Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

From Budget-Aware Preferences to Optimal Composition: A Dual-Stage Framework for Wireless Energy Service Optimization

School of Computer Science and Technology, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, 255000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jing Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 42 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072381

Received 25 August 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In the wireless energy transmission service composition optimization problem, a key challenge is accurately capturing users’ preferences for service criteria under complex influencing factors, and optimally selecting a composition solution under their budget constraints. Existing studies typically evaluate satisfaction solely based on energy transmission capacity, while overlooking critical factors such as price and trustworthiness of the provider, leading to a mismatch between optimization outcomes and user needs. To address this gap, we construct a user satisfaction evaluation model for multi-user and multi-provider scenarios, systematically incorporating service price, transmission capacity, and trustworthiness into the satisfaction assessment framework. Furthermore, we propose a Budget-Aware Preference Adjustment Model that predicts users’ baseline preference weights from historical data and dynamically adjusts them according to budget levels, thereby reflecting user preferences more realistically under varying budget constraints. In addition, to tackle the composition optimization problem, we develop a Reflective-Evolutionary Large Language Model—Guided Ant Colony Optimization algorithm, which leverages the reflective evolution capability of large language models to iteratively generate and refine heuristic information that guides the search process. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework effectively integrates personalized preferences with budget sensitivity, accurately predicts users’ preferences, and significantly enhances their satisfaction under complex constraints.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of smart devices and wireless charging technologies, wireless energy transmission has become a core service in domains such as the Internet of Things (IoT), smart cities, and smart houses [1,2]. It enables users to conveniently obtain energy without physical constraints [3,4]. However, most existing studies on user satisfaction focus primarily on maximizing transmission capacity, while overlooking key factors such as service price and provider trustworthiness [5,6]. In practice, providers vary significantly in capacity, pricing, and reliability, and ignoring this heterogeneity often leads to mismatches between optimization results and actual user needs, especially under budget constraints [7]. For instance, users may prioritize price with limited budgets, put greater emphasis on reliability when the resource is abundant. As a result, how to incorporate historical user feedback and budget levels to predict personalized satisfaction weights—and how to select optimal provider combinations under such constraints—has become a critical challenge in wireless energy service composition [8,9].

To tackle this problem, we propose a user satisfaction evaluation model for multi-user and multi-provider scenarios, integrating provider trust, price, and transmission capacity. We further introduce the Budget-Aware Preference Adjustment Model (BAPAM), which uses Ridge Regression [10] to predict users’ baseline preference weights from historical data and dynamically adjust them in response to real-time budget conditions, thereby better reflecting actual user intent.

Even with accurate preference modeling, it remains difficult to efficiently identify the optimal service combination. A single service rarely satisfies all user expectations, making multi-provider compositions necessary. Yet, such problems involve high-dimensional, multi-objective constraints [11], posing significant challenges for traditional methods to find high-quality solutions.

To address this problem, we propose a Reflective-Evolutionary Large Language Model-Guided Ant Colony Optimization (RELLM-A) method, which iteratively generates and evolves heuristic functions through a reflective LLM module, guiding the Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)-based search toward regions of higher satisfaction. Experimental results under various constraints demonstrate that the RELLM-A method consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines, highlighting its effectiveness in personalized service composition.

In summary, the main contributions of this work are as follows:

1. We propose a multi-dimensional user satisfaction model that considers service price, trustworthiness, and transmission capacity.

2. We propose a BAPAM model, which dynamically predicts user preference weights based on budget levels, addressing the common limitation of static or fixed-weight assumptions.

3. We develop a RELLM-A method, which employs a reflective evolutionary large language model to guide ant colony optimization, thereby improving the quality of service composition solutions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work; Section 3 defines the problem and presents mathematical formulations; Sections 4 and 5 describe the proposed algorithmic models in detail; Section 6 presents the experimental design and analysis; Section 7 discusses future work; and Section 8 concludes the paper.

2.1 Multi-Factor User Satisfaction Modeling

User satisfaction modeling plays a crucial role in the service composition problem. Early studies emphasized objective indicators such as energy capacity, latency, and bandwidth [9]. For instance, He et al. [6] and Shi et al. [12] developed Radio Frequency (RF)-based wireless charging systems for shared bikes and indoor devices, respectively, to enhance operational efficiency and user experience.

In contrast, real-world satisfaction is shaped by subjective factors like price, trustworthiness, and service capacity [7]. While recent works have begun incorporating trust and pricing into the satisfaction model, most still face two major limitations: limited factor coverage and static user preference assumptions [13]. Thus, building multi-factor, dynamic satisfaction functions has become an emerging direction in wireless energy service research.

2.2 Budget-Aware User Preference Adjustment Mechanisms

User preferences are not static but dynamically shift with budget constraints—favoring price under limited budgets and emphasizing quality and trust under ample budgets. However, traditional models often assume fixed weights, ignoring such shifts. For example, Kassak et al. [14] combined global and individual weights to model static preferences, while Zhou and Han [15] introduced a graph-based ranking method capturing pairwise feedback. Yet, these models lack budget adaptability. To address this problem, we propose a budget-aware dynamic weighting mechanism based on Ridge Regression, which adjusts user preferences with trustworthiness, service capacity, and price according to budget levels.

2.3 Service Composition Optimization

Service composition is a classical combination optimization problem often modeled as knapsack variants or task allocation [16]. Heuristic algorithms like the ACO, the Genetic Algorithm (GA), and the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) are widely adopted due to their flexibility [17], with the ACO particularly effective in handling complex constraints [18]. Applications include the RF energy management [19] and mobile device charging strategies [20].

However, traditional heuristics are static and struggle with dynamic user preferences. Recent work explores using LLMs to generate adaptive heuristics, leveraging their capabilities in code generation and task planning [21]. Reflective prompting further enhances performance by iteratively refining outputs based on feedback [22]. Inspired by this, we design a reflective-evolutionary LLM-guided ACO to dynamically optimize service composition and improve user satisfaction. Recent research in edge computing and intelligent transportation systems (ITS) has also explored advanced learning- and game-theoretic approaches for dynamic resource allocation. For example, Zhang et al. proposed a Stackelberg game-based multi-agent framework for resource allocation and task offloading in Mobile Edge Computing-enabled cooperative ITS, achieving adaptive behavior among multiple agents [23]. While such approaches focus on latency-aware offloading and hierarchical resource control, our work addresses preference-driven service selection under budget constraints, with an emphasis on subjective satisfaction modeling and dynamic heuristic function. These directions are complementary: their game-theoretic equilibrium learning inspires possible future integration with our reflective LLM-guided optimization framework.

3 Scenario Model and Definitions

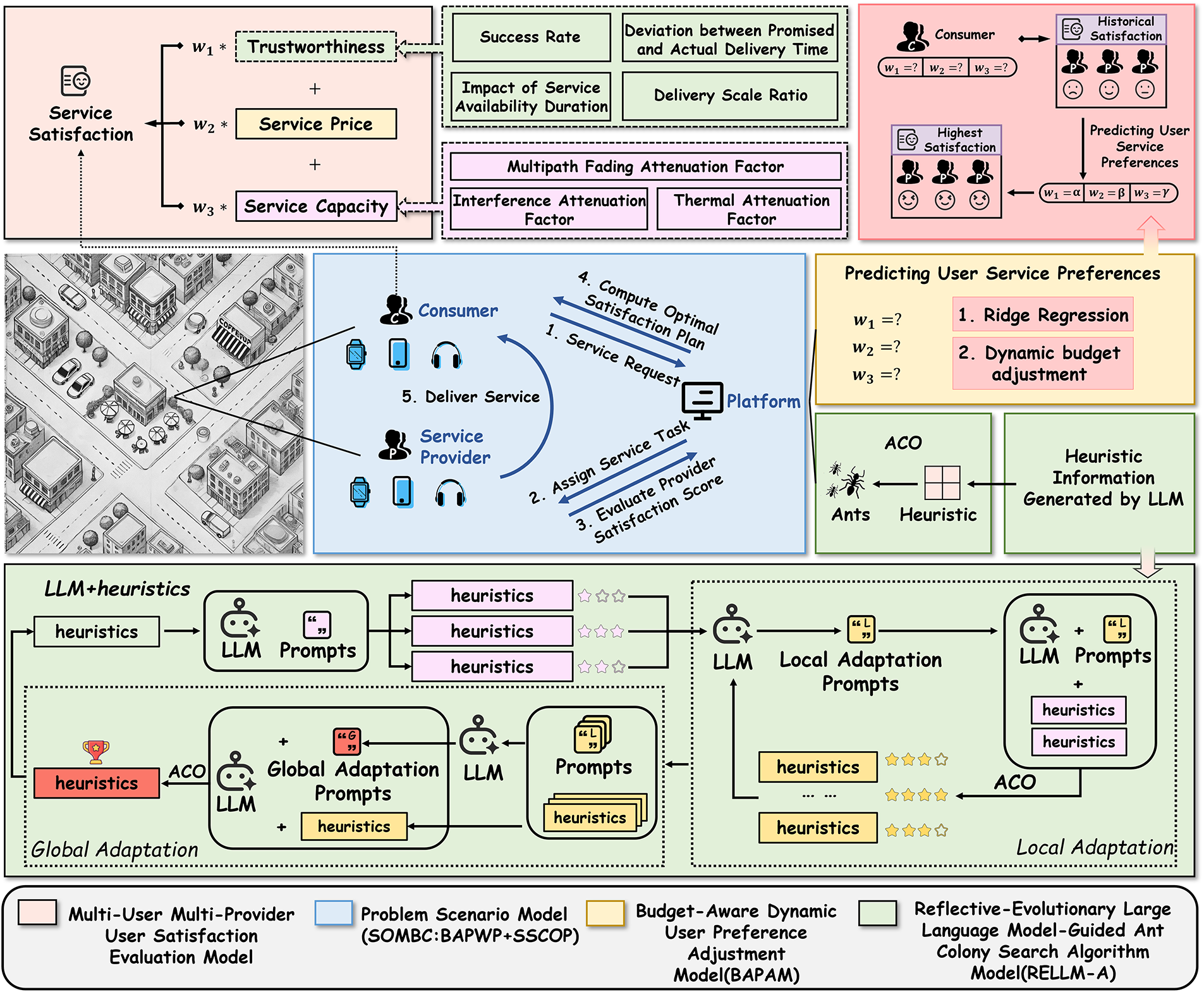

We illustrate the wireless energy service composition problem as Fig. 1. The framework consists of four models: the scenario model, the multi-user multi-provider satisfaction evaluation model, the budget-aware preference adjustment model (BAPAM), and the reflective-evolutionary large language model-guided ant colony optimization (RELLM-A) model. The details of these models are presented in subsequent sections.

Figure 1: Service model diagram for multiple users and multiple providers

The blue module in Fig. 1 represents the problem scenario addressed in this study. Specifically, the considered scenario primarily takes place in public venues such as cafes or restaurants. When a user’s wireless energy device is low on power, the user sends a service request to the energy service platform based on his or her budget. Upon receiving the request, the platform dispatches scheduling information to energy providers, evaluates each provider comprehensively, and computes user satisfaction. Subsequently, the platform derives the optimal composition scheme that maximizes overall satisfaction and sends the solution back to the user, after which selected providers deliver services.

We define this problem as the Satisfaction Optimization under Multi-user Budget Constraints (SOMBC). The SOMBC problem aims at maximizing the overall user satisfaction in a multi-user, multi-provider environment by jointly considering personalized preferences and budget limitations.

To better formalize the SOMBC, we decompose it into two interrelated sub-problems: the Budget-Aware Preference Weight Prediction (BAPWP) problem and the Satisfaction-driven Service Composition Optimization Problem (SSCOP).

– The BAPWP predicts user preference weights with three criteria: trustworthiness, capacity, and price, by leveraging historical service feedback and budget constraints.

– The SSCOP identifies the optimal composition solution under given preference weights so as to maximize satisfaction within user budgets.

Definition 1(Energy Service Composition): We optimize wireless energy service composition under budget constraints while maximizing user satisfaction [9]. Let

The satisfaction of user

where

In practice, user satisfaction may exhibit diminishing returns or nonlinear interactions across different service dimensions. However, due to the lack of large-scale behavioral data and in favor of algorithmic tractability, we adopt a linear approximation as a foundational model. This simplification is also consistent with prior studies for Quality of Experience (QoE) estimation and preference-aware service allocation in IoT and edge computing systems [24].

The optimization objective of the SOMBC is defined as follows:

where

In this process, the platform address three major computational challenges: (i) satisfaction is jointly influenced by trustworthiness, price, and service capacity, making it difficult to design an effective evaluation function that integrates these heterogeneous factors; (ii) user preferences evolve with budget conditions, requiring dynamic prediction of their tendencies; and (iii) the service composition process should find a solution with maximizes global satisfaction under budget constraints.

To tackle these challenges, we develop models and methods from three perspectives: satisfaction modeling, dynamic preference prediction, and composition optimization.

3.2 Multi-User Multi-Provider User Satisfaction Evaluation Model

The upper-left module in Fig. 1 illustrates the user satisfaction evaluation model. In this model, a user’s satisfaction is defined as weighted a sum of trustworthiness, price, and service capacity.

Definition 2(Trustworthiness): Trustworthiness measures a provider’s historical reliability and delivery capability. It is typically inferred from historical interactions and multi-dimensional performance indicators [5,25]:

where

To better reflect the stochastic nature of real-world wireless QoS, we introduce a zero-mean Gaussian disturbance

To improve robustness and realism [27], stochastic trust modeling has been widely adopted in prior work, particularly in IoT and service-oriented computing area.

Definition 3(Success Rate): The success rate measures the stability and reliability of a service in historical service interactions [28]. It reflects the provider’s ability to avoid service interruptions, delays, or failures during execution. A higher success rate indicates that the provider is reliable in practice and consistently delivers services. The specific definition is as follows:

where

Definition 4(Delivery Scale Ratio): The delivery scale ratio reflects the degree of alignment between the actual amount of energy delivered by a provider and the amount it originally promised during service execution. It directly characterizes the credibility and execution capability of the provider in fulfilling its service commitments. The specific definition is as follows:

where

Definition 5(Time Lag Penalty): The Time Lag Penalty reflects penalties if the provider fails to complete the task within the promised timeframe [29]. It evaluates the provider’s temporal reliability with a binary criterion: if the completion time does not exceed the deadline, the delivery is deemed punctual; otherwise, the provider is penalized as follows:

where

Definition 6 (Duration Factor): The Duration Factor assesses how well the duration of a current service matches the provider’s historical average service duration [30]. The historical average reflects the provider’s typical service rhythm and stability, while significant deviation from it may reduce user satisfaction. The historical average duration is defined as:

where

Based on this, the Duration Factor

where

Definition 7(Service Price): Service price refers to the cost charged by a provider for delivering the energy service. In real-world competitive markets, service pricing follows a nonlinear pattern that reflects increasing marginal costs, quality-based price discrimination, and market saturation effects [31,32]. Accordingly, we define the price

In Eq. (13),

This formulation balances two core observations in service economics. First, usually, providers with higher trust scores charge more, but the price sensitivity to trust reduces as reputation improves [33]. Second, service capacity is a strong driver of pricing in wireless/edge markets where congestion and scarcity make marginal costs non-linear [32]. By combining these nonlinear components, our model offers a more realistic representation of pricing strategies in dynamic and quality-differentiated environment [31].

Definition 8(Service Capacity): Taking wireless wearable devices as an example, the service capacity

where

Definition 9(Energy Transmission Power): The effective energy transmission power

where

In practical wireless energy transmission scenarios, several factors such as interference from surrounding devices, multi-path fading caused by environmental reflections, and device overheating can significantly impact the energy transmission performance. To enhance the practical realism of the model and better simulate the deployment condition, we introduce three correction factors in the received power formulation: interference attenuation [34], multipath fading attenuation [35], and thermal attenuation [36].

Definition 10 (Interference Attenuation Factor): In wireless energy transmission scenarios, interference from surrounding devices or signals degrades the transmission quality. The interference attenuation factor

where

Definition 11 (Multi-path Fading Attenuation Factor): Due to reflections and scattering in the real environment, multi-path fading occurs during energy transmission. The factor

where

Definition 12(Thermal Attenuation Factor): Device overheating during prolonged energy transmission may reduce the transmission efficiency. The thermal attenuation factor

where T is the current device temperature,

The satisfaction function not only captures the inherent variability of the QoS but also models user heterogeneity in terms of cost sensitivity, trust perception, and preference. Crucially, the weight coefficients are dynamically adjusted based on historical preference learning and budget-awareness mechanisms.

4 Budget-Aware Preference Adjustment Model

In the BAPWP problem, users exhibit significant differences in how they prioritize different QoS criteria, and these preferences dynamically shift in response to varying budget conditions [8,9]. Therefore, developing a modeling mechanism that captures both personalized preferences and budget sensitivity is essential for achieving accurate satisfaction prediction.

The upper-right module in Fig. 1 is the BAPAM module. This mechanism consists of two main stages: base preference modeling and budget-aware adjustment.

In the first stage, we apply Ridge Regression [37] to learn a user’s base preference weights by fitting historical satisfaction feedback from past service interactions across three service dimensions (trust, capacity, and price).

Specifically, let

where

In the second stage, to characterize the effect of budget variations on user decision-making behavior, we introduce a budget adjustment factor [38] defined as:

where B (resp.

User preferences may respond to budget changes in nonlinear ways—exhibiting threshold effects, diminishing sensitivity, or saturation behavior, as the reviewer correctly noted. However, incorporating such dynamics would require reliable empirical data to model user behavior accurately.

Based on

where

We introduce a budget-aware re-weighting strategy that transforms static base preferences into dynamically adjusted preferences under current budget conditions. Compared to conventional static models, our approach cares more how users shift their focus among QoS criteria in response to budget changes. This improves the accuracy of satisfaction estimation and personalized service recommendation, thereby addressing the BAPWP problem and providing reliable input for the subsequent SSCOP task.

5 Reflective-Evolutionary Large Language Model-Guided Ant Colony Search Algorithm Model

In this section, to efficiently solve the SSCOP problem, we propose a RELLM-A algorithm. The overall framework of the RELLM-A is depicted in the green module of Fig. 1. The core idea is to integrate a dual-level reflective mechanism with evolutionary search, leveraging the code generation and refinement capabilities of the LLMs. The LLM-generated heuristics are then embedded into the ACO framework, guiding the ants toward optimal solutions. Within this framework, the ACO serves as the underlying optimization engine. The ACO is a population-based meta-heuristic inspired by the foraging behavior of ants, where pheromones are released and evaporated to reinforce good candidates and suppress poor ones.

More specifically, the RELLM-A framework consists of two complementary modules: the Local Adaptation Module and the Global Adaptation Module.

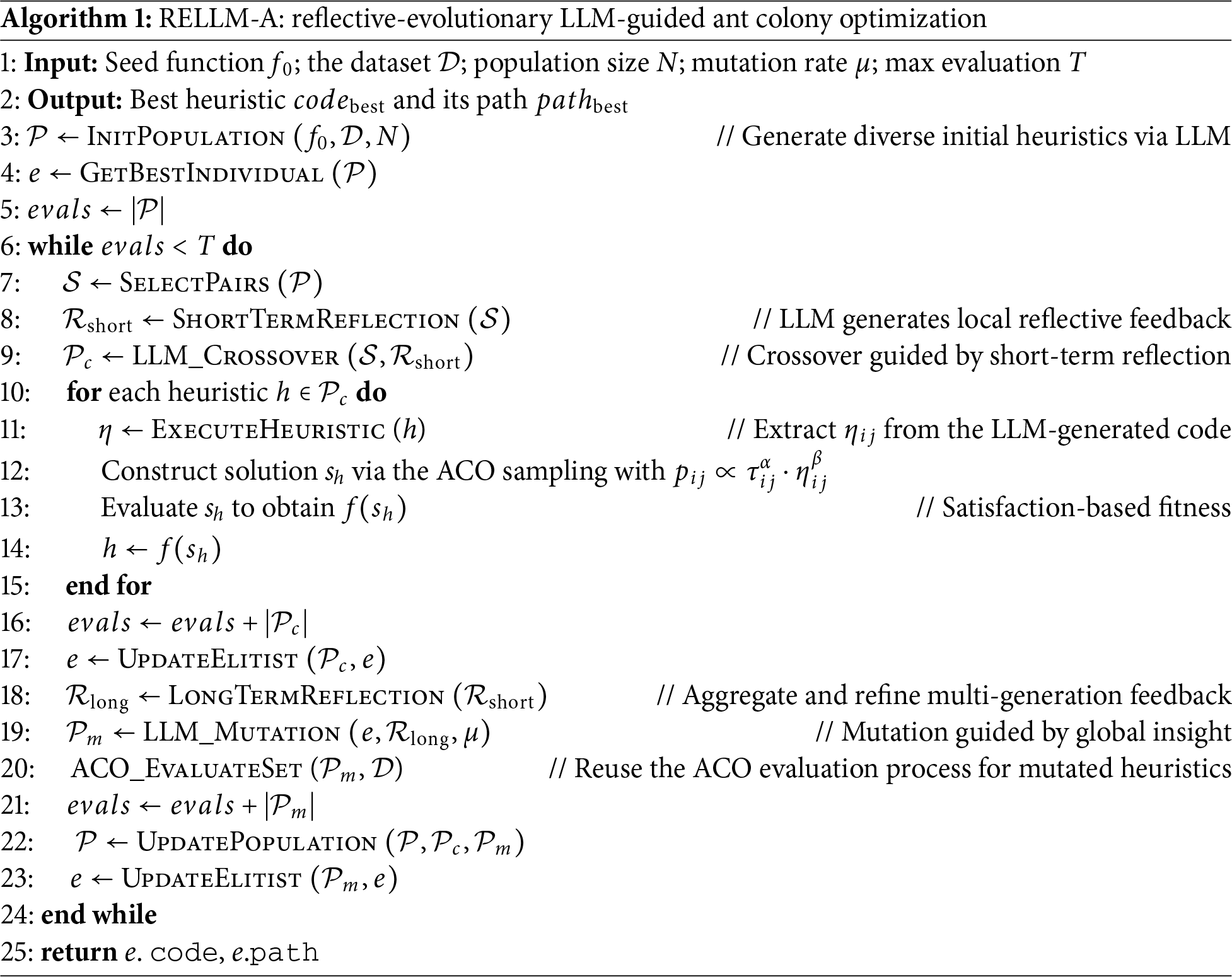

5.1.1 Initialization of the Population and Baseline Evaluation

In the initialization of the algorithm, a clear task specification is given, including the description of the problem, the structure of the function, and performance evaluation metrics (lines 1–2.)

To ensure the reliability and effectiveness of the initial population, we use a domain-expert-designed heuristic function (referred to as the seed function) as the baseline individual. Based on this seed, the LLM generates a diverse set of heuristic code variants under a consistent System Prompt and a well-defined User Prompt. These LLM-generated code candidates constitute the initial population, denoted as

All individuals in the initial population are subjected to a standardized evaluation procedure, during which their performance is measured using the defined objective function. This ensures consistency and fairness across the evaluation process.

5.1.2 Short-Term Reflection-Driven Crossover Generation

In each generation

Guided by this reflection, function signatures of the parents are preserved and the short-term reflection with segments of both

5.2.1 Long-Term Reflection-Guided Mutation Optimization

After completing the short-term reflection and crossover of each generation, the algorithm collects all short-term reflection texts and consolidates them into the Long-Term Reflection. This long-term reflection captures common issues and optimization patterns across heuristics and is combined with reflections from previous generations to form a cross-generational reflection knowledge base (line 17).

Using the current generation’s Elitist individual as the base template, the algorithm injects the long-term reflection knowledge into a Mutation Prompt, guiding the LLM to perform multiple controlled mutation operations and generate new code variants (line 18). The children are integrated into the ACO framework and evaluated (line 19). After evaluation, the children are merged with the crossover offsprings to form the next generation

5.2.2 Performance Evaluation and Gradient-Based Update Mechanism

Each generated individual is evaluated using a unified scoring function, where the objective is mapped to the total satisfaction value. The performance of each code variant is recorded, forming a history trajectory of objective values (lines 5, 20). The local reflection stage emphasizes short-term improvement, which increases the quality of the crossover offsprings. In contrast, the global reflection stage provides long-term strategic guidance, ensuring the population converges toward the global optimum steadily (line 6).

All steps, including code generation, reflection, and evaluation, are executed within a standardized runtime environment and dataset, guaranteeing fairness and comparability across individuals. The integration of code and reflection ensures that every generation follows a gradient-like trajectory toward improved performance, enabling the ant colony population to efficiently search within the heuristic function space.

5.2.3 Termination Criteria and Final Output

The algorithm terminates when the total number of evaluations reaches a pre-defined upper bound

In summary, the RELLM-A achieves dynamic heuristic guidance for the multi-user multi-provider service composition problem by deeply integrating the reflective evolution capabilities of the LLMs with the ACO. The LLM continuously optimizes heuristic functions at both the local and global levels, enabling the ant colony to explore the solution space with greater efficiency and adaptability. Compared to traditional ACO with fixed heuristics, the RELLM-A dynamically adapts its search strategy to the structure of each problem instance, maintaining high solution quality and stability under complex constraints. This fusion paradigm introduces sustainable learning and self-evolution capabilities into swarm intelligence algorithms and lays a solid foundation for solving complex multi-dimensional composition optimization problems. The overall execution procedure is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

In Algorithm 1, the LLM serves as the core driver of code generation, reflection, and optimization, with its performance highly dependent on prompt design. For high-quality outputs, we develop a series of structured, context-aware prompts tailored to sub-modules such as initial generation, short- and long-term reflection, crossover, and mutation. Each prompt is customized to its functional goal and context, enhancing the LLM’s knowledge transfer and generalization, and ultimately improving the evolution performance of the heuristic method.

5.2.4 Justification and Analytical Properties of the RELLM-A

Design rationale. The RELLM-A treats the heuristic as a learnable object. Each generation runs two feedback loops: (i) short-term reflection compares weaker and stronger code on the same instance to synthesize crossover variants; and (ii) long-term reflection aggregates reusable patterns that perform mutations. New off-springs are evaluated and an elitist individual is retained; thus the best-so-far

The complexity, time, and memory. For U users, M providers, and

Theoretical stance. As with classical ACO on Non-deterministic Polynomial-hard problems, we do not claim global optimisation. The RELLM-A provides (i) robust non-degradation via elitist retention (

Practical note. Runtime is dominated by the ACO evaluations (data- and ant-linear). The LLM guidance trades a modest, controllable wall-time overhead for better heuristics and does not change the asymptotic scaling; memory grows linearly with the problem size and mildly with the population size.

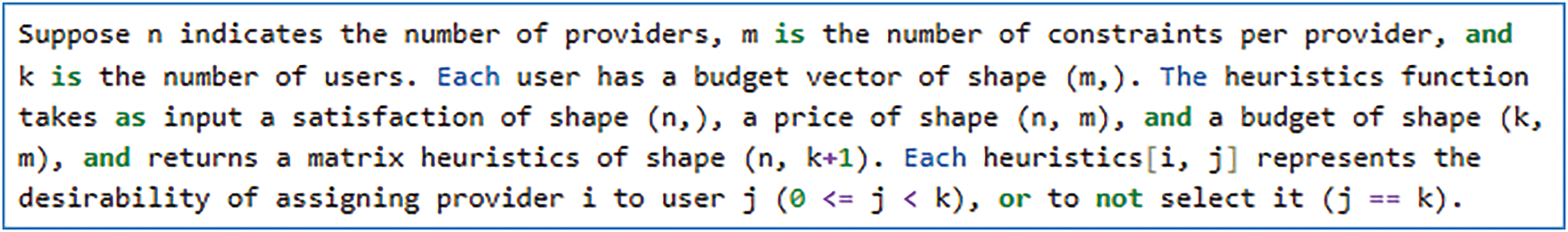

To provide a more intuitive illustration of the algorithm’s internal process, Fig. 2 shows a prompt example at the function generation stage. This function description prompt defines the signature of the function, the structure and semantics of input/output tensors, with precise annotations for variables’ roles. This ensures that the LLM fully understands the objectives and constraints associated with the heuristic function.

Figure 2: Problem description prompt used for function generation at the initial stage

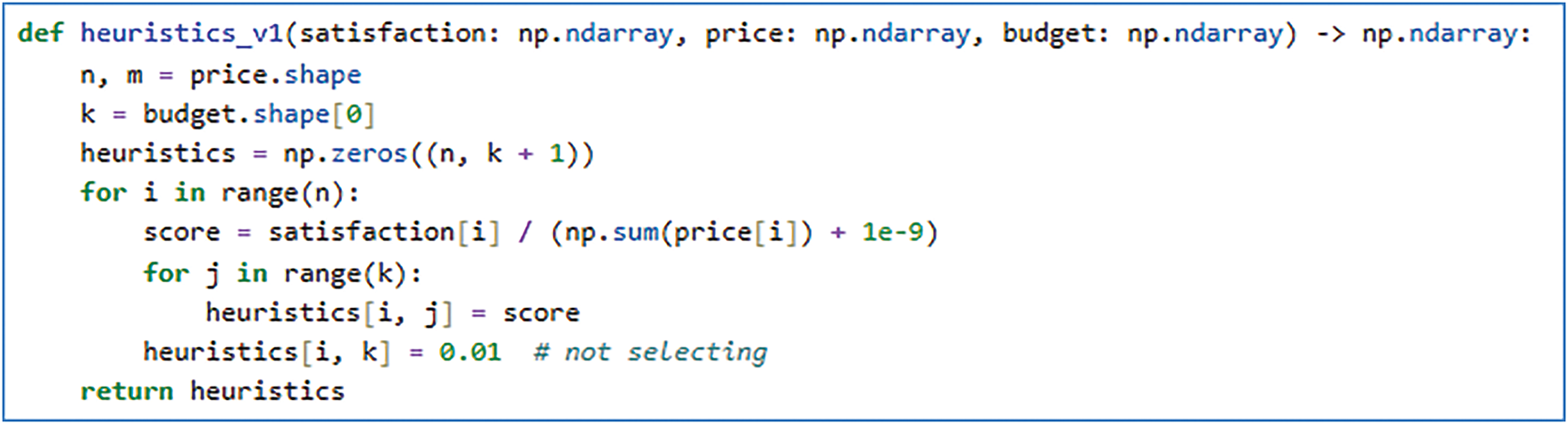

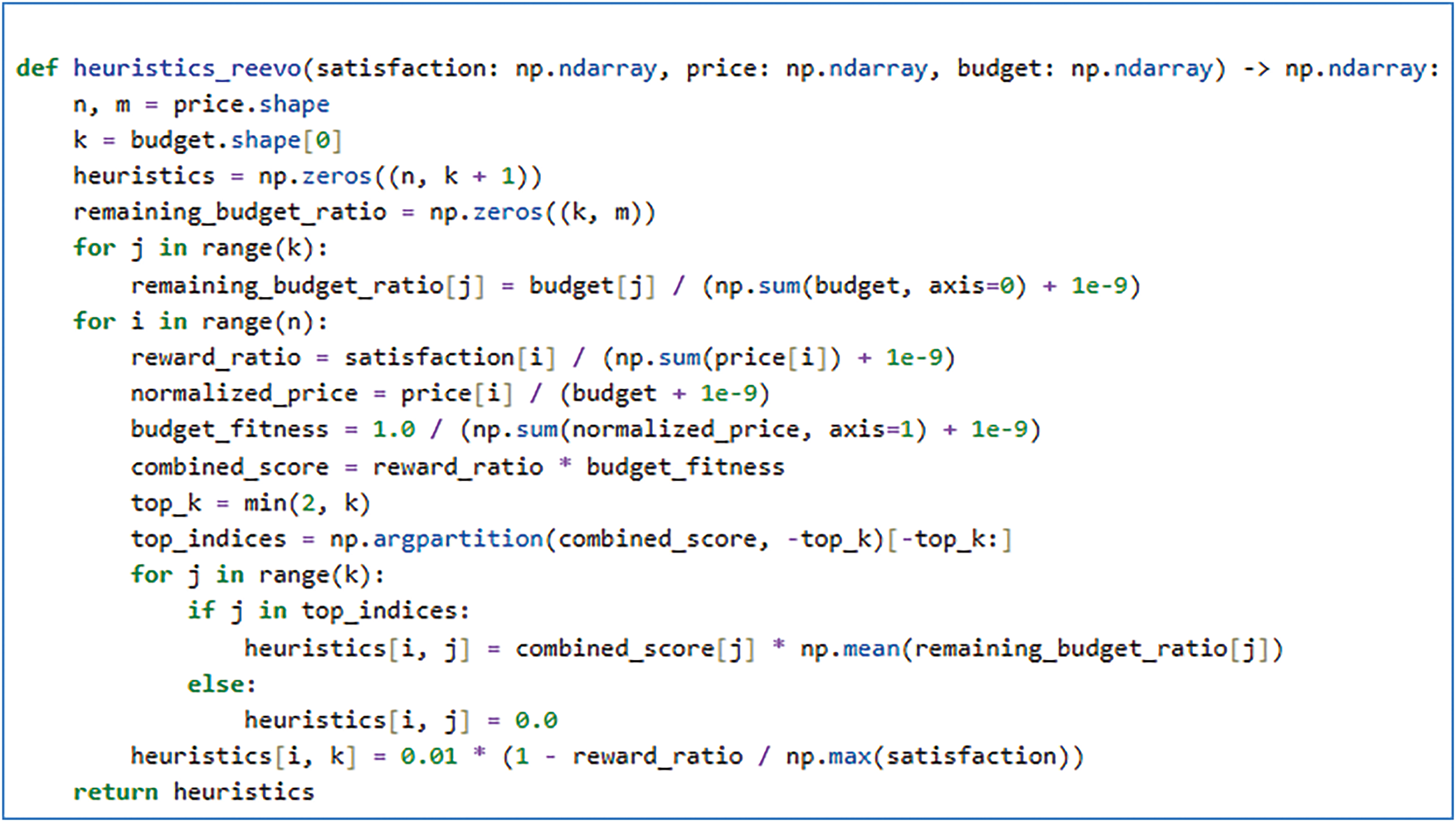

To further control the generation of function, we supplement the abstract prompt with a human-crafted reference function used as an example during inference, as shown in Fig. 3. This referring function demonstrates a basic heuristic scoring strategy based on the ratio of satisfaction to the price, and provides the LLM with structural, naming, and logical guidance. It reduces the risk of producing invalid or semantically misaligned functions.

Figure 3: Initial function

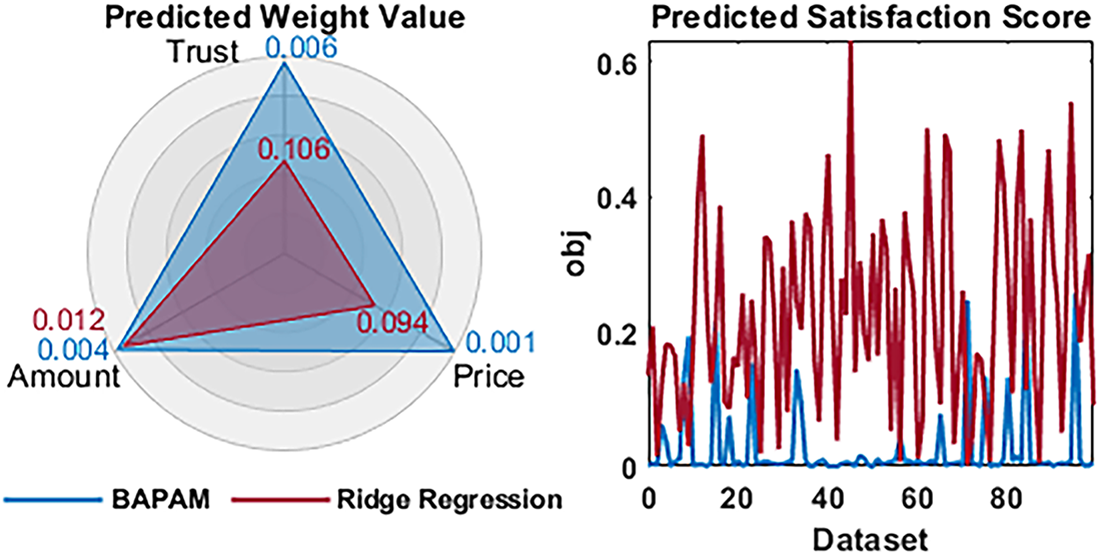

Building on this foundation, we introduce a reflective-evolution mechanism that iteratively refines heuristic functions with local and global adaptation. As shown in Fig. 4, the final evolved function—obtained via multi-round reflection and elitism—encodes logic such as budget ratio, normalized price, and satisfaction-based scoring, enhancing both adaptability and search efficiency. Importantly, this complexity is not manually predefined in prompts or templates, but emerges through iterative refinement, demonstrating the flexibility and generative capacity of the LLMs in heuristic design for composition optimization.

Figure 4: Optimized heuristic generated by the algorithm

6 Experimental Design and Result Analysis

This section systematically evaluates the effectiveness of the RELLM-A method. Experimental Setup: Experiments are conducted using the DeepSeek-V3-0324 LLM on a workstation with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU and Intel i9-9900K CPU.

Dataset Construction: Following Kwon et al. [39], we construct training, validation, and test sets for the wireless energy service composition problem, which is modeled as a Multi-dimensional Multiple Knapsack Problem (MMKP), where user budgets represent knapsack capacities, service prices correspond to item weights, and satisfaction levels reflect item values.

To better simulate the real-world environment, we design two types of providers: (1) Trap-type providers with high trust and capacity but high prices; (2) Lightweight high-quality providers offering moderate satisfaction at lower cost.

The QoS criteria are independently sampled from predefined distributions and randomly shuffled to avoid positional bias. The Overall satisfaction is computed considering three criteria. The budgets of Users are calculated based on average service prices and counts of providers, with a scaling factor to balance the feasibility and difficulty. This setup enables more rigorous evaluation of algorithm performance under complex constraints.

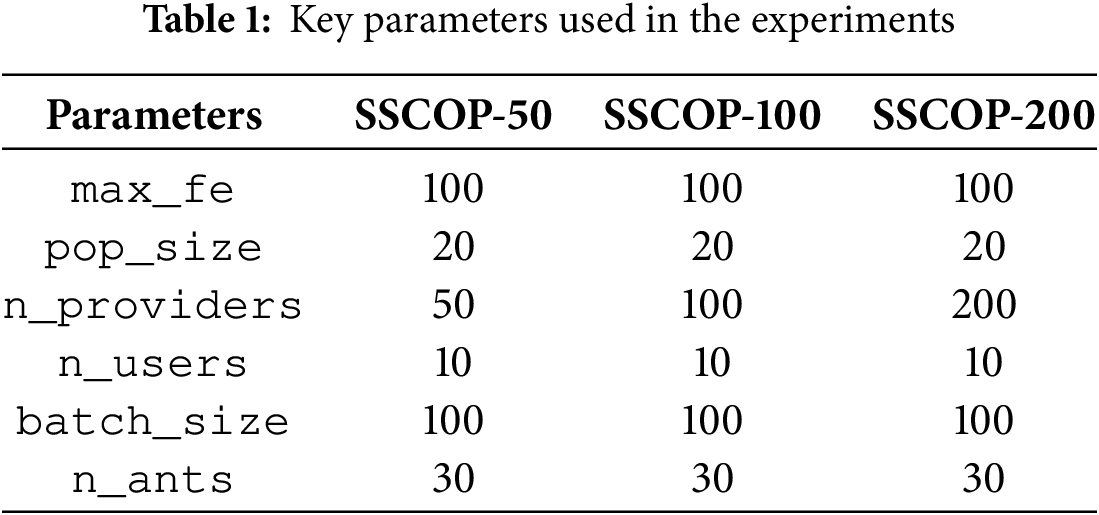

6.1 Experiment 1: Evaluating the BAPAM in Solving the BAPWP Problem

This experiment evaluates the BAPAM’s effectiveness in solving the BAPWP problem. The BAPAM first learns users’ baseline preferences from historical data, and then dynamically adjusts weights based on budget conditions—emphasizing the reliability when budgets are ample, and prioritizing price when budgets are tight. This two-stage approach captures both users’ long-term preferences and their adaptive behavior under varying budget constraints.

Fig. 5 (left) shows that the BAPAM achieves a larger radar area than the ridge regression baseline, indicating more accurate recovery of users’ preference weights. Fig. 5 (right) further demonstrates that the BAPAM yields smaller and more stable gaps between predicted and optimal satisfaction, highlighting its effectiveness in downstream service composition.

Figure 5: The accuracy of the BAPAM in dynamically predicting preference weights of users

6.2 Experiment 2: Evaluation of the RELLM-A for Solving the SSCOP Problem

To evaluate the practical effectiveness of the RELLM-A on the SSCOP, we conduct a comparison against several mainstream baselines under the objective of maximizing user satisfaction. The SSCOP, formulated as a MMKP [40], selects an optimal solution under budget constraints—a task known for its non-linearity and Non-deterministic Polynomial-hard complexity [41].

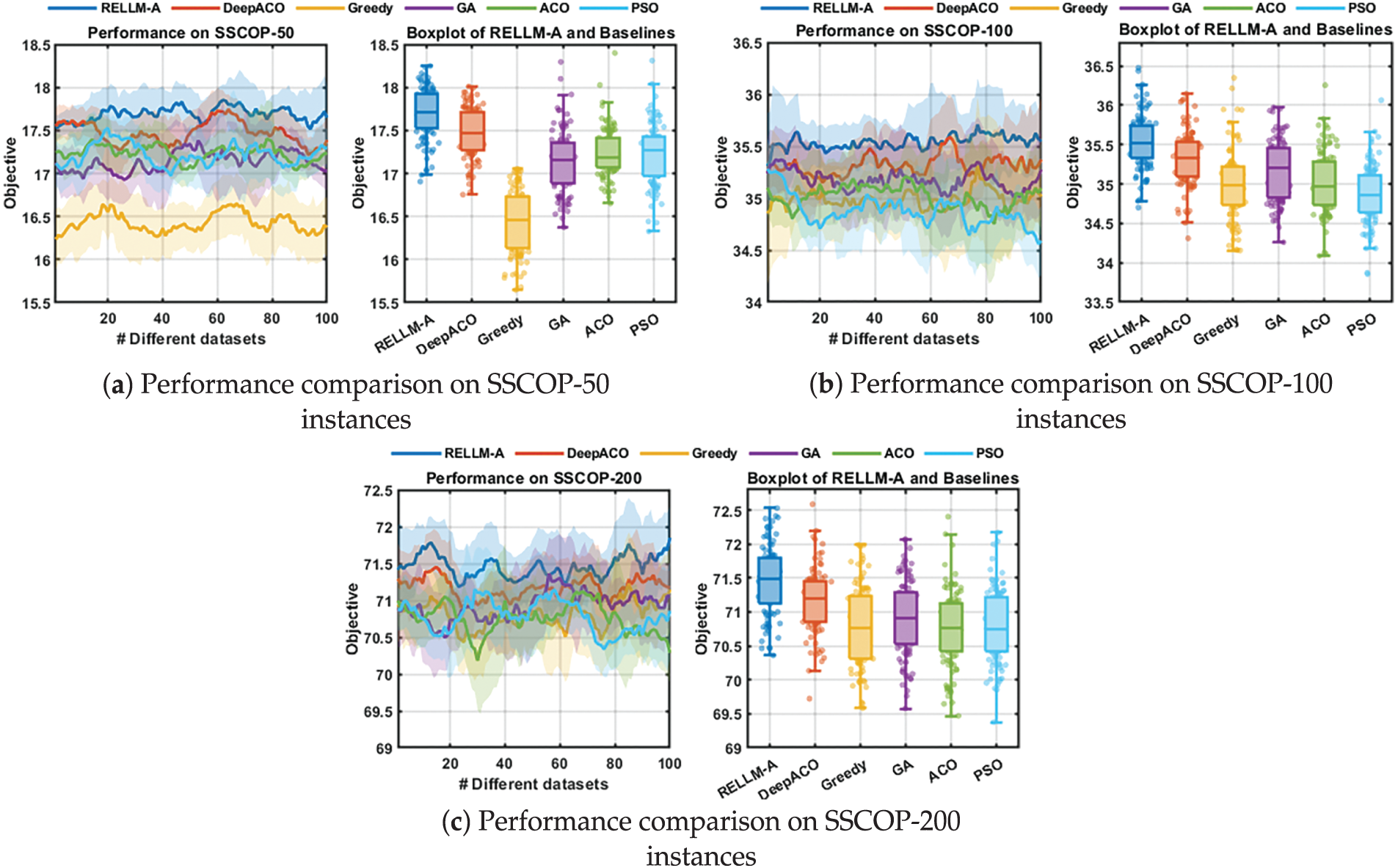

Experiments are conducted on datasets with 50, 100, and 200 users and providers to assess the scalability and robustness. The RELLM-A employs its reflective-evolutionary LLM module to generate instance-specific heuristics, while the ACO component handles construction and evaluation of the solution.

Parameter settings follow the guidelines of Kwon et al. [39], with further adjustments based on scenario complexity, convergence stability, and evolutionary depth. The scenarios reflect multi-agent service allocation settings in the real world. Key parameters are summarized in Table 1.

We compare the RELLM-A against six representative baseline methods, including: Greedy, the GA, the PSO, Standard ACO, a state-of-the-art variant called DeepACO, which integrates deep reinforcement learning into the ACO framework [42], and a variant that employs only the LLM-generated heuristic functions, referred to as the LLM-A. The results are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Comparison of the RELLM-A algorithm with other algorithms on the SSCOP problem: (a) performance on SSCOP-50 instances, (b) performance on SSCOP-100 instances, and (c) performance on SSCOP-200 instances. The horizontal axis represents different problem instances, and the vertical axis shows the maximum satisfaction value achieved by each algorithm

Fig. 6 compares the performance of algorithms across different problem sizes, with the number of candidate services set to 50, 100, and 200. In each subfigure, the line chart presents the satisfaction values achieved on 100 randomly generated problem instances, and the boxplot summarizes the distribution of these values for each algorithm. The horizontal axis represents different instances, and the vertical axis shows the maximum user satisfaction achieved by the selected service composition. It can be observed that the RELLM-A achieves the highest average satisfying value and clearly outperforms the DeepACO and other heuristic algorithms in many individual instances, demonstrating its superior capability in locating high-quality solutions. Compared to the standard ACO, which relies on fixed, hand-crafted heuristic functions in searching, the RELLM-A integrates an LLM to dynamically generate and evolve heuristics via reflective prompting. This captures instance-specific patterns better and adapts its search behavior accordingly, leading to more effective exploration. Moreover, as the dataset scale increases from 50 to 200, the RELLM-A maintains the best performance in terms of both stability and mean quality, further validating its scalability and robust performance in service composition scenarios.

In summary, the RELLM-A outperforms referring algorithms on the SSCOP task, shows broad adaptability and strong generalization ability in handling complex composition problems. Furthermore, by evaluating across multiple data scales, this experiment shows the applicability of the proposed LLM-guided heuristic search method in the real world.

6.3 Experiment 3: Model Comparison and Parameter Sensitivity

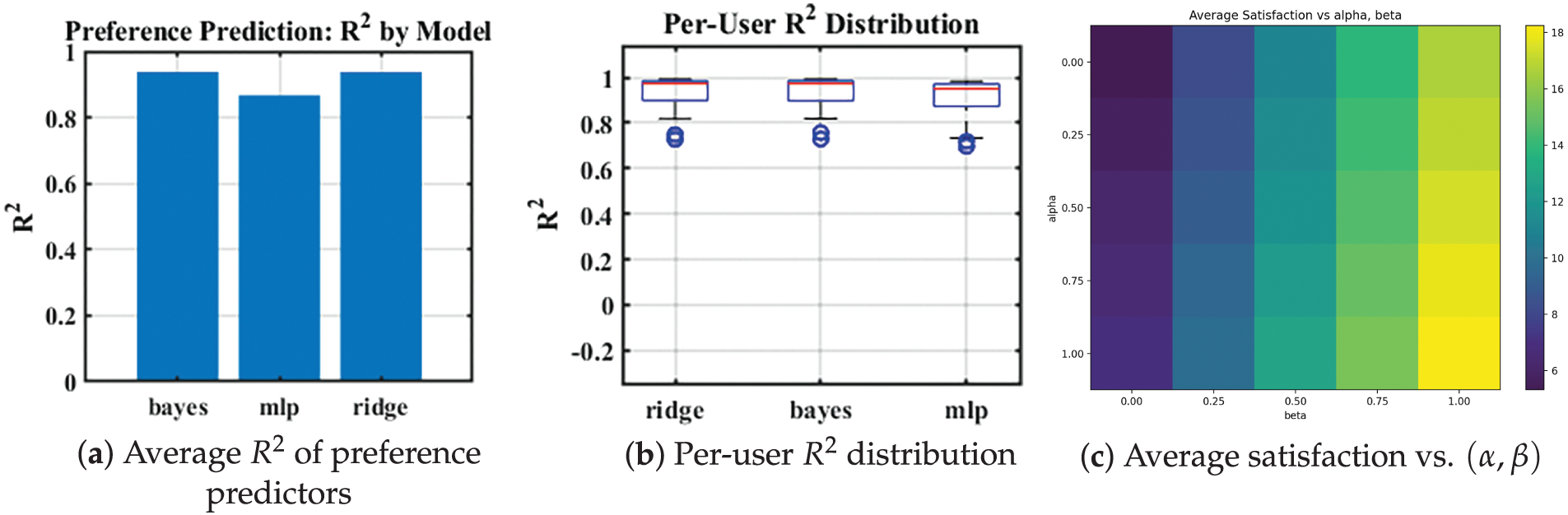

The experiments below evaluate (i) preference prediction and (ii) sensitivity to budget-adjustment parameters. The results are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Model comparison and parameter sensitivity. (a,b) Compare Ridge, Bayesian Ridge, and the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) as preference predictors. (c) Reports average satisfaction across a grid of budget-adjustment coefficients

Fig. 7a,b shows that linear regularized models (Ridge and Bayesian Ridge) deliver the most accurate and the tightest per-user distributions, while the neural MLP is less stable on the same data. This supports our choice of a ridge-type estimator: it is competitive with a Bayesian alternative but simpler to tune, more interpretable (direct coefficients on trust, capacity, and price), and more robust at the sample sizes available. Hence, the ridge-based baseline is not only standard but also empirically justified for our setting.

Fig. 7c reports average satisfaction under a grid of budget-response coefficients. The surface exhibits a clear and monotonic pattern: increasing the capacity-side coefficient leads to larger gains than increasing the trust-side coefficient, indicating that the system is more sensitive to capacity re-weighting. This analysis shows our results are not tied to a single parameter pick; instead, the conclusions remain consistent across a broad range, and it informs reasonable defaults (e.g., using a higher capacity coefficient than the trust coefficient when budgets rise).

Because we adopt a linear budget-adjustment rule as a baseline, the cross-sections of the sensitivity surface are near-linear in one dimension. This is intentional for interpretability and stability under limited data. We agree that diminishing returns or thresholds are plausible in practice; in future work we will replace the linear rule with log/sigmoid or piecewise scaling when sufficient behavioral data are available to identify those nonlinearities.

Together, these results demonstrate that (i) the ridge-based preference learner is a justified and competitive choice among standard alternatives and (ii) the conclusions are not fragile to the budget parameters, with a clear and interpretable sensitivity pattern that highlights the dominant role of capacity-side adjustments.

Recent work such as Mohajer et al. explores dynamic adaptability through resource slicing and reinforcement learning [43]. While their approach focuses on traffic prediction and fine-grained control of computing and bandwidth resources using a Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic (TD3)-based actor-critic framework, our work addresses a complementary setting which focuses on budget-aware user preferences and service selection under trustworthiness, capacity, and pricing constraints. The strengths of the work [43] in dynamic system-level adaptability could be integrated into our framework in future work—for example, by making provider attributes time-varying based on traffic prediction, or adapting our budget-response parameters using online learning. These directions are orthogonal but compatible, and we consider them promising extensions to enhance adaptability under non-stationary conditions.

We present a budget-aware service composition framework with an LLM-guided hyper-heuristic adopt the ACO. High-quality real-world datasets that jointly consider price, capacity, and trust criteria are scarce; therefore, part of our evaluation uses synthetic data and simplified pricing/capacity abstractions. In the future, we will (i) calibrate and validate the pricing/capacity modules on real data and report efficiency metrics (e.g., satisfaction per monetary unit and per delivered energy), (ii) model time-varying QoS criteria via traffic-aware priors, and (iii) integrate adaptive controllers (e.g., TD3) to tune budget-response coefficients online. These will strengthen computational rigor and practical relevance without altering the core design.

This study tackles the Satisfaction Optimization under Multi-user Budget Constraints (SOMBC) problem by decomposing it into two sub-problems: Budget-Aware Preference Weight Prediction (BAPWP) and Satisfaction-driven Service Composition Optimization (SSCOP). To address the BAPWP, we propose a Budget-Aware Preference Adjustment Model (BAPAM), which extends ridge regression with a budget adjustment factor to better capture users’ preference weights. For the SSCOP, we develop a Reflective-Evolutionary LLM-Guided Ant Colony Optimization (RELLM-A) method, where the LLMs iteratively generate and refine heuristic functions to guide the ACO search. Experimental results verify the effectiveness and generalization of the BAPAM + RELLM-A framework, which integrates personalized preference modeling with budget-constrained global optimization to enhance user satisfaction in wireless energy service scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62472264, and the Natural Science Distinguished Youth Foundation of Shandong Province under Grant ZR2025QA13.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology and writing, Haotian Zhang; supervision and project administration, Jing Li; formal analysis, Ming Zhu; review, Zhiyong Zhao; editing, Hongli Su; data curation, Liming Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jing Li, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Huda SA, Arafat MY, Moh S. Wireless power transfer in wirelessly powered sensor networks: a review of recent progress. Sensors. 2022;22(8):2952. doi:10.3390/s22082952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Meng K, Zhao S, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Zhang S, He Q, et al. A wireless textile-based sensor system for self-powered personalized health care. Matter. 2020;2(4):896–907. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2019.12.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kurs A, Karalis A, Moffatt R, Joannopoulos JD, Fisher P, Soljacic M. Wireless power transfer via strongly coupled magnetic resonances. Sci. 2007;317(5834):83–6. doi:10.1126/science.1143254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. He S, Chen J, Jiang F, Yau DK, Xing G, Sun Y. Energy provisioning in wireless rechargeable sensor networks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2012;12(10):1931–42. doi:10.1109/tmc.2012.161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lakhdari A, Abusafia A, Bouguettaya A. Crowdsharing wireless energy services. In: 2020 IEEE 6th International Conference on Collaboration and Internet Computing (CIC); 2020 Dec 1–3; Atlanta, GA, USA: IEEE. p. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

6. He S, Hu K, Li S, Fu L, Gu C, Chen J. A robust RF-based wireless charging system for dockless bike-sharing. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2023;23(3):2395–406. doi:10.1109/tmc.2023.3255980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Abusafia A, Bouguettaya A, Lakhdari A, Yangui S. Context-aware trustworthy IoT energy services provisioning. In: International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing; 2023 Nov 28–Dec 1; Rome, Italy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 167–85. [Google Scholar]

8. Abusafia A, Bouguettaya A, Lakhdari A. Maximizing consumer satisfaction of IoT energy services. In: International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing; 2022 Nov 29–Dec 2; Seville, Spain. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 395–412. [Google Scholar]

9. Abusafia A, Bouguettaya A, Lakhdari A. Quality of experience optimization in iot energy services. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS); 2022 Jul 10–16; Barcelona, Spain: IEEE. p. 91–6. [Google Scholar]

10. Hoerl RW. Ridge regression: a historical context. Technometrics. 2020;62(4):420–5. doi:10.1080/00401706.2020.1742207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Karp RM. Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In: Complexity of computer computations. The IBM research symposia series. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 2010. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2001-2_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shi L, Kabelac Z, Katabi D, Perreault D. Wireless power hotspot that charges all of your devices. In: Proceedings of the 21st Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; 2015 Sep 7–11; Paris, France. p. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

13. Dhungana A, Bulut E. Peer-to-peer energy sharing in mobile networks: applications, challenges, and open problems. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020;97(3):102029. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2019.102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kassak O, Kompan M, Bielikova M. User preference modeling by global and individual weights for personalized recommendation. Acta Polytech Hung. 2015;12(8):27–41. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhou W, Han W. Personalized recommendation via user preference matching. Inf Process Manag. 2019;56(3):955–68. [Google Scholar]

16. Li X, Fang W, Zhu S, Zhang X. An adaptive binary quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization algorithm for the multidimensional knapsack problem. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;86(6):101494. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhou X, Ma H, Gu J, Chen H, Deng W. Parameter adaptation-based ant colony optimization with dynamic hybrid mechanism. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;114(2):105139. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang J, Zhuang Y. An improved ant colony optimization algorithm for solving a complex combinatorial optimization problem. Appl Soft Comput. 2010;10(2):653–60. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2009.08.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zungeru AM, Ang LM, Prabaharan S, Seng KP. Radio frequency energy harvesting and management for wireless sensor networks. Green Mobile Dev Net Energy Optimiz Scaveng Tech. 2012;13:341–68. doi:10.1201/b10081-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ma C, An S, Wang W, Lin D, Li M, Sun L. Wireless sensor network charging strategy based on modified ant colony algorithm. Int J Mater Mech Mechatron Manuf. 2020;8(3):155–61. doi:10.18178/ijmmm.2020.8.3.499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Senkerik R, Viktorin A, Kadavy T, Kovac J, Janku P, Pekar L, et al. Open and closed source models for LLM-generated metaheuristics solving engineering optimization problem. In: International Conference on the Applications of Evolutionary Computation (Part of EvoStar). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2025 p. 372–85. [Google Scholar]

22. Ye H, Wang J, Cao Z, Berto F, Hua C, Kim H, et al. Reevo: large language models as hyper-heuristics with reflective evolution. Adv Neural Inf Process. 2024;37:43571–608. [Google Scholar]

23. Zhang S, Tong X, Chi K, Gao W, Chen X, Shi Z. Stackelberg game-based multi-agent algorithm for resource allocation and task offloading in MEC-enabled C-ITS. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2025. doi:10.1109/tits.2025.3553487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hoßfeld T, Heegaard PE, Skorin-Kapov L, Varela M. Deriving QoE in systems: from fundamental relationships to a QoE-based service-level quality index. Qual User Exp. 2020;5(1):7. doi:10.1007/s41233-020-00035-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Abusafia A, Lakhdari A, Bouguettaya A. Service-based wireless energy crowdsourcing. In: International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing; 2022 Nov 29–Dec 2; Seville, Spain. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 653–68. [Google Scholar]

26. Mohammadi V, Rahmani AM, Darwesh AM, Sahafi A. Trust-based recommendation systems in Internet of Things: a systematic literature review. Hum Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2019;9(1):21. doi:10.1186/s13673-019-0183-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pourmohseni S, Ashtiani M, Azirani AA. A computational trust model for social IoT based on interval neutrosophic numbers. Inf Sci. 2022;607(3):758–82. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.05.124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Storey C, Cankurtaran P, Papastathopoulou P, Hultink EJ. Success factors for service innovation: a meta-analysis. J Prod Innov Manage. 2016;33(5):527–48. doi:10.1111/jpim.12307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lakhdari A, Bouguettaya A. Fluid composition of intermittent IoT energy services. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC); 2022 Nov 7–11; Beijing, China: IEEE. p. 329–36. [Google Scholar]

30. Bolton RN. A dynamic model of the duration of the customer’s relationship with a continuous service provider: the role of satisfaction. Market Sci. 1998;17(1):45–65. doi:10.1287/mksc.17.1.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wilson RB. Nonlinear pricing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

32. Sengupta S, Chatterjee M. An economic framework for dynamic spectrum access and service pricing. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2009;17(4):1200–13. doi:10.1109/tnet.2008.2007758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Obloj T, Capron L. Role of resource gap and value appropriation: effect of reputation gap on price premium in online auctions. Strateg Manage J. 2011;32(4):447–56. doi:10.1002/smj.902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Pan C, Chen J, Benesty J. Microphone array beamforming with high flexible interference attenuation and noise reduction. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2022;30:1865–76. doi:10.1109/taslp.2022.3178227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ren Z, Wang G, Chen Q, Li H. Modelling and simulation of Rayleigh fading, path loss, and shadowing fading for wireless mobile networks. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2011;19(2):626–37. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2010.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang H, Zhu C, Jin W, Tang J, Wu Z, Chen K, et al. A linear-power-regulated wireless power transfer method for decreasing the heat dissipation of fully implantable microsystems. Sensors. 2022;22(22):8765. doi:10.3390/s22228765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. McDonald GC. Ridge regression. WIREs Comput Stat. 2009;1(1):93–100. [Google Scholar]

38. Yao Y, Yu J, Cao J, Liu Z. Budget-aware scheduling for hyperparameter optimization process in cloud environment. In: International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing; 2021 Dec 3–5; Virtual Event. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 278–92. [Google Scholar]

39. Kwon YD, Choo J, Kim B, Yoon I, Gwon Y, Min S. POMO: policy optimization with multiple optima for reinforcement learning. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:21188–98. [Google Scholar]

40. Islam MI, Akbar MM. Heuristic algorithm of the multiple-choice multidimensional knapsack problem (MMKP) for cluster computing. In: 2009 12th International Conference on Computers and Information Technology; 2009 Dec 21–23; Dhaka, Bangladesh: IEEE; 2009. p. 157–61. [Google Scholar]

41. Osorio MA, Cuaya G. Hard problem generation for MKP. In: Sixth Mexican International Conference on Computer Science (ENC’05); 2005 Sep 26–30; Puebla, Mexico: IEEE; 2005. p. 290–5. [Google Scholar]

42. Ye H, Wang J, Cao Z, Liang H, Li Y. DeepACO: neural-enhanced ant systems for combinatorial optimization. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;36:43706–28. [Google Scholar]

43. Mohajer A, Hajipour J, Leung VC. Dynamic offloading in mobile edge computing with traffic-aware network slicing and adaptive TD3 strategy. IEEE Commun Lett. 2024;29(1):95–9. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2024.3501956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools