Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Visual Detection Algorithms for Counter-UAV in Low-Altitude Air Defense

1 College of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Shaanxi University of Science and Technology, Xi’an, 710021, China

2 School of Electronics and Information, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710139, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongbo Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Object Detection: Methods and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 32 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072406

Received 26 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

To address the challenge of real-time detection of unauthorized drone intrusions in complex low-altitude urban environments such as parks and airports, this paper proposes an enhanced MBS-YOLO (Multi-Branch Small Target Detection YOLO) model for anti-drone object detection, based on the YOLOv8 architecture. To overcome the limitations of existing methods in detecting small objects within complex backgrounds, we designed a C2f-Pu module with excellent feature extraction capability and a more compact parameter set, aiming to reduce the model’s computational complexity. To improve multi-scale feature fusion, we construct a Multi-Branch Feature Pyramid Network (MB-FPN) that employs a cross-level feature fusion strategy to enhance the model’s representation of small objects. Additionally, a shared detail-enhanced detection head is introduced to address the large size variations of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) targets, thereby improving detection performance across different scales. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model achieves consistent improvements across multiple benchmarks. On the Det-Fly dataset, it improves precision by 3%, recall by 5.6%, and mAP50 by 4.5% compared with the baseline, while reducing parameters by 21.2%. Cross-validation on the VisDrone dataset further validates its robustness, yielding additional gains of 3.2% in precision, 6.1% in recall, and 4.8% in mAP50 over the original YOLOv8. These findings confirm the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in enhancing UAV detection performance under complex scenarios.Keywords

With the rapid development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, significant conveniences have been introduced into many aspects of modern life. However, regulatory frameworks and monitoring capabilities have not kept pace with the exponential increase in drone usage. This disparity has led to a growing number of non-compliant UAV operations, posing serious threats to public safety and social order [1]. Existing counter-drone methods primarily include radar detection, radio-frequency detection, and acoustic detection [2]. However, each approach suffers from inherent limitations. For example, radar performance is affected by the drone’s shape, material, and flight speed, which can create blind spots and reduce detection accuracy. Radio-frequency monitoring struggles to identify drones operating in radio-silent mode. Acoustic detection is highly sensitive to environmental noise, resulting in poor performance in detecting micro or silent drones [3]. Consequently, achieving precise detection of UAVs remains a significant challenge.

In recent years, the rapid advancement of deep learning–based computer vision has provided new solutions to this challenge. Representative two-stage algorithms, such as R-CNN [4], Fast R-CNN [5], and Cascade R-CNN [6], have been successfully applied to counter-UAV tasks and have demonstrated promising results. He et al. [7] utilized a Res2Net backbone to enhance multi-receptive field feature extraction and proposed a hybrid feature pyramid structure to improve multi-level feature fusion, achieving robust performance on a custom UAV detection dataset. Zhang et al. [8] introduced Dynamic R-CNN, which adaptively optimizes training by adjusting the IoU threshold for label assignment and modifying the regression loss function based on the statistical characteristics of proposal boxes, thereby enabling more efficient utilization of training samples.

Two-stage object detection algorithms have demonstrated significant progress in counter-unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) tasks; however, their high model complexity and substantial computational demands present considerable challenges for practical deployment, particularly on resource-constrained outdoor edge devices. In contrast, single-stage detectors, including the YOLO series [9–11], SSD [12], and Cascade RetinaNet [13], achieve a better balance between accuracy and efficiency by significantly improving inference speed while maintaining high detection precision. These advantages render them particularly suitable for UAV detection scenarios requiring real-time performance.

Despite extensive research on UAV detection, performance in real-world scenarios remains unsatisfactory. The primary challenge stems from the fact that drones often appear as extremely small objects in images, occupying only a few pixels. Consequently, their feature representations are highly susceptible to background clutter and noise, imposing stringent demands on detection algorithms to extract fine-grained features from such small targets. Furthermore, during operation, drones are frequently obscured by obstacles such as trees and buildings, resulting in partial or complete occlusion. This not only leads to the loss of critical visual information but also severely impedes reliable detection. Additionally, the rapid movement of drones often introduces motion blur, while variations in viewing angles and complex environmental conditions, including interference from birds, aircraft, and other visually similar objects, can significantly degrade image quality and ultimately reduce detection accuracy.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this study introduces a novel drone detection model, termed MBS-YOLO. Built upon the single-stage YOLOv8 architecture as its baseline, the proposed model achieves notable improvements in detection accuracy while simultaneously reducing computational complexity. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• By incorporating a CGLU structure [14] in place of the channel multi-layer perceptron within the PoolFormerBlock [15], a lightweight C2f-Pu module is developed. This design leverages pooling operations instead of convolutions, substantially reducing parameter redundancy in the feature extraction component.

• The proposed weighted multi-branch feature fusion network captures multi-scale information through dedicated branches that process features at different hierarchical levels. An adaptive fusion mechanism dynamically balances the contributions of each branch, effectively mitigating information loss and fusion deficiencies commonly observed in single-path designs.

• To enhance small object detection, a dedicated detection head improves localization accuracy via shared convolutional layers augmented with detail enrichment mechanisms. This design strengthens multi-scale feature representation and facilitates efficient information exchange across scales.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on object detection algorithms relevant to anti-UAV applications. Section 3 provides a detailed introduction to the MBS-YOLO anti-UAV detection model. Section 4 presents a series of comparative experiments along with an extensive analysis of the results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the study and suggests directions for future research.

In addressing challenges such as susceptibility to occlusion and substantial scale variations in drone detection, considerable research has focused on developing UAV detection algorithms based on the YOLO series.

Bo et al. [16] introduced the YOLOv7-GS model, incorporating the InceptionNeXt module at the end of the Neck to strengthen multi-scale feature extraction. Additionally, they designed the SPPFCSPC-SR module to better preserve fine-grained details of small targets during pooling and to enhance the model’s attention to them. To further improve small object detection, Wu et al. [17] added a dedicated detection layer for small targets to the YOLOv8n model, yielding a 7.5% increase in mAP. Qu et al. [18] proposed the YOLOv8_CAT model, whose primary innovation is the integration of a Combined Attention Mechanism (CAT) into YOLOv8, allowing the network to focus more effectively on critical features and regions. While all three methods enhance detection accuracy, they also impose increased computational demands. The DRBD-YOLOv8 model, proposed by Jiang et al. [19], enhances feature extraction and fusion through the incorporation of an RCELAN attention mechanism and a BiFPN module, while significantly reducing computational complexity. This approach provides a valuable reference for reducing computational costs in similar applications. Liu et al. [20] designed a Reinforced Multiscale Feature (RMF) module to effectively integrate multi-scale features, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to handle shape and structural variations. Zhang et al. [21] replaced the original Intersection over Union (IoU) loss with the Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD) metric, which effectively improves the detection accuracy of small targets while maintaining high inference speed. Yasmine et al. [22] integrated a Transformer block with a C3TR attention mechanism to enhance the focus on salient features and improve target distinguishability in complex backgrounds. Wen et al. [23] reduced model parameters and improved computational efficiency by pruning redundant detection layers dedicated to large objects, while maintaining high detection accuracy. Zhang et al. [24] proposed the YOLO-MARS model, which incorporates a parallel-path structure and depthwise separable convolutions to enhance multi-scale small object recognition capability. Bakirci [25] conducted a systematic performance comparison between YOLOv8n and YOLOv8x, highlighting the greater suitability of YOLOv8n for edge device deployment. This work offers a valuable theoretical basis for developing drone vision models that effectively balance detection accuracy and inference speed.

2.2 Multi-Scale Feature Fusion-Based Approaches

Additionally, researchers have also demonstrated that multi-scale feature fusion can effectively enhance the detection performance for small UAV targets. Zhang and Sun [26] developed a context-aware small object detection algorithm incorporating a Dense Information Enhancement Module (DIEM) to aggregate contextual cues, effectively reducing both false positives and false negatives. Similarly, Gao et al. [27] proposed a multi-level feature fusion network that employs skip connections to effectively integrate shallow and deep features, thereby enabling the aggregation of contextual information across multiple feature levels and allowing the model to more accurately capture fine-grained details of small objects. Wang et al. [28] proposed the Cross-Stage Partial Network (CSPNet), whose core idea is the introduction of a cross-stage partial (CSP) structure. Unlike traditional Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), CSPNet splits the feature map into a partial feature flow and an enhanced feature fusion path, thereby reducing redundancy during feature propagation and ensuring that only the most relevant and critical features are processed. Bi et al. [29] further developed a multi-scale cross-stage partial network, which integrates multi-scale feature information through channel recombination. This design expands the receptive field of targets and enhances the model’s adaptability to complex scenes. Lyu et al. [30] designed a bidirectional feature propagation mechanism that integrates both forward (from shallow to deep layers) and backward (from deep to shallow layers) feature propagation pathways to enhance information flow throughout the network. This bidirectional design facilitates more effective retention and utilization of multi-level features. Zhu et al. [31] proposed an Improved Feature Pyramid Network (ImFPN), which introduces a similarity-based fusion module to adaptively integrate multi-scale features, thereby enhancing detection performance for objects of varying sizes. Gao et al. [32] proposed a Multi-Scale Spatial Mamba (MSpa-Mamba) module, which employs a multi-scale strategy to reduce computational costs and mitigate feature redundancy across multiple scanning paths, thereby achieving efficient spatial feature modeling.

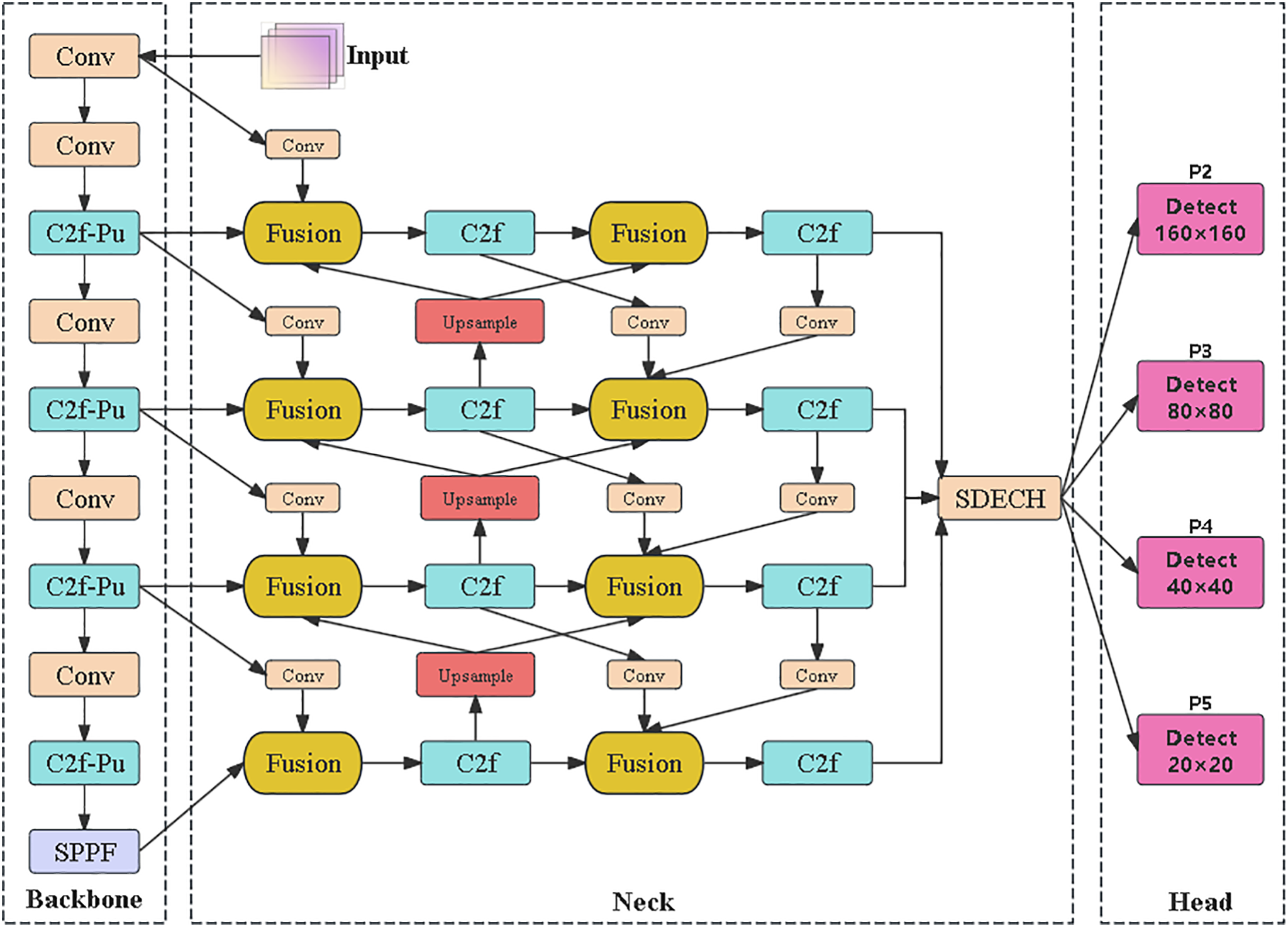

Building upon the YOLOv8 architecture, we propose MBS-YOLO (Multi-Branch Small Target Detection YOLO), a novel model designed for enhanced detection of small objects in complex scenes. The overall architecture is illustrated in Fig. 1. Key improvements include optimization of the backbone network through the newly developed C2f-Pu module, integration of a Multi-branch Weighted Feature Fusion Pyramid Network (MB-FPN) for effective multi-scale feature aggregation, and implementation of a Shared Detail-Enhanced Convolution Detection Head (SDECH) to improve localization accuracy and feature representation. By efficiently combining multi-scale feature fusion with refined feature details, the model significantly enhances small object detection performance. This architecture not only improves detection accuracy but also reduces computational complexity.

Figure 1: MBS-YOLO model structure

3.1 Lightweight Feature Extraction Module

In YOLOv8, the C2f module primarily facilitates multi-scale feature fusion by extracting both high-level and low-level information from hierarchical feature maps. However, the fusion process requires multiple convolutional operations, which increase the model’s computational complexity and slow down both training and inference. To address the issues of low computational efficiency and limited inference speed caused by these repeated convolutions, we introduce a lightweight C2f-Pu module. This module strategically replaces the original C2f structure in the deeper layers with a novel combination of a PoolFormer block and a Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (CGLU).

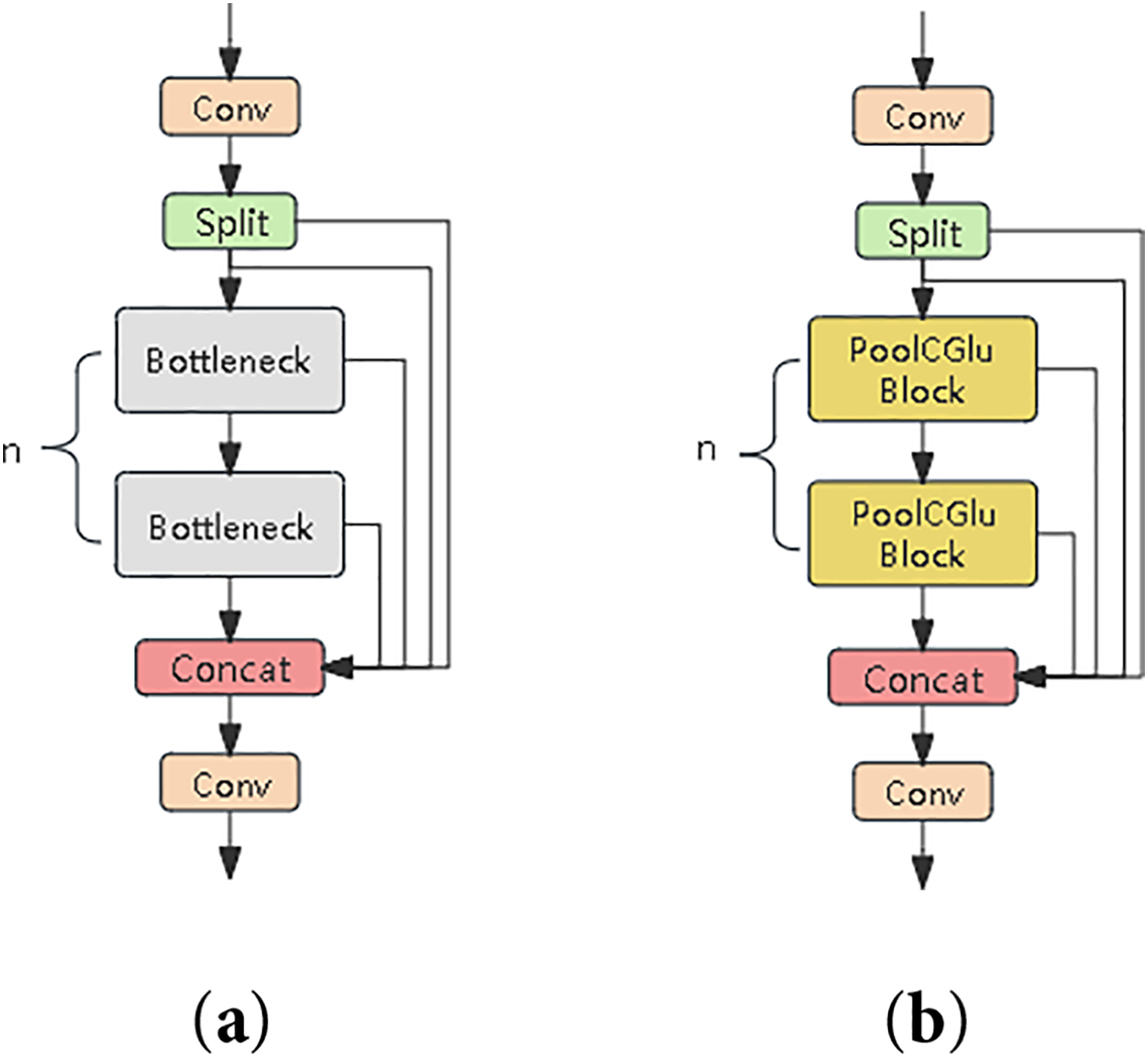

As shown in Fig. 2a, the PoolFormer block comprises four main components: a pooling layer for efficient feature downsampling, a normalization layer to ensure training stability, a channel-wise multi-layer perceptron (Channel MLP) for cross-channel interactions, and residual connections to facilitate gradient flow during optimization. For an input feature tensor T ∈ ℝ(C × H × W), the pooling operation is formally defined in Eq. (1). The integration of the CGLU further enhances the nonlinear representation capacity through gating mechanisms. Experimental results indicate that this structural modification substantially reduces the number of parameters while maintaining competitive detection accuracy, thereby achieving an effective trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance.

where T′ denotes the output feature map after pooling (maintaining identical spatial dimensions H × W with the input), K is the pooling kernel size, (*i*, *j*) index the spatial coordinates of the feature map, (*p*, *q*) represent local offsets within the pooling kernel, and the subtracted term T:i,j serves to eliminate input self-influence, thereby preventing feature redundancy caused by residual connections.

Figure 2: Structure diagram of the module. (a) schematic of PoolFormerBlock (b) schematic of CGLu

The PoolFormer Block effectively reduces computational complexity by replacing certain convolution operations with pooling operations. However, its channel-wise multi-layer perceptron (MLP) is limited to linear channel interactions and cannot capture spatial relationships among neighboring pixels, which may result in the loss of local feature details. To address this limitation, the Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (CGLU) is introduced as a replacement for the MLP layer within the PoolFormer Block. This modification significantly enhances the discriminative capability of features while introducing only minimal computational overhead.

The CGLU employs a dual-branch architecture consisting of a value branch and a gating branch. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the value branch performs channel-wise feature extraction through linear projection. The resulting output tensor maintains the same dimensions as the input, preserving the original representational capacity without introducing additional spatial information. Meanwhile, the gating branch uses 3 × 3 depthwise convolutions to expand the local receptive field and generates spatially localized gating signals through activation functions. This mechanism enables dynamic, region-specific enhancement of feature maps.

The PoolFormerBlock module reconstructed by CGLu is named PoolCGlu_Block and applied to the C2f structure to replace the original Bottleneck component, resulting in the optimized C2f-Pu structure shown in Fig. 3b, which contrasts with the baseline C2f structure shown in Fig. 3a. C2f-Pu demonstrates significant advantages in terms of model complexity and can fully meet the requirements of real-time object detection.

Figure 3: Comparison diagram of C2f and C2f-Pu structures. (a) Schematic of C2f (b) Schematic of C2f-Pu

3.2 Multi-Branch Weighted Feature Fusion Network

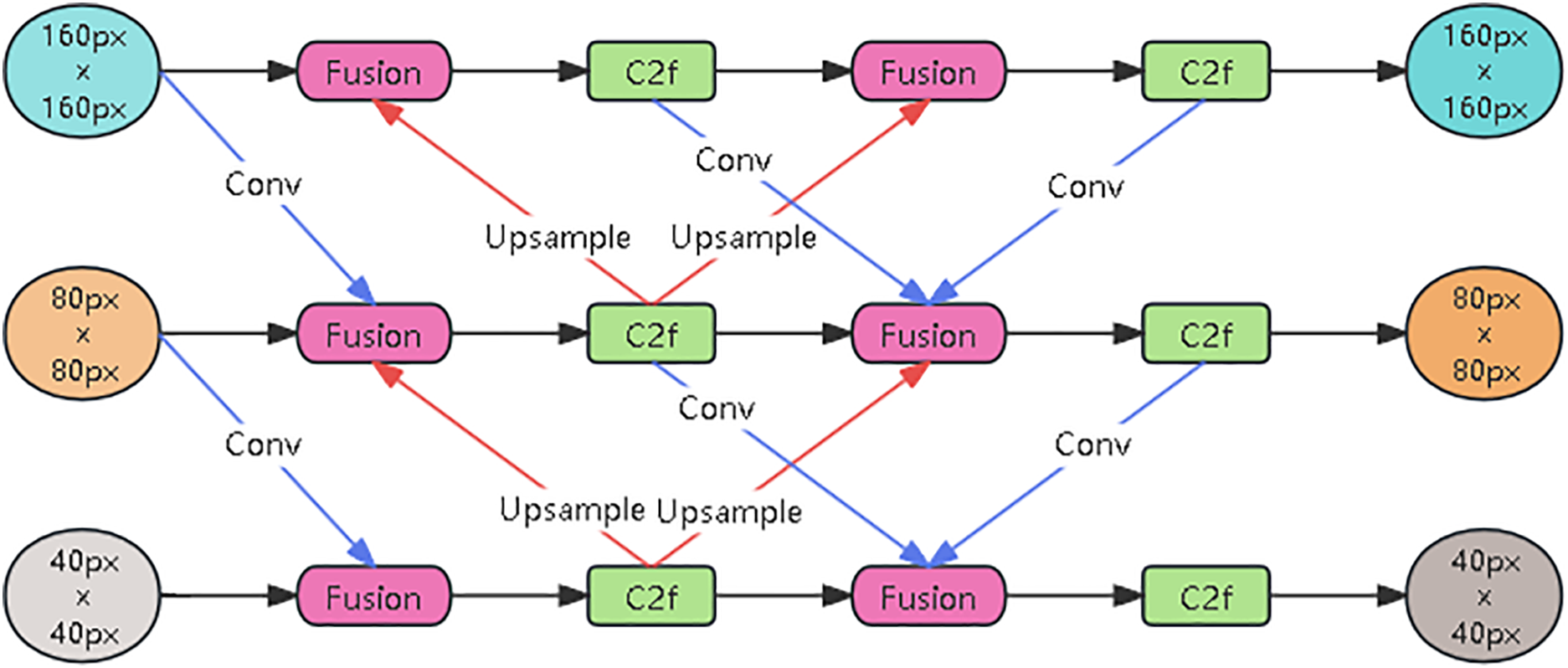

The neck network of YOLOv8 employs a combination of FPN and PAN. While the top-down and bottom-up pathways enhance multi-scale feature processing, interactions between shallow and deep features are limited to adjacent levels. After multiple downsampling operations, pixel-level information of small objects becomes highly compressed, and a substantial amount of redundant features is propagated during feature fusion, leading to the loss of fine-grained details and inaccurate localization of small targets. To overcome these limitations, this paper proposes a Multi-Branch Weighted Feature Fusion Network (MB-FPN) based on a weighted feature fusion mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Multi-branch weighted feature fusion pyramid network

The proposed architecture employs parallel branches to extract multi-level features from shallow, middle, and deep layers, thereby capturing information across multiple scales. Shallow features retain fine spatial details, mid-level features encode local structures, and deep features provide high-level semantic information. By integrating these heterogeneous representations through an adaptive weighting mechanism, the MB-FPN enriches semantic content and facilitates the direct propagation of shallow features to deeper layers. This design significantly enhances the model’s representational capacity and improves its performance in small object detection tasks.

To further enhance the expressive capacity of multilevel features, we introduce a weighted feature fusion module (Fusion) that aggregates information across different pathways using a learnable weighting strategy. Unlike conventional fusion approaches, which often suffer from redundant or imbalanced contributions, this module adaptively normalizes and reweights each feature map, ensuring that complementary information is effectively preserved without introducing additional parameters. The dynamic weight allocation mechanism allows the network to automatically emphasize informative features while suppressing less relevant ones, thereby improving adaptability to diverse input distributions and enhancing overall detection performance.

Weighted feature fusion is implemented via the fast normalization method described in Eq. (2). In this process, the normalized weights are applied to the input feature maps, followed by a weighted summation to produce the fused feature representation.

where Ii denotes the input feature map, wi represents the corresponding learnable weight optimized via backpropagation, and ϵ is a small constant introduced to prevent division by zero, thereby ensuring numerical stability during gradient computation.

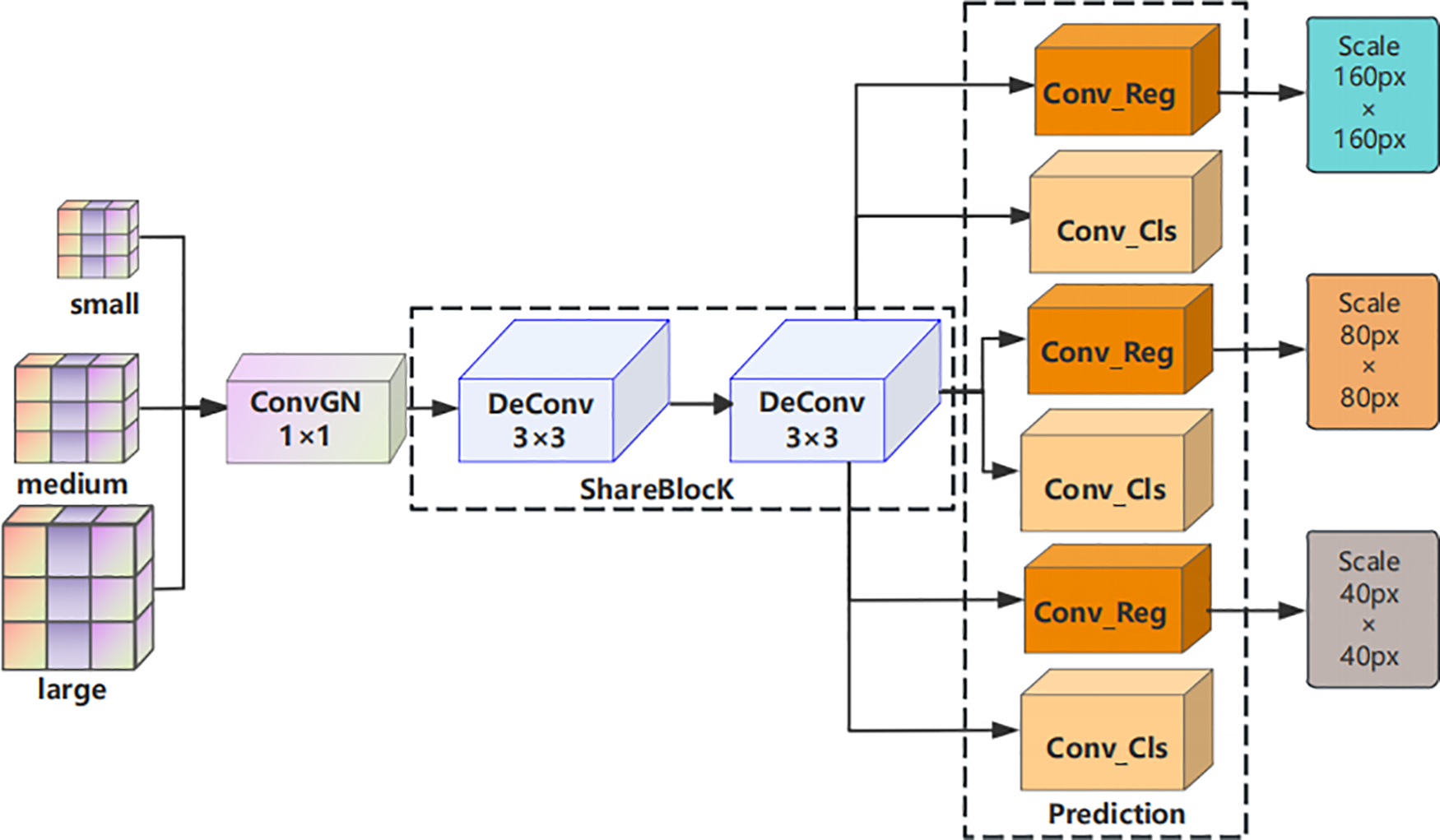

3.3 Shared Detail Enhancement Convolutional Detection Network

In multi-scale object detection tasks, features at different scales typically encode semantic information at varying levels. Although convolutional layers at each scale focus on object features of different sizes, they still share some underlying representations. In YOLOv8, however, each scale employs independent convolutional operations and detection heads, leading to isolated processing of feature maps. This strategy overlooks the complementary relationships between features across scales and the potential for inter-scale information exchange, while also introducing considerable computational redundancy. To address these limitations, this paper introduces shared convolutional operations across different scales and proposes a Shared and Detail-Enhanced Convolutional Detection Head (SDECH), whose structure is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Structure of the shared detail-enhanced convolutional detection head

The SDECH detection head initially processes multi-scale feature maps through a 1 × 1 convolution followed by group normalization before passing them into the detail-enhanced convolutional layers. This standardized processing enhances feature representations across all scales, enabling the network to effectively extract and share information between different levels. Consequently, a richer and more integrated feature representation is produced, which benefits the subsequent regression and classification convolutions. Finally, the feature maps are resized via a scaling operation to ensure that the output predictions are spatially aligned with the original input image dimensions.

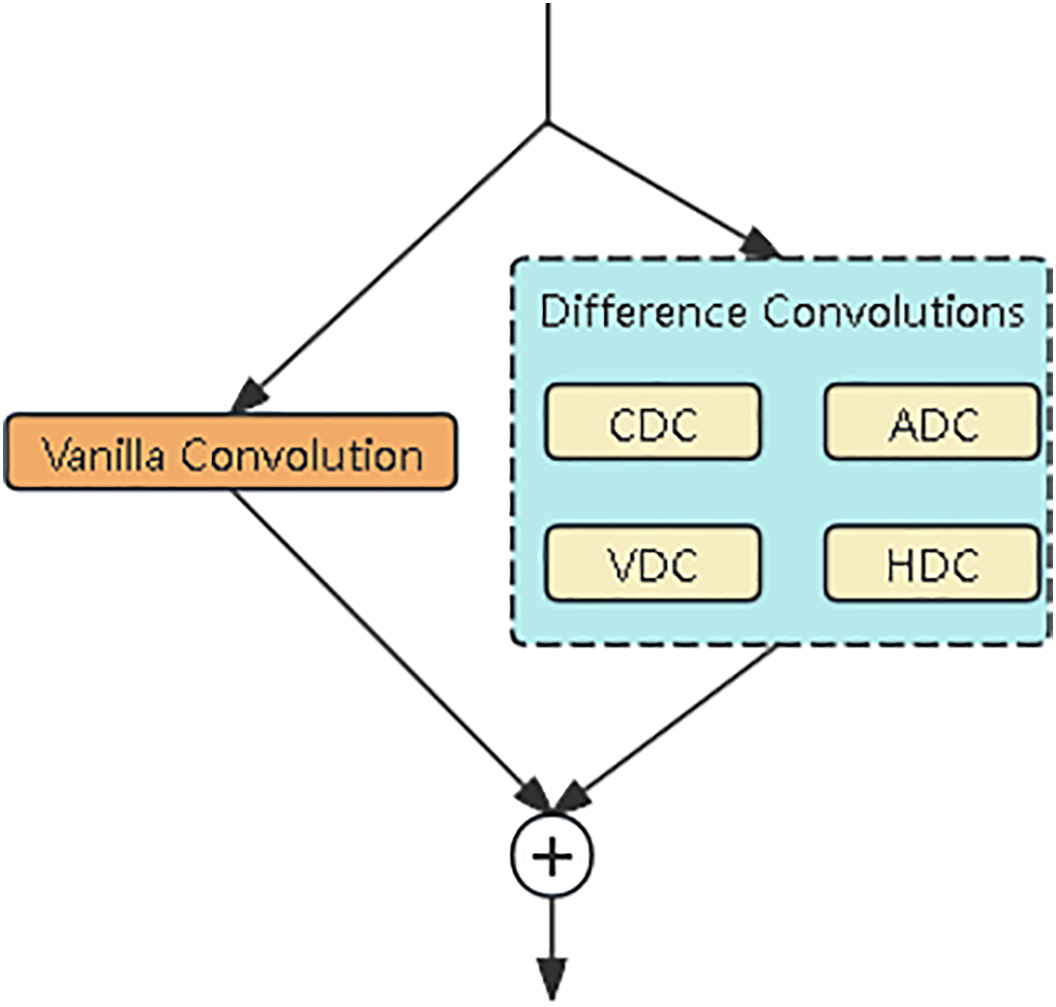

Among these modules, ConvGN standardizes feature maps to ensure consistency across different scales. Although this strategy effectively reduces computational overhead, such simplification may compromise model accuracy. To address this limitation, we replace the shared convolution layer with a detail-enhanced convolution [33] layer. The DEConv module integrates structural, textural, and other fine-grained information into the convolution process, employing a multi-branch parallel architecture to enhance the extraction of detailed features. The overall structure is illustrated in Fig. 6. The DEConv module comprises four directional differential convolution operators: central differential convolution (CDC), angular differential convolution (ADC), horizontal differential convolution (HDC), and vertical differential convolution (VDC), combined with standard convolution. Specifically, CDC extracts centrally symmetric features, ADC captures gradient variations along diagonal directions, and HDC and VDC enhance structural perception in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. By integrating these multi-directional geometric features, this hybrid convolutional architecture significantly strengthens feature representation and improves generalization performance, effectively leveraging the advantages of traditional local descriptors.

Figure 6: The structure of the detail-enhanced convolution (DEConv) module

In addition, to mitigate the loss of detailed information and positional accuracy for small objects caused by increasing network depth, we introduce a high-resolution small object detection layer (P2 layer) into the original YOLOv8 architecture. This layer generates relatively high-resolution feature maps at 160 × 160 pixels through 4× downsampling, thereby improving the network’s ability to capture fine-grained details of small objects and enhancing detection performance for densely packed or diminutive targets.

In the preparation of this manuscript, artificial intelligence tools were utilized to assist with English language refinement and structural adjustments. No AI tools were employed in the core research process, including model design, data analysis, or experimental validation.

4.1 Experimental Environment and Dataset

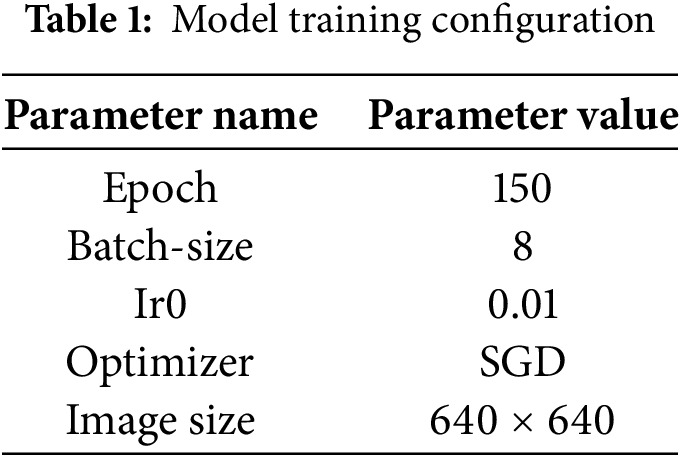

The experimental platform used was Windows 11 operating system, CPU i7-12650H, graphics card NVIDIA RTX 3080, experimental environment based on Pytorch 1.13 framework, Python 3.9 compilation environment, and Cuda version 11.6. The parameter settings are shown in Table 1.

During training, all input images are uniformly resized to 640 × 640 pixels, with each image representing approximately 72 × 72 m of actual ground area. The average size of target objects captured by the drone is 32 × 32 pixels, corresponding to roughly 0.25% of the total image area. Experimental results indicate that this configuration maintains high detection accuracy even for small objects (<32 × 32 pixels). The training process is conducted over 150 epochs, with automatic mixed precision enabled to accelerate convergence and reduce memory consumption. To prevent overfitting and optimize computational efficiency, an early stopping mechanism is employed, triggering if no improvement is observed over 50 consecutive epochs. All other training parameters are retained at their default system settings.

The Det-Fly dataset is a specialized collection designed for monocular camera-based aerial-to-aerial visual detection tasks, focusing on micro unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The dataset was captured using a DJI Mavic 2 drone observing other flying target drones, encompassing a diverse range of real-world scenarios, including sky, urban, rural, and mountainous environments. Each scenario contributes approximately 20%–30% of the total dataset. For model training and evaluation, the dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and testing subsets in a 7:2:1 ratio. Notably, around 50% of the target objects occupy less than 5% of the image area, making this dataset particularly suitable for evaluating small object detection performance.

To further evaluate the generalization capability of the improved MBS-YOLO model beyond the Det-Fly dataset, the VisDrone2019 dataset was employed. This dataset, collected via drone-based aerial photography, comprises 8629 high-resolution images covering diverse environments, multiple object categories, and varying object densities. The dataset is divided into a training set of 6471 images, a validation set of 548 images, and a test set of 1610 images. It contains annotations for 10 object categories, including people, pedestrians, bicycles, cars, vans, heavy trucks, tricycles, covered tricycles, buses, and motorcycles. Notably, approximately 60% of the targets are small objects (<32 pixels), making VisDrone2019 particularly suitable for evaluating dense small object detection performance and the robustness of the proposed model.

The Anti-UAV Tracking dataset serves as a benchmark dataset established by the Anti-UAV Challenge and Workshop. It comprises 410 high-quality video sequences, primarily captured against complex backgrounds such as clouds, buildings, mountains, and forests. Furthermore, the small flying UAV targets exhibit inconsistent flight and acceleration speeds, along with diverse motion patterns and trajectories, which collectively increase the difficulty of accurate target tracking. It is important to note that this dataset is designated for testing purposes only and is not intended for model training.

To comprehensively evaluate the detection performance of the model, several quantitative metrics are employed. Precision (P) measures the accuracy of positive predictions, Recall (R) evaluates the model’s ability to identify true positive samples, and Mean Average Precision (mAP) provides an overall assessment of detection performance. In addition, model parameter count (Parameters, Para), computational complexity (floating point operations, GFLOPs), and frames per second (FPS) are used to assess deployment feasibility and inference efficiency. The specific calculation methods for P, R, and mAP are defined as follows:

where TP (True Positive) represents the count of positive samples correctly predicted by the model, FP (False Positive) denotes negative samples erroneously classified as positive, and FN (False Negative) indicates positive samples that were missed in the detection process due to algorithmic limitations.

4.3 Experimental Data and Analysis

4.3.1 C2f-Pu Module Deployment Location Optimization Experiment

To assess the effect of deploying the C2f-Pu module at different positions within the YOLOv8 network, we conducted a series of experiments comparing module replacements across various layers. By controlling for other variables and performing multiple controlled trials, we analyzed how the placement of the module influences detection accuracy. The experimental results are summarized in Table 2.

As indicated in Table 2, replacing the original module with the lightweight C2f-Pu module results in a substantial reduction in parameter count and a significant increase in FPS (frames per second) for the YOLOv8n model. This improvement primarily arises because pooling operations function as local aggregation processes that require neither parameter learning nor complex computations, whereas convolutional operations involve extensive multiply-accumulate operations. By replacing convolutions with pooling, the parameters associated with these convolutions are eliminated, thereby reducing the overall model parameter count and computational complexity during inference. However, this substitution also leads to the loss of certain fine spatial details, resulting in varying degrees of decline in other evaluation metrics.

Among these, “Replace Backbone” refers to substituting all C2f modules in the Backbone section of Fig. 1 with C2f-Pu, whereas “Replace Neck” indicates replacing all C2f modules in the Neck section of Fig. 1 with C2f-Pu. “Full replacement” denotes simultaneously replacing all C2f modules in both the Backbone and Neck sections of the YOLOv8n model with C2f-Pu. Under this configuration, the model achieves the fastest detection speed and the lowest parameter count, but its detection performance is the poorest. In contrast, replacing only the Neck section of the baseline model results in worse overall performance than replacing only the Backbone. This is because the Neck section of the baseline model primarily handles feature fusion, whereas the Backbone contains a large amount of similar or redundant information that supports subsequent tasks such as feature fusion, classification, and localization. Therefore, even after lightweight replacement in the Backbone, sufficient information remains for the Neck to perform effective fusion, minimizing the impact on detection performance. The data indicate that replacing the Backbone slightly reduces precision, recall, and mAP50, while increasing detection speed by 14.3% and reducing the number of parameters by 27.2%.

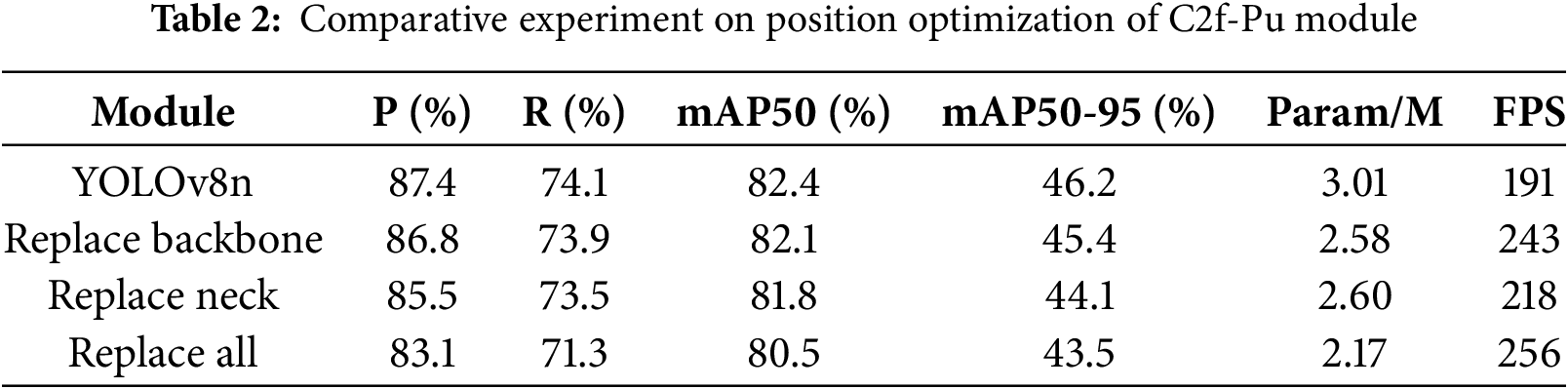

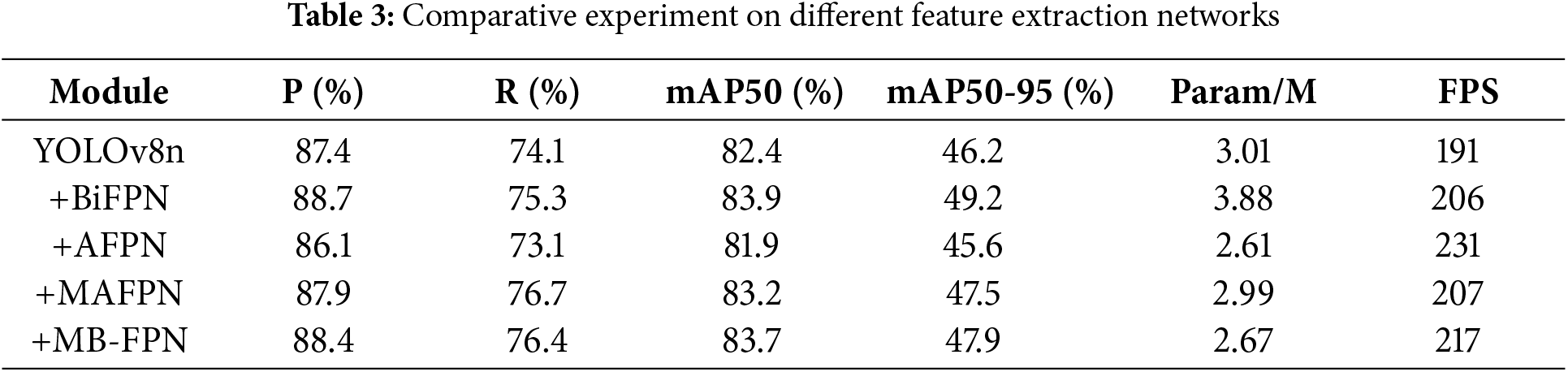

4.3.2 Feature Pyramid Network Comparison Experiment

To validate the detection performance of the MB-FPN network, we conducted comparative experiments with mainstream feature pyramid networks. These include BiFPN [34] (bidirectional feature pyramid network), AFPN [35] (asymptotic feature pyramid network), and MAFPN [36] (multi-branch auxiliary fusion pyramid network). The experimental results are shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, BiFPN employs a weighted feature fusion strategy that effectively integrates features across adjacent layers, achieving the highest detection accuracy. However, this comes at the expense of substantially increased model complexity. In contrast, AFPN utilizes an asymptotic feature fusion approach, which maintains low computational overhead but limits detection performance. MAFPN introduces multi-branch auxiliary fusion, slightly reducing the parameter count compared to the original YOLOv8n while providing noticeable improvements in accuracy and overall performance. Among these approaches, the enhanced MB-FPN stands out by significantly improving detection accuracy, preserving a compact model size, and achieving fast inference speed, making it the most effective overall feature fusion strategy.

4.3.3 Detection Network Comparison Experiment

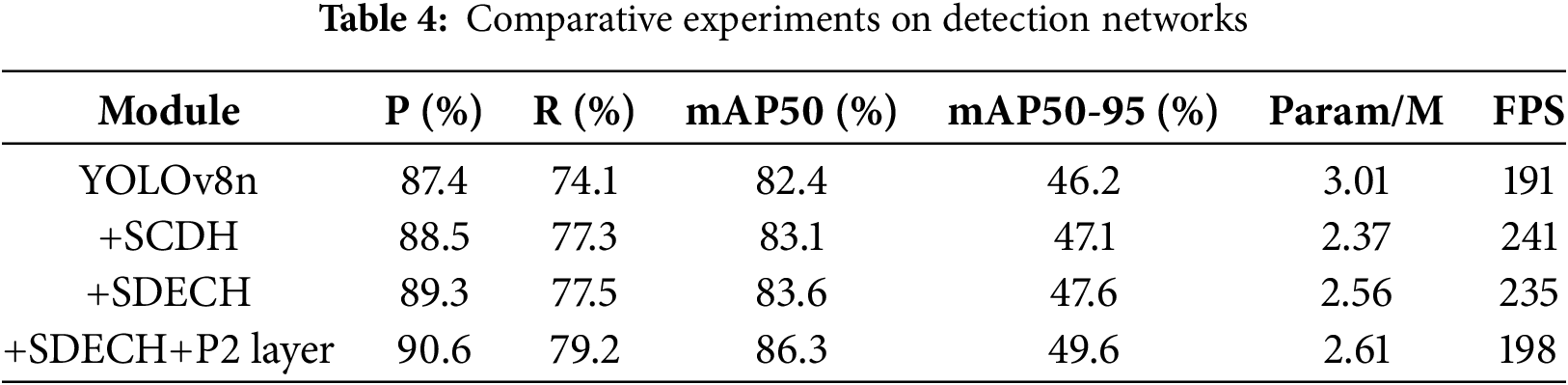

To validate the detection performance of the improved SDECH detection head, we conducted comparative experiments with the original YOLOv8n structure and the shared convolution SCDH detection head [37], and added a small object detection layer to conduct performance comparison analysis. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 presents the ablation study results for the proposed modifications. The incorporation of shared convolutions (SCDH) yielded improvements of 1.1%, 3.2%, and 0.7% in precision (P), recall (R), and mAP50, respectively, while simultaneously enhancing detection speed significantly. The introduction of the enhanced SDECH detection head resulted in a marginal reduction in inference speed; however, the model consistently outperformed the original YOLOv8n across all other metrics, demonstrating that SDECH effectively enhances performance while preserving model efficiency. The subsequent addition of the small object detection layer led to a slight decrease in speed, yet all evaluation metrics exhibited substantial improvements. Even the more stringent metric, mAP50-90, increased by 3.4%, thereby validating the model’s localization capability. The experimental results demonstrate that our proposed SDECH + p2 detection layer significantly improves small object detection performance while maintaining the model’s overall efficiency and feasibility.

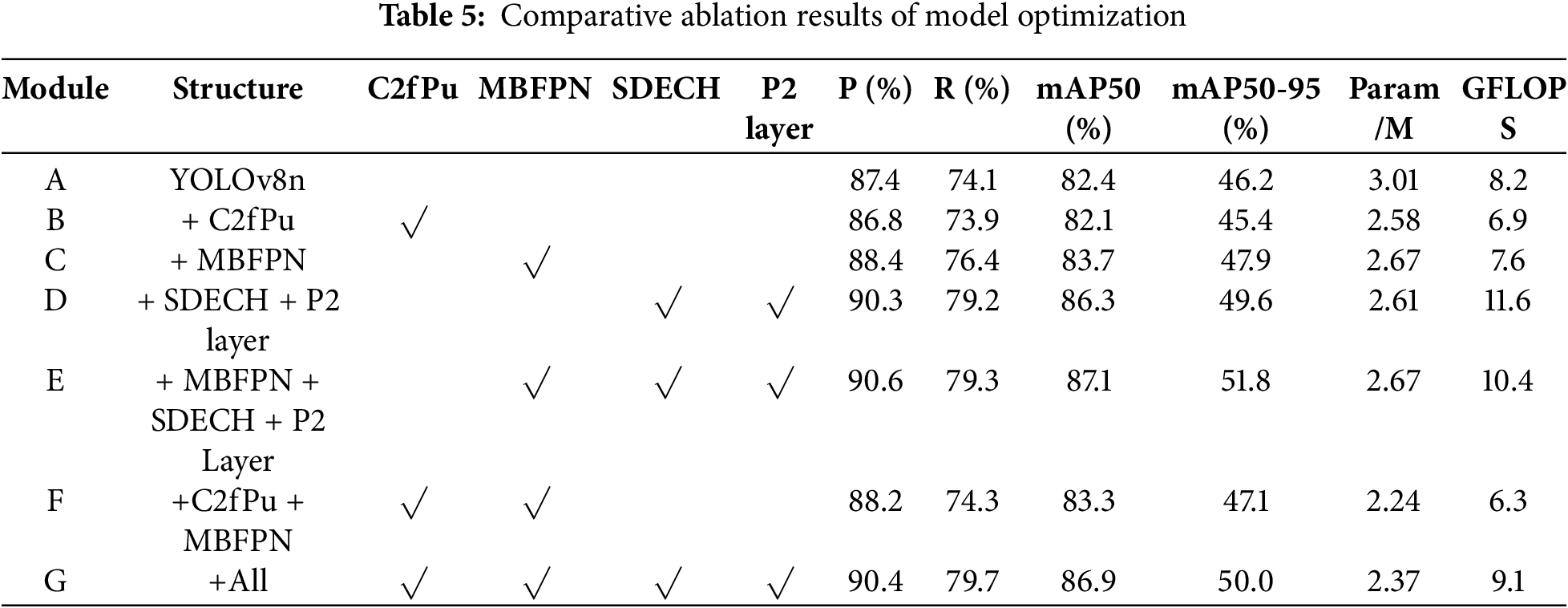

To evaluate the impact of the proposed optimization methods on the performance of the detection model, the experiment used YOLOv8n as the baseline model, added each improvement module in turn, and evaluated the performance on the Det-Fly dataset. The comparison results of the ablation experiment are shown in Table 5, where model A corresponds to the original YOLOv8n baseline model.

Table 5 presents the ablation study results for the improved YOLOv8n variants, illustrating the contributions of each proposed module. Model B replaces the original C2f architecture in the backbone with the C2f-Pu module. Although this modification leads to a slight decrease in detection accuracy (precision, recall, and mAP), it achieves a substantial reduction in both model parameters and computational complexity. This indicates that the C2f-Pu module, by leveraging global feature extraction through pooling, minimizes the impact on accuracy while improving efficiency.

Model C introduces the MB-FPN network architecture, resulting in improvements of 1.0%, 2.3%, and 1.3% in precision, recall, and mAP50, respectively, compared to the baseline. The addition of a weighted feature fusion module further reduces the parameter count, demonstrating its effectiveness in efficient multi-scale feature aggregation.

Model D incorporates a P2 small object detection layer atop the SDECH shared detail enhancement convolutional detection head. This addition effectively boosts detection performance for small objects, with precision, recall, and mAP50 increasing by 2.9%, 5.1%, and 3.9%, respectively. The results indicate that the SDECH head optimizes convolutional feature processing and enhances both inference efficiency and accuracy for fine-grained targets.

Model E combines the improved detection head with the MB-FPN architecture. While the parameter count increases slightly, detection performance is further enhanced, demonstrating the complementary benefits of multi-scale feature fusion and detail-enhanced convolution.

Model F validates the role of the C2f-Pu module within the MB-FPN network, showing that redundant parameters can be removed and model complexity reduced with minimal impact on detection accuracy.

Finally, Model G integrates all proposed improvements. Compared to the YOLOv8n baseline, it achieves gains of 3.0%, 5.6%, and 4.5% in precision, recall, and mAP50, respectively. However, compared to Model E, the mAP50-90 metric decreases by 1.8%, which is attributed to the introduced pooling operations that blur precise object edges and details, thereby reducing localization accuracy. Nevertheless, the incorporation of pooling operations significantly reduces the number of parameters, resulting in a total of only 2.37 million parameters in the refined model. Sacrificing a slight amount of accuracy in exchange for a substantial reduction in parameters is entirely acceptable. The results demonstrate that this optimized architecture enhances detection accuracy while maintaining the model’s lightweight characteristics, making it fully suitable for real-time aerial detection scenarios.

4.3.5 Det-Fly Dataset Comparison Test

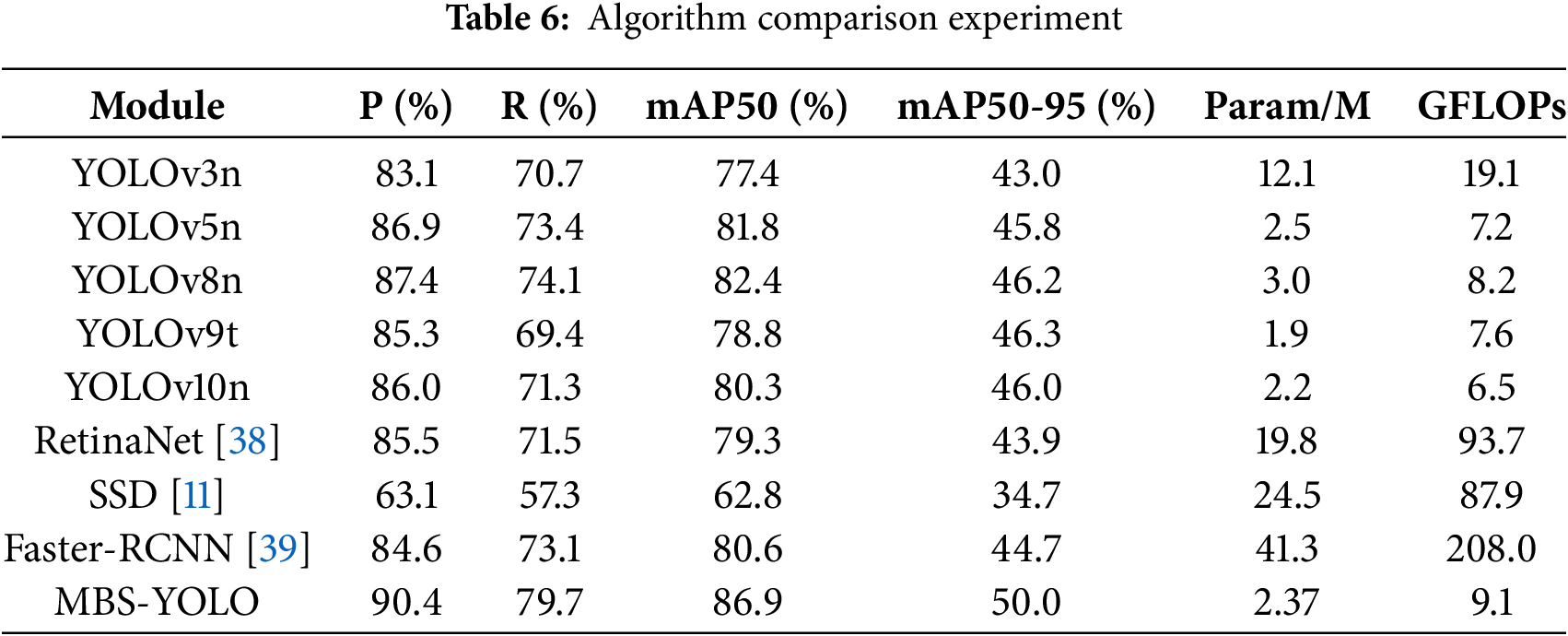

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the improved algorithm in small object detection tasks, we conducted a performance comparison between the proposed MBS-YOLOv8 model and existing mainstream object detection algorithms, including SSD, RetinaNet, Faster RCNN, and other YOLO series algorithms. The experiments were conducted based on the Det-Fly benchmark dataset to validate the model. The quantitative evaluation results of the model performance are shown in Table 6.

As shown in Table 6, the baseline YOLOv8n not only surpasses other YOLO series models but also outperforms a range of mainstream object detection frameworks. The enhanced MBS-YOLOv8 achieves substantial improvements across all evaluation metrics, attaining leading scores in precision (P), recall (R), and mean average precision (mAP). It achieves the highest overall detection accuracy among the compared models, reaching 86.9%. These results demonstrate that the proposed optimizations effectively improve both detection accuracy and model efficiency.

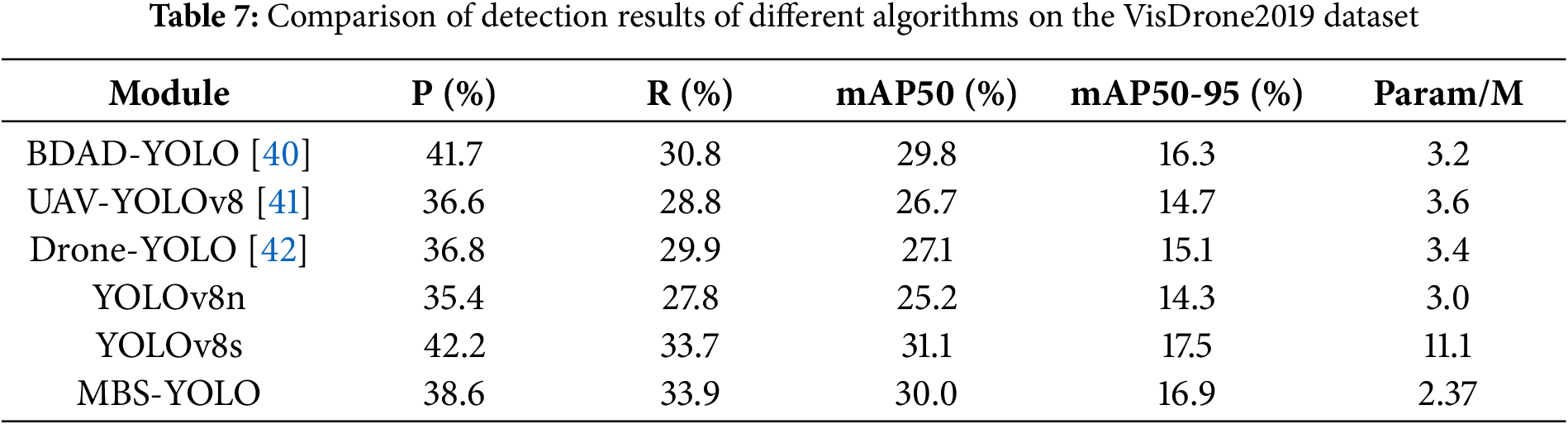

4.3.6 VisDrone2019 Dataset Generalization Experiment

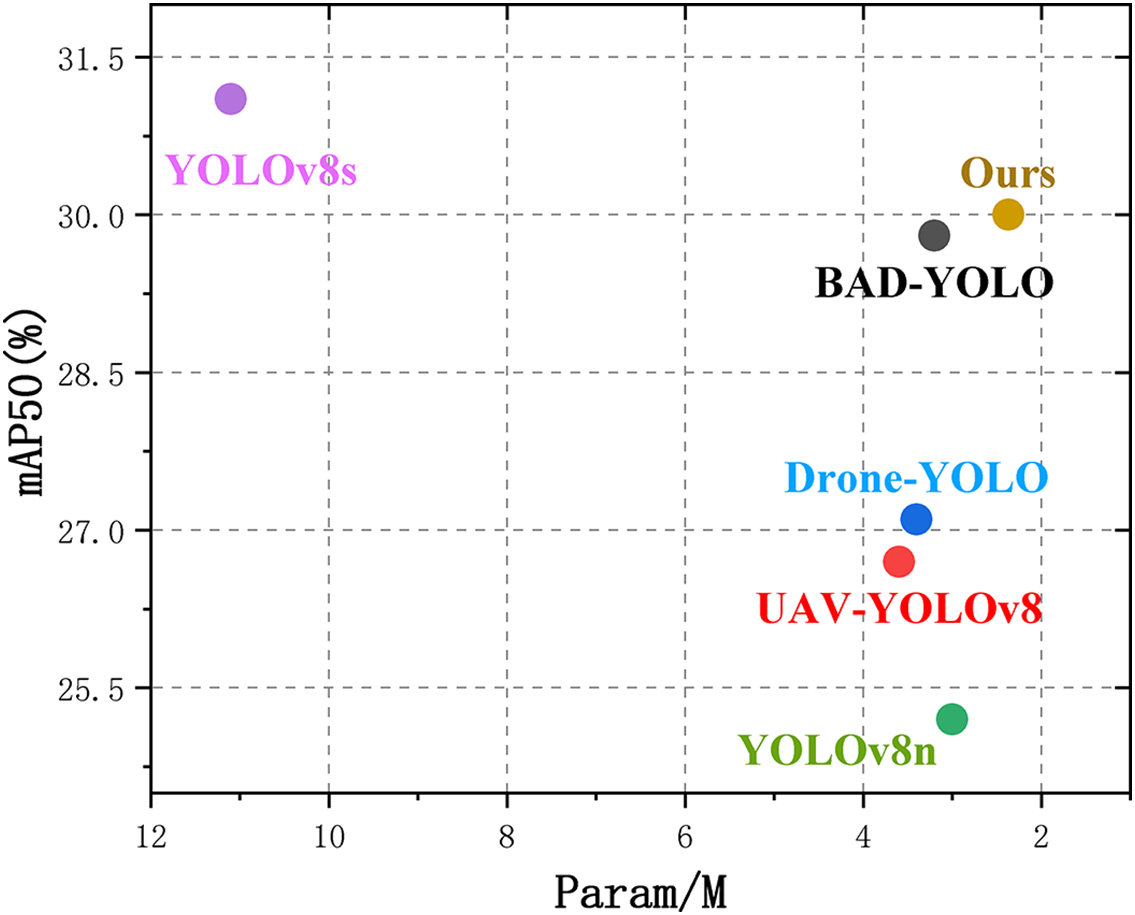

Table 7 and Fig. 7 show that the proposed MBS-YOLO model outperforms recent YOLO-based enhanced models on the VisDrone2019 dataset. The model achieves a precision (P) of 38.6%, recall (R) of 33.9%, mAP50 of 30.0%, and mAP50-90 of 16.9%. Although the mAP50 is 1.1% lower than that of YOLOv8s, the mAP50-90 decreases by only 0.6%, indicating that our model maintains excellent performance under more stringent localization requirements. In addition, the parameter count is reduced by 8.73 million compared to YOLOv8s. Generalization experiments further confirm that MBS-YOLO preserves exceptional generalization capabilities while delivering robust detection performance in complex scenarios.

Figure 7: Algorithm superiority comparison diagram

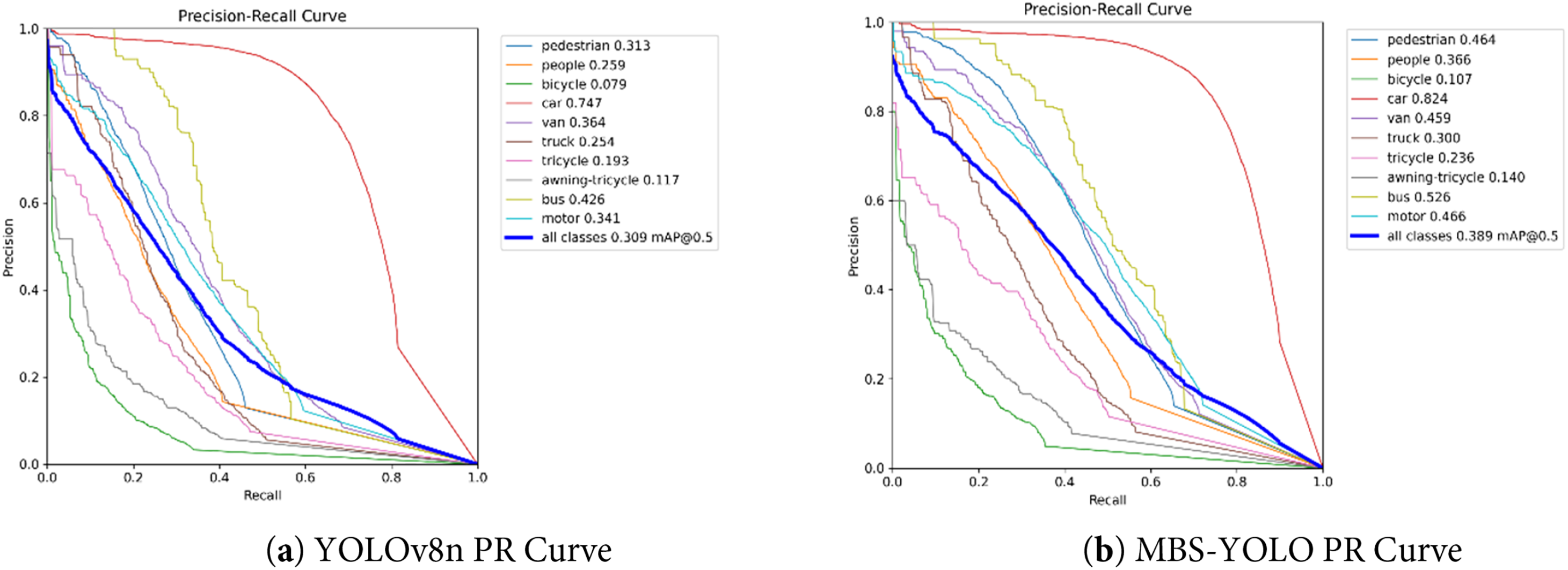

A comparative analysis of detection performance across different object categories was conducted between the proposed MBS-YOLO and the baseline YOLOv8n model, with the results presented in Fig. 8. Fig. 8a shows the detection accuracy curve for YOLOv8n, while Fig. 8b depicts the corresponding results for MBS-YOLO. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed MBS-YOLO achieves substantial improvements in small object detection, particularly under complex scene conditions. Specifically, the mAP50 for pedestrian detection reaches 46.4%, representing a notable increase over the baseline. Furthermore, the average mAP50 across all object categories rises to 38.9%, further validating the effectiveness of the proposed method in enhancing both generalization capability and overall detection performance.

Figure 8: Comparison of detection effects for different recognition targets

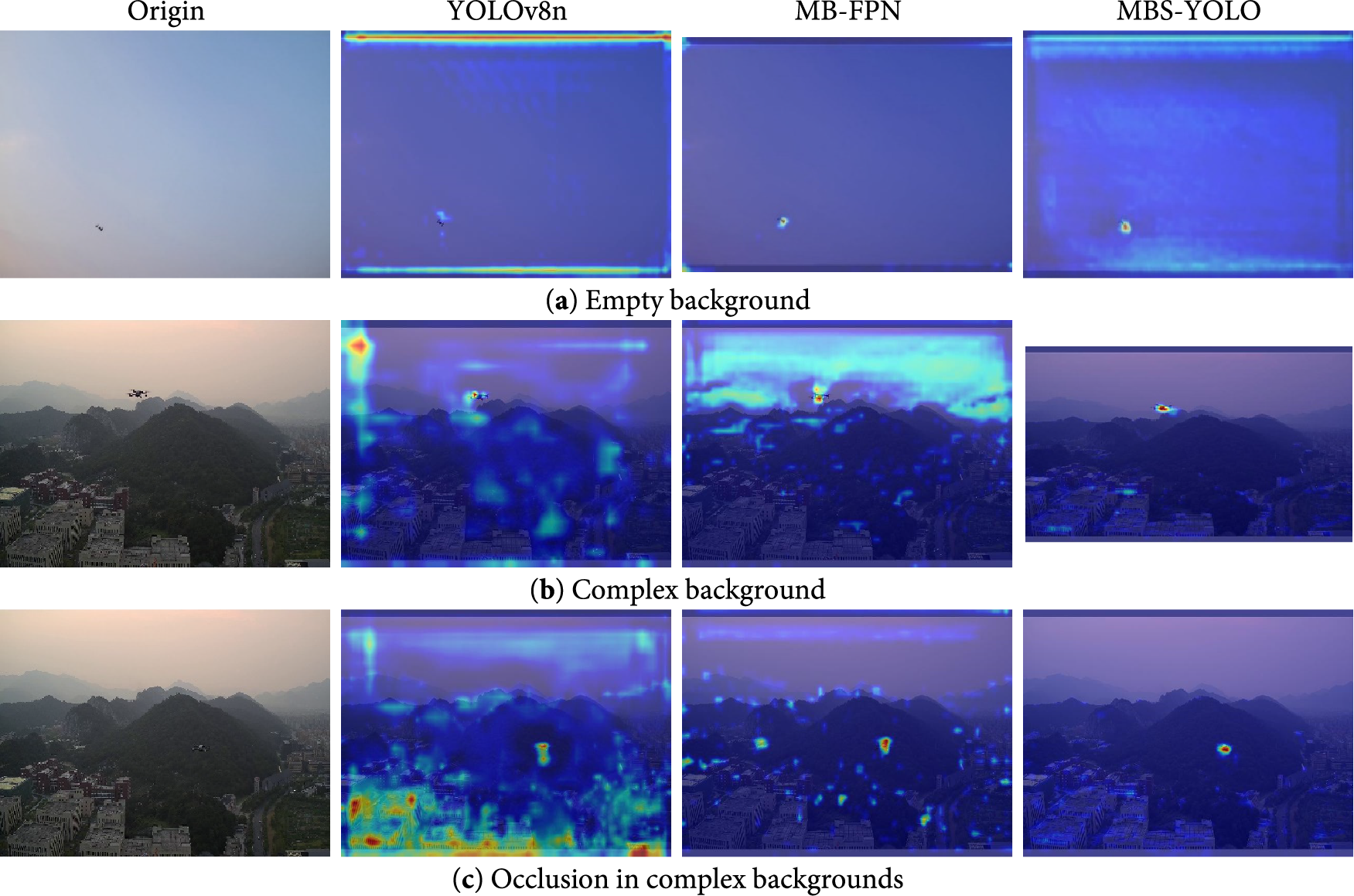

4.4.1 Comparison of Heat Map Detection Results

Fig. 9 presents the heatmap visualization results, demonstrating the improvements of MB-FPN and MBS-YOLO over the original YOLOv8n. Across all three scenarios, the baseline model’s heatmaps exhibit notable local activation deficiencies, indicating that the traditional FPN network struggles to fully capture fine-grained target features. In contrast, the MB-FPN network employs dynamic weighting to fuse multi-branch, cross-level features, effectively integrating high-resolution details from shallow layers with semantic information from deeper layers. As shown in Fig. 9a, in an open background, this mechanism significantly enhances the heat intensity response for small targets. In more complex scenes (Fig. 9b,c), dynamic weighting effectively suppresses background noise while increasing the contrast between target regions and the background. Building upon the MB-FPN architecture, the improved MBS-YOLO further refines the detection head to concentrate the heatmap on target regions while mitigating the effects of strong scattering interference, as illustrated in the last column of Fig. 9. These comparative visualizations confirm the effectiveness of the multi-branch, cross-level fusion strategy in enhancing small object detection performance.

Figure 9: Detection heatmap comparison

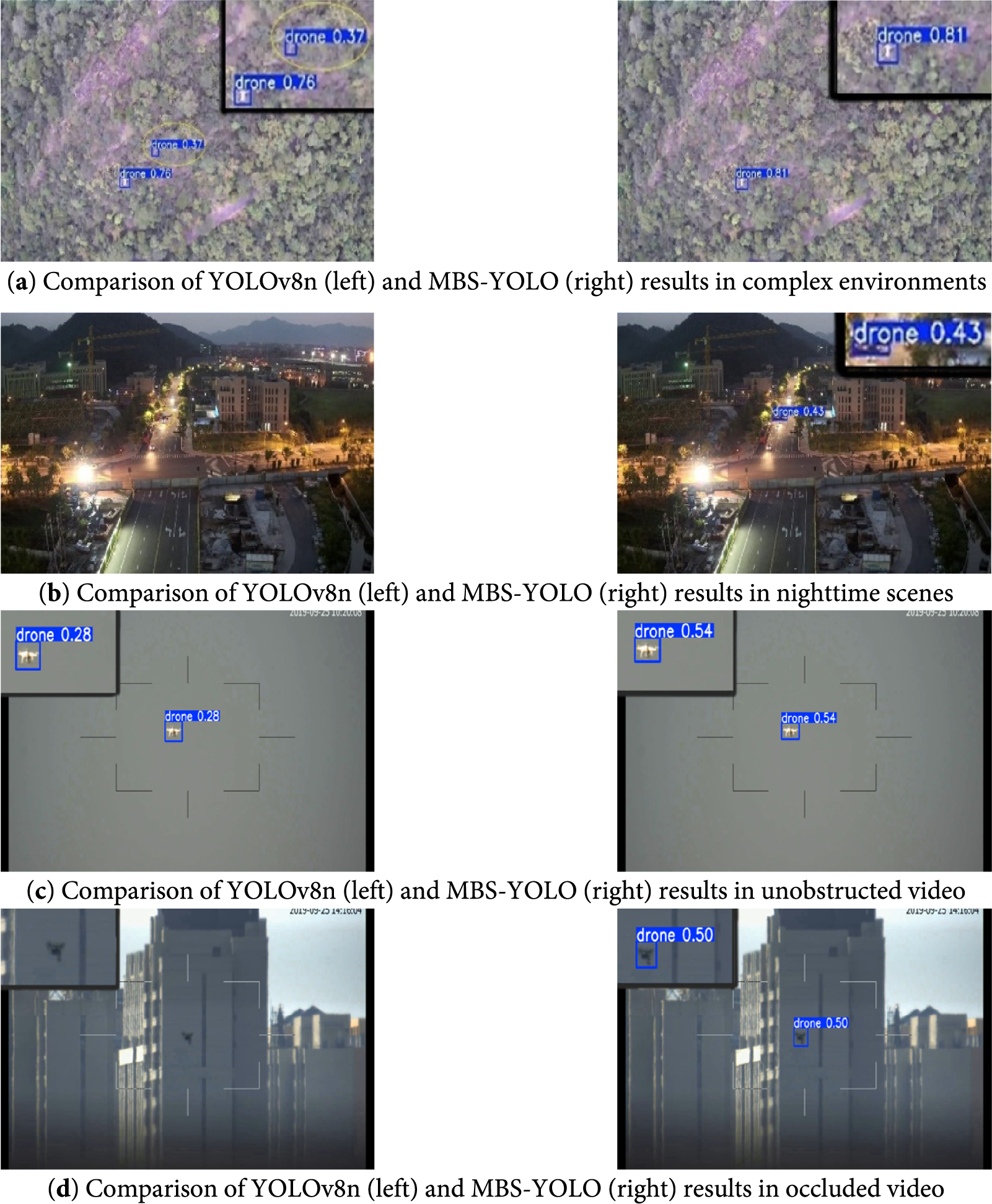

4.4.2 Actual Detection Results

Fig. 10a illustrates that in complex scenes, the baseline YOLOv8n model experiences reduced detection performance, exhibiting missed detections and false positives that lead to suboptimal results. In contrast, MBS-YOLO achieves more accurate detection of small objects under the same conditions, highlighting its enhanced detection capability and robustness. Fig. 10b further demonstrates that under low-light conditions with reduced contrast, MBS-YOLO can reliably identify targets, outperforming YOLOv8n in dark or nighttime environments. Fig. 10c,d provides a comparative analysis of drone video detection performance under both unobstructed and occluded scenarios within the Anti-UAV Tracking dataset. Experimental results show that the proposed algorithm achieves substantially higher detection confidence than the baseline method, while effectively avoiding missed detections even in heavily occluded conditions. These findings validate the practicality and robustness of the optimized algorithm in real-world applications.

Figure 10: Comparison of actual monitoring effects before and after improvements in different scenarios

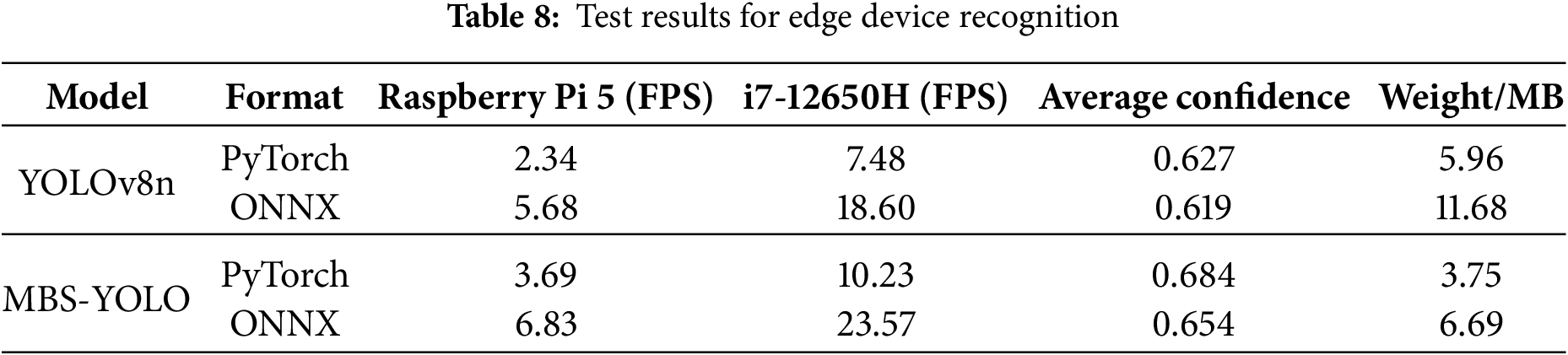

4.4.3 Actual Detection Results

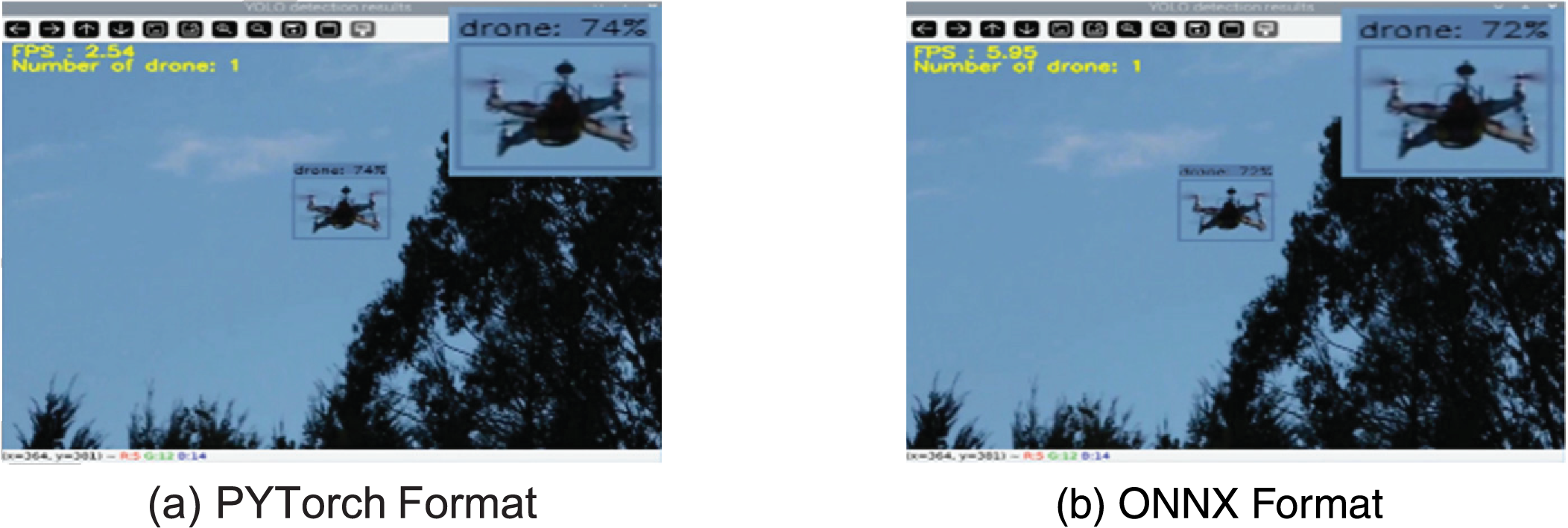

To validate the real-time performance of the MBS-YOLO model on low-computing-power edge devices, this study selected the Raspberry Pi 5 (equipped with a quad-core ARM Cortex-A76 processor running at 2.4 GHz) as a typical edge deployment platform, using a counter-drone tracking video segment as the detection target. No external acceleration devices were used during inference testing to fully reflect its performance under strictly constrained conditions. Experimental data are shown in Table 8.

As shown in Table 8, MBS-YOLO achieves the best overall performance in ONNX format. With an inference speed of 23.57 FPS on a PC platform (Intel Core i7-12650H processor) and a model size of only 6.69 MB, it demonstrates the advantages of its lightweight design and exhibits significantly higher computational efficiency compared to YOLOv8n. Combined with the results in Fig. 11, although conversion from PyTorch to ONNX format causes a slight decrease in detection confidence, it substantially increases the frame rate. This approach enhances performance without relying on external hardware acceleration, making it more practical for real-world deployment. Future implementations may integrate GPU acceleration solutions [43], leveraging their parallel computing capabilities to further improve inference speed and detection efficiency.

Figure 11: Confidence comparison of YOLOv8n formats on raspberry Pi 5

This study examines the limitations of conventional drone detection methods. Conventional methods primarily include radar detection, radio frequency (RF) detection, and acoustic detection. However, each approach has inherent limitations. Radar detection can be affected by a drone’s shape, material, and flight speed, resulting in blind spots. RF monitoring struggles to detect drones operating in radio-silent mode. Acoustic detection is highly susceptible to environmental noise, performing poorly for micro or silent drones. In contrast, deep learning-based methods, particularly the YOLO series of object detection algorithms, provide a flexible and scalable solution for low-altitude UAV surveillance. These methods offer advantages such as high detection accuracy, efficient inference, and strong adaptability to varying operational conditions.

A comprehensive evaluation of multiple models, including YOLOv3n, YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, RetinaNet, SSD, and Faster R-CNN, identified YOLOv8n as the top-performing model, achieving a precision of 87.4%, a recall of 74.1%, and an mAP50 of 82.4%. With only 3.0 million parameters and a computational cost of 8.2 GFLOPs, the model demonstrates an excellent balance between efficiency and accuracy.

To address the challenge of detecting unauthorized drones in low-altitude urban environments, we propose MBS-YOLO, a model based on the YOLOv8 framework. By integrating a lightweight C2f-Pu module, a multi-branch weighted feature fusion network (MB-FPN), and a shared detail-enhancement convolutional detection head (SDECH), the model significantly improves detection performance for small-scale targets.

In subsequent edge deployment experiments, the MBS-YOLO model was evaluated and compared with the baseline YOLOv8n on both the Raspberry Pi 5 platform and a PC platform. The Raspberry Pi 5 served as a lightweight edge computing device, forming the experimental setup alongside the PC. On the PC, using CPU-only inference in the Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) format, the model achieved an inference speed of 23.57 FPS. These results indicate that, despite the limited computational capacity of the edge platform, the model maintains the essential capability to support real-time UAV monitoring in low-altitude security scenarios. With GPU-accelerated hardware, such as the Jetson Orin Nano, detection speed is expected to improve further, more effectively meeting the requirements for real-time processing in complex environments.

However, under challenging environmental conditions, such as heavy rain or dense fog, detection performance remains limited. These conditions often cause image degradation, feature blurring, and increased noise interference. Consequently, the model’s perceptual capabilities are significantly impaired. Future research should prioritize adaptive learning and data augmentation strategies specifically designed for harsh weather conditions, thereby enhancing the model’s feature discrimination in rainy and foggy scenarios. Additionally, integrating complementary sensor data, such as infrared or radar inputs, could mitigate the limitations of visible-light imagery, ultimately improving the model’s performance in real-world applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants whose scholarly contributions and diligent efforts significantly enhanced this research, as well as the assistance of artificial intelligence tools, which were employed for language refinement and formatting support.

Funding Statement: This research is partially supported by the Key R&D Program of Xianyang City, Shaanxi Province (L2024-ZDYF-ZDYF-GY-0043).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Minghui Li; experimental design, data analysis, supplementary experiments, and manuscript revision: Hongbo Li; draft manuscript preparation: Hongbo Li, Jiaqi Zhu; data collection: Xupeng Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All publicly available datasets are used in the study. Code availability: https://github.com/oniusr/MBS-YOLO.git (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chamola V, Kotesh P, Agarwal A, Naren, Gupta N, Guizani M. A comprehensive review of unmanned aerial vehicle attacks and neutralization techniques. Ad Hoc Netw. 2021;111(3):102324. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2020.102324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Lykou G, Moustakas D, Gritzalis D. Defending airports from UAS: a survey on cyber-attacks and counter-drone sensing technologies. Sensors. 2020;20(12):3537. doi:10.3390/s20123537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Park S, Kim HT, Lee S, Joo H, Kim H. Survey on anti-drone systems: components, designs, and challenges. IEEE Access. 2021;9:42635–59. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3065926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. p. 580–7. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2014.81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Girshick R. Fast R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. p. 1440–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cai Z, Vasconcelos N. Cascade R-CNN: delving into high quality object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 2018. p. 6154–62. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2018.00644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. He J, Liu M, Yu C. UAV reaction detection based on multi-scale feature fusion. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML); 2022 Oct 28–30; Xi’an, China. p. 640–3. doi:10.1109/ICICML57342.2022.10009808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang H, Chang H, Ma B, Wang N, Chen X. Dynamic R-CNN: towards high quality object detection via dynamic training. In: Vedaldi A, Bischof H, Brox T, Frahm JM, editors. Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 260–75. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58555-6_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li C, Li L, Jiang H, Weng K, Geng Y, Li L, et al. YOLOv6: a single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv.2209.02976. 2022. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Qiu J. YOLOv8: a state-of-the-art object detection model. arXiv.2403.14457. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2403.14457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang H, Chang H, Ma B, Shan S, Chen X. Cascade RetinaNet: maintaining consistency for single-stage object detection. arXiv.1907.06881. 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1907.06881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shi D. Transnext: robust foveal visual perception for vision transformers. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 17773–83. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yu W, Luo M, Zhou P, Si C, Zhou Y, Wang X, et al. MetaFormer is actually what you need for vision. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 10809–19. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bo C, Wei Y, Wang X, Shi Z, Xiao Y. Vision-based anti-UAV detection based on YOLOv7-GS in complex backgrounds. Drones. 2024;8(7):331. doi:10.3390/drones8070331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu K, Chen Y, Lu Y, Yang Z, Yuan J, Zheng E. SOD-YOLO: a high-precision detection of small targets on high-voltage transmission lines. Electronics. 2024;13(7):1371. doi:10.3390/electronics13071371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qu X, Zheng Y, Zhou Y, Su Z. YOLO v8_CAT: enhancing small object detection in traffic light recognition with combined attention mechanism. In: Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC); 2024 Dec 13–16; Chengdu, China. p. 706–10. doi:10.1109/ICCC62609.2024.10941967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jiang P, Yang X, Wan Y, Zeng T, Nie M, Liu Z. DRBD-YOLOv8: a lightweight and efficient anti-UAV detection model. Sensors. 2024;24(22):7148. doi:10.3390/s24227148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Liu M, Chen Y, Xie J, He L, Zhang Y. LF-YOLO: a lighter and faster YOLO for weld defect detection of X-ray image. IEEE Sens J. 2023;23(7):7430–9. doi:10.1109/jsen.2023.3247006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang R, Liu M, Li Z. Research on fast detection method of infrared small targets under resource-constrained conditions. J Infrared Millim Waves. 2024;43(4):582–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.11972/j.issn.1001-9014.2024.04.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yasmine G, Maha G, Hicham M. Anti-drone systems: an attention based improved YOLOv7 model for a real-time detection and identification of multi-airborne target. Intell Syst Appl. 2023;20(2):200296. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2023.200296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wen S, Li L, Ren W. A lightweight and effective YOLO model for infrared small object detection. Int J Patt Recogn Artif Intell. 2025;39(8):2551009. doi:10.1142/s0218001425510097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang G, Peng Y, Li J. YOLO-MARS: an enhanced YOLOv8n for small object detection in UAV aerial imagery. Sensors. 2025;25(8):2534. doi:10.3390/s25082534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Bakirci M. Enhancing vehicle detection in intelligent transportation systems via autonomous UAV platform and YOLOv8 integration. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164(5):112015. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Sun S. Small target detection algorithm based on context and feature interaction. Sci Technol Innov. 2024;22:10–12,18. doi:10.15913/j.cnki.kjycx.2024.22.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gao RZ, Li SN, Li XH. Research on pedestrian and vehicle detection algorithms in robot vision. Mach Des Manuf. 2023(10):277–80. doi:10.19356/j.cnki.1001-3997.2023.10.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang CY, Mark Liao HY, Wu YH, Chen PY, Hsieh JW, Yeh IH. CSPNet: a new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2020 Jun 14–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1571–80. doi:10.1109/CVPRW50498.2020.00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bi Z, Jing L, Sun C, Shan M. YOLOX++ for transmission line abnormal target detection. IEEE Access. 2023;11:38157–67. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3268106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lyu Y, Vosselman G, Xia GS, Yang MY. Bidirectional multi-scale attention networks for semantic segmentation of oblique UAV imagery. ISPRS Ann Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci. 2021;V-2-2021:75–82. doi:10.5194/isprs-annals-v-2-2021-75-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhu L, Lee F, Cai J, Yu H, Chen Q. An improved feature pyramid network for object detection. Neurocomputing. 2022;483(2):127–39. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.02.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gao F, Jin X, Zhou X, Dong J, Du Q. MSFMamba: multiscale feature fusion state space model for multisource remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63:5504116. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2025.3535622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chen Z, He Z, Lu ZM. DEA-net: single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2024;33(1):1002–15. doi:10.1109/TIP.2024.3354108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Chen J, Mai H, Luo L, Chen X, Wu K. Effective feature fusion network in BIFPN for small object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2021 Sep 19–22; Anchorage, AK, USA. p. 699–703. doi:10.1109/ICIP42928.2021.9506347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yang G, Lei J, Zhu Z, Cheng S, Feng Z, Liang R. AFPN: asymptotic feature pyramid network for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC); 2023 Oct 1–4; Honolulu, Oahu, HI, USA. p. 2184–9. doi:10.1109/SMC53992.2023.10394415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang Z, Guan Q, Zhao K, Yang J, Xu X, Long H, et al. Multi-branch auxiliary fusion YOLO with re-parameterization heterogeneous convolutional for accurate object detection. In: Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision; 2024 Oct 18–20; Urumqi, China. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. p. 492–505. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-8858-3_34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yan JH, Ran TX. Lightweight UAV image target detection algorithm based on YOLOv8. J Graph. 2024;45(6):1328–37. doi:10.11996/JG.j.2095-302X.2024061328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollar P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(2):318–27. doi:10.1109/tpami.2018.2858826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Sun JY, Xu MJ, Zhang JP, Yan MX, Cao W, Hou AL. Optimized and improved YOLOv8 target detection algorithm from UAV perspective. Comput Eng Appl. 2025;61(1):109–20. doi:10.3778/j.issn.1002-8331.2405-0030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang G, Chen Y, An P, Hong H, Hu J, Huang T. UAV-YOLOv8: a small-object-detection model based on improved YOLOv8 for UAV aerial photography scenarios. Sensors. 2023;23(16):7190. doi:10.3390/s23167190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang Z. Drone-YOLO: an efficient neural network method for target detection in drone images. Drones. 2023;7(8):526. doi:10.3390/drones7080526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Song Z, Ban S, Hu D, Xu M, Yuan T, Zheng X, et al. A lightweight YOLO model for rice panicle detection in fields based on UAV aerial images. Drones. 2025;9(1):1. doi:10.3390/drones9010001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools