Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Privacy-Preserving Personnel Detection in Substations via Federated Learning with Dynamic Noise Adaptation

1 Guiyang Power Supply Bureau, Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guiyang, 563000, China

2 Information Center, Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guiyang, 563000, China

3 School of Computer and Communication Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, 100083, China

4 Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guiyang, 563000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xuyang Wu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Object Detection and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 35 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072081

Received 19 August 2025; Accepted 07 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

This study addresses the risk of privacy leakage during the transmission and sharing of multimodal data in smart grid substations by proposing a three-tier privacy-preserving architecture based on asynchronous federated learning. The framework integrates blockchain technology, the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) for distributed storage, and a dynamic differential privacy mechanism to achieve collaborative security across the storage, service, and federated coordination layers. It accommodates both multimodal data classification and object detection tasks, enabling the identification and localization of key targets and abnormal behaviors in substation scenarios while ensuring privacy protection. This effectively mitigates the single-point failures and model leakage issues inherent in centralized architectures. A dynamically adjustable differential privacy mechanism is introduced to allocate privacy budgets according to client contribution levels and upload frequencies, achieving a personalized balance between model performance and privacy protection. Multi-dimensional experimental evaluations, including classification accuracy, F1-score, encryption latency, and aggregation latency, verify the security and efficiency of the proposed architecture. The improved CNN model achieves 72.34% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.72 in object detection and classification tasks on infrared surveillance imagery, effectively identifying typical risk events such as not wearing safety helmets and unauthorized intrusion, while maintaining an aggregation latency of only 1.58 s and a query latency of 80.79 ms. Compared with traditional static differential privacy and centralized approaches, the proposed method demonstrates significant advantages in accuracy, latency, and security, providing a new technical paradigm for efficient, secure data sharing, object detection, and privacy preservation in smart grid substations.Keywords

As critical nodes in smart grids, substations generate multimodal operational data including equipment condition monitoring streams, power load profiles, and inspection imagery [1,2]. These data types serve as determining factors for real-time dispatch and condition-based maintenance while simultaneously encompassing the confidentiality of physical infrastructure topologies and consumer electricity usage patterns [3]. Notably, spatial characteristics within the data potentially revealing equipment lay-outs through infrared thermography containing geolocation coordinates-introduce additional privacy vulnerabilities [4,5]. Any leakage during transmission could enable targeted attacks on critical power facilities, jeopardizing the secure and stable operation of power systems [6]. Consequently, establishing a multimodal data privacy preservation framework for substations holds paramount significance for ensuring power system security and advancing next-generation grid infrastructure, representing a mission-critical technology for intelligent substation implementation.

Existing substation data privacy preservation technologies predominantly rely on data anonymization and centralized federated learning [7,8]. Traditional anonymization solutions are prone to the curse of dimensionality when handling the high-dimensional spatiotemporal correlations inherent in substation multimodal data, resulting in excessive noise injection that drastically degrades data utility while remaining vulnerable to adversarial attacks exposing sensitive information [9]. The centralized architecture of conventional federated learning aggregates global model parameters on a single server, creating systemic privacy leakage risks from model inversion attacks and parameter theft [10,11]. Furthermore, its synchronous update mechanism requires plaintext gradient transmission, amplifies privacy exposure through spatiotemporal correlation inference based on substation operational characteristics. These limitations necessitate a decentralized privacy-preserving federated framework that incorporates asynchronous collaboration mechanisms and multimodal differential perturbation to address the spatiotemporal correlation challenges inherent in substation data, thereby ensuring comprehensive privacy protection. However, existing applications of AFL in smart grid scenarios still face several critical challenges. First, most AFL methods rely on static or uniform differential privacy strategies, lacking personalized privacy-utility trade-off regulation mechanisms. Second, the asynchronous nature of AFL can easily trigger consistency and robustness issues during global aggregation without centralized coordination. Furthermore, existing research rarely addresses the system-level feasibility of real-world smart grid deployments, exhibiting insufficient attention to the design and validation of trusted collaboration and scalable storage mechanisms among substations.

Current research focuses on integrating blockchain with differential privacy techniques in the power grid domain to address privacy protection and fair exchange issues in data sharing. Fotiou et al. [12] proposed a privacy-preserving statistics marketplace based on local differential privacy and blockchain. This scheme protects data providers’ privacy using local differential privacy technology and utilizes blockchain smart contracts to achieve fair exchange and immutable data log recording. It is applicable to smart grid measurement data sharing scenarios, demonstrating feasibility through experimental validation for scales involving hundreds or even thousands of data providers. Zheng et al. [13] proposed a decentralized mechanism called DDP based on differential privacy for privacy-preserving computation in smart grid, which extends data sanitization from value domain to time domain by injecting Laplace noise distributively and using random permutation to shuffle measurement sequences, thus enforcing differential privacy and preventing sensitive power usage mode inference, with experiments demonstrating its outstanding performance in privacy and utility. Fan et al. [14] proposed a decentralized privacy-preserving data aggregation (DPPDA) scheme for the smart grid based on blockchain. The scheme uses the leader election algorithm to select a smart meter in the residential area as a mining node to build a block, and the node adopts the Paillier cryptosystem algorithm to aggregate user power consumption data. Meanwhile, Boneh-Lynn-Shacham short signature and SHA-256 function are applied to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of user data. Security analysis shows that the scheme meets the security and privacy requirements of smart grid data aggregation, and experimental results demonstrate that it is more efficient than existing competing schemes in terms of computation and communication overhead.

Asynchronous federated learning, with its unique decentralized architecture and efficient asynchronous parameter exchange mechanisms, can adapt to the diverse computing capabilities of substation edge devices and fluctuations in network environments, while effectively avoiding single-point failure risks inherent in centralized architectures [15,16]. This technology opens a feasible path for ensuring multimodal data privacy security in substations. In recent years, some scholars have introduced asynchronous federated learning into power systems to achieve distributed model training under data privacy protection. Li et al. [17] innovatively proposed a decentralized asynchronous adaptive federated learning algorithm that focuses on secure prediction of distributed power data, making the prediction process of distributed data more flexible, secure, and reliable. Simultaneously, Liu et al. [18] proposed a novel asynchronous decentralized federated learning framework. Under this framework, each photovoltaic power station can not only independently train local models but also actively participate in collaborative fault diagnosis through model parameter exchange. This method significantly improves the model’s generalization capability while ensuring diagnostic accuracy. The global model is formed through distributed aggregation, effectively avoiding potential failures in central nodes and substantially reducing communication overhead and training time. Experimental and numerical simulation results fully verify the effectiveness and practicality of this method. Wu et al. [19] designed a privacy-preserving federated learning framework for transformer fault diagnosis that incorporates multi-level data sharing mechanisms and adaptive differential privacy protection measures. Experimental results demonstrate that this method exhibits outstanding diagnostic accuracy in identifying different types of transformer faults. Beyond power systems, recent studies have further explored federated learning in other critical infrastructures. For instance, federated learning has been applied to intrusion detection, enabling collaborative anomaly detection across distributed networks without exposing raw data, which demonstrates its strong potential in network security [20,21]. In addition, conditional generative adversarial networks have been combined with federated learning in satellite–terrestrial integrated networks, providing secure and efficient cross-domain data generation and model training [22,23]. These works highlight the broad applicability of federated learning across different domains, while our study specifically addresses the privacy-preserving challenges in smart grid substations by integrating asynchronous federated learning with blockchain and dynamic differential privacy mechanisms.

Although numerous studies have been conducted on federated learning and privacy protection, the following limitations persist: most existing research focuses on synchronous federated learning frameworks, which struggle to adapt to the asynchronous distributed characteristics of substation environments; secondly, differential privacy often employs fixed budgets, failing to account for contribution disparities among different clients, thereby compromising model utility; finally, while blockchain and storage integration primarily emphasize data integrity and traceability, they lack deep integration with differential privacy mechanisms.

To address the privacy leakage risks facing substation data and the challenge of decentralized trust establishment, this paper proposes a three-layer privacy-preserving architecture for substation data based on asynchronous federated learning. Compared to certain fully decentralized federated learning approaches, AFL maintains a degree of decentralization while achieving higher communication efficiency and stronger fault tolerance. This makes it particularly well-suited for substation environments characterized by imbalanced computational resources and inconsistent communication quality among nodes. Furthermore, through the integration of PBFT consensus mechanisms and smart contracts, AFL in this study simultaneously addresses collaborative security and decentralized training efficiency, representing a practical deployment solution under current grid system constraints. The contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) A three-layer model architecture for privacy-preserving substation data is proposed, leveraging asynchronous federated learning. This architecture comprises a storage layer, service layer, and federated collaboration layer, achieving substation data privacy preservation through decentralized implementation. The framework employs blockchain to ensure data immutability, enhances off-chain storage efficiency via the IPFS, and resolves the single point failure issues inherent in traditional centralized federated learning.

(2) A differential privacy mechanism based on dynamic noise-tuning is proposed. During model training, Laplace noise is innovatively added to intermediate results to optimize differential privacy protection effectiveness. By dynamically adjusting noise injection strategies, the mechanism balances model performance and privacy strength while protecting sensitive parameter confidentiality. Experimental verification demonstrates its significant reduction of parameter leakage risks.

(3) An asynchronous federated aggregation method integrating PBFT and smart contract collaboration is proposed. The PBFT consensus algorithm ensures parameter consistency among distributed nodes and resists malicious node attacks. By leveraging smart contracts to automatically execute model aggregation logic, this method significantly addresses the centralization dependency and data trust storage issues in traditional federated learning.

2.1 Asynchronous Federated Learning

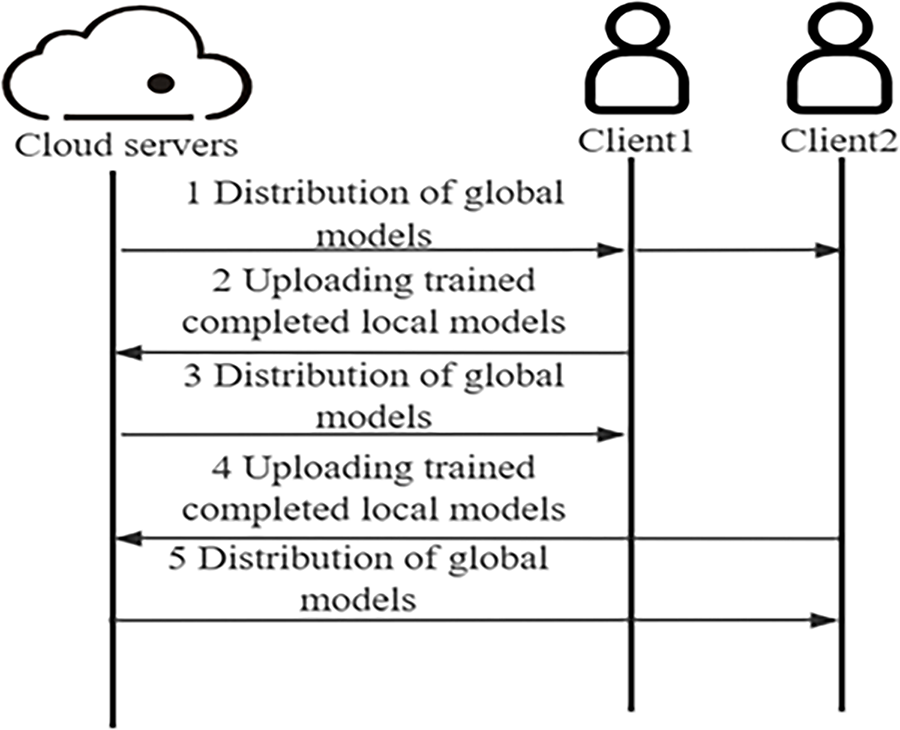

In Asynchronous Federated Learning, the server prioritizes collaboration with clients that have completed training without waiting for all clients to finish training before aggregation [24]. When a client completes its training, it immediately communicates with the server to obtain the latest global model and then initiates the next round of local training. The advantages are that no client remains idle, and the global model can promptly integrate the latest local model parameters uploaded by clients [25]. However, there are also drawbacks: the communication strategy causes a significant increase in data transmission volume since each client must communicate individually with the server; clients with limited computational capabilities have longer local training cycles, during which the global model may have undergone multiple updates through interactions with computationally powerful clients, resulting in weaker clients using outdated global models uploading these parameters may degrade global model quality [26]; frequent communication between the server and powerful clients may lead to model bias. Fig. 1 illustrates the basic process of asynchronous federated learning.

Figure 1: Fundamental workflow of asynchronous federated learning

Asynchronous Federated Learning (FedAsync) [27] is a classical asynchronous federated learning algorithm. Compared with synchronous federated learning, a key distinction of asynchronous federated learning lies in its avoidance of global synchronization locks to schedule device operations. The pseudocode is as follows (Algorithm 1):

The core concept of differential privacy lies in enhancing privacy protection by adding differentially private noise to the model’s raw gradients [28]. The Laplace mechanism is a canonical implementation of differential privacy, operating by injecting Laplacian-distributed random noise offsets to all data when generating target outputs [29]. The relevant definitions are as follows:

(1) Neighboring Datasets: For any two adjacent datasets

Through the random mechanism

(2) Global Sensitivity: For a query function

where

(3) Laplace Mechanism: This mechanism achieves

The Laplace mechanism satisfies the

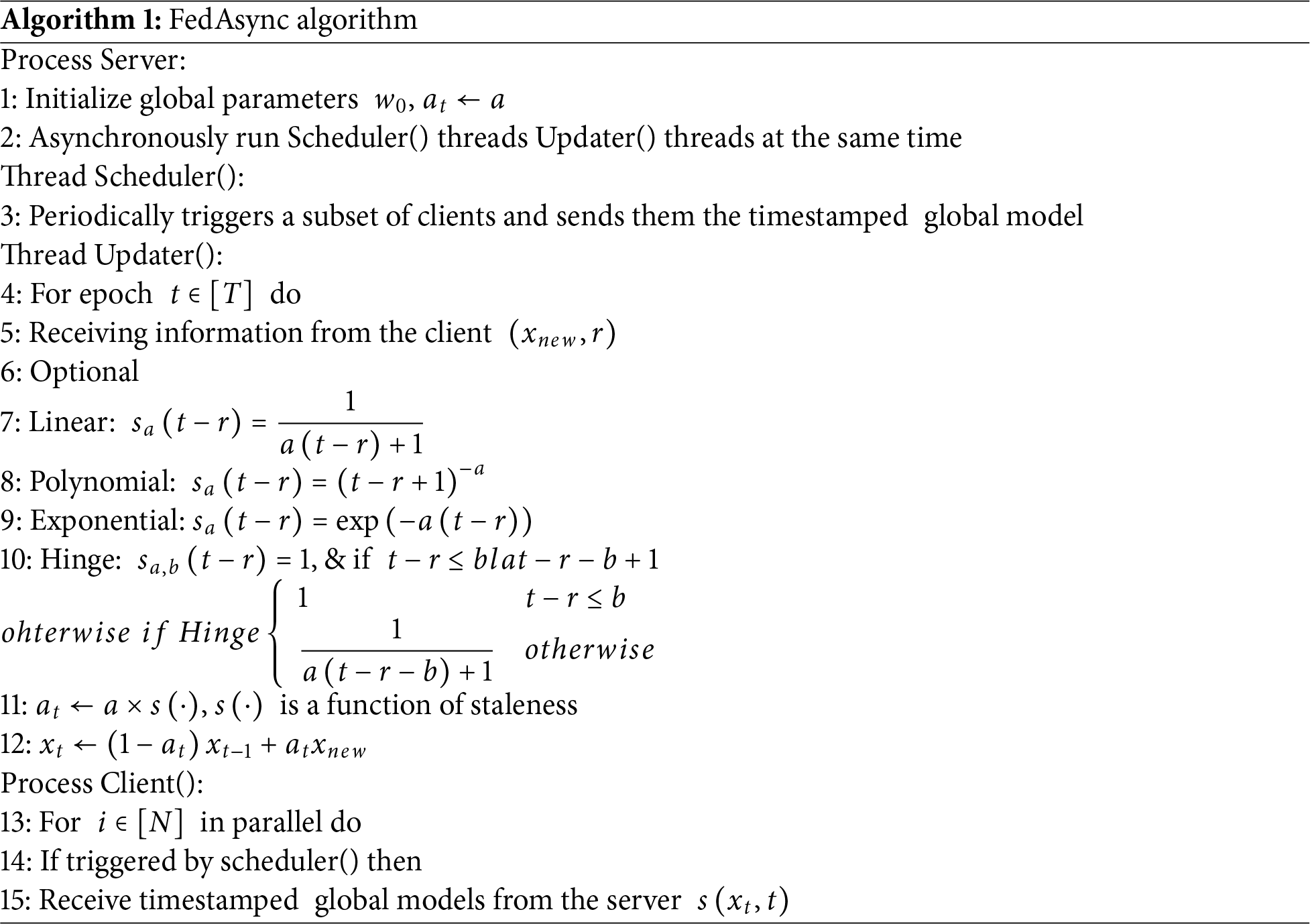

Blockchain technology establishes a distributed ledger system where information storage is achieved through chronologically ordered blocks [30]. Each block contains a finite set of transaction records, cryptographically linked to its predecessor via hash pointers, thereby forming an immutable chained architecture [31]. The structural configuration of blockchain is depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Blockchain architecture diagram

Within the blockchain technology framework, smart contracts serve as indispensable components that autonomously execute predefined rules and agreements upon condition fulfillment. The execution outcomes are immutably recorded on the blockchain network as tamper-evident and irreversible transaction records, requiring no external entity intervention. The flexibility of smart contracts manifests in their programmability through various programming languages to accommodate complex business logic requirements.

Consensus mechanisms constitute the core technology enabling coordinated operations among distributed nodes to maintain data consistency [32]. Given blockchain’s decentralized nature, reliance on centralized authorities for transaction validation becomes infeasible. Consensus protocols thus play a pivotal role in ensuring all network nodes maintain identical ledger replicas with accurately recorded transactions [33]. As foundational elements of blockchain systems, these mechanisms effectively resolve the Byzantine Generals Problem in distributed environments.

IPFS constitutes a decentralized peer-to-peer network for distributed file storage and sharing, designed to establish a unified file system integrating global computing resources [34]. By employing content-based addressing-where each file is uniquely identified and retrieved via cryptographic hash identifiers-IPFS enhances data reliability and accessibility through distributed storage [35].

IPFS’s decentralized architecture inherently aligns with the decentralized storage requirements for substation privacy protection. Through encrypted sharding and hash verification mechanisms, this approach effectively mitigates leakage risks associated with centralized sensitive data storage while ensuring data integrity and traceability, thereby providing foundational support for high-reliability, privacy-first data sharing in smart grid systems. However, practical deployment may face challenges: IPFS could introduce model upload and indexing delays during cross-substation synchronization, while blockchain platforms may encounter throughput bottlenecks under high-frequency model submissions. Future work should integrate off-chain computation to asynchronously process model validation and aggregation, enhancing system scalability and practicality.

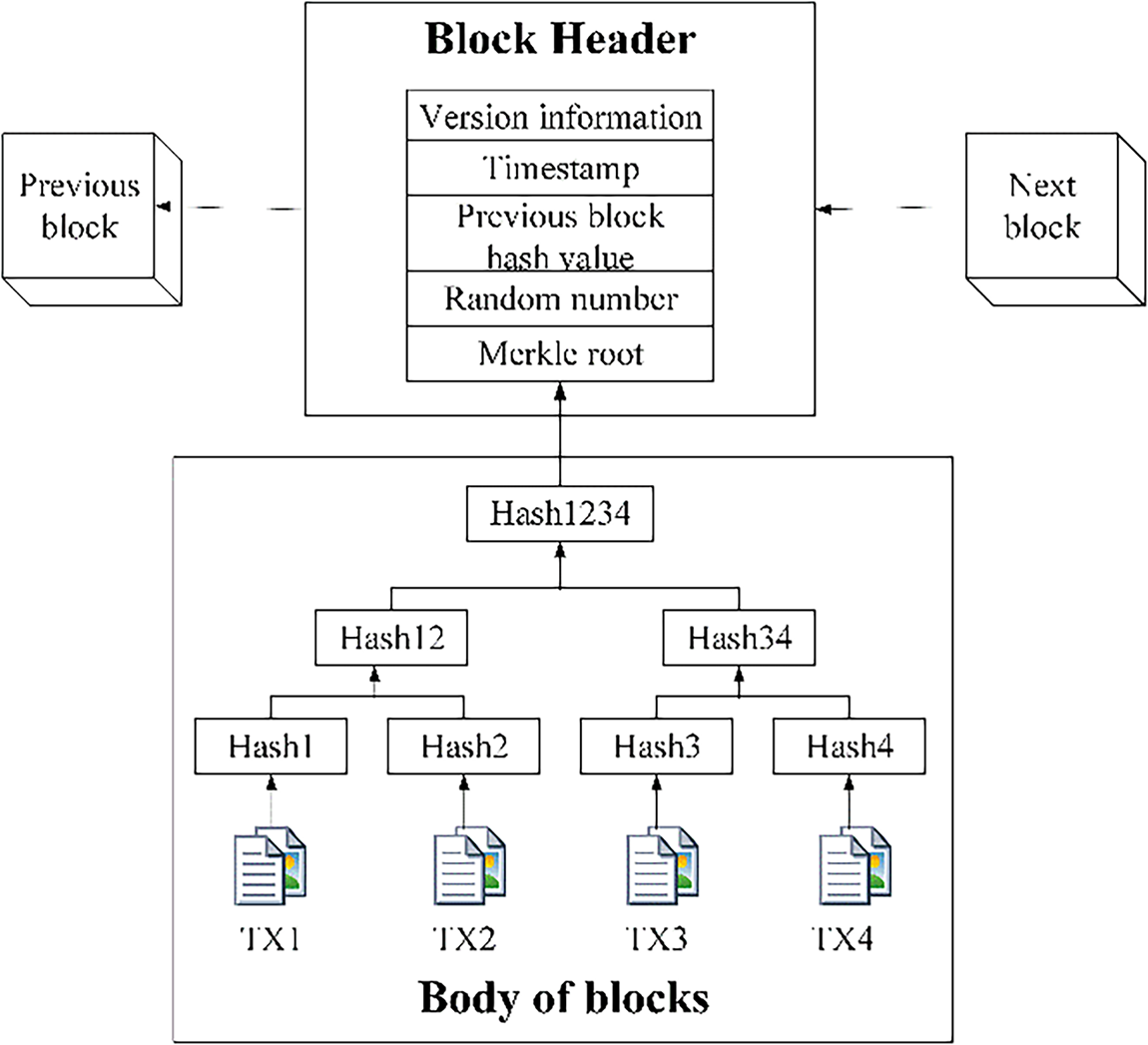

3.1 AFL Substation Data Privacy Protection System Framework

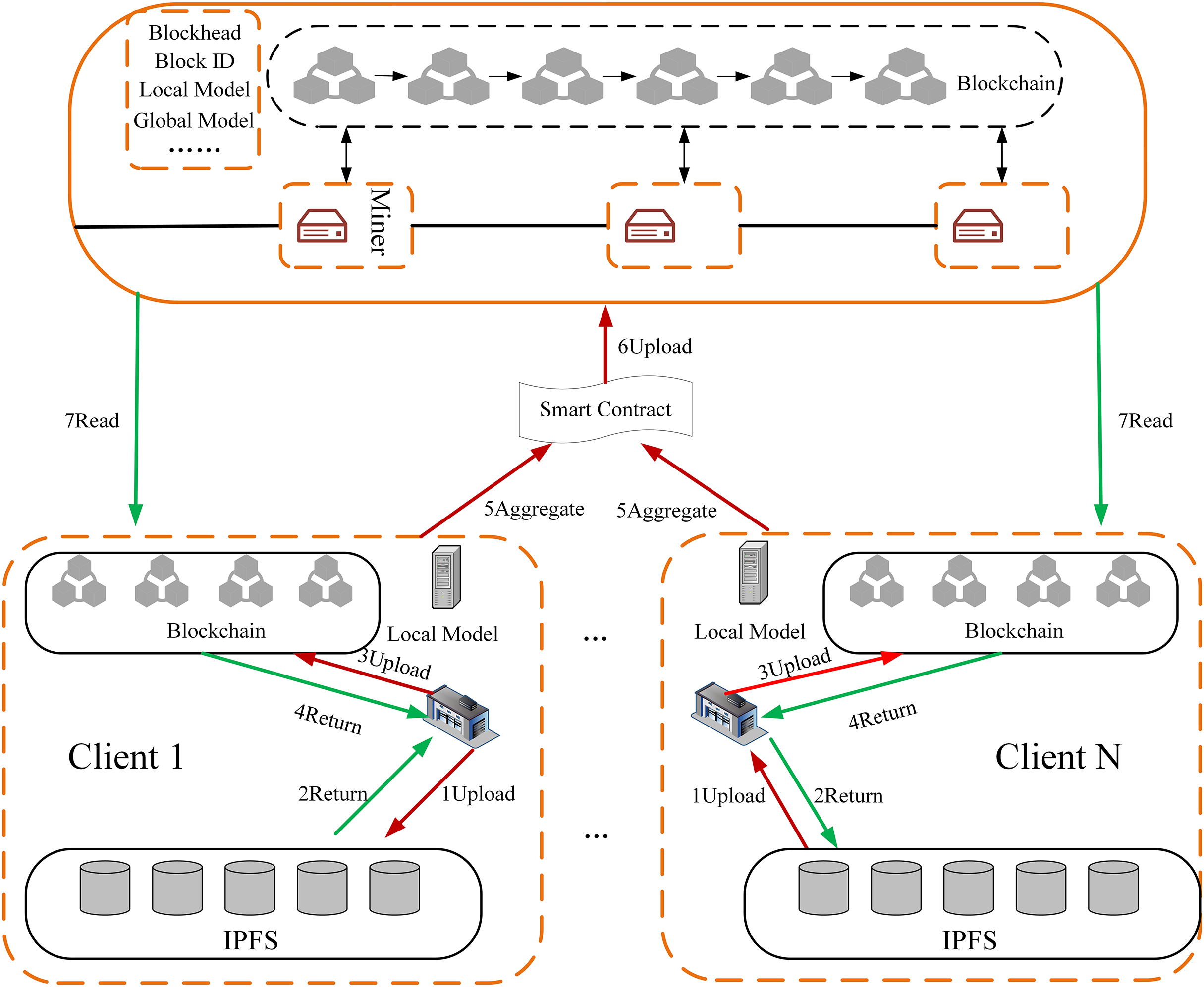

The proposed asynchronous federated learning model for substation data privacy consists of three layers, as shown in Fig. 3. The storage layer employs IPFS for secure off-chain data storage, complementing blockchain to enhance decentralization; the service layer handles operational workflows with local model training, blockchain-audited processes, and certificate-based authentication; while the federated collaboration layer orchestrates cross-substation model training using blockchain and smart contracts, which aggregate local models to update global parameters-achieving privacy-preserving optimization through decentralized synchronization.

Figure 3: Asynchronous federated learning-based system model for substation data privacy preservation

The model assumes there are n substations, with each substation

This framework employs the PBFT consensus algorithm for model aggregation, leveraging its high fault tolerance to rigorously validate client parameters before aggregation-mitigating malicious nodes while ensuring stringent data consistency beyond lightweight alternatives. For decentralized security, substations register on-chain, encrypt data via ECC for dual on/off-chain storage, and utilize smart contracts for global model aggregation. This dual mechanism eliminates central server reliance, prevents tampering, and secures both data privacy and training processes.

3.2 AFL Processes for Substations

Within the substation data privacy framework, AFL enables decentralized model training as shown in Fig. 4. Authenticated substations sign/store data on IPFS, receiving unique hashes which are digitally signed and uploaded to the blockchain; following on-chain verification and broadcast, each substation retrieves initial parameters from the federation layer, trains local models using its dataset, uploads models to global nodes, and invokes smart contracts for parameter aggregation, generating an updated global model whose parameters are stored on-chain and synchronized across all substations; this process iterates from local retraining until model convergence, with IPFS handling distributed storage, blockchain recording metadata, and smart contracts executing aggregation.

Figure 4: Asynchronous federated learning workflow for substations

To address client training inconsistencies in AFL, the system implements an asynchronous aggregation trigger and integrates directional consistency verification within PBFT consensus-applying penalizing weighting to clients whose parameters persistently deviate from the global optimization direction, thereby enhancing model stability.

3.3 Dynamically Tuned Differential Privacy Mechanism

To resolve temporal inconsistencies in asynchronous federated learning that challenge uniform DP, this paper proposes a dynamic DP mechanism. This approach jointly optimizes privacy granularity through: (1) A server-side DP budget allocation system using contribution factors and upload frequency factors to dynamically assign client-specific budgets; and (2) Client-level adaptive perturbation intensity adjustment collectively enabling balanced privacy protection and model performance despite update heterogeneity.

After the server receives the perturbed gradient

where the model parameter change

The training round index is denoted by

where

where

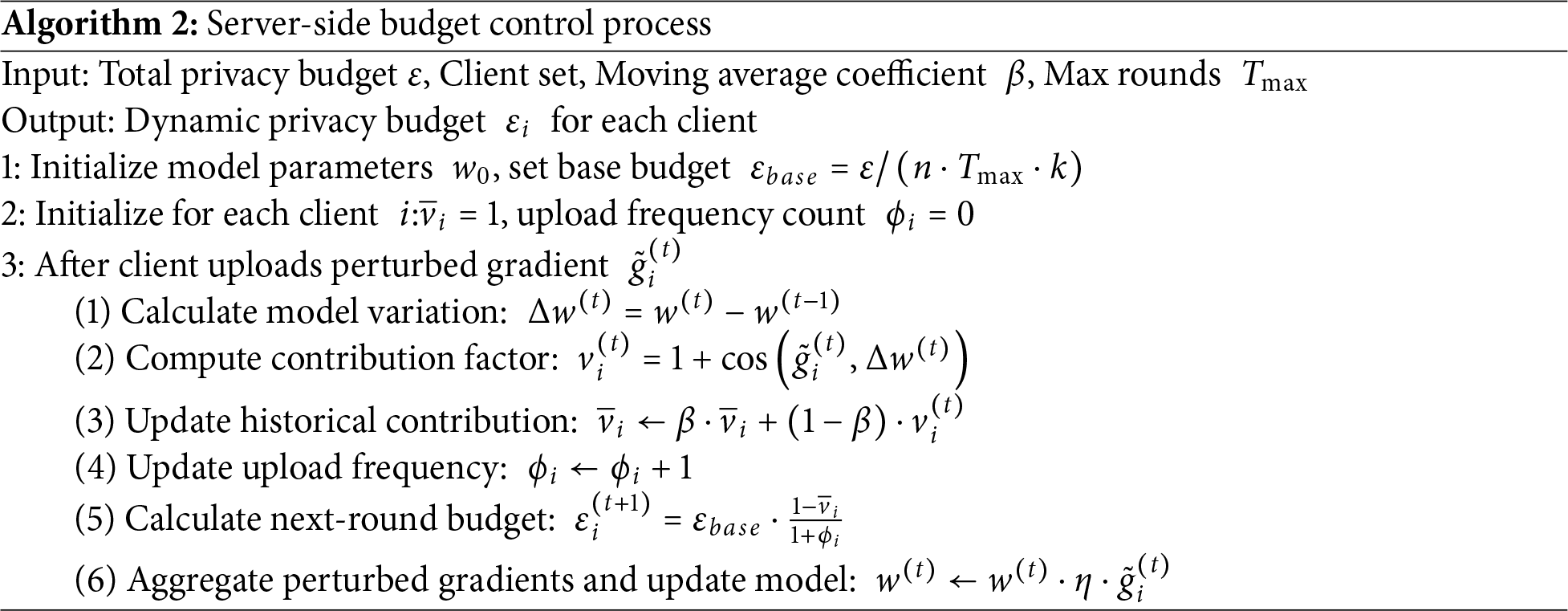

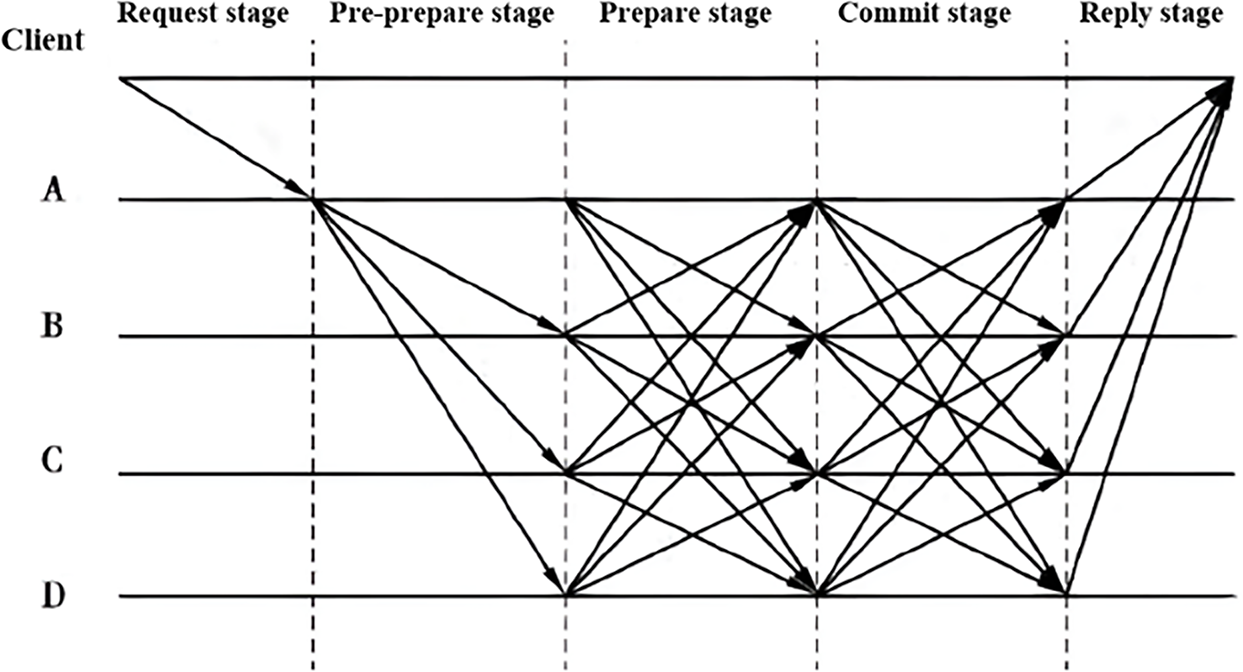

This mechanism achieves personalized privacy protection and rational resource allocation by dynamically adjusting budget distribution according to client behavioral characteristics. The server-side asynchronous differential privacy budget control algorithm is described as follows (Algorithm 2).

Differential privacy aggregation logic processes verified client gradients via clipping, noise injection (base budget

The client first records the current gradient norm:

A historical norm collection

where

This step bounds the

Adding Laplace Noise:

Finally, the client uploads the perturbed gradients to the server for participation in global model updating. The client-side gradient clipping and noise perturbation algorithm are described as follows (Algorithm 3).

On the client side (Algorithm 3), both local clipping and noise injection operations have a complexity of

3.4 PBFT and Smart Contract-Coordinated Asynchronous Federated Aggregation

3.4.1 PBFT Consensus Algorithm Construction

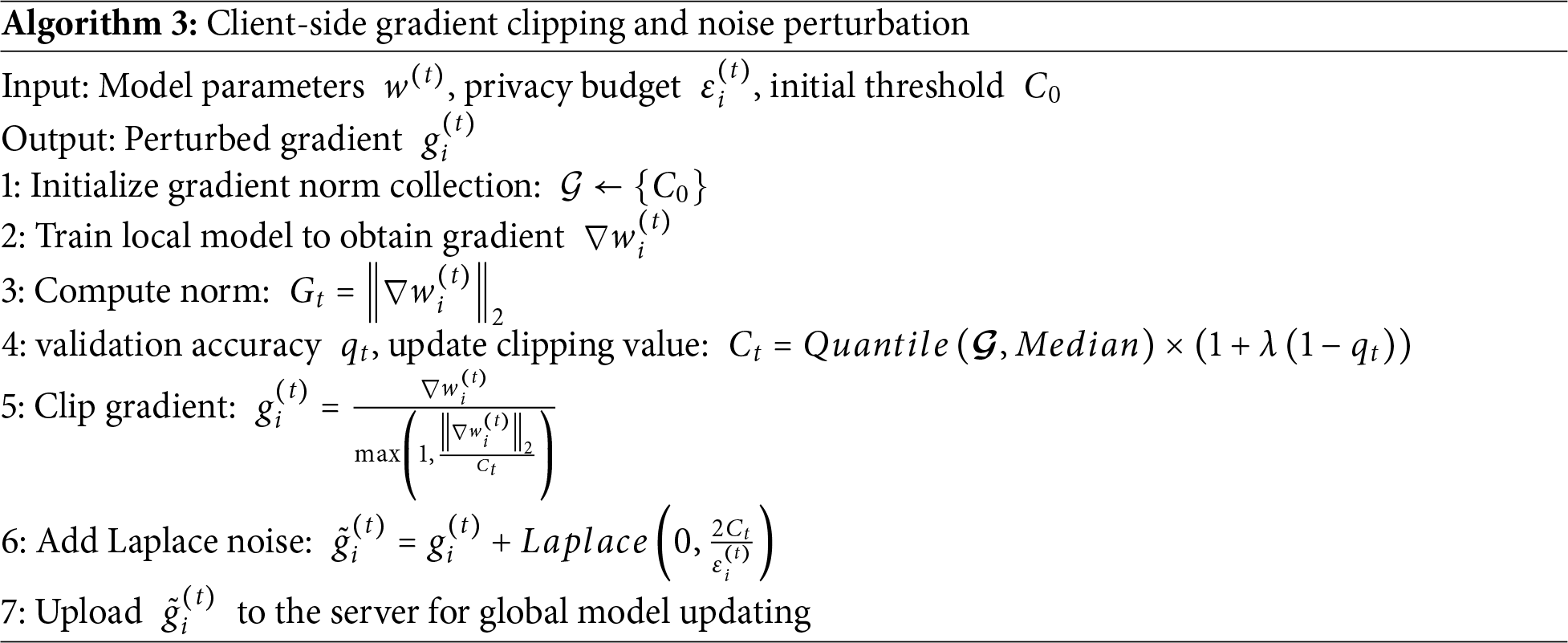

The PBFT consensus algorithm demonstrates superior scalability, enabling sustained high-efficiency operation amid expanding substation node quantities and complex environments—delivering robust security for reliable substation data interactions. The consensus process of the algorithm is detailed in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: PBFT algorithm

Within the PBFT consensus framework, the primary node initiates aggregation proposals while replicas validate requests. If the primary consecutively fails to broadcast valid proposals, the system automatically triggers rotation—promoting the next designated replica. Nodes transmitting falsified digests or demonstrating persistent unresponsiveness are excluded to prevent Byzantine attacks from compromising global aggregation. The contract layer enforces response timeouts and rotation logic, maintaining robustness with a tolerance limit of

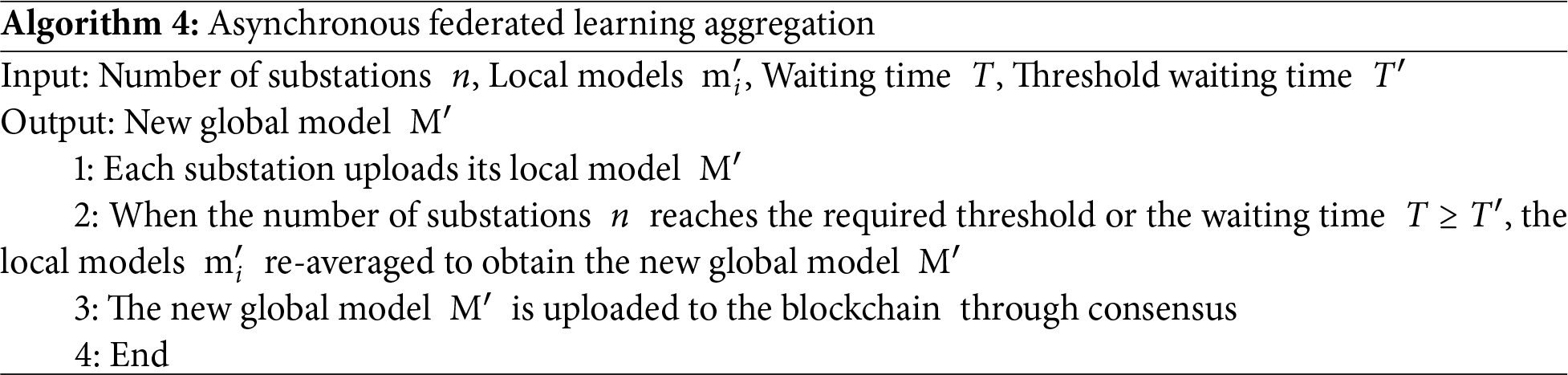

Solidity-implemented smart contracts encode PBFT consensus logic to interface with substation devices via Go, facilitating bidirectional blockchain interactions: devices upload immutable operational data to the chain and autonomously adjust states based on PBFT-validated instructions. Upon meeting response thresholds or time limits, contracts trigger on-chain aggregation—executing parameter averaging using stored digests, then broadcast updated global models through event mechanisms. This entirely decentralized workflow ensures tamper-resistant ordering and autonomous contract execution for asynchronous federated learning. The asynchronous federated learning aggregation algorithm is detailed as follows (Algorithm 4).

This study employs a power grid-provided dataset comprising 5000 infrared surveillance units (4000 static images, 100 video clips of 5–30 s duration) collected from 5 distinct substations (1000 units per substation). Due to the limited number of infrared image samples, this study employed random data augmentation techniques (flipping, rotation, scaling, etc.) during training to expand the effective sample size; meanwhile, the risks of overfitting were mitigated through multi-client federated aggregation and the regularization effect of differential privacy noise. Video key frames are extracted as image sequences to capture spatiotemporal behavior patterns. CNN is selected as the foundational model for its superior spatial feature extraction capability in identifying local structural variations within infrared imagery, aligning with technical objectives while enabling industrial-grade deployment.

All samples undergo preprocessing/normalization with multi-category annotation: 3200 normal behavior instances, 800 unauthorized entry, 600 illegal operation, and 400 not wearing a safety helmet, demonstrating a controlled class imbalance that aligns with real-world substation operational profiles.

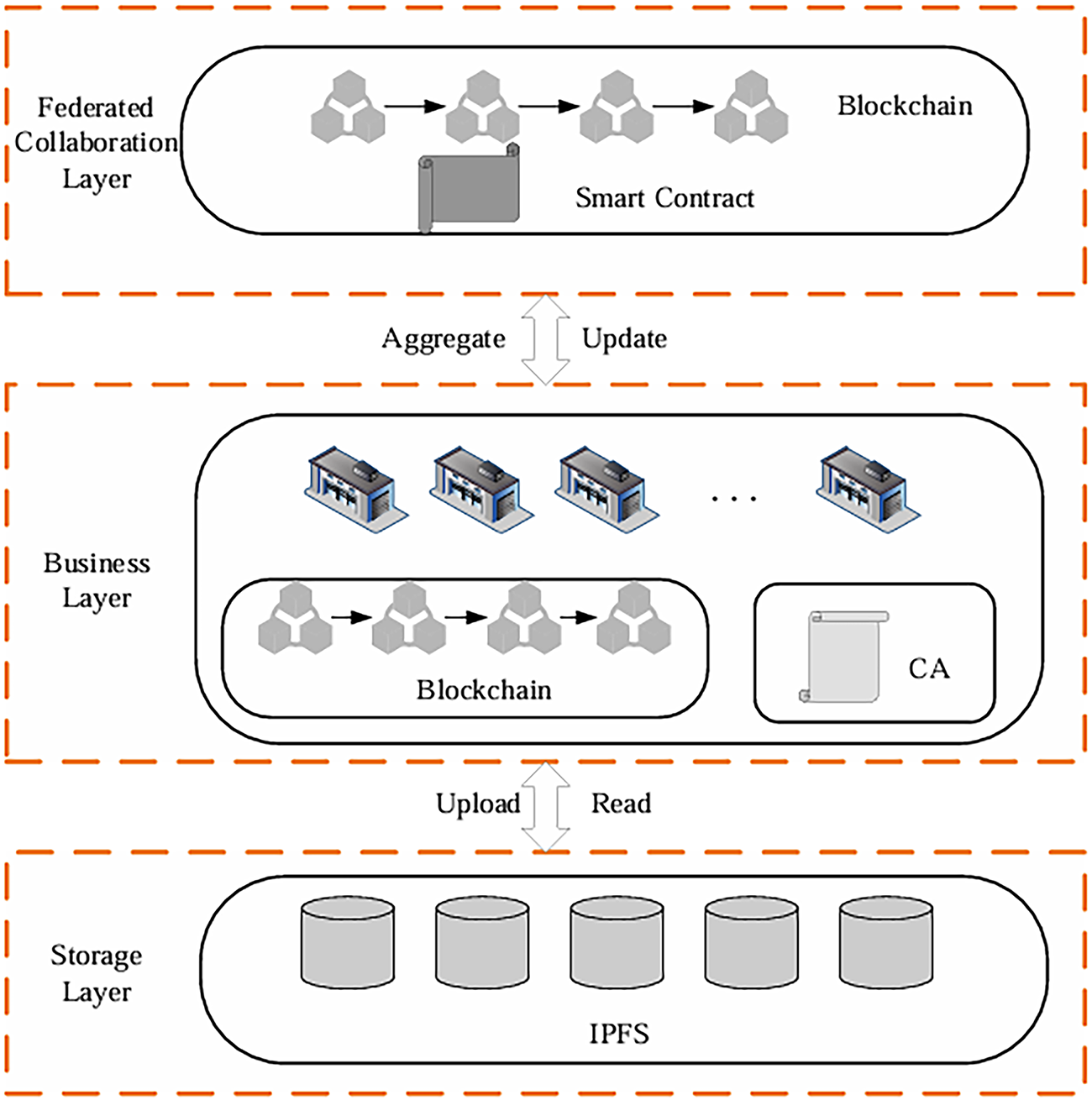

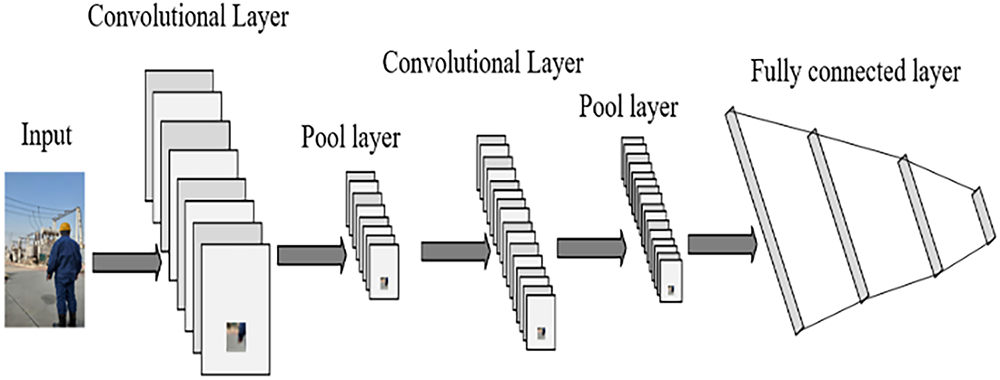

The PBFT consensus was deployed on a testbed consisting of 5 substation nodes. Each node operated on industrial-grade hardware. The blockchain platform utilized Hyperledger Fabric 2.4 with a block size of 1 MB and transaction throughput capped at 350 TPS. Network latency was emulated using Linux Traffic Control to simulate WAN conditions. The CNN architecture comprises two convolutional layers (30 channels for low-level feature extraction, 80 channels for high-level spatial feature capture) followed by five fully connected layers. Optimized for substation data characteristics and task requirements, pooling layers enhance robustness and computational efficiency through dimensionality reduction, while fully connected layers integrate convolutional features to refine classification performance. This network efficiently processes substation multi-modal data, achieving an optimal balance between computational efficiency and classification accuracy, as shown in Fig. 6. Model performance and privacy preservation were evaluated using accuracy, loss, and F1-score metrics.

Figure 6: Improved CNN architecture schematic

4.1 Analysis of Key Performance Indicators of the Model

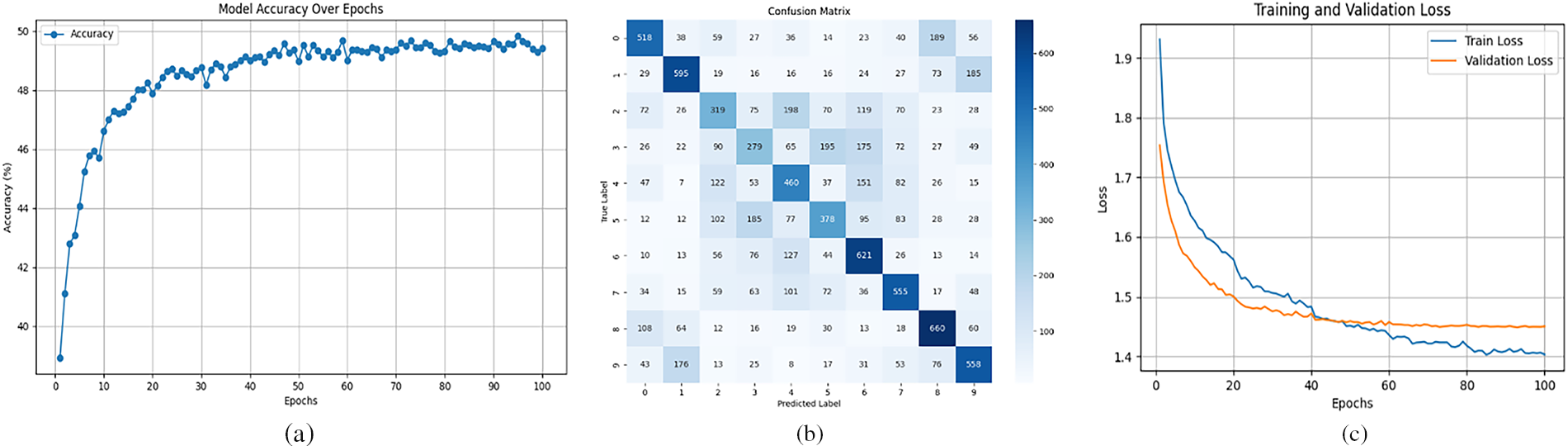

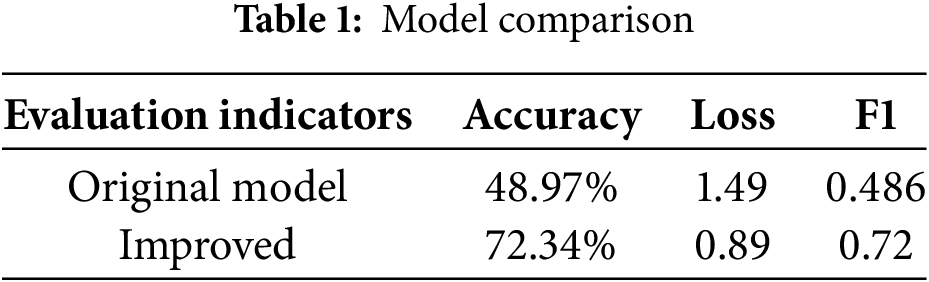

The proposed asynchronous federated learning model initially employs a baseline CNN architecture for training, achieving an accuracy of 49.03%, an F1-score of 0.486, and a loss of 1.49. As shown in Fig. 7, the experimental results demonstrate suboptimal model performance prior to architectural optimization.

Figure 7: Performance metrics of the baseline CNN architecture. (a) Model accuracy; (b) Confusion matrix; (c) Model loss

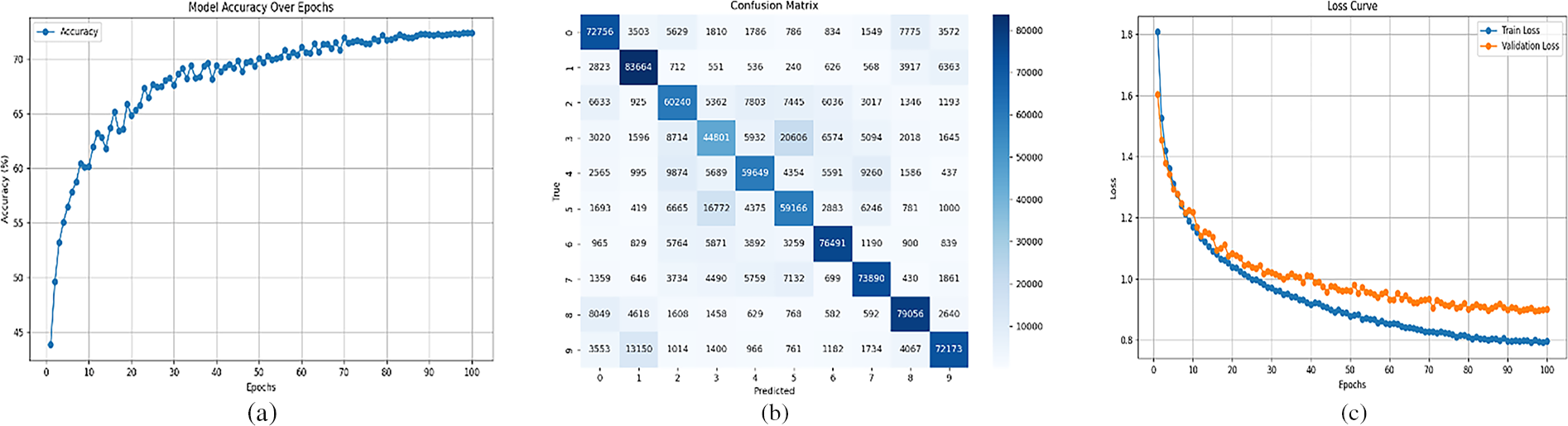

Building upon the original CNN architecture, an enhanced CNN model was developed with the application of data augmentation techniques to improve the diversity of the training dataset. For learning rate scheduling, the Cosine Annealing Learning Rate Scheduler was employed to dynamically adjust learning rates, enabling smoother model convergence. Additionally, early stopping and regularization methods were incorporated during the training process. To evaluate the enhanced CNN architecture, a comparative analysis was conducted against a baseline model. This baseline model was trained on an identical dataset encompassing the multi-modal information from substations utilized for the enhanced model. Furthermore, an equivalent number of training epochs was applied to both models during the training process. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Performance metrics of the improved CNN architecture. (a) Model accuracy; (b) Confusion matrix; (c) Model loss

The experimental results demonstrate that the enhanced model achieves an accuracy of 72.34%, an F1-score of 0.72, and a loss of 0.89, representing significant improvements over the baseline CNN model. Comparative metrics of the original and enhanced models are summarized in Table 1.

4.2 Privacy-Preserving Data Encryption and Model Aggregation Performance Analysis

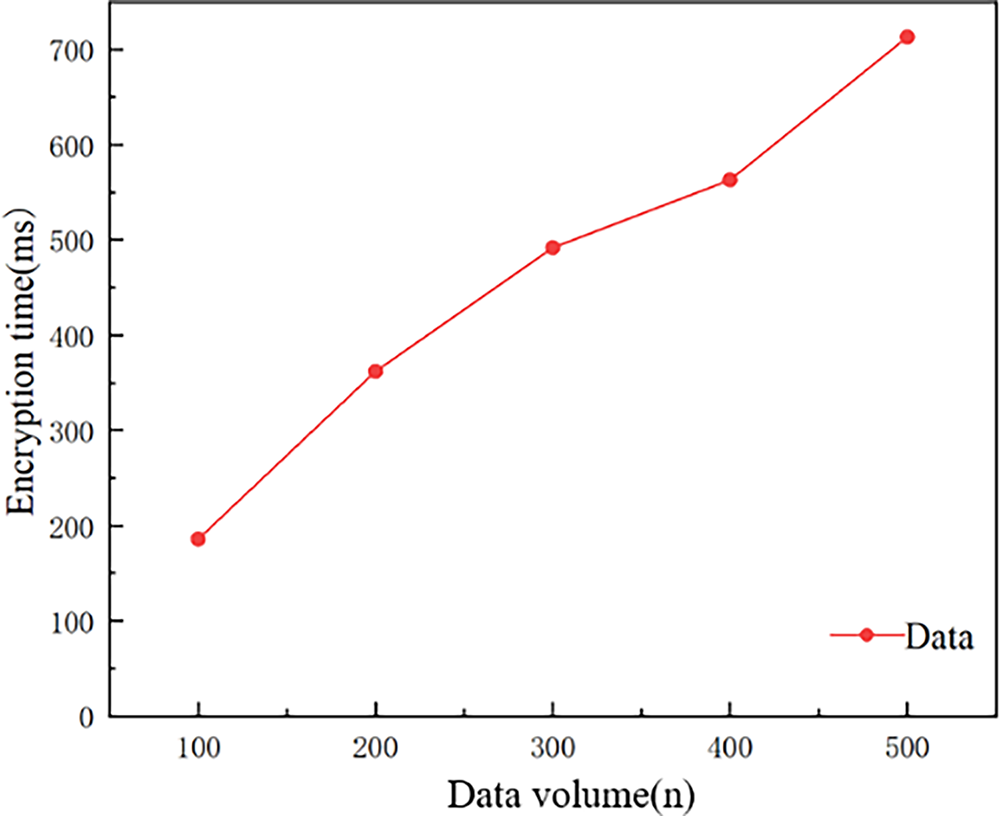

To validate the efficiency of data encryption and successful decryption post-encryption, datasets ranging from 100 to 500 samples were encrypted using the SM2 algorithm. The encryption time was measured for each dataset size, with test results shown in Fig. 9. Empirical results demonstrate that encryption time increases proportionally with data volume, exhibiting a linear growth trend as the dataset size escalates.

Figure 9: Data encryption delay

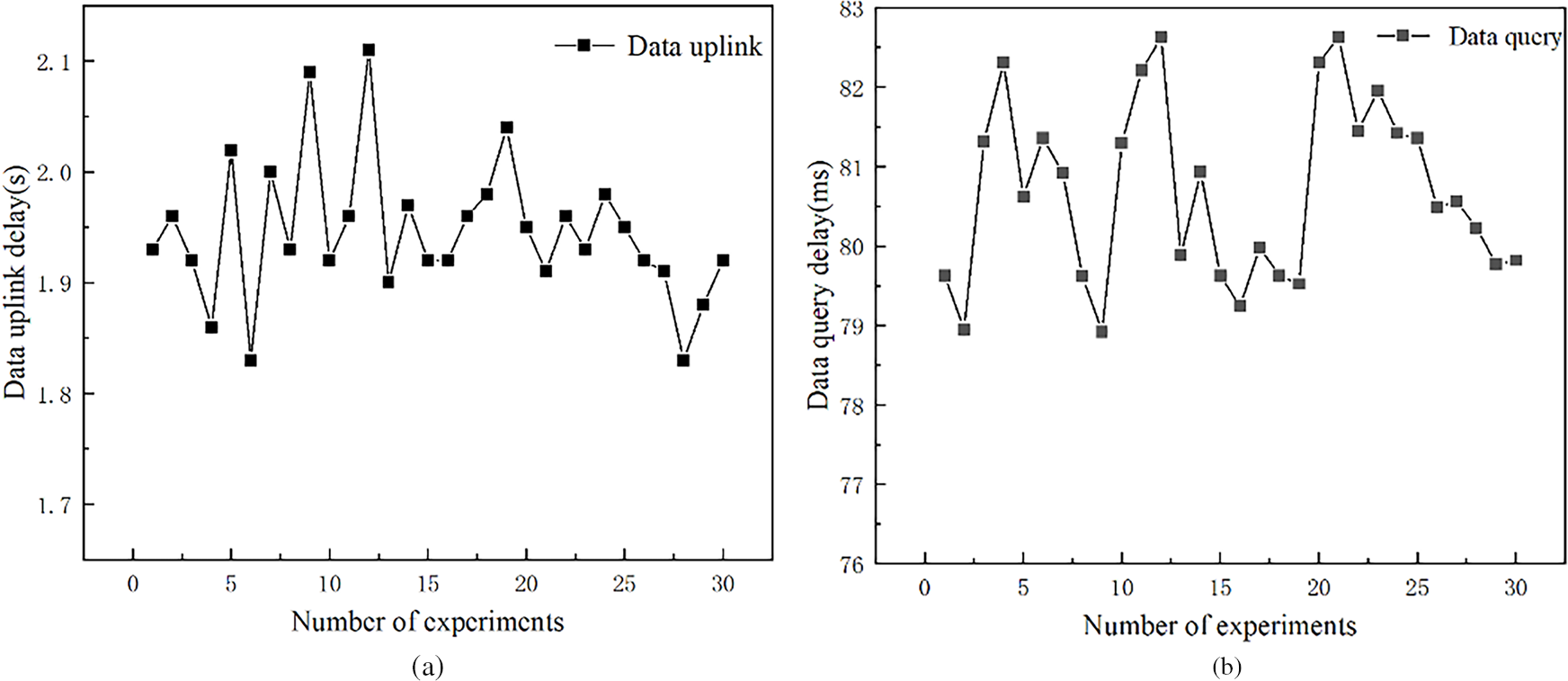

Subsequently, the aggregation-to-chain latency and query latency were tested to evaluate the effectiveness of the asynchronous federated learning model aggregation. Each test round comprised 30 trials. The aggregation-to-chain latency results are depicted in Fig. 10a. Experimental results indicate an average aggregation-to-chain latency of 1.58 s. Furthermore, query latency tests were conducted on the aggregated on-chain data, as shown in Fig. 10b. The results demonstrate an average query latency of 80.79 ms, confirming the model’s capability to meet substation requirements for data aggregation and query operations.

Figure 10: Model aggregation performance benchmarking. (a) Aggregation-to-Chain latency; (b) Query latency

4.3 Numerical Results of Dynamic Noise Tuned Differential Privacy Mechanism

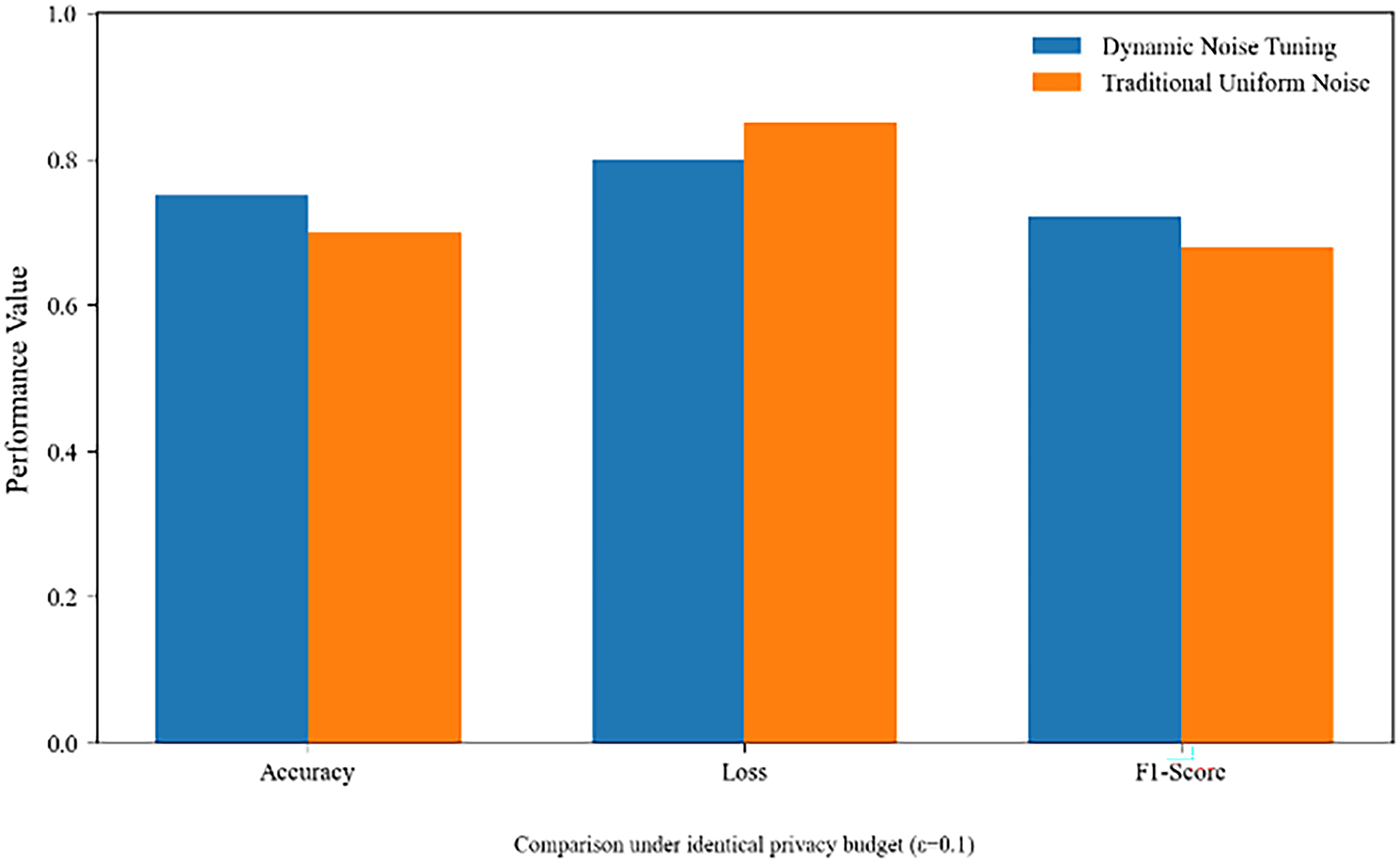

To ensure a rigorously fair comparison between the proposed dynamic differential privacy mechanism and the static uniform noise-injection approach, both schemes were allocated an identical privacy budget (

Figure 11: Feasibility analysis of differential privacy mechanisms

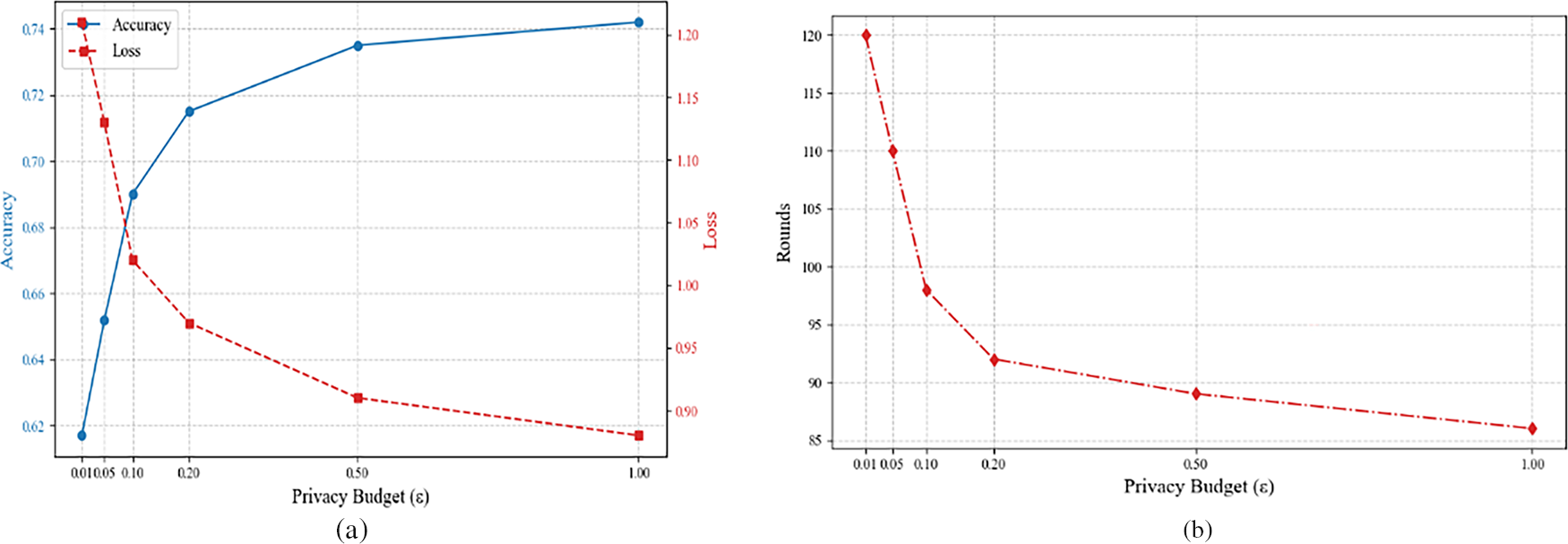

Fig. 12 comprehensively quantifies the impact of privacy budget

Figure 12: Model performance with privacy budget. (a) Privacy budget and model accuracy/loss relationship; (b) Relationship between privacy budget and model convergence

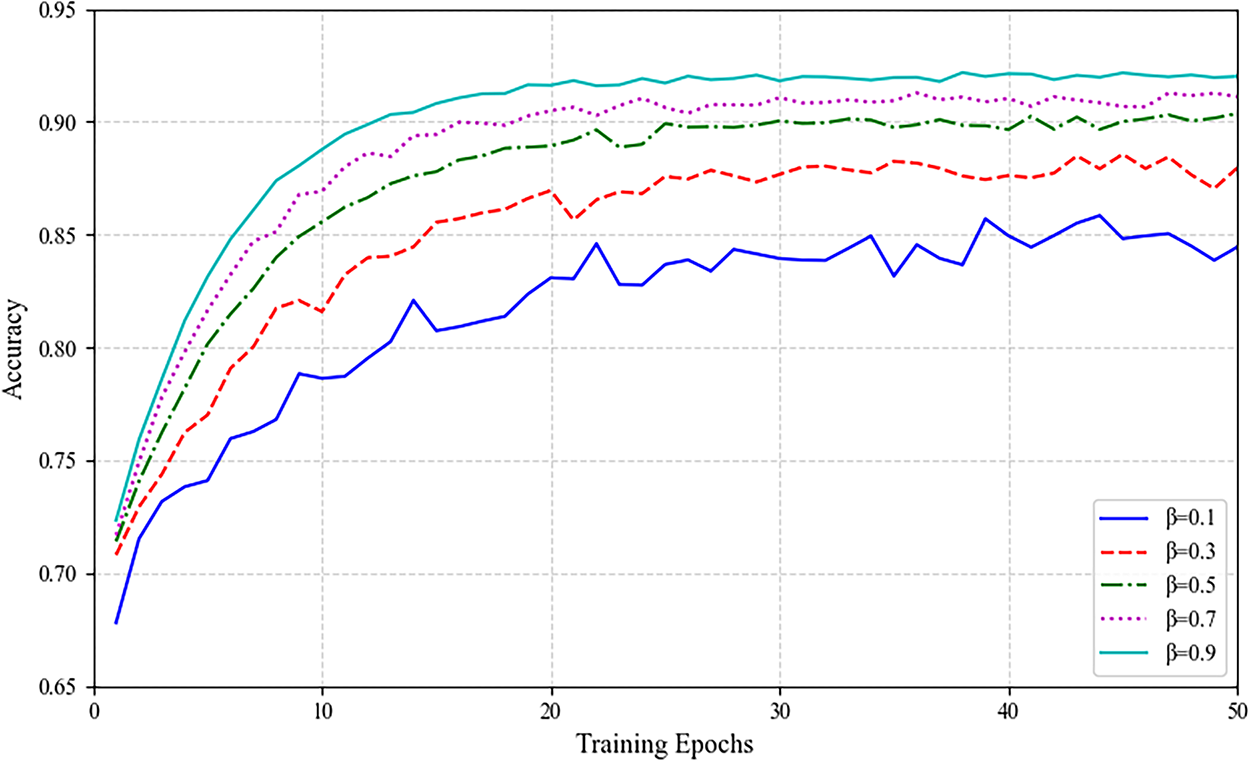

Fig. 13 experimental results demonstrate the convergence behaviors under different

Figure 13: Convergence comparison under different

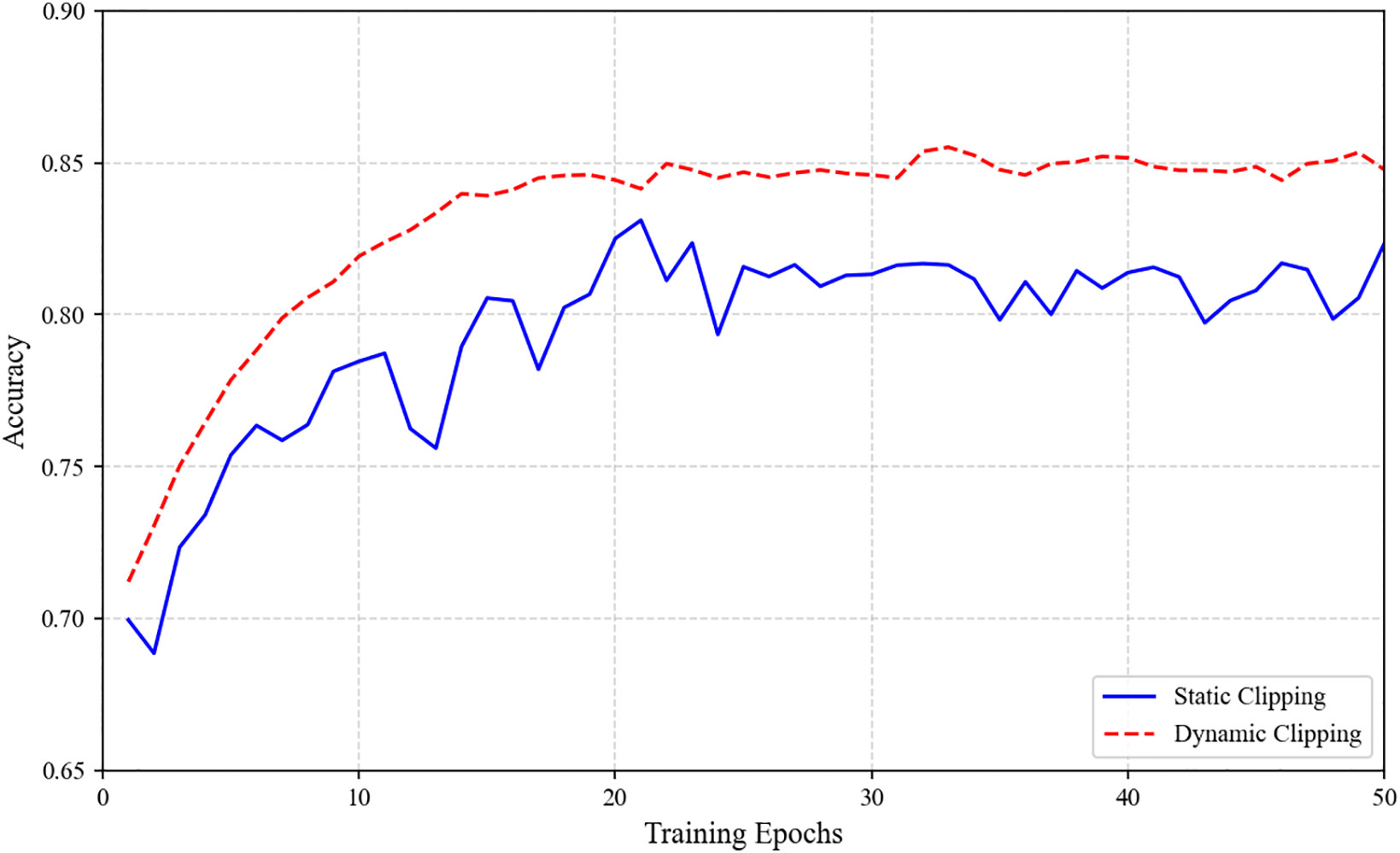

Fig. 14 quantitatively demonstrates the performance superiority of dynamic clipping over static methods: dynamic clipping achieves significantly higher initial accuracy and maintains persistent performance advantages throughout the training trajectory. Although both methods converge to comparable final accuracy, dynamic clipping stabilizes at target precision 20 epochs earlier, empirically validating that adaptive gradient clipping mechanisms substantially accelerate convergence efficiency while enhancing training stability.

Figure 14: Performance advantage of dynamic clipping and static clipping

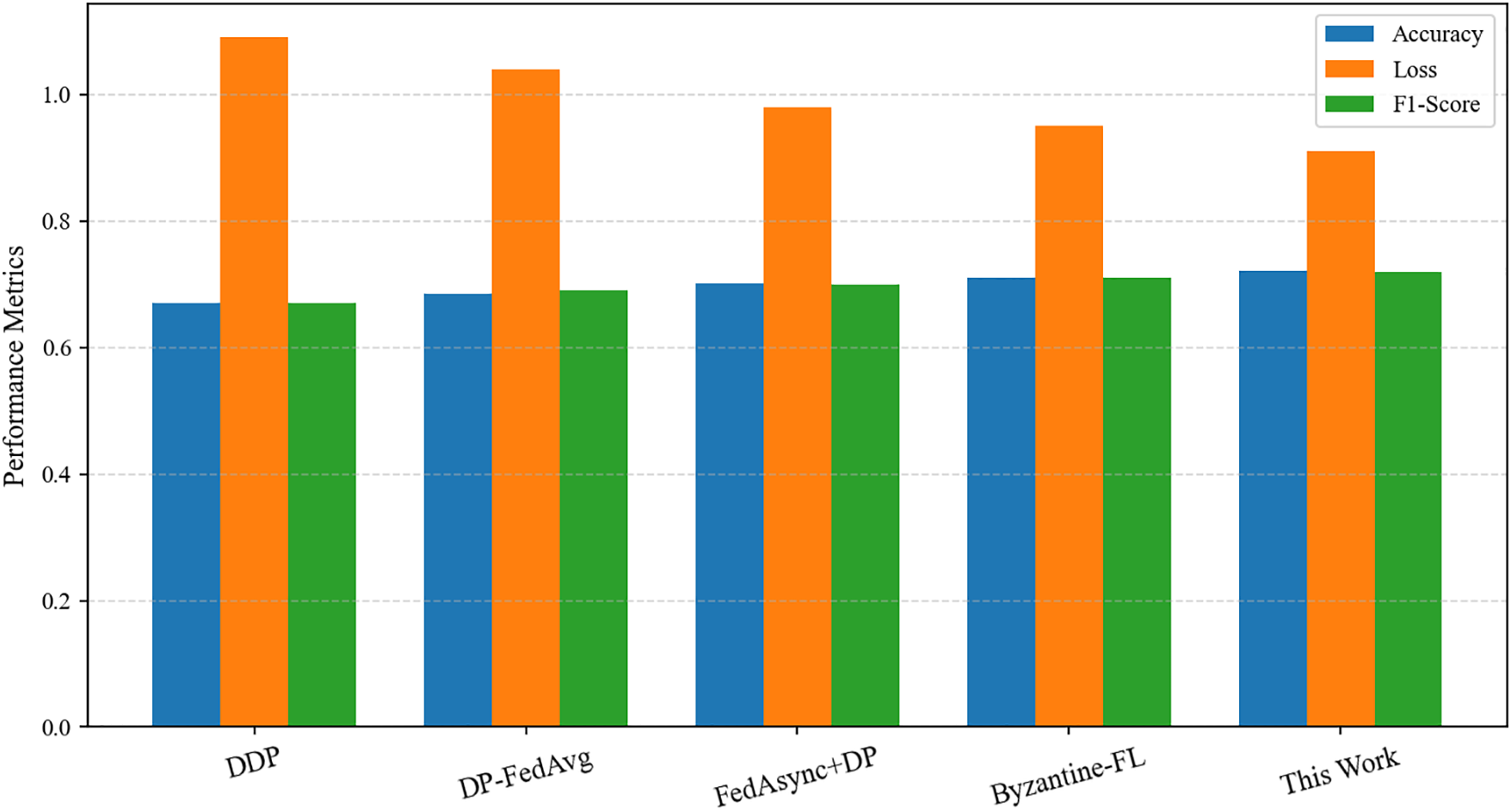

Fig. 15 presents a comparative analysis between our proposed method and several baseline approaches, including DDP, DP-FedAvg, FedAsync with static DP, and a Byzantine-resilient federated learning method. The results demonstrate that while DDP achieves the highest performance in a centralized environment, it provides no privacy protection. DP-FedAvg introduces strong noise to ensure privacy but at the cost of reduced model accuracy. FedAsync with DP shows certain efficiency advantages in asynchronous training, yet its improvements in the privacy-utility trade-off remain limited. The Byzantine-resilient method exhibits robustness against malicious updates; however, its overall accuracy is still lower than our approach due to additional aggregation constraints. In contrast, our proposed method outperforms all baselines, achieving the highest accuracy and F1-score while maintaining the lowest loss value. These results highlight the comprehensive advantages of our dynamic privacy budget allocation mechanism in terms of utility, convergence stability, and robustness.

Figure 15: Comparison of performance between the proposed method and traditional federated learning

To address the challenges of centralized single-point failures and synchronous gradient leakage in substation data privacy protection, this paper proposes a three-tiered architecture for substation data privacy preservation based on asynchronous federated learning. The architecture achieves privacy protection through a dynamic noise-tuning mechanism while enhancing decentralized aggregation efficiency via the integration of PBFT and smart contract-coordinated consensus. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed architecture significantly improves model performance while ensuring substation data privacy. Specifically, the enhanced CNN model exhibits a 23.37% improvement in accuracy and a 0.234 increase in F1-score compared to the baseline model. Additionally, the data aggregation-to-chain latency (1.58 s) and query latency (80.79 ms) meet substation operational requirements, providing a viable solution for smart grid data privacy protection.

Future research may be directed toward several important extensions of the present work. First, algorithmic optimization remains a crucial avenue, particularly through the development of more efficient strategies for dynamic privacy budget allocation and lightweight aggregation mechanisms, with the aim of reducing computational and communication overhead in resource-constrained environments. Second, the applicability and robustness of privacy-preserving federated learning frameworks merit further validation in complex and large-scale grid environments, including cross-regional and multi-node scenarios, where heterogeneous data and dynamic conditions pose additional challenges. Finally, the design of cross-regional blockchain interoperability protocols constitutes a promising research direction, as such protocols are essential for enabling secure, scalable, and collaborative data exchange across heterogeneous blockchain infrastructures in power system applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 61605004, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number FRF-TP-19-016A2, and Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd. 2024 first batch of services (2024–2026 technology R&D services for science and technology projects (in addition to national and SGCC key projects)), grant number 060100KC23100012.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yuewei Tian, Xuyang Wu and Fang Ren; methodology, Yuewei Tian, Xuyang Wu and Fang Ren; software, Fang Ren; validation, Fang Ren; formal analysis, Xuyang Wu; investigation, Yang Su; resources, Xuyang Wu; data curation, Xuyang Wu; writing—original draft preparation, Xuyang Wu and Fang Ren; writing—review and editing, Yuewei Tian and Fang Ren; visualization, Yujia Wang and Lisa Guo; supervision, Fang Ren; project administration, Lei Cao; funding acquisition, Fang Ren. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Xuyang Wu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu B, Hu Y. Analysis of substation joint safety control system and model based on multi-source heterogeneous data fusion. IEEE Access. 2023;11:35281–97. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3264707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhou F, Wen G, Ma Y, Geng H, Huang R, Pei L, et al. A comprehensive survey for deep-learning-based abnormality detection in smart grids with multimodal image data. Appl Sci. 2022;12(11):5336. doi:10.3390/app12115336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hasan MK, Habib AA, Shukur Z, Ibrahim F, Islam S, Razzaque MA. Review on cyber-physical and cyber-security system in smart grid: standards, protocols, constraints, and recommendations. J Netw Comput Appl. 2023;209:103540. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2022.103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Livada Č, Glavaš H, Baumgartner A, Jukić D. The dangers of analyzing thermographic radiometric data as images. J Imaging. 2023;9(7):143. doi:10.3390/jimaging9070143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sutherland N, Marsh S, Priestnall G, Bryan P, Mills J. InfraRed thermography and 3D-data fusion for architectural heritage: a scoping review. Remote Sens. 2023;15(9):2422. doi:10.3390/rs15092422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdelkader S, Amissah J, Kinga S, Mugerwa G, Emmanuel E, Mansour DA, et al. Securing modern power systems: implementing comprehensive strategies to enhance resilience and reliability against cyber-attacks. Results Eng. 2024;23:102647. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Luan Z, Lai Y, Xu Z, Gao Y, Wang Q. Federated learning-based insulator fault detection for data privacy preserving. Sensors. 2023;23(12):5624. doi:10.3390/s23125624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Fernández JD, Menci SP, Lee CM, Rieger A, Fridgen G. Privacy-preserving federated learning for residential short-term load forecasting. Appl Energy. 2022;326(1):119915. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Putrama IM, Martinek P. Enhancing protection in high-dimensional data: distributed differential privacy with feature selection. Inf Process Manag. 2024;61(6):103870. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2024.103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yazdinejad A, Dehghantanha A, Karimipour H, Srivastava G, Parizi RM. A robust privacy-preserving federated learning model against model poisoning attacks. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:6693–708. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2024.3420126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sharma A, Marchang N. A review on client-server attacks and defenses in federated learning. Comput Secur. 2024;140:103801. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fotiou N, Pittaras I, Siris VA, Polyzos GC, Anton P. A privacy-preserving statistics marketplace using local differential privacy and blockchain: an application to smart-grid measurements sharing. Blockchain Res Appl. 2021;2(1):100022. doi:10.1016/j.bcra.2021.100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zheng Z, Wang T, Bashir AK, Alazab M, Mumtaz S, Wang X. A decentralized mechanism based on differential privacy for privacy-preserving computation in smart grid. IEEE Trans Comput. 2022;71(11):2915–26. doi:10.1109/TC.2021.3130402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fan H, Liu Y, Zeng Z. Decentralized privacy-preserving data aggregation scheme for smart grid based on blockchain. Sensors. 2020;20(18):5282. doi:10.3390/s20185282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alsharif MH, Kannadasan R, Wei W, Nisar KS, Abdel-Aty AH. A contemporary survey of recent advances in federated learning: taxonomies, applications, and challenges. Internet Things. 2024;27:101251. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shabbir A, Manzoor HU, Manzoor MN, Hussain S, Zoha A. Robustness against data integrity attacks in decentralized federated load forecasting. Electronics. 2024;13(23):4803. doi:10.3390/electronics13234803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Q, Liu D, Cao H, Liao X, Lai X, Cui W. Decentralized asynchronous adaptive federated learning algorithm for securely prediction of distributed power data. Front Energy Res. 2024;11:1340639. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2023.1340639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Q, Yang B, Wang Z, Zhu D, Wang X, Ma K, et al. Asynchronous decentralized federated learning for collaborative fault diagnosis of PV stations. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2022;9(3):1680–96. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2022.3150182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wu Q, Dong C, Guo F, Wang L, Wu X, Wen C. Privacy-preserving federated learning for power transformer fault diagnosis with unbalanced data. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(4):5383–94. doi:10.1109/TII.2023.3333914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Khraisat A, Alazab A, Singh S, Jan T, Gomez AJr. Survey on federated learning for intrusion detection system: concept, architectures, aggregation strategies, challenges, and future directions. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(1):1–38. doi:10.1145/3687124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li J, Tong X, Liu J, Cheng L. An efficient federated learning system for network intrusion detection. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(2):2455–64. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2023.3236995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jiang W, Han H, Zhang Y, Mu J, Shankar A. Intrusion detection with federated learning and conditional generative adversarial network in satellite-terrestrial integrated networks. Mob Netw Appl. 2024;2024(4):1–14. doi:10.1007/s11036-024-02435-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhao L, Geng S, Tang X, Hawbani A, Sun Y, Xu L, et al. ALANINE: a novel decentralized personalized federated learning for heterogeneous LEO satellite constellation. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(8):6945–60. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3545429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun S, Zhang Z, Pan Q, Liu M, Wang Y, He T, et al. Staleness-controlled asynchronous federated learning: accuracy and efficiency tradeoff. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(12):12621–34. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3416216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ji Y, Chen L. FedQNN: a computation–communication-efficient federated learning framework for IoT with low-bitwidth neural network quantization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(3):2494–507. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3213650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wan Y, Qu Y, Ni W, Xiang Y, Gao L, Hossain E. Data and model poisoning backdoor attacks on wireless federated learning, and the defense mechanisms: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2024;26(3):1861–97. doi:10.1109/COMST.2024.3361451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li J, Jiang M, Qin Y, Zhang R, Ling SH. Intelligent depression detection with asynchronous federated optimization. Complex Intell Systems. 2023;9(1):115–31. doi:10.1007/s40747-022-00729-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Gao Q, Sun H, Wang Z. DP-EPSO: differential privacy protection algorithm based on differential evolution and particle swarm optimization. Opt Laser Technol. 2024;173(1):110541. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.110541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sathish Kumar G, Premalatha K, Uma Maheshwari G, Rajesh Kanna P, Vijaya G, Nivaashini M. Differential privacy scheme using Laplace mechanism and statistical method computation in deep neural network for privacy preservation. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;128(2):107399. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Parida NK, Jatoth C, Reddy VD, Hussain MM, Faizi J. Post-quantum distributed ledger technology: a systematic survey. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):20729. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-47331-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Feng Q, He D, Zeadally S, Khan MK, Kumar N. A survey on privacy protection in blockchain system. J Netw Comput Appl. 2019;126:45–58. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2018.10.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lashkari B, Musilek P. A comprehensive review of blockchain consensus mechanisms. IEEE Access. 2021;9:43620–52. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3065880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yue K, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y, Zhao L, Rong C, et al. A survey of decentralizing applications via blockchain: the 5G and beyond perspective. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2021;23(4):2191–217. doi:10.1109/COMST.2021.3115797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Balduf L, Henningsen S, Florian M, Rust S, Scheuermann B. Monitoring data requests in decentralized data storage systems: a case study of IPFS. In: 2022 IEEE 42nd International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS); 2022 Jul 10–13; Bologna, Italy. p. 658–68. doi:10.1109/ICDCS54860.2022.00069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shi R, Cheng R, Han B, Cheng Y, Chen S. A closer look into IPFS: accessibility, content, and performance. Proc ACM Meas Anal Comput Syst. 2024;8(2):1–31. doi:10.1145/3656015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Nabavirazavi S, Taheri R, Shojafar M, Iyengar SS. Impact of aggregation function randomization against model poisoning in federated learning. In: 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom); 2023 Nov 1–3; Exeter, UK. p. 165–72. doi:10.1109/TrustCom60117.2023.00043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Nabavirazavi S, Taheri R, Ghahremani M, Iyengar SS. Model poisoning attack against federated learning with adaptive aggregation. In: Adversarial multimedia forensics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-49803-9_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools