Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

BearFusionNet: A Multi-Stream Attention-Based Deep Learning Framework with Explainable AI for Accurate Detection of Bearing Casting Defects

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, East West University, Dhaka, 1212, Bangladesh

2 Department of Computer Science, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016, USA

3 Centre for Image and Vision Computing (CIVC), COE for Artificial Intelligence, Faculty of Artificial Intelligence and Engineering (FAIE), Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, 63100, Malaysia

4 Department of Computer Science, New York Institute of Technology, New York, NY 10023, USA

5 AI and Big Data Department, Endicott College, Woosong University, Daejeon, 34606, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Jia Uddin. Email: ; Hezerul Abdul Karim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 33 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071771

Received 12 August 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Manual inspection of onba earing casting defects is not realistic and unreliable, particularly in the case of some micro-level anomalies which lead to major defects on a large scale. To address these challenges, we propose BearFusionNet, an attention-based deep learning architecture with multi-stream, which merges both DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 for feature extraction with a classification head inspired by VGG19. This hybrid design, figuratively beaming from one layer to another, extracts the enormity of representations on different scales, backed by a pre-preprocessing pipeline that brings defect saliency to the fore through contrast adjustment, denoising, and edge detection. The use of multi-head self-attention enhances feature fusion, enabling the model to capture both large and small spatial features. BearFusionNet achieves an accuracy of 99.66% and Cohen’s kappa score of 0.9929 in Kaggle’s Real-life Industrial Casting Defects dataset. Both McNemar’s and Wilcoxon signed-rank statistical tests, as well as five-fold cross-validation, are employed to assess the robustness of our proposed model. To interpret the model, we adopt Grad-Cam visualizations, which are the state of the art standard. Furthermore, we deploy BearFusionNet as a web-based system for near real-time inference (5–6 s per prediction), which enables the quickest yet accurate detection with visual explanations. Overall, BearFusionNet is an interpretable, accurate, and deployable solution that can automatically detect casting defects, leading to significant advances in the innovative industrial environment.Keywords

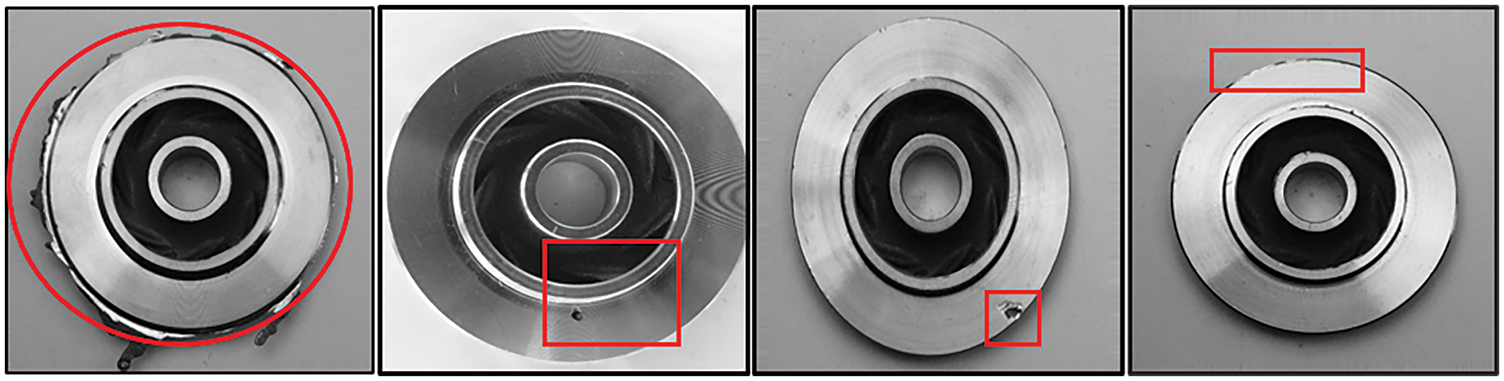

Diagnosing casting defects in bearings is considered an essential yet error-prone activity in industrial manufacturing, often leading to unnoticed defects, expensive failures, and lower product quality [1]. Elements in motion, such as rolling bearings, cause nearly 40% of the breakdowns recorded by electric motors and are highly susceptible to this kind of problem [2]. By discovering these problems at an early stage, it becomes possible to maintain the motors accordingly, resulting in less downtime and increased reliability of the machines. Traditional methods for fault detection, such as vibration analysis, motor current signature analysis (MCSA), and acoustic emission monitoring, often fail to identify minor defects like micro-cracks, small holes, and surface porosities, despite their troublesome conditions and noise [3,4]. Fig. 1 shows typical casting defects found in bearings, such as flash, small holes and cracks, which can be used as definite visual aids in identifying the nature of defects that will cause inaccurate defect detection.

Figure 1: Common casting defects in bearings: flash, small holes, and cracks

Recent advancements in deep learning, particularly in convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have highlighted the potential for automating defect detection in industrial systems. However, a notable limitation of these models is their performance in identifying fine defects and their lack of interpretability an essential factor in high-stakes environments [5]. For example, CNNs trained on spectrograms have achieved classification accuracies exceeding 99% on specific datasets [6]. Nonetheless, their practical application in real-world industrial settings is limited by high computational costs and unclear decision-making processes. Additionally, while current attention mechanisms aid in feature extraction, they often struggle to capture the multi-scale information necessary for accurately localizing defects across various types and textures [7].

To address the challenges in defect recognition for bearing castings, we propose BearFusionNet, a hybrid deep-learning architecture designed to improve detection accuracy. BearFusionNet combines DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2, incorporating multi-head self-attention (MHSA) modules to separate and extract features from input images effectively. The model’s multi-stream attention capabilities enable it to pinpoint critical regions with subtle or overlapping defects accurately, enhancing detection performance. Additionally, we utilize Grad-CAM for visualization, which provides interpretable insights into the model’s decision-making process, ensuring transparency for practical applications in real-world settings.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

• Multi-Head Attention Mechanism: By integrating a Multi-Head Attention mechanism into a pre-trained model framework, we enhance the detection of subtle defects. This integration enables the model to consider multiple relevant features simultaneously, thereby improving the quality of feature representation.

• Deep Feature Fusion: We introduce a novel deep feature fusion architecture that merges DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 with the fully connected layers of VGG19. Incorporating multi-scale features through Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) significantly improves defect classification performance, particularly for complex and overlapping defects.

• Improved Accuracy and Reduced Misclassification: Our approach achieves an accuracy of 99.66% with only two misclassifications on the Kaggle Real-Life Industrial Dataset of Casting Product Defects. This demonstrates the effectiveness of our method in defect detection, even under challenging conditions.

• Model Explainability: We employ Grad-CAM visualization techniques to provide interpretable insights into the model’s decision-making process. This is a crucial aspect of industrial applications that necessitate transparency and trust in predictive outcomes.

• Real-Time Testing Deployment: To enhance the practical application of the model in quality control and predictive maintenance, we have deployed it as a web application. This allows for real-time testing and performance evaluation on new and unseen defect samples.

BearFusionNet outperforms existing models in terms of both classification accuracy and interpretability, positioning it as a robust alternative for industrial defect detection applications. This innovative hybrid architecture, featuring sophisticated preprocessing techniques and design elements optimized for explainability, ensures high accuracy and transparency essential attributes for real-time industrial settings. We also present a robust image preprocessing pipeline that utilizes Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE), non-local means denoising, and Canny edge detection. Future research will aim to expand the training dataset for the model, enhance its computational efficiency, and evaluate its performance across various industrial environments. These efforts will contribute to refining the model’s applicability and effectiveness in practical scenarios.

Bearing fault detection plays a crucial role in predictive maintenance and ensures the reliability of industrial machinery. This section examines traditional signal-based methods, explores advancements in deep learning for defect detection, and analyzes attention-based architectures and hybrid approaches [8–10]. It highlights their limitations, which inspire the development of our proposed BearFusionNet framework.

2.1 Conventional Signal-Based Techniques

Traditional fault diagnosis relies heavily on analyzing vibration or current signals in both the time and frequency domains [11,12]. Time-domain features, such as Root Mean Square (RMS), kurtosis, and crest factor, effectively identify significant anomalies, but they often miss micro-defects. In contrast, frequency-domain techniques, including Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and envelope analysis, help isolate specific fault frequencies (e.g., BPFO, BPFI) [13,14]. However, they are sensitive to noise and rely on stationary assumptions. More advanced time-frequency methods, such as Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) [15], Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) [16], and Wavelet Packet Transform (WPT) [17], improve the localization of transient events in non-stationary conditions. However, these approaches still require expert-tuned thresholds and face challenges with scalability in real-world factory environments.

2.2 Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods

Researchers typically use handcrafted feature extraction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and mutual information in conventional machine learning pipelines [18–20]. They then apply classifiers such as Support Vector Machine, K-Nearest Neighbor, or Random Forest [21]. While these methods prove effective, they show limited adaptability to new defect types and variations in operational conditions [22]. In contrast, deep learning models, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained on spectrograms or envelope signals, achieve accuracy rates exceeding 99% on benchmark datasets like CWRU [23] and Paderborn [24]. However, many of these models remain single-stream and lack interpretability. Additionally, numerous studies in this field do not implement robust evaluation strategies, including cross-validation or statistical testing, which restricts their generalizability beyond specific datasets.

2.3 Attention Mechanisms and Interpretability

Attention mechanisms gain significant traction in fault diagnosis, enhancing performance and transparency [25]. Convolutional attention modules, such as Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), dynamically adjust the weighting of spatial and channel features, while Transformer-based self-attention improves the modeling of long-range dependencies [26]. However, most applications focus on signal data and often overlook the integration of spatial textures derived from visual defect cues. Moreover, visual interpretability remains limited, as few models provide attention explanations that align with regions examined by experts [27].

2.4 Transfer Learning and Domain Adaptation

To overcome data scarcity, transfer learning strategies such as Deep Adaptation Networks (DAN) and Domain-Adversarial Training (DAT) have been explored [2,28]. These models achieve >97% accuracy across domains but often do not address surface-level defect localization or operate on grayscale imagery, which is common in industrial casting inspection.

2.5 Hybrid Architectures and Real-Time Constraints

Recent hybrid models leverage the strengths of various architectures. For instance, HiDraNet [29] incorporates multiscale CNN blocks, achieving an impressive 99.8% accuracy on the Kaggle casting dataset; however, it lacks explainability tools and does not report on statistical robustness. Benbarrad et al. [30] employ EfficientNetB0 for IoT-integrated inspections but achieve a lower accuracy of 96.88% and omit real-time latency analysis. Ensemble approaches, like those from Stephen et al. [31], achieve 100% accuracy on Northeastern University (NEU) defect images by combining Inception, DenseNet, and Xception, but incur high computational costs that render them unsuitable for deployment on edge devices.

There are some limitations that exist in the existing models in the literature. The majority of methods are signal based and ignore useful image-based information. Multistream architectures that can represent complementary spatial features are only used in a small number of models. Although high accuracy is often obtained, explainability and robustness are not well studied. In addition, computational cost and real-time deployment issues are rarely considered in sufficient detail. Moreover, the identification of model stability by use of statistical testing or internationalizing real-time web applications is less in the literature. The existence of these gaps highlights the necessity of our proposed BearFusionNet which combines the use of DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 backbones with multi head self-attention. This model is validated through 5 Fold CV, Grad-CAM and Wilcoxon tests and is available as a live demo for detecting casting defects in Industry 4.0 environments.

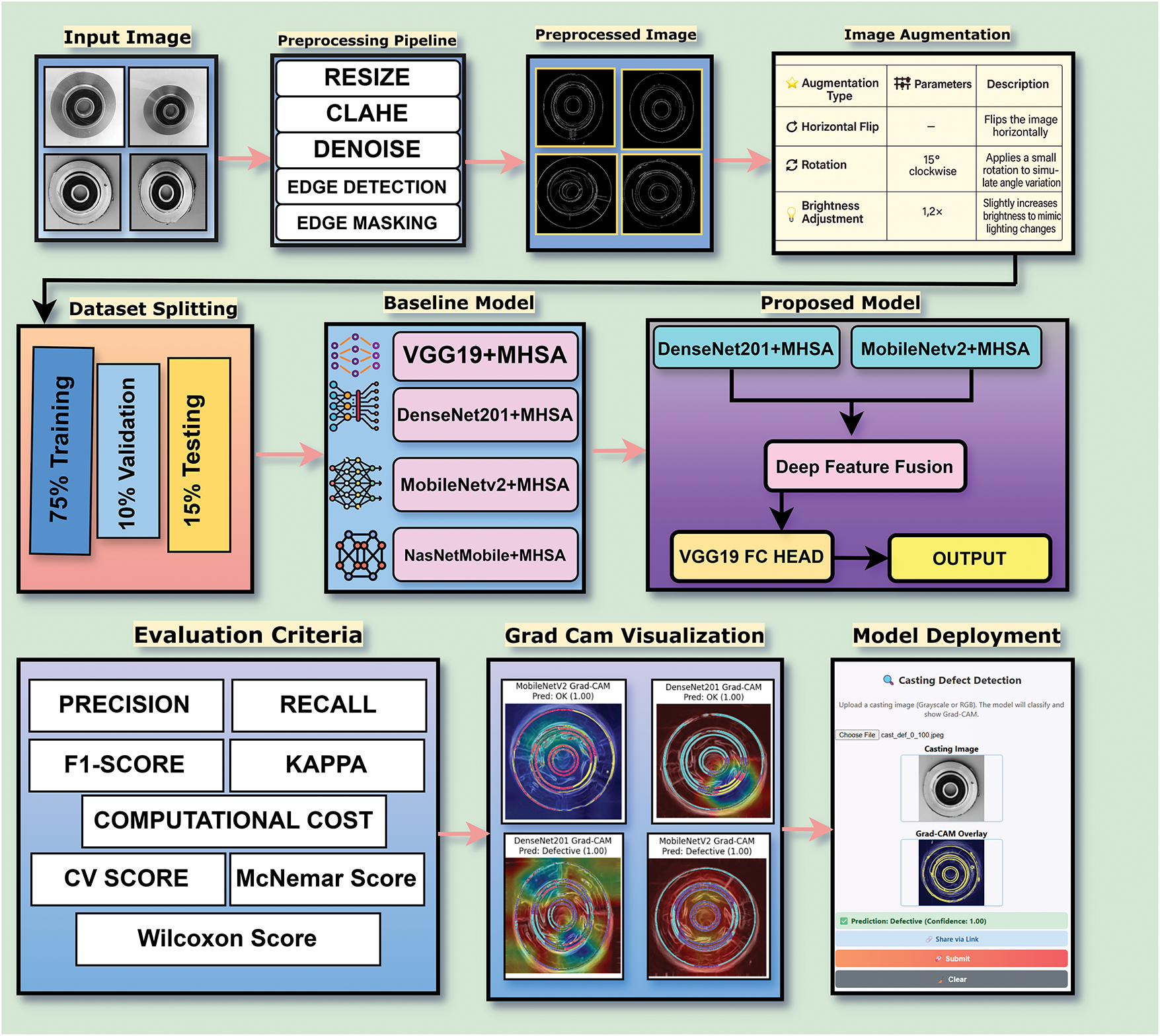

The proposed methodology for detecting casting defects in bearings follows a systematic pipeline that includes image preprocessing, data augmentation, model training, and evaluation. Grayscale images are enhanced using Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) and edge detection to improve feature clarity. Data augmentation helps ensure robustness against variations in the dataset. A hybrid deep learning model is then used for classification. The overall workflow is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Proposed workflow diagram

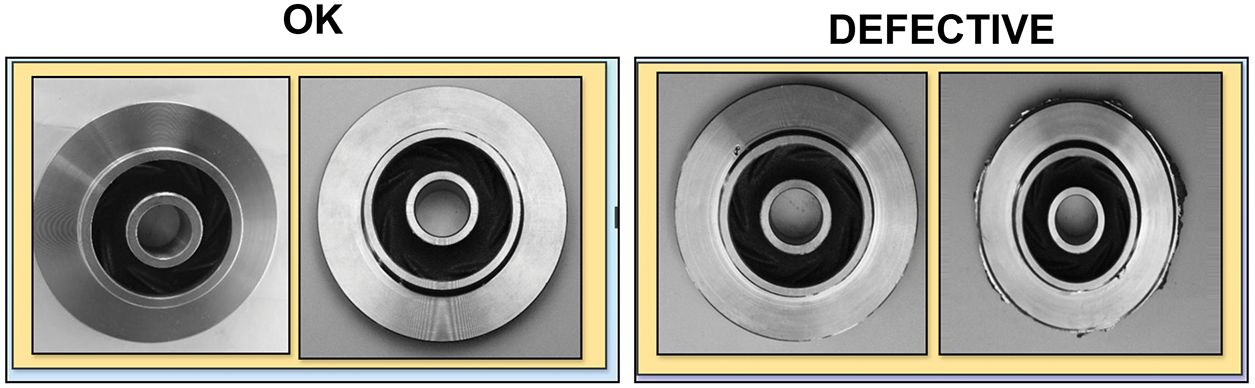

For this study, we utilized a publicly available dataset published on Kaggle, titled Real-life Industrial Dataset of Casting Product Defects [32]. This dataset comprises 1300 grayscale images of industrial bearing.The dataset was captured under controlled laboratory conditions with consistent lighting, using a Canon EOS 1300D DSLR camera [30]. It consists of two classes: 781 images of defective castings (def_front) and 519 images of non-defective or accepted castings (ok_front). Each original image measures 512

Figure 3: Sample images from the dataset illustrating (a) non-defective casting (ok_front) and (b) defective casting (def_front). These examples highlight the visual differences between accepted and defective products

3.2 Image Preprocessing and Feature Enhancement

To ensure consistent input dimensions and reduce computational overhead during model training and processing, we resize all images to 256

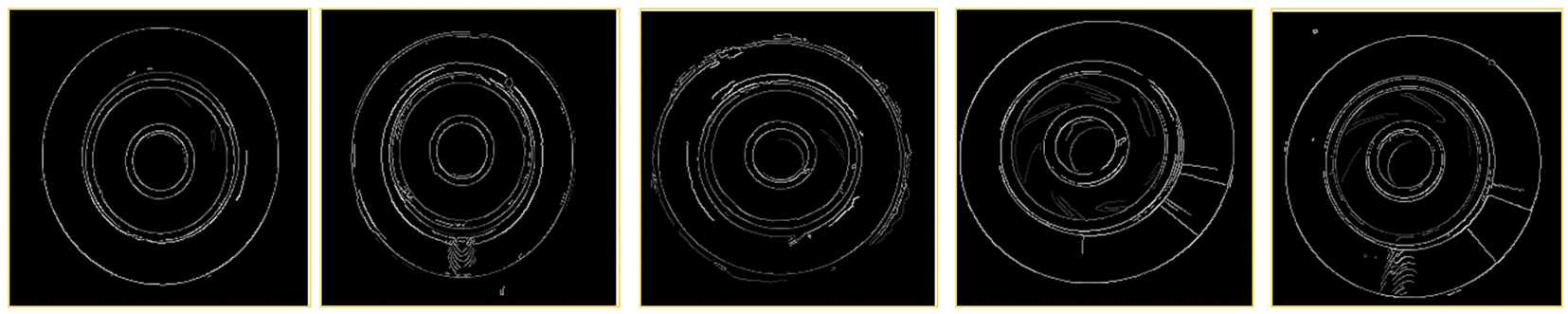

We apply non-local denoising to reduce irrelevant visual noise while preserving crucial structural boundaries. This technique effectively maintains edge integrity while removing high-frequency noise components introduced during imaging, making it an appropriate choice for our context. In the subsequent stage, we perform edge detection using a gradient-based method to pinpoint abrupt intensity transitions in the image, typically associated with defect boundaries or surface discontinuities.

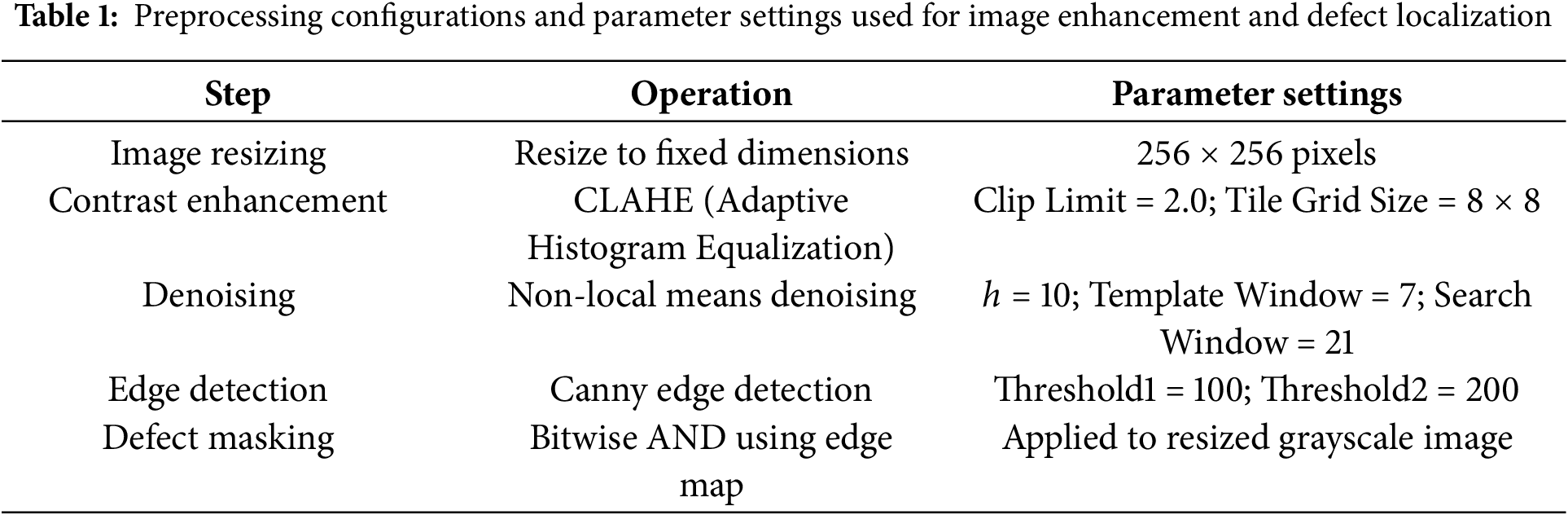

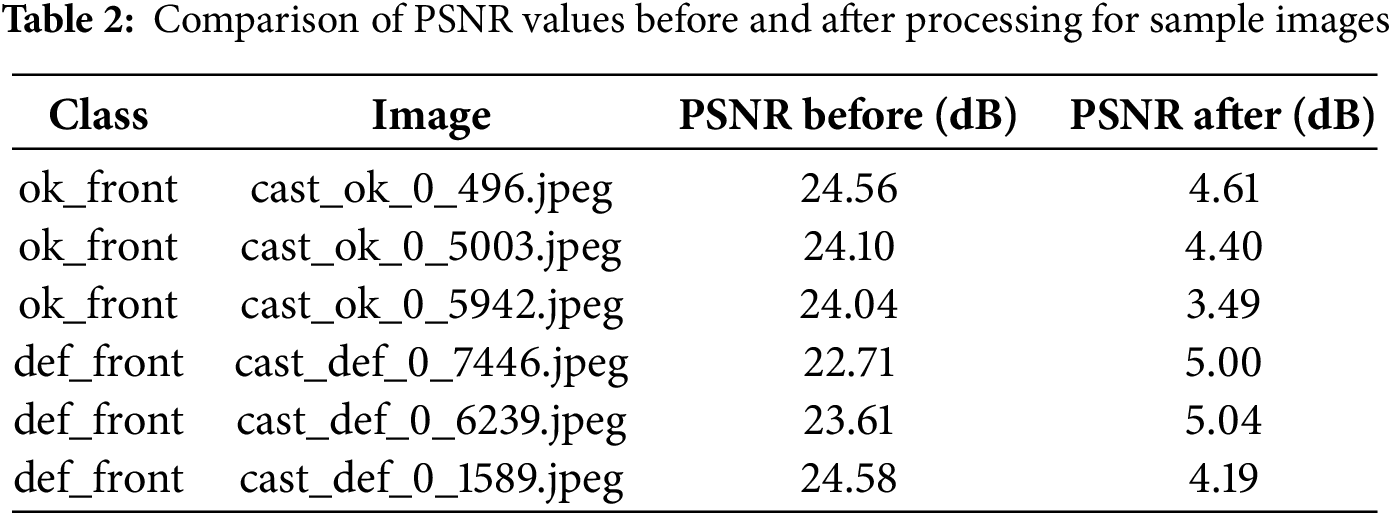

Finally, we conduct a binary masking operation using the previously computed edge map as a spatial filter. This process isolates potential defect regions without being affected by irrelevant background textures. Our multi-stage preprocessing approach enhances defect visibility, standardizes image quality, and accurately localizes casting flaws with high precision [34]. We present a comprehensive summary of each processing step and the parameter configurations used in Table 1. To demonstrate the efficacy of the techniques employed in emphasizing defect features while minimizing noise and irrelevant background information, we illustrate Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) values before and after preprocessing in Table 2.

Table 2 compares the PSNR values of selected images before and after preprocessing. Before processing, the PSNR values range from approximately 22 to 25 dB, indicating that these images closely resemble the originals. However, after preprocessing, we observe a notable decrease in PSNR around 3.5 to 5 dB. This reduction is particularly evident with our edge detection and masking techniques, which intentionally modify the images to highlight defects. This degree of reduction shows that preprocessing significantly enhances defect features while minimizing irrelevant background information, thus improving feature visibility for analysis purposes.

Fig. 4 shows the final preprocessed image obtained after applying all preprocessing steps.

Figure 4: Preprocessing pipeline for bearing casting defect detection

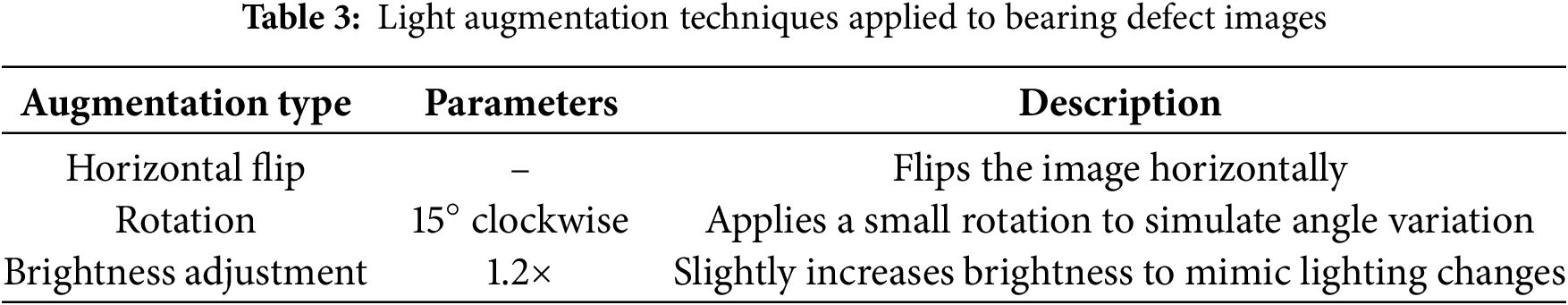

The dataset included 1300 images showcasing different bearing conditions, which is quite limited for training a deep-learning model. Light data augmentation techniques were utilized to enhance model performance and reduce the chances of overfitting. Light enhancement was applied to maintain the actual characteristics of bearing defects without unrealistic distortion that would be created through heavy enhancement, as this would lead to bias and overfitting. Subtle variations such as horizontal flipping, slight rotations, and brightness adjustments were applied, ensuring that the key features of defects remained unchanged. This method maintained the structural integrity of the bearing faults while enabling better model generalization. Table 3 shows an overview of the augmentation techniques.

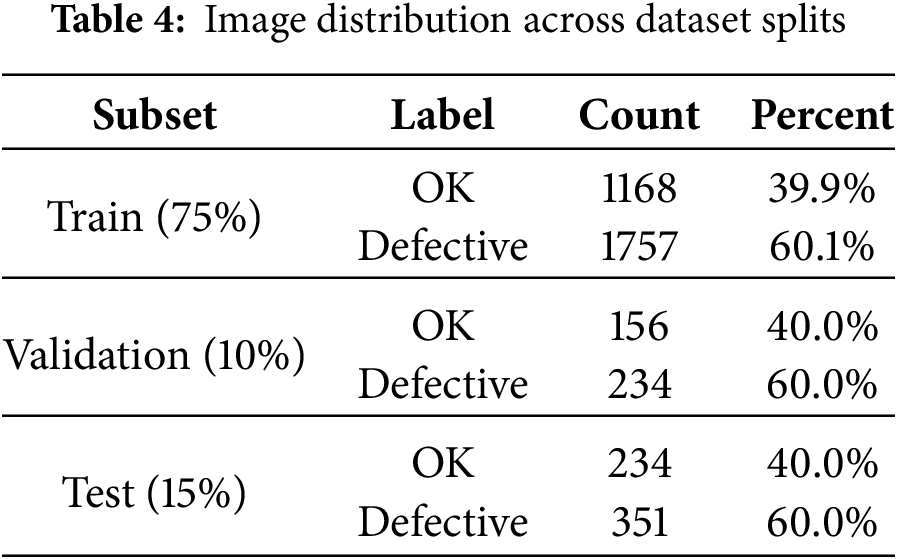

3.4 Dataset Split and Class Distribution

Following data augmentation, the final dataset consisted of 3900 labeled images categorized into two classes: OK and Defective. The dataset was divided into training (75%, 2925 images), validation (10%, 390 images), and test (15%, 585 images) subsets using a stratified sampling method to ensure class balance. The Defective class comprised approximately 60% of each subset, while the OK class made up around 40%, as indicated in Table 4.

Multihead self-attention (MHSA) enhances CNN models by utilizing their ability to simultaneously model complex spatial relationships across different areas of an image. Unlike traditional convolutional approaches, MHSA operates with multiple attention heads in parallel, allowing it to concentrate on the most significant features. This study integrates a 4-head MHSA module into four state-of-the-art baseline models: VGG19, MobileNetV2, NASNetMobile, and DenseNet. This integration includes convolutional layers and culminates in a classification stage. The attention heads effectively learn distinct feature dependencies, enabling the models to better emphasize regions of interest for kidney stone detection while minimizing noise from less informative areas. This attention mechanism enriches the feature representation by infusing it with additional information beneficial for classification.

3.6 Baseline Models with Multi-Head Attention

Four state-of-the-art convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures such as VGG19, MobileNetV2, NASNetMobile, and DenseNet201 serve as baseline models for bearing defect classification, providing a strong foundation due to their effectiveness in various visual recognition tasks, architectural diversity, and suitability for transfer learning in scenarios with limited labeled data, common in industrial applications. VGG19 features 19 layers of

3.7 Proposed BearFusionNet: A Hybrid Attention Fusion Model

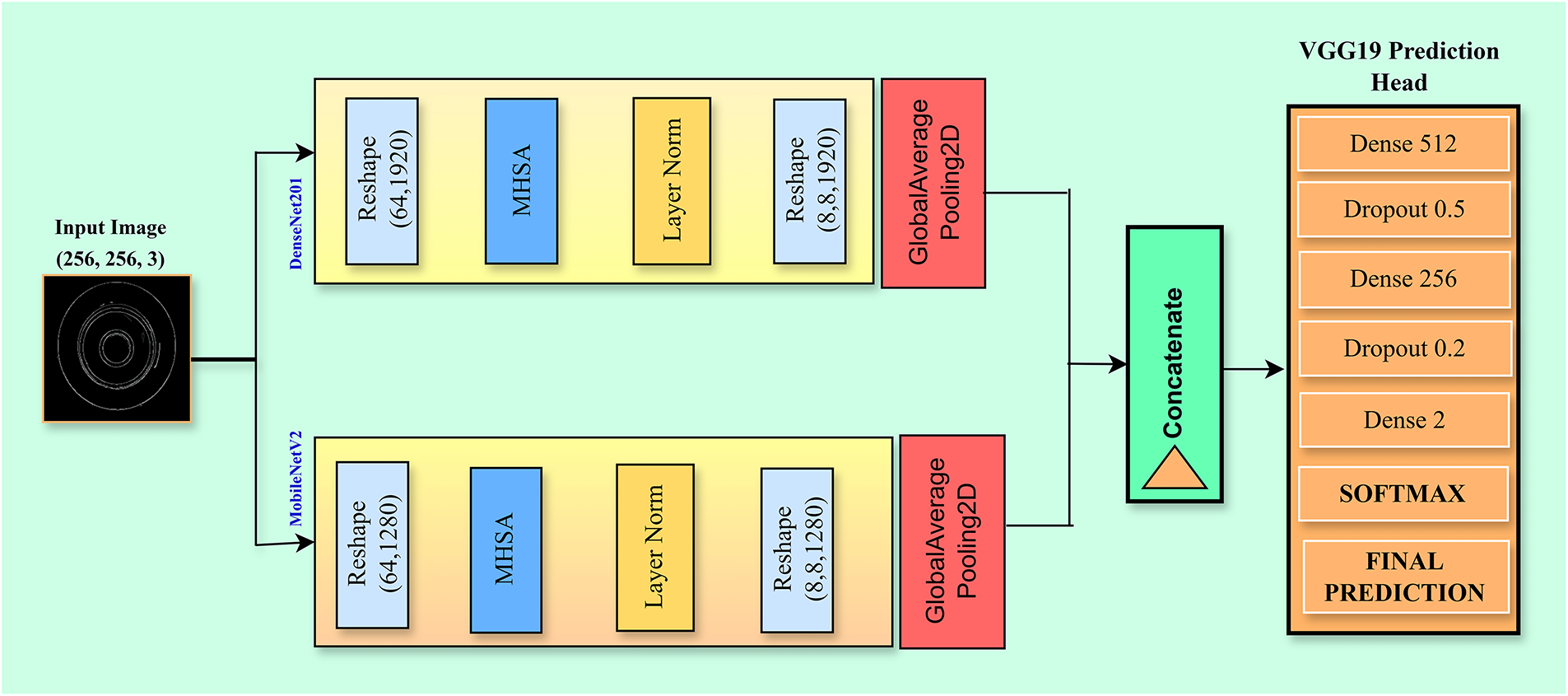

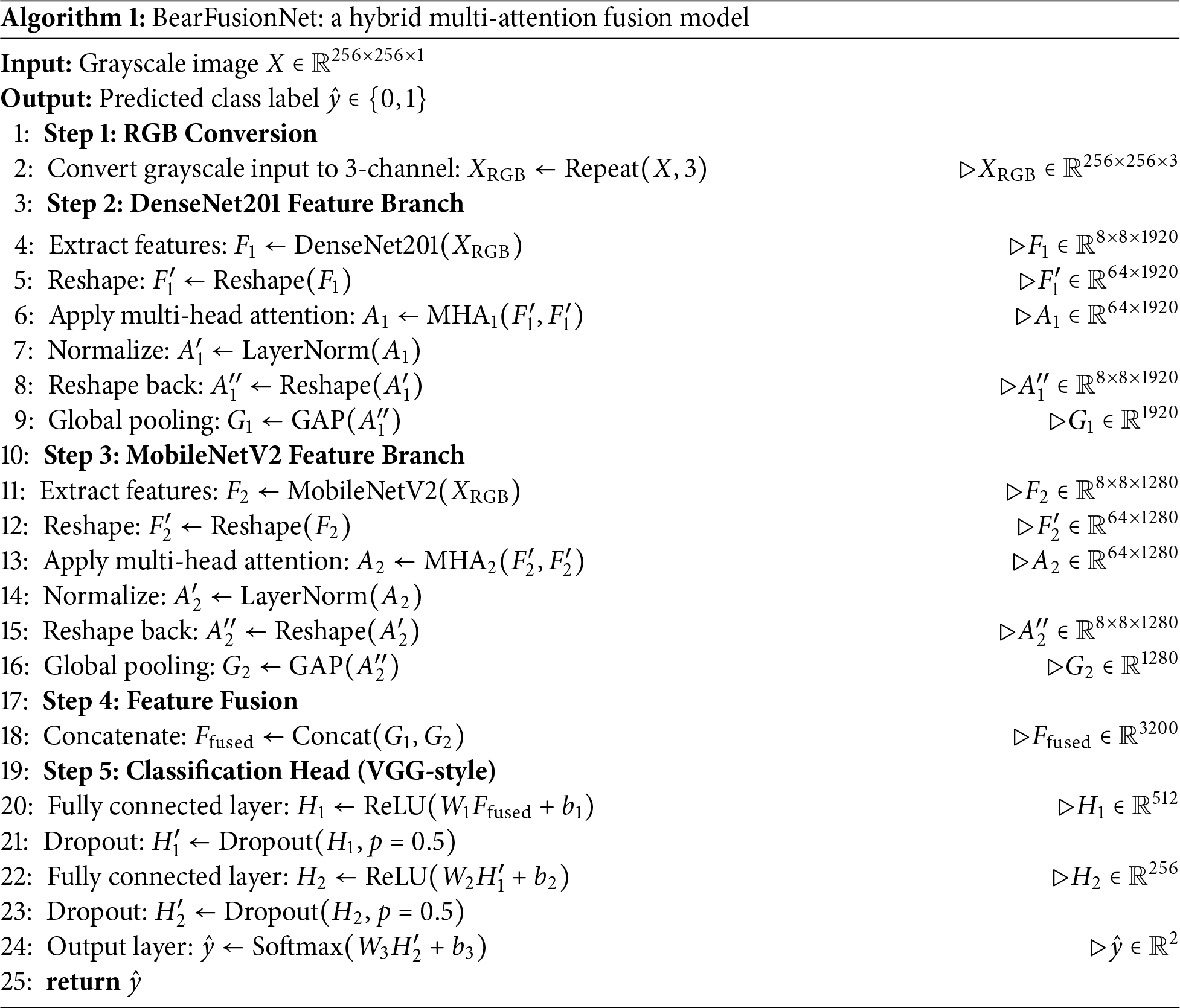

This study presents BearFusionNet, a hybrid architecture designed explicitly for classifying bearing casting defects. We combine two state-of-the-art convolutional neural networks DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 and enhance them with MHSA to effectively capture the input images detailed and complementary features. Each backbone extracts features, which we reshape and process through the MHSA layers, allowing the model to learn long-range spatial dependencies crucial for identifying minor casting defects. Next, we pool and concatenate the attention enhanced features from both models to create a fused representation that retains the strengths of each. We feed this fused output into a fully connected classification head inspired by the VGG19 architecture, incorporating dense layers and dropout techniques to promote improved generalization. This paper introduces the BearFusionNet architecture to harness the complementary strengths of these models, resulting in a robust and efficient system for accurately detecting bearing casting defects. Fig. 5 illustrates the detailed architecture of the proposed BearFusionNet. Also, Algorithm 1 formally describes the step-by-step computational flow of the model.

Figure 5: Proposed BearFusionNet architecture

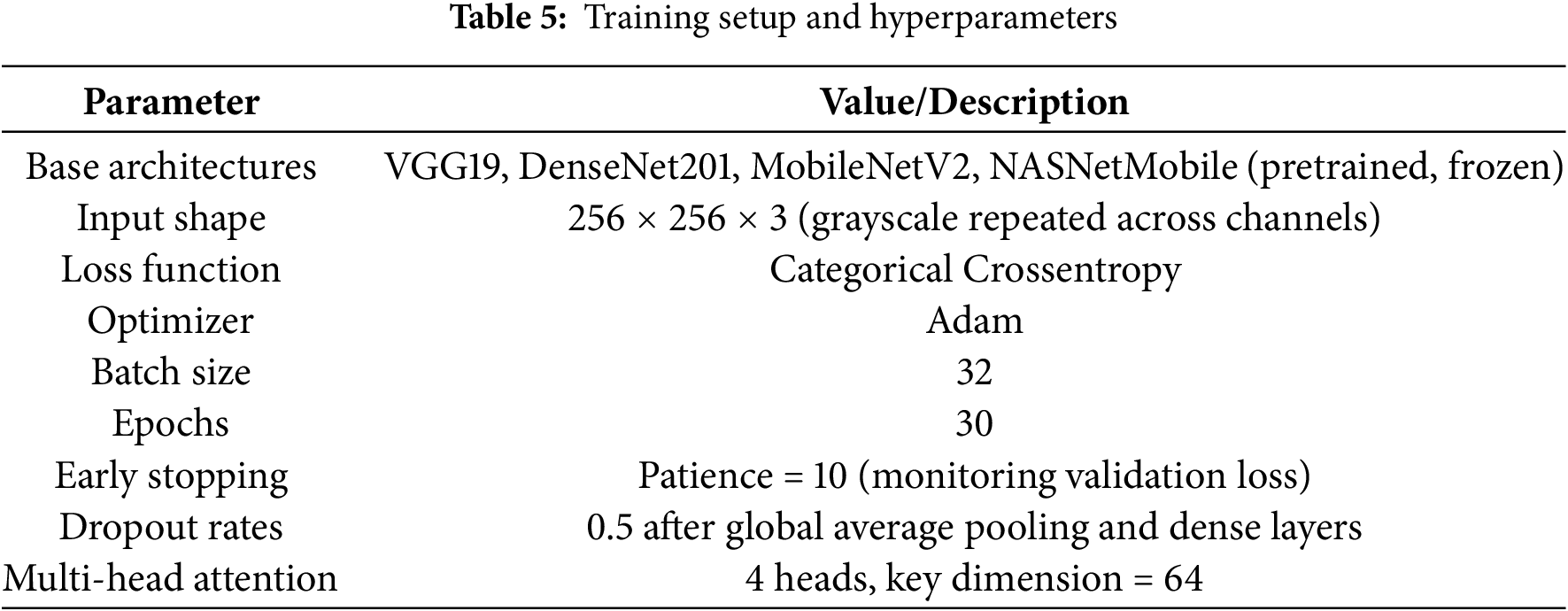

This section outlines the training configuration, key hyperparameters, and model complexity used to evaluate BearFusionNet and baseline models in the casting defect detection task.

3.8.1 Training Setup and Hyperparameters

The study utilized four pre trained convolutional neural network models—VGG19, DenseNet201, MobileNetV2, and NASNetMobile as frozen feature extractors. In addition, it incorporated MHSA and dropout to enhance feature representations and introduce regularization. The details of the training setup, including hyperparameters and optimization strategies, are outlined in Table 5. These parameters were selected through empirical tuning, guided by prior literature and validation performance, to achieve stable training and optimal generalization across all models.

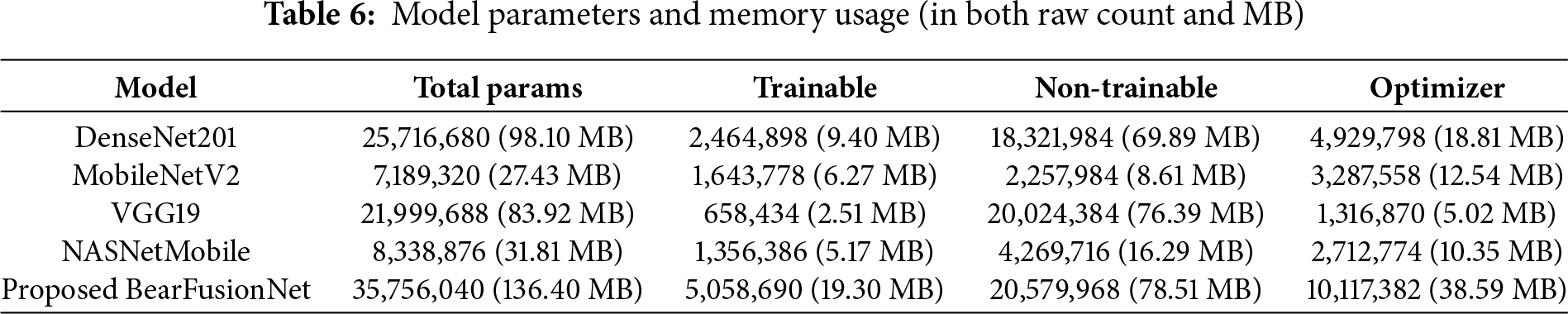

Table 6 presents the number of parameters and the memory consumption for each model. BearFusionNet exhibits the highest total and trainable parameters, reflecting its hybrid architecture that integrates multiple pre-trained backbones and employs multi-head attention. In comparison, DenseNet201 and VGG19 also feature substantial parameter sizes, while MobileNetV2 and NASNetMobile are designed to be more lightweight. The trainable weights, which the optimizer adjusts during training, correspond to these parameters. This increased complexity enables BearFusionNet to learn more nuanced feature representations, contributing to its superior performance in classification accuracy.

3.9 Proposed Model Decision Making

We used Grad-CAM to explain the model’s predictions. Grad-CAM is important because it highlights areas of interest by using the gradients of the final convolutional layers. This helps in visualizing the model and makes it easier to understand and trust.

3.10 Demo Web Application Deployment

The proposed model can be deployed as a real-time web application capable of integrating with IoT enabled camera systems in industrial environments. This prototype enables continuous automated monitoring and swift defect detection along the production line, showcasing its potential to enhance quality control and operational efficiency through timely interventions.

This section presents the experimental results of the intelligent bearing fault detection system. We evaluate the generalization performance independently during the training, validation, and testing phases. We employ a five-fold cross-validation technique to assess the consistency of various data splits. Additional analyses confirm the reliability of classification and examine the framework’s potential for real-time deployment. The following sections discuss the key findings and their implications.

4.1 Training, Validation, and Testing Performance

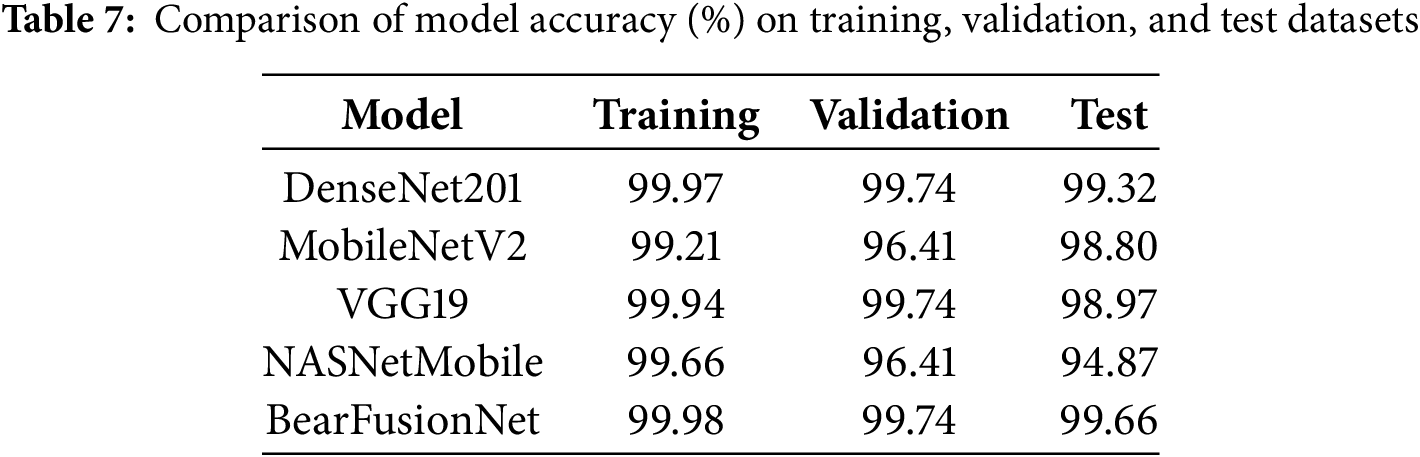

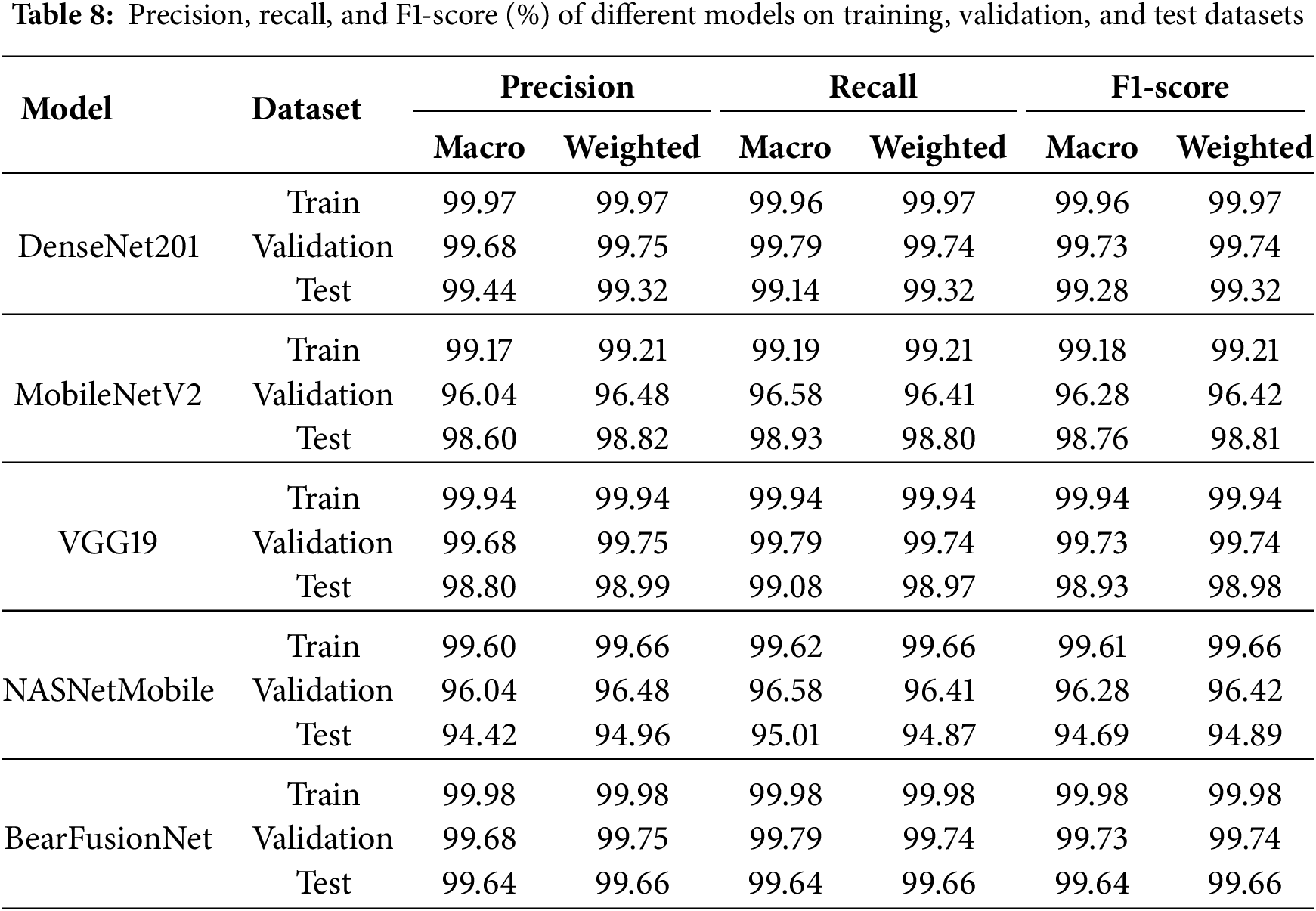

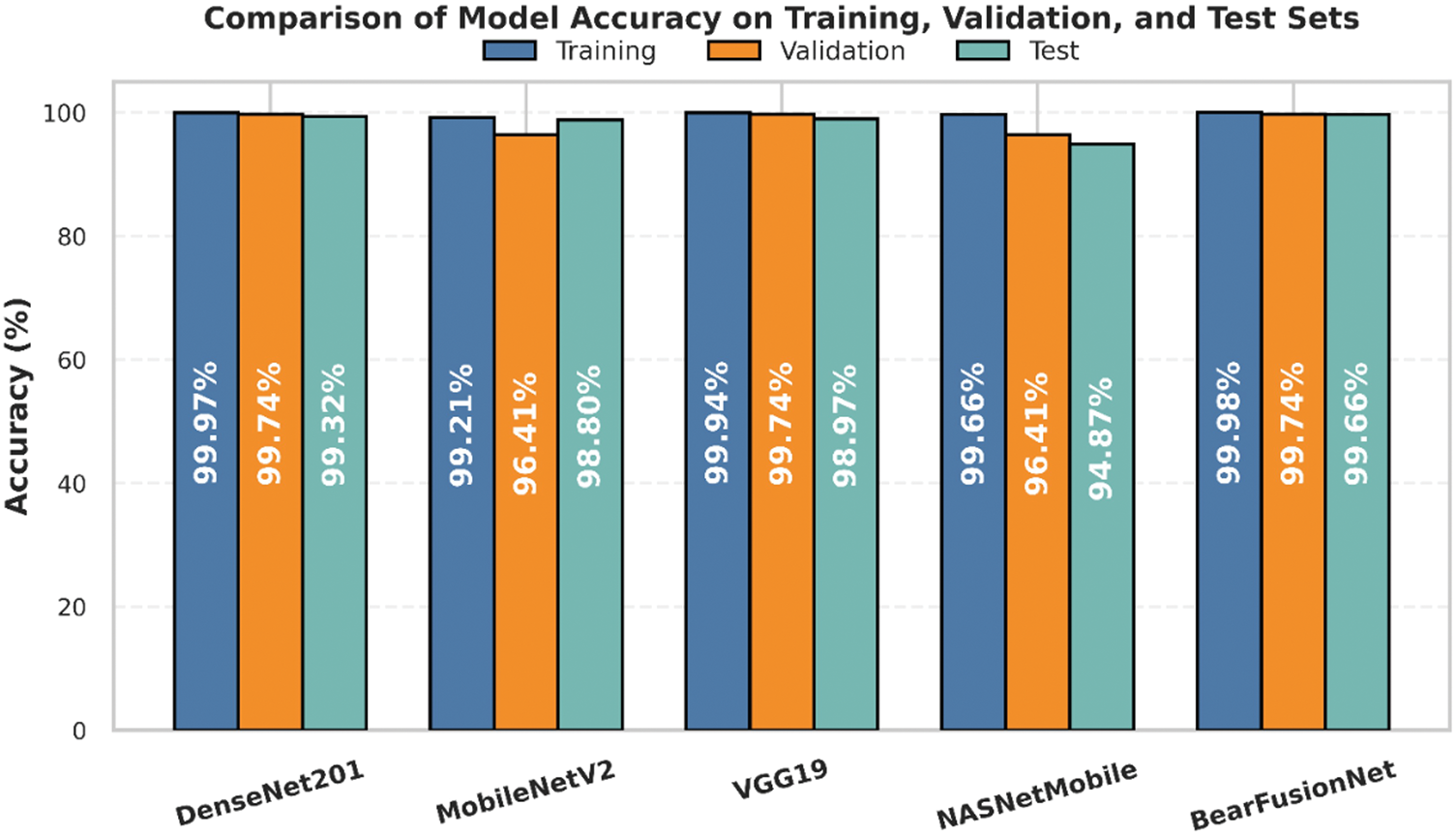

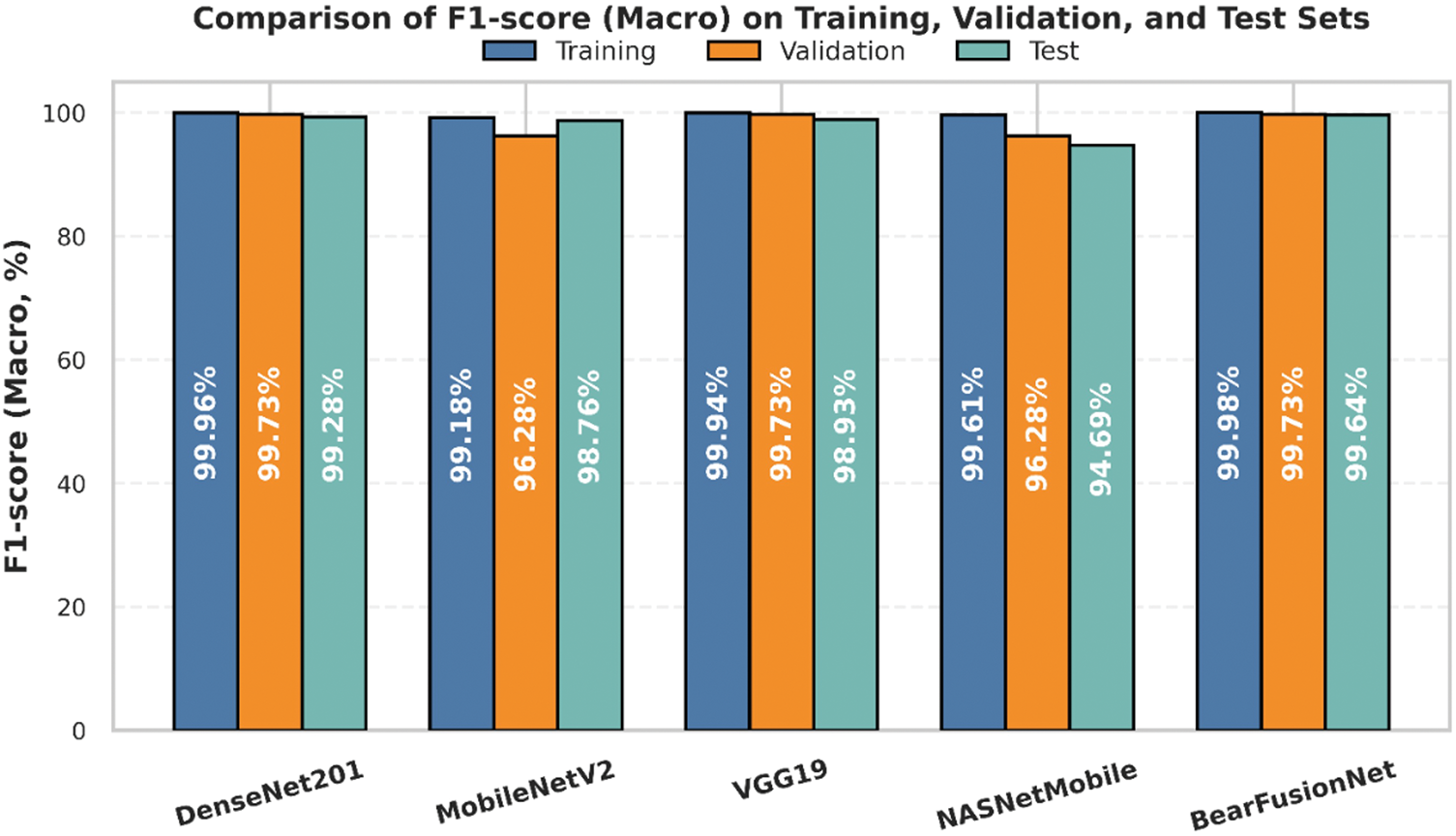

Table 7 presents a comparative summary of classification accuracies among five deep learning models evaluated on training, validation, and test sets. The proposed BearFusionNet surpasses all baseline architectures, showcasing exceptional performance with consistently high accuracy levels throughout all stages: 99.98% during training, 99.74% on the validation set, and 99.66% on the test set. This impressive performance indicates that BearFusionNet effectively extracts data patterns while demonstrating outstanding generalization capabilities, evidenced by the minimal difference of just 0.32% between training and test accuracies. Among the baseline models, DenseNet201 and VGG19 exhibit strong results, achieving test accuracies of 99.32% and 98.97%, respectively. These findings suggest that, although they adeptly learn discriminative features, their generalization slightly falls short compared to BearFusionNet. In contrast, MobileNetV2 and NASNet Mobile encounter significant performance challenges, particularly on the validation and test sets. While NASNet Mobile attains an accuracy of 99.66% on the training set, this figure declines to 94.87% on the test set, indicating overfitting and a lack of generalization in this defect detection task. BearFusionNet’s consistent performance across all data partitions underscores its suitability for real-time, high-precision manufacturing environments, where reliability and extremely low error tolerance prove crucial.

In addition to these accuracy results, Table 8 provides a comprehensive overview of precision, recall, and F1 scores across all datasets. These supplementary metrics offer a complete picture of the models’ abilities to identify defective and non-defective samples accurately, further reinforcing the high classification consistency and robustness of BearFusionNet.

Table 8 compares the evaluated models’ precision, recall, and F1 scores across training, validation, and test datasets. Notably, the proposed BearFusionNet achieves outstanding results at every stage, with macro and weighted indicators exceeding 99.6%. This accuracy underscores its robust capability to distinguish between defective and non-defective samples while minimizing classification errors. In contrast, DenseNet201 and VGG19 rank lower, with their metrics remaining above 98% across all splits. However, their test set scores fall slightly below those on the training data, suggesting a somewhat diminished generalization ability compared to BearFusionNet. Conversely, MobileNetV2 and NASNet Mobile significantly overfit their validation and test scores, leading to increasingly unstable performance on unseen data.

The comparative diagram illustrates the model’s performance at various evaluation stages, as shown in Fig. 6. The top plot displays the training, validation, and test accuracy, indicating that BearFusionNet achieves the highest accuracy across all phases. The bottom plot presents the corresponding macro F1 scores, further demonstrating the balanced and stable performance of BearFusionNet. Combined with the quantitative results, these visualizations emphasize the model’s robustness and effectiveness under diverse data distributions.

Figure 6: Comparison of training, validation, and test accuracy (%) and macro F1-scores (%) across all evaluated models. The first plot shows model-wise accuracy performance, while the second illustrates corresponding macro F1-scores, highlighting consistency and generalization capabilities

A stratified 5-fold cross-validation procedure rigorously examines BearFusionNet’s strength and generalizability. This approach reduces potential bias from any single train-test split, as each data sample contributes to training and validating different folds. Such thorough evaluation is essential for determining model reliability in real-world settings, where data distribution may not remain consistent.

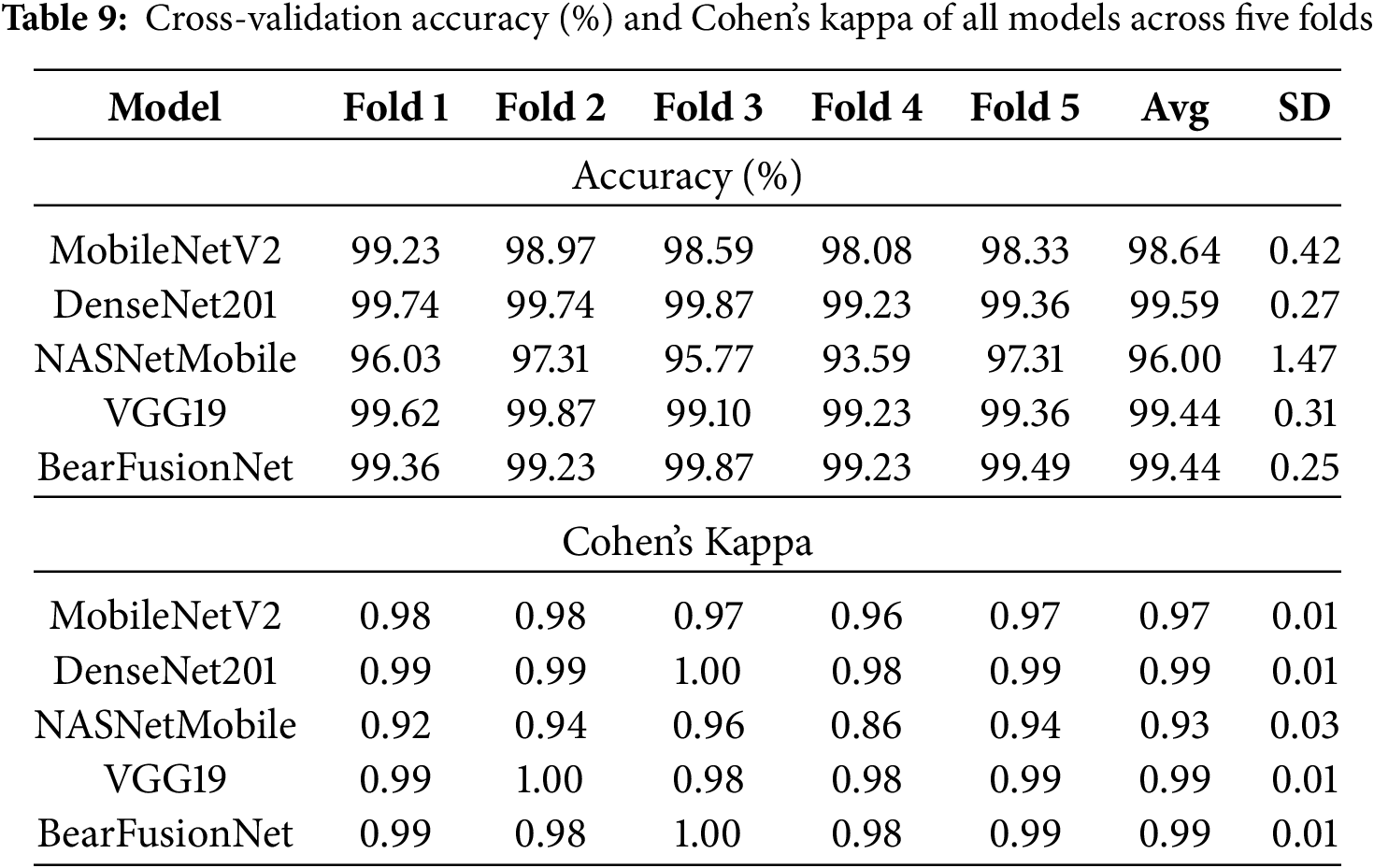

Table 9 summarizes the detailed outcomes of accuracy and Cohen kappa coefficients for all compared models across the five folds. The mean values and standard deviations presented are crucial, as they indicate the steadiness and robustness of model replication. BearFusionNet consistently achieves a significantly higher average accuracy of 99.44% with a very low standard deviation of 0.25%, reflecting both high accuracy and minimal variance across data splits. This outcome highlights the model’s strong generalization capabilities on unseen data beyond the training sample.

Results from DenseNet201 and VGG19 demonstrate similar stability, with average accuracies exceeding 99.4% and low variance, underscoring their effective performance in classification tasks. Conversely, NASNetMobile exhibits a significantly larger variance (SD = 1.47%) and a lower overall average accuracy of 96.00%, indicating challenges in achieving stable predictive results. Cohen’s kappa, which assesses classification agreement beyond chance, further aligns with these trends: BearFusionNet, DenseNet201, and VGG19 all yield values near or exceeding 0.98, signifying high classification consistency. In contrast, the lower kappa score for NASNetMobile reflects its diminished resilience.

These results substantiate BearFusionNet as an exceptionally stable and effective architecture for defect detection. Its robustness in cross-validation is critical for deployment in industrial applications, where consistent accuracy is essential under varying operating conditions.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the performance trend of all evaluated models reflects the outcomes from cross-validation employing a 5-fold approach. The plots display the accuracies and Cohen Kappa values, providing insights into the consistency and stability of each model across the different folds. This analysis allows for assessing how reliably each model performed during validation.

Figure 7: Five-fold cross-validation results: accuracy (%) and Cohen’s kappa across all evaluated models. The plot illustrates the consistency of model performance across folds, highlighting both predictive accuracy and agreement reliability

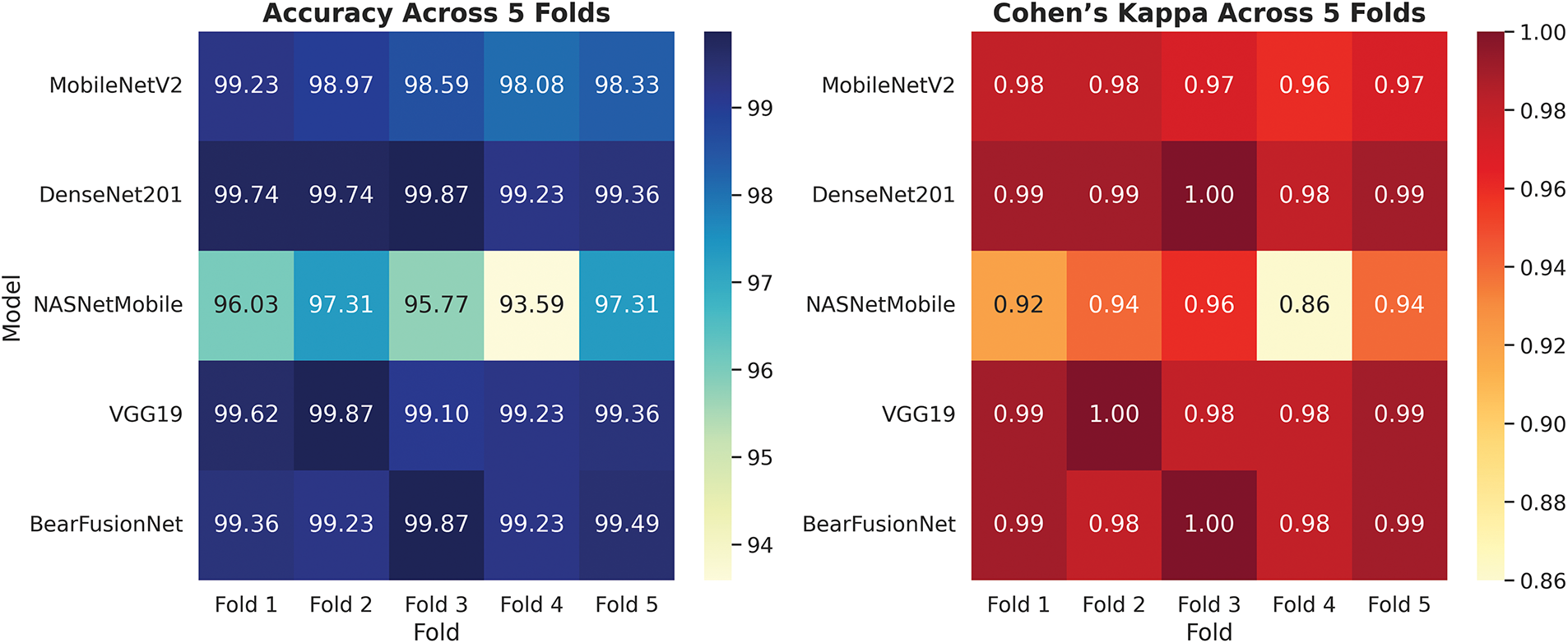

4.3 Model Reliability Assessment via Kappa Score

Fig. 8 reinforces the comparative accuracy of the measured models in terms of their Cohen Kappa values. The visualization clearly illustrates that BearFusionNet is the most stable and reliable model, boasting the highest kappa value of 0.9929. This finding demonstrates nearly perfect consistency between the predicted and actual labels, regardless of class distribution. The results also indicate that DenseNet201 and VGG19 exhibit high reliability, with kappa measures of 0.9857 and 0.9787, respectively, suggesting a strong classification consistency. MobileNetV2 closely follows, achieving a commendable score of 0.9805, which indicates that it remains dependable despite its lightweight architecture. However, the kappa score of 0.8938 reveals less consensus in classification, notably trailing behind the larger-scale NASNetMobile and its smaller version, highlighting the previously observed variation during cross-validation. These outcomes validate the efficacy of BearFusionNet in terms of accuracy and its ability to provide reliable and replicable predictions across various data clusters—an essential trait for real-world applications where model consistency is paramount.

Figure 8: Cohen’s kappa score of all evaluated model

4.4 Model Interpretation via Visualizations

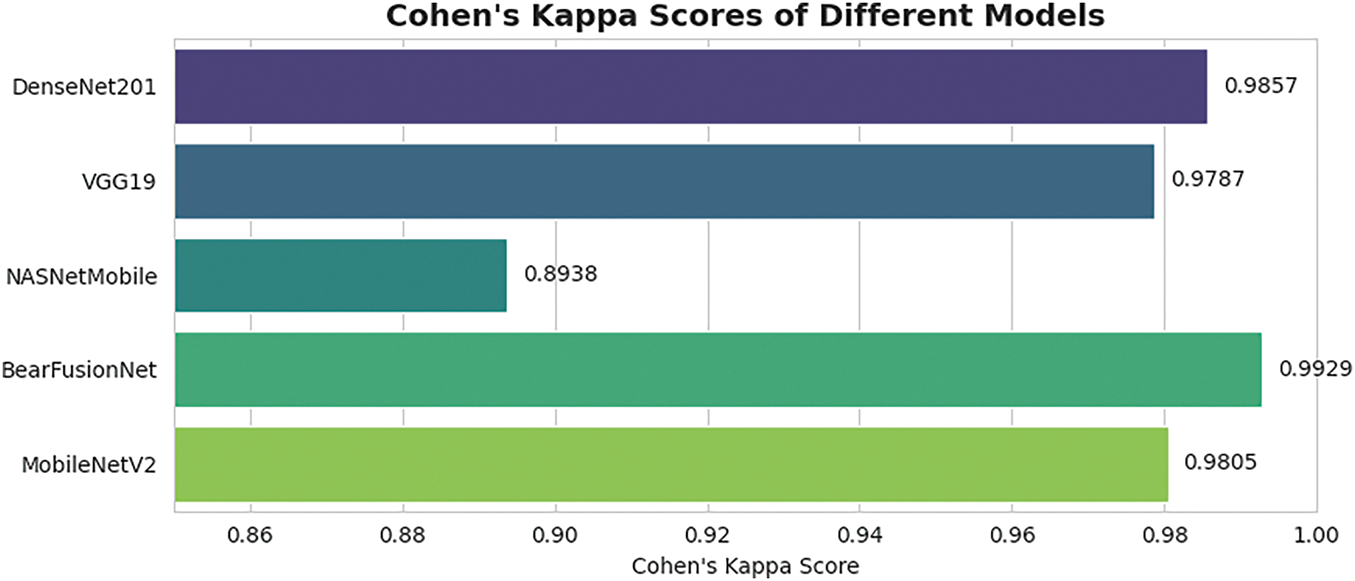

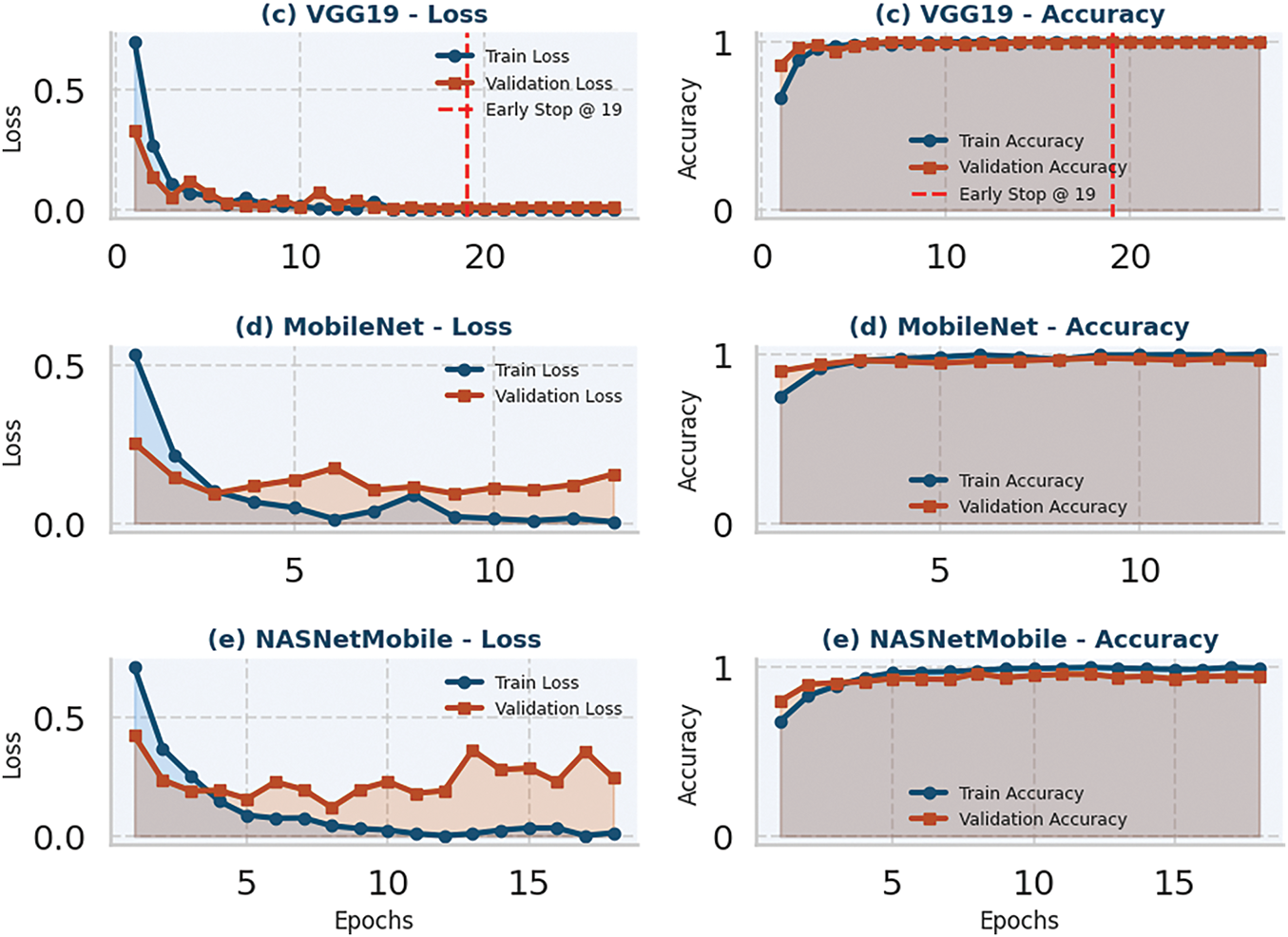

The learning curves of all the studied models, including the proposed BearFusionNet, are presented in Fig. 9. BearFusionNet curves indicate a stable training pattern, with training and validation being close to each other and not showing any apparent overfitting. The stabilization of the validation accuracy supports the point of early stopping. DenseNet201 and VGG19 also converge smoothly, but their curves have small fluctuations as opposed to BearFusionNet. In comparison, MobileNetV2 and NASNetMobile are stable, and validation performance deviates compared to training and indicates overfitting. Among these, NASNetMobile is the poorest, because its validation accuracy is decreasing in spite of sustained increases in training accuracy. Altogether, the learning curves support the quantitative results and indicate that BearFusionNet is the most reliable model in quality inspection. Nevertheless, they offer only a partial view of model behavior and do not fully capture class level decision dynamics. To analyze each model’s prediction reliability, particularly in terms of false positives and negative, we present a confusion matrix analysis next in Table 10.

Figure 9: Training and loss curves for different models: (a) BearFusionNet, (b) DenseNet201, (c) VGG19, (d) MobileNetv2, and (e) NASNetMobile. Each subplot shows the progression of training and validation loss and accuracy over epochs

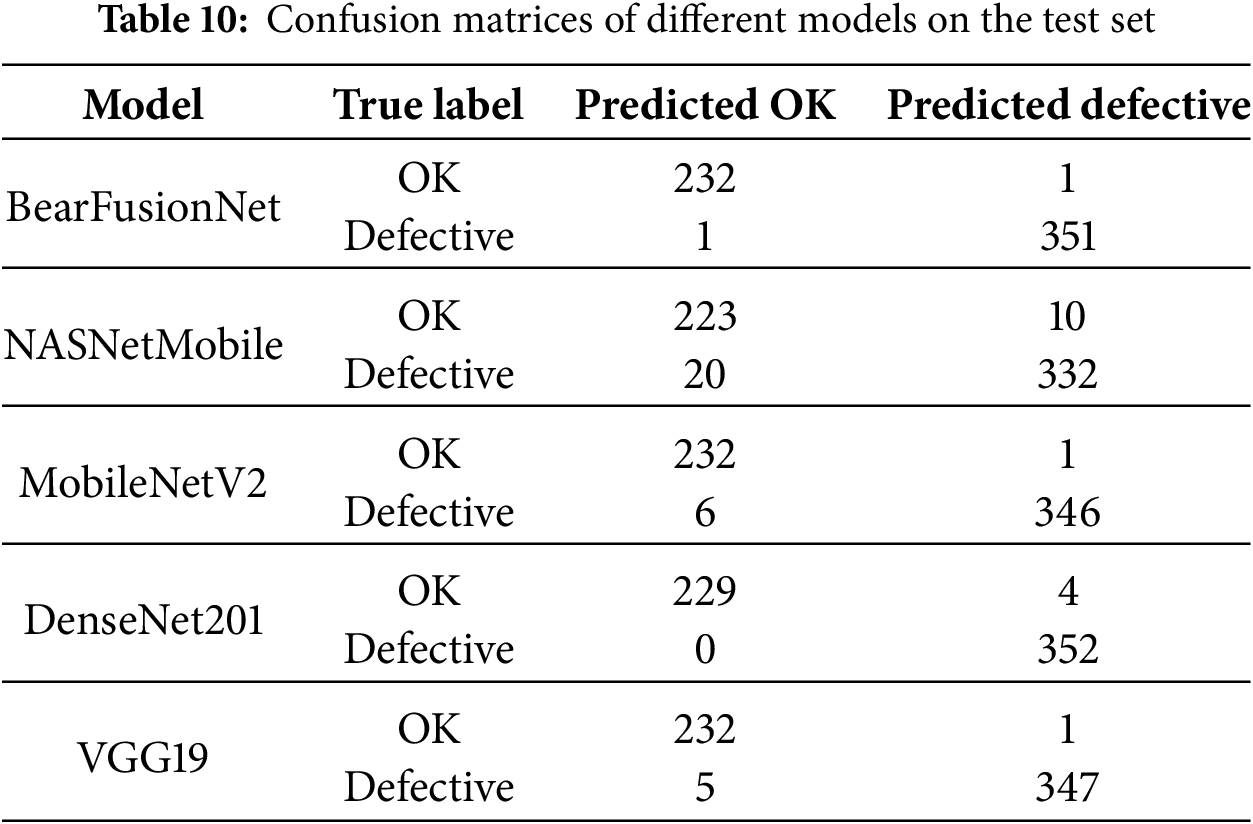

Table 10 displays the confusion matrices for all tested models, enabling a detailed analysis of their classification reliability. The proposed BearFusionNet demonstrates remarkable consistency, accurately identifying 351 defective cases and 232 non-defective ones, with just one error in each category. This nearly balanced performance reflects its strength and practicality, particularly in high-stakes industrial settings where false alerts and missed defects incur significant costs. DenseNet201 excels with the highest recall (FN = 0), successfully identifying all faulty cases while experiencing a slight increase in false positives (FP = 4). VGG19 also exhibits considerable discriminative ability, maintaining a low error rate across both categories. Overall, while MobileNetV2 performs adequately, it overlooks a small number of defective examples, resulting in a somewhat lower recall (FN = 6). On the contrary, NASNetMobile shows notable performance degradation, recording 10 false positives and 20 false negatives, indicating a lack of generalization and a tendency to overfit. These findings align with the trends observed in the validation metrics and cross-validation, further affirming the superiority of BearFusionNet. The low-error performance evident in its confusion matrix reinforces its suitability for high-precision defect detection scenarios.

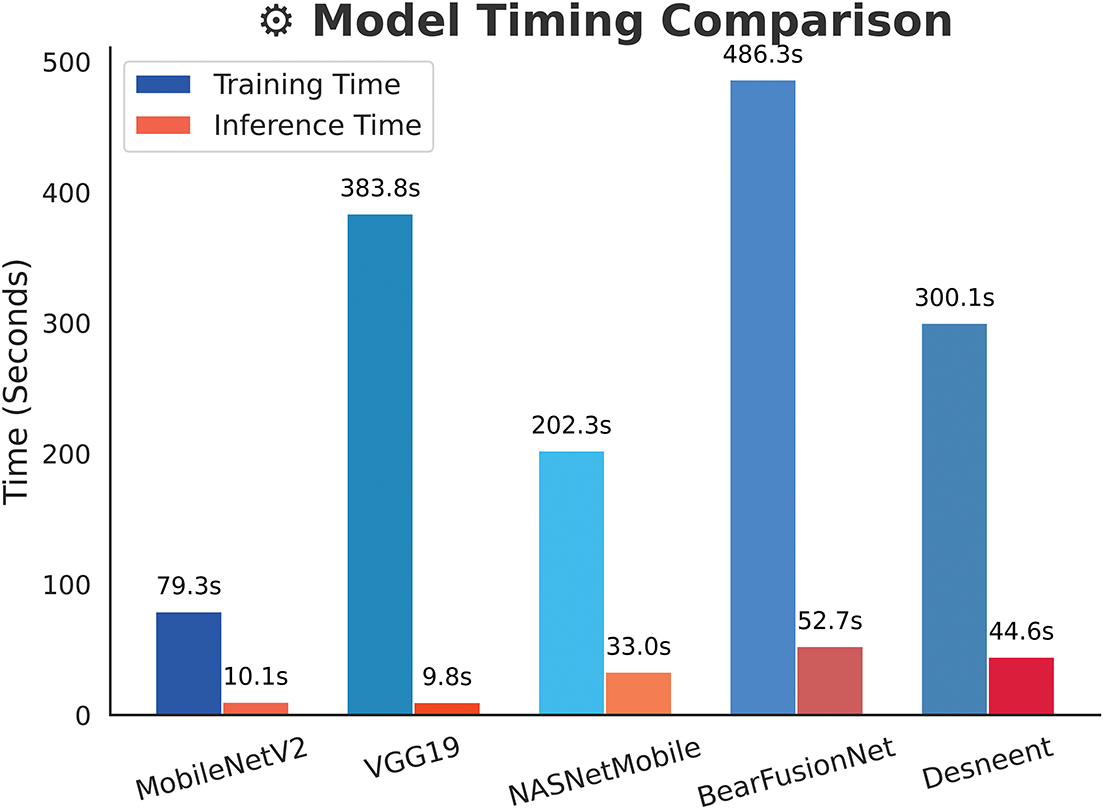

4.5 Computational Cost Analysis

A further computational cost analysis assesses the feasibility of the proposed system in practical applications, particularly in manufacturing, where time is crucial for accuracy. Fig. 10 illustrates the training and inference times (in seconds) of all the evaluated models, providing comparative insights regarding their efficiency. Based on the timing results, it is clear that BearFusionNet achieves the highest classification performance but incurs the highest training cost at 486.3 s compared to VGG19 and Desneent, which require 383.8 and 300.1 s, respectively. These numbers reflect the complexity and depth of the models, thus indicating their strong predictive power. The longer training time of BearFusionNet justifies its superior generalization and reliability. MobileNetV2, on the other hand, stands out as the fastest in training, requiring only 79.3 s, which aligns with its lightweight design. NASNetMobile falls in between with a training time of 202.3 s. Regarding inference time, an essential measure for real-time applications, BearFusionNet records the slowest latency at 52.7 s, which may pose challenges in highly time-sensitive situations. Nevertheless, despite the fact that BearFusionNet requires a little longer overall inference time, the per sample inference time is relatively short, at just 0.09 s, which is within reach of most industrial inspection work. DesneNet and NASNetMobile follow closely with 44.6 and 33.0 s, respectively. MobileNetV2 and VGG19 demonstrate the most efficient inference times at 10.1 and 9.8 s, indicating that these networks excel in real-time or edge-based systems.

Figure 10: Training and inference time comparison across all evaluated models. BearFusionNet shows the highest training and inference time due to its deep architecture, while MobileNetV2 and VGG19 demonstrate the fastest execution times, suitable for time-sensitive applications

BearFusionNet maintains acceptable accuracy and performance relative to its high computational cost. The inference time remains reasonable for many industrial tasks, prioritizing classification accuracy over sub-second response times. However, when a low-latency response is critical, one might opt for lighter models like MobileNetV2 or VGG19 despite their lower robustness and generalization.

This analysis supports the argument that deep and complex architectures require greater resources; however, this requirement is justifiable when heightened accuracy and stability are essential in critical systems. Consequently, a trade-off between performance and efficiency emerges based on the specific operational constraints present in the deployment environment.

4.6 Statistical Validation of Proposed BearFusionNet Using McNemar’s and Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests

To statistically evaluate the performance of BearFusionNet on the primary test data, we employ the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test and the McNemar Test to comprehensively assess the model’s stability and accuracy. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test yields a test statistic of 0.0000 and a p-value of 0.1797, indicating a difference in the median performance of the prediction outcomes across the groups. Since this p-value exceeds the significance level of 0.05, it suggests that the observed changes are not statistically significant, meaning there are no systematic differences in the accuracy of BearFusionNet’s predictions. Similarly, the McNemar Test, which examines changes in classification error patterns among paired observations, produces a statistic of 0.5 and a p-value of 0.4795. This result further reinforces the conclusion that the reasons behind the model’s prediction errors remain largely consistent, affirming its classification behavior’s trustworthiness on the test set. These statistical analyses demonstrate that BearFusionNet is a robust model with consistent performance, and its predictive capabilities on new data are not compromised by random variability, overfitting, or bias. This reliability enhances the model’s applicability in practical settings.

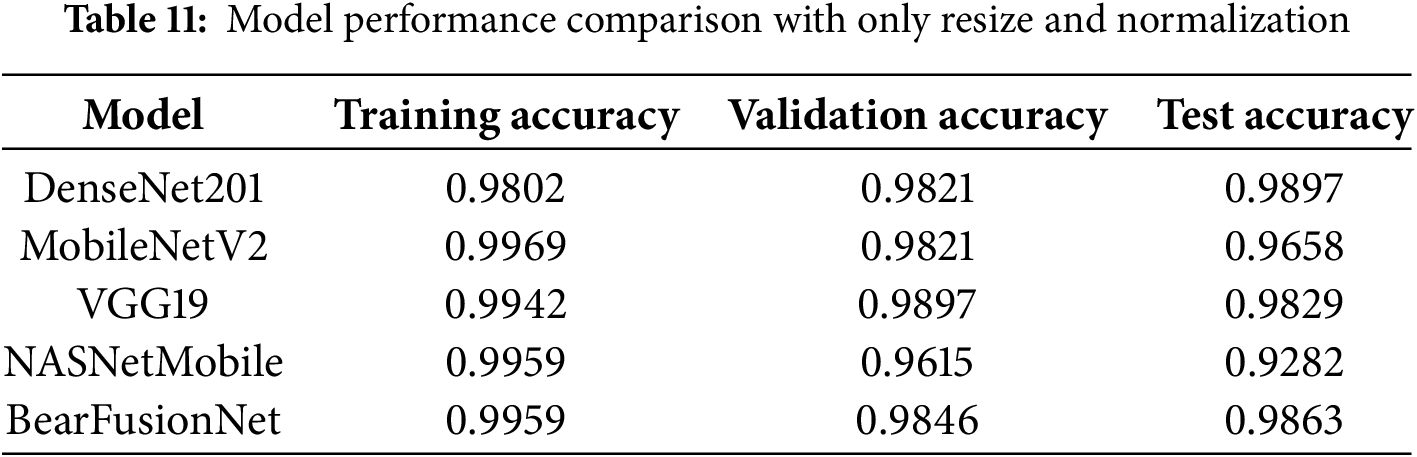

4.7 Impact of Preprocessing on All Baseline Classifier

As it appears in the above Table 7 with advanced preprocessing, all models obtained high training, validation and test accuracy, and the difference between them is minimal, meaning strong generalization and robustness. In cases where resizing and normalization alone were used to train the models, most of the architectures still achieved high training accuracy, but their test performance decrease noticeably as observed in Table 11. This effect shows that, whereas deep networks are able to learn representations of minimally processed images, the lack of advanced preprocessing methods limits their ability to generalize to unknown data, in particular in identifying subtle and low contrast defects in bearing castings. The empirical evidence supports the effect of simple preprocessing on model performance, as reported in Table 11. Training the models solely on image resizing and normalization, DenseNet201 had a test accuracy drop of 0.35%, MobileNetV2 had the worst drop of 2.29%, VGG19 had a drop of 0.69%, NASNetMobile had a drop of 2.21%, and the proposed BearFusionNet had a drop of 1.04%. These results show that lightweight models like MobileNetV2 and NASNetMobile are especially sensitive to input quality degradation and would suffer a much bigger performance drop when not run through more complex preprocessing procedures, but deeper models would exhibit smaller but significant drops. Even the suggested BearFusionNet though robust, gains better performance when using multi stage preprocessing to emphasize new defects, minimize background noise, and aid in more consistent and accurate bearing casting defect detection.

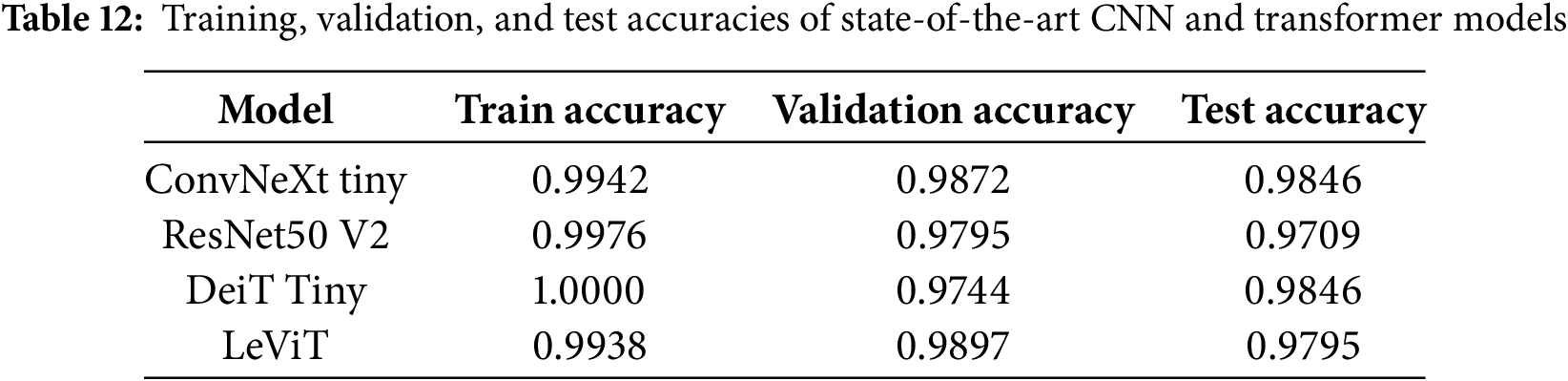

4.8 Benchmarking with Modern CNN and Transformer Architectures

Table 12 presents the training, validation, and test accuracy of a few state of the art models compared to the proposed model, such as two CNN based models (ConvNeXt Tiny and ResNet50v2) and two transformer based models (DeiT Tiny and LeViT-128S). In order to establish a fair comparison, all models were trained with the identical preprocessing, batch size, optimizer and epochs as the baseline models. As much as these models gained high accuracy in the training stage, they typically performed lower in the validation and test sets than BearFusionNet and the base CNNs. The gap between training and test accuracy is observed to be larger than the gap before training indicating that there is a probability of overfitting which may be due to the small size and complexity of the bearing defect samples. These results indicate that contemporary architectures may not always result in better generalization in specialized industrial tasks. Meanwhile, the baseline CNNs and BearFusionNet showed more stability in accuracy on training, validation, and test data, meaning that they could extract the relevant features and do not suffer generalization. BearFusionNet combines feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and advancee preprocessing, which contribute to a more stable performance of the feature fusion based models over individual state-of-the-art CNN and transformer models that underline the strengths of designing models that are specifically adapted to industrial data.

4.9 Visual Interpretation of Bearing Faults Using Grad-CAM in BearFusionNet

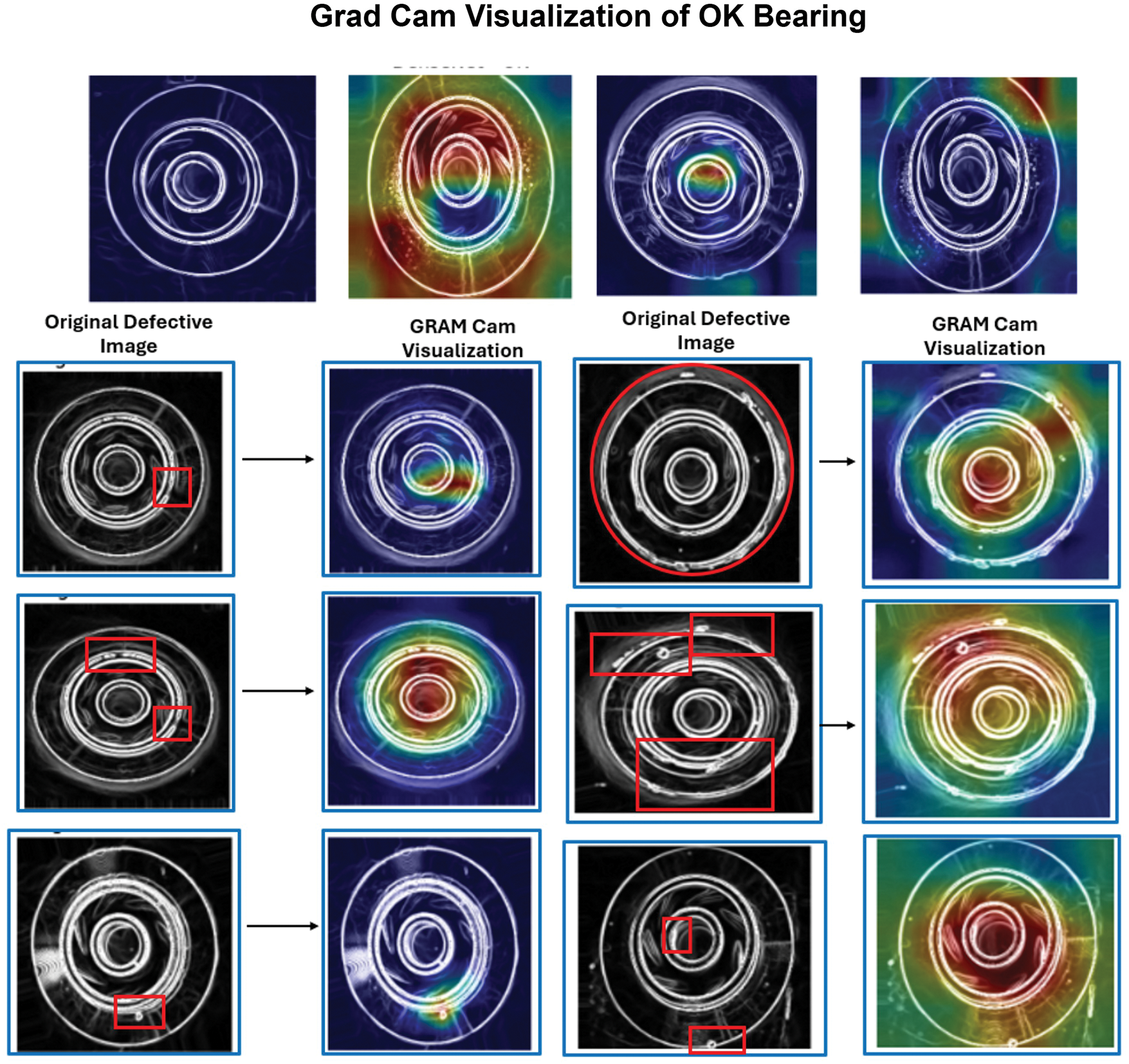

To enhance the interpretability of the features, we apply Grad-CAM exclusively to the final convolutional blocks of the DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 branches within the BearFusionNet architecture before deep feature fusion. We then process the resulting amalgamated representations through a VGG 19-style fully connected classification head. Fig. 11 illustrates examples from both branches of the Grad-CAM analysis, showcasing the model’s attention concentration under various bearing fault conditions. The top row highlights samples of faulty bearings, while the bottom row features typical cases. DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 effectively analyze critical fault areas, including surface wear, pits, and structural defects. The complementary attention maps emphasize the strength of multi-branch deep feature fusion in highlighting significant regions, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Subsequent visual inspections and specialist confirmations show that the identified locations closely align with known physical defect areas within the bearing components. This alignment reinforces the diagnostic reliability of the model and supports its effectiveness in practical applications related to predictive maintenance and condition monitoring.

Figure 11: Grad-CAM visualizations from BearFusionNet: the top row corresponds to normal(OK), while the bottom row highlights defective bearing regions

Based on the experimental results, BearFusionNet performs best among all considered baseline models regarding key indicators, including accuracy, Cohen kappa, precision, recall, and F1-score. With an overall test accuracy of 99.66% and a Cohen kappa of 0.9929, BearFusionNet demonstrates a near ideal agreement with proper labels, signaling high classification consistency and reliability. The macro and weighted precision, recall, and F1 scores consistently exceed the 99.6% mark, indicating the model’s capacity to correctly predict non-defective and defective bearing samples with very low error rates. Following the quantitative evaluation presented in Tables 7 and 9 Training, validation, test accuracies and Cohen’s Kappa were used to evaluate all the models, and then cross-validation was carried out to determine the consistency and stability. Other analyses, such as misclassification patterns and generalization, were also taken into account to have a thorough performance assessment. Some of the baseline models, including VGG19, have had similar cross validation results, but BearFusionNet had a better overall performance on the combined evaluation metrics. These quantitative results highlight the effectiveness of this work’s major contributions. The feature fusion characteristic of DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2, combined with Multi-Head Self-Attention modules, enables the model to swiftly identify subtle and overlapping defects that traditional models struggle to capture. Fusing these features with a fully connected classifier head inspired by VGG19 enhances the model’s discriminative capacity and reduces misclassification errors. The progressive preprocessing pipeline improves defect localization and feature saliency through techniques like CLAHE, non-local means denoising, and the Canny edge detector, which boosts model integrity under challenging imaging conditions. This preprocessing is crucial for achieving high precision and recall values, directly translating to reducing false positives and negatives. Statistical tests, including the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank and McNemar tests, confirm that BearFusionNet’s performance remains stable and does not vary due to random factors or biases. This statistical validation strengthens the model’s credibility for use in serious industries. Moreover, Grad-CAM visualizations reveal that BearFusionNet focuses on significant areas of defects, providing interpretative and diagnostic value. It is crucial in maintenance scenarios, where understanding model decisions informs better operational choices. Although BearFusionNet requires more supporting computations during training, it maintains a relatively low inference latency, making it affordable for real-time manufacturing processes that demand high accuracy in defect detection. BearFusionNet is a web app on Hugging Face using Gradio. It allows users to upload images and receive real-time predictions with confidence scores and Grad-CAM explanations. This convenient demonstration illustrates the model’s precision and explainability and is a potential solution for Industry 4.0 innovative factory implementations. BearFusionNet achieves high accuracy, strong kappa scores, and robust precision-recall measures while employing an innovative preprocessing and multi-branch attention fusion strategy. This makes it a stable and interpretable model in bearing defect diagnosis. Grad-CAM visualizations emphasize that the model focuses on meaningful defect regions, such as surface wear and pits, providing interpretable insights into its decisions. It enhances trust in the model’s predictions and supports practical diagnostic applications, representing a breakthrough in intelligent defective detection systems at the industrial quality inspection level.

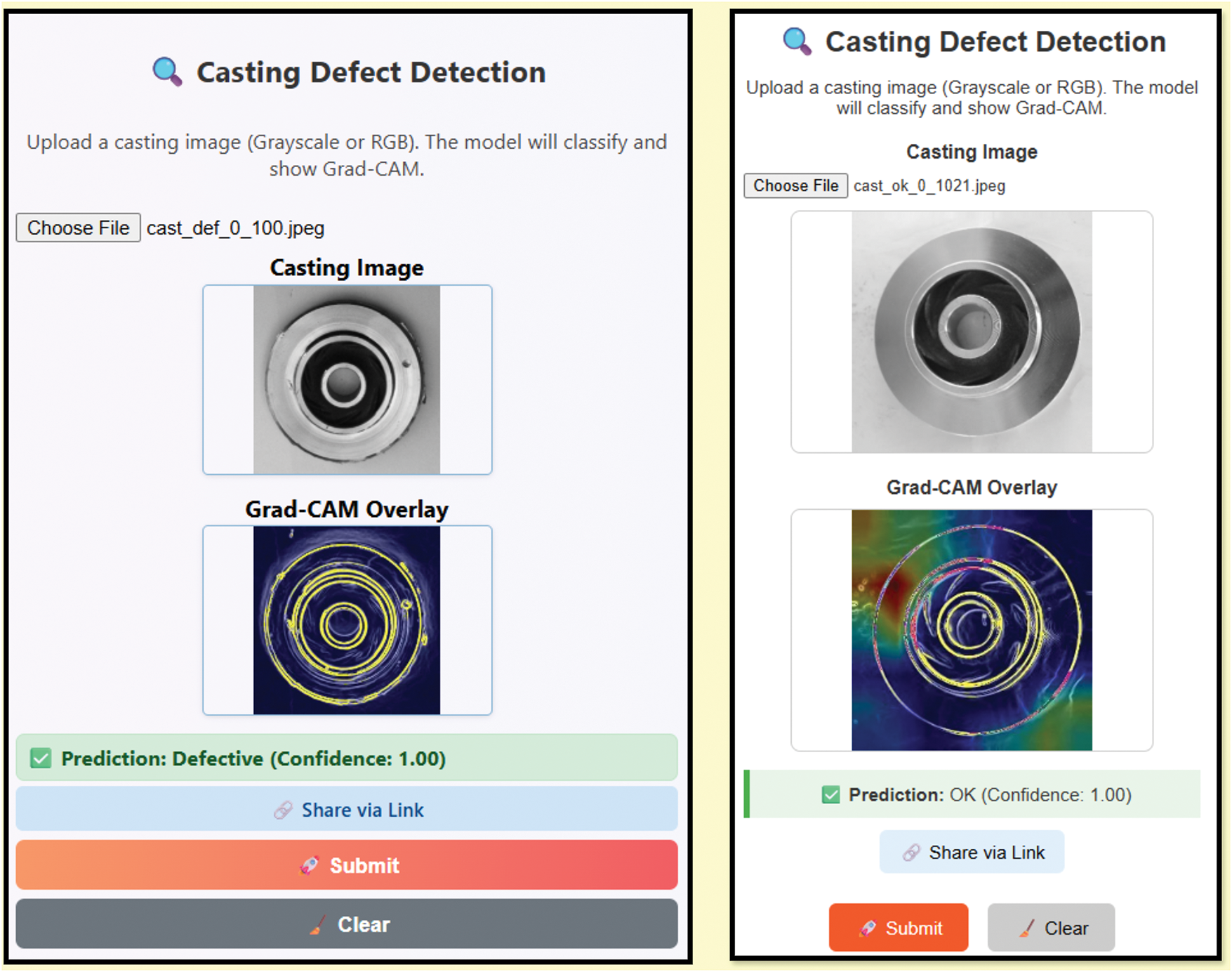

To further assess the practical utility of BearFusionNet in the context of Industry 4.0, Fig. 12 illustrates its implementation in a real-time web application built on the Gradio platform hosted by Hugging Face. This application showcases the model’s capability to classify defects in production quality and provide visual explanations. Users upload images and receive immediate predictions, confidence scores, and Grad-CAM heatmaps. In testing, the web application took around 5–6 s per prediction, with Grad-CAM visualizations, because of the constraints of the Hugging Face Gradio CPU environment, not using a GPU. The model can provide substantially faster predictions in industrial environments, where there are available high performance computing resources. We analyze ten test images from the internet to evaluate their performance. The first image, which exhibits a visible defect, is identified as defective with a confidence score of 100%, and the Grad-CAM visualization highlights the defective area in bright yellow. The second defect-free image is also predicted correctly with 100% confidence; however, the Grad-CAM output reveals some red and yellow activations, indicating the model’s sensitivity to minor patterns. While this serves as a demonstration application, it underscores the potential for the practical application of BearFusionNet. This model integrates with IoT-enabled industrial cameras and a central dashboard to deliver real-time quality control results, detection statistics, and inspection process trends, thus contributing to the development of automated, explainable, and data-driven quality control systems in an innovative factory environment aligned with Industry 4.0.

Figure 12: Defective and OK prediction made via web application

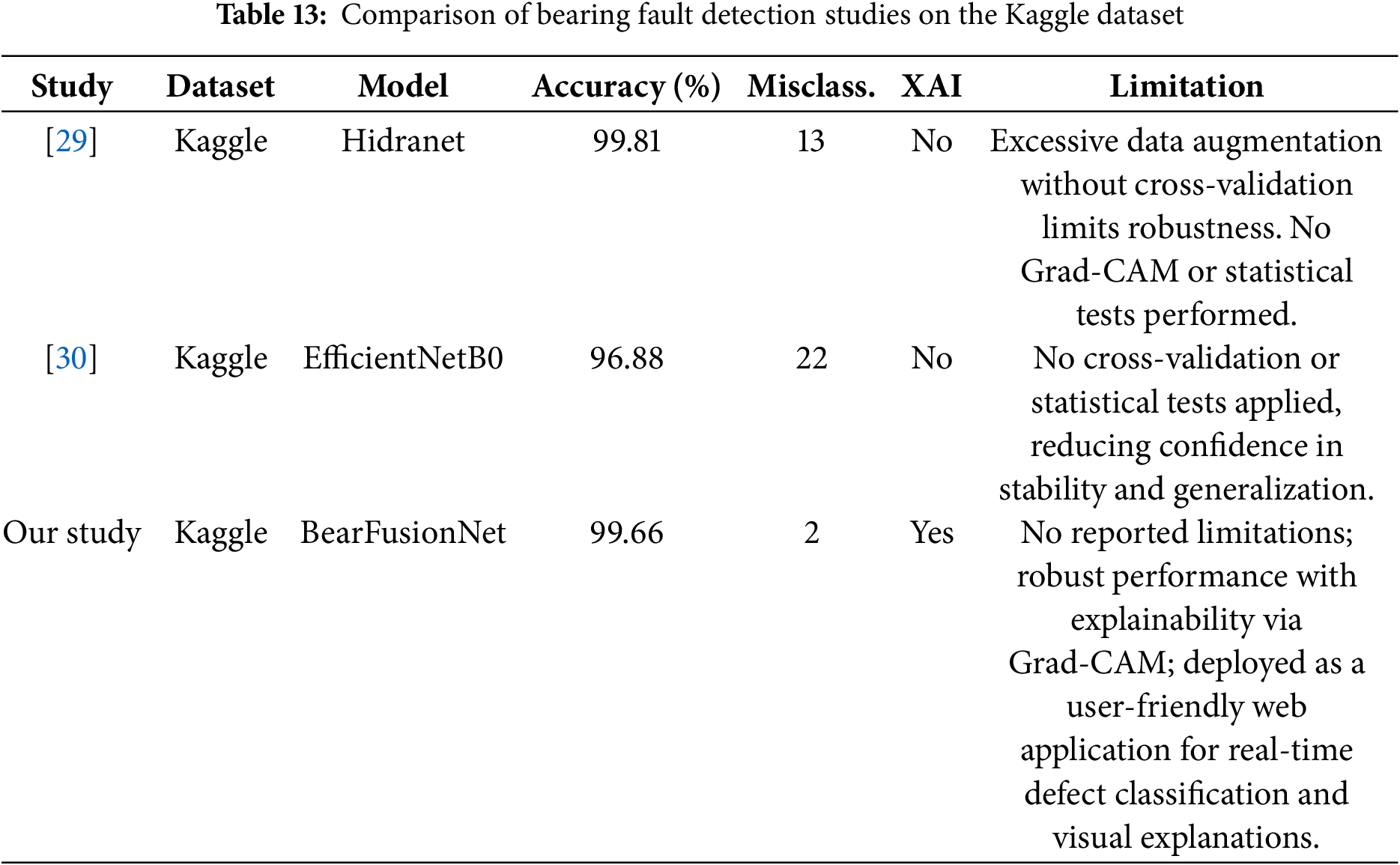

4.12 Comparative Analysis with Previous Studies

The comparison presented in Table 13 outlines the advantages of BearFusionNet over prior research involving the Kaggle bearing faults identification dataset. Although the study by [29] achieves the highest accuracy at 99.81%, it suffers from significant methodological flaws. Specifically, it relies heavily on data augmentation without implementing cross-validation or statistical significance testing, which renders its findings less reliable and broadly applicable. Furthermore, the absence of an explainability framework limits understanding of the model’s decision-making process. Similarly, reference [30] reports a lower accuracy of 96.88% under the same limitations, lacking cross-validation, statistical testing, and explainability methodologies, which diminishes confidence in the model’s stability and robustness.

In contrast, our study demonstrates competitive performance, with BearFusionNet achieving an accuracy of 99.66% and only two misclassifications, highlighting its high performance and strong generalization capabilities. Notably, BearFusionNet employs Grad-CAM to interpret model predictions, enhancing its confidence and practicality. Our study faces no significant limitations, reflecting a more robust and balanced experimental design. This reinforces the potential of BearFusionNet as an effective, interpretable model suitable for deployment in industrial anomaly detection. Furthermore, BearFusionNet became an accessible web application that facilitates real-time defect classification with visual explanations. It underscores its practical relevance and readiness for integration into Industry 4.0 innovative factory systems, features not offered by the other studies reviewed.

To sum up, this paper introduces BearFusionNet, a multi-stream attention-based deep learning framework that automates identifying bearing casting flaws with high accuracy. By concisely combining DenseNet201 and MobileNetV2 feature extractors with a VGG19-style classification head, BearFusionNet reliably extracts multi-scale features using parallel attention modes. This approach allows seamless coarse and fine-grained information integration, dramatically improving overall error rates in defect classification tasks.

BearFusionNet evaluates against the Kaggle Real-Life Industrial Dataset of Casting Product Defects, achieving 99.66% accuracy, a 99.66% F1 score, and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.9929, with a low misclassification rate. The model demonstrates reliability and stability through statistical tests such as McNemar’s and Wilcoxon Signed-Rank. Confusion matrix analysis reveals equal detection capacity, with minimal false negatives, fostering confidence in industrial quality assurance outcomes. A demo web application of BearFusionNet, hosted on Hugging Face, allows users to upload images for real-time defect classification with visual explanations via Grad-CAM heatmaps. This interactive demo illustrates the model’s accuracy and explainability and its potential for smooth integration in Industry 4.0, where real-time monitoring and explainable AI are crucial for innovative production. Although it is very accurate, BearFusionNet might have constraints with real-world manufacturing since the retraining has to be done periodically because over time fault patterns and defects may change.

In future work, we will dedicate efforts to training BearFusionNet on larger, more heterogeneous data sets to enhance its performance across different defect types and manufacturing conditions. They examine its operational efficiency through real-time implementation and testing. Additionally, they plan to refine the model further using confusion matrix-based feedback to reduce misclassification. The vision includes developing a user-friendly dashboard that combines BearFusionNet with other applicable real-time defect detection and reporting models. This initiative helps make quick decisions and improve quality control processes, thus enhancing manufacturing efficiency. These efforts reinforce BearFusionNet’s role in promoting innovative manufacturing practices aligned with Industry 4.0 goals, serving as a consistent, precise, and interpretable tool for automated defect detection.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the authorities of Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia, for their support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia (Grant Number: PostDoc(MMUI/240029)).

Author Contributions: Md. Ehsanul Haque: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization. Md. Nurul Absur: Data Collection, Data Analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. Fahmid Al Farid: Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. Md Kamrul Siam: Writing—Review & Editing, Resources, Visualization. Jia Uddin: Corresponding Author, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project Administration. Hezerul Abdul Karim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: You can access the dataset from here: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ravirajsinh45/real-life-industrial-dataset-of-casting-product (accessed on 27 June 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang HB, Zhang CY, Cheng DJ, Zhou KL, Sun ZY. Detection transformer with multi-scale fusion attention mechanism for aero-engine turbine blade cast defect detection considering comprehensive features. Sensors. 2024;24(5):1663. doi:10.3390/s24051663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hakim M, Omran AAB, Ahmed AN, Al-Waily M, Abdellatif A. A systematic review of rolling bearing fault diagnoses based on deep learning and transfer learning: taxonomy, overview, application, open challenges, weaknesses and recommendations. Ain Shams Eng J. 2023;14(4):101945. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2022.101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Niu G, Dong X, Chen Y. Motor fault diagnostics based on current signatures: a review. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2023;72:1–19. [Google Scholar]

4. Haque ME, Zabin M, Uddin J. EnsembleXAI-motor: a lightweight framework for fault classification in electric vehicle drive motors using feature selection, ensemble learning, and explainable AI. Machines. 2025;13(4):314. doi:10.3390/machines13040314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alenezi M, Anayi F, Packianather M, Shouran M. Enhancing transformer protection: a machine learning framework for early fault detection. Sustainability. 2024;16(23):10759. doi:10.3390/su162310759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jung H, Choi S, Lee B. Rotor fault diagnosis method using CNN-based transfer learning with 2D sound spectrogram analysis. Electronics. 2023;12(3):480. doi:10.3390/electronics12030480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li H, Liu Y, Xu H, Yang K, Kang Z, Huang M, et al. A multi-scale attention mechanism for detecting defects in leather fabrics. Heliyon. 2024;10(16):e35957. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bahgat BH, Elhay EA, Sutikno T, Elkholy MM. Revolutionizing motor maintenance: a comprehensive survey of state-of-the-art fault detection in three-phase induction motors. Int J Power Electron Drive Syst. 2024;15(3):1968–89. doi:10.11591/ijpeds.v15.i3.pp1968-1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cheng DJ, Wang S, Zhang HB, Sun ZY. A novel framework for low-contrast and random multi-scale blade casting defect detection by an adaptive global dynamic detection transformer. Comput Ind. 2024;162:104138. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2024.104138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mohiuddin M, Islam MS, Uddin J. Feature optimization for machine learning based bearing fault classification. Indones J Electr Eng Inform. 2024;12(3):610–24. doi:10.52549/ijeei.v12i3.5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alghassi A. Generalized anomaly detection algorithm based on time series statistical features. In: Implementing Industry 4.0: the model factory as the key enabler for the future of manufacturing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

12. Yadav E, Chawla V. An explicit literature review on bearing materials and their defect detection techniques. Mater Today Proc. 2022;50(2):1637–43. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Luo X, Wang H, Han T, Zhang Y. FFT-trans: enhancing robustness in mechanical fault diagnosis with Fourier transform-based transformer under noisy conditions. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2024;73:1–12. doi:10.1109/tim.2024.3381688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tang L, Tian H, Huang H, Shi S, Ji Q. A survey of mechanical fault diagnosis based on audio signal analysis. Measurement. 2023;220(12):113294. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Manhertz G, Bereczky A. STFT spectrogram based hybrid evaluation method for rotating machine transient vibration analysis. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2021;154(1):107583. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu Z, Ding K, Lin H, He G, Du C, Chen Z. A novel impact feature extraction method based on EMD and sparse decomposition for gear local fault diagnosis. Machines. 2022;10(4):242. doi:10.3390/machines10040242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Guan Y, Xiao Y, Cui Y, Xu D. Analysis and optimal design of mid-range WPT system based on multiple repeaters. IEEE Trans Indust Appl. 2021;58(1):1092–100. doi:10.1109/tia.2021.3072931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mamun AA, Ray PC, Nasib MRU, Das A, Uddin J, Absur MN. Optimizing deep learning for skin cancer classification: a computationally efficient CNN with minimal accuracy trade-off. arXiv:2505.21597. 2025. [Google Scholar]

19. Absur MN. Anomaly detection in biomedical data and image using various shallow and deep learning algorithms. In: Jacob IJ, Kolandapalayam Shanmugam S, Bestak R, editor. Data intelligence and cognitive informatics. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

20. Nova SN, Rahman MS. Hosen ASMS. In: Deep learning in biomedical devices: perspectives, applications, and challenges. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 13–35. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-4189-4_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jawad SM, Jaber AA. A data-driven approach based bearing faults detection and diagnosis: a review. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2021. Vol. 1094. [Google Scholar]

22. Park S, Youm S. Establish a machine learning based model for optimal casting conditions management of small and medium sized die casting manufacturers. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):17163. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-44449-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Aydın T, Erdem E, Erkayman B, Engin Kocadağistan M, Teker T. A novel bearing fault detection approach using a convolutional neural network. Mater Testing. 2024;66(4):478–92. doi:10.1515/mt-2023-0334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang Z, Luo L, Ma J, Zhang H, Yang L, Wu Z. Enhancing bearing fault diagnosis in real damages: a hybrid multi-domain generalization network for feature comparison. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74(19):1–11. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3556828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lv H, Chen J, Pan T, Zhang T, Feng Y, Liu S. Attention mechanism in intelligent fault diagnosis of machinery: a review of technique and application. Measurement. 2022;199(2):111594. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sun B, Hu W, Wang H, Wang L, Deng C. Remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearings based on CBAM-CNN-LSTM. Sensors. 2025;25(2):554. doi:10.3390/s25020554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang H, Dai X, Shi L, Li M, Liu Z, Wang R, et al. Data-augmentation based CBAM-ResNet-GCN method for unbalance fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. IEEE Access. 2024;12(5):34785–99. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3368755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhong Z, Xie H, Wang Z, Zhang Z. Domain adversarial transfer learning bearing fault diagnosis model incorporating structural adjustment modules. Sensors. 2025;25(6):1851. doi:10.3390/s25061851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Diep QB. Identifying defective casting products using hierarchical defect recognition architecture: a computer vision approach. Adv Mech Eng. 2025;17(4):16878132251332681. doi:10.1177/16878132251332681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Benbarrad T, Salhaoui M, Kenitar SB, Arioua M. Intelligent machine vision model for defective product inspection based on machine learning. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2021;10(1):7. doi:10.3390/jsan10010007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Stephen O, Madanian S, Nguyen M. A robust deep learning ensemble-driven model for defect and non-defect recognition and classification using a weighted averaging sequence-based meta-learning ensembler. Sensors. 2022;22(24):9971. doi:10.3390/s22249971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Dabhi R. Real-life industrial dataset of casting product for quality inspection; 2018 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ravirajsinh45/real-life-industrial-dataset-of-casting-product. [Google Scholar]

33. Srivastava G, Rawat TK. Histogram equalization: a comparative analysis & a segmented approach to process digital images. In: 2013 Sixth International Conference on Contemporary Computing (IC3); 2013 Aug 8–10; Noida, India. p. 81–5. [Google Scholar]

34. Zhao J, Zhang R, Chen S, Duan Y, Wang Z, Li Q. Enhanced infrared defect detection for UAVs using wavelet-based image processing and channel attention-integrated SSD model. IEEE Access. 2024;12:188787–96. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3516080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools