Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Action Recognition via Shallow CNNs on Intelligently Selected Motion Data

1 Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering, Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology, Topi, 23460, Pakistan

2 Department of AI and DS, FAST School of Computering, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 College of Engineering and Technology, American University of the Middle East, Egaila, 54200, Kuwait

4 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Usman Haider. Email: ; Saeed Mian Qaisar. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 96 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071251

Received 03 August 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Deep neural networks have achieved excellent classification results on several computer vision benchmarks. This has led to the popularity of machine learning as a service, where trained algorithms are hosted on the cloud and inference can be obtained on real-world data. In most applications, it is important to compress the vision data due to the enormous bandwidth and memory requirements. Video codecs exploit spatial and temporal correlations to achieve high compression ratios, but they are computationally expensive. This work computes the motion fields between consecutive frames to facilitate the efficient classification of videos. However, contrary to the normal practice of reconstructing the full-resolution frames through motion compensation, this work proposes to infer the class label from the block-based computed motion fields directly. Motion fields are a richer and more complex representation of motion vectors, where each motion vector carries the magnitude and direction information. This approach has two advantages: the cost of motion compensation and video decoding is avoided, and the dimensions of the input signal are highly reduced. This results in a shallower network for classification. The neural network can be trained using motion vectors in two ways: complex representations and magnitude-direction pairs. The proposed work trains a convolutional neural network on the direction and magnitude tensors of the motion fields. Our experimental results show 20Keywords

The performance of deep neural networks has recently improved due to the vast amount of labeled data, novel deep architectures, and the availability of inexpensive parallel computing. These algorithms are now used in every industry, from object detection [1] to action recognition [2] and image classification [3], among others. The discriminative power of deep neural networks is attributed to increasing depth and higher representational capacity. However, this increases the cost of inference. Assume that a user has to classify a video stream recorded at 30 frames per second (fps) with a resolution of

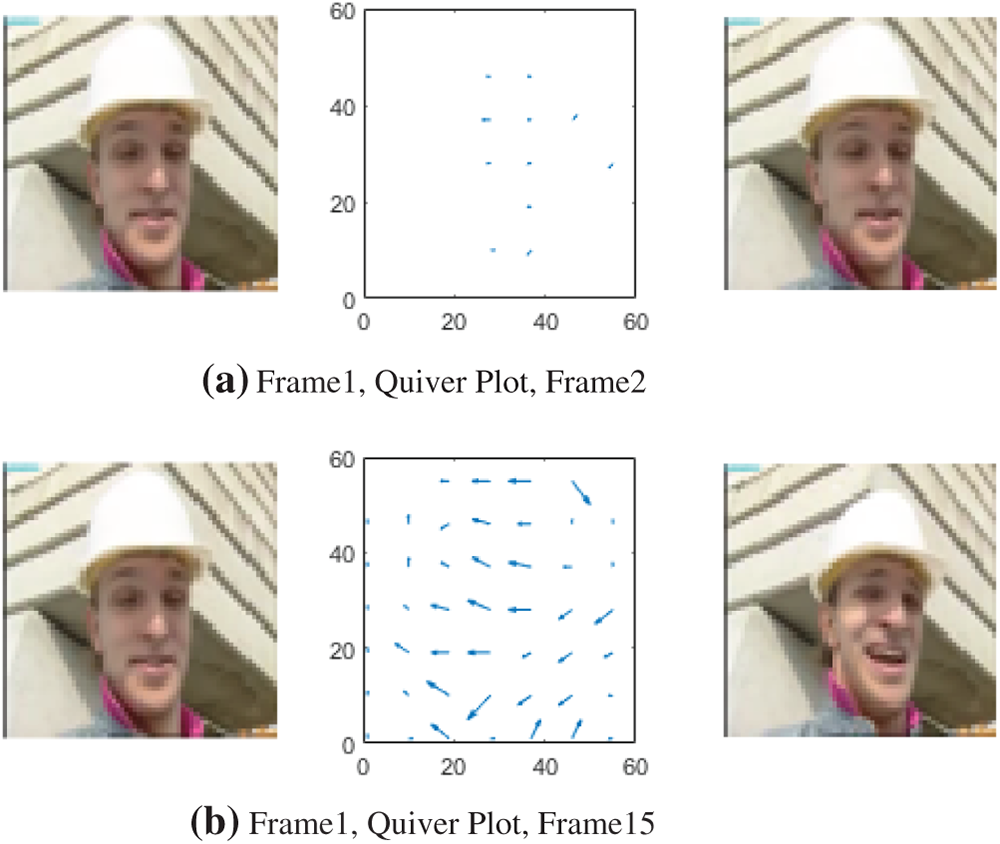

However, this work proposes computing the training and inference of a deep learning algorithm on motion fields instead of full-resolution frames and reconstructed pixel representations. Therefore, the cost of video reconstruction via motion compensation is avoided, and other benefits, such as faster training, reduced overfitting, and accelerated inference, are also obtained. Fig. 1 shows the motion fields computed for consecutive frames for the same video stream. It can be observed that highly correlated frames contain redundant information, which may not be necessary for classification.

Figure 1: The foreman video stream and the corresponding motion vectors computed with block matching algorithms. It can be observed that a high degree of temporal correlation exists between frames 1 and 2 compared to frames 1 and 15

In this work, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is utilized to predict the class label of the video stream. Conventionally, a CNN classifies an image based on the intensity level of each pixel. However, motion vectors have a complex representation in the form of

Despite the success of CNNs in video classification, their computational complexity often limits their deployment on resource-constrained devices. Traditional methods rely on reconstructing full-resolution frames, resulting in high bandwidth and storage costs. This work addresses these challenges by directly using motion fields for classification, eliminating the need for pixel-based reconstructions.

This research proposes an efficient gesture recognition method that uses sparse CNNs trained directly in intelligently selected motion fields. The primary contributions of this work are summarized as follows.

• Proposed a preprocessing method based on motion fields computed using block matching algorithms, significantly reducing input dimensionality and computational complexity.

• Developed a sparse CNN architecture specifically tailored for motion-field-based gesture recognition, which achieves similar accuracy to traditional dense CNNs trained on full-resolution frames.

• Conducted comparative validation experiments against CNNs trained on full-resolution and randomly downsampled frames, demonstrating that the proposed method achieves superior computational efficiency without sacrificing accuracy.

• Evaluated and validated the effectiveness of the proposed approach using three recognized datasets, ensuring robustness and general applicability of the methodology.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The related work is discussed in Section 2, followed by Section 3.1, which explains the cost of inference with a CNN. Block matching algorithms and motion field computations are discussed in Section 3.2. The proposed methodology is given in Section 3.3. The experimental results and discussion are presented in Sections 4 and 5, respectively. Finally, in Section 6, the article concludes by summarizing the key lessons learned and providing directions for future research.

As discussed in Section 1, CNNs have achieved excellent classification performance in various applications, including object detection, image classification, and semantic segmentation. However, their computational complexity remains high, hindering their deployment for real-time applications, especially on resource-limited devices. In the literature, researchers have proposed various ways to accelerate inference with deep convolutional networks. These methods accelerate convolutions without significantly compromising network performance. These techniques include i. Factorization and Decomposition of convolutional kernels [4,5], ii. pruning [6], iii. separable convolutions [7], and iv. quantization [8].

Reference [5] has proposed a simple two-step method to increase the speed of convolutional layers. This method is based on tensor fine-tuning and decomposition. Nonlinear least squares are used for computing the low-rank decomposition of the 4-dimensional kernel tensor. These 4D kernels are decomposed into a smaller number of rank-one tensors. This research resulted in a significant reduction in inference time, accompanied by a modest decline in accuracy. For an 8.5

The Depth-wise separable convolutions followed by pointwise convolutions, called Xception [7]. This architecture was inspired by the Inception model [12]. However, the Xception model replaced the Inception module with depth-wise separable convolutions. Xception outperformed Inception V3 [4], for significant image classification problems. The most modern architecture in Inception was proposed by [13], known as ResNet.

Pruning is another promising technique to reduce redundancy in the model. Pruning induces sparsity in the network data at various granularities: layer, feature maps, kernels, and intra-kernel. As selecting a suitable pruning candidate is very important, several types of research have focused on acceleration. The pruning technique in [14] reduced the network size. Image compression using distinctiveness units was proposed by [15]. They kept the maximum functionality of the compression layer neurons based on their distinctiveness, improving image compression. In another work, reference [6] proposed a data structure to induce structured sparsity in network data.

In recent years, action recognition techniques have evolved toward using compressed video representations and efficient temporal modeling, particularly on challenging datasets such as HMDB51. The Temporal Segment Network (TSN) [16] employs a sparse temporal sampling strategy in conjunction with a ConvNet-based architecture to facilitate efficient learning across entire video sequences, achieving an accuracy of 69.4%. The Slow-I-Fast-P (SIFP) model [17] further advances compressed video processing through a dual-pathway design: a slow path for sparsely sampled I-frames and a fast path for densely sampled pseudo-optical flow, generated using an unsupervised loss-based method. This approach achieves 72.3% accuracy on HMDB51 while reducing dependency on traditional optical flow methods. Additionally, recent studies have explored deep learning architectures, such as 3D ResNet-50 and Vision Transformers (ViT), combined with LSTM for activity recognition [18]. The 3D ResNet-50, pre-trained on large-scale datasets, directly captures spatiotemporal features from video clips under supervised learning, achieving a validation accuracy of 48.9%. In contrast, the ViT-LSTM model utilizes self-supervised DINO pretraining to encode spatial features, followed by LSTM-based temporal modeling, which provides a semi-supervised alternative and achieves an accuracy of 41.9%. While these approaches show promising results, they typically require significant computational resources and longer inference times.

Another promising direction in recent research is the use of advanced deep learning models designed specifically for efficient and accurate human action recognition. A Vision Transformer-based approach, ViTHAR, has been proposed to address challenges such as occlusion, background clutter, and inter-class similarity by modeling long-range spatial and temporal dependencies in video data [19]. This method was evaluated on the UCF101 and HMDB51 datasets, achieving recognition accuracies of 96.53% and 79.45%, respectively, and outperforming several prior deep learning baselines. In parallel, spiking neural networks have been explored for their ability to deliver ultralow-latency inference. A scalable dual threshold mapping (SDM) framework has been introduced to convert conventional artificial neural networks into spiking neural networks while retaining competitive accuracy [20]. This approach achieved 92.94% top-1 accuracy on UCF101 and 67.71% on HMDB51 using only four inference steps, thus significantly reducing latency and energy consumption.

Furthermore, convolutional neural network variants have also been optimized for real-time action recognition. A residual R(2+1)D CNN model has been developed, which factorizes 3D convolutions into separate spatial and temporal components, reducing computational complexity without sacrificing performance [21]. When tested on the UCF101 dataset, this method achieved an accuracy of 82%, demonstrating a balance between efficiency and accuracy suitable for practical deployment. Together, these approaches highlight how transformer-based models, biologically inspired spiking architectures, and optimized CNN variants contribute to advancing the field of human action recognition on standard benchmarks.

Additionally, motion-based representations have gained attention for their ability to capture temporal dynamics with lower computational overhead directly. Prior studies have shown that motion fields offer a more direct and efficient alternative to traditional optical flow or motion vectors [22,23]. These works demonstrate that modeling the direction and magnitude of motion can effectively capture human movement patterns. To further incorporate temporal modeling, hybrid architectures have been proposed, such as the one in [24], which combines a deep residual network for spatial feature extraction with a residual structured Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) for temporal sequence modeling. This design significantly improves classification accuracy on the HMDB51 and Olympic Sports datasets, with pruning techniques applied to manage overfitting caused by the network’s increased depth.

Another well-known method for image representation and activity recognition from videos is contrastive learning, which combines self-supervised and fully supervised learning. Due to the temporal nature of videos, a novel temporal contrastive learning technique is proposed [25]. This method introduces two loss methods that improve the classification performance of videos: local-local and global-local temporal methods. Local-local contrastive loss addresses non-overlapping frames within a video. On the other hand, global-local loss targets the discrimination between timesteps extracted from the feature maps of a video clip, which increases the temporal diversity of the features learned. Their proposed contrastive method has outperformed the state-of-the-art method, 3D ResNet-18. The model is trained and tested on a benchmarked dataset, including UCF101 and HMDB51. UCF101 achieves a classification accuracy of 82.4%. At the same time, the classification accuracy for the HMDB51 dataset is 53.9%.

Recently, Complex-Valued Neural Networks (CV-NNs) have gained popularity in deep learning research [26]. Complex numbers have richer representations than real numbers. Due to the limited availability of complex, non-linear activation functions, this area requires further exploration. Recent studies have extended the use of CVNNs to non-visual modalities, where complex-valued architectures have been applied to human activity recognition from WiFi Channel State Information by combining CVNNs with complex transformers [27]. The proposed work adheres to a straightforward philosophy. If complex tasks can be learned from training data, then a real-valued network based on vector magnitude and direction maps can also learn to solve classification problems. This results in efficient training and inference, mitigating overfitting. However, to the best of our knowledge, no existing work has applied complex-valued CNNs or ANNs directly for video-based human activity recognition, which remains an open research direction.

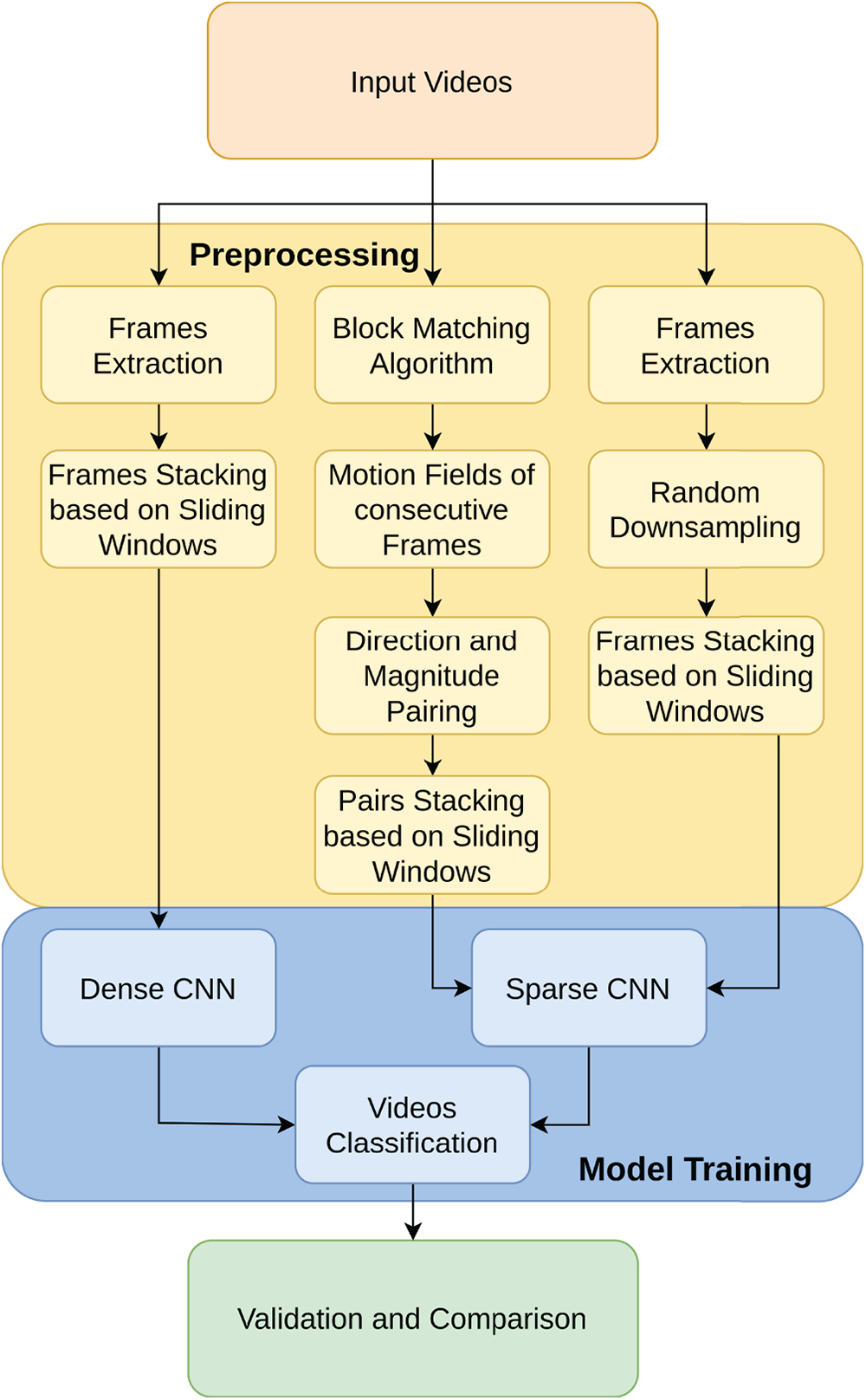

This section outlines the approach used to address the video classification problem by leveraging CNNs and motion fields. The overall methodology comprises three key steps: using full-resolution frames, motion fields-based classification, and a random downsampling mechanism, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Overall system block diagram

First, CNNs are employed for efficient video sequence classification by processing either full-resolution frames, downsampled frames, or motion fields extracted from the frames. To reduce computational complexity without sacrificing accuracy, the study proposes using motion fields as input to the CNN, rather than high-resolution images. Motion fields are computed using block-matching algorithms, providing both magnitude and direction information for frame-to-frame motion.

Finally, various CNN architectures are explored, including networks designed for full-resolution, downsampled, and motion-field-based inputs. The details of each stage are described in the following subsections.

CNNs are a class of artificial neural networks explicitly designed for computer vision tasks. Their computational complexity depends on several factors, including the number of hidden layers, feature maps, convolution kernel sizes, and the size of weight matrices in fully connected layers. Consider two consecutive layers with

Reducing input frame dimensions can decrease computational complexity. Instead of random downsampling, which may lead to performance loss, this study proposes using Block Matching Algorithms (BMAs) to compute motion fields. BMAs reduce input dimensions without significant data loss, thereby accelerating inference [28–30].

In this work, the CNN is trained on motion fields instead of full-resolution and downsampled frames. By using BMAs, the proposed method calculates magnitude and direction matrices from motion fields, thereby reducing input frame dimensions and enhancing computational efficiency.

Motion fields represent the displacement between two consecutive video frames. This displacement is calculated based on pixel intensities and can be measured at various granularities, such as pixel or block level. Since pixel-level motion estimation is computationally expensive, this work employs block-level motion estimation with non-overlapping blocks.

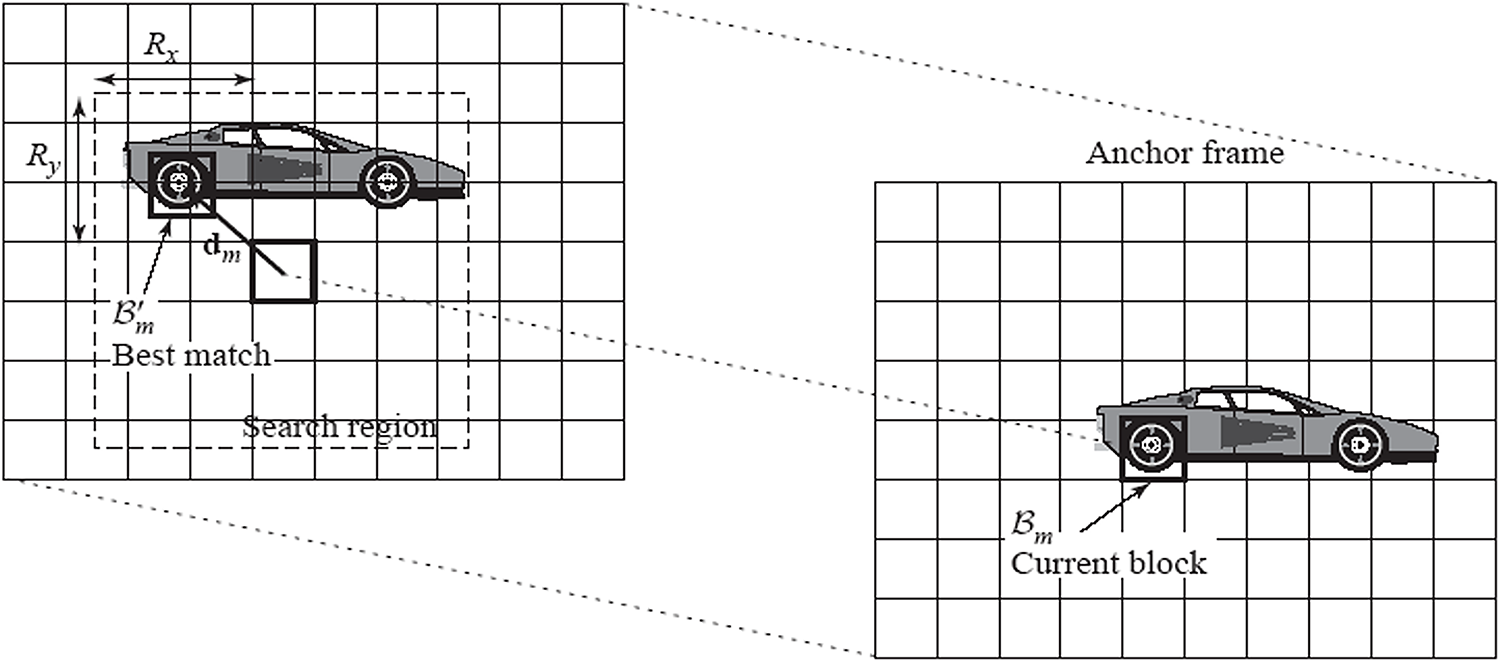

Block-based motion estimation is performed using BMAs, which identify the movement of each block between a pair of frames. Each frame is divided into fixed-size blocks (e.g.,

The block size and search window size have a significant influence on motion field quality. Smaller blocks produce denser motion fields with higher computational costs, while larger blocks generate less dense but computationally efficient fields. A larger search window can yield more refined motion vectors, but also increases computation time.

The process involves dividing frames into blocks, searching for the best match for each block in the previous frame within a predefined search window, and encoding the horizontal and vertical displacements as motion vectors. The aggregation of motion vectors constitutes the motion field for the frame pair. Fig. 3 illustrates this process [28]. Fig. 3 depicts the block matching process using an anchor and current frame, where a block

Figure 3: Estimating motion between consecutive frames using BMAs [28]

This study finds that dense motion fields are not always necessary for an accurate classification. Less dense fields offer better generalization and reduce overfitting. The quality of motion fields is also influenced by the block-matching criteria used during motion estimation. Common similarity metrics include the Sum of Absolute Differences (SAD) and the Mean Squared Error (MSE), which compute the difference between the corresponding pixel intensities in the current and reference blocks. Once the most similar block is identified within the search window, the horizontal and vertical displacement between the current block and the matched block is recorded as a motion vector.

Here,

3.3 Proposed Methodology for Video Classification

In this work, we exploit the motion fields to classify video sequences as an alternative to pixels in the frame for the classification task. We perform this classification using conventional CNNs. We can significantly reduce the computations required for inference by utilizing the motion fields for classification. Furthermore, our experimental results demonstrate that employing motion fields enhances generalization and mitigates network overfitting. Three different CNN architectures are explored to classify the video sequences. These architectures perform classification based on the nature and size of the input. Each network was explored using various sliding window lengths and different block sizes for downsampling frames and motion field vectors, as full-resolution frames are independent of block sizes. Among the competing networks, simpler networks with better generalization and faster convergence are reported. Further details are provided in the next section.

3.3.1 CNN Employing Full-Resolution Frames

In the first scenario, frames from the video sequences are extracted and concatenated to form three-dimensional (3D) arrays. For robust training, we propose using overlapping blocks and concatenating the data in 3D arrays using sliding windows. Let H, W, and N represent the height, width, and number of frames, respectively, in the video sequence and

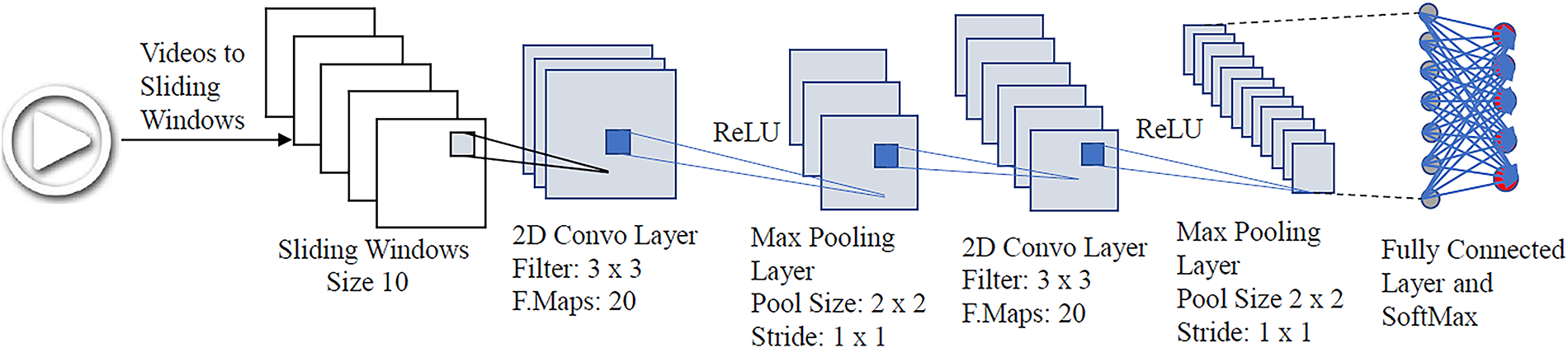

Figure 4: CNN architecture for classification based on the full-resolution frames

3.3.2 CNN Trained with Downsampled Frames

For our second scenario, we reduce the spatial resolution of the frames by downsampling them with a factor of M. This downsampling can be performed by utilizing different pixel decimation patterns. In this work, we employ two very simple sub-sampling patterns. For a fair comparison, we downsampled the frames to match the dimensions of the motion fields constructed by the motion vectors. Hence, if the size of blocks utilized for constructing the motion field was

3.3.3 CNN Exploring Motion Field Extracted from the Frames

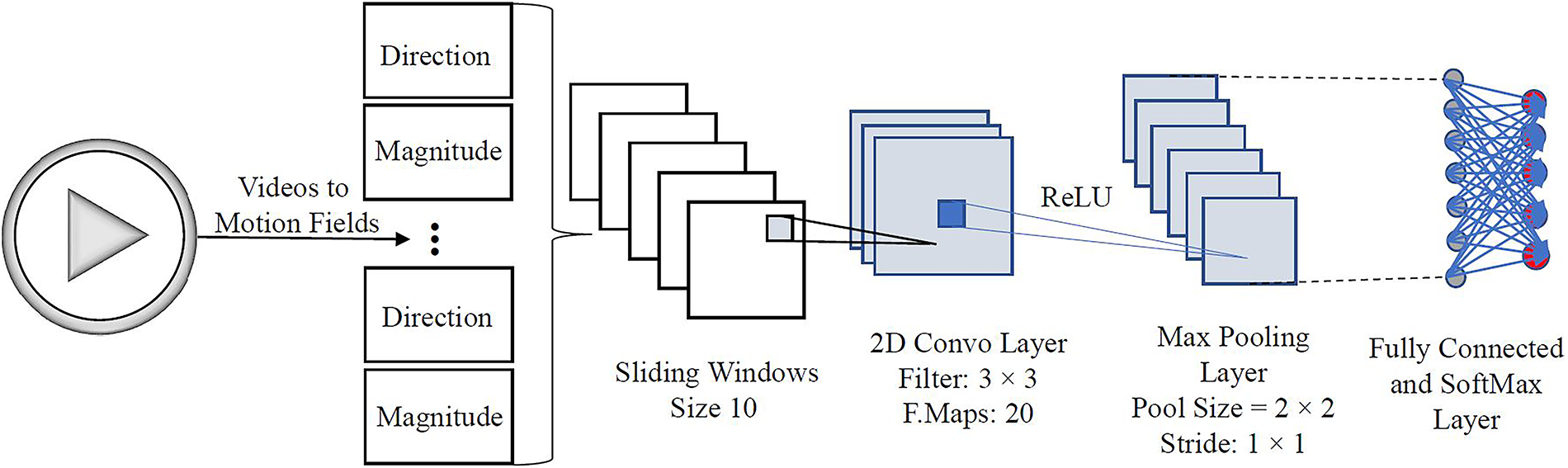

In this configuration, the use of motion fields for video classification is explored. Motion fields are constructed by estimating motion for all blocks in a frame as defined in Section 3.2. As motion vectors are calculated for blocks of size

Figure 5: CNN architecture for classification based on the motion fields

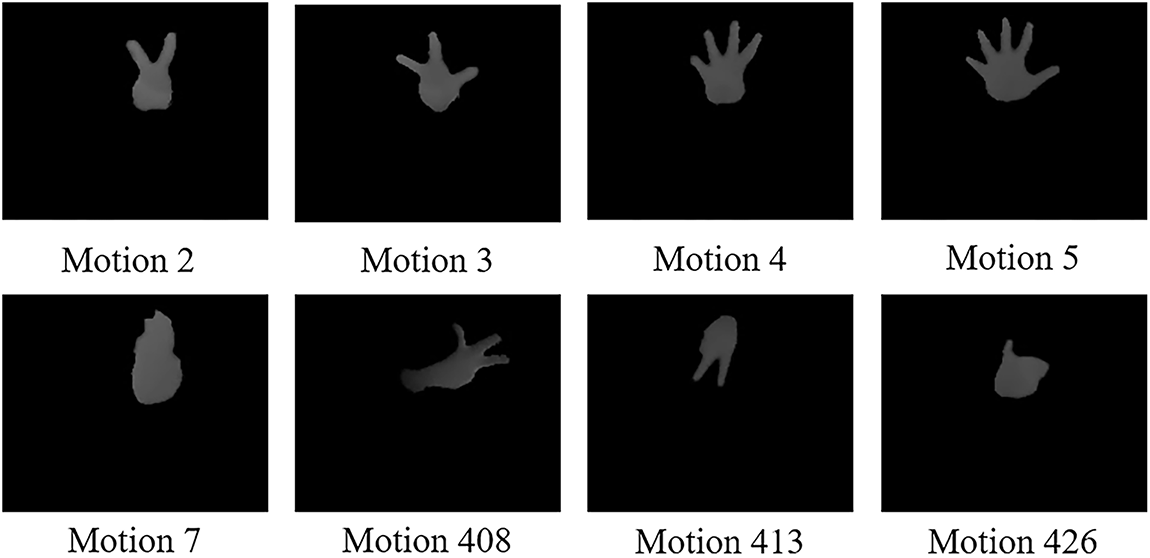

In this work, we evaluate the proposed approach with the hand gesture recognition dataset (HGds) [31] and validate the proposed methodology on the Human Motion DataBase (HMDB51) [32] along with the University of Central Florida (UCF101) dataset [33]. The HGds dataset is partitioned into training and validation sets using an 80:20 ratio, whereas the HMDB51 dataset follows a 70:30 split for training and testing purposes. The HGds dataset comprises several video sequences featuring annotated hand gestures. The dataset is generated by employing 11 subjects. Each subject simulates 5 different videos of the same gesture. These video sequences consist of grayscale frames of

Figure 6: Sample frames and labels from the HGds dataset [31]

The HMDB51 dataset comprises a total of 51 different motions, but the videos are in their raw form, and some of the videos feature almost no motion, such as smiling. We have manually investigated all the videos and filtered out those videos that have either zero motion or are in raw format. After filtration, only 14 motions are selected, which are: cartwheel, catch, climb, climb-stairs, flic-flac, handstand, pullup, pushup, push, bike-ride, ride-horses, situp, sword, and walk. Within these motions, there are an average of 40 videos from different individuals performing the motions.

In addition to HMDB51, we also employ the UCF101 dataset for validation. UCF101 comprises 13,320 unconstrained YouTube videos spanning 101 action categories, grouped into 25 source groups, each with 4–7 clips. The videos are stored at a standard resolution of

The rest of this Section presents experimental evaluations with the input vector in three different forms: pixel representation of size

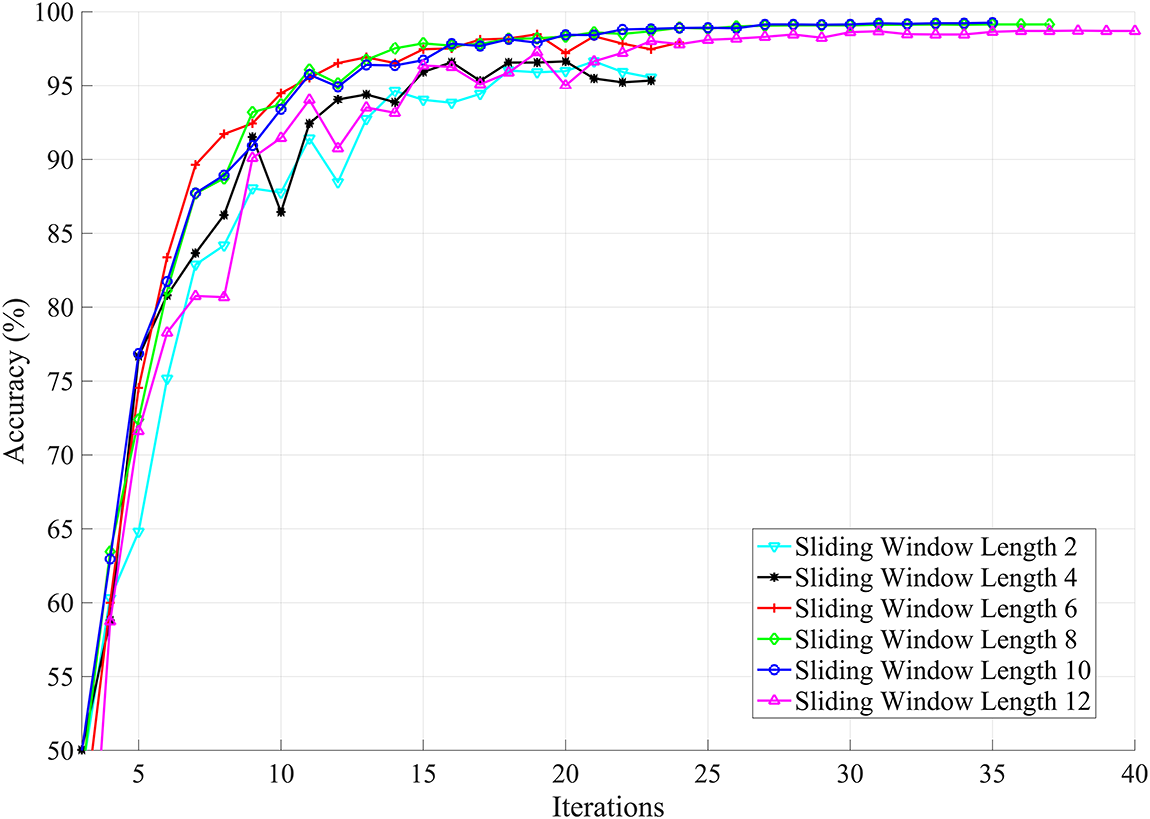

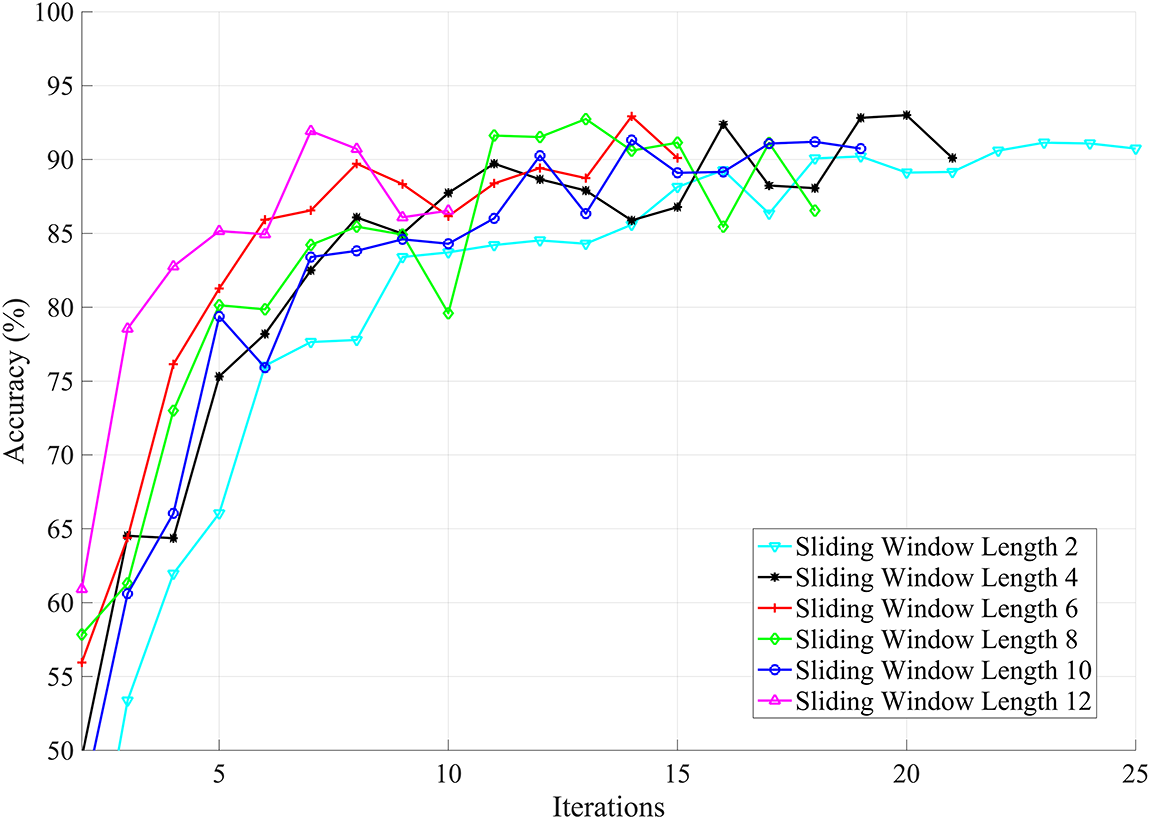

The first experiment trains a CNN to classify video sequences based on pixel intensity levels. For this experiment, the block size is irrelevant since the frames are processed as a whole and no motion estimation is computed. However, the effect of the sliding window’s length is essential and is evaluated through several experiments. A sliding window consists of N consecutive frames and constitutes the input vector. The length of the sliding window, therefore, determines the amount of information available to the network for classification. Fig. 7 represents the classification accuracy for different sliding window configurations. The

Figure 7: The effect of sliding window on accuracy for full-resolution frames. Results are reported on the held-out validation set

Furthermore, for larger windows, performance improvements are observed. However, this also causes an increase in the cost of training and inference. It is therefore crucial to find an optimal sliding window length that strikes a good balance between complexity and accuracy. Our experimental results show that a sliding window of length 10 is optimal among the others.

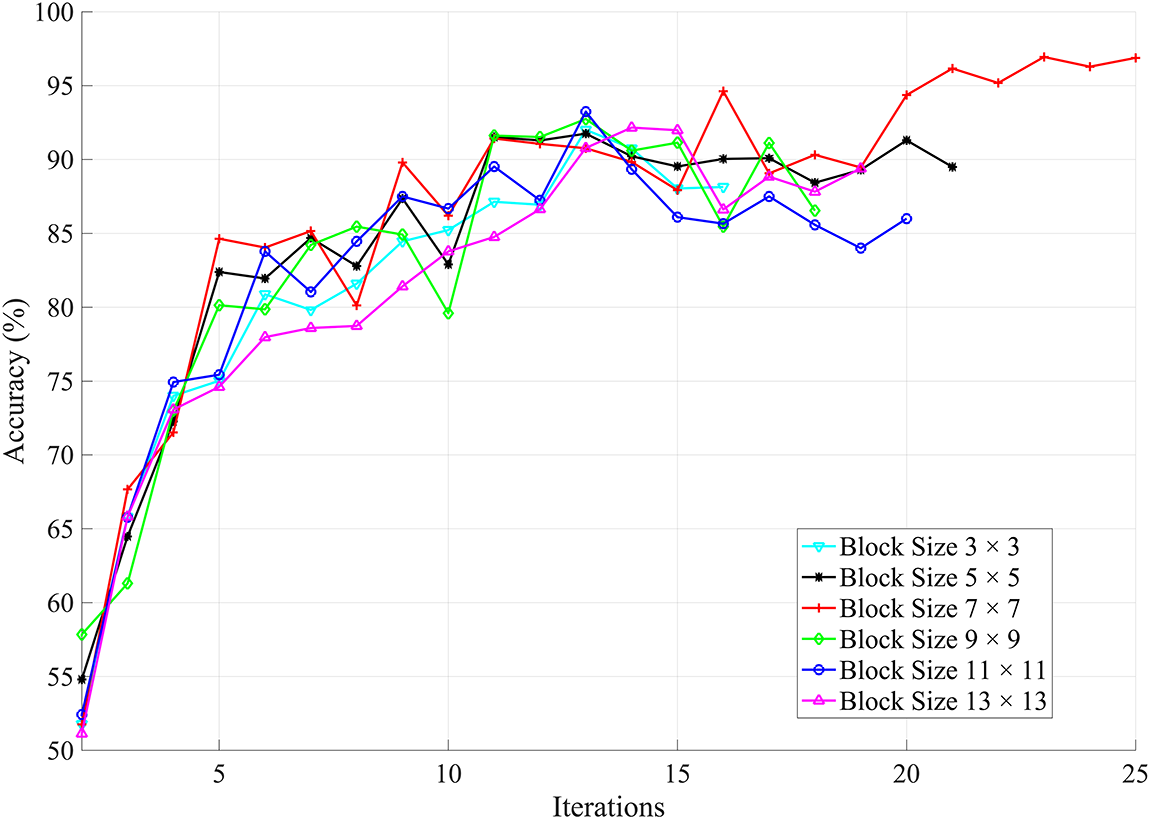

A naive approach to reducing the cost of inference is to randomly downsample the input frames. In the second type of experiment, a shallower network is trained on the downsampled dataset, resulting in reduced computational cost. However, our results show that useful information is lost and the classification performance is negatively affected. We have evaluated two experiments on the downsampled data. In this set of experiments, the length of the sliding window is kept constant while the block size is varied as shown in Fig. 8. A larger block size means greater loss of information and vice versa. It has been observed that even for smaller blocks, network training is not satisfactory, and the validation accuracy is lower compared to the trained network on full-resolution frames. This is attributed to the loss of information due to the initial random downsampling of the input frames. It is, therefore, difficult to obtain improved performance with this network on the downsampled frames. For the same downsampled dataset, another set of experiments is conducted. We kept the block size constant to

Figure 8: Validation accuracy of different blocks for downsampled frames

Figure 9: The effect of varying the sliding window length for downsampled frames. The block size is fixed to

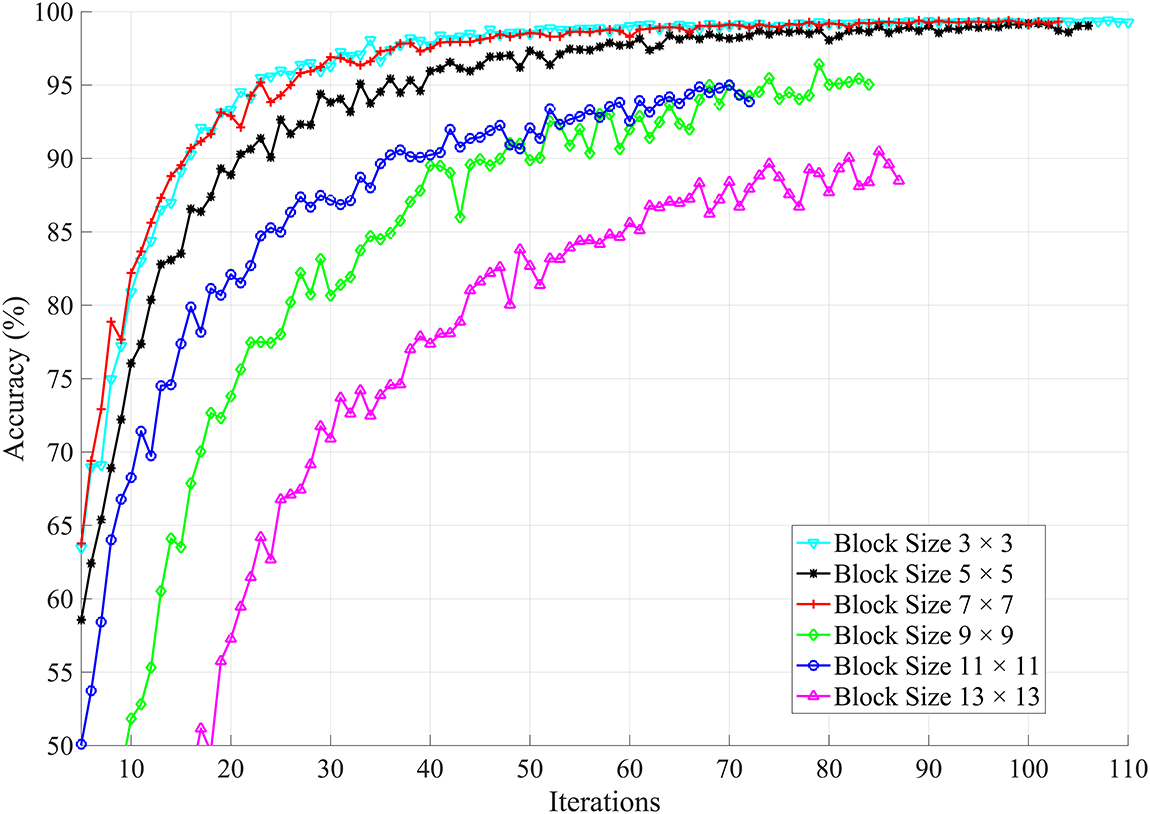

A heuristic approach for reducing the cost of inference involves first computing block-based motion vectors in the video sequence, thereby reducing the input dimensions. In the third set of experiments, a shallow network is trained on the block-based motion field vectors. Fig. 10 shows the effect of varying the block size on the network performance. At the same time, the sliding window is fixed at a length of 10, based on experimental evaluations of full-resolution frames. Larger block sizes mean fewer motion vectors and vice versa. If the block size is too small, the resulting motion field is of large dimension which means lesser acceleration of the network. On the other hand, large block sizes generate low-resolution motion fields which result in faster computation at the cost of performance degradation. We extensively performed experiments to find out an optimal block size for motion estimation that does not affect the network performance and accelerates inference. We conclude that the optimal block size is

Figure 10: The effect of varying the block size for motion field vectors. The sliding window is fixed to 10 frames

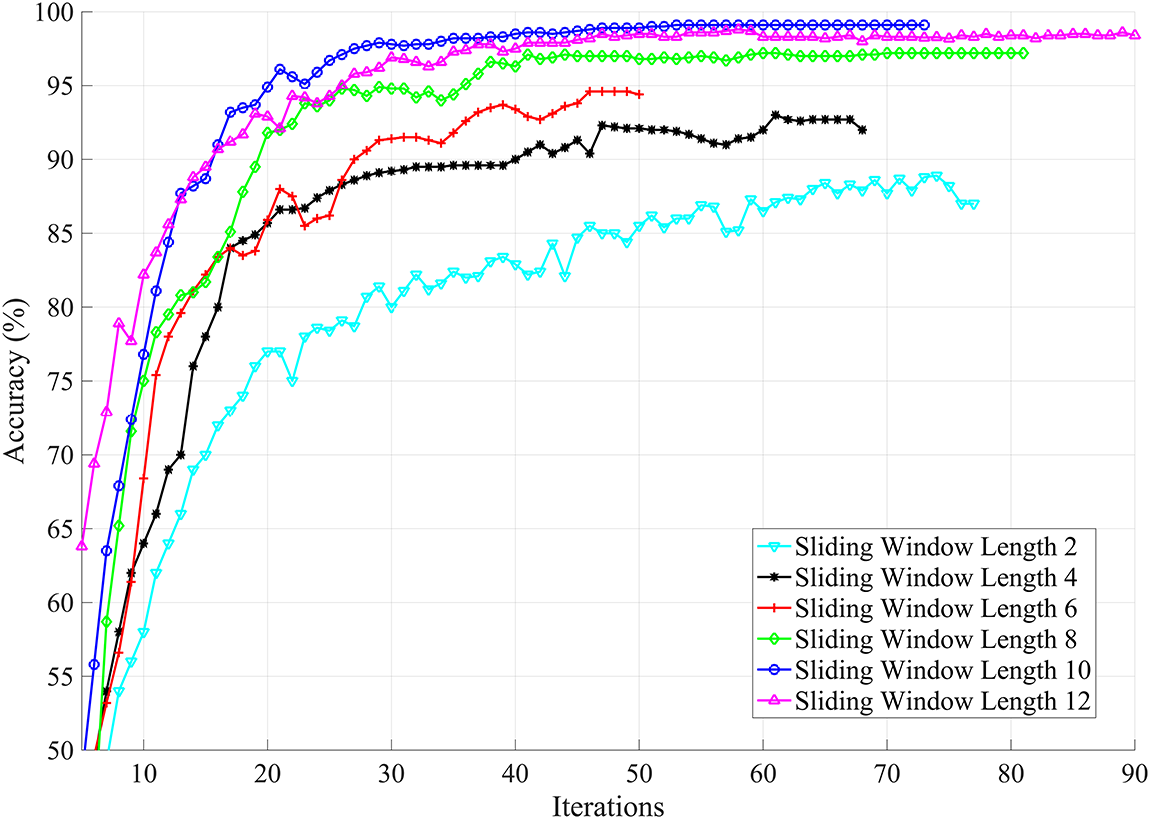

Fig. 11 represents the effect of the sliding window on the network performance, where the block size is kept constant. As shown by earlier experiments, the block size of

Figure 11: For a fixed block size, larger sliding window yield superior results. However, this also increases the cost of inference

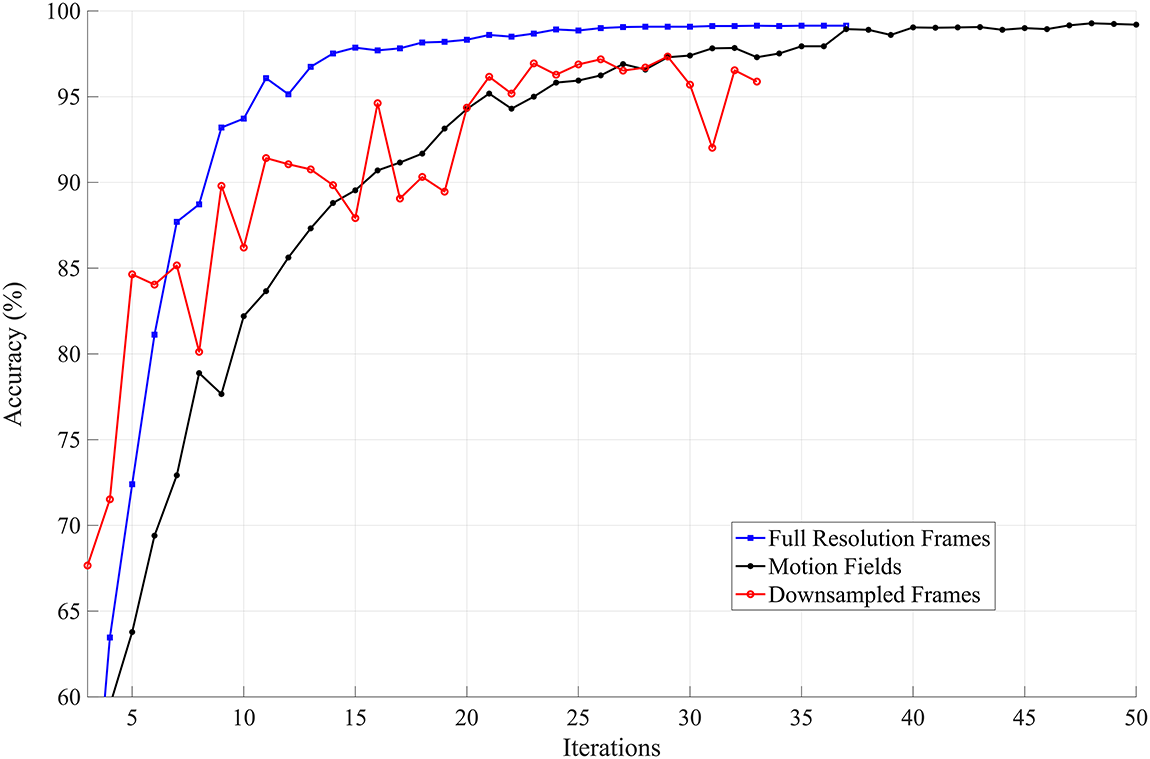

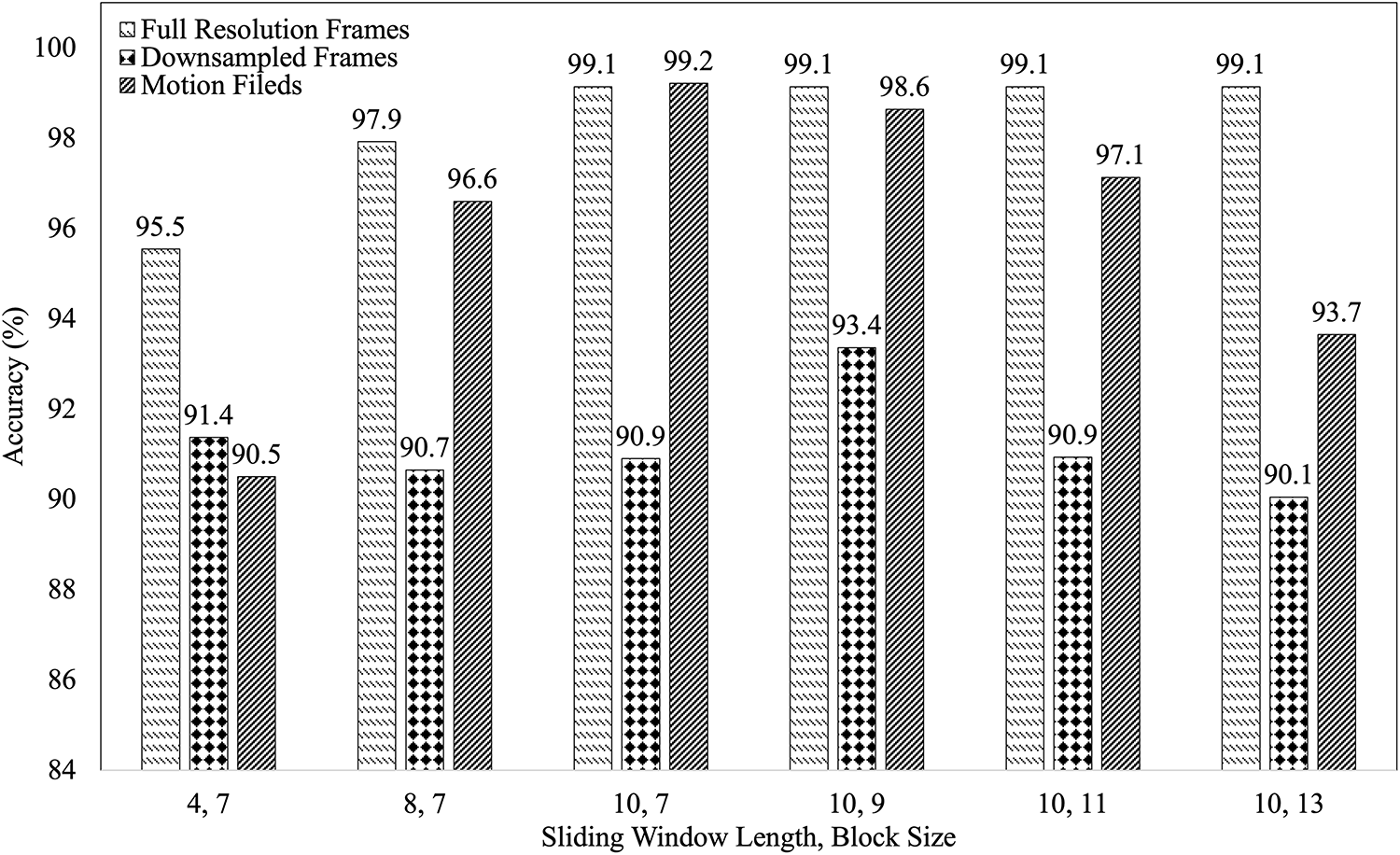

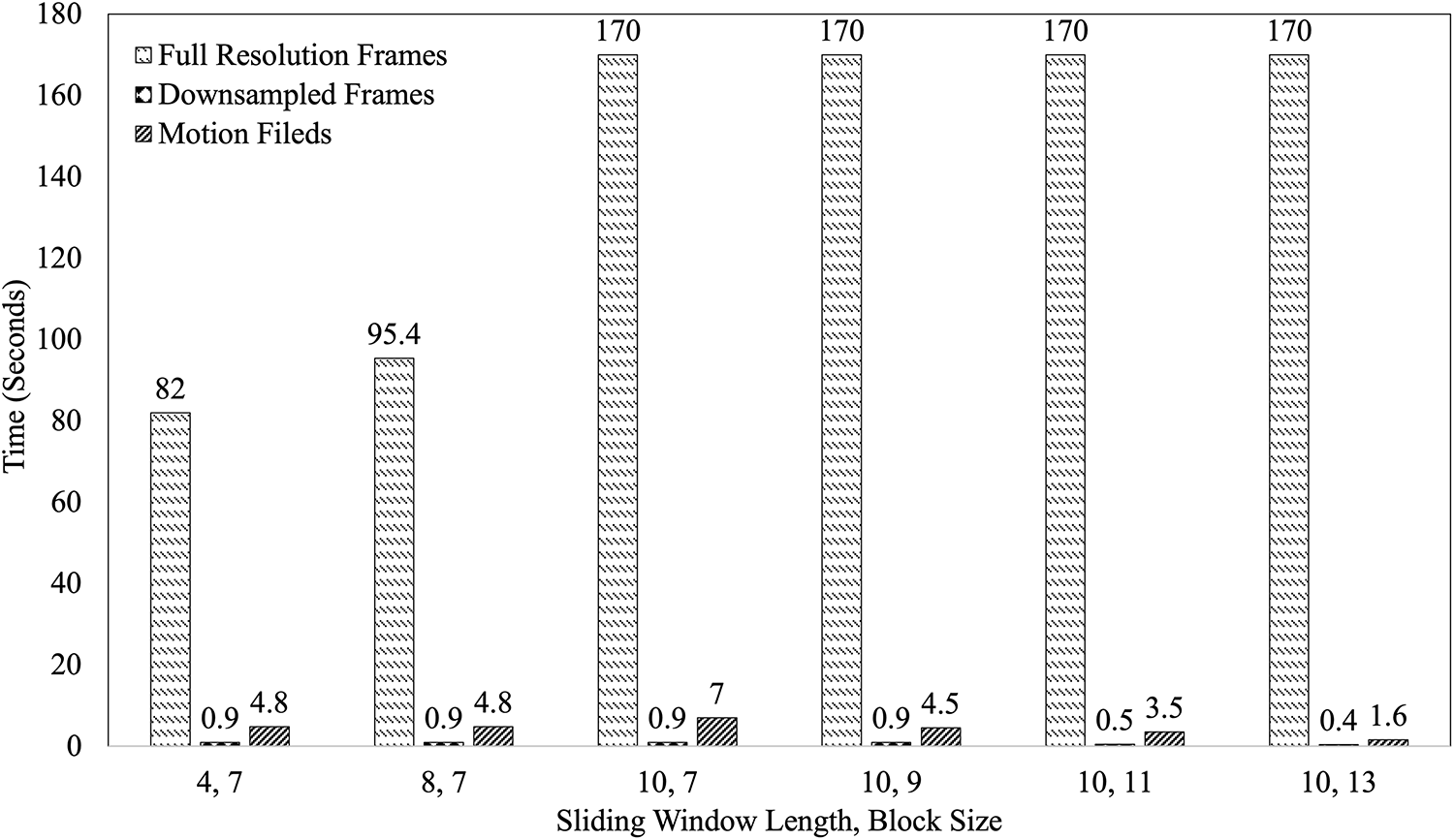

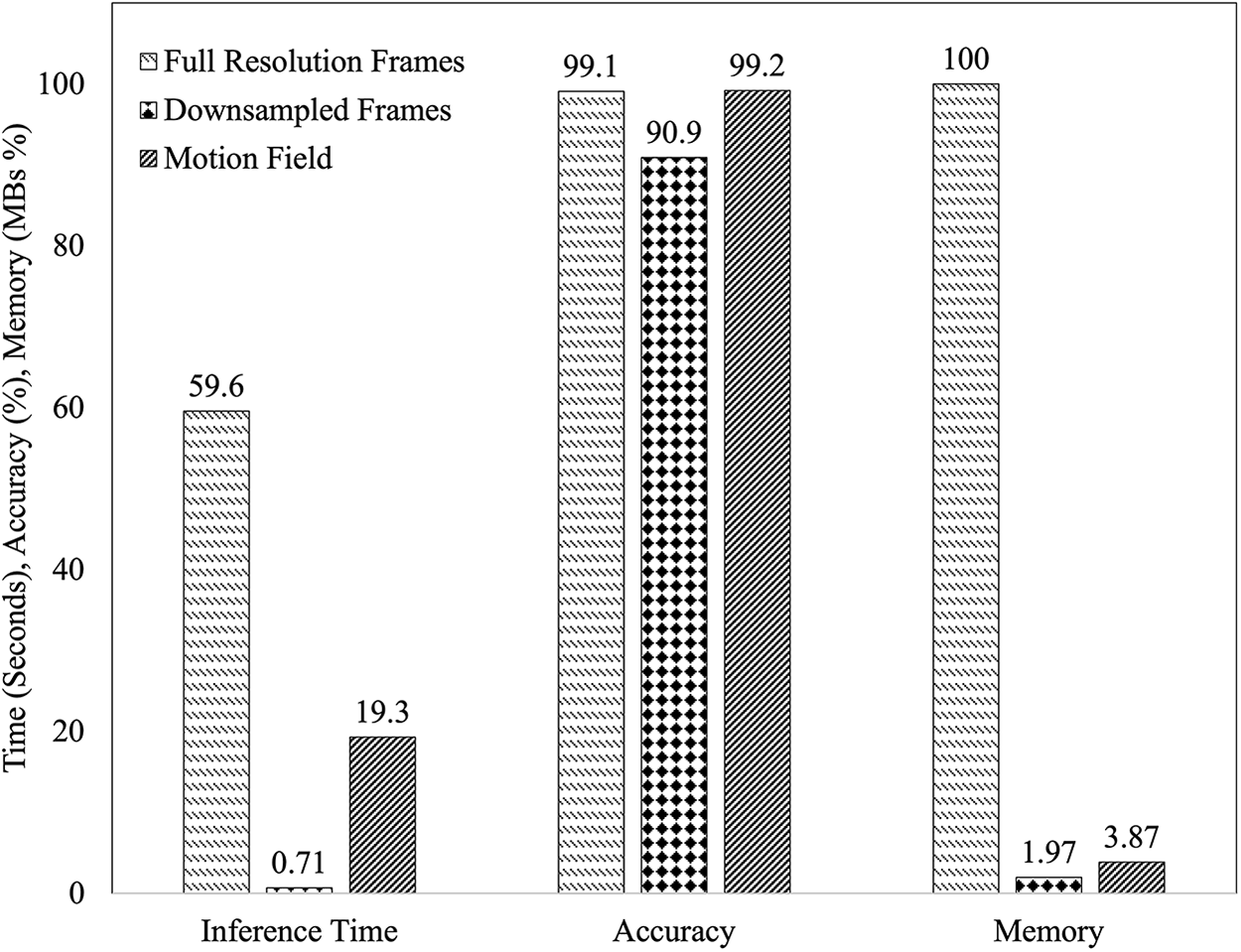

Fig. 12 presents an overall comparison of the networks when motion fields, full-resolution frames, and downsampled frames are used for hand gesture classification. The accuracy plots show that by employing motion fields, we achieve the same accuracy as that of the full-resolution images but with much less computational burden. The best average accuracy for our proposed technique is 99. 21%, which is slightly better than the best average accuracy for the full-resolution frames, i.e., 99.14%. The downsampling of frames results in the worst average accuracy. Although our proposed technique requires more iterations for training, the network’s training is almost 20 times faster than that of the network using full-resolution frames, thanks to the lightweight network. The training time consumed by the motion fields network is comparatively equal to the training time for downsampled frames. However, the performance is similar to the full-resolution frames. Our experiments suggest that employing motion fields enables us to achieve the same accuracy as with full-resolution images, but at a significantly lower computational cost. Fig. 13 compares the approaches described for different sliding windows and block sizes.

Figure 12: The network performance on training data. Results are reported on the held-out validation set

Figure 13: The classification performance comparison of the three approaches for different block sizes and sliding window lengths

Fig. 14 shows the computational complexity of the three approaches. It can be observed that the computational complexity of the original-dimension images is significantly higher compared to the other two approaches. When the length of the sliding window is 10, the time consumed for training is almost 3 h on a 3 GHz Quad-core CPU. Since the input images are of very low dimensions, that is, 144

Figure 14: The inference time comparisons of the three approaches for different block sizes and sliding window lengths

Figure 15: Comparison of accuracy and memory (in percentage) and inference time (in secs). Memory is scaled with 4950.2 MB mapped to 100%

4.2 Validation of the Proposed Method on HMDB51 and UCF101

We further validated the proposed methodology on the HMDB51 and UCF101 datasets, which are more complex and noisy than the HGds dataset. From Section 4, we concluded that a block size of 7

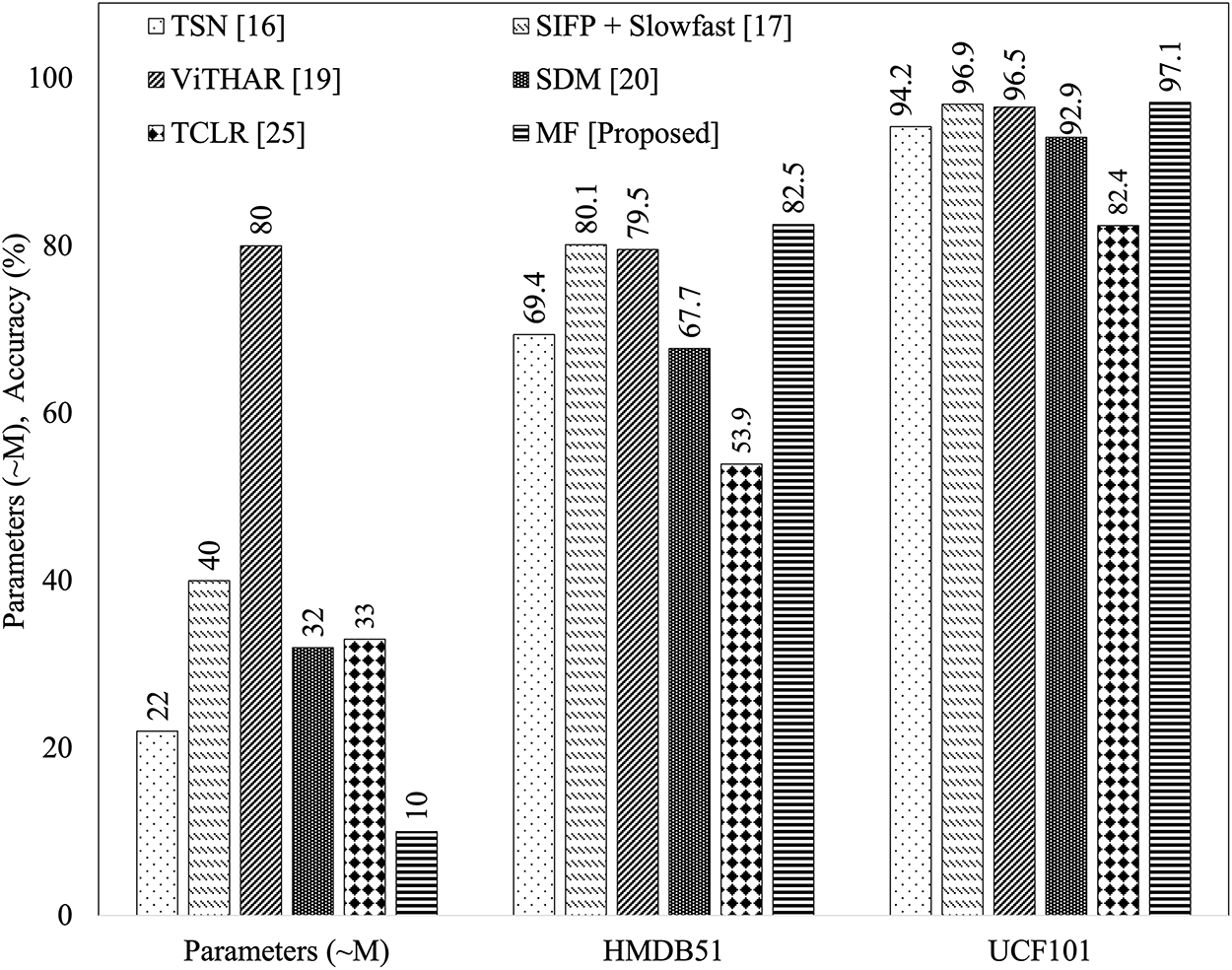

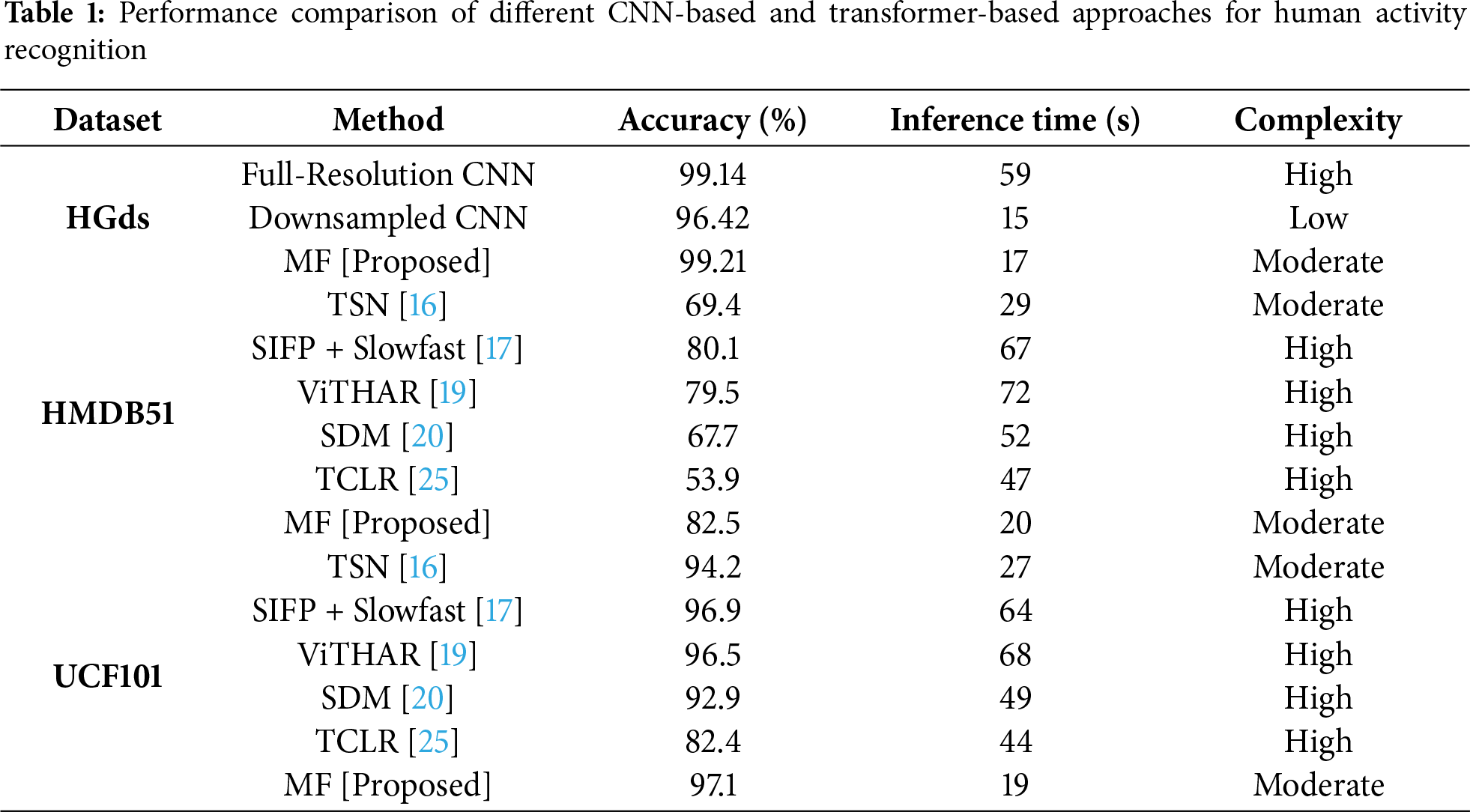

A comparison of recent deep learning-based algorithms for human activity recognition is presented on both the HMDB51 and UCF101 datasets in Fig. 16. The TSN [16] achieved accuracies of 69.4% and 94.2% with approximately 22 M parameters. The SIFP architecture combined with Slowfast [17] improved recognition performance to 80.1% and 96.9% with about 40 M parameters. ViTHAR [19], a transformer-based approach, reported 79.5% and 96.5% accuracies but required nearly 80 M parameters. Spiking neural networks such as SDM [20] achieved 67.7% and 92.9% with 32 M parameters. A contrastive learning method, TCLR [25], achieved accuracies of 53.9% and 82.4% with approximately 33 M parameters.

Figure 16: Accuracy and parameter comparison of the proposed MF method with TSN [16], SIFP+Slowfast [17], ViTHAR [19], SDM [20], and TCLR [25] on the HMDB51 and UCF101 datasets

In comparison, our proposed motion fields (MF) approach significantly outperformed these state-of-the-art methods, achieving accuracies of 82.5% and 97.1% on HMDB51 and UCF101, respectively, while requiring only 10 M parameters. Fig. 16 shows the accuracy and parameter comparisons between the proposed and existing methods on the HMDB51 and UCF101 datasets.

The proposed method leverages motion fields instead of full-resolution frames to improve video classification efficiency. In this section, we analyze the impact of key parameters, including block size and sliding window length, on the performance and computational complexity of the classification task.

The block size used for motion estimation plays a crucial role in determining the trade-off between computational cost and classification accuracy. Smaller block sizes generate denser motion fields, capturing more detailed motion information but increasing the computational overhead. Conversely, larger block sizes reduce the computational burden by simplifying the input representation, though they may sacrifice some motion details, potentially affecting accuracy.

Our experimental results indicate that a block size of

5.2 Effect of Sliding Window Length

The sliding window length determines how many consecutive frames are stacked together to form an input vector for the network. A shorter sliding window provides a limited temporal context, which can accelerate training but may result in lower classification accuracy due to incomplete motion representation. In contrast, a longer sliding window offers a richer temporal context, enhancing the network’s ability to distinguish between complex gestures at the cost of increased computational complexity. However, increasing the sliding window results in model overfitting due to dense CNN architectures.

Empirical evaluation revealed that a sliding window length of 10 provides an optimal trade-off, delivering robust classification performance without imposing excessive resource requirements. This configuration achieved efficient training and inference while maintaining high classification accuracy across multiple datasets.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we compared its performance with both full-resolution and downsampled frame-based CNNs, as well as state-of-the-art approaches such as TSN [16], SIFP+Slowfast [17], ViTHAR [19], SDM [20], and TCLR [25]. Table 1 summarizes the results across three benchmark datasets: HGds, HMDB51, and UCF101.

The results demonstrate that the proposed motion fields (MF) approach achieves similar accuracy to full-resolution CNNs on HGds but with substantially lower inference time and moderate complexity. On HMDB51, the MF approach attained the highest accuracy of 82.5%, outperforming TSN, SIFP+Slowfast, ViTHAR, SDM, and TCLR while being significantly more efficient in terms of inference time. Likewise, on UCF101, the proposed method achieved the top accuracy of 97.1% with only 19 s of inference, demonstrating superior performance and efficiency compared to all state-of-the-art baselines.

The findings emphasize the efficiency of using motion fields for video classification. The dimensionality reduction achieved through block-wise motion estimation does not compromise classification accuracy. The systematic optimization of block size and sliding window length enables the network to strike a balance between computational cost and performance, making the method suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

In conclusion, the proposed approach demonstrates significant improvements in computational efficiency and training time without sacrificing accuracy. The results suggest that motion fields-based classification offers a practical alternative to traditional pixel-based methods, particularly for applications requiring real-time performance on edge devices.

6 Conclusions and Future Directions

This research investigates dimensionality reduction using motion fields to improve the efficiency of video classification in computer vision applications. Traditional methods rely on full-resolution frames, resulting in high computational costs and increased communication bandwidth requirements for cloud-based inference. In contrast, the proposed method leverages motion fields to reduce input dimensions, enabling faster and more efficient inference while maintaining high classification accuracy.

Our results show that the motion-field-based approach offers

Additionally, the use of simpler networks trained on motion fields minimizes the risk of overfitting and enhances generalization. The study validates the viability of motion fields for video classification and demonstrates their potential for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

One of the key advantages of the proposed method is its ability to maintain high classification performance using lightweight CNN architectures, making it suitable for real-time applications on edge or low-power devices. It also eliminates the need for complex motion estimation techniques, such as optical flow, thereby reducing both preprocessing and inference times.

However, the approach also possesses some limitations. The quality of motion fields depends heavily on the block matching parameters and may be sensitive to noise or scene complexity. Additionally, while effective on the selected datasets, further validation is needed across diverse video domains to ensure broader applicability.

In the future, we plan to extend this approach to more complex tasks, such as semantic segmentation, and evaluate its performance on edge devices to support real-time applications. Further optimization of network architectures and input representations may yield additional improvements in both accuracy and efficiency for various real-world scenarios.

Acknowledgement: This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R896), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are grateful to Dr. Sajid Anwar (deceased) for his pioneering contribution in designing and formulating the main idea. Unfortunately, he departed very early without tasting the fruit of his hard work. The authors dedicate this work to him. They are grateful to the Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology, FAST School of Computing, and American University of the Middle East for their technical and logistical support. They are also thankful to the American University of the Middle East and Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for the financial support.

Funding Statement: Supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R896).

Author Contributions: All authors contributed equally to the conceptualization and development of this work. Jalees Ur Rahman was responsible for model design, experimental setup, visualization, and drafting the original manuscript. Muhammad Hanif and Usman Haider managed the data analysis. Muhammad Hanif, Usman Haider and Saeed Mian Qaisar validated the results. Muhammad Hanif, Usman Haider, Saeed Mian Qaisar and Sarra Ayouni reviewed and edited the manuscript. Saeed Mian Qaisar and Sarra Ayouni secured financial support. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The study utilizes publicly available online datasets. All dataset references and access links are included in the paper. No proprietary or restricted data were used. The authors confirm that all data can be accessed from the online repositories cited.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pal SK, Pramanik A, Maiti J, Mitra P. Deep learning in multi-object detection and tracking: state of the art. Appl Intell. 2021;51(21):6400–29. doi:10.1007/s10489-021-02293-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Manakitsa N, Maraslidis GS, Moysis L, Fragulis GF. A review of machine learning and deep learning for object detection, semantic segmentation, and human action recognition in machine and robotic vision. Technologies. 2024;12(2):15. doi:10.3390/technologies12020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Haider U, Hanif M, Rashid A, Hussain SF. Dictionary-enabled efficient training of ConvNets for image classification. Image Vis Comput. 2023;135(1):104718. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2023.104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Talaei Khoei T, Ould Slimane H, Kaabouch N. Deep learning: systematic review, models, challenges, and research directions. Neural Comput Applicat. 2023;35(31):23103–24. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-08957-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lyu Z, Yu T, Pan F, Zhang Y, Luo J, Zhang D, et al. A survey of model compression strategies for object detection. Multim Tools Applicat. 2024;83(16):48165–236. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17192-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Anwar S, Hwang K, Sung W. Structured pruning of deep convolutional neural networks. ACM J Emerg Technol Comput Syst (JETC). 2017;13(3):32. doi:10.1145/3005348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1251–8. [Google Scholar]

8. Anwar S, Hwang K, Sung W. Fixed point optimization of deep convolutional neural networks for object recognition. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2015 Apr 19–24; Brisbane, QLD, Australia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1131–5. [Google Scholar]

9. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhang X, Zhou X, Lin M, Sun J. Shufflenet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 6848–56. [Google Scholar]

11. Freeman I, Roese-Koerner L, Kummert A. Effnet: an efficient structure for convolutional neural networks. In: 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2018 Oct 7–10; Athens, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

12. Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, Sermanet P, Reed S, Anguelov D, et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

13. Szegedy C, Ioffe S, Vanhoucke V, Alemi AA. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In: Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017 Feb 4–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press. p. 4278–84. [Google Scholar]

14. Sietsma, Dow. Neural net pruning-why and how. In: IEEE 1988 International Conference On Neural Networks; 1988 Jul 24–27;San Diego, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 325–33. [Google Scholar]

15. Gedeon T, Harris D. Progressive image compression. In: Proceedings of 1992 IJCNN International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1992. p. 403–7. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang L, Xiong Y, Wang Z, Qiao Y, Lin D, Tang X, et al. Temporal segment networks: towards good practices for deep action recognition. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Swizterland: Springer; 2016. p. 20–36. [Google Scholar]

17. Li J, Wei P, Zhang Y, Zheng N. A slow-i-fast-p architecture for compressed video action recognition. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2020 Oct 12–16; Seattle, WA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM. p. 2039–47. [Google Scholar]

18. Surek GAS, Seman LO, Stefenon SF, Mariani VC, Coelho LDS. Video-based human activity recognition using deep learning approaches. Sensors. 2023;23(14):6384. doi:10.3390/s23146384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Divya Rani R, Prabhakar C. ViTHAR: vision transformers for human action recognition in videos. In: 024 Fourth International Conference on Multimedia Processing, Communication & Information Technology (MPCIT); 2024 Dec 13–14; Shivamogga, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 358–63. [Google Scholar]

20. You H, Zhong X, Liu W, Wei Q, Huang W, Yu Z, et al. Converting artificial neural networks to ultralow-latency spiking neural networks for action recognition. IEEE Transact Cognit Develop Syst. 2024;16(4):1533–45. doi:10.1109/tcds.2024.3375620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Murugan N, Sathasivam S. Real-time human action recognition by using R (2+1) D convolutional neural network. In: 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence For Internet of Things (AIIoT). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

22. Zhang B, Wang L, Wang Z, Qiao Y, Wang H. Real-time action recognition with enhanced motion vector CNNs. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 2718–26. [Google Scholar]

23. True J, Khan N. Motion vector extrapolation for video object detection. J Imaging. 2023;9(7):132. doi:10.3390/jimaging9070132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang M, Yi Y, Tian G. A new depth residual network combined recurrent with residual structure for human action recognition from videos. In: Wu F, Liu J, Chen Y, editors. International Conference on Computer Graphics, Artificial Intelligence, and Data Processing (ICCAID 2021). Bellingham, WA, USA: SPIE; 2022. Vol. 12168, p. 34–8. [Google Scholar]

25. Dave I, Gupta R, Rizve MN, Shah M. TCLR: temporal contrastive learning for video representation. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2022;219:103406. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2022.103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Guberman N. On complex valued convolutional neural networks. arXiv:1602.09046. 2016. [Google Scholar]

27. Sheng X, Yang Y. Human activity recognition with WiFi channel state information by complex-valued neural network. In: 2025 37th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1275–80. [Google Scholar]

28. Pandian SIA, Bala GJ, George BA. A study on block matching algorithms for motion estimation. Int J Comput Sci Eng. 2011;3(1):34–44. [Google Scholar]

29. Bhavsar DD, Gonawala RN. Three step search method for block matching algorithm. In: Proceedings of IRF International Conference; 2014 Apr 13; Pune, India. p. 101–4. [Google Scholar]

30. Je C, Park HM. Optimized hierarchical block matching for fast and accurate image registration. Signal Process Image Commun. 2013;28(7):779–91. doi:10.1016/j.image.2013.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Molina J, Pajuelo JA, Escudero-Viñolo M, Bescós J, Martínez JM. A natural and synthetic corpus for benchmarking of hand gesture recognition systems. Mach Vision Appl. 2014;25(4):943–54. doi:10.1007/s00138-013-0576-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kuehne H, Jhuang H, Garrote E, Poggio T, Serre T. HMDB: a large video database for human motion recognition. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2011 Nov 6–13; Barcelona, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 2556–63. [Google Scholar]

33. Soomro K, Zamir AR, Shah M. Ucf101: a dataset of 101 human actions classes from videos in the wild. arXiv:1212.0402. 2012. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools