Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DRL-Based Task Scheduling and Trajectory Control for UAV-Assisted MEC Systems

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110169, China

2 School of Information Science and Engineering, Shenyang Ligong University, Shenyang, 110159, China

* Corresponding Authors: Sai Xu. Email: ; Jun Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligent Computation and Large Machine Learning Models for Edge Intelligence in industrial Internet of Things)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 56 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071865

Received 13 August 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In scenarios where ground-based cloud computing infrastructure is unavailable, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) act as mobile edge computing (MEC) servers to provide on-demand computation services for ground terminals. To address the challenge of jointly optimizing task scheduling and UAV trajectory under limited resources and high mobility of UAVs, this paper presents PER-MATD3, a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm with prioritized experience replay (PER) into the Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE) framework. Specifically, PER-MATD3 enables each agent to learn a decentralized policy using only local observations during execution, while leveraging a shared replay buffer with prioritized sampling and centralized critic during training to accelerate convergence and improve sample efficiency. Simulation results show that PER-MATD3 reduces average task latency by up to 23%, improves energy efficiency by 21%, and enhances service coverage compared to state-of-the-art baselines, demonstrating its effectiveness and practicality in scenarios without terrestrial networks.Keywords

In recent years, frequent natural disasters, emergencies, and regional conflicts have severely damaged terrestrial communication and cloud computing infrastructure, making it difficult for user terminals to obtain timely and effective processing for their computation-intensive and delay-sensitive tasks [1,2]. Air-ground integrated networks leverage the high mobility and rapid deployment capabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), employing UAVs as aerial edge servers to provide ground terminals with low-latency computing and reliable communication services [3–5]. Owing to its practical relevance and technical promise, this paradigm has attracted significant attention from both academia and industry [6,7].

In UAV-assisted mobile edge computing (UAV-assisted MEC) systems, several fundamental challenges remain in achieving efficient and reliable task scheduling. First, UAVs are subject to limited onboard energy, which constrains their flight time and computational capacity, thereby necessitating a balance between energy consumption and processing performance. Second, in multi-UAV scenarios, trajectory planning becomes increasingly complex, as each UAV must coordinate its path while satisfying energy, communication, and collision-avoidance constraints. Collectively, these challenges highlight the need for task scheduling mechanism that can adapt to dynamic environmental conditions while maintaining energy efficiency.

Existing research related to this study primarily focuses on the joint optimization of task latency and energy consumption, along with unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) trajectory control, which are predominantly addressed using deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based approaches.

To jointly minimize task latency and energy consumption in dynamic environments. Tang et al. [8] deploy unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as mobile edge computing nodes in an air-ground collaborative network to deliver AI services, enabling rapid response to ground users’ task requests and reducing overall system energy consumption. Zhao et al. [9] address dynamic network environments by considering the mobility of both end devices and UAVs, and propose a PER-DDPG-based task offloading method that jointly optimizes task offloading success rate and system energy consumption, thereby improving overall system efficiency. Li et al. [10] present a UAV-assisted MEC model based on MADDPG, which jointly optimizes task offloading ratios and the UAV’s 3D trajectory to achieve a favorable trade-off among system latency, energy consumption, and throughput. Paper [11] introduces a fairness-aware optimization framework for a hybrid dual-layer UAV architecture combining fixed-wing and rotary-wing UAVs, and employs the MATD3 algorithm to minimize system latency while ensuring fair service delivery among users. Ma et al. [12] develop a blockchain-assisted edge resource allocation framework that combines DRL-based server bidding with Stackelberg game-driven incentive mechanisms, enabling efficient and cost-aware resource trading in distributed edge environments.

UAV trajectory control is essential for enhancing computation performance and energy efficiency in UAV-assisted MEC systems. Seid et al. [13] jointly optimized trajectories and resource allocation using TD3 to minimize energy and delay, and Yin et al. [14] developed QEMUOT, which leverages MATD3 to co-optimize UAV paths and offloading ratios for improved coverage and efficiency. Gao et al. [15] propose a multi-objective reinforcement learning algorithm that jointly optimizes task latency and system energy consumption by controlling UAV trajectories and task offloading decisions. Wu et al. [16] enhanced coordination efficiency using an attention-based DRL approach for joint offloading and resource allocation. Zhang et al. [17] propose a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based strategy for joint task offloading and resource allocation in air-to-ground networks, enabling a UAV swarm to provide computation offloading services for ground IoT devices.

Although significant progress has been made in task scheduling and trajectory control for UAV-assisted MEC systems, most existing approaches focus primarily on minimizing either task latency or energy consumption in isolation. To address this challenge, this paper proposes PER-MATD3, a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm that jointly optimizes task latency, energy efficiency, and user coverage. PER-MATD3 adopts the centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) paradigm, allowing agents to learn coordinated policies using global information during training while executing based only on local observations. It further incorporates prioritized experience replay (PER) to accelerate learning by focusing on high-impact experiences, thereby improving both multi-agent coordination and training efficiency. The main contributions are as follows:

(1) We model a UAV-assisted MEC system with randomly distributed user terminals, multiple UAVs, and a ground base station. Terminals generate delay-sensitive, computation-intensive tasks, which can be processed by UAVs or offloaded via UAVs to the base station.

(2) We propose PER-MATD3, a joint optimization algorithm based on the Multi-Agent Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MATD3) with prioritized experience replay, improving stability, sample efficiency.

(3) Simulation results show that PER-MATD3 achieves fast convergence and effectively reduces task latency, energy consumption, and user coverage.

2 System Model and Problem Description

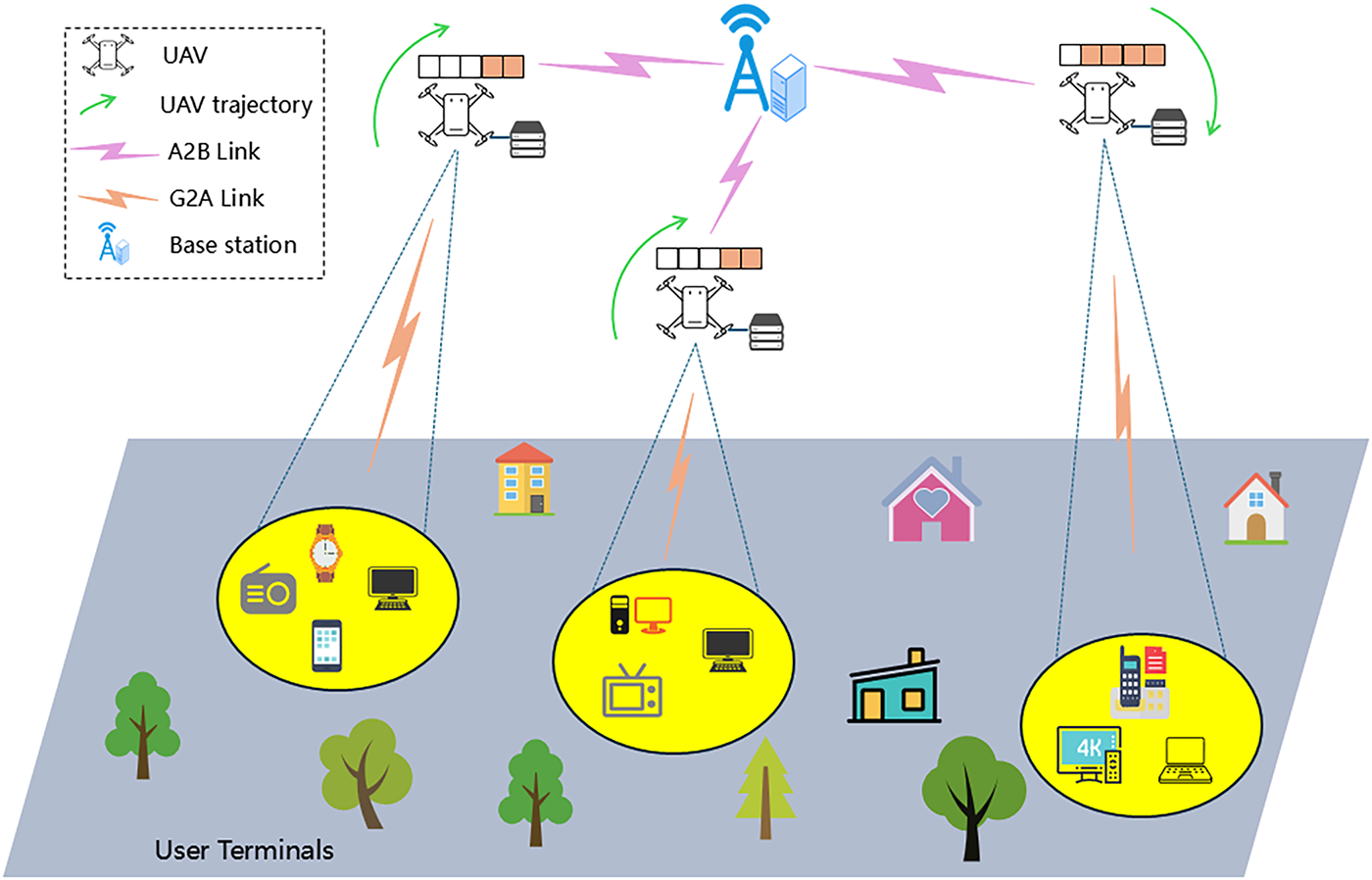

In emergency scenarios such as natural disasters, large-scale accidents, or temporary public events, terrestrial cloud infrastructure may be damaged or unavailable, leaving ground user terminals unable to access reliable computational resources. To address this challenge, this paper investigates a UAV-assisted mobile edge computing (MEC) system, as illustrated in Fig. 1, comprising a set of user terminals

Figure 1: UAV-assisted MEC system architecture

The system operates over discrete time slots

In this paper, UAVs are assumed to fly at a fixed altitude H, with control focused on horizontal trajectories. The horizontal position of UAV

To prevent collisions, a minimum safety distance

Each UAV is also constrained to operate within a fixed rectangular area, so its position

Limited computational resources at terminals and UAVs require implementing FIFO task queues to buffer tasks orderly and ensure sequential execution under high concurrency.

(1) UT queue model

Each user terminal

Let

where

(2) UAV queue model

When a terminal’s computational capacity is insufficient, tasks are offloaded to UAVs. Each UAV

where

(1) G2A communication model

The Ground-to-Air (G2A) link may be blocked by buildings. Therefore, the channel model accounts for both Line-of-Sight (LoS) and Non-Line-of-Sight (NLoS) conditions to better reflect real-world propagation. The path loss between terminal and UAV is thus given by:

where

where the value of

In summary, the data transmission rate between the terminal

where

(2) A2B communication model

The Air-to-Base Station (A2B) link may be obstructed by obstacles like high-rise buildings; thus, both LoS and NLoS conditions are considered to accurately model the channel. The path loss between UAV

The transmission rate is denoted as:

where

(1) Local computing model

When terminal

where

fm is the computing resources of the user terminal.

Local task processing consumes energy dependent on the allocated CPU frequency, calculated as:

where

(2) Offloading to the UAV computing model

When a terminal cannot process a task locally, it offloads it to its associated UAV. At time slot

where

When a task is offloaded to the UAV, the system energy consumption comprises the user terminal’s transmission energy

where

(3) Offloading to the base station

When a task’ computational demand exceeds the UAV’s capacity, it is offloaded to the ground base station. Assuming sufficient base station resources and immediate processing, the total delay includes UAV-to-base station transmission and base station processing times.

where

When a task is offloaded to the base station, the system energy consumption consists of the UAV’s transmission energy

where

To minimize end-to-end task delay and overall energy consumption, this paper proposes a joint optimization framework integrating UAV trajectory planning, task offloading, and resource allocation. Based on the offloading decision

The optimization objective minimizes a weighted sum of delay and energy consumption:

where

The optimization problem (P1) is modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP)

(1) State space

User terminals observe local task information and the position of the UAV they are currently associated with, represented as

(2) Action space

Terminals decide task offloading

(3) Reward function

The reward guides agents to minimize total system cost under constraints. If all constraints are met, the reward equals the negative cost; otherwise, a penalty is applied. Formally:

When the flight trajectory of the UAV violates

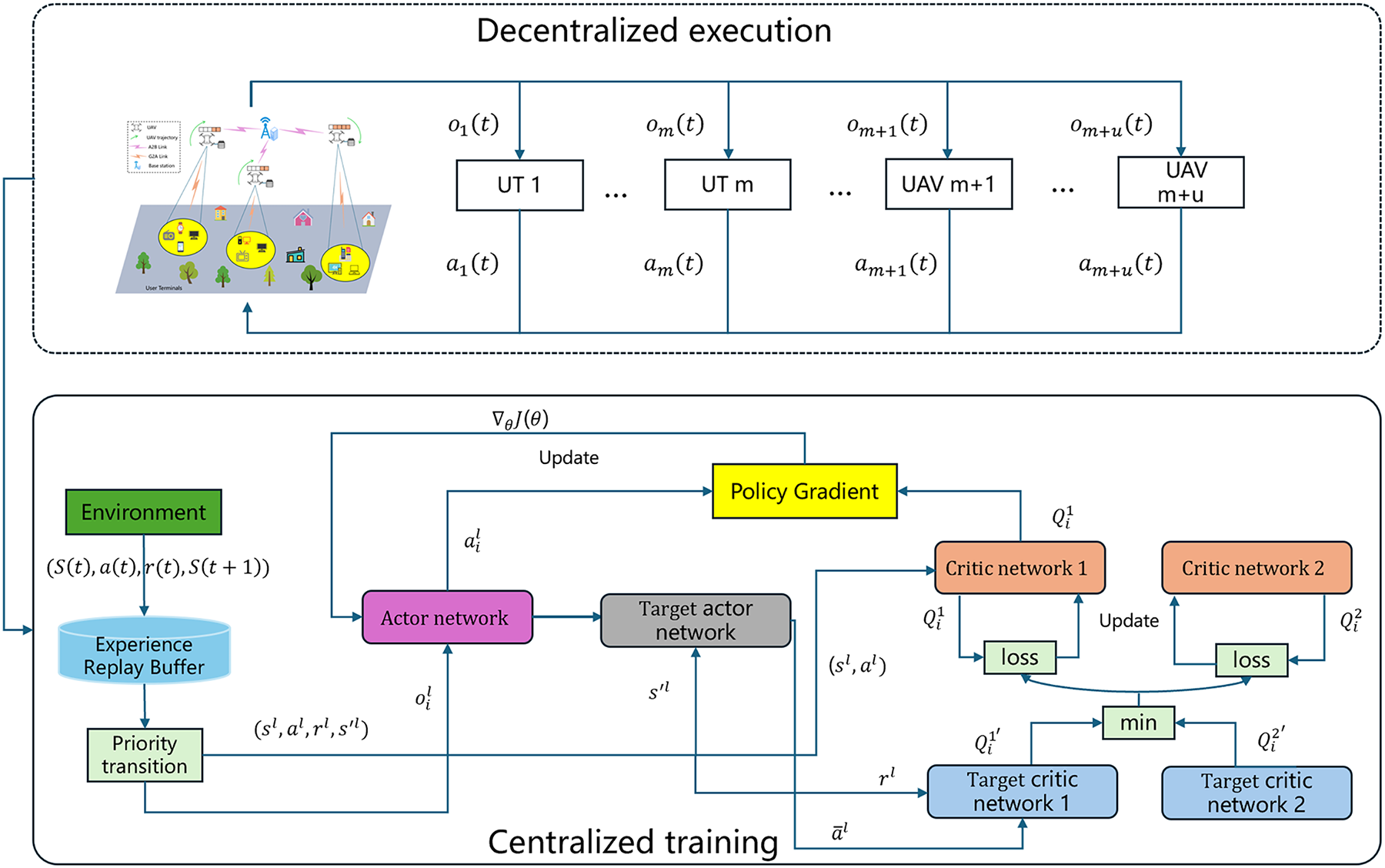

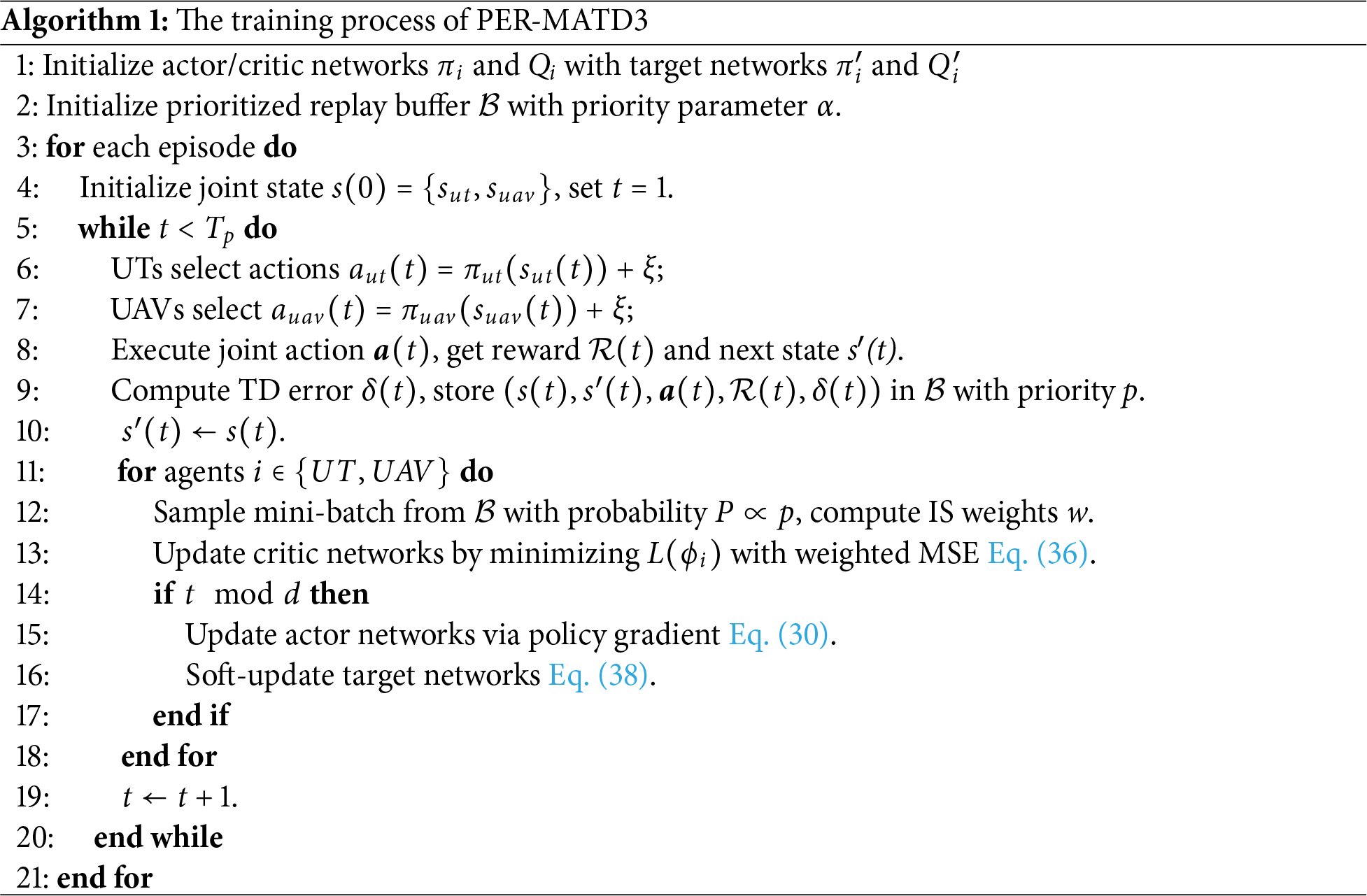

In multi-agent UAV-assisted MEC networks, the high-dimensional continuous action space challenges traditional RL methods like Q-learning, DQN, and PG. To address this, we propose PER-MATD3, a prioritized experience replay extension of MATD3. Building on TD3’s twin critics, target policy smoothing, and delayed updates to reduce overestimation and improve stability, PER-MATD3 prioritizes samples with high TD errors to accelerate convergence and enhance performance in complex multi-agent settings.

Leveraging centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE), critics use global information to overcome partial observability, while actors act on local observations for scalability. Dual-delay updates and prioritized replay further stabilize training and improve adaptability in high-dimensional, continuous, and collaborative environments.

The PER-MATD3 framework, illustrated in Fig. 2. Each agent

Figure 2: PER-MATD3 algorithm framework

Actor networks are optimized via policy gradient methods during centralized training, with the policy gradient computed as follows:

where L denotes the mini-batch size sampled via prioritized experience replay. Each agent’s two Critic networks independently estimate Q-values, and the minimum is used to enhance stability and accuracy. Critic training follows the Temporal-Difference (TD) principle, leveraging the same prioritized replay mechanism as the Actor. The TD target for each sample is computed as:

where

where

where D is the replay buffer size,

where

To mitigate value overestimation caused by sharp fluctuations in the Actor’s output for state

where

Critic network parameters are updated using Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss, and the loss function is defined as follows:

Therefore, the parameters of the Actor and Critic main network of each

where

PER-MATD3 uses delayed policy updates: Critics update every step for rapid adaptation, while Actors update every

where

The computational complexity of PER-MATD3 includes two phases: interaction with the environment and training with prioritized experience replay. The interaction phase with M + N agents over T time slots costs

4 Simulation Experiments and Performance Analysis

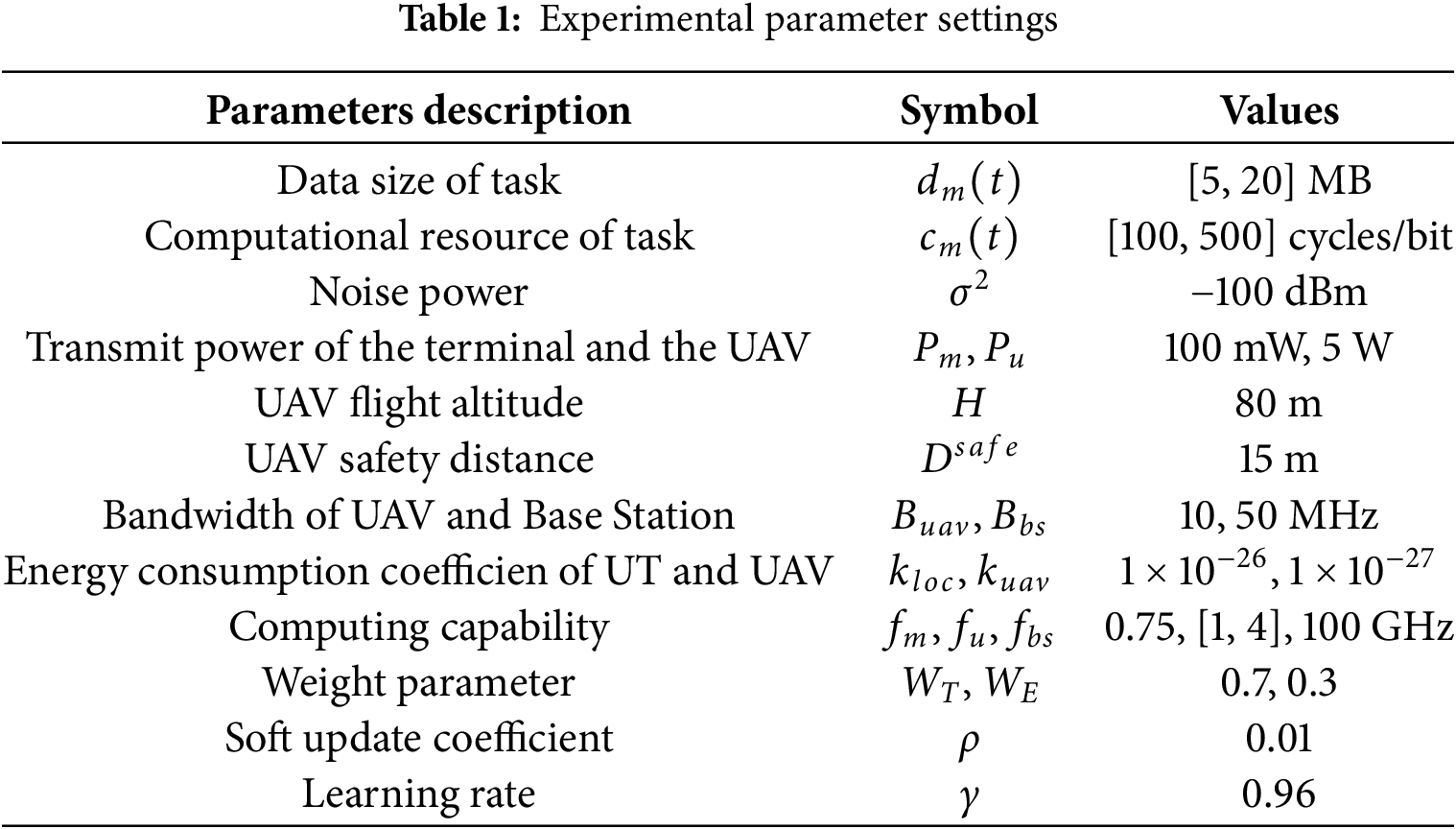

In order to verify the effectiveness of the algorithm proposed in this paper, we consider a UAV-assisted MEC scenario consisting of three UAVs and multiple ground user terminals and an edge base station. Among them, the UAVs fly in an area of 400

In this paper, three classical reinforcement learning algorithms—MATD3 [19], MADDPG [20], and PPO [21]—are used as baseline benchmarks. MATD3 extends TD3 to multi-agent settings, improving stability and reducing overestimation in continuous action spaces, making it suitable for coordinated UAV task offloading. MADDPG enables centralized training with decentralized execution, allowing multiple UAVs to learn cooperative strategies. PPO is a single-agent policy gradient method that provides stable and efficient updates, serving as a baseline for independent UAV scenarios. We compare these algorithms under the same simulation settings in terms of convergence speed, training stability, and average system task latency and energy consumption, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method.

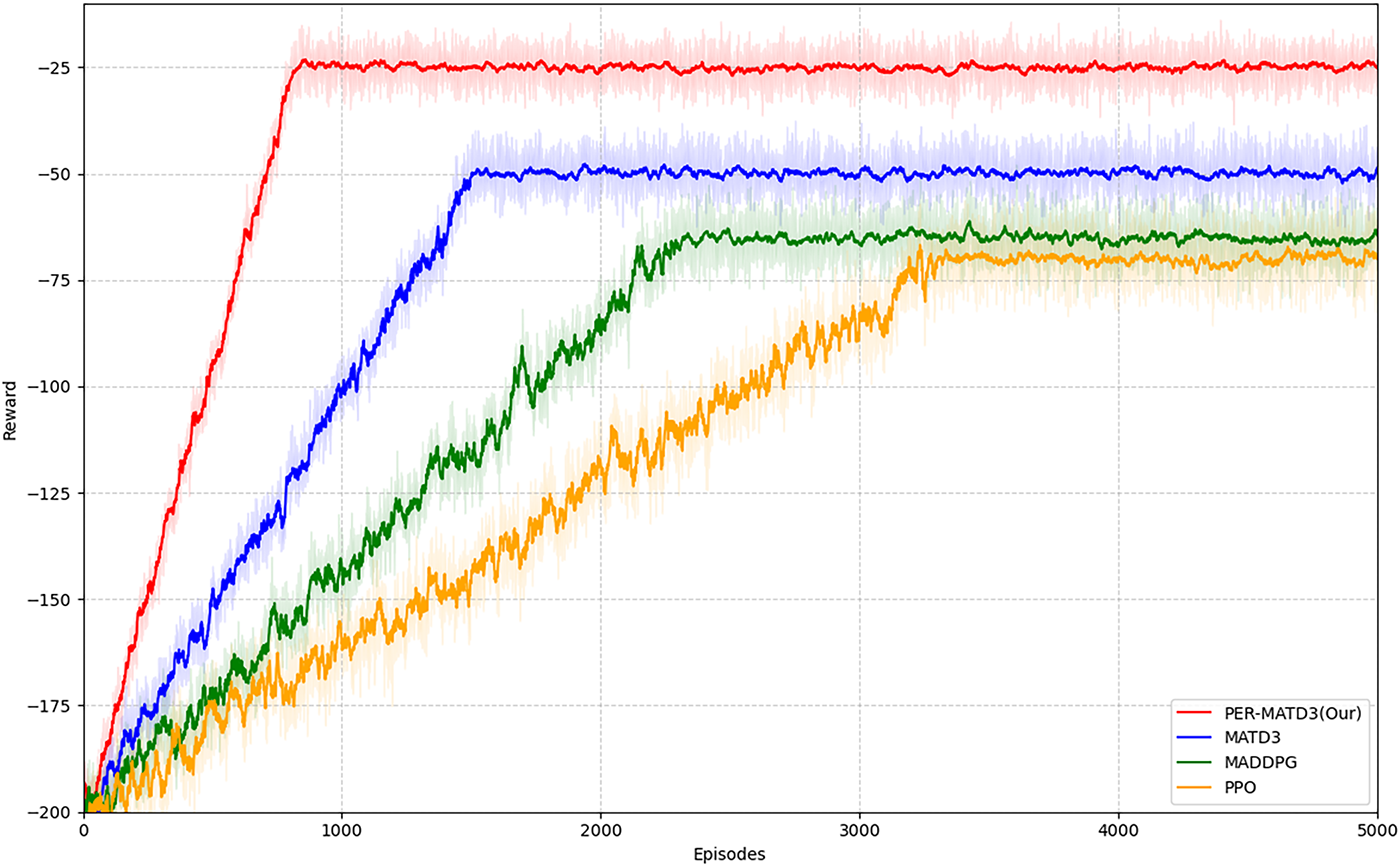

Fig. 3 presents the training convergence curves of the compared algorithms in terms of average episode reward. PER-MATD3 achieves rapid improvement in the early training phase and stabilizes after approximately 1000 episodes, demonstrating fast convergence and high policy stability. In contrast, MATD3 converges more slowly, while MADDPG and PPO continue to exhibit significant oscillations beyond 1000 episodes, indicating poorer learning stability. This improved convergence is attributed to the integration of prioritized experience replay and the dual-Q network architecture, which together enhance learning efficiency and mitigate value overestimation.

Figure 3: Algorithm convergence performance comparison

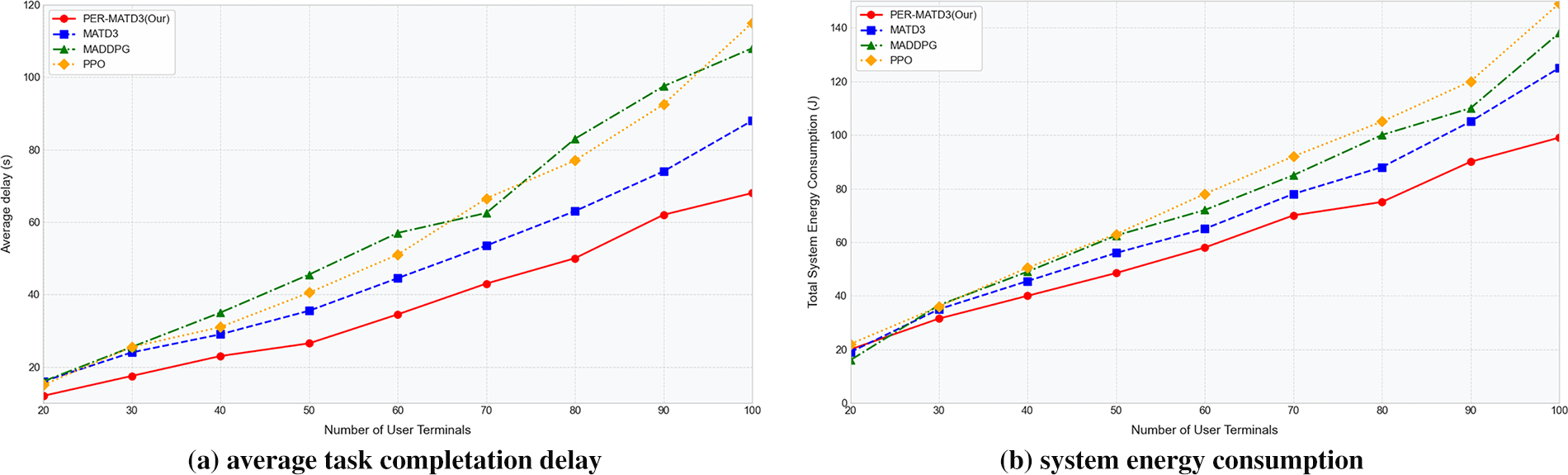

Fig. 4 compares the performance of different algorithms under varying numbers of user terminals. Fig. 4a depicts the average task completion delay of each algorithm as the number of user terminals increases from 20 to 100. With more terminals generating delay-sensitive tasks, task completion delay rises for all methods due to limited computational and communication resources. Nevertheless, the proposed PER-MATD3 consistently achieves the lowest delay, demonstrating superior decision efficiency. Specifically, when the number of terminals reaches 100, PER-MATD3 reduces the average delay by 22.7% compared to MATD3. Notably, beyond 60 terminals, PER-MATD3 maintains low and stable latency, while other algorithms exhibit significant delay spikes, indicating better robustness and scalability under heavy load. Fig. 4b shows the system’s total energy consumption with increasing user terminals. As the number of user terminals increases from 20 to 100, the system’s total energy consumption gradually rises due to higher task loads and intensified resource contention. It can be observed from the results that PER-MATD3 consistently achieves the lowest energy consumption among all methods, demonstrating its superior resource scheduling and energy efficiency. Specifically, at 100 terminals, PER-MATD3 reduces energy consumption by 20.8% compared to MATD3. This improvement is attributed to the enhanced learning efficiency of prioritized experience replay, which assigns higher sampling priority to more informative transitions, thereby accelerating convergence to energy-efficient offloading and UAV trajectory policies.

Figure 4: Comparison of algorithm performance with different terminal numbers

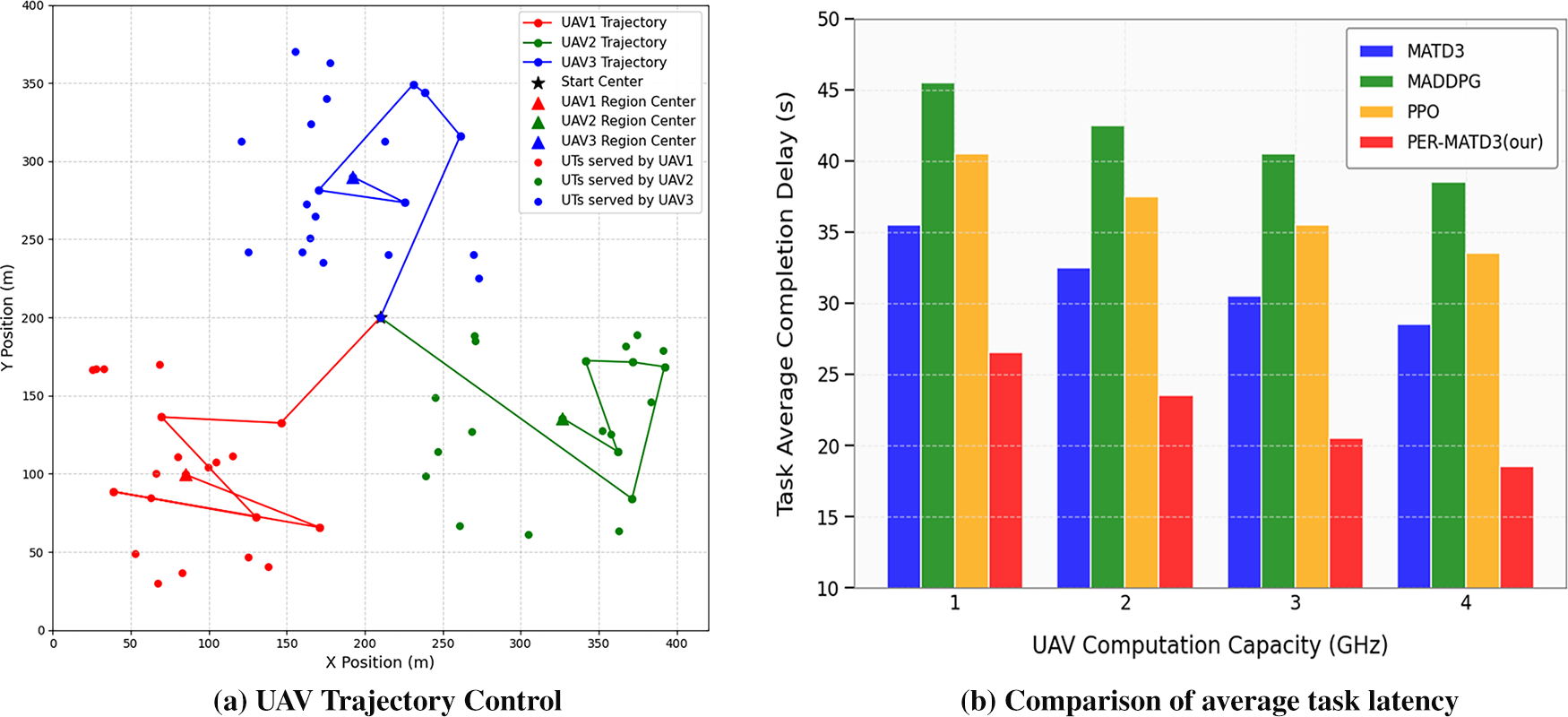

Fig. 5a depicts the deployment and trajectory planning of three UAVs in a planar coordinate system. All UAVs are launched from the center of the experimental area, and they fly in different directions to avoid inter-UAV collisions. Each UAV determines its destination by optimizing its trajectory to cover the maximum number of user terminals (UTs) within its communication range. Consequently, the UAVs converge to the centroids of three high-density UT clusters and hover there to provide stable computation offloading services. This strategy achieves efficient spatial coverage, reduces transmission delay, and improves overall system performance. Fig. 5b compares the average task delay under varying UAV computing capacities with 50 UTs. As the UAV computation capacity increases from 1 to 4 GHz, tasks are processed more faster, leading to shorter queuing delays and less offloading to the base station, which significantly reduces overall latency. PER-MATD3 consistently achieves the lowest latency. Experimental results show that PER-MATD3 achieves the best performance overall.

Figure 5: UAV trajectory control and task latency under varying computing power

This paper addresses the joint optimization of task offloading, resource allocation, and UAV trajectory control in multi-UAV-assisted MEC networks by proposing PER-MATD3. Leveraging a centralized training and distributed execution framework, it accelerates policy convergence and improves sample efficiency through prioritized replay. Simulations demonstrate that PER-MATD3 outperforms existing methods in task delay and energy consumption, confirming its robustness in dynamic environments. Future work will incorporate inter-task dependencies and user mobility to enhance scalability and real-world applicability.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely thank all those who supported and contributed to this research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 61701100.

Author Contributions: Sai Xu: conceptualization, methodology and writing; Jun Liu: supervision, project administration and funding acquisition; Shengyu Huang: software, validation, visualizatio; Zhi Li: conceptualization, methodology and formal analysis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li S, Liu G, Li L, Zhang Z, Fei W, Xiang H. A review on air-ground coordination in mobile edge computing: key technologies, applications and future directions. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2024;30(3):1359–86. doi:10.26599/tst.2024.9010142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xu X, Han M, Xie N, Li G. Joint resource allocation methodology for space-air-ground collaboration. In: 2025 5th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE); 2025 Jan 10–12; Guangzhou, China. p. 849–53. [Google Scholar]

3. Liu C, Zhong Y, Wu R, Ren S, Du S, Guo B. Deep reinforcement learning based 3D-trajectory design and task offloading in UAV-enabled MEC system. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2025;74(2):3185–95. doi:10.1109/tvt.2024.3469977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao M, Zhang R, He Z, Li K. Joint optimization of trajectory, offloading, caching, and migration for UAV-assisted MEC. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(3):1981–98. doi:10.1109/tmc.2024.3486995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pervez F, Sultana A, Yang C, Zhao L. Energy and latency efficient joint communication and computation optimization in a multi-UAV-assisted MEC network. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2024;23(3):1728–41. doi:10.1109/twc.2023.3291692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hui M, Chen J, Yang L, Lv L, Jiang H, Al-Dhahir N. UAV-Assisted mobile edge computing: optimal design of UAV altitude and task offloading. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2024;23(10):13633–47. doi:10.1109/twc.2024.3403536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ma L, Li N, Guo Y, Wang X, Yang S, Huang M, et al. Learning to optimize: reference vector reinforcement learning adaption to constrained many-objective optimization of industrial copper burdening system. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;52(12):12698–711. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2021.3086501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Tang J, Nie J, Zhang Y, Duan Y, Xiong Z, Niyato D. Air-ground collaborative edge intelligence for future generation networks. IEEE Netw. 2023;37(2):118–25. doi:10.1109/mnet.008.2200287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao N, Ye Z, Pei Y, Liang Y-C, Niyato D. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in UAV-assisted mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2022;21(9):6949–60. doi:10.1109/twc.2022.3153316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li F, Gu C, Liu DS, Wu YX, Wang HX. DRL-based joint task scheduling and trajectory planning method for UAV-assisted MEC scenarios. IEEE Access. 2024;12:156224–34. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3479312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li H, Qu L, Chen W, Shao D. Fairness-aware joint optimization of 3D trajectory and task offloading in multi-UAV edge computing systems. In: 2025 21st International Conference on the Design of Reliable Communication Networks (DRCN); 2025 May 12–15; Ningbo, China. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

12. Ma L, Qian Y, Yu G, Li Z, Wang L, Li Q, et al. TBCIM: two-level blockchain-aided edge resource allocation mechanism for federated learning service market. IEEE/ACM Transact Netw. 2025. doi:10.1109/TON.2025.3589017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Seid AM, Boateng GO, Mareri B, Sun G, Jiang W. Multi-agent DRL for task offloading and resource allocation in multi-UAV enabled IoT edge network. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2021;18(4):4531–47. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2021.3096673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yin J, Tang Z, Lou J, Guo J, Cai H, Wu X, et al. QoS-aware energy-efficient multi-UAV offloading ratio and trajectory control algorithm in mobile-edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(24):40588–602. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3452111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gao Z, Yang L, Dai Y. MO-AVC: deep-reinforcement-learning-based trajectory control and task offloading in multi-UAV-enabled MEC systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(7):11395–414. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3329869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wu G, Liu Z, Fan M, Wu K. Joint task offloading and resource allocation in multi-UAV multi-server systems: an attention-based deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2024;73(8):11964–78. doi:10.1109/tvt.2024.3377647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Q, Gao A, Wang Y, Zhang S, Ng SX. Multiple dual-function UAVs cooperative computation offloading in hybrid mobile edge computing systems. In: ICC 2024-IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2024 Jun 9–13; Denver, CO, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

18. Shao Z, Yang H, Xiao L, Su W, Chen Y, Xiong Z. Deep reinforcement learning-based resource management for UAV-assisted mobile edge computing against jamming. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(12):13358–74. doi:10.1109/tmc.2024.3432491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ackermann J, Gabler V, Osa T, Sugiyama M. Reducing overestimation bias in multi-agent domains using double centralized critics. arXiv:1910.01465. 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. Du J, Kong Z, Sun A, Kang J, Niyato D, Chu X, et al. MADDPG-based joint service placement and task offloading in MEC empowered air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(6):10600–15. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3326820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv:1707.06347. 2017. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools