Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

TopoMSG: A Topology-Aware Multi-Scale Graph Network for Social Bot Detection

1 School of Computer and Cyber Sciences, Communication University of China, Beijing, 100024, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Media Convergence and Communication, Communication University of China, Beijing, 100024, China

3 School of Data Science and Intelligent Media, Communication University of China, Beijing, 100024, China

* Corresponding Author: Qi Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 47 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071661

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Social bots are automated programs designed to spread rumors and misinformation, posing significant threats to online security. Existing research shows that the structure of a social network significantly affects the behavioral patterns of social bots: a higher number of connected components weakens their collaborative capabilities, thereby reducing their proportion within the overall network. However, current social bot detection methods still make limited use of topological features. Furthermore, both graph neural network (GNN)-based methods that rely on local features and those that leverage global features suffer from their own limitations, and existing studies lack an effective fusion of multi-scale information. To address these issues, this paper proposes a topology-aware multi-scale social bot detection method, which jointly learns local and global representations through a co-training mechanism. At the local level, topological features are effectively embedded into node representations, enhancing expressiveness while alleviating the over-smoothing problem in GNNs. At the global level, a clustering attention mechanism is introduced to learn global node representations, mitigating the over-globalization problem. Experimental results demonstrate that our method effectively overcomes the limitations of single-scale approaches. Our code is publicly available at https://anonymous.4open.science/r/TopoMSG-2C41/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).Keywords

Social bots are automated programs operating on social media platforms, where malicious bots pose significant threats to network security through large-scale retweeting, rumor dissemination, election interference, and extremist propaganda [1,2]. Social bot detection therefore serves as a crucial safeguard for maintaining cyberspace security and enhancing platform credibility.

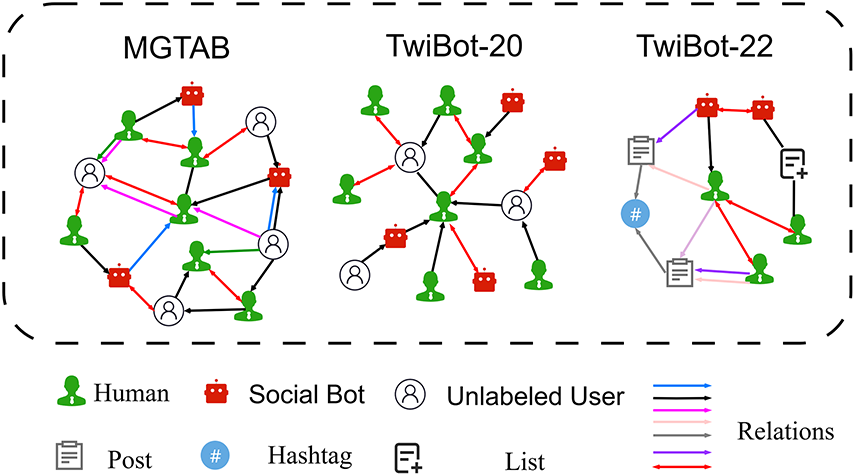

Existing social bot detection datasets are typically constructed on graph structures; however, the underlying sampling strategies differ substantially, leading to pronounced topological variations across datasets. As illustrated in Fig. 1, MGTAB [3] constructs a scale-free graph by retaining only edges that are semantically relevant to a given topic, resulting in a highly clustered local structure. TwiBot-20 [4], collected using a breadth-first search strategy, exhibits a hierarchical and tree-like topology characterized by relatively sparse connectivity. TwiBot-22 [5], which also employs breadth-first sampling but incorporates heterogeneous relationships, further weakens inter-user connectivity and produces an even looser graph structure.

Figure 1: Topological structure features across datasets. Relationships between entities include followers, friends, comments, retweets, and other interactions

Cummings [6] argue that structural diversity in social networks fosters broader knowledge sharing and enables users to verify information more rapidly, thereby impeding bot-driven misinformation. Zhou et al. [7] further demonstrate that as the number of connected components among neighboring nodes increases, the proportion of bots decreases. On the one hand, additional connectivity paths allow users to cross-check the authenticity of message sources more swiftly; on the other hand, the intricate structure dilutes coordination among bots and their accomplices. Consequently, we argue that the network topology, and in particular the structure of connected components, provides a salient signal for social bot detection.

Existing graph-neural-network (GNN) approaches to social-bot detection are largely confined to single-scale feature extraction, relying either on local neighborhoods or on global graph structures, while the efficacy of multi-scale modeling remains under-explored. Moreover, each paradigm suffers from intrinsic limitations. Message-passing models aggregate features from immediate neighbors and achieve strong empirical performance; however, they are prone to over-smoothing and over-squashing [8]: as the number of GNN layers increases, node representations become indistinguishable, yielding a sharp drop in accuracy. Graph Transformers (GT) equipped with global attention can capture long-range dependencies and global topology, yet they confront the local-global chaos problem [9]. These models frequently overlook informative neighbors, leading to overfitting and excessive globalization [10].

Therefore, social bot detection faces two key challenges: (a) How to effectively leverage topological features, in particular connected components that have been proven to correlate closely with the proportion of social bots. (b) How to decouple message-passing and global attention mechanisms so that local and global features can be learned independently and more effectively.

To address these issues, we propose a topology-aware, multi-scale social-bot detection framework. Locally, we encode per-relation connected-component features via Persistent Homology, a topological-data-analysis tool that has recently advanced deep learning [11] and delivered state-of-the-art results on graph classification. By summarizing rich topological signatures for each edge type, persistent homology enables our model to achieve competitive accuracy with fewer GNN layers, mitigating over-smoothing. Globally, we introduce a cluster-wise attention mechanism that partitions the graph into structural clusters and restricts attention to within-cluster nodes, alleviating the excessive globalization inherent in vanilla Graph Transformers. Finally, a local-global co-training strategy adaptively balances the contributions of local message-passing and global attention. Our unified model jointly exploits multi-scale topological information, yielding significant gains in both accuracy and robustness.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

• We are the first to apply Persistent Homology to social bot detection, enhancing node representations by capturing multi-scale topological structures under heterogeneous node relationships, while also mitigating over-smoothing and over-squashing caused by deep GNN stacks.

• To mitigate over-globalization in Graph Transformers, we propose a clustered global attention mechanism that partitions the graph into non-overlapping clusters, effectively reducing the over-reliance of Graph Transformers on global attention and alleviating local-global chaos caused by over-globalizing.

• We employ a collaborative training framework that jointly optimizes the local and global feature modules through a shared objective, with learnable weights to automatically balance their contributions and prevent one from dominating the learning process.

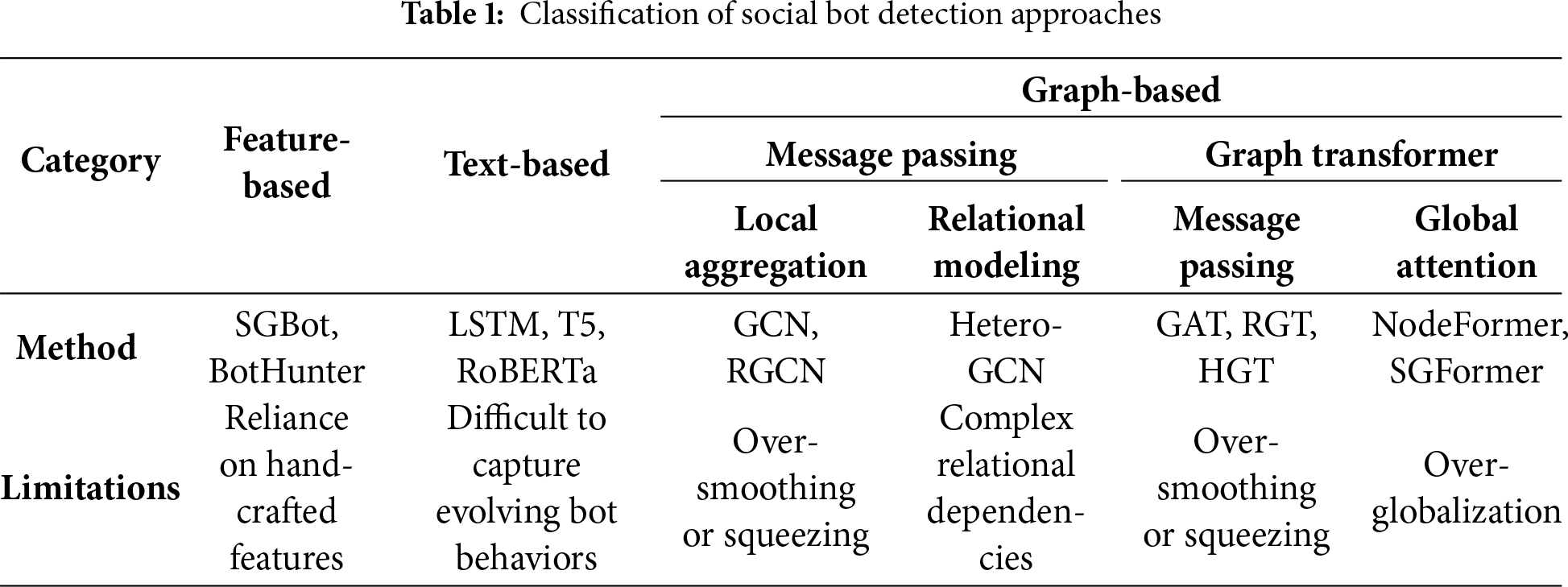

Social bot detection approaches can be broadly divided into three categories: feature-based, text-based, and graph-based methods, as summarized in Table 1. Feature-based methods rely on handcrafted user features such as profile, content, timing, and social behavior [12,13]. Text-based methods leverage sequential models like LSTM [14] or pre-trained language models such as T5 [15] and RoBERTa [16] to capture linguistic patterns. However, advanced bots now mimic genuine users by stealing real content and behaviors, evading detection based on textual and behavioral cues. As a result, methods exploiting social network structure—particularly graph neural networks (GNNs)—have become dominant, as bots still struggle to replicate authentic topological interaction patterns.

Social networks are essentially complex graph structures constituted by massive user interactions, excelling in capturing collective behaviors and propagation patterns compared to text analysis methods. Existing graph-based methods can be broadly categorized into two main types: message-passing-based methods, including GCN [17] and RGCN [18], and graph-transformer-based methods. While message-passing-based methods have been effective in modeling local graph structures, recent advancements have shown that graph-transformer-based methods, leveraging the powerful capabilities of transformers, are particularly suited for capturing global dependencies and complex interaction patterns in social networks. As a result, we focus primarily on graph-transformer-based approaches, which have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in social bot detection tasks. Existing graph transformer approaches can be categorized into two main types: message-passing-based and global-attention-based.

Graph Attention Networks (GATs) [19] demonstrate unique advantages in social bot detection. The classic GAT adaptively assigns inter-node weights through attention mechanisms to capture the most relevant interaction patterns. Inspired by this, the Relational Graph Transformer (RGT) [20] introduces multi-relational attention mechanisms that dynamically adjust weights across semantically distinct relationships, enhancing modeling capacity for complex social networks. The Heterogeneous Graph Transformer (HGT) [21] further designs specialized attention mechanisms for diverse user types and interaction patterns in social networks through explicit modeling of the heterogeneity of nodes and edges. These message-passing-based GNNs not only enable flexible node aggregation but also capture diverse structural features, achieving state-of-the-art performance in bot detection tasks.

Transformers provide theoretical foundations for GNNs to capture global features through learnable fully-connected attention graphs [22]. NodeFormer [23] proposes an all-pair message passing paradigm that reduces computational complexity to linear scale via kernelized Gumbel-Softmax operators, enabling efficient signal propagation on large graphs. SGFormer [24] introduces a simplified graph transformer architecture that resolves quadratic overhead through single-layer attention modeling. Despite their demonstrated potential in capturing long-range dependencies, global attention mechanisms remain underexplored in social bot detection.

This section formally introduces key concepts employed in our work.

Persistent Homology: Topological structures are defined as features invariant under continuous deformations [11]. Persistent homology identifies multi-scale topological signatures by tracking homology group evolution across filtration scales. Different homology orders represent dimensional features: 0-order (connected components), 1-order (cycles), and 2-order (cavities).

For a

This filtration induces birth/death events of topological structures (connected components, cycles, voids). Each structure is associated with a birth-death pair

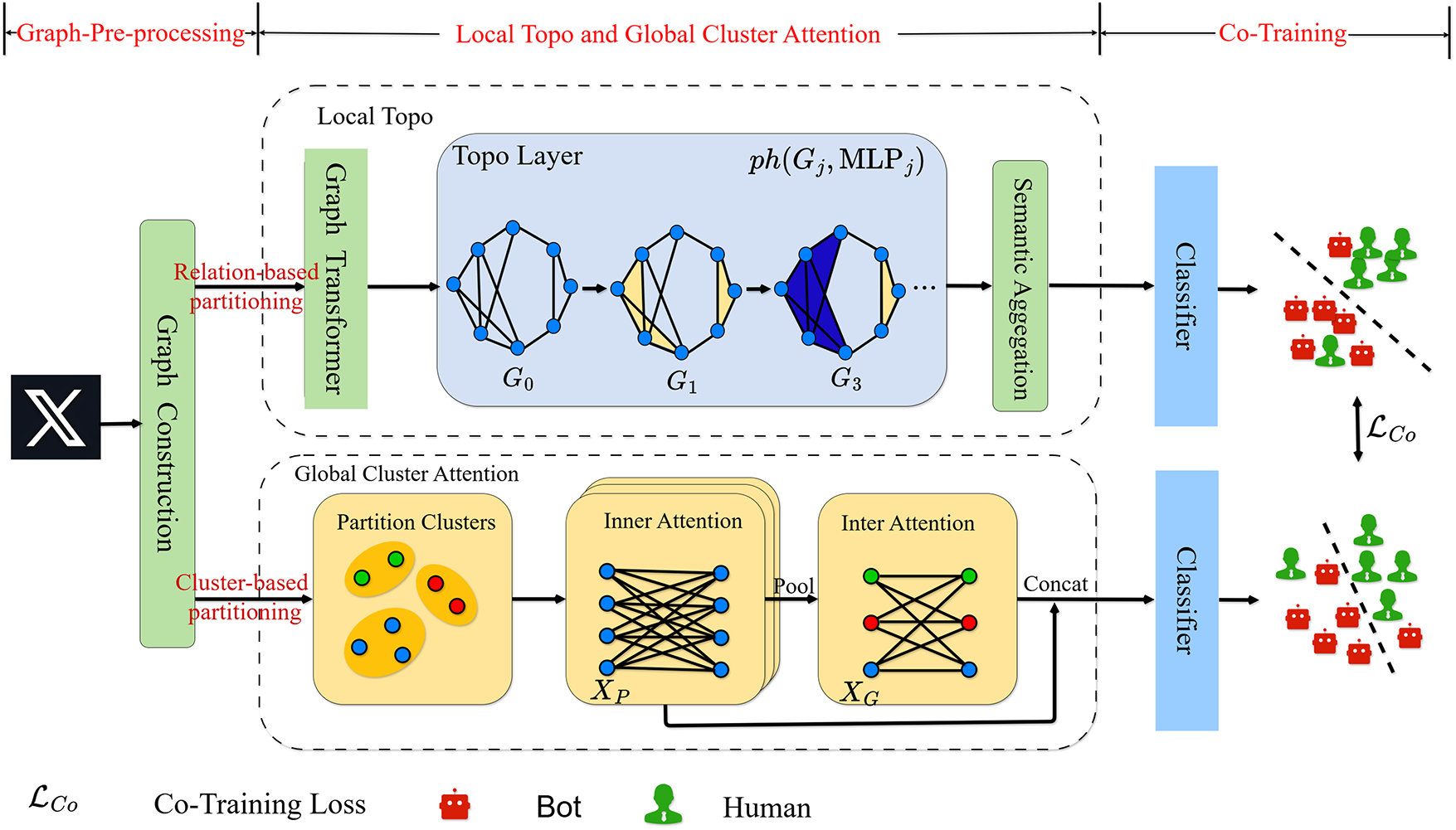

We propose a topology-aware multi-scale detection model. As shown in Fig. 2, the TopoMSG framework integrates persistent homology-based topological learning with multi-head global attention through a co-training strategy to jointly learn local and global representations. Specifically, the TopoLayer captures local multi-scale topological patterns from relation-based subgraphs and incorporates these topological features into node embeddings. In parallel, the Global Cluster Attention module captures high-level structural dependencies by modeling interactions among node clusters through inner- and inter-cluster attention. Finally, these heterogeneous features are fused through a co-training mechanism that jointly optimizes both branches under a shared loss function

Figure 2: TopoMSG is a graph learning framework that integrates local and global topological features. It first extracts multi-scale local topological patterns via persistent homology, then captures global structural information through a cluster-based attention mechanism, and finally fuses features from heterogeneous modules using a co-training strategy to enhance the discriminative power of node representations

4.1 Local Topo Relational Graph Transformer

To address the limited utilization of topological features and mitigate over-smoothing and over-squashing caused by stacking multiple GNN layers, we propose the Local Topo Relational Graph Transformer module. This module builds on the architecture of RGT [20] and utilizes the attention mechanism to learn diverse node representations under each relation. Given user feature vectors

where

The message-passing mechanism and multi-head self-attention mechanisms have demonstrated outstanding performance in the field of graph neural networks. Consequently, we employ Graph Transformer layers (GTLayer) to extract shallow topological representations of nodes. The hidden representations

where

where

where

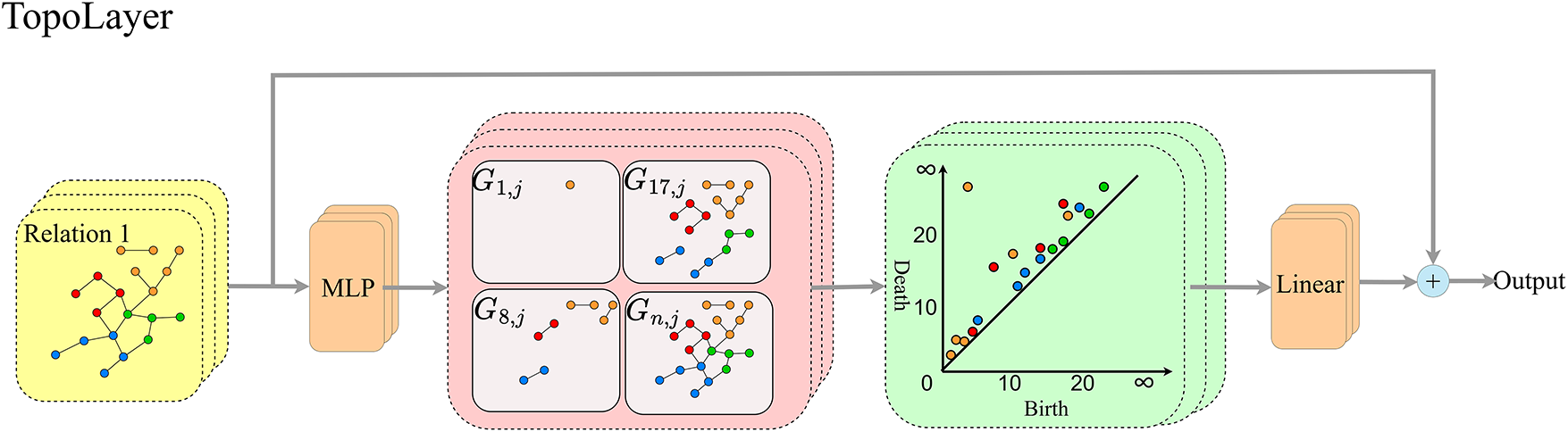

Figure 3: TopoLayer framework: We employ persistent homology to filter nodes, capturing their birth and death times during the topological evolution of the network. These times are used as topological features. Features with short persistence—i.e., those whose birth and death times are close and lie near the diagonal in the persistence diagram—are regarded as noise in the network

At last, using semantic aggregation networks [20] to aggregate node representations across relations while preserving the relation heterogeneity entailed in the social networks:

where

Finally, fuse the node representations by aggregating the outputs from all attention heads according to their normalized weights:

where

In this subsection, we describe the architecture of TopoLayer in detail. The TopoLayer shown in Fig. 3 corresponds to the same module depicted in Fig. 2, where Fig. 2 illustrates the overall architecture. We employ persistent homology from topological data analysis to reveal multi-scale hidden shape features (e.g., 0-dimensional connected components, 1-dimensional cycles, 2-dimensional voids). Specifically, we input a graph

where

This process yields a collection of persistence diagrams:

where

where

where

Global-Attention-Based Graph Transformers are effective at capturing long-range dependencies, outperforming traditional message-passing mechanisms. However, they can suffer from over-globalization, where attention weights overly favor higher-order neighbors and neglect important information from lower-hop neighbors. To mitigate this, we introduce Global Cluster Attention, which restricts the model’s focus within clusters, preserving both local and global structural information. Using Metis [26], we partition the graph into M non-overlapping clusters and remove edges enabling the nodes to focus more on intra-cluster information. To obtain the attention for nodes within each cluster, for the k-th cluster, we have:

where

And then, we feed the cluster representations

Then, we concat intra-cluster and inter-cluster node representation:

where

We implement co-training to dynamically balance local-global feature importance. Sequentially, we feed the output of Local Topo Graph Transformer

Finally, by utilizing the collaborative training loss function, we not only enhance the model’s ability to fit the ground-truth labels but also strengthen the collaborative consistency between the two modules:

where

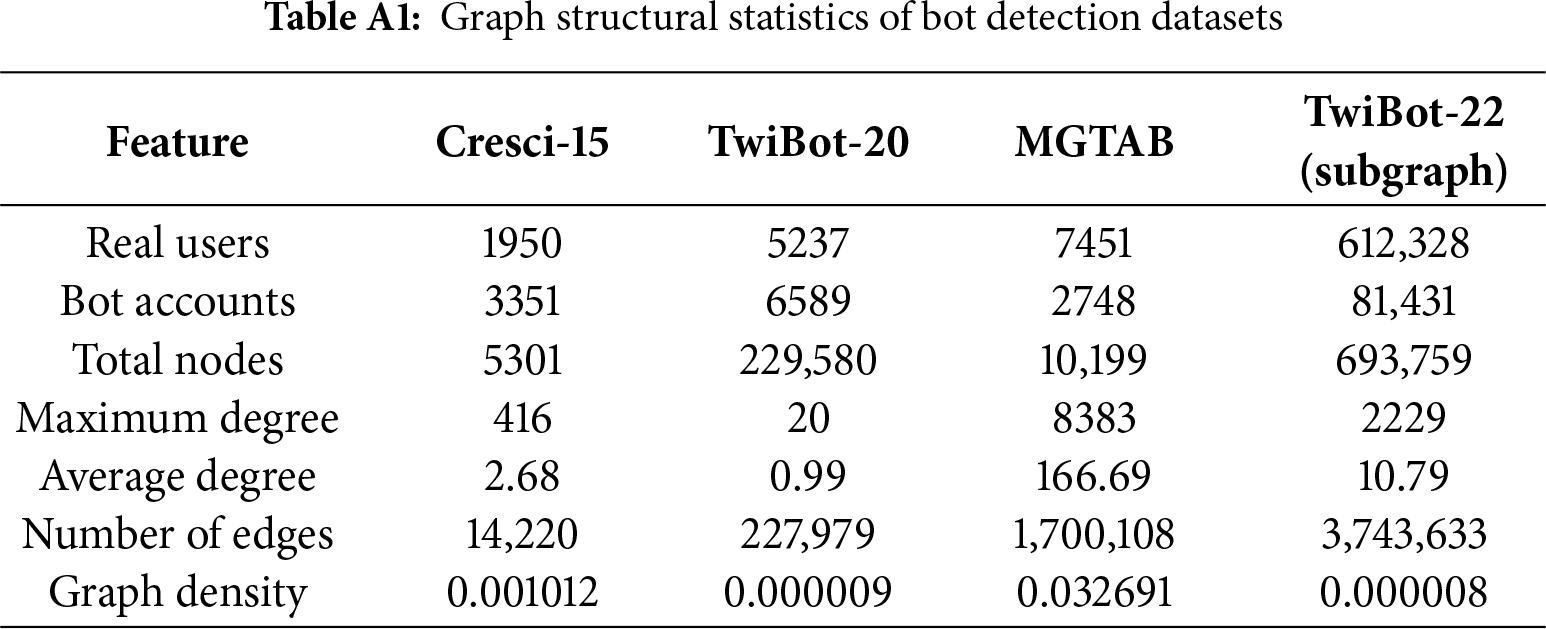

We used three publicly available datasets for social bot detection: MGTAB, TwiBot-20, and a subgraph of TwiBot-22. The TwiBot-22 subgraph was constructed by extracting user-to-user relations from the full dataset and removing isolated nodes to ensure connectivity. Table A1 summarizes the structural statistics of these datasets. The datasets vary in size and connectivity. TwiBot-22 (subgraph) is the largest, MGTAB is densely connected, and TwiBot-20 is relatively sparse, presenting different challenges for bot detection.

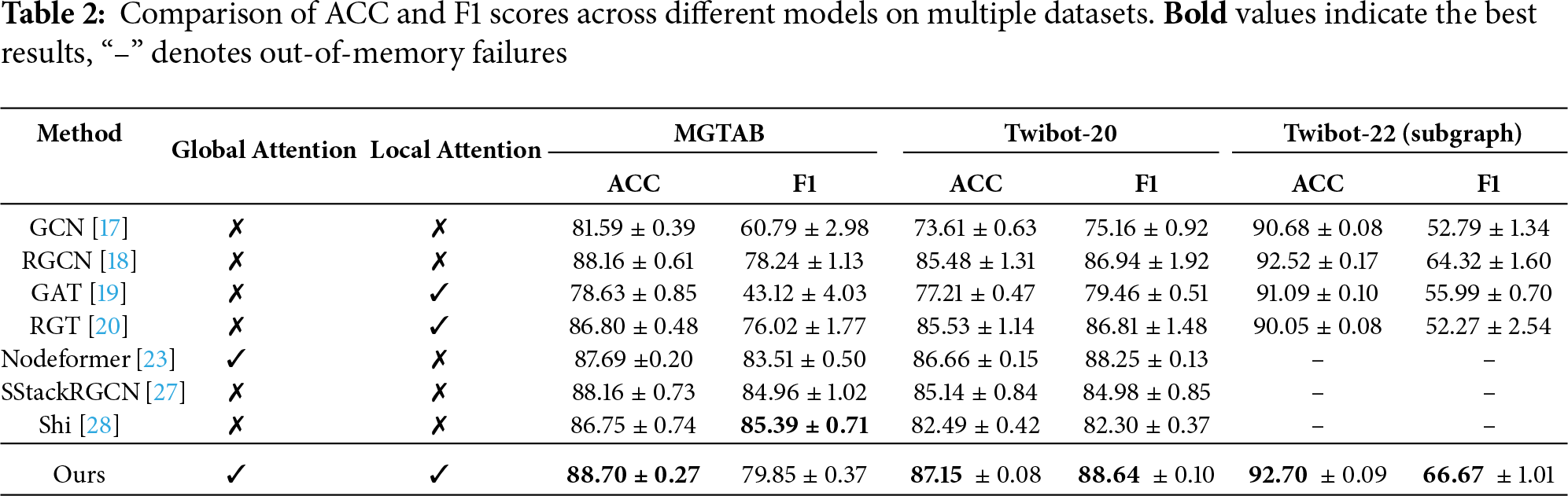

We compared our model with some classical and state-of-the-art models on graph neural networks to verify the effectiveness of our optimizations and improvements for graph neural networks.

• Message Passing: Message Passing Aggregate messages from neighboring nodes to update each node’s feature representation. Such as: GCN, RGCN

• Local Attention: Local Attention employ self-attention to compute message or aggregation weight. Such as RGT

• Global Attention: Global attention mechanisms allow each node to compute its attention weights with respect to all other nodes in the graph. Such as Nodeformer

• Data Augmentation: Data Augmentation improves generalization by generating diverse training samples or graph views through node, edge, or feature perturbations. Such as: SHI, SStackGNN

All experiments were conducted on a single RTX 3090 GPU. Each model was trained for 200 epochs and optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.02,

In our experiments, we compared different baseline models by categorizing them based on local attention and global attention mechanisms. The results reported in Table 2 are averaged over five independent runs. From the results, we can draw the following conclusions:

• For graph datasets with complex structures, local information plays a crucial role; in contrast, graphs with simpler structures rely more on global information to capture bot characteristics. Specifically, on the MGTAB dataset, the RGCN model which is based on message-passing mechanisms and effectively exploits local neighborhood information achieves an accuracy of 88.16%, outperforming the NodeFormer model that employs global attention mechanisms. However, on the TwiBot series of datasets, where edges are sparsely sampled, message-passing-based models perform suboptimally.

• In imbalanced dataset MGTAB, global features significantly improve recall performance. The NodeFormer model achieves the highest F1-score of 83.51% on the MGTAB dataset, which contains 7451 genuine users and 2748 bot accounts. This demonstrates the effectiveness of global feature modeling in handling class imbalance.

• Compared to methods focusing on single-scale information processing, our model effectively integrates both local and global information, achieving the best classification accuracy across three different datasets with an average improvement of approximately 0.5 percentage points. This result highlights the strong generalization capability of our model across datasets with varying sampling strategies.

In this section, we analyze our model to address the following questions:

• RQ1: Does each component of our model contribute significantly to the overall performance?

• RQ2: Does the use of heterogeneous graphs help the model capture more topological structural information?

• RQ3: Does TopoLayer help alleviate the problems of over-smoothing and over-squeezing?

• RQ4: Can our model learn more discriminative node representations?

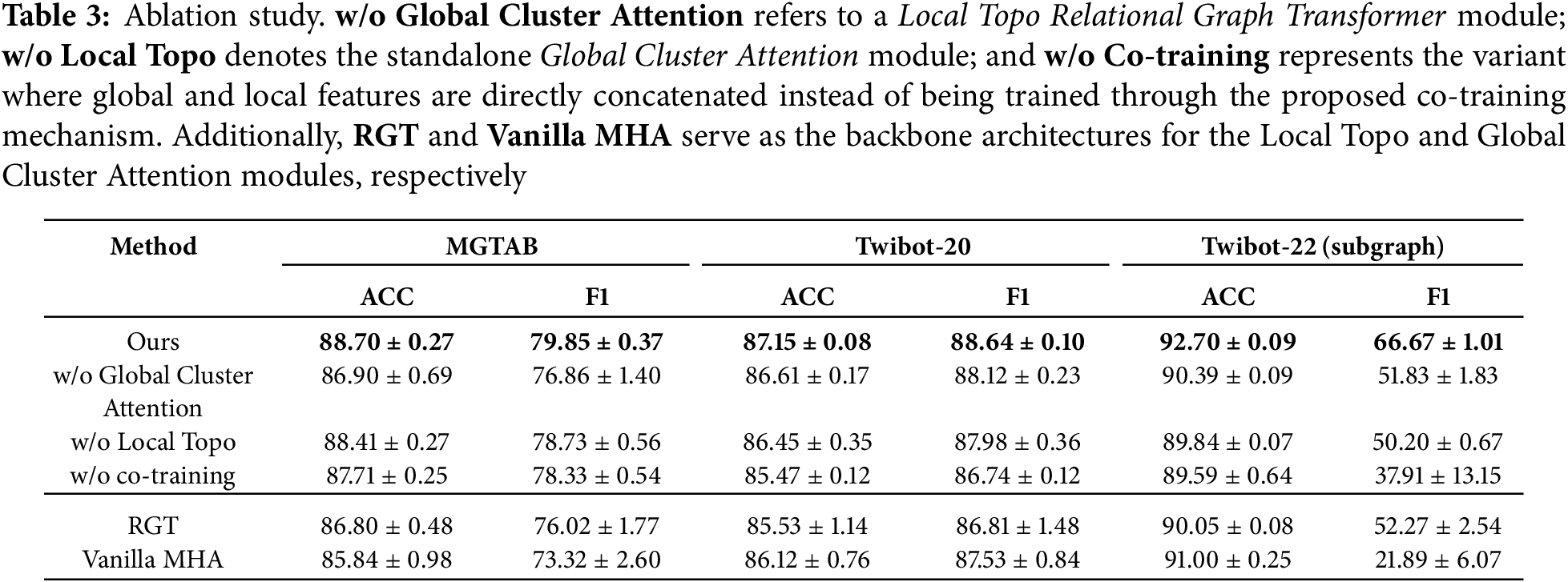

Ablation Study (RQ1): We design and conduct a series of ablation experiments to evaluate the contribution of each component in our model. Table 3 summarizes the role of key modules in the overall architecture. Experimental results show that the Local Topo module significantly outperforms its baseline RGT across all three datasets, with an improvement of 1.08% on the TwiBot-20 dataset. The Global Cluster Attention module also surpasses Vanilla MHA by 2.57% on the MGTAB dataset, which has complex local structures, indicating that the clustering mechanism effectively alleviates the over-globalizing issue caused by standard global attention. Removing the co-training mechanism and replacing it with direct feature concatenation leads to a substantial performance drop—even falling below the performance of either individual module (as observed on TwiBot-20 and TwiBot-22). This demonstrates that local and global features cannot be effectively fused through simple concatenation, and the proposed co-training strategy enables complementary learning between the two, thereby improving the overall model performance.

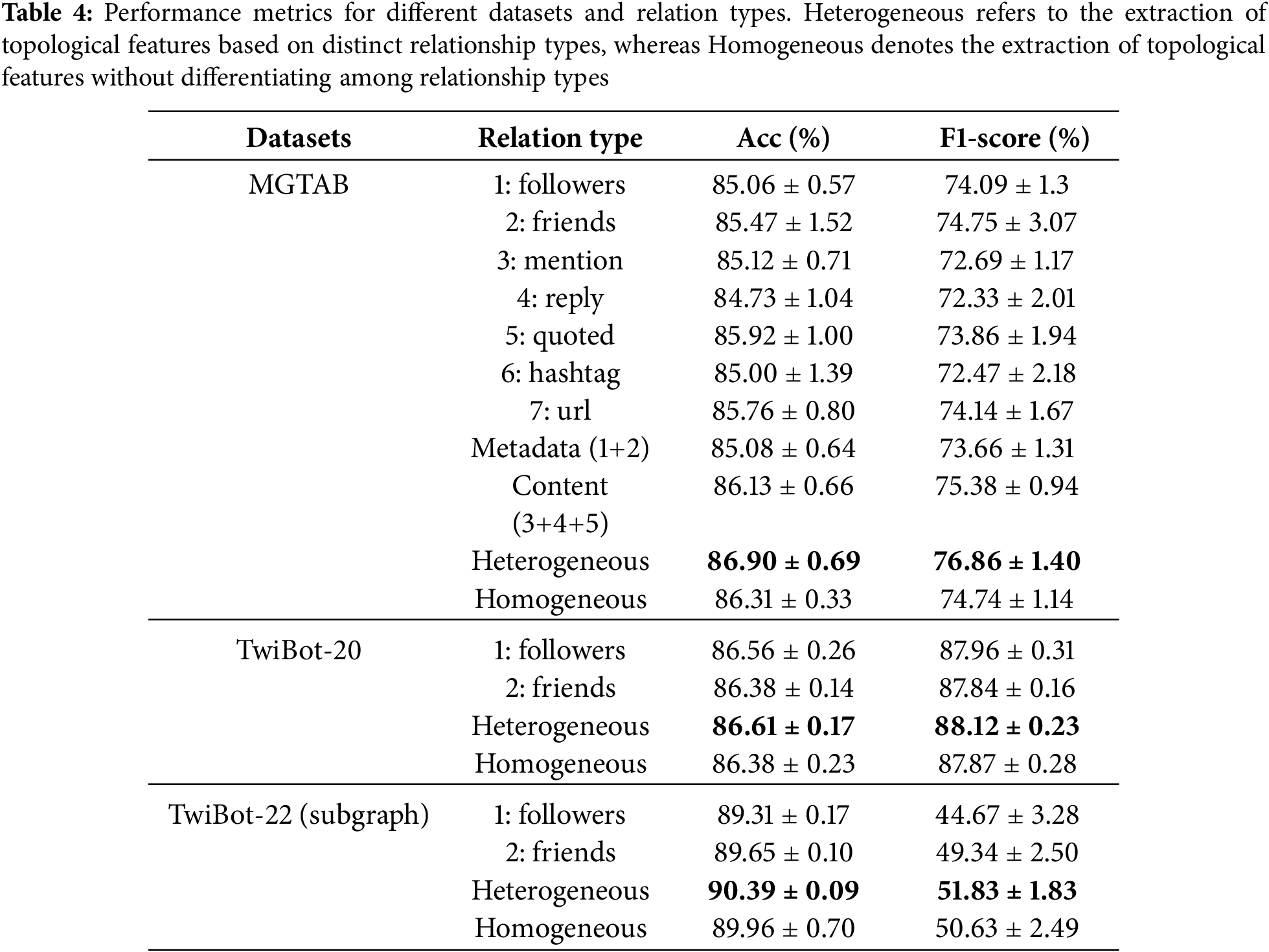

Relational Topology Analysis (RQ2): To assess how different relation types in heterogeneous graphs affect the Local Topo module, we evaluate various relation combinations. As shown in Table 4, leveraging relational heterogeneity improves accuracy by an average of 0.42 percentage points (86.90%, 86.61%, 90.39% across datasets) over homogeneous graph-based methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing diverse bot behaviors. Using only a single relation type significantly degrades performance. Ablation studies on MGTAB show that content-based topological structures boost both accuracy and F1-score by over 1%, indicating that real users exhibit more complex interaction patterns than bots can mimic. Thus, relational topology provides valuable discriminative signals for detection.

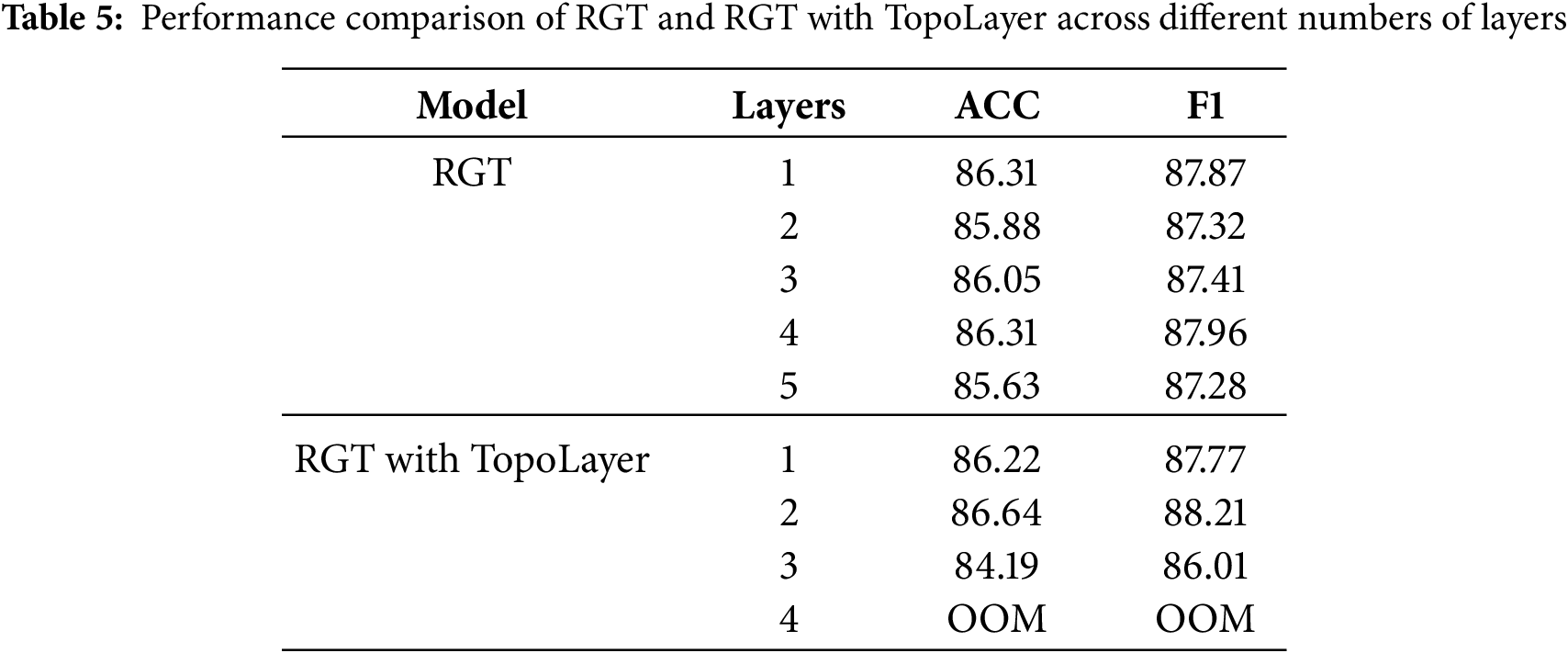

Over-Smoothing & Over-Squeezing Analysis (RQ3): To address RQ3, we conducted experiments on model performance and the number of GNN layers using the TwiBot-20 dataset. The purpose is to verify whether stacking too many layers causes node features to converge to indistinguishable representations and to demonstrate that our model effectively mitigates this risk. As shown in the Table 5, the RGT model exhibits a decline in performance as the number of layers increases from 1 to 2, achieving optimal performance (F1 score of 87.96) only when stacked up to 4 layers. This indicates that increasing the number of layers can cause performance degradation due to node representations becoming too similar, leading to over-smoothing and over-squeezing. However, with the addition of the TopoLayer, performance improves as the number of layers increases from 1 to 2. Our TopoLayer allows the model to reach excellent performance earlier, reducing the number of GNN layers needed and thus avoiding the risks associated with over-smoothing and over-squeezing.

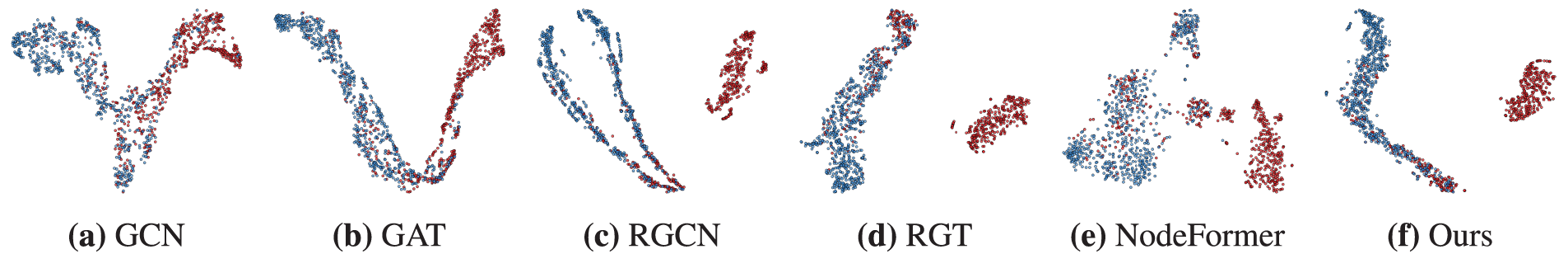

Representation Study (RQ4): To address RQ4, we conducted a two-dimensional visualization of the generated node representations using t-SNE on the TwiBot-20 dataset, as shown in Fig. 4. The results reveal that traditional methods such as GCN and GAT exhibit significant overlap between bot and genuine accounts, indicating limited discriminative capability in the learned embeddings. Although RGCN achieves relatively better separation, it produces two distinct cluster centers for bot accounts, suggesting potential inconsistency in its representation learning. NodeFormer, while capturing some global structure, yields scattered embeddings for bot nodes, which may contribute to its suboptimal classification performance. In contrast, both RGT and our model generate more compact and well-separated clusters. Notably, our model produces the tightest and most cohesive grouping of bot nodes, with genuine users clearly separated, indicating stronger intra-class consistency and reduced ambiguity in classification—consistent with its superior performance in downstream evaluation.

Figure 4: TwiBot-20 dataset account node representation visualization. Blue denotes Bot accounts and red denotes Human accounts

We use the Metis toolkit for node clustering to enable subgraph partitioning and feature extraction. On large-scale graphs, this step incurs notable initialization overhead during training, motivating the exploration of more efficient and scalable partitioning methods to improve overall training efficiency.

In this paper, we propose a topology-aware multi-scale graph network for social bot detection, aiming to address two key challenges: the underutilization of topological features and the issue of local-global chaos. Specifically, we design both global and local modules to separately model node representations at different scales, thereby mitigating the interference caused by local-global chaos. Meanwhile, we incorporate Persistent Homology, a technique from topological data analysis, into node embeddings to explicitly capture topological information. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that our method significantly improves the accuracy of bot detection across multiple datasets, highlighting the importance of topological features and opening up new possibilities for incorporating topological information into graph-based detection models. As future work, we aim to adapt high-order topological features from graph to node classification by mapping global structural features to individual nodes, enhancing their representational power and ability to capture higher-order dependencies.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Media Convergence and Communication and the Key Laboratory of Convergent Media and Intelligent Technology (Communication University of China), Ministry of Education.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (Grant No. CUCAI2511).

Author Contributions: Junhui Xu designed the study, implemented the algorithm, and wrote the manuscript. Qi Wang supervised the research and provided strategic guidance. Chichen Lin contributed to the conceptual framework. Weijian Fan provided technical support on persistent homology implementation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, Qi Wang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Datasets

In this section, we analyze key structural properties of social bot detection datasets, including node and edge counts, degree distribution, and graph density. Graph density measures the overall connectivity of a graph, with higher values indicating denser structures.

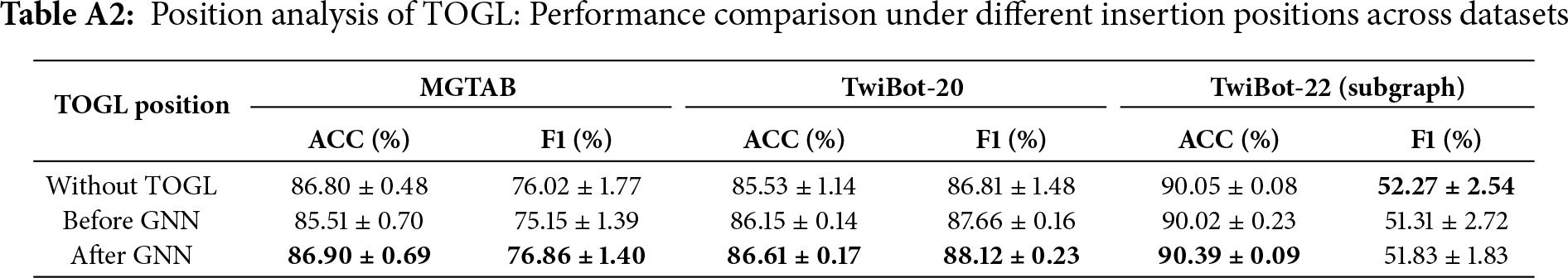

Appendix B Layer Placement Study

As noted in [29], strong node features can weaken structural effects. To study topological layer placement, we insert it before or after GNN layers. Table A2 shows that placing it after GNN layers improves performance, while placing it before GNN layers degrades it.

References

1. Berger JM, Morgan J. The ISIS Twitter Census: defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter; 2015. [Google Scholar]

2. Deb A, Luceri L, Badaway A, Ferrara E. Perils and challenges of social media and election manipulation analysis: the 2018 us midterms. In: Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference; 2019 May 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 237–47. doi:10.1145/3308560.3316486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shi S, Qiao K, Liu Z, Yang J, Chen C, Chen J, et al. Mgtab: a multi-relational graph-based twitter account detection benchmark. Neurocomputing. 2025;647(1):130490. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.130490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Feng S, Wan H, Wang N, Li J, Luo M. Twibot-20: a comprehensive twitter bot detection benchmark. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2021 Nov 1–5; Virtual. p. 4485–94. doi:10.1145/3459637.3482019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Feng S, Tan Z, Wan H, Wang N, Chen Z, Zhang B, et al. Twibot-22: towards graph-based twitter bot detection. In: NIPS’22: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 35254–69. [Google Scholar]

6. Cummings JN. Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Manag Sci. 2004;50(3):352–64. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1030.0134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhou M, Zhang D, Wang Y, Geng Y-A, Dong Y, Tang J. LGB: language model and graph neural network-driven social bot detection. IEEE Transact Know Data Eng. 2025;37(8):4728–42. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2025.3573748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rusch TK, Bronstein MM, Mishra S. A survey on oversmoothing in graph neural networks. arXiv:2303.10993. 2023. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2303.10993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang X, Zhu Y, Shi H, Liu Y, Hong C. Graph triple attention network: a decoupled perspective. arXiv:3690624.3709223. 2024. doi:10.1145/3690624.3709223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xing Y, Wang X, Li Y, Huang H, Shi C. Less is more: on the over-globalizing problem in graph transformers. arXiv:2405.01102. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2405.01102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zia A, Khamis A, Nichols J, Tayab UB, Hayder Z, Rolland V, et al. Topological deep learning: a review of an emerging paradigm. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(4):77. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10710-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang KC, Varol O, Hui PM, Menczer F. Scalable and generalizable social bot detection through data selection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34:1096–103. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Beskow DM, Carley KM. Bot-hunter: a tiered approach to detecting & characterizing automated activity on twitter. In: SBP-BRiMS: International Conference on Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction and Behavior Representation in Modeling And Simulation; 2018 Jul 10–13; Washington, DC, USA. Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

14. Wei F, Nguyen UT. Twitter bot detection using bidirectional long short-term memory neural networks and word embeddings. In: 2019 First IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA); 2019 Dec 12–14; Los Angeles, CA, USA. p. 101–9. doi:10.1109/TPS-ISA48467.2019.00021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

16. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. Roberta: a robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.1169. 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. Kipf TN, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1609.02907. 2016. [Google Scholar]

18. Feng S, Wan H, Wang N, Luo M. BotRGCN: twitter bot detection with relational graph convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining; 2021 Nov 8–11; Virtual Event, The Netherlands. p. 236–9. doi:10.1145/3487351.3488336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Veličković P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv:1710.10903. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1710.10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Feng S, Tan Z, Li R, Luo M. Heterogeneity-aware twitter bot detection with relational graph transformers. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36:3977–85. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i4.20314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang X, Ji H, Shi C, Wang B, Ye Y, Cui P, et al. Heterogeneous graph attention network. In: The World Wide Web Conference; 2019 May 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 2022–32. doi:10.1145/3308558.3313562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Waswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez A, et al. Attention is all you need. In: 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017); 2017 Dec 4–7; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. Wu Q, Zhao W, Li Z, Wipf DP, Yan J. Nodeformer: a scalable graph structure learning transformer for node classification. In: NIPS’22: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 27387–401. [Google Scholar]

24. Wu Q, Zhao W, Yang C, Zhang H, Nie F, Jiang H, et al. Simplifying and empowering transformers for large-graph representations. In: Thirty-Seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023 Dec 10; New Orleans, LA, USA. Vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

25. Horn M, De Brouwer E, Moor M, Moreau Y, Rieck B, Borgwardt K. Topological graph neural networks. arXiv:2102.07835. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2102.07835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Karypis G, Kumar V. A fast and high quality multilevel scheme for partitioning irregular graphs. SIAM J Scient Comput. 1998;20(1):359–92. doi:10.1137/S1064827595287997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shi S, Chen J, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Fu C, et al. Sstackgnn: graph data augmentation simplified stacking graph neural network for twitter bot detection. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2024;17(1):106. doi:10.1007/s44196-024-00496-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Shi S, Qiao K, Chen C, Yang J, Chen J, Yan B. Over-sampling strategy in feature space for graphs based class-imbalanced bot detection. In: Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024; 2024 May 13–17; Singapore. p. 738–41. doi:10.1145/3589335.3651544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Borgwardt K, Ghisu E, Llinares-López F, O’Bray L, Rieck B. Graph kernels: state-of-the-art and future challenges. Foundat Trends® Mach Learn. 2020;13(5–6):531–712. doi:10.1561/2200000076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools