Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

EARAS: An Efficient, Anonymous, and Robust Authentication Scheme for Smart Homes

1 Department of Cybersecurity, Air University Islamabad, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

2 Department of Computer Science, Air University Islamabad, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer, Qassim University, Buraydah, 51452, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Information Systems, Taraz University named after M.Kh.Dulaty, Taraz, 080000, Kazakhstan

5 Institute of Computer Science and IT, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Peshawar, 25130, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Suliman A. Alsuhibany. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 30 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071452

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Cyber-criminals target smart connected devices for spyware distribution and security breaches, but existing Internet of Things (IoT) security standards are insufficient. Major IoT industry players prioritize market share over security, leading to insecure smart products. Traditional host-based protection solutions are less effective due to limited resources. Overcoming these challenges and enhancing the security of IoT Devices requires a security design at the network level that uses lightweight cryptographic parameters. In order to handle control, administration, and security concerns in traditional networking, the Gateway Node offers a contemporary networking architecture. By managing all network-level computations and complexity, the Gateway Node relieves IoT devices of these responsibilities. In this study, we introduce a novel privacy-preserving security architecture for gateway-node smart homes. Subsequently, we develop Smart Homes, An Efficient, Anonymous, and Robust Authentication Scheme (EARAS) based on the foundational principles of this security architecture. Furthermore, we formally examine the security characteristics of our suggested protocol that makes use of methodology such as ProVerif, supplemented by an informal analysis of security. Lastly, we conduct performance evaluations and comparative analyses to assess the efficacy of our scheme. Performance analysis shows that EARAS achieves up to 30% to 54% more efficient than most protocols and lower computation cost compared to Banerjee et al.’s scheme, and significantly reduces communication overhead compared to other recent protocols, while ensuring comprehensive security. Our objective is to provide robust security measures for smart homes while addressing resource constraints and preserving user privacy.Keywords

The IoT rapid expansion underscores the importance of security protocols in various industries, including smart homes, healthcare, industrial automation, and transportation, enhancing quality of life for disadvantaged communities [1]. IoT devices offer automation and real-time data analysis, but also pose security risks due to vulnerabilities and unauthorized access, with many users unaware of these risks [2]. Robust authentication mechanisms are crucial for data integrity and confidentiality in IoT environments, but conventional cryptographic techniques may struggle with limited resources and evolving ecosystems. Important studies [3] highlight the need for improved security architecture in IoT environments, focusing on encryption, authentication, and addressing potential security risks such as malicious attacks, data leaks, and unauthorized user access, thereby enhancing system functionality and user privacy [4]. Solutions balance security and resource efficiency, enabling secure IoT device authentication with minimal computational overhead. Various schemes use symmetric or asymmetric encryption in smart home environments such as PrivHome [5] and SKIA-SH [6] emphasize symmetric lightweight efficiency, while asymmetric schemes such as Shuai et al. [7] and Dey and Hossain [8] offer stronger security at the cost of computational overhead [9]. Smart home automation is designed to provide personalized services to homeowners, focusing on convenience, energy efficiency, security, and timely operations within the home. However, each approach has its limitations, with symmetric key schemes being lightweight but prone to vulnerabilities, and asymmetric schemes offering high security at the cost of computational complexity. Researchers propose secure smart home authentication methods to enhance user experience and optimize IoT interfaces, addressing vulnerabilities like parallel session attacks and user impersonation [10].

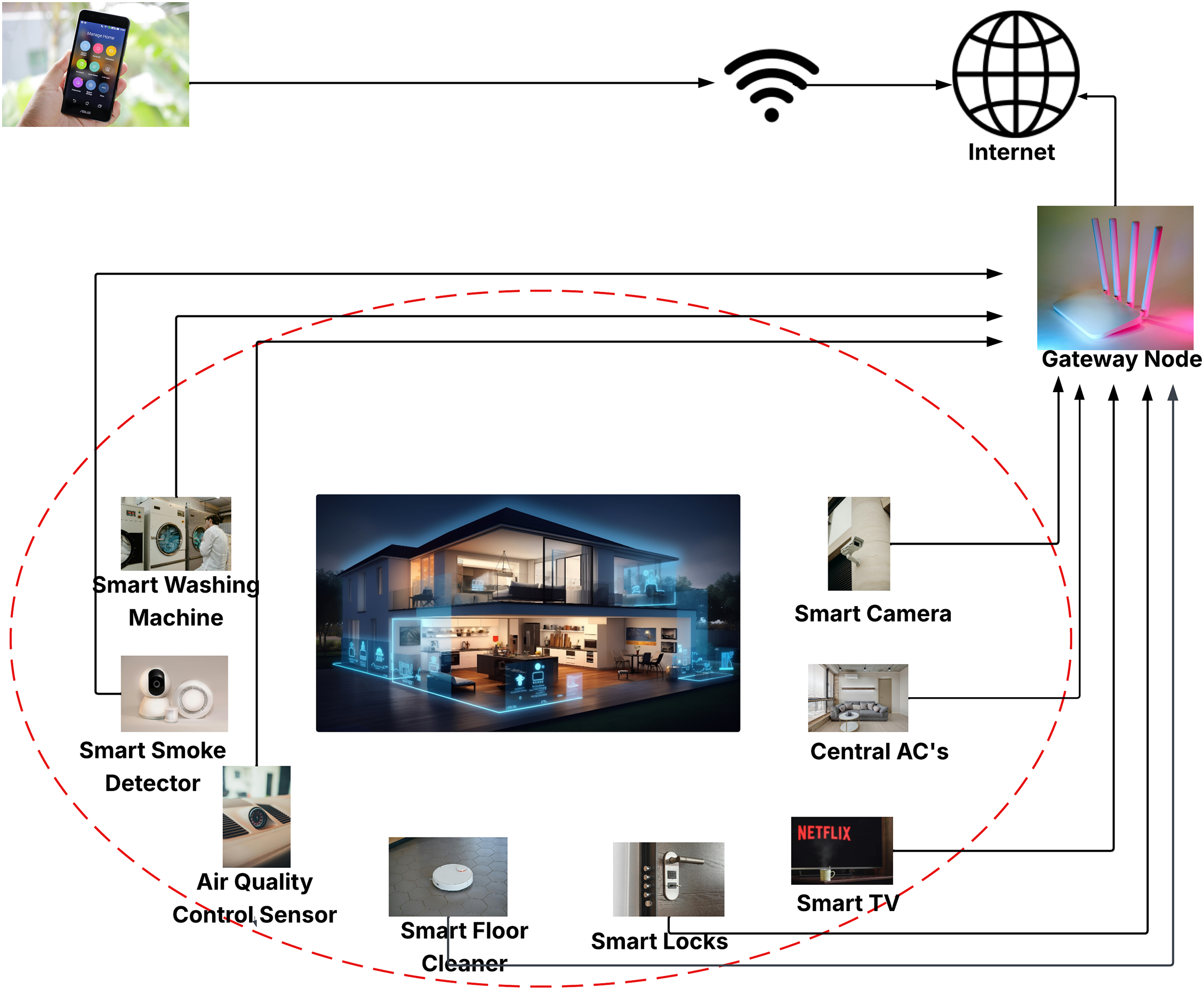

A proposed privacy-protective scheme for smart meters in decentralized smart homes uses consortium blockchain for secure data storage and elliptic curve point multiplication for enhanced efficiency, demonstrating improved results [11]. For smart home applications, Shuai et al. suggest An anonymous authentication system based on Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) that uses the random number approach to thwart clock synchronization problems and replay assaults [7], Ali et al. [12]. A proposed privacy-protective scheme for smart meters in decentralized smart homes uses consortium blockchain for secure data storage and elliptic curve point multiplication for enhanced efficiency, demonstrating improved results. A secure session key establishment protocol was introduced by Dey and Hossian [8] that uses public key cryptosystems for smart home settings. They demonstrated that their protocol is resilient to various attacks. However, some researchers [13] have identified several security weaknesses in Dey and Hossian’s protocol [8], including susceptibility to device compromise and known-key attacks, as well as its failure to guarantee anonymity and confidentiality. Robust and lightweight mutual-authentication scheme (RLMA), a lightweight mutual authentication technique for safe connections in resource-constrained smart environments, was presented by Monga, Kim, Kumar, G.S. Gaba, and Kumar in 2020. It performs better than current systems, as confirmed by security analysis and performance evaluation [13]. The smart home architecture diagram shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Smart homes architecture diagram

The novelty of EARAS compared to prior authentication schemes lies in:

• Anonymity: Ensures that user identities remain concealed during the authentication process, preventing tracking and profiling.

• Privacy Protection against Eavesdropping: Safeguards sensitive communication from being intercepted and exploited by adversaries.

• Resistance to Replay Attacks: Effectively detects and blocks repeated authentication attempts using captured credentials, maintaining system integrity.

Research on smart home authentication has evolved along several key directions. Lightweight symmetric-key approaches have been widely explored due to their efficiency for resource-constrained IoT devices. For example, PrivHome [5] and SKIA-SH [6] utilize symmetric primitives to provide authenticated communication with low computational cost. These methods improve practicality but often face limitations in resisting insider attacks, stolen verifiers, and ensuring full anonymity. Similarly, Fakroon et al. [14] focused on low-cost authentication, but their schemes remain vulnerable to impersonation and parallel session attacks. A comprehensive survey on IoT authentication schemes and their security assessment has been presented in recent work [15]. Asymmetric and ECC-based approaches offer stronger cryptographic assurances. Shuai et al. [7] developed an ECC-based anonymous authentication scheme resilient against replay and synchronization attacks. Dey and Hossain [8] introduced a public key-based session establishment protocol, while Zhang et al. [16] proposed a lightweight Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) protocol for smart grids. Although effective against many attacks, these protocols increase computational and communication overhead, reducing their feasibility in smart home contexts. Biometric and multi-factor schemes represent another trend. Hussain and Chaudhry [17] introduced a cloud-based privacy-preserving biometric system for IoT, while Irshad et al. [18] employed fuzzy extractors for secure key agreement. Such works improve resistance against stolen verifiers and impersonation attacks but raise privacy concerns and require more complex infrastructure. Comparative analyses and surveys (e.g., [19–22]) consistently highlight gaps in existing schemes. Kaur and Kumar [23] showed weaknesses in two-factor schemes, proposing improvements but still leaving traceability and scalability issues unresolved. Reviews such as AlJanah et al. [20] and Yan et al. [21] emphasize the need for multi-level, interaction-based authentication and more energy-efficient gateway protocols. According to Gope et al. (2025), IoT authentication can be achieved through a lightweight and privacy-preserving reconfigurable scheme [24].

We seek to design an authentication scheme that strongly resists impersonation, replay attempts, weak anonymity, and eavesdropping. Our proposed EARAS scheme fulfills these goals by ensuring anonymity through the encryption of user and mobile identities, safeguarding privacy with shared secret keys that protect session data from eavesdropping, and resisting replay attacks using session counters, nonces, and hash-based randomness, thereby offering a robust and privacy-preserving authentication framework for smart homes.

3 Review of Banerjee’s et al. Scheme [25]

This paper discusses security concerns with anonymous user authentication in smart home settings, highlighting the growing importance of IoT and the vulnerability of sensitive information. It proposes a new scheme that maintains efficiency, improves security, and includes remote registration for reduced communication and computation overheads.

3.1 Adversary Model and Assumptions

Before presenting the attacks on Banerjee’s et al. scheme, we first define the assumed adversary model and the underlying assumptions to clearly state the security context. The adversary

• Insider Threat: A privileged insider (e.g., administrator or registration authority staff) may access stored verifier tables or system parameters, thereby gaining sensitive information such as

• Stolen Verifier Assumption: If the Gateway Node (GWN) is compromised, the adversary can obtain the master key MK and other authentication values stored on the device.

• Eavesdropping and Tampering: The adversary can intercept, replay, and modify authentication messages exchanged over the public channel between the user, GWN, and IoT device (SD).

• Attack Surfaces: The protocol is vulnerable at multiple points of interaction: (i) user-to-GWN communication, (ii) GWN-to-SD communication, and (iii) registration authority storage.

These assumptions define the boundaries under which the subsequent attacks are analyzed. Based on this adversary model, the vulnerabilities in Banerjee’s et al. scheme are detailed in the following subsections.

3.2 Stolen Gateway Node Attack

Let an adversary (

3.3 Attack Using Tampered Verifier

In the scheme of Banerjee et al. [25], a verifier table is maintained over the Registration Authority (RA), which contains the parameters

Banerjee’s study demonstrates that a successful authentication can be forged by

1. The adversary (

2. The

3. By employing Eq. (1),

4. Next

5. Finally,

After receiving the message, GWN will compute the following to check the legitimacy of the user:

1. First, the Gateway Node retrieves

2. Next GWN will compute

and

3. Finally, the Gateway Node verifies user authenticity by confirming whether

The attacker fakes a login so the gateway thinks it’s the real user.

3.5 Attack Using a Fake Gateway Node Directed towards SD

After authenticating the user, GWN will send a message containing

The

Upon receiving the message SD will compute the following:

1. First, the SD will extract

2. Now the

So, the Eq. (10) will be true and authentication achieved successfully, hence the protocol is prone to the impersonation attack by GWN. The attacker pretends to be the gateway and sends false commands to devices.

3.6 Gateway Node Impersonation Attack towards User

As shown in Section 3.7 that an

1. Firstly

2.

3. Finally,

The protocol is susceptible to Gateway Node impersonation attack on the user, as U checks the authenticity of the GWN by checking the condition

3.7 IoT Device Impersonation & Parallel Session Attack

The message’s address can enable an

1. Now if

2.

3. The

Hence from Eq. (16) It is evident that the protocol is susceptible to parallel session key attack.

4.

Following receipt of the message, GWN will follow these steps to verify the validity of the IoT Device:

1. GWN will retrieve

2. The GWN will check the subsequent equation to authenticate the Smart dev.

The Eq. (21) will be passed successfully as

This section introduces a lightweight anonymous authentication protocol for two GWN-enabled smart home scenarios, ensuring privacy and security by requiring smart entities to authenticate and confirm message freshness.

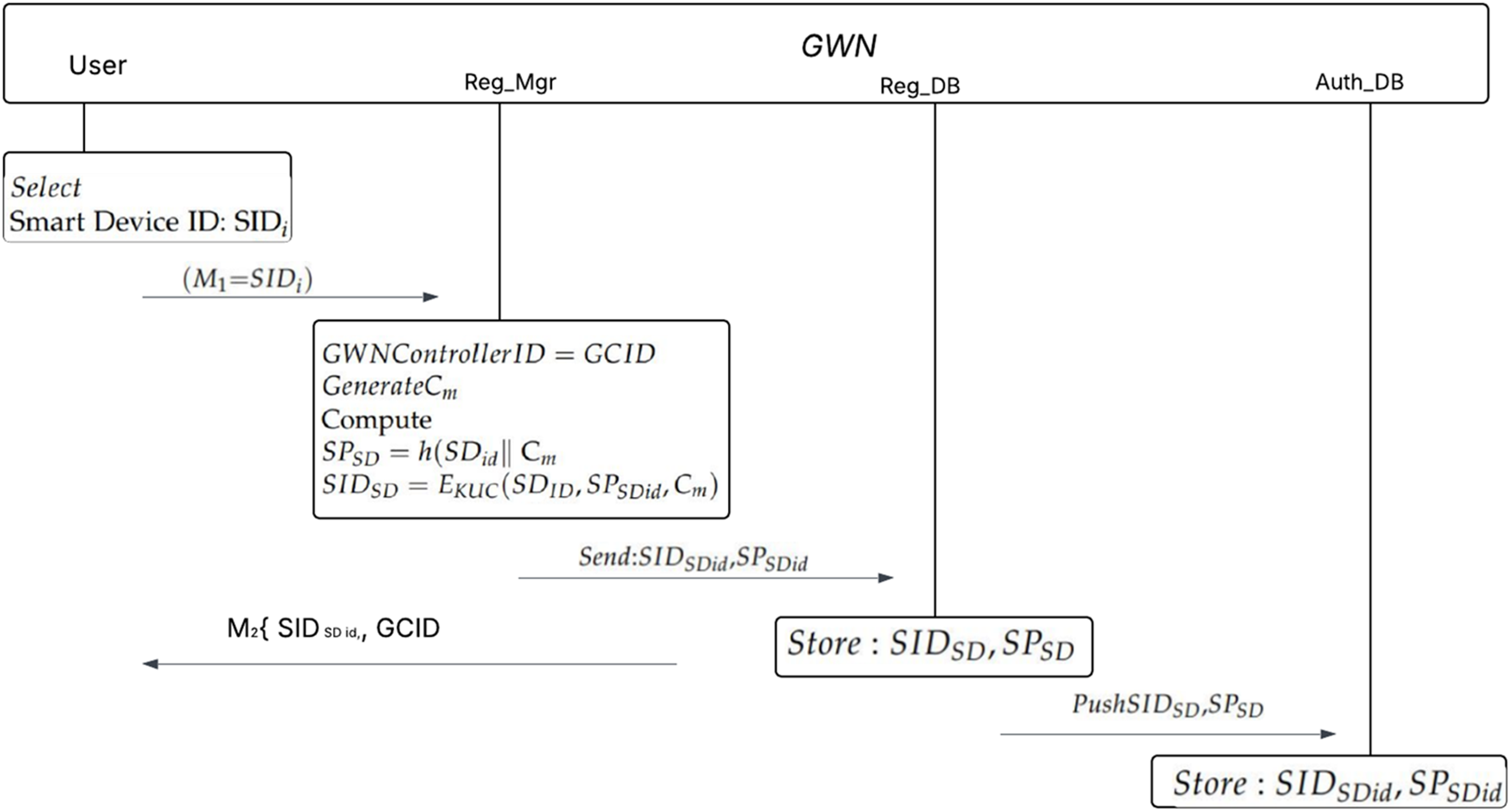

4.1 User to GWN Proposed Registration Scheme

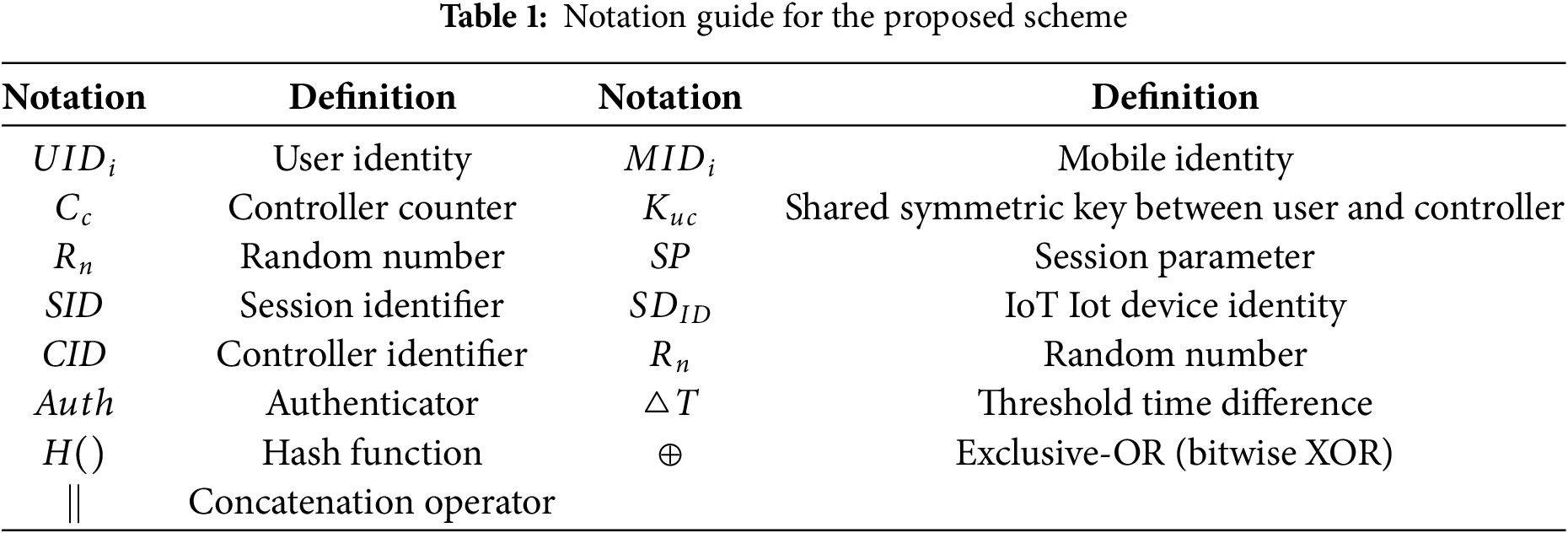

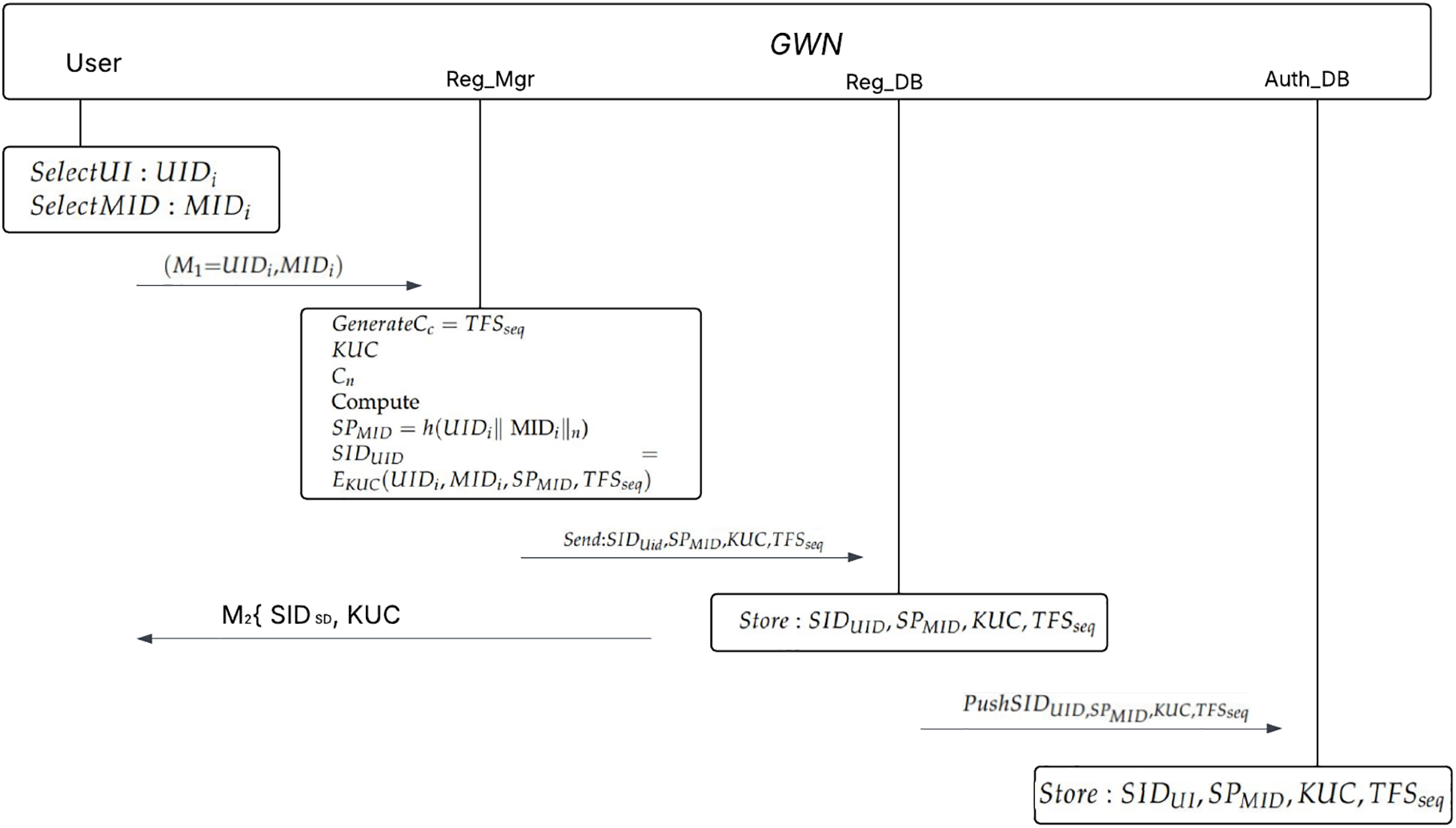

The registration process for smart home users using mobile devices involves two main stages: IoT smart device and user registration in Fig. 2. Notations of the proposed scheme as shown in Table 1.

Figure 2: User to GWN controller registration scheme

The smart home administrator is responsible for configuring the GWN controller and managing user and IoT device registration. The steps in the process are as follows:

• User IDs (UID) and mobile phone (MID) identities are linked, with each user requesting registration from a secure channel.

• The GWN controller uses a 64-bit counter,

4.2 Iot Device to GWN Proposed Registration Scheme

1) Similarly, the SD with identity

2) The GWN controller CID plus a nonce

Figure 3: Iot Device To GWN controller registration scheme

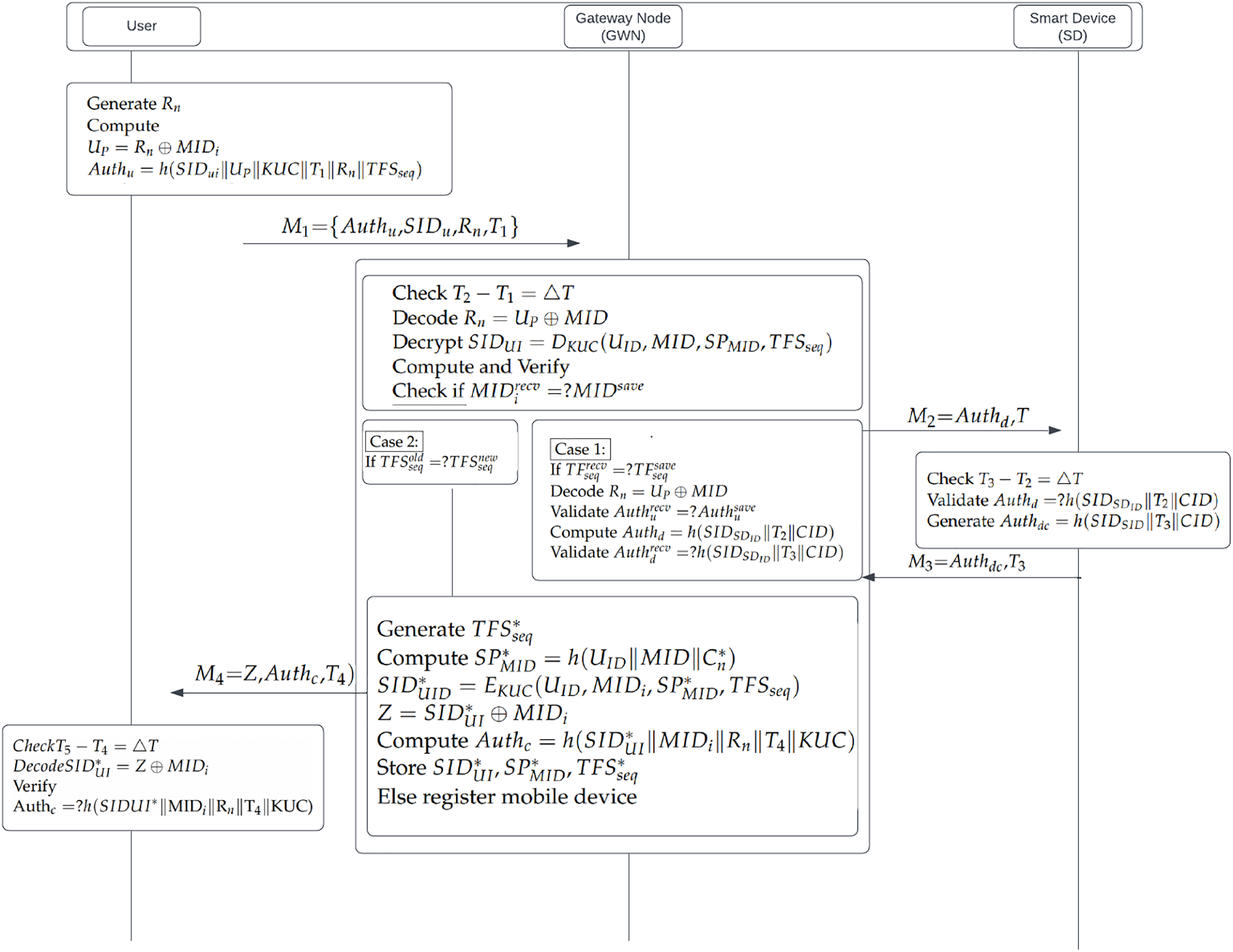

Since the user session identification is dependent on the GWN controller session parameter, the proposed approach calls for a first step for registered users who intend to use smart home services and repeating this step when utilizing a new mobile device to connect with the GWN. The following steps are the part of authentication scheme:

Step 1:

The user-generated random number

Step 2:

Upon receiving the message

If the comparison verifies that

The user sends a previous

Case 1: The controller retrieves

Case 2: When the controller anticipates a new

If the user sends an authentication request from a new mobile device, the verification

Figure 4: Authentication and Login phase of a proposed scheme

To ensure the effectiveness of cryptographic protocols, it is crucial to thoroughly assess the participants and potential adversaries involved, and address any potential threats promptly the following aspects need to be addressed:

• Can the recipient determine the sender’s identity?

• Does the recipient have the ability to confirm that the message they received is current and Tempered?

• Does the recipient have the capability to confirm that the message is not merely a repetition of a past message?

• Can the system analyst or investigator discern the identity of the communicating parties?

• There are two primary areas for the proposed protocol’s security analysis: formal and informal.

In future, it would also be important to analyze the resistance of EARAS against known-key attacks and device compromise scenarios. Prior studies [13] have shown that the exposure of session keys or the compromise of IoT devices can severely weaken protocol resilience. Incorporating these aspects into the evaluation framework would further strengthen the robustness assessment of EARAS.

5.1 Informal Security Analysis

The informal security analysis of cryptographic protocols uses expert judgment and common sense reasoning to identify security objectives, assess key components, and consider adversarial scenarios, complementing formal methods for greater assurance.

The proposed protocol ensures high anonymity by securely encrypting user identities and mobile information through channels

5.1.2 Privacy Protection against Eavesdropping

The proposed scheme encrypts

The user and controller are aware of

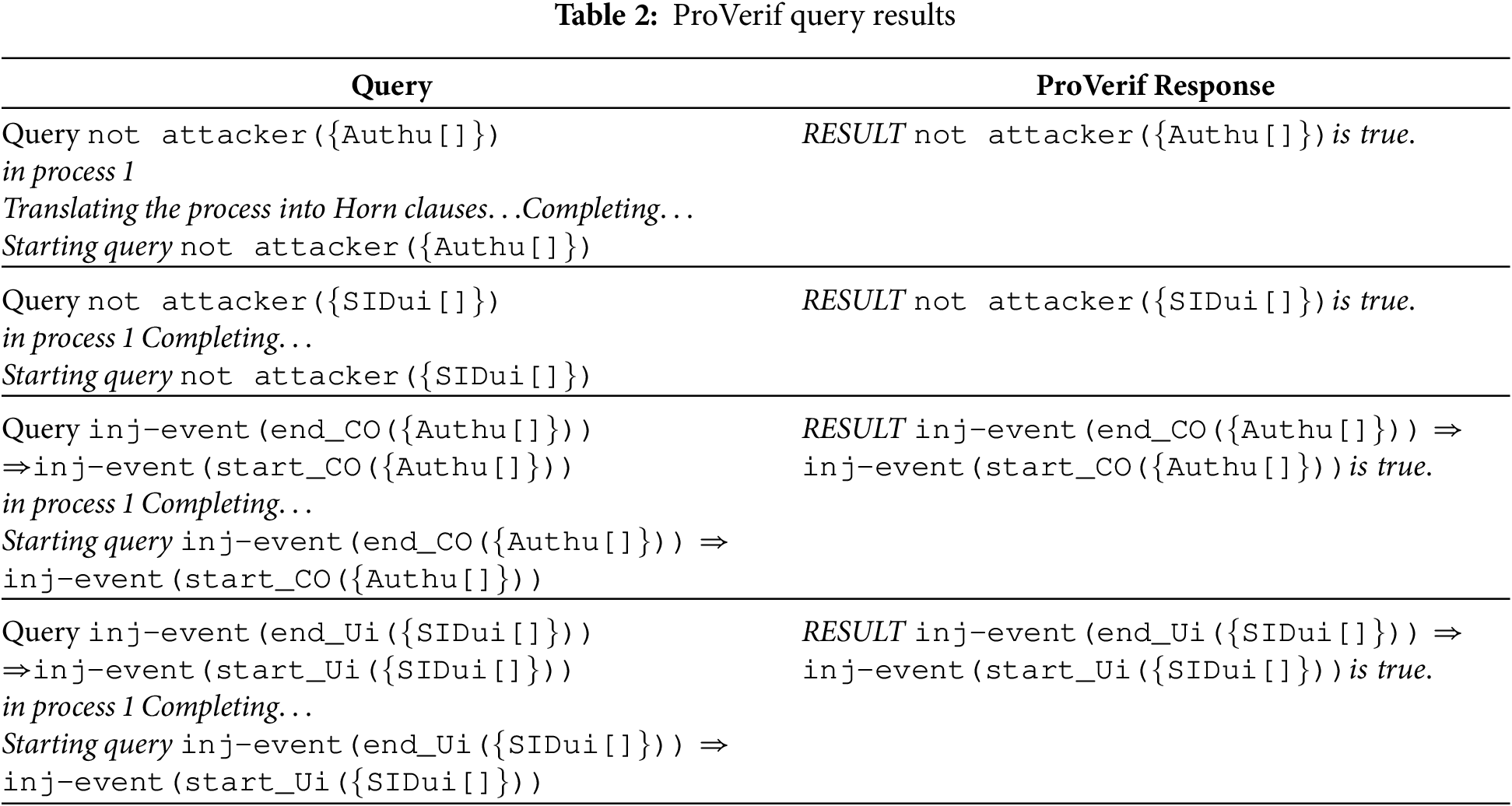

Formal security analysis is a rigorous methodical examination of cryptographic protocols, ensuring their security properties through definition of objectives, model creation, mathematical notation, and verification using well known automated tool ProVerif, thereby ensuring robust security. ProVerif is an automated formal verification tool used to analyze and prove the security properties of cryptographic protocols. Table 2 contains the comprehensive procedure for each query and its corresponding outcomes. Informal techniques are frequently used in conjunction with it to provide a comprehensive assessment.

The EARAS technique is thoroughly analyzed, focusing on performance, communication overhead, and computational considerations, providing detailed comparisons and breakdowns of each stage’s computational overhead.

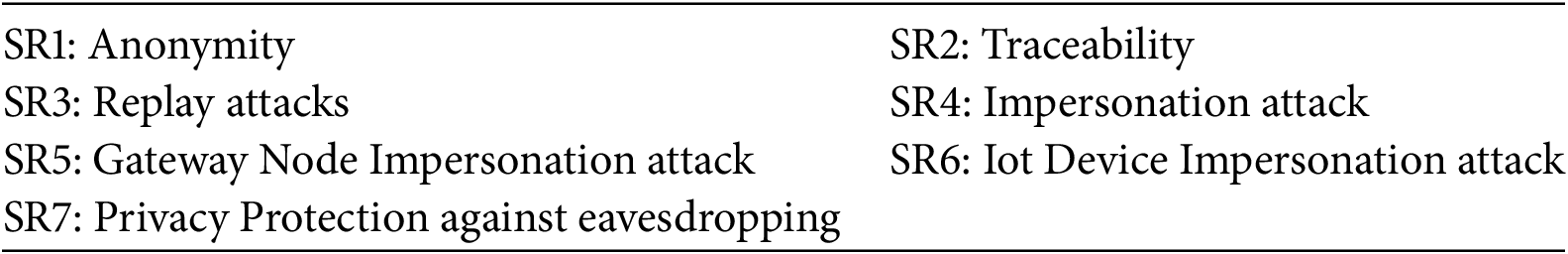

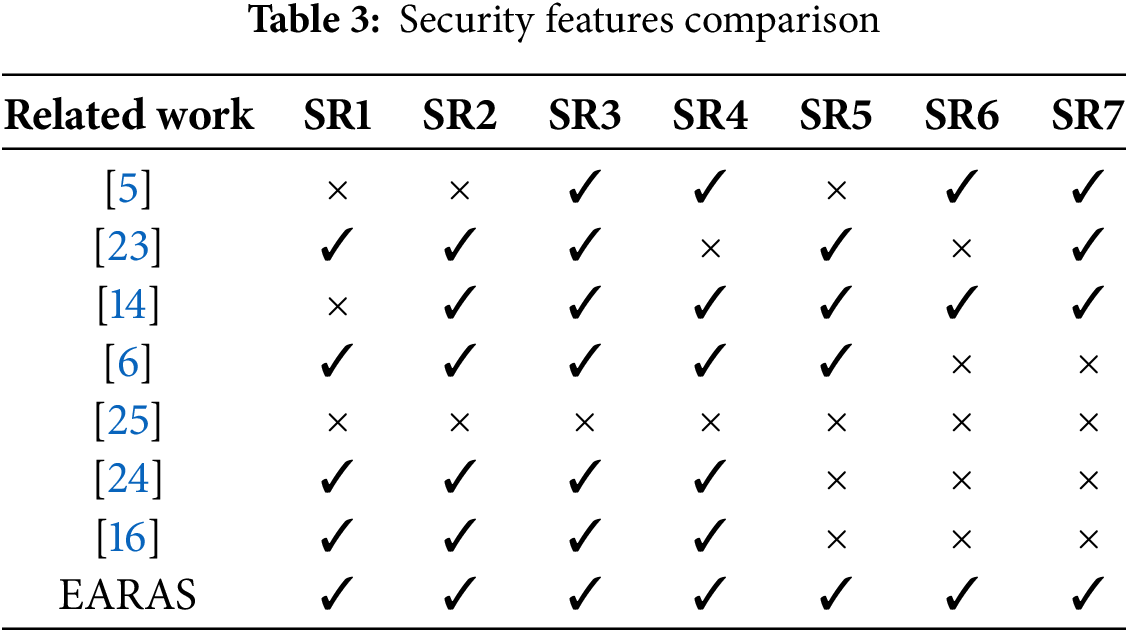

This section compares the suggested protocol with current protocols using lightweight symmetric key primitives. It compares security requirements, calculation cost, communication cost, and storage complexity, contrasting the security, execution time, and running time of the suggested protocol.

Table 3 compares the suggested protocol’s security requirements to those of the current symmetric key-based protocols.

Section 2 clearly outlines the vulnerabilities of the current schemes [5,6,14,16,23–25], and which are also reproduced in Table 3.

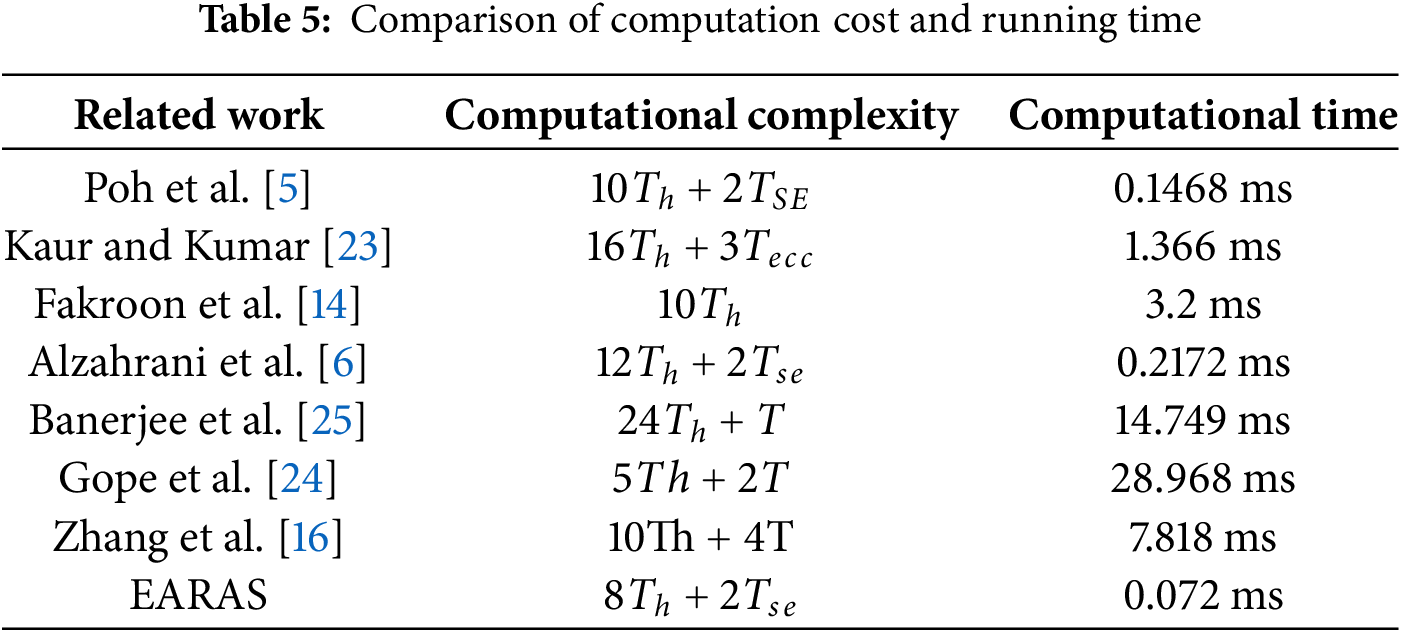

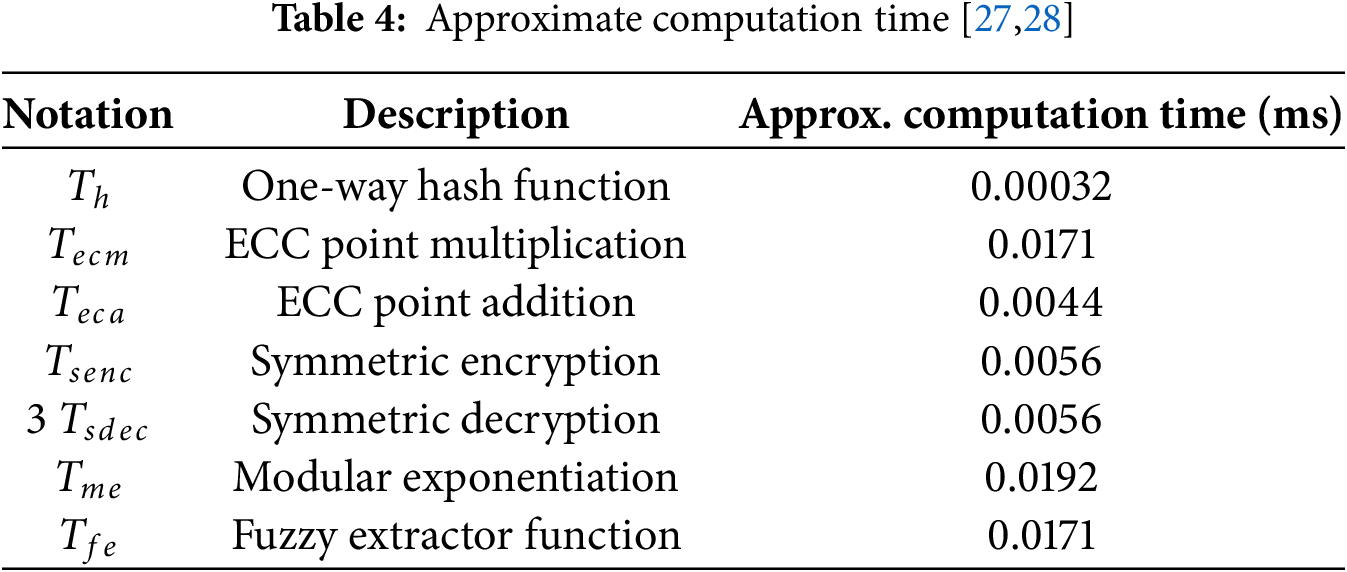

Analysis of the computational cost of the suggested plan and current schemes is explained in this section. Some notations are presented for analysis:

• CC = Computation cost;

•

•

The computation time for 28.968 and 7.181 ms is demonstrated by the experiments of Zhang et al. [16] and Gope et al. [24]. The experiment by Kilinc and Yanik [26] demonstrates that the computation time for

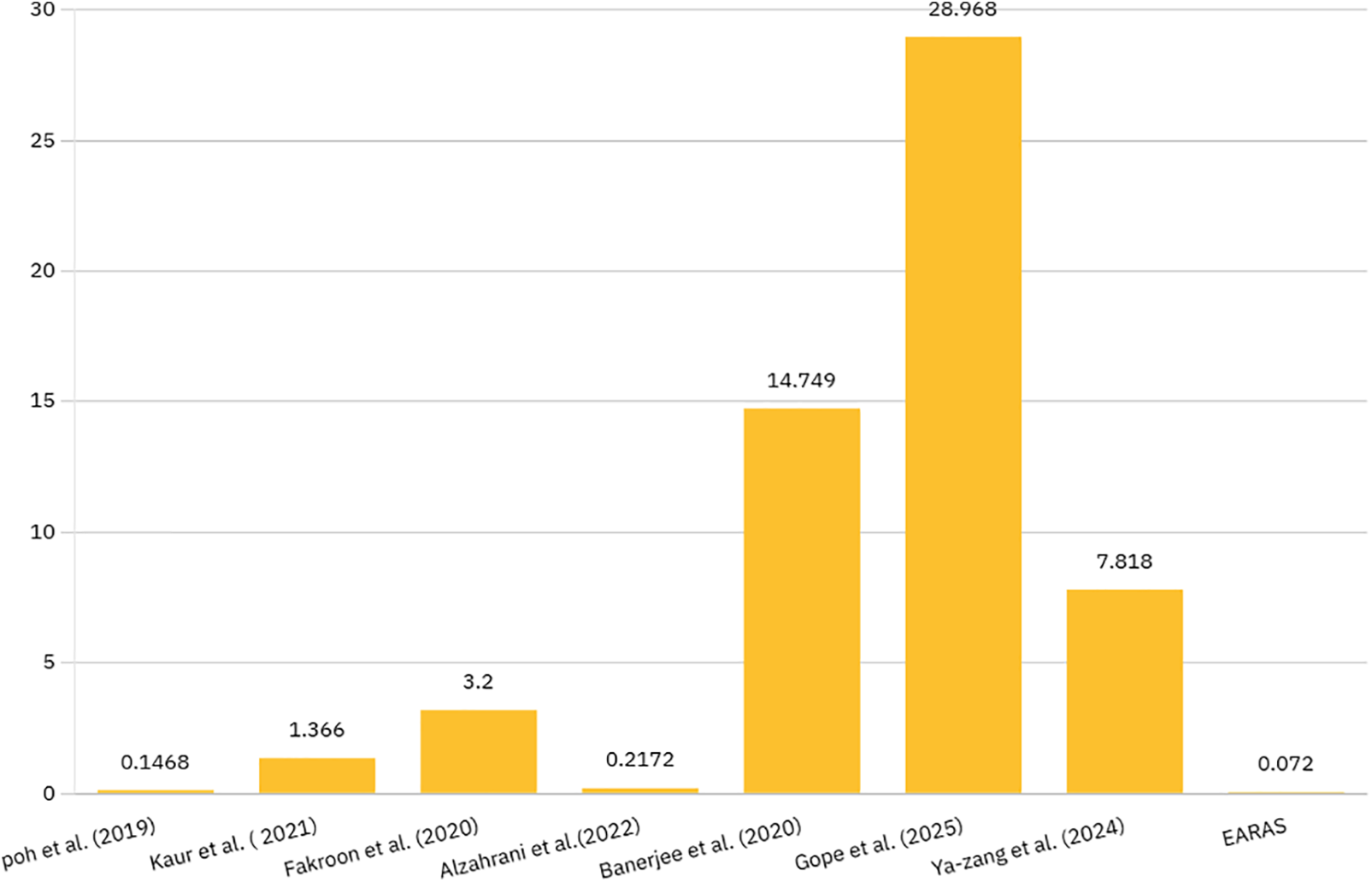

In comparison to other current systems, the suggested scheme, which incorporates the key exchange process, showed a shorter predicted computational time, as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 5. The suggested protocol’s total computation time is 0.072 ms. The protocol described in [14] costs

Figure 5: Computation cost comparison (Poh et al. [5], Kaur and Kumar [23], Fakroon et al. [14], Alzahrani et al. [6], Banerjee et al. [25], Gope et al. [24], Zhang et al. [16])

A protocol [24] takes 28.968 ms to execute the authentication verification phases. A protocol presented in [23] incurs 16

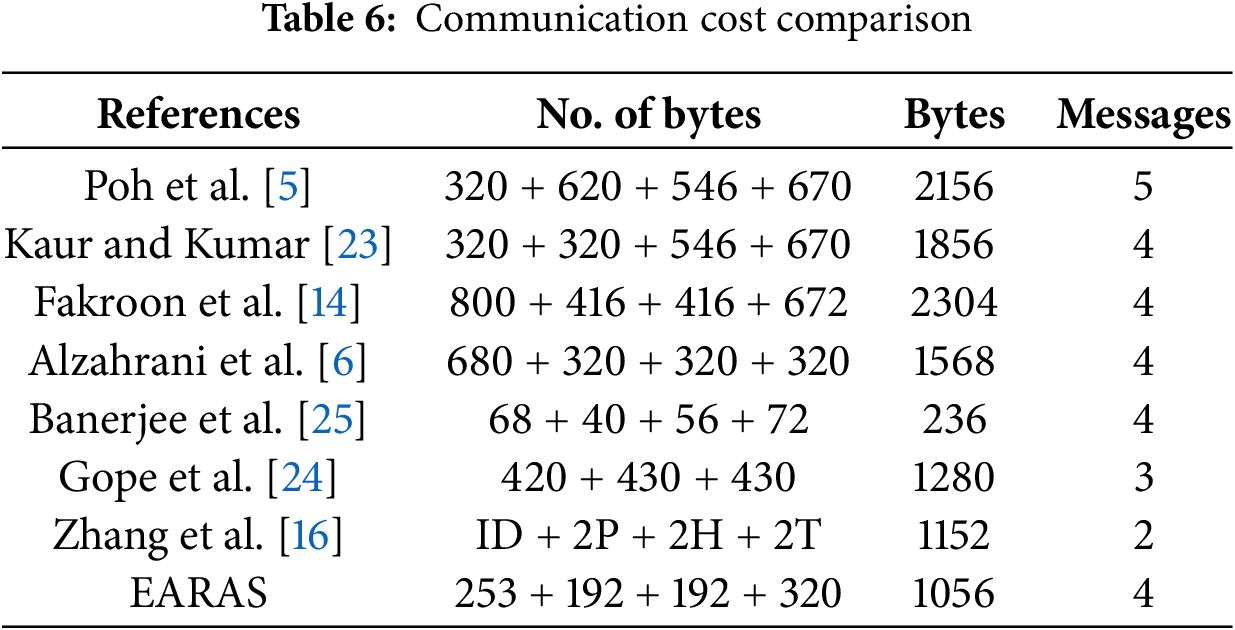

6.3 Communication Cost Analysis

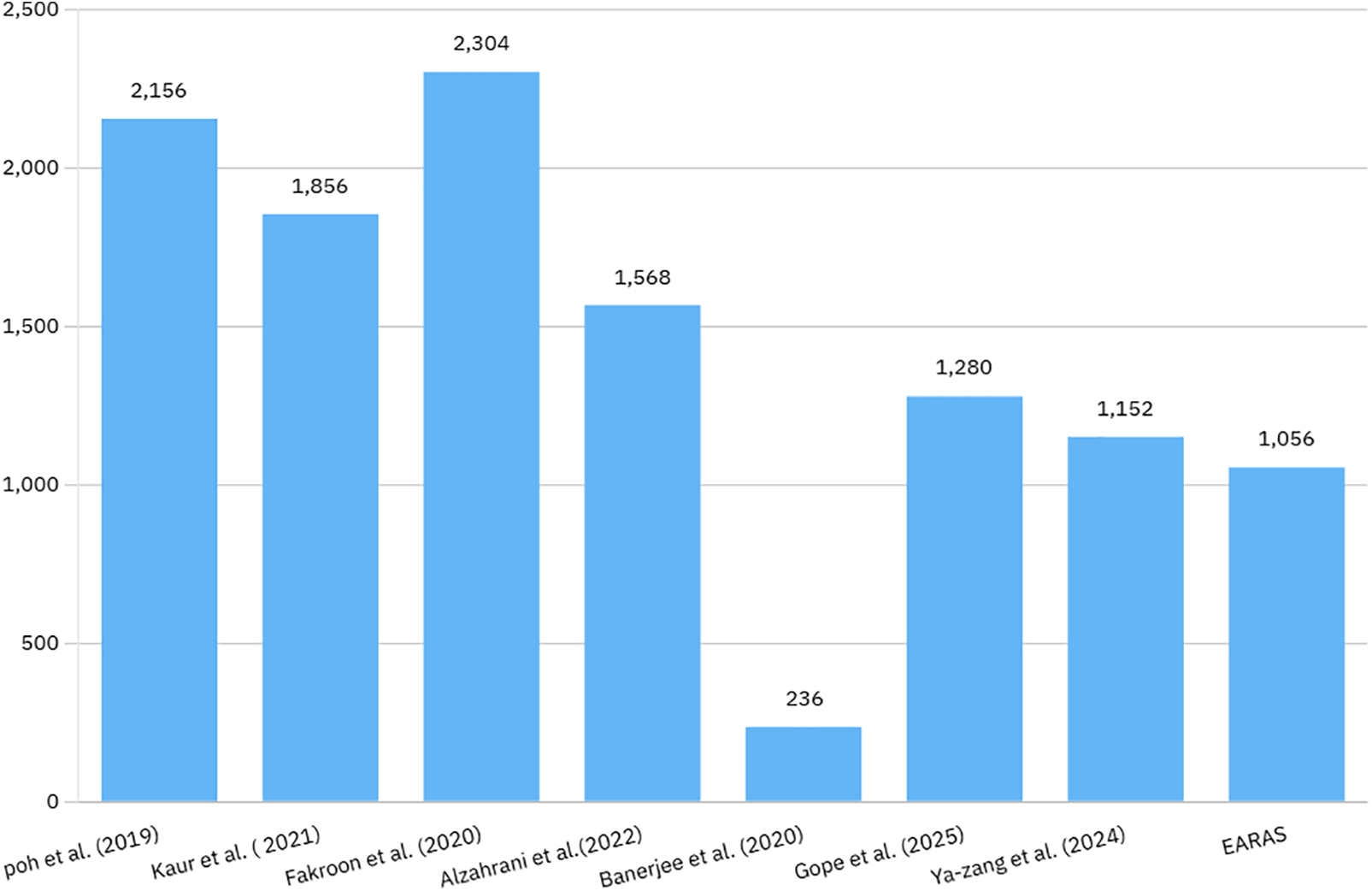

The table presents a computational cost analysis of a proposed protocol, comparing its communication costs with existing protocols, involving 352 bits of parameters sent and received. The suggested protocol has a less communication cost than the protocols of [5,14,23] and [6,16] but a higher communication cost than [25]. However, only the suggested protocol offers the necessary security.

The proposed protocol balances communication efficiency and security, outperforming existing protocols in cost while providing comprehensive security features, making it suitable for security-sensitive contexts. The findings of the evaluation of the communication costs between our suggested plan and other similar plans are shown in Table 6 and Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Communication cost (Poh et al. [5], Kaur and Kumar [23], Fakroon et al. [14], Alzahrani et al. [6], Banerjee et al. [25], Gope et al. [24], Zhang et al. [16])

We emphasized security, a crucial component of the smart ecosystem that has frequently been overlooked by both researchers and industry leaders. Insufficient or nonexistent authentication procedures in smart ecosystems lead to attacks, questioning users’ trust. To address this, a smart, secure home system based on GWN aims to transfer processing complexity to a centralized controller. The study presents a new security architecture for smart homes using GWN and introduces the EARAS (An Efficient, Anonymous, and Robust Authentication Scheme), aiming to maintain privacy while ensuring successful authentication. The ProVerif tool was used for both formal and informal analyses, confirming the scheme’s practicality and safety for IoT devices with limited resources, making it suitable for various smart system applications. In future, integrating searchable encryption with GWN would allow users to perform secure queries over encrypted smart home data without revealing sensitive information. This approach directly complements EARAS by extending privacy preservation beyond authentication to data access and management. The current validation of EARAS has focused on analytical evaluation and formal verification, with performance results obtained through comparative benchmarks. As a next step, future work will involve implementing and testing the scheme in simulation tools (e.g., NS-3, OMNeT++) and real-world smart home environments to provide deeper insights into its robustness and efficiency.

Acknowledgement: The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, data analysis: Muntaham Inaam Hashmi, Muhammad Ayaz Khan, and Suliman A. Alsuhibany; literature review, discussion, writing—original draft preparation, data downloading: Muntaham Inaam Hashmi, Muhammad Ayaz Khan, Khwaja Mansoor ul Hassan and Asfandyar Khan; writing—review and editing: Muntaham Inaam Hashmi, Ainur Abduvalova, Muhammad Ayaz Khan, Suliman A. Alsuhibany, and Asfandyar Khan; visualization: Muntaham Inaam Hashmi and Muhammad Ayaz Khan; supervision: Khwaja Mansoor ul Hassan, Suliman A. Alsuhibany. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will made available on request.

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve human participants, human data, or animal subjects, and therefore ethics approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Makkonen T, Inkinen T. Inclusive smart cities? Technology-driven urban development and disabilities. Cities. 2024;154:105334. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2024.105334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Vardakis G, Hatzivasilis G, Koutsaki E, Papadakis N. Review of smart-home security using the Internet of Things. Electronics. 2024;13(16):3343. doi:10.3390/electronics13163343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Raza A, Khan S, Shrivastava S, Ashraf MWA, Wang T, Wu K, et al. A lightweight group-based SDN-driven encryption protocol for smart home IoT devices. Comput Netw. 2024;250:110537. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Khan MN, Rahman HU, Hussain T, Yang B, Qaisar SM. Enabling trust in automotive IoT: lightweight mutual authentication scheme for electronic connected devices in Internet of Things. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(3):5065–78. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3410300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Poh GS, Gope P, Ning J. PrivHome: privacy-preserving authenticated communication in smart home environment. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2019;18(3):1095–107. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2019.2914911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alzahrani BA, Barnawi A, Albarakati A, Irshad A, Khan MA, Chaudhry SA. SKIA-SH: a symmetric key-based improved lightweight authentication scheme for smart homes. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2022;2022(1):8669941. doi:10.1155/2022/8669941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shuai M, Yu N, Wang H, Xiong L. Anonymous authentication scheme for smart home environment with provable security. Comput Secur. 2019;86:132–46. [Google Scholar]

8. Dey S, Hossain A. Session-key establishment and authentication in a smart home network using public key cryptography. IEEE Sens Lett. 2019;3(4):1–4. doi:10.1109/lsens.2019.2905020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Raghu N, Mahesh T, Vivek V, Kumaran SY, Kannanugo N, Vishwanatha S. IoT-enabled safety and secure smart homes for elderly people. In: Future of digital technology and AI in social sectors. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2025. p. 297–328. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-5533-6.ch011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Anwarul S. Enhancing energy efficiency and safety in smart homes. In: CyberMedics: navigating AI and security in the medical field. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2025. [Google Scholar]

11. Zhang S, Rong J, Wang B. A privacy protection scheme of smart meter for decentralized smart home environment based on consortium blockchain. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2020;121:106140. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ali Z, Chaudhry SA, Ramzan MS, Al-Turjman F. Securing smart city surveillance: a lightweight authentication mechanism for unmanned vehicles. IEEE Access. 2020;8:43711–24. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2977817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gaba GS, Kumar G, Monga H, Kim TH, Kumar P. Robust and lightweight mutual authentication scheme in distributed smart environments. IEEE Access. 2020;8:69722–33. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2986480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fakroon M, Alshahrani M, Gebali F, Traore I. Secure remote anonymous user authentication scheme for smart home environment. Internet Things. 2020;9:100158. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2020.100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yalli JS, Hasan MH, Jung LT, Al-Selwi SM. Authentication schemes for Internet of Things (IoT) networks: a systematic review and security assessment. Internet of Things. 2025;30:101469. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang Y, Chen J, Wang S, Ma K, Hu S. Lightweight anonymous authentication and key agreement protocol for a smart grid. Energies. 2024;17(18):4550. doi:10.3390/en17184550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hussain S, Chaudhry SA. Comments on “biometrics-based privacy-preserving user authentication scheme for cloud-based industrial internet of things deployment”. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(6):10936–40. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2934947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Irshad A, Usman M, Chaudhry SA, Bashir AK, Jolfaei A, Srivastava G. Fuzzy-in-the-loop-driven low-cost and secure biometric user access to server. IEEE Trans Reliability. 2020;70(3):1014–25. doi:10.1109/tr.2020.3021794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. El-Hajj M, Fadlallah A, Chamoun M, Serhrouchni A. A survey of internet of things (IoT) authentication schemes. Sensors. 2019;19(5):1141. doi:10.3390/s19051141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. AlJanah S, Zhang N, Tay SW. A survey on smart home authentication: toward secure, multi-level and interaction-based identification. IEEE Access. 2021;9:130914–27. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3114152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yan W, Wang Z, Wang H, Wang W, Li J, Gui X. Survey on recent smart gateways for smart home: systems, technologies, and challenges. Trans Emerg Telecomm Technol. 2022;33(6):e4067. doi:10.1002/ett.4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Beniwal G, Singhrova A. A systematic literature review on IoT gateways. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inform Sci. 2022;34(10):9541–63. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.11.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kaur D, Kumar D. Cryptanalysis and improvement of a two-factor user authentication scheme for smart home. J Inf Secur Appl. 2021;58:102787. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gope P, Fei H, Sikdar B. Lightweight and privacy-preserving reconfigurable authentication scheme for IoT devices. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2025;18(2):912–25. doi:10.1109/tsc.2025.3536314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Banerjee S, Odelu V, Das AK, Chattopadhyay S, Park Y. An efficient, anonymous and robust authentication scheme for smart home environments. Sensors. 2020;20(4):1215. doi:10.3390/s20041215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kilinc HH, Yanik T. A survey of SIP authentication and key agreement schemes. IEEE Commun Surv Tut. 2013;16(2):1005–23. [Google Scholar]

27. Liu H, Kadir A, Liu J. Keyed hash function using hyper chaotic system with time-varying parameters perturbation. IEEE Access. 2019;7:37211–9. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2896661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Challa S, Das AK, Odelu V, Kumar N, Kumari S, Khan MK, et al. An efficient ECC-based provably secure three-factor user authentication and key agreement protocol for wireless healthcare sensor networks. Comput Electr Eng. 2018;69:534–54. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools