Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Constraint Intensity-Driven Evolutionary Multitasking for Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization

1 Smart City College, Beijing Union University, Beijing, 100101, China

2 Luban (Beijing) E-commerce Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, 102308, China

* Corresponding Author: Mingming Xiao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Evolutionary Optimization Approaches: Theory and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 51 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072036

Received 18 August 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In a wide range of engineering applications, complex constrained multi-objective optimization problems (CMOPs) present significant challenges, as the complexity of constraints often hampers algorithmic convergence and reduces population diversity. To address these challenges, we propose a novel algorithm named Constraint Intensity-Driven Evolutionary Multitasking (CIDEMT), which employs a two-stage, tri-task framework to dynamically integrates problem structure and knowledge transfer. In the first stage, three cooperative tasks are designed to explore the Constrained Pareto Front (CPF), the Unconstrained Pareto Front (UPF), and theKeywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileConstrained multi-objective optimization problems (CMOPs) frequently arise in practical scenarios, including portfolio optimization, resource scheduling, and engineering system design, where multiple conflicting objectives must be optimized simultaneously under a set of nonlinear inequality and equality constraints [1,2]. In contrast to unconstrained problems, CMOPs introduce structural complexity by partitioning the search space into feasible and infeasible regions, often resulting in fragmented and irregular solution landscapes. Such complexity poses substantial difficulties for evolutionary algorithms in maintaining convergence, feasibility, and diversity within the feasible domain.

To address these challenges, various constraint-handling techniques(CHT) have been proposed, including penalty-based approaches, constraint dominance principles (CDP), and

Motivated by these limitations, recent studies have explored evolutionary multitasking (EMT) as a promising paradigm for enhancing constrained optimization. The EMT framework aims to leverage inter-task knowledge transfer by simultaneously solving multiple related tasks, thereby improving convergence efficiency and solution diversity [8,9]. In the context of CMOPs, multitasking strategies often incorporate auxiliary tasks, typically those with relaxed constraints or unconstrained objectives, to support the optimization of the primary constrained task. By sharing potentially useful solutions across tasks, these approaches seek to accelerate the discovery of feasible and high-quality solutions.

However, existing multitasking-based CMOPs algorithms face several persistent challenges. Many assume implicit compatibility among tasks and overlook the constraint-induced heterogeneity that may exist between search spaces. When the unconstrained Pareto front (UPF) and the constrained Pareto front (CPF) exhibit minimal overlap or structural dissimilarity, unfiltered knowledge transfer may introduce detrimental guidance that compromises search effectiveness. Moreover, most current methods lack adaptive mechanisms to evaluate the contribution of transferred solutions in real time. These limitations reduce the robustness and scalability of EMT approaches in solving CMOPs with diverse constraint landscapes. This observation underscores the need for a more flexible and empirically informed multitasking framework—one that dynamically recognizes problem structure, guides task-specific strategy design, and selectively transfers knowledge based on its actual utility to the optimization process.

In response to these challenges, this study proposes a novel algorithm named Constraint-Intensity Driven Evolutionary Multi-Tasking (CIDEMT), which explicitly incorporates constraint landscape characteristics into the design of multitasking strategies for CMOPs. Specifically, the proposed method is designed to:

(1) Develop a two-task, three-task co-evolutionary framework that integrates multiple constraint-handling principles to support both global exploration and local exploitation;

(2) Construct a constraint-intensity-based (i.e., the degree of overlap between the distributions of CPF and UPF)classification mechanism that differentiates CMOPs according to the degree of overlap between the constrained and unconstrained Pareto fronts, thereby enabling adaptive, task-specific strategy selection;

(3) Implement a dynamic knowledge transfer strategy that quantitatively evaluates the contribution of auxiliary solutions to the primary task, promoting beneficial transfer while suppressing negative influence;

(4) Validate the proposed algorithm through comprehensive experiments on benchmark and real-world CMOPs, assessing performance in terms of convergence accuracy, feasibility rate, and solution diversity.

Together, these efforts yield a robust and generalizable optimization framework that effectively bridges constraint modeling with evolutionary multitasking, advancing the state of the art in solving CMOPs under complex and heterogeneous constraint conditions.

2.1 Constraint-Handling Techniques

Constrained multi-objective optimization problems (CMOPs) involve the simultaneous optimization of multiple conflicting objectives subject to complex nonlinear constraints. Existing constraint-handling Techniques (CHT) can be broadly categorized into three main categories: (1) penalty-based approaches, which embed constraint violations into the objective function via penalty terms but often require careful and problem-dependent tuning of penalty parameters [8]; (2) CDP-based methods, which promote feasible solutions by leveraging dominance relationships but may reduce population diversity and lead to premature convergence [9]; and (3)

2.2 Multi-Stage and Multi-Population Strategies

To address the limitations of traditional constraint-handling methods, researchers have investigated advanced evolutionary frameworks, particularly those based on multi-stage and multi-population designs. Multi-stage approaches aim to sequentially exploit different search dynamics to improve performance. For example, Fan et al. proposed the push-pull search (PPS) to solve CMOPs. In the framework, which alternates between unconstrained global exploration (push stage) and constrained local refinement (pull stage) [12]. Qiao [13] uses dynamic constraint adjustment to maximize the improvement in population feasibility. In contrast, LR [14] leverages Gaussian processes to enhance the quality of offspring generation. Ma et al. introduced a three-phase model comprising a learning phase, a classification phase, and an evolutionary phase. This framework leverages knowledge of the constraint landscape to guide the search direction more effectively [15]. Similarly, Feng et al. developed the Adaptive Trade-off Evolutionary Algorithm (ATEA), which integrates exploratory, trade-off, and developmental phases to dynamically balance convergence, diversity and feasibility [16].

In parallel, Unlike a single population that utilizes different strategies to enhance the performance of the algorithm [17], multiple populations are more about cooperation among the different populations. Utilizing multi-population co-optimization strategies have been designed to enhance search robustness and solution feasibility. Tian et al. proposed the Constrained Cooperative Multi-Objective Optimization (CCMO) framework, which employs weakly coupled constrained and unconstrained populations that evolve towards the CPF and UPF, respectively. These populations interact through an adaptive environmental selection mechanism [18]. To further enhance cooperation, Wang et al. presented a bidirectional search framework that coordinates dual populations via a dynamic selection strategy [19]. Qiao et al. [20] introduced a co-evolutionary approach featuring a dynamic constraint-handling mechanism and a feedback-driven resource allocation scheme, enabling efficient use of computational resources across populations. Additionally, Ming proposed the Constrained Multi-Objective Evolutionary Strategy (CMOES), which identifies promising feasible regions and adaptively tunes

2.3 Evolutionary Multitasking for CMOPs

Evolutionary multitasking (EMT) has emerged as a promising optimization paradigm in which multiple related tasks are tackled simultaneously through inter-task knowledge transfer. Unlike conventional multi-population methods that typically focus on population-level interactions, EMT emphasizes task-level information sharing to enhance optimization efficiency. Qiao et al. introduced evolutionary multitasking (EMT)-based constrained multiobjective optimization (EMCMO), which dynamically explores useful information for the primary task through a trial-and-error mechanism [22]. Ming et al. proposed CMOEMT, which formulates a CMOPs as a three-tasks multitasking model, enabling knowledge sharing to accelerate convergence and improve solution diversity [23].

Despite their demonstrated potential, EMT-based methods still encounter several critical challenges. First, they often assume implicit transferability of solutions across tasks, overlooking potential dissimilarities between the CPF and the UPF. Second, most existing approaches lack adaptive transfer mechanisms that can assess the relevance and utility of shared solutions in real-time. Third, inappropriate or negative knowledge transfer may misguide the search process, impair convergence, and lead to inefficient resource usage. These issues underscore the need for more flexible and problem-aware EMT frameworks tailored to the characteristics of individual CMOPs.

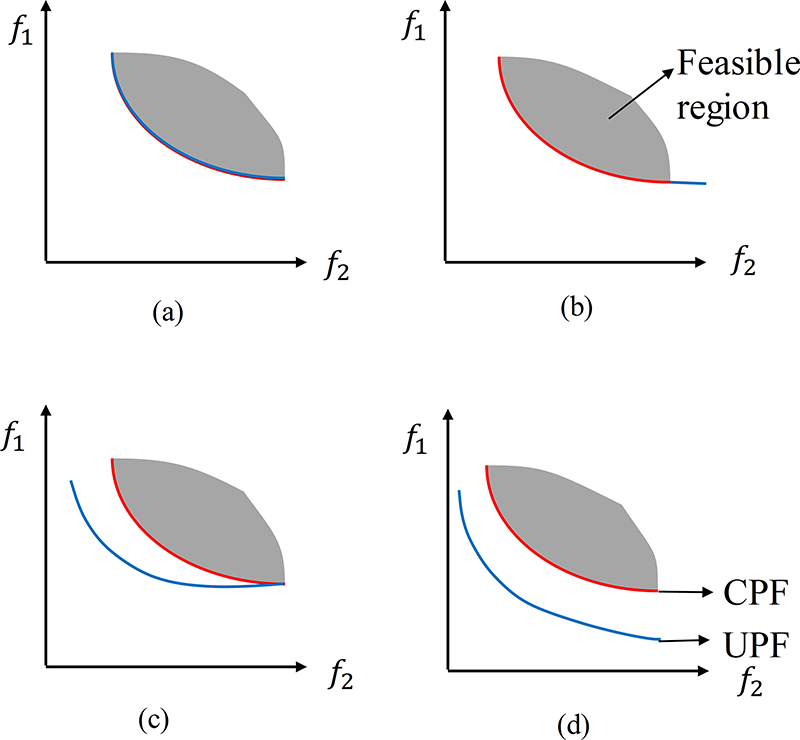

One of the pivotal developments in constrained multi-objective problem (CMOP) research is the classification of problem types based on the relationship between the CPF and the UPF. Ma and Wang [24] proposed a four-category taxonomy to describe these relationships, as shown in Fig. 1. This taxonomy provides critical guidance for the design and selection of constraint-handling techniques and knowledge transfer mechanisms, as different CPF-UPF configurations entail distinct optimization challenges.

Figure 1: Four relationships CPF and UPF, where the grey area denotes the feasible region, the blue line denotes the UPF, and the red line denotes the CPF. (a) CPF coincides with UPF, (b) CPF is a subset of UPF, (c) CPF and UPF partially overlap, and (d) CPF and UPF are completely disjoint

As illustrated in Fig. 1, recognizing the CPF-UPF relationship early in the search process enables the selection of more suitable evolutionary strategies for each scenario. This not only improves algorithmic robustness but also helps avoid inefficient search paths or detrimental knowledge transfers.

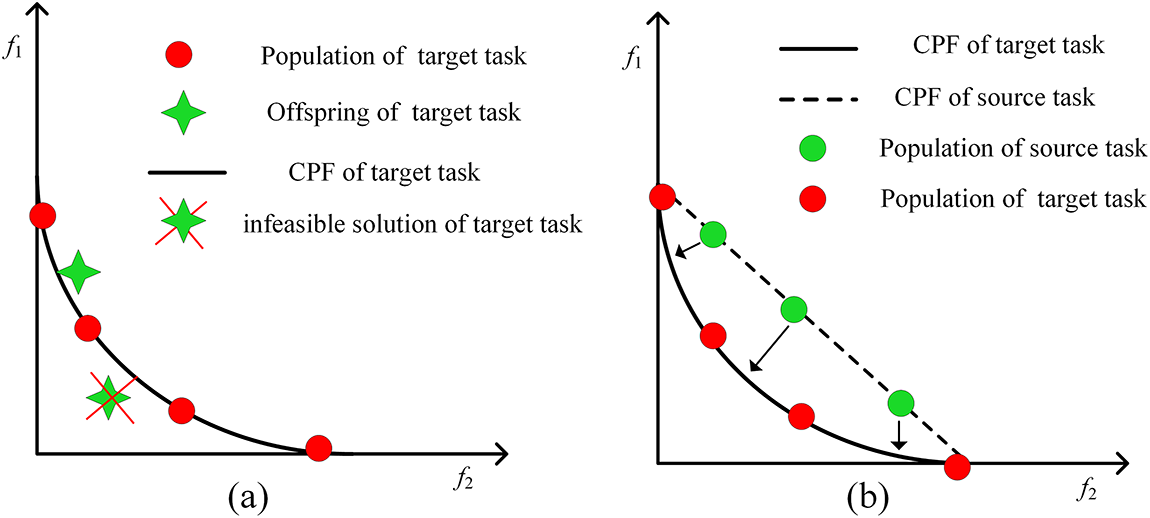

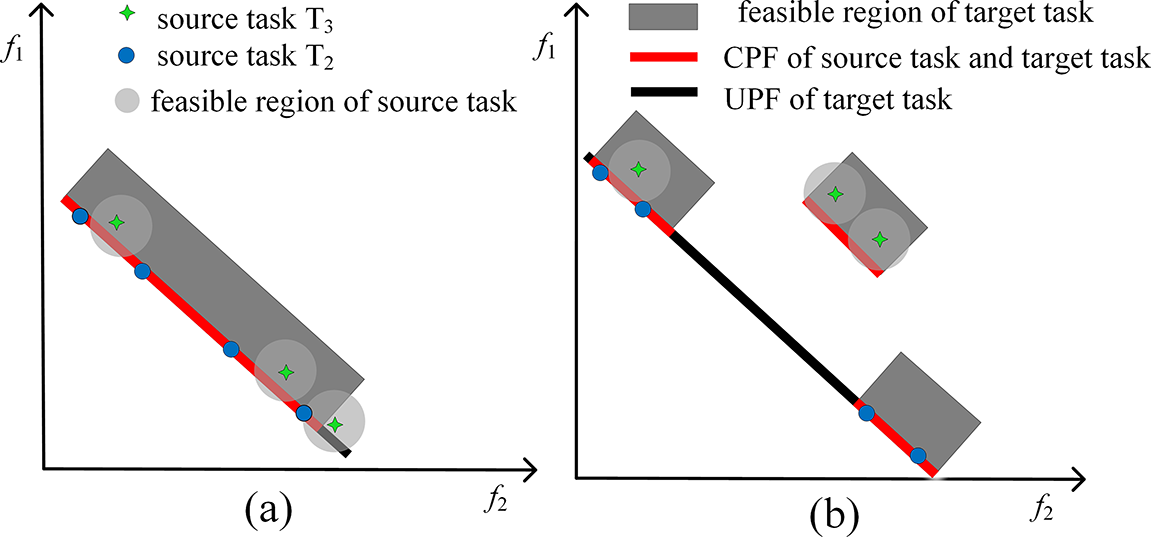

Additionally, Fig. 2 illustrates the impact of knowledge transfer between tasks with similar constraint structures. Specifically, feasible and non-dominated solutions obtained from a source task with a comparable CPF can provide superior initialization for the target task, thereby accelerating convergence and enhancing search efficiency. Conversely, when irrelevant or mismatched solutions are transferred without filtering, they may misguide the search process or lead to performance degradation. These observations underscore the need for adaptive knowledge transfer mechanisms that prioritize effective and contextually relevant information while minimizing negative transfers.

Figure 2: The functions of multitasking and knowledge transfer in solving CMOP. (a) Target task without knowledge transfer assistance. (b) The target task is assisted by knowledge transfer from the source task

Collectively, these insights reinforce the motivation for a multitasking framework that not only incorporates CPF-UPF structural awareness but also integrates adaptive transfer strategies tailored to the characteristics of constraints. These considerations form the foundation for developing the proposed CIDEMT algorithm.

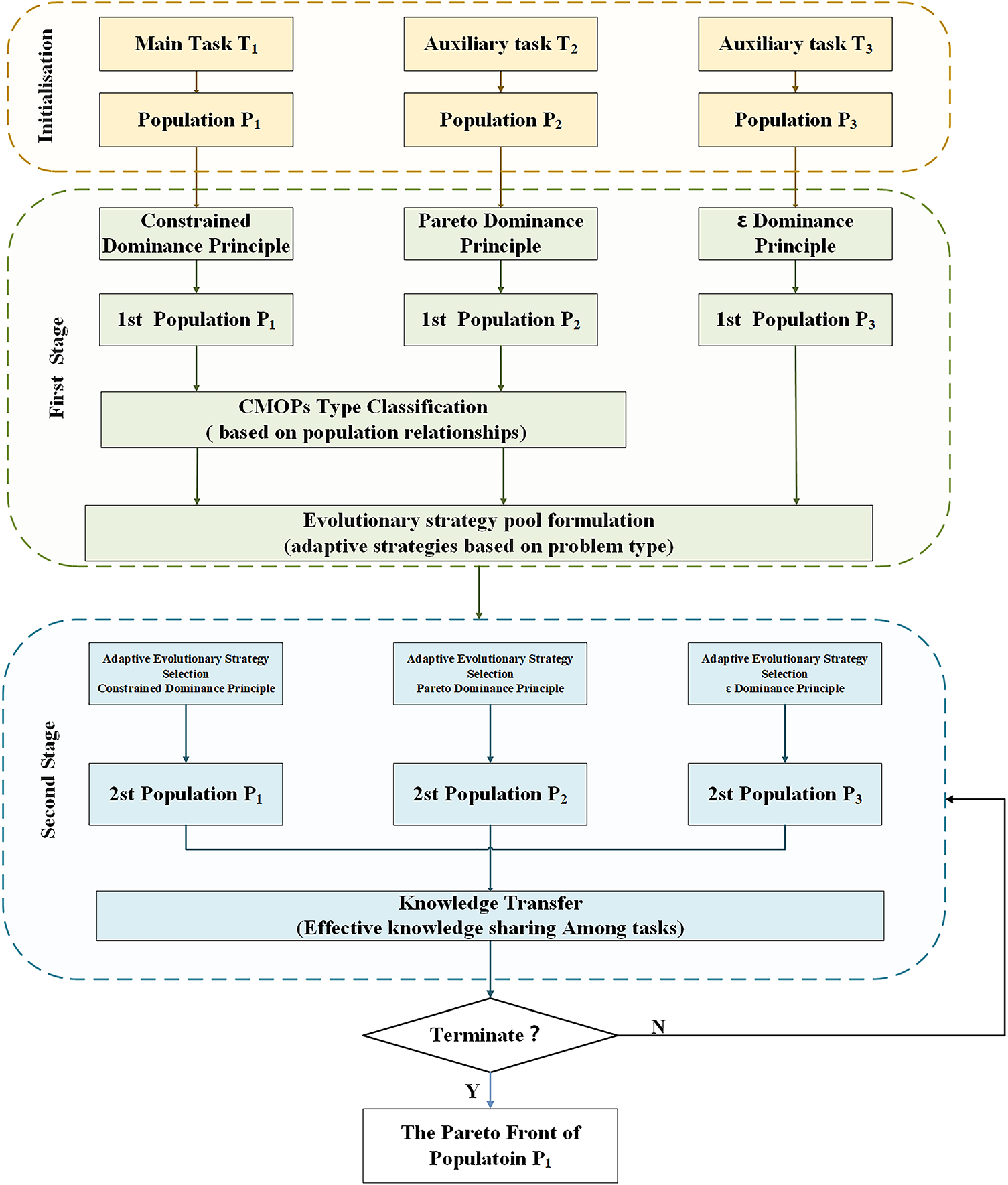

The proposed Constraint-Intensity Driven Evolutionary Multi-Tasking (CIDEMT) algorithm employs a two-stage, three-task evolutionary multitasking framework (see Fig. 3) to address CMOPs, characterized by complex and heterogeneous constraint landscapes. In the first stage, three cooperative tasks are initialized:

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of CIDEMT

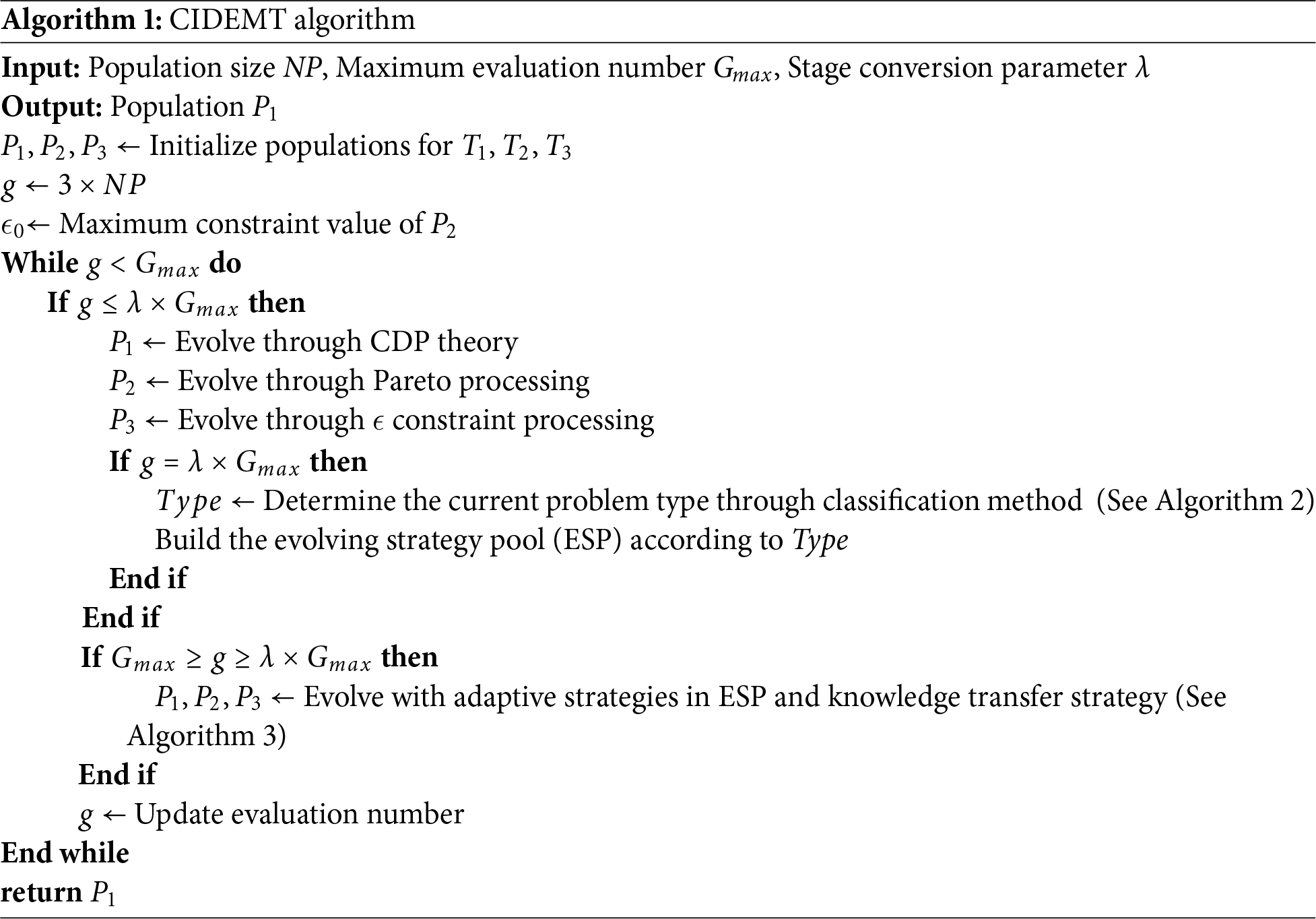

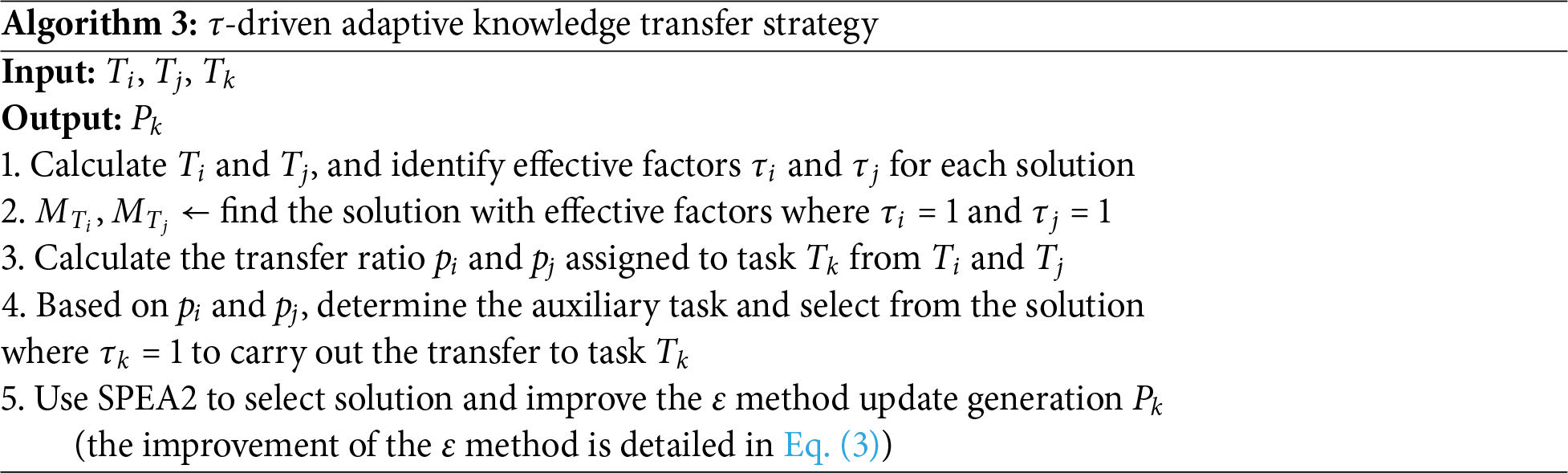

Algorithm 1 describes the detailed implementation of CIDEMT. The process begins by initializing the population of the three tasks based on a predetermined population size, NP. In the first stage, each of the three tasks generates its own children, utilizing CDP, the Pareto dominance principle, and the

In the second stage, offspring are generated using adaptive selection of evolutionary strategies. Additionally, to more effectively find beneficial solutions and reduce computational resources, a

Our approach differs from previous multi-task algorithms, such as CMOEMT and those that use Gaussian processes to generate offspring. Instead, we leverage the specific characteristics of the problem to define operators for offspring generation. Furthermore, we introduce dynamic adjustment and a pull-push search mechanism for task

3.2 Constraint Intensity-Driven Optimization Strategy

3.2.1 CPF-UPF-Based Problem Classification Mechanism

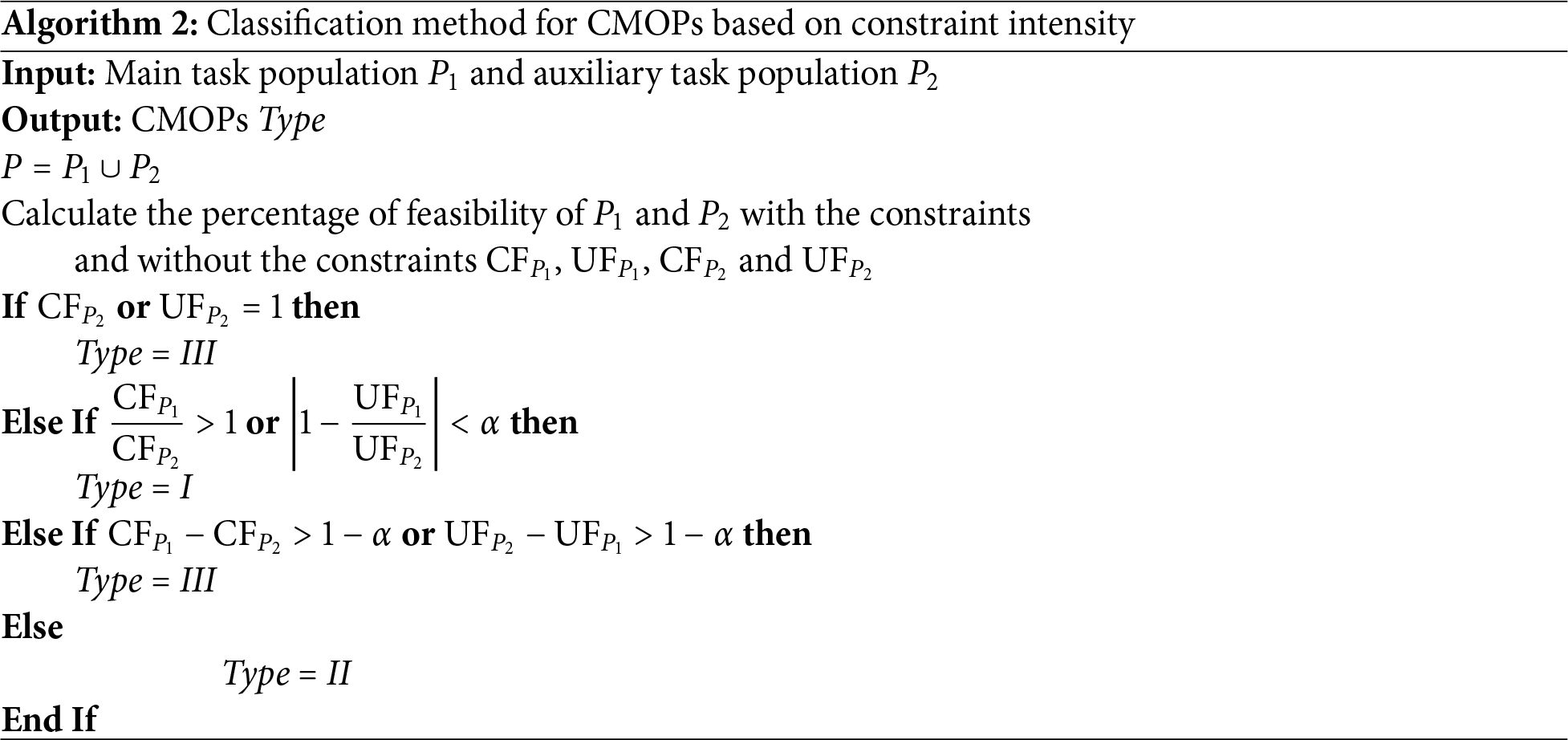

To tailor search strategies to problem characteristics, CIDEMT classifies CMOPs based on the Constraint Intensity—structural overlap between the CPF and the UPF. Three problem types are defined: Type I: CPF and UPF completely overlap; Type II: CPF and UPF partially overlap; Type III: CPF and UPF are disjoint.

The classification is achieved via Algorithm 2, which analyzes the feasibility proportions under CDP and Pareto dominance in merged populations from tasks

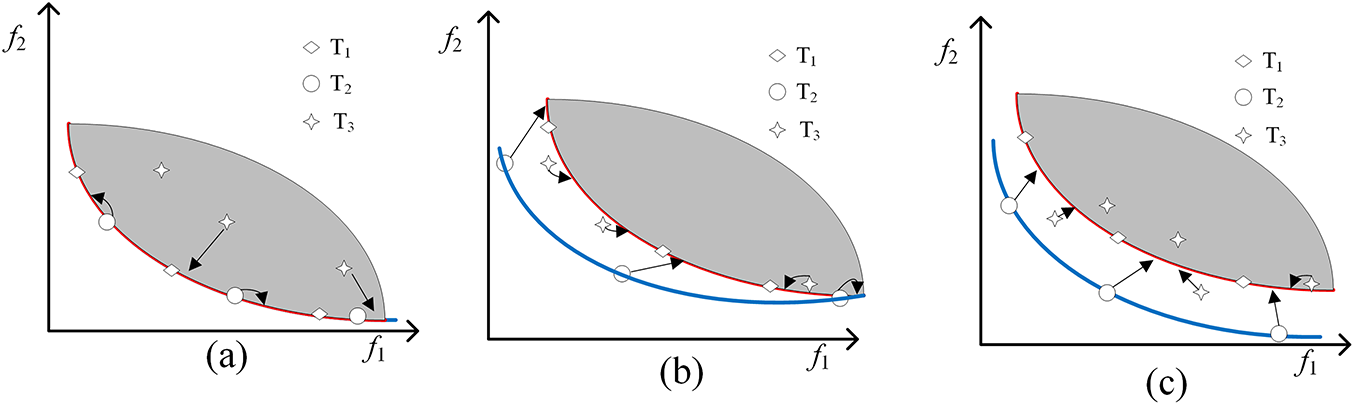

Rationale for Problem Reclassification, the reclassification of problem types is motivated by the need to tailor evolutionary strategies based on the structural relationship between the CPF and the UPF. As illustrated in Fig. 1a,b, when CPF and UPF completely overlap, the primary task

In contrast, Fig. 1d represent cases where CPF and UPF are non-overlapping. To address these, the algorithm must exploit the non-intersecting regions to generate solutions beneficial for task

Fig. 1c presents a hybrid case in which CPF and UPF partially overlap. Here, it is essential to maintain exploration around the UPF (

3.2.2 Evolutionary Strategies Pool Constructed

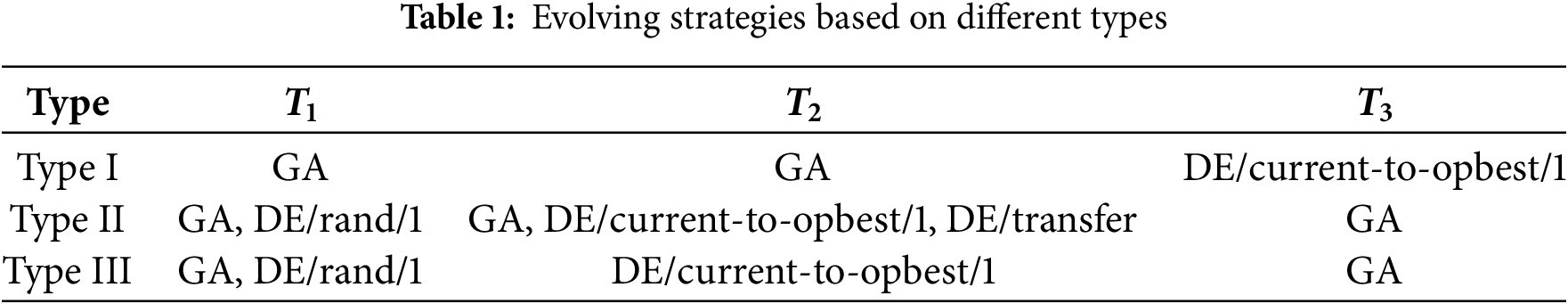

These types are not only descriptive but also directly impact the design of evolutionary strategies (Table 1). For instance, Type I problems are simplified due to constraint equivalence, while Type III problems require targeted exploitation from non-overlapping auxiliary fronts. This optimization-aware classification bridges the gap between problem structure and algorithmic behavior.

The formulation of evolutionary strategies is guided by the CPF-UPF relationship identified in the problem classification. As detailed in Table 1, for Type I problems, where the CPF is entirely coincident with the UPF, both tasks

As shown in Fig. 4a, for Type I problems, Given the complete overlap between CPF and UPF, these problems essentially reduce to unconstrained multi-objective optimization problems, thus eliminating the need for complex constraint-handling mechanisms.

Figure 4: (a) In Type I problems, tasks

For Type II Problem’s Strategy Formulation, task

GA provides baseline search capabilities across all tasks. The DE/rand/1 operator enhances exploration by using purely stochastic vector differences, effectively preventing premature convergence near the UPF and enabling the discovery of promising feasible regions in its vicinity. The DE/transfer operator facilitates knowledge transfer from task

Task

For Type III Problem’s Strategy Formulation. For the strategy largely retains the operator configurations used in Type II for tasks

3.3

After each task generates offspring based on the designed evolutionary operators, the challenge arises in selecting the solutions that are most beneficial to the main task from among all the individuals. To address this, we propose the following methods:

In our framework, the original CMOP is designated as the main task, while auxiliary tasks are treated as concurrent source tasks for potential knowledge transfer. The subsequent analysis focuses on two representative problem types illustrated in Fig. 5: Type I and Type II. In both cases, the CPF is partially or wholly surrounded by a large infeasible region. Under such circumstances, solutions from source tasks can enhance convergence and diversity of the main task by contributing valuable information, as indicated by the blue and green regions.

Figure 5: (a) Example of the impact of knowledge transfer on the main task in Type I problems; (b) Example of the impact of knowledge transfer on the main task in Type II problems

For Type I problems (Fig. 5a), if the source task’s solutions have already reached the CPF while the main task’s solutions have not, the CPF-aligned solutions from the source task can serve as a promising initialization, guiding the main task toward feasible regions more efficiently. For Type II problems (Fig. 5b), where the feasible region of the source task partially overlaps with that of the main task, feasible non-dominated solutions from the source task can assist the main task by uncovering unexplored feasible areas. Additionally, relaxed auxiliary tasks may traverse into the feasible region of the main task, further expanding the search space. In these illustrations, light-colored regions represent the relaxed feasible boundaries

The specific design is as follows: In the second stage, further optimization is achieved through a

The effectiveness of a solution

(1) For

(2) For

(3) For

Here,

where

3.4 Cooperation Mechanisms among Tri-Task

To sum up, the CIDEMT framework integrates intra-task optimization with inter-task knowledge sharing to effectively address complex constraint landscapes in CMOPs. Within each task, evolutionary operators are customized based on the task’s constraint characteristics. Moreover, CIDEMT selects corresponding evolutionary operations based on the characteristics of its problem constraints.

At the inter-task level, a

In this context,

This hybrid mechanism not only accelerates convergence under complex constraints but also enhances the population’s adaptability and robustness during evolutionary search.

3.5 Computational Complexity Analysis

The computational complexity of CIDEMT primarily stems from mating selection, evolutionary operators, population classification, and adaptive knowledge transfer. In the first stage, the three task populations evolve independently, with each task contributing O (

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed CIDEMT algorithm, it is experimentally compared with six state-of-the-art algorithms: CMOES [21], EMCMO [22], CMOEMT [23], MTCMO [13], APSEA [30], and IMCMOEAD [14]. The comparisons are conducted on three benchmark test suites-DOC [31], LIRCMOP [32], and DASCMOP [33]-as well as eight real-World constrained multi-objective optimization problems: Pressure Vessel Design (PVD) [34], Gear Train Design (GTD) [35], Car Side Impact Design (CSID) [36], Water Resources Management(WRM), Simply Supported I-beam Design (SID) [37], Gear Box Design (GBD) [38], Bulk Carrier Design (BCD) [39], Multi-product Batch Plant (MBP) [40], Haverly’s Pooling Problem (HPP) [41], Reactor Network Design (RND) [42], Process Synthesis Problem (PSP) [43], Synchronous Optimal Pulse-width Modulation of 3-level Inverters (SOPM) [44] and Optimal Droop Setting for Minimizing Active and Reactive Power Loss (MARP) [45]. All experiments were performed on the Platemo [46] platform. To assess the statistical significance of performance differences, the Wilcoxon rank sum test is applied at a 0.05 significance level. Test outcomes are represented by the symbols ‘+’, ‘–’ and ‘=’, denoting that the benchmark algorithm performs significantly better than, worse than, or comparably to CIDEMT, respectively.

4.2 Performance Indicators and Parameter Settings

• Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) [47]

The IGD metric evaluates algorithm performance with respect to both convergence and diversity. Its formal definition is provided below:

where

• Hypervolume (HV) [48]

HV metric measures the proximity of the obtained non-dominated solution set to the true PF. A larger HV value indicates that the solution set is closer to the true PF, reflecting superior performance in terms of convergence and diversity.

where

To ensure the fairness and reproducibility of the experiments, all algorithms were configured according to the parameter settings specified in their original publications. A consistent configuration was applied across all compared methods. Specifically, the population size for each task was set to NP = 100. The maximum number of function evaluations was limited to

In this section, we analyze the performance of the CIDEMT model with respect to the benchmark models in terms of IGD and HV metrics for the LIRCMOP, DASCMOP and DOC problems.

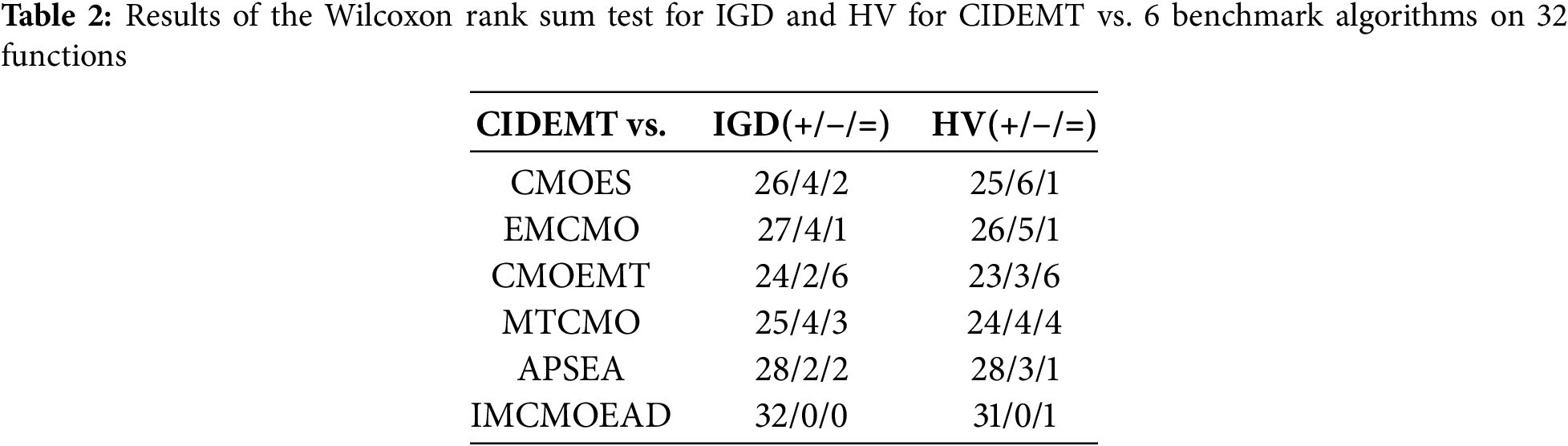

As summarized in Table 2, CIDEMT consistently outperforms the compared algorithms in most cases. Specifically, against CMOES, CIDEMT yields 26 superior, 2 comparable, and 4 inferior IGD results, demonstrating improved convergence and solution quality. Compared to EMCMO, CIDEMT achieves 27 better, 1 equal, and 4 worse IGD scores, again indicating robust improvement in the approximation of the Pareto front. Furthermore, CIDEMT obtains 32 superior IGD values compared to IMCMOEAD, underscoring its stability and competitiveness. In terms of HV, CIDEMT also performs favorably. It achieves 25 better, 1 equal, and 6 worse HV results than CMOES, reflecting enhanced diversity and solution spread. The comparison with APSEA is particularly notable: CIDEMT surpasses APSEA in 28 cases, demonstrating superior coverage across the boundaries.

Although CIDEMT performs well on most benchmark problems, it exhibits certain limitations when tackling complex problems with specific structural characteristics. For example, in problems with narrow feasible regions and high dimensionality (e.g., LIRCMOP1, LIRCMOP13, and LIRCMOP14), the use of

Although CIDEMT is not specifically designed for high-dimensional constrained multi-objective problems, we have conducted scalability tests on such problems to further demonstrate the generality of the algorithm. The experimental results show that CIDEMT performs well in terms of scalability compared to the benchmark algorithms, effectively handling high-dimensional constrained multi-objective optimization tasks while maintaining stable performance. Detailed results and analysis can be found in Tables S14 and S15 of the supplementary materials, where readers can refer for more comprehensive insights.

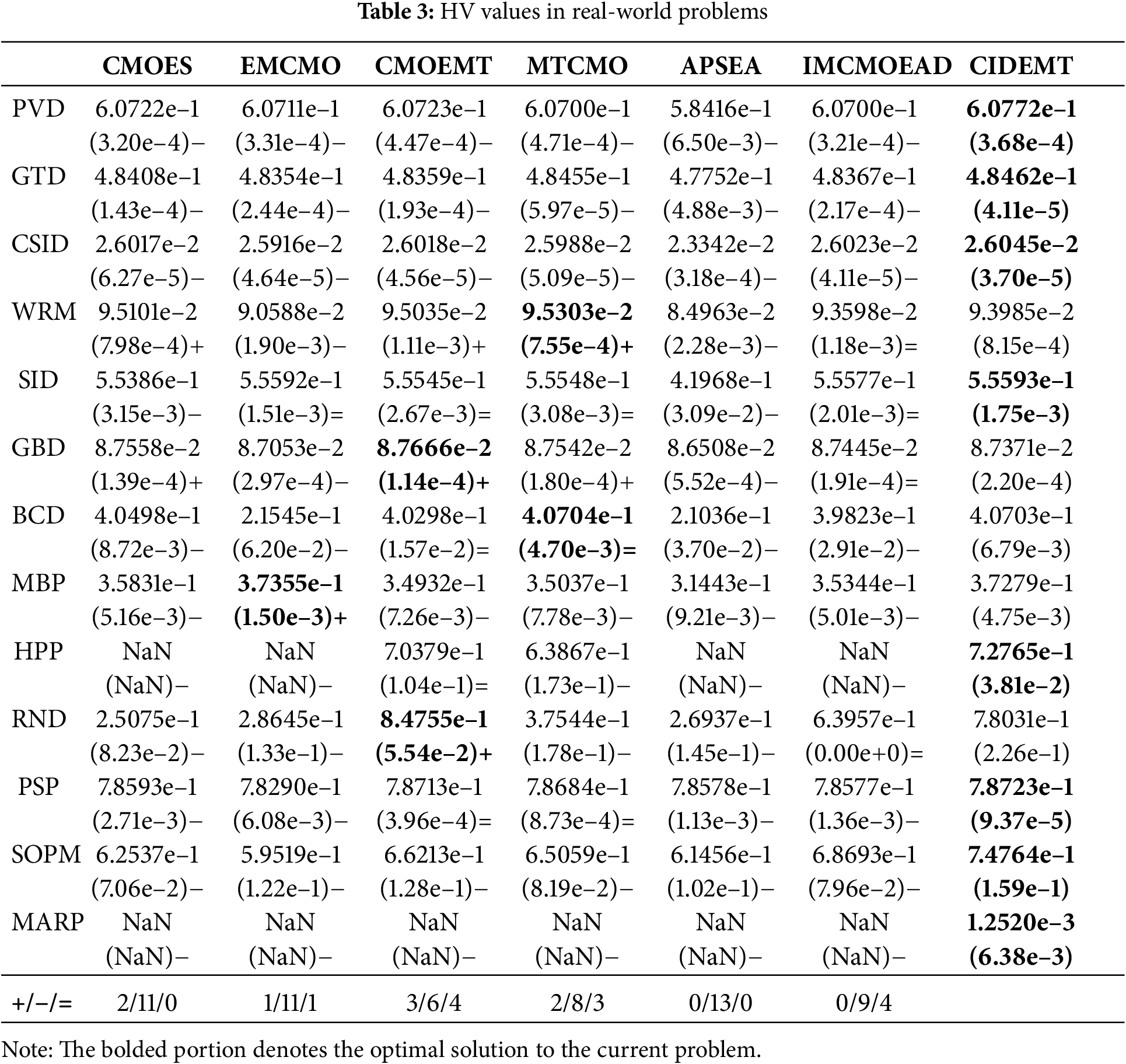

Regarding real-world constrained multi-objective problems, as shown in Table 3, CIDEMT attains the highest HV values in 8 out of 13 test cases. In contrast, EMCMO, CMOEMT, and MTCMO secure the best HV performance in only 1, 2, and 2 cases, respectively. In some real-world CMOPs, numerous objectives and complex constraints result in a highly discrete and heterogeneous feasible space. This makes it difficult for CIDEMT to capture scattered feasible regions, especially when they are sparse or fragmented, limiting its convergence and distribution performance. Nonetheless, it remains competitive compared to benchmark algorithms.

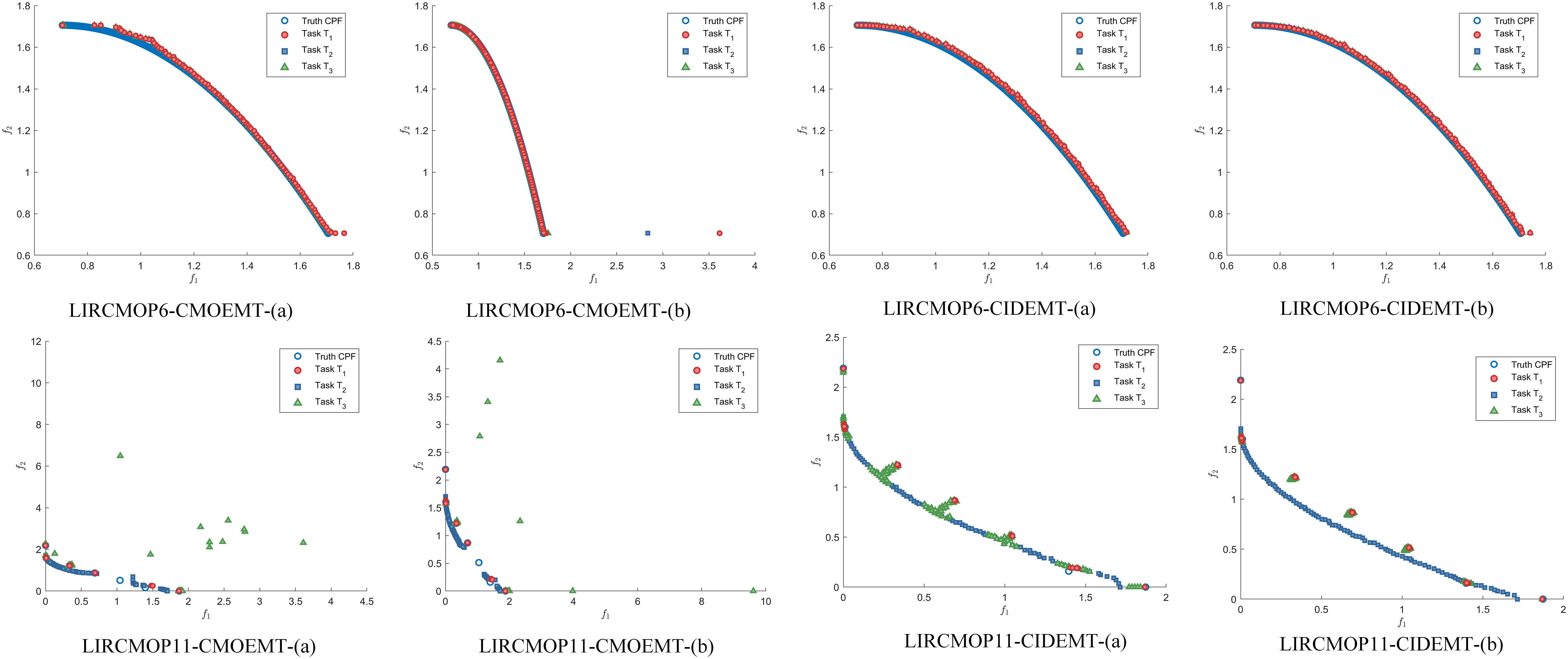

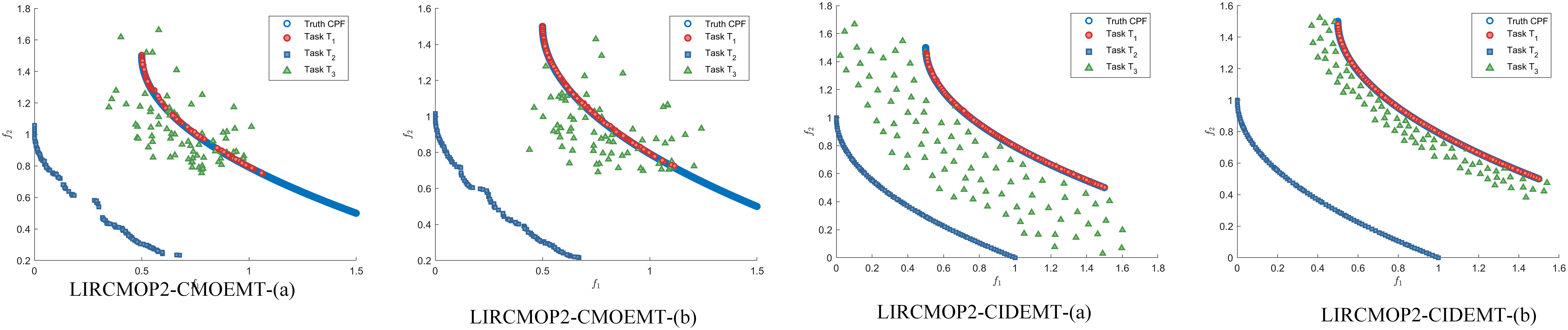

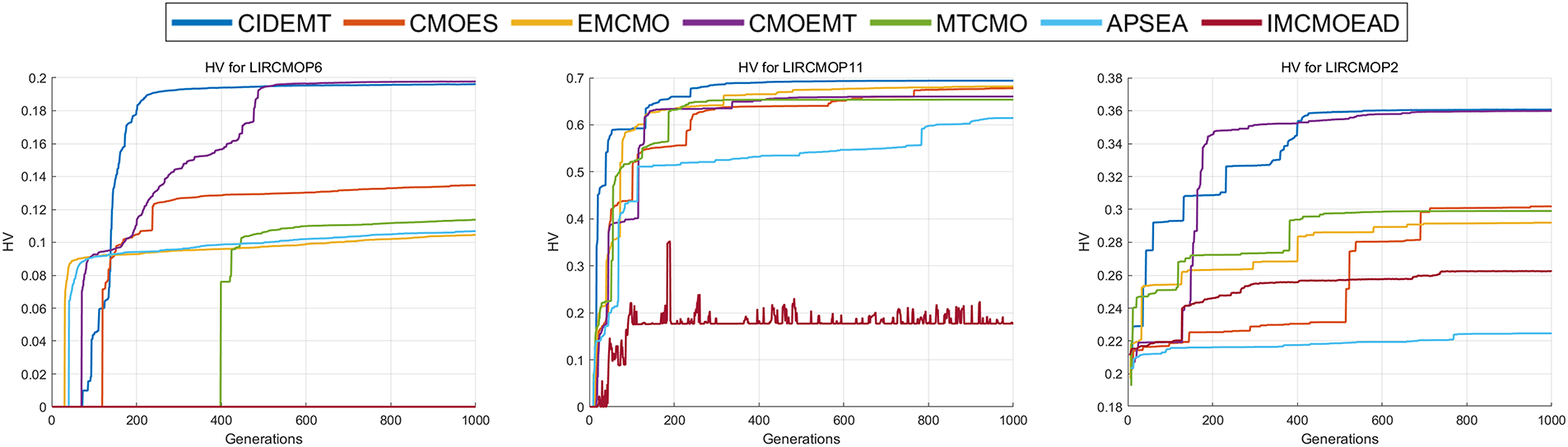

To better visualize the solution quality, Fig. 6 presents the final solution distributions of CIDEMT and and the CMOEMT algorithm, which also addresses three tasks, at both the mid-term and final stages across three different problem types. On the LIRCMOP6 problem of type I, both CIDEMT and CMOEMT showed good convergence, but their convergence speeds were not as fast as that of CIDEMT. For LIRCMOP11 and LIRCMOP2, which belong to type II and type III problems, compared to CMOEMT and CIDMET, due to the collaboration among tasks, each task achieves better convergence, thereby enhancing the excellent performance of the final solution. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 7, for the three types of problems, when the number of iterations is the same, CIDEMT converges faster than the benchmark algorithm. One limitation is that, due to the complex computations involved in the knowledge transfer process, the running time is somewhat disadvantaged compared to the baseline algorithm. Future efforts will focus on optimizing the runtime to improve efficiency. More detailed results are presented in Supplementary Materials Figs. S1–S8 and Table S7.

Figure 6: Distribution of mid-term and final solutions of CIDEMT and CMOEMT across three different problem types. (a) indicates the intermediate solution, (b) indicates the final solution

Figure 7: Comparison of convergence speeds of different algorithms

Overall, CIDEMT exhibits strong and consistent performance across both synthetic and real-world CMOPs. Its advantage in terms of IGD and HV metrics validates the effectiveness of the proposed multi-tasking and knowledge transfer mechanisms. Future work could further enhance CIDEMT’s generalizability by integrating hybrid strategies or extending its application to broader domains of multi-objective optimization.

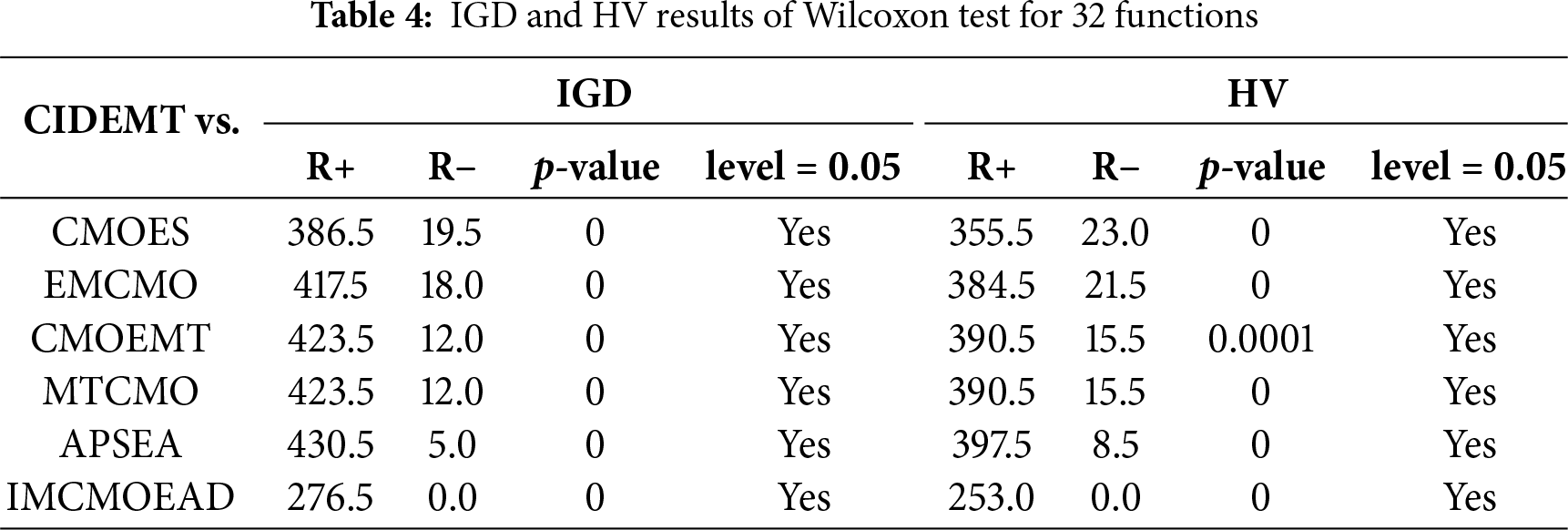

4.4 Effectiveness Analysis of CIDEMT and Benchmark Algorithms

Table 4 presents the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test across 32 benchmark functions. All p-values are below 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences between CIDEMT and the compared algorithms. Furthermore, the R+ values are consistently and substantially greater than the R- values, further validating the superior performance of CIDEMT.

As shown in Table 4, CIDEMT consistently outperforms the benchmark algorithms in terms of both IGD and HV metrics. Notably, CIDEMT demonstrates significant advantages over CMOES, EMCMO, CMOEMT, MTCMO, APSEA, and IMCMOEAD. The corresponding p-values for these comparisons are all zero, confirming that CIDEMT achieves statistically better or equivalent performance across these tests.

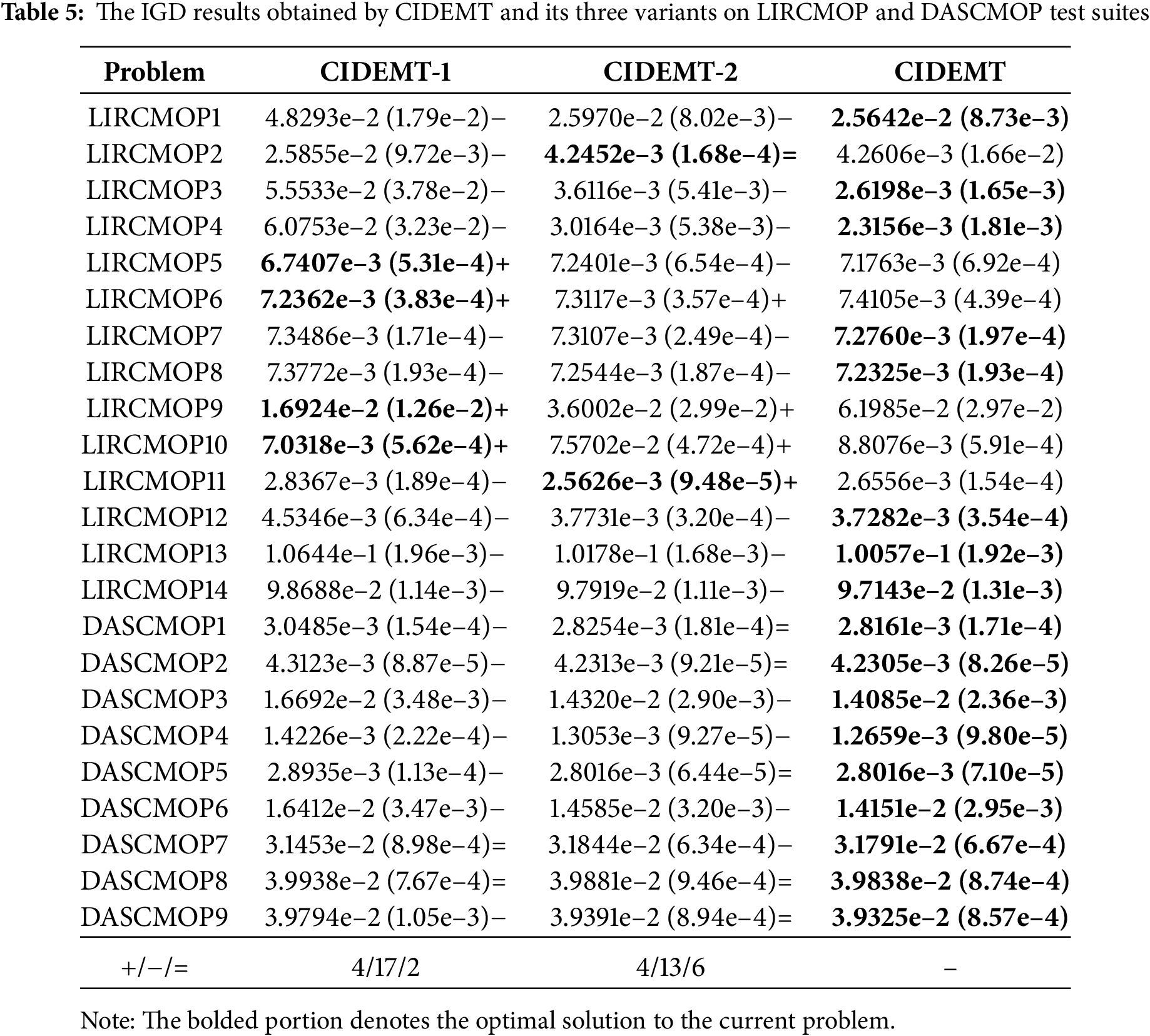

As shown in Table 5, an ablation study was conducted to further validate the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive evolution strategy pool (ESP) based on problem type, as well as the enhanced knowledge transfer mechanism. Two variants of CIDEMT were designed for comparison. CIDEMT-1 employs only the improved knowledge transfer strategy without utilizing adaptive strategies from the problem-type-based ESP. Conversely, CIDEMT-2 adopts adaptive strategies from the ESP during the optimization process but excludes the knowledge transfer mechanism.

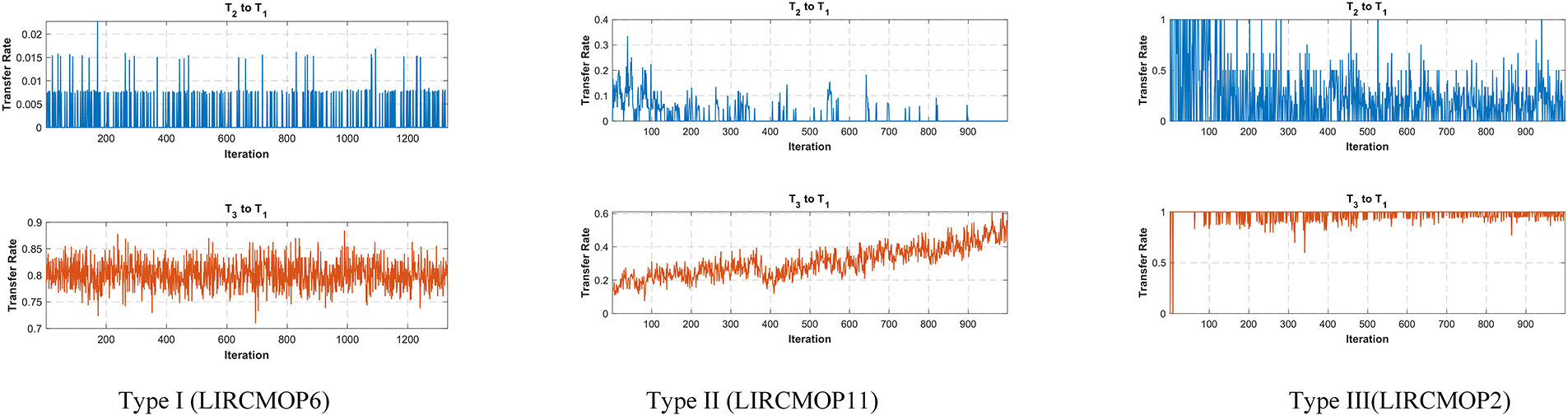

According to the results summarized in Table 5, CIDEMT achieved the best IGD averages across all DASCMOP benchmark problems and obtained eight optimal IGD values on the LIRCMOP benchmark, indicating overall superior performance. To illustrate the impact of knowledge transfer, we recorded the transfer process from auxiliary tasks

Figure 8: The CIDEMT in the knowledge transfer rates across the three types of problems

To further validate the effectiveness of its components, we conducted the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The results show that CIDEMT achieved statistically significant advantages over CIDEMT-1 and CIDEMT-2 on 17 and 14 benchmark problems, respectively. These experimental results confirm that both the problem-type-aware strategy selection and the enhanced knowledge transfer significantly contribute to improved convergence and diversity, thereby validating the effectiveness of the full CIDEMT framework.

This study proposes a two-stage, tri-task optimization algorithm—CIDEMT (Constraint-Intensity Driven Evolutionary Multi-Tasking)—which leverages the structural relationships between the constrained Pareto front (CPF) and the unconstrained Pareto front (UPF) to address constrained multi-objective optimization problems (CMOPs). By dynamically integrating auxiliary tasks, CIDEMT assists the main task in escaping local optima through adaptive strategy evolution and a

Extensive experiments conducted on three benchmark suites and eight real-world problems demonstrate that CIDEMT significantly outperforms six state-of-the-art algorithms in terms of IGD, HV, and statistical significance (Wilcoxon rank-sum test). These results confirm CIDEMT’s effectiveness and robustness in solving CMOPs with complex constraint structures.

Despite its strong empirical performance, CIDEMT still faces challenges in handling high-dimensional CMOPs, particularly regarding convergence speed and computational efficiency. As the number of objectives increases, identifying an accurate CPF becomes more difficult, potentially leading to longer optimization times. Future research will focus on enhancing CIDEMT’s scalability by incorporating multi-agent models to address operator selection in multitasking scenarios, thereby enabling more efficient search strategies. These improvements aim to broaden CIDEMT’s applicability and strengthen its performance in solving large-scale, real-world multi-objective optimization problems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 61972040, and the Science and Technology Research and Development Project funded by China Railway Material Trade Group Luban Company.

Author Contributions: Leyu Zheng conceptualized the study and wrote the manuscript. Mingming Xiao contributed to the concept, idea of the study and the revision of the manuscript. Ke Li contributed to the review of the manuscript. Yi Ren contributed to the review of the manuscript. Chang Sun review of experimental data of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.072036/s1.

References

1. Hemici M, Zouache D. A multi-population evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective constrained portfolio optimization problem. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(Suppl 3):3299–340. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10604-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pan JS, Yu N, Chu SC, Zhang A, Yan B, Watada J. Innovative approaches to task scheduling in cloud computing environments using an advanced willow catkin optimization algorithm. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(2):2495–520. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.058450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Song S, Zhang K, Zhang L, Wu N. A dual-population algorithm based on self-adaptive epsilon method for constrained multi-objective optimization. Inf Sci. 2024;655(6):119906. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ming F, Gong W, Wang L, Gao L. A constraint-handling technique for decomposition-based constrained many-objective evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2023;53(12):7783–93. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2023.3299570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhu Q, Zhang Q, Lin Q. A constrained multiobjective evolutionary algorithm with detect-and-escape strategy. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2020;24(5):938–47. doi:10.1109/tevc.2020.2981949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang W, Chen L, Li Y, Zhang J. A constrained multi/many-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm with a two-level balance scheme. IEEE Access. 2021;9:122509–31. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lagaros ND, Kournoutos M, Kallioras NA, Nordas AN. Constraint handling techniques for metaheuristics: a state-of-the-art review and new variants. Optim Eng. 2023;24(4):2251–98. doi:10.1007/s11081-022-09782-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ray T, Tai K, Seow KC. Multiobjective design optimization by an evolutionary algorithm. Eng Optim. 2001;33(4):399–424. doi:10.1080/03052150108940926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Deb K, Pratap A, Agarwal S, Meyarivan TAMT. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: nSGA-II. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2002;6(2):182–97. doi:10.1109/4235.996017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Takahama T, Sakai S. Constrained optimization by the ε constrained differential evolution with an archive and gradient-based mutation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation; 2010 Jul 18–23; Barcelona, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2010. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

11. Wang W, Xu L, Chau K. C

12. Fan Z, Li W, Cai X, Li H, Wei C, Zhang Q, et al. Push and pull search for solving constrained multi-objective optimization problems. Swarm Evol Comput. 2019;44(1):665–79. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qiao K, Yu K, Qu B, Liang J, Song H, Yue C, et al. Dynamic auxiliary task-based evolutionary multitasking for constrained multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2023;27(3):642–56. doi:10.1109/tevc.2022.3175065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Farias LR, Araújo AF. An inverse modeling constrained multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC); 2024 Oct 6–9; Kobe, Japan. Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 3727–32. [Google Scholar]

15. Ma Y, Shen B, Pan A, Xue J. Constraint landscape knowledge assisted constrained multiobjective optimization. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;90(2):101685. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Feng J, Liu S, Yang S, Zheng J, Liu J. An adaptive tradeoff evolutionary algorithm with composite differential evolution for constrained multi-objective optimization. Swarm Evol Comput. 2023;83(3):101386. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2023.101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang J, Wang W, Chau K. An improved golden jackal optimization algorithm based on multi-strategy mixing for solving engineering optimization problems. J Bionic Eng. 2024;21(2):1092–115. doi:10.1007/s42235-023-00469-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tian Y, Zhang T, Xiao J, Zhang X, Jin Y. A coevolutionary framework for constrained multiobjective optimization problems. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2020;25(1):102–16. [Google Scholar]

19. Wang Y, Huang K, Gong W, Ming F. Bi-directional search based on constraint relaxation for constrained multi-objective optimization problems with large infeasible regions. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;239(1):122492. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Qiao K, Chen Z, Qu B, Yu K, Yue C, Chen K, et al. A dual-population evolutionary algorithm based on dynamic constraint processing and resource allocation for constrained multi-objective optimization problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(3):121707. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ming F, Gong W, Jin Y. Even search in a promising region for constrained multi-objective optimization. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2024;11(2):474–86. doi:10.1109/jas.2023.123792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Qiao K, Yu K, Qu B, Liang J, Song H, Yue C. An evolutionary multitasking optimization framework for constrained multiobjective optimization problems. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2022;26(2):263–77. doi:10.1109/tevc.2022.3145582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ming F, Gong W, Wang L, Gao L. Constrained multiobjective optimization via multitasking and knowledge transfer. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2024;28(1):77–89. doi:10.1109/tevc.2022.3230822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ma Z, Wang Y. Evolutionary constrained multiobjective optimization: test suite construction and performance comparisons. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2019;23(6):972–86. doi:10.1109/tevc.2019.2896967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zitzler E, Laumanns M, Thiele L. SPEA2: improving the strength Pareto evolutionary algorithm. In: TIK-report. Vol. 103. Zürich, Switzerland: ETH Zurich; 2001. doi:10.3929/ethz-a-004284029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Deb K, Agrawal RB. Simulated binary crossover for continuous search space. Complex Syst. 1995;9(2):115–48. [Google Scholar]

27. Deb K, Goyal M. A combined genetic adaptive search (GeneAS) for engineering design. Comput Sci Inform. 1996;26:30–45. [Google Scholar]

28. Liang J, Qiao K, Yuan M, Yu K, Qu B, Ge S, et al. Evolutionary multi-task optimization for parameters extraction of photovoltaic models. Energy Convers Manage. 2020;207:112509. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tan KC, Feng L, Jiang M. Evolutionary transfer optimization—a new frontier in evolutionary computation research. IEEE Comput Intell Mag. 2021;16(1):22–33. doi:10.1109/mci.2020.3039066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tian Y, Wang R, Zhang Y, Zhang X. Adaptive population sizing for multi-population based constrained multi-objective optimization. Neurocomputing. 2025;621(1):129296. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu ZZ, Wang Y. Handling constrained multiobjective optimization problems with constraints in both the decision and objective spaces. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2019;23(5):870–84. doi:10.1109/tevc.2019.2894743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fan Z, Li W, Cai X, Huang H, Fang Y, You Y, et al. An improved epsilon constraint-handling method in MOEA/D for CMOPs with large infeasible regions. arXiv:1707.08767. 2017. [Google Scholar]

33. Fan Z, Li W, Cai X, Li H, Wei C, Zhang Q, et al. Difficulty adjustable and scalable constrained multiobjective test problem toolkit. Evol Comput. 2020;28(3):339–78. doi:10.1162/evco_a_00259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kannan BK, Kramer SN. An augmented Lagrange multiplier based method for mixed integer discrete continuous optimization and its applications to mechanical design. J Mech Des. 1994;116(2):405–11. doi:10.1115/1.2919393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ray T, Liew KM. A swarm metaphor for multiobjective design optimization. Eng Optim. 2002;34(2):141–53. doi:10.1080/03052150210915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jain H, Deb K. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point based nondominated sorting approach, part II: handling constraints and extending to an adaptive approach. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2013;18(4):602–22. doi:10.1109/tevc.2013.2281534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang HZ, Gu YK, Du X. An interactive fuzzy multi-objective optimization method for engineering design. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2006;19(5):451–60. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2005.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Steven G. Evolutionary algorithms for single and multicriteria design optimization. A. Osyczka. Springer Verlag, Berlin, 2002, ISBN 3-7908-1418-01. Struct Multidisc Optim. 2002;24(1):88–9. [Google Scholar]

39. Parsons MG, Scott RL. Formulation of multicriterion design optimization problems for solution with scalar numerical optimization methods. J Ship Res. 2004;48(1):61–76. doi:10.5957/jsr.2004.48.1.61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dhiman G, Kumar V. Multi-objective spotted hyena optimizer: a multi-objective optimization algorithm for engineering problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2018;150(6):175–97. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2018.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Floudas CA, Pardalos PM. A collection of test problems for constrained global optimization algorithms. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

42. Ryoo HS, Sahinidis NV. Global optimization of nonconvex NLPs and MINLPs with applications in process design. Comput Chem Eng. 1995;19(5):551–66. doi:10.1016/0098-1354(94)00097-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kocis GR, Grossmann IE. A modelling and decomposition strategy for the MINLP optimization of process flowsheets. Comput Chem Eng. 1989;13(7):797–819. doi:10.1016/0098-1354(89)85053-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Rathore AK, Holtz J, Boller T. Synchronous optimal pulsewidth modulation for low-switching-frequency control of medium-voltage multilevel inverters. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2010;57(7):2374–81. doi:10.1109/tie.2010.2047824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kumar A, Jha BK, Dheer DK, Singh D, Misra RK. Nested backward/forward sweep algorithm for power flow analysis of droop regulated islanded microgrids. IET Gen Trans Distrib. 2019;13(14):3086–95. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2019.0388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tian Y, Cheng R, Zhang X, Jin Y. PlatEMO: a MATLAB platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization [educational forum]. IEEE Comput Intell Mag. 2017;12(4):73–87. doi:10.1109/mci.2017.2742868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Bosman PA, Thierens D. The balance between proximity and diversity in multiobjective evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2003;7(2):174–88. doi:10.1109/tevc.2003.810761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zitzler E, Thiele L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: a comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2002;3(4):257–71. doi:10.1109/4235.797969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools