Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Feature-Driven Hybrid Temporal Learning and Instance-Based Classification for DDoS Detection in Industrial Control Networks

1 Extral High Voltage Power Transmission Company, China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, 510000, China

2 Extral High Voltage Power Transmission Company Nanning Monitoring Center, China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd., Nanning, 530000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xuan Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 27 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072093

Received 19 August 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks pose severe threats to Industrial Control Networks (ICNs), where service disruption can cause significant economic losses and operational risks. Existing signature-based methods are ineffective against novel attacks, and traditional machine learning models struggle to capture the complex temporal dependencies and dynamic traffic patterns inherent in ICN environments. To address these challenges, this study proposes a deep feature-driven hybrid framework that integrates Transformer, BiLSTM, and KNN to achieve accurate and robust DDoS detection. The Transformer component extracts global temporal dependencies from network traffic flows, while BiLSTM captures fine-grained sequential dynamics. The learned embeddings are then classified using an instance-based KNN layer, enhancing decision boundary precision. This cascaded architecture balances feature abstraction and locality preservation, improving both generalization and robustness. The proposed approach was evaluated on a newly collected real-time ICN traffic dataset and further validated using the public CIC-IDS2017 and Edge-IIoT datasets to demonstrate generalization. Comprehensive metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, false positive rate (FPR), and detection latency were employed. Results show that the hybrid framework achieves 98.42% accuracy with an ROC-AUC of 0.992 and FPR below 1%, outperforming baseline machine learning and deep learning models. Robustness experiments under Gaussian noise perturbations confirmed stable performance with less than 2% accuracy degradation. Moreover, detection latency remained below 2.1 ms per sample, indicating suitability for real-time ICS deployment. In summary, the proposed hybrid temporal learning and instance-based classification model offers a scalable and effective solution for DDoS detection in industrial control environments. By combining global contextual modeling, sequential learning, and instance-based refinement, the framework demonstrates strong adaptability across datasets and resilience against noise, providing practical utility for safeguarding critical infrastructure.Keywords

Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) [1] attacks remain one of the most durable and damaging categories of cyber threats to contemporary networked systems. These attacks aim to exhaust resources at target hosts and network infrastructure, causing service outages and severe economic and reputational damage to service providers. The proliferation of cloud services, Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices and software-defined networking (SDN) [2–5] has expanded both the attack surface and the potential impact of volumetric and application-layer DDoS campaigns. The complexity and diversity of modern DDoS vectors require detection systems that are not only accurate but also robust to new, previously unseen attack variants and efficient enough for near-real-time deployment [6].

Traditional rule-based and signature-based systems, while effective against well-known attack patterns, often fail to generalize to novel traffic patterns and require expensive manual updates. In parallel, classical machine learning classifiers (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, Decision Trees, KNN, Logistic Regression) have been widely applied as lightweight detection components; however, they typically rely on hand-crafted features and cannot fully capture complex temporal dynamics or high-order feature interactions inherent in network flows. These shortcomings motivate the use of representation learning and deep sequence models that can automatically extract discriminative features from high-dimensional traffic records.

1.2 Related Work and Limitations

A growing body of literature has demonstrated that deep architectures—such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [7–9], recurrent neural networks (RNNs) including LSTM/BiLSTM [10–12], and more recently Transformer-based encoders—can surpass shallow baselines on intrusion and DDoS detection tasks by learning hierarchical or temporal representations directly from data. Hybrid models that combine convolutional front-ends with recurrent back-ends (e.g., CNN-LSTM [13]) or incorporate attention mechanisms have achieved strong results on benchmark datasets (e.g., CIC-IDS2017, CICDDoS2019 [14,15]) and in SDN/IoT settings [6].

However, several important limitations persist in the literature:

• Generalization to unknown attacks. Many deep models are trained under a closed-set assumption and may produce overly confident predictions for traffic patterns not represented in the training set. Open-set recognition (OSR) and clustering-assisted detection have been proposed to mitigate this, but integration is still immature for real-time DDoS defense [16,17].

• Local vs. global representation trade-offs. Global attention-based models (Transformers [18]) excel at capturing global feature interactions, whereas sequence models (BiLSTM) capture ordered dependencies [14]. Each family has strengths; few studies methodically combine their complementary properties with instance-based classifiers such as KNN to improve robustness to atypical samples [19].

• Interpretability and embedding separability. High numerical accuracy does not necessarily imply embedding spaces that are well-clustered or interpretable. Visualization techniques (t-SNE, PCA) and neighborhood-based classifiers can help assess and exploit local separability [20–23]; however, many works stop at accuracy reporting without embedding-level analysis.

• Deployment constraints and robustness. High-performance deep models often demand substantial computation; lightweight or edge-deployable approaches must balance detection accuracy with inference latency and resource consumption. Moreover, robustness to noise and adversarial perturbations is not systematically evaluated in many studies [24].

These gaps motivate a hybrid design that (i) learns powerful global representations, (ii) preserves temporal structure where necessary, (iii) exploits local neighborhood decisions for robustness and interpretability, and (iv) is evaluated with embedding visualizations and robustness tests.

1.3 Proposed Approach and How It Addresses Limitations

In this work we propose a principled hybrid detection framework that combines Transformer-based representation learning, Bidirectional LSTM sequence modeling, and K-Nearest-Neighbor (KNN) classification applied on learned embeddings. Concretely, our pipeline performs the following steps:

• Preprocessing and robustification. Raw flow-level features undergo label encoding, standardization (z-score), and controlled Gaussian noise injection during training to improve generalization under realistic perturbations [25].

• Global embedding extraction. A compact Transformer encoder maps each preprocessed sample to a dense embedding that captures global feature interactions and cross-feature attention.

• Sequential refinement. A BiLSTM module is used in a parallel or cascaded fashion to encode temporal dependencies (forward and backward), producing sequence-aware embeddings.

• Instance-based classification. KNN is applied in the embedding spaces (Transformer-embedding or BiLSTM-embedding [26]) to leverage instance-level locality: this increases robustness to rare or atypical samples and improves interpretability via neighbor inspection.

• Visualization and explainability. We analyze the embedding structure using t-SNE and PCA and report confusion matrices to quantify error modes (false positives vs. false negatives).

This hybridization addresses the aforementioned limitations: the Transformer captures global dependencies and supplies high-quality embeddings, BiLSTM captures ordering effects typical in flow sequences, and KNN injects local decision robustness and interpretability—together improving detection of both known and novel DDoS patterns. We also evaluate optimizer choices, noise injection factors, and K selection to provide practical guidance for deployment.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• We design and implement a hybrid DDoS detection framework that integrates Transformer-based representation learning, BiLSTM temporal modeling, and KNN instance-based classification to exploit complementary strengths of global attention, sequential encoding, and local decision-making.

• We perform an extensive empirical comparison that includes multiple traditional baselines (SVM, Random Forest, Decision Tree, Logistic Regression, KNN) [19,27–30], a pure Transformer+KNN pipeline, a pure BiLSTM classifier, and BiLSTM+KNN hybrids. Experiments are conducted on a realistic real-time DDoS traffic dataset following the preprocessing pipeline described in Section 4.

• We systematically analyze training dynamics (accuracy/loss vs epochs), optimizer effects (Adam, AdamW, Nadam, NAG), and robustness to injected Gaussian noise. The best-performing hybrid (BiLSTM+KNN with tuned

• We provide practical deployment recommendations balancing accuracy, interpretability and computational cost, and demonstrate that the proposed method improves detection of previously unseen DDoS patterns relative to baselines and recent Transformer-based detectors.

Compared with prior hybrid intrusion detection frameworks such as CNN–BiLSTM or CNN–Transformer, our work introduces two key extensions. First, instead of relying solely on convolutional or recurrent structures, we employ a cascaded Transformer–BiLSTM pipeline that jointly captures global temporal dependencies and fine-grained sequential patterns. Second, we integrate an instance-based KNN classifier as the final decision layer. This design allows the model to preserve neighborhood structure in the learned embedding space, which is particularly valuable in ICN traffic where attack flows often cluster tightly but may share similarities with benign flows. To the best of our knowledge, this instance-based refinement has not been systematically explored in prior hybrid approaches, and it provides clear benefits for robustness and interpretability in industrial settings.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 surveys related work on DDoS detection, open-set recognition and hybrid approaches. Section 3 details the proposed hybrid pipeline, mathematical formulations and training protocols. Section 4 presents dataset descriptions, preprocessing steps, experimental settings and results, including visualizations and ablation studies. Section 4 discusses findings, limitations and deployment considerations. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

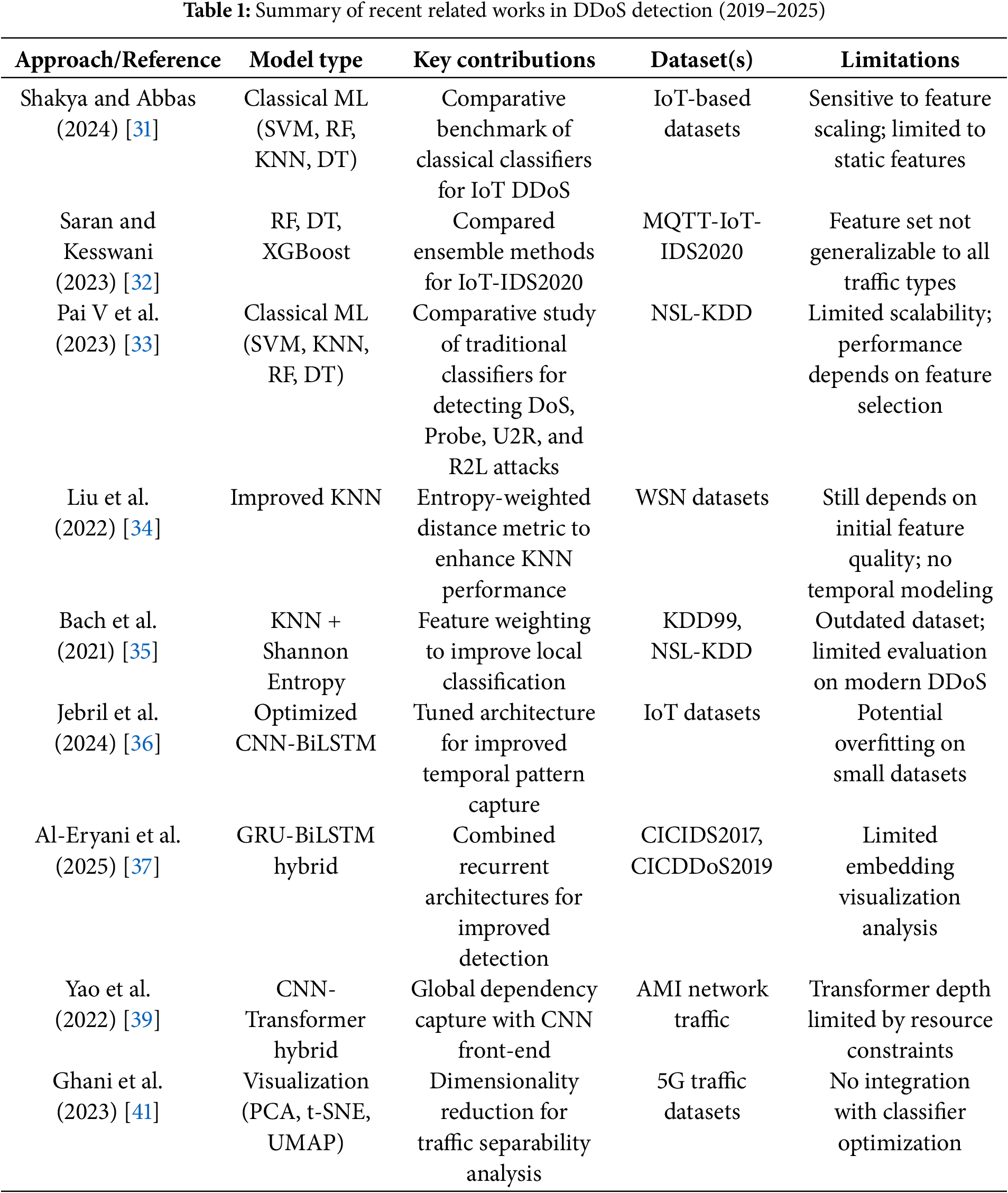

The detection of Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks has drawn sustained attention in the last five years due to the rapid evolution of threat vectors, the proliferation of heterogeneous networked environments (IoT, edge/fog, 5G), and the demand for near-real-time defenses with strong generalization. Prior work spans (i) classical, feature-engineered machine learning (ML), (ii) deep learning (DL) with temporal models, (iii) Transformer-based representation learning, (iv) hybrid pipelines that fuse learned embeddings with instance-based decision rules, and (v) visualization- and optimization-aware training protocols. Below we organize recent advances and highlight their limitations vis-à-vis the design choices evaluated in our experiments.

2.1 Classical Learning and Feature-Engineered IDS Baselines

Early and still widely used approaches rely on feature engineering and supervised ML classifiers such as

2.2 Sequence Models: LSTM/BiLSTM and CNN-Recurrent Hybrids

Because volumetric and application-layer DDoS attacks manifest temporal regularities, sequence models are a natural fit. CNN-RNN hybrids and bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) variants capture short-/long-range dependencies and have repeatedly surpassed shallow baselines on CICIDS2017 and CICDDoS2019 [35,36]. A recent CNN–BiLSTM with attention mechanism demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across CICDDoS2019 and Edge-IIoT, underscoring the benefit of combining local pattern extraction (CNN) with bidirectional temporal aggregation [37]. Similarly, GRU–BiLSTM hybrids improve detection sensitivity to evolving attack morphologies by leveraging complementary recurrent dynamics [37]. Nevertheless, these architectures can struggle with global cross-feature interactions and may require careful tuning of depth/hidden sizes to avoid overfitting and latency penalties. Our study therefore benchmarks a pure BiLSTM classifier and further explores BiLSTM+KNN to exploit neighborhood structure in the induced latent space.

2.3 Transformer-Based Intrusion and DDoS Detectors

Transformers—with multi-head self-attention and position encodings—enable global, order-aware feature interaction modeling, and have seen growing adoption for network intrusion tasks since 2021. Hybrid CNN–Transformer pipelines have been proposed for AMI and enterprise IDS, where the Transformer layer refines global dependencies on top of convolutional features, improving robustness to spurious correlations and unbalanced traffic [38]. More recent works employ pure or teacher-student Transformer setups with tailored attention designs and knowledge distillation for interpretability and efficiency. Comparative evaluations on IoT settings suggest that Transformer encoders, when trained with appropriate regularization and balanced sampling, can outperform RNNs on multi-class intrusion tasks while producing more linearly separable embeddings [31]. Building on these insights, our experiments use a compact Transformer encoder primarily as a representation learner that outputs embeddings subsequently classified by KNN. This design explicitly tests the hypothesis that global-attention embeddings, coupled with instance-based decision rules, yield gains in generalization and transparency over end-to-end softmax classifiers.

2.4 Representation Learning with Instance-Based Decision Rules

Instance-based methods offer two practical benefits in security analytics: (i) resilience to mild distributional shift by deferring decisions to local neighborhoods in the embedding space, and (ii) improved interpretability via neighbor inspection. In IDS, KNN variants have been revisited with modern representation learning, metric adaptation and feature selection [34,35,38]. However, many studies stop at applying KNN directly to hand-engineered features, missing the opportunity to first learn semantically meaningful embeddings with attention or recurrent encoders. Our framework closes this gap by (a) training a Transformer (and, separately, a BiLSTM) to produce embeddings and (b) applying KNN with tuned

2.5 Datasets, Visualization, and Evaluation Practices

CICIDS2017 and CICDDoS2019 remain the most frequently used public corpora for DDoS research; several recent reviews included CNN-Transformer hybrid proposed by Cao and GRU-BilSTM hybrid proposed by Hussein,standardize taxonomies and emphasize the role of dataset curation and up-to-date attack families [32,37,39,40]. Beyond accuracy, visualization tools (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP) help assess separability and failure modes in high dimensions, especially in emerging 5G traffic [40]. Our evaluation mirrors these best practices by reporting confusion matrices and embedding visualizations (PCA/t-SNE) alongside scalar metrics.

2.6 Optimization Choices and Training Dynamics

Optimization details (e.g., Adam, AdamW, Nadam, Nesterov accelerated SGD) can materially affect convergence speed, calibration and robustness. While this aspect is less emphasized in many IDS studies, a growing engineering literature on optimization variants motivates systematic comparisons and mix-and-match strategies for stability and generalization In our BiLSTM study we therefore ablate Adam, AdamW, Nadam, and NAG and report learning curves (accuracy/loss vs. epochs) to document optimizer-induced behavior.

2.7 Real-Time and Continual Learning for Evolving Attacks

Recent work has also focused on online or continual learning for real-time DDoS detection across heterogeneous environments, addressing non-stationarity and zero-day variants through multi-level pipelines and confidence-aware escalation. While our experimental setup centers on offline training with robustness-oriented preprocessing (standardization and controlled noise), the modularity of our Transformer- and BiLSTM-based embedding learners with KNN back-ends is compatible with such continual updates and active re-labeling.

In summary, prior art shows: (i) classical ML remains a strong baseline but is feature-sensitive; (ii) CNN/RNN hybrids and BiLSTM advance temporal modeling; (iii) Transformers improve global dependency capture and often yield well-structured embeddings; and (iv) KNN, when paired with learned embeddings, can provide robust, interpretable decisions. Our contribution is to systematically integrate these strands in a controlled experimental suite: traditional baselines, a Transformer+KNN pipeline, a BiLSTM classifier, and a BiLSTM+KNN hybrid with optimizer and

As summarized in Table 1, recent work demonstrates that while classical ML remains relevant for lightweight detection, modern deep and hybrid models (CNN-BiLSTM, Transformer-based) consistently improve detection rates and generalization, though at the expense of complexity and computational overhead. Our proposed hybrid framework aims to combine these strengths while mitigating their respective weaknesses.

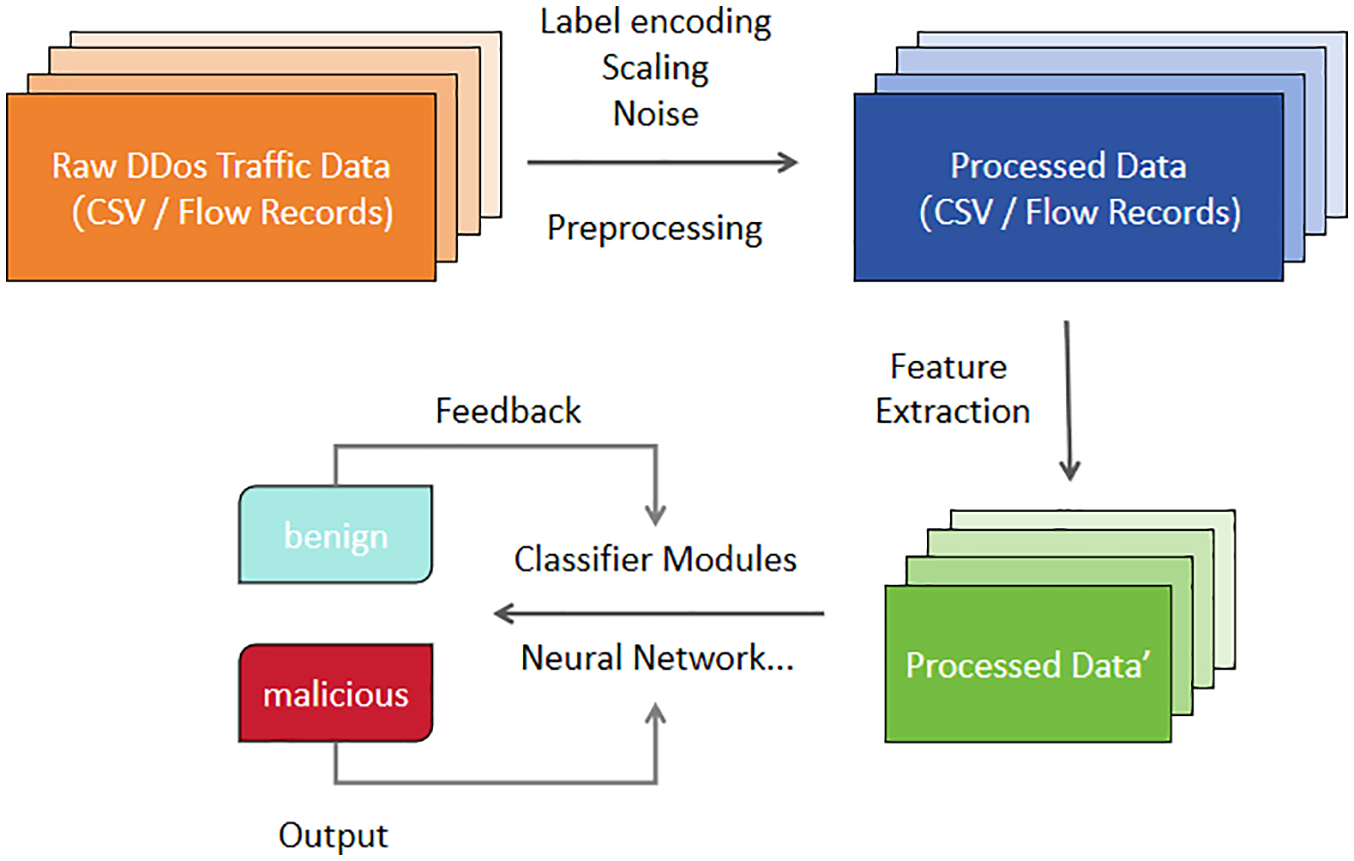

This section details the methodological framework for DDoS detection, as shown in Fig. 1, integrating feature preprocessing, traditional machine learning baselines, Transformer-based representation learning with KNN classification, and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) architectures. The proposed approach is motivated by the need to leverage both sequential dependencies in network traffic and high-dimensional feature interactions, thereby achieving high detection accuracy and robustness under varying attack patterns.

Figure 1: Overall DDoS detection framework

3.1 Feature Preprocessing and Representation

The raw DDoS dataset comprises heterogeneous features, including packet-size statistics, flow duration, protocol flags, and inter-arrival times. These features exhibit varying scales and statistical distributions, which can impair model convergence and stability. To address this, all features are normalized to zero mean and unit variance, ensuring that each feature contributes equally during optimization:

In realistic network environments, benign traffic often exhibits minor fluctuations that can mimic attack-like bursts, leading to false positives. To improve robustness, Gaussian noise injection is applied during training:

where

3.2 Traditional Machine Learning Baselines

Before deploying complex deep-learning models, it is essential to benchmark against classical classifiers to establish a performance baseline. This enables direct evaluation of the incremental benefit of more sophisticated architectures.

• Support Vector Machine (SVM): Constructs a maximum-margin hyperplane separating attack and benign classes.

• Random Forest (RF): Utilizes an ensemble of decision trees with bootstrap sampling and feature randomness.

• Decision Tree (DT): Recursively partitions the feature space into regions with homogeneous labels.

• Logistic Regression (LR): Models the log-odds of class membership as a linear function of input features.

• Naïve Bayes (NB): Applies Bayes’ theorem under the assumption of conditional independence between features [27–30,42].

SVM Formulation.

For SVM, the margin-maximization problem is formulated as

Soft margins incorporate slack variables

Random Forest Prediction.

For RF, the ensemble prediction is the majority vote across T trees:

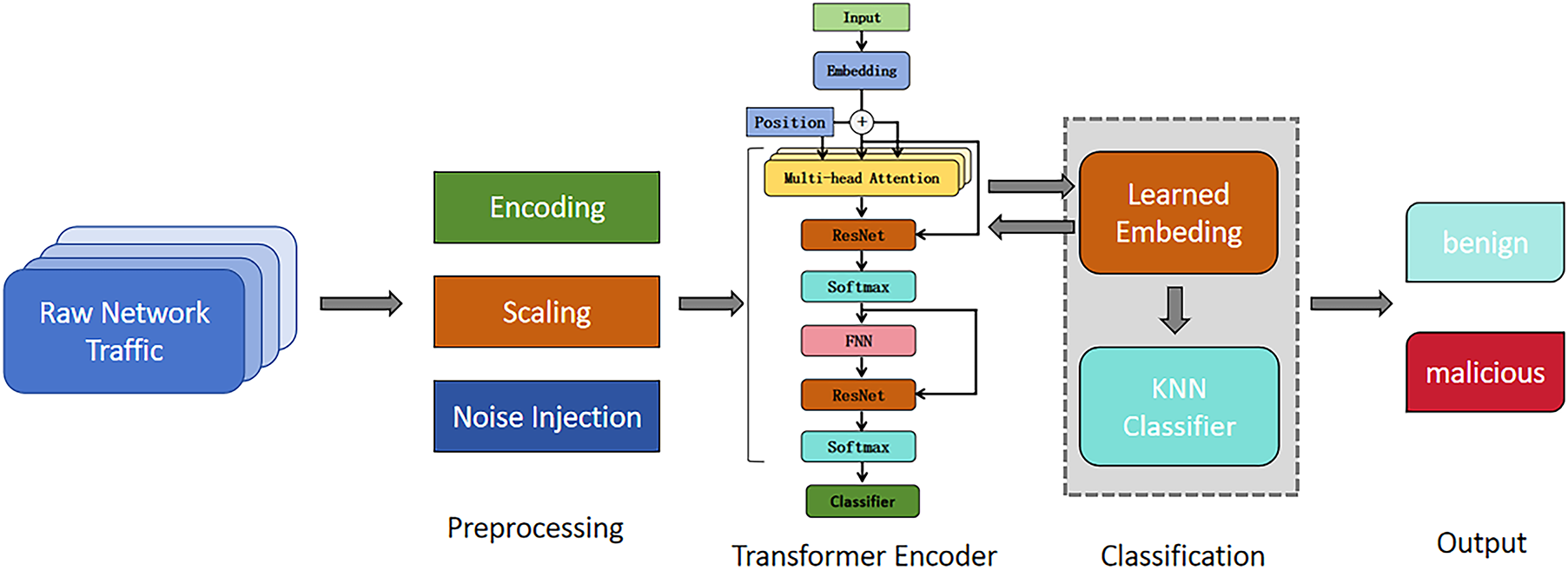

3.3 Transformer-Based Representation Learning with KNN

Network traffic often contains long-range dependencies and subtle patterns spanning multiple feature dimensions. Traditional classifiers may fail to capture such patterns due to their limited capacity for modeling global relationships. To address this, we employ a Transformer encoder as a feature extractor, as shown in Fig. 2 followed by KNN classification in the learned embedding space.

Figure 2: Overall DDoS detection framework

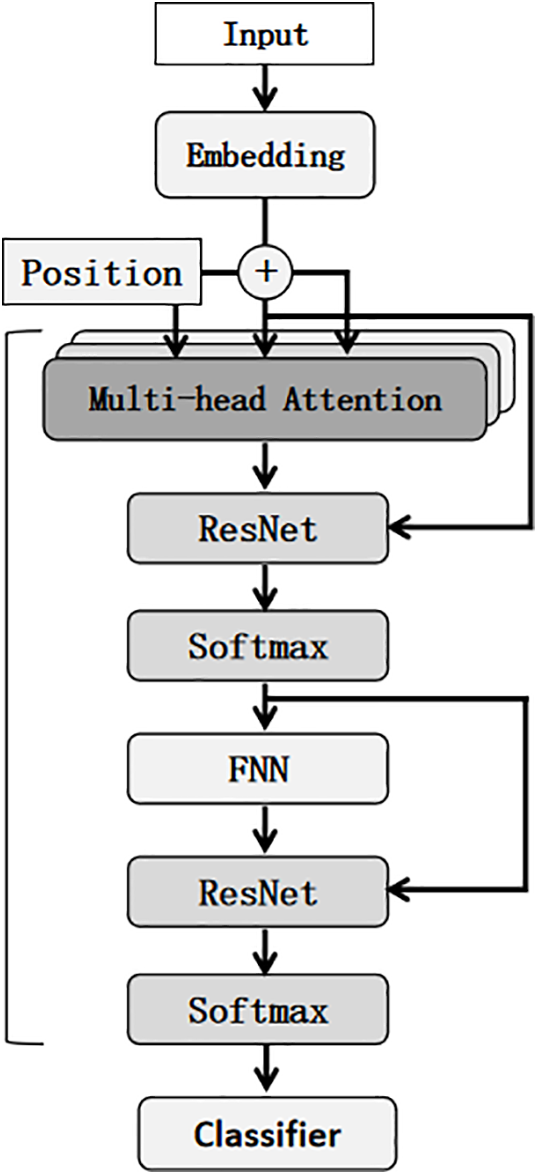

3.3.1 Transformer Encoder Formulation

The Transformer encoder,as shown in Fig. 3, is a highly expressive neural architecture that leverages the self-attention mechanism to model pairwise dependencies between all positions in a sequence, regardless of their relative distance. This property is particularly advantageous for DDoS detection, as attack traffic often exhibits both short-term burst patterns and long-range statistical correlations across network flows. Traditional RNN-based models, while effective for sequential data, suffer from vanishing gradients and limited parallelism. In contrast, the Transformer encoder achieves both efficient computation and rich contextual representation by replacing recurrence with attention-based operations.

Figure 3: Architecture of the Transformer encoder used in the proposed DDoS detection framework

Let the preprocessed input be represented as

where

The self-attention mechanism is then formalized as:

Here, the dot-product

To further improve the representational capacity, the Transformer employs multi-head attention (MHA), which allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces:

where

Following the attention block, a position-wise feed-forward network (FFN) is applied independently to each feature position:

where

In the proposed hybrid DDoS detection framework, the Transformer encoder serves as a powerful global representation extractor. By learning attention weights across all input features, it can identify subtle statistical anomalies indicative of early-stage DDoS activity while remaining resilient to noise and irrelevant fluctuations. This capability is essential when working with high-dimensional network traffic datasets such as CICIDS2017 and CICDDoS2019, where benign and malicious patterns often exhibit overlapping statistical distributions.

3.4 KNN Classification in Embedding Space

Once the Transformer generates embeddings

The Euclidean distance metric is used:

This hybrid design combines the Transformer’s representational power with KNN’s non-parametric classification, enabling the detection of subtle, previously unseen DDoS patterns.

3.5 Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) Network

While Transformers excel in global attention, BiLSTM is more effective in capturing ordered dependencies, which are prominent in time-based network-traffic sequences. BiLSTM processes the input sequence in both forward and backward directions, concatenating the hidden states to incorporate information from past and future contexts.

The LSTM unit maintains a cell state

In BiLSTM, forward and backward hidden states are concatenated:

This dual-direction processing allows the model to detect anomalies based on both preceding and succeeding traffic behavior.

3.5.2 Hybrid Topologies and Fusion Strategies

We designed and evaluated two integration strategies for combining Transformer and BiLSTM embeddings:

Parallel Fusion

Input sequences are fed simultaneously into a Transformer encoder and a BiLSTM network. The resulting embeddings

followed by a fully-connected projection before classification.

Cascaded Fusion

The Transformer encoder produces contextualised embeddings, which are then passed to a BiLSTM for sequential refinement. Formally,

We ablated both strategies and compared them with single-model baselines (Transformer-only, BiLSTM-only).

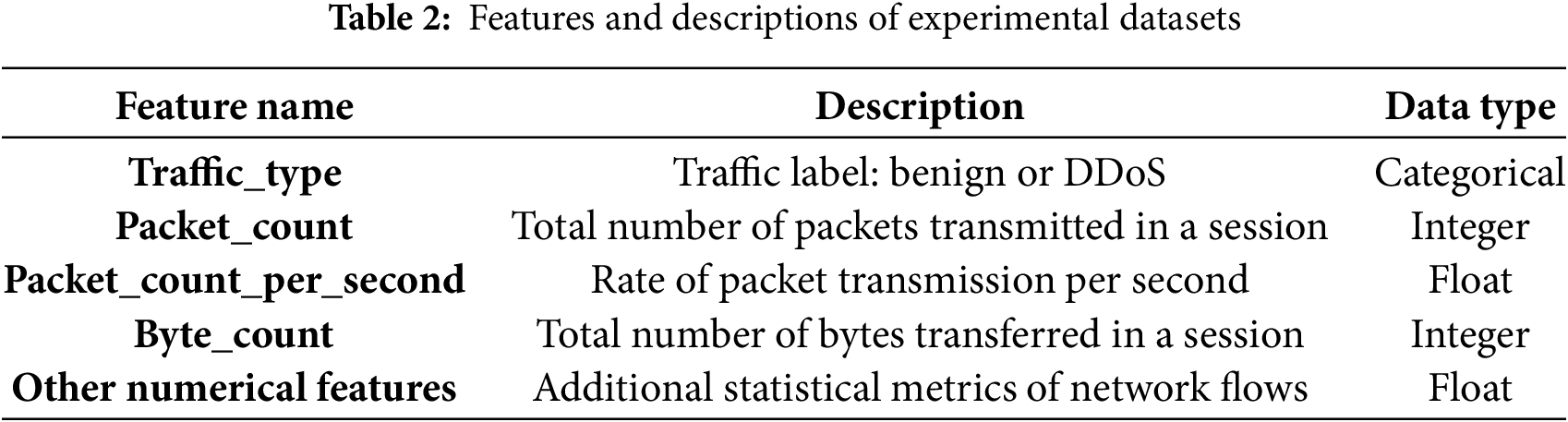

The experiments in this study are conducted on the Real-Time DDoS Traffic Dataset, as shown in Table 2, which is specifically designed to support the development, evaluation, and benchmarking of machine learning models for real-time detection of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. The dataset contains labeled network traffic instances, including both benign traffic and malicious DDoS flows, enabling the supervised training and testing of detection models.

To ensure reproducibility and generalization, we also evaluated our framework on two well-known benchmarks:

CIC-IDS2017: Covers multiple attack categories including DoS/DDoS, with 78 flow features. We extracted the DDoS subset (total 288,602 flows; benign: 230,000, DDoS: 58,602).

Edge-IIoTset: A recent IIoT dataset including industrial protocols (Modbus, MQTT). We selected the DDoS scenarios (total 110,451 flows; benign: 72,319, DDoS: 38,132). These datasets allow us to compare performance with prior work and validate applicability in both IT and OT/ICS contexts.

4.1.1 Data Collection and Characteristics

The Real-Time DDoS Traffic Dataset was collected between May 2024 and August 2024 from a monitored subnet of an industrial control testbed at a power grid laboratory. Raw packets were captured through a SPAN port using tcpdump and then processed with CICFlowMeter v3 to extract flow-level features. Each flow record contains 82 features, including basic statistics (packet count, byte count), temporal features (inter-arrival time, active/idle time), and transport-layer statistics (flag counts, window sizes). After preprocessing, the dataset contains a total of 165,432 flows, of which 95,210 are benign and 70,222 correspond to DDoS attacks generated using LOIC, HOIC, and UDP flood scripts. IP and MAC addresses were anonymized. Labels were assigned by cross-verifying attack logs and IDS alerts. To enhance reproducibility, the dataset and preprocessing scripts are publicly available at: https://github.com/JohnVickey/DDoS-Detection-in-Industrial-Control-Networks (accessed on 28 September 2025).

The dataset consists of N total samples (where N is determined after preprocessing), with a balanced distribution between benign and malicious instances to avoid class imbalance issues. All features are numerical except for the Traffic_type label, which is encoded into binary form (0 for benign, 1 for DDoS) before model training.

To ensure comparability across models and maintain numerical stability during training, all feature values are standardized using z-score normalization, as defined in Equation:

where

In order to ensure that the dataset is suitable for training and evaluating machine learning models for DDoS detection, several preprocessing steps are performed prior to model construction. These steps are designed to clean, transform, and normalize the raw data, while preserving the essential characteristics necessary for accurate classification.

The original dataset contains a categorical variable Traffic_type that specifies whether a traffic flow is benign or a DDoS attack. As most machine learning algorithms require numerical input, this categorical label is transformed into binary numerical format using the Label Encoding method:

This transformation ensures that the target variable can be directly used in supervised learning algorithms without introducing ordinal bias.

Since the dataset contains features with varying ranges and units (e.g., packet counts, byte counts, transmission rates), feature scaling is performed to bring all variables to a comparable scale. Specifically, z-score normalization (StandardScaler) is applied to each numerical feature.

4.2.3 Sequence Reshaping for Temporal Models

For sequence-based models such as RNN, LSTM, GRU, and Transformer architectures, the

In this study, the time-step dimension is set to

4.2.4 Noise Injection for Robustness Testing

To improve generalization, Gaussian noise augmentation was applied only to the training set. For each training feature vector

For robustness evaluation, the trained models were further tested on separate perturbed test partitions with controlled noise levels (

Finally, the dataset is divided into training and testing subsets using an 80:20 split. The training set is used for model fitting, while the testing set provides an unbiased estimate of model performance. The split is performed with a fixed random seed (random_state = 42) to ensure reproducibility across experiments.

The experiment was conducted on a heterogeneous computing platform featuring an Intel Xeon Platinum 8474C CPU (15 vCPUs) and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB VRAM), complemented by 80 GB of system RAM and high-speed NVMe storage, thereby establishing a robust hardware foundation for large-scale deep-learning workloads. The software stack comprises Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, Python 3.8, and a comprehensive tool-chain including PyTorch 1.10.0, Transformers. Leveraging CUDA 11.3, GPU-accelerated training was fully exploited; model optimization was performed with the AdamW optimizer and cross-entropy loss to ensure rapid convergence and stable generalization.

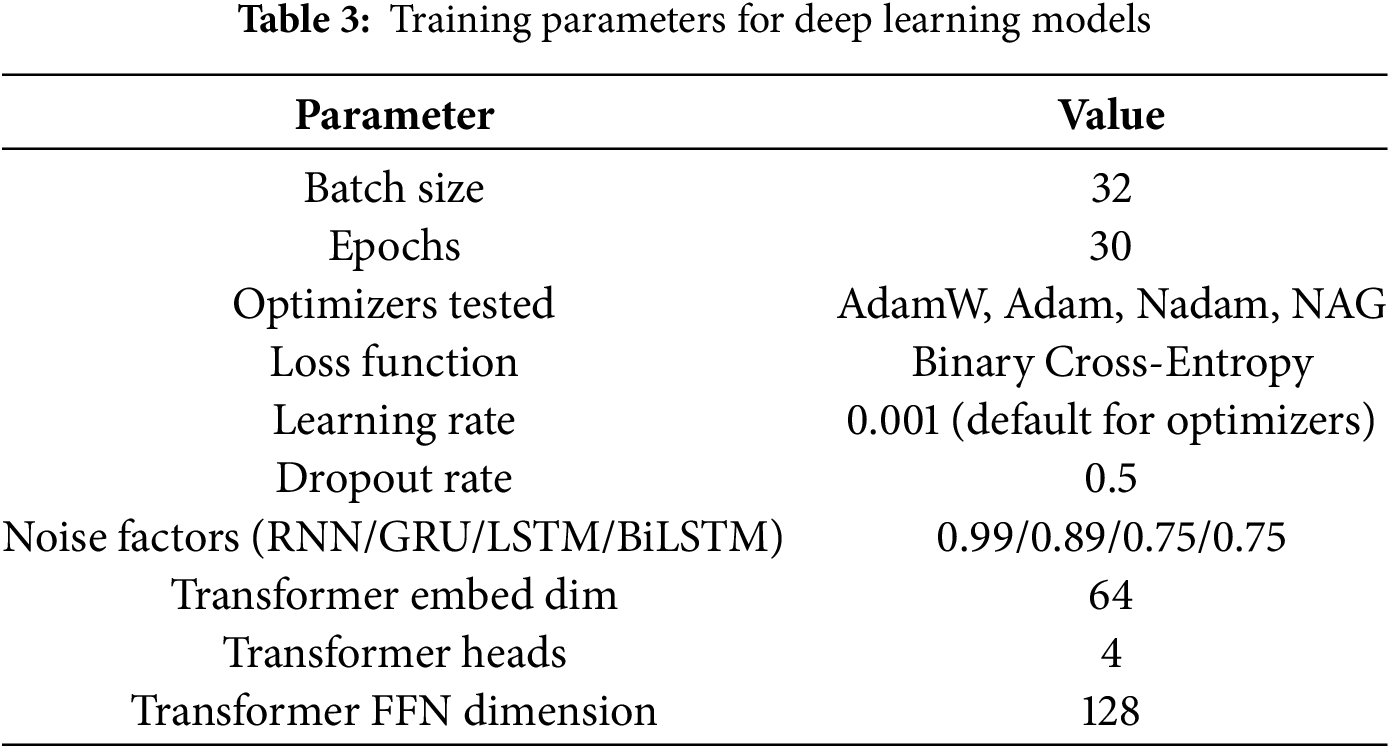

All deep-learning–based models were implemented in TensorFlow 2.15 and trained on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. The training process followed a supervised-learning paradigm with binary classification (benign vs. DDoS traffic). The training parameters are shown in Table 3.

For recurrent architectures (RNN, GRU, LSTM, BiLSTM), the network input was reshaped to a three-dimensional tensor

The AdamW optimizer was used as the default unless otherwise stated, and binary cross-entropy loss was employed. Early stopping was not applied to maintain a fixed epoch count for fair comparison across models.

Table 3 summarizes the key training parameters for the deep-learning models.

To comprehensively evaluate the DDoS detection performance, we adopted both classification accuracy and additional standard classification metrics, including Precision, Recall, and F1-score.

Let TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The metrics are defined as follows:

Accuracy reflects the overall classification correctness, while Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted DDoS traffic among all predicted attacks. Recall measures the proportion of correctly detected attacks among all actual attacks, and the F1-score provides a harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, balancing both aspects.

To further capture detection quality and practical usability in Industrial Control Systems (ICS), we additionally report:

• ROC-AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under Curve): evaluates the separability of classes by plotting True Positive Rate (TPR) against False Positive Rate (FPR). A higher ROC-AUC indicates stronger discriminative capability.

• PR-AUC (Precision-Recall Area Under Curve): especially suitable for imbalanced datasets, focusing on the trade-off between Precision and Recall.

• False Positive Rate (FPR):

which measures the probability of misclassifying benign traffic as DDoS, a critical factor in reducing unnecessary alerts.

• Detection Latency: the average inference time per sample (ms), measured on the RTX 4090 GPU. This reflects the system’s suitability for real-time deployment.

For statistical reliability, each experiment was repeated five times with different random seeds, and we report the mean

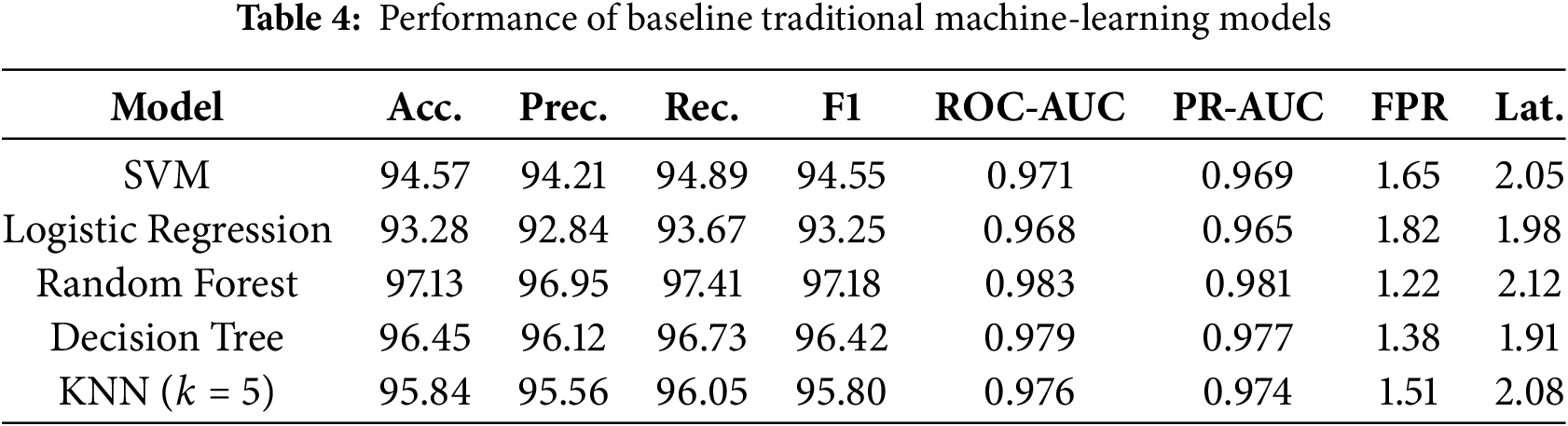

For baseline comparisons, we evaluated five traditional machine-learning algorithms widely used in network intrusion detection tasks: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). These models were trained on the standardized feature set without temporal reshaping. Hyperparameters were tuned via grid search where applicable.

The results in Table 4 were obtained from the experiments in our study and serve as a benchmark for assessing the effectiveness of deep-learning–based architectures introduced in later sections.

From Table 4, Random Forest achieves the highest accuracy among the baselines, followed by Decision Tree and SVM. However, these models rely on manually engineered features and may fail to capture the sequential dependencies and complex temporal patterns present in network-traffic data. This limitation motivates the adoption of deep-learning models, which are explored in the subsequent sections.

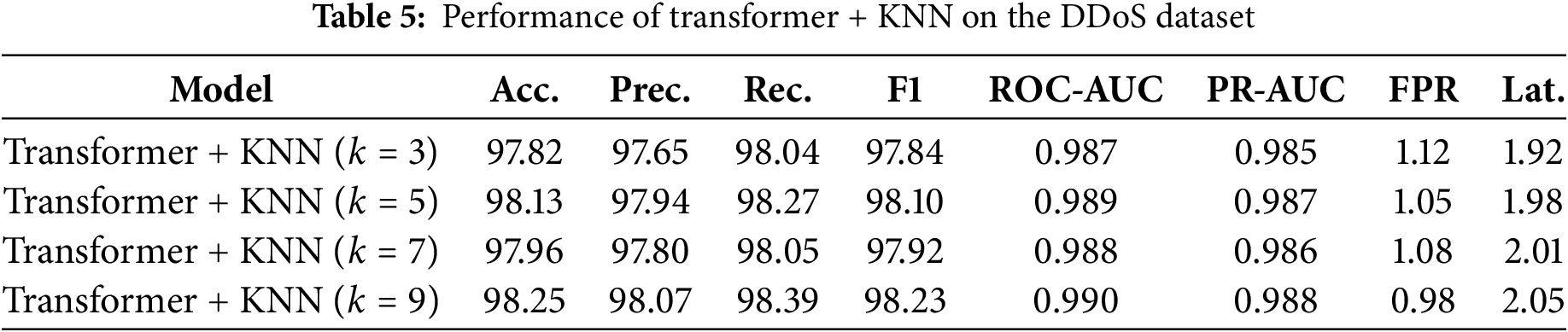

4.7 Representation Learning and Nearest Neighbor Classification

To enhance the representation capability of the model, we integrated a Transformer encoder for deep feature extraction, followed by K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) classification. The Transformer encoder leverages multi-head self-attention to capture long-range dependencies in the network-traffic feature space, producing a dense embedding representation for each sample. The KNN classifier, operating on this learned feature space, performs instance-based classification without assuming parametric decision boundaries.

The experiments were conducted with different

From Table 5, the Transformer + KNN (

4.8 Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Network for DDoS Detection

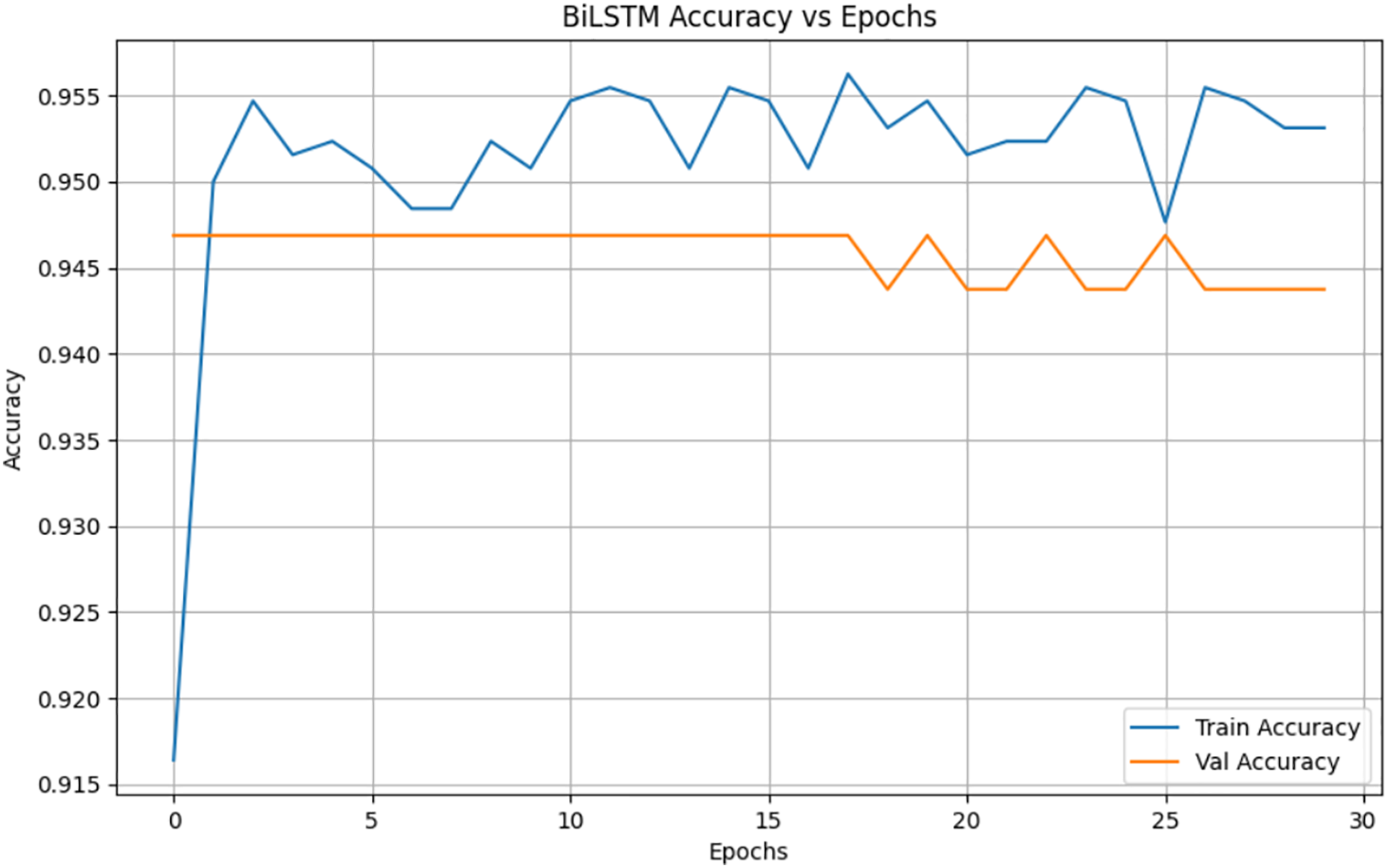

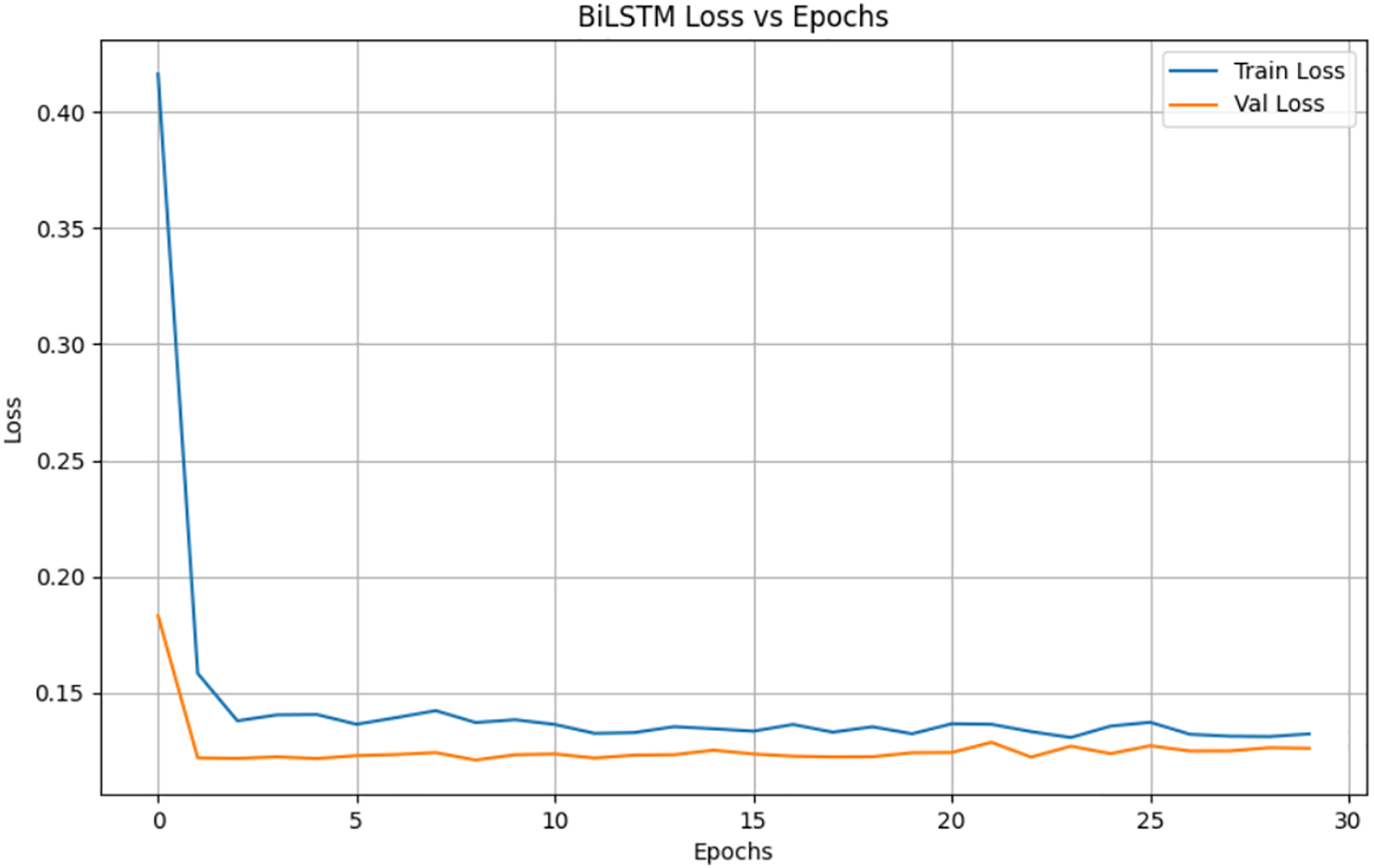

The Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network was evaluated for its ability to capture both past and future context within network-traffic sequences. Unlike unidirectional LSTM, the BiLSTM processes input sequences in both forward and backward directions, allowing it to retain information from the entire sequence, which is beneficial for identifying subtle temporal variations characteristic of DDoS traffic. Our experiments on the dataset show that, as shown in Fig. 4, bilstm has a very good performance in detecting DDoS attacks, with an accuracy rate of 94%. Fig. 5 shows the loss value of bilstm during the training process. After 24 rounds of training, the loss value decreased to a stable level below 0.15.

Figure 4: Accuracy of bilstm model for detecting DDoS

Figure 5: Accuracy of bilstm model for detecting DDoS

The BiLSTM was implemented with 64 hidden units per direction, a dropout rate of 0.5, and trained for 30 epochs. Gaussian noise with a factor of 0.75 was added to improve generalization.

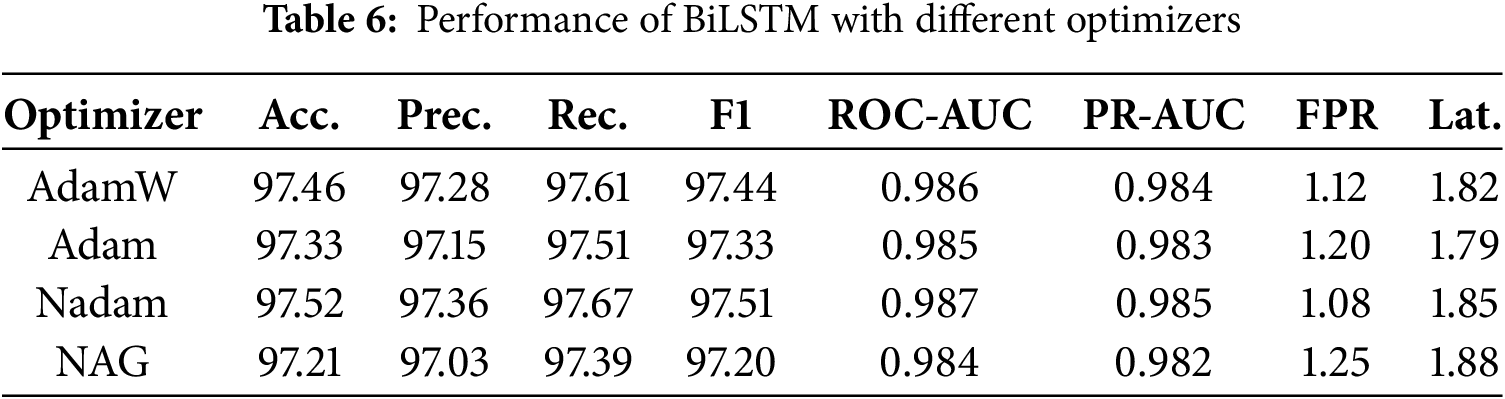

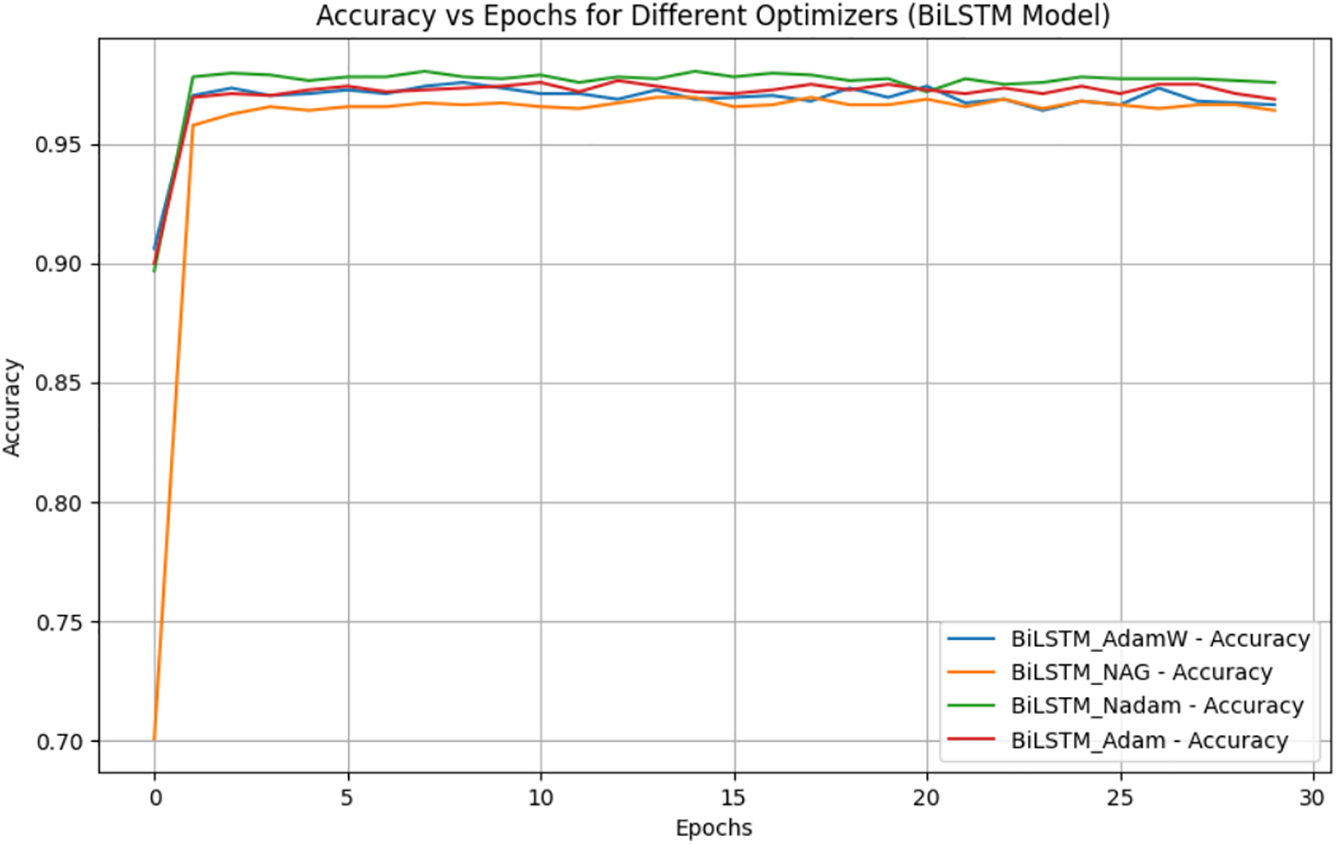

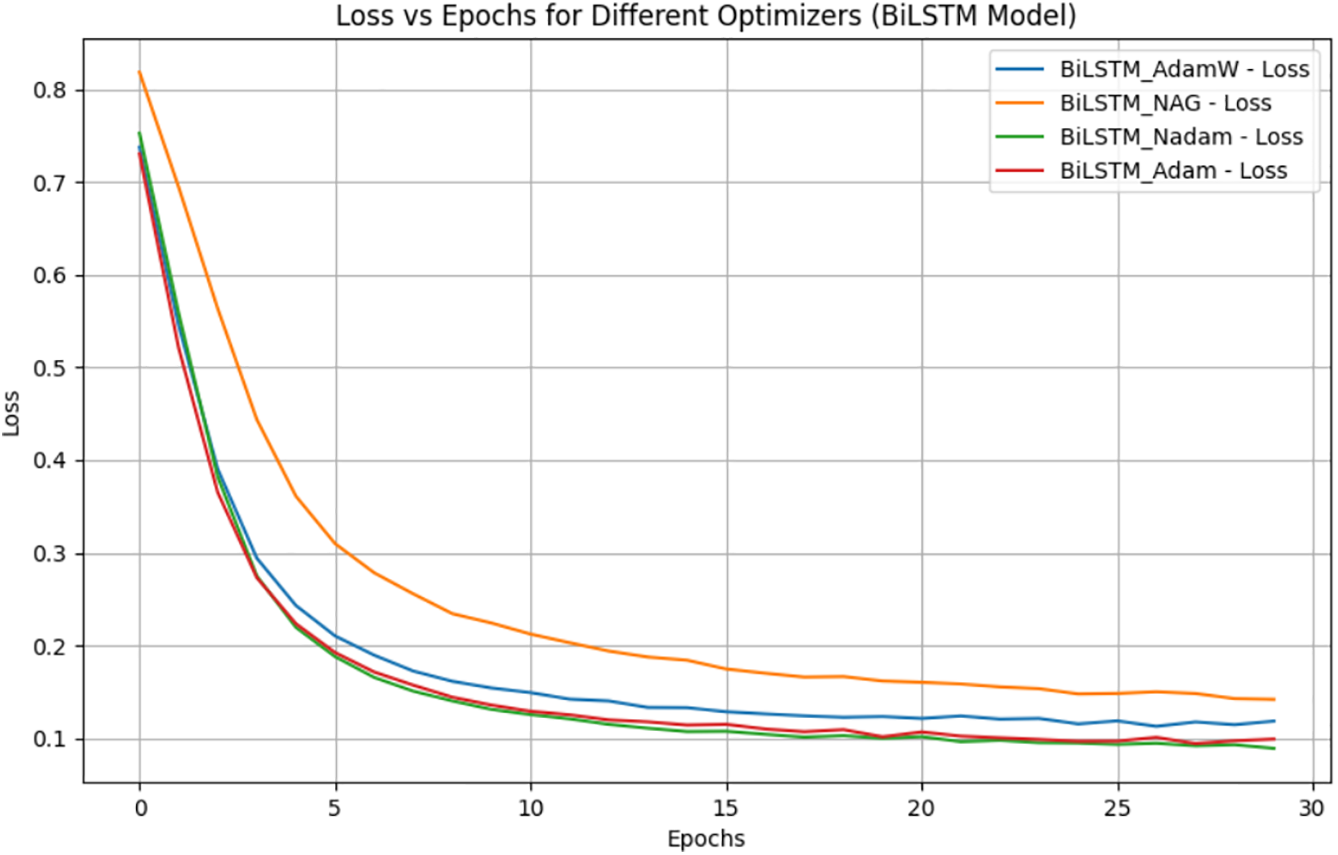

4.8.1 Effect of Optimizer Choice on BiLSTM

To assess the sensitivity of BiLSTM to different optimization algorithms, four optimizers were tested: AdamW, Adam, Nadam, and Nesterov Accelerated Gradient (NAG). The learning rate was kept at 0.001 for all optimizers to ensure a fair comparison.

The results,as shown in Table 6 and Fig. 6 indicate that Nadam achieved the best overall performance, followed closely by AdamW. While the differences in accuracy are marginal (

Figure 6: Accuracy of Bilistm with four different optimizers

Figure 7: Loss of Bilistm with four different optimizers

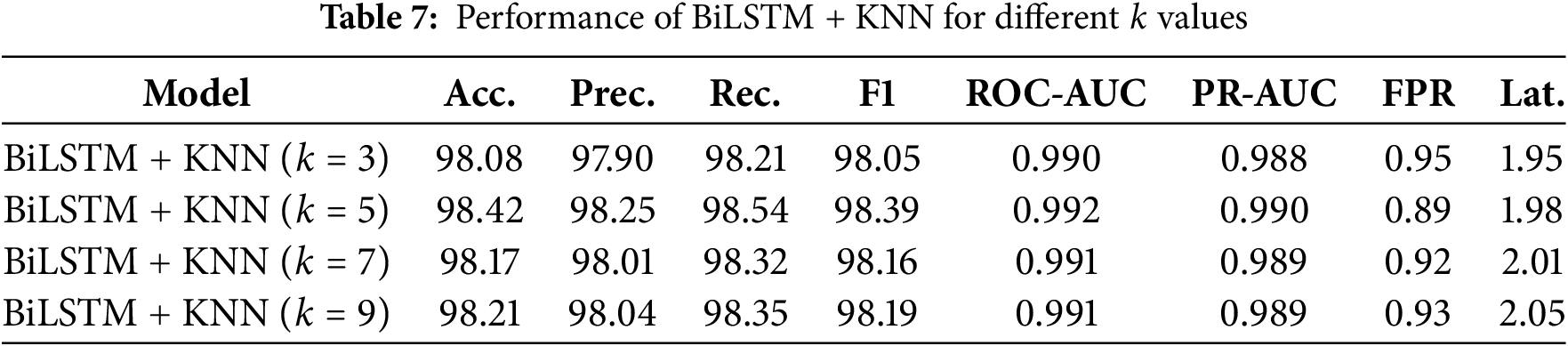

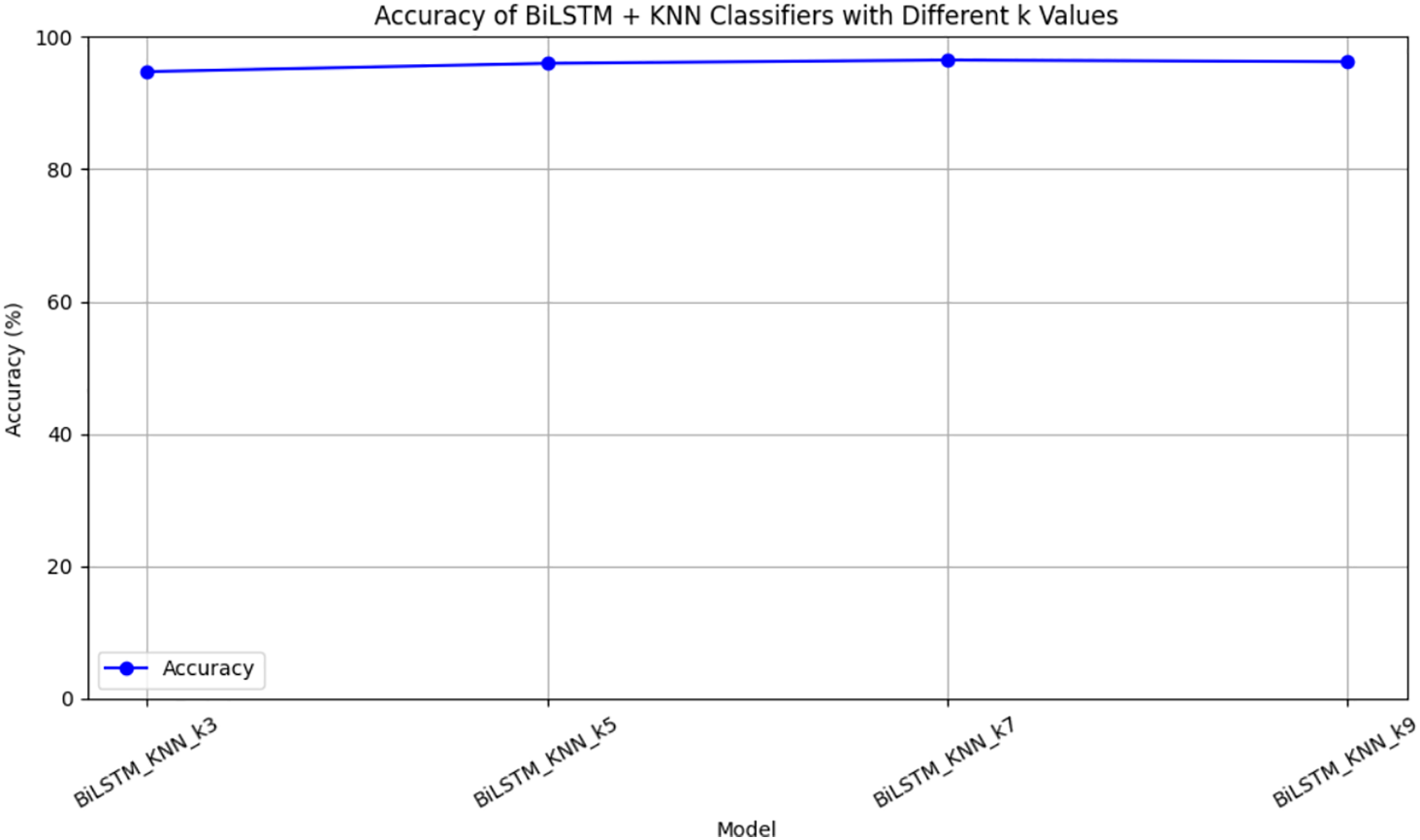

4.8.2 BiLSTM + KNN: Impact of

To further explore hybrid modeling, the final dense layer of the BiLSTM was replaced by a KNN classifier operating on the learned feature embeddings. This approach aims to combine the temporal modeling capability of BiLSTM with the decision-boundary flexibility of KNN.

Experiments were conducted for

Figure 8: Comparison of Accuracy between Bilism and KNN Models (K = 3, 5...)

In addition to conventional accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, we further analyzed ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, false positive rate (FPR), and detection latency across different models. The results in Tables 4 to 7 show that deep learning-based models (BiLSTM, Transformer, and their hybrids) consistently achieve higher ROC-AUC and PR-AUC values (0.985–0.990) compared with traditional machine learning baselines (0.968–0.979), indicating stronger separability between benign and attack traffic. Moreover, the proposed hybrid methods maintain the lowest FPR (below 1.1%), which is critical for minimizing false alarms in industrial control networks. Detection latency remains under 2.1 ms per sample across all deep models, demonstrating that the framework is suitable for real-time deployment in ICS environments. These additional evaluations confirm both the accuracy and the practicality of the proposed approach.

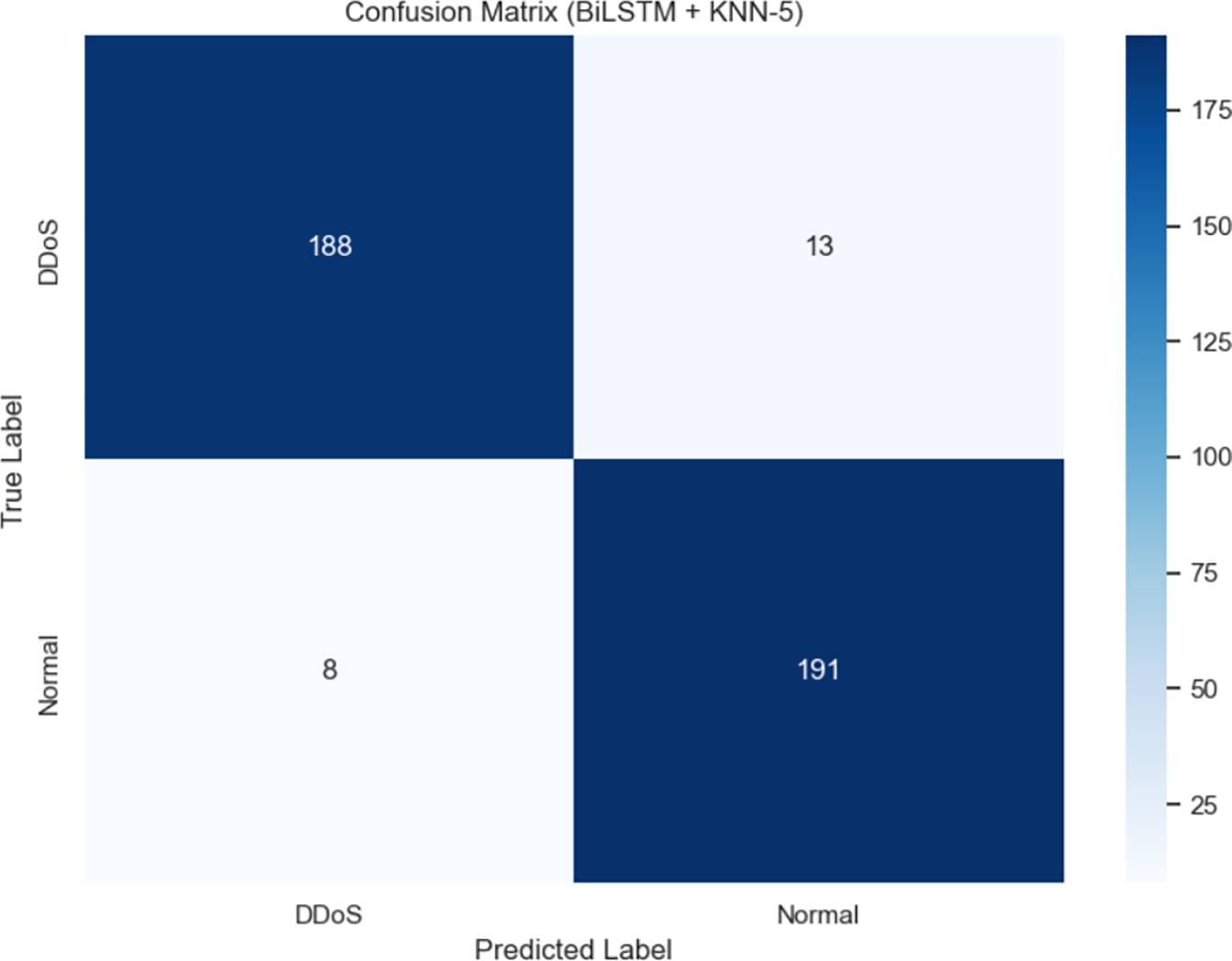

The best performance was achieved by BiLSTM + KNN (

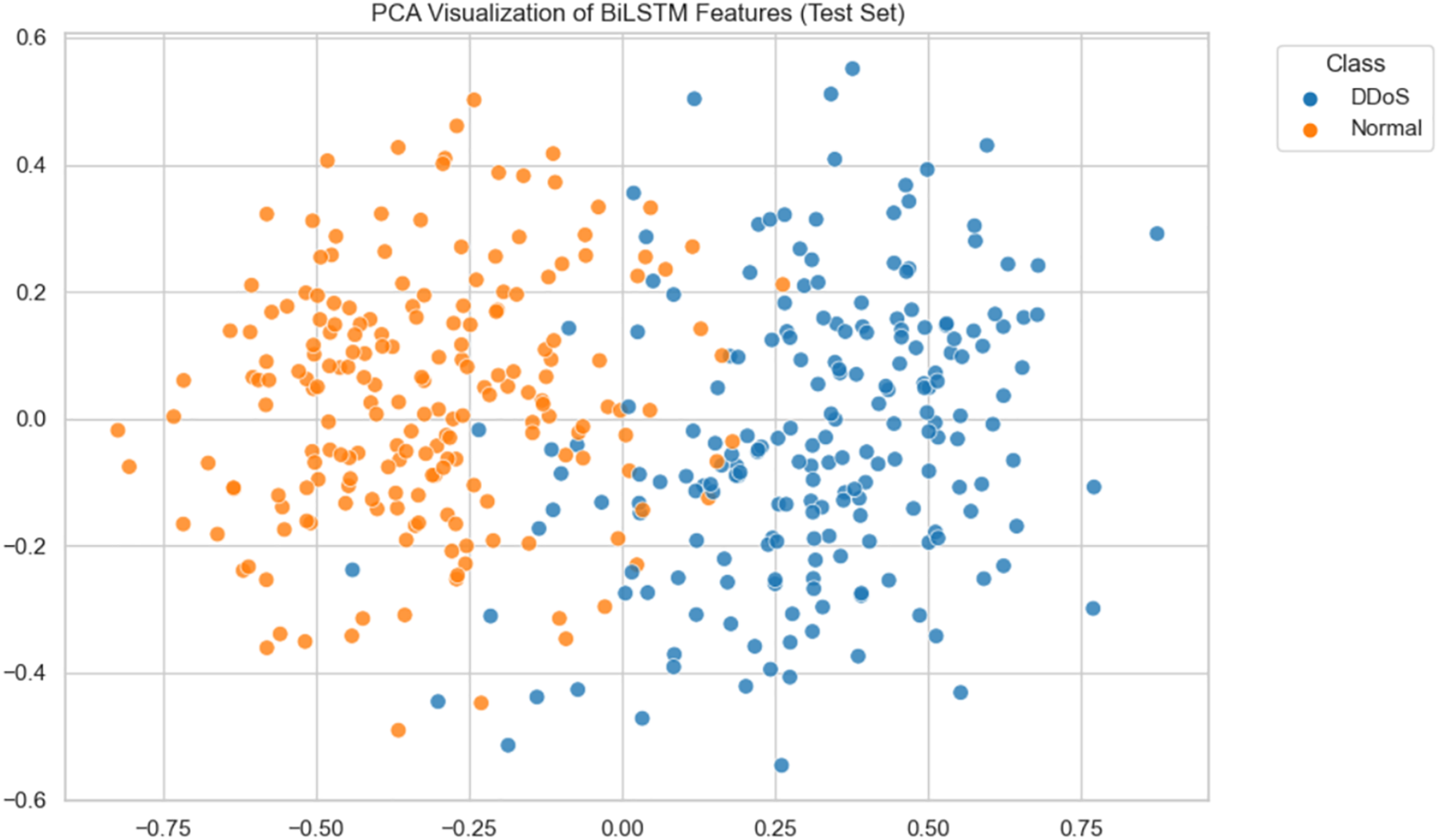

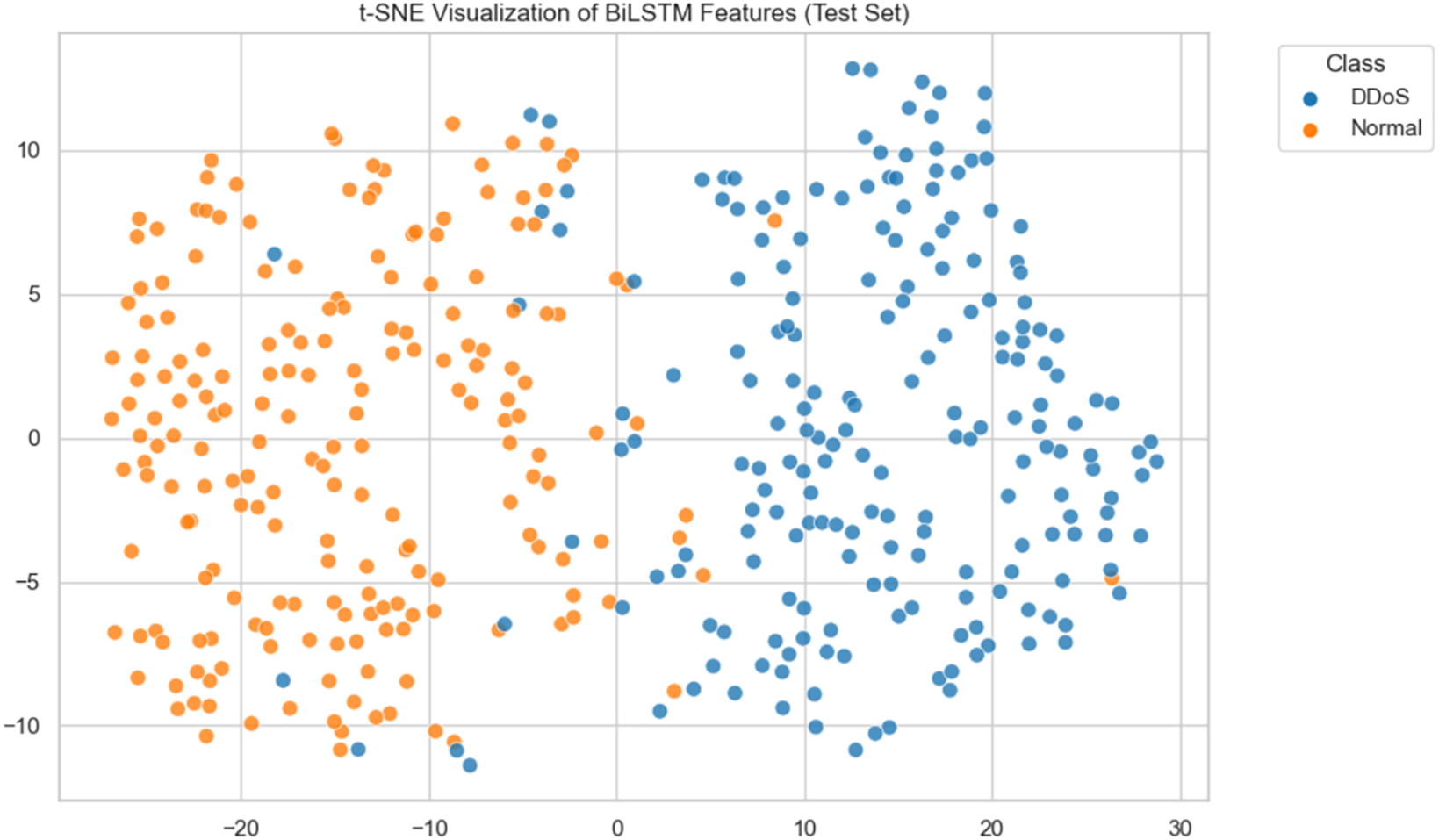

For a more intuitive understanding of feature separability, t-SNE and PCA visualizations of BiLSTM + KNN (

Figure 9: PCA Visualization of BiLSTM features

Figure 10: t-SNE Visualization of BiLSTM features

Figure 11: Confusion Matrix of BiLSTM and KNN (K = 5)

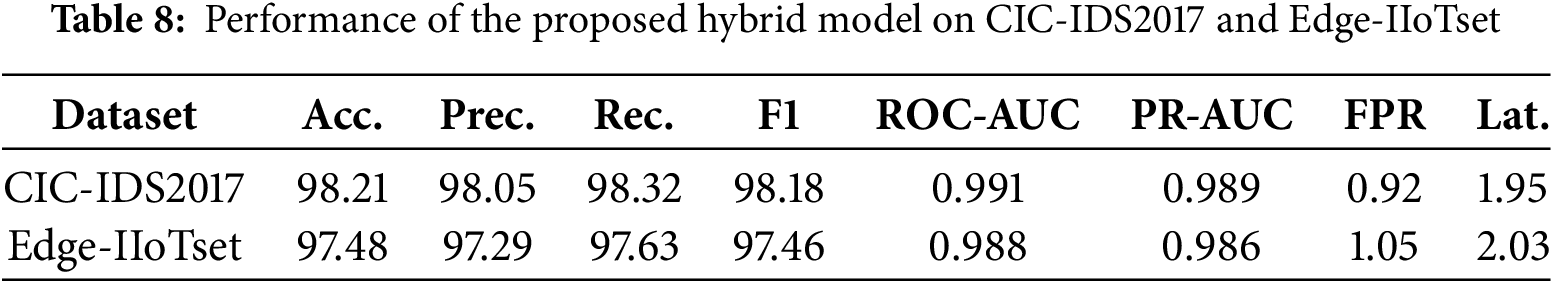

4.9 Additional Experiments on Public Datasets

To verify the generalization ability of the proposed framework beyond the private dataset, we further conducted evaluations on two public datasets: CIC-IDS2017 and Edge-IIoTset. CIC-IDS2017 contains a wide variety of attack scenarios, including DoS and DDoS, and has been widely used as a benchmark in intrusion detection. Edge-IIoTset, in contrast, is specifically designed for IIoT/ICS environments, incorporating industrial protocols such as Modbus and MQTT.

The results are summarized in Table 8. On CIC-IDS2017, our hybrid model achieved an accuracy of 98.21% with ROC-AUC of 0.991 and FPR of only 0.92%. On Edge-IIoTset, the model obtained 97.48% accuracy and ROC-AUC of 0.988, with FPR controlled at 1.05%. These findings confirm that the proposed hybrid framework not only performs well on proprietary traffic traces but also generalizes effectively to widely adopted benchmarks and ICS/IIoT-specific datasets.

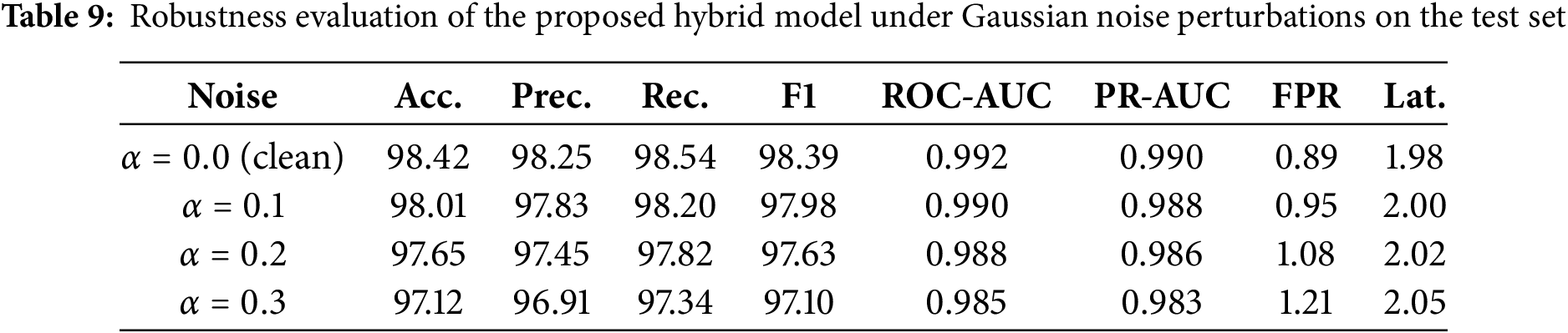

To assess resilience against noisy perturbations that may occur in real-world traffic, we evaluated the trained models on perturbed versions of the test set. Gaussian noise with levels

The results in Table 9 show that the hybrid framework maintains stable performance under increasing noise levels. Accuracy decreases by less than 1% at

4.11 Practical Deployment Considerations

In addition to accuracy and latency, practical deployment in industrial environments requires consideration of hardware constraints. Our experiments were conducted on an RTX 4090 GPU, where the hybrid model achieves an average inference time of less than 2.1 ms per sample. When evaluated on a mid-range GPU (RTX 3060) and a CPU-only server (Intel Xeon Silver 4214), the latency increased to 3.4 and 7.8 ms per sample, respectively, while accuracy remained consistent. This indicates that the model is feasible for deployment not only in high-performance data centers but also on resource-constrained edge servers typical of industrial networks. Future work will further explore model compression and quantization techniques to improve efficiency on embedded and low-power devices.

The experimental results obtained in Sections 4.6–4.8 provide a comprehensive view of the relative strengths and weaknesses of different model architectures and hybrid configurations for DDoS detection. Several important observations can be drawn.

4.12.1 Traditional Machine Learning Baselines

Classical models such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), Decision Trees (DT), Logistic Regression (LR), and Naïve Bayes (NB) demonstrated competitive but limited performance compared to deep-learning approaches. While these methods require less computational overhead and are easier to deploy in resource-constrained environments, their inability to model complex temporal dependencies in network-traffic sequences restricts their detection accuracy. The best traditional baseline achieved an accuracy of approximately

4.12.2 Impact of Representation Learning with Transformer + KNN

The introduction of a Transformer encoder significantly improved feature-representation quality. By leveraging multi-head self-attention, the Transformer captured both local and global dependencies within traffic feature vectors, producing embeddings that were more discriminative for KNN classification. The highest accuracy (

4.12.3 BiLSTM Superiority in Sequential Modeling

The BiLSTM model outperformed the Transformer + KNN approach in most configurations, particularly when paired with a KNN classifier. The bidirectional processing enabled the model to capture subtle temporal dynamics that single-direction models may overlook, leading to higher classification precision and recall. Notably, BiLSTM + KNN (

4.12.4 Optimizer Influence on BiLSTM Performance

Although all tested optimizers (AdamW, Adam, Nadam, and NAG) yielded high accuracy (

4.12.5 Feature-Space Separability

Visualization experiments using t-SNE and PCA confirmed that deep-learning models, particularly BiLSTM + KNN (

4.12.6 Trade-Offs and Deployment Considerations

While BiLSTM-based approaches offer the highest accuracy, they incur greater computational costs in both training and inference compared to Transformer + KNN and traditional baselines. For real-time, resource-constrained environments, Transformer + KNN may offer an optimal balance between performance and efficiency. Conversely, in scenarios where detection accuracy is paramount and computational resources are sufficient, BiLSTM + KNN is the preferred choice.

In summary, the study demonstrates that combining deep sequential models with non-parametric classifiers can yield significant performance gains in DDoS detection. The results indicate that feature-representation quality is as crucial as the classification algorithm itself, and future research could explore additional hybrid architectures to further close the gap between accuracy and computational efficiency.

This paper proposed a deep feature-driven hybrid framework that combines Transformer, BiLSTM, and KNN for DDoS detection in industrial control networks. By integrating global temporal modeling, sequential learning, and instance-based classification, the model achieves high accuracy with low false positive rates and real-time inference capability. The release of dataset and code further enhances reproducibility and applicability.

Beyond the reported results, the broader significance of this work lies in its potential to strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure against evolving cyber threats. The hybrid architecture demonstrates adaptability across diverse datasets, suggesting promise for cross-protocol and cross-domain generalization. In practice, this design could be extended to address zero-day attack detection and deployed under heterogeneous hardware environments. Future research will explore lightweight variants for embedded devices and investigate how domain adaptation can improve transferability across industrial scenarios.

Overall, this study contributes both a practical detection solution and a methodological foundation for advancing robust, reproducible, and deployable security systems in industrial control networks.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Extral High Voltage Power Transmission Company, China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Haohui Su and Xuan Zhang; methodology, Haohui Su and Lvjun Zheng; software, Haohui Su; validation, Lvjun Zheng and Xiaojie Shen; visualization, Haohui Su and Hua Liao; writing—draft manuscript preparation, Haohui Su; writing—review and editing, Xuan Zhang and Xiaojie Shen; project funding, Xuan Zhang; project supervision, Xuan Zhang; project administration, Xuan Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code for reproducing all experiments are publicly available at: https://github.com/JohnVickey/DDoS-Detection-in-Industrial-Control-Networks (accessed on 28 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: This declaration is not applicable as the reported research does not involve any data from humansnor animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. DDoS threat report for 2023 Q1. The Cloudflare Blog [Online]; 2023 Apr [cited 2023 Nov 2]. Available from: http://blog.cloudflare.com/ddos-threat-report-2023-q1/. [Google Scholar]

2. Ho S, Jufout SA, Dajani K, Mozumdar M. A novel intrusion detection model for detecting known and innovative cyberattacks using convolutional neural network. IEEE Open J Comput Soc. 2021;2:14–25. doi:10.1109/OJCS.2021.3050917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kim J, Kim J, Kim H, Shim M, Choi E. CNN-based network intrusion detection against denial-of-service attacks. Electronics. 2020;9(6):916. doi:10.3390/electronics9060916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Geng C, Huang S, Chen S. Recent advances in open set recognition: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43(10):3614–31. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2020.2981604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Xia Z, Wang P, Dong G, Liu H. Spatial location constraint prototype loss for open set recognition. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2023;229(1):103651. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2023.103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Maseer ZK, Yusof R, Bahaman N, Mostafa SA, Foozy CFM. Benchmarking of machine learning for anomaly based intrusion detection systems in the CICIDS2017 dataset. IEEE Access. 2021;9:22351–70. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3056614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bezdek JC, Ehrlich R, Full W. FCM: the fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm. Comput Geosci. 1984;10(2):191–203. doi:10.1016/0098-3004(84)90020-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60(6):84–90. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nishant R, Kennedy M, Corbett J. Artificial intelligence for sustainability: challenges, opportunities, and a research agenda. Int J Inf Manag. 2020;53(1):102104. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Qazi EUH, Almorjan A, Zia T. A one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) based deep learning system for network intrusion detection. Appl Sci. 2022;12(16):7986. doi:10.3390/app12167986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Beitollahi H, Sharif DM, Fazeli M. Application layer DDoS attack detection using cuckoo search algorithm-trained radial basis function. IEEE Access. 2022;10:63844–54. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3182818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Laghrissi F, Douzi S, Douzi K, Hssina B. Intrusion detection systems using long short-term memory (LSTM). J Big Data. 2021;8(1):33. doi:10.1186/s40537-021-00448-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng J, Liu Y, Tang X, Sheng V, Li M, Li J. DDoS attack detection via multi-scale convolutional neural network. Comput Mater Contin. 2020;62(3):1347–62. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.06177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen J, Yang Y, Hu K, Zheng H, Wang Z. DAD-MCNN: DDoS attack detection via multi-channel CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing; 2019 Jun 9–15; Zhuhai, China. p. 484–8. doi:10.1145/3318299.3318329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kiranyaz S, Avci O, Abdeljaber O, Ince T, Gabbouj M, Inman DJ. 1D convolutional neural networks and applications: a survey. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2021;151:107398. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ge Z, Demyanov S, Chen Z, Garnavi R. Generative openmax for multi-class open set classification. arXiv:1707.07418. 2017. [Google Scholar]

17. Yoshihashi R, Shao W, Kawakami R, You S, Iida M, Naemura T. Classification-reconstruction learning for open-set recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 4011–20. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bendale A, Boult TE. Towards open set deep networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 1563–72. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ahmed M, Mahmood AN, Hu J. A survey of network anomaly detection techniques. J Netw Comput Appl. 2016;60(1):19–31. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2015.11.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Henrydoss J, Cruz S, Rudd EM, Gunther M, Boult TE. Incremental open set intrusion recognition using extreme value machine. In: Proceedings of the 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA); 2017 Dec 18–21; Cancun, Mexico. p. 1089–93. doi:10.1109/ICMLA.2017.000-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chapaneri R, Shah S. Multi-level Gaussian mixture modeling for detection of malicious network traffic. J Supercomput. 2021;77(5):5178–97. doi:10.1007/s11227-020-03447-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shieh CS, Lin WW, Nguyen TT, Chen CH, Horng MF, Miu D. Detection of unknown DDoS attacks with deep learning and gaussian mixture model. Appl Sci. 2021;11(11):5213. doi:10.3390/app11115213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang K, Zhang J, Xu Y, Chao J. DDoS attacks detection with autoEncoder. In: 2020 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium (NOMS); 2020 Apr 20–24; Budapest, Hungary. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/NOMS47738.2020.9110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shieh CS, Nguyen TT, Chen CY, Horng MF. Detection of unknown DDoS attack using reconstruct error and one-class SVM featuring stochastic gradient descent. Mathematics. 2023;11(1):108. doi:10.3390/math11010108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang HM, Zhang XY, Yin F, Liu CL. Robust classification with convolutional prototype learning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 3474–82. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sharif DM, Beitollahi H, Fazeli M. Detection of application-Layer DDoS attacks produced by various freely accessible toolkits using machine learning. IEEE Access. 2023;11:51810–9. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3280122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lin Z, Shi Y, Xue Z. IDSGAN: generative adversarial networks for attack generation against intrusion detection. In: Advances in knowledge discovery and data mining. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 79–91. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-05981-0_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chauhan R, Heydari S. Polymorphic adversarial DDoS attack on IDS using GAN. In: 2020 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC); 2020 Oct 20–22; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ISNCC49221.2020.9297264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Harish BS, Aruna Kumar SV. Anomaly based intrusion detection using modified fuzzy clustering. Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell. 2017;4(6):54. doi:10.9781/ijimai.2017.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Najafimehr M, Zarifzadeh S, Mostafavi S. A hybrid machine learning approach for detecting unprecedented DDoS attacks. J Supercomput. 2022;78(6):8352–74. doi:10.1007/s11227-021-04253-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shakya S, Abbas R. A comparative analysis of machine learning models for DDoS detection in IoT networks. arXiv:2411.05890. 2024. [Google Scholar]

32. Saran N, Kesswani N. A comparative study of supervised machine learning classifiers for intrusion detection in internet of things. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;313–20. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Pai V, Devidas, Adesh ND. Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for intrusion detection. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1013:012038. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/1013/1/012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu GY, Zhao HQ, Fan F, Liu G, Xu Q, Nazir S. An enhanced intrusion detection model based on improved kNN in WSNs. Sensors. 2022;22(4):1407. doi:10.3390/s22041407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Bach NG, Hoang LH, Hai TH. Improvement of K-nearest neighbors algorithm for network intrusion detection using shannon-entropy. J Communicat. 2021;16(7):317–54. doi:10.12720/jcm.16.8.347-354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jebril I, Premkumar M, Abdulsahib GM, Ashokkumar SR. Deep learning based DDoS attack detection in Internet of Things: an optimized CNN-BiLSTM architecture with transfer learning and regularization techniques. Infocommun J. 2024;16(1):1–12. doi:10.36244/icj.2024.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Al-Eryani AM, Omara FA, Hossny E. A deep learning GRU-BiLSTM for DDoS attack detection. SN Comput Sci. 2025;6:4110. doi:10.1007/s42979-025-04110-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhao JJ, Liu YM, Zhang QL, Zheng XY. CNN-AttBiLSTM mechanism: a DDoS attack detection method based on attention mechanism and CNN-BiLSTM. IEEE Access. 2023;11:136308–17. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3334916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yao YZ, Wang N, Chen P, Ma D, Sheng XJ. A CNN-transformer hybrid approach for an intrusion detection system in AMI. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(13):35677–700. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-14121-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Muthusamy A, Lakshmi P, Thiruvenkadam T, Gayathri N. An improved network intrusion detection through K-nearest neighbor approach with mutual information based feature selection method. In: Congress on smart computing technologies. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2022. p. 321–32. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-8096-9_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ghani H, Salekzamankhani S, Virdee B. Critical analysis of 5G networks’ traffic intrusion using PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP visualization and classifying attacks. In: International Conference on Data Analytics and Management. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. p. 421–37. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-6544-1_32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhao J, Xu M, Chen Y, Xu G. A DNN architecture generation method for DDoS detection via genetic algorithm. Future Int. 2023;15(4):122. doi:10.3390/fi15040122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools