Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Domain-Aware Transformer for Multi-Domain Neural Machine Translation

1 College of Information Engineering and Artificial Intelligence, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, 471023, China

2 School of Foreign Languages, Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

3 School of Electronics and Information, Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

* Corresponding Author: Juwei Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing AI Applications through NLP and LLM Integration)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 68 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072392

Received 26 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In multi-domain neural machine translation tasks, the disparity in data distribution between domains poses significant challenges in distinguishing domain features and sharing parameters across domains. This paper proposes a Transformer-based multi-domain-aware mixture of experts model. To address the problem of domain feature differentiation, a mixture of experts (MoE) is introduced into attention to enhance the domain perception ability of the model, thereby improving the domain feature differentiation. To address the trade-off between domain feature distinction and cross-domain parameter sharing, we propose a domain-aware mixture of experts (DMoE). A domain-aware gating mechanism is introduced within the MoE module, simultaneously activating all domain experts to effectively blend domain feature distinction and cross-domain parameter sharing. A loss balancing function is then added to dynamically adjust the impact of the loss function on the expert distribution, enabling fine-tuning of the expert activation distribution to achieve a balance between domains. Experimental results on multiple Chinese-to-English and English-to-French datasets demonstrate that our proposed method significantly outperforms baseline models in both BLEU, chrF, and COMET metrics, validating its effectiveness in multi-domain neural machine translation. Further analysis of the probability distribution of expert activations shows that our method achieves remarkable results in both domain differentiation and cross-domain parameter sharing.Keywords

In recent years, neural machine translation has developed rapidly. Neural machine translation models based on encoder-decoder structures are trained using large amounts of bilingual corpora and can achieve higher translation quality than traditional methods in multiple language pairs [1,2]. However, some general fields have massive corpora, while some specialized fields have scarce corpora. Moreover, a model trained in general fields can hardly accurately translate the professional terms in medical reports, nor can it understand the rigorous sentence structures in legal documents. How to make neural machine translation models effectively adapt to various fields has become a new research hotspot.

To solve this problem, researchers proposed multi-domain neural machine translation, hoping that the model can adapt to multiple domains at the same time. In order to build a model that performs well on multiple domains, several challenges must be overcome. The first problem is the imbalance of domain data. The amount of training corpus owned by different fields varies greatly. During the training process, some fields have a much greater impact on the model than others, which weakens the influence of other fields on the model. The second is domain confusion. The translated texts in the real world come from a wide range of sources. Different fields not only use different words, but also have significantly different language features and expressions. Multi-domain neural machine translation models need to learn the language styles and knowledge expressions of multiple fields at the same time during training, which easily leads to the dilution and confusion of domain features [3,4].

To address the above challenges, researchers have proposed two basic methods to build a multi-domain neural machine translation model. One method is domain adaptation based on pre-training and fine-tuning, that is, training a basic model on a massive general corpus, and then using the prior knowledge acquired by the model to continue training the pre-trained model on a specific domain to quickly adapt to the target domain [5,6]. However, the effectiveness of this method is highly dependent on the fit between the pre-trained model and the underlying task. When there are large differences between the pre-training corpus and the target corpus, the strong general language prior knowledge formed in the pre-training stage may conflict with the language style or terminology of the specific domain, and in turn interfere with the model’s learning of the new domain. Another method is to use multi-domain data joint training from scratch. This method mixes data from all related domains and trains a single model from scratch. Although this method abandons the starting advantage brought by pre-training, it avoids the above-mentioned knowledge conflict and data scale and parameter mismatch problems by directly learning the data distribution of the specific task [7].

Given the disadvantages of pre-trained models in terms of domain mismatch and difficulty in fine-tuning, in recent years, more and more research has been devoted to using multi-domain corpora to build a unified neural machine translation model so that it can maintain good translation performance across multiple domains. In multi-domain neural machine translation, the two most important issues are domain adaptation [8] and cross-domain parameter sharing. In order to solve the problem of domain differentiation, existing studies have introduced explicit domain labels as auxiliary information. Multi-domain translation can be regarded as multi-task learning with the same loss function. In order to enable the model to distinguish different tasks, researchers often design explicit task labels for each subtask to enable the model to distinguish tasks [9]. Similarly, in multi-domain translation, there are corresponding domain labels; that is, the model hopes that the domain information of the sentence will be provided as explicit information to guide the translation process. This type of method often achieves good results in practice because it has explicit domain information to guide the model’s domain differentiation, and can make the model more interpretable and controllable. In order to solve the parameter sharing problem, researchers have also used various methods to enable parameters to be shared between different domains, hoping that the information carried by these parameters can be used by different domains [10].

In summary, domain discrimination and cross-domain parameter sharing are not only the core challenges of multi-domain neural machine translation, but also a pair of mutually constrained contradictions. In order to alleviate this contradiction, the method in this paper introduces explicit domain labels to guide MoE routing and uses domain-differentiated attention to enable attention to dynamically route data from different domains, thereby enhancing the domain discrimination ability of the model. At the same time, we use the improved DMoE to enable cross-domain parameter sharing between domains. In general, the contributions of our work are as follows:

(1) We propose a Domain-Aware Multi-Head Attention module that combines the domain perception capabilities of MoE with multi-head attention, thereby explicitly improving the attention’s ability to distinguish domain features and enhancing the model’s domain adaptability.

(2) We propose an improved activation mechanism for the mixture of expert module and construct a Domain-Aware Mixture of Experts (DMoE) model. This mechanism optimizes the activation strategy and introduces a new load-balancing loss function, enabling the model to dynamically select experts to participate in the calculation based on input features, thereby enhancing domain discrimination capabilities and promoting cross-domain knowledge sharing and transfer.

(3) Experimental results on multi-domain English-Chinese and English-French datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method.

The academic community has conducted extensive and in-depth research on the domain adaptation problem of neural machine translation models. Kobus et al. [11] introduced domain information into the machine translation model by adding domain information indicators to the source text, making the neural network focus on the domain of each sentence pair. Tars and Fishel [12] went a step further and regarded different text domains as different languages, introducing a multilingual translation method and adding domain embedding as a separate input feature to each source sentence word. Both methods can improve the performance of recurrent neural networks in multi-domain neural machine translation. In order to avoid the problem that training a neural machine translation system on simple mixed data may reduce the performance of the model suitable for each component domain, Britz et al. [13] proposed three domain discrimination methods: discriminator networks, adversarial learning, and target-side domain tokens, and achieved this goal by jointly learning domain discrimination and translation. Zeng et al. [14] generated two gated vectors based on the sentence representations produced by the domain classifier and the adversarial domain classifier, and used them to construct domain-specific and domain-shared annotations for subsequent translation prediction through different attention models, and used the attention weights derived from the target-side domain classifier to adjust the weights of the target words in the training target. In order to achieve effective domain knowledge sharing and capture fine-grained domain-specific knowledge, Jiang et al. [15] proposed a novel multi-domain neural machine translation model. In their model, it is assumed that each word has a domain ratio, which represents the word’s domain preference. Then, word representation is obtained by embedding it into various domains based on the domain ratio. This is achieved through a carefully designed multi-head dot product attention module. Finally, the weighted average of the word-level domain ratio is taken and incorporated into the model to enhance the model’s domain recognition ability. In order to solve the problem that the method of mixing data from multiple domains to obtain a multi-domain neural machine translation model may cause parameter interference between domains, Huang et al. [16] introduced a multi-domain adaptive neural machine translation method, which learns domain-specific sub-layer latent variables and uses Gumbel-Softmax reparameterization technology to simultaneously train model parameters and domain-specific sub-layer latent variables. Since then, researchers have gradually focused on optimizing the training process of multi-domain neural machine translation through reinforcement learning and dynamic sampling strategies. Allemann et al. [17] proposed two reinforcement learning algorithms, Teacher-Student Curriculum Learning and Deep Q-Network, to automatically optimize the training order of multilingual NMT, enabling the model to adaptively balance the training ratio of high- and low-resource languages. The Meta-DMoE framework proposed by Zhong et al. [18] achieves domain adaptation during testing by performing meta-distillation from multi-domain expert models, effectively alleviating the problem of domain shift. Pham et al. [19] proposed the Multi-Domain Automated Curriculum (MDAC) framework, which leverages reinforcement learning to dynamically adjust the sampling ratio of multi-domain data to address domain distribution mismatch and continuously optimize the training process. Overall, these efforts have improved the adaptability and training efficiency of multi-domain translation models through reinforcement learning or dynamic strategies. However, these approaches often struggle to achieve an ideal balance between modeling flexibility, parameter sharing, and computational efficiency. Their scalability is particularly limited when dealing with large-scale, multi-domain data, and they still have significant shortcomings in parameter isolation and cross-domain transfer capabilities. To overcome these bottlenecks, researchers have begun to focus on model architectures with dynamic routing and modular structures, the most representative of which is the MoE method.

The MoE was first proposed by Jacobs et al. [20]. It provides a new connection between two apparently different approaches: multi-layer supervised networks and competitive learning, by introducing a gate control mechanism to dynamically combine multiple expert sub-networks to adapt to different inputs. The core idea of the mixture of experts is to refer to multiple neural network submodules as experts. A gating network dynamically selects certain experts to participate in the calculation based on the input content, rather than activating all experts every time. This significantly improves the model’s parameter size and expressiveness without significantly increasing computational costs. Although MoE has been proposed for a long time, it has not been widely used in large-scale scenarios due to the limitation of computing resources. It was not until Shazeer et al. [21] proposed a scalable and sparse MoE layer to solve the problem of increasing model capacity without significantly increasing computational costs that its application in large-scale models became possible. This was the first time that the MoE was introduced into the neural machine translation model, and the effectiveness of the MoE in large models was proved, laying a solid foundation for the subsequent development of large models. In recent years, MoE has been further developed in works such as GShard [22] and Switch Transformer [23]. Researchers are increasingly using MoE for large-scale multilingual neural machine translation and multi-tasks, in which MoE has demonstrated strong scalability and computational efficiency.

Although existing studies have explored domain-aware attention mechanisms and modular methods, there are still certain limitations. Zhang et al. [24] proposed a lightweight mixture of experts model MoA, which explicitly characterizes the heterogeneity between languages through a phased training strategy and clustering modeling, thereby improving parameter efficiency and training stability while ensuring performance; while Chirkova et al. [25] applied sparse mixture of experts to multi-domain NMT in their research and introduced a domain randomization mechanism to enhance the robustness of the model in unknown domains or incorrect domain labels. However, although these two methods have certain innovations in structural design, they still have problems such as computational complexity, high implementation difficulty, and hyperparameter sensitivity, and their improvement in large-scale modeling and domain generalization capabilities is still relatively limited. In addition, Zhang et al. [26] proposed that domain-aware self-attention (DASA) only relies on explicit domain labels to assist attention differentiation, but fails to truly enhance the domain discrimination ability of the attention module; Gururangan et al. [27] proposed DEMix layer leaves different domains to independent experts, but ignores the potential knowledge sharing between domains.

In contrast, this paper combines the conditional computation mechanism of a Mixture of Experts with an attention structure to propose an improved expert activation method. This method not only utilizes domain labels to strengthen the domain discrimination of attention but also fully unleashes the potential of MoE in cross-domain knowledge sharing and transfer, thereby achieving stronger domain adaptation capabilities. Furthermore, this paper introduces the Mixture of Experts mechanism into the Transformer framework and proposes a new domain adaptation method. Compared with existing methods, our method has more flexible routing strategies, more efficient parameter sharing, and is more scalable when dealing with large-scale data. Subsequent experimental results demonstrate that our proposed model outperforms several state-of-the-art methods in both stability and performance when trained on English-Chinese and English-French datasets.

MoE is commonly used in multi-task learning. By assigning different experts to each task, a single model maintains high performance across diverse tasks. This paper treats translation tasks in different domains as independent subtasks, introducing a MoE into the neural machine translation model to more efficiently build multi-domain translation models, thereby improving the performance of neural machine translation models in multiple domains.

Eq. (1) represents the calculation process of the MoE, where

In current applications, not all experts are usually activated; only the top-k experts with the highest weights are retained, which saves computing resources and improves model performance. As shown in Eqs. (2) and (3), the MoE selects the most relevant K experts for each token through a dynamic router and only calculates the output of these K experts, thereby improving computing efficiency and model performance.

One of the main modules of the Transformer architecture is the multi-head attention mechanism proposed by Vaswani et al. [28]. Instead of performing a single attention function, the multi-head attention mechanism allows the model to jointly focus on information from different representation subspaces at different positions. This is achieved by projecting queries, keys, and values n times using different, learnable linear projection matrices. These parallel attention heads can focus on different aspects of the input sequence, and their outputs are concatenated and re-projected to obtain the final output. Eqs. (4)–(6) represent the computation process of multi-head attention. For a given sequence H, it is represented as Q, K, and V.

where

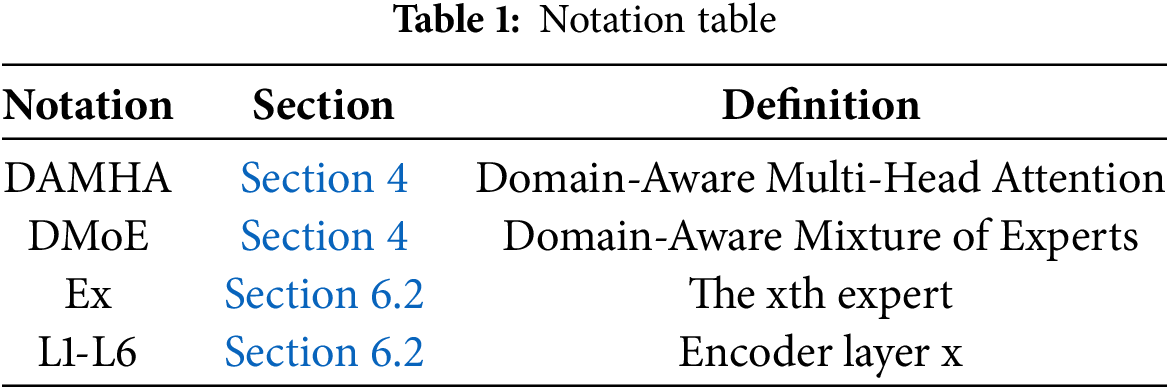

To improve the reader’s comprehensibility and the reproducibility of the experiment, this paper has unified the main symbols and diagram identifiers that appear in the text, as shown in Table 1.

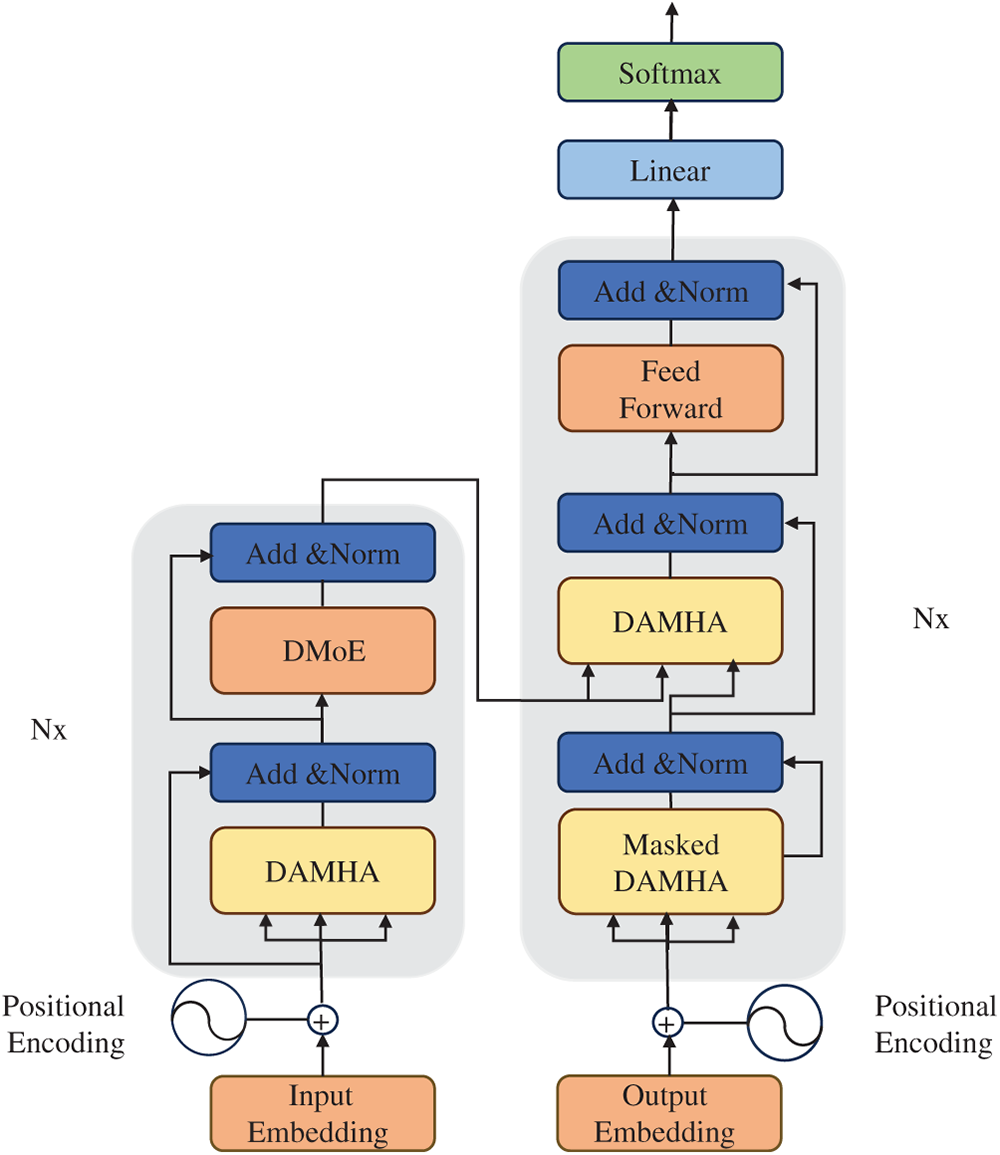

In order to solve the domain adaptability problem of models in multi-domain neural machine translation, we expect the model to have two key capabilities: 1) the ability to distinguish inputs from different domains. 2) the ability to share parameters between different domains. In addition, we also need to maintain a balance between the two capabilities to maintain the expressive power of the model. However, the mainstream neural machine translation model architecture represented by Transformer does not have the above capabilities in its original design. To this end, we proposed an improved model based on the Transformer. As shown in Fig. 1, the overall model is based on the Transformer framework. To more effectively handle multi-domain translation tasks, we improved the multi-head attention mechanism and feedforward neural network in the encoder and introduced two new modules: Domain-Aware Multi-Head Attention (DAMHA) and Domain-Aware Mixture of Experts (DMoE).

Figure 1: Our proposed model architecture

4.1 Domain-Aware Multi-Head-Attention

To improve the model’s domain differentiation capability, we introduce MoE into the multi-head attention layer. This mechanism leverages the characteristics of conditional computation, enabling the model to dynamically select appropriate subnetworks based on the different domains of the input sequence. By introducing the MoE module, the multi-head attention layer can dynamically route domain information, thereby enabling the model to have a certain degree of fine-grained feature modeling capabilities and enhancing its ability to differentiate between different domains [26].

Specifically, by replacing the linear mapping in the multi-head attention with MoE, attention can also perceive the domain information of the input sequence. This design not only enhances the model’s ability to model domain features but also further improves the model’s domain discrimination and context modeling flexibility, as shown in Eqs. (7) and (8).

where

4.2 Domain-Aware Mixture of Experts

Simply relying on the model’s domain differentiation ability is not enough to solve the problem. Given the limited expression space of the model, the model should also have the ability to share parameters across domains. When replacing the feedforward neural network with the MoE module, we improve it in two aspects to achieve cross-domain parameter sharing. First, regarding the expert activation strategy, we require the MoE to simultaneously activate all experts during the forward computation to fully utilize the expressive power of each expert. Second, we optimize the gating mechanism. Unlike traditional Top-k gating, the MoE in our model assigns the optimal expert probability combination based on the input sample information. These improvements not only strengthen the model’s ability to model domain characteristics but also improve its overall stability and enable natural parameter sharing across different domains.

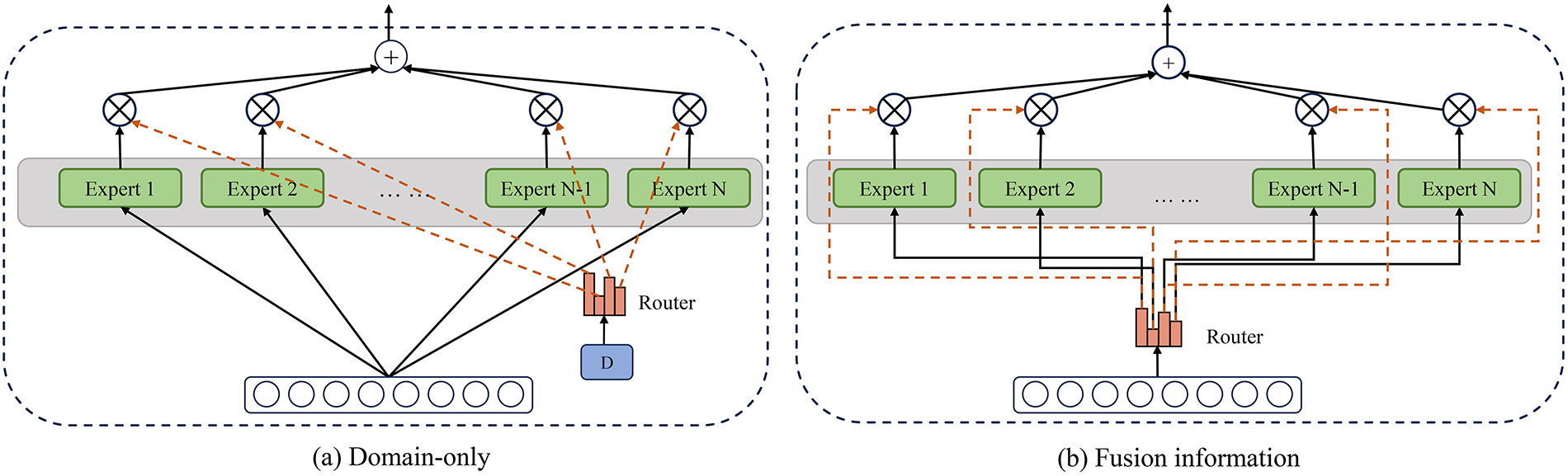

Although MoE can provide the model with efficient and scalable multi-domain learning capabilities, its performance is usually dependent on large-scale data. Some studies have found that simply introducing MoE cannot fully utilize the capabilities of the expert module and may even cause mutual interference between experts from different fields. To alleviate this problem, forcing experts to achieve domain-specific specialization is crucial to reduce negative transfer and improve domain-specific generalization. In our model, we introduce domain labels to decouple the language features of different domains, forcing experts to learn language information from different domains to improve the model’s ability to distinguish and generalize in various domains [27]. We call this module Domain-Aware MoE(DMoE). In our model, two modes are used to control the generation of the gating mechanism probability in the mixture of experts. Fig. 2 show the structures of these two modes.

Figure 2: The structure of the two modes

4.2.1 Use Only Domain Information

As shown in Eq. (9), domain information is used to control the generation of the gating probability. This pattern ensures that no matter how the sentence information is abstracted and extracted by the attention module, the gate probability is always activated by the domain information.

where

4.2.2 Using Domain Information and Sentence Fusion Information

Relying solely on domain information to guide expert selection works well in domain differentiation tasks, but it is not robust enough in more complex scenarios. To address this, we adopt the second model shown in Eq. (10), which fuses sentence and domain information to guide expert selection using a fusion approach.

where

To keep the model stable, we also introduce a balanced loss function for the DMoE to constrain the selection of experts. Without this constraint, in the face of complex situations, the DMoE will lose its original design intention. Regardless of the input of the gating network, the activation probability of each layer of the gating network will be biased towards selecting a specific expert, making the probability distribution of each domain tend to be the same. When training a multi-domain neural machine translation model, we define two loss functions, of which the translation task loss is the core. Eq. (11) defines the loss function, and the goal of translation is to minimize this loss.

where

Then there is the load balancing loss of the DMoE, as shown in Eq. (12). We define this load balancing loss based on the mean square error to limit the probability distribution of experts in the gating module so that the usage frequency of each expert is close to uniform, thereby ensuring that all experts can be fully utilized.

where

However, in our experiments, while directly using

where

Finally, our loss function is shown in Eq. (14):

where

In our experiments, we found that if too much constraint is imposed on the DMoE, the expressive power of the model will be reduced, which is not conducive to the model selecting the appropriate expert probability distribution for each field. To alleviate this problem, as shown in Eqs. (15) and (16), we choose the sine function as the adjustment strategy for the influencing factor, which gradually strengthens the model’s constraint on the DMoE in the early stage, maintains stability in the middle stage, and gradually weakens the influence in the later stage, thereby guiding the gating network to select experts in different fields, improving the expressive power of the model, and enabling the model to adapt to complex domain characteristics.

among them,

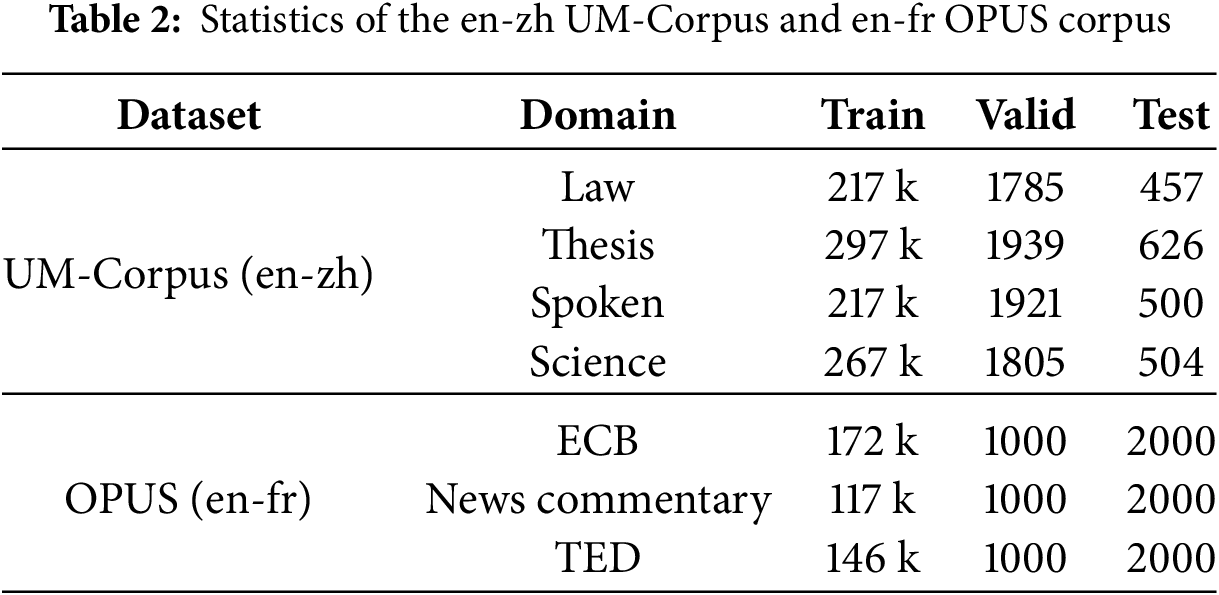

Experimental setup to verify the effectiveness of this method in multi-domain translation tasks, this paper uses data from the four fields of Law, Thesis, Spoken, and Science in the English-Chinese UM-Corpus [29] dataset, and data from three fields in the English-French OPUS [30] corpus, including ECB data made from European Central Bank documents, the News Commentary parallel corpus provided by WMT for training SMT, and the TED speech subtitle parallel corpus provided by CASMACA. All data were deduplicated and character segmented. The statistics of the training set, validation set, and test set of each dataset are shown in Table 2.

All experiments in this paper were conducted on the open source model architecture OpenNMT (https://github.com/OpenNMT/OpenNMT-py, accessed on 23 October 2025). To ensure the controllability and fairness of the experiments, the batch size of all models proposed in this paper was set to 64, the word embedding vector dimension was set to 512, the hidden layer dimension was set to 2048, the encoder and decoder layers were both 6, and the Adam [31] optimizer was used. All comparative experiments in this paper strictly followed the parameter settings provided in the original paper to ensure the comparability of the results. In addition to the pre-trained model, all experiments used the Jieba tool for Chinese word segmentation, and the default word segmentation was used for French and English. All experiments were run on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 graphics card. Unless otherwise specified, the remaining parameters of our experiments were kept default. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the model, we used BLEU [32], chrF [33], and COMET as the main evaluation indicators for all experiments. The COMET indicator is calculated using the wmt22-comet-da model [34].

Baseline: Baseline [28] model is obtained by training the standard Transformer model from scratch using mixed-domain data.

Transformer-Big: Transformer-big [28] model with larger parameter capacity is obtained by training the Transformer-big model from scratch using mixed-domain data.

Word-Level Adaptive Layer-Wise Domain Mixing (WALDM): Proposed by Jiang et al. [15], it achieves more refined cross-domain knowledge sharing and specific domain modeling through an adaptive hierarchical word-level domain mixing mechanism. As a comparative experiment, we use the best-performing model E/DC in the paper, which is a method that applies the fusion of word-level domain ratios in both the encoder and decoder.

Learning Domain Specific Sub-Layer Latent Variable (LDSPSLV): Proposed by Huang et al. [16], this method learns domain-specific sub-layer latent variables and uses Gumbel-Softmax reparameterization to simultaneously train model parameters and domain-specific sub-layer latent variables, and stabilizes model performance through pre-normalization.

Domain-Aware Self-Attention (DASA): Zhang et al. [26] proposed a domain-aware self-attention mechanism to translate sentences from different domains in a single model. Through word-level unsupervised learning of the domain attention network, the model learns a joint representation of the domain and the translation model.

MBART-50: Tang et al. [35] proposed a pre-trained cross-lingual generative model. This model has strong cross-lingual modeling capabilities and is widely used in multi-language and multi-domain translation tasks. Specifically, we use the mBART-50 model and fine-tune it on part of the data on the downstream multi-domain translation task to help demonstrate the performance improvement of our method in multi-domain translation.

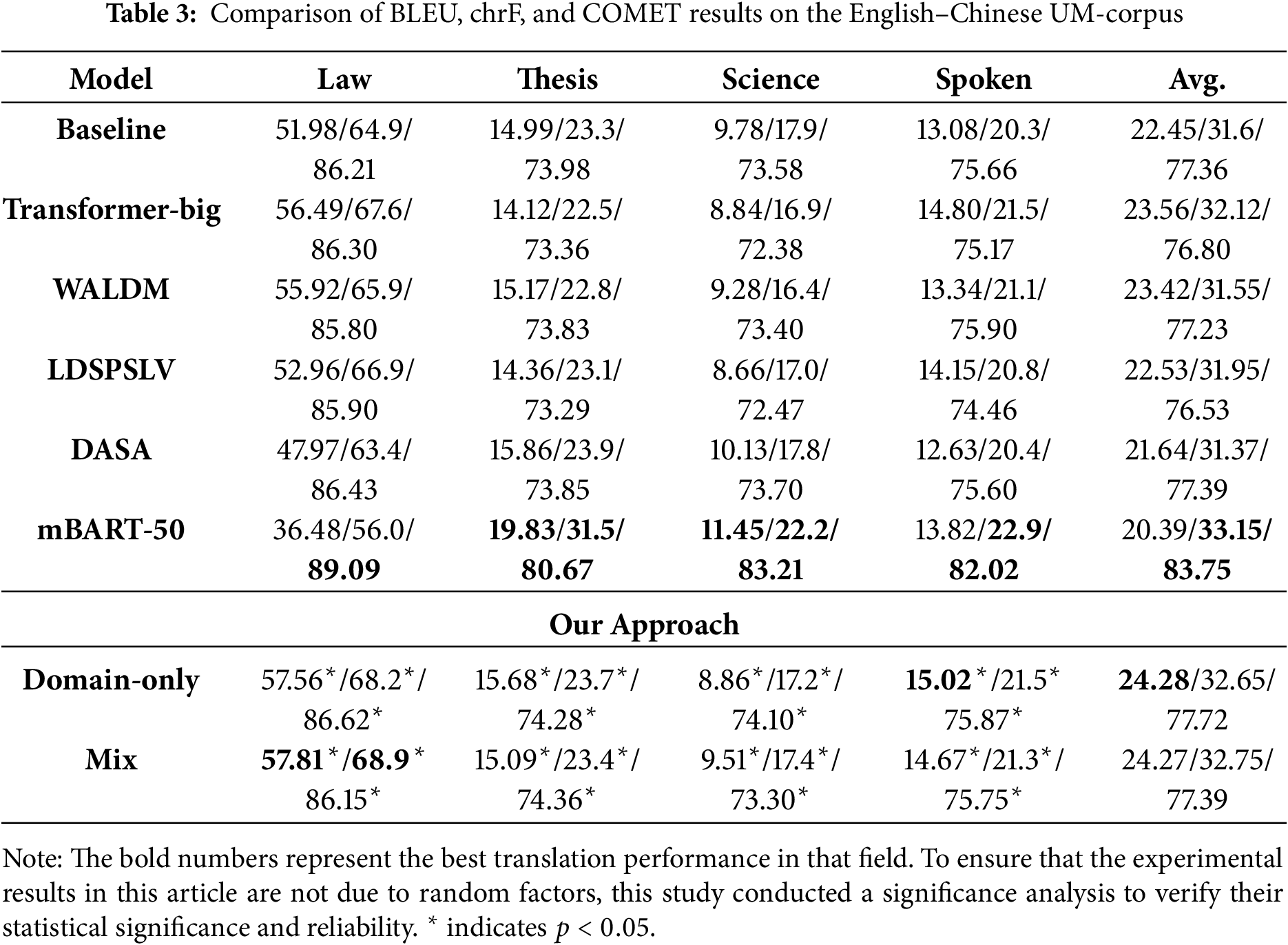

Table 3 show the BLEU, chrF, and COMET results from comparative experiments on Chinese and English datasets. The experimental results show that the models exhibit similar trends across the three evaluation metrics, with each metric showing a simultaneous increase or decrease. Specifically, our proposed method achieves significant improvements in BLEU scores over previous methods, with an average improvement of 3.87 over the pre-trained model mBART-50. However, in terms of chrF and COMET, the average score of mBART-50 is higher than our best model, with a 0.4 point increase in chrF and a 6.03 point increase in COMET.

The performance of mBART-50 and the method proposed in this paper on the BLEU, chrF, and COMET indicators reflects the different dimensions of translation quality that the three evaluation indicators focus on. Due to the differences in the calculation methods of BLEU, chrF, and COMET, the BLEU evaluation indicator focuses more on term selection and expression accuracy, chrF emphasizes local consistency at the character level, and is more sensitive to word meaning replacement, synonym conversion, or word order changes. COMET is a semantic evaluation indicator based on a neural network. It comprehensively examines the semantic adequacy and fluency of the translation by encoding the semantic representation of the source sentence, reference translation and system translation.

The method proposed in this paper performs well on the BLEU evaluation indicator, demonstrating its advantages in overall translation accuracy in terms of term selection and expression accuracy. In terms of the ChrF and COMET metrics, mBART-50 performs better, which reflects the inherent advantages of large-scale pre-trained models in semantic representation and contextual understanding. Although the model proposed in this paper achieves significant improvements in lexical-level precision matching, there is still room for improvement in capturing deeper semantic consistency and fluency. Specifically, on the BLEU evaluation metric, the improvement achieved by our method over mBART-50 is mostly in the law domain. Although mBART-50 achieved the highest scores in thesis/science domains in comparative experiments, it was still inferior to the Transformer baseline model in the law domain. This indicates that when the downstream tasks of the pre-trained model differ significantly from the style of the pre-training data, fine-tuning often fails to achieve good results. On the chrF and COMET evaluation metrics, the gap between our model and mBART-50 on law has narrowed, allowing mBART-50 to surpass it in average chrF and COMET score. Furthermore, its advantage on the COMET metric demonstrates that pre-trained models still have potential advantages in capturing semantic consistency and translation fluency.

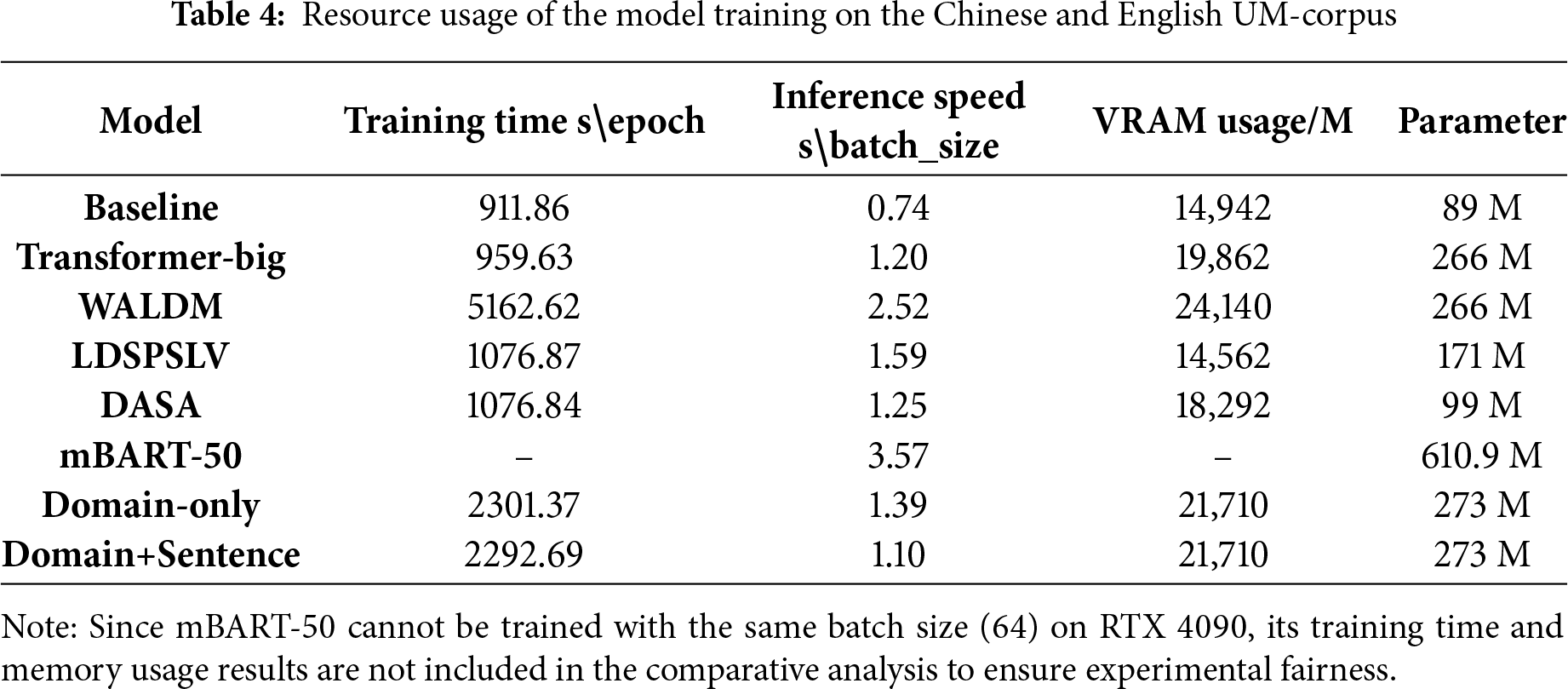

Table 4 shows the training results of the model on the Chinese-English UM-Corpus corpus. From the perspectives of runtime speed and resource consumption, the proposed model significantly outperforms mBART-50 in both parameter efficiency and hardware resource usage. Our model achieves similar performance while using fewer parameters. Due to the large parameter count of approximately 610 M, mBART-50 cannot be trained with a batch size of 64 on an RTX 4090. Its video memory usage and training time are significantly higher than those of our model. In contrast, our model has only approximately 273 M parameters and occupies approximately 21.7 GB of video memory, allowing for stable training on the same hardware. Furthermore, during inference, our model achieves an average inference time of only 1.10 s per batch, compared to 3.57 s per batch for mBART-50, representing an inference speed increase of more than twofold.

Compared to the Baseline, Transformer-big, WALDM, LDSPSLV, and DASA models, the proposed model achieves superior results in both BLEU, chrF, and COMET, with improvements of 1.83/1.15/0.36, 0.72/0.62/0.92, 0.85/0.8/0.49, 1.74/1.2/1.19, and 2.63/1.37/0.33, respectively. These experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms the comparison methods in both specific domains and average scores across multiple domains. While these comparison methods achieve better scores than the baseline models in specific domains, they perform worse than the baseline models in other domains. In terms of resource efficiency, our model achieves stable training and efficient inference under the same hardware conditions while maintaining high translation quality and a large number of parameters. Its inference speed is superior to WALDM (2.52 s/batch) and Transformer-big (1.20 s/batch).

Although experimental results on the English-Chinese UM-Corpus dataset show that our model performs well in terms of translation performance and resource utilization efficiency, experiments on this dataset alone are still insufficient to fully verify the effectiveness and generalization ability of the model. To further evaluate the model’s generalization capabilities, we conducted further experiments on a multi-domain English-French dataset.

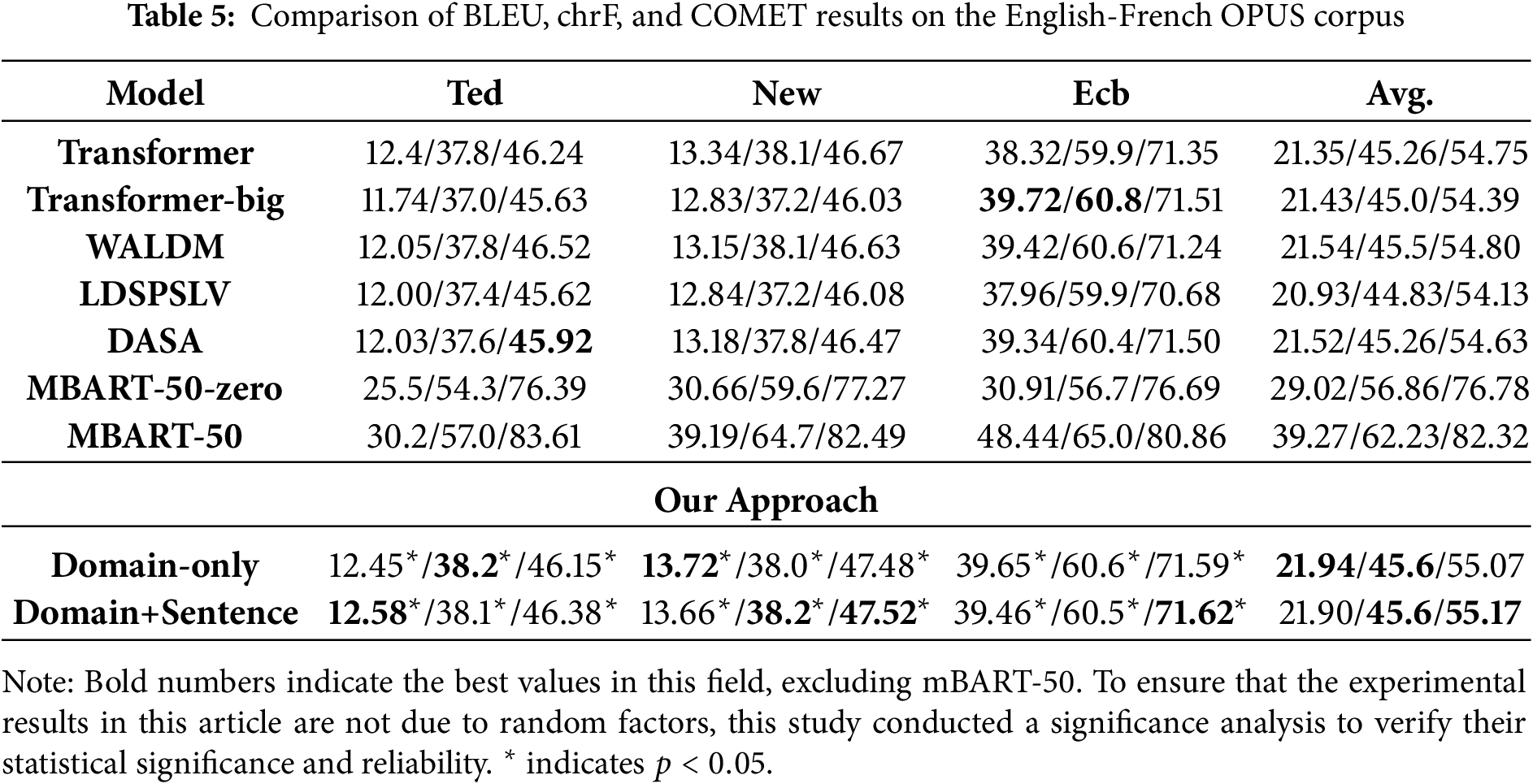

Table 5 show the BLEU, chrF, and COMET metrics of our comparison models on the English-French multi-domain translation dataset, respectively. The results show that our proposed model performs roughly the same on the English-French corpus as on the English-Chinese corpus. Compared to the Baseline, Transformer-big, WALDM, LDSPSLV, and DASA models, our proposed model achieves superior results in both BLEU and chrF, with improvements of 0.55/0.34/0.42, 0.47/0.6/0.78, 0.4/0.1/0.37, 1.01/0.77/1.04, and 0.42/0.34/0.54, respectively. The results further demonstrate that our model can still achieve significant improvements on the English-French multi-domain translation corpus, indicating that the model has good generalization capabilities in cross-domain transfer and verifying the potential of our method in practical multi-domain machine translation applications.

Notably, mBART-50 significantly outperforms other models on the OPUS English-French dataset, even surpassing our proposed model, achieving an average BLEU score improvement of 17.33 points, and the chrF, and COMET evaluation indicators were improved by 16.63 and 27.15 points, respectively. To further analyze these results, we conducted a zero-shot performance evaluation of mBART-50. Despite not using our dataset at all during training, mBART-50 achieved excellent results. Compared with our proposed model, the average scores on the BLEU, chrF, and COMET evaluation indicators were improved by 29.02, 11.26, and 21.62, respectively. This unusual result draws our attention. In fact, mBART-50 uses a large amount of OPUS language data during pre-training, and we speculate that this is the reason for its particularly strong performance on the OPUS English-French dataset. We believe its superior performance is primarily due to the inherent advantages of pre-trained models, including shared modeling of large-scale multilingual knowledge, enhanced cross-lingual semantic representation capabilities, and stronger parameter generalization. In contrast, our proposed model, which belongs to a non-pre-trained paradigm and, while relatively faster in training and inference time, lacks large-scale multi-domain pre-training corpora; its semantic alignment and cross-lingual transfer capabilities are relatively limited. Furthermore, mBART-50’s model parameters and pre-training data scale far exceed those of the model used in this study. This, in part, results in higher expressive power and more comprehensive distribution fit, explaining its significant lead on the OPUS English-French dataset.

Comparative experiments on two corpora, as well as evaluations based on two translation quality metrics, demonstrate the remarkable effectiveness of our proposed method in multi-domain neural machine translation tasks. Our model achieved the best results on the English-Chinese dataset and the best results on the English-French dataset, with the exception of mBART-50. The experimental results show that mBART-50 performs particularly well on the OPUS English-French dataset, further validating our previous view that when the training knowledge of the pre-trained model is highly consistent with the downstream task, the pre-trained model can achieve excellent performance; however, when the training data of the pre-trained model differs significantly from the downstream task, its performance on the downstream task is often limited due to the large number of model parameters, making it difficult to achieve ideal results.

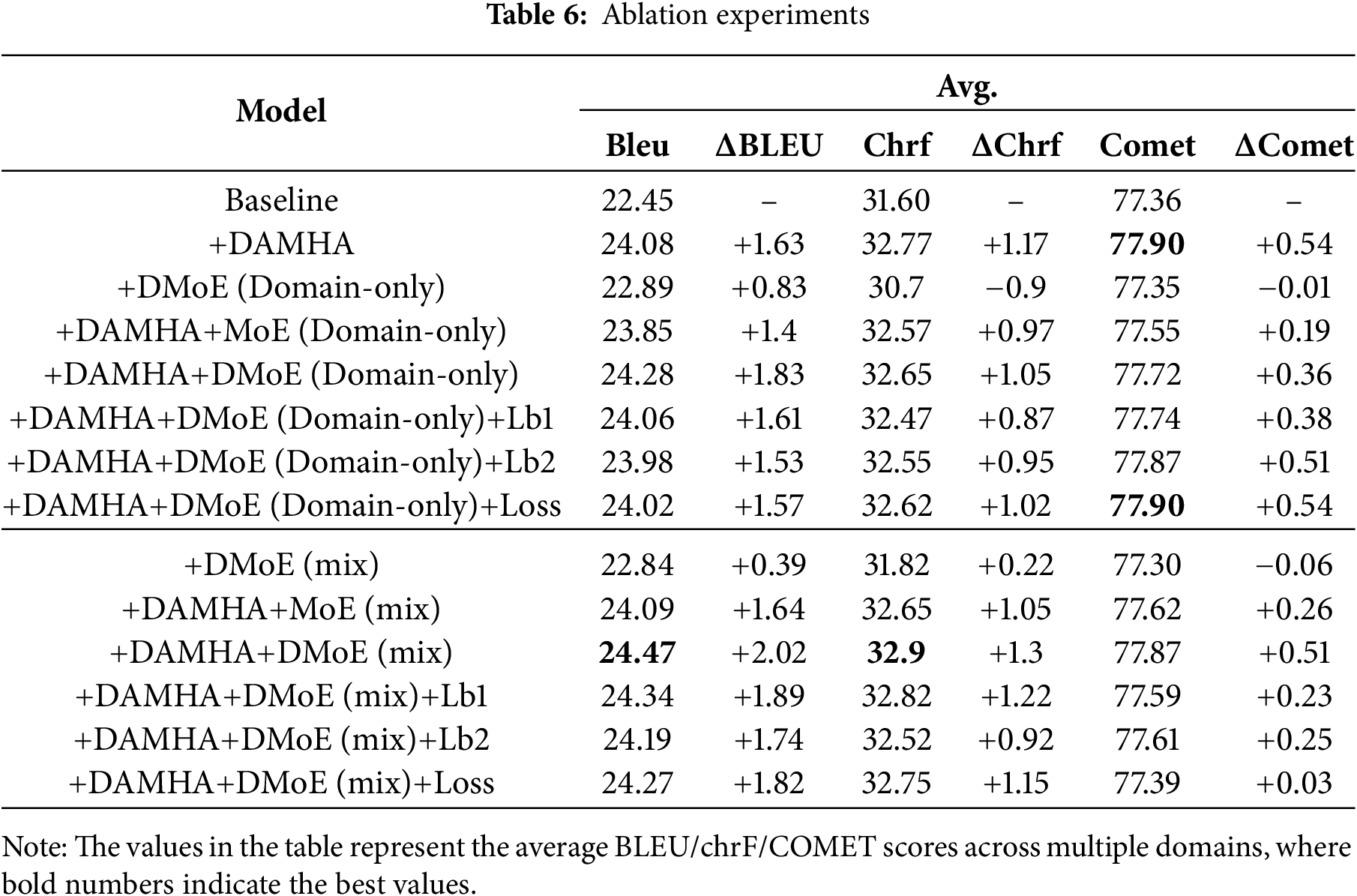

To further explore the overall impact of our proposed module, we conducted an ablation experiment based on English-Chinese translation. Using the standard Transformer model (Baseline) as a comparison, we gradually introduced different submodules, including Domain-Aware Multi-Head-Attention (DAMHA), MoE, DMoE, and their variants (Domain-only and Mixed modes). We also further investigated the impact of different loss function designs (Lb1, Lb2, and Loss) on model performance. The experimental results are shown in Table 6.

5.3.1 Impact of Modules on Performance

Table 6 shows the ablation test results for each module. Compared to the baseline model, the introduction of DAMHA improves BLEU by 1.63 points, ChrF by 1.17, and COMET by 0.54, demonstrating that the domain-aware attention mechanism effectively captures domain differences and improves translation quality. Introducing DMoE (Domain-only) or DMoE (mixed) alone only slightly improves BLEU, slightly decreases ChrF, and remains largely unchanged on COMET, indicating that expert structures relying solely on domain division are unable to fully model cross-domain features. Combining DAMHA with DMoE improves BLEU by 1.83 points, ChrF by 1.05, and COMET by 0.36, validating their complementary capabilities in domain modeling and expert selection. In both Mixed and Domain-only modes, the introduction of DMoE outperforms the traditional MoE. Specifically, in Domain-only mode, the model adding the DAMHA and DMoE (Domain-only) modules improves by 0.43, 0.08, and 0.17, respectively, compared to the model adding the DAMHA and MoE (Domain-only) modules. In Mixed mode, the model adding the DAMHA and DMoE (Mix) modules improves BLEU, ChrF, and COMET by 0.38, 0.25, and 0.25, respectively, compared to the model adding the DAMHA and MoE (Mix) modules. These results demonstrate that, whether in single-domain modeling or cross-domain mixed scenarios, DMoE can more fully capture domain differences and enhance collaboration between experts, thereby achieving higher translation accuracy and semantic consistency.

5.3.2 Impact of Loss on Performance

As shown in Table 6, in both DMoE modes, different loss modules (Lb1, Lb2, and Loss) have a certain impact on model performance. In the Domain-only mode, the performance change of different loss designs is minimal compared to the domain-only mode. After adding Lb1, Lb2, and Loss, BLEU scores all decrease slightly by approximately 0.2 to 0.3 points, and ChrF scores change within

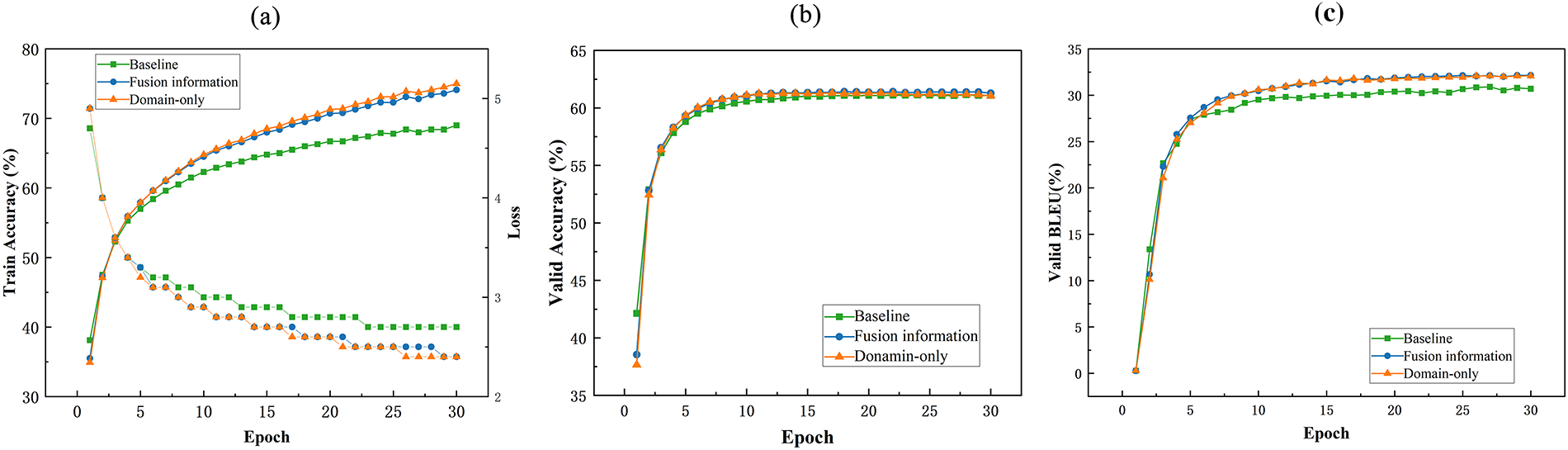

6.1 Model Convergence and Generalization Analysis

Fig. 3a shows the curves of accuracy and loss as the number of iterations changes during training for our model and the comparison model. The accuracy of all three models shows a steady upward trend with increasing iterations, with our model improving significantly faster than the baseline model. After training for more than 10 epochs, the training accuracy of our model is approximately 5% higher than that of the baseline model. At the same time, the training loss of all three models steadily decreases, with the decrease in our model’s loss being more pronounced and smoother. After training for more than 10 epochs, the training loss of our model is 2 lower than that of the baseline model.

Figure 3: Comparison of training and validation performance (accuracy, loss, and BLEU) between the proposed model and the baseline

Fig. 3b,c shows the changes in validation accuracy and BLEU scores over the number of training iterations for our model and the comparison model. The overall trends are consistent with those observed on the training set. Our model consistently outperforms the baseline model in BLEU scores on the training set, and after sufficient training, the BLEU scores are approximately 1.2 points higher. However, the differences in accuracy between the different models on the validation set are minimal, indicating that validation accuracy is not a good indicator of translation quality. The reason for this is that verification accuracy is a strict metric for word-by-word alignment, while BLEU measures the n-gram similarity of the entire translation, so the two are often inconsistent.

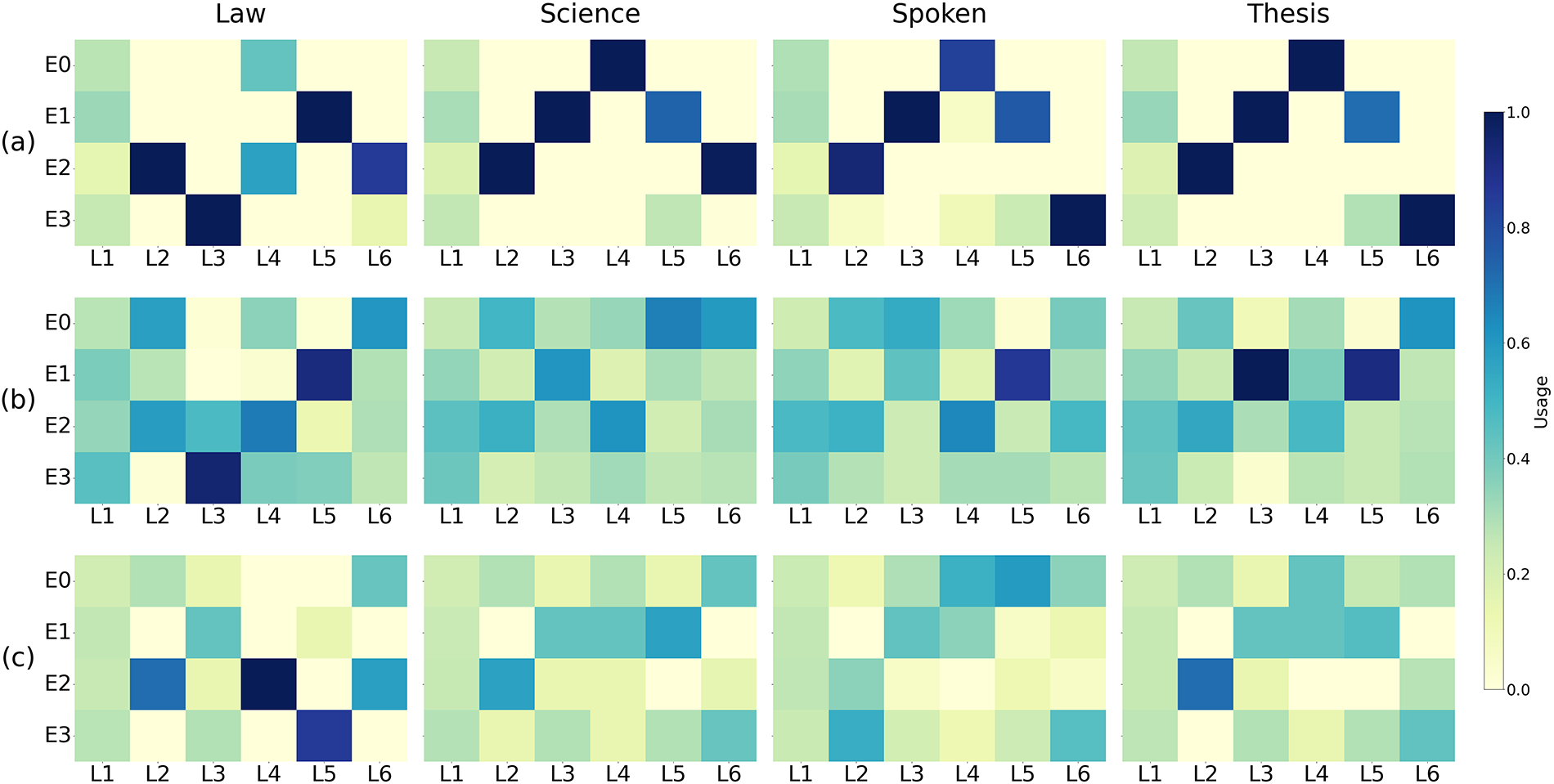

6.2 Expert Activation Visualization Analysis

To further verify the model’s cross-domain parameter sharing capabilities, we visualized the activation probability distributions of experts from different domains. Fig. 4b shows the activation probability distributions of experts when domain-only information is used as the input to the DMoE gating. The activation distribution of experts is much flatter, indicating that the gating network can more easily learn discriminative information from domain features, thereby achieving balanced utilization of experts.

Figure 4: Probability distribution of activating experts in different fields. This figure shows the model’s expert usage in four domains (Law, Science, Spoken, and Thesis). The color shades reflect the activation frequency (usage) of the experts at different layers. Darker colors indicate more frequent use of the expert in that layer or domain

However, when using fusion domain and sentence information as input to the gating network without applying a balanced loss function (as shown in Fig. 4a), the gating network fails and the activation probability distribution becomes significantly unbalanced. Across different domains, almost the same expert is activated in each layer of the DMoE, while the remaining experts are barely utilized, leading to the emergence of the super-expert phenomenon. This activation distribution not only leaves a large number of parameters in the model unused but also limits the model’s expressive power, affecting its robustness and generalization. On this basis, we further introduced balanced loss into the gating network, with the results shown in Fig. 4c. Compared to the expert activation probability distribution in Fig. 4a, the expert activation distribution in Fig. 4c is more uniform, and all experts can be fully utilized. Although fusion information contains more complex features, by adding loss balanced constraints to the expert activation probability distribution, all experts can be fully utilized. Moreover, each domain has a certain difference in the activation of experts. This activation distribution makes it easier for the model to form parameter sharing between domains when performing domain differentiation, thereby improving the overall generalization ability of the model.

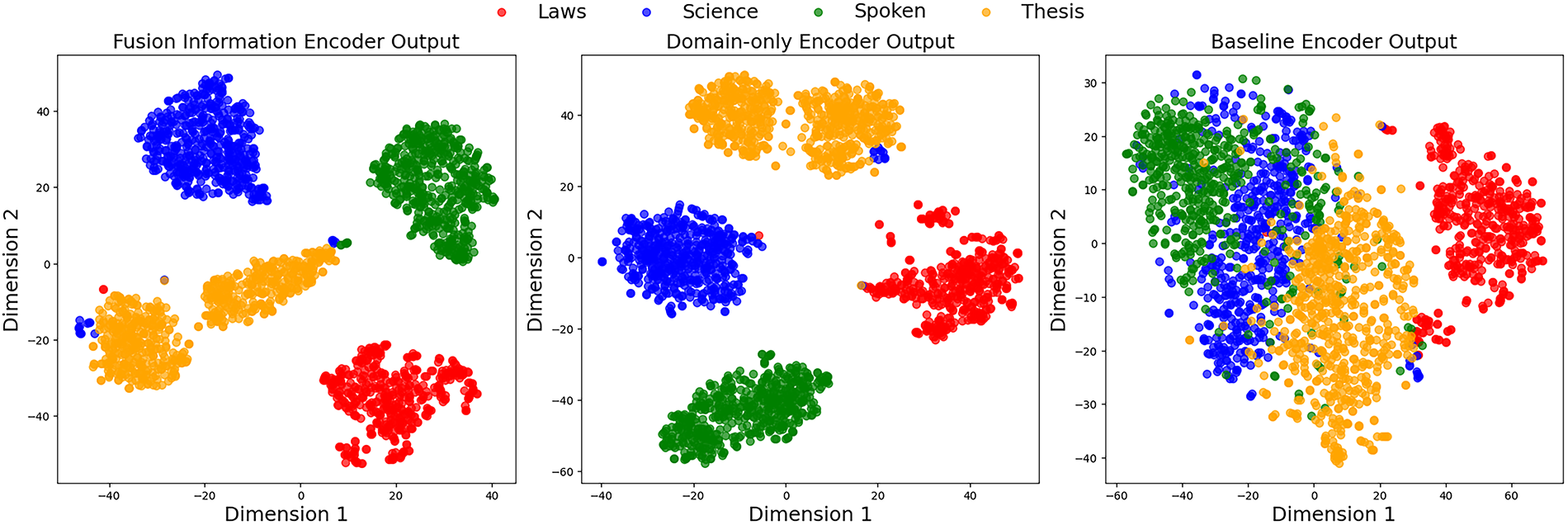

6.3 Visualization of Sentence Representations Analysis

To explore the model’s domain discrimination, we used t-SNE [36] to reduce the high-dimensional sentence vectors of the four domains to two dimensions, visualizing sentences from different domains in the representation space. Fig. 5 compares the encoder’s ability to discriminate between different domains between our proposed method and the baseline method. Compared to the baseline method, our proposed method effectively identifies the domain characteristics of the input information, whether using domain-only information or fusion information as the input to the gating network. Sentence representations from different domains cluster in distinct regions, ensuring that information from each domain is fully represented, demonstrating the model’s domain discrimination ability. The baseline method, on the other hand, fails to distinguish domain information from different inputs. Language information from various domains is mixed together, making it difficult for the model to distinguish information from each domain, which can easily lead to domain confusion.

Figure 5: t-SNE visualization of encoder sentence representation

This paper proposes a domain adaptation method for multi-domain neural machine translation. In order to solve the problems of domain differentiation and cross-domain parameter sharing in multi-domain neural machine translation, by improve the Transformer model, introducing MoE, and proposing the Domain-Aware Multi-Head-Attention and Domain-Aware MoE modules. The former effectively enhances the domain perception ability of the attention by introducing MoE and domain information in the attention calculation, thereby enhancing the domain differentiation ability of the model. The latter introduces a domain-aware gating network and activates all domain experts. By adding a loss balancing function, it dynamically adjusts the influencing factors of the loss function to achieve refined training of model parameters and achieve an organic balance between domain differentiation and cross-domain parameter sharing. Comparative experiments on multi-domain neural machine translation datasets show that the method proposed in this paper can outperform existing strong baseline models in terms of BLEU and chrF scores. At the same time, comparative experiments on English-Chinese and English-French datasets demonstrate the generalizability of our proposed method. Future work will further explore the adaptability and generalization of this method in low-resource and cross-lingual scenarios, focusing on how to maintain translation quality and parameter sharing despite data scarcity and a wide range of domains. We plan to combine multilingual pre-trained models with strategies such as continuous learning to enhance the model’s transferability and scalability to new languages and domains. Furthermore, we will incorporate lightweight design techniques (such as parameter sharing, knowledge distillation, and sparse expert structures) to optimize the model architecture, reduce parameter size and computational overhead, and thus improve training and inference efficiency. In addition, we also plan to evaluate the feasibility of deploying this method in actual multi-domain translation systems, thereby providing a more efficient, robust, and scalable solution for multi-domain neural machine translation.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2004163) and Key Research and Development Program of Henan Province (No. 251111211200).

Author Contributions: Research conceptualization and model building: Shuangqing Song; Data collection: Shuangqing Song, Yuan Chen; Experiment design: Shuangqing Song, Juwei Zhang, Xuguang Hu; Manuscript preparation: Shuangqing Song, Yuan Chen; Manuscript review: Shuangqing Song, Xuguang Hu, Juwei Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All training datasets used in this study are publicly available. The implementation code of the model can be obtained from the corresponding author (Juwei Zhang) upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bahdanau D, Cho K, Bengio Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv:1409.0473. 2016. [Google Scholar]

2. Sutskever I, Vinyals O, Le QV. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. arXiv:1409.3215. 2014. [Google Scholar]

3. Saunders D. Domain adaptation and multi-domain adaptation for neural machine translation: a survey. J Artif Intell Res. 2022;75:351–424. doi:10.1613/jair.1.13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chu C, Dabre R. Multilingual multi-domain adaptation approaches for neural machine translation. arXiv:1906.07978. 2019. [Google Scholar]

5. Lu J, Zhang J. Towards unified multi-domain machine translation with mixture of domain experts. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2023;31:3488–98. doi:10.1109/taslp.2023.3316451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Currey A, Mathur P, Dinu G. Distilling multiple domains for neural machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 4500–11. [Google Scholar]

7. Gu S, Feng Y, Liu Q. Improving domain adaptation translation with domain invariant and specific information. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 3081–91. [Google Scholar]

8. Zheng X, Zhang Z, Huang S, Chen B, Xie J, Luo W, et al. Non-parametric unsupervised domain adaptation for neural machine translation. In: Findings of the association for computational linguistics: EMNLP 2021. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 4234–41. [Google Scholar]

9. Dong D, Wu H, He W, Yu D, Wang H. Multi-task learning for multiple language translation. In: Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2015. p. 1723–32. [Google Scholar]

10. Deng Y, Yu H, Yu H, Duan X, Luo W. Factorized transformer for multi-domain neural machine translation. In: Findings of the association for computational linguistics: EMNLP 2020. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 4221–30. [Google Scholar]

11. Kobus C, Crego J, Senellart J. Domain control for neural machine translation. In: RANLP 2017—recent advances in natural language processing meet deep learning. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2017. p. 372–8. [Google Scholar]

12. Tars S, Fishel M. Multi-domain neural machine translation. arXiv:1805.02282. 2018. [Google Scholar]

13. Britz D, Le Q, Pryzant R. Effective domain mixing for neural machine translation. In: Proceedings of the Second Conference on Machine Translation. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2017. p. 118–26. [Google Scholar]

14. Zeng J, Su J, Wen H, Liu Y, Xie J, Yin Y, et al. Multi-domain neural machine translation with word-level domain context discrimination. In: 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2018). Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. p. 447–57. [Google Scholar]

15. Jiang H, Liang C, Wang C, Zhao T. Multi-domain neural machine translation with word-level adaptive layer-wise domain mixing. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 1823–34. [Google Scholar]

16. Huang S, Feng C, Shi G, Li Z, Zhao X, Li X, et al. Learning domain specific sub-layer latent variable for multi-domain adaptation neural machine translation. ACM Trans Asian Low-Resour Lang Inf Process. 2024;23(6):1–15. doi:10.1145/3661305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Allemann A, Atrio Á. R, Popescu-Belis A. Optimizing the training schedule of multilingual NMT using reinforcement learning. arXiv:2410.06118. 2024. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhong T, Chi Z, Gu L, Wang Y, Yu Y, Tang J. Meta-DMoE: adapting to domain shift by meta-distillation from mixture-of-experts. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems: Proceedings of the 36th NeurIPS Conference. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2022. p. 22243–57. [Google Scholar]

19. Pham MQ, Crego J, Yvon F. Multi-domain adaptation in neural machine translation with dynamic sampling strategies. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation (EAMT); 2022 Jun 1–3; Ghent, Belgium. p. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

20. Jacobs RA, Jordan MI, Nowlan SJ, Hinton GE. Adaptive mixtures of local experts. Neural Comput. 1991;3(1):79–87. doi:10.1162/neco.1991.3.1.79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shazeer N, Mirhoseini A, Maziarz K, Davis A, Le Q, Hinton G, et al. Outrageously large neural networks: the sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. arXiv:1701.06538. 2017. [Google Scholar]

22. Lepikhin D, Lee H, Xu Y, Chen D, Firat O, Huang Y, et al. GShard: scaling giant models with conditional computation and automatic sharding. arXiv:2006.16668. 2020. [Google Scholar]

23. Fedus W, Zoph B, Shazeer N. Switch transformers: scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. arXiv:2101.03961v3. 2022. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhang F, Tu M, Liu S, Yan J. A lightweight mixture-of-experts neural machine translation model with stage-wise training strategy. In: Findings of the Association for computational linguistics: NAACL. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 2381–92 doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chirkova N, Nikoulina V, Meunier JL, Bérard A. Investigating the potential of sparse mixtures-of-experts for multi-domain neural machine translation. arXiv:2407.01126. 2024. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhang S, Liu Y, Xiong D, Zhang P, Chen B. Domain-aware self-attention for multi-domain neural machine translation. In: INTERSPEECH 2021; 2021 Aug 30–Sep 3; Brno, Czechia. p. 2047–51. [Google Scholar]

27. Gururangan S, Lewis M, Holtzman A, Smith N, Zettlemoyer L. DEMix layers: disentangling domains for modular language modeling. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 5557–76. [Google Scholar]

28. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

29. Tian L, Wong DF, Chao LS, Quaresma P, Oliveira F, Lu Y, et al. UM-Corpus: a large English-Chinese parallel corpus for statistical machine translation. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation; 2014 May 26–31; Reykjavik, Iceland. p. 1837–42. [Google Scholar]

30. Tiedemann J. Parallel data, tools and interfaces in OPUS. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation; 2012 May 21–27; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 2214–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2014. [Google Scholar]

32. Papineni K, Roukos S, Ward T, Zhu WJ. BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics-ACL ’02; Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2001. 311 p. [Google Scholar]

33. Popović M. chrF: character n-gram F-score for automatic MT evaluation. In: Proceedings of the Tenth Workshop on Statistical Machine Translation. Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2015. p. 392–5. [Google Scholar]

34. Rei R, De Souza JGC, Alves D, Zerva C, Farinha AC, Glushkova T, et al. COMET-22: unbabel-IST, 2022 submission for the metrics shared task. In: Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT). Sturgis, MI, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 578–85. [Google Scholar]

35. Tang Y, Tran C, Li X, Chen PJ, Goyal N, Chaudhary V, et al. Multilingual translation with extensible multilingual pretraining and finetuning. arXiv:2008.00401. 2020. [Google Scholar]

36. van der Maaten L, Hinton G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J Mach Learn Res. 2008;9:2579–605. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools