Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LP-YOLO: Enhanced Smoke and Fire Detection via Self-Attention and Feature Pyramid Integration

1 Graduate School, Hunan Institute of Engineering, Xiangtan, 411104, China

2 College of Materials and Chemical Engineering, Hunan Institute of Engineering, Xiangtan, 411104, China

3 College of Electrical and Information Engineering, Hunan Institute of Engineering, Xiangtan, 411104, China

* Corresponding Author: Haiqiao Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Attention Mechanism-based Complex System Pattern Intelligent Recognition and Accurate Prediction)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 63 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072058

Received 18 August 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Accurate detection of smoke and fire sources is critical for early fire warning and environmental monitoring. However, conventional detection approaches are highly susceptible to noise, illumination variations, and complex environmental conditions, which often reduce detection accuracy and real-time performance. To address these limitations, we propose Lightweight and Precise YOLO (LP-YOLO), a high-precision detection framework that integrates a self-attention mechanism with a feature pyramid, built upon YOLOv8. First, to overcome the restricted receptive field and parameter redundancy of conventional Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), we design an enhanced backbone based on Wavelet Convolutions (WTConv), which expands the receptive field through multi-frequency convolutional processing. Second, a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) is employed to achieve bidirectional feature fusion, enhancing the representation of smoke features across scales. Third, to mitigate the challenge of ambiguous object boundaries, we introduce the Frequency-aware Feature Fusion (FreqFusion) module, in which the Adaptive Low-Pass Filter (ALPF) reduces intra-class inconsistencies, the offset generator refines boundary localization, and the Adaptive High-Pass Filter (AHPF) recovers high-frequency details lost during down-sampling. Experimental evaluations demonstrate that LP-YOLO significantly outperforms the baseline YOLOv8, achieving an improvement of 9.3% in mAP@50 and 9.2% in F1-score. Moreover, the model is 56.6% and 32.4% smaller than YOLOv7-tiny and EfficientDet, respectively, while maintaining real-time inference speed at 238 frames per second (FPS). Validation on multiple benchmark datasets, including D-Fire, FIRESENSE, and BoWFire, further confirms its robustness and generalization ability, with detection accuracy consistently exceeding 82%. These results highlight the potential of LP-YOLO as a practical solution with high accuracy, robustness, and real-time performance for smoke and fire source detection.Keywords

Smoke and fire source detection play a crucial role in fire early warning and environmental monitoring [1]. Taking petrochemical plants as an example, the high density of production workshops, along with the storage and use of large quantities of flammable, explosive, and toxic chemicals within the plant, poses significant risks. In the event of a fire, not only can production be disrupted and economic losses incurred, but chain reactions may also occur, leading to severe environmental pollution and posing a major threat to personnel safety and property [2]. Therefore, achieving rapid and accurate early fire detection and timely warning has become a core requirement for safe production [3]. In recent years, fire source and smoke detection technologies have received significant attention both domestically and internationally in plant safety management and have gradually become integral components of intelligent monitoring systems.

With the rapid advancement of deep learning, smoke and fire source detection methods based on deep neural networks have become a dominant research trend. Such approaches automatically extract discriminative features of smoke, including color and texture, thereby improving detection accuracy and robustness [4]. For instance, Ref. [5] proposed a smoke detection method that integrates a numerical transformation–attention module with non-maximum suppression. By incorporating multi-directional detection, Soft-SPP [6], and a joint weighting strategy, this method effectively addresses challenges such as subtle smoke features and highly variable complex backgrounds. Zhan et al. [7] introduced a detection framework that combines a compound network with adjacent layers and a recursive feature pyramid, significantly enhancing detection accuracy in complex aerial scenarios. Similarly, Ref. [8] proposed a fire and smoke detection model based on DETR [9], which improves detection efficiency through a normalization-based attention module and a multi-scale deformable attention mechanism. Although these studies provide valuable insights into smoke detection models, further optimization remains necessary with respect to real-time performance and detection accuracy. To this end, we propose LP-YOLO, a high-precision smoke and fire source detection method built upon YOLOv8. LP-YOLO leverages multi-scale feature fusion and key region enhancement mechanisms to achieve both higher detection accuracy and improved computational efficiency, thereby enabling fast and precise identification of smoke targets. The specific innovations of this study are as follows:

(1) To overcome the limitations of conventional convolutional neural networks in image processing—namely, restricted receptive fields and rapid parameter growth—this study constructs a WTConv-enhanced backbone. By leveraging wavelet transform for multi-frequency response convolution, the proposed backbone effectively enlarges the receptive field while mitigating excessive parameter expansion.

(2) To improve information utilization and enhance detection accuracy during feature fusion, a BiFPN-based neck is designed. Through a bidirectional fusion mechanism, the network optimizes the extraction and integration of target features. In addition, a weighted fusion strategy is incorporated to strengthen the contribution of information-rich features to the final detection outcomes.

(3) To address intra-class inconsistencies and ambiguous target boundaries, a Frequency-aware Feature Fusion (FreqFusion) module is introduced. Specifically, the Adaptive Low-Pass Filter (ALPF) reduces intra-class variations and refines boundary representation, the offset generator alleviates feature inconsistencies, and the Adaptive High-Pass Filter (AHPF) restores high-frequency details lost during down-sampling. Together, these components improve boundary sharpness and feature consistency.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 introduces the current research status of smoke and fire source detection. Section 2 reviews related literature and prior studies. Section 3 describes the overall architecture of the proposed network in detail. Section 4 presents the experimental results and comparative analyses on the public D-Fire dataset. Section 5 discusses the advantages of the proposed model and outlines potential directions for future development. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2.1 Traditional Smoke and Fire Detection

Traditional smoke and fire source detection approaches primarily include threshold-based and edge-based methods [10,11]. Threshold-based methods distinguish target and non-target regions by defining thresholds for grayscale or other feature values [12]; however, their performance degrades significantly under varying illumination or complex backgrounds, resulting in poor robustness. Edge-based methods rely on detecting boundary features [13], which are effective when target contours are distinct, but perform poorly when dealing with thin, diffuse, or irregularly shaped smoke. To improve detection accuracy, Ref. [14] proposed a method combining color segmentation with texture feature extraction, employing CoHDLBP and CoLBP descriptors and an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) classifier for recognition. Avgeris et al. [15] developed a three-layer CPSS system [16] for early fire detection, which integrates IoT sensor nodes [17] with edge computing for real-time data processing. Similarly, the literature [18] applied federated averaging, adaptive matrix estimation, and proximity algorithms to aggregate sensor data, enabling rapid smoke detection in smart home edge environments. Although these traditional image-processing-based approaches demonstrate certain effectiveness, they generally rely on manually designed features and entail high computational complexity. Consequently, their real-time performance is limited, making them less suitable for practical monitoring in complex environments.

2.2 Deep Learning-Based Smoke and Fire Detection

Recent advancements in deep learning have promoted its extensive application in smoke and fire source detection. Deep learning algorithms automatically learn features from data through multi-layer neural networks, enabling efficient feature extraction and target recognition [5]. Compared with traditional detection methods, deep learning-based approaches exhibit superior feature representation capabilities [19]. For instance, Khan et al. [20] proposed a convolutional neural network framework for smoke detection based on EfficientNet [21], which is effective under both clear and hazy conditions, thereby improving detection accuracy. Peng and wang [22] introduced a hybrid smoke detection algorithm that combines handcrafted features with deep learning features; in this approach, potential smoke regions are first extracted using handcrafted algorithms and subsequently processed by an improved SqueezeNet [23] model for detection. Yin et al. [24] developed a lightweight network incorporating an attention mechanism and an enhanced up-sampling strategy to improve detection of thin and small smoke regions in the early stages of fire. Similarly, literature [25] proposed a novel fire detection model integrating an enhanced Swin Transformer module [26] with an efficient channel attention mechanism, which effectively reduces false positives and enhances detection performance in complex environments. Li et al. [27] presented SMWE-GFPNNet, a high-precision smoke detection network for forest fires, where the Swin Multi-dimensional Window Extractor (SMWE) captures global smoke texture features and the Guillotine Feature Pyramid Network (GFPN) improves robustness against interference. To address the challenge of detecting small-scale fires and smoke in forest environments, Lin et al. [28] proposed LD-YOLO, a lightweight dynamic model based on YOLOv8, incorporating GhostConv [29], DySample [30], and Shape-IoU techniques to enhance detection accuracy. Literature [31] developed an intelligent fire detection system (IFDS) leveraging YOLOv8, cloud computing, and IoT technologies for real-time data processing, thereby improving fire detection reliability. Building on these studies, this paper proposes a high-precision smoke detection method that integrates a self-attention mechanism with a feature pyramid, further enhancing detection accuracy and robustness in complex industrial environments.

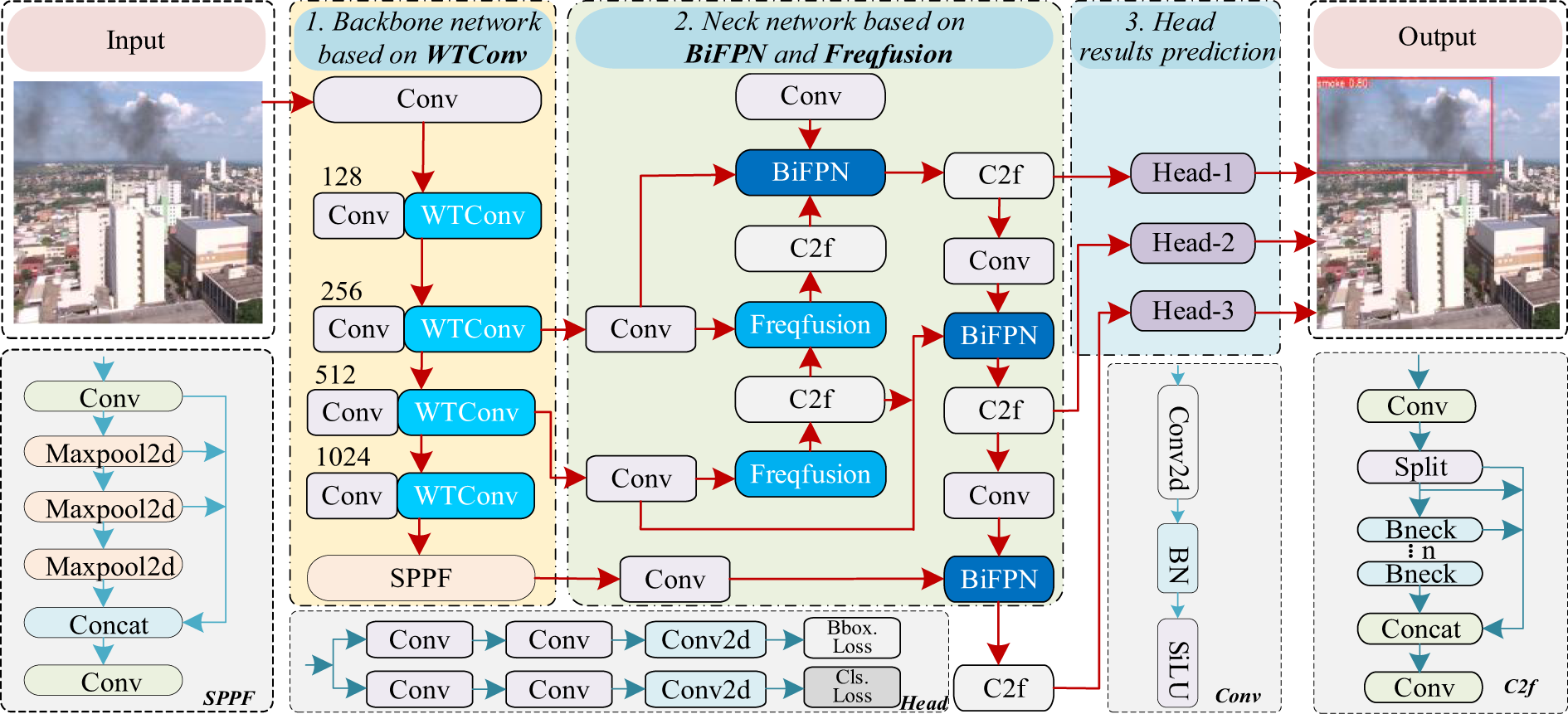

This study enhances the backbone and neck of YOLOv8 to develop a high-precision, high-speed, and lightweight smoke and fire source detection model. The overall architecture is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overall structure of the LP-YOLO method

In the backbone, Wavelet Convolutions (WTConv) are incorporated to expand the receptive field by leveraging multi-frequency responses derived from wavelet transformations. In the neck, a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) is employed to strengthen multi-scale feature interactions through bidirectional fusion in both top-down and bottom-up pathways. To further improve detection accuracy, a Frequency-aware Feature Fusion (FreqFusion) module is introduced, which refines the model’s ability to balance low- and high-frequency information within target images. Collectively, the three modules establish a coherent collaborative mechanism: WTConv enriches the receptive field with frequency-domain information, BiFPN ensures efficient multi-scale feature propagation and integration, and FreqFusion enhances boundary discrimination by restoring high-frequency details and reducing intra-class inconsistencies. Their synergistic effect systematically addresses the main limitations of traditional YOLOv8 in smoke and fire detection, namely restricted receptive fields, insufficient multi-scale feature fusion, and weak boundary clarity.

3.1 WTConv: Field Expansion and Low-Frequency Capture

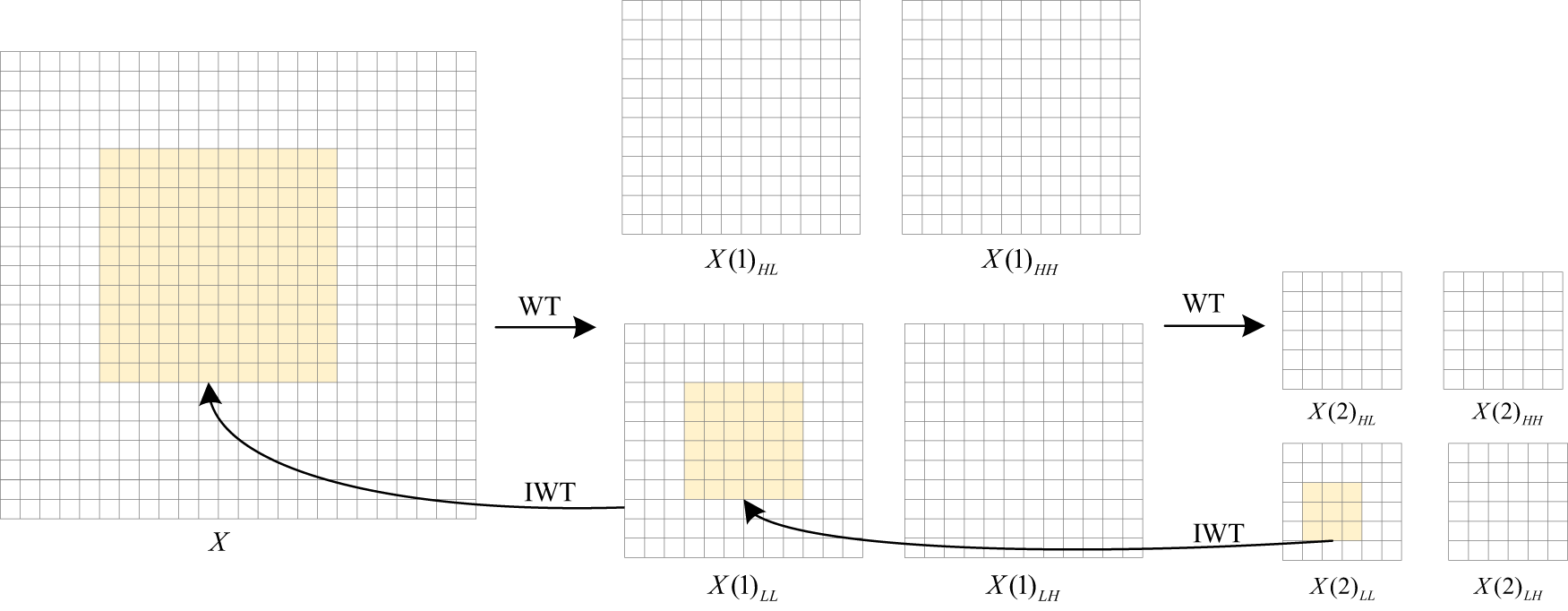

The features of smoke and fire sources typically comprise a mixture of low-frequency and high-frequency information. Specifically, the shape features of the targets often exhibit strong spatial consistency in the low-frequency components, whereas boundary details and texture information are more prominent in the high-frequency components [32]. Although conventional convolutional operations can capture certain target features, they are limited in processing low-frequency information and in expanding the receptive field [33]. To overcome these limitations, WTConv [34] is introduced into the backbone network of YOLOv8. As illustrated in Fig. 2, WTConv decomposes the input image into multiple frequency components, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to capture both global shape and fine-grained target features.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of WTConv

We adopt the Haar wavelet basis for decomposition, as it provides a simple and efficient orthogonal transformation with compact support, which has been widely applied in real-time visual detection tasks. In our implementation, a single-level wavelet decomposition (L = 1) is used, since deeper decompositions (L > 2) increase computational cost and tend to dilute high-frequency information that is crucial for smoke and fire boundary characterization. We empirically found that one-level decomposition achieves a good trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

First, the input target image is filtered using wavelet transformation to obtain the low-frequency and high-frequency components, as shown in Eq. (1):

here,

here,

Due to the linearity of the wavelet transform and its inverse transform, the low-frequency and high-frequency outputs can be effectively combined, as shown in Eq. (5).

Furthermore, to enhance feature representation, we use multi-level cascading operations to strengthen the fusion of frequency information. In each layer, we perform wavelet decomposition on the low-frequency component

Through this multi-level cascading wavelet transformation approach, the proposed method can better integrate features from different frequency ranges, enhancing the model’s accuracy in capturing smoke and fire targets.

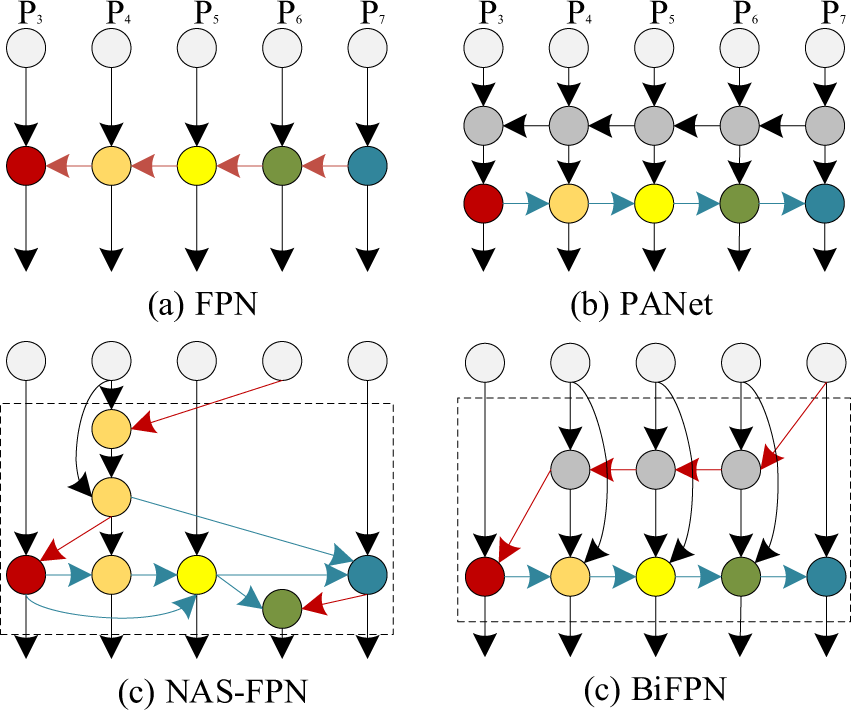

3.2 BiFPN: Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Optimization

Smoke and fire sources exhibit characteristics such as multi-scale representation, low contrast, and substantial morphological variability. Traditional unidirectional feature pyramids, such as FPN (Fig. 3a) and PANet (Fig. 3b), may suffer from information loss during feature propagation, as illustrated in Fig. 3d. To address this limitation, BiFPN [35] employs bidirectional feature fusion combined with a weighted fusion mechanism, enhancing the representation of target features and improving the robustness of smoke and fire detection networks.

Figure 3: Traditional feature pyramids and BiFPN

In BiFPN, each feature map not only propagates information from higher layers but also receives information from lower layers, thereby strengthening the interaction among features at different scales. Moreover, BiFPN introduces learnable weights to adaptively adjust the contribution of features at each scale to the final fusion result, optimizing the overall information flow. For a given set of input feature maps at multiple scales, the fused output generated by BiFPN is formulated as shown in Eq. (7).

here,

Each bidirectional path in BiFPN is treated as an individual feature network layer, and these layers can be repeated multiple times to facilitate higher-level feature fusion. The result is a streamlined bidirectional network that enhances the network’s ability to fuse target features, enabling it to more effectively leverage smoke and fire information across different scales, thereby improving the performance of object detection.

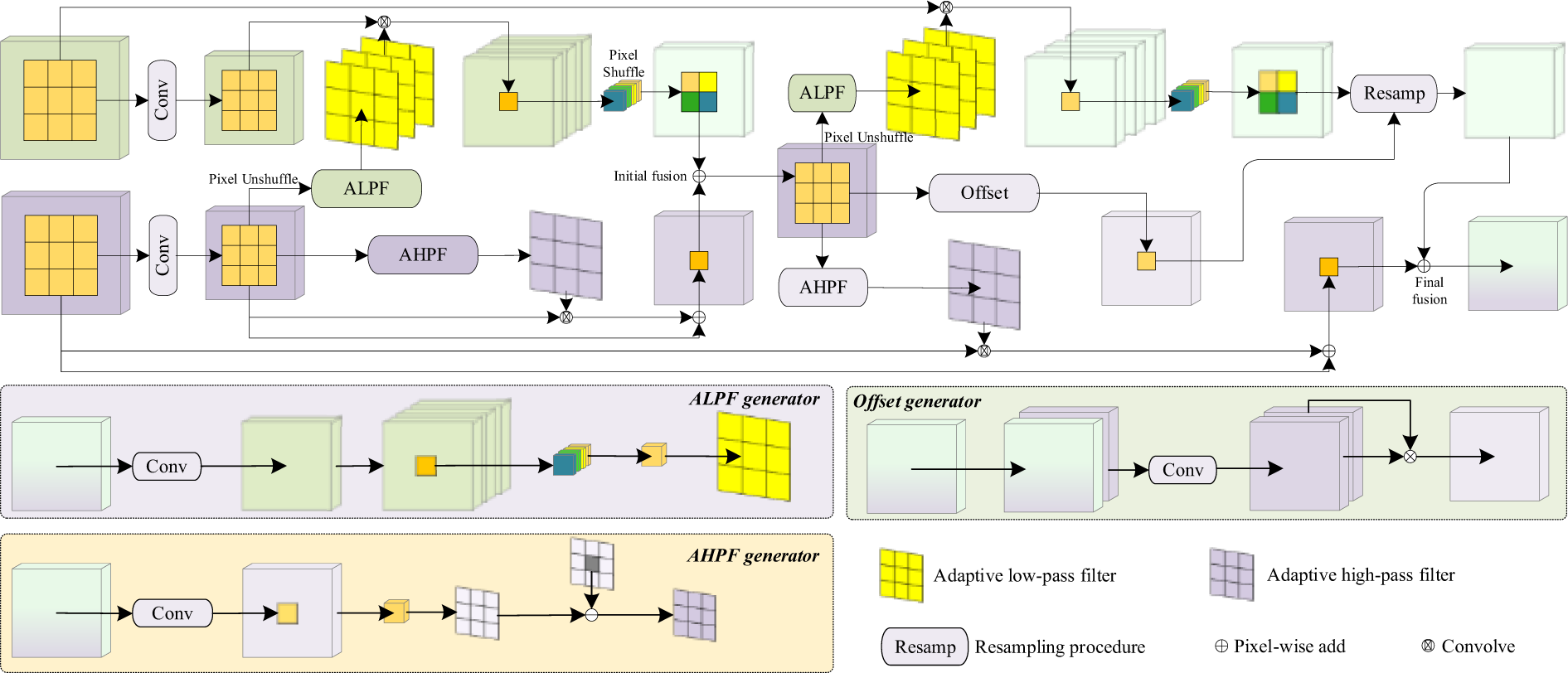

3.3 FreqFusion: Boundary Optimization

FreqFusion [36] is an innovative feature fusion method, as shown in Fig. 4. FreqFusion leverages frequency domain information to enhance the fusion process. The core concept is to achieve intra-class consistency enhancement and boundary detail optimization through the use of an Adaptive Low-Pass Filter (ALPF) generator, an offset generator, and an Adaptive High-Pass Filter (AHPF) generator.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of the FreqFusion module

Firstly, the ALPF generator learns a spatially adaptive low-pass filter to smooth the high-level features, making the intra-class features more consistent, as expressed by:

where

where

Given the low contrast and blurred boundaries of smoke and fire sources, the ALPF component in FreqFusion reduces instability within target regions, thereby improving intra-class consistency. The offset generator enhances the structural information of smoke and fire edges, resulting in clearer boundaries. Additionally, the AHPF component restores blurred details, enhancing the contrast between the target and background, which leads to more precise detection and recognition. Therefore, FreqFusion significantly improves perception accuracy in smoke and fire detection tasks, enhancing the adaptability of UAV-based detection systems in complex environments.

4.1 Experimental Setup and Experimental Data

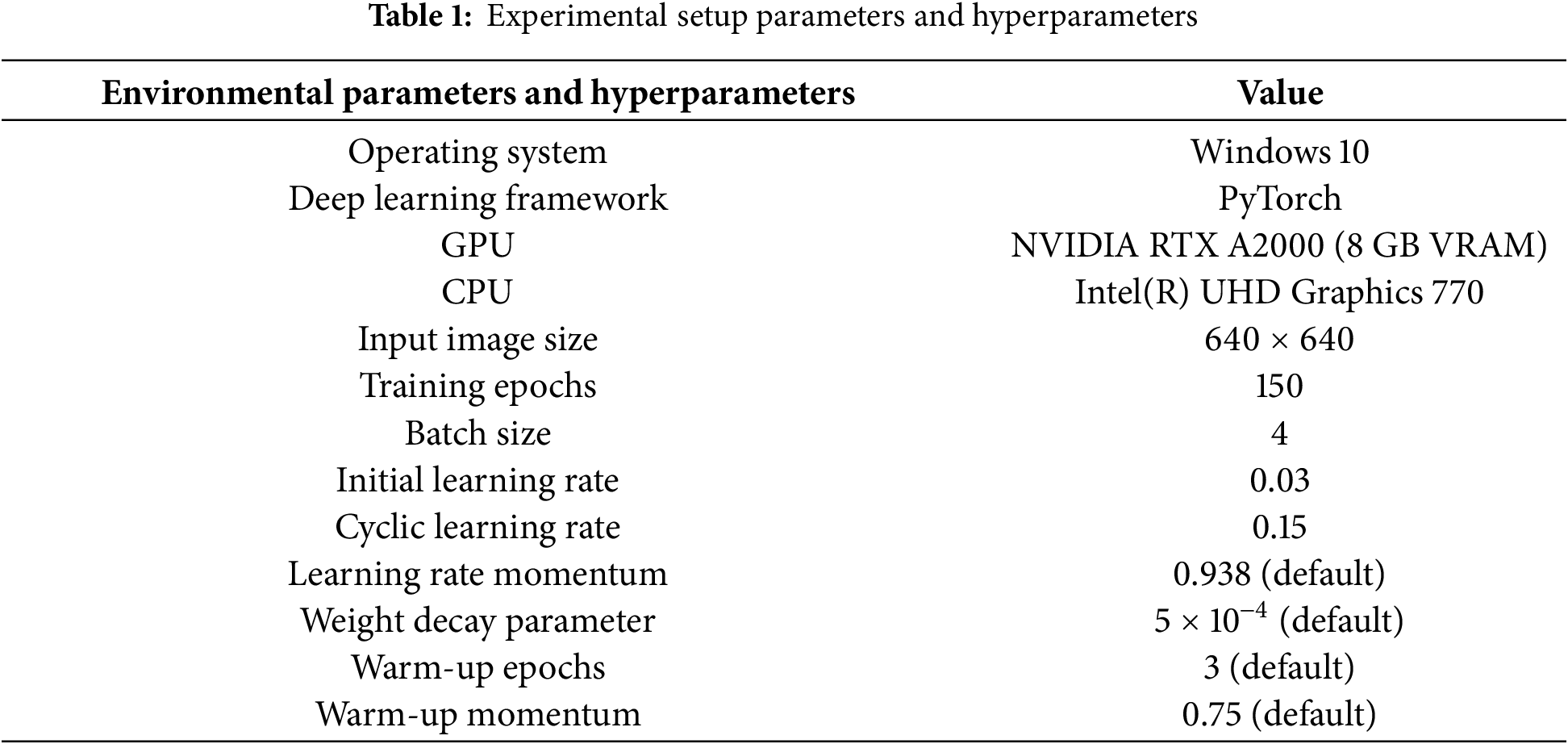

The experiments were conducted on a Windows 10 system using PyTorch, with an NVIDIA RTX A2000 GPU and Intel UHD Graphics 770 CPU, and all input images were resized to 640 × 640. The model was trained for 150 epochs with standard YOLOv8n data augmentation and optimization strategies, with detailed settings summarized in Table 1.

The experiments in this study employ the publicly available smoke and fire dataset, D-Fire [37], which contains images collected from both UAV platforms and handheld cameras, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization ability in real-world environments. The dataset comprises 21,000 images in total, including 9838 background images without targets, 1164 images containing fire only, 5867 images containing smoke only, and 4658 images containing both fire and smoke. In addition, it provides 14,692 fire annotations and 11,865 smoke annotations. For preprocessing, the dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets at a ratio of 6:2:2. Specifically, the training set consists of 12,600 images, the validation set includes 4200 images, and the test set comprises 4200 images, supplemented by additional UAV-captured samples for evaluation.

The performance of the proposed algorithm was evaluated from two main perspectives: detection accuracy and computational efficiency. Detection accuracy was quantified using precision, recall, F1-score, average precision (AP), and mean average precision (mAP). The specific formulations for these evaluation metrics are presented as follows:

here, TP denotes the number of true positive samples, TN denotes the number of true negative samples, FP denotes the number of false positive samples, and FN denotes the number of false negative samples.

A lower parameter count (Params) and reduced giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPS) indicate that the model demands less computational cost and fewer hardware resources. In practical engineering applications, frames per second (FPS) is an important performance metric, particularly for lightweight detection tasks where real-time processing is essential. FPS is computed based on the detection response time, as expressed in the following equation:

here, Tp denotes the time required for image preprocessing, Ti denotes the inference time, and Tn denotes the time for post-processing.

4.3 Comparative Analysis of Results

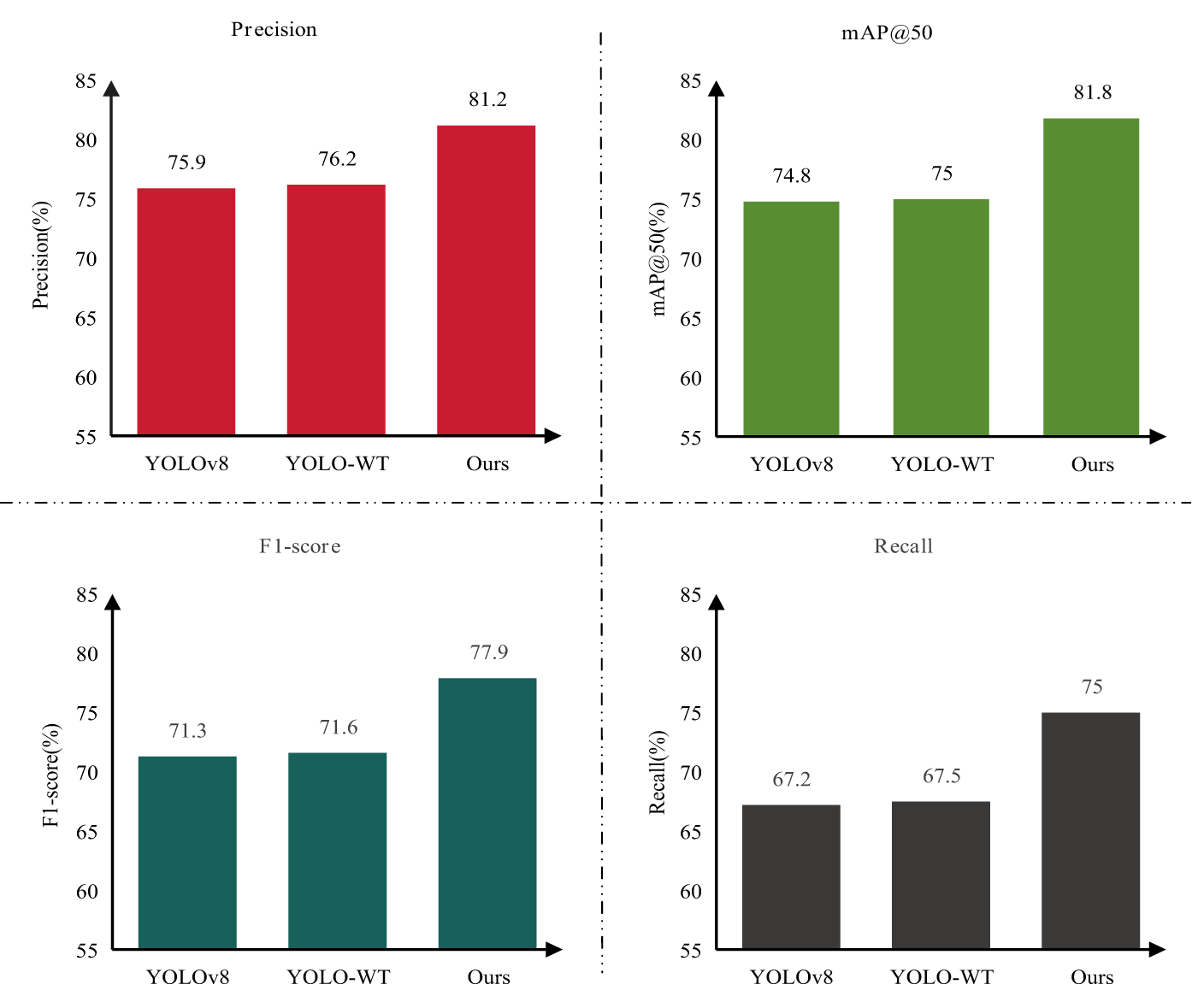

4.3.1 Ablation Experiment on Backbone Network

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed backbone network optimization, a systematic ablation study was conducted to examine its impact on object detection performance. The original YOLOv8 model was adopted as the baseline. Subsequently, the WTConv module was integrated into the backbone to enhance feature extraction capabilities, resulting in the optimized variant, denoted as YOLO-WT. Finally, a comparative analysis was performed among YOLOv8, YOLO-WT, and the full proposed model. The corresponding experimental results are summarized in Fig. 5, illustrating the performance improvements achieved by each modification.

Figure 5: Ablation experiment on backbone network

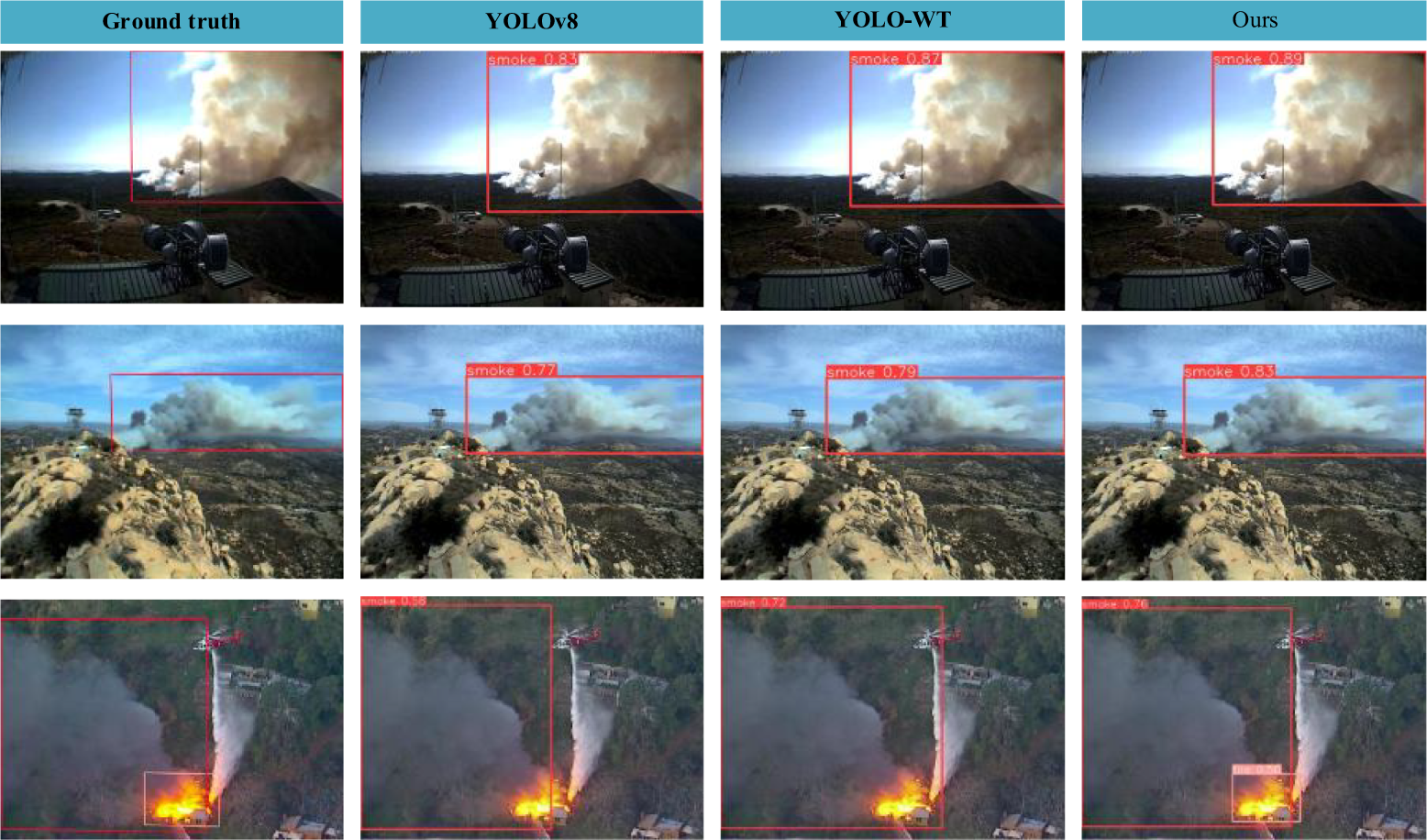

The experimental results demonstrate that after optimizing the backbone network with WTConv, YOLO-WT outperforms the original YOLOv8 in terms of Precision, mAP@50, F1-score, and Recall, indicating the effectiveness of the backbone optimization in enhancing detection accuracy. Furthermore, Fig. 6 provides a more intuitive comparison of different methods on smoke and fire detection tasks. It can be observed that both YOLOv8 and YOLO-WT still exhibit a certain degree of missed detections, whereas the proposed method not only substantially reduces missed detections but also achieves the highest overall detection accuracy, further validating its superiority.

Figure 6: Visualization results of ablation experiment on the backbone network

4.3.2 Ablation Experiment on Neck Network

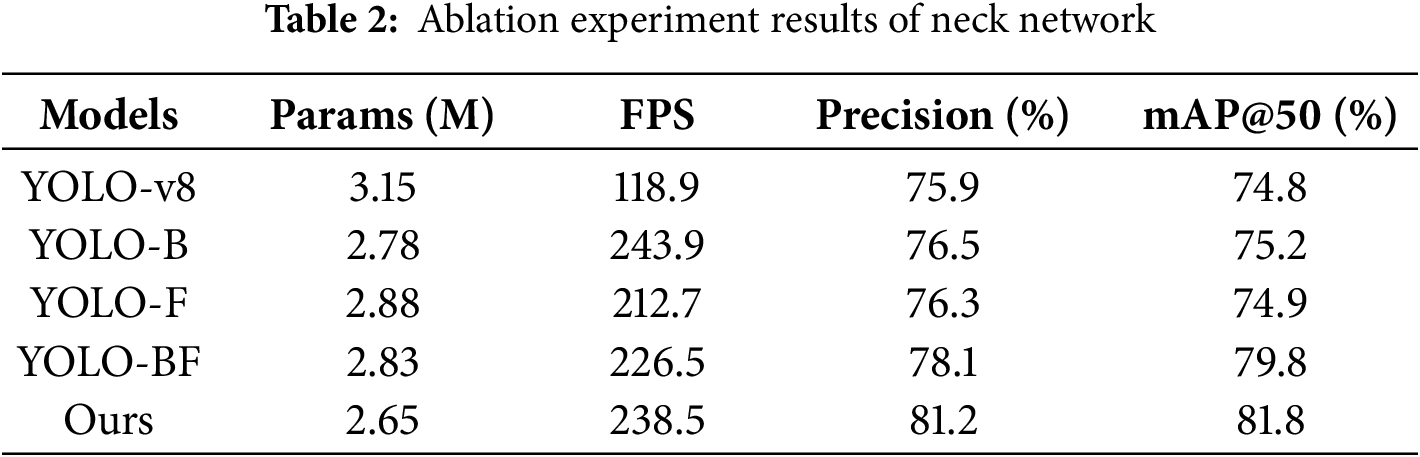

In the neck network ablation experiment, the BiFPN and FreqFusion modules were introduced to optimize the neck network, and three ablation models were constructed: YOLO-B (only BiFPN introduced), YOLO-F (only FreqFusion introduced), and YOLO-BF (both BiFPN and FreqFusion introduced). The detailed experimental results are shown in Table 2.

From the experimental results presented in Table 2, it can be observed that YOLO-BF achieves a reduction in the number of parameters compared to YOLOv8, decreasing the model size from 3.15 to 2.83M and thereby reducing computational complexity. Meanwhile, the inference speed increased from 118.9 to 226.5 FPS, significantly enhancing real-time performance. In terms of detection accuracy, Precision improved from 75.9% to 78.1%, and mAP@50 increased from 74.8% to 79.8%, indicating that the optimized neck network not only improves detection accuracy but also accelerates inference. Notably, the proposed LP-YOLO model achieves the smallest parameter count of only 2.65M, with a Precision of 81.2% and mAP@50 of 81.8%, surpassing all compared models in both accuracy and real-time performance.

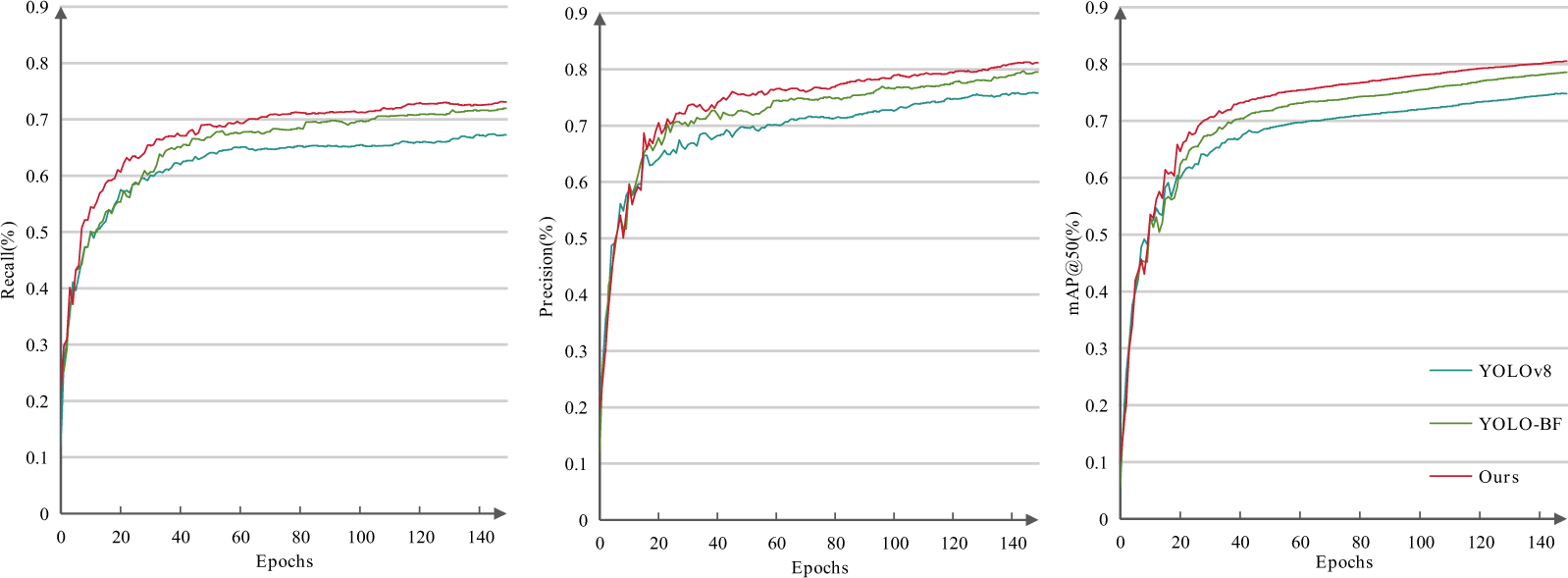

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the optimized model and verify its convergence and stability during training, the training processes of different models were further analyzed. Fig. 7 illustrates the variation trends of Precision, Recall, and mAP@50 for YOLOv8, YOLO-BF, and the proposed LP-YOLO over 150 training epochs, highlighting the superior and stable learning behavior of the proposed method.

Figure 7: Ablation experiment results curve for neck network

As shown in Fig. 7, compared to YOLOv8, YOLO-BF exhibits significant improvements in Precision, and mAP@50, indicating that the optimization of feature extraction and fusion by the BiFPN and Freqfusion modules is effective. Additionally, the proposed method, LP-YOLO, demonstrates the best convergence trend throughout the entire training process, ultimately achieving the highest Precision, Recall, and mAP@50. This further validates that the proposed optimization strategy significantly enhances the overall performance of the object detection model, achieving a better balance between accuracy, speed, and computational efficiency.

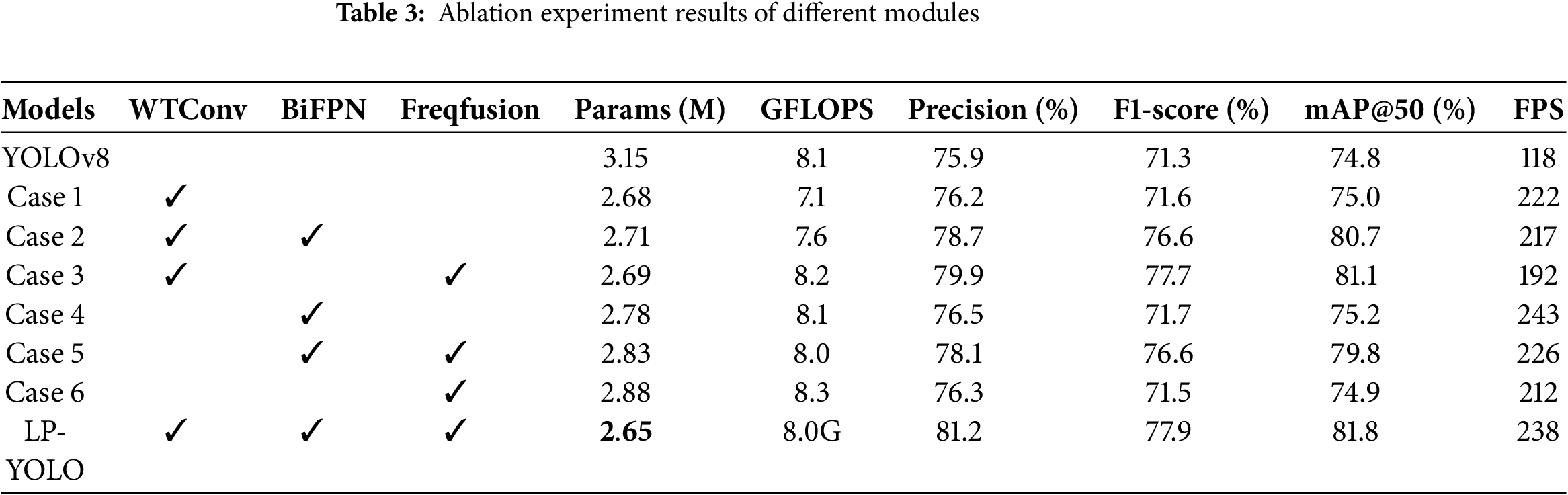

4.3.3 Ablation Experiment of Different Modules

In the ablation study, YOLOv8 was employed as the baseline model, while Case 1 through Case 6 were constructed by progressively introducing different optimization modules in order to assess their individual contributions. The results presented in Table 3 demonstrate that incorporating WTConv in Case 1 reduces the parameter count from 3.15 to 2.68 million while simultaneously enhancing detection accuracy, as precision increases from 75.9 to 76.2 percent and mAP@50 increases from 74.8 to 75.0 percent.

Moreover, the inference speed improves markedly from 118 to 222 frames per second, which indicates the effectiveness of WTConv in promoting lightweight design and computational efficiency. Additional gains are achieved when BiFPN or FreqFusion are combined with WTConv. In particular, Case 3 attains a mAP@50 of 81.1 percent, corresponding to an improvement of 6.3 percentage points compared with YOLOv8, thereby demonstrating the substantial contribution of FreqFusion to detection accuracy. By contrast, the introduction of BiFPN alone in Case 4 or its combination with FreqFusion in Case 5 yields moderate improvements in accuracy but also increases the parameter count and computational demand, and the overall performance remains lower than that of Case 3. Case 6, which incorporates only FreqFusion, achieves the highest inference speed of 243 frames per second. However, its precision and mAP@50 values are lower than those of LP-YOLO, suggesting that relying on a single module enhances speed at the expense of balanced detection performance. In comparison, LP-YOLO, which integrates WTConv, BiFPN, and FreqFusion, achieves the most favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency. The model requires only 2.65 million parameters, representing a reduction of 15.9 percent relative to YOLOv8, while attaining the highest overall performance across all evaluation metrics. LP-YOLO achieves a precision of 81.2 percent, an F1-score of 77.9 percent, a mAP@50 of 81.8 percent, and an inference speed of 238 frames per second. These findings demonstrate that LP-YOLO not only reduces model complexity but also substantially improves accuracy and real-time detection capability.

In conclusion, relative to YOLOv8, LP-YOLO achieves a superior trade-off between model compactness, detection accuracy, and computational efficiency, underscoring its strong potential for practical deployment in smoke and fire detection applications.

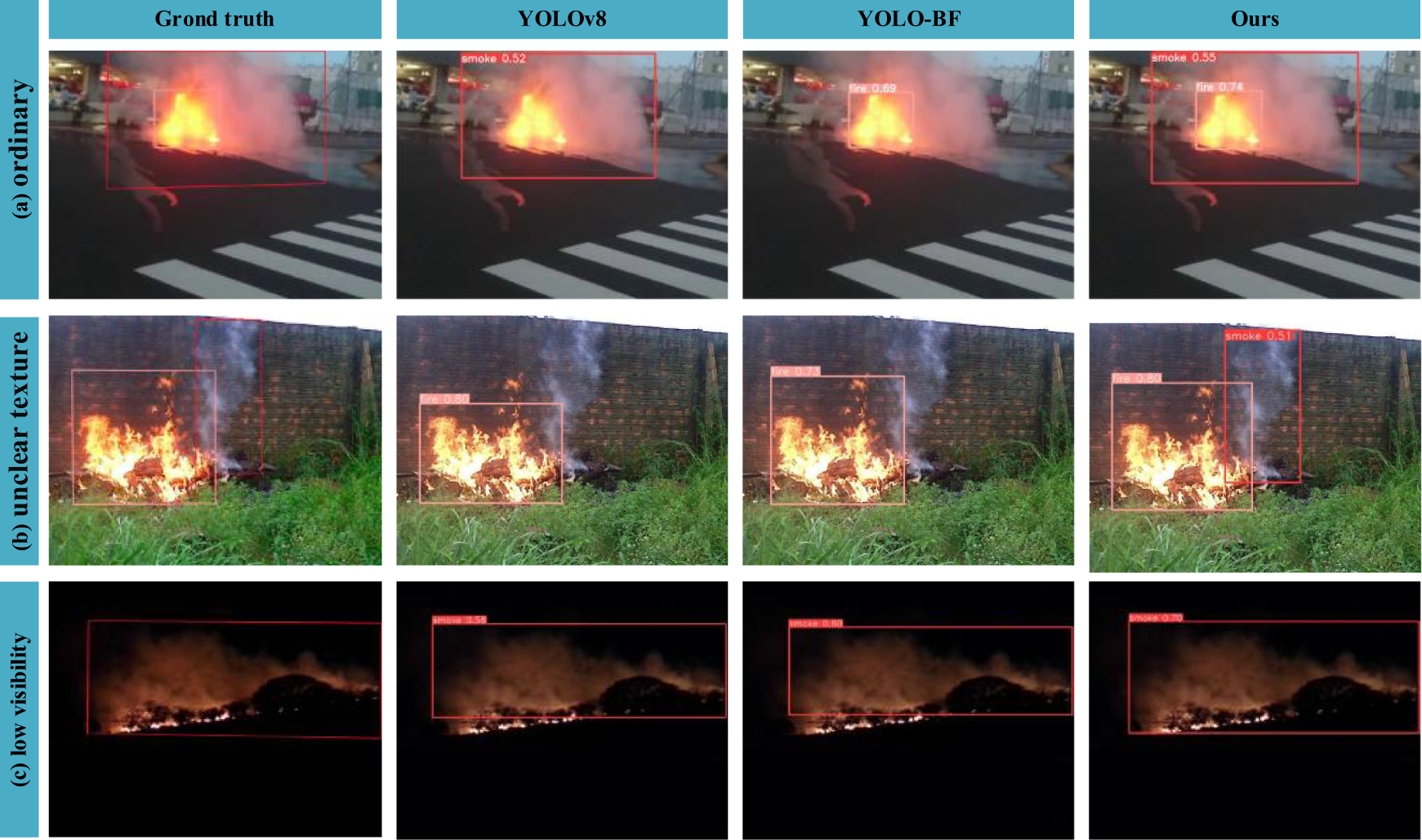

4.3.4 Smoke and Fire Detection in Different Scenarios

In real-world smoke and fire detection scenarios, the robustness of the model is critical due to the complexity and diversity of environmental conditions. To comprehensively assess the model’s detection performance in various challenging environments, three representative scenarios were selected for comparison experiments, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Visualization comparison of object detection in different scenarios

Fig. 8a illustrates the detection results for a common fire scenario. The original YOLOv8 model experiences missed detections, while the improved model proposed in this paper can detect the targets more reliably, showing higher detection accuracy and stability. Detecting smoke and fire with blurry textures is more challenging than detecting standard fire scenes. In Fig. 8b, the original method struggles to identify targets with ambiguous features, leading to missed detections or false positives. However, the proposed model, through feature fusion and boundary optimization, successfully detects low-contrast target areas, demonstrating that the method is more effective at capturing both local and global features, thus improving detection capabilities in complex environments. In the night-time detection experiment shown in Fig. 8c, due to insufficient lighting and significant variations in smoke and fire transparency, detection difficulty further increases. The original YOLOv8 is severely impacted by the low-light environment, resulting in lower detection accuracy. In contrast, the proposed method maintains the highest detection accuracy even under low visibility conditions, successfully detecting smoke and fire targets at night.

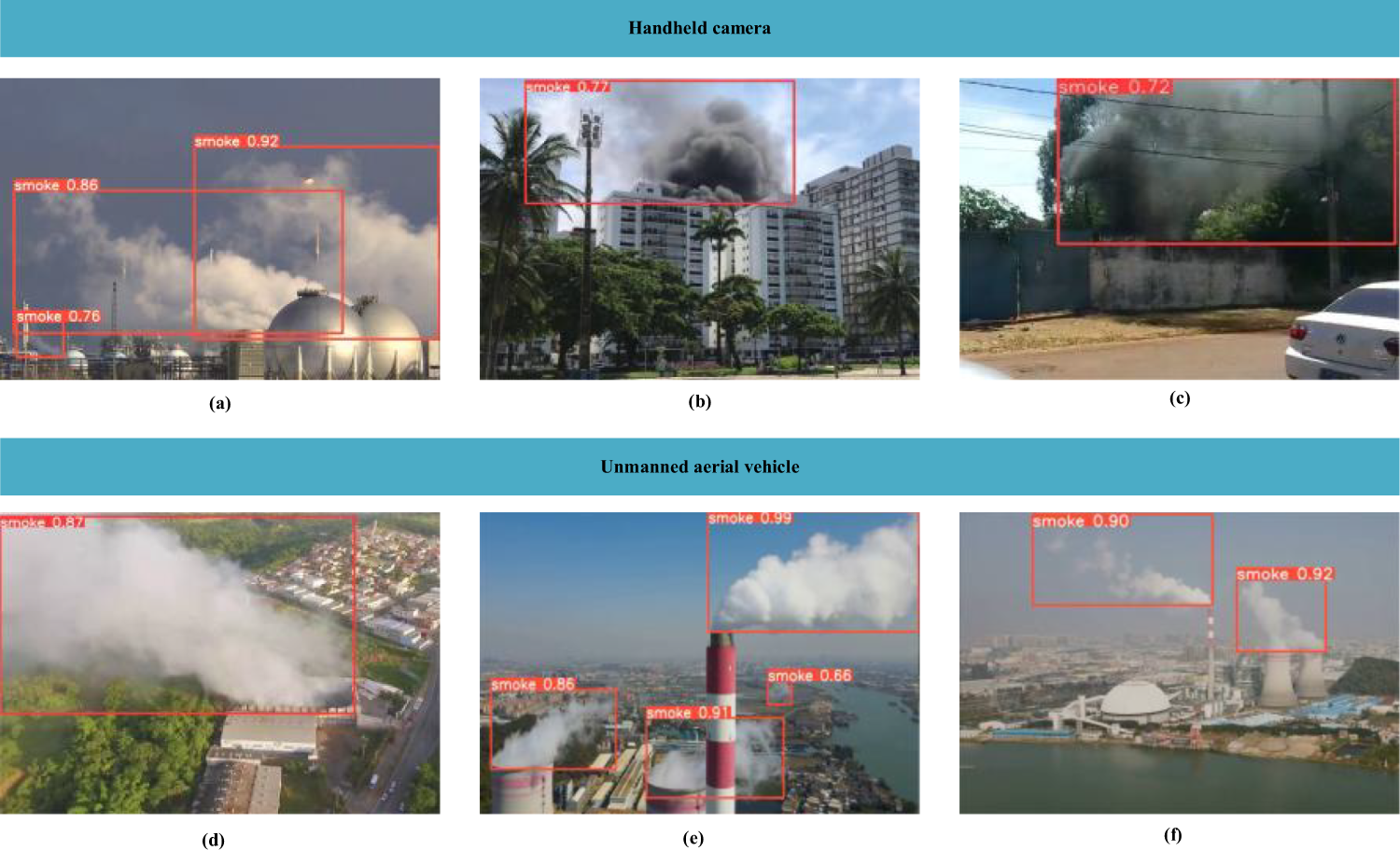

To further examine the adaptability of the proposed model under different acquisition conditions, we separately evaluated its performance on the two subsets of the D-Fire dataset: handheld camera and UAV scenes. As illustrated in Fig. 9a–c, the detection results on handheld camera scenes show that the model can accurately identify smoke and flame regions with clear contours and low false positives. Similarly, in Fig. 9d–f, the results on UAV scenes demonstrate that the model maintains stable detection performance even in high-altitude and large-scale monitoring scenarios, where targets appear relatively small and environmental interference is more complex. These results indicate that the proposed model achieves consistently high accuracy in both handheld and UAV conditions, reflecting its robustness across diverse shooting devices.

Figure 9: Detection results of the proposed model under different acquisition conditions

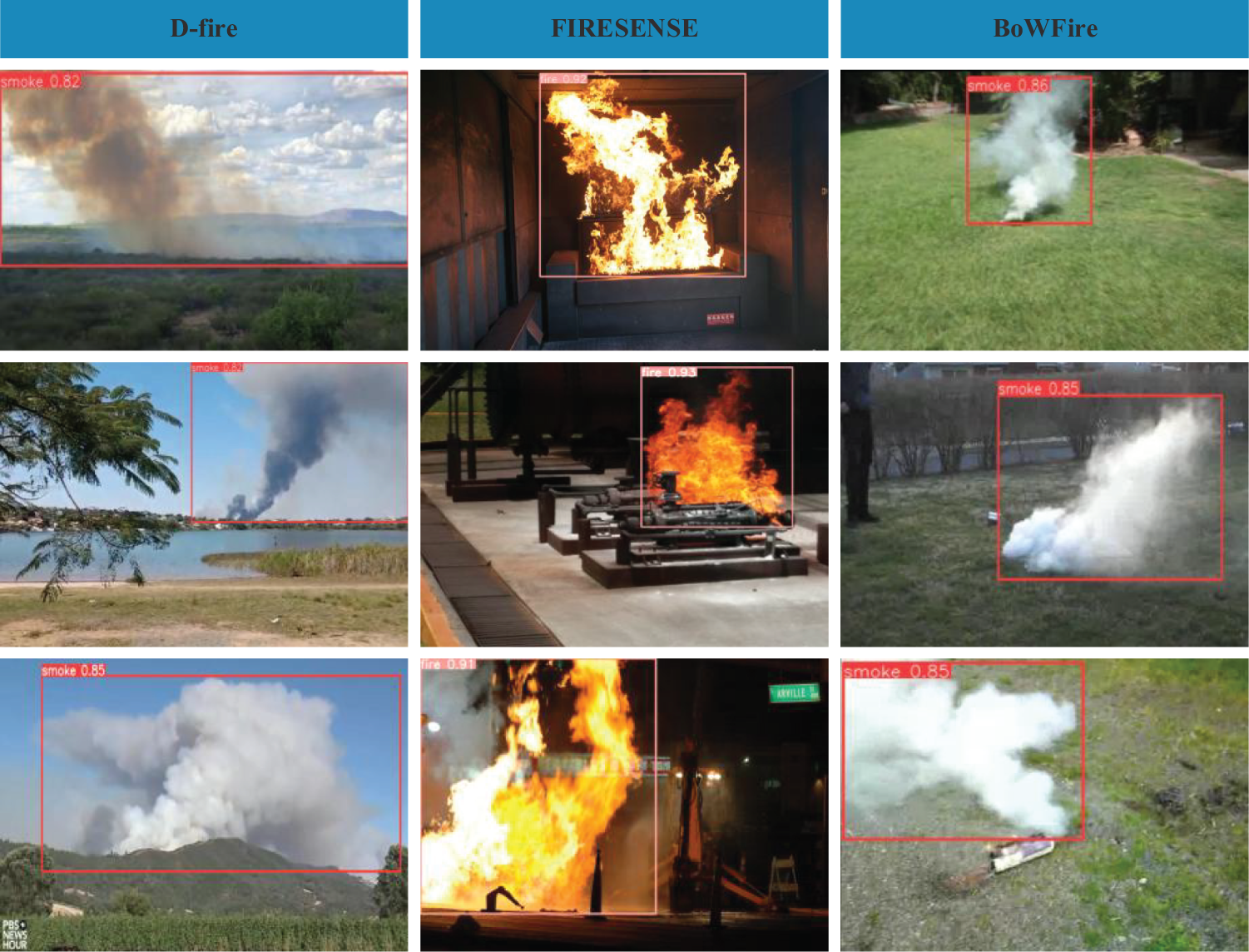

On the basis of training with the D-Fire dataset [37], the proposed model was further validated on two widely used benchmark datasets, FIRESENSE [38] and BoWFire [39]. As illustrated in Fig. 10, LP-YOLO consistently achieves detection accuracy above 82 percent across these datasets, which provides strong evidence of its generalization capability. The results show that the model is able to accurately detect smoke and fire targets of varying scales, densities, and shapes under diverse background conditions. This indicates that LP-YOLO is robust not only to environmental variability but also to changes in scene complexity and target appearance. Compared with evaluation on a single dataset, validation across multiple heterogeneous datasets offers more convincing evidence of the robustness and adaptability of the proposed method. The consistent performance across different benchmarks highlights its potential for practical deployment in real-world fire monitoring and early-warning systems across various platforms.

Figure 10: LP-YOLO was validated on three distinct datasets

4.3.5 Comparison with Multiple Methods

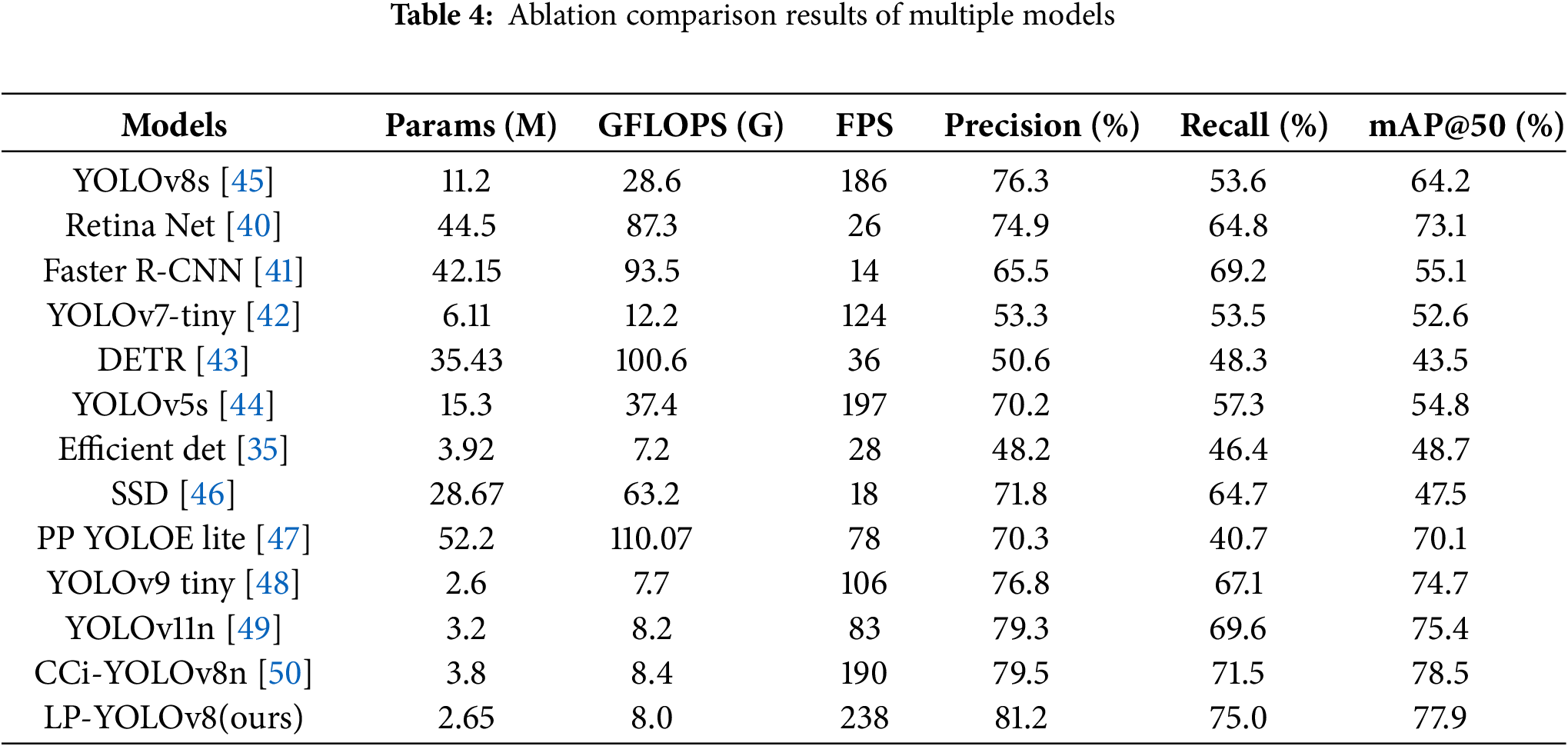

In this paper, the proposed method, LP-YOLOv8, was evaluated through extensive experiments and compared with mainstream detection models including RetinaNet [40], Faster R-CNN [41], YOLOv7-tiny [42], DETR [43], YOLOv5s [44], YOLOv8s [45], EfficientDet [35], SSD [46], PP YOLOE lite [47], YOLOv9 tiny [48], YOLOv11n [49] and CCi-YOLOv8n [50]. As summarized in Table 4, LP-YOLOv8 achieves a model size of 2.65M parameters, which is 56.6% smaller than YOLOv7-tiny and 76.3% smaller than YOLOv8s, demonstrating a clear advantage in resource-constrained scenarios. Among lightweight models, LP-YOLOv8 is also significantly more compact than PP YOLOE lite (52.2 M parameters), highlighting its suitability for edge deployment. In terms of inference speed, LP-YOLOv8 reaches 238 FPS, which is the highest among all compared models. This speed is over nine times faster than Faster R-CNN (14 FPS) and nearly ten times faster than SSD (18 FPS), and exceeds other fast models such as YOLOv5s (197 FPS) and YOLOv8s (186 FPS). Compared to PP YOLOE lite (78 FPS), LP-YOLOv8 is more than three times faster, ensuring real-time monitoring capability in large-scale, complex environments such as petrochemical plants and forest areas.

To provide a more comprehensive computational analysis, we additionally evaluated memory footprint and estimated power consumption on an edge GPU (NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier). LP-YOLOv8 requires approximately 2.1 GB of GPU memory, which is 45%–60% lower than conventional YOLO variants, and its estimated power consumption is around 12 W, indicating high feasibility for mobile or embedded platforms. In comparison, models such as Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet require more than 6 GB memory and consume over 25 W, significantly limiting their edge deployment potential. Despite its lightweight design, LP-YOLOv8 maintains state-of-the-art detection accuracy, with Precision 81.2%, Recall 75.0%, and mAP@0.5 77.9%, outperforming YOLOv8s (64.2%) and PP YOLOE lite (70.1%). These results demonstrate that LP-YOLOv8 provides an excellent balance between accuracy, speed, and computational efficiency, offering a convincing advantage over both mainstream and lightweight detection models for real-time edge deployment.

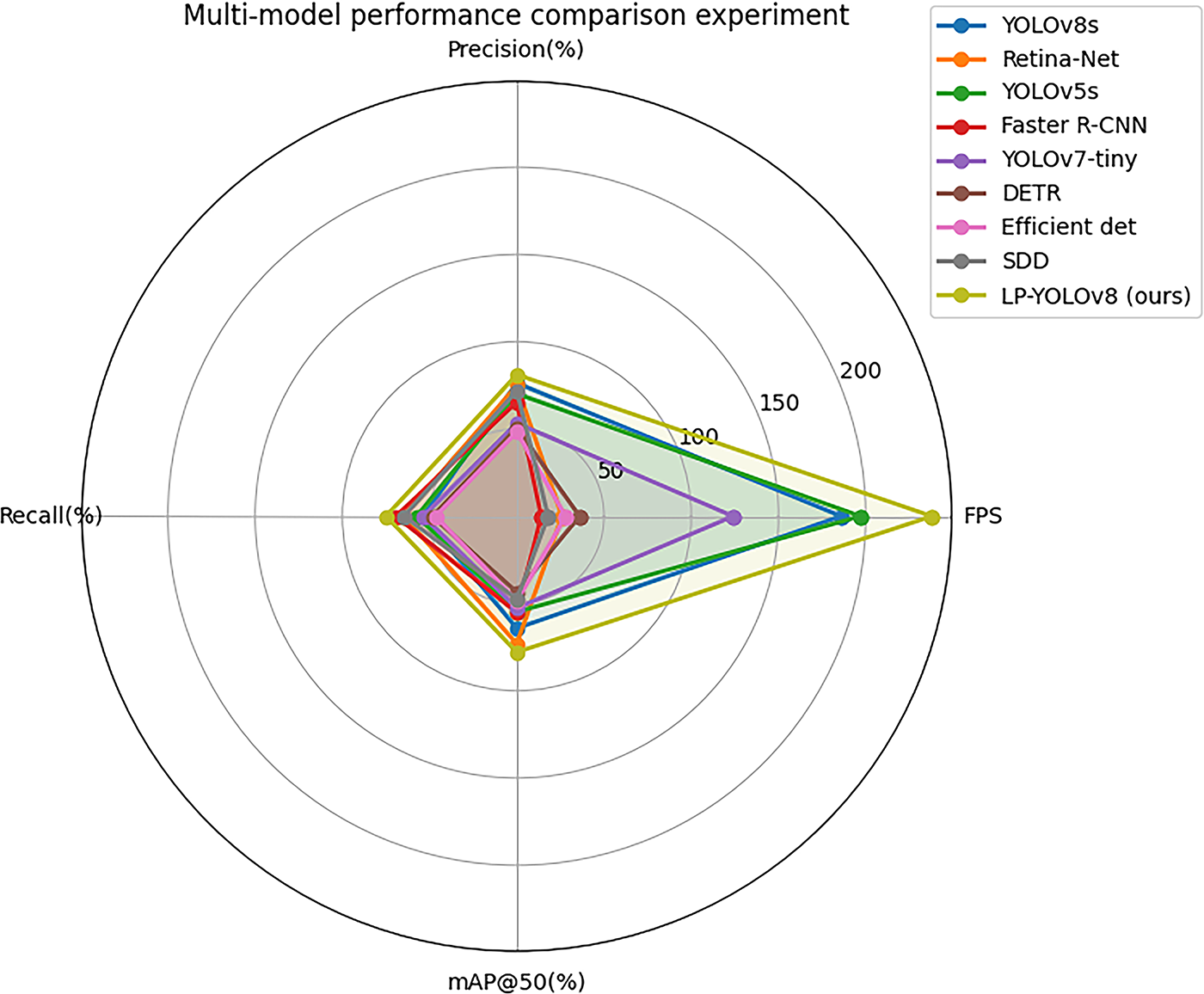

To better present the experimental results, Fig. 11 visually compares the performance of LP-YOLO with multiple models across various evaluation metrics. The radar chart clearly demonstrates that LP-YOLO outperforms other models in terms of accuracy, mAP@50, and real-time performance. The radar chart for LP-YOLO exhibits a larger coverage area, indicating that it offers the best overall performance.

Figure 11: Radar chart comparing the performance of multiple models

The proposed LP-YOLO model demonstrates substantial advantages over existing object detection algorithms across multiple metrics. The experimental evaluation is divided into two main parts: stepwise ablation studies and multi-model comparison experiments. The ablation studies indicate that, compared to the original YOLOv8, LP-YOLO improves Precision by 6.5%, mAP@50 by 9.3%, and F1-score by 9.2%, while achieving a high detection speed of 238 FPS. In the multi-model comparison experiments, the superior performance of LP-YOLO in complex smoke and fire detection scenarios is further validated through comparisons with mainstream detection algorithms, including RetinaNet, DETR, and EfficientDet.

Firstly, LP-YOLO excels in model lightweighting, with its model size reduced by 56.6% and 76.3% compared to YOLOv7-tiny and YOLOv8s, respectively. Compared to classic algorithms like Faster R-CNN and Retina Net, LP-YOLO maintains a smaller model size while offering better practicality. Secondly, LP-YOLO also performs exceptionally well in real-time detection, with an inference speed of 238 FPS, far surpassing the 36 FPS and 26 FPS achieved by DETR and Retina Net. The high FPS enables LP-YOLO to rapidly detect fire sources and smoke dispersion in complex environments, enhancing the response speed of fire monitoring systems. LP-YOLO achieves a recall rate of 75.0%, significantly higher than other models, reducing the occurrence of missed detections. This enables the system to capture more target information in complex fire scenarios, improving robustness and reliability.

Despite the overall strong performance of LP-YOLO, certain limitations remain. As shown in Fig. 12, while the model can detect small flames effectively, ultra-small fire instances or initial smoke plumes may still be missed, leading to false negatives. In addition, in complex environments with dense smoke, strong background clutter, or overlapping objects, false positives can occur. These failure cases indicate that the current model has limitations in capturing extremely fine-grained features and distinguishing subtle targets from background noise. Future improvements could include multi-scale data augmentation, adaptive confidence thresholding, incorporation of temporal information from video sequences, or fusion with complementary sensors (e.g., thermal or infrared) to enhance detection of tiny or ambiguous targets and reduce false positives, thereby improving reliability in challenging scenarios.

Figure 12: Minor fire hazard missed during detection

In this paper, we propose LP-YOLO, a high-precision smoke and fire source detection method based on the YOLOv8 framework, which integrates self-attention mechanisms and advanced feature pyramid networks. By introducing WTConv into the backbone, wavelet transformations are employed to perform convolutional processing with multi-frequency responses on target images, significantly expanding the receptive field while avoiding excessive parameter growth. The BiFPN bidirectional feature fusion mechanism enables smoke and fire features to be integrated in both top-down and bottom-up directions, optimizing feature extraction and improving detection accuracy. Additionally, the FreqFusion module, comprising ALPF, offset generator, and AHPF components, reduces intra-class inconsistencies, refines target boundaries, and strengthens high-frequency information, further enhancing localization precision. Experimental results on the publicly available D-Fire dataset demonstrate that LP-YOLO outperforms the baseline YOLOv8 model, with improvements of 6.5% in Precision, 9.3% in mAP@50, and 9.2% in F1-score, while achieving a high detection speed of 238 FPS. Validation on multiple benchmark datasets, including D-Fire, FIRESENSE, and BoWFire, further confirms its robustness and generalization capability, with detection accuracy consistently exceeding 82%. These results highlight the significant advantages of the proposed method in terms of accuracy, speed, and robustness. In conclusion, LP-YOLO not only enhances the precision of smoke and fire source detection but also demonstrates excellent reliability in complex environments, indicating broad application potential.

Acknowledgement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Scientific Research Project of the Hunan Provincial Department of Education, the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, and the Postgraduate Scientific Research and Innovation Project of Hunan Province.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62203163), the Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Education Department (No. 24A0519), the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2025JJ60407), and the Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Project of Hunan Province (No. CX20241000).

Author Contributions: Qing Long: methodology, data collection and analysis, paper writing. Bing Yi: supervision, project administration. Haiqiao Liu: funding acquisition, supervision, writing. Zhiling Peng: data collection and analysis, paper editing. Xiang Liu: paper editing and proofreading. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Koltunov A, Ustin SL, Quayle B, Schwind B, Ambrosia VG, Li W. The development and first validation of the GOES early fire detection (GOES-EFD) algorithm. Remote Sens Environ. 2016;184:436–53. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2016.07.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ku W, Lee G, Lee JY, Kim DH, Park KH, Lim J, et al. Rational design of hybrid sensor arrays combined synergistically with machine learning for rapid response to a hazardous gas leak environment in chemical plants. J Hazard Mater. 2024;466:133649. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.133649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Solórzano A, Eichmann J, Fernández L, Ziems B, Jiménez-Soto JM, Marco S, et al. Early fire detection based on gas sensor arrays: multivariate calibration and validation. Sens Actuat B Chem. 2022;352:130961. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2021.130961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bahhar C, Ksibi A, Ayadi M, Jamjoom MM, Ullah Z, Soufiene BO, et al. Wildfire and smoke detection using staged YOLO model and ensemble CNN. Electronics. 2023;12(1):228. doi:10.3390/electronics12010228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sathishkumar VE, Cho J, Subramanian M, Naren OS. Forest fire and smoke detection using deep learning-based learning without forgetting. Fire Ecol. 2023;19(1):9. doi:10.1186/s42408-022-00165-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Stergiou A, Poppe R, Kalliatakis G. Refining activation downsampling with softpool. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 10337–46. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhan J, Hu Y, Zhou G, Wang Y, Cai W, Li L. A high-precision forest fire smoke detection approach based on ARGNet. Comput Electron Agric. 2022;196:106874. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2022.106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Y, Zhang W, Liu Y, Jing R, Liu C. An efficient fire and smoke detection algorithm based on an end-to-end structured network. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;116:105492. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhu X, Su W, Lu L, Li B, Dai J. Deformable DETR: deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2010.04159. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2010.04159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang G, Li B, Luo J, He L. A self-adaptive wildfire detection algorithm with two-dimensional Otsu optimization. Math Probl Eng. 2020;2020(1):3735262. doi:10.1155/2020/3735262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Muhammad K, Khan S, Palade V, Mehmood I, de Albuquerque VHC. Edge intelligence-assisted smoke detection in foggy surveillance environments. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;16(2):1067–75. doi:10.1109/TII.2019.2915592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ding Y, Wang M, Fu Y, Wang Q. Forest smoke-fire net (FSF neta wildfire smoke detection model that combines MODIS remote sensing images with regional dynamic brightness temperature thresholds. Forests. 2024;15(5):839. doi:10.3390/f15050839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang J, Zhang X, Zhang C. A lightweight smoke detection network incorporated with the edge cue. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241:122583. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Prema CE, Suresh S, Krishnan MN, Leema N. A novel efficient video smoke detection algorithm using co-occurrence of local binary pattern variants. Fire Technol. 2022;58(5):3139–65. doi:10.1007/s10694-022-01306-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Avgeris M, Spatharakis D, Dechouniotis D, Kalatzis N, Roussaki I, Papavassiliou S. Where there is fire there is smoke: a scalable edge computing framework for early fire detection. Sensors. 2019;19(3):639. doi:10.3390/s19030639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang FY. The emergence of intelligent enterprises: from CPS to CPSS. IEEE Intell Syst. 2010;25(4):85–8. doi:10.1109/MIS.2010.104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Madakam S, Ramaswamy R, Tripathi S. Internet of Things (IoTa literature review. J Comput Commun. 2015;3(5):164–73. doi:10.4236/jcc.2015.35021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nikul Patel A, Srivastava G, Kumar Reddy Maddikunta P, Murugan R, Yenduri G, Reddy Gadekallu T. A trustable federated learning framework for rapid fire smoke detection at the edge in smart home environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(23):37708–17. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3439228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang S, Huang Q, Yu M. Advancements in remote sensing for active fire detection: a review of datasets and methods. Sci Total Environ. 2024;943:173273. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Khan S, Muhammad K, Hussain T, Del Ser J, Cuzzolin F, Bhattacharyya S, et al. DeepSmoke: deep learning model for smoke detection and segmentation in outdoor environments. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;182(1):115125. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tan M, Le QV. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. arXiv:1905.11946. 2019. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1905.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Peng Y, Wang Y. Real-time forest smoke detection using hand-designed features and deep learning. Comput Electron Agric. 2019;167:105029. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2019.105029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Iandola FN, Han S, Moskewicz MW, Ashraf K, Dally WJ, Keutzer K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50× fewer parameters and <0.5 MB model size. arXiv:1602.07360. 2016. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1602.07360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yin H, Chen M, Fan W, Jin Y, Hassan SG, Liu S. Efficient smoke detection based on YOLO v5s. Mathematics. 2022;10(19):3493. doi:10.3390/math10193493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang D, Qian Y, Lu J, Wang P, Hu Z, Chai Y. Fs-yolo: fire-smoke detection based on improved YOLOv7. Multimed Syst. 2024;30(4):215. doi:10.1007/s00530-024-01359-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 9992–10002. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.00986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li R, Hu Y, Li L, Guan R, Yang R, Zhan J, et al. SMWE-GFPNNet: a high-precision and robust method for forest fire smoke detection. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;289:111528. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lin Z, Yun B, Zheng Y. LD-YOLO: a lightweight dynamic forest fire and smoke detection model with dysample and spatial context awareness module. Forests. 2024;15(9):1630. doi:10.3390/f15091630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Han K, Wang Y, Tian Q, Guo J, Xu C, Xu C. GhostNet: more features from cheap operations. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1577–86. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu W, Lu H, Fu H, Cao Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 6004–14. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.00554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Talaat FM, ZainEldin H. An improved fire detection approach based on YOLO-v8 for smart cities. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(28):20939–54. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-08809-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Forootaninia Z, Narain R. Frequency-domain smoke guiding. ACM Trans Graph. 2020;39(6):1–10. doi:10.1145/3414685.3417842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chaturvedi S, Khanna P, Ojha A. A survey on vision-based outdoor smoke detection techniques for environmental safety. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2022;185:158–87. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2022.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Finder SE, Amoyal R, Treister E, Freifeld O. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. p. 363–80. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72949-2_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tan M, Pang R, Le QV. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 10778–87. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chen L, Fu Y, Gu L, Yan C, Harada T, Huang G. Frequency-aware feature fusion for dense image prediction. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(12):10763–80. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3449959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. de Venâncio PVAB, Lisboa AC, Barbosa AV. An automatic fire detection system based on deep convolutional neural networks for low-power, resource-constrained devices. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(18):15349–68. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07467-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollar P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2999–3007. doi:10.1109/iccv.2017.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chino DYT, Avalhais LPS, Rodrigues JF, Traina AJM. BoWFire: detection of fire in still images by integrating pixel color and texture analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2015 28th SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images; 2015 Aug 26–29; Salvador, Brazil. p. 95–102. doi:10.1109/SIBGRAPI.2015.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang Y, Wang C, Zhang H, Dong Y, Wei S. Automatic ship detection based on RetinaNet using multi-resolution Gaofen-3 imagery. Remote Sens. 2019;11(5):531. doi:10.3390/rs11050531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Carion N, Massa F, Synnaeve G, Usunier N, Kirillov A, Zagoruyko S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. p. 213–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Stoken A, Borovec J, Kwon Y, Michael K, et al. YOLOv5 by ultralytics (version 7.0) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3908559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ultralytics YOLOv8 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

46. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Xu S, Wang X, Lv W, Cai D, He X. PP-YOLOE: an evolved version of YOLO. arXiv:2203.16250. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2203.16250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Mark Liao HY. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Khanam R, Hussain M. YOLOv11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725. 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Lv K, Wu R, Chen S, Lan P. CCi-YOLOv8n: enhanced fire detection with CARAFE and context-guided modules. In: Advanced intelligent computing technology and applications. Singapore: Springer; 2025. p. 128–40. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-9901-8_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools