Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ProRE: A Protocol Message Structure Reconstruction Method Based on Execution Slice Embedding

Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Fei Kang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 37 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071552

Received 07 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Message structure reconstruction is a critical task in protocol reverse engineering, aiming to recover protocol field structures without access to source code. It enables important applications in network security, including malware analysis and protocol fuzzing. However, existing methods suffer from inaccurate field boundary delineation and lack hierarchical relationship recovery, resulting in imprecise and incomplete reconstructions. In this paper, we proposeKeywords

Protocol Reverse Engineering (PRE) reconstructs protocol functionality by parsing the structure and semantics of communication messages, with increasingly widespread applications. In network security, PRE is used to analyze malware communication mechanisms and traffic characteristics [1], helping security researchers understand attackers’ command and control protocols. In IoT security, where numerous devices use proprietary protocols lacking documentation, PRE becomes essential for discovering security vulnerabilities. In threat detection, it facilitates understanding and monitoring of unknown applications’ network behavior. As protocols become increasingly encrypted and complex, traditional manual analysis has become inadequate, making automated PRE techniques crucial.

Message structure recovery is one of the most fundamental tasks in PRE, providing crucial support for further inferring protocol semantics and state machines. Its primary goal is to reconstruct the message structure of communication protocols without access to source code. Depending on the application scenario, methods are typically classified into Network Trace-based (NetT-based) [2,3] and Execution Trace-based (ExeT-based) [4–8] approaches. NetT-based methods parse field formats through statistical analysis of captured traffic data, but often perform poorly with insufficient traffic samples. Our research focuses on ExeT-based methods, which achieve relatively accurate recovery by dynamically tracing message processing without requiring large amounts of traffic. However, existing ExeT-based methods face significant limitations in inference effectiveness. Two key challenges persist:

• First, unreasonable boundary delineation methods lead to inaccurate recovery. Field division relies on precise byte representation forms, yet existing methods typically employ only low-level features as approximations, such as program operator [4] or basic block [5] sequences. Without high-level abstraction of protocol semantics, these approaches are prone to errors when representing complex programs.

• Second, absence of hierarchical relationship recovery results in incomplete message structures. Multiple relationships exist among message fields [6], yet existing methods focus solely on sequential relationships, overlooking parallel and nested relationships. This limitation prevents complete restoration of message structures and comprehensive evaluation metrics.

To address these challenges, we propose ProRE, a novel method for Protocol field structures Reconstruction based on program execution slice embedding. ProRE precisely extracts code execution slices from the protocol parsing process at runtime, converts them into high-dimensional semantic vectors using a data flow-sensitive assembly language model, and introduces hierarchical clustering algorithms to iteratively aggregate these vectors, thereby completely recovering protocol field structural relationships including nesting and parallelism. This method achieves precise characterization of field boundaries by mapping program semantics to vector space, and reconstructs the protocol’s inherent structure through hierarchical clustering trees, significantly improving recovery accuracy and completeness.

We summarize our contributions as follows:

• We propose a protocol message structure reconstruction method based on execution slice embedding, integrating protocol reverse analysis and program semantic analysis through code slice embedding and hierarchical clustering to address inaccurate and incomplete field recovery challenges.

• We develop a data flow-sensitive assembly language model that converts execution code slices into embeddings, achieving precise characterization of protocol field semantics.

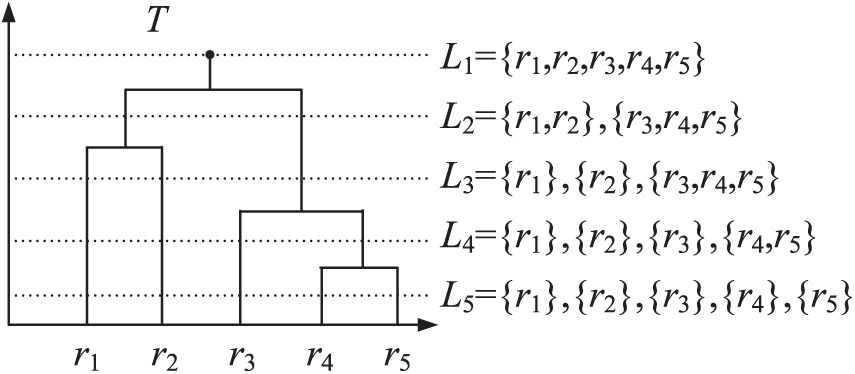

• We introduce hierarchical clustering to protocol field recovery tasks for the first time, which can not only divide sequential fields but also restore structural relationships. We also propose a structured evaluation method using the cophenetic correlation coefficient for comprehensive protocol structure assessment.

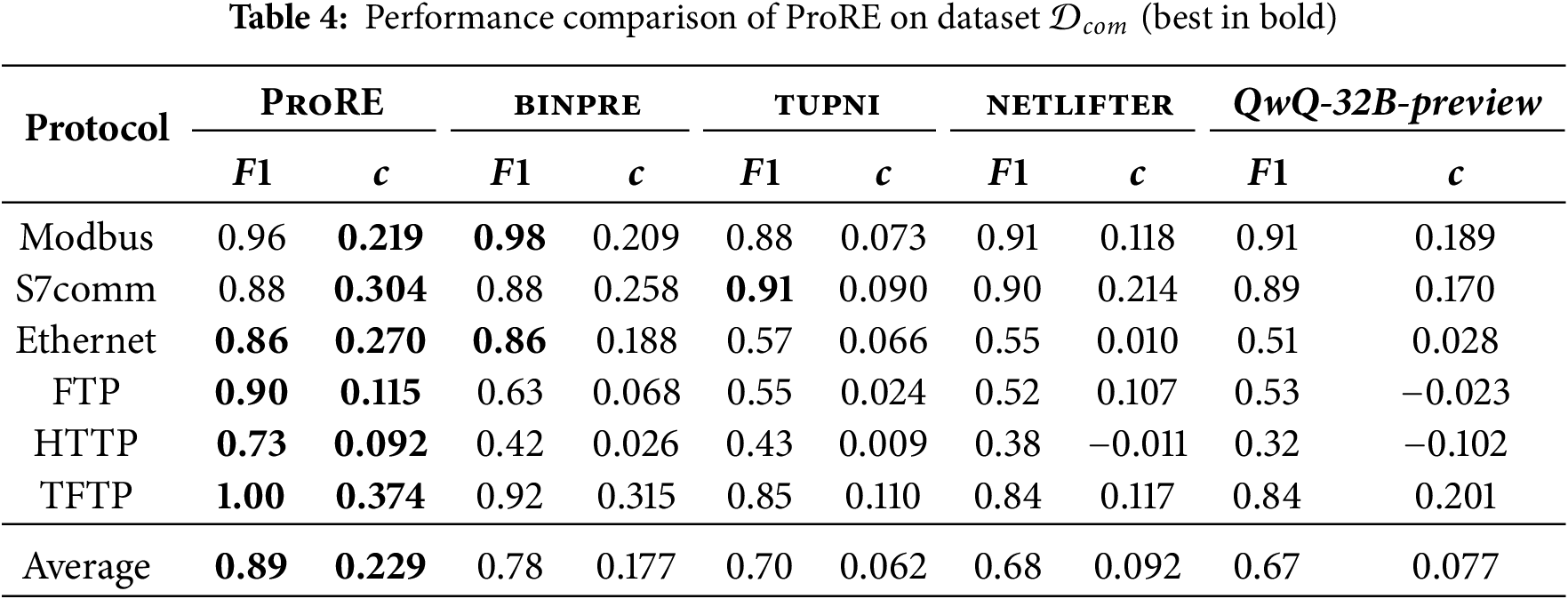

• We design and implement the ProRE. Evaluation on two datasets containing 12 protocols shows that ProRE achieves an average F1 score of 0.85 and a cophenetic correlation coefficient of 0.189, improving by 19% and 0.126% respectively over state-of-the-art methods (including binpre, tupni, netlifter, and QwQ-32B-preview), demonstrating significant superiority in both accuracy and completeness of field structure recovery. Case study shows that ProRE effectively applies to practical malware analysis scenarios, successfully identifying Duke steganographic data and Mirai botnet protocol message structures. We also open-source this work to facilitate future research.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in code embedding and protocol field recovery, highlighting existing gaps. Section 3 presents background knowledge and motivates our approach through concrete examples. Section 4 details our methodology, including execution code slicing, slice embedding, and hierarchical clustering techniques. Section 5 describes the implementation details. Section 6 presents comprehensive experimental evaluation, including performance comparisons, ablation studies, and case studies on real malware. Section 7 discusses time consumption, generalization capability, and limitations. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

This section reviews existing approaches in code embedding and protocol field recovery, examining their techniques and limitations to establish the context for our proposed method.

Code embedding is a program representation method that achieves semantic abstraction by converting program code into numerical vectors, commonly applied in code similarity detection and vulnerability analysis. These methods treat code as natural language, learning embedding representations by training deep learning models. The most intuitive embedding method is one-hot encoding [9,10], which uses fixed-dimension vectors to map instructions, but limited by abstraction capability, cannot fully represent syntactic and semantic information. Some works [11–14] analogize instructions and basic blocks to words and sentences, respectively, constructing code embedding vectors through representation learning with strong generality. However, they cannot capture semantics of specific code fragments and lack abstraction of data flow relationships.

This paper constructs a data flow-sensitive assembly language model to convert slice code of protocol processing into embedding vectors, better representing execution semantics of communication programs and supporting protocol analysis.

Protocol Reverse Engineering (PRE) infers network protocol specifications from traffic or program binaries [15,16], enabling applications like traffic classification [17] and protocol vulnerability detection [4,5]. Field structure recovery is one of the core tasks, typically divided into two categories based on application scenarios. NetT-based methods [2,3] infer message formats through statistical analysis of traffic. However, their accuracy depends on rich, high-quality traffic, which is difficult to obtain in practice. ExeT-based methods [4–8] do not rely on traffic data, identifying field boundaries by dynamically analyzing communication program execution traces and clustering semantically similar bytes. However, their recovery results remain inaccurate or incomplete.

BinPRE [4], the current state-of-the-art, approximates field semantics through operator sequences extracted during protocol parsing. However, these low-level features fail to capture complex program semantics, leading to frequent field over-segmentation when execution sequences differ significantly. Tupni [7] employs taint analysis for data tracking but cannot handle nested field structures, limiting its applicability to modern protocols. AIFORE [5] utilizes basic block analysis for rapid processing but lacks the semantic depth required for accurate boundary detection. AutoFormat [6] combines instruction addresses with function call stacks to achieve comprehensive tracing, yet suffers from excessive computational overhead and tendency toward over-segmentation. Netlifter [18] attempts static analysis to avoid runtime costs but misses critical dynamic execution paths essential for accurate protocol reconstruction.

We improve field structure recovery performance through: (1) embedding code slices as representations in semantic space; (2) applying hierarchical clustering algorithms to restore message formats.

In this section, we introduce the underlying background, key concepts, and the motivation that drives our proposed approach.

We consider the following scenario: a security analyst needs to determine the protocol message format of a network communication program. They cannot obtain source code or protocol specification descriptions in any form. They possess a binary executable without source code or debug symbols that can be correctly disassembled and decompiled. This program can run on a dynamic instrumentation platform to record message exchanges with communication peers. While our method is architecture-agnostic, we assume the program runs on Windows x86 for evaluation purposes.

Protocol Reverse Engineering

Protocol reverse engineering infers protocol specifications by analyzing network traffic or program execution behavior without protocol documentation. Protocol specifications typically contain three core elements: Message Format, Protocol Semantics, and State Machine. Message format defines the structured organization of messages, including field boundaries, types, and hierarchical relationships; protocol semantics describes the meaning and processing logic of each field; state machine characterizes the protocol dynamic behavior and state transition rules. This paper focuses specifically on message format recovery.

Program Slicing

Program slicing is a program analysis technique that extracts statement subsets related to specific computations from programs, such as protocol parsing portions in communication programs. For a given slicing criterion (typically a program location and variable), a program slice contains all statements that may affect that variable’s value. In dynamic program slicing, slices are computed based on specific execution paths, enabling more precise capture of actual data dependencies. Dynamic slicing typically follows these steps: (1) Execute the program and record execution traces; (2) Construct dynamic data dependency graphs; (3) Collect relevant statements by traversing the dependency graph backward from the slicing criterion.

Code Representation Learning

Code representation learning maps program code into continuous vector space such that semantically similar code fragments are proximate in vector space. Early methods primarily encoded programs based on structural features (such as abstract syntax trees and control flow graphs). Recently, inspired by natural language processing advances, researchers have applied deep learning techniques to code understanding tasks. The Transformer architecture demonstrates excellent performance in code representation learning due to its powerful sequence modeling capabilities. Through pre-training tasks (such as masked language models), models learn code syntactic structures and semantic patterns.

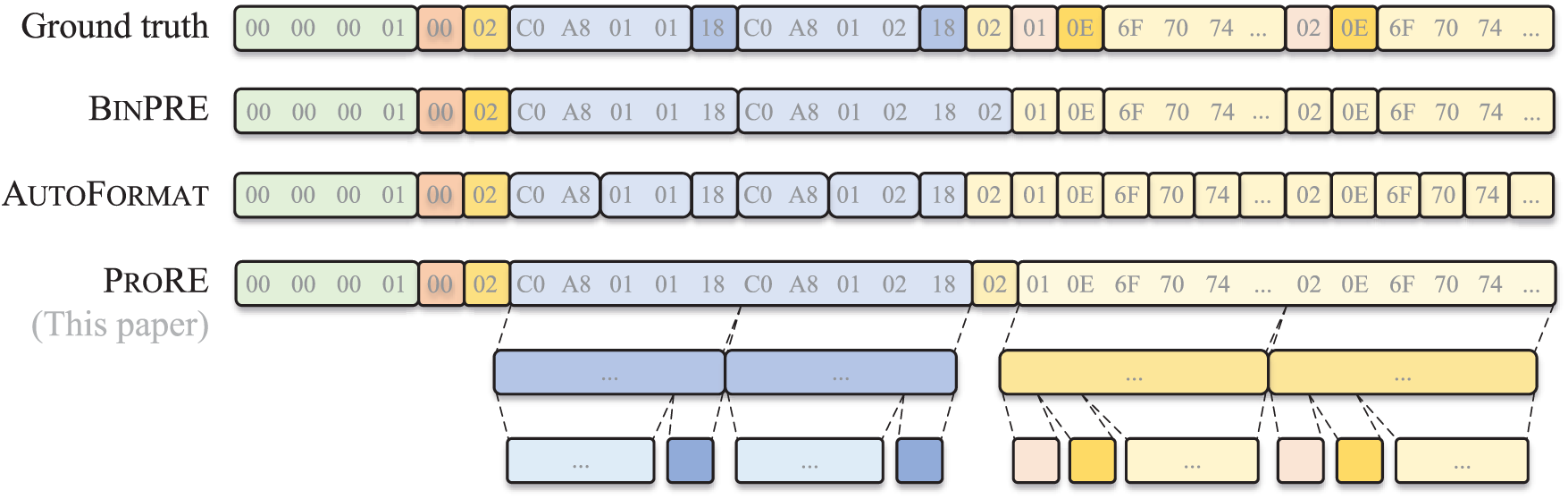

Existing protocol field recovery methods face significant challenges in accurately identifying field boundaries and recovering hierarchical structures. To illustrate these limitations, we analyzed message field parsing results on an example communication program. Fig. 1 demonstrates how current state-of-the-art methods perform, where binpre [4] represents the latest ExeT-based approach and AutoFormat [6] serves as a classic baseline.

Figure 1: Message parsing results of existing methods on communication sample

Challenge 1 (C1): Existing methods employ inadequate boundary delineation approaches, resulting in inaccurate recovery.

Field division is typically considered a message byte clustering process [4], where bytes with similar semantics merge into protocol fields. Existing methods approximate these semantics through low-level program features during protocol parsing, such as instruction addresses, function call stacks, with data reference records [6], or operator sequences [4]. However, since these features cannot accurately reflect program semantics, errors frequently occur. As shown in Fig. 1, when execution sequences corresponding to different bytes of the same field differ significantly, excessive clustering and field over-segmentation may result, such as bytes 7–10 and 12–15 recovered by AutoFormat. Conversely, highly similar execution sequences may cause under-segmentation errors, such as bytes 10 and 11 recovered by binpre.

Recent advances in code pre-trained language models [11–13] provide opportunities for precisely representing program semantics. In this paper, ProRE designs a data flow-sensitive assembly language model to convert program traces into embedding vectors as abstract byte representations. This approach better abstracts program semantic features, thereby improving field division accuracy.

Challenge 2 (C2): Existing methods lack hierarchical relationship recovery, resulting in incomplete message structures.

Multiple relationships exist among message fields [6], yet existing methods focus solely on sequential relationships, ignoring parallel and nested relationships. This limitation prevents complete restoration of message structures and comprehensive evaluation metrics. As shown in Fig. 1, neither binpre nor AutoFormat recover the nested message structure. They divide all bytes into field clusters at the same level, creating difficulties for inferring field semantics and understanding message structures.

To address this challenge, we introduce hierarchical clustering methods to message field recovery for the first time. ProRE gradually restores messages inherent structure by iteratively clustering fields. As shown in Fig. 1, it completely extracts nested results (light blue and light yellow fields) and parallel structures (dark blue and dark yellow fields). Additionally, we introduce structured evaluation methods for field recovery, providing comprehensive assessment of message parsing results.

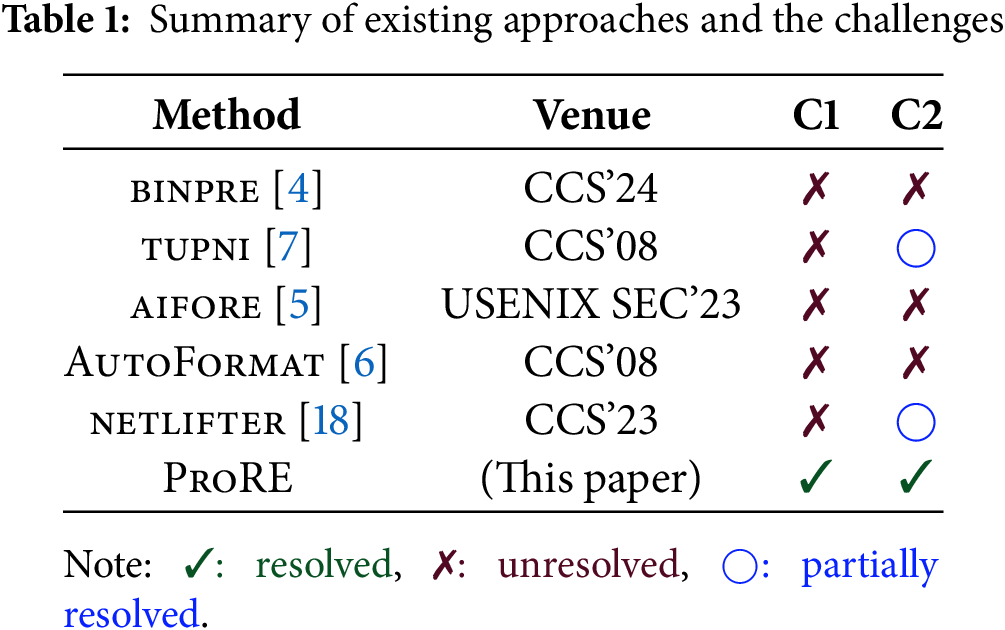

We have also analyzed existing similar works, as shown in Table 1, and they generally have the problems involved in the above two challenges. Among them, although tupni supports the recovery of some cross-field dependencies and netlifter can partially extract the structural relationships existing in decompiled code, they are not as complete and accurate as ProRE.

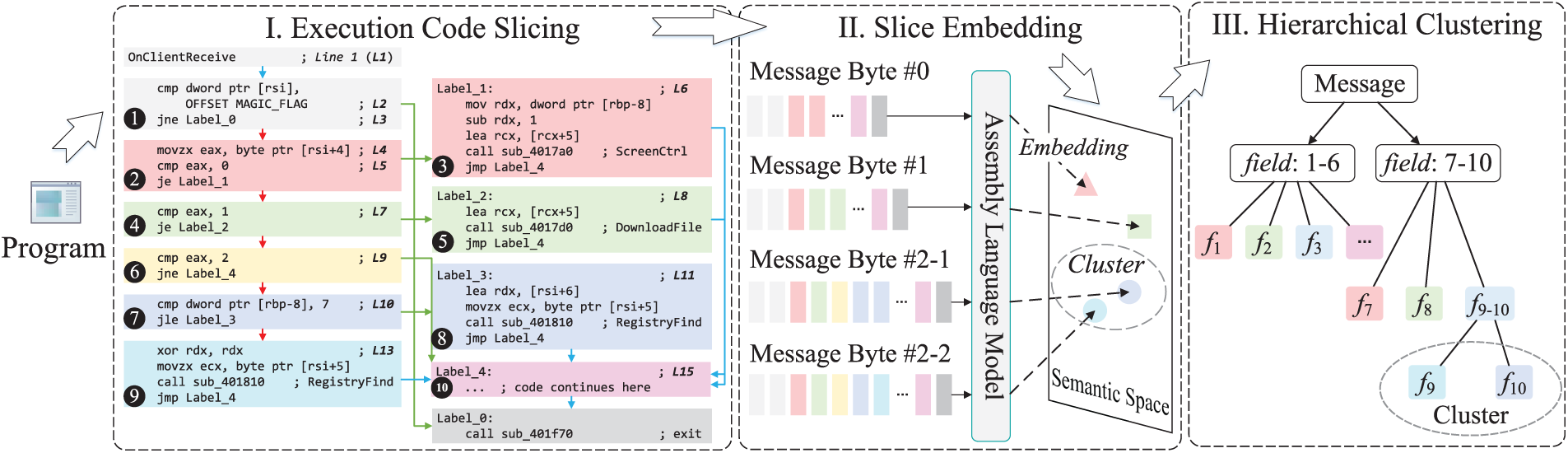

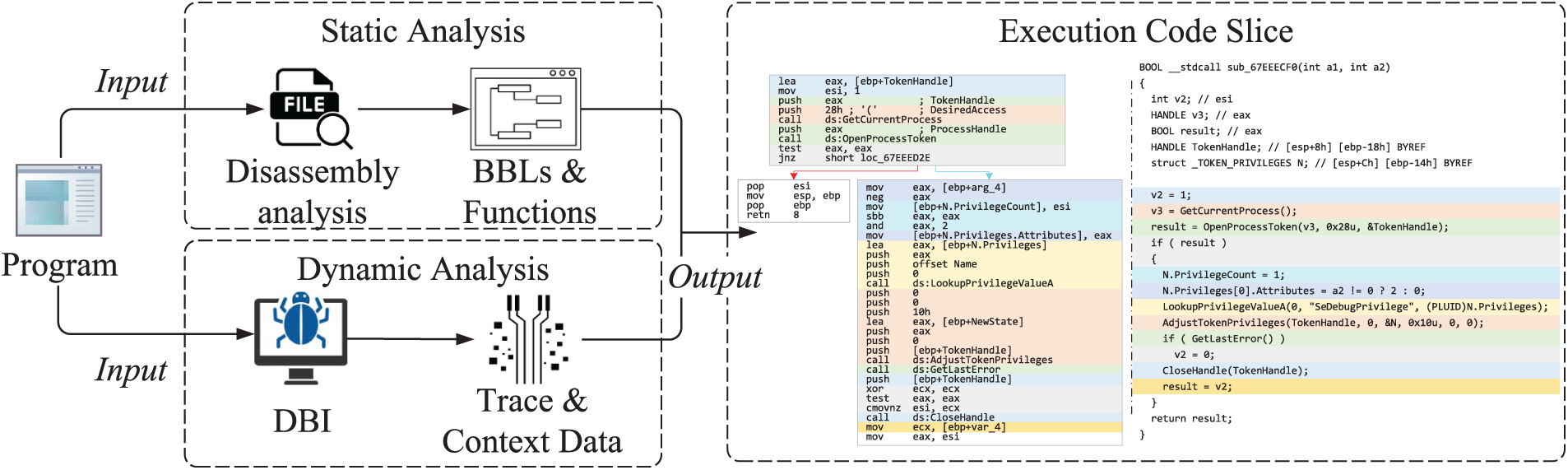

Our methodology addresses the fundamental challenges in protocol field recovery through a three-phase approach that progressively transforms program execution traces into structured protocol representations. Fig. 2 presents the overall framework of ProRE, which consists of three integrated phases: execution code slicing (Section 4.1), slice embedding (Section 4.2), and hierarchical clustering (Section 4.3).

Figure 2: Overall framework of ProRE. It takes a communication program as input and outputs inferred protocol field structures via three main phases

Formally, for communication program P, we define the following:

Definition 1 (Message Byte-Guided Code Slice): Given a slicing criterion

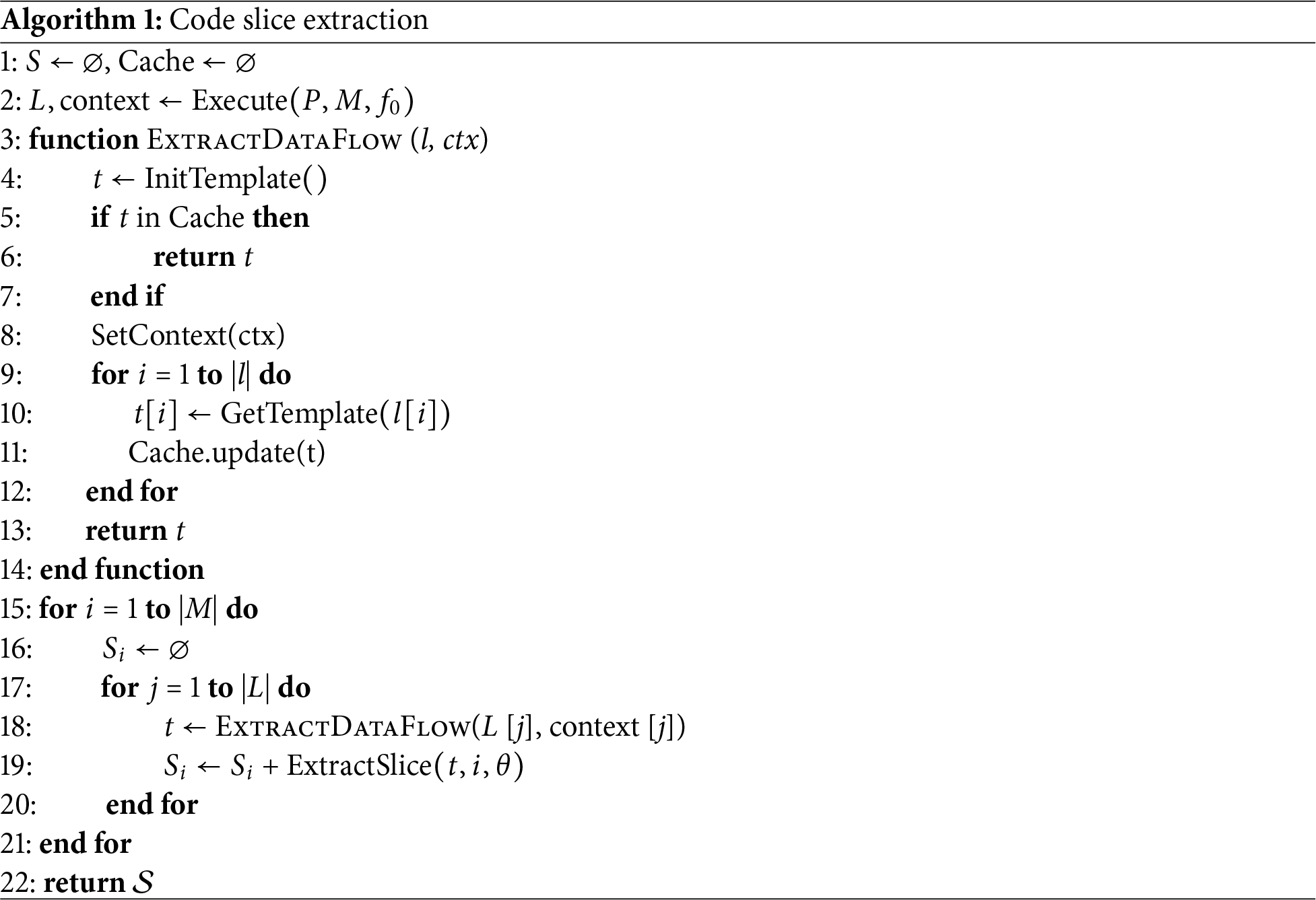

For clarity, we describe the message reception process by default; the technical principles for the sender remain consistent. To accurately extract code fragments from the protocol parsing process, we perform hybrid static-dynamic analysis on the communication program, then extract code slices as shown in Fig. 3. Specifically, we first record disassembled instruction sequences indexed by address on the static analysis engine, along with basic blocks (BBLs) and functions information. To separate slice sets S corresponding to different message bytes, ProRE executes a code slice extraction algorithm, as shown in Algorithm 1.

Figure 3: Slice extraction process. Colors identify processing code for different message bytes

Slice extraction accuracy directly affects subsequent analysis quality. Traditional static slicing methods often produce excessive code due to path explosion and pointer alias analysis difficulties. While dynamic slicing offers greater precision, it requires balancing execution efficiency and coverage. We adopt a hybrid strategy: collecting necessary runtime information through lightweight online instrumentation, then performing detailed data flow analysis offline. This design ensures both analysis accuracy and minimal impact on program execution.

Specifically, ProRE first performs Dynamic Binary Instrumentation (DBI) on the program, recording execution traces and context data after receiving messages. Then, ProRE traverses basic blocks on the execution path, extracting code slices based on data flow templates. Templates record data propagation relationships during each basic block’s execution. To minimize impact on actual program execution, ProRE’s template generation occurs offline and employs caching mechanisms to prevent repeated analysis. We introduce a caching mechanism based on the following observation: a significant portion of data flow analysis time is spent analyzing internal instructions of known APIs, whose data flow propagation relationships are well-documented. Based on these specifications, we manually extracted and compiled 1684 API semantic summaries from commonly used standard libraries, containing information about parameter variable types and data flow propagation directions. This approach alleviates unnecessary overhead in data flow analysis.

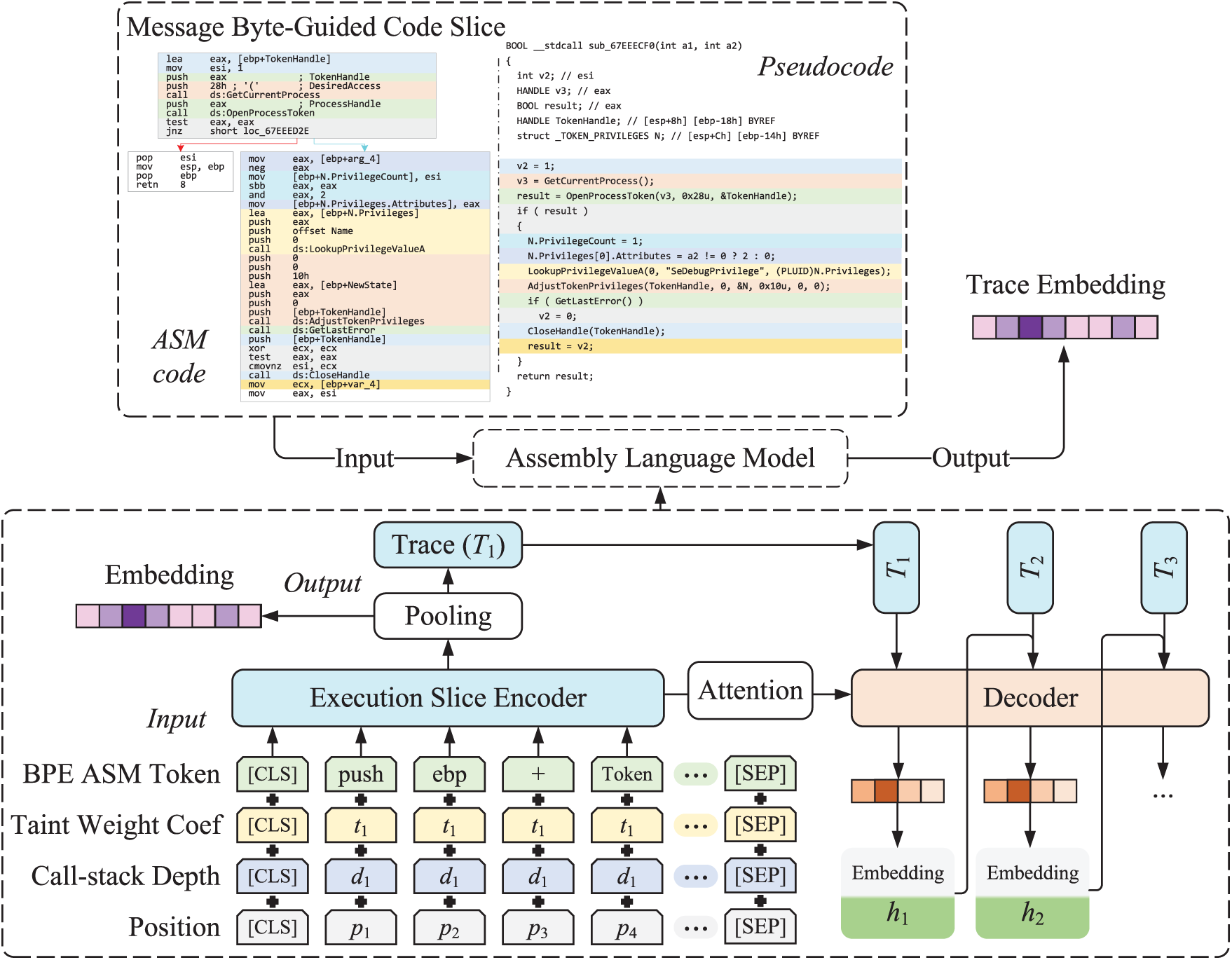

Recent advances in code pre-trained language models [11–13] provide new opportunities for precisely representing program semantics. These models learn not only syntactic structures but also highly abstract semantics by converting code into vector representations. Inspired by this progress, we design a data flow-sensitive assembly language model as shown in Fig. 4, which represents byte semantics by converting code slices into embedding vectors to better support field recovery. The fundamental assumption is that a mapping exists from program code space to abstract semantic space that equivalently expresses program semantics in vector space. We approximate this semantic mapping through an attention mechanism-based Transformer encoder-decoder model.

Figure 4: Architecture of the data flow-sensitive assembly language model

Building code embedding models that meet protocol reverse analysis requirements presents challenges. Unlike general code language models, communication program analysis requires greater focus on message processing, particularly data flow relationships between instructions, which existing methods have not achieved. Therefore, we construct a data flow-sensitive assembly language model with specialized input encoding layers and training strategies.

Input Encoding Layer

As shown in Fig. 4, the model’s input comprises four encoding components. BPE Assembly (ASM) Token employs byte pair encoding to tokenize assembly instructions and builds a 30 K-token vocabulary. Taint Weight Coefficient calculates each instruction’s impact weight on message bytes based on taint analysis results, enabling the model to focus on code fragments closely related to message processing while excluding irrelevant segments. This coefficient is calculated from the intersection size between memory regions read/written by instructions and message input taint regions. Call Stack Depth helps the model understand instructions relative positions in the program, as code at the same hierarchical depth typically exhibits closer semantic relevance. We set the program entry point as the initial stack bottom and return instructions relative offset on the function call stack. Position encodes instructions absolute order. To balance training efficiency and effectiveness, we set the maximum sequence length to 1024 tokens, with exceeding instruction tokens truncated.

Training Tasks

We enhance the model’s awareness of program semantics in message processing through three pre-training tasks.

• Masked Language Model (MLM): This task captures assembly instruction syntax fundamentals. Following standard MLM settings [19], we randomly select 15% of tokens for masking: 80% replaced by [MASK] tokens, 10% replaced by random tokens, and 10% unchanged. By predicting masked original tokens, the model learns syntactic structures and contextual semantics of assembly instructions. The loss function is:

where M denotes masked positions,

• Context Window Prediction (CWP): This task captures program control dependencies by predicting whether two instructions co-occur within the same control branch’s influence range. For instructions

where

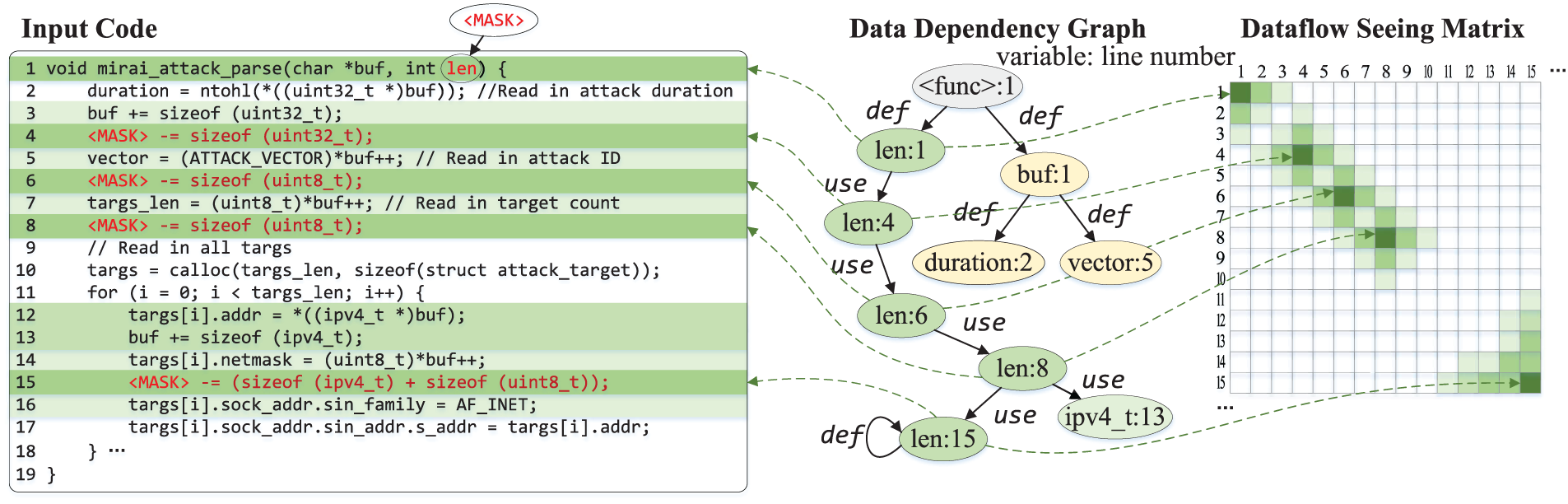

• Def-Use Prediction (DUP): This task explicitly models data dependencies between instructions. Fig. 5 shows a decompiled code fragment of Mirai attack message parsing, where “len” is a masked message field from which we extract Def-Use relationships on its data dependency graph. For statement

Figure 5: Def-Use prediction task with dataflow seeing matrix. Green positions indicate code fragments receiving model focus, with darker colors indicating higher attention weights

where

The total training objective combines three tasks as a weighted sum:

where

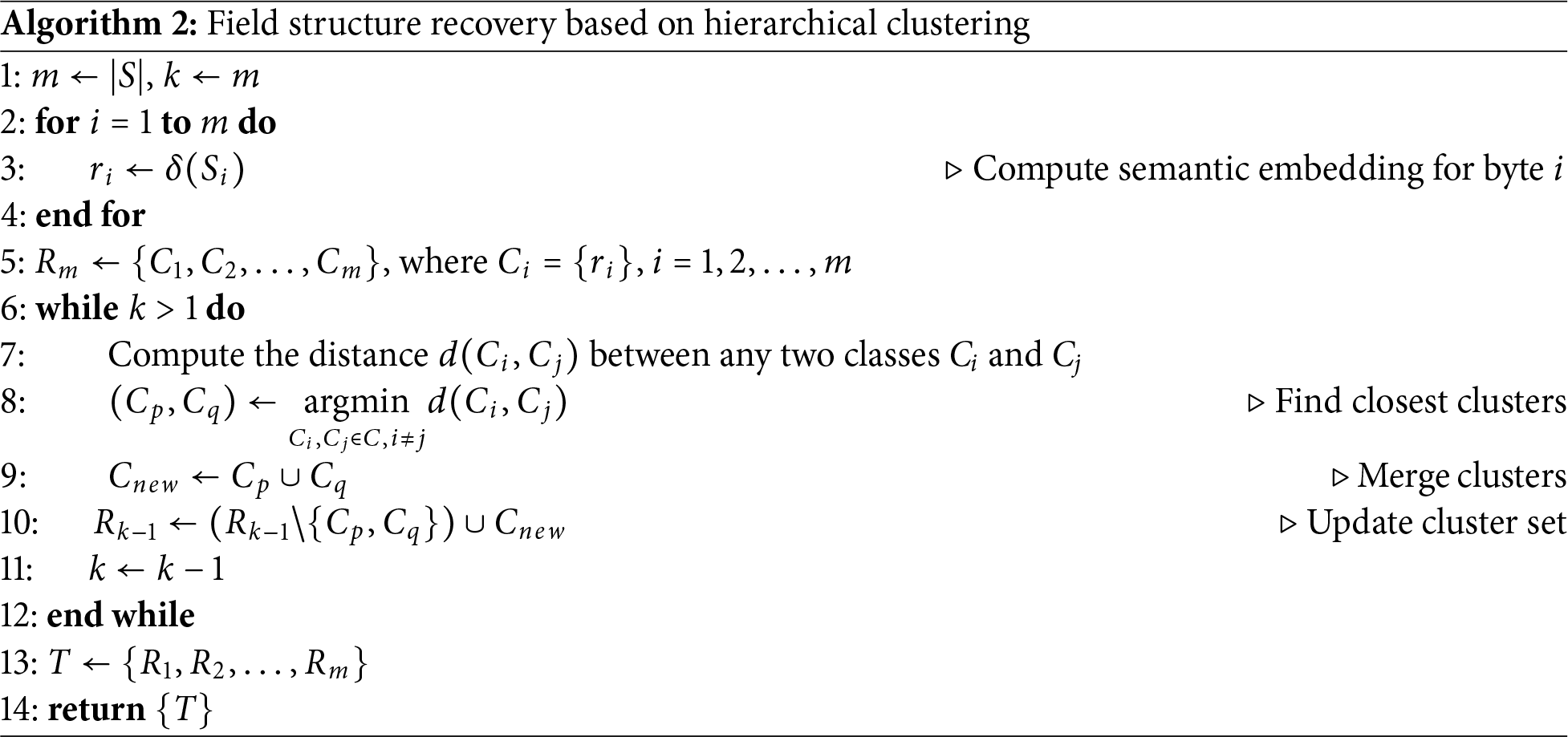

Considering the inherent hierarchical structure of protocol messages [6], we represent fields using sets and express field nesting relationships through set inclusion. Our core insight is that the process of deconstructing nested fields naturally reflects message structure. Processing traces of different sub-fields within the same parent field exhibit greater similarity than those across different parent fields. By comparing semantic similarities between different bytes, we can restore message nested structure. To achieve field structure recovery, we introduce hierarchical clustering methods.

Hierarchical clustering is an unsupervised learning method that organizes data by constructing nested cluster hierarchies. It begins with each data point as a separate cluster, iteratively merging the most similar cluster pairs until all data points belong to a single cluster. This method offers several advantages: (1) no requirement to pre-specify cluster numbers; (2) ability to reveal multi-scale data structures; (3) generated dendrograms intuitively display data hierarchical relationships. In protocol analysis scenarios, hierarchical clustering particularly suits capturing nested protocol field structures.

ProRE’s hierarchical clustering process is described in Algorithm 2. The core concept builds hierarchical structures by iteratively merging field classes with the closest semantics. Taking slice embeddings representing byte semantics as input, it performs clustering by calculating distances at different levels to recover field structures.

Definition 2 (Abstraction Extraction Function): For element

where

For code slice

Definition 3 (

then

Our goal is to generate the field cluster tree T, represented as an

Figure 6: Field cluster tree

Definition 4 (Semantic Distance):

The hierarchical clustering process starts from

ProRE uses IDA Pro [20] and Intel Pin [21] as static and dynamic analysis engines, respectively. The assembly language model consists of a 12-layer Transformer encoder-decoder. Each layer contains standard multi-head self-attention mechanisms and feed-forward neural network (FFN) modules. The attention mechanism uses 12 attention heads, and the FFN layer uses GELU activation function. To enhance generalization capability, we apply Dropout (rate = 0.1) in attention and FFN layers. During pre-training, we use FP16 mixed precision training for acceleration with a batch size of 256. The learning rate peak is set to 5e-4 with linear warmup. We set

Our evaluation aims to answer the following research questions:

• RQ1: What is the overall performance of ProRE in field structure recovery?

• RQ2: How does ProRE compare with other baseline methods?

• RQ3: Are the implementations of ProRE’s modules beneficial for improving effectiveness?

• RQ4: How effective is ProRE in real-world tasks?

This section introduces the datasets, baseline methods, and metrics for experimental evaluation.

We selected evaluation datasets from both common communication programs and malicious samples based on the following principles: (1) diverse protocol types; (2) message structures ranging from simple to complex; (3) real-world applicability with broad representativeness.

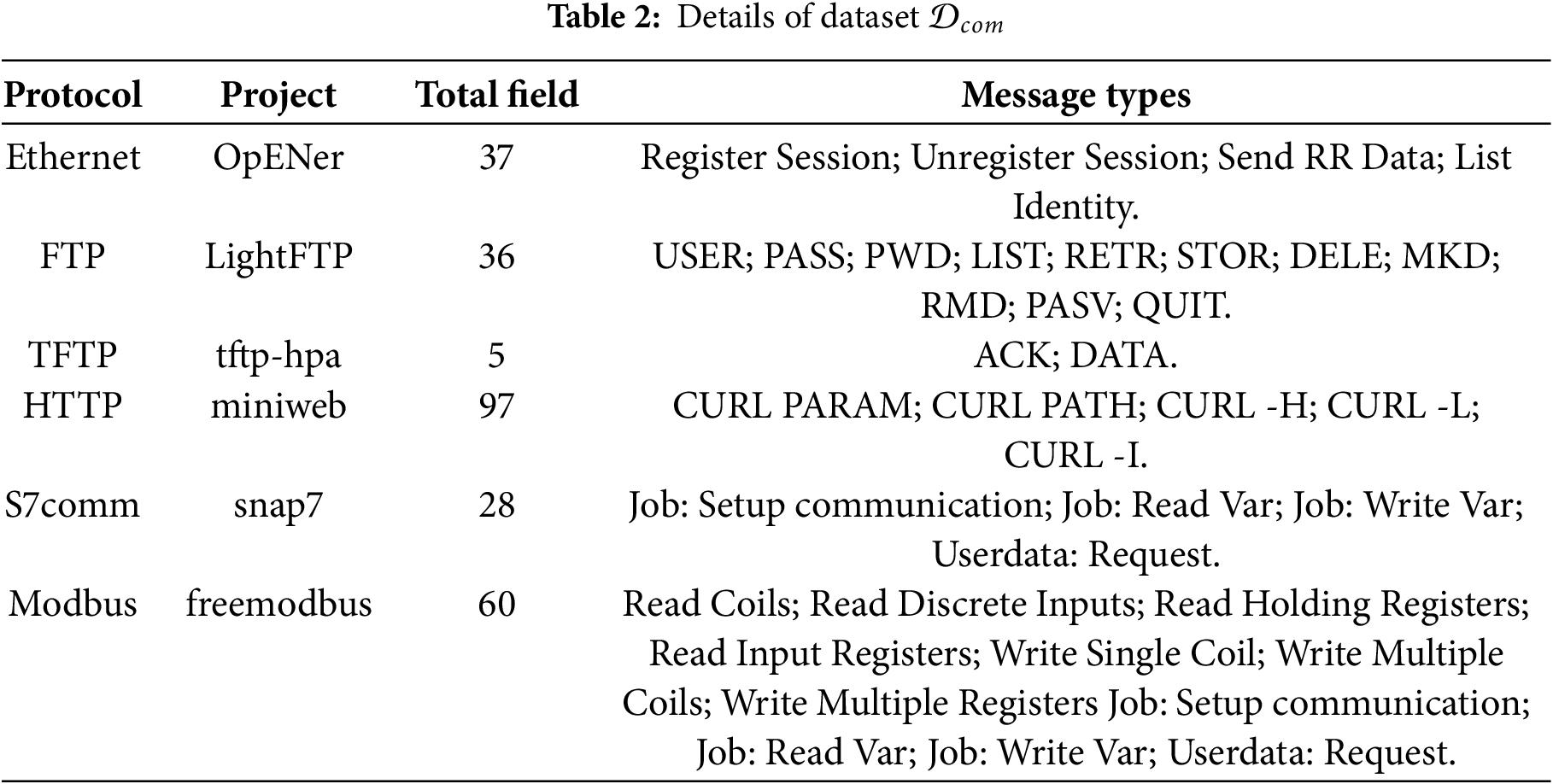

Common Protocol Dataset (

We curated a common protocol set

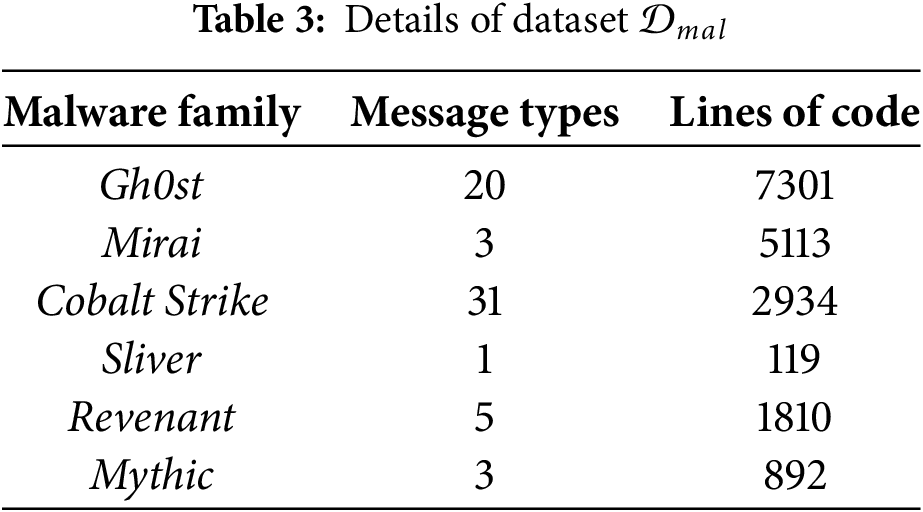

Malicious Protocol Dataset (

Existing research lacks protocol benchmarks for malware, so we manually created a sample set from six popular malware families to evaluate ProRE in malicious protocol analysis, as shown in Table 3. Among these, Gh0st uses a custom binary protocol, while Mirai implements lightweight IoT protocols. Cobalt Strike and Sliver represent modern C2 frameworks with complex protocol designs. The samples range from simple single-field protocols (Sliver) to complex multi-layered structures (Mythic) with multiple message types. All selected families are actively deployed in real attacks, with publicly available samples and verifiable protocol behaviors.

We compare ProRE with following methods:

• binpre [4]: The state-of-the-art ExeT-based method. We supplemented its support for floating-point extension instructions and ported it to the Windows platform for broader analysis applicability.

• tupni [7]: A classic work in state-of-the-art ExeT-based protocol reverse analysis methods, using an open-source reimplementation [4].

• netlifter [18]: Aims to lift protocol implementation code to BNF protocol format. For fair comparison, we used decompiled code fragments parsing protocols as input and wrote targeted stub code to drive netlifter, also performing unified conversion of its original BNF output.

• QwQ-32B-preview [22]: We use the latest open-source large reasoning model (LRM) as a representative of LLM-based inference methods. For fair comparison, we carefully designed prompts for field structure recovery tasks, specifying the correspondence between fields and variables.

We did not consider more well-known ExeT-based methods [6] as their performance has been surpassed by state-of-the-art work [4]. Due to fundamental differences in application scenarios and technical principles, NetT-based methods [2,3] are also not within our comparison scope.

We use the following metrics for evaluation.

Slice

For two code slices, let the relatedness score (

Field Recovery

We use macro-F1 score and cophenetic correlation coefficient (

where

with

We propose using the cophenetic correlation coefficient (

where

The field structure recovery performance on the common protocol dataset

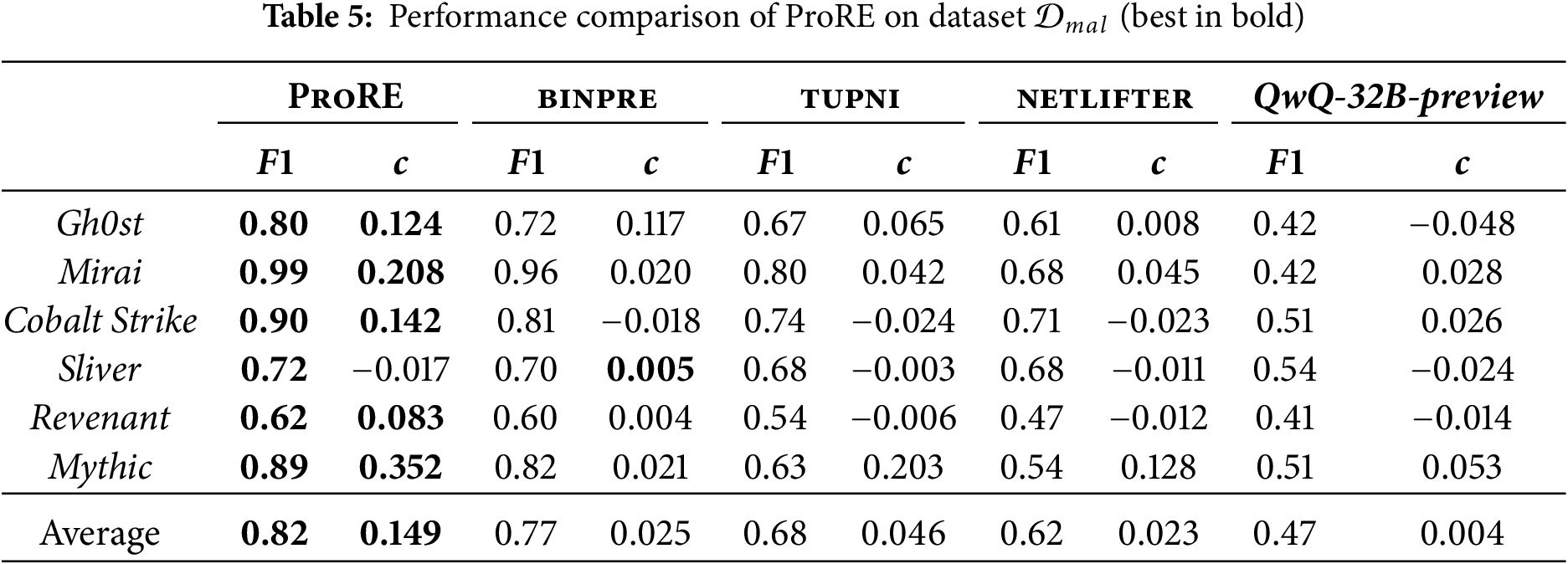

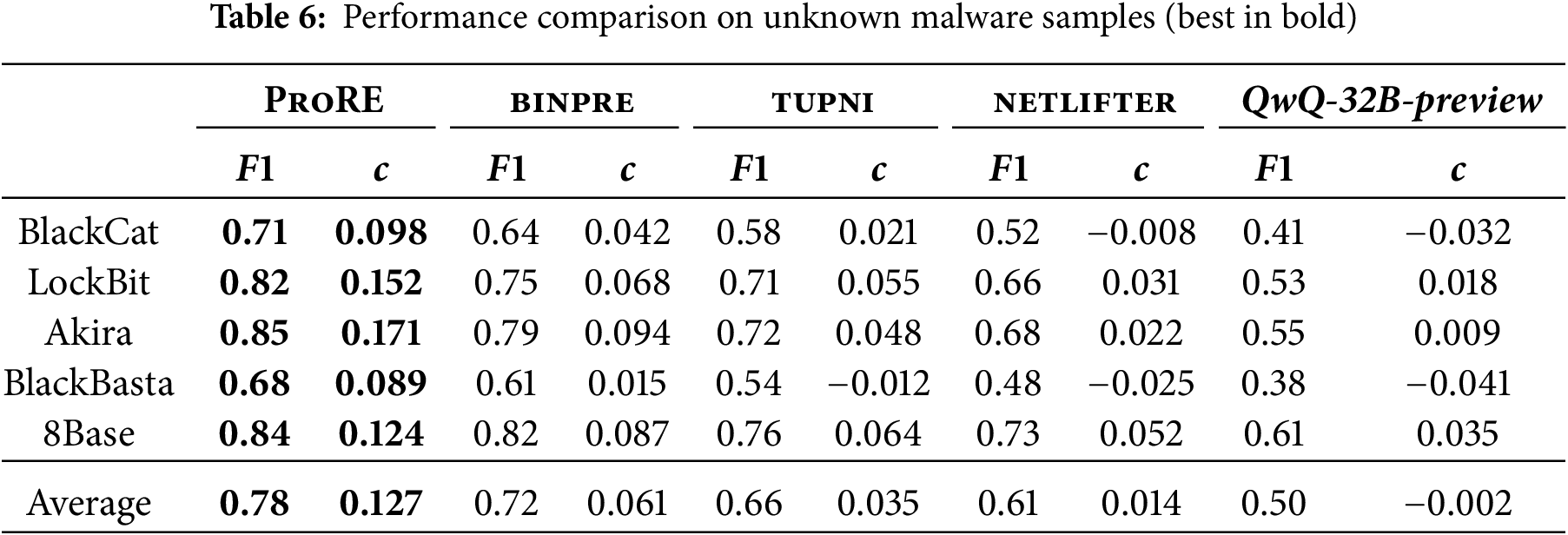

The performance on the malware protocol dataset

To evaluate generalization capability on unknown malware, Table 6 presents the performance comparison between ProRE and baseline methods across 5 unknown samples. These samples were selected from the public platform [25], with initial disclosure dates after June 2025. Sample types were identified using the commercial detection platform [26], and we manually analyzed the communication protocol message structures. Results demonstrate that ProRE maintains robust performance on unknown samples, achieving an average F1 score of 0.78 and cophenetic correlation coefficient of 0.127, outperforming all baseline methods by 6%–28% and 0.066–0.129, respectively. Even for complex protocols with nested encryption layers such as BlackCat, ProRE successfully identifies field boundaries through semantic understanding of data transformation operations. This indicates that ProRE generalizes effectively to unknown malware protocols. However, tupni shows the steepest performance decline on unknown samples (average F1 of 0.66), indicating poor adaptability to novel protocol patterns. netlifter’s static analysis approach results in highly variable performance, from moderate success on structured protocols like 8Base (F1 of 0.73) to near failure on encrypted protocols like BlackCat (F1 of 0.52). The QwQ-32B-preview model exhibits the poorest generalization (average F1 of 0.50), suggesting that its training on general code corpora provides insufficient protocol-specific knowledge.

We analyze the code slicing module, assembly language model, and clustering algorithm to evaluate their impact on overall performance.

Code Slicing Module

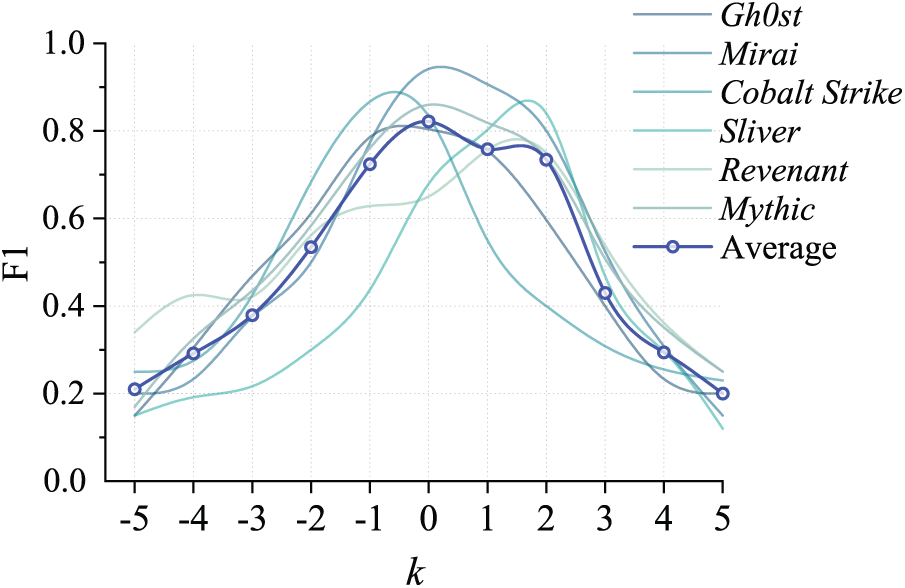

For code slice extraction, we evaluate through field structure recovery

Figure 7:

Assembly Language Model

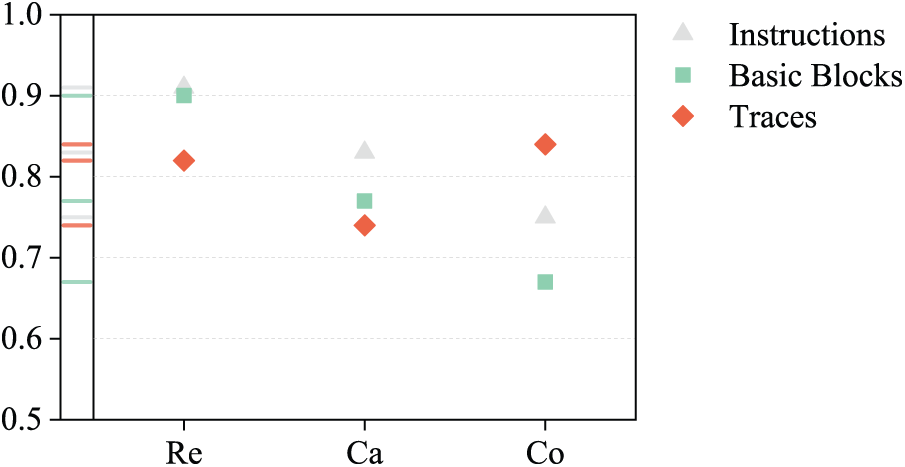

To comprehensively evaluate current slice performance, we generate embedding vectors for instruction, basic block, and trace-level code, respectively. Results in Fig. 8 show that, ProRE assembly language model maintains relatively stable embedding quality across different granularities. Among them, basic block-level achieves higher average relatedness score of 0.88, indicating slice embeddings at this granularity are closer to actual results; trace-level has higher coherence score, reflecting better generalization capability in semantic expression for program execution records of certain length, but inferior to the other two granularities in relatedness and categorization; instruction-level has higher categorization score, reflecting more accurate and concentrated semantic expression.

Figure 8: Assembly language model evaluation on ProRE

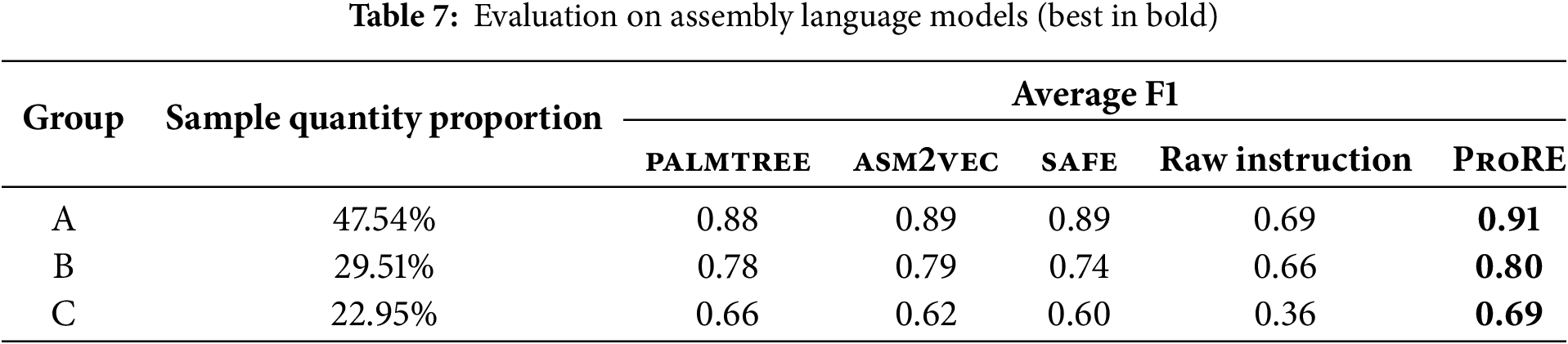

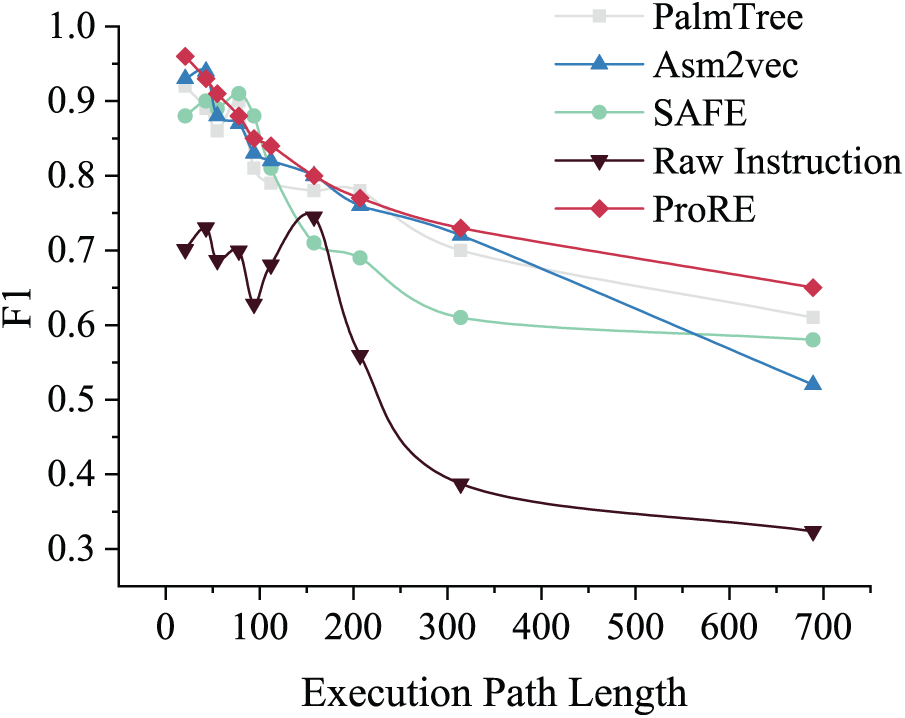

To compare performance of different assembly language models, we selected palmtree [13], asm2vec [12], safe [11], and raw instruction sequences as instances of abstraction extraction function

Figure 9: Comparison with other assembly language models

Results show that when protocol processing paths are short (not exceeding 100), F1 scores for field recovery are similar across different assembly language models. As path length increases, F1 scores gradually decrease, but ProRE still maintains the highest average F1 of 0.83. When path length exceeds 300, ProRE performs more stably, with average F1 scores 13% higher than other models. Average F1 scores for palmtree, safe, and asm2vec are 80.4%, 80.7%, and 78.6%, respectively. Their limitations are: (1) palmtree and safe cannot handle library functions, losing partial semantic information. (2) asm2vec is limited by context window and cannot capture long-distance semantic relationships. Using raw instruction sequences lacks sufficient semantic abstraction capability, having the worst field structure recovery ability compared to assembly models, with F1 scores 19.3% lower on average.

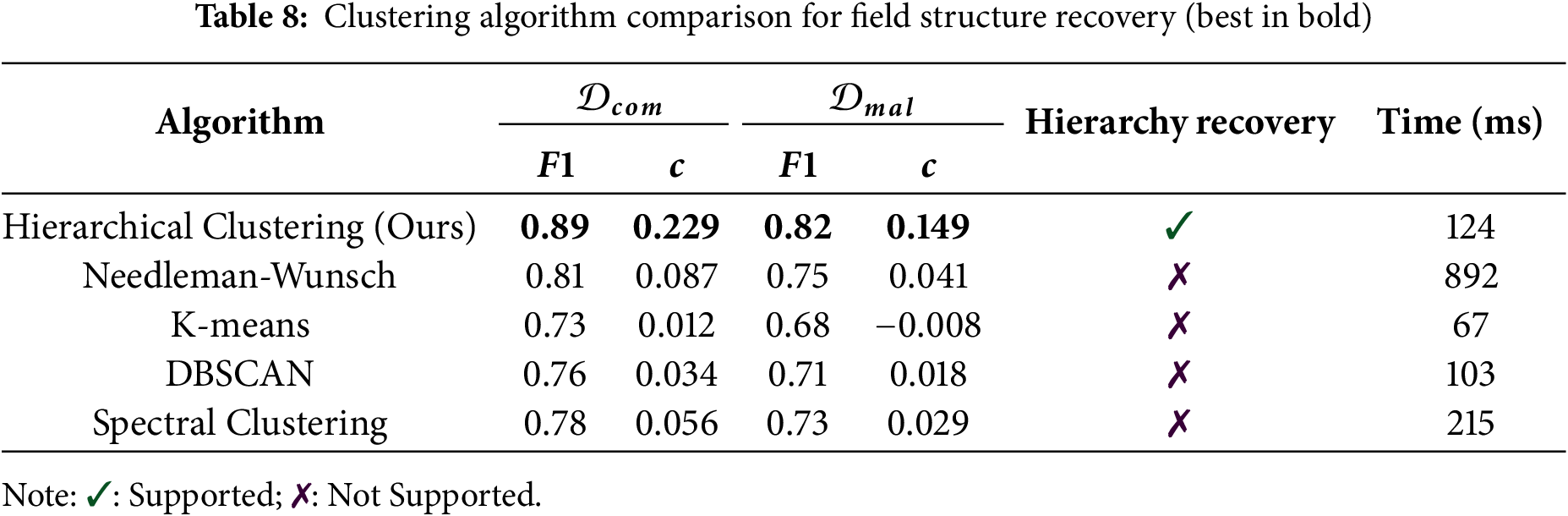

Clustering Algorithm

To validate the effectiveness of hierarchical clustering in protocol field structure recovery, we compared it with various classical clustering algorithms, including Needleman-Wunsch [27], K-means, DBSCAN, and spectral clustering. We adapted these algorithms for protocol field recovery tasks by using byte-level slice embeddings as input.

The results in Table 8 demonstrate that hierarchical clustering provides significant advantages in protocol field recovery. While Needleman-Wunsch achieves reasonable F1 scores through sequence alignment, it cannot capture nested field relationships, resulting in significantly lower cophenetic correlation coefficients (0.087 vs. 0.229 on

We select two representative samples to validate ProRE in real-world malware analysis.

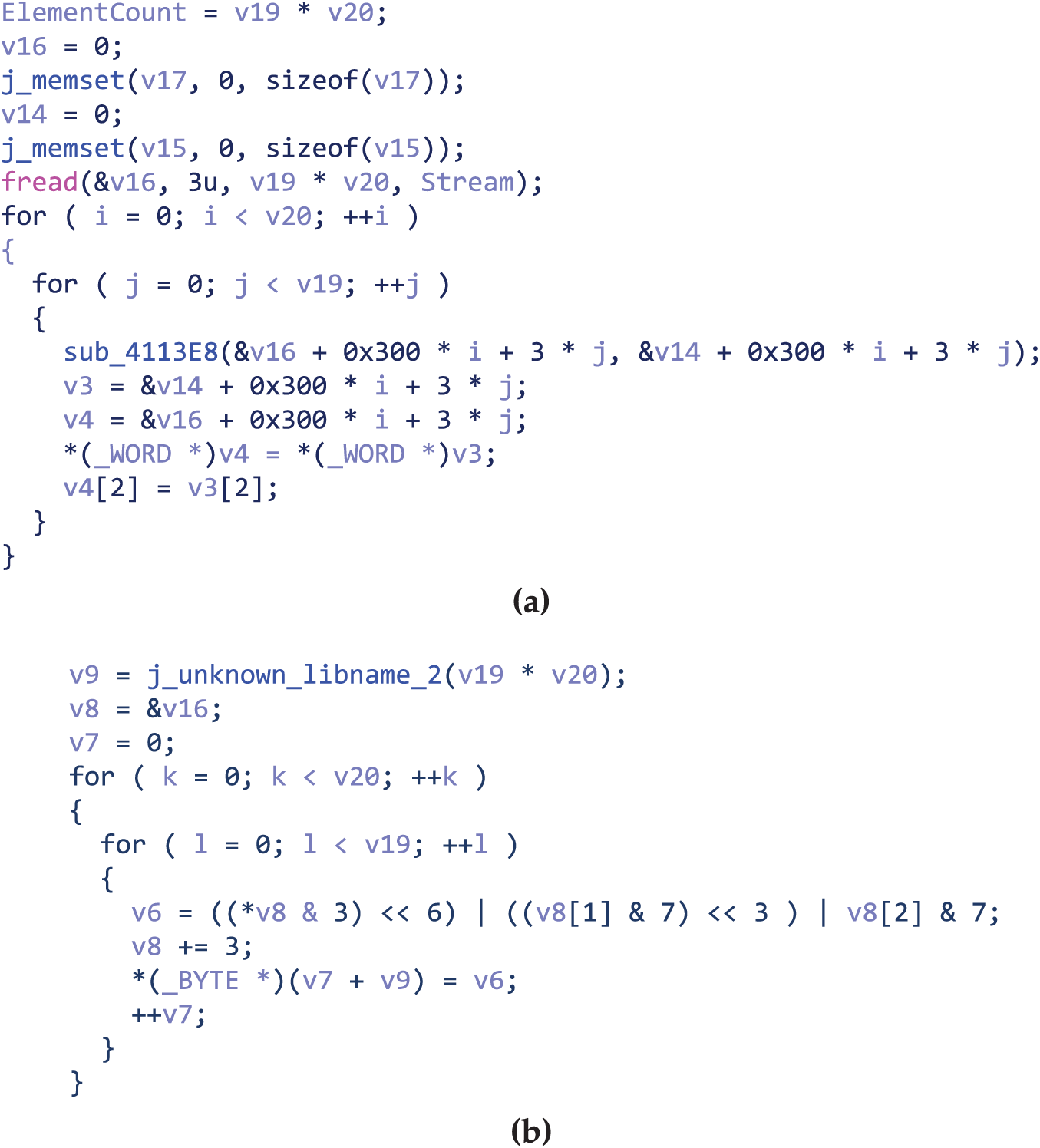

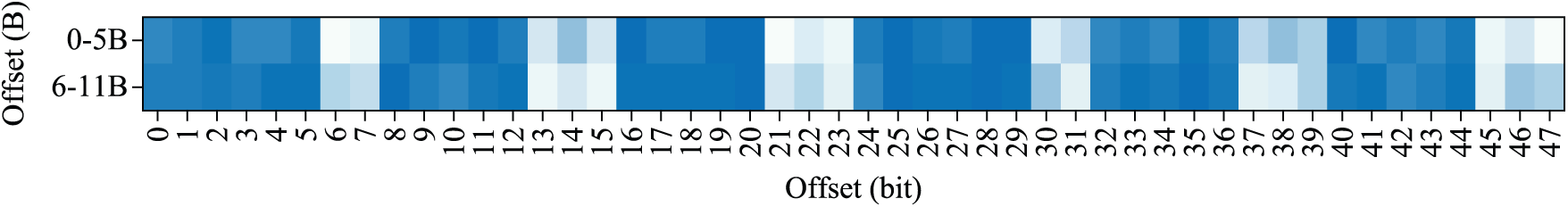

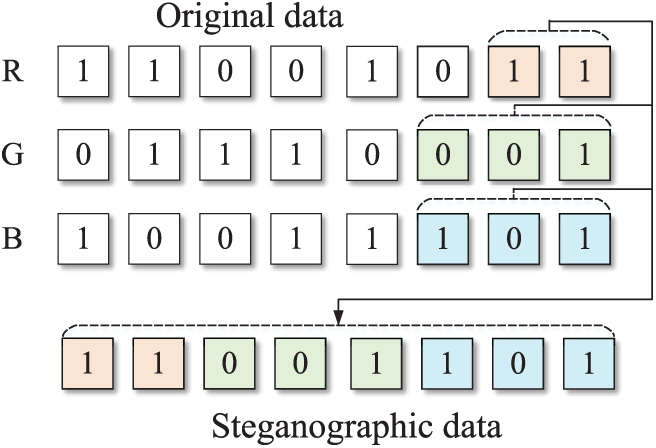

6.4.1 Duke Steganographic Protocol

Duke [28] samples use LSB (Least Significant Bit) algorithm to extract steganographic data from bitmap images. Fig. 10 shows key code fragments of the sample processing image data: (a) shows regular bitmap data reading portion, (b) shows LSB steganographic data extraction portion. We generate code slice embeddings for each bit of the image and perform visual analysis. As shown in Fig. 11, specific positions in each group of three bytes, such as bits 7–8 of the first byte, bits 6–8 of the second byte, and bits 6–8 of the third byte, show obvious semantic differences from other bits. These positions exactly correspond to steganographic data bits extracted by the LSB algorithm (Fig. 12). Experimental results show that ProRE accurately identified execution semantic differences when malicious code processes different data types through slice embedding, recovering steganographic protocol structures.

Figure 10: Duke malware code fragments

Figure 11: Duke code slice embedding visualization

Figure 12: LSB algorithm process

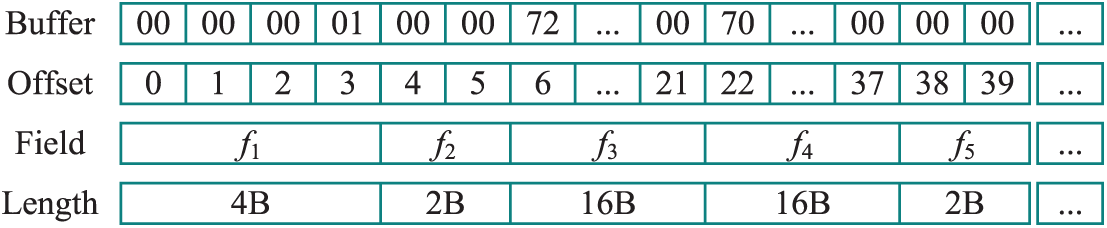

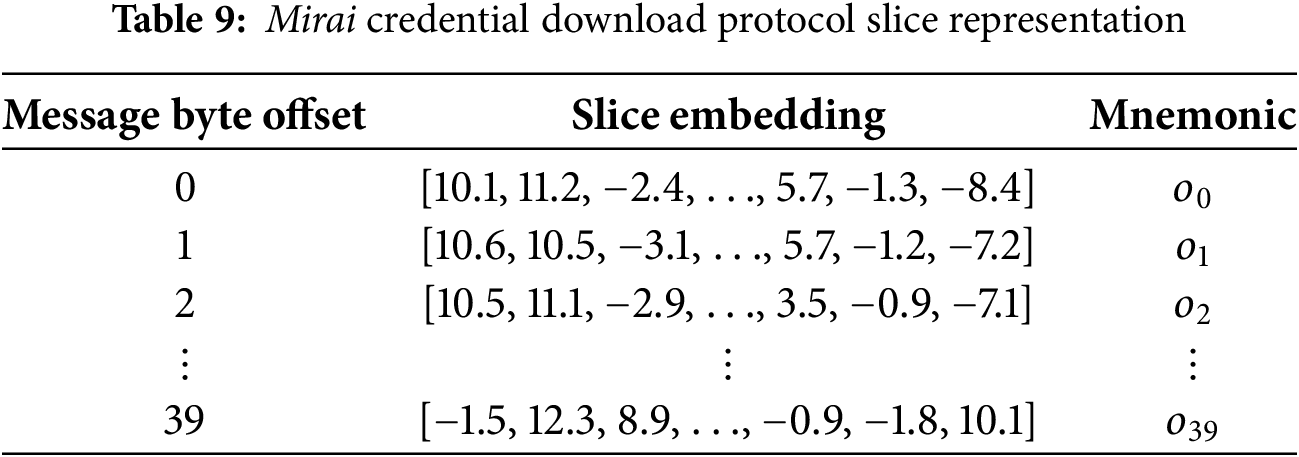

6.4.2 Mirai Credential Download Protocol

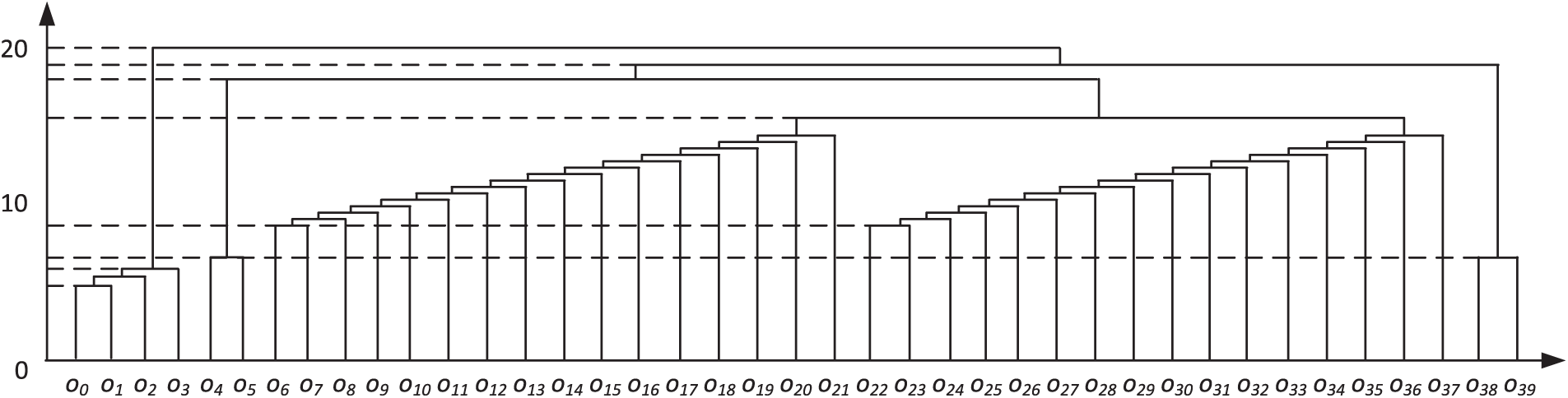

Mirai [17] is a botnet program that implements covert attacks by infecting and controlling large numbers of IoT devices. A sample from this family (MD5: 3df80916a0d54cdf5eb3d476b4ae176d) has a credential download protocol containing 40 bytes of data payload. Fig. 13 shows the hexadecimal representation of the protocol message. We extract code slice embeddings corresponding to each byte (see Table 9) and apply hierarchical clustering algorithm to generate the field cluster tree. Analysis results show that the message has clear field boundaries at offsets 0–3, 4–5, 6–21, 22–37, and 38–39 bytes, completely matching the actual field structure (Fig. 14). Notably, fields 6–21, 22–37 and bytes 4–5, 38–39 are relatively close in semantic distance, corresponding to username and password data in credentials, respectively, demonstrating ProRE’s ability to capture similarities in message processing logic.

Figure 13: Mirai credential download protocol message structure

Figure 14: Mirai protocol field tree

In this section, we discuss the time consumption and generalization ability of ProRE, encrypted message processing, and its limitations.

Time Consumption

ProRE’s main computational overhead comes from: (1) dynamic execution trace collection, (2) code slice embedding computation, and (3) hierarchical clustering process. In our experiments, processing a 40-byte message takes an average of 3.2 s, with slice extraction accounting for 43.0%, embedding computation 35.6%, and clustering 21.4%. While this overhead is higher than simple static analysis methods, considering the significant improvement in analysis accuracy, this trade-off is acceptable. Additionally, ProRE adopts an online instrumentation execution plus offline data flow simulation design, separating necessary instrumentation code for tracking execution from data flow analysis code, reducing runtime analysis burden.

Generalization Capability

Our method has been validated on x86 architecture, but its core ideas can be extended to other architectures. The assembly language model can be adapted by retraining on the target instruction set, while slice extraction and hierarchical clustering algorithms are architecture-agnostic. Future work could explore cross-architecture transfer learning to reduce training costs on new architectures.

Encrypted Message

Most malware adopts encrypted protocols for communication. Similar to previous work [8,29], ProRE begins analysis from identified unencrypted message buffers to bypass the impact of encryption/decryption functions on data flow analysis accuracy. ProRE captures the data propagation path of raw message buffers from the network, and when standard cryptographic API calls exist in the path, it updates the analysis starting point

Limitations

Despite ProRE achieving excellent performance, several limitations remain that we plan to address in future work: First, for protocols containing only single long fields (like Sliver), byte-level slice extraction may lead to over-segmentation. This can be mitigated by implementing adaptive granularity analysis that dynamically adjusts the slicing unit based on preliminary field length estimation. We are exploring multi-scale slicing approaches that combine byte, word, and block-level analysis. Second, when protocols use complex encryption or obfuscation techniques, execution slices may not accurately reflect true field boundaries. To address this, we plan to integrate symbolic execution techniques to reason about data transformations and develop encryption-aware slicing algorithms that can identify and handle cryptographic boundaries. Third, the current instrumentation engine [21] is limited by applicable architectures and platforms. We are developing a platform-agnostic intermediate representation layer that can abstract away architecture-specific details, enabling ProRE to support multiple binary analysis platforms [31–33] without significant modifications.

This paper proposes ProRE, a protocol message structure reconstruction method based on execution slice embedding. Addressing the shortcomings of existing methods in field boundary division and hierarchical relationship recovery, we design three key techniques: (1) execution slice extraction based on data flow dependencies to precisely capture protocol parsing processes; (2) a data flow-sensitive assembly language model to achieve high-quality vector representation of program semantics; (3) hierarchical clustering algorithm to completely recover protocol nested structures. Evaluation on a dataset containing 12 protocols shows that ProRE achieves an average F1 score of 0.85 and cophenetic correlation coefficient of 0.189, improving by 19% and 0.126 respectively over state-of-the-art baseline methods (including binpre, tupni, netlifter, and QwQ-32B-preview), demonstrating significant superiority in both accuracy and completeness of field structure recovery. Case studies further validate ProRE’s effectiveness in practical malware analysis.

ProRE enables security analysts to rapidly understand unknown protocols in malware analysis, reducing analysis time from days to hours. The hierarchical structure recovery capability provides crucial insights for vulnerability assessment, as nested field relationships often indicate potential parsing vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the method’s success on encrypted protocols like Duke demonstrates its applicability to modern malware that employs sophisticated evasion techniques. Organizations can integrate ProRE into their threat intelligence pipelines to automatically extract protocol specifications from captured malware samples, enhancing their defensive capabilities.

Several promising research directions emerge from this work. First, extending ProRE to handle stateful protocol analysis would enable complete protocol state machine recovery. Second, developing cross-architecture transfer learning techniques could reduce the training overhead when adapting to new processor architectures. Third, integrating ProRE with fuzzing frameworks could enable structure-aware protocol fuzzing for vulnerability discovery. Finally, investigating the use of large language models to generate human-readable protocol documentation from recovered structures could bridge the gap between automated analysis and human understanding.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hui Shu; methodology, Yuyao Huang; software, Yuyao Huang; validation, Yuyao Huang; investigation, Fei Kang; writing—original draft preparation, Yuyao Huang; writing—review and editing, Hui Shu, Fei Kang; supervision, Fei Kang; funding acquisition, Hui Shu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Available at: https://github.com/Mal-PRE/ProRE (accessed on 12 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang S, Sun F, Zhang H, Zhan D, Li S, Wang J. EDSM-based binary protocol state machine reversing. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69(3):3711–25. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.016562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Luo Z, Liang K, Zhao Y, Wu F, Yu J, Shi H, et al. DynPRE: protocol reverse engineering via dynamic inference. In: Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2024; 2024 Feb 26–Mar 1; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

3. Chandler J, Wick A, Fisher K. BinaryInferno: a semantic-driven approach to field inference for binary message formats. In: Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2023; 2023 Feb 27–Mar 3; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

4. Jiang J, Zhang X, Wan C, Chen H, Sun H, Su T. BinPRE: enhancing field inference in binary analysis based protocol reverse engineering. In: Proceedings of the 2024 on ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2024 Oct 14–18; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 3689–703. [Google Scholar]

5. Shi J, Wang Z, Feng Z, Lan Y, Qin S, You W, et al. AIFORE: smart fuzzing based on automatic input format reverse engineering. In: 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23); 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA. p. 4967–84. [Google Scholar]

6. Lin Z, Jiang X, Xu D, Zhang X. Automatic protocol format reverse engineering through context-aware monitored execution. In: Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2008; 2008 Feb 10–13; San Diego, CA, USA. Vol. 8, p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

7. Cui W, Peinado M, Chen K, Wang HJ, Irun-Briz L. Tupni: automatic reverse engineering of input formats. In: Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2008 Oct 27–31; Alexandria VA, USA. p. 391–402. [Google Scholar]

8. Caballero J, Poosankam P, Kreibich C, Song D. Dispatcher: enabling active botnet infiltration using automatic protocol reverse-engineering. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2009 Nov 9–13; Chicago IL, USA. p. 621–34. [Google Scholar]

9. Raff E, Barker J, Sylvester J, Brandon R, Catanzaro B, Nicholas CK. Malware detection by eating a whole EXE. In: The Workshops of the The Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018 Feb 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI Press; 2018. p. 268–76. [Google Scholar]

10. Guo W, Mu D, Xing X, Du M, Song D. DEEPVSA: facilitating value-set analysis with deep learning for postmortem program analysis. In: 28th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 19); Santa Clara, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 1787–804. [Google Scholar]

11. Massarelli L, Di Luna GA, Petroni F, Baldoni R, Querzoni L. Safe: self-attentive function embeddings for binary similarity. In: Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment: 16th International Conference, DIMVA 2019; Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 309–29. [Google Scholar]

12. Ding SH, Fung BC, Charland P. Asm2vec: boosting static representation robustness for binary clone search against code obfuscation and compiler optimization. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security And Privacy (sp); 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 472–89. [Google Scholar]

13. Li X, Qu Y, Yin H. Palmtree: Learning an assembly language model for instruction embedding. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2021 Nov 15–19; New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 3236–51. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang H, Qu W, Katz G, Zhu W, Gao Z, Qiu H, et al. Jtrans: jump-aware transformer for binary code similarity detection. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2022 Jul 18–22; New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

15. Huang Y, Shu H, Kang F, Guang Y. Protocol reverse-engineering methods and tools: a survey. Comput Commun. 2022;182:238–54. [Google Scholar]

16. Kleber S, Maile L, Kargl F. Survey of protocol reverse engineering algorithms: decomposition of tools for static traffic analysis. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2019;21(1):526–61. doi:10.1109/comst.2018.2867544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Antonakakis M, April T, Bailey M, Bernhard M, Bursztein E, Cochran J, et al. Understanding the mirai botnet. In: 26th USENIX Security Symposium; 2017 Aug 16–18; Vancouver, BC, Canada: USENIX Association. p. 1093–110. [Google Scholar]

18. Shi Q, Shao J, Ye Y, Zheng M, Zhang X. Lifting network protocol implementation to precise format specification with security applications. In: Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2023 Nov 26–30; Copenhagen, Denmark. p. 1287–301. [Google Scholar]

19. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Rock Hill, CA, USA: ACL; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

20. Hex-Rays. IDA Pro: a powerful disassembler, decompiler and a versatile debugger; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 27]. Available from: https://hex-rays.com/ida-pro. [Google Scholar]

21. Luk CK, Cohn R, Muth R, Patil H, Klauser A, Lowney G, et al. Pin: building customized program analysis tools with dynamic instrumentation. In: Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation; 2005 Jun 12–15; Chicago, IL, USA. p. 190–200. [Google Scholar]

22. Team Q. QwQ: reflect deeply on the boundaries of the unknown; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 27]. Available from: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwq-32b-preview/. [Google Scholar]

23. Schnabel T, Labutov I, Mimno D, Joachims T. Evaluation methods for unsupervised word embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2015 Sep 17–21; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 298–307. [Google Scholar]

24. Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nature Meth. 2020;17:261–72. doi:10.1038/s41592-020-0772-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. VirusShare. VirusShare.com is a repository of malware samples to provide security researchers, incident responders, forensic analysts, and the morbidly curious access to samples of live malicious code; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://virusshare.com. [Google Scholar]

26. VirusTotal. Analyse suspicious files, domains, IPs and URLs to detect malware and other breaches, automatically share them with the security community; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.virustotal.com. [Google Scholar]

27. Likic V. The Needleman-Wunsch algorithm for sequence alignment. Lecture given at the 7th Melbourne Bioinformatics Course. Australia: Bi021 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, University of Melbourne; 2008. [Google Scholar]

28. 42 PANU. Report title about duke malware; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/tag/duke-malware/. [Google Scholar]

29. Wang Z, Jiang X, Cui W, Wang X, Grace M. Automatic reverse engineering of encrypted messages. In: Computer Security ESORICS 2009: 14th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security; 2009 Sep 21–23; Saint-Malo, France. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2009. p. 200–15. [Google Scholar]

30. Meijer C, Moonsamy V, Wetzels J. Where’s Crypto?: automated identification and classification of proprietary cryptographic primitives in binary code. In: 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21); 2021 Aug 11–13; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 555–72. [Google Scholar]

31. DynamoRIO. Dynamic instrumentation tool platform; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 27]. Available from: https://dynamorio.org/. [Google Scholar]

32. Nethercote N, Seward J. Valgrind: a framework for heavyweight dynamic binary instrumentation. ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 2007;42(6):89–100. [Google Scholar]

33. Triton. Triton is a dynamic binary analysis library; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 27]. Available from: https://triton-library.github.io/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools