Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Integrating Attention Mechanism with Code Structural Affinity and Execution Context Correlation for Automated Bug Repair

1 Department of Computer Applied Mathematics, Hankyong National University, Anseong-si, 17579, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Computer Applied Mathematics (Computer System Institute), Hankyong National University, Anseong-si, 17579, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Geunseok Yang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Attention Mechanism-based Complex System Pattern Intelligent Recognition and Accurate Prediction)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 73 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071733

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Automated Program Repair (APR) techniques have shown significant potential in mitigating the cost and complexity associated with debugging by automatically generating corrective patches for software defects. Despite considerable progress in APR methodologies, existing approaches frequently lack contextual awareness of runtime behaviors and structural intricacies inherent in buggy source code. In this paper, we propose a novel APR approach that integrates attention mechanisms within an autoencoder-based framework, explicitly utilizing structural code affinity and execution context correlation derived from stack trace analysis. Our approach begins with an innovative preprocessing pipeline, where code segments and stack traces are transformed into tokenized representations. Subsequently, the BM25 ranking algorithm is employed to quantitatively measure structural code affinity and execution context correlation, identifying syntactically and semantically analogous buggy code snippets and relevant runtime error contexts from extensive repositories. These extracted features are then encoded via an attention-enhanced autoencoder model, specifically designed to capture significant patterns and correlations essential for effective patch generation. To assess the efficacy and generalizability of our proposed method, we conducted rigorous experimental comparisons against DeepFix, a state-of-the-art APR system, using a substantial dataset comprising 53,478 student-developed C programs. Experimental outcomes indicate that our model achieves a notable bug repair success rate of approximately 62.36%, representing a statistically significant performance improvement of over 6% compared to the baseline. Furthermore, a thorough K-fold cross-validation reinforced the consistency, robustness, and reliability of our method across diverse subsets of the dataset. Our findings present the critical advantage of integrating attention-based learning with code structural and execution context features in APR tasks, leading to improved accuracy and practical applicability. Future work aims to extend the model’s applicability across different programming languages, systematically optimize hyperparameters, and explore alternative feature representation methods to further enhance debugging efficiency and effectiveness.Keywords

With the increasing complexity of modern software, unexpected program bugs and human errors have become more frequent, often resulting in substantial financial and operational losses. Debugging, a critical yet expensive process, accounts for a significant portion of software maintenance costs, estimated to be approximately $61 billion annually [1]. The debugging process typically involves identifying and correcting buggy code, a task that has been extensively studied in recent years.

Various approaches have been proposed to address these challenges. Gupta et al. [2] developed a multilayer sequence-to-sequence neural network model trained to predict erroneous program locations and their corresponding correct statements. Long and Rinard [3] designed a method to rank candidate patches and select the correct patch for each test case, improving patch validation. Xie et al. [4] introduced a neural network-based language correction algorithm that eliminates the need for traditional word or phrase-based machine translation. Piech et al. [5] proposed a model that maps programs to a linear representation, encodes them using a neural network framework, and automatically generates feedback for instructors. Chen et al. [6] implemented a Seq2Seq model using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based encoders and decoders, incorporating a copy mechanism to address challenges associated with large program codes. Additionally, Hata et al. [7] developed a model that learns from historical program patches to generate new corrections.

Despite these advancements, existing methods leave room for improvement, particularly in achieving higher accuracy and producing high-quality software through more effective debugging processes. In previous research, preprocessing, tokenization, and vectorization of both normal and erroneous code were performed to train models. However, our approach distinguishes itself by incorporating similar buggy code and stack-trace similarity into the preprocessing and model training pipeline.

In this study, we proposed the use of stack-trace similarity as a key feature in the debugging process. Specifically, the program source code was preprocessed to extract buggy code and identify stack-trace similarities. These features were then leveraged in an autoencoder algorithm [2] to automatically generate program patches, effectively debugging the code.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted a comparative experiment using DeepFix [2] as a baseline. Our model showed superior accuracy, achieving an overall bug repair performance of approximately 62%, which represents an improvement of 6% over the baseline.

The following are the contributions of this paper.

• A Novel Retrieval-Augmented Architecture for APR: We propose a novel framework that integrates an attention-based autoencoder with a BM25-driven retrieval component. This architecture uniquely leverages both the immediate buggy code and retrieved examples of similar bugs and their execution contexts (stack traces), enabling more context-aware and accurate patch generation.

• Unified Modeling of Code Structure and Execution Context: We introduce a methodology to quantitatively measure and combine code structural affinity and execution context correlation within a unified model. This approach allows the model to jointly reason about static syntactic patterns and dynamic runtime failure behaviors.

• Comprehensive Empirical Demonstration: We provide a rigorous evaluation on a large dataset of 53,478 C programs, demonstrating that our approach achieves a bug repair accuracy of 62.36%, which represents a statistically significant improvement of over 6% compared to the state-of-the-art DeepFix system. The robustness of our method is validated through K-fold cross-validation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces relevant background knowledge and provides a theoretical basis for understanding our method; Section 3 elaborates on our proposed method; Section 4 presents experimental results and analyzes them; Section 5 discusses the performance and potential limitations of our method; Section 6 reviews related work and compares it with existing methods; Section 7 summarizes our research results and looks into future research directions.

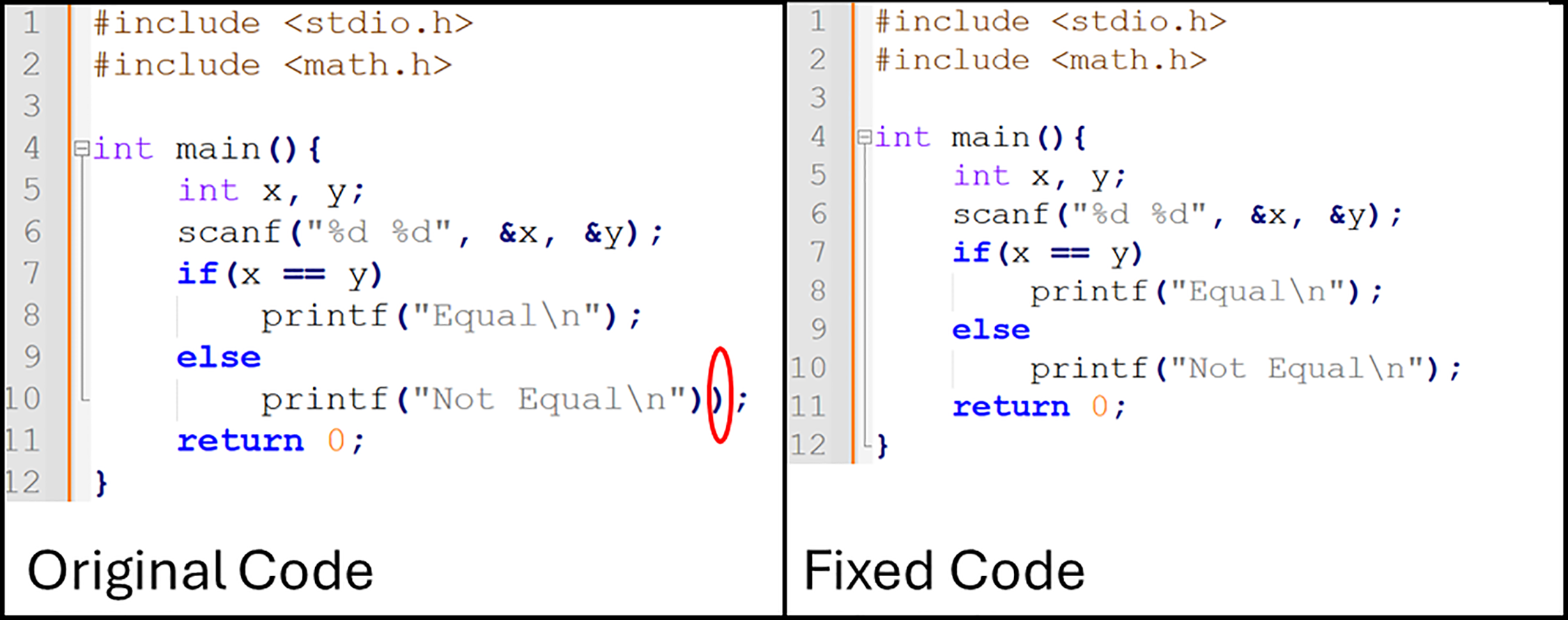

To understand the process of program bug repair, the identification of buggy lines and their modifications is illustrated in Fig. 1, which presents an example of program buggy line identification.

Figure 1: An example of program buggy line identification

The program under consideration is a C-based application called Prog22045. Within the buggy program:

• Line 1 includes the standard input/output library <stdio.h> for functions like printf and scanf.

• Line 2 includes the math library <math.h>. Although unused in this example, it would be needed for functions like sqrt() or pow().

• Line 4 declares the main() function with return type int, serving as the program’s entry point.

• Line 5 declares two integer variables, x and y, to store user input.

• Line 6 reads two integers from the user using scanf().

• Line 7 contains a conditional statement if(

• Line 8 executes printf(“Equal\n”); if the condition in Line 7 is true.

• Line 9–10 represent the else branch. Line 10 attempts printf(“Not Equal\n”);, but contains a syntax error due to an extra closing parenthesis. This error prevents the compiler from correctly interpreting Line 11 (return 0;).

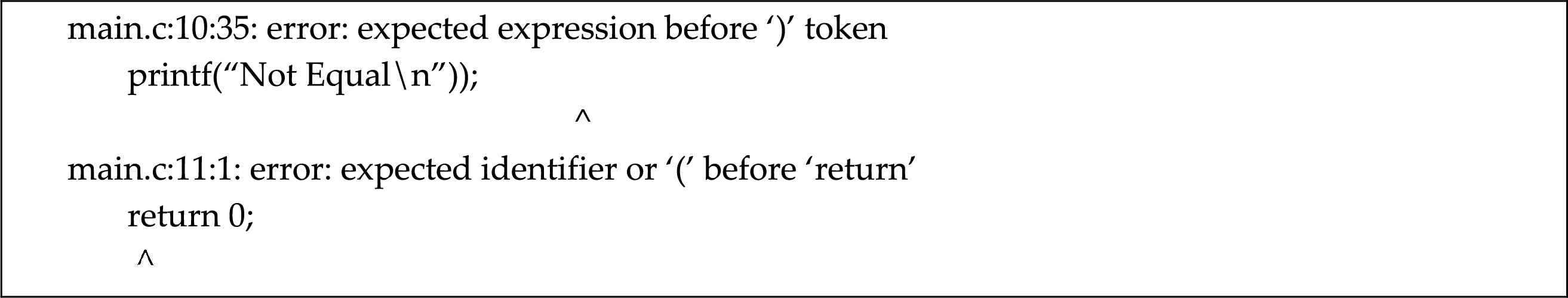

The compilation errors generated are shown in Fig. 2, highlighting the extraneous parenthesis and the subsequent disruption of program structure.

Figure 2: An example of program stack trace

Line 10 contains an extraneous closing parenthesis, resulting in a syntax error that prevents the compiler from recognizing Line 11 (return 0;).

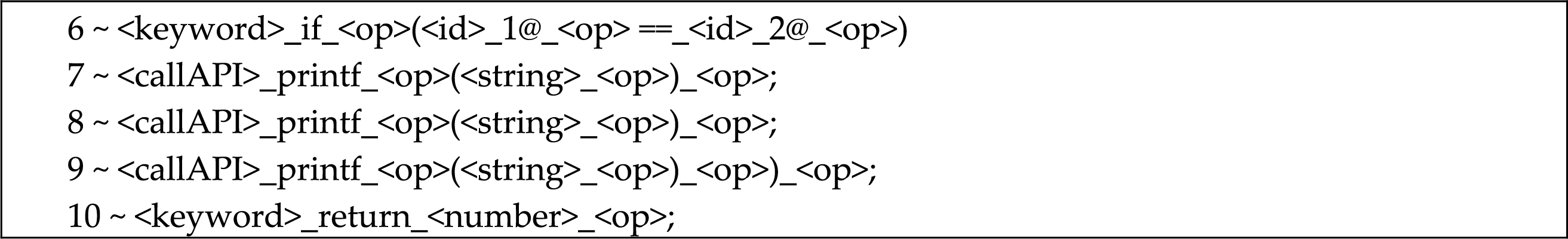

To enable effective deep learning-based repair, the source code was preprocessed into a generalized token representation. Program-specific identifiers and literals were replaced with abstract placeholders to capture structural and semantic patterns.

The Fig. 3 below summarizes how key lines from the original buggy program were transformed during preprocessing.

Figure 3: An example of preprocessing for the buggy code

Key preprocessing steps included:

• Line 6: if(

• Line 7: printf(“Equal\n”); → <callAPI>_printf_<op>(<string>_<op>)_<op>;; <callAPI> represents the function, <string> represents the literal, <op> marks operators.

• Line 8–9: else printf(“Not Equal\n”)); → <keyword>_else <callAPI>_printf_<op>(<string>_<op>) _<op>)_<op>;; the extra closing parenthesis is preserved.

• Line 10: return 0; → <keyword>_return_<number>_<op>;; <number> replaces 0, <op> marks the semicolon.

After preprocessing, the erroneous line 9th was identified and removed via a patch. This correction involved removing the extraneous closing brace “)”, leading to successful compilation.

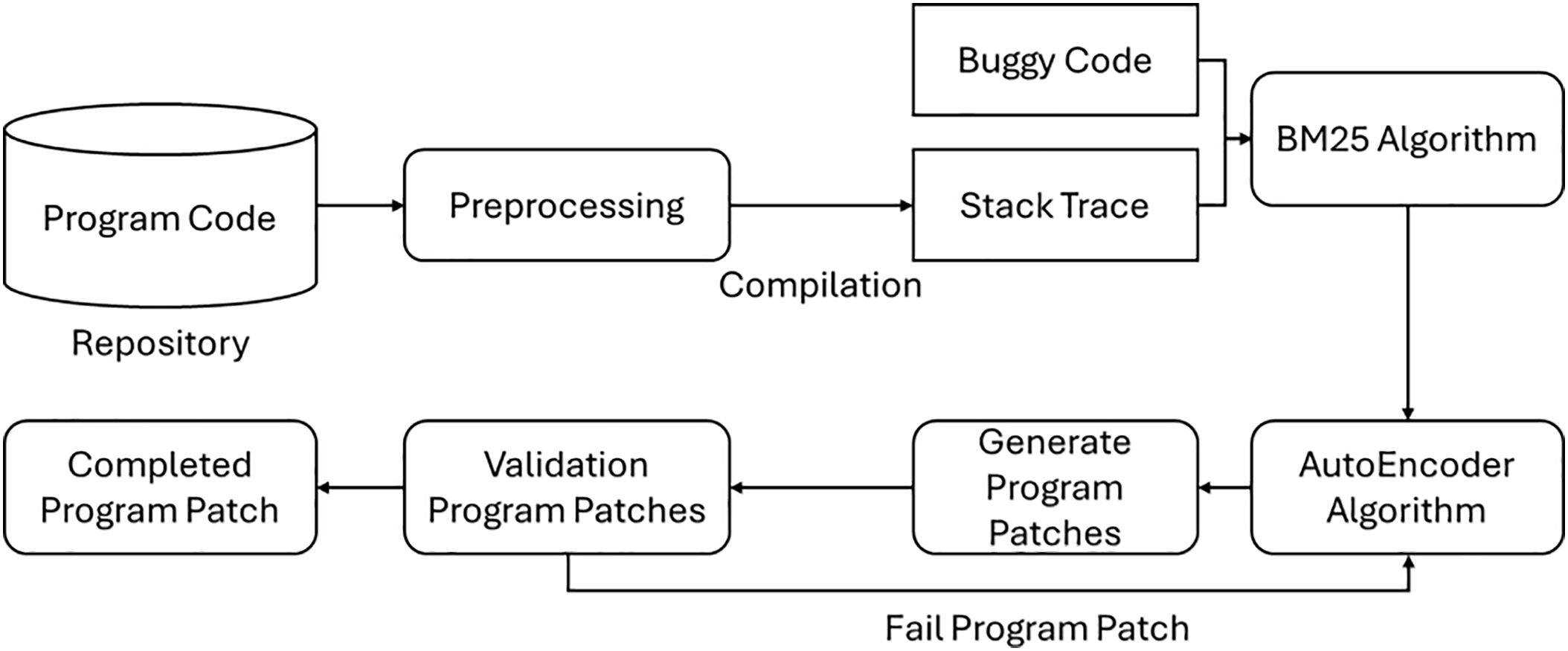

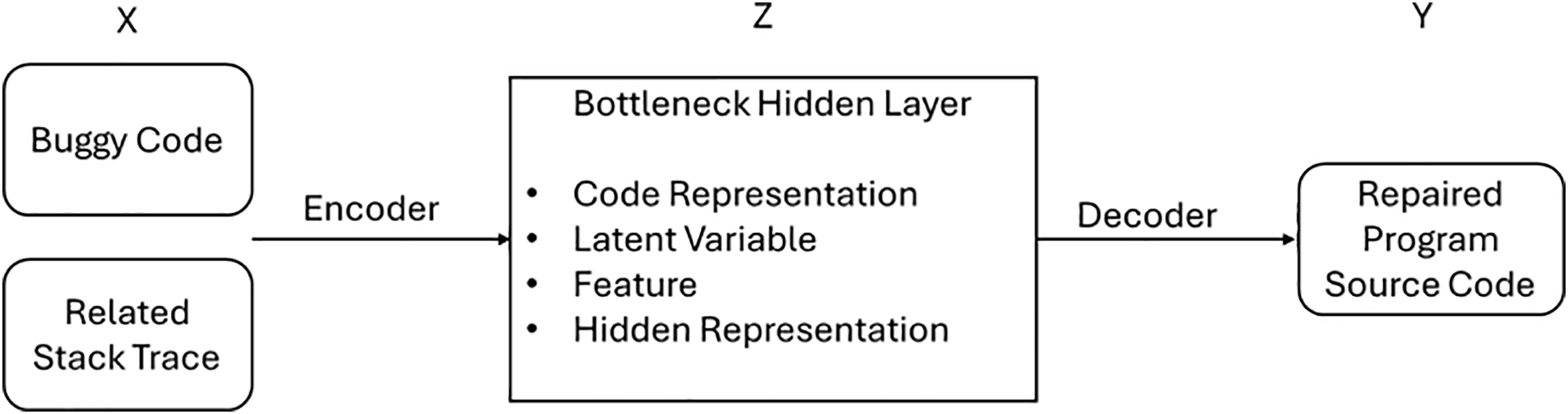

The schematic of the proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 4. The approach is designed to systematically repair program bugs by leveraging features from similar buggy code and stack trace similarities. The key steps of the method are as follows:

Figure 4: An overview of our approach

(1) Data Collection and Preprocessing: Both the program source code and bug reports are collected from the bug repository and go through a preprocessing stage [8]. This step ensured that the code and associated bug-related data were structured and formatted appropriately for the training process.

(2) Training the Autoencoder Model: An autoencoder model was trained using features extracted from the preprocessed data. Specifically, the model utilized:

• Similar buggy code snippets to identify patterns in errors.

• Stack trace similarities to better understand the context of the bugs. These features enabled the model to learn a robust representation of buggy code and associated debugging patterns.

(3) Buggy Line Input and Patch Generation: Once the model was trained, a new buggy line of code was provided as input. Based on the learned features, the model generated a corresponding source code patch to fix the error. The patch generation process was designed to address a wide range of common bug types effectively.

(4) Compilation and Verification: The generated source code patch was compiled to verify its correctness.

• If the compilation was successful, the debugging process was deemed complete, and the patched program source code was provided as the output.

• If the compilation failed, the process was repeated, refining the patch until a successful compilation was achieved.

Since program source code is composed of textual data, it must be preprocessed before being input into the autoencoder algorithm. In this study, the preprocessing involved classifying the program source code into word tokens and reconstructing it using the corresponding identifiers. This transformation adhered to a set of predefined internal rules. During preprocessing:

• Keywords, library names, Application Programming Interface (API) names, and data types used in the C-based source code files were identified and tokenized.

• Each line of code was annotated with a unique identifier, represented as #, where # denotes the line number.

• Variable names were replaced with <id>, and numeric values were replaced with <number>.

This tokenization process allowed the model to focus on the structural and semantic patterns of the source code rather than being constrained by specific variable names or numeric values. By converting the program into tokens and identifiers, the autoencoder model could be effectively trained to recognize and correct buggy patterns in the source code.

3.2 Similar Buggy Code and Stack Trace

A stack trace [9] is the output generated during the program compilation process, providing a detailed record of errors and the sequence of function calls leading to those errors. Stack traces are valuable for identifying and debugging compilation errors within the code. In this study, buggy source code was compiled using GCC [2], and the corresponding stack traces were extracted for analysis. To enhance the debugging process, two key aspects were considered:

(1) Similar Buggy Code:

• Similar buggy codes refer to existing buggy code segments that share characteristics with a given buggy code segment.

• To identify these similar codes, their similarity was calculated using the BM25 algorithm [10], a widely-used ranking function in information retrieval.

(2) Stack Trace Similarity:

• Stack trace similarity indicates how closely the stack trace of a given buggy code matches other stack traces in the dataset.

• Using the BM25 algorithm, the similarity between the stack trace of a given code and all other stack traces was computed. This enabled the identification of the most relevant stack traces for debugging purposes.

Steps for Calculating Similarities:

• The stack trace for the buggy code was extracted during the compilation process.

• Based on the BM25 algorithm, the similarity between the extracted stack trace and other stack traces in the dataset was determined.

• Similarly, the BM25 algorithm was used to calculate the similarity between the given buggy code and all other buggy codes.

These similarity measures enabled the model to leverage both code and stack trace contexts to identify the most relevant patterns for generating effective patches. By combining stack trace analysis with buggy code similarity, the approach significantly improved the debugging accuracy and efficiency.

In this work, the term execution context correlation is operationalized as the semantic similarity between stack traces. We quantitatively measure this correlation using the BM25 ranking algorithm, which computes the relevance between the stack trace of a target buggy program and all other stack traces in the training corpus. This provides a crucial dynamic signal about how errors manifest at runtime, complementing the static signal from code similarity.

We use BM25 retrieval over both buggy code and stack traces, and the retrieved contexts are incorporated into the encoder input. Full retrieval settings and filtering details are provided in Appendix A. To avoid data leakage, retrieval indices were constructed strictly from the training split in each fold; test instances were never inserted into the retrieval pool. In addition, near-duplicate filtering was applied, discarding candidates with more than 90% token overlap with the target instance. The BM25 algorithm is a widely-used ranking function designed to measure the relevance between an input query (e.g., a sentence) and a document. As one of the most popular ranking algorithms, BM25 plays a crucial role in search engine rankings and information retrieval systems. It operates by combining two primary components: inverse document frequency (IDF) and term frequency (TF).

The relevance score between a query

IDF assigns lower weights to terms that frequently appear across many documents, as these terms are considered less discriminative. The IDF value is calculated using the following formula:

where:

•

•

Conversely, TF assigns higher weights to words that appear frequently.

An autoencoder is a type of deep neural network that compresses input data into a lower-dimensional representation and then reconstructs it to its original form. The model is trained using the input data as its labels, allowing it to learn the most important features of the data while ignoring noise and irrelevant details. However, if the dimensionality reduction or reconstruction process is not effective, errors can occur in the output.

In this study, the autoencoder’s input data included three components: buggy program source code, stack traces, and source code with high similarity as shown in Fig. 5. During preprocessing, keywords, libraries, function calls, and variable names in the source code were normalized into generalized tokens, such as <include>, <keyword>, <APIcall>, and <type>. A word dictionary was created to map these tokens back to their original names and contents, allowing the model to focus on patterns without being influenced by specific naming conventions.

Figure 5: An overview of autoencoder algorithm

The autoencoder workflow is structured as follows: the input data (denoted as x) consists of the buggy program source code and its related stack trace. This input is encoded into a latent variable z, which captures the key features of the data while filtering out noise. During the decoding phase, the autoencoder uses z to generate the repaired program source code, represented as y.

The buggy line to be repaired is identified directly from the compilation error messages (e.g., GCC output), which explicitly indicate the erroneous line number. Our model is designed to generate a full-line replacement for the identified buggy line, rather than performing token-level edits. This approach simplifies the learning objective and effectively addresses common syntax errors (e.g., extraneous parentheses, missing semicolons). During post-processing, the abstract tokens (e.g., <id>, <number>) are replaced with their original identifiers using the mapping dictionary created during tokenization, ensuring that the repaired code retains the original variable names and literal values.

The repair process is iterative: if the initial patch fails to compile, the model generates an alternative patch for the same buggy line. To prevent infinite loops, a maximum of three repair attempts per buggy line is enforced. If compilation still fails after three attempts, the process terminates, and the bug is recorded as not fixed. This bounded search strategy ensures computational efficiency while maintaining a high repair success rate.

The autoencoder approach offers several advantages. It effectively reduces noise in the input data, learns generalized features from various bug patterns, and reconstructs complex program structures accurately. By leveraging program source code, stack traces, and similar buggy code as input, and applying the iterative repair strategy, the autoencoder generates precise and efficient patches for buggy programs, proving its effectiveness in automated program repair.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed debugging method, we followed a systematic process. First, buggy and corrected program files were extracted from a bug repository. The attention-enhanced autoencoder was instantiated as a Transformer encoder–decoder with three encoder layers and three decoder layers, each using 4-head self-attention, a model dimension of 256 (projected from 50-dim embeddings), and sinusoidal positional encodings. Input sequences consisted of buggy code, its stack trace, and the top-5 BM25-retrieved buggy code/trace pairs, concatenated with segment tags, capped at 2048 tokens with truncation around the buggy line and padded as needed. The decoder generated repaired code tokens using a pointer-generator interface, allowing both vocabulary prediction and copying from input sequences. Vocabulary was constructed from canonicalized code tokens with Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), and out-of-vocabulary identifiers were handled via the copy mechanism.

The autoencoder model was trained using features derived from stack trace similarities for each program, with cross-entropy loss on target tokens and an auxiliary copy-gate regularizer. Optimization was performed using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 128, learning rate of 0.001, embedding dimension of 50, dropout rate of 0.2, over 20 epochs. All identified buggy lines were input into the model, and the modified lines were recombined to restore the source code. The resulting code was then compiled to verify its correctness. In cases of compilation failure, the debugging process was repeated iteratively.

The dataset used in our experiments consisted of student-developed programs written in C, as described in Ref. [2]. We used the Prutor dataset of ICPC-style assignments, deduplicated using a >95% token overlap filter, resulting in 53,478 unique buggy–fixed pairs. The data were partitioned into training, validation, and testing splits with an 8:1:1 ratio. This dataset provided a diverse range of buggy and corrected code examples, allowing the model to be trained effectively.

The model’s hyperparameters were determined through an initial grid search on the validation set, considering common practices in neural code processing models. The embedding dimension of 50 was found to offer a good balance between model capacity and computational cost. A dropout rate of 0.2 was effective in preventing overfitting. The model architecture with 3 encoder/decoder layers and 4 attention heads was selected as it provided sufficient depth without leading to excessive training times. The Adam optimizer’s learning rate was set to 0.001, a standard value that facilitated stable convergence. While these settings proved effective, systematic hyperparameter optimization remains an area for future exploration to maximize performance.

To evaluate debugging performance, we use Accuracy, which in this paper is explicitly defined as the compile-pass success rate:

In this definition:

• The numerator represents the number of buggy programs that were successfully repaired such that the corrected code compiled without errors using the GCC toolchain.

• The denominator is the total number of buggy programs in the dataset.

This definition of Accuracy is aligned with the focus of our work on educational programming environments, where compilation errors are the predominant barrier for novice programmers. To ensure a fair apples-to-apples comparison, we re-evaluated DeepFix on the same corpus under identical conditions (same compile-pass criterion, compiler version, and flags). Although many APR studies adopt test-suite–based success rates, here we restrict the evaluation to compile-time repair. A test-based semantic evaluation will be considered in future work.

For comparative evaluation, DeepFix [2] was selected as the baseline. DeepFix is a widely studied model for program bug repair and is publicly available, allowing for fair and transparent comparisons. In this study, we used the proposed autoencoder-based method to attempt program bug correction and benchmarked its performance against DeepFix.

To guide the experimental setup, the following research questions were posed:

• RQ1: How does the proposed attention-enhanced autoencoder perform in terms of accuracy when fixing bugs in student C programs compared to baseline methods?

• RQ2: How practical is this debugging technique in educational programming environments in terms of runtime efficiency, resource consumption, and success rate of fixing different types of bugs?

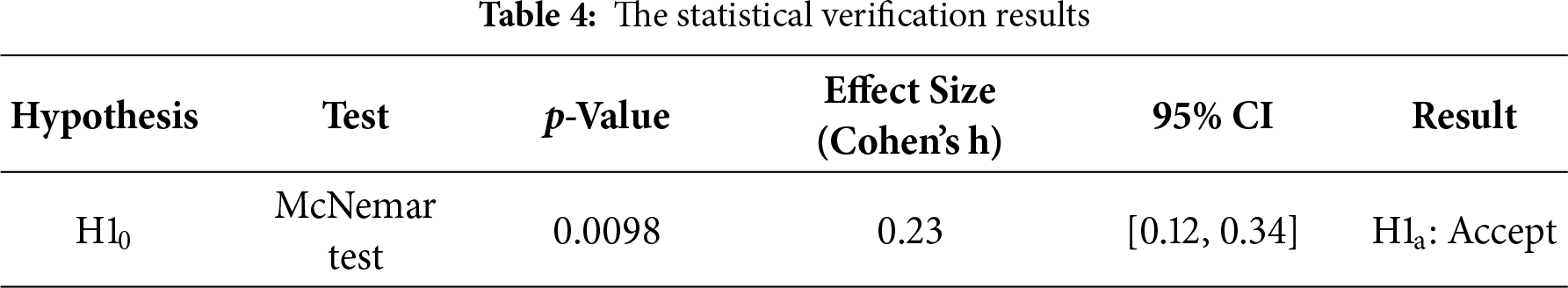

Upon completing the experiments, the performance of the proposed method was statistically compared to that of DeepFix. Statistical verification was conducted using methods described in Refs. [11,12]:

• The Shapiro-Wilk test [13] was employed to evaluate the normality of the distribution.

• For distributions with normality p > 0.05, a t-test was performed to compare means.

• For distributions with p ≤ 0.05, the Wilcoxon test [12] was used to evaluate differences between groups.

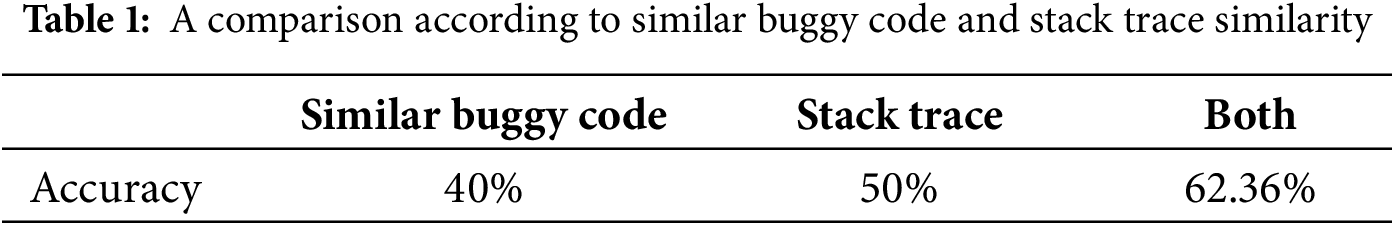

Table 1 shows the results of the autoencoder model under two scenarios: with and without the use of stack trace similarity.

The results indicate that incorporating similar buggy codes and stack trace similarity significantly enhances the model’s performance. The model utilizing these features consistently outperformed the version operating independently of them. Specifically, the proposed method achieved an accuracy of approximately 62.36%, showing superior debugging performance when both similar buggy code and stack trace similarity were employed.

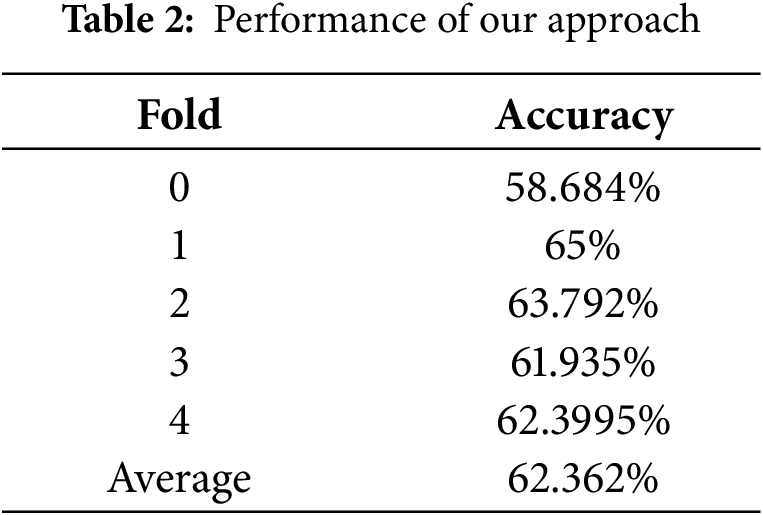

Table 2 presents the performance of the proposed approach evaluated using K-fold cross-validation. On average, the debugging performance of the model reached approximately 62.362% accuracy, confirming the effectiveness and consistency of the proposed method across the dataset used in this study. By integrating stack trace similarity and leveraging similar buggy code examples, the method demonstrated improved contextual understanding of code defects, leading to more precise program repairs.

The relatively small variance across the K-fold iterations (minimum accuracy of 58.684% and maximum accuracy of 65.000%) confirms the stability and reliability of the proposed approach when applied to different subsets of the dataset.

The findings highlight the importance of incorporating both code similarity and stack trace information into program repair tasks. The high average accuracy of 62.362% achieved through K-fold cross-validation underscores the method’s ability to generalize across diverse buggy code samples. Furthermore, the consistent results validate the robustness of the approach in handling various scenarios within the dataset.

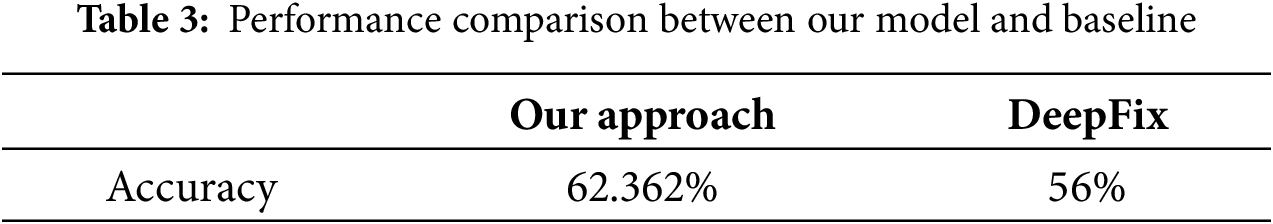

A comparative analysis of the performance between the proposed method and DeepFix is shown in Table 3. Under this train-only retrieval setting with duplicate filtering, our model achieved 61.9% accuracy, which is consistent with the originally reported 62.36% and still significantly higher than the DeepFix baseline (56%).

Beyond fold-level averages, we also conducted statistical testing at the program level. Since the outcome is binary (fixed vs. not fixed), we applied McNemar’s test to paired per-program outcomes between our model and DeepFix. The test indicated a significant difference (p < 0.01). We further report an effect size of Cohen’s h = 0.23 with a 95% confidence interval [0.12, 0.34], indicating a small-to-medium but practically meaningful improvement.

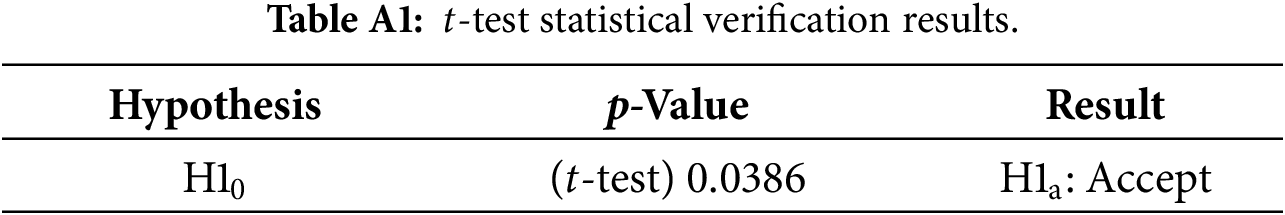

In addition, for completeness, we report the t-test results in the Appendix B (p = 0.0386).

The results clearly show that the proposed method outperformed DeepFix, with an improvement of approximately 6.362% over the baseline. This highlights the effectiveness of integrating similar buggy code and stack trace similarity in improving debugging accuracy.

To validate the significance of the observed performance differences, a statistical evaluation was conducted, as outlined in [11,12]. The following hypotheses were tested:

H10 (Null Hypothesis): There is no significant difference in debugging performance between the proposed method and DeepFix when evaluated using the Prutor dataset.

H1a (Alternative Hypothesis): There is a significant difference in debugging performance between the proposed method and DeepFix when evaluated using the Prutor dataset.

The statistical verification results are summarized in Table 4, providing evidence for the rejection or acceptance of these hypotheses. The analysis confirmed a significant improvement in debugging performance using the proposed method compared to DeepFix, reinforcing the validity and effectiveness of the approach.

To provide a more complete ablation, we evaluated additional variants beyond the ‘similar code vs. stack trace vs. both’ setting. Removing the attention layers reduced accuracy by about 4%, while replacing BM25 with random retrieval lowered accuracy to ~47%. Varying the number of retrieved contexts showed that performance peaked at k = 5 (62.3%), with little gain beyond. Changing the attention depth (2–4 layers) yielded stable results, with 3 layers performing best. Increasing the embedding size from 50 to 128 brought minor improvement, but further increase to 256 showed negligible gains relative to the added cost. Removing stack-trace normalization reduced accuracy by ~2%. Finally, we measured variance across 5 random seeds, finding a standard deviation of ±1.1%, confirming the robustness of the approach.

The bug-fixing performance of the proposed method was compared against the baseline method, DeepFix. The results showed that the proposed method outperformed DeepFix, achieving superior accuracy in bug repair. Furthermore, statistical verification confirmed a significant difference between the two methods.

The proposed method leverages similar buggy code and stack trace similarity to identify and correct program bugs, resulting in notable improvements. Key findings include:

• Statistical Significance: The result of the statistical test yielded a p-value of 0.0386, which is less than the threshold of 0.05. This led to the rejection of the null hypothesis (H10) and the acceptance of the alternative hypothesis (H1a). The results indicate that the proposed method provides significantly better bug repair performance than DeepFix.

• Impact of Stack Trace Similarity: The results highlighted the effectiveness of incorporating stack trace similarity. The proposed method that included stack trace similarity showed better bug correction performance compared to the approach without it.

• Buggy Code and Stack Trace Similarity: Program bug repair was successfully achieved by utilizing similar buggy code and stack trace similarity. The method efficiently generated patches when a buggy line was provided as input.

In addition, the decision to set the number of folds (K) to 5 in the cross-validation process was based on the following considerations:

• Dataset Size: The dataset used in this study was sufficiently large, allowing for meaningful partitioning into four folds. This provided a balance between training and validation sets, ensuring each subset retained adequate representation of the data’s characteristics.

• Computational Efficiency: K value of 5 provided a practical compromise between computational cost and statistical robustness. Higher K values, while potentially offering finer-grained validation, would have significantly increased the computational overhead without a proportional gain in insights.

• Empirical Consistency: Preliminary experiments indicated that using 5 folds produced stable and consistent performance metrics, further validating this choice as appropriate for the study’s objectives.

Although the experimental results are promising, certain factors may pose threats to the validity of the findings:

• Scalability and Runtime Performance: The current study establishes the effectiveness of our approach in terms of repair accuracy on a dataset of academic C programs. A thorough investigation of its scalability to very large industrial codebases and its runtime performance in real-time debugging scenarios is an important area for future work. The computational complexity of the core Transformer model is O(n2) with respect to the input sequence length. While our input was capped at 2048 tokens, handling arbitrarily large files would require additional strategies, such as sliding windows or hierarchical models. We consider the optimization of the framework for efficiency and its evaluation on massive codebases as a critical next step for practical adoption.

• Dataset Specificity: The model was trained and tested using a dataset of C-based student programs. While the dataset is extensive, it may not fully represent all possible scenarios in C programming. This limitation suggests the need for further verification to establish the model’s applicability to a broader range of C programs, including real-world industrial codebases.

• Generality across Languages: The model has been tailored specifically for debugging C programs, leaving its applicability to other programming languages unexplored. Expanding this research to include additional programming languages such as Python, Java, or JavaScript would help assess its generality and robustness across diverse codebases.

• Hyperparameter Optimization: The autoencoder algorithm used in this study employed standard hyperparameter settings. While these settings yielded good results, they may not represent the optimal configuration. Future work should focus on systematically fine-tuning hyperparameters to maximize the model’s performance and explore the use of advanced optimization techniques to enhance debugging capabilities.

• K-Fold Parameter Sensitivity: While K = 5 was justified based on dataset size and computational efficiency; the choice may still influence the model’s performance metrics. Exploring the impact of varying K values on performance would provide additional insights into the robustness of the cross-validation process.

White et al. [14] developed a model that prioritizes statements to detect localized errors, identify code similarities, and generate patches. Li et al. [15] proposed a two-layer recurrent neural network for automated program repair by modifying buggy lines and adjacent code. Le Goues et al. [16] introduced a genetic programming-based debugging method exploiting program redundancy and limiting mutation search space. Hendrycks et al. [17] evaluated code generation models like GPT using the APPS benchmark. Li et al. [18] focused on tasks requiring algorithmic understanding and Natural Language Processing (NLP) for program solutions. Tufano et al. [19] trained an encoder-decoder model on GitHub data for bug fixing. Lutellier et al. [20] used convolutional neural networks in ensemble training for automated bug fixing. Campos et al. [21] proposed a real-time mechanism for semantic bug patching in JavaScript.

Kim et al. [22] developed a pattern-based repair method using manually written patches. Saha et al. [23] proposed ELIXIR to construct expressive recovery representations. Nguyen et al. [24] used graph-based representations to identify code peers. Smith et al. [25] addressed overfitting in patch generation by refining test evaluation. Qi et al. [26] introduced RSRepair, a random search-based tool. Martinez and Monperrus [27] presented Astor, a program recovery library. Nguyen et al. [28] combined symbolic execution and program synthesis. Le et al. [29] designed HDRepair to mine debugging patterns. Liu et al. [30] introduced AVATAR for static analysis corrections. White et al. [31] linked lexical and syntactic patterns with deep learning.

Long et al. [32] created a genesis inference algorithm for patch generation. Le Goues et al. [33] presented GenProg for C program repair. Tan and Roychoudhury [34] developed Relifix for regression errors. Xiong et al. [35] proposed ACS for condition synthesis. Puri et al. [36] published multilingual programming datasets. Ren et al. [37] evaluated debugging at token, syntax tree, and program levels. Wang et al. [38] proposed CodeT5, an identifier-aware unified pre-trained encoder-decoder model designed for code understanding and generation tasks across multiple programming languages. Tang et al. [39] employed Codex models for autocomplete and synthesis.

Bouzenia et al. [40] proposed RepairAgent, a fully autonomous LLM-driven APR system that dynamically gathers information, retrieves repair ingredients, and validates patches. RepairAgent repaired 164 bugs on Defects4J, including 39 previously unfixable, setting a new standard in APR. Jiang et al. [41] evaluated ten code language models (CLMs) and deep learning (DL)-based APR models across multiple benchmarks, showing fine-tuned CLMs significantly outperform vanilla models and DL techniques. Xia and Zhang [42] introduced conversational APR, iteratively guiding LLMs using feedback. Le Goues et al. [43] presented RAP-Gen, integrating retrieval and generation for CodeT5-based patching. Joshi et al. [44] proposed RING, a multilingual repair engine with prompt engineering for multiple languages. Jin et al. [45] developed InferFix, combining static analysis with retrieval-augmented LLM generation, achieving top-1 fix accuracy of 76.8% for Java. Xia and Zhang [46] proposed AlphaRepair, a cloze-style APR using large pre-trained models for zero-shot multilingual repair. Li et al. [47] introduced DEAR, combining spectrum-based fault localization with tree-based LSTM models for multi-hunk/multi-statement bug fixing. Huang et al. [48] conducted a comprehensive study on fine-tuning large language models of code (LLMCs) for automated program repair, evaluating multiple pre-trained architectures and repair scenarios, and showed that fine-tuned LLMCs outperform existing APR tools. Fan et al. [49] systematically investigated using Codex to repair programs generated by LLMs, highlighting the potential of APR techniques to fix common mistakes in auto-generated code and suggesting combinations of LLMs with APR for enhanced repair. Zubair et al. [50] explored the use of large language models for program repair, providing insights into their capabilities and limitations in addressing software bugs.

Huang et al. [51] surveyed the landscape of automated program repair techniques, reviewing patch generation methods, advantages and disadvantages of each approach, and future opportunities. Ahmed et al. [52] introduced SynShine, a machine-learning-based tool that improves syntax error fixing for novice programmers by leveraging compiler diagnostics and large neural models. Zhang et al. [53] presented a systematic survey of learning-based automated program repair, detailing workflows, key components, datasets, evaluation metrics, and open research challenges. Gao et al. [54] offered a comprehensive review of APR techniques, discussing search-based, constraint-based, and learning-based methods, patch overfitting, and industrial applications. Yasunaga and Liang [55] proposed Break-It-Fix-It (BIFI), an unsupervised approach that iteratively generates bad and fixed code pairs to improve repair accuracy without labeled data. Yin et al. [56] developed ThinkRepair, a self-directed LLM-based APR framework that collects pre-fixed knowledge and interacts with LLMs to efficiently fix bugs, achieving superior results on benchmark datasets.

Unlike these works, this research employs an autoencoder for noise reduction and feature learning, integrates multiple contextual features, and statistically validates performance, achieving superior real-time bug repair efficiency and accuracy compared to DeepFix.

Debugging is an essential yet time-consuming process for developers, often requiring significant effort to identify and fix errors in program code. To enhance developer productivity, the automation of bug fixing represents a critical advancement. In this study, we proposed a novel debugging approach that utilizes similar buggy code and stack trace similarity to automate the repair process.

The proposed method involves preprocessing program source code to extract features, calculating stack trace similarity for a given source code, and identifying similar buggy code. By leveraging these features, the model applied various fixes to each buggy line iteratively until the program was successfully debugged. This automated process not only reduced manual effort but also improved debugging efficiency and accuracy.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our approach, we compared its performance against a widely recognized baseline, DeepFix. The results showed that the proposed model achieved a significant improvement in bug repair accuracy, surpassing DeepFix by approximately 6% and achieving an overall performance of 62%. These findings underscore the potential of our method to enhance automated program repair.

In future work, we aim to further refine the model by incorporating additional features and exploring new similarity measures. By expanding the range of features and improving the model’s ability to capture relevant patterns, we hope to achieve even higher accuracy and broader applicability across various programming languages and scenarios. This ongoing effort will contribute to advancing the state-of-the-art in automated debugging and program repair, paving the way for more efficient and reliable software development processes.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors did not receive any specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jinfeng Ji designed and implemented the core algorithm. Geunseok Yang supervised the research, analyzed the results, and contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve human participants or animals, and thus ethical approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

We maintain two BM25 indices, one for buggy code and one for stack traces. At query time, we retrieve the top-5 neighbors from each index using BM25 (k1 = 1.2, b = 0.75). Final relevance is computed as 0.5 × score_code + 0.5 × score_stack. Retrieved pairs are concatenated with the buggy code and stack trace into a single sequence, separated by [SEP] tokens, so that the encoder can jointly attend over all segments. Duplicate results are removed, and any overlap with the evaluation set is excluded to avoid leakage.

References

1. Boehm BW. Software engineering economics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 1981. [Google Scholar]

2. Gupta R, Pal S, Kanade A, Shevade S. DeepFix: fixing common C language errors by deep learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2017;31(1):1345–51. doi:10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Long F, Rinard M. Automatic patch generation by learning correct code. In: Proceedings of the 43rd Annual ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages; 2016 Jan 20–22; St. Petersburg, FL, USA. p. 298–312. doi:10.1145/2837614.2837617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xie Z, Avati A, Arivazhagan N, Jurafsky D, Ng AY. Neural language correction with character-based attention. arXiv:1603.09727. 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. Piech C, Huang J, Nguyen A, Phulsuksombati M, Sahami M, Guibas L. Learning program embeddings to propagate feedback on student code. Int Conf Mach Learn. 2015;37:1093–102. [Google Scholar]

6. Chen Z, Kommrusch SJ, Tufano M, Pouchet LN, Poshyvanyk D, Monperrus M. Sequencer: sequence-to-sequence learning for end-to-end program repair. IIEEE Trans Software Eng. 2021;1:1943–59. doi:10.1109/tse.2019.2940179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hata H, Shihab E, Neubig G. Learning to generate corrective patches using neural machine translation. arXiv:1812.07170. 2018. [Google Scholar]

8. Kao A, Poteet SR. Natural language processing and text mining. London, UK: Springer; 2007. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-754-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aho AV, Lam MS, Sethi R, Ullman JD, Compilers: principles, techniques, and tools. 2nd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

10. Robertson S, Zaragoza H. The probabilistic relevance framework: BM25 and beyond. FNT Inf Retr. 2009;3(4):333–89. doi:10.1561/1500000019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Montgomery DC, Runger GC, Applied statistics and probability for engineers. 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2018. [Google Scholar]

12. Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biom Bull. 1945;1(6):80. doi:10.2307/3001968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika. 1965;52(3–4):591–611. doi:10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. White M, Tufano M, Martinez M, Monperrus M, Poshyvanyk D. Sorting and transforming program repair ingredients via deep learning code similarities. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 26th International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER); 2019 Feb 24–27; Hangzhou, China. p. 479–90. doi:10.1109/saner.2019.8668043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li Y, Wang S, Nguyen TN. DLFix: context-based code transformation learning for automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering; 2020 Oct 5–11; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 602–14. doi:10.1145/3377811.3380345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Le Goues C, Nguyen T, Forrest S, Weimer W. GenProg: a generic method for automatic software repair. IIEEE Trans Software Eng. 2012;38(1):54–72. doi:10.1109/tse.2011.104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hendrycks D, Basart S, Kadavath S, Mazeika M, Arora A, Guo E, et al. Measuring coding challenge competence with APPS. arXiv:2105.09938. 2021. [Google Scholar]

18. Li Y, Choi D, Chung J, Kushman N, Schrittwieser J, Leblond R, et al. Competition-level code generation with AlphaCode. arXiv:2203.07814. 2022. [Google Scholar]

19. Tufano M, Watson C, Bavota G, Di Penta M, White M, Poshyvanyk D. An empirical study on learning bug-fixing patches in the wild via neural machine translation. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2019;28(4):1–29. doi:10.1145/3340544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lutellier T, Pham HV, Pang L, Li Y, Wei M, Tan L. CoCoNuT: combining context-aware neural translation models using ensemble for program repair. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2020 Jul 18–22; Virtual. p. 101–14. doi:10.1145/3395363.3397369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Campos D, Restivo A, Sereno Ferreira H, Ramos A. Automatic program repair as semantic suggestions: an empirical study. In: Proceedings of the 2021 14th IEEE Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST); 2021 Apr 12–16; Porto de Galinhas, Brazil. p. 217–28. doi:10.1109/ICST49551.2021.00032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kim D, Nam J, Song J, Kim S. Automatic patch generation learned from human-written patches. In: Proceedings of the 2013 35th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2013 May 18–26; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 802–11. doi:10.1109/ICSE.2013.6606626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Saha RK, Lyu Y, Yoshida H, Prasad MR. Elixir: effective object-oriented program repair. In: Proceedings of the 2017 32nd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE); 2017 Oct 30–Nov 3; Urbana, IL, USA. p. 648–59. doi:10.1109/ASE.2017.8115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nguyen TT, Nguyen HA, Pham NH, Al-Kofahi J, Nguyen TN. Recurring bug fixes in object-oriented programs. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering—Volume 1; 2010 May 1–8; Cape Town, South Africa. p. 315–24. doi:10.1145/1806799.1806847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Smith EK, Barr ET, Le Goues C, Brun Y. Is the cure worse than the disease? Overfitting in automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the 2015 10th Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering; 2015 Aug 30–Sep 4; Bergamo, Italy. p. 532–43. doi:10.1145/2786805.2786825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Qi Y, Mao X, Lei Y, Dai Z, Wang C. The strength of random search on automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Software Engineering; 2014 May 31–Jun 7; Hyderabad, India. p. 254–65. doi:10.1145/2568225.2568254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Martinez M, Monperrus M. ASTOR: a program repair library for Java (demo). In: Proceedings of the 25th International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2016 Jul 18–20; Saarbrücken, Germany. p. 441–4. doi:10.1145/2931037.2948705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nguyen HDT, Qi D, Roychoudhury A, Chandra S. SemFix: program repair via semantic analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2013 35th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2013 May 18–26; San Francisco, CA, USA; 2013. p. 772–81. doi:10.1109/ICSE.2013.6606623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Le XBD, Lo D, Le Goues C. History driven program repair. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution, and Reengineering (SANER); 2016 Mar 14–18; Osaka, Japan. p. 213–24. doi:10.1109/SANER.2016.76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu K, Koyuncu A, Kim D, Bissyande TF. Avatar: fixing semantic bugs with fix patterns of static analysis violations. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 26th International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER); 2019 Feb 24–27; Hangzhou, China. p. 1–12. doi:10.1109/saner.2019.8667970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. White M, Tufano M, Vendome C, Poshyvanyk D. Deep learning code fragments for code clone detection. In: Proceedings of the 31st IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering; 2016 Sep 3–7; Singapore. p. 87–98. doi:10.1145/2970276.2970326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Long F, Amidon P, Rinard M. Automatic inference of code transforms for patch generation. In: Proceedings of the 2017 11th Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering; 2017 Sep 4–8; Paderborn, Germany. p. 727–39. doi:10.1145/3106237.3106253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Le Goues C, Dewey-Vogt M, Forrest S, Weimer W. A systematic study of automated program repair: fixing 55 out of 105 bugs for $8 each. In: Proceedings of the 2012 34th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2012 Jun 2–9; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 3–13. doi:10.1109/ICSE.2012.6227211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tan SH, Roychoudhury A. Relifix: automated repair of software regressions. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM 37th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering; 2015 May 16–24; Florence, Italy. p. 471–82. doi:10.1109/ICSE.2015.65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xiong Y, Wang J, Yan R, Zhang J, Han S, Huang G, et al. Precise condition synthesis for program repair. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2017 May 20–28; Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 416–26. doi:10.1109/ICSE.2017.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Puri R, Kung DS, Janssen G, Zhang W, Domeniconi G, Zolotov V, et al. CodeNet: a large-scale AI for code dataset for learning a diversity of coding tasks. arXiv:2105.12655. 2021. [Google Scholar]

37. Ren S, Guo D, Lu S, Zhou L, Liu S, Tang D, et al. CodeBLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of code synthesis. arXiv:2009.10297. 2020. [Google Scholar]

38. Wang Y, Wang W, Joty S, Hoi SCH. CodeT5: identifier-aware unified pre-trained encoder-decoder models for code understanding and generation. arXiv:2109.00859. 2021. [Google Scholar]

39. Tang L, Ke E, Singh N, Verma N, Drori I. Solving probability and statistics problems by program synthesis. arXiv:2111.08267. 2021. [Google Scholar]

40. Bouzenia I, Devanbu P, Pradel M. RepairAgent: an autonomous, LLM-based agent for program repair. arXiv:2403.17134. 2024. [Google Scholar]

41. Jiang N, Liu K, Lutellier T, Tan L. Impact of code language models on automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2023 May 14–20; Melbourne, Australia. p. 1430–42. doi:10.1109/ICSE48619.2023.00125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Xia CS, Zhang L. Conversational automated program repair. arXiv:2301.13246. 2023. [Google Scholar]

43. Le Goues C, Pradel M, Roychoudhury A, Chandra S. Automatic program repair. IEEE Softw. 2021;38(4):22–7. doi:10.1109/ms.2021.3072577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Joshi H, Cambronero Sanchez J, Gulwani S, Le V, Verbruggen G, Radiček I. Repair is nearly generation: multilingual program repair with LLMs. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(4):5131–40. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i4.25642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Jin M, Shahriar S, Tufano M, Shi X, Lu S, Sundaresan N, et al. InferFix: end-to-end program repair with LLMs. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering; 2023 Dec 3–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 1646–56. doi:10.1145/3611643.3613892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Xia CS, Zhang L. Less training, more repairing please: revisiting automated program repair via zero-shot learning. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering; 2022 Nov 14–18; Singapore. p. 959–71. doi:10.1145/3540250.3549101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Li Y, Wang S, Nguyen TN. DEAR: a novel deep learning-based approach for automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering; 2022 May 25–27; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 511–23. doi:10.1145/3510003.3510177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Huang K, Meng X, Zhang J, Liu Y, Wang W, Li S, et al. An empirical study on fine-tuning large language models of code for automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the 2023 38th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE); 2023 Sep 11–15; Luxembourg. p. 1162–74. doi:10.1109/ASE56229.2023.00181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Fan Z, Gao X, Mirchev M, Roychoudhury A, Tan SH. Automated repair of programs from large language models. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2023 May 14–20; Melbourne, Australia. p. 1469–81. doi:10.1109/ICSE48619.2023.00128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zubair F, Al-Hitmi M, Catal C. The use of large language models for program repair. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2025;93(2):103951. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2024.103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Huang K, Xu Z, Yang S, Sun H, Li X, Yan Z, et al. A survey on automated program repair techniques. arXiv:2303.18184. 2023. [Google Scholar]

52. Ahmed T, Ledesma NR, Devanbu P. SynShine: improved fixing of syntax errors. IIEEE Trans Software Eng. 2023;49(4):2169–81. doi:10.1109/tse.2022.3212635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zhang Q, Fang C, Ma Y, Sun W, Chen Z. A survey of learning-based automated program repair. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2024;33(2):1–69. doi:10.1145/3631974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Gao X, Noller Y, Roychoudhury A. Program repair. arXiv:2211.12787. 2022. [Google Scholar]

55. Yasunaga M, Liang P. Break-it-fix-it: unsupervised learning for program repair. Int Conf Mach Learn. 2021;139:11941–52. [Google Scholar]

56. Yin X, Ni C, Wang S, Li Z, Zeng L, Yang X. Thinkrepair: self-directed automated program repair. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2024 Sep 16–20; Vienna, Austria. p. 1274–86. doi:10.1145/3650212.3680359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools