Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MDGET-MER: Multi-Level Dynamic Gating and Emotion Transfer for Multi-Modal Emotion Recognition

1 School of Software Engineering, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Nanchang, 330013, China

2 Nanchang Key Laboratory of Virtual Digital Engineering and Cultural Communication, Nanchang, 330013, China

* Corresponding Author: Junhua Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 34 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071207

Received 02 August 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In multi-modal emotion recognition, excessive reliance on historical context often impedes the detection of emotional shifts, while modality heterogeneity and unimodal noise limit recognition performance. Existing methods struggle to dynamically adjust cross-modal complementary strength to optimize fusion quality and lack effective mechanisms to model the dynamic evolution of emotions. To address these issues, we propose a multi-level dynamic gating and emotion transfer framework for multi-modal emotion recognition. A dynamic gating mechanism is applied across unimodal encoding, cross-modal alignment, and emotion transfer modeling, substantially improving noise robustness and feature alignment. First, we construct a unimodal encoder based on gated recurrent units and feature-selection gating to suppress intra-modal noise and enhance contextual representation. Second, we design a gated-attention cross-modal encoder that dynamically calibrates the complementary contributions of visual and audio modalities to the dominant textual features and eliminates redundant information. Finally, we introduce a gated enhanced emotion transfer module that explicitly models the temporal dependence of emotional evolution in dialogues via transfer gating and optimizes continuity modeling with a comparative learning loss. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms state-of-the-art models on the public MELD and IEMOCAP datasets.Keywords

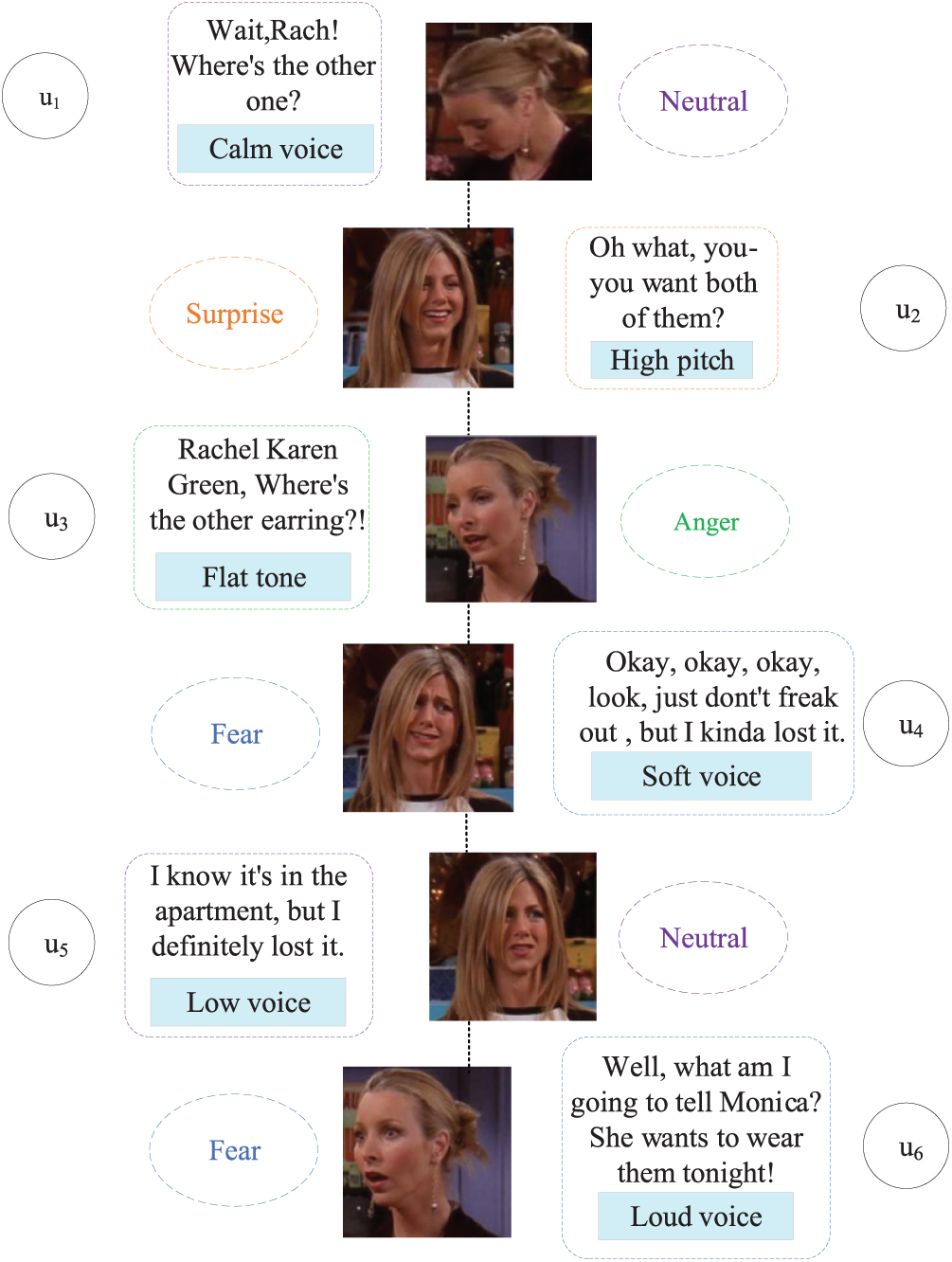

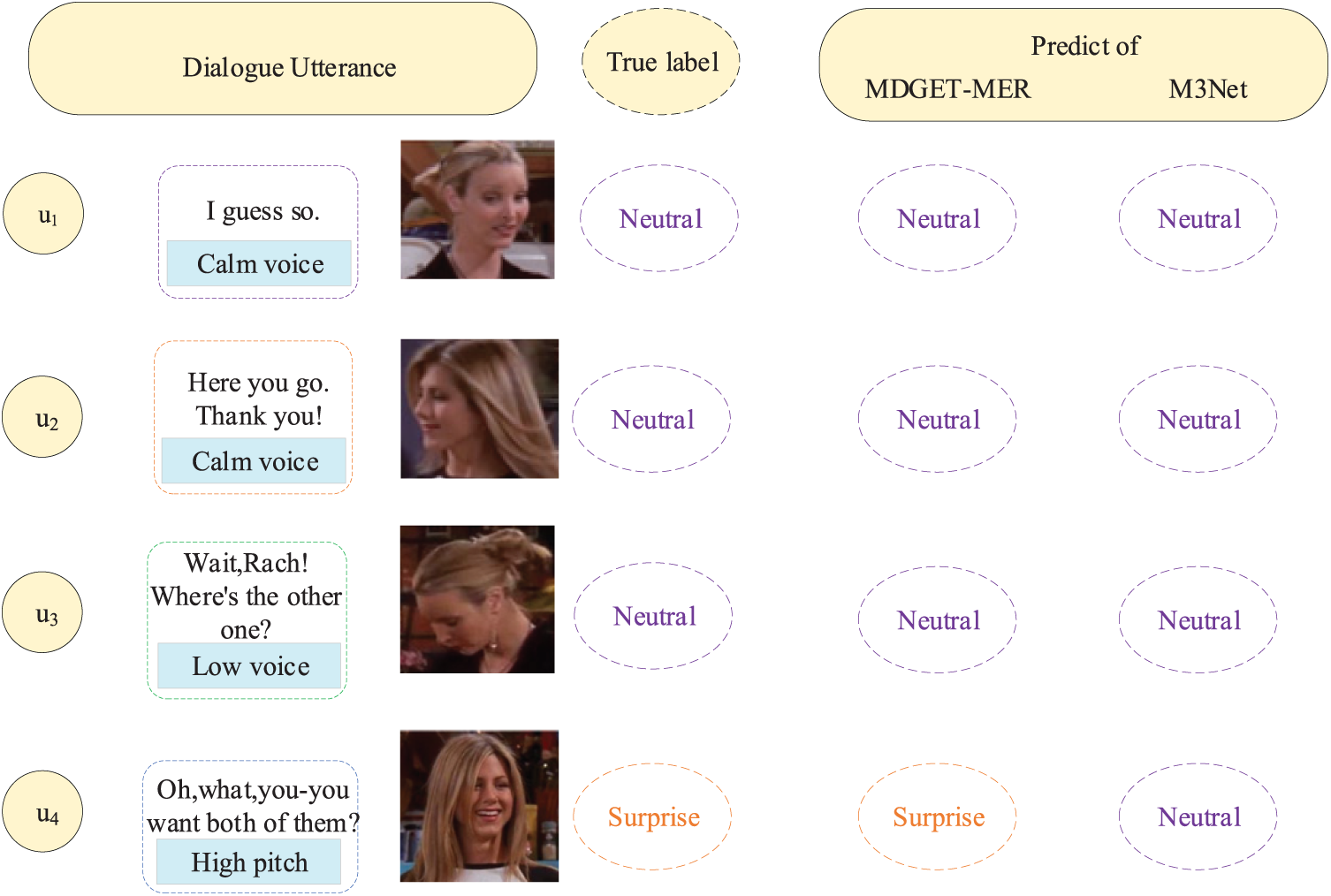

Multi-modal emotion recognition aims to emulate human emotion understanding by fusing text, visual, and audio information and is widely used in intelligent interactive systems. Although unimodal research in text analysis [1–3] and speech recognition [4–6] has advanced, human emotional expression often exhibits cross-modal inconsistency. As shown in Fig. 1, taking utterance

Figure 1: Examples of multi-modal dataset

At the same time, the inherent heterogeneity of multi-modal data, noise interference and the dynamic evolution characteristics of emotional state make this field still have a broad space for exploration. Current mainstream methods—such as DialogueRNN [7], which relies on static weight fusion, or graph convolutional networks [8] that attempt to model cross-modal interactions—have made notable progress. However, they generally suffer from several key limitations: Firstly, it is difficult for them to dynamically adjust the complementary strength between cross-modalities according to modal quality and context, resulting in insufficient noise suppression [9]. Secondly, the filtering mechanism for uni-modal internal and cross-modal redundant information is weak; finally, most methods ignore the transfer modeling of emotional states in dialogues [10], and rely too much on the context consistency hypothesis, which makes it difficult to effectively capture the synergy of multi-modal cues when emotions change.

However, these methods still have obvious limitations. In particular, it is difficult to dynamically adjust the cross-modal complementary strength, resulting in insufficient noise suppression. The uni-modal and cross-modal redundancy filtering mechanisms are weak, and the emotion transfer modeling is generally ignored [11], and the context consistency assumption is over-reliant. To address these limitations, we propose a multi-level dynamic gating and emotion transfer framework for multi-modal emotion recognition. We employ gated unimodal encoders to suppress noise and reduce heterogeneity, and a gated-attention cross-modal encoder to dynamically calibrate the complementary contributions of audio and visual modalities relative to text. In addition, we introduce a gated enhanced emotion transfer module to explicitly model the temporal dependence of emotion evolution in dialogues, thereby jointly improving recognition performance and robustness.

In summary, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a multi-level dynamic gating and emotion transfer framework for multi-modal emotion recognition. A dynamic gating mechanism is applied throughout unimodal encoding, cross-modal alignment, and emotion transfer modeling, significantly improving noise robustness and feature alignment.

• We design gated recurrent units and a gated-attention mechanism to optimize model performance from the perspectives of unimodal noise suppression and cross-modal dynamic weight distribution, which effectively improves recognition accuracy in scenes with emotional transitions.

• We introduce an emotion transfer perception module that, together with comparative learning constraints on the transfer process, enhances the model’s adaptability to dynamic dialogue scenarios. We validate the effectiveness and the synergistic contribution of the proposed modules on public datasets.

The research of Multi-modal Emotion Recognition (MER) continues to deepen, mainly focusing on the core directions of cross-modal interaction modeling, context-dependent capture, noise and heterogeneity mitigation, and emotional evolution modeling.

Cross-modal interaction modeling forms the basis of MER. Early fusion strategies, such as simple feature concatenation or static weight fusion [3,12], outperform uni-modal approaches but often overlook deep inter-modal correlations, which may exacerbate the heterogeneity gap and noise interference [9]. With technological progress, graph neural networks (GNNs) have become powerful tools for capturing complex cross-modal dependencies. For instance, Shi et al. [8] proposed a modality calibration strategy to refine utterance and speaker representations at both contextual and modal levels, coupled with emotion-aligned hypergraph and line graph fusion to optimize cross-modal semantic transfer and emotional pathway learning. Chen et al. [13] innovatively fused multi-frequency features via hypergraph networks to enhance high-order relationship modeling. Meng et al. [14] further designed a multi-modal heterogeneous graph to enable dynamic semantic aggregation. Meanwhile, the Transformer architecture is also widely used for feature alignment and interaction. Mao et al. [15] designed a hierarchical Transformer to manage contextual preferences within modalities and employed multi-granularity interactive fusion to distinguish modal contributions. Hu et al. [16] deeply integrated audio/visual features with text and combined cross-modal contrastive learning to optimize difference representation.

Given the inherent sequential nature of dialogue, context and dialogue structure modeling is crucial. Majumder et al. [7] used recurrent networks (such as RNN) to model dialogue sequences, but did not explicitly deal with modal heterogeneity. Subsequent studies have significantly strengthened the understanding of context: Fu et al. [17] embedded an emotional transmission mechanism to coordinate temporal information flow on the basis of integrating text ambidexterity and audio-visual information; Ai et al. [18] constructed speaker relation graph and event graph to optimize the semantic representation and aggregation process. Meng et al. [14] used heterogeneous graph structure to integrate richer context cues. Furthermore, the two-level decoupling mechanism proposed by Li et al. [19] aims to coordinate modal features and dialogue context, and improves the fineness of context modeling.

Dealing with the inherent noise (especially visual/audio modality) and heterogeneity of multi-modal data is a key challenge to improve the robustness of the model. The research in this direction focuses on feature filtering and dynamic weighting strategies. For example, Zeng et al. [20] introduced modal modulation loss to learn the contribution weight of each mode, and designed a filtering module to actively remove cross-modal noise. Yu et al. [21] used emotional labels to generate anchors to guide comparative learning, and optimized decision boundaries to enhance the robustness of the model. Li et al. [22] used the attention mechanism to dynamically fuse modalities and perceived the influence of emotional transfer on the importance of modalities. However, it is worth noting that the existing methods have obvious limitations in dynamically calibrating the complementary intensity, for example, how to dynamically adjust the supplementary degree of audio/visual modality to the dominant text modality according to the quality and relevance of speech/image content, and fine-grained noise suppression. For example, there are still obvious limitations in distinguishing informative visual cues from irrelevant background noise, and the robustness to the inherent noise of visual/audio modality needs to be further improved.

The flow and transfer of emotions in conversation (emotional evolution modeling) is the core of understanding emotional dynamics. Bansal et al. [23] first proposed an explicit emotional transfer component to capture the ups and downs in dialogue. The follow-up work attempts to deepen the understanding of the transfer process: Tu et al. [24] integrated the common sense knowledge base to provide background support for the reasoning and transfer of emotional states; Hu et al. [16] combined the adversarial training strategy to optimize the representation learning in the process of emotion transfer. Nevertheless, most of the existing methods rely on static context consistency assumptions, and it is difficult to deal with emotional mutation scenarios adaptively. In such cases, emotions shift drastically, requiring the model to quickly integrate and weigh new evidence from different modalities that may conflict or complement each other. Current methods still lack sufficient capability to address this collaborative challenge.

In summary, although the current research has made progress in multi-modal fusion and context modeling, collaborative optimization of dynamic gating mechanisms and emotion transfer remains insufficient.

Given a dialogue containing

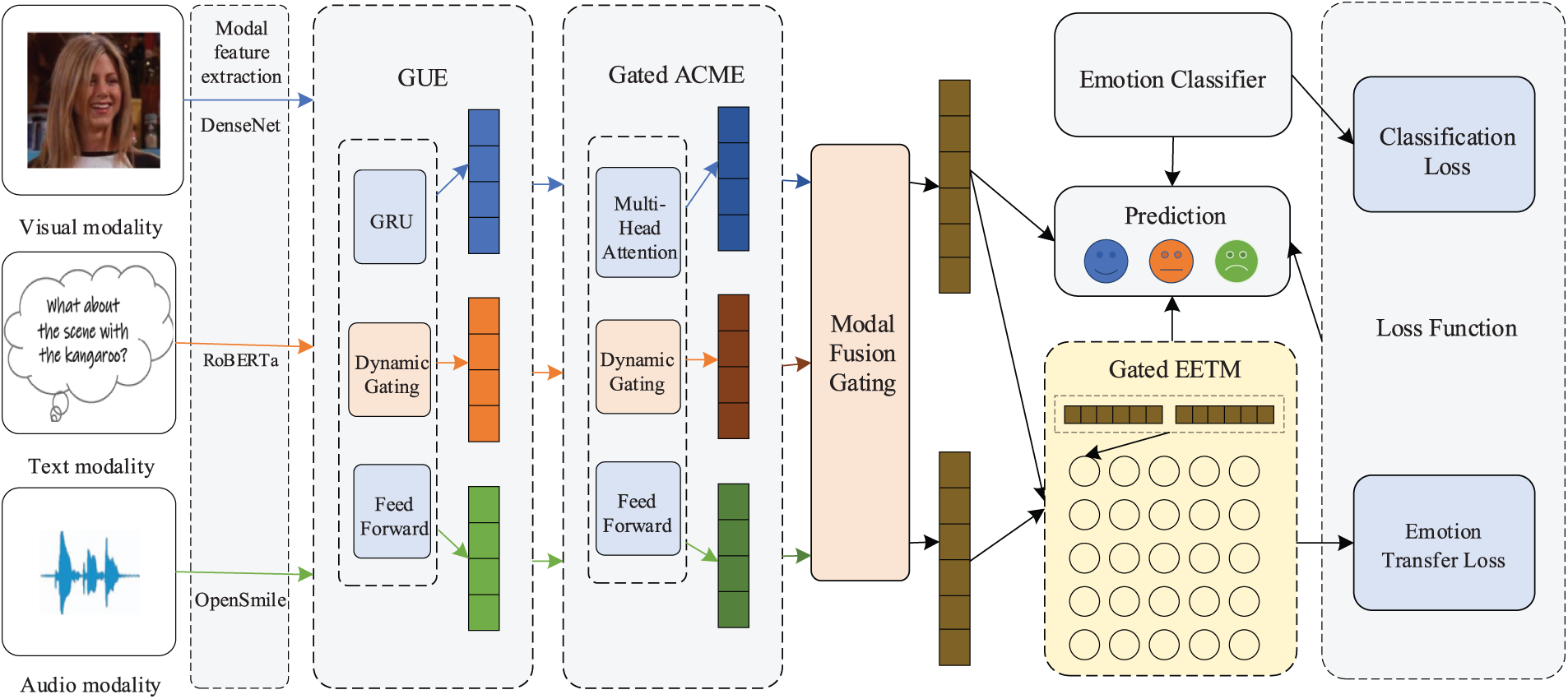

To address the aforementioned challenges in multi-modal emotion recognition, we propose a model named Multi-level Dynamic Gating and Emotion Transfer for Multi-modal Emotion Recognition (MDGET-MER). The neural network architecture constructed under this framework consists of five main components: a feature extractor for each modality, a Gated Uni-modal Encoder (GUE), a Gated Attention-based Cross-Modal Encoder (Gated ACME), a Gated Enhanced Emotion Transfer Module (Gated EETM), and an emotion classifier, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Each component is described in detail in the following sections.

Figure 2: Architecture of MDGET-MER

• Text modality: Liu et al. [25] proposed a RoBERTa pre-trained language model based on multi-layer Transformer architecture, which optimizes text representation ability through mask language modeling and dynamic mask strategy. After fine-tuning the model, we extracts the [CLS] label embedding of the last layer as the semantic feature of the text.

• Audio modality: Eyben et al. [26] proposed an OpenSmile modular speech signal processing toolkit, which supports batch extraction of audio parameters such as fundamental frequency and energy. In this paper, an audio feature extraction system is constructed with reference to this method to achieve efficient feature processing of speech signals.

• Visual modality: Huang et al. [27] proposed a DenseNet model based on dense blocks, which enhances the ability of feature reuse.

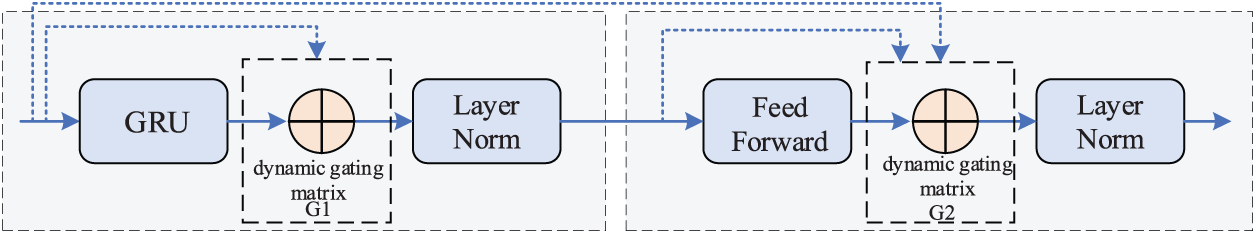

Inspired by the Transformer architecture, we propose a Gated Uni-modal Encoder (GUE) to encode utterances within each modality. In the GUE framework, a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is first employed to encode the original features. A gating mechanism then dynamically adjusts the fusion ratio between the original features and the encoded features, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness to noise and improving its ability to extract contextual emotional cues. The network structure of GUE is shown in Fig. 3. Specifically, the structure of GUE can be formalized as:

where

Figure 3: The network structure of GUE

FC(·) and dropout(·) represent the fully connected network and dropout operation, respectively, and α(·) represents the activation function.

The GUE is applicable to three modalities at the same time through the shared parameter mechanism. That is

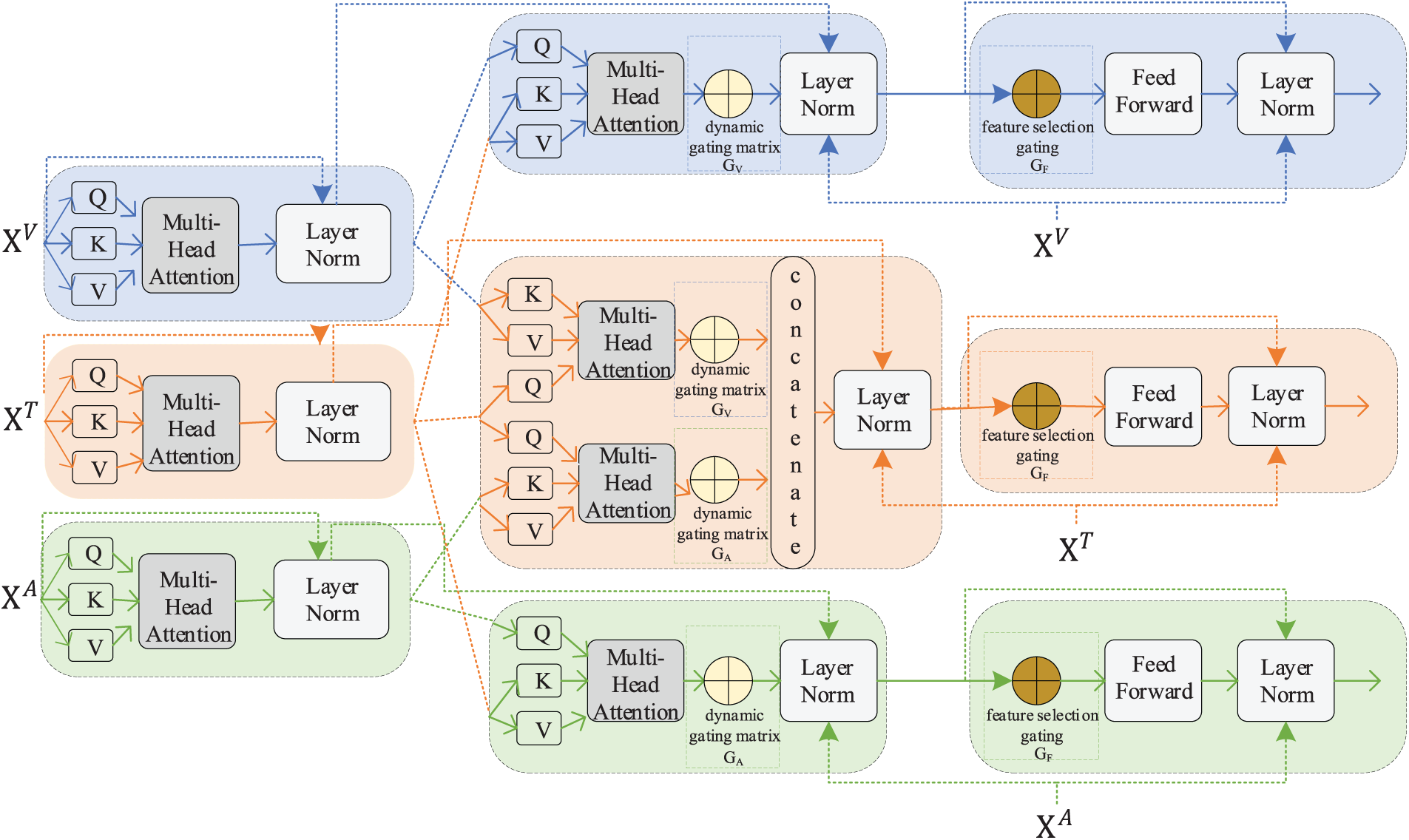

3.5 Gated Attention-Based Cross-Modal Encoder

We design a gated attention-based cross-modal encoder (Gated ACME) to effectively extract and integrate complementary information from multi-modal emotional data. By incorporating a dynamic gating mechanism, this module adaptively calibrates the contribution weights of visual and audio modalities during cross-modal interactions, thereby enhancing the dominance of text features while selectively fusing relevant complementary cues from non-text modalities. This design aims to mitigate redundancy and noise, ensuring robust and context-aware multi-modal representation learning. As shown in Fig. 4, referring to the Transformer structure, The Gated ACME is primarily composed of an attention network layer, a feedforward network layer, and dynamic gating. Numerous studies in multi-modal emotion recognition have indicated that the quantity of emotional information embedded in visual and audio modalities is generally lower than that in textual modalities, thereby limiting the range of emotional expression in these modalities [15,28]. Based on this hypothesis, we takes visual and audio features as complementary information to supplement the emotional expression of text features, and introduces dynamic gating to dynamically adjust the complementary intensity of visual and audio modalities to the text. In turn, textual features of utterances are used to enhance visual and audio representations. In addition, in GUE, it is difficult for GRU to pay attention to the global context information of the utterances. Therefore, a self-attention layer is employed to capture global contextual emotional cues prior to cross-modal interaction. The designed Gated ACME consists of the following three stages:

Figure 4: The network structure of gated ACME

• Improve the global context awareness of utterances. The feature matrixs from the three modalities

where MHA(·) denotes a multi-headed attention network.

• Cross-modal interaction modeling is performed, and a dynamic gating mechanism is introduced to dynamically adjust the supplementary strength of visual and audio modalities to the text. The above results are input into four MHA networks in pairs and the information of each modality is updated. Next, information updates for each modality will be described separately.

• For the information update of the text modality, the gated weight is first generated:

where

where

where CAT(·) denotes the concatenation operation.

• For the information update of visual modality, the gating weight is first generated:

• Then the gating weight is applied to cross-modal attention output:

• where

• The information updating process of audio modality is similar to that of visual modality:

• The expression ability and stability of the model are improved, and the feedforward network is enhanced. Before the feature is transmitted to the feedforward network, feature selection gating is introduced to filter redundant information:

where

3.6 Gated Enhanced Emotion Classifier

After multi-layer GUE and Gated ACME coding, the final feature matrix

where

where

where

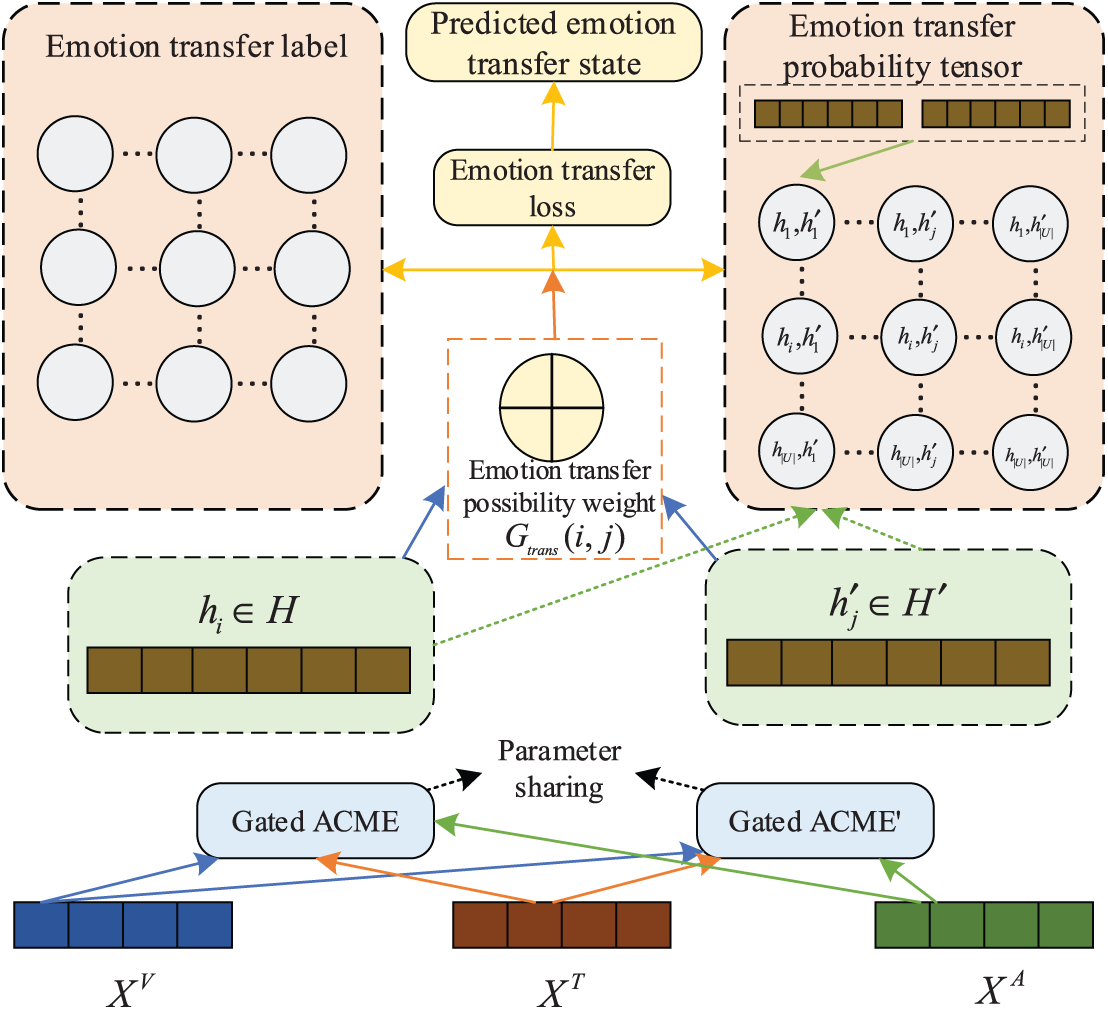

3.7 Gated Enhanced Emotion Transfer Module

To enhance the model’s capacity for capturing the dynamic evolution of emotions within dialogues, we introduce a gated enhanced emotion transfer module (Gated EETM). This module explicitly models emotion transition patterns through a transfer gating mechanism, which suppresses spurious emotional associations between unrelated utterances. By emphasizing contextual emotional shifts and reducing reliance on static context assumptions, Gated EETM improves the recognition of emotional changes and reinforces the model’s adaptability in conversational scenarios. As shown in Fig. 5, The Gated LESM consists of three main steps, namely, first constructing the probability tensor of emotion transfer, then generating the label matrix of emotion transfer, and finally using the loss of emotion transfer for training.

Figure 5: The network structure of gated EETM. Gated EETM consists of three key steps: (1) Constructing the emotion transfer probability tensor: Two parameter-shared Gated ACME modules process the input multi-modal features to generate two representationally distinct yet emotionally consistent feature matrices. (2) Generating the Emotion Transfer Label Matrix: Based on the ground-truth emotion labels, a binary emotion transfer label matrix is constructed. (3) Emotion Transfer Loss for Training: The emotion transfer probability tensor is passed through a fully connected layer to predict transfer states

• Emotion transfer probability: Inspired by Gao et al. [29], we use two parameter-shared Gated ACMEs to process the input multi-modal features, the output

where

where

• Emotion transfer label: Using the real emotion labels from the dataset, the emotion transfer state between adjacent utterances is marked. Specifically, if the real emotions of the two utterances are the same, their emotional transfer state is marked as 0, indicating that there is no emotional transfer; on the contrary, if their real emotions are different, the emotional transfer state is marked as 1, indicating that emotional transfer has occurred. Through the above operation, a

• Emotion transfer loss: After constructing the emotion transfer probability and label, a loss function is defined to train the model. The gated enhanced emotion transfer module is a binary auxiliary task, which aims to correctly distinguish the emotional transfer state between utterances. This encourages the model to capture emotional dynamics and reduce over-reliance on contextual information. Firstly, in order to obtain the predicted emotion transfer state

where

where the gating threshold

We combine the classification loss

where

4 Experiment and Results Analysis

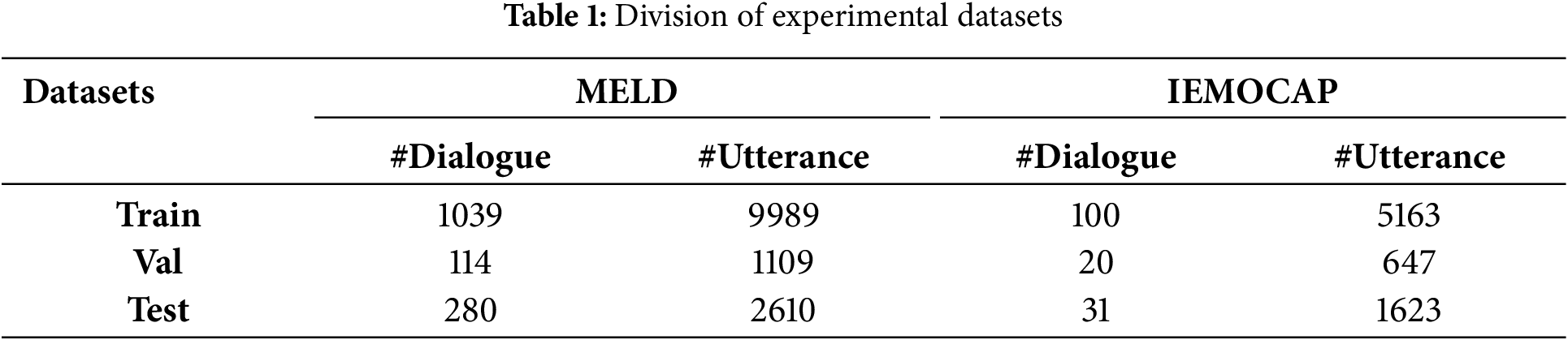

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted experiments on the publicly available multi-modal emotional dialogue datasets MELD [31] and IEMOCAP [32]. A brief description of each dataset is provided below.

• MELD dataset: This dataset is a multi-modal sentiment analysis dataset, including more than 1400 dialogues and more than 13,000 utterances from the TV series ‘Friends’. There are seven emotional categories in the dataset, namely anger, disgust, sadness, joy, surprise, fear and neutral.

• IEMOCAP dataset: This dataset is a performance-based multi-modal multi-speaker dataset composed of two-person dialogues, including text, visual and audio modalities. The dataset contains 151 dialogues and 7433 utterances, which are labeled with six emotional categories: happy, sad, neutral, angry, excited and frustrated.

The statistical information of MELD and IEMOCAP is shown in Table 1.

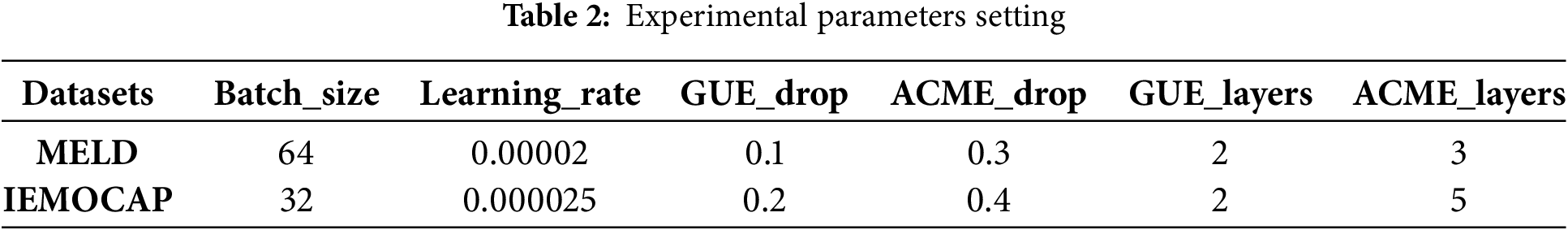

4.2 Model Evaluation and Training Details

We used accuracy (ACC) and weighted F1 score (w-F1) as the main evaluation indicators, and used F1 score as an evaluation indicator for each individual emotional category.

All experiments in this paper are conducted on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 graphics card, using CUDA 11.8 version and deep learning framework PyTorch 2.5.0, using AdamW as the optimizer, the number of heads of all MHA networks is set to 8, and the L2 regularization factor is set to 0.00001. The other parameters of the model are shown in Table 2, where Batch_size is the batch size, Learning_rate is the learning rate, GUE_drop is the random inactivation rate of GUE, ACME_ drop is the random inactivation rate of Gated ACME, GUE_layers represents the number of network layers of GUE, and ACME_layers represents the number of network layers of Gated ACME.

4.3 Comparative Experimental Analysis

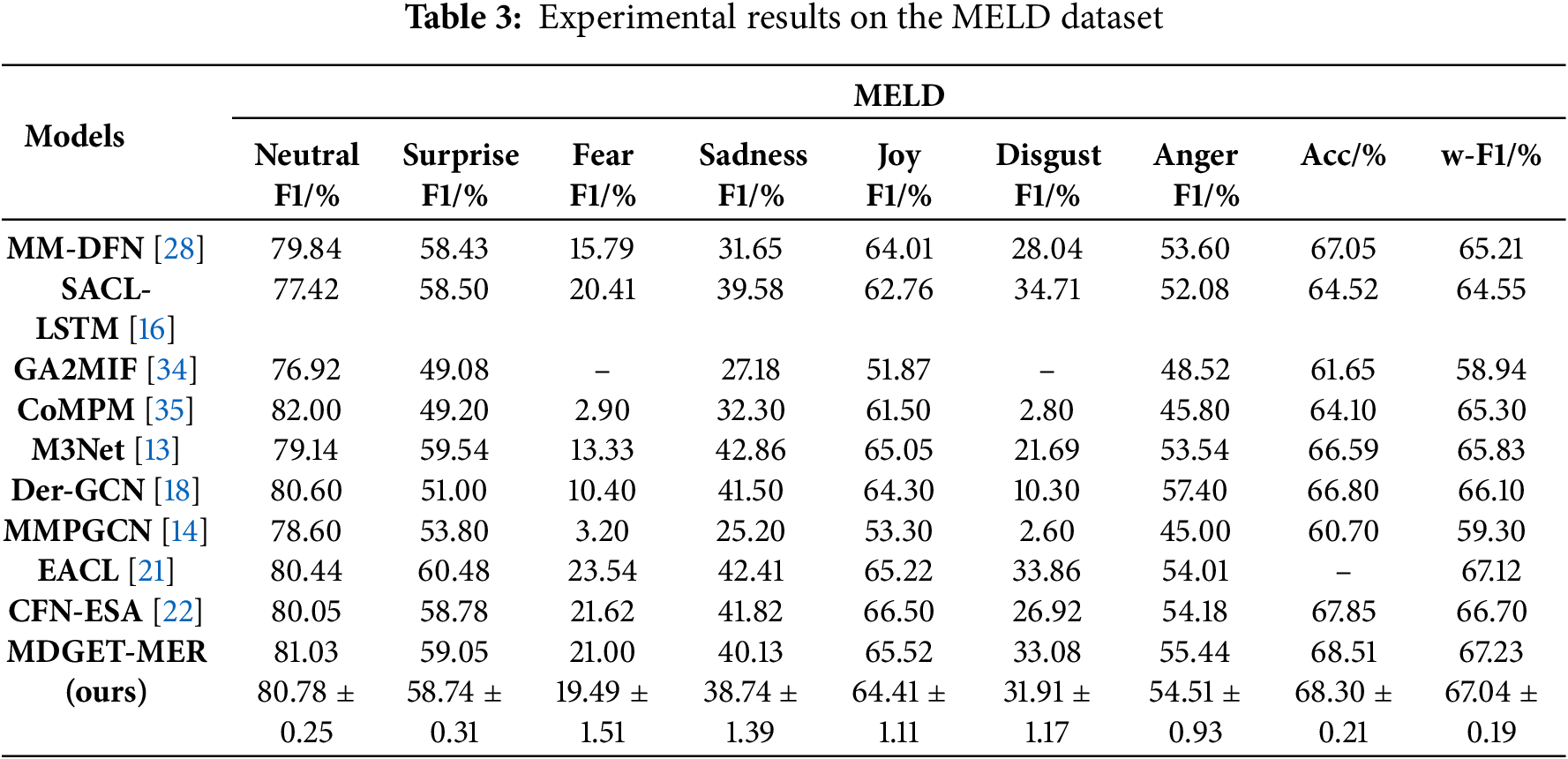

4.3.1 Comparison to Baselines on the MELD Dataset

We conduct a comprehensive evaluation of MDGET-MER on the MELD dataset and compared it with nine comparison models. As shown in Table 3, on the MELD dataset, MDGET-MER is significantly better than all comparison models with an accuracy of 68.51% and a weighted F1 score of 67.23%, which is 0.66 and 0.53 percentage points higher than the optimal comparison model CFN-ESA (67.85% Acc/66.70% w-F1). Multi-modal emotion recognition studies have shown that, disgust and anger noise is higher. For example, in the MELD dataset, the study [33] can significantly improve the classification accuracy of these two categories by introducing sample weighted focus contrast (SWFC) loss, indirectly proving its high noise characteristics. The advantage of MDGET-MER is particularly prominent in the high-noise emotion category. For example, the F1 score of MDGET-MER in the ‘disgust’ category is 33.08%, which is much higher than 26.92% of CFN-ESA and 2.60% of MMPGCN, which verifies the effective suppression of visual and audio noise by dynamic gating mechanism. In the ‘fear’ category, the F1 score (21.00%) is slightly lower than that of EACL (21.62%), but significantly better than that of CoMPM (2.90%), indicating that the model is more adaptable to low SNR modes. In addition, MDGET-MER achieved an F1 score of 81.03% in the neutral category, which is 0.98% higher than that of CFN-ESA, highlighting the ability of text-led cross-modal interaction design to strengthen the semantic core.

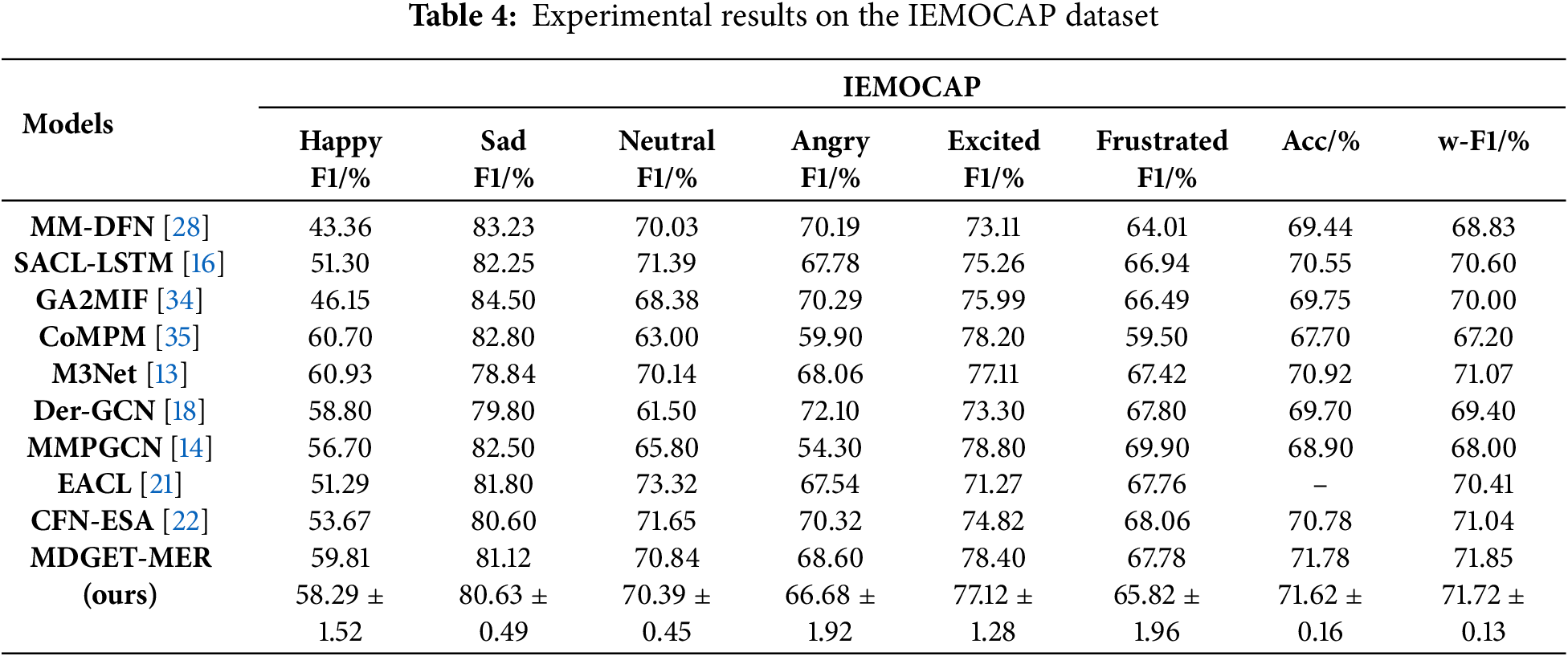

4.3.2 Comparison to Baselines on the IEMOCAP Dataset

Similarly, in order to fully verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we also compare MDGET-MER with 9 comparison models on the IEMOCAP dataset. As shown in Table 4, MDGET-MER is significantly superior to all comparison models with an accuracy of 71.78% and a weighted F1 score of 71.85%, and is 1.00 and 0.81 percentage points higher than the optimal comparison model CFN-ESA (70.78% Acc/71.04% w-F1), respectively. In fine-grained emotion analysis, MDGET-MER’s ability to model complex emotional states is further highlighted: for example, the F1 score of the ‘excited’ category reaches 78.40%, which is 3.58 percentage points higher than that of CFN-ESA (74.82%), reflecting the enhancement effect of cross-modal dynamic alignment on positive emotions. Notably, MDGET-MER achieved an F1 score of 59.81% in ‘Happy’, which is more balanced than EACL (51.29%), indicating that it balanced the strength and diversity of modal contributions through a multi-level gating mechanism.

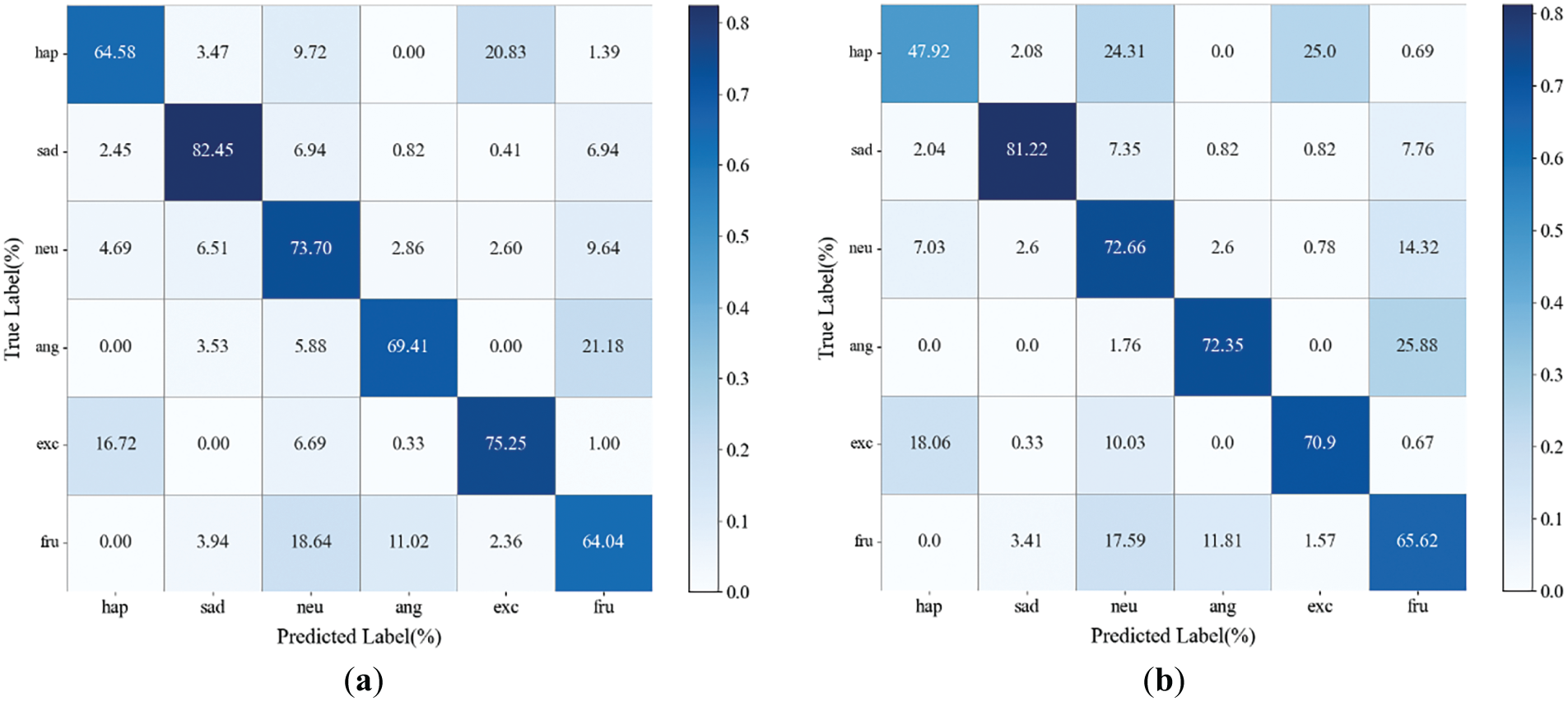

Fig. 6 describes the confusion matrix of MDGET-MER and GA2MIF on the IEMOCAP dataset. MDGET-MER had higher correct recognition rates in happy (64.58% vs. 47.92%), excited (75.25% vs. 70.9%) and sad (82.45% vs. 81.22%) categories, and more significant inhibition of cross-category misclassifications such as happy → excited and neutral → happy (such as happy misclassification as excited is only 20.83%, lower than 25.0% of GA2 MIF). Neutral misjudged as happy is only 4.69%, lower than 7.03% of GA2MIF. Even if GA2MIF has a local accuracy advantage in angry recognition (72.35% vs. 69.41%), the misjudgment of MDGET-MER is still more concentrated (for example, the misjudgment of angry as frustrated is only 21.18%, lower than 25.88% of GA2MIF). On the whole, MDGET-MER has more accurate fine-grained distinction between positive emotions (happy, excited) and negative emotions (sad), less cross-category confusion, and more advantages in the stability and accuracy of emotion recognition.

Figure 6: Comparison of confusion matrices between MDGET-MER and GA2MIF. hap, sad, neu, ang, exc, fru denote happy, sad, neutral, angry, excited, and frustrated, respectively: (a) Confusion matrix of MDGET-MER; (b) Confusion matrix of GA2MIF

4.4 Ablation Experimental Analysis

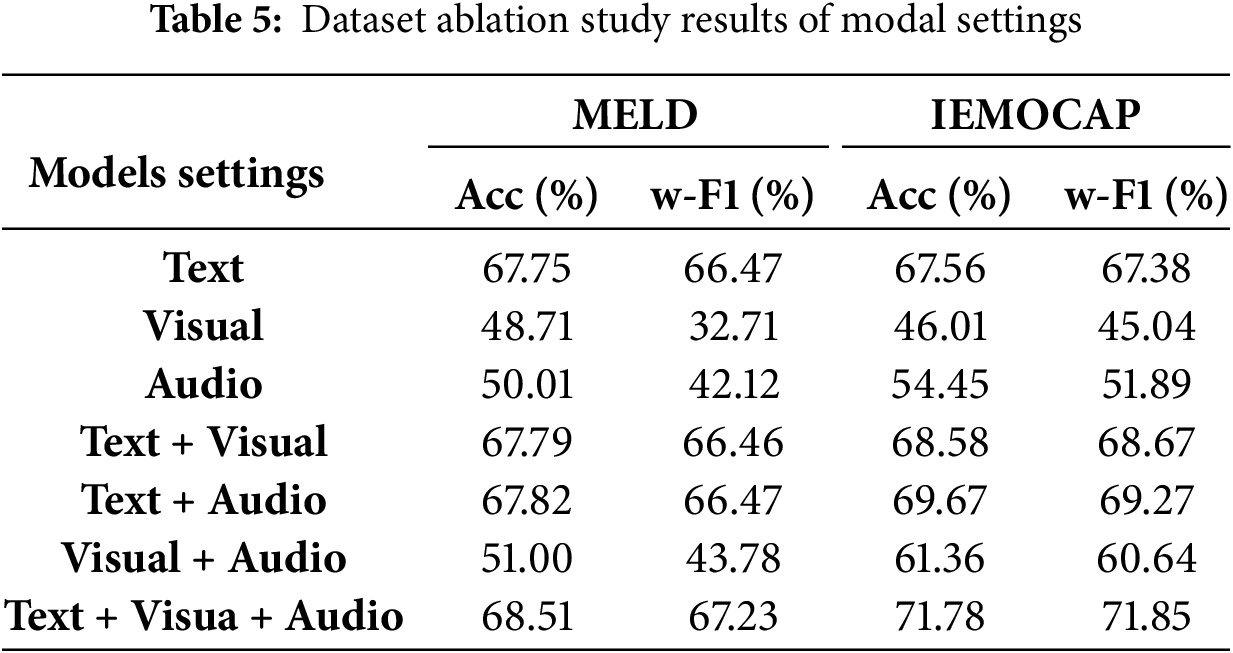

4.4.1 The Importance of Multi-Modality

In order to verify the importance of text, visual and audio modalities to MDGET-MER, we conduct ablation experiments on MELD and IEMOCAP datasets, as shown in Table 5. The experimental results show that the text modality plays a dominant role in multi-modal emotion recognition. Under the single modality setting, the accuracy of MELD and IEMOCAP is 67.75% and 67.56%, respectively, and the weighted F1 score is 66.47% and 67.38%, which is significantly better than that of vision (MELD Acc: 48.71%; IEMOCAP Acc: 46.01%) and audio (MELD Acc: 50.01%; iEMOCAP Acc: 54.45%), which verifies that text features contain the most abundant emotional semantic information. For example, in the MELD dataset, the weighted F1 score of the pure visual modality is only 32.71%, which is much lower than 66.47% of the text modality, indicating that facial expressions and body movements are susceptible to environmental noise.

In the dual-modal experiment, the text + audio combination performed best: the accuracy and weighted F1 score of IEMOCAP increase to 69.67% and 69.27%, respectively, which increase by 2.11 and 1.89 percentage points compare with the pure text mode, indicating that audio features such as speech tone can effectively supplement the implicit emotional cues of the text. The accuracy of text + visual combination on MELD (67.79%) is close to that of pure text model (67.75%), suggesting that the contribution of visual modality in short dialogue scenes is limited. It is worth noting that the accuracy of visual + audio combination (MELD: 51.00%; IEMOCAP: 61.36%) is significantly lower than other dual-modal settings, confirming that the model is difficult to effectively capture cross-modal emotional associations when there is a lack of text dominance.

When the text + visual + audio tri-modality is fused, the model performance reaches the peak: the accuracy of MELD and IEMOCAP is 68.51% and 71.78%, respectively, which is 0.69 and 2.11 percentage points higher than the optimal bi-modal combination (text + audio), and the weighted F1 score is increased by 0.76 and 2.58 percentage points. This result verifies the multi-modal synergy effect: for example, in the ‘excited’ category of IEMOCAP, the visual modality and the audio modality adaptively strengthen the supplement to the text through the dynamic gating mechanism, so that the F1 score is 4.3% higher than that of the dual modality. Experiments show that MDGET-MER maximizes the utilization of complementary information while suppressing noise through text-driven cross-modal interaction design. Especially in complex scenes where visual/audio modalities provide key clues (such as facial expressions or speech urgency in the ‘anger’ category), three-modal fusion is significantly better than single-modal or dual-modal settings, providing a robust and efficient solution for dialogue emotion recognition.

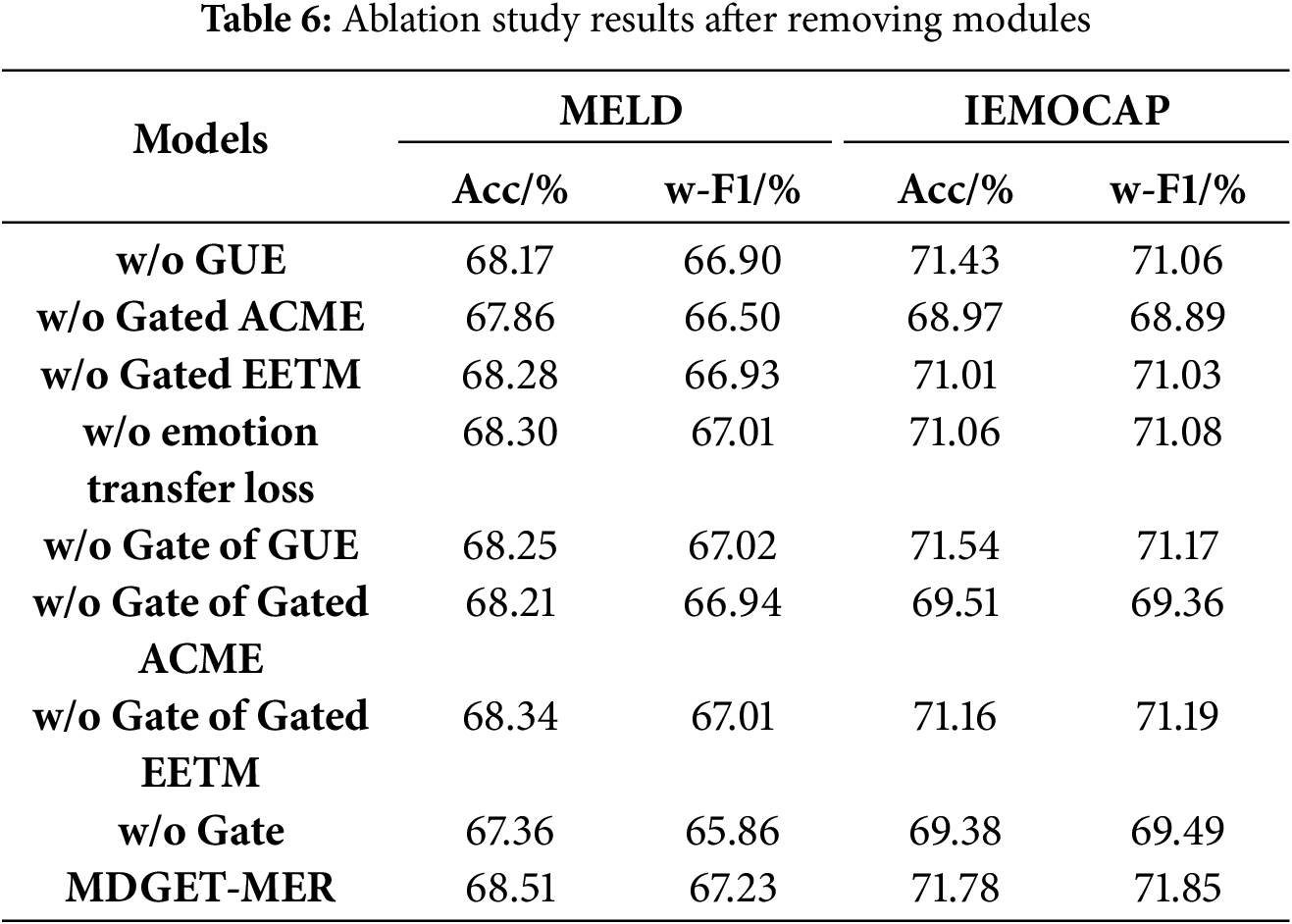

4.4.2 The Importance of Each Module

In order to verify the synergy of each module in MDGET-MER, we analyze the contribution of its core components through four ablation experiments, as shown in Table 6.

Firstly, after removing the Gated Uni-modal Encoder (GUE), the accuracy of MELD and IEMOCAP decrease to 68.17% and 71.43%, respectively (0.34 and 0.35 percentage points lower than the complete model), and the weighted F1 score decreased by 0.33 and 0.79 percentage points, respectively. Experiments show that the ability of GUE to suppress single-modal noise through dual dynamic gating is crucial to model robustness, especially when there is inherent noise in visual and audio modalities, which verifies its key role in the purification of original features.

Secondly, after removing the Gated Attention-based Cross-Modal Encoder (Gated ACME), the performance of the model is significantly degraded: the accuracy of IEMOCAP plummeted to 68.97% (2.81 percentage points lower than the complete model), and the weighted F1 score decrease by 2.96 percentage points. It can be seen from the results that the cross-modal dynamic interaction design can accurately capture the complementary information of the auxiliary modes.

Then, when the Gated Enhanced Emotion Transfer Module (Gated EETM) is removed, the accuracy of MELD decreased slightly to 68.28%, and the weighted F1 score decreases by 0.30 percentage points. In IEMOCAP, the accuracy rate decreased by 0.77 percentage points. Because it can not explicitly model the law of emotion transfer, the optimization ability of context dependence biasis weakened, indicating that this module is more critical to the modeling of emotion mutation in long dialogue scenes.

Finally, when the hierarchical gating mechanism is completely removed, the model performance suffered the greatest loss: the weighted F1 scores of MELD and IEMOCAP fell to 65.86% and 69.49%, respectively (1.37 and 2.36 percentage points lower than the complete model). The results show that the dynamic gating mechanism systematically optimizes the overall performance through synergy, and verifies the enhancement effect of gating design on complex emotional expression.

4.4.3 The Importance of Gating

In order to deeply analyze the specific contribution of each stage of gating in the dynamic gating mechanism, we further design ablation experiments to systematically remove the gating units in each key module of the model (as shown in Table 6) to evaluate its impact on the overall performance.

Firstly, after removing gate of GUE, the performance of the model on MELD and IEMOCAP decrease slightly (MELD Acc: 68.25%, w-F1: 67.02%; IEMOCAP Acc: 71.54%, w-F1: 71.17%). This shows that although the dual dynamic gating in GUE is not the biggest driving force for performance improvement, its role in noise filtering and feature enhancement has a fundamental contribution to model robustness. After removal, the sensitivity of the model to single-mode noise increases slightly.

Secondly, removing gate of Gated ACME causes significant damage to model performance, especially on the IEMOCAP dataset (IEMOCAP Acc: 69.51%, w-F1: 69.36%, 2.27% Acc/2.49% w-F1 lower than the complete model). This strongly verifies that dynamic gating in Gated ACME is the key pillar of model performance. The gating is responsible for dynamically calibrating the complementary strength of visual/audio modalities to text features and feature selection. Its removal causes the model to fail to effectively suppress cross-modal redundant information and adaptively adjust the modal contribution, which seriously weakens the efficiency of cross-modal dynamic alignment and complementary information utilization.

Then, after removing gate of Gated EETM, the performance of the model on MELD decreases the least (Acc: 68.34%, w-F1: 67.01%), while on IEMOCAP decreases significantly (Acc: 71.16%, w-F1: 71.19%). And after removing the emotion transfer loss, the performance of the model on MELD decreases the least (Acc: 68.30%, w-F1: 67.01%), while on IEMOCAP decreases significantly (Acc: 71.06%, w-F1: 71.08%). This difference indicates that the gating of Gated EETM plays a more significant role in modeling more complex emotional evolution dependence and inhibiting false associations in long dialogues (such as IEMOCAP). Removing this gating weakens the model’s ability to focus on key cues in emotional mutation scenarios.

Finally, when all gating mechanisms are removed, the model performance suffers the greatest loss (MELD Acc: 67.36%, w-F1: 65.86%; IEMOCAP Acc: 69.38%, w-F1: 69.49%) is much lower than the performance of removing any single stage gating. This clearly shows that the gating mechanism in GUE, Gated ACME and Gated EETM does not operate in isolation, but jointly optimizes the noise robustness, cross-modal dynamic alignment ability and emotional evolution modeling accuracy of the model through synergy, and achieves a systematic improvement in overall performance.

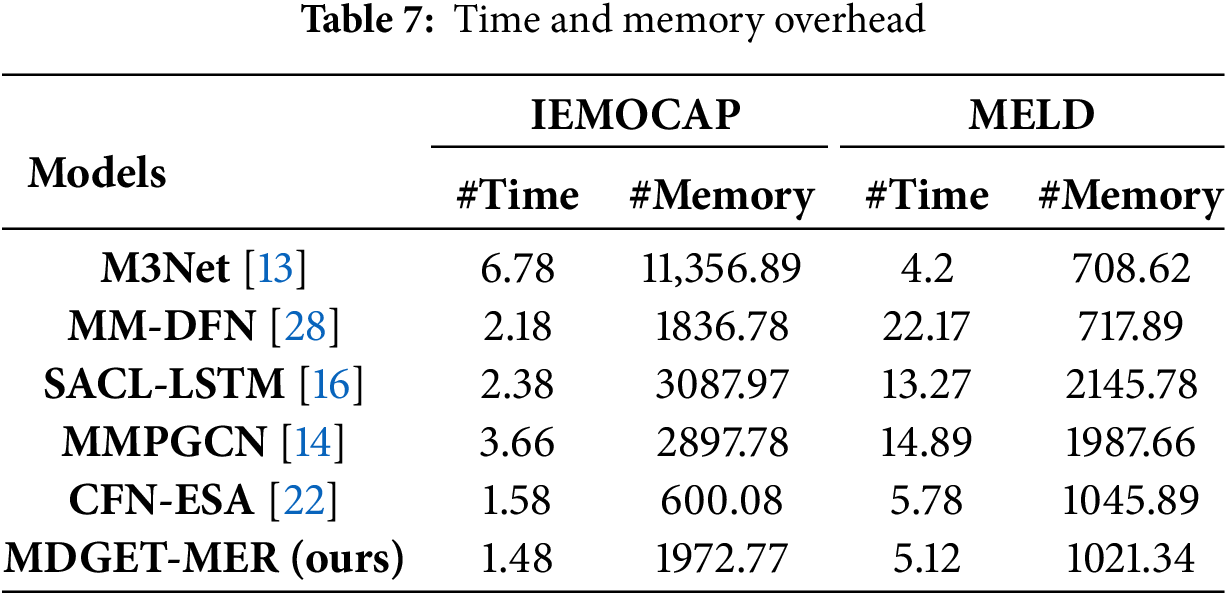

In Table 7, we present the running time and memory usage of our proposed model alongside several baseline methods for the MER task on both datasets. Compared to other models, M3Net and CFN-ESA demonstrate significantly lower time consumption on the MELD dataset, while CFN-ESA also achieves competitive time efficiency on IEMOCAP. MM-DFN and SACL-LSTM exhibit considerably higher running times across both datasets. In terms of memory usage, CFN-ESA consumes the least memory on MELD, while our model shows the most efficient memory utilization on IEMOCAP. M3Net and SACL-LSTM require substantially more memory across the datasets. Overall, our proposed MDGET-MER not only achieves strong performance metrics but also maintains a favorable balance between computational time and memory efficiency.

The term “Time” refers to the duration(s) required for training and testing in each epoch, and “Memory” refers to the consumption (MB) of allocated and reserved memory.

This section shows a case of emotional transfer. Fig. 7 shows a dialogue scenario in the IEMOCAP dataset. When the speaker continuously outputs multiple sentences with neutral real emotions, the existing models (such as M3Net) tend to misjudge the subsequent utterance as neutral. This is due to its over-reliance on historical context, which leads to the failure of the model to effectively capture the cross-modal complementary information of the current utterance, thus making it difficult to model the instantaneous dynamic evolution of emotions.

Figure 7: A conversational case in the IEMOCAP dataset

In contrast, MDGET-MER can collaboratively optimize the fusion of contextual dependencies and current multi-modal cues through a gated enhanced emotion transfer module. Gated EETM explicitly captures the emotional transfer information, so that the model can strengthen the current cue in the face of emotional changes rather than relying too much on the historical context, so as to accurately identify the real emotion-surprise of the subsequent utterance in this case.

In order to solve the problem of emotional semantic alignment caused by modal heterogeneity, noise interference and emotional evolution complexity in dialogue scenes, we propose multi-level dynamic gating and emotion transfer for multi-modal emotion recognition. The dynamic gating mechanism runs through the whole process of uni-modal coding, cross-modal alignment and emotion transfer modeling. Firstly, the Gated Uni-modal Encoder (GUE) is used to suppress the single-mode noise and narrow the heterogeneity gap, so as to enhance the discrimination of the original features. Secondly, a Gated Attention-based Cross-Modal Encoder (Gated ACME) is designed to dynamically calibrate the complementary strength of visual and audio modalities to the dominant features of the text, and to filter redundant information by combining feature selection gating. Finally, a Gated Enhanced Emotion Transfer Module (Gated EETM) is introduced to explicitly model the evolution of emotions by comparative learning, so as to alleviate the conflict between context dependence and emotional mutation. Experiments show that the accuracy and weighted F1 score of MDGET-MER on MELD and IEMOCAP dataset are better than the existing comparison model. In the future, we will explore from the direction of deep integration of multi-modal emotion recognition and dynamic gating mechanism, and use real-time perception of emotional state to optimize the context understanding and emotional response of multi-modal empathetic dialogue generation, so as to further improve the emotional consistency and empathy depth of generated dialogue.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the Fanying Special Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Scientific research project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education, the Doctoral startup fund of Jiangxi University of Technology.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by “the Fanying Special Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62341307”, “the Scientific research project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education, grant number GJJ200839” and “the Doctoral startup fund of Jiangxi University of Technology, grant number 205200100402”.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Musheng Chen and Xiaohong Qiu; methodology, Musheng Chen and Qiang Wen; software, Qiang Wen and Wenqing Fu; validation, Junhua Wu and Wenqing Fu; formal analysis, Musheng Chen and Qiang Wen; investigation, Junhua Wu; resources, Qiang Wen; data curation, Qiang Wen; writing—original draft preparation, Qiang Wen and Musheng Chen; writing—review and editing, Musheng Chen and Xiaohong Qiu; visualization, Qiang Wen; supervision, Junhua Wu; project administration, Musheng Chen; funding acquisition, Musheng Chen, Junhua Wu and Xiaohong Qiu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are openly available in (MELD) at (1810.02508v6) and (IEMOCAP) at (1804.05788v3) reference numbers [31,32].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Notations

| The following notations are used in this manuscript: | |

| Notation | Meaning |

| A dialogue containing | |

| The emotional label | |

| The feature representation of | |

| The feature matrixs; n is the number of utterances, d is the feature dimension | |

| [;] | The feature splicing operation |

| A sigmoid function | |

| The dynamic gating matrixs | |

| The gated parameter matrixs | |

| Learnable parameters | |

| Element-by-element multiplication | |

| α( ) | The activation function |

| The final feature matrix | |

| A gated weighted fusion feature | |

| |E| | The number of emotions |

| The predicted emotion | |

| The L2 regularization coefficient | |

| n(i) | The number of utterances in the i-th dialogue |

| N | The number of all dialogues in the training set |

| The probability distribution of the predicted emotion label of the j-th utterance in the i-th conversation | |

| The truth label | |

| Emotion transfer possibility weight | |

| The feature vectors of the i-th and j-th statements | |

| The gating threshold | |

| The probability distribution of the predicted emotion transfer label | |

| The classification loss | |

| Emotion transfer loss | |

| The learnable parameters of all gating mechanisms | |

| A compromise parameter whose value is in the range of [0, 1] | |

| W | A set of all learnable parameters except the gating mechanism |

References

1. Jiao W, Lyu M, King I. Real-time emotion recognition via attention gated hierarchical memory network. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(5):8002–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i05.6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Nie W, Chang R, Ren M, Su Y, Liu A. I-GCN: incremental graph convolution network for conversation emotion detection. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2022;24:4471–81. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3118881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li S, Yan H, Qiu X. Contrast and generation make BART a good dialogue emotion recognizer. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(10):11002–10. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i10.21348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Shen W, Chen J, Quan X, Xie Z. DialogXL: all-in-one XLNet for multi-party conversation emotion recognition. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(15):13789–97. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i15.17625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Latif S, Rana R, Khalifa S, Jurdak R, Schuller BW. Multitask learning from augmented auxiliary data for improving speech emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2023;14(4):3164–76. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2022.3221749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou Y, Liang X, Gu Y, Yin Y, Yao L. Multi-classifier interactive learning for ambiguous speech emotion recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2022;30:695–705. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2022.3145287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Majumder N, Poria S, Hazarika D, Mihalcea R, Gelbukh A, Cambria E. DialogueRNN: an attentive RNN for emotion detection in conversations. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2019;33(1):6818–25. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33016818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Shi J, Li M, Bai L, Cao F, Lu K, Liang J. MATCH: modality-calibrated hypergraph fusion network for conversational emotion recognition. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2025 Aug 16–22; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 6164–72. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2025/686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhan Y, Yu J, Yu Z, Zhang R, Tao D, Tian Q. Comprehensive distance-preserving autoencoders for cross-modal retrieval. In: Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2018 Oct 22–26; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1137–45. doi:10.1145/3240508.3240607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ghosal D, Majumder N, Gelbukh A, Mihalcea R, Poria S. COSMIC: commonsense knowledge for emotion identification in conversations. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020; 2020 Nov 16–20; Online. p. 2470–81. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.findings-emnlp.224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shen W, Wu S, Yang Y, Quan X. Directed acyclic graph network for conversational emotion recognition. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2021 Aug 1–6; Online. p. 1551–60. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Poria S, Cambria E, Hazarika D, Majumder N, Zadeh A, Morency LP. Context-dependent sentiment analysis in user-generated videos. In: Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2017 Jul 30–Aug 4; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 873–83. doi:10.18653/v1/p17-1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen F, Shao J, Zhu S, Shen HT. Multivariate, multi-frequency and multimodal: rethinking graph neural networks for emotion recognition in conversation. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 10761–70. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Meng T, Shou Y, Ai W, Du J, Liu H, Li K. A multi-message passing framework based on heterogeneous graphs in conversational emotion recognition. Neurocomputing. 2024;569(1):127109. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.127109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mao Y, Liu G, Wang X, Gao W, Li X. DialogueTRM: exploring multi-modal emotional dynamics in a conversation. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021; 2021 Nov 7–11; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. p. 2694–04. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.findings-emnlp.229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hu D, Bao Y, Wei L, Zhou W, Hu S. Supervised adversarial contrastive learning for emotion recognition in conversations. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 10835–52. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Fu Y, Yan X, Chen W, Zhang J. Feature-enhanced multimodal interaction model for emotion recognition in conversation. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;309:112876. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ai W, Shou Y, Meng T, Li K. DER-GCN: dialog and event relation-aware graph convolutional neural network for multimodal dialog emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(3):4908–21. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3367940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li B, Fei H, Liao L, Zhao Y. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2023 Oct 29–Nov 3; Ottawa, ON, Canada. p. 5923–34. doi:10.1145/3581783.3612053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zeng Y, Mai S, Hu H. Which is making the contribution: modulating unimodal and cross-modal dynamics for multimodal sentiment analysis. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021; 2021 Nov 7–11; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. p. 1262–74. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.findings-emnlp.109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yu F, Guo J, Wu Z, Dai X. Emotion-anchored contrastive learning framework for emotion recognition in conversation. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024; 2024 Jun 16–21; Mexico City, Mexico. p. 4521–34. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.findings-naacl.282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li J, Wang X, Liu Y, Zeng Z. CFN-ESA: a cross-modal fusion network with emotion-shift awareness for dialogue emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2024;15(4):1919–33. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2024.3389453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bansal K, Agarwal H, Joshi A, Modi A. Shapes of emotions: multimodal emotion recognition in conversations via emotion shifts. In: Proceedings of the First Workshop on Performance and Interpretability Evaluations of Multimodal, Multipurpose, Massive-Scale Models; 2022 Oct 12–17; Virtual. p. 44–56. [Google Scholar]

24. Tu G, Wang J, Li Z, Chen S, Liang B, Zeng X, et al. Multiple knowledge-enhanced interactive graph network for multimodal conversational emotion recognition. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024; 2024 Nov 12–16; Miami, FL, USA. p. 3861–74. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.findings-emnlp.222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. RoBERTa: a robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692. 2019. [Google Scholar]

26. Eyben F, Weninger F, Gross F, Schuller B. Recent developments in opensmile, the munich open-source multimedia feature extractor. In: Proceedings of the 21st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2013 Oct 21–25; Barcelona, Spain. p. 835–8. doi:10.1145/2502081.2502224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, Weinberger KQ. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2261–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hu D, Hou X, Wei L, Jiang L, Mo Y. MM-DFN: multimodal dynamic fusion network for emotion recognition in conversations. In: ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022 May 23–27; Singapore. p. 7037–41. doi:10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9747397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gao T, Yao X, Chen D. SimCSE: simple contrastive learning of sentence embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2021 Nov 7–11; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. p. 6894–910. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cipolla R, Gal Y, Kendall A. Multi-task learning using uncertainty to weigh losses for scene geometry and semantics. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7482–91. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Poria S, Hazarika D, Majumder N, Naik G, Cambria E, Mihalcea R. MELD: a multimodal multi-party dataset for emotion recognition in conversations. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul 28–Aug 2; Florence, Italy. p. 527–36. doi:10.18653/v1/p19-1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Busso C, Bulut M, Lee CC, Kazemzadeh A, Mower E, Kim S, et al. IEMOCAP: interactive emotional dyadic motion capture database. Lang Resour Eval. 2008;42(4):335–59. doi:10.1007/s10579-008-9076-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shi T, Huang SL. MultiEMO: an attention-based correlation-aware multimodal fusion framework for emotion recognition in conversations. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 14752–66. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li J, Wang X, Lv G, Zeng Z. GA2MIF: graph and attention based two-stage multi-source information fusion for conversational emotion detection. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2024;15(1):130–43. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2023.3261279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lee J, Lee W. CoMPM: context modeling with speaker’s pre-trained memory tracking for emotion recognition in conversation. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2022 Jul 10–15; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 5669–79. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.naacl-main.416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools