Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Support Vector–Guided Class-Incremental Learning: Discriminative Replay with Dual-Alignment Distillation

College of Computer and Artificial Intelligence, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, 730050, China

* Corresponding Author: Yixin Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 88 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071021

Received 29 July 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Modern intelligent systems, such as autonomous vehicles and face recognition, must continuously adapt to new scenarios while preserving their ability to handle previously encountered situations. However, when neural networks learn new classes sequentially, they suffer from catastrophic forgetting—the tendency to lose knowledge of earlier classes. This challenge, which lies at the core of class-incremental learning, severely limits the deployment of continual learning systems in real-world applications with streaming data. Existing approaches, including rehearsal-based methods and knowledge distillation techniques, have attempted to address this issue but often struggle to effectively preserve decision boundaries and discriminative features under limited memory constraints. To overcome these limitations, we propose a support vector–guided framework for class-incremental learning. The framework integrates an enhanced feature extractor with a Support Vector Machine classifier, which generates boundary-critical support vectors to guide both replay and distillation. Building on this architecture, we design a joint feature retention strategy that combines boundary proximity with feature diversity, and a Support Vector Distillation Loss that enforces dual alignment in decision and semantic spaces. In addition, triple attention modules are incorporated into the feature extractor to enhance representation power. Extensive experiments on CIFAR-100 and Tiny-ImageNet demonstrate effective improvements. On CIFAR-100 and Tiny-ImageNet with 5 tasks, our method achieves 71.68% and 58.61% average accuracy, outperforming strong baselines by 3.34% and 2.05%. These advantages are consistently observed across different task splits, highlighting the robustness and generalization of the proposed approach. Beyond benchmark evaluations, the framework also shows potential in few-shot and resource-constrained applications such as edge computing and mobile robotics.Keywords

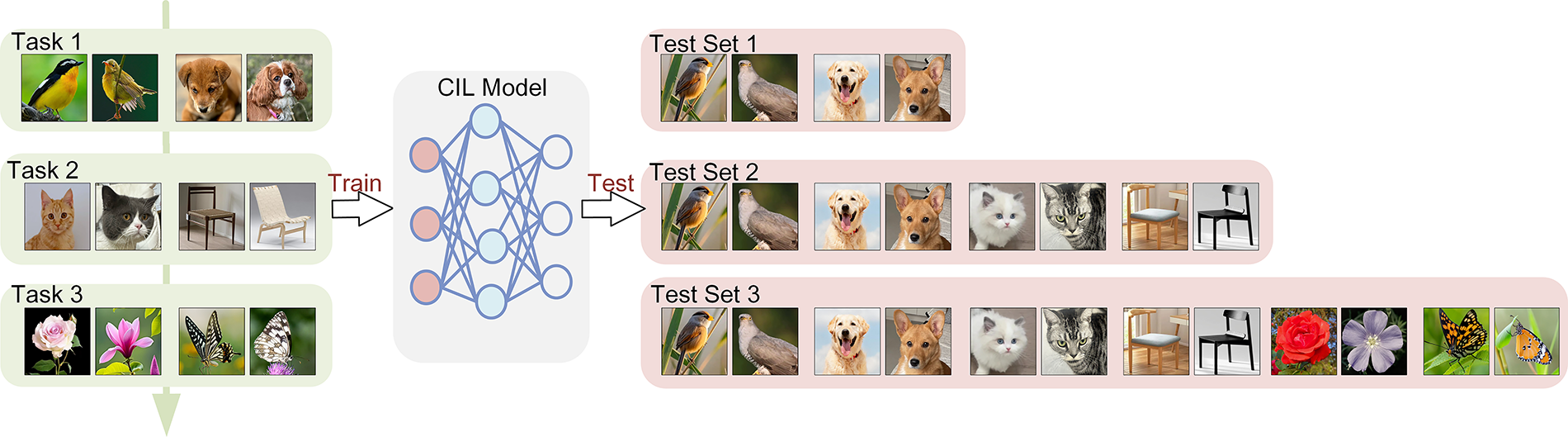

In recent years, machine learning has achieved remarkable success in various domains such as image recognition [1], object detection and semantic segmentation. However, most existing research is based on static environments, where tasks are predefined and all data are accessible during each training session. In contrast, real-world scenarios are often dynamic [2], requiring systems to continuously adapt to new information—a fundamental challenge in the field of continual learning within artificial intelligence. For example, autonomous driving systems must continually recognize new traffic signs or unexpected road conditions, while face recognition systems may need to adapt to new users or appearance changes caused by lighting or aging. These scenarios demand learning models that can adapt to new challenges while retaining previously acquired knowledge. Class-incremental learning (CIL), as a core subproblem of continual learning, has attracted significant research attention [3] and has emerged as a promising solution to this issue. It allows models to learn new classes in incoming tasks while preserving recognition capabilities for previously seen ones, thereby maintaining overall performance in evolving environments. As illustrated in Fig. 1, in the CIL setting, new tasks with non-overlapping classes arrive sequentially, and the model must incrementally learn to classify all encountered classes. After each task, the model is evaluated on the cumulative set of all classes seen so far. However, catastrophic forgetting remains a critical challenge in CIL [4]. Models trained on new tasks tend to become biased toward novel classes, resulting in a substantial performance drop on earlier tasks and severely limiting the practical deployment of such systems in dynamic contexts.

Figure 1: The class-incremental learning scenario. Non-overlapping classes arrive sequentially across multiple tasks (Task 1, Task 2, Task 3, …). During each training phase, the model learns new classes while attempting to retain knowledge of previous ones. At test time, the model is evaluated on all classes encountered up to that point, with the test set expanding cumulatively. An ideal CIL model should maintain high performance on both newly learned classes and previously learned ones without catastrophic forgetting

Prior studies have explored four primary strategies to mitigate catastrophic forgetting: parameter regularization, knowledge distillation, architectural modification and rehearsal-based methods. Among these, rehearsal-based approaches are the most widely used and empirically effective. These methods maintain a fixed-size memory buffer to retain a subset of old class samples or their feature representations, which are then combined with new class data during training. By explicitly reintroducing information from previous tasks, rehearsal methods help reduce forgetting of old knowledge to some extent. To further enhance knowledge retention, many recent works combine rehearsal with knowledge distillation. Distillation guides the new model to mimic the behavior of the previous one, ensuring that responses to old classes are preserved while adapting to new ones. In this way, knowledge is effectively transferred from the old model to the new one, enabling continuous learning while alleviating the impact of catastrophic forgetting.

However, current methods often struggle to effectively capture key discriminative features in complex visual tasks. This limitation becomes more pronounced when there is high visual similarity between new and previously learned classes, which can lead to feature confusion and classification errors. Although rehearsal mechanisms help preserve historical information to some extent, selecting the most representative and informative samples or features under limited memory budgets remains an open and important problem. In addition, existing knowledge distillation strategies tend to emphasize consistency in output distributions, while paying limited attention to the stability of classification decision boundaries. As a result, the model’s ability to distinguish old classes may degrade during the learning of new tasks.

To address these limitations, we propose a Support Vector–Guided Class-Incremental Learning framework that strengthens knowledge retention through a discriminative replay mechanism and improves knowledge transfer stability via a dual-alignment distillation strategy. The overall architecture is decoupled: a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier is introduced to generate support vectors, which are used to select the most representative historical samples for subsequent replay and distillation. Additionally, we design a feature extractor enhanced with triple attention modules to improve the discriminative power of learned representations. Specifically, our main contributions can be summarized as follows.

1. We propose a decoupled framework that integrates an enhanced feature extraction network with an SVM classifier, explicitly exploiting the boundary-critical nature of support vectors. The support vectors characterize the decision boundaries of old classes and are used to guide both replay and distillation. The feature extraction network incorporates channel attention, spatial attention and class-sensitive attention to boost the model’s ability to represent key regions effectively.

2. Building on this architecture, we design a joint feature retention strategy that combines decision boundary proximity with feature diversity metrics. This ensures both coverage and discriminative capability for old-class representations under limited memory.

3. Furthermore, we introduce a Support Vector Distillation Loss (SVDL), designed around the properties of support vectors, which achieves dual alignment in decision and semantic spaces. By enforcing decision-direction consistency and semantic feature alignment on key samples, this distillation constraint effectively mitigates the drift of old-class decision boundaries during new-task learning.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 presents our proposed method. Section 4 provides experimental results and analysis. Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future directions.

The core challenge in class-incremental learning lies in the stability-plasticity dilemma: the model must be plastic enough to acquire new knowledge, yet stable enough to retain old knowledge [3]. Catastrophic forgetting arises when neural networks overwrite previously learned representations while adapting to new tasks. To address this issue, existing approaches can be understood through four main categories on how to preserve old knowledge: (1) constraining parameter updates to protect important weights (parameter regularization), (2) transferring knowledge from the old model to the new one (knowledge distillation), (3) isolating or expanding network capacity for different tasks (network architecture) and (4) explicitly replaying historical information during training (rehearsal methods). In the following subsections, we review representative works within each category.

Parameter regularization methods aim to preserve knowledge from previous tasks by constraining updates to important model parameters. A representative example is Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC), proposed by Kirkpatrick et al. [5], which estimates the importance of each parameter to prior tasks using the Fisher information matrix. It then penalizes changes to these important parameters, thereby reducing interference with previously acquired knowledge. To address the limitations of EWC in capturing the trajectory of parameter updates, Zenke et al. [6] introduced Synaptic Intelligence (SI), which estimates parameter importance in an online manner by tracking their contribution to the change in the loss function over time. These methods enable continual learning without requiring additional memory to store past data. However, they often fall short in modeling the potential correlations or dependencies across different tasks.

Knowledge distillation methods mitigate forgetting by encouraging the new model to produce outputs consistent with those of the old model when evaluated on the same data [7]. Li et al. [8] introduced Learning without Forgetting (LwF), one of the earliest works in this direction, by applying distillation to class-incremental learning. LwF fine-tunes the model on new tasks while aligning the logits of current samples between the old and new models, helping to retain knowledge of previously learned classes. PODNet [9] advances this idea by introducing a spatial distillation loss that preserves structural information in feature maps, rather than applying element-wise matching. Yang et al. [10] further proposed DRTAD, which dynamically adjusts the distillation loss weights based on model size and the number of learned classes, making the learning process more adaptive and effective. Despite their success, these methods tend to apply global constraints over the entire output distribution, without specifically targeting decision-sensitive regions in the feature space where forgetting is most critical.

Network architecture strategies aim to improve the model’s flexibility by modifying its structure. However, the introduction of new tasks typically results in increased model parameters, which in turn raises storage and computational costs. Shmelkov et al. [11] proposed a dual-branch architecture in which a frozen copy of the original network is preserved to compute distillation loss, while an additional output branch is added to accommodate new classes. This design helps maintain consistent responses to previously learned classes during incremental training and thereby alleviates catastrophic forgetting. Kim et al. [12] argued that existing approaches tend to underestimate the importance of intra-class and cross-task knowledge for new classes. They introduced a “split-and-bridge” architecture, which constructs task-specific upper sub-networks while sharing lower layers, achieving a balance between structural isolation and cross-task knowledge fusion. To mitigate the growing parameter overhead in architecture-based approaches, recent studies have proposed compressing the model after each incremental step to restore its original size, thus reducing memory and computation burden [13–15]. These methods typically freeze the old feature extractor, train new modules to expand the representational capacity, and apply model compression at the end of each increment to better balance stability and plasticity.

Rehearsal methods can be divided into exemplar rehearsal and feature rehearsal, depending on the type of data stored. Exemplar rehearsal methods are intuitive and effective, as they store real samples from past tasks, which faithfully represent previously learned concepts. A notable example is iCaRL, introduced by Rebuffi et al. in 2016 [16], which selects a small set of representative exemplars from old classes using a herding algorithm. The model is then trained using both cross-entropy loss and knowledge distillation, and classification is performed using a nearest class mean strategy. To address the data imbalance between old and new classes, Wu et al. [17] proposed adding a simple linear model, BiC, to calibrate the network’s outputs. A major limitation of exemplar rehearsal is the overhead of storing and managing historical data. Moreover, practical applications often impose privacy constraints that prohibit the storage of real samples. To overcome this, Iscen et al. [18] suggested storing deep feature vectors of old classes instead of raw images. However, feature rehearsal methods suffer from feature degradation, as stored features become outdated over time. Yu et al. [19] proposed maintaining class prototypes, which represent the mean feature vectors corresponding to each class. In addition, they introduced a Semantic Drift Compensation (SDC) strategy to alleviate the problem of prototype drift. PASS, proposed by Zhu et al. [7], retains only class means and enhances them with Gaussian noise during rehearsal, which helps preserve the decision boundaries learned in earlier tasks. While feature rehearsal offers advantages in terms of memory efficiency and privacy, it still faces challenges such as representation decay and prototype instability.

In practical applications such as autonomous driving or surveillance systems, models must continuously recognize new object categories (e.g., new traffic signs, emerging threats) while maintaining performance on existing ones, often under strict memory and privacy constraints. Such scenarios share common characteristics: data typically arrives in a streaming fashion with limited storage capacity and restricted access to historical samples. The goal of class-incremental learning is to enable the model to gradually learn different classes while retaining its recognition ability for previously learned ones. Suppose there exists a training dataset consisting of

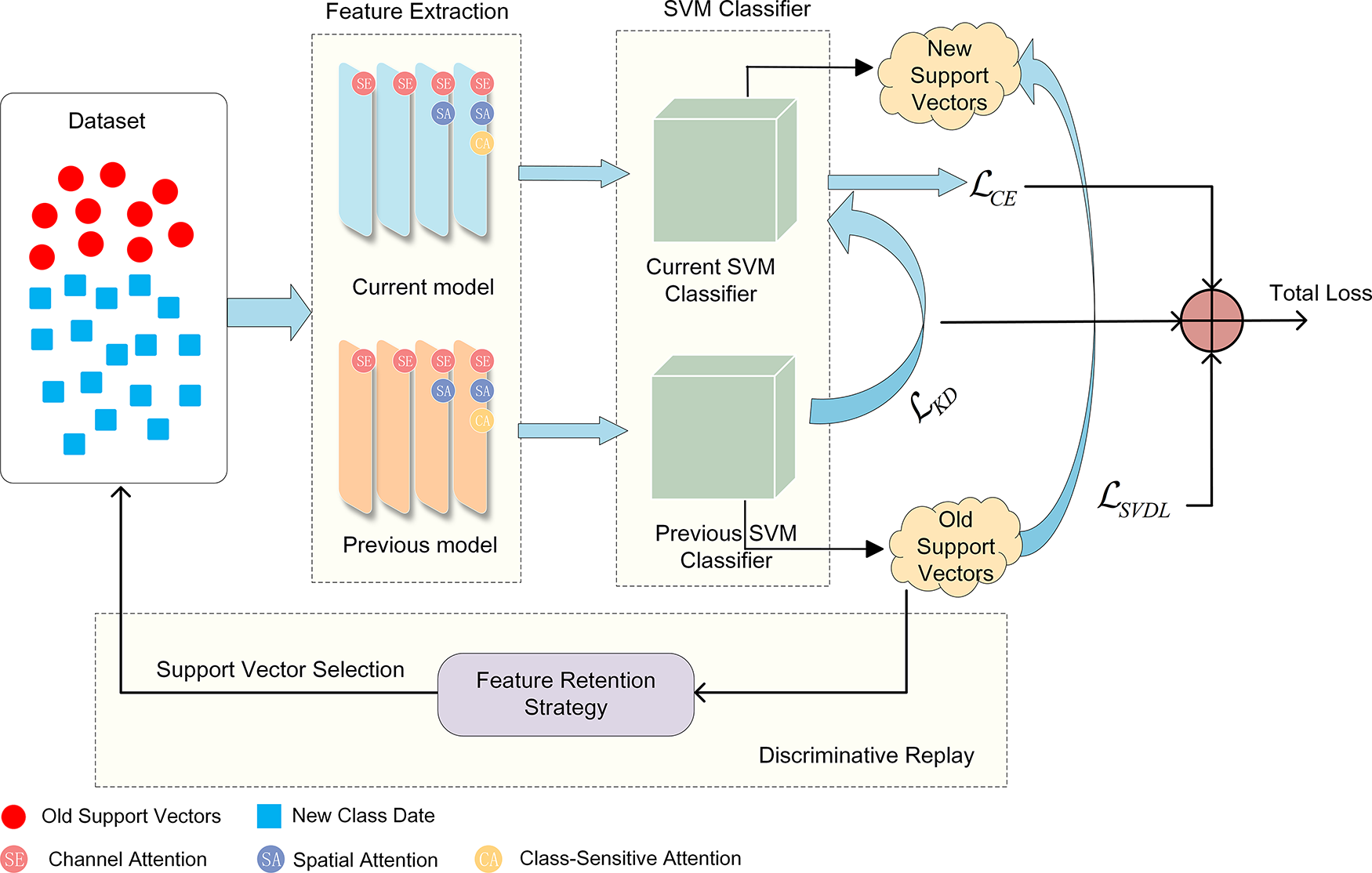

Based on the problem formulation in Section 3.1, this paper proposes a support vector–guided framework with a decoupled structure between the feature extractor and the classifier. The overall process is as follows: first, the input image is passed through a ResNet-18 network enhanced with triple attention mechanisms for feature extraction. Then, the extracted feature vector is classified by an SVM classifier. At each incremental stage, the model is trained using new class samples from the current task along with the support vectors retained from the previous stage. The feature extraction network is optimized jointly using cross-entropy loss, conventional knowledge distillation loss, and support vector distillation loss, thereby balancing the learning of new categories and the retention of old knowledge. During training, the SVM automatically generates support vectors. The model then applies a joint feature retention strategy to select representative samples from them for use in subsequent rehearsal. The complete process of the proposed method for each incremental task is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Workflow of the proposed support vector–guided class-incremental learning framework. The input data and retained support vectors pass through a ResNet-18 backbone with triple attention modules for enhanced feature extraction. The SVM classifier generates support vectors, which are selected using a feature retention strategy and used for discriminative replay. The model is trained with a joint loss function combining cross-entropy (

3.2.1 Enhanced Feature Extraction Network

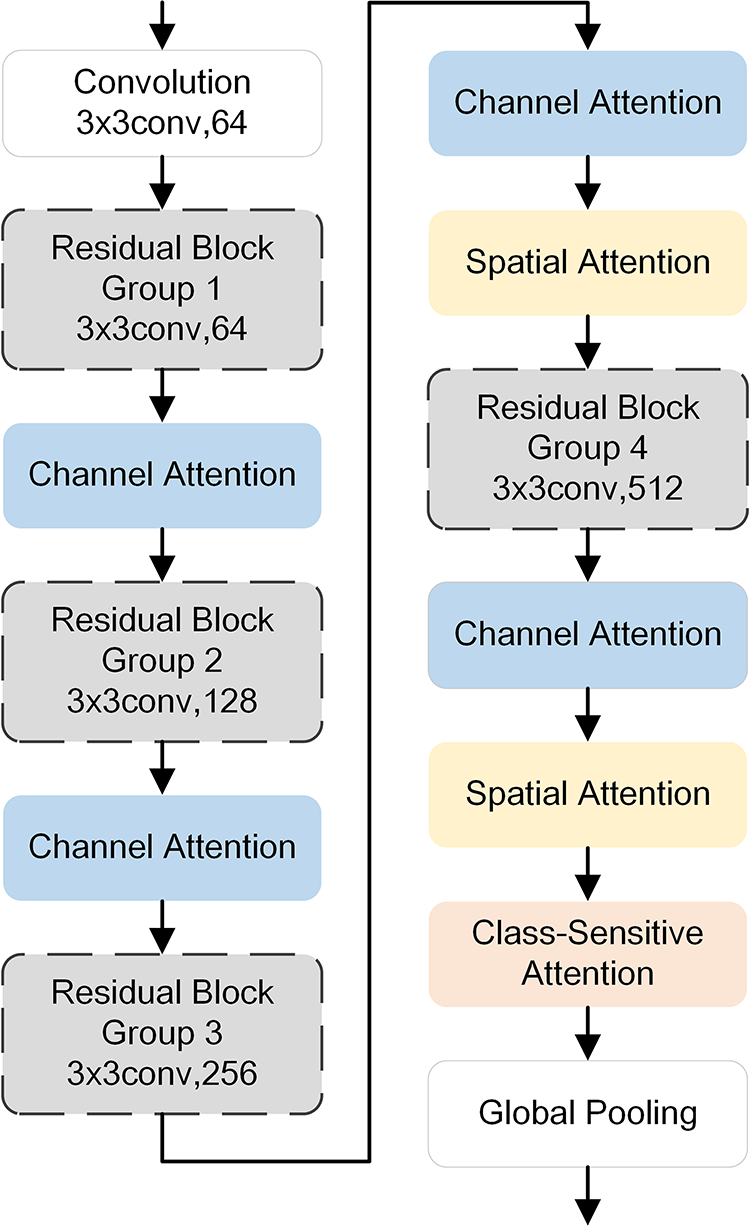

We integrate three existing attention mechanisms—channel attention [20], spatial attention [21] and class-sensitive attention [22]—into a ResNet-18 backbone to construct a triple-attention enhanced feature extraction network that improves the discriminative representation of features. The overall network structure is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Architecture of the enhanced feature extraction network with integrated triple attention mechanisms. The network consists of sequential residual blocks, each followed by a corresponding attention module (channel, spatial and class-sensitive attention). This hierarchical feature enhancement path improves the model’s ability to focus on discriminative regions at different levels of abstraction, contributing to better feature representation in the class-incremental learning setting

The ResNet-18 backbone consists of four residual blocks. In this work, the three complementary attention mechanisms are inserted at different levels. Channel attention is applied after each residual block to reweight the original feature maps, allowing the network to highlight important feature channels. Spatial attention modules are added after the third and fourth residual blocks to further reweight the feature maps at the pixel level, guiding the model to focus on the most discriminative regions of the image. A class-sensitive attention module is added after the final residual block to adaptively adjust the feature keypoints based on class-specific information. In real-world incremental learning scenarios such as autonomous driving or video surveillance, incoming data often contain subtle inter-class differences and noise. The use of multi-level attention mechanisms ensures that the network can emphasize critical features while suppressing irrelevant variations, thereby improving robustness in such practical settings. In the context of class-incremental learning, as new categories are introduced, the weight matrix

where

The three attention modules are integrated in a sequential manner and inserted after the outputs of different residual blocks, forming a hierarchical feature enhancement path from the channel level to the spatial and then to the class level. This design is also modular and adaptable, and can be applied to deeper or lighter backbones, making it suitable for a range of future scenarios.

In this method, Support Vector Machine (SVM) is adopted as the classifier, and its generated support vectors are used to guide sample selection and knowledge retention during the incremental learning stages. SVM seeks the optimal hyperplane by maximizing the classification margin, thereby achieving an optimal decision boundary. Unlike conventional neural networks based on Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM), SVM follows the principle of Structural Risk Minimization (SRM), which enables it to suppress overfitting more effectively under limited data conditions and improves the overall generalization capability of the model. This property is particularly beneficial in real-world class-incremental learning scenarios, where training data are usually limited, imbalanced and arrive in a streaming fashion. In such settings, the margin-maximization nature of SVM provides stable decision boundaries and alleviates catastrophic forgetting more reliably than purely neural classifiers. Furthermore, SVM can construct nonlinear decision boundaries without explicitly computing high-dimensional mappings, making it well-suited for handling the high-dimensional feature vectors produced by deep feature extractors. In class-incremental learning, where data distributions are often limited, SVM demonstrates greater stability compared to other classifiers such as neural networks or k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), as its decision only depends on the support vectors.

Support vectors are boundary samples naturally selected during SVM training, and they fully determine the final decision hyperplane. The dual formulation of the SVM indicates that the classification decision function can be written as Eq. (2),

where SV denotes the set of support vectors obtained during SVM training,

where

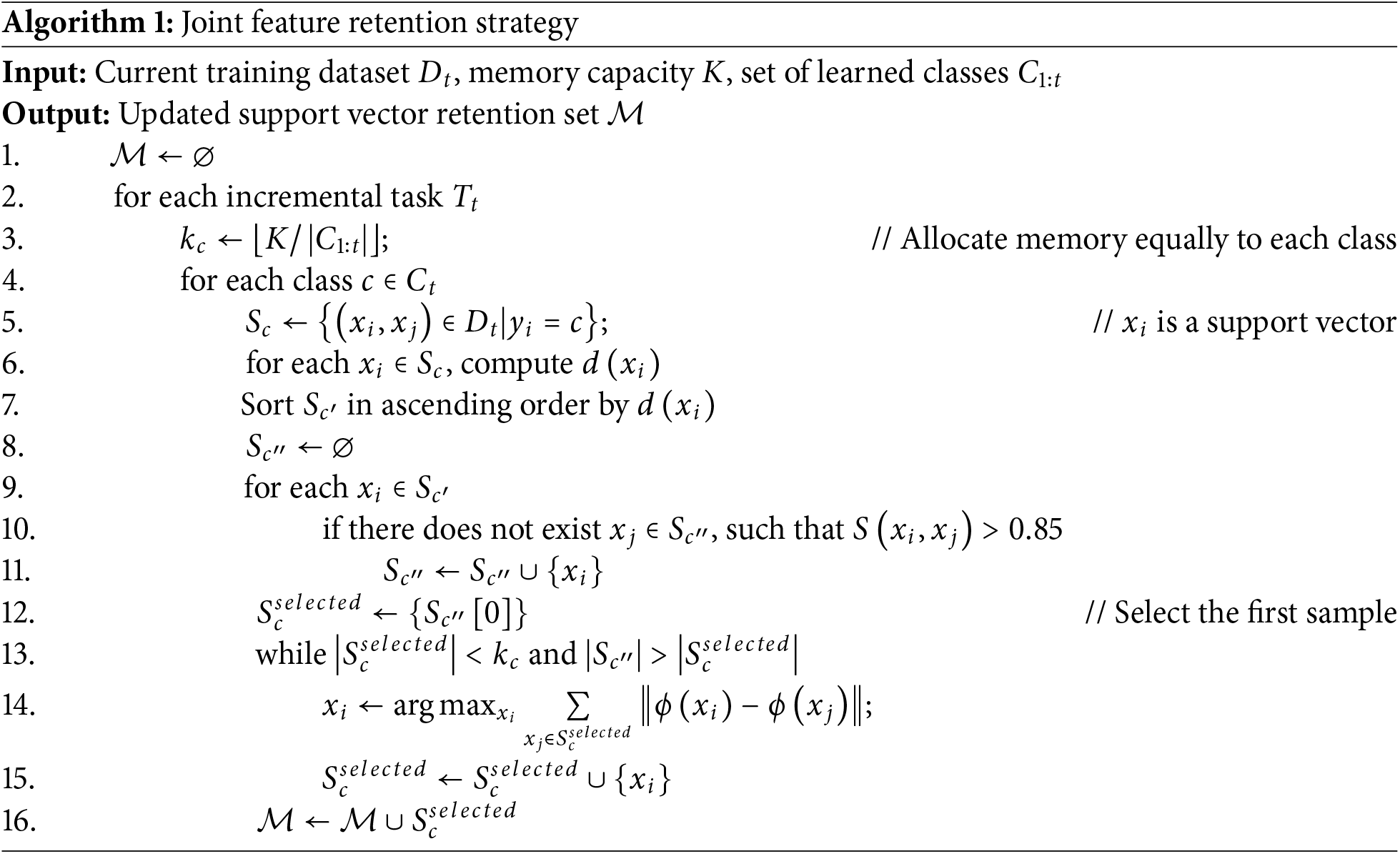

3.3 Joint Feature Retention Strategy

To avoid class imbalance, we allocate memory space equally across all classes. Suppose the total memory capacity is

We first prioritize support vectors that are closest to the decision boundary. These vectors tend to reflect hard-to-classify examples and are more susceptible to interference from new classes. The distance from a support vector to the decision hyperplane is computed as Eq. (4),

where

However, using only decision boundary distance may result in overly concentrated samples, making it difficult to cover the entire feature space of each class. Therefore, we further introduce feature diversity constraints based on both similarity and spatial coverage. First, we use cosine similarity to evaluate the feature similarity between support vectors. The similarity function is defined in Eq. (5).

If the similarity between two support vectors exceeds a threshold

3.4 Support Vector Distillation Loss

To further alleviate the problem of catastrophic forgetting in class-incremental learning, we propose a Support Vector Distillation Loss (SVDL) based on the SVM classifier. Unlike existing methods, SVDL focuses on preserving the classification discriminability of the new model on the support vectors, ensuring that the decision boundaries at these critical samples do not shift. This distillation mechanism maintains knowledge from two complementary perspectives: decision alignment and semantic alignment, forming a dual-alignment distillation strategy. Specifically, SVDL consists of two components: the decision boundary alignment loss and the semantic feature alignment loss, which constrain and retain prior knowledge from the perspectives of model decision directions and intermediate semantic structures, respectively.

The decision boundary alignment loss is designed to ensure that the classification direction of the new model on the support vectors remains consistent with that of the old model, thereby maintaining the stability of decision boundaries for previously learned classes. It is defined as Eq. (6)

where

where

where

In addition to the Support Vector Distillation Loss introduced above, we also adopt the standard cross-entropy loss as the classification loss during incremental learning to learn new categories in the current task, as defined in Eq. (9):

where

Meanwhile, we employ a knowledge distillation loss to preserve the consistency of overall output distributions for old classes, as shown in Eq. (10):

where

Finally, the total loss function used during training is given by Eq. (11):

where

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conduct experiments on two benchmark datasets widely used in class-incremental learning: CIFAR-100 and Tiny-ImageNet. CIFAR-100 consists of 100 classes, each containing 600 RGB images with a resolution of 32 × 32 pixels. In total, the dataset includes 50,000 training images and 10,000 test images. Tiny-ImageNet is a subset extracted from the larger ImageNet dataset. It contains 200 classes, each with 500 training images, 50 validation images and 50 test images, with a higher resolution of 64 × 64 pixels. Compared to CIFAR-100, Tiny-ImageNet provides more categories and higher image resolution, making the experimental setting closer to real-world applications. A comparison between the two datasets is illustrated in Fig. 4. The ResNet-18 backbone extracts 512-dimensional feature vectors from input images, which are then classified by the SVM. To align with the problem definition of class-incremental learning, the dataset is randomly divided into multiple incremental tasks, with no overlap in class types between different tasks.

Figure 4: Example images from CIFAR-100 and Tiny-ImageNet datasets. The higher resolution and larger number of classes in Tiny-ImageNet provide a more realistic experimental setting for class-incremental learning

This paper adopts Average Accuracy (Avg) as the evaluation metric, which represents the average classification accuracy of all known classes at any given time. It is defined as Eq. (12):

where

All experiments were conducted in a Python 3.10 environment with CUDA 11.8 and PyTorch 2.0.1. During training, the image batch size was set to 128, and the objective function was optimized using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). The total number of training epochs was 100, with an initial learning rate of 0.1, which was decayed to 10% of its current value at the 30th, 60th and 80th epochs. The weight decay was set to 5 × 10−4 and the momentum to 0.9. For the SVM classifier, the RBF kernel was used with a regularization parameter of 10.

Following the common protocol in most existing class-incremental learning studies, each dataset was divided into two parts: half of the classes were used for training in the initial phase, while the remaining classes were equally split into T asks for the subsequent incremental phases. The rehearsal memory size K was set to 2000 and remained fixed throughout the learning process, regardless of the number of classes. As more classes are learned, fewer exemplars can be stored per class, and the available memory is evenly allocated across all previously learned classes.

4.3 Comparison with Existing Methods

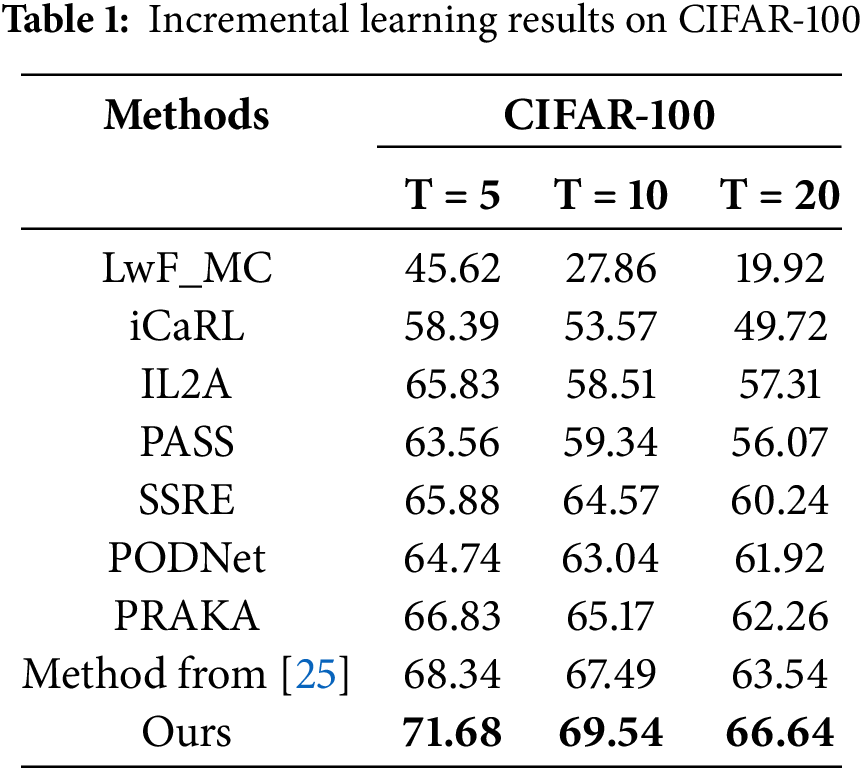

Since our method follows a feature rehearsal setting, we mainly compare it with several representative feature rehearsal methods, including IL2A [23], PASS [7], SSRE [24] and Method-from [25]. The baselines are carefully selected to ensure fairness and representativeness, taking into account both recency and consistency with our experimental setting. In addition, although LwF_MC [9] is strictly an exemplar-free approach, it is widely adopted as a baseline in class-incremental learning and is therefore retained here for reference. To further verify the effectiveness of our approach, we also include comparisons with commonly used exemplar rehearsal methods, such as iCaRL [16] and PODNet [9]. The results are reported in Tables 1 and 2, which present the average classification accuracy of each method on the CIFAR-100 and Tiny-ImageNet datasets, respectively, under different numbers of incremental tasks (T = 5, 10, 20). All results are obtained under consistent experimental settings for fairness and comparability.

As shown in Table 1, our method consistently outperforms all compared approaches on the CIFAR-100 dataset. With an increasing number of incremental tasks (T = 5, 10, 20), the average accuracy of all methods decreases due to the effect of catastrophic forgetting. Nevertheless, our approach still achieves competitive final accuracies of 71.68%, 69.54% and 66.64% under the three task settings. Among the exemplar-based rehearsal methods, iCaRL and PODNet exhibit more pronounced performance degradation as the number of tasks increases, suggesting their limited ability to retain knowledge of earlier classes in long-term incremental scenarios. In contrast, our method employs a support vector–guided exemplar selection strategy that prioritizes representative samples near the decision boundary. Combined with the proposed dual-alignment distillation mechanism, it enables more effective transfer of critical knowledge, thereby mitigating forgetting. Notably, when T = 20, our method outperforms SSRE and Method-from [25] by 6.40% and 3.10%, respectively, demonstrating stronger boundary preservation and adaptability in scenarios with expanding class space. Meanwhile, the triple-attention–enhanced feature extractor plays a key role in improving feature representation, further reducing class confusion between old and new categories.

According to the results in Table 2, our method also performs strongly on the more challenging Tiny-ImageNet dataset. Particularly at T = 20, it surpasses iCaRL by a large margin of 16.27%. Among feature rehearsal methods, PRAKA [26] and Method-from [25] exhibit relatively stable performance as task number increases. However, our method shows a clear advantage in maintaining the semantic structure of old classes. When T = 20, it achieves 4.35% and 1.64% higher accuracy than PRAKA and Method-from- [25], respectively, validating its superior robustness and generalization capability under complex incremental learning scenarios.

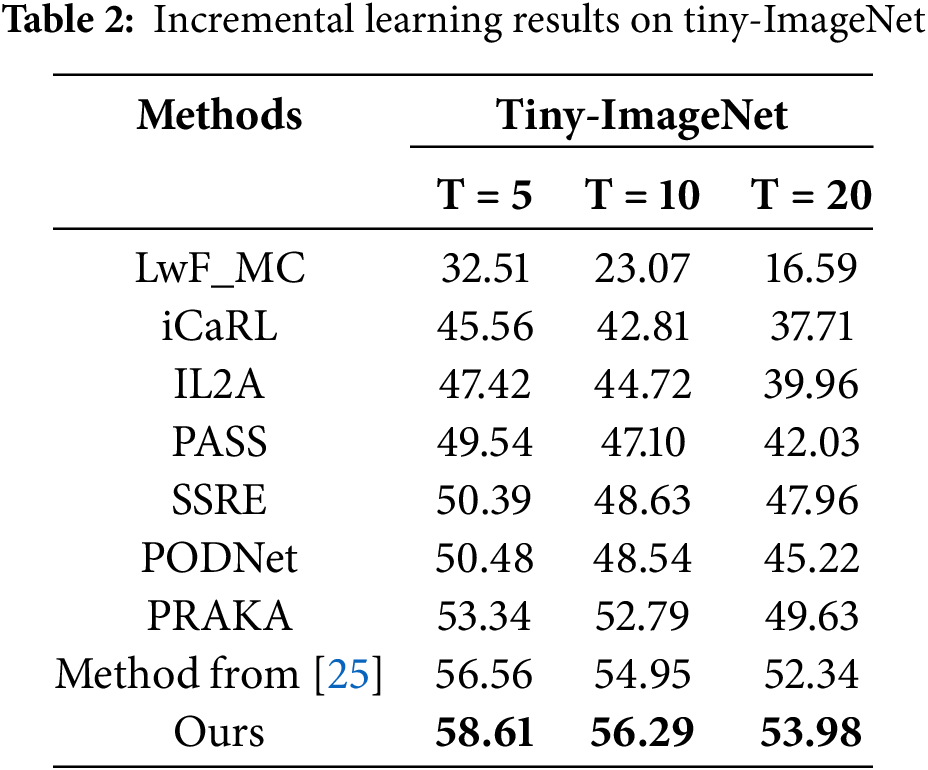

To determine the optimal configuration of loss function weights, this section investigates the effects of three key hyperparameters: the trade-off factor α in the Support Vector Distillation Loss (SVDL), and the loss weights λ1 and λ2 in the total loss function. These three parameters are method-specific hyperparameters newly introduced in our framework that directly control the balance between different learning objectives. Other hyperparameters follow standard settings commonly used in class-incremental learning literature (as detailed in Section 4.2) and are therefore not the focus of this sensitivity analysis.

The coefficient α balances the relative importance between the decision-boundary alignment loss and the semantic feature alignment loss in SVDL. Fig. 5 illustrates the trend of model accuracy under different values of α. As α increases from 0.1 to 0.7, the model’s average accuracy improves, peaking at α = 0.7. However, further increasing α to 0.9 results in a drop in accuracy. This suggests that while aligning decision boundaries is critical for preserving classification performance, an excessively large α suppresses the preservation of semantic features and thus harms the model’s generalization ability. When α is close to 0, the model essentially ignores boundary alignment, leading to significant shifts in decision boundaries for old classes when learning new ones. Conversely, a large α value weakens semantic alignment, reducing the model’s ability to maintain the structural stability of old classes. Therefore, α = 0.7 is adopted as the optimal setting in this work.

Figure 5: Accuracy variation under different values of α. The coefficient α balances decision-boundary alignment loss and semantic feature alignment loss in SVDL (Eq. (8)). Results on CIFAR-100 with T = 10 show that accuracy peaks at α = 0.7 (69.54%). Low α values (≤0.1) fail to preserve decision boundaries, while high values (≥0.9) over-suppress semantic alignment. This validates the necessity of dual alignment and justifies α = 0.7 as the optimal setting

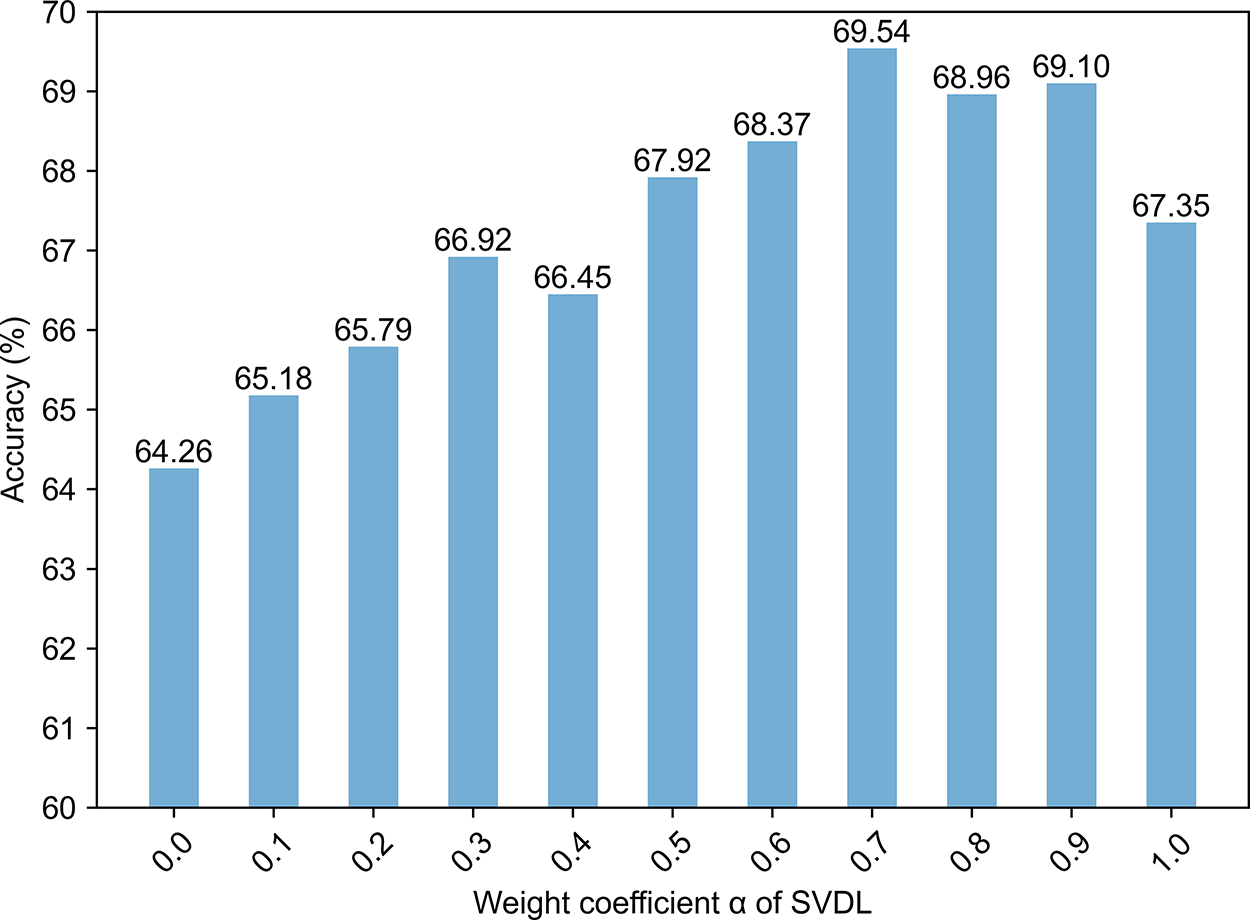

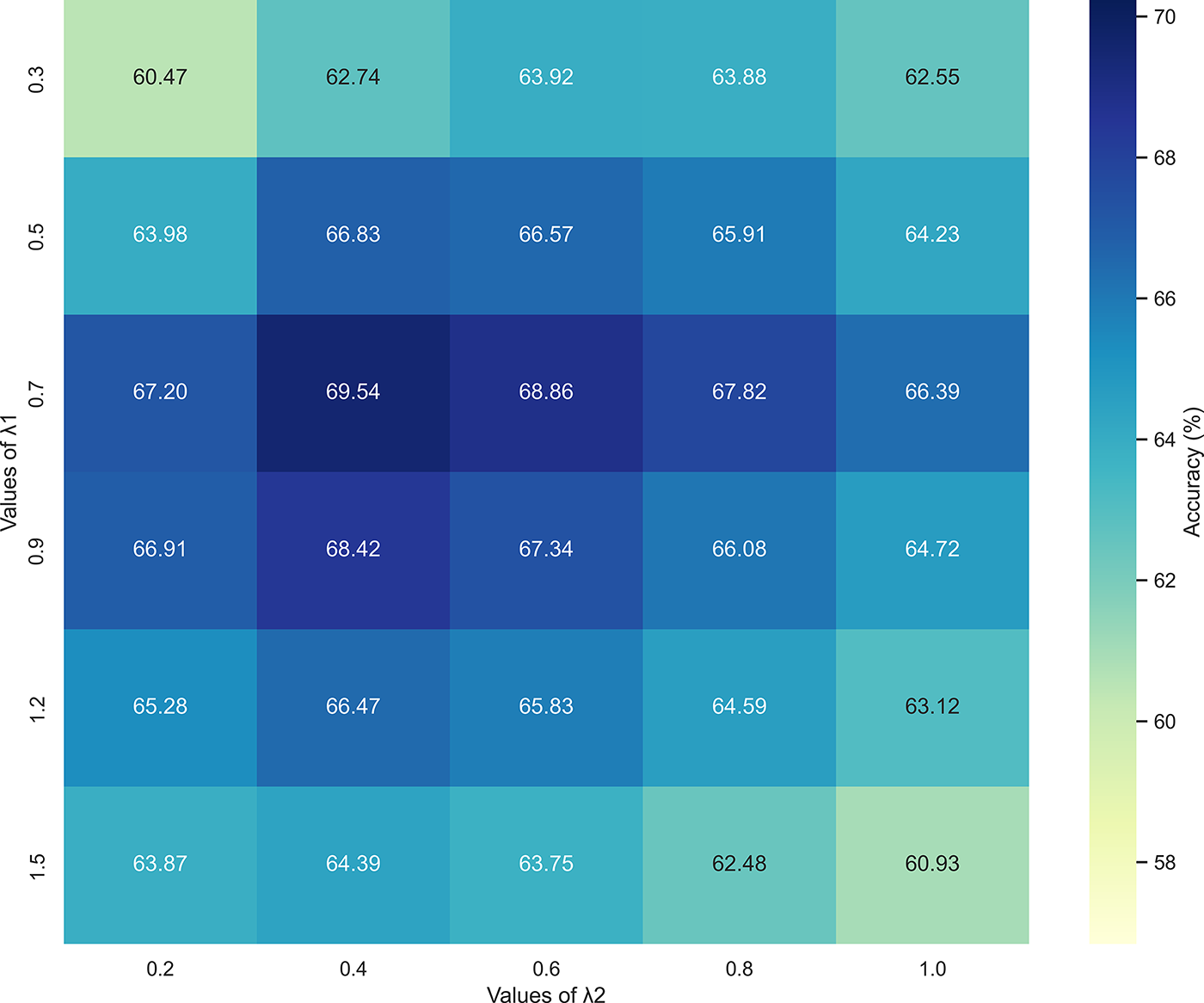

The weights λ1 and λ2 are used to balance the knowledge distillation loss and the SVDL component within the total loss function. Fig. 6 shows the impact of different combinations of these two hyperparameters on the model’s classification accuracy. The results indicate that the model achieves the best accuracy when λ1 = 0.7 and λ2 = 0.4. A small λ1 leads to insufficient retention of old class knowledge and exacerbates catastrophic forgetting. On the other hand, setting λ1 too high (e.g., above 0.7) may overemphasize old knowledge and hinder the model’s ability to learn new classes. As for λ2, values below 0.4 reduce the effectiveness of SVDL in maintaining the stability of decision boundaries, while values greater than 0.4 may cause the model to overfit to the stored support vectors, decreasing its ability to generalize across the overall data distribution.

Figure 6: Accuracy variation under different values of λ1 and λ2. The parameters λ1 and λ2 weight the knowledge distillation loss and SVDL in Eq. (11). Optimal accuracy (69.54%) is achieved at λ1 = 0.7, λ2 = 0.4. The heatmap reveals an interaction effect: balanced values preserve old knowledge while enabling new class learning, whereas excessively high values impair performance

Furthermore, Fig. 6 also reveals an interaction effect between λ1 and λ2. When λ1 is relatively high (e.g., 0.7) and λ2 is moderately set (e.g., 0.4), the model is capable of preserving old knowledge while efficiently learning new classes. However, when both are large (e.g., λ1 = 1.2 and λ2 = 0.8), the relative weight of cross-entropy loss is diminished, which negatively impacts the model’s ability to learn new categories, leading to an overall performance degradation.

To evaluate the effectiveness of each component in the proposed method, we conduct a series of ablation experiments on the CIFAR-100 dataset with the number of tasks set to 10.

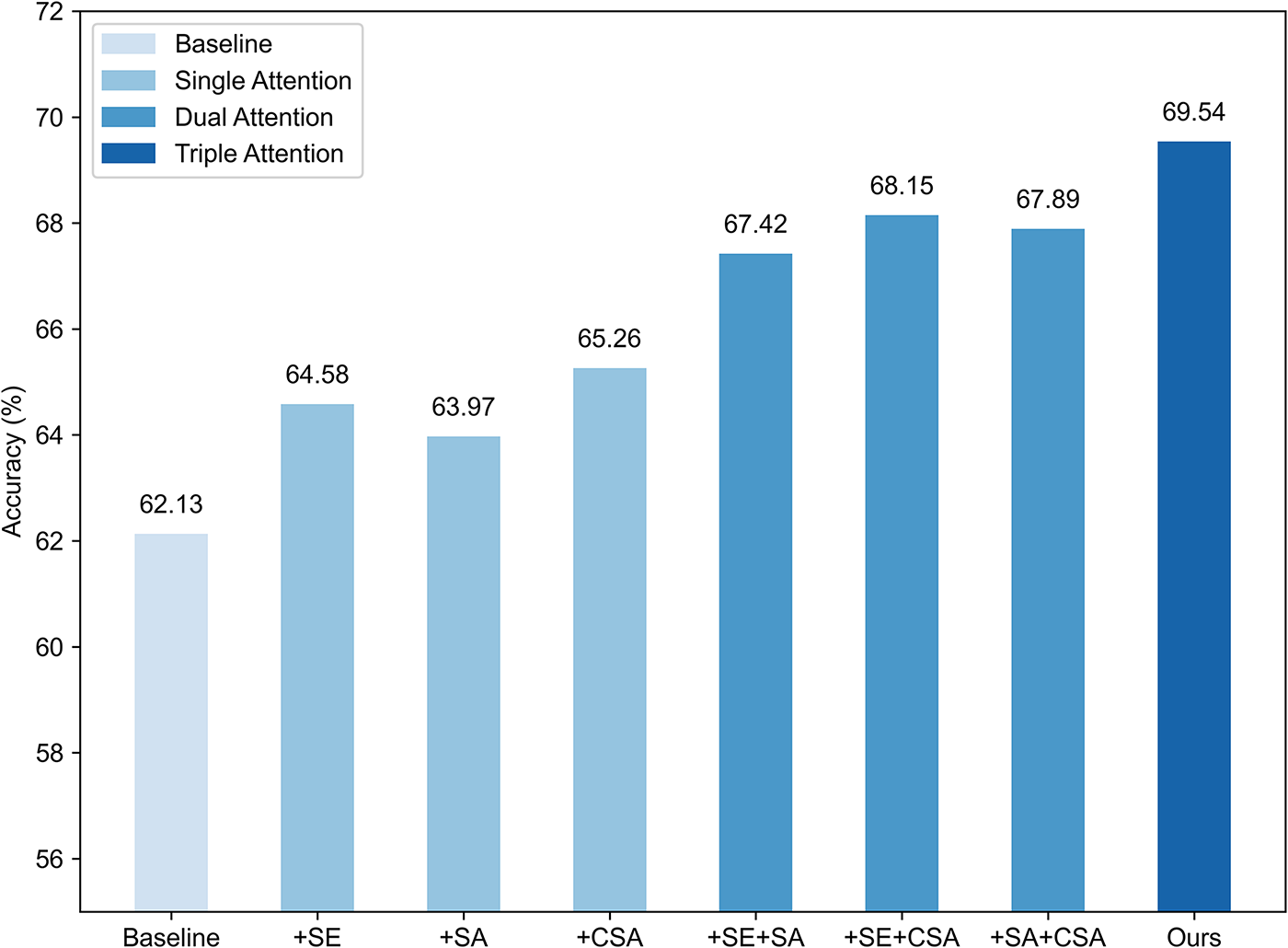

4.5.1 Ablation on Attention Modules

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed triple-attention mechanism, we perform an ablation analysis on this module. As shown in Fig. 7, the baseline model, which uses ResNet-18 as the feature extractor and SVM for classification without any attention mechanisms, achieves an accuracy of 63.2%. When individual attention modules are introduced, performance improves to varying degrees. Specifically, the class-sensitive attention brings the most significant improvement (+3.9%), followed by spatial attention (+3.1%) and channel attention (+2.7%). These results indicate that class-sensitive attention plays a particularly important role in enhancing class discrimination under incremental learning, while spatial and channel attention also contribute to stronger feature representation. When two attention modules are combined, further improvements are observed. The full triple-attention mechanism yields a total improvement of 6.3 percentage points over the baseline, confirming the complementary benefits of the three attention types.

Figure 7: Ablation study on attention mechanisms. Comparison of classification accuracy under different attention configurations on CIFAR-100 (T = 10). The baseline (ResNet-18 + SVM) achieves 63.2%. Adding individual attention modules improves performance, with class-sensitive attention (+3.9%) being most effective. The full triple-attention mechanism yields 69.54%, a 6.3% improvement over baseline, demonstrating the complementary benefits of channel, spatial and class-sensitive attention

4.5.2 Ablation on the Joint Feature Retention Strategy

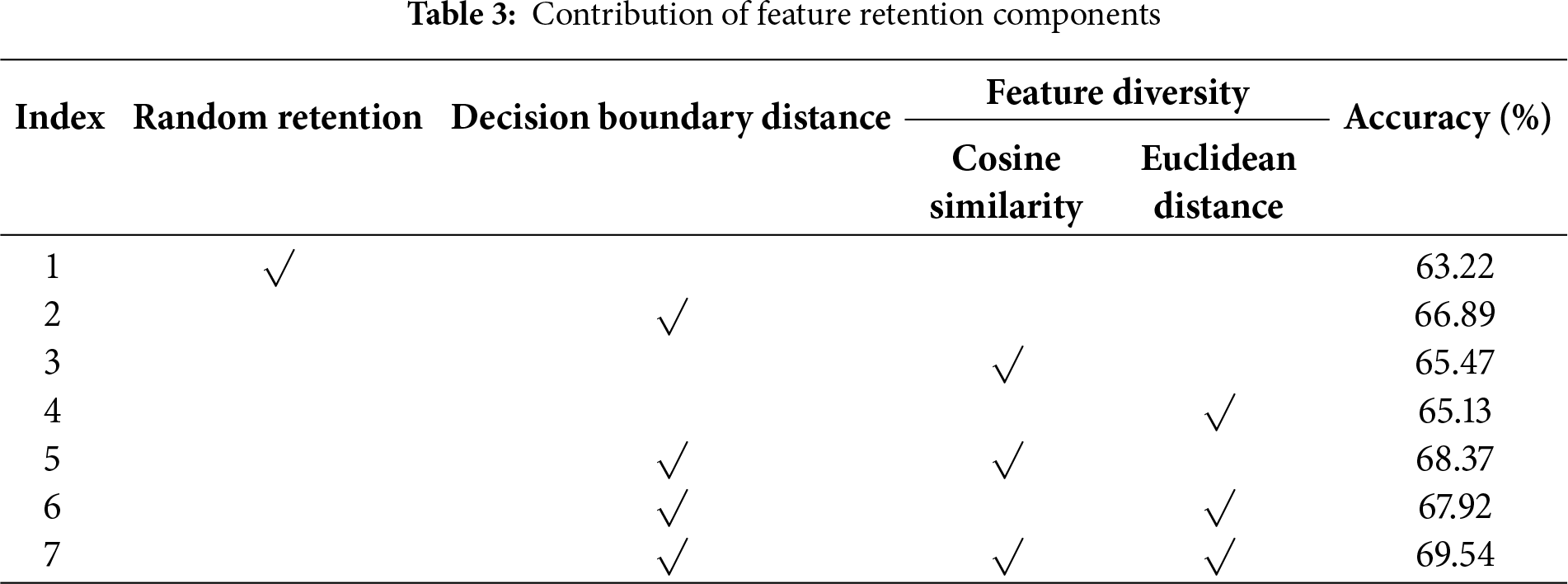

This subsection presents an ablation study on the joint feature retention strategy. Table 3 shows how different feature retention strategies affect the overall performance of the model. The random retention strategy yields the lowest accuracy, indicating that naive sample selection under limited memory fails to preserve critical decision-related information. The decision-boundary distance–based strategy significantly outperforms random retention, with an improvement of 3.67%, which confirms the importance of support vectors near the classification boundary in maintaining the decision hyperplane.

Joint strategies outperform individual strategies in all cases. Among them, the combination of decision-boundary distance and cosine similarity achieves a slightly higher accuracy (68.37%) than the combination with Euclidean distance (67.92%), suggesting that cosine similarity is more effective in removing redundant features. Finally, the full strategy that integrates decision-boundary distance with both diversity metrics reaches the highest accuracy, outperforming random retention by 6.32%. These results validate the proposed retention strategy, which prioritizes samples near decision boundaries while ensuring broad coverage of the feature space. This enables the model to preserve more knowledge of old classes under limited memory, thereby mitigating catastrophic forgetting.

4.5.3 Ablation Study on Loss Functions

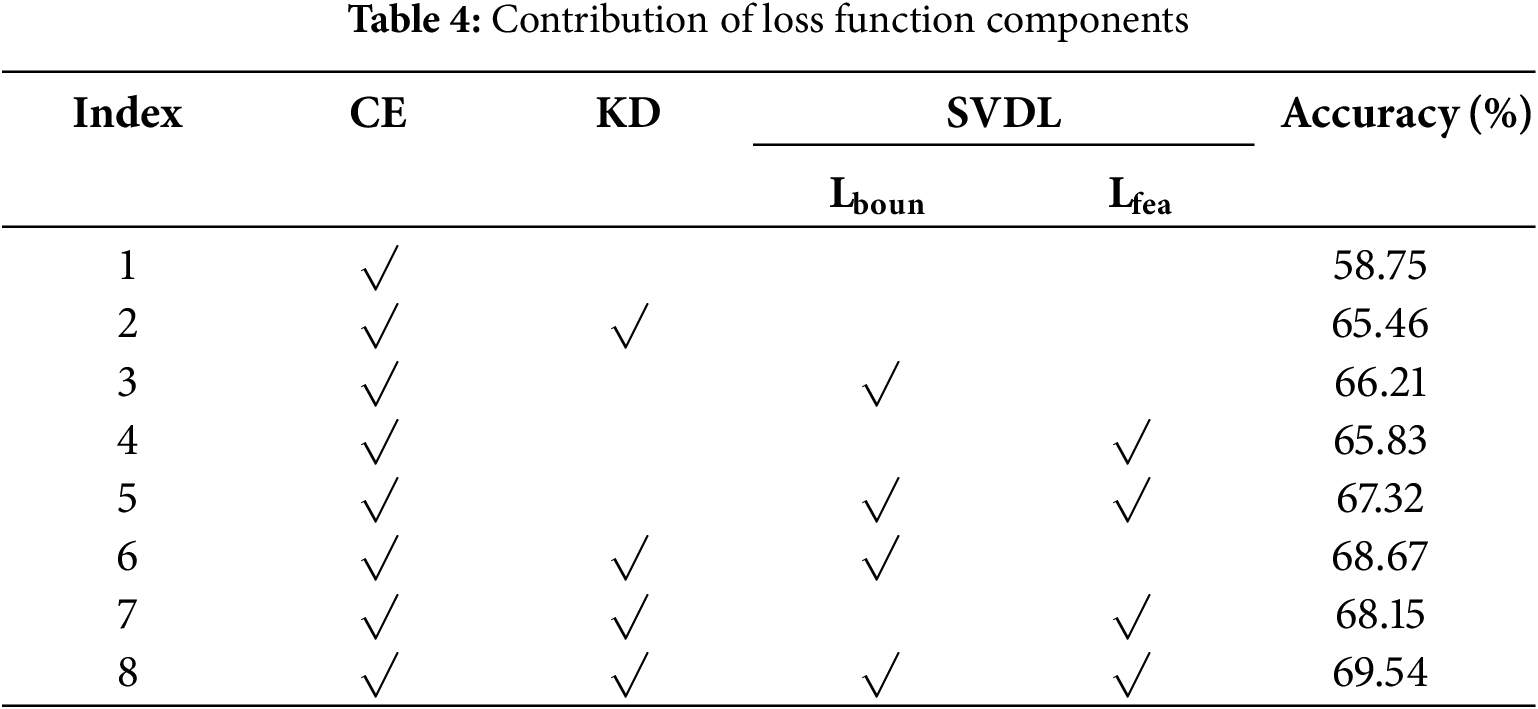

This subsection conducts an ablation study on the components of the loss function. As shown in Table 4, using only the cross-entropy loss (CE) leads to relatively low accuracy. When the knowledge distillation (KD) loss is added, the accuracy increases to 65.46%, indicating that KD is effective in preserving the overall knowledge of previously learned classes. The two components of the proposed support vector distillation loss—namely, the decision boundary alignment loss (Lboun) and the semantic feature alignment loss (Lfea)—were also examined. When each of them is combined individually with CE, the accuracy slightly surpasses that of the CE + KD configuration. Further improvements are observed when CE, Lboun and Lfea are combined, demonstrating the complementary effects of boundary preservation and feature consistency. The full loss function achieves the highest accuracy of 69.54%, representing a 10.79% improvement over using CE alone.

4.6 Comparison under Few-Shot Settings

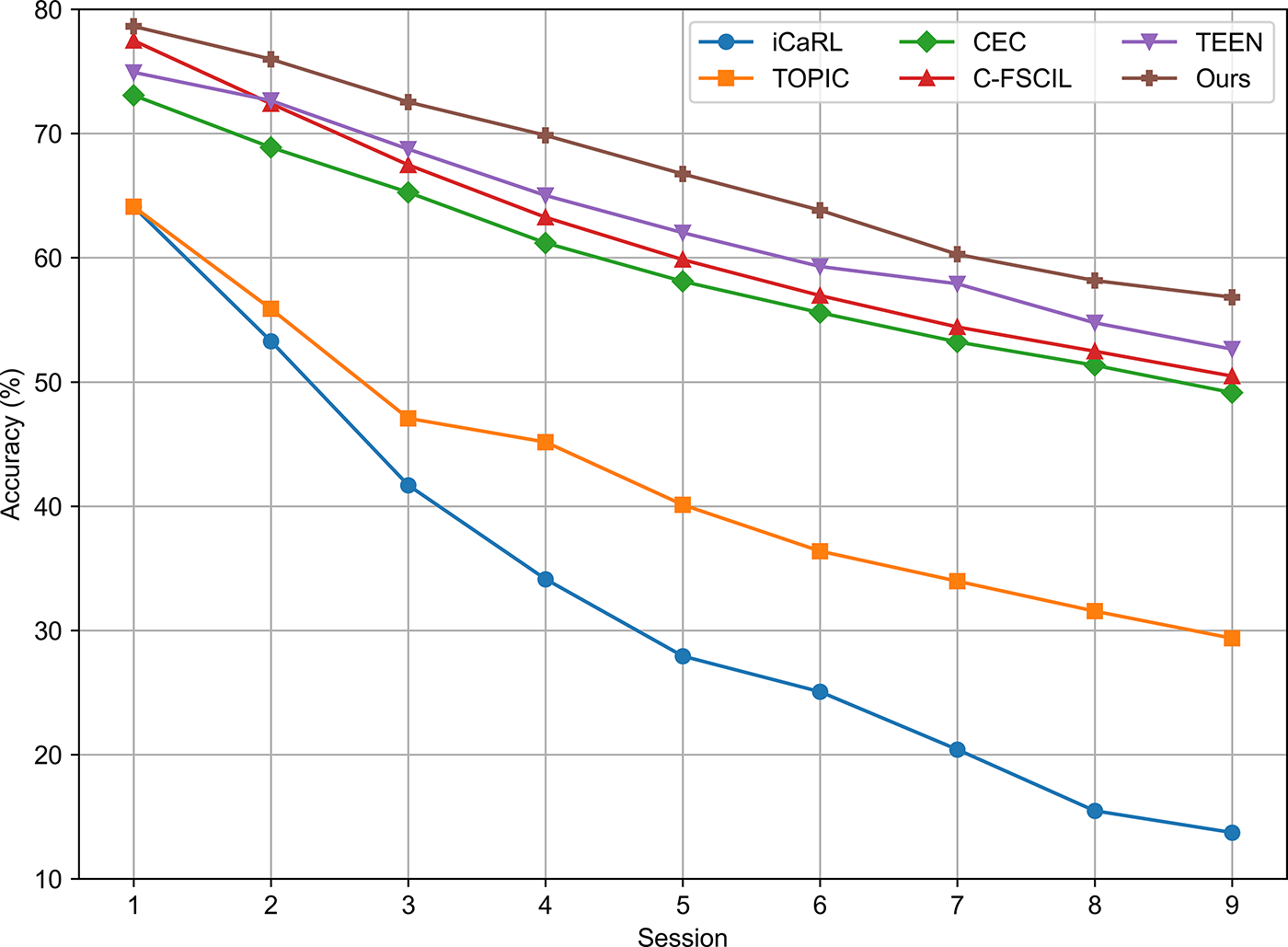

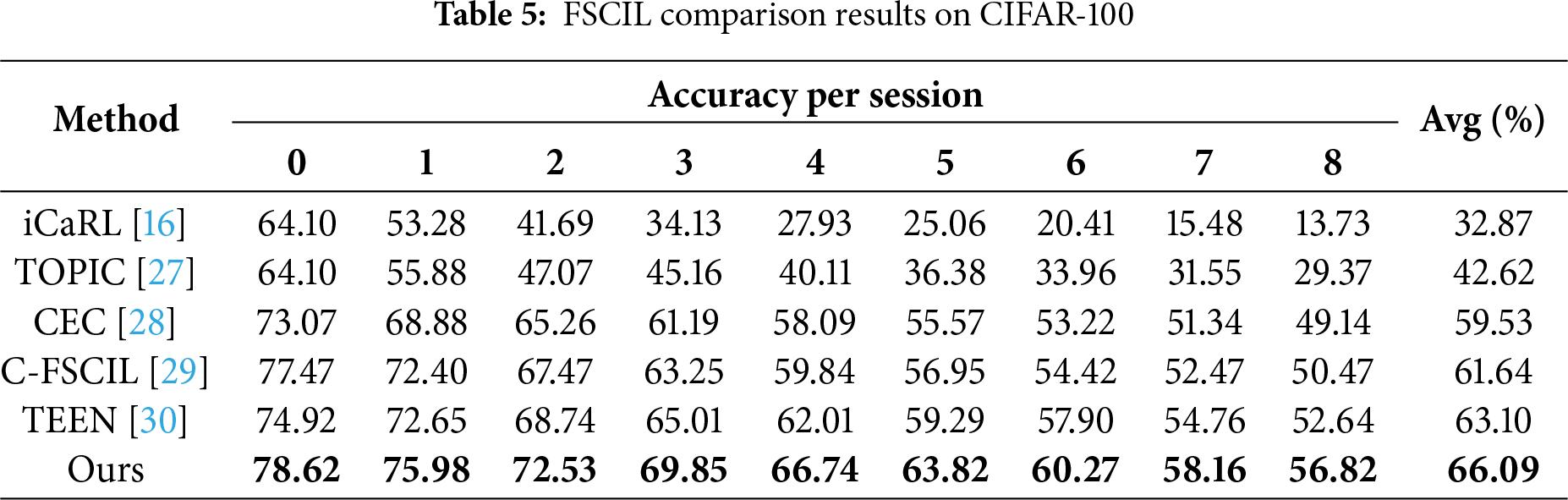

To further evaluate the generalization ability of the proposed method in resource-constrained scenarios, we conduct experiments on the CIFAR-100 dataset under the Few-Shot Class Incremental Learning (FSCIL) setting. FSCIL emphasizes the model’s ability to continually learn new categories with only a few samples, making it a more practical and challenging task. Following common task settings in FSCIL, the 100 classes are divided into 60 base classes and 40 novel classes. A 5-way 5-shot configuration is adopted, meaning that in each incremental phase, 5 new classes are introduced with 5 samples per class. The entire process includes one base session and 8 incremental sessions. Table 5 and Fig. 8 present the comparison results between our method and other FSCIL approaches.

Figure 8: Performance comparison in few-shot class-incremental learning on CIFAR-100. Accuracy under 5-way 5-shot setting. Our method maintains higher accuracy throughout and exhibits more gradual performance decline compared to baselines

From the Table 5 and Fig. 8, it can be observed that our method demonstrates strong feature extraction ability during the base session and exhibits a more gradual performance decline across incremental phases compared to other methods. After the 8th incremental session, our method still maintains an accuracy of 56.82%, which is nearly 40 percentage points higher than the classical class-incremental method iCaRL. Compared with TEEN, a representative approach in the FSCIL domain, our method consistently achieves higher accuracy in each session, with a final average improvement of 2.99%. These results indicate the effectiveness of our method under the few-shot class-incremental learning setting.

4.7 Efficiency and Scalability Discussion

We acknowledge that compared with a simple linear classifier, employing an SVM at each incremental stage introduces additional computational cost. Specifically, the training time of one incremental phase on CIFAR-100 is around 1.2× that of a prototype-based linear classifier under the same hardware setup (NVIDIA RTX 3090, batch size = 128), while the overall memory usage remains under 6 GB. In our framework, the overhead is limited because the number of stored support vectors is significantly smaller than the total dataset size, and the training complexity mainly depends on these support vectors rather than the full data scale. During inference, the runtime per image increases by less than 10% compared with a standard ResNet-18 model, since the additional operations mainly come from the SVM decision layer and attention modules. The total model size increases by only 3%–4% relative to the ResNet-18 backbone, and the computational cost grows approximately linearly with the number of incremental tasks while memory remains bounded by the fixed support vector buffer (K = 2000). Therefore, the additional cost mainly lies in boundary optimization, which is acceptable for mid-scale continual learning tasks. These results indicate that the proposed framework maintains reasonable efficiency and scalability for mid-scale continual learning applications.

This paper proposes a support vector–guided method for class-incremental learning that effectively mitigates the problem of catastrophic forgetting by combining discriminative replay with a dual-alignment distillation strategy. The method adopts a decoupled architecture between the feature extractor and the classifier. In the feature extraction stage, it integrates channel attention, spatial attention and category-sensitive attention to enhance the model’s ability to capture critical regions in images. In the classification and replay stages, it leverages the boundary discrimination capability of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) to design a sample selection strategy based on decision boundary distance and feature diversity, enabling compact yet discriminative replay. Additionally, a support vector distillation loss is proposed to preserve the structural stability of prior knowledge through both decision-level and semantic-level alignment.

Extensive experiments on CIFAR-100 and Tiny-ImageNet demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework. On the 5-task setting, our method achieves 71.68% and 58.61% average accuracy, with improvements of 3.34% and 2.05% over strong baselines. These improvements are consistently observed across different task configurations (T = 5, 10, 20), confirming both the robustness and generalization ability of the approach. Beyond benchmark evaluations, the framework also shows promise in few-shot and resource-constrained scenarios. In addition, the proposed framework maintains reasonable training and inference efficiency, with computational overhead increasing approximately linearly with the number of incremental tasks.

Overall, this work not only provides an effective technical solution to catastrophic forgetting, but also contributes to a deeper understanding of how boundary-critical features can be exploited to balance stability and plasticity in continual learning. For larger-scale applications, the computational burden could be further reduced by applying approximate or online SVM variants, or by pruning redundant support vectors. We regard the integration of such techniques as an important direction for future work, together with extending the framework to larger-scale datasets and more complex environments, and exploring model lightweighting and adaptive attention mechanisms to enhance practicality and cross-domain transferability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Gansu Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant number 25JRRA074), the Gansu Provincial Key R&D Science and Technology Program (grant number 24YFGA060) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 62161019).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows. Study conception and design: Moyi Zhang and Yixin Wang; analysis and interpretation of the results: Yixin Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Yixin Wang and Yu Cheng; revision and editing: Yu Cheng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the CIFAR-100 dataset at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 11 November 2025) and in the Tiny-ImageNet dataset at http://cs231n.stanford.edu/tiny-imagenet-200.zip (accessed on 11 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhao G, Sun Z, Liu Y. Image recognition based on self-distillation and spatial attention mechanism. Int J Mod Phys C. 2025;36(10):2542001. doi:10.1142/s012918312542001x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen J, Xiang Y. A robust and anti-forgettiable model for class-incremental learning. Appl Intell. 2023;53(11):14128–45. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-04239-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhou DW, Wang QW, Qi ZH, Ye HJ, Zhan DC, Liu Z. Class-incremental learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(12):9851–73. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3429383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. McCloskey M, Cohen NJ. Catastrophic interference in connectionist networks: the sequential learning problem. In: Psychology of learning and motivation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1989. p. 109–65. [Google Scholar]

5. Kirkpatrick J, Pascanu R, Rabinowitz N, Veness J, Desjardins G, Rusu AA, et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(13):3521–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611835114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zenke F, Poole B, Ganguli S. Continual learning through synaptic intelligence. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, Australia. p. 6072–82. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhu F, Zhang XY, Wang C, Yin F, Liu CL. Prototype augmentation and self-supervision for incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 5867–76. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.00581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Z, Hoiem D. Learning without forgetting. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40(12):2935–47. doi:10.1109/tpami.2017.2773081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Douillard A, Cord M, Ollion C, Robert T, Valle E. PODNet: pooled outputs distillation for small-tasks incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 86–102. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58565-5_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yang H, He W, Shan Z, Fang X, Chen X. Class incremental learning via dynamic regeneration with task-adaptive distillation. Comput Commun. 2024;215(7):130–9. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2023.12.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shmelkov K, Schmid C, Alahari K. Incremental learning of object detectors without catastrophic forgetting. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 3420–9. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kim JY, Choi DW. Split-and-bridge: adaptable class incremental learning within a single neural network. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(9):8137–45. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i9.16991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang FY, Zhou DW, Liu L, Ye HJ, Bian Y, Zhan DC, et al. BEEF: Bi-compatible class incremental learning via energy based expansion and fusion. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2023 May 1–5; Kigali, Rwanda. p. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

14. Chen X, Chang X. Dynamic residual classifier for class incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 18697–706. [Google Scholar]

15. Feng Z, Zhou M, Gao Z, Stefanidis A, Sui Z. SCREAM: knowledge sharing and compact representation for class incremental learning. Inf Process Manag. 2024;61(3):103629. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rebuffi SA, Kolesnikov A, Sperl G, Lampert CH. iCaRL: incremental classifier and representation learning. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5533–42. [Google Scholar]

17. Wu Y, Chen Y, Wang L, Ye Y, Liu Z, Guo Y, et al. Large scale incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 374–82. [Google Scholar]

18. Iscen A, Zhang J, Lazebnik S, Schmid C. Memory-efficient incremental learning through feature adaptation. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 699–715. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58517-4_41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yu L, Twardowski B, Liu X, Herranz L, Wang K, Cheng Y, et al. Semantic drift compensation for class-incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 6980–9. [Google Scholar]

20. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. [Google Scholar]

21. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

22. Sevugan P, Rudhrakoti V, Kim TH, Gunasekaran M, Purushotham S, Chinthaginjala R, et al. Class-aware feature attention-based semantic segmentation on hyperspectral images. PLoS One. 2025;20(2):e0309997. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0309997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhu F, Cheng Z, Zhang XY, Liu C. Class incremental learning via dual augmentation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:14306–18. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhu K, Zhai W, Cao Y, Luo J, Zha ZJ. Self-sustaining representation expansion for non-exemplar class-incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 9286–95. [Google Scholar]

25. Sun XP, Yu L, Xu CS. Feature space enhanced replay and bias correction based incremental learning method. Pattern Recognit Artif Intell. 2024;37(8):729–40. [Google Scholar]

26. Shi W, Ye M. Prototype reminiscence and augmented asymmetric knowledge aggregation for non-exemplar class-incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 1772–81. [Google Scholar]

27. Tao X, Hong X, Chang X, Dong S, Wei X, Gong Y. Few-shot class-incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 12180–9. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhang C, Song N, Lin G, Zheng Y, Pan P, Xu Y. Few-shot incremental learning with continually evolved classifiers. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 12450–9. [Google Scholar]

29. Hersche M, Karunaratne G, Cherubini G, Benini L, Sebastian A, Rahimi A. Constrained few-shot class-incremental learning. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 9047–57. [Google Scholar]

30. Wang QW, Zhou DW, Zhang YK, Zhan DC, Ye HJ. Few shot class incremental learning via training free prototype calibration. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:15060–76. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools