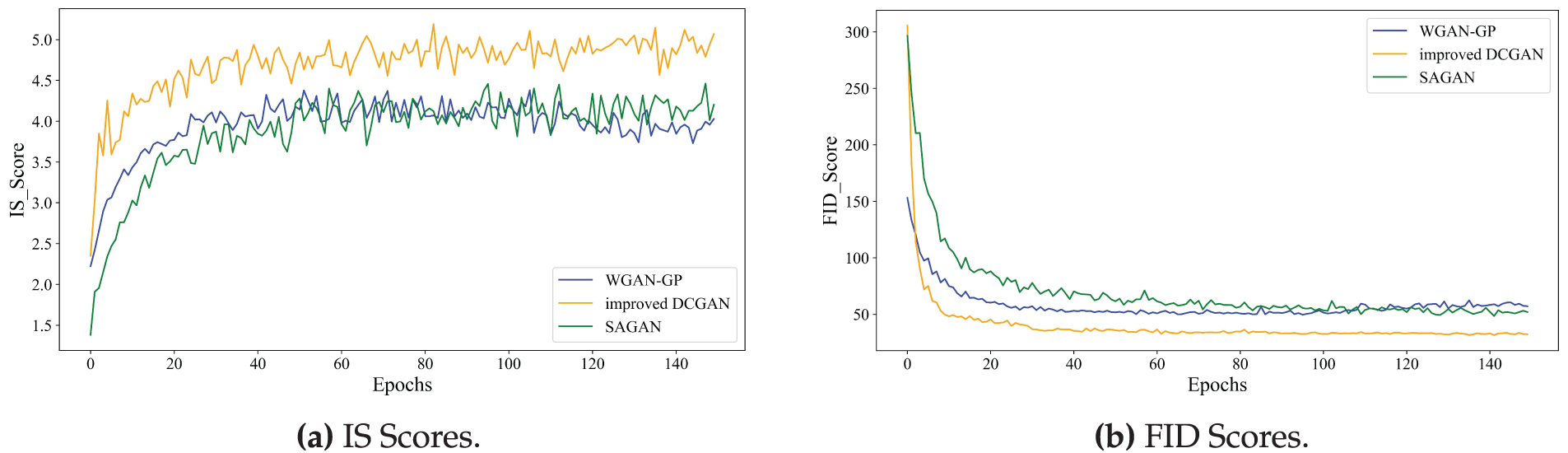

As shown in Fig. 8a,b, the trends of IS and FID on the CIFAR-10 dataset before and after the DCGAN enhancement are presented. The results demonstrate that the average IS improves by 38.46% between rounds 60 and 150, with a significantly smoother curve, indicating improved stability. Meanwhile, the average FID decreases by 56.52% over the same period. These improvements indicate that the quality and diversity of the generated images have increased, and their distribution becomes more aligned with that of the real data.

Figure 8: Comparison of IS and FID Scores Before and After Improvement. (a) IS Scores. (b) FID Scores

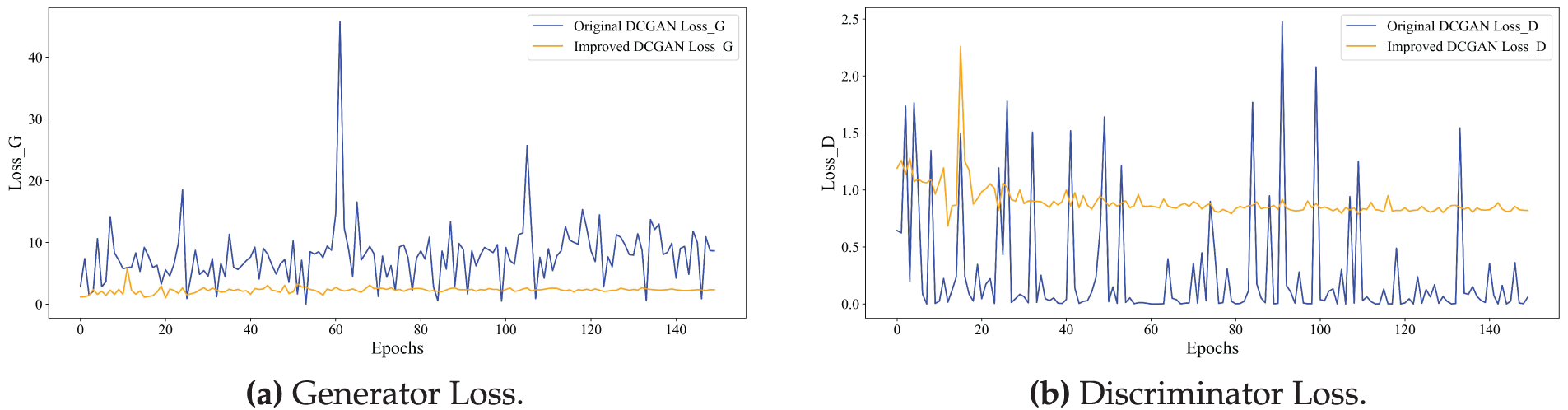

In addition, Fig. 9a,b illustrates the loss curves of the generator and discriminator, respectively. The improved DCGAN demonstrates significantly enhanced training stability and convergence efficiency, as evidenced by the reduced amplitude of loss fluctuations. This improvement indicates that the optimization of the loss function and model architecture effectively enhances the robustness and reliability of the training process.

Figure 9: Comparison of generator and discriminator loss before and after improvement. (a) Generator loss. (b) Discriminator loss

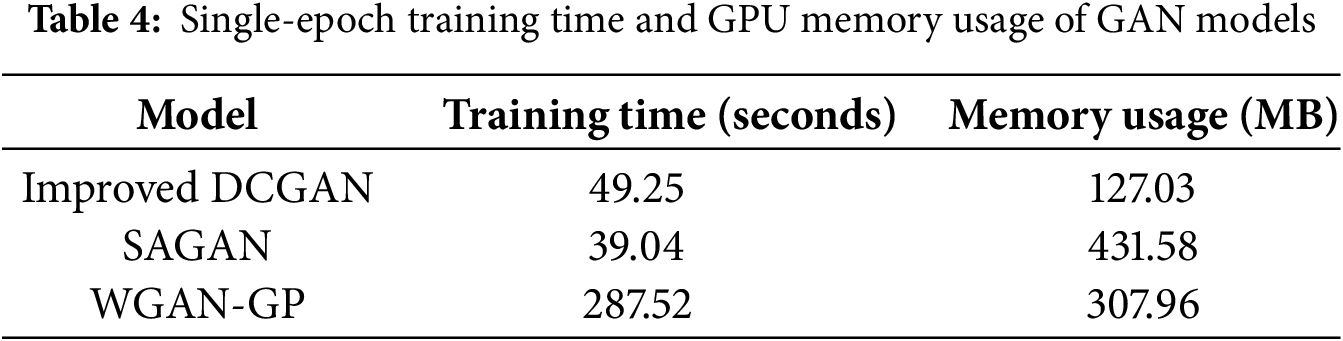

To further evaluate the performance of the improved DCGAN, we compare it with the Self-Attention Generative Adversarial Network (SAGAN) and the Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP). In the comparative experiments, the batch size and number of training epochs for SAGAN and WGAN-GP were kept consistent with those of DCGAN, while all other hyperparameters (such as learning rate, optimizer settings, and latent space dimension) followed their original implementations. The evaluation focuses on three key aspects: the quality of the generated images (measured by IS and FID scores), training efficiency, and computational resource consumption.

Fig. 10a,b illustrates the IS and FID scores of the three GAN models during training. Between epochs 60 and 150, the improved DCGAN achieves IS scores that are 17.67% and 20.30% higher than those of SAGAN and WGAN-GP, respectively. Meanwhile, its FID scores are 39.63% and 38.44% lower than those of SAGAN and WGAN-GP, respectively. These results indicate that the improved DCGAN generates images with higher quality and greater similarity to the real data distribution.

Figure 10: Comparison of IS and FID scores across different GANs. (a) IS Scores. (b) FID Scores

As shown in Table 4, the improved DCGAN exhibits the most efficient memory usage, consuming 70.56% and 58.76% less GPU memory compared to SAGAN and WGAN-GP, respectively, making it more suitable for resource-constrained environments. The increased memory usage in SAGAN results from the introduction of attention mechanisms, which significantly increase computational overhead. In contrast, the high resource demand of WGAN-GP stems from its training routine, which requires five discriminator updates for each generator update.

Although the improved DCGAN incorporates a hybrid loss function and additional network layers, which slightly increases computational complexity, the relatively low resolution of the CIFAR-10 dataset allows for the use of only the first eight layers of VGG16 in the perceptual loss calculation. This keeps memory overhead limited. However, the inclusion of perceptual loss introduces an additional forward pass, and the hinge loss increases optimization complexity, resulting in a slightly longer training time compared to SAGAN.

5.3 Attack Evaluation of CASBA

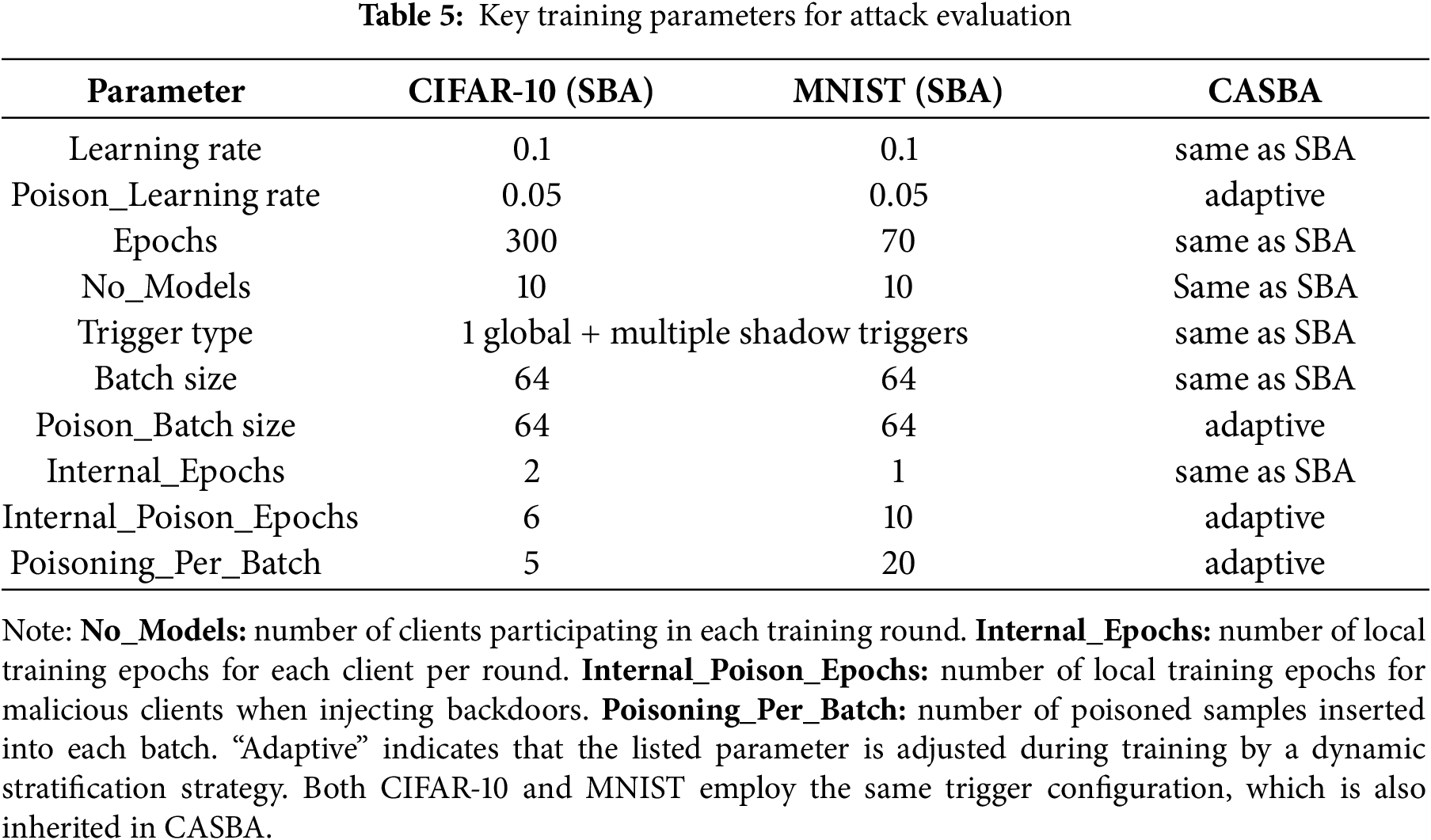

To evaluate the attack performance of CASBA, this study conducts comparative experiments against the SBA method under single-shot attack (Attack A-S) and multi-shot attack (Attack A-M) scenarios. The evaluation focuses on attack success rate (the effectiveness of a complete attack) and attack persistence (the sustained attack success rate after n training rounds). Experimental parameter settings are summarized in Table 5.

To ensure fairness, all experiments used the same setup for global and local triggers. Based on earlier DBA results showing pretrained models boost attack effectiveness [7], ResNet models pretrained for 10 and 200 epochs were tested on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets, respectively.

Attack A-S means each attacker has only one chance to inject local updates containing backdoor triggers into the global model. To ensure the backdoor survives aggregation, attackers scale up their local gradients to overwhelm benign updates. This means Attack A-S have a larger impact on the main task but significantly enhance attack effectiveness.

Attack A-M means each attacker can inject backdoors over multiple consecutive rounds of model updates, using a “small but continuous” approach to gradually influence the global model. This causes less impact on the main task, while the attack effectiveness accumulates over time.

In the Attack A-S scenario, taking CIFAR-10 as an example, the attacker injects the global trigger at round 201, and shadow triggers at rounds 203, 205, 207, and 209, while other participants are randomly selected from benign clients.

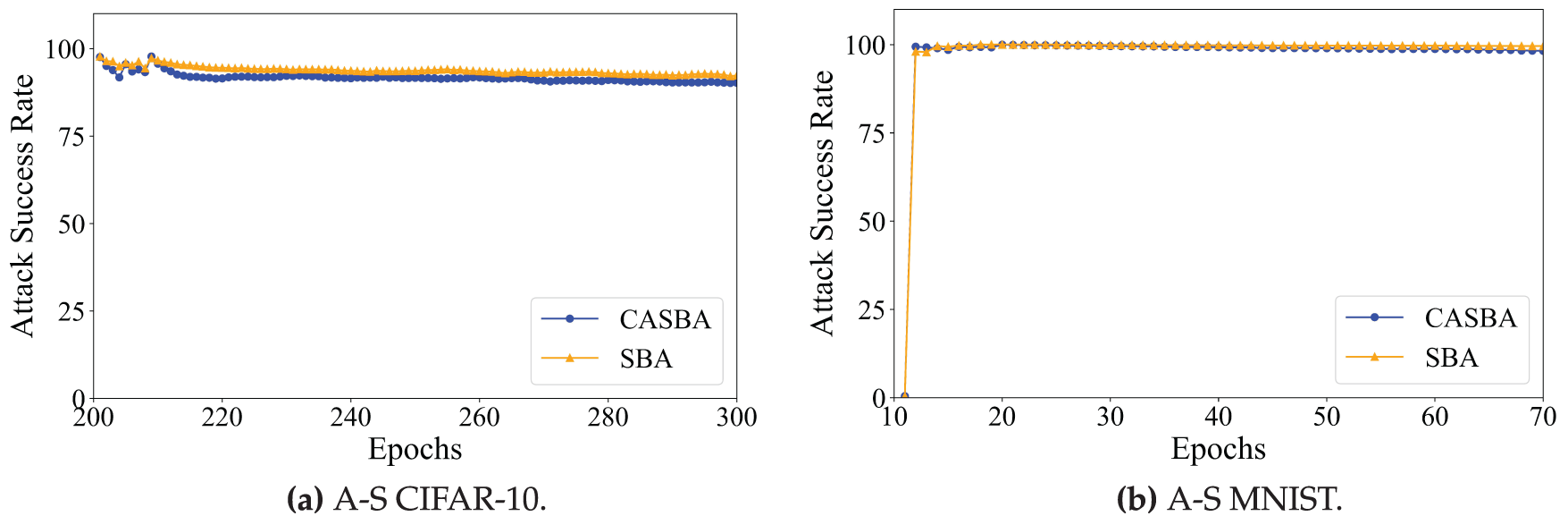

Fig. 11a,b illustrates the attack success rates of CASBA compared to SBA. On CIFAR-10, CASBA’s success rate decreases by 2.1%; on MNIST, it decreases by 1.35%. Although the attack success rate drops slightly, CASBA improves attack stealth by adaptive adjustment and the introduction of GAN, making the attack harder to detect while maintaining good attack persistence. This achieves a balance between stealth and persistence with minimal sacrifice in attack effectiveness.

Figure 11: A-S CIFAR-10 and A-S MNIST. (a) A-S CIFAR-10. (b) A-S MNIST

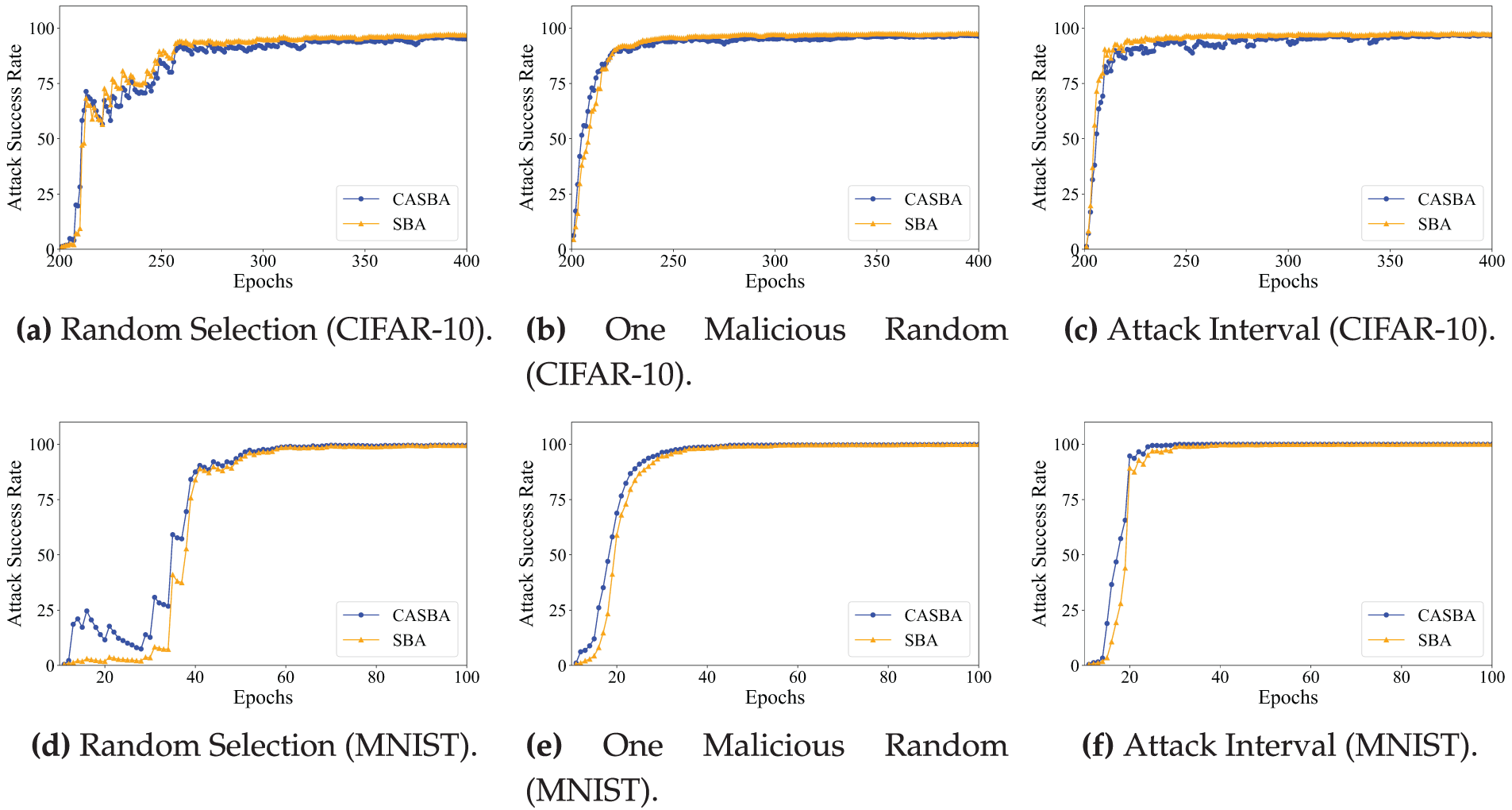

In the Attack A-M scenario, three client selection strategies were employed: (1) completely random selection of clients, which may result in some rounds without any malicious clients; (2) selecting one malicious client randomly in each round, supplemented by randomly chosen benign clients; (3) selecting clients based on the attack intervals of malicious clients, with the remainder filled by randomly selected benign clients. The attack intervals are assigned according to device capabilities (from strongest to weakest) as 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10.

As shown in Fig. 12a–f, the final attack success rates of CASBA and SBA are highly comparable across all client selection strategies, indicating that the introduction of the dynamic stratification mechanism and the use of GAN has negligible impact on overall attack effectiveness. However, in practical deployments, these mechanisms significantly enhance the stealthiness of the attack, making it more difficult to detect or defend against.

Figure 12: Comparison of A-M strategies in CIFAR-10 and MNIST with different client selection methods. (a) Random Selection (CIFAR-10). (b) One Malicious Random (CIFAR-10). (c) Attack Interval (CIFAR-10). (d) Random Selection (MNIST). (e) One Malicious Random (MNIST). (f) Attack Interval (MNIST)

5.4 Trigger Stealthiness Evaluation

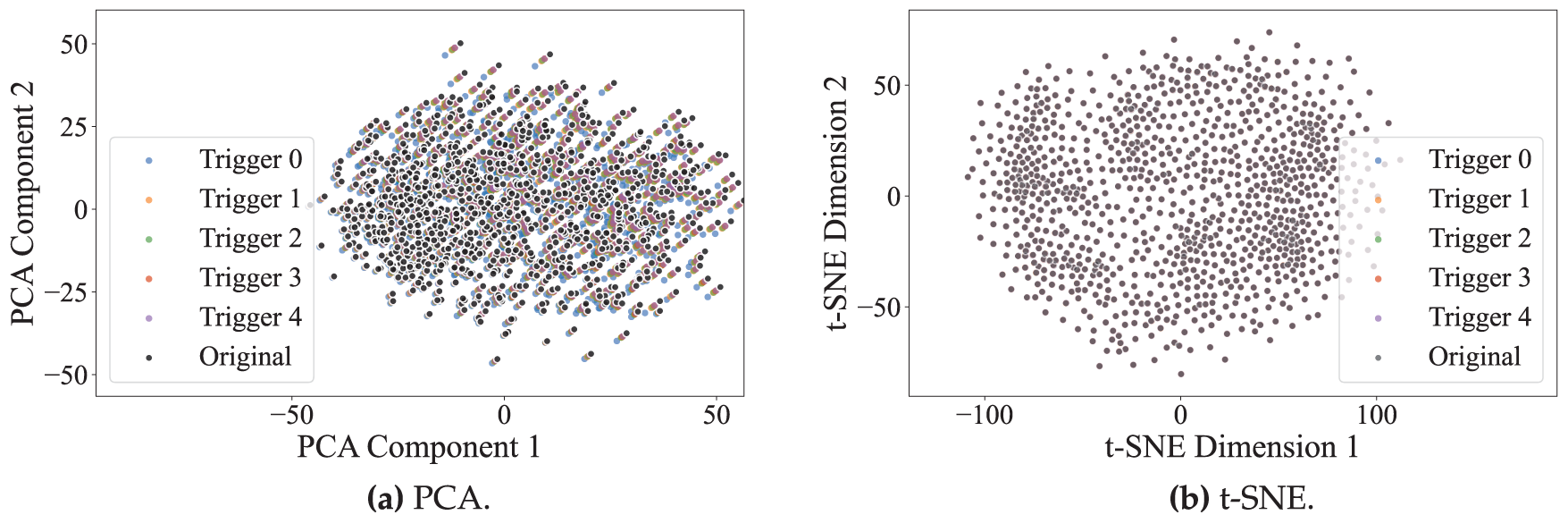

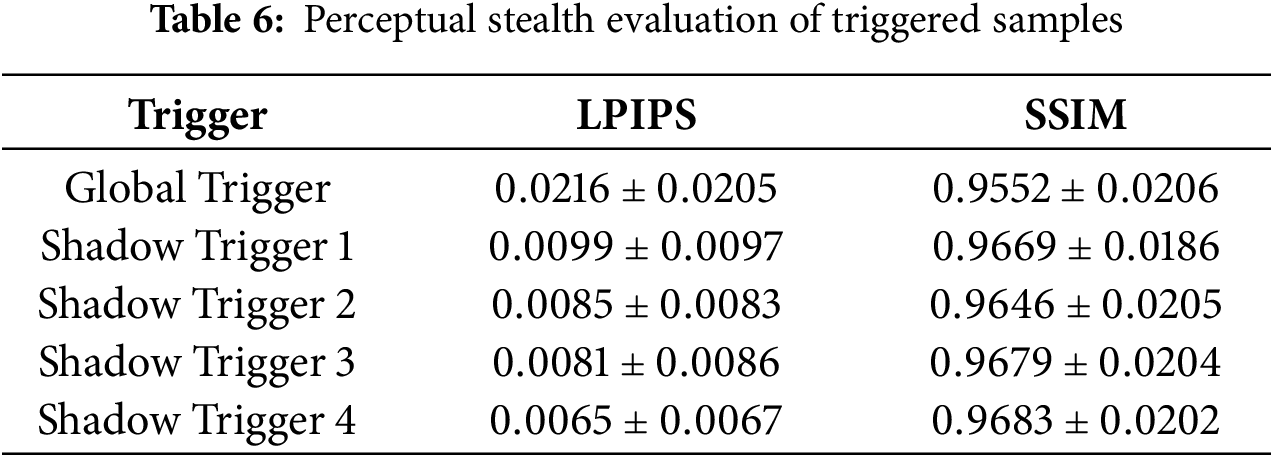

To evaluate the stealthiness of the designed triggers, this study uses 1000 generated samples from CIFAR-10, each embedded with either a global trigger or shadow triggers, and analyzes their stealthiness from three perspectives: pixel-level, semantic-level, and perceptual similarity metrics.

1) Pixel-level Visualization

In the pixel space, we employ Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to perform dimensionality reduction and visualization of the samples.

PCA is a classical linear dimensionality reduction method that projects high-dimensional data onto a low-dimensional space by extracting directions of maximum variance, effectively preserving the global structure while reducing complexity.

t-SNE is a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method that preserves local structures by mapping high-dimensional distances to probabilities in a low-dimensional space, making it well-suited for complex nonlinear data such as images or text.

As shown in Fig. 13a,b, the distributions of the two types of samples in the low-dimensional space are highly overlapping, indicating that the triggers introduce minimal perturbation to the pixel-level distribution of the images.

Figure 13: Pixel-level visualization of CIFAR-10 samples: (a) PCA. (b) t-SNE

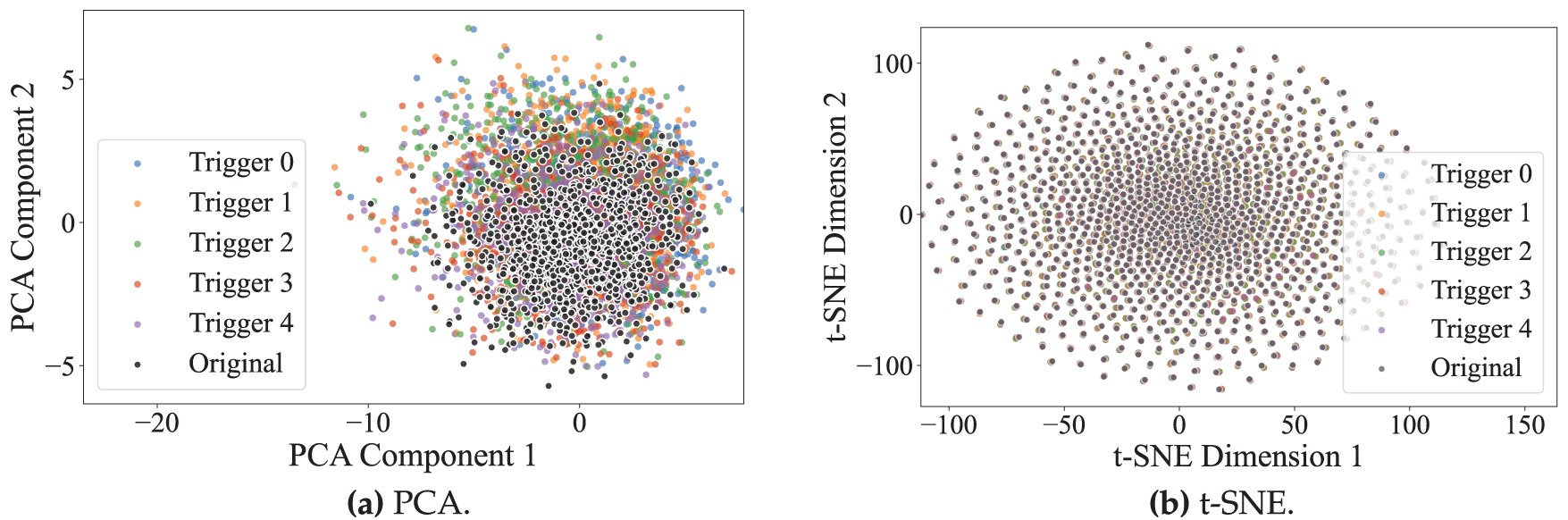

2) Semantic-level Visualization

Furthermore, we extract deep features using a pre-trained ResNet-18 and perform PCA and t-SNE visualizations in the feature space. As shown in Fig. 14a,b, a certain semantic discrepancy between the two types of samples can be observed in the PCA space, which may reflect slight shifts in the global distribution of deep features. However, the two sample types remain highly overlapping in the t-SNE space, indicating that the triggers have minimal impact on the core semantic information of the images. This demonstrates that the triggers maintain a high level of stealth even at the deep semantic level.

Figure 14: Semantic-level Visualization of CIFAR-10 samples: (a) PCA. (b) t-SNE

3) Perceptual Similarity Metrics

To quantitatively assess the perceptual similarity between trigger-embedded samples and the original samples, we compute Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) as the primary evaluation metrics. The results are presented as follows:

LPIPS and SSIM are used to evaluate the perceptual and structural similarity between original and trigger-embedded images. LPIPS measures perceptual differences using deep features from a pre-trained model, with values ranging from 0 to 1; smaller values indicate higher perceptual similarity, making samples harder to distinguish visually. SSIM assesses luminance, contrast, and structural consistency, also ranging from 0 to 1; higher values indicate greater structural and visual consistency and minimal disruption from the trigger.

As shown in Table 6, all triggers exhibit very low LPIPS (

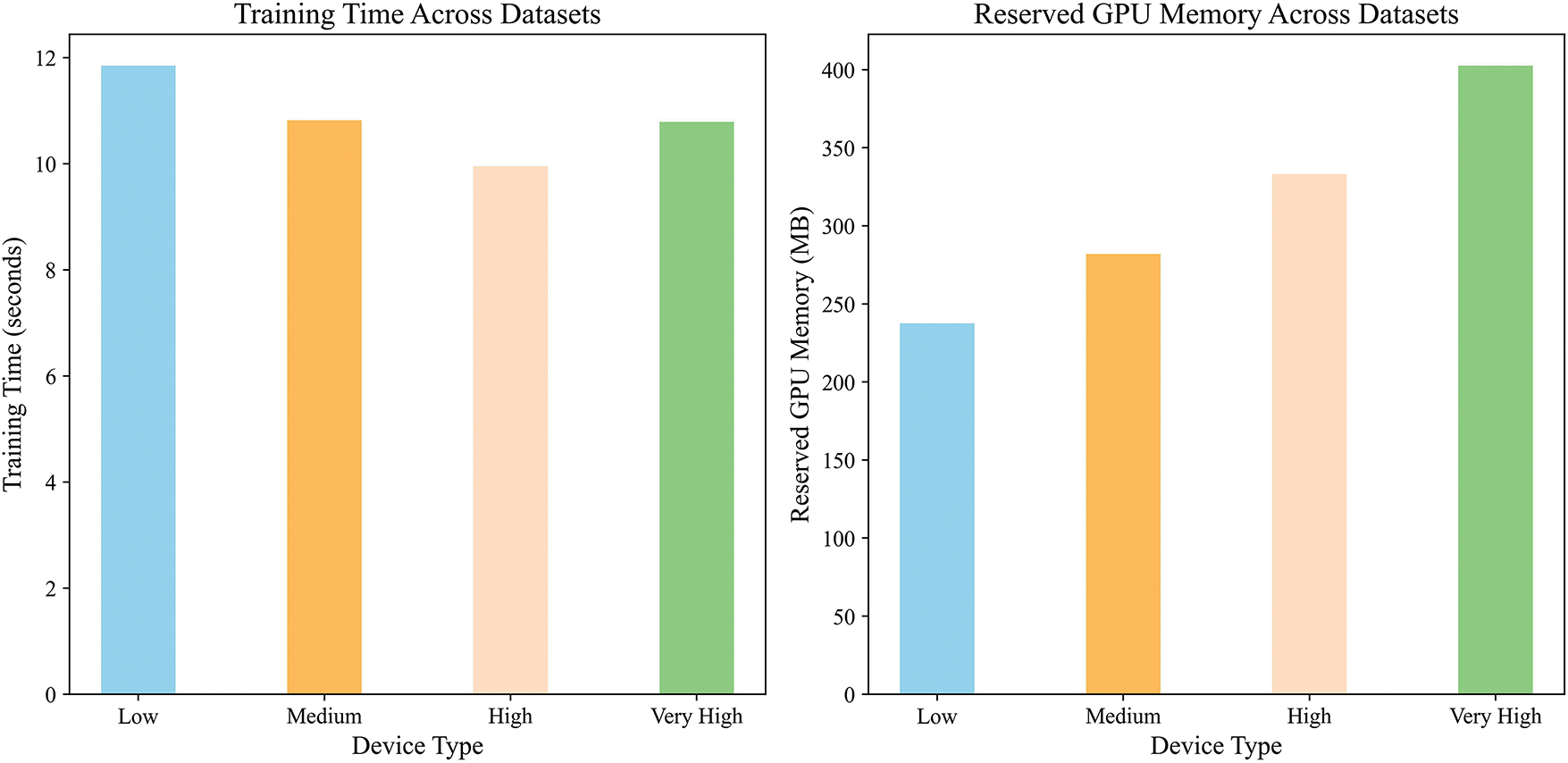

5.5 Resource Usage Evaluation of CASBA

To evaluate the resource consumption differences between CASBA and SBA attributable to the dynamic stratification strategy, this study excludes the use of GAN and focuses solely on the stratification mechanism. Experiments were conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset, and key resource metrics were collected using system monitoring tools, with particular attention paid to the impact on memory usage and training efficiency.

Specifically, we measured the GPU memory usage during a single training batch and the total local training time for each client device. The experiments involved four types of devices categorized by computational capacity: low, medium, high, and very high. For devices categorized as high in computational capacity (as opposed to very high), CASBA uses the same training parameters as SBA. In contrast, for resource-constrained devices (low and medium categories), the dynamic stratification strategy reduces the computational load per iteration to lower overall resource consumption.

As illustrated in Fig. 15, the local training time across different device types remains generally consistent (left), indicating that the dynamic stratification strategy does not significantly increase the training burden on any specific device, thereby ensuring consistent training efficiency. Meanwhile, the GPU memory usage exhibits an adaptive pattern with both increases and decreases across device types (right): on low-capacity devices (Low), memory consumption is significantly reduced, effectively alleviating resource constraints; whereas on high-capacity devices (Very High), memory usage slightly increases, demonstrating that the dynamic stratification strategy can allocate resources based on device capabilities, thereby enhancing the overall adaptability and scalability of the system. On average, GPU memory usage is reduced by 5.8%, further highlighting the efficiency of the proposed approach in heterogeneous environments.

Figure 15: Resource usage comparison across device configurations

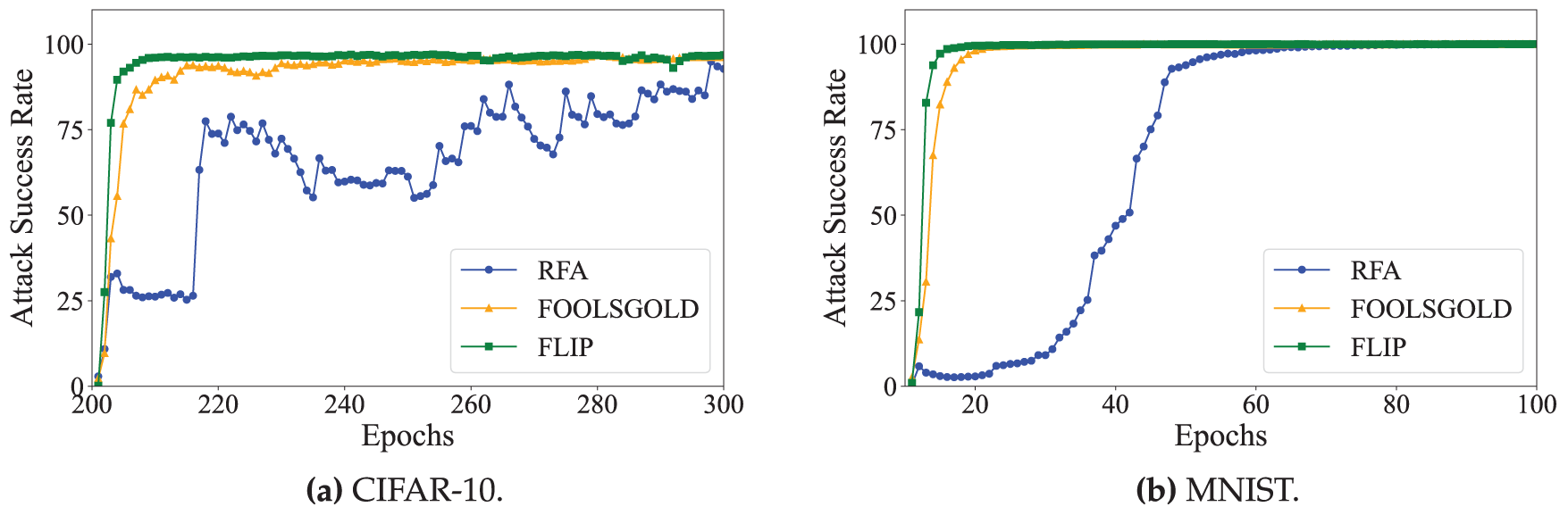

5.6 Robustness Evaluation of CASBA

To assess the robustness of CASBA against FL backdoor defenses, we conducted experiments replacing the standard FedAvg aggregation with three widely adopted defense mechanisms: Robust Federated Aggregation (RFA) [35], FoolsGold [14], and Federated Learning Provable defense framework (FLIP) [36]. Given that Attack A-S scenarios involve aggressive scaling strategies that make attacks more detectable, we instead evaluate CASBA under Attack A-M settings, which better reflect the complexity of real-world FL environments. Specifically, we configure RFA and FLIP with four attackers per round, and FoolsGold with two attackers per round to emulate collaborative Sybil-style attacks.

FoolsGold mitigates the impact of Sybil attacks by analyzing the similarity among client updates and down-weighting those that appear overly coordinated. RFA, on the other hand, employs an approximation of the geometric median rather than the conventional weighted mean, allowing it to detect and filter out anomalous updates that significantly deviate from the norm. In our experiments, RFA is run with a maximum of four iterations per round, and both the convergence and minimum distance thresholds are set to their default values.

FLIP leverages benign clients to generate pseudo backdoor samples via trigger inversion and combines them with augmented data for adversarial training, thereby strengthening the global model. On the server side, low-confidence samples are filtered using a threshold

Since RFA and FLIP are more sensitive to high-intensity attacks, we reduce the attack strength of each participating attacker to counteract these defenses.

As shown in Fig. 16a,b, CASBA exhibits fluctuating attack success rates on the CIFAR-10 dataset during the initial rounds, primarily due to RFA’s removal of highly deviant updates. However, as the training progresses, the cumulative effect of the attack intensifies, ultimately leading to a high success rate. On the MNIST dataset, the attack progresses more gradually. This is attributed to the simplicity of the dataset, which enables RFA to more easily detect aggressive attack patterns. Nevertheless, as training continues, even low-intensity attacks gradually accumulate, eventually overcoming RFA’s defense and achieving a sharp increase in attack success.

Figure 16: Attack success rate of CASBA under RFA, FoolsGold and FLIP defenses. (a) CIFAR-10. (b) MNIST

In contrast, FoolsGold is effectively bypassed by CASBA on both datasets. On CIFAR-10, the attack success rate rapidly climbs to 94.4% within just 30 rounds and remains stable thereafter. On MNIST, the effect is even more pronounced, with a success rate of 98.1% achieved by the 10th round.

Similar to FoolsGold, FLIP performs well against single-trigger and persistent attacks but is largely ineffective against CASBA. This is because CASBA violates FLIP’s trigger consistency assumption: multiple malicious clients employ non-identical shadow triggers, preventing the emergence of a single invertible trigger in the global model. Moreover, the redundancy among shadow triggers ensures that the backdoor remains effective even if some patterns are weakened, rendering FLIP largely incapable of reducing the attack success rate.

In summary, the experimental results validate the effectiveness and robustness of CASBA against all three defense mechanisms. By leveraging dynamic stratification and multi-shot collaboration, CASBA can effectively evade detection by RFA, FoolsGold, and FLIP, exhibiting strong adaptability and attack performance.

This paper proposes a novel Capability-Adaptive Shadow Backdoor Attack (CASBA), which addresses the challenge of device heterogeneity in federated learning by introducing a dynamic, tiered attack strategy. By incorporating an enhanced DCGAN model to generate high-quality synthetic data, CASBA improves both the stealth and adaptability of backdoor attacks.

Through experiments on the CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets, the results demonstrate that CASBA achieves high attack success rates and persistence in both single-shot and multi-shot attack scenarios. The dynamic stratification strategy can adaptively adjust parameters according to the computational and communication capabilities of devices, thereby optimizing resource utilization efficiency and enabling low-capacity devices to effectively participate in the attack. In addition, CASBA successfully bypasses mainstream backdoor defense mechanisms (e.g., RFA, FoolsGold, and FLIP) in robustness evaluations, highlighting its effectiveness under complex defense settings. Overall, by incorporating dynamic stratification and GAN-based generation, CASBA not only ensures strong attack performance but also significantly enhances stealthiness and resource efficiency.

We acknowledge that CIFAR-10 and MNIST are relatively simple datasets and may not fully capture the scalability of the proposed method in more complex scenarios. Nevertheless, the experimental results sufficiently validate the core mechanisms and potential of CASBA. Future work can further explore CASBA’s performance in more sophisticated environments from the following perspectives:

1) Validation in Realistic Heterogeneous Environments: Test CASBA on real federated learning platforms or more complex simulated heterogeneous setups to evaluate practical performance.

2) Optimizing the Adaptive Mechanism: Design real-time parameter adjustment strategies to dynamically respond to evolving defense mechanisms.

3) Multimodal Backdoor Attacks: Explore cross-modal trigger design and dynamic generation to enhance attack flexibility and robustness.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely appreciate the support provided by the high-performance computing platform of the School of Computer Science and Technology of Harbin University of Science and Technology. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the use of GPT-4o (OpenAI) to assist in translating this manuscript from Chinese to English, improving the readability and clarity of the initial draft. All final content was reviewed and approved by the authors.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62172123) and the Key Research and Development Program of Heilongjiang Province, China (Grant No. 2022ZX01A36).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Hongwei Wu, Chao Ma; Methodology: Hongwei Wu, Chao Ma; Software: Guojian Li, Zi Ye; Formal analysis: Guojian Li, Zi Ye; Investigation: Guojian Li; Resources: Hongwei Wu; Writing—original draft preparation: Guojian Li, Hanyun Zhang; Writing—review and editing: Hongwei Wu, Chao Ma, Zi Ye; Visualization: Guojian Li, Hanyun Zhang; Supervision: Hongwei Wu, Chao Ma, Zi Ye; Funding acquisition: Chao Ma. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in CIFAR-10 at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 18 September 2025) and MNIST at https://huggingface.co/datasets/ylecun/mnist (accessed on 18 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BY. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Singh A, Zhu J, editors. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2017 Apr 20–22; Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA. Vol. 54. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

2. Bagdasaryan E, Veit A, Hua Y, Estrin D, Shmatikov V. How to backdoor federated learning. In: Chiappa S, Calandra R, editors. Proceedings of the Twenty Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2020 Aug 26–28; Remote. Vol. 108. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2020. p. 2938–48. [Google Scholar]

3. Jang J, Oh Y, Ryu G, Choi D. Data reconstruction attack with label guessing for federated learning. J Internet Technol. 2023;24(4):893–903. [Google Scholar]

4. Devi M, Nandal P, Sehrawat H. Federated learning-enabled lightweight intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks: a cybersecurity approach against DDoS attacks in smart city environments. Intell Syst Appl. 2025;27:200553. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2025.200553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xue M, He C, Wang J, Liu W. Backdoors hidden in facial features: a novel invisible backdoor attack against face recognition systems. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2021;14(3):1458–74. doi:10.1007/s12083-020-01031-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yan J, Gupta V, Ren X. BITE: textual backdoor attacks with iterative trigger injection. In: Rogers A, Boyd-Graber J, Okazaki N, editors. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. Rock Hill, SC, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p. 12951–68. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xie C, Huang K, Chen P-Y, Li B. DBA: distributed backdoor attacks against federated learning. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2020 Apr 26–30; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. p. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

8. Ren Q, Zheng Y, Yang C, Li Y, Ma J. Shadow backdoor attack: multi-intensity backdoor attack against federated learning. Comput Secur. 2024;139:103740. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Saha A, Subramanya A, Pirsiavash H. Hidden trigger backdoor attacks. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):11957–65. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang D, Wen S, Jolfaei A, Haghighi MS, Nepal S, Xiang Y. On the neural backdoor of federated generative models in edge computing. ACM Trans Internet Technol. 2021;22(2):43:1–21. doi:10.1145/3425662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu J, Peng C, Tan W, Shi C. Federated learning backdoor attack based on frequency domain injection. Entropy. 2024;26(2):164. doi:10.3390/e26020164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Q, Wu Y, Xuan H, Wu H. FLARE: a backdoor attack to federated learning with refined evasion. Mathematics. 2024;12(23):3751. doi:10.3390/math12233751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Z, Panda A, Song L, Yang Y, Mahoney M, Mittal P, et al. Neurotoxin: durable backdoors in federated learning. In: Chaudhuri K, Jegelka S, Song L, Szepesvari C, Niu G, Sabato S, editors. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. Vol. 162. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 26429–46. [Google Scholar]

14. Fung C, Yoon CJM, Beschastnikh I. Mitigating Sybils in federated learning poisoning. arXiv:1808.04866. 2018. [Google Scholar]

15. Cho HH, Zeng JY, Tsai MY. Efficient defense against adversarial attacks on multimodal emotion AI models. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2025. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2025.3551886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Nguyen T, Doan KD, Wong KS. FLAT: latent-driven arbitrary-target backdoor attacks in federated learning. arXiv:2508.04064. 2025. [Google Scholar]

17. Radford A, Metz L, Chintala S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1511.06434. 2016. [Google Scholar]

18. Mirza M, Osindero S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv:1411.1784. 2014. [Google Scholar]

19. Odena A, Olah C, Shlens J. Conditional image synthesis with auxiliary classifier GANs. In: Precup D, Teh YW, editors. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, NSW, Australia. Vol. 70. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 2642–51. [Google Scholar]

20. Arjovsky M, Chintala S, Bottou L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In: Precup D, Teh YW, editors. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, NSW, Australia. Vol. 70. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 214–23. [Google Scholar]

21. Gulrajani I, Ahmed F, Arjovsky M, Dumoulin V, Courville AC. Improved training of Wasserstein GANs. In: Guyon I, Von Luxburg U, Bengio S, Wallach H, Fergus R, Vishwanathan S, et al. editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 30. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

22. Zhang H, Goodfellow I, Metaxas D, Odena A. Self-attention generative adversarial networks. In: Chaudhuri K, Salakhutdinov R, editors. Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. Vol. 97. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2019. p. 7354–63. [Google Scholar]

23. Karras T, Laine S, Aila T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 4401–10. [Google Scholar]

24. Kang M, Shim W, Cho M, Park J. Rebooting ACGAN: auxiliary classifier GANs with stable training. In: Ranzato M, Beygelzimer A, Dauphin Y, Liang PS, Wortman Vaughan J, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 34. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2021. p. 23505–18. [Google Scholar]

25. Brock A, Donahue J, Simonyan K. Large scale GAN training for high fidelity natural image synthesis. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2019 May 6–9; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

26. Sun W, Gao B, Xiong K, Wang Y. A GAN-based data poisoning attack against federated learning systems and its countermeasure. arXiv:2405.11440. 2024. [Google Scholar]

27. Devi M, Nandal P, Sehrawat H. A lightweight approach for intrusion detection in WSNs based on DCGAN. Int J Inf Technol. 2025;17(2):951–7. doi:10.1007/s41870-024-02347-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abdelmoniem AM, Ho CY, Papageorgiou P, Bilal M, Canini M. On the impact of device and behavioral heterogeneity in federated learning. arXiv:2102.07500. 2021. [Google Scholar]

29. Ye M, Fang X, Du B, Yuen PC, Tao D. Heterogeneous federated learning: state-of-the-art and research challenges. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(3):79. doi:10.1145/3625558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang C, Wang Q, Xu M, Chen Z, Bian K, Liu Y, et al. Characterizing impacts of heterogeneity in federated learning upon large-scale smartphone data. In: WWW ’21: The Web Conference 2021; 2021 Apr 19–23; Ljubljana, Slovenia. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 935–46. doi:10.1145/3442381.3449851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Qin Y, Li Y, Ma W, Yang H, Hu F. Adaptive randomization via Mahalanobis distance. Stat Sin. 2024;34(1):353. doi:10.5705/ss.202020.0440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Krizhevsky A. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto; Technical Report. 2009. [Google Scholar]

33. LeCun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hsu TMH, Qi H, Brown M. Measuring the effects of non-identical data distribution for federated visual classification. arXiv:1909.06335. 2019. [Google Scholar]

35. Pillutla K, Kakade SM, Harchaoui Z. Robust aggregation for federated learning. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2022;70:1142–54. doi:10.1109/TSP.2022.3153135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang K, Tao G, Xu Q, Cheng S, An S, Liu Y, et al. FLIP: a provable defense framework for backdoor mitigation in federated learning. In: The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2023); 2023 May 1–5; Kigali, Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools