Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Speech Emotion Recognition Based on the Adaptive Acoustic Enhancement and Refined Attention Mechanism

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, 255000, China

2 Library, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

* Corresponding Author: Chunyan Liang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 87 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071011

Received 29 July 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

To enhance speech emotion recognition capability, this study constructs a speech emotion recognition model integrating the adaptive acoustic mixup (AAM) and improved coordinate and shuffle attention (ICASA) methods. The AAM method optimizes data augmentation by combining a sample selection strategy and dynamic interpolation coefficients, thus enabling information fusion of speech data with different emotions at the acoustic level. The ICASA method enhances feature extraction capability through dynamic fusion of the improved coordinate attention (ICA) and shuffle attention (SA) techniques. The ICA technique reduces computational overhead by employing depth-separable convolution and an h-swish activation function and captures long-range dependencies of multi-scale time-frequency features using the attention weights. The SA technique promotes feature interaction through channel shuffling, which helps the model learn richer and more discriminative emotional features. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared to the baseline model, the proposed model improves the weighted accuracy by 5.42% and 4.54%, and the unweighted accuracy by 3.37% and 3.85% on the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS datasets, respectively. These improvements were confirmed to be statistically significant by independent samples t-tests, further supporting the practical reliability and applicability of the proposed model in real-world emotion-aware speech systems.Keywords

Speech emotion recognition (SER) is a core technology of intelligent interaction systems and has crucial application value in the fields of affective computing and human–machine dialogue. The SER methods analyze speech waveforms, extract features, and classify them into corresponding emotional categories, thus helping computers to understand and respond better to human emotional expressions.

Before the rise of deep learning, SER primarily relied on handcrafted acoustic features such as mel frequency cepstral coefficient (MFCC), pitch, and formants, along with standardized feature sets like IS09 and eGeMAPS [1]. Traditional classifiers including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM), and Hidden Markov Models (HMM) [2,3] were then used for emotion classification. While these approaches achieved certain success on small-scale datasets, they heavily depended on manual feature engineering, limiting their ability to automatically capture complex emotional patterns. Moreover, they exhibited restricted capacity in modeling nonlinear feature relationships and contextual dependencies [4].

With the advent of deep learning, SER has entered the era of end-to-end learning. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been widely adopted due to their strong local feature extraction capabilities [5,6], while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), have become mainstream for their proficiency in modeling temporal sequences [7]. Multi-level fusion strategies have emerged to combine spatial and temporal features, with hybrid CNN-LSTM models showing particular effectiveness [8]. To improve feature representation quality, attention mechanisms have been introduced to enhance feature fusion and capture global dependencies [9]. Recently, advanced architectures including Transformer models have been increasingly adopted to capture multi-scale information and long-range dependencies [10].

Recently, the field has witnessed a paradigm shift towards self-supervised learning and large-scale pretrained speech encoders. Wav2vec 2.0 [11] pioneered contrastive self-supervised pretraining, achieving superior SER performance when fine-tuned on benchmark datasets [12]. HuBERT [13] further advanced speech representation learning through masked prediction tasks. In parallel, multimodal SER has gained momentum by integrating audio, visual, and textual information, with recent works exploring cross-modal attention mechanisms [14] and transformer-based joint learning approaches. Advanced multimodal frameworks have also emerged that employ hierarchical fusion architectures to systematically integrate diverse modalities [15], demonstrating the potential of automated optimization in multimodal emotion recognition systems.

Despite these advances, SER still faces persistent challenges such as limited training data, class imbalance, and inadequate modeling of fine-grained emotional cues. Traditional data augmentation techniques, including noise injection and time-domain transformations, can increase data diversity but often distort emotion-related acoustic features [16]. Interpolation-based methods like Mixup [17] may introduce ambiguous emotional cues by indiscriminately mixing samples, hindering robust feature learning. Moreover, existing attention mechanisms—though widely adopted—often incur high computational costs and limited adaptability [18]. Approaches such as SE [19] and CA [20] rely on fixed architectures that restrict adaptive weighting and fail to capture cross-channel dependencies, thereby limiting the modeling of critical emotional frequency components. These issues highlight the necessity of emotion-preserving augmentation strategies and flexible attention modules that jointly leverage global context modeling and fine-grained channel interaction.

To address the limitations of existing data augmentation and attention mechanisms in SER, this study proposes a novel model named AAM-ICASA-MACNN, built upon a multi-attention convolutional neural network architecture. The model integrates two key components: the Adaptive Acoustic Mixup (AAM) module and the Improved Coordinate and Shuffle Attention (ICASA) mechanism. Specifically, AAM enhances training data by performing emotion-consistent interpolation of features and labels, guided by similarity-based sample selection and dynamic interpolation coefficients. This strategy enriches sample diversity and improves model generalization while preserving emotion-related acoustic cues. Meanwhile, ICASA combines improved coordinate attention (ICA) and shuffle attention (SA) [21] to enhance feature representation. ICA replaces traditional convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions [22] and introduces an adaptive dimensionality reduction strategy that dynamically adjusts channel weights based on the importance of input features, thereby reducing computational overhead and boosting expressive power. SA further promotes fine-grained cross-channel interactions through channel grouping and shuffling, effectively capturing the nuanced relationships between fundamental frequency trajectories and formant structures in speech signals.

The main contributions of this work are as follows.

• We propose a novel SER model, AAM-ICASA-MACNN, that integrates acoustic-aware data augmentation and improved attention mechanisms to enhance generalization and emotional feature learning.

• We design an AAM strategy that performs similarity-guided and dynamically weighted Mixup, effectively increasing data diversity and mitigating class imbalance without compromising emotional fidelity.

• We develop an ICASA mechanism that fuses ICA and SA to capture global dependencies and fine-grained channel interactions with reduced computational cost, yielding superior representation learning for emotion recognition.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the proposed AAM-ICASA-MACNN model in detail, explaining the design of the AAM strategy, the ICASA mechanism, and their integration into the MACNN architecture which serves as the baseline model. Section 3 presents the experimental setup, results, and analysis conducted on the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS datasets. Finally, Section 4 draws conclusions and outlines future research directions.

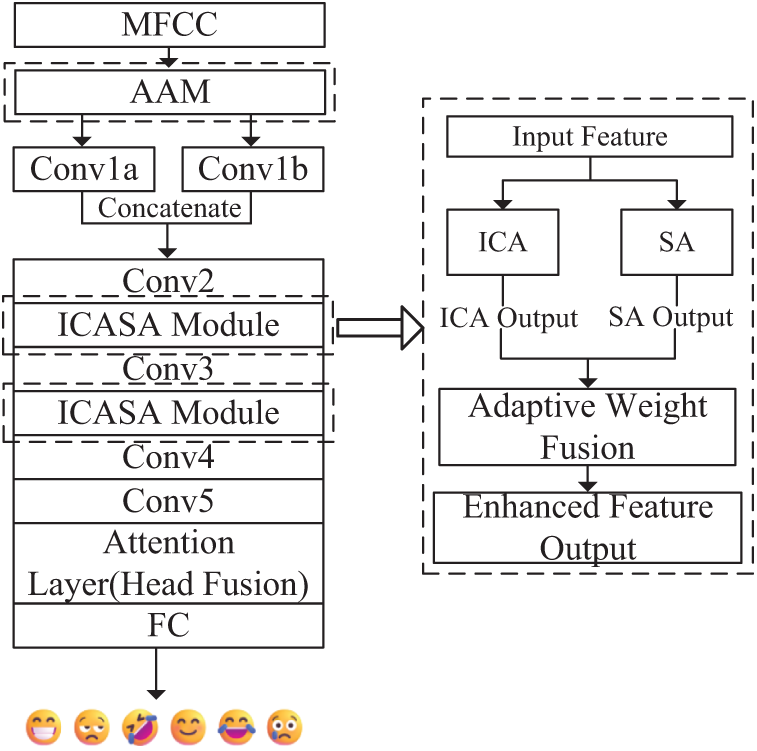

The overall architecture of the proposed AAM-ICASA-MACNN model is presented in Fig. 1. First, the AAM method is used to enhance the input data to improve data diversity and robustness. Next, the enhanced data are fed to the feature extraction network to conduct in-depth feature learning using the input MFCC [23]. The network starts with two parallel convolutional layers, Conv1a and Conv1b, that extract horizontal and vertical texture information, respectively. Then, the feature representations are processed through a series of convolutional layers and ICASA modules to extract richer features gradually. Afterward, the features are passed to the attention layer, and the feature representation is further optimized using a multi-head fusion mechanism. Finally, the final decision output for emotion classification is obtained by the fully connected (FC) layer.

Figure 1: The structure of the SER system based on the AAM-ICASA-MACNN model

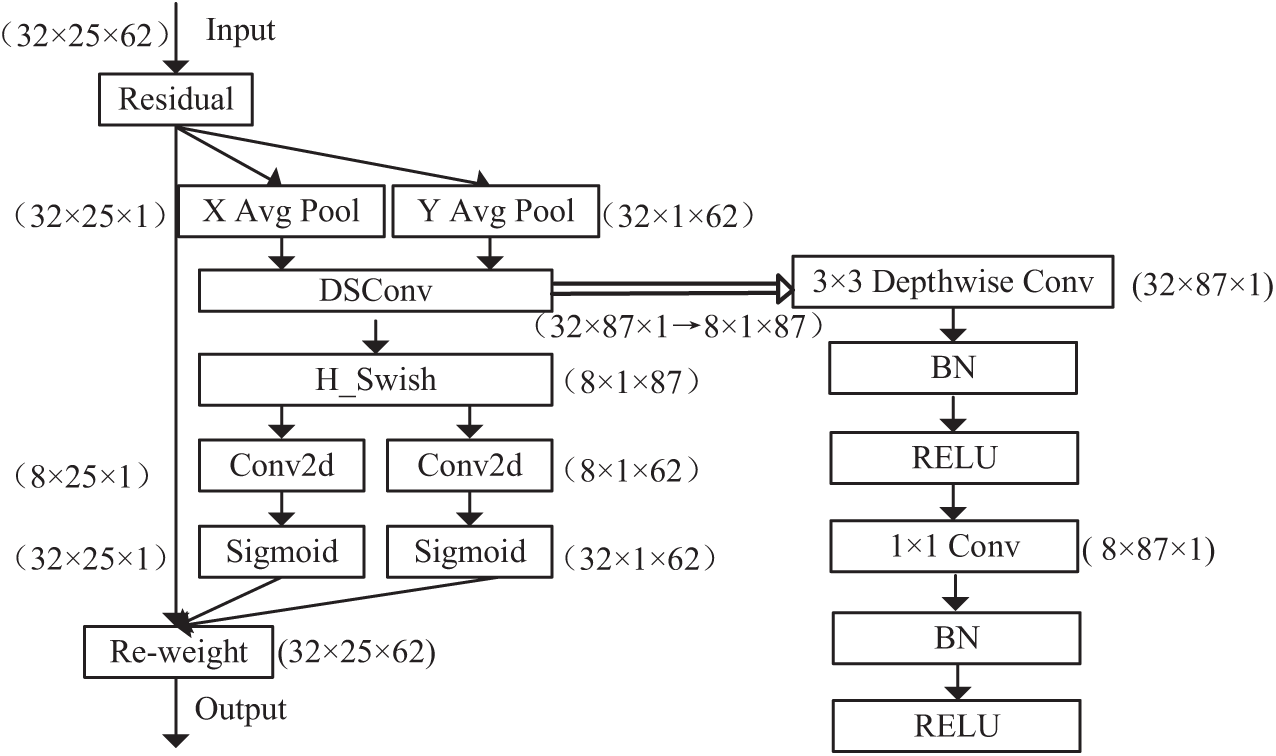

Specific settings of the convolutional layers are provided in Table 1. A batch normalization (BN) layer and a ReLU non-linear transformation unit are added after each convolutional layer. In addition, after the Conv2 and Conv3 layers, a max-pooling operation with a kernel size of two is introduced to reduce the feature map’s spatial size, thus improving the model’s computational efficiency.

2.1 Adaptive Acoustic Mixup (AAM) Method

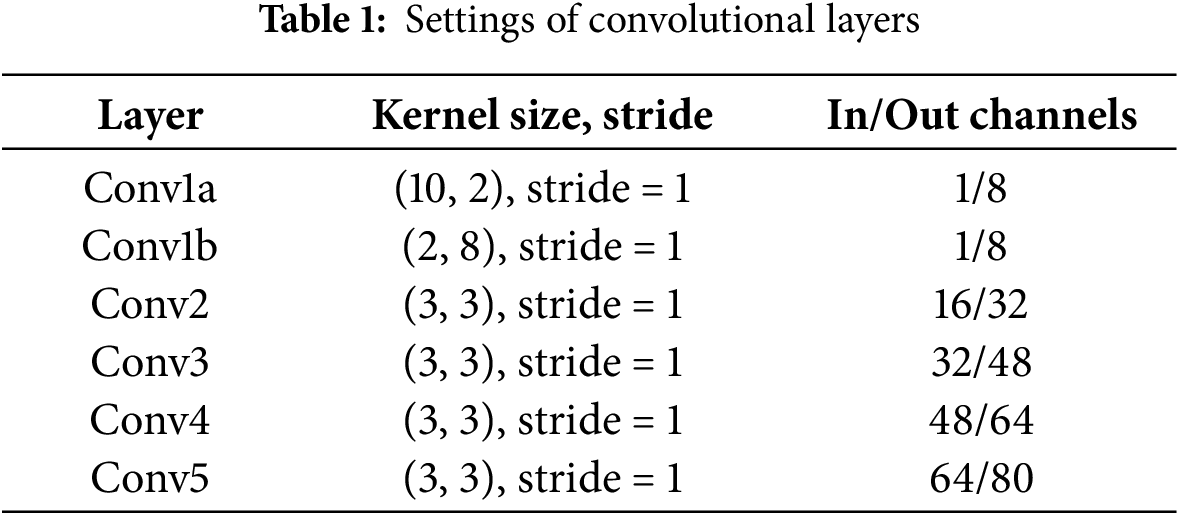

To improve the model’s generalization ability, this paper employs the Adaptive Acoustic Mixup (AAM) method to increase data diversity and optimize the model training process. Compared with the traditional MixUp data augmentation method, the AAM method introduces two key factors, namely acoustic similarity and classification difficulty, during the sample mixing process to achieve a more targeted augmentation strategy. The specific procedure is shown in Algorithm 1.

The specific steps of the AAM method are as follows.

Step 1: Acoustic Similarity Calculation.

Given

when

Acoustic similarity between utterances is evaluated on MFCC features, which effectively capture prosodic and spectral information relevant to emotional expression. Utterances with similar acoustic patterns are considered to share emotional proximity. Within each mini-batch, (same-emotion) and negative (different-emotion) sample pairs are randomly selected for similarity computation to maintain a balanced emotional distribution.

Step 2: Classification Difficulty Calculation.

To guide the interpolation toward more informative regions of the data space, the classification difficulty of each sample is estimated using its cross-entropy loss:

where

Step 3: Interpolation Coefficient Determination.

The interpolation coefficient

where

Step 4: New Training Sample Generation.

New training samples are generated via linear interpolation:

where

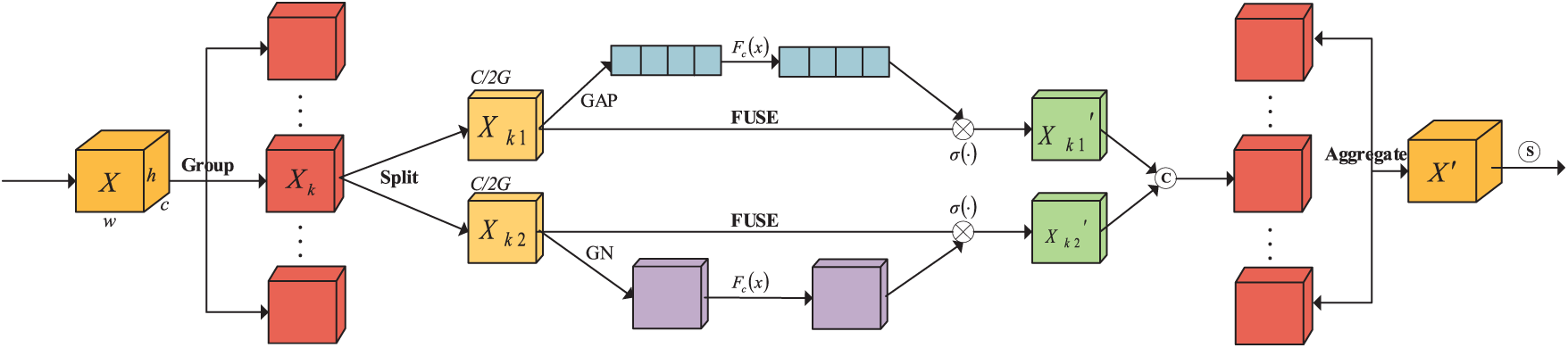

This study proposes an improved dual-path attention mechanism named ICASA, aiming to improve the effectiveness of emotional feature capturing from speech signals. The ICASA mechanism combines the improved coordinate attention and shuffle attention strategies and achieves effective collaboration of the two attention features through the adaptive fusion of learnable weight parameters. Different from using the fixed fusion coefficients set manually, this study introduces

where

Channel shuffling is used to enhance the cross-channel information interaction, and the optimized attention mechanism is employed to enhance the fusion of global and local features.

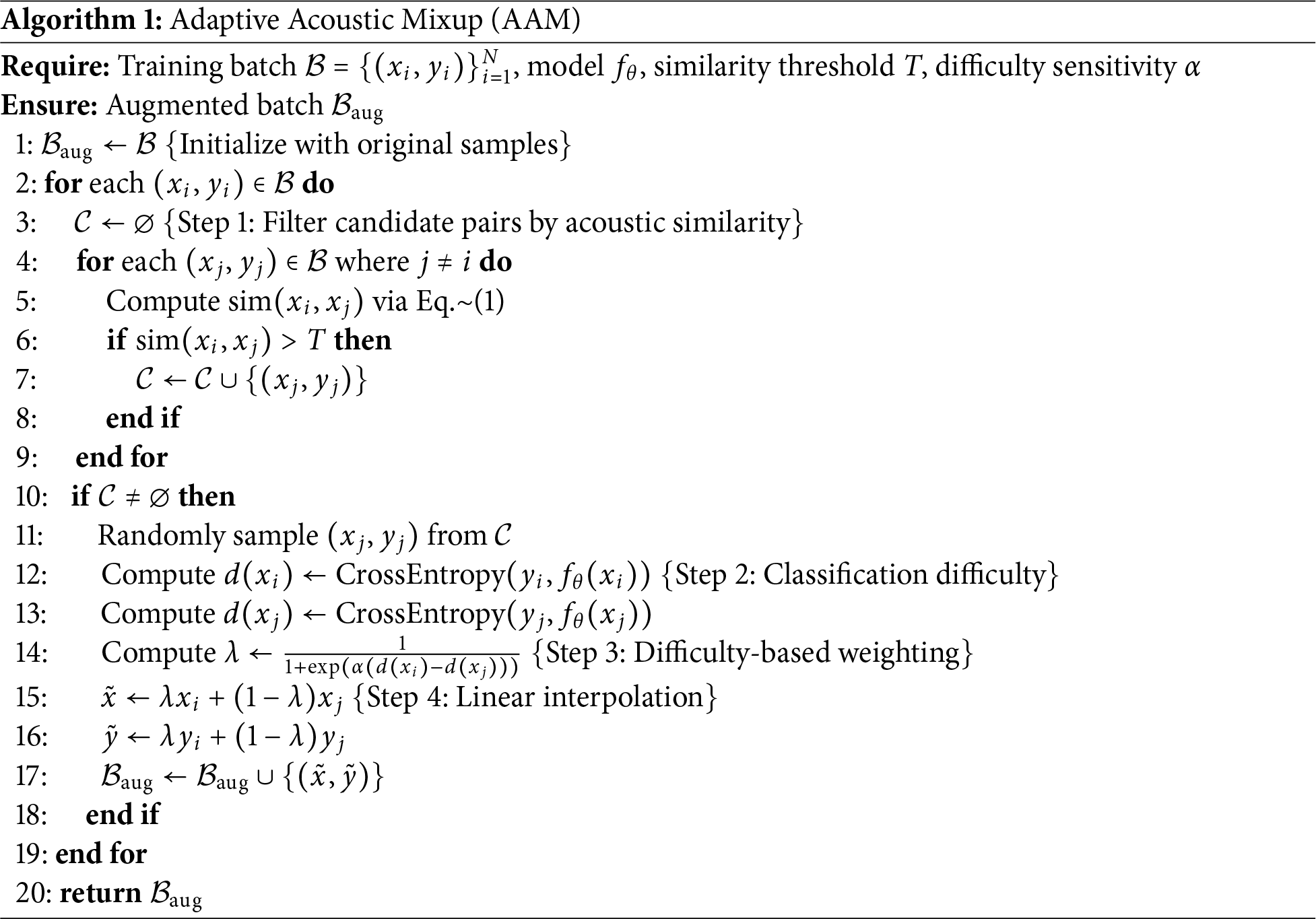

Based on the coordinate attention mechanism, this study designs an improved coordinate attention module, called the ICA module. The CA module can effectively fuse feature information in the horizontal and vertical directions by introducing a directional attention mechanism, thus enhancing the spatiotemporal feature modeling ability of SER. However, the CA faces certain limitations when processing high-dimensional and complex speech features, particularly in deep networks, where insufficient feature interaction limits the modeling effect of fine-grained emotional information. To solve these problems, the proposed ICA module adds depth separable convolution on the CA model, decomposing the traditional convolution operation into depth- and point-wise convolutions, thus reducing computational costs while retaining rich feature information. In addition, the ICA module combines an efficient h_swish activation function to enhance the non-linear expression ability of the model and optimize feature interaction and information flow, achieving efficient and accurate enhancement of speech emotion features. The structure of the ICA module is displayed in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The structure of the ICA model

The operation of the ICA module is as follows.

(1). Coordinate Information Embedding: Global average pooling is performed on the input feature map along the horizontal (time-domain) and vertical (frequency-domain) directions to aggregate the feature information in the two directions, generating two feature maps with the sizes of

where W and H represent the width and height of the feature map coordinates, respectively; and

(2). Feature Processing: The pooled features are concatenated in the channel dimension, and then depth-separable convolution is used for dimensionality reduction, and the h_swish activation function is selected for non-linear activation of the concatenated features to generate a compact feature representation with global perception ability, which can be expressed as follows:

where

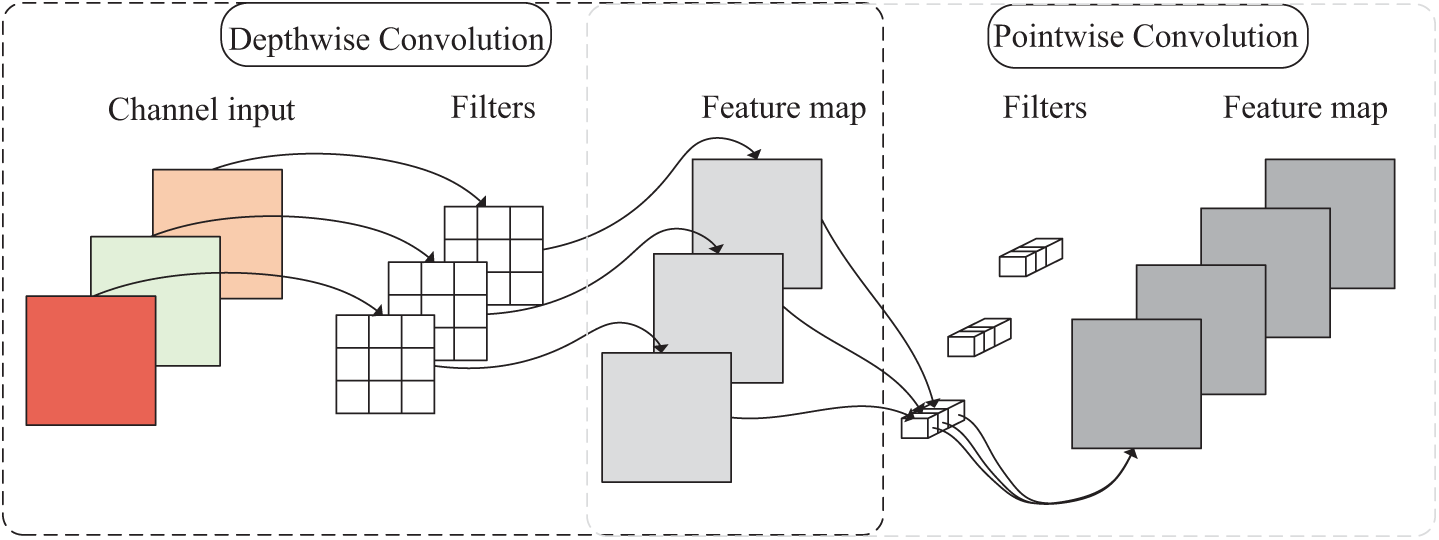

Depth-separable convolution is an important component of lightweight neural networks and can efficiently extract emotional features in SER tasks while reducing computational costs. Its core idea is to split the traditional convolution into two stages. In the first stage, depth-wise convolution performs convolution independently on each speech feature channel in the spatial dimension, capturing local time-frequency patterns at the frame level and strengthening short-term dynamic features. In the second stage, point-wise convolution uses a

Figure 3: Illustration of the depth-separable convolution

(3). Attention Weight Generation: An input feature tensor

where

The final output of the ICA module is expressed by:

where

To improve the model’s performance in SER tasks, this study adopts the SA mechanism to enhance the fluidity and interaction ability of information between channels. The SA module uses a grouping processing strategy to model speech features hierarchically. First, the input features are divided into multiple groups, inside each of which the shuffle unit dynamically combines the channel and spatial two-dimensional attention mechanisms to simultaneously achieve background noise suppression and emotional saliency region enhancement. Next, the multi-group features are aggregated and reorganized. Then, all sub-features are summarized, and a channel shuffle operation is performed to promote complementary fusion between heterogeneous features, which enhances both the robustness of feature representation and the efficiency of information transfer while improving the accuracy of speech emotion classification. The SA module’s structure is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The structure of the SA model

The specific operational principle of the SA model is as follows. For an input feature map

In the channel attention branch, first, a global average pooling operation is used to compress the features along the channel axis. By aggregating the global response information in the spatial dimension, a channel statistical vector

Then, a linear transformation

where

In the spatial attention branch, first, a group normalization (GN) operation is performed on input feature tensor

where

Then,

3 Analysis of Experimental Results

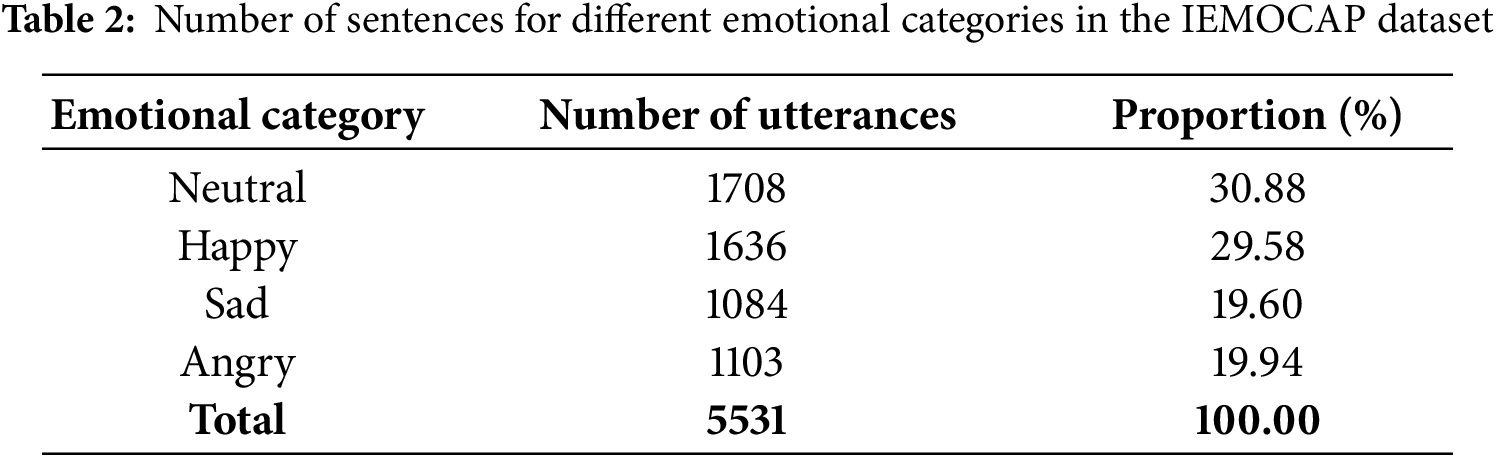

The speech emotion datasets used in this study included IEMOCAP [24] and RAVDESS [25] datasets. The IEMOCAP dataset was approximately 12 h long and divided into 5 parts. Each dialogue was performed by an actor and an actress, with a total of 10 actors participating. The dataset was further divided into two major parts, “impro” (improvised performance) and “script” (scripted reading), based on whether the actors read the script. In the SER task, actors could express emotions more freely during improvised performances without the constraints of scripted reading. Therefore, this study selected four representative emotions, neutral, happy, sad, and angry, from the “impro” part for in-depth research. The specific emotional categories and their numbers of samples are shown in Table 2.

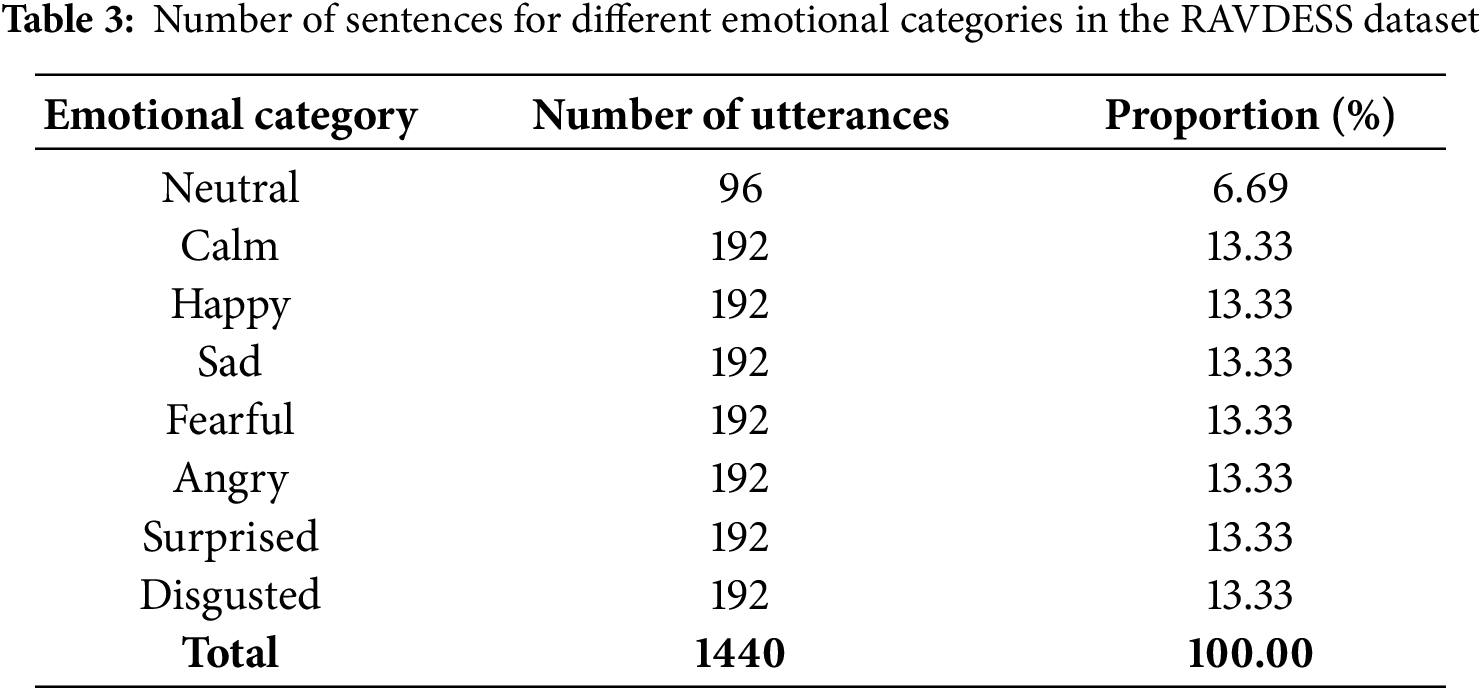

The RAVDESS dataset contains 1440 utterances from 24 professional actors (12 males and 12 females). The actors read the matching words with a neutral North American accent, covering emotions including neutral, calm, happy, sad, fearful, angry, surprised, and disgusted. Each emotion was expressed at two different intensity levels, and each speech clip lasts for 3 s. The specific emotional categories and the number of samples are presented in Table 3.

To ensure leak-resistant evaluation, we used speaker-independent partitioning. For IEMOCAP, session-based cross-validation was applied, using each session once as test and the remaining four for training, with results averaged over five folds. For RAVDESS, 6-fold speaker-independent cross-validation was used, holding out four speakers per fold (2 male, 2 female; 240 utterances) for testing, and training on the remaining 20 speakers (1200 utterances), with fold-averaged results. This setup prevents speaker overlap, ensures reliable generalization assessment, and maintains gender balance. All reported metrics, including prior improvements, are based on this evaluation.

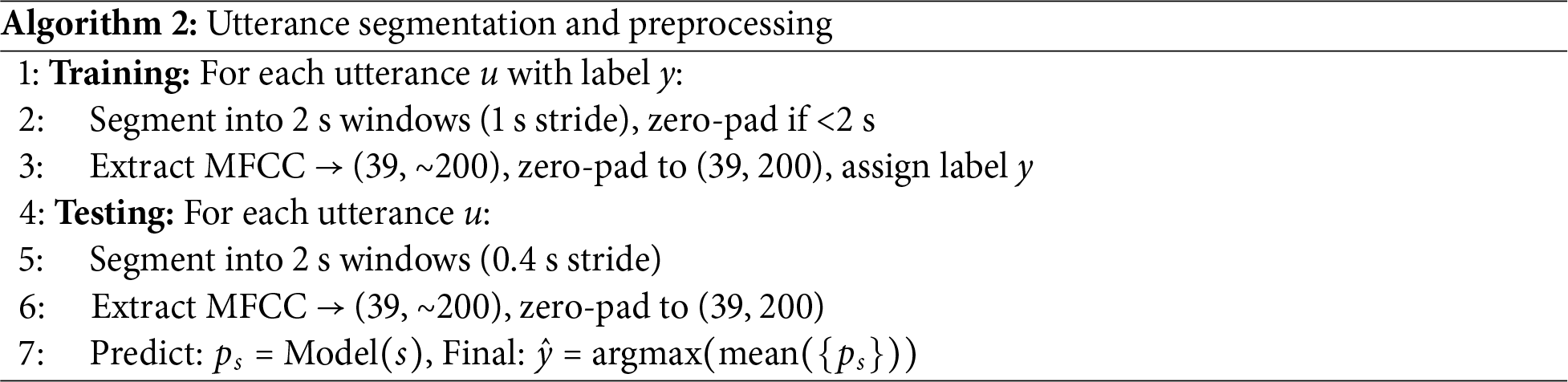

All experiments were implemented in PyTorch 2.1 (FP32) with CUDA 12.1 and cuDNN 8.9 on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. MFCC features (39-dimensional: 13 static coefficients plus first- and second-order derivatives) were extracted using 26 Mel filter banks, 25 ms Hamming window, and 10 ms frame shift. To handle variable-length utterances, a segment-based strategy was adopted (Algorithm 2) [26]. Each utterance was divided into 2-s windows with 1-s stride during training (50% overlap) and 0.4-s stride during testing (80% overlap) for denser temporal sampling and more robust aggregation. Each segment yields 200 frames (2 s

For computational efficiency evaluation, all model variants used identical MFCC preprocessing and input dimensions (39

In this study, three standard metrics were employed to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model: weighted accuracy (WA), unweighted accuracy (UA), and F1-score (F1).

WA represents the overall classification accuracy across all samples, with each class weighted by its sample size:

where

UA evaluates the average per-class recall, mitigating the impact of class imbalance and reflecting the model’s generalization ability across categories:

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall and is particularly useful for imbalanced classification tasks. For each class

Per-class F1-scores are reported for each emotion category to provide detailed performance analysis across different emotional states.

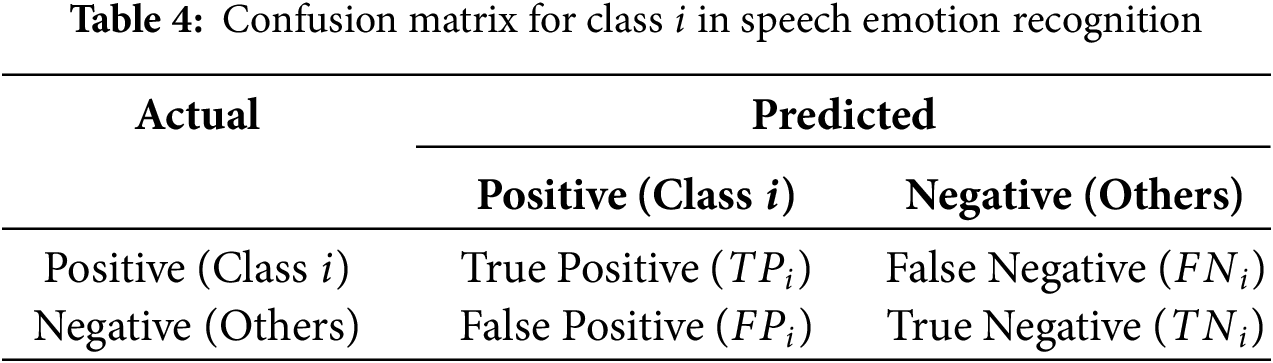

The meanings of TP, FP, FN, and TN are summarized in Table 4.

3.4.1 AAM Role in Data Augmentation and Parameter Analysis

To systematically verify the effectiveness and applicability of the AAM method in data augmentation, this study conducted four types of experiments: (1) validating whether MFCC-based acoustic similarity correlates with emotional proximity by analyzing label match rates under different thresholds T; (2) examining how variations in the acoustic similarity threshold T influence the model’s effectiveness, thereby evaluating the robustness of AAM to this key parameter; (3) analyzing the impact of the interpolation coefficient sensitivity

The specific experimental procedure was as follows.

(1) Correlation Analysis between Acoustic Similarity and Emotion Labels

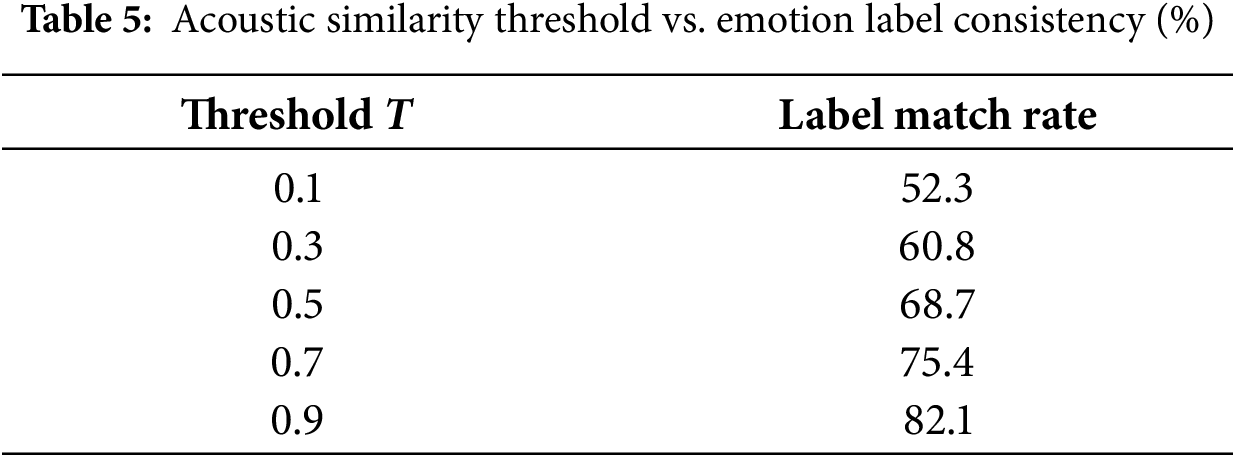

To validate that MFCC-based acoustic similarity reflects emotion-relevant information, we analyzed utterance pairs from IEMOCAP and measured their cosine similarity in MFCC space. Table 5 shows that as the similarity threshold T increases, the proportion of pairs sharing the same emotion label (label match rate) rises consistently, reaching 75.4% at

Although the label match rate at a higher threshold (T = 0.9) is slightly higher than at T = 0.7 (75.4%), using T = 0.9 would substantially reduce the number of sample pairs available for mixing. This would limit the diversity of augmented data and potentially hinder the generalization benefits of the Adaptive Acoustic Mixup method. Therefore, T = 0.7 is chosen as a balanced setting that maintains high emotion consistency while providing sufficient sample coverage for effective data augmentation.

Additionally, this correlation pattern suggests that MFCC similarity at

(2) Impact of Acoustic Similarity Threshold T in AAM

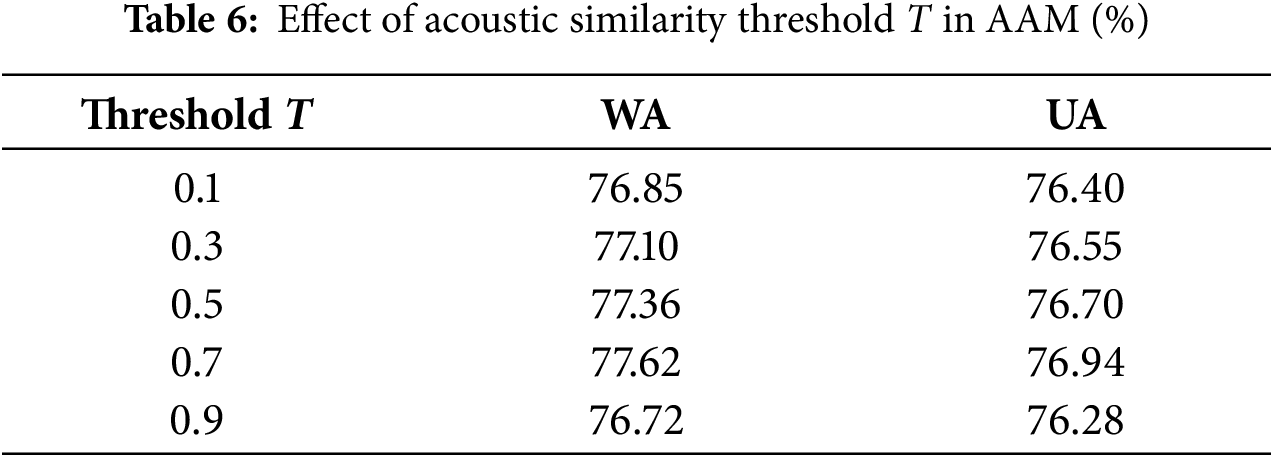

To assess the sensitivity of this hyperparameter and explore whether performance can be further improved through optimization, we conducted a series of experiments by varying T from 0.1 to 0.9. As shown in Table 6, the model achieved optimal performance when

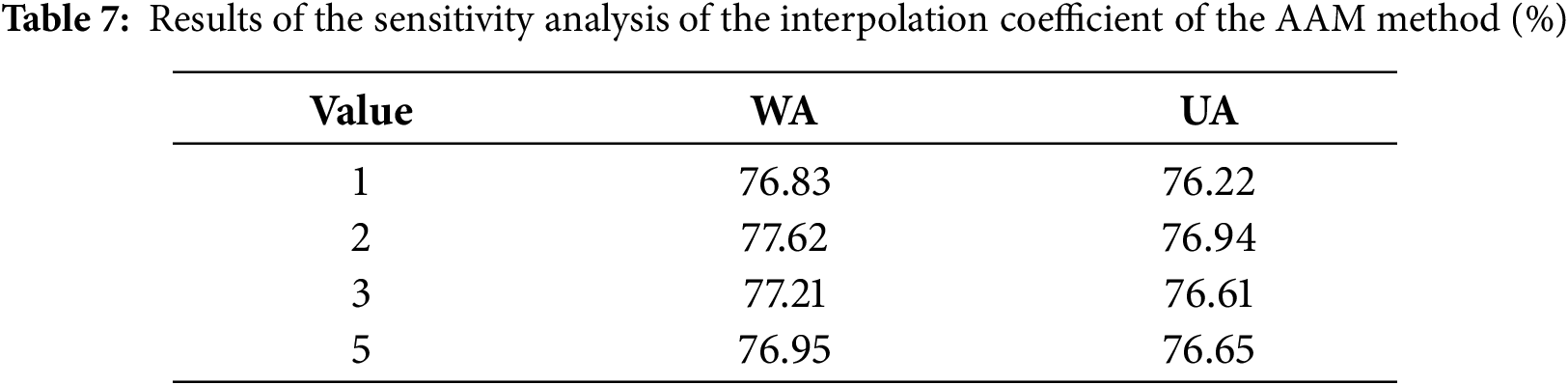

(3) Sensitivity Analysis of Sensitivity

To verify the rationality of a hyperparameter

The experimental results are shown in Table 7, where it can be seen that as the

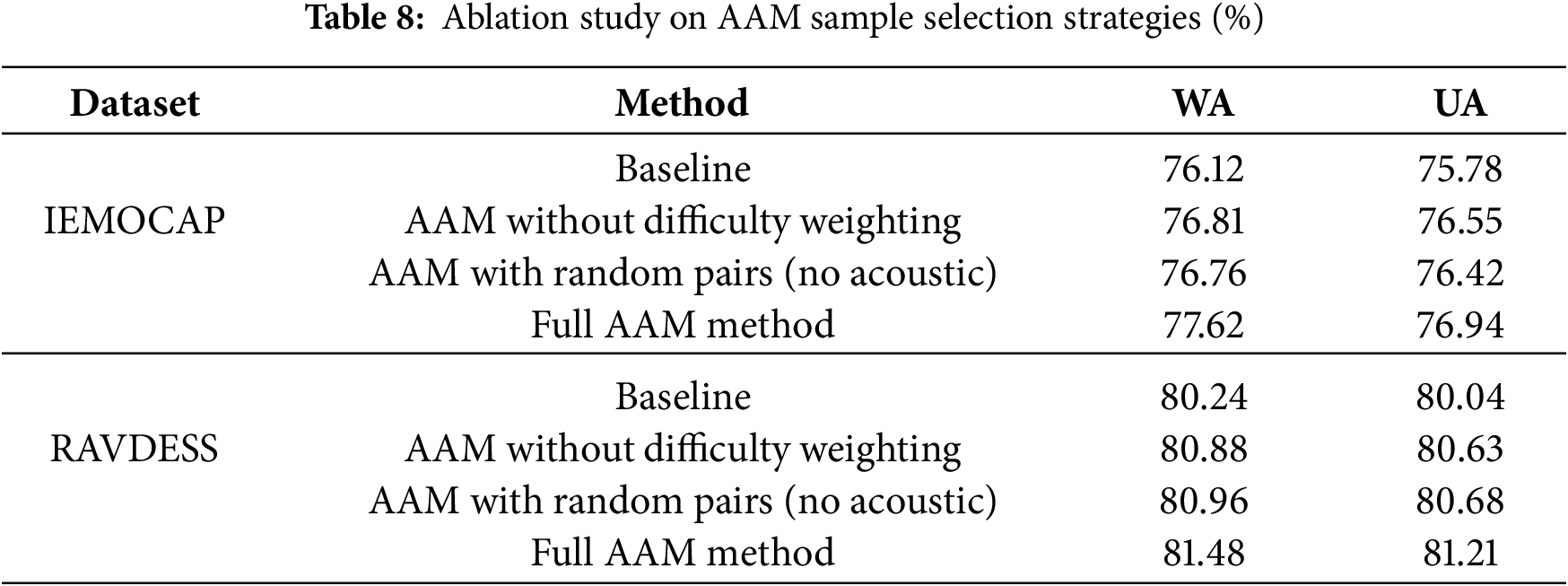

(4) Ablation Study on AAM Sample Selection Strategies

To verify the specific contributions of the sample selection strategies in AAM, an ablation study was conducted on the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS dataset by testing two variants: one where the difficulty weighting mechanism was removed, and another where samples were randomly paired without considering acoustic similarity. As shown in Table 8, compared to the baseline without data augmentation, both AAM with random pairing and AAM without difficulty weighting improved model performance; however, the full AAM method, which combines acoustic similarity pairing and difficulty weighting, achieved the best results, confirming the importance of these strategies in enhancing data augmentation effectiveness.

These findings reveal that acoustic similarity and difficulty-aware sampling strategies each contribute substantially to AAM’s effectiveness. When combined, these complementary approaches create a synergistic effect that enables the model to leverage more informative and challenging augmented samples, ultimately enhancing its generalization capabilities.

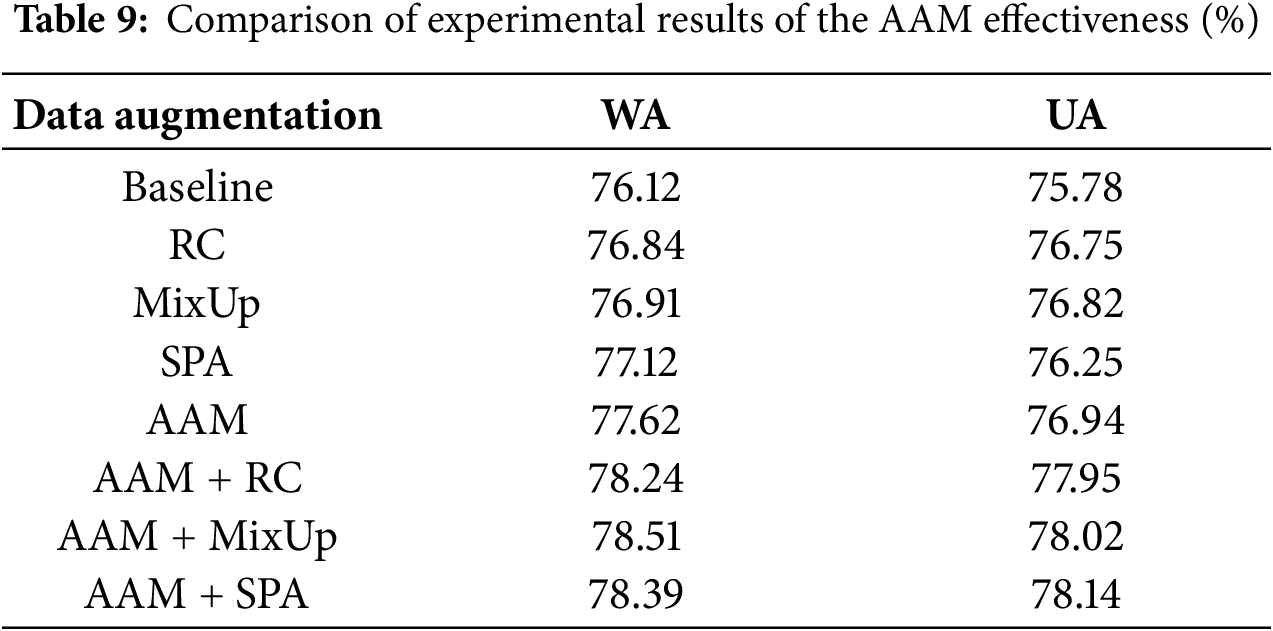

(5) Verification of the combined effect of AAM and other data augmentation methods

To comprehensively verify the effectiveness and combination ability of the AAM method in data augmentation, this study conducted multiple groups of comparative experiments on the IEMOCAP dataset. The experiments compared the baseline model without data augmentation, the model with AAM alone, the model with other mainstream data augmentation methods, and the model combining AAM with these methods.

As shown in Table 9, all methods improved performance to varying degrees. Among them, AAM achieved superior results, outperforming the baseline by 1.50% and 1.16% in WA and UA, respectively. Moreover, AAM also surpassed the second-best SPA method. When combined with other approaches, AAM brought further gains, with AAM+MixUp and AAM+SPA achieving the best overall performance. These results demonstrate both the effectiveness of AAM and its strong compatibility with other data augmentation techniques.

In conclusion, the AAM method could not only effectively improve the SER performance but also show good extensibility and adaptability when used in combination with mainstream augmentation methods, reflecting its strong practical value. Therefore, subsequent experiments on the AAM-augmented data were performed.

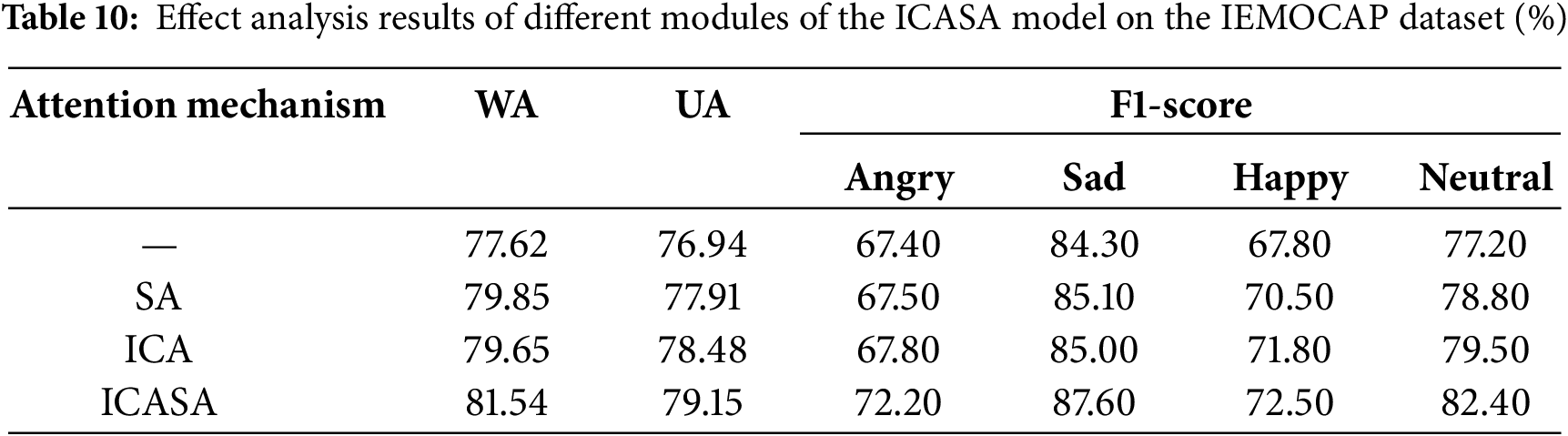

3.4.2 Necessity Analysis of ICASA Modules

This study conducted a series of ablation experiments to verify the effectiveness of each module in the ICASA model. The experimental results on the IEMOCAP dataset are shown in Table 10. The experiments compared models without attention mechanism, with only SA, with only ICA, and with ICASA. As shown in Table 10, the ICASA model achieved the best performance; compared to the model without attention, WA and UA improved by 3.92% and 2.21%, respectively, confirming its effectiveness. In this section and subsequent tables, “—” indicates the AAM-MACNN model (without attention) used as the ablation reference.

The ICASA could effectively compress redundant information while retaining key feature expressions using the improved coordinate attention mechanism, thus enhancing the information interaction between features. The shuffle attention improved the multi-channel collaboration and discrimination ability through channel recombination. Thus, the synergistic effect of the two modules could significantly improve the model’s performance in complex emotion recognition tasks.

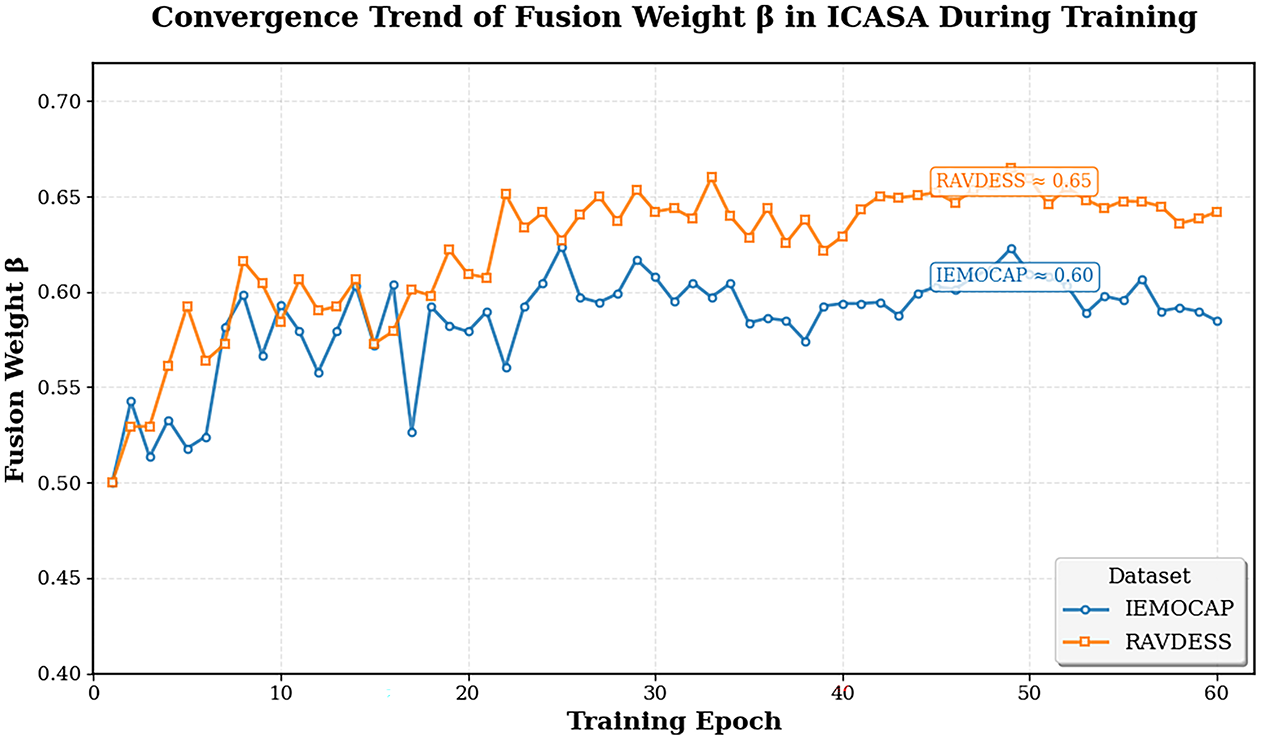

To illustrate the dynamic behavior of the learnable fusion weight

Figure 5: The changing curve of the learnable fusion weight in the ICASA model

As shown in Fig. 5, with the increase in the training epoch number, the

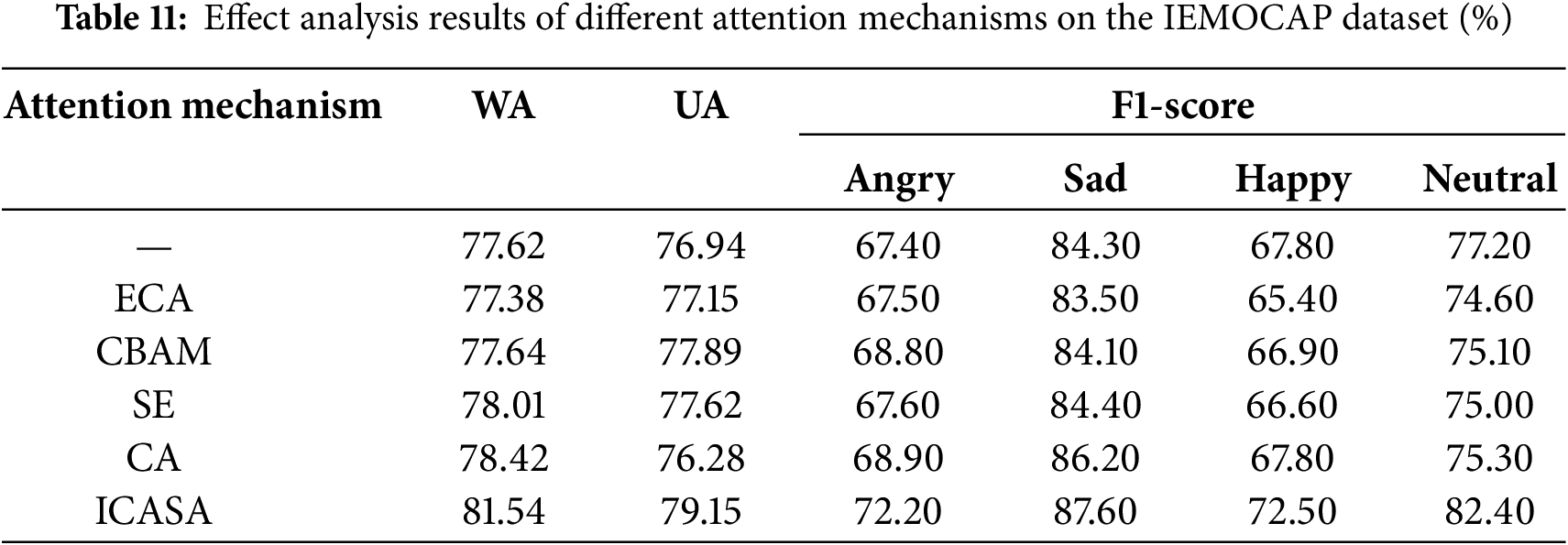

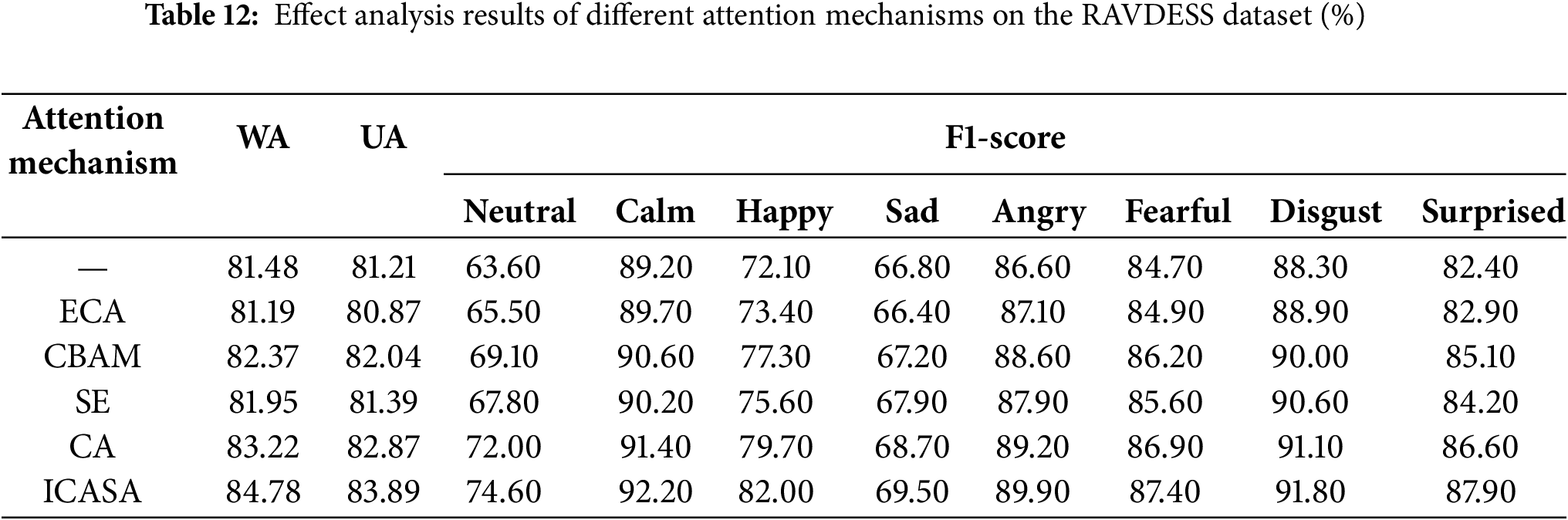

3.4.3 Comparative Analysis of ICASA and Other Attention Mechanisms

To evaluate the ICASA’s effectiveness, this experiment compared the performance of the ICASA and four mainstream attention mechanisms, including the ECA [29], CBAM [30], SE [19], and CA mechanisms. The comparison results on the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS datasets are presented in Tables 11 and 12, respectively. The experimental results indicated that the ICASA module outperformed the four mainstream attention mechanisms in terms of weighted and unweighted accuracy, further verifying its effectiveness and advancement in SER tasks.

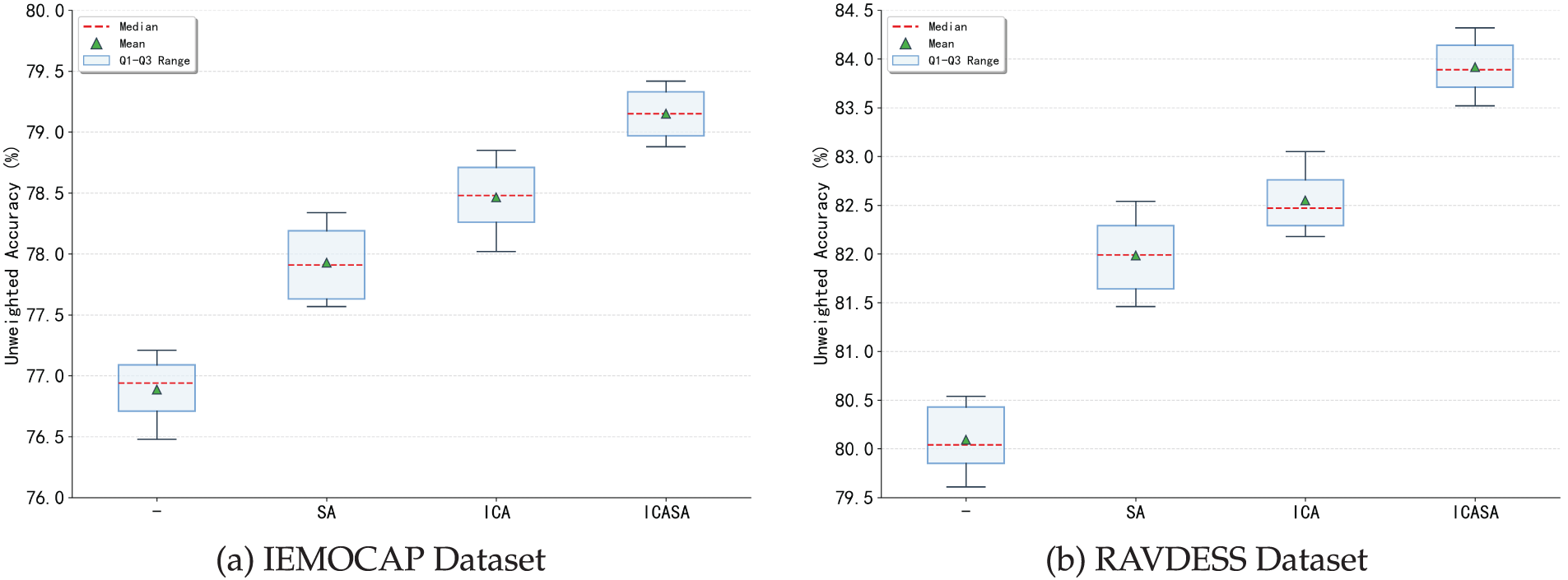

The average weighted and unweighted accuracy for different attention mechanisms on the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS datasets are displayed in Fig. 6, where the horizontal axis represents different attention mechanisms, and the vertical axis indicates the classification accuracy index. In the box plot presented in Fig. 6, the central dashed line represents the median value of the model’s accuracy, the upper and lower edges of the box correspond to the third (Q3) and first (Q1) quartiles, respectively, and the box height reflects the model performance’s stability; the extension range of the vertical solid line shows the extreme value distribution of each model in multiple experiments, and the triangular symbol in the box indicates the model’s average accuracy.

Figure 6: Box plots of various attention mechanisms on the two datasets

As shown in Fig. 6, the proposed model’s weighted accuracy showed a stable growth trend from left to right and reached its peak on the ICASA. In addition, the box height indicated that the proposed AAM-ICASA-MACNN model had the smallest fluctuation range on the two datasets and the best stability among all the models.

3.4.4 Model Performance Evaluation

Overall Performance Metrics

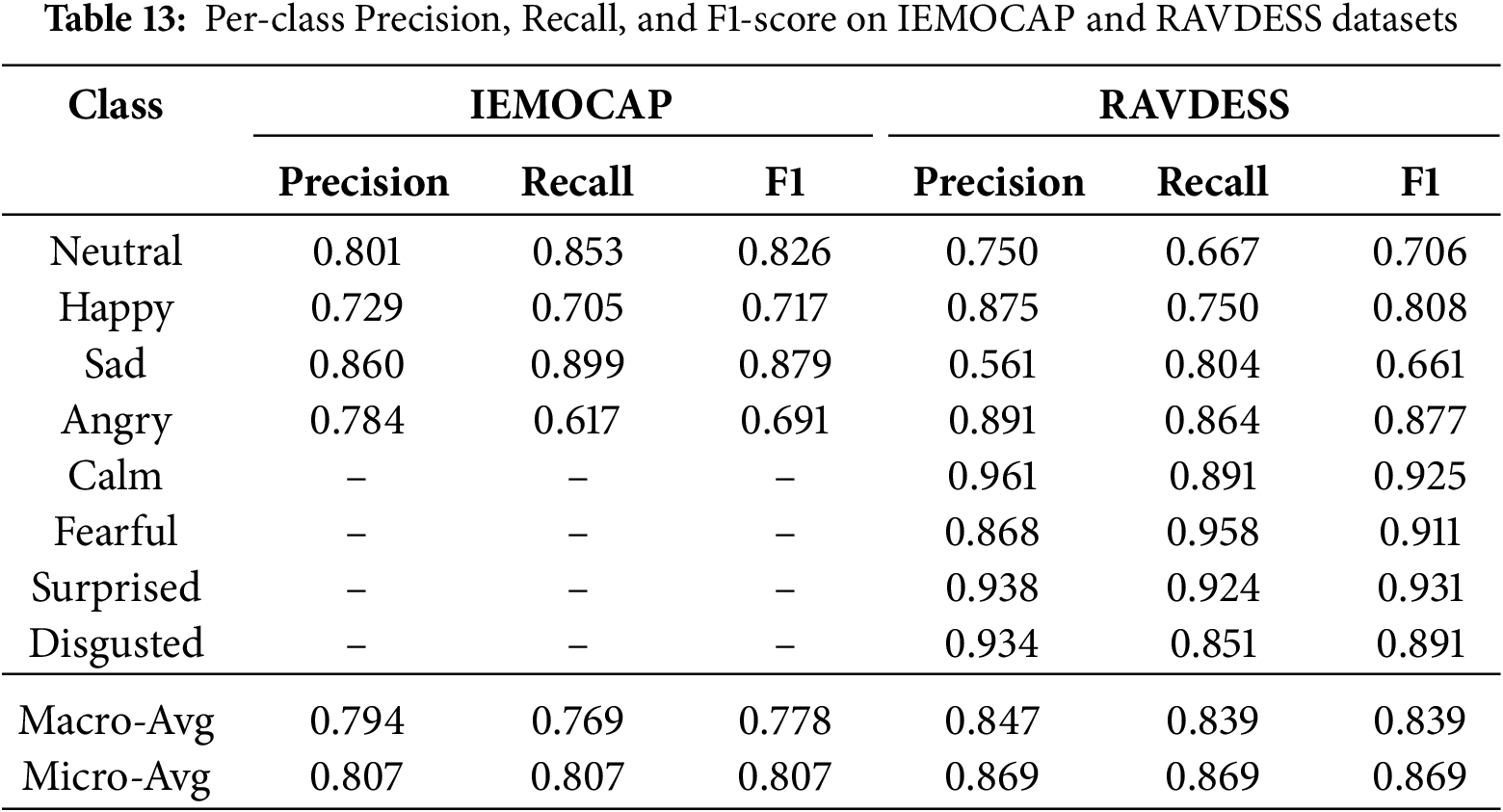

To provide a detailed performance evaluation, Table 13 presents the per-class precision, recall, and F1-scores for both the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS datasets side by side. Macro- and micro-averages are included to reflect the model’s overall balance and global performance.

Feature and Class-Level Analysis

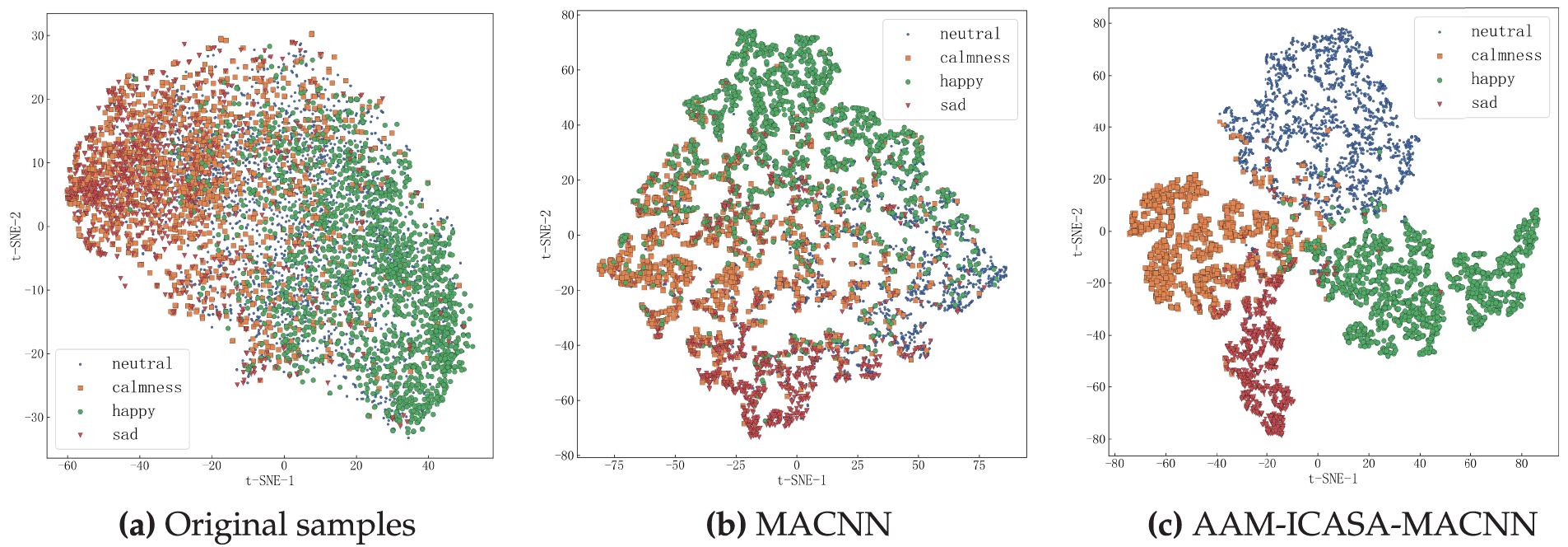

The t-SNE visualization results of the features extracted by different models on the IEMOCAP dataset are presented in Fig. 7; Fig. 7a shows the distribution of the original features; Fig. 7b depicts the distribution of the features of the baseline model; Fig. 7c displays the distribution of the features of the proposed AAM-ICASA-MACNN model. In Fig. 7, different icons denote different emotion categories, and the closer the clustering, the higher the feature discrimination degree, and the stronger the emotion discrimination ability of the model. The distribution of the original samples of the IEMOCAP dataset showed that there was a significant overlap between different emotion categories, which increased the difficulty of classification. In contrast, the features extracted by the proposed model showed tighter intra-class aggregation and clearer inter-class boundaries in the t-SNE visualization, effectively reducing the category overlap and achieving a significant improvement in the model’s emotion feature extraction performance and discrimination ability.

Figure 7: The t-SNE visualization of features on the IEMOCAP dataset

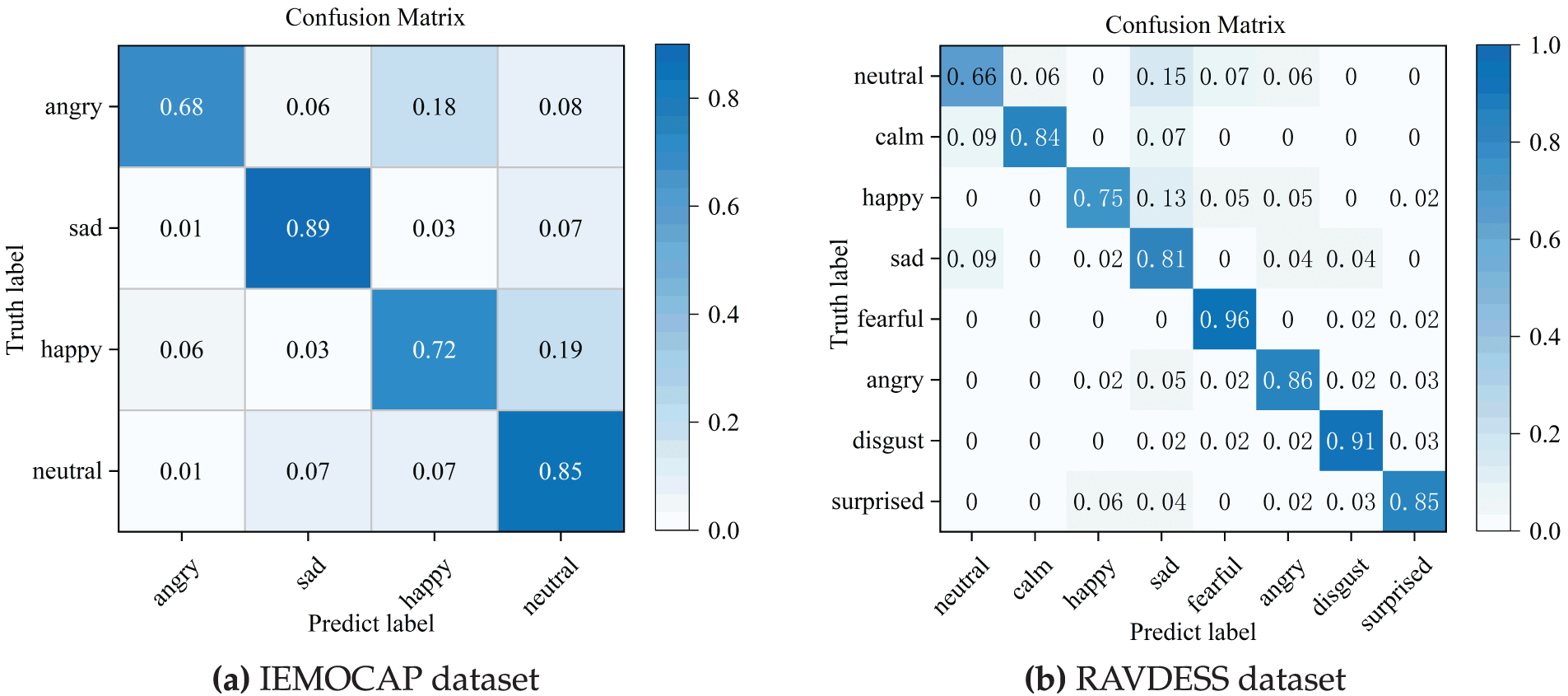

The confusion matrix of the AAM-ICASA-MACNN model on the two datasets are presented in Fig. 8. On the IEMOCAP dataset, the sad and neutral categories achieved recognition accuracies above 80%, with sad reaching 89%. In contrast, angry and happy were the most challenging, with accuracies of 69% and 74%, respectively. Notably, 18% of angry samples were misclassified as happy, and 19% of happy samples were predicted as neutral. These errors are mainly due to overlapping acoustic and prosodic characteristics, including speaking rate, energy, and intonation, which make angry and happy particularly hard to separate. Additionally, happy speech exhibits strong speaker-dependent variability, and some utterances share similar rhythm and energy profiles with neutral speech, further increasing misclassification.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix on the two datasets

On the RAVDESS dataset, fearful and disgusted emotions were recognized with high reliability, achieving over 90% accuracy, while neutral and happy remained the most confusable categories, with 67% and 75% accuracy, respectively. Approximately 15% of neutral samples were misclassified as sad, reflecting strong prosodic and spectral overlap between the two emotions. The relatively small number of neutral samples further limited the model’s capacity to learn discriminative features, contributing to the lower performance.

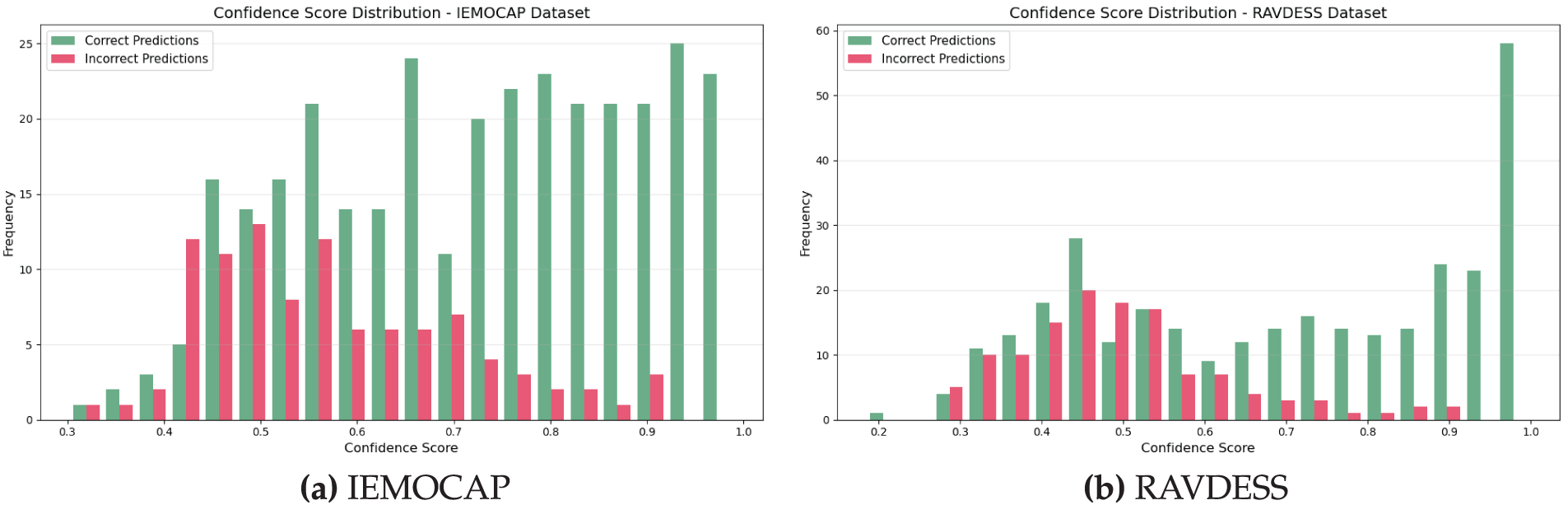

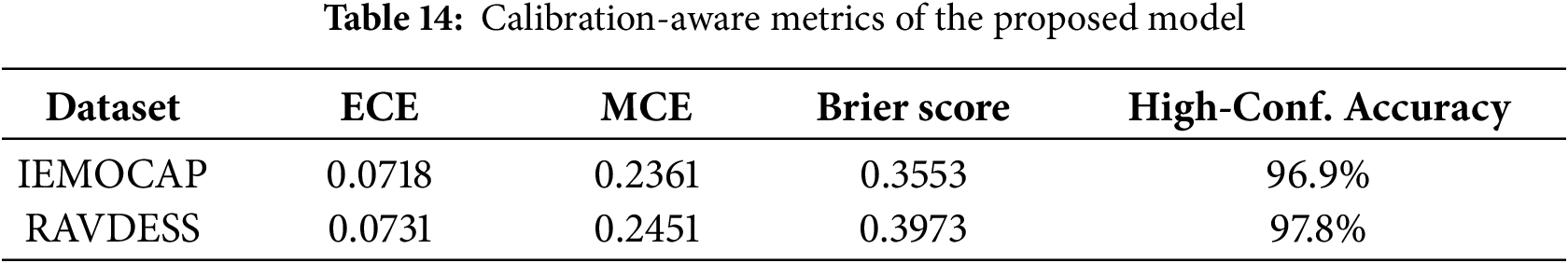

In addition to confusion matrix analysis, we conducted a calibration study to assess the reliability of the model’s predicted probabilities. The Expected Calibration Error (ECE) was 0.0718 on IEMOCAP and 0.0731 on RAVDESS, both below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.1, indicating well-aligned confidence estimates. Fig. 9 shows confidence score distributions where correct predictions (green) concentrate in high-confidence regions while incorrect predictions (red) are skewed toward lower-confidence bins, demonstrating reliable confidence estimation. Table 14 reports calibration-aware metrics including Maximum Calibration Error (MCE), Brier Score, and high-confidence accuracy exceeding 96.9% on both datasets, confirming the model’s robustness and deployment readiness for practical applications.

Figure 9: Confidence score distributions

3.4.5 Robustness and Fairness Analysis

To systematically evaluate the proposed model’s robustness and fairness, we perform a series of experiments on the RAVDESS dataset under diverse acoustic and demographic conditions.

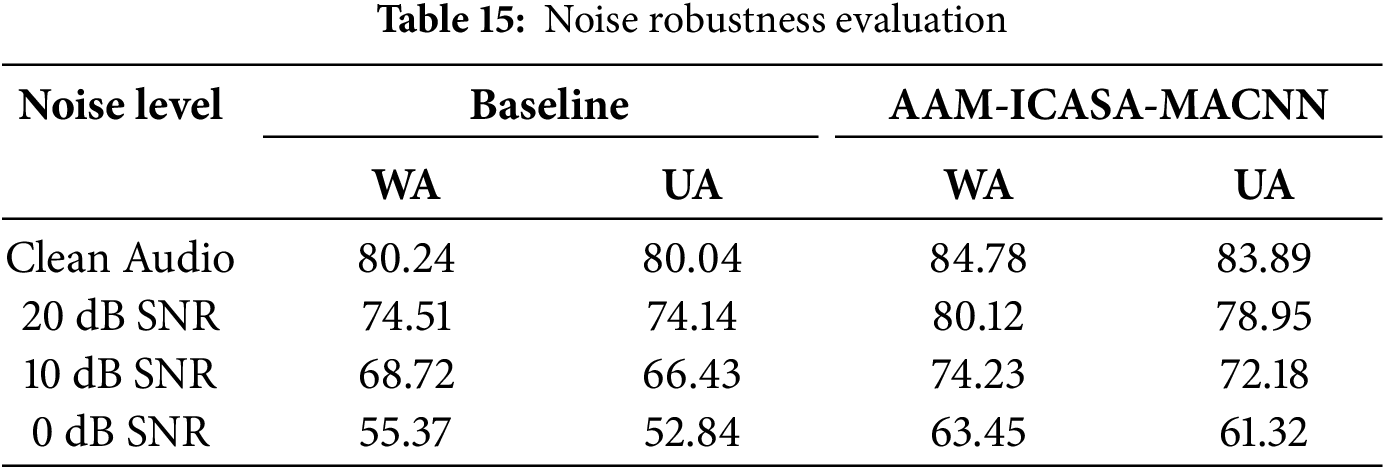

We first evaluate noise robustness by adding additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) at different SNR levels. As shown in Table 15, our model consistently outperforms the baseline across all noise levels and still achieves 63.45% WA at 0 dB SNR, indicating strong robustness for practical deployment.

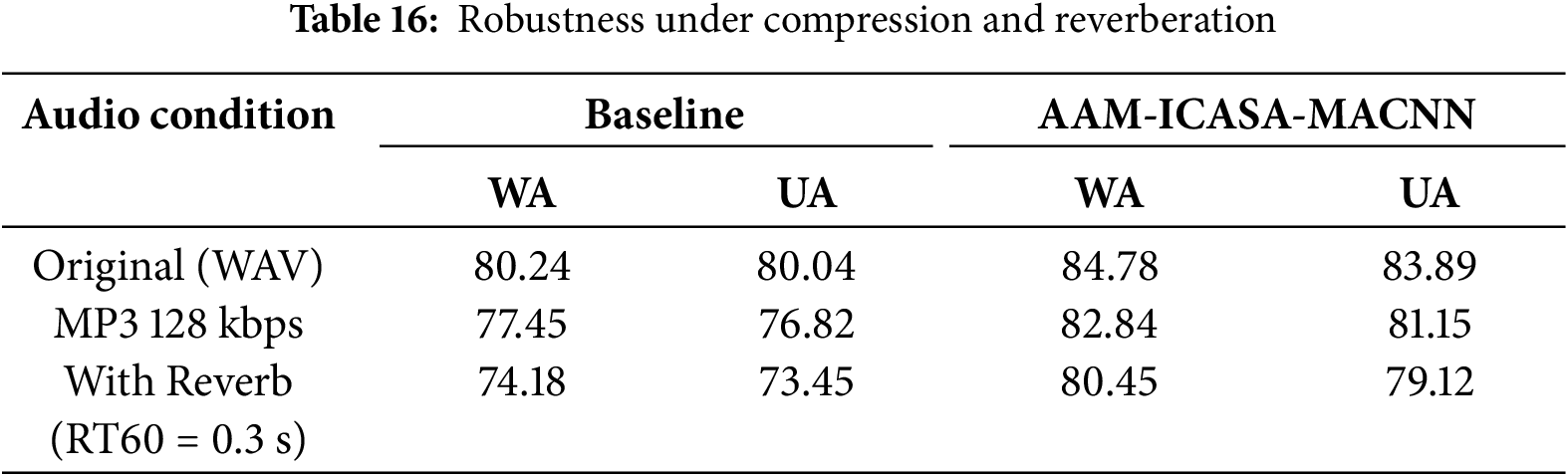

We then examine the impact of audio compression and reverberation on model performance. As shown in Table 16, the model maintains high recognition accuracy under MP3 compression and shows reasonable robustness to moderate reverberation, indicating good tolerance to real-world channel distortions and acoustic environments.

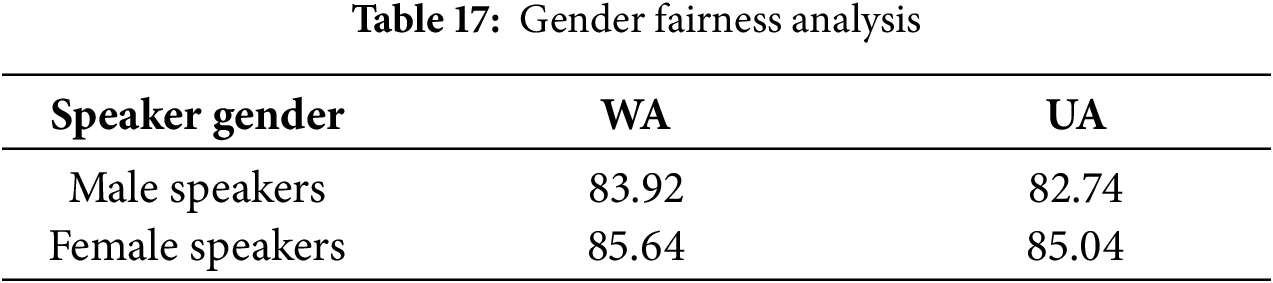

To assess demographic fairness, we compare recognition performance between male and female speakers. Table 17 shows a small WA gap of 1.72%, suggesting that the model performs consistently across genders.

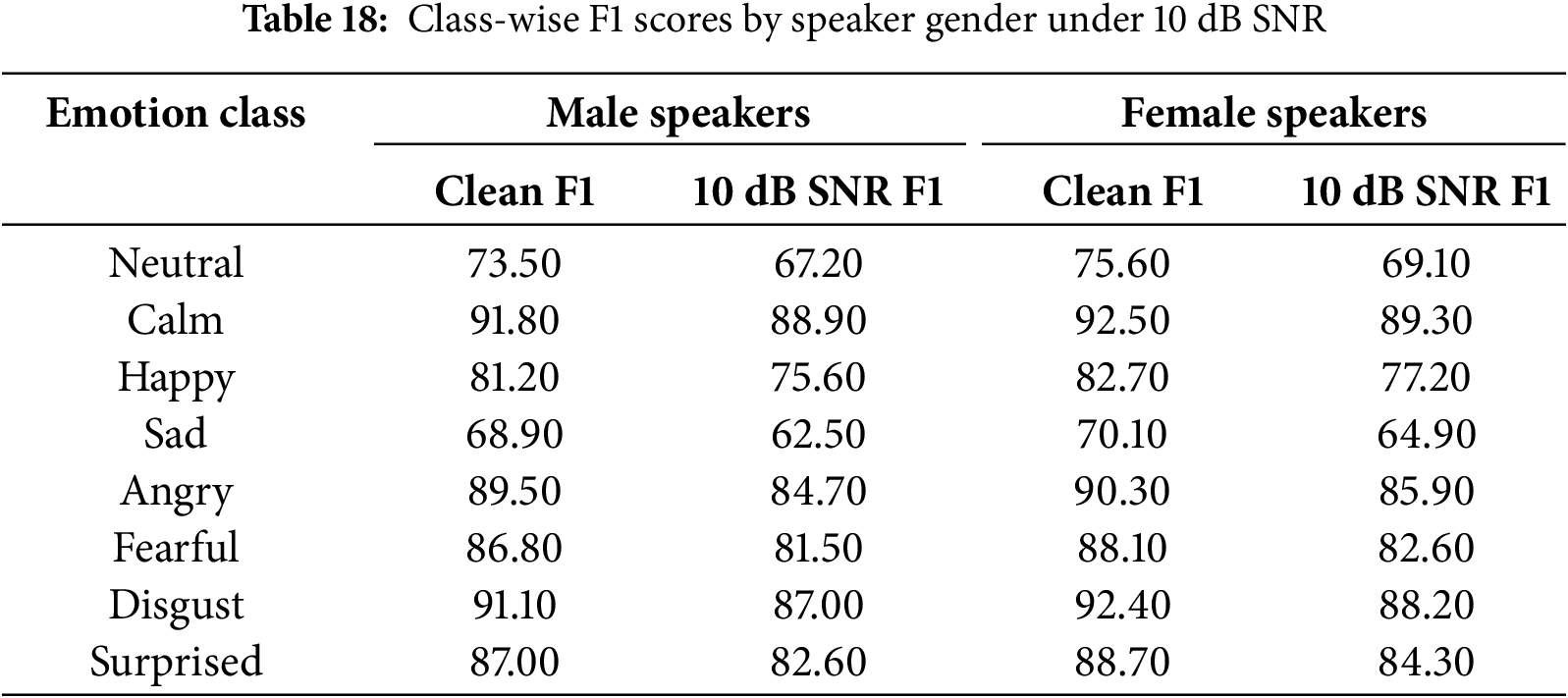

Finally, we report class-wise F1 scores for both genders under 10 dB SNR. As shown in Table 18, performance degradation is consistent across classes and genders, confirming both robustness and fairness of the proposed model.

3.4.6 Model Performance and Computational Efficiency Analysis

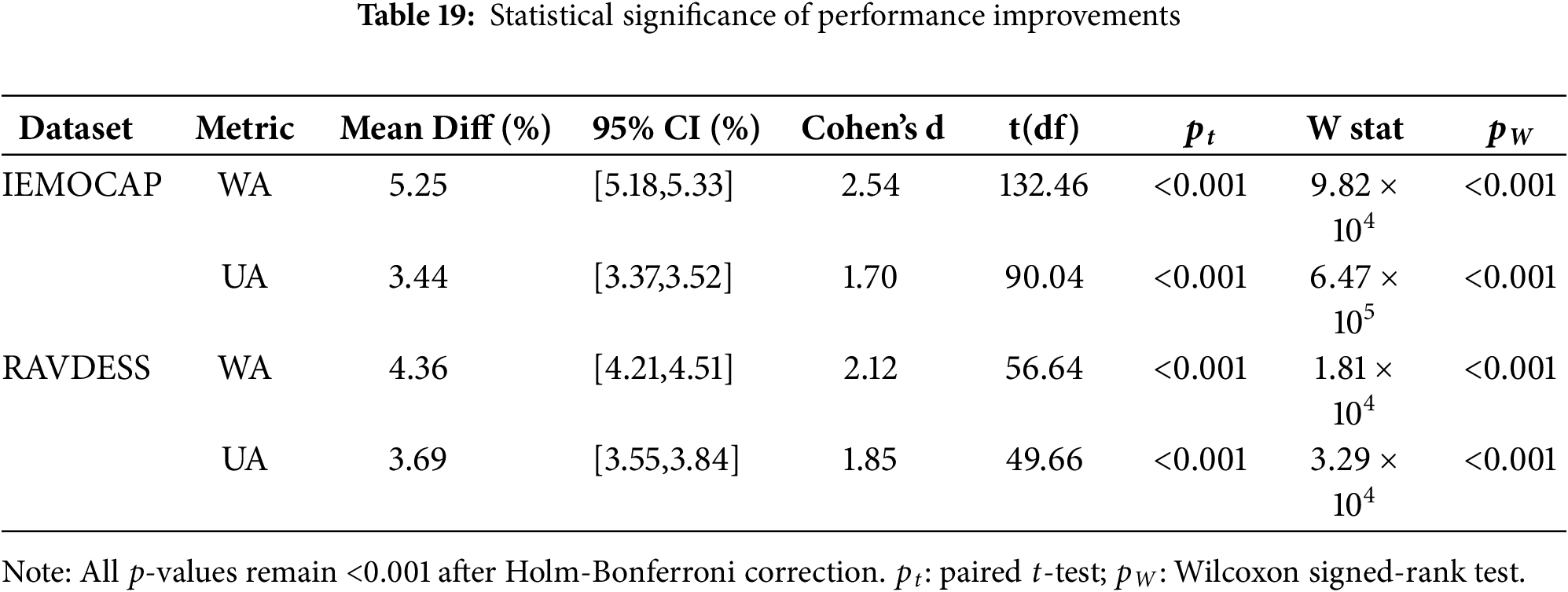

To ensure robust statistical evaluation, we conducted utterance-level paired tests comparing predictions on each test utterance pooled from all cross-validation folds (5531 for IEMOCAP; 1440 for RAVDESS). As shown in Table 19, all improvements are statistically significant under both parametric (paired t-test) and non-parametric (Wilcoxon signed-rank) tests (all p < 0.001 after Holm-Bonferroni correction), with effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranging from 1.70 to 2.54 and 95% confidence intervals confirming gains of 3.4%–5.3%.

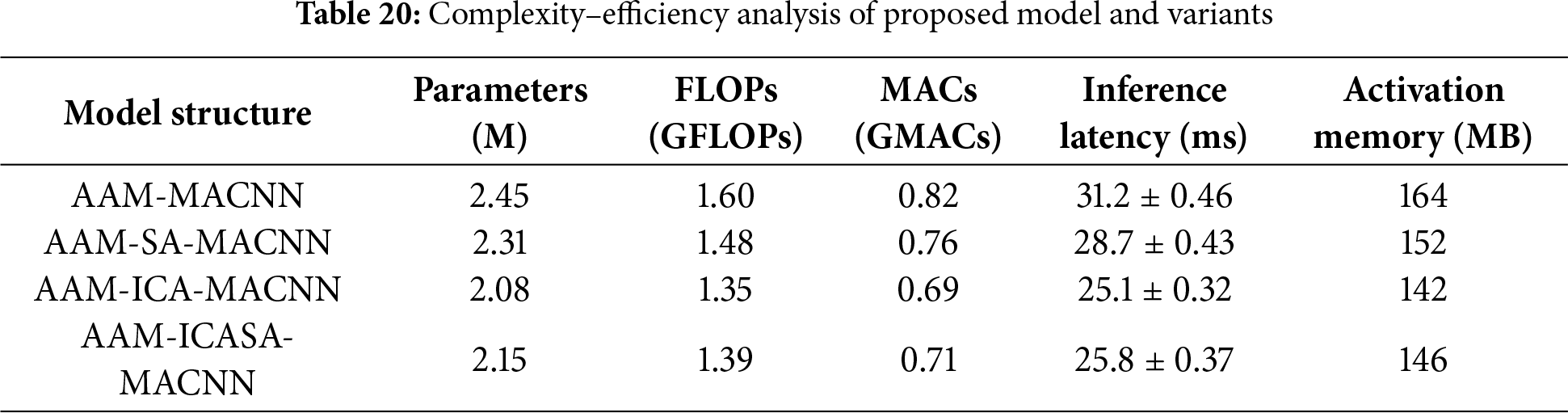

To assess computational efficiency, Table 20 compares AAM-MACNN and its variants.AAM-ICA-MACNN achieves the highest structural efficiency with 15.1% fewer parameters and 15.6% fewer FLOPs. The proposed AAM-ICASA-MACNN slightly increases parameters (2.15 M vs. 2.08 M) due to adaptive modulation, yet maintains a 12.2% parameter reduction and 17.3% latency improvement over the AAM-MACNN, with only 0.04 GFLOPs (2.9%) overhead. These results confirm a superior efficiency–accuracy balance achieved through refined attention and semantic integration.

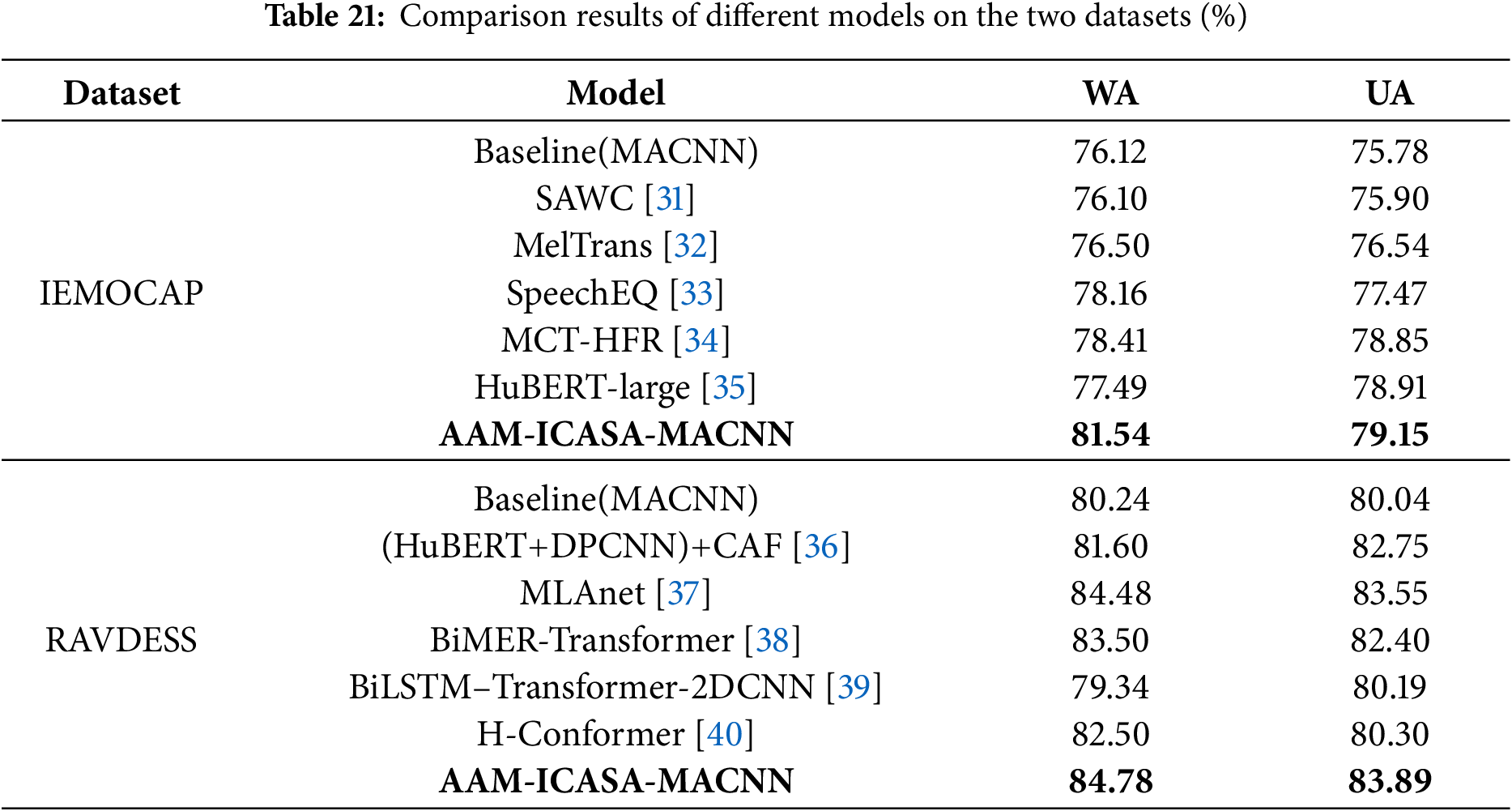

3.4.7 Comparison Experiments with Different Models

To verify the superiority of the proposed model, we compared it with several representative advanced SER models on both datasets, as presented in Table 21. On IEMOCAP, the proposed model achieved WA and UA improvements of 3.13%–5.38% and 0.24%–3.33% respectively over models such as SAWC, MelTrans, and HuBERT-large. On RAVDESS, compared with H-Conforme, MLAnet, and BiMER-Transformer, our model demonstrated WA and UA gains of 0.30%–3.28% and 0.34%–3.34% respectively, confirming the effectiveness and superior performance of the proposed method in speech emotion recognition.

This study presents an improved SER model named AAM-ICASA-MACNN, which employs an adaptive acoustic mixup strategy to dynamically augment training samples, effectively enhancing the model’s generalization performance and mitigating data imbalance. In addition, an improved dual-path attention mechanism, ICASA, is proposed to further enhance the feature extraction ability by dynamically fusing the improved coordinate attention and shuffle attention. The experimental results show that the proposed method can achieve significant performance improvement on the IEMOCAP and RAVDESS speech emotion datasets compared to the existing methods, which verifies the superiority.

In future work, the model could be further improved by integrating generative adversarial networks for more robust data augmentation and applying lightweight neural architecture search to achieve a better balance between model complexity and recognition performance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 12204062, and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province under Grant No. ZR2022MF330.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, methodology, and writing, Jun Li; supervision and project administration, Chunyan Liang; validation and data curation, Zhiguo Liu; formal analysis and visualization, Fengpei Ge. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All datasets used in this study are publicly available: IEMOCAP (https://github.com/Samarth-Tripathi/IEMOCAP-Emotion-Detection, accessed on 23 October 2025) and RAVDESS (https://zenodo.org/records/1188976, accessed on 23 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. de Lope J, Graña M. An ongoing review of speech emotion recognition. Neurocomputing. 2023;528:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wani TM, Gunawan TS, Qadri SAA, Kartiwi M, Ambikairajah E. A comprehensive review of speech emotion recognition systems. IEEE Access. 2021;9:47795–814. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3068651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li B. Speech emotion recognition based on CNN-Transformer with different loss function. J Comput Commun. 2025;13(3):103–15. doi:10.4236/jcc.2025.133001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. El Ayadi M, Kamel MS, Karray F. Survey on speech emotion recognition: features, classification schemes, and databases. Pattern Recognit. 2011;44(3):572–87. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2010.09.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhao J, Wang F, Li K, Wei Y, Tang S, Zhao S, et al. Temporal-frequency state space duality: an efficient paradigm for speech emotion recognition. In: ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2025 Apr 6–11; Ottawa, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10890265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Trigeorgis G, Ringeval F, Brueckner R, Marchi E, Nicolaou MA, Schuller B, et al. Adieu features? End-to-end speech emotion recognition using a deep convolutional recurrent network. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2016 Mar 20–25; Shanghai, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 5200–4. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2016.7472626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xu F, Yang H, Hu Y. DA-KWFormer: a domain adaptation network with k-weight transformer for speech emotion recognition. In: National Conference on Man-Machine Speech Communication; 2024. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 347–58. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-1045-7_29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen C, Zhang P. TRNet: two-level Refinement Network leveraging speech enhancement for noise robust speech emotion recognition. Appl Acoust. 2024;225:109752. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2024.109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Singh J, Saheer LB, Faust O. Speech emotion recognition using attention model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):4945. doi:10.3390/ijerph20064945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tang X, Huang J, Lin Y, Dang T, Cheng J. Speech emotion recognition Via CNN-transformer and multidimensional attention mechanism. Speech Commun. 2025;158:103242. doi:10.1016/j.specom.2024.103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Baevski A, Zhou Y, Mohamed A, Auli M. wav2vec 2.0: a framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. arXiv:2006.11477. 2020. [Google Scholar]

12. Upadhyay SG, Salman AN, Busso C, Lee C-C. Mouth articulation-based anchoring for improved cross-corpus speech emotion recognition. In: ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2025 Apr 6–11; Ottawa, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10890262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hsu W-N, Bolte B, Tsai Y-HH, Lakhotia K, Salakhutdinov R, Mohamed A. HuBERT: self-supervised speech representation learning by masked prediction of hidden units. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2021;29:3451–60. doi:10.1109/taslp.2021.3122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yoon S, Byun S, Jung K. Multimodal speech emotion recognition using audio and text. In: IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT); 2018 Dec 18–21; Okinawa, Japan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 112–8. doi:10.1109/SLT.2018.8639583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Long K, Xie G, Ma L, Li Q, Huang M, Lv J, et al. Enhancing multimodal learning via hierarchical fusion architecture search with inconsistency mitigation. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2025;34:5458–72. doi:10.1109/TIP.2025.3599673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kakuba S, Poulose A, Han DS. Attention-based multi-learning approach for speech emotion recognition with dilated convolution. IEEE Access. 2022;10:122302–13. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3223593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Carvalho C, Abad A. AC-Mix: self-supervised adaptation for low-resource automatic speech recognition using agnostic contrastive mixup. In: ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2025 Apr 6–11; Hyderabad, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–5. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2410.14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Goron E, Asai L, Rut E, Dinov M. Improving domain generalization in speech emotion recognition with Whisper. In: ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 11631–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10447591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Saleem N, Elmannai H, Bourouis S, Trigui A. Squeeze-and-excitation 3D convolutional attention recurrent network for end-to-end speech emotion recognition. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;161:111734. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hou Q, Zhou D, Feng J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 13713–22. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang QL, Yang YB. Sa-net: shuffle attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In: ICASSP 2021–2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021 Jun 6–11; Toronto, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 2235–9. doi:10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yalamanchili B, Anne KR, Samayamantula SK. Correction to: speech emotion recognition using time distributed 2D-convolution layers for CAPSULENETS. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(20):31267. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15079-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mishra SP, Warule P, Deb S. Speech emotion recognition using MFCC-based entropy feature. Signal Image Video Process. 2024;18(1):153–61. doi:10.1007/s11760-023-02716-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Antoniou N, Katsamanis A, Giannakopoulos T, Narayanan S. Designing and Evaluating speech emotion recognition systems: a reality check case study with IEMOCAP. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2023;14(3):2045–58. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2022.3164953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Luna-Jiménez C, Griol D, Callejas Z, Kleinlein R, Montero JM, Fernández-Martínez F. Multimodal emotion recognition on RAVDESS dataset using transfer learning. Sensors. 2021;21(22):7665. doi:10.3390/s21227665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu X, Mou Y, Ma Y, Liu C, Dai Z. Speech emotion detection using sliding window feature extraction and ANN. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 5th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP); 2020 Jul 20–22; Nanjing, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 746–50. doi:10.1109/ICSIP49896.2020.9339340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang Y, Li B, Fang H, Meng Q. Spectrogram transformers for audio classification. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST); 2022 Oct 17–19; Beijing, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/IST55454.2022.9827731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ding K, Li R, Xu Y, Du X, Deng B. Adaptive data augmentation for mandarin automatic speech recognition. Appl Intell. 2024;54(7):5674–87. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05354-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kim B, Kwon Y. Searching for effective preprocessing method and CNN-based architecture with efficient channel attention on speech emotion recognition. arXiv:2409.04007. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2409.04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Nidhi, Verma B. A lightweight convolutional swin transformer with cutmix augmentation and CBAM attention for compound emotion recognition. Appl Intell. 2024;54(12):6789–805. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05432-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Santoso J, Yamada T, Makino S, Ishizuka K, Hiramura T. Speech emotion recognition based on attention weight correction using word-level confidence measure. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2021; 2021 Aug 30–Sep 3; Brno, Czech Republic. p. 1947–51. doi:10.21437/Interspeech.2021-411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. You X. MelTrans: mel-spectrogram relationship-learning for speech emotion recognition via transformers. Sensors. 2024;24(11):3456. doi:10.3390/s24113456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kang Z, Peng J, Wang J, Xiao J. Speecheq: speech emotion recognition based on multi-scale unified datasets and multitask learning. arXiv:2206.13101. 2022. [Google Scholar]

34. Ma Z, Chen M, Zhang H, Zheng Z, Chen W, Li X, et al. Emobox: multilingual multi-corpus speech emotion recognition toolkit and benchmark. arXiv:2406.07162. 2024. [Google Scholar]

35. Shome D, Etemad A. Speech emotion recognition with distilled prosodic and linguistic affect representations. In: ICASSP 2024–2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 May 19–24; Rhodes, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 11976–80. doi:10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10447315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yu S, Meng J, Fan W, Chen Y, Zhu B, Yu H, et al. Speech emotion recognition using dual-stream representation and cross-attention fusion. Electronics. 2024;13(11):2178. doi:10.3390/electronics13112178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu K, Wang D, Wu D, Liu Y, Feng J. Speech emotion recognition via multi-level attention network. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2022;29:2278–82. doi:10.1109/LSP.2022.3218995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Song Y, Zhou Q. Bi-modal bi-task emotion recognition based on transformer architecture. Appl Artif Intell. 2024;38(1):2356992. doi:10.1080/08839514.2024.2356992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kim S, Lee S-P. A BiLSTM-transformer and 2D CNN architecture for emotion recognition from speech. Electronics. 2023;12(19):4034. doi:10.3390/electronics12194034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao P, Liu F, Zhuang X. Speech sentiment analysis using hierarchical conformer networks. Appl Sci. 2022;12(16):8076. doi:10.3390/app12168076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools